ヌエバ・エスパーニャ副王領

New Spain, Virreinato de Nueva España,

Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl

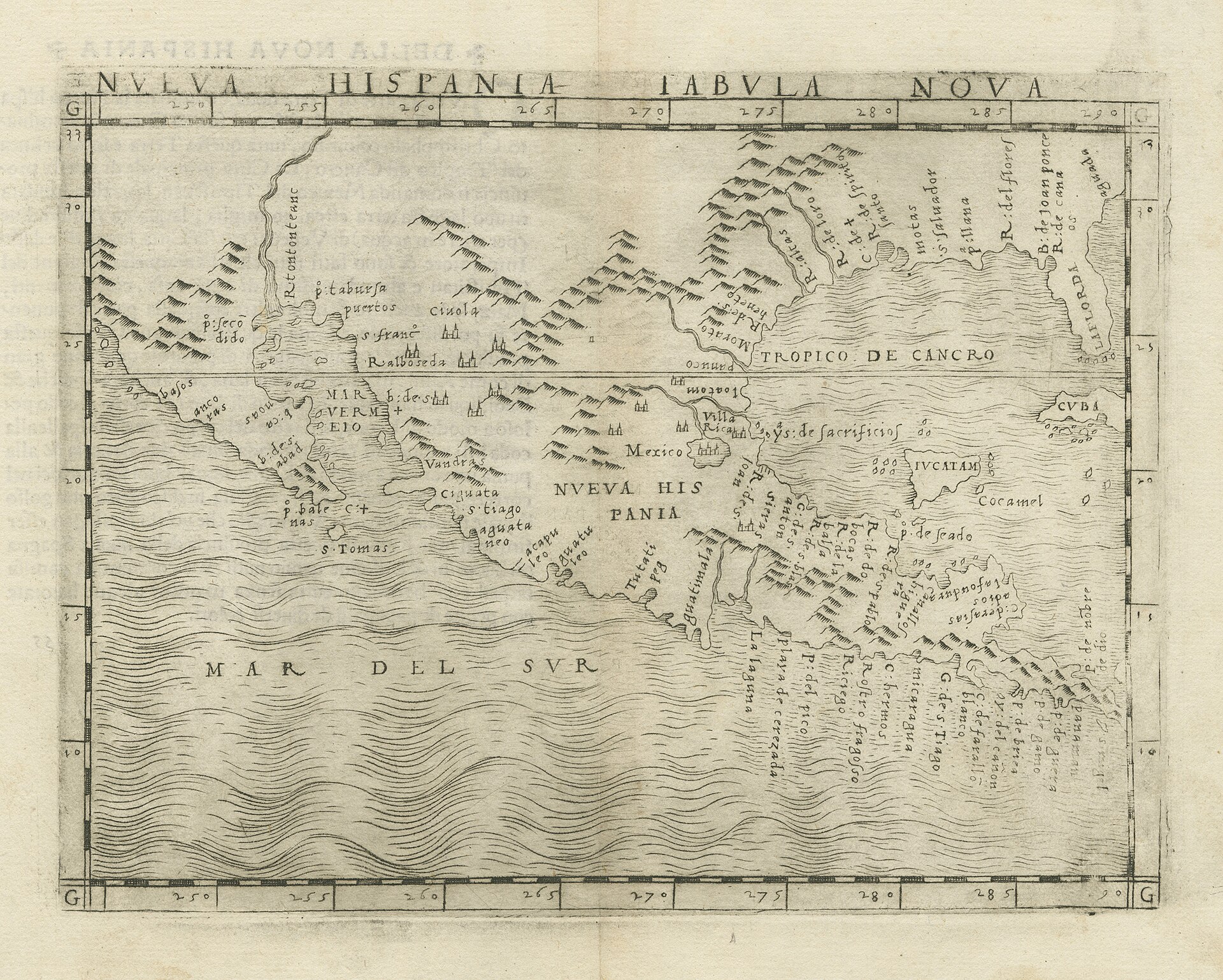

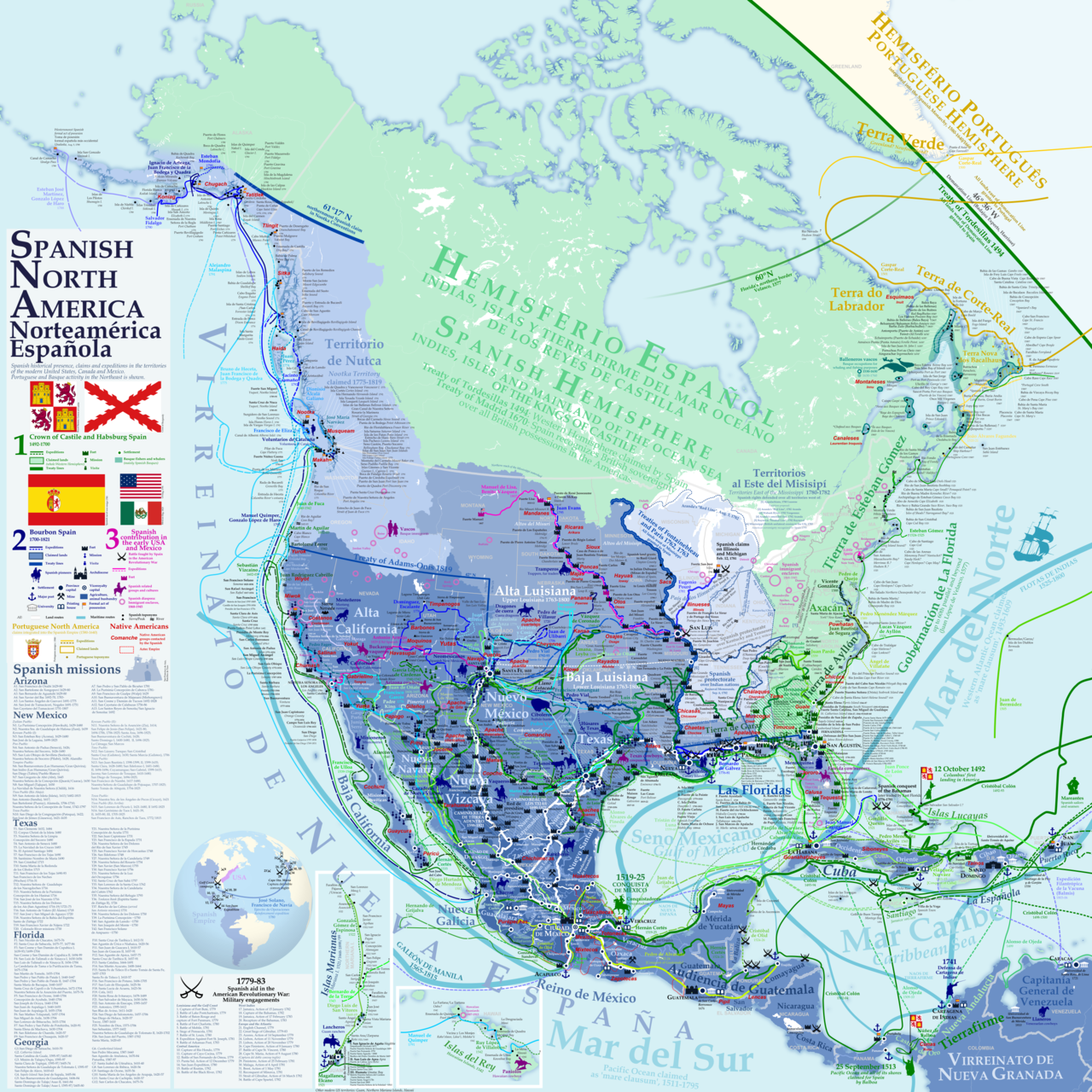

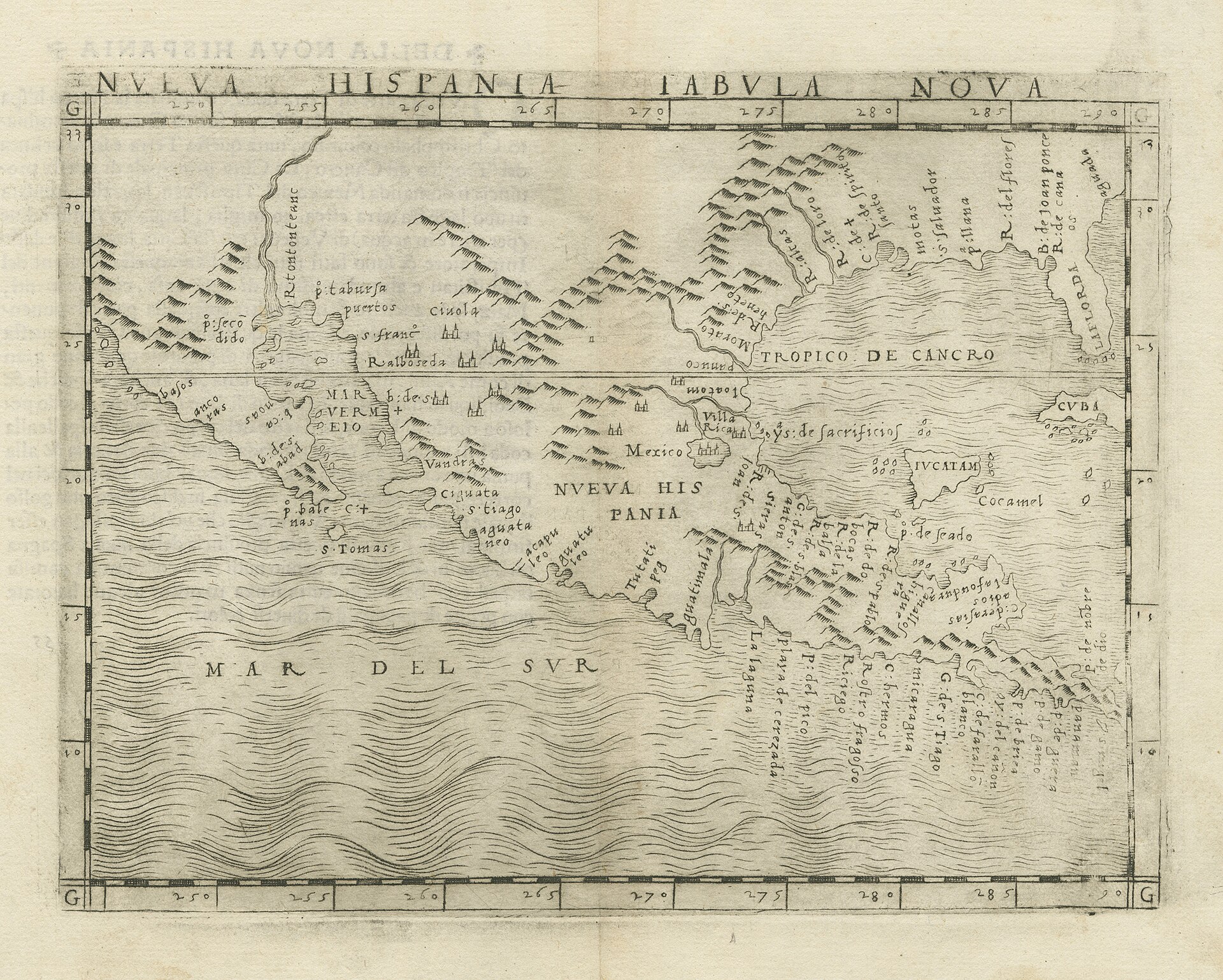

Giacomo Gastaldi's 1548 map of New Spain, Nueva Hispania Tabula Nova

☆ヌエバ・エスパーニャ(正式名称:ヌエバ・エスパーニャ副王領、スペイン語: Virreinato de Nueva España [birejˈnato ðe ˈnweβa esˈpaɲa] ⓘ、ナワトル語: Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl)は、もともとはヌエバ・エスパーニャ王国であり、ハプスブルク家スペインによって設立されたスペイン帝国の不可分の領土であった。 スペインによるアメリカ大陸征服の過程で確立された複数の領土のひとつであり、首都はメキシコシティに置かれた。その管轄区域は、主にメキシコと南西部の アメリカ合衆国となった地域を中心に、北米の南部と西部の広大な地域から構成されていたが、カリフォルニア、フロリダ、ルイジアナも含まれていた。また、 メキシコ、イスパニョーラ島やマルティニーク島のようなカリブ海地域、さらにはコロンビアのような南米北部、フィリピンやグアムを含む太平洋諸島も含まれ ていた。アジアの植民地には、台湾の「スペイン領台湾」も含まれていた。

| New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain (Spanish:

Virreinato de Nueva España [birejˈnato ðe ˈnweβa esˈpaɲa] ⓘ; Nahuatl:

Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl),[4] originally the Kingdom of New Spain,

was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established

by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several domains established during the

Spanish conquest of the Americas, and had its capital in Mexico City.

Its jurisdiction comprised a large area of the southern and western

portions of North America, mainly what became Mexico and the

Southwestern United States, but also California, Florida and Louisiana;

Central America as Mexico, the Caribbean like Hispaniola and Martinica,

and northern parts of South America, even Colombia; several Pacific

archipelagos, including the Philippines and Guam. Additional Asian

colonies included "Spanish Formosa", on the island of Taiwan. After the 1521 Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, conqueror Hernán Cortés named the territory New Spain, and established the new capital, Mexico City, on the site of Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec Empire. Central Mexico became the base of expeditions of exploration and conquest, expanding the territory claimed by the Spanish Empire. With the political and economic importance of the conquest, the crown asserted direct control over the densely populated realm. The crown established New Spain as a viceroyalty in 1535, appointing as viceroy Antonio de Mendoza, an aristocrat loyal to the monarch rather than the conqueror Cortés. New Spain was the first of the viceroyalties that Spain created, the second being Peru in 1542, following the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire. Both New Spain and Peru had dense indigenous populations at conquest as a source of labor and material wealth in the form of vast silver deposits, discovered and exploited beginning in the mid-1500s. New Spain developed strong regional divisions based on local climate, topography, distance from the capital and the Gulf Coast port of Veracruz, size and complexity of indigenous populations, and the presence or absence of mineral resources. Central and southern Mexico had dense indigenous populations, each with complex social, political, and economic organization, but no large-scale deposits of silver to draw Spanish settlers. By contrast, the northern area of Mexico was arid and mountainous, a region of nomadic and semi-nomadic indigenous populations, which do not easily support human settlement. In the 1540s, the discovery of silver in Zacatecas attracted Spanish mining entrepreneurs and workers, to exploit the mines, as well as crown officials to ensure the crown received its share of revenue. Silver mining became integral not only to the development of New Spain, but also to the enrichment of the Spanish crown, which marked a transformation in the global economy. New Spain's port of Acapulco became the New World terminus of the transpacific trade with the Philippines via the Manila galleon. New Spain became a vital link between Spain's New World empire and its East Indies empire. From the beginning of the 19th century, the kingdom fell into crisis, aggravated by the 1808 Napoleonic invasion of Iberia and the forced abdication of the Bourbon monarch, Charles IV. This resulted in a political crisis in New Spain and much of the Spanish Empire in 1808, which ended with the government of Viceroy José de Iturrigaray. Conspiracies of American-born Spaniards sought to take power, leading to the Mexican War of Independence, 1810–1821. At its conclusion in 1821, the viceroyalty was dissolved and the Mexican Empire was established. Former royalist military officer turned insurgent for independence Agustín de Iturbide would be crowned as emperor. |

ヌエバ・エスパーニャ(正式名称:

