社会の起源

Origins of society

☆ 社会の発生、すなわち人間特有の社会組織の進化的な出現は、進化生物学、人類学、先史学、旧石器時代考古学において重要なテーマである[1][2]。確か なことはほとんど知られていないが、ホッブズ[3]やルソー[4]以来、哲学的、道徳的、進化論的な疑問が何度も何度も投げかけられ、議論が繰り返されて きた。

| The origins of society

— the evolutionary emergence of distinctively human social organization

— is an important topic within evolutionary biology, anthropology,

prehistory and palaeolithic archaeology.[1][2] While little is known

for certain, debates since Hobbes[3] and Rousseau[4] have returned

again and again to the philosophical, moral and evolutionary questions

posed. |

社会の発生、すなわち

人間特有の社会組織の進化的な出現は、進化生物学、人類学、先史学、旧石器時代考古学において重要なテーマである[1][2]。確かなことはほとんど知ら

れていないが、ホッブズ[3]やルソー[4]以来、哲学的、道徳的、進化論的な疑問が何度も何度も投げかけられ、議論が繰り返されてきた。 |

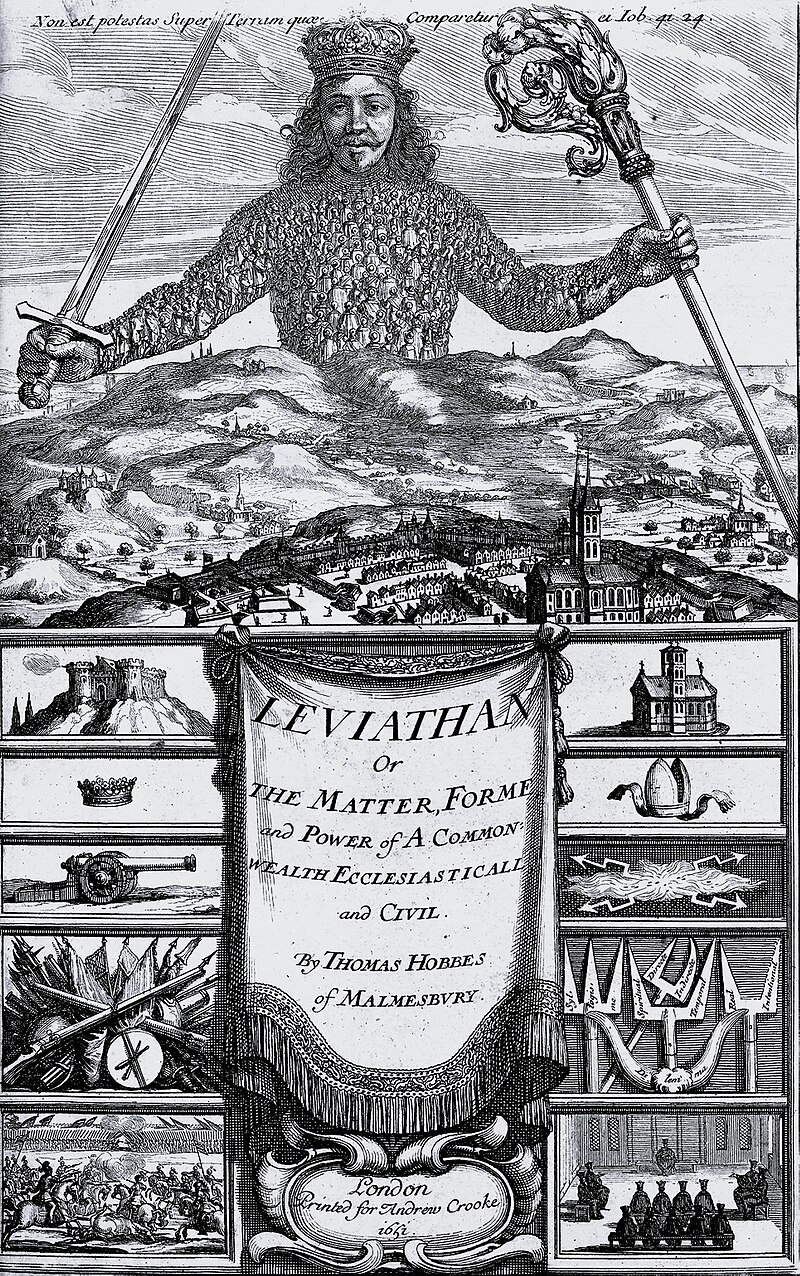

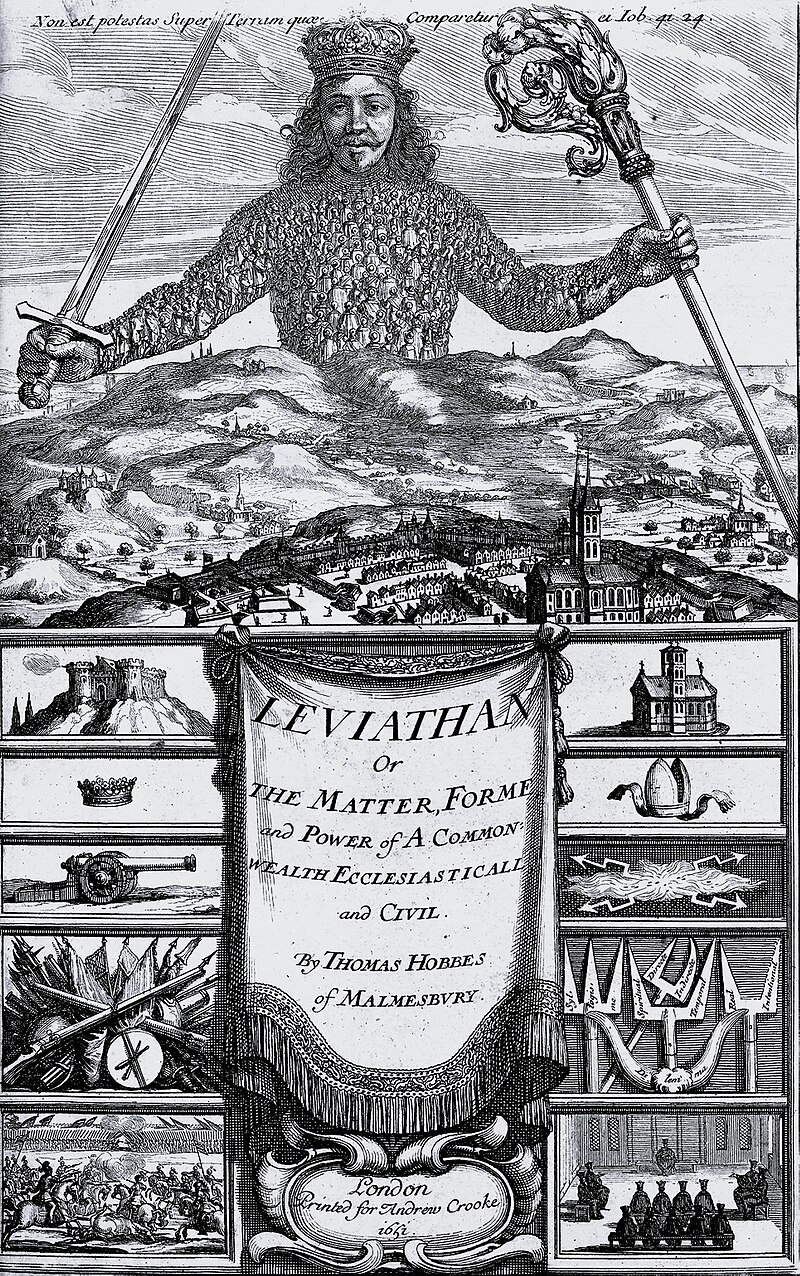

| Social origins in nature Origin of social groups Thomas Hobbes  Frontispiece of "Leviathan," by Abraham Bosse, with input from Hobbes Arguably the most influential theory of human social origins is that of Thomas Hobbes, who in his Leviathan[5] argued that without strong government, society would collapse into Bellum omnium contra omnes — "the war of all against all": In such condition, there is no place for industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving, and removing, such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. — "Chapter XIII: Of the Natural Condition of Mankind As Concerning Their Felicity, and Misery.", Leviathan Hobbes' innovation was to attribute the establishment of society to a founding 'social contract', in which the Crown's subjects surrender some part of their freedom in return for security. If Hobbes' idea is accepted, it follows that society could not have emerged prior to the state. This school of thought has remained influential to this day.[6] Prominent in this respect is British archaeologist Colin Renfrew (Baron Renfrew of Kaimsthorn), who points out that the state did not emerge until long after the evolution of Homo sapiens. The earliest representatives of our species, according to Renfrew, may well have been anatomically modern, but they were not yet cognitively or behaviourally modern. For example, they lacked political leadership, large-scale cooperation, food production, organised religion, law or symbolic artefacts. Humans were simply hunter-gatherers, who — much like extant apes — ate whatever food they could find in the vicinity. Renfrew controversially suggests that hunter-gatherers to this day think and socialise along lines not radically different from those of their nonhuman primate counterparts. In particular, he says that they do not "ascribe symbolic meaning to material objects" and for that reason "lack fully developed 'mind.'"[citation needed] However, hunter-gatherer ethnographers emphasise that extant foraging peoples certainly do have social institutions — notably institutionalised rights and duties codified in formal systems of kinship.[7] Elaborate rituals such as initiation ceremonies serve to cement contracts and commitments, quite independently of the state.[8] Other scholars would add that insofar as we can speak of "human revolutions" — "major transitions" in human evolution[9] — the first was not the Neolithic Revolution but the rise of symbolic culture that occurred toward the end of the Middle Stone Age.[10][11] Arguing the exact opposite of Hobbes's position, anarchist anthropologist Pierre Clastres views the state and society as mutually incompatible: genuine society is always struggling to survive against the state.[12] Jean-Jacques Rousseau  Rousseau in 1753 Like Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued that society was born in a social contract. In Rousseau's case, however, sovereignty is vested in the entire populace, who enter into the contract directly with one another. "The problem", he explained, "is to find a form of association which will defend and protect with the whole common force the person and goods of each associate, and in which each, while uniting himself with all, may still obey himself alone, and remain as free as before." This is the fundamental problem of which the Social Contract provides the solution. The contract's clauses, Rousseau continued, may be reduced to one — "the total alienation of each associate, together with all his rights, to the whole community. Each man, in giving himself to all, gives himself to nobody; and as there is no associate over whom he does not acquire the same right as he yields others over himself, he gains an equivalent for everything he loses, and an increase of force for the preservation of what he has". In other words: "Each of us puts his person and all his power in common under the supreme direction of the general will, and, in our corporate capacity, we receive each member as an indivisible part of the whole." At once, in place of the individual personality of each contracting party, this act of association creates a moral and collective body, composed of as many members as the assembly contains votes, and receiving from this act its unity, its common identity, its life and its will.[13] By this means, each member of the community acquires not only the capacities of the whole but also, for the first time, rational mentality: The passage from the state of nature to the civil state produces a very remarkable change in man, by substituting justice for instinct in his conduct, and giving his actions the morality they had formerly lacked. Then only, when the voice of duty takes the place of physical impulses and right of appetite, does man, who so far had considered only himself, find that he is forced to act on different principles, and to consult his reason before listening to his inclinations. — Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract and Discourses. Trans. G. D. H. Cole. New edition. London & Melbourne: Dent. Book I Ch. 8. Sir Henry Sumner Maine In his influential book, Ancient Law (1861), Maine argued that in early times, the basic unit of human social organisation was the patriarchal family:  Sir Henry James Sumner Maine The effect of the evidence derived from comparative jurisprudence is to establish the view of the primeval condition of the human race which is known as the Patriarchal Theory. — Maine, H. S. 1861. Ancient Law. London: John Murray. p. 122. Hostile to French revolutionary and other radical social ideas, Maine's motives were partly political. He sought to undermine the legacy of Rousseau and other advocates of man's natural rights by asserting that originally, no one had any rights at all – ‘every man, living during the greater part of his life under the patriarchal despotism, was practically controlled in all his actions by a regimen not of law but of caprice’.[14] Not only were the patriarch's children subject to what Maine calls his ‘despotism’: his wife and his slaves were equally affected. The very notion of kinship, according to Maine, was simply a way of categorizing those who were forcibly subjected to the despot's arbitrary rule. Maine later added a Darwinian strand to this argument. In his The Descent of Man, Darwin had cited reports that a wild-living male gorilla would monopolise for itself as large a harem of females as it could violently defend. Maine endorsed Darwin's speculation that ‘primeval man’ probably 'lived in small communities, each with as many wives as he could support and obtain, whom he would have jealously guarded against all other men’.