心の哲学

Philosophy of mind

☆心の哲学(Philosophy of mind)

とは、心の本質と、身体や外界との関係を扱う哲学の一分野である。

心身問題は心の哲学における典型的な課題だが、意識の難問や特定の心的状態の本質など、他にも多くの問題が扱われる。[1][2] [3]

精神の側面として研究されるものには、精神的出来事、精神的機能、精神的特性、意識とその神経相関、精神の存在論、認知と思考の本質、そして精神と身体の

関係などがある。

二元論と一元論は、心身問題に関する二つの中心的な思想体系である。ただし、どちらのカテゴリーにも明確に当てはまらない微妙な見解も生じている。

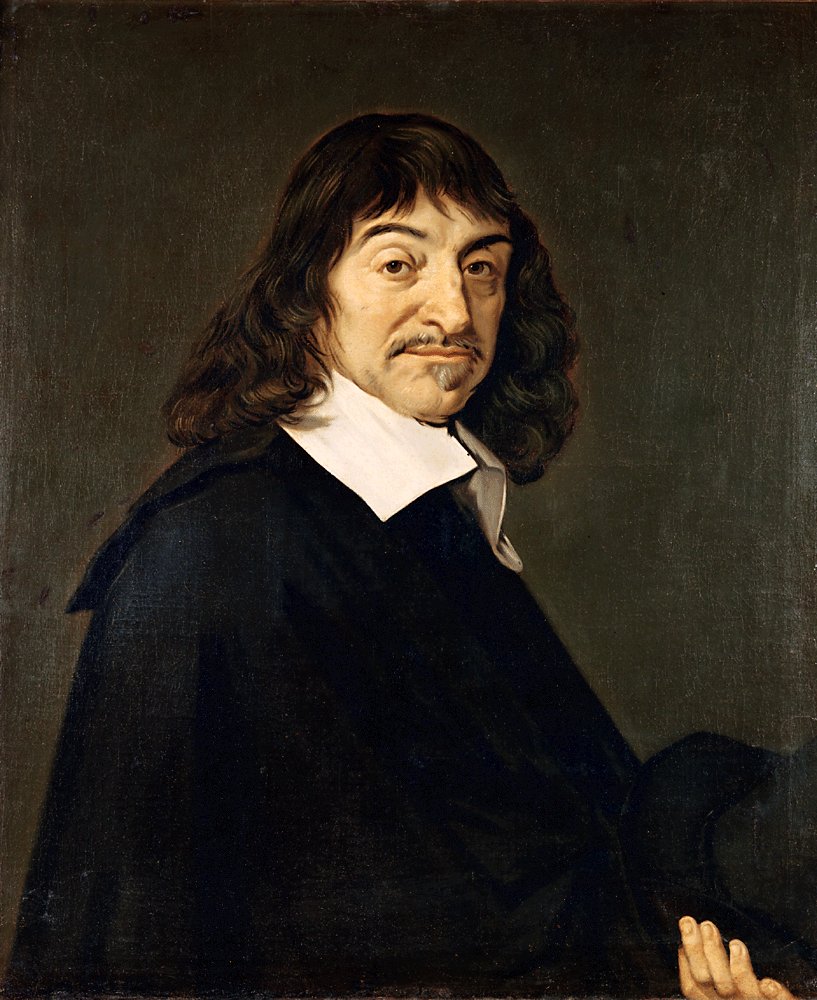

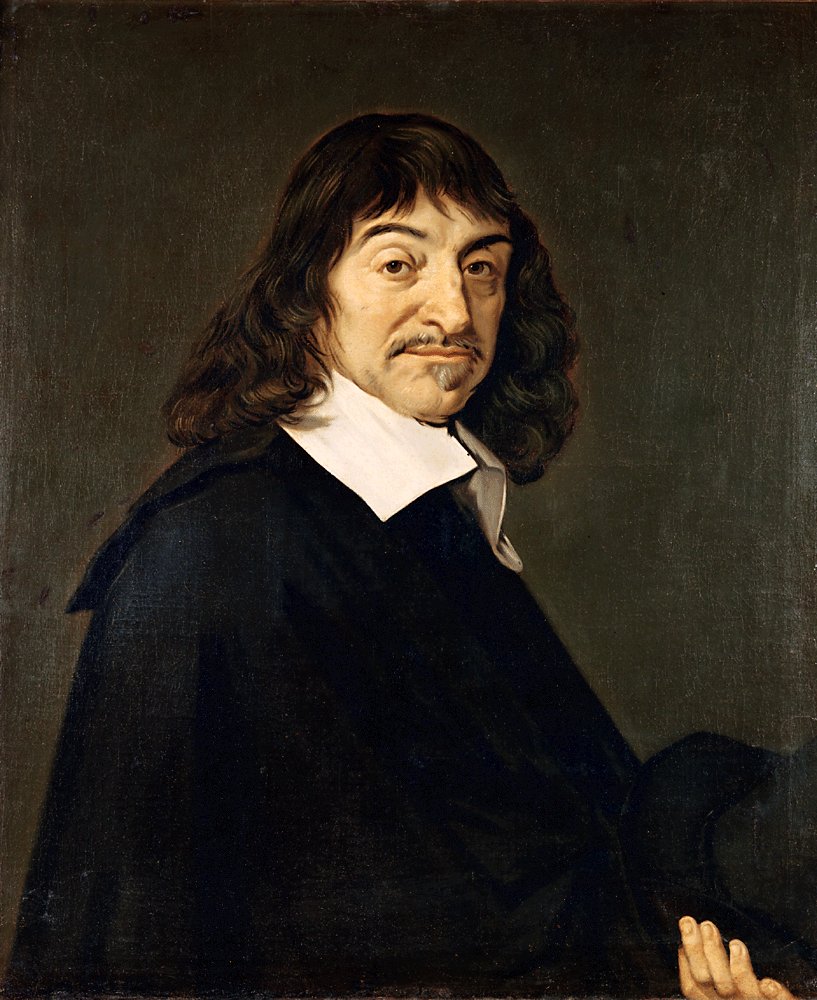

二元論は17世紀のルネ・デカルトによって西洋哲学に導入された[4]。デカルトのような実体二元論者は、精神は独立して存在する実体だと主張する。一

方、特性二元論者は、精神は脳から生じ、脳に還元できない独立した特性の集合体であり、別個の実体ではないと主張する[5]。

一元論は、心と身体は存在論的に区別不能な実体であり、依存関係にある実体ではないとする立場である。この見解は17世紀の合理主義者バルーフ・スピノザ

によって提唱された[6]。物理主義者は、物理理論によって仮定された実体のみが存在し、物理理論が進化を続けるにつれて、精神過程は最終的にこれらの実

体を用いて説明されると主張する。物理主義者は、精神的性質を物理的性質に還元する可能性について様々な立場を維持している(その多くは互換性のある形態

の属性二元論を採用している)[7][8]

[9][10][11][12]。こうした精神的性質の存在論的地位は依然不明確である[11][13][14]。観念論者は、心こそが存在する全てであ

り、外部世界はそれ自体が精神的であるか、あるいは心によって創り出された幻想であると主張する。エルンスト・マッハやウィリアム・ジェームズのような中

立的一元論者は、世界の事象はそれらが関わる関係性のネットワークによって精神的(心理的)なものか物理的なものかのいずれかと見なせると主張する。一

方、スピノザのような二重側面一元論者は、別の何らかの中立的な実体が存在し、物質と精神の両方がこの未知の実体の属性であるという立場を堅持する。20

世紀および21世紀において最も一般的な一元論は、すべて物理主義の変種であった。これらの立場には、行動主義、類型同一性理論、異常一元論、機能主義が

含まれる。[15]

現代の心哲学者の大半は、還元主義的物理主義か非還元主義的物理主義のいずれかの立場を採用し、それぞれ異なる方法で心が身体から分離したものではないと

主張している。[15]

これらのアプローチは科学分野、特に社会生物学、計算機科学(特に人工知能)、進化心理学、そして様々な神経科学において特に影響力を持っている。

[16][17][18] [19]

還元主義的物理主義者は、あらゆる精神的状態と性質は、最終的には生理学的過程や状態の科学的説明によって解明されると主張する。[20][21]

[22]

非還元主義的物理主義者は、精神が独立した実体ではないものの、精神的性質は物理的性質に付随するものである、あるいは精神的記述や説明に用いられる述語

や語彙は不可欠であり、物理科学の言語や低次レベルの説明に還元できないと論じる。[23][24]

神経科学の進歩はこれらの問題の解明に寄与したが、解決には程遠い。現代の精神哲学者は、主観的性質や精神状態・属性の意図性が如何にして自然主義的に説

明し得るかを問い続けている。[25] [26]

心に関する物理主義理論の問題点から、現代の哲学者の中には、伝統的な実体二元論の見解を擁護すべきだと主張する者もいる。この観点からすれば、この理論

は首尾一貫しており、「心と身体の相互作用」といった問題も合理的に解決できるのだ。[27]

| Philosophy of mind

is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of the mind and

its relation to the body and the external world. The mind–body problem is a paradigmatic issue in philosophy of mind, although a number of other issues are addressed, such as the hard problem of consciousness and the nature of particular mental states.[1][2][3] Aspects of the mind that are studied include mental events, mental functions, mental properties, consciousness and its neural correlates, the ontology of the mind, the nature of cognition and of thought, and the relationship of the mind to the body. Dualism and monism are the two central schools of thought on the mind–body problem, although nuanced views have arisen that do not fit one or the other category neatly. Dualism finds its entry into Western philosophy thanks to René Descartes in the 17th century.[4] Substance dualists like Descartes argue that the mind is an independently existing substance, whereas property dualists maintain that the mind is a group of independent properties that emerge from and cannot be reduced to the brain, but that it is not a distinct substance.[5] Monism is the position that mind and body are ontologically indiscernible entities, not dependent substances. This view was espoused by the 17th-century rationalist Baruch Spinoza.[6] Physicalists argue that only entities postulated by physical theory exist, and that mental processes will eventually be explained in terms of these entities as physical theory continues to evolve. Physicalists maintain various positions on the prospects of reducing mental properties to physical properties (many of whom adopt compatible forms of property dualism),[7][8][9][10][11][12] and the ontological status of such mental properties remains unclear.[11][13][14] Idealists maintain that the mind is all that exists and that the external world is either mental itself, or an illusion created by the mind. Neutral monists such as Ernst Mach and William James argue that events in the world can be thought of as either mental (psychological) or physical depending on the network of relationships into which they enter, and dual-aspect monists such as Spinoza adhere to the position that there is some other, neutral substance, and that both matter and mind are properties of this unknown substance. The most common monisms in the 20th and 21st centuries have all been variations of physicalism; these positions include behaviorism, the type identity theory, anomalous monism and functionalism.[15] Most modern philosophers of mind adopt either a reductive physicalist or non-reductive physicalist position, maintaining in their different ways that the mind is not something separate from the body.[15] These approaches have been particularly influential in the sciences, especially in the fields of sociobiology, computer science (specifically, artificial intelligence), evolutionary psychology and the various neurosciences.[16][17][18][19] Reductive physicalists assert that all mental states and properties will eventually be explained by scientific accounts of physiological processes and states.[20][21][22] Non-reductive physicalists argue that although the mind is not a separate substance, mental properties supervene on physical properties, or that the predicates and vocabulary used in mental descriptions and explanations are indispensable, and cannot be reduced to the language and lower-level explanations of physical science.[23][24] Continued neuroscientific progress has helped to clarify some of these issues; however, they are far from being resolved. Modern philosophers of mind continue to ask how the subjective qualities and the intentionality of mental states and properties can be explained in naturalistic terms.[25][26] The problems of physicalist theories of the mind have led some contemporary philosophers to assert that the traditional view of substance dualism should be defended. From this perspective, this theory is coherent, and problems such as "the interaction of mind and body" can be rationally resolved.[27] |

