死の人格化

Personifications of death

★「一般に、人間は生前よりも死後においてより多くの権威をもつ。遺言は、まだ存命中の人間が与える命令よりも大きい権威をもっている。……等々。その理由は、死者に対して対抗することが実質的に不可能だからである」(アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ 2010:58)

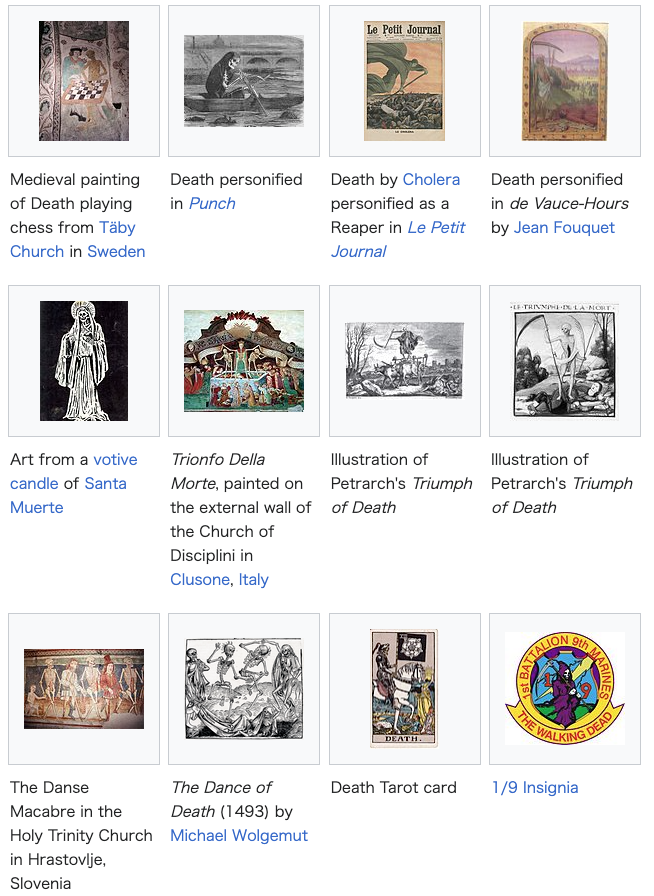

☆ 死の擬人化(人格化)は多くの宗教や神話に見られる。より近代的な物語では、死神(通常は鎌を振り回す、マントをまとった骸骨として描かれる)が魂を刈り 取るためにやって来て、被害者の死を引き起こす。死の亡霊は単に魂送りの役目を果たす慈悲深い存在であり、魂と肉体の最後のつながりを優しく断ち切り、亡 くなった人を死後の世界へと導くだけで、犠牲者がいつどのようにして死ぬかをコントロールする力は持っていないという考えもある。死は男性の姿で擬人化さ れることが多いが、文化によっては死は女性の姿で表されることもある(例えば、スラブ神話のマルザンナやメキシコのサンタ・ムエルテなど)。死はまた、黙 示録の四騎士の一人としても描かれている。死の目撃例のほとんどは臨死状態の時に起こっている。[1]

Statue

of Death, personified as a human skeleton dressed in a shroud and

clutching a scythe, at the Cathedral of Trier in Trier, Germany -

人間の骨格が包み布をまとい、大鎌を握りしめている姿で具現化された「死の像」が、ドイツ・トリーアのトリーア大聖堂にある。

| Personifications

of death are found in many religions and mythologies. In more modern

stories, a character known as the Grim Reaper (usually depicted as a

berobed skeleton wielding a scythe) causes the victim's death by coming

to collect that person's soul. Other beliefs hold that the spectre of

death is only a psychopomp, a benevolent figure who serves to gently

sever the last ties between the soul and the body, and to guide the

deceased to the afterlife, without having any control over when or how

the victim dies. Death is most often personified in male form, although

in certain cultures death is perceived as female (for instance,

Marzanna in Slavic mythology, or Santa Muerte in Mexico). Death is also

portrayed as one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Most claims of

