オペレーションズ・リサーチ

Operations research

☆ オペレーションズ・リサーチ(英:operational research) (米空軍専門コード:Operations Analysis)は、意思決定を改善するための分析手法の開発と適用を扱う学問分野であり、しばしばORの頭文字で短縮される。 モデリング、統計学、最適化など、他の数理科学の技法を採用し、オペレーションズ・リサーチは意思決定問題の最適解またはそれに近い解を導き出す。実践的 な応用に重点を置いているため、オペレーションズ・リサーチは他の多くの学問分野、特に経営工学と重なり合っている。オペレーションズ・リサーチは多くの 場合、実世界の目的の極値、すなわち最大値(利益、パフォーマン ス、歩留まり)または最小値(損失、リスク、コスト)を決定することに関心がある。第二次世界大戦前の軍事活動に端を発し、その手法は様々な産業における 問題にまで発展している[3]。

| Operations research

(British English: operational research) (U.S. Air Force Specialty Code:

Operations Analysis), often shortened to the initialism OR, is a

discipline that deals with the development and application of

analytical methods to improve decision-making.[1] The term management

science is occasionally used as a synonym.[2] Employing techniques from other mathematical sciences, such as modeling, statistics, and optimization, operations research arrives at optimal or near-optimal solutions to decision-making problems. Because of its emphasis on practical applications, operations research has overlapped with many other disciplines, notably industrial engineering. Operations research is often concerned with determining the extreme values of some real-world objective: the maximum (of profit, performance, or yield) or minimum (of loss, risk, or cost). Originating in military efforts before World War II, its techniques have grown to concern problems in a variety of industries.[3] |

オペレーションズ・リサーチ(英:operational

research)(米空軍専門コード:Operations

Analysis)は、意思決定を改善するための分析手法の開発と適用を扱う学問分野であり、しばしばORの頭文字で短縮される。 モデリング、統計学、最適化など、他の数理科学の技法を採用し、オペレーションズ・リサーチは意思決定問題の最適解またはそれに近い解を導き出す。実践的 な応用に重点を置いているため、オペレーションズ・リサーチは他の多くの学問分野、特に経営工学と重なり合っている。オペレーションズ・リサーチは多くの 場合、実世界の目的の極値、すなわち最大値(利益、パフォーマン ス、歩留まり)または最小値(損失、リスク、コスト)を決定することに関心がある。第二次世界大戦前の軍事活動に端を発し、その手法は様々な産業における 問題にまで発展している[3]。 |

| Overview Operations research (OR) encompasses the development and the use of a wide range of problem-solving techniques and methods applied in the pursuit of improved decision-making and efficiency, such as simulation, mathematical optimization, queueing theory and other stochastic-process models, Markov decision processes, econometric methods, data envelopment analysis, ordinal priority approach, neural networks, expert systems, decision analysis, and the analytic hierarchy process.[4] Nearly all of these techniques involve the construction of mathematical models that attempt to describe the system. Because of the computational and statistical nature of most of these fields, OR also has strong ties to computer science and analytics. Operational researchers faced with a new problem must determine which of these techniques are most appropriate given the nature of the system, the goals for improvement, and constraints on time and computing power, or develop a new technique specific to the problem at hand (and, afterwards, to that type of problem). The major sub-disciplines (but not limited to) in modern operational research, as identified by the journal Operations Research[5] and The Journal of the Operational Research Society [6] are: Computing and information technologies Financial engineering Manufacturing, service sciences, and supply chain management Policy modeling and public sector work Revenue management Simulation Stochastic models Transportation theory Game theory for strategies Linear programming Nonlinear programming Integer programming in NP-complete problem specially for 0-1 integer linear programming for binary Dynamic programming in Aerospace engineering and Economics Information theory used in Cryptography, Quantum computing Quadratic programming for solutions of Quadratic equation and Quadratic function |

概要 オペレーションズ・リサーチ(OR)は、意思決定や効率性の向上を追求するために適用される、シミュレーション、数理最適化、待ち行列理論やその他の確率 過程モデル、マルコフ決定過程、計量経済学的手法、データ包絡分析、順序優先度アプローチ、ニューラルネットワーク、エキスパート・システム、決定分析、 分析的階層過程[4]など、幅広い問題解決技法や手法の開発と利用を包含する。これらの技法のほぼすべてが、システムを記述しようとする数学的モデルの構 築を伴う。これらの分野のほとんどが計算的・統計的な性質を持つため、ORはコンピュータサイエンスや分析学とも強い結びつきがある。新たな問題に直面し たオペレーショナル・リサーチャーは、システムの性質、改善目標、時間や計算能力の制約を考慮した上で、これらの手法のどれが最も適切かを判断しなければ ならない。 オペレーションズ・リサーチ誌[5]およびオペレーショナル・リサーチ学会誌[6]によって特定された、現代のオペレーションズ・リサーチにおける主要な下位学問分野(ただし、これに限定されるものではない)は以下の通りである: コンピューティングと情報技術 金融工学 製造、サービス科学、サプライチェーンマネジメント 政策モデリングおよび公共部門 収益管理 シミュレーション 確率モデル 輸送理論 戦略ゲーム理論 線形計画法 非線形計画法 NP完全問題における整数計画法,特に0-1整数計画法,2値計画法における線形計画法 航空宇宙工学や経済学における動的計画法 暗号、量子コンピュータにおける情報理論 二次方程式や二次関数の解を求める二次計画法 |

