オリバー・ウェンデル・ホームズ・ジュニア

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. 1841-1935

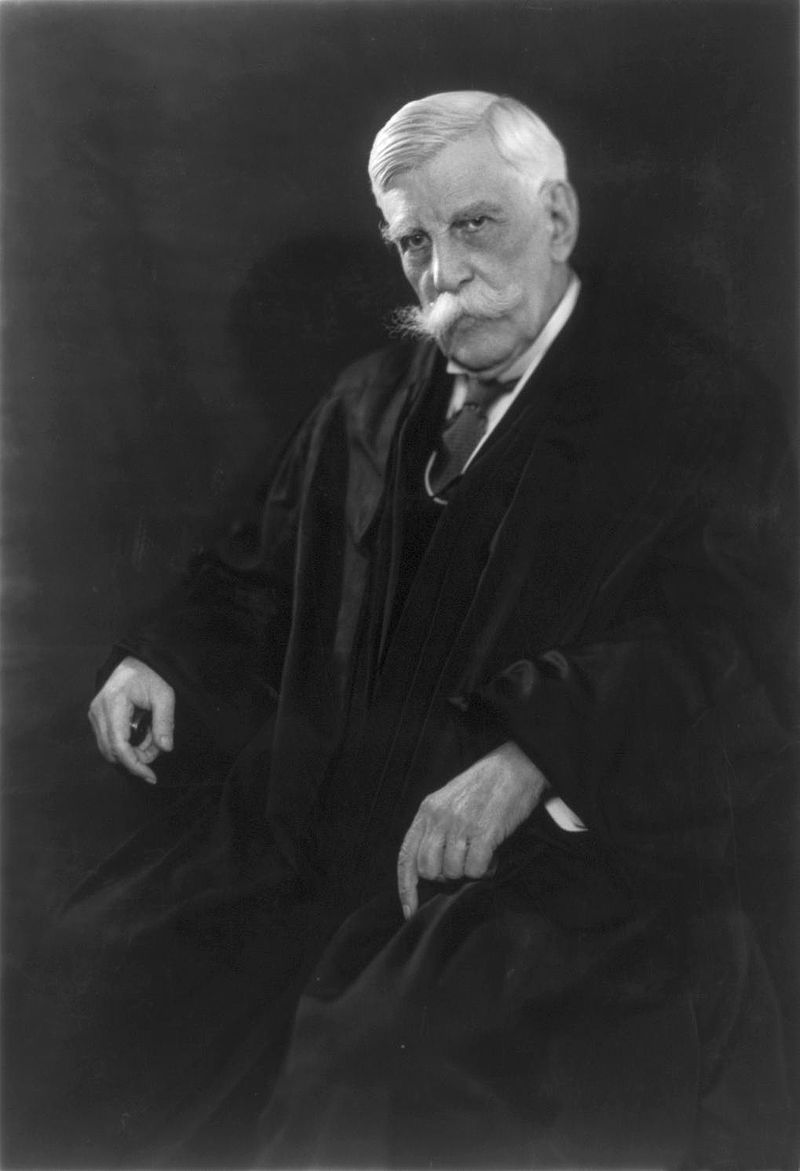

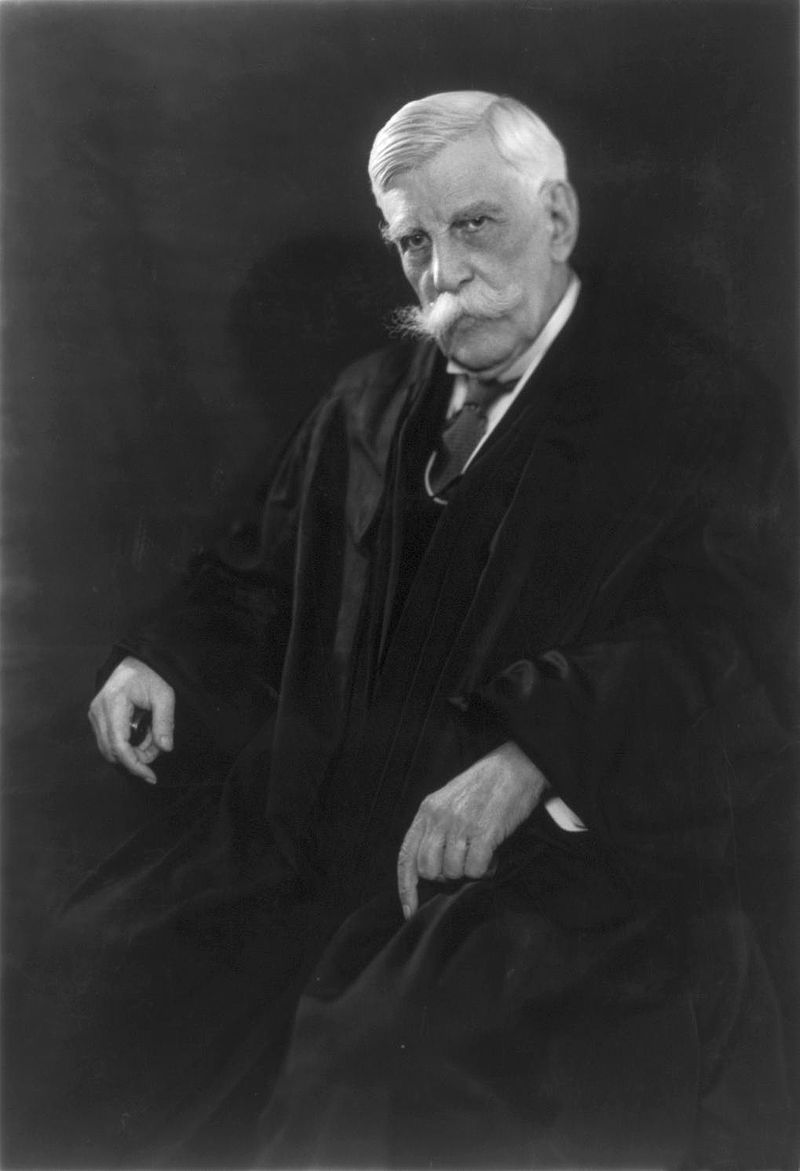

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., circa 1930. Edited photograph from the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

☆ オリバー・ウェンデル・ホームズ・ジュニア(1841年3月8日 - 1935年3月6日)は、1902年から1932年まで連邦最高裁判所判事補を務めたアメリカの法学者である 。ホームズは、最も広く引用される最高裁判所判事の一人であり、歴史上最も影響力のあるアメリカの裁判官の一人である。ホームズは90歳で法廷を退いた が、これは最高裁判事の最高齢記録である。1902年にセオドア・ルーズベルト大統領によって任命された連邦最高裁判事在任中は、州の経済規制の合憲性を支持し、憲法修正第1条の下での広範な言論 の自由を主張するようになった。その後、シェンク対アメリカ合衆国裁判(1919年)では、「言論の自由は、劇場で虚偽の火事を叫びパニックを引き起こし た人間を保護することはできない」という印象的な格言とともに、徴兵反対派に対する刑事制裁を全会一致で支持し、画期的な「明白かつ現在の危険」テストを 策定した。同年末、エイブラムス対アメリカ合衆国裁判(1919年)における有名な反対意見で、彼は「真実の最良のテストは、市場の競争の中でそれ 自身を受け入れる思想の力である。いずれにせよ、これがわが憲法の理論である。すべての人生が実験であるように、憲法もまた実験なのだ」。さらに彼は、 「われわれは、われわれが嫌悪し、死を招くと信じている意見の表明を規制しようとする試みに対して、永遠に警戒を怠らないべきである」と付け加えた。

| Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

(March 8, 1841 – March 6, 1935) was an American jurist who served as an

associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1902 to 1932.[A]

Holmes is one of the most widely cited Supreme Court justices and among

the most influential American judges in history, noted for his long

service, pithy opinions—particularly those on civil liberties and

American constitutional democracy—and deference to the decisions of

elected legislatures. Holmes retired from the court at the age of 90,

an unbeaten record for oldest justice on the Supreme Court.[B] He

previously served as a Brevet Colonel in the American Civil War, in

which he was wounded three times, as an associate justice and chief

justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, and as Weld

Professor of Law at his alma mater, Harvard Law School. His positions,

distinctive personality, and writing style made him a popular figure,

especially with American progressives.[2] During his tenure on the U.S. Supreme Court, to which he was appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1902, he supported the constitutionality of state economic regulation and came to advocate broad freedom of speech under the First Amendment, after, in Schenck v. United States (1919), having upheld for a unanimous court criminal sanctions against draft protestors with the memorable maxim that "free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic" and formulating the groundbreaking "clear and present danger" test.[3] Later that same year, in his famous dissent in Abrams v. United States (1919), he wrote that "the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.... That, at any rate, is the theory of our Constitution. It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment." He added that "we should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions that we loathe and believe to be fraught with death...."[4] He was one of only a handful of justices known as a scholar; The Journal of Legal Studies has identified Holmes as the third-most-cited American legal scholar of the 20th century.[5] Holmes was a legal realist, as summed up in his maxim, "The life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience",[6] and a moral skeptic[7] opposed to the doctrine of natural law. His jurisprudence and academic writing influenced much subsequent American legal thinking, including the judicial consensus upholding New Deal regulatory law and the influential American schools of pragmatism, critical legal studies, and law and economics.[citation needed] |

オ

リバー・ウェンデル・ホームズ・ジュニア(1841年3月8日 -

1935年3月6日)は、1902年から1932年まで連邦最高裁判所判事補を務めたアメリカの法学者である[A]

。ホームズは、最も広く引用される最高裁判所判事の一人であり、歴史上最も影響力のあるアメリカの裁判官の一人である。ホームズは90歳で法廷を退いた

が、これは最高裁判事の最高齢記録である[B]。それ以前は、アメリカ南北戦争で3度負傷したブレビト大佐、マサチューセッツ州最高裁判事補および最高裁

判事、母校ハーバード大学ロースクールのウェルド教授を務めた。その地位、独特の個性、文体から、特にアメリカの進歩主義者に人気のある人物であった

[2]。 1902年にセオドア・ルーズベルト大統領によって任命された連邦最高裁判事在任中は、州の経済規制の合憲性を支持し、憲法修正第1条の下での広範な言論 の自由を主張するようになった。その後、シェンク対アメリカ合衆国裁判(1919年)では、「言論の自由は、劇場で虚偽の火事を叫びパニックを引き起こし た人間を保護することはできない」という印象的な格言とともに、徴兵反対派に対する刑事制裁を全会一致で支持し、画期的な「明白かつ現在の危険」テストを 策定した[3]。同年末、エイブラムス対アメリカ合衆国裁判(1919年)における有名な反対意見で、彼は「真実の最良のテストは、市場の競争の中でそれ 自身を受け入れる思想の力である。いずれにせよ、これがわが憲法の理論である。すべての人生が実験であるように、憲法もまた実験なのだ」。さらに彼は、 「われわれは、われわれが嫌悪し、死を招くと信じている意見の表明を規制しようとする試みに対して、永遠に警戒を怠らないべきである」と付け加えた [4]。 『法学研究ジャーナル』誌は、ホームズを20世紀で3番目に多く引用されたアメリカの法学者と認定している[5]。ホームズは、「法の生命は論理ではな かった:それは経験であった」という彼の格言に要約されるように、法の現実主義者であり[6]、自然法の教義に反対する道徳懐疑主義者[7]であった。彼 の法学と学術的著作は、ニューディール規制法を支持する司法のコンセンサスや、プラグマティズム、批判的法学、法と経済学といった影響力のあるアメリカの 学派を含め、その後のアメリカの法的思考に多くの影響を与えた[要出典]。 |

