プラトン『共和国』

Plato's Republic

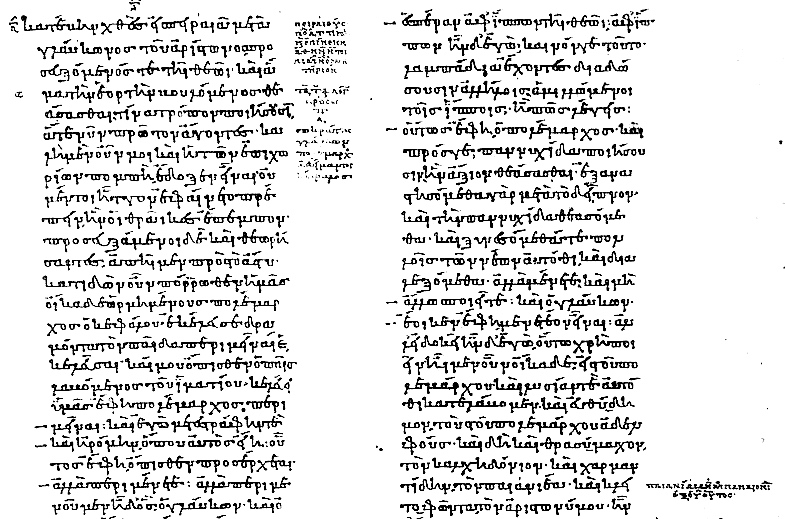

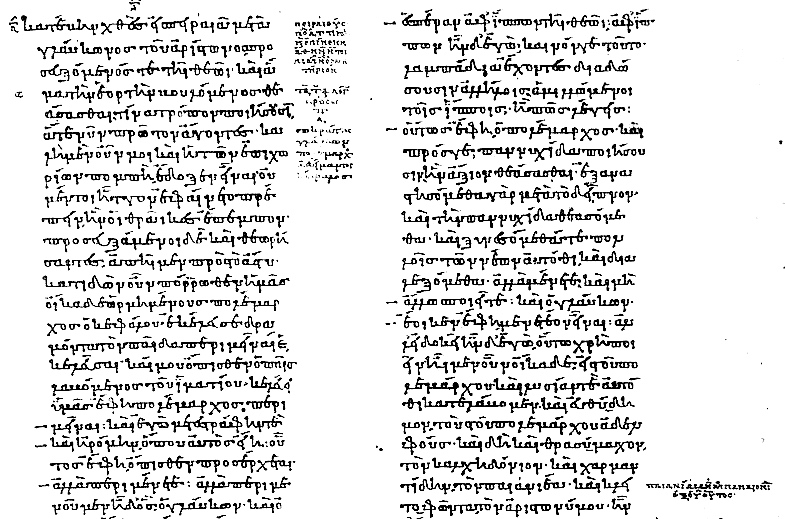

Title page of the oldest complete manuscript: Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Gr. 1807 (late 9th century)

☆ 日本語では『国家』と題されてきたプラトンの『共和国』(ギリシャ語: Πολιτεία, Politeia訳; ラテン語: De Republica[1])は、紀元前375年頃にプラトンによって書かれた、正義(δικαιοσύνη)、正義の都市国家の秩序と性格、正義の人間に 関するソクラテスの対話である。プラトンの最もよく知られた著作であり、知的にも歴史的にも世界で最も影響力のある哲学と政治理論の著作の一つであ る。

| Book I: Aging, Love and the Definitions of Justice See also: Thrasymachus and List of speakers in Plato's dialogues While visiting Athens's port, Piraeus, with Glaucon, Socrates is invited to join Polemarchus for a dinner and festival. They eventually end up at Polemarchus' house where Socrates encounters Polemarchus' father Cephalus. In his first philosophical conversation with the group members, Socrates gets into a conversation with Cephalus. The first real philosophical question posed by Plato in the book is when Socrates asks "is life painful at that age, or what report do you make of it?"[9] when speaking to the aged Cephalus. Cephalus answers by saying that many are unhappy about old age because they miss their youth, but he finds that "old age brings us profound repose and freedom from this and other passions. When the appetites have abated, and their force is diminished, the description of Sophocles is perfectly realized. It is like being delivered from a multitude of furious masters."[9] The repose gives him time to dedicate himself to sacrifices and justice so that he is prepared for the afterlife. Socrates then asks his interlocutors for a definition of justice. Three are suggested: Cephalus: To give each what is owed to them (331c) Polemarchus: To give to each what is appropriate to him (332c) Thrasymachus: What is advantageous for the stronger (338c) Socrates refutes each definition in turn: One may owe it to someone to return them a knife one has borrowed, but if he has since gone mad and would only harm himself with it, returning the knife would not be just. Polemarchus suggests that what is appropriate is to do good to friends and bad to enemies, but harming someone tends to make them unjust, and so on his definition, justice would tend to create injustice. If it is just to do what rulers (the stronger) say and rulers make mistakes about their advantage, then it is just to do what is disadvantageous for the stronger. Thrasymachus then responds to this refutation by claiming that insofar as the stronger make mistakes, they are not in that regard the stronger. Socrates refutes Thrasymachus with a further argument: Crafts aim at the good of their object, and therefore to rule is for the benefit of the ruled and not the ruler. At this point, Thrasymachus claims that the unjust person is wiser than the just person, and Socrates gives three arguments refuting Thrasymachus. However, Thrasymachus ceases to engage actively with Socrates's arguments, and Socrates himself seems to think that his arguments are inadequate, since he has not offered any definition of justice. The first book ends in aporia concerning the essence of justice. |

第I巻 老い、愛、そして正義の定義 以下も参照: スラシマコスとプラトンの対話における話者のリスト グラウコンとアテネの港ピレウスを訪れていたソクラテスは、ポレマルコスの夕食と祭りに招かれる。ソクラテスはポレマルコスの父セファロスと出会う。 グループメンバーとの最初の哲学的会話で、ソクラテスはセファロスと会話に入る。本書でプラトンが投げかけた最初の本格的な哲学的問いは、ソクラテスが年 老いたセファロスと話す際に「その年齢では人生は苦痛なのか、それともどのような報告をするのか」[9]と問う場面である。 セファロスは、多くの人は若い頃を懐かしんで老年を不幸に思うものだと答えるが、彼は「老年は深い安息と、この情念や他の情念からの自由をもたらしてくれ る。食欲が衰え、その力が弱まったとき、ソフォクレスの描写が完璧に実現する。それは、多数の猛烈な主人から解放されるようなものである」[9]。安息は 彼に犠牲と正義に身を捧げる時間を与え、死後の世界に備えるようにする。 ソクラテスは、正義の定義を対談者に求める。3つが提案されます: セファルス:それぞれに負うべきものを与えること (331c) ポレマルコス: それぞれにふさわしいものを与えること (332c) トラジマコス より強いために有利なもの (338c) ソクラテスはそれぞれの定義に順番に反論する: 人は人に借りたナイフを返す義務があるかもしれないが、もしその人がその後気が狂って、ナイフで自分を傷つけるだけなら、ナイフを返すことは正義ではない。 ポレマルコスは、友に善をなし、敵に悪をなすことが適切であるが、人を傷つけることはその人を不公平にする傾向がある、だから彼の定義では、正義は不公平を生む傾向がある、と指摘する。 支配者(より強い者)の言うとおりにするのが正義であり、支配者がその優位について間違いを犯すのであれば、より強い者にとって不利なことをするのが正義ということになる。 スラジマコスはこの反論に対して、強い者が間違いを犯す限り、その点では強い者ではないと主張する。ソクラテスはスラシマコスにさらに反論する: 工芸品はその対象の善を目指すものであり、したがって支配することは被支配者の利益のためであって、支配者のためではない」。 この時点で、トラジマコスは不正な人は公正な人よりも賢明であると主張し、ソクラテスはトラジマコスに反論する3つの論拠を示す。しかし、スラジマコスは ソクラテスの議論に積極的に関与しなくなり、ソクラテス自身も、正義の定義を提示していない以上、彼の議論は不十分だと考えているようだ。第1巻は正義の 本質に関するアポリアで終わる。 |

|

Book II: Glaucon and Adeimantus's Challenge Main article: Ring of Gyges Glaucon and Adeimantus are unsatisfied with Socrates's defense of justice. They ask Socrates to defend justice against an alternative view that they attribute to many. According to this view, the origin of justice is in social contracts. Everyone would prefer to get away with harm to others without suffering it themselves, but since they cannot, they agree not to do harm to others so as not to suffer it themselves. Moreover, according to this view, all those who practice justice do so unwillingly and out of fear of punishment, and the life of the unpunished unjust man is far more blessed than that of the just man. Glaucon would like Socrates to prove that justice is not only desirable for its consequences, but also for its own sake. To demonstrate the problem, he tells the story of Gyges, who – with the help of a ring that turns him invisible – achieves great advantages for himself by committing injustices. Many think that anyone would and should use the ring as Gyges did if they had it. Glaucon uses this argument to challenge Socrates to defend the position that the just life is better than the unjust life. Adeimantus supplements Glaucon's speech with further arguments. He suggests that the unjust should not fear divine judgement, since the very poets who wrote about such judgement also wrote that the gods would grant forgiveness to those who made religious sacrifice. |