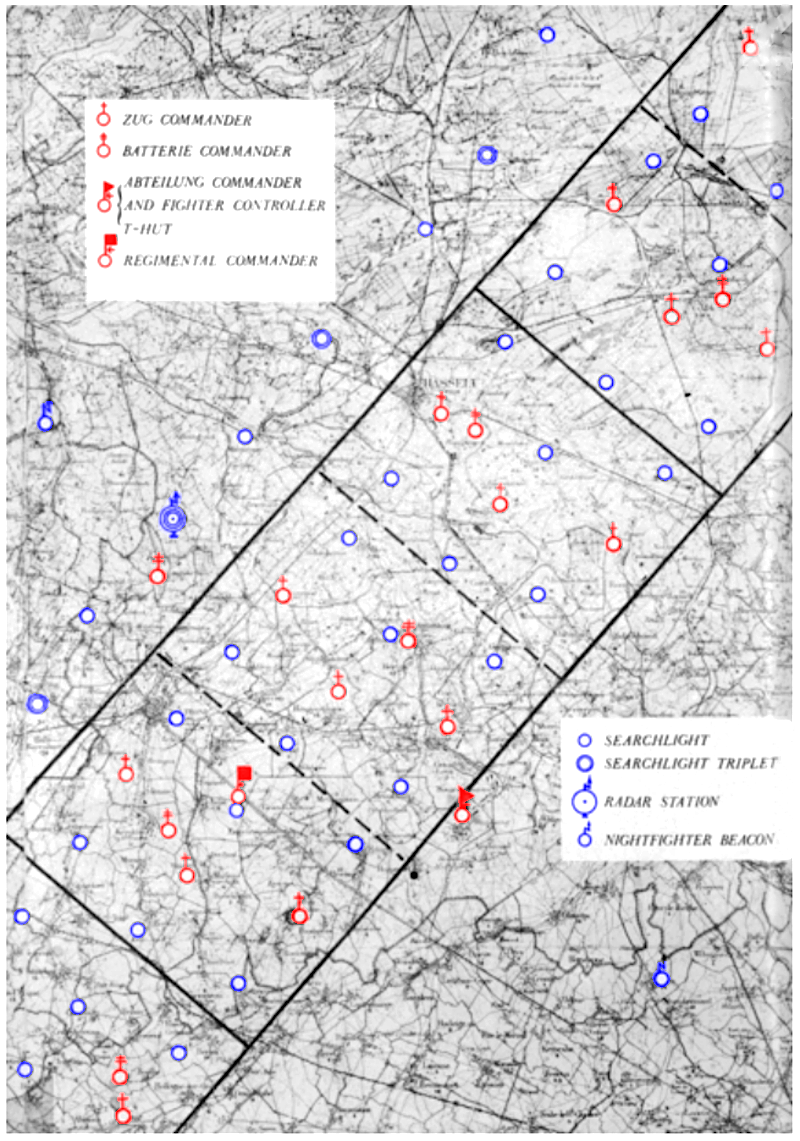

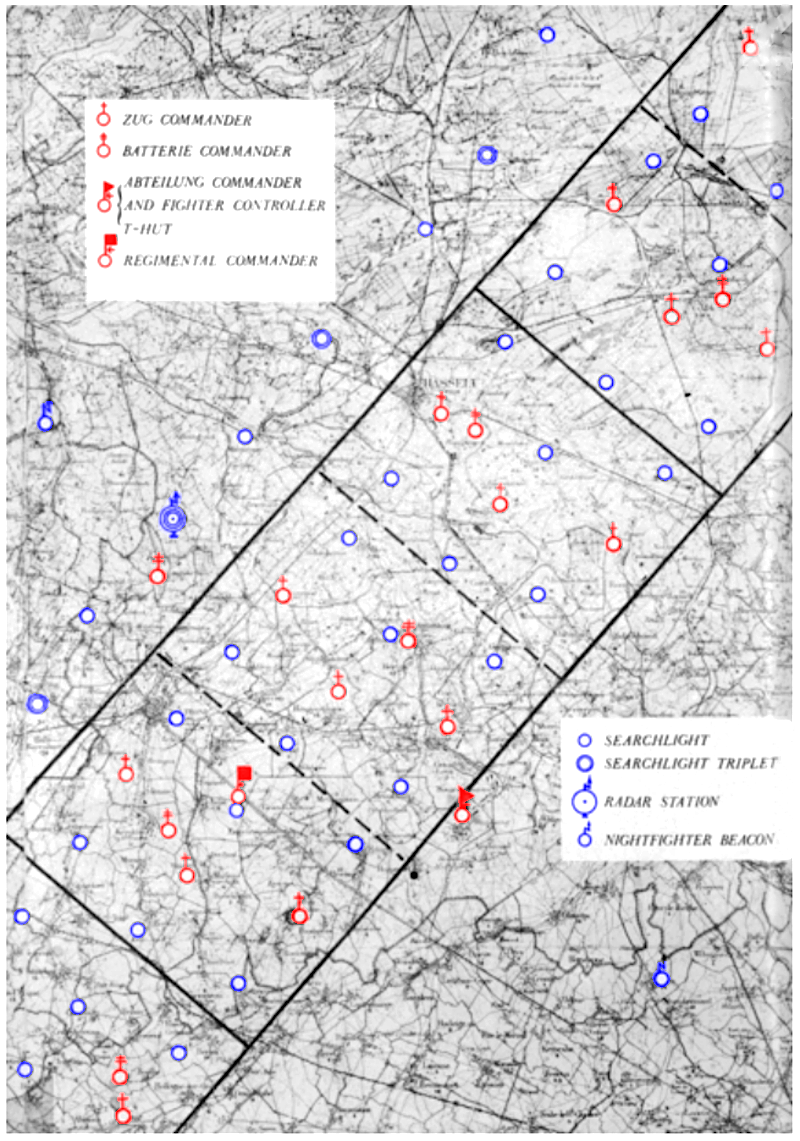

| History In the decades after the two world wars, the tools of operations research were more widely applied to problems in business, industry, and society. Since that time, operational research has expanded into a field widely used in industries ranging from petrochemicals to airlines, finance, logistics, and government, moving to a focus on the development of mathematical models that can be used to analyse and optimize sometimes complex systems, and has become an area of active academic and industrial research.[3] Historical origins In the 17th century, mathematicians Blaise Pascal and Christiaan Huygens solved problems involving sometimes complex decisions (problem of points) by using game-theoretic ideas and expected values; others, such as Pierre de Fermat and Jacob Bernoulli, solved these types of problems using combinatorial reasoning instead.[7] Charles Babbage's research into the cost of transportation and sorting of mail led to England's universal "Penny Post" in 1840, and to studies into the dynamical behaviour of railway vehicles in defence of the GWR's broad gauge.[8] Beginning in the 20th century, study of inventory management could be considered[by whom?] the origin of modern operations research with economic order quantity developed by Ford W. Harris in 1913. Operational research may[original research?] have originated in the efforts of military planners during World War I (convoy theory and Lanchester's laws). Percy Bridgman brought operational research to bear on problems in physics in the 1920s and would later attempt to extend these to the social sciences.[9] Modern operational research originated at the Bawdsey Research Station in the UK in 1937 as the result of an initiative of the station's superintendent, A. P. Rowe and Robert Watson-Watt.[10] Rowe conceived the idea as a means to analyse and improve the working of the UK's early-warning radar system, code-named "Chain Home" (CH). Initially, Rowe analysed the operating of the radar equipment and its communication networks, expanding later to include the operating personnel's behaviour. This revealed unappreciated limitations of the CH network and allowed remedial action to be taken.[11] Scientists in the United Kingdom (including Patrick Blackett (later Lord Blackett OM PRS), Cecil Gordon, Solly Zuckerman, (later Baron Zuckerman OM, KCB, FRS), C. H. Waddington, Owen Wansbrough-Jones, Frank Yates, Jacob Bronowski and Freeman Dyson), and in the United States (George Dantzig) looked for ways to make better decisions in such areas as logistics and training schedules. Second World War The modern field of operational research arose during World War II.[dubious – discuss] In the World War II era, operational research was defined as "a scientific method of providing executive departments with a quantitative basis for decisions regarding the operations under their control".[12] Other names for it included operational analysis (UK Ministry of Defence from 1962)[13] and quantitative management.[14] During the Second World War close to 1,000 men and women in Britain were engaged in operational research. About 200 operational research scientists worked for the British Army.[15] Patrick Blackett worked for several different organizations during the war. Early in the war while working for the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) he set up a team known as the "Circus" which helped to reduce the number of anti-aircraft artillery rounds needed to shoot down an enemy aircraft from an average of over 20,000 at the start of the Battle of Britain to 4,000 in 1941.[16]  A Liberator in standard RAF green/dark earth/black night bomber finish as originally used by Coastal Command In 1941, Blackett moved from the RAE to the Navy, after first working with RAF Coastal Command, in 1941 and then early in 1942 to the Admiralty.[17] Blackett's team at Coastal Command's Operational Research Section (CC-ORS) included two future Nobel prize winners and many other people who went on to be pre-eminent in their fields.[18][19] They undertook a number of crucial analyses that aided the war effort. Britain introduced the convoy system to reduce shipping losses, but while the principle of using warships to accompany merchant ships was generally accepted, it was unclear whether it was better for convoys to be small or large. Convoys travel at the speed of the slowest member, so small convoys can travel faster. It was also argued that small convoys would be harder for German U-boats to detect. On the other hand, large convoys could deploy more warships against an attacker. Blackett's staff showed that the losses suffered by convoys depended largely on the number of escort vessels present, rather than the size of the convoy. Their conclusion was that a few large convoys are more defensible than many small ones.[20] While performing an analysis of the methods used by RAF Coastal Command to hunt and destroy submarines, one of the analysts asked what colour the aircraft were. As most of them were from Bomber Command they were painted black for night-time operations. At the suggestion of CC-ORS a test was run to see if that was the best colour to camouflage the aircraft for daytime operations in the grey North Atlantic skies. Tests showed that aircraft painted white were on average not spotted until they were 20% closer than those painted black. This change indicated that 30% more submarines would be attacked and sunk for the same number of sightings.[21] As a result of these findings Coastal Command changed their aircraft to using white undersurfaces. Other work by the CC-ORS indicated that on average if the trigger depth of aerial-delivered depth charges were changed from 100 to 25 feet, the kill ratios would go up. The reason was that if a U-boat saw an aircraft only shortly before it arrived over the target then at 100 feet the charges would do no damage (because the U-boat wouldn't have had time to descend as far as 100 feet), and if it saw the aircraft a long way from the target it had time to alter course under water so the chances of it being within the 20-foot kill zone of the charges was small. It was more efficient to attack those submarines close to the surface when the targets' locations were better known than to attempt their destruction at greater depths when their positions could only be guessed. Before the change of settings from 100 to 25 feet, 1% of submerged U-boats were sunk and 14% damaged. After the change, 7% were sunk and 11% damaged; if submarines were caught on the surface but had time to submerge just before being attacked, the numbers rose to 11% sunk and 15% damaged. Blackett observed "there can be few cases where such a great operational gain had been obtained by such a small and simple change of tactics".[22]  Map of Kammhuber Line Bomber Command's Operational Research Section (BC-ORS), analyzed a report of a survey carried out by RAF Bomber Command.