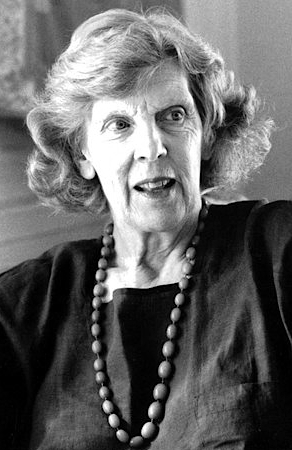

フィリッパ・フット

Philippa Foot, 1920-2010

1939年のフィリッパ・フット

☆

フィリッパ・ルース・フット FBA(旧姓ボザンクェート、1920年10月3日 -

2010年10月3日)は、イギリスの哲学者であり、現代の徳倫理学の創始者の一人である。彼女の作品はアリストテレスの倫理学に影響を受けている。ジュ

ディス・ジャーヴィス・トムソンとともに、彼女は「トロリー問題」を考案したことで知られている。[1][2]

彼女はアメリカ哲学協会の会員に選出された。

| Philippa Ruth Foot

FBA (née Bosanquet; 3 October 1920 – 3 October 2010) was an English

philosopher and one of the founders of contemporary virtue ethics. Her

work was inspired by Aristotelian ethics. Along with Judith Jarvis

Thomson, she is credited with inventing the trolley problem.[1][2] She

was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society. |

フィ

リッパ・ルース・フット FBA(旧姓ボザンクェート、1920年10月3日 -

2010年10月3日)は、イギリスの哲学者であり、現代の徳倫理学の創始者の一人である。彼女の作品はアリストテレスの倫理学に影響を受けている。ジュ

ディス・ジャーヴィス・トムソンとともに、彼女は「トロリー問題」を考案したことで知られている。[1][2]

彼女はアメリカ哲学協会の会員に選出された。 |

| Biography Born Philippa Ruth Bosanquet in Owston Ferry, North Lincolnshire, she was the daughter of Esther Cleveland (1893–1980) and Captain William Sidney Bence Bosanquet (1893–1966) of the Coldstream Guards of the British Army. Her paternal grandfather was barrister and judge Sir Frederick Albert Bosanquet, Common Serjeant of London from 1900 to 1917. Her maternal grandfather was the 22nd and 24th President of the United States, Grover Cleveland.[3][4] Foot was educated privately and at Somerville College, Oxford, 1939–1942, where she attained a first-class degree in philosophy, politics, and economics. Her association with Somerville, interrupted only by government service as an economist from 1942 to 1947, continued for the rest of her life. She was a lecturer in philosophy, 1947–1950; fellow and tutor, 1950–1969; senior research fellow, 1969–1988; and honorary fellow, 1988–2010. She spent many hours there in debate with G. E. M. Anscombe and learnt from her about Wittgenstein's analytic philosophy and a new moral perspective: Foot said "I learned every thing from her".[5][6] In the 1960s and 1970s, Foot held a number of visiting professorships in the United States, including at Cornell, MIT, Berkeley, and City University of New York. She was appointed Griffin Professor of Philosophy at the University of California, Los Angeles in 1976 and taught there until 1991, dividing her time between the United States and Britain.[7] Contrary to common belief, Foot was not a founder of Oxfam. She joined the organization about six years after its foundation. She was an atheist.[8] She was once married to the historian M. R. D. Foot,[9] and at one time shared a flat with the philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch.[10] She died in 2010 on her 90th birthday.[11] She lived at 15 Walton Street from 1972 until 2010, and is commemorated by an Oxfordshire Blue Plaque on the house.[12] |

