ペドロ・パラモ

Pedro Páramo, por Juan Rulfo (1955)

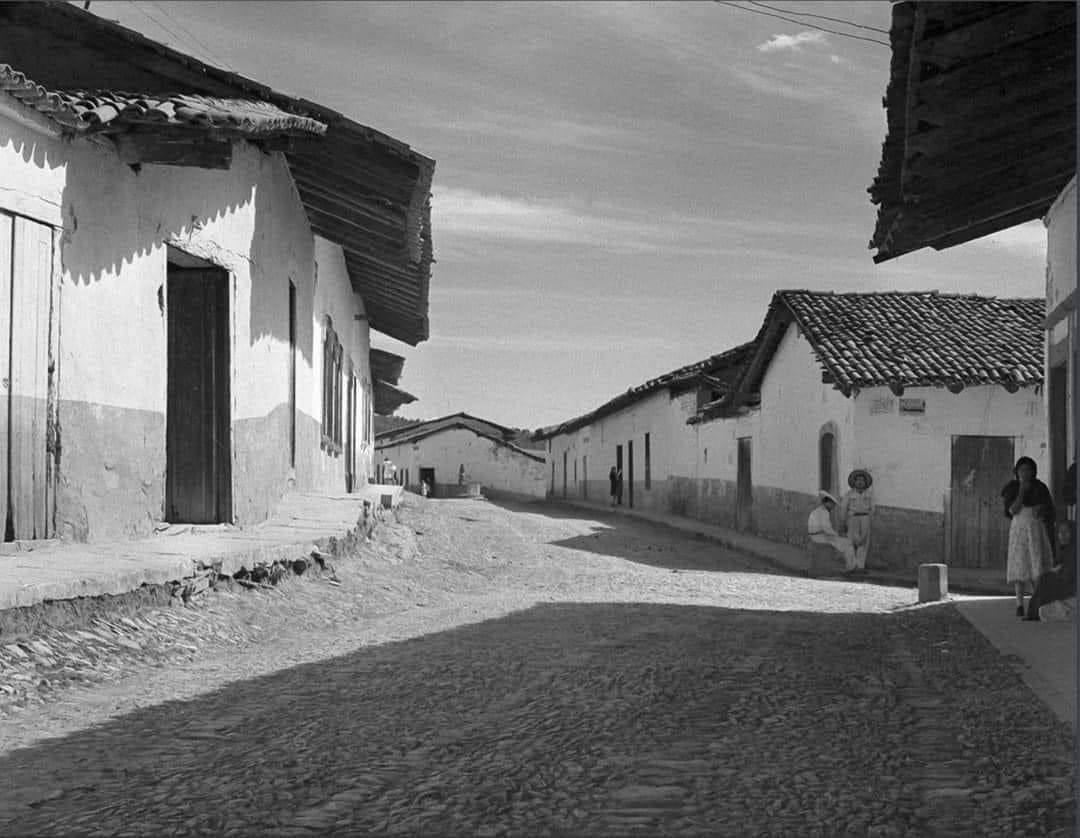

☆ 『ペドロ・パラモ』はメキシコの作家フアン・ルルフォが1955年に発表した小説である。この小説は、フアン・プレシアードという男が、死の床にある母親 と、コマラという町で初めてプレシアードの父親であるペドロ・パラモに会う約束をするが、(実際には、あるいは幻想的には)文字通りのゴーストタウン、つまり、幽霊のような人物が住んでいる町に出くわすという 物語である。小説の過程で、これらの幽霊のような住人たちは、プレシアードの無謀な父親ペドロ・パラモとその町の中心的存在など、コマラの生活と死後の世 界についての詳細を明らかにする。

| Pedro Páramo

is a novel by Mexican writer Juan Rulfo, first published in 1955. The

novel tells the story of Juan Preciado, a man who promises his mother

on her deathbed to meet Preciado's father for the first time in the

town of Comala only to come across a literal ghost town, that is,

populated by spectral characters. During the course of the novel, these

ghostly inhabitants reveal details about life and afterlife in Comala,

including that of Preciado's reckless father, Pedro Páramo, and his

centrality for the town.[1][2] Initially, the novel was met with cold

critical reception and sold only two thousand copies during the first

four years; later, however, the book became highly acclaimed.[3] Páramo

was a key influence on Latin American writers such as Gabriel García

Márquez. Pedro Páramo has been translated into more than 30 different

languages and the English version has sold more than a million copies

in the United States. Gabriel García Márquez has said that he felt blocked as a novelist after writing his first four books and that it was only his life-changing discovery of Pedro Páramo in 1961 that opened his way to the composition of his masterpiece, One Hundred Years of Solitude. Moreover, García Márquez claimed that he "could recite the whole book, forwards and backwards."[4] Jorge Luis Borges considered Pedro Páramo to be one of the greatest texts written in any language.[5][6] |

『ペ

ドロ・パラモ』はメキシコの作家フアン・ルルフォが1955年に発表した小説である。この小説は、フアン・プレシアードという男が、死の床にある母親と、

コマラという町で初めてプレシアードの父親に会う約束をするが、文字通りのゴーストタウン、つまり、幽霊のような人物が住んでいる町に出くわすという物語

である。小説の過程で、これらの幽霊のような住人たちは、プレシアードの無謀な父親ペドロ・パラモとその町の中心的存在など、コマラの生活と死後の世界に

ついての詳細を明らかにする。ペドロ・パラモは30以上の言語に翻訳され、英語版はアメリカで100万部以上売れた。 ガブリエル・ガルシア・マルケスは、最初の4冊を書いた後、小説家としての閉塞感を感じ、1961年にペドロ・パラモに出会って人生が変わり、代表作『百 年の孤独』執筆への道が開けたと語っている。さらに、ガルシア・マルケスは「この本全体を前にも後ろにも暗唱することができる」と主張した[4]。ホル ヘ・ルイス・ボルヘスは、ペドロ・パラモをあらゆる言語で書かれた最も偉大な文章のひとつとみなした[5][6]。 |

| Plot Narrative structure The story begins with the first-person account of Juan Preciado, who promises his mother on her deathbed that he will return to Comala to meet his father, Pedro Páramo. His narration is interspersed with fragments of third-person dialogue from the life of Pedro Páramo, who lived in a time when Comala was a robust, living town, instead of the ghost town Juan now sees. The two major competing narrative voices present alternative visions of Comala, one living and one populated with the spirits of the dead. The novel is set in the fictional town of Comala and its surroundings, a reference to the real town of Comala in the Mexican state of Colima, close to Juan Rulfo's homeland. Summary The sequence of events for the plot is broken up in the work in a nonlinear fashion and is at times difficult to discern and the same occurs with the characters as it is often impossible at first for the reader even to tell which characters are alive or dead.[7][8] The earliest moment in the story is Fulgor Sedano's arrival at Media Luna. His old patrón, Don Lucas, informs him that his son Pedro Páramo is totally useless and that he should go and get a new job when he dies. Later, Pedro's grandfather dies, and when his family prays for him after his death to help shorten his time in Purgatory, Pedro instead thinks about playing with Susana San Juan, the love of his life. They would fly kites near the village, and Pedro would help Susana fly hers. He is scolded for taking so long in the outhouse by his mother while he recalls this event. Soon after Señora San Juan dies, the San Juan family moves to the mining region. Exploring the Andromeda mine, Señor San Juan lowers Susana at the end of a rope into the old mine shaft. Searching for gold coins, Susana only finds a skeleton. Later in her life, her husband Florencio dies, and she's driven mad by the belief that he's still alive. When Lucas Páramo is mistakenly killed at a wedding, Pedro later massacres most of the wedding guests. Fulgor Sedano informs Pedro about his father's debts to the Preciado family. To relieve these debts, they concoct a plan to marry Dolores Preciado. When Sedano tries to convince her, she informs him that she's menstruating and cannot be married so soon. Osorio later warns Dolores not to sleep with Pedro on their wedding night, so she begs Eduviges Dyada to sleep with him in her place. Eduviges agrees, but Pedro is too drunk to have sex. Pedro's son Miguel is killed when, travelling to Contla, he jumps over a fence with his horse. Despite Miguel's cruel and irredeemable nature, Father Rentería absolves him after Pedro pays him in gold coins. Father Rentería remembers how Miguel killed his brother and raped his niece. Dorotea later confesses to Father Rentería that she was trafficking girls for Miguel Páramo; the priest cannot forgive her. Pedro Páramo seeks to add Toribio Aldrete's land to his estate, and when Toribio visits the home of Eduviges, Pedro Páramo and Fulgor Sedano hang him. Later, Eduviges kills herself out of despair. Living in the Media Luna estate, Dolores Preciado leaves Pedro Páramo to live with her sister. At the onset of the Mexican Revolution, the countryside has become too dangerous, and the San Juan family returns to Comala. When Señor San Juan dies, his ghost visits the crazed Susana, who only laughs. A stuttering man (Spanish: El Tartamudo) arrives at Pedro's house and informs him that revolutionaries have captured and killed Fulgor Sedano. To protect himself, Pedro invites local revolutionaries to his house for supper, promising them money and support. Pedro informs a revolutionary leader, El Tilcuate, that the money has run out and that he should raid a larger town for supplies. When Susana San Juan dies, she refuses absolution by the priest, and Father Rentería pretends to give her last sacraments. The people of Comala have a large party, greatly annoying Pedro, who is mourning the loss of Susana. Out of spite, he lets the town die of starvation. The wife of Abundio Martínez, Refugia, dies of this starvation. He heads into town to drink, and finds Damiana Cisneros, the cook at the Media Luna. Abundio Martínez stabs her to death, captured and dragged to the Media Luna. There, Abundio kills Pedro Páramo, revealing that he's one of his illegitimate sons. As he dies, he thinks of Susana and sees the ghost of Damiana. Dolores Preciado dies, and on her deathbed, she charges her son Juan to head to Comala and find his father Pedro Páramo. There, he finds the ghosts of Abundio, Eduviges, and Damiana, who tell him the stories of the town. He meets an incestuous couple, Donis and his sister, and spends the night at their house. Haunted by the ghosts of Comala, Juan dies of fright, buried in a shared grave with Dorotea. Trapped in his grave, he experiences the story and life of Pedro Páramo. |

