ポール・ファイアーベント

Paul Karl Feyerabend, 1924-1994

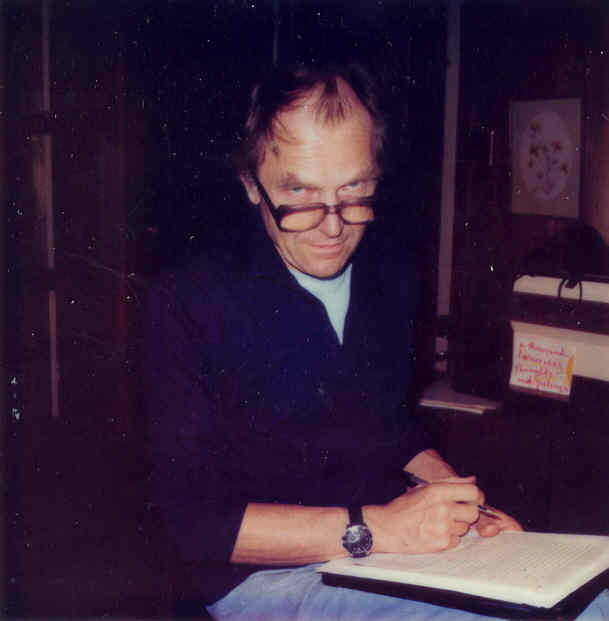

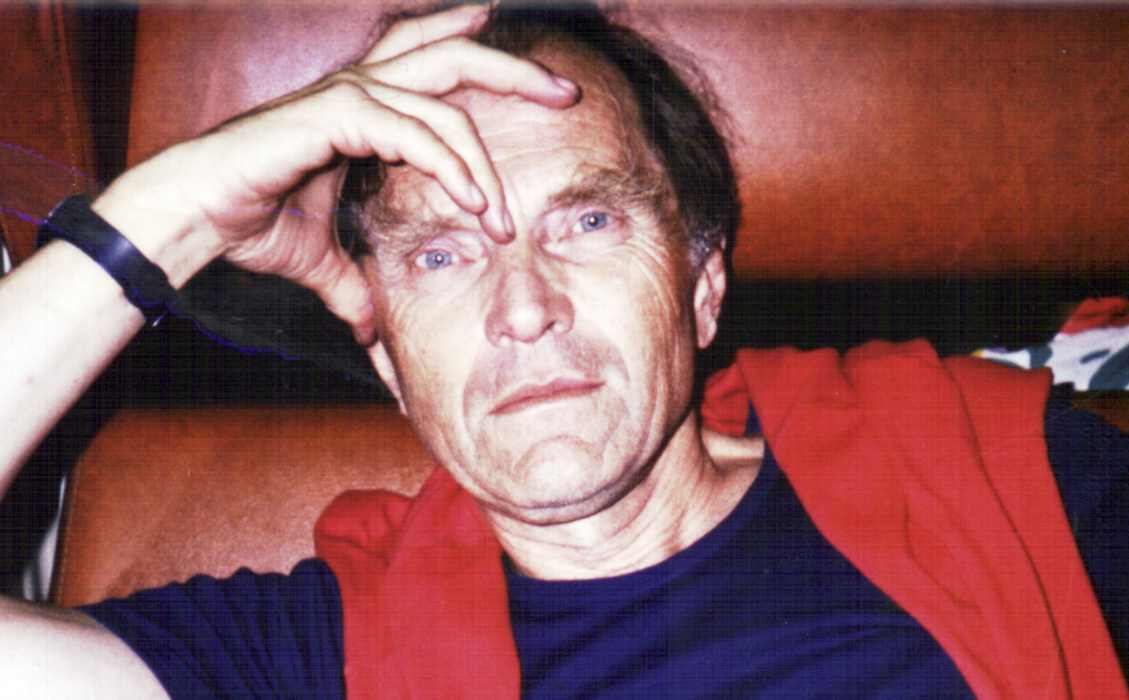

The philosopher Paul Feyerabend in Berkeley.

☆ ポール・カール・ファイアーベント(Paul Karl Feyerabend、 ドイツ語: [ˈfaɪɐˌʔaˌ 1924年1月13日 - 1994年2月11日)はオーストリアの哲学者で、科学哲学の研究で最もよく知られている。1955年から1958年までブリストル大学で科学哲学の講師 を務めた後、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校で30年間(1958年から1989年まで)教鞭をとった。その後、ユニヴァーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドン (1967-1970年)、ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス(1967年)、ベルリン工科大学(1968年)、イェール大学(1969年)、オー クランド大学(1972年、1975年)、サセックス大学(1974年)、チューリッヒ工科大学(1980-1990年)で教鞭をとる。また、ミネソタ大 学(1958-1962年)、スタンフォード大学(1967年)、カッセル大学(1977年)、トレント大学(1992年)で講義やレクチャーシリーズを 行った[13]。ファイアーベントの最も有名な著作は『方法論に抗して』(1975年)で、科学的探究には普遍的に有効な方法論的ルールは存在しないと主 張した。彼はま た、いくつかのエッセイや著書『Science in a Free Society』(1978年)の中で、科学の政治に関連するトピックについても書いている。ファイアーベントの晩年の著作には、『芸術としての科学』 (Wissenschaft als Kunst, 1984)、『理性との決別』(Farewell to Reason, 1987)、『知識に関する3つの対話』(Three Dialogues on Knowledge, 1991)、1970年代からファイアーベントが亡くなる1994年までのエッセイを集めた『豊かさの征服』(Conquest of Abundance, 1999)などがある。未完の草稿は2009年に『Naturphilosophie』(英訳『2016 Philosophy of Nature』)として死後に発表された。この著作には、ホメロス時代から20世紀半ばまでの自然哲学史に関するファイアーベントの再構成が収められて いる。これらの著作やその他の出版物において、ファイアーベントは科学と倫理、古代哲学、芸術哲学、政治哲学、医学、物理学の歴史と哲学の接点にある数 多くの問題について書いている。ファイアーベントの最後の著作は、『時間を殺す』と題された自伝であり、死の床で完成させた[14]。ファイアーベントの 膨大な書簡やナクラスの他の資料が出版され続けている[15]。ポール・ファイアーベントは、20世紀における最も重要な科学哲学者の一人として認識され ている。トーマス・クーン、イムレ・ラカトス、N.R.ハンソ ンと並んで、科学哲学の歴史的転換における重要な人物としてしばしば言及され、科学的多元主義に関する彼の研究は、スタンフォード学派や多くの現代科学哲 学に多大な影響を与えている。ファイアーベントは科学的知識の社会学においても重要な人物であった[13]。彼の講義は非常に聴講者が多く、国際的な注 目を集めた[17]: 「ヒューマニストは、私の古風な感覚では、芸術と科学の両方の一部である必要がある。ポール・ファイアーベントはヒューマニストだった。彼は楽しくも あった」[18]。

★池田光穂「科学における認識論的ア ナーキズムについて」『現代思想』42巻12号、Pp.192-203、2014年8月[pdf] password with only four letters alfabet "c*s*c*d*"

| Paul Karl Feyerabend (German:

[ˈfaɪɐˌʔaːbm̩t]; January 13, 1924 – February 11, 1994) was an Austrian

philosopher best known for his work in the philosophy of science. He

started his academic career as lecturer in the philosophy of science at

the University of Bristol (1955–1958); afterwards, he moved to the

University of California, Berkeley, where he taught for three decades

(1958–1989). At various points in his life, he held joint appointments

at the University College London (1967–1970), the London School of

Economics (1967), the FU Berlin (1968), Yale University (1969), the

University of Auckland (1972, 1975), the University of Sussex (1974),

and, finally, the ETH Zurich (1980–1990). He gave lectures and lecture

series at the University of Minnesota (1958-1962), Stanford University

(1967), the University of Kassel (1977) and the University of Trento

(1992).[13] Feyerabend's most famous work is Against Method (1975), wherein he argued that there are no universally valid methodological rules for scientific inquiry. He also wrote on topics related to the politics of science in several essays and in his book Science in a Free Society (1978). Feyerabend's later works include Wissenschaft als Kunst (Science as Art) (1984), Farewell to Reason (1987), Three Dialogues on Knowledge (1991), and Conquest of Abundance (released posthumously in 1999) which collect essays from the 1970s until Feyerabend's death in 1994. The uncompleted draft of an earlier work was released posthumously, in 2009, as Naturphilosophie (English translation of 2016 Philosophy of Nature). This work contains Feyerabend's reconstruction of the history of natural philosophy from the Homeric Period until the mid-20th century. In these works and other publications, Feyerabend wrote about numerous issues at the interface between history and philosophy of science and ethics, ancient philosophy, philosophy of art, political philosophy, medicine, and physics. Feyerabend's final work was his autobiography, entitled Killing Time, which he completed on his deathbed.[14] Feyerabend's extensive correspondence and other materials from his Nachlass continue to be published.[15] Paul Feyerabend is recognized as one of the most important philosophers of science of the 20th century. In a 2010 poll, he was ranked as the 8th most significant philosopher of science.[16] He is often mentioned alongside Thomas Kuhn, Imre Lakatos, and N.R. Hanson as a crucial figure in the historical turn in philosophy of science, and his work on scientific pluralism has been markedly influential on the Stanford School and on much contemporary philosophy of science. Feyerabend was also a significant figure in the sociology of scientific knowledge.[13] His lectures were extremely well-attended, attracting international attention.[17] His multifaceted personality is eloquently summarized in his obituary by Ian Hacking: "Humanists, in my old-fashioned sense, need to be part of both arts and sciences. Paul Feyerabend was a humanist. He was also fun."[18] In line with this humanistic interpretation and the concerns apparent in his later work, the Paul K. Feyerabend Foundation was founded in 2006 in his honor. The Foundation "...promotes the empowerment and wellbeing of disadvantaged human communities. By strengthening intra and inter-community solidarity, it strives to improve local capacities, promote the respect of human rights, and sustain cultural and biological diversity." In 1970, the Loyola University of Chicago assigned to Feyerabend its Doctor of Humane Letters Degree honoris causa. Asteroid (22356) Feyerabend is named after him.[19] |

ポール・カール・ファイアーベント(Paul Karl Feyerabend、

ドイツ語: [ˈfaɪɐˌʔaˌ 1924年1月13日 -

1994年2月11日)はオーストリアの哲学者で、科学哲学の研究で最もよく知られている。1955年から1958年までブリストル大学で科学哲学の講師

を務めた後、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校で30年間(1958年から1989年まで)教鞭をとった。その後、ユニヴァーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドン

(1967-1970年)、ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス(1967年)、ベルリン工科大学(1968年)、イェール大学(1969年)、オー

クランド大学(1972年、1975年)、サセックス大学(1974年)、チューリッヒ工科大学(1980-1990年)で教鞭をとる。また、ミネソタ大

学(1958-1962年)、スタンフォード大学(1967年)、カッセル大学(1977年)、トレント大学(1992年)で講義やレクチャーシリーズを

行った[13]。 ファイアーベントの最も有名な著作は『方法論に抗して』(1975年)で、科学的探究には普遍的に有効な方法論的ルールは存在しないと主張した。彼はま た、いくつかのエッセイや著書『Science in a Free Society』(1978年)の中で、科学の政治に関連するトピックについても書いている。ファイアーベントの晩年の著作には、『芸術としての科学』 (Wissenschaft als Kunst, 1984)、『理性との決別』(Farewell to Reason, 1987)、『知識に関する3つの対話』(Three Dialogues on Knowledge, 1991)、1970年代からファイアーベントが亡くなる1994年までのエッセイを集めた『豊かさの征服』(Conquest of Abundance, 1999)などがある。未完の草稿は2009年に『Naturphilosophie』(英訳『2016 Philosophy of Nature』)として死後に発表された。この著作には、ホメロス時代から20世紀半ばまでの自然哲学史に関するファイアーベントの再構成が収められて いる。これらの著作やその他の出版物において、ファイアーベントは科学と倫理、古代哲学、芸術哲学、政治哲学、医学、物理学の歴史と哲学の接点にある数 多くの問題について書いている。ファイアーベントの最後の著作は、『時間を殺す』と題された自伝であり、死の床で完成させた[14]。ファイアーベントの膨大な書簡やナクラスの他の資料が出版され続けている[15]。 ポール・ファイアーベントは、20世紀における最も重要な科学哲学者の一人として認識されている。トーマス・クーン、イムレ・ラカトシュ、N.R.ハンソ ンと並んで、科学哲学の歴史的転換における重要な人物としてしばしば言及され、科学的多元主義に関する彼の研究は、スタンフォード学派や多くの現代科学哲 学に多大な影響を与えている。ファイアーベントは科学的知識の社会学においても重要な人物であった[13]。彼の講義は非常に聴講者が多く、国際的な注 目を集めた[17]: 「ヒューマニストは、私の古風な感覚では、芸術と科学の両方の一部である必要がある。ポール・フファイアーベントはヒューマニストだった。彼は楽しくも あった」[18]。 この人文主義的な解釈と、彼の後年の著作に見られる懸念に沿って、ポール・K・ファイアーベント財団が2006年、彼に敬意を表して設立された。同財団 は「...恵まれない人間社会のエンパワーメントとウェルビーイングを促進する。コミュニティ内およびコミュニティ間の連帯を強化することで、地域の能力 を向上させ、人権の尊重を促進し、文化的・生物学的多様性を維持することに努めている。" 1970年、シカゴ・ロヨラ大学は名誉博士号を授与した。小惑星(22356)ファイヤーアベンドは彼にちなんで命名された[19]。 |

