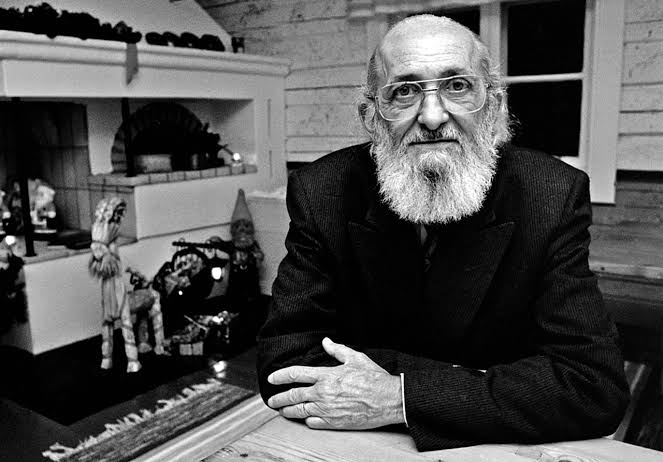

パウロ・フレイレ

Paulo Reglus Neves Freire, 1921-1997

☆ パウロ・レグルス・ネヴェス・フレイレ[ラ](1921年9月19日 - 1997年5月2日)はブラジルの教育者、哲学者であり、批判的教育学の主要な提唱者であった。彼の影響力のある著作『被抑圧者の教育学』は、一般的に批 判的教育学運動の基礎となったテキストの一つと考えられており、Google Scholarによれば2016年時点で社会科学分野で3番目に引用された書籍である。

| Paulo Reglus Neves Freire[a] (19

September 1921 – 2 May 1997) was a Brazilian educator and philosopher

who was a leading advocate of critical pedagogy. His influential work

Pedagogy of the Oppressed is generally considered one of the

foundational texts of the critical pedagogy movement,[37][38][39] and

was the third most cited book in the social sciences as of 2016

according to Google Scholar.[40] |

パ ウロ・レグルス・ネヴェス・フレイレ[ラ](1921年9月19日 - 1997年5月2日)はブラジルの教育者、哲学者であり、批判的教育学の主要な提唱者であった。彼の影響力のある著作『被抑圧者の教育学』は、一般的に批 判的教育学運動の基礎となったテキストの一つと考えられており[37][38][39]、Google Scholarによれば2016年時点で社会科学分野で3番目に引用された書籍である[40]。 |

| Biography Freire was born on 19 September 1921 to a middle-class family in Recife, the capital of the northeastern Brazilian state of Pernambuco. He became familiar with poverty and hunger from an early age as a result of the Great Depression. In 1931 his family moved to the more affordable city of Jaboatão dos Guararapes, 18 km west of Recife. His father died on 31 October 1934.[41] During his childhood and adolescence, Freire ended up four grades behind, and his social life revolved around playing pick-up football with other poor children, from whom he claims to have learned a great deal. These experiences would shape his concerns for the poor and would help to construct his particular educational viewpoint. Freire stated that poverty and hunger severely affected his ability to learn. These experiences influenced his decision to dedicate his life to improving the lives of the poor: "I didn't understand anything because of my hunger. I wasn't dumb. It wasn't lack of interest. My social condition didn't allow me to have an education. Experience showed me once again the relationship between social class and knowledge".[42] Eventually, his family's misfortunes turned around and their prospects improved.[42] Freire enrolled in law school at the University of Recife in 1943. He also studied philosophy, more specifically phenomenology, and the psychology of language. Although admitted to the legal bar, he never practiced law and instead worked as a secondary school Portuguese teacher. In 1944, he married Elza Maia Costa de Oliveira, a fellow teacher. The two worked together and had five children.[43] In 1946, Freire was appointed director of the Pernambuco Department of Education and Culture. Working primarily among the illiterate poor, Freire began to develop an educational praxis that would have an influence on the liberation theology movement of the 1970s. In 1940s Brazil, literacy was a requirement for voting in presidential elections.[44][45]  Freire in 1963 In 1961, he was appointed director of the Department of Cultural Extension at the University of Recife. In 1962, he had the first opportunity for large-scale application of his theories, when, in an experiment, 300 sugarcane harvesters were taught to read and write in just 45 days. In response to this experiment, the Brazilian government approved the creation of thousands of cultural circles across the country.[46] The 1964 Brazilian coup d'état put an end to Freire's literacy effort, as the ruling military junta did not endorse it. Freire was subsequently imprisoned as a traitor for 70 days. After a brief exile in Bolivia, Freire worked in Chile for five years for the Christian Democratic Agrarian Reform Movement and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. In 1967, Freire published his first book, Education as the Practice of Freedom. He followed it up with his most famous work, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, which was first published in 1968. After a positive international reception of his work, Freire was offered a visiting professorship at Harvard University in 1969. The next year, Pedagogy of the Oppressed was published in Spanish and English, vastly expanding its reach. Because of political feuds between Freire, a Christian socialist, and Brazil's successive right-wing authoritarian military governments, the book went unpublished in Brazil until 1974, when, starting with the presidency of Ernesto Geisel, the military junta started a process of slow and controlled political liberalisation.[citation needed] Following a year in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Freire moved to Geneva to work as a special education advisor to the World Council of Churches. During this time Freire acted as an advisor on education reform in several former Portuguese colonies in Africa, particularly Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique. In 1979, he first visited Brazil after more than a decade of exile, eventually moving back in 1980. Freire joined the Workers' Party (PT) in São Paulo and acted as a supervisor for its adult literacy project from 1980 to 1986. When the Workers' Party won the 1988 São Paulo mayoral elections in 1988, Freire was appointed municipal Secretary of Education. Freire is widely considered the grandfather of Critical Education Theory. Freire died of heart failure on 2 May 1997, in São Paulo.[47] |