[citation needed] For the survey, Bomber Command inspected all bombers returning from bombing raids over Germany over a particular period. All damage inflicted by German air defenses was noted and the recommendation was given that armor be added in the most heavily damaged areas. This recommendation was not adopted because the fact that the aircraft were able to return with these areas damaged indicated the areas were not vital, and adding armor to non-vital areas where damage is acceptable reduces aircraft performance. Their suggestion to remove some of the crew so that an aircraft loss would result in fewer personnel losses, was also rejected by RAF command. Blackett's team made the logical recommendation that the armor be placed in the areas which were completely untouched by damage in the bombers who returned. They reasoned that the survey was biased, since it only included aircraft that returned to Britain. The areas untouched in returning aircraft were probably vital areas, which, if hit, would result in the loss of the aircraft.[23] This story has been disputed,[24] with a similar damage assessment study completed in the US by the Statistical Research Group at Columbia University,[25] the result of work done by Abraham Wald.[26] When Germany organized its air defences into the Kammhuber Line, it was realized by the British that if the RAF bombers were to fly in a bomber stream they could overwhelm the night fighters who flew in individual cells directed to their targets by ground controllers. It was then a matter of calculating the statistical loss from collisions against the statistical loss from night fighters to calculate how close the bombers should fly to minimize RAF losses.[27] The "exchange rate" ratio of output to input was a characteristic feature of operational research. By comparing the number of flying hours put in by Allied aircraft to the number of U-boat sightings in a given area, it was possible to redistribute aircraft to more productive patrol areas. Comparison of exchange rates established "effectiveness ratios" useful in planning. The ratio of 60 mines laid per ship sunk was common to several campaigns: German mines in British ports, British mines on German routes, and United States mines in Japanese routes.[28] Operational research doubled the on-target bomb rate of B-29s bombing Japan from the Marianas Islands by increasing the training ratio from 4 to 10 percent of flying hours; revealed that wolf-packs of three United States submarines were the most effective number to enable all members of the pack to engage targets discovered on their individual patrol stations; revealed that glossy enamel paint was more effective camouflage for night fighters than conventional dull camouflage paint finish, and a smooth paint finish increased airspeed by reducing skin friction.[28] On land, the operational research sections of the Army Operational Research Group (AORG) of the Ministry of Supply (MoS) were landed in Normandy in 1944, and they followed British forces in the advance across Europe. They analyzed, among other topics, the effectiveness of artillery, aerial bombing and anti-tank shooting. After World War II In 1947, under the auspices of the British Association, a symposium was organized in Dundee. In his opening address, Watson-Watt offered a definition of the aims of OR: "To examine quantitatively whether the user organization is getting from the operation of its equipment the best attainable contribution to its overall objective."[10] With expanded techniques and growing awareness of the field at the close of the war, operational research was no longer limited to only operational, but was extended to encompass equipment procurement, training, logistics and infrastructure. Operations research also grew in many areas other than the military once scientists learned to apply its principles to the civilian sector. The development of the simplex algorithm for linear programming was in 1947.[29] In the 1950s, the term Operations Research was used to describe heterogeneous mathematical methods such as game theory, dynamic programming, linear programming, warehousing, spare parts theory, queue theory, simulation and production control, which were used primarily in civilian industry. Scientific societies and journals on the subject of operations research were founded in the 1950s, such as the Operation Research Society of America (ORSA) in 1952 and the Institute for Management Science (TIMS) in 1953.[30] Philip Morse, the head of the Weapons Systems Evaluation Group of the Pentagon, became the first president of ORSA and attracted the companies of the military-industrial complex to ORSA, which soon had more than 500 members. In the 1960s, ORSA reached 8000 members.[citation needed] Consulting companies also founded OR groups. In 1953, Abraham Charnes and William Cooper published the first textbook on Linear Programming.[citation needed] In the 1950s and 1960s, chairs of operations research were established in the U.S. and United Kingdom (from 1964 in Lancaster) in the management faculties of universities. Further influences from the U.S. on the development of operations research in Western Europe can be traced here. The authoritative[citation needed] OR textbooks from the U.S. were published in Germany in German language and in France in French (but not in Italian[citation needed]), such as the book by George Dantzig "Linear Programming"(1963) and the book by C. West Churchman et al. "Introduction to Operations Research"(1957). The latter was also published in Spanish in 1973, opening at the same time Latin American readers to Operations Research. NATO gave important impulses for the spread of Operations Research in Western Europe; NATO headquarters (SHAPE) organised four conferences on OR in the 1950s – the one in 1956 with 120 participants – bringing OR to mainland Europe. Within NATO, OR was also known as "Scientific Advisory" (SA) and was grouped together in the Advisory Group of Aeronautical Research and Development (AGARD). SHAPE and AGARD organized an OR conference in April 1957 in Paris. When France withdrew from the NATO military command structure, the transfer of NATO headquarters from France to Belgium led to the institutionalization of OR in Belgium, where Jacques Drèze founded CORE, the Center for Operations Research and Econometrics at the Catholic University of Leuven in 1966.[citation needed] With the development of computers over the next three decades, Operations Research can now solve problems with hundreds of thousands of variables and constraints. Moreover, the large volumes of data required for such problems can be stored and manipulated very efficiently."[29] Much of operations research (modernly known as 'analytics') relies upon stochastic variables and a therefore access to truly random numbers. Fortunately, the cybernetics field also required the same level of randomness. The development of increasingly better random number generators has been a boon to both disciplines. Modern applications of operations research includes city planning, football strategies, emergency planning, optimizing all facets of industry and economy, and undoubtedly with the likelihood of the inclusion of terrorist attack planning and definitely counterterrorist attack planning. More recently, the research approach of operations research, which dates back to the 1950s, has been criticized for being collections of mathematical models but lacking an empirical basis of data collection for applications. How to collect data is not presented in the textbooks. Because of the lack of data, there are also no computer applications in the textbooks.[31] |

