情念

Passion as Emotion, 情動としての情念

Frederick

Goodall's Passionate Encounter

★情熱=情念(ギリシャ語 πάσχω 「苦しむ、作用される(キリスト受苦を意味する)」、後期ラテン語(主にキリスト教)passio 「情熱、苦しみ」(ラテン語 pati 「苦しむ」、分詞:passus から)は、特定の人物や物に対する強く難解な、あるいはほとんど制御できない感情や 傾動を表すために使われる言葉である。この一般論としての「情念」を説明した後に、哲学上の情念ならびに、デカルト「魂の情念」について解 説する。

☆イエスの受難(ラテン語のpatior、「苦しむ、耐える、耐え忍ぶ」から)[1]とは、

正典とされる4つの福音書で描かれている、イエスの死の直前の短い期間のことである。キリスト教では毎年聖週間に記念される。[2]

受難には、イエスがエルサレムに入城した際の勝利の行進、神殿清め、油注ぎ、最後の晩餐、苦悩、逮捕、サンヘドリンとピラトによる裁判、磔刑と死、埋葬な

ど、その他の出来事も含まれる。これらの出来事を記述した4つの正典福音書の部分は、受難物語として知られている。キリスト教のいくつかのコミュニティで

は、受難の記念には、イエスの母マリアの悲しみを偲ぶ「悲しみの金曜日」も含まれる。

受難という言葉はより一般的な用法となり、キリスト教の殉教者の苦しみと死についても使われるようになった。時にはラテン語の「パッシオ

(passio)」という形も使われる。[3]

| Passion (Greek πάσχω

"to suffer, to be acted on"[1] and Late Latin (chiefly Christian[2])

passio "passion; suffering" (from Latin pati "to suffer"; participle:

passus)) is a term used to denote strong and intractable or barely

controllable emotion or inclination with respect to a particular person

or thing. Passion can range from eager interest in, or admiration for,

an idea, proposal, or cause; to enthusiastic enjoyment of an interest

or activity; to strong attraction, excitement, or emotion towards a

person. It is particularly used in the context of romance or sexual

desire, though it generally implies a deeper or more encompassing

emotion than that implied by the term lust, often incorporating ideas

of ecstasy and/or suffering. Denis Diderot (1713-1784) describes passions as "penchants, inclinations, desires and aversions carried to a certain degree of intensity, combined with an indistinct sensation of pleasure or pain, occasioned or accompanied by some irregular movement of the blood and animal spirits, are what we call passions. They can be so strong as to inhibit all practice of personal freedom, a state in which the soul is in some sense rendered passive; whence the name passions. This inclination or so-called disposition of the soul, is born of the opinion we hold that a great good or a great evil is contained in an object which in and of itself arouses passion".[3] Diderot further breaks down pleasure and pain, which he sees as the guiding principles of passion, into four major categories: 1. Pleasures and pains of the senses 2. Pleasures of the mind or of the imagination 3. Our perfection or our imperfection of virtues or vices 4. Pleasures and pains in the happiness or misfortunes of others Modern pop-psychologies and employers tend to favor and even encourage the expression of a "passion"; previous generations sometimes expressed more nuanced viewpoints.[4] |

情熱=情念(ギリシャ語 πάσχω

「苦しむ、作用される(キリスト受苦を意味する)」[1]、後期ラテン語(主にキリスト教[2])passio 「情熱、苦しみ」(ラテン語 pati

「苦しむ」、分詞:passus

から)は、特定の人物や物に対する強く難解な、あるいはほとんど制御できない感情や傾動を表すために使われる言葉である。情熱は、アイデア、提案、または

原因に対する熱心な関心や賞賛、興味や活動の熱心な楽しみ、人に対する強い魅力、興奮、または感情など、様々なものがある。特に恋愛や性的欲求の文脈で使

われるが、一般的には欲望という言葉が意味するものより深く、より包括的な感情を意味し、しばしばエクスタシーや苦しみの考えを取り入れることがある。 ドゥニ・ディドロ(1713-1784)は、情熱=情念について次のように述べている。 「情熱、傾向、欲望、嫌悪は、ある程度の強さに達し、快楽や苦痛のはっきりしない感覚と結びつき、血液や動物霊の不規則な動きによって引き起こされたり、 伴ったりするもので、我々が情熱と呼ぶものである。この情熱は、個人の自由を阻害するほど強く、魂がある意味で受動的になっている状態であり、そのため情 熱と呼ばれる。この魂の傾き、いわゆる気質は、大きな善や大きな悪が、それ自体で情熱を呼び起こす対象に含まれているという私たちの意見から生まれたもの である」[3]。 ディドロはさらに、情熱=情念の指導原理とする快楽と苦痛を4つの大きなカテゴリーに分類する。 1. 五感の快楽と苦痛 2. 心や想像力の快楽 3. 美徳や悪徳の完全性、不完全性 4. 他人の幸福や不幸を喜ぶこと、苦しむこと 現代の大衆心理学や雇用主は「情熱」の表現を支持し、奨励する傾向にあるが、以前の世代はもっと微妙な視点を表現することもあった[4]。 |

| Emotion The standard definition for emotion is a "Natural instinctive state of mind deriving from one's circumstances, mood, or relationships with others".[5] Emotion,[6] William James describes emotions as "corporeal reverberations such as surprise, curiosity, rapture, fear, anger, lust, greed and the like." These are all feelings that affect our mental perception. Our body is placed into this latter state, which is caused by one's mental affection. This state gives signals to our body which cause bodily expressions. The philosopher Robert Solomon developed his own theory and definition of emotion. His view is that emotion is not a bodily state, but instead a type of judgment. "It is necessary that we choose our emotions, in much the same way that we choose our actions"[7] With regard to the relationship between emotion and our rational will, Solomon believes that people are responsible for their emotions. Emotions are rational and purposive, just as actions are. "We choose an emotion much as we choose a course of action."[8] Recent studies, also traditional studies have placed emotions to be a physiological disturbance. William James takes such consciousness of emotion to be not a choice but a physical occurrence rather than a disturbance. It is an occurrence that happens outside of our control, and our bodies are just affected by these emotions. We produce these actions based on the instinctive state that these feelings lead us towards. This concept of emotion was derived from passion. Emotions were created as a category within passion. |

感情 感情の標準的な定義は、"人の状況、気分、または他者との関係から派生する自然な本能的心の状態 "である[5] 。感情[6] William Jamesは、感情を "驚き、好奇心、うっとり、恐怖、怒り、欲、および同様のような身体的反響 "として記述している。これらはすべて、私たちの精神的な知覚に影響を与える感情である。私たちの身体は、この後者の状態に置かれ、それは自分の精神的な 愛情によって引き起こされる。この状態は、私たちの身体にシグナルを与え、身体的な表現を引き起こす。 哲学者のロバート・ソロモンは、感情について独自の理論と定義を展開した。それは、「感情とは身体の状態ではなく、判断の一種である」というものである。 「感情と理性的意志の関係については、ソロモンは人は自分の感情に責任があると考える。感情は行動と同じように合理的であり、目的を持っている。「我々は 行動を選択するのと同じように感情を選択する」[8]と述べている。ウィリアム・ジェームズはそのような感情の意識を、選択ではなく、障害というよりむし ろ物理的な発生であると捉えている。それは、私たちのコントロールの及ばないところで起こる出来事であり、私たちの身体はその感情の影響を受けているだけ なのである。その感情が導く本能的な状態に基づいて、私たちはこうした行動を生み出す。 この感情という概念は、情熱から派生したものです。感情は、情熱の中のカテゴリーとして作られた。 |

| Reason Strong Desire for something: In whatever context, if someone desires for something and that desire has some strong feeling or emotion is defined in terms of passion. Passion has no boundary, being passionate about something which is boundless can be sometimes dangerous, In which person forget about everything and is fully determined towards the particular thing-(Sanyukta) In his wake, Stoics like Epictetus emphasized that "the most important and especially pressing field of study is that which has to do with the stronger emotions...sorrows, lamentations, envies...passions which make it impossible for us even to listen to reason".[9] The Stoic tradition still lay behind Hamlet's plea to "Give me that man That is not passion's slave, and I will wear him In my heart's core",[10] or Erasmus's lament that "Jupiter has bestowed far more passion than reason – you could calculate the ratio as 24 to one".[11] It was only with the Romantic movement that a valorisation of passion over reason took hold in the Western tradition: "the more Passion there is, the better the Poetry".[12] The recent concerns of emotional intelligence have been to find a synthesis of the two forces—something that "turns the old understanding of the tension between reason and feeling on its head: it is not that we want to do away with emotion and put reason in its place, as Erasmus had it, but instead find the intelligent balance of the two".[13] |

理性 何かに対する強い欲望:どんな状況であれ、誰かが何かを欲し、その欲望が何らかの強い感情や感覚を持っている場合、それは情熱という言葉で定義されます。 情熱には境界がない。無限の何かに熱中することは、時に危険であり、人はすべてを忘れ、特定のことに向かって完全に決意する-(Sanyukta) エピクテトスのようなストア派は、「最も重要で特に緊急な研究分野は、より強い感情...悲しみ、嘆き、嫉妬...理性に耳を傾けることさえ不可能にする 情熱に関係するものである」ことを強調した[9]。 [ハムレットの「情熱の奴隷でない男をよこせ、そうすれば彼を私の心の芯に着せてやる」という懇願の背景にはストア派の伝統がまだあり[10]、エラスム スの「ジュピターが理性よりはるかに多くの情熱を与えた、その割合は24対1として計算できる」という嘆きもあった[11]。理性を超えた情熱の価値化が 西洋伝統に定着したのは、ロマン派の動向からだった。「より多くの情熱があればあるほど、より良い詩が生まれる」[12]。 感情知能の最近の関心事は2つの力の統合を見つけることであり、それは「理性と感情の間の緊張の古い理解を覆すものであり、エラスムスが持っていたよう に、感情を排除してその場所に理性を置きたいのではなく、代わりに2つの知的バランスを見つけたい」ものであった[13]。 |

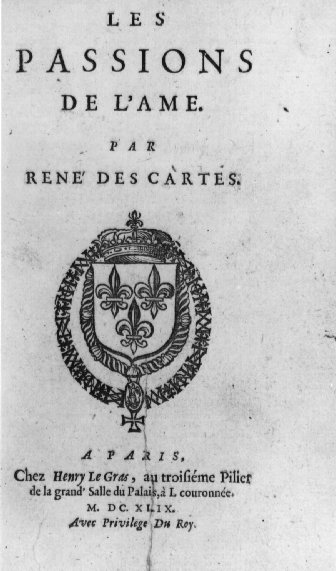

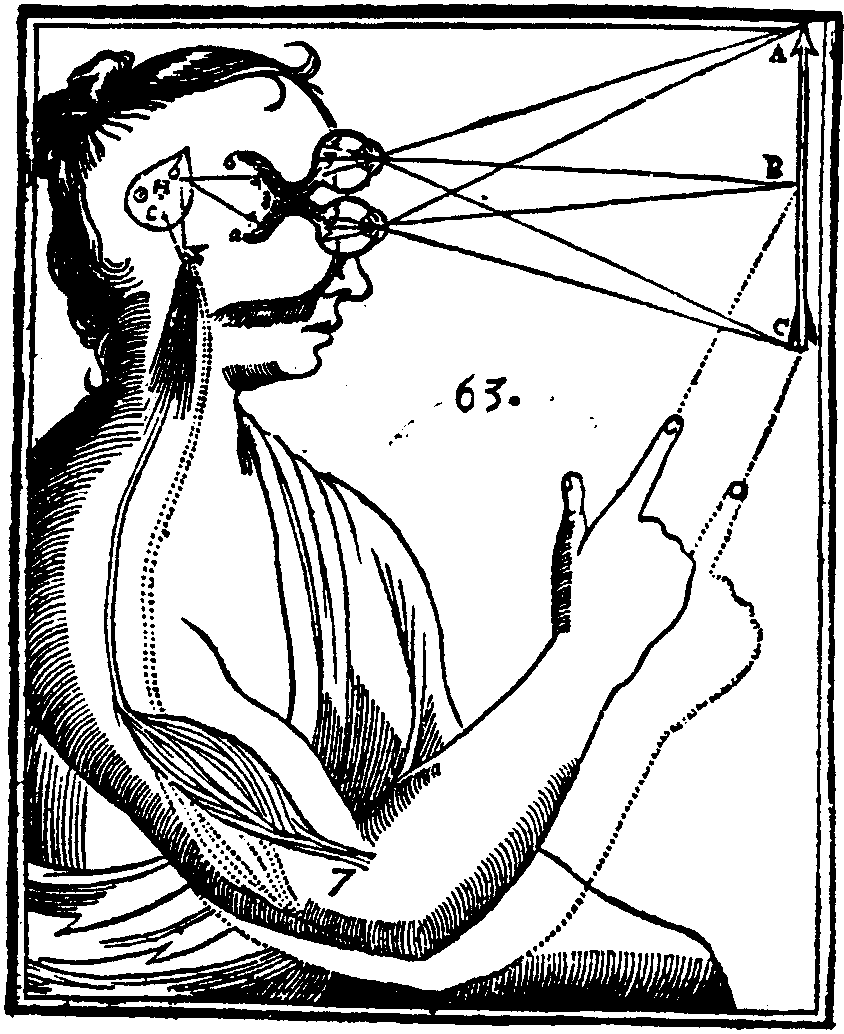

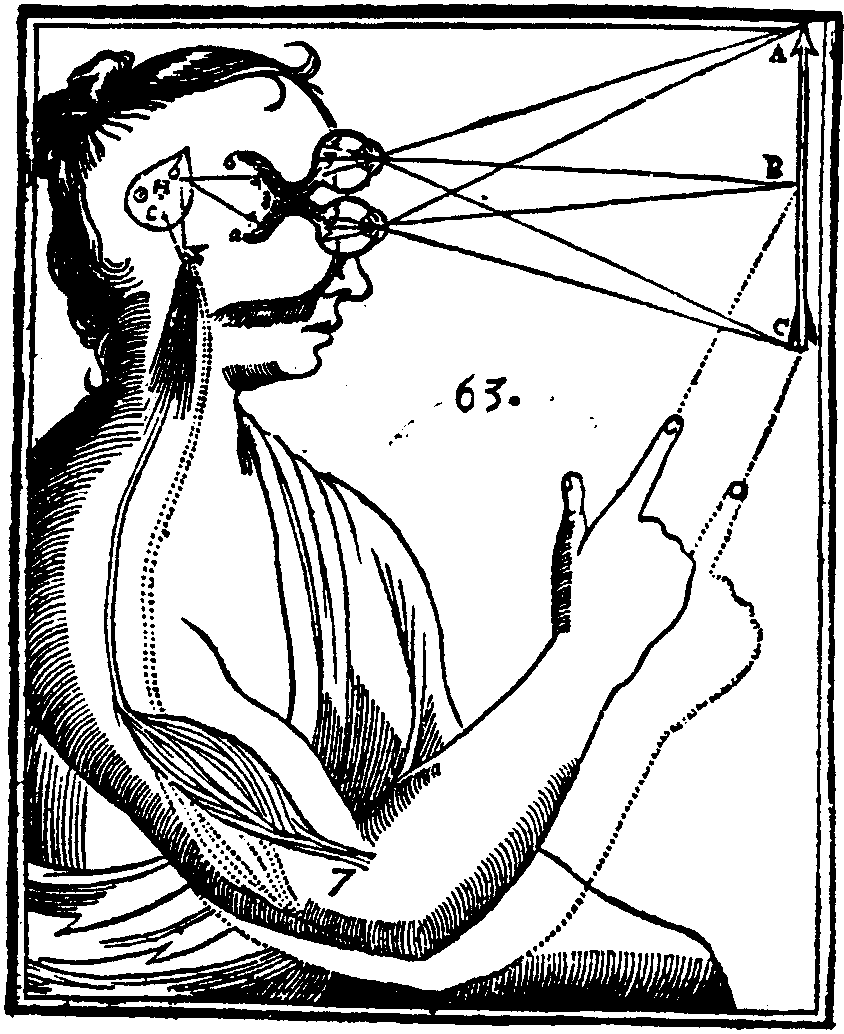

| "Descartes' Error" Antonio Damasio studied what ensued when something "severed ties between the lower centres of the emotional brain...and the thinking abilities of the neocortex".[14] He found that while "emotions and feelings can cause havoc in the processes of reasoning...the absence of emotion and feeling is no less damaging";[15] and was led to "the counter-intuitive position that feelings are typically indispensable for rational decisions".[16] The passions, he concluded, "have a say on how the rest of the brain and cognition go about their business. Their influence is immense...[providing] a frame of reference – as opposed to Descartes' error...the Cartesian idea of a disembodied mind".[17] |