心の哲学とは、心の本質と、身体や外界との関係を扱う哲学の一分野であ

る。 心身問題は心の哲学における典型的な課題だが、意識の難問や特定の心的状態の本質など、他にも多くの問題が扱われる。[1][2] [3] 精神の側面として研究されるものには、精神的出来事、精神的機能、精神的特性、意識とその神経相関、精神の存在論、認知と思考の本質、そして精神と身体の 関係などがある。 二元論と一元論は、心身問題に関する二つの中心的な思想体系である。ただし、どちらのカテゴリーにも明確に当てはまらない微妙な見解も生じている。 二元論は17世紀のルネ・デカルトによって西洋哲学に導入された[4]。デカルトのような実体二元論者は、精神は独立して存在する実体だと主張する。一 方、特性二元論者は、精神は脳から生じ、脳に還元できない独立した特性の集合体であり、別個の実体ではないと主張する[5]。 一元論は、心と身体は存在論的に区別不能な実体であり、依存関係にある実体ではないとする立場である。この見解は17世紀の合理主義者バルーフ・スピノザ によって提唱された[6]。物理主義者は、物理理論によって仮定された実体のみが存在し、物理理論が進化を続けるにつれて、精神過程は最終的にこれらの実 体を用いて説明されると主張する。物理主義者は、精神的性質を物理的性質に還元する可能性について様々な立場を維持している(その多くは互換性のある形態 の属性二元論を採用している)[7][8] [9][10][11][12]。こうした精神的性質の存在論的地位は依然不明確である[11][13][14]。観念論者は、心こそが存在する全てであ り、外部世界はそれ自体が精神的であるか、あるいは心によって創り出された幻想であると主張する。エルンスト・マッハやウィリアム・ジェームズのような中 立的一元論者は、世界の事象はそれらが関わる関係性のネットワークによって精神的(心理的)なものか物理的なものかのいずれかと見なせると主張する。一 方、スピノザのような二重側面一元論者は、別の何らかの中立的な実体が存在し、物質と精神の両方がこの未知の実体の属性であるという立場を堅持する。20 世紀および21世紀において最も一般的な一元論は、すべて物理主義の変種であった。これらの立場には、行動主義、類型同一性理論、異常一元論、機能主義が 含まれる。[15] 現代の心哲学者の大半は、還元主義的物理主義か非還元主義的物理主義のいずれかの立場を採用し、それぞれ異なる方法で心が身体から分離したものではないと 主張している。[15] これらのアプローチは科学分野、特に社会生物学、計算機科学(特に人工知能)、進化心理学、そして様々な神経科学において特に影響力を持っている。 [16][17][18] [19] 還元主義的物理主義者は、あらゆる精神的状態と性質は、最終的には生理学的過程や状態の科学的説明によって解明されると主張する。[20][21] [22] 非還元主義的物理主義者は、精神が独立した実体ではないものの、精神的性質は物理的性質に付随するものである、あるいは精神的記述や説明に用いられる述語 や語彙は不可欠であり、物理科学の言語や低次レベルの説明に還元できないと論じる。[23][24] 神経科学の進歩はこれらの問題の解明に寄与したが、解決には程遠い。現代の精神哲学者は、主観的性質や精神状態・属性の意図性が如何にして自然主義的に説 明し得るかを問い続けている。[25] [26] 心に関する物理主義理論の問題点から、現代の哲学者の中には、伝統的な実体二元論の見解を擁護すべきだと主張する者もいる。この観点からすれば、この理論 は首尾一貫しており、「心と身体の相互作用」といった問題も合理的に解決できるのだ。[27] |

| Mind–body problem Main article: Mind–body problem  Illustration of mind–body dualism by René Descartes. Inputs are passed by the sensory organs to the pineal gland, and from there to the immaterial spirit. The mind–body problem concerns the explanation of the relationship that exists between minds, or mental processes, and bodily states or processes.[1] The main aim of philosophers working in this area is to determine the nature of the mind and mental states/processes, and how—or even if—minds are affected by and can affect the body. Perceptual experiences depend on stimuli that arrive at our various sensory organs from the external world, and these stimuli cause changes in our mental states, ultimately causing us to feel a sensation, which may be pleasant or unpleasant. For example, someone's desire for a slice of pizza will tend to cause that person to move his or her body in a specific manner and direction to obtain what he or she wants. The question, then, is how it can be possible for conscious experiences to arise out of a lump of gray matter endowed with nothing but electrochemical properties.[15] A related problem is how someone's propositional attitudes (e.g. beliefs and desires) cause that individual's neurons to fire and muscles to contract. These comprise some of the puzzles that have confronted epistemologists and philosophers of mind from the time of René Descartes.[4] |

心身問題 詳細な記事: 心身問題  ルネ・デカルトによる心身二元論の図解。感覚器官から松果体に情報が伝達され、そこから非物質的な精神へと渡される。 心身問題は、精神(あるいは精神過程)と身体状態・過程との間に存在する関係の説明に関わる。[1] この分野で研究する哲学者の主な目的は、精神と精神状態・過程の本質を明らかにし、精神が身体に影響を受けるか、あるいは身体に影響を与えるか、その方法 や可能性を解明することである。 知覚体験は、外界から様々な感覚器官に届く刺激に依存する。これらの刺激は精神状態に変化を引き起こし、最終的に快または不快な感覚を生じさせる。例え ば、ピザの一切れを欲する欲求は、その人格が望むものを得るために特定の方法と方向で身体を動かす傾向を生む。そこで問題となるのは、電気化学的特性しか 備えていない灰白質の塊から、いかにして意識的経験が生じうるのかということだ。[15] 関連する問題は、個人の命題的態度(例えば信念や欲求)が、いかにしてその個人のニューロンを放電させ、筋肉を収縮させるかである。これらはルネ・デカルトの時代から認識論者や心哲学者が直面してきた難問の一部を構成している。[4] |

| Dualist solutions to the mind–body problem See also: Mind in eastern philosophy Dualism is a set of views about the relationship between mind and matter (or body). It begins with the claim that mental phenomena are, in some respects, non-physical.[5] Mind and body (Indriya) are different functions of prakriti and so a form of property dualism may be found in the ancient Indian philosophical schools of Samkhya and Yoga (ca. 6th c. BCE). Wrongly conflating purusha ("spirit", or better, pure consciousness) with mind or manas (a development of non-conscious prakriti) while correctly distinguishing purusha and prakriti (two eternally-different ontological entities)[28] leads to the erroneous conclusion that Samkhya supports mind-body dualism, specifically substance dualism. Yet both mind and body are equally non-conscious (jaDaa) in Samkhya and, while they are different developments of prakriti, they are both made up of gunas. In Western philosophy, the earliest discussions of dualist ideas are in the writings of Plato who suggested that humans' intelligence (a faculty of the mind or soul) could not be identified with, or explained in terms of, their physical body.[29][30] However, the best-known version of dualism is due to René Descartes (1641), and holds that the mind is a non-extended, non-physical substance, a "res cogitans".[4] Descartes was the first to clearly identify the mind with consciousness and self-awareness, and to distinguish this from the brain, which was the seat of intelligence. He was therefore the first to formulate the mind–body problem in the form in which it still exists today.[4] |

心身問題に対する二元論的解決策 関連項目:東洋哲学における心 二元論とは、心と物質(あるいは身体)の関係に関する一連の見解である。それは、精神現象が、ある点において非物理的であるという主張から始まる。[5] 心と身体(インドリヤ)はプラクリティの異なる機能であり、したがって古代インドの哲学学派であるサンキヤとヨーガ(紀元前6世紀頃)には、ある種の属性 二元論が見出される。プルシャ(「精神」、より正確には純粋意識)を心やマナス(非意識的なプラクリティの発達形態)と誤って混同しつつ、プルシャとプラ クリティ(永遠に異なる二つの存在論的実体)を正しく区別する[28]ことは、サンキヤが心身二元論、特に実体二元論を支持するという誤った結論につなが る。しかし、サンキヤにおいて心と身体は等しく非意識的(ジャダー)であり、プラクリティの異なる発展形態ではあるが、どちらもグナで構成されている。 西洋哲学において、二元論的思想の最も初期の議論はプラトンの著作に見られる。彼は人間の知性(心または魂の能力)が、その物理的身体と同定したり、身体 の観点から説明したりすることはできないと示唆した。[29][30] しかし最も有名な二元論はルネ・デカルト(1641年)によるもので、精神は非延展的で非物理的な実体、「思考する実体(res cogitans)」であると主張する。[4] デカルトは初めて、精神を明確に意識と自己認識と同一視し、知性の座である脳と区別した。したがって彼は、今日まで存在する形で心身問題を初めて定式化し たのである。[4] |

| Arguments for dualism The most frequently used argument in favor of dualism appeals to the common-sense intuition that conscious experience is distinct from inanimate matter. If asked what the mind is, the average person would usually respond by identifying it with their self, their personality, their soul, or another related entity. They would almost certainly deny that the mind simply is the brain, or vice versa, finding the idea that there is just one ontological entity at play to be too mechanistic or unintelligible.[5] Modern philosophers of mind think that these intuitions are misleading, and that critical faculties, along with empirical evidence from the sciences, should be used to examine these assumptions and determine whether there is any real basis to them.[5] According to philosophers like Thomas Nagel and Frank Jackson, the mental and the physical seem to have quite different, and perhaps irreconcilable, properties.[31][32] Mental events have a subjective quality, whereas physical events do not. So, for example, one can reasonably ask what a burnt finger feels like, or what a blue sky looks like, or what nice music sounds like to a person. But it is meaningless, or at least odd, to ask what a surge in the uptake of glutamate in the dorsolateral portion of the prefrontal cortex feels like. Philosophers of mind call the subjective aspects of mental events "qualia" or "raw feels".[31] There are qualia involved in these mental events that seem particularly difficult to reduce to anything physical. David Chalmers explains this argument by stating that we could conceivably know all the objective information about something, such as the brain states and wavelengths of light involved with seeing the color red, but still not know something fundamental about the situation – what it is like to see the color red.[33] If consciousness (the mind) can exist independently of physical reality (the brain), one must explain how physical memories are created concerning consciousness. Dualism must therefore explain how consciousness affects physical reality. One possible explanation is that of a miracle, proposed by Arnold Geulincx and Nicolas Malebranche, where all mind–body interactions require the direct intervention of God. Another argument that has been proposed by C. S. Lewis[34] is the Argument from Reason: if, as monism implies, all of our thoughts are the effects of physical causes, then we have no reason for assuming that they are also the consequent of a reasonable ground. Knowledge, however, is apprehended by reasoning from ground to consequent. Therefore, if monism is correct, there would be no way of knowing this—or anything else—we could not even suppose it, except by a fluke. The zombie argument is based on a thought experiment proposed by Todd Moody, and developed by David Chalmers in his book The Conscious Mind. The basic idea is that one can imagine one's body, and therefore conceive the existence of one's body, without any conscious states being associated with this body. Chalmers' argument is that it seems possible that such a being could exist because all that is needed is that all and only the things that the physical sciences describe about a zombie must be true of it. Since none of the concepts involved in these sciences make reference to consciousness or other mental phenomena, and any physical entity can be by definition described scientifically via physics, the move from conceivability to possibility is not such a large one.[35] Others such as Dennett have argued that the notion of a philosophical zombie is an incoherent,[36] or unlikely,[37] concept. It has been argued under physicalism that one must either believe that anyone including oneself might be a zombie, or that no one can be a zombie—following from the assertion that one's own conviction about being (or not being) a zombie is a product of the physical world and is therefore no different from anyone else's. This argument has been expressed by Dennett who argues that "Zombies think they are conscious, think they have qualia, think they suffer pains—they are just 'wrong' (according to this lamentable tradition) in ways that neither they nor we could ever discover!"[36] See also the problem of other minds. Avshalom Elitzur has described himself as a "reluctant dualist". One argument Elitzur makes in favor of dualism is an argument from bafflement. According to Elitzur, a conscious being can conceive of a P-zombie version of his/herself. However, a P-zombie cannot conceive of a version of itself that lacks corresponding qualia.[38] Christian List argues that the existence of first-person perspectives is evidence against physicalist views of consciousness.[39] According to List, first-personal phenomenal facts cannot supervene on third-person physical facts. However, List argues that this also refutes versions of dualism that have purely third-personal metaphysics. List has proposed a model he calls the "many-worlds theory of consciousness" in order to reconcile the subjective nature of consciousness without lapsing into solipsism.[40] |

二元論の主張 二元論を支持する最も頻繁に用いられる論拠は、意識的経験が無生物の物質とは異なるという常識的直観に訴えるものである。心が何かと問われれば、普通の人 は通常、それを自己や人格、魂、あるいは他の関連する実体と同一視して答えるだろう。彼らはほぼ確実に、心が単に脳であるとか、その逆であるとかいう考え を否定するだろう。つまり、存在論的に単一の実体が作用しているという考えは、あまりに機械論的であるか、あるいは理解不能だと感じるのだ。[5] 現代の心哲学者は、こうした直観は誤解を招くものであり、批判的思考力と科学からの経験的証拠を用いて、これらの前提を検証し、それらに真の根拠があるか どうかを判断すべきだと考えている。[5] トーマス・ネーゲルやフランク・ジャクソンといった哲学者によれば、精神的現象と物理的現象は全く異なる、おそらく調和不可能な性質を持つように見える。 [31][32] 精神的現象には主観的性質があるが、物理的現象にはない。例えば、火傷した指の感覚や、青空の見た目、心地よい音楽の響きを人格に尋ねることは合理的だ。 しかし、前頭前野背外側部におけるグルタミン酸の取り込み急増がどんな感じか尋ねることは、無意味か、少なくとも奇妙だ。 心哲学者は、精神的出来事の主観的側面を「クオリア」または「生の感覚」と呼ぶ。[31] これらの精神的出来事にはクオリアが関与しており、特に物理的な何かに還元するのが困難に見える。デイヴィッド・チャーマーズはこの議論を、例えば赤色を 見る際の脳状態や光の波長といった客観的情報を全て知り得ても、その状況の本質的な何か――赤色を見る体験そのもの――は依然として知ることができないと 説明している。[33] もし意識(精神)が物理的現実(脳)から独立して存在し得るなら、意識に関する物理的記憶がどのように生成されるかを説明しなければならない。したがって 二元論は、意識が物理的現実にどのように影響するかを説明する必要がある。一つの説明として、アーノルド・ヘウリンクスとニコラ・マレブランシュが提唱し た「奇跡説」がある。これは全ての心身相互作用が神の直接介入を必要とするというものである。 C・S・ルイス[34]が提唱した別の論証は「理性からの論証」である。もし一元論が示唆するように、我々の思考がすべて物理的原因の結果であるならば、 それらが合理的な根拠の結果でもあると仮定する理由はない。しかし知識は、根拠から結果へと推論することによって把握される。したがって、一元論が正しい ならば、このこと(あるいは他のいかなることも)を知る方法はない。偶然を除けば、それを仮定することすらできないのだ。 ゾンビの議論は、トッド・ムーディが提案し、デイヴィッド・チャーマーズが著書『意識の心』で発展させた思考実験に基づいている。基本概念は、自らの身体 を想像し、したがって自らの身体の存在を概念化することが可能でありながら、この身体に意識状態が一切結びついていない状態を想定できるというものだ。 チャーマーズの論点は、物理科学がゾンビについて記述する事柄のすべてが、かつそれだけが真であることが必要条件である以上、そのような存在が存在する可 能性はあり得るように思われるというものだ。物理科学に関わる概念は意識や他の精神的現象に言及せず、また物理的実体は定義上物理学によって科学的に記述 可能であるため、想像可能性から可能性への移行はそれほど大きな飛躍ではない[35]。デネットら他の論者は、哲学的ゾンビの概念は矛盾している [36]、あるいはありえない[37]概念だと主張している。物理主義の立場では、自己を含む誰もがゾンビである可能性を認めざるを得ないか、あるいは誰 もゾンビになり得ないと主張せざるを得ない。これは、ゾンビである(あるいはそうでない)という自己の確信が物理世界の産物であり、したがって他者と何ら 異なるものではないという主張から導かれる。この議論はデネットによって「ゾンビは自分が意識を持っていると思い込み、クオリアを所有していると思い込 み、苦悩を経験していると思い込む。彼らは(この嘆かわしい伝統によれば)単に『間違っている』だけだ。しかもその誤りは、彼ら自身も我々も決して発見で きない形で存在する!」[36] と表現されている。他者の心の問題も参照のこと。 アヴシャロム・エリツールは自らを「不本意な二元論者」と称している。 |