歴史 第二次世界大戦後の数十年間、オペレーションズ・リサーチのツールは、ビジネス、産業、社会における問題に広く応用されるようになった。それ以来、オペ レーションズ・リサーチは、石油化学から航空会社、金融、ロジスティクス、政府まで幅広い産業で広く利用される分野に拡大し、時には複雑なシステムの分析 や最適化に利用できる数理モデルの開発に重点を置くようになり、学術的にも産業的にも活発な研究が行われる分野となった[3]。 歴史的起源 17世紀、数学者のブレーズ・パスカルとクリスティアン・ホイヘンスは、ゲーム理論的なアイデアと期待値を用いて、時に複雑な決定を伴う問題(点の問題) を解決した。 [チャールズ・バベッジの郵便物の輸送と仕分けのコストに関する研究は、1840年のイギリスの普遍的な「ペニー・ポスト」につながり、GWRの広軌を擁 護するための鉄道車両の力学的挙動に関する研究につながった。オペレーショナルリサーチは、第一次世界大戦中の軍事計画者の努力(輸送船団理論とランチェ スターの法則)に端を発しているかもしれない。パーシー・ブリッジマンは1920年代にオペレーショナルリサーチを物理学の問題に適用し、後にこれを社会 科学に拡張しようと試みた[9]。 近代的なオペレーション・リサーチは、1937年にイギリスのボーズィー研究ステーションで、同ステーションの管理責任者であったA.P.ロウとロバー ト・ワトソン=ワットの発案によって始まった[10]。ロウは、コードネーム「チェーン・ホーム」(CH)と呼ばれるイギリスの早期警戒レーダー・システ ムの作動を分析し改善する手段として、このアイデアを思いついた。当初、ロウはレーダー機器とその通信網の運用を分析し、後に運用要員の行動にも対象を広 げた。これによってCHネットワークの未認識の限界が明らかになり、改善策が講じられるようになった[11]。 イギリスの科学者(パトリック・ブラケット(後のブラケット卿OM PRS)、セシル・ゴードン、ソリー・ザッカーマン(後のザッカーマン男爵OM、KCB、FRS)、C.H.ワディントン、オーウェン・ワンズブロウ・ ジョーンズ、フランク・イェーツ、ジェイコブ・ブロノウスキー、フリーマン・ダイソンなど)、アメリカの科学者(ジョージ・ダンツィグ)は、兵站や訓練ス ケジュールなどの分野でより良い決定を下す方法を模索した。 第二次世界大戦 作戦研究(OR)という近代的な分野は第二次世界大戦中に生まれた[dubious - discuss]。第二次世界大戦の時代には、作戦研究は「その管理下にある作戦に関する意思決定のための定量的根拠を行政部門に提供する科学的手法」と 定義されていた[12]。作戦分析(1962年から英国国防省)[13]や定量的管理[14]などの他の名称もあった。 第二次世界大戦中、イギリスでは1,000人近くの男女が作戦研究に従事していた。約200人の作戦研究科学者がイギリス陸軍で働いていた[15]。 パトリック・ブラケットは戦争中、いくつかの異なる組織で働いていた。戦争初期に王立航空機施設(RAE)で働いていたとき、彼は「サーカス」として知ら れるチームを立ち上げ、バトル・オブ・ブリテンの開始時には平均20,000発以上あった敵機を撃墜するのに必要な高射砲弾の数を、1941年には 4,000発に減らすのに貢献した[16]。  沿岸軍で使用されていた標準的なRAFグリーン/ダークアース/ブラックの夜間爆撃機仕上げのリベレーター。 1941年、ブラケットは RAE から海軍に移り、最初は空軍沿岸軍司令部に勤務した後、1942年の早い時期に提督府に移った[17] 。沿岸軍司令部作戦研究部(CC-ORS)のブラケットのチームには、後にノーベル賞を受賞する2人のほか、各分野で卓越した業績を残す多くの人物が含ま れていた[18][19]。イギリスは海運の損失を減らすために輸送船団システムを導入したが、商船に軍艦を随伴させるという原則は一般に受け入れられて いたものの、輸送船団は小さいほうがいいのか大きいほうがいいのかは不明であった。船団は最も遅いメンバーの速度で移動するため、小さな船団はより速く移 動することができる。また、小さな輸送船団はドイツのUボートに発見されにくいという議論もあった。一方、大きな輸送船団は、攻撃者に対してより多くの軍 艦を配備することができる。ブラケットのスタッフは、輸送船団が被る損害は、輸送船団の規模よりもむしろ、護衛艦の数に大きく依存することを示した。彼ら の結論は、多数の小さな輸送船団よりも少数の大きな輸送船団の方が防御力が高いというものであった[20]。 潜水艦を狩り、破壊するためにRAF沿岸コマンドが使用した方法の分析を行っているとき、アナリストの一人が、航空機は何色であったかと質問した。そのほ とんどが爆撃機部隊のものであったため、夜間作戦のために黒く塗られていた。CC-ORSの提案で、灰色の北大西洋の空で昼間に活動する航空機をカモフ ラージュするのに最適な色かどうかのテストが行われた。テストの結果、白く塗られた航空機は、黒く塗られた航空機よりも平均して20%近づくまで発見され なかった。この変化は、同じ発見数で30%多くの潜水艦が攻撃され、撃沈されることを示していた[21]。 これらの発見の結果、沿岸軍司令部は航空機の下面を白に変更した。 CC-ORSによる他の研究では、空中投下型爆雷のトリガー深度を平均して100フィートから25フィートに変更した場合、殺傷率は上昇することが示され た。その理由は、Uボートが目標上空に到着する直前に航空機を発見した場合、100フィートでは爆雷のダメージはなく(Uボートは100フィートまで降下 する時間がなかったため)、目標から遠く離れた地点で航空機を発見した場合は、水中で進路を変更する時間があったため、爆雷の20フィートのキルゾーン内 に入る可能性は少なかったからである。潜水艦の位置が推測できる深度で破壊を試みるよりも、標的の位置がよく分かっている水面近くで攻撃する方が効率的 だったのだ。設定を100フィートから25フィートに変更する前は、沈没したUボートの1%が撃沈され、14%が損傷した。もし潜水艦が水面で捕捉された としても、攻撃を受ける直前に潜航する時間があれば、撃沈は11%、損傷は15%に上昇した。ブラケットは「このような小さくて単純な戦術の変更によっ て、これほど大きな作戦上の利益が得られたケースはほとんどないだろう」と観察している[22]。  カンムフーバーラインの地図 この調査のために、爆撃機部隊は特定の期間にドイツ上空を空襲して帰還したすべての爆撃機を検査した。ドイツ防空によるすべての損害が記録され、最も損害 の大きかった部分に装甲を追加するよう勧告が出された。この勧告が採用されなかったのは、これらの部分が損傷したまま帰還できたという事実が、その部分が 重要でないことを示していたからであり、損傷が許容される重要でない部分に装甲を追加することは、航空機のパフォーマティビティを低下させるからである。 また、航空機の損失が人的損失の減少につながるように、乗組員の一部を除去するという彼らの提案も、空軍司令部によって却下された。ブラケットのチーム は、帰還した爆撃機の損傷がまったくない部分に装甲を配置するという論理的な勧告を行った。彼らは、この調査は英国に帰還した機体のみを対象としているた め、偏りがあると推論した。この話には異論があり[24]、米国ではコロンビア大学の統計研究グループ[25]がアブラハム・ヴァルトの研究の成果として 同様の損害評価調査を完了している[26]。 ドイツが防空線をカンムフーバーラインに編成したとき、イギリスは、イギリス空軍の爆撃機が爆撃機の流れに乗って飛行すれば、地上管制官によって目標に指 示された個々のセルで飛行する夜間戦闘機を圧倒できることに気づいた。そして、RAF の損失を最小化するために爆撃機がどの程度接近して飛行すべきかを計算するために、夜間戦闘機による統計的損失に対する衝突による統計的損失を計算するこ とが問題となった[27]。 インプットに対するアウトプットの「為替レート」比は作戦研究の特徴であった。連合国航空機の飛行時間数と所定地域での U ボート目撃数を比較することで、より生産的な哨戒地域に航空機を再配分することが可能であった。交換率の比較によって、作戦計画に有用な「効果比」が確立 された。沈没艦1隻につき敷設機雷60個という比率は、いくつかの作戦に共通していた: イギリスの港におけるドイツの機雷、ドイツの航路におけるイギリスの機雷、日本の航路におけるアメリカの機雷である[28]。 作戦研究は、訓練比率を飛行時間の4パーセントから10パーセントに増加させることによって、マリアナ諸島から日本を爆撃するB-29のオンターゲット爆撃率を2倍にした。 陸上では、補給省(MoS)の陸軍作戦研究グループ(AORG)の作戦研究部門が1944年にノルマンディーに上陸し、ヨーロッパを前進するイギリス軍を追った。彼らは、とりわけ大砲、空爆、対戦車射撃の有効性を分析した。 第二次世界大戦後 1947年、英国協会の後援のもと、ダンディーでシンポジウムが開催された。ワトソン=ワットは開会の辞で、ORの目的の定義を述べた: 「ユーザー組織がその機器の操作から、その全体的な目的に対して達成可能な最良の貢献を得ているかどうかを定量的に調べること」[10]であった。 戦争末期には、技術が拡大され、この分野に対する認識が高まるにつれて、作戦研究はもはや作戦だけに限定されるものではなく、装備品の調達、訓練、兵站、 およびインフラストラクチャーを包含するまでに拡大された。科学者がその原理を民間部門に応用することを学ぶと、オペレーションズ・リサーチは軍事以外の 多くの分野でも発展した。線形計画法のためのシンプレックス・アルゴリズムの開発は、1947年のことであった[29]。 1950年代には、オペレーションズ・リサーチという用語は、ゲーム理論、動的計画法、線形計画法、倉庫管理、予備品理論、待ち行列理論、シミュレーショ ン、生産管理など、主に民間産業で使用されていた異種の数学的手法を表すために使用されるようになった。オペレーションズ・リサーチを主題とする科学学会 や学術誌は、1952年の米国オペレーションズ・リサーチ学会(ORSA)や1953年の経営科学研究所(TIMS)など、1950年代に設立された [30]。国防総省の兵器システム評価グループの責任者であったフィリップ・モースがORSAの初代会長に就任し、軍産複合体の企業をORSAに引きつ け、すぐに500人以上の会員を持つに至った。1960年代には、ORSAの会員数は8000人に達した[要出典]。コンサルティング会社もORグループ を設立した。1953年、エイブラハム・チャーンズとウィリアム・クーパーは線形計画法の最初の教科書を出版した。 1950年代と1960年代には、米国と英国(1964年からはランカスター)で大学の経営学部にオペレーションズ・リサーチの講座が設置された。西ヨー ロッパにおけるオペレーションズ・リサーチの発展に対する米国からのさらなる影響は、ここにも見て取れる。米国発の権威ある[要出典]ORの教科書は、ド イツではドイツ語で、フランスではフランス語で出版された(イタリア語はない[要出典])。後者は1973年にスペイン語でも出版され、同時にラテンアメ リカの読者にオペレーションズ・リサーチを紹介した。NATO本部(SHAPE)は1950年代にオペレーションズ・リサーチに関する会議を4回開催し、 1956年の会議には120人が参加した。NATO内では、ORは「科学諮問」(SA)としても知られ、航空研究開発諮問グループ(AGARD)にまとめ られていた。SHAPEとAGARDは1957年4月にパリでOR会議を開催した。フランスがNATO軍司令部機構から脱退すると、NATO本部がフラン スからベルギーに移ったため、ベルギーでORが制度化され、ジャック・ドレーズが1966年にルーヴェン・カトリック大学にオペレーションズリサーチ・エ コノメトリックスセンター(CORE)を設立した[要出典]。 その後30年にわたるコンピュータの発達により、オペレーションズ・リサーチは数十万の変数と制約条件を持つ問題を解くことができるようになった。さら に、そのような問題に必要な大量のデータを、非常に効率的に保存・操作できるようになった」[29]。オペレーションズ・リサーチ(現代では「分析学」と して知られる)の多くは、確率変数と、それゆえ真に乱数へのアクセスに依存している。幸運なことに、サイバネティクスの分野でも同じレベルのランダム性が 求められた。より優れた乱数発生器の開発は、両分野に恩恵をもたらした。オペレーションズ・リサーチの現代的な応用には、都市計画、サッカー戦略、緊急時 計画、産業と経済のあらゆる側面の最適化、そして間違いなくテロ攻撃計画、そして間違いなくテロ攻撃対策計画が含まれる可能性がある。最近では、1950 年代にさかのぼるオペレーションズ・リサーチの研究アプローチは、数学的モデルの集合体でありながら、応用のためのデータ収集という経験的基盤が欠けてい るという批判がある。どのようにデータを収集するかは、教科書には示されていない。データが不足しているため、教科書にはコンピュータの応用例もない [31]。 |

