パレーシア

Parrhesia

☆ 修辞学において、パレーシア(ギリシャ語: παρρησία)とは、率直な発言、自由に話すことである。それは、言論の自由だけでなく、個人的な危険を冒してでも、共通の利益のために真実を語る義 務を意味する。パレーシアという用語の最も古い使用記録は紀元前5世紀のエウリピデスによるものである。パレーシアとは文字通り「すべてを話すこと」、ひ いては「自由に話すこと」、「大胆に話すこと」、「大胆さ」を意味する。

★

「多くのフーコーエピゴーネンはパレーシア(福蔵なく大胆に話す実践)をええもんだというがコメディ演劇の伝統のなかではパレーシアを実践するのは[悪そ

うな]大物や道化やトリックスターでありその実践倫理は反権威やあけすけな真実暴露など下品といわれているものなのだ」——垂水源之介(2025.11.15)

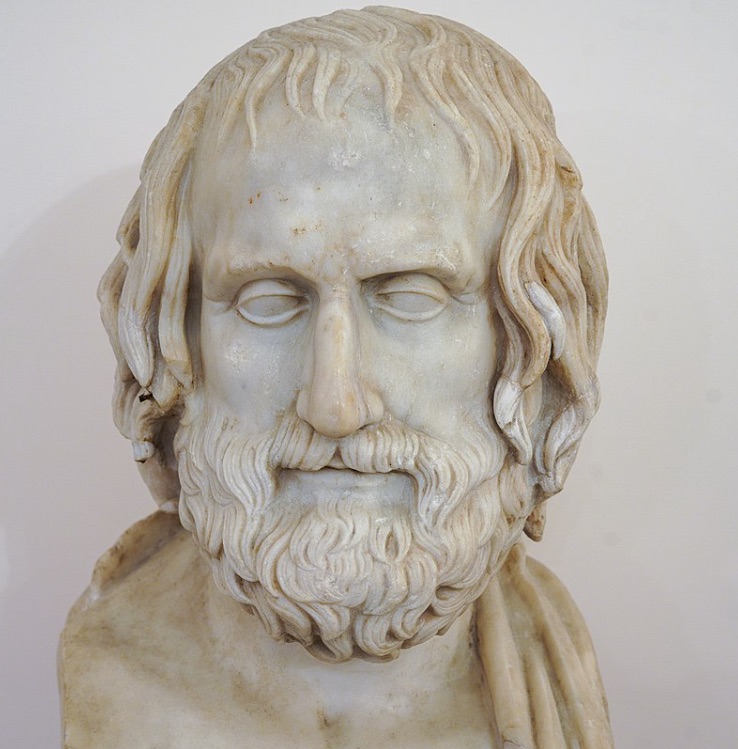

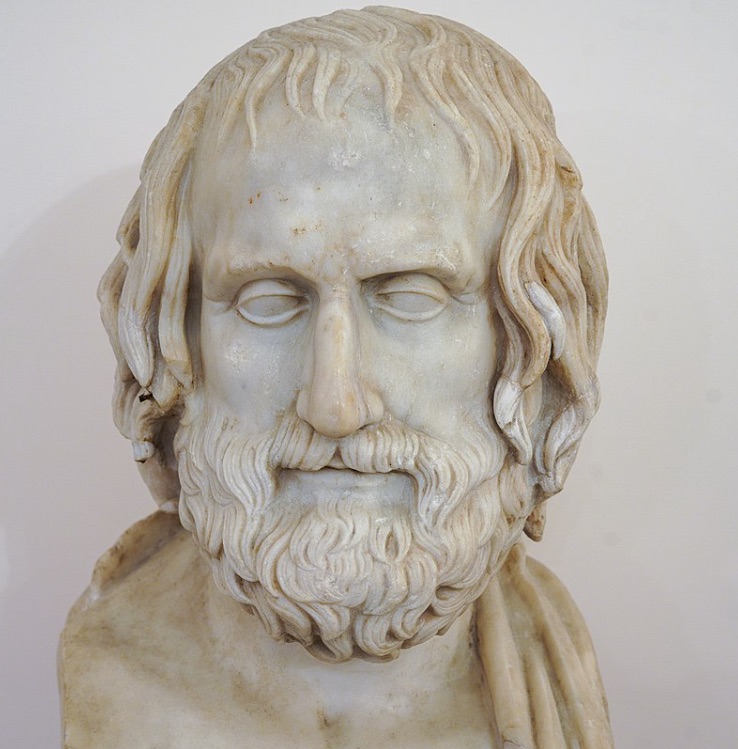

| Euripides[a]

(c. 480 – c. 406 BC) was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with

Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek

tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient

scholars attributed ninety-five plays to him, but the Suda

says it was ninety-two at most. Of these, eighteen or nineteen have

survived more or less complete (Rhēsos is suspect).[3] There are many

fragments (some substantial) of most of his other plays. More of his

plays have survived intact than those of Aeschylus and Sophocles

together, partly because his popularity grew as theirs

declined[4][5]—he became, in the Hellenistic Age, a cornerstone of

ancient literary education, along with Homer, Demosthenes, and

Menander.[6] Euripides is identified with theatrical innovations that have profoundly influenced drama down to modern times, especially in the representation of traditional, mythical heroes as ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances. This new approach led him to pioneer developments that later writers adapted to comedy, some of which are characteristic of romance. He also became "the most tragic of poets",[nb 1] focusing on the inner lives and motives of his characters in a way previously unknown.[7][8] He was "the creator of ... that cage which is the theatre of Shakespeare's Othello, Racine's Phèdre, of Ibsen and Strindberg," in which "imprisoned men and women destroy each other by the intensity of their loves and hates".[9] But he was also the literary ancestor of comic dramatists as diverse as Menander and George Bernard Shaw.[10] His contemporaries associated him with Socrates as a leader of a decadent intellectualism. Both were frequently lampooned by comic poets such as Aristophanes. Socrates was eventually put on trial and executed as a corrupting influence. Ancient biographies hold that Euripides chose a voluntary exile in old age, dying in Macedonia,[11] but recent scholarship casts doubt on these sources. |

