ペラギウス主義

Pelagianism

☆

ペラギウス主義(Pelagianism)とは、人間の堕落が人間の本性を汚さず、神の恩寵によって人間は自由意志を持ち、人間の完全性を達成できるとするキリスト教神学の立場であ

る。ブリテン諸島の禁欲主義者かつ哲学者ペラギウス(紀元355年頃 -

420年頃)は、神は信者に不可能なことを命じることはできず、したがって全ての神の戒めを満たすことは可能でなければならないと教えた。また、他人の罪

のために人を罰するのは不当だとし、したがって幼児は無垢な状態で生まれると説いた。ペラギウスは罪深い行為に対する言い訳を一切認めず、すべてのキリス

ト教徒は、その社会的地位に関わらず、非の打ちどころのない罪のない生活を送るべきだと教えた。

「ペラギウス主義」は、その対抗者であるアウグスティヌスによって大きく定義づけられ、正確な定義は今なお曖昧なままである。ペラギウス主義は当時のキリ

スト教世界、特にローマのエリート層や修道僧の間でかなりの支持を得ていたが、恩寵、予定説、自由意志について対立する見解を持つアウグスティヌスとその

支持者たちから攻撃を受けた。ペラギウス論争ではアウグスティヌスが勝利を収めた。ペラギウス主義は418年のカルタゴ公会議で断固として非難され、ロー

マ・カトリック教会と東方正教会によって異端と見なされている。その後何世紀にもわたり、「ペラギウス主義」は様々な形で、正統的でない信念を持つキリス

ト教徒に対する異端の非難として用いられてきた。しかし、神学と宗教研究の両分野における近年の学術研究は、ペラギウスの信念が、彼の反対者や現代の主流

派キリスト教徒の信念とどれほど大きく異なっていたのかについて疑問を投げかけている。

| Pelagianism is a

Christian theological position that holds that the fall did not taint

human nature and that humans by divine grace have free will to achieve

human perfection. Pelagius (c. 355 – c. 420 AD), an ascetic and

philosopher from the British Isles, taught that God could not command

believers to do the impossible, and therefore it must be possible to

satisfy all divine commandments. He also taught that it was unjust to

punish one person for the sins of another; therefore, infants are born

blameless. Pelagius accepted no excuse for sinful behaviour and taught

that all Christians, regardless of their station in life, should live

unimpeachable, sinless lives. To a large degree, "Pelagianism" was defined by its opponent Augustine, and exact definitions remain elusive. Although Pelagianism had considerable support in the contemporary Christian world, especially among the Roman elite and monks, it was attacked by Augustine and his supporters, who had opposing views on grace, predestination and free will. Augustine proved victorious in the Pelagian controversy; Pelagianism was decisively condemned at the 418 Council of Carthage and is regarded as heretical by the Roman Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox Church. For centuries afterward, "Pelagianism" was used in various forms as an accusation of heresy for Christians who hold unorthodox beliefs. However, more recent scholarship in both theology and religious studies has questioned how strongly Pelagius's beliefs differed from those of his opponents and from modern mainstream Christians. |

ペラギウス主義とは、人間の堕落が人間の本性を汚さず、神の恩寵によっ

て人間は自由意志を持ち、人間の完全性を達成できるとするキリスト教神学の立場である。ブリテン諸島の禁欲主義者かつ哲学者ペラギウス(紀元355年頃

-

420年頃)は、神は信者に不可能なことを命じることはできず、したがって全ての神の戒めを満たすことは可能でなければならないと教えた。また、他人の罪

のために人を罰するのは不当だとし、したがって幼児は無垢な状態で生まれると説いた。ペラギウスは罪深い行為に対する言い訳を一切認めず、すべてのキリス

ト教徒は、その社会的地位に関わらず、非の打ちどころのない罪のない生活を送るべきだと教えた。 「ペラギウス主義」は、その対抗者であるアウグスティヌスによって大きく定義づけられ、正確な定義は今なお曖昧なままである。ペラギウス主義は当時のキリ スト教世界、特にローマのエリート層や修道僧の間でかなりの支持を得ていたが、恩 寵、予定説、自由意志(grace, predestination and free will)について対立する見解を持つアウグス ティヌスとその 支持者たちから攻撃を受けた。ペラギウス論争ではアウグスティヌスが勝利を収めた。ペラギウス主義は418年のカルタゴ公会議で断固として非難され、ロー マ・カトリック教会と東方正教会によって異端と見なされている。その後何世紀にもわたり、「ペラギウス主義」は様々な形で、正統的でない信念を持つキリス ト教徒に対する異端の非難として用いられてきた。しかし、神学と宗教研究の両分野における近年の学術研究は、ペラギウスの信念が、彼の反対者や現代の主流 派キリスト教徒の信念とどれほど大きく異なっていたのかについて疑問を投げかけている。 |

| Background Main article: Christianity in late antiquity Further information: Christianity in the 4th century and Christianity in the 5th century During the fourth and fifth centuries, the Church was experiencing rapid change due to the Constantinian shift to Christianity.[1] Many Romans were converting to Christianity, but they did not necessarily follow the faith strictly.[2] As Christians were no longer persecuted, they faced a new problem: how to avoid backsliding and nominal adherence to the state religion while retaining the sense of urgency originally caused by persecution. For many, the solution was adopting Christian asceticism.[1] Early Christianity was theologically diverse. While Western Christianity taught that the inevitability of death was the result of the fall of man, a Syrian tradition subscribed to by the second-century figures Theophilus and Irenaeus asserted that mortality preceded the fall. Around 400, the doctrine of original sin was just emerging in Western Christianity, deriving from the teaching of Cyprian that infants should be baptized for the sin of Adam. Other Christians followed Origen in the belief that infants are born in sin due to their failings in a previous life. Rufinus the Syrian, who came to Rome in 399 as a delegate for Jerome, followed the Syrian tradition, declaring that man had been created mortal and that each human is only punished for his own sin.[3] Pelagius (c. 355 – c. 420)[4] was an ascetic layman, probably from the British Isles, who moved to Rome in the early 380s.[5][6] Like Jerome, Pelagius criticized what he saw as an increasing laxity among Christians, instead promoting higher moral standards and asceticism.[4][7][6] He opposed Manicheanism because of its fatalism and determinism[1] and argued for the possibility of a sinless life.[8] Although Pelagius preached the renunciation of earthly wealth,[9] his ideas became popular among parts of the Roman elite.[5][7][1] Historian Peter Brown argued that Pelagianism appealed "to a powerful centrifugal tendency in the aristocracy of Rome—a tendency to scatter, to form a pattern of little groups, each striving to be an elite, each anxious to rise above their neighbours and rivals—the average upper‐class residents of Rome."[10] The powerful Roman administrator Paulinus of Nola was close to Pelagius and the Pelagian writer Julian of Eclanum,[11] and the former Roman aristocrat Caelestius was described by Gerald Bonner as "the real apostle of the so-called Pelagian movement".[8] Many of the ideas Pelagius promoted were mainstream in contemporary Christianity, advocated by such figures as John Chrysostom, Athanasius of Alexandria, Jerome, and even the early Augustine.[12][13] |

背景 主な記事: 後期古代のキリスト教 詳細情報: 4世紀のキリスト教と5世紀のキリスト教 4世紀から5世紀にかけて、教会はコンスタンティヌス帝のキリスト教への転換により急速な変化を経験していた[1]。多くのローマ人がキリスト教に改宗し たが、必ずしも厳格に信仰を守っていたわけではない[2]。キリスト教徒が迫害されなくなったことで、新たな問題に直面した。迫害によって生じた当初の切 迫感を保ちつつ、信仰の衰退や国教への形だけの帰依をどう避けるかである。多くの人々にとって、その解決策はキリスト教的禁欲主義の採用であった。[1] 初期キリスト教は神学的に多様だった。西洋キリスト教が死の必然性を人間の堕落の結果と教えた一方、2世紀のテオフィロスやイレネウスが支持したシリアの 伝統は、死が堕落以前に存在したと主張した。400年頃、西洋キリスト教では原罪の教義がようやく現れ始めた。これはキプリアヌスの教え、すなわち幼児は アダムの罪のために洗礼を受けるべきだという考えに由来する。他のキリスト教徒はオリゲネスに従い、幼児は前世の過ちゆえに罪を帯びて生まれると信じた。 399年にヒエロニムスの使節としてローマに来たシリアのルフィヌスはシリアの伝統を継承し、人間は死すべき存在として創造され、各人は自らの罪のみを罰 されると宣言した。[3] ペラギウス(約355年 - 約420年)[4]は、おそらくブリテン諸島出身の禁欲的な平信徒で、380年代初頭にローマへ移住した[5][6]。ヒエロニムスと同様に、ペラギウス はキリスト教徒の間で増大する弛緩を批判し、代わりに高い道徳基準と禁欲主義を提唱した。[4][7][6] 彼はマニ教の宿命論と決定論に反対し[1]、罪のない生活の可能性を主張した[8]。ペラギウスは世俗の富の放棄を説いたが[9]、その思想はローマのエ リート層の一部で人気を博した。[5][7][1] 歴史家ピーター・ブラウンは、ペラギウス主義が「ローマ貴族階級に存在する強力な遠心力——分散し、小さな集団を形成し、それぞれがエリートとなることを 目指し、隣人やライバルより優位に立とうとする傾向——すなわちローマの上流階級住民の平均的な傾向」に訴えかけたと論じた。[10] 有力なローマ行政官パウリヌス・ノラヌスはペラギウスやペラギウス派の著述家ユリアヌス・エクラヌムと親交があった[11]。また元ローマ貴族カエレス ティウスはジェラルド・ボナーによって「いわゆるペラギウス運動の真の使徒」と評された。ペラギウスが提唱した思想の多くは、当時のキリスト教界では主流 であり、ヨハネス・クリュソストモス、アレクサンドリアのアタナシオス、ヒエロニムス、さらには初期のアウグスティヌスといった人物たちによっても支持さ れていたのである。 |