| Problems addressed Critical path analysis or project planning: identifying those processes in a multiple-dependency project which affect the overall duration of the project Floorplanning: designing the layout of equipment in a factory or components on a computer chip to reduce manufacturing time (therefore reducing cost) Network optimization: for instance, setup of telecommunications or power system networks to maintain quality of service during outages Resource allocation problems Facility location Assignment Problems: Assignment problem Generalized assignment problem Quadratic assignment problem Weapon target assignment problem Bayesian search theory: looking for a target Optimal search Routing, such as determining the routes of buses so that as few buses are needed as possible Supply chain management: managing the flow of raw materials and products based on uncertain demand for the finished products Project production activities: managing the flow of work activities in a capital project in response to system variability through operations research tools for variability reduction and buffer allocation using a combination of allocation of capacity, inventory and time[32][33] Efficient messaging and customer response tactics Automation: automating or integrating robotic systems in human-driven operations processes Globalization: globalizing operations processes in order to take advantage of cheaper materials, labor, land or other productivity inputs Transportation: managing freight transportation and delivery systems (Examples: LTL shipping, intermodal freight transport, travelling salesman problem, driver scheduling problem) Scheduling: Personnel staffing Manufacturing steps Project tasks Network data traffic: these are known as queueing models or queueing systems. Sports events and their television coverage Blending of raw materials in oil refineries Determining optimal prices, in many retail and B2B settings, within the disciplines of pricing science Cutting stock problem: Cutting small items out of bigger ones. Finding the optimal parameter (weights) setting of an algorithm that generates the realisation of a figured bass in Baroque compositions (classical music) by using weighted local cost and transition cost rules Operational research is also used extensively in government where evidence-based policy is used. |