プロット 物語の構造 物語はフアン・プレシアードの一人称の語りから始まる。彼は死の床にある母に、父ペドロ・パラモに会うためにコマラに戻ることを約束する。彼の語りには、 ペドロ・パラモが生きた時代の三人称の台詞が断片的に挿入される。ペドロ・パラモは、コマラが現在のようなゴーストタウンではなく、力強く生きた町であっ た時代に生きていた。2つの主要な語り手は、生きているコマラと死者の霊が住んでいるコマラの代替的なビジョンを提示する。 この小説は架空の町コマラとその周辺を舞台にしているが、これはフアン・ルルフォの故郷に近いメキシコのコリマ州にある実在の町コマラにちなんだものであ る。 あらすじ プロットの一連の出来事は作中で非直線的に分断されており、時に判別が困難である。また、登場人物についても同様で、読者はどの人物が生きているのか死ん でいるのかさえ、最初はわからないことが多い[7][8]。 物語の中で最も早い場面は、フルゴール・セダーノがメディア・ルナに到着する場面である。彼の老パトロンであるドン・ルーカスは、息子のペドロ・パラモは まったく役に立たないので、死んだら新しい仕事を見つけに行くべきだと彼に告げる。その後、ペドロの祖父が亡くなり、煉獄にいる時間を短くするために家族 が死後のペドロのために祈ると、ペドロは代わりに生涯の恋人であるスサーナ・サン・フアンと遊ぶことを考える。村の近くで凧揚げをし、ペドロはスサーナの 凧揚げを手伝う。ペドロは、この出来事を思い出しながら、母に外小屋に長居することを叱られる。セニョーラ・サン・ファンが亡くなって間もなく、サン・ ファン一家は鉱山地帯に移り住む。アンドロメダ鉱山を探検するため、セニョール・サン・フアンはスサーナを古い坑道にロープで下ろす。金貨を探していたス サーナは骸骨を見つける。その後、夫のフロレンシオが亡くなり、スサーナは彼がまだ生きているという思い込みから気が狂ってしまう。 結婚式でルーカス・パラモが誤って殺されると、ペドロはその後、結婚式の招待客のほとんどを虐殺する。フルゴール・セダーノはペドロに、プレシアード家に 対する父の借金のことを話す。その借金を返済するため、彼らはドロレス・プレシアードと結婚する計画を練る。セダーノが彼女を説得しようとすると、彼女は 生理中で、すぐに結婚はできないと告げる。後日、オソリオはドロレスに初夜にペドロと寝てはいけないと忠告し、彼女はエドゥビジェス・ディアダに自分の代 わりにペドロと寝てくれるよう頼む。エドゥビジェスは承諾するが、ペドロは酔っ払っていてセックスどころではなかった。 ペドロの息子ミゲルは、コントラに向かう途中、馬で柵を飛び越えて死んでしまう。ミゲルは残酷で救いようのない性格だったが、レンテリア神父はペドロが金 貨を支払った後、彼を赦す。レンテリア神父は、ミゲルが兄を殺し、姪を犯したことを思い出す。ドロテアは後に、ミゲル・パラモのために少女を人身売買して いたことをレンテリア神父に告白するが、神父は彼女を許すことができない。 ペドロ・パラモはトリビオ・アルドレテの土地を自分の領地に加えようとし、トリビオがエドゥビジェスの家を訪れたとき、ペドロ・パラモとフルゴール・セダ ノは彼を絞首刑にする。その後、エドゥビジェスは絶望のあまり自殺する。メディア・ルナの屋敷に住むドロレス・プレシアードは、ペドロ・パラモのもとを去 り、妹と暮らすようになる。 メキシコ革命が勃発すると、田舎は危険な状態になり、サン・ファン一家はコマラに戻る。セニョール・サン・フアンが死ぬと、彼の亡霊が狂ったスサーナのも とを訪れるが、スサーナは笑うだけだった。ペドロの家に吃音の男(スペイン語:El Tartamudo)がやってきて、革命軍がフルゴール・セダノを捕らえて殺したと告げる。ペドロは自分の身を守るため、地元の革命家たちを夕食に招き、 金と支援を約束する。ペドロは革命家のリーダー、エル・ティルクアテに、金が尽きたので物資を調達するために大きな町を襲うべきだと伝える。 スサーナ・サン・フアンが死ぬとき、彼女は神父の赦免を拒否し、レンテリア神父が最後の秘跡を与えるふりをする。コマラの人々は大宴会を開き、スサーナを 失ったペドロを大いに困らせる。腹いせに、彼は町を飢えで死なせてしまう。アブンディオ・マルティネスの妻レフーギアもこの飢えで死んでしまう。酒を飲み に町に向かった彼は、メディア・ルナのコック、ダミアナ・シスネロスを見つける。アブンディオ・マルティネスは彼女を刺し殺し、捕らえられてメディア・ル ナに引きずり込まれる。そこでアブンディオはペドロ・パラモを殺し、彼が隠し子の一人であることを明かす。死ぬ間際、彼はスサーナを思い、ダミアナの亡霊 を見る。 ドロレス・プレシアードが亡くなり、死の床で彼女は息子フアンにコマラに向かい、父ペドロ・パラモを探すよう命じる。そこで彼はアブンディオ、エドゥビ ジェス、ダミアナの亡霊を見つけ、町の話を聞く。近親相姦のカップル、ドニスとその妹に出会い、彼らの家で一夜を過ごす。コマラの亡霊に取り憑かれたフア ンは、ドロテアと共同の墓に埋葬されて怯え死ぬ。墓に閉じ込められた彼は、ペドロ・パラモの物語と人生を体験する。 |

| Themes A major theme in the book is people's hopes and dreams as sources of the motivation they need to succeed. Hope is each character's central motive for action. As Dolores tells her son, Juan, to return to Comala, she hopes that he will find his father and get what he deserves after all of these years. Despair is the other main theme in the novel. Each character's hopes lead to despair since none of their attempts to attain their goals are successful.[9] Juan goes to Comala instilled with the hope that he will meet and finally get to know his father. He fails to accomplish this and dies fearful, having lost all hope. Pedro hopes that Susana San Juan will return to him after so long. He was infatuated with her as a young boy and recalls flying kites with her in his youth. When she finally returns to him, she has gone mad and behaves as though her first husband were still alive. Nevertheless, Pedro hopes that she will eventually come to love him. Dorotea says that Pedro truly loved Susana and wanted nothing but the best for her.[9] Father Rentería lives in hope that he will someday be able to fully fulfill his vows as a Catholic priest, telling Pedro that his son will not go to heaven, instead of pardoning him for his many sins in exchange for a lump of gold.[2] Ghosts and the ethereal nature of the truth are also recurrent themes in the text.[1][2] When Juan arrives in Comala it is a ghost town, yet this is only gradually revealed to the reader. For example, in an episode with Damiana Cisneros, Juan talks to her believing that she is alive. They walk through the town together until he becomes suspicious as to how she knew that he was in town, and he nervously asks, "Damiana Cisneros, are you alive?" This encounter shows the truth as fleeting, always changing, and impossible to pin down. It is difficult to truly know who is dead and who is alive in Comala.[1] Sometimes the order and nature of events that occur in the work are not as they first seem. For example, midway through the book, the original chronology is subverted when the reader finds out that much of what has preceded was a flashback to an earlier time.[9] |

テーマ この本の主要なテーマは、成功に必要な動機の源としての人々の希望と夢である。希望は各登場人物の行動の中心的動機である。ドロレスが息子のフアンにコマ ラに戻るように言うとき、彼女は彼が父親を見つけ、長い年月の末に彼にふさわしいものを得ることを望んでいる。絶望はこの小説のもうひとつの主要テーマで ある。各登場人物の希望は、目標を達成しようとする試みがどれも成功しなかったことから、絶望に至る[9]。 フアンは、父に会い、ついに父を知ることができるという希望を抱いてコマラに行く。彼はそれを果たせず、希望を失って恐れをなして死ぬ。 ペドロは、スサーナ・サン・フアンが久しぶりに自分のもとに戻ってくることを願う。彼は少年時代に彼女に夢中になり、若い頃に彼女と凧揚げをしたことを思 い出す。ようやく彼のもとに戻ってきたとき、彼女は気が狂っており、最初の夫がまだ生きているかのように振る舞っていた。それでもペドロは、彼女がやがて 自分を愛してくれることを願う。ドロテアは、ペドロは本当にスサーナを愛しており、彼女にとって最良のことだけを望んでいたと言う[9]。 レンテリア神父は、いつかカトリックの司祭としての誓いを完全に果たせるようになることを願いながら生きており、ペドロに、息子は天国に行けないと告げ、 代わりに金塊と引き換えに彼の多くの罪を赦すのだった[2]。 幽霊と真実の幽玄な性質もまた、本文中で繰り返し登場するテーマである[1][2]。フアンがコマーラに到着したとき、そこはゴーストタウンであったが、 そのことは読者に徐々に明らかにされていく。例えば、ダミアナ・シスネロスとのエピソードで、フアンは彼女が生きていると信じて話しかける。二人は一緒に 町を歩くが、なぜ彼女が自分が町にいることを知っているのかと不審に思い、緊張しながら 「ダミアナ・シスネロス、生きているのか?」と尋ねる。この出会いは、真実が儚く、常に変化し、突き止めることが不可能であることを示している。コマラで は、誰が死んで誰が生きているのかを本当に知ることは難しい[1]。 作中で起こる出来事の順序や性質が、最初の印象通りでないことがある。例えば、本書の中盤で、読者はそれまでの出来事の多くが以前の時代へのフラッシュ バックであったことを知り、当初の時系列は覆される[9]。 |

| Interpretation Critics primarily consider Pedro Páramo as either a work of magic realism or a precursor to later works of magic realism; this is the standard Latin American interpretation.[10][3][11] However, magical realism is a term coined to note the juxtaposition of the surreal to the mundane, with each bearing traits of the other. It is a means of adding surreal or supernatural qualities to a written work while avoiding total disbelief.[1][12][9] Pedro Páramo is unlike other works of this type because the primary narrator states clearly in the second paragraph of the novel that his mind has filled with dreams and that he has given flight to illusion and that a world has formed in his mind around the hopes of finding a man named Pedro Páramo. Likewise, several sections into this narration, Juan Preciado states that his head has filled with noises and voices. He is unable to distinguish living persons from apparitions. Certain critics believe that particular qualities of the novel, including the narrative fragmentation, the physical fragmentation of characters, and the auditory and visual hallucinations described by the primary narrator, suggest that this novel's journey and visions may be more readily associated with the sort of breakdown of the senses present in schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like conditions rather than with magical realism.[12][13] |

解釈 批評家たちは主にペドロ・パラモをマジック・リアリズムの作品、あるいは後のマジック・リアリズムの先駆けであると考えている。『ペドロ・パラモ』がこのタ イプの他の作品と異なるのは、主要な語り手が小説の第2段落で、彼の心は夢で満たされ、幻想に逃避し、ペドロ・パラモという男を見つけるという希望を中心 にした世界が彼の心の中に形成されていると明言している点である[1][12][9]。同様に、このナレーションの数節でフアン・プレシアードは、頭の中 が雑音と声でいっぱいになったと述べている。生きている人間と幻影の区別がつかないのだ。ある批評家は、物語の断片化、登場人物の物理的な断片化、主要な 語り手によって描写される幻聴や幻視など、この小説の特殊な性質は、この小説の旅と幻視が、魔術的リアリズムというよりはむしろ、精神分裂病や精神分裂病 に似た病態に見られる感覚の崩壊と結びつきやすいことを示唆していると考えている[12][13]。 |

| Meaning of title The title underscores the importance of the character of Pedro Páramo. His life and decisions are key to the survival of the town of Comala. His last name means "barren plain" or "wasteland", which is what the town of Comala becomes as a result of his manipulations.[1] He is not only responsible for the economic well-being of the town but also for the existence of many of its inhabitants. Among his offspring are Abundio, Miguel, and Juan, and countless others. He is regularly depicted raping women, and even Dorotea cannot keep track of all the women he has slept with.[9] He is also responsible for the town's security. He strikes a deal with the revolutionary army mainly in his own self-interest and for protection. But being the owner of such a large swath of land, he is, by extension, in charge of the physical well-being of the town.[12][2] An example of his power is his decision to allow Comala to starve and do nothing with the fields and with the crops. The town withers because of his apathy and indifference. The entire novel centers on his actions, appetites and desires.[9] |

