人種の「血の一滴」ルール

One-drop rule

☆

ワン・ドロップ・ルール(The

one-drop rule)は、20 世紀の米国で顕著だった人種分類の法的原則だった。この原則は、アフリカ系の祖先(「黒人の血」が 1

滴でも)[1][2]

を持つ人は、すべて黒人(歴史的にはニグロまたは有色人種)とみなされる、と定めていた。これは、異なる社会経済層や民族グループ間の混血の子供たちを、

異なるグループにおける祖先の割合に関係なく、より低い地位のグループに自動的に分類する、低血統主義の一例です[3]。

この概念は、20

世紀初頭に一部の米国の州で法律として成文化されました[4]。これは、南部の長い人種間相互作用の歴史の中で発展した「見えない黒さ」の原則[5]と関

連していた。この歴史には、奴隷制が人種的階級制度として固まり、後に分離政策が導入されたことが含まれる。この規則は、1967年のロービング対バージ

ニア州判決で最高裁によって違法とされたが、それ以前は、異人種間の結婚を阻止し、一般に権利や平等な機会を否定し、白人至上主義を維持するために用いら

れていた。

| The one-drop rule

was a legal principle of racial classification that was prominent in

the 20th-century United States. It asserted that any person with even

one ancestor of African ancestry ("one drop" of "black blood")[1][2] is

considered black (Negro or colored in historical terms). It is an

example of hypodescent, the automatic assignment of children of a mixed

union between different socioeconomic or ethnic groups to the group

with the lower status, regardless of proportion of ancestry in

different groups.[3] This concept became codified into the law of some U.S. states in the early 20th century.[4] It was associated with the principle of "invisible blackness"[5] that developed after the long history of racial interaction in the South, which had included the hardening of slavery as a racial caste system and later segregation. Before the rule was outlawed by the Supreme Court in the Loving v. Virginia decision of 1967, it was used to prevent interracial marriages and in general to deny rights and equal opportunities and uphold white supremacy. |

ワン・ドロップ・ルール(The one-drop rule)

は、20

世紀の米国で顕著だった人種分類の法的原則だった。この原則は、アフリカ系の祖先(「黒人の血」が 1 滴でも)[1][2]

を持つ人は、すべて黒人(歴史的にはニグロまたは有色人種)とみなされる、と定めていた。これは、異なる社会経済層や民族グループ間の混血の子供たちを、

異なるグループにおける祖先の割合に関係なく、より低い地位のグループに自動的に分類する、低血統主義の一例です[3]。 この概念は、20 世紀初頭に一部の米国の州で法律として成文化されました[4]。これは、南部の長い人種間相互作用の歴史の中で発展した「見えない黒さ」の原則[5]と関 連していた。この歴史には、奴隷制が人種的階級制度として固まり、後に分離政策が導入されたことが含まれる。この規則は、1967年のロービング対バージ ニア州判決で最高裁によって違法とされたが、それ以前は、異人種間の結婚を阻止し、一般に権利や平等な機会を否定し、白人至上主義を維持するために用いら れていた。 |

| Antebellum conditions Further information: Partus sequitur ventrem, Children of the plantation, Quadroon, and High yellow See also: Casta Before the American Civil War, free individuals of mixed race (free people of color) were considered legally white if they had less than either one-eighth or one-quarter African ancestry (only in Virginia).[6] Many mixed-race people were absorbed into the majority culture based simply on appearance, associations and carrying out community responsibilities. These and community acceptance were the more important factors if a person's racial status were questioned, not their documented ancestry. Based on late 20th-century DNA analysis and a preponderance of historical evidence, US president Thomas Jefferson is widely believed to have fathered the six mixed-race children with his slave Sally Hemings, who was herself three-quarters white and a paternal half-sister of his wife Martha Wayles Jefferson.[quote 1] Four of them survived to adulthood.[7] Under Virginia law of the time, while their seven-eighths European ancestry would have made them legally white if they'd been free, being born to an enslaved mother made them automatically enslaved from birth. Jefferson allowed the two oldest to escape in 1822 (freeing them legally was a public action he elected to avoid because he would have had to gain permission from the state legislature); the two youngest he freed in his 1826 will. Three of the four entered white society as adults. Subsequently, their descendants identified as white. Although racial segregation was adopted legally by southern states of the former Confederacy in the late 19th century, legislators resisted defining race by law as part of preventing interracial marriages. In 1895, in South Carolina during discussion, George D. Tillman said, It is a scientific fact that there is not one full-blooded Caucasian on the floor of this convention. Every member has in him a certain mixture of ... colored blood .... It would be a cruel injustice and the source of endless litigation, of scandal, horror, feud, and bloodshed to undertake to annul or forbid marriage for a remote, perhaps obsolete trace of Negro blood. The doors would be open to scandal, malice, and greed.[8] The one-drop rule was not formally codified as law until the 20th century, from 1910 in Tennessee to 1930 as one of Virginia's "racial integrity laws", with similar laws in several other states in between. |

南北戦争前の状況 詳細情報:Partus sequitur ventrem、プランテーションの子供たち、クアドローン、ハイイエロー 関連項目:カスタ アメリカ南北戦争以前、混血の自由人(自由有色人種)は、アフリカ系の祖先が 8 分の 1 未満、または 4 分の 1 未満であれば(バージニア州のみ)、法的に白人とみなされていました[6]。多くの混血の人々は、その外見、交友関係、地域社会での責任の遂行といった理 由だけで、多数派文化に吸収されました。人の人種的地位が疑問視された場合、その文書による祖先ではなく、こうした要素や地域社会での受容がより重要な要 素となりました。 20 世紀後半の DNA 分析と、歴史的証拠の優位性から、米国大統領トーマス・ジェファーソンは、自身の奴隷であるサリー・ヘミングス(自身は 4 分の 3 が白人であり、ジェファーソンの妻マーサ・ウェイルズ・ジェファーソンの父方の異母姉妹)との間に 6 人の混血の子供たちをもうけたと広く信じられている。[引用 1] そのうち 4 人は成人まで生き延びた。[7] 当時のバージニア州法では、彼らの7/8がヨーロッパ系祖先であるため、自由であれば法的に白人として認められたはずだったが、奴隷の母親から生まれたた め、出生時から自動的に奴隷となった。ジェファーソンは1822年に2人の長男を逃亡させた(法的に解放することは、州議会から許可を得る必要があったた め、公的な措置を避けるために選択した); 1826 年の遺言で 2 人の末っ子を解放した。4 人のうち 3 人は、成人して白人社会に入った。その後、彼らの子孫は白人として認識された。 19 世紀後半、旧南軍諸州では人種差別が法的に採用されたが、立法者は、人種間の結婚を防ぐ一環として、人種を法律で定義することに抵抗した。1895 年、サウスカロライナ州での議論の中で、ジョージ・D・ティルマンは次のように述べた。 この大会会場には、純血の白人は 1 人もいないというのは科学的な事実だ。すべての参加者は、何らかの有色人種の血を混血している。遠い、おそらくはすでに消滅したニグロの血を理由に、結婚 を無効にしたり、禁止したりすることは、残酷な不正であり、無限の訴訟、スキャンダル、恐怖、争い、流血の原因となるだろう。スキャンダル、悪意、貪欲の 扉が開かれることになる。[8] ワン・ドロップ・ルールは、20世紀になって初めて法律として正式に制定された。1910年にテネシー州で、1930年にバージニア州の「人種純潔法」の 一つとして制定され、その間に他のいくつかの州でも同様の法律が制定された。 |

| Native Americans Prior to colonization, and still in traditional communities, the idea of determining belonging by degree of "blood" was, and is, unheard of. Native American tribes did not use blood quantum law until the U.S. government introduced the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, instead determining tribal status on the basis of kinship, lineage and family ties.[9] However, many land cession treaties, particularly during Indian removal in the 19th century, contained provisions for "mixed-blood" descendants of European and native ancestry to receive either parcels of land ceded in the treaty, or a share in a lump sum of money, with specifications as to the degree of tribal ancestry required to qualify. Though these did not typically apply a one-drop rule, determining the ancestry of individual claimants was not straightforward, and the process was often rife with fraud.[10] Among patrilineal tribes, such as the Omaha, historically a child born to an Omaha mother and a white father could belong officially to the Omaha tribe only if the child were formally adopted into it by a male citizen.[note 1] In contemporary practice, tribal laws around citizenship and parentage can vary widely between nations. Between 1904 and 1919, tribal members with any amount of African ancestry were disenrolled from the Chitimacha tribe of Louisiana, and their descendants have since then been denied tribal membership.[12] |