経歴 フィリッパ・ルース・ボサンケットは、イギリス・ノースリンカンシャー州オウストン・フェリーで生まれ、エスター・クリーブランド(1893-1980) と、イギリス陸軍コールドストリーム・ガーズのウィリアム・シドニー・ベンチ・ボサンケット大尉(1893-1966)の娘であった。父方の祖父は弁護士 で裁判官のサー・フレデリック・アルバート・ボサンケットであり、1900年から1917年までロンドンの最高裁判所長官を務めた。母方の祖父は第22代 および第24代アメリカ合衆国大統領のグローバー・クリーブランドである。 フットは、1939年から1942年まで、オックスフォードのソマーヴィル・カレッジで教育を受け、哲学、政治学、経済学の分野で最優秀の成績を収めた。 1942年から1947年にかけては、経済学者として政府に勤務した時期を除いて、ソマーヴィル・カレッジとの関わりは生涯続いた。彼女は1947年から 1950年まで哲学の講師、1950年から1969年まで研究員および講師、1969年から1988年まで上級研究員、1988年から2010年まで名誉 研究員を務めた。彼女はそこで多くの時間をG. E. M. アンコムと議論に費やし、彼女からウィトゲンシュタインの分析哲学と新しい道徳観について学んだ。フットは「彼女からあらゆることを学んだ」と述べてい る。[5][6] 1960年代と1970年代には、フットはアメリカ国内の複数の大学で客員教授を務めた。コーネル大学、マサチューセッツ工科大学、カリフォルニア大学 バークレー校、ニューヨーク市立大学などである。1976年にはカリフォルニア大学ロサンゼルス校のグリフィン哲学教授に任命され、1991年まで同校で 教鞭をとり、アメリカとイギリスを行き来していた。 一般に信じられていることとは逆に、フットはオックスファムの創設者ではなかった。彼女は同団体の創設から約6年後に参加した。彼女は無神論者であった。 [8] 彼女は歴史家のM. R. D. Footと結婚していたことがあり[9]、また、ある時期には哲学者であり小説家でもあるアイリス・マードックとアパートを共有していたこともある。 [10] 彼女は2010年に90歳の誕生日を迎えた日に死去した。[11] 彼女は1972年から2010年までウォルトン・ストリート15番地に住んでおり、この家にはオックスフォードシャー・ブルー・プラークが掲げられ彼女を 偲んでいる。 12] |

| Critique of non-cognitivism Foot's work in the 1950s and 1960s sought to revive Aristotelian ethics in modernity, competing with its major rivals, modern deontology and consequentialism (the latter a term dubbed by Anscombe). Some of her work was crucial to a re-emergence of normative ethics within analytic philosophy, notably her critiques of consequentialism, non-cognitivism, and Nietzsche. Foot's approach was influenced by the later work of Wittgenstein, although she seldom dealt explicitly with his materials. She had the opportunity to listen to Wittgenstein lecture once or twice.[13] In her earlier career, Foot's works were meta-ethical in character, pertaining to the nature and status of moral judgment and language. Her essays "Moral Arguments" and "Moral Beliefs" were significant in dethroning non-cognitivism as the dominant meta-ethical theory of preceding decades.[citation needed] Though non-cognitivism may be traced back to Hume's Is–ought problem, its most explicit formulations are found in the works of A. J. Ayer, C. L. Stevenson, and R. M. Hare, who focused on abstract or "thin" ethical concepts such as good/bad and right/wrong. They argued that moral judgments do not express propositions, i.e., that they are not truth-apt, but express emotions or imperatives. Thus, fact and value are independent of each other.[citation needed] This analysis of abstract or "thin" ethical concepts was contrasted with more concrete or "thick" concepts, such as cowardice, cruelty, and gluttony. Such attributes do not swing free of the facts, yet they carry the same "practicality" that "bad" or "wrong" do. They were intended to combine the particular, non-cognitive "evaluative" element championed by the theory with the descriptive element. One could detach the evaluative force by employing them in an "inverted commas sense", as one does in attempting to articulate thoughts in a system one opposes, for example by putting "unmanly" or "unladylike" in quotation marks. That leaves purely descriptive expressions that apply to actions, whereas employing such expressions without the quotation marks would add the non-cognitive extra of "and such action is bad".[citation needed] Foot objected to this distinction and its underlying account of thin concepts. Her defense of the cognitive and truth-evaluable character of moral judgment made the essays crucial in bringing the question of the rationality of morality to the fore.[citation needed] Practical considerations involving "thick" ethical concepts – "but it would be cruel", "it would be cowardly", "it's for her to do", or "I promised her I wouldn't do it" – move people to act one way rather than another, but remain as purely descriptive as any other judgment pertaining to human life. They differ from thoughts such as "it would be done on a Tuesday" or "it would take about three gallons of paint" not by admixing what she considers a non-factual, attitude-expressing, "moral" element, but simply by the fact that people have reason not to do things that are cowardly or cruel. Her lifelong devotion to the question is apparent in all periods of her work.[citation needed] |

