オタ・ベンガ

Ota Benga, c.1883-March 20, 1916

☆ オタ・ベンガ(1883年頃[2] - 1916年3月20日)は、1904年にミズーリ州セントルイスで開催されたルイジアナ・パーチェス博覧会の展示や、1906年にブロンクス動物園で開催 された人間動物園の展示に登場したことで知られるムブティ(コンゴのピグミー)人である。ベンガはアフリカ先住民の奴隷商人から、博覧会用のアフリカ人を 探していた実業家サミュエル・フィリップス・ヴァーナー[3]によって買い取られ、アメリカに連れて行かれた。ブロンクス動物園にいる間、ベンガは動物園 のモンキーハウスに展示される前と後に敷地内を散歩することが許された。ベンガはオランウータンと一緒の檻に入れられたが、これは彼の人間性を傷つけるも のであり、社会ダーウィニズムを助長するものとみなされた[4]。 原始的なイメージを高めるため、そしておそらく猿から身を守るために、彼には機能的な弓矢が与えられた。セントルイスの博覧会終了後、ヴァーナーとともに アフリカを短期間訪れた以外は、ベンガは残りの生涯をアメリカ、主にヴァージニアで過ごした。 国民各地のアフリカ系アメリカ人の新聞は、ベンガの処遇に強く反対する社説を掲載した。黒人教会の代表団のスポークスマンであるロバート・スチュアート・ マッカーサーは、ニューヨーク市長のジョージ・B・マクレラン・ジュニアにブロンクス動物園からの解放を嘆願した。1906年末、市長はベンガをブルック リンのハワード黒人孤児院を監督していたジェームズ・H・ゴードンに保護した。 1910年、ゴードンはベンガがバージニア州リンチバーグで保護されるよう手配し、衣服代と削った歯にキャップを被せる費用を支払った。こうすることで、 ベンガは地元の社会に受け入れられやすくなった。ベンガは英語の手ほどきを受け、リンチバーグのタバコ工場で働き始めた。 彼はアフリカに戻ろうとしたが、1914年に第一次世界大戦が勃発し、旅客船の旅はすべて中止された。ベンガはうつ病を発症し、1916年に自殺した [6]。

| Ota Benga

(c. 1883[2] – March 20, 1916) was a Mbuti (Congo pygmy) man, known for

being featured in an exhibit at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition

in St. Louis, Missouri, and as a human zoo exhibit in 1906 at the Bronx

Zoo. Benga had been purchased from native African slave traders by the

explorer Samuel Phillips Verner,[3] a businessman searching for African

people for the exhibition, who took him to the United States. While at

the Bronx Zoo, Benga was allowed to walk the grounds before and after

he was exhibited in the zoo's Monkey House. Benga was placed in a cage

with an orangutan, regarded as both an offense to his humanity and a

promotion of social Darwinism.[4] To enhance the primitive image and presumably protect himself if need be from the ape, he was given a functional bow and arrow. He used this instead to shoot at visitors who mocked him and partially as a result of this the exhibition was ended.[5] Except for a brief visit to Africa with Verner after the close of the St. Louis fair, Benga lived in the United States, mostly in Virginia, for the rest of his life. African-American newspapers around the nation published editorials strongly opposing Benga's treatment. Robert Stuart MacArthur, spokesman for a delegation of black churches, petitioned New York City Mayor George B. McClellan Jr. for his release from the Bronx Zoo. In late 1906, the mayor released Benga to the custody of James H. Gordon, who supervised the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn. In 1910, Gordon arranged for Benga to be cared for in Lynchburg, Virginia, where he paid for his clothes and to have his sharpened teeth capped. This would enable Benga to be more readily accepted in local society. Benga was tutored in English and began to work at a Lynchburg tobacco factory. He tried to return to Africa, but the outbreak of World War I in 1914 stopped all passenger ship travel. Benga developed depression and died by suicide in 1916.[6] |

オタ・ベンガ(1883年頃[2] -

1916年3月20日)は、1904年にミズーリ州セントルイスで開催されたルイジアナ・パーチェス博覧会の展示や、1906年にブロンクス動物園で開催

された人間動物園の展示に登場したことで知られるムブティ(コンゴのピグミー)人である。ベンガはアフリカ先住民の奴隷商人から、博覧会用のアフリカ人を

探していた実業家サミュエル・フィリップス・ヴァーナー[3]によって買い取られ、アメリカに連れて行かれた。ブロンクス動物園にいる間、ベンガは動物園

のモンキーハウスに展示される前と後に敷地内を散歩することが許された。ベンガはオランウータンと一緒の檻に入れられたが、これは彼の人間性を傷つけるも

のであり、社会ダーウィニズムを助長するものとみなされた[4]。 原始的なイメージを高めるため、そしておそらく猿から身を守るために、彼には機能的な弓矢が与えられた。セントルイスの博覧会終了後、ヴァーナーとともに アフリカを短期間訪れた以外は、ベンガは残りの生涯をアメリカ、主にヴァージニアで過ごした。 国民各地のアフリカ系アメリカ人の新聞は、ベンガの処遇に強く反対する社説を掲載した。黒人教会の代表団のスポークスマンであるロバート・スチュアート・ マッカーサーは、ニューヨーク市長のジョージ・B・マクレラン・ジュニアにブロンクス動物園からの解放を嘆願した。1906年末、市長はベンガをブルック リンのハワード黒人孤児院を監督していたジェームズ・H・ゴードンに保護した。 1910年、ゴードンはベンガがバージニア州リンチバーグで保護されるよう手配し、衣服代と削った歯にキャップを被せる費用を支払った。こうすることで、 ベンガは地元の社会に受け入れられやすくなった。ベンガは英語の手ほどきを受け、リンチバーグのタバコ工場で働き始めた。 彼はアフリカに戻ろうとしたが、1914年に第一次世界大戦が勃発し、旅客船の旅はすべて中止された。ベンガはうつ病を発症し、1916年に自殺した [6]。 |