略歴 フレイレは1921年9月19日、ブラジル北東部ペルナンブーコ州の州都レシフェの中流家庭に生まれた。世界大恐慌の影響で、幼い頃から貧困と飢餓を身近 に感じていた。1931年、一家はレシフェの西18kmにある、より物価の安いジャボアタン・ドス・グアララペス市に引っ越す。父親は1934年10月 31日に死去した[41]。 幼少期から青年期にかけて、フレイレは4学年遅れの成績に終わり、社会生活は他の貧しい子どもたちとピックアップ・アップ・フットボールをすることが中心 だった。このような経験が、貧しい人々に対する彼の関心を形成し、彼特有の教育観を構築する助けとなった。フレイレは、貧困と飢餓が彼の学習能力に深刻な 影響を与えたと述べている。これらの経験は、貧困層の生活改善に人生を捧げるという彼の決断に影響を与えた。私は頭が悪かったわけではありません。興味が なかったわけでもない。私の社会的状況は教育を受けることを許さなかった。社会階級と知識の関係を、経験によって改めて思い知らされた」[42]。やがて 彼の家族の不幸は好転し、前途は好転した[42]。 フレイレは1943年にレシフェ大学の法学部に入学。哲学、特に現象学と言語心理学も学んだ。弁護士資格を得たが、弁護士として活動することはなく、中等 学校のポルトガル語教師として働いた。1944年、教師仲間のエルザ・マイア・コスタ・デ・オリヴェイラと結婚。二人は共に働き、5人の子供をもうけた [43]。 1946年、フレイレはペルナンブーコ州教育文化局の局長に任命される。主に読み書きのできない貧しい人々の間で働きながら、フレイレは1970年代の解 放の神学運動に影響を与えることになる教育実践を展開し始めた。1940年代のブラジルでは、識字は大統領選挙で投票するための条件であった[44] [45]。  1963年のフレイレ 1961年、フレイレはレシフェ大学の文化普及学部長に任命される。1962年、300人のサトウキビ刈り取り労働者を対象に、わずか45日間で読み書き を教えるという実験が行われた。この実験を受けて、ブラジル政府は全国に何千もの文化サークルを設立することを承認した[46]。 1964年のブラジルのクーデターにより、フレイレの識字教育活動は終わりを告げた。その後、フレイレは反逆者として70日間投獄された。ボリビアに一時 亡命した後、フレイレはチリでキリスト教民主主義農地改革運動と国連食糧農業機関のために5年間働いた。1967年、フレイレは最初の著書『自由の実践と しての教育』を出版。続いて、最も有名な著作『被抑圧者の教育学』を1968年に出版。 彼の著作が国際的に高く評価され、フレイレは1969年にハーバード大学の客員教授に就任した。翌年、『被抑圧者の教育学』はスペイン語と英語で出版さ れ、その影響力は大きく拡大した。キリスト教社会主義者であるフレイレとブラジルの歴代右派権威主義軍事政権との政治的確執のため、本書は1974年にエ ルネスト・ガイゼルの大統領就任を皮切りに軍事政権がゆっくりと統制された政治的自由化のプロセスを開始するまで、ブラジルでは未発表のままだった[要出 典]。 マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジでの1年間に続き、フレイレはジュネーブに移り、世界教会協議会の特別教育顧問として働く。この間、フレイレはアフリカのいくつかの旧ポルトガル植民地、特にギニアビサウとモザンビークで教育改革のアドバイザーを務めた。 1979年、10年以上にわたる亡命生活を終えて初めてブラジルを訪れ、1980年には再びブラジルに戻った。フレイレはサンパウロで労働者党(PT)に 入り、1980年から1986年まで同党の成人識字率向上プロジェクトの監督を務めた。1988年のサンパウロ市長選挙で労働者党が勝利すると、フレイレ は市の教育長官に任命された。 フレイレは批判的教育理論の祖父として広く知られている。 フレイレは1997年5月2日、心不全のためサンパウロで死去した[47]。 |

