ニコライ・ベルジャーエフ

Nikolai

Alexandrovich Berdyaev, 1874-1948

Nikolai

Alexandrovich Berdyaev, 1874-1948

☆ ニコライ・アレクサンドロヴィッチ・ベルジャエフ(/bərˈdjɛ, -jɛv/;[1] Russian: Никола́й Алекса́ндрович Бердя́ев; 1874年3月18日[O.S.3月6日] - 1948年3月24日)は、ロシアの哲学者、神学者、キリスト教実存主義者で、人間の自由と人間の実存的精神的意義を強調した。姓の英語表記には 「Berdiaev 」や 「Berdiaeff」、名の英語表記には 「Nicolas 」や 「Nicholas 」がある。

| Nikolai Alexandrovich Berdyaev

(/bərˈdjɑːjɛf, -jɛv/;[1] Russian: Никола́й Алекса́ндрович Бердя́ев; 18

March [O.S. 6 March] 1874 – 24 March 1948) was a Russian philosopher,

theologian, and Christian existentialist who emphasized the existential

spiritual significance of human freedom and the human person.

Alternative historical spellings of his surname in English include

"Berdiaev" and "Berdiaeff", and of his given name "Nicolas" and

"Nicholas". |

ニコライ・

アレクサンドロヴィッチ・ベルジャエフ(/bərˈdjɛ, -jɛv/;[1] Russian: Никола́й Алекса́ндрович

Бердя́ев; 1874年3月18日[O.S.3月6日] -

1948年3月24日)は、ロシアの哲学者、神学者、キリスト教実存主義者で、人間の自由と人間の実存的精神的意義を強調した。姓の英語表記には

「Berdiaev 」や 「Berdiaeff」、名の英語表記には 「Nicolas 」や 「Nicholas 」がある。 |

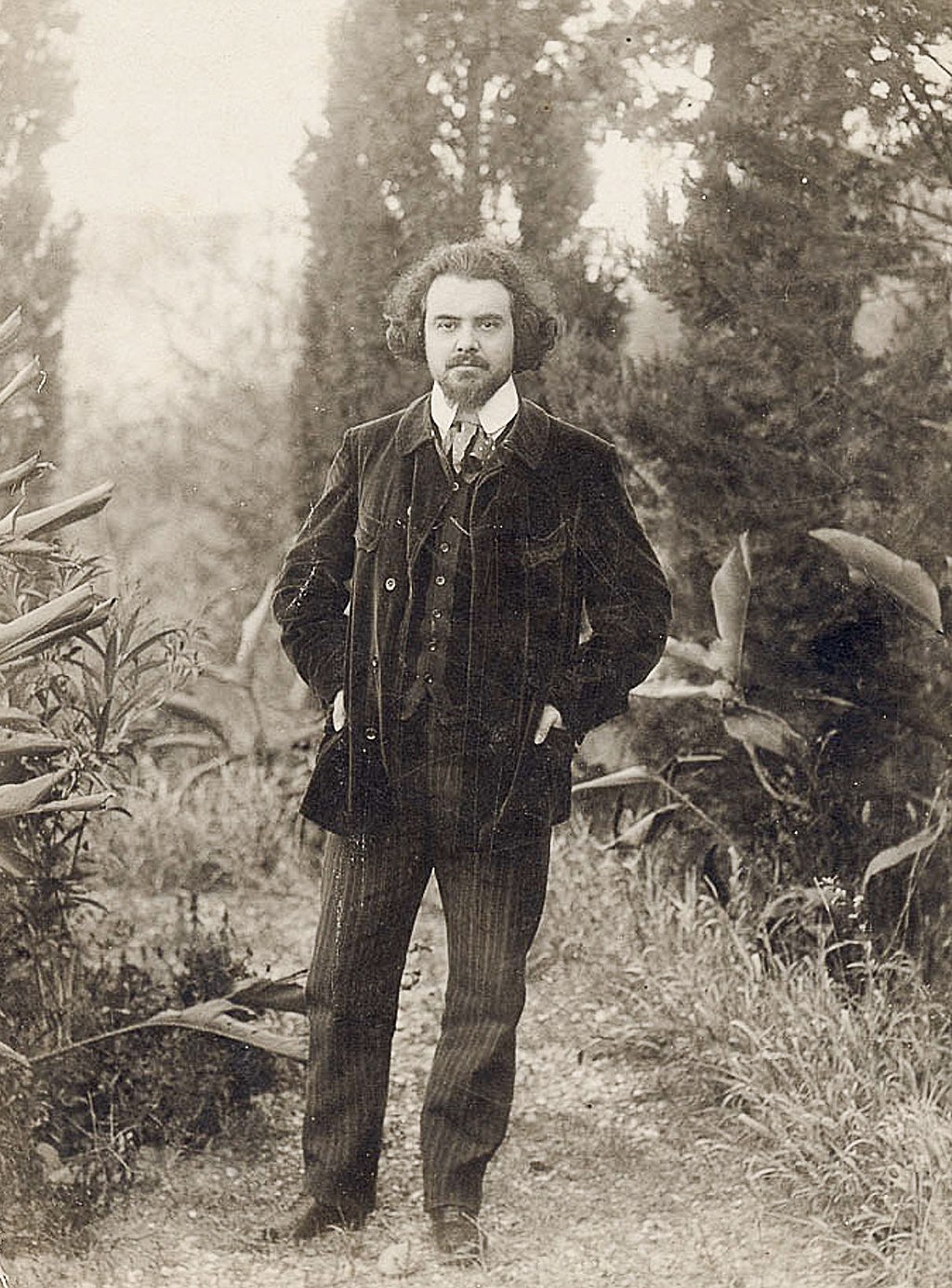

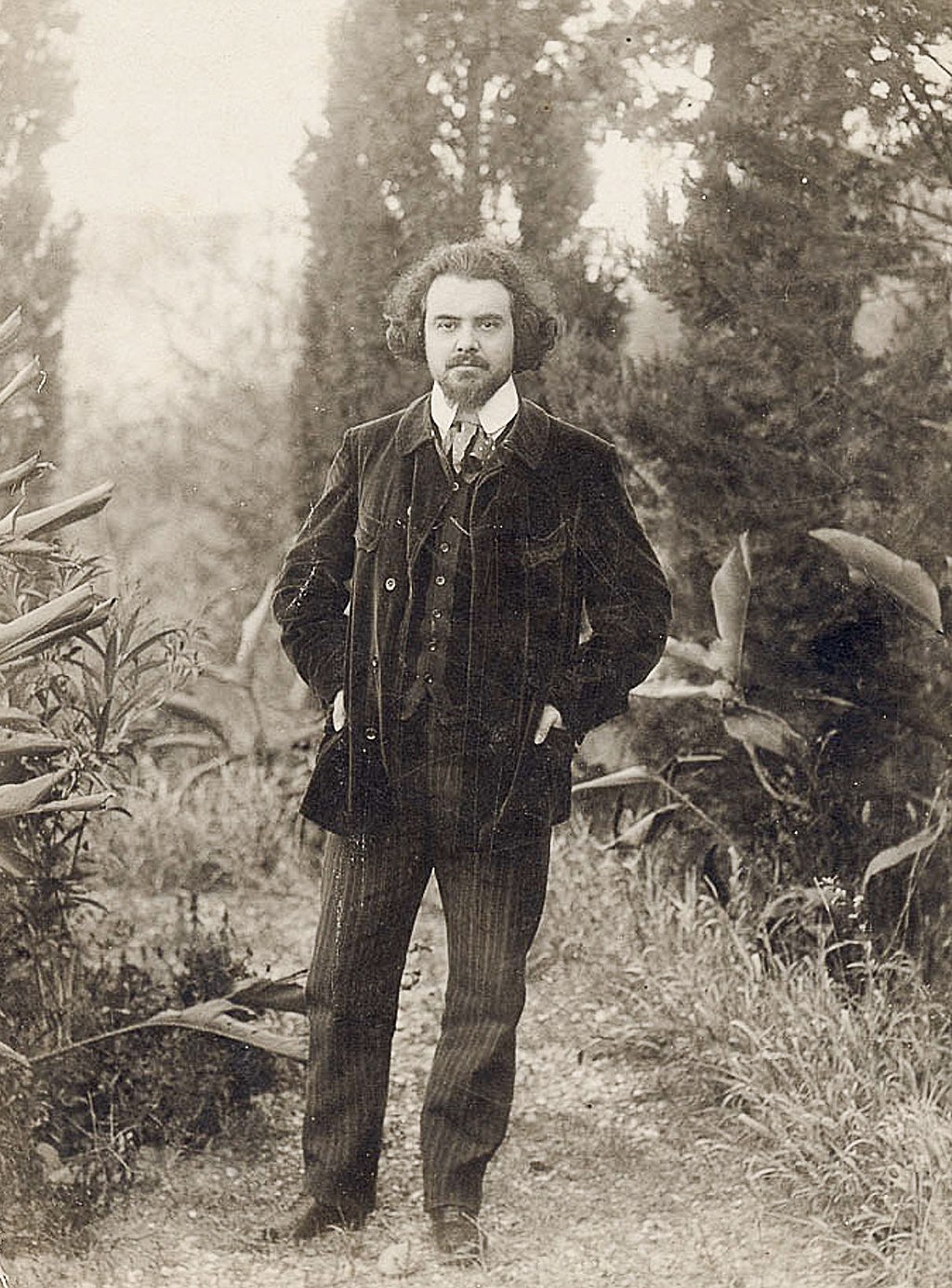

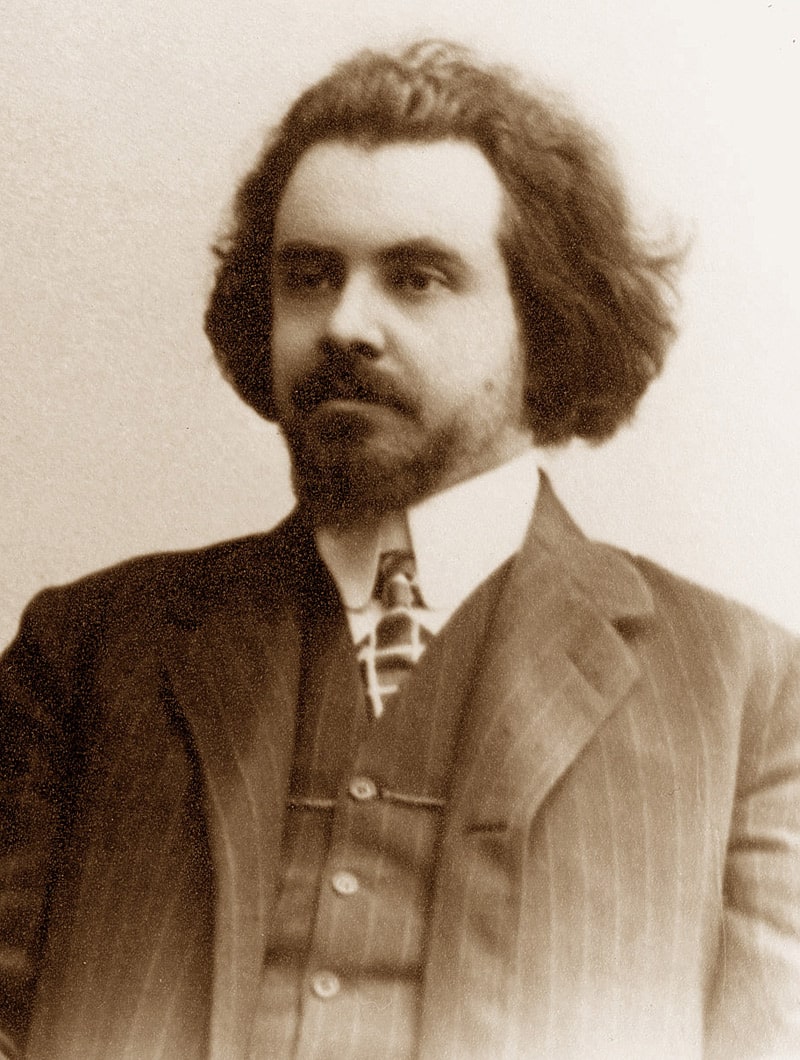

| Biography Nikolai Berdyaev was born near Kiev in 1874 to an aristocratic military family.[2] His father, Alexander Mikhailovich Berdyaev, came from a long line of Russian nobility. Almost all of Alexander Mikhailovich's ancestors served as high-ranking military officers, but he resigned from the army quite early and became active in the social life of the aristocracy. Nikolai's mother, Alina Sergeevna Berdyaeva, was half-French and came from the top levels of both French and Russian nobility. He also had Polish and Tatar origins.