タイトルの意味 このタイトルは、ペドロ・パラモという人物の重要性を強調している。彼の人生と決断は、コマラの町の存続の鍵を握っている。彼の名字は「不毛の平原」や 「荒れ地」を意味し、彼の策略の結果コマラの町はこうなった。彼の子孫には、アブンディオ、ミゲル、フアンなど数え切れないほどいる。彼は定期的に女性を 強姦する描写があり、ドロテアでさえ彼が寝たすべての女性を把握することができない。革命軍と取引するのは、主に彼の私利私欲と保身のためである。しか し、これほど広大な土地の所有者である彼は、ひいては町の物理的な幸福の責任者でもある[12][2]。彼の力の一例として、コマラを飢えさせ、畑や作物 に何もさせないという彼の決断がある。彼の無関心と無気力のせいで、町は枯れていく。小説全体の中心は彼の行動、食欲、欲望にある[9]。 |

| Characters Main characters Pedro Páramo Pedro Páramo is both protagonist and antagonist since his acts are at cross-purposes. He is capable of decisive action, as when he eliminated his debt and took over more land, but is unable to use that decisiveness to do any good for the community. He resembles a tragic hero in the way that he longs for Susana and is totally unable to get over her death. His one fatal flaw is her. He cannot function without her or the incentive of her. Pedro serves as a fertility god figurehead in the work. He not only literally impregnates many of the town's women, but he has many children (the priest brings many to his doorstep). He also is in charge of the well-being of Comala, but also can "cross his arms" and let Comala die. This shows that he has the power of life and fertility over the town. Pedro's name has great significance in the work. Pedro is derived from the Greek petrus, meaning 'rock', and Páramo, meaning 'barren plain'. This is ironic since in the end of the work Pedro collapses "like a pile of rocks" after observing what his land had become.[14] Susana San Juan She is the love of Pedro's life. They grew up together. Her mother died friendless, and later her father Bartolomé is killed in the Andromeda mine by Sedano so that Pedro can marry her. She loved her first husband very much and went mad when he died. She thinks that he is still living, and she "talks" to him several times in the work. She appeared to have loved him for his body and not for his personality. She might have had sex with Pedro, but it is apparent that he wanted to have her. They were never married since he had never divorced Dolores. He is full of grief when she dies and refuses to work anymore and lets the town die. She is commonly portrayed and symbolized as the rain and water. In the passages that she is in, there is a backdrop with it raining. Such an example of this is the scene with Justina, Susana, and the cat. The entire background is the rain; it is raining torrents, and the valley is flooded.[14] Juan Preciado – narrator Juan is one of the two narrators in the work. He recounts his story for the first half of the work, up until his death.[14] He comes to Comala in order to find his father, his mother's last wish. He finds the town abandoned and dies of fright from the ghosts. He is then buried in the same grave as Dorotea, whom he talks with. It is apparent that he dies without the proper sacraments and is now stuck in purgatory.[2] Fulgor Sedano – mentor He is the administrator of the Media Luna. Initially warned by Pedro's father not to trust him, he eventually becomes enforcing hand of Pedro's schemes. He had been around the estate for many years serving the former patrons, Pedro's father Lucas and Lucas's father before that. He knows what to do and how to do it and boasts a number of achievements, including getting Dolores to marry Pedro. He is killed by a band of revolutionaries who view him as an embodiment of the privileged estate that they are fighting against. He also is responsible for having Toribio Aldrete hanged because he was trying to get the land surveyed to prove his right to some of it.[14] Miguel Páramo He and Juan are both sons of Pedro Páramo. Miguel is the only son recognized by Pedro and was thus being groomed as the next Páramo heir. Miguel's character is the exact opposite to Juan. He is wild and a rapist, while Juan is quiet and respectful of women. He is fearless, whereas Juan dies of fear. He has a horse and rides it often, whereas Juan does not and has to travel by foot. His wantonness contrasts the calmness of Juan despite their shared parentage. Additionally, he is known for liking loose women and for murdering Ana's father. He also rapes Ana when he goes to her to apologize to her for killing him. He is thrown from his horse when going to another village to meet his current lover.[14] Dorotea – narrator Town's beggar. She is the second narrator in the work. She tells the story of Comala before Pedro died after she is buried in the grave with Juan. Her storytelling dominates the second half of the work. She was known for being homeless and living on the charity of the people in the town. She had always tried to have children but had "the heart of a mother but a womb of a whore". She was known for her eccentric behavior by thinking that she had had a baby.[14] Father Rentería Town's priest. He is really not the main character, but he possesses all the characteristics of one; for which he could considered an antihero. He tries to stand up to Pedro and not give absolution to his son, Miguel. He has only the best intentions in mind but is unable to carry them out. His brother was killed by Miguel, and his niece was raped by Miguel as well when he came to apologize to her. He takes some gold to absolve Miguel, and he feels poorly about it, throwing himself in a corner and crying to the Lord.[14] He goes to another town to try to get himself forgiven of his sins so that he could continue to give the sacraments to the people of Comala. The other priest refuses, but they talk about how everything that grows in their region tastes sour and bitter. It is directly Father Rentería's fault that so many souls are stuck in Comala. He had failed in his duty to absolve those people and administer the last rite to them, and thus, they died and were unable to go to heaven. He is later mentioned as having joined the Cristero War.[14] Minor characters Eduviges Dyada Town's prostitute and good friend of Dolores Preciado. They promised to die together and help each other through the afterlife. She had died years ago and greets Juan when he arrives at Comala. She tells him of how she almost "came within a hair of being his mother" since she had to go and sleep with Pedro on their wedding night. She tells of her relationship and relations with Miguel Páramo and how it was she who saw his ghost before it left. Her sister, María Dyada, tells the priest that her suicide was out of despair and that she was a really good woman. He refuses to help her, and thus, her ghost remains in the town and purgatory. She dies with the idea that Abundio is a good man and does not know about him murdering Damiana.[14] Dolores Preciado She was Juan's mother. She was wooed into marriage to Pedro by Sedano who said he thought of nothing but her all day and night and that her eyes were beautiful. Pedro owed her family the most money of all the other families, and her sisters had already moved to the city. She was married to annul the debt. Later, she is staring at a buzzard and wishes to be like it so that she could fly to her sister in the city. Pedro gets mad enough and dismisses her for good. They are never officially divorced. Her dying wish is for Juan to go and see his father and "make him pay for all those years he put us out of his mind".[14] Abundio Martínez He's another illegitimate son of Pedro's who works as the town's mail carrier. He is deaf because a rocket once went off near his ear. After that he did not talk much, and he became depressed. Later, his wife dies. He goes to get drunk at a local bar. Upon leaving he sees Damiana Cisneros and asks her for some money to bury his wife. He startles her, and she begins to scream. He then kills her, is captured, vomits, and is dragged to town. Eduviges calls him a good man.[14] Inocencio Osorio He is the town's seer. He is the one who tells Dolores not to sleep with Pedro on her wedding night. His nickname is "Cockleburr" since he is well known to be able to stick to any horse and break it.[14] Damiana Cisneros She is the cook at the Media Luna and the ghost who takes Juan from Eduviges's house on that first night. She is sad to hear that Eduviges is still wandering the earth. Juan takes a while to realize that she is really a ghost and for a time, thinks that she is still alive. She was murdered by Abundio. She was also one of Dolores's good friends, and Juan knew about her when he arrived at Comala.[14] Toribio Aldrete He is a property surveyor. He was splitting and dividing up Pedro's land and was going to build fences. He is stopped by a plot by Pedro and Sedano. They plot to try to stop him from doing the survey and draw up a warrant against him. Sedano goes to Eduviges's house one night with a drunken Aldrete and hangs him and throws away the keys to the room. He remains there in spirit and wakes Juan on his first night in Comala with his death screams.[14] Donis and his wife/sister These two are some of the last living people in the town. Donis is suspicious of Juan and his motives for being there and thinks that he is a serious criminal, perhaps a murderer, and does not want him to spend the night. Donis is engaged in an incestuous relationship with his sister, started in an attempt to repopulate the town, although they once asked a bishop riding through town to marry them which he furiously refused, demanding they stop their relationship and "live like men". His wife/sister starts to like Juan after the first night and does a little extra to try to get him some more food since they have so little. She trades some of the old sheets for food and coffee with her older sister. Donis is glad that Juan showed up since he could now leave the town and have his wife/sister taken care of.[14] Justina She is Susana's caregiver. She has taken care of her for many years, since she was born. She cried when Susana was dying, and Susana told her to stop crying. Justina is scared one day by the ghost of Bartolomé, who tells her to leave the town since Susana would be well cared for.[14] |