| Pedagogy There is no such thing as a neutral education process. Education either functions as an instrument which is used to facilitate the integration of generations into the logic of the present system and bring about conformity to it, or it becomes the "practice of freedom", the means by which men and women deal critically with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world. — Jane Thompson, drawing on Paulo Freire[48] Freire contributed a philosophy of education which blended classical approaches stemming from Plato and modern Marxist, post-Marxist, and anti-colonialist thinkers. His Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968) can be read as an extension of, or reply to, Frantz Fanon's The Wretched of the Earth (1961), which emphasized the need to provide native populations with an education which was simultaneously new and modern, rather than traditional, and anti-colonial – not simply an extension of the colonizing culture. In Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Freire, reprising the oppressors–oppressed distinction, applies the distinction to education, championing that education should allow the oppressed to regain their sense of humanity, in turn overcoming their condition. Nevertheless, he acknowledges that for this to occur, the oppressed individual must play a role in their liberation. No pedagogy which is truly liberating can remain distant from the oppressed by treating them as unfortunates and by presenting for their emulation models from among the oppressors. The oppressed must be their own example in the struggle for their redemption.[49] Likewise, oppressors must be willing to rethink their way of life and to examine their own role in oppression if true liberation is to occur: "Those who authentically commit themselves to the people must re-examine themselves constantly".[50] Freire believed education could not be divorced from politics; the act of teaching and learning are considered political acts in and of themselves. Freire defined this connection as a main tenet of critical pedagogy. Teachers and students must be made aware of the politics that surround education. The way students are taught and what they are taught serves a political agenda. Teachers, themselves, have political notions they bring into the classroom.[51] Freire believed that Education makes sense because women and men learn that through learning they can make and remake themselves, because women and men are able to take responsibility for themselves as beings capable of knowing—of knowing that they know and knowing that they don't.[52] Criticism of the "banking model" of education Main article: Banking model of education In terms of pedagogy, Freire is best known for his attack on what he called the "banking" concept of education, in which students are viewed as empty accounts to be filled by teachers. He notes that "it transforms students into receiving objects [and] attempts to control thinking and action, lead[ing] men and women to adjust to the world, inhibit[ing] their creative power."[53] The basic critique was not entirely novel, and paralleled Jean-Jacques Rousseau's conception of children as active learners, as opposed to a tabula rasa view, more akin to the banking model.[54] John Dewey was also strongly critical of the transmission of mere facts as the goal of education. Dewey often described education as a mechanism for social change, stating that "education is a regulation of the process of coming to share in the social consciousness; and that the adjustment of individual activity on the basis of this social consciousness is the only sure method of social reconstruction".[55] Freire's work revived this view and placed it in context with contemporary theories and practices of education, laying the foundation for what would later be termed critical pedagogy. Culture of silence According to Freire, unequal social relations create a "culture of silence" that instills the oppressed with a negative, passive and suppressed self-image; learners must, then, develop a critical consciousness in order to recognize that this culture of silence is created to oppress.[56] A culture of silence can also cause the "dominated individuals [to] lose the means by which to critically respond to the culture that is forced on them by a dominant culture."[57] He considers social, race and class dynamics to be interlaced into the conventional education system, through which this culture of silence eliminates the "paths of thought that lead to a language of critique."[58] |

教育学 中立的な教育過程など存在しない。教育は、世代を現在のシステムの論理に統合し、それに適合させるために使われる道具として機能するか、あるいは、男女が 現実と批判的に向き合い、自分たちの世界の変革に参加する方法を発見するための手段である「自由の実践」となるかのどちらかである。 - ジェーン・トンプソンは、パウロ・フレイレ[48]を参考にしている。 フレイレは、プラトンに由来する古典的アプローチと、現代のマルクス主義、ポスト・マルクス主義、反植民地主義の思想家を融合させた教育哲学に貢献した。 彼の『被抑圧者の教育学』(1968年)は、フランツ・ファノンの『惨めな大地』(1961年)の延長、あるいはそれに対する返答として読むことができ る。 被抑圧者の教育学』においてフレイレは、抑圧者と被抑圧者の区別を繰り返しつつ、その区別を教育に適用し、教育によって抑圧された人々が人間としての感覚 を取り戻し、ひいてはその状態を克服できるようにすべきであると唱えている。とはいえ、そのためには被抑圧者が解放の役割を果たさなければならない。 真に解放的な教育学は、被抑圧者を不幸な者として扱い、被抑圧者の中から模範となる人物を提示することによって、被抑圧者から距離を置くことはできない。被抑圧者は、彼らの救済のための闘いにおいて、彼ら自身の模範とならなければならない。 同様に、抑圧者は、真の解放が起こるのであれば、自らの生き方を見直し、抑圧における自らの役割を検証することを厭わなければならない: 「真に人民のために身を捧げる者は、絶えず自分自身を再検討しなければならない」[50]。 フレイレは、教育は政治から切り離すことはできないと考え、教えることと学ぶことはそれ自体が政治的行為であると考えた。フレイレはこの関係を批判的教育 学の主要な信条として定義した。教師も生徒も、教育を取り巻く政治に気づかなければならない。生徒が教わる方法や教わる内容は、政治的な意図に奉仕するも のである。フレイレは次のように考えていた。 教育が意味を持つのは、女性も男性も、学ぶことを通して、自分自身を作り、作り変えることができることを学ぶからであり、女性も男性も、知ることのできる存在として、自分自身に責任を持つことができるからである。 教育の「銀行モデル」への批判 主な記事 教育の銀行モデル 教育学に関してフレイレが最もよく知られているのは、彼が教育の「銀行」概念と呼ぶものに対する攻撃である。この基本的な批判はまったく目新しいものでは なく、ジャン=ジャック・ルソーの、銀行モデルに近いタブラ・ラサ的な見方とは対照的な、能動的な学習者としての子どもの概念と類似していた。デューイは しばしば教育を社会変革のメカニズムとして説明し、「教育とは、社会意識を共有するようになる過程を調整するものであり、この社会意識に基づいて個人の活 動を調整することが、社会再建の唯一の確実な方法である」と述べていた[55]。フレイレの仕事はこの見解を復活させ、現代の教育の理論と実践との文脈に 位置づけ、後に批判的教育学と呼ばれるものの基礎を築いた。 沈黙の文化 フレイレによれば、不平等な社会関係は、被抑圧者に否定的で受動的で抑圧された自己イメージを植え付ける「沈黙の文化」を生み出す。そして学習者は、この 沈黙の文化が抑圧するために生み出されたものであることを認識するために、批判的な意識を発達させなければならない[56]。沈黙の文化はまた、「支配さ れた個人が、支配的な文化によって強制された文化に批判的に反応する手段を失う」原因にもなりうる[57]。 彼は社会的、人種的、階級的な力学が従来の教育システムの中に織り込まれていると考えており、この沈黙の文化によって「批評の言語につながる思考の道筋」が排除されると考えている[58]。 |