its appearance occur in states of near-death.[1] |

死の擬人化(人格化)は多くの宗教や神話に見られる。より近代的な物語では、死神

(通常は鎌を振り回す、マントをまとった骸骨として描かれる)が魂を刈り取るためにやって来て、被害者の死を引き起こす。死の亡霊は単に魂送りの役目を果

たす慈悲深い存在であり、魂と肉体の最後のつながりを優しく断ち切り、亡くなった人を死後の世界へと導くだけで、犠牲者がいつどのようにして死ぬかをコン

トロールする力は持っていないという考えもある。死は男性の姿で擬人化されることが多いが、文化によっては死は女性の姿で表されることもある(例えば、ス

ラブ神話のマルザンナやメキシコのサンタ・ムエルテなど)。死はまた、黙示録の四騎士の一人としても描かれている。死の目撃例のほとんどは臨死状態の時に

起こっている。[1] |

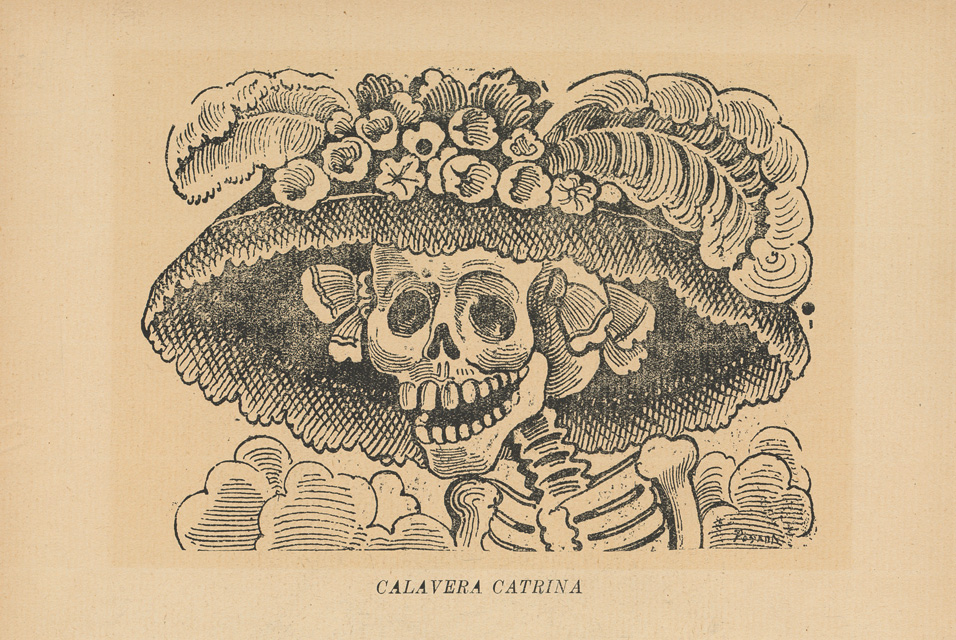

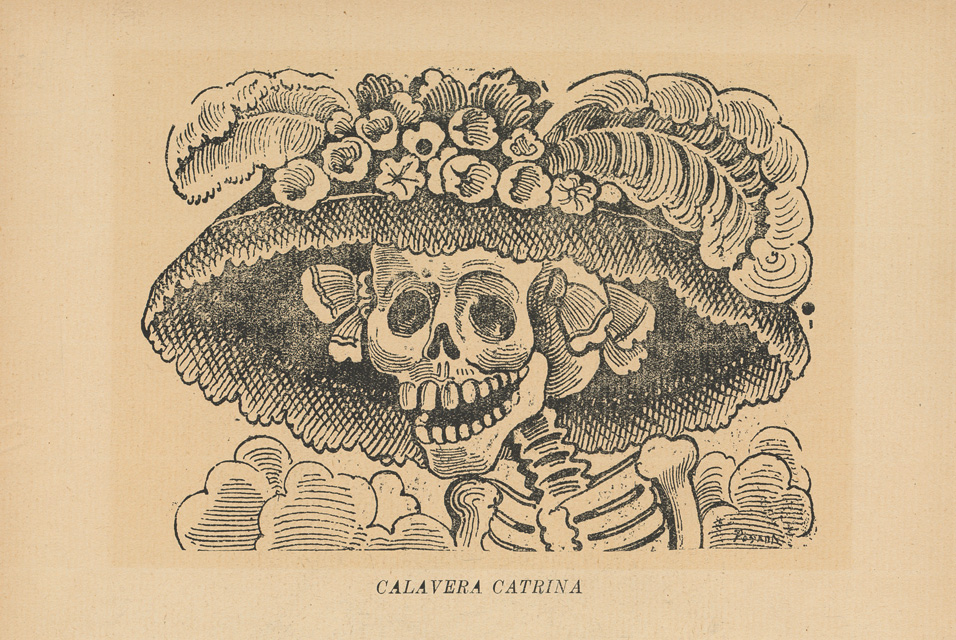

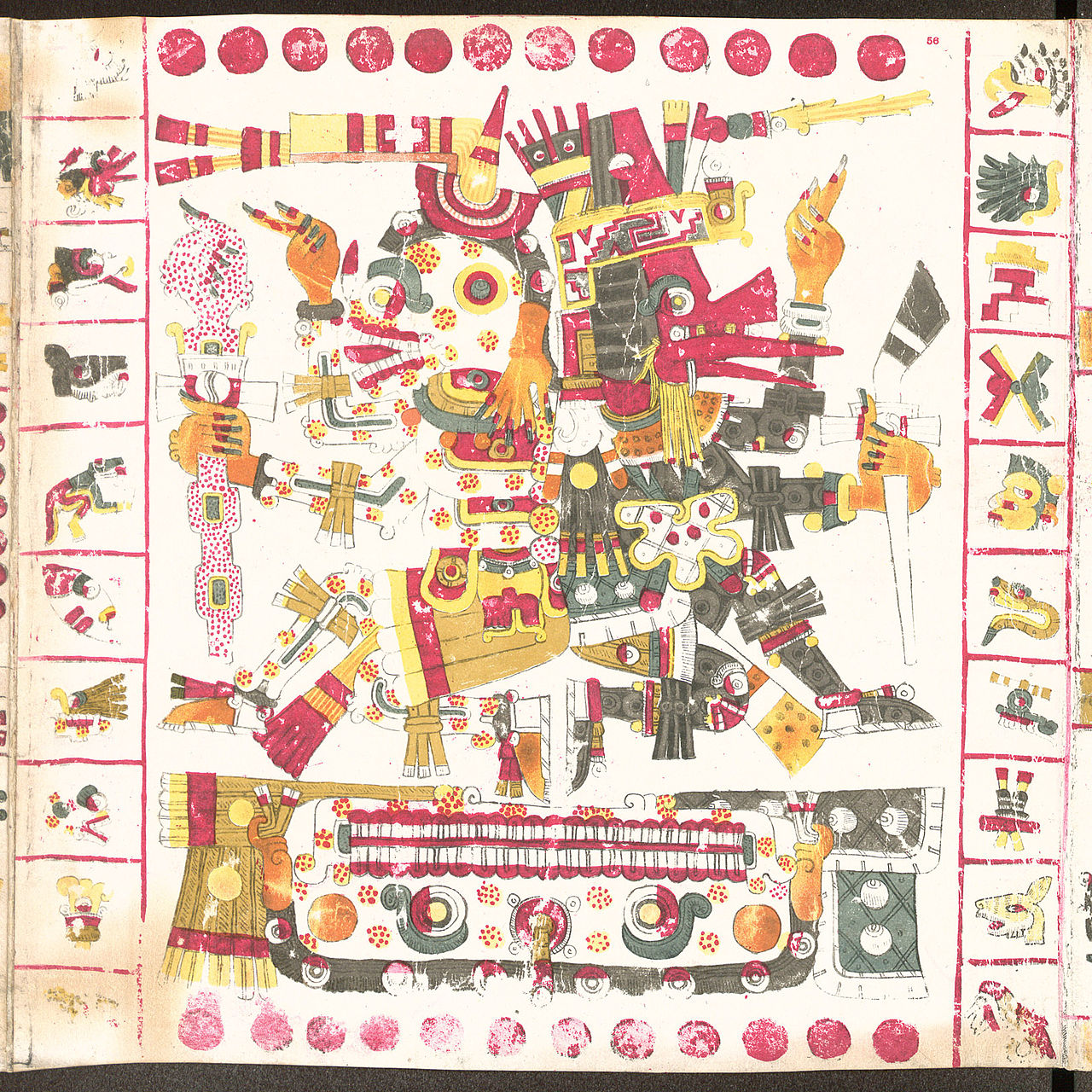

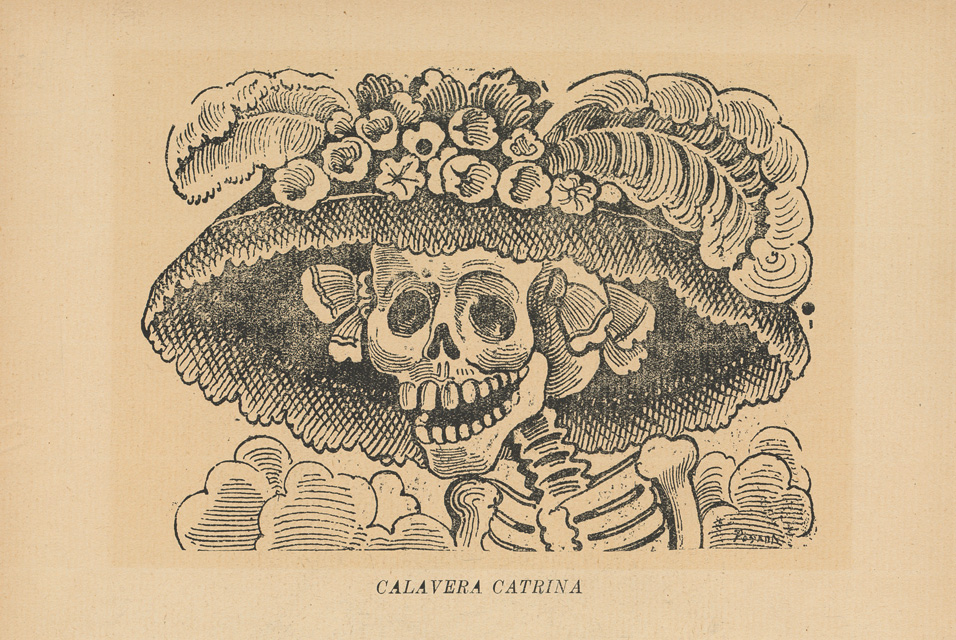

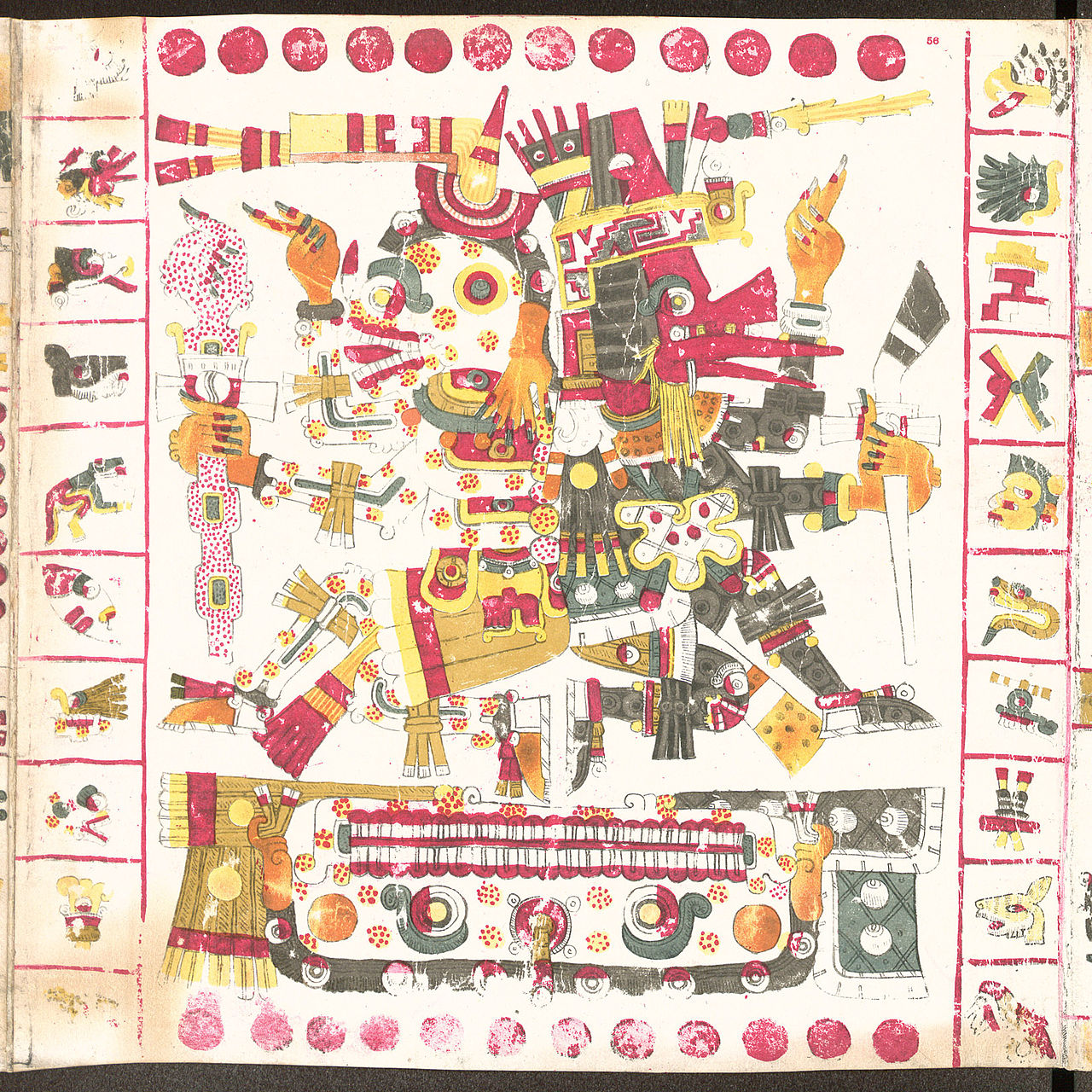

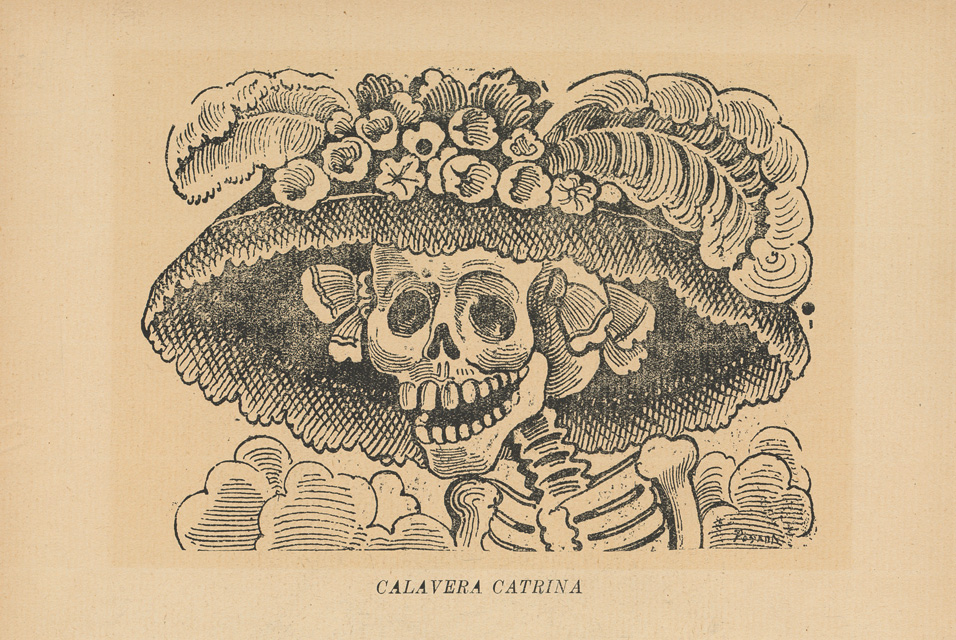

| By region This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Americas Latin America As is the case in many Romance languages (including French, Portuguese, Italian, and Romanian), the Spanish word for death, muerte, is (like Latin mors/mortis whence it derives) a feminine noun. As such, it is common in Spanish-speaking cultures to personify death as a female figure. A common term for the personification of death across Latin America is "la Parca" from one of the three Roman Parcae, a figure similar to the Anglophone Grim Reaper, though usually depicted as female and without a scythe.  Mictlantecutli in the Codex Borgia In Aztec mythology, Mictecacihuatl is the "Queen of Mictlan" (the Aztec underworld), ruling over the afterlife with her husband Mictlantecuhtli. Other epithets for her include "Lady of the Dead," as her role includes keeping watch over the bones of the dead. Mictecacihuatl was represented with a fleshless body and with jaw agape to swallow the stars during the day. She presided over the ancient festivals of the dead, which evolved from Aztec traditions into the modern Day of the Dead after synthesis with Spanish cultural traditions.[citation needed] Mictlāntēcutli, is the Aztec god of the dead and the king of Mictlan, depicted as a skeleton or a person wearing a toothy skull.[2] He is one of the principal gods of the Aztecs and is the most prominent of several gods and goddesses of death and the underworld. His headdress was shown decorated with owl feathers and paper banners and he wore a necklace of human eyeballs,[2] while his earspools were made from human bones.[3] He was not the only Aztec god to be depicted in this fashion, as numerous other deities had skulls for heads or else wore clothing or decorations that incorporated bones and skulls. In the Aztec world, skeletal imagery was a symbol of fertility, health and abundance, alluding to the close symbolic links between life and death.[4] There was also the goddess of suicide, Ixtab. She was a minor goddess in the scale of Maya mythology. She was also known as The Hangwoman as she came to help along those who had killed themselves.  La Calavera Catrina, one of José Guadalupe Posada's Catrina engravings (1910–1913) Our Lady of the Holy Death (Santa Muerte) is a female deity or folk saint of Mexican folk religion, whose popularity has been growing in Mexico and the United States in recent years. Since the pre-Columbian era, Mexican culture has maintained a certain reverence towards death, as seen in the widespread commemoration of the Day of the Dead. La Calavera Catrina, a character symbolizing death, is also an icon of the Mexican Day of the Dead. San La Muerte (Saint Death) is a skeletal folk saint venerated in Paraguay, northeast Argentina. As the result of internal migration in Argentina since the 1960s, the veneration of San La Muerte has been extended to Greater Buenos Aires and the national prison system as well. Saint Death is depicted as a male skeleton figure usually holding a scythe. Although the Catholic Church in Mexico has attacked the devotion of Saint Death as a tradition that mixes paganism with Christianity and is contrary to the Christian belief of Christ defeating death, many devotees consider the veneration of San La Muerte as being part of their Catholic faith. The rituals connected and powers ascribed to San La Muerte are very similar to those of Santa Muerte; the resemblance between their names, however, is coincidental. In Guatemala, San Pascualito is a skeletal folk saint venerated as "King of the Graveyard." He is depicted as a skeletal figure with a scythe, sometimes wearing a cape and crown. He is associated with death and the curing of diseases. In the African-Brazilian religion Umbanda, the orixá Omolu personifies sickness and death as well as healing. The image of the death is also associated with Exu, lord of the crossroads, who rules cemeteries and the hour of midnight. In Haitian Vodou, the Gede are a family of spirits that embody death and fertility. The most well-known of these spirits is Baron Samedi. |