[3][4]  Nikolai Berdyaev in 1910  Nikolai Berdyaev in 1912 Berdyaev decided on an intellectual career and entered the Kiev University in 1894. It was a time of revolutionary fervor among the students and the intelligentsia. He became a Marxist for a period and was arrested in a student demonstration and expelled from the university. His involvement in illegal activities led in 1897 to three years of internal exile to Vologda in northern Russia.[5]: 28 A fiery 1913 article, entitled "Quenchers of the Spirit", criticising the rough purging of Imiaslavie Russian monks on Mount Athos by the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church using tsarist troops, caused him to be charged with the crime of blasphemy, the punishment for which was exile to Siberia for life. The World War and the Bolshevik Revolution prevented the matter coming to trial.[6] Berdyaev's disaffection culminated, in 1919, with the foundation of his own private academy, the "Free Academy of Spiritual Culture". It was primarily a forum for him to lecture on the hot topics of the day and to present them from a Christian point of view. He also presented his opinions in public lectures, and every Tuesday, the academy hosted a meeting at his home because official Soviet anti-religious activity was intense at the time and the official policy of the Bolshevik government, with its Soviet anti-religious legislation, strongly promoted state atheism.[5] In 1920, Berdiaev became professor of philosophy at the University of Moscow. In the same year, he was accused of participating in a conspiracy against the government; he was arrested and jailed. The feared head of the Cheka, Felix Dzerzhinsky, came in person to interrogate him,[7]: 130 and he gave his interrogator a solid dressing down on the problems with Bolshevism.[5]: 32 Novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in his book The Gulag Archipelago recounts the incident as follows: [Berdyaev] was arrested twice; he was taken in 1922 for a midnight interrogation with Dzerjinsky; Kamenev was also there.... But Berdyaev did not humiliate himself, he did not beg, he firmly professed the moral and religious principles by virtue of which he did not adhere to the party in power; and not only did they judge that there was no point in putting him on trial, but he was freed. Now there is a man who had a "point of view"![8] After being expelled from Russia, Berdyaev and other émigrés went to Berlin, where he founded an academy of philosophy and religion, but economic and political conditions in the Weimar Republic caused him and his wife to move to Paris in 1923. He transferred his academy there, and taught, lectured and wrote, working for an exchange of ideas with the French and European intellectual community, and participated in a number of international conferences.[9] |

