ペリパトス派

Peripatetic school; 逍遥学派

☆ ペリパトス学派は、紀元前335年にアリストテレスによって古代アテネ のリセウムに創設された哲学学派である。哲学的、科学的な探求を行う非公式な機関であった。 ペリパトス(peripatetic)とは、古代ギリシャ語のπεριπατητικός(peripatētikós)を音訳したもので、「歩くこと」 「歩き回ること」を意味する。アリストテレスが創設したペリパトス学派は、実際には単にペリパトスとして知られていた。 [アリストテレスの学派がこのように呼ばれるようになったのは、メンバーたちが集まっていたリセウムのペリパトイ(「歩道」、屋根付きや列柱付きのものも ある)に由来する。アリストテレスが講義中に歩き回る習慣があったことからこの名がついたという伝説は、スミルナのヘルミッポスから始まったのかも しれない。紀元前3世紀半ば以降、学派は衰退し、ローマ帝国時代になって 復活した。

★

ペリパトス派は、日本語ではお散歩の意味の逍遥(しょうよう)から音をとって逍遥学派と言われます

| The Peripatetic

school was a philosophical school founded in 335 BC by Aristotle in

the Lyceum in Ancient Athens. It was an informal institution whose

members conducted philosophical and scientific inquiries. After the

middle of the 3rd century BC, the school fell into decline, and it was

not until the Roman Empire that there was a revival. |

ペリパトス学派は、紀元前335年にアリストテレスによって古代アテネ

のリセウムに創設された哲学学派である。哲学的、科学的な探求を行う非公式な機関であった。紀元前3世紀半ば以降、学派は衰退し、ローマ帝国時代になって

復活した。 |

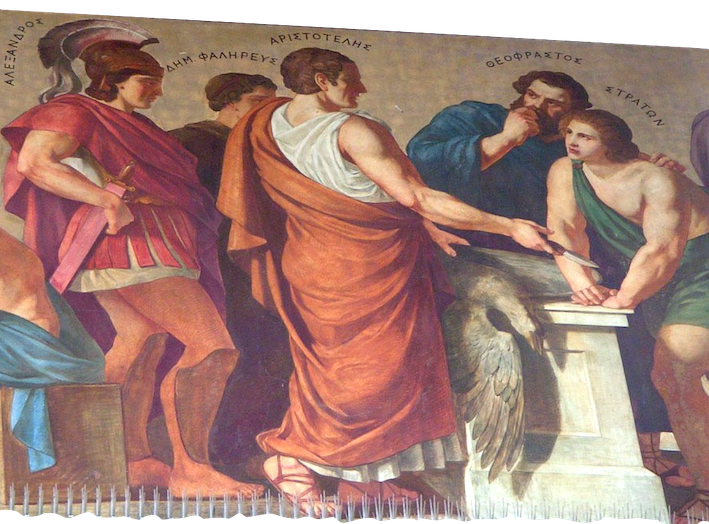

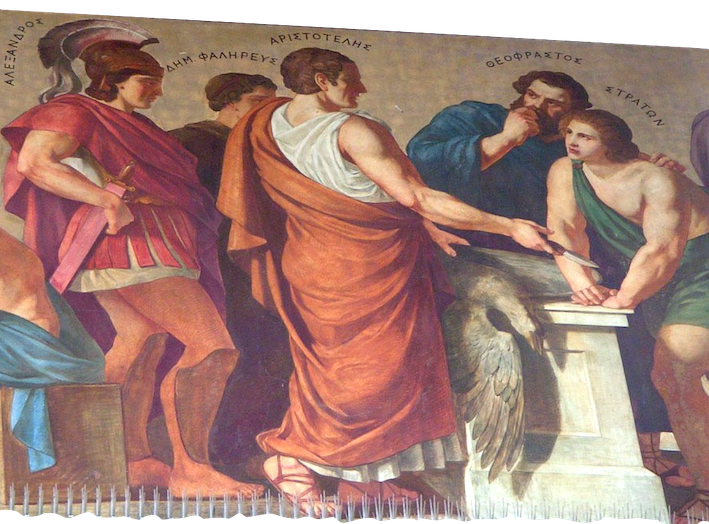

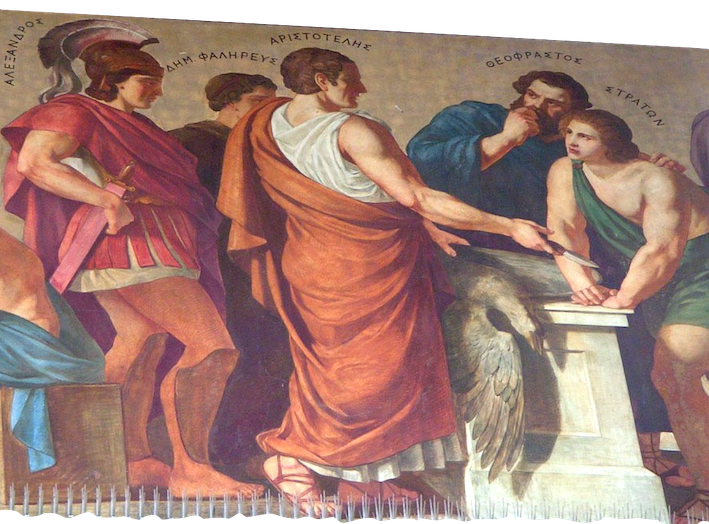

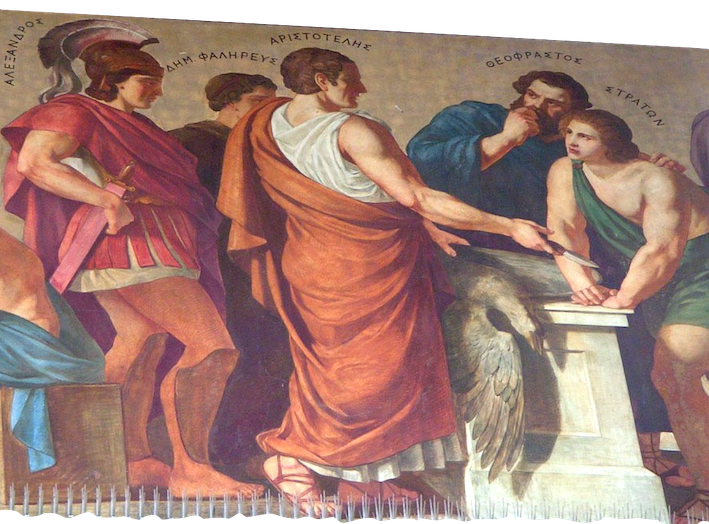

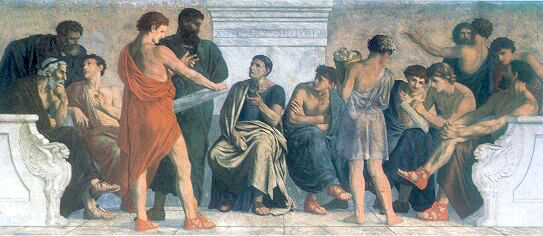

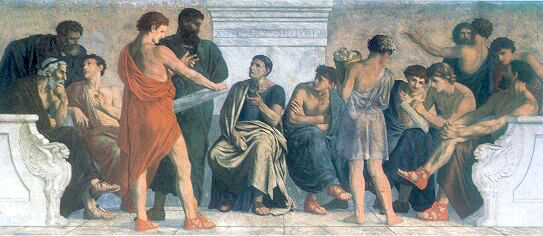

History Aristotle and his disciples – Alexander, Demetrius, Theophrastus, and Strato, in an 1888 fresco in the portico of the National University of Athens The term peripatetic is a transliteration of the ancient Greek word περιπατητικός (peripatētikós), which means "of walking" or "given to walking about".[1] The Peripatetic school, founded by Aristotle,[2] was actually known simply as the Peripatos.[3] Aristotle's school came to be so named because of the peripatoi ("walkways", some covered or with colonnades) of the Lyceum where the members met.[4] The legend that the name came from Aristotle's alleged habit of walking while lecturing may have started with Hermippus of Smyrna.