ヌエバ・エスパーニャ副王領、スペイン語: Virreinato de Nueva España [birejˈnato ðe ˈnweβa

esˈpaɲa] ⓘ、ナワトル語: Yankwik Kaxtillan

Birreiyotl)は、もともとはヌエバ・エスパーニャ王国であり、ハプスブルク家スペインによって設立されたスペイン帝国の不可分の領土であった。

スペインによるアメリカ大陸征服の過程で確立された複数の領土のひとつであり、首都はメキシコシティに置かれた。その管轄区域は、主にメキシコと南西部の

アメリカ合衆国となった地域を中心に、北米の南部と西部の広大な地域から構成されていたが、カリフォルニア、フロリダ、ルイジアナも含まれていた。また、

メキシコ、イスパニョーラ島やマルティニーク島のようなカリブ海地域、さらにはコロンビアのような南米北部、フィリピンやグアムを含む太平洋諸島も含まれ

ていた。アジアの植民地には、台湾の「スペイン領台湾」も含まれていた。 1521年のスペインによるアステカ帝国征服の後、征服者であるエルナン・コルテスは、その領土を「ヌエバ・エスパーニャ(新スペイン)」と名付け、アス テカ帝国の首都テノチティトランの跡地に、新首都メキシコシティを建設した。メキシコ中央部は、スペイン帝国の領土を拡大するための探検と征服の拠点と なった。征服の政治的・経済的重要性に伴い、スペイン王は人口の密集した地域を直接統治下に置いた。スペイン王は1535年にヌエバ・エスパーニャを副王 領に定め、征服者コルテスではなく王に忠誠を誓う貴族のアントニオ・デ・メンドーサを副王に任命した。ヌエバ・エスパーニャはスペインが最初に作った副王 領であり、2番目はインカ帝国を征服した後の1542年に作られたペルーである。ヌエバ・エスパーニャとペルーの両地域は、征服当時、広大な銀鉱床が発見 され、1500年代半ばから採掘が開始された労働力と物質的富の源として、先住民が密集していた。 ヌエバ・エスパーニャは、気候、地形、首都およびベラクルス湾岸の港からの距離、先住民の人口規模と複雑さ、鉱物資源の有無などに基づいて、地域ごとの強 い区分が形成された。メキシコ中央部および南部には、それぞれ複雑な社会、政治、経済組織を持つ先住民の人口密集地があったが、スペイン人入植者を惹きつ けるような大規模な銀鉱床は存在しなかった。それに対し、メキシコ北部は乾燥した山岳地帯であり、遊牧民や半遊牧民の原住民が住む地域であったため、簡単 に人間が定住できるような場所ではなかった。1540年代、サカテカスで銀が発見されたことにより、スペインの鉱山事業家や労働者が鉱山開発に集まり、ま た、王冠が収益の一部を受け取れるよう王宮の役人も集まった。銀鉱山は、ヌエバ・エスパーニャの発展だけでなく、スペイン王家の富の増大にも不可欠なもの となり、世界経済の変革をもたらした。ヌエバ・エスパーニャの港町アカプルコは、マニラ・ガレオン船によるフィリピンとの太平洋貿易の終着点となった。ヌ エバ・エスパーニャは、スペインのニューワールド帝国と東インド帝国を結ぶ重要なリンクとなった。 19世紀の初頭から、王国は危機に陥り、1808年のナポレオンのイベリア半島侵攻とブルボン朝君主カルロス4世の退位強要により、事態はさらに悪化し た。これにより、1808年にはヌエバ・エスパーニャとスペイン帝国の大部分で政治危機が発生し、ホセ・デ・イトゥリガライ副王の統治で幕を閉じた。アメ リカ生まれのスペイン人による陰謀が権力を握ろうとし、1810年から1821年にかけてのメキシコ独立戦争へとつながった。1821年の終結により、副 王領は廃止され、メキシコ帝国が樹立された。元王党派の軍人であり、独立派に寝返ったアグスティン・デ・イトゥルビデが皇帝として即位した。 |

| The Crown and the Viceroyalty of New Spain The Kingdom of New Spain was established on 18 August 1521, following the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, as a New World kingdom ruled by the Crown of Castile. The initial funds for exploration came from Queen Isabella.[5][6] Although New Spain was a dependency of Castile, it (Mexico) was a kingdom and not a colony, subject to the presiding monarch on the Iberian Peninsula.[7][8] The monarch had sweeping power in the overseas territories, with not just sovereignty over the realm but also property rights. All power over the state came from the monarch. The crown had sweeping powers over the Catholic Church in its overseas territories, and via the Patronato real, a grant by the papacy to the crown to oversee the Church in all aspects save doctrine. The Viceroyalty of New Spain was created by royal decree on October 12, 1535, in the Kingdom of New Spain with a viceroy appointed as the king's "deputy" or substitute. This was the first New World viceroyalty and one of only two that the Spanish Empire administered in the continent until the 18th-century Bourbon Reforms. |

スペイン王冠領とヌエバ・エスパーニャ副王領 ヌエバ・エスパーニャ王国は、1521年8月18日、スペインによるアステカ帝国征服の後、カスティーリャ王冠領の統治下にある新世界王国として設立され た。 探検の初期資金は女王イザベラから提供された。[5][6] ヌエバ・エスパーニャはカスティーリャの属領であったが、メキシコは王国であり、植民地ではなく、イベリア半島の君主の統治下にあった。[7][8] 君主は海外領土において広範な権限を有しており、その権限は領土の主権だけでなく財産権にも及んでいた。国家に対するすべての権限は君主から与えられたも のである。王冠は海外領土におけるカトリック教会に対して広範な権限を有しており、教義以外のすべての側面において教会を監督する権限を教皇から与えられ ていた。1535年10月12日、ヌエバ・エスパーニャ王国で国王の「代理人」または「代行者」として任命された総督を擁するヌエバ・エスパーニャ副王領 が勅令によって創設された。これは新世界における最初の副王領であり、18世紀のブルボン朝改革までスペイン帝国が大陸で管理した2つの副王領のうちの1 つであった。 |

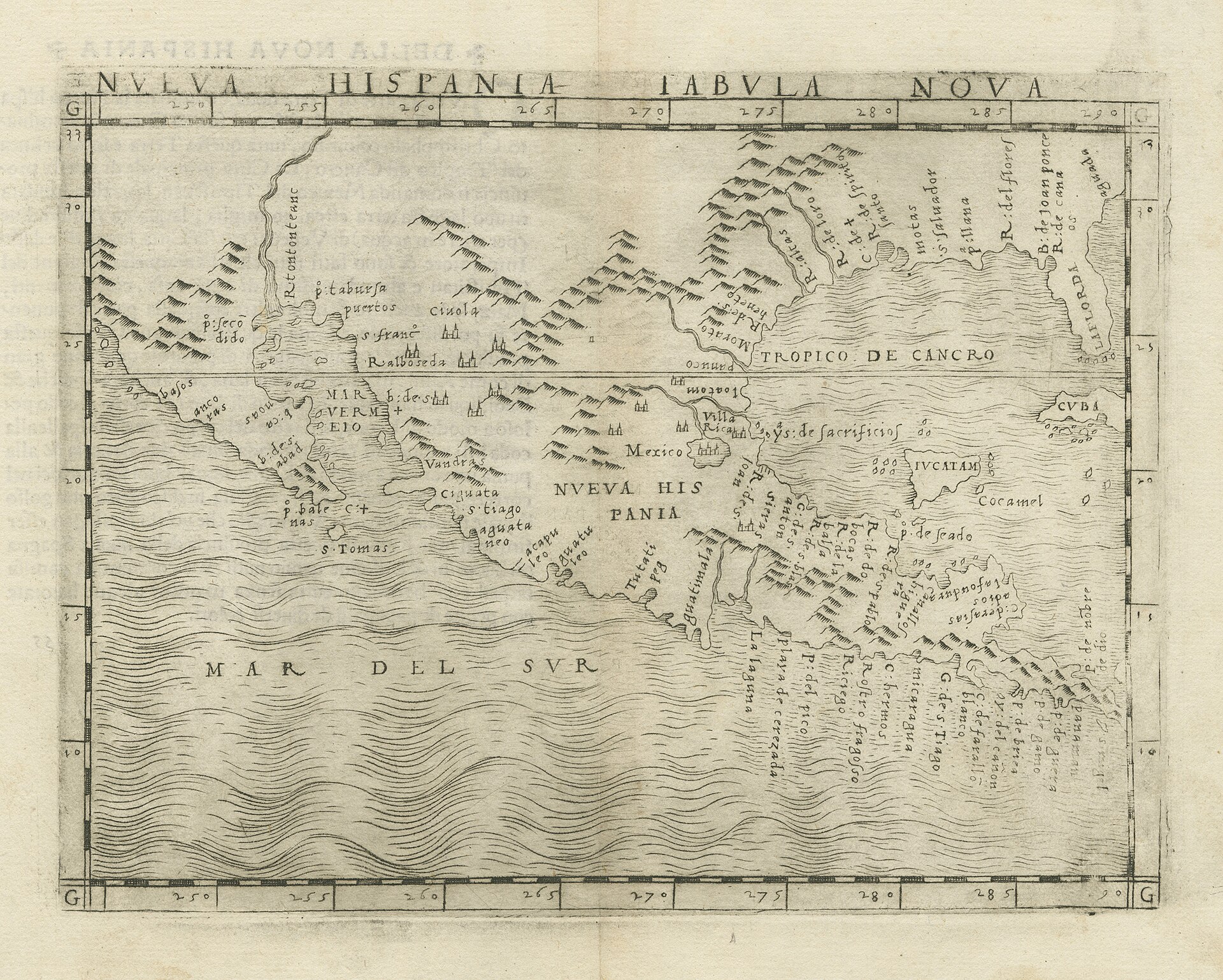

| Territorial extent of the overseas Spanish Empire Main article: Spanish Empire  Giacomo Gastaldi's 1548 map of New Spain, Nueva Hispania Tabula Nova At its greatest extent, the Spanish crown claimed on the mainland of the Americas much of North America south of Canada, that is: all of modern Mexico and Central America except Panama; most of the United States west of the Mississippi River, plus the Floridas. The Spanish West Indies, settled prior to the conquest of the Aztec Empire, also came under New Spain's jurisdiction: Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, the Cayman Islands, Trinidad, Martinica and the Bay Islands.[9][10][11] New Spain also claimed jurisdiction over the overseas territories of the Spanish East Indies in Asia and Oceania: the Philippine Islands, the Mariana Islands, the Caroline Islands, parts of Taiwan, and parts of the Moluccas. Although asserting sovereignty over this vast realm, it did not effectively control large swaths. Other European powers, including England, France, and the Netherlands established colonies in territories Spain claimed.  Spanish historical presence, claimed territories, and expeditions in North America Much of what was called in the United States the "Spanish borderlands", is territory that attracted few Spanish settlers, with less dense indigenous populations and apparently lacking in mineral wealth. Huge deposits of gold in California were discovered immediately after it was incorporated into the U.S. following the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). The northern region of New Spain in the colonial era was considered marginal to Spanish interests compared to the most densely populated and lucrative areas of central Mexico. To shore up its claims in North America in the eighteenth century as other powers encroached on its claims, the crown sent expeditions to the Pacific Northwest, which explored and claimed the coast of British Columbia and Alaska.[12] Religious missions and fortified presidios were established to shore up Spanish control on the ground. On the mainland, the administrative units included Las Californias, that is, the Baja California peninsula, still part of Mexico and divided into Baja California and Baja California Sur; Alta California (modern Arizona, California, Nevada, Utah, western Colorado, and southern Wyoming); (from the 1760s) Louisiana (including the western Mississippi River basin and the Missouri River basin); Nueva Extremadura (the modern states of Coahuila and Texas); and Santa Fe de Nuevo México (parts of Texas and New Mexico).[13] |

スペイン領海外帝国の領土範囲 詳細は「スペイン帝国」を参照  ジャコモ・ガスタルディによる1548年のヌエバ・エスパーニャ(ヌエバ・イスパニア)の地図「タブラ・ノヴァ」 スペイン領は、最大時にはアメリカ大陸本土のカナダ以南の北米の大半、すなわち、現在のメキシコとパナマを除く中米全域、ミシシッピ川以西のアメリカ合衆 国の大部分、それにフロリダ諸島を領有していた。アステカ帝国征服以前に植民地化されていた西インド諸島もヌエバ・エスパーニャの管轄下に置かれた。 キューバ、イスパニョーラ島、プエルトリコ、ジャマイカ、ケイマン諸島、トリニダード、マルティニーク、ベイ島などである。[9][10][11] また、ヌエバ・エスパーニャはアジアとオセアニアのスペイン領東インドの海外領土の管轄権も主張していた。フィリピン諸島、マリアナ諸島、カロリン諸島、 台湾の一部、モルッカ諸島の一部などである。この広大な領域に対する主権を主張していたものの、その大部分を効果的に支配することはできなかった。イギリ ス、フランス、オランダなど他のヨーロッパ諸国は、スペインが領有権を主張する領域に植民地を建設した。  北米におけるスペインの歴史的影響力、領有権主張、探検 米国で「スペイン国境地域」と呼ばれる地域の多くは、スペイン人入植者がほとんどおらず、先住民の人口密度も低く、鉱物資源も乏しい地域であった。 メキシコ・アメリカ戦争(1846年~1848年)の後に米国に併合されたカリフォルニアには、膨大な量の金鉱が存在することがすぐに発見された。植民地 時代のヌエバ・エスパーニャの北部地域は、メキシコ中央部の人口が最も密集し、利益が大きい地域と比較すると、スペインの利害関係の対象としては限定的な 地域と考えられていた。18世紀に他の列強がその領有権を主張し始めたため、スペインは北米における自国の主張を強化するために、太平洋北西部に探検隊を 派遣し、ブリティッシュコロンビア州とアラスカの海岸を探検し、領有権を主張した。 現地におけるスペインの支配を強化するために、宗教宣教と要塞化されたプレシディオが設置された。本土では、行政単位としてラス・カリフォルニアス (Las Californias)、すなわち、現在でもメキシコの一部であり、バハ・カリフォルニア(Baja California)とバハ・カリフォルニア・スル(Baja California Sur)に分かれているバハ・カリフォルニア半島、アルタ・カリフォルニア(Alta California)(現在のアリゾナ州、カリフォルニア州、ネバダ州、ユタ州、コロラド州西部、ワイオミング州南部)、(1760年代以降)ルイジア ナ(ミシシッピ川西部流域およびミズーリ川流域を含む)、ヌエバ・エクストレマドゥーラ(Nueva Extremadura)(現在のコアウイラ州およびテキサス州)、サンタフェ・デ・ヌエボ・メヒコ(Santa Fe de Nuevo México)(テキサス州およびニューメキシコ州の一部)が存在した。テキサス州とニューメキシコ州の一部)。[13] |

| Government Main article: Spanish colonization of the Americas § Civil governance  In 1794  In 1819 Viceroyalty The Viceroyalty was administered by a viceroy residing in Mexico City and appointed by the Spanish monarch, who had administrative oversight of all of these regions, although most matters were handled by the local governmental bodies, which ruled the various regions of the viceroyalty. First among these were the audiencias, which were primarily superior tribunals, but which also had administrative and legislative functions. Each of these was responsible to the Viceroy of New Spain in administrative matters (though not in judicial ones), but they also answered directly to the Council of the Indies. Captaincies general and governorates The Captaincy Generals were the second-level administrative divisions and these were relatively autonomous from the viceroyalty. The viceroy was captain-general of those provinces that remained directly under his command. Santo Domingo (1535); Philippines (1565); Puerto Rico (1580); Cuba (1608); Guatemala (1609); Yucatán (1617); Commandancy General of the Provincias Internas (1776) (analogous to a dependent captaincy general). Two governorates, third-level administrative divisions, were established, the Governorate of Spanish Florida (Spanish: La Florida) and the Governorate of Spanish Louisiana (Spanish: Luisiana). High courts The high courts, or audiencias, were established in major areas of Spanish settlement. In New Spain the high court was established in 1527, prior to the establishment of the viceroyalty. The First Audiencia was headed by Hernán Cortés's rival Nuño de Guzmán, who used the court to deprive Cortés of power and property. The crown dissolved the First Audiencia and established the Second Audiencia.[14] The audiencias of New Spain were Santo Domingo (1511, effective 1526, predated the Viceroyalty); Mexico (1527, predated the Viceroyalty); Panama (1st one, 1538–1543); Guatemala (1543); Guadalajara (1548); Manila (1583). Audiencia districts further incorporated the older, smaller divisions known as governorates (gobernaciones, roughly equivalent to provinces), which had been originally established by conquistador-governors known as adelantados. Provinces which were under military threat were grouped into captaincies general, such as the Captaincies General of the Philippines (established 1574) and Guatemala (established in 1609), which were joint military and political commands with a certain level of autonomy. The viceroy was captain-general of those provinces that remained directly under his command. |