ネイティブアメリカン 植民地化以前、そして今でも伝統的なコミュニティでは、「血」の程度によって所属を決定するという考え方は、まったく聞かれたことのないものでした。ネイ ティブアメリカンの部族は、1934年に米国政府がインディアン再編成法を制定するまで、血の混合の割合による法律を使用せず、親族関係、血統、家族の絆 に基づいて部族の地位を決定していました。[9] しかし、多くの土地割譲条約、特に 19 世紀のインディアン追放の際に締結された条約には、ヨーロッパ人と先住民との混血の子孫に対して、条約で割譲された土地の一部、または一括の金銭の分配を 受ける権利を、部族の祖先の血の混合の割合に応じて付与する条項が含まれていた。これらの規定は通常、ワン・ドロップ・ルールを適用していなかったが、個 々の請求者の祖先の判定は簡単ではなく、そのプロセスはしばしば不正行為に満ちていた。[10] オマハ族のような父系部族では、歴史的に、オマハ族の母親と白人の父親の間に生まれた子供は、男性市民によって正式に養子縁組されない限り、オマハ族に正 式に属することはできなかった。[注 1] 現代の実務では、市民権や親子の関係に関する部族の法律は、国民によって大きく異なる。 1904 年から 1919 年にかけて、アフリカ系の祖先を持つ部族員は、ルイジアナ州のチティマチャ族から部族登録を抹消され、その子孫はそれ以来、部族の会員資格を拒否されてい る。[12] |

| 20th century and contemporary

times In 20th-century America, the concept of the one-drop rule has been primarily applied by European Americans to those of native African ancestry, when some Whites were trying to maintain some degree of overt or covert white supremacy. The poet Langston Hughes wrote in his 1940 memoir: You see, unfortunately, I am not black. There are lots of different kinds of blood in our family. But here in the United States, the word 'Negro' is used to mean anyone who has any native African blood at all in his veins. In Africa, the word is more pure. It means all African, therefore black. I am brown.[13] This rule meant many mixed-race people, of diverse ancestry, were simply seen as African-American, and their more diverse ancestors forgotten and erased, making it difficult to accurately trace ancestry in the present day. Many descendants of those who were enslaved native Africans and trafficked by Europeans and Americans have assumed they have Native American ancestry. Henry Louis Gates Jr.'s 2006 PBS documentary on the genetic makeup of African Americans, African American Lives, focused on these stories of Native American heritage in African-American communities. DNA test results showed, after African, primarily European ancestors for all but two of the celebrities interviewed.[14] However, many critics point to the limitations of DNA testing for ancestry, especially for minority populations.[15][16][17] During World War II, Colonel Karl Bendetsen stated that anyone with "one drop of Japanese blood" was liable for forced internment in camps.[18] Today there are no enforceable laws in the U.S. in which the one-drop rule is applicable. Sociologically, however, while the concept has in recent years become less acceptable within the Black community, with more people identifying as biracial, research has found that in White society, it is still common to associate biracial children primarily with the individual's non-White ancestry.[1][19] |

20 世紀と現代 20 世紀のアメリカでは、一部の白人が、ある種の明白または隠れた白人至上主義を維持しようとしていたため、アフリカ系アメリカ人に対して「ワン・ドロップ・ ルール」の概念が主に適用されていました。詩人のラングストン・ヒューズは、1940 年の回顧録で次のように書いています。 残念ながら、私は黒人ではないのです。私の家族には、さまざまな種類の血が流れている。しかし、ここアメリカでは、「ニグロ」という言葉は、アフリカ系の 血をまったく流している人を指す。アフリカでは、この言葉はより純粋な意味を持つ。すべてのアフリカ人、つまり黒人を指す。私は茶色だ。[13] この規則により、多様な祖先を持つ多くの混血の人々は、単にアフリカ系アメリカ人として見なされ、彼らのより多様な祖先は忘れ去られ、消去されてしまい、 現在では祖先を正確に追跡することが困難になっている。 ヨーロッパ人やアメリカ人によって奴隷として連れてこられたアフリカ系先祖を持つ多くの人々は、自分たちがネイティブアメリカンの先祖を持つと信じてき た。ヘンリー・ルイ・ゲイツ・ジュニアが2006年に制作したPBSのドキュメンタリー『African American Lives』は、アフリカ系アメリカ人コミュニティにおけるネイティブアメリカンの先祖に関する物語に焦点を当てた。DNA検査の結果、インタビューを受 けた有名人のうち2人を除き、アフリカ系に次いで主にヨーロッパ系の祖先が判明した。[14] しかし、多くの批判者は、特に少数民族の祖先調査におけるDNA検査の限界を指摘している。[15][16][17] 第二次世界大戦中、カール・ベンデセン大佐は、「1滴でも日本人の血を引く者」は強制収容所の収容対象になると述べた。[18] 今日、米国には、ワン・ドロップ・ルールが適用される強制的な法律は存在しません。しかし、社会学的には、近年、黒人コミュニティではこの概念が受け入れ られにくくなっており、混血であると自認する人も増えていますが、白人社会では、混血の子供たちを主にその個人の非白人の祖先と関連付ける傾向が依然とし て一般的であることが研究で明らかになっています。[1][19] |