Interactionist dualism Portrait of René Descartes by Frans Hals (1648) Interactionist dualism, or simply interactionism, is the particular form of dualism first espoused by Descartes in the Meditations.[4] In the 20th century, its major defenders have been Karl Popper and John Carew Eccles.[41] It is the view that mental states, such as beliefs and desires, causally interact with physical states.[5] Descartes's argument for this position can be summarized as follows: Seth has a clear and distinct idea of his mind as a thinking thing that has no spatial extension (i.e., it cannot be measured in terms of length, weight, height, and so on). He also has a clear and distinct idea of his body as something that is spatially extended, subject to quantification and not able to think. It follows that mind and body are not identical because they have radically different properties.[4] Seth's mental states (desires, beliefs, etc.) have causal effects on his body and vice versa: A child touches a hot stove (physical event) which causes pain (mental event) and makes her yell (physical event), this in turn provokes a sense of fear and protectiveness in the caregiver (mental event), and so on. Descartes' argument depends on the premise that what Seth believes to be "clear and distinct" ideas in his mind are necessarily true. Many contemporary philosophers doubt this.[42][43][44] For example, Joseph Agassi suggests that several scientific discoveries made since the early 20th century have undermined the idea of privileged access to one's own ideas. Freud claimed that a psychologically-trained observer can understand a person's unconscious motivations better than the person himself does. Duhem has shown that a philosopher of science can know a person's methods of discovery better than that person herself does, while Malinowski has shown that an anthropologist can know a person's customs and habits better than the person whose customs and habits they are. He also asserts that modern psychological experiments that cause people to see things that are not there provide grounds for rejecting Descartes' argument, because scientists can describe a person's perceptions better than the person themself can.[45][46] |

相互作用的二元論 フランツ・ハルス作 ルネ・デカルトの肖像 (1648年) 相互作用的二元論、あるいは単に相互作用論とは、デカルトが『省察』で初めて提唱した二元論の特殊な形態である[4]。20世紀においては、カール・ポ パーとジョン・カレウ・エクルズがその主要な擁護者であった[41]。これは、信念や欲望といった精神的状態が物理的状態と因果的に相互作用するという見 解である[5]。 デカルトのこの立場に対する論証は、以下のように要約できる: セスは、空間的広がりを持たない(つまり長さ、重さ、高さなどで測れない)思考する存在としての心について、明晰かつ区別された観念を持っている。また、 空間的に広がり、量化可能であり、思考できないものとしての身体についても、明晰かつ区別された観念を持っている。したがって、心と身体は根本的に異なる 性質を持つため同一ではない。[4] セスが持つ精神状態(欲求、信念など)は身体に因果的影響を与え、その逆もまた然りだ。例えば子供が熱いストーブに触れる(物理的出来事)と痛みが生じ (精神的出来事)、叫び声を上げる(物理的出来事)。これが養育者に恐怖心や保護欲を喚起する(精神的出来事)といった連鎖が起こる。 デカルトの議論は、セスが心の中で「明晰かつ区別された」と信じる観念が必然的に真実であるという前提に依存している。多くの現代哲学者はこれを疑ってい る[42][43][44]。例えばジョセフ・アガッシは、20世紀初頭以降のいくつかの科学的発見が、自己の観念への特権的アクセスという考えを弱体化 させたと示唆している。フロイトは、心理学的訓練を受けた観察者が、人格よりもその人格の無意識の動機を理解できると主張した。デュエムは、科学哲学者が 人格よりもその人格の発見方法を理解できることを示し、マリノフスキーは、人類学者が人格よりもその人格の習慣や慣習を理解できることを示した。彼はま た、存在しないものを人に見せる現代の心理実験が、デカルトの主張を退ける根拠となると主張する。なぜなら科学者は、人格以上にその人格の知覚を正確に記 述できるからだ。[45][46] |

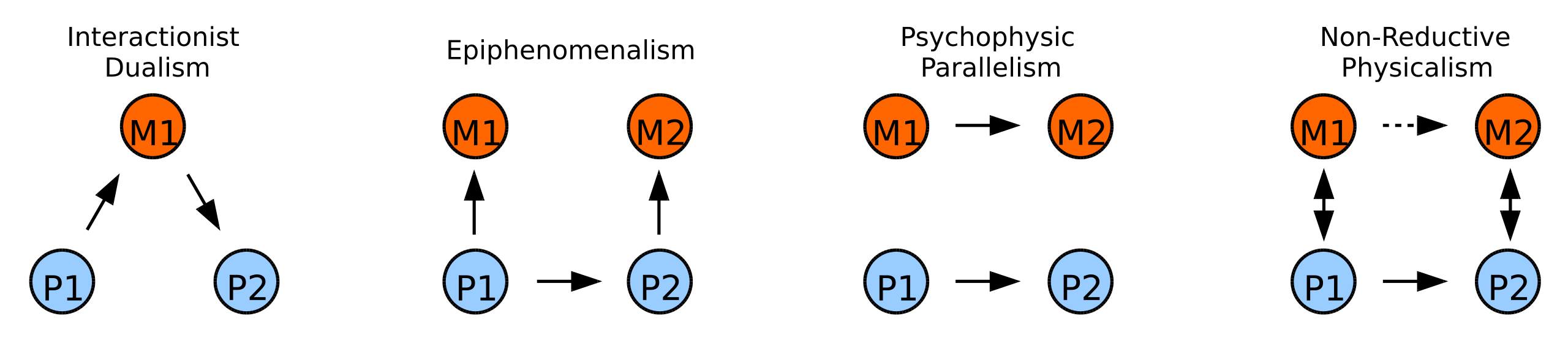

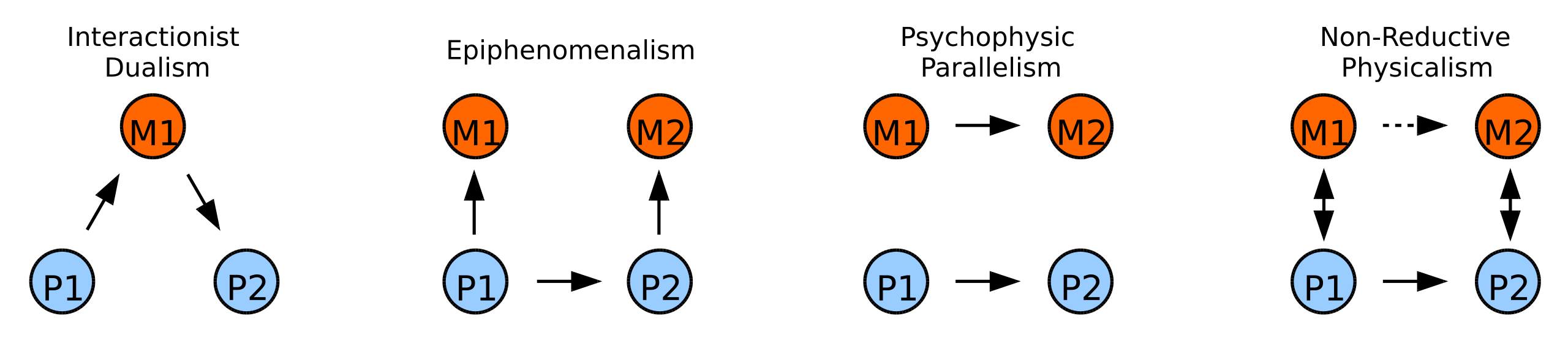

Other forms of dualism Four varieties of dualism. The arrows indicate the direction of the causal interactions. Occasionalism is not shown. Psychophysical parallelism Psychophysical parallelism, or simply parallelism, is the view that mind and body, while having distinct ontological statuses, do not causally influence one another. Instead, they run along parallel paths (mind events causally interact with mind events and brain events causally interact with brain events) and only seem to influence each other.[47] This view was most prominently defended by Gottfried Leibniz. Although Leibniz was an ontological monist who believed that only one type of substance, the monad, exists in the universe, and that everything is reducible to it, he nonetheless maintained that there was an important distinction between "the mental" and "the physical" in terms of causation. He held that God had arranged things in advance so that minds and bodies would be in harmony with each other. This is known as the doctrine of pre-established harmony.[48] Occasionalism Occasionalism is the view espoused by Nicholas Malebranche as well as Islamic philosophers such as Abu Hamid Muhammad ibn Muhammad al-Ghazali that asserts all supposedly causal relations between physical events, or between physical and mental events, are not really causal at all. While body and mind are different substances, causes (whether mental or physical) are related to their effects by an act of God's intervention on each specific occasion.[49] Property dualism Property dualism is the view that the world is constituted of one kind of substance – the physical kind – and there exist two distinct kinds of properties: physical properties and mental properties. It is the view that non-physical, mental properties (such as beliefs, desires and emotions) inhere in some physical bodies (at least, brains). Sub-varieties of property dualism include: 1. Emergent materialism asserts that when matter is organized in the appropriate way (i.e., in the way that living human bodies are organized), mental properties emerge in a way not fully accountable for by physical laws.[5] These emergent properties have an independent ontological status and cannot be reduced to, or explained in terms of, the physical substrate from which they emerge. They are dependent on the physical properties from which they emerge, but opinions vary as to the coherence of top–down causation, that is, the causal effectiveness of such properties. A form of emergent materialism has been espoused by David Chalmers and the concept has undergone something of a renaissance in recent years,[50] but it was already suggested in the 19th century by William James. 2. Epiphenomenalism is a doctrine first formulated by Thomas Henry Huxley.[51] It consists of the view that mental phenomena are causally ineffectual, where one or more mental states do not have any influence on physical states or mental phenomena are the effects, but not the causes, of physical phenomena. Physical events can cause other physical and mental events, but mental events cannot cause anything since they are just causally inert by-products (i.e., epiphenomena) of the physical world.[47] This view has been defended by Frank Jackson.[52] 3. Non-reductive physicalism is the view that mental properties form a separate ontological class to physical properties: mental states (such as qualia) are not reducible to physical states. The ontological stance towards qualia in the case of non-reductive physicalism does not imply that qualia are causally inert; this is what distinguishes it from epiphenomenalism. 4. Panpsychism is the view that all matter has a mental aspect, or, alternatively, all objects have a unified center of experience or point of view. Superficially, it seems to be a form of property dualism, since it regards everything as having both mental and physical properties. However, some panpsychists say that mechanical behaviour is derived from the primitive mentality of atoms and molecules—as are sophisticated mentality and organic behaviour, the difference being attributed to the presence or absence of complex structure in a compound object. So long as the reduction of non-mental properties to mental ones is in place, panpsychism is not a (strong) form of property dualism; otherwise it is. |