経歴 ニコライ・ベルジャエフは1874年、キエフ近郊の貴族の軍人の家に生まれた。アレクサンドル・ミハイロヴィチの先祖はほとんど全員が高級軍人であった が、彼はかなり早い時期に軍を辞め、貴族の社交界で活躍するようになった。ニコライの母アリーナ・セルゲーヴナ・ベルディヤエヴァはフランス人とのハーフ で、フランスとロシアの両貴族のトップレベルの出身だった。また、ポーランド人とタタール人の出自も持っていた[3][4]。  1910年当時のニコライ・ベルジャエフ  1912年のニコライ・ベルジャエフ ベルジャエフは知的キャリアを志し、1894年にキエフ大学に入学した。当時は学生や知識人の間で革命熱が高まっていた。一時マルクス主義者となり、学生 デモで逮捕され、大学を追放された。非合法活動への関与が原因で、1897年から3年間、ロシア北部のヴォログダに亡命した[5]: 28。 1913年、ロシア正教会の聖シノドスがツァーリズムの軍隊を使ってアトス山のイミアスラヴィー・ロシア人修道士を厳しく粛清したことを批判する 「Quenchers of the Spirit(精神を鎮める者たち)」と題する激しい論文を発表したことで、彼は神を冒涜した罪に問われ、その罰として終身シベリア追放となった。世界大 戦とボリシェヴィキ革命により、この問題は裁判に持ち込まれることはなかった[6]。 1919年、ベルジャイエフの不満は、彼自身の私立アカデミーである「精神文化自由アカデミー」の設立によって頂点に達した。このアカデミーは主に、当時 のホットな話題について、キリスト教の観点から講義を行う場であった。彼は公開講座でも自分の意見を発表し、毎週火曜日にはアカデミー主催の集会が自宅で 開かれた。当時、ソビエトの公的な反宗教活動は激しく、ソビエト反宗教法制を持つボリシェヴィキ政府の公式政策は、国家的な無神論を強く推進していたから である[5]。 1920年、ベルディアエフはモスクワ大学の哲学教授となる。同年、彼は政府に対する陰謀に参加した罪に問われ、逮捕され投獄された。チェカの首領として 恐れられていたフェリックス・ドゥゼルジンスキーが直接彼を尋問しに来た[7]: 130、彼はボリシェヴィズムの問題点について尋問官を徹底的にこき下 ろした[5]: 32 小説家アレクサンドル・ソルジェニーツィンはその著書『収容所群島』の中で、この事件を次のように語っている: [ベルジャヤエフは)2度逮捕された。1922年、彼は真夜中にドゼルジンスキーとの尋問のために連行され、カメネフもそこにいた......。しかし、 ベルジャヤエフは自らを辱めず、物乞いもせず、政権党に固執しないという道徳的・宗教的原則をしっかりと公言した。今ここに「視点」を持っていた男がい る![8]。 ロシアから追放された後、ベルディヤエフと他の移住者はベルリンに行き、そこで哲学と宗教のアカデミーを設立したが、ワイマール共和国の経済的・政治的状 況により、1923年に彼と彼の妻はパリに移住した。そこでアカデミーを移転し、教え、講義し、執筆し、フランスやヨーロッパの知識人社会との意見交換に 努め、多くの国際会議に参加した[9]。 |

| Philosophical work According to Marko Markovic, Berdyaev "was an ardent man, rebellious to all authority, an independent and "negative" spirit. He could assert himself only in negation and could not hear any assertion without immediately negating it, to such an extent that he would even be able to contradict himself and to attack people who shared his own prior opinions".[5] According to Marina Makienko, Anna Panamaryova, and Andrey Gurban, Berdyaev's works are "emotional, controversial, bombastic, affective and dogmatic".[10]: 20 They summarise that, according to Berdyaev, "man unites two worlds – the world of the divine and the natural world. ... Through the freedom and creativity the two natures must unite... To overcome the dualism of existence is possible only through creativity.[10]: 20 David Bonner Richardson described Berdyaev's philosophy as Christian existentialism and personalism.[11] Other authors, such as political theologian Tsoncho Tsonchev, interpret Berdyaev as "communitarian personalist" and Slavophile. According to Tsonchev, Berdyaev's philosophical thought rests on four "pillars": freedom, creativity, person, and communion.[12] One of the central themes of Berdyaev's work was philosophy of love.[13]: 11 At first he systematically developed his theory of love in a special article published in the journal Pereval (Russian: Перевал) in 1907.[13] Then he gave gender issues a notable place in his book The Meaning of the Creative Act (1916).[13] According to him, 1) erotic energy is an eternal source of creativity, 2) eroticism is linked to beauty, and eros means search for the beautiful.[13]: 11 He also published works about Russian history and the Russian national character. In particular, he wrote about Russian nationalism:[14] The Russian people did not achieve their ancient dream of Moscow, the Third Rome. The ecclesiastical schism of the seventeenth century revealed that the muscovite tsardom is not the third Rome. The messianic idea of the Russian people assumed either an apocalyptic form or a revolutionary; and then there occurred an amazing event in the destiny of the Russian people. Instead of the Third Rome in Russia, the Third International was achieved, and many of the features of the Third Rome pass over to the Third International. The Third International is also a Holy Empire, and it also is founded on an Orthodox faith. The Third International is not international, but a Russian national idea. Though sometimes quoted as a Christian anarchist for his emphasis on theology and critique of statist and Marxist socialism, Berdyaev did not self-identify as such and differentiated himself from Tolstoy.[15] |

哲学的業績 マルコ・マルコヴィッチによれば、ベルニャエフは「熱烈な人物で、あらゆる権威に反抗的で、独立心旺盛で 「否定的 」な精神を持っていた。彼は否定においてのみ自己を主張することができ、いかなる主張も即座に否定することなしには聞くことができなかった。... 自由と創造性によって、二つの性質は一つにならなければならない。存在の二元論を克服することは、創造性によってのみ可能である。 デイヴィッド・ボナー・リチャードソンは、ベルジャエフの哲学をキリスト教的実存主義と個人主義であるとした[11]。 政治神学者のツォンチョ・ツォンチェフのような他の著者は、ベルジャエフを「共同体主義的個人主義者」であり、スラヴ主義者であると解釈している。ツォン チェフによれば、ベルジャエフの哲学的思想は、自由、創造性、人格、共同体という4つの「柱」によって成り立っている[12]。 ベルジャエフの仕事の中心テーマのひとつは愛の哲学であった[13]: 11 当初、彼は1907年に雑誌『ペレヴァル』(ロシア語:Перевал)に掲載された特別論文において、愛に関する理論を体系的に展開した[13]。その 後、彼は著書『創造的行為の意味』(1916年)において、ジェンダーの問題に注目すべき位置を与えた[13]。彼によれば、1)エロティシズムのエネル ギーは創造性の永遠の源泉であり、2)エロティシズムは美と結びついており、エロスとは美の探求を意味する[13]: 11 彼はまた、ロシアの歴史とロシアの国民性についての著作も発表した。特にロシアのナショナリズムについて次のように書いている[14]。 ロシア人は、モスクワという第三のローマという古くからの夢を実現することはできなかった。17世紀の教会分裂は、モスクワが第三のローマではないことを 明らかにした。ロシア人のメシア思想は、黙示録的な形か革命的な形をとっていた。ロシアにおける第三のローマの代わりに、第三インターナショナルが実現 し、第三ローマの特徴の多くが第三インターナショナルに引き継がれた。第三インターナショナルもまた神聖帝国であり、正統派の信仰に基づいている。第三イ ンターナショナルは国際的なものではなく、ロシアの民族的な思想である。 神学を重視し、国家主義やマルクス主義の社会主義を批判したことから、キリスト教アナキストとして引用されることもあったが、ベルジャヤエフはそのように自認しておらず、トルストイとは一線を画していた[15]。 |