[15] Under pressure to spell out exactly what he meant by the term 'patriarchy', Maine clarified that ‘sexual jealousy, indulged through power, might serve as a definition of the Patriarchal Family’.[16] Lewis Henry Morgan  Lewis H. Morgan In his influential book, Ancient Society (1877), its title echoing Maine's Ancient Law, Lewis Henry Morgan proposed a very different theory. Morgan insisted that throughout the earlier periods of human history, neither the state nor the family existed. It may be here premised that all forms of government are reducible to two general plans, using the word plan in its scientific sense. In their bases the two are fundamentally distinct. The first, in the order of time, is founded upon persons, and upon relations purely personal, and may be distinguished as a society (societas). The gens is the unit of this organization; giving as the successive stages of integration, in the archaic period, the gens, the phratry, the tribe, and the confederacy of tribes, which constituted a people or nation (populus). At a later period a coalescence of tribes in the same area into a nation took the place of a confederacy of tribes occupying independent areas. Such, through prolonged ages, after the gens appeared, was the substantially universal organization of ancient society; and it remained among the Greeks and Romans after civilization supervened. The second is founded upon territory and upon property, and may be distinguished as a state (civitas). — Morgan, L. H. 1877. Ancient Society. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr, p. 6. In place of both family and state, according to Morgan, was the gens — nowadays termed the 'clan' — based initially on matrilocal residence and matrilineal descent. This aspect of Morgan's theory, later endorsed by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, is nowadays widely considered discredited (but for a critical survey of the current consensus, see Knight 2008, 'Early Human Kinship Was Matrilineal'[17]). Friedrich Engels  Friedrich Engels Friedrich Engels built on Morgan's ideas in his 1884 essay, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State in the light of the researches of Lewis Henry Morgan. His primary interest was the position of women in early society, and — in particular — Morgan's insistence that the matrilineal clan preceded the family as society's fundamental unit. 'The mother-right gens', wrote Engels in his survey of contemporary historical materialist scholarship, 'has become the pivot around which the entire science turns...' Engels argued that the matrilineal clan represented a principle of self-organization so vibrant and effective that it allowed no room for patriarchal dominance or the territorial state. The first class antagonism which appears in human history coincides with the development of the antagonism between man and woman in monogamian marriage, and the first class oppression with that of the female sex by the male. — Engels, F. 1940 [1884] The origin of the family, private property and the state. London: Lawrence and Wishart. Emile Durkheim  Émile Durkheim Emile Durkheim considered that in order to exist, any human social system must counteract the natural tendency for the sexes to promiscuously conjoin. He argued that social order presupposes sexual morality, which is expressed in prohibitions against sex with certain people or during certain periods — in traditional societies particularly during menstruation. One first fact is certain: that is, that the entire system of prohibitions must strictly conform to the ideas that primitive man had about menstruation and about menstrual blood. For all these taboos start only with the onset of puberty: and it is only when the first signs of blood appear that they reach their maximum rigour. — Durkheim, E. 1963 [1898]. La prohibition de l'inceste et ses origines. L'Année Sociologique 1: 1–70. Reprinted as Incest. The nature and origin of the taboo, trans. E. Sagarin. New York: Stuart, p. 81. The incest taboo, wrote Durkheim in 1898, is no more than a particular example of something more basic and universal - the ritualistic setting apart of 'the sacred' from 'the profane'. This begins as the segregation of the sexes, each of which - at least on important occasions - is 'sacred' or 'set apart' from the other. 'The two sexes', as Durkheim explains, 'must avoid each other with the same care as the profane flees from the sacred and the sacred from the profane.' Women as sisters act out the role of 'sacred' beings invested 'with an isolating power of some sort, a power which holds the masculine population at a distance.' Their menstrual blood in particular sets them in a category apart, exercising a 'type of repulsing action which keeps the other sex far from them'. In this way, the earliest ritual structure emerges — establishing morally regulated 'society' for the first time.[18] Sigmund Freud Charles Darwin pictured early human society as resembling that of apes, with one or more dominant males jealously guarding a harem of females.[19] In his myth of the 'Primal Horde', Sigmund Freud later took all this as his starting point but then postulated an insurrection mounted by the tyrant's own sons: All that we find there is a violent and jealous father who keeps all the females for himself and drives away his sons as they grow up…. One day the brothers who had been driven out came together, killed and devoured their father and so made an end of the patriarchal horde. — Freud, S. 1965 [1913]. Totem and Taboo. London: Routledge, p. 141. Following this, the band of brothers were about to take sexual possession of their mothers and sisters when suddenly they were overcome with remorse. In their contradictory emotional state, their dead father now became stronger than the living one had been. In memory of him, the brothers revoked their deed by forbidding the killing and eating of the 'totem' (as their father had now become) and renouncing their claim to the women who had just been set free. In this way, the two fundamental taboos of primitive society – not to eat the totem and not to marry one's sisters – were established for the first time. Marshall Sahlins A related but less dramatic version of Freud's 'sexual revolution' idea was proposed in 1960 by American social anthropologist Marshall Sahlins.