| Early life As a member of the Mbuti people,[7] Ota Benga lived in equatorial forests near the Kasai River in what was then the Congo Free State. His people were attacked by the Force Publique, established by King Leopold II of Belgium as a militia to oppress the local people and communities, most of whom were used as forced laborers in the extraction and exploitation of Congo's massive supply of rubber.[8] Benga's wife and two children were slaughtered; he survived because he was on a hunting expedition when the Force Publique attacked his village. He was later captured by slave traders from the enemy "Baschelel" (Bashilele) tribe.[4][9] In 1904, American businessman and explorer Samuel Phillips Verner traveled to Africa,[10] under contract from the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, to bring back an assortment of pygmies to be part of an exhibition.[11] Verner came across Benga while en route to a Batwa pygmy village visited previously. He purchased Benga from the Bashilele slave traders, giving them a pound of salt and a bolt of cloth in exchange.[12][4] Verner later claimed he had rescued Benga from cannibals.[13] The two spent several weeks together before reaching the Batwa village. The villagers did not trust the muzungu ("white man"). Verner was unable to recruit any villagers to join him for travel to the United States until Benga said that the muzungu had saved his life, and spoke of the bond that had grown between them and his own curiosity about the world Verner came from. Four Batwa, all male, ultimately decided to accompany them. Verner also recruited other Africans who were not pygmies: five men from the Bakuba, including the son of King Ndombe, ruler of the Bakuba; and other related peoples.[14][15] |

生い立ち ムブティ族の一員として[7]、オタ・ベンガは当時のコンゴ自由国のカサイ川近くの赤道直下の森林に住んでいた。ベルギー国王レオポルド2世が民兵組織と して設立したフォース・ピュブリックは、コンゴに大量に供給されるゴムの採掘と搾取のための強制労働者として、地元の人々とコミュニティを抑圧するために 設立された[8]。その後、彼は敵対する「バシェレル」(バシレレ)部族の奴隷商人に捕らえられた[4][9]。 1904年、アメリカの実業家で探検家のサミュエル・フィリップス・ヴァーナーは、ルイジアナ・パーチェス博覧会[10]の契約により、ピグミーの品々を 展示会の一部として持ち帰るためにアフリカを訪れた[11]。彼はバシレレの奴隷商人からベンガを購入し、引き換えに塩1ポンドと布1反を渡した[12] [4]。後にヴァーナーはベンガを人食い人種から救い出したと主張した[13]。 2人はバトワの村に着くまで数週間を共に過ごした。村人たちはムズング(「白人」)を信用していなかった。ヴァーナーは、ベンガがムズングに命を救われた と言い、二人の間に芽生えた絆とヴァーナーが来た世界についての好奇心について話すまで、アメリカへの旅に参加してくれる村人を集めることができなかっ た。最終的に4人のバトワ(全員男性)が同行することになった。ヴァーナーはピグミーではない他のアフリカ人、バクバの支配者であるンドンベ王の息子を含 むバクバ出身の5人の男、その他の関連民族も勧誘した[14][15]。 |

