ポーリン・ボーティ

Pauline Boty (6 March 1938 - 1

July 1966)

☆

げんちゃんはこちら(genchan_tetsu.html)

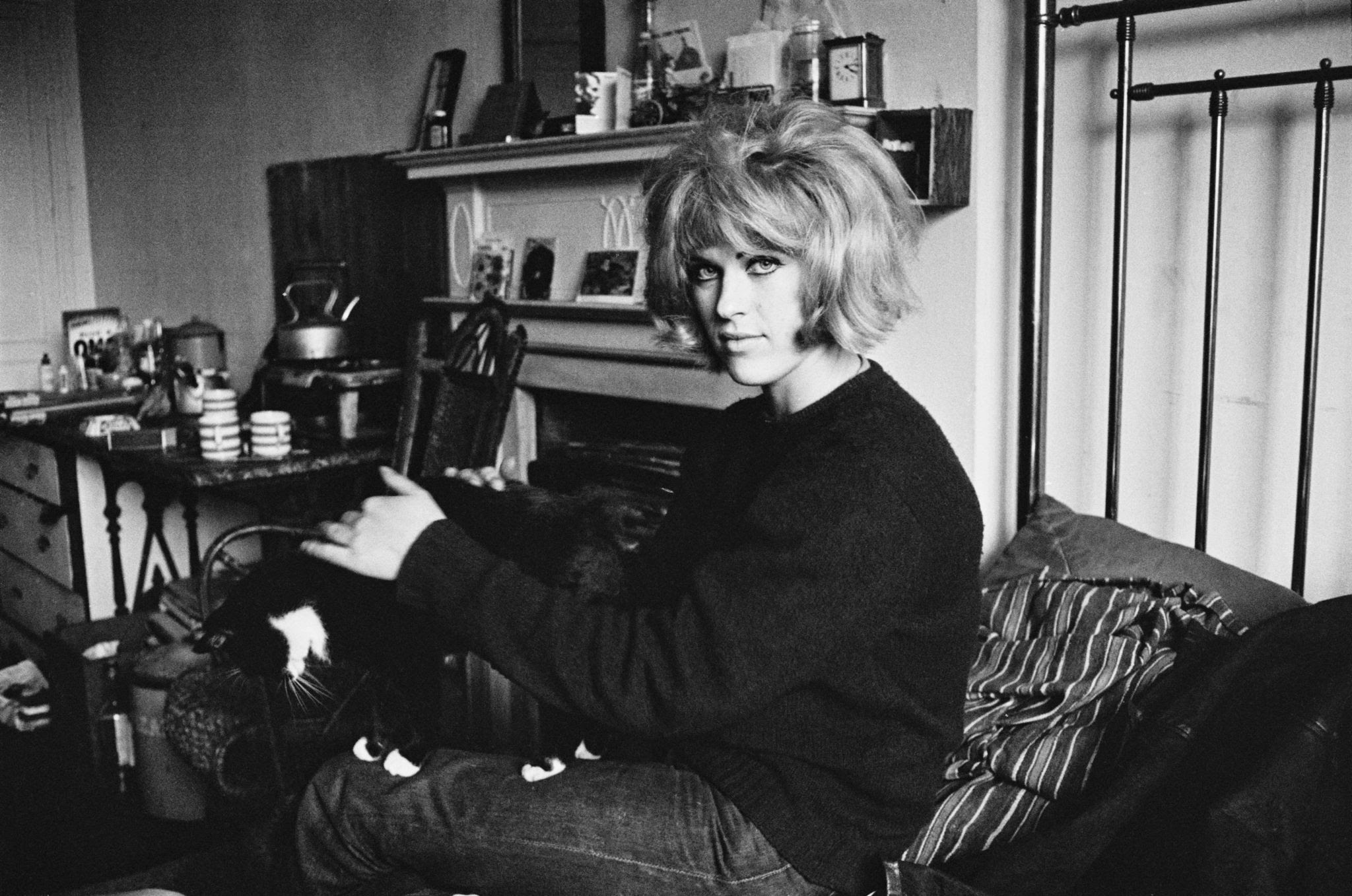

| Pauline Boty (6

March 1938 – 1 July 1966) was a British painter and co-founder of the

1960s' British Pop art movement of which she was the only acknowledged

female member. Boty's paintings and collages often demonstrate a joy in

self-assured femininity and female sexuality, as well as criticism

(both overt and implicit) of the "man's world" in which she lived. Her

rebellious art, combined with her free-spirited lifestyle, has made

Boty a herald of 1970s' feminism. |

ポーリーン・ボティ(1938年3月6日 -

1966年7月1日)はイギリスの画家で、1960年代のブリティッシュ・ポップ・アートの共同創設者。ボティの絵画やコラージュは、自己主張の強い女性

らしさや女性のセクシュアリティへの喜びを示すと同時に、彼女が生きる「男の世界」への批判(あからさまにも暗黙的にも)を示すことが多い。彼女の反抗的

な芸術と自由奔放なライフスタイルが相まって、ボティは1970年代のフェミニズムの先駆者となった。 |

| Life and works Early life and education Pauline Veronica Boty was born in Carshalton, Surrey, in 1938 into a middle-class Catholic family. The youngest of four children, she had three older brothers and a stern father who made her keenly aware of her position as a girl.[1] In 1954 she won a scholarship to the Wimbledon School of Art,[2] which she attended despite her father's disapproval. Boty's mother, on the other hand, was supportive, having herself been a frustrated artist and denied parental permission to attend the Slade School of Fine Art.[3] Boty earned an Intermediate diploma in lithography (1956) and a National Diploma in Design in stained glass (1958). Her schoolmates called her "The Wimbledon Bardot" on account of her resemblance to the French film star Brigitte Bardot.[3] Encouraged by her tutor Charles Carey to explore collage techniques, Boty's painting became more experimental. Her work showed an interest in popular culture early on.[4] In 1957 one of her pieces was shown at the Young Contemporaries exhibition alongside work by Robyn Denny, Richard Smith and Bridget Riley. She studied at the School of Stained Glass at the Royal College of Art (1958–61). She had wanted to attend the School of Painting, but was dissuaded from applying as admission rates for women were much lower in that department.[5] Despite the institutionalised sexism at her college, Boty was one of the stronger students in her class, and in 1960 one of her stained-glass works was included in the travelling exhibition Modern Stained Glass organised by the Arts Council. Boty continued to paint on her own in her student flat in west London and in 1959 she had three more works selected for the Young Contemporaries exhibition. During this time she also became friends with other emerging Pop artists, such as David Hockney, Derek Boshier, Peter Phillips and Peter Blake.  Self-portrait in stained glass, circa 1958 While at the Royal College of Art, Boty engaged in a number of extracurricular activities. She sang, danced, and acted in risqué college reviews, published her poetry in an alternative student magazine, and was a knowledgeable presence in the film society where she developed her interest, especially in European new wave cinema.