プラットフォーム資本主義

Platform capitalism

☆ プ ラットフォーム資本主義とは、異なるユーザーグループ(通常は消費者と生産者)間の交流、取引、サービスを促進する上で、デジタルプラットフォームが中 心的な役割を果たす経済およびビジネスモデルである。この資本主義モデルは、インターネットやデジタル技術の台頭とともに拡大し、小売や運輸からメディア や労働市場に至るまで、経済のさまざまな分野に変革をもたらした。[1][2] プラットフォーム資本主義の主な特徴は、クラウドソーシング、シェアリングエコノミー、ギグエコノミー、プラットフォームエコノミーの4つである。

| Platform

capitalism is an economic and business model in which digital

platforms play a central role in facilitating interactions,

transactions, and services between different user groups, typically

consumers and producers. This model of capitalism has emerged and

expanded with the rise of the Internet and digital technologies,

transforming various sectors of the economy from retail and

transportation to media and labor markets.[1][2] Four main facets of

platform capitalism are: crowdsourcing, sharing economy, gig economy

and platform economy.[3][4] |

プラットフォーム資本主義とは、異なるユーザーグループ(通常は消費者

と生産者)間の交流、取引、サービスを促進する上で、デジタルプラットフォームが中心的な役割を果たす経済およびビジネスモデルである。この資本主義モデ

ルは、インターネットやデジタル技術の台頭とともに拡大し、小売や運輸からメディアや労働市場に至るまで、経済のさまざまな分野に変革をもたらした。

[1][2]

プラットフォーム資本主義の主な特徴は、クラウドソーシング、シェアリングエコノミー、ギグエコノミー、プラットフォームエコノミーの4つである。[3]

[4] |

| Key characteristics of platform

capitalism include: Network effects: the value of the platform increases exponentially as more users join, attracting even more users in a self-reinforcing cycle. This creates a dynamic where leading platforms can dominate markets, benefiting from economies of scale and scope; Data driven marketing and monetization: platforms collect vast amounts of user data, which is used to personalize experiences, target advertising, develop new products and services and refine algorithms. This data-centric approach enhances efficiency and user engagement; 'Asset-Light' business models: many platforms don't own the physical assets necessary to provide the services they offer, instead, they rely on the resources of their users and partners; Disruption of traditional industries: platforms are disrupting traditional industries (taxi industry, hospitality industry, old media industries such as television, music, radio and film, brick and mortar retails, banking and financial services etc.) by cutting out intermediaries and directly connecting producers with consumers; Algorithmic Governance: platforms use algorithms to manage and regulate interactions, determine rankings, and set prices. These algorithms play a crucial role in shaping the platform's ecosystem and can influence market dynamics and user behavior significantly; Regulatory challenges: the rapid growth and novel business models of platforms often outpace existing regulation. Thus, this leads to debates over issues like worker classification, data privacy, and market power; Global Reach and scalability: platforms enable businesses to scale rapidly and reach a global audience with relatively low marginal costs. |

プラットフォーム資本主義の主な特徴は以下の通りである。 ネットワーク効果:プラットフォームの価値は、ユーザーが増えるにつれて指数関数的に高まり、さらに多くのユーザーを引き寄せるという自己強化サイクルが 生まれる。これにより、規模の経済と範囲の経済の恩恵を受け、有力なプラットフォームが市場を独占できるという力学が生まれる。 データ主導のマーケティングと収益化:プラットフォームは膨大な量のユーザーデータを収集し、それを利用して、体験のパーソナライズ、ターゲット広告、新 製品や新サービスの開発、アルゴリズムの改良を行う。このデータ中心のアプローチは、効率性とユーザーエンゲージメントを高める。 アセットライトなビジネスモデル:多くのプラットフォームは、提供するサービスに必要な物理的資産を所有しておらず、その代わりにユーザーやパートナーの リソースに依存している。 伝統的産業の破壊:プラットフォームは、仲介者を排除し、生産者と消費者とを直接的に結びつけることで、伝統的産業(タクシー業界、ホスピタリティ業界、 テレビ、音楽、ラジオ、映画などの旧来型メディア業界、実店舗小売業、銀行および金融サービスなど)を破壊している。 アルゴリズムによる管理:プラットフォームは、アルゴリズムを使用してやりとりを管理・調整し、ランキングを決定し、価格を設定する。これらのアルゴリズ ムは、プラットフォームのエコシステムを形成する上で重要な役割を果たし、市場力学やユーザーの行動に大きな影響を与える可能性がある。 規制上の課題:プラットフォームの急速な成長と新しいビジネスモデルは、既存の規制を上回る場合が多い。そのため、労働者の分類、データプライバシー、市 場力といった問題について議論が巻き起こっている。 グローバルなリーチと拡張性:プラットフォームは、ビジネスが比較的低い限界費用で急速に規模を拡大し、世界中のオーディエンスにリーチすることを可能に する。 |

| Examples of platform capitalism

include: e-commerce platforms (Amazon, Alibaba, eBay), social media

platforms (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, X), ride-hailing platforms

(Uber, Lyft), short-term rental platforms (Airbnb), online travel

booking platforms (Expedia, Booking.com, Kayak), video-sharing

platforms (YouTube, TikTok), search engine platforms (Google Search,

Microsoft Bing), web mapping platforms (Google Maps, Apple Maps, Petal

Maps), app marketplaces platforms (Google Play, App Store) streaming

platforms (Netflix, Disney+, Apple TV+, Amazon Prime Video), music

streaming platforms (Spotify, Apple Music, Deezer), fintech platforms

(PayPal), food delivery platforms (Just Eat, DoorDash, Deliveroo),

crowdfunding platforms (GoFundMe, Patreon), freelancing platforms

(Upwork, Fiverr), online learning platforms (Coursera, Udemy, Khan

Academy, edX), voice and video calling platforms (Skype, Zoom), e-book

hosting platforms (Kindle, Apple Books), career and job search

platforms (Indeed, Monster.com, Glassdoor), manual work platforms

(Helpling, Taskrabbit, MyHammer), video games marketplace platforms

(Steam, Epic Games Store), dating platforms (Tinder, Bumble, OkCupid),

pornographic platforms (Pornhub, XVideos, xHamster), subscription-based

content platforms (OnlyFans), telemedicine platforms (WebMD, Teladoc

Health), and generative artificial intelligence platforms (GPT-4o,

Claude 3.5, Gemini, Llama, Copilot, Grok). |

プラットフォーム資本主義の例としては、eコマースプラットフォーム

(Amazon、Alibaba、eBay)、ソーシャルメディアプラットフォーム(Facebook、Twitter、Instagram、X)、配車

プラットフォーム(Uber、Lyft)、短期賃貸プラットフォーム(Airbnb)、オンライン旅行予約プラットフォーム(Expedia、

Booking.com、Kayak)、動画共有プラットフォーム(YouTube、TikTok)、検索エンジンプラットフォーム(Google

Search、Microsoft Bing)、ウェブ マッピングプラットフォーム(Google Maps、Apple Maps、Petal

Maps)、アプリマーケットプレイスプラットフォーム(Google Play、App

Store)、ストリーミングプラットフォーム(Netflix、Disney+、Apple TV+、Amazon Prime

Video)、音楽ストリーミングプラットフォーム(Spotify、Apple

Music、Deezer)、フィンテックプラットフォーム(PayPal)、フードデリバリープラットフォーム(Just

Eat、DoorDash、Deliveroo)、クラウドファンディングプラットフォーム(GoFundMe、Patreon)、フリーランス

プラットフォーム(Upwork、Fiverr)、オンライン学習プラットフォーム(Coursera、Udemy、Khan

Academy、edX)、音声およびビデオ通話プラットフォーム(Skype、Zoom)、電子書籍ホスティングプラットフォーム(Kindle、

Apple

Books)、キャリアおよび求人検索プラットフォーム(Indeed、Monster.com、Glassdoor)、マニュアル作業プラットフォーム

(Helpling、Taskrabbit、MyHammer)、ビデオゲームマーケットプレイスプラットフォーム(Steam 、Epic

Games

Store)、出会い系プラットフォーム(Tinder、Bumble、OkCupid)、ポルノプラットフォーム(Pornhub、XVideos、

xHamster)、サブスクリプションベースのコンテンツプラットフォーム(OnlyFans)、遠隔医療プラットフォーム(WebMD、

Teladoc Health)、生成型人工知能プラットフォーム(GPT-4o、Claude

3.5、Gemini、Llama、Copilot、Grok)などである。 |

| In this business model both

hardware and software are used as a foundation (platform) for other

actors to conduct their own business.[5][6] Platform capitalism has been both praised for its innovation, user empowerment and market efficiency[7] and criticized for its potential for exploitation, market concentration, algorithmic bias and privacy concerns[8][9] by various authors. The trends identified in platform capitalism have similarities with those described under the heading of surveillance capitalism.[10] Technology companies build platforms that entire industries rely on, and those industries can easily collapse due to the decisions of those technology companies.[11] The possible effect of platform capitalism on open science has been discussed.[12] Platform capitalism has been contrasted with platform cooperativism. Companies that try to focus on fairness and sharing, instead of just profit motive, are described as cooperatives, whereas more traditional and common companies that focus solely on profit, like Airbnb and Uber, are platform capitalists (or cooperativist platforms vs capitalist platforms). In turn, projects like Wikipedia, which rely on unpaid labor of volunteers, can be classified as commons-based peer-production initiatives.[13]: 31, 36 |

このビジネスモデルでは、ハードウェアとソフトウェアの両方が、他の事

業者が独自の事業を行うための基盤(プラットフォーム)として使用される。[5][6] プラットフォーム資本主義は、その革新性、ユーザーの権限強化、市場効率性について賞賛される一方で[7]、搾取の可能性、市場の集中、アルゴリズムの偏 り、プライバシーの懸念について批判されている[8][9]。プラットフォーム資本主義で指摘されている傾向は、監視資本主義の見出しで説明されているも のとの類似性がある[10]。テクノロジー企業は、業界全体が依存するプラットフォームを構築しており、それらの業界は、それらのテクノロジー企業の決定 により簡単に崩壊する可能性がある[11]。 オープンサイエンスに対するプラットフォーム資本主義の影響の可能性については議論されている。 プラットフォーム資本主義は、プラットフォーム協同組合主義と対比されている。利益追求ではなく、公平性や共有に重点を置こうとする企業は協同組合と表現 される。一方で、AirbnbやUberのように、利益追求のみに重点を置く伝統的で一般的な企業はプラットフォーム資本主義(または協同組合主義プラッ トフォーム対資本主義プラットフォーム)である。また、ボランティアの無償労働に依存するWikipediaのようなプロジェクトは、コモンズに基づくピ アプロダクションの取り組みとして分類することができる。[13]: 31, 36 |

| Enshittification Platform economy |

エンシット化 プラットフォーム経済 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Platform_capitalism |

|

| Enshittification,

also known as crapification and platform decay, is a pattern in which

online products and services decline in quality. Initially, vendors

create high-quality offerings to attract users, then they degrade those

offerings to better serve business customers, and finally degrade their

services to users and business customers to maximize profits for

shareholders. Writer Cory Doctorow coined the neologism "enshittification" in November 2022, though he was not the first to describe and label the concept.[1][2] The American Dialect Society selected it as its 2023 Word of the Year while the Australian Macquarie Dictionary selected it as its word of the year for 2024. Doctorow advocates for two ways to reduce enshittification: upholding the end-to-end principle, which asserts that platforms should transmit data in response to user requests rather than algorithm-driven decisions; and guaranteeing the right of exit—that is, enabling a user to leave a platform without data loss, which requires interoperability. These moves aim to uphold the standards and trustworthiness of online platforms, emphasize user satisfaction, and encourage market competition. |