エウリピデス[a](紀元前480年頃-紀元前406年頃)は、古典期アテネの悲劇家。アイスキュロス、ソフォクレスとともに、全作品が現存する古代ギリシアの悲劇家3人のうちの1人である。古代の学者の中には、彼の戯曲を95作とする者もいたが、『スーダ辞典』によれば、せいぜい92作であった。このうち、多かれ少なかれ完全な形で現存しているのは18~19作品(『レーソスは疑わしい』)である[3]。エウリピデスはヘレニズム時代において、ホメロス、デモステネス、メナンダーと並んで古代文学教育の礎石となった[6]。 ※レーソスは、ギリシャ神話の主人公で、トラーキアの王. エウリピデスは、現代に至るまで戯曲に多大な影響を及ぼしている演劇上の革新、特に、伝統的で神話的な英雄を、非日常的な状況に置かれた普通の人々として 表現することに共感している。この新しいアプローチは、後の作家たちが喜劇に取り入れたり、ロマンスに特徴的なものを生み出したりする先駆けとなった。彼 はまた「最も悲劇的な詩人」[nb 1]となり、それまで知られていなかった方法で登場人物の内面や動機に焦点を当てた。シェイクスピアの『オセロ』やラシーヌの『フェードル』、イプセンや ストリンドベリの『檻』の創造者」であり、そこでは「監禁された男女が愛と憎しみの激しさによって互いを破壊し合う」[9]。しかし彼はまた、メナンダー やジョージ・バーナード・ショーといった多様な喜劇作家の文学的祖先でもあった[10]。 同時代の人々は彼を退廃的な知識主義の指導者としてソクラテスと結びつけていた。両者ともアリストファネスのような喜劇詩人によって頻繁に揶揄された。ソ クラテスは最終的に裁判にかけられ、堕落させたとして処刑された。古代の伝記によれば、エウリピデスは老年期に自主的な流浪を選び、マケドニアで死んだと されているが[11]、最近の研究ではこれらの資料に疑問が投げかけられている。 |

| In

rhetoric, parrhesia (Greek: παρρησία) is candid speech, speaking

freely.[1] It implies not only freedom of speech, but the obligation to

speak the truth for the common good, even at personal risk. Etymology The earliest recorded use of the term parrhesia is by Euripides in the fifth century B.C.[2][3] Parrhesia means literally "to speak everything" and by extension "to speak freely", "to speak boldly", or "boldness".[4] |

修辞学において、パレーシア(ギリシャ語: παρρησία)とは、率直な発言、自由に話すことである[1]。それは、言論の自由だけでなく、個人的な危険を冒してでも、共通の利益のために真実を語る義務を意味する。 語源 パレーシアという用語の最も古い使用記録は紀元前5世紀のエウリピデスによるものである[2][3]。パレーシアとは文字通り「すべてを話すこと」、ひいては「自由に話すこと」、「大胆に話すこと」、「大胆さ」を意味する[4]。 |

| Usage in ancient Greece In the Classical period, parrhesia was a fundamental component of the Athenian democracy.[citation needed] In the courts or the Ecclesia, the assembly of citizens, Athenians were free to say almost anything. In the Dionysia, playwrights such as Aristophanes made full use of their right to ridicule whomever they chose.[5] Outside of the theatre or government however, there were limits to what might be said; freedom to discuss politics, morals, religion, or to criticize people would depend upon the context: by whom it was said, and when, and how, and where.[6] If one was seen as immoral, or held views that went contrary to popular opinion, then there were great risks involved in making use of such an unrestricted freedom of speech, such as being charged with impiety (asebeia). This was the pretext under which Socrates was executed in 399 BCE, for dishonoring the gods and corrupting the young.[5] Though perhaps Socrates was punished for his close association with many of the participants in the Athenian coup of 411 BCE, because it was believed that Socrates' philosophical teachings had served as an intellectual justification for their seizure of power.[7][better source needed] In later Hellenistic philosophy, parrhesia was a defining characteristic of the Cynic philosophers, as epitomized in the shamelessness of Diogenes of Sinope.[8] According to Philodemus, parrhesia was also used by the Epicureans in the form of frank criticism of each other that was intended to help the target of criticism achieve the cessation of pain and reach a state of ataraxia.[9] In the Greek New Testament, parrhesia is the ability of Jesus or his followers to hold their own in discourse before political and religious authorities such as the Pharisees.[10][1][11] |