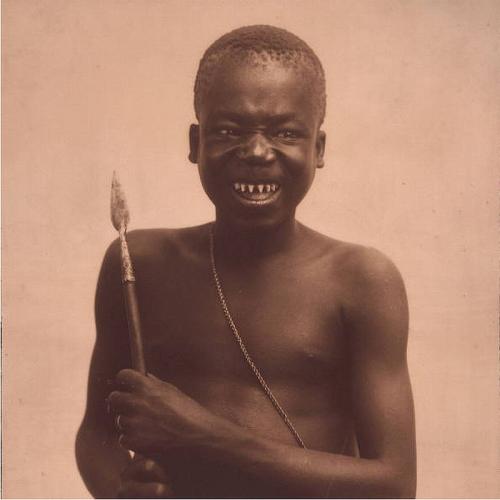

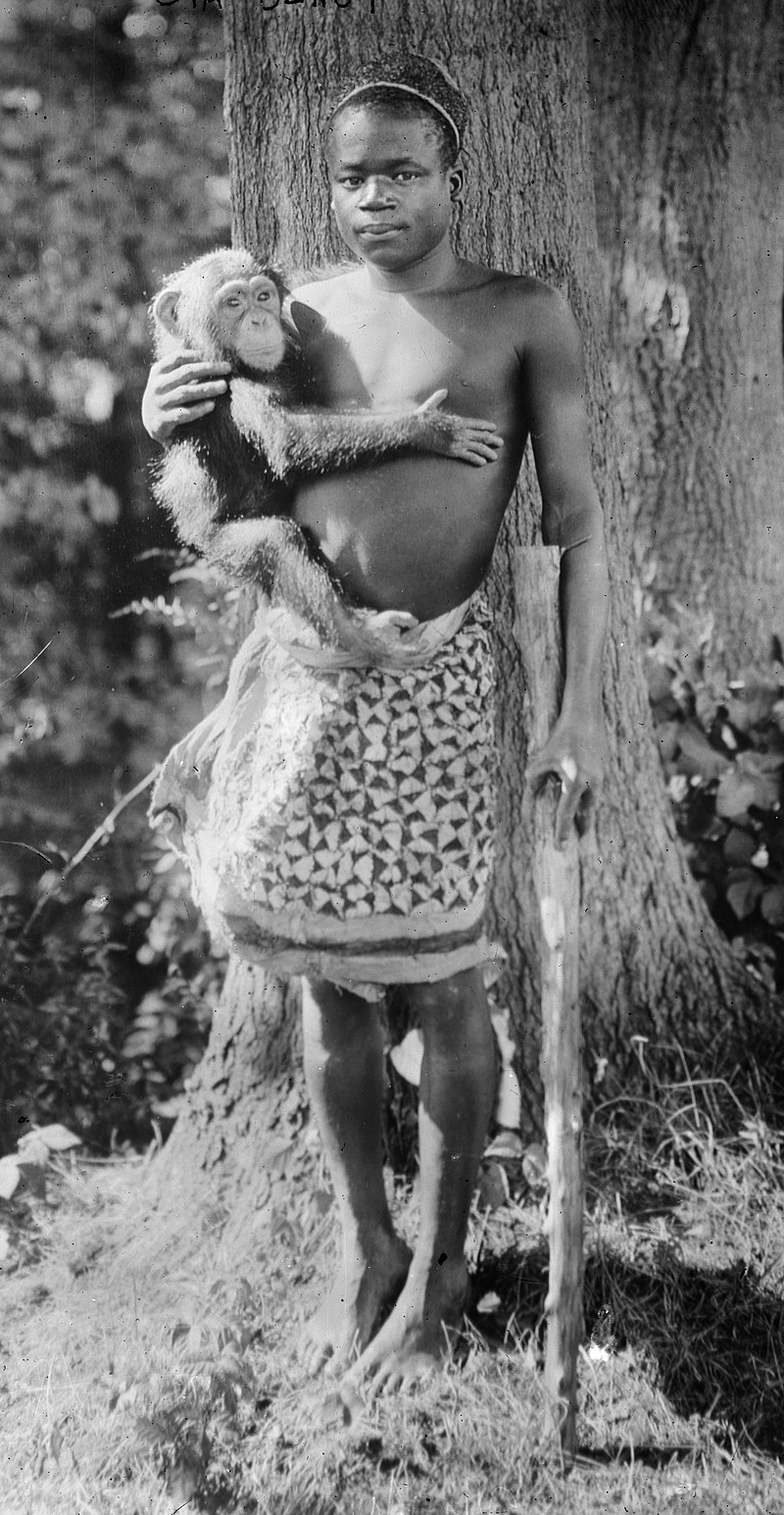

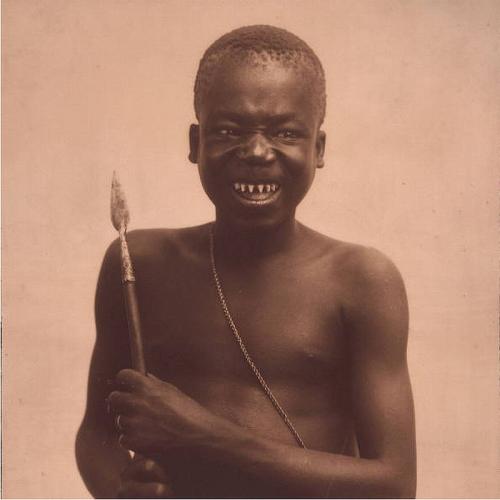

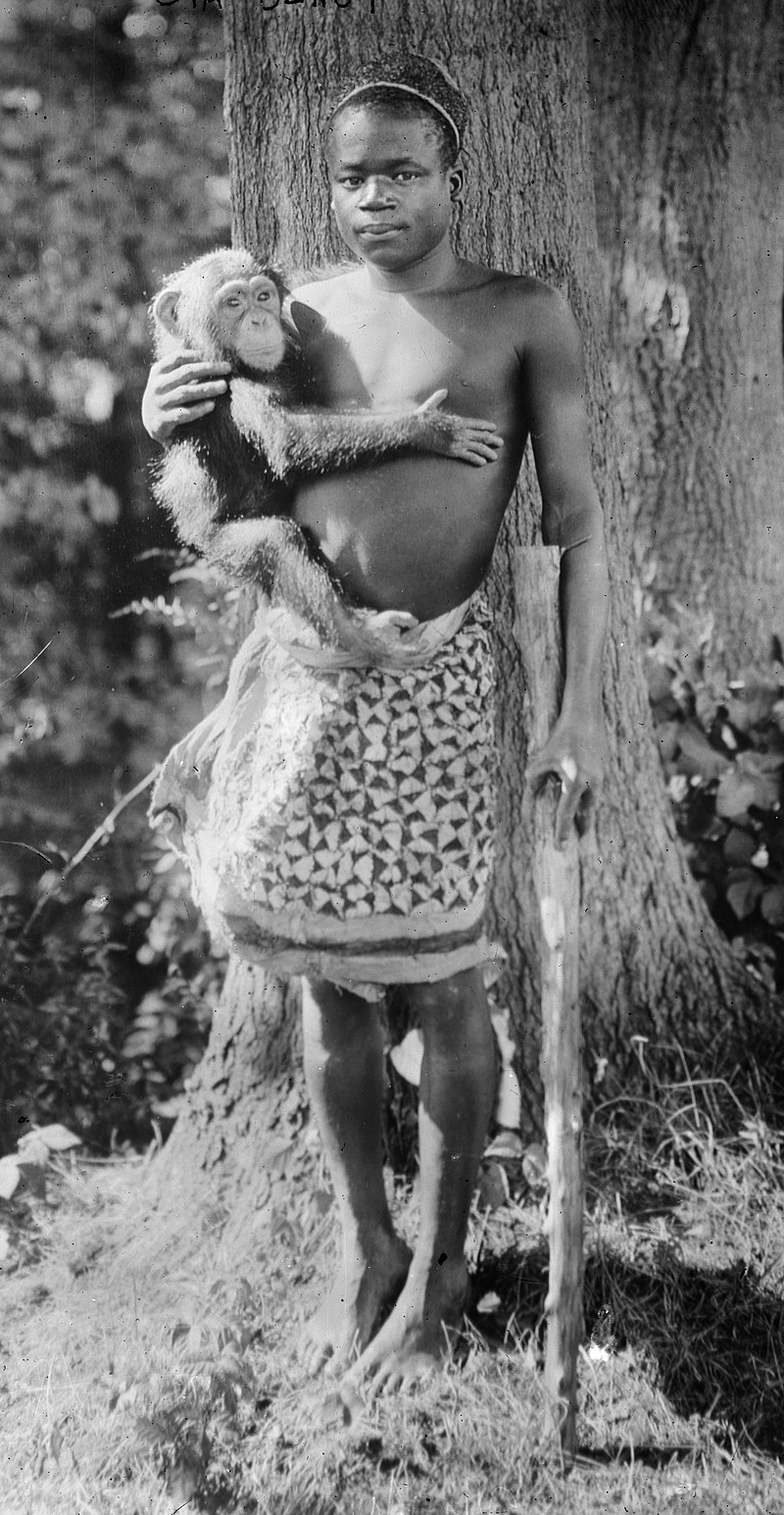

| Exhibitions St. Louis World Fair  Benga (second from left) and the Batwa in St. Louis The group was taken to St. Louis, Missouri, in late June 1904 without Verner, as he had been taken ill with malaria. The Louisiana Purchase Exposition had already begun, and the Africans immediately became the center of attention. Benga was particularly popular, and his name was reported variously by the press as Artiba, Autobank,[16] Ota Bang, and Otabenga. He had an amiable personality, and visitors were eager to see his teeth that had been filed to sharp points in his early youth as ritual decoration. The Africans learned to charge for photographs and performances. One newspaper account promoted Benga as "the only genuine African cannibal in America", and claimed that "[his teeth were] worth the five cents he charges for showing them to visitors".[14]  Benga in 1904 When Verner arrived a month later, he realized the pygmies were more prisoners than performers. Their attempts to congregate peacefully in the forest on Sundays were thwarted by the crowds' fascination with them. McGee's attempts to present a "serious" scientific exhibit were also overturned. On July 28, 1904, the Africans performed to the crowd's preconceived notion that they were "savages", resulting in the First Illinois Regiment being called in to control the mob. Benga and the other Africans eventually performed in a warlike fashion, imitating Native Americans they saw at the Exhibition.[17] The Apache leader Geronimo (featured as "The Human Tyger" – with special dispensation from the Department of War)[16] grew to admire Benga, and gave him one of his arrowheads.[18] American Museum of Natural History Benga accompanied Verner when he returned the other Africans to the Congo. He briefly lived amongst the Batwa while continuing to accompany Verner on his African adventures. He married a Batwa woman who later died of snakebite, but little is known of this second marriage. Not feeling that he belonged with the Batwa, Benga chose to return with Verner to the United States.