[20] Somehow, he writes, the world of primate brute competition and sexual dominance was turned upside-down: The decisive battle between early culture and human nature must have been waged on the field of primate sexuality…. Among subhuman primates sex had organized society; the customs of hunters and gatherers testify eloquently that now society was to organize sex…. In selective adaptation to the perils of the Stone Age, human society overcame or subordinated such primate propensities as selfishness, indiscriminate sexuality, dominance and brute competition. It substituted kinship and co-operation for conflict, placed solidarity over sex, morality over might. In its earliest days it accomplished the greatest reform in history, the overthrow of human primate nature, and thereby secured the evolutionary future of the species. — Sahlins, M. D. 1960 The origin of society. Scientific American 203(3): 76–87. Christopher Boehm Once a prehistoric hunting band institutionalized a successful and decisive rebellion, and did away with the alpha-male role permanently... it is easy to see how this institution would have spread. — Boehm, C. 2000. Journal of Consciousness Studies 7, 1–2 pp. 79–101; p. 97. If we accept Rousseau's line of reasoning, no single dominant individual is needed to embody society, to guarantee security, or to enforce social contracts. The people themselves can do these things, combining to enforce the general will. A modern origins theory along these lines is that of evolutionary anthropologist Christopher Boehm. Boehm argues that ape social organisation tends to be despotic, typically with one or more dominant males monopolising access to the locally available females. But wherever there is dominance, we can also expect resistance. In the human case, resistance to being personally dominated intensified as humans used their social intelligence to form coalitions. Eventually, a point was reached when the costs of attempting to impose dominance became so high that the strategy was no longer evolutionarily stable, whereupon social life tipped over into 'reverse dominance' — defined as a situation in which only the entire community, on guard against primate-style individual dominance, is permitted to use force to suppress deviant behaviour.[21] Ernest Gellner Human beings, writes social anthropologist Ernest Gellner, are not genetically programmed to be members of this or that social order. You can take a human infant and place it into any kind of social order and it will function acceptably. What makes human society so distinctive is the fabulous range of quite different forms it takes across the world. Yet in any given society, the range of permitted behaviours is quite narrowly constrained. This is not owing to the existence of any externally imposed system of rewards and punishments. The constraints come from within — from certain compulsive moral concepts which members of the social order have internalised. The society installs these concepts in each individual's psyche in the manner first identified by Emile Durkheim, namely, by means of collective rituals such as initiation rites. Therefore, the problem of the origins of society boils down to the problem of the origins of collective ritual. How is a society established, and a series of societies diversified, whilst each of them is restrained from chaotically exploiting that wide diversity of possible human behaviour? A theory is available concerning how this may be done and it is one of the basic theories of social anthropology. The way in which you restrain people from doing a wide variety of things, not compatible with the social order of which they are members, is that you subject them to ritual. The process is simple: you make them dance around a totem pole until they are wild with excitement, and become jellies in the hysteria of collective frenzy; you enhance their emotional state by any device, by all the locally available audio-visual aids, drugs, music and so on; and once they are really high, you stamp upon their minds the type of concept or notion to which they subsequently become enslaved. — Gellner, E. 1988. Origins of Society. In A. C. Fabian (ed.), Origins. The Darwin College Lectures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.128–140; p. 130. Gender and origins This section may be unbalanced toward certain viewpoints. Please improve the article by adding information on neglected viewpoints, or discuss the issue on the talk page. (June 2020) Main article: Female cosmetic coalitions Feminist scholars — among them palaeoanthropologists Leslie Aiello and Camilla Power — take similar arguments a step further, arguing that any reform or revolution which overthrew male dominance must have been led by women. Evolving human females, Power and Aiello suggest, actively separated themselves from males on a periodic basis, using their own blood (and/or pigments such as red ochre) to mark themselves as fertile and defiant: The sexual division of labor entails differentiation of roles in food procurement, with logistic hunting of large game by males, co-operation and exchange of products. Our hypothesis is that symbolism arose in this context. To minimize energetic costs of travel, coalitions of women began to invest in home bases. To secure this strategy, women would have to use their attractive, collective signal of impending fertility in a wholly new way: by signalling refusal of sexual access except to males who returned "home" with provisions. Menstruation — real or artificial — while biologically the wrong time for fertile sex, is psychologically the right moment for focusing men's minds on imminent hunting, since it offers the prospect of fertile sex in the near future. — Power, C. and L. C. Aiello 1997. Female proto-symbolic strategies. In L. D. Hager (ed.), Women in Human Evolution. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 153–171; p. 159. In similar vein, anthropologist Chris Knight argues that Boehm's idea of a 'coalition of everyone' is hard to envisage, unless — along the lines of a modern industrial picket line — it was formed to co-ordinate 'sex-strike' action against badly behaving males: ....male dominance had to be overthrown because the unending prioritising of male short-term sexual interests could lead only to the permanence and institutionalisation of behavioural conflict between the sexes, between the generations and also between rival males. If the symbolic, cultural domain was to emerge, what was needed was a political collectivity — an alliance — capable of transcending such conflicts. ... Only the consistent defence and self-defence of mothers with their offspring could produce a collectivity embodying interests of a sufficiently broad, universalistic kind. — Knight, C. 1991. Blood Relations. Menstruation and the origins of culture. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, p. 514 In virtually all hunter-gatherer ethnographies, according to Knight, a persistent theme is that 'women like meat',[22] and that they determinedly use their collective bargaining power to motivate men to hunt for them and bring home their kills — on pain of exclusion from sex.[23][24] Arguments about women's crucial role in domesticating males — motivating them to cooperate — have also been advanced by anthropologists Kristen Hawkes,[25] Sarah Hrdy[26] and Bruce Knauft[27] among others. Meanwhile, other evolutionary scientists continue to envisage uninterrupted male dominance, continuity with primate social systems and the emergence of society on a gradualist basis without revolutionary leaps.