エンシットフィケーション(Enshittification)は、ク

ラプティフィケーション(Crapification)やプラットフォーム・デケイ(Platform

Decay)とも呼ばれ、オンライン製品やサービスの質が低下するパターンを指す。当初、ベンダーはユーザーを引き付けるために質の高い製品やサービスを

提供するが、その後、ビジネス顧客により良いサービスを提供するためにそれらの質を低下させ、最終的には株主の利益を最大化するためにユーザーやビジネス

顧客へのサービスを低下させる。 作家のコリー・ドクトロウは2022年11月に「エンシットフィケーション」という新語を造語したが、この概念を最初に説明し、名付けたのは彼ではなかっ た。[1][2] アメリカ方言学会は2023年の年間流行語に、またオーストラリア・マッコーリー辞書は2024年の年間流行語に、それぞれこの語を選出した。 ドクトロウは、エンシット化を減らすための2つの方法を提唱している。1つは、プラットフォームはアルゴリズム主導の決定ではなく、ユーザーの要求に応じ てデータを送信すべきであるとするエンドツーエンドの原則を支持すること、もう1つは、相互運用性を確保し、ユーザーがデータを損失することなくプラット フォームを離れることを可能にする、つまり退出の権利を保証することである。これらの動きは、オンラインプラットフォームの基準と信頼性を維持し、ユー ザーの満足度を重視し、市場競争を促すことを目的としている。 |

| History and definition "Enshittification" was first used by Cory Doctorow in a blog post in November 2022,[3] which was later republished in Locus in January 2023.[4] He expanded on the concept in another blog post[5] that was republished in the January 2023 edition of Wired:[6] Here is how platforms die: first, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die. I call this enshittification, and it is a seemingly inevitable consequence arising from the combination of the ease of changing how a platform allocates value, combined with the nature of a "two-sided market", where a platform sits between buyers and sellers, hold each hostage to the other, raking off an ever-larger share of the value that passes between them. In a 2024 op-ed in the Financial Times, Doctorow argued that "'enshittification' is coming for absolutely everything" with "enshittificatory" platforms leaving humanity in an "enshittocene".[7] Doctorow argues that new platforms offer useful products and services at a loss, as a way to gain new users. Once users are locked in, the platform then offers access to the userbase to suppliers at a loss, and once suppliers are locked-in, the platform shifts surpluses to shareholders.[8] Once the platform is fundamentally focused on the shareholders, and the users and vendors are locked in, the platform no longer has any incentive to maintain quality. Enshittified platforms that act as intermediaries can act as both a monopoly on services and a monopsony on customers, as high switching costs prevent either from leaving even when alternatives technically exist.[6] Doctorow has described the process of enshittification as happening through "twiddling": the continual adjustment of the parameters of the system in search of marginal improvements of profits, without regard to any other goal.[9] Enshittification can be seen as a form of rent-seeking.[6] To solve the problem, Doctorow has called for two general principles to be followed: The first is a respect of the end-to-end principle, which holds that the role of a network is to reliably deliver data from willing senders to willing receivers. When applied to platforms, this entails users being given what they asked for, not what the platform prefers to present. For example, users would see all content from users they subscribed to, allowing content creators to reach their audience without going through an opaque algorithm; and in search engines, exact matches for search queries would be shown before sponsored results, rather than afterwards.[10] The second is the right of exit, which holds that users of a platform can easily go elsewhere if they are dissatisfied with it. For social media, this requires interoperability, countering the network effects that "lock in" users and prevent market competition between platforms. For digital media platforms, it means enabling users to switch platforms without losing the content they purchased that is locked by digital rights management.[10] The American Dialect Society selected "enshittification" as its 2023 Word of the Year.[7][11] In November 2024, the Australian Macquarie Dictionary selected it as its word of the year, defining it as follows:[12] The gradual deterioration of a service or product brought about by a reduction in the quality of service provided, especially of an online platform, and as a consequence of profit-seeking. |

歴史と定義 「エンシットフィケーション」という用語は、2022年11月にコリー・ドクターがブログ投稿で初めて使用したものであり[3]、その後2023年1月の 『Locus』誌で再掲載された[4]。彼は、別のブログ投稿でこの概念をさらに掘り下げ[5]、その投稿は『Wired』誌2023年1月号で再掲載さ れた[6]: プラットフォームが死ぬのは、こうだ。まず、プラットフォームはユーザーに対して良いサービスを提供する。次に、ビジネス顧客のためにユーザーを悪用し、 最終的に、ビジネス顧客を悪用して、自分たちのためにすべての価値を取り戻そうとする。そして、死ぬのだ。私はこれを「エンシット化」と呼んでいるが、こ れはプラットフォームが価値配分方法を変更するのが容易であることと、「両面市場」の性質が組み合わさった結果、避けられないように見える。両面市場と は、プラットフォームが売り手と買い手の間に位置し、それぞれを人質として、両者間でやり取りされる価値のより大きなシェアをむさぼり食う市場である。 2024年のフィナンシャル・タイムズ紙の社説で、ドクトロウは「『エンシット化』がすべてに訪れる」と主張し、「エンシット化」プラットフォームが人類 を「エンシット世紀」に導くと論じた。[7] ドクターロウは、新しいプラットフォームは、新しいユーザーを獲得する方法として、有益な製品やサービスを赤字で提供すると主張している。いったんユー ザーがロックインされると、プラットフォームはユーザーベースへのアクセスをサプライヤーに赤字で提供し、いったんサプライヤーがロックインされると、プ ラットフォームは黒字を株主に移行させる。[8] プラットフォームが根本的に株主を重視し、ユーザーとベンダーがロックインされると、プラットフォームはもはや品質を維持するインセンティブを持たなくな る。仲介者として機能するプラットフォームが独占化すると、高いスイッチングコストが原因で、技術的には代替手段が存在していても、ユーザーがプラット フォームを離れることを妨げるため、プラットフォームはサービスにおける独占と顧客における独占の両方を実現できる。[6] ドクターフは、エンシット化のプロセスを 「いじくり回す」ことによって起こると説明している。すなわち、利益の限界的な改善を追求するために、他の目標を一切考慮せずにシステムのパラメータを絶 えず調整することである。[9] エンシット化はレントシーキングの一形態と見なすことができる。[6] この問題を解決するために、ドクトロウは2つの一般原則に従うことを呼びかけている。 1つ目は、エンドツーエンドの原則を尊重することである。これは、ネットワークの役割は、送信者が送信したいデータを、受信者が受信したい相手に確実に届 けることであるという考え方である。プラットフォームに適用する場合、これは、プラットフォームが提示したいものではなく、ユーザーが要求したものをユー ザーに提供することを意味する。例えば、ユーザーは購読しているユーザーのコンテンツをすべて閲覧でき、コンテンツ制作者は不透明なアルゴリズムを介さず にオーディエンスにリーチできる。また、検索エンジンでは、検索クエリに完全に一致する結果がスポンサー付きの結果よりも前に表示されるようになる。 2つ目は、プラットフォームのユーザーが、そのプラットフォームに不満がある場合、簡単に他のプラットフォームに移行できるという「退出の権利」である。 ソーシャルメディアの場合、これは相互運用性を必要とし、ユーザーを「ロックイン」してプラットフォーム間の市場競争を妨げるネットワーク効果に対抗す る。デジタルメディアプラットフォームの場合、これは、デジタル著作権管理によってロックされた購入済みコンテンツを失うことなく、ユーザーがプラット フォームを切り替えられることを意味する。 アメリカ方言学会は「enshittification」を2023年のワード・オブ・ザ・イヤーに選出した。[7][11] 2024年11月、オーストラリアン・マッコーリー・ディクショナリーは「enshittification」をその年の単語に選び、次のように定義し た。[12] サービスや製品の質が徐々に低下すること。特にオンラインプラットフォームにおいて、サービス品質の低下が利益追求の結果として引き起こされる。 |

| Reception and impact Doctorow's concept has been cited by various scholars and journalists as a framework for understanding the decline in quality of online platforms. Discussions about enshittification have appeared in numerous media outlets, including analyses of how tech giants like Facebook, Google, and Amazon have shifted their business models to prioritize profits at the expense of user experience.[13] This phenomenon has sparked debates about the need for regulatory interventions and alternative models to ensure the integrity and quality of digital platforms.[14] The Macquarie Dictionary named "enshittification" as its 2024 word of the year, selected by both the committee's and people's choice votes for only the third time since the inaugural event in 2006.[15] |

受容と影響 ドクトロウの概念は、オンラインプラットフォームの質の低下を理解するための枠組みとして、さまざまな学者やジャーナリストによって引用されている。 エンシッティフィケーションに関する議論は、Facebook、Google、Amazonなどの大手テクノロジー企業が、ユーザーエクスペリエンスを犠 牲にして利益を優先するビジネスモデルへとシフトしていることの分析を含め、多数のメディアで取り上げられている。[13] この現象は、デジタルプラットフォームの完全性と質を確保するための規制介入や代替モデルの必要性に関する議論を巻き起こしている。[14] マッコーリー辞典は、「enshittification」を2024年の流行語に選出した。これは、2006年の初回以来、委員会と一般投票の両方で選 出された3回目の言葉である。[15] |