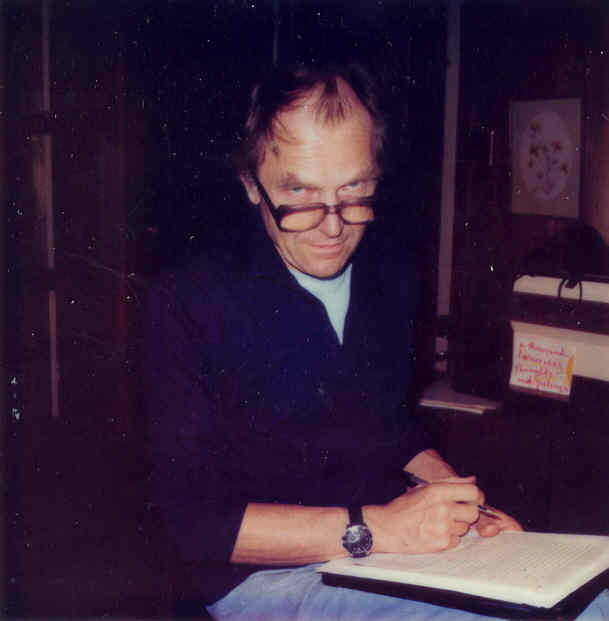

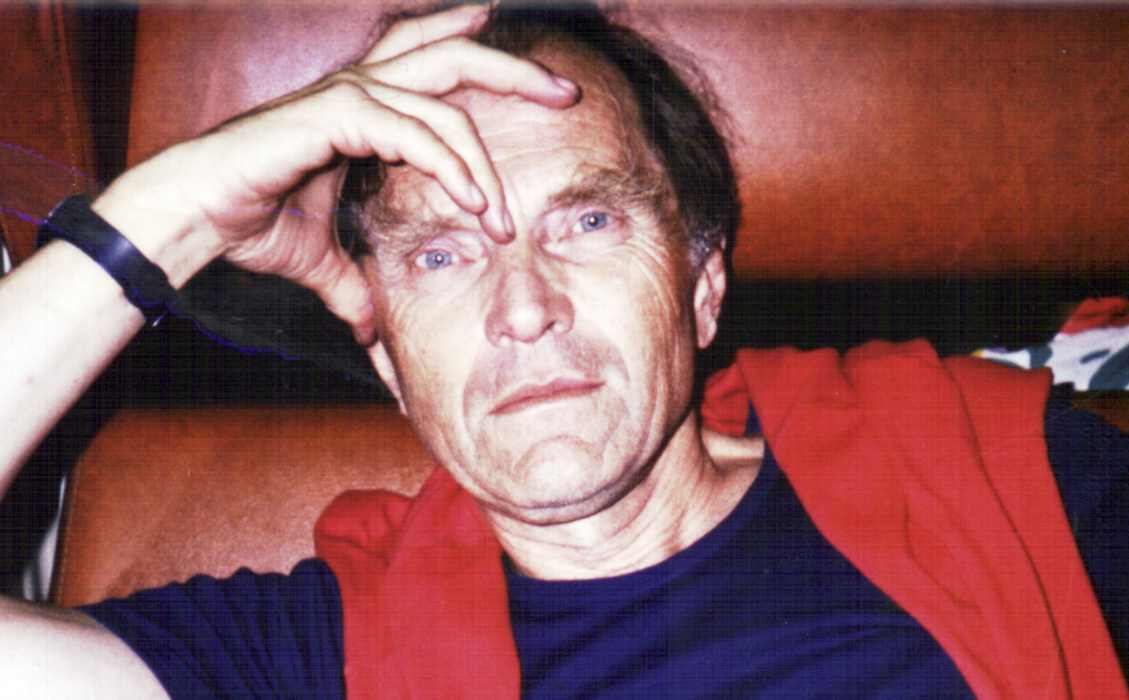

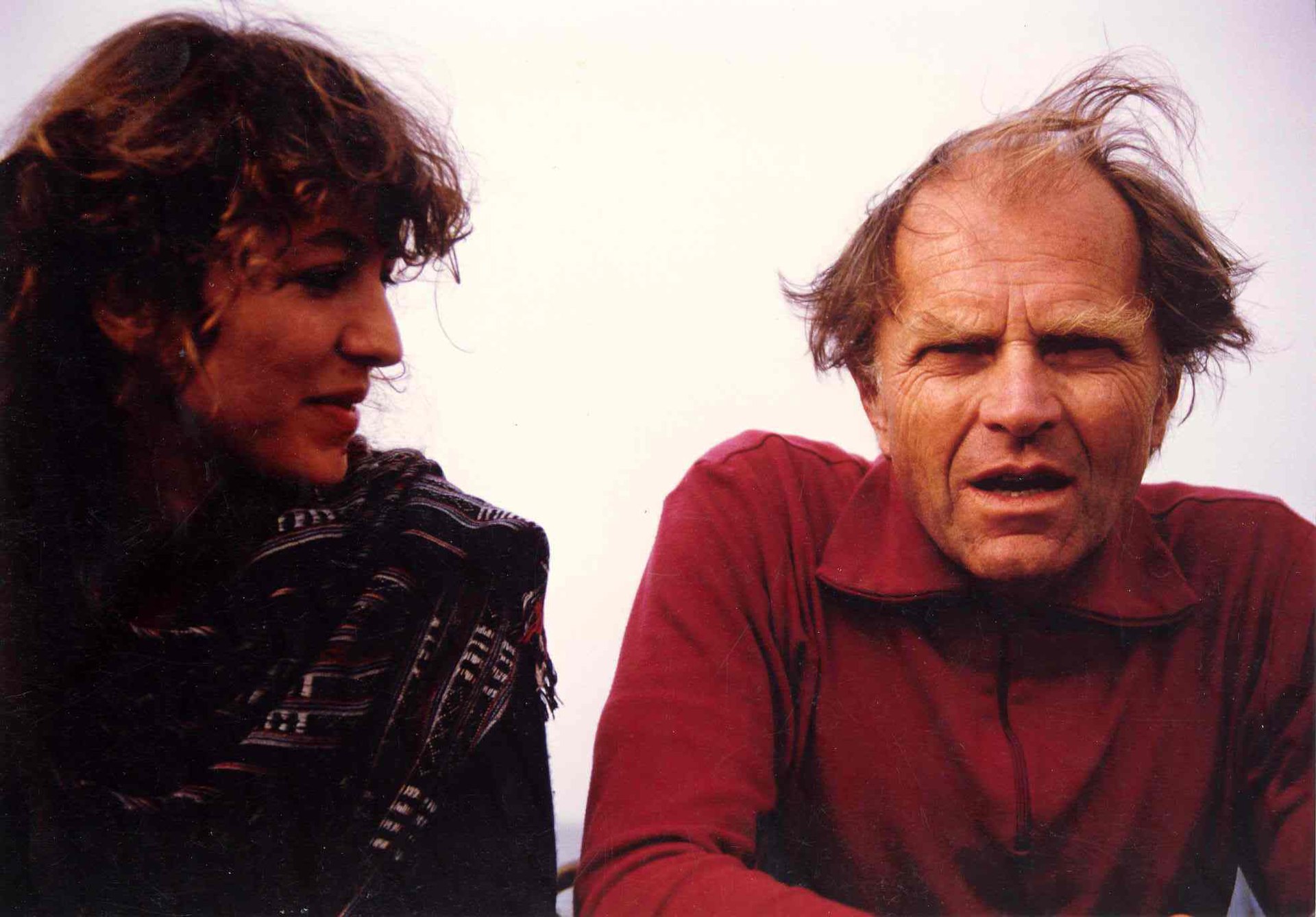

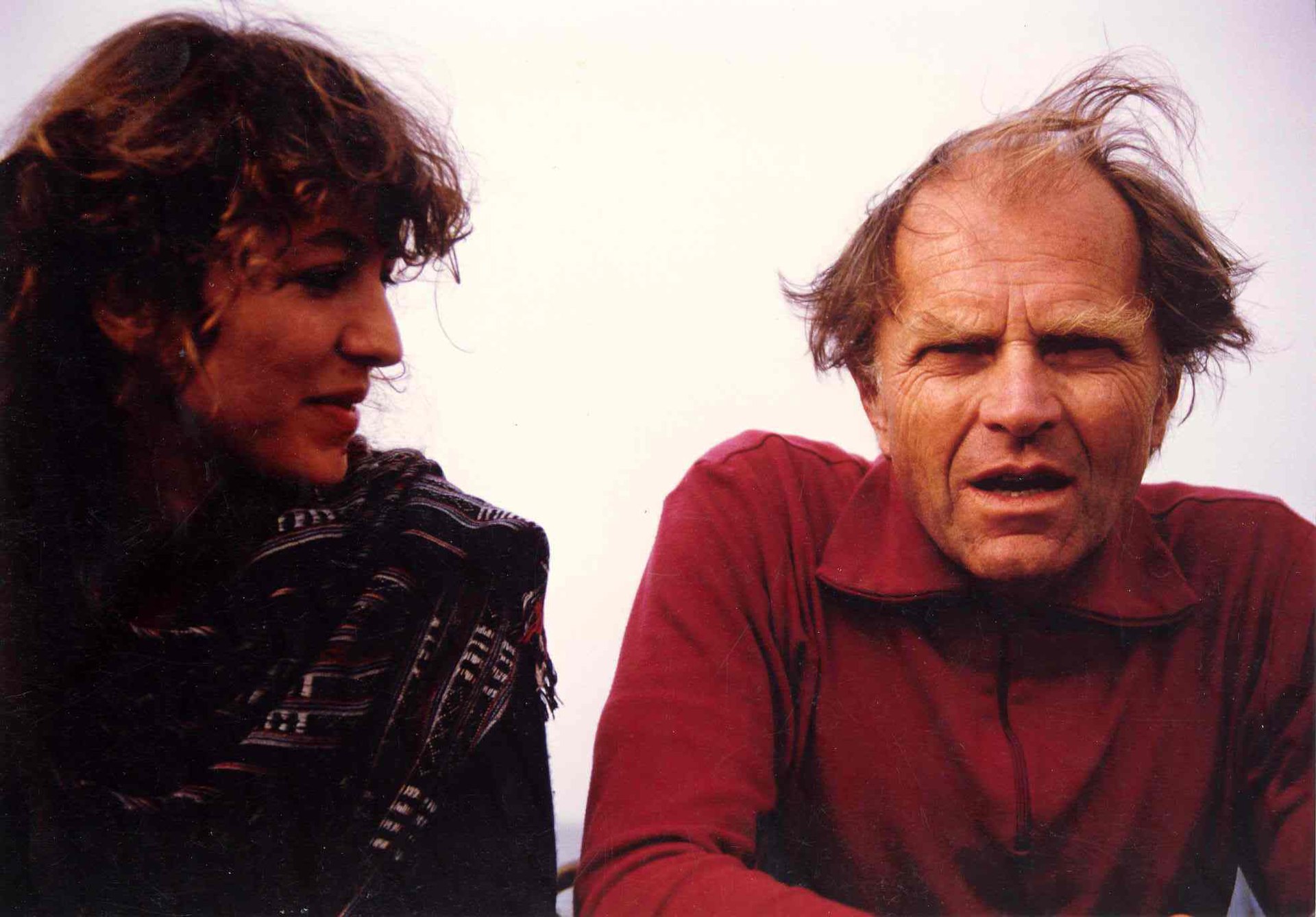

| Biography Early life Feyerabend was born in 1924 in Vienna.[20][21] His paternal grandfather was the illegitimate child of a housekeeper, Helena Feierabend, who introduced the 'y' into 'Feyerabend.'[22] His father, originally from Carinthia, was an officer in the merchant marine in World War I in Istria and a civil servant in Vienna until he died due to complications from a stroke. His mother's family came from Stockerau. She was a seamstress and died on July 29,1943 by suicide. The family lived in a working-class neighborhood (Wolfganggasse) where gypsy musicians, over-the-top relatives, illusionists, sudden accidents, and heated quarrels were part of everyday life. In his autobiography Feyerabend remembers a childhood in which magic and mysterious events were separated by dreary 'commonplace' only by a slight change of perspective[23] — a theme later found in his work. Raised Catholic, Feyerabend attended the Realgymnasium, where he excelled as a Vorzugsschüler (top student), especially in physics and mathematics. At 13 he built, with his father, his own telescope, which allowed him to become an observer for the Swiss Institute of Solar Research.[24] He was inspired by his teacher Oswald Thomas and developed a reputation as knowing more than the teachers.[25] A voracious reader, especially of mystery and adventure novels and plays, Feyerabend casually stumbled onto philosophy. Works by Plato, Descartes, and Büchner awoke his interest in the dramatic power of argument. He later encountered philosophy of science through the works of Mach, Eddington, and Dingler and was fascinated by Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra and his depiction of the "lonely man."[26] During high school, Feyerabend also began his lifelong interest in singing. He sang in a choir under Leo Lehner and was later introduced to opera and inspired by performances from George Oeggl and Hans Hotter. He later trained formally under the tutelage of Adolf Vogel and others.[27] Nazi Occupation of Austria and World War II Feyerabend's parents were both welcoming of the Anschluss. His mother was entranced by Hitler's voice and demeanor and his father was similarly impressed by Hitler's charisma and later joined the Nazi Party.[28] Feyerabend himself was unmoved by the Anschluss or World War II, which he saw as an inconvenience that got in the way of reading and astronomy. Feyerabend was in the Hitler Youth as a part of compulsory policies and sometimes rebelled, praising the British or claiming he had to leave a meeting to attend Mass, and sometimes conformed, bringing in members who missed meetings.[29] After the war, Feyerabend recounts that he "did not accept the aims of Nazism" and that he "hardly knew what they were."[30] Later, he wondered why he did not see the occupation and war as moral problems. They were just "inconveniences" and his reactions—recalled with uncommon honesty—were suggested by accidental moods and circumstances rather than by a "well defined outlook".[30] “Looking back, I notice a rather unstable combination of contrariness and a tendency to conform. A critical judgement or a feeling of unease could be silenced or turned into its opposite by an almost imperceptible counter-force. It was like a fragile cloud dispersed by heat. On other occasions I would not listen to reason or Nazi common sense and would cling to unpopular ideas. This ambivalence (which survived for many years and was weakened only recently) seems to have been connected with my ambivalence towards people: I wanted to be close to them, but I also wanted to be left alone.” — From his autobiography, Killing Time, p 40-41 After graduating from high school, in April 1942 Feyerabend was drafted into the German Arbeitsdienst (working service),[31] received basic training in Pirmasens, and was assigned to a unit in Quelerne en Bas, near Brest. He described the work he did during that period as monotonous: "we moved around in the countryside, dug ditches, and filled them up again."[32] After a short leave he volunteered for officer school. In his autobiography he writes that he hoped the war would be over by the time he had finished his education as an officer. This turned out not to be the case. From December 1943 on, he served as an officer on the northern part of the Eastern Front, was decorated with an Iron cross, and attained the rank of lieutenant.[33] When the German army started its retreat from the advancing Red Army, Feyerabend was hit by three bullets while directing traffic. One hit him in the spine which left him wheel-chaired for a year and partially paralyzed for the rest of his life. He later learned to walk with a crutch, but was left impotent and plagued by intermittent bouts of severe pain for the rest of his life. Post-WWII, PhD, and early career in England  Feyerabend with his friend Roy Edgley After getting wounded in action, Feyerabend was hospitalized in and around Weimar where he spent more than a year recovering and where he witnessed the end of the war and Soviet occupation. The mayor of Apolda gave him a job in the education sector and he, then still on two crutches, worked in public entertainment including writing speeches, dialogues, and plays. Later, at the music academy in Weimar, he was granted a scholarship and food stamps and took lessons in Italian, harmony, singing, enunciation, and piano. He also joined the Cultural Association for the Democratic Reform of Germany, the only association he ever joined.[34] As Feyerabend moved back to Vienna, he was permitted to pursue a PhD at the University of Vienna. He originally intended to study physics, astronomy, and mathematics (while continuing to practice singing) but decided to study history and sociology to understand his wartime experiences.[35] He became dissatisfied, however, and soon transferred to physics and studied astronomy, especially observational astronomy and perturbation theory, as well as differential equations, nuclear physics, algebra, and tensor analysis. He took classes with Hans Thirring, Hans Leo Przibram, and Felix Ehrenhaft. He also had a small role in a film directed by G.W. Pabst and joined the Austrian College where he frequented their speaker series in Alpbach. Here, in 1948, Feyerabend met Karl Popper who made a positive impression on him.[36] He was also influenced by the Marxist playwright Bertolt Brecht, who invited him to be his assistant at the East Berlin State Opera, but Feyerabend turned down the offer.[37] A possible reason was Feyerabend's instinctive aversion to group thinking, which, for instance, made him staunchly refuse joining any Marxist Leninist organizations despite having friends there and despite voting communist in the early Austrian election.[37] In Vienna, Feyerabend organized the Kraft Circle, where students and faculty discussed scientific theories (he recalled five meetings about non-Einsteinian interpretations of the Lorentz transformations)[38] and often focused on the problem of the existence of the external world. There, he also met Elizabeth Anscombe who, in turn, led Feyerabend to meet Ludwig Wittgenstein. In the years between 1949 and 1952, Feyerabend traveled in Europe and exchanged with philosophers and scientists, including Niels Bohr. He also married his first wife (Jacqueline,‘to be able to travel together and share hotel rooms’),[39] divorced, and became involved in various romantic affairs, despite his physical impotence. Cycles of amorous excitement, dependence, isolation, and renewed dependence characterized his relations with women for a good part of his life.[40] He drew great pleasure from opera, which he could attend even five days a week, and from singing (he resumed his lessons even if his crutch excluded an operatic career). Attending opera and singing (he had an excellent tenor voice) remained constant passions throughout his life. In 1951, he earned his doctorate with a thesis on basic statements (Zur Theorie der Basissätze) under Victor Kraft's supervision.[41] In 1952-53, thanks to a British Council scholarship, he continued his studies at the London School of Economics where he focused on Bohm's and von Neumann's work in quantum mechanics and on Wittgenstein's later works, including Remarks on the Foundations of Mathematics and Philosophical Investigations. He also attended Popper's lectures on logic and scientific method and became convinced that induction was irrational. During this time, he developed an early version of his theory of incommensurability, which he thought was a triviality, and was encouraged to develop it further by Popper, H.L.A. Hart, Peter Geach, and Georg Henrik von Wright.[42] He met many others including J.O. Wisdom, A. I. Sabra, Joseph Agassi, and Martin Buber.[43] After his return to Vienna, Feyerabend met often with Viktor Frankl and with Arthur Pap,[44] who offered him a position as his research assistant at the University of Vienna. Thanks to Pap, he became acquainted with Herbert Feigl. During this time, Feyerabend worked on the German translation of Popper's The Open Society and Its Enemies and often met with Herbert Feigl and Philipp Frank. Franck argued that Aristotle was a better empiricist than Copernicus, an argument that became influential on Feyerabend's primary case study in Against Method. In 1955, Feyerabend successfully applied for a lectureship at the University of Bristol with letters of reference[45] from Karl Popper and Erwin Schrödinger and started his academic career. In 1956, he met Mary O’Neill, who became his second wife – another passionate love affair that soon ended in separation.