| Pelagian controversy In 410, Pelagius and Caelestius fled Rome for Sicily and then North Africa due to the Sack of Rome by Visigoths.[8][14] At the 411 Council of Carthage, Caelestius approached the bishop Aurelius for ordination, but instead he was condemned for his belief on sin and original sin.[15][16][a] Caelestius defended himself by arguing that this original sin was still being debated and his beliefs were orthodox. His views on grace were not mentioned, although Augustine (who had not been present) later claimed that Caelestius had been condemned because of "arguments against the grace of Christ."[17] Unlike Caelestius, Pelagius refused to answer the question as to whether man had been created mortal, and, outside of Northern Africa, it was Caelestius' teachings which were the main targets of condemnation.[15] In 412, Augustine read Pelagius' Commentary on Romans and described its author as a "highly advanced Christian."[18] Augustine maintained friendly relations with Pelagius until the next year, initially only condemning Caelestius' teachings, and considering his dispute with Pelagius to be an academic one.[8][19] Jerome attacked Pelagianism for saying that humans had the potential to be sinless, and connected it with other recognized heresies, including Origenism, Jovinianism, Manichaeanism, and Priscillianism. Scholar Michael Rackett noted that the linkage of Pelagianism and Origenism was "dubious" but influential.[20] Jerome also disagreed with Pelagius' strong view of free will. In 415, he wrote Dialogus adversus Pelagianos to refute Pelagian statements.[21] Noting that Jerome was also an ascetic and critical of earthly wealth, historian Wolf Liebeschuetz suggested that his motive for opposing Pelagianism was envy of Pelagius' success.[22] In 415, Augustine's emissary Orosius brought charges against Pelagius at a council in Jerusalem, which were referred to Rome for judgement.[19][23] The same year, the exiled Gallic bishops Heros of Arles and Lazarus of Aix accused Pelagius of heresy, citing passages in Caelestius' Liber de 13 capitula.[8][24] Pelagius defended himself by disavowing Caelestius' teachings, leading to his acquittal at the Synod of Diospolis in Lod, which proved to be a key turning point in the controversy.[8][25][26] Following the verdict, Augustine convinced two synods in North Africa to condemn Pelagianism, whose findings were partially confirmed by Pope Innocent I.[8][19] In January 417, shortly before his death, Innocent excommunicated Pelagius and two of his followers. Innocent's successor, Zosimus, reversed the judgement against Pelagius, but backtracked following pressure from the African bishops.[8][25][19] Pelagianism was later condemned at the Council of Carthage in 418, after which Zosimus issued the Epistola tractoria excommunicating both Pelagius and Caelestius.[8][27] Concern that Pelagianism undermined the role of the clergy and episcopacy was specifically cited in the judgement.[28] At the time, Pelagius' teachings had considerable support among Christians, especially other ascetics.[29] Considerable parts of the Christian world had never heard of Augustine's doctrine of original sin.[27] Eighteen Italian bishops, including Julian of Eclanum, protested against the condemnation of Pelagius and refused to follow Zosimus' Epistola tractoria.[30][27] Many of them later had to seek shelter with the Greek bishops Theodore of Mopsuestia and Nestorius, leading to accusations that Pelagian errors lay beneath the Nestorian controversy over Christology.[31] Both Pelagianism and Nestorianism were condemned at the Council of Ephesus in 431.[32][31] With its supporters either condemned or forced to move to the East, Pelagianism ceased to be a viable doctrine in the Latin West.[30] Despite repeated attempts to suppress Pelagianism and similar teachings, some followers were still active in the Ostrogothic Kingdom (493–553), most notably in Picenum and Dalmatia during the rule of Theoderic the Great.[33] Pelagianism was also reported to be popular in Britain, as Germanus of Auxerre made at least one visit (in 429) to denounce the heresy. Some scholars, including Nowell Myres and John Morris, have suggested that Pelagianism in Britain was understood as an attack on Roman decadence and corruption, but this idea has not gained general acceptance.[8][34] |

ペラギウス論争 410年、ペラギウスとカエレスティウスは西ゴート族によるローマ略奪のため、ローマからシチリアを経て北アフリカへ逃れた[8][14]。411年のカ ルタゴ公会議で、カエレスティウスはアウレリウス司教に叙階を求めたが、罪と原罪に関する彼の信仰が非難された。[15][16][a] ケレスティウスは、この原罪の概念は未だ議論中であり、自身の見解は正統であると主張して自己弁護した。彼の恩寵に関する見解は言及されなかったが、後に アウグスティヌス(彼はその場にはいなかった)は、ケレスティウスが「キリストの恩寵に対する反論」のために非難されたと主張した。[17] ケレスティウスとは異なり、ペラギウスは「人間は死すべき存在として創造されたか」という問いに答えることを拒んだ。北アフリカ以外では、非難の主な対象 はケレスティウスの教えであった。[15] 412年、アウグスティヌスはペラギウスの『ローマ人への手紙注解』を読み、その著者を「高度に洗練されたキリスト教徒」と評した。[18] アウグスティヌスは翌年までペラギウスと友好関係を維持し、当初はカエレスティウスの教えのみを非難し、ペラギウスとの論争を学問的なものと見なしてい た。[8][19] ヒエロニムスは、人間に罪のない状態になる可能性があると主張するペラギウス主義を攻撃し、オリゲネス主義、ヨヴィニアヌス主義、マニ教、プリスキリアヌ ス主義など、他の既知の異端思想と結びつけた。学者マイケル・ラケットは、ペラギウス主義とオリゲネス主義の関連性は「疑わしい」が影響力があったと指摘 している[20]。ヒエロニムスはまた、ペラギウスの強い自由意志観にも反対した。415年、彼はペラギウスの主張を反駁するため『ペラギウス派に対する 対話』を著した。[21] 歴史家ヴォルフ・リーベシュッツは、ヒエロニムスが禁欲主義者であり世俗の富を批判していた点に着目し、ペラギウス主義への反対動機はペラギウスの成功に 対する妬みであったと示唆している。[22] 415年、アウグスティヌスの使節オロシウスがエルサレム公会議でペラギウスに対する告発を行い、その裁定はローマに委ねられた。[19][23] 同年、追放されたガリアの司教アルルのヘロスとエクス=アン=プロヴァンスのラザロは、カエレスティウスの『13章の書』の箇所を引用し、ペラギウスを異 端と告発した。[8][24] ペラギウスはカエレスティウスの教えを否定することで自己弁護し、ロドのディオスポリス公会議で無罪判決を得た。これは論争における重要な転換点となっ た。[8] [25][26] この判決を受け、アウグスティヌスは北アフリカの二つの公会議を説得し、ペラギウス主義を非難させた。その結論は教皇イノセント1世によって部分的に承認 された。[8][19] 417年1月、死の直前にイノセントはペラギウスとその信奉者二人を破門した。後継者のゾシムスはペラギウスに対する判決を覆したが、アフリカの司教たち の圧力により撤回した。[8][25][19] ペラギウス主義は後に418年のカルタゴ公会議で非難され、ゾシモスはペラギウスとカエレスティウスの両者を破門する『破門書簡』を発布した。[8] [27] 判決文では、ペラギウス主義が聖職者や司教職の役割を損なう懸念が特に指摘された。[28] 当時、ペラギウスの教えはキリスト教徒、特に他の禁欲主義者の間でかなりの支持を得ていた。[29] キリスト教世界のかなりの部分では、アウグスティヌスの原罪の教義を聞いたこともなかった。[27] エクラヌムのユリアヌスを含む18人のイタリア司教がペラギウスの非難に抗議し、ゾシモスの『追放の書簡』に従うことを拒否した。[30][27] 彼らの多くは後に、ギリシャ系司教モプスエスティアのテオドロスやネストリオスに庇護を求める羽目になり、キリスト論をめぐるネストリウス論争の根底にペ ラギウスの誤謬が潜んでいるとの非難を招いた。[31] ペラギウス主義もネストリウス主義も、431年のエフェソス公会議で非難された。[32] [31] 支持者が破門されるか東方へ移住を余儀なくされたため、ペラギウス主義はラテン系西ローマにおいて存続可能な教義ではなくなった。[30] ペラギウス主義や類似の教えを繰り返し抑圧しようとしたにもかかわらず、一部の信奉者はオストロゴート王国(493–553)で活動し続けていた。特にテ オドリック大王の治世下のピケヌムとダルマチア地方で顕著であった。[33] ペラギウス主義はブリタニアでも流行したと伝えられており、オセールのアウグスティヌスは異端を糾弾するため少なくとも一度(429年)訪問した。ノー ウェル・マイレスやジョン・モリスら一部の学者は、ブリタニアにおけるペラギウス主義はローマの退廃と腐敗への攻撃として理解されていたと示唆している が、この見解は広く受け入れられていない。[8][34] |

| Pelagius' teachings Free will and original sin The idea that God had created anything or anyone who was evil by nature struck Pelagius as Manichean.[35] Pelagius taught that humans were free of the burden of original sin, because it would be unjust for any person to be blamed for another's actions.[29] According to Pelagianism, humans were created in the image of God and had been granted conscience and reason to determine right from wrong, and the ability to carry out correct actions.[36] If "sin" could not be avoided it could not be considered sin.[35][24] In Pelagius' view, the doctrine of original sin placed too little emphasis on the human capacity for self-improvement, leading either to despair or to reliance on forgiveness without responsibility.[37] He also argued that many young Christians were comforted with false security about their salvation leading them to relax their Christian practice.[38] Pelagius believed that Adam's transgression had caused humans to become mortal, and given them a bad example, but not corrupted their nature,[39] while Caelestius went even further, arguing that Adam had been created mortal.[40] He did not even accept the idea that original sin had instilled fear of death among humans, as Augustine said. Instead, Pelagius taught that the fear of death could be overcome by devout Christians, and that death could be a release from toil rather than a punishment.[41] Both Pelagius and Caelestius reasoned that it would be unreasonable for God to command the impossible,[37][24] and therefore each human retained absolute freedom of action and full responsibility for all actions.[29][36][b] Pelagius did not accept any limitation on free will, including necessity, compulsion, or limitations of nature. He believed that teaching a strong position on free will was the best motivation for individuals to reform their conduct.[36] |

ペラギウスの教え 自由意志と原罪 神が本質的に悪なるものや者を創造したという考えは、ペラギウスにとってマニ教的であった[35]。ペラギウスは、人間の行為を他者の責任に帰するのは不 当であるため、人間は原罪の重荷から解放されていると教えた[29]。ペラギウス主義によれば、人間は神の姿に似せて創造され、善悪を判断する良心と理 性、そして正しい行為を実行する能力を与えられていた。[36] 「罪」が避けられないものならば、それは罪とは見なせない。[35][24] ペラギウスの見解では、原罪の教義は人間の自己改善能力を過小評価し、絶望か、責任を伴わない赦しへの依存のいずれかに陥らせるとした。[37] また彼は、多くの若いキリスト教徒が救いについて誤った安心感を与えられ、キリスト教的実践を怠るようになっていると主張した。[38] ペラギウスは、アダムの背きが人間を死すべき存在とし、悪い手本を与えたが、その本質を腐敗させたわけではないと信じた[39]。一方カエレスティウスは さらに踏み込み、アダムは最初から死すべき存在として創造されたと主張した[40]。彼はアウグスティヌスが述べたように、原罪が人間に死への恐怖を植え 付けたという考えさえも認めなかった。代わりにペラギウスは、敬虔なキリスト教徒なら死の恐怖を克服でき、死は罰ではなく労苦からの解放となり得ると教え た[41]。ペラギウスもカエレスティウスも、神が不可能なことを命じるのは不合理だと論じた[37][24]。したがって人間は絶対的な行動の自由と、 全ての行為に対する完全な責任を保持すると考えた。[29][36][b] ペラギウスは、必然性、強制、自然の制約を含むあらゆる自由意志への制限を認めなかった。彼は、自由意志について強い立場を教えることが、個人が自らの行 いを改める最良の動機となると信じていた。[36] |