| Legislation and practice Both before and after the American Civil War, many people of mixed ancestry who "looked white" and were of mostly white ancestry were legally absorbed into the white majority. State laws established differing standards. For instance, an 1822 Virginia law stated that to be defined as mulatto (that is, multi-racial), a person had to have at least one-quarter (equivalent to one grandparent) African ancestry.[6]: 68 Social acceptance and identity were historically the keys to racial identity. Virginia's one-fourth standard remained in place until 1910, when the standard was changed to one sixteenth. In 1930, even the one sixteenth standard was abandoned in favor of a more stringent standard. The act defined a person as legally "colored" (black) for classification and legal purposes if the individual had any African ancestry. Although the Virginia legislature increased restrictions on free blacks following the Nat Turner's Rebellion of 1831, it refrained from establishing a one-drop rule. When a proposal was made by Travis H. Eppes and debated in 1853, representatives realized that such a rule could adversely affect whites, as they were aware of generations of interracial relationships. During the debate, a person wrote to the Charlottesville newspaper: [If a one-drop rule were adopted], I doubt not, if many who are reputed to be white, and are in fact so, do not in a very short time find themselves instead of being elevated, reduced by the judgment of a court of competent jurisdiction, to the level of a free negro.[6]: 230 The state legislators agreed. No such law was passed until 1924, assisted by the fading recollection of such mixed familial histories. In the 21st century, such interracial family histories are being revealed as individuals undergo DNA genetic analysis. The Melungeons are a group of multiracial families of mostly European and African ancestry whose ancestors were free in colonial Virginia. They migrated to the frontier in Kentucky and Tennessee. Their descendants have been documented over the decades as having tended to marry persons classified as "white".[20] Their descendants became assimilated into the majority culture from the 19th to the 20th centuries. Pursuant to Reconstruction later in the 19th century, southern states acted to impose racial segregation by law and restrict the liberties of blacks, specifically passing laws to exclude them from politics and voting. From 1890 to 1908, all of the former Confederate states passed such laws, and most preserved disfranchisement until after passage of federal civil rights laws in the 1960s. At the South Carolina constitutional convention in 1895, an anti-miscegenation law and changes that would disfranchise blacks were proposed. Delegates debated a proposal for a one-drop rule to include in these laws. George D. Tillman said the following in opposition: If the law is made as it now stands respectable families in Aiken, Barnwell, Colleton, and Orangeburg will be denied the right to intermarry among people with whom they are now associated and identified. At least one hundred families would be affected to my knowledge. They have sent good soldiers to the Confederate Army, and are now landowners and taxpayers. Those men served creditably, and it would be unjust and disgraceful to embarrass them in this way. It is a scientific fact that there is not one full-blooded Caucasian on the floor of this convention. Every member has in him a certain mixture of ... colored blood. The pure-blooded white has needed and received a certain infusion of darker blood to give him readiness and purpose. It would be a cruel injustice and the source of endless litigation, of scandal, horror, feud, and bloodshed to undertake to annul or forbid marriage for a remote, perhaps obsolete trace of Negro blood. The doors would be open to scandal, malice, and greed; to statements on the witness stand that the father or grandfather or grandmother had said that A or B had Negro blood in their veins. Any man who is half a man would be ready to blow up half the world with dynamite to prevent or avenge attacks upon the honor of his mother in the legitimacy or purity of the blood of his father.[8][21] In 1865, Florida passed an act that both outlawed miscegenation and defined the amount of black ancestry needed to be legally defined as a "person of color". The act stated that "every person who shall have one-eighth or more of negro blood shall be deemed and held to be a person of color." (This was the equivalent of one great-grandparent.) Additionally, the act outlawed fornication, as well as the intermarrying of white females with men of color.Citation needed However, the act permitted the continuation of marriages between white persons and persons of color that were established before the law was enacted.[22] The one-drop rule was not made law until the early 20th century.Citation needed This was decades after the Civil War, emancipation, and the Reconstruction era. It followed restoration of white supremacy in the South and the passage of Jim Crow racial segregation laws. In the 20th century, it was also associated with the rise of eugenics and ideas of racial purity.[citation needed] From the late 1870s on, white Democrats regained political power in the former Confederate states and passed racial segregation laws controlling public facilities, and laws and constitutions from 1890 to 1910 to achieve disfranchisement of most blacks. Many poor whites were also disfranchised in these years, by changes to voter registration rules that worked against them, such as literacy tests, longer residency requirements and poll taxes. The first challenges to such state laws were overruled by Supreme Court decisions which upheld state constitutions that effectively disfranchised many. White Democratic-dominated legislatures proceeded with passing Jim Crow laws that instituted racial segregation in public places and accommodations, and passed other restrictive voting legislation. In Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court allowed racial segregation of public facilities, under the "separate but equal" doctrine. Jim Crow laws reached their greatest influence during the decades from 1910 to 1930. Among them were hypodescent laws, defining as black anyone with any black ancestry, or with a very small portion of black ancestry.[3] Tennessee adopted such a "one-drop" statute in 1910, and Louisiana soon followed. Then Texas and Arkansas in 1911, Mississippi in 1917, North Carolina in 1923, Alabama and Georgia in 1927, and Virginia in 1930. During this same period, Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Utah retained their old "blood fraction" statutes de jure, but amended these fractions (one-sixteenth, one-thirty-second) to be equivalent to one-drop de facto.[23] Before 1930, individuals of visible mixed European and African ancestry were usually classed as mulatto, or sometimes as black and sometimes as white, depending on appearance. Previously, most states had limited trying to define ancestry before "the fourth degree" (great-great-grandparents). But, in 1930, due to lobbying by southern legislators, the Census Bureau stopped using the classification of mulatto. Documentation of the long social recognition of mixed-race people was lost, and they were classified only as black or white. The binary world of the one-drop rule disregarded the self-identification both of people of mostly European ancestry who grew up in white communities, and of people who were of mixed race and identified as American Indian. In addition, Walter Plecker, Registrar of Statistics, ordered application of the 1924 Virginia law in such a way that vital records were changed or destroyed, family members were split on opposite sides of the color line, and there were losses of the documented continuity of people who identified as American Indian, as all people in Virginia had to be classified as white or black. Over the centuries, many Indian tribes in Virginia had absorbed people of other ethnicities through marriage or adoption, but maintained their cultures. Suspecting blacks of trying to "pass" as Indians, Plecker ordered records changed to classify people only as black or white, and ordered offices to reclassify certain family surnames from Indian to black. Since the late 20th century, Virginia has officially recognized eight American Indian tribes and their members; the tribes are trying to gain federal recognition. They have had difficulty because decades of birth, marriage, and death records were misclassified under Plecker's application of the law. No one was classified as Indian, although many individuals and families identified that way and were preserving their cultures. In the case of mixed-race American Indian and European descendants, the one-drop rule in Virginia was extended only so far as those with more than one-sixteenth Indian blood. This was due to what was known as the "Pocahontas exception". Since many influential First Families of Virginia (FFV) claimed descent from the American Indian Pocahontas and her husband John Rolfe of the colonial era, the Virginia General Assembly declared that an individual could be considered white if having no more than one-sixteenth Indian "blood" (the equivalent of one great-great-grandparent). The eugenist Madison Grant of New York wrote in his book, The Passing of the Great Race (1916): "The cross between a white man and an Indian is an Indian; the cross between a white man and a Negro is a Negro; the cross between a white man and a Hindu is a Hindu; and the cross between any of the three European races and a Jew is a Jew."[24] As noted above, Native American tribes which had patrilineal descent and inheritance, such as the Omaha, classified children of white men and Native American women as white. |