政府 詳細は「スペインによるアメリカ大陸の植民地化」の「市民統治」を参照  1794年  1819年 副王領 副王領は、スペイン国王によって任命され、メキシコシティに居住する副王によって統治された。国王はこれらの地域のすべてを行政的に監督したが、ほとんど の事項は副王領のさまざまな地域を統治する地方自治体によって処理された。その筆頭はオーディエンシア(audiencias)であり、これは主に高等裁 判所であったが、行政および立法機能も有していた。 これらの各機関は、行政事項に関してはヌエバ・エスパーニャ副王に責任を負っていたが(ただし司法事項に関してはそうではなかった)、インド審議会にも直 接に責任を負っていた。 キャプテンシー・ジェネラルと総督府 キャプテンシー・ジェネラルは、副王領から比較的自治権を持った第2レベルの行政区分であった。総督は、直接の指揮下にあるそれらの州の最高司令官であっ た。サント・ドミンゴ(1535年)、フィリピン(1565年)、プエルトリコ(1580年)、キューバ(1608年)、グアテマラ(1609年)、ユカ タン(1617年)、プロビデンシアス・インテルナス総督府(1776年)(従属的な最高司令官に相当)。3番目の行政区分である2つの総督領、スペイン 領フロリダ総督領(スペイン語:ラ・フロリダ)とスペイン領ルイジアナ総督領(スペイン語:ルイジアナ)が設置された。 高等裁判所 高等裁判所(オーディエンシア)は、スペイン人入植地の主要地域に設置された。ヌエバ・エスパーニャでは、副王領が設置される前の1527年に高等裁判所 が設置された。第1高等裁判所は、エルナン・コルテスのライバルであったヌニョ・デ・グスマンが主宰し、同裁判所を利用してコルテスの権力と財産を奪っ た。スペイン王は第一審議会を解散し、第二審議会を設立した。[14] ヌエバ・エスパーニャの審議会は、サント・ドミンゴ(1511年、事実上1526年、副王領より古い)、メキシコ(1527年、副王領より古い)、パナマ (最初のもの、1538年~1543年)、グアテマラ(1543年)、グアダラハラ(1548年)、マニラ(1583年)であった。 アウディエンシア管区はさらに、アドランテードとして知られる征服者総督によって当初設置された、より古く、より小さな行政区分である総督領 (gobernaciones、州とほぼ同義)を組み込んだ。軍事的脅威にさらされていた州は、フィリピン総督領(1574年設置)やグアテマラ総督領 (1609年設置)といったキャプテンシー・ジェネラルにまとめられた。これらは、一定の自治権を持つ軍事的・政治的指揮権を統合したものだった。総督 は、その指揮下に直接残ったそれらの州の総督であった。 |

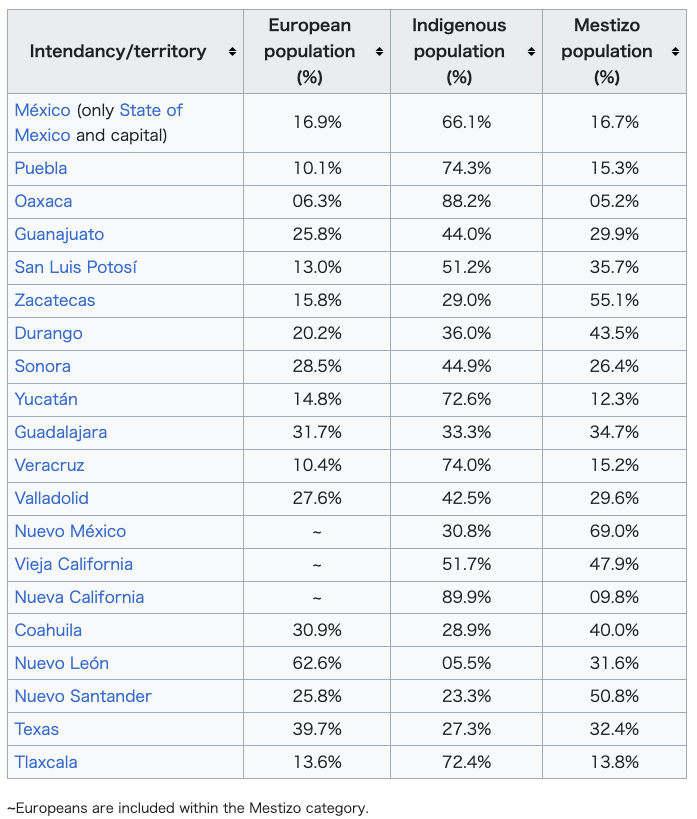

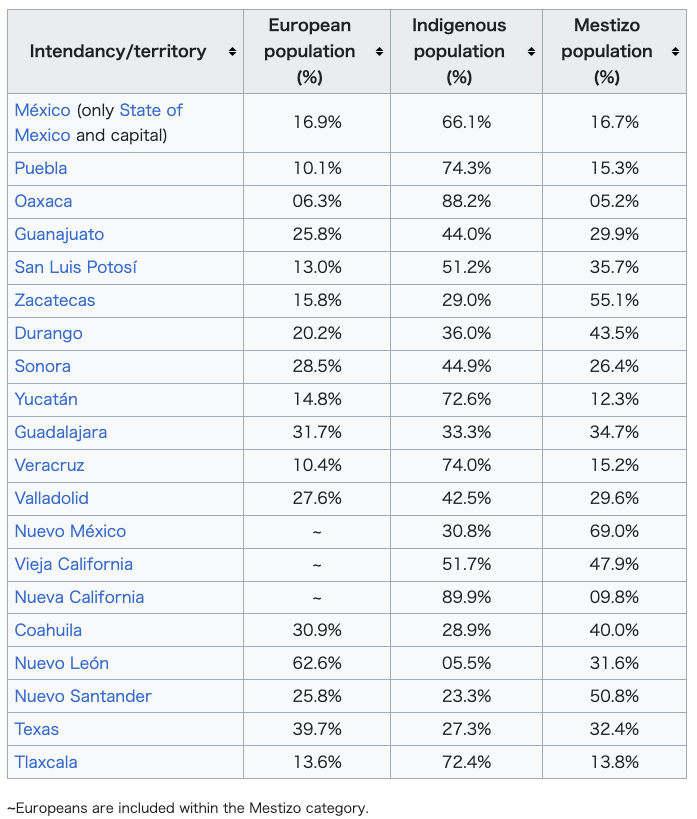

Official document of the New Spain government in Nahuatl announcing the transfer of powers from the outgoing viceroy Félix Berenguer de Marquina to José de Iturrigaray, who would serve until his arrest for his support of popular sovereignty in 1808. Local-level administration At the local level there were over two hundred districts, in both indigenous and Spanish areas, which were headed by either a corregidor (also known as an alcalde mayor) or a cabildo (town council), both of which had judicial and administrative powers. In the late 18th century the Bourbon dynasty began phasing out the corregidores and introduced intendants, whose broad fiscal powers cut into the authority of the viceroys, governors and cabildos. Despite their late creation, these intendancies so affected the formation of regional identity that they became the basis for the nations of Central America and the first Mexican states after independence. Intendancies of the 1780s As part of the sweeping eighteenth-century administrative and economic changes known as the Bourbon Reforms, the Spanish crown created new administrative units called intendancies, to strengthen central control over the viceroyalty. Some measures aimed to break the power of local elites in order to improve the economy of the empire. Reforms included the improvement of public participation in communal affairs, distribution of undeveloped lands to the indigenous and Spaniards, ending the corrupt practices of local crown officials, encouraging trade and mining, and establishing a system of territorial division similar to the model created by the government of France, already adopted in Spain.[15][16] The establishment of intendancies was strongly resisted by the viceroyalties and general captaincies similar to the opposition in the Iberian Peninsula when the reform was adopted. Royal audiencias and ecclesiastical hierarchs opposed the reform for its intervention in economic issues, for its centralist politics, and the forced ceding of many of their functions to the intendants. In New Spain, these units generally corresponded to the regions or provinces that had developed earlier in the center, South, and North.[17][18] Many of the intendancy boundaries became Mexican state boundaries after independence. The intendancies were created between 1764 and 1789, with the greatest number in the mainland in 1786: 1764 La Habana (later subdivided); 1766 Nueva Orleans; 1784 Puerto Rico; 1786 México, Veracruz, Puebla de Los Ángeles, Guadalajara, Guanajuato, Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí, Sonora, Durango, Oaxaca, Guatemala, San Salvador, Comayagua, León, Santiago de Cuba, Puerto Príncipe; 1789 Mérida.[19][20] |

ナワトル語で書かれたヌエバ・エスパーニャ政府の公式文書で、退任するフェリックス・ベレンゲル・デ・マルキナ副王からホセ・デ・イトゥリガライへの権限移譲を発表したもの。イトゥリガライは、1808年に人民主権を支持したとして逮捕されるまでその地位にあった。 地方レベルの行政 地方レベルでは、先住民居住区とスペイン人居住区の両方に200以上の地区があり、それぞれコレヒドール(アルカルデ・マジョールとも呼ばれる)またはカ ビルド(町議会)が統治していた。コレヒドールとカビルドは司法権と行政権を有していた。18世紀後半、ブルボン朝はコレヒドールを廃止し、代わって行政 権限の広い知事を導入した。この知事の権限は、副王、総督、カビルドの権限を侵すものであった。誕生は遅かったものの、これらの知事管区は地域アイデン ティティの形成に大きな影響を与え、独立後の中央アメリカ諸国やメキシコ最初の州の基礎となった。 1780年代の知事管区 18世紀に起こった広範囲にわたる行政・経済改革(ブルボン朝改革)の一環として、スペイン王は知事管区と呼ばれる新たな行政単位を創設し、総督府に対す る中央政府の統制を強化した。帝国の経済を改善するために、地方エリートの権力を弱めることを目的とした措置もあった。改革には、公共事業への市民参加の 改善、先住民とスペイン人への未開墾地の分配、地方の王族役人の汚職慣行の廃止、貿易と採鉱の奨励、スペインで既に採用されていたフランス政府のモデルに 類似した地域分割システムの確立などが含まれていた。 インテンデンシアの設立は、改革が採用された際のイベリア半島での反対運動と同様に、副王領や一般キャプテンシーから強く抵抗された。王立オーディエンシ アや教会のヒエラルクスは、経済問題への介入、中央集権政治、およびインテンデントへの多くの機能の強制譲渡を理由に、この改革に反対した。ヌエバ・エス パーニャでは、これらのユニットは概して、中央部、南部、北部で先に発展した地域や州に対応していた。[17][18] 多くのインテンデンシアの境界は、独立後にメキシコの州の境界となった。インテンデンシアは1764年から1789年の間に設置され、1786年には本土 で最も多い数となった。1764年:ラ・ハバナ(後に分割)、1766年:ヌエバ・オルレアン、1784年:プエルトリコ、1786年:メキシコ、ベラク ルス、プエブラ・デ・ロス・アンヘレス、グアダラハラ、グアナフアト、サカテカス、サン・ルイス・ポトシ、ソノラ、ドゥランゴ、オアハカ、グアテマラ、サ ンサルバドル 、コマイアガ、レオン、サンティアゴ・デ・クーバ、プエルト・プリンシペ、1789年メリダ。[19][20] |

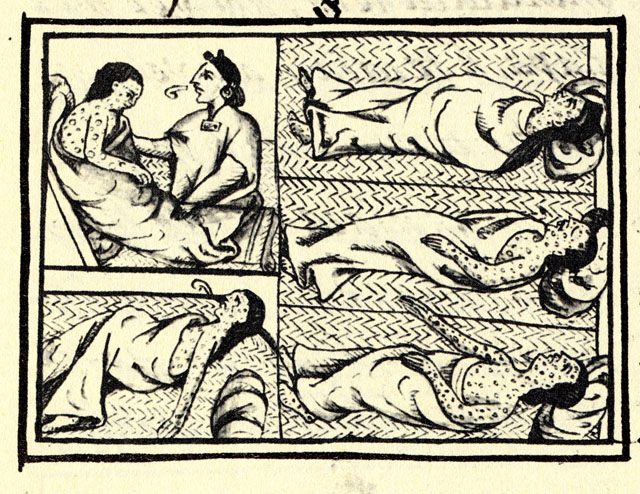

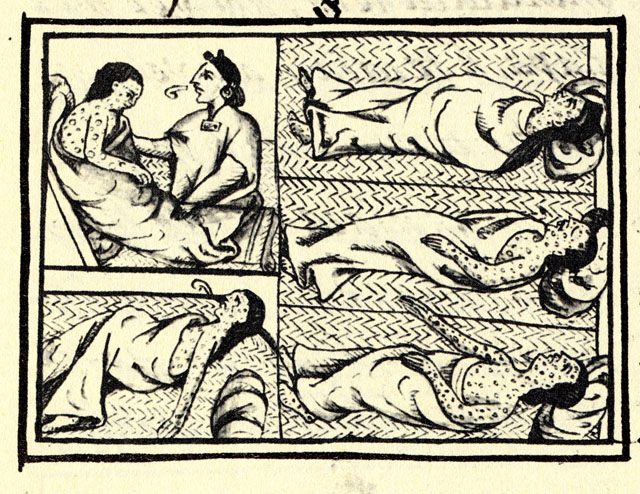

| History of New Spain Main article: History of New Spain The history of mainland New Spain spans three hundred years from the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire (1519–1521) to the collapse of Spanish rule in the Mexican War of Independence (1810–1821). Beginning with the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire in 1521 by Hernán Cortés, Spanish rule was established, leading to the creation of governing bodies like the Council of the Indies and the Audiencia to maintain control. It involved the forced conversion of indigenous populations to Catholicism and the blending of Spanish and indigenous cultures. During the 16th and 17th centuries, Spanish settlers founded major cities such as Mexico City, Puebla, and Guadalajara, turning New Spain into a vital part of the Spanish Empire. The discovery of silver in Zacatecas and Guanajuato significantly boosted the economy, leading to conflicts like the Chichimeca War. Missions and presidios were established in northern frontiers, aiding in the expansion and control of territories that later became part of the southwestern United States. The 18th century saw the implementation of the Bourbon Reforms, which aimed to modernize and strengthen the colonial administration and economy. These reforms included the creation of intendancies, increased military presence, and the centralization of royal authority. The expulsion of the Jesuits and the establishment of economic societies, were part of the efforts to enhance efficiency and revenue for the crown. The decline of New Spain culminated in the early 19th century with the Mexican War of Independence. Following Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla's 1810 Cry of Dolores, the insurgent army waged an eleven-year war against Spanish rule. The eventual alliance between royalist military officer Agustín de Iturbide and insurgent leader Vicente Guerrero led to the successful campaign for independence. In 1821, New Spain officially became the independent nation of Mexico, ending three centuries of Spanish colonial rule. |