[28] Sociobiological theories Robert Trivers I consider Trivers one of the great thinkers in the history of Western thought. It would not be too much of an exaggeration to say that he has provided a scientific explanation for the human condition: the intricately complicated and endlessly fascinating relationships that bind us to one another. — Steven Pinker on Robert Trivers In his 1985 book, Social Evolution,[29] Robert Trivers outlines the theoretical framework used today by most evolutionary biologists to understand how and why societies are established. Trivers sets out from the fundamental fact that genes survive beyond the death of the bodies they inhabit, because copies of the same gene may be replicated in multiple different bodies. From this, it follows that a creature should behave altruistically to the extent that those benefiting carry the same genes — 'inclusive fitness', as this source of cooperation in nature is termed.[30] Where animals are unrelated, cooperation should be limited to 'reciprocal altruism' or 'tit-for-tat'.[31] Where previously, biologists took parent-offspring cooperation for granted, Trivers predicted on theoretical grounds both cooperation and conflict — as when a mother needs to wean an existing baby (even against its will) in order to make way for another.[32] Previously, biologists had interpreted male infanticidal behaviour as aberrant and inexplicable or, alternatively, as a necessary strategy for culling excess population.[33] Trivers was able to show that such behaviour was a logical strategy by males to enhance their own reproductive success at the expense of conspecifics including rival males. Ape or monkey females whose babies are threatened have directly opposed interests, often forming coalitions to defend themselves and their offspring against infanticidal males.[34] Human society, according to Trivers, is unusual in that it involves the male of the species investing parental care in his own offspring — a rare pattern for a primate. Where such cooperation occurs, it's not enough to take it for granted: in Trivers' view we need to explain it using an overarching theoretical framework applicable to humans and nonhumans alike.[35] Everybody has a social life. All living creatures reproduce and reproduction is a social event, since at its bare minimum it involves the genetic and material construction of one individual by another. In turn, differences between individuals in the number of their surviving offspring (natural selection) is the driving force behind organic evolution. Life is intrinsically social and it evolves through a process of natural selection which is itself social. For these reasons social evolution refers not only to the evolution of social relationships between individuals but also to deeper themes of biological organization stretching from gene to community. — Robert Trivers, 1985. Social Evolution. Menlo Park, California: Benjamin/Cummings, p. vii. Robin Dunbar  Robin Dunbar Robin Dunbar originally studied gelada baboons in the wild in Ethiopia, and has done much to synthesise modern primatological knowledge with Darwinian theory into a comprehensive overall picture. The components of primate social systems 'are essentially alliances of a political nature aimed at enabling the animals concerned to achieve more effective solutions to particular problems of survival and reproduction'.[36] Primate societies are in essence 'multi-layered sets of coalitions'.[37] Although physical fights are ultimately decisive, the social mobilisation of allies usually decides matters and requires skills that go beyond mere fighting ability. The manipulation and use of coalitions demands sophisticated social — more precisely political — intelligence. Usually but not always, males exercise dominance over females. Even where male despotism prevails, females typically gang up with one another to pursue agendas of their own. When a male gelada baboon attacks a previously dominant rival so as to take over his harem, the females concerned may insist on their own say in the outcome. At various stages during the fighting, the females may 'vote' among themselves on whether to accept the provisional outcome. Rejection is signalled by refusing to groom the challenger; acceptance is signalled by going up to him and grooming him. According to Dunbar, the ultimate outcome of an inter-male 'sexual fight' always depends on the female 'vote'.[38] Dunbar points out that in a primate social system, lower-ranking females will typically suffer the most intense harassment. Consequently, they will be the first to form coalitions in self-defence. But maintaining commitment from coalition allies involves much time-consuming manual grooming, putting pressure on time-budgets. In the case of evolving humans, who were living in increasingly large groups, the costs would soon have outweighed the benefits — unless some more efficient way of maintaining relationships could be found. Dunbar argues that 'vocal grooming' — using the voice to signal commitment — was the time-saving solution adopted, and that this led eventually to speech. Dunbar goes on to suggest (citing evolutionary anthropologist Chris Knight[39][40]) that distinctively human society may have been evolved under pressure from female ritual and 'gossiping' coalitions established to dissuade males from fighting one another and instead cooperate in hunting for the benefit of the whole camp: If females formed the core of these early groups, and language evolved to bond these groups, it naturally follows that the early human females were the first to speak. This reinforces the suggestion that language was first used to create a sense of emotional solidarity between allies. Chris Knight has argued a passionate case for the idea that language first evolved to allow the females in these early groups to band together to force males to invest in them and their offspring, principally by hunting for meat. This would be consistent with the fact that, among modern humans, women are generally better at verbal skills than men, as well as being more skilful in the social domain. — Dunbar, R. I. M. 1996. Grooming, Gossip and the Evolution of Language. London: Faber and Faber, p. 149. Dunbar stresses that this is currently a minority theory among specialists in human origins — most still support the 'bison-down-at-the-lake' theory attributing early language and cooperation to the imperatives of men's activities such as hunting. Despite this, he argues that 'female bonding may have been a more powerful force in human evolution than is sometimes supposed'.[41] Although still controversial, the idea that female coalitions may have played a decisive role has subsequently received strong support from a number of anthropologists including Sarah Hrdy,[42] Camilla Power,[43] Ian Watts.[44] and Jerome Lewis.[45] It is also consistent with recent studies by population geneticists (see Verdu et al. 2013 [46] for Central African Pygmies; Schlebusch 2010[47] for Khoisan) showing a deep-time tendency to matrilocality among African hunter-gatherers. |