登場人物 主な登場人物 ペドロ・パラモ ペドロ・パラモは主人公であると同時に敵役でもある。借金をなくし、さらに土地を手に入れたときのように、彼は断固とした行動をとることができるが、その 決断力を地域社会のために役立てることはできない。スサーナを慕い、彼女の死を乗り越えることがまったくできないという点で、彼は悲劇のヒーローに似てい る。彼の致命的な欠点は彼女である。彼は彼女なしには、あるいは彼女という誘因なしには機能しないのだ。ペドロは、この作品では豊穣の神の姿をしている。 彼は文字通り町の女性の多くを孕ませるだけでなく、多くの子供を産む(司祭が彼の門前に多くの子供を連れてくる)。彼はまた、コマラの幸福を管理している が、「腕を組んで」コマラを死なせることもできる。これは、彼が町の生命と豊穣の力を持っていることを示している。ペドロの名前は作品の中で大きな意味を 持っている。ペドロはギリシャ語で「岩」を意味するペトリュスと「不毛の平原」を意味するパラモに由来する。作品の最後で、ペドロは自分の土地がどうなっ てしまったかを見て、「岩の山のように」倒れてしまうのだから、これは皮肉なことである[14]。 スサーナ・サンファン 彼女はペドロの生涯の恋人である。二人は一緒に育った。ペドロが彼女と結婚するために、彼女の母は友人を失ったまま亡くなり、その後、彼女の父バルトロメ はセダーノによってアンドロメダ鉱山で殺される。彼女は最初の夫をとても愛していたが、彼が死んだとき気が狂ってしまった。彼女は彼がまだ生きていると思 い、作中で何度も彼と「会話」する。彼女はペドロの人格ではなく、体だけを愛していたようだ。彼女はペドロとセックスしたかもしれないが、彼が彼女を欲し がっていたことは明らかだ。ペドロはドロレスと離婚していないため、二人は結婚していない。彼女が死んだとき、彼は悲しみでいっぱいになり、もう働くこと を拒否し、町を滅亡させる。彼女は一般的に雨や水として描かれ、象徴されている。彼女が登場する箇所には、雨が降っている背景がある。ジュスティーナ、ス サーナ、猫のシーンがその例だ。背景はすべて雨で、滔々と雨が降り、谷は水浸しになっている[14]。 フアン・プレシアード - 語り手 フアンは、この作品に登場する二人の語り手のうちの一人である。彼は作品の前半、死ぬまでの物語を語る[14]。町は廃墟と化し、亡霊に怯えて死ぬ。そし てドロテアと同じ墓に埋葬され、ドロテアと語り合う。彼は適切な秘跡を受けずに死に、煉獄から抜け出せないでいることがわかる[2]。 フルゴール・セダーノ - 指導者 メディア・ルナの管理者。当初はペドロの父から彼を信用するなと警告されていたが、やがてペドロの陰謀の執行者となる。ペドロの父ルーカスとその前のルー カスの父という、かつてのパトロンに長年仕えてきた。何をどうすべきか熟知しており、ドロレスをペドロと結婚させるなど、数々の功績を誇る。ドロレスをペ ドロと結婚させるなど、数々の功績を誇るが、革命派の一団に殺される。また、トリビオ・アルドレテを絞り首に処したのも、彼が土地の一部の権利を証明する ために測量させようとしていたからである[14]。 ミゲル・パラモ ミゲルとフアンは共にペドロ・パラモの息子である。ミゲルはペドロに認められた唯一の息子であり、そのため次のパラモの後継者として育てられていた。ミゲ ルの性格はフアンとは正反対である。フアンが物静かで女性を敬うのに対し、彼は乱暴で強姦魔である。彼は恐れを知らないが、フアンは恐怖のあまり死んでし まう。彼は馬を所有し、頻繁に馬に乗るが、フアンは馬に乗らず、徒歩で移動しなければならない。親が同じであるにもかかわらず、フアンの冷静さとは対照的 である。加えて、彼はふしだらな女が好きで、アナの父親を殺したことで知られている。また、アナを殺したことを謝りに行ったアナを強姦する。現在の恋人に 会うために別の村に行く際、馬から投げ落とされる[14]。 ドロテア - 語り手 町の乞食。作中2人目の語り手。フアンと一緒に墓に埋葬された後、ペドロが死ぬ前のコマラの話をする。彼女の語りは作品の後半を支配する。彼女はホームレ スとして知られ、町の人々の施しで暮らしていた。彼女はいつも子供を作ろうとしていたが、「母の心はあるが、子宮は娼婦のよう」だった。彼女は、自分が子 供を産んだと思い込むという風変わりな行動で知られていた[14]。 レンテリア神父 町の司祭。主人公ではないが、主人公の特徴をすべて備えている。ペドロに立ち向かい、息子のミゲルに赦免を与えようとしない。彼は善意だけを持っている が、それを実行することができない。彼の兄はミゲルに殺され、謝罪に来た姪もミゲルにレイプされた。彼はミゲルを赦すためにいくばくかの金貨を手にする が、そのことを哀れに思い、隅に身を投げて主に泣きつく[14]。 ミゲルはコマーラの人々に秘跡を与え続けるために、自分の罪を許してもらおうと別の町に行く。もう一人の神父は拒否するが、二人は自分たちの地域で育つも のはすべて酸っぱくて苦い味がすると話す。多くの魂がコマラで立ち往生しているのは、直接的にはレンテリア神父のせいだ。彼はその人たちを赦し、最後の儀 式を執り行う義務を怠った。彼は後にクリステロ戦争に参加したと言及されている[14]。 主な登場人物 エドゥビジェス・ディアダ 町の娼婦でドロレス・プレシアードの親友。一緒に死んで死後の世界で助け合うことを約束した。彼女は数年前に亡くなっており、コマラに到着したフアンを出 迎える。彼女は、結婚初夜にペドロと寝なければならなかったため、「彼の母親になりかけた」ことを彼に話す。ミゲル・パラモとの関係、そして彼の亡霊が 去っていくのを見たのも彼女であったことを話す。妹のマリア・ディアダは神父に、彼女の自殺は絶望からであり、彼女は本当にいい女だったと話す。司祭は彼 女を助けようとせず、そのため彼女の亡霊は町と煉獄にとどまる。彼女は、アブンディオは善人であり、彼がダミアナを殺したことを知らないという考えを抱い て死ぬ[14]。 ドロレス・プレシアード フアンの母親。昼も夜も彼女のことしか考えず、彼女の瞳は美しいと言うセダーノに口説かれ、ペドロと結婚する。ペドロは彼女の家族に他の家族の中で最も多 くの借金があり、彼女の姉妹はすでに都会へ引っ越していた。彼女は借金を帳消しにするために結婚したのだ。その後、彼女はハシビロコウを見つめていて、自 分もハシビロコウのようになりたい、そうすれば都会にいる妹のところへ飛んでいけると願う。ペドロは怒って彼女を追い出す。二人は正式に離婚することはな かった。彼女の死に際の願いは、フアンが父親に会いに行き、「私たちのことを忘れさせた数年間のツケを払わせる」ことだった[14]。 アブンディオ・マルティネス ペドロのもう一人の隠し子で、町の郵便配達をしている。ロケットが耳の近くで爆発したため耳が聞こえない。それ以来あまり話さなくなり、鬱病になる。その 後、妻が亡くなる。彼は地元のバーで酔っぱらう。帰り際にダミアナ・シスネロスを見かけ、妻を埋葬するための金をくれと頼む。彼は彼女を驚かせ、悲鳴を上 げ始める。そして彼女を殺し、捕らえられ、嘔吐し、町に引きずり込まれる。エドゥビジェスは彼を善人と呼ぶ[14]。 イノセンシオ・オソリオ 町の占い師。ドロレスに初夜にペドロと寝てはいけないと告げる。どんな馬にもくっついて壊してしまうことで有名なため、あだ名は「バッタ」[14]。 ダミアナ・シスネロス メディア・ルナのコックであり、最初の夜にエドゥビジェスの家からフアンを連れ去った幽霊である。エドゥビジェスがまだ地上をさまよっていると聞いて悲し む。フアンは、彼女が本当に幽霊であることを理解するのに時間がかかり、一時はまだ生きていると思っていた。彼女はアブンディオに殺された。彼女はドロレ スの親友でもあり、フアンはコマラに来たときに彼女のことを知っていた[14]。 トリビオ・アルドレテ 不動産調査員。ペドロの土地を分割し、柵を作ろうとしていた。ペドロとセダーノの陰謀によって阻止される。ペドロとセダノは、ペドロの測量を止めさせよう と企み、ペドロに対して令状を発行する。ある夜、セダーノは酔ったアルドレテと共にエドゥビジェスの家に行き、彼を吊るして部屋の鍵を捨てる。彼は霊と なってそこに残り、コマラでの最初の夜、フアンを死の叫び声で目覚めさせる[14]。 ドニスとその妻/妹 この二人は、この町で最後の生き残りである。ドニスはフアンと彼がそこにいる動機を疑っており、彼が重大な犯罪者、おそらく殺人犯であると考え、一夜を過 ごさせようとしない。ドニスは妹と近親相姦の関係にあり、町を再繁殖させるために始めたのだが、町を通りかかった司教に結婚を申し込んだところ、司教は猛 烈に拒否し、関係をやめて「男らしく生きろ」と要求した。彼の妻である姉は、最初の夜を過ごした後、フアンを気に入り始める。彼女は古いシーツを姉と食べ 物やコーヒーと交換する。ドニスは、フアンが町を出て、妻や妹の面倒を見てもらえるようになったので、フアンが現れたことを喜ぶ[14]。 フスティーナ スサーナの介護人。スサーナが生まれてから長年世話をしてきた。スサーナが死ぬ間際に泣いてしまい、スサーナに「泣くな」と言われる。ある日、バルトロメ の亡霊に怯えたジュスティーナは、スサーナは大切にされているはずだから、この町を去るようにと言われる[14]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pedro_P%C3%A1ramo |