ヌエバ・エスパーニャの歴史 詳細は「ヌエバ・エスパーニャの歴史」を参照 ヌエバ・エスパーニャ本土の歴史は、スペインによるアステカ帝国征服(1519年-1521年)からメキシコ独立戦争(1810年-1821年)におけるスペイン支配の崩壊までの300年間に及ぶ。 1521年のエルナン・コルテスによるアステカ帝国征服を皮切りにスペインの支配が確立し、支配を維持するためにインディアス審議会やオーディエンシアのような統治機関が設立された。先住民の強制的なカトリックへの改宗やスペイン文化と先住民文化の融合が行われた。 16世紀から17世紀にかけて、スペイン人入植者たちはメキシコシティ、プエブラ、グアダラハラなどの主要都市を建設し、ヌエバ・エスパーニャをスペイン 帝国の重要な一部へと変貌させた。サカテカスとグアナフアトで銀が発見されたことにより経済は著しく活性化し、チチメカ戦争のような紛争を引き起こした。 北部の国境には伝道所や要塞が建設され、後にアメリカ南西部の一部となる領土の拡大と支配に貢献した。18世紀には、植民地行政と経済の近代化と強化を目 的としたブルボン朝の改革が実施された。これらの改革には、行政長官職の創設、軍の増強、王権の集中などが含まれた。イエズス会の追放と経済組合の設立 は、王権の効率性と収益性を高めるための取り組みの一環であった。 ヌエバ・エスパーニャの衰退は、19世紀初頭のメキシコ独立戦争で頂点に達した。ミゲル・イダルゴ・イ・コスティージャが1810年に「苦渋の叫び」を叫 んだ後、反乱軍はスペイン支配に対して11年間にわたる戦争を繰り広げた。最終的に王党派の軍人、アグスティン・デ・イトゥルビデと反乱軍の指導者ビセン テ・ゲレロが同盟を結んだことで、独立運動は成功を収めた。1821年、ヌエバ・エスパーニャは正式にメキシコとして独立し、3世紀にわたるスペインの植 民地支配に終止符が打たれた。 |

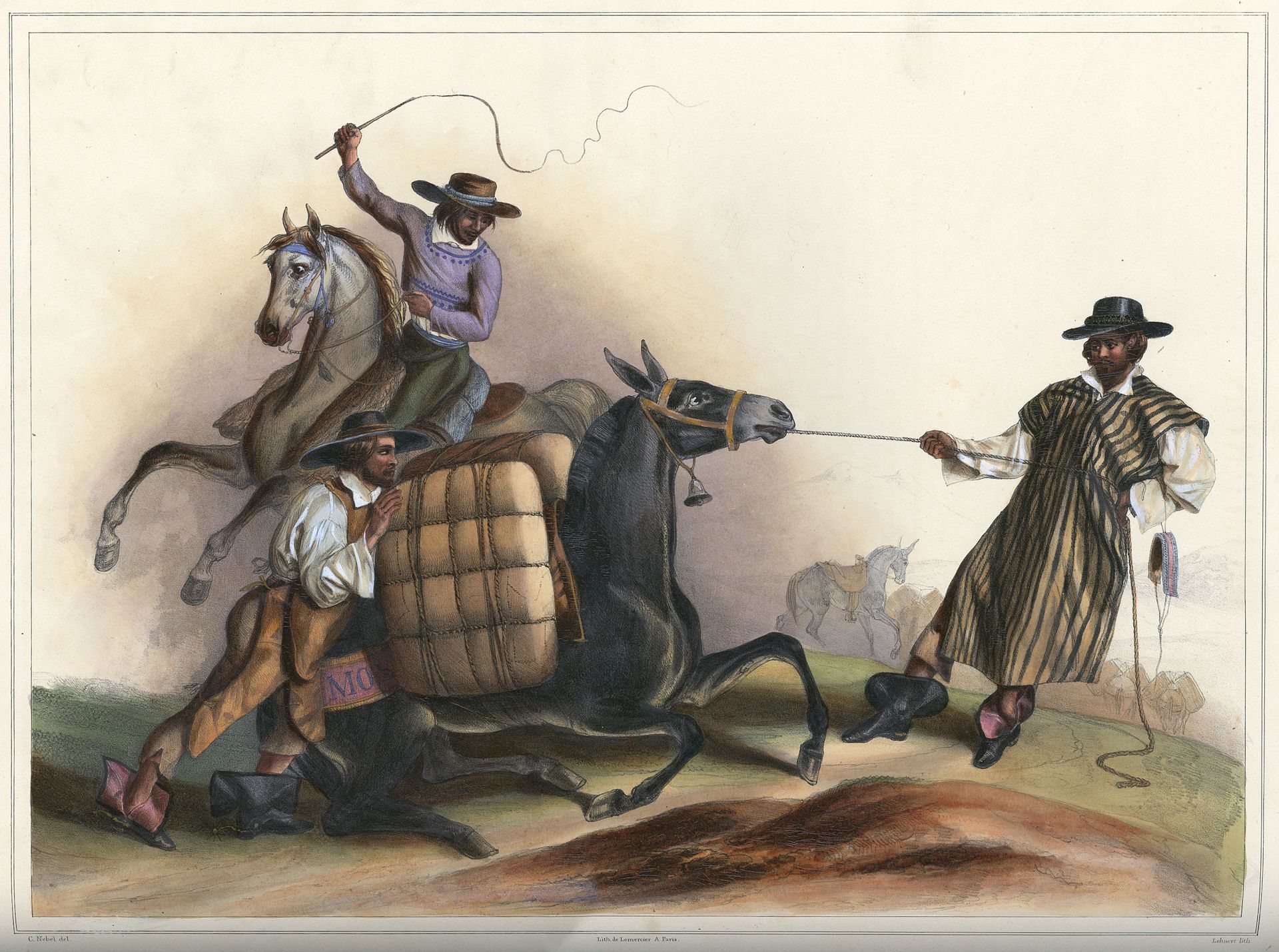

| Economy Main article: Economic history of Mexico § Economic history of New Spain, 1521-1821  Silver coin minted in New Spain. Silver was its most important export, starting in the 16th century. 8 reales Carlos III - 1778.  Indigenous man collecting cochineal with a deer tail by José Antonio de Alzate y Ramírez (1777). Cochineal was New Spain's most important export product after silver and its production was almost exclusively in the hands of indigenous cultivators.  Arrieros in Mexico. Mules were the main way cargo was moved overland, engraving by Carl Nebel.  Pedro de Alvarado, one of the first negotiators to hold office in Hibueras where he founded the towns of San Pedro Sula and Guatemala During the era of the conquest, in order to pay off the debts incurred by the conquistadors and their companies, the new Spanish governors awarded their men grants of native tribute and labor, known as encomiendas. In New Spain these grants were modeled after the tribute and corvee labor that the Mexica rulers had demanded from native communities. This system came to signify the oppression and exploitation of natives, although its originators may not have set out with such intent. In short order the upper echelons of patrons and priests in the society lived off the work of the lower classes. Due to some horrifying instances of abuse against the indigenous peoples, Bishop Bartolomé de las Casas suggested bringing black slaves to replace them. Fray Bartolomé later repented when he saw the even worse treatment given to the black slaves. In colonial Mexico, Encomenderos de Negros were specialized middlemen during the first half of the seventeenth century. While encomendero (alternatively, encomenderos de indios) generally refers to men granted the labor and tribute of a particular indigenous group in the immediate post-conquest era, encomenderos de negros were Portuguese slave dealers who were permitted to operate in Mexico for the slave trade.[citation needed] In Peru, the other discovery that perpetuated the system of forced labor, the mit'a, was the enormously rich single silver mine discovered at Potosí, but in New Spain, labor recruitment differed significantly. With the exception of silver mines worked in the Aztec period at Taxco, southwest of Tenochtitlan, the Mexico's mining region was outside the area of dense indigenous settlement. Labor for the mines in the north of Mexico had a workforce of black slave labor and indigenous wage labor, not draft labor.[21] Indigenous who were drawn to the mining areas were from different regions of the center of Mexico, with a few from the north itself. With such diversity they did not have a common ethnic identity or language and rapidly assimilated to Hispanic culture. Although mining was difficult and dangerous, the wages were good, which is what drew the indigenous labor.[21] The Viceroyalty of New Spain was the principal source of income for Spain in the eighteenth century, with the revival of mining under the Bourbon Reforms. Important mining centers like Zacatecas, Guanajuato, San Luis Potosí and Hidalgo had been established in the sixteenth century and suffered decline for a variety of reasons in the seventeenth century, but silver mining in Mexico out-performed all other Spanish overseas territories in revenues for the royal coffers. The fast red dye cochineal was an important export in areas such as central Mexico and Oaxaca in terms of revenues to the crown and stimulation of the internal market of New Spain. Cacao and indigo were also important exports for the New Spain, but was used through rather the vice royalties rather than contact with European countries due to piracy, and smuggling.[22] The indigo industry in particular also helped to temporarily unite communities throughout the Kingdom of Guatemala due to the smuggling.[22] There were two major ports in New Spain, Veracruz the viceroyalty's principal port on the Atlantic, and Acapulco on the Pacific, terminus of the Manila galleon. In the Philippines Manila near the South China Sea was the main port. The ports were fundamental for overseas trade, stretching a trade route from Asia, through the Manila galleon to the Spanish mainland. These were ships that made voyages from the Philippines to Mexico, whose goods were then transported overland from Acapulco to Veracruz and later reshipped from Veracruz to Cádiz in Spain. So then, the ships that set sail from Veracruz were generally loaded with merchandise from the East Indies originating from the commercial centers of the Philippines, plus the precious metals and natural resources of Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. During the 16th century, Spain held the equivalent of US$1.5 trillion (1990 terms) in gold and silver received from New Spain. However, these resources did not translate into development for the Metropolis (mother country) due to Spanish Roman Catholic Monarchy's frequent preoccupation with European wars (enormous amounts of this wealth were spent hiring mercenaries to fight the Protestant Reformation), as well as the incessant decrease in overseas transportation caused by assaults from companies of British buccaneers, Dutch corsairs and pirates of various origin. These companies were initially financed by, at first, by the Amsterdam stock market, the first in history and whose origin is owed precisely to the need for funds to finance pirate expeditions, as later by the London market. The above is what some authors call the "historical process of the transfer of wealth from the south to the north". |

経済 詳細は「メキシコの経済史」を参照 1521年から1821年のヌエバ・エスパーニャの経済史  ヌエバ・エスパーニャで鋳造された銀貨。16世紀から銀は最も重要な輸出品であった。8レアルカルロス3世 - 1778年。  ホセ・アントニオ・デ・アルサテ・イ・ラミレス作「コチニールを採取する先住民」(1777年)。コチニールは銀に次いで重要な新スペインの輸出品であり、その生産はほぼ専ら先住民の栽培農家の手に委ねられていた。  メキシコのラバ使いたち。陸上での貨物輸送の主な手段はラバであった。カール・ネーベル作の版画。  ペドロ・デ・アルバラードは、ヒビエラスで役職に就いた最初の交渉人の一人であり、サン・ペドロ・スラとグアテマラの町を建設した 征服時代には、征服者とその会社が負った負債を返済するために、スペインの新しい総督は、エンコミエンダとして知られる先住民の貢納と労働の権利を部下た ちに与えた。ヌエバ・エスパーニャでは、これらの権利は、メシカの支配者が先住民のコミュニティに要求していた貢納と強制労働をモデルとしていた。この制 度は、その創始者たちがそのような意図を持っていたわけではないかもしれないが、やがて先住民に対する抑圧と搾取を意味するようになった。 つまり、社会の上層部であるパトロンや司祭たちは、下層階級の労働によって生計を立てていたのである。 先住民に対するひどい虐待の例があったため、司教バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスは、彼らに代わる黒人奴隷を連れてくることを提案した。 しかし、後にバルトロメ修道士は、黒人奴隷がさらにひどい扱いを受けているのを見て後悔した。 植民地時代のメキシコでは、17世紀前半に、エンコミエンダドス・デ・ニグロス(Encomenderos de Negros)と呼ばれる専門の中間業者が活躍していた。エンコミエンダドス(Encomenderos)は一般的に、征服直後の時代に特定の先住民グ ループの労働力と貢納を授けられた男性を指すが、エンコミエンダドス・デ・ニグロスは、奴隷貿易のためにメキシコで活動することを許可されたポルトガル人 奴隷商人であった。 ペルーでは、強制労働制度であるミタを永続させたもう一つの発見は、ポトシで発見された非常に豊富な銀鉱山であったが、ヌエバ・エスパーニャでは、労働力 の徴集は大きく異なっていた。アステカ時代にテノチティトランの南西にあるタスコで採掘されていた銀鉱山を除いて、メキシコの鉱山地帯は先住民の密集した 居住地域の外にあった。メキシコ北部の鉱山では、黒人奴隷労働者と先住民の賃金労働者が労働力として働いており、徴集労働者は存在しなかった。[21] 鉱山地域に集められた先住民は、メキシコ中央部の異なる地域から来ており、北部出身者は少数であった。 このように多様であったため、彼らには共通の民族アイデンティティや言語はなく、急速にヒスパニック文化に同化していった。 鉱山労働は困難で危険であったが、賃金は良かったため、先住民は労働力として集められた。[21] ヌエバ・エスパーニャ副王領は、ブルボン朝の改革による鉱業の復活により、18世紀のスペインの主な収入源となった。 サカテカス、グアナフアト、サン・ルイス・ポトシ、イダルゴといった重要な鉱業の中心地は16世紀に確立されたが、17世紀にはさまざまな理由により衰退 した。しかし、メキシコの銀鉱業は、スペインの海外領土のなかでも、王室の財源として最高の収益を上げていた。 メキシコ中央部やオアハカなどの地域では、赤色染料のコチニールが重要な輸出品であり、王冠への収入とヌエバ・エスパーニャの国内市場の活性化という点で 重要な役割を果たしていた。カカオと藍もヌエバ・エスパーニャにとって重要な輸出品であったが、海賊行為や密輸のため、ヨーロッパ諸国との接触よりもむし ろ副王領を通じて使用されていた。[22] 特に藍産業は、密輸によりグアテマラ王国中の地域を一時的に団結させるのに役立った。[22] ヌエバ・エスパーニャには2つの主要港があった。ベラクルスは副王領の主要な大西洋側の港であり、アカプルコは太平洋側でマニラ・ガレオンの終着点であっ た。フィリピンでは南シナ海に近いマニラが主要港であった。これらの港は海外貿易に不可欠であり、マニラ・ガレオン船を通じてアジアからスペイン本土へと 貿易ルートを広げていた。 これらの船はフィリピンからメキシコまで航海し、メキシコで積み込んだ品物をアカプルコからベラクルスまで陸路で輸送し、その後ベラクルスからスペインの カディスまで再出荷した。つまり、ベラクルスから出航する船には、フィリピンの商業の中心地から運ばれた東インド諸島の商品、そしてメキシコ、中米、カリ ブ海の貴金属や天然資源が積まれていた。16世紀、スペインはヌエバ・エスパーニャから受け取った金銀で、1兆5000億米ドル(1990年基準)相当の 資産を保有していた。 しかし、スペイン・ローマ・カトリック君主国がヨーロッパの戦争にしばしば関与していたため(この莫大な富は、プロテスタント改革派と戦う傭兵を雇うため に費やされた)、また、イギリス海賊団、オランダの私掠船団、およびさまざまな出自の海賊団による攻撃により海外輸送が絶え間なく減少したため、これらの 資源はメトロポリス(母国)の発展にはつながらなかった。これらの会社は当初、史上初の証券取引所であるアムステルダム証券取引所によって、そして後にロ ンドン証券取引所によって、資金調達を行っていた。これらは、海賊遠征の資金調達というニーズに端を発している。以上が、一部の著者が「南から北への富の 移転の歴史的プロセス」と呼ぶものである。 |

| Regions of mainland New Spain In the colonial period, basic patterns of regional development emerged and strengthened.[23] European settlement and institutional life was built in the Mesoamerican heartland of the Aztec Empire in Central Mexico. The South (Oaxaca, Michoacán, Yucatán, and Central America) was a region of dense indigenous settlement of Mesoamerica, but without exploitable resources of interest to Europeans, the area attracted few Europeans, while the indigenous presence remained strong. The North was outside the area of complex indigenous populations, inhabited primarily by nomadic and hostile northern indigenous groups. With the discovery of silver in the north, the Spanish sought to conquer or pacify those peoples in order to exploit the mines and develop enterprises to supply them. Nonetheless, much of northern New Spain had sparse indigenous population and attracted few Europeans. The Spanish crown and later the Republic of Mexico did not effectively exert sovereignty over the region, leaving it vulnerable to the expansionism of the United States in the nineteenth century. Regional characteristics of colonial Mexico have been the focus of considerable study.[23][24] For those based in the vice-regal capital of Mexico City, everywhere else were the "provinces". Even in the modern era, "Mexico" for many refers solely to Mexico City, with the pejorative view that anywhere outside the capital is a hopeless backwater.[25] "Fuera de México, todo es Cuauhtitlán" ["outside of Mexico City, it's all Podunk"],[26][27] that is, poor, marginal, and backward, in short, the periphery. The picture is far more complex, however; while the capital is enormously important as the center of institutional, economic, and social power, the provinces played a significant role in colonial Mexico. Regions (provinces) developed and thrived to the extent that they became sites of economic production and tied into networks of trade. "Spanish society in the Indies was import-export oriented at the very base and in every aspect," and the development of many regional economies was typically centered on support of that export sector.[28] |

