フィリップ・ロス

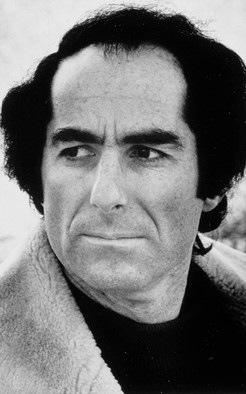

Philip Roth,

1933-2018

| Philip Milton Roth

(/rɒθ/;[1] March 19, 1933 – May 22, 2018)[2] was an American novelist

and short-story writer. Roth's fiction—often set in his birthplace of

Newark, New Jersey—is known for its intensely autobiographical

character, for philosophically and formally blurring the distinction

between reality and fiction, for its "sensual, ingenious style" and for

its provocative explorations of American identity.[3] He first gained

attention with the 1959 short story collection Goodbye, Columbus, which

won the U.S. National Book Award for Fiction.[4][5] Ten years later, he

published the bestseller Portnoy's Complaint. Nathan Zuckerman, Roth's

literary alter ego, narrates several of his books. A fictionalized Roth

narrates some of his others, such as the alternate history The Plot

Against America. Roth was one of the most honored American writers of his generation.[6] He received the National Book Critics Circle award for The Counterlife, the PEN/Faulkner Award for Operation Shylock, The Human Stain, and Everyman, a second National Book Award for Sabbath's Theater, and the Pulitzer Prize for American Pastoral. In 2001, Roth received the inaugural Franz Kafka Prize in Prague. In 2005, the Library of America began publishing his complete works, making him the second author so anthologized while still living, after Eudora Welty.[7] Harold Bloom named him one of the four greatest American novelists of his day, along with Cormac McCarthy, Thomas Pynchon, and Don DeLillo. James Wood wrote: "More than any other post-war American writer, Roth wrote the self—the self was examined, cajoled, lampooned, fictionalized, ghosted, exalted, disgraced but above all constituted by and in writing. Maybe you have to go back to the very different Henry James to find an American novelist so purely a bundle of words, so restlessly and absolutely committed to the investigation and construction of life through language... He would not cease from exploration; he could not cease, and the varieties of fiction existed for him to explore the varieties of experience."[8] |

フィリップ・ミルトン・ロス(Philip Milton

Roth、/rɒθ/、1933年3月19日 -

2018年5月22日)は、アメリカの小説家、短編作家。ロスの小説は、彼の出身地であるニュージャージー州ニューアークを舞台にすることが多く、強烈な

自伝的要素、現実と虚構の境界を哲学的・形式的に曖昧にする手法、

「官能的で独創的なスタイル」、そしてアメリカ人のアイデンティティに関する挑発的な探求で知られている。[3]

1959年に発表した短編小説集『さよなら、コロンバス』で注目を集め、全米図書賞小説部門を受賞した。[4][5]

10年後、ベストセラー『ポートノイの苦悩』を発表。ロスの文学上の分身であるネイサン・ザッカーマンは、彼の作品のいくつかで語り手として登場する。ま

た、代替歴史小説『アメリカを襲った陰謀』など、他の作品の一部は、架空の人物であるロスが語り手として登場している。 ロスは、同世代で最も栄誉あるアメリカ人作家の一人だった。彼は、『The Counterlife』で全米図書評論家協会賞、『Operation Shylock』、『The Human Stain』、『Everyman』でペン/フォークナー賞、『Sabbath's Theater』で2度目の全米図書賞、『American Pastoral』でピューリッツァー賞を受賞した。2001年、ロスはプラハで第1回フランツ・カフカ賞を受賞した。2005年、ライブラリー・オブ・ アメリカは彼の全作品集の出版を開始し、彼はエウドラ・ウェルティに次ぐ、存命中の作家として2人目の全作品集が刊行された作家となった。[7] ハロルド・ブルームは、コルム・マッカーシー、トマス・ピンチョン、ドン・デリーロと共に、彼を同時代の4人の偉大なアメリカ小説家の一人として挙げた。 ジェームズ・ウッドは次のように書いている: 「戦後のアメリカ作家の中で、ロスは最も自己を描いた作家だ。自己は検証され、からかわれ、風刺され、虚構化され、幽霊化され、称賛され、汚名を着せられ たが、何よりも、執筆によって構成され、執筆の中に存在していた。おそらく、これほど純粋に言葉の塊であり、言語を通じて人生を探求し構築することに、こ れほど執拗かつ絶対的に専心したアメリカの小説家を見つけるには、まったく異なるヘンリー・ジェイムズにまでさかのぼらなければならないだろう... 彼は探求を止めなかった。彼は止められなかったのだ。そして、さまざまな経験を探求するために、さまざまな小説が存在していたのだ」[8] |

| Early life and academic pursuits Philip Roth was born in Newark, New Jersey, on March 19, 1933,[9] and grew up at 81 Summit Avenue in the Weequahic neighborhood.[9] He was the second child of Bess (née Finkel) and Herman Roth, an insurance broker.[10] Roth's family was Jewish, and his parents were second-generation Americans. His paternal grandparents came from Kozlov near Lviv (then Lemberg) in Austrian Galicia, and his mother's ancestors were from the region of Kyiv in Ukraine. He graduated from Newark's Weequahic High School in or around 1950.[11] In 1969, Arnold H. Lubasch wrote in The New York Times that the school "has provided the focus for the fiction of Philip Roth, the novelist who evokes his era at Weequahic High School in the highly acclaimed Portnoy's Complaint. Besides identifying Weequahic High School by name, the novel specifies such sites as the Empire Burlesque, the Weequahic Diner, the Newark Museum and Irvington Park, all local landmarks that helped shape the youth of the real Roth and the fictional Portnoy, both graduates of Weequahic class of '50." The 1950 Weequahic Yearbook calls Roth a "boy of real intelligence, combined with wit and common sense". He was known as a comedian during his time at school.[12] |

幼少期と学業 フィリップ・ロス(Philip Roth)は、1933年3月19日にニュージャージー州ニューアークで生まれ[9]、ウィーカヒック地区にあるサミット・アベニュー81番地で育った [9]。彼は、ベス(旧姓フィンケル)と保険ブローカーのハーマン・ロス夫妻の2番目の子供だった[10]。ロスの家族はユダヤ人で、両親は2世アメリカ 人だった。父方の祖父母はオーストリア・ガリツィアのコズロフ(当時のレムベルク)近郊出身で、母方の祖先はウクライナのキエフ地方出身だった。1950 年ごろ、ニューアークのウィーカーヒック高校を卒業した。[11] 1969年、アーノルド・H・ルバッシュはニューヨーク・タイムズ紙で、この学校は「小説家フィリップ・ロスが、高い評価を受けた『ポートノイの苦情』で ウィーカヒック高校での時代を彷彿とさせる小説の舞台となった」と書いている。小説では、ウィーカーヒック高校の名前を明示するだけでなく、エンパイア・ バーレスク、ウィーカーヒック・ダイナー、ニューアーク美術館、アーヴィングトン・パークなど、実在のロスとフィクションのポートノイの青春を形作った地 元のランドマークも具体的に挙げられている。両者はともにウィーカーヒック高校の1950年卒業生だ。1950年のウィーカーヒック高校の年鑑では、ロス は「知性、ユーモア、常識を兼ね備えた少年」と評されている。彼は学生時代、コメディアンとして知られていた。[12] |

| Academic career Roth attended Rutgers University in Newark for a year, then transferred to Bucknell University in Pennsylvania, where he earned a B.A. magna cum laude in English and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. He received a fellowship to attend the University of Chicago, where he earned an M.A. in English literature[13] in 1955 and briefly worked as an instructor in the university's writing program.[14] That same year, rather than wait to be drafted, Roth enlisted in the army, but suffered a back injury during basic training and was given a medical discharge. He returned to Chicago in 1956 to study for a PhD in literature, but dropped out after one term.[15] Roth was a longtime faculty member at the University of Pennsylvania, where he taught comparative literature until retiring from teaching in 1991.[14] |

学歴 ロスは、ニューアークのラトガース大学に 1 年間通った後、ペンシルベニア州のバックネル大学に転校し、英語学で優等学位(magna cum laude)を取得、ファイ・ベータ・カッパ会員に選出された。シカゴ大学に奨学金で入学し、1955 年に英文学の修士号を取得[13]、同大学のライティング・プログラムで短期間講師を務めた。[14] 同年、徴兵を待つ代わりに陸軍に入隊したが、基礎訓練中に背中に負傷し、除隊となった。1956年にシカゴに戻り、文学の博士号取得のために勉強を始めた が、1学期で中退した。[15] ロスは、ペンシルベニア大学で長年にわたり教鞭をとり、1991年に教職を退くまで比較文学を教えた。[14] |