| Sin and virtue He is a Christian who shows compassion to all, who is not at all provoked by wrong done to him, who does not allow the poor to be oppressed in his presence, who helps the wretched, who succors the needy, who mourns with the mourners, who feels another's pain as if it were his own, who is moved to tears by the tears of others, whose house is common to all, whose door is closed to no one, whose table no poor man does not know, whose food is offered to all, whose goodness all know and at whose hands no one experiences injury, who serves God all day and night, who ponders and meditates upon his commandments unceasingly, who is made poor in the eyes of the world so that he may become rich before God. —On the Christian Life, a Pelagian treatise[43][c] In the Pelagian view, by corollary, sin was not an inevitable result of fallen human nature, but instead came about by free choice[44] and bad habits; through repeated sinning, a person could corrupt their own nature and enslave themself to sin. Pelagius believed that God had given man the Old Testament and Mosaic Law in order to counter these ingrained bad habits, and when that wore off over time God revealed the New Testament.[35] However, because Pelagius considered a person to always have the ability to choose the right action in each circumstance, it was therefore theoretically possible (though rare) to live a sinless life.[29][45][36] Jesus Christ, held in Christian doctrine to have lived a life without sin, was the ultimate example for Pelagians seeking perfection in their own lives, but there were also other humans who were without sin—including some notable pagans and especially the Hebrew prophets.[35][46][d] This view was at odds with that of Augustine and orthodox Christianity, which taught that Jesus was the only man free of sin.[47] Pelagius did teach Jesus' vicarious atonement for the sins of mankind and the cleansing effect of baptism, but placed less emphasis on these aspects.[35] Pelagius taught that a human's ability to act correctly was a gift of God,[45] as well as divine revelation and the example and teachings of Jesus. Further spiritual development, including faith in Christianity, was up to individual choice, not divine benevolence.[29][48] Pelagius accepted no excuse for sin, and argued that Christians should be like the church described in Ephesians 5:27, "without spot or wrinkle".[38][45][49][50] Instead of accepting the inherent imperfection of man, or arguing that the highest moral standards could only be applied to an elite, Pelagius taught that all Christians should strive for perfection. Like Jovinian, Pelagius taught that married life was not inferior to monasticism, but with the twist that all Christians regardless of life situation were called to a kind of asceticism.[1] Pelagius taught that it was not sufficient for a person to call themselves a Christian and follow the commandments of scripture; it was also essential to actively do good works and cultivate virtue, setting themselves apart from the masses who were "Christian in name only", and that Christians ought to be extraordinary and irreproachable in conduct.[38] Specifically, he emphasized the importance of reading scripture, following religious commandments, charity, and taking responsibility for one's actions, and maintaining modesty and moderation.[36][e] Pelagius taught that true virtue was not reflected externally in social status, but was an internal spiritual state.[36] He explicitly called on wealthy Christians to share their fortunes with the poor. (Augustine criticized Pelagius' call for wealth redistribution.)[9] |

罪と徳 彼はキリスト教徒だ すべての人に慈愛を示す者 自分に害をなされても決して怒らない者 貧しい者が目の前で虐げられるのを許さない者 悲惨な者を助け 困窮する者を救い 嘆く者と共に嘆き 他人の痛みを自らの痛みのように感じ 他人の涙に涙を流し その家はすべての人に開かれ その門は誰にも閉ざされず その食卓を知らぬ貧者はおらず その食物は全ての人に供され その善は万人に知られその手によって傷つけられる者はおらず 昼も夜も神に仕え その戒めを絶えず思索し黙想する 世の目に貧しき者とされ神の前で富む者となるためである —『キリスト教生活について』ペラギウス派論文[43][c] ペラギウス派の見解によれば、帰結として罪は堕落した人間性の必然的結果ではなく、自由意志[44]と悪しき習慣によって生じる。繰り返される罪によって 人は自らの本性を腐敗させ、罪に自らを隷属させうる。ペラギウスは、神が旧約聖書とモーセの律法を授けたのは、こうした根深い悪しき習慣に対抗するためで あり、それが時と共に色あせた後、神は新約聖書を啓示したと考えた[35]。しかしペラギウスは、人はあらゆる状況において常に正しい行動を選択する能力 を有すると考えたため、理論上は(稀ではあるが)罪のない人生を送ることも可能であった。[29][45][36] キリスト教教義において罪のない生涯を送ったとされるイエス・キリストは、自らの生涯に完全さを求めるペラギウス派にとって究極の模範であった。しかし、 罪のない人間は他にも存在した——著名な異教徒や、特にヘブライの預言者たちを含む。[35][46][d] この見解は、イエスだけが罪のない唯一の人間であると教えたアウグスティヌスや正統派キリスト教の立場と対立していた。[47] ペラギウスは、イエスが人類の罪のために身代わりとなった贖罪と、洗礼の清めの効果については教えたが、これらの側面にはあまり重点を置かなかった。 [35] ペラギウスは、人間が正しく行動する能力は神の賜物であると教えた。[45] 神の啓示やイエスの模範と教えも同様である。キリスト教への信仰を含むさらなる霊的成長は、神の慈悲ではなく個人の選択に委ねられると主張した。[29] [48] ペラギウスは罪に対する言い訳を一切認めず、キリスト教徒はエフェソの信徒への手紙5章27節に描かれた教会のように「しみやしわのない」存在であるべき だと主張した。[38][45][49][50] ペラギウスは、人間に内在する不完全性を受け入れることも、最高の道徳基準がエリート層にしか適用できないと主張することもせず、全てのキリスト教徒が完 全性を追求すべきだと教えた。ヨヴィニアヌスと同様に、ペラギウスは結婚生活が修道生活に劣らないと教えたが、生活状況に関わらず全てのキリスト教徒が修 道的な生き方に召されているという独自の解釈を加えた。[1] ペラギウスは、自らをキリスト教徒と称し聖書の戒律に従うだけでは不十分だと教えた。積極的に善行を行い徳を養い、「名ばかりのキリスト教徒」たる大衆か ら自らを隔てることも不可欠であり、キリスト教徒は行動において非凡かつ非難の余地のない存在であるべきだと説いた。[38] 具体的には、聖書を読むこと、宗教的戒律に従うこと、慈善活動、自らの行動に対する責任の自覚、謙虚さと節度を保つことの重要性を強調した。[36] [e] ペラギウスは、真の徳は社会的地位といった外見に現れるものではなく、内面の精神的状態であると教えた。[36] 彼は富裕なキリスト教徒に対し、明示的に富を貧しい者と分かち合うよう呼びかけた。(アウグスティヌスはペラギウスの富の再分配要求を批判した。) [9] |

| Baptism and judgment Because sin in the Pelagian view was deliberate, with people responsible only for their own actions, infants were considered without fault in Pelagianism, and unbaptized infants were not thought to be sent to hell.[51] Like early Augustine, Pelagians believed that infants would be sent to purgatory.[52] Although Pelagius rejected that infant baptism was necessary to cleanse original sin, he nevertheless supported the practice because he felt it improved their spirituality through a closer union with Jesus.[53] For adults, baptism was essential because it was the mechanism for obtaining forgiveness of the sins that a person had personally committed and a new beginning in their relationship with God.[35][45] After death, adults would be judged by their acts and omissions and consigned to everlasting fire if they had failed: "not because of the evils they have done, but for their failures to do good".[38] He did not accept purgatory as a possible destination for adults.[19] Although Pelagius taught that the path of righteousness was open to all, in practice only a few would manage to follow it and be saved. Like many medieval theologians, Pelagius believed that instilling in Christians the fear of hell was often necessary to convince them to follow their religion where internal motivation was absent or insufficient.[38] |

洗礼と審判 ペラギウス派の考えでは、罪は意図的なものであり、人は自らの行為にのみ責任を負うとされた。したがって、幼児は過失がないとみなされ、洗礼を受けていな い幼児が地獄に送られるとは考えられなかった。[51] 初期のアウグスティヌスと同様に、ペラギウス派は幼児が煉獄に送られると信じていた。[52] ペラギウスは原罪を清めるために幼児洗礼が必要だとする見解を拒否したが、それでも洗礼がイエスとのより密接な結びつきを通じて彼らの霊性を高めると考え たため、その慣行を支持した。[53] 成人にとって洗礼は不可欠であった。なぜならそれは、個人が自ら犯した罪の赦しを得、神との関係において新たな出発をするための手段であったからである。 [35][45] 死後、成人は自らの行為と怠りによって裁かれ、失敗した場合には永遠の火に投げ込まれる。「彼らが犯した悪のためではなく、善を行わなかった怠りゆえに」 である。[38] 彼は成人の行き先として煉獄の存在を認めなかった。[19] ペラギウスは義の道は誰にでも開かれていると教えたが、実際にはごく少数の者だけがそれを歩み救われると考えた。多くの中世神学者と同様、ペラギウスは内 発的動機が欠如または不十分な信徒に対し、宗教的実践を促すために地獄への畏怖を植え付けることがしばしば必要だと信じていた。[38] |