ヌエバ・エスパーニャ本土の地域 植民地時代には、地域開発の基本的なパターンが現れ、強化された。[23] ヨーロッパ人の入植と制度上の生活は、中央メキシコのアステカ帝国の中米の中心地に築かれた。南(オアハカ、ミチョアカン、ユカタン、および中米)は、メ ソアメリカにおける先住民の密集した居住地域であったが、ヨーロッパ人が関心を寄せるような利用可能な資源がなかったため、この地域にはヨーロッパ人がほ とんど移住せず、先住民の存在が依然として強かった。 北部は、複雑な先住民の集団が住む地域外にあり、主に遊牧民や敵対的な北部の先住民グループが住んでいた。北部で銀が発見されると、スペイン人は鉱山開発 やそれらを供給する事業を展開するために、それらの人々を征服または平和的に服従させようとした。しかし、ヌエバ・エスパーニャ北部の大部分は先住民の人 口密度が低く、ヨーロッパ人の移住も少なかった。スペイン王権および後のメキシコ共和国は、この地域に対して有効な主権を行使することができず、19世紀 にはアメリカ合衆国の膨張主義に対して無防備な状態であった。 植民地時代のメキシコの地域的特性については、多くの研究がなされている。[23][24] 副王領の首都メキシコシティを拠点とする人々にとって、それ以外の地域はすべて「地方」であった。現代においても、多くの人々にとって「メキシコ」とはメ キシコシティのみを指し、首都以外の地域は見捨てられた僻地であるという否定的な見方がある。「Fuera de México, todo es Cuauhtitlán」(「メキシコシティの外はすべてポドゥンク」)[26][27]、つまり、貧しく、辺境で、遅れた地域、つまり周辺地域である。 しかし、実際にはもっと複雑である。首都は制度、経済、社会の中心地として非常に重要であるが、植民地時代のメキシコでは地方も重要な役割を果たしてい た。地方(州)は経済生産の場となり、貿易ネットワークに組み込まれるほどに発展し、繁栄した。「インドにおけるスペイン社会は、あらゆる面で輸出入を基 本としていた」ため、多くの地域経済の発展は、典型的にその輸出部門の支援を中心としていた。[28] |

| Central region Mexico City, capital of the viceroyalty Main article: History of Mexico City  The Plaza Mayor of Mexico City, 1695, by Cristóbal de Villalpando Mexico City was the center of the Central region, and the hub of New Spain. The development of Mexico City itself was vitally important to the development of New Spain as a whole. It was the seat of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, the Archdiocese of the Catholic Church, the Holy Office of the Inquisition, the merchants' guild (consulado), and home of the most elite families in the Kingdom of New Spain. Mexico City was the single most populous city, not just in New Spain, but for many years the entire Western Hemisphere, with a high concentration of mixed-race castas. Veracruz to Mexico City Significant regional development grew along the main transportation route from the capital east to the port of Veracruz. Alexander von Humboldt called this area, Mesa de Anahuac, which can be defined as the adjacent valleys of Puebla, Mexico, and Toluca, enclosed by high mountains, along with their connections to the Gulf Coast port of Veracruz and the Pacific port of Acapulco, where over half the population of New Spain lived.[29] These valleys were linked trunk lines, or main routes, facilitating the movement of vital goods and people to get to key areas.[30] Even in the relatively richly endowed region of Mexico, the difficulty of transit of people and goods in the absence of rivers and level terrain remained a major challenge to the economy of New Spain. This challenge persisted during the post-independence years until the late nineteenth-century construction of railroads. In the colonial era and up until the railroads were built in key areas in post-independence in the late nineteenth century, mule trains were the main mode of transporting goods. Pack mules were used because unpaved roads, mountainous terrain, and seasonal flooding could not generally accommodate carts. In the late eighteenth century, the crown devoted some resources to study and remedy the poor roads. The Camino Real (royal road) between the port of Veracruz and the capital had some short sections paved and bridges constructed. The construction was done despite protests from some indigenous settlements when the infrastructure improvements, which sometimes included rerouting the road through communal lands. The Spanish crown finally decided that road improvement was in the interests of the state for military purposes, as well as for fostering commerce, agriculture, and industry, but the lack of state involvement in the development of physical infrastructure was to have lasting effects, constraining development until the late nineteenth century.[31][32] Despite the road improvements, transit was still difficult, particularly for heavy military equipment. Although the crown had ambitious plans for both the Toluca and Veracruz portions of the king's highway, improvements were limited to a localized network.[33] Even where infrastructure was improved, transit on the Veracruz-Puebla main road had other obstacles, with wolves attacking mule trains, killing animals, and rendering some sacks of foodstuffs unsellable because they were smeared with blood.[34] The north-south Acapulco route remained a mule track through mountainous terrain. |

中央地域 メキシコシティ、副王領の首都 詳細は「メキシコシティの歴史」を参照  1695年のメキシコシティのソカロ、クリストバル・デ・ビジャランダ作 メキシコシティは中央地域の中心であり、ヌエバ・エスパーニャの中心地であった。メキシコシティ自体の発展は、ヌエバ・エスパーニャ全体の発展にとって極 めて重要であった。ここは、ヌエバ・エスパーニャ副王領、カトリック教会の大司教区、異端審問の聖職者、商人組合(コンスラド)の本拠地であり、ヌエバ・ エスパーニャ王国で最も有力な家々の本拠地でもあった。メキシコシティは、ヌエバ・エスパーニャだけでなく、長年にわたり西半球全体でも最も人口の多い都 市であり、混血カースタが集中していた。 ベラクルスからメキシコシティ 首都から東のベラクルス港へと向かう主要交通ルートに沿って、この地域は著しく発展した。アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルトは、この地域を「メサ・デ・ アナワク(Mesa de Anahuac)」と呼んだ。これは、プエブラ、メキシコ、トルーカの隣接する渓谷を高い山々に囲まれた地域と定義し、さらに、ベラクルス (Veracruz)のメキシコ湾岸の港とアカプルコ(Acapulco)の太平洋岸の港を結び、ヌエバ・エスパーニャの人口の半分以上が暮らしていた地 域と定義したものである。[29] これらの渓谷は幹線や主要ルートで結ばれており、重要な地域への物資や人の移動を促進していた。[30] メキシコの中でも比較的恵まれた地域であったとしても、川や平地がなく、人や物の輸送が困難であったことは、ヌエバ・エスパーニャの経済にとって大きな課 題であった。この課題は、19世紀後半に鉄道が敷設されるまで、独立後の時代を通じて続いた。植民地時代、および19世紀後半の独立後の主要地域に鉄道が 敷設されるまでは、ラバの隊商が主な輸送手段であった。舗装されていない道路や山岳地帯、季節的な洪水により、一般的に荷車は使用できなかったため、ラバ が使われた。 18世紀後半には、スペイン王室は劣悪な道路事情の調査と改善にいくつかの資源を割いた。ベラクルス港と首都を結ぶカミノ・レアル(王の道)には、短い区 間が舗装され、橋が建設された。インフラの改善には、時には共同所有地を通る道路のルート変更も含まれていたため、一部の先住民集落から抗議の声が上がっ たが、建設は行われた。スペイン王は最終的に、道路の改良は軍事目的だけでなく、商業、農業、工業の発展のためにも国家の利益になると判断したが、物理的 インフラの開発への国家の関与の欠如は長期的な影響を及ぼし、19世紀後半まで開発を抑制することとなった。[31][32] 道路の改良にもかかわらず、特に大型の軍用装備の輸送は依然として困難であった。 スペイン王室は、王の道のうちトルーカとベラクルス間の区間について野心的な計画を持っていたが、改善は局所的なネットワークに限定されていた。[33] インフラが改善された地域でも、ベラクルスとプエブラを結ぶ主要道路の交通には、ラバの隊商を襲って動物を殺す狼の存在や、血で汚れて売れなくなった食料 の袋など、他の障害があった。[34] アカプルコを南北に結ぶルートは、 山岳地帯を通るラバの道だった。 |

| Veracruz, port city and province Veracruz was the first Spanish settlement founded in what became New Spain, and it endured as the only viable Gulf Coast port, the gateway for Spain to New Spain. The difficult topography around the port affected local development and New Spain as a whole. Going from the port to the central plateau entailed a daunting 2000 meter climb from the narrow tropical coastal plain in just over a hundred kilometers. The narrow, slippery road in the mountain mists was treacherous for mule trains, and in some cases mules were hoisted by ropes. Many tumbled with their cargo to their deaths.[35] Given the transport constraints, only high-value, low-bulk goods continued to be shipped in the transatlantic trade, which stimulated local production of foodstuffs, rough textiles, and other products for a mass market. Although New Spain produced considerable sugar and wheat, these were consumed exclusively in the colony even though there was demand elsewhere. Philadelphia, not New Spain, supplied Cuba with wheat.[36] The Caribbean port of Veracruz was small, with its hot, pestilential climate not a draw for permanent settlers: its population never topped 10,000.[37] Many Spanish merchants preferred living in the pleasant highland town of Jalapa (1,500 m). For a brief period (1722–76) the town of Jalapa became even more important than Veracruz, after it was granted the right to hold the royal trade fair for New Spain, serving as the entre for goods from Asia via Manila galleon through the port of Acapulco and European goods via the flota (convoy) from the Spanish port of Cádiz.[38] Spaniards also settled in the temperate area of Orizaba, east of the Citlaltepetl volcano. Orizaba varied considerably in elevation from 800 metres (2,600 ft) to 5,700 metres (18,700 ft) (the summit of the Citlaltepetl volcano), but "most of the inhabited part is temperate".[39] Some Spaniards lived in semitropical Córdoba, which was founded as a villa in 1618, to serve as a Spanish base against runaway slave (cimarrón) predations on mule trains traveling the route from the port to the capital. Some cimarrón settlements sought autonomy, such as one led by Gaspar Yanga, with whom the crown concluded a treaty leading to the recognition of a largely black town, San Lorenzo de los Negros de Cerralvo, later called the municipality of Yanga.[40] European diseases immediately affected the multiethnic Indian populations in the Veracruz area and for that reason Spaniards imported black slaves as either an alternative to indigenous labor or its complete replacement in the event of a repetition of the Caribbean die-off. A few Spaniards acquired prime agricultural lands left vacant by the indigenous demographic disaster. Portions of the province could support sugar cultivation and as early as the 1530s sugar production was underway. New Spain's first viceroy, Don Antonio de Mendoza established an hacienda on lands taken from Orizaba.[41] Indians resisted cultivating sugarcane themselves, preferring to tend their subsistence crops. As in the Caribbean, black slave labor became crucial to the development of sugar estates. During the period 1580–1640 when Spain and Portugal were ruled by the same monarch and Portuguese slave traders had access to Spanish markets, African slaves were imported in large numbers to New Spain and many of them remained in the region of Veracruz. But even when that connection was broken and prices rose, black slaves remained an important component of Córdoba's labor sector even after 1700. Rural estates in Córdoba depended on African slave labor, who were 20% of the population there, a far greater proportion than any other area of New Spain, and greater than even nearby Jalapa.[42] In 1765 the crown created a monopoly on tobacco, which directly affected agriculture and manufacturing in the Veracruz region. Tobacco was a valuable, high-demand product. Men, women, and even children smoked, something commented on by foreign travelers and depicted in eighteenth-century casta paintings.[43] The crown calculated that tobacco could produce a steady stream of tax revenues by supplying the huge Mexican demand, so the crown limited zones of tobacco cultivation. It also established a small number of factories of finished products, and licensed distribution outlets (estanquillos).[44] The crown also set up warehouses to store up to a year's worth of supplies, including paper for cigarettes, for the factories.[45] With the establishment of the monopoly, crown revenues increased and there is evidence that despite high prices and expanding rates of poverty, tobacco consumption rose while at the same time, general consumption fell.[46] In 1787 during the Bourbon Reforms Veracruz became an intendancy, a new administrative unit. |

