ニブフ

Nivkh people

Nivkh people (ethnic group in Karafuto aka Sakhalin)

☆ ニヴフ族、またはギリヤーク族(ニヴク族、またはニヴキ族、またはギリヤーク族とも: Нивхгу、Nʼivxgu(アムール)またはНиғвңгун、Nʼiɣvŋgun(サハリン東部)「人々」)[3]は、サハリン島の北半分、隣接す るロシア本土のアムール川下流域と沿岸に居住する先住民族グループである。歴史的には満州の一部にも居住していた可能性がある。

The Nivkh, or Gilyak

(also Nivkhs or Nivkhi, or Gilyaks; ethnonym: Нивхгу, Nʼivxgu (Amur) or

Ниғвңгун, Nʼiɣvŋgun (E. Sakhalin) "the people"),[3] are an Indigenous

ethnic group inhabiting the northern half of Sakhalin Island and the

lower Amur River and coast on the adjacent Russian mainland.

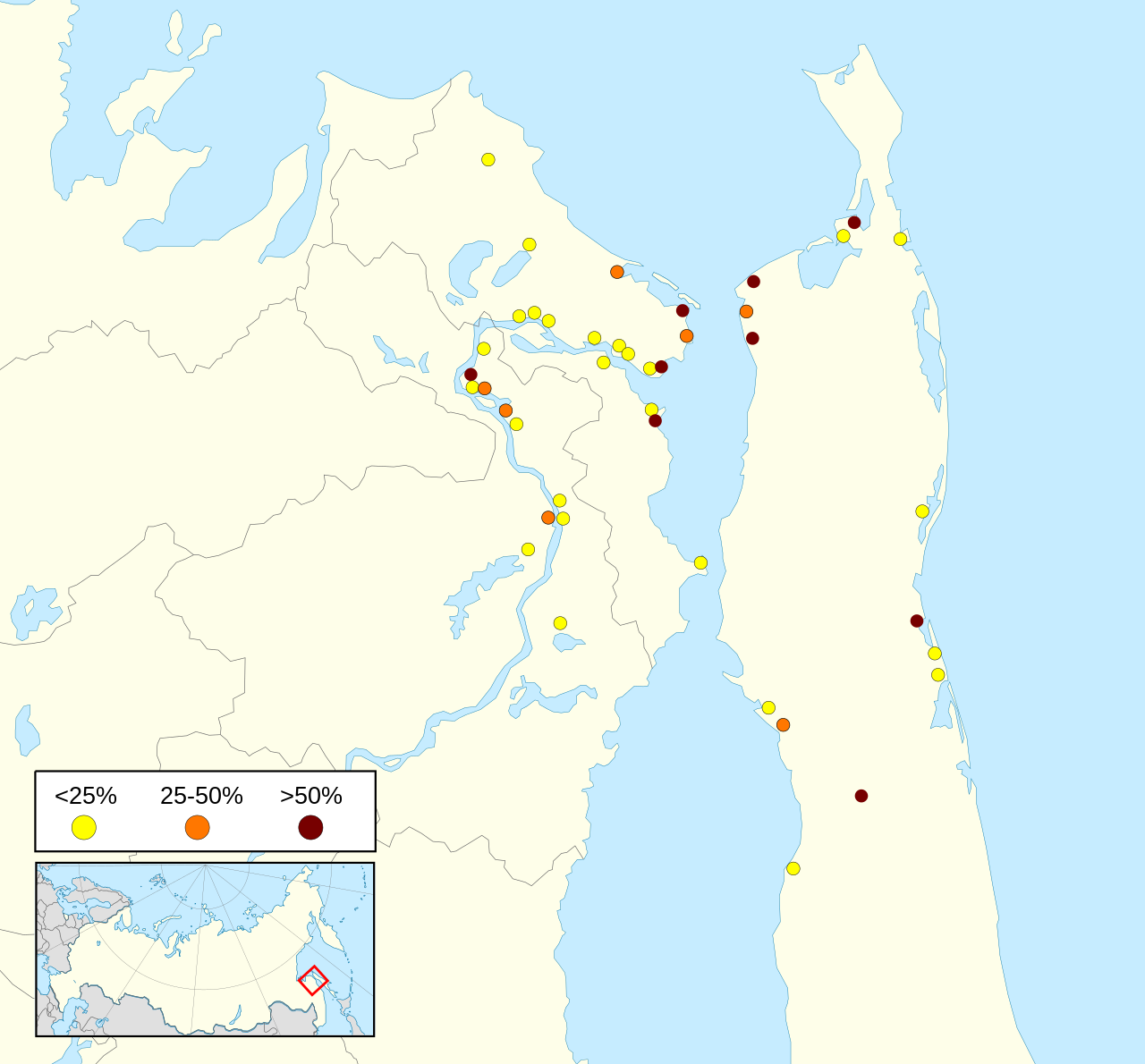

Historically, they may have inhabited parts of Manchuria. Settlements with Nivkh populations according to the Russian Census of 2002 (excluding Khabarovsk, Poronaysk and Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk).  Settlement of Nivkhs in the Far Eastern Federal District by urban and rural settlements in%, 2010 census Nivkh were traditionally fishermen, hunters, and dog breeders. They were semi-nomadic, living near the coasts in the summer and wintering inland along streams and rivers to catch salmon. The land the Nivkh inhabit is characterized as taiga forest with cold snow-laden winters and mild summers with sparse tree cover.[4] The Nivkh are believed to be the original inhabitants of the region, and to derive from a proposed Neolithic people that migrated from the Transbaikal region during the Late Pleistocene.[5] The Nivkh had long maintained trade and cultural relations with neighboring China and Japan. Previously within Qing China's sphere of influence, the Russian Empire annexed the region following two treaties in 1858 and 1860. Subsequently, traditional Nivkh lifestyle was significantly altered by colonization and collectivization.[6][7] Today, the Nivkh live in Russian-style housing and with the overfishing and pollution of the streams and seas, they have adopted many foods from Russian cuisine. The Nivkh practice shamanism, which is important for the winter Bear Festival, though some have converted to Russian Orthodoxy.[8] The population of Nivkhs has decreased with each of the last two censuses: 3,842 (2021 Census);[9] 4,652 (2010 Russian census);[10] 5,287 (2002 Census);[11] . Most speak Russian today, while less than 5 percent speak their native Nivkh language. Nivkh is considered a language isolate or small family, although it is grouped for convenience with the Paleosiberian languages. Nivkh is divided into four dialects or languages.[12] |

ニ

ヴフ族、またはギリヤーク族(ニヴク族、またはニヴキ族、またはギリヤーク族とも:

Нивхгу、Nʼivxgu(アムール)またはНиғвңгун、Nʼiɣvŋgun(サハリン東部)「人々」)[3]は、サハリン島の北半分、隣接す

るロシア本土のアムール川下流域と沿岸に居住する先住民族グループである。歴史的には満州の一部にも居住していた可能性がある。 2002年ロシア国勢調査による、ニヴフ族人口の居住地(ハバロフスク、ポロナイスク、ユジノサハリンスクを除く)。  極東連邦管区におけるニブフ人の都市・農村別居住率(%)、2010年国勢調査 ニヴフ族は伝統的に漁師、狩猟民、犬飼育民であった。彼らは半遊牧民で、夏は海岸近くに住み、冬は鮭を獲るために沢や川に沿って内陸に入る。ニヴフ族はこ の地域の原住民であり、更新世後期にトランスバイカル地方から移住してきた新石器時代の人々から派生したと考えられている[5]。 ニヴフ族は近隣の中国や日本と長い間貿易や文化的な関係を維持していた。以前は清国の勢力圏内にあったが、1858年と1860年の2度の条約によりロシ ア帝国がこの地域を併合した。その後、ニヴフ族の伝統的な生活様式は植民地化と集団化によって大きく変化した[6][7]。今日、ニヴフ族はロシア式の住 居に住み、乱獲と河川や海の汚染に伴い、ロシア料理から多くの食品を取り入れている。ニヴフ族はシャーマニズムを実践しており、これは冬の熊祭りに重要な 意味を持つが、ロシア正教に改宗した者もいる[8]。 ニヴフ族の人口は、過去2回の国勢調査のたびに減少している: 3,842人(2021年国勢調査)、[9] 4,652人(2010年ロシア国勢調査)、[10] 5,287人(2002年国勢調査)、[11] 。現在、ほとんどの人がロシア語を話し、母語であるニヴフ語を話す人は5%未満である。ニヴフ語は、便宜上パレオシベリアの諸言語とグループ分けされてい るが、孤立した言語、あるいは小さな語族と考えられている。ニヴフ語は4つの方言または言語に分かれている[12]。 |

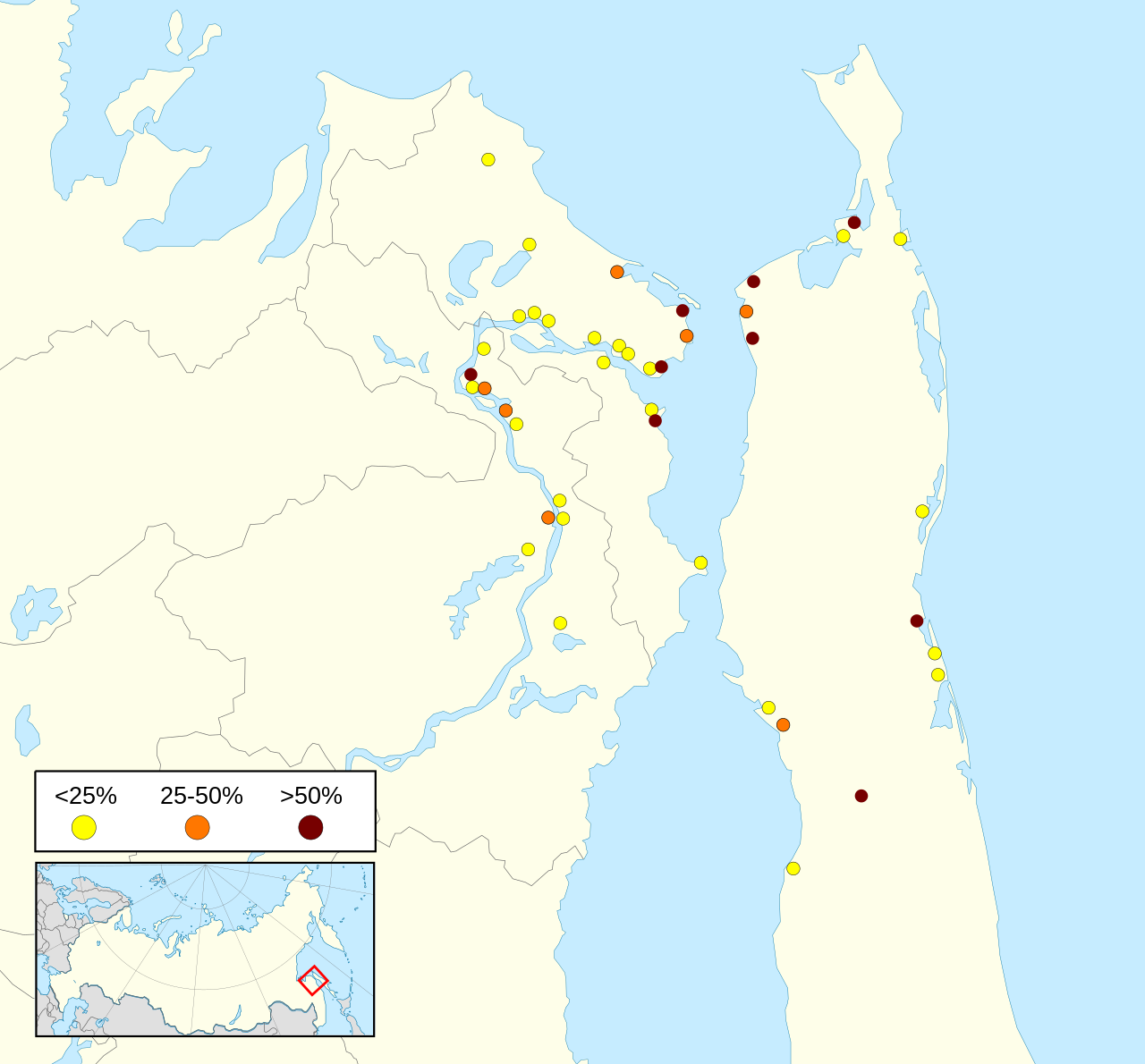

Total population 5,800 (est.) Regions with significant populations Russia Khabarovsk Krai: 2,452 (2002) Sakhalin Oblast: 2,450 (2002) Saint Petersburg: 35 (2002) Jewish Autonomous Oblast: 32 (2002) Primorsky Krai: 29 (2002) 4,652[1] Ukraine 584 (2001)[2] Languages Nivkh, Russian Religion Shamanism, Russian Orthodox Christianity Related ethnic groups Paleosiberians, Ainu, Okhotsk, Mishihase, Mosan, Kamchadals, and Ulchi |