[46] After presenting a paper on the measurement problem at the 1957 symposium of the Colston Research Society in Bristol, Feyerabend was invited to the University of Minnesota by Michael Scriven. There, he exchanged with Herbert Feigl, Ernst Nagel, Wilfred Sellars, Hilary Putnam, and Adolf Grünbaum. Soon afterwards, he met Gilbert Ryle who said of Feyerabend that he was "clever and mischievous like a barrel of monkeys."[47] Berkeley, Zurich and retirement  Feyerabend later in life. Photograph by Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend Feyerabend's primary academic appointment was at the University of California at Berkeley. While he was hired there in 1958, he spent part of his first years in the United States at the University of Minnesota, working closely with Herbert Feigl and Paul Meehl after rejecting a job offer from Cornell.[48] In California, he met and befriended Rudolf Carnap, whom he described as a "wonderful person, gentle, understanding, not at all as dry as would appear from some (not all) of his writings",[49] and Alfred Tarski, among others. He also married for a third time. At Berkeley, Feyerabend mostly lectured on general philosophy and philosophy of science. During the student revolution, he also lectured on revolutionaries (Lenin, Mao, Mill, and Cohn-Bendit).[50] He often invited students and outsiders, including Lenny Bruce and Malcolm X, to guest lecture on a variety of issues including gay rights, racism, and witchcraft. He supported the students but did not support student strikes. John Searle attempted to get Feyerabend fired from his position for hosting lectures off-campus.[51] As Feyerabend was highly marketable in academia and personally restless, he kept accepting and leaving university appointments while holding more 'stable' positions in Berkeley and London. For instance, starting in 1968, he spent two terms at Yale, which he describes as boring, feeling that most there did not have "ideas of their own."[52] There, however, he did meet Jeffrey Bub, and the two became friends. He remembered attempting to give everyone in graduate seminars 'As', which was strongly resisted by the students at Yale. He also asked students in his undergraduate classes to build something useful, like furniture or short films, rather than term papers or exams.[53] In the same years, he accepted a new chair in philosophy of science in Berlin and a professorship in Auckland (New Zealand). In Berlin, he faced a 'problem' as he was assigned two secretaries, fourteen assistants and an impressive office with antique furniture and an anteroom, which "gave him the willies": “...I wrote and mailed my own letters, including official ones ... never had a mailing list or any list of my publications, and I threw away most of the offprints that were sent to me... That took me out of the academic landscape, but it also simplified my life. ... [In Berlin] the secretaries were soon used by my less independent colleagues and by the assistants. "Look," I said to them, "I was given 80,000 marks for starting a new library; go and buy all the books you want and run as many seminars as you like. Don't ask me-- be independent!". Most of the assistants were revolutionaries, and two of them were sought by the police. Yet, they didn't buy Che Guevara or Mao, or Lenin; they bought books on logic! "We have to learn how to think," they said, as if logic has anything to do with that. — From his autobiography, Killing Time, p 132 While teaching at the London School of Economics, Imre Lakatos often 'jumped in' during Feyerabend's lectures and started defending rationalist arguments. The two "differed in outlook, character and ambitions" but became very close friends. They often met at Lakatos' luxurious house in Turner Woods, which included an impressive library. Lakatos had bought the house for representation purposes and Feyerabend often made gentle fun of it, choosing to help Lakatos' wife to wash dishes after dinner rather than engaging in scholarly debates with 'important guests' in the library. "Don't worry" – Imre would say to his guests – "Paul is an anarchist".[54] Lakatos and Feyerabend planned to write a dialogue volume in which Lakatos would defend a rationalist view of science and Feyerabend would attack it. This planned joint publication was put to an end by Lakatos's sudden death in 1974. Feyerabend was devastated by it.  Feyerabend, Kuhn, Hoyningen-Huene and colleagues after a seminar at ETH Zurich Feyerabend had become more and more aware of the limitation of theories – no matter how well conceived – compared with the detailed, idiosyncratic issues encountered in the course of scientific practice. The "poverty of abstract philosophical reasoning" became one of the "feelings" that motivated him to pull together the collage of observations and ideas that he had conceived for the project with Imre Lakatos, whose first edition was published in 1975 as Against Method.[55] Feyerabend added to it some outrageous passages and terms, including about an 'anarchistic theory of knowledge', for the sake of provocation and in memory of Imre. He mostly wanted to encourage attention to scientific practice and common sense rather than to the empty 'clarifications' of logicians, but his views were not appreciated by the intellectuals who were then directing traffic in the philosophical community, who tended to isolate him.[56] Against Method also suggested that "approaches not tied to scientific institutions" may have value, and that scientists should work under the control of the larger public-- views not appreciated by all scientists either. Some gave him the dubious fame of 'worst enemy of science'.[57] Moreover, Feyerabend was aware that "scientific jargon" – read literally, world for word, could reveal not only "nonsense", as found out by John Austin, "but also inhumanity. With the Dadaists Feyerabend realized that "the language of philosophers, politicians, theologians" had similarities with "brute in-articulations". He exposed that by "avoiding scholarly ways of presenting a view" and using "common locutions and the language of show business and pulp instead".[58] In his autobiography, Feyerabend describes how the community of 'intellectuals' seemed to "...take a slight interest in me, lift me up to his own eye level, took a brief look at me, and drop me again. After making me appear more important than I ever thought I was, it enumerated my shortcomings and put me back on my place."[59] This treatment left him all but indifferent. During the years following the publication of Against Method and the critical reviews that followed – some of which as scathing as superficial – he suffered from bouts of ill health and depression. While medical doctors could not do anything for him, some help came from alternative therapies (e.g., Chinese herbal medicines, acupuncture, diet, massage). He also kept moving among academic appointments (Auckland, Brighton, Kassel). Towards the end of the 1970s, Feyerabend was assigned a position as Professor of Philosophy at the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule (ETH) in Zurich. There, he ran well attended lectures, including on the Theatetus, Timeaus, and Aristotle's physics as well as public debates and seminars for the non-academic public. Through the 1980s, he enjoyed alternating between posts at ETH Zurich and UC Berkeley. In 1983, he also met Grazia Borrini, who would become his fourth and final wife.[60] She heard of Feyerabend from train passengers in Europe and attended his seminar in Berkeley. They were married in 1989, when they both decided to try to have children, for which they needed medical assistance due to Feyerabend's war injury.[61] Feyerabend claims that he finally understood the meaning of love because of Grazia. This had a dramatic impact on his worldview ("Today it seems to me that love and friendship play a central role and that without them even the noblest achievements and the most fundamental principles remain pale, empty and dangerous").[62] It is also in those years that he developed what he describes as "...a trace of a moral character”.[63] “...a moral character cannot be created by argument, 'education' or an act of will. It cannot be created by any kind of planned action, whether scientific, political, moral or religious. Like true love, it is a gift, not an achievement. It depends on accidents, such as parental affection, some kind of stability, friendship, and-- following therefrom-- on a delicate balance between self-confidence and concern for others. We can create conditions that favor the balance; we cannot create the balance itself. Guilt, responsibility, obligation-- these ideas make sense when the balance is given. They are empty words, even obstacles, when it is lacking.” — From his autobiography, Killing Time, p 174  Paul Feyerabend and Grazia Borrini Feyerabend (Crete, 1980s) In 1989, Feyerabend voluntarily left Berkeley for good. After his mandatory retirement also from Zurich, in 1990, he continued to give lectures, including often in Italy, published papers and book reviews for Common Knowledge, and worked on his posthumously released Conquest of Abundance and on his autobiography-- the volumes for which writing became for him "a 'pleasurable activity', almost like composing a work of art".[64] He remained based in Meilen, in Switzerland, but often spent time with his wife in Rome. After a short period of suffering from an inoperable brain tumor, he died in 1994 at the Genolier Clinic, overlooking Lake Geneva, Switzerland. He had just turned 70. He is buried in his family grave, in Vienna. |