[19] Verner eventually arranged for Benga to stay in a spare room at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City while he was tending to other business. Verner negotiated with the curator Henry Bumpus over the presentation of his acquisitions from Africa and potential employment. While Bumpus was put off by Verner's request of what he thought was the prohibitively high salary of $175 a month and was not impressed by the man's credentials, he was interested in Benga. Benga initially enjoyed his time at the museum, where he was given a Southern-style linen suit to wear when he entertained. He became homesick for his own culture.[20] In 1992 the writers Bradford and Blume imagined his feelings: What at first held his attention now made him want to flee. It was maddening to be inside – to be swallowed whole – so long. He had an image of himself, stuffed, behind glass, but somehow still alive, crouching over a fake campfire, feeding meat to a lifeless child. Museum silence became a source of torment, a kind of noise; he needed birdsong, breezes, trees.[21] The disaffected Benga attempted to find relief by exploiting his employers' presentation of him as a 'savage'. He tried to slip past the guards as a large crowd was leaving the premises; when asked on one occasion to seat a wealthy donor's wife, he pretended to misunderstand, instead hurling the chair across the room, just missing the woman's head. Meanwhile, Verner was struggling financially and had made little progress in his negotiations with the museum. He soon found another home for Benga.[20] Bronx Zoo At the suggestion of Bumpus, Verner took Benga to the Bronx Zoo in 1906. William Hornaday, director of the zoo, initially enlisted Benga to help maintain the animal habitats. However, Hornaday saw that people took more notice of Benga than the animals at the zoo, and he eventually created an exhibition to feature Benga.[9] At the zoo, Benga was allowed to roam the grounds, but there is no record that he was ever paid for his work.[4] He became fond of an orangutan named Dohong, "the presiding genius of the Monkey House", who had been taught to perform tricks and imitate human behavior.[22] The events leading to his "exhibition" alongside Dohong were gradual:[4] Benga spent some of his time in the Monkey House exhibit, and the zoo encouraged him to hang his hammock there, and to shoot his bow and arrow at a target. On the first day of the exhibit, September 8, 1906, visitors found Benga in the Monkey House.[4]  Ota Benga at the Bronx Zoo, with Polly the chimpanzee Verner brought from the Congo, in 1906. Only five promotional photos exist of Benga's time here, none of them in the "Monkey House"; cameras were not allowed.[23] Soon, a sign on the exhibit read: The African Pygmy, "Ota Benga." Age, 23 years. Height, 4 feet 11 inches.[a] Weight, 103 pounds.