法律と慣習 南北戦争の前後、多くの「白人に見える」混血の人々は、その祖先の大半が白人であったため、法的に白人多数派に吸収された。州法によって異なる基準が定め られていた。例えば、1822 年のバージニア州法では、ムラート(つまり多民族)と定義されるには、その人物の祖先の少なくとも 4 分の 1(祖父母に相当)がアフリカ系でなければならないと規定されていた[6]: 68 。社会的な受容とアイデンティティは、歴史的に人種的アイデンティ ティの鍵となってきた。バージニア州の 4 分の 1 の基準は、1910 年に 16 分の 1 に変更されるまで維持された。1930 年には、16 分の 1 の基準も、より厳格な基準に取って代わられた。この法律では、アフリカ系の祖先を持つ人は、分類および法的目的において、法的に「有色人種」(黒人)と定 義された。 1831 年のナット・ターナーの反乱を受けて、バージニア州議会は自由黒人に対する制限を強化しましたが、ワン・ドロップ・ルールは制定しませんでした。1853 年にトラヴィス・H・エップスによって提案が提出され、議論が行われた際、議員たちは、何世代にもわたる人種間の関係を知っていたため、このようなルール は白人に悪影響を与える可能性があることを認識しました。議論の中で、ある人物がシャーロッツビル新聞に次のような手紙を送りました。 [ワン・ドロップ・ルールが採用された場合]、白人であると評判で、実際に白人である多くの人々が、ごく短期間のうちに、地位が向上するどころか、管轄裁 判所による判決によって、自由の身であるニグロと同じレベルにまで格下げされることになるだろう。 州議会議員たちもこれに同意した。このような法律は、そのような混血の家族の歴史の記憶が薄れていくにつれて、1924年まで成立しなかった。21世紀に は、DNA遺伝子解析によって、このような異人種間の家族の歴史が明らかになってきている。 メルンジョンは、主にヨーロッパとアフリカの祖先を持つ多民族の家族集団で、その祖先は植民地時代のバージニア州で自由の身だった。彼らはケンタッキー州 とテネシー州の国境地域に移住した。その子孫は、何十年にもわたって「白人」に分類される人物と結婚する傾向があることが記録されている[20]。その子 孫は、19 世紀から 20 世紀にかけて、多数派文化に同化していった。 19 世紀後半の復興に伴い、南部諸州は、人種差別を法律で規定し、黒人の自由を制限する措置を講じ、特に、黒人を政治や投票から排除する法律を可決した。 1890年から1908年にかけて、元南軍州のすべてがこのような法律を制定し、大多数は1960年代の連邦公民権法成立後も黒人の選挙権剥奪を維持し た。1895年のサウスカロライナ州憲法制定会議では、混血禁止法と黒人の選挙権剥奪を目的とした改正案が提案された。代表たちは、これらの法律に「ワ ン・ドロップ・ルール」を盛り込む提案について議論した。ジョージ・D・ティルマンは、この提案に反対して次のように述べた。 この法律が現在のまま成立した場合、エイケン、バーンウェル、コレトン、オレンジバーグの立派な家系の家族は、現在交流があり、親しい関係にある人々との 結婚の権利を否定されることになる。私の知る限り、少なくとも100の家族が影響を受ける。彼らは南軍に優秀な兵士を送り出し、現在土地所有者であり納税 者だ。あの男たちは名誉ある服務を果たした。彼らをこのように困らせることは不公正で恥辱的な行為だ。この会議場の床に純血の白人は一人もいないという科 学的事実がある。すべての会員は、何らかの有色人種の血を混ぜている。純血の白人は、準備と目的意識を養うために、ある種のより暗い血の注入を必要とし、 それを受けてきた。遠い、おそらくはすでに消滅したニグロの血の痕跡を理由に、結婚を無効にしたり、禁止したりすることは、残酷な不正であり、果てしない 訴訟、スキャンダル、恐怖、確執、流血の原因となるだろう。それは、スキャンダル、悪意、貪欲の扉を開き、証人席で、父親や祖父、祖母が A や B にはニグロの血が流れていると証言する事態を招くでしょう。半分でも男である者は、父親の血の正当性や純潔、あるいは母親の名誉を傷つける攻撃を阻止した り、復讐したりするために、世界半分をダイナマイトで爆破する用意があるでしょう。[8][21] 1865年、フロリダ州は、人種間結婚を違法とする法律を可決し、「有色人種」と法的に定義されるために必要な黒人の祖先の割合を規定した。この法律は、 「ニグロの血を 8 分の 1 以上持つ者は、有色人種とみなされ、そのように扱われる」と定めていた。(これは、1人の曽祖父母に相当する。)さらに、この法律は、淫行、および白人女 性と有色人種の男性の結婚も違法とした。引用が必要 ただし、この法律は、法律が施行される前に成立した白人と有色人種の間の結婚は継続することを認めた。[22] ワン・ドロップ・ルールは、20 世紀初頭まで法律として制定されなかった。引用が必要 これは、南北戦争、奴隷解放、そして復興時代から数十年後のことだった。これは、南部における白人至上主義の復活と、ジム・クロウ人種差別法の成立に続く ものだった。20 世紀には、優生学や人種的純潔の思想の台頭とも関連していた。[要出典] 1870年代後半以降、元南部連合州で白人民主党が政治権力を回復し、公共施設を規制する人種隔離法、および1890年から1910年にかけての法律と憲 法を制定し、大多数の黒人の選挙権を剥奪した。この期間、多くの貧しい白人も、識字試験、居住期間の延長、投票税などの投票登録規則の変更により、選挙権 を剥奪された。 このような州法に対する最初の異議申し立ては、多くの人々の選挙権を事実上剥奪した州憲法を支持する最高裁判所の判決によって却下された。白人民主党が支 配する州議会は、公共の場所や宿泊施設における人種差別を規定したジム・クロウ法を可決し、その他の制限的な投票法を可決した。プレッシー対ファーガソン 事件において、最高裁判所は「分離だが平等」の原則に基づき、公共施設における人種差別を容認した。 ジム・クロウ法は、1910 年から 1930 年までの数十年間に、その影響力が最も大きくなった。その中には、黒人の祖先を持つ者、あるいはごくわずかな黒人の祖先を持つ者をすべて黒人と定義する、 低血統法があった。テネシー州は 1910 年にこのような「一滴の血」法を採用し、ルイジアナ州もすぐにそれに追随した。その後、1911年にテキサス州とアーカンソー州、1917年にミシシッピ 州、1923年にノースカロライナ州、1927年にアラバマ州とジョージア州、1930年にバージニア州が同法を採用した。同じ期間中、フロリダ州、イン ディアナ州、ケンタッキー州、メリーランド州、ミズーリ州、ネブラスカ州、ノースダコタ州、ユタ州は、旧来の「血統割合」法(法的には)を維持したが、こ れらの割合(16分の1、32分の1)を事実上「ワン・ドロップ」に相当するように改正した。[23] 1930 年以前は、ヨーロッパとアフリカの混血であることが外見から明らかな個人は、通常、ムラート、あるいは外見に応じて黒人または白人に分類されていました。 以前は、ほとんどの州では、「4 親等」(曽祖父母)までの祖先までしか祖先の定義を試みていませんでした。しかし、1930 年、南部議員たちのロビー活動により、国勢調査局はムラートの分類の使用を中止した。混血の人々の長い社会的認識に関する文書は失われ、彼らは黒人か白人 かにしか分類されなくなった。 一滴のルールによる二元的な世界は、白人コミュニティで育った、主にヨーロッパ系の祖先を持つ人々、および混血でアメリカインディアンと自認する人々の自 己認識を無視していた。さらに、統計登録官のウォルター・プレッカーは、1924年のバージニア州法を適用して、戸籍記録の変更や破棄、家族を人種によっ て分け、アメリカインディアンと自認する人々の連続性を記録した文書が失われるような措置を命じた。何世紀にもわたり、バージニア州の多くのインディアン 部族は、結婚や養子縁組によって他の民族の人々を受け入れてきたが、自分たちの文化は維持してきた。黒人がインディアンを装っているのではないかと疑った プレッカーは、人々を黒人か白人かにのみ分類するように記録の変更を命じ、特定の家族の姓をインディアンから黒人に再分類するよう当局に指示した。 20 世紀後半以降、バージニア州は 8 つのアメリカインディアン部族とその部員を公式に認定しており、これらの部族は連邦政府による認定を目指している。しかし、プレッカーによる法律の適用に より、何十年にもわたる出生、結婚、死亡の記録が誤って分類されていたため、その認定は難航している。多くの個人や家族がインディアンであると認識し、そ の文化を保存していたにもかかわらず、インディアンとして分類された者は誰もいなかった。 アメリカインディアンとヨーロッパ人の混血の場合、バージニア州の「一滴の血」の規則は、インディアン血が 16 分の 1 以上の人々にのみ適用された。これは、「ポカホンタス例外」として知られるものによるものだった。バージニア州には、植民地時代のアメリカインディアン、 ポカホンタスとその夫ジョン・ロルフを祖先とする、影響力のある「ファースト・ファミリー(FFV)」が多く存在したため、バージニア州議会は、インディ アン「血」が 16 分の 1 以下(曽祖父母の 1 人に相当)であれば、その人は白人と見なすことができると宣言した。 ニューヨークの優生学者マディソン・グラントは、著書『The Passing of the Great Race(1916年)』の中で、次のように記している。「白人とインディアンとの混血はインディアンであり、白人とニグロとの混血はニグロであり、白人 とヒンズー教徒との混血はヒンズー教徒であり、3 つのヨーロッパ人種とユダヤ人との混血はユダヤ人である」[24]。前述のように、オマハ族など、父系による血統と相続を持つネイティブアメリカン部族 は、白人男性とネイティブアメリカン女性の子供たちを白人として分類していた。 |

| Plecker case Main article: Walter Plecker Through the 1940s, Walter Plecker of Virginia[25] and Naomi Drake of Louisiana[26] had an outsized influence. As the Registrar of Statistics, Plecker insisted on labeling mixed-race families of European-African ancestry as black. In 1924, Plecker wrote, "Two races as materially divergent as the White and Negro, in morals, mental powers, and cultural fitness, cannot live in close contact without injury to the higher." In the 1930s and 1940s, Plecker directed offices under his authority to change vital records and reclassify certain families as black (or colored) (without notifying them) after Virginia established a binary system under its Racial Integrity Act of 1924. He also classified people as black who had formerly self-identified as Indian. When the United States Supreme Court struck down Virginia's law prohibiting inter-racial marriage in Loving v. Virginia (1967), it also declared Plecker's Virginia Racial Integrity Act and the one-drop rule unconstitutional. Many people in the U.S., among various ethnic groups, continue to have their own concepts related to the one-drop idea. They may still consider those multiracial individuals with any African ancestry to be black, or at least non-white (if the person has other minority ancestry), unless the person explicitly identifies as white.[citation needed] On the other hand, the Black Power movement and some leaders within the black community also claimed as black those persons with any visible African ancestry, in order to extend their political base and regardless of how those people self-identified.[citation needed] |

プレッカー事件 主な記事:ウォルター・プレッカー 1940年代を通じて、バージニア州のウォルター・プレッカー[25]とルイジアナ州のナオミ・ドレイク[26]は、非常に大きな影響力を持っていまし た。統計登録官として、プレッカーは、ヨーロッパとアフリカの混血の家族を黒人として分類することを主張しました。1924年、プレッカーは「白人とニグ ロのように、道徳、知力、文化的な適応力において物質的に大きく異なる2つの人種は、より高次の文化に害を及ぼすことなく、密接に接触して共存することは できない」と書いている。1930年代から1940年代にかけて、プレッカーは、1924年にバージニア州が人種純潔法(Racial Integrity Act)に基づく二元制度を導入した後、自分の権限下にある機関に対して、戸籍記録を変更し、特定の家族を(彼らに通知することなく)黒人(または有色人 種)に再分類するよう指示した。また、以前はインディアンと自己認識していた人々も黒人に分類した。米国最高裁判所は、Loving v. Virginia (1967) において、異人種間の結婚を禁止するバージニア州の法律を無効とした際、プレッカーのバージニア州人種純潔法およびワン・ドロップ・ルールも違憲であると 宣言した。 米国では、さまざまな民族グループに属する多くの人々が、ワン・ドロップの考えに関する独自の概念を持ち続けている。彼らは、アフリカ系の祖先を持つ多民 族の人々は、その人が明確に白人であると自認していない限り、黒人、あるいは少なくとも非白人であるとみなしているかもしれない。一方、ブラック・パワー 運動や黒人コミュニティの一部の指導者たちは、政治的基盤を拡大するため、その人自身の認識に関係なく、目に見えるアフリカ系の祖先を持つ人々も黒人であ ると主張した。 |