| Examples Airbnb Once a disruptor competing with established hotel chains, Airbnb now charges nightly rates exceeding those of existing hotels.[16] This is a direct result of Airbnb now charging customers and hosts a mark-up of over 45% in service fees on transactions that use the online platform.[citation needed] Amazon See also: Criticism of Amazon In Doctorow's original post, he discussed the practices of Amazon. The online retailer began by wooing users with goods sold below cost and (with an Amazon Prime subscription) free shipping. Once its user base was solidified, more sellers began to sell their products through Amazon. Finally, Amazon began to add fees to increase profits. In 2023, over 45% of the sale price of items went to Amazon in the form of various fees.[citation needed] Doctorow described advertisement within Amazon as a payola scheme in which sellers bid against one another for search-ranking preference, and said that the first five pages of a search for "cat beds" were half advertisements.[6] Doctorow has also criticised Amazon's Audible service, which controls over 90% of the audiobook market and applies mandatory digital rights management (DRM) to all audio books. He pointed out that this meant that a user leaving the platform would lose access to their audiobook library. Doctorow decided in 2014 to not sell his audiobooks via Audible anymore but produce them himself even though that meant earning a lot less than he would have by letting Amazon "slap DRM" on his books. He has since then published over half a dozen of his audiobooks independently as Amazon's system would not distribute them without DRM.[17][18] See also: Criticism of Facebook According to Doctorow, Facebook offered a good service until it had reached a "critical mass" of users, and it became difficult for people to leave because they would need to convince their friends to go with them. Facebook then began to add posts from media companies into feeds until the media companies too were dependent on traffic from Facebook, and then adjusted the algorithm to prioritise paid "boosted" posts. Business Insider agreed with the view that Facebook was being enshittified, adding that it "constantly floods users' feeds with sponsored (or 'recommended') content, and seems to bury the things people want to see under what Facebook decides is relevant".[19] Doctorow pointed at the Facebook metrics controversy, in which video statistics were inflated on the site, which led to media companies over-investing in Facebook and collapsing. He described Facebook as "terminally enshittified".[6] Google Search See also: Criticism of Google Doctorow cites Google Search as one example, which became dominant through relevant search results and minimal ads, then later degraded through increased advertising, search engine optimization, and outright fraud, benefitting its advertising customers, which was followed by Google's collusion to rig the ad market through Jedi Blue to recapture value for itself. Doctorow also cites Google's firing of 12,000 employees in January 2023, which coincided with a stock buyback scheme which "would have paid all their salaries for the next 27 years", as well as Google's rush to research an AI search chatbot, "a tool that won't show you what you ask for, but rather, what it thinks you should see".[6][10][20][21][22] Netflix After years of competing fiercely in the "streaming wars", Netflix emerged as the main winner in the early 2020s.[23] Once it had achieved a quasi-monopolistic position, Netflix proceeded to raise prices, introduce an ad-supported tier, with Netflix also discontinuing its cheapest ad-free plan in the UK and Canada in 2024,[24] as well as a crack down on password sharing.[25] Reddit users protest the changes on r/place. "Spez" is the username of the Reddit CEO, Steve Huffman. See also: 2023 Reddit API controversy In 2023, shortly after its initial filings for an initial public offering, Reddit announced that it would begin charging fees for API access, a move that would effectively shut down many third-party apps by making them cost-prohibitive to operate.[26] The CEO, Steve Huffman, stated that it was in response to AI firms scraping data without paying Reddit for it, but coverage linked the move to the upcoming IPO; the move shut down large numbers of third party apps, forcing users to use official Reddit apps that provided more profit to the company.[26][27][28] Moderators on the site conducted a blackout protest against the company's new policy, although the changes ultimately went ahead. Many third party Reddit apps such as the Apollo app were shut down because of the new fees.[29][27][30] In September 2024, Reddit announced that moderators will no longer have the ability of changing subreddit accessibility from "public" to "private" without approval from Reddit staff. This was widely interpreted by moderators as a punitive change in response to the 2023 API protests.[31] Main article: Twitter under Elon Musk The term was applied to the changes to Twitter in the wake of its 2022 acquisition by Elon Musk.[32][20] This included the closure of the service's API to stop interoperable software from being used, suspending users for posting (rival service) Mastodon handles in their profiles, and placing restrictions on the ability to view the site without logging in. Other changes included temporary rate limits for the number of tweets that could be viewed per day, the introduction of paid subscriptions to the service in the form of Twitter Blue,[32] and the reduction of moderation.[33] Musk had the algorithm modified to promote his own posts above others, which caused users' feeds to be flooded with his content in February 2023.[34] In April 2024, Musk announced that new users would have to pay a fee to be able to post.[35] The changes led to a dramatic decline in revenue for the company. The increase in hate speech on the platform, particularly antisemitism and Islamophobia during the Israel–Hamas war, led to some organisations pulling advertisements.[36] According to internal documents seen by The New York Times in late 2023, the losses from advertisers were projected to cost the company $75 million by the end of the year.[37] Musk delivered an interview on November 29, in which he told advertisers leaving the website to "go fuck yourself."[38][39] By August 2024, revenue had fallen 84% compared to before Musk's leadership.[40] Uber See also: Controversies involving Uber App-based ridesharing company Uber gained market share by ignoring local licensing systems such as taxi medallions while also keeping consumer costs artificially low by subsidizing rides via venture capital funding.[41] Once they achieved a duopoly with competitor Lyft, the company implemented surge pricing to increase the cost of travel to riders and dynamically adjust the payments made to drivers.[41] The suitability of Uber surge pricing as an example of the phenomenon of enshittification is questionable, however, as surge pricing has been found to increase the quantity of drivers during periods when the surge pricing is in effect and a reallocation of rides to those who receive the most benefit from them.[42][43] This increase in quantity has been found to increase the availability of Ubers for riders, keeping waiting times low and ride completion rates high during periods of surge pricing.[42][43] Unity See also: Unity (game engine) § Runtime fee reception The proposed (and eventually abandoned) changes to the Unity game engine's licensing model in 2023 were described by Gameindustry.biz as an example of enshittification, as the changes would have applied retroactively to projects which had already been in development for years while degrading quality for both developers and end users, while increasing fees.[44] While the Unity Engine itself is not a two-sided market, the move was related to Unity's position as a provider of mobile free-to-play services to developers, including in-app purchase systems.[45] In response to these changes, many game developers announced their intention to abandon Unity for an alternative engine, despite the significant switching cost of doing so, with game designer Sam Barlow specifically using the word enshittification when describing the new fee policy as the motive.[46] Use of the Unity engine at game jams declined rapidly in 2024 as indie developers switched to other engines. Unity usage at the Global Game Jam declined to 36% that year, from 61% in 2023. The GMTK Game Jam also reported a major decline in Unity usership.[47][48] Dating apps The market for dating apps has been cited as an example of enshittification due to the conflict between the dating apps' ostensible goal of matchmaking, and their operators' desire to convert users to the paid version of the app and retaining them as paying users indefinitely by keeping them single, creating a perverse incentive that leads performance to decline over time as efforts at monetization begin to dominate.[49] Mathematical modeling has suggested that it is in the financial interests of app operators to offer their user base a sub-optimal experience.[50] |

例 Airbnb かつては既存のホテルチェーンと競合するディスラプターであったAirbnbは、現在では既存のホテルの宿泊料金を上回る料金を請求している。[16]こ れは、Airbnbがオンラインプラットフォームを利用した取引において、顧客とホストに45%以上のサービス料を請求している直接的な結果である。[要 出典] Amazon 関連項目:Amazonに対する批判 Doctorowのオリジナル投稿では、Amazonの慣行について論じている。オンライン小売業者は、原価割れで商品を販売し、(Amazonプライム の加入者には)送料無料でユーザーを魅了することから始めた。ユーザー基盤が固まると、より多くの販売業者がAmazonを通じて商品を販売するように なった。最終的にAmazonは利益を増やすために手数料を加え始めた。2023年には、商品の販売価格の45%以上が、さまざまな手数料という形で Amazonに支払われた。[要出典] ドクトロウはAmazon内の広告を、売り手が検索順位の優位性を求めて互いに入札するペイオラの仕組みであると表現し、「猫用ベッド」の検索結果の最初 の5ページは半分が広告であると述べた。 また、オーディオブック市場の90%以上を占め、すべてのオーディオブックに強制的なデジタル著作権管理(DRM)を適用しているAmazonの Audibleサービスについても批判している。このサービスを利用しているユーザーがプラットフォームを離れると、オーディオブックのライブラリへのア クセスが失われることを指摘している。ドクターロウは2014年に、Amazonに「DRMを適用」させるよりも収入は大幅に減るが、オーディオブックを Audibleで販売するのをやめ、自分で制作することにした。AmazonのシステムではDRMなしでは配信できないため、それ以来、彼は6冊以上の オーディオブックを独自に出版している。[17][18] 関連項目:Facebookへの批判 ドクトロウによると、Facebookはユーザー数が「臨界点」に達するまでは良いサービスを提供していたが、ユーザーがFacebookを退会するのは 難しくなった。なぜなら、退会するには友人たちを説得する必要があるからだ。Facebookはその後、メディア企業の投稿をフィードに追加し始め、メ ディア企業もFacebookからのトラフィックに依存するようになった。そして、有料の「ブースト」投稿を優先するようアルゴリズムを調整した。ビジネ ス・インサイダーは、Facebookがエンシット化しているという見解に同意し、さらに「Facebookは常にスポンサー付き(または『推奨』)コン テンツをユーザーのフィードに大量に流し込み、人々が本当に見たいものをFacebookが関連性ありと判断したものに埋もれさせてしまっている」と付け 加えた。[19] ドクトロウは、Facebookのメトリクス論争を指摘し、その中で動画の統計がサイト上で水増しされていたことが、メディア企業がFacebookに過 剰投資し、破綻する原因となった。彼はFacebookを「末期のエンシット化」と表現した。[6] Google検索 関連項目:Googleへの批判 ドクターロウはGoogle検索を一例として挙げ、関連性の高い検索結果と最小限の広告で優位に立ったが、その後、広告の増加、検索エンジン最適化、そし て明らかな不正行為によって劣化し、広告主の利益につながった。また、ドクターロウは2023年1月にGoogleが12,000人の従業員を解雇したこ とにも言及している。これは自社株買い戻し計画と時期が重なっており、「今後27年間の給与をすべて支払うことになった」という。また、 また、GoogleがAI検索チャットボットの研究に急ぐようになったことも挙げている。「AI検索チャットボットは、ユーザーが求めるものを表示するの ではなく、むしろ、ユーザーが見るべきだとAIが考えるものを表示するツールである」[6][10][20][21][22] Netflix ストリーミング戦争」で激しい競争を何年も繰り広げた後、Netflixは2020年代初頭に主要な勝者として浮上した。[23] 一旦準独占的地位を獲得すると、Netflixは値上げを進め、広告付きプランを導入し、Netflixは2024年に英国とカナダで最も安い広告なしプ ランを廃止し、[24] パスワード共有の取り締まりも強化した。[25] Redditユーザーはr/placeで変更に抗議している。「Spez」はRedditのCEOであるスティーブ・ハフマンのユーザー名である。 参照:2023年のReddit API論争 2023年、新規株式公開の申請直後に、RedditはAPIアクセスへの課金を開始すると発表した。この動きは、運用コストを理由に多くのサードパー ティ製アプリを事実上閉鎖するものとなった。[26] CEOのスティーブ・ハフマンは、AI企業がRedditに料金を支払うことなくデータをスクレイピングしていることへの対応であると述べたが が、報道ではこの動きは間近に迫ったIPOに関連していると指摘した。この動きにより、多数のサードパーティ製アプリが閉鎖され、ユーザーは公式の Redditアプリを使用せざるを得なくなり、同社により多くの利益をもたらすこととなった。[26][27][28] サイトのモデレーターたちは、同社の新しい方針に対してブラックアウト抗議を行ったが、最終的には変更が実施された。アポロアプリのような多くのサード パーティ製Redditアプリは、この新たな料金を理由に閉鎖された。[29][27][30] 2024年9月、Redditはモデレーターがサブレディットのアクセスを「公開」から「非公開」に変更する権限を、Redditスタッフの承認なしには もはや持たないことを発表した。これは、2023年のAPI抗議に対する懲罰的な変更であると、モデレーターの間で広く解釈された。[31] 詳細は「イーロン・マスク時代のTwitter」を参照 この用語は、2022年のイーロン・マスクによる買収を受けてTwitterに実施された変更に適用された。これには、相互運用可能なソフトウェアの使用 を阻止するためのサービスAPIの閉鎖、プロフィールに(競合サービスである)Mastodonのハンドル名を投稿したユーザーの停止、ログインせずにサ イトを表示する機能への制限が含まれていた。その他の変更点としては、1日に閲覧できるツイート数の一時的な制限、Twitter Blueという有料購読サービスの導入[32]、およびモデレーションの削減[33]などがあった。マスクは、自身の投稿を他の投稿よりも優先的に表示さ せるためにアルゴリズムを変更させた その結果、2023年2月にはユーザーのフィードが同氏のコンテンツで溢れかえった。[34] 2024年4月、マスクは新規ユーザーは投稿するために料金を支払わなければならないと発表した。[35] この変更により、同社の収益は劇的に減少した。プラットフォーム上でのヘイトスピーチの増加、特にイスラエル・ハマス戦争中の反ユダヤ主義とイスラム恐怖 症により、一部の組織が広告を取り下げた。2023年後半にニューヨーク・タイムズが入手した内部文書によると、広告主からの損失により、同社の損失は と予測されていた。[37] 2023年11月29日、マスクはインタビューに応じ、ウェブサイトを去る広告主に対して「くたばれ」と述べた。[38][39] 2024年8月までに、マスクが経営陣に加わる前の収益と比較して、収益は84%減少した。[40] Uber 関連項目:Uberを巡る論争 アプリベースのライドシェアリング企業であるUberは、タクシーメダリオンなどの地域ライセンス制度を無視することで市場シェアを拡大し、同時にベン チャーキャピタルからの資金提供により乗車料金を人為的に低く抑えていた。[41] 同社はライバル企業であるLyftと独占状態を築くと、サージプライシングを実施して乗客の料金を引き上げ、ドライバーへの支払いを動的に調整した。 [41] 現象の例としてUberのサージプライシングが適切かどうかは しかし、サーチャージ制はサーチャージ制が実施されている期間にドライバーの数を増やし、その恩恵を最も受ける人たちに配車が再割り当てされることが分 かっているため、Uberのサーチャージ制を例として挙げることの妥当性には疑問が残る。[42][43] この量の増加は、サーチャージ制が実施されている期間に配車可能なUberの台数を増やし、待ち時間を短く保ち、配車完了率を高く保つことが分かってい る。[42][43] Unity 関連項目: Unity (ゲームエンジン) § ランタイム料金の受付 2023年にUnityゲームエンジンのライセンスモデルに提案された(最終的に放棄された)変更は、Gameindustry.bizによってエンシフ ティフィケーションの例として説明された。この変更は、すでに何年も開発が進められているプロジェクトに遡及的に適用され、 開発者とエンドユーザーの両方にとって品質が低下する一方で、料金は増加した。[44] Unityエンジン自体は二面市場ではないが、この動きは、アプリ内購入システムを含む、開発者向けのモバイル無料プレイサービスのプロバイダーとしての Unityの立場に関連している。[45] これらの変更を受けて、多くのゲーム開発者は、Unityを放棄して代替エンジンを使用する意向を発表したが、ゲームデザイナーのサム・バーロウは、この 新しい料金ポリシーを動機として説明する際、特に「エンシフティフィケーション(enshittification)」という言葉を使用した。[46] インディーズ開発者が他のエンジンに切り替えたため、2024年にはゲームジャムでのUnityエンジンの使用が急速に減少した。グローバルゲームジャム におけるUnityの使用率は、2023年の61%から、同年には36%に減少した。GMTKゲームジャムでも、Unityの使用率が大幅に減少したこと が報告されている。[47][48] 出会い系アプリ 出会い系アプリ市場は、見かけ上の目的である「お見合い」と、運営者の「ユーザーを有料版に転換し、ユーザーを独身のままに保って無期限に有料ユーザーと して維持する」という欲望との間の対立により、エンシットフィケーションの例として挙げられている。収益化への取り組みが優勢になるにつれ、長期的にはパ フォーマンスが低下するという逆説的なインセンティブが生み出される。[49] 数学的モデリングでは、アプリ運営者にとって、ユーザーベースに最適ではない体験を提供することが財務的に有利であることが示唆されている。[50] |