第II巻:グラウコンとアデイマントスの挑戦 主な記事 ギュゲスの指輪 グラウコンとAdeimantusは正義のソクラテスの擁護に満足していない。彼らはソクラテスに、多くの人が持っているとする別の見解から正義を守るよ う求める。この見解によると、正義の起源は社会契約にある。誰もが他者に危害を加えても、自分自身はそれに苦しむことなく済ませることを望むが、それがで きないので、他者に危害を加えないことに同意して、自分自身がそれに苦しまないようにする。さらに、この見解によれば、正義を実践する者はすべて、不本意 ながら、罰を恐れてそうするのであり、罰せられない不正義な人間の人生は、正義な人間の人生よりもはるかに恵まれている。グラウコンはソクラテスに、正義 はその結果だけでなく、それ自身のためにも望ましいものであることを証明してほしいと思っている。この問題を証明するために、彼はギュゲスの話をする。 ギュゲスは、自分を透明にする指輪の助けを借りて、不正を犯すことで大きな利益を得る。指輪があれば、誰でもギュゲスのように指輪を使うだろうし、使うべ きだと考える人も多い。グラウコンはこの議論を使って、公正な人生は不正な人生よりも優れているという立場を守るようソクラテスに挑む。 アデイマントスはグラウコンの演説をさらに論証で補う。なぜなら、そのような裁きについて書いた詩人たちも、宗教的な犠牲を捧げる者には神々が赦しを与えると書いているからである。 |

|

Book II–IV: The city and the soul See also: Plato's theory of soul and Cardinal virtues Socrates suggests that they use the city as an image to seek how justice comes to be in the soul of an individual. After attributing the origin of society to the individual not being self-sufficient and having many needs which he cannot supply himself, Socrates first describes a "healthy state" made up of producers who make enough for a modest subsistence, but Glaucon considers this hardly different than "a city of pigs." Socrates then goes on to describe the luxurious city, which he calls "a fevered state".[10] Acquiring and defending these luxuries requires a guardian class to wage wars. They then explore how to obtain guardians who will not become tyrants to the people they guard. Socrates proposes that they solve the problem with an education from their early years. He then prescribes the necessary education, beginning with the kind of stories that are appropriate for training guardians. They conclude that stories that ascribe evil to the gods or heroes or portray the afterlife as bad are untrue and should not be taught. They also decide to regulate narrative and musical style so as to encourage the four cardinal virtues: wisdom, courage, justice and temperance. Socrates avers that beautiful style and morally good style are the same. In proposing their program of censored education, they are repurifying the luxurious or feverish city. Socrates counters the objection that people raised in censorship will be too naive to judge concerning vice by arguing that adults can learn about vice once their character has been formed; before that, they are too impressionable to encounter vice without danger. They suggest that the second part of the guardians' education should be in gymnastics. With physical training they will be able to live without needing frequent medical attention: physical training will help prevent illness and weakness. Socrates claims that any illness requiring constant medical attention is too unhealthy to be worth living. By analogy, any society that requires constant litigation is too unhealthy to be worth maintaining. Socrates asserts that both male and female guardians be given the same education, that all wives and children be shared, and that they be prohibited from owning private property so that guardians will not become possessive and keep their focus on the good of the whole city. He adds a third class distinction between auxiliaries (rank and file soldiers) and guardians (the leaders who rule the city). In the fictional tale known as the myth or parable of the metals, Socrates presents the Noble Lie (γενναῖον ψεῦδος, gennaion pseudos), to convince everyone in the city to perform their social role. All are born from the womb of their mother country, so that all are siblings, but their natures are different, each containing either gold (guardians), silver (auxiliaries), or bronze or iron (producers). If anyone with a bronze or iron nature rules the city, it will be destroyed. Socrates claims that if the people believed "this myth...[it] would have a good effect, making them more inclined to care for the state and one another."[11] Socrates claims the city will be happiest if each citizen engages in the occupation that suits them best. If the city as a whole is happy, then individuals are happy. In the physical education and diet of the guardians, the emphasis is on moderation, since both poverty and excessive wealth will corrupt them (422a1). He argues that a city without wealth can defend itself successfully against wealthy aggressors. Socrates says that it is pointless to worry over specific laws, like those pertaining to contracts, since proper education ensures lawful behavior, and poor education causes lawlessness (425a–425c).[12] Socrates proceeds to search for wisdom, courage, and temperance in the city, on the grounds that justice will be easier to discern in what remains (427e). They find wisdom among the guardian rulers, courage among the guardian warriors (or auxiliaries), temperance among all classes of the city in agreeing about who should rule and who should be ruled. Finally, Socrates defines justice in the city as the state in which each class performs only its own work, not meddling in the work of the other classes (433b). The virtues discovered in the city are then sought in the individual soul. For this purpose, Socrates creates an analogy between the parts of the city and the soul (the city–soul analogy).[13] He argues that psychological conflict points to a divided soul, since a completely unified soul could not behave in opposite ways towards the same object, at the same time, and in the same respect (436b).[14] He gives examples of possible conflicts between the rational, spirited, and appetitive parts of the soul, corresponding to the rulers, auxiliaries, and producing classes in the city.[15] Having established the tripartite soul, Socrates defines the virtues of the individual. A person is wise if he is ruled by the part of the soul that knows "what is beneficial for each part and for the whole," courageous if his spirited part "preserves in the midst of pleasures and pains" the decisions reached by the rational part, and temperate if the three parts agree that the rational part lead (442c–d).[16] They are just if each part of the soul attends to its function and not the function of another. It follows from this definition that one cannot be just if one does not have the other cardinal virtues.[14] In this regard, Plato can be seen as a progenitor of the concept of 'social structures'. |