扱われる問題 クリティカルパス分析またはプロジェクト計画:複数の依存関係にあるプロジェクトにおいて、プロジェクト全体の期間に影響を与えるプロセスを特定する。 フロアプランニング:工場内の設備やコンピューターチップ上の部品のレイアウトを設計し、製造時間を短縮する(つまりコストを削減する)。 ネットワークの最適化:例えば、停電時にサービスの質を維持するための電気通信網や電力系統網の設定など 資源配分問題 施設の配置 割り当て問題 割り当て問題 一般化割り当て問題 二次割り当て問題 兵器目標割り当て問題 ベイズ探索理論:ターゲットを探す 最適探索 経路決定:バスの経路をできるだけ少なくなるように決めるなど サプライチェーンマネジメント:完成品に対する不確実な需要に基づいて原材料や製品の流れを管理する プロジェクト生産活動:変動性削減のためのオペレーションズリサーチツールや、キャパシティ、在庫、時間の配分の組み合わせを用いたバッファ配分を通じて、システムの変動性に対応した資本プロジェクトにおける作業活動の流れを管理する[32][33]。 効率的なメッセージングと顧客対応戦術 自動化:人間主導のオペレーションプロセスにおいて、ロボットシステムを自動化または統合する。 グローバル化:安価な材料、労働力、土地、その他の生産性インプットを活用するために、オペレーションプロセスをグローバル化する。 輸送:貨物の輸送および配送システムの管理(例:LTL輸送、複合一貫輸送など LTL輸送、複合一貫輸送、巡回セールスマン問題、ドライバーのスケジューリング問題) スケジューリング: 人員配置 製造ステップ プロジェクトタスク ネットワーク・データ・トラフィック:これらは待ち行列モデルまたは待ち行列システムとして知られている。 スポーツイベントとそのテレビ中継 石油精製における原料の混合 多くの小売業やB2Bの場面で、価格決定科学の分野の中で最適価格を決定する。 在庫削減問題:大きな商品から小さな商品を切り出す。 重み付けされた局所コストと遷移コストルールを使用して、バロック音楽(クラシック音楽)のフィギュアドバスの実現を生成するアルゴリズムの最適なパラメータ(重み)設定を見つける。 オペレーショナルリサーチは、エビデンスに基づく政策が用いられる政府機関でも広く利用されている。 |