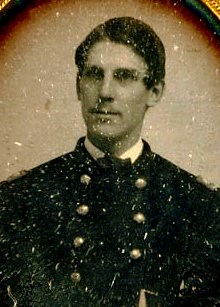

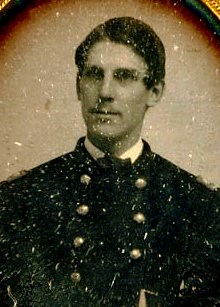

| Early life Holmes was born in Boston, Massachusetts, to the prominent writer and physician Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. and Amelia Lee Jackson Holmes. Both his parents were of English descent, and all his ancestors had come to North America from England during the early colonial period as part of the Puritan migration to New England.[8] His mother opposed slavery and fulfilled her domestic role as traditionally understood.[9] Dr. Holmes was a leading figure in Boston intellectual and literary circles. Mrs. Holmes was connected to the leading families; Henry James Sr., Ralph Waldo Emerson, and other transcendentalists were family friends. Known as "Wendell" in his youth, Holmes became lifelong friends with the brothers William James and Henry James Jr. Holmes accordingly grew up in an atmosphere of intellectual achievement and early on formed the ambition to be a man of letters like Emerson. He retained an interest in writing poetry throughout his life.[10] While still in Harvard College he wrote essays on philosophic themes and asked Emerson to read his attack on Plato's idealist philosophy. Emerson famously replied, "If you strike at a king, you must kill him." He supported the abolitionist movement that thrived in Boston society during the 1850s. At Harvard, he was a member of Alpha Delta Phi fraternity, the Hasty Pudding and the Porcellian Club; his father had also been a member of both clubs. In the Pudding, he served as Secretary and Poet, as had his father.[11] Holmes graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Harvard in 1861, and, in the spring of that year, after President Abraham Lincoln called for volunteers following the firing on Fort Sumter, he enlisted in the Massachusetts militia but returned briefly to Harvard College to participate in commencement exercises.[12] Civil War  Holmes in his uniform, 1861 During his senior year of college, at the outset of the American Civil War, Holmes enlisted in the Fourth Battalion of Infantry in the Massachusetts militia, then in July 1861, with his father's help, received a commission as second lieutenant in the Twentieth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry.[13] He saw considerable combat during his service, taking part in the Peninsula Campaign, and the Wilderness, suffering wounds at the Battle of Ball's Bluff, Antietam, and Chancellorsville, and suffered from a near-fatal case of dysentery. He particularly admired and was close to Henry Livermore Abbott, a fellow officer in the 20th Massachusetts. Holmes rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel, but eschewed command of his regiment upon his promotion. Abbott took command of the regiment in his place and was later killed.[citation needed] In September 1863, while recovering at the Holmes family home on Charles Street in Boston from his third major combat injury, Holmes was promoted to colonel, but never returned to the 20th Massachusetts because the unit had been largely destroyed. Upon his recovery, in January 1864 Holmes was appointed aide-de-camp of General Horatio Wright, then Division Commander of VI Corps, and later in command of the Corps. Holmes served with Wright during General Grant's campaign down to Petersburg, returning to Washington with the Sixth Corps when the Capital was threatened in July 1864. On July 17, 1864, Holmes was mustered out at the end of his enlistment term, returning to Boston and enrolling at Harvard Law School later that year.[13] Holmes is said to have shouted to Abraham Lincoln to take cover during the Battle of Fort Stevens, although this is commonly regarded as apocryphal.[14][15][16][17] Holmes himself expressed uncertainty about who had warned Lincoln ("Some say it was an enlisted man who shouted at Lincoln; others suggest it was General Wright who brusquely ordered Lincoln to safety. But for a certainty, the 6 foot 4 inch Lincoln, in frock coat and top hat, stood peering through field glasses from behind a parapet at the onrushing rebels.")[18] and other sources state he likely was not present on the day Lincoln visited Fort Stevens.[19] |

生い立ち ホームズはマサチューセッツ州ボストンで、著名な作家で医師のオリバー・ウェンデル・ホームズ・シニアとアメリア・リー・ジャクソン・ホームズの間に生ま れた。両親はともにイギリス系で、ホームズの先祖はすべて、植民地時代初期にイギリスからニューイングランドへ移住した清教徒の一員として北米に渡ってい た[8]。ホームズ夫人は有力な一族とつながっており、ヘンリー・ジェームズ・シニア、ラルフ・ウォルドー・エマーソン、その他の超越論者たちは家族ぐる みの友人であった。 若い頃は「ウェンデル」と呼ばれていたホームズは、ウィリアム・ジェームズとヘンリー・ジェームズ・ジュニアの兄弟と生涯の友人となった。ホームズはそれ に従って知的達成の雰囲気の中で育ち、早くからエマーソンのような文人になりたいという野心を抱いた。ハーバード・カレッジ在学中、彼は哲学的なテーマで エッセイを書き、プラトンの観念論哲学に対する攻撃をエマソンに読んでくれるよう頼んだ。エマソンが "王を攻撃するならば、王を殺さなければならない "と答えたことは有名である。1850年代のボストン社会で盛んだった奴隷廃止運動を支持。ハーバード大学では、アルファ・デルタ・ファイ友愛会、ヘイス ティ・プディング、ポーセリアン・クラブのメンバーであった。1861年、ホームズはハーバード大学をPhi Beta Kappaで卒業し、その年の春、エイブラハム・リンカーン大統領がサムター要塞への発砲を受けて志願兵を募った後、マサチューセッツ州民兵に入隊した が、卒業式に参加するためにハーバード大学に短期間戻った[12]。 南北戦争  軍服姿のホームズ(1861年 大学4年の時、アメリカ南北戦争が始まると、ホームズはマサチューセッツ州民兵歩兵第4大隊に入隊し、1861年7月、父親の援助でマサチューセッツ州義 勇歩兵第20連隊の少尉に任官した。 [13]彼は従軍中にかなりの戦闘を経験し、半島作戦と荒野に参加し、ボールズ・ブラフの戦い、アンティータム、チャンセラーズビルで負傷し、赤痢で瀕死 の重傷を負った。第20マサチューセッツの同僚将校ヘンリー・リバモア・アボットを特に尊敬し、親しくしていた。ホームズは中佐まで昇進したが、昇進と同 時に連隊の指揮を放棄した。アボットが代わりに連隊の指揮を執り、後に戦死した[要出典]。 1863年9月、3度目の大怪我からボストンのチャールズ・ストリートにあるホームズ家で療養中、ホームズは大佐に昇進したが、マサチューセッツ第20連 隊は大部分が破壊されていたため、復帰することはなかった。回復後の1864年1月、ホームズは当時第6軍団の師団長であったホレイショ・ライト将軍の副 官に任命され、後に軍団の指揮官となった。ホームズはグラント将軍のピーターズバーグまでの遠征でライトと共に従軍し、1864年7月に首都が脅かされた 時には第6軍団と共にワシントンに戻った。1864年7月17日、ホームズは入隊期間を終えて退役し、ボストンに戻って同年末にハーバード大学ロースクー ルに入学した[13]。 ホームズはフォート・スティーブンスの戦いでエイブラハム・リンカーンに身を隠すように叫んだと言われているが、これは一般に偽話とみなされている [14][15][16][17]。 ホームズ自身は、誰がリンカーンに警告したのか定かでないことを表明している(「リンカーンに叫んだのは下士官であったという説もあれば、リンカーンに無 愛想に安全な場所に避難するように命じたのはライト将軍であったという説もある。しかし確実に言えることは、フロックコートにトップハット姿の6フィート 4インチのリンカーンが、突進してくる反乱軍を欄干の後ろから野戦メガネ越しに覗き込んで立っていたということだ」[18])[18]、また他の情報源に よれば、リンカーンがスティーブンス砦を訪れた日、彼はその場にいなかった可能性が高いとしている[19]。 |

| Legal career Lawyer  Holmes about 1872, aged 31 In the summer of 1864, Holmes returned to the family home in Boston, wrote poetry, and debated philosophy with his friend William James, pursuing his debate with philosophic idealism, and considered re-enlisting. By the fall, when it became clear that the war would soon end, Holmes enrolled in Harvard Law School, "kicked into the law" by his father, as he later recalled.[20] He attended lectures there for a single year, reading extensively in theoretical works, and then clerked for a year in his cousin Robert Morse's office. In 1866, he received a Bachelor of Laws degree from Harvard, was admitted to the Massachusetts bar, and after a long visit to London to complete his education went into law practice in Boston. He joined a small firm, and in 1872 married a childhood friend, Fanny Bowditch Dixwell, buying a farm in Mattapoisett, Massachusetts, the following year.[21] Their marriage lasted until her death on April 30, 1929. They never had children together. They did adopt and raise an orphaned cousin, Dorothy Upham. Fanny disliked Beacon Hill society, and devoted herself to embroidery. She was described as devoted, witty, wise, tactful, and perceptive.[citation needed] Whenever he could, Holmes visited London during the social season of spring and summer, and during the years of his work as a lawyer and judge in Boston he formed romantic friendships with English women of the nobility, with whom he corresponded while at home in the United States. The most important of these was his friendship with the Anglo-Irish Clare Castletown, the Lady Castletown, whose family estate in Ireland, Doneraile Court, he visited several times, and with whom he may have had a brief affair.[22][23] He formed his closest intellectual friendships with British men, and became one of the founders of what was soon called the "sociological" school of jurisprudence in Great Britain, followed a generation later by the "legal realist" school in America.[citation needed] Holmes practiced admiralty law and commercial law in Boston for fifteen years. It was during this time that he did his principal scholarly work, serving as an editor of the new American Law Review, reporting decisions of state supreme courts, and preparing a new edition of Kent's Commentaries, which served practitioners as a compendium of case law, at a time when official reports were scarce and difficult to obtain. He summarized his hard-won understanding in a series of lectures, collected and published as The Common Law in 1881.[citation needed] The Common Law Main article: The Common Law (book) The Common Law has been continuously in print since 1881 and remains an important contribution to jurisprudence. The book also remains controversial, for Holmes begins by rejecting various kinds of formalism in law. In his earlier writings he had expressly denied the utilitarian view that law was a set of commands of the sovereign, rules of conduct that became legal duties. He rejected as well the views of the German idealist philosophers, whose views were then widely held, and the philosophy taught at Harvard, that the opinions of judges could be harmonized in a purely logical system. In the opening paragraphs of the book, he famously summarized his own view of the history of the common law: The life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience. The felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, intuitions of public policy, avowed or unconscious, even the prejudices which judges share with their fellow-men, have had a good deal more to do than the syllogism in determining the rules by which men should be governed. The law embodies the story of a nation's development through many centuries, and it cannot be dealt with as if it contained only the axioms and corollaries of a book of mathematics.[6] In The Common Law, Holmes wrote that, even though the law "uses the language of morality, it necessarily ends in external standards not dependent on the consciousness of the individual" or on his moral culpability. Foreseeability of harm was the key: "the general basis of criminal liability was knowledge, at the time of action, of facts from which common experience showed that certain harmful results were likely to follow."[24] Tort liability, similarly, was imposed when circumstances were "such as would have led a prudent man to perceive danger, although not necessarily to foresee the specific harm".[25] Likewise, with respect to contracts, "The law has nothing to do with the actual state of the parties' minds. In contract, as elsewhere, it must go by externals, and judge parties by their conduct."[26] In the book, Holmes set forth his view that the only source of law, properly speaking, was a judicial decision enforced by the state. Judges decided cases on the facts, and then wrote opinions afterward presenting a rationale for their decision. The true basis of the decision was often an "inarticulate major premise", however. A judge was obliged to choose between contending legal arguments, each posed in absolute terms, and the true basis of his decision was sometimes drawn from outside the law, when precedents were lacking or were evenly divided.[citation needed] The common law evolves because civilized society evolves, and judges share the common preconceptions of the governing class. These views endeared Holmes to the later advocates of legal realism and made him one of the early founders of law and economics jurisprudence. Holmes famously contrasted his own scholarship with the abstract doctrines of Christopher Columbus Langdell, dean of Harvard Law School, who viewed the common law as a self-enclosed set of doctrines. Holmes viewed Langdell's work as akin to the German philosophic idealism he had for so long resisted, opposing it with his own scientific materialism.[27] State court judge We cannot all be Descartes or Kant, but we all want happiness. And happiness, I am sure from having known many successful men, cannot be won simply by being counsel for great corporations and having an income of fifty thousand dollars. An intellect great enough to win the prize needs other food beside success. The remoter and more general aspects of the law are those which give it universal interest. It is through them that you not only become a great master in your calling, but connect your subject with the universe and catch an echo of the infinite, a glimpse of its unfathomable process, a hint of the universal law. -- Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr, "The Path of the Law", 10 Harvard Law Review 457, 478 (1897) Holmes was considered for a federal court judgeship in 1878 by President Rutherford B. Hayes, but Massachusetts Senator George Frisbie Hoar persuaded Hayes to nominate another candidate. In the fall of 1882, Holmes became a professor at Harvard Law School, accepting an endowed professorship that had been created for him, largely through the efforts of Louis D. Brandeis. On Friday, December 8, 1882, Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts associate justice Otis Lord decided to resign, giving outgoing Republican governor John Davis Long a chance to appoint his successor, if he could do so before the Massachusetts Governor's Council adjourned at 3 pm. Holmes's partner George Shattuck proposed him for the vacancy, Holmes quickly agreed, and there being no objection by the council, he took the oath of office on December 15, 1882. His resignation from his professorship, after only a few weeks and without notice, was resented by the law school faculty, with James Bradley Thayer finding Holmes's conduct "selfish" and "thoughtless".[28] On August 2, 1899, Holmes became chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court following the death of Walbridge A. Field. During his service on the Massachusetts court, Holmes continued to develop and apply his views of the common law, usually following precedent faithfully. He issued few constitutional opinions in these years, but carefully developed the principles of free expression as a common-law doctrine. He departed from precedent to recognize workers' right to organize trade unions and to strike, as long as no violence was involved, and coercion was not exerted through impermissible means such as secondary boycotts, stating in his opinions that fundamental fairness required that workers be allowed to combine to compete on an equal footing with employers. He continued to give speeches and to write articles that added to or extended his work on the common law, most notably "Privilege, Malice and Intent",[29] in which he presented his view of the pragmatic basis of the common-law privileges extended to speech and the press, which could be defeated by a showing of malice, or of specific intent to harm. This argument would later be incorporated into his famous opinions concerning the First Amendment.[citation needed] Famously, he observed in McAuliffe v. Mayor of New Bedford (1892) that a policeman may have a constitutional right to talk politics, but he has no constitutional right to be a policeman.[30] He also published an address, "The Path of the Law",[31] which is best known for its prediction theory of law, that "[t]he prophecies of what the courts will do in fact, and nothing more pretentious, are what I mean by law", and for its "bad man" perspective on the law that "[i]f you really want to know the law and nothing else, you must look at it as a bad man, who cares only for the material consequences which such knowledge enables him to predict".[31] |

