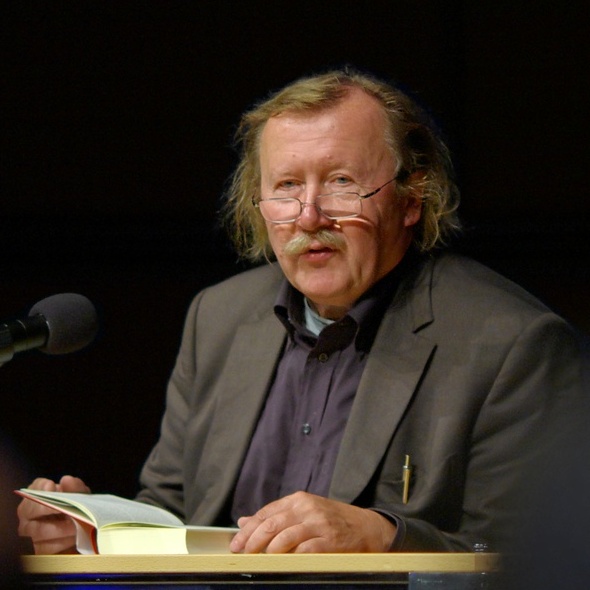

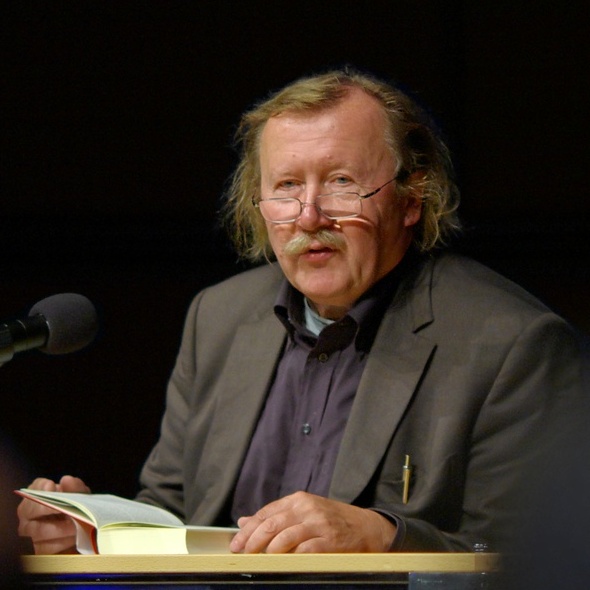

ペーター・スローターダイク

Peter Sloterdijk, b.1947

☆

ペーター・スローターダイク(Peter Sloterdijk /ˈʊ; German: [ˈɪ];

1947年6月26日生まれ)はドイツの哲学者、文化理論家。カールスルーエ芸術デザイン大学教授(哲学、メディア論)。2002年から2012年までド

イツのテレビ番組「Das Philosophische Quartett」の共同司会を務めた。

| Peter Sloterdijk

(/ˈsloʊtərdaɪk/; German: [ˈsloːtɐˌdaɪk]; born 26 June 1947) is a German

philosopher and cultural theorist. He is a professor of philosophy and

media theory at the University of Art and Design Karlsruhe. He

co-hosted the German television show Das Philosophische Quartett from

2002 until 2012. |

ペー

ター・スローターダイク(Peter Sloterdijk /ˈʊ; German: [ˈɪ];

1947年6月26日生まれ)はドイツの哲学者、文化理論家。カールスルーエ芸術デザイン大学教授(哲学、メディア論)。2002年から2012年までド

イツのテレビ番組「Das Philosophische Quartett」の共同司会を務めた。 |

| Biography Sloterdijk's father was Dutch, his mother German. He studied philosophy, German studies and history at the University of Munich and the University of Hamburg from 1968 to 1974. In 1975, he received his PhD from the University of Hamburg. In the 1980s, he worked as a freelance writer, and published his Kritik der zynischen Vernunft in 1983. Sloterdijk has since published a number of philosophical works acclaimed in Germany. In 2001, he was named chancellor of the University of Art and Design Karlsruhe, part of the Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe. His best-known Karlsruhe student and former assistant is Marc Jongen, a member of the Bundestag.[1] In 2002, Sloterdijk began to co-host Das Philosophische Quartett ("The Philosophical Quartet"), a show on the German ZDF television channel devoted to discussing key contemporary issues in-depth.[2] |

略歴 父はオランダ人、母はドイツ人。1968年から1974年までミュンヘン大学とハンブルク大学で哲学、ドイツ学、歴史学を学ぶ。1975年、ハンブルク大 学で博士号を取得。1980年代はフリーライターとして活動し、1983年に『Kritik der zynischen Vernunft』を出版した。以来、ドイツで高く評価される哲学的著作を数多く発表している。2001年、カールスルーエ芸術デザイン大学(カールス ルーエ芸術メディアセンター)の学長に就任した。カールスルーエの教え子で元アシスタントとして最もよく知られているのは、連邦議会議員のマルク・ヨンゲ ンである[1]。2002年、スロテルダイクはドイツのテレビ局ZDFの番組「Das Philosophische Quartett」(「哲学カルテット」)の共同司会を務め、現代の重要な問題について徹底的に議論することに専念した[2]。 |

| Philosophical stance Sloterdijk rejects the existence of dualisms—body and soul, subject and object, culture and nature, etc.—since their interactions, "spaces of coexistence", and common technological advancement create hybrid realities. Sloterdijk's ideas are sometimes referred to as posthumanism,[3] and seek to integrate different components that have been, in his opinion, erroneously considered detached from each other. Consequently, he proposes the creation of an "ontological constitution" that would incorporate all beings—humans, animals, plants, and machines. |