非認識論批判 フットの1950年代と1960年代の研究は、近代におけるアリストテレス的倫理の復興を目指し、主要なライバルである近代義務論と帰結主義(後者はアン コムが名付けた用語)と競い合った。彼女の研究の中には、分析哲学における規範倫理の再興に重要なものもあり、特に帰結主義、非認識論、ニーチェに対する 批判は顕著である。フットのアプローチは、ウィトゲンシュタインの後の研究に影響を受けているが、彼女はウィトゲンシュタインの資料を明示的に扱うことは ほとんどなかった。彼女はウィトゲンシュタインの講義を一度か二度聴く機会があった。 初期のキャリアにおいて、フットの作品は道徳判断と言語の本質と地位に関するメタ倫理的な性格を持っていた。彼女のエッセイ「Moral Arguments」と「Moral Beliefs」は、非認知主義を、それまでの数十年間の支配的なメタ倫理理論の地位から引きずり下ろす上で重要な役割を果たした。 非認知説はヒュームの「である〈対〉であるべき問題」に遡ることができるが、その最も明確な定式化は、A. J. エイヤー、C. L. スティーブンソン、R. M. ヘアの著作に見られる。彼らは、善悪や正誤といった抽象的または「薄っぺらな」倫理的観念に焦点を当てた。彼らは、道徳的判断は命題を表現するものではな く、すなわち、真実を表現するものではなく、感情や命令を表現するものであると主張した。したがって、事実と価値は互いに独立している。 この抽象的または「薄い」倫理概念の分析は、より具体的または「濃い」概念、例えば臆病、残酷、大食などと対比される。 このような属性は事実から自由にはならないが、「悪い」または「間違っている」と同じ「実用性」を持つ。 それらは、理論が擁護する特定の非認知的な「評価的」要素と記述的要素を組み合わせることを意図していた。例えば「unmanly(男らしくない)」や 「unladylike(淑女らしくない)」を引用符で囲むように、反対するシステムの中で考えを明確にしようとする際に用いるように、「倒置法」でそれ らを用いることで評価的な力を切り離すことができる。そうすると、行動に適用される純粋に記述的な表現が残る。一方、引用符を用いずにそのような表現を用 いると、「そしてそのような行動は悪い」という非認知的要素が追加されることになる。[要出典] フットは、この区別と、その根底にある「薄い概念」の説明に異議を唱えた。彼女は、道徳的判断の認知性と真偽評価可能性を擁護し、道徳の合理性の問題を前面に押し出す上で、この論文を極めて重要なものとした。 「しかしそれは残酷だ」、「それは臆病だ」、「彼女がすべきだ」、「私は彼女にそれをしないと約束した」といった「厚みのある」倫理的概念を伴う実際的な 考慮事項は、人々をある行動へと駆り立てるが、それは人間の生活に関する他の判断と同様に、純粋に記述的なものである。「火曜日にやるだろう」や「3ガロ ンほどのペンキが必要だろう」といった考えとは異なり、それは、彼女が事実ではないと考え、態度を表現する「道徳」的要素を混ぜ合わせるのではなく、単に 人々が臆病や残酷なことをしない理由を持っているという事実によるものである。彼女の生涯にわたるこの問題への献身は、彼女の作品のすべての時代において 明白である。 |

| Morality and reasons It is on the "why be moral?" question (which for her may be said to divide into the questions "why be just?", "why be temperate?", etc.) that her doctrine underwent a series of reversals. |