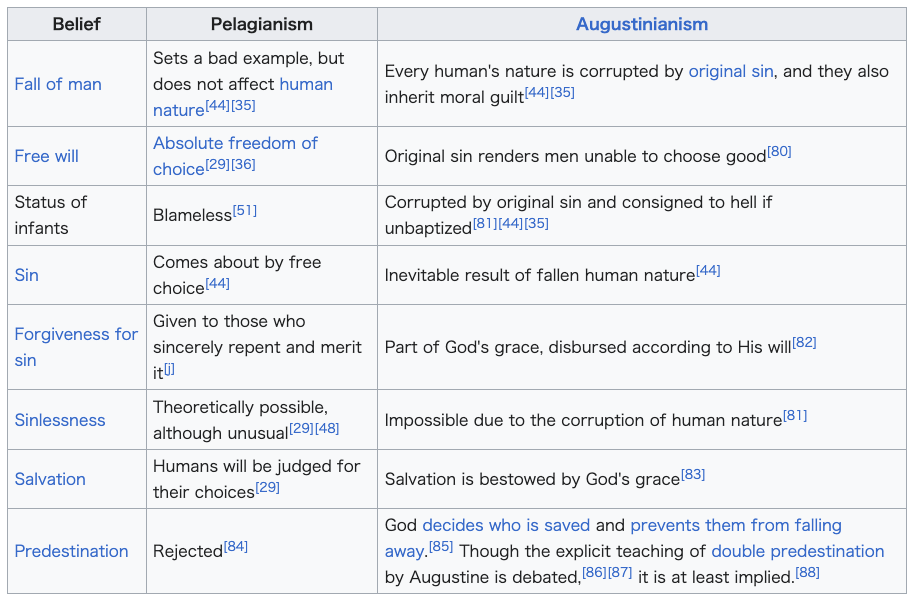

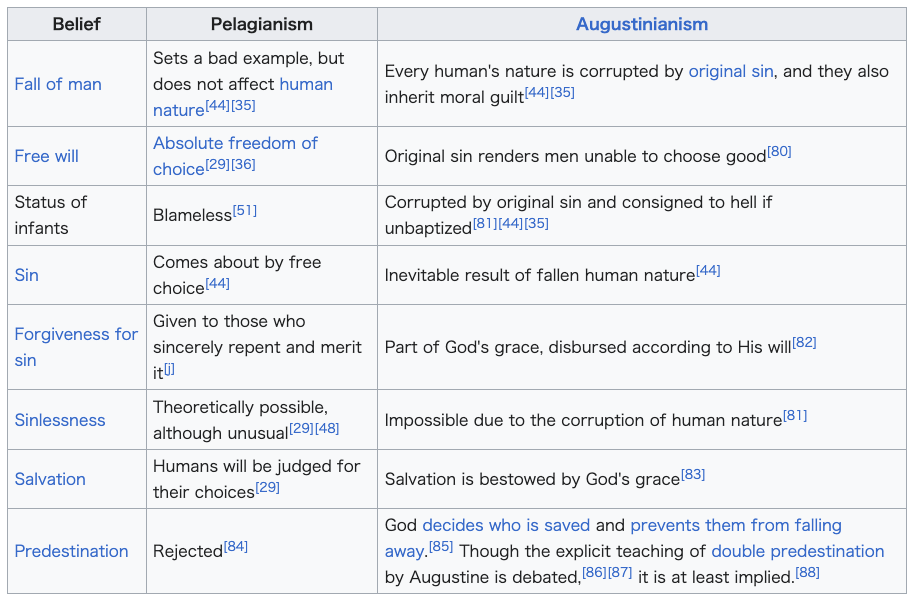

| Comparison Significant influences on Pelagius included Eastern Christianity, which had a more positive view of human nature,[37][54][53] and classical philosophy, from which he drew the ideas of personal autonomy and self-improvement.[1] After having previously credited Cicero's lost Hortensius for his eventual conversion to Christianity,[55] Augustine accused Pelagius' idea of virtue of being "Ciceronian", taking issue with the ideology of the dialogue's author as having overemphasized the role of human intellect and will.[56][f] Although his teachings on original sin were novel, Pelagius' views on grace, free will and predestination were similar to those of contemporary Greek-speaking theologians such as Origen, John Chrysostom, and Jerome.[53] Theologian Carol Harrison commented that Pelagianism is "a radically different alternative to Western understandings of the human person, human responsibility and freedom, ethics and the nature of salvation" which might have come about if Augustine had not been victorious in the Pelagian controversy.[1] According to Harrison, "Pelagianism represents an attempt to safeguard God's justice, to preserve the integrity of human nature as created by God, and of human beings' obligation, responsibility and ability to attain a life of perfect righteousness."[58] However, this is at the expense of downplaying human frailty and presenting "the operation of divine grace as being merely external".[58] According to scholar Rebecca Weaver, "what most distinguished Pelagius was his conviction of an unrestricted freedom of choice, given by God and immune to alteration by sin or circumstance."[59] Definition What Augustine called "Pelagianism" was more his own invention than that of Pelagius.[40][60] According to Thomas Scheck, Pelagianism is the heresy of denying Catholic Church teaching on original sin, or more specifically the beliefs condemned as heretical in 417 and 418.[61][g] In her study, Ali Bonner (a lecturer at the University of Cambridge) found that there was no one individual who held all the doctrines of "Pelagianism", nor was there a coherent Pelagian movement,[60] although these findings are disputed.[62][63] Bonner argued that the two core ideas promoted by Pelagius were "the goodness of human nature and effective free will" although both were advocated by other Christian authors from the 360s. Because Pelagius did not invent these ideas, she recommended attributing them to the ascetic movement rather than using the word "Pelagian".[60] Later Christians used "Pelagianism" as an insult for theologically orthodox Christians who held positions that they disagreed with. Historian Eric Nelson defined genuine Pelagianism as rejection of original sin or denial of original sin's effect on man's ability to avoid sin.[64] Even in recent scholarly literature, the term "Pelagianism" is not clearly or consistently defined.[65] Pelagianism and Augustinianism See also: Augustinianism Pelagius' teachings on human nature, divine grace, and sin were opposed to those of Augustine, who declared Pelagius "the enemy of the grace of God".[29][18][h] Augustine distilled what he called Pelagianism into three heretical tenets: "to think that God redeems according to some scale of human merit; to imagine that some human beings are actually capable of a sinless life; to suppose that the descendants of the first human beings to sin are themselves born innocent".[30][i] In Augustine's writings, Pelagius is a symbol of humanism who excluded God from human salvation.[18] Pelagianism shaped Augustine's ideas in opposition to his own on free will, grace, and original sin,[68][69][70] and much of The City of God is devoted to countering Pelagian arguments.[47] Another major difference in the two thinkers was that Pelagius emphasized obedience to God for fear of hell, which Augustine considered servile. In contrast, Augustine argued that Christians should be motivated by the delight and blessings of the Holy Spirit and believed that it was treason "to do the right deed for the wrong reason".[38] According to Augustine, credit for all virtue and good works is due to God alone,[71] and to say otherwise caused arrogance, which is the foundation of sin.[72] According to Peter Brown, "For a sensitive man of the fifth century, Manichaeism, Pelagianism, and the views of Augustine were not as widely separated as we would now see them: they would have appeared to him as points along the great circle of problems raised by the Christian religion".[73] John Cassian argued for a middle way between Pelagianism and Augustinianism, in which the human will is not negated but presented as intermittent, sick, and weak,[58] and Jerome held a middle position on sinlessness.[74] In Gaul, the so-called "semi-Pelagians" disagreed with Augustine on predestination (but recognized the three Pelagian doctrines as heretical) and were accused by Augustine of being seduced by Pelagian ideas.[75] According to Ali Bonner, the crusade against Pelagianism and other heresies narrowed the range of acceptable opinions and reduced the intellectual freedom of classical Rome.[76] When it came to grace and especially predestination, it was Augustine's ideas, not Pelagius', which were novel.[77][78][79]  |

比較 ペラギウスに大きな影響を与えたのは、人間性に対してより肯定的な見解を持っていた東方キリスト教[37][54][53]と、個人の自律性と自己研鑽の 思想を彼に与えた古典哲学であった[1]。かつてはキリスト教への改宗の契機をキケロの失われた著作『ホルテンシウス』に帰していたが[55]、 アウグスティヌスはペラギウスの徳の概念を「キケロ的」と非難し、対話篇の著者が人間の知性と意志の役割を過度に強調した思想に異議を唱えた[56] [f]。原罪に関する教えは革新的であったが、ペラギウスの恩寵・自由意志・予定説に関する見解は、オリゲネス、ヨハネス・クリュソストモス、ヒエロニム スといった当時のギリシア語圏神学者たちと類似していた。[53] 神学者キャロル・ハリソンは、ペラギウス主義は「人間の本性、人間の責任と自由、倫理、救いの本質に関する西洋の理解とは根本的に異なる代替案」であり、 アウグスティヌスがペラギウス論争で勝利していなければ、このような思想が生まれた可能性があると指摘している。[1] ハリソンによれば、「ペラギウス主義は神の正義を守り、神によって創造された人間性の完全性を維持し、完全なる義の生活に到達する人間の義務・責任・能力 を保とうとする試みである」。[58] しかしこれは、人間の弱さを軽視し「神の恵みの働きを単なる外的なものとして提示する」代償を伴う。[58] 学者レベッカ・ウィーバーによれば、「ペラギウスを最も特徴づけたのは、神によって与えられ、罪や状況によって変容されない無制限の選択の自由への確信で あった」。[59] 定義 アウグスティヌスが「ペラギウス主義」と呼んだものは、ペラギウス自身の教義というより、むしろアウグスティヌス自身の創作であった。[40][60] トーマス・シェックによれば、ペラギウス主義とは原罪に関するカトリック教会の教え、より具体的には417年と418年に異端として非難された信念を否定 する異端である。[61] [g] アリ・ボナー(ケンブリッジ大学講師)の研究によれば、「ペラギウス主義」の教義を全て保持した個人は存在せず、一貫したペラギウス運動もなかったとされ る[60]。ただしこの見解には異論もある。[62][63] ボナーは、ペラギウスが提唱した二つの核心的観念は「人間本性の善性」と「実効的自由意志」であると論じた。ただしこれらはいずれも360年代の他のキリ スト教著述家によっても主張されていた。ペラギウスがこれらの観念を発明したわけではないため、彼女は「ペラギウス主義」という用語を用いるよりも、禁欲 主義運動に帰属させることを推奨した。[60] 後世のキリスト教徒は、自らの神学に反する立場を取る正統派キリスト教徒を侮蔑する意味で「ペラギウス主義」を用いた。歴史家エリック・ネルソンは、真の ペラギウス主義を「原罪の否定、あるいは原罪が人間の罪回避能力に及ぼす影響の否定」と定義した[64]。近年の学術文献においても、「ペラギウス主義」 という用語は明確かつ一貫した定義がなされていない。[65] ペラギウス主義とアウグスティヌス主義 関連項目: アウグスティヌス主義 ペラギウスの人間性・神の恩寵・罪に関する教義は、アウグスティヌスのそれとは対立した。アウグスティヌスはペラギウスを「神の恩寵の敵」と宣言した。 [29][18][h] アウグスティヌスはペラギウス主義を三つの異端的教義に集約した:「神の救いは人間の功績の尺度に基づいて行われると考えること」「人間には実際に罪のな い生活が可能だと想像すること」「最初の罪を犯した人類の子孫は生まれながらに無罪であると推測すること」。[30][i] アウグスティヌスの著作において、ペラギウスは人間の救済から神を排除したヒューマニズムの象徴である。[18] ペラギウス主義は、自由意志、恩寵、原罪に関するアウグスティヌスの思想形成に反対論として影響を与えた[68][69][70]。そして『神の国』の大 部分はペラギウス派の主張への反論に費やされている[47]。両思想家のもう一つの大きな相違点は、ペラギウスが地獄への恐怖に基づく神への服従を強調し たのに対し、アウグスティヌスはこれを卑屈な態度と見なした点である。これに対しアウグスティヌスは、キリスト教徒は聖霊の喜びと祝福によって動機づけら れるべきだと主張し、「誤った理由で正しい行いをする」ことは背信行為だと信じた[38]。アウグスティヌスによれば、あらゆる徳と善行の功績は神のみに 帰属する[71]。それ以外の主張は傲慢を生み、それが罪の根源となる。[72] ピーター・ブラウンによれば、「五世紀の感受性豊かな人間にとって、マニ教、ペラギウス主義、そしてアウグスティヌスの見解は、現代の我々が考えるほどに は大きく隔たっていなかった。それらはいずれも、キリスト教が提起した問題という大円環上の点として彼には映ったであろう」。[73] ジョン・カッシアンはペラギウス主義とアウグスティヌス主義の中間道を主張した。そこでは人間の意志は否定されず、断続的で病み弱く弱いものと提示された [58]。またヒエロニムスは罪の無さについて中間的な立場を取った。[74] ガリアでは、いわゆる「半ペラギウス派」が予定説に関してアウグスティヌスと対立した(ただし三つのペラギウス的教義は異端と認めていた)。彼らはアウグ スティヌスからペラギウス思想に惑わされていると非難された。[75] アリ・ボナーによれば、ペラギウス主義やその他の異端に対する弾圧は、許容される意見の範囲を狭め、古典ローマ時代の知的自由を損なった。[76] 恵み、特に予定説に関して言えば、新しかったのはペラギウスの思想ではなく、アウグスティヌスの思想であった。[77][78][79]  |

| According

to Nelson, Pelagianism is a solution to the problem of evil that

invokes libertarian free will as both the cause of human suffering and

a sufficient good to justify it.[89] By positing that man could choose

between good and evil without divine intercession, Pelagianism brought

into question Christianity's core doctrine of Jesus' act of

substitutionary atonement to expiate the sins of mankind.[90] For this

reason, Pelagianism became associated with nontrinitarian

interpretations of Christianity which rejected the divinity of

Jesus,[91] as well as other heresies such as Arianism, Socinianism, and

mortalism (which rejected the existence of hell).[64] Augustine argued

that if man "could have become just by the law of nature and free will

... amounts to rendering the cross of Christ void".[89] He argued that

no suffering was truly undeserved, and that grace was equally

undeserved but bestowed by God's benevolence.[92] Augustine's solution,

while it was faithful to orthodox Christology, worsened the problem of

evil because according to Augustinian interpretations, God punishes

sinners who by their very nature are unable not to sin.[64] The

Augustinian defense of God's grace against accusations of arbitrariness

is that God's ways are incomprehensible to mere mortals.[64][93] Yet,

as later critics such as Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz asserted, asking "it

is good and just because God wills it or whether God wills it because

it is good and just?", this defense (although accepted by many Catholic

and Reformed theologians) creates a God-centered morality, which, in

Leibniz' view "would destroy the justice of God" and make him into a

tyrant.[94] |

ネルソンに

よれば、ペラギウス主義は悪の問題に対する解決策であり、人間の苦しみを引き起こす原因であると同時に、それを正当化する十分な善として、リバタリアン的

自由意志を主張するものである。[89]