地域別 この節には検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分である。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。 出典の無い内容は疑問視あるいは除去される可能性がある。 (2023年10月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) アメリカ ラテンアメリカ 多くのロマンス諸語(フランス語、ポルトガル語、イタリア語、ルーマニア語など)と同様に、スペイン語で「死」を意味する「muerte」は(ラテン語の 「mors/mortis」に由来する)女性名詞である。そのため、スペイン語圏では死を女性として擬人化することが一般的である。ラテンアメリカで死を 擬人化した一般的な用語は、ローマ神話の3柱のパーセポネスのうちの1柱である「la Parca」であり、英語圏の死神に似た存在であるが、通常は女性として描かれ、大鎌は持っていない。  ボルジア写本に描かれたミクトランテュクトリ アステカ神話では、ミクトカカワトルは「ミクトランの女王」(アステカの冥界)であり、夫のミクトランテュクトリとともに死後の世界を統治している。ミク トカカワトルの別称には「死者の女王」もあり、死者の骨を見守る役割があるためである。ミクトカシウアトルは、肉のない身体で、口を大きく開けて昼間に星 を飲み込む姿で表現されていた。彼女は古代の死者の祭りを司っていたが、それはアステカの伝統からスペインの文化伝統と融合して現代の死者の日に発展し た。ミクトランテクトリは、アステカの死者の神であり、 ミクトランの王であり、骸骨または髑髏をかぶった人物として描かれている。[2] アステカの主要な神の一人であり、死と冥界を司る数多の神々の中でも最も著名な神である。彼の頭飾りはフクロウの羽と紙の旗で飾られており、人間の眼球の ネックレスを身に着けていた。[2] また、耳栓は人間の骨でできていた。[3] このような姿で描かれるアステカの神は彼だけではない。他の多くの神々も頭が頭蓋骨であったり、骨や頭蓋骨を組み込んだ衣服や装飾品を身に着けていた。ア ステカの世界では、骨格のイメージは豊穣、保健、そして豊かさの象徴であり、生と死の密接な象徴的つながりを暗示していた。[4] また、自殺の女神イシュタブもいた。彼女はマヤ神話の規模ではマイナーな女神であった。彼女は自殺した人々を手助けすることから、「絞首刑執行人」とも呼 ばれていた。  ラ・カレヴェラ・カタリナは、ホセ・グアダルーペ・ポサダによるカタリナの版画(1910年~1913年)の一つである。 聖なる死の聖母(サンタ・ムエルテ)は、メキシコの民間信仰における女神または民間聖人であり、近年メキシコおよび米国で人気が高まっている。コロンブス 到来以前の時代から、メキシコ文化では死に対するある種の畏敬の念が保たれており、死者の日の記念行事の広範な普及に見られる。死を象徴するキャラクター であるラ・カレラ・カトリーナは、メキシコの死者の日の象徴でもある。 サン・ラ・ムエルテ(聖なる死)は、アルゼンチン北東部のパラグアイで崇拝されている骸骨の民間聖人である。1960年代以降のアルゼンチン国内の移住の 結果、サン・ラ・ムエルテの崇拝はブエノスアイレス首都圏や同国の刑務所システムにも広がっている。聖なる死は、大抵は鎌を手にした男性の骸骨として描か れる。メキシコのカトリック教会は、異教とキリスト教を混ぜ合わせた伝統であり、キリストが死を打ち負かしたというキリスト教の信仰に反するとして、サ ン・ラ・ムエルテへの信仰を攻撃しているが、多くの信者はサン・ラ・ムエルテへの崇拝をカトリック信仰の一部であると考えている。サン・ラ・ムエルテに関 連する儀式やその力は、サンタ・ムエルテのものと非常に似ているが、両者の名称が偶然似ているだけである。 グアテマラでは、サン・パスカルートは「墓地の王」として崇められている骸骨の民間聖人である。彼は骸骨の姿で鎌を手にしており、時にはマントと王冠を身に着けている。彼は死と病の治癒と関連付けられている。 アフリカ系ブラジル人の宗教であるウンバンダでは、オリシャ(精霊)のオムルは、病や死を具現化すると同時に、それらを癒やす存在でもある。死のイメージは、墓地や真夜中を司る、交差点の主であるエクスとも関連付けられている。 ハイチ・ヴードゥーでは、ゲデは死と豊穣を体現する精霊の一族である。この精霊の中で最も有名なのはバロン・サムディである。 |

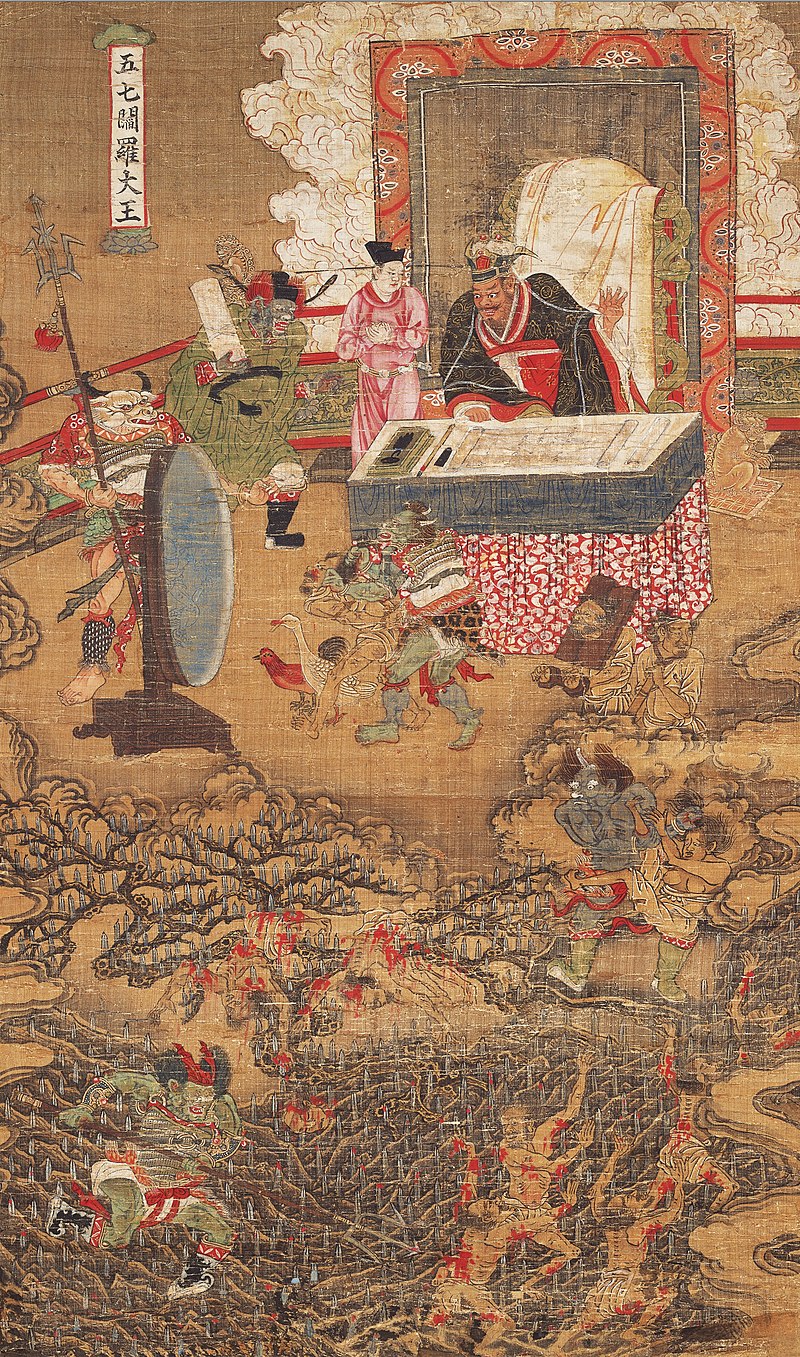

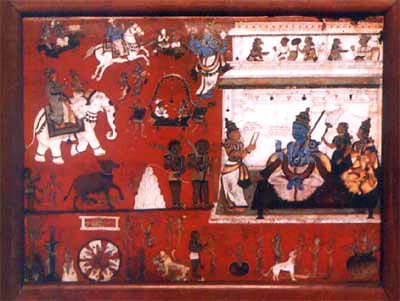

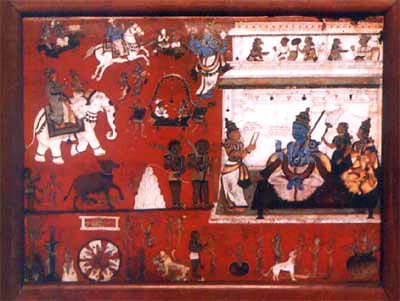

| Asia East Asia  Skeleton Fantasy Show by Li Song (1190-1264)  A depiction of Yanluo, one of the Ten Kings of Hell. See also: Life replacement narratives Yama was introduced to Chinese mythology through Buddhism. In China, he is known as King Yan (t 閻王, s 阎王, p Yánwáng) or Yanluo (t 閻羅王, s 阎罗王, p Yánluówáng), ruling the ten gods of the underworld Diyu. He is normally depicted wearing a Chinese judge's cap and traditional Chinese robes and appears on most forms of hell money offered in ancestor worship. From China, Yama spread to Japan as the Great King Enma (閻魔大王, Enma-Dai-Ō), ruler of Jigoku (地獄); Korea as the Great King Yeomra (염라대왕), ruler of Jiok (지옥); and Vietnam as Diêm La Vương, ruler of Địa Ngục or Âm Phủ. Separately, in Korean mythology, death's principal figure is the "Netherworld Emissary" Jeoseungsaja (저승사자, shortened to Saja (사자)). He is depicted as a stern and ruthless bureaucrat in Yeomna's service. A psychopomp, he escorts all – good or evil – from the land of the living to the netherworld when the time comes.[5] One of the representative names is Ganglim (강림), the Saja who guides the soul to the entrance of the underworld. According to legend, he always carries Jeokpaeji (적패지), the list with the names of the dead written on a red cloth. When he calls the name of Jeokpaeji three times, the soul leaves the body and follows him inevitably. The Kojiki relates that the Japanese goddess Izanami was burnt to death giving birth to the fire god Hinokagutsuchi. She then entered a realm of perpetual night called Yomi-no-Kuni. Her husband Izanagi pursued her there but discovered his wife was no longer as beautiful as before. After an argument, she promised she would take a thousand lives every day, becoming a goddess of death, as well as giving birth to the gods, Raijin and Fūjin, while dead. There are also death gods called shinigami (死神), which are closer to the Western tradition of the Grim Reaper; while common in modern Japanese arts and fiction, they were essentially absent in traditional mythology. |