| Legacy and reception Since the publication of the English-language edition in 1970, Pedagogy of the Oppressed has had a large impact in education and pedagogy worldwide,[59] especially as a defining work of critical pedagogy. According to Israeli writer and education reform theorist Sol Stern, it has "achieved near-iconic status in America's teacher-training programs".[60] Connections have also been made between Freire's non-dualism theory in pedagogy and Eastern philosophical traditions such as the Advaita Vedanta.[61] In 1977, the Adult Learning Project, based on Freire's work, was established in the Gorgie-Dalry neighborhood of Edinburgh, Scotland.[62] This project had the participation of approximately 200 people in the first years, and had among its aims to provide affordable and relevant local learning opportunities and to build a network of local tutors.[62] In Scotland, Freire's ideas of popular education influenced activist movements[63] not only in Edinburgh but also in Glasgow.[64] Freire's major exponents in North America are bell hooks,[65] Henry Giroux, Peter McLaren, Donaldo Macedo, Antonia Darder, Joe L. Kincheloe, Shirley R. Steinberg, Carlos Alberto Torres, and Ira Shor.[66] One of McLaren's edited texts, Paulo Freire: A Critical Encounter, expounds upon Freire's impact in the field of critical pedagogy. McLaren has also provided a comparative study concerning Paulo Freire and Argentinian revolutionary icon Che Guevara. Freire's work influenced the radical math movement in the United States, which emphasizes social justice issues and critical pedagogy as components of mathematical curricula.[67] In South Africa, Freire's ideas and methods were central to the 1970s Black Consciousness Movement, often associated with Steve Biko,[68][69] as well as the trade union movement in the 1970s and 1980s, and the United Democratic Front in the 1980s.[70] The radical doctor Abu Baker Asvat was among the many prominent anti-apartheid activists who used Freire's methods.[71] Today there is a Paulo Freire Project at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Pietermaritzburg[72] and Abahlali baseMjondolo, a radical movement of the urban poor, continues to use Freirian methods.[73] In 1991, the Paulo Freire Institute was established in São Paulo to extend and elaborate upon his theories of popular education. The institute has started projects in many countries and is headquartered at the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, where it actively maintains the Freire archives. Its director is UCLA professor Carlos Torres, the author of several Freirean works, including the 1978 A praxis educativa de Paulo Freire.[74][75] In 1999 PAULO, a national training organisation named in honour of Freire, was established in the United Kingdom. This agency was approved by the New Labour Government to represent some 300,000 community-based education practitioners working across the UK. PAULO was given formal responsibility for setting the occupational training standards for people working in this field.[76] The Paulo and Nita Freire Project for International Critical Pedagogy was founded at McGill University. Here Joe L. Kincheloe and Shirley R. Steinberg worked to create a dialogical forum for critical scholars around the world to promote research and re-create a Freirean pedagogy in a multinational domain.[77] After the death of Kincheloe, the project was transformed into a virtual global resource.[78] In 2012, a group of educators in Western Massachusetts, United States, received permission to name a public school after Freire. The Holyoke, Massachusetts, Paulo Freire Social Justice Charter School opened in September 2013.[79] The school moved to the former Pope Francis Catholic High School building in Chicopee, Massachusetts, in 2019.[80] In 2012, Paolo Freire Charter High School opened in Newark, New Jersey. The state closed the school in 2017 due to lagging test scores and lack of "instructional rigor."[81] Shortly before his death, Freire was working on a book of ecopedagogy, a platform of work carried on by many of the Freire Institutes and Freirean Associations around the world today. It has been influential in helping to develop planetary education projects such as the Earth Charter as well as countless international grassroots campaigns in the spirit of Freirean popular education generally.[82] Freirean literacy methods have been adopted throughout the developing world. In the Philippines, Catholic "basal Christian communities" adopted Freire's methods in community education. Papua New Guinea, Freirean literacy methods were used as part of the World Bank-funded Southern Highlands Rural Development Program's Literacy Campaign. Freirean approaches also lie at the heart of the "Dragon Dreaming" approach to community programs that have spread to 20 countries by 2014.[83] |