古代ギリシャにおける用法 古典期において、パレーシアはアテナイ民主主義の基本的な要素であった[要出典]。裁判所や市民の集会であるエクレシアでは、アテナイ人はほとんど何を 言っても自由であった。ディオニュシアでは、アリストファネスのような劇作家たちが、自分たちが選んだ者を嘲笑する権利をフルに活用していた[5]。 政治、道徳、宗教を論じたり、人を批判したりする自由は、いつ、誰が、どのように、どこで発言するかという文脈によって決まる[6]。不道徳と見なされた り、民意に反する意見を持ったりした場合、不敬罪(アセベイア)に問われるなど、このような無制限の言論の自由を利用することには大きなリスクが伴う。こ れはソクラテスが前399年に神々を汚し、若者を堕落させたとして処刑された口実であった[5]が、おそらくソクラテスは前411年のアテネのクーデター の参加者の多くと密接な関係にあったために処罰されたのであろう。 フィロデモスによれば、パレーシアはエピクロス主義者たちによっても、互いを率直に批判するという形で用いられており、批判の対象が苦痛の停止を達成し、アタラクシアの状態に達するのを助けることを目的としていた[9]。 ギリシャ語の新約聖書では、パリシアとはイエスやその従者たちがファリサイ派のような政治的・宗教的権威の前で談話をする際に自分の意見を貫き通す能力のことである[10][1][11]。 |

| Usage in rabbinic Jewish writings Parrhesia appears in Midrashic literature as a condition for the transmission of Torah. Connoting open and public communication, parrhesia appears in combination with the term δῆμος (dimus, short for dimosia), translated coram publica, in the public eye, i.e. open to the public.[12] As a mode of communication it is repeatedly described in terms analogous to a commons. Parrhesia is closely associated with an ownerless wilderness of primary mytho-geographic import, the Midbar Sinai in which the Torah was initially received. The dissemination of Torah thus depends on its teachers cultivating a nature that is as open, ownerless, and sharing as that wilderness.[13] The term is important to advocates of Open Source Judaism.[14] Here is the text from the Mekhilta where the term dimus parrhesia appears (see bolded text). "ויחנו במדבר" (שמות פרק יט פסוק ב) נתנה תורה דימוס פרהסייא במקום הפקר, שאלו נתנה בארץ ישראל, היו אומרים לאומות העולם אין להם חלק בה, לפיכך נתנה במדבר דימוס פרהסייא במקום הפקר, וכל הרוצה לקבל יבא ויקבל...[15] Torah was given over dimus parrhesia in a maqom hefker (a place belonging to no one). For had it been given in the Land of Israel, they would have had cause to say to the nations of the world, “you have no share in it.” Thus was it given dimus parrhesia, in a place belonging to no one: “Let all who wish to receive it, come and receive it!” Explanation: Why was the Torah not given in the land of Israel? In order that the peoples of the world should not have the excuse for saying: "Because it was given in Israel's land, therefore we have not accepted it."[16] ...דבר אחר: שלא להטיל מחלוקת בין השבטים שלא יהא זה אומר בארצי נתנה תורה וזה אומר בארצי נתנה תורה לפיכך נתנה תורה במדבר דימוס בפרהסיא במקום הפקר, בשלשה דברים נמשלה תורה במדבר באש ובמים לומר לך מה אלו חנם אף דברי תורה חנם לכל באי עולם. [17] Another reason: To avoid causing dissension among the tribes [of Israel]. Else one might have said: In my land the Torah was given. And the other might have said: In my land the Torah was given. Therefore, the Torah was given in the Midbar (wilderness, desert), dimus parrhesia, in a place belonging to no one. To three things the Torah is likened: to the Midbar, to fire, and to water. This is to tell one that just as these three things are free to all who come into the world, so also are the words of the Torah free to all who come into the world. The term "parrhesia" is also used in Modern Hebrew (usually spelled פרהסיה), meaning [in] public. |

ラビ時代のユダヤ教文献における用法 Parrhesiaは、ミドラシュ文献にトーラー伝達の条件として登場する。パルヘシアは 開かれた公のコミュニケーションという意味で、δῆμος(dimus、dimosiaの略)という用語と組み合わされて登場し、coram publica(公の目)と訳されている。パレーシアは、神話地理学的に重要な意味を持つ所有者のいない荒野、すなわちトーラーが最初に受容されたミッド バル・シナイと密接に結びついている。したがって、トーラーを広めるには、その教師がその荒野のように開かれ、所有者を持たず、共有する性質を培うことが 重要である[13]。この用語は、オープンソース・ユダヤ主義の提唱者にとって重要である[14]。 「ויחנו במדבר" (שמות פרק יט פסוק ב) נתנה תורה דימוס פרהסייא במקום הפקר, שאלו נתנה בארץ ישראל, היו אומרים לאומות העולם אין להם חלק בה, לפיכך נתנה במדבר דימוס פרהסייא במקום הפקר, וכל הרוצה לקבל יבא ויקבל...[15] 【ヘブライ語からのgoogle translator】彼らは砂漠で野営するだろう」(出エジプト記19章2節)。律法は荒れ果てた地の代わりにペルハシヤの領地を与えた。律法がイスラ エルの地に与えたものなら、世界の国々には何もないと言うだろう。その一部であるため、彼女は荒れ果てた場所にペルハシヤのデミスを荒野に与えた、そして それを受け取りたい人は誰でも来てそれを受け取る。 【英訳からの翻訳】トラーはマコム・ヘフカー(誰のものでもない場所)でディムス・パルヘシア(パレーシア)の 上に与えられた。もしそれがイスラエルの地で与えられていたならば、彼らは世界の国々に対して、"あなたがたには何の分け前もない "と言わなければならなかったであろう。このように、それは誰のものでもない場所で与えられたのだ: "これを受けたい者は皆、来て受けなさい!" 説明: なぜ律法はイスラエルの地で与えられなかったのか?それは、世界の民に言い訳をさせないためである: 「イスラエルの地で授けられたので、私たちはそれを受け入れなかったのです」[16]。 ..דבר אחר: שלא להטיל מחלוקת בין השבטים שלא יהא זה אומר בארצי נתנה תורה וזה אומר בארצי נתנה תורה לפיכך נתנה תורה במדבר דימוס בפרהסיא במקום הפקר, בשלשה דברים נמשלה תורה במדבר באש ובמים לומר לך מה אלו חנם אף דברי תורה חנם לכל באי עולם. [17] 【ヘブライ語からのgoogle translator】もう一つのことは、部族間に不和を生じさせないことである。そうならないようにしよう。これは、私の国ではトーラーが与えられたこ とを意味し、これは私の国でもトーラーが与えられたことを意味する。したがって、トーラーは砂漠の中で与えられました。砂漠の代わりに砂漠を、3 つの点でトーラーは砂漠で火と水に例えられた。これらの言葉がどのような自由であるかを言うと、トーラーの言葉さえも世界中の誰にとっても自由なのだ。 【英訳からの翻訳】 もう一つの理由がある: イスラエルの]部族間の不和を避けるためである。そうでなければ、こう言ったかもしれない: わたしの土地で律法が授けられました。と言ったかもしれない: 私の土地で律法が与えられた。それゆえ、律法はミッドバル(荒野、砂漠)、ディムス・パルヘシア(誰のものでもない場所)で与えられた。ミッドバル、火、 水。これは、この3つのものがこの世に生まれてくるすべての人に自由であるように、律法の言葉もこの世に生まれてくるすべての人に自由であることを伝えて いる。 現代ヘブライ語では、"parrhesia"(通常 "פרהסיה "と綴る)という用語も使われ、[人前で]という意味である。 |