「デカルトの過ち」 アントニオ・ダマシオは何かが「感情的な脳の低次中枢と...新皮質の思考能力の間の絆を断ち切った」ときに起こることを研究した[14]。 彼は「感情や気持ちが推論のプロセスに混乱を引き起こすことができるが...感情と気持ちの欠如も同様にダメージを与える」ことを見つけ、「感情は合理的 な決定にとって通常不可欠であるという直感に反する立場」へ導かれた[15]。 情念、彼は「脳の残りの部分と認識がどう事業を進めるかに発言権がある」と結論付けている。その影響力は絶大であり、デカルトの誤り、つまり実体のない心 というデカルト的な考えとは対照的に、参照枠を提供している」[17]。 |

| In marriage A tension or dialectic between marriage and passion can be traced back in Western society at least as far as the Middle Ages, and the emergence of the cult of courtly love. Denis de Rougemont has argued that 'since its origins in the twelfth century, passionate love was constituted in opposition to marriage'.[18] Stacey Oliker writes that while "Puritanism prepared the ground for a marital love ideology by prescribing love in marriage", only from the eighteenth century has "romantic love ideology resolved the Puritan antagonism between passion and reason"[19] in a marital context. (Note though that Saint Paul spoke of loving one's wife in Ephesians 5.) |

結婚における情念 結婚と情熱の間の緊張や弁証法は、西洋社会では少なくとも中世までさかのぼることができ、宮廷恋愛のカルトの出現があった。ドゥニ・ド・ルージュモンは 「12世紀におけるその起源以来、情熱的な愛は結婚に対立するものとして構成されていた」と論じている[18]。ステイシー・オリカーは、「ピューリタニ ズムは結婚における愛を規定することによって結婚愛の思想のための基盤を準備したが」、18世紀からのみ「ロマンチックな愛の思想は情熱と理性の間の ピューリタンの対立を結婚の文脈で解決」[19]しているのだとしている[19]。(ただし、聖パウロはエペソ人への手紙5章で、妻を愛することを語って いる)。 |

| Intellectual passions George Bernard Shaw "insists that there are passions far more exciting than the physical ones...'intellectual passion, mathematical passion, passion for discovery and exploration: the mightiest of all passions'".[20] His contemporary, Sigmund Freud, argued for a continuity (not a contrast) between the two, physical and intellectual, and commended the way "Leonardo had energetically sublimated his sexual passions into the passion for independent scientific research".[21] |

知的な情熱 ジョージ・バーナード・ショーは「肉体的なものよりもはるかに刺激的な情熱があると主張している...知的情熱、数学的情熱、発見と探求の情熱:すべての 情熱の中で最も強大なもの」[20]。 彼と同時代のジークムント・フロイトは、肉体性と知的の間の連続性(対比ではなく)を主張し、「レオナルドが精力的に彼の性的情熱を独自の科学研究の情熱 に昇華した」方法を高く評価している[21]。 |

| As a motivation in an occupation There are different reasons individuals are motivated in an occupation. These may include a passion for the occupation, for a firm, or for an activity. When Canadian managers or professionals score as passionate about their occupation they tend to be less obsessive about their behavior while on their job, resulting in more work being done and more work satisfaction. These same individuals have higher levels of psychological well-being.[22] When people genuinely enjoy their profession and are motivated by their passion, they tend to be more satisfied with their work and more psychologically healthy.[citation needed] When managers or professionals are unsatisfied with their profession they tend to also be dissatisfied with their family relationships and to experience psychological distress.[23] Other reasons people are more satisfied when they are motivated by their passion for their occupation include the effects of intrinsic and external motivations. When Canadian managers or professionals do a job to satisfy others, they tend to have lower levels of satisfaction and psychological health. Also, these same individuals have shown they are motivated by several beliefs and fears concerning other people.[23] Thirdly, though some individuals believe one should not work extreme hours, many prefer it because of how passionate they are about the occupation. On the other hand, this may also put a strain on family relationships and friendships.[citation needed] The balance of the two is something that is hard to achieve and it is always hard to satisfy both parties.[citation needed] |

職業における動機づけとして 個人が職業に意欲を持つ理由はさまざまである。その中には、職業に対する情熱、会社に対する情熱、あるいは活動に対する情熱が含まれる。カナダの管理職や 専門家が自分の職業に対して情熱的であるとスコアした場合、彼らは仕事中に自分の行動に対してあまり執着しない傾向があり、その結果、より多くの仕事が行 われ、より多くの仕事の満足度を得ることができる。これらの同じ個人は心理的幸福のレベルが高い[22] 人々は純粋に自分の職業を楽しみ、その情熱によって動機づけられているとき、彼らは仕事により満足し、より心理的に健康になる傾向がある [citation needed] 管理者や専門家が自分の職業に満足していないとき、彼らはまた彼らの家族関係に不満を感じ、心理的苦痛を経験する傾向がある[23] 人々が職業に対する情熱で動機づけられるとより満足するというその他の理由は、内的動機および外的動機の影響を含んでいる。カナダの管理職や専門職が他人 を満足させるために仕事をする場合、満足度と心理的健康度が低くなる傾向がある。また、これらの同じ人たちは、他者に関するいくつかの信念や恐怖によって 動機づけられていることが示されている[23] 第3に、極端な長時間労働はすべきでないと考える個人もいるが、多くの人はその職業にどれほど情熱を持っているかという理由で、それを好むのである。一方 で、これは家族関係や友人関係に負担をかける可能性もある[要出典]。両者のバランスをとることは難しいことであり、両者を満足させることは常に困難であ る[要出典]。 |

| Work enjoyment vs. inner

pressures There are different components that qualify as reasons for considering an individual as a workaholic. Burke & Fiksenbaum refer to Spence and Robbins (1992) by stating two of the three workaholism components that are used to measure workaholism. These include feeling driven to work because of inner pressure and work enjoyment. Both of these affect an individual differently and each has different outcomes. To begin, work enjoyment brings about more positive work outcomes and is unrelated to health indicators. Inner pressure, on the other hand, is negatively related with work outcomes and has been related negatively to measures of psychological health. Burke & Fiksenbaum make a reference to Graves et al. (2006) when examining work enjoyment and inner pressures. Work enjoyment and inner pressure were tested with performance ratings. The former was positively related to performance ratings while the latter interfered with the performance-enhancing aspects of work enjoyment. Burke & Fiksenbaum refer to Virick and Baruch (2007) when explaining how these two workaholism components affect life satisfaction. Not surprisingly, inner pressure lowered the balance between work-life and life satisfaction but enhanced people's performance at their occupation, whereas work enjoyment led to a positive balance between the two. Again, when managers and professionals are passionate about their occupation and put in many hours, they then become concerned that their occupation will satisfy personal relationships and the balance must then be found according to the importance levels of the individual.[23] Motivation and outcomes The researchers indicate different patterns of correlations between these two components. These patterns include antecedents and consequences. The two components offer unique motivations or orientations to work which result in its effects on work and well-being. Inner pressures will hinder performance while work enjoyment will smooth performance. Inner pressures of workaholism have characteristics such as persistence, rigidity, perfectionism, and heightened levels of job stress. This component is also associated[by whom?] with working harder, not smarter. On a more positive note, individuals who enjoy their work will have higher levels of performance for several reasons. These include creativity, trust in their colleagues, and reducing levels of stress.[23] Good and bad workaholics Burke and Fiksenbaum refer to Schaufeli, Taris, and Bakker (2007) when they made a distinction between an individual good workaholics and bad workaholics. A good workaholic will score higher on measures of work engagement and a bad workaholic will score higher on measures of burnout. They[who?] also suggest why this is – some individuals work because they are satisfied, engaged, and challenged and to prove a point. On the other hand, the opposite kind work hard because they are addicted to work; they see that the occupation makes a contribution to finding an identity and purpose.[23] Desire in an occupation Passion and desire go hand in hand, especially as a motivation. Linstead & Brewis refer to Merriam-Webster to say that passion is an "intense, driving, or overmastering feeling or conviction". This suggests that passion is a very intense emotion, but can be positive or negative. Negatively, it may be unpleasant at times. It could involve pain and has obsessive forms that can destroy the self and even others. In an occupation, when an individual is very passionate about their job, they may be so wrapped up in work that they cause pain to their loved ones by focusing more on their job than on their friendships and relationships. This is a constant battle of balance that is difficult to achieve and only an individual can decide where that line lies.[citation needed] Passion is connected to the concept of desire. In fact, they are inseparable, according to a (mostly western) way of thinking related to Plato, Aristotle, and Augustine. These two concepts cause individuals to reach out for something, or even someone. They both can either be creative or destructive and this dark side can very well be dangerous to the self or to others.[2] |

仕事の楽しみと内なるプレッシャー 個人をワーカホリックとみなす理由として、さまざまな構成要素がある。Burke & Fiksenbaumは、Spence and Robbins(1992)を参考に、ワーカホリックの測定に使われる3つの要素のうち2つを挙げている。これらは、内なる圧力のために仕事に駆り立てら れる感じと仕事の楽しみを含んでいる。この2つは、個人への影響が異なり、それぞれ異なる結果をもたらす。まず、仕事の楽しみは、よりポジティブな仕事の 成果をもたらし、健康指標とは無関係である。一方、内なる圧力は、仕事の成果と負の相関があり、心理的健康の指標とも負の相関があるとされています。 Burke & Fiksenbaumは、Gravesら(2006)を参考に、仕事の楽しさと内なるプレッシャーを検証している。仕事の楽しみと内なるプレッシャーは、 業績評価とともに検証された。前者は業績評価と正の相関があり、後者は仕事を楽しむことの業績向上的側面を妨害するものであった。Burke & Fiksenbaumは、Virick and Baruch(2007)を参照しながら、この2つのワーカホリックの構成要素がどのように生活満足度に影響を及ぼすかを説明している。当然のことなが ら、内なる圧力は、仕事と生活の満足度のバランスを低下させる一方で、人々の職業におけるパフォーマンスを向上させ、一方、仕事を楽しむことは、この2つ のバランスをポジティブにすることにつながった。繰り返しになるが、管理職や専門家が自分の職業に情熱を持ち、多くの時間を費やすとき、次に彼らは自分の 職業が個人的な関係を満たすことを心配し、その後、個人の重要度に従ってバランスを見つける必要がある[23]。 動機づけと成果 研究者たちは、この2つの構成要素の間に、さまざまな相関のパターンを示しています。これらのパターンには、先行要因と帰結が含まれる。この2つの構成要 素は、仕事に対するユニークな動機づけや方向づけを提供し、その結果、仕事と幸福に影響を与える。内なる圧力はパフォーマンスを妨げ、仕事を楽しむことは パフォーマンスを円滑にする。ワーカホリックの内なる圧力は、粘り強さ、厳格さ、完璧主義、仕事のストレスのレベルの高さなどの特徴を持っています。この 要素はまた、より賢く働くのではなく、より懸命に働くことと関連している(誰によって?もっとポジティブなことを言えば、仕事を楽しんでいる人は、いくつ かの理由でより高いレベルのパフォーマンスを発揮することができます。これらには、創造性、同僚への信頼、ストレスレベルの低減が含まれる[23]。 良いワーカホリックと悪いワーカホリック バークとフィクセンバウムは、Schaufeli, Taris, and Bakker (2007)を参照して、個人の良い仕事中毒と悪い仕事中毒を区別している。良いワーカホリックは、仕事への関与の指標でより高いスコアとなり、悪いワー カホリックは、燃え尽きの指標でより高いスコアとなります。彼ら[誰?]はまた、これがなぜなのかを示唆しています - 一部の個人は、彼らが満足し、従事し、挑戦し、ポイントを証明するために働いています。一方、正反対の種類の人は、仕事にはまるから一生懸命働く。彼ら は、その職業がアイデンティティと目的を見つけることに貢献していると考える[23]。 職業における欲望 情熱と欲求は、特に動機づけとして相性が良い。Linstead & Brewisは、Merriam-Websterを参照して、情熱とは「強烈な、原動力となる、または支配的な感情または確信」であると述べている。これ は、情熱が非常に激しい感情であることを示唆しているが、ポジティブにもネガティブにもなりうる。ネガティブな場合は、時に不愉快になることがあります。 痛みを伴うこともあり、自己や他人をも破壊する強迫観念のようなものもある。職業で言えば、仕事に非常に熱中している場合、仕事に没頭するあまり、友人関 係や人間関係よりも仕事に集中し、大切な人を苦しめてしまうことがある。これは達成するのが難しいバランスの絶え間ない戦いであり、その線引きがどこにあ るかを決めることができるのは個人だけである[citation needed] 情熱は欲求の概念と結びついている。実際、プラトン、アリストテレス、アウグスティヌスに関連する(主に西洋の)考え方によれば、これらは切り離すことが できないものである。この2つの概念は、個人が何か、あるいは誰かを求めて手を伸ばす原因となる。それらは両方とも創造的であるか破壊的であるかのどちら かで、この暗黒面は自己または他者にとって危険である可能性が非常に高い[2]。 |