|

| Juan Nepomuceno Carlos

Pérez Rulfo Vizcaíno(Apulco,3

4 16 de mayo de 1917-Ciudad de México, 7 de enero de 1986) fue un

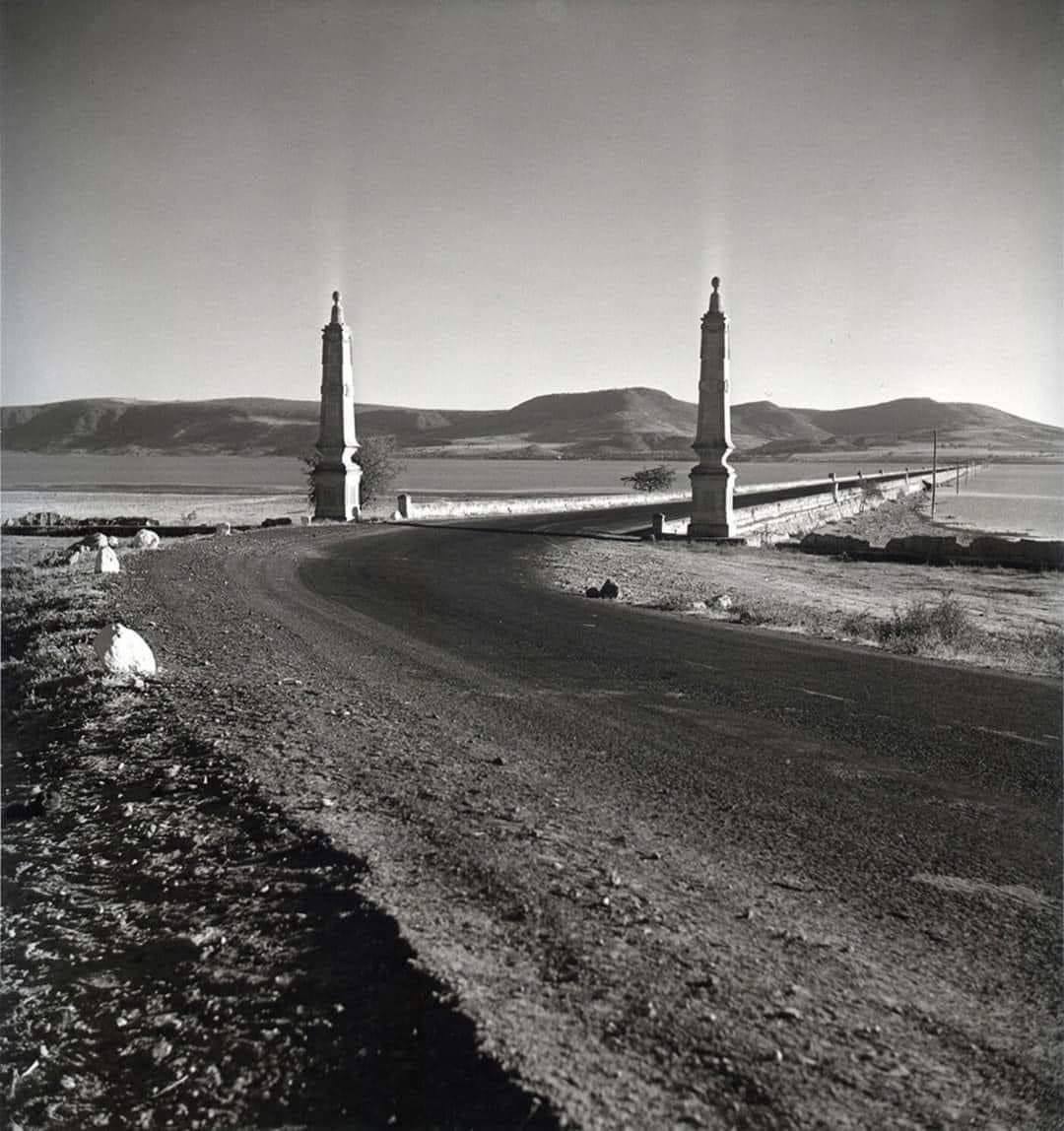

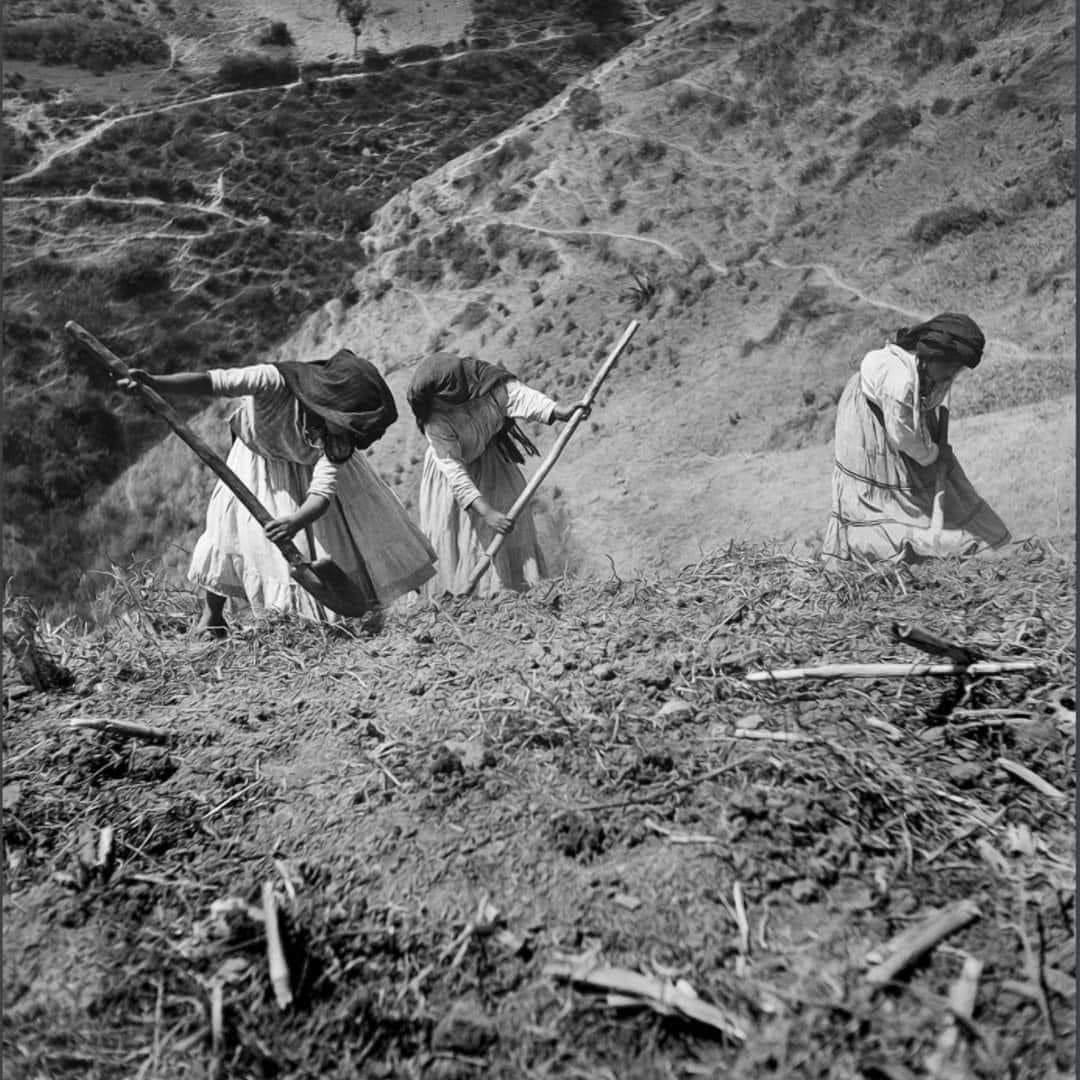

escritor, guionista y fotógrafo mexicano, perteneciente a la Generación

del 52.56 Es considerado uno de los escritores hispanoamericanos más

importantes del siglo xx.789 Su reputación se asienta en dos de sus

tres obras narrativas: el libro de cuentos El Llano en llamas,

publicado en 1953, y su novela Pedro Páramo, publicada en 1955.68 En sus obras se presenta una combinación de realidad y fantasía, cuya acción se desarrolla en escenarios rurales y posteriores a la Revolución Mexicana10 y a la Guerra cristera.6 Caracterizado como una leyenda de México, Rulfo se reconocía como un individuo introvertido, tímido y enigmático. Era silencioso, realista, celoso de su intimidad, crítico y creativo.11 Sus historias evidencian los aportes a la literatura hispanoamericana y mundial, en ellas muestra tradiciones cristianas e indígenas presentando diversas situaciones socioeconómicas de pueblos con carencias, falta de oportunidades, soledad, guerra, relación entre la naturaleza y el hombre, formas de composición humana, ejemplos de relaciones entre el hombre y el mundo, realidades concretas y medioambientales.6 Sus personajes representan y reflejan la tipicidad del lugar con sus grandes problemas socioculturales, enhebrados con un mundo quimérico.6 La obra de Rulfo, y sobre todo Pedro Páramo, es el parteaguas de la literatura mexicana que marca el fin de la novela revolucionaria, lo que permitió las experimentaciones narrativas, como es el caso de la generación de mediados del siglo xx en México o los escritores posteriores pertenecientes al boom latinoamericano.6 Es ampliamente considerado como padre del realismo mágico en la literatura. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_Rulfo |

フ

アン・ネポムセノ・カルロス・ペレス・ルルフォ・ビスカイノ(アプルコ、1917年5月16日-メキシコ・シティ、1986年1月7日)は、メキシコの作

家、脚本家、写真家で、52年世代に属する。 20世紀を代表するスペイン系アメリカ人作家の一人とされる。 1953年刊行の短編集『El

Llano en llamas』と、1955年刊行の小説『Pedro Páramo』の2作で知られる。 彼の作品は、現実とファンタジーを融合させたもので、メキシコ革命とクリステロ戦争の余波を受けた田園風景が舞台となっている。メキシコの伝説として知ら れるルルフォは、内向的で内気な謎めいた人物だった。寡黙で、現実的で、自分のプライバシーに嫉妬し、批判的で、創造的だった。 彼の物語は、キリスト教と土着の伝統を示し、不足、機会不足、孤独、戦争、自然と人間の関係、人間構成の形態、人間と世界の関係の例、具体的で環境的な現 実を持つ人々の多様な社会経済状況を提示し、ヒスパノ・アメリカ文学と世界文学に貢献した証拠である。 彼の登場人物は、キメラ的な世界に通された大きな社会文化的問題を持つこの土地の典型性を表し、反映している6。 ルルフォの作品、とりわけペドロ・パラモは、メキシコ文学における分水嶺であり、メキシコの20世紀半ばの世代や、ラテンアメリカ・ブームに属する後の作 家たちのように、物語の実験を可能にした革命小説の終焉を示すものである6。 |

フアン・ルルフォ(スペイン語: Juan Rulfo,

本名:フアン・ネポムセーノ・カルロス・ペレス=ルルフォ・ビスカイーノ、スペイン語: Juan Nepomuceno Carlos

Pérez-Rulfo Vizcaíno, 1917年5月16日[1] -

1986年1月7日)は、メキシコの小説家、写真家。ラテンアメリカの作家のなかでも重要な作家のひとりであるルルフォは、2冊の薄い本、『ペドロ・パラ

モ(Pedro Páramo)』(1955年)と短編集『燃える平原(El llano en

llamas)』(1953年。『殺さねえでくれ(¡Diles que no me

maten!)』を含む)によって評価されている。20世紀最高のスペイン語作家を選ぶアルファグアラ社の催した投票では、ホルヘ・ルイス・ボルヘスとと

もにルルフォも選ばれた。 フアン・ルルフォ(スペイン語: Juan Rulfo,

本名:フアン・ネポムセーノ・カルロス・ペレス=ルルフォ・ビスカイーノ、スペイン語: Juan Nepomuceno Carlos

Pérez-Rulfo Vizcaíno, 1917年5月16日[1] -

1986年1月7日)は、メキシコの小説家、写真家。ラテンアメリカの作家のなかでも重要な作家のひとりであるルルフォは、2冊の薄い本、『ペドロ・パラ

モ(Pedro Páramo)』(1955年)と短編集『燃える平原(El llano en

llamas)』(1953年。『殺さねえでくれ(¡Diles que no me

maten!)』を含む)によって評価されている。20世紀最高のスペイン語作家を選ぶアルファグアラ社の催した投票では、ホルヘ・ルイス・ボルヘスとと

もにルルフォも選ばれた。初期の人生 ルルフォは、ハリスコ州サユラ(Sayula)の父方の祖父の家で生まれた。1923年に父親が殺されたのに続き、1927年には母親も亡くなった。ルル フォは祖母に引き取られ、サン・ガブリエルで育った。地主だったルルフォの一族の財産は、メキシコ革命と1926年から1928年にかけてのクリステロ戦 争(Cristero War。クリステロス反乱ともいう。メキシコ革命後のメキシコ政府に対するローマ・カトリック教会Integralistの反乱)によって失われた。 1927年11月に母親が心臓発作で亡くなった時、ルルフォは10歳だった。その1年後には二人の叔父も亡くなり、ルルフォはルイス・シルバ学校に 1928年から1932年までいた。小学校の6年と特別の7年目を終えてから、簿記係の免許を得たが、その職業には一度も就かなかった。1932年から 1934年まで神学校(高等学校相当)に通い、大学にも進もうとしたが、グアダラハラ大学がストライキで封鎖されていたことと、予備校課程を取っていな かったことから断念した。その代わり、メキシコシティに行き、まず国立陸軍士官学校に3ヶ月在籍し、それからメキシコ国立自治大学で法律の勉強を希望し た。1936年、ルルフォは政府のために働く叔父ダビッド・ペレス・ルルフォを通じて出入国管理事務所の文書係に就職し、大学の文学課程を聴講できること ができた。 代表作 ルルフォは、同僚のエフレン・エルナンデスの指導で著作を始めた。1944年、文芸雑誌『パン(Pan)』」を共同で立ち上げた。出入国管理事務所のなか で昇進し、派遣員としてメキシコを旅した。1946年、出入国管理事務所を辞し、グッドリッチ・エウスカディの主任となった。ルルフォの穏やかな性格は、 卸売セールスマンに向いており、1952年に会社の車にラジオを欲したという理由でクビを切られるまで、南メキシコ中を旅して回った。 1948年4月、ルルフォは、グアダラハラでクララ・アパリシオと結婚した。ルルフォはロックフェラー財団が支援するCentro Mexicano de Escritoresの特別研究員となった。それで1952年から1954年にかけて、ルルフォの名を有名にする2冊の本を書くことができた。 最初の本は、苛酷な現実を描いた短編集『燃える平原』(1953年)で、メキシコ革命とクリステロス反乱の時代のメキシコの田舎にまつわる話を中心とした ものだった。この短編集のなかでとくに有名なものが、処刑されることになった老人が主人公の「殺さねえでくれ」と、傷ついた息子を背負って医者を探す男を 描いた「犬の声は聞こえんか(¿No oyes ladrar los perros?)」である。 二番目の本『ペドロ・パラモ』(1955年)は、短めの長編小説である。フアン・プレシアドという名前の男が、父親を探して、死んだ母親の故郷コマラに やってくる。そこは文字通りのゴーストタウンで、幽霊の住民が住んでいた。発表当時の反応は、冷ややかかつ批判的で、最初の4年間でわずか2000部しか 売れなかったが、その後高い評価を受けることになった。『ペドロ・パラモ』はガブリエル・ガルシア=マルケスなどラテンアメリカの作家たちに重大な影響を 与えた。 ガブリエル・ガルシア=マルケスは、最初の4冊の本を書いた後、小説家として八方ふさがりになったように感じ、1961年に『ペドロ・パラモ』を見つけ、 人生を変わったと述べている。ガブリエル=マルケスは、「(ルルフォの公刊されたすべては全部合わせても)合計300ページしかない。だが、それはソポク レスが我々に残したものとほぼ同じページ数で、やはりソポクレス同様に永遠に残るものと信じている」と語っている。  後期の生涯 2冊の本を出した後、ルルフォは、実質的に物語体のフィクションの執筆を辞めたものの、メキシコ文学界の主要人物であることに変わりはなかった。1956 年から、映画およびテレビの脚本を書き始めた。ルルフォが原案で、カルロス・フエンテスとガブリエル・ガルシア=マルケスが脚本を担当したメキシコ映画 『El gallo de oro(黄金の軍鶏)』[2]はそのなかでも最も有名な作品である。また、ガルシア=マルケス原作の『En este pueblo no hay ladrones(この村に泥棒はいない)』[3]では(ガルシア=マルケスと一緒に)役者として出演もしている。 生前に出版したものは僅かだったが、ルルフォは優れた写真家でもあった。1960年にはグアダラハラで作品を展示している。しかし、それ以降は、1980 年にルルフォの名声が高まって、ベジャス・アルテス宮殿で作品が展示されるまでなかった。現在、ルルフォ財団によって世界中で展示されたルルフォの写真の 本が多数ある。さらに、1962年から亡くなる年まで、ルルフォはメキシコの政府機関INI(国立先住民局、Instituto Nacional Indigenista)出版部のディレクターならびに編集長を勤めた。ルルフォの下でINIは当時のメキシコ先住民コミュニティの生活を記録した写真集 のシリーズを出版した。 1960年代にルルフォはハリスコ州でのクリステロス反乱を扱った『La cordillera(山脈)』というタイトルの2冊めの長編小説を書いていると語ったが、それは出版されることも誰かに見せることもなく破棄された。少 数のパッセージと全体のアウトラインだけが、死後出版されたルルフォのノートブックのなかに残っている。 1970年、ルルフォはメキシコ国民文学賞を受賞した。1980年には、メキシコ言語アカデミア(Academia Mexicana de la Lengua)会員に選ばれ、ベジャス・アルテス宮殿で讃えられた。1983年には、文学に対する貢献でアストゥリアス皇太子賞(Premios Príncipe de Asturias)を受賞した。 ヘビースモーカーだったルルフォは1986年、メキシコシティで肺癌で亡くなった。68歳。息子で映画監督のフアン・カルロス・ルルフォ(Juan Carlos Rulfo, 1964年 - )は1999年、亡き父親の思い出に映画『Del olvido al no me acuerdo』[4]を捧げた。 日本語訳 ペドロ・パラモ(訳:杉山晃、増田義郎。岩波文庫) 燃える平原(訳:杉山晃。書肆風の薔薇・叢書アンデスの風) |