| Modern scholarship Michel Foucault developed the concept of parrhesia as a mode of discourse in which people express their opinions and ideas candidly and honestly, avoiding the use of manipulation, rhetoric, or broad generalizations.[18] Foucault's interpretation of parrhesia is in contrast to the contemporary Cartesian model of requiring irrefutable evidence for truth. Descartes equated truth with the indubitable, believing that what cannot be doubted must be true.[citation needed] Until speech is examined or criticized to see if it is subject to doubt, its truth cannot be evaluated by this standard. Foucault asserted that the classical Greek concept of parrhesia rested on several criteria. A person who engages in parrhesia is only recognized as doing so if they possess a credible connection to the truth. This entails acting as a critic of either oneself, popular opinions, or societal norms. The act of revealing this truth exposes the individual to potential risks, yet the critic persists in speaking out due to a moral, social, and/or political responsibility. Additionally, in public contexts, a practitioner of parrhesia should hold a less empowered social position compared to those to whom the truth is being conveyed. Foucault described the classic Greek parrhesiastes as someone who takes a risk by speaking honestly, even when it might lead to negative consequences. This risk isn't always about life-threatening situations. For instance, when you tell a friend they're doing something wrong, knowing it might make them angry and harm your friendship, you're acting as a parrhesiastes. Parrhesia is closely tied to having the courage to speak the truth despite potential dangers, including social repercussions, political scandal, or even matters of life and death.[19]: 15–16 Parrhesia involves speaking openly. This involves a distinct connection to truth via honesty, a link to personal life through facing danger, a certain interaction with oneself or others through critique, and a specific relationship with moral principles through freedom and responsibility. Specifically, it's a form of speaking where the speaker shares their personal truth, even risking their life because they believe truth-telling is a duty to help others and themselves. In parrhesia, the speaker opts for honesty over persuasion, truth over falsehood or silence, the risk of death over safety, criticism over flattery, and moral obligation over self-interest or indifference.[19]: 19–20 The parrhesiastes speaks without reservation. For instance, Demosthenes, in his discourses "On the Embassy" and "First Philippic," emphasizes the importance of speaking with parrhesia, without holding back or hiding anything.[20] |

現代の学問 ミシェル・フーコーは、人々が操作やレトリック、大雑把な一般化の使用を避け、率直かつ正直に自分の意見や考えを述べる言説の様式として、パレーシアの概念を発展させた[18]。フーコーのパレーシアの解釈は、真理に反論の余地のない証拠を必要とする現代のデカルトのモデルとは対照的である。デカルトは真理を明白なものと同一視し、疑うことができないものは真理に違いないと信じていた。 18- Foucault, Michel (Oct–Nov 1983), Discourse and Truth: the Problematization of Parrhesia (six lectures), The University of California at Berkeley. フーコーは、古典ギリシアにおけるパレーシアの概念はいくつかの基準に基づいていると主張した。パレーシアを行う人は、真理との信頼できる結びつきがある場合にのみ、パレーシアを行っていると認められる。そのためには、自分自身、世間一般の意見、社会規範のいずれかを批判する行動をとることが必要である。この真実を明らかにする行為は、個人を潜在的な危険にさらすが、批判者は道徳的、社会的、政治的責任のために発言し続ける。さらに、公的な文脈では、パレーシアの実践者は、真実を伝えようとする相手と比較して、社会的な立場が弱いはずである。 フーコーは、古典的なギリシャのパレーシアについて、たとえそれが否定的な結果を招くかもしれない場合でも、正直に話すことでリスクを取る人だと述べている。このリスクは、必ずしも命に関わるような状況とは限らない。たとえば、友だちが何か間違ったことをしているとき、友だちを怒らせ、友情を損なうかもしれないとわかっていながら、それを伝えるとき、あなたはパレーシアとして行動しているのだ。パレーシアは、社会的反響や政治的スキャンダル、あるいは生死に関わる問題など、潜在的な危険にもかかわらず真実を語る勇気を持つことと密接に結びついている[19]: 15-16 - Michel Foucault (1983). Fearless Speech. パレーシアには、率直に話すことが含まれる。これには、 正直さを通じての真実との明確なつながり、危険に直面することによる個人的な生活とのつながり、批評を通じての自分自身や他者との特定の相互作用、自由と 責任を通じての道徳原理との特定の関係が含まれる。具体的には、真実を語ることは他者や自分自身を助ける義務であると信じているため、話し手が命を賭して でも個人的な真実を共有する話し方である。パレーシアでは、話し手は説得よりも正直さを、虚偽や沈黙よりも真実を、安全よりも死の危険を、お世辞よりも批 判を、自己利益や無関心よりも道徳的義務を選ぶ[19]: 19-20 パレーシアをおこなう人(parrhesiastes)は遠慮なく語る。例えば、デモステネスはその言説「大使について」や「第一ピリピ書」において、遠慮したり隠したりすることなくパレーシアをもって語ることの重要性を強調している[20]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parrhesia |