| Theology and relations with Russian Orthodox Church Berdyaev was a member of the Russian Orthodox Church,[16][17] and believed Orthodoxy was the religious tradition closest to early Christianity.[18]: at unk. Nicholas Berdyaev was an Orthodox Christian, however, it must be said that he was an independent and somewhat a "liberal" kind. Berdyaev also criticized the Russian Orthodox Church and described his views as anticlerical.[6] Yet he considered himself closer to Orthodoxy than either Catholicism or Protestantism. According to him, "I can not call myself a typical Orthodox of any kind; but Orthodoxy was near to me (and I hope I am nearer to Orthodoxy) than either Catholicism or Protestantism. I never severed my link with the Orthodox Church, although confessional self-satisfaction and exclusiveness are alien to me."[16] Berdyaev is frequently presented as one of the important Russian Orthodox thinkers of the 20th century.[19][20][21] However, neopatristic scholars such as Florovsky have questioned whether his philosophy is essentially Orthodox in character, and emphasize his western influences.[22] But Florovsky was savaged in a 1937 Journal Put' article by Berdyaev.[23] Paul Valliere has pointed out the sociological factors and global trends which have shaped the Neopatristic movement, and questions their claim that Berdyaev and Vladimir Solovyov are somehow less authentically Orthodox.[20] Berdyaev affirmed universal salvation, as did several other important Orthodox theologians of the 20th century.[24] Along with Sergei Bulgakov, he was instrumental in bringing renewed attention to the Orthodox doctrine of apokatastasis, which had largely been neglected since it was expounded by Maximus the Confessor in the seventh century,[25] although he rejected Origen's articulation of this doctrine.[26][27] The aftermath of the Russian Revolution and Civil War, along with Soviet efforts towards the separation of church and state, caused the Russian Orthodox émigré diaspora to splinter into three Russian Church jurisdictions: the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (separated from Moscow Patriarchate until 2007), the parishes under Metropolitan Eulogius (Georgiyevsky) that went under the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, and parishes that remained under the Moscow Patriarchate. Berdyaev was among those that chose to remain under the omophorion of the Moscow Patriarchate. He is mentioned by name on the Korsun/Chersonese Diocesan history as among those noted figures who supported the Moscow Patriarchate West-European Eparchy (in France now Korsun eparchy).[28] Currently, the house in Clamart in which Berdyaev lived, now comprises a small "Berdiaev-museum" and attached Chapel in name of the Holy Spirit,[29] under the omophorion of the Moscow Patriarchate. On 24 March 2018, the 70th anniversary of Berdyaev's death, the priest of the Chapel served panikhida-memorial prayer at the Diocesan cathedral for eternal memory of Berdyaev,[30] and later that day the Diocesan bishop Nestor (Sirotenko) presided over prayer at the grave of Berdyaev.[31] |

神学とロシア正教会との関係 ベルジャエフはロシア正教会の信者であり[16][17]、正教が初期キリスト教に最も近い宗教的伝統であると考えていた[18]。 ニコライ・ベルジャエフは正教徒であったが、しかし彼は独立主義者であり、やや「リベラル」なタイプであったと言わざるを得ない。ベルジャエフはまた、ロ シア正教会を批判し、自身の見解を反正教会的であると述べている[6]。しかし、彼は自分自身をカトリックやプロテスタントよりも正教に近いと考えてい た。彼によれば、「私は自分自身を典型的な正教徒とは呼べないが、正教はカトリックやプロテスタントよりも身近な存在であった。告白的な自己満足と排他性 は私にとって異質なものだが、私は正教会とのつながりを断ち切ったことはない」[16]。 しかし、フロロフスキーのような新教派の研究者たちは、彼の哲学が本質的に正統派のものであるかどうかを疑問視しており、西洋からの影響を強調している [22]。 [ポール・ヴァリエールは、ネオパトリスティック運動を形成してきた社会学的要因と世界的傾向を指摘し、ベルジャエフとウラジーミル・ソロヴィヨフがどこ か正統的でないという彼らの主張に疑問を呈している[20]。 ベルジャヤエフは、20世紀の他の数人の重要な正教会の神学者たちと同様に、普遍的な救済を肯定していた[24]。 セルゲイ・ブルガーコフとともに、彼は、7世紀に告白者マクシムスによって説かれて以来、ほとんど無視されていたアポカタスタシスの正教会の教義に再び注 目を集めることに貢献した[25]が、彼はこの教義のオリゲンの明確な表現を否定した[26][27]。 ロシア革命と内戦の余波は、教会と国家の分離に向けたソビエトの努力とともに、ロシア正教会の移住者であるディアスポラを3つのロシア教会の管轄区域に分 裂させる原因となった。ベルディヤエフは、モスクワ総主教庁のオモフォリオンの下に留まることを選択した教区の一つであった。コルスン/チェルソン教区史 には、モスクワ総主教庁西ヨーロッパ教区(フランスでは現在のコルスン教区)を支持した著名人の一人として彼の名前が記されている[28]。 現在、ベルディアエフが住んでいたクラマートの家は、モスクワ総主教庁のオモフォリオンの下、小さな「ベルディアエフ博物館」と聖霊の名による付属礼拝堂 [29]で構成されている。ベルディアエフ没後70周年にあたる2018年3月24日、チャペルの司祭はベルディアエフの永遠の記憶のために教区聖堂でパ ニキダ=記念の祈りを捧げ[30]、その日のうちに教区司教ネストル(シロテンコ)がベルディアエフの墓での祈りを司式した[31]。 |