弁護士キャリア 弁護士  1872年頃、31歳のホームズ 1864年の夏、ホームズはボストンの実家に戻り、詩を書き、友人のウィリアム・ジェームズと哲学的観念論について討論を重ね、再入隊を考えた。秋にな り、戦争がまもなく終結することが明らかになると、ホームズは父に「法律の道に蹴飛ばされた」と後に回想しているように、ハーバード大学ロースクールに入 学した[20]。同校の講義に1年間出席し、理論的な著作を幅広く読んだ後、従兄弟のロバート・モースの事務所で1年間事務員を務めた。1866年、彼は ハーバード大学で法学士号を取得し、マサチューセッツ州弁護士資格を得た。1872年に幼なじみのファニー・ボウディッチ・ディクスウェルと結婚し、翌年 マサチューセッツ州マタポイセットに農場を購入した[21]。二人の間に子供はいなかった。しかし、孤児のいとこ、ドロシー・アファムを養子として迎え、 育てた。ファニーはビーコンヒルの社交界を嫌い、刺繍に没頭した。彼女は献身的で、機知に富み、賢く、機転が利き、鋭敏だったと言われている[要出典]。 ボストンで弁護士や裁判官として働いていた頃、ホームズは可能な限り春と夏の社交シーズンにロンドンを訪れ、英国貴族の女性たちとロマンチックな友情を育 んだ。そのなかでも最も重要なのは、アイルランドのドネライユ・コート(Doneraile Court)を何度か訪れ、短期間の不倫関係を持ったと思われるアングロ・アイルランドのクレア・キャッスルタウン(Clare Castletown)との友情であった。 ホームズはボストンで15年間、海事法と商法を修めた。この間、新しい『アメリカン・ロー・レビュー』の編集者を務め、州の最高裁判所の判決を報告し、 『ケント注解』の新版を作成した。彼は、苦労して得た理解を一連の講義にまとめ、1881年に『コモン・ロー』として出版した[要出典]。 コモン・ロー 主な記事 コモン・ロー (書籍) コモン・ロー』は1881年以来絶えることなく版を重ね、現在でも法学への重要な貢献となっている。本書はまた、ホームズが法学における様々な形式主義を 否定するところから始まっているため、論争の的ともなっている。それ以前の著作では、法は主権者の命令であり、法的義務となる行動規則であるとする功利主 義的見解を明確に否定していた。彼は、当時広く信じられていたドイツの観念論哲学者の見解や、ハーバード大学で教えられていた、裁判官の意見は純粋に論理 的な体系の中で調和させることができるという哲学も否定した。この本の冒頭で、コモン・ローの歴史についての彼自身の見解をまとめたのは有名な話である: 法の生命は論理ではない。時代の必然性、道徳的・政治的理論、公然・非公然を問わず公序良俗の直感、さらには裁判官が同胞と共有する偏見でさえも、人が統 治されるべきルールを決定する上で、対論よりもはるかに大きな役割を果たしてきたのである。法律は、何世紀にもわたる国家の発展の物語を具現化したもので あり、あたかも数学書の公理と定理だけを含んでいるかのように扱うことはできない[6]。 ホームズは『コモン・ロー』の中で、法律が「道徳の言葉を用いているとしても、それは必然的に、個人の意識に依存しない、あるいは個人の道徳的責任に依存 しない、外的な基準で終わっている」と書いている。損害の予見可能性が鍵であった。「刑事責任の一般的な根拠は、行為時に、一般的な経験によって特定の有 害な結果が生じる可能性が高いことが示された事実を知っていたことである」[24]。同様に、不法行為責任も、「必ずしも具体的な損害を予見する必要はな いが、慎重な人間に危険を察知させるような」状況であった場合に課されるものであった[25]。同様に、契約に関しても、「法律は当事者の実際の心の状態 とは何の関係もない。契約においては、他の場所と同様に、外形によって判断し、当事者の行為によって判断しなければならない」[26]。 この本の中でホームズは、法の唯一の源泉は、正しく言えば、国家によって執行される司法判断であるという見解を示した。裁判官は事実に基づいて事件を判断 し、その後に判断の根拠を示す意見を書いた。しかし、その決定の真の根拠は、しばしば「明瞭でない大前提」であった。判事は、それぞれが絶対的な言葉で提 起される、対立する法的主張の中から選択することを余儀なくされ、判例が欠如していたり、意見が真っ二つに分かれていたりする場合には、その判断の真の根 拠が法の外から引き出されることもあった[要出典]。 コモン・ローが進化するのは文明社会が進化するからであり、裁判官は支配階級の共通の先入観を共有する。このような見解から、ホームズは後の法リアリズム の提唱者たちに気に入られ、法経済学の初期の創始者の一人となった。ホームズは、コモン・ローを自閉した一連の教義とみなすハーバード大学ロースクール学 長クリストファー・コロンバス・ラングデルの抽象的な教義と自身の学問を対比させたことは有名である。ホームズはラングデルの研究を、彼が長い間抵抗して きたドイツの哲学的観念論に似ていると考え、自身の科学的唯物論と対立させた[27]。 州裁判所判事 私たちはみなデカルトやカントになることはできませんが、幸福を望んで います。そして幸福は、多くの成功者を知ってきた経験から確信するが、単に大企業の顧問弁護士になって5万ドルの収入を得るだけでは獲得できない。賞を獲 得するほどの知性には、成功のほかに別の糧が必要なのだ。法律のより奥深く、より一般的な側面こそが、法律に普遍的な面白さを与えているのだ。このような ものによって、あなたは自分の職業において偉大な達人になるだけではなく、自分の主題を宇宙と結びつけ、無限の響きをとらえ、その底知れぬプロセスを垣間 見、普遍的な法則のヒントをつかむことができるのである。——オリバー・ウェンデル・ホームズ・ジュニア、「法の道」、10 Harvard Law Review 457, 478 (1897) ホームズは1878年、ラザフォード・B・ヘイズ大統領によって連邦裁判所判事の候補者として検討されたが、マサチューセッツ州上院議員ジョージ・フリス ビー・ホアーは、別の候補者を指名するようヘイズを説得した。1882年秋、ホームズはハーバード大学ロースクールの教授となり、主にルイス・D・ブラン デイスの尽力によって創設された冠講座を受け入れた。1882年12月8日金曜日、マサチューセッツ州最高裁判所判事オーティス・ロードは辞任を決意し、 マサチューセッツ州知事会が午後3時に閉会する前に辞任することができれば、共和党のジョン・デイヴィス・ロング知事に後任を指名する機会を与えることに なった。ホームズのパートナーであったジョージ・シャタックが空席の後任としてホームズを推薦すると、ホームズはすぐに同意し、評議会の反対もなく、 1882年12月15日に就任の宣誓を行った。ジェームズ・ブラッドリー・セイヤーは、ホームズの行為を「利己的」で「軽率」であると評価した[28]。 1899年8月2日、ホームズは、ウォルブリッジ・A・フィールドの死去に伴い、マサチューセッツ州最高判事の裁判長に就任した。 マサチューセッツ州裁判所在任中、ホームズは慣習法に関する自身の見解を発展させ適用し続け、通常は判例に忠実に従った。この間、憲法に関する意見はほと んど出さなかったが、表現の自由の原則をコモン・ローの教義として慎重に発展させた。彼は、暴力を伴わず、二次的なボイコットのような許されない手段で強 制力を行使しない限り、労働者が労働組合を組織し、ストライキを行う権利を認めるために判例から逸脱し、基本的な公正さには、労働者が使用者と対等な立場 で競争するために団結することが許されることが必要であると意見書で述べた。彼はその後も講演を行い、コモン・ローに関する仕事を加えたり拡張したりする 記事を書き続けたが、中でも「特権、悪意、意図」[29]では、言論と報道に認められたコモン・ローの特権の実際的な根拠についての見解を示し、悪意、す なわち具体的な害意の提示によって特権を否定することができるとした。この議論は後に、憲法修正第1条に関する彼の有名な意見に取り入れられることになる [要出典]。 有名なところでは、McAuliffe v. Mayor of New Bedford(McAuliffe対ニューベッドフォード市長事件、1892年)において、彼は次のように述べた。 警察官には政治を語る憲法上の権利はあっても、警察官である憲法上の権利はない[30]。 彼はまた、「裁判所が実際に何をするかという予言であり、それ以上の気取ったものは何もない」という法の予言理論や、「もしあなたが本当に法を知りたいの であれば、そのような知識によって予測することができる物質的な結果にしか関心を持たない悪人として法を見なければならない」という法に対する「悪人」の 視点[31]で最もよく知られている演説「法の道」[31]を発表している。 |