[b] Brought from the Kasai River, Congo Free State, South Cen- tral Africa, by Dr. Samuel P. Verner. Ex- hibited each afternoon during September.[24] Hornaday considered the exhibit a valuable spectacle for visitors; he was supported by Madison Grant, Secretary of the New York Zoological Society, who lobbied to put Ota Benga on display alongside apes at the Bronx Zoo. A decade later, Grant became prominent nationally as a racial anthropologist and eugenicist.[25] African-American clergymen immediately protested to zoo officials about the exhibit. Said James H. Gordon, Our race, we think, is depressed enough, without exhibiting one of us with the apes ... We think we are worthy of being considered human beings, with souls.[4] Gordon thought the exhibit was hostile to Christianity and was effectively a promotion of Darwinism: The Darwinian theory is absolutely opposed to Christianity, and a public demonstration in its favor should not be permitted.[4] A number of clergymen backed Gordon.[26] In defense of the depiction of Benga as a lesser human, an editorial in The New York Times suggested: We do not quite understand all the emotion which others are expressing in the matter ... It is absurd to make moan over the imagined humiliation and degradation Benga is suffering. The pygmies ... are very low in the human scale, and the suggestion that Benga should be in a school instead of a cage ignores the high probability that school would be a place ... from which he could draw no advantage whatever. The idea that men are all much alike except as they have had or lacked opportunities for getting an education out of books is now far out of date.[27] After the controversy, Benga was allowed to roam the grounds of the zoo. In response to the situation, as well as verbal and physical prods from the crowds, he became more mischievous and somewhat violent.[28] Around this time, an article in The New York Times quoted Robert Stuart MacArthur as saying, "It is too bad that there is not some society like the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. We send our missionaries to Africa to Christianize the people, and then we bring one here to brutalize him."[24] The zoo finally removed Benga from the grounds. Verner was unsuccessful in his continued search for employment, but he occasionally spoke to Benga. The two had agreed that it was in Benga's best interests to remain in the United States despite the unwelcome spotlight at the zoo.[29] Toward the end of 1906, Benga was released into Reverend Gordon's custody.[4] |