神の介入なしに人間が善と悪のどちらかを選択できると仮定することで、ペラギウス主義はキリスト教の中核教義である、人類の罪を贖うためのイエスの身代わ

りの贖罪行為を疑問視したのである。このためペラギウス主義は、イエスの神性を否定する非三位一体的キリスト教解釈[91]や、アリウス主義・ソッツィー

ニ派・地獄の存在を否定するモータル主義[64]といった異端思想と結びつけられた。アウグスティヌスは「もし人間が自然法と自由意志によって義となるこ

とができたなら…それはキリストの十字架を無効にするに等しい」と論じた。[89]

彼は、いかなる苦しみも真に不当なものではないと主張し、恵みも同様に不当ながら神の慈愛によって授けられるものだと述べた。[92]

アウグスティヌスの解決策は正統的キリスト論に忠実ではあったが、悪の問題を悪化させた。なぜならアウグスティヌス的解釈によれば、神は本質的に罪を犯さ

ざるを得ない罪人を罰するからである。[64]

神の恵みが恣意的だと非難されることに対するアウグスティヌスの弁明は、神の御業は凡人には理解不能だというものだ。[64] [93]

しかし、後の批判者であるゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツらが「それは神が望むから善であり正義なのか、それとも善であり正義だから神が望む

のか?」と問うたように、この弁明(多くのカトリックや改革派神学者には受け入れられたが)は神中心の道徳観を生み出す。ライプニッツの見解では、これは

「神の正義を破壊し」、神を暴君にしてしまうのである。[94] |

| Pelagianism and Judaism One of the most important distinctions between Christianity and Judaism is that the former conventionally teaches justification by faith, while the latter teaches that man has the choice to follow divine law. By teaching the absence of original sin and the idea that humans can choose between good and evil, Pelagianism advocated a position close to that of Judaism.[95] Pelagius wrote positively of Jews and Judaism, recommending that Christians study Old Testament (i.e., the Tanakh) law — a sympathy not commonly encountered in Christianity after Paul.[48] Augustine was the first to accuse Pelagianism of "Judaizing",[96] which became a commonly heard criticism of it.[91][96] However, although contemporary rabbinic literature tends to take a Pelagian perspective on the major questions, and it could be argued that the rabbis shared a worldview with Pelagius, there were minority opinions within Judaism (such as the Essenes) which argued for ideas more similar to Augustine's.[97] Overall, Jewish discourse did not discuss free will and emphasized God's goodness in his revelation of the Torah.[98] |

ペラギウス主義とユダヤ教 キリスト教とユダヤ教の最も重要な相違点の一つは、前者が伝統的に信仰による義認を教えるのに対し、後者は人間が神の律法に従う選択権を持つと教えること だ。原罪の不在と人間が善悪を選択できるという考えを説くペラギウス主義は、ユダヤ教に近い立場を主張した。[95] ペラギウスはユダヤ人とユダヤ教を肯定的に論じ、キリスト教徒が旧約聖書(すなわちタナハ)の律法を学ぶよう勧めた。これはパウロ以降のキリスト教では珍 しい共感であった。[48] ペラギウス主義を「ユダヤ化」と非難したのはアウグスティヌスが最初であり、[96] これが同主義に対する一般的な批判となった。[91][96] しかし、当時のラビ文学は主要な問題についてペラギウス的視点を取る傾向があり、ラビたちがペラギウスと世界観を共有していたと主張することも可能だが、 ユダヤ教内部には(エッセネ派のような)少数派の意見も存在し、彼らはアウグスティヌスの思想により近い考えを主張していた。[97] 全体として、ユダヤ教の議論は自由意志について論じず、トーラーの啓示における神の善性を強調していた。[98] |

| Later responses Semi-Pelagian controversy Main article: Semi-Pelagian controversy The resolution of the Pelagian controversy gave rise to a new controversy in southern Gaul in the fifth and sixth centuries, retrospectively called by the misnomer "semi-Pelagianism".[99][100] The "semi-Pelagians" all accepted the condemnation of Pelagius, believed grace was necessary for salvation, and were followers of Augustine.[100] The controversy centered on differing interpretations of the verse 1 Timothy 2:4:[59] "For this is good and acceptable in the sight of God our Savior, who desires all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth."[101] Augustine and Prosper of Aquitaine assumed that God's will is always effective and that some are not saved (i.e., opposing universal reconciliation). Their opponents, based on the tradition of Eastern Christianity, argued that Augustinian predestination contradicted the biblical passage.[100][102] John Cassian, whose writings survived, argued for prevenient grace that individuals could accept or reject. Other semi-Pelagians were said to undermine the essential role of God's grace in salvation and argue for a median between Augustinianism and Pelagianism, although these alleged writings are no longer extant.[103] At the Council of Orange in 529, called and presided over by the Augustinian Caesarius of Arles, semi-Pelagianism was condemned but Augustinian ideas were also not accepted entirely: the synod advocated synergism, the idea that human freedom and divine grace work together for salvation.[104][100] Christians often used "Pelagianism" as a criticism to imply that the target denied God's grace and strayed into heresy.[34] Later Augustinians criticized those who asserted a meaningful role for human free will in their own salvation as covert "Pelagians" or "semi-Pelagians".[18] |

後の反論 半ペラギウス論争 詳細な記事: 半ペラギウス論争 ペラギウス論争の決着は、5世紀から6世紀にかけて南ガリアで新たな論争を引き起こした。これは後世、誤った名称「セミ・ペラギウス主義」と呼ばれるよう になった。[99][100]「セミ・ペラギウス派」は全員、ペラギウスの破門を認め、救いには恩寵が必要だと信じ、アウグスティヌスの追随者であった。 [100] この論争は、テモテへの手紙一 2:4[59]「これは、すべての人が救われ、真理を知るようになることを望んでおられる、私たちの救い主である神の御前で、良くて喜ばれることだからで ある」[101]という聖句の解釈の相違を中心としていた。アウグスティヌスとアクイタニアのプロスペルは、神の意志は常に実効性があり、救われない者も いる(すなわち普遍的和解に反対する)と仮定した。対する反対派は東方キリスト教の伝統に基づき、アウグスティヌスの予定説が聖句に矛盾すると主張した [100][102]。著作が残るヨハネス・カッシアンは、個人が受け入れも拒絶も可能な「先行的恩寵」を論じた。他の半ペラギウス派は、救いにおける神 の恩寵の本質的役割を損ない、アウグスティヌス主義とペラギウス主義の中間を主張したと言われるが、これらのとされる著作は現存しない。[103] 529年のオレンジ公会議では、アルルのアウグスティヌス派カエサリウスが招集・主宰し、半ペラギウス主義は非難されたが、アウグスティヌス派の思想も完 全には受け入れられなかった。この公会議は協同説、すなわち人間の自由意志と神の恩寵が協力して救いを成し遂げるという考えを提唱したのである。 [104] [100] キリスト教徒はしばしば「ペラギウス主義」を批判用語として用い、対象が神の恵みを否定し異端に陥ったことを示唆した。[34] 後世のアウグスティヌス派は、自らの救済において人間の自由意志が重要な役割を果たすと主張する者を、隠れた「ペラギウス主義者」あるいは「半ペラギウス 主義者」として非難した。[18] |

| Pelagian manuscripts During the Middle Ages, Pelagius' writings were popular but usually attributed to other authors, especially Augustine and Jerome.[105] Pelagius' Commentary on Romans circulated under two pseudonymous versions, "Pseudo-Jerome" (copied before 432) and "Pseudo-Primasius", revised by Cassiodorus in the sixth century to remove the "Pelagian errors" that Cassiodorus found in it. During the Middle Ages, it passed as a work by Jerome.[106] Erasmus of Rotterdam printed the commentary in 1516, in a volume of works by Jerome. Erasmus recognized that the work was not really Jerome's, writing that he did not know who the author was. Erasmus admired the commentary because it followed the consensus interpretation of Paul in the Greek tradition.[107] The nineteenth-century theologian Jacques Paul Migne suspected that Pelagius was the author, and William Ince recognized Pelagius' authorship as early as 1887. The original version of the commentary was found and published by Alexander Souter in 1926.[107] According to French scholar Yves-Marie Duval [fr], the Pelagian treatise On the Christian Life was the second-most copied work during the Middle Ages (behind Augustine's The City of God) outside of the Bible and liturgical texts.[105][c] |

ペラギウスの写本 中世において、ペラギウスの著作は広く読まれたが、通常は他の著者、特にアウグスティヌスやヒエロニムスに帰属させられていた。[105] ペラギウスの『ローマ人への手紙注解』は、二つの偽名版本として流通した。「偽ヒエロニムス」(432年以前に写本)と「偽プリマシウス」である。後者は 6世紀にカッシオドルスが改訂し、同氏が発見した「ペラギウス的誤謬」を除去した。中世の間、この書物はヒエロニムスの著作として流通した。[106] ロッテルダムのエラスムスは1516年、ヒエロニムス著作集の一巻としてこの注解書を印刷した。エラスムスは、この著作が実際にはヒエロニムスのものでは ないことを認識し、著者が誰であるかはわからないと記している。エラスムスは、この注釈がギリシャの伝統におけるパウロの解釈のコンセンサスに従っている ことを高く評価した。19世紀の神学者ジャック・ポール・ミグネは、ペラギウスが著者ではないかと疑い、ウィリアム・インスは1887年に早くもペラギウ スの著作者であることを認めた。この注釈の原本は、1926年にアレクサンダー・サウターによって発見、出版された。フランスの学者イヴ=マリー・デュ ヴァルによれば、ペラギウスの論文『キリスト教生活について』は、聖書と典礼文書を除けば、中世において(アウグスティヌスの『神の国』に次いで)2番目 に多く複製された作品であった。 |

| Early modern era During the modern era, Pelagianism continued to be used as an epithet against orthodox Christians. However, there were also some authors who had essentially Pelagian views according to Nelson's definition.[64] Nelson argued that many of those considered the predecessors to modern liberalism took Pelagian or Pelagian-adjacent positions on the problem of evil.[109] For instance, Leibniz, who coined the word theodicy in 1710, rejected Pelagianism but nevertheless proved to be "a crucial conduit for Pelagian ideas".[110] He argued that "Freedom is deemed necessary in order that man may be deemed guilty and open to punishment."[111] In De doctrina christiana, John Milton argued that "if, because of God's decree, man could not help but fall ... then God's restoration of fallen man was a matter of justice not grace".[112] Milton also argued for other positions that could be considered Pelagian, such as that "The knowledge and survey of vice, is in this world ... necessary to the constituting of human virtue."[113] Jean-Jacques Rousseau made nearly identical arguments for that point.[113] John Locke argued that the idea that "all Adam's Posterity [are] doomed to Eternal Infinite Punishment, for the Transgression of Adam" was "little consistent with the Justice or Goodness of the Great and Infinite God".[114] He did not accept that original sin corrupted human nature, and argued that man could live a Christian life (although not "void of slips and falls") and be entitled to justification.[111] Nelson argues that the drive for rational justification of religion, rather than a symptom of secularization, was actually "a Pelagian response to the theodicy problem" because "the conviction that everything necessary for salvation must be accessible to human reason was yet another inference from God's justice". In Pelagianism, libertarian free will is necessary but not sufficient for God's punishment of humans to be justified, because man must also understand God's commands.[115] As a result, thinkers such as Locke, Rousseau and Immanuel Kant argued that following natural law without revealed religion must be sufficient for the salvation of those who were never exposed to Christianity because, as Locke pointed out, access to revelation is a matter of moral luck.[116] Early modern proto-liberals such as Milton, Locke, Leibniz, and Rousseau advocated religious toleration and freedom of private action (eventually codified as human rights), as only freely chosen actions could merit salvation.[117][k] 19th-century philosopher Søren Kierkegaard dealt with the same problems (nature, grace, freedom, and sin) as Augustine and Pelagius,[81] which he believed were opposites in a Hegelian dialectic.[119] He rarely mentioned Pelagius explicitly[81] even though he inclined towards a Pelagian viewpoint. However, Kierkegaard rejected the idea that man could perfect himself.[120] |