[5] Unlike Plato (428/7–348/7 BC), Aristotle (384–322 BC)[2] was not a citizen of Athens and so could not own property; he and his colleagues therefore used the grounds of the Lyceum as a gathering place, just as it had been used by earlier philosophers such as Socrates.[6] Aristotle and his colleagues first began to use the Lyceum in this way about 335 BC,[7] after which Aristotle left Plato's Academy and Athens, and then returned to Athens from his travels about a dozen years later.[8] Because of the school's association with the gymnasium, the school also came to be referred to simply as the Lyceum.[6] Some modern scholars argue that the school did not become formally institutionalized until Theophrastus took it over, at which time there was private property associated with the school.[9] Originally at least, the Peripatetic gatherings were probably conducted less formally than the term "school" suggests: there was likely no set curriculum or requirements for students or even fees for membership.[10] Aristotle did teach and lecture there, but there was also philosophical and scientific research done in partnership with other members of the school.[11] It seems likely that many of the writings that have come down to us in Aristotle's name were based on lectures he gave at the school.[12] Among the members of the school in Aristotle's time were Theophrastus, Phanias of Eresus, Eudemus of Rhodes, Aristoxenus, and Dicaearchus. Much like Plato's Academy, there were in Aristotle's school junior and senior members, the junior members generally serving as pupils or assistants to the senior members who directed research and lectured. The aim of the school, at least in Aristotle's time, was not to further a specific doctrine, but rather to explore philosophical and scientific theories; those who ran the school worked as equal partners.[13] |