| Brain rot – Poor quality online

content Dead Internet theory – Conspiracy theory on online bot activity Echo chamber (media) – Situation that reinforces beliefs by repetition inside a closed system Embrace, extend, and extinguish – Anti-competitive Microsoft business strategy Freemium – Free product where the extras require payment Link rot – Phenomenon of URLs tending to cease functioning Planned obsolescence – Policy of planning or designing a product with an artificially limited useful life |

脳の腐敗 – 質の悪いオンラインコンテンツ デッド・インターネット理論 – オンラインボット活動に関する陰謀論 エコーチェンバー(メディア) – 閉鎖的なシステム内で繰り返し主張されることで、信念が強化される状況 抱擁、拡張、消滅 – 反競争的なマイクロソフトのビジネス戦略 フリーミアム – 追加機能には料金が必要な無料製品 リンク腐敗 – URLが機能しなくなる傾向にある現象 計画的陳腐化 – 製品の耐用年数を人為的に制限して計画または設計する方針 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enshittification |

|

| The platform economy

encompasses economic and social activities facilitated by digital

platforms.[1] These platforms — such as Amazon, Airbnb, Uber, Microsoft

and Google — serve as intermediaries between various groups of users,

enabling interactions, transactions, collaboration, and innovation.[2]

The platform economy has experienced rapid growth, disrupting

traditional business models and contributing significantly to the

global economy.[3] Platform businesses are characterized by their reliance on network effects, where the platform's value increases as more users join. This has allowed many platform companies to scale quickly and achieve global influence. Platform economies have also introduced novel challenges, such as the rise of precarious work arrangements in the gig economy, reduced labor protections, and concerns about tax evasion by platform operators. In addition, critics argue that platforms contribute to market concentration and increase inequality. Historically, platforms have roots in pre-digital economic systems, with examples of matchmaking and exchange-based systems dating back millennia. However, the rise of the internet in the 1990s enabled the rapid expansion of online platforms, starting with pioneers like Craigslist and eBay. Since the financial crisis of 2007–08, the platform economy has further expanded with the growth of sharing economy services like Airbnb and labor market platforms such as TaskRabbit. The increasing prominence of platforms has attracted attention from scholars, governments, and regulators, with many early assessments praising their potential to enhance productivity and create new markets. In recent years, concerns about the social and economic impacts of the platform economy have grown. Critics have highlighted issues such as technological unemployment, the displacement of traditional jobs with precarious forms of labor, and declining tax revenues. Some scholars and policymakers have also raised alarms about the potential psychological effects of excessive platform use and its impact on social cohesion. As a result, there has been a shift towards more regulatory scrutiny of platforms, particularly in the European Union, where new regulations have been proposed to ensure fair competition and worker protections. Despite these challenges, platforms continue to be a dominant force in the global economy, with ongoing debates about how best to manage their influence. |

プラットフォーム経済は、デジタルプラットフォームによって促進される

経済および社会活動を包含する。[1]

これらのプラットフォーム(Amazon、Airbnb、Uber、Microsoft、Googleなど)は、さまざまなユーザーグループ間の仲介役と

なり、交流、取引、コラボレーション、イノベーションを可能にする。[2]

プラットフォーム経済は急速に成長しており、従来のビジネスモデルを破壊し、世界経済に大きく貢献している。[3] プラットフォームビジネスは、ネットワーク効果に依存しているという特徴があり、より多くのユーザーが参加するにつれてプラットフォームの価値が高まる。 このため、多くのプラットフォーム企業が急速に規模を拡大し、世界的な影響力を獲得することが可能となっている。また、プラットフォーム経済は、ギグエコ ノミーにおける不安定な労働形態の増加、労働者保護の縮小、プラットフォーム運営者による脱税の懸念など、新たな課題ももたらしている。さらに、プラット フォームは市場の集中化と格差の拡大を助長しているという批判もある。 歴史的に見ると、プラットフォームはデジタル化以前の経済システムにその起源があり、何千年も前の見合いや交換をベースとしたシステムがその例である。し かし、1990年代のインターネットの台頭により、CraigslistやeBayなどの先駆者たちを皮切りに、オンラインプラットフォームの急速な拡大 が可能となった。2007年から2008年の金融危機以降、プラットフォーム経済は、Airbnbのようなシェアリングエコノミーサービスや TaskRabbitのような労働市場プラットフォームの成長により、さらに拡大した。プラットフォームの存在感が高まるにつれ、学者や政府、規制当局の 注目を集めるようになり、多くの初期評価では、生産性を向上させ、新たな市場を生み出す可能性を賞賛する声が上がった。 近年では、プラットフォーム経済が社会や経済に与える影響に対する懸念が高まっている。批判派は、技術的失業、不安定な労働形態への置き換えによる従来の 雇用の減少、税収の減少といった問題を指摘している。一部の学者や政策立案者からは、プラットフォームの過剰利用による潜在的な心理的影響や、社会の結束 力への影響に対する懸念も示されている。その結果、特に欧州連合(EU)では、プラットフォームに対する規制の監視が強化される傾向にある。公正な競争と 労働者の保護を確保するための新たな規制が提案されている。こうした課題があるにもかかわらず、プラットフォームは依然として世界経済の主要な原動力であ り、その影響力をどのように管理するのが最善かについて、現在も議論が続いている。 |

| History The concept of platforms facilitating economic and social exchanges predates the digital era by centuries. Early examples include matchmaking services in China dating back to at least 1100 BC, where intermediaries connected potential marriage partners. Similarly, ancient grain exchanges in Greece and medieval fairs have been compared to modern transactional platforms.[4][5] Over time, geographic areas known for specific types of production, like certain industrial clusters, have also functioned as innovation platforms, a concept that was further formalized in the 1980s with the emergence of technology platforms such as Wintel.[6][7] The rise of the internet transformed platform-based businesses by dramatically improving connectivity and communication. Online platforms such as Craigslist and eBay emerged in the 1990s, while later social media platforms like Myspace and collaborative platforms like Wikipedia followed in the early 2000s. The financial crisis of 2007–08 spurred the creation of new platform models, including asset-sharing platforms like Airbnb and labor platforms such as TaskRabbit.[8] Despite the long history of platform-like systems, it wasn’t until the 1990s that scholars began to focus on platforms as a distinct business model. Early research primarily examined innovation platforms without special emphasis on digital platforms. By the late 1990s, understanding of the broader "platform economy" remained limited.[9] The term "platform" has since expanded to include digital matchmakers and multi-sided markets, as described by Jean-Charles Rochet and Jean Tirole in their seminal work on platform competition.[10] In an academic context, "platform" often refers to systems that facilitate interactions between different groups, such as Uber, Airbnb, or TaskRabbit. However, platforms can also encompass non-digital matchmakers, such as business parks and nightclubs, or other entities that enable interactions beyond simple transactions.[11] Scholars like Carliss Y. Baldwin and C. Jason Woodard define a platform as a system with stable core components and more variable peripheral components, enabling flexibility and innovation.[12] The development and impact of platforms continue to evolve, with ongoing academic and business discussions exploring their long-term implications and the ways they reshape markets, industries, and societal practices. |

歴史 経済や社会的な交流を促進するプラットフォームの概念は、デジタル時代よりも何世紀も前から存在している。その初期の例としては、少なくとも紀元前 1100年まで遡る中国の結婚相手紹介サービスがある。仲介者が結婚相手となる可能性のある者同士を引き合わせた。同様に、古代ギリシャの穀物取引所や中 世の市も、現代の取引プラットフォームと比較されている。[4][5] 特定の種類の生産で知られる地理的地域、例えば特定の産業クラスターも、イノベーションプラットフォームとして機能してきた。この概念は、ウィンテルのよ うなテクノロジープラットフォームの出現により、1980年代にさらに明確化された。[6][7] インターネットの台頭は、接続性とコミュニケーションを劇的に改善し、プラットフォームベースのビジネスを変革した。1990年代には CraigslistやeBayなどのオンラインプラットフォームが登場し、2000年代初頭にはMyspaceのようなソーシャルメディアプラット フォームやWikipediaのようなコラボレーションプラットフォームが続いた。2007年から2008年にかけての金融危機は、Airbnbのような 資産共有プラットフォームやTaskRabbitのような労働プラットフォームなど、新しいプラットフォームモデルの創出を促した。 プラットフォームのようなシステムは長い歴史があるにもかかわらず、学者たちがプラットフォームを独自のビジネスモデルとして注目し始めたのは1990年 代になってからである。初期の研究では、主にイノベーション・プラットフォームが調査されたが、デジタル・プラットフォームに特別な重点が置かれたわけで はなかった。1990年代後半になっても、より広義の「プラットフォーム経済」に対する理解は限定的なままであった。[9] その後、「プラットフォーム」という用語は、ジャン=シャルル・ロシェとジャン・ティロールがプラットフォーム競争に関する画期的な研究で説明しているよ うに、デジタル仲介者や多面市場を含むものへと拡大した。[10] 学術的な文脈では、「プラットフォーム」は、Uber、Airbnb、TaskRabbitなどの異なるグループ間のやりとりを促進するシステムを指すこ とが多い。しかし、プラットフォームには、ビジネスパークやナイトクラブなどのデジタル以外の仲介者、あるいは単純な取引を超えたやりとりを可能にするそ の他の事業体も含まれる。[11] カールリス・Y・ボールドウィンやC・ジェイソン・ウッドダードなどの学者は、プラットフォームを、安定したコアコンポーネントとより可変的な周辺コン ポーネントを持つシステムと定義し、柔軟性とイノベーションを可能にするものとしている。[12] プラットフォームの開発と影響力は進化を続けており、その長期的な影響と市場、産業、社会慣行を再形成する方法について、学術界と産業界で継続的な議論が 行われている。 |