アジア 東アジア  李嵩(1190年-1264年)による『骨壺幻想劇  『十王』の一人である閻羅の描写。 参照:人生の入れ替わり物語 閻魔は仏教を通じて中国神話に導入された。中国では、閻王(t 閻王、s 阎王、p Yánwáng)または閻羅王(t 閻羅王、s 阎罗王、p Yánluówáng)として知られ、冥界の十神を統治する。通常、中国の裁判官の帽子と伝統的な中国のローブを身にまとった姿で描かれ、祖先崇拝で供え られるほとんどの地獄のお金にも登場する。中国から日本には閻魔大王(えんまだいおう)として、地獄の支配者として伝わった。韓国には、閻魔大王(ヨムラ デワン)として、地獄の支配者として伝わった。ベトナムには、地獄の支配者として、ディエム・ラ・ヴォンとして伝わった。 また、韓国の神話では、死の主要な象徴は「冥界の使者」である「チョスンサジャ(저승사자、略してサジャ(사자))」である。彼はヨムナの厳しい非情な官 僚として描かれている。死者の魂を現世から黄泉の国へと導く「魂送りの神」であり、善人も悪人も、その時が来れば黄泉の国へと導く。代表的な名称のひとつ に、魂を冥府の入り口まで導く「カンリム(강림)」というサジャがある。伝説によると、彼は常に「赤い布に書かれた死者の名簿」である「赤帛纏(チョクペ ジ、적패지)」を携えている。赤い布に書かれた死者の名簿である「赤牌地(Jeokpaeji)」の名を3回呼ぶと、魂は肉体から離れ、必然的に彼に従う ことになる。 古事記によると、日本の女神イザナミは火の神ヒノカグツチを産み落とす際に焼け死んだ。その後、イザナミは常夜の国と呼ばれる永遠の闇の領域へと入って いった。夫のイザナギは彼女を追いかけたが、妻はもはや以前のように美しい姿ではなくなっていた。口論の末、彼女は毎日千の命を奪うことを約束し、死の女 神となり、雷神と風神を死産した。また、西洋の死神の伝統に近い「死神(しにがみ)」と呼ばれる死の神もいる。現代の日本の芸術やフィクションでは一般的 であるが、伝統的な神話には基本的に登場しない。 |

| India This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  Yama, the Hindu lord of death, presiding over his court in hell The Sanskrit word for death is mrityu (cognate with Latin mors and Lithuanian mirtis), which is often personified in Dharmic religions. In Hindu scriptures, the lord of death is called King Yama (यम राज, Yama Rāja). He is also known as the King of Karmic Justice (Dharmaraja) as one's karma at death was considered to lead to a just rebirth. Yama rides a black buffalo and carries a rope lasso to lead the soul back to his home, called Naraka, pathalloka, or Yamaloka. There are many forms of reapers, although some say there is only one who disguises himself as a small child. His agents, the Yamadutas, carry souls back to Yamalok. There, all the accounts of a person's good and bad deeds are stored and maintained by Chitragupta. The balance of these deeds allows Yama to decide where the soul should reside in its next life, following the theory of reincarnation. Yama is also mentioned in the Mahabharata as a great philosopher and devotee of the Supreme Brahman. Western Asia Main article: Mot (god) The Canaanites of the 12th- and 13th-century BC Levant personified death as the god Mot (lit. "Death"). He was considered a son of the king of the gods, El. His contest with the storm god Baʿal forms part of the Ba'al Cycle from the Ugaritic texts. The Phoenicians also worshipped death under the name Mot and a version of Mot later became Maweth, the devil or angel of death in Judaism.[6][7] |

インド この節には出典が全く示されていない。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。出典のない項目は、異議申し立てにより削除される場合があります。 (2024年11月) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  ヤマ、死のヒンドゥー教の神、地獄で裁判所を主宰する 死を意味するサンスクリット語はmrityu(ラテン語のmorsやリトアニア語のmirtisと語族関係にある)であり、ダルマの宗教ではしばしば擬人化される。 ヒンドゥー教の聖典では、死の神はヤマ王(यम राज、Yama Rāja)と呼ばれている。死の際に人が行った行為(カルマ)は、次の生まれ変わりに反映されると考えられていたため、ヤマ王はカルマの裁きを行う王 (Dharmaraja)としても知られている。ヤマは黒い水牛に乗り、魂をナラカ、パールタロカ、ヤマロカと呼ばれる彼の家に導くための縄の投げ縄を携 えている。 死神にはさまざまな姿があるが、幼子に化けた1人だけだという説もある。 彼の代理人であるヤマドゥタは、魂をヤマロカに導く。 そこで、人格の善行と悪行の記録はすべて、チトラグプタによって保管・管理される。これらの行いのバランスによって、転生論に従って、魂が来世でどこに宿 るかをヤマが決定する。ヤマは『マハーバーラタ』でも、偉大な哲学者であり至高のブラフマンへの帰依者として言及されている。 西アジア 詳細は「モト (神)」を参照 紀元前12世紀から13世紀のレバント地方のカナン人は、死を神「モト(文字通り「死」の意)」として擬人化した。彼は神々の王であるエルの息子と考えら れていた。嵐の神バアルとの争いは、ウガリットのテキストに登場するバアル・サイクルの一部である。フェニキア人もまた、死を「モト」の名で崇拝し、モト のバージョンは後にモーセとなり、ユダヤ教における死の天使または悪魔となった。 |

| Europe Baltic  A European depiction of Death as a skeleton wielding a scythe  "Death" (Nāve; 1897) by Janis Rozentāls Latvians named Death Veļu māte, but for Lithuanians it was Giltinė, deriving from the word gelti ("to sting"). Giltinė was viewed as an old, ugly woman with a long blue nose and a deadly venomous tongue. The legend tells that Giltinė was young, pretty, and communicative until she was trapped in a coffin for seven years. Her sister was the goddess of life and destiny, Laima, symbolizing the relationship between beginning and end. Like the Scandinavians, Lithuanians and Latvians later began using Grim Reaper imagery for death. |

ヨーロッパ バルト  大鎌を振りかざす骸骨として描かれたヨーロッパの「死」の概念  ヤニス・ローゼンタール作「死」(Nāve; 1897年) ラトビア人は「死」をVeļu māteと呼んでいたが、リトアニア人にとっては「死」はGiltinėであり、これは「刺す」を意味する「gelti」という言葉に由来する。ギルティ ネは、青い長い鼻と猛毒の舌を持つ年老いた醜い女性と見なされていた。伝説によると、ギルティネは棺に閉じ込められて7年間を過ごすまでは若く、美しく、 社交的な女性であった。彼女の姉は、始まりと終わりとの関係を象徴する、生命と運命の女神ライマであった。 スカンジナビア人と同様に、リトアニア人とラトビア人は後に死神のイメージを死の象徴として使うようになった。 |