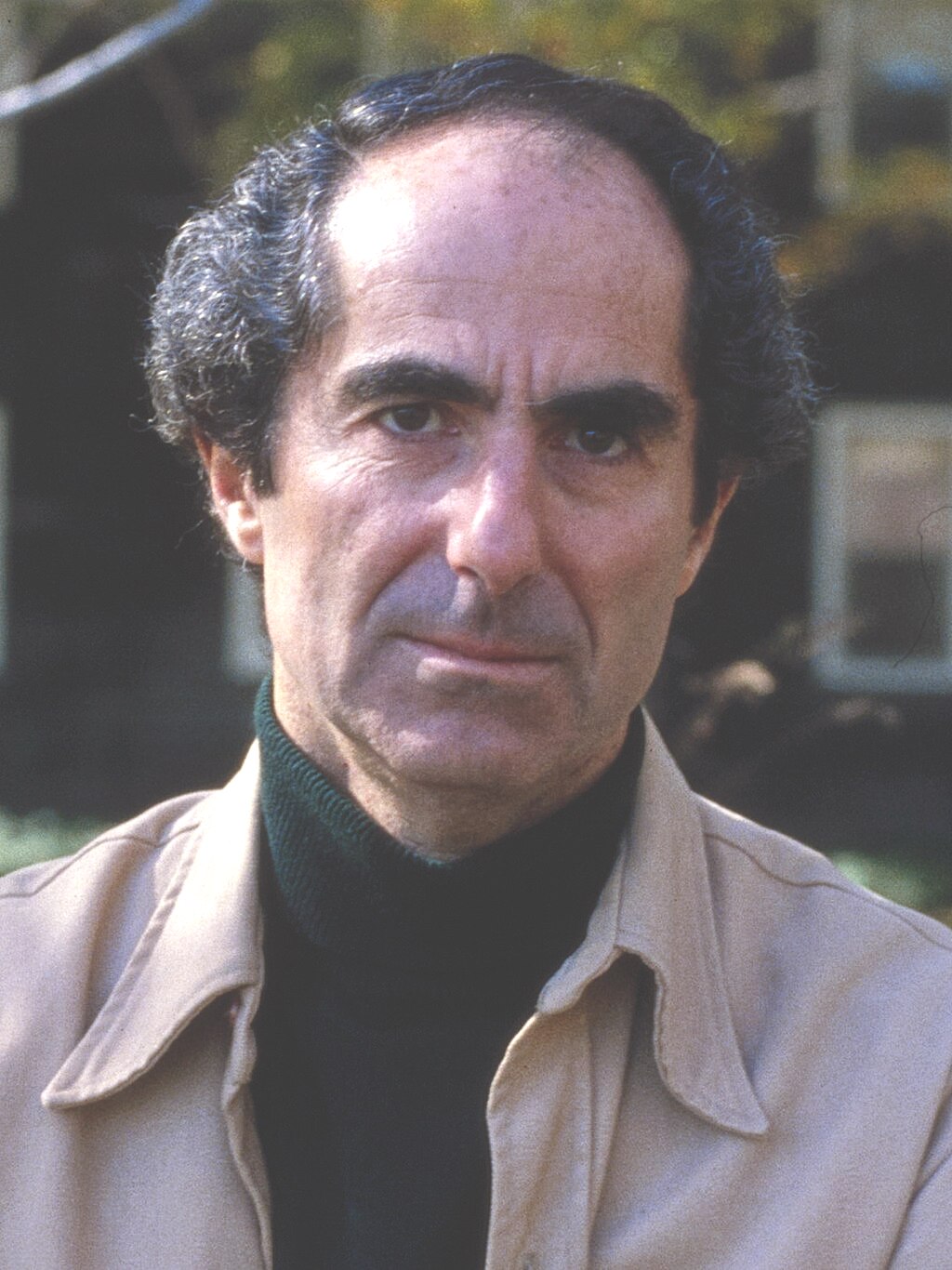

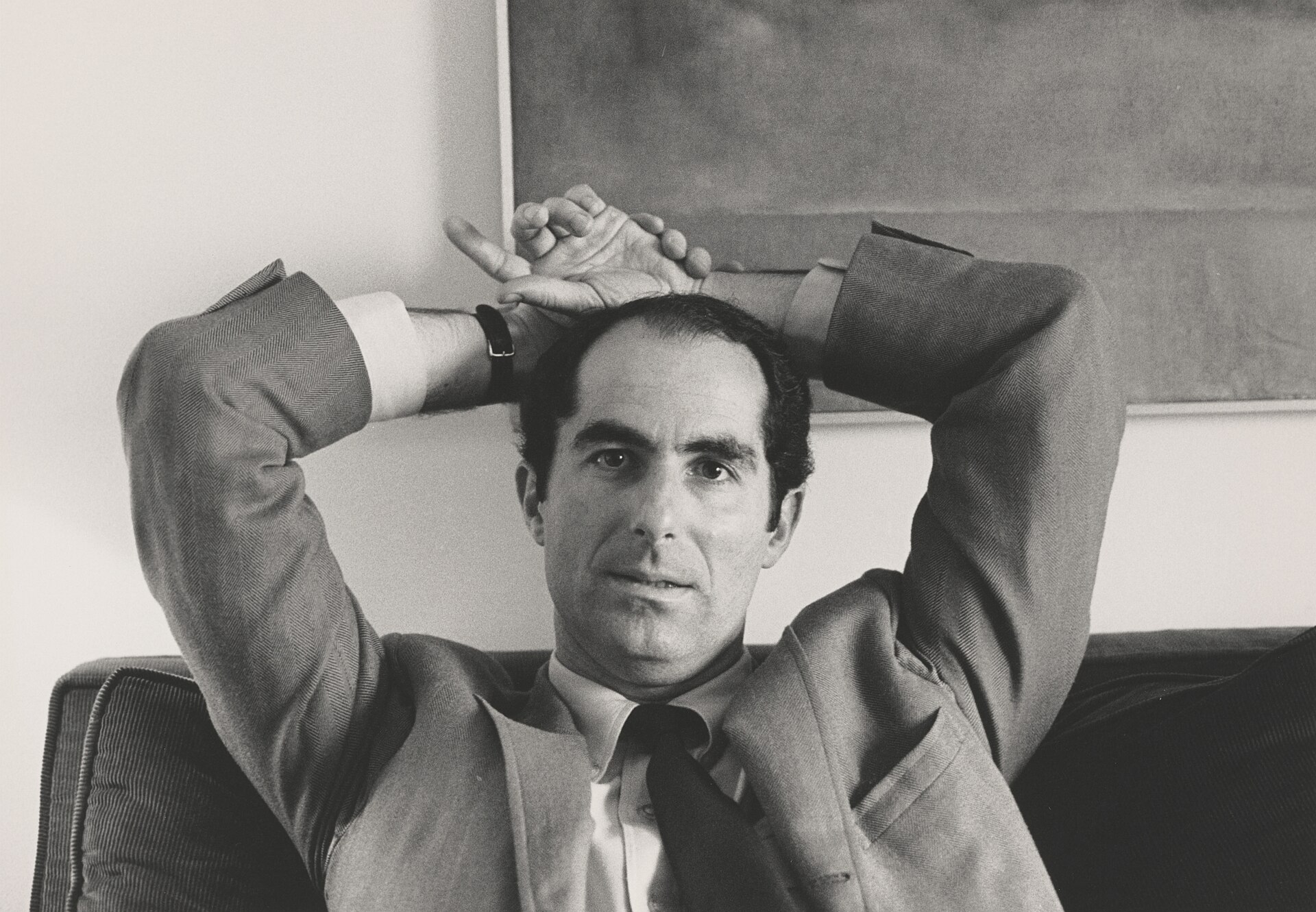

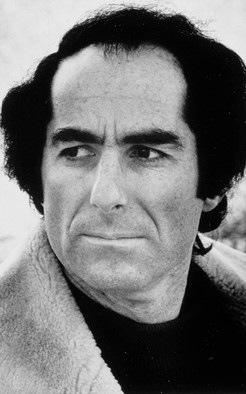

Writing career Roth in 1967 Roth's work first appeared in print in the Chicago Review while he was studying, and later teaching, at the University of Chicago.[16][17][18] His first book, Goodbye, Columbus, contains the novella Goodbye, Columbus and four short stories. It won the National Book Award in 1960. He published his first full-length novel, Letting Go, in 1962. In 1967 he published When She Was Good, set in the WASP Midwest in the 1940s. It is based in part on the life of Margaret Martinson Williams, whom Roth married in 1959.[15] The publication in 1969 of his fourth and most controversial novel, Portnoy's Complaint, gave Roth widespread commercial and critical success, causing his profile to rise significantly.[5][19] During the 1970s Roth experimented in various modes, from the political satire Our Gang (1971) to the Kafkaesque The Breast (1972). By the end of the decade Roth had created his alter ego Nathan Zuckerman. In a series of highly self-referential novels and novellas that followed between 1979 and 1986, Zuckerman appeared as either the main character or an interlocutor.  Roth in 1973 Sabbath's Theater (1995) may have Roth's most lecherous protagonist, Mickey Sabbath, a disgraced former puppeteer. It won his second National Book Award.[20] In complete contrast, American Pastoral (1997), the first volume of his so-called American Trilogy, focuses on the life of virtuous Newark star athlete Swede Levov, and the tragedy that befalls him when his teenage daughter becomes a domestic terrorist during the late 1960s. It won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.[21] The Dying Animal (2001) is a short novel about eros and death that revisits literary professor David Kepesh, protagonist of two 1970s works, The Breast and The Professor of Desire (1977). In The Plot Against America (2004), Roth imagines an alternative American history in which Charles Lindbergh, aviator hero and isolationist, is elected U.S. President in 1940, and the U.S. negotiates an understanding with Hitler's Nazi Germany and embarks on its own program of anti-Semitism. Roth's novel Everyman, a meditation on illness, aging, desire, and death, was published in May 2006. It was Roth's third book to win the PEN/Faulkner Award, making him the only person so honored. Exit Ghost, which again features Nathan Zuckerman, was released in October 2007. It was the last Zuckerman novel.[22] Indignation, Roth's 29th book, was published on September 16, 2008. Set in 1951, during the Korean War, it follows Marcus Messner's departure from Newark to Ohio's Winesburg College, where he begins his sophomore year. In 2009, Roth's 30th book, The Humbling, was published. It tells the story of the last performances of Simon Axler, a celebrated stage actor. Roth's 31st book, Nemesis, was published on October 5, 2010. According to the book's notes, Nemesis is the last in a series of four "short novels", after Everyman, Indignation and The Humbling. In October 2009, during an interview with Tina Brown of The Daily Beast to promote The Humbling, Roth considered the future of literature and its place in society, stating his belief that within 25 years the reading of novels will be regarded as a "cultic" activity:[23] I was being optimistic about 25 years really. I think it's going to be cultic. I think always people will be reading them but it will be a small group of people. Maybe more people than now read Latin poetry, but somewhere in that range. ... To read a novel requires a certain amount of concentration, focus, devotion to the reading. If you read a novel in more than two weeks you don't read the novel really. So I think that kind of concentration and focus and attentiveness is hard to come by—it's hard to find huge numbers of people, large numbers of people, significant numbers of people, who have those qualities[.] When asked about the prospects for printed versus digital books, Roth was equally downbeat:[24] The book can't compete with the screen. It couldn't compete beginning with the movie screen. It couldn't compete with the television screen, and it can't compete with the computer screen. ... Now we have all those screens, so against all those screens a book couldn't measure up.  Roth in 2017 This was not the first time Roth had expressed pessimism about the future of the novel and its significance in recent years. Talking to The Observer's Robert McCrum in 2001, he said, "I'm not good at finding 'encouraging' features in American culture. I doubt that aesthetic literacy has much of a future here."[23] In an October 2012 interview with the French magazine Les Inrockuptibles, Roth announced that he would be retiring from writing[25] and confirmed subsequently in Le Monde that he would no longer publish fiction.[26] In a May 2014 interview with Alan Yentob for the BBC, Roth said, "this is my last appearance on television, my absolutely last appearance on any stage anywhere."[27] Reflecting on his writing career, in an afterword written on the 25th anniversary of the publication of Portnoy's Complaint, Roth wrote, "I wished to dazzle in my very own way and to dazzle myself no less than anyone else."[28] To inspire himself to write, he recalled thinking, "All you have to do is sit down and work!"[28] |

執筆活動 1967年のロス ロスの作品は、シカゴ大学在学中、そして同大学で教鞭を執っていた頃に『シカゴ・レビュー』誌で初めて掲載された。[16][17][18] 彼の最初の著作『さよなら、コロンバス』には、同名の短編小説と4つの短編小説が収録されている。この作品は1960年に全米図書賞を受賞した。1962 年に最初の長編小説『手放す』を発表。1967年には、1940年代のWASP(白人アングロサクソン・プロテスタント)が支配する中西部を舞台にした 『彼女が良かった頃』を発表。この作品は、ロスが1959年に結婚したマーガレット・マーティンソン・ウィリアムズの生涯を部分的に基にしている。 [15] 1969年に発表された、4作目であり最も物議を醸した小説『ポートノイの苦情』は、ロスに商業的および批評的な大成功をもたらし、彼の知名度は大幅に高 まった。[5][19] 1970年代、ロスは政治風刺小説『Our Gang』(1971年)からカフカ風小説『The Breast』(1972年)まで、さまざまな手法を試みた。1970年代末までに、ロスは自身の分身であるネイサン・ズッカーマンを創造した。1979 年から1986年にかけて発表された一連の高度に自己言及的な小説と中編小説で、ズッカーマンは主人公または対話者として登場した。  1973年のロス 『サバスの劇場』(1995年)には、ロス作品の中で最も好色な主人公、不名誉な元人形師ミッキー・サバスが登場する。この作品は、ロスに2度目の全米図書賞をもたらした。 [20] これとは対照的に、いわゆる「アメリカ三部作」の第一作『アメリカン・パストラル』(1997年)は、ニュージャージー州ニューアークの模範的なスターア スリート、スウェード・レヴォフの生涯と、1960年代後半に彼の10代の娘が国内テロリストとなることで訪れる悲劇を描いた作品だ。この作品はピュー リッツァー賞を受賞した。[21] 『死の動物』(2001年)は、1970年代の2作『乳房』(1970年)と『欲望の教授』(1977年)の主人公である文学教授デヴィッド・ケペッシュ を再登場させた、エロスと死をテーマにした短編小説だ。『アメリカに対する陰謀』(2004年)では、航空英雄で孤立主義者のチャールズ・リンドバーグが 1940年にアメリカ大統領に選出され、アメリカがヒトラーのナチス・ドイツと理解を交わし、独自の反ユダヤ主義政策を推進する代替歴史を描いている。 病気、老い、欲望、死について考察した小説『エブリマン』は、2006年5月に出版された。この作品は、ロスにとって3作目のPEN/フォークナー賞受賞 作となり、同賞を2度受賞した唯一の人格となった。再びネイサン・ズッカーマンを主人公にした『Exit Ghost』は2007年10月に刊行された。これはズッカーマンシリーズ最後の作品となった。[22] ロスの29作目『Indignation』は2008年9月16日に刊行された。1951年の朝鮮戦争中を舞台に、マーカス・メッサーナーがニュージャー ジー州ニューアークからオハイオ州ワインズバーグ大学へ進学し、2年生としての生活を始める物語だ。2009 年、ロスの 30 冊目の作品『The Humbling』が刊行された。この作品は、著名な舞台俳優、サイモン・アクスラーの最後の公演の物語だ。ロスの 31 冊目の作品『Nemesis』は、2010 年 10 月 5 日に刊行された。同書の注記によると、『ネメシス』は『エブリマン』『インディグネーション』『ザ・ハンブリング』に続く4作目の「短編小説」シリーズ最 終作だ。2009年10月、ティナ・ブラウンとの『ザ・デイリー・ビースト』のインタビューで『ザ・ハンブリング』の宣伝を行った際、ロスは文学の未来と 社会におけるその位置付けについて語り、25年以内に小説の読書が「カルト的な」活動と見なされるようになるだろうと述べた:[23] 私は、25 年後については本当に楽観的だった。カルト的なものになると思う。人々は常に小説を読むだろうが、それはごく少数の人々だろう。おそらく、ラテン語の詩を 読む人よりも多いだろうが、その程度だろう。... 小説を読むには、ある程度の集中力、注意力、読書への献身が必要だ。2 週間以上かけて小説を読むなら、それは小説を読んだとは言えない。そういう集中力、注意力、注意力は、なかなか得難いものだと思う。そういう資質を持つ 人、つまり、膨大な数、膨大な人数、かなりの人数を見つけることは難しい[。 印刷本と電子書籍の将来について尋ねられたロスは、同様に悲観的な見方を示した[24]。 本はスクリーンと競争できない。映画スクリーンが登場した時から、競争は不可能だった。テレビスクリーンとも競争できなかったし、コンピュータのスクリーンとも競争できない。... 今はあらゆるスクリーンが普及しており、本はそのすべてに対抗することはできない。  2017年のロス ロスが小説の将来とその重要性について悲観的な見方を示したのは、ここ数年のことではない。2001年にオブザーバーのロバート・マックラムとのインタ ビューで、彼は「私はアメリカの文化に『励みになる』特徴を見つけるのが苦手だ。この国では、美的リテラシーにあまり将来性はないと思う」と語っている [23]。2012年10月、フランスの雑誌『Les Inrockuptibles』のインタビューで、ロスは執筆活動を引退すると発表し[25]、その後『Le Monde』紙でも、小説の出版は今後行わないことを明らかにした[26]。2014年5月、BBCのアルアン・イェントブとのインタビューで、ロスは 「これは私のテレビ出演の最後の登場であり、あらゆる舞台での最後の登場だ」と述べた[27]。 執筆キャリアを振り返り、『ポートノイの不満』の出版25周年を記念したあとがきで、ロスは「私は自分だけの方法で人々を驚かせ、他者と同じように自分自 身をも驚かせたいと願った」と書いた[28]。執筆の動機として、彼は「座って働くだけだ!」と自分に言い聞かせたことを回想している[28]。 |