第II巻-第IV巻:都市と魂 こちらも参照: プラトンの魂と枢機卿の徳に関する理論 ソクラテスは、個人の魂に正義がどのように生まれるかを追求するために、都市をイメージとして使うことを提案する。ソクラテスは、社会の起源を、個人が自 給自足できず、自分では賄えない多くの欲求を持っていることに帰結させた後、まず、ささやかな生計を立てるのに十分な生産者からなる「健全な国家」につい て述べるが、グラウコンは、これは「豚の都市」とほとんど変わらないと考える。次にソクラテスは、「熱狂的な状態」と呼ぶ贅沢な都市について述べる [10]。これらの贅沢品を獲得し、防衛するためには、戦争を行う守護者階級が必要である。 そして、守護する人々に対して暴君とならないような守護者をどのように獲得するかを探る。ソクラテスは、幼少期からの教育で問題を解決することを提案す る。そして、後見人を育てるのにふさわしい物語の種類から、必要な教育を説く。神々や英雄を悪と決めつけたり、死後の世界を悪いものとして描いたりする物 語は真実ではないので、教えるべきでないという結論に達する。彼らはまた、知恵、勇気、正義、節制という四大徳を奨励するために、物語や音楽のスタイルを 規制することを決定する。ソクラテスは、美しいスタイルと道徳的に良いスタイルは同じであると主張する。検閲された教育プログラムを提案することで、彼ら は贅沢な、あるいは熱狂的な都市を再浄化しようとしている。ソクラテスは、検閲で育てられた人々は悪徳について判断するには素朴すぎるという反論に対し て、大人は人格が形成された後に悪徳について学ぶことができるのであって、それ以前は危険なしに悪徳に遭遇するには感受性が強すぎると主張する。 彼らは、保護者の教育の第二段階として体操を勧める。身体を鍛えることで、病気や衰弱を防ぐことができるからだ。ソクラテスは、常に医療を必要とする病気は不健康すぎて生きる価値がないと主張する。類推すると、常に訴訟を必要とする社会は不健康すぎて維持する価値がない。 ソクラテスは、男性と女性の両方の後見人に同じ教育を与えること、すべての妻と子供を共有すること、私有財産の所有が禁止されている後見人が所有欲になら ないように、都市全体の利益に彼らの焦点を維持することを主張します。さらに彼は、補助兵(一流の兵士)と守護兵(都市を支配する指導者)の間に第三階級 の区別を加えている。 金属の神話またはたとえ話として知られる架空の物語の中で、ソクラテスは、都市のすべての人が自分の社会的役割を果たすように説得するために、高貴な嘘 (γενναῖον ψεῦδος, gennaion pseudos)を提示します。全員が母なる国の子宮から生まれ、兄弟であるが、その性質はそれぞれ異なり、金(守護者)、銀(補助者)、青銅または鉄 (生産者)のいずれかを含んでいる。青銅や鉄の性質を持つ者が都市を支配すれば、その都市は破壊される。ソクラテスは、もし民衆が「この神話を信じれ ば......(中略)良い効果があり、国家と互いを気遣うようになる」[11]と主張し、各市民が自分に最も適した職業に従事すれば、都市は最も幸福に なると主張する。都市全体が幸福であれば、個人も幸福である。 貧しさも過度の富も彼らを堕落させるので(422a1)、守護者たちの体育と食事においては、中庸が強調される。ソクラテスは、富のない都市は富裕な侵略 者からうまく身を守ることができると主張する。ソクラテスは、適切な教育は合法的な行動を保証し、貧しい教育は無法を引き起こすので、契約に関する法律の ような特定の法律について心配することは無意味であると言う(425a-425c)[12]。 ソクラテスは、残されたものから正義を見分けることが容易になるという理由で、知恵、勇気、節制を都市で探すことを進める(427e)。彼らは守護的な支 配者の中に知恵を、守護的な戦士(あるいは補助者)の中に勇気を、誰が支配し、誰が支配されるべきかについて合意する都市のすべての階級の中に節制を見出 す。最後に、ソクラテスは都市における正義を、各階級が自分の仕事だけを行い、他の階級の仕事に干渉しない状態と定義している(433b)。 都市で発見された徳は、次に個人の魂に求められる。この目的のために、ソクラテスは都市の部分と魂の部分とのアナロジー(都市と魂のアナロジー)を作り出 す[13]。完全に統一された魂が、同じ対象に対して、同じ時間に、同じ点で反対の行動をとることはありえないので、心理的葛藤は魂の分裂を指し示してい ると彼は主張する(436b)。 [14] 彼は魂の理性的な部分、精神的な部分、食欲的な部分の間に起こりうる対立の例をあげ、それは都市の支配者、補助者、生産者階級に対応する[15]。各部分 にとって、また全体にとって何が有益であるか」を知っている魂の部分によって支配されているならば、人は賢明であり、理性的な部分によって到達された決断 を「快楽と苦痛のただ中で維持する」気骨のある部分によって支配されているならば、勇気があり、理性的な部分が導くことに三つの部分が同意するならば、節 制的である(442c-d)[16]。この定義から、他の枢要徳がなければ公正であることはできないということになる[14]。この点で、プラトンは「社 会構造」の概念の祖先とみなすことができる。 |

|

Book V–VI: The Ship of State Main article: Ship of State See also: Form of the Good and Plato's political philosophy Socrates, having to his satisfaction defined the just constitution of both city and psyche, moves to elaborate upon the four unjust constitutions of these. Adeimantus and Polemarchus interrupt, asking Socrates instead first to explain how the sharing of wives and children in the guardian class is to be defined and legislated, a theme first touched on in Book III. Socrates is overwhelmed at their request, categorizing it as three "waves" of attack against which his reasoning must stand firm. These three waves challenge Socrates' claims that both male and female guardians ought to receive the same education human reproduction ought to be regulated by the state and all offspring should be ignorant of their actual biological parents such a city and its corresponding philosopher-king could actually come to be in the real world. In Books V–VII the abolition of riches among the guardian class (not unlike Max Weber's bureaucracy) leads controversially to the abandonment of the typical family, and as such no child may know his or her parents and the parents may not know their own children. Socrates tells a tale which is the "allegory of the good government". The rulers assemble couples for reproduction, based on breeding criteria. Thus, stable population is achieved through eugenics and social cohesion is projected to be high because familial links are extended towards everyone in the city. Also the education of the youth is such that they are taught of only works of writing that encourage them to improve themselves for the state's good, and envision (the) god(s) as entirely good, just, and the author(s) of only that which is good. Socrates' argument is that in the ideal city, a true philosopher with understanding of forms will facilitate the harmonious co-operation of all the citizens of the city—the governance of a city-state is likened to the command of a ship, the Ship of State. This philosopher-king must be intelligent, reliable, and willing to lead a simple life. However, these qualities are rarely manifested on their own, and so they must be encouraged through education and the study of the Good. |

第V-VI巻:国家の船 主な記事 国家の船 以下も参照: 善の形態とプラトンの政治哲学 ソクラテスは、都市と精神の公正な構成を満足のいくまで定義した後、これらの4つの不公正な構成について詳しく説明しようとする。Adeimantusと Polemarchusは中断し、代わりに、まずソクラテスは、保護者クラスの妻と子の共有がどのように定義され、法制化されるべきかを説明するように求 め、テーマが最初に第III巻で触れた。ソクラテスは、彼らの要求に圧倒され、彼の推論を堅持する必要があります攻撃の 3 つの "波 "として分類します。これらの 3 つの波は、ソクラテスの主張に挑戦する 男性も女性も同じ教育を受けるべきである。 人間の生殖は国家によって規制されるべきであり、すべての子孫は実際の生物学的両親を知らないべきである。 このような都市とそれに対応する哲学者王は、現実の世界に実際に存在しうるのである。 書籍 V ~ VII で保護者階級の富の廃止 (マックス ・ ウェーバーの官僚主義に似ていない) 典型的な家族の放棄に物議を醸すにつながるし、そのようなどの子も自分の親を知ることができないし、親は自分の子供を知らないことがあります。ソクラテス は、「善政の寓話」である物語を語る。支配者は繁殖基準に基づいて、繁殖のためのカップルを組み立てる。こうして、優生学によって安定した人口が達成さ れ、家族的なつながりが都市のすべての人に広がっているため、社会的結束は高いと予測される。また、青少年の教育は、国家の利益のために自らを向上させる ことを奨励し、神(たち)が完全に善であり、正義であり、善であるものだけを創造する者であることを思い描くような文章作品のみを教えるようなものであ る。 ソクラテスの主張は、理想的な都市では、形式を理解する真の哲学者が、都市の全市民の調和のとれた協力を促進するというものである。この哲学王は、知的で 信頼でき、質素な生活を送ることを厭わない人物でなければならない。しかし、これらの資質はそれだけではほとんど現れないので、教育と善の研究を通じて奨 励されなければならない。 |

|

Book VI–VII: Allegories of the Sun, Divided Line, and Cave Main articles: Analogy of the Sun, Analogy of the Divided Line, and Allegory of the Cave See also: Problem of universals, Platonic epistemology, and Theory of Forms The Allegory of the Cave primarily depicts Plato's distinction between the world of appearances and the 'real' world of the Forms.,[17] Just as visible objects must be illuminated in order to be seen, so must also be true of objects of knowledge if light is cast on them. Plato imagines a group of people who have lived their entire lives as prisoners, chained to the wall of a cave in the subterranean so they are unable to see the outside world behind them. However a constant flame illuminates various moving objects outside, which are silhouetted on the wall of the cave visible to the prisoners. These prisoners, through having no other experience of reality, ascribe forms to these shadows such as either "dog" or "cat". Plato then goes on to explain how the philosopher is akin to a prisoner who is freed from the cave. The prisoner is initially blinded by the light, but when he adjusts to the brightness he sees the fire and the statues and how they caused the images witnessed inside the cave. He sees that the fire and statues in the cave were just copies of the real objects; merely imitations. This is analogous to the Forms. What we see from day to day are merely appearances, reflections of the Forms. The philosopher, however, will not be deceived by the shadows and will hence be able to see the 'real' world, the world above that of appearances; the philosopher will gain knowledge of things in themselves. At the end of this allegory, Plato asserts that it is the philosopher's burden to reenter the cave. Those who have seen the ideal world, he says, have the duty to educate those in the material world. Since the philosopher recognizes what is truly good only he is fit to rule society according to Plato. |