歴史 アリストテレスとその弟子たち(アレクサンダー、デメトリアス、テオフラストス、ストラトス)。 ペリパトス(peripatetic)とは、古代ギリシャ語のπεριπατητικός(peripatētikós)を音訳したもので、「歩くこと」 「歩き回ること」を意味する[1]。アリストテレスが創設したペリパトス学派[2]は、実際には単にペリパトスとして知られていた。 [アリストテレスの学派がこのように呼ばれるようになったのは、メンバーたちが集まっていたリセウムのペリパトイ(「歩道」、屋根付きや列柱付きのものも ある)に由来する[4]。アリストテレスが講義中に歩き回る習慣があったことからこの名がついたという伝説は、スミルナのヘルミッポスから始まったのかも しれない[5]。 プラトン(BC428/7-348/7)とは異なり、アリストテレス(BC384-322)[2]はアテネ市民ではなかったため、財産を所有することがで きなかった。そのため、彼と彼の同僚たちは、ソクラテスなど以前の哲学者たちが利用していたように、リセウムの敷地を集会場として利用していた。 [6]アリストテレスとその同僚たちがリセウムをこのように利用し始めたのは紀元前335年頃であり[7]、その後アリストテレスはプラトンのアカデミー とアテネを離れ、十数年後に旅からアテネに戻った。 [現代の学者の中には、学校が正式に制度化されたのはテオフラストスが引き継いでからであり、その時点では学校に私有財産が付随していたと主張する者もい る[9]。 少なくとも当初は、ペリパテスの集会は「学校」という言葉が示すほど正式なものではなかったと思われる。 [11]アリストテレスの名で私たちに伝わっている著作の多くは、アリストテレスがアカデミーで行った講義に基づいている可能性が高い[12]。プラトン のアカデミーのように、アリストテレスの学校にも下級生と上級生がおり、下級生は一般に、研究の指導や講義を行う上級生の弟子や助手を務めていた。少なく ともアリストテレスの時代においては、学派の目的は特定の教義を推し進めることではなく、むしろ哲学的・科学的理論を探求することであり、学派を運営する 者たちは対等なパートナーとして働いていた[13]。 |

Sometime shortly after the death

of Alexander the Great in June 323 BC, Aristotle left Athens to avoid

persecution by anti-Macedonian factions in Athens, due to his ties to

Macedonia.[14] After Aristotle's death in 322 BC, his colleague

Theophrastus succeeded him as head of the school. The most prominent

member of the school after Theophrastus was Strato of Lampsacus, who

increased the naturalistic elements of Aristotle's philosophy and

embraced a form of atheism. After the time of Strato, the Peripatetic

school fell into a decline. Lyco was famous more for his oratory than

his philosophical skills, and Aristo for his biographical studies.[15]