| Influences and themes Much of Roth's fiction revolves around semi-autobiographical themes, while self-consciously and playfully addressing the perils of establishing connections between Roth and his fictional lives and voices.[29] Examples of this close relationship between the author's life and his characters' include narrators and protagonists such as David Kepesh and Nathan Zuckerman as well as the character "Philip Roth", who appears in The Plot Against America and of whom there are two in Operation Shylock. Critic Jacques Berlinerblau noted in The Chronicle of Higher Education that these fictional voices create a complex and tricky experience for readers, deceiving them into believing they "know" Roth.[29] In Roth's fiction the question of authorship is intertwined with the theme of the idealistic, secular Jewish son who attempts to distance himself from Jewish customs and traditions, and from what he perceives as the sometimes suffocating influence of parents, rabbis, and other community leaders.[30] Roth's fiction has been described by critics as pervaded by "a kind of alienation that is enlivened and exacerbated by what binds it".[30] Roth's first work, Goodbye, Columbus, was an irreverently humorous depiction of the life of middle-class Jewish Americans and received highly polarized reviews;[5] one reviewer found it infused with self-loathing. In response, Roth, in his 1963 essay "Writing About Jews" (collected in Reading Myself and Others), maintained that he wanted to explore the conflict between the call to Jewish solidarity and his desire to be free to question the values and morals of middle-class Jewish Americans uncertain of their identities in an era of cultural assimilation and upward social mobility:[31] The cry 'Watch out for the goyim!' at times seems more the expression of an unconscious wish than of a warning: Oh that they were out there, so that we could be together here! A rumor of persecution, a taste of exile, might even bring with it the old world of feelings and habits—something to replace the new world of social accessibility and moral indifference, the world which tempts all our promiscuous instincts, and where one cannot always figure out what a Jew is that a Christian is not. In Roth's fiction the exploration of "promiscuous instincts" within the context of Jewish lives, mainly from a male viewpoint, plays an important role. In the words of critic Hermione Lee:[32] Philip Roth's fiction strains to shed the burden of Jewish traditions and proscriptions. ... The liberated Jewish consciousness, let loose into the disintegration of the American Dream, finds itself deracinated and homeless. American society and politics, by the late sixties, are a grotesque travesty of what Jewish immigrants had traveled towards: liberty, peace, security, a decent liberal democracy. While Roth's fiction has strong autobiographical influences, it also incorporates social commentary and political satire, most obviously in Our Gang and Operation Shylock. From the 1990s on, Roth's fiction often combined autobiographical elements with retrospective dramatizations of postwar American life. Roth described American Pastoral and the two following novels as a loosely connected "American trilogy". Each of these novels treats aspects of the postwar era against the backdrop of the nostalgically remembered Jewish American childhood of Nathan Zuckerman, in which the experience of life on the American home front during the Second World War features prominently.[citation needed] American Pastoral looks at the legacy of the 1960s, as Swede Levov's daughter becomes an antiwar terrorist. I Married a Communist (1998), in which radio actor Ira Ringold is revealed as a communist sympathizer, is set in the McCarthy era. The Human Stain, in which classics professor Coleman Silk's secret history is revealed, explores identity politics in the late 1990s. In much of Roth's fiction, the 1940s, comprising Roth's and Zuckerman's childhood, mark a high point of American idealism and social cohesion. A more satirical treatment of the patriotism and idealism of the war years is evident in Roth's comic novels, such as Portnoy's Complaint and Sabbath's Theater. In The Plot Against America, the alternate history of the war years dramatizes the prevalence of anti-Semitism and racism in America at the time, despite the promotion of increasingly influential anti-racist ideals during the war. In his fiction, Roth portrayed the 1940s, and the New Deal era of the 1930s that preceded it, as a heroic phase in American history. A sense of frustration with social and political developments in the United States since the 1940s is palpable in the American trilogy and Exit Ghost, but had already been present in Roth's earlier works that contained political and social satire, such as Our Gang and The Great American Novel. Writing about the latter, Hermione Lee points to the sense of disillusionment with "the American Dream" in Roth's fiction: "The mythic words on which Roth's generation was brought up—winning, patriotism, gamesmanship—are desanctified; greed, fear, racism, and political ambition are disclosed as the motive forces behind the 'all-American ideals'."[32] Although Roth's writings often explored the Jewish experience in America, Roth rejected being labeled a Jewish American writer. "It's not a question that interests me. I know exactly what it means to be Jewish and it's really not interesting," he told the Guardian newspaper in 2005. "I'm an American."[33] Roth was a baseball fan, and credited the game with shaping his literary sensibility. In an essay published in The New York Times on Opening Day, 1973, Roth wrote that "baseball, with its lore and legends, its cultural power, its seasonal associations, its native authenticity, its simple rules and transparent strategy, its longueurs and thrills, its spaciousness, its suspensefulness, its heroics, its nuances, its lingo, its 'characters,' its peculiarly hypnotic tedium, its mythic transformation of the immediate, was the literature of my boyhood... Of course, as time passed neither the flavor and suggestiveness of Red Barber's narration, nor specific details, vivid and revealing even as Rex Barney's pre-game hot dog, could continue to satisfy a developing literary appetite; there is no doubt, however, that they helped sustain me until I was old enough and literate enough to begin to respond to the great inventors of narrative detail and masters of narrative voice and perspective, like James and Conrad and Dostoyevsky and Bellow."[34] Baseball features in several of Roth's novels; the hero of Portnoy's Complaint dreams of playing like Duke Snider, and Nicholas Dawidoff called The Great American Novel "one of the most eccentric baseball novels ever written".[35] American Pastoral alludes to John R. Tunis's baseball novel The Kid from Tomkinsville. In a speech on his 80th birthday, Roth emphasized the importance of realistic detail in American literature: the passion for specificity, the hypnotic materiality of the world one is in, is all but at the heart of the task to which every American novelist has been enjoined since Herman Melville and his whale and Mark Twain and his river: to discover the most arresting, evocative verbal depiction of every last American thing. Without strong representation of the thing—animate or inanimate—without the crucial representation of what is real, there is nothing. Its concreteness, its unabashed focus on all the particulars, a fervor for the singular and a profound aversion to generalities is fiction's lifeblood. It is from a scrupulous fidelity to the blizzard of specific data that is a personal life, it is from the force of its uncompromising particularity, from its physicalness, that the realistic novel, the insatiable realistic novel with its multitude of realities, derives its ruthless intimacy. And its mission: to portray humanity in its particularity.[36] |

影響とテーマ ロスの小説の多くは、半自伝的なテーマを中心に展開しており、ロスと彼の小説の登場人物や声との関連性を意識的に、かつ遊び心を持って表現している。 [29] 作家の生涯と登場人物の間の密接な関係を示す例としては、デビッド・ケペシュやネイサン・ズッカーマンといった語り手や主人公、そして『アメリカ陰謀』に 登場する「フィリップ・ロス」というキャラクターが挙げられる。このキャラクターは『オペレーション・シャイロック』には2人登場する。批評家のジャッ ク・ベルリンブラウは『ザ・クロニクル・オブ・ハイアー・エデュケーション』で、これらの架空の声が読者に複雑で厄介な体験をもたらし、彼らが「ロスを 知っている」と錯覚させるとしている。[29] ロス氏の小説では、作者という存在の問題は、ユダヤ人の慣習や伝統、そして両親、ラビ、その他のコミュニティの指導者たちによる、時には息苦しいと感じる 影響から距離を置こうとする、理想主義的な世俗的なユダヤ人の息子というテーマと絡み合っている。[30] ロスの小説は、批評家たちから「それを結びつけるものによって活気づけられ、悪化している一種の疎外感」に満ちている、と評されている。[30] ロスの最初の作品『さよなら、コロンバス』は、中流階級のユダヤ系アメリカ人の生活を不遜なユーモアで描いたもので、評価は二極化した。[5] ある批評家は、この作品に自己嫌悪が溢れていると評した。これに対し、ロスは1963年のエッセイ「ユダヤ人について書くこと」(『Reading Myself and Others』に収録)で、ユダヤ人としての団結の呼びかけと、文化的な同化と社会的上昇の時代においてアイデンティティに迷う中流階級のユダヤ系アメリ カ人の価値観や道徳を疑問視する自由を求める欲望との間の矛盾を探求したいと主張した:[31] 「ゴイムに気をつけろ!」という叫びは、時には警告というよりも、無意識の願望の表現のように聞こえる:ああ、彼らがそこにいて、私たちがここに一緒にい られるなら!迫害の噂、流刑の味わいさえも、古い世界の感情や習慣を呼び戻すかもしれない——新しい世界の社会的アクセス可能性と道徳的無関心、私たちの 放埓な本能を誘惑する世界、そしてユダヤ人とキリスト教徒の違いが常に明確でない世界——を置き換えるものとして。 ロスの小説では、主に男性視点から、ユダヤ人の生活における「放埓な本能」の探求が重要な役割を果たしている。批評家ハーミオネ・リーの言葉によれば:[32] フィリップ・ロスの小説は、ユダヤ人の伝統と禁忌の重荷から脱却しようと苦闘している。... 解放されたユダヤ人の意識は、アメリカンドリームの崩壊の中に放り出され、根を失い、故郷を失った状態にある。1960年代後半のアメリカ社会と政治は、 ユダヤ人移民たちが目指してきた自由、平和、安全、そして良識ある自由民主主義の、グロテスクな滑稽劇と化していた。 ロスの小説は自伝的な影響が強いが、社会風刺や政治風刺も取り入れており、そのことは『Our Gang』や『Operation Shylock』で最も顕著だ。1990年代以降、ロスの小説は自伝的要素と戦後アメリカ生活の回顧的ドラマ化を組み合わせることが多くなった。ロスは 『アメリカン・パストラル』と続く2作を、緩やかに連なる「アメリカ三部作」と表現した。これらの小説は、ナサニエル・ズッカーマンの懐かしむユダヤ系ア メリカ人の幼少期を背景に、戦後時代の様々な側面を描いている。特に第二次世界大戦中のアメリカ本土での生活体験が重要な役割を果たしている。[出典が必 要] 『アメリカン・パストラル』は、スウェード・レヴォフの娘が反戦テロリストとなることで、1960年代の遺産を考察している。『私は共産党員と結婚した』 (1998年)では、ラジオ俳優のイラ・リングゴールドが共産党支持者であることが明かされ、マッカーシー時代を舞台にしている。『ヒューマン・ステイ ン』では、古典文学教授コールマン・シルクの秘密の過去が明かされ、1990年代後半のアイデンティティ政治が探求されている。 ロスの小説の多くでは、ロスとズッカーマンの幼少期を含む1940年代が、アメリカの理想主義と社会的結束の頂点として描かれている。戦争時代の愛国心と 理想主義に対するより風刺的な描写は、ロスのコメディ小説『ポートノイの不満』や『サバスの劇場』などに顕著だ。『アメリカを覆う陰謀』では、戦争中の代 替史が、戦争中にますます影響力を持つようになった反人種差別主義の理想にもかかわらず、当時のアメリカに蔓延していた反ユダヤ主義や人種主義をドラマ チックに描いている。ロスの小説では、1940年代とその前の1930年代のニューディール時代が、アメリカ史における英雄的な時代として描かれている。 1940年代以降のアメリカ社会と政治の動向に対する不満は、『アメリカ三部作』と『エグジット・ゴースト』に明確に表れているが、政治的・社会的風刺を 含む『アワー・ギャング』や『ザ・グレート・アメリカン・ノベル』などの初期作品にも既に存在していた。後者について、ハーミオネ・リーは、ロスの小説に おける「アメリカン・ドリーム」への幻滅感を指摘している: 「ロス世代が育った神話的な言葉、すなわち勝利、愛国心、ゲームマンシップは、その神聖性を失い、貪欲、恐怖、人種主義、政治野心が『オールアメリカンな 理想』の背後にある原動力であることが明らかになった」[32]。ロスの作品は、アメリカにおけるユダヤ人の経験についてよく取り上げていたが、ロスは、 ユダヤ系アメリカ人作家というレッテルを嫌っていた。「それは私にとって興味のない問題だ。ユダヤ人であることが何を意味するかはよく分かっているが、そ れは本当に興味のないことだ」と彼は2005年にガーディアン紙に対して語っている。「私はアメリカ人だ。」[33] ロスは野球ファンであり、そのゲームが自分の文学的感性を形作ったと語っている。1973年の開幕日にニューヨーク・タイムズ紙に掲載されたエッセイの中 で、 「野球は、その伝承と伝説、文化的影響力、季節との結びつき、自然な本物感、シンプルなルールと透明な戦略、退屈さと興奮、広大さ、緊張感、英雄的行為、 微妙なニュアンス、専門用語、独自のキャラクター、特有の催眠的な退屈さ、現実を神話的に変容させる力——これらが私の少年時代の文学だった……」 もちろん、時が経つにつれ、レッド・バーバーのナレーションの味わい深さや暗示性、レックス・バーニーの試合前のホットドッグのように鮮やかで示唆に富む 具体的な詳細も、成長する文学的欲求を満たし続けることはできなかった。しかし、それらが、私が十分に年を取り、文学的な知識を身につけて、ジェームズや コンラッド、ドストエフスキー、ベロウのような物語の細部の発明者や、物語の語り手と視点の達人たちに反応し始めるまで、私を支えてくれたことは疑いよう がない。[34] ベースボールはロスのいくつかの小説に登場する。ポートノイの不満の主人公はデューク・スナイダーのようにプレーすることを夢見ており、ニコラス・ダヴィ ドフは『グレート・アメリカン・ノベル』を「最も奇抜なベースボール小説の一つ」と呼んだ。[35] 『アメリカン・パストラル』はジョン・R・チューニスのベースボール小説『トムキンズビルの少年』に言及している。 80歳の誕生日のスピーチで、ロスはアメリカ文学における現実的な細部の重要性を強調した。 細部への情熱、自分がいる世界の催眠的な物質性は、ハーマン・メルヴィルと彼のクジラ、マーク・トウェインと彼の川以来、すべてのアメリカ小説家に課せら れた使命、すなわち、アメリカのあらゆるものの最も印象的で、想像力をかき立てる言葉による描写を発見することの核心にある。生物であれ無生物であれ、物 事を力強く表現すること、現実を忠実に表現することがなければ、何も生まれない。その具体性、細部にまで妥協のない焦点、特異なものへの熱意、そして一般 化に対する深い嫌悪は、フィクションの生命線だ。個人的な人生という、膨大な具体的なデータに対する細心の忠実さ、その妥協のない個別性、その物理性か ら、現実主義小説、すなわち、マルチチュードの現実を持つ飽くなき現実主義小説は、その冷酷な親密さを引き出している。そして、その使命は、人間性をその 個別性で描写することだ。[36] |

| Personal life While at Chicago in 1956, Roth met Margaret Martinson, who became his first wife in 1959. Their separation in 1963, and Martinson's subsequent death in a car crash in 1968, left a lasting mark on Roth's literary output. Martinson was the inspiration for female characters in several of Roth's novels, including Lucy Nelson in When She Was Good and Maureen Tarnopol in My Life as a Man.[37] Roth was an atheist who once said, "When the whole world doesn't believe in God, it'll be a great place."[38][39] He also said during an interview with The Guardian: "I'm exactly the opposite of religious, I'm anti-religious. I find religious people hideous. I hate the religious lies. It's all a big lie ... It's not a neurotic thing, but the miserable record of religion—I don't even want to talk about it. It's not interesting to talk about the sheep referred to as believers. When I write, I'm alone. It's filled with fear and loneliness and anxiety—and I never needed religion to save me."[40] In 1990, Roth married his longtime companion, English actress Claire Bloom, with whom he had been living since 1976. When Bloom asked him to marry her, "cruelly, he agreed, on condition that she signed a pre-nuptial agreement that would give her very little in the event of a divorce—which he duly demanded two years later."[citation needed] He also stipulated that Bloom's daughter Anna Steiger—from her marriage to Rod Steiger—not live with them.[41] They divorced in 1994, and Bloom published a 1996 memoir, Leaving a Doll's House, that depicted Roth as a misogynist and control freak. Some critics have detected parallels between Bloom and the character Eve Frame in Roth's I Married a Communist (1998).[15] The novel Operation Shylock (1993) and other works draw on a post-operative breakdown,[42][43][44] as well as Roth's experience of the temporary side effects of the sedative Halcion (triazolam), prescribed post-operatively in the 1980s.[45][46] |