展覧会 セントルイス万博  セントルイスでのベンガ(左から2番目)とバトワ族 1904年6月下旬、ヴァーナーがマラリアにかかったため、一行はヴァーナー抜きでミズーリ州セントルイスに向かった。ルイジアナ購入博覧会はすでに始 まっており、アフリカ人はたちまち注目の的となった。ベンガは特に人気があり、彼の名前はマスコミによってアルティバ、オートバンク、オタバン、オタベン ガなどさまざまに報道された[16]。彼は愛想のいい性格で、若い頃に儀式の装飾として鋭く削られた彼の歯を見ようと、観光客は熱望した。アフリカ人は写 真やパフォーマティに料金を取ることを学んだ。ある新聞記事はベンガを「アメリカで唯一の本物のアフリカ人食人鬼」と宣伝し、「彼の歯は訪問者に見せるの に5セントの価値がある」と主張した[14]。  1904年のベンガ 1ヵ月後にヴァーナーが到着すると、彼はピグミーたちがパフォーマーというより囚人であることに気づいた。日曜日に森に平和的に集まろうとする彼らの試み は、群衆が彼らに魅了されることによって阻止された。まじめな」科学的展示を行おうとしたマクギーの試みも失敗に終わった。1904年7月28日、アフリ カ人たちは「野蛮人」という群衆の先入観を覆すパフォーマティビティを披露し、その結果、暴徒を制圧するためにイリノイ州第一連隊が招集された。アパッチ の指導者ジェロニモ(陸軍省の特別許可を得て「人間タイガー」として登場)[16]はベンガを賞賛するようになり、彼の矢じりの1つを贈った[18]。 アメリカ自然史博物館 ベンガはヴァーナーが他のアフリカ人をコンゴに帰還させる際に同行した。彼はヴァーナーのアフリカの冒険に同行し続けながら、短期間バトワの間で暮らし た。後に蛇に噛まれて死んだバトワ族の女性と結婚したが、この再婚についてはほとんど知られていない。ベンガはバトワに居場所を感じず、ヴァーナーととも にアメリカに戻ることを選んだ[19]。 ヴァーナーは最終的に、ベンガがニューヨークのアメリカ自然史博物館の空き部屋に滞在できるように手配した。ヴァーナーは学芸員のヘンリー・バンパスと、 アフリカからの収集品の展示や雇用の可能性について交渉した。バンパスはヴァーナーが要求した月給175ドルという法外な高給に尻込みし、彼の資格にも感 銘を受けなかったが、ベンガには興味を示した。ベンガは当初、接待の際に着る南部風のリネンスーツを与えられ、美術館での生活を楽しんでいた。彼は自国の 文化にホームシックになった[20]。 1992年、作家のブラッドフォードとブルーメは彼の気持ちを想像した: 最初は彼の関心を引いていたものが、今では逃げ出したくなる。中にいること、つまり丸ごと飲み込まれることが、これほど長く続くのは気が狂いそうだった。 彼は、剥製にされ、ガラスの向こうで、しかしなぜかまだ生きていて、偽のキャンプファイヤーの上にしゃがみこみ、生気のない子供に肉を食べさせている自分 の姿を思い浮かべていた。博物館の静寂は苦しみの源となり、一種の騒音となった。彼には鳥のさえずり、そよ風、木々が必要だった。 彼は鳥のさえずり、風、木々を必要としていた[21]。不満を抱いていたベンガは、雇い主が彼を「野蛮人」として見せていることを利用することで、救いを 見つけようとした。ある時、裕福な篤志家の妻に席を譲るよう頼まれると、彼は誤解したふりをして椅子を部屋中に投げつけ、女性の頭をかすめた。一方、 ヴァーナーは財政的に苦しく、美術館との交渉はほとんど進展していなかった。彼はすぐにベンガの別の家を見つけた[20]。 ブロンクス動物園 バンパスの提案で、ヴァーナーは1906年にベンガをブロンクス動物園に連れて行った。動物園の園長であったウィリアム・ホーナデーは、当初ベンガに動物 の生息地の維持管理を手伝わせた。しかし、動物園の動物たちよりもベンガの方が注目されていることを知ったホーナデイは、最終的にベンガをフィーチャーし た展覧会を企画した[9]。動物園でベンガは敷地内を歩き回ることを許されたが、その仕事に対して報酬が支払われたという記録はない[4]。 ベンガはモンキーハウスの展示室で過ごすようになり、動物園はベンガにハンモックを吊るしたり、弓矢を的に向けて射ることを勧めた。1906年9月8日の展示初日、来園者はモンキーハウスにいるベンガを見つけた[4]。  1906年、バーナーがコンゴから連れてきたチンパンジーのポリーとともにブロンクス動物園にいたオタ・ベンガ。ベンガがここにいた頃の宣伝用の写真は5枚しか残っていないが、「モンキーハウス」での写真はない。 間もなく、展示品にはこう書かれていた: アフリカのピグミー、「オタ・ベンガ」。 年齢、23歳。身長、4フィート11インチ[a]。 体重、103ポンド[b]。 南アフリカ、コンゴ自由州のカサイ川から連れてこられた。 サミュエル・P・ヴァーナー博士によってアフリカ南部、コンゴ自由州のカサイ川から持ち込まれた。9月中、毎日午後に行われた。 9月中、毎日午後に展示された[24]。 ホーナデイは、この展示が来園者にとって貴重な見世物であると考えた。彼は、ニューヨーク動物学協会の秘書であるマディソン・グラントに支持され、ブロン クス動物園で類人猿と並んでオタ・ベンガを展示するよう働きかけた。10年後、グラントは人種人類学者、優生思想家として国民に知られるようになった [25]。 アフリカ系アメリカ人の聖職者たちは、すぐに動物園関係者にこの展示について抗議した。ジェームズ・H・ゴードンは言った、 我々の人種は、猿と一緒に展示しなくても、十分に落ち込んでいると思う。私たちは、魂を持った人間として扱われる価値があると思います」[4]。 ゴードンは、この展示はキリスト教に敵対するものであり、事実上ダーウィニズムの宣伝であると考えていた: ダーウィンの理論はキリスト教に絶対に反対であり、それを支持する公のデモンストレーションは許可されるべきではない[4]。 多くの聖職者がゴードンを支持した[26]。ベンガを劣った人間として描いたことを擁護するために、『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙の社説はこう提言した: この件に関して他の人々が表明しているすべての感情が理解できない。ベンガが受けている想像上の屈辱や劣等感に対して呻くのは馬鹿げている。ピグミー は......人間の範疇では非常に低い存在であり、ベンガが檻の代わりに学校に入るべきだという意見は、学校が......ベンガにとって何のメリット もない場所である可能性が高いことを無視している。人はみな、書物以外の教育を受ける機会があったりなかったりすることを除けば、よく似ているという考え 方は、もはや時代遅れである[27]。 論争の後、ベンガは動物園の敷地内を歩き回ることが許された。ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙の記事は、ロバート・スチュアート・マッカーサーの言葉を引用 し、「児童虐待防止協会のような協会がないのは残念だ。私たちは人々をキリスト教化するためにアフリカに宣教師を送り、そして残忍な仕打ちをするためにこ こに連れてきたのだ」[24]。 動物園はついにベンガを敷地から追い出した。ヴァーナーは就職活動を続けてもうまくいかなかったが、時折ベンガと話をした。2人は、動物園で歓迎されない スポットライトを浴びているにもかかわらず、アメリカに留まることがベンガにとって最善の利益であることに同意していた[29]。 1906年の終わり頃、ベンガはゴードン牧師のもとに釈放された[4]。 |