[5] She was also an active participant in Anti-Ugly Action, a group of RCA students involved in the stained glass, and later architecture, courses who protested against new British architecture that they considered offensive and of poor quality.[6][7] Career Boty was at her most productive two years after graduating from college. She developed a signature Pop style and iconography. Her first group show, "Blake, Boty, Porter, Reeve" was held in November 1961 at A.I.A. Gallery in London and was hailed as one of the first British Pop art shows. She exhibited twenty collages, including Is it a bird, is it a plane? and a rose is a rose is a rose, which demonstrated her interest in drawing from both high and low popular culture sources in her art (the first title references the Superman comic, the second quotes the American expatriate poet Gertrude Stein).[8] The following spring Boty, Peter Blake, Derek Boshier and Peter Phillips were featured in Ken Russell's BBC Monitor documentary film Pop Goes the Easel, which was aired on 22 March 1962.[9] Boty's appearance in Pop Goes the Easel marked the beginning of her brief acting career. She landed roles in an Armchair Theatre play for ITV ("North City Traffic Straight Ahead", 1962) and an episode of the BBC series Maigret ("Peter the Lett", 1963). She also appeared on stage in Frank Hilton's comedy Day of the Prince[10] at the Royal Court, and in Riccardo Aragno's (from the novel by Anthony Powell) Afternoon Men[11] at the New Arts Theatre. (Boty, a regular on the club scene in London, was also a dancer on Ready Steady Go!). Although acting was lucrative, it was a distraction from painting, which remained her main priority. Yet the men in her life encouraged her to pursue acting, as it was a more conventional career choice for women in the early 1960s.[12] The popular press picked up on her glamorous actress persona, often undermining her legitimacy as an artist by referring to her physical appearance. Scene ran a front-page article in November 1962 that included the following remarks: "Actresses often have tiny brains. Painters often have large beards. Imagine a brainy actress who is also a painter and also a blonde, and you have Pauline Boty."[13] Her unique position as Britain's only female Pop artist gave Boty the chance to redress sexism in her life as well as her art. Her early paintings were sensual and erotic, celebrating female sexuality from a woman's point of view. Her canvases were set against vivid, colourful backgrounds and often included close-ups of red flowers, presumably symbolic of the female sex.