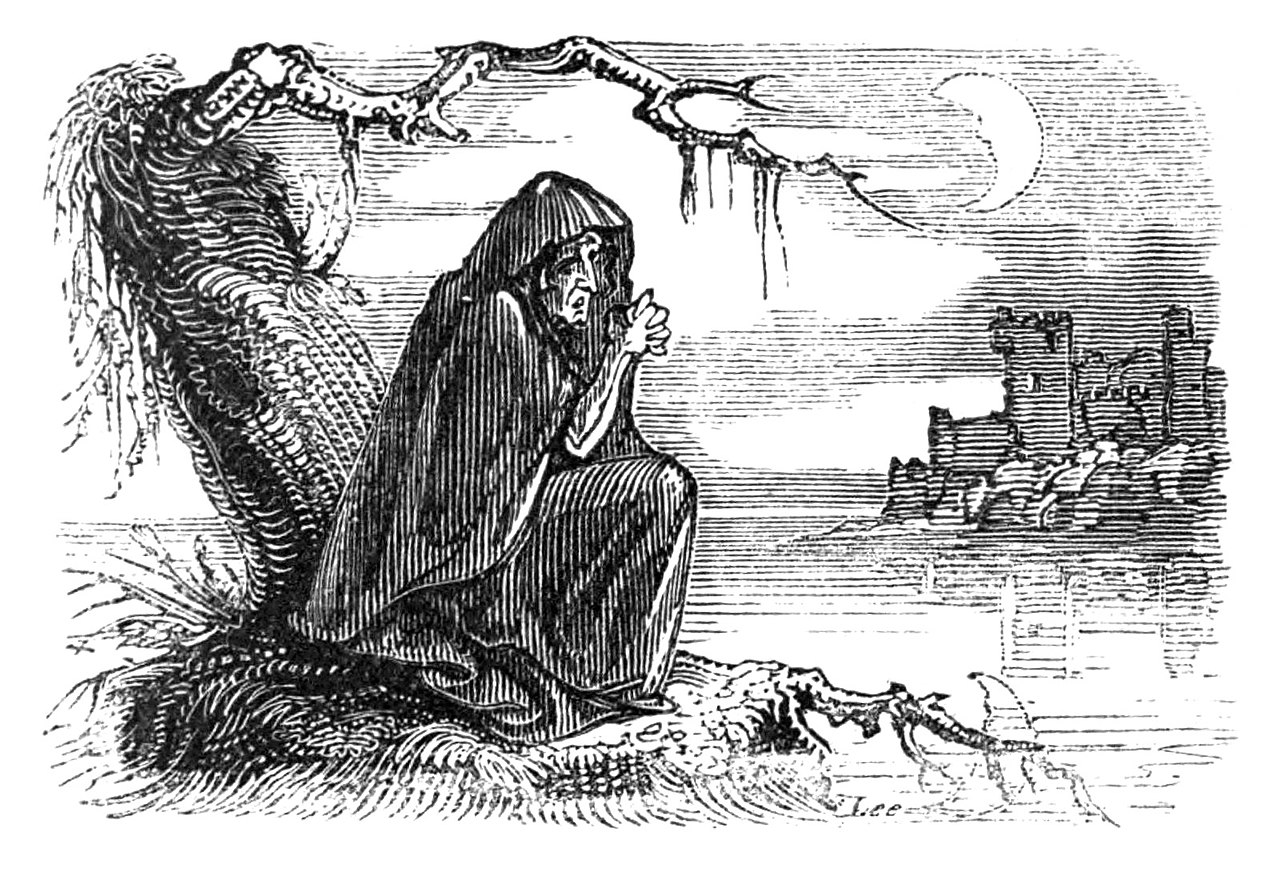

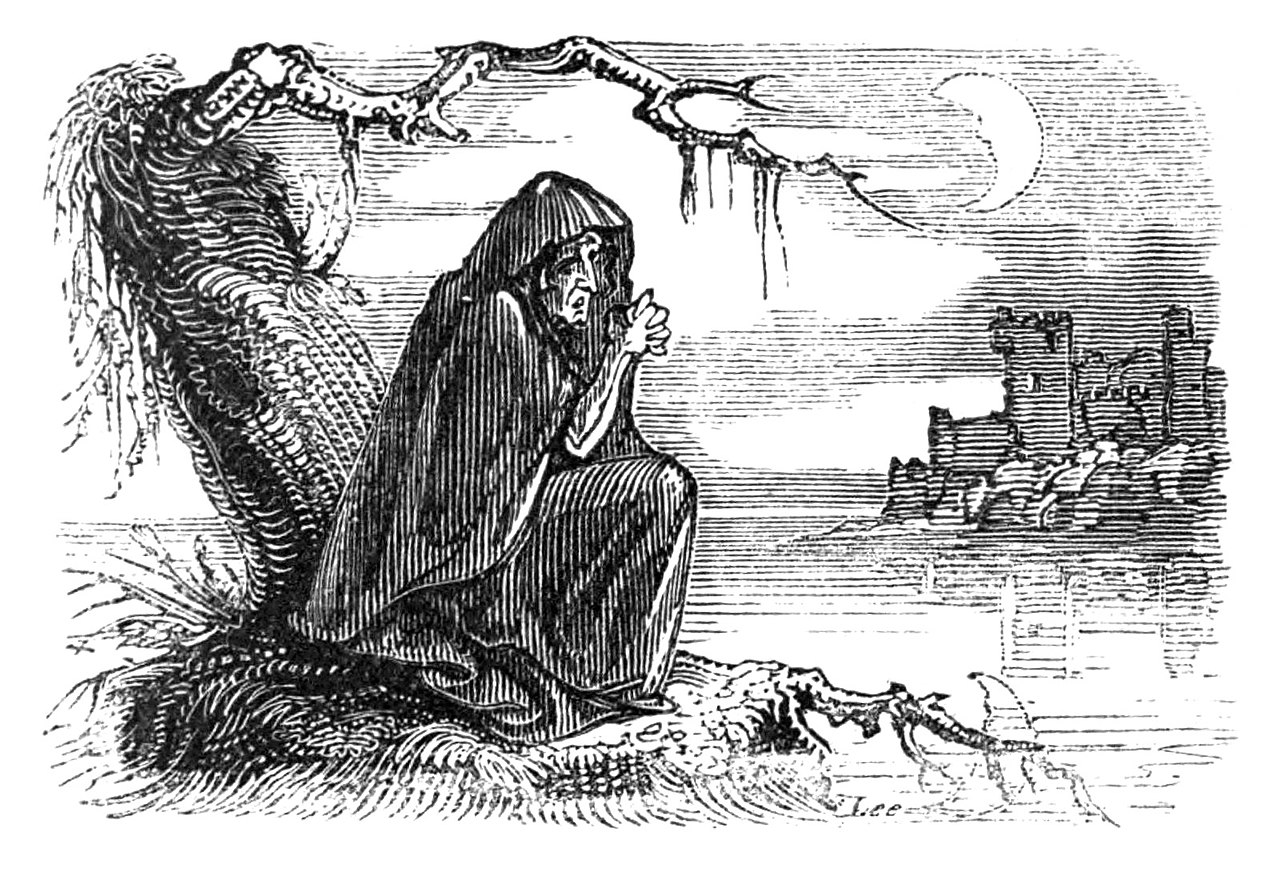

Celtic Bunworth Banshee, "Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland", by Thomas Crofton Croker, 1825 In Breton folklore, a spectral figure called the Ankou (or Angau in Welsh) portends death. Usually, the Ankou is the spirit of the last person that died within the community and appears as a tall, haggard figure with a wide hat and long white hair or a skeleton with a revolving head. The Ankou drives a deathly wagon or cart with a creaking axle. The cart or wagon is piled high with corpses and a stop at a cabin means instant death for those inside.[8] Irish mythology features a similar creature known as a dullahan, whose head would be tucked under their arm (dullahans were not one, but an entire species). The head was said to have large eyes and a smile that could reach the head's ears. The dullahan would ride a black horse or a carriage pulled by black horses, and stop at the house of someone about to die, and call their name, and immediately the person would die. The dullahan did not like being watched, and it was believed that if a dullahan knew someone was watching them, they would lash that person's eyes with their whip, which was made from a spine; or they would toss a basin of blood on the person, which was a sign that the person was next to die. Gaelic lore also involves a female spirit known as Banshee (Modern Irish Gaelic: bean sí pron. banshee, literally fairy woman), who heralds the death of a person by shrieking or keening. The banshee is often described as wearing red or green, usually with long, disheveled hair. She can appear in a variety of forms, typically that of an ugly, frightful hag, but in some stories she chooses to appear young and beautiful. Some tales recount that the creature was actually a ghost, often of a specific murdered woman or a mother who died in childbirth. When several banshees appeared at once, it was said to indicate the death of someone great or holy. In Ireland and parts of Scotland, a traditional part of mourning is the keening woman (bean chaointe), who wails a lament – in Irish: Caoineadh, caoin meaning "to weep, to wail." In Scottish folklore there was a belief that a black, dark green or white dog known as a Cù Sìth took dying souls to the afterlife. Comparable figures exist in Irish and Welsh stories. In Welsh Folklore, Gwyn ap Nudd is the escort of the grave, the personification of Death and Winter who leads the Wild Hunt to collect wayward souls and escort them to the Otherworld, sometimes it is Maleagant, Arawn or Afallach in a similar position. |

ケルト バンワース・バンシー、「アイルランド南部の妖精伝説と伝統」、トーマス・クロフトン・クロッカー著、1825年 ブルターニュの民話では、アンコウ(ウェールズ語ではアンガウ)と呼ばれる幽霊が死を予言する。通常、アンコウはコミュニティ内で最後に亡くなった人物の 霊であり、幅広の帽子と長い白髪をまとった背の高い痩せこけた姿、あるいは首が回転する骸骨として現れる。 アンコウは軋む車軸の死の馬車や荷車を走らせる。 荷車や馬車には死体が山積みされており、小屋に立ち寄ると中の者は即死する。 アイルランド神話には、頭部を腕の下に隠す(デュラハンは1体ではなく、1つの種族である)デュラハンという同様の怪物が登場する。その頭部には大きな目 があり、耳まで届くような笑顔を浮かべていると伝えられている。デュラハンは黒馬に乗っていたり、黒馬が引く馬車に乗っていたりし、死を目前にした人物の 家に立ち寄り、その人物の名前を呼ぶと、その人物はすぐに死んでしまう。ドゥラハンは見られていることを嫌い、ドゥラハンが誰かに見られていることに気づ くと、背骨でできた鞭でその人物の目を打つか、あるいはその人物に血の入った洗面器を投げつけると信じられていた。 ゲール族の言い伝えには、バンシー(現代アイルランド・ゲール語:bean sí、発音:banshee、文字通り妖精の女性)と呼ばれる女性の霊も登場する。バンシーは、金切り声や泣き叫ぶような声で人の死を予告する。バンシー は赤や緑の服を着て、長い乱れた髪をしていると描写されることが多い。さまざまな姿で現れるが、典型的には醜く恐ろしい老婆の姿である。しかし、若い美し い姿で現れることもあるという話もある。ある物語では、この生き物は実際には亡霊であり、特定の殺害された女性や出産で命を落とした母親の亡霊であると語 られている。 複数のバンシーが同時に現れた場合、それは偉大なる人物や聖人の死を意味するとされた。 アイルランドやスコットランドの一部では、伝統的な喪に服す方法としてキーニング・ウーマン(bean chaointe)と呼ばれる嘆き悲しむ女性がおり、アイルランド語で「嘆き悲しむ」を意味する「Caoineadh, caoin」と称される嘆きを上げる。 スコットランドの民話では、死にかけている魂を死後の世界へ導くのは、Cù Sìth(クー・シス)と呼ばれる黒、深緑、または白の犬であるという信仰があった。アイルランドやウェールズの物語にも同様の存在が登場する。 ウェールズの民話では、グウィン・アプ・ヌッドは墓の護衛であり、死と冬の化身であり、迷える魂を集めるワイルドハントを率いてあの世へ護送する。時には、同様の役目を担うマレガント、アラウン、アファラハが護衛を務めることもある。 |

| Hellenic Main article: Thanatos In Greek mythology, Thanatos, the personification of death, is one of the offspring of Nyx (Night). Like her, he is seldom portrayed directly. He sometimes appears in art as a winged and bearded man, and occasionally as a winged and beardless youth. When he appears together with his twin brother, Hypnos, the god of sleep, Thanatos generally represents a gentle death. Thanatos, led by Hermes psychopompos, takes the shade of the deceased to the near shore of the river Styx, whence the ferryman Charon, on payment of a small fee, conveys the shade to Hades, the realm of the dead. Homer's Iliad 16.681, and the Euphronios Krater's depiction of the same episode, have Apollo instruct the removal of the heroic, semi-divine Sarpedon's body from the battlefield by Hypnos and Thanatos, and conveyed thence to his homeland for proper funeral rites.[citation needed] Among the other children of Nyx are Thanatos' sisters, the Keres, blood-drinking, vengeful spirits of violent or untimely death, portrayed as fanged and taloned, with bloody garments. |

ヘレニズム 詳細は「タナトス」を参照 ギリシア神話において、死の擬人化であるタナトスは、ニュクス(夜)の子供のうちの一人である。彼女と同様に、タナトスは直接的に描かれることはほとんど ない。翼と髭のある老人として、あるいは翼と無髭の若者として芸術作品に描かれることもある。眠りの神ヒュプノス(ヒュプノス)という双子の兄弟とともに 描かれる場合、タナトスは一般的に穏やかな死を象徴する。タナトスは、ヘルメス・プシュケポスに導かれ、亡くなった人の魂を川の岸辺まで連れて行き、そこ から渡し守のカロンが少額の手数料を受け取って、死者の国であるハデスまで運ぶ。ホメロスの『イーリアス』16.681や、エウフロニオス・クラテルの同 エピソードの描写では、アポロが半神半人の英雄サルペードオンの遺体を戦場からヒュプノスとタナトスに運び出させ、 そして、故郷に運ばれ、適切な葬儀が行われた。[要出典] ニュクスの他の子供たちの中には、タナトスの姉妹であるケレスがいる。ケレスは、血を吸う、復讐心に燃える、暴力的または早すぎる死の精霊であり、牙と鉤 爪を持ち、血まみれの衣服を身にまとっている。 |

| Scandinavia Hel (1889) by Johannes Gehrts, pictured here with her hound Garmr In Scandinavia, Norse mythology personified death in the shape of Hel, the goddess of death and ruler over the realm of the same name, where she received a portion of the dead.[9] In the times of the Black Plague, Death would often be depicted as an old woman known by the name of Pesta, meaning "plague hag", wearing a black hood. She would go into a town carrying either a rake or a broom. If she brought the rake, some people would survive the plague; if she brought the broom, however, everyone would die.[10] Scandinavians later adopted the Grim Reaper with a scythe and black robe. Today, Ingmar Bergman's 1957 film The Seventh Seal features one of the world's most famous representations of this personification of Death.[citation needed] |

スカンジナビアの ヘル(1889年)ヨハネス・ゲールツ作、猟犬ガルムと写る 北欧では、北欧神話において死はヘルという女神の姿で具現化され、死の女神として、また同名の領域を支配する存在として描かれ、死者の一部を受け取ってい た。[9] ペストが流行した時代には、死はペスタという名で知られる老婆として描かれることが多く、ペスタとは「疫病の魔女」を意味する。ペスタは黒いフードを身に まとっていた。ペスタは熊手か箒を携えて町を歩き回った。もしペスタが熊手を持ってきた場合は、ペストの流行から生き延びる人もいるが、ほうきを持ってき た場合は、誰もが死ぬことになる。 スカンジナビア人は後に、大鎌と黒衣をまとった死神を採り入れた。今日、イングマール・ベルイマンの1957年の映画『第七の封印』は、この死の擬人化を表現した世界で最も有名な作品の一つである。 |

| Slavic "Fairy tale", drawing by Taras Shevchenko. Death is depicted as a female skeleton with a scythe. In Poland, Death – Śmierć or kostuch – has an appearance similar to the Grim Reaper, although its robe was traditionally white instead of black. Because the word śmierć is feminine in gender, death is frequently portrayed as a skeletal old woman, as depicted in 15th-century dialogue "Rozmowa Mistrza Polikarpa ze Śmiercią" (Latin: "Dialogus inter Mortem et Magistrum Polikarpum"). In Serbia and other South Slavic countries, the Grim Reaper is well known as Smrt ("Death") or Kosač ("Reaper"). Slavic people found this very similar to the Devil and other dark powers. One popular saying about death is: Smrt ne bira ni vreme, ni mesto, ni godinu ("Death does not choose a time, place or year" – which means death is destiny.)[original research?] Morana is a Slavic goddess of winter time, death and rebirth. A figurine of the same name is traditionally created at the end of winter/beginning of spring and symbolically taken away from villages to be set in fire and/or thrown into a river, that takes her away from the world of the living. In the Czech Republic, the medieval Prague Astronomical Clock carries a depiction of Death striking the hour. A version first appeared in 1490.[11][12] |