| Supreme Court Justice Overview  In the year of his appointment to the US Supreme Court Soon after the death of Associate Justice Horace Gray in July 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt made known his intention to appoint Holmes as Gray's successor; it was the president's stated desire to fill the vacancy with someone from Massachusetts.[32] The nomination was supported by Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, the junior senator from Massachusetts, but was opposed by its senior senator, George Frisbie Hoar, who was also chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee. Hoar was a strenuous opponent of imperialism, and the legality of the annexation of Puerto Rico and the Philippines was expected to come before the Court. Lodge, like Roosevelt, was a strong supporter of imperialism, which Holmes was expected to support as well.[33] Despite Hoar's opposition, the president moved ahead on the matter. On December 2, 1902, he formally submitted the nomination and Holmes was confirmed by the United States Senate on December 4.[34] He was sworn into office on December 8.[1] On the bench, Holmes did vote to support the administration's position favoring the annexation of former Spanish colonies in the "Insular Cases". However, he later disappointed Roosevelt by dissenting in Northern Securities Co. v. United States, a major antitrust prosecution;[35] the majority of the court opposed Holmes and sided with Roosevelt's belief that Northern Securities violated the Sherman Antitrust Act.[35] The dissent by Holmes permanently damaged his formerly close relationship with Roosevelt.[36] Holmes was known for his pithy, frequently quoted opinions. In more than twenty-nine years on the Supreme Court bench, he ruled on cases spanning the whole range of federal law. He is remembered for prescient opinions on topics as varied as copyright law, the law of contempt, the antitrust status of professional baseball, and the oath required for citizenship. Holmes, like most of his contemporaries, viewed the Bill of Rights as codifying privileges obtained over the centuries in English and American common law, and he established that view in numerous opinions for the Court. He is considered one of the greatest judges in American history and embodies for many the traditions of the common law. A eugenicist, he authored the majority opinion upholding forced sterilization.[37] Tens of thousands of the procedures followed.[38] From the departure of William Howard Taft on February 3, 1930, until Charles Evans Hughes became chief justice on February 24, 1930, Holmes briefly acted as the chief justice and presided over court sessions.[citation needed] Noteworthy Supreme Court opinions Otis v. Parker Beginning with his first opinion for the Court in Otis v. Parker (1903), Holmes exhibited his tendency to defer to legislatures, which two years later he did most famously in his dissenting opinion in Lochner v. New York (1905). In Otis v. Parker, the Court, in an opinion by Holmes, upheld the constitutionality of a California statute that provided that "all contracts for the sales of shares of the capital stock of any corporation or association on margin, or to be delivered at a future day, shall be void...." Holmes he wrote that, as a general proposition, "neither a state legislature nor a state constitution can interfere arbitrarily with private business or transactions.... But general propositions do not carry us far. While the courts must exercise a judgment of their own, it by no means is true that every law is void which may seem to the judges who pass upon it excessive, unsuited to its ostensible end, or based upon conceptions of morality with which they disagree. Considerable latitude must be allowed for differences of view.... If the state thinks that an admitted evil cannot be prevented except by prohibiting a calling or transaction not in itself necessarily objectionable, the courts cannot interfere, unless ... they can see that it 'is a clear, unmistakable infringement of rights secured by the fundamental law.'"[39] Lochner v. New York Main article: Lochner v. New York In his dissenting opinion in Lochner v. New York (1905), Holmes supported labor, not out of sympathy for workers, but because of his tendency to defer to legislatures. In Lochner, the Court struck down a New York statute that prohibited employees (spelled "employes" at the time) from being required or permitted to work in a bakery more than sixty hours a week. The majority found that the statute "interferes with the right of contract between the employer and employes", and that the right of contract, though not explicit in the Constitution, "is part of the liberty of the individual protected by the Fourteenth Amendment", under which no state may "deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law." In his brief dissent, Holmes said that the majority had reached its decision on the basis of the economic theory of laissez faire, but that the Constitution does not prevent the states from interfering with the liberty to contract. "The Fourteenth Amendment", Holmes wrote, "does not enact Mr. Herbert Spencer's Social Statics", which advocates laissez faire. Schenck v. United States Main article: Schenck v. United States In a series of opinions surrounding the World War I Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, Holmes held that the freedom of expression guaranteed by federal and state constitutions simply declared a common-law privilege for speech and the press, even when those expressions caused injury, but that the privilege could be defeated by a showing of malice or intent to do harm. Holmes came to write three unanimous opinions for the Supreme Court that arose from prosecutions under the 1917 Espionage Act because in an earlier case, Baltzer v. United States, he had circulated a powerfully expressed dissent, when the majority had voted to uphold a conviction of immigrant socialists who had circulated a petition criticizing the draft. Apparently learning that he was likely to publish this dissent, the government (perhaps alerted by Justice Louis D. Brandeis, newly appointed by President Woodrow Wilson) abandoned the case, and it was dismissed by the Court. The chief justice then asked Holmes to write opinions that could be unanimous, upholding convictions in three similar cases, where there were jury findings that speeches or leaflets were published with an intent to obstruct the draft, a crime under the 1917 law. Although there was no evidence that the attempts had succeeded, Holmes, in Schenck v. United States (1919), held for a unanimous Court that an attempt, purely by language, could be prosecuted if the expression, in the circumstances in which it was uttered, posed a "clear and present danger" that the legislature had properly forbidden. In his opinion for the Court, Holmes famously declared that the First Amendment would not protect a person "falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic". Abrams v. United States Main article: Abrams v. United States Later in 1919, however, in Abrams v. United States, Holmes dissented. The Wilson Administration was vigorously prosecuting those suspected of sympathies with the recent Russian Revolution, as well as opponents of the war against Germany. The defendants in this case were socialists and anarchists, recent immigrants from Russia who opposed the apparent efforts of the United States to intervene in the Russian Civil War. They were charged with violating the Sedition Act of 1918, which was an amendment to the Espionage Act of 1917 that made criticisms of the government or the war effort a crime. Abrams and his co-defendants were charged with distributing leaflets (one in English and one in Yiddish) that called for a "general strike" to protest the U.S. intervention in Russia. A majority of the Court voted to uphold the convictions and sentences of ten and twenty years, to be followed by deportation, while Holmes dissented. The majority claimed to be following the precedents already set in Schenck and the other cases in which Holmes had written for the Court, but Holmes insisted that the defendants' leaflets neither threatened to cause any harm nor showed a specific intent to hinder the war effort.[40] Holmes condemned the Wilson Administration's prosecution and its insistence on draconian sentences for the defendants in passionate language: "Even if I am technically wrong [regarding the defendants' intent] and enough can be squeezed from these poor and puny anonymities to turn the color of legal litmus paper ... the most nominal punishment seems to me all that possibly could be inflicted, unless the defendants are to be made to suffer, not for what the indictment alleges, but for the creed that they avow ... ." Holmes then went on to explain the importance of freedom of thought in a democracy: [W]hen men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe ... that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out. That, at any rate, is the theory of our Constitution. It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment.[41] In writing this dissent, Holmes may have been influenced by Zechariah Chafee's article "Freedom of Speech in War Time".[42][43] Chafee had criticized Holmes's opinion in Schenck for failing to express in more detail and more clearly the common-law doctrines upon which he relied. In his Abrams dissent, Holmes did elaborate somewhat on the decision in Schenck, roughly along the lines that Chafee had suggested. Although Holmes evidently believed that he was adhering to his own precedent, some later commentators accused Holmes of inconsistency, even of seeking to curry favor with his young admirers.[44] In Abrams, the majority opinion relied on the clear-and-present-danger formulation of Schenck, claiming that the leaflets showed the necessary intent, and ignoring that they were unlikely to have any effect. By contrast, the Supreme Court's current formulation of the clear and present danger test, stated in 1969 in Brandenburg v. Ohio, holds that "advocacy of the use of force or of law violation" is protected by the First Amendment "unless such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action". Silverthorne Lumber Co. v. United States Main article: Silverthorne Lumber Co. v. United States In Silverthorne Lumber Co. v. United States (1920), Holmes ruled that any evidence obtained, even indirectly, from an illegal search was inadmissible in court. He reasoned that otherwise, police would have an incentive to circumvent the Fourth Amendment to obtain derivatives of the illegally obtained evidence. This later became known as the "fruit of the poisonous tree" doctrine.[45] Buck v. Bell Main article: Buck v. Bell In 1927, Holmes wrote the 8–1 majority opinion in Buck v. Bell, a case that upheld the Virginia Sterilization Act of 1924 and the forced sterilization of Carrie Buck, who was claimed to be mentally defective. Later scholarship has shown that the suit was collusive, in that "two eugenics enthusiasts ... had chosen Buck as a bit player in a test case that they had devised" and "had asked Buck's guardian to challenge [the Virginia sterilization law]".[46] In addition, Carrie Buck was probably of normal intelligence.[47][48] The argument made on her behalf was principally that the statute requiring sterilization of institutionalized persons was unconstitutional, violating what today is called "substantive due process". Holmes repeated familiar arguments that statutes would not be struck down if they appeared on their face to have a reasonable basis. In support of his argument that the interest of "public welfare" outweighs the interest of individuals in their bodily integrity, he argued: We have seen more than once that the public welfare may call upon the best citizens for their lives. It would be strange if it could not call upon those who already sap the strength of the State for these lesser sacrifices, often not felt to be such by those concerned, to prevent our being swamped with incompetence. It is better for all the world if, instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes. [citation omitted] Three generations of imbeciles are enough.[49] Sterilization rates under eugenics laws in the United States climbed from 1927 until Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942), in which the U.S. Supreme Court declared unconstitutional an Oklahoma statute that provided for the sterilization of "habitual criminals".[50] Buck v. Bell continues to be cited occasionally in support of due process requirements for state interventions in medical procedures. For instance, in 2001, the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit cited Buck v. Bell to protect the constitutional rights of a woman coerced into sterilization without procedural due process.[51] The court stated that error and abuse will result if the state does not follow the procedural requirements, established by Buck v. Bell, for performing an involuntary sterilization.[51] Buck v. Bell was also cited briefly, though not discussed, in Roe v. Wade, in support of the proposition that the Court does not recognize an "unlimited right to do with one's body as one pleases".[52] However, although Buck v. Bell has not been overturned, "the Supreme Court has distinguished the case out of existence".[53] |