| As a motivation for hobbies Hobbies require a certain level of passion in order to continue engaging in the hobby. Singers, athletes, dancers, artists, and many others describe their emotion for their hobby as a passion. Although this might be the emotion they're feeling, passion is serving as a motivation for them to continue their hobby. Recently there has been a model to explain different types of passion that contribute to engaging in an activity. Dualistic model According to researchers who have tested this model, "A dualistic model in which passion is defined as a strong inclination or desire toward a self-defining activity that one likes (or even loves), that one finds important (high valuation), and in which one invests time and energy."[25] It is proposed that there exist two types of passion. The first type of passion is harmonious passion. "A harmonious passion refers to a strong desire to engage in the activity that remains under the person's control."[25] This is mostly obtained when the person views their activity as part of their identity. Furthermore, once an activity is part of the person's identity then the motivation to continue the specific hobby is even stronger. The harmony obtained with this passion is conceived when the person is able both to freely engage in or to stop the hobby. It's not so much that the person is forced to continue this hobby, but on his or her own free will is able to engage in it. For example, if a girl loves to play volleyball, but she has a project due the next day and her friends invite her to play, she should be able to say "no" on the basis of her own free will. The second kind of passion in the dualistic model is obsessive passion. Being the opposite of harmonious passion. This type has a strong desire to engage in the activity, but it's not under the person's own control and he or she is forced to engage in the hobby. This type of passion has a negative effect on a person where they could feel they need to engage in their hobby to continue, for example, interpersonal relationships, or "fit in" with the crowd. To change the above example, if the girl has an obsessive passion towards volleyball and she is asked to play with her friends, she will likely say "yes" even though she needs to finish her project for the next day. Intrinsic motivation Since passion can be a type of motivation in hobbies then assessing intrinsic motivation is appropriate. Intrinsic motivation helps define these types of passion. Passion naturally helps the needs or desires that motivate a person to some particular action or behavior.[26] Certain abilities and hobbies can be developed early and the innate motivation is also something that comes early in life. Although someone might know how to engage in a hobby, this doesn't necessarily mean they are motivated to do it. Christine Robinson makes the point in her article that, " ...knowledge of your innate motivation can help guide action toward what will be fulfilling."[26] Feeling satisfied and fulfilled builds the passion for the hobby to continue a person's happiness. Fictional examples In Margaret Drabble's The Realms of Gold, the hero flies hundreds of miles to reunite with the heroine, only to miss her by 24 hours – leaving the onlookers "wondering what grand passion could have brought him so far...a quixotic look about him, a look of harassed desperation".[27] When the couple do finally reunite, however, the heroine is less than impressed. "'If you ask me, it was a very childish gesture. You're not twenty-one now, you know'. 'No, I know. It was my last fling'".[28] In Alberto Moravia's 1934, the revolutionary double-agent, faced with the girl he is betraying, "was seized by violent desire...he never took his eyes off my bosom...I believe those two dark spots at the end of my breasts were enough to make him forget tsarism, revolution, political faith, ideology, and betrayal".[29] |

趣味のモチベーションとして 趣味は、その趣味を続けるために、ある種の情熱が必要だ。歌手、スポーツ選手、ダンサー、アーティストなど、多くの人が趣味に対する感情を「情熱」と表現 します。しかし、この情熱は、趣味を続けるための動機づけとして機能しているのである。最近、ある活動に取り組む際に、情熱の種類を説明するモデルがあ る。 二元論モデル このモデルを検証した研究者によると、「情熱とは、自分が好き(あるいは愛)であり、自分が重要だと思い(高い評価)、自分が時間やエネルギーを投資する 自己定義的活動に対する強い傾きや欲求と定義する二元論モデル」[25]であり、情熱には2種類存在することが提案されている。第一のタイプの情熱は調和 的な情熱である。 「調和的な情熱とは、その人のコントロール下にある活動に従事したいという強い欲求を指す」[25]。これは、その人が自分の活動をアイデンティティの一 部として捉えているときに得られることがほとんどである。さらに、いったん活動がその人のアイデンティティの一部となれば、特定の趣味を継続する動機はさ らに強くなる。この情熱の調和は、その人がその趣味に自由に取り組んだり、やめたりすることができたときに得られるものである。強制的に続けさせられるの ではなく、自分の意志で、その趣味に取り組むことができる。例えば、バレーボールが好きな女の子が、翌日提出のプロジェクトがあるのに、友達に誘われた ら、自分の自由意志に基づいて「NO」と言えるはずである。 二元論モデルにおける第二の情熱は、強迫的な情熱である。調和的情熱の反対であること。このタイプは、その活動に従事したいという強い欲求を持っている が、その人自身のコントロール下にあるわけではなく、その趣味に従事することを余儀なくされている。このタイプの情熱は、例えば対人関係を続けるため、あ るいは群衆に「溶け込む」ために趣味に従事する必要があると感じる可能性があり、人にマイナスの影響を与えます。例えば、バレーボールに夢中になっている 女の子が、友達と遊ぼうと誘われたら、次の日の課題を終わらせなければならないのに、「はい」と答えてしまいそうである。 内発的動機づけ 情熱は趣味における動機の一種であるため、内発的動機づけを評価することが適切である。内発的動機づけは、このような情熱のタイプを定義するのに役立つ。 情熱は、人をある特定の行動や行為に動機づけるニーズや欲求を自然に支援します[26]。特定の能力や趣味は早期に開発することができ、生来の動機もまた 人生の早い段階で得られるものである。誰かが趣味に従事する方法を知っているかもしれないが、これは必ずしもその人がその趣味に意欲的であることを意味し ない。クリスティン・ロビンソンの論文では、「...生来の動機を知ることで、充実感を得るための行動を導くことができる」[26]と指摘している。 フィクションの例 マーガレット・ドラブルの「金の領域」では、主人公はヒロインと再会するために何百マイルも飛行するが、24時間遅れで彼女に会い、見物人に「どんな壮大 な情熱が彼をここまで連れてきたのだろう...彼についてのquixotic look、嫌がらせ絶望の表情」を残す。 27] しかしカップルがついに再会したとき、ヒロインはあまり感心していない。しかし、ようやく再会した二人に、ヒロインはあまり感心しない。「私に言わせれ ば、とても子供っぽい仕草でした。あなたはもう21歳じゃないんだから」。「いいえ、わかっています。それは私の最後の浮気だった」[28]。 アルベルト・モラヴィアの1934年では、革命的な二重スパイは、彼が裏切っている少女を前にして、「激しい欲望にとらわれ...彼は私の胸から目を離さ なかった...私の胸の先にあるその二つの黒い点だけで、彼に皇帝制、革命、政治的信仰、思想、裏切り行為を忘れさせるに十分だったと私は思っています」 [29]。 |

| Crime of passion Eros Eroticism Limerence Affection Attraction Courtly love Love Passions (philosophy) Pathos Romantic love Enthusiasm Sympathy Zest (positive psychology) |

情熱の罪 エロス エロティシズム 痴情 愛情 魅力 宮廷愛 恋愛 情熱(哲学) パトス ロマンチックな愛 熱狂 共感 情熱(ポジティブ心理学) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Passion_(emotion) |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

***

☆イエスの受難(Passion of Jesus)

| The Passion

(from Latin patior, "to suffer, bear, endure")[1] is the short final

period before the death of Jesus, described in the four canonical

gospels. It is commemorated in Christianity every year during Holy

Week.[2] The Passion may include, among other events, Jesus's triumphal entry into Jerusalem, his cleansing of the Temple, his anointing, the Last Supper, his agony, his arrest, his trials before the Sanhedrin and before Pilate, his crucifixion and death, and his burial. Those parts of the four canonical Gospels that describe these events are known as the Passion narratives. In some Christian communities, commemoration of the Passion also includes remembrance of the sorrow of Mary, the mother of Jesus, on the Friday of Sorrows. The word passion has taken on a more general application and now may also apply to accounts of the suffering and death of Christian martyrs, sometimes using the Latin form passio.[3] |

イエスの受難(ラテン語のpatior、「苦しむ、耐える、耐え忍ぶ」

から)[1]とは、正典とされる4つの福音書で描かれている、イエスの死の直前の短い期間のことである。キリスト教では毎年聖週間に記念される。[2] 受難には、イエスがエルサレムに入城した際の勝利の行進、神殿清め、油注ぎ、最後の晩餐、苦悩、逮捕、サンヘドリンとピラトによる裁判、磔刑と死、埋葬な ど、その他の出来事も含まれる。これらの出来事を記述した4つの正典福音書の部分は、受難物語として知られている。キリスト教のいくつかのコミュニティで は、受難の記念には、イエスの母マリアの悲しみを偲ぶ「悲しみの金曜日」も含まれる。 受難という言葉はより一般的な用法となり、キリスト教の殉教者の苦しみと死についても使われるようになった。時にはラテン語の「パッシオ (passio)」という形も使われる。[3] |

| Narratives according to the four

canonical gospels Accounts of the Passion are found in the four canonical gospels, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Three of these, Matthew, Mark, and Luke, known as the Synoptic Gospels, give similar accounts. The Gospel of John account varies significantly.[4] Scholars do not agree on which events surrounding the death of Jesus should be considered part of the Passion narrative, and which ones merely precede and succeed the actual Passion narrative itself. For example, Puskas and Robbins (2011) commence the Passion after Jesus's arrest and before his resurrection, thus only including the trials, crucifixion and death of Jesus.[4] In Pope Benedict XVI's Jesus of Nazareth: Holy Week (2011), the term Passion completely coincides with the crucifixion and death of Jesus; it does not include earlier events and specifically excludes the burial and resurrection.[5] Others such as Matson and Richardson (2014) take a broader approach and consider the triumphal entry, the last supper, the trial before Pilate, the crucifixion, the burial, and the resurrection collectively as constituting the so-called "Passion Week".[6] |

正典とされる4つの福音書による物語 受難の記述は、正典とされる4つの福音書、マタイ、マルコ、ルカ、ヨハネに見られる。このうちマタイ、マルコ、ルカの3つは共観福音書として知られ、類似 した記述がある。ヨハネによる福音書の記述は大きく異なる。 学者の間では、イエスの死にまつわる出来事のうち、どの出来事を受難の物語の一部と見なし、どの出来事を単に受難の物語の前後にある出来事と見なすかにつ いて意見が一致していない。例えば、PuskasとRobbins (2011) は、イエスの逮捕から復活までの出来事をパッションとしており、裁判、磔、死のみを含めている。[4] ベネディクト16世の著書『ナザレのイエス:聖週』 (2011) では、パッションという用語は完全にイエスの磔と死と一致しており、それ以前の出来事は含まれておらず、特に埋葬と復活は除外されている。 [5] また、マソンやリチャードソン(2014年)などの研究者はより広義のアプローチをとり、凱旋入場、最後の晩餐、ピラトの裁判、磔、埋葬、復活をまとめ て、いわゆる「受難週」を構成するものとしている。[6] |

Comprehensive narrative 16th century Bolestný Kristus z Chebu, Cheb, Czech Republic Taking an inclusive approach, the "Passion" may include: Triumphal entry into Jerusalem: some people welcome Jesus when he enters Jerusalem. The Cleansing of the Temple: Jesus expels livestock merchants and money-changers from the Temple of Jerusalem. The Anointing of Jesus by a woman during a meal a few days before Passover. Jesus says that for this she will always be remembered. The Last Supper shared by Jesus and his disciples in Jerusalem. Jesus gives final instructions, predicts his betrayal, and tells them all to remember him. Jesus predicts the Denial of Peter: on the path to Gethsemane after the meal, Jesus tells the disciples they will all fall away that night. After Peter protests he will not, Jesus says Peter will deny him thrice before the cock crows. The Agony in the Garden: later that night at Gethsemane, Jesus prays while the disciples rest. Luke 22:43–44 adds that Jesus was terrified, and sweating blood; however, the oldest manuscripts of the Gospel of Luke do not contain these two verses, the other three canonical gospels do not mention this event either, and various manuscripts contain these verses elsewhere, even in the Gospel of Matthew (suggesting repeated attempts at insertion); thus, most modern scholars consider this tradition a later Christian interpolation, probably to counter docetism.[7][8][9] The Arrest of Jesus: then Judas Iscariot leads in either "a detachment of soldiers and some officials from the chief priests and Pharisees"[10] (accompanied according to Luke's Gospel by the chief priests and elders),[11] or a "large crowd armed with swords and clubs, sent from the chief priests and elders of the people,"[12][13] which arrests Jesus; all his disciples run away. During the arrest in Gethsemane, someone (Peter according to John) takes a sword and cuts off the ear of the high priest's servant, Malchus. The Sanhedrin trial of Jesus at the high priest's palace, later that night. The arresting party brings Jesus to the Sanhedrin (Jewish supreme court); according to Luke's Gospel, Jesus is beaten by his Jewish guards prior to his examination;[14] the court examines him, in the course of which, according to John's Gospel, Jesus is struck in the face by one of the Jewish officials;[15] the court determine he deserves to die. According to Matthew's Gospel, the court then "spat in his face and struck him with their fists."[16] They then send him to Pontius Pilate. According to the synoptic gospels, the high priest who examines Jesus is Caiaphas; in John, Jesus is also interrogated by Annas, Caiaphas' father-in-law. The Denial of Peter in the courtyard outside the high priest's palace, the same time. Peter has followed Jesus and joined the mob awaiting Jesus' fate; they suspect he is a sympathizer, so Peter repeatedly denies he knows Jesus. Suddenly, the cock crows and Peter remembers what Jesus had said. Pilate's trial of Jesus, early morning. Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea, questions Jesus, but cannot find any fault with him (according to some gospels, Pilate explicitly declares Jesus's innocence); however, the Jewish leaders and the crowd demand Jesus' death; Pilate gives them the choice of saving Barabbas, a criminal, or saving Jesus. In response to the screaming mob Pilate sends Jesus out to be crucified. The Way of the Cross: Jesus and two other convicts are forced to walk to their place of execution. According to the Synoptics, Simon of Cyrene is forced to carry Jesus's cross, while John writes that Jesus carried his cross himself. The Crucifixion of Jesus: Jesus and the two other convicts are nailed to crosses at Golgotha, a hill outside Jerusalem, later morning through mid afternoon. Various sayings of Jesus on the cross are recorded in the gospels before he dies. The Burial of Jesus: the body of Jesus is taken down from the cross and put in a tomb by Joseph of Arimathea (and Nicodemus according to John). The Resurrection of Jesus: Jesus rises from the dead, leaving behind an empty tomb and reportedly appearing to several of his followers. |