哲学的スタンス スローターダイクは、身体と魂、主体と客体、文化と自然など、二元論の存在を否定する。なぜなら、それらの相互作用、「共存の空間」、共通の技術的進歩が ハイブリッドな現実を生み出すからである。スローターダイクの考えは、ポストヒューマニズムと呼ばれることもあり[3]、彼の考えでは、誤って互いに切り 離されて考えられてきたさまざまな構成要素を統合しようとするものである。その結果、彼は人間、動物、植物、機械など、すべての存在を統合する「存在論的 憲法」の創設を提案している。 |

| Philosophical style In the style of Nietzsche[citation needed], Sloterdijk remains convinced that contemporary philosophers have to think dangerously and let themselves be "kidnapped" by contemporary "hyper-complexities": they must forsake our present humanist and nationalist world for a wider horizon at once ecological and global.[4] Sloterdijk's philosophical style strikes a balance between the firm academicism of a scholarly professor and a certain sense of anti-academicism (witness his ongoing interest in the ideas of Osho, of whom he became a disciple in the late seventies).[5] Taking a sociological stance, Andreas Dorschel sees Sloterdijk's timely innovation at the beginning of the 21st century in having introduced the principles of celebrity into philosophy.[6] Sloterdijk himself, viewing exaggeration as necessary to catch attention, describes the way he presents his ideas as "hyperbolic" (hyperbolisch).[7] |

哲学のスタイル ニーチェ[要出典]のスタイルで、スローターダイクは、現代の哲学者は危険な思考をし、現代の「超複雑性」に自らを「誘拐」されなければならないと確信し ている。 [4] スローターダイクの哲学的スタイルは、学者教授の確固としたアカデミズムと、ある種の反アカデミズム(70年代後半に弟子となったオショーの思想に関心を 持ち続けていることを目撃してほしい)の間でバランスをとっている。 [社会学的な立場から、アンドレアス・ドルシェールは、21世紀初頭におけるスローターダイクのタイムリーな革新は、哲学にセレブリティの原理を導入した ことにあると見ている[6]。スローターダイク自身、誇張は注目を集めるために必要だと考えており、自分の考えを提示する方法を「ハイパーボリック」 (hyperbolisch)と表現している[7]。 |

| Major Works Critique of Cynical Reason The Kritik der zynischen Vernunft, published by Suhrkamp in 1983 (and in English as Critique of Cynical Reason, 1987), became the best-selling work on philosophy in the German language since the Second World War and launched Sloterdijk's career as an author.[8] Spheres The trilogy Spheres is the philosopher's magnum opus. The first volume was published in 1998, the second in 1999, and the last in 2004. Spheres deals with "spaces of coexistence", spaces commonly overlooked or taken for granted which conceal information crucial to developing an understanding of humanity. The exploration of these spheres begins with the basic difference between mammals and other animals: the biological and utopian comfort of the mother's womb, which humans try to recreate through science, ideology, and religion. From these microspheres (ontological relations such as fetus-placenta) to macrospheres (macro-uteri such as states), Sloterdijk analyzes spheres where humans try but fail to dwell and traces a connection between vital crises (e.g., emptiness and narcissistic detachment) and crises created when a sphere shatters. Sloterdijk has said that the first paragraphs of Spheres are "the book that Heidegger should have written", a companion volume to Being and Time, namely, "Being and Space".[citation needed] He was referring to his initial exploration of the idea of Dasein, which is then taken further as Sloterdijk distances himself from Heidegger's positions.[9] Nietzsche Apostle On 25 August 2000, in Weimar, Sloterdijk gave a speech on Nietzsche; the occasion was the centennial of the latter philosopher's death. The speech was later printed as a short book[10] and translated into English.[11] Sloterdijk presented the idea that language is fundamentally narcissistic: individuals, states and religions use language to promote and validate themselves. Historically however, Christianity and norms in Western culture have prevented orators and authors from directly praising themselves, so that for example they would instead venerate God or praise the dead in eulogies, to demonstrate their own skill by proxy. In Sloterdijk's account, Nietzsche broke with this norm by regularly praising himself in his own work. For examples of classical Western "proxy-narcissism", Sloterdijk cites Otfrid of Weissenburg, Thomas Jefferson and Leo Tolstoy, each of whom prepared edited versions of the four Gospels: the Evangelienbuch, the Jefferson Bible and the Gospel in Brief, respectively. For Sloterdijk, each work can be regarded as "a fifth gospel" in which the editor validates his own culture by editing tradition to conform to his own historical situation. With this background, Sloterdijk explains that Nietzsche also presented his work Thus Spoke Zarathustra as a kind of fifth gospel. In Sloterdijk's account, Nietzsche engages in narcissism to an embarrassing degree, particularly in Ecce Homo, promoting a form of individualism and presenting himself and his philosophy as a brand. However, just as the Christian Gospels were appropriated by the above editors, so too was Nietzsche's thought appropriated and misinterpreted by the Nazis. Sloterdijk concludes the work by comparing Nietzsche's individualism with that of Ralph Waldo Emerson, as in Self-Reliance. |