第VI巻~第VII巻:太陽、分割線、洞窟の寓話 主な記事 太陽の寓意、分割線の寓意、洞窟の寓意 以下も参照: 普遍の問題、プラトン認識論、形式論 『洞窟の寓意』は主に、プラトンが見た目の世界と形相の「現実」の世界を区別していることを描いている。 プラトンは、地下の洞窟の壁に鎖でつながれ、背後の外の世界を見ることができない囚人として生きてきた人々の一団を想像する。しかし、絶え間ない炎が外の さまざまな動く物体を照らし、それが囚人たちの目に見える洞窟の壁にシルエットとして映る。囚人たちは、他に現実を経験することがないため、これらの影に 「犬」や「猫」といった形を当てはめる。プラトンは、哲学者がいかに洞窟から解放された囚人に似ているかを説明する。囚人は最初、光に目がくらむが、明る さに慣れると、火と彫像が見え、それらが洞窟の中で目撃されたイメージの原因であることがわかる。洞窟の中の火や彫像は、実在するもののコピーに過ぎず、 模造品に過ぎないのだ。これは「形」に似ている。私たちが日々目にしているものは、形相の反映にすぎない。しかし、哲学者は影に惑わされることなく、「本 当の」世界を見ることができる。この寓話の最後に、プラトンは、洞窟に再び入ることは哲学者の責務であると主張する。理想世界を見た者は、物質世界の人々 を教育する義務があると言う。プラトンによれば、哲学者は何が真に善いかを認識しているので、彼だけが社会を支配するのに適している。 |

|

Book VIII–IX: Plato's five regimes In Books VIII–IX stand Plato's criticism of the forms of government. Plato categorized governments into five types of regimes: aristocracy, timocracy, oligarchy, democracy, and tyranny. The starting point is an imagined, alternate aristocracy (ruled by a philosopher-king); a just government ruled by a philosopher king, dominated by the wisdom-loving element. Aristocracy degenerates into timocracy when, due to miscalculation on the part of its governing class, the next generation includes persons of an inferior nature, inclined not just to cultivating virtues but also producing wealth. In a timocracy, governors will apply great effort in gymnastics and the arts of war, as well as the virtue that pertains to them, that of courage. As the emphasis on honor is compromised by wealth accumulation, it is replaced by oligarchy. The oligarchic government is dominated by the desiring element, in which the rich are the ruling class. Oligarchs do, however, value at least one virtue, that of temperance and moderation—not out of an ethical principle or spiritual concern, but because by dominating wasteful tendencies they succeed in accumulating money. As this socioeconomic divide grows, so do tensions between social classes. From the conflicts arising out of such tensions, the poor majority overthrow the wealthy minority, and democracy replaces the oligarchy preceding it. In democracy, the lower class grows bigger and bigger. A visually appealing demagogue is soon lifted up to protect the interests of the lower class, who can exploit them to take power in order to maintain order. Democracy then degenerates into tyranny where no one has discipline and society exists in chaos. In a tyrannical government, the city is enslaved to the tyrant, who uses his guards to remove the best social elements and individuals from the city to retain power (since they pose a threat), while leaving the worst. He will also provoke warfare to consolidate his position as leader. In this way, tyranny is the most unjust regime of all. In parallel to this, Socrates considers the individual or soul that corresponds to each of these regimes. He describes how an aristocrat may become weak or detached from political and material affluence, and how his son will respond to this by becoming overly ambitious.The timocrat in turn may be defeated by the courts or vested interests; his son responds by accumulating wealth in order to gain power in society and defend himself against the same predicament, thereby becoming an oligarch. The oligarch's son will grow up with wealth without having to practice thrift or stinginess, and will be tempted and overwhelmed by his desires,[18] so that he becomes democratic, valuing freedom above all.[18] The democratic man is torn between tyrannical passions and oligarchic discipline, and ends up in the middle ground: valuing all desires, both good and bad. The tyrant will be tempted in the same way as the democrat, but without an upbringing in discipline or moderation to restrain him. Therefore, his most base desires and wildest passions overwhelm him, and he becomes driven by lust, using force and fraud to take whatever he wants. The tyrant is both a slave to his lusts, and a master to whomever he can enslave. Socrates points out the human tendency to be corrupted by power leads down the road to timocracy, oligarchy, democracy and tyranny. From this, he concludes that ruling should be left to philosophers, who are the most just and therefore least susceptible to corruption. This "good city" is depicted as being governed by philosopher-kings; disinterested persons who rule not for their personal enjoyment but for the good of the city-state (polis). The philosophers have seen the "Forms" and therefore know what is good. They understand the corrupting effect of greed and own no property and receive no salary. They also live in sober communism, eating and sleeping together. |

第VIII巻〜第IX巻

プラトンの5つの体制 第VIII巻から第IX巻にかけて、プラトンは政府の形態を批判している。プラトンは政府を、貴族制、タイモクラシー、寡頭制、民主制、専制政治の5つの体制に分類した。 出発点は、想像上の代替的な貴族制(哲学者王によって支配される)であり、知恵を愛する要素によって支配される哲学者王によって支配される公正な政府であ る。アリストクラシーがティモクラシーに堕落するのは、統治者層の誤算により、次の世代に徳の涵養だけでなく富の生産にも傾倒した劣等な性質を持つ者が含 まれる場合である。タイモクラシーでは、統治者たちは体操や戦争術、そしてそれらに関連する美徳である勇気に多大な努力を傾ける。名誉の重視が富の蓄積に よって損なわれると、それは寡頭政治に取って代わられる。寡頭政治は欲望的要素によって支配され、富裕層が支配階級となる。しかし、オリガルヒは少なくと もひとつの美徳、節制と節度を重んじる。それは倫理的原則や精神的関心からではなく、浪費的傾向を支配することで蓄財に成功するからである。 このような社会経済的格差が拡大するにつれ、社会階級間の緊張も高まる。こうした緊張から生じる対立から、貧しい多数派が裕福な少数派を打倒し、民主主義 がそれに先立つ寡頭政治に取って代わる。民主主義では、下層階級がますます大きくなる。視覚に訴えるデマゴーグがすぐに持ち上げられ、下層階級の利益を守 り、秩序を維持するために下層階級を利用して権力を握ることができる。そして民主主義は、誰も規律を持たず、社会が混沌として存在する専制政治へと堕落す る。専制政治では、街は専制君主の奴隷となる。専制君主は、権力を維持するために(彼らは脅威となるため)警護兵を使って街から最良の社会的要素や個人を 排除し、一方で最悪のものは残す。彼はまた、指導者としての地位を固めるために戦争を引き起こす。このように、専制政治は最も不公正な体制である。 これと並行して、ソクラテスは、これらの各体制に対応する個人または魂を検討します。彼は、貴族が政治的、物質的な豊かさから弱くなったり、切り離された りすることがあり、彼の息子が過度に野心的になることでこれに対応する方法を説明する。オリガルヒの息子は、倹約や吝嗇を実践することなく富を得て成長 し、欲望に誘惑され、圧倒される[18]。専制君主も民主主義者と同じように誘惑に駆られるが、彼を抑制する規律や節度の教育を受けていない。そのため、 最も卑しい欲望と最も荒々しい情熱に圧倒され、欲望に駆られ、欲しいものは何でも手に入れようと力や詐欺を使うようになる。暴君は自分の欲望の奴隷である と同時に、奴隷にできるものなら誰にでもする主人でもある。ソクラテスは、権力によって堕落する人間の傾向が、タイモクラシー、寡頭政治、民主主義、専制 政治へとつながることを指摘する。そこから彼は、統治は最も公正で、それゆえ腐敗の影響を受けにくい哲学者に任せるべきだと結論づける。この「善良な都 市」は、哲学者の王によって統治されるものとして描かれている。哲学者の王は、個人的な楽しみのためではなく、都市国家(ポリス)の善のために統治する利 害関係のない人物である。哲学者たちは「かたち」を見てきたため、何が善であるかを知っている。彼らは貪欲の堕落を理解し、財産を持たず、給料も受け取ら ない。また、冷静な共産主義に基づき、寝食を共にしている。 |