最高裁判所判事 概要  連邦最高裁判事に任命された年 1902年7月にホレス・グレイ判事補が死去した直後、セオドア・ルーズベルト大統領はホームズをグレイ判事の後任に指名する意向を明らかにした。ホアは 帝国主義に強く反対しており、プエルトリコとフィリピンの併合の合法性が法廷で争われることが予想されていた。ロッジはルーズベルトと同じく帝国主義の強 力な支持者であり、ホームズも帝国主義を支持すると予想されていた[33]。 ホアの反対にもかかわらず、大統領はこの問題を進めた。1902年12月2日、大統領は正式に指名を提出し、ホームズは12月4日に合衆国上院で承認された[34]。 就任後、ホームズは「島嶼事件」において旧スペイン植民地の併合を支持する政権の立場を支持する票を投じた。しかし、その後、反トラスト法に関する重大な訴追であったノーザン・セキュリティーズ対アメリカ合衆国事件では反対意見を述べ、ルーズベルトを失望させた[35]。 ホームズはその簡潔な意見で知られ、頻繁に引用された。29年以上最高裁判事に在任し、連邦法の全範囲に及ぶ事件で判決を下した。著作権法、侮辱法、プロ 野球の反トラスト法、市民権に必要な宣誓など、さまざまなテーマに関する先見の明のある意見で知られている。ホームズは、同時代の多くの裁判官と同様、権 利章典を英米の慣習法で何世紀にもわたって得られてきた特権を成文化したものと考え、法廷での数多くの意見でその見解を確立した。彼はアメリカ史上最も偉 大な裁判官の一人とされ、多くの人々にコモン・ローの伝統を体現している。優生主義者であった彼は、強制不妊手術を支持する多数意見を提出した。 1930年2月3日にウィリアム・ハワード・タフトが退任してから、チャールズ・エヴァンス・ヒューズが1930年2月24日に最高裁長官に就任するまでの間、ホームズは一時的に最高裁長官を務め、裁判長を務めた[要出典]。 注目すべき最高裁判所意見 オーティス対パーカー事件 ホームズは、オーティス対パーカー事件(1903年)での最初の法廷意見から、立法府に従う傾向を示し、その2年後のロッヒナー対ニューヨーク事件 (1905年)での反対意見で最も有名である。オーティス対パーカー事件では、ホームズの意見に基づき、「いかなる会社または団体の資本株式の信用売り、 または将来の引渡しのための契約はすべて無効である」と規定したカリフォルニア州法の合憲性を支持した。ホームズは、一般的な命題として、「州議会も州憲 法も、個人の事業や取引に恣意的に干渉することはできない。しかし、一般的な命題は私たちを遠ざけるものではない。裁判所は独自の判断を行使しなければな らないが、判決を下す裁判官にとって、過度であったり、表向きの目的にそぐわなかったり、あるいは裁判官の同意しない道徳観に基づいていると思われる法律 がすべて無効であるとは決して言えない。見解の相違については、かなりの自由裁量が認められなければならない......。国家が、それ自体必ずしも好ま しくない行為や取引を禁止する以外に、認められた悪を防止することができないと考える場合、裁判所は、......それが『基本法によって保障された権利 の明白かつ紛れもない侵害である』と見なすことができない限り、干渉することはできない」[39]。 ロッホナー対ニューヨーク事件 主な記事 ロッホナー対ニューヨーク事件 ロヒナー対ニューヨーク裁判(1905年)の反対意見で、ホームズは労働者を支持したが、それは労働者への同情からではなく、立法府に従うという彼の傾向 からであった。ロッホナー事件では、従業員(当時は "employes "と表記)がパン工場で週60時間以上働くことを要求または許可することを禁止するニューヨークの法令を破棄した。多数派は、この法令は「雇用者と被用者 の間の契約権を妨害するもの」であり、契約権は憲法には明記されていないものの、「憲法修正第14条によって保護される個人の自由の一部」であり、いかな る国家も「法の適正な手続きなしに、生命、自由、または財産を奪うことはできない」と判断した。ホームズは短い反対意見の中で、多数派はレッセフェールと いう経済理論に基づいて判決を下したが、憲法は州が契約の自由に干渉することを妨げてはいないと述べた。「憲法修正第14条は、自由放任を主張するハー バート・スペンサーの『社会統計学』を制定するものではない」とホームズは書いた。 シェンク対アメリカ合衆国事件 主な記事 シェンク対アメリカ合衆国裁判 1917年の第一次世界大戦スパイ法と1918年の扇動法をめぐる一連の意見の中で、ホームズは、連邦憲法と州憲法が保障する表現の自由は、たとえその表 現が損害を与えるものであっても、言論と報道に対するコモンロー上の特権を宣言しているにすぎず、悪意や害悪を与える意図を示すことによって、その特権は 失われる可能性があるとした。ホームズは、1917年のスパイ防止法に基づく訴追に起因する3つの全会一致の意見を最高裁に提出することになったが、その 理由は、それ以前の事件であるバルツァー対合衆国において、徴兵制を批判する嘆願書を配布した移民の社会主義者の有罪判決を支持する多数決がなされた際、 力強く表明した反対意見を配布したからである。彼がこの反対意見を発表する可能性があることを知った政府は(おそらくウッドロー・ウィルソン大統領によっ て新たに任命されたルイス・D・ブランディス判事によって警告されたのだろう)、この訴訟を放棄し、法廷によって却下された。その後、裁判長はホームズ に、1917年の法律では犯罪とされていた徴兵を妨害する意図で演説やビラが発行されたという陪審員の認定があった3件の類似の事件で有罪判決を支持す る、全員一致の意見を書くよう依頼した。これらの企てが成功したという証拠はなかったが、ホームズはシェンク対合衆国事件(1919年)において、満場一 致の法廷を代表して、純粋に言葉による企てであっても、その表現が発せられた状況において、立法府が適切に禁止した「明白かつ現在の危険」をもたらすもの であれば、起訴することができると判示した。ホームズは法廷意見の中で、憲法修正第1条は「劇場で虚偽の火事を叫び、パニックを引き起こした」者を保護し ないと宣言したことは有名である。 エイブラムス対合衆国 主な記事 エイブラムス対アメリカ合衆国事件 しかしその後1919年、エイブラムス対合衆国の裁判で、ホームズは反対意見を述べた。ウィルソン政権は、最近のロシア革命に共鳴していると疑われる人々 や、対独戦争反対派を精力的に訴追していた。この事件の被告は社会主義者と無政府主義者で、ロシアから最近移住してきた人々であり、ロシア内戦に介入しよ うとするアメリカの明らかな努力に反対していた。彼らは1918年の扇動法違反の罪に問われた。扇動法は1917年に制定されたスパイ活動法を改正したも ので、政府や戦争活動に対する批判を犯罪とするものであった。エイブラムスとその共同被告は、米国のロシア介入に抗議する「ゼネスト」を呼びかけるビラ (英語とイディッシュ語)を配布した罪に問われた。法廷の多数決で有罪判決が支持され、10年と20年の刑が言い渡され、その後国外追放となったが、ホー ムズは反対した。多数派は、シェンクや、ホームズが法廷のために執筆した他の事件ですでに決められた判例に従っていると主張したが、ホームズは、被告たち のビラには、危害を加える恐れも、戦争努力を妨げる具体的な意図も示されていないと主張した[40]。 ホームズは、ウィルソン政権の訴追と、被告たちに対する強権的な量刑の主張を、情熱的な言葉で非難した: 「たとえ私が(被告たちの意図に関して)技術的に間違っていて、これらの貧しくちっぽけな匿名から、法的なリトマス試験紙の色に変わるほどのものを絞り出 すことができたとしても......被告たちを、起訴状が主張していることのためではなく、被告たちが公言している信条のために苦しませるのでない限 り......最も名目的な処罰が、私に与えられる可能性のあるすべてであるように思える......」。続いてホームズは、民主主義における思想の自由 の重要性を説いた: [人々は、時が多くの戦う信仰を動揺させることを理解したとき、真理の最良のテストは、市場の競争の中で自分自身を受け入れてもらうための思想の力であ り、真理こそが、自分たちの願いを安全に実行することができる唯一の根拠であると信じるようになるかもしれない。いずれにせよ、これがわが憲法の理論であ る。すべての人生が実験であるように、これは実験なのである[41]。 この反対意見を書くにあたって、ホームズはゼカリア・チャーフィーの論文「戦時下における言論の自由」[42][43]の影響を受けたと思われる。 チャーフィーは、シェンクにおけるホームズの意見を、ホームズが依拠したコモンローの学説をより詳細に、より明確に表現していないと批判していた。ホーム ズは、エイブラムスの反対意見の中で、シェンクの判決について、チャーフィーが示唆したような線に沿って、いくらか詳しく述べている。エイブラムスでは、 多数意見はシェンクの「明白かつ現在の危険」という定式に依拠し、ビラには必要な意図が示されていると主張し、ビラが効果をもたらす可能性が低いことは無 視した。これとは対照的に、1969年にブランデンブルグ対オハイオ事件で示された、「武力行使や法律違反の擁護」は、「そのような擁護が差し迫った無法 行為を扇動したり生じさせたりすることを目的とし、かつそのような行為を扇動したり生じさせたりする可能性がない限り」、憲法修正第1条によって保護され るとするのが、最高裁判所の現在の明確かつ現在の危険性テストの定式化である。 シルバーソーン・ランバー社対アメリカ合衆国事件 主な記事 シルバーソーン・ランバー社対合衆国事件 シルバーソーン・ランバー社対アメリカ合衆国裁判(1920年)において、ホームズは、違法な捜査によって間接的にでも得られた証拠は、裁判では認められ ないと裁定した。そうでなければ、警察は憲法修正第4条を迂回して、違法に入手した証拠の派生物を手に入れようとする動機を持つことになるからである。こ れは後に「毒の木の実」の原則と呼ばれるようになった[45]。 バック対ベル事件 主な記事 バック対ベル事件 1927年、ホームズはバック対ベル事件で8対1の多数意見を書き、1924年のバージニア州不妊手術法と精神障害者であると主張されたキャリー・バック の強制不妊手術を支持した。後の研究によれば、この訴訟は結託したものであり、「2人の優生学愛好家が......自分たちが考案したテストケースのビッ トプレーヤーとしてバックを選び」、「バックの後見人に(ヴァージニア不妊化法に)異議を申し立てるよう依頼していた」[46]。ホームズは、法令がその 表面上合理的な根拠を持っているように見えれば、それが打ち壊されることはないというおなじみの主張を繰り返した。公共の福祉」の利益は、個人の身体的完 全性の利益を上回るとする彼の主張を支持し、次のように主張した: 公共の福祉が最良の市民の生命を求めることがあることを、私たちは何度も見てきた。私たちが無能な人間で溢れかえるのを防ぐために、すでに国家の力を支え ている人々に、しばしば関係者にはそう感じられないような、より小さな犠牲を求められないとしたら、それはおかしなことである。堕落した子孫を犯罪で処刑 するのを待ったり、その無能さのために飢え死にさせたりするのではなく、社会が明らかに不適格な者たちがその種を絶やさないようにすることができれば、全 世界のためになる。強制予防接種を支える原則は、卵管切断をカバーするのに十分広い。[引用略]無能な人間は3世代も続ければ十分である[49]。 米国における優生学法に基づく不妊手術率は、1927年からスキナー対オクラホマ裁判(316 U.S. 535、1942年)まで上昇し、連邦最高裁は「常習的犯罪者」の不妊手術を規定したオクラホマ州法を違憲とした[50]。例えば、2001年、第8巡回 区連邦控訴裁判所は、手続き上の適正手続きなしに不妊手術を強要された女性の憲法上の権利を保護するために、バック対ベル裁判を引用した[51]。バック 対ベル裁判は、ロー対ウェイド裁判においても、「自分の身体を好きなように扱う無制限の権利」を認めないという命題を支持するために、論じられてはいない が、わずかに引用されている[52]。しかし、バック対ベル裁判は覆されてはいないものの、「最高裁はこの裁判を存在しないものとして区別している」 [53]。 |