|

| ミシェル・フーコーにおけるパレーシアと民主主義の循環的成立について 池田 信虎 『フランス哲学・思想研究』2023 年 28 巻 p. 130-141 発行日: 2023/09/01 公開日: 2023/10/01 DOIhttps://doi.org/10.51086/sfjp.28.0_130 へのコメント |

【コメント】 ……そのなか、すべてを話す、大胆に話すというエウリピデス的用法が、古代ローマでは、「悪しきパレーシア」と良き(=本来)のパレーシアと弁別的に使わ れる。つまり、大胆に話す、正直にはなしている、全部を話している、という外面的態度を、検閲する。大胆に話す、正直にはなしている、全部を話している、 という外面的態度を、検閲する「真理」の検閲機能が登場したわけですよ。ラカニアンであれば、すべての言説に真理探究が含まれることは自明で、嘘ですら真 理を領域を占めるらしい(例:お前が嘘を言っているのは真実だ)。ということは、真理とは全部のことであり、真理の要素間に矛盾があっても、真理をめぐる 言説は、信虎氏言うように循環的構造(=堂々めぐり)を取らざるをえない。僕だったら、これで、ようやく、1980年代のフーコー氏は、カントの判断力批 判の第一部を趣味判断こそがデモクラシー体制における政治的判断にほからないというアーレントの議論死後7年後(1982)に出版される政治学講義(ロナ ルド・ベイナー『政治的判断力』法政大出版局,1988)に到達するわけだ。(2023年10月3日) |

| Parrhesia

(eingedeutscht auch Parrhesie) stammt aus dem Griechischen (παρρησία)

und bedeutet Redefreiheit oder über alles sprechen. Der Begriff wurde

von Michel Foucault verwendet, um das Konzept eines Diskurses zu

beschreiben, in dem man offen und wahrhaftig seine eigene Meinung und

seine Ideen ausspricht, ohne rhetorische Elemente, manipulative Rede

oder Generalisierungen zu verwenden. Es gibt mehrere Bedingungen für die antike und traditionelle Idee von Parrhesia. Einer, der Parrhesia verwendet, wird nur als solcher erkannt, wenn er eine glaubwürdige Beziehung zur Wahrheit hat, wenn er sich selbst oder populäre Meinungen der Kultur kritisiert, wenn die Offenbarung dieser Wahrheit ihn in Gefahr bringt, und er dennoch die Wahrheit spricht, weil er es als seine moralische, soziale und/oder politische Pflicht erachtet, dies zu tun. Weiterhin muss eine Parrhesia-sprechende Person in einer sozialen Position sein, die unterhalb derjenigen ist, die sie kritisiert. Beispielsweise ein Schüler, der die Wahrheit seiner Lehrerin gegenüber ausspricht, wäre ein zutreffendes Beispiel von Parrhesia; ein Lehrer, der die Wahrheit seiner Schülerin mitteilt, jedoch nicht. Foucault beschreibt Parrhesia so: “More precisely, parrhesia is a verbal activity in which a speaker expresses his personal relationship to truth, and risks his life because he recognizes truth-telling as a duty to improve or help other people (as well as himself). In parrhesia, the speaker uses his freedom and chooses frankness instead of persuasion, truth instead of falsehood or silence, the risk of death instead of life and security, criticism instead of flattery, and moral duty instead of self-interest and moral apathy.” „Genauer gesagt, ist Parrhesia eine verbale Aktivität, in der ein Sprecher seine persönliche Beziehung zur Wahrheit äußert und dabei sein Leben riskiert, weil er das Aussprechen der Wahrheit als Pflicht erkennt, um andere Menschen zum Besseren zu bekehren oder ihnen zu helfen (wie auch sich selbst). In Parrhesia verwendet der Sprecher seine Freiheit und wählt Offenheit statt Überzeugungskraft, Wahrheit statt Lüge oder Schweigen, das Risiko des Todes statt Lebensqualität und Sicherheit, Kritik anstelle von Schmeichelei, sowie moralische Pflicht anstelle von Eigeninteresse und moralischer Apathie.“ – Michel Foucault[1] |

Parrhesia(ドイツ語ではパレーシアとも)はギリシャ語(παρρησία)に由来し、言論の自由や何事についても語る自由を意味する。この言葉はミシェル・フーコーによって、修