| Platformization Platformization refers to the increasing prevalence of large digital platforms that act as intermediaries between users, facilitating economic and social interactions in the public sphere.[13][14][15] The term was first introduced by Anne Helmond, who described it as "the rise of the platform as the dominant computational, infrastructural, and economic model of the web" and examined how platforms extend their boundaries into new areas of the internet.[16] This process includes the extension of platform infrastructure into diverse domains, encapsulating new areas of economic and social activity. Helmond's work has been built upon by other scholars, such as Nieborg and Poell, who describe platformization as the expansion of economic and infrastructural extensions of platforms into the web. These extensions affect how cultural content is produced, distributed, and consumed.[16] Platformization often involves the use of application programming interfaces (APIs) and software development kits (SDKs), which allow third-party developers to integrate with platforms, decentralizing data collection while centralizing data processing.[17] Some scholars have compared the role of digital platforms to traditional infrastructure, such as railroads and utilities. Plantin, Lagoze, and Edwards argue that platforms now function as essential infrastructure, similar to the monopolies of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[18] Business studies scholars have emphasized the network effects associated with platform corporations, where the value of a platform increases as more users participate.[19] Critics, however, have raised concerns about how platformization can lead to the concentration of capital and wealth among a small number of business owners. For example, Trebor Scholz has argued that labor exploitation is a systemic feature of crowdsourced platforms such as Amazon's Mechanical Turk.[20] In the 2010s, the concept of platformization evolved from describing platforms as static entities to viewing them as part of a larger process of digital transformation. Helmond highlighted how platforms use APIs and SDKs to integrate third-party data into their operations, facilitating the decentralization of data collection and the centralization of data processing.[16] Critics such as Poell and Nieborg have argued that this process reshapes cultural practices and influences governance, markets, and data infrastructures.[17] Simplified definitions of platformization exist, with one common interpretation being the creation of a marketplace that charges users for access. However, more nuanced definitions, like those of Poell and Nieborg, emphasize the broader institutional dimensions of platformization, including data infrastructures, markets, and governance.[21] Business model The platform business model involves generating profits by facilitating interactions between two or more distinct groups of users. This model predates the internet; for example, newspapers with classified ads sections have long employed a similar approach. With the advent of digital technology, the platform model has been increasingly adopted, but success is not guaranteed. While some digital-native firms have quickly reached multibillion-dollar valuations and gained strong brand loyalty, many platform startups fail.[22][23][24] Companies that focus on the platform model range from "born-social" startups to traditional businesses that incorporate platform strategies into their operations. Other firms may rely on third-party platforms rather than managing their own. A 2016 survey by Accenture found that 81% of executives expected platform-based models to be central to their growth strategies within three years.[25][23] Research by McKinsey & Company in 2019 showed that firms using platforms, either their own or third-party, achieved on average a 1.4% higher annual EBIT growth than those without a platform strategy.[26] Platform operations differ significantly from traditional business models, where the primary focus is on selling goods or services. In contrast, transaction platforms primarily connect different user groups. For example, a conventional taxi company sells transportation services, whereas a platform company connects drivers with passengers.[27] A notable feature of platform businesses is their reliance on network effects, where the platform's value increases as more people use it. This often results in providing free services to one group of users to attract a larger audience, which then generates demand for the revenue-generating side, such as advertisers.[28] The shift toward platforms has posed challenges for some established businesses. For instance, companies like BlackBerry Limited and Nokia lost market share to platform-oriented firms like Apple and Google's Android in the early 2010s, as they failed to adapt to the growing importance of ecosystems over products.[29][30] |

プラットフォーム化 プラットフォーム化とは、ユーザー間の仲介役として機能し、公共の場における経済的・社会的交流を促進する大規模なデジタルプラットフォームの普及が拡大 していることを指す。[13][14][15] この用語は、Anne Helmondが最初に使用したもので、彼女はこれを「 ウェブの支配的な計算、インフラ、および経済モデルとしてのプラットフォームの台頭」と表現し、プラットフォームがインターネットの新しい領域に境界を拡 大していく様子を検証した。[16] このプロセスには、経済および社会活動の新しい領域を包含する、プラットフォームのインフラの多様な領域への拡大が含まれる。 ヘルモンドの研究は、ニーボーグやポエルといった他の学者たちによってさらに発展し、プラットフォーム化を、プラットフォームの経済およびインフラのウェ ブへの拡大と表現している。これらの拡張は、文化コンテンツの制作、流通、消費に影響を与える。[16] プラットフォーム化には、アプリケーション・プログラミング・インターフェース(API)やソフトウェア開発キット(SDK)の使用が伴うことが多く、こ れによりサードパーティの開発者はプラットフォームと統合することができ、データ収集の分散化とデータ処理の集中化が可能になる。[17] 一部の学者は、デジタルプラットフォームの役割を、鉄道や公益事業などの従来のインフラストラクチャと比較している。プランタン、ラゴーズ、エドワーズ は、プラットフォームは現在、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭の独占企業と同様に、不可欠なインフラストラクチャとして機能していると主張している。 経営学の学者たちは、プラットフォーム企業に関連するネットワーク効果を強調しており、より多くのユーザーが参加するにつれてプラットフォームの価値が高 まるとしている。[19] しかし、批判派は、プラットフォーム化が少数の事業主の間で資本と富の集中につながる可能性について懸念を表明している。例えば、トレバー・ショルツは、 AmazonのMechanical Turkのようなクラウドソーシングプラットフォームでは、労働搾取がシステム的な特徴であると主張している。[20] 2010年代には、プラットフォーム化の概念は、プラットフォームを静的な存在として説明するものから、デジタル変革というより大きなプロセスの一部とし て捉えるものへと進化している。ヘルモンドは、プラットフォームがAPIやSDKを使用してサードパーティのデータを自社の業務に統合し、データ収集の分 散化とデータ処理の集中化を促進していることを強調した。[16] ポエルやニーボーグなどの批評家は、このプロセスが文化的な慣行を再形成し、ガバナンス、市場、データインフラストラクチャに影響を与えると主張してい る。[17] プラットフォーム化の定義は単純化されているが、その一般的な解釈の1つは、ユーザーにアクセス料金を課す市場の創出である。しかし、Poellや Nieborgのようなより微妙な定義では、データインフラ、市場、ガバナンスなど、プラットフォーム化のより広範な制度的側面を強調している。 ビジネスモデル プラットフォーム・ビジネスモデルは、2つ以上の異なるユーザーグループ間のやりとりを促進することで利益を生み出す。このモデルはインターネット以前か ら存在しており、例えば、広告欄のある新聞は長い間同様のアプローチを採用してきた。デジタル技術の登場により、プラットフォームモデルはますます採用さ れるようになってきたが、成功が保証されているわけではない。デジタルネイティブ企業の中には、すぐに数十億ドルの評価額に達し、強いブランドロイヤリ ティを獲得した企業もあるが、多くのプラットフォーム新興企業は失敗している。 プラットフォームモデルに重点を置く企業は、「ソーシャルネイティブ」のスタートアップから、プラットフォーム戦略を業務に取り入れる従来の企業まで多岐 にわたる。また、独自のプラットフォームを管理するのではなく、サードパーティのプラットフォームに依存する企業もある。2016年のアクセンチュアの調 査では、経営幹部の81%が3年以内にプラットフォームベースのモデルが成長戦略の中心になると予想していることが分かった。[25][23] 2019年のマッキンゼー・アンド・カンパニーの調査では、自社またはサードパーティのプラットフォームを使用している企業は、プラットフォーム戦略を持 たない企業よりも平均で1.4%高いEBITの年間成長率を達成していることが分かった。[26] プラットフォーム事業は、商品やサービスの販売を主な目的とする従来のビジネスモデルとは大きく異なる。それに対し、取引プラットフォームは主に異なる ユーザーグループを結びつける。例えば、従来のタクシー会社は輸送サービスを販売しているが、プラットフォーム企業はドライバーと乗客を結びつける。 プラットフォームビジネスの顕著な特徴は、ネットワーク効果に依存している点であり、プラットフォームの価値は、より多くの人々が利用するにつれて高ま る。その結果、より多くの利用者を引き付けるために、あるグループのユーザーに対して無料サービスを提供することが多く、これにより広告主などの収益を生 み出す側への需要が生まれる。 プラットフォームへの移行は、一部の既存企業にとって課題となっている。例えば、BlackBerry LimitedやNokiaなどの企業は、製品よりもエコシステムが重要視されるようになったことに適応できず、2010年代初頭にAppleや GoogleのAndroidなどのプラットフォーム志向の企業に市場シェアを奪われた。[29][30] |

| Platforms The creation and functioning of platforms involve technical development, network effects, and, in many cases, the cultivation of ecosystems. These platforms, which facilitate interactions between two or more groups of users, can be categorized into several types based on their main utility. Platform creation The process of creating a platform includes developing technical functionality and fostering network effects. For many platforms, building a robust ecosystem of third-party contributors is also essential.[31] Technical functionality Developing core technical functionality can be relatively inexpensive. For example, Courtney Boyd Myers suggested that a platform like Twitter could be built with minimal costs. However, a platform aiming to attract a substantial user base must be developed to at least the level of a minimum viable product (MVP), which includes a well-polished user experience layer. Boyd Myers reported estimates ranging from $50,000 to $250,000 for developing an MVP like Twitter, while more complex platforms, such as Uber, could cost between $1 and $1.5 million.[31] While building technical functionality is often manageable, attracting a large user base for network effects can be more challenging.[32] Network effects Main article: Network effects Platforms benefit significantly from network effects, which increase the platform's value as more users join. However, the value of these effects can sometimes be overstated, as seen in the "grab all the eyeballs fallacy," where attracting users does not always lead to successful monetization.[33][34] Ecosystems Digital platforms often cultivate ecosystems of independent contributors who add value beyond basic platform use. For instance, app developers create third-party applications for platforms like Facebook. Traditional companies entering platform markets may already have an established ecosystem of partners, while startups often expose their platforms via publicly accessible APIs or offer incentives to attract partners.[35] Platform owners usually promote their ecosystems, although competition between the platform owner and participants can occasionally arise.[36][37] Types of platforms Platforms are often categorized based on the primary utility they provide. The four common types of platforms are transaction, innovation, integrated, and investment platforms.[38] Transaction platforms Transaction platforms, also called two-sided markets or multisided markets, facilitate interactions between different groups of users, often involving buying and selling. These platforms are the most common, with examples including Amazon and eBay.[38] Innovation platforms Main article: Innovation intermediary Innovation platforms provide a foundation upon which third parties can develop complementary products and services. Companies like Microsoft and Intel are examples of innovation platforms, offering technological frameworks that enable ecosystem innovation.[38][39] Integrated platforms Integrated platforms combine features of both transaction and innovation platforms. Apple, Google, and Alibaba are considered integrated platforms, operating multiple discrete services. Some integrated platforms derive synergies from combining innovation and transaction functions.[40] Investment platforms Investment platforms act as holding vehicles for multiple platform businesses or invest in platform companies without operating a major platform themselves.[38] Platform cooperativism Main article: Platform cooperative Platform cooperativism involves platforms owned and run by the participants, often in contrast to privately owned platforms. These cooperatives may compete with traditional platforms or offer new models for user engagement in sectors like local governance.[41][42] |