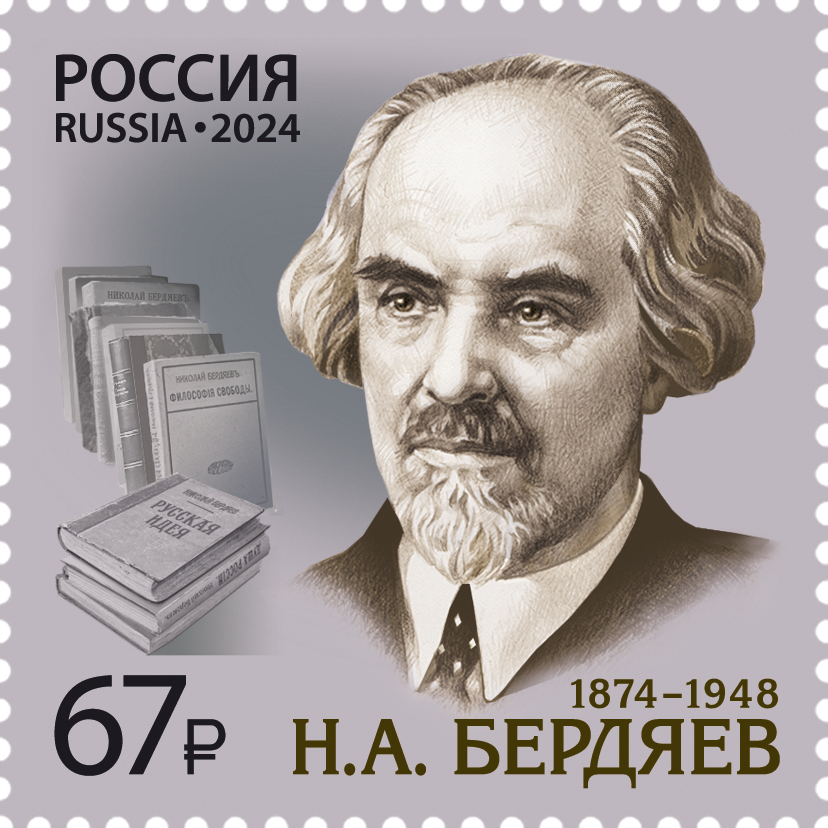

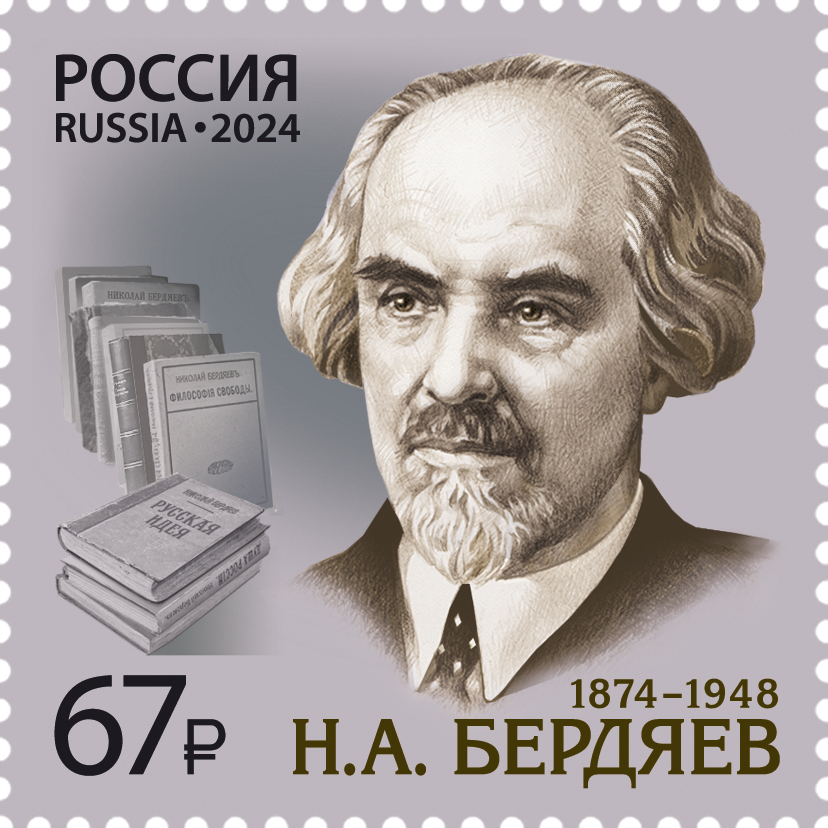

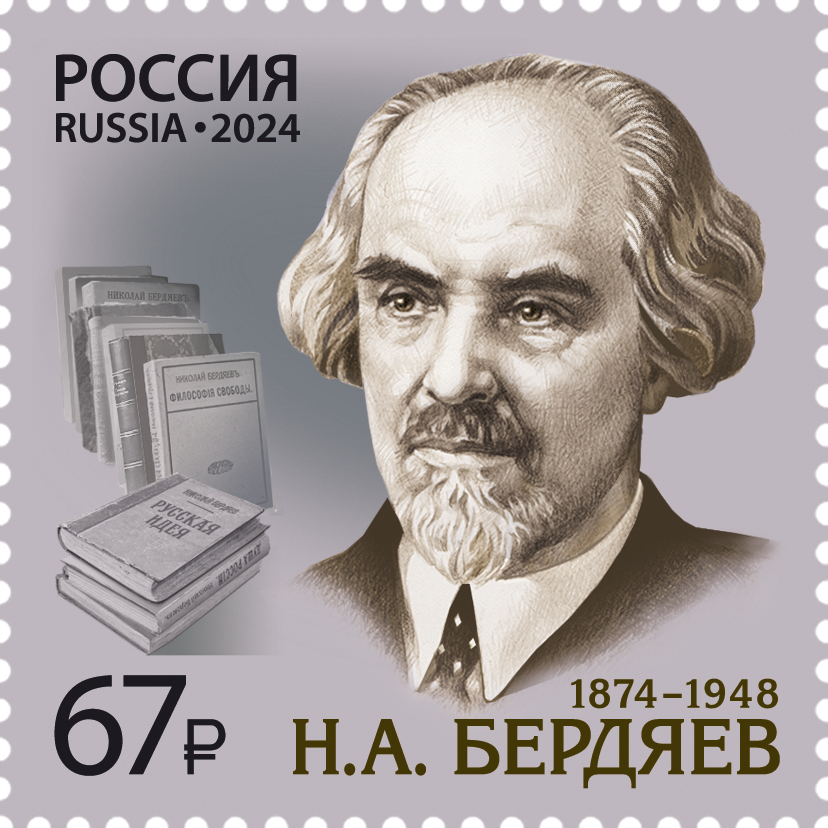

Works Berdyaev on a 2024 stamp of Russia In 1901 Berdyaev opened his literary career so to speak by work on Subjectivism and Individualism in Social Philosophy. In it, he analyzed a movement then beginning in Imperial Russia that "at the beginning of the twentieth-century Russian Marxism split up; the more cultured Russian Marxists went through a spiritual crisis and became founders of an idealist and religious movement, while the majority began to prepare the advent of Communism". He wrote "over twenty books and dozens of articles."[32] The first date is of the Russian edition, the second date is of the first English edition Subjectivism and Individualism in Societal Philosophy (1901) The New Religious Consciousness and Society (1907) (Russian: Новое религиозное сознание и общественность, romanized: Novoe religioznoe coznanie i obschestvennost, includes chapter VI "The Metaphysics of Sex and Love")[33] Sub specie aeternitatis: Articles Philosophic, Social and Literary (1900–1906) (1907; 2019) ISBN 9780999197929 ISBN 9780999197936 Vekhi – Landmarks (1909; 1994) ISBN 9781563243912 The Spiritual Crisis of the Intelligentsia (1910; 2014) ISBN 978-0-9963992-1-0 The Philosophy of Freedom (1911; 2020) ISBN 9780999197943 ISBN 9780999197950 Aleksei Stepanovich Khomyakov (1912; 2017) ISBN 9780996399258 ISBN 9780999197912 "Quenchers of the Spirit" (1913; 1999) The Meaning of the Creative Act (1916; 1955) ISBN 978-15973126-2-2 The Crisis of Art (1918; 2018) ISBN 9780996399296 ISBN 9780999197905 The Fate of Russia (1918; 2016) ISBN 9780996399241 Dostoevsky: An Interpretation (1921; 1934) ISBN 978-15973126-1-5 Oswald Spengler