[14][15] She painted her male idols—Elvis, French actor Jean-Paul Belmondo, British writer Derek Marlowe—as sex symbols, just as she did actresses Monica Vitti and Marilyn Monroe. Like Andy Warhol, she recycled publicity and press photographs of celebrities in her art. Her 1963 portrait of her friend Celia Birtwell, Celia and Her Heroes, shows the textile designer surrounded by a Peter Blake painting, a David Hockney portrait and an image of Elvis Presley.[16] She exhibited in several more group shows before staging her first solo exhibition at Grabowski Gallery in the autumn of 1963. The show was a critical success. Boty continued to take on additional acting jobs. She was a presenter on the radio programme Public Ear in 1963–64, and in the following year, she was typecast yet again in the role of 'the seductive Maria' in a BBC serial. In June 1963 she married the literary agent Clive Goodwin (1932–1978) after a ten-day romance.[17] Her marriage disappointed others such as Peter Blake and her married lover, the television director Philip Saville, whom she had met towards the end of her student days and had worked for.[18] (Their affair is said to have provided the material for a screenplay by Frederic Raphael for the movie Darling (1965).)[19] Boty and Goodwin's Cromwell Road flat became a central hang-out for many artists, musicians, and writers, including Bob Dylan (whom Boty brought to England[20]), David Hockney, Peter Blake, Michael White, Kenneth Tynan, Troy Kennedy Martin, John McGrath, Dennis Potter and Roger McGough.[21] Goodwin, to be later a member of the founding editorial team of the radical journal Black Dwarf, is said to have encouraged Boty to include political content in her paintings.[17] Her paintings did become more overtly critical over time. Countdown to Violence depicts a number of harrowing current events, including the Birmingham riot of 1963, the Assassination of John F. Kennedy and the Vietnam War. Cuba Si (1963) references the Cuban revolution. The collage painting It's a Man's World I (1964) juxtaposes images of patriarchal icons The Beatles, Albert Einstein, Lenin, Muhammad Ali, Marcel Proust and other men. In It's a Man's World II (1965–66) she redisplayed female nudes from fine art and soft-core pornographic sources to signify newly liberated "female eroticism".[22] Her last known painting, BUM,[23] was commissioned by Kenneth Tynan for Oh, Calcutta! and was completed in 1966.[24] Death In June 1965 Boty became pregnant. During a prenatal exam, a tumour was discovered and she was diagnosed with cancer[25] (malignant Thymoma). She refused to have an abortion and also refused to receive chemotherapy treatment that might have harmed the foetus.[26] Instead she smoked marijuana to ease the pain of her terminal condition. She continued to entertain her friends and even sketched The Rolling Stones during her illness.[18] Her daughter, Katy (later Boty)[27] Goodwin, was born on 12 February 1966. Pauline Boty died at the Royal Marsden Hospital on 1 July that year.[28] She was 28 years old. Her daughter, Boty Goodwin, died of an overdose on 12 November 1995 aged 29.[29] |