Although Critolaus was more philosophically active, none of the

Peripatetic philosophers in this period seem to have contributed

anything original to philosophy.[16] The reasons for the decline of the

Peripatetic school are unclear. Stoicism and Epicureanism provided many

answers for those people looking for dogmatic and comprehensive

philosophical systems, and the scepticism of the Middle Academy may

have seemed preferable to anyone who rejected dogmatism.[17] Later

tradition linked the school's decline to Neleus of Scepsis and his

descendants hiding the works of Aristotle and Theophrastus in a cellar

until their rediscovery in the 1st century BC, and even though this

story may be doubted, it is possible that Aristotle's works were not

widely read.[18] Aristotle's School, a painting from the 1880s by Gustav Adolph Spangenberg The names of the first seven or eight scholarchs (leaders) of the Peripatetic school are known with varying levels of certainty. A list of names with the approximate dates they headed the school is as follows (all dates BC):[19] Aristotle (c. 334 – 322) Theophrastus (322–288) Strato of Lampsacus (288 – c. 269) Lyco of Troas (c. 269 – 225) Aristo of Ceos (225 – c. 190) Critolaus (c. 190 – 155) Diodorus of Tyre (c. 140) Erymneus (c. 110) There are some uncertainties in this list. It is not certain whether Aristo of Ceos was the head of the school, but since he was a close pupil of Lyco and the most important Peripatetic philosopher in the time when he lived, it is generally assumed that he was. It is not known if Critolaus directly succeeded Aristo, or if there were any leaders between them. Erymneus is known only from a passing reference by Athenaeus.[20] Other important Peripatetic philosophers who lived during these centuries include Eudemus of Rhodes, Aristoxenus, Dicaearchus, and Clearchus of Soli. |

紀元前323年6月にアレクサンドロス大王が死去した直後、アリストテ

レスはマケドニアとの関係からアテネの反マケドニア派による迫害を避けるためにアテネを離れた。テオフラストス以降の学派の最も著名なメンバーはランプサ

コスのストラトで、彼はアリストテレス哲学の自然主義的要素を強め、一種の無神論を受け入れた。ストラトの時代以降、ペリパトス派は衰退した。リュコは哲

学的能力よりも弁舌で有名であり、アリストは伝記研究で有名であった[15]。クリトラウスはより哲学的に積極的であったが、この時期のペリパトス派の哲

学者は誰も哲学に独創的な貢献をしたとは思えない。ストイシズムとエピクロス主義は、独断的で包括的な哲学体系を求める人々に多くの答えを提供し、中期?

アカデミーの懐疑主義は、独断主義を否定する人々にとって好ましいと思われたのかもしれない[17]。後の伝承では、学派の衰退は、スセプシスのネレウス

とその子孫が紀元前1世紀に再発見されるまでアリストテレスとテオフラストスの著作を地下室に隠していたことに関連しており、この話は疑われても、アリス

トテレスの著作が広く読まれなかった可能性はある[18]。 グスタフ・アドルフ・シュパンゲンベルクによる1880年代の絵画「アリストテレスの学校」 ペリパトス学派の最初の7、8人のスコラーク(指導者)の名前は、さまざまなレベルで確実に知られている。その名前と、彼らが学派を率いたおおよその年代 は以下の通りである(すべて紀元前)[19]。 アリストテレス(334年頃-322年) テオフラストス(322年-288年) ランプサコスのストラト(288年~269年頃) トロアスのリュコ(269年頃-225年) ケオスのアリスト(225年~190年頃) クリトラウス(190年頃-155年) ティアのディオドロス(140年頃) エリムネウス(110年頃) このリストにはいくつかの不確定要素がある。ケオスのアリストが学派の長であったかどうかは定かではないが、彼はリュコの近習であり、彼が生きた時代にお いて最も重要なペリパトス哲学者であったことから、一般的には彼が長であったと考えられている。クリトラウスがアリストの後を直接継いだのか、あるいは彼 らの間に指導者がいたのかはわかっていない。エリムネウスはアテナイオスによる一節の言及によってのみ知られている[20]。この数世紀に生きた他の重要 なペリパトス哲学者には、ロードスのエウデムス、アリストクセヌス、ディカイアケウス、ソリのクレアルコスがいる。 |

| In 86 BC, Athens was sacked by

the Roman general Lucius Cornelius Sulla; all the schools of philosophy

in Athens were badly disrupted, and the Lyceum ceased to exist as a

functioning institution. Ironically, this event seems to have brought

new life to the Peripatetic school. Sulla brought the writings of

Aristotle and Theophrastus back to Rome, where they became the basis of

a new collection of Aristotle's writings compiled by Andronicus of

Rhodes which forms the basis of the Corpus Aristotelicum which exists

today.[16] Later Neoplatonist writers describe Andronicus, who lived

around 50 BC, as the eleventh scholarch of the Peripatetic school,[21]

which would imply that he had two unnamed predecessors. There is

considerable uncertainty over the issue, and Andronicus' pupil Boethus

of Sidon is also described as the eleventh scholarch.[22] It is quite

possible that Andronicus set up a new school where he taught Boethus. Whereas the earlier Peripatetics had sought to extend and develop Aristotle's works, from the time of Andronicus the school concentrated on preserving and defending his work.[23] The most important figure in the Roman era is Alexander of Aphrodisias (c. 200 AD) who wrote commentaries on Aristotle's writings. With the rise of Neoplatonism (and Christianity) in the 3rd century, Peripateticism as an independent philosophy came to an end, but the Neoplatonists sought to incorporate Aristotle's philosophy within their own system, and produced many commentaries on Aristotle's works. |