道徳と理由 「なぜ道徳的であるべきなのか?」という問い(これは彼女にとって、「なぜ正義であるべきなのか?」「なぜ節制すべきなのか?」など、いくつかの問いに分けることができる)について、彼女の教義は一連の転換を経験した。 |

| "Why be moral?" – early work In "Moral Beliefs", Foot argued that the received virtues – courage, temperance, justice, and so on – are typically good for their bearer. They make people stronger, so to speak, and condition to happiness. This holds only typically, since the courage of a soldier, for instance, might happen to be precisely his downfall, yet is in some sense essential: possession of sound arms and legs is good as well. However, damaged legs may happen to exclude someone from conscription that assigns contemporaries to their deaths. So people have reason to act in line with the canons of these virtues and avoid cowardly, gluttonous, and unjust action. Parents and guardians who want the best for children will steer them accordingly.[citation needed] The "thick" ethical concepts that she emphasized in her defense of moral judgment's cognitive character were precisely those associated with such "profitable" traits, i. e., virtues; this is how such descriptions differ from randomly chosen descriptions of action. The crucial point was that the difference between "just action" and "action performed on Tuesday" (for example) was not a matter of superadded "emotive" meaning, as in Ayer and Stevenson, nor a latent imperative feature, as in Hare. It is just that justice makes its bearer strong, which gives us a reason to cultivate it in ourselves and our loved ones by keeping to the corresponding actions.[citation needed] So Foot's philosophy must address Nietzsche and the Platonic immoralists: perhaps the received ostensible virtues in fact warp or damaged the bearer. She suggests that modern and contemporary philosophers (other than Nietzsche) fear to pose this range of questions because they are blinded by an emphasis on a "particular just act" or a particular courageous act, rather than the traits that issue from them. It seems that an agent might come out the loser by such act. The underlying putative virtue is the object to consider.[citation needed] |

「なぜ道徳的であるべきなのか」―初期の作品 「道徳的信念」において、フットは、一般的に受け入れられている美徳、すなわち勇気、節制、正義などは、その持ち主にとって典型的に良いものであると論じ た。それらは、いわば人を強くし、幸福へと導く。これは典型的な場合のみに当てはまる。例えば、兵士の勇気が、まさにその兵士の破滅につながることもある が、ある意味では不可欠である。健全な手足を持つことは良いことでもある。しかし、足に障害があるために、同世代の人々を死に追いやる徴兵から除外される 可能性もある。そのため、人々はこれらの美徳の規範に従って行動し、臆病、大食、不正な行動を避ける理由がある。子供にとって最善を望む親や保護者は、子 供たちを適切に導くだろう。 彼女が道徳的判断の認知的な性格を擁護する際に強調した「厚みのある」倫理的概念は、まさにそのような「有益な」特性、すなわち美徳に関連するものであっ た。これが、そのような記述がランダムに選ばれた行動の記述と異なる点である。重要な点は、「正しい行動」と「火曜に行われる行動」(例えば)の違いは、 エイヤーやスティーヴンソンのように「感情的な」意味が付け加えられたものでも、ヘアーのように潜在的な命令的特徴でもないということだ。正義がその担い 手を強くするということだけだ。それゆえ、私たち自身や愛する人たちに正義を育む理由となり、それに対応する行動を維持することになるのだ。 したがって、フットの哲学はニーチェやプラトン主義的不道徳主義者たちに言及しなければならない。おそらく、一般的に受け入れられている表向きの美徳は、 実際にはその持ち主をゆがめたり傷つけたりしている。彼女は、近代および現代の哲学者(ニーチェ以外)がこのような幅広い問題を提起することを恐れている のは、彼らが「特定の公正な行為」や特定の勇敢な行為ではなく、それらから生じる特徴に重点を置くことで盲目になっているからだと示唆している。そのよう な行為によって、行為者が敗者となる可能性があるように思われる。根底にあると想定される美徳こそが、検討の対象である。[要出典] |