生涯と作品 生い立ちと教育 ポーリン・ヴェロニカ・ボティは1938年、サリー州カーショルトンでカトリック系の中流家庭に生まれた。4人きょうだいの末っ子である彼女には3人の兄 がおり、厳格な父親は彼女に少女としての立場を強く意識させた[1]。一方、ボティの母親は、自分自身がアーティストとして挫折し、スレード美術学校への 入学を親に拒否された経験から、協力的であった[3] 。家庭教師のチャールズ・キャリーからコラージュ技法の探求を勧められ、ボティの絵画はより実験的なものとなった。1957年、彼女の作品はヤング・コン テンポラリーズ展でロビン・デニー、リチャード・スミス、ブリジット・ライリーの作品とともに展示された[4]。 ロイヤル・カレッジ・オブ・アートのステンドグラス学校で学ぶ(1958-61年)。大学の制度化された性差別にもかかわらず、ボティはクラスでも優秀な 生徒の一人であり、1960年にはアーツ・カウンシルが企画した「モダン・ステンドグラス」展に彼女のステンドグラス作品が出品された。ボティはロンドン 西部の学生アパートで独学で絵を描き続け、1959年にはヤング・コンテンポラリーズ展に3点が入選した。この時期、デヴィッド・ホックニー、デレク・ボ シエ、ピーター・フィリップス、ピーター・ブレイクといった新進のポップ・アーティストたちとも親交を深めた。  ステンドグラスに描かれた自画像、1958年頃 ロイヤル・カレッジ・オブ・アート在学中、ボティはさまざまな課外活動を行った。彼女は歌い、踊り、きわどい大学評に出演し、オルタナティヴな学生雑誌に 詩を発表し、映画研究会では知識豊富な存在として、特にヨーロッパのニューウェーブ映画に興味を持った[5]。また、ステンドグラス、後に建築コースに所 属するRCAの学生で構成されたグループ、アンチ・アグリー・アクションにも積極的に参加し、不快で質の悪いと考えるイギリスの新しい建築に抗議した [6][7]。 キャリア ボティが最も充実していたのは、大学を卒業した2年後である。彼女は特徴的なポップ・スタイルと図像を開発した。彼女の最初のグループ展「Blake, Boty, Porter, Reeve」は1961年11月にロンドンのA.I.A.ギャラリーで開催され、イギリス初のポップ・アート展の一つとして賞賛された。彼女は、「Is it a bird, is it a plane? 」や「a rose is a rose is a rose」を含む20点のコラージュ作品を展示し、彼女の芸術において、ハイ・カルチャーとロー・カルチャーの両方からの引用に関心があることを示した (最初のタイトルはスーパーマンのコミックを参照し、2つ目のタイトルはアメリカの海外在住詩人ガートルード・スタインの言葉を引用している)[8]。 翌年の春、ボティ、ピーター・ブレイク、デレク・ボシエ、ピーター・フィリップスは、ケン・ラッセルのBBCモニターのドキュメンタリー映画『Pop Goes the Easel』に登場し、1962年3月22日に放映された[9]。 Pop Goes the Easel』への出演が、彼女の短い女優としてのキャリアの始まりとなった。ITVのアームチェア・シアターの舞台(『North City Traffic Straight Ahead』、1962年)やBBCのシリーズ『Maigret』のエピソード(『Peter the Lett』、1963年)に出演。また、ロイヤル・コートで上演されたフランク・ヒルトンのコメディ『王子の日』[10]や、ニュー・アーツ・シアターで 上演されたリッカルド・アラーニョの『午後の男たち』[11]にも出演した。(ロンドンのクラブシーンの常連だったボティは、『レディ・ステディ・ ゴー!』のダンサーでもあった)。女優業は儲かったが、彼女の最優先事項であり続けた絵画から目をそらすものだった。しかし、1960年代初頭には、女優 業は女性にとってより一般的な職業であったため、彼女を取り巻く男性たちは女優業を勧めた[12]。大衆紙は彼女のグラマラスな女優としてのペルソナを取 り上げ、しばしば彼女の外見に言及することで、アーティストとしての正当性を損ねた。