| Jurisprudential contributions Critique of formalism Main article: Legal formalism From his earliest writings, Holmes demonstrated a lifelong belief that the decisions of judges were consciously or unconsciously result-oriented and reflected the mores of the class and society from which judges were drawn. In his 1881 book The Common Law,[6] Holmes argued that legal rules are not deduced through formal logic but rather emerge from an active process of human self-government.[54] He expressed this idea most famously in The Common Law with the statement, "The life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience".[6] His philosophy represented a departure from the prevailing jurisprudence of the time: legal formalism, which held that law was an orderly system of rules from which decisions in particular cases could be deduced.[55] Holmes sought to consciously reinvent the common law – to modernize it as a tool for adjusting to the changing nature of modern life, as judges of the past had done more or less unconsciously.[54] He has been classed with the philosophic pragmatists, although pragmatism is what he attributed to the law, rather than his personal philosophy.[C] Central to his thought was the notion that the law, as it had evolved in modern societies, was concerned with the material results of a defendant's actions. A judge's task was to decide which of two parties before him would bear the cost of an injury. Holmes argued that the evolving common law standard was that liability would fall upon a person whose conduct failed to reflect the prudence of a "reasonable man". If a construction worker throws a beam onto a crowded street: he does an act which a person of ordinary prudence would foresee is likely to cause death ..., and he is dealt with as if he foresaw it, whether he does so in fact or not. If a death is caused by the act, he is guilty of murder. But if the workman has a reasonable cause to believe that the space below is a private yard from which everyone is excluded, and which is used as a rubbish-heap, his act is not blameworthy, and the homicide is a mere misadventure.[6] This "objective standard" adopted by common-law judges, Holmes thought, reflected a shift in community standards, away from condemnation of a person's act toward an impersonal assessment of its value to the community. In the modern world, the advances made in biology and the social sciences should allow a better conscious determination of the results of individual acts and the proper measure of liability for them.[56] This belief in the pronouncements of science concerning social welfare, although he later doubted its applicability to law in many cases, accounts for his enthusiastic endorsement of eugenics in his writings, and his opinion in the case of Buck v. Bell.[citation needed] Legal positivism Main article: Legal positivism In 1881, in The Common Law, Holmes brought together into a coherent whole his earlier articles and lectures concerning the history of the common law (judicial decisions in England and the United States), which he interpreted from the perspective of a practicing lawyer. What counted as law, to a lawyer, was what judges did in particular cases. Law was what the state would enforce, through violence if necessary; echoes of his experience in the Civil War were often present in his writings. Judges decided where and when the force of the state would be brought to bear, and judges in the modern world tended to consult facts and consequences when deciding what conduct to punish. The decisions of judges, viewed over time, determined the rules of conduct and the legal duties by which all are bound. Judges did not and should not consult any external system of morality, certainly not a system imposed by a deity.[citation needed] Being a legal positivist, Holmes brought himself into constant conflict with scholars who believed that legal duties rested upon natural law, a moral order of the kind invoked by Christian theologians and other philosophic idealists. He believed instead "that men make their own laws; that these laws do not flow from some mysterious omnipresence in the sky, and that judges are not independent mouthpieces of the infinite."[57]: 49 "The common law is not a brooding omnipresence in the sky."[58] Rather than a set of abstract, rational, mathematical, or in any way unworldly set of principles, Holmes said: "[T]he prophecies of what the courts will do in fact, and nothing more pretentious, are what I mean by the law."[31]: 458 His belief that law, properly speaking, was a set of generalizations from what judges had done in similar cases, determined his view of the Constitution of the United States. As a justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, Holmes rejected the argument that the text of the Constitution should be applied directly to cases that came before the court, as if it were a statute. He shared with most of his fellow judges the belief that the Constitution carried forward principles derived from the common law, principles that continued to evolve in American courts. The text of the Constitution itself, as originally understood, was not a set of rules, but only a directive to courts to consider the body of the common law when deciding cases that arose under the Constitution. It followed that constitutional principles adopted from the common law were evolving, as the law itself evolved: "A word [in the Constitution] is not a crystal, transparent and unchanged, it is the skin of a living thought".[59] General propositions do not decide concrete cases. —Holmes's dissent in Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45, 76 (1905) The provisions of the Constitution are not mathematical formulas that have their essence in form, they are organic, living institutions transplanted from English soil. Their significance is vital, not formal; it is to be gathered not simply by taking the words and a dictionary but by considering their origin and the line of their growth.[60] Holmes also insisted on the separation of "ought" and "is", confusion of which he saw as an obstacle in understanding the realities of the law.[31]: 457 "The law is full of phraseology drawn from morals, and talks about rights and duties, malice, intent, and negligence – and nothing is easier in legal reasoning than to take these words in their moral sense".[57]: 40 [31]: 458 "Therefore nothing but confusion can result from assuming that the rights of man in a moral sense are equally rights in the sense of the Constitution and the law".[57]: 40 Holmes said, "I think our morally tinted words have caused a great deal of confused thinking".[61]: 179 Nevertheless, in rejecting morality as a form of natural law outside of and superior to human enactments, Holmes was not rejecting moral principles that were the result of enforceable law: "The law is the witness and external deposit of our moral life. Its history is the history of the moral development of the race. The practice of it, in spite of popular jests, tends to make good citizens and good men. When I emphasize the difference between law and morals I do so with reference to a single end, that of learning and understanding the law."[31]: 457 Holmes's insistence on the material basis of law, on the facts of a case, has led some to characterize him as unfeeling, however. George Washington University law professor Jeffrey Rosen summarized Holmes's views this way: "Holmes was a cold and brutally cynical man who had contempt for the masses and for the progressive laws he voted to uphold ... an aristocratic nihilist who once told his sister that he loathed 'the thick-fingered clowns we call the people'."[62] Reputation as a dissenter Although Holmes did not dissent frequently—during his 29 years on the U.S. Supreme Court, he wrote only 72 separate opinions, whereas he penned 852 majority opinions—his dissents were often prescient and acquired so much authority that he became known as "The Great Dissenter". Chief Justice Taft complained that "his opinions are short, and not very helpful".[63] Two of his most famous dissents were in Abrams v. United States and Lochner v. New York.[64] |

法学的貢献 形式主義批判 主な記事 法形式主義 ホームズは初期の著作から、裁判官の判断は意識的あるいは無意識的に結果重視のものであり、裁判官の出身階級や社会の風俗を反映したものであるという信念 を終生持ち続けた。1881年の著書『コモン・ロー』[6]において、ホームズは、法規則は形式的な論理によって導き出されるものではなく、むしろ人間の 自治の能動的なプロセスから生まれるものであると主張した[54]。この考えを『コモン・ロー』の中で最も有名に表現したのは、「法の生命は論理ではな かった。それは経験であった」という記述であった[6]。 [ホームズは、コモン・ローを意識的に再発明すること、すなわち、過去の裁判官が多かれ少なかれ無意識のうちに行ってきたように、コモン・ローを現代生活 の変化に適応するための道具として近代化することを目指した[54]。彼は哲学的プラグマティストに分類されているが、プラグマティズムは彼の個人的な哲 学というよりもむしろ法律に帰属するものであった[C]。 彼の思想の中心は、近代社会で発展してきたように、法は被告の行為の物質的な結果に関係しているという考え方であった。裁判官の仕事は、目の前にいる二人 の当事者のうちどちらが損害の費用を負担するかを決定することであった。ホームズは、進化したコモンローの基準は、「合理的な人間」の思慮を反映しない行 為をした者に責任が及ぶというものだと主張した。建設作業員が混雑した道路に梁を投げ入れたとする: 通常の思慮分別のある者であれば、死者が出る可能性があると予見できる行為をしたのであれば、実際にそうであろうとなかろうと、それを予見していたかのよ うに扱われる。その行為によって死者が出た場合、殺人罪が成立する。しかし、作業員が、その下の空間が、誰もが立ち入ることのできない私有の庭であり、ゴ ミ捨て場として使用されていると信じるに足る合理的な理由がある場合には、その行為に罪はなく、殺人は単なる不注意である[6]。 コモンローの裁判官が採用したこの「客観的基準」は、個人の行為を非難することから、共同体にとっての価値を非人間的に評価することへと、共同体の基準が 変化したことを反映しているとホームズは考えていた。現代世界では、生物学と社会科学の進歩により、個人の行為の結果とそれに対する責任の適切な尺度をよ り意識的に決定することができるはずである[56]。社会福祉に関する科学の発表に対するこの信念は、後に多くの場合において法律への適用を疑問視するよ うになったが、彼の著作における優生学の熱心な支持と、バック対ベル事件における彼の意見[要出典]を物語っている。 法実証主義 主な記事 法実証主義 1881年、ホームズは『コモン・ロー』(The Common Law)の中で、コモン・ロー(イギリスとアメリカにおける司法判決)の歴史に関するそれまでの論文や講義を、実務家弁護士の立場から解釈して、首尾一貫 した全体像にまとめた。弁護士にとって法律とは、特定の事件で裁判官が行ったことを指す。彼の著作には、南北戦争での経験がしばしば反映されている。裁判 官は、国家の力がいつどこで発揮されるかを決定し、近代世界の裁判官は、どのような行為を罰するかを決定する際に、事実と結果を考慮する傾向があった。裁 判官の判断は、時とともに、すべての人が拘束される行動の規則と法的義務を決定した。裁判官は外部の道徳体系を参考にすることはなかったし、また参考にす べきではなかった。 法実証主義者であったホームズは、法的義務は自然法、つまりキリスト教神学者やその他の哲学的観念論者が唱えた種類の道徳的秩序に基づいていると考える学 者たちと常に対立することになった。彼はその代わりに、「人間は自分自身で法律を作るものであり、これらの法律は天空に存在する神秘的な全知全能の存在か ら流れてくるものではなく、裁判官は無限の独立した口利きではない」と信じていた[57]: 49 「コモン・ローは天空にうごめく遍在的存在ではない」[58]。抽象的、合理的、数学的、あるいはいかなる意味でもこの世に存在しない原則の集合ではな く、ホームズはこう述べている: 「裁判所が実際に何をするかという予言であり、それ以上の気取ったものではない、それが私の言う法である」[31]: 458 法とは、正しく言えば、裁判官が類似の事件で行ってきたことを一般化したものであるという彼の信念が、合衆国憲法に対する彼の見解を決定づけた。連邦最高 裁判所の判事として、ホームズは、憲法条文をあたかも法令のように、法廷に提出された事案に直接適用すべきだという主張を否定した。彼は、憲法はコモン・ ローに由来する原則を継承するものであり、その原則はアメリカの法廷で発展し続けるものであるという信念を、同僚の裁判官の多くと共有していた。当初理解 されていた憲法の条文そのものは規則ではなく、憲法の下で発生した事件を判断する際にコモン・ローの体系を考慮するよう裁判所に指示したものに過ぎなかっ た。コモン・ローから採用された憲法の原則は、法律そのものが進化するにつれて進化していったのである: 「憲法の)言葉は透明で不変の結晶ではなく、生きた思想の皮膚である」[59]。 一般的な命題は具体的な事例を決定するものではない。 -ロッホナー対ニューヨーク裁判におけるホームズの反対意見、198 U.S. 45, 76 (1905) 憲法の規定は、形式に本質を持つ数式ではなく、英国の土壌から移植された有機的で生きた制度である。その意義は形式的なものではなく重要なものであり、単に単語や辞書を引くだけでなく、その起源や成長の過程を考慮することで得られるものである[60]。 ホームズはまた「ought」と「is」の分離を主張しており、その混同は法の現実を理解する上での障害となっていると考えていた[31]: 457 「法は道徳から引き出された言い回しで満ちており、権利と義務、悪意、故意、過失について語られている-そしてこれらの言葉を道徳的な意味でとらえること ほど、法的推論において容易なことはない」[57]: 40 [31]: 458 「したがって、道徳的な意味での人間の権利が、憲法や法律の意味でも同様に権利であると仮定することから生じるのは、混乱以外の何ものでもない」 [57]: 40 ホームズは、「我々の道徳的な色彩を帯びた言葉が、多くの混乱を引き起こしていると思う」と述べている[61]: 179 とはいえ、人間の制定法の外にあり、それに優越する自然法の一形態としての道徳を否定するにあたって、ホームズは、強制可能な法の結果である道徳原理を否 定していたわけではない: 「法はわれわれの道徳的生活の証人であり、外的な預かり物である。法の歴史は、民族の道徳的発展の歴史である。世間の嘲笑にもかかわらず、法の実践は善良 な市民と善良な人間を作る傾向がある。私が法と道徳の違いを強調するのは、法を学び理解するという一つの目的に関連してのことである」[31]: 457 しかし、ホームズの、事件の事実という法の物質的基礎に対する主張は、彼を無感情であると評する人もいる。ジョージ・ワシントン大学のジェフリー・ローゼ ン教授は、ホームズの見解をこのように要約している: ホームズは冷淡で残忍な皮肉屋であり、大衆を軽蔑し、自分が支持することに票を投じた進歩的な法律を軽蔑していた......貴族的なニヒリストであり、 妹に『民衆と呼ばれる太い指の道化師』を憎んでいると語ったこともある」[62]。 反対論者としての評判 ホームズは頻繁に反対意見を述べることはなかったが、連邦最高裁判事に在任した29年間に書いた単独意見はわずか72件であった。タフト最高裁長官は「彼 の意見は短く、あまり参考にならない」と苦言を呈した[63]。彼の最も有名な反対意見の2つは、エイブラムス対アメリカ合衆国裁判とロヒナー対ニュー ヨーク裁判であった[64]。 |