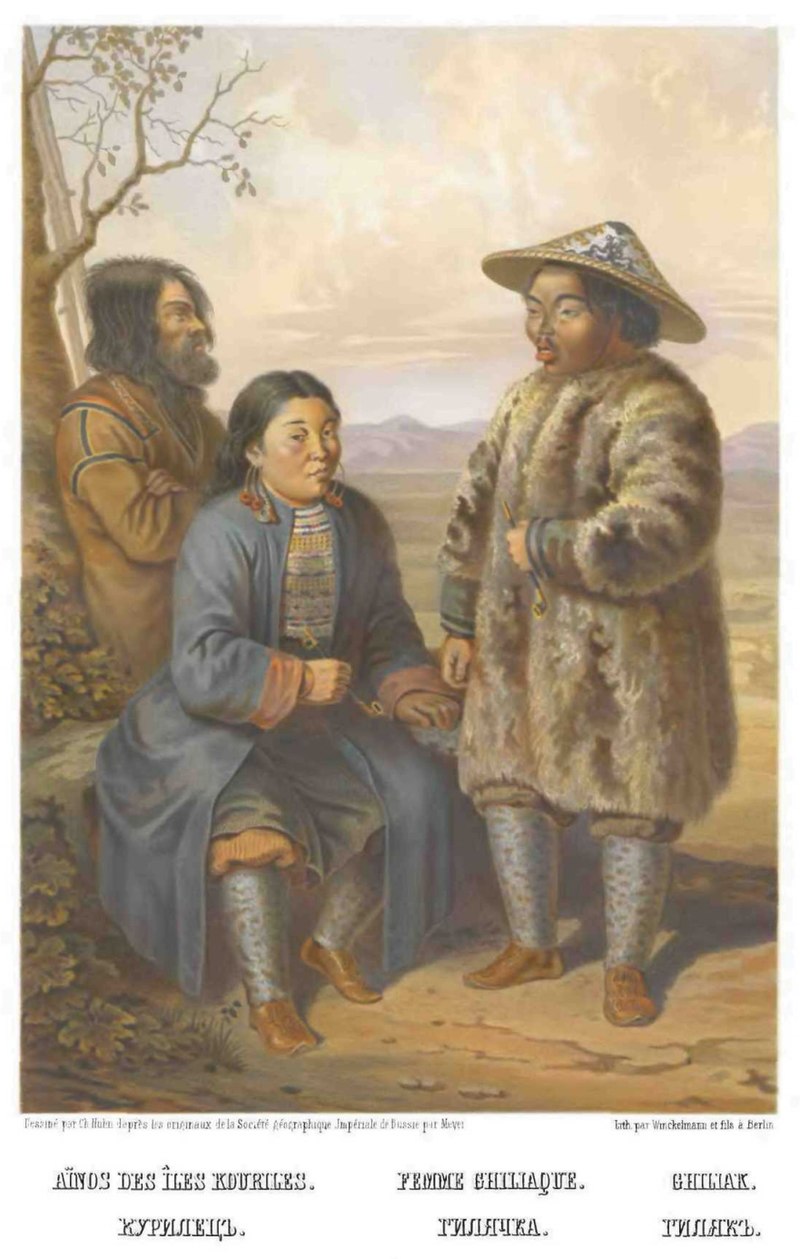

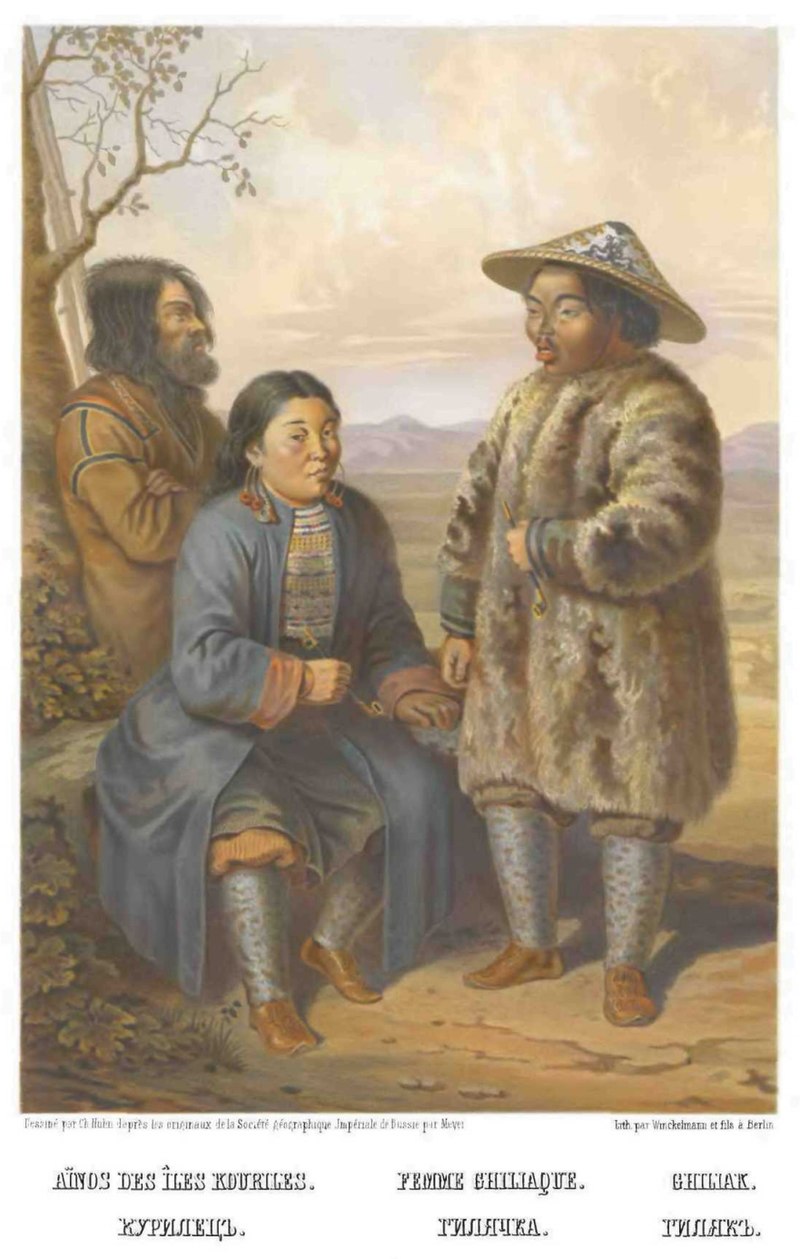

Etymology Nivkh (plural Nivkhgu in the Nivkh language), an endonym, means "person" in the Nivkh language. They may also be referred to as Nivkhi in 1920s Western literature, due to the romanization of the Russian term plural "нивхи" from "нивх" (nivkh). In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Russian explorers first termed the group Gilyak (also Giliaks or Giliatski). The etymology of the name "Gilyak" is disputed by linguists, with some believing the name originated from an exonym given to the Nivkhs by a nearby Tungusic group. Other scholars believe that "Gilyak" derives from Kile, another nearby Tungusic group that the Russians had mistakenly named Nivkhs.[4] "Gilyak" is the Russian rendering of terms derived from the Tungusic "Gileke" and Manchu-Chinese "Gilemi" (Gilimi, Gilyami) for culturally similar peoples of the Amur River region, and was applied principally to the Nivkh in Western literature.[13] ++++++++++++++ 語源 ニヴク(ニヴク語では複数形ニヴクグ)はニヴク語で「人」を意味する。1920年代の西洋の文献では、ロシア語の複数形 「нивхи 」が 「нивх」(nivkh)にローマ字変換されたため、ニヴヒと呼ばれることもある。17世紀から18世紀にかけて、ロシアの探検家たちは最初にこのグ ループをギリヤーク(ギリヤクスまたはギリヤツキーとも)と呼んだ。ギリヤーク」という名称の語源については言語学者たちの間でも論争があり、近隣のツン グース系民族がニヴフ族に与えた異名に由来するという説もある。ギリヤーク」は、アムール川流域の文化的に類似した民族を表すツングース語の「ギレケ」や 満州語・中国語の「ギレミ」(ギリミ、ギリャーミ)に由来する用語をロシア語に翻訳したものであり、西洋の文献では主にニヴフ族に適用されていた [13]。  Nivkh people (ethnic group in Karafuto aka Sakhalin)  Giliak, Nivkh men. |

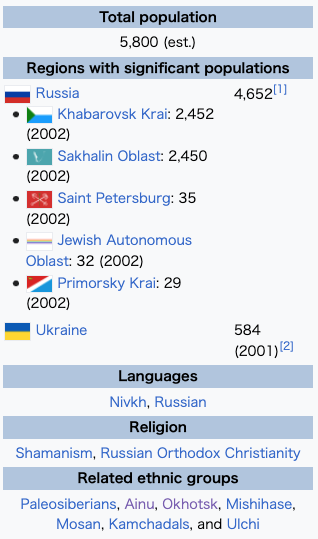

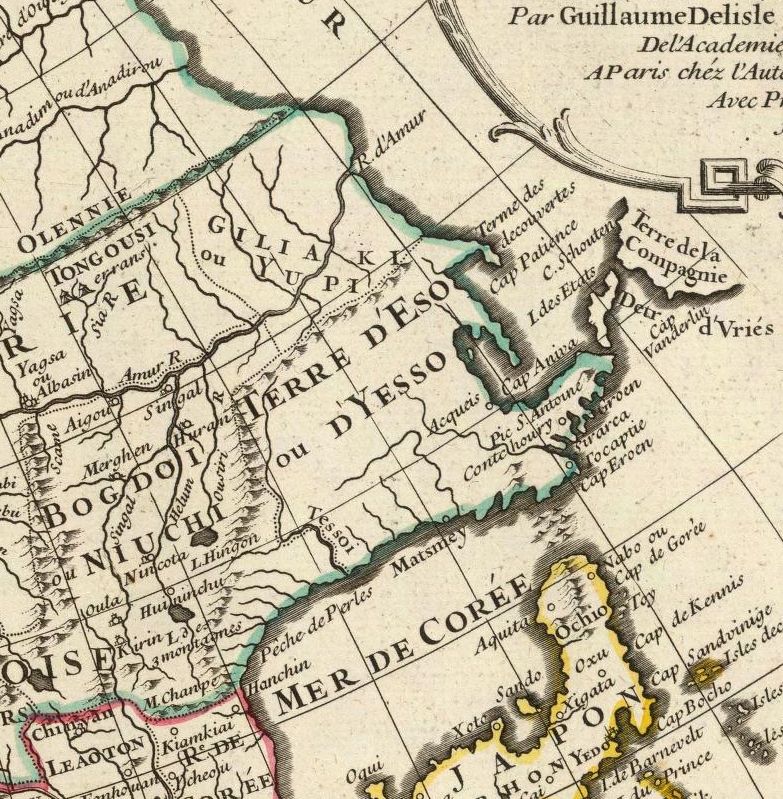

Origins Giliaki or Yupi (meaning "[people wearing clothes made of] fish-skin"; a Chinese exonym also used for the Nani people) on an early-18th-century French map depicting the Vries Strait and the Strait of Tartary. The origins of the Nivkh are hard to discern from current archaeological research. Their subsistence by fishing and coastal sea-mammal hunting is very similar to the Koryak and Itelmen on the Kamchatka Peninsula. The rigging of dog-sledges is also similar to these Chukotko-Kamchatkan groups. Spiritual beliefs are similar to those of the Northwest Coast Indians of North America, whose ancestors migrated from this area.[8] The Nivkh are physically and genetically different from the surrounding peoples, and scholars believe they are the Indigenous inhabitants of the area. The current archaeological model suggests that a sub-Arctic microlithic culture originating from the Transbaikal region migrated across Siberia and populated the Amur and Sakhalin region during the Late Pleistocene, or perhaps earlier.[5] Scientists believe that people of this culture were the first to migrate eastward into the Americas.[14] The microlithic culture was technologically adept in the harsh climate of Siberia during the last ice age. After the ice receded, Tungusic peoples from the south pressed into the warmer northern areas, soon dominating the settled peoples. The Nivkh are considered the last surviving ethnic group able to adapt to the warmer climate and not be assimilated or squeezed out by the newcomers, hence the Nivkh isolate language.[15] The earliest archeological radiocarbon dating for Northern Sakhalin as of 2004 is the Neolithic Age Imchin Site 2, dated to 4950–4570 BCE near the Tym' River estuary on the west coast.[16] Michael Fortescue suggests that Nivkh might be related to the Mosan languages of North America (however, Mosan is generally considered a Sprachbund rather than a language family).[17] Fortescue also presents evidence that Nivkh is related to the Chukotko-Kamchatkans, forming a Chukotko-Kamchatkan–Amuric family,[18] though the evidence was judged to be "insufficient" by Glottolog.[19] More recently, Sergei Nikolaev argued in two papers for a systematic relationship between Nivkh and the Algic languages of North America and a more distant relationship between these two together and the Wakashan languages of coastal British Columbia.[20][21] |