略歴 生い立ち 父方の祖父は家政婦のヘレナ・ファイアーベントの隠し子で、「ファイアーベント」に「y」を導入した[22]。父親はカリンシア出身で、第一次世界大戦で はイストリアで商船士官を務め、脳卒中の合併症で亡くなるまでウィーンで公務員をしていた。母親はシュトッケラウ出身。彼女はお針子で、1943年7月 29日に自殺で亡くなった。一家は、ジプシー音楽家、大げさな親戚、イリュージョニスト、突然の事故、激しい喧嘩が日常生活の一部であった労働者階級の地 区(ヴォルフガングガッセ)に住んでいた。ファイアーベントは自伝の中で、魔法や神秘的な出来事が、ほんの少し視点を変えるだけで、退屈な「ありふれた もの」と隔てられた子供時代を回想している[23]。 カトリック教徒として育ったファイアーベントは、レアルギムナジウムに通い、特に物理学と数学で優秀な成績を修めた。13歳のとき、父親と一緒に自分の 望遠鏡を作り、そのおかげでスイス太陽研究所の観測員になることができた。プラトン、デカルト、ビュヒナーの作品に出会い、議論のドラマチックな力に興味 を持った。その後、マッハ、エディントン、ディングラーの作品を通して科学哲学に出会い、ニーチェの『ツァラトゥストラはかく語りき』と彼の描く「孤独な 人間」に魅了された。レオ・レーナーのもとで合唱団で歌い、後にオペラに出会い、ジョージ・オーグルやハンス・ホッターの演奏に感銘を受ける。その後、ア ドルフ・フォーゲルらの指導の下、正式に訓練を受けた[27]。 ナチスによるオーストリア占領と第二次世界大戦 ファイアーベントの両親は、ともにナチスドイツの占領を歓迎していた。母親はヒトラーの声と態度に魅了され、父親も同様にヒトラーのカリスマ性に感銘を 受け、後にナチ党に入党する。戦後、ファイアーベントは「ナチズムの目的を受け入れなかった」「ナチズムが何なのかほとんど知らなかった」と語ってい る。それらは単なる「不都合」であり、彼の反応は「明確に定義された展望」によるものではなく、偶然の気分や状況によって示唆されたものであったと、珍し く正直に回想している[30]。 「振り返ってみると、反対主義と順応傾向の、かなり不安定な組み合わせに気づく。批判的な判断や不安感は、ほとんど気づかれないほどの反力によって沈黙さ せられたり、その反対へと転化させられたりした。それはまるで、熱で飛ばされるもろい雲のようだった。また、理性やナチスの常識に耳を傾けず、人気のない 考えに固執することもあった。この両価性は(何年も続き、最近になって弱まったが)、私の人間に対する両価性と関係していたようだ: 人々の近くにいたかったが、一人にしてほしかったのだ。 - 自伝『キリングタイム』P40-41より 高校卒業後の1942年4月、ファイアーベントはドイツの労働奉仕団に徴兵され[31]、ピルマゼンスで基礎訓練を受け、ブレスト近郊のケレルヌ・ア ン・バスの部隊に配属された。その時期の仕事は単調で、「田園地帯を動き回り、溝を掘り、また埋めた」[32]と述べている。自伝の中で彼は、将校として の教育を終える頃には戦争が終わっていることを望んでいたと書いている。しかし、そうはならなかった。1943年12月から、彼は東部戦線北部で将校とし て勤務し、鉄十字勲章を授与され、中尉の階級に就いた[33]。ドイツ軍が進撃する赤軍から撤退を開始したとき、ファイアーベントは交通整理中に3発の 銃弾を受けた。そのうちの1発が背骨に命中し、彼は1年間車椅子生活を余儀なくされ、残りの人生は半身不随となった。その後、松葉杖を使って歩けるように なったが、インポテンツとなり、生涯、断続的な激痛に悩まされた。 第二次世界大戦後、博士号取得、イギリスでの初期キャリア  ファイアーベントと友人のロイ・エッジリー 戦場で負傷した後、ファイアーベントはワイマールとその周辺で入院し、1年以上を療養に費やし、終戦とソ連の占領を目の当たりにした。アポルダ市長から 教育部門の仕事を与えられ、松葉杖をつきながら、演説、台詞、劇の執筆など大衆娯楽に携わった。その後、ワイマールの音楽学校で奨学金とフードスタンプを 与えられ、イタリア語、和声、歌、発音、ピアノのレッスンを受けた。また、ドイツの民主的改革のための文化協会に入会した。 ウィーンに戻ったファイアーベントは、ウィーン大学で博士号を取得することを許された。彼は当初、物理学、天文学、数学を(歌の練習を続けながら)学ぶ つもりだったが、戦時中の経験を理解するために歴史学と社会学を学ぶことにした。ハンス・サーリング、ハンス・レオ・プルジブラム、フェリックス・エーレ ンハフトの授業を受けた。また、G.W.パブスト監督の映画にちょい役で出演したり、アルプバッハで開催されたオーストリア・カレッジの講演会に足繁く 通ったりもした。1948年、ここでファイアーベントはカール・ポパーと出会い、彼に好意的な印象を与えた[36]。マルクス主義者の劇作家ベルトル ト・ブレヒトからも影響を受け、東ベルリン国立歌劇場の助手に誘われたが、ファイアーベントはその申し出を断った[37]。その理由として考えられるの は、ファイアーベントの集団思考に対する本能的な嫌悪感であり、例えば、マルクス主義者レーニン主義者の団体に友人がいたにもかかわらず、またオースト リアの初期の選挙で共産主義者に投票したにもかかわらず、彼は断固としてその団体への参加を拒否した[37]。 ウィーンでは、ファイアーベントはクラフト・サークルを組織し、学生や教授陣が科学理論について議論し(ローレンツ変換の非アインシュタイン的解釈につ いて5回の会合があったと回想している)[38]、しばしば外界の存在の問題に焦点を当てていた。そこでエリザベス・アンスコムに出会い、そのアンスコム はファイアーベントをルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインに導いた。1949年から1952年にかけて、ファイアーベントはヨーロッパを旅行し、ニー ルス・ボーアを含む哲学者や科学者と交流した。また、最初の妻(ジャクリーヌ、「一緒に旅行し、ホテルの部屋をシェアするため」)と結婚し、[39]離婚 し、身体的にインポテンツであったにもかかわらず、様々な恋愛関係に発展した。週に5日でも通うことができたオペラと、歌うこと(松葉杖のためにオペラの キャリアを断たれてもレッスンを再開した)から大きな喜びを得た。オペラに通うことと歌うこと(彼は優れたテノールの声を持っていた)は、彼の生涯を通じ て絶え間ない情熱であり続けた。1951年、ヴィクトル・クラフトの指導の下、基本声明(Zur Theorie der Basissätze)に関する論文で博士号を取得した[41]。 1952年から53年にかけて、ブリティッシュ・カウンシルの奨学金を得て、ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスで研究を続け、量子力学におけるボー ムとフォン・ノイマンの研究、そして『数学の基礎についての考察』や『哲学的探究』を含むウィトゲンシュタインの後期の著作に焦点を当てた。また、ポパー の論理学と科学的方法に関する講義を聴講し、帰納法は非合理的であると確信した。この時期、彼は些細なことだと考えていた非可換性の理論の初期バージョン を開発し、ポパー、H.L.A.ハート、ピーター・ゲーアッハ、ゲオルク・ヘンリック・フォン・ライトらからさらに発展させるように勧められた[42]。 O・ウィズダム、A・I・サブラ、ジョセフ・アガシ、マルティン・ブーバーなどであった[43]。ウィーンに戻った後、ファイアーベントはヴィクトー ル・フランクルやアーサー・パップ[44]としばしば会い、パップからウィーン大学での研究助手としての地位を提供された。パップのおかげで、彼はヘルベ ルト・フェイグルと知り合いになった。この時期、ファイアーベントはポパーの『開かれた社会とその敵』のドイツ語訳に取り組み、ヘルベルト・フェイグル やフィリップ・フランクとしばしば会っていた。フランクは、アリストテレスがコペルニクスよりも優れた経験論者であると主張し、この主張は『方法論に抗し て』におけるファイヤアーベンドの主要な事例研究に影響を与えた。 1955年、ファイヤアーベンドはカール・ポパーとエルヴィン・シュレーディンガーからの推薦状[45]を携えてブリストル大学の講義に応募し、学術的な キャリアをスタートさせた。1956年、2番目の妻となるメアリー・オニールと出会い、これもまた情熱的な恋愛であったが、すぐに別れることになった [46]。1957年にブリストルで開催されたコルストン研究会のシンポジウムで測定問題に関する論文を発表した後、ファイヤアーベンドはマイケル・スク リヴェンによってミネソタ大学に招かれた。そこでヘルベルト・フェイグル、エルンスト・ネーゲル、ウィルフレッド・セラーズ、ヒラリー・パットナム、アド ルフ・グリュンバウムらと交流した。その直後、彼はギルバート・ライル(Gilbert Ryle)と出会い、彼はファイアーベントについて「猿の樽のように賢く、いたずら好きである」と評した[47]。 バークレー、チューリヒ、引退  晩年のファイアーベント。写真:Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend ファイヤアーベンドの主な任地はカリフォルニア大学バークレー校であった。1958年にカリフォルニア大学バークレー校に採用されたが、コーネル大学から の内定を辞退した後、アメリカでの最初の数年間をミネソタ大学で過ごし、ハーバート・フェイグルやポール・ミールらと緊密に仕事をした[48]。カリフォ ルニアでは、ルドルフ・カルナップと出会い、親交を深めた。ルドルフ・カルナップは、「素晴らしい人物で、穏やかで、理解力があり、彼の著作の一部(すべ てではない)から見て取れるほどドライではない」と評している[49]。彼はまた3度目の結婚をした。バークレー校では、主に一般哲学と科学哲学を講義。 学生革命の時期には、革命家(レーニン、毛沢東、ミル、コーン=ベンディット)についての講義も行った[50]。彼はしばしば、レニー・ブルースやマルコ ムXを含む学生や部外者を招き、同性愛者の権利、人種差別、魔術など様々な問題についてゲスト講義を行った。彼は学生を支援したが、学生のストライキは支 持しなかった。ジョン・サールは、学外で講義を開いたことを理由にファイアーベントを解雇しようとした[51]。 ファイアーベントは学界で高い市場価値があり、個人的にも落ち着きがなかったため、バークレーやロンドンでより「安定した」職に就きながら、大学の任命 を受けたり離れたりを繰り返していた。例えば、1968年からはイェール大学で2期を過ごしたが、そこではほとんどの人が「自分の考え」を持っていないと 感じ、退屈だったと語っている[52]。彼は大学院のセミナーで全員に「As」を与えようとしたが、イェールの学生たちから強い抵抗を受けたことを覚えて いる。また、学部の授業では、学生に学期末の論文や試験ではなく、家具や短編映画など、何か役に立つものを作るように求めた[53]。同じ年に、彼はベル リンで科学哲学の新しい椅子を、オークランド(ニュージーランド)で教授職を受け入れた。ベルリンでは、2人の秘書、14人のアシスタント、アンティーク 家具と控室のある印象的なオフィスを与えられたため、「問題」に直面した: 「......私は、公式のものも含め、自分で手紙を書いて郵送した......メーリングリストも、私の出版物のリストも持っていなかったし、送られて きたオフプリントのほとんどは捨ててしまった......。それは私をアカデミックな世界から引き離したが、同時に私の生活を簡素化した。... [ベルリンでは)秘書はすぐに、あまり自立していない同僚や助手たちに使われるようになった。「いいかい、私は彼らに言ったんだ。『私は新しい図書館を立 ち上げるために8万マルクをもらったんだ。私に頼むな、独立しろ!」と言った。助手のほとんどは革命家で、そのうちの2人は警察に追われた。しかし、彼ら はチェ・ゲバラや毛沢東やレーニンを買ったのではなく、論理学の本を買ったのだ!「私たちは考える方法を学ばなければならない」と彼らは言った。 - 自伝『キリング・タイム』132頁より ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスで教えていたイムレ・ラカトシュは、ファイアーベントの講義中にしばしば「飛び入り」し、合理主義者の議論を擁護 し始めた。2人は「見通し、性格、野心において異なっていた」が、非常に親しい友人となった。二人はターナー・ウッズにあるラカトスの豪邸でしばしば会っ た。ラカトシュはこの家を表象のために買ったのだが、ファイアーベントはしばしばそれをやんわりと揶揄し、図書館で「重要な客人」と学術的な議論を交わす よりも、夕食後にラカトシュの妻が皿洗いをするのを手伝う方を選んだ。「ラカトシュとファイヤーアーベントは、ラカトシュが合理主義的な科学観を擁護し、ファイ ヤーアーベントがそれを攻撃する対話集を書く予定であった。この共同出版の計画は、1974年にラカトシュが急死したことで頓挫した。ファイアーベントは そのことに打ちのめされた。  チューリヒ工科大学でのセミナー後のファイアーベント、クーン、ホイニンゲン=ヒューネと同僚たち。 ファイアーベントは、科学的実践の過程で遭遇する詳細で特異な問題に比べて、理論がいかによく考えられたものであっても、その限界にますます気づくよう になっていた。抽象的な哲学的推論の貧しさ」は、イムレ・ラカトシュと のプロジェクトのために構想した観察とアイデアのコラージュをまとめる動機となった 「感情」のひとつとなった。彼は主に、論理学者の空疎な「解明」ではなく、科学的実践と常識への注意を促したかったのだが、彼の見解は、当時哲学界の交通 整理をしていた知識人たちには理解されず、彼を孤立させる傾向があった[56]。 また、『方法論に抗して』では、「科学的制度に縛られないアプローチ」にも価値があり、科学者はより大きな一般大衆の統制の下で働くべきであると示唆した が、この見解もすべての科学者には理解されなかった。さらに、ファイアーベントは、「科学的専門用語」は、ジョン・オースティンが発見したように、文字 通り、一語一語読むと、「ナンセンス」であるだけでなく、「非人間性」を露呈する可能性があることを認識していた。ダダイストたちとともに、ファイアーベ ントは「哲学者、政治家、神学者の言葉」が「粗野な術語」と類似していることに気づいた。彼は「学術的な見解の提示の仕方を避け」、代わりに「一般的な 言い回しやショービジネスやパルプの言葉」を使うことによって、それを暴露した[58]。 自伝の中で、ファイアーベントは「知識人」のコミュニティがどのように見えたかについて述べている。私が思っていた以上に私を重要人物に見せかけた後、 私の欠点を列挙し、私を元の場所に戻した」[59]。アゲインスト・メソッド』出版後の数年間、彼は体調不良とうつ病に悩まされた。医師は何もしてやれな かったが、代替療法(漢方薬、鍼治療、食事療法、マッサージなど)には助けられた。彼はまた、オークランド、ブライトン、カッセルと、学問的な任地を転々 とした。 1970年代末、ファイアーベントはチューリッヒのアイトゲーネ工科大学(ETH)の哲学教授に就任した。そこでは、『テアテトス』、『ティメアス』、 アリストテレスの『物理学』などの講義を行い、また、学術関係者以外の一般市民を対象とした公開討論会やセミナーを開催し、多くの聴衆を集めた。1980 年代までは、チューリッヒ工科大学とカリフォルニア大学バークレー校で交互に研究を行った。1983年、4人目にして最後の妻となるグラツィア・ボリーニ と出会う[60]。彼女はヨーロッパの列車の乗客からファイアーベントのことを聞き、バークレーで開かれた彼のセミナーに参加した。ふたりは1989年 に結婚したが、そのとき、ファイアーベントの戦傷のために医療的な援助を必要とする子供をつくろうと決意した[61]。ファイアーベントは、グラツィ アのおかげでようやく愛の意味を理解することができたと主張している。これは彼の世界観に劇的な影響を与えた(「今日、私には愛と友情が中心的な役割を果 たし、それなしには最も崇高な業績や最も基本的な原則でさえも、淡く、空虚で、危険なままであるように思える」)[62]。また、彼が「...道徳的性格 の痕跡」と表現するものを発達させたのもこの頃である[63]。 ...道徳的な性格は、議論や『教育』や意志の行為によって生み出されることはない。科学的であれ、政治的であれ、道徳的であれ、宗教的であれ、どのよう な種類の計画的な行動によっても創造することはできない。真の愛と同じように、それは賜物であり、達成ではない。それは、親の愛情、ある種の安定、友情、 そしてそれに続く、自信と他者への配慮の微妙なバランスといった偶然に左右される。私たちはバランスを保つための条件を作り出すことはできるが、バランス そのものを作り出すことはできない。罪悪感、責任、義務......こうした考えは、バランスが与えられたときに意味をなす。バランスが欠けているときに は、それらは空虚な言葉であり、障害にさえなる。" - 自伝『時間を殺す』174ページより  ポール・ファイアーベントとグラツィア・ボリーニ・ファイアーベント(1980年代、クレタ島) 1989年、ファイアーベントは自主的にバークレーを去った。1990年にチューリヒを定年退職した後も、しばしばイタリアで講演を行い、『コモン・ナ レッジ』に論文や書評を発表し、遺作となった『豊かさの克服』と自伝の執筆に取り組んだ。手術不可能な脳腫瘍を患った後、1994年、スイスのレマン湖を 望むジェノリエ・クリニックで死去。70歳になったばかりだった。ウィーンの家族の墓に埋葬されている。 |