遺産と受容 1970年に英語版が出版されて以来、『被抑圧者の教育学』は世界中の教育と教育学に大きな影響を与えてきた[59]。イスラエルの作家であり教育改革理 論家のソル・スターンによれば、この本は「アメリカの教員養成課程において、ほぼ象徴的な地位を獲得した」[60]。教育学におけるフレイレの非二元論 と、アドヴァイタ・ヴェーダーンタのような東洋哲学の伝統との関連性も指摘されている[61]。 1977年には、フレイレの著作に基づいた成人学習プロジェクトがスコットランドのエディンバラのゴーギー・ダリー地区に設立された[62]。このプロ ジェクトは、最初の数年間で約200人が参加し、手頃な価格で適切な地域学習の機会を提供し、地域の家庭教師のネットワークを構築することを目的としてい た[62]。 スコットランドでは、フレイレの大衆教育の考え方は、エディンバラだけでなくグラスゴーでも活動家の運動[63]に影響を与えた[64]。 北米におけるフレイレの主な支持者は、ベル・フックス、ヘンリー・ジルー、ピーター・マクラーレン、ドナルド・マセド、アントニア・ダーダー、ジョー・ L・キンチェロ、シャーリー・R・スタインバーグ、カルロス・アルベルト・トーレス、アイラ・ショールである[66]: A Critical Encounter)は、批判的教育学の分野におけるフレイレの影響について解説している。マクラーレンはまた、パウロ・フレイレとアルゼンチンの革命家 チェ・ゲバラに関する比較研究も行っている。フレイレの作品は、数学カリキュラムの構成要素として社会正義の問題や批判的教育学を強調するアメリカの急進 的数学運動に影響を与えた[67]。 南アフリカでは、フレイレの思想と方法は1970年代の黒人意識運動の中心であり、しばしばスティーブ・ビコと関連していた[68][69]。 [70]急進的な医師であったアブ・ベイカー・アスヴァットは、フレイレの手法を用いた多くの著名な反アパルトヘイト活動家の一人であった[71]。 今日、ピータマリッツバーグのクワズール・ナタール大学にはパウロ・フレイレ・プロジェクトがあり[72]、都市貧困層の急進的な運動であるアバーリ・ ベース・ムジョンドーロはフレイレの手法を用い続けている[73]。 1991年、パウロ・フレイレ研究所がサンパウロに設立され、フレイレの民衆教育の理論を発展させ、より精巧にすることを目的としている。この研究所は多 くの国でプロジェクトを開始し、UCLA教育情報学大学院に本部を置き、フレイレのアーカイブを積極的に管理している。所長はUCLAのカルロス・トレス 教授であり、1978年の『A praxis educativa de Paulo Freire』など、フレイレの著作がある[74][75]。 1999年、フレイレに敬意を表して命名された全国的な研修組織PAULOがイギリスに設立された。この機関は、イギリス全土で働く約30万人のコミュニ ティベースの教育実践者を代表する機関として、新労働党政府によって承認された。PAULOは、この分野で働く人々の職業訓練基準を設定する正式な責任を 与えられた[76]。 国際批判的教育学のためのパウロ&ニタ・フレイレ・プロジェクトがマギル大学に設立された。ここでジョー・L・キンチェロとシャーリー・R・スタインバー グは、研究を促進し、多国籍の領域でフレイレ的教育学を再創造するために、世界中の批判的研究者のための対話的フォーラムを創設することに取り組んだ [77]。 2012年、米国マサチューセッツ州西部の教育者グループは、公立学校にフレイレの名前を冠する許可を得た。マサチューセッツ州ホリヨークのパウロ・フレ イレ・ソーシャル・ジャスティス・チャーター・スクールは2013年9月に開校した[79]。同校は2019年にマサチューセッツ州チコピーの旧ポープ・ フランシス・カトリック高校の校舎に移転した[80]。 2012年、ニュージャージー州ニューアークにパオロ・フレイレ・チャーター・ハイスクールが開校。テストの点数の低迷と「指導の厳しさ」の欠如のため、州は2017年に同校を閉鎖した[81]。 死の直前、フレイレはエコペダゴジーの本に取り組んでいた。それは、地球憲章のような惑星教育プロジェクトや、一般的にフレイレの民衆教育の精神に基づく無数の国際的な草の根運動の発展を支援する上で影響力を持っている[82]。 フレイレの識字法は、発展途上国の至るところで採用されている。フィリピンでは、カトリックの「基層キリスト教共同体」がフレイレの方法を地域教育に取り 入れた。パプアニューギニアでは、世界銀行が資金を提供した南部高地農村開発プログラムの識字率向上キャンペーンの一環として、フレイレの識字法が用いら れた。フレイレのアプローチは、2014年までに20カ国に広がったコミュニティ・プログラムへの「ドラゴン・ドリーミング」アプローチの中核にもある [83]。 |