私生活 1956年にシカゴ滞在中に、ロスはマーガレット・マーティンソンと出会い、1959年に最初の妻となった。1963年に2人は別居し、1968年にマー ティンソンが自動車事故で亡くなり、ロスの文学作品に永続的な影響を残した。マーティンソンは、ロスの小説『When She Was Good』のルーシー・ネルソンや『My Life as a Man』のモーリーン・タルノポルなど、複数の作品に登場する女性キャラクターのモデルとなった。[37] ロスは無神論者であり、「全世界が神を信じなくなったとき、この世界は素晴らしい場所になるだろう」と述べたことがある[38][39]。また、ガーディ アン紙とのインタビューでは、「私は宗教とは正反対の、反宗教的な人間だ。宗教的な人々は嫌いだ。宗教の嘘が嫌いだ。すべては大きな嘘だ……これは神経質 な問題ではなく、宗教の悲惨な歴史だ——それについて話す気もない。信者と呼ばれる羊たちについて話すのは興味がない。私が書く時、私は一人だ。恐怖と孤 独と不安に満ちている——そして、私を救うために宗教は必要なかった。」[40] 1990年、ロスは長年連れ添ったパートナーであるイギリス人女優のクレア・ブルームと結婚した。二人は1976年から同棲していた。ブルームが結婚を申 し込んだ際、「残酷にも、彼は離婚時に彼女にほとんど何も与えないという婚前契約に署名することを条件に同意した——そして彼は2年後、その契約を履行さ せた。」[出典が必要] また、ブルームの娘アンナ・スタイガー(ロッド・スタイガーとの結婚による)が彼らと住まないことも条件とした。[41] 彼らは1994年に離婚し、ブルームは1996年に回顧録『Leaving a Doll's House』を出版し、ロートを女性蔑視者で支配欲の強い人物として描いた。一部の批評家は、ブルームとロートの『I Married a Communist』(1998年)のキャラクター・イヴ・フレームとの類似性を指摘している。[15] 小説『オペレーション・シャイロック』(1993年)などの作品は、手術後の精神崩壊[42][43][44]、および1980年代に手術後に処方された鎮静剤ハルシオン(トリアゾラム)の一時的な副作用の経験に基づいている[45][46]。 |

| Death and burial Roth died at a Manhattan hospital of heart failure on May 22, 2018, at the age of 85.[47][15][48] Roth was buried at the Bard College Cemetery in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, where in 1999 he taught a class. He had originally planned to be buried next to his parents at the Gomel Chesed Cemetery in Newark, but changed his mind about 15 years before his death, in order to be buried close to where his friend Norman Manea is writer in residence,[49] and near other Jews "to whom he could talk".[50] Roth expressly banned any religious rituals from his funeral service, though it was noted that, the day after his burial, a pebble had been placed on top of his tombstone in accordance with Jewish tradition.[51] |

死と埋葬 ロスは2018年5月22日、85歳でマンハッタンの病院で心不全により死去した。[47][15][48] ロスは、1999年に教鞭をとったニューヨーク州アナンドール・オン・ハドソンにあるバード・カレッジ墓地に埋葬された。当初は、ニューアークのゴメル・ チェセド墓地に両親の隣に埋葬される予定だったが、死の約15年前に、友人であるノーマン・マネアがレジデントライターを務める場所[49]、そして「話 ができる」他のユダヤ人たちに近く埋葬されるよう、考えを変えた。[50] ロスは、自分の葬儀では宗教的な儀式を一切行わないことを明言していたが、埋葬の翌日、ユダヤ教の伝統に従って、彼の墓石の上に小石が置かれていたことが 確認されている[51]。 |

| List of works Main article: Philip Roth bibliography "Zuckerman" novels Zuckerman Bound (1979–1985) The Ghost Writer (1979) Zuckerman Unbound (1981) The Anatomy Lesson (1983) The Prague Orgy (1985) The Counterlife (1986) American Pastoral (1997) I Married a Communist (1998) The Human Stain (2000) Exit Ghost (2007) "Roth" novels and memoirs The Facts: A Novelist's Autobiography (1988) Deception: A Novel (1990) Patrimony: A True Story (1991) Operation Shylock: A Confession (1993) The Plot Against America (2004) "Kepesh" novels The Breast (1972) The Professor of Desire (1977) The Dying Animal (2001) "Nemeses" novels Everyman (2006) Indignation (2008) The Humbling (2009) Nemesis (2010) Fiction with other protagonists Goodbye, Columbus and Five Short Stories (1959) Letting Go (1962) When She Was Good (1967) Portnoy's Complaint (1969) Our Gang (1971) The Great American Novel (1973) My Life as a Man (1974) Sabbath's Theater (1995) |

作品一覧 主な記事:フィリップ・ロス著作リスト 「ズッカーマン」シリーズ ズッカーマン・バウンド (1979–1985) ゴーストライター (1979) ズッカーマン・アンバウンド (1981) 解剖学レッスン (1983) プラハの乱交 (1985) カウンターライフ (1986) アメリカン・パストラル (1997) 私は共産主義者と結婚した (1998) 人間の汚れ (2000) ゴーストの出口 (2007) 「ロス」小説および回顧録 事実:小説家の自伝 (1988) 欺瞞:小説 (1990) 遺産:実話 (1991) オペレーション・シャイロック:告白 (1993) アメリカに対する陰謀 (2004) 「ケペッシュ」小説 乳房 (1972) 欲望の教授 (1977) 死の動物 (2001) 「ネメシス」小説 エブリマン (2006) 憤慨 (2008) 屈辱 (2009) ネメシス (2010) 他の主人公が登場する小説 さよなら、コロンバスと5つの短編 (1959) 手放す (1962) 彼女が良かった頃 (1967) ポートノイの不満 (1969) 『私たちのギャング』(1971年 『偉大なるアメリカ小説』(1973年 『男としての人生』(1974年 『サバスの劇場』(1995年 |

| Awards and nominations Two of Roth's works won the National Book Award for Fiction; four others were finalists. Two won National Book Critics Circle awards; another five were finalists. Roth won three PEN/Faulkner Awards (for Operation Shylock, The Human Stain, and Everyman) and a Pulitzer Prize for his 1997 novel American Pastoral.[21] In 2001, The Human Stain was awarded the United Kingdom's WH Smith Literary Award for the best book of the year, as well as France's Prix Médicis Étranger. Also in 2001, the MacDowell Colony awarded Roth the 42nd Edward MacDowell Medal.[52] In 2002, Roth was awarded the National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.[53] In 2003, literary critic Harold Bloom named Roth one of the four major American novelists still at work, along with Cormac McCarthy, Thomas Pynchon, and Don DeLillo.[54] The Plot Against America (2004) won the Sidewise Award for Alternate History in 2005 and the Society of American Historians' James Fenimore Cooper Prize. Roth was also awarded the United Kingdom's WH Smith Literary Award for the best book of the year, an award he received twice.[55] In October 2005, Roth was honored in his hometown when then-mayor Sharpe James presided over the unveiling of a street sign in Roth's name on the corner of Summit and Keer Avenues, where Roth lived for much of his childhood, a setting prominent in The Plot Against America. A plaque on the house where the Roths lived was unveiled. In May 2006, he received the PEN/Nabokov Award, and in 2007 he received the PEN/Faulkner award for Everyman, making him the award's only three-time winner. In April 2007, he received the first PEN/Saul Bellow Award for Achievement in American Fiction.[56] The May 21, 2006, issue of The New York Times Book Review announced the results of a letter that was sent to what the publication described as "a couple of hundred prominent writers, critics, editors and other literary sages, asking them to identify 'the single best work of American fiction published in the last 25 years'". American Pastoral tied for fifth, and The Counterlife, Operation Shylock, Sabbath's Theater, The Human Stain and The Plot Against America received multiple votes. In the accompanying essay, A. O. Scott wrote: "Over the past 15 years, Roth's output has been so steady, so various and (mostly) so excellent that his vote has been, inevitably, split. If we had asked for the single best writer of fiction of the past 25 years, he would have won." Scott notes that "The Roth whose primary concern is the past—the elegiac, summarizing, conservative Roth—is preferred over his more aesthetically radical, restless, present-minded doppelgänger by a narrow but decisive margin."[57] In 2009, Roth received the German newspaper Die Welt's Welt-Literaturpreis.[58] President Barack Obama awarded Roth the 2010 National Humanities Medal in the East Room of the White House on March 2, 2011.[59][60] In May 2011, Roth was awarded the Man Booker International Prize for lifetime achievement in fiction on the world stage, the fourth winner of the biennial prize.[61] One of the judges, Carmen Callil, a publisher of the feminist Virago house, withdrew in protest, referring to Roth's work as "Emperor's clothes". She said "he goes on and on and on about the same subject in almost every single book. It's as though he's sitting on your face and you can't breathe ... I don't rate him as a writer at all ...".[62] Observers noted that Callil had a conflict of interest, having published a book by Claire Bloom (Roth's ex-wife) that criticized Roth and lambasted their marriage.[62] In response, one of the two other Booker judges, Rick Gekoski, remarked: In 1959 he writes Goodbye, Columbus and it's a masterpiece, magnificent. Fifty-one years later he's 78 years old and he writes Nemesis and it is so wonderful, such a terrific novel ... Tell me one other writer who 50 years apart writes masterpieces ... If you look at the trajectory of the average novel writer, there is a learning period, then a period of high achievement, then the talent runs out and in middle age they start slowly to decline. People say why aren't Martin [Amis] and Julian [Barnes] getting on the Booker prize shortlist, but that's what happens in middle age. Philip Roth, though, gets better and better in middle age. In the 1990s he was almost incapable of not writing a masterpiece—The Human Stain, The Plot Against America, I Married a Communist. He was 65–70 years old, what the hell's he doing writing that well?[63] In 2012 Roth received the Prince of Asturias Award for literature.[64] On March 19, 2013, his 80th birthday was celebrated in public ceremonies at the Newark Museum.[65] One prize that eluded Roth was the Nobel Prize in Literature, though he was a favorite of bookmakers and critics for decades.[66][67][68] Ron Charles of The Washington Post wrote that "thundering obituaries" around the world noted that "he won every other honor a writer could win", sometimes even two or three times, except the Nobel Prize.[69] Roth worked hard to obtain his many awards, spending large amounts of time "networking, scratching people's backs, placing his people in positions, voting for them" in order to increase his chances of receiving awards.[70] Films Eight of Roth's novels and short stories have been adapted as films: Goodbye, Columbus; Portnoy's Complaint; The Human Stain; The Dying Animal, adapted as Elegy; The Humbling; Indignation; and American Pastoral. In addition, The Ghost Writer was adapted for television in 1984.[71] In 2014 filmmaker Alex Ross Perry made Listen Up Philip, which was influenced by Roth's work. HBO dramatized Roth's The Plot Against America in 2020 as a six-part series starting Zoe Kazan, Winona Ryder, John Turturro, and Morgan Spencer. |

受賞およびノミネート ロスの作品のうち 2 作品は、全米図書賞(フィクション部門)を受賞し、4 作品は最終選考に残った。2 作品は全米図書評論家協会賞を受賞し、5 作品は最終選考に残った。ロスは、3 回の PEN/フォークナー賞(『オペレーション・シャイロック』、『人間の汚れ』、『エブリマン』)と、1997 年の小説『アメリカン・パストラル』でピューリッツァー賞を受賞している。 2001年には、『人間の汚れ』が、英国のWHスミス文学賞の年間最優秀作品賞、およびフランスのメディシス外国文学賞を受賞した。また、2001年に は、マクダウェル・コロニーから第42回エドワード・マクダウェル・メダルが授与された。[52] 2002年には、アメリカ文学への貢献が認められ、全米図書財団から全米図書財団メダルが授与された。[53] 2003年、文学評論家のハロルド・ブルームは、ロスは、コーマック・マッカーシー、トマス・ピンチョン、ドン・デリーロと並んで、現在活躍中の4人のア メリカ人小説家の一人であると評価した。[54] 『アメリカに対する陰謀』(2004年)は、2005年にサイドワイズ・アワードの代替歴史部門賞、およびアメリカ歴史家協会(Society of American Historians)のジェームズ・フェニモア・クーパー賞を受賞した。また、英国の WH スミス文学賞の年間最優秀作品賞も 2 度受賞している。[55] 2005年10月、ロスは故郷で、当時の市長シャープ・ジェームズが、ロスが幼少期の大半を過ごしたサミット・アベニューとキーア・アベニューの角に、ロ スの名前にちなんで名付けられた道路標識の除幕式を執り行いました。ロス一家が住んでいた家には、記念のプレートが掲げられました。2006年5月、彼は PEN/ナボコフ賞を受賞し、2007年には『エブリマン』でPEN/フォークナー賞を受賞し、同賞の3度目の受賞者となった。2007年4月、彼はアメ リカ小説における業績を称える最初のPEN/ソール・ベロー賞を受賞した。[56] 2006年5月21日号の『ニューヨーク・タイムズ・ブックレビュー』は、同誌が「数百人の著名な作家、評論家、編集者、その他の文学の賢人」に送った手 紙の結果を発表し、「過去25年間に出版されたアメリカの小説の中で最高の作品」を選出するよう求めた。『アメリカン・パストラル』は5位タイとなり、 『カウンターライフ』『オペレーション・シャイロック』『サバスの劇場』『ヒューマン・ステイン』『アメリカに対する陰謀』は複数の票を獲得した。付随す るエッセイでA.O.スコットは次のように書いている:「過去15年間、ロスの作品は、その量、多様性、そして(主に)その質の高さから、彼の票は必然的 に分かれた。過去 25 年間の最高の小説作家を 1 人選ぶよう求められたなら、彼は間違いなく優勝していただろう」と述べています。スコットは、「過去を主な関心事とする、哀歌的、総括的、保守的なロス が、より美的に過激で、落ち着きがなく、現在志向の彼の分身よりも、僅差ながら決定的な差で好まれている」と述べています。[57] 2009年、ロスはドイツの新聞「ディ・ヴェルト」のヴェルト文学賞を受賞した。 2011年3月2日、バラク・オバマ大統領は、ホワイトハウスのイーストルームで、ロスに2010年国家人文科学メダルを授与した。 2011年5月、ロスは世界文学における生涯功績を称えるマン・ブッカー国際賞を受賞し、この2年ごとに授与される賞の4人目の受賞者となった。[61] 審査員の1人、フェミニスト出版社ヴィラゴのカーメン・カリルは、ロスの作品を「皇帝の新しい服」と表現し、抗議して審査を辞退した。彼女は、「彼はほぼ すべての作品で、同じ主題について延々と繰り返し語っている。まるで、あなたの顔の上に座って、息もできないような感じだ...私は、彼を作家としてまっ たく評価していない...」と述べた。[62] 観察者たちは、カリルは、ロスを批判し、彼らの結婚を激しく非難したクレア・ブルーム(ロスの元妻)の著書を出版しており、利益相反にあると指摘した。 [62] これに対し、他の 2 人のブッカー賞審査員のうちの 1 人、リック・ゲコスキは次のように述べている。 1959 年に彼は『さよなら、コロンバス』を執筆し、それは傑作、素晴らしい作品だった。51 年後、78 歳の彼は『ネメシス』を執筆し、それはとても素晴らしい、素晴らしい小説だ... 50 年の間隔で傑作を執筆した作家をもう 1 人挙げてみろ... 平均的な小説家の軌跡を見ると、学習期、そして高い成果を上げる時期があり、その後才能が枯渇し、中年になって徐々に衰退し始める。マーティン(アミス) やジュリアン(バーンズ)がブッカー賞の最終候補に選ばれないのはなぜだ、と人々は言うが、それは中年になると当然のことだ。しかし、フィリップ・ロスは 中年になってますます良くなっている。 |