他の形の二元論 四種類の二元論。矢印は因果的相互作用の方向を示す。機会主義は図示されていない。 心身並行説 心身並行説、あるいは単に並行説とは、心と身体は存在論的な地位こそ異なるものの、互いに因果的に影響し合うことはないという見解である。代わりに、それ らは並行した経路を辿る(心の事象は心の事象と因果的に相互作用し、脳の事象は脳の事象と因果的に相互作用する)だけで、互いに影響し合っているように見 えるに過ぎない[47]。この見解はゴットフリート・ライプニッツによって最も顕著に擁護された。ライプニッツは宇宙に単一の物質(モナド)のみが存在 し、万物はこれに還元されると信じる存在論的一元論者であったが、それでも因果関係において「精神的」と「物理的」の間に重要な区別があると主張した。彼 は神が予め物事を配置し、精神と身体が互いに調和するようにしたと考えた。これは予め調和説として知られる。[48] 機会主義 機会主義とは、ニコラ・マレブランシュやアブー・ハミド・ムハンマド・イブン・ムハンマド・アル=ガザーリーといったイスラム哲学者たちが主張した見解で ある。物理的出来事間、あるいは物理的・精神的出来事間の因果関係とされるものは、実際には全く因果関係ではないと主張する。身体と精神は異なる物質であ るが、原因(精神的か物理的かを問わず)はその結果と、各々の特定の機会に神の介入という行為によって関連づけられるのである。[49] 属性二元論 属性二元論とは、世界は一つの種類の物質(物理的な種類)で構成されており、二つの異なる種類の属性(物理的属性と精神的属性)が存在するという見解であ る。非物理的な精神的性質(信念、欲求、感情など)が、何らかの物理的身体(少なくとも脳)に内在するという見解である。性質二元論の亜種には以下が含ま れる: 1. 新生物質論は、物質が適切な方法で組織化されると(すなわち、生きている人間の身体が組織化される方法で)、物理法則では完全に説明できない形で精神的性 質が新生すると主張する。[5] こうした創発的性質は独立した存在論的地位を持ち、創発元の物理的基盤に還元したり、それによって説明したりすることはできない。それらは創発元の物理的 性質に依存するが、トップダウン因果関係、すなわちこうした性質の因果的有効性に関する見解は分かれている。デヴィッド・チャーマーズは一種の新生物質論 を提唱しており、この概念は近年再評価されている[50]が、ウィリアム・ジェームズによって19世紀に既に示唆されていた。 2. 随伴現象論はトーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリーによって初めて提唱された学説である。[51] これは精神的現象が因果的に無効であるという見解であり、一つ以上の精神的状態が物理的状態に影響を与えない、あるいは精神的現象は物理的現象の結果では あるが原因ではないとする。物理的出来事は他の物理的・精神的出来事を引き起こし得るが、精神的出来事は物理世界の単なる因果的に不活性な副産物(すなわ ち付随現象)であるため、何ものも引き起こせない。[47] この見解はフランク・ジャクソンによって擁護されている。[52] 3. 非還元的物理主義とは、精神的性質が物理的性質とは別の存在論的クラスを形成するという見解である。すなわち、心的状態(クオリアなど)は物理的状態に還 元できない。非還元的物理主義におけるクオリアへの存在論的立場は、クオリアが因果的に無力であることを意味しない。これが付随現象論との相違点である。 4. 全心論とは、あらゆる物質が精神的な側面を持つ、あるいは全ての物体が統一された経験の中心点や視点を持つという見解である。表面的には、あらゆるものに 精神的性質と物理的性質の両方があると見なすため、一種の性質二元論のように思える。しかし一部の汎精神論者は、機械的行動は原子や分子の原始的な精神性 から派生したものであり、高度な精神性や有機的行動も同様に派生したものであると主張する。その差異は複合物における複雑な構造の有無に起因するとされ る。非精神的性質を精神的性質に還元する仕組みが機能している限り、汎精神論は(強固な)性質二元論ではない。そうでない場合はそうである。 |

| Dual aspect theory Dual aspect theory or dual-aspect monism is the view that the mental and the physical are two aspects of, or perspectives on, the same substance. (Thus it is a mixed position, which is monistic in some respects). In modern philosophical writings, the theory's relationship to neutral monism has become somewhat ill-defined, but one proffered distinction says that whereas neutral monism allows the context of a given group of neutral elements and the relationships into which they enter to determine whether the group can be thought of as mental, physical, both, or neither, dual-aspect theory suggests that the mental and the physical are manifestations (or aspects) of some underlying substance, entity or process that is itself neither mental nor physical as normally understood. Various formulations of dual-aspect monism also require the mental and the physical to be complementary, mutually irreducible and perhaps inseparable (though distinct).[53][54][55] Experiential dualism This is a philosophy of mind that regards the degrees of freedom between mental and physical well-being as not synonymous thus implying an experiential dualism between body and mind. An example of these disparate degrees of freedom is given by Allan Wallace who notes that it is "experientially apparent that one may be physically uncomfortable—for instance, while engaging in a strenuous physical workout—while mentally cheerful; conversely, one may be mentally distraught while experiencing physical comfort".[56] Experiential dualism notes that our subjective experience of merely seeing something in the physical world seems qualitatively different from mental processes like grief that comes from losing a loved one. This philosophy is a proponent of causal dualism, which is defined as the dual ability for mental states and physical states to affect one another. Mental states can cause changes in physical states and vice versa. However, unlike cartesian dualism or some other systems, experiential dualism does not posit two fundamental substances in reality: mind and matter. Rather, experiential dualism is to be understood as a conceptual framework that gives credence to the qualitative difference between the experience of mental and physical states. Experiential dualism is accepted as the conceptual framework of Madhyamaka Buddhism. Madhayamaka Buddhism goes further, finding fault with the monist view of physicalist philosophies of mind as well in that these generally posit matter and energy as the fundamental substance of reality. Nonetheless, this does not imply that the cartesian dualist view is correct, rather Madhyamaka regards as error any affirming view of a fundamental substance to reality. In denying the independent self-existence of all the phenomena that make up the world of our experience, the Madhyamaka view departs from both the substance dualism of Descartes and the substance monism—namely, physicalism—that is characteristic of modern science. The physicalism propounded by many contemporary scientists seems to assert that the real world is composed of physical things-in-themselves, while all mental phenomena are regarded as mere appearances, devoid of any reality in and of themselves. Much is made of this difference between appearances and reality.[56] Indeed, physicalism, or the idea that matter is the only fundamental substance of reality, is explicitly rejected by Buddhism. In the Madhyamaka view, mental events are no more or less real than physical events. In terms of our common-sense experience, differences of kind do exist between physical and mental phenomena. While the former commonly have mass, location, velocity, shape, size, and numerous other physical attributes, these are not generally characteristic of mental phenomena. For example, we do not commonly conceive of the feeling of affection for another person as having mass or location. These physical attributes are no more appropriate to other mental events such as sadness, a recalled image from one's childhood, the visual perception of a rose, or consciousness of any sort. Mental phenomena are, therefore, not regarded as being physical, for the simple reason that they lack many of the attributes that are uniquely characteristic of physical phenomena. Thus, Buddhism has never adopted the physicalist principle that regards only physical things as real.[56] |

二重側面理論 二重側面理論、あるいは二重側面一元論とは、精神的側面と物理的側面が同一の実体の二つの側面、あるいは二つの見方であるとする見解である。(したがって これは混血の立場であり、ある点では一元的である) 現代の哲学文献では、この理論と中立的一元論との関係はやや曖昧になっているが、一つの区別として、中立的一元論は特定のニュートラル要素群の文脈とそれ らの要素が形成する関係性によって、その群を精神的・物理的・両方・あるいはどちらでもないものとして捉えられるかを決定する一方、 二面性理論は、精神的要素と物理的要素が、それ自体が通常理解される精神的でも物理的でもない、何らかの根底にある実体・存在・過程の顕現(あるいは側 面)であると示唆する。二面性一元論の様々な定式化では、精神的要素と物理的要素が補完的であり、相互に還元不可能で、おそらく不可分(ただし区別可能) であることも要求される。[53][54][55] 経験的二元論 これは、精神的・身体的健康の自由度の程度が同義ではないとみなす心哲学であり、それゆえに身体と精神の間に経験的二元論が存在することを示唆する。こう した異なる自由度の例としてアラン・ウォレスは、「例えば激しい運動中に身体的には不快でありながら精神的には明るい状態にあること、逆に身体的には快適 でありながら精神的には混乱している状態にあることが経験的に明らかである」と指摘している。[56] 体験的二元論は、物理世界で単に何かを見るという主観的経験が、愛する人を失う悲しみといった精神的プロセスとは質的に異なる、と指摘する。この哲学は因 果的二元論を支持する。因果的二元論とは、精神的状態と物理的状態が互いに影響し合う二重の能力と定義される。精神的状態は物理的状態に変化を引き起こ し、その逆もまた然りである。 しかし、デカルト主義や他の体系とは異なり、経験的二元論は現実において心と物質という二つの根本的実体を仮定しない。むしろ、経験的二元論は精神的状態 と物理的状態の経験の質的差異を認める概念的枠組みとして理解されるべきだ。経験的二元論は中観仏教の概念的枠組みとして受け入れられている。 中観派仏教はさらに踏み込み、物理主義的な心哲学の一元論的見解にも問題があると指摘する。これらの哲学は概して物質とエネルギーを現実の根本的実体とし て想定するからだ。とはいえ、これはデカルト主義二元論の見解が正しいことを意味するわけではない。むしろ中観派は、現実に対する根本的実体を肯定するあ らゆる見解を誤りとみなす。 中観派の見解は、我々の経験世界を構成するあらゆる現象の独立した自己存在を否定することで、デカルトの実体二元論と、現代科学の特徴である実体一元論 (すなわち物理主義)の両方から離脱する。多くの現代科学者が提唱する物理主義は、現実世界は物理的な「物自体」で構成され、全ての精神的現象は単なる表 象に過ぎず、それ自体に何ら実在性を持たないと主張しているようだ。この表象と実在の差異が大きく強調されている。[56] 実際、物理主義、すなわち物質が現実の唯一の根本的実体であるという考えは、仏教によって明示的に否定されている。 中観派の立場では、精神的現象は物理的現象と比べて、現実性の点で優劣はない。常識的な経験の観点から見れば、物理的現象と精神的現象の間には種類の違い が確かに存在する。前者は一般的に質量、位置、速度、形状、大きさ、その他多くの物理的属性を持つが、これらは精神的現象には通常見られない特徴である。 例えば、他者への愛情の感情が質量や位置を持つとは、通常考えられない。こうした物理的属性は、悲しみや幼少期の記憶の想起、バラの視覚的知覚、あるいは あらゆる種類の意識といった他の精神的現象にも同様に当てはまらない。したがって精神的現象は、物理現象に特有の属性を多く欠いているという単純な理由か ら、物理的とは見なされない。こうして仏教は、物理的なもののみを実在と見なす物理主義の原理を決して採用してこなかったのである。[56] |

| Monist solutions to the mind–body problem In contrast to dualism, monism does not accept any fundamental divisions. The fundamentally disparate nature of reality has been central to forms of eastern philosophies for over two millennia. In Indian and Chinese philosophy, monism is integral to how experience is understood. Today, the most common forms of monism in Western philosophy are physicalist.[15] Physicalistic monism asserts that the only existing substance is physical, in some sense of that term to be clarified by our best science.[57] However, a variety of formulations (see below) are possible. Another form of monism, idealism, states that the only existing substance is mental. Although pure idealism, such as that of George Berkeley, is uncommon in contemporary Western philosophy, a more sophisticated variant called panpsychism, according to which mental experience and properties may be at the foundation of physical experience and properties, has been espoused by some philosophers such as Alfred North Whitehead[58] and David Ray Griffin.[50] Phenomenalism is the theory that representations (or sense data) of external objects are all that exist. Such a view was briefly adopted by Bertrand Russell and many of the logical positivists during the early 20th century.[59] A third possibility is to accept the existence of a basic substance that is neither physical nor mental. The mental and physical would then both be properties of this neutral substance. Such a position was adopted by Baruch Spinoza[6] and was popularized by Ernst Mach[60] in the 19th century. This neutral monism, as it is called, resembles property dualism. Physicalistic monisms Behaviorism Main article: Behaviorism Behaviorism dominated philosophy of mind for much of the 20th century, especially the first half.[15] In psychology, behaviorism developed as a reaction to the inadequacies of introspectionism.[57] Introspective reports on one's own interior mental life are not subject to careful examination for accuracy and cannot be used to form predictive generalizations. Without generalizability and the possibility of third-person examination, the behaviorists argued, psychology cannot be scientific.[57] The way out, therefore, was to eliminate the idea of an interior mental life (and hence an ontologically independent mind) altogether and focus instead on the description of observable behavior.[61] Parallel to these developments in psychology, a philosophical behaviorism (sometimes called logical behaviorism) was developed.[57] This is characterized by a strong verificationism, which generally considers unverifiable statements about interior mental life pointless. For the behaviorist, mental states are not interior states on which one can make introspective reports. They are just descriptions of behavior or dispositions to behave in certain ways, made by third parties to explain and predict another's behavior.[62] Philosophical behaviorism has fallen out of favor since the latter half of the 20th century, coinciding with the rise of cognitivism.[1] |

心身問題に対する一元論的解決策 二元論とは対照的に、一元論は根本的な区分を一切認めない。現実の根本的に異なる性質は、二千年以上にわたり東洋哲学の諸形態において中心的な位置を占め てきた。インドや中国の哲学において、一元論は経験の理解に不可欠な要素である。今日、西洋哲学における最も一般的な一元論は物理主義である[15]。物 理主義的一元論は、存在する唯一の物質は物理的であると主張する。その物理的という用語の意味は、我々の最良の科学によって明確にされるべきである [57]。しかし、様々な定式化(以下参照)が可能である。一元論の別の形態である観念論は、唯一存在する実体は精神的であると述べる。ジョージ・バーク リーのような純粋観念論は現代西洋哲学では珍しいが、より洗練された汎精神論と呼ばれる変種は、精神的経験と性質が物理的経験と性質の基盤にある可能性を 主張し、アルフレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッドやデイヴィッド・レイ・グリフィンといった一部の哲学者によって支持されてきた。[50] 現象論とは、外部対象の表象(あるいは感覚データ)のみが実在するという理論である。この見解は20世紀初頭、バートランド・ラッセルや多くの論理実証主 義者によって一時的に採用された[59]。第三の可能性として、物理的でも精神的でもない基礎的実体の存在を認める立場がある。この場合、精神的・物理的 性質は共にこの中立的実体の属性となる。この立場はバルーフ・スピノザ[6]が採用し、19世紀にエルンスト・マッハ[60]によって普及した。この「中 立的一元論」と呼ばれる立場は、属性二元論に類似している。 物理的一元論 行動主義 詳細記事: 行動主義 行動主義は20世紀の大半、特に前半において心哲学を支配した。[15] 心理学において行動主義は、内省主義の不備への反動として発展した[57]。自己の内面的精神生活に関する内省的報告は、正確性を慎重に検証する対象とな らず、予測可能な一般化を形成するために使用できない。一般化可能性と第三者による検証の可能性がなければ、心理学は科学的になり得ないと行動主義者は主 張した。[57] したがって解決策は、内面的精神生活(ひいては存在論的に独立した心)という概念そのものを消去法による排除し、代わりに観察可能な行動の記述に焦点を当 てることだった。[61] こうした心理学の発展と並行して、哲学的行動主義(論理的行動主義とも呼ばれる)が発展した。[57] これは強い検証主義を特徴とし、内面的精神生活に関する検証不可能な主張を概して無意味と見なす. 行動主義者にとって、精神状態とは内省によって報告できる内面的状態ではない。それは単に、第三者が他者の行動を説明し予測するために、行動や特定の行動 傾向を記述したものに過ぎない。[62] 哲学的行動主義は、認知主義の台頭と時期を同じくして、20世紀後半以降、支持を失っている。[1] |