主な著作 皮肉な理性批判(邦訳「シニカル理性批判」) 1983年にSuhrkamp社から出版された『Kritik der zynischen Vernunft』(英語版は『Critique of Cynical Reason』、1987年)は、第二次世界大戦以降、ドイツ語圏で最も売れた哲学書となり、スローターダイクの作家としてのキャリアをスタートさせた [8]。 球体 三部作『球体』は哲学者の大作である。第1巻は1998年、第2巻は1999年、最終巻は2004年に出版された。 『Spheres』は「共存の空間」を扱っており、一般的に見過ごされ、あるいは当然視されている空間には、人間性を理解する上で極めて重要な情報が隠され ている。これらの圏域の探求は、哺乳類と他の動物との基本的な違いである、母親の胎内という生物学的かつユートピア的な安らぎから始まる。このようなミク ロ圏(胎児と胎盤のような存在論的関係)からマクロ圏(国家のようなマクロ的存在)に至るまで、スローターダイクは、人間が住もうとしても住めない圏を分 析し、生命的危機(空虚感や自己愛的離脱など)と圏が砕け散るときに生じる危機との関連を追跡する。 スローターダイクは、『球体』の最初の段落は「ハイデガーが書くべきだった本」であり、『存在と時間』の姉妹編である『存在と空間』であると述べている。 ニーチェの使徒 2000年8月25日、ワイマールでスローターダイクはニーチェについてのスピーチを行った。スローターダイクは、言語とは基本的に自己愛的なものであ り、個人、国家、宗教は自己を宣伝し、正当化するために言語を使用するという考えを示した。しかし歴史的に見ると、キリスト教と西洋文化の規範は、弁士や 作家が直接的に自らを称賛することを妨げてきた。そのため、たとえば彼らは代わりに神を崇め、あるいは弔辞の中で死者を讃え、代理人として自らの手腕を示 すのである。スローターダイクの説明によれば、ニーチェはこの規範を破り、自作の中で定期的に自らを賞賛した。 古典的な西洋の「代理ナルシシズム」の例として、スローターダイクはヴァイセンブルクのオトフリッド、トーマス・ジェファーソン、レオ・トルストイを挙げ ている。彼らはそれぞれ4つの福音書の編集版(それぞれ『福音書』、『ジェファーソン聖書』、『福音書簡集』)を準備していた。スローターダイクにとっ て、各作品は「第五の福音書」とみなすことができ、編者は自らの歴史的状況に適合するように伝統を編集することで、自らの文化を正当化したのである。この ような背景からスローターダイクは、ニーチェもまた『ツァラトゥストラはかく語りき』を第五の福音書として発表したと説明する。スローターダイクの説明で は、ニーチェは恥ずかしくなるほどナルシシズムに走り、特に『Ecce Homo』では個人主義を推し進め、自分自身と自分の哲学をブランドとして提示している。しかし、キリスト教の福音書が上記の編集者によって流用されたよ うに、ニーチェの思想もまたナチスによって流用され、誤読されたのである。スローターダイクは、『自己信頼』のように、ニーチェの個人主義とラルフ・ワル ド・エマーソンの個人主義を比較することで、この著作を結んでいる。 |

| Globalization Sloterdijk also argues that the current concept of globalization lacks historical perspective. In his view it is merely the third wave in a process of overcoming distances (the first wave being the metaphysical globalization of the Greek cosmology and the second the nautical globalization of the 15th and 16th centuries). The difference for Sloterdijk is that, while the second wave created cosmopolitanism, the third is creating a global provincialism. Sloterdijk's sketch of a philosophical history of globalization can be found in Im Weltinnenraum des Kapitals (2005; translated as In the World Interior of Capital), subtitled "Die letzte Kugel" ("The final sphere"). In an interview with Noema Magazine, Sloterdijk expanded upon the idea of “planetary co-immunism”, referring to the need to "share the means of protection even with the most distant members of the family of man/woman" when faced with shared threats such as pandemics.[12] Rage and Time Main article: Rage and Time In his Zorn und Zeit (translated as Rage and Time), Sloterdijk characterizes the emotion of rage as a psychopolitical force throughout human history. The political aspects are especially pronounced in the Western tradition, beginning with the opening words of Homer's Iliad, "Of the rage of Achilles, son of Peleus, sing, O Goddess...". Sloterdijk acknowledges the contributions of psychoanalysis for our understanding of strong emotional attitudes: "In conformity with its basic erotodynamic approach, psychoanalysis brought much hatred to light, the other side of life." (Rage and Time, p. 14) Importantly, for Sloterdijk, Judeo-Christian conceptions of God ultimately "piggyback" on the feelings of rage and resentment, creating "metaphysical revenge banks". For Sloterdijk, "God thus becomes the location of a transcendent repository of suspended human rage-savings and frozen plans of revenge."[13] |