| Thought Philosophy of science Kraft Circle, hidden variables, and no-go proofs During Feyerabend's PhD, he describes himself as a "raving positivist."[65] He was the head organizer of the 'Kraft circle' which discussed many issues in the foundations of physics and on the nature of basic statements, which was the topic of his dissertation. In 1948, Feyerabend wrote a short paper in response to Schrödinger's paper "On the Peculiarity of the Scientific Worldview." Here, Feyerabend argued that Schrödinger's demand that scientific theories present are Anschaulich (i.e., intuitively visualizable) is too restrictive. Using the example of the development of Bohr's atomic theory, he claims that theories that are originally unvisualizable develop new ways of making phenomena visualizable.[66] His unpublished paper, "Philosophers and the Physicists" argues for a naturalistic understanding of philosophy where philosophy is "petrified" without physics and physics is "liable to become dogmatic" without philosophy.[67] Feyerabend's early career is also defined by a focus on technical issues within the philosophy of quantum mechanics. Feyerabend argues that von Neumann's 'no-go' proof only shows that the Copenhagen interpretation is consistent with the fundamental theorems of quantum mechanics but it does not logically follow from them. Therefore, causal theories of quantum mechanics (like Bohmian mechanics) are not logically ruled out by von Neumann's proof.[68] After meeting David Bohm in 1957, Feyerabend became an outspoken defender of Bohm's interpretation and argued that hidden variable approaches to quantum mechanics should be pursued to increase the testability of the Copenhagen Interpretation.[9] Feyerabend also provided his own solution to the measurement problem in 1957, although he soon came to abandon this solution. He tries to show that von Neumann's measurement scheme can be made consistent without the collapse postulate. His solution anticipates later developments of decoherence theory.[69] Empiricism, pluralism, and incommensurability Much of Feyerabend's work from the late 1950s until the late 1960s was devoted to methodological issues in science. Specifically, Feyerabend offers several criticisms of empiricism and offers his own brand of theoretical pluralism. One such criticism concerns the distinction between observational and theoretical terms. If an observational term is understood as one whose acceptance can be determined by immediate perception, then what counts as 'observational' or 'theoretical' changes throughout history as our patterns of habituation change and our ability to directly perceive entities evolve.[70] On another definition, observation terms are those that can be known directly and with certainty whereas theoretical terms are hypothetical. Feyerabend argues that all statements are hypothetically, since the act of observation requires theories to justify its veridicality.[71] To replace empiricism, Feyerabend advances theoretical pluralism as a methodological rule for scientific progress. On this view, proliferating new theories increases the testability of previous theories that might be well-established by observations. This is because some tests cannot be unearthed without the invention of an alternative theory.[72] One example Feyerabend uses repeatedly is Brownian motion which was not a test of the second law of classical thermodynamics.[73] To become a test, it must be first explained by an alternative theory – namely, Einstein's kinetic theory of gases – which formally contradicts the accepted theory. By proliferating new theories, we increase the number of indirect tests of our theories. This makes theoretical pluralism central to Feyerabend's conception of scientific method. Eventually, Feyerabend's pluralism incorporates what he calls the "principle of tenacity."[74] The principle of tenacity allows scientists to pursue theories regardless of the problems it may possess. Examples of problems might include recalcitrant evidence, theoretical paradoxes, mathematical complexity, or inconsistency with neighboring theories. Feyerabend learned of this idea from Kuhn, who argued that without tenacity all theories would have been prematurely abandoned.[75] This principle complements the "principle of proliferation", which admonishes us to invent as many theories as possible, so that those invented theories can become plausible rivals.[76] In his "Empiricism, Reduction, and Experience" (1962), Feyerabend outlines his theory of incommensurability. His theory appears in the same year as Thomas Kuhn's discussion of incommensurability in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, but the two were developed independently.[77] According to Feyerabend, some instances of theory change in the history of science do not involve a successor theory that retains its predecessor as a limiting case. In other words, scientific progress does not always involve producing a theory that is a generalization of the previous theory. This is because the successor theory is formally inconsistent with the previous theory attempting to explain the same domain of phenomena.[78] Moreover, the two theories do not share the same empirical content and, therefore, cannot be compared by the same set of observation statements. For example, Buridan's impetus principle has no analogue in classical mechanics. The closest analogue would be momentum, but the two notions are qualitatively distinct (impetus causes motion whereas momentum is the result of motion). Furthermore, Feyerabend claims that there can be no 'parallel notion' of impetus that is explicable within classical mechanics. Any parallel notion that gives non-zero values must assume that inertial movements happen in a resisting medium, which is inconsistent with the assumption in classical mechanics that inertial motion happens in empty space. Therefore, "the concept of impetus, as fixed by the usage established in the impetus theory, cannot be defined in a reasonable way within Newton's theory [since] the usage involves laws... which are inconsistent with Newtonian physics."[79] In response to criticisms of Feyerabend's position, he clarifies that there are other ways in which theories can be compared such as comparing the structures of infinite sets of elements to detect isomorphisms,[80] comparing "local grammars" ,[81] or building a model of a theory within its alternative.[82] Incommensurability, however, only arises if scientists make the choice to interpret theories realistically. Theories interpreted instrumentally cannot be incommensurable, on Feyerabend's view. Feyerabend's pluralism is supported by what he calls the 'pragmatic theory of meaning' which he developed in his dissertation.[10] Here, he explicitly resuscitates Neurath and Carnap's physicalism from the 1930s. According to the pragmatic theory of meaning, language consists of two parts. First, there is the characteristic of a language which is a series of noises produced under specific experimental situations. On Feyerabend's views, human observation has no special epistemic status – it is just another kind of measuring apparatus. The characteristic of a language comes from placing observers in the presence of phenomena and instructing them to make specific noises when a phenomenon is sensed. These noises, to become statements (or parts of a language with meaning), must then be interpreted. Interpretation comes from a theory, whose meaning is given is learned though not necessarily through ostension.[83] Once we have an interpreted characteristic, we have statements that can be used to test theories. Departure from Popper Beginning in at least the mid-to-late 1960s, Feyerabend distanced himself from Popper both professionally and intellectually. There is a great amount of controversy about the source and nature of Feyerabend's distancing from Popper.[5] Joseph Agassi claims that it was caused by the student revolutions at Berkeley, which somehow promoted Feyerabend's move towards epistemological anarchism defended in the 1970s.[84] Feyerabend's friend Roy Edgley claims that Feyerabend became distanced from Popper as early as the mid-1950s, when he went to Bristol and then Berkeley and was more influenced by Thomas Kuhn and the Marxism of David Bohm.[85] Feyerabend's first paper that explicitly repudiates Popper is his two-part paper on Niels Bohr's conception of complementarity.[86] According to Popper, Bohr and his followers accepted complementarity as a consequence of accepting positivism. Popper was the founder of the theory of falsification, which Feyerabend was very critical of. He meant that no science is perfect, and therefore can't be proven false.[87] Once one repudiates positivism as a philosophical doctrine, Popper claims, one undermines the principle of complementarity. Against this, Feyerabend claims that Bohr was a pluralist who attempting to pursue a realistic interpretation of quantum mechanics (the Bohr-Kramer-Slater conjecture) but abandoned it due to its conflict with the Bothe-Geiger and Compton-Simon experiments.[88] While Feyerabend concedes that many of Bohr's follows (notably, Leon Rosenfeld) accept the principle of complementarity as a philosophical dogma, he contends that Bohr accepted complementarity because it was entangled with an empirically adequate physical theory of microphysics. Anarchist phase See also: Against Method In the 1970s, Feyerabend outlines an anarchistic theory of knowledge captured by the slogan 'anything goes.' The phrase 'anything goes' first appears in Feyerabend's paper "Experts in a Free Society" and is more famously proclaimed at the end of the first chapter of Against Method.[89] Feyerabend's epistemological anarchism has been the source of contention amongst scholars. Some claim that epistemological anarchism is not a positive view of scientific method, but the conclusion of a reductio ad absurdum of 'rationalism' (the view that there are universal and unchanging rational rules for scientific reasoning). In Feyerabend's words, "'anything goes' is not a 'principle' I hold... but the terrified exclamation of a rationalist who takes a closer look at history."[90] On this interpretation, Feyerabend aims to show that no methodological view can be held as fixed and universal and therefore the only fixed and universal rule would be "anything goes" which would be useless. On another interpretation, Feyerabend is claiming that scientists should be unscrupulous opportunists who choose methodological rules that make sense within a given situation.[76] On this view, there are no 'universal' methodological rules but there are local rules of scientific reasoning that should be followed. The use of the phrase 'opportunism' comes from Einstein[91] which denotes an inquirer who changes their beliefs and techniques to fit the situation at hand, rather than pre-judge individual events with well-defined methods or convictions. Feyerabend thinks that this is justified because "no two individuals (no two scientists; no two pieces of apparatus; no two situations) are ever exactly alike and that procedures should therefore be able to vary also."[92] On a third interpretation, epistemological anarchism is a generalization of his pluralism that he had been developing throughout the 1950s and 1960s.[76] On this view, Feyerabend did not have an anarchist 'turn' but merely generalized his positive philosophy on a more general view. Epistemological anarchism is synonymous with a pluralism without limits, where one can proliferate any theory one wishes and one can tenaciously develop any theory for as long as one wishes. Relatedly, because methods depend on empirical theories for their utility, one can employ any method one wishes in attempt to make novel discoveries. This does not mean that we can believe anything we wish – our beliefs must still stand critical scrutiny – but that scientific inquiry has no intrinsic constraints.[93] The only constraints on scientific practice are those that are materially forced upon scientists. Moreover, Feyerabend also thought that theoretical anarchism was desirable because it was more humanitarian than other systems of organization, by not imposing rigid rules on scientists. For is it not possible that science as we know it today, or a "search for the truth" in the style of traditional philosophy, will create a monster? Is it not possible that an objective approach that frowns upon personal connections between the entities examined will harm people, turn them into miserable, unfriendly, self-righteous mechanisms without charm or humour? "Is it not possible," asks Kierkegaard, "that my activity as an objective [or critico-rational] observer of nature will weaken my strength as a human being?" I suspect the answer to many of these questions is affirmative and I believe that a reform of the sciences that makes them more anarchic and more subjective (in Kierkegaard's sense) is urgently needed. Against Method (3rd ed.). p. 154.[94] According to this "existential criteria",[95] methodological rules can be tested by the kinds of lives that they suggest. Feyerabend's position was seen as radical, because it implies that philosophy can neither succeed in providing a general description of science, nor in devising a method for differentiating products of science from non-scientific entities like myths. To support his position that methodological rules generally do not contribute to scientific success, Feyerabend analyzed counterexamples to the claim that (good) science operates according to the methodological standards invoked by philosophers during Feyerabend's time (namely, inductivism and falsificationism). Starting from episodes in science that are generally regarded as indisputable instances of progress (e.g. the Copernican Revolution), he argued that these episodes violated all common prescriptive rules of science. Moreover, he claimed that applying such rules in these historical situations would actually have prevented scientific revolution.[96] His primary case study is Galileo's hypothesis that the Earth rotates on its axis. Metaphysics of abundance See also: Conquest of Abundance In Feyerabend's later work, especially in Conquest of Abundance, Feyerabend articulates a metaphysical theory in which the universe around us is 'abundant' in the sense that it allows for many realities to be accepted simultaneously. According to Feyerabend, the world, or 'Being' as he calls it, is pliable enough that it can change in accordance with the ways in which we causally engage with the world.[97] In laboratories, for example, scientists do not simply passively observe phenomena but actively intervene to create phenomena with the help of various techniques. This makes entities like 'electrons' or 'genes' real because they can be stably used in a life that one may live. Since our choices about what lives we should live depend on our ethics and our desires, what is 'real' depends on what plays a role in a life that we think is worth living. Feyerabend calls this 'Aristotle's principle' as he believes that Aristotle held the same view.[98] Being, therefore, is pliable enough to be manipulated and transformed to make many realities that conform to different ways of living in the world.[99] However, not all realities are possible. Being resists our attempts to live with it in certain ways and so not any entity can be declared as 'real' by mere stipulation. In Feyerabend's words, "I do not assert that any [form of life] will lead to a well-articulated and livable world. The material humans...face must be approached in the right way. It offers resistance; some constructions (some incipient cultures - cargo cults, for example) find no point of attack in it and simply collapse"[100] This leads Feyerabend to defend the disunity of the world thesis that was articulated by many members of the Stanford School. There are many realities that cannot be reduced to one common 'Reality' because they contain different entities and processes.[101] This makes it possible that some realities contain gods while others are purely materialistic, although Feyerabend thought that materialistic worldviews were deficient in many unspecified ways.[95] Feyerabend's ideas about a 'conquest of abundance' were first voiced in Farewell to Reason, and the writings of the late 1980s and early 1990s experiment with different ways of expressing the idea, including many of the articles and essays published as part two of Conquest of Abundance. A new theme of this later work is the ineffability of Being, which Feyerabend developed with reference to the work of the Christian mystic, Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite. The remarks on ineffability in Conquest of Abundance are too unsystematic to definitively interpret. Philosophy of mind Eliminative materialism Along with a number of mid-20th century philosophers (most notably, Wilfrid Sellars, Willard Van Orman Quine, and Richard Rorty), Feyerabend was influential in the development of eliminative materialism, a radical position in the philosophy of mind. On some definitions, eliminative materialism holds that all that exists are material processes and, therefore, our ordinary, common-sense understanding of the mind ("folk psychology") is false. It is described by a modern proponent, Paul Churchland, as follows: "Eliminative materialism is the thesis that our commonsense conception of psychological phenomena constitutes a radically false theory, a theory so fundamentally defective that both the principles and the ontology of that theory will eventually be displaced, rather than smoothly reduced, by completed neuroscience."[102] Feyerabend wrote on eliminative materialism in three short papers published in the early sixties.[78][103] The most common interpretation of these papers is that he was an early forerunner of eliminative materialism. This was a major influence on Patricia and Paul Churchland. As Keeley observes,[104] "[Paul Churchland] has spent much of his career carrying the Feyerabend mantle forward." More recent scholarship claims that Feyerabend was never an eliminative materialist and merely aimed to show that common criticisms against eliminative materialism were methodologically faulty. Specifically, on this interpretation, while Feyerabend defended eliminative materialism from arguments from acquaintance and our intuitive understanding of the mind but did not explicitly claim that eliminative materialism was true. In doing so, Feyerabend leaves open the possibility that dualism is true but this would have to be shown through scientific arguments rather than philosophical stipulation.[105] In any case, Feyerabend explicitly disavows materialism in his later philosophical writings. Cognitive plasticity Feyerabend briefly entertains and is sympathetic to the hypothesis that there are no innate, cognitive limitations imposed upon the human brain. By this he meant that there were no intrinsic limitations about what we can conceive or understand. Spread out through Feyerabend's writings are passages that suggest that this is confirmed by evidence at the time in the mind-brain sciences. Specifically, he claims that "until now only two or three per cent of the inbuilt circuits of the brain have been utilised. A large variety of [change] is therefore possible."[106] The brain, therefore, is largely plastic and can be adapted in numerous unknown ways. Similarly, he cites Nietzsche's philological findings about changes in perception from classical to Hellenistic Greece.[107] He also criticizes E.O. Wilson's claim that genes limit "human ingenuity" which he claims can only be discovered by acting as if there are no limits to the kinds of lives humans can live.[108] While Feyerabend's remarks on this subject are vague and merely suggestive, they have received uptake and confirmation in more recent research.[109] Political philosophy See also: Science in a Free Society Expertise in a free society Starting from the argument that a historical universal scientific method does not exist, Feyerabend argues that science does not deserve its privileged status in western society.[110] Since scientific points of view do not arise from using a universal method which guarantees high quality conclusions, he thought that science has no intrinsic claim to intellectual authority over other intellectual traditions like religion or myths.[111] Based on these arguments, Feyerabend defended the idea that science should be separated from the state in the same way that religion and state are separated in a modern secular society[112] He envisioned a free society in which "all traditions have equal rights and equal access to the centres of power."[111] For example, parents should be able to determine the ideological context of their children's education, instead of having limited options because of scientific standards. According to Feyerabend, science should also be subjected to democratic control: not only should the subjects that are investigated by scientists be determined by popular election, scientific assumptions and conclusions should also be supervised by committees of lay people.[113] He thought that citizens should use their own principles when making decisions about these matters. He rejected the view that science is especially "rational" on the grounds that there is no single common "rational" ingredient that unites all the sciences but excludes other modes of thought.[114] Feyerabend thought that scientific expertise was partially exaggerated by needless uses of jargon and technical language[115] and that many contributions towards science were made by laypeople.[116] Rather than distinguish between "experts" and "laypeople" and privileged the former, Feyerabend distinguishes between "cranks" and "respectable researchers" which is defined by the virtues of inquirers rather than their credentials. In Feyerabend's words, "The distinction between the crank and the respectable thinker lies in the research that is done once a certain point of view is adopted. The crank usually is content with defending the point of view in its original, undeveloped, metaphysical form, and he is not prepared to test its usefulness in all those cases which seem to favor the opponent, or even admit that there exists a problem. It is this further investigation, the details of it, the knowledge of the difficulties, of the general state of knowledge, the recognition of objections, which distinguishes the 'respectable thinker' from the crank. The original content of his theory does not"[117] According to this view, we cannot identify who counts as a crank based on the content of their beliefs. Someone who believes in flat earth theory, climate change denial, or astrology – for example – are not necessarily cranks, depending on how they defend those beliefs from criticism.[118] Democracy and science funding Feyerabend thought that science funding agencies should be subject to democratic oversight.[119] On this view, the allocation of funds for research should not be decided by practicing scientists exclusively, as is often the case with peer review. Rather, there should be supervision from taxpayers who determine research priorities. Because of this, Feyerabend defended to Baumann amendment which proposed that there should be Congressional veto power over the National Science Foundation's budget proposals.[120] According to Feyerabend, this follows both from the fact that outsider criticism is necessary for science to flourish and from a right to knowledge which he believed was central to a free society. Ancient philosophy Aristotle Feyerabend greatly admired Aristotle's philosophy, largely due to its productivity.[121] According to Feyerabend, Aristotle was an early epitome of naturalistic philosophy whose scientific research was part and parcel with his epistemology.[122] He also claims that Aristotle was one of the most empiricist scientists in history[123] and that his work in physics and mathematics continues to pay dividends after the scientific revolution.[124] Xenophanes and the rise of rationalism See also: Farewell to Reason In Farewell to Reason, Feyerabend criticizes Popper's claim that Xenophanes, who Feyerabend calls a "conceited bigmouth" with "considerable charm",[125] was the first to engage in rational criticism in his arguments against anthropomorphic gods. According to Feyerabend, Xenophanes's theological writings can only constitute a criticism if the premises would be accepted by his opponents. Otherwise, Xenophanes is merely rejecting the Homeric gods. In the Iliad, and elsewhere, Feyerabend interprets Homer as accepting the view that universe is subdivided into parts with different laws and qualitative features and do not aggregate into a unified whole. This informs Homer's theology since there can be no coherent knowledge of the whole of the universe, only detailed understandings of isolated parts of the universe.[126] Feyerabend further argues that some thinkers who came after Xenophanes, such as Aeschylus and Sophocles, also rejected Xenophanes premise that the gods cannot be anthropomorphic.[127] Additionally, Xenophanes represents the beginning of a tyrannical ideology which enforces 'truth' and 'morality' upon all as if there was a single universe that could be captured in a single worldview.[128] Feyerabend also criticizes Xenophanes's pretensions to have developed a conception of God that has no human features, arguing that Xenophanes's God still engages in human activities (such as thinking or hearing).[129] Moreover, he argues that Xenophanes God more resembles a monster as it becomes detached from human affairs and is therefore more morally problematic than the Homeric gods.[129] |