|

| Juan Nepomuceno Carlos Pérez Rulfo Vizcaínonota

1(Apulco,34 16 de mayo de 1917-Ciudad de México, 7 de enero de 1986)

fue un escritor, guionista y fotógrafo mexicano, perteneciente a la

Generación del 52.56 Es considerado uno de los escritores

hispanoamericanos más importantes del siglo xx.789 Su reputación se

asienta en dos de sus tres obras narrativas: el libro de cuentos El

Llano en llamas, publicado en 1953, y su novela Pedro Páramo, publicada

en 1955.68 En sus obras se presenta una combinación de realidad y fantasía, cuya acción se desarrolla en escenarios rurales y posteriores a la Revolución Mexicana10 y a la Guerra cristera.6 Caracterizado como una leyenda de México, Rulfo se reconocía como un individuo introvertido, tímido y enigmático. Era silencioso, realista, celoso de su intimidad, crítico y creativo.11 Sus historias evidencian los aportes a la literatura hispanoamericana y mundial, en ellas muestra tradiciones cristianas e indígenas presentando diversas situaciones socioeconómicas de pueblos con carencias, falta de oportunidades, soledad, guerra, relación entre la naturaleza y el hombre, formas de composición humana, ejemplos de relaciones entre el hombre y el mundo, realidades concretas y medioambientales.6 Sus personajes representan y reflejan la tipicidad del lugar con sus grandes problemas socioculturales, enhebrados con un mundo quimérico.6 La obra de Rulfo, y sobre todo Pedro Páramo, es el parteaguas de la literatura mexicana que marca el fin de la novela revolucionaria, lo que permitió las experimentaciones narrativas, como es el caso de la generación de mediados del siglo xx en México o los escritores posteriores pertenecientes al boom latinoamericano.6 Es ampliamente considerado como padre del realismo mágico en la literatura. Biografía Primeros años y formación Juan Nepomuceno Carlos Pérez Rulfo Vizcaíno nació el 16 de mayo de 1917 en Apulco, estado de Jalisco, México.56 Fue hijo de Juan Nepomuceno Pérez Rulfo y de María Vizcaíno Arias de Pérez Rulfo.6 Rulfo contaba con seis años cuando, debido a la Guerra Cristera que sufrió México en la época, su padre fue asesinado por Guadalupe Nava Palacios en junio de 1923.6 Cuatro años más tarde, en noviembre de 1927, su madre falleció.68 En 1922 Rulfo inició sus estudios de primaria en el Colegio de las Josefinas.6 Sin embargo, en 1926 la Guerra Cristera causó el cese del colegio y que Rulfo fuese en 1927 al Colegio Luis Silva, en Guadalajara, por decisión de su tío, quien era su tutor por aquel entonces.6 En 1929 se trasladó a San Gabriel, donde vivió con su abuela. No obstante, posteriormente acabó en el orfanato Luis Silva (actualmente Instituto Luis Silva) en Guadalajara, del que no obtuvo muy buenos recuerdos y él mismo calificó como «correccional» en una entrevista de 1977.3 En 1930 participó en la revista México y en 1933 intentó ingresar a la Universidad de Guadalajara pero, al estar esta en huelga, optó por trasladarse a la Ciudad de México, donde asistió de oyente en el Colegio de San Ildefonso. En 1934 comenzó a escribir sus primeros trabajos literarios y a colaborar en la revista América.12 Asimismo, entre 1934 y 1938 Rulfo asistió a conferencias en la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de México en donde escuchó conferencias de, entre otros, los filósofos Antonio Caso y Eduardo García Máynez, el antropólogo y arqueólogo Alfonso Caso, el político Vicente Lombardo Toledano y del historiador del arte Justino Fernández.6 En 1937 Rulfo comenzó a trabajar en del Archivo para la Secretaría de Gobernación,6 y a su vez, forjó ese año una amistad con el poeta Efrén Hernández.6 A partir de 1938 viajó por algunas regiones de México en comisiones de servicio de la Secretaría de Gobernación, a la par que comenzó a publicar sus cuentos más relevantes en diversas revistas literarias. Desde 1941 Rulfo trabajó como agente de migración en Guadalajara;6 lugar en el que conoció y forjó amistad con el escritor Juan José Arreola.6 A partir de 1946 se dedicó, también, a la labor fotográfica, en la que realizó notables composiciones. Además, trabajó para la compañía Goodrich-Euzkadi de 1947 a 1952 como capataz, ahí al morir Don Ángel Urraza, Don Martin Oyamburu socio de la Euzkadi, al ver su capacidad escritora le encarga la revista mapa.6 En 1947 se casó con Clara Angelina Aparicio Reyes, a quien había conocido en 1944,6 y con quien tuvo cuatro hijos (Claudia Berenice, Juan Francisco, Juan Pablo y Juan Carlos). De 1954 a 1957 fue colaborador de la Comisión del Papaloapan y editor en el Instituto Nacional Indigenista en la Ciudad de México.13 Trayectoria literaria. El Llano en llamas.  Portada de Pedro Páramo. En 1945 Rulfo publicó, para la revista Pan de Guadalajara y la revista América, de México, el cuento «Nos han dado la tierra».6 Establecido ya definitivamente en Ciudad de México,6 en 1946 publicó su cuento «Macario» en la revistas Pan y América, y en 1947 su cuento «Es que somos muy pobres» en esta última revista.6 En 1948 publicó «La Cuesta de las Comadres» y en 1950 «Talpa» y «El Llano en llamas». En 1951 la revista América publicó su cuento «¡Diles que no me maten!». Dos años más tarde, en 1953, Rulfo publicó el libro de cuentos El Llano en llamas en la colección Letras Mexicanas del Fondo de Cultura Económica.8 Este incluía quince relatos de los cuales algunos ya habían sido editados previamente en distintas revistas.8 Entre 1952 y 1954, el escritor fue becario del Centro Mexicano de Escritores, en donde, durante su segundo año como becado, concluyó y leyó fragmentos de su primera novela, Pedro Páramo.6 La misma, había sido mencionada a su esposa Clara Angelina Aparicio Reyes entre febrero y marzo de 1947, afirmando Rulfo que tenía en mente publicarla y mencionándole un posible título:6 No he hecho sino leer un poquito y querer escribir algo que no se ha podido y que si lo llego a escribir se llamará Una estrella junto a la luna. Entre septiembre de 1953 y 1954, Rulfo ya había entregado el manuscrito original de la novela al Fondo de Cultura Económica y había empezado a publicar adelantos de la misma en tres revistas distintas de Ciudad de México (respectivamente Las Letras Patrias, Universidad de México y Dintel).6 En esta primera revista, el título de la novela era Una estrella junto a la luna, en la segunda, Los murmullos y en la tercera, los fragmentos mostrados se encontraban bajo el título de Comala.6 Finalmente, Rulfo publicó Pedro Páramo en 1955.6 Esta fue un éxito en la carrera literaria del escritor, y le valió numerosas reseñas positivas (entre otras, por las revistas México en la Cultura y Universidad de México).6 El escritor Carlos Blanco Aguinaga publicó en la Revista Mexicana de Literatura (fundada por los también escritores Carlos Fuentes y Emmanuel Carballo) tras la publicación de la obra un texto en donde ya se empezó a hablar «del estilo de Rulfo».6 Además, Carlos Fuentes publicó un corto ensayo de la novela en la revista francesa L’Esprit des Lettres y la misma ganó el mismo año de su publicación el Premio Xavier Villaurrutia.614 La novela, además, fue muy estimada por autores como Jorge Luis Borges, quien dijo de esta: "Pedro Páramo es una de las mejores novelas de las literaturas de lengua hispánica, y aun de toda la literatura".15 Gabriel García Márquez por su parte, escribió lo siguiente al recordar su primera lectura de la novela: "Álvaro Mutis subió a grandes zancadas los siete pisos de mi casa con un paquete de libros, separó del montón el más pequeño y corto, y me dijo muerto de risa: ¡Lea esa vaina, carajo, para que aprenda! Era Pedro Páramo. Aquella noche no pude dormir mientras no terminé la segunda lectura. Nunca, desde la noche tremenda en que leí la Metamorfosis de Kafka en una lúgubre pensión de estudiantes de Bogotá —casi diez años atrás— había sufrido una conmoción semejante. Al día siguiente leí El llano en llamas, y el asombro permaneció intacto." 16 A su vez, la escritora estadounidense Susan Sontag manifestó de Pedro Páramo que: "La novela de Rulfo no es sólo una de las obras maestras de la literatura mundial del siglo XX, sino uno de los libros más influyentes de este mismo siglo."17 Entre 1956 y 1958, Rulfo escribió su segunda novela, El gallo de oro.18 De esta, el escritor relató:8 Antes de que pasara a la imprenta un productor cinematográfico se interesó en ella, desglosándola para adaptarla al cine. Dicha obra, al igual que las anteriores, no estaba escrita con esa finalidad. En resumen, no regresó a mis manos sino como script y ya no me fue fácil reconstruirla. La misma sirvió como base a Gabriel García Marquéz y Carlos Fuentes para el guion de la película homónima de Roberto Gavaldón estrenada en 1964.19 La novela no fue publicada sino hasta 1980 tras la insistencia de amigos de Rulfo,8 en una edición descuidada.18 La edición de 2010 corrigió muchos errores,20 y actualmente existen traducciones de esta al alemán, italiano, francés y portugués.20 Labor como historiador, fotógrafo y guionista de cine Una faceta poco conocida de Rulfo fue la de historiador. En este rubro Rulfo escribió un libro acerca de la conquista y colonización de Nueva Galicia, hoy Jalisco. Este fue un libro poco conocido, debido a que fue distribuido de manera gratuita entre los clientes de una compañía privada de Guadalajara. Rulfo además argumentaba que es necesario conocer nuestro pasado para trabajar en favor del lugar del que somos originarios: Una persona que conoce su pasado confía más en su trabajo y tiene conciencia del lugar donde vive y tiene el valor suficiente para saber defenderlo y poder trabajar con entusiasmo y con amor al lugar donde nació.21 Como fotógrafo, Rulfo dejó un legado de más de 6,000 mil negativos.22 Sumado a lo anterior, publicó un libro con una selección de 100 fotografías. La editorial RM, dedicada principalmente a la fotografía y al arte contemporáneo, publicó varios libros de fotografías de Rulfo; imágenes en las que el artista capturó edificios, paisajes y pueblos pequeños, así como artistas, escritores, amigos y familiares. En 1956, el director de cine Emilio «el Indio» Fernández le solicitó a Rulfo guiones para cine. El escritor, en colaboración con Juan José Arreola, realizó algunos de ellos. Últimos años y fallecimiento Después de haber concluido sus dos obras, Rulfo abandonó la escritura de libros. En marzo de 1974, durante un diálogo estudiantil en la Universidad Central de Venezuela, justificó ese abandono por la muerte de su tío Celerino, quien «le platicaba todo». El tío Celerino existió realmente y, con él, Rulfo recorrió muchos pueblos y escuchó sus historias, las cuales eran consideradas por él como fantasiosas.23 El escritor Enrique Vila-Matas, en su libro Bartleby y compañía, describió esta justificación por parte de Rulfo como una de las más creativas que haya conocido.24 Para el escritor César Leante, Rulfo quiso evitar la repetición de evocar la crueldad y el dolor expresados en El Llano en llamas y Pedro Páramo.25 La esencia de la explicación de Leante se asemeja a la declaración de Rulfo acerca de que, al escribir Pedro Páramo, pensaba frecuentemente en salir de la ansiedad, porque la escritura lo llevaba al sufrimiento.26 En 1974 Rulfo viajó a Europa para participar en el Congreso de Estudiantes de la Universidad de Varsovia. Fue invitado a integrarse a la comitiva presidencial viajando por Alemania, Checoslovaquia, Austria y Francia. El 9 de julio de 1976 fue elegido miembro de la Academia Mexicana de la Lengua y tomó posesión de la silla XXXV el 25 de septiembre de 1980.27 Rulfo falleció la tarde del 7 de enero de 1986, a causa de un cáncer de pulmón. Su fallecimiento conmocionó a la comunidad cultural de México. Juan José Arreola, tras su muerte, expresó que la obra de Rulfo era la más notable realización del impulso de un pueblo: No puedo creerlo; no puedo decir que esté muerto. Él no ha muerto; ha nacido con todos los que amamos la literatura; no creo en las letras universales, creo en las letras de Sayula; su obra es la más notable realización del impulso de un pueblo. Rulfo consagró la voz de la tierra. Nadie puede continuar su obra, ni él mismo se atrevió a hacerlo.28 El escritor y periodista mexicano Carlos Monsiváis, por su parte, escribió acerca de su admiración por Rulfo: Ya no se escucha sino el silencio de las soledades. Admirar profundamente a un gran narrador es todavía un lujo a nuestro alcance.28 |