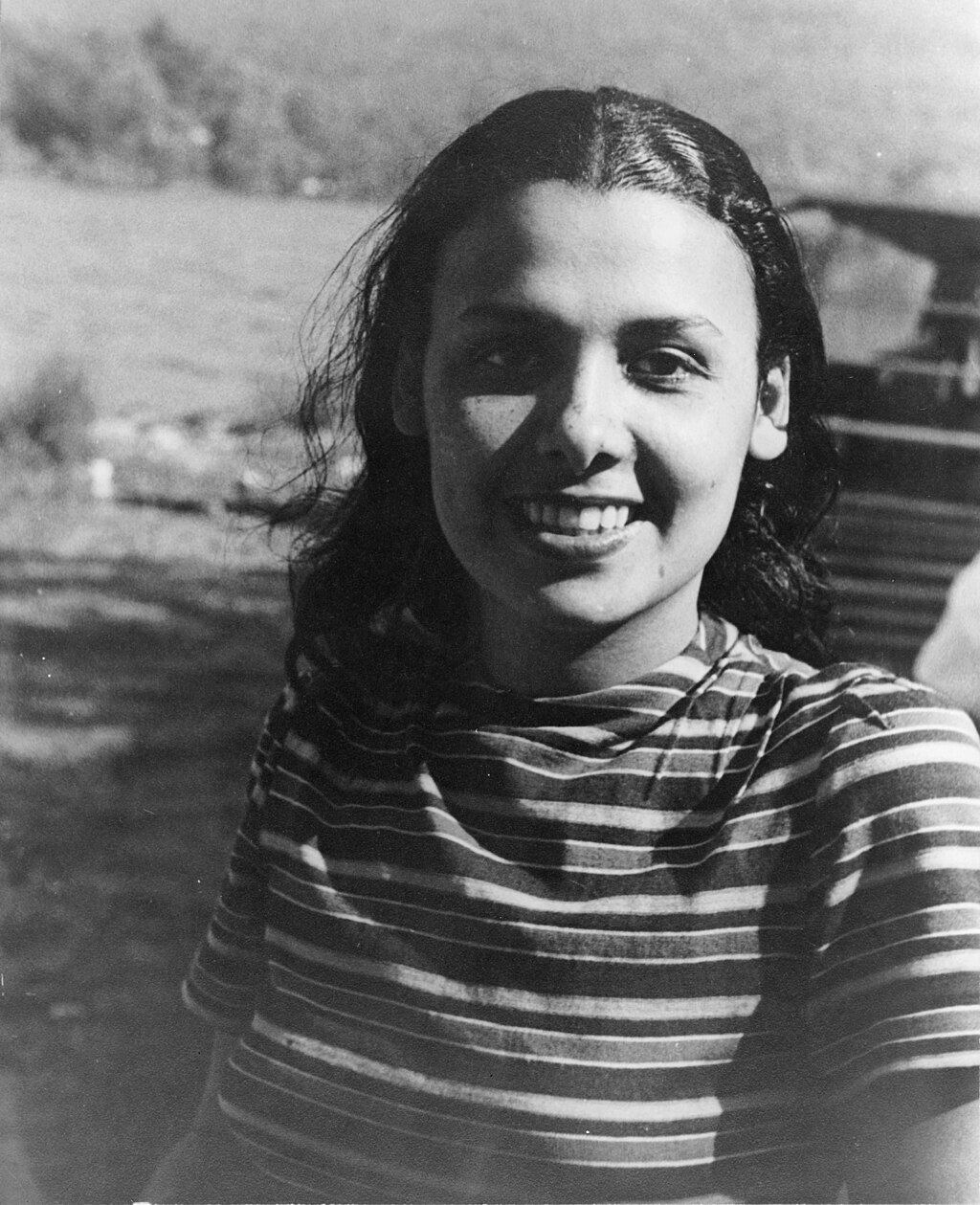

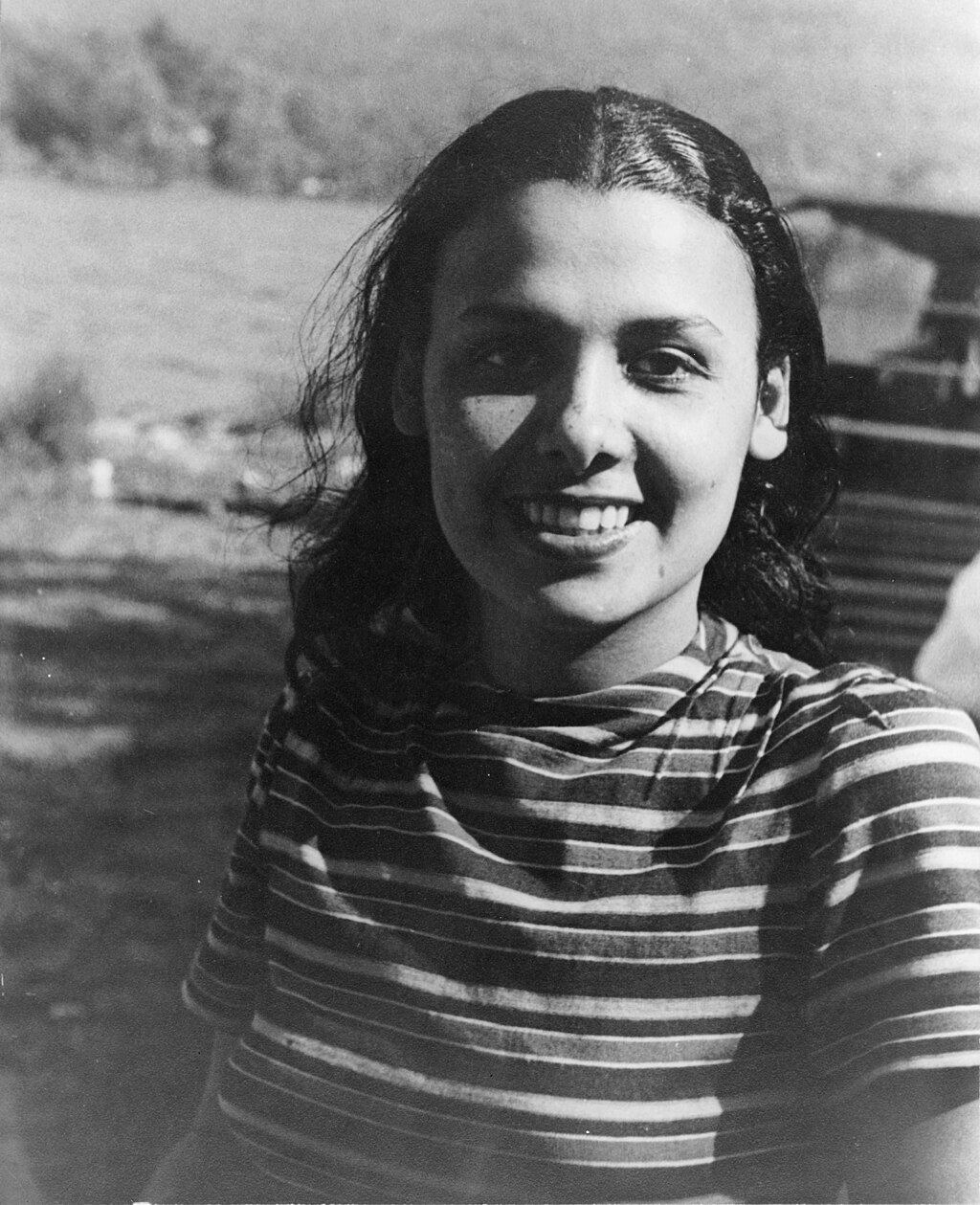

| Other countries of the Americas Main article: Race and ethnicity in Latin America  Rice and Powell (on the left) are considered black in the US. Bush and Rumsfeld (on the right) are considered white. Among the colonial slave societies, the United States was nearly unique in developing the one-drop rule; it derived both from the Southern slave culture (shared by other societies) and the aftermath of the American Civil War, emancipation of slaves, and Reconstruction. In the late 19th century, Southern whites regained political power and restored white supremacy, passing Jim Crow laws and establishing racial segregation by law. In the 20th century, during the Black Power movement, black race-based groups claimed all people of any African ancestry as black in a reverse way, to establish political power. In colonial Spanish America, many soldiers and explorers took indigenous women as wives. Native-born Spanish women were always a minority. The colonists developed an elaborate classification and caste system that identified the mixed-race descendants of blacks, Amerindians, and whites by different names, related to appearance and known ancestry. Racial caste not only depended on ancestry or skin color, but also could be raised or lowered by the person's financial status or class.  Lena Horne was reportedly descended from the John C. Calhoun family, and both sides of her family were a mixture of African-American, Native American, and European American descent. The same racial culture shock has come to hundreds of thousands of dark-skinned immigrants to the United States from Cuba, Colombia, Venezuela, Panama, and other Latin American nations. Although many are not considered black in their homelands, they have often been considered black in US society. According to The Washington Post, their refusal to accept the United States' definition of black has left many feeling attacked from all directions. At times, white and black Americans might discriminate against them for their lighter or darker skin tones; African Americans might believe that Afro-Latino immigrants are denying their blackness. At the same time, the immigrants think lighter-skinned Latinos dominate Spanish-language television and media. A majority of Latin Americans possess some African or American Indian ancestry. Many of these immigrants feel it is difficult enough to accept a new language and culture without the additional burden of having to transform from white to black. Yvette Modestin, a dark-skinned native of Panama who worked in Boston, said the situation was overwhelming: "There's not a day that I don't have to explain myself."[27] Professor J. B. Bird has said that Latin America is not alone in rejecting the historical US notion that any visible African ancestry is enough to make one black: In most countries of the Caribbean, Colin Powell would be described as a Creole, reflecting his mixed heritage. In Belize, he might further be described as a "High Creole", because of his extremely light complexion.[28] |