思想 科学の哲学 クラフト・サークル、隠れた変数、ノーゴー証明 ファイヤアーベンドの博士課程時代、彼は自らを「熱狂的な実証主義者」[65]であったと述べている。彼は「クラフト・サークル」の代表幹事であり、物理 学の基礎や基本的な記述の性質に関する多くの問題について議論していた。1948年、ファイアーベントはシュレーディンガーの論文 "On the Peculiarity of the Scientific Worldview "に対して短い論文を書いた。ここでファイヤアーベンドは、シュレーディンガーが要求する科学理論がアンショリッヒ(直感的に視覚化できる)であること は、あまりにも限定的であると主張した。彼の未発表論文である「哲学者と物理学者」は、哲学は物理学なしでは「石化」し、物理学は哲学なしでは「独断的に なりやすい」という哲学の自然主義的理解を主張している[67]。 ファイアーベントの初期のキャリアは、量子力学の哲学における技術的な問題に焦点を当てたものであった。ファイアーベントは、フォン・ノイマンの 「ノー・ゴー」証明は、コペンハーゲン解釈が量子力学の基本定理と矛盾しないことを示すだけで、そこから論理的に導かれるものではないと主張している。 1957年にデイヴィッド・ボームと出会った後、ファイアーベントはボームの解釈を積極的に擁護するようになり、コペンハーゲン解釈の検証可能性を高め るために、量子力学に対する隠れ変数のアプローチを追求すべきだと主張した[9]。 ファイアーベントはまた、1957年に測定問題に対する彼自身の解決策を提供したが、彼はすぐにこの解決策を放棄するようになった。彼は、フォン・ノイ マンの測定スキームが崩壊仮定なしに整合性を持たせることができることを示そうとした。彼の解決策は後のデコヒーレンス理論の発展を先取りしている [69]。 経験主義、多元主義、非整合性 1950年代後半から1960年代後半までのファイアーベントの研究の多くは、科学における方法論の問題に費やされていた。具体的には、ファイ アーベントは経験主義に対するいくつかの批判を提示し、彼独自の理論的多元主義を提唱している。そのひとつが、観察用語と理論用語の区別に関する批判であ る。も し観察的用語が、その受け入れが即時的な知覚によって決定されうるものとして理解されるならば、何が「観察的」あるいは「理論的」としてカウントされるか は、我々の慣れのパターンが変化し、実体を直接知覚する能力が進化するにつれて、歴史を通じて変化する[70]。ファイアーベントは、観察という行為は その真実性を正当化するための理論を必要とするため、すべての記述は仮説的であると主張している[71]。 経験主義に取って代わるために、ファイアーベントは科学の進歩のための方法論的ルールとして理論的多元主義を提唱している。この見解によれば、新しい理 論を増殖させることは、観察によって確立されたかもしれない以前の理論の検証可能性を高めることになる。ファイアーベントが繰り返し用いる例のひとつ が、古典熱力学の第二法則のテストではなかったブラウン運動である[73]。 テストとなるためには、まず代替理論、すなわちアインシュタインの気体の運動論によって説明されなければならない。新しい理論を増殖させることで、われわ れの理論の間接的な検証の数を増やすことができる。このことが、ファイアーベントの科学的方法の概念において、理論的多元主義を中心的なものにしてい る。 最終的に、ファイアーベントの多元主義には、彼が「粘り強さの原理」[74]と呼ぶものが組み込まれている。粘り強さの原理によって、科学者は、それが 持つかもしれない問題にかかわらず、理論を追求することができる。問題の例としては、難解な証拠、理論的パラドックス、数学的複雑さ、近隣の理論との矛盾 などが挙げられる。ファイアーベントは、粘り強さがなければすべての理論は早々に放棄されていただろうと主張するクーンからこの考え方を学んだ [75]。この原則は「増殖の原則」を補完するものであり、可能な限り多くの理論を発明し、発明された理論がもっともらしいライバルとなるようにすること を戒めている[76]。 ファイアーベントは『経験論、還元論、経験論』(1962年)の中で、非整合性の理論を概説している。彼の理論は『科学革命の構造』におけるトーマス・ クーンによる非整合性の議論と同じ年に登場するが、両者は独立して発展したものである[77]。ファイアーベントによれば、科学の歴史における理論変化 のいくつかの事例は、限定的事例として前任者を保持する後継理論を伴わない。言い換えれば、科学の進歩は、常に前の理論の一般化である理論を生み出すこと を伴わない。さらに、2つの理論は同じ経験的内容を共有しておらず、したがって、同じ一連の観察記述によって比較することはできない。例えば、ビュリダン の推進力原理は古典力学に類似していない。最も近い類例は運動量であろうが、この2つの概念は質的に異なる(推進力が運動を引き起こすのに対し、運動量は 運動の結果である)。さらにファイアーベントは、古典力学の中で説明可能な推進力の「並列概念」は存在し得ないと主張している。ゼロでない値を与える平 行概念は、慣性運動が抵抗する媒質の中で起こると仮定しなければならない。これは、慣性運動が何もない空間で起こるという古典力学の仮定と矛盾する。した がって、「インペトゥス理論で確立された用法によって固定されたインペトゥスの概念は、ニュートンの理論の中で合理的な方法で定義することはできない。 「しかし、非整合性は、科学者が理論を現実的に解釈することを選択した場合にのみ生じる。ファイアーベントの見解によれば、道具的に解釈された理論は両 立しえない。 ファイアーベントの多元主義は、彼が学位論文で展開した「意味の語用論」と呼ばれるものによって支えられている。意味の語用論によれば、言語は2つの部 分から構成されている。第一に、特定の実験的状況下で生成される一連のノイズである言語の特徴である。ファイアーベントの見解では、人間の観察は特別な 認識論的地位を持たない。言語の特徴は、観察者を現象の前に置き、現象が感知されたときに特定のノイズを発するように指示することから生まれる。これらの 雑音は、ステートメント(あるいは意味を持つ言語の一部)となるためには、解釈されなければならない。解釈は理論に由来するものであり、その意味は学習さ れたものであるが、必ずしもオステンションによって与えられるものではない[83]。ひとたび解釈された特徴が得られれば、理論を検証するために使用でき るステートメントが得られる。 ポパーからの出発 少なくとも1960年代半ばから後半にかけて、ファイアーベントはポパーから専門的にも知的にも距離を置くようになった。ジョセフ・アガシは、ポパーか らの離脱はバークレー校での学生革命が原因であり、それが1970年代に定義された認識論的アナーキズムへのファイヤアーベンドの動きを促進したと主張し ている[5]。 [84]ファイアーベントの友人であるロイ・エッジリーは、ファイアーベントがポパーから距離を置くようになったのは、ブリストル、そしてバークレー に行き、トーマス・クーンやデイヴィッド・ボームのマルクス主義の影響を受けるようになった1950年代半ばのことだと主張している[85]。 ポパーによれば、ボーアとその支持者たちは実証主義を受け入れた結果として相補性を受け入れた。ポパーは、ファイアーベントが非常に批判的であった反証 理論の創始者である。ポパーは、哲学的教義として実証主義を否定すれば、相補性の原理を損なうことになると主張している。これに対してファイヤアーベンド は、ボーアは量子力学の現実的な解釈(ボーア・クラマー・スレーター予想)を追求しようとしたが、ボーテ・ガイガー実験やコンプトン・サイモン実験との衝 突のためにそれを放棄した多元論者であったと主張している[88]。ファイヤアーベンドは、ボーアの追随者(特にレオン・ローゼンフェルド)の多くが相補 性の原理を哲学的教義として受け入れていることを認めながらも、ボーアが相補性を受け入れたのは、それが微物理学の経験的に適切な物理理論と絡み合ってい たからだと主張している。 アナーキスト段階 こちらも参照: 方法論に反対して 1970年代、ファイアーベントは「何でもあり」というスローガンで捉えた無政府主義的な知識理論の概要を述べている。この「何でもあり」というフレー ズは、ファイアーベントの論文「自由社会における専門家」に初めて登場し、『方法論に抗して』の第1章の最後で宣言されたことでより有名である。認識論 的アナーキズムは科学的方法に対する肯定的な見解ではなく、「合理主義」(科学的推論には普遍的で不変の合理的ルールが存在するという見解)の不条理帰納 法の結論であると主張する者もいる。ファイアーベントの言葉を借りれば、「『何でもあり』は私が抱いている『原理』ではなく、歴史をよく見ている合理主 義者のおどおどした感嘆詞である」[90]。この解釈によれば、ファイアーベントは、いかなる方法論的見解も固定的かつ普遍的なものとして保持すること はできず、したがって唯一の固定的かつ普遍的な規則は「何でもあり」であり、それは無意味であることを示すことを目的としている。 別の解釈では、ファイアーベントは、科学者は与えられた状況の中で理にかなった方法論的ルールを選択する不謹慎な日和見主義者であるべきだと主張してい る[76]。この見解では、「普遍的な」方法論的ルールは存在しないが、従うべき科学的推論の局所的ルールは存在する。日和見主義」という語句の使用はア インシュタイン[91]に由来するものであり、明確に定義された方法や信念をもって個々の事象を事前に判断するのではなく、目の前の状況に合わせて信念や 技法を変化させる探究者を示している。ファイアーベントは、「2人の個人(2人の科学者、2つの装置、2つの状況)は全く同じであることはなく、した がって手順も変化しうるはずである」[92]ので、これは正当化されると考えている。 第三の解釈では、認識論的アナーキズムは彼が1950年代から1960年代にかけて展開していた多元主義を一般化したものである[76]。認識論的アナー キズムは限界のない多元主義と同義であり、そこでは人は望む限りどのような理論でも増殖させることができ、望む限りどのような理論でも粘り強く発展させる ことができる。それに関連して、方法はその有用性を経験的理論に依存するため、新しい発見をするためにどんな方法を用いることもできる。しかし、科学的探 究には本質的な制約がない[93]。科学的実践に対する唯一の制約は、科学者に物質的に強制されるものである。さらに、ファイアーベントは、理論的ア ナーキズムは、科学者に厳格な規則を課さないことによって、他の組織システムよりも人道的であるため、望ましいと考えた。 今日のような科学、つまり伝統的な哲学のような「真理の探究」が、モンスターを生み出す可能性はないのだろうか?調査対象間の個人的なつながりを嫌う客観 的なアプローチが、人々を傷つけ、魅力もユーモアもない、惨めで不親切で独善的なメカニズムに変えてしまう可能性はないのだろうか?「キルケゴールは問 う。「自然を客観的(あるいは批評的理性的)に観察する私の活動が、人間としての力を弱めてしまうということはありえないだろうか?私は、これらの質問の 多くに対する答えは肯定的であり、(キルケゴールの意味において)科学をよりアナーキーで、より主観的なものにするような科学の改革が緊急に必要であると 考えている。方法論に抗して(第3版)』p.154.[94]。 この「実存的基準」によれば[95]、方法論的ルールは、それが示唆する生活の種類によって検証されうる。ファイアーベントの立場は、哲学が科学の一般 的な記述を提供することにも、科学の産物を神話のような非科学的な存在から区別するための方法を考案することにも成功できないことを示唆しているため、急 進的であると見なされた。 ファイアーベントは、方法論的ルールは一般的に科学の成功に寄与しないという彼の立場を支持するために、ファイアーベントが生きた時代に哲学者たちが 唱えた方法論的基準(すなわち帰納主義や反証主義)に従って(優れた)科学が運営されているという主張に対する反例を分析した。彼は、一般に進歩の紛れも ない例と見なされている科学のエピソード(コペルニクス的革命など)から出発し、これらのエピソードは科学の一般的な規定規則にすべて違反していると主張 した。さらに彼は、このような歴史的状況においてそのような規則を適用すれば、実際に科学革命を防ぐことができたと主張している[96]。彼の主な事例研 究は、地球は自転しているというガリレオの仮説である。 豊かさの形而上学 以下も参照: 豊かさの征服 ファイアーベントの後期の著作、特に『豊かさの征服』において、ファイアーベントは、私たちを取り巻く宇宙は、多くの現実を同時に受け入れることがで きるという意味で「豊か」であるという形而上学的理論を明確にしている。ファイアーベントによれば、世界、あるいは彼が言うところの「存在」は、私たち が世界と因果的に関わる方法に従って変化することができるほど柔軟である[97]。例えば、研究室では、科学者は単に現象を受動的に観察するのではなく、 様々な技術の助けを借りて現象を創造するために積極的に介入する。これによって「電子」や「遺伝子」のような実体が実在することになる。どのような人生を 生きるべきかについての私たちの選択は、私たちの倫理観と欲望に依存するので、何が「実在」であるかは、私たちが生きる価値があると考える人生において、 何が役割を果たすかに依存する。ファイアーベントはこれを「アリストテレスの原理」と呼んでおり、アリストテレスも同じ見解を持っていたと考えている [98]。 したがって、存在とは、世界におけるさまざまな生き方に適合する多くの現実を作るために操作され、変形されるのに十分柔軟である[99]。しかし、すべて の現実が可能であるわけではない。存在とは、ある特定の方法でそれとともに生きようとする私たちの試みに抵抗するものであり、したがって、どのような存在 であっても、単なる規定によって「実在」と宣言できるわけではない。ファイアーベントの言葉を借りよう、 「私は、どのような(生命の)形態であっても、明瞭で住みやすい世界につながるとは断言しない。人間が直面する物質は、正しい方法でアプローチされなけれ ばならない。それは抵抗を提供する。ある種の構築物(たとえば貨物カルトのような初期の文化)は、そこに攻撃のポイントを見出すことができず、単に崩壊し てしまう」[100]。 このことからファイアーベントは、スタンフォード学派の多くのメンバーによって主張された世界の不統一というテーゼを擁護することになる。ファイアーベン トは唯物論的な世界観は多くの不特定多数の点で欠陥があると考えていたが、このことはある現実が神々を含んでいる一方で他の現実が純粋に唯物論的であ ることを可能にしている[101]。 豊かさの征服」に関するファイアーベントの考えは、『理性との決別』で初めて表明され、1980年代後半から1990年代前半にかけての著作は、『豊か さの征服』の第2部として出版された論文やエッセイの多くを含め、この考えを表現するさまざまな方法を試している。この後期の著作の新たなテーマは「存在 の無能性」であり、ファイアーベントは、キリスト教の神秘家アレオパギテ人擬ディオニュシオスの著作を参照しながら、これを発展させていった。豊かさの 克服』における無能性についての考察は、あまりにも体系的でないため、明確に解釈することはできない。 心の哲学 排除的唯物論 20世紀半ばの哲学者たち(特に、ウィルフリッド・セラーズ、ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワイン、リチャード・ローティ)とともに、心の哲学におけ る急進的な立場である排除的唯物論の発展に影響を与えた。ある定義によれば、排除的唯物論は、存在するものはすべて物質的過程であり、したがって、心につ いての通常の常識的理解(「民俗心理学」)は誤りであるとする。現代の提唱者であるポール・チャーチランドは、これを次のように説明している: 「排除的唯物論とは、心理現象に関する我々の常識的な概念が根本的に誤った理論であり、その理論の原理と存在論の両方が、完成された神経科学によってス ムーズに縮小されるのではなく、最終的には置き換えられるような、根本的に欠陥のある理論であるというテーゼである」[102]。 これらの論文の最も一般的な解釈は、彼が排除的唯物論の初期の先駆者であったというものである[78][103]。これはパトリシアとポール・チャーチラ ンドに大きな影響を与えた。Keeleyが観察しているように、[104]「[ポール・チャーチランドは]キャリアの大半をファイアーベントのマントル を継承することに費やしてきた」。より最近の研究では、ファイアーベントは決して排除的唯物論者ではなく、単に排除的唯物論に対する一般的な批判が方法 論的に誤りであることを示すことを目的としていたと主張している。具体的には、ファイアーベントは知見や心についての直感的な理解からの議論から排除的 唯物論を擁護したが、排除的唯物論が真であるとは明確に主張しなかったという解釈である。そうすることで、ファイアーベントは二元論が真である可能性を 残しているが、これは哲学的な規定ではなく、科学的な議論によって示されなければならない。 認知的可塑性 ファイアーベントは、人間の脳には生得的な認知的限界は存在しないという仮説を短期間提示し、それに同調した。つまり、人間が考えたり理解したりするこ とに、本質的な限界はないということである。ファイアーベントの著作には、このことが当時の心脳科学における証拠によって確認されたことを示唆する文章 が散見される。具体的には、「これまで、脳の内蔵回路の2、3パーセントしか利用されてこなかった」と主張している。したがって、脳は大部分が可塑的であ り、未知の数多くの方法で適応させることができる」[106]。同様に、彼は古典ギリシャからヘレニズムギリシャへの知覚の変化に関するニーチェの言語学 的な発見を引用している[107]。彼はまた、遺伝子が「人間の独創性」を制限しているというE.O.ウィルソンの主張を批判しており、それは人間が生き られる人生の種類に制限がないかのように振る舞うことによってのみ発見できると主張している[108]。 政治哲学 こちらも参照: 自由社会における科学 自由社会における専門知識 歴史的に普遍的な科学的方法は存在しないという議論から出発して、ファイアーベントは科学が西洋社会における特権的地位に値しないと論じている [110]。科学的な視点は、質の高い結論を保証する普遍的な方法を用いることから生じるものではないため、彼は科学が宗教や神話のような他の知的伝統に 対する知的権威を本質的に主張するものではないと考えた[111]。 これらの議論に基づき、ファイアーベントは、近代世俗社会において宗教と国家が分離されているのと同じように、科学は国家から分離されるべきであるとい う考えを擁護していた[112]。彼は「すべての伝統が平等な権利と権力の中心への平等なアクセスを有する」自由な社会を構想していた[111]。ファイ アーベントによれば、科学はまた民主的な統制を受けるべきであり、科学者によって調査される対象が民衆の選挙によって決定されるべきであるだけでなく、 科学的な仮定や結論もまた一般人の委員会によって監督されるべきである。彼は科学が特に「合理的」であるという見解を否定しており、その理由はすべての科 学を統合するが他の思考様式を排除する単一の共通の「合理的」な要素は存在しないからである[114]。 専門家」と「一般人」を区別して前者を優遇するのではなく、ファイアーベントは「変人」と「立派な研究者」を区別しており、それは彼らの資格よりもむしろ探究者の美徳によって定義されている。ファイアーベントの言葉を借りれば 変人」と「立派な研究者」の区別は、ある視点が採用された後の研究にある。変人は通常、その観点を元の、未発達の、形而上学的な形で擁護することに満足 し、相手に有利と思われるすべてのケースでその有用性を検証する用意はないし、問題が存在することさえ認めない。立派な思想家」と変人を区別するのは、こ のようなさらなる調査、その詳細、困難についての知識、知識の一般的な状態、反論の認識である。彼の理論の本来の内容はそうではない」[117]。 この見解によれば、誰が変人であるかは、その信念の内容に基づいて特定することはできない。例えば、平らな地球理論、気候変動否定論、占星術を信じている人が、批判からどのようにそれらの信念を守るかによって、必ずしも変人であるとは限らない[118]。 民主主義と科学資金 ファイアーベントは、科学資金提供機関は民主的な監視を受けるべきだと考えていた[119]。この見解によれば、研究資金の配分は、しばしば査読がそう であるように、実践的な科学者によってのみ決定されるべきではない。むしろ、研究の優先順位を決定する納税者からの監視があるべきである。このため、ファ イアーベントはバウマン修正案を擁護した。バウマン修正案は、全米科学財団の予算案に対する議会の拒否権を認めるべきだと提案したものである [120]。ファイアーベントによれば、これは、科学が発展するためには部外者の批判が必要であるという事実と、彼が自由社会の中心であると信じた知識 への権利の両方から導かれるものである。 古代哲学 アリストテレス ファイアーベントによれば、アリストテレスは初期の自然主義哲学の典型であり、その科学的研究は彼の認識論と一体のものであった[122]。また彼は、 アリストテレスは歴史上最も経験主義的な科学者の一人であり[123]、物理学と数学における彼の研究は科学革命の後にも配当され続けていると主張してい る[124]。 クセノファネスと合理主義の台頭 以下も参照: 理性との決別 ファイアーベントは『理性との決別』の中で、「かなりの魅力」を持ちながら「うぬぼれの強い大言壮語」と呼ぶクセノファネスが、擬人化された神々に反対 する議論の中で初めて合理的批判を行ったというポパーの主張を批判している[125]。ファイアーベントによれば、クセノファネスの神学的著作が批判と なりうるのは、その前提が彼の反対者にも受け入れられる場合のみである。そうでなければ、クセノファネスはホメロスの神々を否定しているにすぎない。ファ イアーベントは、『イリアス』やその他の作品において、ホメロスは宇宙が異なる法則や質的特徴を持つ部分に細分化され、統一された全体には集約されない という見解を受け入れていると解釈している。このことはホメロスの神学に影響を及ぼしており、宇宙全体についての首尾一貫した知識は存在しえず、宇宙の孤 立した部分についての詳細な理解のみが存在しうるからである。 [127]さらに、クセノファネスは、あたかも単一の世界観で捉えることができる単一の宇宙が存在するかのように、「真理」と「道徳」を万人に強制する専 制的なイデオロギーの始まりを象徴している[128]。 またファイアーベントは、クセノファネスの神は依然として人間的な活動(思考や聴覚など)を行っていると主張し、人間的な特徴を持たない神の概念を開発 したというクセノファネスの自惚れを批判している[129]。さらに彼は、クセノファネスの神は人間的な問題から切り離されることでより怪物に似ており、 それゆえホメロスの神々よりも道徳的に問題があると主張している[129]。 |