包括的な物語 16世紀 ボレスニー・クリストス・ズ・ヘブ、ヘブ、チェコ共和国 包括的なアプローチを取る場合、「受難」には以下が含まれる可能性がある。 エルサレムへの凱旋入場:イエスがエルサレムに入場した際、一部の人々はイエスを歓迎した。 神殿の清め:イエスはエルサレムの神殿から家畜商人や両替商を追い出した。 過越祭の数日前の食事中に、ある女性がイエスに油を注いだ。イエスは、この女性は永遠に記憶されるだろうと語った。 エルサレムで、イエスと弟子たちが最後の晩餐を共にした。イエスは最後の指示を与え、裏切られることを予言し、皆に自分を覚えておくようにと告げた。 イエスはペテロの否認を予言する:食事の後、ゲッセマネへの道すがら、イエスは弟子たちに、その夜皆が自分を見捨てるだろうと告げる。ペテロがそうはしな いと抗議すると、イエスは「鶏が鳴く前に、あなたは三度わたしを知らないと言うだろう」と告げる。 ゲッセマネの苦悩:その夜遅く、ゲッセマネで、イエスは祈り、弟子たちは休んでいる。ルカによる福音書22章43-44節には、イエスが恐怖に震え、血の 汗を流したと付け加えているが、ルカによる福音書の最古の写本にはこの2節は含まれておらず、他の3つの正典福音書にもこの出来事は記されておらず、さま ざまな写本がこの2節をマタイによる福音書など他の箇所に挿入している(挿入の試みが繰り返し行われたことを示唆している)。そのため、現代のほとんどの 学者は、この伝承は後世のキリスト教徒による挿入であり、おそらくドクエティスムに対抗するためのものだと考えている。 [7][8][9] イエスの逮捕:その後、ユダ・イスカリオテが「兵士たちと祭司長やファリサイ派の指導者たちから派遣された役人たち」[10](ルカによる福音書による と、祭司長や長老たちも同行していた)[11]、あるいは「祭司長や民の長老たちから派遣された剣やこん棒で武装した大群衆」[12][13]を先導し て、イエスを逮捕する。弟子たちはみな逃げ去った。ゲッセマネでの逮捕の際、ある人物(ヨハネによるとペトロ)が剣を取り、大祭司のしもべマルコスの耳を 切り落とした。 その夜遅く、大祭司の屋敷でサンヘドリンによるイエスの裁判が行われた。逮捕した者たちがイエスをサンヘドリン(ユダヤ人の最高裁判所)に連行する。ルカ による福音書によると、イエスは尋問を受ける前にユダヤ人の護衛官たちに殴られた。[14] 裁判所はイエスを尋問し、その過程で、ヨハネによる福音書によると、ユダヤ人の役人の一人がイエスの顔を平手打ちした。[15] 裁判所はイエスに死罪がふさわしいと決定した。マタイによる福音書によると、裁判官たちは「イエスの顔に唾を吐きかけ、こぶしでなぐった」[16]。その 後、彼らはイエスをポンテオ・ピラトのもとに送った。共観福音書によると、イエスを尋問した大祭司はカヤパである。ヨハネによる福音書では、イエスはカヤ パの義父であるアンナスにも尋問されている。 同じ時刻、大祭司の宮殿の外の中庭でのペテロの否認。ペテロはイエスに従い、イエスの運命を待つ暴徒に加わっていた。彼らはペテロがイエスの支持者である と疑い、ペテロはイエスを知らないと繰り返し否定した。突然、鶏が鳴き、ペテロはイエスの言ったことを思い出した。 朝早く、ピラトによるイエスの裁判が行われる。ユダヤの総督ポンテオ・ピラトがイエスに尋問するが、イエスに非を見いだすことができない(福音書によって は、ピラトはイエスの無実を明確に宣言している)。しかし、ユダヤの指導者と群衆はイエスの死を要求し、ピラトは彼らに犯罪者バラバを救うか、イエスを救 うかの選択を迫る。群衆の叫び声に応えて、ピラトはイエスを十字架につけるために外へ送り出す。 十字架の道行き:イエスと他の2人の囚人は、処刑場まで歩かされる。 共観福音書によると、シモン・クレネ人がイエスの十字架を背負わされたが、ヨハネは、イエスがご自分の十字架を背負われたと書いている。 イエスの磔刑:イエスと他の2人の囚人は、エルサレム郊外の丘であるゴルゴタで、朝から昼過ぎにかけて十字架に釘付けにされる。十字架上のイエスのさまざ まな言葉は、福音書に、彼が死ぬ前に記録されている。 イエスの埋葬:アリマタヤのヨセフ(ヨハネによる福音書ではニコデモ)によって、イエスの遺体が十字架から降ろされ墓に安置される。 イエスの復活:イエスは死からよみがえり、空の墓を残し、数人の信者の前に姿を現したと伝えられている。 |

| Differences between the

canonical gospels The Gospel of Luke states that Pilate sends Jesus to be judged by Herod Antipas because as a Galilean he is under his jurisdiction. Herod is excited at first to see Jesus and hopes Jesus will perform a miracle for him; he asks Jesus several questions but Jesus does not answer. Herod then mocks him and sends him back to Pilate after giving him an "elegant" robe to wear.[17] All the Gospels relate that a man named Barabbas[18] was released by Pilate instead of Jesus. Matthew, Mark and John have Pilate offer a choice between Jesus and Barabbas to the crowd; Luke lists no choice offered by Pilate, but represents the crowd demanding his release.  Icon of the Passion, detail showing (left) the Flagellation and (right) Ascent to Golgotha (fresco by Theophanes the Cretan, Stavronikita Monastery, Mount Athos). In all the Gospels, Pilate asks Jesus if he is King of the Jews and Jesus replies "So you say". Once condemned by Pilate, he was flogged before execution. The canonical gospels, except Luke, record that Jesus is then taken by the soldiers to the Praetorium where, according to Matthew and Mark, the whole contingent of soldiers has been called together. They place a purple robe on him, put a crown of thorns on his head, and according to Matthew, put a rod in his hand. They mock him by hailing him as "King of the Jews", paying homage and hitting him on the head with the rod. According to the Gospel of John, Pilate has Jesus brought out a second time, wearing the purple robe and the crown of thorns, in order to appeal his innocence before the crowd, saying Ecce homo, ("Behold the man"). But, John represents, the priests urge the crowd to demand Jesus's death. Pilate resigns himself to the decision, washing his hands (according to Matthew) before the people as a sign that Jesus's blood will not be upon him. According to the Gospel of Matthew they replied, "His blood be on us and on our children!"[19] Mark and Matthew record that Jesus is returned his own clothes, prior to being led out for execution. According to the Gospel accounts he is forced, like other victims of crucifixion, to drag his own cross to Golgotha,[20] the location of the execution. The three Synoptic Gospels refer to a man called Simon of Cyrene, who is made to carry the cross (Mark 15:21, Matthew 27:32, Luke 23:26), while in the Gospel of John (19:17), Jesus is made to carry his own cross. The Gospel of Mark gives the names of Simon's children, Alexander and Rufus. However, the Gospel of Luke refers to Simon carrying the cross after Jesus, in that it states: "they laid hold upon one Simon, a Cyrenian, coming out of the country, and on him they laid the cross, that he might bear it after Jesus".[21] Luke adds that Jesus's female followers follow, mourning his fate, but that he responds by quoting Hosea 10:8. |

正典福音書間の相違点 ルカによる福音書は、イエスがガリラヤ人であるため、ピラトの管轄下にあるとして、ピラトがイエスをヘロデ・アンティパスのもとに送って裁くようにしたと 述べている。ヘロデは最初、イエスに会うと興奮し、イエスが自分に奇跡を行ってくれることを期待した。ヘロデはイエスにいくつか質問をしたが、イエスは答 えなかった。ヘロデはイエスをあざけり、イエスに着るための「上等な」衣を与えた後、ピラトのもとに送り返した。[17] すべての福音書は、ピラトがイエスの代わりにバラバという名の男を釈放したと伝えている。マタイ、マルコ、ヨハネは、ピラトが群衆に対してイエスとバラバ のどちらかを選ぶように提示したと伝えている。ルカはピラトが提示した選択肢については記載していないが、群衆がバラバの釈放を要求したと伝えている。  受難の図、左は鞭打ち、右はゴルゴタへの道行き(クレタ島のテオフィロスによるフレスコ画、アトス山スタヴロニキタ修道院)。 すべての福音書において、ピラトはイエスに「あなたはユダヤ人の王なのか」と尋ね、イエスは「あなたがそう言うのなら」と答えた。ピラトによって一度死刑 を宣告されたイエスは、処刑前に鞭打ちの刑に処された。正典福音書(ルカ福音書を除く)は、イエスが兵士たちによって総督府に連れて行かれたことを記録し ている。マタイとマルコによると、総督府には兵士たちが全員集められていた。兵士たちはイエスに紫の衣を着せ、茨の冠を頭に載せ、マタイによると手に杖を 持たせた。そして「ユダヤ人の王」と呼びながらイエスをあざけり、敬意を表して杖で頭を打った。 ヨハネによる福音書によると、ピラトはイエスを再び外へ連れ出し、紫の衣と茨の冠を身に着けさせた。群衆の前でイエスの無実を訴えるためである。ピラトは 「見よ、人間だ」と言った。しかし、ヨハネは、祭司たちが群衆にイエスの死を要求するよう促したと伝えている。ピラトはイエスの血の責任は自分にはないと いう意思表示として、民衆の前で手を洗う(マタイによる福音書による)という行動に出た。マタイによる福音書によると、民衆は「その血は我々と我々の子供 たちにある!」と答えた。 マルコとマタイは、イエスが処刑のために連れ出される前に、自分の服を返されたと記録している。福音書によると、イエスは他の磔の犠牲者たちと同様に、ゴ ルゴタ(処刑場所)まで自分の十字架を運ばされたとされる。三つの共観福音書は、シモン・クレネ人と呼ばれる人物が十字架を運ばされたと伝えている(マル コによる福音書15:21、マタイによる福音書27:32、ルカによる福音書23:26)。一方、ヨハネによる福音書(19:17)では、イエスが自分の 十字架を運ばされたとされている。マルコによる福音書には、シモンの子供たち、アレクサンデルとルフォスの名前が記されている。しかし、ルカによる福音書 では、シモンがイエスの後に十字架を運んだと述べている。「彼らは、シメオンというクレネ人を見つけ、その上に十字架を担がせた。イエスが死んでから埋葬 するまで、それを持たせるためである」[21] ルカは、イエスの女性信奉者たちがイエスの運命を嘆きながら後に続いたが、イエスはホセア書10章8節を引用してそれに応えたと付け加えている。 |

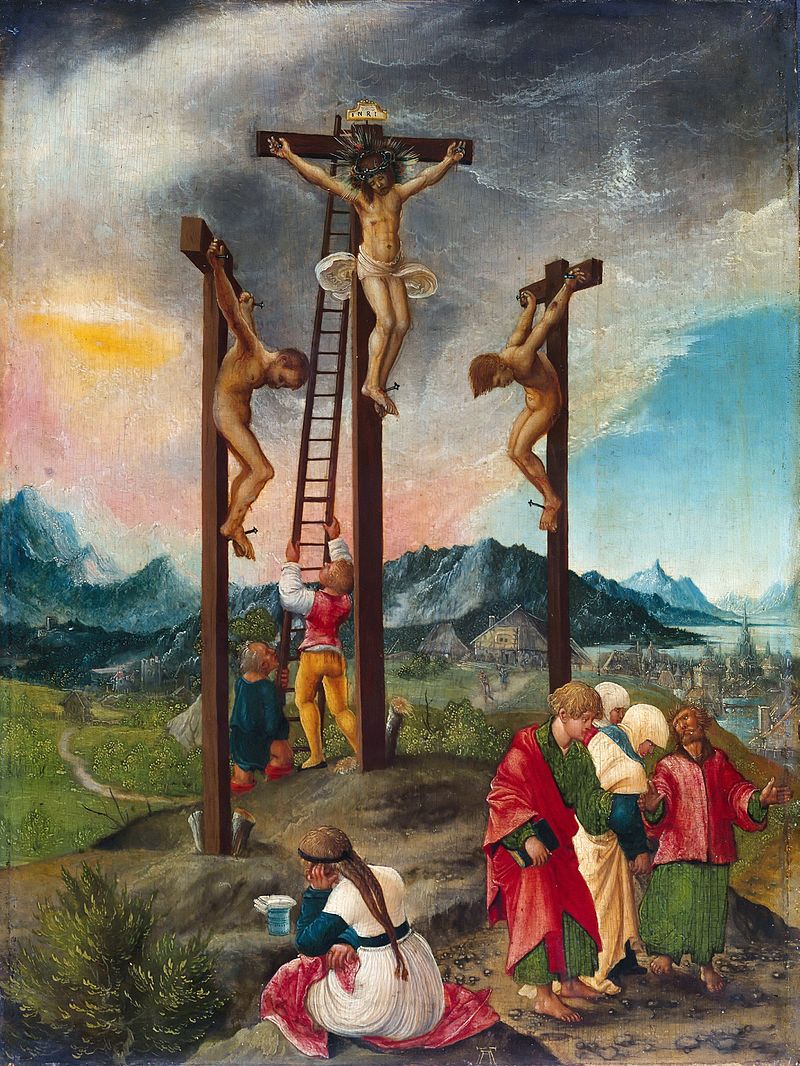

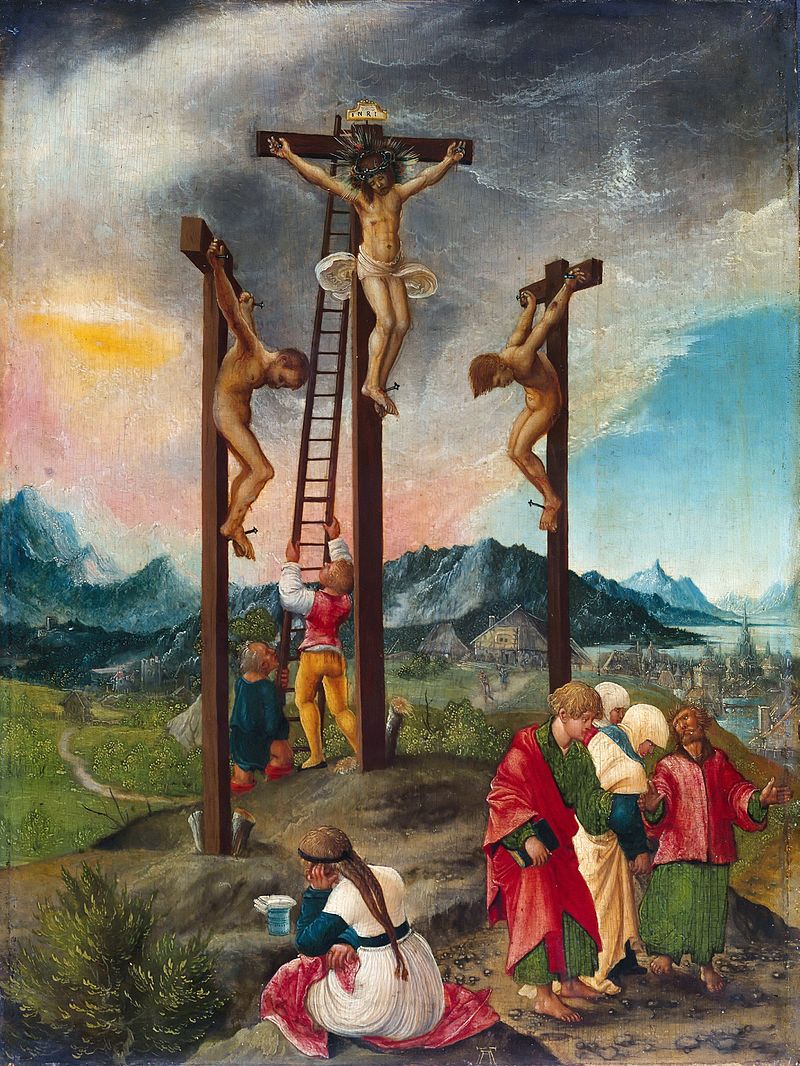

Crucifixion by Albrecht Altdorfer (c. 1526) The Synoptic Gospels state that on arrival at Golgotha, Jesus is offered wine laced with myrrh to lessen the pain, but he refuses it. Jesus is then crucified, according to Mark, at "the third hour" (9 a.m.) the morning after the Passover meal, but according to John he is handed over to be crucified at "the sixth hour" (noon) the day before the Passover meal, although many resolve this by saying that the Synoptics use Jewish time, and that John uses Roman time. Pilate has a plaque fixed to Jesus's cross inscribed, (according to John) in Hebrew, Greek and Latin – Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudeorum,[22] meaning Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews. Mark has the plaque say simply, King of the Jews. The Gospels then state that the soldiers divide Jesus's clothes among themselves, except for one garment for which they cast lots. The Gospel of John claims that this fulfills a prophecy from Psalms 22:18. Some of the crowd who have been following taunt Jesus by saying, "He trusts in God; let God deliver him now!" The statement suggests that Jesus might perform a miracle to release himself from the cross. According to the Gospels, two thieves are also crucified, one on each side of him. According to Luke, one of the thieves reviles Jesus, while the other declares Jesus innocent and begs that he might be remembered when Jesus comes to his kingdom (see Penitent thief). John records that Mary, his mother, and two other women stand by the cross as does a disciple, described as the one whom Jesus loved. Jesus commits his mother to this disciple's care. According to the synoptics, the sky becomes dark at midday and the darkness lasts for three hours, until the ninth hour when Jesus cries out Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani? ("My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?").[23] The centurion standing guard, who has seen how Jesus has died, declares Jesus innocent (Luke) or the "Son of God" (Matthew, Mark). John says that, as was the custom, the soldiers come and break the legs of the thieves, so that they will die faster, but that on coming to Jesus they find him already dead. A soldier pierces his side with a spear. According to the Gospel of Matthew, Judas, the betrayer, is filled with remorse and tries to return the money he was paid for betraying Jesus. When the high priests say that that is his affair, Judas throws the money into the temple, goes off, and hangs himself.[24] However, according to the Book of Acts 1:18, Judas was not remorseful, took the money and bought a field from it, whereupon he suddenly fell and died. |