and the Decline of Europe (1922) The Meaning of History (1923; 1936) ISBN 978-14128049-7-4 The Philosophy of Inequality (1923; 2015) ISBN 978-0-9963992-0-3 The End of Our Time [a.k.a. The New Middle Ages] (1924; 1933) ISBN 978-15973126-5-3 Leontiev (1926; 1940) Freedom and the Spirit (1927–8; 1935) ISBN 978-15973126-0-8 The Russian Revolution (1931; anthology) The Destiny of Man (1931; translated by Natalie Duddington 1937) ISBN 978-15973125-6-1 Lev Shestov and Kierkegaard N. A. Beryaev 1936 Christianity and Class War (1931; 1933) The Fate of Man in the Modern World (1934; 1935) Solitude and Society (1934; 1938) ISBN 978-15973125-5-4 The Bourgeois Mind (1934; anthology) The Origin of Russian Communism (1937; 1955) Christianity and Anti-semitism (1938; 1952) Slavery and Freedom (1939) ISBN 978-15973126-6-0 The Russian Idea (1946; 1947) Spirit and Reality (1946; 1957) ISBN 978-15973125-4-7 The Beginning and the End (1947; 1952) ISBN 978-15973126-4-6 Towards a New Epoch" (1949; anthology) Dream and Reality: An Essay in Autobiography (1949; 1950) alternate title: Self-Knowledge: An Essay in Autobiography ISBN 978-15973125-8-5 The Realm of Spirit and the Realm of Caesar (1949; 1952) Divine and the Human (1949; 1952) ISBN 978-15973125-9-2 "The Truth of Orthodoxy", Vestnik of the Russian West European Patriarchal Exarchate, translated by A.S. III, Paris, 1952, retrieved 27 September 2017 Truth and Revelation (n.p.; 1953) Astride the Abyss of War and Revolutions: Articles 1914–1922 (n.p.; 2017) ISBN 9780996399272 ISBN 9780996399289 Sources '"Bibliographie des Oeuvres de Nicolas Berdiaev" établie par Tamara Klépinine' published by the Institut d'études Slaves, Paris 1978 Berdyaev Bibliography on www.cherbucto.net By-Berdyaev Online Articles Index |