フアン・ネポムセノ・カルロス・ペレス・ルルフォ・ビスカジノタ1世(アプルコ、1917年5月16日-メキシコ・シティ、1986年1月7日)はメキシコの作家、脚本家、写真家で、52年世代の一員である56。 メキシコの伝説として知られるルルフォは、自らを内向的で内気な謎めいた人物と認識していた。彼は寡黙で、現実的で、親密であることに嫉妬し、批判的で創造的だった11。 ルルフォの物語は、彼がスペイン系アメリカ人および世界文学に貢献した証拠であり、キリスト教と先住民族の伝統を示し、不足、機会不足、孤独、戦争、自然 と人間の関係、人間構成の形態、人間と世界の関係の例、具体的で環境的な現実など、多様な社会経済状況を提示している6。 ルルフォの作品、とりわけペドロ・パラモは、メキシコ文学の分水嶺であり、20世紀半ばのメキシコの世代やラテンアメリカのブームに属する後期の作家たち のように、物語の実験を可能にした革命的小説の終焉を示すものである6。 略歴 生い立ちと修業時代 1917年5月16日、メキシコのハリスコ州アプルコでフアン・ネポムセノ・ペレス・ルルフォとマリア・ビスカイアス・デ・ペレス・ルルフォの息子として 生まれる6。ルルフォが6歳のとき、当時メキシコが苦しんでいたクリステロ戦争により、1923年6月に父親がグアダルーペ・ナバ・パラシオスに殺される 6。 1922年、ルルフォはコレヒオ・デ・ラス・ホセフィナスで小学校の勉強を始めたが6、1926年のクリステロ戦争で学校は閉鎖され、ルルフォは1927 年、当時家庭教師をしていた叔父の意向でグアダラハラのコレヒオ・ルイス・シルバに進学した6。1930年には雑誌『メヒコ』に参加し、1933年にはグ アダラハラ大学に入学しようとしたが、大学がストライキ中であったため、メキシコシティに移り、サン・イルデフォンソ大学に入学した。1934年から 1938年にかけて、ルルフォはメキシコシティの哲学・文字学部の講義にも出席し、哲学者のアントニオ・カソやエドゥアルド・ガルシア・マイネス、人類学 者で考古学者のアルフォンソ・カソ、政治家のビセンテ・ロンバルド・トレダーノ、美術史家のフスティーノ・フェルナンデスらの講義を聴いた6。 1938年以降、ルルフォは行政長官の依頼でメキシコのいくつかの地方を旅行し、同時にさまざまな文芸誌に代表的な短編小説を発表し始める。1941年以 降、ルルフォはグアダラハラで移住斡旋業を営み6、そこで作家フアン・ホセ・アレオラと知り合い、友人となった。1947年には、1944年に知り合った クララ・アンジェリーナ・アパリシオ・レイエスと結婚し6、4人の子供(クラウディア・ベレニス、ファン・フランシスコ、ファン・パブロ、ファン・カルロ ス)をもうけた。1954年から1957年まで、パパロアパン委員会の協力者であり、メキシコ・シティのインスティトゥート・ナシオナル・インディヘニス タの編集者でもあった13。 文学の軌跡 El Llano en llamas.  ペドロ・パラモの表紙。 1945年、ルルフォはグアダラハラの雑誌『パン』とメキシコの雑誌『アメリカ』に短編小説『Nos han dado la tierra』を発表した6。1946年、メキシコ・シティに定住すると、雑誌『パン』と『アメリカ』に短編小説『マカリオ』を、1947年には後者の雑 誌に短編小説『Es que somos muy pobres』を発表した6。1951年、『アメリカ』誌に短編小説 「Diles que no me maten 」を発表する! 2年後の1953年、ルルフォは短編集『El Llano en llamas』をFondo de Cultura EconómicaのLetras Mexicanasコレクションに掲載した8。 1952年から1954年にかけて、作家はメキシコ作家センター(Centro Mexicano de Escritores)の奨学生となり、奨学生としての2年目に処女作『ペドロ・パラモ(Pedro Páramo)』6を完成させ、その断片を読んだ。 私は少し本を読んだだけで、何か書きたいと思ったが、それは不可能だった。 1953年9月から1954年にかけて、ルルフォはすでに小説の原稿を経済文化基金に提出し、メキシコシティの3つの異なる雑誌(それぞれ、Las Letras Patrias、Universidad de México、Dintel)にプレビューを掲載し始めていた6 。 1955年、ルルフォはついに『ペドロ・パラモ』を出版した6。この作品はルルフォの文学者としてのキャリアにおいて成功を収め、多くの好意的な批評を得 た(雑誌『México en la Cultura』や『Universidad de México』など)。 6 作家カルロス・ブランコ・アギナガは、この作品の出版後、Revista Mexicana de Literatura(仲間の作家カルロス・フエンテスとエマニュエル・カルバロが設立)に文章を発表し、その中で「ルルフォのスタイル」について語り始 めた6。さらに、カルロス・フエンテスはフランスの雑誌『L'Esprit des Lettres』にこの小説に関する短いエッセイを発表し、この小説は出版された年にザビエル・ビジャウルティア賞を受賞した6。 14 この小説は、ホルヘ・ルイス・ボルヘスなどの作家からも高く評価された: 「ペドロ・パラモはスペイン文学の、いや、すべての文学のなかでも最高の小説のひとつだ」15。 ガブリエル・ガルシア・マルケス(Gabriel García Márquez)は、この小説を初めて読んだときのことを思い出して、次のように書いている: 「アルバロ・ムティスは、私の家の7階から本の束を持って這い上がってきて、本の山から一番小さくて短い本を取り出して、私に言った!ペドロ・パラモだっ た。その夜、私は2冊目を読み終えるまで眠れなかった。ボゴタの薄汚い学生寮でカフカの『変身』を読んだ恐ろしい夜以来、つまり10年近く前だが、これほ どの衝撃を受けたことはなかった。翌日、『燃える平原』を読んだが、驚きはそのままだった」。16 一方、アメリカの作家スーザン・ソンタグはペドロ・パラモについて次のように述べている: 「ルルフォの小説は、20世紀の世界文学の傑作のひとつであるだけでなく、20世紀で最も影響力のある本のひとつである」17。 1956年から1958年にかけて、ルルフォは2作目の小説『金のコケッコー(El gallo de oro)』を書いた18。 この小説について、作家は次のように語っている。この作品は、前の作品と同様、そのために書かれたのではない。要するに、脚本として私の手元に戻ってきただけで、それを再構成するのは容易ではなかった。 ガブリエル・ガルシア・マルケスとカルロス・フエンテスが、ロベルト・ガバルドン監督による1964年の同名映画の脚本を執筆する際の下敷きとなった。 歴史家、写真家、映画脚本家としての仕事 ルルフォの仕事であまり知られていないのは、歴史家としての仕事である。この分野で、ルルフォはヌエバ・ガリシア(現在のハリスコ州)の征服と植民地化に ついての本を書いた。この本は、グアダラハラの民間会社の顧客に無料で配布されたため、あまり知られていなかった。ルルフォはまた、自分の出身地のために 働くためには、自分の過去を知ることが必要だと主張した: 自分の過去を知っている人は、自分の仕事に自信が持てるし、自分が住んでいる場所を意識し、その場所を守る方法を知る勇気がある。 写真家として、ルルフォは6,000,000枚以上のネガを残した22。写真と現代美術を専門とする出版社RMは、ルルフォの写真集を数冊出版した。ルルフォは、建物、風景、小さな町、芸術家、作家、友人、親族を撮影した写真で構成されている。 1956年、映画監督のエミリオ・「エル・インディオ」・フェルナンデスがルルフォに映画の脚本を依頼した。ルルフォは、フアン・ホセ・アレオラと共同で、そのうちのいくつかを制作した。 晩年と死 2つの作品を書き上げた後、ルルフォは本を書くことをやめた。1974年3月、ベネズエラ中央大学での学生対談の中で、彼はこの断筆を「すべてを話してく れた」叔父セレリーノの死によって正当化した。セレリーノ叔父は本当に存在し、ルルフォは叔父と一緒に多くの村を旅し、空想的と思われる叔父の話に耳を傾 けた23。 作家のエンリケ・ビラ=マタスは、その著書『バートルビーと仲間たち』の中で、ルルフォ側のこの正当化を、彼が知る限り最も創造的なもののひとつと評して いる24。作家のセサル・レアンテにとって、ルルフォは『エル・ラノ・エン・リャマ』と『ペドロ・パラモ』で表現された残酷さと苦痛を呼び起こすことの繰 り返しを避けたかったのだ25。 1974年、ルルフォはワルシャワ大学の学生大会に参加するためにヨーロッパを訪れた。ルルフォは、ドイツ、チェコスロバキア、オーストリア、フランスを 歴訪する大統領一行に招待された。1976年7月9日、メキシコ言語アカデミーの会員に選出され、1980年9月25日にXXXVの議長に就任した27。 ルルフォは1986年1月7日夜、肺がんのため死去した。彼の死はメキシコの文化界に衝撃を与えた。 フアン・ホセ・アレオラは死後、ルルフォの作品は民族の衝動を最も顕著に実現したものだと語った: 信じられない。彼が死んだとは言えない。私は普遍的な文学を信じているのではなく、サユラの文学を信じているのだ。ルルフォは大地の声を聖別した。ルルフォは大地の声を聖別したのだ。誰も彼の仕事を引き継ぐことはできない。 メキシコの作家でジャーナリストのカルロス・モンシバイスは、ルルフォへの賞賛をこう記している: もはや孤独の沈黙しか聞こえない。偉大なストーリーテラーを深く賞賛することは、まだ手の届く贅沢なことなのだ28。 |