|

Book X: Myth of Er See also: Myth of Er Concluding a theme brought up most explicitly in the Analogies of the Sun and Divided Line in Book VI, Socrates finally rejects any form of imitative art and concludes that such artists have no place in the just city. He continues on to argue for the immortality of the psyche and espouses a theory of reincarnation. He finishes by detailing the rewards of being just, both in this life and the next. Artists create things but they are only different copies of the idea of the original. "And whenever any one informs us that he has found a man who knows all the arts, and all things else that anybody knows, and every single thing with a higher degree of accuracy than any other man—whoever tells us this, I think that we can only imagine to be a simple creature who is likely to have been deceived by some wizard or actor whom he met, and whom he thought all-knowing, because he himself was unable to analyze the nature of knowledge and ignorance and imitation."[19] And the same object appears straight when looked at out of the water, and crooked when in the water; and the concave becomes convex, owing to the illusion about colours to which the sight is liable. Thus every sort of confusion is revealed within us; and this is that weakness of the human mind on which the art of conjuring and deceiving by light and shadow and other ingenious devices imposes, having an effect upon us like magic.[19] He speaks about illusions and confusion. Things can look very similar, but be different in reality. Because we are human, at times we cannot tell the difference between the two. And does not the same hold also of the ridiculous? There are jests which you would be ashamed to make yourself, and yet on the comic stage, or indeed in private, when you hear them, you are greatly amused by them, and are not at all disgusted at their unseemliness—the case of pity is repeated—there is a principle in human nature which is disposed to raise a laugh, and this which you once restrained by reason, because you were afraid of being thought a buffoon, is now let out again; and having stimulated the risible faculty at the theatre, you are betrayed unconsciously to yourself into playing the comic poet at home. With all of us, we may approve of something, as long we are not directly involved with it. If we joke about it, we are supporting it. Quite true, he said. And the same may be said of lust and anger and all the other affections, of desire and pain and pleasure, which are held to be inseparable from every action—in all of them poetry feeds and waters the passions instead of drying them up; she lets them rule, although they ought to be controlled, if mankind are ever to increase in happiness and virtue.[19] Sometimes we let our passions rule our actions or way of thinking, although they should be controlled, so that we can increase our happiness. |

第X巻 エル神話 こちらも参照: エル神話 ソクラテスは、第VI巻の「太陽と分割線の相似」で最も明確に取り上げられたテーマを締めくくるに当たり、最終的にあらゆる模倣芸術を否定し、そのような 芸術家は公正な都市に居場所がないと結論づける。彼は精神の不滅性を主張し、輪廻転生の理論を支持し続ける。そして最後に、現世と来世の両方において、公 正であることの報酬について詳述する。芸術家は物事を創造するが、それはオリジナルのアイデアの異なるコピーに過ぎない。「そして、芸術のすべてと、誰も が知っている他のすべてのこと、そして他のどんな人間よりも高い精度であらゆることを知る人間を見つけたと告げる者がいるときはいつでも、そのように告げ る者が誰であれ、私たちは、彼が出会った魔法使いか役者にだまされた可能性が高い単純な生き物であると想像することしかできないと思う。 また、同じ物でも、水の中から見るとまっすぐに見え、水の中にいると曲がって見える。このように、あらゆる種類の混乱がわれわれの中に現れる。これこそ、 光と影やその他の巧妙な仕掛けによって、われわれに魔術のような効果を与え、欺く術が課している人間の心の弱さである[19]。 彼は錯覚と混乱について語っている。物事は非常に似ているように見えても、実際には異なることがある。私たちは人間であるため、時にはその2つの違いを見分けることができない。 また、滑稽なことについても同じことが言えるのではないだろうか。自分では恥ずかしくて言えないような冗談でも、喜劇の舞台では、あるいは私的な場では、 それを聞くと大いに面白がり、その見苦しさには全く嫌悪感を抱かない; 劇場で笑いのツボを刺激されたあなたは、無意識のうちに裏切られ、家で滑稽な詩人を演じることになる。 私たちは皆、自分が直接関与しない限り、何かを承認することができる。冗談で言っているのであれば、私たちはそれを支持しているのです」。 その通りだ。そして同じことが、欲望や怒りや他のすべての情念や、欲望や苦痛や快楽など、あらゆる行為と切り離すことができないとされるものについても言える。 私たちは時に、幸福を増大させるために、制御されるべきにもかかわらず、情熱に自分の行動や考え方を支配させてしまうことがある。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Republic_(Plato) |

| Republic

(Greek: Πολιτεία, translit. Politeia; Latin: De Republica[1]) is a

Socratic dialogue, authored by Plato around 375 BC, concerning justice

(δικαιοσύνη), the order and character of the just city-state, and the

just man.[2] It is Plato's best-known work, and one of the world's most

influential works of philosophy and political theory, both

intellectually and historically.[3][4] In the dialogue, Socrates discusses the meaning of justice and whether the just man is happier than the unjust woman with various Athenians and foreigners.[5] He considers the natures of existing regimes and then proposes a series of hypothetical cities in comparison, culminating in Kallipolis (Καλλίπολις), a utopian city-state ruled by a class of philosopher-kings. They also discuss ageing, love, theory of forms, the immortality of the soul, and the role of the philosopher and of poetry in society.[6] The dialogue's setting seems to be the time of the Peloponnesian War.[7] |

『共

和国』(ギリシャ語: Πολιτεία, Politeia訳; ラテン語: De

Republica[1])は、紀元前375年頃にプラトンによって書かれた、正義(δικαιοσύνη)、正義の都市国家の秩序と性格、正義の人間に

関するソクラテスの対話である[2]。プラトンの最もよく知られた著作であり、知的にも歴史的にも世界で最も影響力のある哲学と政治理論の著作の一つであ

る[3][4]。 対話の中でソクラテスは、正義の意味や、正義の男は不公平な女よりも幸福であるかどうかについて、様々なアテナイ人や外国人と議論する[5]。 彼は既存の体制の本質を考察し、次に、哲学者の王たちによって統治されるユートピア都市国家であるカリポリス(Καλλίπολις)を頂点とする、比較 のための一連の仮想都市を提案する。この対話の舞台はペロポネソス戦争の時代と思われる[7]。 |

| Place in Plato's corpus Republic is generally placed in the middle period of Plato's dialogues. However, the distinction of this group from the early dialogues is not as clear as the distinction of the late dialogues from all the others. Nonetheless, Ritter, Arnim, and Baron—with their separate methodologies—all agreed that the Republic was well distinguished, along with Parmenides, Phaedrus and Theaetetus.[8] However, the first book of the Republic, which shares many features with earlier dialogues, is thought to have originally been written as a separate work, and then the remaining books were conjoined to it, perhaps with modifications to the original of the first book.[8] |