グローバリゼーション スローターダイクはまた、現在のグローバリゼーションの概念には歴史的視点が欠けていると主張する。彼の見解では、グローバリゼーションは距離を克服する 過程における第三の波に過ぎない(第一の波はギリシャ宇宙論の形而上学的グローバリゼーションであり、第二の波は15世紀から16世紀にかけての航海的グ ローバリゼーションである)。スローターダイクにとっての違いは、第二の波がコスモポリタニズムを生み出したのに対し、第三の波はグローバル・プロバティ ズムを生み出しているという点である。スローターダイクによるグローバリゼーションの哲学史のスケッチは、『資本の世界内部』(Im Weltinnenraum des Kapitals、2005年、邦訳『資本の世界内部』)に収められている。スローターダイクは『Noema Magazine』誌のインタビューで、パンデミックのような共通の脅威に直面したとき、「人間/女という家族の最も遠いメンバーとも防御手段を共有す る」必要性に言及し、「惑星的共同免疫主義」の考えを拡大した[12]。 怒りと時間 主な記事 怒りと時間 スローターダイクは『怒りと時間』(Zorn und Zeit)の中で、人類の歴史を通して怒りの感情を心理政治的な力として特徴づけている。ホメロスの『イーリアス』の冒頭の言葉「ペレウスの子アキレウス の憤怒を、女神よ歌え」から始まる。スローターダイクは、強い感情的態度を理解するための精神分析の貢献を認めている: 「精神分析は、その基本的なエロトダイナミック・アプローチに従って、人生の裏側である多くの憎悪を明るみに出した。(重要なのは、スローターダイクに とって、ユダヤ・キリスト教的な神の概念は、究極的には怒りや恨みの感情に「おんぶにだっこ」であり、「形而上学的な復讐銀行」を作り出しているというこ とである。スローターダイクにとって、「神はこうして、宙吊りにされた人間の怒り貯蓄と凍結された復讐計画の超越的な保管場所の場所となる」[13]。 |

| Reprogenetics dispute Shortly after Sloterdijk conducted a symposium on philosophy and Heidegger, he stirred up controversy with his essay "Regeln für den Menschenpark" ("Rules for the Human Park", 1999).[14] In this text, Sloterdijk regards cultures and civilizations as "anthropogenic hothouses," installations for the cultivation of human beings; just as we have established wildlife preserves to protect certain animal species, so too ought we to adopt more deliberate policies to ensure the survival of Aristotle's zoon politikon. "The taming of man has failed", Sloterdijk laments. "Civilisation's potential for barbarism is growing; the everyday bestialisation of man is on the increase." Because of the eugenic policies of the Nazis in Germany's recent history, such discussions are seen in Germany as carrying a sinister load. Breaking a German taboo on the discussion of genetic manipulation, Sloterdijk's essay suggests that the advent of new genetic technologies requires more forthright discussion and regulation of "bio-cultural" reproduction. In the eyes of Habermas, this made Sloterdijk a "fascist". Sloterdijk replied that this was, itself, resorting to "fascist" tactics to discredit him.[15] The core of the controversy was not only Sloterdijk's ideas but also his use of the German words Züchtung ("breeding", "cultivation") and Selektion ("selection"). Sloterdijk rejected the accusation of Nazism, which he considered alien to his historical context. Still, the paper started a controversy in which Sloterdijk was strongly criticized, both for his alleged usage of a fascist rhetoric to promote Plato's vision of a government with absolute control over the population, and for committing a non-normative, simplistic reduction of the bioethical issue itself. This second criticism was based on the vagueness of Sloterdijk's position on how exactly society would be affected by developments in genetic science. After the controversy multiplied positions both for and against him, Die Zeit published an open letter from Sloterdijk to Habermas in which he vehemently accused Habermas of "criticizing behind his back" and espousing a view of humanism that Sloterdijk had declared dead.[16] |

リプロジェネティックス論争 スローターダイクは、哲学とハイデガーに関するシンポジウムを開催した直後、エッセイ『人間公園の規則』(「Regeln für den Menschenpark」、1999年)で論争を巻き起こした[14]。この文章でスローターダイクは、文化や文明を「人為的温室」、つまり人間を栽培 するための施設と見なしている。 「人間の飼いならしは失敗した」とスローターダイクは嘆く。「文明が野蛮になる可能性は高まっている。人間の日常的な獣化が進んでいるのだ。 ドイツの最近の歴史におけるナチスの優生政策のせいで、ドイツではこのような議論は不吉なものだとみなされている。遺伝子操作の議論に対するドイツのタ ブーを破り、スローターダイクのエッセイは、新しい遺伝子技術の出現により、「生物文化的」生殖についてより率直な議論と規制が必要であることを示唆して いる。ハーバーマスの目には、これがスローターダイクを「ファシスト」と映った。論争の核心はスローターダイクの思想だけでなく、彼がZüchtung (「繁殖」、「栽培」)とSelektion(「選択」)というドイツ語を使ったことだった。スローターダイクはナチズムの非難を拒否した。それでも、こ の論文は論争を引き起こし、スローターダイクは、プラトンの人口絶対管理政府構想を推進するためにファシズム的なレトリックを用いたという疑惑と、生命倫 理問題そのものを非規範的で単純化したことの両方から、強く批判された。この第二の批判は、遺伝子科学の発展によって社会が具体的にどのような影響を受け るかについてのスローターダイクの立場が曖昧であることに基づいていた。賛否両論が巻き起こった後、ディ・ツァイトはスローターダイクからハーバーマスへ の公開書簡を発表し、その中でハーバーマスは「陰で批判」しており、スローターダイクが死んだと宣言したヒューマニズムの見解を支持していると激しく非難 した[16]。 |