| Honors 1960 National Book Award for Goodbye, Columbus[4] 1960 National Jewish Book Award for Goodbye, Columbus[72] 1975 National Book Award finalist for My Life as A Man[73] 1978 NBCCA finalist for The Professor Of Desire 1980 Pulitzer Prize finalist for The Ghost Writer[21] 1980 National Book Award finalist for The Ghost Writer[73] 1980 NBCCA finalist for The Ghost Writer 1984 National Book Award finalist for The Anatomy Lesson[73] 1984 NBCCA finalist for The Anatomy Lesson 1986 National Book Critics Circle Award (NBCCA) for The Counterlife 1987 National Book Award finalist for The Counterlife[73] 1988 National Jewish Book Award for The Counterlife[72] 1991 National Book Critics Circle Award (NBCCA) for Patrimony[73] 1994 PEN/Faulkner Award for Operation Shylock 1994 Pulitzer Prize finalist for Operation Shylock[21] 1995 National Book Award for Sabbath's Theater[20] 1996 Pulitzer Prize finalist for Sabbath's Theater[21] 1997 International Dublin Literary Award longlist for Sabbath's Theater 1998 Pulitzer Prize for American Pastoral[21] 1998 NBCCA finalist for American Pastoral 1998 Ambassador Book Award of the English-Speaking Union for I Married a Communist[73] 1998 National Medal of Arts[73] 1999 International Dublin Literary Award longlist for American Pastoral 2000 Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger (France) for American Pastoral 2000 International Dublin Literary Award shortlist for I Married a Communist 2000 National Jewish Book Award for The Human Stain[72] 2001 Franz Kafka Prize 2001 PEN/Faulkner Award for The Human Stain 2001 Gold Medal In Fiction from The American Academy of Arts and Letters[73] 2001 42nd Edward MacDowell Medal from the MacDowell Colony 2001 WH Smith Literary Award for The Human Stain 2002 International Dublin Literary Award longlist for The Human Stain 2002 Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters from the National Book Foundation[53] 2002 Prix Médicis Étranger (France) for The Human Stain 2005 NBCCA finalist for The Plot Against America 2005 Sidewise Award for Alternate History for The Plot Against America 2005 James Fenimore Cooper Prize for Best Historical Fiction for The Plot Against America 2005 Nominee for Man Booker International Prize 2005 WH Smith Literary Award for The Plot Against America 2006 PEN/Nabokov Award for lifetime achievement 2007 PEN/Faulkner Award for Everyman[73] 2007 PEN/Saul Bellow Award for Achievement in American Fiction 2008 International Dublin Literary Award longlist for Everyman 2009 International Dublin Literary Award longlist for Exit Ghost 2010 The Paris Review Hadada Prize 2011 National Humanities Medal for 2010 2011 Man Booker International Prize 2012 Library of Congress Creative Achievement Award for Fiction 2012 Prince of Asturias Awards for literature[61] 2013 PEN/Allen Foundation Literary Service Award for lifetime achievement and advocacy.[74][75][76] 2013 Commander of the Legion of Honor by the Republic of France.[77] |

受賞 1960年 『さよなら、コロンバス』で全米図書賞[4 1960年 『さよなら、コロンバス』で全米ユダヤ人図書賞[72 1975年 『My Life as A Man』で全米図書賞最終候補作[73] 1978年 『The Professor Of Desire』でNBCCA最終候補作 1980年 『The Ghost Writer』でピューリッツァー賞最終候補作[21] 1980年 『The Ghost Writer』で全米図書賞最終候補作[73] 1980年 『The Ghost Writer』でNBCCA最終候補作 1984年 『The Anatomy Lesson』で全米図書賞最終候補作[73] 1984年 『解剖学のレッスン』でNBCCA賞最終候補作 1986年 『カウンターライフ』で全米図書評論家協会賞(NBCCA)を受賞 1987年 『カウンターライフ』で全米図書賞最終候補作[73] 1988年 『カウンターライフ』で全米ユダヤ人図書賞を受賞[72] 1991年 『遺産』で全米図書評論家協会賞(NBCCA)を受賞[73] 1994年 『オペレーション・シャイロック』でペン/フォークナー賞を受賞 1994年 『オペレーション・シャイロック』でピューリッツァー賞の最終候補作に選出される[21] 1995年 『サバスの劇場』で全米図書賞を受賞[20] 1996年 『サバスの劇場』でピューリッツァー賞の最終候補作に選出される[21] 1997年 『サバスの劇場』でダブリン国際文学賞のロングリストに選出される。 1998年 『アメリカン・パストラル』でピューリッツァー賞を受賞[21]。 1998年 『アメリカン・パストラル』でNBCCAの最終候補作に選出される。 1998年 『私は共産主義者と結婚した』で英語圏連合のアンバサダー・ブック・アワードを受賞[73]。 1998年 ナショナル・メダル・オブ・アーツを受賞[73]。 1999年 『アメリカン・パストラル』でダブリン国際文学賞のロングリストに選出される。 2000年 『アメリカン・パストラル』で、フランス最優秀外国文学賞(Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger)を受賞 2000年 『私は共産主義者と結婚した』で、国際ダブリン文学賞の最終候補作に選出される 2000年 『人間の汚れ』で、全米ユダヤ人図書賞を受賞[72] 2001年 フランツ・カフカ賞を受賞 2001年 『人間の汚れ』で、PEN/フォークナー賞を受賞 2001年 アメリカ芸術文学アカデミーから、フィクション部門金賞を受賞[73] 2001 マクダウェル・コロニーより第42回エドワード・マクダウェル・メダルを受賞 2001 『人間の汚れ』でWHスミス文学賞を受賞 2002 『人間の汚れ』で国際ダブリン文学賞の最終候補作に選出される 2002 ナショナル・ブック・ファウンデーションよりアメリカ文学への貢献を称えるメダルを受賞[53] 2002 『人間の汚れ』でフランス・メディシス外国文学賞を受賞 2005年 『アメリカを覆う陰謀』でNBCCA最終候補作 2005年 『アメリカを覆う陰謀』でサイドワイズ・アワード(代替歴史部門)受賞 2005年 『アメリカを覆う陰謀』でジェームズ・フェニモア・クーパー賞(最優秀歴史小説部門)受賞 2005年 マン・ブッカー国際賞候補作 2005年 『アメリカを覆う陰謀』でWHスミス文学賞受賞 2006年 PEN/ナボコフ賞(生涯功労賞)受賞 2007年 『エブリマン』でペン/フォークナー賞[73] 2007年 ペン/ソール・ベロー賞(アメリカ小説部門 2008年 『エブリマン』でダブリン国際文学賞のロングリストに選出 2009年 『出口の幽霊』でダブリン国際文学賞のロングリストに選出 2010年 パリ・レビュー・ハダダ賞 2011年 2010年の人文科学分野における国家功労賞 2011年 マン・ブッカー国際賞 2012年 図書館議会創造的業績賞(小説部門) 2012年 アストゥリアス皇太子賞(文学部門)[61] 2013年 PEN/アレン財団文学サービス賞(生涯功績と提唱活動)[74][75][76] 2013年 フランス共和国からレジオンドヌール勲章コマンドゥール章を受章。[77] |

| Legacy John Updike, considered by many Roth's chief literary rival, said in 2008, "He's scarily devoted to the novelist's craft... [he] seems more dedicated in a way to the act of writing as a means of really reshaping the world to your liking. But he's been very good to have around as far as goading me to become a better writer." Roth spoke at Updike's memorial service, saying, "He is and always will be no less a national treasure than his 19th-century precursor, Nathaniel Hawthorne."[86] After Updike's memorial at the New York Public Library, Roth told Charles McGrath, "I dream about John sometimes. He's standing behind me, watching me write." Asked who was better, Roth said, "John had more talent, but I think maybe I got more out of the talent I had." McGrath agreed with that assessment, adding that Updike might be the better stylist, but Roth's work was more consistent and "much funnier". McGrath added that in the 1990s Roth "underwent a kind of sea change and, borne aloft by that extraordinary second wind, produced some of his very best work": Sabbath's Theater and the American Trilogy (American Pastoral, I Married a Communist, and The Human Stain).[87] Another admirer of Roth's work is Bruce Springsteen. Roth read Springsteen's autobiography, Born to Run, and Springsteen praised Roth's American Trilogy: "I'll tell you, those three recent books by Philip Roth just knocked me on my ass.... To be in his sixties making work that is so strong, so full of revelations about love and emotional pain, that's the way to live your artistic life. Sustain, sustain, sustain."[88] Roth left his book collection and more than $2 million to the Newark Public Library.[89][90] In 2021, the Philip Roth Personal Library opened for public viewing in the Newark Public Library.[91] In April 2021, W. W. Norton & Company published Blake Bailey's authorized biography of Roth, Philip Roth: The Biography. Publication was halted two weeks after release due to sexual assault allegations against Bailey.[92][93][94][95] Three weeks later, in May 2021, Skyhorse Publishing announced that it would release a paperback, ebook, and audiobook versions of the biography.[96] Roth had asked his executors "to destroy many of his personal papers after the publication of the semi-authorized biography on which Blake Bailey had recently begun work.... Roth wanted to ensure that Bailey, who was producing exactly the type of biography he wanted, would be the only person outside a small circle of intimates permitted to access personal, sensitive manuscripts, including the unpublished Notes for My Biographer (a 295-page rebuttal to his ex-wife's memoir) and Notes on a Slander-Monger (another rebuttal, this time to a biographical effort from Bailey's predecessor). 'I don't want my personal papers dragged all over the place,' Roth said. The fate of Roth's personal papers took on new urgency in the wake of Norton's decision to halt distribution of the biography. In May 2021, the Philip Roth Society published an open letter[97] imploring Roth's executors 'to preserve these documents and make them readily available to researchers.'"[98][99][100] After Roth's death, Harold Bloom told the Library of America: "Philip Roth's departure is a dark day for me and for many others. His two greatest novels, American Pastoral and Sabbath's Theater, have a controlled frenzy, a high imaginative ferocity, and a deep perception of America in the days of its decline. The Zuckerman tetralogy remains fully alive and relevant, and I should mention too the extraordinary invention of Operation Shylock, the astonishing achievement of The Counterlife, and the pungency of The Plot Against America. His My Life as a Man still haunts me. In one sense Philip Roth is the culmination of the unsolved riddle of Jewish literature in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The complex influences of Kafka and Freud and the malaise of American Jewish life produced in Philip a new kind of synthesis. Pynchon aside, he must be estimated as the major American novelist since Faulkner."[101] The New York Times asked several prominent authors to name their favorite work by Roth. The responses were varied; Jonathan Safran Foer chose Patrimony, Roth's memoir of his father's illness: "Much has been written about Roth since he died. In keeping with the unseemliness of our profession, we all have something to say. The responses have overflowed with a kind of blunt adoration that would be perfectly un-Rothlike if they weren't the efforts of children agonizing over the right way to bury our father. None of it feels right, perhaps because nothing could. Roth's words dressed his father for death, and they dressed so many of us for life. How does one properly acknowledge that? How does one say thank you for the thousand almost-invisible preparations? This morning, as I was getting my children dressed for school, I felt the profound gratitude of a 'little son.'"[102] Joyce Carol Oates told The Guardian: "Philip Roth was a slightly older contemporary of mine. We had come of age in more or less the same repressive 50s era in America—formalist, ironic, 'Jamesian', a time of literary indirection and understatement, above all impersonality—as the high priest TS Eliot had preached: 'Poetry is an escape from personality.' Boldly, brilliantly, at times furiously, and with an unsparing sense of the ridiculous, Philip repudiated all that. He did revere Kafka—but Lenny Bruce as well. (In fact, the essential Roth is just that anomaly: Kafka riotously interpreted by Lenny Bruce.) But there was much more to Philip than furious rebellion. For at heart he was a true moralist, fired to root out hypocrisy and mendacity in public life as well as private. Few saw The Plot Against America as actual prophecy, but here we are. He will abide."[103] |