プラトンにおける位置づけ 『共和国』は一般にプラトンの対話篇の中期に位置づけられる。しかし、初期対話篇との区別は、後期対話篇との区別ほど明確ではない。それにもかかわらず、 リッター、アーニム、バロンは、それぞれの方法論で、共和国がパルメニデス、パイドロス、テアエトスとともによく区別されていることに同意した[8]。 しかし、それ以前の対話篇と多くの特徴を共有する『共和国』の第一篇は、もともとは独立した著作として書かれ、その後、おそらく第一篇の原典に修正を加えながら、残りの著作が結合されたと考えられている[8]。 |

| Aristotle

systematises many of Plato's analyses in his Politics, and criticizes

the propositions of several political philosophers for the ideal

city-state. Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, wrote his version of an ideal society, Zeno's Republic, in opposition to Plato's Republic.[20] Zeno's Republic was controversial and was viewed with some embarrassment by some of the later Stoics due to its defenses of free love, incest, and cannibalism and due to its opposition to ordinary education and the building of temples, law-courts, and gymnasia. The English title of Plato's dialogue is derived from Cicero's De re publica, written some three centuries later.[21][citation needed] Cicero's dialogue imitates Plato's style and treats many of the same topics, and Cicero's main character Scipio Aemilianus expresses his esteem for Plato and Socrates. Augustine of Hippo wrote his The City of God; Augustine equally described a model of the "ideal city", in his case the eternal Jerusalem, using a visionary language not unlike that of the preceding philosophers. Middle Ages Ibn Rushd Islamic philosophers were much more interested in Aristotle than Plato, but not having access to Aristotle's Politics, Ibn Rushd (Averroes) produced instead a commentary on Plato's Republic. He advances an authoritarian ideal, following Plato's paternalistic model. Absolute monarchy, led by a philosopher-king, creates a justly ordered society. This requires extensive use of coercion,[22] although persuasion is preferred and is possible if the young are properly raised.[23] Rhetoric, not logic, is the appropriate road to truth for the common man. Demonstrative knowledge via philosophy and logic requires special study. Rhetoric aids religion in reaching the masses.[24] Following Plato, Ibn Rushd accepts the principle of women's equality. They should be educated and allowed to serve in the military; the best among them might be tomorrow's philosophers or rulers.[25][26] He also accepts Plato's illiberal measures such as the censorship of literature. He uses examples from Arab history to illustrate just and degenerate political orders.[27] Gratian The medieval jurist Gratian in his Decretum (ca 1140) quotes Plato as agreeing with him that "by natural law all things are common to all people."[28] He identifies Plato's ideal society with the early Church as described in the Acts of the Apostles. "Plato lays out the order", Gratian comments, "for a very just republic in which no one considers anything his own."[29] Thomas More Thomas More, when writing his Utopia, invented the technique of using the portrayal of a "utopia" as the carrier of his thoughts about the ideal society. More's island Utopia is also similar to Plato's Republic in some aspects, among them common property and the lack of privacy.[30][31][32][33] Hegel Hegel respected Plato's theories of state and ethics much more than those of the early modern philosophers such as Locke, Hobbes and Rousseau, whose theories proceeded from a fictional "state of nature" defined by humanity's "natural" needs, desires and freedom. For Hegel this was a contradiction: since nature and the individual are contradictory, the freedoms which define individuality as such are latecomers on the stage of history. Therefore, these philosophers unwittingly projected man as an individual in modern society onto a primordial state of nature. Plato however had managed to grasp the ideas specific to his time: Plato is not the man to dabble in abstract theories and principles; his truth-loving mind has recognized and represented the truth of the world in which he lived, the truth of the one spirit that lived in him as in Greece itself. No man can overleap his time, the spirit of his time is his spirit also; but the point at issue is, to recognize that spirit by its content.[34] For Hegel, Plato's Republic is not an abstract theory or ideal which is too good for the real nature of man, but rather is not ideal enough, not good enough for the ideals already inherent or nascent in the reality of his time; a time when Greece was entering decline. One such nascent idea was about to crush the Greek way of life: modern freedoms—or Christian freedoms in Hegel's view—such as the individual's choice of his social class, or of what property to pursue, or which career to follow. Such individual freedoms were excluded from Plato's Republic: Plato recognized and caught up the true spirit of his times, and brought it forward in a more definite way, in that he desired to make this new principle an impossibility in his Republic.[35] Greece being at a crossroads, Plato's new "constitution" in the Republic was an attempt to preserve Greece: it was a reactionary reply to the new freedoms of private property etc., that were eventually given legal form through Rome. Accordingly, in ethical life, it was an attempt to introduce a religion that elevated each individual not as an owner of property, but as the possessor of an immortal soul. 20th century P. Oxy. 3679, manuscript from the 3rd century AD, containing fragments of Plato's Republic. Mussolini admired Plato's The Republic, which he often read for inspiration.[36] The Republic expounded a number of ideas that fascism promoted, such as rule by an elite promoting the state as the ultimate end, opposition to democracy, protecting the class system and promoting class collaboration, rejection of egalitarianism, promoting the militarization of a nation by creating a class of warriors, demanding that citizens perform civic duties in the interest of the state, and utilizing state intervention in education to promote the development of warriors and future rulers of the state.[37] Plato was an idealist, focused on achieving justice and morality, while Mussolini and fascism were realist, focused on achieving political goals.[38] Martin Luther King Jr. nominated The Republic as the one book he would have taken to a desert island, alongside the Bible.[39] 21st century In 2001, a survey of over 1,000 academics and students voted the Republic the greatest philosophical text ever written. Julian Baggini argued that although the work "was wrong on almost every point, the questions it raises and the methods it uses are essential to the western tradition of philosophy. Without it we might not have philosophy as we know it."[40] In 2021, a survey showed that The Republic is the most studied book in the top universities in the United States.[41][42] Cultural influence Plato's Republic has been influential in literature and art. Aldous Huxley's Brave New World has a dystopian government that bears a resemblance to the form of government described in the Republic, featuring the separation of people by professional class, assignment of profession and purpose by the state, and the absence of traditional family units, replaced by state-organized breeding.[43] The Orwellian dystopia depicted in the novel 1984 had many characteristics in common with Plato's description of the allegory of the Cave as Winston Smith strives to liberate himself from it.[44] In the early 1970s the Dutch composer Louis Andriessen composed a vocal work called De Staat, based on the text of Plato's Republic.[45] In Robert A. Heinlein's Starship Troopers, his citizen can be compared to a Platonic Guardian, without the communal breeding and property, but still having a militaristic base. Although there are significant differences in the specifics of the system, Heinlein and Plato both describe systems of limited franchise, with a political class that has supposedly earned their power and wisely governs the whole. Republic is specifically attacked in Starship Troopers. The arachnids can be seen as much closer to a Republic society than the humans.[46] The film The Matrix models Plato's Allegory of the Cave.[47] In fiction, Jo Walton's 2015 novel The Just City explored the consequences of establishing a city-state based on the Republic in practice. See also Ring of Gyges: Cultural influences |