その他のアメリカ大陸諸国 主な記事:ラテンアメリカの人種と民族  ライスとパウエル(左)は、米国では黒人と見なされている。ブッシュとラムズフェルド(右)は白人と見なされている。 植民地時代の奴隷社会の中で、一滴の血の原則を確立したのは、ほぼ米国だけでした。この原則は、南部奴隷文化(他の社会にも見られた)と、南北戦争、奴隷 解放、そして復興の余波から生まれました。19 世紀後半、南部の白人は政治権力を取り戻し、白人至上主義を復活させ、ジム・クロウ法(人種差別法)を制定し、人種差別を法律で規定しました。20 世紀、ブラック・パワー運動の中で、黒人種に基づく団体は、政治力を確立するために、アフリカ系の祖先を持つすべての人々を黒人であると逆の主張をした。 植民地時代のスペイン領アメリカでは、多くの兵士や探検家が先住民の女性を妻とした。スペイン生まれの女性は常に少数派だった。入植者たちは、黒人、アメ リカ先住民、白人の混血の子孫を、容姿や既知の祖先に応じて異なる名前で識別する、精巧な分類およびカースト制度を開発した。人種カーストは、祖先や肌の 色だけでなく、その人物の経済状況や階級によっても上昇または下降する可能性があった。  レナ・ホーンは、ジョン・C・カルフーン家の末裔であると伝えられており、彼女の家族は、アフリカ系アメリカ人、ネイティブアメリカン、ヨーロッパ系アメ リカ人の混血だった。 キューバ、コロンビア、ベネズエラ、パナマ、その他のラテンアメリカ諸国から米国に移住した、何十万人もの浅黒い肌の移民たちも、同じ人種文化のショック を受けている。彼らの多くは、母国では黒人とは見なされていないが、米国社会ではしばしば黒人と見なされてきた。ワシントン・ポスト紙によると、アメリカ 合衆国の黒人定義を受け入れないことは、多くの移民をあらゆる方向から攻撃されていると感じさせている。白人や黒人のアメリカ人は、彼らの肌の色が明るい または暗いことを理由に差別する可能性がある。アフリカ系アメリカ人は、アフリカ系ラテンアメリカ人移民が自分の黒人性を否定していると考えるかもしれな い。同時に、移民たちは、肌の色が明るいラテンアメリカ人がスペイン語のテレビやメディアを支配していると感じている。ラテンアメリカ人の大半は、アフリ カやインディアンを祖先に持ってる。これらの移民の多くは、新しい言語や文化を受け入れるだけで十分難しいのに、白人から黒人に変身しなければならないと いう追加の負担は耐え難いと感じてる。ボストンで働いていた、パナマ出身の浅黒い肌のイヴェット・モデスティン氏は、この状況を「自分について説明しなけ ればならない日が一日もない」と表現してる[27]。 J. B. バード教授は、目に見えるアフリカ系の祖先がいるだけで黒人であるとみなすという、米国の歴史的な考え方を拒否しているのはラテンアメリカだけではないと 述べています。 カリブ海のほとんどの国では、コリン・パウエルは、その混血の血統を反映して、クレオールと表現されるでしょう。ベリーズでは、彼の非常に明るい肌の色か ら、「ハイ・クレオール」とさらに表現されるかもしれません。[28] |

Brazil The Brazilian footballer Ronaldo declares himself white, but 64% of Brazilians consider him pardo, according to Datafolha survey.[29]  The Brazilian actress Camila Pitanga declares herself black, but only 27% of Brazilians consider her as such, according to Datafolha survey.[29] People in many other countries have tended to treat race less rigidly, both in their self-identification and how they regard others. Unlike the United States, in Brazil, people tend to consider phenotype rather than genotype. A European-looking person will be considered white, even if they have some degree of ancestry from other races. Brazil has a racial category "pardo" (mestizo or mulatto) specifically for people who, in terms of appearance, do not fully fit as white, nor fully as black. According to an survey of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistic, to define their own race, Brazilians take into account skin color (73.8%) and family origin (61.6%), as well as physical features (hair, mouth, nose), mentioned by 53.5%. For 24.9%, culture and tradition also play a role in classification, along with economic origin or social class (13.5%) and political or ideological choice (2.9%). 96% of those surveyed said they can identify their race, which debunks the myth that many people in Brazil do not recognize the concept of race.[30] Puerto Rico During the Spanish colonial period, Puerto Rico had laws such as the Regla del Sacar or Gracias al Sacar, by which a person of black ancestry could be considered legally white so long as the individual could prove that at least one person per generation in the last four generations had also been legally white. Thus persons of some black ancestry with known white lineage were classified as white, the opposite of the "one-drop rule" in the United States.[31] |

ブラジル ブラジルのサッカー選手、ロナウドは自分自身を白人だと公言しているが、データフォラ社の調査によると、ブラジル人の 64% は彼を「パルド」と認識している。[29]  ブラジルの女優、カミラ・ピタンガは自分自身を黒人だと公言しているが、データフォラ社の調査によると、ブラジル人の 27% しか彼女を黒人だと認識していない。[29] 他の多くの国々では、自己認識や他者に対する見方において、人種をそれほど厳格に扱わない傾向がある。米国とは異なり、ブラジルでは、人々は遺伝子型より も表現型を重視する傾向がある。ヨーロッパ系の外見の人物は、たとえ他の人種をある程度祖先に持つ場合でも、白人と見なされる。ブラジルには、外見上、白 人とも黒人とも完全には当てはまらない人々のために、「パルド」(メスティゾ、またはムラート)という人種カテゴリーが特別に設けられている。 ブラジル地理統計庁の調査によると、ブラジル人は自分の人種を定義する際に、肌の色(73.8%)と家族の出身(61.6%)に加え、53.5% が挙げた身体的特徴(髪、口、鼻)も考慮している。24.9% は、経済的な出身や社会階級(13.5%)、政治的またはイデオロギー的な選択(2.9%)とともに、文化や伝統も分類の要素となっていると答えている。 調査対象者の 96% は、自分の人種を識別できると答え、ブラジルでは多くの人々が人種の概念を認識していないという通説を覆している。[30] プエルトリコ スペイン植民地時代、プエルトリコには「レグラ・デル・サカル」または「グラシアス・アル・サカル」という法律があり、黒人の祖先を持つ人は、過去 4 世代のうち 1 世代に少なくとも 1 人が法的に白人であったことを証明できれば、法的に白人とみなされるというものでした。したがって、白人の血統が明らかな黒人の祖先を持つ人は、米国の 「ワン・ドロップ・ルール」とは逆の、白人と分類されていました。[31] |