| Estilo En la narrativa de Rulfo los personajes apenas actúan. Ellos fundamentalmente piensan, recuerdan y transmiten sus miedos, sus odios y sus remordimientos, mueren y vuelven a morir. De este modo, se podría calificar a la narrativa de Rulfo como una narrativa de «conciencia», en un sentido no oficial. Los ambientes y los mismos personajes carecen de toda ubicación y rostro, pero no por eso parecen ser menos reales. Esto último se debe a la recreación de personajes como si fueran «gente común y corriente que no tiene nada especial».3 Así, la magnificencia de estos recae en el lector por la historia de violencia que guardan tras de sí. En el fondo de la creación literaria de Rulfo se encuentra la Revolución Mexicana y la Revolución Cristera, así como sus consecuencias. El campo mexicano descrito en su obra continúa con el problema del latifundismo, a pesar de las reformas de Lázaro Cárdenas; la Revolución no consiguió que el latifundismo mexicano se extinguiera. Rulfo reflejó en su obra la frustración de los campesinos y la soledad absoluta a la que se enfrentan los pueblos. Esta mencionada soledad en la obra de Rulfo no es más que resultado de la Revolución, al menos desde el punto de vista del escritor. También puede observarse como tema principal en la obra de Rulfo la relación padre-hijo. Ambas revoluciones provocaron la destrucción de familias y dejaron a su paso muchos hijos en situación de orfandad (el propio Rulfo es un ejemplo de esto). Además, la estructura latifundista multiplicó la descendencia ilegítima:29 El caso es que nuestras madres nos malparieron en un petate aunque éramos hijos de Pedro Páramo. Y lo más chistoso es que él nos llevó a bautizar. Con usted debe haber pasado lo mismo, ¿no? La figura del padre es un eje principal en la creación literaria de Rulfo. Por un lado se le ve como una nostalgia y, por otro, como una presencia odiada. La muerte es otro de los temas a destacar en la obra de Rulfo. Esta casi nunca es narrada de una manera brutal, sino que procura una «estilización» en su tratamiento, basada fundamentalmente en el uso de la metáfora y la comparación. En pasajes de la novela Pedro Páramo de Rulfo resulta notoria la influencia del novelista estadounidense William Faulkner, según comentó el filólogo examigo de Rulfo Antonio Alatorre, en entrevista que a este último le hicieron redactores del diario mexicano El Universal en noviembre de 1998, que fue publicada el 31 de octubre de 2010.30 |

スタイル ルルフォの物語では、登場人物はほとんど行動しない。彼らは基本的に考え、恐怖、憎しみ、自責の念を思い出し、伝え、死に、また死ぬ。このように、ルル フォの物語は、非公式な意味での「良心」の物語と言える。環境と登場人物自体には場所も顔もないが、それゆえに現実味がないわけではない。後者は、登場人 物をあたかも「特別なものを持たない普通の人」であるかのように再現しているためである3。このように、彼らの壮大さが読者に迫ってくるのは、彼らの背後 に横たわる暴力の歴史があるからである。 ルルフォの創作の背景には、メキシコ革命とクリステロ革命、そしてその結末がある。彼の作品に描かれたメキシコの田舎は、ラサロ・カルデナスの改革にもか かわらず、ラティフンディスモの問題に悩まされ続けている。革命はメキシコのラティフンディスモを消滅させることに成功しなかった。ルルフォは、農民のフ ラストレーションと、人々が直面する絶対的な孤独を作品に反映させた。ルルフォの作品におけるこの孤独は、少なくとも作家の視点から見れば、革命の結果に ほかならない。 父と息子の関係もまた、ルルフォの作品の主要なテーマとして見ることができる。どちらの革命も家族の破壊をもたらし、その影響で多くの子供たちが孤児となった(ルルフォ自身がその例である)。さらに、ラティフンディスタの構造は非嫡出子を増やした29。 ペドロ・パラモの子供であるにもかかわらず、私たちの母親は私たちを子宮に入れた。そして一番おかしいのは、彼が洗礼を受けるために私たちを連れて行ったことだ。あなたも同じだったに違いない。 父親という存在は、ルルフォの文学創作における主要な軸である。一方ではノスタルジアとして、他方では憎むべき存在として見られる。 死はルルフォの作品のもう一つのテーマである。死が残酷に語られることはほとんどなく、むしろ比喩と比較の使用に基づいた「様式化」に努めている。 ルルフォの友人で言語学者であるアントニオ・アラトーレが、1998年11月にメキシコの新聞『エル・ユニバーサル』の編集者に行ったルルフォへのインタビュー(2010年10月31日付)で語っている30。 |

| Obras Cuentos 1953: El llano en llamas Novelas 1955: Pedro Páramo 1980: El gallo de oro Otros 1984: Dónde quedó nuestra historia. Hipótesis sobre historia regional31 1995: Los cuadernos de Juan Rulfo32 2000: Aire de las colinas. Cartas a Clara33 2010: 100 fotografías de Juan Rulfo34 2022: Una mentira que dice la verdad35 |

作品紹介 短編小説 1953年:エル・リャーノ・エン・リャマス 小説 1955年:ペドロ・パラモ 1980年:金色のコケッコー その他 1984年:我々の歴史はどこにあるのか?地域史に関する仮説31 1995年:フアン・ルルフォのノート32 2000: コリーナの空気。クララへの手紙33 2010年:フアン・ルルフォの写真100点34 2022年:真実を語る嘘35 |

Sobre Rulfo Busto de Rulfo en el Parque Juan Rulfo en Ciudad de México.  Casa de Cultura Juan Rulfo. Filmografía Cine 1960: El despojo (cortometraje de Antonio Reynoso basado en una idea de Rulfo) 1964: El gallo de oro (película dirigida por Roberto Gavaldón y adaptada al cine por Carlos Fuentes y Gabriel García Márquez)3637 1965: La fórmula secreta (película dirigida por Rubén Gámez basada en El gallo de oro)18 1972: El Rincón de las Vírgenes (película dirigida por Alberto Isaac la cual adapta los cuentos Anacleto Morones y El día del derrumbe) 1985: Diles que no me maten (película venezolana dirigida por Freddy Siso, adaptación del cuento homónimo incluido en El llano en llamas) 1986: El imperio de la fortuna (película dirigida por Arturo Ripstein basada en El gallo de oro)18 2008: Purgatorio (película dirigida por Roberto Rochín basada en los relatos Paso del Norte, Pedazo de noche y Cleotilde) Televisión 1982: El gallo de oro (telenovela colombiana de la productora RTI protagonizada por Frank Ramírez y Amparo Grisales basada en la novela homónima) 2000: La caponera (telenovela colombiana de la productora RTI basada en El gallo de oro para Caracol Televisión) Bibliografía 1990: El sonido en Rulfo (Julio Estrada) 1993: Los caminos de la creación en Juan Rulfo (Sergio López Mena) 1998: Revisión crítica de la obra de Juan Rulfo (Sergio López Mena) 1996: Juan Rulfo. Toda la obra (edición por Claude Fell) 2004: Noticias sobre Juan Rulfo, 1784- 2003 (Alberto Vital Díaz) 2007: Juan Rulfo. El regreso al paraíso (Fernando Barrientos del Monte) 2017: Noticias sobre Juan Rulfo. La biografía (Alberto Vital) Fotografía 2002: Juan Rulfo. Letras e imágenes (edición por Víctor Jiménez) 2006: Tríptico para Juan Rulfo (Víctor Jiménez) 2010: 100 fotografías de Juan Rulfo (edición por Andrew Dempsey) |

ルルフォについて メキシコシティのフアン・ルルフォ公園にあるルルフォの胸像。  フアン・ルルフォ文化の家 フィルモグラフィ 映画 1960: El despojo(ルルフォのアイデアを基にしたアントニオ・レイノソ監督の短編映画)。 1964: El gallo de oro(ロベルト・ガバルドン監督作品、カルロス・フエンテスとガブリエル・ガルシア・マルケスが映画化)3637 1965年:秘密の腕(El gallo de oroを基にしたルベン・ガメス監督作品)18 1972: El Rincón de las Vírgenes(短編小説Anacleto MoronesとEl día del derrumbeを映画化したアルベルト・イサク監督作品) 1985:Diles que no me maten(ベネズエラ映画、フレディ・シソ監督、『El llano en llamas』に収録された同名の物語の映画化) 1986年:El imperio de la fortuna(アルトゥーロ・リプスタイン監督作品、原作はEl gallo de oro)18 2008: Purgatorio(短編『Paso del Norte』、『Pedazo de noche』、『Cleotilde』を基にしたロベルト・ロチン監督作品)。 テレビ 1982: El gallo de oro(フランク・ラミレスとアンパロ・グリサレス主演、同名小説を基にしたRTI社によるコロンビアのテレビドラマ) 2000: La caponera(『El gallo de oro』を原作としたRTI社によるコロンビアのテレノベラ、Caracol Televisiónで放映) 参考文献 1990: ルルフォの音(フリオ・エストラーダ) 1993: フアン・ルルフォにおける創造の道(セルヒオ・ロペス・メナ) 1998: フアン・ルルフォの批評(セルヒオ・ロペス・メナ) 1996: フアン・ルルフォ。Toda la obra(クロード・フェル版) 2004: Juan Rulfo, 1784- 2003のノート(アルベルト・ビタル・ディアス著) 2007: フアン・ルルフォ。楽園への帰還(フェルナンド・バリエントス・デル・モンテ) 2017年:フアン・ルルフォに関するニュース。伝記(アルベルト・ビタール) 写真 2002年:フアン・ルルフォ。手紙と写真(ビクトル・ヒメネス版) 2006: フアン・ルルフォのためのトリプティク(ビクトル・ヒメネス版) 2010年:フアン・ルルフォの写真100点(アンドリュー・デンプシー編) |

| Premios, becas y reconocimientos 1952: Beca del Centro Mexicano de Escritores8 1955: Premio Xavier Villaurrutia por Pedro Páramo14 1970: Premio Nacional de Literatura38 1980: Año Rulfo por el Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes. 1983: Premio Príncipe de Asturias de las Letras (1983)39 1985: Doctor honoris causa por la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México40 |

賞、奨学金、受賞歴 1952年:メキシコ作家センターより奨学金8 1955年:ペドロ・パラモにザビエル・ビジャウルティア賞14 1970年:国民文学賞38 1980年:ルルフォ・イヤー、国立芸術学院(Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes)より授与される。 1983年:アストゥリアス皇太子文学賞39 1985年:メキシコ国立自治大学より名誉博士号を授与される40。 |

| https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_Rulfo |

|

Del

olvido Al No Me Acuerdo Película Documental Completa Juan Carlos Rulfo

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

|

4 |

|

5 |

|

6 |

|

7 |

|

8 |

|

9 |

|

10 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