レガシー ロスの文学上の最大のライバルと評されるジョン・アップダイクは、2008年に「彼は小説家の技に恐ろしいほど専心している... [彼は] 自分の好みに合わせて世界を再構築する手段としての執筆行為に、ある意味でより献身的に取り組んでいるようだ」と語っている。しかし、私をより良い作家に 成長させるという点では、彼はとても良い存在だった」と語っている。ロスはアップダイクの追悼式で、「彼は、19 世紀の先人であるナサニエル・ホーソーンと並ぶ、まさに国宝のような存在であり、これからもそうあり続けるだろう」と述べた[86]。ニューヨーク公立図 書館で開催されたアップダイクの追悼式の後、ロスはチャールズ・マクグラスに、「時々、ジョンの夢を見る。彼は私の後ろに立って、私が書くのを見ている」 と語った。どちらが優れていたか尋ねられたロスは、「ジョンは才能があったが、私は自分の才能をもっと活かしたかもしれない」と答えた。マクグラスはそれ に同意し、アップダイクはスタイルが優れていたかもしれないが、ロスの作品はより一貫性があり「ずっと面白い」と付け加えた。マクグラスはさらに、 1990年代にロスは「一種の転換期を迎え、その驚くべき第二の風に乗って、最も優れた作品の一部を生み出した」と述べた:『サバスの劇場』と『アメリカ ン・トリロジー』(『アメリカン・パストラル』『私は共産党員と結婚した』『人間の汚れ』)。[87] ロスの作品を称賛するもう一人の人物はブルース・スプリングスティーンだ。ロスはスプリングスティーンの自伝『ボーン・トゥ・ラン』を読み、スプリングス ティーンはロスの『アメリカン・トリロジー』を称賛した:「あなたに言おう、フィリップ・ロスの最近の3冊の本は、私を打ちのめした……。60代で、愛と 感情の苦痛についての啓示に満ちた、これほど強い作品を創作する——それが芸術家として生きるべき道だ。持続し、持続し、持続する。」[88] ロスは、自分の蔵書と 200 万ドル以上の財産をニューアーク公立図書館に遺贈した。[89][90] 2021 年、フィリップ・ロス個人図書館がニューアーク公立図書館内で一般公開された。[91]2021年4月、W. W. ノートン&カンパニーは、ブレイク・ベイリーによるロスの公認伝記『フィリップ・ロス:伝記』を出版した。ベイリーに対する性的暴行疑惑のため、発売から 2 週間後に出版は中止された。[92][93][94][95] 3 週間後の 2021 年 5 月、スカイホース・パブリッシングは、この伝記のペーパーバック、電子書籍、オーディオブックを発売すると発表した。[96] ロスは、遺言執行者に「ブレイク・ベイリーが最近着手した半公認の伝記の出版後、彼の個人的な書類の多くを破壊する」よう依頼していた。ロスは、自分が望 んだ通りの伝記を執筆していたベイリーが、親しい友人以外の唯一の人物として、未発表の『Notes for My Biographer』(元妻の回顧録に対する 295 ページにわたる反論)や『Notes on a Slander-Monger』(ベイリーの先代による伝記に対する別の反論)などの、個人的で機密性の高い原稿にアクセスできることを確保したかったの です。私の個人的な書類をあちこちに持ち回ってほしくない」とロスは述べた。ノートンが伝記の発売中止を決定したことで、ロスの個人的な書類の行方が新た な緊急課題となった。2021年5月、フィリップ・ロス協会は公開書簡[97] を発表し、ロスの遺言執行者に「これらの文書を保存し、研究者が容易に閲覧できるようにしてください」と懇願した。[100] ロスが亡くなった後、ハロルド・ブルームはライブラリー・オブ・アメリカに次のように語っている。「フィリップ・ロスの死は、私だけでなく多くの人々に とって暗い日だ。彼の2つの最高傑作『アメリカン・パストラル』と『サバスの劇場』は、抑制された狂乱、高い想像力、そして衰退しつつあるアメリカに対す る深い洞察力を持っている。『ザッカーマン四部作』は依然として生き生きと関連性を保っており、また『オペレーション・シャイロック』の非凡な創造性、 『カウンターライフ』の驚異的な成就、『アメリカに対する陰謀』の辛辣さも言及すべきだ。彼の『私の男としての生涯』は今も私を悩ませている。ある意味で は、フィリップ・ロスは20世紀と21世紀のユダヤ文学の未解決の謎の頂点と言えるだろう。カフカとフロイトの複雑な影響と、アメリカユダヤ人の生活の倦 怠感が、フィリップに新しいタイプの統合を生み出した。ピンチョンを除けば、彼はフォークナー以来のアメリカを代表する小説家として評価されなければなら ない。[101] ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は、著名な作家数人に、ロスのお気に入りの作品を挙げてほしいと依頼した。回答はさまざまで、ジョナサン・サフラン・フォアは、 ロスの父親の病気について書いた回顧録『パトリモニー』を選んだ。「ロスの死後、多くのことが書かれた。私たちの職業の不適切さにふさわしく、皆が何かを 言わなければならない。回答は、もしそれが父親を埋葬する正しい方法に苦悩する子供たちの努力でなければ、完全にロスらしくないような率直な崇拝で溢れて いた。何も正しいように感じないのは、おそらく何も正しいものがないからだろう。ロスの言葉は、彼の父親を死に備えさせただけでなく、私たち多くの者を人 生に備えさせた。それをどのように適切に感謝すればいいのか?千ものほとんど見えない準備に対して、どのように「ありがとう」と言えばいいのか?今朝、子 供たちを学校に送るために服を着せながら、私は『小さな息子』としての深い感謝の気持ちを感じた。」[102] ジョイス・キャロル・オースはガーディアン紙に次のように語っている。「フィリップ・ロスは、私より少し年上の同世代の人だった。私たちは、ほぼ同じ抑圧 的な 1950 年代のアメリカで成人した。その時代は、形式主義、皮肉、ジェームズ主義、文学の間接表現と控えめな表現、そして何よりも非人格性が流行していた。その時 代、大祭司 T.S. エリオットは「詩は人格からの逃避である」と説いていた。フィリップは、大胆かつ見事に、時には激怒し、そして容赦のない滑稽感をもって、そのすべてを否 定した。彼はカフカを崇拝していたが、レニー・ブルースも同様だった。(実際、本質的なロスはまさにその異常さだ:カフカをレニー・ブルースが暴れ回って 解釈したような存在だ。)しかし、フィリップには激しい反逆心だけではない多くの面があった。本質的に彼は真の道徳家であり、公私を問わず、偽善と虚偽を 根絶しようとして燃えていた。 『アメリカに対する陰謀』を実際の予言と見なした人は少なかったが、ここに私たちはいる。彼は永遠に生き続けるだろう。」[103] |

| Sources Brauner, David (1969) Getting in Your Retaliation First: Narrative Strategies in Portnoy's Complaint in Royal, Derek Parker (2005) Philip Roth: New Perspectives on an American Author, chapter 3 Greenberg, Robert (Winter 1997). "Transgression in the Fiction of Philip Roth". Twentieth Century Literature. 43 (4). Hofstra University: 487–506. doi:10.2307/441747. JSTOR 441747. Archived from the original on March 9, 2007. Saxton, Martha (1974) Philip Roth Talks about His Own Work Literary Guild June 1974, n.2. Also published in Philip Roth, George John Searles (1992) Conversations with Philip Roth p. 78 |

出典 Brauner, David (1969) Getting in Your Retaliation First: Narrative Strategies in Portnoy's Complaint in Royal, Derek Parker (2005) Philip Roth: New Perspectives on an American Author, chapter 3 グリーンバーグ、ロバート(1997年冬)。「フィリップ・ロス小説における越境」。20世紀文学。43 (4)。ホフストラ大学:487–506。doi:10.2307/441747。JSTOR 441747。2007年3月9日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。 サクストン、マーサ (1974) フィリップ・ロースが自身の作品について語る リテラリー・ギルド 1974年6月、n.2。フィリップ・ロース、ジョージ・ジョン・サールズ (1992) 『フィリップ・ロースとの対話』 p. 78 にも掲載。 |

| Further reading and literary criticism Balint, Benjamin, "Philip Roth's Counterlives," Books & Ideas, May 5, 2014. Bloom, Harold, ed., Modern Critical Views of Philip Roth, Chelsea House, New York, 2003. Bloom, Harold and Welsch, Gabe, eds., Modern Critical Interpretations of Philip Roth's Portnoy's Complaint. Broomall, Penn.: Chelsea House, 2003. Cooper, Alan, Philip Roth and the Jews (SUNY Series in Modern Jewish Literature and Culture). Albany: SUNY Press, 1996. Dean, Andrew. Metafiction and the Postwar Novel: Foes, Ghosts, and Faces in the Water, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2021. Finkielkraut, Alain, "La plaisanterie" [on The Human Stain], in Un coeur intelligent. Paris: Stock/Flammarion, 2009. Finkielkraut, Alain, "La complainte du désamour" (on The Professor of Desire), in Et si l'amour durait. Paris: Stock, 2011. Hayes, Patrick. Philip Roth: Fiction and Power, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2014. Kinzel, Till, Die Tragödie und Komödie des amerikanischen Lebens. Eine Studie zu Zuckermans Amerika in Philip Roths Amerika-Trilogie (American Studies Monograph Series). Heidelberg: Universitaetsverlag Winter, 2006. Miceli, Barbara, 'Escape from the Corpus: The Pain of Writing and Illness in Philip Roth's The Anatomy Lesson' in Bootheina Majoul and Hanen Baroumi, The Poetics and Hermeuetics of Pain and Pleasure, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2022: 55–62. Milowitz, Steven, Philip Roth Considered: The Concentrationary Universe of the American Writer. New York: Routledge, 2000. Morley, Catherine, The Quest for Epic in Contemporary American Literature. New York: Routledge, 2008. Parrish, Timothy, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Philip Roth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. Pierpont, Claudia Roth Roth Unbound: A Writer and His Books. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013. Podhoretz, Norman, "The Adventures of Philip Roth," Commentary (October 1998), reprinted as "Philip Roth, Then and Now" in The Norman Podhoretz Reader. New York: Free Press, 2004. Posnock, Ross, Philip Roth's Rude Truth: The Art of Immaturity. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006. Royal, Derek Parker, Philip Roth: New Perspectives on an American Author. Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2005. Safer, Elaine B., Mocking the Age: The Later Novels of Philip Roth (SUNY Series in Modern Jewish Literature and Culture). Albany: SUNY Press, 2006. Schmitt, Sebastian, Fifties Nostalgia in Selected Novels of Philip Roth (MOSAIC: Studien und Texte zur amerikanischen Kultur und Geschichte, Vol. 60). Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2017 (Open Access: https://www.wvt-online.com/media/9783868217407.pdf). Searles, George J., ed., Conversations With Philip Roth. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 1992. Searles, George J., The Fiction of Philip Roth and John Updike. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1984. Shostak, Debra B., Philip Roth: Countertexts, Counterlives. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2004. Simic, Charles, "The Nicest Boy in the World," The New York Review of Books 55, no. 15 (October 9, 2008): 4–7. Swirski, Peter, "It Can't Happen Here, or Politics, Emotions, and Philip Roth's The Plot Against America." American Utopia and Social Engineering in Literature, Social Thought, and Political History. New York, Routledge, 2011. Taylor, Benjamin. Here We Are: My Friendship with Philip Roth. New York: Penguin Random House, 2020. Wolcott, James, "Sisyphus at the Selectric" (review of Blake Bailey, Philip Roth: The Biography, Cape, April 2021, 898 pp., ISBN 978 0 224 09817 5; Ira Nadel, Philip Roth: A Counterlife, Oxford, May 2021, 546 pp., ISBN 978 0 19 984610 8; and Benjamin Taylor, Here We Are: My Friendship with Philip Roth, Penguin, May 2020, 192 pp., ISBN 978 0 525 50524 2), London Review of Books, vol. 43, no. 10 (May 20, 2021), pp. 3, 5–10. Wolcott: "He's a great writer but is he a great writer? And what does 'great writer' mean now anyhow?" (p. 10.) Wöltje, Wiebke-Maria, My finger on the pulse of the nation: Intellektuelle Protagonisten im Romanwerk Philip Roths (Mosaic, 26). Trier: WVT, 2006. |

さらに読むべき文献と文学批評 Balint, Benjamin, 「Philip Roth『s Counterlives,」 Books & Ideas, May 5, 2014. Bloom, Harold, ed., Modern Critical Views of Philip Roth, Chelsea House, New York, 2003. Bloom, Harold and Welsch, Gabe, eds., Modern Critical Interpretations of Philip Roth』s Portnoy's Complaint. ペンシルベニア州ブルームオール:チェルシー・ハウス、2003年。 クーパー、アラン、『フィリップ・ロスとユダヤ人』(SUNY 現代ユダヤ文学・文化シリーズ)。アルバニー:SUNY プレス、1996年。 ディーン、アンドルー。『メタフィクションと戦後小説:敵、幽霊、そして水面に映る顔たち』、オックスフォード大学出版局、オックスフォード、2021年。 フィンキエルクラウト、アラン、『ラ・プレザントリー』 [『人間の汚れ』について]、『Un coeur intelligent』所収。パリ:ストック/フラマルイオン、2009年。 フィンキエルクラウト、アラン、『ラ・コンプレイント・デュ・デザモール』 (『欲望の教授』について)、『Et si l'amour durait』所収。パリ:ストック、2011年。 ヘイズ、パトリック。『フィリップ・ロス:フィクションと権力』、オックスフォード大学出版局、オックスフォード、2014年。 キンツェル、ティル。『アメリカの生活の悲劇と喜劇。フィリップ・ロスのアメリカ三部作におけるズッカーマンのアメリカに関する研究』(アメリカ研究モノグラフシリーズ)。ハイデルベルク:ユニバーシタエツトスヴェルラッグ・ヴィンター、2006年。 ミチェリ、バーバラ、「コーパスからの脱出:フィリップ・ロスの『解剖学レッスン』における執筆の苦痛と病気」『痛みの詩学と解釈学』ブースティーナ・マジュールとハネン・バロウミ編、ケンブリッジ・スカラーズ・パブリッシング、2022年:55–62。 ミロウィッツ、スティーブン、『フィリップ・ロス考:アメリカ人作家の集中宇宙』。ニューヨーク:Routledge、2000年。 モーリー、キャサリン、『現代アメリカ文学における叙事詩の探求』。ニューヨーク:Routledge、2008年。 パリッシュ、ティモシー編、『フィリップ・ロス・コンパニオン』。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局、2007年。 ピアポント、クラウディア・ロート 『Roth Unbound: A Writer and His Books』 ニューヨーク:ファラー・ストラウス・ギル、2013年。 ポドホレッツ、ノーマン、「フィリップ・ロスの冒険」 『コメンタリー』 (1998年10月)、『The Norman Podhoretz Reader』 に「Philip Roth, Then and Now」として再掲載。ニューヨーク:フリープレス、2004年。 ポズノック、ロス、『フィリップ・ロスの無礼な真実:未熟さの芸術』。プリンストン:プリンストン大学出版局、2006年。 ロイヤル、デレク・パーカー、『フィリップ・ロス:アメリカ人作家に関する新しい視点』。サンタバーバラ:Praeger、2005年。 Safer, Elaine B., Mocking the Age: The Later Novels of Philip Roth (SUNY Series in Modern Jewish Literature and Culture). Albany: SUNY Press, 2006. Schmitt, Sebastian, Fifties Nostalgia in Selected Novels of Philip Roth (MOSAIC: Studien und Texte zur amerikanischen Kultur und Geschichte, Vol. 60). トリーア:Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier、2017 年(オープンアクセス:https://www.wvt-online.com/media/9783868217407.pdf)。 Searles, George J., ed., Conversations With Philip Roth. ジャクソン:ミシシッピ大学出版、1992 年。 サールズ、ジョージ・J.、『フィリップ・ロスとジョン・アップダイクの小説』 (The Fiction of Philip Roth and John Updike)。カーボンデール:サザン・イリノイ大学出版、1984年。 ショスタック、デブラ・B.、『フィリップ・ロス:カウンターテキスト、カウンターライフ』 (Philip Roth: Countertexts, Counterlives)。コロンビア:サウスカロライナ大学出版、2004年。 シミック、チャールズ、「世界で一番いい子」『ニューヨーク・レビュー・オブ・ブックス』55、第 15 号(2008 年 10 月 9 日):4–7。 スウィルスキー、ピーター、「それはここでは起こらない、あるいは政治、感情、そしてフィリップ・ロスの『アメリカに対する陰謀』」『文学、社会思想、政治史におけるアメリカのユートピアと社会工学』。ニューヨーク、Routledge、2011年。 テイラー、ベンジャミン。『Here We Are: My Friendship with Philip Roth』 ニューヨーク:Penguin Random House、2020年。 ウォルコット、ジェームズ、「Sisyphus at the Selectric」(ブレイク・ベイリー著『Philip Roth: The Biography』の書評、Cape、2021年4月、898ページ、 ISBN 978 0 224 09817 5;イラ・ネデル『フィリップ・ロス:カウンターライフ』、オックスフォード、2021年5月、546頁、ISBN 978 0 19 984610 8;およびベンジャミン・テイラー『ここに私たちはいる:フィリップ・ロスとの友情』、ペンギン、2020年5月、192頁、 ISBN 978 0 525 50524 2)、『ロンドン・レビュー・オブ・ブックス』第43巻第10号(2021年5月20日)、3、5–10ページ。ウォルコット:「彼は素晴らしい作家だけ ど、偉大な作家なのか?そもそも、今、「偉大な作家」ってどういう意味なのか? (p. 10.) Wöltje, Wiebke-Maria, My finger on the pulse of the nation: Intellektuelle Protagonisten im Romanwerk Philip Roths (Mosaic, 26). Trier: WVT, 2006. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Roth |