| Management science Main article: Management science The field of management science (MS) is known as using operations research models in business.[34] Stafford Beer characterized this in 1967.[35] Like operational research itself, management science is an interdisciplinary branch of applied mathematics devoted to optimal decision planning, with strong links with economics, business, engineering, and other sciences. It uses various scientific research-based principles, strategies, and analytical methods including mathematical modeling, statistics and numerical algorithms to improve an organization's ability to enact rational and meaningful management decisions by arriving at optimal or near-optimal solutions to sometimes complex decision problems. Management scientists help businesses to achieve their goals using the scientific methods of operational research. The management scientist's mandate is to use rational, systematic, science-based techniques to inform and improve decisions of all kinds. Of course, the techniques of management science are not restricted to business applications but may be applied to military, medical, public administration, charitable groups, political groups or community groups. Management science is concerned with developing and applying models and concepts that may prove useful in helping to illuminate management issues and solve managerial problems, as well as designing and developing new and better models of organizational excellence.[36] Related fields Some of the fields that have considerable overlap with Operations Research and Management Science include:[37] Artificial Intelligence Business analytics Computer science Data mining/Data science/Big data Decision analysis Decision intelligence Engineering Financial engineering Forecasting Game theory Geography/Geographic information science Graph theory Industrial engineering Inventory control Logistics Mathematical modeling Mathematical optimization Probability and statistics Project management Policy analysis Queueing theory Simulation Social network/Transportation forecasting models Stochastic processes Supply chain management Systems engineering Applications Applications are abundant such as in airlines, manufacturing companies, service organizations, military branches, and government. The range of problems and issues to which it has contributed insights and solutions is vast. It includes:[36] Scheduling (of airlines, trains, buses etc.) Assignment (assigning crew to flights, trains or buses; employees to projects; commitment and dispatch of power generation facilities) Facility location (deciding most appropriate location for new facilities such as warehouses; factories or fire station) Hydraulics & Piping Engineering (managing flow of water from reservoirs) Health Services (information and supply chain management) Game Theory (identifying, understanding; developing strategies adopted by companies) Urban Design Computer Network Engineering (packet routing; timing; analysis) Telecom & Data Communication Engineering (packet routing; timing; analysis) [38] Management is also concerned with so-called soft-operational analysis which concerns methods for strategic planning, strategic decision support, problem structuring methods. In dealing with these sorts of challenges, mathematical modeling and simulation may not be appropriate or may not suffice. Therefore, during the past 30 years[vague], a number of non-quantified modeling methods have been developed. These include:[citation needed] stakeholder based approaches including metagame analysis and drama theory morphological analysis and various forms of influence diagrams cognitive mapping strategic choice robustness analysis |

マネジメント・サイエンス 主な記事 経営科学 マネジメント・サイエンス(MS)の分野は、ビジネスにおいてオペレーションズ・リサーチ・モデルを使用することで知られている[34]。スタッフォー ド・ビアは1967年にこれを特徴付けた[35]。オペレーションズ・リサーチそのものと同様に、マネジメント・サイエンスは最適な意思決定計画に専念す る応用数学の学際的な一分野であり、経済学、経営学、工学、その他の科学との強い結びつきがある。科学的研究に基づく様々な原則、戦略、および数学的モデ リング、統計学、数値アルゴリズムを含む分析手法を用い、時に複雑な意思決定問題に対する最適解またはそれに近い解を導き出すことで、合理的で意味のある 経営上の意思決定を行う組織の能力を向上させる。マネジメント・サイエンティストは、オペレーショナル・リサーチの科学的手法を使って、企業の目標達成を 支援する。 経営科学者の使命は、合理的、体系的、科学的根拠に基づく技法を用いて、あらゆる種類の意思決定に情報を与え、改善することである。もちろん、経営科学の 技法はビジネスへの応用に限定されるものではなく、軍事、医療、行政、慈善団体、政治団体、地域団体などにも応用することができる。 経営科学は、経営上の問題を明らかにし、経営上の問題を解決するのに役立つと思われるモデルや概念を開発し、適用すること、また、組織の卓越性に関する新しく優れたモデルを設計し、開発することに関係している[36]。 関連分野 オペレーションズ・リサーチやマネジメント・サイエンスとかなり重複する分野には、以下のようなものがある[37]。 人工知能 ビジネスアナリティクス コンピュータサイエンス データマイニング/データサイエンス/ビッグデータ 意思決定分析 意思決定インテリジェンス エンジニアリング 金融工学 予測 ゲーム理論 地理・地理情報科学 グラフ理論 経営工学 在庫管理 ロジスティクス 数理モデリング 数理最適化 確率統計学 プロジェクト管理 政策分析 待ち行列理論 シミュレーション 社会ネットワーク/交通予測モデル 確率過程 サプライチェーンマネジメント システム工学 応用分野 航空会社、製造業、サービス業、軍部、政府機関など、その用途は多岐にわたる。システムエンジニアリングが洞察と解決に貢献した問題や課題の範囲は膨大である。それには以下が含まれる[36]。 スケジューリング(航空会社、列車、バスなど) 割り当て(乗務員をフライト、列車、バスに割り当てる、従業員をプロジェクトに割り当てる、発電施設のコミットメントとディスパッチする) 施設の立地(倉庫、工場、消防署などの新しい施設の最適な立地を決定する) 水理・配管エンジニアリング(貯水池からの水の流れを管理する) 医療サービス(情報とサプライチェーンの管理) ゲーム理論(企業が採用する戦略の特定、理解、開発) 都市デザイン コンピュータネットワーク工学 (パケットルーティング、タイミング、分析) 電気通信・データ通信工学 (パケットルーティング、タイミング、分析) [38] 経営はまた、戦略的計画、戦略的意思決定支援、問題構造化手法のための手法に関係する、いわゆるソフト・オペレーション分析にも関係している。このような 種類の課題に対処する際、数学的モデリングやシミュレーションは適切でなかったり、十分でなかったりする。したがって、過去30年間[vague]、多く の非定量化モデリング手法が開発されてきた。これらには以下が含まれる[要出典]。 メタゲーム分析やドラマ理論を含むステークホルダーベースのアプローチ 形態素解析や様々な形のインフルエンス・ダイアグラム 認知マッピング 戦略的選択 ロバストネス分析 |

| Societies and journals Societies The International Federation of Operational Research Societies (IFORS)[39] is an umbrella organization for operational research societies worldwide, representing approximately 50 national societies including those in the US,[40] UK,[41] France,[42] Germany, Italy,[43] Canada,[44] Australia,[45] New Zealand,[46] Philippines,[47] India,[48] Japan and South Africa.[49] For the institutionalization of Operations Research, the foundation of IFORS in 1960 was of decisive importance, which stimulated the foundation of national OR societies in Austria, Switzerland and Germany. IFORS held important international conferences every three years since 1957.[50] The constituent members of IFORS form regional groups, such as that in Europe, the Association of European Operational Research Societies (EURO).[51] Other important operational research organizations are Simulation Interoperability Standards Organization (SISO)[52] and Interservice/Industry Training, Simulation and Education Conference (I/ITSEC)[53] In 2004, the US-based organization INFORMS began an initiative to market the OR profession better, including a website entitled The Science of Better[54] which provides an introduction to OR and examples of successful applications of OR to industrial problems. This initiative has been adopted by the Operational Research Society in the UK, including a website entitled Learn About OR.[55] Journals of INFORMS The Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS) publishes thirteen scholarly journals about operations research, including the top two journals in their class, according to 2005 Journal Citation Reports.[56] They are: Decision Analysis[57] Information Systems Research[58] INFORMS Journal on Computing[59] INFORMS Transactions on Education[60] (an open access journal) Interfaces[61] Management Science Manufacturing & Service Operations Management Marketing Science Mathematics of Operations Research Operations Research Organization Science[62] Service Science[63] Transportation Science Other journals These are listed in alphabetical order of their titles. 4OR-A Quarterly Journal of Operations Research: jointly published the Belgian, French and Italian Operations Research Societies (Springer); Decision Sciences published by Wiley-Blackwell on behalf of the Decision Sciences Institute European Journal of Operational Research (EJOR): Founded in 1975 and is presently[when?] by far the largest operational research journal in the world, with its around 9,000 pages of published papers per year. In 2004, its total number of citations was the second largest amongst Operational Research and Management Science journals; INFOR Journal: published and sponsored by the Canadian Operational Research Society; Journal of Defense Modeling and Simulation (JDMS): Applications, Methodology, Technology: a quarterly journal devoted to advancing the science of modeling and simulation as it relates to the military and defense.[64] Journal of the Operational Research Society (JORS): an official journal of The OR Society; this is the oldest continuously published journal of OR in the world, published by Taylor & Francis; Military Operations Research (MOR): published by the Military Operations Research Society; Omega - The International Journal of Management Science; Operations Research Letters; Opsearch: official journal of the Operational Research Society of India; OR Insight: a quarterly journal of The OR Society published by Palgrave;[65] Pesquisa Operacional, the official journal of the Brazilian Operations Research Society Production and Operations Management, the official journal of the Production and Operations Management Society TOP: the official journal of the Spanish Statistics and Operations Research Society.[66] |