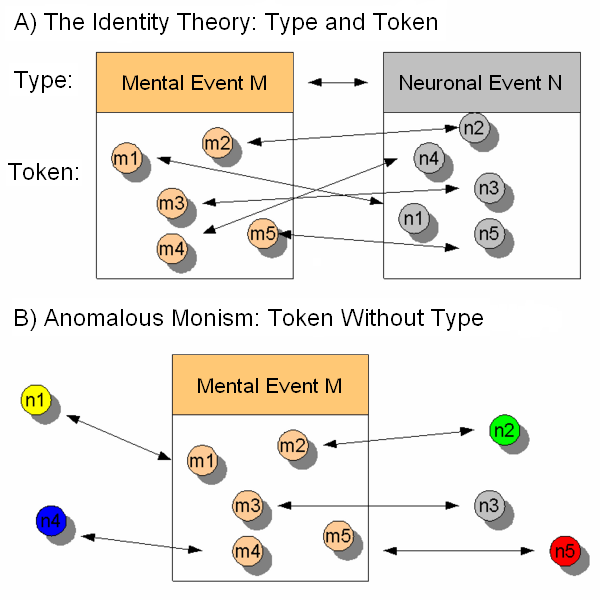

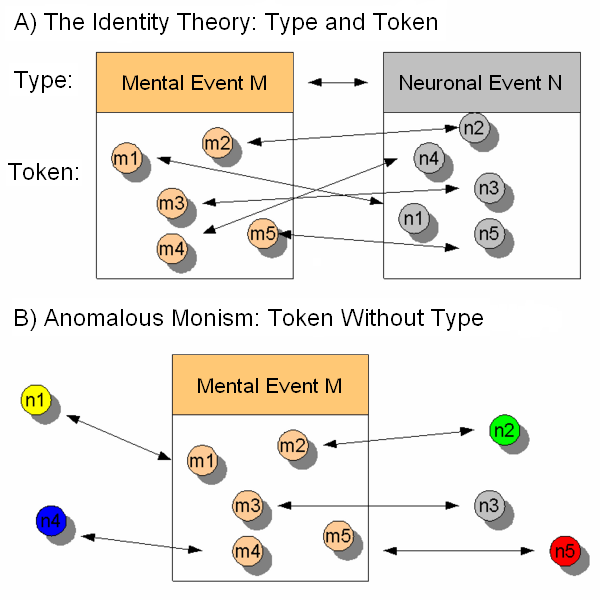

| dentity theory Main article: Type physicalism Type physicalism (or type-identity theory) was developed by Jack Smart[22] and Ullin Place[63] as a direct reaction to the failure of behaviorism. These philosophers reasoned that, if mental states are something material, but not behavioral, then mental states are probably identical to internal states of the brain. In very simplified terms: a mental state M is nothing other than brain state B. The mental state "desire for a cup of coffee" would thus be nothing more than the "firing of certain neurons in certain brain regions".[22]  The classic Identity theory and Anomalous Monism in contrast. For the Identity theory, every token instantiation of a single mental type corresponds (as indicated by the arrows) to a physical token of a single physical type. For anomalous monism, the token–token correspondences can fall outside of the type–type correspondences. The result is token identity. On the other hand, even granted the above, it does not follow that identity theories of all types must be abandoned. According to token identity theories, the fact that a certain brain state is connected with only one mental state of a person does not have to mean that there is an absolute correlation between types of mental state and types of brain state. The type–token distinction can be illustrated by a simple example: the word "green" contains four types of letters (g, r, e, n) with two tokens (occurrences) of the letter e along with one each of the others. The idea of token identity is that only particular occurrences of mental events are identical with particular occurrences or tokenings of physical events.[64] Anomalous monism (see below) and most other non-reductive physicalisms are token-identity theories.[65] Despite these problems, there is a renewed interest in the type identity theory today, primarily due to the influence of Jaegwon Kim.[22] Functionalism Main article: Functionalism (philosophy of mind) Functionalism was formulated by Hilary Putnam and Jerry Fodor as a reaction to the inadequacies of the identity theory.[24] Putnam and Fodor saw mental states in terms of an empirical computational theory of the mind.[66] At about the same time or slightly after, D.M. Armstrong and David Kellogg Lewis formulated a version of functionalism that analyzed the mental concepts of folk psychology in terms of functional roles.[67] Finally, Wittgenstein's idea of meaning as use led to a version of functionalism as a theory of meaning, further developed by Wilfrid Sellars and Gilbert Harman. Another one, psychofunctionalism, is an approach adopted by the naturalistic philosophy of mind associated with Jerry Fodor and Zenon Pylyshyn. Mental states are characterized by their causal relations with other mental states and with sensory inputs and behavioral outputs. Functionalism abstracts away from the details of the physical implementation of a mental state by characterizing it in terms of non-mental functional properties. For example, a kidney is characterized scientifically by its functional role in filtering blood and maintaining certain chemical balances.[66] Non-reductive physicalism Main article: Physicalism Non-reductionist philosophers hold firmly to two essential convictions with regard to mind–body relations: 1) Physicalism is true and mental states must be physical states, but 2) All reductionist proposals are unsatisfactory: mental states cannot be reduced to behavior, brain states or functional states.[57] Hence, the question arises whether there can still be a non-reductive physicalism. Donald Davidson's anomalous monism[23] is an attempt to formulate such a physicalism. He "thinks that when one runs across what are traditionally seen as absurdities of Reason, such as akrasia or self-deception, the personal psychology framework is not to be given up in favor of the subpersonal one, but rather must be enlarged or extended so that the rationality set out by the principle of charity can be found elsewhere."[68] Davidson uses the thesis of supervenience: mental states supervene on physical states, but are not reducible to them. "Supervenience" therefore describes a functional dependence: there can be no change in the mental without some change in the physical–causal reducibility between the mental and physical without ontological reducibility.[69] Weak emergentism Main article: Emergentism Weak emergentism is a form of "non-reductive physicalism" that involves a layered view of nature, with the layers arranged in terms of increasing complexity and each corresponding to its own special science. Some philosophers like C. D. Broad[70] hold that emergent properties causally interact with more fundamental levels, while others maintain that higher-order properties simply supervene over lower levels without direct causal interaction. The latter group therefore holds a less strict, or "weaker", definition of emergentism, which can be rigorously stated as follows: a property P of composite object O is emergent if it is metaphysically impossible for another object to lack property P if that object is composed of parts with intrinsic properties identical to those in O and has those parts in an identical configuration.[citation needed] Sometimes emergentists use the example of water having a new property when Hydrogen H and Oxygen O combine to form H2O (water). In this example, there "emerges" a new property of a transparent liquid that would not have been predicted by understanding hydrogen and oxygen as gases. This is analogous to physical properties of the brain giving rise to a mental state. Emergentists try to solve the notorious mind–body gap this way. One problem for emergentism is the idea of causal closure in the world that does not allow for a mind-to-body causation.[71] Eliminative materialism Main article: Eliminative materialism If one is a materialist and believes that all aspects of our common-sense psychology will find reduction to a mature cognitive neuroscience, and that non-reductive materialism is mistaken, then one can adopt a final, more radical position: eliminative materialism. There are several varieties of eliminative materialism, but all maintain that our common-sense "folk psychology" badly misrepresents the nature of some aspect of cognition. Eliminativists such as Patricia and Paul Churchland argue that while folk psychology treats cognition as fundamentally sentence-like, the non-linguistic vector/matrix model of neural network theory or connectionism will prove to be a much more accurate account of how the brain works.[20] The Churchlands often invoke the fate of other, erroneous popular theories and ontologies that have arisen in the course of history.[20][21] For example, Ptolemaic astronomy served to explain and roughly predict the motions of the planets for centuries, but eventually this model of the Solar System was eliminated in favor of the Copernican model. The Churchlands believe the same eliminative fate awaits the "sentence-cruncher" model of the mind in which thought and behavior are the result of manipulating sentence-like states called "propositional attitudes". Sociologist Jacy Reese Anthis argues for eliminative materialism on all faculties of mind, including consciousness, stating, "The deepest mysteries of the mind are within our reach."[72] |

同一性理論 主な記事: タイプ物理主義 タイプ物理主義(またはタイプ同一性理論)は、行動主義の失敗への直接的な反応として、ジャック・スマート[22]とウリン・プレイス[63]によって発 展させた。これらの哲学者は、もし精神状態が物質的なものでありながら行動的でないならば、精神状態はおそらく脳の内部状態と同一であると論じた。非常に 簡略化して言えば:精神状態Mは脳状態Bに他ならない。したがって「コーヒーを一杯欲する」という精神状態は、「特定の脳領域における特定のニューロンの 発火」に過ぎない。[22]  対照的に、古典的な同一性理論と異常一元論。同一性理論では、単一の精神的タイプの各トークン実例は(矢印が示すように)単一の物理的タイプの物理的トー クンに対応する。異常一元論では、トークン間の対応関係がタイプ間の対応関係から外れることがある。その結果がトークン同一性である。 一方で、上記を認めたとしても、あらゆるタイプの同一性理論を放棄しなければならないわけではない。個体同一性理論によれば、特定の脳状態が個人の単一の 精神状態と結びついているという事実が、精神状態のタイプと脳状態のタイプとの間に絶対的な相関関係があることを意味するわけではない。タイプとトークン の区別は単純な例で説明できる。「緑」という単語には4種類の文字(g, r, e, n)が含まれ、eが2トークン(出現)、他の文字がそれぞれ1トークンずつ存在する。トークン同一性の考え方は、特定の精神的事象の出現だけが、特定の物 理的事象の出現またはトークンと同一であるというものだ。[64] 異常一元論(後述)およびその他の非還元的な物理主義のほとんどは、トークン同一性理論である。[65] こうした問題があるにもかかわらず、今日、タイプ同一性理論に対する関心が再び高まっている。これは主に、ジェグウォン・キムの影響によるものである。 [22] 機能主義 主な記事:機能主義(心に関する哲学) 機能主義は、同一性理論の不備に対する反応として、ヒラリー・パトナムとジェリー・フォドルによって提唱された。[24] パトナムとフォドルは、精神状態を経験的な心の計算理論の観点から捉えた。[66] ほぼ同時期、あるいはその少し後に、D.M.アームストロングとデビッド・ケロッグ・ルイスは、フォークサイコロジーの精神概念を機能的役割の観点から分 析する機能主義のバージョンを提唱した。[67] 最後に、ウィトゲンシュタインの「意味は使用である」という考えは、ウィルフリッド・セラーズとギルバート・ハーマンによってさらに発展された、意味の理 論としての機能主義の一形態につながった。もう一つの機能主義、すなわち精神機能主義は、ジェリー・フォドルやゼノン・ピリシンに関連する自然主義的な精 神哲学によって採用されたアプローチである。 精神状態は、他の精神状態や感覚入力、行動出力との因果関係によって特徴づけられる。機能主義は、精神状態を非精神的な機能的特性で特徴づけることで、そ の物理的実装の詳細から抽象化する。例えば、腎臓は、血液をろ過し、特定の化学的バランスを維持するという機能的役割によって科学的に特徴づけられる。 非還元主義的物理主義 主な記事:物理主義 非還元主義の哲学者は、心身関係に関して 2 つの本質的な確信を固く保持している。1)物理主義は真実であり、精神状態は物理的状態であるべきである。しかし、2)すべての還元主義的提案は不満足で ある。精神状態は、行動、脳の状態、機能的状態に還元することはできない。[57] したがって、非還元主義的物理主義が依然として存在しうるかどうかという疑問が生じる。ドナルド・デイヴィッドソンの異常一元論[23]は、そのような物 理主義を定式化しようとする試みである。彼は「伝統的に理性の不合理と見なされてきたもの、例えばアクラシアや自己欺瞞に遭遇した時、個人的心理学の枠組 みを放棄して非個人の枠組みを採用すべきではなく、むしろ慈善の原則によって示される合理性を他の場所で発見できるよう、その枠組みを拡大または拡張しな ければならない」と考えている。[68] デイヴィッドソンは超位性(supervenience)の命題を用いる:精神状態は物理状態に超位するが、それらに還元されない。「超位性」はしたがっ て機能的依存性を記述する:物理的状態に何らかの変化が伴わなければ精神的状態に変化は起こり得ない——精神的・物理的間の因果的還元可能性は存在する が、存在論的還元可能性は存在しない。[69] 弱き創発主義 詳細記事: 創発主義 弱き創発主義は「非還元的物理主義」の一形態であり、自然を階層的に捉える。各層は複雑性の増大に従って配置され、それぞれが独自の特殊科学に対応する。 C. D. ブロード[70]ら一部の哲学者は、創発的性質がより基礎的なレベルと因果的に相互作用すると主張する。他方、高次性質は直接的な因果的相互作用なしに低 次レベルに単に乗上るとする立場もある。後者のグループはより緩やかな、すなわち「弱」な創発主義の定義を採用しており、厳密には次のように述べられる: 複合対象Oの性質Pが創発的であるとは、Oと同一の内在的性質を持つ部分から構成され、かつそれらの部分が同一の配置にある別の対象が、性質Pを欠くこと が形而上学的に不可能である場合を指す。[出典が必要] 創発論者は、水素Hと酸素Oが結合してH2O(水)を形成する際に水が新たな性質を持つ例を挙げる。この例では、水素と酸素を気体として理解しても予測で きなかった透明な液体という新たな性質が「創発」する。これは脳の物理的性質が精神状態を生み出すことに類似している。創発論者はこの方法で悪名高い心身 問題の解決を試みる。創発論にとっての問題の一つは、心から身体への因果関係を許容しない、世界における因果的閉鎖性の概念である。[71] 消去法による唯物論 詳細記事: 消去法による唯物論 もし唯物論者であり、常識的な心理学のあらゆる側面が成熟した認知神経科学に還元されると信じ、非還元的唯物論は誤りだと考えるならば、最終的かつより急進的な立場、すなわち消去法による唯物論を採用できる。 消去法による唯物論にはいくつかの種類があるが、いずれも我々の常識的「フォークサイコロジー」が認知の何らかの側面の本質を著しく誤って表現していると 主張する。パトリシア・チャーチランドやポール・チャーチランドのような消去法による論者は、フォークサイコロジーが認知を基本的に文のようなものと扱う 一方で、非言語的なベクトル/行列モデルによるニューラルネットワーク理論やコネクショニズムこそが、脳の働きをはるかに正確に説明するものと証明される と論じる。[20] チャーチランド夫妻は、歴史の中で生まれた他の誤った大衆理論や存在論の末路をしばしば引き合いに出す。[20][21] 例えば、プトレマイオスの天文学は数世紀にわたり惑星の運動を説明し概ね予測するのに役立ったが、最終的にこの太陽系モデルはコペルニクスモデルに消去法 による取って代わられた. チャーチランド夫妻は、思考や行動が「命題的態度」と呼ばれる文のような状態を操作する結果であるとする「文処理モデル」の精神論にも、同じ消去法による 運命が待っていると信じている。社会学者ジェイシー・リース・アンシスは、意識を含む精神のあらゆる機能について消去法による唯物論を主張し、「精神の最 も深い謎は我々の手の届く範囲にある」と述べている。[72] |