自然における社会起源 社会集団の起源 トマス・ホッブズ  アブラハム・ボスによる『リヴァイアサン』の扉絵。ホッブズの意見も反映されている 人間社会起源に関する理論の中で最も影響力があると考えられるのは、トマス・ホッブズの理論である。ホッブズは『リヴァイアサン』[5]の中で、強力な政府が存在しなければ、社会は「万人の万人に対する戦争」に崩壊すると主張した。 このような状況では、産業の余地はない。なぜなら、産業の成果は不確実であり、その結果、大地の文化も、航海も、海路で輸入される可能性のある商品の利用 も、広々とした建物も、移動や撤去に多くの力を必要とするものの移動手段も、 力が必要なものの移動や移動手段がない。地球の表面に関する知識がない。時間の概念がない。芸術がない。文字がない。社会がない。そして、何よりも悪いこ とに、絶え間ない恐怖と暴力的な死の危険がある。そして、人間の生活は孤独で貧しく、不快で野蛮で短く、悲惨である。 — 『リヴァイアサン』第13章「幸福と悲惨に関する人間の自然状態」 ホッブスの革新的な考え方は、社会の成立を「社会契約」という概念に帰することだった。この契約では、王の臣民は安全と引き換えに自由の一部を放棄する。 ホッブスの考え方が受け入れられるなら、国家以前に社会は存在し得なかったことになる。この学説は今日でも影響力を保っている[6]。この点において著名 な人物は、イギリスの考古学者コリン・レンフルー(カイムスホルン男爵レンフルー)である。レンフルーは、ホモ・サピエンスが進化してからかなり経ってか ら初めて国家が誕生したと指摘している。レンフルーによると、我々の種の最も古い代表者は、解剖学的には現代人であったかもしれないが、認知的・行動的に はまだ現代人ではなかった。例えば、政治的なリーダーシップ、大規模な協力関係、食糧生産、組織化された宗教、法律、象徴的な人工物などがなかった。人間 は、単に狩猟採集民であり、現存する類人猿と同様に、近所で手に入る食糧を何でも食べていた。レンフルーは、狩猟採集民は今日でも、霊長類とは根本的に異 なるわけではない考えや社会生活を送っていると、物議を醸すような主張をしている。特に、彼らは「物質的なものに象徴的な意味を付与しない」ため、「十分 に発達した『心』を持たない」とレンフルーは言う[出典が必要]。 しかし、狩猟採集民族の民族誌学者たちは、現存する採集民族には確かに社会制度が存在することを強調している。特に、正式な親族制度に規定された制度化さ れた権利と義務である[7]。例えば、イニシエーション・セレモニーのような精巧な儀式は、国家とは全く関係なく、契約や約束を固める役割を果たしている [8]。他の学者は、「人間の革命」について語ることができる限りにおいて、「人間の進化における大きな転換」[9]、つまり、最初のものは新石器革命で はなく、中石器時代の終わり頃に起こった象徴文化の台頭であったと付け加えるだろう[10][ 11] ホッブズの立場とは正反対の主張をする無政府主義の文化人類学者ピエール・クラストルは、国家と社会は互いに相容れないものであると捉えている。真の社会は常に国家に対して生き残りをかけて闘っているのだ。 ジャン=ジャック・ルソー  1753年のルソー ジャン=ジャック・ルソーはホッブスと同様に、社会は社会契約によって生まれたと主張した。しかし、ルソーの場合は主権は国民全体に与えられており、国民 は互いに直接契約を結ぶ。 「問題は、各構成員の個人と財産を全体の共同の力によって守り、保護する形態の結合を見つけ、各人が全体と結びつきながらも、自分自身だけに従い、以前と 同じように自由であり続けることである」と彼は説明している。これは『社会契約』が提示する根本的な問題であり、その解決策でもある。ルソーはさらに、こ の契約の条項は1つに集約できると述べた。「各構成員が、すべての権利とともに、共同体全体に対して完全に疎外されること」である。各人は、すべての人々 に自分自身を捧げることで、誰にも自分自身を捧げない。そして、自分が他の人々に与えるのと同じ権利を、自分に対して得られない構成員はいないため、失う ものすべてに対して等価のものを手に入れ、自分が持つものを維持するための力を得ることができる。言い換えれば、 「私たち一人一人が、個人の人格と全力を、一般意志の最高指導のもとに共有し、法人として、各構成員を全体の一部として不可分の存在として受け入れる」。 この結社の行為は、各契約当事者の個人的な人格に代わって、即座に、道徳的かつ集合的な体を生み出す。この体は、議会の投票権を持つ人数と同じ数のメン バーで構成され、この行為からその統一性、共通のアイデンティティ、生命、意志を受け取る[13]。この方法により、共同体の各メンバーは全体の能力だけ でなく、初めて合理的な精神性も獲得する。 自然状態から市民国家への移行は、人間の行動において本能を正義に置き換え、かつて欠けていた道徳性を行動に与えることによって、人間において非常に顕著 な変化をもたらす。そして、義務の声が肉体的衝動や食欲の権利に取って代わることで、それまで自分自身のことしか考えてこなかった人間は、異なる原則に 従って行動し、自分の本能に耳を傾ける前に理性を考慮しなければならないことに気づく。 — ジャン・ジャック・ルソー、『社会契約論』および『諸弁論』。G. D. H. コール訳。新装版。ロンドンおよびメルボルン:Dent。第1巻第8章。 ヘンリー・サマー・メイン卿 メインは、影響力のあった著書『古代法』(1861年)の中で、初期の人間の社会組織の基本単位は家父長制家族であったと主張した。  ヘンリー・ジェイムズ・サムナー・メイン卿 比較法学から得られた証拠の影響は、家父長制理論として知られる人類の原始的条件の概念を確立することである。 — メイン、H. S. 1861. Ancient Law. London: John Murray. p. 122. フランス革命やその他の急進的社会思想に敵対的であったメインの動機は、部分的に政治的なものであった。彼は、もともと人間は誰一人として権利を持ってい なかったと主張することで、ルソーやその他の自然権論者の遺産を弱体化させようとした。すなわち、「家父長的専制政治の下で人生の大部分を過ごした人間 は、法律ではなく気まぐれによって、すべての行動が実質的に管理されていた」[14]のである。家長の子供たちがメインが「専制政治」と呼ぶものに服従し ていただけでなく、彼の妻や奴隷たちも同様に影響を受けていた。メインによれば、親族という概念は、専制君主による恣意的な支配に強制的に服従させられた 人々を分類する方法に過ぎなかった。メインは後に、この議論にダーウィンの考え方を加えた。ダーウィンは『人間の由来』の中で、野生のゴリラのオスは、暴 力的に防衛できる限り多くのメスをハーレムとして独占するという報告を引用していた。メインは、ダーウィンの推測を肯定した。「原始人」はおそらく「小さ なコミュニティに住み、自分が養い、手に入れることができるだけの数の妻を持ち、他の男性から嫉妬深く守っていた」[15]。「家父長制」という言葉が何 を意味するのかを明確に説明するよう迫られたメインは、 「権力によって甘やかされた性的嫉妬は、父権制家族の定義として役立つかもしれない」と明言した[16]。 ルイス・ヘンリー・モーガン  Lewis H. Morgan ルイス・ヘンリー・モーガンは、影響力のあった著書『古代社会』(1877年)で、メインの『古代法』を思わせるタイトルを付け、全く異なる理論を提唱した。