| Welfare state dispute Another dispute emerged after Sloterdijk's article "Die Revolution der gebenden Hand" (13 June 2009; transl. "The revolution of the giving hand")[17][18] in the Frankfurter Allgemeine, one of Germany's most widely read newspapers. There Sloterdijk claimed that the national welfare state is a "fiscal kleptocracy" that had transformed the country into a "swamp of resentment" and degraded its citizens into "mystified subjects of tax law". Sloterdijk opened the text with the famous quote of leftist critics of capitalism (made famous in the 19th century by Proudhon in his "What Is Property?") "Property is theft", stating, however, that it is nowadays the modern state that is the biggest taker. "We are living in a fiscal grabbing semi-socialism – and nobody calls for a fiscal civil war."[19][20] He repeated his statements and stirred up the debate in his articles titled "Kleptokratie des Staates" (transl. "Kleptocracy of the state") and "Aufbruch der Leistungsträger" (transl. "Uprising of the performers") in the German monthly Cicero – Magazin für politische Kultur.[21][22][23] According to Sloterdijk, the institutions of the welfare state lend themselves to a system that privileges the marginalized, but relies, unsustainably, on the class of citizens who are materially successful. Sloterdijk's provocative recommendation was that income taxes should be deeply reduced, the difference being made up by donations from the rich in a system that would reward higher givers with social status. Achievers would be praised for their generosity, rather than being made to feel guilty for their success, or resentful of society's dependence on them.[24] In January 2010, an English translation was published, titled "A Grasping Hand – The modern democratic state pillages its productive citizens", in Forbes[25] and in the Winter 2010 issue of City Journal.[26] Sloterdijk's 2010 book, Die nehmende Hand und die gebende Seite, contains the texts that triggered the 2009–2010 welfare state dispute. |

福祉国家論争 スローターダイクが、ドイツで最も広く読まれている新聞のひとつであるフランクフルター・アルゲマイネ紙に「Die Revolution der gebenden Hand」(2009年6月13日、訳注:「与える手の革命」)[17][18]という記事を掲載した後、別の論争が勃発した。スローターダイクはそこ で、国民福祉国家は「財政クレプトクラシー」であり、国民を「恨みの沼地」に変え、「税法の神秘化された臣民」に堕落させたと主張した。 スローターダイクは冒頭で、資本主義を批判する左翼の有名な言葉(19世紀にプルードンによって『財産とは何か』で有名になった)を引用し、「財産は窃盗 である」と述べた。彼はドイツの月刊誌『Cicero - Magazin für politische Kultur』に掲載した「Kleptokratie des Staates」(訳注:「国家のクレプトクラシー[泥棒政治]」)や「Aufbruch der Leistungsträger」(訳注:「パフォーマーの蜂起」)と題する論文で、自分の発言を繰り返し、議論をあおった[21][22][23]。 スローターダイクによれば、福祉国家の制度は、社会から疎外された人々を優遇する一方で、物質的に成功した市民層に持続不可能な形で依存するシステムであ る。スローターダイクの挑発的な提言は、所得税を大幅に減税し、その差額を富裕層からの寄付金で補うというものである。達成者は、成功したことに罪悪感を 感じたり、社会が彼らに依存していることに憤慨したりするのではなく、その寛大さが賞賛されることになる[24]。 2010年1月、『フォーブス』誌[25]と『シティ・ジャーナル』誌2010年冬号に、「A Grasping Hand - The modern democratic state pillages its productive citizens 」と題された英訳が掲載された[26]。スローターダイクの2010年の著書『Die nehmende Hand und die gebende Seite』には、2009年から2010年にかけての福祉国家論争のきっかけとなった文章が収められている。 |

| Honours and awards 1993: Ernst Robert Curtius Prize for Essay Writing[27] 2000: Friedrich Märker Prize for Essay Writing[28] 2001: Christian Kellerer Prize for the future of philosophical thought[29][30] 2005: Business Book Award for the Financial Times Deutschland[28] 2005: Sigmund Freud Prize for Scientific Prose[27] 2005: Austrian Decoration for Science and Art[31] 2006: Commander of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres[28] 2008: Lessing Prize for Criticism [de][32] 2008: Cicero Prize [de][33] 2008: Internationaler Mendelssohn-Preis zu Leipzig [de] (category Social Responsibility)[34] 2009: BDA award for architectural criticism[32] 2013: Ludwig Börne Prize[27] 2021: European Prize for Political Culture of the Hans Ringier Foundation (50,000 Franc)[35][36] Honorary doctorates 2011: Honorary doctorate from the University of Nijmegen, Netherlands[37] 2023: Honorary doctorate from the West University of Timișoara, Romania[38] |

栄誉と賞 1993年:エルンスト・ロバート・クルティウス賞(エッセイ部門)[27]。 2000: フリードリヒ・メルカー賞(エッセイ部門)[28 2001年:クリスティアン・ケレラー賞(哲学思想の未来)[29][30]。 2005: フィナンシャル・タイムズ・ドイチュランド』誌ビジネス書賞[28]。 2005: ジークムント・フロイト科学散文賞[27] 2005: オーストリア科学芸術勲章[31] 2006: 芸術文化勲章コマンダー[28] 2008: レッシング評論賞[32 2008: キケロ賞[デ][33] 2008: ライプツィヒ国際メンデルスゾーン賞(社会的責任部門)[34]。 2009: BDA賞(建築批評部門)[32 2013: ルートヴィヒ・ベルネ賞[27] 2021: ハンス・リンジェ財団のヨーロッパ政治文化賞(5万フラン)[35][36]。 名誉博士号 2011: オランダのナイメーヘン大学から名誉博士号を授与される[37]。 2023: ルーマニアのティミシュオアラ西大学から名誉博士号を授与される[38]。 |