| Racial mixtures of blacks and

whites in modern America Given the intense interest in ethnicity, genetic genealogists and other scientists have studied population groups. Henry Louis Gates Jr. publicized such genetic studies on his two series African American Lives, shown on PBS, in which the ancestry of prominent figures was explored. His experts discussed the results of autosomal DNA tests, in contrast to direct-line testing, which survey all the DNA that has been inherited from the parents of an individual.[17] Autosomal tests focus on SNPs.[17] The specialists on Gates' program summarized the make-up of the United States population by the following: 58 percent of African Americans have at least 12.5% European ancestry (equivalent of one great-grandparent); 19.6 percent of African Americans have at least 25% European ancestry (equivalent of one grandparent); 1 percent of African Americans have at least 50% European ancestry (equivalent of one parent) (Gates is one of these, he discovered, having a total of 51% European ancestry among various distant ancestors); and 5 percent of African Americans have at least 12.5% Native American ancestry (equivalent to one great-grandparent).[32] In 2002, Mark D. Shriver, a molecular anthropologist at Penn State University, published results of a study regarding the racial admixture of Americans who identified as white or black:[33] Shriver surveyed a 3,000-person sample from 25 locations in the United States and tested subjects for autosomal genetic make-up: Of those persons who identified as white: Individuals had an average 0.7% black ancestry, which is the equivalent of having 1 black and 127 white ancestors among one's 128 5×great-grandparents. Shriver estimates that 70% of white Americans have no African ancestors (in part because a high proportion of current whites are descended from more recent immigrants from Europe of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, rather than those early migrants to the colonies, who in some areas lived and worked closely with Africans, free, indentured or slave, and formed relations with them). Among the 30% of identified whites who have African ancestry, Shriver estimates their black racial admixture is 2.3%; the equivalent of having had three black ancestors among their 128 5×great-grandparents.[33] Among those who identified as black: The average proportion of white ancestry was 18%, the equivalent of having 22 white ancestors among their 128 5×great-grandparents. About 10% have more than 50% white ancestry. Black people in the United States are more racially mixed than white people, reflecting historical experience here, including the close living and working conditions among the small populations of the early colonies, when indentured servants, both black and white, and slaves, married or formed unions. Mixed-race children of white mothers were born free, and many families of free people of color were started in those years. 80 percent of the free African-American families in the Upper South in the censuses of 1790 to 1810 can be traced as descendants of unions between white women and African men in colonial Virginia, not of slave women and white men. In the early colony, conditions were loose among the working class, who lived and worked closely together. After the American Revolutionary War, their free mixed-race descendants migrated to the frontiers of nearby states along with other primarily European Virginia pioneers.[20] The admixture also reflects later conditions under slavery, when white planters or their sons, or overseers, frequently raped African women.[34] There were also freely chosen relationships among individuals of different or mixed races. Shriver's 2002 survey found different current admixture rates by region, reflecting historic patterns of settlement and change, both in terms of populations who migrated and their descendants' unions. For example, he found that the black populations with the highest percentage of white ancestry lived in California and Seattle, Washington. These were both majority-white destinations during the Great Migration of 1940–1970 of African Americans from the Deep South of Louisiana, Texas and Mississippi. Blacks sampled in those two locations had more than 25% white European ancestry on average.[33] As noted by Troy Duster, direct-line testing of the Y-chromosome and mtDNA (mitochondrial DNA) fails to pick up the heritage of many other ancestors.[15] DNA testing has limitations and should not be depended on by individuals to answer all questions about heritage.[15] Duster said that neither Shriver's research nor Gates' PBS program adequately acknowledged the limitations of genetic testing.[15][35] Similarly, the Indigenous Peoples Council on Biocolonialism (IPCB) notes that: "Native American markers" are not found solely among Native Americans. While they occur more frequently among Native Americans, they are also found in people in other parts of the world.[36] Genetic testing has shown three major waves of ancient migration from Asia among Native Americans but cannot distinguish further among most of the various tribes in the Americas. Some critics of testing believe that more markers will be identified as more Native Americans of various tribes are tested, as they believe that the early epidemics due to smallpox and other diseases may have altered genetic representation.[15][35] Much effort has been made to discover the ways in which the one-drop rule continues to be socially perpetuated today. For example, in her interview of black/white adults in the South, Nikki Khanna uncovers that one way the one-drop rule is perpetuated is through the mechanism of reflected appraisal. Most respondents identified as black, explaining that this is because both black and white people see them as black as well.[37] |

現代アメリカにおける黒人と白人の人種的混合 民族性に強い関心が寄せられていることを受け、遺伝系図学者やその他の科学者たちは、人口集団の研究を行ってきました。ヘンリー・ルイス・ゲイツ・ジュニ アは、PBS で放送された 2 つのシリーズ「アフリカ系アメリカ人の生活」で、著名人の祖先を探求したこのような遺伝子研究を公表しました。彼の専門家たちは、個人の両親から受け継い だすべての DNA を調査する直系検査とは対照的に、常染色体 DNA 検査の結果について議論しました。[17] 常染色体検査はSNPに焦点を当ててるんだ。[17] ゲイツ氏の番組に出演した専門家たちは、アメリカの人口の構成を次のように要約してるよ。 アフリカ系アメリカ人の58%は、少なくとも12.5%のヨーロッパの祖先(曾祖父母の1人に相当)を持ってる。 アフリカ系アメリカ人の19.6%は、ヨーロッパ系祖先の割合が25%以上(祖父母の1人に相当); アフリカ系アメリカ人の1%は、ヨーロッパ系祖先の割合が50%以上(親の1人に相当)(ゲイツ氏はこのグループに該当し、遠縁の祖先全体で51%のヨー ロッパ系祖先を有することが判明しました);および アフリカ系アメリカ人の5%は、先住民の祖先が12.5%以上(曾祖父母の1人に相当)いる。[32] 2002年、ペンシルベニア州立大学の分子人類学者マーク・D・シュライバーは、白人または黒人と自己認識するアメリカ人の人種的混血に関する研究結果を 発表した:[33] シュライバーは、米国 25 箇所の 3,000 人のサンプルを調査し、被験者の常染色体遺伝子の構成を検査した。 白人であると自己認識した人の中で 個人は平均 0.7% の黒人の祖先を持っており、これは 128 人の 5 世代前の祖父母のうち 1 人が黒人、127 人が白人であることに相当する。 シュリバーは、白人アメリカ人の70%はアフリカ系祖先を持たないと推定している(これは、現在の白人の多くが19世紀後半から20世紀初頭のヨーロッパ からの移民の子孫であり、植民地時代にアフリカ人と自由人、契約労働者、奴隷として共に生活し働いた初期の移民の子孫ではないためだ)。 アフリカ系祖先を持つと特定された白人の30%のうち、シュリバーは黒人との混血率が2.3%と推定している。これは、128人の5×曾祖父母の中に3人 の黒人祖先がいることに相当する。[33] 黒人であると自己認識した人の中で: 白人の祖先の平均割合は18%で、これは128人の5×曾祖父母のうち22人が白人であることに相当する。 約10%は白人の祖先が50%以上を占めている。 米国の黒人は、白人よりも人種的に混血の割合が高い。これは、初期の植民地時代、黒人と白人の契約労働者と奴隷が、結婚したり組合を結成したりして、少人 数の集団で密接に暮らし、労働していたという歴史的経験を反映している。白人の母親を持つ混血の子供たちは自由の身で生まれ、その当時、多くの自由人であ る有色人種の家族が誕生した。1790 年から 1810 年にかけての人口調査によると、南部北部における自由アフリカ系アメリカ人の家族の 80% は、植民地時代のバージニア州で白人女性とアフリカ人男性との結婚によって生まれた子孫であり、奴隷の女性と白人男性との結婚によって生まれた子孫ではな いことがわかる。植民地初期、労働者階級は、一緒に暮らし、一緒に働くという緩やかな生活を送っていた。アメリカ独立戦争後、彼らの自由の身分の混血の子 孫たちは、主にヨーロッパ出身のバージニアの開拓者たちとともに、近隣の州の国境地域に移住した[20]。この混血は、白人のプランテーション所有者やそ の息子たち、監督者がアフリカ系の女性を頻繁に強姦した、その後の奴隷制度下の状況も反映している[34]。また、異なる人種や混血の人々の間で、自由に 選択した関係も存在した。 シュライバー氏の 2002 年の調査では、移住者とその子孫の結合の両面において、歴史的な定住と変化のパターンを反映して、地域によって現在の混血の割合が異なることが明らかに なった。例えば、彼は、白人祖先の割合が最も高い黒人人口は、カリフォルニア州とワシントン州シアトルに居住していると指摘した。これらの地域は、 1940年から1970年のアフリカ系アメリカ人の大移動(ディープサウスからルイジアナ州、テキサス州、ミシシッピ州への移住)の際、白人が多数派を占 める移住先だった。これらの2つの地域で採集された黒人のサンプルは、平均で25%を超える白人ヨーロッパ系祖先を有していた。[33] トロイ・ダスターが指摘するように、Y染色体とmtDNA(ミトコンドリアDNA)の直接系検査は、多くの他の祖先の遺産を検出できない。[15] DNA検査には限界があり、個人は遺産に関するすべての質問に答えるためにこれに依存すべきではない。[15] ダスターは、シュリバーの研究もゲイツのPBS番組も、遺伝的検査の限界を十分に認識していないと述べた。[15][35] 同様に、先住民バイオコロニアリズム評議会(IPCB)は、「ネイティブアメリカンマーカー」はネイティブアメリカンだけに存在するわけではないと指摘し ている。ネイティブアメリカンに多く見られるものの、世界の他の地域の人々にも見られる。[36] 遺伝子検査では、ネイティブアメリカンにアジアからの 3 つの大きな移住の波があったことが明らかになっているが、南北アメリカ大陸のさまざまな部族のほとんどについては、それ以上の区別は不可能である。検査の 批判者の中には、さまざまな部族の先住民が検査を受けるにつれ、より多くのマーカーが特定されるだろうと主張する者もいる。彼らは、天然痘や他の病気によ る早期の流行が遺伝的構成を変化させた可能性があると考えている。[15][35] ワン・ドロップ・ルールが今日でも社会的に永続している仕組みを明らかにするために、多くの努力が払われてきた。例えば、ニッキー・カンナは、南部で黒人 /白人の成人を対象に行ったインタビューで、ワン・ドロップ・ルールが永続している理由の一つは、反射的評価のメカニズムにあることを明らかにしている。 ほとんどの回答者は、自分たちを黒人だと認識しており、その理由として、黒人も白人も彼らを黒人だと認識しているからだと説明している。[37] |