近世 近代においても、ペラギウス主義は正統派キリスト教徒に対する蔑称として用いられ続けた。しかし、ネルソンの定義によれば、本質的にペラギウス的見解を持 つ著者も一部存在した[64]。ネルソンは、現代自由主義の先駆者と見なされる多くの人々が、悪の問題に関してペラギウス的あるいはペラギウスに近い立場 を取っていたと主張した。[109] 例えば、1710年に「神義論」という言葉を造語したライプニッツは、ペラギウス主義を否定しながらも、結局「ペラギウス思想の重要な媒介者」となった。 [110] 彼は「人間が有罪とされ、罰を受ける可能性を持つためには、自由が不可欠であると見なされる」と主張した。[111] ジョン・ミルトンは『キリスト教教義論』において「もし神の定めゆえに人間が堕落せざるを得なかったならば…神による堕落した人間の回復は恩寵ではなく正 義の問題である」と論じた[112]。ミルトンはまた「悪の認識と観察は、この世において…人間の美徳を構成するために必要である」といった、ペラギウス 的と見なされ得る他の立場も主張した。[113] ジャン=ジャック・ルソーもほぼ同様の論拠を提示した。[113] ジョン・ロックは「アダムの罪のために、すべての子孫が永遠の無限の罰に定められている」という考えは「偉大で無限なる神の正義や善性とはほとんど整合し ない」と主張した。[114] 彼は原罪が人間の本性を堕落させるという考えを受け入れず、人間は(過ちや失敗が全くないわけではないが)キリスト教的な生活を送ることができ、義認を受 ける資格があると主張した。[111] ネルソンは、宗教の合理的正当化を求める動きは世俗化の兆候ではなく、実は「神義論問題に対するペラギウス的応答」であったと論じる。なぜなら「救いに必 要な全ては人間の理性にアクセス可能でなければならないという確信は、神の正義から導かれるさらなる推論であった」からである。ペラギウス主義において、 自由意志は神の懲罰を正当化するために必要だが十分ではない。なぜなら人間は神の命令を理解しなければならないからだ[115]。その結果、ロック、ル ソー、イマヌエル・カントといった思想家は、啓示された宗教なしに自然法に従うことが、キリスト教に触れたことのない者の救済には十分であると主張した。 ロックが指摘したように、啓示へのアクセスは道徳的幸運の問題だからである。[116] ミルトン、ロック、ライプニッツ、ルソーといった近世初期の自由主義の先駆者たちは、宗教的寛容と私的行動の自由(後に人権として法典化された)を提唱し た。なぜなら、救済に値するのは自由意志で選ばれた行動だけだからだ。[117][k] 19世紀の哲学者ソレン・キルケゴールは、アウグスティヌスとペラギウスが扱ったのと同じ問題(自然、恩寵、自由、罪)を扱った[81]。彼はこれらを ヘーゲル的弁証法における対立概念と見なした[119]。ペラギウスの見解に傾倒していたにもかかわらず、キルケゴールはペラギウスを明示的に言及するこ とはほとんどなかった[81]。しかし、キルケゴールは人間が自らを完成させられるという考えを拒否した。[120] |

| Contemporary responses John Rawls was a critic of Pelagianism, an attitude that he retained even after becoming an atheist. His anti-Pelagian ideas influenced his book A Theory of Justice, in which he argued that differences in productivity between humans are a result of "moral arbitrariness" and therefore unequal wealth is undeserved.[121] In contrast, the Pelagian position would be that human sufferings are largely the result of sin and are therefore deserved.[91] According to Nelson, many contemporary social liberals follow Rawls rather than the older liberal-Pelagian tradition.[122] The conflict between Pelagius and the teachings of Augustine was a constant theme throughout the works of Anthony Burgess, in books including A Clockwork Orange, Earthly Powers, A Vision of Battlements and The Wanting Seed.[123] Mateusz Morawiecki, the prime minister of Poland between 2017 and 2023, declared his support for Pelagianism.[124] Scholarly reassessment During the 20th century, Pelagius and his teachings underwent a reassessment.[125][53] In 1956, John Ferguson wrote: If a heretic is one who emphasizes one truth to the exclusion of others, it would at any rate appear that [Pelagius] was no more a heretic than Augustine. His fault was in exaggerated emphasis, but in the final form his philosophy took, after necessary and proper modifications as a result of criticism, it is not certain that any statement of his is totally irreconcilable with the Christian faith or indefensible in terms of the New Testament. It is by no means so clear that the same may be said of Augustine.[126][125] Thomas Scheck writes that although Pelagius' views on original sin are still considered "one-sided and defective":[53] An important result of the modern reappraisal of Pelagius's theology has been a more sympathetic assessment of his theology and doctrine of grace and the recognition of its deep rootedness in the antecedent Greek theologians... Pelagius's doctrine of grace, free will and predestination, as represented in his Commentary on Romans, has very strong links with Eastern (Greek) theology and, for the most part, these doctrines are no more reproachable than those of orthodox Greek theologians such as Origen and John Chrysostom, and of St. Jerome.[53] |

現代の反応 ジョン・ロールズはペラギウス主義の批判者であり、無神論者となった後もその姿勢を貫いた。彼の反ペラギウス思想は著書『正義論』に影響を与え、そこでは 人間の生産性の差は「道徳的恣意性」の結果であり、したがって富の不平等は不当であると論じている。[121] これに対しペラギウス派の立場は、人間の苦しみは主に罪の結果であり、したがって当然の報いであるとするものだ。[91] ネルソンによれば、現代の社会自由主義者の多くは、古い自由主義的ペラギウス派の伝統ではなく、ロールズに従っている。[122] ペラギウスとアウグスティヌスの教えとの対立は、アンソニー・バージェスの作品、特に『時計じかけのオレンジ』、『地上の権力』、『城壁のビジョン』、『欲する種』などで繰り返し取り上げられたテーマである。[123] 2017年から2023年までポーランドの首相を務めたマテウシュ・モラヴィエツキは、ペラギウス主義を支持すると表明した。[124] 学術的な再評価 20 世紀、ペラギウスとその教えは再評価された。[125][53] 1956 年、ジョン・ファーガソンは次のように書いている。 異端者とは、ある真実を強調して他の真実を排除する者であるならば、いずれにせよ、[ペラギウス] はアウグスティヌスほど異端者ではなかったように思われる。彼の過ちは誇張した強調にあったが、批判の結果として必要かつ適切な修正を経て、彼の哲学が最 終的にたどり着いた形では、彼の主張がキリスト教の信仰と全く相容れないもの、あるいは新約聖書から見て擁護できないものであるとは必ずしも言えない。ア ウグスティヌスについても同じことが言えるかどうかは、決して明らかではない。[126][125] トーマス・シェックは、ペラギウスの原罪に関する見解が依然として「偏った欠陥のあるもの」と見なされていると記している:[53] ペラギウスの神学に対する現代的な再評価の重要な成果は、彼の神学と恩寵の教義に対するより理解ある評価と、それが先行するギリシャ神学者たちに深く根ざ していることの認識である... ペラギウスの『ローマ人への手紙注解』に示された恩寵・自由意志・予定説の教義は、東方(ギリシャ)神学と非常に強い関連性を持つ。そしてこれらの教義の 大部分は、オリゲネスやヨハネス・クリュソストモスといった正統派ギリシャ神学者や聖ヒエロニムスの教義と比べても、非難されるべきものではない。 [53] |

| Tabula rasa Indeterminism |

白紙状態 不確定性 |

| a. According to Marius Mercator, Caelestius was deemed to hold six heretical beliefs:[16] Adam was created mortal Adam's sin did not corrupt other humans Infants are born into the same state as Adam before the fall of man Adam's sin did not introduce mortality Following God's law enables man to enter the Kingdom of Heaven There were other humans, besides Christ, who were without sin b. Scriptural passages cited to support this argument include Deuteronomy 30:15, Ecclesiasticus 15:14–17, and Ezekiel 18:20 and 33:12, 16.[42] c. At the Council of Diospolis, On the Christian Life was submitted as an example of Pelagius' heretical writings. Scholar Robert F. Evans argues that it was Pelagius' work, but Ali Bonner disagrees.[108] d. The Hebrew Bible figures claimed as sinless by Pelagius include Abel, Enoch, Melchizedek, Lot, and Noah.[42] At the Synod of Diospolis, Pelagius went back on the claim that other humans besides Jesus had lived sinless lives, but insisted that it was still theoretically possible.[26] e. Scriptural passages cited for the necessity of works include Matthew 7:19–22, Romans 2:13, and Titus 1:1.[42] f. According to Augustine, true virtue resides exclusively in God and humans can know it only imperfectly.[57] g. Scheck and F. Clark summarize the condemned beliefs as follows: "Adam's sin injured only himself, so that his posterity were not born in that state of alienation from God called original sin It was accordingly possible for man, born without original sin or its innate consequences, to continue to live without sin by the natural goodness and powers of his nature; therefore, justification was not a process that must necessarily take place for man to be saved Eternal life was, consequently, open and due to man as a result of his natural good strivings and merits; divine interior grace, though useful, was not necessary for the attainment of salvation."[61] h. The phrase (inimici gratiae) was repeated more than fifty times in Augustine's anti-Pelagian writings after Diospolis.[66] i. Robert Dodaro has a similar list: "(1) that human beings can be sinless; (2) that they can act virtuously without grace; (3) that virtue can be perfected in this life; and (4) that fear of death can be completely overcome".[67] j. Pelagius wrote: "pardon is given to those who repent, not according to the grace and mercy of God, but according to their own merit and effort, who through repentance will have been worthy of mercy".[39] k. This is the opposite of the Augustinian argument against excessive state power, which is that human corruption is such that man cannot be trusted to wield it without creating tyranny, what Judith Shklar called "liberalism of fear".[118] |