シーン』は1962年11月に一面トップで次のような記事を掲載し た。画家は大きな髭を生やしていることが多い。画家でもあり、ブロンドでもある頭脳明晰な女優を想像してほしい。 英国唯一の女性ポップ・アーティストというユニークな立場は、芸術だけでなく、人生においても性差別を是正する機会をボティに与えた。彼女の初期の絵画は 官能的でエロティックであり、女性の視点から女性のセクシュアリティを賛美していた。彼女のキャンバスは鮮やかで色彩豊かな背景を持ち、しばしば女性の性 を象徴していると思われる赤い花のクローズアップが描かれていた[14][15]。エルヴィス、フランスの俳優ジャン=ポール・ベルモンド、イギリスの作 家デレク・マーロウといった男性アイドルを、女優のモニカ・ヴィッティやマリリン・モンローと同じようにセックス・シンボルとして描いた。アンディ・ ウォーホルのように、彼女は有名人の広報写真や報道写真を作品に再利用した。1963年に発表した友人セリア・バートウェルの肖像画『Celia and Her Heroes』には、ピーター・ブレイクの絵、デヴィッド・ホックニーの肖像画、エルヴィス・プレスリーの写真に囲まれたテキスタイル・デザイナーが描か れている[16]。この個展は大成功を収めた。ボティはさらに女優の仕事を引き受けた。1963年から64年にかけてはラジオ番組『パブリック・イヤー』 の司会者を務め、翌年にはBBCの連続ドラマで「魅惑的なマリア」役を演じ、またもやタイプキャストされた。 1963年6月、彼女は文芸エージェントのクライヴ・グッドウィン(1932-1978)と10日間のロマンスの末に結婚した[17]。彼女の結婚は、 ピーター・ブレイクや、彼女が学生時代の終わりに出会い、仕事をしたことのある既婚の恋人、テレビディレクターのフィリップ・サヴィルなどの他の人々を失 望させた[18](彼らの情事は、フレデリック・ラファエルが映画『ダーリン』(1965)のために書いた脚本の素材になったと言われている)[19]。 ボティとグッドウィンのクロムウェル・ロードのアパートは、ボブ・ディラン(ボティがイギリスに連れてきた[20])、デヴィッド・ホックニー、ピー ター・ブレイク、マイケル・ホワイト、ケネス・タイナン、トロイ・ケネディ・マーティン、ジョン・マクグラス、デニス・ポッター、ロジャー・マクゴーな ど、多くの芸術家、ミュージシャン、作家の中心的なたまり場となった[21]。グッドウィンは、後に急進的な雑誌『ブラック・ドワーフ』の創刊編集チーム の一員となり、ボティの絵画に政治的な内容を盛り込むよう勧めたと言われている[17]。 彼女の絵画は、時間の経過とともに、よりあからさまに批判的なものとなっていった。暴力へのカウントダウン』には、1963年のバーミンガム暴動、ジョ ン・F・ケネディ暗殺、ベトナム戦争など、悲惨な時事問題が数多く描かれている。Cuba Si』(1963年)はキューバ革命に言及している。コラージュ作品『It's a Man's World I』(1964年)は、ビートルズ、アルバート・アインシュタイン、レーニン、モハメド・アリ、マルセル・プルーストなど、家父長制の象徴である男たちの イメージを並置している。It's a Man's World II』(1965-66)では、新たに解放された「女性のエロティシズム」を意味するために、ファイン・アートとソフトコア・ポルノから女性のヌードを再 展示した[22]。彼女の最後の絵画として知られる『BUM』[23]は、『オー、カルカッタ!』のためにケネス・タイナンに依頼され、1966年に完成 した[24]。 死 1965年6月、ボティは妊娠。妊婦検診で腫瘍が発見され、癌[25](悪性胸腺腫)と診断された。彼女は中絶を拒否し、胎児に害を及ぼす可能性のある化 学療法を受けることも拒否した[26]が、その代わりに末期症状の痛みを和らげるためにマリファナを吸った。1966年2月12日、娘のケイティ(後のボ ティ)[27]・グッドウィンが誕生。ポーリーン・ボティは同年7月1日、ロイヤル・マースデン病院で死去。娘のボティ・グッドウィンは1995年11月 12日、過剰摂取により29歳で死去[29]。 |