起源 ヴリース海峡と韃靼海峡を描いた18世紀初頭のフランス地図に描かれたギリアキまたはユピ(「魚の皮でできた服を着た人々」の意。 ニヴフ族の起源は、現在の考古学的研究からは判別が難しい。漁業と沿岸での海棲哺乳類の狩猟で生計を立てていた彼らは、カムチャッカ半島のコリャーク族や イテルメン族と非常によく似ている。犬ぞりの装備もこれらのチュコトコ・カムチャツカン・グループに似ている。精神的な信仰は、この地域から祖先が移住し てきた北米北西部沿岸のインディアンと類似している[8]。ニヴフ族は物理的にも遺伝的にも周辺の民族とは異なっており、学者たちは彼らがこの地域の先住 民であると考えている。現在の考古学的モデルは、トランスバイカル地方に起源を持つ亜北極圏の小石器文化が、更新世後期、もしくはそれ以前にシベリアを横 断し、アムールやサハリン地方に移住したことを示唆している[5]。 この小石器文化は、最後の氷河期のシベリアの厳しい気候の中で技術的に優れていた。氷が後退した後、南方からツングース系民族が温暖な北方地域に押し寄 せ、やがて定住民族を支配するようになった。2004年現在、北サハリンで最も古い放射性炭素年代測定は新石器時代のイムチン遺跡2であり、西海岸のティ ム川河口付近で紀元前4950年から4570年に年代測定されている[16]。 マイケル・フォーテスキューは、ニヴフ語が北米のモサン語族と関連している可能性を示唆している(ただし、モサン語族は一般的に語族というよりもむしろ語 群であると考えられている)[17]。フォーテスキューはまた、ニヴフ語がチュコトコ・カムチャッカン語族と関連しており、チュコトコ・カムチャッカン 語・アムール語族を形成しているという証拠を提示している[18]が、その証拠はグロットログによって「不十分」であると判断された[19]。 より最近では、セルゲイ・ニコラエフが2つの論文で、ニブフと北アメリカのアルギック諸語の系統的な関係、そしてこれら2つの言語とブリティッシュ・コロンビア沿岸部のワカシャン諸語の間のより遠い関係を主張した[20][21]。 |

| History Pre-modern history The Sakhalin Nivkhs populated the island during the Late Pleistocene period, when the island was connected to the Continent of Asia via the exposed Strait of Tartary. When the ice age receded, the oceans rose and the Nivkh were split into two groups.[22] It is suggested that the Nivkh people were present in a wide area of Northeast Asia and influenced other people and their cultures. Nivkhs may be related to the Susuya, Okhotsk, and Tobinitai culture that reached Hokkaido and met the Satsumon culture.[23] Several historians suggest that the Nivkh were present in the kingdom of Goguryeo. There are indications that the ancestors of the Nivkh may have played a much more prominent role in pre- and protohistorical Manchuria.[24] Nivkh lands extended along the northern coast of Manchuria from the Russian fortress at Tugur Bay eastward to the mouth of the Amur River at Nikolayevsk, then south through the Strait of Tartary as far as De Castries Bay. Formerly their territories had extended westwards at least as far as the Uda river and the Shantar Islands until pushed out by the Manchus and, later, the Russians.[citation needed] The earliest mention of the Nivkh in history is believed to be a 12th-century Chinese chronicle, referring to a people called Jílièmí (Chinese: 吉列迷), who were in contact with the Mongol rulers of Yuan China.[12] They had been allied with the Mongols since 1263, and the Mongols invaded Sakhalin to aid the Nivkh against the Ainu, who had been encroaching on Sakhalin from Hokkaido.[25] In 1643, Vassili Poyarkov was the first Russian to write of the Nivkh, calling them Gilyak, a Tungus exonym, by which they would be referred until the 1920s.[26] After the Yuan period, Ainu and Nivkh of Sakhalin became tributaries to the Ming dynasty of China after Manchuria came under Ming rule as part of the Nurgan Regional Military Commission. Boluohe, Nanghar and Wuliehe were Yuan posts set up to receive tribute from the Ainu after their war with the Yuan ended in 1308. Ming Chinese outposts in Sakhalin and the Amur river area received animal skin tribute from Ainu on Sakhalin, Uilta and Nivkh in the 15th century after the Tyr-based Yongning Temple was set up along with the Nurkan (Nurgan) outposts by the Yongle emperor in 1409. The Ming also held the post at Wuliehe and received marten pelt fur tribute from assistant commander Alige in 1431 from Sakhalin after the Ming assigned titles like weizhenfu (official charged with subjugation), zhihui qianshi (assistance commander), zhihui tongzhi (vice commander) and Zhihuishi (commander) to Sakhalin Indigenous headmen. The Ming received tribute from the headmen of Alingge, Tuolingha, Sanchiha and Zhaluha in 1437. The position of headman among Sakhalin Indigenous peoples was inherited paternally from father to son and the sons came with their fathers to Wuliehe. Ming officials gave silk uniforms with the appropriate rank to the Sakhalin Ainu, Uilta and Nivkh after they paid tribute. The Maritime Province region had the Ming "system for subjugated peoples' implementers in it for the Sakhalin Indigenous peoples. [clarification needed] Sakhalin received iron tools from mainland Asia through this trade, as Tungus groups joined in from 1456-1487. Local Indigenous hierarchies had Ming Chinese given political offices integrated with them. The Ming system on Sakhalin was imitated by the Qing.[27] Nivkh women in Sakhalin married Han Chinese Ming officials when the Ming took tribute from Sakhalin and the Amur river region.[28][29] Local Sakhalin native chiefs had their daughters taken as wives by Manchu officials, as sanctioned by the Qing dynasty when the Qing exercised jurisdiction in Sakhalin and took tribute from them.[30][29] Due to Ming rule in Manchuria, Chinese cultural and religious influence such as Chinese New Year, the "Chinese god", Chinese motifs like the dragon, spirals, scrolls, and material goods like agriculture, husbandry, heating, iron cooking pots, silk, and cotton spread among the Amur natives like the Udeghes, Ulchis, and Nanais.[31] Tsarist Russia and Imperial Japan For many centuries, the Nivkh were tributaries of the Manchus. After the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689, they functioned as intermediaries between the Russians, Manchu and Japanese, and also the Ainu, who were vassals of the Japanese. Early contact with the southern Sakhalin Ainu was generally hostile, although trade between the two was apparent.[32] The Nivkh suffered severely from the Cossack conquest and imposition of Tsarist Russians; they called the latter kinrsh (devils).[33] The Russian Empire gained complete control over Nivkh lands after the 1858 Treaty of Aigun and the 1860 Convention of Peking.[26] The Russians established a penal colony (katorga) on Sakhalin, which operated from 1857 to 1906. They transported numerous Russian criminal and political exiles there, including Lev Sternberg, an important early ethnographer of the Nivkh. The Nivkh were soon outnumbered; they were sometimes employed as prison guards and to track escaped convicts.[7] The Nivkh suffered epidemics of smallpox, plague, and influenza, brought by the immigrants and spread in the crowded, unsanitary prison environment.[34] Though the Empire of Japan never controlled the northern part of Sakhalin, Japan and Russia jointly ruled the island as part of the 1855 Treaty of Shimoda. From the 1875 Treaty of Saint Petersburg until the 1905 Treaty of Portsmouth, Russia governed all of Sakhalin. From 1905 to 1945, Sakhalin was partitioned between Russia and Japan along the 50th N parallel. Russia allowed Japanese entrepreneur fishermen in Nivkh lands from the 1880s until 1948.[35] The Russian Priamur governor-generalship had difficulty finding Russian labour and allowed Japanese and Nivkh fishermen to develop the area, though they were heavily taxed. Russian authorities prevented the Nivkh from fishing in prior coastal and river systems via bans and high taxes from cached fish. The first of many incidents of over-exploitation of fisheries by the Japanese (and later the Russians) on the Tartar Strait and lower Amur occurred in 1898. It drove many Nivkhs into starvation if they could not import expensive Russian foods.[35] Under Soviet rule  A Nivkh village in the early-20th century Russia underwent the October Revolution forming the Soviet Union in 1922. The new government altered prior Russian Imperial policies towards the Nivkh that were in line with communist ideology. Soviet officials embraced the autonym Nivkh to replace the old term Gilyak, as a hallmark for new native self-determination.[36] A brief autonomous okrug was created for the Nivkh.[citation needed] The government granted them extensive fishing rights, which were not rescinded until the 1960s.[36] But, other Soviet policies proved devastating. The Nivkh were forced into mass agricultural and industrial labour collectives called kolkhoz.[26] Nivkh fishermen were difficult to convert to agricultural practices because of their belief that ploughing the earth was a sin.[26] The Nivkh were soon working and living as a second-class minority group among the massive Russian labour force.[36] These collectives irrevocably altered the lifestyle of the Nivkh. The traditional hunter-gatherer lifestyle disappeared.[36] Soviet authorities showcased the Nivkh as a 'model' nation for a culture quickly transforming from the Neolithic to a socialist industrial model. They banned the use of the Nivkh language from schools and the public square. The Russian language was mandated and russification of the Nivkh accelerated. Many Nivkh stories, beliefs, and clan ties were forgotten by new generations.[36] From 1945 to 1948, many Nivkh, as well as half of the Oroks and all of the Sakhalin Ainu, who had been living under Japanese jurisdiction in the southern half of Sakhalin, were forced to move to Japan along with the ethnic Japanese settlers. Many indigenous people would later return to the area.[37] According to "Modern Ainu: The Romance of Ethnic Migration" (現代のアイヌ : 民族移動のロマン, by Kosuge Sugawara, 1966 under Genbunsha), these Nivkh people in Japan resided in Abashiri, Hakodate, and Sapporo. One notable displaced Nivkh from Karafuto to Abashiri was Chiyo Nakamura (1906–1969), a shaman from Poronaisk (Japanese: 敷香町, romanized: Shisuka-machi).[38][39][40] By 2004, the Nivkh-Orok community in Abashiri had apparently vanished.[41] Chuner Taksami, an anthropologist, is considered the first modern Nivkh literary figure and supporter of Siberian rights.[36] In the post-Soviet Russian commonwealth of nations, the Nivkh have fared better than the Ainu or the Itelmens, but worse than the Chukchi or the Tuvans. The Soviet government in 1962 resettled many of the Nivkh into fewer, denser settlements, such that Sakhalin settlements had been reduced from 82 to 13 by 1986.[42] This relocation was accomplished via the Soviet collectives that the Nivkh had become so dependent on. The closure of state-funded amenities such as a school or electricity generator prompted citizenry to move into government-preferred settlements.[36] After the Soviet collapse With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the kolkhoz collectives were abandoned. The Nivkh were dependent on the state-funded collectives, and with their dissolution, rapid economic hardship ensued for the already impoverished populace.[43] At present, the Nivkh living in the north of Sakhalin see their future threatened by the giant offshore oil extraction projects known as Sakhalin-I and Sakhalin-II, operated by foreign Western firms. Since January 2005, the Nivkh, led by their elected leader Alexey Limanzo, have engaged in non-violent protest actions, demanding an independent ethnological assessment of Shell's and Exxon's plans. Solidarity actions have been staged in Moscow, New York City and later in Berlin.[44] The monthly Nivkh newspaper, Nivkh Dif, established in 1990, is published in the West-Sakhalin dialect and is headquartered in the village of Nekrasovka.[45] |