アルブレヒト・アルトドルファーによる磔刑(1526年頃) 共観福音書によると、ゴルゴタに到着したイエスは、痛みを和らげるためにミルラを混ぜた葡萄酒を差し出されるが、それを拒否した。マルコによると、イエス は過ぎ越しの祭りの翌朝の「3時」(午前9時)に磔にされたとされるが、ヨハネによると、イエスは過ぎ越しの祭りの前日の「6時」(正午)に磔にされるた めに引き渡されたとされる。しかし、多くの人は、共観福音書はユダヤ時間を使用しており、ヨハネはローマ時間を使用していると主張して、この問題を解決し ている。ピラトは、ヘブライ語、ギリシャ語、ラテン語で書かれた(ヨハネによる福音書によると)銘板をイエスの十字架に固定した。その銘板には、 Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudeorum(ナザレ人イエス、ユダヤ人の王)と書かれていた。マルコによる福音書では、その銘板には「ユダヤ人の王」とだけ書かれていた。福音書に よると、兵士たちはイエスの衣服を自分たちで分配し、一枚の衣服だけはくじ引きで決めた。ヨハネによる福音書は、この出来事が詩篇第22篇18節の預言を 成就したと主張している。群衆の一部は、イエスをあざけり、「神を頼りにしているのなら、神が救ってくださるはずだ!」と言った。この発言は、イエスが十 字架から降ろされるために奇跡を起こすかもしれないことを示唆している。 福音書によると、イエスの両側に2人の強盗が十字架につけられた。ルカによる福音書によると、一人の盗人はイエスをののしったが、もう一人はイエスが無実 であると主張し、イエスが御国にお戻りになる時には自分も覚えていてほしいと懇願した(「悔い改めた盗人」を参照)。 ヨハネによる福音書には、イエスの母マリアと二人の女性が十字架の傍らに立ち、イエスが愛しておられた弟子もそこにいたと記されている。イエスは母をこの 弟子に託した。共観福音書によると、正午に空が暗くなり、その暗闇は3時間続き、9時になるとイエスが「エロイ、エロイ、ラマ・サバクタニ(わが神、わが 神、なぜ私をお見捨てになったのですか)」と叫んだ。[23] イエスの死を目撃した衛兵は、イエスが無実である(ルカによる福音書)または「神の子」である(マタイによる福音書、マルコによる福音書)と宣言した。 ヨハネは、慣例に従って兵士たちがやって来て、強盗たちの足を折って早く死なせるが、イエスのところに来た時にはすでに死んでいたと述べている。兵士が槍 でイエスのわきを突く。 マタイによる福音書によると、裏切り者のユダは後悔の念に駆られ、イエスを裏切るために受け取った金を返そうとする。大祭司が「それは彼の勝手だ」と言う と、ユダは金を神殿に投げ入れ、立ち去り、首を吊って自殺した。[24] しかし、使徒行伝1:18によると、ユダは後悔せず、その金で畑を買い、そこで突然倒れて死んだ。 |

Narrative according to the

Gospel of Peter The Veil of Veronica, painting by Domenico Fetti (c. 1620). Further claims concerning the Passion are made in some non-canonical early writings. Another passion narrative is found in the fragmentary Gospel of Peter, long known to scholars through references, and of which a fragment was discovered in Cairo in 1884. The narrative begins with Pilate washing his hands, as in Matthew, but the Jews and Herod refuse this. Joseph of Arimathea, before Jesus has been crucified, asks for his body, and Herod says he is going to take it down to comply with the Jewish custom of not leaving a dead body hung on a tree overnight. Herod then turns Jesus over to the people who drag him, give him a purple robe, crown him with thorns, and beat and flog him. There are also two criminals, crucified on either side of him and, as in Luke, one begs Jesus for forgiveness. The writer says Jesus is silent as they crucify him, "...as if in no pain."[25] Jesus is labeled the King of Israel on his cross and his clothes are divided and gambled over. As in the canonical Gospels, darkness covers the land. Jesus is also given vinegar to drink. Peter has "My Power, My Power, why have you forsaken me?" as the last words of Jesus, rather than "My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?" as quoted in Mark. He is then "taken up", possibly a euphemism for death or maybe an allusion to heaven.[26] Peter then has a resurrection, similar to the other books. Serapion of Antioch urged the exclusion of the Gospel of Peter from the Church because Docetists were using it to bolster their theological claims, which Serapion rejected.[27] Many modern scholars also reject this conclusion, as the statement about Jesus being silent "as if in no pain" seems to be based on Isaiah's description of the suffering servant, "as a sheep that before its shearers is silent, so he opened not his mouth." (Isaiah 53:7).[26] |

ペトロによる福音書に基づく物語 ヴェロニカのヴェール、ドメニコ・フェッティによる絵画(1620年頃)。 受難に関するさらなる主張は、正典ではない初期のいくつかの文献にも見られる。もう一つの受難物語は、断片的なペトロによる福音書に見られ、その断片は 1884年にカイロで発見された。 この物語は、マタイによる福音書と同様に、ピラトが手を洗う場面から始まるが、ユダヤ人とヘロデはこれを拒否する。アリマタヤのヨセフは、イエスが十字架 に架けられる前に、その遺体を引き取ることを願い出る。ヘロデ王は、死体を一晩中木に架けっぱなしにしないというユダヤの慣習に従うために、遺体を降ろす つもりだと述べる。ヘロデ王はその後、イエスを民衆に引き渡し、民衆はイエスを引っ張って行き、紫の衣を着せ、茨で冠を被せ、鞭打ち、むち打った。 また、イエスの両側に2人の犯罪者が十字架につけられ、ルカによる福音書のように、そのうちの1人がイエスに許しを請う。著者は、イエスが十字架につけら れる間、イエスは「まるで苦痛を感じていないかのように」沈黙していたと記している[25]。イエスは十字架に架けられ、その衣服は分けられ、賭けの対象 となった。 正典の福音書にあるように、辺りは暗闇に包まれた。イエスは酢を飲まされる。ペトロは、マルコによる福音書で引用されている「わが神、わが神、どうして私 を見捨てられたのですか」ではなく、「わが力、わが力、どうして私を見捨てられたのですか」というイエスの最後の言葉として「わが力、わが力」と記録して いる。その後、イエスは「引き上げられた」とあり、これはおそらく死を婉曲的に表現したものか、あるいは天国を暗示したものかもしれない。[26] ペトロはその後、他の福音書と同様に復活する。 アンティオキアのセラピオンは、ドクエティストたちが彼らの神学的主張を補強するためにペトロの手紙を使用しているとして、ペトロの手紙を教会から排除す るよう強く求めた。セラピオンはこれを否定した。[27] イエスが「まるで苦痛を感じていないかのように」沈黙しているという記述は、苦しむしもべについてのイザヤの描写、「毛を刈る者の前に物を言わない羊のよ うに、彼は口を開かなかった」に基づいているように見えるため、多くの現代の学者もこの結論を否定している。(イザヤ書53:7)[26] |

| The trials of Jesus The gospels provide differing accounts of the trial of Jesus. Mark describes two separate proceedings, one involving Jewish leaders and one in which the Roman prefect for Judea, Pontius Pilate, plays the key role. Both Matthew and John's accounts generally support Mark's two-trial version. Luke, alone among the gospels, adds yet a third proceeding: having Pilate send Jesus to Herod Antipas. The non-canonical Gospel of Peter describes a single trial scene involving Jewish, Roman, and Herodian officials.[28][29] |

イエスの裁判 福音書は、イエスの裁判について異なる記述をしている。マルコによる福音書は、2つの別々の裁判について記述しており、1つはユダヤ教の指導者たちを巻き 込んだ裁判、もう1つはユダヤ属州の総督ポンテオ・ピラトが重要な役割を果たす裁判である。マタイとヨハネによる福音書は、概ねマルコによる福音書の2つ の裁判の記述を支持している。ルカによる福音書は、福音書の中で唯一、さらに3つ目の裁判を付け加えている。それは、ピラトがイエスをヘロデ・アンティパ に送るというものである。正典外のペトロによる福音書では、ユダヤ人、ローマ人、ヘロデ家の役人たちによる単独の裁判の場面が描かれている。[28] [29] |

| Biblical prophecies This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Old Testament prophecy  Christ as Man of Sorrows by Pietro Lorenzetti, c. 1330 (Lindenau-Museum, Altenburg) Christians interpret at least three passages of the Old Testament as prophecies about Jesus' Passion. The first and most obvious is the one from Isaiah 52:13–53:12 (either 8th or 6th century BC).[30] This prophetic oracle describes a sinless man who will atone for the sins of his people. By his voluntary suffering, he will save sinners from the just punishment of God. The death of Jesus is said to fulfill this prophecy. For example, "He had no form or comeliness that we should look at him, and no beauty that we should desire him. He was despised and rejected by men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief; and as one from whom men hide their faces he was despised, and we esteemed him not. Surely he has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows; yet we esteemed him stricken, smitten by God, and afflicted. But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities; upon him was the chastisement that made us whole, and with his stripes we are healed" (53:2–5).[31] The second prophecy of Christ's Passion is the ancient text which Jesus himself quoted, while he was dying on the cross. From the cross, Jesus cried with a loud voice, "Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani?" which means, "My God, my God, why hast Thou forsaken me?" These words of Jesus were a quotation of the ancient HE. King David, in Psalm 22, foretold the sufferings of the messiah. For example, "I am a worm and no man, the reproach of men and the outcast of the people. All who see me, laugh me to scorn, they draw apart their lips, and wag their heads: 'He trusts in the Lord: let him free him, let him deliver him if he loves him.' Stand not far from me, for I am troubled; be thou near at hand: for I have no helper. ...Yea, dogs are round about me; a company of evildoers encircle me; they have pierced my hands and feet – I can count all my bones – they stare and gloat over me; they divide my garments among them, and for my raiment they cast lots" (Psalm 22:7–19). The words "they have pierced my hands and feet" are disputed, however.[32] The third main prophecy of the Passion is from the Book of the Wisdom of Solomon. Protestant Christians place it in the Apocrypha, Catholics and Eastern Orthodox among the deuterocanonical books. But it was written about 150 BC, and many have understood these verses (12–20 of chapter 2) as a direct prophecy of Jesus' Passion. For example, "Let us lie in wait for the just, because he is not for our turn. ...He boasteth that he hath the knowledge of God, and calleth himself the son of God ... and glorieth that he hath God for his father. Let us see then if his words be true. ...For if he be the true son of God, he will defend him, and will deliver him from the hands of his enemies. Let us examine him by outrages and tortures. ...Let us condemn him to a most shameful death. ...These things they thought, and were deceived, for their own malice blinded them" (Wisdom 2:12–20). In addition to the above, it deserves to be mentioned that at least three other, less elaborate messianic prophecies were fulfilled in Jesus' crucifixion, namely, the following Old Testament passages: "Many are the afflictions of the just man; but the Lord delivers him from all of them. He guards all his bones: not even one of them shall be broken" (Psalm 34:20). "And they gave me gall for my food, and in my thirst they gave me vinegar to drink" (Psalm 69:21). "And they shall look upon me whom they have pierced; and they shall mourn for him as one mourneth for an only son; and they shall grieve over him, as the manner is to grieve for the death of the firstborn" (Zechariah 12:10).[33] |