| "Why be moral?" – middle work Fifteen years later, in the essay "Morality as a System of Hypothetical Imperatives", she reversed this when it came to justice and benevolence, that is, the virtues that especially regard other people. Although everyone has reason to cultivate courage, temperance and prudence, whatever the person desires or values, still, the rationality of just and benevolent acts must, she thought, turn on contingent motivations. Although many found the thesis shocking, on her (then) account, it is meant to be, in a certain respect, inspiring: in a famous reinterpretation of a remark of Kant,[14] she says that "we are not conscripts in the army of virtue, but volunteers";[15]: 170 the fact that we have nothing to say in proof of the irrationality of at least some unjust people should not alarm us in our own defence and cultivation of justice and benevolence: "it did not strike the citizens of Leningrad that their devotion to the city and its people during the terrible years of the siege was contingent".[citation needed] |

「なぜ道徳的であるべきなのか」 - 中間作品 15年後、エッセイ「道徳は仮言的命令の体系である」において、彼女は正義と博愛、つまり特に他者を配慮する美徳に関しては、この考えを覆した。 勇気、節制、思慮深さを育む理由は誰にでもあるが、人格が何を望み、何を重視するかに関わらず、正義と博愛に基づく行為の合理性は、偶発的な動機に左右さ れるべきであると彼女は考えた。この論文は多くの人々にとって衝撃的であったが、彼女(当時)の主張によれば、ある意味では鼓舞する意図があった。カント の有名な発言を再解釈したもの[14]の中で、彼女は「私たちは美徳の軍隊に徴兵された兵士ではなく、志願兵である」[15]:170と述べている。少な くとも一部の不正な人々の非合理性を証明するために、私たちが何も言うことがないという事実は、私たち自身の正当性と博愛の育成を擁護する上で私たちを不 安にさせるべきではない。「レニングラード包囲の悲惨な時期に、市民たちが自分たちの街とその人々への献身が偶然の産物であったことに気づかなかった」 [要出典] |

| "Why be moral?" – later work Foot's book Natural Goodness attempts a different line. The question that we have most reason to do ties into the good working of practical reason. This in turn is tied to the idea of the species of an animal providing a measure of good and bad in the operations of its parts and faculties. Just as one has to know what kind of animal is meant, for instance to decide whether its eyesight is good or bad, the question of whether a subject's practical reason is well developed depends on the kind of animal it is. This idea is developed in the light of a concept of animal kinds or species as implicitly containing "evaluative" content, which may be criticized on contemporary biological grounds. However, it is arguable even on that basis that it is deeply entrenched in human cognition. In this case, what makes for a well-constituted practical reason depends on us being human beings marked by certain possibilities of emotion and desire, a certain anatomy, neurological organization, and so forth.[citation needed] Once this step is taken, it becomes possible to argue in a new way for the rationality of moral considerations. Humans begin with the conviction that justice is a genuine virtue. So a conviction that well-constituted human practical reason operates with considerations of justice means that taking account of other people in that sort of way is "how human beings live together." (The thought that this is how they live must be understood in a sense compatible with the fact that actual individuals often do not – just as dentists understand the thought that "human beings have n teeth" in a way that is compatible with many people having fewer.) There is nothing incoherent in the thought that practical reasoning that takes account of others and their good might characterize some kind of rational and social animal.[citation needed] Similarly, there is nothing incoherent in the idea of a form of rational life. Such considerations are alien, where they can only be imposed by damaging and disturbing the individual. There is nothing analytical about the rationality of justice and benevolence. Human conviction that justice is a virtue and that considerations of justice are genuine reasons for action assumes that the kind of rational being we are, namely human beings, is of the first type. There is no reason to think such a rational animality is impossible, and so none to suspect that considerations of justice are frauds.[citation needed] It might be suggested that this is precisely not the case, that human beings are of the second kind, thus that the justice and benevolence we esteem are artificial and false. Foot would hold that machismo and ladylikeness considerations are artificial and false; they are matters of "mere convention", which tend to put one off the main things. As far as justice is concerned, that was the position of the "immoralists" Callicles and Thrasymachus in Plato's dialogues, and as far as benevolence is concerned, that was the view of Friedrich Nietzsche.[citation needed] With Callicles and Nietzsche, this is apparently to be shown by claiming that justice and benevolence respectively can be inculcated only by warping the emotional apparatus of the individual. Foot's book ends by attempting to defuse the evidence Nietzsche brings against what might be called the common-sense position. She proceeds by accepting his basic premise that a way of life inculcated by damaging the individual's passions, filling one with remorse, resentment and so forth, is wrong. She employs exactly the Nietzschean form of argument against some forms of femininity, for example, or exaggerated forms of etiquette acceptance. However, she claims that justice and benevolence "suit" human beings and there is no reason to accept Callicles' or Nietzsche's critiques in this case.[citation needed] |