スラブ語 「おとぎ話」、タラス・シェフチェンコによる絵。死は、大鎌を持った女性の骸骨として描かれている。 ポーランドでは、死神(Śmierćまたはkostuch)は、その衣は伝統的に黒ではなく白であるものの、外見はグリム童話の死神に似ている。 śmierćという単語は女性名詞であるため、15世紀の対話「Rozmowa Mistrza Polikarpa ze Śmiercią」(ラテン語:「Dialogus inter Mortem et Magistrum Polikarpum」)に描かれているように、死はしばしば骸骨の老婆として描かれる。 セルビアやその他の南スラヴ諸国では、死神は「Smrt(「死」)」または「Kosač(「刈り手」)」としてよく知られている。スラヴ民族は、これを悪 魔やその他の暗黒の力と非常に似ていると考えている。死に関するよく知られたことわざに、「Smrt ne bira ni vreme, ni mesto, ni godinu(「死は時も場所も選ばない。つまり、死は運命である)」というものがある。 モラナは、スラブ神話における冬、死、再生の女神である。同じ名前の置物は、伝統的に冬の終わりから春の始まりにかけて作られ、象徴的に村から持ち去られ、火に投じられたり川に投げ捨てられたりして、生者の世界から遠ざけられる。 チェコ共和国では、中世のプラハ天文時計に死の像が描かれており、時を告げている。このバージョンは1490年に初めて登場した。[11][12] |

| The Low Countries In the Netherlands, and to a lesser extent in Belgium, the personification of Death is known as Magere Hein ("Thin Hein") or Pietje de Dood ("Peter the Death").[13] Historically, he was sometimes simply referred to as Hein or variations thereof such as Heintje, Heintjeman and Oom Hendrik ("Uncle Hendrik"). Related archaic terms are Beenderman ("Bone-man"), Scherminkel (very meager person, "skeleton") and Maaijeman ("mow-man", a reference to his scythe).[14] The concept of Magere Hein predates Christianity, but was Christianized and likely gained its modern name and features (scythe, skeleton, black robe etc.) during the Middle Ages. The designation "Meager" comes from its portrayal as a skeleton, which was largely influenced by the Christian "Dance of Death" (Dutch: dodendans) theme that was prominent in Europe during the late Middle Ages. "Hein" was a Middle Dutch name originating as a short form of Heinric (see Henry (given name)). Its use was possibly related to the comparable German concept of "Freund Hein."[citation needed] Notably, many of the names given to Death can also refer to the Devil; it is likely that fear of death led to Hein's character being merged with that of Satan.[14][15] In Belgium, this personification of Death is now commonly called Pietje de Dood "Little Pete, the Death."[16] Like the other Dutch names, it can also refer to the Devil.[17] |

低地諸国 オランダでは、またベルギーでも程度は低いが、死の擬人化は「痩せたハイン(Magere Hein)」または「ピーテ・デ・ドート(Pietje de Dood)」として知られている。[13] 歴史的には、単に「ハイン」または「ハインチェ(Heintje)」、「ハインチェマン(Heintjeman)」、「オム・ヘンドリク(Oom Hendrik)(ヘンドリクおじさん)」など、そのバリエーションで呼ばれることもあった。関連する古い用語としては、Beenderman(「骨 男」)、Scherminkel(非常に貧弱な人格、「骸骨」)、Maaijeman(「刈り取り男」、彼の鎌を指す)などがある。[14] 「マヘレ・ハイン」の概念はキリスト教以前から存在していたが、キリスト教化され、中世の時代に現代の名称と特徴(大鎌、骸骨、黒衣など)が定着したと考 えられる。「マヘレ」という名称は、骸骨として描かれることから来ているが、これは中世後期にヨーロッパで盛んに描かれたキリスト教の「死の舞踏」(オラ ンダ語:ドゥーデンドゥース)のテーマに強く影響されたものである。「ハイン」は中世オランダ語の名前で、ハインリック(ヘンリー(人名)を参照)の短縮 形として生まれた。その使用は、ドイツ語の「フロイント・ハイン」という同等の概念と関連している可能性がある。注目すべきは、死に与えられた名前の多く が、悪魔を指すこともあるということである。死への恐怖が、ハインの性格をサタンのそれと融合させることにつながった可能性が高い。 ベルギーでは、この死神の擬人化は現在では一般的に「Little Pete, the Death(小さなピート、死神)」と呼ばれている。[16] 他のオランダ語の名称と同様に、悪魔を指す場合もある。[17] |

Western Europe Death from the Cary-Yale Tarot Deck (15th century) In Western Europe, Death has commonly been personified as an animated skeleton since the Middle Ages.[18] This character, which is often depicted wielding a scythe, is said to collect the souls of the dying or recently dead. In English and German culture, Death is typically portrayed as male, but in French, Spanish, and Italian culture, it is not uncommon for Death to be female.[19] In England, the personified "Death" featured in medieval morality plays, later regularly appearing in traditional folk songs.[20] The following is a verse of "Death and the Lady" (Roud 1031) as sung by Henry Burstow in the nineteenth century: Fair lady, throw those costly robes aside, No longer may you glory in your pride. Take leave of all sour carnal vain delight I'm come to summon you away this night.[20] In the late 1800s, the character of Death became known as the Grim Reaper in English literature. The earliest appearance of the name "Grim Reaper" in English is in the 1847 book The Circle of Human Life:[21][22][23] All know full well that life cannot last above seventy, or at the most eighty years. If we reach that term without meeting the grim reaper with his scythe, there or there about, meet him we surely shall. |

西ヨーロッパ カリー・エール・タロット・デッキ(15世紀)の「死」 西欧では、中世以来、死は一般的に動く骸骨として擬人化されてきた。[18] このキャラクターは、大鎌を振り回している姿で描かれることが多く、死にかけている人や最近亡くなった人の魂を集めるといわれている。英語やドイツ語圏で は、死は男性として描かれるのが一般的だが、フランス語、スペイン語、イタリア語圏では、死が女性として描かれることも珍しくない。[19] イングランドでは、擬人化された「死」が中世の道徳劇で取り上げられ、後に伝統的な民謡にも定期的に登場するようになった。[20] 19世紀にヘンリー・バーストウが歌った「死と貴婦人」(Roud 1031)の歌詞は以下の通りである。 美しい貴婦人よ、高価なローブを脱ぎ捨てなさい。 もはや、あなたの誇りに酔いしれることはできない。 あらゆる酸っぱい肉欲的な空しい喜びから離れよ。 今宵、汝を連れ去りに来たのだ。[20] 1800年代後半には、英語文学において死のキャラクターは「死神」として知られるようになった。英語で「死神」という名称が最初に登場したのは、1847年の書籍『人間の生命の環』である。[21][22][23] 誰もが、人生は70歳、あるいはせいぜい80歳までしか続かないことをよく知っている。死神が大鎌を持って現れずにその期限を迎えたとしても、その辺り、あるいはその辺りで、必ずや死神に出くわすことになるだろう。 |

| In Abrahamic religions See also: Destroying angel (Bible) This section should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. See why. (January 2022) The "Angel of the Lord" smites 185,000 men in the Assyrian camp (II Kings 19:35). When the Angel of Death passes through to smite the Egyptian first-born, God prevents "the destroyer" (shâchath) from entering houses with blood on the lintel and side posts (Exodus 12:23). The "destroying angel" (mal'ak ha-mashḥit) rages among the people in Jerusalem (II Sam. 24:16). In I Chronicles 21:15 the "angel of the Lord" is seen by King David standing "between the earth and the heaven, having a drawn sword in his hand stretched out over Jerusalem." The biblical Book of Job (33:22) uses the general term "destroyers" (memitim), which tradition has identified with "destroying angels" (mal'ake Khabbalah), and Prov. 16:14 uses the term the "angels of death" (mal'ake ha-mavet). The angel Azra'il is sometimes referred as the Angel of Death as well.[24] Jewish tradition also refers to Death as the Angel of Dark and Light, a name which stems from Talmudic lore. There is also a reference to "Abaddon" (The Destroyer), an angel who is known as the "Angel of the Abyss". In Talmudic lore, he is characterized as archangel Michael.[25] |

アブラハムの宗教において 関連項目: 破壊の天使(聖書) この節では、英語以外の言語の内容の言語を、適切なISO 639コードとともに、{{lang}}、転写言語には{{transliteration}}、音声表記には{{IPA}}を用いて指定する。ウィキペ ディアの多言語サポートテンプレートも使用できる。その理由はこちらを参照。 (2022年1月) 「主の使い」はアッシリア陣営の18万5千人の男たちを打ち殺した(列王記第2 19:35)。 死の使いがエジプトの長子を打ち殺すために通り過ぎるとき、神は「破壊者」(shâchath)が門口の鴨居と柱に血がついた家々に入らないようにした (出エジプト記 12:23)。「破壊の天使」(mal'ak ha-mashḥit)はエルサレムの人々の間で猛威を振るった(第二サムエル記24:16)。第一歴代誌21:15では、「主の天使」が「地と天の間、 手に抜き身の剣を持って、エルサレムの上に身を乗り出して」立つ姿がダビデ王の目に映ったとある。聖書のヨブ記(33:22)では一般的な用語「破壊者」 (memitim)が用いられており、これは伝統的に「破壊の天使」(mal'ake Khabbalah)と同一視されている。また、箴言16:14では「死の天使」(mal'ake ha-mavet)という用語が用いられている。天使アズライルは、死の天使とも呼ばれることがある。 ユダヤ教の伝承では、死は「闇と光の天使」とも呼ばれ、この名称はタルムードの伝承に由来する。「アバドン」(破壊者)という天使も「深淵の天使」として知られている。タルムードの伝承では、彼は大天使ミカエルとして特徴づけられている。[25] |

In Judaism La mort du fossoyeur (Death of the gravedigger) by Carlos Schwabe In Hebrew scriptures, Death (Maweth/Mavet(h)) is sometimes personified as a devil or angel of death (e.g., Habakkuk 2:5; Job 18:13).[6] In both the Book of Hosea and the Book of Jeremiah, Maweth/Mot is mentioned as a deity to whom God can turn over Judah as punishment for worshiping other gods.[26] The memitim are a type of angel from biblical lore associated with the mediation over the lives of the dying. The name is derived from the Hebrew word מְמִיתִים (mᵊmītīm – "executioners", "slayers", "destroyers") and refers to angels that brought about the destruction of those whom the guardian angels no longer protected.[27] While there may be some debate among religious scholars regarding the exact nature of the memitim, it is generally accepted that, as described in the Book of Job 33:22, they are killers of some sort.[28] |

ユダヤ教では 「墓堀人の死」(ラ・モール・デュ・フォセイユ)という作品の作者はカルロス・シュワブ ヘブライ語聖書では、死(マウェト/マヴェト)は時に悪魔や死の天使として擬人化される(例:ハバクク書2章5節、ヨブ記18章13節)。[6] ホセア書と モーセ記とエレミヤ書では、マウェト/モトは、他の神々を崇拝した罰として神がユダを譲り渡すことのできる神として言及されている。[26] メミタイトは、聖書に伝わる天使の一種で、死にかけている人の命を仲介するものとされている。この名称はヘブライ語のמְמִיתִים(mᵊmītīm - 「処刑人」、「殺し屋」、「破壊者」)に由来し、守護天使がもはや守護しなくなった人々を滅ぼした天使を指す。。memitimの正確な性質については宗 教学者の間で議論があるかもしれないが、一般的に、ヨブ記33:22に記述されているように、彼らは何らかの殺人者であると受け入れられている。[28] |