学会とジャーナル 学会 国際オペレーションズリサーチ学会連合(IFORS)[39]は、世界中のオペレーションズリサーチ学会の統括組織であり、米国、[40]英国、[41] フランス、[42]ドイツ、イタリア、[43]カナダ、[44]オーストラリア、[45]ニュージーランド、[46]フィリピン、[47]インド、 [48]日本、南アフリカの学会を含む約50の国民学会を代表している。 [オペレーションズリサーチの制度化にとって、1960年のIFORSの設立は決定的に重要であり、オーストリア、スイス、ドイツの国民OR協会の設立を 促した。IFORSは1957年以来、3年ごとに重要な国際会議を開催している[50]。IFORSの構成メンバーは、欧州の欧州オペレーションズリサー チ学会連合(EURO)のような地域グループを形成している[51]。その他の重要なオペレーションズリサーチ組織としては、シミュレーション相互運用性 標準化機構(SISO)[52]、インターサービス/産業訓練・シミュレーション・教育会議(I/ITSEC)[53]がある。 2004年には、米国を拠点とする組織であるINFORMSが、ORの専門職をよりよく売り込むためのイニシアチブを開始し、「The Science of Better」[54]と題するウェブサイトを開設した。このイニシアチブは英国のOR学会でも採用されており、「Learn About OR」と題されたウェブサイトがある[55]。 INFORMSのジャーナル INFORMS(Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences)は、オペレーションズ・リサーチに関する13の学術誌を発行しており、2005年のJournal Citation Reportsによれば、その中のトップ2の学術誌が含まれている[56]: 意思決定分析[57] 情報システム研究[58] INFORMS Journal on Computing[59]である。 INFORMS Transactions on Education[60](オープンアクセスジャーナル) インターフェイス[61] マネジメントサイエンス 製造・サービスオペレーション管理 マーケティング科学 オペレーションズリサーチの数学 オペレーションズ・リサーチ 組織科学[62] サービス科学[63] 交通科学 その他のジャーナル タイトルのアルファベット順に並べる。 4OR-A Quarterly Journal of Operations Research:ベルギー、フランス、イタリアのオペレーションズ・リサーチ学会が共同で発行している(Springer); Decision Sciences:Decision Sciences Instituteの委託を受け、Wiley-Blackwellから出版されている。 European Journal of Operational Research (EJOR): 1975年に創刊され、年間約9,000ページの論文を掲載する、現在[いつ?]世界最大のオペレーションズ・リサーチ誌である。2004年の総引用回数 は、オペレーショナル・リサーチおよびマネジメント・サイエンス誌の中で第2位であった; INFORジャーナル:カナダ運用研究協会が発行・後援する; Journal of Defense Modeling and Simulation (JDMS): Applications, Methodology, Technology:軍事・防衛に関連するモデリングとシミュレーションの科学を発展させることを目的とした季刊誌[64]。 ジャーナル・オブ・オペレーショナル・リサーチ・ソサエティ(JORS):OR ソサエティの機関誌; Military Operations Research (MOR):軍事オペレーションズ・リサーチ学会発行; オメガ:国際経営科学ジャーナル; オペレーションズ・リサーチ・レターズ Opsearch:インドオペレーションズ・リサーチ学会の機関誌; ORインサイト:パルグレイブが発行するOR学会の季刊誌[65]。 Pesquisa Operacional:ブラジル・オペレーションズ・リサーチ学会の機関誌。 Pesquisa Operacional:ブラジルオペレーションズ・リサーチ学会の機関誌。 TOP: スペイン統計・オペレーションズ学会機関誌[66]。 |

Operations research topics Black box analysis Dynamic programming Inventory theory Optimal maintenance Real options valuation Artificial intelligence Operations researchers Operations researchers (category) George Dantzig Leonid Kantorovich Tjalling Koopmans Russell L. Ackoff Stafford Beer Alfred Blumstein C. West Churchman William W. Cooper Robert Dorfman Richard M. Karp Ramayya Krishnan Frederick W. Lanchester Thomas L. Magnanti Alvin E. Roth Peter Whittle Related fields Behavioral operations research Big data Business engineering Business process management Database normalization Engineering management Geographic information systems Industrial engineering Industrial organization Managerial economics Military simulation Operational level of war Power system simulation Project production management Reliability engineering Scientific management Search-based software engineering Simulation modeling Strategic management Supply chain engineering System safety Wargaming |

オペレーションズ・リサーチのトピック ブラックボックス分析 動的計画法 在庫理論 最適メンテナンス リアルオプション評価 人工知能 オペレーションズ研究者 オペレーションズ研究者(カテゴリ) ジョージ・ダンツィヒ レオニード・カントロヴィッチ ティヤリング・クープマンス ラッセル・L・アッコフ スタフォード・ビア アルフレッド・ブラムシュタイン C. ウェスト・チャーチマン ウィリアム・W・クーパー ロバート・ドーフマン リチャード・M・カープ ラマイヤ・クリシュナン フレデリック・W・ランチェスター トーマス・L・マグナンティ アルビン・E・ロス ピーター・ウィトル 関連分野 行動オペレーションズリサーチ ビッグデータ ビジネスエンジニアリング ビジネスプロセス管理 データベース正規化 エンジニアリング・マネジメント 地理情報システム 経営工学 産業組織 経営経済学 軍事シミュレーション 戦争の作戦レベル 電力系統シミュレーション プロジェクト生産管理 信頼性工学 科学的管理 検索ベースのソフトウェア工学 シミュレーションモデリング 戦略的マネジメント サプライチェーンエンジニアリング システム安全性 ウォーゲーム |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operations_research |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