| Mysterianism Main article: New mysterianism Some philosophers take an epistemic approach and argue that the mind–body problem is currently unsolvable, and perhaps will always remain unsolvable to human beings. This is usually termed New mysterianism. Colin McGinn holds that human beings are cognitively closed in regards to their own minds. According to McGinn human minds lack the concept-forming procedures to fully grasp how mental properties such as consciousness arise from their causal basis.[73] An example would be how an elephant is cognitively closed in regards to particle physics. A more moderate conception has been expounded by Thomas Nagel, which holds that the mind–body problem is currently unsolvable at the present stage of scientific development and that it might take a future scientific paradigm shift or revolution to bridge the explanatory gap. Nagel posits that in the future a sort of "objective phenomenology" might be able to bridge the gap between subjective conscious experience and its physical basis.[74] Linguistic criticism of the mind–body problem Each attempt to answer the mind–body problem encounters substantial problems. Some philosophers argue that this is because there is an underlying conceptual confusion.[75] These philosophers, such as Ludwig Wittgenstein and his followers in the tradition of linguistic criticism, therefore reject the problem as illusory.[76] They argue that it is an error to ask how mental and biological states fit together. Rather it should simply be accepted that human experience can be described in different ways—for instance, in a mental and in a biological vocabulary. Illusory problems arise if one tries to describe the one in terms of the other's vocabulary or if the mental vocabulary is used in the wrong contexts.[76] This is the case, for instance, if one searches for mental states of the brain. The brain is simply the wrong context for the use of mental vocabulary—the search for mental states of the brain is therefore a category error or a sort of fallacy of reasoning.[76] Today, such a position is often adopted by interpreters of Wittgenstein such as Peter Hacker.[75] However, Hilary Putnam, the originator of functionalism, has also adopted the position that the mind–body problem is an illusory problem which should be dissolved according to the manner of Wittgenstein.[77] Naturalism and its problems The thesis of physicalism is that the mind is part of the material (or physical) world. Such a position faces the problem that the mind has certain properties that no other material thing seems to possess. Physicalism must therefore explain how it is possible that these properties can nonetheless emerge from a material thing. The project of providing such an explanation is often referred to as the "naturalization of the mental".[57] Some of the crucial problems that this project attempts to resolve include the existence of qualia and the nature of intentionality.[57] |

ミステリアニズム 主な記事: 新ミステリアニズム 一部の哲学者は認識論的アプローチを取り、心身問題は現在解決不可能であり、おそらく人類にとって永遠に解決不能であると主張する。これは通常、新ミステ リアニズムと呼ばれる。コリン・マクギンは、人間は自らの心に関して認知的に閉ざされていると主張する。マクギンによれば、人間の精神は、意識といった精 神的特性がどのようにその因果的基盤から生じるかを完全に把握するための概念形成手続きを欠いている[73]。例を挙げれば、象が素粒子物理学に関して認 知的に閉ざされているようなものだ。 より穏健な見解をトーマス・ネーゲルが展開している。彼は心身問題は現在の科学発展段階では解決不能であり、説明の隔たりを埋めるには将来の科学的パラダ イム転換や革命が必要かもしれないと主張する。ネーゲルは将来、ある種の「客観的現象学」が主観的意識体験とその物理的基盤の隔たりを埋められるかもしれ ないと提唱している。[74] 心身問題に対する言語批判 心身問題への解答を試みるあらゆる試みは重大な問題に直面する。一部の哲学者は、その根本に概念的混乱があるからだと主張する。[75] ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインや言語批判の伝統を継ぐその追随者らのようなこれらの哲学者は、したがってこの問題を幻想として退ける。[76] 彼らは、精神的状態と生物学的状態がどう整合するかを問うこと自体が誤りだと主張する。むしろ人間の経験は異なる方法で記述可能だと単純に受け入れるべき だ——例えば精神的用語と生物学的用語でそれぞれ記述するのだ。一方の用語で他方を記述しようと試みたり、精神的用語を誤った文脈で用いたりすると、幻想 的な問題が生じるのだ。[76] 例えば脳の精神的状態を探求する場合がこれに当たる。脳は精神用語を用いるには単に不適切な文脈である。ゆえに脳の精神状態を探求することはカテゴリー誤 謬、あるいは一種の推論の誤謬となる。[76] 今日、このような立場はピーター・ハッカーのようなウィトゲンシュタイン解釈者によってしばしば採用されている。[75] しかし、機能主義の創始者であるヒラリー・パトナムもまた、心身問題はウィトゲンシュタインの手法に従って解消すべき幻想的な問題であるという立場を取っ ている。[77] 自然主義とその問題 物理主義の命題は、心は物質的(あるいは物理的)世界の一部であるというものだ。このような立場は、心に他の物質的物体が持たないような特性が存在する問 題に直面する。したがって物理主義は、こうした性質が物質からいかにして生じうるかを説明せねばならない。この説明を試みる企ては「精神の自然化」と呼ば れることが多い。[57] この企てが解決を試みる核心的問題には、クオリアの存在や意図性の本質が含まれる。[57] |

| Qualia Main article: Qualia Many mental states seem to be experienced subjectively in different ways by different individuals.[33] And it is characteristic of a mental state that it has some experiential quality, e.g. of pain, that it hurts. However, the sensation of pain between two individuals may not be identical, since no one has a perfect way to measure how much something hurts or of describing exactly how it feels to hurt. Philosophers and scientists therefore ask where these experiences come from. The existence of cerebral events, in and of themselves, cannot explain why they are accompanied by these corresponding qualitative experiences. The puzzle of why many cerebral processes occur with an accompanying experiential aspect in consciousness seems impossible to explain.[31] Yet it also seems to many that science will eventually have to explain such experiences.[57] This follows from an assumption about the possibility of reductive explanations. According to this view, if an attempt can be successfully made to explain a phenomenon reductively (e.g., water), then it can be explained why the phenomenon has all of its properties (e.g., fluidity, transparency).[57] In the case of mental states, this means that there needs to be an explanation of why they have the property of being experienced in a certain way. The 20th-century German philosopher Martin Heidegger criticized the ontological assumptions underpinning such a reductive model, and claimed that it was impossible to make sense of experience in these terms. This is because, according to Heidegger, the nature of our subjective experience and its qualities is impossible to understand in terms of Cartesian "substances" that bear "properties". Another way to put this is that the very concept of qualitative experience is incoherent in terms of—or is semantically incommensurable with the concept of—substances that bear properties.[78] This problem of explaining introspective first-person aspects of mental states and consciousness in general in terms of third-person quantitative neuroscience is called the explanatory gap.[79] There are several different views of the nature of this gap among contemporary philosophers of mind. David Chalmers and the early Frank Jackson interpret the gap as ontological in nature; that is, they maintain that qualia can never be explained by science because physicalism is false. There are two separate categories involved and one cannot be reduced to the other.[80] An alternative view is taken by philosophers such as Thomas Nagel and Colin McGinn. According to them, the gap is epistemological in nature. For Nagel, science is not yet able to explain subjective experience because it has not yet arrived at the level or kind of knowledge that is required. We are not even able to formulate the problem coherently.[33] For McGinn, on other hand, the problem is one of permanent and inherent biological limitations. We are not able to resolve the explanatory gap because the realm of subjective experiences is cognitively closed to us in the same manner that quantum physics is cognitively closed to elephants.[81] Other philosophers liquidate the gap as purely a semantic problem. This semantic problem, of course, led to the famous "Qualia Question", which is: Does Red cause Redness? |

クオリア メイン記事: クオリア 多くの精神状態は、異なる個人によって主観的に異なる方法で経験されるようだ。[33] そして精神状態の特徴は、何らかの経験的性質、例えば痛みの場合、それが痛いという性質を持つことだ。しかし、二人の個人間の痛みの感覚は同一ではないか もしれない。なぜなら、何かがどれほど痛いのかを完璧に測定する方法も、痛みがどのように感じられるかを正確に記述する方法も、誰にもないからだ。した がって哲学者や科学者は、こうした経験がどこから来るのか問う。脳内の事象そのものの存在は、なぜそれらが対応する質的経験と結びつくのかを説明できな い。多くの脳内プロセスが意識における経験的側面を伴って起こる理由という難問は、説明不可能に思える。[31] しかし同時に、科学はいずれこうした経験を説明せざるを得ないとも多くの者は考えている。[57]これは還元主義的説明の可能性に関する前提から導かれ る。この見解によれば、ある現象(例えば水)を還元的に説明することができれば、その現象がなぜそのすべての特性(例えば流動性、透明性)を持つのかを説 明できることになる。[57] 精神状態の場合、これは、なぜそれらが特定の方法で経験されるという特性を持つのかについての説明が必要であることを意味する。 20 世紀のドイツの哲学者マーティン・ハイデガーは、このような還元主義的モデルを支える存在論的仮定を批判し、この用語では経験を理解することは不可能だと 主張した。ハイデガーによれば、私たちの主観的経験とその性質の本質は、「特性」を持つデカルト主義的な「実体」の用語では理解できないからである。別の 言い方をすれば、質的経験という概念そのものが、特性を担う実体という概念とは、意味的に整合性が取れない、あるいは意味的に共約不可能なということだ。 精神状態や意識全般について、内省的な一人称的側面を、三人称的な定量的神経科学の観点から説明するというこの問題は、説明のギャップと呼ばれている。 [79] この隔たりに関する見解は、現代の心哲学者の間で幾つか異なる。デイヴィッド・チャーマーズや初期のフランク・ジャクソンは、この隔たりを存在論的なもの と解釈する。つまり、物理主義は誤りであるため、クオリアは科学によって決して説明され得ないと主張する。二つの別個のカテゴリーが関与しており、一方は 他方に還元できないというのだ。[80] トーマス・ネーゲルやコリン・マクギンらによる代替的見解では、この隔たりは認識論的性質を持つとされる。ネーゲルによれば、科学が主観的経験を説明でき ないのは、必要な知識のレベルや種類に到達していないためだ。我々はその問題を首尾一貫して定式化することすらできない[33]。一方マクギンにとって、 問題は恒久的かつ本質的な生物学的限界にある。我々が説明の隔たりを解消できないのは、主観的経験の領域が、象にとって量子物理学が認知的に閉ざされてい るのと同じように、我々にとって認知的に閉ざされているからだ。[81] 他の哲学者たちは、この隔たりを純粋に意味論的問題として解消する。この意味論的問題は、もちろん有名な「クオリア問題」、すなわち「赤は赤さを引き起こ すのか?」という問いへとつながる。 |

| Intentionality Main article: Intentionality  John Searle—one of the most influential philosophers of mind, proponent of biological naturalism (Berkeley 2002) Intentionality is the capacity of mental states to be directed towards (about) or be in relation with something in the external world.[26] This property of mental states entails that they have contents and semantic referents and can therefore be assigned truth values. When one tries to reduce these states to natural processes there arises a problem: natural processes are not true or false, they simply happen.[82] It would not make any sense to say that a natural process is true or false. But mental ideas or judgments are true or false, so how then can mental states (ideas or judgments) be natural processes? The possibility of assigning semantic value to ideas must mean that such ideas are about facts. Thus, for example, the idea that Herodotus was a historian refers to Herodotus and to the fact that he was a historian. If the fact is true, then the idea is true; otherwise, it is false. But where does this relation come from? In the brain, there are only electrochemical processes and these seem not to have anything to do with Herodotus.[25] |