ベラクルス、港湾都市および州 ベラクルスは、ヌエバ・エスパーニャとなる地域にスペイン人が最初に建設した入植地であり、スペインがヌエバ・エスパーニャへの玄関口として唯一利用可能 なメキシコ湾岸の港として存続した。 港湾周辺の地形が険しかったため、地域の開発やヌエバ・エスパーニャ全体の発展にも影響を与えた。 港湾から中央高原へ向かうには、わずか100キロメートル余りの距離で、熱帯の狭い海岸平野から2000メートルの標高差を登らなければならなかった。山 霧の中の狭く滑りやすい道路は、ラバの隊商にとっては危険であり、場合によってはラバをロープで吊り上げることもあった。多くのラバが積荷とともに転落し て死んだ。 輸送手段の制約により、大西洋貿易では価値が高くかさばらない商品のみが輸送され続けたが、これは大量市場向けの食料品、粗野な織物、その他の製品の現地 生産を刺激した。 ヌエバ・エスパーニャではかなりの砂糖と小麦が生産されていたが、それらは他の地域でも需要があったにもかかわらず、専ら植民地内で消費されていた。 キューバに小麦を供給していたのは、ヌエバ・エスパーニャではなくフィラデルフィアだった。 カリブ海の港であるベラクルスは小さく、高温多湿で疫病が流行しやすい気候であったため、定住者には人気がなかった。人口は1万人を超えることはなかっ た。[37] 多くのスペイン人商人は、標高1,500メートルの高原の町ハラパでの生活を好んだ。ハラパの町は、1722年から1776年の短期間、ヌエバ・エスパー ニャの王立交易会の開催権を獲得したことにより、ベラクルスよりもさらに重要な町となった。マニラ・ガレオン船を経由してアカプルコ港に到着するアジアか らの商品と、スペインのカディス港からフリート(護衛船団)で運ばれてくるヨーロッパからの商品の中継地点として機能したためである。 スペイン人はまた、シトラルテペトル火山の東にあるオリサバの温暖な地域にも定住した。オリサバの標高は800メートル(2,600フィート)から 5,700メートル(18,700フィート)(シトラルテペトル火山の山頂)までかなり変化しているが、「人が住んでいる部分のほとんどは温帯気候であ る」[39]。一部のスペイン人は、1618年にヴィラとして建設された亜熱帯のコルドバに住んでいた。これは、 。シマロン居住区の中には自治を求めるものもあり、その代表格であるガスパール・ヤンガが率いる集団は、スペイン王と条約を結び、大部分が黒人の町サン・ ロレンソ・デ・ロス・ニグロス・デ・セラルボ(後にヤンガの自治体と呼ばれる)の設立を認めることとなった。 ヨーロッパの疫病は、すぐにベラクルス地域の多民族インディアン人口に影響を与えた。そのため、スペイン人は先住民の労働力の代替、あるいはカリブ海での 大量死が繰り返された場合の完全な代替として、黒人奴隷を輸入した。少数のスペイン人は、先住民の人口災害によって空いた主要な農地を手に入れた。州の一 部では砂糖栽培が可能であり、1530年代には早くも砂糖生産が始まっていた。ヌエバ・エスパーニャの初代副王ドン・アントニオ・デ・メンドーサは、オリ サバから奪った土地に大農園を設立した。 インディアンは自分たちでサトウキビを栽培することを好まず、自給用の作物を育てることを好んだ。カリブ海地域と同様に、サトウキビ農園の開発には黒人奴 隷労働力が不可欠となった。1580年から1640年の間、スペインとポルトガルが同じ君主によって統治され、ポルトガルの奴隷商がスペイン市場にアクセ スできたため、アフリカ人奴隷が大量にヌエバ・エスパーニャに輸入され、その多くがベラクルス州の地域に留まった。しかし、そのつながりが断たれ、価格が 上昇したにもかかわらず、1700年以降も黒人奴隷はコルドバの労働力の重要な要素であり続けた。コルドバの農場はアフリカ人奴隷労働に依存しており、彼 らは人口の20%を占め、これはヌエバ・エスパーニャの他のどの地域よりもはるかに高い割合であり、近隣のハラパよりも高かった。 1765年、王冠はタバコの専売制を敷いたが、これはベラクルス地域の農業と製造業に直接的な影響を与えた。タバコは需要の高い貴重な商品であった。男 性、女性、そして子供までもがタバコを吸っていたが、これは外国からの旅行者によって言及され、18世紀の風俗画にも描かれている。王冠は、メキシコ国内 の膨大な需要を満たすことで、タバコから安定した税収が得られると計算し、タバコの栽培地域を限定した。また、完成品の製造工場を少数設置し、販売所(エ ストゥンシージョ)に販売許可を与えた。[44] さらに、1年分の供給量に相当するタバコの紙を保管する倉庫を設置した。[45] 専売制の確立により、王家の収入は増加し、高価格と貧困率の拡大にもかかわらず、タバコの消費量は増加し、一方で一般消費は減少したという証拠がある。 [46] 1787年のブルボン朝改革により、ベラクルスはインテンデンシア(intendancy)という新たな行政単位となった。 |

| Valley of Puebla Founded in 1531 as a Spanish settlement, Puebla de los Angeles quickly rose to the status of Mexico's second-most important city. Its location on the main route between the viceregal capital and the port of Veracruz, in a fertile basin with a dense indigenous population, largely not held in encomienda, made Puebla a destination for later arriving Spaniards. If there had been significant mineral wealth in Puebla, it could have been even more prominent a center for New Spain, but its first century established its importance. In 1786 it became the capital of an intendancy of the same name.[47] It became the seat of the richest diocese in New Spain in its first century, with the seat of the first diocese, formerly in Tlaxcala, moved there in 1543.[48] Bishop Juan de Palafox asserted that the income from the diocese of Puebla was twice that of the archbishopic of Mexico, due to the tithe income derived from agriculture.[49] In its first hundred years, Puebla was prosperous from wheat farming and other agriculture, as the ample tithe income indicates, plus manufacturing woolen cloth for the domestic market. Merchants, manufacturers, and artisans were important to the city's economic fortunes, but its early prosperity was followed by stagnation and decline in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[50] The foundation of the town of Puebla was a pragmatic social experiment to settle Spanish immigrants without encomiendas to pursue farming and industry.[51] Puebla was privileged in a number of ways, starting with its status as a Spanish settlement not founded on existing indigenous city-state, but with a significant indigenous population. It was located in a fertile basin on a temperate plateau in the nexus of the key trade triangle of Veracruz–Mexico City–Antequera (Oaxaca). Although there were no encomiendas in Puebla itself, encomenderos with nearby labor grants settled in Puebla. And despite its foundation as a Spanish city, sixteenth-century Puebla had Indians resident in the central core.[51] Administratively Puebla was far enough from Mexico City (approximately 160 km or 100 mi) so as not to be under its direct influence. Puebla's Spanish town council (cabildo) had considerable autonomy and was not dominated by encomenderos. The administrative structure of Puebla "may be seen as a subtle expression of royal absolutism, the granting of extensive privileges to a town of commoners, amounting almost to republican self-government, in order to curtail the potential authority of encomenderos and the religious orders, as well as to counterbalance the power of the viceregal capital."[52]  An Indian Wedding and Flying Pole, c. 1690 During the "golden century" from its founding in 1531 until the early 1600s, Puebla's agricultural sector flourished, with small-scale Spanish farmers plowing the land for the first time, planting wheat and vaulting Puebla to importance as New Spain's breadbasket, a role assumed by the Bajío (including Querétaro) in the seventeenth century, and Guadalajara in the eighteenth.[53] Puebla's wheat production was the initial source of its prosperity, but it emerged as a manufacturing and commercial center, "serving as the inland port of Mexico's Atlantic trade".[54] Economically, the city was exempted from the alcabala (sales tax) and almojarifazgo (import/export duties) for its first century (1531–1630), which helped promote commerce. Puebla built significant textile production in workshops (obrajes) supplying New Spain and markets as far away as Guatemala and Peru. Transatlantic ties between a particular Spanish town, Brihuega, and Puebla demonstrated the close connection between the two settlements. The growth in Puebla's manufacturing sector did not simply coincide with immigration from Brihuega but was crucial to "shaping and driving Puebla's economic development".[55] Brihuega immigrants came to Mexico with expertise in textile production, and the transplanted briocenses provided capital to create large-scale obrajes. Although obrajes in Brihuega were small-scale enterprises, quite a number of them in Puebla employed up to 100 workers. Supplies of wool, water for fulling mills, and labor (free indigenous, incarcerated Indians, black slaves) were available. Although much of Puebla's textile output was rough cloth, it also produced higher quality dyed cloth with cochineal from Oaxaca and indigo from Guatemala.[56] But by the eighteenth century, Querétaro had displaced Puebla as the mainstay of woolen textile production.[57] In 1787, Puebla became an intendancy as part of the new administrative structuring of the Bourbon Reforms. |

プエブラの谷 1531年にスペイン人の入植地として創設されたプエブラ・デ・ロス・アンヘレスは、急速にメキシコ第2の都市へと成長した。 総督府の首都とベラクルス港を結ぶ主要ルート上に位置し、先住民の人口が密集する肥沃な盆地にあったプエブラは、エンコミエンダ制の対象となっていなかっ たため、後にやってきたスペイン人たちの目的地となった。プエブラに鉱物資源が豊富にあったならば、ヌエバ・エスパーニャの中心都市としてさらに重要な地 位を占めることができたかもしれないが、最初の1世紀でその重要性が確立された。1786年には、同名のインテンデンシアの首都となった。 プエブラは、その最初の1世紀において、ヌエバ・エスパーニャで最も裕福な司教区の所在地となり、1543年には、それまでトラスカラにあった最初の司教 区の所在地がプエブラに移された。[48] プエブラ司教フアン・デ・パラフォックスは、農業から得られる什分の一税収入により、プエブラ司教区の収入はメキシコ大司教区の2倍であると主張した。 [49] プエブラは、最初の100年間、小麦の農業やその他の農業で繁栄し、 十分な什分の一税収入が示すように、国内市場向けの羊毛織物の製造も行われていた。商人、製造業者、職人たちは市の経済にとって重要であったが、17世紀 と18世紀には初期の繁栄は停滞と衰退を招いた。 プエブラの町の建設は、エンコミエンダを持たないスペイン人移民を定住させ、農業と工業を推進するという実用的な社会実験であった。[51] プエブラは、いくつかの点で特権的な立場にあった。まず、既存の先住民の都市国家ではなく、先住民の人口がかなり多いスペイン人入植地として建設されたと いう点である。プエブラは、ベラクルス、メキシコシティ、オアハカ(アンテケラ)を結ぶ主要な貿易三角地帯の中にある、温帯の高原の肥沃な盆地に位置して いた。プエブラ自体にはエンコミエンダは存在しなかったが、近隣の労働許可証を持つエンコミエンダの所有者たちはプエブラに定住した。また、スペイン人に よる都市として建設されたにもかかわらず、16世紀のプエブラにはインディアンが中心部に居住していた。 行政上、プエブラはメキシコシティから十分離れており(約160kmまたは100マイル)、メキシコシティの直接的な影響下には置かれていなかった。プエ ブラのスペイン人町議会(cabildo)はかなりの自治権を有しており、エンコンディエロたちに支配されることはなかった。プエブラの行政機構は「王家 の絶対主義の微妙な表現と見なすことができる。平民の町に広範な特権を付与することで、事実上共和制の自治を実現し、エンコミエンダ所有者や修道会の潜在 的な権力を抑制するとともに、副王の首都の権力に対抗しようとしたのである」[52]。  インディアンの結婚式とポール、1690年頃 1531年の創設から1600年代初頭までの「黄金の世紀」の間、プエブラの農業部門は繁栄し、スペイン人の小規模農家が初めて土地を耕し、小麦を植え、 プエブラをヌエバ・エスパーニャの穀倉地帯として重要な都市へと押し上げた。この役割は17世紀にはバヒオ(ケレタロを含む)、18世紀にはグアダラハラ が担うことになる。[53] プエブラの小麦生産は 小麦生産がプエブラの繁栄の最初の源であったが、やがて製造業と商業の中心地として発展し、「メキシコの大西洋貿易の内陸港としての役割を果たした」 [54]。経済的には、プエブラ市は最初の100年間(1531年から1630年)はアルカバラ(売上税)とアルモハリファゴ(輸出入関税)が免除され、 それが商業の促進につながった。 プエブラは、ニュー・スペインや遠くグアテマラやペルーにまで商品を供給する織物工房(obrajes)で、重要な織物生産を築き上げた。スペインのブリ ウエガという町とプエブラの間の大西洋をまたいだつながりは、この2つの入植地の緊密な関係を示していた。プエブラの製造業の成長は、単にブリウエガから の移民と一致したというだけでなく、「プエブラの経済発展の形成と推進」に不可欠であった。 ブリウエガからの移民は繊維生産の専門知識を持ってメキシコにやって来た。そして、ブリウエガから移住した人々は、大規模な織物工場を設立するための資本 を提供した。ブリウエガの織物工場は小規模な企業であったが、プエブラでは100人もの労働者を雇用する工場も数多くあった。羊毛、縮絨工場用の水、労働 力(自由な先住民、収監されたインディアン、黒人奴隷)が利用可能であった。プエブラの織物の多くは粗野な布であったが、オアハカ産のコチニールで染めた 布やグアテマラ産の藍で染めた布など、より高品質な布も生産されていた。[56] しかし18世紀には、ケレタロがプエブラに代わって毛織物生産の中心地となっていた。[57] 1787年、プエブラはブルボン朝改革による新たな行政機構の一部として、知事管区となった。 |

| Valley of Mexico Mexico City dominated the Valley of Mexico, but the valley continued to have dense indigenous populations challenged by growing, increasingly dense Spanish settlement. The Valley of Mexico had many former Indian city-states that became Indian towns in the colonial era. These towns continued to be ruled by indigenous elites under the Spanish crown, with an indigenous governor and a town councils.[58][59] The Indian towns close to the capital were the most desirable ones for encomenderos to hold and for the friars to evangelize. The capital was provisioned by the indigenous towns, and its labor was available for enterprises that ultimately created a colonial economy. The gradual drying up of the central lake system created more dry land for farming, but the sixteenth-century population declines allowed Spaniards to expand their acquisition of land. One region that retained strong Indian land holding was the southern fresh water area, with important suppliers of fresh produce to the capital. The area was characterized by intensely cultivated chinampas, human-made extensions of cultivable land into the lake system. These chinampa towns retained a strong indigenous character, and Indians continued to hold the majority of that land, despite its closeness to the Spanish capital. A key example is Xochimilco.[60][61][62] Texcoco in the pre-conquest period was one of the three members of the Aztec Triple Alliance and the cultural center of the empire. It fell on hard times in the colonial period as an economic backwater. Spaniards with any ambition or connections would be lured by the closeness of Mexico City, so that the Spanish presence was minimal and marginal.[63] Tlaxcala, the major ally of the Spanish against the Aztecs of Tenochtitlan, also became something of a backwater, but like Puebla it did not come under the control of Spanish encomenderos. No elite Spaniards settled there, but like many other Indian towns in the Valley of Mexico, it had an assortment of small-scale merchants, artisans, farmers and ranchers, and textile workshops (obrajes).[64] |

メキシコ湾 メキシコシティはメキシコ湾を支配していたが、この地域にはスペイン人の入植が増加し、人口密度が高まるにつれ、先住民の人口密度の高い地域が存在し続け た。メキシコ湾には、植民地時代にインディアンの町となった元のインディアンの都市国家が数多くあった。これらの町はスペイン王の下で先住民エリート層に よって統治され、先住民の知事と町議会が置かれた。[58][59] 首都に近いインディアンの町は、エンコミエンダ所有者や修道士にとって最も魅力的な町であった。 首都は先住民の町から物資が供給され、その労働力は最終的に植民地経済を生み出す事業に利用された。中央の湖の水系が徐々に干上がったことで、農業に適し た乾燥地が増えたが、16世紀の人口減少によりスペイン人は土地の獲得を拡大することができた。インディアンの土地所有が強かった地域の一つは、首都に新 鮮な農産物を供給する重要な地域であった南部の淡水地域であった。この地域は、湖の生態系に人為的に耕作地を広げたチンアンパ(chinampas)が特 徴的であった。これらのチンアンパの町は、先住民の性格を強く残しており、スペインの首都に近かったにもかかわらず、インディアンがその土地の大半を所有 し続けた。その代表的な例がソチミルコ(Xochimilco)である。[60][61][62] 征服前のテスココは、アステカの三つ同盟の3つのメンバーの1つであり、帝国の文化の中心地であった。植民地時代には経済的に遅れた地域として苦境に立た された。野心やコネを持つスペイン人は、メキシコシティに近いという理由で魅了されたが、スペイン人の存在は最小限で限定的であった。 アステカのテノチティトランに対するスペインの主要な同盟国であったトラスカラも僻地のような存在となったが、プエブラと同様にスペインの恩恵を受ける者 たちの支配下には置かれなかった。エリートスペイン人はそこに定住することはなかったが、メキシコ盆地の他の多くのインディアンの町と同様に、小規模な商 人、職人、農民、牧場主、織物工房(obrajes)などが集まっていた。[64] |