プラットフォーム プラットフォームの構築と機能には、技術開発、ネットワーク効果、そして多くの場合、生態系の育成が関わっている。 複数のユーザーグループ間の交流を促進するこれらのプラットフォームは、主な用途に基づいていくつかの種類に分類することができる。 プラットフォームの構築 プラットフォームの構築プロセスには、技術機能の開発とネットワーク効果の育成が含まれる。 多くのプラットフォームでは、サードパーティの貢献者による強固な生態系の構築も不可欠である。 技術的機能 中核となる技術的機能の開発は比較的安価に済ませることができる。例えば、コートニー・ボイド・マイヤーズは、Twitterのようなプラットフォームは 最小限のコストで構築できると提案している。しかし、多くのユーザーを惹きつけることを目的とするプラットフォームは、少なくともMVP(Minimum Viable Product)レベルまで開発する必要がある。MVPには、洗練されたユーザーエクスペリエンス層が含まれる。Boyd Myersは、TwitterのようなMVPの開発には5万ドルから25万ドルの費用がかかるだろうと推定している。一方で、Uberのようなより複雑な プラットフォームでは、100万ドルから150万ドルの費用がかかる可能性がある。[31] 技術的な機能の構築は多くの場合対応可能であるが、ネットワーク効果による多くのユーザー基盤の獲得はより困難である。[32] ネットワーク効果 詳細は「ネットワーク効果」を参照 プラットフォームはネットワーク効果から多大な恩恵を受け、より多くのユーザーが参加することでプラットフォームの価値が高まる。しかし、この効果の価値 は時に過大評価されることがあり、これは「グラブ・オール・ザ・アイボリーズ(グラブ・オール・ザ・アイボリーズの誤謬)」として知られ、ユーザーを惹き つけることが必ずしも収益化の成功につながるわけではないことを示している。 エコシステム デジタルプラットフォームは、基本的なプラットフォームの利用以上の価値を付加する独立した貢献者たちのエコシステムを醸成することが多い。例えば、アプ リ開発者はFacebookのようなプラットフォーム向けのサードパーティアプリケーションを作成する。プラットフォーム市場に参入する従来の企業は、す でにパートナーのエコシステムを確立している場合があるが、新興企業は一般に公開されているAPIを介して自社のプラットフォームを公開したり、パート ナーを誘致するためのインセンティブを提供したりすることが多い。プラットフォームの所有者は通常、自社のエコシステムを推進するが、プラットフォームの 所有者と参加者の間で競争が生じることもある。 プラットフォームの種類 プラットフォームは、主に提供する機能に基づいて分類されることが多い。一般的なプラットフォームには、取引、イノベーション、統合、投資の4つのタイプ がある。 取引プラットフォーム 取引プラットフォームは、2者間市場または多者間市場とも呼ばれ、異なるユーザーグループ間のやりとりを促進し、多くの場合、売買を伴う。このタイプのプ ラットフォームは最も一般的であり、AmazonやeBayなどがその例である。 イノベーションプラットフォーム 詳細は「イノベーション仲介」を参照 イノベーションプラットフォームは、第三者が補完的な製品やサービスを開発できる基盤を提供する。マイクロソフトやインテルなどの企業は、イノベーション プラットフォームの例であり、エコシステムイノベーションを可能にする技術的枠組みを提供している。 統合プラットフォーム 統合プラットフォームは、取引プラットフォームとイノベーションプラットフォームの両方の機能を兼ね備えている。アップル、グーグル、アリババは、複数の 独立したサービスを運営する統合プラットフォームであると考えられている。一部の統合プラットフォームは、イノベーション機能と取引機能を組み合わせるこ とで相乗効果を生み出している。 投資プラットフォーム 投資プラットフォームは、複数のプラットフォーム事業を保有する手段として機能したり、自ら主要なプラットフォームを運営することなく、プラットフォーム 企業に投資したりする。 プラットフォーム・コーポラティズム 詳細は「プラットフォーム・コーポレーション」を参照 プラットフォーム・コーポラティズムは、参加者が所有し運営するプラットフォームを指し、多くの場合、民間所有のプラットフォームと対比される。これらの 協同組合は、従来のプラットフォームと競合する場合もあれば、地方自治などの分野において、ユーザー参加の新しいモデルを提供するケースもある。[41] [42] |

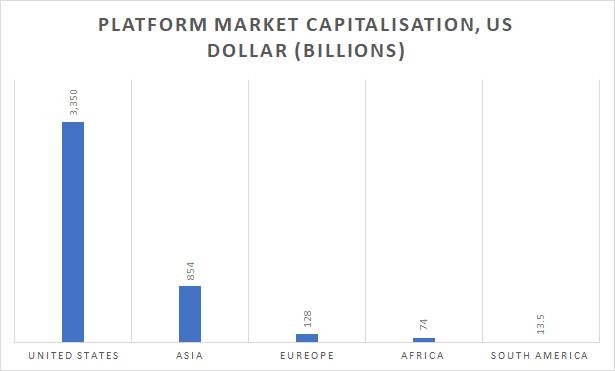

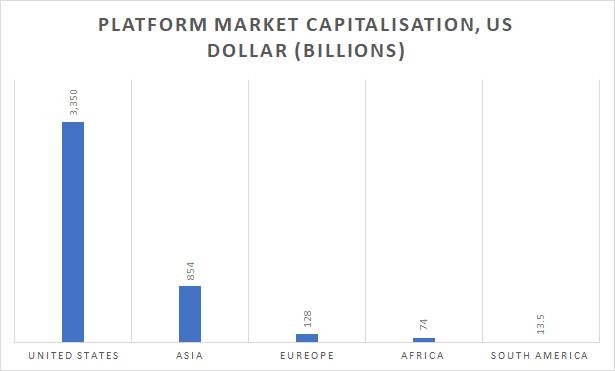

| Global distribution,

international development, and geostrategy Platforms are often analyzed based on their distribution and varying impacts across different geographic regions. Early discussions speculated that the rise of the platform economy could help the United States maintain its global dominance. While the largest platform companies by market capitalization remain US-based, platforms in Asia, especially India and China, have been growing rapidly. Some commentators have predicted that the platform economy will contribute to a shift of economic power toward Asia.[43][44][45] Africa  An M-Pesa agent in Tanzania. M-Pesa provides a form of financial inclusion for people without bank accounts. Several successful platforms have emerged in Africa, many of which are homegrown. Africa has been credited with "leapfrogging" fixed-line internet and developing mobile apps directly. In the field of mobile money, Kenya's M-Pesa brought global attention to the technology.[46][47] M-Pesa has expanded beyond Africa to Asia and Eastern Europe, allowing users to send and receive money via SMS. Other platforms, such as Ushahidi, have also had significant social impacts in Africa. While platforms in Africa often utilize SMS, the uptake of smartphones has increased, with mobile internet adoption outpacing global averages.[48] The rise of platforms has brought both opportunities and challenges to Africa. While there has been less disruption to legacy industries due to the relatively undeveloped economic infrastructure, some businesses have still struggled to adapt.[49] By 2017, some of the enthusiasm surrounding Africa’s platform economy had cooled due to declining commodity prices, but optimism remained. A global survey identified only one African platform company valued over $1 billion: Naspers, based in Cape Town.[50] Asia Asia is home to some of the world's largest platform companies. By 2016, Asia had 82 platform companies valued at over $930 billion, with most of these based in China.[38] China's platform economy is dominated by homegrown companies like Alibaba and Tencent, while foreign platforms like eBay have struggled to gain market share.[51] Outside China, Asian platforms have seen rapid growth in sectors like e-commerce. However, the region has had less success in social media and search until the rise of platforms like TikTok. In some countries, Western platforms remain dominant, such as Facebook in India, where it has become the most popular social media platform.[52] Europe Europe has a significant number of platform companies, though few are valued over $1 billion. In 2016, there were only 27 such companies in Europe, compared to much larger numbers in Asia and North America.[38] The European Commission has promoted the creation of the GAIA-X platform to provide the European Union with digital autonomy, aiming to reduce reliance on American and Chinese platform providers.[53] North America  Market capitalization of platform companies by region, based on 2015 United Nations data. North America, particularly the United States, remains the global leader in platform companies by market capitalization. A 2016 survey found that 63 US-based platform companies were valued over $1 billion, with 44 located in the San Francisco Bay Area. These companies, including Google, Amazon, Apple, and Facebook, accounted for 52% of the global market value of platform companies.[38] South America As of early 2016, South America had only three platform companies valued over $1 billion: MercadoLibre, Despegar.com, and B2W.[54] The region is home to a number of startups, particularly in Brazil and Argentina, where the local market has encouraged a global outlook.[55] The platform-based gig economy has not grown as fast in South America as in other regions, partially due to a large informal labor market. However, some scholars have noted that Latin America's tradition of worker-organized activism may provide valuable lessons for workers in other regions facing economic challenges posed by platforms.[56] |

グローバルな流通、国際的な展開、地政学 プラットフォームは、その流通と地理的地域ごとのさまざまな影響に基づいて分析されることが多い。初期の議論では、プラットフォーム経済の台頭が米国の世 界的な優位性を維持するのに役立つ可能性があると推測されていた。時価総額で最大のプラットフォーム企業は依然として米国を拠点としているが、アジア、特 にインドと中国のプラットフォームは急速に成長している。一部の論者は、プラットフォーム経済が経済力のシフトをアジアに向かわせるだろうと予測してい る。[43][44][45] アフリカ  タンザニアのM-Pesaエージェント。M-Pesaは、銀行口座を持たない人々にも金融サービスを提供する。 アフリカでは、多くの国で自国発のプラットフォームが成功を収めている。アフリカでは、固定回線インターネットを飛び越えて直接モバイルアプリを開発する 「リープフロッグ型発展」が起こっている。モバイルマネーの分野では、ケニアの M-Pesa がこの技術に世界的な注目を集めた。[46][47] M-Pesa はアフリカを越えてアジアや東ヨーロッパにも拡大し、ユーザーは SMS 経由で送金や受金ができるようになった。 Ushahidi のような他のプラットフォームも、アフリカで大きな社会的影響を与えている。 アフリカのプラットフォームは SMS を活用することが多いが、スマートフォンの普及率も増加しており、モバイルインターネットの普及率は世界平均を上回っている。[48] プラットフォームの台頭は、アフリカにチャンスと課題の両方をもたらした。経済インフラが比較的未発達であるため、従来型の産業への打撃は限定的であった が、一部の企業は適応に苦戦している。2017年までに、商品価格の下落により、アフリカのプラットフォーム経済を取り巻く熱狂は冷めたが、楽観的な見方 は残っている。世界規模の調査では、10億ドル以上の評価額を持つアフリカのプラットフォーム企業は、ケープタウンに拠点を置くNaspers社1社のみ であることが判明した。 アジア アジアには世界最大規模のプラットフォーム企業がいくつか存在する。2016年までに、アジアには9300億ドル以上の評価額を持つプラットフォーム企業 が82社あり、その大半が中国に拠点を置いている。[38] 中国のプラットフォーム経済は、アリババやテンセントなどの国産企業が支配しているが、eBayのような外国のプラットフォームは市場シェアの獲得に苦戦 している。[51] 中国国外では、アジアのプラットフォームがeコマースなどの分野で急速に成長している。しかし、この地域ではTikTokのようなプラットフォームの台頭 までは、ソーシャルメディアや検索ではあまり成功していない。一部の国では、インドにおけるFacebookのように、依然として欧米のプラットフォーム が優勢であり、Facebookは最も人気の高いソーシャルメディアプラットフォームとなっている。 ヨーロッパ ヨーロッパには多数のプラットフォーム企業があるが、10億ドル以上の評価額を持つ企業は少ない。2016年には、ヨーロッパにはそのような企業が27社 しかなく、アジアや北米にははるかに多くの企業が存在していた。[38] 欧州委員会は、欧州連合(EU)にデジタル上の自立性を提供することを目的としたGAIA-Xプラットフォームの構築を推進しており、アメリカと中国のプ ラットフォームプロバイダーへの依存を減らすことを目指している。[53] 北米  地域別のプラットフォーム企業の時価総額(2015年の国連データに基づく)。 北米、特に米国は、時価総額ベースでプラットフォーム企業における世界的なリーダーであり続けている。2016年の調査では、米国を拠点とする63社のプ ラットフォーム企業の評価額が10億ドルを超え、そのうち44社がサンフランシスコ湾岸地域に拠点を置いていることが分かった。Google、 Amazon、Apple、Facebookなどのこれらの企業は、プラットフォーム企業のグローバル市場価値の52%を占めている。 南アメリカ 2016年初頭の時点で、南アメリカには10億ドル以上の評価額を持つプラットフォーム企業はMercadoLibre、Despegar.com、 B2Wの3社のみである。[54] この地域には、特にブラジルとアルゼンチンで、グローバルな視野を奨励する地元市場を背景に、多数のスタートアップ企業が存在している。[55] プラットフォームを基盤とするギグエコノミーは、非公式労働市場が大きいことも一因となり、他の地域ほど南米では急速に成長していない。しかし、一部の学 者は、プラットフォームがもたらす経済的課題に直面している他の地域の労働者にとって、労働者による組織的な活動というラテンアメリカの伝統が貴重な教訓 をもたらす可能性があると指摘している。[56] |