聖書の預言 この節は検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。この記事を改善するために、この節に参考文献や出典を追加してくださる協力者を求 めています。 出典の明らかでない内容は、削除される可能性があります。 (2019年10月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 旧約聖書の預言  ピエトロ・ロレンツェッティによる「悲しみのキリスト」 1330年頃(リンデンアウ・ミュージアム、アルテンブルク) キリスト教徒は、少なくとも旧約聖書の3つの箇所をイエスの受難に関する預言として解釈している。 最も明白なものは、イザヤ書52章13節から53章12節(紀元前8世紀または6世紀)である。[30] この預言は、民の罪を償う罪のない男について述べている。自発的な苦しみによって、罪人を神の正当な処罰から救うのだ。イエスの死はこの予言を成就したと される。例えば、「彼は、私たちが彼を見るべき姿かたちもなく、私たちが彼を慕うほどの美しさもなかった。彼は人々から軽蔑され、拒絶された。悲しみの男 であり、悲しみを知っていた。人々が顔を隠すような者として軽蔑され、私たちは彼を尊重しなかった。確かに彼は私たちの苦悩を担い、私たちの悲しみを背 負った。それでも私たちは彼を打ちのめされ、神に打たれ、苦しめられた者だと考えた。しかし彼は私たちの背信のゆえに傷つけられ、私たちの不義のために砕 かれた。彼の上に私たちが癒されるための懲らしめがあった。そして、彼の鞭傷によって私たちは癒された」(53:2-5)。[31] キリストの受難に関する第二の預言は、イエスが十字架上で死ぬ間際に引用した古代のテキストである。十字架上で、イエスは「エリ、エリ、レマ・サバクタ ニ」と大声で叫んだ。これは「わが神、わが神、どうして私をお見捨てになったのですか」という意味である。イエスのこの言葉は、古代のHE.王ダビデが詩 篇22篇でメシアの受難を予言した言葉を引用したものである。例えば、「わたしは虫けらのように、人の子とも思われず、人のそしり、民のさげすえとなって いる。わたしを見る者は皆、わたしをあざ笑い、唇をゆがめ、頭を振って言う。『主を頼みとしているのなら、主が彼を救い、主が彼を助けられるように。主を 愛しておられるなら、救ってくださるように。』わたしは悩んでいるから、遠くに立たないでほしい。近くにいてほしい。わたしには助ける者がいないのだか ら。... そうだ、犬どもが私を取り囲んでいる。悪を行う者どもが私を取り囲んでいる。彼らは私の手と足を刺し貫いた。私の骨をすべて数えることができる。彼らは私 を見つめ、嘲笑している。彼らは私の衣を自分たちで分けた。私の着る物を得るために、彼らはくじを引いた」(詩篇22:7-19)。しかし、「彼らは私の 手と足を刺し貫いた」という表現については議論がある。[32] 受難に関する3つ目の主な預言は、ソロモンの知恵の書からのものである。プロテスタントのキリスト教徒はこれを外典に、カトリックと東方正教会は第二正典 に分類している。しかし、これは紀元前150年頃に書かれたものであり、多くの人々はこれらの節(第2章12-20節)をイエスの受難の直接的な預言とし て理解している。例えば、「正しい者を待ち伏せしよう。なぜなら、彼は我々の番ではないからだ。彼は神を知っていると自慢し、自分を神の子と呼んでいる。 そして、神を自分の父として誇っている。では、彼の言葉が真実かどうか見てみよう。もし彼が真の神の子であるなら、彼は神を擁護し、敵の手から救い出すだ ろう。暴挙や拷問によって彼を調べよう。...最も恥ずべき死に方をさせよう。...彼らはそう考え、欺かれた。彼らの悪意が彼らを盲目にしたのだ」(知 恵の書2:12-20)。 上記のことに加え、少なくとも3つの他の、あまり精巧ではない救世主に関する予言がイエスの磔刑によって成就したことを述べる価値がある。すなわち、以下 の旧約聖書の箇所である。 「正しい人には多くの苦しみがある。しかし、主は彼をすべての苦しみから救い出される。主は彼すべての骨を守り、そのうちの一つさえも折られないようにさ れる」(詩篇34:20)。 「彼らは私に苦いものを食べさせ、のどの渇きに苦しむ私に酢を飲ませた」(詩篇69:21)。 「彼らは私を刺し貫いたが、そののち、彼らは私を嘆き悲しむ。彼らはひとり子を葬るように私を葬り、長子の死を嘆くように、私を嘆く」(ゼカリヤ書12: 10)[33] |

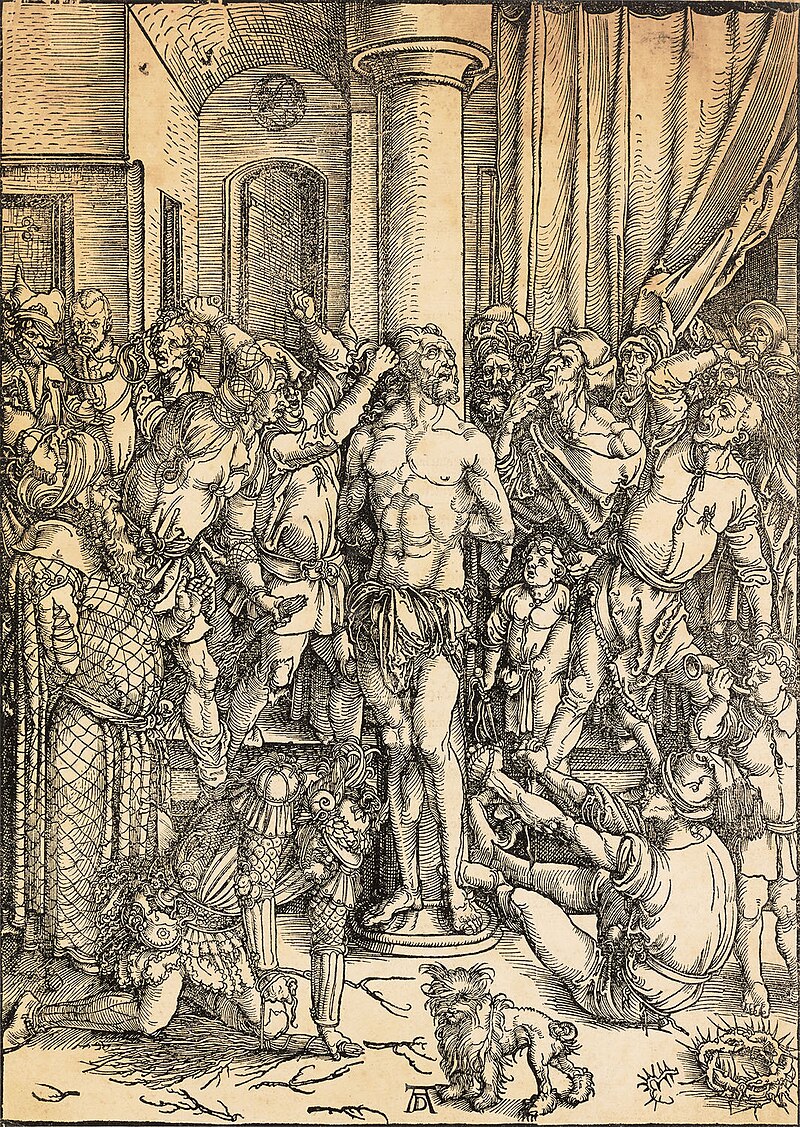

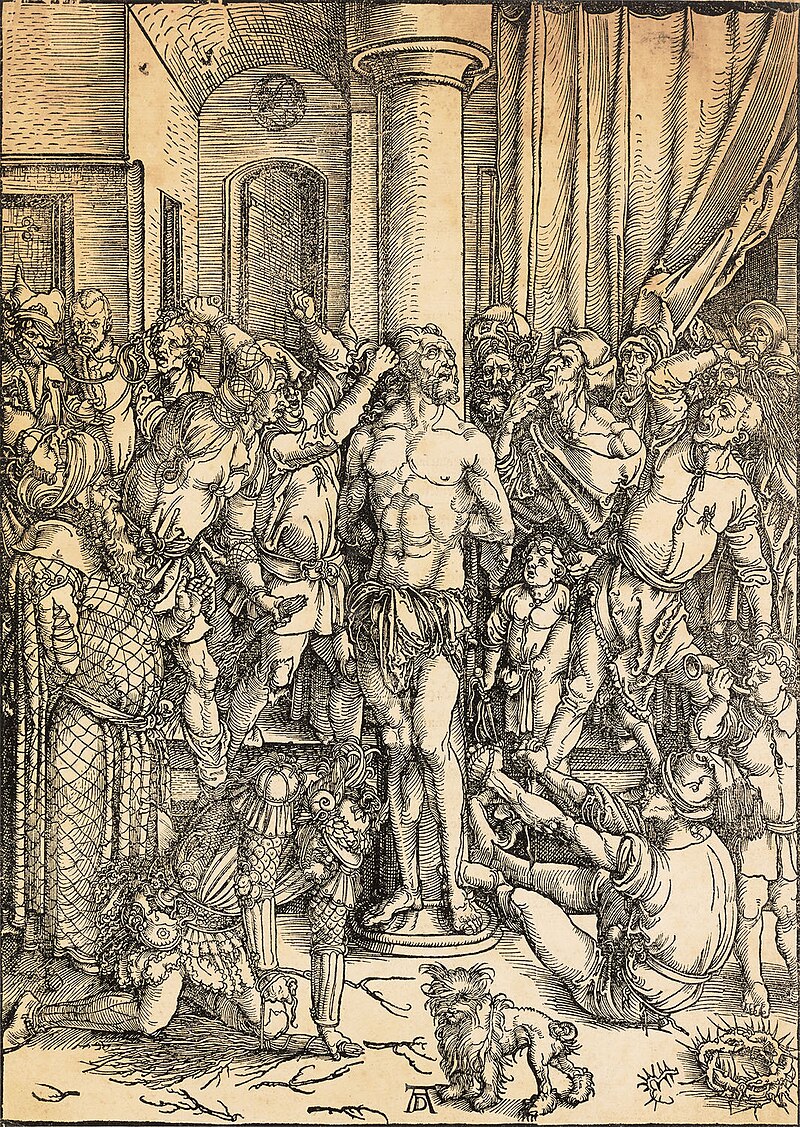

New Testament prophecy Fragment of the Pillar of the Flagellation, Hagios Georgios Patriarchal Church, Istanbul. The Gospel explains how these old prophecies were fulfilled in Jesus' crucifixion. "So the soldiers came and broke the legs of the first, and of the other who had been crucified with Jesus; but when they came to Jesus and saw that he was already dead, they did not break his legs. But one of the soldiers pierced his side with a spear, and at once there came out blood and water. ...For these things took place that the scripture might be fulfilled, 'Not a bone of him shall be broken.' And again another scripture says, 'They shall look on him whom they have pierced'" (John 19:32–37). In the Gospel of Mark, Jesus is described as prophesying his own Passion and his Resurrection three times: On the way to Caesarea Philippi, predicting that the Son of Man will be killed and rise within three days. After the transfiguration of Jesus, again predicting that the Son of Man will be killed and rise within three days. On the way to Jerusalem, predicting that the Son of Man will be delivered to the leading Pharisees and Sadducees, be condemned to death, delivered to the Gentiles, mocked, scourged, killed, and rise within three days. Christians argue that these are cases of genuine and fulfilled prophecy and many scholars see Semitic features and tradition in Mark 9:31.[34]  Albrecht Dürer, The Scourging of Christ, circa 1511. After the third prophecy, the Gospel of Mark states that the brothers James and John ask Jesus to be his left and right hand men, but Jesus asks if they can drink from the "cup" he must drink from. They say that they can do this. Jesus confirms this, but says that the places at his right and left hand are reserved for others. Many Christian see this as being a reference to the two criminals at Jesus's crucifixion, thus relating to the Passion. The "cup" is sometimes interpreted as the symbol of his death, in the light of Jesus's prayer at Gethsemane "Let this cup be taken from me!"[35] |

新約聖書の預言 鞭打ちの柱の断片、イスタンブールのアヤソフィア総主教教会。 福音書は、これらの古い預言がイエスの磔刑においてどのように成就したかを説明している。 「そこで兵士たちがやって来て、最初につけられた人とイエスと一緒に十字架につけられた他の人の足を折った。しかし、イエスのところに来て、イエスがすで に死んでおられたのを見て、その足を折ることはしなかった。しかし、兵士のひとりが槍でイエスのわきを突き刺すと、すぐに血と水が流れ出た。...これら のことが起こったのは、聖書の言葉が実現するためであった。「彼には、ひとつの骨も砕かれない」。また、別の聖書の言葉にも、「彼らは、自分たちが刺し貫 いた人を見守る」とある。(ヨハネによる福音書19:32-37) マルコによる福音書では、イエスがご自身の受難と復活を3度予言したと記されている。 1度目は、カエサレア・フィリピに向かう途中で、人の子が殺され、3日以内に復活することを予言した。 2度目は、イエスの変貌の後、再び人の子が殺され、3日以内に復活することを予言した。 エルサレムに向かう途中、人の子が指導的なパリサイ人やサドカイ人に引き渡され、死刑を宣告され、異邦人に引き渡され、嘲笑され、鞭打たれ、殺され、3日 以内に復活することを予言する。 キリスト教徒は、これらは真実であり、成就した予言であると主張しており、多くの学者はマルコによる福音書9章31節にセム族の特徴と伝統を見ている。  アルブレヒト・デューラー作『キリストの鞭打ち』、1511年頃 3番目の予言の後、マルコによる福音書では、ヤコブとヨハネの兄弟がイエスに「自分たちの左と右に座るように」と頼むが、イエスは「自分が飲まねばならな い杯」を彼らも飲めるかと尋ねる。彼らは「できます」と答える。イエスはそれを確認するが、自分の右と左の席は他の者たちのために確保されていると述べ る。多くのキリスト教徒は、この箇所をイエスの磔刑の際にいた2人の犯罪者に言及していると解釈し、受難と関連づけている。「杯」は、ゲッセマネの園での イエスの祈り「この杯を私から取りのけてください!」[35]を踏まえて、イエスの死の象徴であると解釈されることもある。 |

Liturgical use The Arma Christi on the back of an Austrian altarpiece of 1468. Main article: Holy Week Most Christian denominations will read one or more narratives of the Passion during Holy Week, especially on Good Friday. In the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church, a large cross depicting the crucified Christ is brought out into the church and each of the faithful come forward to venerate the cross. Rather than having the Gospel read solely by the priest, whole congregations participate in the reading of the Passion Gospel during the Palm Sunday Mass and the Good Friday service. These readings have the Priest read the part of Christ, a narrator read the narrative, other reader(s) reading the other speaking parts, and either the choir or the congregation reading the parts of crowds (i.e.: when the crowd shouts "Crucify Him! Crucify Him!").[36] In the Byzantine Rite of the Eastern Orthodox and Greek-Catholic Churches, the Matins service for Good Friday is called Matins of the Twelve Passion Gospels, and is notable for the interspersal of twelve readings from the Gospel Book detailing chronologically the events of the Passion – from the Last Supper to the burial in the tomb – during the course of the service. The first of these twelve readings is the longest Gospel reading of the entire liturgical year. In addition, every Wednesday and Friday throughout the year is dedicated in part to the commemoration of the Passion.[37] During Holy Week/Passion Week Congregations of the Moravian Church (Herrnhuter Bruedergemeine) read the entire story of Jesus's final week from a Harmony of the Gospels prepared for that purpose since 1777. Daily meetings are held, some times two or three times a day, to follow the events of the day. During the course of the reading, the Congregation sings hymn verses to respond to the events of the text. Most liturgical churches hold some form of commemoration of the Crucifixion on the afternoon of Good Friday. Sometimes, this will take the form of a vigil from noon to 3:00 pm, the approximate time that Jesus hung on the cross. Sometimes there will be a reenactment of the Descent from the Cross; for instance, at Vespers in the Byzantine (Eastern Orthodox and Greek-Catholic) tradition.  El Greco's Jesus Carrying the Cross, 1580. |