意図性 メイン記事: 意図性  ジョン・サール——最も影響力のある心哲学者の一人、生物学的自然主義の提唱者(Berkeley 2002) 意図性とは、心的状態が外部世界の何かに向けられる(それについて)あるいはそれとの関係を持つ能力である。[26] この心的状態の特性は、それらが内容と意味論的参照対象を持ち、したがって真偽値を割り当てられることを意味する。これらの状態を自然過程に還元しようと すると問題が生じる:自然過程は真でも偽でもない、単に起こるだけである。[82] 自然過程が真か偽かと言うのは全く意味をなさない。しかし心的観念や判断は真か偽かである。では心的状態(観念や判断)がどうして自然過程となり得るの か?観念に意味的価値を割り当てられる可能性は、そうした観念が事実についてのものであることを意味する。例えば「ヘロドトスは歴史家であった」という観 念は、ヘロドトスと彼が歴史家であったという事実を参照する。事実が真ならば観念も真であり、そうでなければ偽である。しかしこの関係はどこから来るの か?脳内には電気化学的過程しか存在せず、それらはヘロドトスとは何の関係もないように見える。[25] |

| Philosophy of perception Main article: Philosophy of perception Philosophy of perception is concerned with the nature of perceptual experience and the status of perceptual objects, in particular how perceptual experience relates to appearances and beliefs about the world. The main contemporary views within philosophy of perception include naive realism, enactivism and representational views.[2][3][83] |

知覚の哲学 主な記事: 知覚の哲学 知覚の哲学は、知覚的経験の本質と知覚対象の地位、特に知覚的経験が世界の表象や信念とどのように関連するかを扱う。現代の知覚哲学における主な見解には、素朴実在論、エンアクティビズム、表象論的見解が含まれる。[2][3][83] |

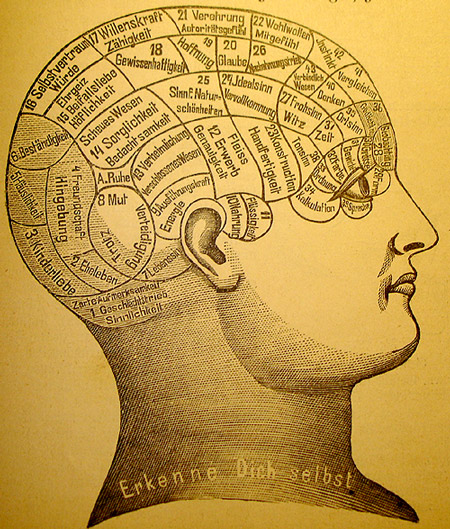

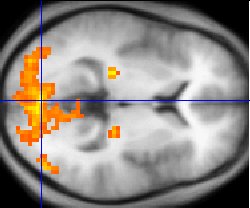

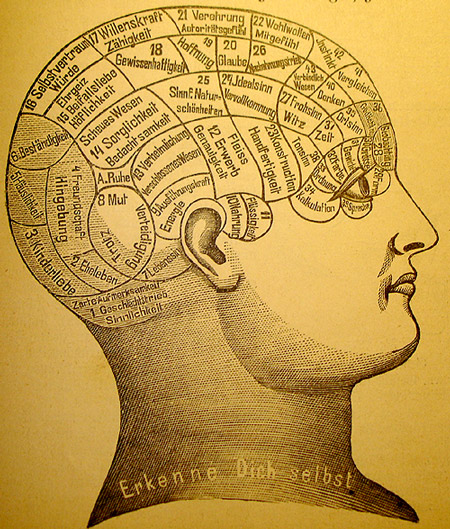

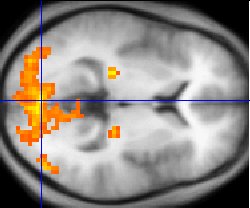

Philosophy of mind and science A phrenological mapping of the brain – phrenology was among the first attempts to correlate mental functions with specific parts of the brain although it is now widely discredited. Humans are corporeal beings and, as such, they are subject to examination and description by the natural sciences. Since mental processes are intimately related to bodily processes (e.g., embodied cognition theory of mind), the descriptions that the natural sciences furnish of human beings play an important role in the philosophy of mind.[1] There are many scientific disciplines that study processes related to the mental. The list of such sciences includes: biology, computer science, cognitive science, cybernetics, linguistics, medicine, pharmacology, and psychology.[84] Neurobiology Main article: Neuroscience The theoretical background of biology, as is the case with modern natural sciences in general, is fundamentally materialistic. The objects of study are, in the first place, physical processes, which are considered to be the foundations of mental activity and behavior.[85] The increasing success of biology in the explanation of mental phenomena can be seen by the absence of any empirical refutation of its fundamental presupposition: "there can be no change in the mental states of a person without a change in brain states."[84] Within the field of neurobiology, there are many subdisciplines that are concerned with the relations between mental and physical states and processes:[85] Sensory neurophysiology investigates the relation between the processes of perception and stimulation.[86] Cognitive neuroscience studies the correlations between mental processes and neural processes.[86] Neuropsychology describes the dependence of mental faculties on specific anatomical regions of the brain.[86] Lastly, evolutionary biology studies the origins and development of the human nervous system and, in as much as this is the basis of the mind, also describes the ontogenetic and phylogenetic development of mental phenomena beginning from their most primitive stages.[84] Evolutionary biology furthermore places tight constraints on any philosophical theory of the mind, as the gene-based mechanism of natural selection does not allow any giant leaps in the development of neural complexity or neural software but only incremental steps over long time periods.[87]  Since the 1980s, sophisticated neuroimaging procedures, such as fMRI (above), have furnished increasing knowledge about the workings of the human brain, shedding light on ancient philosophical problems. The methodological breakthroughs of the neurosciences, in particular the introduction of high-tech neuroimaging procedures, has propelled scientists toward the elaboration of increasingly ambitious research programs: one of the main goals is to describe and comprehend the neural processes which correspond to mental functions (see: neural correlate).[85] Several groups are inspired by these advances. Neurophilosophy Main article: Neurophilosophy Neurophilosophy is an interdisciplinary field that examines the intersection of neuroscience and philosophy, particularly focusing on how neuroscientific findings inform and challenge traditional arguments in the philosophy of mind, offering insights into the nature of consciousness, cognition, and the mind-brain relationship. Patricia Churchland argues for a deep integration of neuroscience and philosophy, emphasizing that understanding the mind requires grounding philosophical questions in empirical findings about the brain. Churchland challenges traditional dualistic and purely conceptual approaches to the mind, advocating for a materialistic framework where mental phenomena are understood as brain processes. She posits that philosophical theories of mind must be informed by advances in neuroscience, such as the study of neural networks, brain plasticity, and the biochemical basis of cognition and behavior. Churchland critiques the idea that introspection or purely conceptual analysis can sufficiently explain consciousness, arguing instead that empirical methods can illuminate how subjective experiences arise from neural mechanisms.[88] An unsolved question in neuroscience and the philosophy of mind is the binding problem, which is the problem of how objects, background, and abstract or emotional features are combined into a single experience.[89] It is considered a "problem" because no complete model exists. The binding problem can be subdivided into the four areas of perception, neuroscience, cognitive science, and the philosophy of mind. It includes general considerations on coordination, the subjective unity of perception, and variable binding.[90] Another related problem is known as the boundary problem.[91] The boundary problem is essentially the inverse of the binding problem, and asks how binding stops occurring and what prevents other neurological phenomena from being included in first-person perspectives, giving first-person perspectives hard boundaries. Computer science Main article: Computer science Computer science concerns itself with the automatic processing of information (or at least with physical systems of symbols to which information is assigned) by means of such things as computers.[92] From the beginning, computer programmers have been able to develop programs that permit computers to carry out tasks for which organic beings need a mind. A simple example is multiplication. It is not clear whether computers could be said to have a mind. Could they, someday, come to have what we call a mind? This question has been propelled into the forefront of much philosophical debate because of investigations in the field of artificial intelligence (AI). Within AI, it is common to distinguish between a modest research program and a more ambitious one: this distinction was coined by John Searle in terms of a weak AI and strong AI. The exclusive objective of "weak AI", according to Searle, is the successful simulation of mental states, with no attempt to make computers become conscious or aware, etc. The objective of strong AI, on the contrary, is a computer with consciousness similar to that of human beings.[93] The program of strong AI goes back to one of the pioneers of computation Alan Turing. As an answer to the question "Can computers think?", he formulated the famous Turing test.[94] Turing believed that a computer could be said to "think" when, if placed in a room by itself next to another room that contained a human being and with the same questions being asked of both the computer and the human being by a third party human being, the computer's responses turned out to be indistinguishable from those of the human. Essentially, Turing's view of machine intelligence followed the behaviourist model of the mind—intelligence is as intelligence does. The Turing test has received many criticisms, among which the most famous is probably the Chinese room thought experiment formulated by Searle.[93] The question about the possible sensitivity (qualia) of computers or robots still remains open. Some computer scientists believe that the specialty of AI can still make new contributions to the resolution of the "mind–body problem". They suggest that based on the reciprocal influences between software and hardware that takes place in all computers, it is possible that someday theories can be discovered that help us to understand the reciprocal influences between the human mind and the brain (wetware).[95] Psychology Main article: Psychology Psychology is the science that investigates mental states directly. It uses generally empirical methods to investigate concrete mental states like joy, fear or obsessions. Psychology investigates the laws that bind these mental states to each other or with inputs and outputs to the human organism.[96] An example of this is the psychology of perception. Scientists working in this field have discovered general principles of the perception of forms. A law of the psychology of forms says that objects that move in the same direction are perceived as related to each other.[84] This law describes a relation between visual input and mental perceptual states. However, it does not suggest anything about the nature of perceptual states. The laws discovered by psychology are compatible with all the answers to the mind–body problem already described. Cognitive science Cognitive science is the interdisciplinary scientific study of the mind and its processes. It examines what cognition is, what it does, and how it works. It includes research on intelligence and behavior, especially focusing on how information is represented, processed, and transformed (in faculties such as perception, language, memory, reasoning, and emotion) within nervous systems (human or other animals) and machines (e.g. computers). Cognitive science consists of multiple research disciplines, including psychology, artificial intelligence, philosophy, neuroscience, linguistics, anthropology, sociology, and education.[97] It spans many levels of analysis, from low-level learning and decision mechanisms to high-level logic and planning; from neural circuitry to modular brain organization. Over the years, cognitive science has evolved from a representational and information processing approach to explaining the mind to embrace an embodied perspective of it. Accordingly, bodily processes play a significant role in the acquisition, development, and shaping of cognitive capabilities.[98] For instance, Rowlands (2012) argues that cognition is enactive, embodied, embedded, affective and (potentially) extended. The position is taken that the "classical sandwich" of cognition sandwiched between perception and action is artificial; cognition has to be seen as a product of a strongly coupled interaction that cannot be divided this way.[99][100] Near-death research Main article: Near-death studies In the field of near-death research, the following phenomenon, among others, occurs: For example, during some brain operations the brain is artificially and measurably deactivated. Nevertheless, some patients report during this phase that they have perceived what is happening in their surroundings, that is, that they have had consciousness. Patients also report experiences during a cardiac arrest. There is the following problem: As soon as the brain is no longer supplied with blood and thus with oxygen after a cardiac arrest, the brain ceases its normal operation after about 15 seconds, that is, the brain falls into a state of unconsciousness.[101] |