モーガンは、人類の歴史の初期には国家も家族も存在していなかったと主張した。 ここで前提としておくべきことは、あらゆる形態の政府は、科学的な意味で「計画」という言葉を使うならば、2つの一般的な計画に還元できるということであ る。 2つの計画は、その基盤において根本的に異なる。 まず、時間的な順序で言えば、1つ目は個人と純粋に個人的な関係に基づいており、社会(societas)として区別できる。ゲンスは、この組織の単位で あり、統合の段階として、原始時代にはゲンス、フラトリ、部族、部族連合があり、それらが国民や国家(ポピュラス)を構成していた。後期の時代には、独立 した地域を占める部族連合に代わって、同じ地域に住む部族が国家として統合された。このような組織は、長い年月を経て、氏族が出現した後、古代社会のほぼ 普遍的な組織となった。そして、文明が到来した後も、ギリシャ人やローマ人の間では存続していた。2つ目は、領土と財産を基盤としており、国家(シヴィタ ス)として区別される。 — モーガン、L. H. 1877. Ancient Society. シカゴ:チャールズ・H・カー、6ページ。 モーガンによると、氏族は家族と国家の両方の代わりとなるもので、現在では「氏族」と呼ばれている。氏族は、当初は母系居住と母系継承を基本としていた。 モーガンの理論のこの側面は、後にカール・マルクスとフリードリヒ・エンゲルスによって支持されたが、現在では広く信用されていないと考えられている(た だし、現在のコンセンサスに関する批判的な調査については、ナイト著 2008年『初期の人類親族関係は母系であった』[17]を参照)。 フリードリヒ・エンゲルス  フリードリヒ・エンゲルス フリードリヒ・エンゲルスは、1884年に発表した論文『家族の起源、私有財産、国家』で、ルイス・ヘンリー・モーガンの研究を踏まえ、モーガンの考えを 発展させた。彼の主な関心は、初期社会における女性の地位、特に、モーガンが主張した、母系氏族が社会の基本単位としての家族よりも先行していたという見 解であった。「母権氏族」は、エンゲルスが当時の唯物史観の学説を調査したうえで、「科学全体の軸となっている」と記している。エンゲルスは、母系氏族は 自己組織化の原則を体現しており、その原則は活力と効果に富むため、家父長制や領土国家の支配の余地を与えないと主張した。 人類史に初めて現れた階級対立は、一夫一婦制の結婚における男女の対立の進展と一致し、また、女性に対する男性による最初の階級的抑圧も一致している。 — エンゲルス、F. 1940 [1884]『家族・私有財産・国家の起源』。ロンドン:ローレンス・アンド・ウィシャート社。 エミール・デュルケーム  Émile Durkheim エミール・デュルケームは、人間の社会システムが存続するためには、男女が混交する自然な傾向を打ち消さなければならないと考えた。彼は、社会秩序は性的 道徳を前提としていると主張し、特定の相手や特定の期間における性行為を禁じることで、それを表現した。特に伝統的な社会では、月経期間中がそうであっ た。 まず間違いなく言えるのは、あらゆる禁止の体系は、原始人が月経や月経血について抱いていた考え方に厳密に従わなければならないということだ。というの も、これらのタブーはすべて思春期の始まりとともに始まるものであり、血の兆候が現れることで初めて、その厳格さが極限に達するからだ。 — デュルケーム、E. 1963 [1898]. La prohibition de l'inceste et ses origines. L'Année Sociologique 1: 1–70. Incest. The nature and origin of the taboo, trans. E. Sagarin. New York: Stuart, p. 81. 1898年にデュルケームは、近親相姦のタブーは、より基本的で普遍的なものの特定の例にすぎない、と書いている。これは、少なくとも重要な場面において は、それぞれが「神聖」または「隔離」されているという、男女の隔離から始まる。デュルケームが説明するように、「2つの性別」は、「神聖なものが神聖な ものから、神聖なものが俗悪なものから逃げるように、互いに同じ注意を払って避ける」必要がある。姉妹としての女性は、「何らかの隔離力、男性を遠ざける 力」を持つ「神聖な」存在の役割を演じる。特に月経の血は、彼女たちを特別なカテゴリーに位置づけ、「他性を遠ざけるような嫌悪感を引き起こす」作用を持 つ。このようにして、最も初期の儀式構造が現れ、初めて道徳的に規制された「社会」が確立された[18]。 ジークムント・フロイト チャールズ・ダーウィンは、初期のヒト社会を類人猿の社会に類似したものと捉え、1人または複数の支配的な男性が、女性たちのハーレムを嫉妬深く守ってい ると考えた[19]。ジークムント・フロイトは、後に「原始的群れ」の神話の中で、これを出発点として、暴君自身の息子たちによる反乱を仮定した。 そこで見いだされるのは、すべての女性を独占し、息子が成長するにつれ追い払う、暴力的で嫉妬深い父親だけである……。ある日、追い出された兄弟たちが力を合わせ、父親を殺して食い尽くし、父権的な一族に終止符を打った。 — フロイト、S. 1965 [1913]. Totem and Taboo. London: Routledge, p. 141. その後、兄弟たちは自分たちの母親や姉妹を性的に所有しようとしたが、突然後悔の念に駆られた。 矛盾した感情状態に陥った彼らは、死んだ父親がかつて生きていたときよりも強くなったと感じた。 父親を偲んで、兄弟たちは「トーテム」(父親がそうであったように)を殺したり食べたりすることを禁じ、解放されたばかりの女性たちに対する権利を放棄す ることで、自分たちの行為を取り消した。このようにして、原始社会の2つの基本的なタブー、すなわちトーテムを食べないことと姉妹と結婚しないことが初め て確立された。 マーシャル・サリンズ フロイトの「性的革命」の考えに関連しているが、それほど劇的ではないバージョンが、1960年にアメリカの社会人類学者マーシャル・サリンズによって提唱された[20]。サリンズは、何らかの理由で、霊長類の熾烈な競争と性的優位の世界がひっくり返ったと書いている。 初期文化と人間性の間の決定的な戦いは、霊長類の性という分野で行われたに違いない。…亜人類の霊長類では、性によって社会が組織されていた。狩猟採集民 の慣習は、今や社会が性を組織化していることを雄弁に物語っている。石器時代の危険に対する選択的適応において、人間社会は、利己心、無差別な性、支配 欲、そして残忍な競争といった霊長類の傾向を克服し、従属させた。それは、対立を親族関係と協力に置き換え、性よりも連帯を、力よりも道徳を重んじた。そ の黎明期において、人類は史上最大の改革、すなわち霊長類としての性質の打倒を成し遂げ、それによって種の進化的未来を確保した。 — Sahlins, M. D. 1960 The origin of society. Scientific American 203(3): 76–87. クリストファー・ボーエム かつて、先史時代の狩猟集団が成功を収めた決定的な反乱を制度化し、アルファオスの役割を永久に取り除いた...この制度がどのように広まったかは容易に想像できる。 — ボーエム、C. 2000. Journal of Consciousness Studies 7, 1–2 pp. 79–101; p. 97. ルソーの論理に従うなら、社会を体現し、安全を保証し、社会契約を強制するために、支配的な個人が一人必要とされることはない。 これらのことは、人々が力を合わせ、一般的な意志を強制することで実現できる。 このような考えに基づく現代的な起源説は、進化人類学者のクリストファー・ボーエムによるものである。 ボーエムは、類人猿の社会組織は専制的な傾向があり、通常、1匹または複数の支配的なオスが、その地域にいるメスへのアクセスを独占すると主張している。 しかし、支配が存在するところには必ず抵抗も存在する。人間の場合、人間が社会的知性を駆使して連合体を形成するにつれ、個人として支配されることへの抵 抗が強まった。やがて、支配を強制しようとするコストが極めて高くなり、その戦略がもはや進化的に安定しなくなった時点で、社会生活は「逆支配」へと転換 した。逆支配とは、霊長類のような個人の支配に警戒心を抱くコミュニティ全体が、逸脱行動を抑制するために武力を行使することが許される状況と定義される [21]。 アーネスト・ゲルナー 社会人類学者アーネスト・ゲルナーは、人間は遺伝的にこの社会秩序やあの社会秩序のメンバーになるようプログラムされているわけではないと書いている。人 間の乳児をどのような社会秩序の中に入れても、問題なく機能する。人間社会を特徴づけているのは、世界中で見られる全く異なる形態の素晴らしい多様性であ る。しかし、どの社会においても、許容される行動の範囲はかなり狭く制限されている。これは、外から押し付けられた報酬と罰のシステムが存在するからでは ない。制約は内側から生じる。つまり、社会秩序の成員が内面化した特定の強迫的な道徳概念から生じるのだ。社会は、エミール・デュルケームが最初に指摘し た方法、すなわち、通過儀礼などの集団儀礼を通じて、これらの概念を各個人の精神に植え付ける。したがって、社会発生の問題は、集団儀礼の発生の問題に集 約される。 社会はどのようにして成立し、また、一連の社会はどのようにして多様化していくのか。その一方で、それぞれの社会は、人間が行いうる可能性の多様性を無秩 序に悪用することから抑制されている。これをどのように行うかに関する理論があり、それは社会人類学の基礎理論の1つである。人々が、自分が所属する社会 秩序と相容れない多種多様なことを行うのを抑制する方法とは、儀式に従わせるということである。そのプロセスは単純である。彼らはトーテムポールを囲んで 踊り狂い、集団の熱狂の中で興奮のあまりぐったりするまで踊り続け、あらゆる手段、つまりその土地で入手可能なあらゆる視聴覚補助器具、薬物、音楽などを 使って彼らの感情状態をさらに高揚させ、彼らが本当にハイになったところで、彼らがその後奴隷となるような概念や観念を彼らの心に刻み込む。 — Gellner, E. 1988. 社会の起源。A. C. ファビアン編『起源。ダーウィン・カレッジ講義』。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版、128-140ページ、130ページ。 性別と起源 このセクションは特定の視点に偏っている可能性があります。無視されている視点に関する情報を追加するなどして記事を改善するか、トークページで議論してください。(2020年6月) メイン記事: 女性の化粧連合 フェミニスト学者たち(古人類学者のレスリー・アイエロやカミラ・パワーを含む)は、同様の議論をさらに一歩進め、男性の支配を覆す改革や革命は、女性が 主導したものでなければならないと主張している。 パワーとアイエロは、進化する人間の女性は、定期的に積極的に男性から自らを隔離し、自らの血(および/または赤土などの色素)を使って、生殖能力があり 反抗的であることを示す印をつけた、と示唆している。 性による労働分業は、食糧調達における役割の分化をもたらし、大型動物の狩猟は男性が担当し、製品の交換や共同作業は女性が行うという形になった。私たち の仮説は、象徴主義はこのような状況から生まれたというものである。移動にかかるエネルギーコストを最小限に抑えるため、女性たちは拠点となる場所を確保 し始めた。この戦略を成功させるには、女性は、生殖能力の高さを示す魅力的な集団的シグナルをまったく新しい方法で利用する必要があった。すなわち、食糧 を「持ち帰る」男性以外には性的接触を拒否するというシグナルを発することである。生理(本物であれ人工であれ)は生物学的には生殖可能なセックスをする には不適切な時期であるが、心理的には、近い将来生殖可能なセックスができるという見通しを与えるため、男性の注意を迫り来る狩りに集中させるには絶好の タイミングである。 — Power, C. and L. C. Aiello 1997. Female proto-symbolic strategies. In L. D. Hager (ed.), Women in Human Evolution. New York and London: 153-171 ページ、159 ページ。 同様の考え方を人類学者のクリス・ナイトは、ボーエムの「全員の連合」という考えは、現代の産業ピケットラインにならって、行儀の悪い男性に対する「セックスストライキ」行動を調整するために結成された場合を除き、想像しづらいと主張している。... 男性の支配は打ち倒されなければならなかった。なぜなら、男性の短期的な性的関心事を優先し続けることは、性差、世代間、またライバル男性間の行動上の対 立の永続化と制度化につながるだけだからである。象徴的、文化的領域が出現するのであれば、そのような対立を乗り越えることのできる政治的集合体、すなわ ち同盟が必要であった。... 母親とその子供たちの一貫した防衛と自衛のみが、十分に広範で普遍的な種類の利益を体現する集合体を生み出すことができる。 — ナイト、C. 1991. 血縁関係。月経と文化の起源。ニューヘブンおよびロンドン:イェール大学出版、514ページ ナイトによると、狩猟採集民族の民族誌では、ほぼすべてにおいて「女性は肉が好き」[22]というテーマが繰り返し取り上げられており、女性は集団交渉力 を利用して、男性たちに狩りをし、獲物を持ち帰るよう強く働きかけている。— セックスから排除されるという罰則を伴う[23][24]。また、男性を飼い慣らし、協力するように動機づけるという女性の重要な役割に関する議論は、人 類学者のクリステン・ホークス[25]、サラ・ハードィ[26]、ブルース・クナフト[27]らによっても進められてきた。一方、他の進化論の科学者たち は、革命的な飛躍を伴わない漸進的な社会の出現、霊長類の社会システムとの連続性、途切れることのない男性の優位性を想定し続けている[28]。 社会生物学説 ロバート・トリバース 私はトリバースを西洋思想史上の偉大な思想家の1人と考えている。人間という存在を科学的に説明しているといっても過言ではない。人間同士を結びつける複雑で無限に魅力的な関係性についてである。 — スティーブン・ピンカーによるロバート・トライバーズ評 ロバート・トライバーズは、1985年に出版した著書『Social Evolution(社会進化)』[29]の中で、進化生物学者たちが現在、社会がどのようにして、なぜ成立するのかを理解するために用いている理論的枠 組みの概要を述べている。