歴史 近代以前の歴史 サハリン・ニヴフ族は、島が露出した韃靼海峡を経由してアジア大陸とつながっていた更新世後期にこの島に居住していた。氷河期が去ると海が上昇し、ニブフ 族は2つのグループに分かれた[22]。ニブフ族は北東アジアの広い地域に存在し、他の人々やその文化に影響を与えたと考えられている。ニブフ族は北海道 に到達し、薩摩文化と出会ったススヤ文化、オホーツク文化、トビニタイ文化と関係があるかもしれない[23]。いくつかの歴史家は、ニブフ族が高句麗王国 に存在したことを示唆している。ニブフ族の祖先は、歴史以前および原史時代の満州において、より重要な役割を果たしていた可能性がある。ニブフ族の土地 は、満州の北海岸に沿って、東はトゥグル湾のロシア要塞からニコライエフスクのアムール川河口まで、南は韃靼海峡を通ってデ・カストリー湾まで広がってい た。かつて彼らの領土は、満州族や後にロシア族に押し出されるまで、少なくともウダ川とシャンタル諸島まで西に広がっていた[要出典]。 歴史上、ニヴフ族に関する最古の記述は12世紀の中国の年代記であると考えられており、元中国のモンゴル人支配者と接触していたジリエミ(中国語:吉列 迷)と呼ばれる人々について言及している[12]。 [1643年、ヴァシリ・ポヤルコフがロシア人として初めてニヴフ族について記し、ツングース人の異称であるギリヤークと呼んだ。 元時代の後、サハリンのアイヌとニブフは、満州がヌルガン地方軍事委員会の一部として明の支配下に入った後、中国の明の朝貢国となった。ボルオヘ、ナンガ ル、ウリエヘは、1308年に元との戦争が終結した後、アイヌから貢物を受け取るために設置された元の拠点であった。サハリンとアムール川流域の明の中国 前哨基地は、1409年に永楽帝によってティルを拠点とする永寧寺がヌルカン(ヌルガン)前哨基地とともに設置された後、15世紀にサハリン、ウイルタ、 ニヴフのアイヌから獣皮の貢ぎ物を受け取った。明もまた武烈河に駐屯し、明がサハリン先住民の庄屋に威震府(服属を命じられた役人)、志会乾史(補佐司令 官)、志会同志(副司令官)、志会士(司令官)などの称号を与えた後、1431年にサハリンからアリゲ司令官補佐からテンの毛皮の貢納を受けた。1437 年、明はアリンゲ、トゥオリンガ、サンチハ、チャルハの庄屋から貢物を受け取った。 サハリン先住民の庄屋の地位は父から子へと受け継がれ、息子たちは父とともに武烈河にやってきた。明の役人は、樺太アイヌ、ウイルタ、ニヴフが貢物を納め た後、それ相応の階級を持つ絹の軍服を与えた。沿海州地域には、明の「被支配民のための制度」が樺太先住民のために実施された。[1456年から1487 年にかけてツングース族がこの貿易に参加したため、サハリンはこの貿易を通じてアジア本土から鉄器を受け取った。先住民の地方階層は明の中国人に政治的役 職を与えて統合させた。サハリンの明のシステムは清に模倣された[27]。 サハリンのニブフ族の女性は、明がサハリンとアムール川流域から朝貢した際に、漢民族の明の役人と結婚した[28][29]。 サハリンの土着の首長たちは、清がサハリンで裁判権を行使し、彼らから朝貢した際に、清朝によって公認されたように、彼らの娘を満州族の役人の妻にした [30][29]。 満州における明の支配により、中国の正月、「中国の神」、龍、螺旋、巻物などの中国のモチーフ、農業、畜産、暖房、鉄鍋、絹、綿などの物質的な商品など、中国の文化的、宗教的な影響がウデゲ、ウルチ、ナナイなどのアムール原住民の間に広まった[31]。 帝政ロシアと帝国日本 何世紀もの間、ニブフ族は満州族の支族であった。1689年のネルチンスク条約以降、彼らはロシア人、満州人、日本人、そして日本人の家臣であったアイヌ 人の仲介者として機能した。樺太南部アイヌとの初期の接触は、両者間の交易は明らかであったものの、概して敵対的であった[32]。 ロシア帝国は1858年のアイグン条約と1860年の北京条約の後、ニブフの土地を完全に支配するようになった[26]。ロシア人はサハリンに流刑地(カ トルガ)を設立し、1857年から1906年まで運営した。ロシア人はサハリンに流刑地(カトルガ)を設立し、1857年から1906年まで運営され、ニ ヴフ族の初期の重要な民族学者であったレフ・シュテルンベルグを含む多くのロシア人犯罪者や政治亡命者をそこに移送した。ニヴフ族はすぐに多勢に無勢とな り、時には刑務所の看守として、また脱獄囚を追跡するために雇われた[7]。ニヴフ族は天然痘、ペスト、インフルエンザの流行に見舞われたが、これは移民 が持ち込んだものであり、混雑した不衛生な刑務所環境で蔓延したものであった[34]。 大日本帝国がサハリンの北部を支配することはなかったが、1855年の下田条約により、日本とロシアは共同でこの島を支配した。1875年のサンクトペテ ルブルク条約から1905年のポーツマス条約まで、ロシアはサハリン全土を統治した。1905年から1945年まで、サハリンは北緯50度線に沿ってロシ アと日本の間で分割された。ロシアは、1880年代から1948年まで、ニヴフ族の土地での日本人企業家漁師を許可していた[35]。ロシアのプリアムー ル総督府は、ロシア人労働者を見つけるのが困難だったため、日本人とニヴフ族の漁師に重税を課しながらも、この地域の開発を許可した。ロシア当局は、ニブ フ族が沿岸や河川水系で漁をすることを禁止し、密漁による高額の税金を課した。1898年、タルタル海峡とアムール川下流域で、日本軍(後にロシア軍)に よる漁業の乱獲が起こった。高価なロシア産食品を輸入できなければ、多くのニヴフ人を飢餓に追い込んだ[35]。 ソビエト支配下  20世紀初頭のニヴフ族の村 ロシアでは1922年に十月革命が起こり、ソビエト連邦が成立した。新政府は、共産主義イデオロギーに沿ったニヴフ族に対するロシア帝国の以前の政策を変 更した。ソ連当局者は、新しい先住民の自決の証として、古いギリヤークという呼び名に代わってニヴフという自称を受け入れた[36]。ニヴフ族の漁民は、 大地を耕すことは罪であるという信念を持っていたため、農耕への転換は困難であった[26]。 これらの集団は、ニヴフ族の生活様式を取り返しのつかないほど変化させた。伝統的な狩猟採集生活様式は姿を消した[36]。ソ連当局はニヴフ族を、新石器 時代から社会主義産業モデルへと急速に変貌する文化の「モデル」国家として紹介した。ソ連当局は、新石器時代から社会主義産業モデルへと急速に変貌する文 化の「モデル」国家として、ニヴフ語を学校や公共の場で使用することを禁止した。ロシア語が義務づけられ、ニヴフ語のロシア化が加速した。多くのニヴフ語 の物語、信仰、一族の絆は新しい世代によって忘れ去られた[36]。 1945年から1948年にかけて、サハリンの南半分で日本の管轄下に住んでいたオロクの半数とサハリンアイヌの全住民と同様に、多くのニヴフ族が日本人 入植者と共に日本への移住を余儀なくされた。後に多くの先住民族がこの地域に戻ることになる[37]: 現代のアイヌ民族移動のロマン』(菅原小菅著、玄文社、1966年)によれば、これらの在日ニブフ人は網走、函館、札幌に居住していた。樺太から網走に移 住した著名なニブフ族のひとりに、ポロナイスク(日本名:敷香町、ローマ字表記:Shisuka-machi)のシャーマンであった中村千代(1906- 1969)がいる[38][39][40]。2004年までに、網走のニブフ・オロクのコミュニティは明らかに消滅した[41]。 ソビエト連邦後のロシアでは、ニブフ族はアイヌ民族やイテルメン族よりはましだが、チュクチ族やトゥワン族よりは不利であった。1962年、ソビエト政府 はニヴフ族の多くをより少ない、より密集した集落に再定住させ、サハリンの集落は1986年までに82から13に減少した[42]。学校や発電機のような 国費で賄われる設備が閉鎖されたことで、市民は政府優先の集落への移住を促された[36]。 ソビエト崩壊後 1991年のソビエト連邦崩壊により、コルホーズ・コレクティブは放棄された。現在、サハリン北部に住むニブフ族は、外国の西側企業によって運営されてい るサハリンIおよびサハリンIIとして知られる巨大な海洋石油採掘プロジェクトによって、自分たちの将来が脅かされていると考えている。2005年1月以 来、ニブフ族は選挙で選ばれた指導者アレクセイ・リマンゾに率いられ、シェルとエクソンの計画に対する独立した民族学的評価を要求し、非暴力の抗議行動に 従事してきた。1990年に創刊された月刊ニヴフ新聞『ニヴフ・ディフ』は西サハリン方言で発行されており、ネクラソフカ村に本部を置いている[45]。 |

| Society Village life The Nivkh were semi-sedentary hunter-gatherers with summer and winter settlements. Nivkh villages consisted of three to four households shared by several families with larger villages rare, and mostly located on the Amur estuary.[46] Households were shared for reasons of community and survival during the harsh cold winters. Villages would last for several decades but were susceptible to floods and sometimes vanished. Many were wiped out during the devastating Amur floods of 1915 and 1968.[46] Often households contained families that were not related. The village was usually composed of people from two to eight different clans, four being standard.[46] In the late fall able-bodied Nivkh men would leave the villages to hunt for game in the surrounding hunting grounds whereas women would gather foods from the forests.[46] Nivkh would move to winter settlements near rivers to survive the harsh snows and catch salmon spawning (see list of Nivkh settlements). The Nivkh were very hospitable, such that the Nanai located upstream on the Amur when faced with hard times would often visit or stay in Nivkh villages.[46] Clan Nivkh clans (khal) were a group of people united by marriage ties, a common derived deity, arranging marriages, and responsible for group dispute resolution. The clan is divided into three exogamous sub-clans.[47] A clan would cooperate with other members on hunts and fishing when away from the village.[47] A Nivkh clan believed they had "one (common) akhmalk or imgi, one fire, one mountain man, one bear, one devil, one tkhusind (ransom, or clan penalty), and one sin."[48] Marriage Marriage tended to be exogamic unlike many paleo-Siberian groups. Although within the clan, marriage is endogamic, while sub-clans are exogamic.[47] Nivkh marriage customs were very complicated and controlled by the clan.[47] Cross-cousin marriage seems to be the original custom with the clan, a latter necessity when the clan was unable to marry individuals without breaking taboo.[47] The bride price was probably introduced by the Neo-Siberians.[47] The dowry was shared by the clan. The number of men generally exceeded the number of women. It was hard to gain wives, as they were few and expensive. This led to the wealthier men having more than one wife and poor men being unable to obtain wives.[48] |

社会 村の生活 ニヴフ族は夏と冬に集落を持つ半定住型の狩猟採集民であった。ニヴフ族の村落は3~4世帯を数家族で共有するもので、大規模な村落はまれで、ほとんどがア ムール河口に位置していた[46]。世帯は共同体としての理由と厳しい寒さの冬を生き延びるために共有されていた。村は数十年続いたが、洪水の影響を受け やすく、消滅することもあった。1915年と1968年の壊滅的なアムール洪水では、その多くが全滅した。村は通常2つから8つの異なる氏族の人々で構成 され、4つが標準であった[46]。 晩秋になると、体力のあるニヴフ族の男性は村を出て周辺の狩猟地で狩猟を行い、女性は森から食料を採集した[46]。ニヴフ族は厳しい雪を生き延び、サケ の産卵を捕るために川の近くの冬の集落に移動した(ニヴフ族の集落のリストを参照)。ニヴフ族は非常にもてなし好きで、アムール川の上流に位置するナナイ 族は苦境に直面すると、しばしばニヴフ族の村を訪れたり、滞在したりした[46]。 氏族 ニヴフ族の一族(カル)は、婚姻の絆によって結ばれた人々の集団であり、共通の由来となる神を持ち、婚姻を手配し、集団の紛争解決を担っていた。クランは 3つの外格的なサブクランに分かれている[47]。 クランは村を離れると狩猟や漁業において他のメンバーと協力する[47]。ニヴフ族のクランは「1つの(共通の)アクマルクまたはイムギ、1つの火、1人 の山男、1人の熊、1人の悪魔、1つのトクシンド(身代金、またはクランの刑罰)、そして1つの罪」があると信じていた[48]。 結婚 結婚は古シベリアの多くの集団とは異なり、外婚的である傾向があった。一族内では結婚は内婚的であるが、亜一族は外婚的である[47]。ニヴフ族の結婚の 習慣は非常に複雑であり、一族によって統制されていた[47]。いとこ同士の結婚は一族との元々の習慣のようであり、一族がタブーを破ることなく個人と結 婚することができなかった場合には、後者の必要性があった。一般的に男性の数が女性の数を上回っていた。妻の数は少なく、高価であったため、妻を得ること は困難であった。そのため裕福な男性は複数の妻を持ち、貧しい男性は妻を得ることができなかった[48]。 |