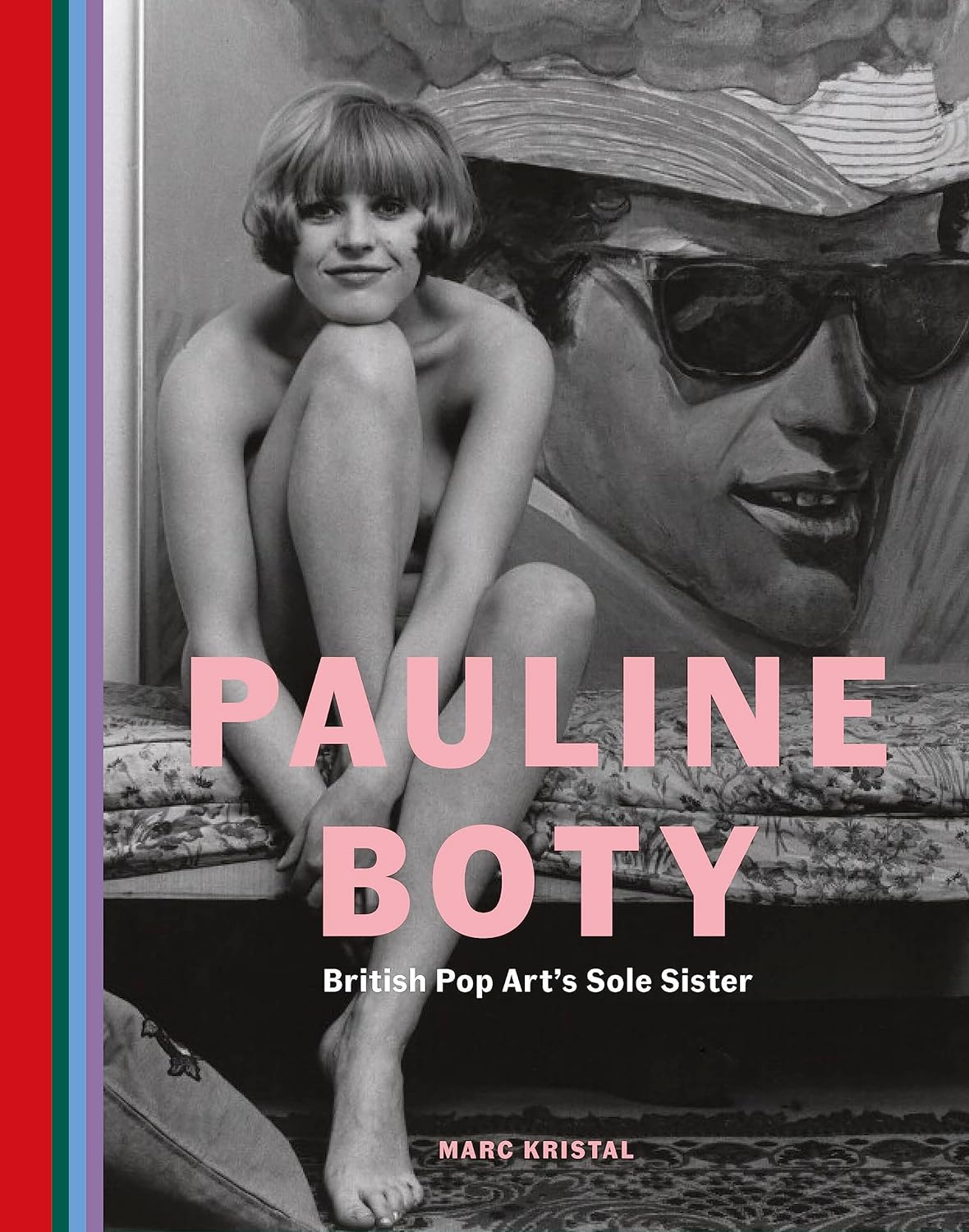

| Legacy After her death, Pauline Boty's paintings were stored away in a barn on her brother's farm and she was largely forgotten for nearly 30 years.[30] Her work was rediscovered in the 1990s, renewing interest in her contribution to Pop art, and gaining her inclusion in several group exhibitions and a major solo retrospective.[29] As of 2013 the location of some of her most sought after paintings is unknown.[25] In December 2013, Adrian Hamilton wrote in The Independent on Sunday, "Ignored for decades after her death – it was nearly 30 years before her first picture was shown – a proper retrospective has had to wait until this year with a show which originated in Wolverhampton and has now opened in the Pallant Gallery in Chichester. Looking at her pictures today, it is simply incredible that it has taken so long. [...] It's not a big exhibition. Given the paucity of her surviving work, it could not be otherwise. But it is one which leaves you eager for more, more of the pictures she did paint and the ones she didn't live long enough for."[31] Boty's life and work also form a major theme in Ali Smith's 2016 novel, Autumn.[32] In November 2019, the New York Times profiled Boty in their Overlooked No More series: "Pauline Boty, Rebellious Pop Artist".[33] |