「なぜ道徳的であるべきなのか」 - 後の作品 フットの著書『自然の善良さ』は異なる路線を試みている。我々が最も理由を持って行うべき問いは、実践理性の適切な働きと結びついている。そして、それ は、その部分や能力の働きにおける善悪の尺度を提供する動物の種の概念と結びついている。例えば、視力が良いか悪いかを判断するには、それがどのような動 物であるかを理解していなければならないのと同様に、主題の実用的な理性が十分に発達しているかどうかという問題は、それがどのような動物であるかによっ て決まる。この考えは、動物種や種が暗黙のうちに「評価的」な内容を含んでいるという概念に照らして展開されているが、これは現代の生物学的な根拠に基づ いて批判される可能性がある。しかし、その根拠に基づいてさえも、それが人間の認知に深く根付いていることは議論の余地がある。この場合、よく構成された 実践的な理性を構成するものは、特定の感情や欲求の可能性、特定の解剖学的構造、神経組織などによって特徴づけられる人間であることに依存している。 この段階を踏めば、道徳的考察の合理性について新たな方法で論じることが可能になる。人間は、正義が真の美徳であるという信念から出発する。したがって、 正しく構成された人間の実践的理性が正義の考察に基づいて機能するという信念は、他者をそのような方法で考慮することが「人間が共に生きる方法」であるこ とを意味する。(彼らはこのように生きているという考えは、実際の個人がしばしばそうではないという事実と矛盾しない形で理解されなければならない。歯科 医が「人間には歯が20本ある」という考えを、多くの人がそれより少ない歯の本数を持っているという事実と矛盾しない形で理解するのと同じである。)他者 とその善を考慮する実践的な推論が、ある種の理性的で社会的な動物を特徴づけるという考えに、矛盾するものは何もない。 同様に、ある種の合理的な生活という考え方にも何ら矛盾はない。そのような考察は、個々人に害を与えたり邪魔をしたりして押し付けることしかできないよう な、よそよそしいものである。正義と博愛の合理性について分析的なものは何もない。正義は美徳であり、正義の考察は行動の真の理由であるという人間の信念 は、我々人間が第一のタイプの合理的な存在であることを前提としている。そのような理性的な動物が存在し得ないという理由はないため、正義の考慮が詐欺で あると疑う理由もない。 これはまさにそうではないという意見もあるかもしれない。人間は第二の類型であり、したがって、我々が尊重する正義や慈悲は人工的で偽りであるという意見 である。フットは、男らしさや女らしさへの配慮は人為的で偽りであり、「単なる慣習」の問題であり、本質的なことから目をそらさせる傾向があると主張す る。正義に関しては、プラトンの対話篇における「不道徳論者」のカリクレスとトラシマコスの立場であり、慈悲に関しては、フリードリヒ・ニーチェの見解で ある。 カリクレスとニーチェによれば、正義と博愛は、個人の感情を歪めることによってのみ教え込むことができるという主張によって、このことが明らかに示され る。フットの著書は、ニーチェが常識的立場と呼ぶかもしれないものに対して持ち出した証拠を鎮静化しようとする試みで終わっている。彼女は、個人の情熱を 傷つけ、後悔や憤りなどで満たすことによって教え込まれる生き方は間違っているという彼の基本的前提を受け入れることで進んでいく。彼女は、例えば女性ら しさの一部の形や、行き過ぎた礼儀作法の受け入れなどに対して、まさにニーチェ的な論法を用いている。しかし、彼女は正義と博愛が人間に「ふさわしい」と 主張しており、この場合、カリクレスやニーチェの批判を受け入れる理由はないと主張している。 |