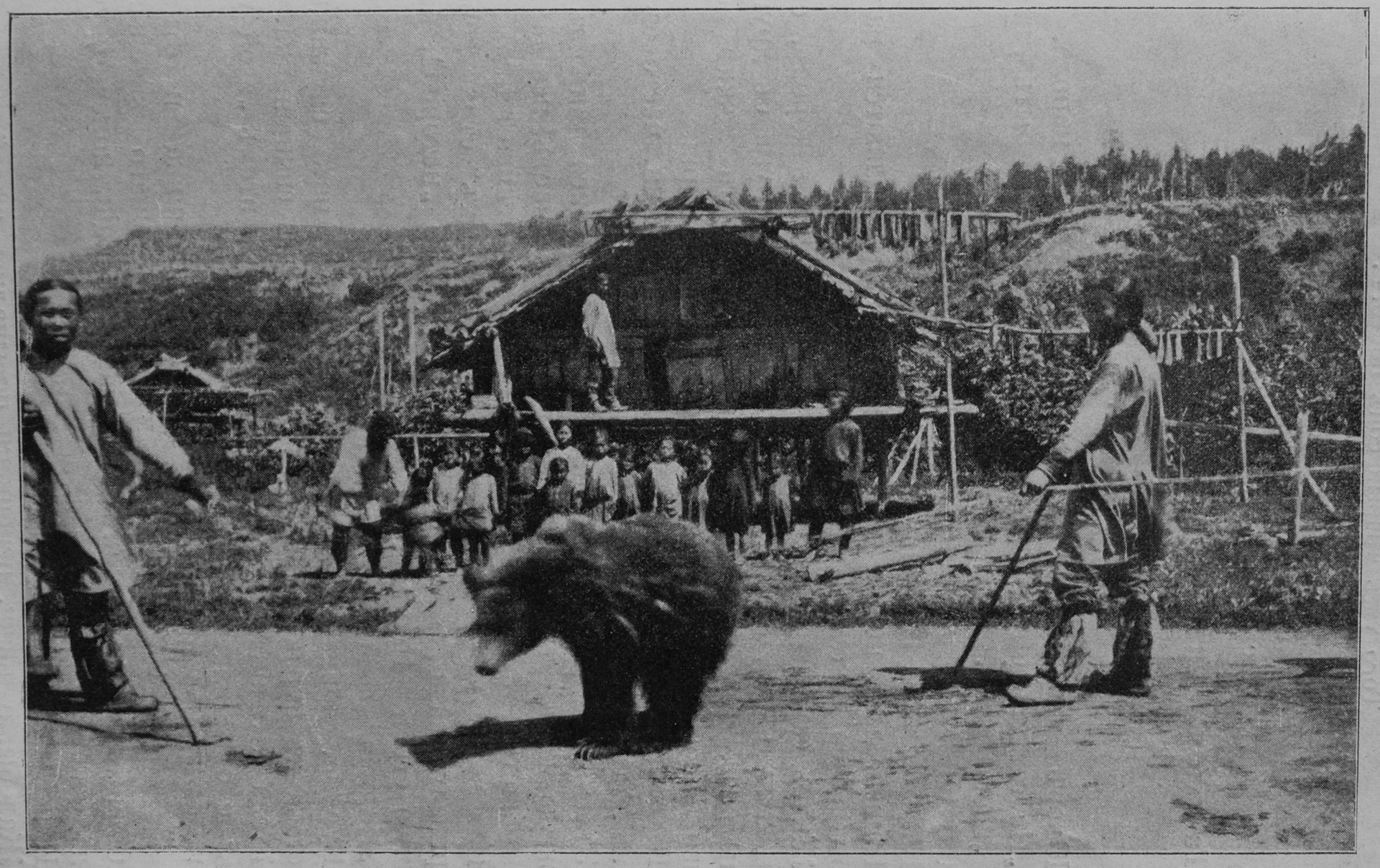

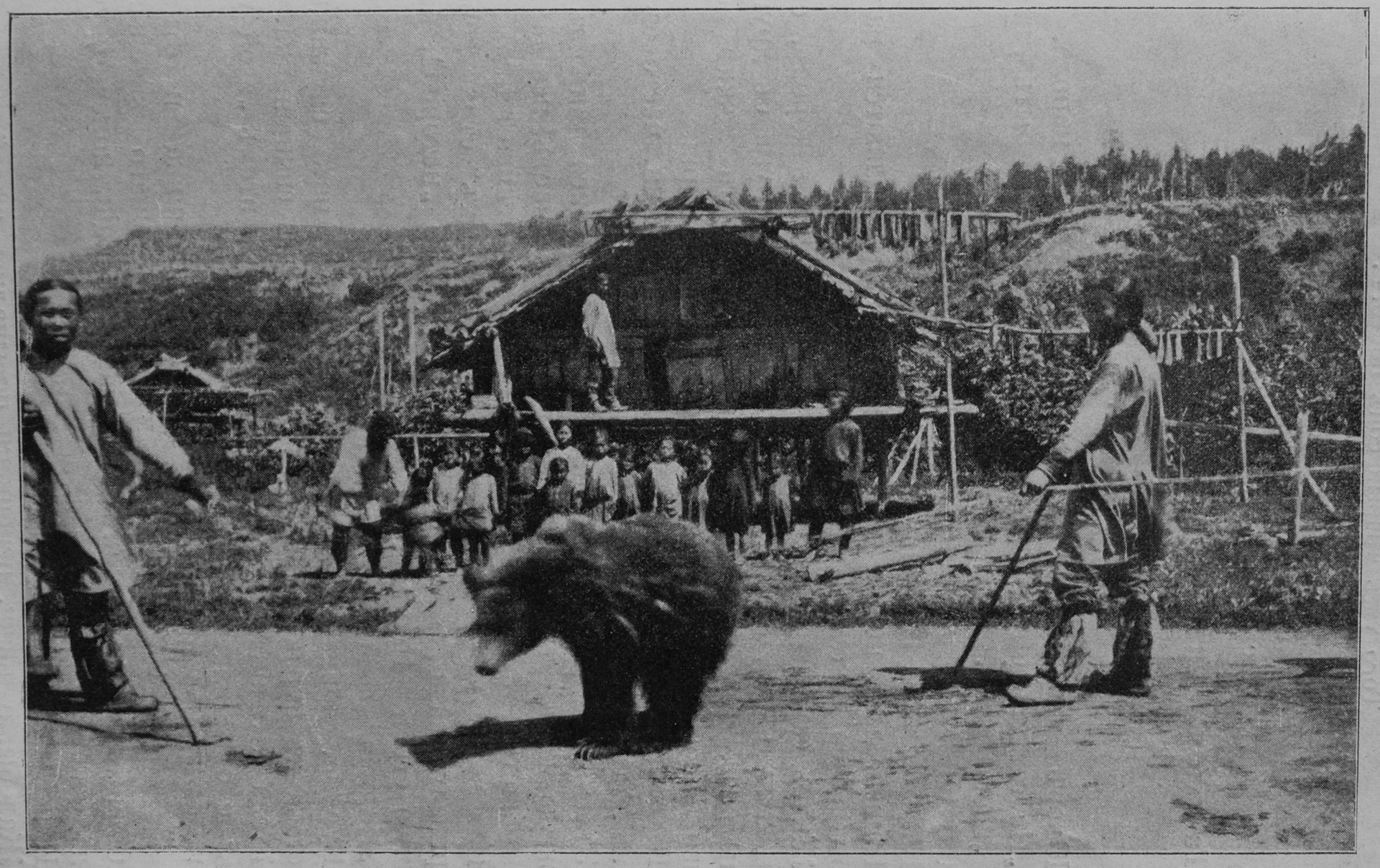

| Religion Nivkh's traditional religion was based on animist beliefs, especially via shamanism, before colonial Russians made efforts to convert the population to Eastern Orthodox Christianity.[49] Nivkh animists believe the island of Sakhalin is a giant beast lying on its belly with the trees of the island as its hair. When the beast is upset, it awakens and trembles the earth causing earthquakes.[50] Nivkh have a pantheon of vaguely defined gods (yz, yzng)[clarification needed] that presided over the mountains, rivers, seas and sky.[51] Nivkhs' have extensive folklore, songs, and mythos of how humans and the universe were created, and of how fantastic heroes, spirits and beasts battled with each other in ancient times. Some Nivkhs have converted to Russian Orthodoxy or other religions, though many still practice traditional beliefs. Fire is especially venerated. It is the symbol of the unity of the clan. Fire is considered a deity of their ancestors, protecting them from evil spirits and guarding their clan from harm.[52] An open flame would be "fed" a leaf of tobacco, spices, or a tipple of vodka in order to please the spirits for protection. Nivkhs would also frequently offer items to the deities by 'feeding'.[53] The sea would be "fed" an item of importance in order that the sea god protects the travellers. Shamanism Shamans' (ch'am) main role was in diagnosing and curing disease for the Nivkh. The rare shamans typically wore an elaborate coats with belts often made of metal.[54] Remedies composed of plant and sometimes animal matter were employed to cure sickness. Talismans were used or offered to patients to prevent sickness.[54] Shamans additionally functioned as a conduit to combat and ward off evil spirits that cause death. A shaman's services usually were compensated with goods, quarters and food.[54] Bear Festival  A bear festival by Nivkh around 1903 Nivkh Shamans also presided over the Bear Festival, a traditional holiday celebrated between January and February depending on the clan. Bears were captured and raised in a corral for several years by local women, who treated the bear like a child.[55] The bear was considered a sacred earthly manifestation of Nivkh ancestors and the gods in bear form (see Bear worship). During the festival, the bear would be dressed in a specially-made ceremonial costume. It would be offered a banquet to take back to the realm of gods to show benevolence upon the clans.[50] After the banquet, the bear would be sacrificed and eaten in an elaborate religious ceremony. Dogs were often sacrificed as well. The bear's spirit returned to the gods of the mountain 'happy' and would then reward the Nivkh with bountiful forests.[56] The festival typically would be arranged by relatives to honour the death of a kinsman. Generally, the Bear Festival was an inter-clan ceremony where a clan of wife-takers restored ties with a clan of wife-givers upon the broken link of the kinsman's death.[57] The Bear Festival was suppressed during Soviet occupation though the festival has had a modest revival since the decline of Soviet Union, albeit as a cultural instead of religious ceremony.[58] A very similar ceremony, Iomante, is practiced by the Ainu people of Japan.[citation needed] |

宗教 ニヴフの伝統的な宗教は、植民地時代のロシア人が住民を東方正教会に改宗させる努力をする以前は、特にシャーマニズムを通じたアニミズム信仰に基づいてい た。ニヴフ族には、山、川、海、空を司る漠然と定義された神々(yz、yzng)[要出典]のパンテオンが存在する[51]。ニヴフ族には、人間と宇宙が どのように創造されたのか、また、古代の幻想的な英雄、精霊、獣がどのように互いに戦ったのかという広範な伝承、歌、神話がある。ロシア正教や他の宗教に 改宗したニブフ人もいるが、多くの人は今でも伝統的な信仰を実践している。火は特に崇拝されている。それは一族の団結の象徴である。火は彼らの祖先の神で あり、彼らを悪霊から守り、一族を災いから守ると考えられている。ニヴフ族はまた、「餌付け」によって神々に品物を捧げることもあった[53]。海は、海 の神が旅人を守るために、重要な品物を「餌付け」される。 シャーマニズム シャーマン(ch'am)の主な役割は、ニヴク族の病気の診断と治療であった。希少なシャーマンは通常、金属製のベルトの付いた凝ったコートを着ていた [54]。シャーマンはさらに、死を引き起こす悪霊と闘い、追い払うためのパイプ役としても機能した。シャーマンの役務は通常、物品、宿舎、食物で補償さ れた[54]。 熊祭り  1903年頃のニヴフによる熊祭り ニヴフ族のシャーマンは熊祭りも主宰していた。熊は地元の女性たちによって捕獲され、数年間家畜小屋で育てられ、子供と同じように扱われた[55]。熊は ニヴフの祖先と熊の姿をした神々の神聖な地上での現れと考えられていた(熊崇拝を参照)。祭りの間、熊は特別に作られた儀式用の衣装を着せられる。宴会の 後、熊は生贄として捧げられ、手の込んだ宗教的儀式で食べられる。犬もしばしば犠牲になった。熊の魂は山の神々のもとへ「幸せ」に戻り、ニヴクに豊かな森 を与えて報いた[56]。一般的に熊祭りは氏族間の儀式であり、近親者の死によって断ち切られた絆を、妻を奪う氏族が妻を与える氏族との絆を回復するもの であった[57]。熊祭りはソビエト連邦の占領下で弾圧されたが、ソビエト連邦の衰退以降、宗教的な儀式ではなく文化的な儀式としてではあるが、ささやか な復活を遂げている[58]。 よく似た儀式であるイオマンテは日本のアイヌ民族によって行われている[要出典]。 |

| Environment The Russian Far East has a cold and harsh climate. In the fish-rich Amur River estuary in the districts of Nixhne-Amruskii and Takhtinskii, winters have high winds and heavy snows with mid-winter usually averaging from −28 to −20 °C (−18 to −4 °F). Summers are wet and moderately warm ranging between 16 and 20 °C (61 and 68 °F). The area's biome is characterized as Taiga and evergreen coniferous forests consisting of larch, yew, birch, maple, lilac, honeysuckle, and extensive low-lying swamp grasses. Higher elevations have spruce, fir, ash, lime, walnut and mountain tops have cedar and lichens. Bears, foxes, sables, hares, Siberian tigers, elks, grouse, and deer typical near the Amur outlet which usually floods during the rainy season.[59][60] Northern Sakhalin is harsher ecologically with mostly Taiga. Winters are longer, with a mean temperature of −19 °C (−2 °F), however, short summers are warmer averaging 15 °C (59 °F) due to warmer Pacific Ocean currents moving around the island. Heavy snows blanket the island of Sakhalin (Yh-mif in Nivkh) during winter, due to monsoon winds blowing from Siberia, drawing humidity as they pass over the Sea of Okhotsk, Sea of Japan, and the Strait of Tartary. Barren tundra dominates the north, with sparse trees such as larch, birch and various grasses, while moving southward, spruce and fir are seen. Bears, foxes, otters, lynx, and reindeer are common wildlife.[60][61] The Island's major rivers are the Tym' and Poronai, rich in fish, especially salmon. Before Russian colonization, Nivkh villages could be found on these rivers approximately every 5 km.[62] The Strait of Tartary is currently only 20 kilometers (12 mi) wide and is shallow enough that an ice bridge forms during the winter that can be traversed by foot or dog-sledge. At the glacial maximum of the Ice Age, sea levels were 100 meters (330 ft) lower than they are today. The Eurasia continent was connected to Sakhalin via the Strait of Tatar and Hokkaidō via the Soya Strait of which humans migrated. This connection explains the similarities of trees, plants, and animals including now-extinct mammoths. The receding ice age warmed the area, allowing greater tree cover and wildlife, thus new resources for the Nivkhs to exploit. The opening of the Soya and then the shallower Strait of Tartary allowed warm pacific currents to bathe the island and the lower Amur River.[63] |