| Influence In philosophy While the immediate academic reception of Feyerabend's most read text, Against Method, was largely negative,[130] Feyerabend is recognized today as one of the most influential philosophers of science of the 20th Century. Feyerabend's arguments against a universal method have become largely accepted, and are often taken for granted by many philosophers of science in the 21st century.[131] His arguments for pluralism moved the topic into the mainstream[132] and his use of historical case studies were influential in the development of the History and Philosophy of Science (HPS) as an independent discipline.[13] His arguments against reductionism were also influential on John Dupré, Cliff Hooker, and Alan Chalmers.[13] He was also one of the intellectual forefathers of social constructivism and science and technology studies, although he participated little in either field during his lifetime.[13] Outside philosophy Feyerabend's analysis of the Galileo affair, where he claims the Church was "on the right track" for censuring Galileo on moral grounds and were empirically correct,[133] was quoted with approval by Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI) in a speech in 1990.[134][135][136][137] In its autobiography, Feyerabend recalls a conversation with Stephen Jay Gould, in 1991,[138] when Gould stated that Against Method's arguments for pluralism motivated him to pursue research on punctuated equilibrium. Feyerabend's work was also influential on several physicists who felt empowered to experiment with approaches different from those of their supervisors as well on many social scientists who were under great pressure to conform to the 'standards' of the natural sciences.[139] Feyerabend's lectures were extremely popular and well-attended. They were often received positively as entertaining, provocative, and funny.[139] The book On the Warrior's Path quotes Feyerabend, highlighting the similarities between his epistemology and Bruce Lee's worldview.[140] Feyerabend's concept of incommensurability was influential in the radical critical approach of Donald Ault in his extensive critical assessment of William Blake's work, especially in Narrative Unbound: Re-Visioning William Blake's The Four Zoas.[141] In 2024, on the centennial of Feyerabend's birth, there is a planned series of conferences, workshops, publications, experimental art, song recitals, and theatre pieces in honor of Feyerabend's life and works.[142] |