| Later life Gordon placed Benga in the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum, a church-sponsored orphanage in Brooklyn that Gordon supervised. As the unwelcome press attention continued, in January 1910, Gordon arranged for Benga's relocation to Lynchburg, Virginia, where he lived with the family of Gregory W. Hayes.[30] So that he could more easily be part of local society, Gordon arranged for Benga's teeth to be capped and bought him American-style clothes. He received tutoring from Lynchburg poet Anne Spencer[31] in order to improve his English, and began to attend elementary school at the Baptist Seminary in Lynchburg.[27] Once he felt his English had improved sufficiently, Benga discontinued his formal education. He began working at a Lynchburg tobacco factory, and began to plan a return to Africa.[32] |

その後の人生 ゴードンはベンガを、ゴードンが監督するブルックリンの教会後援の孤児院、ハワード孤児院に預けた。歓迎されない報道が続いたため、1910年1月、ゴー ドンはベンガをヴァージニア州リンチバーグに移し、そこでグレゴリー・W・ヘイズの家族と暮らすように手配した[30]。 ベンガが地元の社交界に溶け込みやすいように、ゴードンはベンガの歯のかぶせものを手配し、アメリカ風の服を買ってやった。英語を上達させるためにリンチ バーグの詩人アン・スペンサー[31]から個人指導を受け、リンチバーグのバプテスト神学校の小学校に通い始めた[27]。 英語が十分に上達したと感じると、ベンガは正式な教育を打ち切った。リンチバーグのタバコ工場で働き始め、アフリカへの帰還を計画し始めた[32]。 |

| Death In 1914, when World War I broke out, a return to the Congo became impossible as passenger ship traffic ended. Benga became depressed as his hopes for a return to his homeland faded.[32] On March 20, 1916, at the age of 32 or 33, he built a ceremonial fire, chipped off the caps on his teeth, and shot himself in the heart with a borrowed pistol.[33] Benga was buried in an unmarked grave in the black section of the Old City Cemetery, near his benefactor, Gregory Hayes. At some point, the remains of both men went missing. Local oral history indicates that Hayes and Benga were eventually moved from the Old Cemetery to White Rock Hill Cemetery, a burial ground that later fell into disrepair.[34] Benga received a historic marker in Lynchburg in 2017.[35] |

死 1914年、第一次世界大戦が勃発すると、旅客船の往来が途絶え、コンゴへの帰還は不可能となった。1916年3月20日、32歳か33歳の時、彼は儀式用の火を焚き、歯のかぶせを削り、借りたピストルで心臓を撃った[33]。 ベンガはオールド・シティ墓地のブラック・セクションにある無名の墓に埋葬され、彼の恩人であるグレゴリー・ヘイズの近くにあった。ある時点で、2人の遺 骨は行方不明となった。地元のオーラルヒストリーによると、ヘイズとベンガは最終的に旧墓地からホワイト・ロック・ヒル墓地に移された。 |

| Legacy Phillips Verner Bradford, the grandson of Samuel Phillips Verner, together with Author Harvey Blume wrote a book on Benga, entitled Ota Benga: The Pygmy in the Zoo (1992). During his research for the book, Bradford visited the American Museum of Natural History, which holds a life mask and body cast of Ota Benga. The display is still labeled "Pygmy", rather than indicating Benga's name, despite objections beginning a century ago from Verner and repeated by others.[36] Publication of Bradford's book in 1992 inspired widespread interest in Ota Benga's story and stimulated creation of many other works, both fictional and non-fiction, such as: 1994 – John Strand's play, Ota Benga, was produced by the Signature Theater in Arlington, Virginia.[37] 1997 – The play, Ota Benga, Elegy for the Elephant, by Dr. Ben B. Halm, was staged at Fairfield University in Connecticut.[38] 2002 – The Mbuti man was the subject of the short documentary, Ota Benga: A Pygmy in America, directed by Brazilian Alfeu França. He incorporated original movies recorded by Verner in the early 20th century.[39] 2005 – A fictionalized account of his life portrayed in the film Man to Man, starring Joseph Fiennes, Kristin Scott Thomas. 2006 – The Brooklyn-based band Piñataland released a song titled "Ota Benga's Name" on their album Songs from the Forgotten Future Volume 1, which tells the story of Ota Benga.[4] 2007 – McCray's early poems about Benga were adapted as a performance piece; the work debuted at the Columbia Museum of Art in 2007, with McCray as narrator and original music by Kevin Simmonds. 2008 – Benga inspired the character of Ngunda Oti in the film The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.[40] 2010 – The story of Ota Benga was the inspiration for a concept album by the St. Louis musical ensemble May Day Orchestra [41] 2011 – Italian band Mamuthones recorded the song "Ota Benga" in their album Mamuthones.[citation needed] 2012 – Ota Benga Under My Mother's Roof, a poetry collection, was published by Carrie Allen McCray, whose family had taken care of Benga 2012 – Ota Benga the Documentary Film appeared[42] 2015 – Journalist Pamela Newkirk published the biography Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga[43] 2016 – Radio Diaries, a Peabody Award-winning radio show, tells the story of Ota Benga in "The Man in the Zoo" on the Radio Diaries podcast.[44] 2019 – The University of Alabama at Birmingham adapted Ota Benga's story into the musical Savage.[45] 2019 – Williamstown Theatre Festival premiered A Human Being, of a Sort, a play based on Ota Benga's story, written by Jonathan Payne.[46] 2020 – the Wildlife Conservation Society, operator of the Bronx Zoo, apologized for the zoo's treatment of Benga and promotion of eugenics.[47][48] |