紀元前86年、アテネはローマの将軍ルキウス・コルネリウス・スッラに

よって略奪され、アテネのすべての哲学学校は大混乱に陥り、リセウムはその機能を失った。皮肉なことに、この出来事はペリパトス学派に新しい息吹をもたら

したようだ。スッラはアリストテレスとテオフラストスの著作をローマに持ち帰り、それらはロードス島のアンドロニコスによって編纂されたアリストテレスの

新しい著作集の基礎となった。アンドロニクスの弟子であるシドンのボエトゥスもまた11代目のスコラークとして記述されている[22]。アンドロニクスが

新しい学派を設立し、そこでボエトゥスを教えた可能性は十分にある。 ローマ時代における最も重要な人物は、アリストテレスの著作の注釈書を書いたアフロディジアスのアレクサンダー(紀元200年頃)である。3世紀に新プラ トン主義(とキリスト教)が台頭すると、独立した哲学としてのペリパトス主義は終焉を迎えたが、新プラトン主義者たちはアリストテレスの哲学を自分たちの 体系の中に取り込もうとし、アリストテレスの著作に対する多くの注釈書を生み出した。 |

| Influence Main article: Aristotelianism See also: Avicennism, Averroism, Thomism, and Scholasticism The last philosophers in classical antiquity to comment on Aristotle were Simplicius and Boethius in the 6th century AD.[citation needed] After this, although his works were mostly lost to the west, they were maintained in the east where they were incorporated into early Islamic philosophy. Some of the greatest Peripatetic philosophers in the Islamic philosophical tradition were Al-Kindi (Alkindus), Al-Farabi (Alpharabius), Avicenna (Ibn Sina) and Averroes (Ibn Rushd). By the 12th century, Aristotle's works began being translated into Latin (see Latin translations of the 12th century), and Scholastic philosophy gradually developed under such names as Thomas Aquinas, taking its tone and complexion from the writings of Aristotle, the commentaries of Averroes, and The Book of Healing of Avicenna.[24] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peripatetic_school |

影響力 主な記事 アリストテレス主義 以下も参照: アヴィセンナ主義、アヴェロ主義、トミズム、スコラ哲学 古典古代においてアリストテレスについて論じた最後の哲学者は、紀元6世紀のシンプリキウスとボエティウスであった[要出典]。その後、アリストテレスの 著作は西方ではほとんど失われたが、東方では維持され、初期のイスラム哲学に取り入れられた。イスラム哲学の伝統の中で最も偉大なペリパトス哲学者は、ア ル・キンディー(アルキンドゥス)、アル・ファラービー(アルファラビウス)、アヴィセンナ(イブン・シーナ)、アヴェロエス(イブン・ルシュド)であ る。12世紀になると、アリストテレスの著作がラテン語に翻訳され始め(12世紀のラテン語翻訳を参照)、トマス・アクィナスなどの名でスコラ哲学が徐々 に発展し、アリストテレスの著作、アヴェロイスの注釈書、アヴィセンナの『治癒の書』などからその色調や趣を帯びていった[24]。 |

| The Peripatetic axiom is: "Nothing

is in the intellect that was not first in the senses" (Latin: Nihil est

in intellectu quod non sit prius in sensu). It is found in De veritate,

q. 2 a. 3 arg. 19 by Thomas Aquinas.[1] Aquinas adopted this principle from the Peripatetic school of Greek philosophy, established by Aristotle.[where?] Aquinas argued that the existence of God could be proved by reasoning from sense data.[2] He used a variation on the Aristotelian notion of the "active intellect" (Latin: intellectus agens)[3] which he interpreted as the ability to abstract universal meanings from particular empirical data.[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peripatetic_axiom |

ペリパトス派の公理は、「感覚に最初になかったものは知性にはない」

(ラテン語: Nihil est in intellectu quod non sit prius in

sensu)である。これはトマス・アクィナスのDe veritate, q. 2 a. 3 arg. 19 にある[1]。 アクィナスは、アリストテレスによって確立されたギリシア哲学のペリパトス学派からこの原理を採用した[2]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peripatetic_school |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