| Speeches and letters Speeches Only Holmes's legal writings were readily available during his life and in the first years after his death, but he confided his thoughts more freely in talks, often to limited audiences, and more than two thousand letters that have survived. Holmes's executor, John Gorham Palfrey, diligently collected Holmes's published and unpublished papers and donated them (and their copyrights) to Harvard Law School. Harvard Law Professor Mark De Wolfe Howe undertook to edit the papers and was authorized by the school to publish them and to prepare a biography of Holmes. Howe published several volumes of correspondence, beginning with Holmes's correspondence with Frederick Pollock,[65][66] and a volume of Holmes's speeches,[67] before his untimely death. Howe's work formed the basis of much subsequent Holmes scholarship.[citation needed] Holmes's speeches were divided into two groups: public addresses, which he gathered into a slim volume, regularly updated, that he gave to friends and used as a visiting card, and less formal addresses to men's clubs, dinners, law schools, and Twentieth Regiment reunions. All of the speeches are reproduced in the third volume of The Collected Works of Justice Holmes.[68] The public addresses are Holmes's effort to express his personal philosophy in Emersonian, poetic terms. They frequently advert to the Civil War and to death, and express a hope that personal sacrifice, however pointless it may seem, serves to advance the human race toward some as-yet unforeseen goal. This mysterious purpose explained the commitment to duty and honor that Holmes felt deeply himself and that he thought was the birthright of a certain class of men. As Holmes stated at a talk upon receiving an honorary degree from Yale: Why should you row a boat race? Why endure long months of pain in preparation for a fierce half-hour.... Does anyone ask the question? Is there anyone who would not go through all its costs, and more, for the moment when anguish breaks into triumph – or even for the glory of having nobly lost?[69]: 473 In the 1890s, at a time when "scientific" anthropology that spoke of racial differences was in vogue, his observations took on a bleakly Darwinist cast: I rejoice at every dangerous sport which I see pursued. The students at Heidelberg, with their sword-slashed faces, inspire me with sincere respect. I gaze with delight upon our polo-players. If once in a while in our rough riding a neck is broken, I regard it not as a waste, but as a price well paid for the breeding of a race fit for headship and command.[70] This talk was widely reprinted and admired at the time, and may have contributed to the popular name given by the press to the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry (the "Rough Riders") during the Spanish–American War.[citation needed] On May 30, 1895, Holmes gave the address at a Memorial Day function held by the Graduating Class of Harvard University in Boston, Massachusetts. The speech, which came to be known as "The Soldier's Faith", expressed Holmes's view of the conflict between the high ideals that motivated his generation to fight in the Civil War and the reality of a soldier's experience and personal pledge to follow orders into battle.[71] Holmes stated: [T]here is one thing I do not doubt ... and that is that the faith is true and adorable which leads a soldier to throw away his life in obedience to a blindly accepted duty, in a cause which he little understands ... .[70] That the joy of life is living, is to put out all one's powers as far as they will go; that the measure of power is obstacles overcome; to ride boldly at what is in front of you, be it fence or enemy; to pray, not for comfort, but for combat; to keep the soldier's faith against the doubts of civil life, more besetting and harder to overcome than all the misgivings of the battle-field, and to remember that duty is not to be proved in the evil day, but then to be obeyed unquestioning ... .[70] In the conclusion of the speech, Holmes said: We have shared the incommunicable experience of war; we have felt, we still feel, the passion of life to its top.[70] Theodore Roosevelt reportedly admired Holmes's "Soldier's Faith" speech, and it is believed to have contributed to his decision to nominate Holmes to the Supreme Court.[72] Letters Many of Holmes's closest male friends were in England and he corresponded with them regularly and at length, speaking usually of his work. Letters to friends in England such as Harold Laski and Frederick Pollock contain frank discussion of his decisions and his fellow justices. In the United States, letters to male friends Morris R. Cohen, Lewis Einstein, Felix Frankfurter, and Franklin Ford are similar, although the letters to Frankfurter are especially personal. Holmes's correspondence with women in Great Britain and the U.S. was at least as extensive, and in many ways more revealing, but these series of letters have not been published. An extensive selection of letters to Claire Castletown, in Ireland, is included in Honorable Justice: The Life of Oliver Wendell Holmes, by Sheldon Novick.[73] These letters are closer to Holmes's conversation and cast light upon the style he adopted in judicial opinions, which were often designed to be read aloud.[citation needed] In a letter to a contemporary, Holmes made this comment on international comparisons: "Judge not a people by the ferocity of its men, but by the steadfastness of its women."[74] |

スピーチと手紙 講演 生前と死後数年間は、ホームズの法的著作物のみが容易に入手可能であったが、彼は、しばしば限られた聴衆を対象とした講演や、現存する2,000通を超え る手紙の中で、より自由に自分の考えを打ち明けていた。ホームズの遺言執行人であったジョン・ゴーハム・パルフリーは、ホームズの出版済みおよび未発表の 論文を熱心に収集し、ハーバード大学法科大学院に寄贈した。ハーバード大学法学部のマーク・デ・ウルフ・ハウ教授は論文の編集を引き受け、同校から出版と ホームズの伝記の作成を許可された。ハウは、ホームズが早すぎる死を迎える前に、フレデリック・ポロックとの往復書簡から始まる数冊の書簡集[65] [66]とホームズの演説集[67]を出版した。ハウの仕事は、その後の多くのホームズ研究の基礎となった[要出典]。 ホームズの演説は、定期的に更新されるスリムな一冊にまとめられ、友人に贈ったり、訪問カードとして使用したりした公の場での演説と、男性クラブ、晩餐 会、法科大学院、第20連隊の同窓会などでの堅苦しくない演説の2つのグループに分けられた。演説はすべて、『ホームズ判事著作集』(The Collected Works of Justice Holmes)の第3巻に収録されている。これらの演説は、南北戦争や死について頻繁に言及し、個人の犠牲がいかに無意味に思えようとも、人類をまだ見ぬ 目標に向かって前進させるために役立つという希望を表明している。この神秘的な目的は、ホームズ自身が深く感じ、ある種の人間が生まれながらにして持つ権 利だと考えていた義務と名誉への献身を説明するものであった。エール大学から名誉学位を授与されたときの講演で、ホームズはこう述べた: なぜボートレースを漕がなければならないのか。なぜボートレースを漕ぐ必要があるのか?そんな疑問を持つ人はいるだろうか?苦悩が勝利に変わる瞬間のため に、あるいは気高く負けたという栄光のために、あらゆる犠牲を払わず、それ以上のことをしない人がいるだろうか[69]: 473 1890年代、人種の違いについて語る「科学的」人類学が流行していた頃、彼の観察は殺伐としたダーウィン主義的な色彩を帯びていた: 私は、危険なスポーツが追求されるのを見るたびに喜ぶ。ハイデルベルクの学生たちは、剣で斬りつけられた顔で、私に心からの尊敬の念を抱かせる。ハイデル ベルクの学生たちの剣で斬られた顔は、私に心からの尊敬の念を抱かせる。私たちの乱暴な騎乗で、たまに首が折れることがあっても、私はそれを無駄とは考え ず、統率と指揮にふさわしい種族を育成するためによく支払われた代償だと考える[70]。 この談話は当時広く転載され賞賛され、米西戦争中にマスコミによって第1合衆国義勇騎兵隊(「ラフ・ライダーズ」)につけられた通称の一因となったかもしれない[要出典]。 1895年5月30日、ホームズはマサチューセッツ州ボストンで開催されたハーバード大学卒業記念日の行事で演説を行った。この演説は「兵士の信念」とし て知られるようになったが、南北戦争で自分の世代を戦いに駆り立てた高い理想と、兵士の経験や命令に従って戦場に赴くという個人的な誓約の現実との間の葛 藤についてのホームズの見解を表したものであった[71]: [私が疑わないことが一つある......それは、兵士がほとんど理解していない大義のために、盲目的に受け入れた義務に従って命を投げ出すように導く信仰が真実であり、愛すべきものであるということである......[70]。 人生の喜びは生きることであり、その喜びは、自分の持てる力の限りを尽くすことであり、力の尺度とは克服された障害であり、柵であれ敵であれ、目の前にあるものに果敢に立ち向かうことであり、慰めのためではなく、戦闘のために祈ることである。 .. .[70] 演説の最後に、ホームズはこう述べた: われわれは戦争という伝えがたい経験を共有してきた。われわれは生命の情熱をその頂点まで感じてきたし、今も感じている」[70]。 セオドア・ルーズベルトはホームズの「兵士の信念」演説を賞賛していたと伝えられており、ホームズを最高裁判事に指名する決断を下す一因となったと考えられている[72]。 手紙 ホームズの親しい男友達の多くはイギリスにおり、ホームズは彼らと定期的に長文の手紙のやり取りをしていた。ハロルド・ラスキーやフレデリック・ポロック といった英国の友人たちに宛てた手紙には、ホームズの判決や同僚の判事たちについての率直な議論が記されている。アメリカでは、男性の友人であるモリス・ R・コーエン、ルイス・アインシュタイン、フェリックス・フランクファーター、フランクリン・フォードに宛てた手紙も同様であるが、フランクファーターに 宛てた手紙は特に個人的な内容となっている。ホームズと英米の女性たちとの手紙のやり取りは、少なくともこれと同じくらい広範囲に及び、多くの点でより明 らかになったが、これらの一連の手紙は出版されていない。アイルランドのクレア・キャッスルタウンに宛てた手紙の広範なセレクションは、 『Honorable Justice』に収録されている: これらの書簡はホームズの会話に近いものであり、しばしば音読されるように作られていた司法意見において彼が採用した文体に光を当てている[73]。 ホームズは同時代の人物に宛てた手紙の中で、国際比較について次のようにコメントしている: 「ある民族をその男性の凶暴性で判断するのではなく、その女性の堅実性で判断せよ」[74]。 |

Retirement, death, honors and legacy Stamp issued by the U.S. Post Office, 1978 Holmes was widely admired during his last years, and on his ninetieth birthday he was honored on one of the first coast-to-coast radio broadcasts, during which Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, Dean of Yale Law School Charles Edward Clark, and the president of the American Bar Association read encomia; the Bar Association presented him with a gold medal. Holmes served on the Court until January 12, 1932, when his brethren on the Court, citing his advanced age, suggested that the time had come for him to step down. By that time, at 90 years and 10 months of age, he was the oldest justice to serve in the Court's history. (His record has been challenged only by John Paul Stevens, who in 2010 retired at 8 months younger than Holmes had been at his own retirement.) On Holmes's ninety-second birthday, newly inaugurated President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his wife, Eleanor, called on Holmes at his home in Washington, D.C. Holmes died of pneumonia in Washington on March 6, 1935, two days short of his 94th birthday. He was the last living justice of the Fuller Court; he had been between 1925 and 1932 the last justice of that Court to remain on the bench.[citation needed] In his will, Holmes left his residuary estate to the United States government (he had earlier said that "taxes are what we pay for civilized society" in Compañia General de Tabacos de Filipinas vs. Collector of Internal Revenue, 275 U.S. 87, 100 (1927).) After his death, his personal effects included his Civil War officer's uniform still stained with his blood and "torn with shot" as well as the Minié balls that had wounded him three times in separate battles. Holmes was buried beside his wife in Arlington National Cemetery.[75][76]  Holmes's gravesite The United States Postal Service honored Holmes with a Prominent Americans series (1965–1978) 15¢ postage stamp.[citation needed] A bust of Justice Holmes, sculpted by Joseph Kiselewski,[77] was installed in the Hall of Fame for Great Americans at New York University in New York City in 1970. Holmes's papers, donated to Harvard Law School, were kept closed for many years after his death, a circumstance that gave rise to somewhat fanciful accounts of his life. Catherine Drinker Bowen's fictionalized biography Yankee from Olympus was a long-time bestseller, and the 1946 Broadway play and 1950 Hollywood motion picture The Magnificent Yankee were based on a biography of Holmes by Francis Biddle, who had been one of his secretaries. Much of the scholarly literature addressing Holmes's opinions was written before much was known about his life, and before a coherent account of his views was available. The Harvard Law Library eventually relented and made available to scholars the extensive Holmes papers, collected and annotated by Mark DeWolfe Howe, who died before he was able to complete his own biography of the justice. In 1989, the first full biography based on Holmes's papers was published,[78] and several other biographies followed.[79] A bust of Justice Holmes, sculpted by Joseph Kiselewski, was installed at the Hall of Fame for Great Americans in 1970. Congress established the U.S. Permanent Committee for the Oliver Wendell Holmes Devise within the Library of Congress with the funds he left to the United States in his will, which were used to create a memorial garden at the Supreme Court building and to publish an ongoing series on the history of the Supreme Court.[80] Holmes's summer house in Beverly, Massachusetts, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1972, recognition for his contributions to American jurisprudence.[81] Justice Holmes was an honorary member of the Connecticut Society of the Cincinnati.[82] |