アリストテレスは『政治学』においてプラトンの分析の多くを体系化し、理想的な都市国家に関する複数の政治哲学者の命題を批判している。 ストイシズムの創始者であるシティウムのゼノンは、プラトンの『共和国』に対抗して、理想社会についてのゼノンの『共和国』を著した[20]。ゼノンの 『共和国』は、自由恋愛、近親相姦、カニバリズムを擁護し、通常の教育や神殿、法廷、ギムナジウムの建設に反対しているため、論争を呼び、後のストア派の 一部からは困惑の目で見られていた。 プラトンの対話の英語タイトルは、その約3世紀後に書かれたキケロの『De re publica』に由来する[21][要出典]。キケロの対話はプラトンの文体を模倣し、同じトピックの多くを扱っており、キケロの主人公スキピオ・アエ ミリアヌスはプラトンとソクラテスへの尊敬を表明している。 ヒッポのアウグスティヌスも『神の都市』を著した。アウグスティヌスも同様に、「理想都市」のモデル(彼の場合は永遠のエルサレム)を、先の哲学者たちと変わらない幻視的な言葉を使って描写した。 中世 イブン・ルシュド イスラムの哲学者たちは、プラトンよりもアリストテレスに大きな関心を寄せていたが、アリストテレスの『政治学』を入手できなかったイブン・ルシュド(ア ヴェロエス)は、代わりにプラトンの『共和国』の注釈書を著した。彼はプラトンの父権主義的モデルを踏襲し、権威主義的理想を掲げた。哲学者である王が率 いる絶対君主制が、公正に秩序づけられた社会をつくる。そのためには強制を多用する必要があるが[22]、説得が好まれ、若者を適切に育てれば可能である [23]。哲学や論理学による実証的な知識は特別な勉強を必要とする。修辞学は宗教が大衆に到達するのを助ける[24]。 プラトンに従い、イブン・ルシュドは女性の平等の原則を受け入れている。彼女たちは教育を受け、軍務に就くことを許されるべきであり、彼女たちの中で最も 優秀な者は明日の哲学者や支配者になるかもしれない[25][26]。彼はまた、文学の検閲のようなプラトンの非自由主義的措置も受け入れている。彼はア ラブの歴史から、公正な政治秩序と退廃した政治秩序を例証している[27]。 グラティアヌス 中世の法学者であるグラティアヌスは、その『Decretum』(約1140年)の中で、プラトンが「自然法によって万物は万人に共通である」[28]こ とに同意しているとして、プラトンの理想社会を使徒言行録に記述されている初代教会と同一視している。「プラトンは、"誰も何一つ自分のものだと考えない 非常に公正な共和国のための秩序を示した"[29]とグラティアヌスはコメントしている。 トマス・モア トマス・モアは『ユートピア』を書く際に、理想社会についての彼の考えを伝えるものとして「ユートピア」の描写を用いるという技法を発明した。モアの島の ユートピアは、共有財産やプライバシーの欠如など、プラトンの『共和国』と似ている面もある[30][31][32][33]。 ヘーゲル ヘーゲルはプラトンの国家と倫理に関する理論を、ロック、ホッブズ、ルソーといった近世の哲学者の理論よりもはるかに尊重していた。ヘーゲルにとって、こ れは矛盾であった。自然と個人は矛盾するものであるため、そのような個人性を定義する自由は、歴史の舞台では後発のものである。したがって、これらの哲学 者たちは、近代社会における個人としての人間を、知らず知らずのうちに原初的な自然の状態に投影していたのである。しかしプラトンは、その時代特有の思想 を把握していた: プラトンは抽象的な理論や原理をもてあそぶような人間ではない。彼の真理を愛する心は、彼が生きた世界の真理、ギリシャそのものと同じように彼の中に生き た一つの精神の真理を認識し、表現したのである。しかし問題は、その精神をその内容によって認識することである[34]。 ヘーゲルにとって、プラトンの『共和国』は人間の現実的な性質にとって良すぎる抽象的な理論や理想ではなく、むしろ十分に理想的ではなく、彼の時代の現実 の中にすでに内在していた、あるいは芽生えつつあった理想にとって十分ではなかった。ヘーゲルから見れば、近代的な自由、つまりキリスト教的な自由であ り、個人が社会階級や財産、職業を選択できるようなものである。このような個人の自由は、プラトンの『共和国』からは排除されていた: プラトンはその時代の真の精神を認識し、受け止め、より明確な形でそれを前進させた。 ギリシャは岐路に立たされており、プラトンの『共和国』における新しい「憲法」はギリシャを維持しようとする試みであった。それは、最終的にローマを通じ て法的な形を与えられた私有財産などの新しい自由に対する反動的な返答であった。従って、倫理的な生活においては、各個人を財産の所有者としてではなく、 不滅の魂の所有者として高める宗教を導入しようとする試みであった。 20世紀 P. Oxy. 3679、プラトンの『共和国』の断片を含む紀元3世紀の写本。 ムッソリーニはプラトンの『共和国』を賞賛しており、インスピレーションを得るためによく読んでいた[36]。『共和国』には、ファシズムが推進した、究 極の目的である国家を推進するエリートによる支配、民主主義への反対、階級制度の保護と階級協力の推進、平等主義の否定、戦士階級を創設することによる国 家の軍事化の推進、国家の利益のために市民的義務を果たすよう市民に要求すること、戦士や将来の国家支配者の育成を促進するために教育への国家の介入を利 用することなど、多くの思想が説かれていた。 [プラトンは正義と道徳の達成に焦点を当てた理想主義者であり、ムッソリーニとファシズムは政治的目標の達成に焦点を当てた現実主義者であった[38]。 マーティン・ルーサー・キング・ジュニアは、無人島に持っていく本として、聖書と並んで『共和国』を挙げた[39]。 21世紀 2001年、1,000人以上の学者と学生を対象に行われた調査で、『共和国』はこれまで書かれた中で最も偉大な哲学書に選ばれた。ジュリアン・バギニ は、この著作は「ほとんどすべての点で間違っていたが、この著作が提起している問題や用いている方法は、西洋哲学の伝統にとって不可欠なものである。 2021年の調査では、『共和国』はアメリカの一流大学で最も研究されている書物であることが示されている[41][42]。 文化的影響 プラトンの『共和国』は文学や芸術にも影響を与えている。 オルダス・ハクスリーの『ブレイブ・ニュー・ワールド』には、『共和国』に描かれた政府の形態に類似したディストピア政府が登場し、職業階級による人々の 分離、国家による職業と目的の割り当て、伝統的な家族単位の不在を特徴とし、国家が組織した繁殖に置き換えられている[43]。 小説『1984年』で描かれたオーウェル的なディストピアは、洞窟からの解放を目指すウィンストン・スミスの洞窟の寓話に関するプラトンの記述と多くの共通点を持っていた[44]。 1970年代初頭、オランダの作曲家ルイス・アンドリーセンはプラトンの『共和国』のテキストに基づいて『De Staat』と呼ばれる声楽作品を作曲した[45]。 ロバート・A・ハインラインの『スターシップ・トゥルーパーズ』では、彼の市民はプラトン的なガーディアンと比較することができる。制度の具体的な内容に は大きな違いがあるが、ハインラインとプラトンはともに、権力を得て全体を賢く統治するとされる政治階級を持つ、限定的なフランチャイズの制度を描いてい る。共和制は『スターシップ・トゥルーパーズ』で特に攻撃されている。クモ型動物は人間よりも共和制社会に近いと見ることができる[46]。 映画『マトリックス』はプラトンの『洞窟の寓話』をモデルにしている[47]。 フィクションでは、ジョー・ウォルトンの2015年の小説『ジャスト・シティ』が、共和制に基づく都市国家を実際に樹立した場合の結果を探求した。 ギュゲスの指輪」も参照: 文化的影響 |