辞的な要素や操作的な話し方、一般化を用いることなく、自分の意見や考えを率直かつ正直に表現する言説の概念を表すために用いられた。 古代からの伝統的なパレーシアの考え方には、いくつかの条件がある。パレーシアを用いる者は、真理との信頼できる関係がある場合、自分自身や文化の一般 的な意見を批判する場合、この真理の暴露が自分を危険にさらす場合、それでもなお、道徳的、社会的、政治的な義務だと考えて真理を語る場合にのみ、パルレ シアとして認められる。さらに、パレーシアを語る人は、批判する相手よりも社会的立場が下でなければならない。例えば、生徒が教師に真実を語ることはパレーシアの適切な例であるが、教師が生徒に真実を語ることはパルヘシアの例ではない。 フーコーはパレーシアを次のように説明する: 「より正確には、パレーシアとは、話し手が真実との個人的な関係を表現する言語活動であり、(自分自身だけでなく)他の人々を改善したり助けたりする義務 として真実を語ることを認識するために、自分の命を危険にさらすものである。パルレシアでは、話し手は自由を行使し、説得の代わりに率直さを、虚偽や沈黙 の代わりに真実を、生命や安全の代わりに死の危険を、お世辞の代わりに批判を、自己利益や道徳的無関心の代わりに道徳的義務を選択する。" 「より具体的に言えば、パレーシアは、話し手が真理との個人的な関係を表現する言語活動であり、真理を語ることは、(自分自身だけでなく)他の人々を改 心させたり、より良い方向に導くための義務であると認識するため、命がけで行うものである。パパレーシアは、話し手は自由を行使し、説得の代わりに率直さ を、嘘や沈黙の代わりに真実を、生活の質や安全の代わりに死の危険を、お世辞の代わりに批判を、自己利益や道徳的無関心の代わりに道徳的義務を選択する。 " - ミシェル・フーコー[1] |

| Literatur Parrhesia in der Antike Beate Beer: Parrhesia. In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum. Band 26, Hiersemann, Stuttgart 2015, ISBN 978-3-7772-1509-9, Sp. 1014–1033. Dana Fields: Frankness, Greek Culture, and the Roman Empire. Routledge, Abingdon 2020. John T. Fitzgerald (Hrsg.): Friendship, Flattery, and Frankness of Speech. Studies in the New Testament World. Brill, Leiden u. a. 1996, ISBN 90-04-10454-2. Hartmut Leppin: Paradoxe der Parrhesie. Eine antike Wortgeschichte (= Tria Corda. Band 14). Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2022, ISBN 978-3-16-157550-1. – Rezension von David J. DeVore, Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2023.10.39 Erik Peterson: Zur Bedeutungsgeschichte von Παρρησία. In: Reinhold Seeberg Festschrift, hrsg. von Wilhelm Koepp. Scholl, Leipzig 1929. Alene Saxonhouse: Free Speech and Democracy in Ancient Athens. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2006, 85–126. Giuseppe Scarpat: Parrhesia. Storia del termine e delle sue traduzione in Latino. Paideia, Brescia 1964. Giuseppe Scarpat: Parrhesia greca, parrhesia Cristiana. Paideia, Brescia 2001. Ineke Sluiter, Ralph Mark Rosen (Hrsg.): Free speech in classical antiquity. Brill, Leiden 2004. Peter-Ben Smit, Eva van Urk (Hrsg.): Parrhesia. Ancient and Modern Perspectives on Freedom of Speech. Brill, Leiden 2018. Parrhesia in der Moderne Michel Foucault: Das Wahrsprechen des Anderen. Zwei Vorlesungen 1983/84. Frankfurt am Main: Materialis, 1988, ISBN 3-88535-106-4. Michel Foucault, James Pearson (Hrsg.): Diskurs und Wahrheit: Die Problematisierung der Parrhesia. Sechs Vorlesungen, gehalten im Herbst 1983 an der Universität von Berkeley/Kalifornien. Berlin: Merve 1996, ISBN 3-88396-129-9. Michel Foucault: Fearless Speech. Edited by Joseph Pearson. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2001. Michel Foucault: Die Regierung des Selbst und der anderen. Vorlesung am Collège de France 1982/83. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 2009, ISBN 978-3-518-58537-5. Michel Foucault: Der Mut zur Wahrheit: Die Regierung des Selbst und der anderen II. Vorlesung am Collège de France 1983/84. Berlin: Suhrkamp 2010, ISBN 978-3-518-58544-3 (TB-Ausgabe Die Regierung des Selbst und der anderen – Band I und II: ISBN 978-3-518-06174-9). Petra Gehring, Andreas Gelhard (Hrsg.): Parrhesia. Foucault und der Mut zur Wahrheit: philosophisch, philologisch, politisch. Zürich, Berlin: diaphanes 2012, ISBN 978-3-03734-173-5. |

文学 古代におけるパレーシア Beate Beer: Parrhesia. In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum. Volume 26, Hiersemann, Stuttgart 2015, ISBN 978-3-7772-1509-9, Sp. 1014-1033. Dana Fields: Frankness, Greek Culture, and the Roman Empire. Routledge, Abingdon 2020. John T. Fitzgerald (ed.): Friendship, Flattery, and Frankness of Speech. 新約聖書世界の研究。Brill, Leiden et al., 1996, ISBN 90-04-10454-2. Hartmut Leppin: Parrhesiaの逆説。Ancient Word History (= Tria Corda. Vol. 14). Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2022, ISBN 978-3-16-157550-1. - デヴィッド・J・デヴォアによる書評、ブリンマー・クラシカル・レビュー 2023.10.39. エリック・ピーターソン:Παρρησίαの意味の歴史について。In: Reinhold Seeberg Festschrift, edited by Wilhelm Koepp. Scholl, Leipzig 1929. Alene Saxonhouse: Free Speech and Democracy in Ancient Athens. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2006, 85-126. Giuseppe Scarpat: Parrhesia. Storia del termine e dele traduzione in Latino. Paideia, Brescia 1964. Giuseppe Scarpat: Parrhesia greca, parrhesia Cristiana. Paideia, Brescia 2001. Ineke Sluiter, Ralph Mark Rosen (eds.): Free speech in classical antiquity. Brill, Leiden 2004. Peter-Ben Smit, Eva van Urk (eds.): Parrhesia. 言論の自由に関する古代と現代の視点。Brill, Leiden 2018. 現代におけるパレーシア ミシェル・フーコー:他者が語る真実。フランクフルト・アム・マイン:マテリアリス、1988年、ISBN 3-88535-106-4. Michel Foucault, James Pearson (eds.): Discourse and Truth: The Problematisation of Parrhesia. 1983年秋、カリフォルニア州バークレー大学で行われた6つの講義。Berlin: Merve 1996, ISBN 3-88396-129-9. Michel Foucault: Fearless Speech. ジョセフ・ピアソン編。Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2001. ミシェル・フーコー:自己と他者の政府。Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 2009, ISBN 978-3-518-58537-5. ミシェル・フーコー:真実の勇気:自己と他者の統治 II. Berlin: Suhrkamp 2010, ISBN 978-3-518-58544-3 (TB版『自己と他者の政府』第1巻および第2巻:ISBN 978-3-518-06174-9)。 Petra Gehring, Andreas Gelhard (eds.): Parrhesia. Foucault and the courage of truth: philosophical, philological, political. Zurich, Berlin: diaphanes 2012, ISBN 978-3-03734-173-5. |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parrhesia |