典礼での使用 1468年のオーストリアの祭壇画の背面に描かれたアルマ・クリスティ。 詳細は「聖週間」を参照 ほとんどのキリスト教宗派では、聖週間、特に「善き金曜日」に受難の物語を1つまたは複数読む。カトリック教会のローマ典礼では、磔にされたキリストを描 いた大きな十字架が教会に運び込まれ、信者たちは皆、十字架を崇敬するために前に進み出る。聖木曜日ミサと聖金曜日礼拝では、福音書は司祭のみによって朗 読されるのではなく、会衆全員が受難の福音書の朗読に参加する。これらの朗読では、司祭がキリストの役を、語り手が物語を、他の朗読者がその他の台詞を、 そして聖歌隊または会衆が群衆の役(群衆が「十字架につけろ!十字架につけろ!」と叫ぶ場面など)をそれぞれ担当する。[36] 東方正教会およびギリシャ・カトリック教会のビザンチン式典礼では、聖金曜日の早朝の祈りは「十二の受難福音書」と呼ばれ、受難の出来事(最後の晩餐から 墓への埋葬まで)を年代順に詳細に記した福音書からの12の朗読が、早朝の祈りの間に散りばめられていることで知られている。この12の朗読のうち最初の ものは、典礼暦の一年全体を通じて最も長い福音書の朗読である。さらに、一年を通じて毎週水曜日と金曜日は、受難の記念に一部が当てられている。[37] 聖週間/受難週の間、モラヴィア兄弟団(Herrnhuter Bruedergemeine)の信徒たちは、1777年からその目的のために準備された福音書の調和版を用いて、イエスの最後の1週間の物語のすべてを 読む。1日に数回、時には1日に2回または3回、その日の出来事を追うための集会が開催される。朗読の間、信徒たちはテキストの出来事に反応して賛美歌の 節を歌う。 ほとんどの典礼教会では、聖金曜日の午後には何らかの形で磔刑を記念する儀式が行われる。時には、正午から午後3時までの徹夜の祈りという形をとることも あり、これはイエスが十字架にかけられたおおよその時間である。時には、十字架降架の再現が行われることもある。例えば、ビザンチン(東方正教会およびギ リシャ・カトリック)の伝統では、夕方の祈りの際に再現される。  エル・グレコ作「十字架を運ぶキリスト」、1580年。 |

| Devotions Several non-liturgical devotions have been developed by Christian faithful to commemorate the Passion. The Stations of the Cross Main article: Stations of the Cross The Stations of the Cross are a series of religious reflections describing or depicting Christ carrying the cross to his crucifixion. Most Catholic churches, as well as many Anglican, Lutheran, and Methodist parishes, contain Stations of the Cross, typically placed at intervals along the sidewalls of the nave; in most churches, they are small plaques with reliefs or paintings, although in others they may be simple crosses with a numeral in the center.[38][39] The tradition of moving around the Stations to commemorate the Passion of Christ began with Francis of Assisi and extended throughout the Catholic Church in the medieval period. It is most commonly done during Lent, especially on Good Friday, but it can be done on other days as well, especially Wednesdays and Fridays. The Passion Offices The Passion Offices were the special prayers said by various Catholic communities, particularly the Passionist fathers to commemorate the Passion of Christ.[40] The Little Office of the Passion Main article: Little Office of the Passion Another devotion is the Little Office of the Passion created by Francis of Assisi (1181/82–1226). He ordered this office around the medieval association of five specific moments in Jesus's Passion with specific hours of the day. Having then attributed these to hours of the Divine Office, he arrived at this schema:[41] Compline – 21:00 – Jesus's Arrest on the Mount of Olives Matins – 00:00 – Jesus's Trial before the Jewish Sanhedrin Prime – 06:00 – "an interlude celebrating Christ as the light of the new day"[41] Terce – 09:00 – Jesus's Trial before Pontius Pilate Sext – 12:00 – Jesus's Crucifixion None – 15:00 – Jesus's Death Vespers – 18:00 – "recalling and celebrating the entire daily cycle"[41] Acts of reparation The Catholic tradition includes specific prayers and devotions as "acts of reparation" for the sufferings and insults that Jesus endured during his Passion. These "acts of reparation to Jesus Christ" do not involve a petition for a living or deceased beneficiary, but aim to repair the sins against Jesus. Some such prayers are provided in the Raccolta Catholic prayer book (approved by a Decree of 1854, and published by the Holy See in 1898) which also includes prayers as Acts of Reparation to the Virgin Mary.[42][43][44][45] In his encyclical Miserentissimus Redemptor on reparations, Pope Pius XI called acts of reparation to Jesus Christ a duty for Catholics and referred to them as "some sort of compensation to be rendered for the injury" with respect to the sufferings of Jesus.[46] Pope John Paul II referred to acts of reparation as the "unceasing effort to stand beside the endless crosses on which the Son of God continues to be crucified".[47] |

信心 キリスト教の信者たちは、受難を記念するために、典礼以外のいくつかの信心を考案した。 十字架の道行き 詳細は「十字架の道行き」を参照 十字架の道行きは、キリストが十字架を背負って磔にされるまでの様子を描写または説明した一連の宗教的な黙想である。ほとんどのカトリック教会、および多 くの聖公会、ルーテル派、メソジスト派の教会には、通常、身廊の側壁に沿って一定の間隔で十字架の道行きが置かれている。ほとんどの教会では、レリーフま たは絵画が施された小さな板であるが、中には中央に数字が書かれたシンプルな十字架が置かれている場合もある。 [38][39] キリストの受難を追悼するために、これらの「道」を巡るという伝統は、アッシジのフランチェスコによって始められ、中世のカトリック教会全体に広まった。 四旬節の間、特に聖金曜日に最も一般的に行われるが、他の日にも行うことができ、特に水曜日と金曜日に行われる。 受難の祈り 受難の祈り(The Passion Offices)は、キリストの受難を記念するために、さまざまなカトリックの共同体、特にパッション会の修道士たちによって唱えられる特別な祈りであ る。 受難の小祈り 詳細は「受難の小祈り」を参照 もう一つの信心は、アッシジのフランチェスコ(1181/82年-1226年)が創案した「受難の小聖務」である。彼は、中世のイエスの受難における5つ の特定の瞬間を、1日の特定の時間と関連付けるという考えに基づいて、この聖務を定めた。そして、これを神聖な聖務の時間に割り当て、次の図式に到達し た。 夕課 - 21:00 - オリーブ山でのイエスの逮捕 Matins – 00:00 – イエスのユダヤ人サンヘドリン裁判 Prime – 06:00 – 「新しい日の光としてのキリストを祝う幕間」[41] Terce – 09:00 – イエスのポンテオ・ピラト裁判 Sext – 12:00 – イエスの磔刑 なし – 15:00 – イエスの死 夕の祈り – 18:00 – 「1日のサイクル全体を想起し、祝う」[41] 償いの行為 カトリックの伝統では、イエスが受難の際に受けた苦しみや侮辱に対する「償いの行為」として、特定の祈りや信心が含まれている。これらの「イエス・キリス トへの償いの行為」は、生存者または故人のための嘆願を伴うものではなく、イエスに対する罪を償うことを目的としている。このような祈りのいくつかは、カ トリックの祈りの本『Raccolta』に記載されている(1854年の法令により承認され、1898年に教皇庁により出版された)。この本には、聖母マ リアへの償いの行為としての祈りも含まれている。[42][43][44][45] 贖罪に関する回勅『ミゼリコルディスムス・レデンプトーレ』の中で、ピウス11世はイエス・キリストへの贖罪行為をカトリック信者の義務と呼び、イエスの 受難に関して「負わねばならないある種の賠償」と表現した。 ヨハネ・パウロ2世は、償いの行為を「神の子が絶え間なく磔にされ続ける無限の十字架の傍らに立ち続けるための絶え間ない努力」と表現した。[47] |

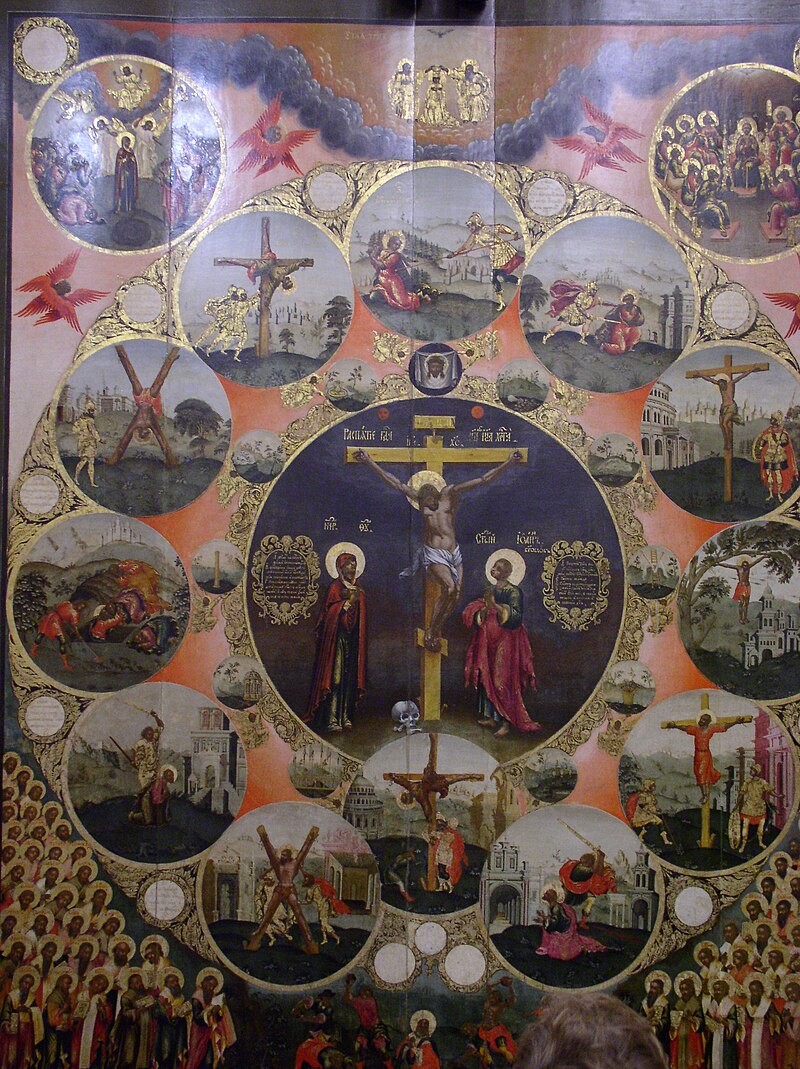

| In the arts Visual art This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) See also: Life of Christ in art  A set of the Stations of the Cross in painted enamel. Each episode of the Passion, such as the Flagellation of Christ or Entombment of Christ, has been represented thousands of times and has developed its own iconographic tradition; the Crucifixion is much the most common and important of these subjects. The Passion is often covered by a cycle of depictions; Albrecht Dürer's print cycles were so popular that he produced three different versions. Andachtsbilder is a term for devotional subjects such as the Man of Sorrows or Pietà, that may not precisely represent a moment in the Passion but are derived from the Passion story. The Arma Christi, or "Instruments of the Passion" are the objects associated with Jesus's Passion, such as the cross, the Crown of Thorns and the Spear of Longinus. Each of the major Instruments has been supposedly recovered as relics which have been an object of veneration among many Christians, and have been depicted in art. Veronica's Veil is also often counted among the Instruments of the Passion; like the Shroud of Turin and Sudarium of Oviedo it is a cloth relic supposed to have touched Jesus. In the Catholic Church, the Passion story is depicted in the Stations of the Cross (via crucis, also translated more literally as "Way of the Cross"). These 14 stations depict the Passion from the sentencing by Pilate to the sealing of the tomb, or with the addition of a 15th, the resurrection. Since the 16th-century representations of them in various media have decorated the naves of most Catholic churches. The Way of the Cross is a devotion practiced by many people on Fridays throughout the year, most importantly on Good Friday. This may be simply by going round the Stations in a church, or may involve large-scale re-enactments, as in Jerusalem. The Sacri Monti of Piedmont and Lombardy are similar schemes on a far larger scale than church Stations, with chapels containing large sculpted groups arranged in a hilly landscape; for pilgrims to tour the chapels typically takes several hours. They mostly date from the late 16th to the 17th century; most depict the Passion, others different subjects as well.[48] |

芸術において 視覚芸術 この節には出典が全く示されていない。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。出典のない項目は、削除される場合があります。 (2019年10月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 関連項目:芸術におけるキリストの生涯  エナメル彩で描かれた一連の十字架の道行き。 キリストの鞭打ちやキリストの埋葬など、受難の各エピソードは数千回も表現され、独自の図像学上の伝統を発展させてきた。磔刑は、これらの主題の中でも最 も一般的で重要なものである。受難はしばしば一連の描写で表現される。アルブレヒト・デューラーの版画シリーズは非常に人気が高く、彼は3つの異なるバー ジョンを制作した。「Andachtsbilder」とは、「悲しみの男」や「ピエタ」のような信心の対象となる主題を指す言葉であり、受難の瞬間を正確 に表現しているわけではないが、受難の物語から派生したものである。「Arma Christi」、すなわち「受難の道具」とは、イエスの受難に関連する物品、例えば十字架、茨の冠、ロンギヌスの槍などを指す。主要な聖遺物のそれぞれ は、多くのキリスト教徒の間で崇敬の対象とされてきた聖遺物として発見されたとされ、美術作品にも描かれている。ヴェロニカのヴェールも、多くの場合、受 難の聖遺物に数えられている。これは、トリノの聖骸布やオビエドの頭巾のように、イエスに触れたとされる布製の聖遺物である。 カトリック教会では、受難の物語は「十字架の道行き」(「ヴィア・クルシス」とも呼ばれるが、より直訳すると「十字架の道」となる)として描かれている。 この14の場面は、ピラトによる判決から墓の封印までを描いているが、15番目の場面として復活が追加されている場合もある。16世紀以降、さまざまなメ ディアで表現されたこれらの作品は、ほとんどのカトリック教会の身廊を飾っている。 十字架の道行きは、年間を通じて金曜日に多くの人々によって実践されている信仰であり、特に聖金曜日に重要視されている。 これは、単に教会で道行きの場を巡るだけでもよいし、エルサレムのように大規模な再現劇を行う場合もある。ピエモンテとロンバルディアのサクリ・モンティ は、教会のステーションよりもはるかに大規模な類似の企画であり、丘陵地帯に配置された大きな彫刻群のある礼拝堂がある。巡礼者が礼拝堂を巡るには通常数 時間を要する。これらは主に16世紀後半から17世紀に作られたもので、ほとんどは受難を描いているが、異なる主題のものもある。[48] |