| Bibliography Freire wrote and co-wrote over 20 books on education, pedagogy and related themes.[86] Some of his works include: Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York, Continuum. Freire, P. (1970). Cultural Action for Freedom. [Cambridge], Harvard Educational Review. Freire, P. (1973). Education for Critical Consciousness. New York, Seabury Press. Freire, P. (1975). Conscientization. Geneva, World Council of Churches. Freire, P. (1976). Education, the Practice of Freedom. London, Writers and Readers Publishing Cooperative. Freire, P. (1978). Pedagogy in Process: The Letters to Guinea-Bissau. New York, A Continuum Book: The Seabury Press. Freire, P. (1985). The Politics of Education: Culture, Power, and Liberation. South Hadley, MA, Bergin & Garvey. Freire, P. & D.P. Macedo (1987). Literacy: Reading the Word & the World. South Hadley, MA, Bergin & Garvey Publishers. Freire, P. & I. Shor (1987). Freire for the Classroom: A Sourcebook for Liberators Teaching. Freire, P. and H. Giroux & P. McLaren (1988). Teachers as Intellectuals: Towards a Critical Pedagogy of Learning. Freire, P. & I. Shor (1988). Cultural Wars: School and Society in the Conservative Restoration, 1969–1984. Freire, P. (1993). Pedagogy of the City. New York, Continuum. Faundez, Antonion, and Paulo Freire (1992). Learning to Question: A Pedagogy of Liberation. Trans. Tony Coates, New York, Continuum. Freire, P. and A.M.A. Freire (1994). Pedagogy of Hope: Reliving Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York, Continuum. Freire, P. (1997). Mentoring the Mentor: A Critical Dialogue with Paulo Freire. New York, P. Lang. Freire, P. & A.M.A. Freire (1997). Pedagogy of the Heart. New York, Continuum. Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of Freedom: Ethics, Democracy and Civic Courage. Lanham, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Freire, P. (1998). Politics and Education. Los Angeles, UCLA Latin American Center Publications. Freire, P. (1998). Teachers as Cultural Workers: Letters to Those Who Dare Teach. Boulder, CO, Westview Press. |

参考文献 フレイレは教育学、教育方法論及び関連テーマについて20冊以上の著作を単独または共著で執筆した。[86] 主な著作は以下の通りである: フレイレ, P. (1970). 『被抑圧者の教育学』. ニューヨーク, コンティニュアム. フレイレ, P. (1970). 『自由のための文化的行動』. [ケンブリッジ], ハーバード教育評論. フレイレ、P. (1973). 批判的意識のための教育。ニューヨーク、シーベリー・プレス。 フレイレ、P. (1975). 意識化。ジュネーブ、世界教会協議会。 フレイレ、P. (1976). 教育、自由の実践。ロンドン、ライターズ・アンド・リーダーズ出版協同組合。 フレイレ、P. (1978). 『進行中の教育学:ギニアビサウへの手紙』. ニューヨーク、A Continuum Book: The Seabury Press. フレイレ、P. (1985). 『教育の政治学:文化、権力、そして解放』. サウス・ハドリー、マサチューセッツ州、Bergin & Garvey. フレイレ、P.、D.P. マセド(1987)。『リテラシー:言葉と世界を読む』。マサチューセッツ州サウスハドリー、バーギン&ガーベイ出版社。 フレイレ、P.、I. ショー(1987)。『教室のためのフレイレ:解放者のための教育資料集』。 フレイレ、P.、H. ジルー、P. マクラレン(1988)。『教師としての知識人:批判的学習教育学に向けて』。 フレイレ、P.、I. ショー(1988)。『文化戦争:保守的復古期における学校と社会、1969-1984』。 フレイレ、P.(1993)。『都市の教育学』。ニューヨーク、コンティニュアム。 ファウンデス、アントニオ、パウロ・フレイレ(1992)。『問うことを学ぶ:解放の教育学』。トニー・コーツ訳、ニューヨーク、コンティニュアム。 フレイレ、P.、A.M.A.フレイレ(1994)。希望の教育学:被抑圧者の教育学を再考する。ニューヨーク、コンティニュアム社。 フレイレ、P.(1997)。メンターを導く:パウロ・フレイレとの批判的対話。ニューヨーク、P.ラング社。 フレイレ、P. & A.M.A.フレイレ(1997)。心の教育学。ニューヨーク、コンティニュアム社。 フレイレ、P.(1998)。『自由の教育学:倫理、民主主義、そして市民的勇気』。ランハム、ローマン&リトルフィールド出版。 フレイレ、P.(1998)。『政治と教育』。ロサンゼルス、UCLAラテンアメリカセンター出版。 フレイレ、P.(1998)。『教師としての文化労働者:教える勇気を持つ者たちへの手紙』。ボルダー、コロラド州、ウェストビュー出版。 |

| Adult education Michael Apple John Asimakopoulos Clodomir Santos de Morais Culture circle Dialogic education Dialogic learning Dialogic pedagogy Raya Dunayevskaya Education in Brazil Lewis Gordon James D. Kirylo Landless Workers' Movement Marxist humanism Paulo Freire University Peer mentoring Popular education Praxis intervention Problem-posing education Rouge Forum Second Episcopal Conference of Latin America Structure and agency |