Assessment Francesca Bria, an early critic of large privately-owned platforms and an advocate for platform cooperativism.[57][42][58] The rise of digital platforms following the Financial crisis of 2007–2008 intensified interest in their impact on society and the global economy. Numerous assessments have been carried out by scholars, think tanks, and governments, focusing on both the overall platform economy and narrower aspects such as the gig economy and social media's psychological effects.[59] Early reviews were largely positive, suggesting that platforms could enhance services, increase productivity, reduce inefficiencies, and create new markets. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank also noted the potential for platform technology to drive growth in less developed countries.[60][59] However, critics have argued that platforms may exacerbate issues like technological unemployment, precarious work conditions, and income inequality. Platforms have also been linked to declining tax revenues and the potential for damaging effects on mental health and community well-being.[57][59][61] |

評価 フランチェスカ・ブリアは、大規模な民間プラットフォームの初期の批判者であり、プラットフォーム・コーポラティズムの提唱者である。[57][42] [58] 2007年から2008年の金融危機に続くデジタルプラットフォームの台頭は、それらが社会や世界経済に与える影響に対する関心を強めた。学者やシンクタ ンク、政府による数多くの評価が行われ、プラットフォーム経済全体と、ギグエコノミーやソーシャルメディアの心理的影響などのより狭い側面が注目されてい る。 初期の評価は概ね肯定的であり、プラットフォームはサービスを向上させ、生産性を高め、非効率性を削減し、新たな市場を生み出す可能性があることを示唆し ていた。国際通貨基金(IMF)と世界銀行も、プラットフォーム技術が発展途上国の成長を促進する可能性について言及している。 しかし、プラットフォームは技術的失業や不安定な労働条件、所得格差などの問題を悪化させる可能性があると批判する声もある。また、プラットフォームは税 収の減少や、精神衛生や地域社会の幸福に悪影響を及ぼす可能性もあると指摘されている。[57][59][61] |

| Social and environmental

externalities Effects on Employment The platform ecosystem has introduced two primary types of jobs: on-demand work, which involves offline tasks such as cleaning, and crowdwork, where tasks are performed virtually. Advocates highlight the accessibility, flexibility, and low entry barriers of these employment opportunities, while critics emphasize their precarious nature.[62][63] Platform economy workers are typically classified as independent contractors or self-employed, a designation that exempts platforms from providing traditional labor protections such as minimum wage, sick leave, and other standards. While flexibility helps some workers, such as caregivers, manage their workloads, it also leads to job insecurity and lower earnings. Many gig economy workers earn below-average pay, exacerbating income inequality[62][63] Platforms employ data and algorithms to manage dispersed workers, standardizing services while bypassing traditional workplace institutions. This practice makes unionization and collective bargaining challenging. However, gig workers have begun adapting to these conditions by developing innovative strategies to organize and advocate for their rights.[62][64] Effects on Consumer and Societal Risks Platforms have disrupted industries such as taxis and hotels, displacing traditional service providers while formalizing previously informal sectors. This restructuring centralizes value capture under platform owners.[62][65] Dominant platforms frequently use exclusivity agreements to lock in users and merchants. While these practices increase profitability for the platforms, they limit consumer choice, stifle competition, and create inefficiencies. Critics argue that such practices exploit consumers and merchants.[62][65] Proponents of platforms argue that they democratize entrepreneurship by liberating underutilized assets, such as rooms through Airbnb or vehicles through Uber. However, detractors counter that platforms concentrate wealth and exacerbate economic inequalities. In sectors such as e-commerce and food delivery, exclusivity agreements can further restrict competition, reducing overall societal welfare.[62] Effects on Markets Platforms continue to disrupt traditional markets by displacing established providers and reorganizing industries. For instance, ride-sharing apps and short-term rental platforms centralize value capture while replacing conventional service providers. [65] Dominant platforms often employ exclusivity agreements to maintain control over users and merchants. These agreements reduce consumer choice and hinder competition, contributing to inefficiencies in the market. Although platforms claim to foster entrepreneurship and better resource utilization, critics highlight their role in creating wealth disparities and limiting economic opportunity. This is particularly evident in sectors such as food delivery and online retail.[62][65] Post-2017 Backlash By 2017, attitudes toward platforms had begun to shift, with some commentators expressing concern over their growing power and influence. In the U.S., tech companies that were once lauded became subjects of growing scrutiny from both ends of the political spectrum.[66] Figures like Evgeny Morozov labeled many platforms "parasitic," feeding off existing social and economic structures.[67] Increased regulation followed in regions like Europe and China, with major platforms facing allegations of anti-competitive practices and calls for stronger oversight.[52][68] Though platform companies experienced increased scrutiny, many remained popular among consumers, as demonstrated by strong financial results in early 2018.[69] By 2021, the "techlash" narrative continued, with further regulatory challenges arising in the U.S., Europe, and China.[70] Lack of Social Security Most platform workers are denied any benefits, including health insurance, paid leave, retirement contribution or even unemployment protection; exclusion is rooted by the end in their status as contractors rather than employees, a distinction that relieves platforms of legal responsibilities. This is also further exacerbated that most of this job security is highly dependent on the rating of users and the algorithm of the platforms, which can arbitrarily lower their visibility or ban them without an appropriate appeals process[71]. Limited Unionization Opportunities Unionization among platform workers is challenging because of how dispersed the nature of platform labor is. Unlike traditional workplaces, platform workers seldom share a physical location which often leads to more difficulty to organize. Additionally most platforms actively resist unionization efforts, often using worker’s status as partners or contractors to avoid recognizing unions. A good example of this can be seen in California where Uber and Lyft drivers pushed for a protection under Assembly Bill 5 (AB5) which tried to reclassify gig workers as employees. AB5 introduced the “ABC test” which tries to ensure that workers classified as employees enjoy and access basic labour protection such as minimum wage, overtime pay, and unemployment insurance. In response the platforms spent more than $110 million lobbying for Proposition 22, which let gig companies remain as contractors. While Proposition 22 had some minor benefits including limited health subsidies for drivers working more than 15 hours a week it didn't provide the important employment protection and continued to exclude drivers from unionization rights. It is documented under the Proposition 22 driver earnings, accounting for expenses that are far from minimum wage requirement. Under federal laws however such as the NLRA still deny independent contractors the same rights as employees.[72] The Decarbonization Divide In addition to the issue of labour, platform economy has also been seen to contribute to the decarbonization divide. This is replicated in areas such as waste management from e-waste or the exploitation of gig workers, where vulnerable communities take the environmental and social costs from platform operations[73]. The rapid obsolescence and advancement of devices used by platform usage resulted in substantial e-waste which was managed informally by workers in developing countries. For instance in Agbogbloshie, Ghana, workers must dismantle hazardous electronic materials like lead and mercury without protective equipment, contributing to severe health risks and environmental degradation[74]. Mitigation Effort for Decarbonization Divide While this issue remains a critical challenge, new emerging efforts aim to surmount these disparities by fostering investment in sustainable practices. Initiatives such as the European Commission's 2040 climate targets and reforms to the Emissions Trading System help bridge the gap by fostering a low-carbon investment path and transformative change. These efforts will be critical in aligning manufacturing and platform operations with broader decarbonization goals, ensuring sustainability across industries and regions.[75] Mitigation Effort for Decarbonization Divide While this issue remains a critical challenge, new emerging efforts aim to surmount these disparities by fostering investment in sustainable practices. Initiatives such as the European Commission's 2040 climate targets and reforms to the Emissions Trading System help bridge the gap by fostering a low-carbon investment path and transformative change. These efforts will be critical in aligning manufacturing and platform operations with broader decarbonization goals, ensuring sustainability across industries and regions[76]. Alternative Paradigms There's a growing interest in alternative priorities for fairness, sustainability, and community empowerment as a response to the present platform economy challenges. Two notable ideas are the rise of cosmolocalism and platform cooperative initiatives. Cosmolocalism Cosmolocalism advances the idea of using global knowledge commons but allows that knowledge to be used for localized production to build up equitable and sustainable economic systems. This approach emphasizes open-source platforms and decentralized technology that reduce heavy reliance on resource-intensive global supply chains. Cosmolocalism challenges the conventional platform economy by promoting technology that serves local needs while drawing on global expertise; this approach aligns with sustainable goals by reducing resource extraction and waste while fostering local autonomy.[77] Platform Cooperativism Platform Cooperativism, on the other hand, proposes platforms that are collectively owned and democratically governed by their workers and users[78]. Unlike other traditional platforms, platform cooperatives distribute profits equitably and empower participants through shared decision-making. |