| Music This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Main articles: Passion (music) and Tenebrae  Fresco depicting the trial and beating of Jesus (17th century, St. John the Baptist Church, Yaroslavl, Russia). The main traditional types of church music sung during Holy Week are Passions, musical settings of the Gospel narratives, both a Catholic and Lutheran tradition, and settings of the readings and responses from the Catholic Tenebrae services, especially those of the Lamentations of Jeremiah the Prophet. The many settings of the Stabat Mater or musical settings of sayings of Jesus on the cross are also commonly performed. The reading of the Passion section of one of the Gospels during Holy Week dates back to the 4th century. It began to be intoned (rather than just spoken) in the Middle Ages, at least as early as the 8th century. Ninth-century manuscripts have litterae significativae indicating interpretive chant, and later manuscripts begin to specify exact notes to be sung. By the 13th century, different singers were used for different characters in the narrative, a practice which became fairly universal by the 15th century, when polyphonic settings of the turba passages began to appear also. (Turba, while literally meaning "crowd", is used in this case to mean any passage in which more than one person speaks simultaneously.) In the later 15th century a number of new styles began to emerge: Responsorial Passions set all of Christ's words and the turba parts polyphonically. Through-composed Passions were entirely polyphonic (also called motet Passions). Jacob Obrecht wrote the earliest extant example of this type. Summa Passionis settings were a synopsis of all four Gospels, including the Seven Last Words (a text later set by Haydn and Théodore Dubois). These were discouraged for church use but circulated widely nonetheless. In the 16th century, settings like these, and further developments, were created for the Catholic Church by Victoria, William Byrd, Jacobus Gallus, Francisco Guerrero, Orlando di Lasso, and Cypriano de Rore.  Russian Orthodox icon of the Passion with scenes of the martyrdom of the Twelve Apostles, symbolizing how all are called to enter into the Passion (Moscow Kremlin). Martin Luther wrote, "The Passion of Christ should not be acted out in words and pretense, but in real life." Despite this, sung Passion performances were common in Lutheran churches right from the start, in both Latin and German, beginning as early as Laetare Sunday (three weeks before Easter) and continuing through Holy Week. Luther's friend and collaborator Johann Walther wrote responsorial Passions which were used as models by Lutheran composers for centuries, and "summa Passionis" versions continued to circulate, despite Luther's express disapproval. Later 16th-century passions included choral "exordium" (introduction) and "conclusio" sections with additional texts. In the 17th century came the development of oratorio passions which led to Johann Sebastian Bach's Passions, accompanied by instruments, with interpolated texts (then called "madrigal" movements) such as sinfonias, other Scripture passages, Latin motets, chorale arias, and more. Such settings were created by Bartholomäus Gesius and Heinrich Schütz. Thomas Strutz wrote a Passion (1664) with arias for Jesus himself, pointing to the standard oratorio tradition of Schütz, Carissimi, and others, although these composers seem to have thought that putting words in Jesus' mouth was beyond the pale. The practice of using recitative for the Evangelist (rather than plainsong) was a development of court composers in northern Germany and only crept into church compositions at the end of the 17th century. A famous musical reflection on the Passion is Part II of Messiah, an oratorio by George Frideric Handel, though the text here draws from Old Testament prophecies rather than from the gospels themselves. The best known Protestant musical settings of the Passion are by Bach, who wrote several Passions, of which two have survived completely, one based on the Gospel of John (the St John Passion), the other on the Gospel of Matthew (the St Matthew Passion). His St Mark Passion was reconstructed in various ways. The Passion continued to be very popular in Protestant Germany in the 18th century, with Bach's second son Carl Philipp Emanuel composing over twenty settings. Gottfried August Homilius composed at least one cantata Passion and four oratorio Passions after all four Evangelists. Many of C. P. E. Bachs performances were in fact works by Homilius. In the 19th century, with the exception of John Stainer's The Crucifixion (1887), Passion settings were less popular, but in the 20th century they have again come into fashion. Two notable settings are the St. Luke Passion (1965) by Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki and the Passio (1982) by Estonian composer Arvo Pärt. Recent examples include The Passion According to St. Matthew (1997), by Mark Alburger, and The Passion According to the Four Evangelists, by Scott King. Andrew Lloyd Webber's Jesus Christ Superstar (book and lyrics by Tim Rice) and Stephen Schwartz's Godspell both contain elements of the traditional passion accounts. Choral meditations on aspects of the suffering of Jesus on the cross include arrangements such as Buxtehude's Membra Jesu Nostri, a 1680 set of seven Passion cantatas, and the first such Lutheran treatment, incorporating lyrics excerpted from a medieval Latin poem and featuring Old Testament verses that prefigure the Messiah as suffering servant. |

音楽 この節には出典が全く示されていない。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。出典のない項目は、削除される場合があります。 (2019年10月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 詳細は「受難曲」および「テネブレ」を参照  イエスの裁判と鞭打ちを描いたフレスコ画(17世紀、ロシア、ヤロスラヴリの洗礼者ヨハネ教会)。 聖週間(セマナ・サンタ)に歌われる教会音楽の主な伝統的な種類には、カトリックとルター派の両方の伝統である福音書の物語を音楽で表現した「受難曲」、 およびカトリックの「テネブレ」の典礼の朗読と応答の音楽表現、特に預言者エレミヤの哀歌がある。 スタバト・マーテルのさまざまな音楽表現や、十字架上のイエスの言葉の音楽表現も一般的に演奏される。 聖週間の間、福音書の受難の箇所が朗読されるのは4世紀にまで遡る。中世の時代には、少なくとも8世紀には、朗読(単に話すのではなく)されるようになっ た。9世紀の写本には、解釈的な聖歌を示す「litterae significativae」が記載されており、それ以降の写本では、歌われる正確な音符が指定されるようになった。13世紀には、物語の異なる登場人 物には異なる歌手が当てられるようになり、この慣習は15世紀にはかなり一般的になり、ポリフォニーによる turba 部分の作曲も現れ始めた。(turba は文字通り「群衆」を意味するが、ここでは同時に複数の人格が話す部分を意味する。) 15世紀後半には、以下のような新しいスタイルが現れ始めた。 レスポンソリアル受難曲は、キリストの言葉とturbaの部分をすべてポリフォニーで構成した。 スルー作曲の受難曲は、全体がポリフォニーで構成された(モテット受難曲とも呼ばれる)。このタイプの現存する最古の例は、ヤコブ・オブレヒトが作曲し た。 サマ・パッシオーニは、4つの福音書の要約で、最後の7つの言葉(後にハイドンとテオドール・デュボワが作曲したテキスト)を含んでいる。これらは教会で の使用は推奨されていなかったが、それでも広く流布された。 16世紀には、ビクトリア、ウィリアム・バード、ヤコバス・ガルス、フランシスコ・ゲレロ、オルランド・ディ・ラッソ、シプリアーノ・デ・ローラといった 作曲家たちによって、カトリック教会のために、このような作品やさらなる発展形が創作された。  十二使徒の殉教の場面を描いたロシア正教の受難のイコン(モスクワのクレムリン)。 マルティン・ルターは「キリストの受難は言葉や見せかけで表現されるべきではなく、現実の生活の中で表現されるべきである」と書いた。にもかかわらず、受 難曲の上演は、ラテン語とドイツ語の両方で、ルター派の教会では当初から一般的であり、早ければレターレ・サンデー(復活祭の3週間前)から聖週間まで続 いた。ルターの友人であり協力者でもあったヨハン・ヴァルターは、レスポンソリ形式の受難曲を作曲し、その作品はルター派の作曲家たちによって何世紀にも わたって模範とされた。また、「最高の受難曲」バージョンは、ルターの明確な反対にもかかわらず、引き続き流通した。 16世紀後半の受難曲には、コーラスによる「エクソルディウム」(導入部)と「コンクルージオ」(結論部)のセクションが追加のテキストとともに含まれて いた。17世紀には、オラトリオ受難曲が発展し、ヨハン・ゼバスティアン・バッハの受難曲では、楽器の伴奏とともに、シンフォニア、その他の聖句、ラテン 語のモテット、コラール・アリアなどの挿入されたテキスト(当時は「マドリガル」の楽章と呼ばれていた)が用いられた。このような設定は、バルトロメウ ス・ゲシウスやハインリヒ・シュッツによって創作された。トーマス・シュトルツは、イエス自身の独唱付きの受難曲(1664年)を作曲し、シュッツやカ リッシミなどの標準的なオラトリオの伝統を踏襲した。しかし、これらの作曲家たちは、イエスの口に言葉を乗せることはタブーであると考えていたようだ。レ チタティーヴォを福音史家(プレインソングではなく)として用いるという慣習は、北ドイツの宮廷作曲家たちによって発展したものであり、教会の作曲に徐々 に浸透し始めたのは17世紀の終わり頃であった。受難を題材にした音楽として有名なのは、ヘンデルのオラトリオ『メサイア』の第2部であるが、この作品で は福音書ではなく、むしろ旧約聖書の預言がテキストとして用いられている。 プロテスタントの音楽作品で最もよく知られているのはバッハの受難曲であり、バッハは数曲の受難曲を作曲したが、そのうち完全に現存しているのは、ヨハネ による福音書に基づく『聖ヨハネ受難曲』と、マタイによる福音書に基づく『聖マタイ受難曲』の2曲である。彼の『聖マルコ受難曲』はさまざまな形で再構成 された。18世紀のプロテスタントのドイツでは、バッハの次男カール・フィリップ・エマニュエルが20以上の受難曲を作曲するなど、受難曲は依然として高 い人気を誇っていた。ゴットフリート・アウグスト・ホミリウスは、少なくとも1つのカンタータ受難曲と、4人の福音記者による4つのオラトリオ受難曲を作 曲した。C. P. E. バッハの演奏の多くは、実際にはホミリウスの作品であった。 19世紀には、ジョン・スタイナー作曲の『磔刑』(1887年)を除いて受難曲はあまり人気がなかったが、20世紀に入ると再び流行した。 注目すべき作品としては、ポーランドの作曲家クシシュトフ・ペンデレツキ作曲の『聖ルカ受難曲』(1965年)と、エストニアの作曲家アルヴォ・ペルト作 曲の『パッシオ』(1982年)がある。最近の例としては、マーク・アルバーガー作曲の『マタイによる受難曲』(1997年)や、スコット・キング作曲の 『四福音書による受難曲』などがある。アンドリュー・ロイド・ウェバー作曲の『ジーザス・クライスト・スーパースター』(台本・歌詞:ティム・ライス)や スティーヴン・シュワルツ作曲の『ゴッドスペル』には、いずれも伝統的な受難物語の要素が含まれている。 イエス・キリストの受難の側面を合唱で表現したものとしては、1680年に作曲されたブクステフーデの「われらの主イエス・キリストの諸部」という7つの 受難カンタータや、中世のラテン語の詩から抜粋した歌詞を組み込み、救世主が苦しむしもべとして予言されている旧約聖書の節をフィーチャーした、最初のル ター派の作品などがある。 |

| Drama and processions This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  Christian Easter passion procession in Stuttgart, Germany  Reenacting the Stations of the Cross in Jerusalem on the Via Dolorosa from the Lions' Gate to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Non-musical settings of the Passion story are generally called Passion plays; these have been very widely performed in traditionally Catholic countries, often in churches as liturgical dramas – for versions with musical settings, see the previous section. One famous cycle is performed at intervals at Oberammergau Germany, another in Sordevolo one of the most important in Italy, and another in the Brazilian state of Pernambuco uses what is considered the largest open-air theater in the world. The Passion figures among the scenes in the English mystery plays in more than one cycle of dramatic vignettes. In the Chester Mystery Plays' portrayal of Christ's Passion, specifically his humiliation before his sentence to crucifixion, the accounts of the Gospels concerning the physical violence visited on Jesus during his trial before the Sanhedrin, and the humiliating crowning of thorns visited upon him in Pilate's palace (or by Herod's soldiers, according to Luke), is further confused by showing both actions as being carried out by jeering Jews.[49] Processions on Palm Sunday commonly re-enact to some degree the entry of Jesus to Jerusalem, traditional ones often using special wooden donkeys on wheels. Holy Week in Spain retains more traditional public processions than other countries, with the most famous, in Seville, featuring floats with carved tableaux showing scenes from the story. In Latin America During the Passion week many towns in Mexico have a representation of the passion. In Spain During the Passion week many cities and towns in Spain have a representation of the Passion. Many Passion poems and prose text circulated in the fifteenth-century Castile, among which there were the first modern translations of earlier Latin Passion texts and Vitae Christi, and also a popular Monotessaron or Pasión de l'eterno principe Jesucristo attributed to a pseudo-Gerson. It was most likely written by Thomas à Kempis, whose Imitation of Christ mentions the Passion a few times, uniquely when talking about the Eucharist.[50] Film There have also been a number of films telling the passion story, with a prominent example being Mel Gibson's 2004 The Passion of the Christ. |

ドラマと行列 この節には検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。 出典の無い内容は疑問視される可能性があり、削除されることがあります。 (2019年10月) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  ドイツのシュトゥットガルトにおけるキリスト教の復活祭の受難行列  エルサレムのヴィア・ドロローサにあるライオンズゲートから聖墳墓教会までの「十字架の道行き」を再現する。 受難物語の音楽以外の設定は一般的に受難劇と呼ばれ、伝統的にカトリックの国々で広く上演されており、典礼劇として教会で上演されることも多い。音楽の設 定については、前のセクションを参照のこと。有名な一連のものは、ドイツのオーバアマガウで定期的に上演され、イタリアで最も重要なもののひとつであるソ ルデヴォーロでも上演されている。また、ブラジルのペルナンブーコ州では、世界最大の野外劇場とされるものを使用している。受難劇は、英国のミステリー劇 の場面の中でも、複数の劇的な場面で取り上げられている。チェスターのミステリー劇で描かれたキリストの受難、特に磔の判決を受ける前の屈辱的な場面で は、サンヘドリンの裁判でイエスに身体的暴力が加えられたことに関する福音書の記述、およびピラトの宮殿(またはルカによるとヘロデの兵士たち)でイエス が茨の冠を被せられた屈辱的な場面が、嘲笑するユダヤ人たちによって両方の行為が行われたと示されることで、さらに混乱している。 [49] 棕櫚の主日の行列では、イエスのエルサレム入場が通常ある程度再現されるが、伝統的な行列では、車輪のついた特別な木製のロバがよく使われる。スペインの 聖週間は、他の国よりも伝統的な公開行列が数多く残っており、中でもセビリアの行列では、物語の場面を彫刻で表現した山車が有名である。 ラテンアメリカでは 受難週の間、メキシコの多くの町で受難の再現が行われる。 スペインでは 受難週の間、スペインの多くの都市や町で受難の再現が行われる。 15世紀のカスティーリャでは、多くの受難の詩や散文が流通し、その中には、それ以前のラテン語の受難のテキストやキリストの生涯の最初の近代的な翻訳も あった。また、疑似ジェルソンに帰せられる人気の高い『単一性説』や『永遠の君主イエス・キリストの受難』もあった。トマス・ア・ケンピスの『キリストの 模範』には受難について数回言及されており、聖体について語る際には独特な表現が用いられている。[50] 映画 受難の物語を描いた映画も数多く制作されており、著名な例としてはメル・ギブソン監督の2004年の映画『パッション』がある。 |

| Other traditions This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The sons of Simon of Cyrene are named as if they might have been early Christian figures known to Mark's intended audience.[51] Paul also lists a Rufus in Romans 16:13. Most garments of the region were made of woven strips of material that were about eight inches wide and included decorative braids from two to four inches (102 mm) wide. The garments could be disassembled and the strips of cloth were frequently recycled. A single garment might hold sections of many different dates. However, in Damascus and Bethlehem cloth was woven on wider looms, some Damascene being 40 inches (1,000 mm) wide. Traditional Bethlehem cloth is striped like pajama material.[52] It would thus appear that Jesus's "seamless robe" was made of cloth from either Bethlehem or Damascus. A tradition linked to icons of Jesus holds that Veronica was a pious woman of Jerusalem who then gave her kerchief to him to wipe his forehead. When he handed it back to her, the image of his face was miraculously impressed upon it. |