成人教育 マイケル・アップル ジョン・アシマコプロス クロドミール・サントス・デ・モライス カルチャーサークル 対話型教育 対話的学習 対話的教育学 ラヤ・ドゥナエフスカヤ ブラジルの教育 ルイス・ゴードン ジェームズ・D・キリロ 土地なし労働者運動 マルクス主義ヒューマニズム パウロ・フレイレ大学 ピアメンタリング 大衆教育 プラクシス介入 問題提起型教育 ルージュ・フォーラム 第2回ラテンアメリカ司教会議 構造と主体性 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paulo_Freire |

|

| Further reading Coben, Diana (1998). Radical Heroes: Gramsci, Freire and the Politics of Adult Education. New York: Garland Press. Darder, Antonia (2015). Freire and Education. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-53840-4. ——— (2017). Reinventing Paulo Freire: A Pedagogy of Love (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-67531-5. Elias, John (1994). Paulo Freire: Pedagogue of Liberation. Florida: Krieger. Ernest, Paul; Greer, Brian; Sriraman, Bharath, eds. (2009). Critical Issues in Mathematics Education. The Montana Mathematics Enthusiast: Monograph Series in Mathematics Education. Charlotte, North Carolina: Information Age Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60752-039-9. Freire, Ana Maria Araújo; Vittoria, Paolo (2007). "Dialogue on Paulo Freire". Interamerican Journal of Education for Democracy. 1 (1): 97–117. Retrieved 16 September 2020. Freire, Paulo, ed. (1997). Mentoring the Mentor: A Critical Dialogue with Paulo Freire. Counterpoints: Studies in the Postmodern Theory of Education. Vol. 60. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-3798-9. Gadotti, Moacir (1994). Reading Paulo Freire: His Life and Work. Translated by Milton, John. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1923-6. Gibson, Richard (1994). The Promethean Literacy: Paulo Freire's Pedagogy of Reading, Praxis and Liberation (dissertation). University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University. Archived from the original on 9 November 2006. Retrieved 16 September 2020. Gottesman, Isaac (2016). The Critical Turn in Education: From Marxist Critique to Poststructuralist Feminism to Critical Theories of Race. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315769967. ISBN 978-1-315-76996-7. Kincheloe, Joe L. (2004). Critical Pedagogy Primer. New York: Peter Lang. Kirylo, James D.; Boyd, Drick (2017). Paulo Freire: His Faith, Spirituality, and Theology. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers. doi:10.1007/978-94-6351-056-1. ISBN 978-94-6351-056-1. Ledwith, Margaret (2015). Community Development in Action: Putting Friere into Practice. United Kingdom: Policy Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1t895zm. ISBN 978-1447312253. Mann, Bernhard, The Pedagogical and Political Concepts of Mahatma Gandhi and Paulo Freire. In: Claußen, B. (Ed.) International Studies in Political Socialization and ion. Bd. 8. Hamburg 1996. ISBN 3-926952-97-0 McLaren, Peter (2000). Che Guevara, Paulo Freire and the Pedagogy of Revolution. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-9533-1. McLaren, Peter; Lankshear, Colin, eds. (1994). Politics of Liberation: Paths from Freire. London: Routledge. McLaren, Peter; Leonard, Peter, eds. (1993). Paulo Freire: A Critical Encounter (PDF). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-42026-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 July 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2020. Mayo, Peter (2004). Liberating Praxis: Paulo Freire's Legacy for Radical Education and Politics. Critical Studies in Education and Culture. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-89789-786-0. Morrow, Raymond A.; Torres, Carlos Alberto (2002). Reading Freire and Habermas: Critical Pedagogy and Transformative Social Change. New York: Teachers College Press. ISBN 978-0-8077-4202-0. O'Cadiz, Maria del Pilar; Wong, Pia Lindquist; Torres, Carlos Alberto (1997). Education and Democracy: Paulo Freire, Social Movements and Educational Reform in São Paulo. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. Roberts, Peter (2000). Education, Literacy, and Humanization Exploring the Work of Paulo Freire. Westport, Connecticut: Bergin & Garvey. Rossatto, César Augusto (2005). Engaging Paulo Freire's Pedagogy of Possibility: From Blind to Transformative Optimism. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-7836-4. Schugurensky, Daniel (2011). Paulo Freire. London: Continuum. Taylor, Paul V. (1993). The Texts of Paulo Freire. Buckingham, England: Open University Press. Torres, Carlos Alberto (2014). First Freire: Early Writings in Social Justice Education. New York: Teachers College Press. ISBN 978-0-8077-5533-4. Vittoria, Paolo (2016). Narrating Paulo Freire: Toward a Pedagogy of Dialogue. London: IEPS Publisher. |