作品 2024年のロシア切手に描かれたベルジャエフ 1901年、ベルジャエフは『社会哲学における主観主義と個人主義』という著作で、いわば文学者としてのキャリアをスタートさせた。その中で彼は、当時帝 政ロシアで始まっていた「20世紀初頭、ロシア・マルクス主義は分裂し、より教養あるロシア・マルクス主義者たちは精神的危機を経験し、観念論的・宗教的 運動の創始者となったが、大多数は共産主義の到来を準備し始めた」という運動を分析した。彼は「20冊以上の著書と数十本の論文」を書いた[32]。 最初の日付はロシア語版、2番目の日付は最初の英語版。 社会哲学における主観主義と個人主義 (1901) 新宗教意識と社会(1907年)(ロシア語: Новое религиозное сознание и общественность, romanized: Novoe religioznoe coznanie i obschestvennost、第VI章「性と愛の形而上学」を含む)[33]。 Sub specie aeternitatis: Articles Philosophic, Social and Literary (1900-1906) (1907; 2019) ISBN 9780999197929 ISBN 9780999197936 ヴェキ-ランドマーク (1909; 1994) ISBN 9781563243912 インテリゲンチアの精神的危機 (1910; 2014) ISBN 978-0-9963992-1-0 自由の哲学 (1911; 2020) ISBN 9780999197943 ISBN 9780999197950 アレクセイ・ステパノヴィチ・ホミャコフ(1912; 2017) ISBN 9780996399258 ISBN 9780999197912 「精神の癒し手』(1913年、1999年) 創造行為の意味』(1916;1955) ISBN 978-15973126-2-2 芸術の危機』(1918年;2018年) ISBN 9780996399296 ISBN 9780999197905 ロシアの運命 (1918; 2016) ISBN 9780996399241 ドストエフスキー 解釈』(1921年、1934年) ISBN 978-15973126-1-5 オズワルド・シュペングラーとヨーロッパの衰退 (1922) 歴史の意味 (1923; 1936) ISBN 978-14128049-7-4 不平等の哲学 (1923; 2015) ISBN 978-0-9963992-0-3 われらの時代の終わり』(1924; 1933) ISBN 978-15973126-5-3 レオンティエフ (1926; 1940) 自由と精神 (1927-8; 1935) ISBN 978-15973126-0-8 ロシア革命 (1931; アンソロジー) 人間の運命』(1931;ナタリー・ダディントン訳 1937) ISBN 978-15973125-6-1 レフ・シェストフとキルケゴール N. A. ベリヤエフ 1936年 キリスト教と階級戦争(1931年、1933年) 現代世界における人間の運命(1934年、1935年) 孤独と社会 (1934; 1938) ISBN 978-15973125-5-4 ブルジョア精神(1934年、アンソロジー) ロシア共産主義の起源(1937年、1955年) キリスト教と反ユダヤ主義(1938年、1952年) 奴隷制と自由 (1939) ISBN 978-15973126-6-0 ロシアの思想(1946;1947) 精神と現実 (1946; 1957) ISBN 978-15973125-4-7 始まりと終わり (1947; 1952) ISBN 978-15973126-4-6 新しい時代に向けて」(1949年、アンソロジー) 夢と現実: An Essay in Autobiography」(1949;1950)別タイトル: 自己認識: 自伝的エッセイ ISBN 978-15973125-8-5 精神の領域とカエサルの領域 (1949; 1952) 神と人間 (1949; 1952) ISBN 978-15973125-9-2 「The Truth of Orthodoxy」, Vestnik of the Russian West European Patriarchal Exarchate, translated by A.S. III, Paris, 1952, retrieved 27 September 2017 真理と啓示』(n.p.; 1953年) 戦争と革命の深淵に立つ: Articles 1914-1922 (n.p.; 2017) ISBN 9780996399272 ISBN 9780996399289 情報源 ニコラ・ベルディアエフ著作書誌」タマラ・クレピニーヌ著 1978年パリ奴隷学院発行 www.cherbucto.net 上のベルディアエフ文献目録 ベルジャエフ・オンライン記事索引 |

| Christian philosophy Vladimir Soloviev Sergei Bulgakov Semyon Frank Pavel Florensky Fyodor Dostoevsky Søren Kierkegaard List of Russian philosophers Nikolai Lossky Orthodox Christian theology Russian Religious Renaissance Vekhi |

キリスト教哲学 ウラジーミル・ソロヴィエフ セルゲイ・ブルガーコフ セミョーン・フランク パヴェル・フロレンスキー フョードル・ドストエフスキー セーレン・キェルケゴール ロシアの哲学者リスト ニコライ・ロスキー 正教神学 ロシア宗教ルネサンス ヴェキ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nikolai_Berdyaev |

|

撮影年代不詳/ Berdyaev's grave, Clamart (France).

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