アマゾン・ジャパン・邦訳小説・フィップ・ロス『ヒューマンステイン』のレヴュー(著者:笑子千万、氏)からの引用

▲「舞台は、ニュージャージー州の都市イーストオレンジ。「人口のほとんどは白人、ユダヤ人

は黒人より少ない」町である。作中人物は、「私」ネイサン・ザッカーマン。ホーソーンのよ

うな静かな生活を楽しむ作家。読書と執筆にいそしんでいたが、前立腺がんの手術のあと人生

と関わることに目覚めた、65歳。アシーナ大学古典学教授コールマン・ブルータス・シルク、

71歳。妻アイリス・ギッテルマン。四人の子どもたち、長男、次男は自然科学系大学教授。長

女リサは特殊学級「字の読めない子どもたち」を指導している。リサの双子の弟マークは、正

統派のユダヤ教信者であり、聖書をテーマにした物語詩人である。父親には反抗的。コールマ

ンの愛人フォーニア・ファーリー、34歳。ベトナム帰還兵レスター・ファーリーと結婚してい

たが、夫の暴力と二人の子どもたちを焼死させたことが原因で離婚。アシーナ大学や郵便局の

清掃婦として働き、仲間と乳牛を飼育している。「読み書きができない女」といわれている。

アシーナ大学言語文学科学科長デルフィーヌ・ルー、フランス人だがアメリカで活躍する野望

を抱いている。金髪のアイスランド系デンマーク人スティーナ・パルソン、コールマンと二年

間交際した。黒人女性エリー・マギー、コールマンがアイリスと結婚する前交際していた。コ

ールマンの姉アーネスティン、シルク家の語部である。「私」はコールマンから彼自身を「主

題」とする小説を依頼され、アーネスティンからシルク家の歴史やコールマンの生い立ちを聞

き、作品『スプーク』を書き上げる予定である。

「私」ネイサンの視点で進行していくが、作中人物の想像、意識の流れ、心理描写などが時

系列ではなく複雑に交じり合っていく。コールマンの「人種差別発言」から、フォーニアとの

二年間の恋愛と二人の死までを縦軸に、各人物像を横軸に整理しながら読み解いていくとわか

りやすい。「ステイン」と「アイデンティティ」という二項のテーマが浮かび上がってくるだ

ろう。

▲「1996年、コールマン教授は、講義に一度も出席していない生徒たちに「spook(ス

プーク)」

という言葉を使った。「おばけ、幽霊」という意味以外に「黒人差別」の解釈も含まれている。

欠席者の一人が黒人女性だったことにより、コールマンは「幽霊」として使用したのだという

釈明も聞き入れられず、自ら大学に採用した黒人教授からも支持を受けられず辞職する。人種

差別主義者のレッテルを貼られた騒動のなかで妻アイリスが病死する。コールマンは「スプー

ク」をテーマに小説を書き始めたが失意のうちに断念しネイサンに依頼する。そして年齢差の

あるフォーニアと恋愛関係にあることも告白する。

▲「ネイサンは、「なぜ教授を辞任しなければならなかったのか?」「なぜ境遇がまったく違う フォーニアと関係したのか?」など、彼の「秘密」を調べ始める。「彼は、秘密、空白の部分 をもっている」「彼の魅力は秘密によるもの」と考える。コールマンの葬儀のあと、妹アーネ スティンがシルク家の歴史、コールマンの秘密を語る。シルク一族は黒人だったのだ。「白人 で通用する黒人と似たタイプのユダヤ人」という複雑な肌色のため、コールマンだけが「白人 のユダヤ人」として、四十年以上を通してきたのだ。シルク家の隣人たちは彼らの肌色を「エ ッグノッグ」(鶏卵にミルクと砂糖を入れてかき混ぜ、ラム酒やブランデーなど加えて飲む飲 み物)と表現していた。白人のアイリスと結婚する前、母親、兄(ウォルター・アントニー・ シルク)、妹と決別し「白人宣言」をしたのだ。母親からは「私の孫の顔を見られないのね」 「雪のように白いくせして奴隷のように考える」と揶揄される。兄からは「お母さんには二度 と近づくな」と宣告される。家族への裏切り、非道さと彼自身が求める自由、エゴイズムとの 葛藤であった。妻になるアイリスには「両親は死んだ、兄弟もいない」と偽る。「アイリスは 白人だが、曲がりくねったもつれ方をした髪、結婚して子どもに縮毛でも説明がつく」「自分 は世界中で最も愚かな理由で妻を選び、世界中の男の中で最も空っぽな男である」と苦悩を深 める。コールマンの子どもたちにも「君たちの祖父母は若くして死に、家には何も残っていな かった、曾祖父はロシアで居酒屋をやっていた」と答えている。子どもたちの「アイデンティ ティ」もないのだ。「人生とは恥知らずなステインに満ちたもの」と、自分の「穢れた決断」 が子どもたちの運命を狂わせるかもしれない。四人とも肌は白いが、彼らの子どもたちの肌色、 髪は未知の世界だ。アーネスティンが言うように「子どもを持たないことが罪滅ぼしなのよ。 子どもに話さないことは残酷なことよ」と兄を非難する。

▲「コールマンが黒人であることは「誰もが知っていた」のだ。母親の生い立ちは逃亡奴隷だっ

たし、「イーストオレンジ高校の卒業生総代の黒人生徒」「ニュージャージー州アマチュアボ

クシングに出場していた黒人少年」などで有名であった。大学時代、ユダヤ人で通した海軍時

代でも「ニガー」「二グロ」と呼ばれていたのだ。交際した女性たち、フォーニア、スティー

ナ、エリーたちの視線も彼が黒人であることを視とおしていた。たとえば、フォーニアは「読

み書きができない」と言われていたが、死後、子どもの遺灰と日記が発見された。演技をして

いたのだ。「未発達な人間が世界に合わせている」という姿勢を強調するためだった。読み書

きができなくとも生きていけるんだ、ということを周囲に認識させたかったのだろう。コール

マンの娘リサの児童指導に対するアンチテーゼかもしれない。彼女はコールマンについて「あ

なたが何者かわかっていた。南部に住んでいたから」と言っている。彼女だけがコールマンか

らすべてを打ち明けられたが、偽りの生き方は、彼の「人生そのものであるし、どうでもいい」

と思っていた。スティーナは、彼に詩を贈っている。「自分が彼に見ているものをどこまで語

れるか?」という内容であり、neck(首)をnegro(黒人)と読ませるような言い回しの言葉

も使っている。コールマンの家のディナーに招待された帰り「私にはできない!」という言葉

を残して走り去る。シルク家が黒人一家であることがはっきりとわかったからだ。黒人女性の

エリーは、コールマンと宝石店やバーに行き、そこの店主や客が白人か黒人か判断させる。コ

ールマンは黒人なのに白人と答えてしまう。彼女は、「あなたは自分で考え出したつもりでし

ょうがちょっと己惚れ過ぎよ」と、コールマンがユダヤ人になりすましていることを皮肉る。

肉親、兄妹、遠くは祖先まで含めたシルク家に縁切りした結果、自分の子どもたちも巻き込み

ながら、アイデンティティを喪失した「宙ぶらりん」な人生を歩むことになったのだ。

▲「なぜ、フォーニアにすべてを打ち明けたのだろう?。コールマンは、自分の虚飾に汚された

「ステイン」に耐えきれなくなったのだろう。「白人としての人生」は終わった、と感じたの

だろう。名誉、学歴、人種へのこだわりなど、すべてを投げうってフォーニアに懺悔したのだ

ろう。彼女は、実母から見放され、継父から児童虐待を受け、十四歳で家出し、夫から暴力を

受け、子どもたちの焼死に遭遇するなど人生の辛酸をなめてきた。コールマンとしては、フォ

ーニアが心を許せる最後のよりどころに思えたのだろう。一方、フォーニアが心を開けるのは

「カラス」だった。町で悪戯を繰り返し、仲間外れにされ「オーデュボン協会」という動物保

護団体に預けられている。フォーは、カラスの「プリンス」と会話しながら、仲間外れにされ

ることが「人種差別」につながり、それは「人間の穢れ」であると思う。「プリンスはカラス

の術を知らないカラス、私は女の術を知らない女」と慰め合う。「ものすごくカラスになりた

い、クロウステイタス(カラス状態)に戻りたい」と思う。

カラスの意味はなんだろう。著者は何も語っていないが、「ノアの方舟」のハトの前に飛び

立ったカラスではなかろうか。ハトはオリーヴの枝を持ち帰ったが、カラスは乾燥地をいち早

く発見し、そこで自由な天地を見つけた。フォーニアはカラスの自由をもちたかったのだろう。

▲「フォーニアと対極的に描かれているのが、フランス人のデルフィーヌ・ルー教授だ。若くし

て言語文学科学科長に就任し、文芸評論家でもある(シルクの敵対者でもあった)。男性にもてないコンプレックスを抱き、

嫉妬心が強く、同僚の女性教授たちから「異邦人、野心家、難しいボキャブラリーを使う文学

評論家」といわれ、経済学教授から「経済政策、マルクス、エンゲルス」の話を聞いていると

「シモーヌ・ド・ボーウォワールのパロディー」(サルトルとボーウォワールの関係)と皮肉

られる。ミラン・クンデラの文学理論を尊重し、自身を「クンデラ的な精神の彷徨」と位置付

けている。チェコからフランスへ移住したクンデラとフランスからアメリカへ野望を抱いて移

住してきた自分を同列に置いているのだ。アメリカ人男性にもてない理由は「学者世界のアメ

リカ語とは違う言語能力と知性」が原因であると分析している。「言葉で理解できるアメリカ

は11%程度だし、アメリカ人男性への理解度はゼロ%だろう」と、パリの心地よい生活を振り

返っている。結局、「移民の視点」でしかアメリカを理解できないもどかしさ、なかなかアメ

リカに溶け込めない自分を発見する。自分というものが「宙ぶらりん」なのだ。フランスを離

れたがアメリカ人になりきれない孤独、アイデンティティの欠落。私は「あそこにもいないし、

ここにもいない」という寂寥感と不安感。それらが、コールマン宛に匿名で手紙を投函させ、

コールマンとフォーニアの死に対して、ギリシャ神話の悪女の典型といわれる「クリュタイメ

ストラ」の名前でメールを発信させ、「悪の種」をまき散らす行為を誘発したのだ。「ミラン

・クンデラ」へのリスペクトを語らせ、痛烈な知識人批判を展開させているルー女史は、著者

の分身だろうと思う。

▲「コールマンを取り巻く女性たちの発言や行為のなかにアメリカが抱えている「病」が浮き彫 りにされていく。人種差別、ベトナム戦争後遺症をはじめとして大学教育の現状まで、さまざ まな問題が語られていく。そして、作中人物すべてがアイデンティティを喪失し、彷徨ってい る。祖国に裏切られた恨み、祖国を捨てたが新天地に溶け込めずにいる孤独感、祖先、肉親と 決別し、親から縁を切られ、どこにも自分の居場所が見つけられない自己存在の不安感などが 蔓延している人物たちを描いた物語である。コールマンの罪と罰の物語でもある。

▲「「私」は、アーネスティン宅に招待され訪問途中に、氷湖で釣りを楽しむレスター・ファー リーと会話する。自己紹介していなのに「ザッカーマンさん」と呼ばれる。彼の手には木工錐 がにぎられている。その恐怖の中で小説『スプーク』は完成させられるのだろうか」。

| The Human Stain

is a novel by Philip Roth, published May 5, 2000. The book is set in

Western Massachusetts in the late 1990s. Its narrator is 65-year-old

author Nathan Zuckerman, who appears in several earlier Roth novels,

including two books that form a loose trilogy with The Human Stain,

American Pastoral (1997) and I Married a Communist (1998).[1] Zuckerman

acts largely as an observer as the complex story of the protagonist,

Coleman Silk, a retired professor of classics, is slowly revealed. A national bestseller, The Human Stain was adapted in 2003 as a film by the same name directed by Robert Benton. |