追加文献(さらに読む) コーベン、ダイアナ(1998)。『急進的英雄たち:グラムシ、フレイレ、そして成人教育の政治学』。ニューヨーク:ガーランド・プレス。 ダルダー、アントニア(2015)。『フレイレと教育』。ニューヨーク:ラウトリッジ。ISBN 978-0-415-53840-4。 ——— (2017). 『パウロ・フレイレの再発見:愛の教育学(第 2 版)』. ニューヨーク:ラウトレッジ. ISBN 978-1-138-67531-5. Elias, John (1994). 『パウロ・フレイレ:解放の教育者』. フロリダ:クリーガー. アーネスト、ポール、グリア、ブライアン、スリラマン、バラト編(2009)。『数学教育における重要な問題』。モンタナ数学愛好家:数学教育モノグラフシリーズ。ノースカロライナ州シャーロット:情報時代出版。ISBN 978-1-60752-039-9。 フレイレ、アナ・マリア・アラウージョ、ヴィットーリア、パオロ(2007)。「パウロ・フレイレに関する対話」。民主主義のための教育に関する米州ジャーナル。1 (1): 97–117。2020年9月16日取得。 フレイレ、パウロ、編(1997)。メンターを指導する:パウロ・フレイレとの批判的対話。対位法:ポストモダン教育理論研究。第60巻。ニューヨーク:ピーター・ラング。ISBN 978-0-8204-3798-9。 ガドッティ、モアシール(1994)。『パウロ・フレイレを読む:その生涯と業績』。ジョン・ミルトン訳。ニューヨーク州立大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-7914-1923-6。 ギブソン、リチャード(1994)。『プロメテウスの識字:パウロ・フレイレの読解・実践・解放の教育学』(博士論文)。ペンシルベニア州ユニバーシティパーク:ペンシルベニア州立大学。2006年11月9日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2020年9月16日に取得。 ゴットスマン、アイザック(2016)。『教育における批判的転回:マルクス主義的批判からポスト構造主義フェミニズム、人種批判理論へ』。ニューヨー ク:ラウトリッジ。doi:10.4324/9781315769967。ISBN 978-1-315-76996-7。 キンチェロー、ジョー・L.(2004)。『批判的教育学入門』。ニューヨーク:ピーター・ラング。 キリロ、ジェームズ・D.;ボイド、ドリック(2017)。『パウロ・フレイレ:その信仰、霊性、神学』。オランダ、ロッテルダム:センス出版社。doi:10.1007/978-94-6351-056-1。ISBN 978-94-6351-056-1。 レドウィズ、マーガレット(2015)。『実践におけるコミュニティ開発:フレイレを実践に活かす』。英国:ポリシー・プレス。doi:10.2307/j.ctt1t895zm。ISBN 978-1447312253。 マン、ベルンハルト、マハトマ・ガンディーとパウロ・フレイレの教育学的・政治学的概念。クラウセン、B. (編) 政治的社会化と教育に関する国際研究。第 8 巻。ハンブルク 1996 年。ISBN 3-926952-97-0 マクラーレン、ピーター (2000)。チェ・ゲバラ、パウロ・フレイレ、そして革命の教育学。メリーランド州ラナム:Rowman & Littlefield。ISBN 978-0-8476-9533-1。 マクラーレン、ピーター;ランクシェア、コリン、編(1994)。解放の政治学:フレイレからの道。ロンドン:Routledge。 マクラーレン、ピーター;レナード、ピーター編(1993)。『パウロ・フレイレ:批判的対話』(PDF)。ロンドン:ラウトリッジ。ISBN 978-0-203-42026-3。2019年7月12日時点のオリジナル(PDF)からアーカイブ。2020年9月16日閲覧。 メイヨー、ピーター(2004)。『解放的実践:急進的教育と政治におけるパウロ・フレイレの遺産』。教育と文化の批判的研究。コネチカット州ウェストポート:プレガー出版社。ISBN 978-0-89789-786-0。 モロー、レイモンド・A.;トーレス、カルロス・アルベルト(2002)。フレイレとハーバーマスを読む:批判的教育学と変革的な社会変化。ニューヨーク:ティーチャーズ・カレッジ・プレス。ISBN 978-0-8077-4202-0。 オキャディス、マリア・デル・ピラール、ウォン、ピア・リンドクイスト、トレス、カルロス・アルベルト(1997)。教育と民主主義:パウロ・フレイレ、社会運動、そしてサンパウロの教育改革。コロラド州ボルダー:ウェストビュー・プレス。 ロバーツ、ピーター(2000)。教育、識字、人間化:パウロ・フレイレの探求。コネチカット州ウェストポート:バーギン&ガーベイ。 ロッサット、セザール・アウグスト(2005)。パウロ・フレイレの可能性の教育学に取り組む:盲目的な楽観主義から変革的な楽観主義へ。ラナム:ローマン&リトルフィールド。ISBN 978-0-7425-7836-4。 シュグレンスキー、ダニエル(2011)。『パウロ・フレイレ』。ロンドン:コンティニュアム。 テイラー、ポール V.(1993)。『パウロ・フレイレのテキスト』。英国バッキンガム:オープン大学出版局。 トーレス、カルロス・アルベルト(2014)。『初期のフレイレ:社会正義教育における初期著作集』。ニューヨーク:ティーチャーズ・カレッジ・プレス。ISBN 978-0-8077-5533-4。 ヴィットーリア、パオロ(2016)。『パウロ・フレイレを語る:対話的教育学へ向けて』。ロンドン:IEPS出版社。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