環境 ロシア極東は寒冷で厳しい気候である。魚の豊富なアムール川河口のニシュネ・アムールスキーとタフティンスキーでは、冬は強風と大雪に見舞われ、真冬の平 均気温は-28~-20℃。夏は湿潤で、16~20℃と適度に暖かい。この地域のバイオームは、カラマツ、イチイ、シラカバ、カエデ、ライラック、スイカ ズラからなるタイガと常緑針葉樹林、そして広大な低湿地の沼沢草である。標高の高い場所にはトウヒ、モミ、トネリコ、ライム、クルミが生え、山の頂上には スギと地衣類が生える。雨季に氾濫するアムール川流域には、クマ、キツネ、サーブル、ノウサギ、シベリアトラ、エルク、ライチョウ、シカが生息している [59][60]。 サハリン北部は生態学的に厳しく、ほとんどがタイガである。冬は長く、平均気温は-19 °C(-2°F)であるが、夏は短く、島の周囲を流れる太平洋の暖流の影響で平均15 °C(59°F)と暖かい。冬は、シベリアから吹き付ける季節風がオホーツク海、日本海、韃靼海峡を通過する際に湿気を引き込むため、サハリン島は大雪に 覆われる。北部は不毛のツンドラが広がり、カラマツ、シラカバ、さまざまな草などの樹木がまばらに生えているが、南下するとトウヒやモミが見られるように なる。クマ、キツネ、カワウソ、オオヤマネコ、トナカイは一般的な野生動物である[60][61]。島の主要な川はティム川とポロナイ川で、魚、特にサケ が豊富である。ロシアの植民地化以前は、ニヴフ族の村はこれらの川で約5kmごとに見つけることができた[62]。 韃靼海峡の幅は現在20キロメートル(12マイル)しかなく、冬には氷の橋が架かり、徒歩や犬ぞりで渡ることができるほど浅い。氷河期の最盛期には、海面 は現在より100メートルも低かった。ユーラシア大陸はタタール海峡、北海道は宗谷海峡を通じてサハリンとつながっており、人類はそこから移動した。この つながりは、樹木、植物、そして今は絶滅したマンモスを含む動物の類似性を説明する。氷河期の後退によってこの地域は暖かくなり、樹木が生い茂り、野生動 物が増え、ニヴフ族が新たな資源を利用できるようになった。宗谷海峡が開通し、さらに浅い韃靼海峡が開通したことで、太平洋の暖流が島とアムール川下流域 を潤すようになった[63]。 |

| Technology Dwellings Nivkhs lived in two types of self-built winter dwellings. The most ancient of these was the ryv (or to). The dwelling was a round dugout about 7.5 meters (23 feet) in diameter, shored up by wooden poles and covered with packed dirt and grass.[64] The ryv had a fireplace in the centre and a smoke hole for light and smoke escape. The other type of dwelling used for winter is the chad ryv similar to the Nanai dio which was modelled after Manchurian and Chinese dwellings of the Amur.[64] The chad ryv were one-room structures with a gable roof and a kang (Chinese furnace) for heating.[46] A nearby shed held sledges, skis, boats, and dogs.[46] Clothing  Nivkh men who wear skiy and kosk Nivkhs traditionally wore robes (skiy for men, hukht for women) having three buttons, fastened on the left side of the body.[64] Winter garments were made of skins from fish, seal, sable, and furs from otter, lynx, fox, and dog. Women's hukht extended below the knee and were light multicoloured with intricate embroideries and various ornaments sewed on the sleeves, collar and hem.[64] Ornaments were coins, bells, or beads made of wood, glass, or metal mostly originating from Manchurian and Chinese traders.[64] Men's skiy were darker coloured, shorter, and had pockets built into the sleeves. Men's clothing were less elaborate with ornaments on the sleeve and left lapel. Men would also wear a loose kilt called a kosk when hunting or travelling on dog-sledge.[64] Boots were made of fish-, seal-, or deerskin, and very watertight. Fur hats (hak) were worn in winter, with the furry tails and ears of the animal often adorning the back and crown of the hat. Summer hats (hiv hak) were conical and made from birch-bark. Since Soviet collectivization, Nivkh mostly wear mass-produced Western clothing, but traditional clothing is worn for holidays and cultural events.[64] |

テクノロジー 住居 ニヴフ族は2種類の自作の冬用住居に住んでいた。その中で最も古くからあるのがリヴ(またはトー)である。この住居は直径7.5メートル(23フィート) ほどの丸い掘っ立て小屋で、木の柱で支えられ、詰めた土と草で覆われていた[64]。ライヴの中心には暖炉があり、明かりと煙を逃がすための煙穴があっ た。冬に使用されるもう一つのタイプの住居は、アムール地方の満州や中国の住居を手本としたナナイ・ディオに似たチャド・ライヴである[64]。チャド・ ライヴは切妻屋根の一室構造で、暖房用のカン(中国の炉)があった[46]。 近くの小屋にはソリ、スキー、ボート、犬などが保管されていた[46]。 衣服  スキイとコスクを着用するニヴフ族の男性 ニヴフ族は伝統的に3つのボタンが付いたローブ(男性はスキ、女性はフクト)を着ており、体の左側に留めていた[64]。冬服は魚、アザラシ、セーブル、 カワウソ、オオヤマネコ、キツネ、イヌなどの毛皮で作られていた。女性のフクトは膝下まであり、淡い多色使いで、袖、襟、裾に複雑な刺繍や様々な装飾が縫 い付けられていた[64]。装飾品は木、ガラス、金属で作られたコイン、鈴、ビーズなどで、主に満州や中国の商人から伝わったものであった[64]。男性 のスキーは色が濃く、丈が短く、袖にポケットが付いていた。男性の衣服は、袖と左の襟に装飾が施された、それほど手の込んだものではなかった。狩猟や犬ぞ りでの移動の際には、男性もコスクと呼ばれるゆったりとしたキルトを着用した[64]。ブーツは魚革、アザラシ革、鹿革で作られ、防水性に優れていた。毛 皮の帽子(hak)は冬に着用され、動物の毛皮の尾と耳が帽子の背中と冠を飾ることが多かった。夏の帽子(hiv hak)は円錐形で、白樺の皮で作られていた。ソビエトの集団化以降、ニヴフ族は主に大量生産された西洋の衣服を着用するが、伝統的な衣服は祝日や文化的 な行事の際に着用される[64]。 |