『ヒューマン・ステイン(The

Human

Stain)』はフィリップ・ロスの小説で、2000年5月5日に出版された。1990年代後半のマサチューセッツ州西部が舞台。語り手は65歳の作家ネ

イサン・ザッカーマンで、『人間の穢れ』と緩やかな三部作を形成している『アメリカン・パストラル』(1997年)、『共産主義者と結婚した私』

(1998年)など、それ以前のロスの小説にも登場している[1]。ザッカーマンは、主人公の引退した古典学教授コールマン・シルクの複雑な物語が徐々に

明らかになるにつれ、主に観察者として行動する。 全米ベストセラーとなった『人間の穢れ』は、2003年にロバート・ベントン監督により同名の映画化された。 |

| Synopsis Coleman Silk is a former professor and dean of the faculty at Athena College, a fictional institution in the Berkshires of western Massachusetts, where he still lives. The story is narrated by Roth's recurring character Nathan Zuckerman, a writer and a neighbor of Silk. In 1996, two years before the main action of the novel, Silk is accused of racism by two African-American students after he wonders aloud whether the reason they have missed all his classes so far is that they are "spooks". Though Silk has no idea they are black, they and others at the college see the term as a racial epithet. When the uproar is about to die down, in Silk's view, he resigns. Soon afterward, his wife, Iris, dies of a stroke that Silk feels is caused by the stress of defending him. In the summer of 1998, just after Iris dies, the 71-year-old Silk approaches Zuckerman and asks him to write a book on the incident. Ranting about it, Silk blames the widespread condemnation of him on, among other things, anti-semitism. Zuckerman is uninterested, but the two begin a brief friendship and Silk tells him his life story. Zuckerman is surprised to learn that Silk is in a relationship with Faunia Farley, a 34-year-old woman who works as a janitor at the college and who everyone including Silk believes (falsely, as it turns out) is illiterate.[2] Zuckerman's version of the story starts when Coleman Silk is a light-skinned black boy in East Orange, New Jersey. Coleman becomes a straight-A student and, in defiance of his father, a quick and clever boxer. A boxing coach suggests that he pass as a Jew. During World War II he drops out of Howard University and joins the Navy, listing his race as white. After the war he studies at New York University and lives in Greenwich Village. When he introduces a white girlfriend to his family and they realize he is "passing", his brother cuts him off from the family. Silk marries Iris, a non-religious Jewish woman, and has four children. His wife and children are unaware of his ancestry; he invents a Jewish background and tells them he's unable to get in touch with his few living relatives. A successful academic career in classics leads to his position of dean, where he raises the faculty's standards by forcing out less academically accomplished professors. Decades later, he returns to teaching and is accused of racism as described above. Some time after his approach to Zuckerman, Silk loses most contact with the people other than Faunia who he is on good terms with, including his children and Zuckerman. In November, Silk and Faunia Farley are killed in a car accident, which Zuckerman suspects was caused by Farley's jealous and abusive ex-husband Lester Farley, a Vietnam War veteran suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. At Silk's funeral, his sister Ernestine reveals his secret to Zuckerman. The novel ends with an encounter between Les Farley and Zuckerman, who is en route to New Jersey to have dinner with the Silk family. Especially in the second half of the novel, there are scenes detailing the thoughts and feelings of other characters, notably Faunia, Les Farley, and Delphine Roux, Silk's main antagonist at Athena. Zuckerman gives his sources for some conversations at which he was not present, but he also says, "I imagine. I am forced to imagine. [...] It is my job. It's now all I do." |

あらすじ コールマン・シルクは、マサチューセッツ州西部のバークシャーにある架空の大学、アテナ・カレッジの元教授で学部長。物語は、ロスが繰り返し登場させる、 作家でシルクの隣人であるネイサン・ザッカーマンが語り手となる。 1996年、この小説のメイン・アクションの2年前、シルクはアフリカ系アメリカ人の学生2人から人種差別の疑いをかけられる。シルクは彼らが黒人だとは 知らなかったが、彼らも大学の他の人々も、この言葉を人種的な蔑称として捉えていた。騒動が収まりかけた頃、シルクから見て彼は辞職する。その直後、妻の アイリスが脳卒中で亡くなるが、シルクは彼を弁護したストレスが原因だと感じている。 アイリスが亡くなった直後の1998年夏、71歳のシルクはザッカーマンに近づき、この事件についての本を書いてほしいと頼む。シルクは、自分への非難が 広まったのは、とりわけ反ユダヤ主義のせいだとわめき散らす。ザッカーマンは興味を示さなかったが、2人は短い友情を育み、シルクは自分の人生を語る。 ザッカーマンは、シルクがフォーニア・ファーリーと交際していることを知り驚く。フォーニアは大学で用務員として働く34歳の女性で、シルクを含め誰もが (結果的には誤って)文盲だと信じていた[2]。 ザッカーマン版の物語は、コールマン・シルクがニュージャージー州イーストオレンジに住む肌の白い黒人少年であったところから始まる。コールマンは成績優 秀な生徒となり、父親に反抗して、すばしっこく賢いボクサーになる。ボクシングのコーチは彼にユダヤ人のふりをするよう勧める。第二次世界大戦中、彼はハ ワード大学を中退して海軍に入隊。 戦後はニューヨーク大学で学び、グリニッジ・ヴィレッジに住む。家族に白人のガールフレンドを紹介したところ、"パッシング "であることがバレてしまい、兄から絶縁される。シルクは無宗教のユダヤ人女性アイリスと結婚し、4人の子供をもうける。妻や子供たちは彼の先祖のことを 知らない。彼はユダヤ人の生い立ちを捏造し、数少ない存命の親戚と連絡が取れないと告げる。 古典の分野で学問的成功を収め、学部長に就任する。そこで彼は、学問的にあまり優秀でない教授を追い出し、学部の水準を高める。数十年後、彼は教職に戻 り、上記のような人種差別で非難される。 ザッカーマンとの接近からしばらくして、シルクは子供たちやザッカーマンを含め、ファウニア以外の仲の良い人々との接触をほとんど失ってしまう。11月、 シルクとフォーニア・ファーリーは交通事故で亡くなる。ザッカーマンは、ファーリーの嫉妬深く虐待的な元夫レスター・ファーリー(ベトナム戦争の帰還兵で 心的外傷後ストレス障害を患っていた)が引き起こした事故ではないかと疑う。シルクの葬儀の席で、彼の妹アーネスティンはザッカーマンに彼の秘密を打ち明 ける。小説は、シルク一家と夕食を共にするためにニュージャージーに向かうレス・ファーリーとザッカーマンの出会いで終わる。 特に小説の後半には、ファウニア、レス・ファーリー、デルフィーヌ・ルー(アテナでのシルクの主な敵対者)など、他の登場人物の考えや感情が詳細に描かれ る場面がある。ザッカーマンは、自分がその場にいなかったいくつかの会話について情報源を示しているが、「私は想像する。想像せざるを得ない。[それが私 の仕事です。それが私の仕事です。 |

| Critical response Themes The Human Stain is the third in a trilogy, following American Pastoral and I Married a Communist, in which Roth explores American morality and its effects. Here he examines the cut-throat and, at times, petty, atmosphere in American academia, in which "political correctness" was upheld.[4] Roth said he wrote the trilogy to reflect periods in the 20th century – the McCarthy years, the Vietnam War, and President Bill Clinton's impeachment – that he thinks are the "historical moments in post-war American life that have had the greatest impact on my generation."[5] Journalist Michiko Kakutani said that in The Human Stain, Roth "explores issues of identity and self-invention in America which he had long explored in earlier works." She wrote the following interpretation: It is a book that shows how the public Zeitgeist can shape, even destroy, an individual's life, a book that takes all of Roth's favorite themes of identity and rebellion and generational strife and refracts them not through the narrow prism of the self but through a wide-angle lens that exposes the fissures and discontinuities of 20th-century life. ... When stripped of its racial overtones, Roth's book echoes a story he has told in novel after novel. Indeed, it closely parallels the story of Nathan Zuckerman, himself another dutiful, middle-class boy from New Jersey who rebelled against his family and found himself exiled, 'unbound' as it were, from his roots.[2] Mark Shechner writes in his 2003 study that in the novel, Roth "explores issues in American society that force a man such as Silk to hide his background, to the point of not having a personal history to share with his children or family. He wanted to pursue an independent course unbounded by racial restraints, but became what he once despised. His downfall to some extent is engineered by Delphine Roux, the young, female, elite, French intellectual who is dismayed to find herself in a New England outpost of sorts, and sees Silk as having become deadwood in academia, the very thing he abhorred at the beginning of his own career."[6] Alleged resemblance to Anatole Broyard In the reviews of the book in both the daily and the Sunday New York Times in 2000, Kakutani and Lorrie Moore suggested that the central character of Coleman Silk might have been inspired by Anatole Broyard, a well-known New York literary editor of the Times.[2][7] Other writers in the academic and mainstream press made the same suggestion.[8][9][10][11][12][13] After Broyard's death in 1990, it had been revealed that he racially passed during his many years employed as a critic at The New York Times.[14] He was of Louisiana Creole ancestry. Roth himself stated that he had not known of Broyard's ancestry when he started writing the book and only learned of it months later.[3][15] In Roth's words, written in "An Open Letter to Wikipedia" and published by The New Yorker: "Neither Broyard nor anyone associated with Broyard had anything to do with my imagining anything in The Human Stain."[3] As stated above, Roth revealed that Coleman Silk was inspired "by an unhappy event in the life of my late friend Melvin Tumin."[3] Reception The novel was well received, became a national bestseller, and won numerous awards. In choosing it for its "Editors' Choice" list of 2000, The New York Times wrote: When Zuckerman and Silk are together and testing each other, Roth's writing reaches an emotional intensity and a vividness not exceeded in any of his books. The American dream of starting over entirely new has the force of inevitability here, and Roth's judgment clearly is that you can never make it all the way. There is no comfort in this vision, but the tranquility Zuckerman achieves as he tells the story is infectious, and that is a certain reward.[16] In April 2013, GQ listed The Human Stain as one of the best books of the 21st century.[17] After Roth died, The New York Times asked several prominent authors to name their favorite work by him. Thomas Chatterton Williams chose The Human Stain, writing that "Roth achieves something here that is very difficult to imagine his mostly domesticated descendants even attempting: He steps fully out of his own backyard and dares to imagine what he cannot possibly know by means of his own personal identity. I came to this gem late, as a 33-year-old 'mixed-race' black man who'd just become the father of a blond-haired, blue-eyed 'black' daughter who could pass for Swedish. Flipping through my paperback now, I smile as I reread the dog-eared pages, their margins overflowing with comments to the effect of: How can he possibly know that? There are many ways to display brilliance through narrative, but one of the most difficult — and courageous — is to render the I-who-is-not-I as vividly as one can render the self."[18] |

クリティカル・レスポンス テーマ The Human Stain』は、『American Pastoral』『I Married a Communist』に続く3部作の3作目で、ロスはアメリカの道徳とその影響について探求している。ロスは、20世紀のマッカーシー時代、ベトナム戦 争、ビル・クリントン大統領の弾劾など、「戦後のアメリカ生活において、私の世代に最も大きな影響を与えた歴史的瞬間」と思われる時代を反映させるため に、この三部作を書いたと語っている[5]。 ジャーナリストの角谷美智子は、『人間の穢れ』においてロスは「以前の作品で長い間探求してきた、アメリカにおけるアイデンティティと自己発明の問題を探 求している」と述べている。彼女は次のように解釈している: この本は、大衆の時代精神がいかに個人の人生を形成し、破壊さえしうるかを示す本であり、アイデンティティや反抗、世代間の争いといったロスが好んで取り 上げたテーマを、自己という狭いプリズムを通してではなく、20世紀の人生の亀裂や不連続性を露呈する広角レンズを通して屈折させた本である。... 人種的な含みを取り除けば、ロスの本は、彼が次から次へと小説で語ってきた物語と呼応する。実際、ネイサン・ズッカーマンもまた、ニュージャージー出身の 従順な中流階級の少年であったが、家族に反抗し、自分のルーツから追放され、いわば「束縛されていない」状態に陥った。 マーク・シェヒナーは2003年の研究で、ロスはこの小説の中で「シルクのような男が、子供や家族と共有する個人的な歴史を持たないほど、自分の生い立ち を隠さざるを得ないアメリカ社会の問題を探求している」と書いている。彼は人種的な制約に縛られない独立した道を追求したかったが、かつて軽蔑していたも のになった。彼の没落をある程度まで仕組んだのは、若い、女性、エリート、フランスの知識人であるデルフィーヌ・ルーである。彼女は、ニューイングランド の前哨基地のような場所に自分がいることに落胆し、シルクが学界の枯れ木になったと見ている。 アナトール・ブロヤードとの類似疑惑 2000年のニューヨーク・タイムズ紙の日刊紙と日曜版の書評で、角谷とロリー・ムーアは、コールマン・シルクという中心人物は、タイムズ紙の有名な ニューヨークの文芸編集者であるアナトール・ブロヤードにインスパイアされたのではないかと示唆した[2]。 [1990年のブロヤードの死後、彼がニューヨーク・タイムズ紙の批評家として長年勤めていた間に人種差別を受けたことが明らかになった[14]。 ロート自身は、この本を書き始めたときにはブロヤードの先祖のことは知らず、数カ月後に初めてそのことを知ったと述べている[3][15]。 ニューヨーカー』誌が出版した「ウィキペディアへの公開書簡」に書かれたロートの言葉を借りれば、「ブロヤードも、ウィキペディアに関係する誰一人とし て、そのようなことはしていない: 「上記のように、ロスはコールマン・シルクが「亡き友人メルヴィン・トゥミンの人生における不幸な出来事から着想を得た」と明かしている[3]。 レセプション この小説は好評を博し、全米ベストセラーとなり、数々の賞を受賞した。ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は、2000年の「エディターズ・チョイス」リストにこの 小説を選び、こう書いている: ザッカーマンとシルクが一緒にいて、互いを試しているとき、ロスの文章は彼のどの本にもない感情の激しさと生々しさに達する。まったく新しくやり直すとい うアメリカン・ドリームは、ここでは必然の力を持っている。このビジョンに安らぎはないが、ザッカーマンがこの物語を語るときに達成した静けさは伝染し、 それは確かな報酬である[16]。 2013年4月、『GQ』は『人間の穢れ』を21世紀のベストブックのひとつに挙げた[17]。 ロスが亡くなった後、ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は何人かの著名な作家に、ロスの作品の中で最も好きなものを挙げてもらった。トーマス・チャタートン・ウィ リアムズは『人間の穢れ』を選び、「ロスはここで、ほとんど飼い慣らされた彼の子孫たちが試みることさえ想像するのが非常に難しいことを成し遂げた: 彼は自分の裏庭から完全に一歩踏み出し、自分自身の個人的なアイデンティティによって知りえないことをあえて想像している。私は33歳の「混血」黒人で、 スウェーデン人と見紛うばかりの金髪碧眼の「黒人」娘の父親になったばかりだった。今、私はペーパーバックをめくりながら、耳ざわりなページを読み返して 微笑んでいる: どうしてそんなことがわかるのだろう?物語を通して輝きを示す方法はたくさんあるが、最も困難な--そして勇気のいる--方法のひとつは、自己を描くのと 同じくらい鮮やかに、私でない私を描くことである」[18]。 |

| Awards Winner New York Times "Editors' Choice" (2000)[16] Koret Jewish Book Award (2000)[19] Chicago Tribune Editor's Pick (2000)[19] WH Smith Literary Award (2001)[19] National Jewish Book Award (2001)[19] PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction (2001)[20] Prix Médicis étranger; Meilleur livre de l'année 2002 Finalist Los Angeles Times Book Prize for fiction (2000).[21] L.L. Winship/PEN New England Award (2001)[19] Adaptations The Human Stain was adapted in 2003 into a film by the same name, directed by Robert Benton and starring Anthony Hopkins and Nicole Kidman. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Human_Stain |

|

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