| Ethics, aesthetics and political philosophy Nearly all Foot's published work relates to normative or meta-ethics. Only once did she move into aesthetics – in her 1970 British Academy Hertz Memorial Lecture, "Morality and Art", in which certain contrasts are drawn between moral and aesthetic judgements.[citation needed] Foot appears never to have taken a professional interest in political philosophy.[citation needed] Geoffrey Thomas of Birkbeck College, London, recalls approaching Foot in 1968, when he was a postgraduate at Trinity College, Oxford, to ask if she would read a draft paper on the relation of ethics to politics. "I've never found political philosophy interesting," she said, adding, "One's bound to interest oneself in the things people around one are talking about," so implying correctly that political philosophy was largely out of favour with Oxford philosophers in the 1950s and 1960s. She still agreed to read the paper, but Thomas never sent it.[16]: 31–58 |

倫理学、美学、政治哲学 フットの発表した作品のほとんどは、規範倫理学またはメタ倫理学に関するものである。彼女が美学の分野に踏み込んだのは、1970年の英国学士院ハーツ記念講演「道徳と芸術」において一度だけである。この講演では、道徳的判断と美的判断の間に一定の対比が描かれている。 フットは政治哲学に専門的な関心を抱いたことは一度もないようである。[要出典] ロンドン大学バークベック・カレッジのジェフリー・トマスは、1968年にオックスフォード大学トリニティ・カレッジの大学院生であったときに、フットに 近づき、倫理と政治の関係に関する論文の草案を読んでくれないかと頼んだことを思い出す。「私は政治哲学に興味を持ったことは一度もない」と彼女は言い、 「自分の周りの人々が話題にしていることには、誰でも興味を持つものだ」と付け加えた。これは、1950年代と1960年代のオックスフォードの哲学者の 間では、政治哲学はほとんど人気がなかったことを正しく暗示している。彼女はそれでも論文を読むことに同意したが、トーマスは論文を送らなかった。 [16]:31-58 |

| Selected works Virtues and Vices and Other Essays in Moral Philosophy, Berkeley: University of California Press/Oxford: Blackwell, 1978 (there are more recent editions) Natural Goodness. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2001 Moral Dilemmas: And Other Topics in Moral Philosophy, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2002 Morality and Art, The British Academy, read 20 May 1970, copyright 1971. Warren Quinn, Morality and Action, ed. Philippa Foot (Introduction, ix–xii), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993 |

主な著作 美徳と悪徳およびその他の道徳哲学エッセイ、バークレー:カリフォルニア大学出版局/オックスフォード:ブラックウェル、1978年(新版あり) 自然の善性。オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局、2001年 道徳的ジレンマ:およびその他の道徳哲学トピック、オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局、2002年 道徳と芸術、英国学士院、1970年5月20日閲覧、1971年著作権。 ウォーレン・クイン、道徳と行動、フィリッパ・フット編(序文、ix-xii)、ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1993年 |

| Judith Jarvis Thomson G. E. M. Anscombe Rosalind Hursthouse Thought experiment Trolley problem |

ジュディス・トムソン G. E. M. アンコム ロザリンド・ハーストハウス 思考実験 トロッコ問題 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philippa_Foot |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