| Works in English translation Critique of Cynical Reason, translation by Michael Eldred; foreword by Andreas Huyssen, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1988. ISBN 0-8166-1586-1 Thinker on Stage: Nietzsche's Materialism, translation by Jamie Owen Daniel; foreword by Jochen Schulte-Sasse, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1989. ISBN 0-8166-1765-1 Theory of the Post-War Periods: Observations on Franco-German relations since 1945, translation by Robert Payne; foreword by Klaus-Dieter Müller, Springer, 2008. ISBN 3-211-79913-3 Terror from the Air, translation by Amy Patton, Los Angeles, Semiotext(e), 2009. ISBN 1-58435-072-5 God's Zeal: The Battle of the Three Monotheisms, Polity Pr., 2009. ISBN 978-0-7456-4507-0 Derrida, an Egyptian, Polity Pr., 2009. ISBN 0-7456-4639-5 Rage and Time, translation by Mario Wenning, New York, Columbia University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-231-14522-0 Neither Sun nor Death, translation by Steven Corcoran, Semiotext(e), 2011. ISBN 978-1-58435-091-0 – Sloterdijk answers questions posed by German writer Hans-Jürgen Heinrichs, commenting on such issues as technological mutation, development media, communication technologies, and his own intellectual itinerary. Bubbles: Spheres Volume I: Microspherology, translation by Wieland Hoban, Los Angeles, Semiotext(e), 2011. ISBN 1-58435-104-7 The Art of Philosophy: Wisdom as a Practice, translation by Karen Margolis, New York, Columbia University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0-231-15870-1 You Must Change Your Life, translation by Wieland Hoban, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-7456-4921-4 In the World Interior of Capital: Towards a Philosophical Theory of Globalization, translation by Wieland Hoban, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-7456-4769-2 Nietzsche Apostle, (Semiotext(e)/Intervention Series), translation by Steve Corcoran, Los Angeles, Semiotext(e), 2013. ISBN 978-1-58435-099-6 Globes: Spheres Volume II: Macrospherology, translation by Wieland Hoban, Los Angeles, Semiotext(e), 2014. ISBN 1-58435-160-8 Foams: Spheres Volume III: Plural Spherology, translation by Wieland Hoban, Los Angeles, Semiotext(e), 2016. ISBN 1-58435-187-X Not Saved: Essays after Heidegger, translation by Ian Alexander Moore and Christopher Turner, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2016. "The Domestication of Human Beings and the Expansion of Solidarities", in J. Koltan (ed.) Solidarity and the Crisis of Trust, translated by Jeremy Gaines, Gdansk: European Solidarity Centre, 2016, pp. 79–93 (http://www.ecs.gda.pl/title,pid,1471.html). What Happened in the 20th Century?, translation by Christopher Turner, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2018. After God, translation by Ian Alexander Moore, Polity Press, 2020. Infinite Mobilization, translation by Sandra Berjan, Polity Press, 2020. Making the Heavens Speak: Religion as Poetry, translation by Robert Hughes, Polity Press, 2022. Prometheus’s Remorse: From the Gift of Fire to Global Arson, translated by Hunter Bolin, Semiotext(e), 2024.[39] |

英訳著作 『冷笑的理性批判』マイケル・エルドレッド訳、アンドレアス・ホイセン序文、ミネアポリス、ミネソタ大学出版、1988年。ISBN 0-8166-1586-1 舞台上の思想家: Nietzsche's Materialism, Jamie Owen Daniel訳; Jochen Schulte-Sasse序文, ミネアポリス, ミネソタ大学出版局, 1989. ISBN 0-8166-1765-1 戦後の理論: 1945年以降の独仏関係に関する考察、ロバート・ペイン訳、クラウス=ディーター・ミュラー序文、シュプリンガー、2008年。ISBN 3-211-79913-3 空からの恐怖』エイミー・パットン訳、ロサンゼルス、Semiotext(e)、2009年。ISBN 1-58435-072-5 神の熱意: 3つの一神教の戦い, ポリティ出版, 2009. ISBN 978-0-7456-4507-0 デリダ、エジプト人』 ポリティ出版、2009年。ISBN 0-7456-4639-5 怒りと時間』マリオ・ウェニング訳、ニューヨーク、コロンビア大学出版局、2010年。ISBN 978-0-231-14522-0 スティーヴン・コーコラン訳『太陽でも死でもない』Semiotext(e)、2011年。ISBN 978-1-58435-091-0 - スローターダイクは、ドイツの作家ハンス・ユルゲン・ハインリヒスが投げかけた質問に答え、技術の変異、開発メディア、コミュニケーション技術、自身の知 的遍歴などの問題についてコメントしている。 泡: Spheres Volume I: Microspherology, Wieland Hoban訳、ロサンゼルス、Semiotext(e)、2011年。ISBN 1-58435-104-7 アート・オブ・フィロソフィー カレン・マーゴリス訳、ニューヨーク、コロンビア大学出版局、2012年。ISBN 978-0-231-15870-1 You Must Change Your Life, Wieland Hoban訳, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-7456-4921-4 資本の世界内部で Wieland Hoban訳『グローバリゼーションの哲学的理論に向けて』ケンブリッジ、ポリティ・プレス、2013年。ISBN 978-0-7456-4769-2 ニーチェの使徒』(Semiotext(e)/Interventionシリーズ)スティーブ・コーコラン訳、ロサンゼルス、Semiotext(e)、2013年。ISBN 978-1-58435-099-6 地球儀 Spheres Volume II: Macrospherology, Wieland Hoban訳、ロサンゼルス、Semiotext(e)、2014年。ISBN 1-58435-160-8 泡: Spheres Volume III: Plural Spherology, Wieland Hoban訳、ロサンゼルス、Semiotext(e)、2016年。ISBN 1-58435-187-x 救われない: ハイデガー以後のエッセイ』イアン・アレクサンダー・ムーア、クリストファー・ターナー訳、ケンブリッジ、ポリティ・プレス、2016年。 「The Domestication of Human Beings and the Expansion of Solidarities」, in J. Koltan (ed.) Solidarity and the Crisis of Trust, translated by Jeremy Gaines, Gdansk: European Solidarity Centre, 2016, pp.79-93 (http://www.ecs.gda.pl/title,pid,1471.html)。 20世紀に何が起こったか』クリストファー・ターナー訳、ケンブリッジ、ポリティ・プレス、2018年。 After God』イアン・アレクサンダー・ムーア訳、ポリティ・プレス、2020年。 無限の動員』サンドラ・ベルジャン訳、ポリティ・プレス、2020年。 Making the Heavens Speak: 詩としての宗教、ロバート・ヒューズ訳、ポリティ・プレス、2022年。 プロメテウスの後悔: プロメテウスの後悔:火の贈り物から世界的放火まで』ハンター・ボリン訳、Semiotext(e)、2024年[39]。 |