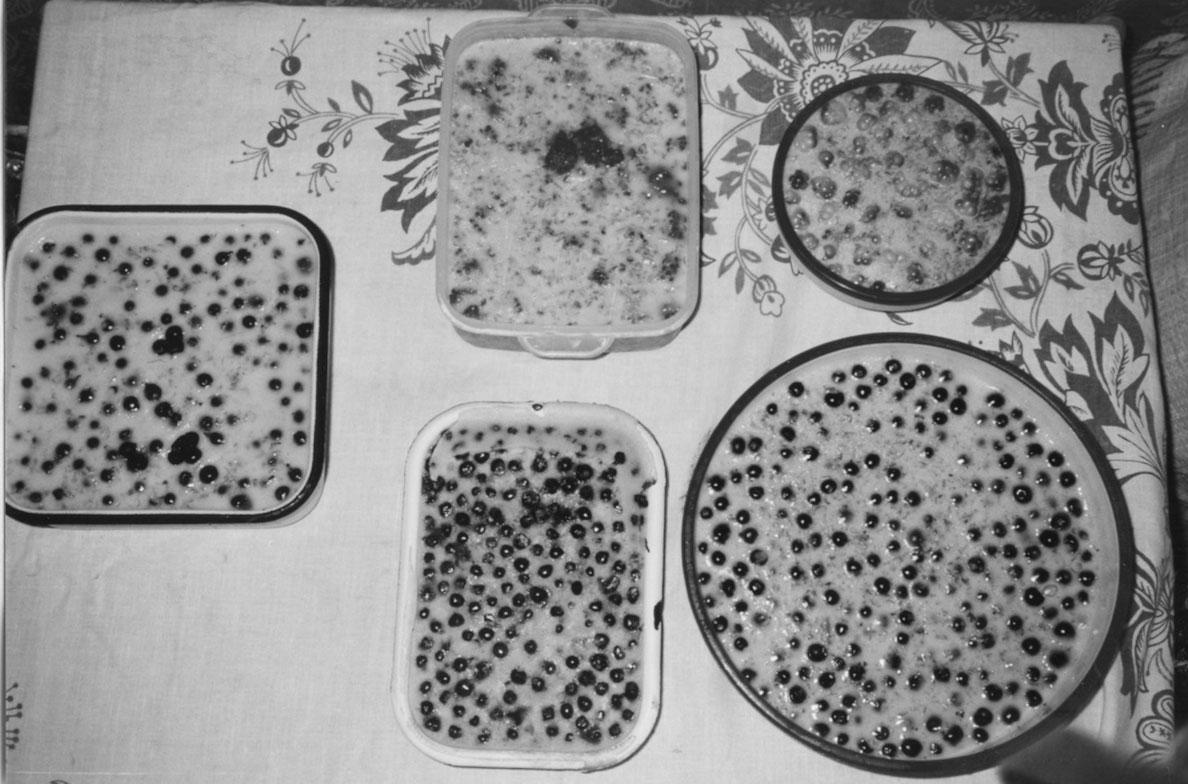

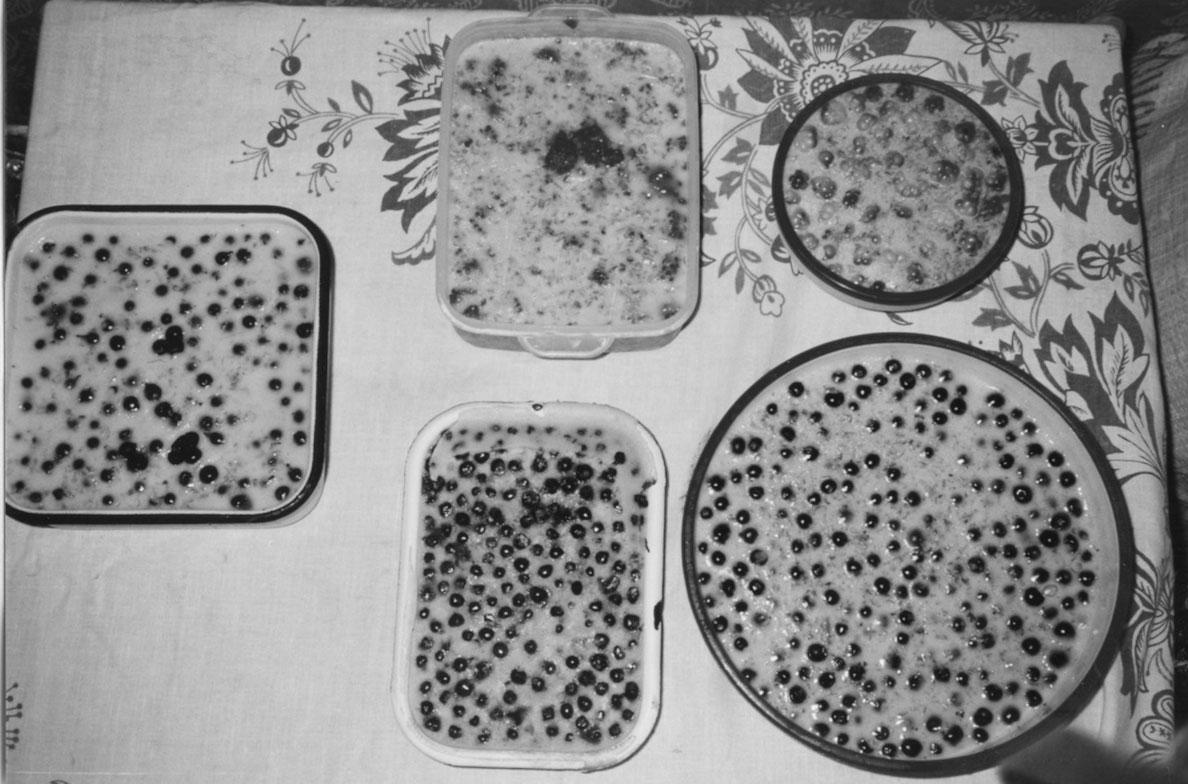

Diet Mos, a traditional Nivkh dish The Nivkh had a diverse diet, as they were semi-sedentary before colonization. Fish was the main source of food for the Nivkh, including pink, Pacific, and chum salmon as well as trout, red eye, burbot and pike found in rivers and streams. Saltwater fishing provided saffron cod, flatfish, and marine goby caught on the littoral coasts of the Strait of Tartary, Sea of Okhotsk, and the Pacific Ocean, though over fishing by Russian and Japanese trawlers has depleted many of these fish stocks. Additionally, industrial pollution such as phenols and heavy metals in the Amur River have devastated fish stocks and damaged the soil of the estuaries.[65] There is a traditional preservation process called yukola, involving slicing the fish in a particular way and drying the strips by hanging them in the frigid air, without salt.[66] The preservation process created a lot of dried fish waste, unpalatable for human consumption but utilized for dog food.[46] Pulverizing dried fish and mixing it with fish skins, water, seal fat, and berries until the mixture had a sour cream consistency is a favorite Nivkh dish called mos.[67] Nivkhs would hunt seal (larga, ringed, ribbon, sea lions), duck, sable, and otters. They would gather various berries, wild leeks, lily bulbs, and nuts.[66] Contacts with the Chinese, Manchu, and Japanese from the 12th century on introduced new foods incorporated in the Nivkhs’ diet, such as salt, sugar, rice, millet, legumes and tea. Russian 19th-century colonisation introduced flour, bread, potatoes, vodka, tobacco, butter, canned vegetables and fruits, and other meats.[68] |

ダイエット ニヴフの伝統料理「モス 植民地化以前は半定住生活を送っていたため、ニヴフ族は多様な食生活を送っていた。魚はニヴフ族にとって主要な食料源であり、カラフトマス、パシフィック サーモン、シロザケのほか、川や小川に生息するマス、レッドアイ、バーボット、パイクなどがあった。海水漁業では、韃靼海峡、オホーツク海、太平洋の沿岸 で漁獲されるコマイ、ヒラメ、海産ハゼが供給されていたが、ロシアや日本のトロール船による乱獲によって、これらの魚資源の多くが枯渇してしまった。さら に、アムール川のフェノール類や重金属などの工業汚染は、魚類資源に壊滅的な打撃を与え、河口の土壌にダメージを与えている[65]。ユコラと呼ばれる伝 統的な保存方法があり、特定の方法で魚をスライスし、塩を加えずに冷気の中で吊るして乾燥させる。 [乾燥させた魚を粉砕し、魚の皮、水、アザラシの脂肪、ベリーと混ぜてサワークリーム状になるまで煮詰めたものは、モスと呼ばれるニヴフ人の好物料理であ る[67]。12世紀以降の中国、満州、日本との接触により、塩、砂糖、米、粟、豆類、茶などの新しい食品がニヴフ族の食生活に取り入れられるようになっ た。19世紀のロシアの植民地化によって、小麦粉、パン、ジャガイモ、ウォッカ、タバコ、バター、野菜や果物の缶詰、その他の肉類が導入された[68]。 |