影響力 哲学において ファイアーベントの最も読まれたテクストである『方法論に抗して』の直接的な学問的評価は概ね否定的であったが[130]、ファイアーベントは今日、 20世紀において最も影響力のある科学哲学者の一人として認識されている。普遍的な方法に対するファイヤアーベンドの主張は、21世紀において多くの科学 哲学者に受け入れられ、しばしば当然のこととして受け止められている[131]。彼の多元主義に対する主張は、このテーマを主流に押し上げ[132]、彼 の歴史的事例研究の使用は、独立した学問分野としての科学史・科学哲学(HPS)の発展に影響を与えた。 [13]還元主義に反対する彼の主張はジョン・デュプレ、クリフ・フッカー、アラン・チャルマーズにも影響を与えた[13]。彼はまた社会構成主義や科学 技術研究の知的祖先の一人でもあったが、生前はどちらの分野にもほとんど参加していなかった[13]。 哲学以外 ガリレオ事件についてのファイアーベントの分析は、教会が道徳的な理由でガリレオを非難したことについては「正しい道を歩んでおり」、経験的に正しかっ たと主張しており[133]、ヨゼフ・ラッツィンガー枢機卿(ローマ教皇ベネディクト16世)が1990年の演説で承認して引用している。 [134][135][136][137]ファイアーベントはその自伝の中で、1991年のスティーヴン・ジェイ・グールドとの会話を回想しており [138]、その際グールドは、多元主義に対するアゲインスト・メソッドの主張が、彼が断続平衡の研究を追求する動機になったと述べている。ファイアーベ ントの著作は、自然科学の「基準」に適合するように強い圧力を受けていた多くの社会科学者だけでなく、指導教官とは異なるアプローチを実験する権限を与 えられていると感じていた何人かの物理学者にも影響を与えた[139]。 ファイアーベントの講義は非常に人気があり、多くの聴衆が集まった。On the Warrior's Path』という本では、ファイアーベントのエピステモロジーとブルース・リーの世界観との類似性が強調されている[140]。ファイアーベントの非 可換性の概念は、ドナルド・オルトによるウィリアム・ブレイクの作品の広範な批評的評価、特に『Narrative Unbound』におけるラディカルな批評的アプローチに影響を与えた: 141]。 2024年、ファイアーベントの生誕100周年に、ファイアーベントの人生と作品に敬意を表して、一連の会議、ワークショップ、出版物、実験芸術、歌のリサイタル、演劇作品が計画されている[142]。 |

| Selected bibliography Feyerabend's Full Bibliography: The Works of P. K. Feyerabend Books Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge, (1975). London: Verso Books.ISBN 1-84467-442-8. The first, 1970 edition, is available for download in pdf form from the Minnesota Center for Philosophy of Science. Follow this link path: Minnesota Studies in the Philosophy of Science > 4. Analyses of Theories & Methods of Physics and Psychology. 1970. Editors: M. Radner and S. Winokur > Open Access > Under the "Whoops!" message click 'Download' The third edition, released in 1993, is the most widely available copy. Science in a Free Society, (1978). London: Verso Books. ISBN 0-8052-7043-4 Science as Art, (1984). Bari: Laterza. ISBN 2-226-13562-6 Farewell to Reason, (1987). London: Verso Books. ISBN 0-86091-184-5, 0860918963 Three Dialogues on Knowledge, (1991). Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell Press.ISBN 0-631-17917-8, 0631179186 Killing Time: The Autobiography of Paul Feyerabend, (1995). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-24531-4, 0226245322 Conquest of Abundance: A Tale of Abstraction versus the Richness of Being, (1999). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-24533-0, 0226245349 Philosophy of Nature, Posthumously published, (2016). Cambridge: Polity Press. ISBN 978-0-7456-5159-0 * Naturphilosophie, Posthumously published, (2009). Berlin: Suhrkamp Verlag. Helmut Heit and Eric Oberheim (Eds.). ISBN 3-518-58514-2. Collected volumes Realism, Rationalism and Scientific Method: Philosophical papers, Volume 1 (1981). P.K. Feyerabend (ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22897-2, 0521316421 Problems of Empiricism: Philosophical Papers, Volume 2 (1981). P.K. Feyerabend (ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23964-8, 0521316413 Knowledge, Science and Relativism: Philosophical Papers, Volume 3 (1999). J. Preston (ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64129-2 Physics and Philosophy: Philosophical Papers, Volume 4 (2015). S. Gattei and J. Agassi (eds.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-88130-7 Correspondences and lectures For and Against Method: Including Lakatos's Lectures on Scientific Method and the Lakatos-Feyerabend Correspondence with Imre Lakatos, (1999). M. Motterlini (ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-46774-0, 0226467759 The Tyranny of Science, (2011). Cambridge: Polity Press. ISBN 0-7456-5189-5, 0745651909. Feyerabend's Formative Years. Volume 1. Feyerabend and Popper: Correspondence and Unpublished Papers, (2020). New York: Springer Press. ISBN 978-3-030-00960-1, 978-3030009601 Articles "Linguistic Arguments and Scientific Method". Telos 03 (Spring 1969). New York: Telos Press, Realism, Rationalism and Scientific Method: Philosophical papers, Volume 1 (1981), ISBN 0-521-22897-2, 0521316421 "How To Defend Society Against Science". Radical Philosophy, no. 11, Summer 03 1975. The Galilean Library, Introductory Readings in the Philosophy of Science edited by E. D. Klemke (1998), ISBN 1-57392-240-4 |

選書目録 ファイヤーアバントの全書誌:P・K・ファイヤーアバント著作集 書籍 『方法への反論:無政府主義的認識論の概説』(1975年)。ロンドン:ヴェルソ・ブックス。ISBN 1-84467-442-8。 初版(1970年)はミネソタ科学哲学センターからPDF形式でダウンロード可能だ。以下のリンク経路をたどれ:ミネソタ科学哲学研究叢書 > 4. 物理学と心理学の理論・方法論の分析(1970年)。編集者:M. ラドナー、S. ウィノカー > オープンアクセス > 「おっと!」というメッセージの下にある『ダウンロード』をクリックせよ 1993年に刊行された第三版が最も入手しやすい。 『自由社会における科学』(1978年)。ロンドン:ヴェルソ・ブックス。ISBN 0-8052-7043-4 『芸術としての科学』(1984年)。バーリ:ラテルツァ。ISBN 2-226-13562-6 『理性への別れ』(1987年)。ロンドン:ヴェルソ・ブックス。ISBN 0-86091-184-5, 0860918963 『知識に関する三つの対話』(1991年)。ホーボーケン:ワイリー・ブラックウェル・プレス。ISBN 0-631-17917-8, 0631179186 『時間殺し:ポール・フェイヤーアバント自伝』(1995年)。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局。ISBN 0-226-24531-4, 0226245322 『豊かさへの征服:抽象化と存在の豊かさとの物語』(1999年)。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局。ISBN 0-226-24533-0, 0226245349 自然哲学、死後出版、(2016)。ケンブリッジ:ポリティ・プレス。ISBN 978-0-7456-5159-0 * 自然哲学、死後出版、(2009)。ベルリン:スールカンプ出版社。ヘルムート・ハイトとエリック・オーバーハイム(編)。ISBN 3-518-58514-2。 論文集 『現実主義、合理主義、科学的方法:哲学論文集 第1巻』(1981年)。P.K.フェイヤーアバント(編)。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 0-521-22897-2, 0521316421 経験主義の問題:哲学論文集 第2巻(1981年)。P.K.フェイヤーアバント(編)。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 0-521-23964-8, 0521316413 知識、科学、相対主義:哲学論文集、第3巻(1999年)。J.プレストン編。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 0-521-64129-2 物理学と哲学:哲学論文集、第4巻(2015年)。S.ガッテイとJ.アガッシ編。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 0-521-88130-7 書簡と講義 方法論の賛否:ラカトシュの科学方法論講義及びイムレ・ラカトシュとフェヤーバーントの書簡集(1999年)。M. モッテルリーニ編。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局。ISBN 0-226-46774-0, 0226467759 『科学の専制』(2011年)。ケンブリッジ:ポリティ・プレス。ISBN 0-7456-5189-5, 0745651909。 フェイヤーアバントの形成期。第1巻。フェイヤーアバントとポッパー:書簡集と未発表論文(2020年)。ニューヨーク:シュプリンガー・プレス。ISBN 978-3-030-00960-1, 978-3030009601 論文 「言語論的議論と科学的方法」『テロス』第3号(1969年春号)。ニューヨーク:テロス出版社、『現実主義、合理主義と科学的方法:哲学論文集』第1巻(1981年)、ISBN 0-521-22897-2, 0521316421 「科学から社会を守る方法」。『ラディカル・フィロソフィー』第11号、1975年夏。ガリレイ図書館、E. D. クレムケ編『科学哲学入門読本』(1998年)、ISBN 1-57392-240-4 |