a. マリウス・メルカトルによれば、カエレスティウスは六つの異端思想を保持していると見なされた[16]: アダムは死すべき者として創造された アダムの罪は他の人類を堕落させなかった 幼児は堕落前の人類と同じ状態に生まれる アダムの罪は死をもたらさなかった 神の律法に従うことで、人間は天国に入ることができる キリスト以外にも、罪のない人間がいた b. この主張を裏付けるために引用された聖書の箇所には、申命記 30:15、シラ書 15:14-17、エゼキエル書 18:20 および 33:12、16 がある。[42] c. ディオスポリス公会議では、『キリスト教生活について』がペラギウスの異端的な著作の一例として提出された。学者ロバート・F・エヴァンスは、この著作はペラギウスの作品であると主張しているが、アリ・ボナーはこれに異議を唱えている。[108] d. ペラギウスが罪のない人物として挙げたヘブライ語聖書の登場人物には、アベル、エノク、メルキゼデク、ロト、ノアが含まれる。[42] ディオスポリス公会議で、ペラギウスは、イエス以外の人間が罪のない生活を送ったという主張を撤回したが、理論的には依然として可能だと主張した。 [26] e. 行為の必要性について引用された聖書箇所には、マタイによる福音書 7:19-22、ローマ人への手紙 2:13、テトスへの手紙 1:1 がある。[42] f. アウグスティヌスによれば、真の徳は神にのみ存在し、人間はそれを不完全な形でしか知ることができない。[57] g. シェックとF.クラークは、非難された信念を以下のように要約している: 「アダムの罪は彼自身のみを傷つけたため、その子孫は原罪と呼ばれる神からの疎外状態に生まれなかった」 したがって、原罪やその生来の結果なしに生まれた人間は、自然の本性の善性と力によって罪なく生き続けることが可能であった。ゆえに、義認は人間が救われるために必然的に起こらねばならない過程ではなかった 結果として、永遠の命は人間の自然な善への努力と功績の結果として開かれ、当然に与えられるものだった。神の内的恩寵は有用ではあるが、救いを得るために必要ではなかった。」[61] h. 「恵みの敵(inimici gratiae)」という表現は、ディオスポリス以降のアウグスティヌスの反ペラギウス論著作において50回以上繰り返された。[66] i. ロバート・ドダロも同様のリストを挙げている:「(1) 人間は罪のない状態になり得る;(2) 恵みなしに徳ある行動が可能である;(3) この世で徳を完成させ得る;(4) 死への恐怖を完全に克服し得る」。[67] j. ペラギウスはこう記した:「赦しは悔い改める者に与えられる。それは神の恩寵と慈悲によるのではなく、彼ら自身の功績と努力による。悔い改めによって慈悲に値する者とされるのだ」。[39] k. これは、国家の過剰な権力に対するアウグスティヌスの主張とは正反対である。アウグスティヌスは、人間の堕落は甚だしく、権力を委ねれば必ず専制を生み出すと主張した。ジュディス・シュクラが「恐怖の自由主義」と呼んだものだ。[118] |

| Sources Beck, John H. (2007). "The Pelagian Controversy: An Economic Analysis". American Journal of Economics and Sociology. 66 (4): 681–696. doi:10.1111/j.1536-7150.2007.00535.x. S2CID 144950796. Bonner, Gerald (2018). The Myth of Pelagianism. British Academy Monograph. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-726639-7. Clark, Mary T. (2005). Augustine. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-8259-3. Bonner, Gerald (2004). "Pelagius (fl. c.390–418), theologian". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21784. Brown, Peter (1970). "The Patrons of Pelagius: the Roman Aristocracy Between East and West". The Journal of Theological Studies. 21 (1): 56–72. doi:10.1093/jts/XXI.1.56. ISSN 0022-5185. JSTOR 23957336. Chadwick, Henry (2001). Augustine: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285452-0. Chronister, Andrew C. (2020). "Ali Bonner, The Myth of Pelagianism". Augustinian Studies. 51 (1): 115–119. doi:10.5840/augstudies20205115. S2CID 213551127. Cohen, Samuel (2016). "Religious Diversity". In Jonathan J. Arnold; M. Shane Bjornlie; Kristina Sessa (eds.). A Companion to Ostrogothic Italy. Leiden, Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 503–532. ISBN 978-9004-31376-7. Dodaro, Robert (2004). Christ and the Just Society in the Thought of Augustine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-45651-7. Elliott, Mark W. (2011). "Pelagianism". In McFarland, Ian A.; Fergusson, David A. S.; Kilby, Karen; Torrance, Iain R. (eds.). The Cambridge Dictionary of Christian Theology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 377–378. ISBN 978-0-511-78128-5. Ferguson, John (1956). Pelagius: A Historical and Theological Study. Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons. Fu, Youde (2015). "Hebrew Justice: A Reconstruction for Today". The Value of the Particular: Lessons from Judaism and the Modern Jewish Experience. Leiden: Brill. pp. 171–194. ISBN 978-90-04-29269-7. Harrison, Carol (2016). "Truth in a Heresy?". The Expository Times. 112 (3): 78–82. doi:10.1177/001452460011200302. S2CID 170152314. James, Frank A. III (1998). Peter Martyr Vermigli and Predestination: The Augustinian Inheritance of an Italian Reformer. Oxford: Clarendon. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015. Keech, Dominic (2012). The Anti-Pelagian Christology of Augustine of Hippo, 396-430. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-966223-4. Keeny, Anthony (2009). An Illustrated Brief History of Western Philosophy. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-7860-0. Kirwan, Christopher (1998). "Pelagianism". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Taylor & Francis. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-K064-1. ISBN 978-0-415-25069-6. Levering, Matthew (2011). Predestination: Biblical and Theological Paths. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-960452-4. Lössl, Josef (20 September 2019). "The myth of Pelagianism. By Ali Bonner. (A British Academy Monograph.) Pp. xviii + 342. Oxford–New York: Oxford University Press (for The British Academy), 2018. 978 0 19 726639 7". The Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 70 (4): 846–849. doi:10.1017/S0022046919001283. S2CID 204479402. Nelson, Eric (2019). The Theology of Liberalism: Political Philosophy and the Justice of God. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-24094-0. Rigby, Paul (2015). The Theology of Augustine's Confessions. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-09492-5. Puchniak, Robert (2008). "Pelagius: Kierkegaard's use of Pelagius and Pelagianism". In Stewart, Jon Bartley (ed.). Kierkegaard and the Patristic and Medieval Traditions. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-6391-1. Rackett, Michael R. (2002). "What's Wrong with Pelagianism?". Augustinian Studies. 33 (2): 223–237. doi:10.5840/augstudies200233216. Rees, Brinley Roderick (1998). Pelagius: Life and Letters. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85115-714-6. Scheck, Thomas P. (2012). "Pelagius's Interpretation of Romans". In Cartwright, Steven (ed.). A Companion to St. Paul in the Middle Ages. Leiden: Brill. pp. 79–114. ISBN 978-90-04-23671-4. Squires, Stuart (2016). "Jerome on Sinlessness: a Via Media between Augustine and Pelagius". The Heythrop Journal. 57 (4): 697–709. doi:10.1111/heyj.12063. Teselle, Eugene (2014). "The Background: Augustine and the Pelagian Controversy". In Hwang, Alexander Y.; Matz, Brian J.; Casiday, Augustine (eds.). Grace for Grace: The Debates after Augustine and Pelagius. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press. pp. 1–13. ISBN 978-0-8132-2601-9. Stump, Eleonore (2001). "Augustine on free will". In Stump, Eleonore; Kretzmann, Norman (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Augustine. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 124–147. ISBN 978-1-1391-7804-4. Visotzky, Burton L. (2009). "Will and Grace: Aspects of Judaising in Pelagianism in Light of Rabbinic and Patristic Exegesis of Genesis". In Grypeou, Emmanouela; Spurling, Helen (eds.). The Exegetical Encounter Between Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity. Leiden: Brill. pp. 43–62. ISBN 978-90-04-17727-7. Weaver, Rebecca (2014). "Introduction". In Hwang, Alexander Y.; Matz, Brian J.; Casiday, Augustine (eds.). Grace for Grace: The Debates after Augustine and Pelagius. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press. pp. xi–xxvi. ISBN 978-0-8132-2601-9. Wetzel, James (2001). "Predestination, Pelagianism, and foreknowledge". In Stump, Eleonore; Kretzmann, Norman (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Augustine. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 49–58. ISBN 978-1-1391-7804-4. |