遺産 サミュエル・フィリップス・ヴァーナーの孫であるフィリップス・ヴァーナー・ブラッドフォードは、作家のハーヴェイ・ブルームとともに、『オタ・ベンガ』 というタイトルのベンガに関する本を書いた: The Pygmy in the Zoo』(1992年)という本を書いた。この本の取材中、ブラッドフォードはアメリカ自然史博物館を訪れ、オタ・ベンガのライフマスクとボディキャスト を所蔵していることを知った。1992年にブラッドフォードが著書を出版したことで、オタ・ベンガの物語に対する関心が広まり、フィクション、ノンフィク ションを問わず、以下のような多くの作品が生み出された: 1994年 - ジョン・ストランドの戯曲『オタ・ベンガ』がヴァージニア州アーリントンのシグネチャー・シアターで上演された[37]。 1997年 - ベン・B・ハルム博士の戯曲『Ota Benga, Elegy for the Elephant』がコネチカット州のフェアフィールド大学で上演された[38]。 2002 - 短編ドキュメンタリー映画『Ota Benga: ブラジル人のアルフェウ・フランサが監督を務めた。20世紀初頭にヴァーナーが記録したオリジナルのムービーが盛り込まれている[39]。 2005年 - ジョセフ・ファインズ、クリスティン・スコット・トーマス主演の映画『Man to Man』で彼の人生をフィクションとして描く。 2006年 - ブルックリンを拠点とするバンド、ピニャタランドがアルバム『Songs from the Forgotten Future Volume 1』に収録されている「Ota Benga's Name」というタイトルの曲をリリース。 2007年 - ベンガに関するマックレイの初期の詩がパフォーマンス作品として脚色され、マックレイがナレーター、ケヴィン・シモンズがオリジナル音楽を担当し、2007年にコロンビア美術館でデビューした。 2008年 - ベンガは映画『ベンジャミン・バトン 数奇な人生』のングンダ・オティのキャラクターに影響を与えた[40]。 2010年 - セントルイスのミュージカル・アンサンブル、メイ・デー・オーケストラのコンセプト・アルバムのインスピレーションとなったオタ・ベンガの物語[41]。 2011年 - イタリアのバンドMamuthonesのアルバム『Mamuthones』に「Ota Benga」が収録された[要出典]。 2012年 - ベンガの面倒を見たキャリー・アレン・マックレイによって詩集『Ota Benga Under My Mother's Roof』が出版される。 2012年 - ドキュメンタリー映画『オタ・ベンガ』が公開[42]。 2015年 - ジャーナリストのパメラ・ニューカークが伝記『Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga』を出版[43]。 2016年 - ピーボディ賞を受賞したラジオ番組『Radio Diaries』が、ポッドキャスト『Radio Diaries』の「The Man in the Zoo」でオタ・ベンガの物語を伝える[44]。 2019年 - アラバマ大学バーミンガム校がオタ・ベンガの物語をミュージカル『サベージ』に脚色した[45]。 2019年 - ウィリアムズタウン・シアター・フェスティバルが、ジョナサン・ペイン脚本によるオタ・ベンガの物語を基にした戯曲『A Human Being, of a Sort』を初演した[46]。 2020年 - ブロンクス動物園を運営する野生動物保護協会が、動物園のベンガに対する扱いと優生学の推進について謝罪した[47][48]。 |

| Similar case Main article: Ishi Ishi, a Native American who has been compared to Benga Similarities have been observed between the treatment of Ota Benga and Ishi, the sole remaining member of the Yahi Native American tribe, who was displayed in California around the same period. Ishi died on March 25, 1916, five days after Ota's death.[49][50] |

類似のケース 主な記事 イシ ベンガと比較されるネイティブ・アメリカン、イシ オタ・ベンガの扱いと、同時期にカリフォルニアで展示されていたヤヒ・インディアン部族の唯一の残存者であるイシの扱いには類似点が見られる。イシは1916年3月25日、オタの死の5日後に死亡した[49][50]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ota_Benga |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