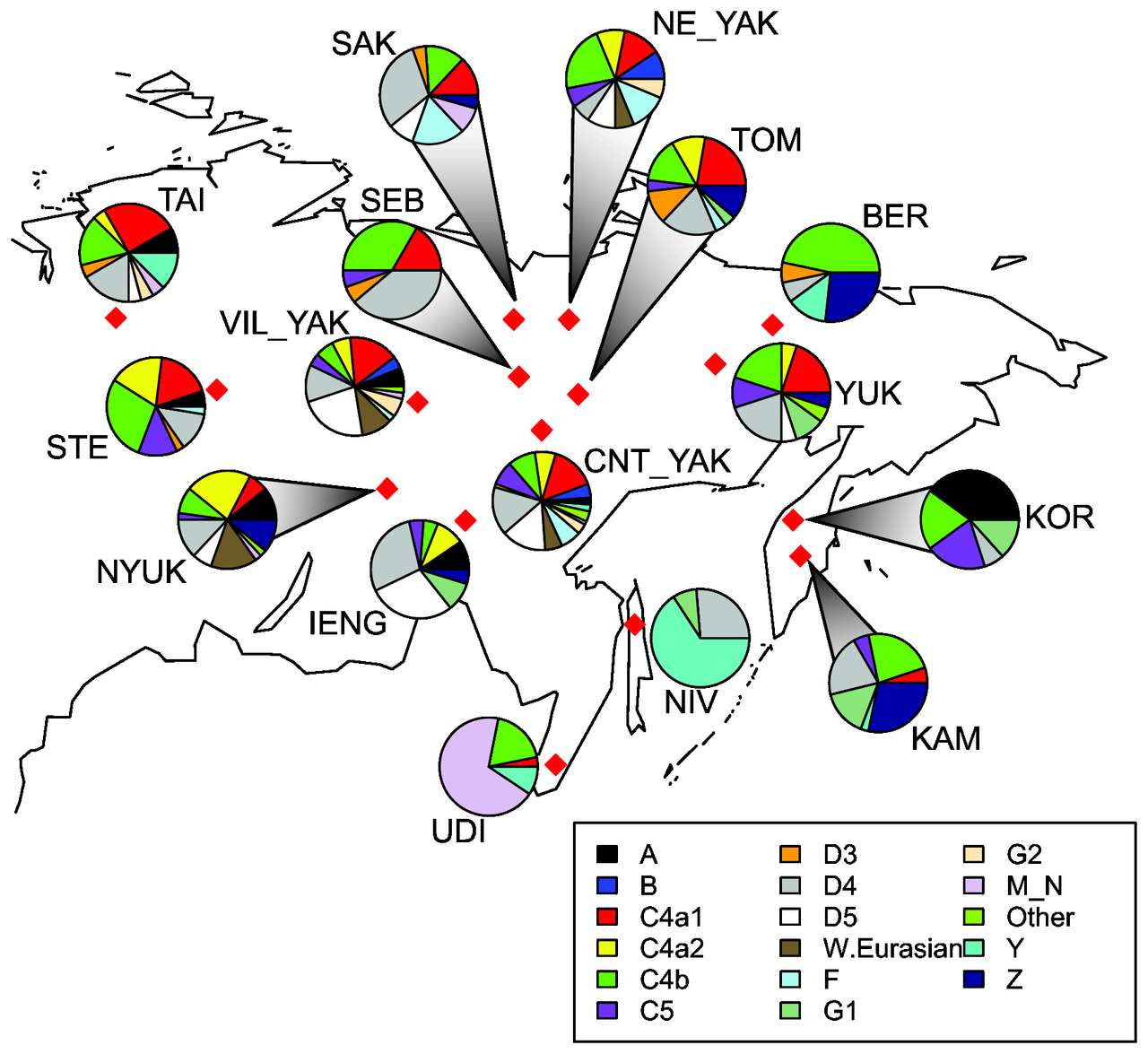

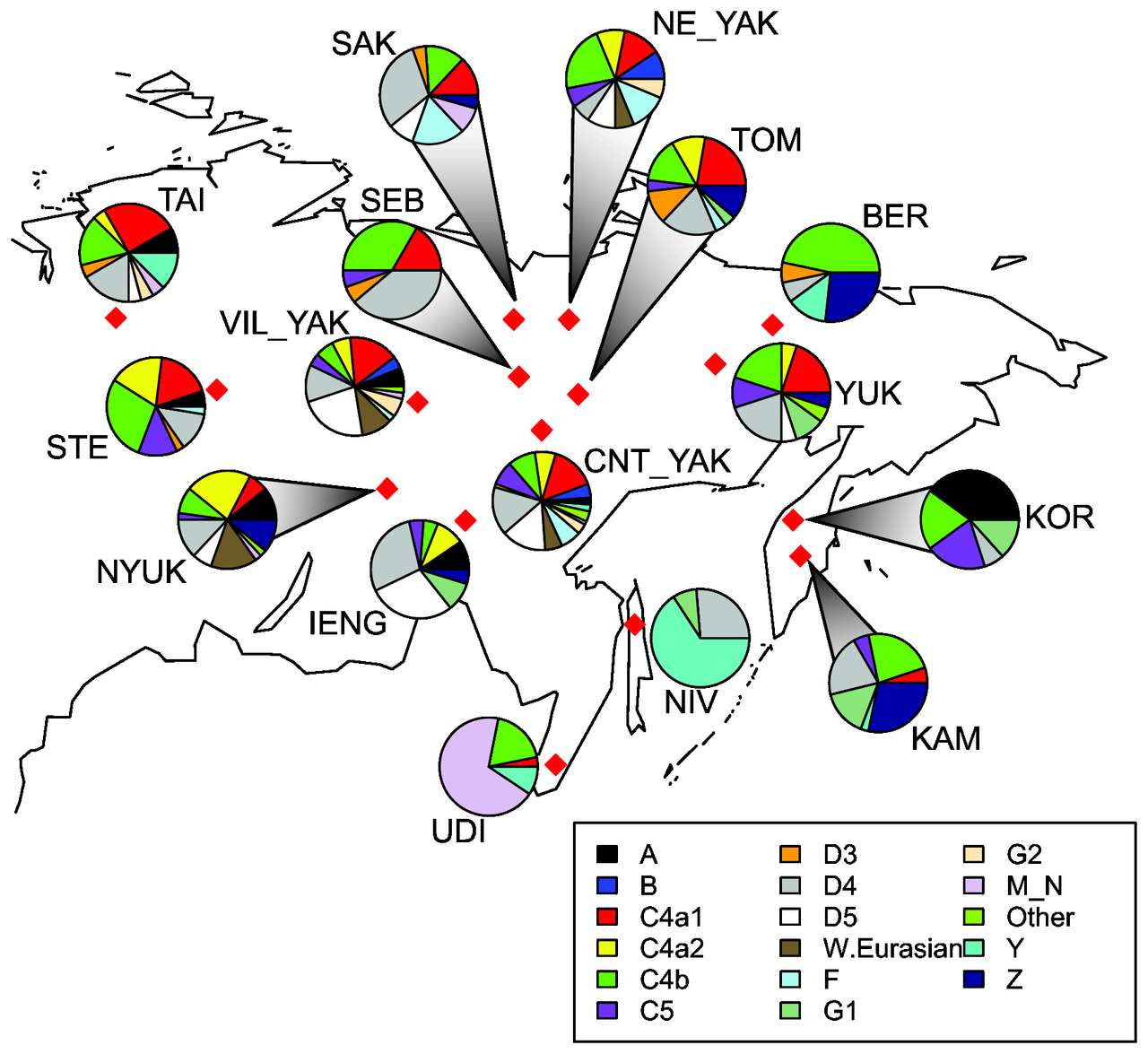

Population genetics 1862 illustration of an Ainu man (left) and a Nivkh couple (right) Y-chromosomal DNA haplogroups Main article: Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup Lell et al. (2002) tested a sample of seventeen Nivkh males and found that six of them (35%) belonged to Haplogroup C-M48, six of them (35%) belonged to haplogroup P-M45(xQ-M3, R-M17), two of them (12%) belonged to haplogroup C-M130(xM48), two of them (12%) belonged to haplogroup K-M9(xO-M119,O-M122,N-Tat,P-M45), and one of them (6%) belonged to haplogroup O-M119.[69] Tajima et al. (2004) tested a sample of twenty-one Nivkh males and found that eight of them (38%) belonged to haplogroup C-M217, a haplogroup which is also common among Koryaks, Itelmens, Yukaghirs, Tungusic peoples, and Mongols; six (29%) belonged to haplogroup K-M9(xO-M122, O-M119, P-P27), four of them (19%) belonged to haplogroup P-P27(xR-SRY10831.2), two of them (9.5%) belonged to R-SRY10831.2, and one of them (4.8%) belonged to Haplogroup BT-SRY10831.1(xC-RPS4Y711, DE-YAP, K-M9).[70] According to the abstract for a doctoral dissertation by Vladimir Nikolaevich Kharkov, a sample of 52 Nivkhs (Нивхи) from Sakhalin Oblast (Сахалинская область) contained the following Y-DNA haplogroups: 71% (37/52) C-M217(xC-M77/M86, C-M407), 7.7% (4/52) O-M324(xO-M134), 7.7% (4/52) Q-M242(xQ-M346), 5.8% (3/52) D-M174, 3.8% (2/52) O-M175(xO-P31, O-M122), 1.9% (1/52) O-P31, and 1.9% (1/52) N-M46/M178.[71] Mitochondrial DNA haplogroups  Mitochondrial DNA study of Siberian peoples. The Nivkh (labelled NIV) can be seen to not be related to the other people. Main article: Human mitochondrial DNA haplogroup Torroni et al. (1993) reported collecting blood samples from 57 "unrelated and unhybridized Nivkh individuals living in Rybnovsk and Nekrasovka villages in northern Sakhalin Island."[72] According to Starikovskaya et al. (2005) and Bermisheva et al. (2005), the members of this sample of Nivkhs belong to haplogroup Y (37/57 = 64.9%), haplogroup D (16/57 = 28.1%), haplogroup G1 (3/57 = 5.3%), and haplogroup M(xC, Z, D, G) (1/57 = 1.8%).[73][74] In another sample of Nivkhs, possibly "those living on the continent" (although there appears to be an error in the original text), Bermisheva et al. (2005) have found the following mtDNA haplogroups: 67.3% (37/55) haplogroup Y, 25.5% (14/55) haplogroup G, 3.6% (2/55) haplogroup D, 1.8% (1/55) haplogroup M(xC, Z, D, G), and 1.8% (1/55) haplogroup N or R(xA, B, F, Y).[74] According to Duggan et al. (2013), the members of a sample of 38 Nivkhs collected in northern Sakhalin belonged to haplogroup Y1a (25/38 = 65.8%), haplogroup D4m2 (10/38 = 26.3%), and haplogroup G1b (3/38 = 7.9%).[75] One identical Y1a haplotype was shared by eight Nivkh individuals, another Y1a haplotype was shared by six Nivkh individuals, and two other Y1a haplotypes were shared by three Nivkh individuals each, indicating a low genetic diversity of this population.[75] Likewise, one identical D4m2 haplotype was shared by four Nivkh individuals, another D4m2 haplotype was shared by two Nivkh individuals, and a third D4m2 haplotype was shared by two or three Nivkh individuals and a Northeast Yakut individual.[75] The authors also have found Haplogroup Y1a in 13.3% (2/15) of Berezovka Evens, 12.5% (3/24) of Taimyr Evenks, 6.5% (2/31) of Udegeys, 2.6% (1/39) of Kamchatka Evens, and 2.3% (2/88) of Central Yakuts, and they have noted that other studies have reported finding this haplogroup in high frequency in the Ulchi and Negidal, in 9%-10% of Koryaks and eastern Evenks, as well as in low frequency in Central and Vilyuy Yakuts. Besides the Nivkhs, the authors also have found mtDNA that belongs to haplogroup D4m2 in 8.7% (2/23) Sakkyryyr Evens, 3.7% (1/27) Tompo Evens, and 3.1% (1/32) Northeast Yakuts, with the Northeast Yakut individual sharing an identical haplotype with several of the Nivkhs. The authors have noted that mtDNA sequences that belong to the same branch of haplogroup D have been found in Evenks, Evens, Yukaghirs, and South Siberian Buryats and Turkic speakers, and another study has reported one instance of D4m2 in a sample of 154 Dolgans.[76] As for G1b, the other mtDNA haplogroup found among Nivkhs, Duggan et al. (2013) also have found it in their samples of Kamchatka Evens (6/39 = 15.4%), Koryaks (2/15 = 13.3%), Yukaghirs (2/20 = 10.0%), Iengra Evenks (2/21 = 9.5%), and Tompo Evens (1/27 = 3.7%), and they have cited Starikovskaya et al. (2005) as evidence for their statement that haplogroup G1 is also common in the Negidal. According to YFull and Dryomov et al. (2020), two members of haplogroup G1b from the Nivkh sample of Duggan et al. (2013) belong to G1b-G16129A!*, whereas the remaining member of haplogroup G1b from that sample belongs to G1b1a-G16244A.[77][78] М. А. Gubina et al. (2013) examined the mitochondrial DNA of a sample of seventeen Nivkhs from the village of Nogliki, Nogliksky District, Sakhalin Oblast and found that they belonged to haplogroup Y (8/17 = 47.1%, all Y1a+T16189C!), haplogroup D (3/17 = 17.6%, including 2/17 D4e5b and 1/17 D4j4a), haplogroup G (3/17 = 17.6%, including 2/17 G1b1-16207 and 1/17 G1b1a-16244), haplogroup H (2/17 = 11.8%), and haplogroup U5 (1/17 = 5.9%).[79] Besides the Western Eurasian influence apparent in the presence of haplogroups H and U5 among Nivkhs of Nogliki, it is also notable that there is no overlap between the Nivkh samples of Duggan et al. (2013) and Gubina et al. (2013) in regard to the subclades of haplogroups D4 and G1b to which they belong except for a single member of G1b1a-G16244A in each sample. |

集団遺伝学 1862年に描かれたアイヌの男性(左)とニブフのカップル(右)のイラスト Y染色体DNAハプログループ 主な記事 ヒトY染色体DNAハプログループ Lell et al. (2002)は17人のニブフ族男性のサンプルを検査し、そのうちの6人(35%)がハプログループC-M48に属し、6人(35%)がハプログループP -M45(xQ-M3、R-M17)に属していることを発見した、 そのうちの2人(12%)はハプログループC-M130(xM48)に属し、そのうちの2人(12%)はハプログループK-M9(xO-M119,O- M122,N-Tat,P-M45)に属し、そのうちの1人(6%)はハプログループO-M119に属していた。 [69] Tajima et al. (2004)は21人のニブフ人男性のサンプルを検査し、8人(38%)がハプログループC-M217に属していることを発見した; 6人(29%)がハプログループK-M9(xO-M122、O-M119、P-P27)に属し、そのうち4人(19%)がハプログループP-P27(xR -SRY10831. 2)、2人(9.5%)がR-SRY10831.2に属し、1人(4.8%)がハプログループBT-SRY10831.1(xC-RPS4Y711、DE -YAP、K-M9)に属していた[70]。 Vladimir Nikolaevich Kharkovによる博士論文の抄録によると、サハリン州(Сахалинская область)の52人のニヴク人(Нивхи)のサンプルは以下のY-DNAハプログループを含んでいた:71%(37/52)C-M217(xC- M77/M86、C-M407)、7. 71%(37/52)C-M217(xC-M77/M86、C-M407)、7.7%(4/52)O-M324(xO-M134)、7.7%(4/52) Q-M242(xQ-M346)、5.8%(3/52)D-M174、3.8%(2/52)O-M175(xO-P31、O-M122)、1.9% (1/52)O-P31、1.9%(1/52)N-M46/M178であった[71]。 ミトコンドリアDNAハプログループ  シベリア民族のミトコンドリアDNA研究。ニヴフ族(NIVと表示)は他の民族とは関係がないことがわかる。 主な記事 ヒトのミトコンドリアDNAハプログループ Torroniら(1993年)は、サハリン島北部のRybnovsk村とNekrasovka村に住む57人の「血縁関係がなく、ハイブリダイズされて いないニヴフ人」から血液サンプルを採取したことを報告している[72]。(Starikovskaya(2005)とBermishevaら (2005)によると、このニヴフ人サンプルに属する人々はハプログループY(37/57 = 64.9%)、ハプログループD(16/57 = 28.1%)、ハプログループG1(3/57 = 5.3%)、ハプログループM(xC、Z、D、G)(1/57 = 1.8%)に属している[73][74]。 ニブフ族の別のサンプル、おそらく「大陸に住む人々」(原文には誤りがあるようであるが)において、Bermishevaら(2005年)は以下の mtDNAハプログループを発見している:67. 3%(37/55)がハプログループY、25.5%(14/55)がハプログループG、3.6%(2/55)がハプログループD、1.8%(1/55)が ハプログループM(xC、Z、D、G)、1.8%(1/55)がハプログループNまたはR(xA、B、F、Y)である[74]。 Dugganら(2013)によると、サハリン北部で収集された38人のニブフ族のサンプルのメンバーは、ハプログループY1a(25/38 = 65.8%)、ハプログループD4m2(10/38 = 26.3%)、ハプログループG1b(3/38 = 7.9%)に属していた。 [75]1つの同一のY1aハプロタイプは8人のニブフ族に、もう1つのY1aハプロタイプは6人のニブフ族に、他の2つのY1aハプロタイプはそれぞれ 3人のニブフ族に共有されており、この集団の遺伝的多様性が低いことを示している。 [75]同様に、1つの同一のD4m2ハプロタイプは4人のニヴフ人で共有され、もう1つのD4m2ハプロタイプは2人のニヴフ人で共有され、3つ目の D4m2ハプロタイプは2人か3人のニヴフ人と北東ヤクート人で共有されていた。 5%(3/24人)、ウデゲイ人の6.5%(2/31人)、カムチャツカ・エヴェン人の2.6%(1/39人)、中央ヤクート人の2.3%(2/88人) にハプログループY1aが見つかっており、他の研究では、このハプログループがウルチ族とネギダル族で高頻度に、コリャーク族と東部エヴェンク族で9% ~10%、中央ヤクート人とヴィリュイ・ヤクート人で低頻度に見つかっていると報告している。ニヴク人以外にも、著者らはサッキール・エヴェン人の 8.7%(2/23)、トンポ・エヴェン人の3.7%(1/27)、北東ヤクート人の3.1%(1/32)でハプログループD4m2に属するmtDNAを 発見しており、北東ヤクート人はニヴク人の数人と同一のハプロタイプを共有している。著者らは、ハプログループDの同じ枝に属するmtDNA配列が、エ ヴェンク人、エヴェンス人、ユカヒール人、南シベリア・ブリヤート人、テュルク語を話す人々で見つかっていることを指摘しており、別の研究では154人の ドルガン人のサンプルでD4m2の例が1つ報告されている[76]。(2013)もカムチャッカ・エヴェンス人(6/39 = 15.4%)、コリャーク人(2/15 = 13.3%)、ユカヒール人(2/20 = 10.0%)、イエングラ・エヴェンス人(2/21 = 9.5%)、トンポ・エヴェンス人(1/27 = 3.7%)のサンプルでG1bを発見しており、Starikovskayaら(2005)を引用して、ハプログループG1がネギダル人にも一般的であると いう記述の根拠としている。YFullとDryomovら(2020)によると、Dugganら(2013)のNivkhサンプルからのハプログループ G1bの2人のメンバーはG1b-G16129Aに属している!*が、そのサンプルからのハプログループG1bの残りのメンバーはG1b1a- G16244Aに属している[77][78]。 М. А. Gubinaら(2013)は、サハリン州ノグリクスキー郡ノグリキ村のニヴク人17人のサンプルのミトコンドリアDNAを調査し、彼らがハプログループ Y(8/17=47. 1%、すべてY1a+T16189C!)、ハプログループD(3/17=17.6%、うちD4e5bが2/17、D4j4aが1/17)、ハプログループ G(3/17=17.6%、うちG1b1-16207が2/17、G1b1a-16244が1/17)、ハプログループH(2/17=11. 8%)、ハプログループH(2/17 = 11.8%)、ハプログループU5(1/17 = 5.9%)である[79]。ノグリキのニヴク人のハプログループHとU5の存在に見られる西ユーラシアの影響に加えて、Duggan et al. (2013)とGubinaら(2013)のハプログループD4とG1bのサブクレードに関しては、各サンプルにG1b1a-G16244Aのメンバーが 1人いる以外は重複していない。 |

| Notable Nivkhs This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Chiyo Nakamura (1906–1969), Japanese Nivkh writer Chuner Taksami (1931–2014), Russian Nivkh ethnographer Vladimir Sangi (b. 1935), Russian Nivkh writer, publicist Alexey Limanzo, President of the Association of Indigenous Peoples of North Sakhalin Region |

著名なニブフ このセクションでは出典を引用していません。信頼できるソースの引用を追加して、このセクションの改善にご協力ください。ソースのないものは、異議申し立てがなされ、削除されることがあります。(2021年10月) (このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 中村千代(1906-1969)日本のニブフ作家 チュネル・タクサミ(1931-2014)ロシアのニブフ民族学者 ウラジーミル・サンギ(1935年生まれ)、ロシアのニブフ語作家、パブリシスト アレクセイ・リマンゾ、北サハリン地域先住民協会会長 |

| List of Nivkh settlements Ainu Itelmen Koryaks Chukchis |

ニヴフ集落一覧 アイヌ イテルメン コリャーク人 チュクチ族 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nivkh_people |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