| Estrés y Libertad: traducción de Paula Kuffer, Buenos Aires, Ediciones Godot, 2017. ISBN 978-987-4086-20-4 Crítica de la razón cínica, Ediciones Siruela; Edición 2019. ISBN 978-841-7996-07-9 Esferas I, Ediciones Siruela; Edición 2003. ISBN 978-847-8446-54-4 Esferas II, Ediciones Siruela; Edición 2014. ISBN 978-847-8447-54-1 Esferas III, Ediciones Siruela; Edición 2014. ISBN 978-847-8449-51-4 |

Estrés y Libertad: Paula Kuffer訳、ブエノスアイレス、エディシオネス・ゴドー、2017年。ISBN 978-987-4086-20-4 Crítica de la razón cínica, Ediciones Siruela; 2019年版。ISBN 978-841-7996-07-9 Spheres I, Ediciones Siruela; 2003年版。ISBN 978-847-8446-54-4 Spheres II, Ediciones Siruela; 2014年版。ISBN 978-847-8447-54-1 Spheres III, Ediciones Siruela; 2014 Edition. ISBN 978-847-8449-51-4 |

| Kritik der zynischen Vernunft, 1983. Der Zauberbaum. Die Entstehung der Psychoanalyse im Jahr 1785, 1985. Der Denker auf der Bühne. Nietzsches Materialismus, 1986. (Thinker on Stage: Nietzsche's Materialism) Kopernikanische Mobilmachung und ptolmäische Abrüstung, 1986. Zur Welt kommen – Zur Sprache kommen. Frankfurter Vorlesungen, 1988. Eurotaoismus. Zur Kritik der politischen Kinetik, 1989. Versprechen auf Deutsch. Rede über das eigene Land, 1990. Weltfremdheit, 1993. Falls Europa erwacht. Gedanken zum Programm einer Weltmacht am Ende des Zeitalters seiner politischen Absence, 1994. Scheintod im Denken – Von Philosophie und Wissenschaft als Übung, Frankfurt am Main (Suhrkamp), 1995. Im selben Boot – Versuch über die Hyperpolitik, Frankfurt am Main (Suhrkamp), 1995. Selbstversuch, Ein Gespräch mit Carlos Oliveira, 1996. Der starke Grund zusammen zu sein. Erinnerungen an die Erfindung des Volkes, 1998. Sphären I – Blasen, Mikrosphärologie, 1998. (Spheres I) Sphären II – Globen, Makrosphärologie, 1999. (Spheres II) Regeln für den Menschenpark. Ein Antwortschreiben zu Heideggers Brief über den Humanismus, 1999. Die Verachtung der Massen. Versuch über Kulturkämpfe in der modernen Gesellschaft, 2000. Über die Verbesserung der guten Nachricht. Nietzsches fünftes Evangelium. Rede zum 100. Todestag von Friedrich Nietzsche, 2000. Nicht gerettet. Versuche nach Heidegger, 2001. Die Sonne und der Tod, Dialogische Untersuchungen mit Hans-Jürgen Heinrichs, 2001. Tau von den Bermudas. Über einige Regime der Phantasie, 2001. Luftbeben. An den Wurzeln des Terrors, 2002. Sphären III – Schäume, Plurale Sphärologie, 2004. (Spheres III) Im Weltinnenraum des Kapitals, 2005. Was zählt, kehrt wieder. Philosophische Dialogue, with Alain Finkielkraut (from French), 2005. Zorn und Zeit. Politisch-psychologischer Versuch, 2006. ISBN 3-518-41840-8 Der ästhetische Imperativ, 2007. Derrida, ein Ägypter, 2007. Gottes Eifer. Vom Kampf der drei Monotheismen, Frankfurt am Main (Insel), 2007. Theorie der Nachkriegszeiten, (Suhrkamp), 2008. Du mußt dein Leben ändern, Frankfurt am Main (Suhrkamp), 2009. Philosophische Temperamente Von Platon bis Foucault, München (Diederichs) 2009. ISBN 978-3-424-35016-6 Die nehmende Hand und die gebende Seite, (Suhrkamp), 2010. Die schrecklichen Kinder der Neuzeit, (Suhrkamp), 2014. Was geschah im 20. Jahrhundert? Unterwegs zu einer Kritik der extremistischen Vernunft, (Suhrkamp), 2016. Das Schelling-Projekt. Ein Bericht. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-518-42524-4. Nach Gott: Glaubens- und Unglaubensversuche. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-518-42632-6 bzw. ISBN 3-518-42632-X. Neue Zeilen und Tage. Notizen 2011–2013. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-518-42844-3. Polyloquien. Ein Brevier. Hrsg. v. Raimund Fellinger, Suhrkamp, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-518-42775-0. Den Himmel zum Sprechen bringen. Über Theopoesie. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2020, ISBN 978-3-518-42933-4. Der Staat streift seine Samthandschuhe ab. Ausgewählte Gespräche und Beiträge 2020–2021. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2021, ISBN 978-3-518-47222-4. Wer noch kein Grau gedacht hat. Eine Farbenlehre. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2022, ISBN 978-3-518-43068-2. Die Reue des Prometheus. Von der Gabe des Feuers zur globalen Brandstiftung. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2023, ISBN 978-3-518-02985-5. |