| North Since portions of northern New Spain became part of the United States' Southwest region, there has been considerable scholarship on the Spanish borderlands in the north. The motor of the Spanish colonial economy was the extraction of silver. In Bolivia, it was from the single rich mountain of Potosí; but in New Spain, there were two major mining sites, one in Zacatecas, the other in Guanajuato. The region farther north of the main mining zones attracted few Spanish settlers. Where there were settled indigenous populations, such as in the present-day state of New Mexico and in coastal regions of Baja and Alta California, indigenous culture retained considerable integrity. Bajío, Mexico's breadbasket The Bajío, a rich, fertile lowland just north of central Mexico, was nonetheless a frontier region between the densely populated plateaus and valleys of Mexico's center and south and the harsh northern desert controlled by nomadic Chichimeca. Devoid of settled indigenous populations in the early sixteenth century, the Bajío did not initially attract Spaniards, who were much more interested in exploiting labor and collecting tribute whenever possible. The region did not have indigenous populations that practiced subsistence agriculture. The Bajío developed in the colonial period as a region of commercial agriculture. The discovery of mining deposits in Zacatecas and Guanajuato in the mid-sixteenth century and later in San Luis Potosí stimulated the Bajío's development to supply the mines with food and livestock. A network of Spanish towns was established in this region of commercial agriculture, with Querétaro also becoming a center of textile production. Although there were no dense indigenous populations or network of settlements, Indians migrated to the Bajío to work as resident employees on the region's haciendas and ranchos or rented land (terrasguerros). From diverse cultural backgrounds and with no sustaining indigenous communities, these indios were quickly hispanized, but largely remained at the bottom of the economic hierarchy.[65] Although Indians migrated willingly to the region, they did so in such small numbers that labor shortages prompted Spanish hacendados to provide incentives to attract workers, especially in the initial boom period of the early seventeenth century. Land owners lent workers money, which could be seen as a perpetual indebtedness, but it can be seen not as coercing Indians to stay but a way estate owners sweetened their terms of employment, beyond their basic wage labor.[66][67] For example, in 1775 the Spanish administrator of a San Luis Potosí estate "had to scour both Mexico City and the northern towns to find enough blue French linen to satisfy the resident employees".[68] Other types of goods they received on credit were textiles, hats, shoes, candles, meat, beans, and a guaranteed ration of maize. However, where labor was more abundant or market conditions depressed, estate owners paid lower wages. The more sparsely populated northern Bajío tended to pay higher wages than the southern Bajío, which was increasingly integrated in the economy of central Mexico.[69] The credit-based employment system often privileged those holding higher ranked positions on the estate (supervisors, craftsmen, other specialists) who were mostly white, and the estates did not demand repayment.[70] In the late colonial period, renting complemented estate employment for many non-Indians in more central areas of the Bajío with access to markets. As with hacendados, renters produced for the commercial market. While these Bajío renters could prosper in good times and achieved a level of independence, drought and other disasters made their choice more risky than beneficial.[71] Many renters retained ties to the estates, diversifying their household's sources of income and level of economic security. In San Luis Potosí, rentals were fewer and estate employment the norm. After a number of years of drought and bad harvests in the first decade of the nineteenth century Hidalgo's 1810 grito appealed more in the Bajío than in San Luis Potosí. In the Bajío estate owners were evicting tenants in favor of renters better able to pay more for land, there was a disruption of previous patterns of mutual benefit between estate owners and renters.[69] |

北部 ヌエバ・エスパーニャ北部の一部が米国南西部の一部となって以来、北部のスペイン国境地域に関する研究が盛んに行われるようになった。スペインの植民地経 済の原動力は銀の採掘であった。ボリビアではポトシの単一の豊かな鉱山からであったが、ヌエバ・エスパーニャでは、サカテカスとグアナフアトの2つの主要 な鉱山があった。 主要な鉱山地帯からさらに北の地域には、スペイン人入植者はほとんどいなかった。現在のニューメキシコ州やバハ・カリフォルニア州およびアルタ・カリフォルニア州の沿岸地域のように、先住民が定住していた地域では、先住民の文化はかなり完全な形で保たれていた。 メキシコの穀倉地帯、バヒオ メキシコ中央部のすぐ北に位置する豊かな低地であるバヒオは、人口密度の高いメキシコ中央部および南部の高原や渓谷と、遊牧民チチメカ族が支配する北部の 過酷な砂漠地帯との間の辺境地域であった。16世紀初頭には定住した先住民の人口が存在しなかったため、スペイン人の関心を引くことはなく、スペイン人は 労働力の搾取や貢納の徴収にしか興味を示さなかった。この地域には自給自足の農業を営む先住民はいなかった。バヒオは植民地時代に商業農業地域として発展 した。 16世紀半ばにサカテカスとグアナフアトで、その後サン・ルイス・ポトシで鉱床が発見されたことにより、鉱山に食料や家畜を供給する地域としてバヒオの開 発が促進された。商業農業地域であるこの地域にはスペインの町々のネットワークが形成され、ケレタロも織物生産の中心地となった。先住民の人口密集地や集 落のネットワークは存在しなかったが、インディアンたちはバヒオの農園や牧場で常勤の従業員として働くため、あるいは土地を借りて(テラスゲロ)移住し た。多様な文化的背景を持ち、先住民族のコミュニティを持たないこれらのインディアンは急速にスペイン化していったが、経済的階層の底辺にとどまることが 多かった。[65] インディアンたちは自ら進んでこの地域に移住したが、その数は少なく、労働力不足を解消するためにスペインの大地主たちは労働者を引き付けるためのインセ ンティブを提供した。特に17世紀初頭の初期の好況期にはその傾向が顕著であった。土地所有者は労働者に金を貸したが、これは永遠に続く負債と見なすこと もできるが、インディアンを強制的に留め置くためではなく、土地所有者が基本賃金労働以上の雇用条件を提示したと見なすこともできる。[66][67] 例えば、1775年には、サン・ルイス・ポトシの土地のスペイン人管理者が「メキシコシティと北部の町を捜し回って、常駐の従業員を満足させるのに十分な 青いフランス製リネンを見つけなければならなかった」という。[68] 彼らが信用取引で受け取ったその他の品目は、織物、帽子、靴、ろうそく、肉、豆、そしてトウモロコシの配給量であった。しかし、労働力がより豊富にある場 合や市場が低迷している場合には、農園主は賃金を低く設定した。人口密度が低い北部バヒオでは、メキシコ中央部の経済に統合されつつあった南部バヒオより も賃金が高くなる傾向があった。[69] 信用に基づく雇用システムでは、農園内でより高い地位にある者(監督者、職人、その他の専門家)が優先されることが多く、彼らの大半は白人であった。農園 側は返済を要求することはなかった。[70] 植民地時代後期には、市場へのアクセスがあるバヒオの中心地域では、多くの非インディアンが農園での雇用に加えて小作人として働くようになった。農園主と 同様に、小作人も商業市場向けに生産を行っていた。こうしたバヒオの小作人は好況時には繁栄し、ある程度の独立性を獲得することができたが、干ばつやその 他の災害により、その選択は有益であるよりもリスクの高いものとなった。 多くの小作人は農園とのつながりを維持し、家計の収入源と経済的な安定性を多様化させた。サン・ルイス・ポトシでは、小作地は少なく、農園での雇用が一般 的であった。19世紀の最初の10年間、干ばつと不作が何年も続いた後、1810年のヒダルゴの叫びは、バヒオ地方でサン・ルイス・ポトシよりも大きな反 響を呼んだ。バヒオ地方では、土地所有者たちは、より多くの地代を支払える借地人に有利になるよう、小作人を立ち退かせた。その結果、土地所有者と借地人 の間の相互利益の関係は崩壊した。[69] |

| Spanish borderlands Areas of northern Mexico were incorporated into the United States in the mid-nineteenth century, following Texas independence and the Mexican–American War (1846–48) and generally known as the "Spanish Borderlands".[72][73] Scholars in the United States have extensively studied this northern region, which became the states of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California.[74][75][76][77] During the period of Spanish rule, this area was sparsely populated even by indigenous peoples.[78] The Presidios (forts), pueblos (civilian towns) and the misiones (missions) were the three major agencies employed by the Spanish crown to extend its borders and consolidate its colonial holdings in these territories. Missions and the northern frontier The town of Albuquerque (modern Albuquerque, New Mexico) was founded in 1706. Other Mexican towns in the region included Paso del Norte (modern Ciudad Juárez), founded in 1667; Santiago de la Monclova in 1689; Panzacola, Tejas in 1681; and San Francisco de Cuéllar (modern city of Chihuahua) in 1709. From 1687, Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, with funding from the Marqués de Villapuente, founded over twenty missions in the Sonoran Desert (in modern Sonora and Arizona). From 1697, Jesuits established eighteen missions throughout the Baja California peninsula. Between 1687 and 1700 several missions were founded in Trinidad, but only four survived as Amerindian villages throughout the 18th century. In 1691, explorers and missionaries visited the interior of Texas and came upon a river and Amerindian settlement on 13 June, the feast day of St. Anthony, and named the location and river San Antonio in his honor. |

スペイン語圏の国境地帯 メキシコ北部の地域は、テキサス独立と米墨戦争(1846年-1848年)を経て、19世紀半ばにアメリカ合衆国に編入され、一般的に「スペイン領国境地 域」として知られている。[72][73] テキサス州、ニューメキシコ州、アリゾナ州、カリフォルニア州となったこの北部地域は、アメリカ合衆国の学者たちによって広く研究されている。[74] [75][76][77] スペイン統治時代には、 この地域には先住民でさえもまばらにしか住んでいなかった。 要塞(プレシディオ)やプエブロ(民間人の町)、ミシオン(布教所)は、スペイン王が国境を広げ、これらの領土における植民地所有地を統合するために用いた3つの主要機関であった。 ミッションと北部の国境 アルバカーキ(現ニューメキシコ州アルバカーキ)の町は1706年に創設された。この地域には、1667年に創設されたパソ・デル・ノルテ(現シウダー・ フアレス)、1689年のサンティアゴ・デ・ラ・モンクロバ、1681年のパンサコラ(テキサス)、1709年のサンフランシスコ・デ・クエジャール(現 チワワ市)などのメキシコの町もあった。1687年以降、エウセビオ・フランシスコ・キノ神父は、ヴィラプエンテ侯爵の資金援助を受け、ソノラ砂漠(現在 のソノラ州とアリゾナ州)に20以上の伝道所を設立した。 1697年以降、イエズス会はバハ・カリフォルニア半島全体に18の伝道所を設立した。1687年から1700年の間に、トリニダードにはいくつかの伝道 所が設立されたが、18世紀を通じて先住民の村として存続したのは4つのみであった。1691年、探検家と宣教師がテキサス州の奥地を訪れ、6月13日、 聖アントニウスの祝日に、川とアメリカインディアンの集落を発見した。彼らはその場所と川を聖アントニウスの名にちなんでサンアントニオと名付けた。 |

New Mexico San Miguel chapel in New Mexico During the term of viceroy Don Luis de Velasco, marqués de Salinas the crown ended the long-running Chichimeca War by making peace with the semi-nomadic Chichimeca indigenous tribes of northern México in 1591. This allowed expansion into the 'Province of New Mexico' or Provincia de Nuevo México. In 1595, Don Juan de Oñate, son of one of the key figures in the silver remining region of Zacatecas, received official permission from the viceroy to explore and conquer New Mexico. As was the pattern of such expeditions, the leader assumed the greatest risk but would reap the largest rewards, so that Oñate would become capitán general of New Mexico and had the authority to distribute rewards to those in the expedition.[79] Oñate pioneered 'The Royal Road of the Interior Land' or El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro between Mexico City and the Tewa village of Ohkay Owingeh, or San Juan Pueblo. He also founded the Spanish settlement of San Gabriel de Yungue-Ouinge on the Rio Grande near the Native American Pueblo, located just north of the modern city of Española, New Mexico.[80] Oñate eventually learned that New Mexico, while it had a settled indigenous population, had little arable land, no silver mines, and possessed few other resources to exploit that would merit large scale colonization. He resigned as governor in 1607 and left New Mexico, having lost much of his personal wealth on the enterprise.[81] In 1610, Pedro de Peralta, a later governor of the Province of New Mexico, established the settlement of Santa Fe near the southern end of the Sangre de Cristo mountain range. Missions were established to convert the indigenous peoples and manage the agricultural industry. The territory's indigenous population resented their forced conversion to Catholicism and suppression of their religion, and the imposition of encomienda system of forced labor. The unrest led to the Pueblo Revolt in 1680, expelling the Spanish, who retreated to Paso del Norte, modern-day Ciudad Juárez.[82] After the return of the Spanish in 1692, the final resolution included a marked reduction of Spanish efforts to eradicate native culture and religion, the issuing of substantial communal land grants to each Pueblo, and a public defender of their rights and for their legal cases in Spanish courts. In 1776 the New Mexico came under the new Provincias Internas jurisdiction. In the late 18th century the Spanish land grant encouraged the settlement by individuals of large land parcels outside Mission and Pueblo boundaries, many of which became ranchos.[83] |

ニューメキシコ ニューメキシコのサンミゲル礼拝堂 ドン・ルイス・デ・ベラスコ・サルナス侯爵が総督を務めていた時代、1591年にメキシコ北部の半遊牧民族チチメカ族と和平を結ぶことで、長年にわたって 続いていたチチメカ戦争が終結した。これにより、「ニューメキシコ州」または「ヌエボ・メヒコ州」への進出が可能となった。1595年、サカテカス州の銀 鉱地域における主要人物の一人の息子であるドン・ファン・デ・オニャテは、副王からニューメキシコの探検と征服の正式な許可を受けた。このような探検のパ ターンでは、リーダーが最大のリスクを負うが、最大の報酬を得る。そのため、オニャテはニューメキシコの総指揮官となり、探検隊のメンバーに報酬を分配す る権限を与えられた。 オニャーテは、メキシコシティとテワ族のオカイ・オウィンゲ村(またはサンファン・プエブロ)を結ぶ「内陸の王の道」または「エル・カミーノ・レアル・ デ・ティエラ・アデンテロ」を開拓した。また、ニューメキシコ州エスパニョーラ市のすぐ北にあるプエブロ族の集落の近く、リオ・グランデ川沿いに、サン・ ガブリエル・デ・ユンゲ・オインゲというスペイン人の入植地を設立した。[80] オニャーテは最終的に、ニューメキシコには先住民の定住人口はいるものの、耕作に適した土地はほとんどなく、銀鉱山もなく、大規模な入植に値するような資 源はほとんどないことを知った。彼は1607年に総督を辞任し、ニューメキシコを去った。この事業で、彼は多くの個人資産を失っていた。 1610年、後にニューメキシコ州知事となるペドロ・デ・ペラルタが、サングレ・デ・クリスト山脈の南端近くにサンタフェの入植地を建設した。先住民の改 宗と農業産業の管理を目的とした伝道所が設立された。この地域の先住民たちは、カトリックへの強制改宗や信仰の弾圧、エンコミエンダ制度による強制労働の 強要に不満を抱いていた。 1680年には、この不満がプエブロの反乱へと発展し、スペイン人は追放され、現在のシウダー・フアレスにあたるパソ・デル・ノルテまで撤退した。 1692年にスペイン人が戻ってきてから、最終的な解決策として、先住民の文化や宗教を根絶しようとするスペインの取り組みが大幅に削減され、プエブロの 各集落に広大な共同土地が交付され、スペインの法廷における彼らの権利と訴訟の弁護が公的に行われることになった。1776年、ニューメキシコはプロビン シアス・インタナス(Provincias Internas)の新たな管轄下に入った。18世紀後半には、スペインの土地割当が、ミッションやプエブロの境界外にある広大な土地の個人による入植を 促し、その多くがランチョとなった。[83] |