心と科学の哲学 脳の頭蓋骨相学的なマッピング――頭蓋骨相学は、精神機能と脳の特定部位を関連付けようとした最初の試みの一つであったが、現在では広く否定されている。 人間は肉体的な存在であり、その意味で自然科学による検証と記述の対象となる。精神過程は身体過程と密接に関連しているため(例:身体化された認知理 論)、自然科学が提供する人間の記述は精神哲学において重要な役割を果たす[1]。精神に関連する過程を研究する科学分野は多数存在する。そのリストには 以下が含まれる:生物学、計算機科学、認知科学、サイバネティクス、言語学、医学、薬理学、心理学。[84] 神経生物学 詳細記事: 神経科学 生物学の理論的背景は、現代自然科学全般と同様に、根本的に唯物論的である。研究対象は第一に物理的プロセスであり、これらが精神的活動と行動の基盤と見 なされている。[85] 生物学が精神的現象の説明において成功を収めていることは、その根本的前提に対する経験的反証が存在しないことからも明らかである: 「脳の状態に変化がなければ、人格の精神状態に変化は起こりえない」[84]。 神経生物学の分野には、精神的状態と物理的状態・過程の関係を扱う多くの下位分野がある[85]:感覚神経生理学は知覚過程と刺激の関連を調査する [86]。認知神経科学は精神的過程と神経過程の相関を研究する。[86] 神経心理学は、精神機能が脳の特定の解剖学的領域に依存する様子を記述する。[86] 最後に、進化生物学は人間の神経系の起源と発達を研究し、これが精神の基盤である限り、最も原始的な段階から始まる精神的現象の個体発生的・系統発生的発 達も記述する。[84] さらに進化生物学は、あらゆる哲学的心理論に厳しい制約を課す。遺伝子に基づく自然淘汰のメカニズムは、神経の複雑性や神経ソフトウェアの発達において飛 躍的な進歩を許さず、長い時間をかけて段階的に進むことしか許さないからだ。[87]  1980年代以降、fMRI(上記)のような高度な神経画像化技術が、人間の脳の働きに関する知見を蓄積し、古くからの哲学的問題に光を当てている。 神経科学の方法論的飛躍、特にハイテク神経画像技術の導入は、科学者たちをより野心的な研究計画の構築へと駆り立てた。主要な目標の一つは、精神機能に対 応する神経プロセスを記述し理解することである(参照:神経相関)。[85] 複数の研究グループがこれらの進展に触発されている。 神経哲学 詳細記事: 神経哲学 神経哲学は、神経科学と哲学の交差点を検証する学際的分野である。特に神経科学的知見が、心哲学における伝統的な議論にどのように情報を提供し、挑戦するかに焦点を当て、意識、認知、心と脳の関係の本質に関する洞察を提供する。 パトリシア・チャーチランドは、神経科学と哲学の深い統合を主張し、心を理解するには哲学的問いを脳に関する経験的知見に根ざす必要があると強調する。 チャーチランドは、精神に対する伝統的な二元論的・純粋概念論的アプローチに異議を唱え、精神現象を脳の過程として理解する唯物論的枠組みを提唱する。彼 女は、神経ネットワークの研究、脳の可塑性、認知と行動の生化学的基盤といった神経科学の進歩が、精神に関する哲学理論に反映されねばならないと主張す る。チャーチランドは、内省や純粋に概念的な分析だけで意識を十分に説明できるという考えを批判し、代わりに経験的手法こそが主観的経験が神経メカニズム からいかに生じるかを明らかにし得ると論じている。[88] 神経科学と心の哲学における未解決の問題が結合問題である。これは、対象、背景、抽象的または感情的な特徴が単一の経験にどのように統合されるかという問 題だ。[89] 完全なモデルが存在しないため「問題」と見なされている。結合問題は知覚、神経科学、認知科学、心哲学の四領域に細分化できる。これには調整に関する一般 的な考察、知覚の主観的統一性、可変結合が含まれる[90]。関連する別の問題は境界問題として知られる。[91] 境界問題は本質的に結合問題の逆であり、結合がどのように停止するのか、また他の神経学的現象が一人称視点に含まれるのを何が防ぎ、一人称視点に明確な境 界を与えるのかを問うものである。 計算機科学 主な記事: 計算機科学 計算機科学は、コンピュータなどの手段による情報の自動処理(あるいは少なくとも情報が付与された記号の物理的システム)を扱う。[92] 当初から、コンピュータプログラマーは、有機体が精神を必要とするような作業をコンピュータに実行させるプログラムを開発してきた。単純な例が乗算であ る。コンピュータが精神を持っていると言えるかどうかは明らかではない。コンピュータは、いつの日か、我々が精神と呼ぶものを持ち得るだろうか? この問いは、人工知能(AI)分野の研究によって、多くの哲学的議論の最前線に押し上げられてきた。 AI分野では、控えめな研究プログラムとより野心的なプログラムを区別するのが一般的だ。この区別はジョン・サールによって「弱いAI」と「強いAI」と いう用語で提唱された。サールによれば、「弱いAI」の唯一の目的は精神状態の成功裏なシミュレーションであり、コンピュータに意識や自覚を持たせようと する試みはない。これに対し「強いAI」の目的は、人間と同様の意識を持つコンピュータを実現することだ。[93] 強AIの構想は計算理論の先駆者アラン・チューリングに遡る。「コンピュータは思考できるか?」という問いへの答えとして、彼は有名なチューリングテスト を提唱した。[94] チューリングは、コンピュータが「思考する」と言えるのは、コンピュータを単独で一室に置き、隣室に人間を配置し、第三者の人間がコンピュータと人間の双 方に同じ質問をした場合、コンピュータの応答が人間の応答と区別がつかないときだと考えた。本質的に、チューリングの機械知能観は行動主義的な心のモデル に従っていた——知能は知能として機能するものである。チューリングテストは多くの批判を受けており、中でも最も有名なのはおそらくサールの中国語の部屋 という思考実験だろう。[93] コンピュータやロボットが感覚(クオリア)を持つ可能性についての疑問は、今なお未解決のままである。一部の計算機科学者は、人工知能の専門性が「心身問 題」の解決に新たな貢献をもたらし得ると信じている。彼らは、全てのコンピューターで生じるソフトウェアとハードウェアの相互影響に基づき、いつの日か人 間の精神と脳(ウェットウェア)の相互影響を理解する手助けとなる理論が発見される可能性を示唆している[95]。 心理学 主な記事: 心理学 心理学は精神状態を直接調査する科学である。一般的に経験的手法を用いて、喜び、恐怖、強迫観念といった具体的な精神状態を調査する。心理学は、これらの精神状態同士、あるいは人間の有機体への入力・出力との結びつきを規定する法則を調査する。[96] その一例が知覚心理学である。この分野の研究者は、形態知覚の一般原理を発見してきた。形態心理学の法則によれば、同じ方向に動く物体は互いに関連してい ると知覚される。[84] この法則は視覚入力と心的知覚状態の関係を記述する。しかし知覚状態の本質については何も示唆しない。心理学が発見した法則は、これまで説明した心身問題 のあらゆる解答と両立する。 認知科学 認知科学とは、心とその過程を学際的に研究する科学である。認知とは何か、何を行い、どのように機能するかを検証する。知能と行動に関する研究を含み、特 に神経系(人間や他の動物)や機械(例えばコンピュータ)内で、情報がどのように表現され、処理され、変換されるか(知覚、言語、記憶、推論、感情などの 機能において)に焦点を当てる。認知科学は心理学、人工知能、哲学、神経科学、言語学、人類学、社会学、教育学など複数の研究分野から構成される。 [97] 分析レベルは多岐にわたり、低次レベルの学習・意思決定メカニズムから高次レベルの論理・計画まで、神経回路からモジュール化された脳組織までを扱う。認 知科学は長年にわたり、心を説明する手法として表象論的・情報処理論的アプローチから、身体化された視点を取り入れる方向に進化してきた。したがって、身 体的プロセスは認知能力の獲得・発達・形成において重要な役割を果たす。[98] 例えばRowlands(2012)は、認知はエンアクティブ(能動的)、エンボディッド(身体化)、エンベデッド(埋め込まれた)、アフェクティブ(情 動的)、そして(潜在的に)エクステンデッド(拡張された)であると主張する。認知が知覚と行動の間に挟まれた「古典的なサンドイッチ」構造は人為的であ り、認知はこのように分割できない強結合的相互作用の産物として捉えるべきだという立場である。[99] [100] 臨死体験研究 詳細記事: 臨死体験研究 臨死体験研究の分野では、とりわけ次のような現象が起きる。例えば、脳手術中に脳が人為的かつ測定可能な形で停止状態に陥る場合がある。それにもかかわら ず、一部の患者はこの段階で周囲で起きていることを知覚していた、つまり意識を持っていたと報告する。患者は心停止中の体験についても報告する。ここで問 題となるのは、心停止後、脳への血液供給が途絶え酸素供給が停止すると、約15秒で脳は正常な機能を停止し、無意識状態に陥るという点である。[101] |

| Philosophy of mind in the continental tradition Most of the discussion in this article has focused on one style or tradition of philosophy in modern Western culture, usually called analytic philosophy (sometimes described as Anglo-American philosophy).[102] Many other schools of thought exist, however, which are sometimes subsumed under the broad (and vague) label of continental philosophy.[102] In any case, though topics and methods here are numerous, in relation to the philosophy of mind the various schools that fall under this label (phenomenology, existentialism, etc.) can globally be seen to differ from the analytic school in that they focus less on language and logical analysis alone but also take in other forms of understanding human existence and experience. With reference specifically to the discussion of the mind, this tends to translate into attempts to grasp the concepts of thought and perceptual experience in some sense that does not merely involve the analysis of linguistic forms.[102] Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason, first published in 1781 and presented again with major revisions in 1787, represents a significant intervention into what will later become known as the philosophy of mind. Kant's first critique is generally recognized as among the most significant works of modern philosophy in the West. Kant is a figure whose influence is marked in both continental and analytic/Anglo-American philosophy. Kant's work develops an in-depth study of transcendental consciousness, or the life of the mind as conceived through the universal categories of understanding. In Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's Philosophy of Mind (frequently translated as Philosophy of Spirit or Geist),[103] the third part of his Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences, Hegel discusses three distinct types of mind: the "subjective mind/spirit", the mind of an individual; the "objective mind/spirit", the mind of society and of the State; and the "Absolute mind/spirit", the position of religion, art, and philosophy. See also Hegel's The Phenomenology of Spirit. Nonetheless, Hegel's work differs radically from the style of Anglo-American philosophy of mind. In 1896, Henri Bergson made in Matter and Memory "Essay on the relation of body and spirit" a forceful case for the ontological difference of body and mind by reducing the problem to the more definite one of memory, thus allowing for a solution built on the empirical test case of aphasia. In modern times, the two main schools that have developed in response or opposition to this Hegelian tradition are phenomenology and existentialism. Phenomenology, founded by Edmund Husserl, focuses on the contents of the human mind (see noema) and how processes shape our experiences.[104] Existentialism, a school of thought founded upon the work of Søren Kierkegaard, focuses on Human predicament and how people deal with the situation of being alive. Existential-phenomenology represents a major branch of continental philosophy (they are not contradictory), rooted in the work of Husserl but expressed in its fullest forms in the work of Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. See Heidegger's Being and Time, Merleau-Ponty's Phenomenology of Perception, Sartre's Being and Nothingness, and Simone de Beauvoir's The Second Sex. |

大陸哲学における心哲学 本稿の議論の大半は、現代西洋文化における一つの哲学様式、すなわち通常分析哲学(英米哲学とも呼ばれる)と呼ばれる伝統に焦点を当ててきた。[102] しかし他にも多くの思想流派が存在し、それらは時に「大陸哲学」という広範(かつ曖昧な)ラベルの下に包括されることがある。いずれにせよ、ここで扱う主 題や方法は多岐にわたるが、精神哲学に関して言えば、このラベルに分類される諸学派(現象学、実存主義など)は、言語や論理分析のみに焦点を当てるのでは なく、人間の存在や経験を理解する他の形態も取り入れる点で、分析学派とは全体的に異なる傾向がある。特に精神に関する議論に言及すると、これは言語形式 の分析のみに留まらない意味で、思考や知覚的経験の概念を把握しようとする試みへとつながる傾向がある。[102] イマヌエル・カントの『純粋理性批判』は、1781年に初版が刊行され、1787年に大幅な改訂を加えて再版された。これは後に精神哲学として知られるよ うになる分野への重要な介入を意味する。カントの最初の批判書は、西洋における近代哲学の最も重要な著作の一つとして広く認められている。カントの影響は 大陸哲学と分析哲学/英米哲学の両方に顕著に表れている。カントの著作は、超越的意識、すなわち普遍的な理解の範疇を通じて構想される精神の営みについて の深い研究を展開している。 ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルの『精神論』(しばしば『精神哲学』または『ガイスト(精神)』と訳される)[103]は、彼の『哲学科 学概論』の第三部であり、ヘーゲルは三つの異なる精神の類型について論じている:個人の精神である「主観的精神」、 「客観的精神」すなわち社会と国家の精神、そして「絶対的精神」すなわち宗教・芸術・哲学の領域である。ヘーゲルの『精神現象学』も参照のこと。とはい え、ヘーゲルの著作は英米の精神哲学の様式とは根本的に異なる。 1896年、アンリ・ベルクソンは『物質と記憶』における「身体と精神の関係に関する試論」で、問題をより明確な記憶の問題に還元することで、身体と精神の存在論的差異を力強く主張した。これにより失語症という実証的検証事例に基づく解決が可能となった。 現代において、このヘーゲル的伝統への応答または対抗として発展した二大流派は現象学と実存主義である。エドムント・フッサールによって創設された現象学 は、人間の精神の内容(ノーマを参照)と、そのプロセスが私たちの経験をどのように形成するかに焦点を当てている。実存主義は、ソレン・キルケゴールの著 作に基づいて創設された思想の学派であり、人間の苦境と、人々が生きているという状況にどのように対処するかに焦点を当てている。実存現象学は、大陸哲学 の主要な一分野(両者は矛盾しない)であり、フッサールの研究に根ざしているが、マーティン・ハイデガー、ジャン=ポール・サルトル、シモーヌ・ド・ボー ヴォワール、モーリス・メルロ=ポンティの研究においてその完全な形が表現されている。ハイデガーの『存在と時間』、メルロ=ポンティの『知覚の現象 学』、サルトルの『存在と無』、シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールの『第二の性』を参照のこと。 |