| Form and functions According to the Midrash, the Angel of Death was created by God on the first day.[29] His dwelling is in heaven, whence he reaches earth in eight flights, whereas Pestilence reaches it in one.[30] He has twelve wings.[31] "Over all people have I surrendered thee the power," said God to the Angel of Death, "only not over this one [i.e. Moses] which has received freedom from death through the Law."[32] It is said of the Angel of Death that he is full of eyes. In the hour of death, he stands at the head of the departing one with a drawn sword, to which clings a drop of gall. As soon as the dying man sees Death, he is seized with a convulsion and opens his mouth, whereupon Death throws the drop into it. This drop causes his death; he turns putrid, and his face becomes yellow.[33] The expression "the taste of death" originated in the idea that death was caused by a drop of gall.[34] The soul escapes through the mouth, or, as is stated in another place, through the throat; therefore, the Angel of Death stands at the head of the patient (Adolf Jellinek, l.c. ii. 94, Midr. Teh. to Ps. xi.). When the soul forsakes the body, its voice goes from one end of the world to the other, but is not heard (Gen. R. vi. 7; Ex. R. v. 9; Pirḳe R. El. xxxiv.). The drawn sword of the Angel of Death, mentioned by the Chronicler (I. Chron. 21:15; comp. Job 15:22; Enoch 62:11), indicates that the Angel of Death was figured as a warrior who kills off the children of men. "Man, on the day of his death, falls down before the Angel of Death like a beast before the slaughterer" (Grünhut, "Liḳḳuṭim", v. 102a). R. Samuel's father (c. 200) said: "The Angel of Death said to me, 'Only for the sake of the honor of mankind do I not tear off their necks as is done to slaughtered beasts'" ('Ab. Zarah 20b). In later representations, the knife sometimes replaces the sword, and reference is also made to the cord of the Angel of Death, which indicates death by throttling. Moses says to God: "I fear the cord of the Angel of Death" (Grünhut, l.c. v. 103a et seq.). Of the four Jewish methods of execution, three are named in connection with the Angel of Death: Burning (by pouring hot lead down the victim's throat), slaughtering (by beheading), and throttling. The Angel of Death administers the particular punishment that God has ordained for the commission of sin. A peculiar mantle ("idra" – according to Levy, "Neuhebr. Wörterb." i. 32, a sword) belongs to the equipment of the Angel of Death (Eccl. R. iv. 7). The Angel of Death takes on the particular form which will best serve his purpose; e.g., he appears to a scholar in the form of a beggar imploring pity (the beggar should receive Tzedakah)(M. Ḳ. 28a). "When pestilence rages in the town, walk not in the middle of the street, because the Angel of Death [i.e., pestilence] strides there; if peace reigns in the town, walk not on the edges of the road. When pestilence rages in the town, go not alone to the synagogue, because there the Angel of Death stores his tools. If the dogs howl, the Angel of Death has entered the city; if they make sport, the prophet Elijah has come" (B. Ḳ. 60b). The "destroyer" (saṭan ha-mashḥit) in the daily prayer is the Angel of Death (Ber. 16b). Midr. Ma'ase Torah (compare Jellinek, "B. H." ii. 98) says: "There are six Angels of Death: Gabriel over kings; Ḳapẓiel over youths; Mashbir over animals; Mashḥit over children; Af and Ḥemah over man and beast." Samael is considered in Talmudic texts to be a member of the heavenly host with often grim and destructive duties. One of Samael's greatest roles in Jewish lore is that of the main angel of death and the head of satans.[35] |

形と機能 ミドラーシュによると、死の天使は神によって初日に創られた。[29] 彼の住まいは天国にあり、そこから8回の飛行で地上に到達する。一方、疫病は1回の飛行で地上に到達する。[30] 彼には12枚の翼がある。[31] 「 汝にすべての民に力を与えた。」と神は死の天使に言った。「ただ、律法によって死から解放されたこの者(すなわちモーゼ)には与えない。」[32] 死の天使は目だらけだと言われている。死の時、死の天使は抜刀して去りゆく者の頭に立つ。その剣には胆汁の滴がまとわりついている。死にかけの男が死を見 るとすぐに、痙攣を起こし、口を開ける。すると死がその滴を口の中に放り込む。この滴が死の原因となり、死者は腐敗し、顔が黄色くなる。[33] 「死の味」という表現は、死が胆汁の滴によって引き起こされるという考えから生まれた。[34] 魂は口から抜け出る、あるいは別の箇所では喉から抜け出る、と述べられている。そのため、死の天使は患者の頭部に立つ(アドルフ・イェリネック、前掲書第 2巻94ページ、ミドラー・テフ・トー・ペシーム第11章)。魂が肉体から離れると、その声は世界の端から端まで響き渡るが、聞こえることはない(創世記 R. vi. 7; 出エジプト記 R. v. 9; Pirḳe R. El. xxxiv.)。年代記編者(I. Chron. 21:15; comp. Job 15:22; Enoch 62:11)が言及する「死の天使」の抜き身の剣は、死の天使が人間の子供たちを殺す戦士として描かれていたことを示している。「人は死ぬ日には屠殺者の 前に立つ獣のように、死の天使の前にひれ伏す」(Grünhut, 「Liḳḳuṭim」, v. 102a)。R.サミュエルの父親(200年頃)は、「死の天使は私に言った。『人間としての名誉のために、屠殺された獣のように彼らの首をはねないの だ』」(『アブ・ザラ 20b』)と述べた。 後の表現では、剣がナイフに置き換えられることもあり、また、窒息死を示す死の天使の紐についても言及されている。 モーセは神にこう言った。「私は死の天使の縄を恐れる」(Grünhut, l.c. v. 103a et seq.)。ユダヤ教の4つの処刑法のうち、死の天使と関連付けられているのは、焼却(熱した鉛を犠牲者の喉に流し込む)、屠殺(斬首)、窒息の3つであ る。死の天使は、神が罪の犯行に対して定めた特定の刑罰を執行する。 死神の装備品には、独特のマント(「idra」 - レヴィによると「Neuhebr. Wörterb.」i. 32、剣)がある(『伝道の書』第4章第7節)。死の天使は、目的に最も適した特定の姿を取る。例えば、学者に対しては哀れみを乞う乞食の姿で現れる(乞 食はツェダカーを受け取るべきである)(M. Ḳ. 28a)。「町に疫病が猛威を振るっているときは、道の真ん中を歩かないこと。なぜなら、死の天使(すなわち疫病)がそこを闊歩しているからだ。町に平和 が支配しているときは、道の端を歩かないこと。疫病が町に猛威を振るっているときは、一人でシナゴーグに行かないこと。なぜなら、死の天使が道具を保管し ているからだ。犬が吠えれば死の天使が町に入ったしるしであり、犬がじゃれ合えば預言者エリヤが来たしるしである」(B. Ḳ. 60b)。日々の祈りにおける「破壊者」(saṭan ha-mashḥit)は死の天使である(Ber. 16b)。Midr. マサエ・トーラー(Jellinek著「B. H.」第2巻98ページ参照)は次のように述べている。「死を司る天使は6人いる。ガブリエルは王を、カフツィエルは若者を、マシュビルは動物を、マシュ ヒトは子供を、アフとヘマーは人間と動物を司る。 サマエルはタルムードのテキストでは、しばしば陰鬱で破壊的な任務を担う天国の軍勢の一員であると考えられている。ユダヤ教の伝承におけるサマエルの最も重要な役割のひとつは、死の天使であり、悪魔の頭であることである。[35] |

Scholars and the Angel of Death The Angel of Death, sculpture of a funeral gondola, Venice. Photo by Paolo Monti, 1951. Talmud teachers of the 4th century associate quite familiarly with him. When he appeared to one on the street, the teacher reproached him with rushing upon him as upon a beast, whereupon the angel called upon him at his house. To another, he granted a respite of thirty days, that he might put his knowledge in order before entering the next world. To a third, he had no access, because he could not interrupt the study of the Talmud. To a fourth, he showed a rod of fire, whereby he is recognized as the Angel of Death (M. K. 28a). He often entered the house of Bibi and conversed with him (Ḥag. 4b). Often, he resorts to strategy in order to interrupt and seize his victim (B. M. 86a; Mak. 10a). The death of Joshua ben Levi in particular is surrounded with a web of fable. When the time came for him to die and the Angel of Death appeared to him, he demanded to be shown his place in paradise. When the angel had consented to this, he demanded the angel's knife, that the angel might not frighten him by the way. This request also was granted to him, and Joshua sprang with the knife over the wall of paradise; the angel, who is not allowed to enter paradise, caught hold of the end of his garment. Joshua swore that he would not come out, and God declared that he should not leave paradise unless he had ever absolved himself of an oath; he had never absolved himself of an oath so he was allowed to remain. The Angel of Death then demanded back his knife, but Joshua refused. At this point, a heavenly voice (bat ḳol) rang out: "Give him back the knife, because the children of men have need of it will bring death." Hesitant, Joshua Ben Levi gives back the knife in exchange for the Angel of Death's name. To never forget the name, he carved Troke into his arm, the Angel of Death's chosen name. When the knife was returned to the Angel, Joshua's carving of the name faded, and he forgot. (Ket. 77b; Jellinek, l.c. ii. 48–51; Bacher, l.c. i. 192 et seq.). |

学者と死の天使 死の天使、葬送ゴンドラの彫刻、ヴェネツィア。1951年、パオロ・モンティ撮影。 4世紀のタルムードの教師たちは、彼と非常に親しく関わっていた。ある者が道で彼に現れたとき、その教師は彼を獣のように突進したと責めた。すると天使 は、その者の家で彼を呼んだ。別の者には、次の世界に入る前に知識を整理できるように、30日間の猶予を与えた。3人目の者には、タルムードの研究を中断 できなかったため、近づくことができなかった。4人目には、火のついた杖を見せ、死の天使として認められた(M. K. 28a)。彼はしばしばビビの家に入り、彼と会話した(Ḥag. 4b)。しばしば、彼は戦略を駆使して犠牲者を妨害し、捕らえた(B. M. 86a; Mak. 10a)。 特に、ヨシュア・ベン・レビの死は寓話の網に包まれている。彼が死ぬ時が来て、死の天使が現れた時、彼は楽園での自分の場所を見せてもらうよう要求した。 天使がこれに同意すると、彼は天使のナイフを要求した。そうすれば、天使がその方法で彼を驚かせないだろうと考えたのだ。この要求もまた彼に認められ、ヨ シュアはナイフを手に楽園の壁を飛び越えた。楽園に入ることを許されていない天使は、ヨシュアの衣の端をつかんだ。ヨシュアは決して出てこないと誓い、神 は彼がその誓いを破棄しない限り楽園から出てはならないと宣言した。ヨシュアは誓いを破棄したことは一度もなかったため、留まることを許された。死の天使 はナイフを返すよう要求したが、ヨシュアは拒否した。この時、天からの声(バット・コール)が響いた。「ナイフを彼に返せ。なぜなら、人の子らには死をも たらすためにナイフが必要なのだ」ためらいながらも、ヨシュア・ベン・レビは死の天使の名と引き換えにナイフを返した。その名を決して忘れないために、彼 は腕に「トロケ」と刻み込んだ。ナイフが天使に返されると、ジョシュアが刻んだ名前は消え、彼はその名前を忘れてしまった。(Ket. 77b; Jellinek, l.c. ii. 48–51; Bacher, l.c. i. 192 et seq.) |

| Rabbinic views The Rabbis found the Angel of Death mentioned in Psalm 89:48, where the Targum translates: "There is no man who lives and, seeing the Angel of Death, can deliver his soul from his hand." Eccl. 8:4 is thus explained in Midrash Rabbah to the passage: "One may not escape the Angel of Death, nor say to him, 'Wait until I put my affairs in order,' or 'There is my son, my slave: take him in my stead.'" Where the Angel of Death appears, there is no remedy, but his name (Talmud, Ned. 49a; Hul. 7b). If one who has sinned has confessed his fault, the Angel of Death may not touch him (Midrash Tanhuma, ed. Buber, 139). God protects from the Angel of Death (Midrash Genesis Rabbah lxviii.). By acts of benevolence, the anger of the Angel of Death is overcome; when one fails to perform such acts the Angel of Death will make his appearance (Derek Ereẓ Zuṭa, viii.). The Angel of Death receives his orders from God (Ber. 62b). As soon as he has received permission to destroy, however, he makes no distinction between good and bad (B. Ḳ. 60a). In the city of Luz, the Angel of Death has no power, and, when the aged inhabitants are ready to die, they go outside the city (Soṭah 46b; compare Sanh. 97a). A legend to the same effect existed in Ireland in the Middle Ages (Jew. Quart. Rev. vi. 336). |