|

| En

la retórica clásica, la parresía era una manera de «hablar con

franqueza o de excusarse por hablar así».1 El término está tomado del

griego παρρησία (παν = todo + ρησις / ρημα = locución / discurso) que

significa literalmente «decirlo todo» y, por extensión, «hablar

libremente», «hablar atrevidamente» o «atrevimiento». Implica no solo

la libertad de expresión sino la obligación de hablar con la verdad

para el bien común, incluso frente al peligro individual. Sin embargo,

para el Diccionario de la Real Academia Española, la parresia (sin

tilde) es la apariencia “de que se habla audaz y libremente al

decir cosas, aparentemente ofensivas, y en realidad gratas o halagüeñas

para aquel a quien se le dicen”2. |

古

典修辞学では、パレーシアは「率直に話すこと、あるいはそう話したことを弁解すること」を意味した1。この用語はギリシャ語のπαρρησία(παν=す

べて+ρησις /

ρημα=locution/演説)から取られたもので、文字通り「すべてを話すこと」を意味し、ひいては「自由に話すこと」「大胆に話すこと」「大胆

さ」をも意味する。これは言論の自由だけでなく、たとえ個人の危機に直面しても、公益のために真実を語る義務を意味している。しかし、

Diccionario de la Real Academia

Españolaによれば、parresia(アクセントなし)とは、「一見不快なことを大胆かつ自由に話すが、実際には言われた相手を喜ばせたり、お世

辞を言ったりすること」2である。 |

| En la Antigua Grecia La parresía tiene sus orígenes en la Antigua Grecia, siendo una forma común de comunicación en algunas de las escuelas del siglo iv a. C, fue la forma de comunicación utilizada por la escuela cínica, era parte de su estilo de vida.3 La parresía también fue el modo de expresión de los epicúreos.4 |

古代ギリシャ パレーシアの起源は古代ギリシャにあり、紀元前4世紀のいくつかの学派では一般的なコミュニケーション形態であった。パレーシアはエピクロス派の表現方法でもあった4。 |

| Uso en el Antiguo Testamento Michel Foucault (1983) resume el concepto de parresía del Antiguo Testamento de la siguiente manera: De manera más precisa, la parresia es una actividad verbal en la cual un hablante expresa su relación personal a la verdad, y corre peligro porque reconoce que decir la verdad es un deber para mejorar o ayudar a otras personas (tanto como a sí mismo). En parresia, el hablante usa su libertad y elige la franqueza en vez de la persuasión, la verdad en vez de la falsedad o el silencio, el riesgo de muerte en vez de la vida y la seguridad, la crítica en vez de la adulación y el deber moral en vez del auto-interés y la apatía moral. |

旧約聖書における使用 ミシェル・フーコー(1983)は、旧約聖書のパレーシアの概念を次のように要約している: より正確には、パレーシアとは、話し手が真理との個人的な関係を表現する言語活動であり、真理を語ることは(自分自身だけでなく)他の人々を改善したり助け たりする義務であると認識しているために危険を伴う。パレジアでは、話し手は自由を行使し、説得よりも率直さを、虚偽や沈黙よりも真実を、生命や安全より も死の危険を、お世辞よりも批判を、自己利益や道徳的無関心よりも道徳的義務を選択する。 |

| Uso en el Nuevo Testamento Un uso relacionado de parresia se encuentra en el Nuevo Testamento griego, en el cual significa "discurso atrevido", la habilidad de los creyentes de mantener su propio discurso delante de las autoridades políticas y religiosas. |