遺産 彼女の死後、ポーリーン・ボティの絵画は兄の農場の納屋に保管され、30年近くほとんど忘れ去られていた[30]。1990年代に彼女の作品が再発見さ れ、ポップ・アートへの貢献に対する関心が再び高まり、いくつかのグループ展や大規模な個展に出品されるようになった[29]。2013年現在、最も人気 のある絵画のいくつかは所在が不明である[25]。 2013年12月、エイドリアン・ハミルトンはインデペンデント・オン・サンデー紙に「彼女の死後何十年もの間無視され、彼女の最初の絵が展示されるまで に30年近くかかったが、適切な回顧展は今年、ウォルバーハンプトンで始まり、現在チチェスターのパラント・ギャラリーで開かれている展覧会まで待たなけ ればならなかった。今日、彼女の写真を見ると、これほど時間がかかったことが信じられない。[大きな展覧会ではありません。現存する彼女の作品の少なさを 考えれば、そうでないことはないだろう。しかし、彼女が描いた絵や長生きできなかった絵をもっと見たいと思わせる展覧会だ」[31]。 ボティの人生と作品は、アリ・スミスの2016年の小説『秋』でも主要なテーマを形成している[32]。 2019年11月、ニューヨーク・タイムズはOverlooked No Moreシリーズでボティを紹介した: 「Pauline Boty, Rebellious Pop Artist」[33]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pauline_Boty |

|

|

|

Pauline Boty, The Only Blonde in the World, 1963. Pauline Boty, The Only Blonde in the World, 1963. |

|

| Permanent collections Smithsonian American Art Museum[37] Tate Museum, London[38][39] National Portrait Gallery, London[40] |

|

| https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/search/actor:boty-pauline-19381966 https://paulineboty.org/ https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person.php?LinkID=mp10131 |

|

Michael

Bracewell on Pauline Boty | TateShots

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099