社会的および環境的外部性 雇用への影響 プラットフォームエコシステムは、主に2つのタイプの仕事を導入している。オンデマンドワークは、清掃などのオフライン作業を伴うものであり、クラウド ワークは、作業がバーチャルに行われるものである。擁護派は、これらの雇用機会の利便性、柔軟性、参入障壁の低さを強調するが、批判派は、その不安定な性 質を強調する。 プラットフォーム経済の労働者は通常、独立請負業者または自営業者として分類され、この分類により、プラットフォームは最低賃金、病欠、その他の基準と いった従来の労働保護を提供する必要がなくなる。柔軟性は、介護者など一部の労働者の業務管理に役立つ一方で、雇用不安定と収入減にもつながる。多くのギ グエコノミーの労働者は平均以下の賃金しか得ておらず、所得格差を悪化させている[62][63] プラットフォームは、分散した労働者を管理するためにデータとアルゴリズムを活用し、従来の職場制度を回避しながらサービスを標準化している。この慣行 は、労働組合の結成や団体交渉を困難にしている。しかし、ギグ・ワーカーは、自分たちの権利を主張し、組織化するための革新的な戦略を開発することで、こ うした状況に適応し始めている。 消費者および社会への影響とリスク プラットフォームは、タクシーやホテルなどの業界を混乱させ、従来のサービスプロバイダーを排除する一方で、それまで非公式であったセクターを公式化して いる。この再編により、価値の獲得はプラットフォームのオーナーに集中することになる。 支配的なプラットフォームは、ユーザーや販売業者を囲い込むために排他的契約を頻繁に利用している。こうした慣行はプラットフォームの収益性を高める一方 で、消費者の選択肢を制限し、競争を阻害し、非効率性を生み出す。こうした慣行は消費者や販売業者を搾取していると批判する声もある。 プラットフォームの支持者たちは、Airbnb による部屋や Uber による車両など、十分に活用されていない資産を解放することで、起業を民主化していると主張している。しかし、批判派は、プラットフォームは富を集中さ せ、経済的不平等を悪化させると反論している。電子商取引や食品配達などの分野では、排他的契約が競争をさらに制限し、社会全体の福祉を低下させる可能性 がある。 市場への影響 プラットフォームは、従来のプロバイダーを排除し、業界を再編することで、従来の市場を混乱させ続けている。例えば、ライドシェアリングアプリや短期賃貸 プラットフォームは、従来のサービスプロバイダーを置き換える一方で、価値の獲得を集中させている。[65] 支配的なプラットフォームは、ユーザーや販売業者に対する支配力を維持するために、排他的契約を結ぶことが多い。こうした契約は消費者の選択肢を狭め、競 争を阻害し、市場の非効率化を招く。プラットフォームは起業家精神を育み、資源利用を向上させると主張しているが、批判派は、プラットフォームが富の格差 を生み出し、経済的機会を制限していると強調している。これは、食品配達やオンライン小売などの分野で特に顕著である。[62][65] 2017年以降の反動 2017年までに、プラットフォームに対する態度に変化が現れ始め、一部の論者はその増大する力と影響力に懸念を表明した。米国では、かつては賞賛されて いたテクノロジー企業が、政治の両極からますます厳しい監視の対象となった。[66] エフゲニー・モロゾフのような人物は、多くのプラットフォームを「寄生」と称し、既存の社会経済構造に依存していると指摘した。[67] ヨーロッパや中国などの地域では規制が強化され、主要なプラットフォームは反競争的行為の疑惑や、より強力な監視を求める声に直面した。 プラットフォーム企業は厳しい監視を受けるようになったが、2018年初頭の好調な財務実績が示すように、多くの企業は消費者から依然として高い人気を維 持している。[69] 2021年までに、「テックラッシュ」の物語は続き、米国、欧州、中国でさらなる規制上の課題が生じた。[70] 社会保障の欠如 ほとんどのプラットフォーム労働者は、健康保険、有給休暇、退職金、さらには失業手当などの給付を一切受けられない。この排除は、彼らが従業員ではなく請 負業者であるという事実を根拠としている。このことは、この雇用保障のほとんどが、ユーザーの評価やプラットフォームのアルゴリズムに大きく依存している ことでさらに悪化している。適切な不服申し立て手続きなしに、彼らの可視性を恣意的に下げたり、彼らを禁止したりすることが可能である[71]。 労働組合化の機会が限られている プラットフォーム労働者の労働組合化は、プラットフォーム労働の性質が分散しているため、困難である。従来の職場とは異なり、プラットフォーム労働者は物 理的な場所を共有することがほとんどないため、労働組合化はより困難になることが多い。さらに、ほとんどのプラットフォームは組合化の取り組みに積極的に 抵抗しており、労働者のパートナーまたは請負業者としての地位を理由に、組合の認定を避けることが多い。この良い例がカリフォルニア州で、Uberと Lyftの運転手たちが、ギグ・ワーカーを従業員として再分類しようとしたアセンブリ・ビル5(AB5)の保護を推進したことである。AB5は、「ABC テスト」を導入し、従業員として分類された労働者が最低賃金、時間外手当、失業保険などの基本的な労働保護を享受し、利用できるようにしようとした。これ に対して、プラットフォーム企業は請負業者としてのギグ・エコノミー企業の存続を認めるプロポジション22のロビー活動に1億1000万ドル以上を費やし た。プロポジション22には、週15時間以上働くドライバーに対する限定的な健康保険補助など、いくつかの小さな利点があったが、重要な雇用保護は提供さ れず、ドライバーの組合化の権利は引き続き排除された。プロポジション22の下では、ドライバーの収入は、最低賃金の要件をはるかに下回る経費を考慮した 上で記録されている。しかし、NLRAなどの連邦法では、独立請負業者に依然として従業員と同じ権利を認めていない[72]。 脱炭素化の格差 労働問題に加えて、プラットフォーム経済は脱炭素化の格差にも寄与している。これは、電子廃棄物(e-waste)の廃棄管理やギグ・ワーカーの搾取など の分野で再現されており、脆弱なコミュニティがプラットフォーム運営による環境的・社会的コストを負担している[73]。プラットフォーム利用で使用され るデバイスの急速な陳腐化と進化により、大量の電子廃棄物が発生し、発展途上国の労働者によって非公式に処理されている。例えばガーナのアグボグロシーで は、労働者は防護具なしで鉛や水銀などの有害な電子材料を解体しなければならず、深刻な健康リスクと環境悪化の一因となっている[74]。 脱炭素化の格差の緩和に向けた取り組み この問題が依然として重大な課題である一方で、持続可能な慣行への投資を促進することで、こうした格差を克服しようとする新たな取り組みも出てきている。 欧州委員会の2040年気候目標や排出量取引制度の改革などのイニシアティブは、低炭素投資の促進と変革を通じて格差の解消に貢献している。こうした取り 組みは、製造業やプラットフォーム事業をより広範な脱炭素化目標に整合させ、産業や地域全体で持続可能性を確保する上で極めて重要である。 脱炭素化の格差を埋める緩和努力 この問題が依然として重大な課題である一方で、持続可能な慣行への投資を促進することで格差を克服しようとする新たな取り組みも出てきている。欧州委員会 の2040年気候目標や排出量取引制度の改革などの取り組みは、低炭素投資の道筋と変革を促進することで格差の解消に役立つ。こうした取り組みは、製造お よびプラットフォームの運用をより広範な脱炭素化目標に整合させ、産業や地域全体で持続可能性を確保する上で極めて重要となるだろう[76]。 代替パラダイム 現在のプラットフォーム経済の課題への対応として、公平性、持続可能性、地域社会の強化を優先する代替案への関心が高まっている。注目すべき2つのアイデ アは、コスモロカリズムの台頭とプラットフォーム協同組合の取り組みである。 コスモロカリズム コスモロカリズムは、グローバルな知識共有の活用という考えを推進するが、その知識を地域に特化した生産に活用し、公平で持続可能な経済システムを構築す ることを可能にする。このアプローチでは、オープンソースプラットフォームと、資源集約型のグローバルなサプライチェーンへの過度な依存を軽減する分散型 テクノロジーが重視される。コスモロカリズムは、グローバルな専門知識を活用しながら地域ニーズに応えるテクノロジーを推進することで、従来のプラット フォーム経済に異議を唱える。このアプローチは、資源採取と廃棄物を削減しながら地域自治を促進することで、持続可能な目標と一致する。[77] プラットフォーム・コーオペラティヴィズム 一方、プラットフォーム・コーオペラティヴィズムは、労働者とユーザーが共同所有し、民主的に運営するプラットフォームを提案している[78]。他の伝統 的なプラットフォームとは異なり、プラットフォーム・コーオペラティブは利益を公平に分配し、意思決定を共有することで参加者に力を与える。 |

| Regulation In their early stages, digital platforms benefited from light regulation, often aided by policies designed to support emerging internet companies. However, the cross-border nature of platforms has made regulation complex.[37] Another challenge is the lack of consensus on what constitutes the platform economy.[79] Critics argue that current laws are insufficient for regulating platform-based businesses, pointing to concerns such as safety standards, tax compliance, labor rights, and competition.[80] Two contrasting regulatory approaches have emerged in the United States and China. In the U.S., platforms have generally operated with limited government oversight. In contrast, China tightly regulates its platform companies, such as Tencent and Baidu, while also shielding them from foreign competition in the domestic market.[81][37] In March 2018, the European Union introduced guidelines for the removal of illegal content from social media platforms, warning that stricter regulations would follow if companies did not improve self-regulation.[82][83] The OECD is exploring regulation of platform work,[84] while the European Commission has launched initiatives to improve working conditions for platform workers.[85] On 15 December 2020, the Commission proposed two key regulations: the Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act, aimed at increasing accountability and competition in the platform economy.[86][87] Labor unions have increasingly represented platform workers. The Fairwork Foundation has been working to establish globally agreeable working conditions, involving collaboration with platform owners, workers, unions, and governments.[88][89] In China, the growth of the platform economy has drawn attention from regulators. On 18 January 2022, the National Development and Reform Commission and seven other departments published guidelines proposing future regulations for the platform economy.[90] |

規制 初期の段階では、デジタルプラットフォームは軽度の規制の恩恵を受けており、新興のインターネット企業を支援する政策によって支援されることも多かった。 しかし、プラットフォームの国境を越えた性質により、規制は複雑化している。[37] プラットフォーム経済を構成するものに関するコンセンサスが欠如していることも、もう一つの課題である。[79] 批判派は、安全基準、税務コンプライアンス、労働者の権利、競争などの懸念を指摘し、プラットフォームベースのビジネスを規制するには現行の法律では不十 分であると主張している。[80] 米国と中国では、対照的な2つの規制アプローチが浮上している。米国では、プラットフォームは概して政府の監督を限定的に受けながら運営されている。一 方、中国ではテンセントやバイドゥなどのプラットフォーム企業を厳しく規制する一方で、国内市場における外国企業との競争から保護している。[81] [37] 2018年3月、欧州連合はソーシャルメディアプラットフォームからの違法コンテンツの削除に関するガイドラインを導入し、企業が自主規制を改善しなけれ ば、より厳しい規制が導入されると警告した。[82][83] OECDはプラットフォームワークの規制を検討しており、[84] 一方、欧州 欧州委員会はプラットフォームワーカーの労働条件改善に向けた取り組みを開始した。[85] 2020年12月15日、欧州委員会はプラットフォーム経済における説明責任と競争を高めることを目的とした2つの主要な規制、デジタルサービス法とデジ タル市場法を提案した。[86][87] 労働組合はプラットフォームワーカーの代表を務めることが増えている。Fairwork Foundationは、プラットフォームの所有者、労働者、労働組合、政府との連携を含め、世界的に合意可能な労働条件の確立に取り組んでいる。 中国では、プラットフォーム経済の成長が規制当局の注目を集めている。2022年1月18日、国家発展改革委員会と7つの他の部門は、プラットフォーム経 済の将来の規制を提案するガイドラインを発表した。 |

| Circular economy Customer to customer Digital ecosystem Gig economy Gig worker List of gig economy companies Platform capitalism Platform evangelism Two-sided market Uberisation Digital services act |

循環型経済 顧客から顧客へ デジタルエコシステム ギグエコノミー ギグワーカー ギグエコノミー企業一覧 プラットフォーム資本主義 プラットフォームの伝道 二面市場 ウーバライゼーション デジタルサービス法 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Platform_economy |

|

Cory Efram Doctorow

(/ˈkɔːri ˈdɒktəroʊ/; born 17 July 1971) is a Canadian-British blogger,

journalist, and science fiction author who served as co-editor of the

blog Boing Boing. He is an activist in favour of liberalising copyright

laws and a proponent of the Creative Commons organization, using some

of its licences for his books. Some common themes of his work include

digital rights management, file sharing, and post-scarcity

economics.[1][2] Cory Efram Doctorow

(/ˈkɔːri ˈdɒktəroʊ/; born 17 July 1971) is a Canadian-British blogger,

journalist, and science fiction author who served as co-editor of the

blog Boing Boing. He is an activist in favour of liberalising copyright

laws and a proponent of the Creative Commons organization, using some

of its licences for his books. Some common themes of his work include

digital rights management, file sharing, and post-scarcity