新約聖書での用法 ギリシャ語の新約聖書では、パレーシアは「大胆な発言」を意味する。 |

| Significados contemporáneos Michel Foucault desarrolló el concepto de parresía (frecuentemente traducido al español como parrhesia) como manera de discurso en el cual uno habla abierta y sinceramente acerca de sí mismo o las propias opiniones sin recurrir a la retórica, la manipulación o la generalización. Pero según Foucault, el que practica la parresía (parrhesiastes) «no es sólo sincero... sino que dice también la verdad». La noción de parresía en sentido foucaultiano está afectada por nuestro modelo cartesiano de experiencia de lo evidente (evidencial experience). A grandes rasgos, para René Descartes la verdad es lo (racionalmente) innegable. En el contexto de una investigación filosófica, lo que puede ser puesto en duda debe ser puesto en duda y, entonces, el discurso que no es examinado o criticado no necesariamente tiene una relación válida con la verdad. Según dice Foucault (1983 §I), en cambio, el «parrhesiastes dice la verdad porque él sabe que se trata de la verdad, y sabe que es verdad porque realmente es verdad».nota 1 Existen varias condiciones que fundaban la noción tradicional de parresia del griego antiguo. Quien recurre a la parresía sostiene una relación creíble hacia la verdad, su posesión de la verdad está garantizada por ciertas cualidades morales; así mismo, es un crítico de sí mismo, o de la opinión popular o de la cultura; revelar la verdad lo coloca en una posición de peligro pero insiste en hablar de la verdad, pues considera que es su obligación moral, social y/o política. Más aún, quien practica la parresía debe estar en una posición social más débil que aquellos a quienes se las revela. Por ejemplo, un pupilo «cantándole las verdades» a su maestro sería un ejemplo preciso de parresía, mientras que un maestro que le dice la verdad a su pupila o pupilo, no. Extrañamente, para Foucault, Sócrates es un caso modélico de parrhesiastes. Esto no parece coherente con su afirmación de que entre los griegos, «el parrhesiastes no parece abrigar ninguna duda acerca de su propia posesión de la verdad». En efecto, esto último no se condice con la confesión socrática de su propia ignorancia (Apología), con la petición de que se le refute en caso de merecerlo (Gorgias), o con la severa crítica a la que el personaje platónico Sócrates expone, sin poderla rebatir, ideas que antes había sostenido (como ocurre con la teoría de las Formas, en el Parménides); tampoco, con la disposición de Sócrates a revisar, hasta el último momento de su vida, las conclusiones antes establecidas (Critón). Una explicación de esta supuesta contradicción en Foucault es que la parresía le permitía al maestro, al filósofo o al médico relacionarse con el discípulo o con el paciente de manera que éste se modificase por sí mismo y se convirtiese en un sujeto de verdad. Así, ni el discípulo era controlado por su maestro, ni se veía imponer la verdad; recibía, en cambio, la verdad subjetivada de este, como estímulo para alcanzar el conocimiento por sus propios medios. |

現代の意味 ミシェル・フーコーは、美辞麗句や操作や一般化に頼ることなく、自分自身や自分の意見を率直に正直に語る言説様式として、パルヘシア(しばしばパレーシア と英訳される)の概念を提唱した。しかし、フーコーによれば、パーレシアの実践者は「誠実であるだけでなく......真実を語っている」のである。フー コー的な意味でのパルヘシアという概念は、デカルト的な証拠経験モデルに影響を受けている。大雑把に言えば、ルネ・デカルトにとって真理とは(合理的に) 否定できないものである。哲学的探求の文脈では、疑問視されうるものは疑問視されねばならず、そのため、検証も批判もされない言説は、必ずしも真理との有 効な関係を持たない。一方、フーコー(1983 §I)によれば、「パルヘシヤ人が真理を語るのは、それが真理であることを知っているからであり、それが真理であることを知っているのは、それが本当に真 理だからである」注1。 伝統的な古代ギリシアのパレシア概念を支えるいくつかの条件がある。パレーシアに頼る者は、真理との信頼できる関係を維持し、真理の所有がある種の道徳的資 質によって保証されていること、自分自身、あるいは世論や文化に対する批判者でもあること、真理を明らかにすることで危険な立場に立たされるが、それが自 分の道徳的、社会的、政治的義務であると考えているため、真理を語ることにこだわること、などである。さらに、パルヘシアの実践者は、それを明かす相手よ りも社会的立場が弱くなければならない。例えば、生徒が教師に「真実を歌う」ことはパレジアの正確な例となるが、生徒に対して真実を語る教師はそうではな い。 不思議なことに、フーコーにとってソクラテスはパレーシアのモデルケースである。このことは、ギリシア人の間では「パルヘシアテスは自分が真理を所有してい ることに疑いを抱いていないようだ」という彼の主張と一致していないように思われる。実際、後者は、ソクラテスが自らの無知を告白すること(『弁明』)、 反論に値するなら反論してほしいという要求(『ゴルギアス』)、プラトン的な性格を持つソクラテスが、それまで自分が抱いていた考え(『パルメニデス』に おける形相論など)を反論することなく、厳しい批判にさらすこと(『パルメニデス』における形相論など)、さらには、ソクラテスが人生の最後の瞬間まで、 以前に確立された結論を修正することを厭わないこと(『クリート』)とも一致しない。フーコーに見られるこの矛盾の一つの説明は、パレーシアによって、教 師、哲学者、医師は、弟子や患者が自らを修正し、真理の主体となるような形で、弟子や患者と関わることができたというものである。したがって、弟子は師匠 に支配されることもなく、真理を押しつけられることもなかった。その代わりに、彼は師匠から主観化された真理を、自らの手段で知識を獲得するための刺激と して受け取ったのである。 |

| Comedia en vivo La parresía es la forma más común de expresión en las comedias en vivo, donde se suele hablar y burlarse de tanto de políticos corruptos (incluso presidentes) como de personalidades famosas sin importar su estatus, posición o autoridad. |

お笑いライブ パレーシアはライブ・コメディで最も一般的な表現形式であり、汚職政治家(大統領を含む)から有名タレントまで、その地位や立場、権威に関係なく、しばしば議論され、嘲笑される。 |

| Escuela cínica Anaideia Adiaforía Epicureísmo Comedia en vivo |

シニックスクール(犬儒派) アナイデイア アディアフォリア エピクロス主義 喜劇 |

| https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parres%C3%ADa |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099