| California In 1602, Sebastián Vizcaíno, the first Spanish presence in the 'New California' (Nueva California) region of the frontier Las Californias province since Cabrillo in 1542, sailed as far north up the Pacific Coast as present-day Oregon, and named California coastal features from San Diego to as far north as the Bay of Monterrey. Not until the eighteenth century was California of much interest to the Spanish crown, since it had no known rich mineral deposits or indigenous populations sufficiently organized to render tribute and do labor for Spaniards. The discovery of huge deposits of gold in the Sierra Nevada foothills did not come until after the U.S. had added California following the Mexican–American War (1846–48). By the middle of the 1700s, the Catholic order of Jesuits had established a number of missions on the Baja (lower) California peninsula. Then, in 1767, King Charles III ordered all Jesuits expelled from all Spanish possessions, including New Spain.[84] New Spain's Visitador General José de Gálvez replaced them with the Dominican Order in Baja California, and the Franciscans were chosen to establish new northern missions in Alta (upper) California. In 1768, Gálvez received the order to "Occupy and fortify San Diego and Monterey for God and the King of Spain". The Spanish colonies there, having far fewer known natural resources and less cultural development than Mexico or Peru, were to combine establishing posts to defend the territory with a perceived responsibility to convert the indigenous people to Catholicism. The method used to "occupy and fortify" was the established Spanish colonial system: missions (misiones, between 1769 and 1833 twenty-one missions were established) aimed at converting the Native Californians to Catholicism, forts (presidios, four total) to protect the missionaries, and secular municipalities (pueblos, three total). Due to the region's great distance from supplies and support in México, the system had to be largely self-sufficient. As a result, the colonial population of California remained small, widely scattered and near the coast. In 1776, the north-western frontier areas came under the administration of the new 'Commandancy General of the Internal Provinces of the North' (Provincias Internas), designed to streamline administration and invigorate growth. The crown created two new provincial governments from the former Las Californias in 1804; the southern peninsula became Baja California, and the ill-defined northern mainland frontier area became Alta California. Once missions and protective presidios were established in an area, large land grants encouraged settlement and establishment of California ranchos. The Spanish system of land grants was not very successful; however, because the grants were merely royal concessions—not actual land ownership. Under later Mexican rule, land grants conveyed ownership, and were more successful at promoting settlement. Rancho activities centered on cattle-raising; many grantees emulated the Dons of Spain, with cattle, horses and sheep the source of wealth. The work was usually done by Native Americans, sometimes displaced and/or relocated from their villages. Native-born descendants of the resident Spanish-heritage rancho grantees, soldiers, servants, merchants, craftsmen and others became the Californios. Many of the less-affluent men took native wives, and many daughters married later English, French and American settlers. After the Mexican War of Independence (1821) and subsequent secularization ("disestablishment") of the missions (1834), Mexican land grant transactions increased the spread of the rancho system. The land grants and ranchos established mapping and land-ownership patterns that are still recognizable in present-day California and New Mexico.[85] |

カリフォルニア 1602年、1542年のカブリヨ以来、辺境のラス・カリフォルニアス州の「ニュー・カリフォルニア」(ヌエバ・カリフォルニア)地域に初めてスペイン人 が足を踏み入れたセバスチャン・ビスカイノが、太平洋岸をオレゴン州まで北上し、サンディエゴからモンテレー湾までの海岸の地形に「カリフォルニア」と名 付けた。 カリフォルニアは、スペイン王にとって興味深い地域となるのは18世紀に入ってからであった。なぜなら、この地域には豊富な鉱物資源があることも知られて いなかったし、スペイン人への貢納や労働に従事するだけの組織化された先住民の集団も存在していなかったからである。シエラネバダ山脈のふもとに膨大な量 の金鉱が発見されたのは、米墨戦争(1846年~1848年)の後、米国がカリフォルニアを併合した後になってからであった。 1700年代半ばには、イエズス会のカトリック教団がバハ・カリフォルニア半島に多くの伝道所を設立していた。その後、1767年にスペイン王カルロス3 世は、ヌエバ・エスパーニャを含むスペイン領土からのイエズス会の追放を命じた。[84] ヌエバ・エスパーニャの総督ホセ・デ・ガルベスは、バハ・カリフォルニアのイエズス会に代わってドミニコ会を派遣し、フランシスコ会はアルタ・カリフォル ニア北部に新たな宣教所を設立することになった。 1768年、ガルベスは「神とスペイン王のためにサンディエゴとモントレーを占領し、要塞化せよ」との命令を受けた。 スペインの植民地は、メキシコやペルーに比べると天然資源も少なく、文化の発展も遅れていたが、領土を守るための拠点の確立と、先住民をカトリックに改宗 させるという自覚的な責任を併せ持つことになった。 「占領と要塞化」という手法は、スペインの植民地システムとして確立されていた。すなわち、ミッション(1769年から1833年の間に21のミッション が設立された)は、カリフォルニア先住民をカトリックに改宗させることを目的としていた。また、宣教師たちを守るための砦(プレシディオ、合計4つ)と世 俗的な自治体(プエブロ、合計3つ)が設置された。メキシコからの物資や支援が届くのが遠く離れた地域であったため、そのシステムはほぼ自給自足でまかな う必要があった。その結果、カリフォルニアの植民地人口は少なく、広く分散し、海岸近くに留まった。 1776年、行政の合理化と活性化を目的として、北西部の辺境地域は「北の内陸地方総督府(Provincias Internas)」の管轄下に置かれた。1804年、スペイン王は旧ラス・カリフォルニアスから2つの新しい州政府を創設した。南の半島はバハ・カリ フォルニアとなり、境界があいまいな北の大陸辺境地域はアルタ・カリフォルニアとなった。 伝道所と防衛要塞が地域に設置されると、広大な土地の割当がカリフォルニア・ランチョの入植と開拓を促進した。スペインの土地割当制度はあまり成功しな かった。なぜなら、割当は単に王族の譲歩に過ぎず、実際の土地所有権ではなかったからだ。後のメキシコ支配下では、土地割当は所有権を譲渡し、入植を促進 する上でより成功を収めた。 牧場での活動は主に家畜の飼育が中心であり、多くの入植者はスペインの貴族たちを手本とし、牛、馬、羊を富の源とした。 通常、こうした作業はアメリカ先住民によって行われたが、時には彼らの村から追われたり、移住させられたりした。 スペイン系入植者、兵士、使用人、商人、職人など、スペイン系入植者の子孫でカリフォルニアで生まれた人々は「カリフォニオス」と呼ばれるようになった。 裕福でない多くの男性は先住民の女性と結婚し、多くの娘たちは後にイギリス人、フランス人、アメリカ人の入植者と結婚した。 メキシコ独立戦争(1821年)とそれに続くミッションの世俗化(1834年)の後、メキシコの土地交付取引により、ランチョ制度はさらに広がった。土地 交付とランチョは、地図作成と土地所有のパターンを確立し、それは現在でもカリフォルニア州とニューメキシコ州で確認することができる。[85] |

| South Yucatán  The cathedral of Mérida, Yucatán The Yucatán Peninsula can be considered a cul-de-sac,[86] and it has unique features, but it also has strong similarities to other areas in the South. The Yucatán Peninsula extends into the Gulf of Mexico and was connected to Caribbean trade routes and Mexico City, far more than some other southern regions, such as Oaxaca.[87] The main Spanish settlements included the inland city of Mérida, where Spanish civil and religious officials had their headquarters and where the many Spaniards in the province lived. The villa of Campeche was the peninsula's port, the key gateway for the whole region. A merchant group developed and expanded dramatically as trade flourished during the seventeenth century.[88] Although that period was once characterized as New Spain's "century of depression", for Yucatán this was certainly not the case, with sustained growth from the early seventeenth century to the end of the colonial period.[89] With dense indigenous Maya populations, Yucatán's encomienda system was established early and persisted far longer than in central Mexico, since fewer Spaniards migrated to the region than in the center.[90] Although Yucatán was a more peripheral area to the colony, since it lacked rich mining areas and no agricultural or other export product, it did have a complex of Spanish settlement, with a whole range of social types in the main settlements of Mérida and the villas of Campeche and Valladolid.[91] There was an important sector of mixed-race "castas", some of whom were fully at home in both the indigenous and Hispanic worlds. Blacks were an important component of Yucatecan society.[92] The largest population in the province was indigenous Maya, who lived in their communities, but which were in contact with the Hispanic sphere via labor demands and commerce.[93] In Yucatán, Spanish rule was largely indirect, allowing these communities considerable political and cultural autonomy. The Maya community, the cah, was the means by which indigenous cultural integrity was maintained. In the economic sphere, unlike many other regions and ethnic groups in Mesoamerica, the Yucatec Maya did not have a pre-conquest network of regular markets to exchange different types of food and craft goods. Perhaps because the peninsula was uniform in its ecosystem local niche production did not develop.[94] Production of cotton textiles, largely by Maya women, helped pay households' tribute obligations, but basic crops were the basis of the economy. The cah retained considerable land under the control of religious brotherhoods or confraternities (cofradías), the device by which Maya communities avoided colonial officials, the clergy, or even indigenous rulers (gobernadores) from diverting of community revenues in their cajas de comunidad (literally community-owned chests that had locks and keys). Cofradías were traditionally lay pious organizations and burial societies, but in Yucatán they became significant holders of land, a source of revenue for pious purposes kept under cah control. "[I]n Yucatán the cofradía in its modified form was the community."[95] Local Spanish clergy had no reason to object to the arrangement since much of the revenue went for payment for masses or other spiritual matters controlled by the priest. A limiting factor in Yucatán's economy was the poor quality of the limestone soil, which could only support crops for two to three years with land cleared through slash-and-burn agriculture. Access to water was also a limiting factor on agriculture, with the limestone escarpment giving way in water filled sinkholes (locally called cenotes), but rivers and streams were generally absent on the peninsula. Individuals had rights to land so long as they cleared and tilled them and when the soil was exhausted, they repeated the process. In general, the Indians lived in a dispersed pattern, which Spanish congregación or forced resettlement attempted to alter. Collective labor cultivated the confraternities' lands, which included raising the traditional maize, beans, and cotton. But confraternities also later pursued cattle ranching, as well as mule and horse breeding, depending on the local situation. There is evidence that cofradías in southern Campeche were involved in inter-regional trade in cacao as well as cattle ranching.[96] Although generally the revenues from crops and animals were devoted to expenses in the spiritual sphere, cofradías' cattle were used for direct aid to community members during droughts, stabilizing the community's food supply.[97] In the seventeenth century, patterns shifted in Yucatán and Tabasco, as the English took territory the Spanish claimed but did not control, especially what became British Honduras (now Belize) and in Laguna de Términos (Isla del Carmen) where they cut logwood. In 1716–17 viceroy of New Spain organized a sufficient ships to expel the foreigners, where the crown subsequently built a fortress at Isla del Carmen.[98] But the British held onto their territory in the eastern portion of the peninsula into the twentieth century. In the nineteenth century, the enclave supplied guns to the rebellious Maya in the Caste War of Yucatan.[99] |

南 ユカタン  ユカタン半島、メリダの大聖堂 ユカタン半島は袋小路とみなすことができるが、[86] 独特の特徴がある一方で、南部の他の地域との強い類似性も見られる。ユカタン半島はメキシコ湾に伸びており、オアハカなどの他の南部地域よりもはるかにカ リブ海貿易ルートやメキシコシティとつながっていた。[87] 主なスペイン人の入植地には、スペインの文民および宗教当局の本部があり、多くのスペイン人が住んでいた内陸の都市メリダがあった。カンペチェの村は半島 の港であり、地域全体の重要な玄関口であった。17世紀に貿易が盛んになるにつれ、商人グループは発展し、飛躍的に拡大した。[88] この時代はかつて「スペインの不況の世紀」と特徴づけられたが、ユカタン半島に関しては、17世紀初頭から植民地時代が終わるまで持続的な成長を遂げたた め、必ずしもそうではなかった。[89] 先住民マヤ族の人口が密集していたため、ユカタン半島のエンコミエンダ制度は早くから確立され、中央メキシコよりもはるかに長く続いた。スペイン人がこの 地域に移住する数が中央よりも少なかったためである。[90] ユカタン半島は、鉱山資源に恵まれず、農業やその他の輸出品もなかったため、植民地としては辺境の地域であったが、スペイン人入植地は複雑に入り組んでお り、主要な入植地であるメリダやカンペチェ、バジャドリドの村々には、さまざまな社会階層が存在していた。[91] 混血の「カスタ」と呼ばれる人々も重要な存在であり、その中には先住民とヒスパニックの両方の世界に完全に溶け込んでいる者もいた。黒人もユカタン社会の 重要な構成員であった。[92] 州内で最も人口の多かったのは先住民のマヤ族で、彼らはコミュニティで生活していたが、労働力需要や商業を通じてヒスパニック圏と接触していた。[93] ユカタンではスペインの支配は間接的なものが主であり、これらのコミュニティにはかなりの政治的・文化的自治が認められていた。マヤのコミュニティである 「カ」は、先住民の文化の完全性を維持する手段であった。経済面では、メソアメリカにおける他の多くの地域や民族集団とは異なり、ユカテク・マヤには、異 なる種類の食料品や工芸品を交換するための、征服前の定期的な市場のネットワークは存在しなかった。おそらく半島は生態系が均一であったため、地域的な ニッチ生産は発展しなかったのである。[94] 主にマヤの女性たちによる綿織物の生産は、家計の貢納義務の支払いに役立ったが、基本的な作物が経済の基盤であった。カは、宗教的な同胞団またはコンフラ テルディア(cofradías)の管理下にかなりの土地を保有していた。これは、マヤ社会が植民地当局者や聖職者、あるいは先住民の支配者 (gobernadores)がカハ・デ・コミュニダード(cajas de comunidad、文字通り、鍵と錠前を備えたコミュニティ所有の貴重品箱)の収入を横領することを回避するための手段であった。コフラディアは伝統的 に敬虔な組織であり、埋葬協会であったが、ユカタンでは土地の重要な所有者となり、カの管理下で維持される敬虔な目的のための収入源となった。「ユカタン では、その形態が変更されたコフラディアがコミュニティであった」[95] 地元のスペイン人聖職者たちは、収入の多くがミサや司祭の管理下にあるその他の精神的な事柄の対価として支払われるため、この取り決めに異議を唱える理由 がなかった。 ユカタン半島の経済における制約要因は、石灰岩質の土壌の質が悪く、焼畑農業で開墾した土地で作物を栽培できるのは2~3年だけだったことである。石灰岩 の断崖が水で満たされた陥没穴(現地ではセノーテと呼ばれる)を形成していたため、水へのアクセスも農業における制約要因であったが、半島には一般的に河 川や小川は存在しなかった。個人は、土地を耕し、開墾する限りその土地に対する権利を有し、土壌が枯渇すると、そのプロセスを繰り返した。一般的に、イン ディアンは分散して暮らしていたが、スペイン人の集会や強制移住により、その生活様式は変化しようとしていた。共同労働により、同好会が所有する土地が耕 され、伝統的なトウモロコシ、豆、綿花が栽培された。しかし、同好会は、地域の状況に応じて、後に牧畜やロバ、馬の飼育も行うようになった。カンペチェ南 部のコフラディアが、カカオの地域間取引や牧畜に従事していたことを示す証拠がある。[96] 一般的には、農作物や家畜から得た収益は精神的な分野の費用に充てられたが、コフラディアの家畜は干ばつの際には地域住民への直接的な支援に用いられ、地 域の食糧供給を安定させていた。[97] 17世紀には、ユカタン半島とタバスコで状況が変化した。スペインが領有権を主張していたものの支配下に置いていなかった地域、特に現在のベリーズにあた るイギリス領ホンジュラスと、ラグーナ・デ・ティエルマス(イスラ・デル・カルメン)で、イギリス人がログウッドの伐採を行った。1716年から1717 年にかけて、ヌエバ・エスパーニャ副王は外国勢力を追放するために十分な数の船団を組織し、その後、スペイン王室はイスラ・デル・カルメンに要塞を建設し た。[98] しかし、イギリス人は20世紀まで半島東部の領土を維持した。19世紀には、この飛び地はユカタンでのカステ戦争で反乱を起こしたマヤ族に銃を供給した。 [99] |