トライバーズは、遺伝子は宿主となる生物の死後も生き続けるという基本的な事実から出発している。なぜなら、同じ遺伝子のコピー が複数の異なる生物体に複製される可能性があるからだ。このことから、利益を得る者が同じ遺伝子を持つ限り、生物は利他的行動を取るべきである、という結 論が導かれる。自然界における協力の源は「包括的適応度」と呼ばれる[30]。動物同士が血縁関係にない場合、協力は「相互利他主義」または「仕返し」に 限定されるべきである[31]。以前は、生物学者たちは親と子の協力関係を当然のこととしていたが、トリバースは理論的根拠に基づいて、協力と対立の両方 を予測した。母親が別の赤ちゃんを迎えるために、すでにいる赤ちゃんを(たとえ赤ちゃんが嫌がっても)断乳する必要がある場合などである[32]。それま では、生物学者は男性の幼児殺害行動を異常で不可解なもの、あるいは過剰な人口を削減するための必要な戦略として解釈していた[33]。トリバースは、そ のような行動が、ライバルである男性を含む同種を犠牲にして自らの繁殖成功を高めるための、男性による論理的な戦略であることを示すことができた。赤ん坊 が危険にさらされている類人猿や猿の雌は、直接対立する利害関係にあり、しばしば連合を組んで、子殺しをする雄から自分と自分の子供を守る[34]。 トリバースによると、人間の社会は、その種の雄が自分の子供に対して親のケアを注ぐという点で、霊長類としては珍しいパターンである点で異例である。この ような協力関係が存在する場合、それを当然のこととして受け入れるだけでは不十分である。トリバースの見解では、人間と非人間の両方に適用できる包括的な 理論的枠組みを用いてそれを説明する必要がある[35]。 誰もが社会生活を送っている。すべての生物は繁殖し、繁殖は社会的な出来事である。なぜなら、少なくとも、ある個体が別の個体によって遺伝的および物質的 に構築されるという側面があるからだ。そして、生き残った子孫の数における個体間の差異(自然淘汰)が、有機的進化の原動力となる。生命は本質的に社会的 であり、自然淘汰という社会的なプロセスを経て進化していく。こうした理由から、社会進化とは、個体間の社会関係だけでなく、遺伝子からコミュニティに至 る生物学的組織というより深いテーマをも指す。 — ロバート・トリバース、1985年。社会進化。カリフォルニア州メンローパーク: ベンジャミン/カミングス、p. vii. ロビン・ダンバー  ロビン・ダンバー ロビン・ダンバーはもともとエチオピアの野生のゲラダヒヒを研究し、ダーウィンの理論と現代霊長類学の知識を総合的な全体像として統合することに多大な貢 献をしてきた。霊長類の社会システムの構成要素は、「基本的に、生存と繁殖に関する特定の問題に対して、より効果的な解決策を実現することを目的とした政 治的性質の同盟である」[36]。霊長類の社会は本質的に「多層的な連合の集合体」[37]である。最終的には物理的な戦いが決定的となるが、通常、同盟 の社会的動員によって物事が決定され、単なる戦闘能力を超えたスキルが必要となる。連合の操作と利用には、洗練された社会的、より正確には政治的知性が求 められる。通常、オスがメスに対して優位性を示す。オスによる専制政治が支配的であっても、メスは通常、互いに団結して自分たちの目的を追求する。オスの ゲラダヒヒがハーレムを奪うために、それまで優位性を示していたライバルを攻撃した場合、関係するメスはその結果について自分たちの意見を主張するかもし れない。争いのさまざまな段階において、メスは暫定的な結果を認めるかどうかについて、自分たちで「投票」を行う。拒否は挑戦者をグルーミングしないこと で示され、受け入れは挑戦者に近づいてグルーミングすることで示される。ダンバーによると、オス同士の「性的争い」の最終的な結果は常にメスの「投票」次 第である[38]。 ダンバーは、霊長類の社会システムでは、下位のメスは通常最も激しい嫌がらせを受けると指摘している。その結果、彼女たちは自衛のために最初に連合体を形 成することになる。しかし、同盟国からの支持を維持するには、多くの時間を要する手によるグルーミングが必要となり、時間的制約にプレッシャーがかかる。 進化する人類の場合、ますます大きなグループで生活するようになると、そのコストはすぐに利益を上回るようになる。しかし、より効率的な人間関係の維持方 法が見つからない限り、この状況は変わらない。ダンバーは、「声によるグルーミング」、つまり声を使ってコミットメントを示すことが、時間節約の解決策と して採用され、これが最終的に言語へとつながったと主張している。ダンバーはさらに、進化人類学者クリス・ナイト[39][40]の説を引用しながら、人 間特有の社会は、女性による儀式や「噂話」の連合体から男性同士の争いをやめさせ、代わりに集団全体の利益のために狩りに協力するよう説得する圧力の下で 進化したのではないかと示唆している。 初期の集団の中心を女性が形成し、言語がこれらの集団を結びつけるために進化したのであれば、初期のヒトの女性が最初に話し始めたのは当然のことである。 これは、言語がまず同盟者間の感情的な連帯感を生み出すために使われたという説を裏付けるものである。クリス・ナイトは、初期のグループ内の女性が力を合 わせて、主に肉食による狩猟を通じて、男性とその子孫に投資をさせることを可能にするために、言語が最初に進化したという説を熱心に主張している。これ は、現代人において、一般的に女性は男性よりも言語能力に優れ、また社会的分野でもより有能であるという事実と一致する。 — Dunbar, R. I. M. 1996. Grooming, Gossip and the Evolution of Language. London: Faber and Faber, p. 149. ダンバーは、これは現在、人類起源の専門家たちの間では少数派説であると強調している。大半の専門家は、初期の言語と協力関係を、狩猟などの男性の活動上 の必要性から生じたとする「バイソン・ダウン・アット・ザ・レイク」説を支持している。それにもかかわらず、彼は「女性の結束は、時に想定されているより も、人類の進化においてより強力な力であった可能性がある」と主張している[41]。まだ議論の余地はあるものの、女性の連合が重要な役割を果たしたとす る考えは、その後、サラ・ハードィ[42]、カミラ・パワー[43]、イアン・ワッツ[44]、 また、ジェローム・ルイス[45]も同様の考え方を支持している。これは、アフリカの狩猟採集民に母系居住の傾向が長い歴史にわたって見られることを示 す、集団遺伝学者による最近の研究とも一致している(中央アフリカのピグミーについては Verdu et al. 2013 [46]、コイサンについては Schlebusch 2010[47] を参照)。 |

| Behavioral modernity Generative anthropology Origin of speech Origin of language Sociocultural evolution |

行動の現代性 生成人類学 言語の起源 言語の起源 社会文化の進化 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Origins_of_society |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