シニカルな理性批判』1983年 魔法の木 1785年の精神分析の出現、1985年。 舞台の上の思想家 ニーチェの唯物論』1986年(Thinker on Stage: Nietzsche's Materialism) コペルニクス的総動員とプトレマイオス的武装解除』(1986年 世界へ来る-言論へ来る。フランクフルト講演、1988年 エウロタオイズム。ポリティカル・キネティクスの批判について, 1989. ドイツ語での約束。自国についてのスピーチ、1990年。 Weltfremdheit、1993年。 ヨーロッパが目覚めれば。政治的不在の時代の終わりにおける世界大国のプログラムについての考察、1994年。 Scheintod im Denken - Von Philosophie und Wissenschaft als Übung, Frankfurt am Main (Suhrkamp), 1995. Im selben Boot - Versuch über die Hyperpolitik, Frankfurt am Main (Suhrkamp), 1995. Selbstversuch, A dialogue with Carlos Oliveira, 1996. 一緒にいる強い理由。人々の発明の記憶, 1998. Spheres I - Bubbles, Microspherology, 1998(球体 I) 球体 II - 球体、マクロスフェロロジー、1999年(球体 II) 人間公園の規則。ハイデガーのヒューマニズムに関する書簡への返信、1999年。 大衆の侮蔑。現代社会における文化的闘争の試み, 2000. 良い知らせの改善について。ニーチェの第五の福音。2000年、フリードリヒ・ニーチェ没後100周年記念講演。 救われない。ハイデガー以後の試み、2001年。 太陽と死、ハンス・ユルゲン・ハインリヒスとの対話的調査、2001年。 バミューダからの露。想像力のいくつかの体制について, 2001. 地震。恐怖の根源、2002年 Spheres III - Foams, Plural Spherology, 2004(球体III) 資本の世界内部で, 2005. What counts, returns. 哲学対話、アラン・フィンキエルクロートとの共著(フランス語より)、2005年。 怒りと時間。政治心理学的実験, 2006年 ISBN 3-518-41840-8 美学的命令』2007年 エジプト人デリダ, 2007. 神の熱意。Vom Kampf der drei Monotheismen, Frankfurt am Main (Insel), 2007. Theorie der Nachkriegszeiten, (Suhrkamp), 2008. Du mußt dein Leben ändern, フランクフルト・アム・マイン (Suhrkamp), 2009. Philosophical Temperaments From Plato to Foucault, Munich (Diederichs), 2009. ISBN 978-3-424-35016-6 Die nehmende Hand und die gebende Seite, (Suhrkamp), 2010. The terrible children of modern times, (Suhrkamp), 2014. 20世紀に何が起こったのか?極端主義的理性の批判に向けて』(Suhrkamp)、2016年。 シェリングプロジェクト。報告書。Suhrkamp, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-518-42524-4. After God: Attempts at belief and unbelief. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-518-42632-6 or ISBN 3-518-42632-X. 新しい行と日々。Suhrkamp, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-518-42844-3. Polyloquies. ブレヴィアリ。ライムント・フェリンガー編、Suhrkamp, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-518-42775-0. 天を語らせる。テオポエトリーについて。Suhrkamp, Berlin 2020, ISBN 978-3-518-42933-4. The state takes off its kid gloves. Selected conversations and contributions 2020-2021. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2021, ISBN 978-3-518-47222-4. 誰がまだ灰色を考えたことがないのか。色彩論。Suhrkamp, Berlin 2022, ISBN 978-3-518-43068-2. プロメテウスの後悔。火の贈り物から世界的放火まで。Suhrkamp, Berlin 2023, ISBN 978-3-518-02985-5. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Sloterdijk |

☆スラヴォイ・ジジェクによるペーター・スローターダイク批判の核心

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