引退、死去、名誉、そして遺産 米国郵便局発行の切手、1978年 ホームズは晩年、広く称賛され、90歳の誕生日には、初の沿岸から沿岸へのラジオ放送のひとつで表彰された。この放送では、チャールズ・エヴァンス・ ヒューズ最高裁長官、チャールズ・エドワード・クラーク・イェール大学ロースクール学部長、アメリカ法曹協会会長が賛辞を述べ、法曹協会から金メダルが贈 られた。ホームズは1932年1月12日まで法廷に在職したが、法廷の同胞たちは、高齢であることを理由に、退任の時期が来たことを示唆した。1932年 1月12日まで法廷に在職したホームズは、高齢であることを理由に、法廷の仲間たちから退任の時期が来たと示唆された。(この記録に挑戦したのは、 2010年に退任したジョン・ポール・スティーブンスのみで、彼はホームズが退任した時よりも8ヶ月若かった)。1935年3月6日、94歳の誕生日を2 日後に控え、ホームズはワシントンで肺炎のため死去した。1925年から1932年にかけては、フラー法廷の最後の判事であった。 ホームズは遺言の中で、遺留分をアメリカ合衆国政府に遺贈した(彼は以前、コンパニア・ジェネラル・デ・タバコス・デ・フィリピナス対内国歳入庁長官、 275 U.S. 87, 100 (1927)において、「税金は文明社会に支払うものである」と述べていた)。彼の死後、彼の遺品には、南北戦争の将校服が血に染まり、「銃弾で引き裂か れた」ままであった。ホームズはアーリントン国立墓地に妻の傍らに埋葬された[75][76]。  ホームズの墓所 米国郵政公社はホームズを称え、著名なアメリカ人シリーズ(1965年~1978年)の15セント切手を発行した[要出典]。 ジョセフ・キセレフスキーが彫刻したホームズ判事の胸像[77]は、1970年にニューヨークのニューヨーク大学にある偉大なアメリカ人の殿堂に設置され た。 ハーバード・ロー・スクールに寄贈されたホームズの書類は、彼の死後長年にわたって非公開とされ、そのことが彼の生涯についていささか空想的な記述を生む 原因となった。キャサリン・ドリンカー・ボウエンのフィクションによる伝記『オリンポスのヤンキー』は長い間ベストセラーとなり、1946年のブロード ウェイ劇と1950年のハリウッド映画『華麗なるヤンキー』は、ホームズの秘書の一人であったフランシス・ビドルによるホームズの伝記に基づいている。 ホームズの意見を扱った学術文献の多くは、彼の生涯についてあまり知られていないうちに書かれたものであり、彼の見解についての首尾一貫した説明が利用で きるようになる前のものであった。しかし、マーク・デウォルフ・ハウは、彼自身の伝記を完成させる前に亡くなってしまった。ジョセフ・キセレフスキーが彫 刻したホームズ判事の胸像は、1970年に偉大なアメリカ人の殿堂に設置された。議会は、ホームズが遺言で米国に遺した資金をもとに、議会図書館内にオリ バー・ウェンデル・ホームズ遺贈のための米国恒久委員会を設立し、その資金は最高裁判所の建物に記念庭園を造成し、最高裁判所の歴史に関する継続的なシ リーズを出版するために使用された[80]。 マサチューセッツ州ビバリーにあるホームズの夏の別荘は、アメリカの法学への貢献が認められ、1972年に国定歴史建造物に指定された[81]。 ホームズ判事はシンシナティ・コネチカット協会の名誉会員であった[82]。 |

| Clerks "Many secretaries formed close friendships with one another", wrote Tony Hiss, son of Alger Hiss, about the special club of clerks of Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. They included: Robert M. Benjamin (later, lawyer for an appeal by Alger Hiss) Laurence Curtis, U.S. Representative Alger Hiss, president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and convicted perjurer Donald Hiss, partner, Covington & Burling law firm Irving Sands Olds, chairman of U.S. Steel H. Chapman Rose, Undersecretary of the United States Treasury[83] Chauncey Belknap, partner at Patterson, Belknap, Webb & Tyler, one of largest law firms in New York during his time, and an attorney for the Rockefeller Foundation[84] In popular culture American actor Louis Calhern portrayed Holmes in the 1946 play The Magnificent Yankee, with Dorothy Gish as Holmes's wife Fanny. In 1950, Calhern repeated his performance in Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's film version The Magnificent Yankee, for which he received his only Academy Award nomination. Ann Harding co-starred in the film. A 1965 television adaptation of the play starred Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne in one of their few appearances on the small screen.[citation needed] In the movie Judgment at Nuremberg (1961), defense advocate Hans Rolfe (Maximilian Schell) quotes Holmes twice. First, with one of his earlier opinions: This responsibility will not be found only in documents that no one contests or denies. It will be found in considerations of a political or social nature. It will be found, most of all in the character of men. Second, on the sterilization laws enacted in Virginia and upheld by the Supreme Court in Buck v. Bell: We have seen more than once that the public welfare may call upon the best citizens for their lives. It would be strange if it could not call upon those who already sap the strength of the State for these lesser sacrifices, often not felt to be such by those concerned, in order to prevent our being swamped by incompetence. It is better for all the world if, instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting Fallopian tubes. [citation omitted] Three generations of imbeciles are enough. This was in relation to Holmes's support for eugenics laws in the United States, which Rolfe argued were not different in principle from the Nazi laws. In the earlier Playhouse 90 television version from 1959, which also quotes Holmes in this context, the tribunal judge Ives, who ultimately presents a dissenting verdict, is played by the actor Wendell Holmes (1914–1962), born Oliver Wendell Holmes.[citation needed] Holmes appears as a minor character in Bernard Cornwell's novels Copperhead and The Bloody Ground, the second and fourth volumes of his Starbuck Chronicles; the novels portray the battles of Ball's Bluff and Antietam, in both of which the young Lieutenant Holmes was wounded in action. The 1960s television sitcom Green Acres starred Eddie Albert as a character named Oliver Wendell Douglas, a Manhattan white-shoe lawyer who gives up the law to become a farmer. His name is a combination of two Supreme Court Justices, Holmes and William O. Douglas. The 1980 comic strip Bloom County features a character named Oliver Wendell Jones, a young computer hacker and gifted scientist. Holmes. "This 75-minute staged reading stars Kevin Reese showcasing the wit and wisdom of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr." Written by Todd C. Peppers, Directed by Mary Hall Surface. World premier at the Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., October 30, 2023. |

事務員たち アルジャー・ヒスの息子であるトニー・ヒスは、オリバー・ウェンデル・ホームズJr.の特別な秘書クラブについて、「多くの秘書が互いに親密な友人関係を築いていた」と書いている。 その中には次のような者がいた: ロバート・M・ベンジャミン(後にアルジャー・ヒスの控訴のための弁護士) ローレンス・カーティス(米国下院議員 アルジャー・ヒス、カーネギー国際平和財団理事長、有罪判決を受けた偽証者 ドナルド・ヒス、コヴィントン&バーリング法律事務所パートナー アーヴィング・サンズ・オールズ、U.S.スチール会長 H. チャップマン・ローズ、米国財務省次官[83]。 チャウンシー・ベルナップ、パターソン・ベルナップ・ウェッブ&タイラー法律事務所のパートナー、ロックフェラー財団の弁護士[84]。 大衆文化では アメリカの俳優ルイス・カルハーンは1946年の舞台『The Magnificent Yankee』でホームズを演じ、ドロシー・ギッシュがホームズの妻ファニーを演じた。1950年、カルハーンはメトロ・ゴールドウィン・メイヤー製作の 映画版『華麗なるヤンキー』で再演し、唯一のアカデミー賞候補となった。この映画ではアン・ハーディングが共演した。1965年のテレビドラマ化では、ア ルフレッド・ラントとリン・フォンタンヌが小さなスクリーンで数少ない出演を果たした[要出典]。 映画『ニュルンベルクの審判』(1961年)では、弁護人のハンス・ロルフ(マクシミリアン・シェル)がホームズの言葉を2度引用している。まず、彼の以前の意見の一つを引用する: この責任は、誰も異議を唱えず、否定もしない文書にのみ見出されるものではない。この責任は、誰も異議を唱えたり否定したりしない文書の中だけに見出されるものではない。この責任は、政治的あるいは社会的な性質の考察の中に見出されるであろう。 第二に、バージニア州で制定され、バック対ベル事件で最高裁が支持した不妊手術法についてである: 公共の福祉が最良の市民の生命を求める可能性があることは、これまで何度も見てきたとおりである。公共の福祉が、無能な市民によって押し流されるのを防ぐ ために、国家の力をすでに支えている人々に、多くの場合関係者にはそうとは思われない、より小さな犠牲を求められないとしたら、それは奇妙なことである。 堕落した子孫を犯罪のために処刑したり、無能のために飢え死にさせたりするのを待つのではなく、社会が明らかに不適格な者がその種を絶やさないようにする ことができれば、世界全体にとって良いことである。強制予防接種を支える原則は、卵管切断をカバーするのに十分広い。[無能な人間は3世代も続ければ十分 だ」。 これは、ホームズがアメリカの優生保護法を支持していたことに関連しており、ロルフはナチスの法律と原理的には変わらないと主張した。この文脈でホームズ の言葉も引用されている1959年のテレビ版『プレイハウス90』では、最終的に反対評決を示す法廷判事アイヴズを、オリヴァー・ウェンデル・ホームズ出 身の俳優ウェンデル・ホームズ(1914~1962)が演じている[要出典]。 ホームズはバーナード・コーンウェルの小説『コッパーヘッド』(Copperhead)と『ブラッディ・グラウンド』(The Bloody Ground)(彼のスターバック年代記の第2巻と第4巻)に脇役として登場する。この小説はボールズ・ブラフとアンティータムの戦いを描いており、その 両方で若きホームズ中尉は戦場で負傷した。 1960年代のテレビ・シットコム『グリーン・エーカーズ』では、エディ・アルバートがオリバー・ウェンデル・ダグラスというキャラクターを演じた。彼の名前は、ホームズとウィリアム・O・ダグラスという2人の最高裁判事を組み合わせたものである。 1980年の漫画『ブルーム・カウンティ』には、オリバー・ウェンデル・ジョーンズという若いコンピューター・ハッカーで才能ある科学者が登場する。 ホームズ 「ケヴィン・リース主演、オリバー・ウェンデル・ホームズ・ジュニア判事のウィットと知恵を紹介する75分の朗読劇。トッド・C・ペッパーズ脚本、メア リー・ホール・サーフェス演出。2023年10月30日、ワシントンD.C.のアリーナ・ステージにて世界初演。 |

| Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States Freedom for the Thought That We Hate List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 2) List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office Prediction theory of law List of people on the cover of Time Magazine: 1920s (March 15, 1926) Skepticism in law List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Fuller Court List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Hughes Court List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Taft Court List of United States Supreme Court cases by the White Court |

憎む思想に自由を 合衆国最高裁判所判事一覧 合衆国最高裁判所事務官一覧(第2席) アメリカ合衆国最高裁判所判事一覧(在任期間別 法の予測理論 タイム誌の表紙を飾った人物のリスト 1920年代(1926年3月15日) 法律における懐疑主義 フラー法廷による合衆国最高裁判所判例リスト ヒューズ法廷による合衆国最高裁判例リスト タフト法廷による合衆国最高裁判所判例リスト ホワイト法廷による合衆国最高裁判所判例リスト |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oliver_Wendell_Holmes_Jr. |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