| Allusions Charles W. Chesnutt, who was of mixed race and grew up in the North, wrote stories and novels about the issues of mixed-race people in southern society in the aftermath of the Civil War. The one-drop rule and its consequences have been the subject of numerous works of popular culture. The American musical Show Boat (1927) opens in 1887 on a Mississippi River boat, after the Reconstruction era and imposition of racial segregation and Jim Crow in the South. Steve, a white man married to a mixed-race woman who passes as white, is pursued by a Southern sheriff. He intends to arrest Steve and charge him with miscegenation for being married to a woman of partly black ancestry. Steve pricks his wife's finger and swallows some of her blood. When the sheriff arrives, Steve asks him whether he would consider a man to be white if he had "negro blood" in him. The sheriff replies that "one drop of Negro blood makes you a Negro in these parts". Steve tells the sheriff that he has "more than a drop of negro blood in me". After being assured by others that Steve is telling the truth, the sheriff leaves without arresting Steve.[38][39] |

言及 混血で北部で育ったチャールズ・チェスナットは、南北戦争後の南部社会における混血の人々の問題について、短編小説や小説を書いた。 ワン・ドロップ・ルールとその影響は、大衆文化の多くの作品の題材となっている。アメリカのミュージカル『ショーボート』(1927年)は、南北戦争後の 南部で人種差別とジム・クロウ法(人種差別法)が施行された1887年、ミシシッピ川を航行する船上で始まる。白人男性で、白人として生活している混血の 女性と結婚したスティーブは、南部の保安官に追われている。保安官は、スティーブを逮捕し、一部黒人の祖先を持つ女性と結婚したとして、人種差別禁止法違 反で起訴しようとしている。スティーブは妻の指を刺し、彼女の血を少し飲み込む。保安官が到着すると、スティーブは、黒人の血が流れている人は白人だと考 えるかどうかを保安官に尋ねる。保安官は、「この地域では、ニグロの血が 1 滴でも混ざっていれば、その人はニグロだ」と答える。スティーブは、自分には「ニグロの血が 1 滴以上混ざっている」と保安官に告げる。他の人たちにスティーブの言うことが真実だと確認された保安官は、スティーブを逮捕せずに立ち去る。[38] [39] |

| Black Indians in the United

States Blood quantum laws Brown paper bag test Cherokee Freedmen Chicano (whiteness of Mexican Americans) Hispanic and Latino Americans Historical race concepts Limpieza de sangre Métis Mestizo Miscegenation Mischling Mixed Race Day Passing Pencil test Quadroon Racial hygiene Pocahontas exception "Who is a Jew?" |

アメリカ合衆国のブラック・インディアン 血の混合比率に関する法律 茶色の紙袋テスト チェロキー・フリードマン チカーノ(メキシコ系アメリカ人の白人性 ヒスパニックおよびラテン系アメリカ人 歴史的な人種の概念 リンピエサ・デ・サングレ メティス メスティゾ 人種混交 ミシュリング 混血の日 パッシング ペンシルテスト クアドローン 人種衛生 ポカホンタスの例外 「ユダヤ人とは誰か? |

| Daniel, G. Reginald. More Than

Black? Multiracial Identity and the New Racial Order. Philadelphia:

Temple University Press. 2002. ISBN 1-56639-909-2. Daniel, G. Reginald. Race and Multiraciality in Brazil and the United States: Converging Paths?. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. 2006. ISBN 0-271-02883-1. Davis, James F., Who Is Black?: One Nation's Definition. University Park PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-271-02172-1. Guterl, Matthew Press, The Color of Race in America, 1900–1940. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-674-01012-4. Moran, Rachel F., Interracial Intimacy: The Regulation of Race & Romance, Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press, 2003. ISBN 0-226-53663-7. Romano, Renee Christine, Race Mixing: Black-White Marriage in Post-War America. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-674-01033-7. Savy, Pierre, "Transmission, identité, corruption. Réflexions sur trois cas d'hypodescendance", L'homme. Revue française d'anthropologie, 182, 2007 ("Racisme, antiracisme et sociétés"), pp. 53–80. Yancey, George, Just Don't Marry One: Interracial Dating, Marriage & Parenting. Judson Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8170-1439-X. |

ダニエル、G. レジナルド。More Than Black?

多民族のアイデンティティと新しい人種秩序。フィラデルフィア:テンプル大学出版。2002年。ISBN 1-56639-909-2。 ダニエル、G. レジナルド。ブラジルとアメリカ合衆国の人種と多民族性:収斂する道?ペンシルベニア州ユニバーシティパーク:ペンシルベニア州立大学出版。2006年。 ISBN 0-271-02883-1。 デイヴィス、ジェームズ F.、『Who Is Black?: One Nation's Definition』 ペンシルベニア州立大学出版局、2001 年。ISBN 0-271-02172-1。 グター、マシュー・プレス、『The Color of Race in America, 1900–1940』 マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局、2004年。ISBN 0-674-01012-4。 モラン、レイチェル F.、『異人種間の親密さ:人種と恋愛の規制』、イリノイ州シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局、2003年。ISBN 0-226-53663-7。 ロマーノ、レニー・クリスティン、『人種の混血:戦後アメリカの黒人と白人の結婚』。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局、2003 年。ISBN 0-674-01033-7。 サヴィ、ピエール、「伝承、アイデンティティ、腐敗。3つの低地位の血統の事例に関する考察」、L'homme。Revue française d『anthropologie、182、2007(「人種主義、反人種主義、社会」)、53-80 ページ。 Yancey, George、Just Don』t Marry One: Interracial Dating, Marriage & Parenting(ただ結婚しないだけ:異人種間の交際、結婚、子育て)。ジャドソン・プレス、2003 年。ISBN 0-8170-1439-X。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One-drop_rule |

Naomi Zack, Race and Mixed Race. 1993.

1. 核心テーマ

人 種の社会的構築性:生物学的根拠のない人種概念が、いかに法的・制度的に維持されてきたかを解明

一 滴ルール批判:黒人祖先が1滴でもあれば黒人とみなす「one-drop rule」が、混血の存在を無視する人種二元論の典型例と指摘

カ テゴリーの暴力:混血者を「人種的裏切り者」扱いする社会構造が、個人のアイデンティティをいかに抑圧するかを哲学的に分析

2. 革新的視点

伝

統的二元論からZack の連続的スペクトル論

3. 現代への影響

2000年米国国勢調査で初めて「複数人種選択」が可能になった政策的転換の理論的支柱

批判的人種理論(CRT)の発展に寄与

多民族国家における国籍と人種の関係再定義の契機

4. 哲学的基盤

現象学とプラグマティズムを融合させ、人種経験の「生きた現実」を理論化。混血の身体が人種カテゴリーを越境する様を分析しています。

5. 批判的検討

「人種概念の完全廃棄」を主張するZackに対し、後の学者からは「人種的不正義と闘うための戦術的ツールとしての人種カテゴリー維持」の必要性が指摘された(例:Sally Haslangerの批判的構築主義)。

この著作は、遺伝子検査の普及で人種の境界がさらに流動化した現代社会において、改めて読み直されるべき古典である。多様性管理の課題に直面する日本企業のダイバーシティ戦略を構築する際にも、重要な示唆を与える内容と言える。

+

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099