ラビの意見 ラビたちは詩篇第89章48節に「死の天使」について言及している箇所を見つけた。タルグム訳では「生きている人間で、死の天使を見て、自分の魂を自分の 手から救い出せる者はいない」と訳されている。ミドラーシュ・ラバーの解釈では、伝道の書第8章4節は次のように説明されている。「人は死の天使から逃れ ることはできず、また『身辺整理を済ませるまで待ってくれ』とか、『息子や奴隷がいるから、代わりに彼らを連れて行ってくれ』などと言うこともできない。 死の天使が現れた場所では、救済策はない。ただし、その名は(タルムード、ネド49a、フール7b)。罪を犯した者が自分の過ちを告白した場合、死の天使 は彼に触れることはできない(ミドラーシュ・タンフーマ、ブーバー編、139)。神は死の天使から守ってくれる(ミドラーシュ・ジェネシス・ラバ68)。 慈悲深い行為によって、死の天使の怒りは克服される。そのような行為を行わない場合、死の天使は姿を現す(デレク・エレッツ・ズータ、viii.)。死の 天使は神から命令を受け取る(ベール、62b)。しかし、破壊の許可を受け取ると、善悪の区別なく殺す(B. Ḳ. 60a)。ルス市では、死の天使には何の力もなく、高齢の住民が死ぬ準備ができたときには、彼らは市外に出て行く(Soṭah 46b; compare Sanh. 97a)。同様の内容の伝説は中世アイルランドにも存在していた(Jew. Quart. Rev. vi. 336)。 |

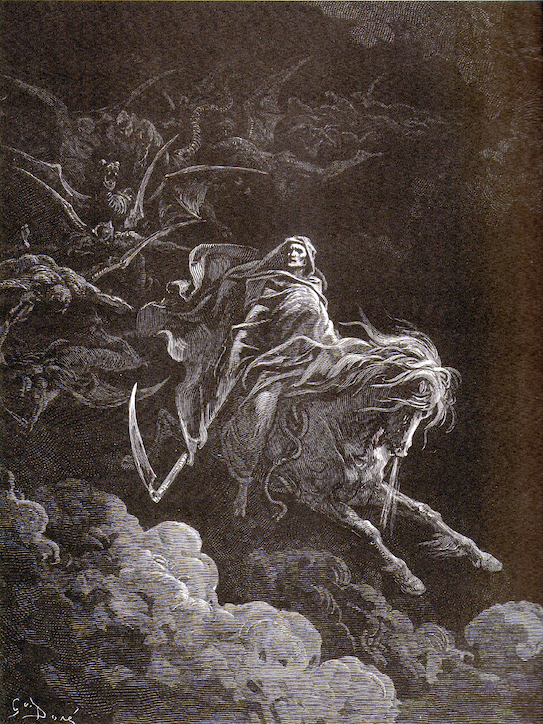

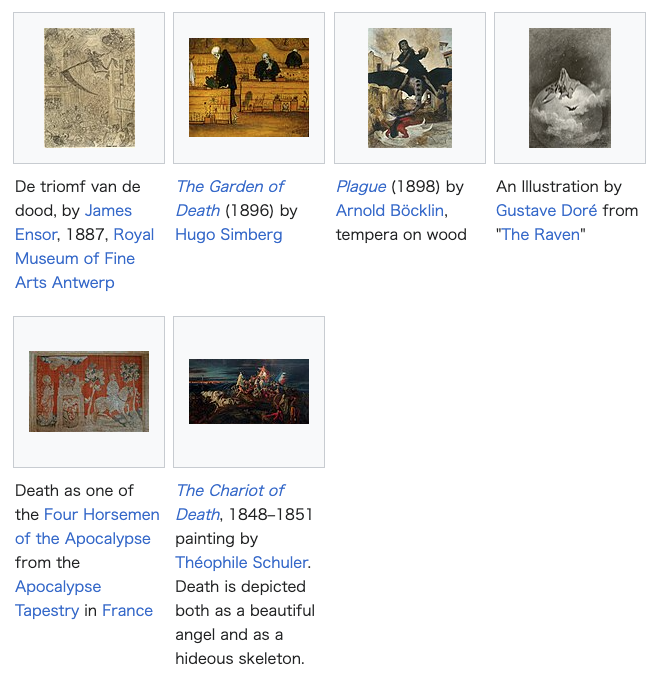

In Christianity Gustave Doré Death on the Pale Horse (1865) – The fourth Horseman of the Apocalypse Death is one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse portrayed in the Book of Revelation, in Revelation 6:7–8.[36] And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him. And power was given unto them over the fourth part of the earth, to kill with sword, and with hunger, and with death, and with the beasts of the earth. — Revelation 6:8, King James Version He is also known as the Pale Horseman whose name is Thanatos, the same as that of the ancient Greek personification of death, and the only one of the horsemen to be named.[citation needed] Paul addresses a personified death in 1 Corinthians 15:55. "O Death, where is your sting? O Hades, where is your victory?" — 1 Corinthians 15:55, New King James Version In some versions, both arms of this verse are addressed to death.[37] The Christian scriptures contain the first known depiction of Abaddon as an individual entity instead of a place. A king, the angel of the bottomless pit; whose name in Hebrew is Abaddon, and in Greek Apollyon; in Latin Exterminans. — Revelation 9:11, Douay–Rheims Bible In Hebrews 2:14 the devil "holds the power of death."[38] Since therefore the children share in flesh and blood, he himself likewise partook of the same things, that through death he might destroy the one who has the power of death, that is, the devil, and deliver all those who through fear of death were subject to lifelong slavery. — Hebrews 2:14–15, English Standard Version Conversely, the early Christian writer Origen believed the destroying angel of Exodus 12:23 to be Satan.[39] Death is stated to be destroyed by the Lake of Fire that burns with sulfur. Death and Hell were thrown into the Lake of Fire. This is the second death. — Revelation 20:14, King James Version The last enemy to be destroyed is death. — 1 Corinthians 15:26, New International Version |

キリスト教において ギュスターヴ・ドレの『死の白い馬』(1865年)は、ヨハネの黙示録の四騎士の4番目である 死を描いている。死は、ヨハネの黙示録のヨハネの黙示録6:7-8で描かれているヨハネの黙示録の四騎士の1人である。 そして、見よ、青白い馬が現れた。それに乗っている者の名は「死」と言い、それに黄泉が従っていた。彼らには、地上の四分の一を支配し、剣と、飢饉と、死をもって、地上の獣を殺す権威が与えられた。 — ヨハネの黙示録 6:8、欽定訳聖書 彼はまた、古代ギリシアの死の擬人化と同じ名前を持つ「死の騎士」として知られ、騎士団の中で唯一名前が付けられている。 パウロは、コリント人への手紙第15章55節で死を擬人化して言及している。 「死よ、お前の針はどこにあるのか。ハデスよ、お前の勝利はどこにあるのか」 — 1コリント15:55、新改訳 いくつかのバージョンでは、この節の両方の腕は死に宛てられている。 キリスト教の聖典には、アバドンが場所ではなく個々の存在として初めて描かれている。 底なしの穴の天使である王。その名はヘブライ語ではアバドン、ギリシャ語ではアポリオン、ラテン語ではエクステルマン。 — ヨハネの黙示録9:11、ドウエ・レイムズ訳聖書 ヘブライ人への手紙2:14では、悪魔は「死の力を持つ」とされている。[38] それゆえ、子らも肉と血とを有している以上、彼自身も同様にそれらを有している。それは、死によって死に支配する者を滅ぼし、死を恐れることによって生涯奴隷状態にあるすべての人々を解放するためである。 — ヘブライ人への手紙 2:14–15、英語標準版 逆に、初期キリスト教の作家オリゲネスは、出エジプト記12:23の破壊の天使をサタンであると信じていた。[39] 死は硫黄で燃える火の池によって滅ぼされると述べられている。 死と地獄は火の池に投げ込まれた。これは第二の死である。 — ヨハネの黙示録20:14、欽定訳聖書 最後に滅ぼされる敵は死である。 — 1コリント15:26、新国際訳聖書 |

| In Islam In Islam, Archangel Azrael is the Malak al-Maut (angel of death). He and his many subordinates[disputed – discuss][citation needed] pull the souls out of the bodies and guide them through the journey of the afterlife. Their appearance depends on the person's deeds and actions: those who did good see a beautiful being, and those who did wrong see a horrific one.[citation needed] Islamic tradition discusses elaborately as to what exactly happens before, during, and after the death. The angel of death appears to the dying to take out their souls. The sinners' souls are extracted in a most painful way while the righteous are treated easily.[40] After the burial, two angels – Munkar and Nakir – come to question the dead to test their faith. The righteous believers answer correctly and live in peace and comfort while the sinners and disbelievers fail and punishments ensue.[40][41] The period or stage between death and resurrection is called barzakh (the interregnum).[40] Death is a significant event in Islamic life and theology. It is seen not as the termination of life, but rather the continuation of life in another form. In Islamic belief, God has made this worldly life a test and a preparation ground for the afterlife; and with death, this worldly life comes to an end.[42] Thus, every person has only one chance to prepare themselves for the life to come where God will resurrect and judge every individual and will entitle them to rewards or punishment, based on their good or bad deeds.[42][43] Death is seen as the gateway to and beginning of the afterlife. In Islamic belief, death is predetermined by God, and the exact time of a person's death is known only to Allah. |

イスラム教において イスラム教において、大天使アズラエルは「死の天使」である。彼と多くの部下たちは[議論の余地あり – 議論する][要出典]、肉体から魂を引き抜き、死後の世界への旅路を導く。彼らの外見は、その人格の行いや行動によって異なる。善行を積んだ者は美しい存 在を目にし、悪行を積んだ者は恐ろしい存在を目にする。[要出典] イスラム教の伝統では、死の前、最中、後に実際に何が起こるのかについて、詳しく論じられている。死の天使は死にかけている人の前に現れ、魂を抜き取る。 罪人の魂は最も苦痛を伴う方法で抜き取られるが、正しい行いをした人の魂は簡単に抜き取られる。[40] 埋葬後、ムンカーとナキールの2人の天使が現れ、死者の信仰心を試すために質問する。正しい信仰を持つ者は正しく答え、安らぎと幸福のうちに暮らす。一 方、罪人や信仰を持たない者は失敗し、罰を受ける。[40][41] 死から復活までの期間または段階は、バルザーク(空白期間)と呼ばれる。[40] 死はイスラム教の生活と神学において重要な出来事である。それは生命の終結ではなく、むしろ別の形での生命の継続と見なされる。イスラム教の信仰では、神 はこの現世での生活を来世のための試練と準備の場としている。そして死によって、この現世での生活は終わりを迎える。[42] したがって、神が復活させ裁きを下す来世に備えるチャンスは、すべての人間に一度きりしかない。神が復活させ、個々を裁き、善行や悪行に基づいて報いある いは罰を与える来世への準備期間である。[42][43] 死は来世への入り口であり始まりであると見なされている。イスラム教では、死は神によってあらかじめ定められており、個々の死の正確な時期はアッラーのみ が知るとされている。 |

|

|

| Ankou Anthropomorphism Danse Macabre Davy Jones's locker Death and the Maiden Death (Tarot card) Death (Discworld) List of death deities Shinigami Skeleton (undead) Skeleton Skull art Veneration of the dead |

アンコウ 擬人観 死の舞踏 デイヴィ・ジョーンズのロッカー 死と乙女 死(タロットカード) 死(ディスクワールド) 死の神の一覧 死神 スケルトン(アンデッド) スケルトン ドクロアート 死者の崇拝 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Personifications_of_death |

Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, Act I, Scene IV by Henry Fuseli (1789)/ ハムレット、デンマークの王子』 第1幕 第4場byヘンリー・フューセリ(1789年

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

cc

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