出典 ベック、ジョン・H. (2007). 「ペラギウス論争:経済学的分析」. 『アメリカ経済社会学雑誌』. 66 (4): 681–696. doi:10.1111/j.1536-7150.2007.00535.x. S2CID 144950796. ボナー、ジェラルド(2018)。『ペラギウス主義の神話』。英国学士院モノグラフ。オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-726639-7。 クラーク、メアリー・T.(2005)。『アウグスティヌス』。ブルームズベリー出版。ISBN 978-1-4411-8259-3。 ボナー、ジェラルド(2004)。「ペラギウス(活動時期約390–418年)、神学者」。『オックスフォード国家人物事典』。オックスフォード大学出版局。doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21784。 ブラウン、ピーター (1970). 「ペラギウスの後援者たち:東西の間のローマ貴族」. 神学研究ジャーナル. 21 (1): 56–72. doi:10.1093/jts/XXI.1.56. ISSN 0022-5185. JSTOR 23957336. チャドウィック、ヘンリー (2001). 『アウグスティヌス:ごく簡単な入門』. オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-19-285452-0. クロニスター、アンドルー C. (2020). 「アリ・ボナー、ペラギウス主義の神話」. 『アウグスティヌス研究』. 51 (1): 115–119. doi:10.5840/augstudies20205115. S2CID 213551127. Cohen, Samuel (2016). 「宗教の多様性」. Jonathan J. Arnold; M. Shane Bjornlie; Kristina Sessa (eds.) 編. 『東ゴート族のイタリア』. ライデン、ボストン:ブリル出版社。503-532 ページ。ISBN 978-9004-31376-7。 ドダロ、ロバート (2004)。『アウグスティヌスの思想におけるキリストと公正な社会』。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-1-139-45651-7。 エリオット、マーク・W。(2011). 「ペラギウス主義」. マクファーランド、イアン A.、ファーガソン、デビッド A. S.、キルビー、カレン、トランス、イアン R. (編). 『ケンブリッジキリスト教神学辞典』. ケンブリッジ: ケンブリッジ大学出版局. pp. 377–378. ISBN 978-0-511-78128-5. ファーガソン、ジョン (1956)。『ペラギウス:歴史的・神学的研究』。ケンブリッジ:W. Heffer & Sons。 フー、ヨウデ (2015)。「ヘブライの正義:今日の再構築」。『特定の価値:ユダヤ教と現代ユダヤ人の経験から得た教訓』。ライデン:ブリル。171-194 ページ。ISBN 978-90-04-29269-7。 ハリソン、キャロル(2016)。「異端における真実?」。The Expository Times。112 (3): 78–82. doi:10.1177/001452460011200302。S2CID 170152314. ジェームズ、フランク・A・III(1998)。『ペテロ・マルティル・ヴェルミグリと予定説:イタリアの宗教改革者におけるアウグスティヌス的継承』。オックスフォード:クラレンドン。2015年12月22日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2015年12月14日に取得。 キーチ、ドミニク(2012)。ヒッポのアウグスティヌス(396-430)の反ペラギウス的キリスト論。オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-966223-4。 キーニー、アンソニー(2009)。図解 西洋哲学の簡明な歴史。ジョン・ワイリー・アンド・サンズ。ISBN 978-1-4051-7860-0。 キルワン、クリストファー(1998)。「ペラギウス主義」。『ラウトリッジ哲学百科事典』。テイラー&フランシス。doi:10.4324/9780415249126-K064-1。ISBN 978-0-415-25069-6。 レヴァリング、マシュー(2011)。『予定説:聖書的・神学的経路』ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-960452-4。 ロースル、ヨーゼフ(2019年9月20日)。「ペラギウス主義の神話。アリ・ボナー著。(英国学士院モノグラフ。)xviii + 342頁。オックスフォード・ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局(英国学士院刊)、2018年。978 0 19 726639 7」。『教会史ジャーナル』70巻4号:846–849頁。doi:10.1017/S0022046919001283。S2CID 204479402. ネルソン、エリック(2019)。『自由主義の神学:政治哲学と神の正義』。ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-674-24094-0。 リグビー、ポール(2015)。『アウグスティヌスの『告白』の神学』。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-1-107-09492-5。 プクニアック、ロバート(2008)。「ペラギウス:キルケゴールによるペラギウスとペラギウス主義の活用」。スチュワート、ジョン・バートリー(編)。 『キルケゴールと教父学・中世伝統』。ファーンハム:アッシュゲート出版。ISBN 978-0-7546-6391-1。 ラケット、マイケル・R.(2002)。「ペラギウス主義の何が問題か?」。『アウグスティヌス研究』33巻2号:223–237頁。doi:10.5840/augstudies200233216。 リース、ブリンリー・ロデリック(1998)。『ペラギウス:生涯と書簡』。ウッドブリッジ:ボイドル&ブリューワー。ISBN 978-0-85115-714-6。 シェック、トーマス・P.(2012)。「ペラギウスのローマ人への手紙解釈」。カートライト、スティーブン(編)。中世における聖パウロの伴侶。ライデン:ブリル。79-114 ページ。ISBN 978-90-04-23671-4。 スクワイアーズ、スチュワート(2016)。「罪のないことに関するジェローム:アウグスティヌスとペラギウスの間の妥協点」。ヘイトロップ・ジャーナル。57 (4): 697–709. doi:10.1111/heyj.12063. テッセル、ユージーン (2014). 「背景:アウグスティヌスとペラギウス論争」. ファン、アレクサンダー Y.; マッツ、ブライアン J.; カシデイ、アウグスティヌス (編). 恵みのための恵み:アウグスティヌスとペラギウス後の議論。ワシントン D.C.:カトリック大学出版局。1-13 ページ。ISBN 978-0-8132-2601-9。 Stump, Eleonore (2001). 「自由意志に関するアウグスティヌス」 Stump, Eleonore; Kretzmann, Norman (eds.) ケンブリッジ・オーガスティン・コンパニオン。ニューヨーク:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。124-147 ページ。ISBN 978-1-1391-7804-4。 Visotzky, Burton L. (2009). 「意志と恩寵:創世記のラビ的および教父的解釈に照らしたペラギウス主義におけるユダヤ教化の側面」。Grypeou, Emmanouela; Spurling, Helen (eds.) 編。古代末期におけるユダヤ人とキリスト教徒の聖書解釈上の出会い。ライデン:ブリル。43-62 ページ。ISBN 978-90-04-17727-7。 ウィーバー、レベッカ (2014). 「序文」. ファン、アレクサンダー Y.; マッツ、ブライアン J.; カシデイ、オーガスティン (編). 『恵みのための恵み:オーガスティンとペラギウス後の議論』. ワシントン D.C.: カトリック大学出版局. pp. xi–xxvi. ISBN 978-0-8132-2601-9. ウェッツェル、ジェームズ (2001). 「宿命、ペラギウス主義、そして予知」. スタンプ、エレオノーレ; クレッツマン、ノーマン (編). 『ケンブリッジ・コンパニオン・トゥ・オーガスティヌス』. ニューヨーク: ケンブリッジ大学出版局. pp. 49–58. ISBN 978-1-1391-7804-4. |

| Further reading Bonner, Gerald (2002). "The Pelagian controversy in Britain and Ireland". Peritia. 16: 144–155. doi:10.1484/J.Peri.3.483. Brown, Peter (1968). "Pelagius and his Supporters: Aims and Environment". The Journal of Theological Studies. XIX (1): 93–114. doi:10.1093/jts/XIX.1.93. JSTOR 23959559. Clark, Elizabeth A. (2014). The Origenist Controversy: The Cultural Construction of an Early Christian Debate. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6311-2. Cyr, Taylor W.; Flummer, Matthew T. (2018). "Free will, grace, and anti-Pelagianism". International Journal for Philosophy of Religion. 83 (2): 183–199. doi:10.1007/s11153-017-9627-0. ISSN 1572-8684. S2CID 171953180. Dauzat, Pierre-Emmanuel [in French] (2010). "Hirschman, Pascal et la rhétorique réactionnaire: Une analyse économique de la controverse pélagienne" [Hirschman, Pascal and reactionary rhetoric: An economic analysis of the Pelagian controversy]. The Tocqueville Review/La revue Tocqueville (in French). 31 (2): 133–154. doi:10.1353/toc.2010.0009. ISSN 1918-6649. S2CID 145615057. Dodaro, Robert (2004). ""Ego miser homo": Augustine, The Pelagian Controversy, and the Paul of Romans 7:7-25". Augustinianum. 44 (1): 135–144. doi:10.5840/agstm20044416. Evans, Robert F. (2010) [1968]. Pelagius: Inquiries and Reappraisals. Eugene: Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-60899-497-7. Lamberigts, Mathijs [in Dutch] (2002). "Recent Research Into Pelagianism With Particular Emphasis on the Role of Julian of Aeclanum". Augustiniana. 52 (2/4): 175–198. ISSN 0004-8003. Markus, Gilbert (2005). "Pelagianism and the 'Common Celtic Church'" (PDF). Innes Review. 56 (2): 165–213. doi:10.3366/inr.2005.56.2.165. Nunan, Richard (2012). "Catholics and evangelical protestants on homoerotic desire: the intellectual legacy of Augustinian and Pelagian theories of human nature". Queer Philosophy. Brill | Rodopi. pp. 329–352. doi:10.1163/9789401208352_039. ISBN 978-94-012-0835-2. Rees, Brinley Roderick (1988). Pelagius: A Reluctant Heretic. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 0-85115-503-0. Scholl, Lindsey Anne (2011). Elizabeth DePalma Digeser (ed.). The Pelagian Controversy: A Heresy in its Intellectual Context (PhD thesis). University of California, Santa Barbara. ISBN 978-1-249-89783-5. ProQuest 3482027. Squires, Stuart (2013). Philip Rousseau (ed.). Reassessing Pelagianism: Augustine, Cassian, and Jerome on the Possibility of a Sinless Life (PhD thesis). Catholic University of America. Squires, Stuart (2019). The Pelagian Controversy: An Introduction to the Enemies of Grace and the Conspiracy of Lost Souls. Eugene: Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-5326-3781-0. Wermelinger, Otto (1975). Rom und Pelagius: die theologische Position der römischen Bischöfe im pelagianischen Streit in den Jahren 411-432 [Rome and Pelagius: the theological position of the Roman bishops during the Pelagian controversy, 411–432] (in German). A. Hiersemann. ISBN 978-3-7772-7516-1. |

参考文献 ボナー、ジェラルド(2002)。「英国とアイルランドにおけるペラギウス論争」。『ペリティア』16: 144–155。doi:10.1484/J.Peri.3.483。 ブラウン、ピーター(1968)。「ペラギウスとその支持者たち:目的と環境」。『神学研究ジャーナル』。XIX (1): 93–114。doi:10.1093/jts/XIX.1.93。JSTOR 23959559。 クラーク、エリザベス・A.(2014)。『オリゲニスト論争:初期キリスト教論争の文化的構築』。プリンストン:プリンストン大学出版局。ISBN 978-1-4008-6311-2。 サイア、テイラー・W.;フラマー、マシュー・T.(2018)。「自由意志、恩寵、反ペラギウス主義」。国際宗教哲学ジャーナル. 83 (2): 183–199. doi:10.1007/s11153-017-9627-0. ISSN 1572-8684. S2CID 171953180. ドーザ, ピエール=エマニュエル [フランス語] (2010). 「ヒルシュマン、パスカルと反動的修辞学:ペラギウス論争の経済学的分析」. トクヴィル・レビュー/ラ・レヴュー・トクヴィル (フランス語). 31 (2): 133–154. doi:10.1353/toc.2010.0009. ISSN 1918-6649. S2CID 145615057. Dodaro, Robert (2004). 「「Ego miser homo」: Augustine, The Pelagian Controversy, and the Paul of Romans 7:7-25」. Augustinianum. 44 (1): 135–144. doi:10.5840/agstm20044416. エヴァンス、ロバート F. (2010) [1968]. ペラギウス:調査と再評価。ユージーン:Wipf and Stock。ISBN 978-1-60899-497-7。 ランベルグツ、マティス [オランダ語] (2002)。「エクラヌムのユリアヌスの役割に特に重点を置いた、ペラギウス主義に関する最近の研究」。Augustiniana. 52 (2/4): 175–198. ISSN 0004-8003. マルクス、ギルバート (2005). 「ペラギウス主義と『共通ケルト教会』」 (PDF). インズ・レビュー. 56 (2): 165–213. doi:10.3366/inr.2005.56.2.165. ヌーナン、リチャード(2012)。「同性愛的欲望に関するカトリックと福音派プロテスタント:アウグスティヌスとペラギウスの人間性理論の知的遺産」。 『クィア哲学』。ブリル | ロドピ。pp. 329–352。doi:10.1163/9789401208352_039。ISBN 978-94-012-0835-2. リース、ブリンリー・ロデリック(1988年)。『ペラギウス:不本意な異端者』。ウッドブリッジ:ボイドル&ブリュワー。ISBN 0-85115-503-0。 Scholl, Lindsey Anne (2011). Elizabeth DePalma Digeser (編). 『ペラギウス論争:知的文脈における異端』 (博士論文). カリフォルニア大学サンタバーバラ校. ISBN 978-1-249-89783-5. ProQuest 3482027. スクワイアーズ、スチュワート (2013)。フィリップ・ルソー (編)。ペラギウス主義の再評価:罪のない人生の可能性に関するアウグスティヌス、カッシアン、ジェローム (博士論文)。カトリック大学アメリカ校。 スクワイアーズ、スチュワート (2019)。『ペラギウス論争:恵みの敵と失われた魂の陰謀入門』。ユージーン:ウィップ・アンド・ストック。ISBN 978-1-5326-3781-0。 ヴェルメリンガー、オットー (1975)。ローマとペラギウス:411年から432年にかけてのペラギウス論争におけるローマ司教たちの神学的立場(ドイツ語)。A. ヒアゼマン。ISBN 978-3-7772-7516-1。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pelagianism |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099