| Criticism Gadamer In his 1934 Plato und die Dichter (Plato and the Poets), as well as several other works, Hans-Georg Gadamer describes the utopic city of the Republic as a heuristic utopia that should not be pursued or even be used as an orientation-point for political development. Rather, its purpose is said to be to show how things would have to be connected, and how one thing would lead to another—often with highly problematic results—if one would opt for certain principles and carry them through rigorously. This interpretation argues that large passages in Plato's writing are ironic, a line of thought initially pursued by Kierkegaard. Popper The city portrayed in Republic struck some critics as harsh, rigid, and unfree; indeed, as totalitarian. Karl Popper gave a voice to that view in his 1945 book The Open Society and Its Enemies, where he singled out Plato's state as a dystopia. Popper distinguished Plato's ideas from those of Socrates, claiming that the former in his later years expressed none of the humanitarian and democratic tendencies of his teacher.[48][49][50] Popper thought Plato's envisioned state totalitarian as it advocated a government composed only of a distinct hereditary ruling class, with the working class—who Popper argues Plato regards as "human cattle"—given no role in decision making. He argues that Plato has no interest in what are commonly regarded as the problems of justice—the resolution of disputes between individuals—because Plato has redefined justice as "keeping one's place".[51] Popper insists that Republic "was meant by its author not so much as a theoretical treatise, but as a topical political manifesto",[52] and Bertrand Russell argues that at least in intent, and all in all not so far from what was possible in ancient Greek city-states, the form of government portrayed in the Republic was meant as a practical one by Plato.[53] Voegelin Many critics have suggested that the dialogue's political discussion actually serves as an analogy for the individual soul, in which there are also many different "members" that can either conflict or else be integrated and orchestrated under a just and productive "government." Among other things, this analogical reading would solve the problem of certain implausible statements Plato makes concerning an ideal political republic.[54] Norbert Blössner (2007)[55] argues that the Republic is best understood as an analysis of the workings and moral improvement of the individual soul with remarkable thoroughness and clarity. This view, of course, does not preclude a legitimate reading of Republic as a political treatise (the work could operate at both levels). It merely implies that it deserves more attention as a work on psychology and moral philosophy than it has sometimes received. Eric Voegelin in Plato and Aristotle (Baton Rouge, 1957), gave meaning to the concept of 'Just City in Speech' (Books II–V). For instance, there is evidence in the dialogue that Socrates himself would not be a member of his 'ideal' state. His life was almost solely dedicated to the private pursuit of knowledge. More practically, Socrates suggests that members of the lower classes could rise to the higher ruling class, and vice versa, if they had 'gold' in their veins—a version of the concept of social mobility. The exercise of power is built on the 'noble lie' that all men are brothers, born of the earth, yet there is a clear hierarchy and class divisions. There is a tripartite explanation of human psychology that is extrapolated to the city, the relation among peoples. There is no family among the guardians, another crude version of Max Weber's concept of bureaucracy as the state non-private concern. Together with Leo Strauss, Voegelin considered Popper's interpretation to be a gross misunderstanding not only of the dialogue itself, but of the very nature and character of Plato's entire philosophic enterprise. The paradigm of the city—the idea of the Good, the Agathon—has manifold historical embodiments, undertaken by those who have seen the Agathon, and are ordered via the vision. The centerpiece of the Republic, Part II, nos. 2–3, discusses the rule of the philosopher, and the vision of the Agathon with the Allegory of the Cave, which is clarified in the theory of forms. The centerpiece is preceded and followed by the discussion of the means that will secure a well-ordered polis (city). Part II, no. 1, concerns marriage, the community of people and goods for the guardians, and the restraints on warfare among the Hellenes. It describes a partially communistic polis. Part II, no. 4, deals with the philosophical education of the rulers who will preserve the order and character of the city-state. In part II, the Embodiment of the Idea, is preceded by the establishment of the economic and social orders of a polis (part I), followed by an analysis (part III) of the decline the order must traverse. The three parts compose the main body of the dialogues, with their discussions of the "paradigm", its embodiment, its genesis, and its decline. The introduction and the conclusion are the frame for the body of Republic. The discussion of right order is occasioned by the questions: "Is justice better than injustice?" and "Will an unjust man fare better than a just man?" The introductory question is balanced by the concluding answer: "Justice is preferable to injustice". In turn, the foregoing are framed with the Prologue (Book I) and the Epilogue (Book X). The prologue is a short dialogue about the common public doxai (opinions) about justice. Based upon faith, and not reason, the Epilogue describes the new arts and the immortality of the soul. Strauss and Bloom Some of Plato's proposals have led theorists like Leo Strauss and Allan Bloom to ask readers to consider the possibility that Socrates was creating not a blueprint for a real city, but a learning exercise for the young men in the dialogue. There are many points in the construction of the "Just City in Speech" that seem contradictory, which raise the possibility Socrates is employing irony to make the men in the dialogue question for themselves the ultimate value of the proposals. In turn, Plato has immortalized this 'learning exercise' in Republic. One of many examples is that Socrates calls the marriages of the ruling class 'sacred'; however, they last only one night and are the result of manipulating and drugging couples into predetermined intercourse with the aim of eugenically breeding guardian-warriors. Strauss and Bloom's interpretations, however, involve more than just pointing out inconsistencies; by calling attention to these issues they ask readers to think more deeply about whether Plato is being ironic or genuine, for neither Strauss nor Bloom present an unequivocal opinion, preferring to raise philosophic doubt over interpretive fact. Strauss's approach developed out of a belief that Plato wrote esoterically. The basic acceptance of the exoteric-esoteric distinction revolves around whether Plato really wanted to see the "Just City in Speech" of Books V–VI come to pass, or whether it is just an allegory. Strauss never regarded this as the crucial issue of the dialogue. He argued against Karl Popper's literal view, citing Cicero's opinion that Republic's true nature was to bring to light the nature of political things.[56] In fact, Strauss undermines the justice found in the "Just City in Speech" by implying the city is not natural, it is a man-made conceit that abstracts away from the erotic needs of the body. The city founded in Republic "is rendered possible by the abstraction from eros".[57] An argument that has been used against ascribing ironic intent to Plato is that Plato's Academy produced a number of tyrants who seized political power and abandoned philosophy for ruling a city. Despite being well-versed in Greek and having direct contact with Plato himself, some of Plato's former students like Clearchus, tyrant of Heraclea; Chaeron, tyrant of Pellene; Erastus and Coriscus, tyrants of Skepsis; Hermias of Atarneus and Assos; and Calippus, tyrant of Syracuse ruled people and did not impose anything like a philosopher-kingship. However, it can be argued whether these men became "tyrants" through studying in the academy. Plato's school had an elite student body, some of whom would by birth, and family expectation, end up in the seats of power. Additionally, it is important that it is by no means obvious that these men were tyrants in the modern, totalitarian sense of the concept. Finally, since very little is actually known about what was taught at Plato's Academy, there is no small controversy over whether it was even in the business of teaching politics at all.[58] |

批評 ガダマー ハンス=ゲオルク・ガダマーは、1934年に発表した『プラトンと詩人』(Plato und die Dichter)や他のいくつかの著作の中で、『共和政』のユートピア的都市を、追求されるべきではなく、政治的発展のための方向付けとしてさえ利用され るべきではない、発見的ユートピアであると述べている。むしろ、その目的は、ある原則を選び、それを厳密に貫くならば、物事がどのように結びつき、ある物 事がどのように別の物事へとつながっていくのか、しばしば非常に問題のある結果をもたらすのかを示すことにあるという。この解釈は、プラトンの著作の大部 分は皮肉であると主張するもので、当初はキルケゴールが追求した考え方であった。 ポパー 共和国』で描かれる都市は、苛酷で、厳格で、自由がなく、まさに全体主義的であると一部の批評家に衝撃を与えた。カール・ポパーは、1945年の著書『開 かれた社会とその敵』の中で、プラトンの国家をディストピアとして取り上げ、その見解を代弁した。ポパーはプラトンの思想をソクラテスの思想と区別し、晩 年のソクラテスは彼の師のような人道主義的、民主主義的な傾向を全く表現していなかったと主張した[48][49][50]。ポパーはプラトンの構想する 国家が全体主義的であると考えており、それは明確な世襲支配階級のみで構成される政府を提唱しているからであり、労働者階級(ポパーはプラトンを「人間の 家畜」とみなしている)は意思決定において何の役割も与えられていないと主張している。彼は、プラトンが正義を「自分の居場所を守ること」と再定義したた めに、一般的に正義の問題とみなされているもの、つまり個人間の紛争の解決にはプラトンは関心がないと主張している[51]。 ポパーは共和国が「理論的な論考としてではなく、時事的な政治的マニフェストとして作者によって意図されていた」と主張しており[52]、バートランド・ ラッセルは、少なくとも意図しており、全体として古代ギリシアの都市国家で可能であったことからそれほど離れてはいないが、共和国で描かれている政府の形 態はプラトンによって実践的なものとして意図されていたと論じている[53]。 ヴォーゲリン 多くの批評家は、この対話の政治的議論は、実際には個人の魂のアナロジーとして機能しており、そこでは多くの異なる「構成員」が存在し、対立することもあ れば、公正で生産的な「政府」の下で統合され、組織化されることもあると示唆している。とりわけ、この類推的な読み方は、プラトンが理想的な政治的共和国 に関して述べているある種のあり得ない記述の問題を解決することになる[54]。ノルベルト・ブロースナー(2007)[55]は、『共和国』は個人の魂 の働きと道徳的向上に関する分析として、驚くべき徹底性と明晰性をもって理解するのが最善であると論じている。もちろん、この見解は『共和国』を政治的論 考として読むことを否定するものではない。ただ、心理学や道徳哲学の著作として、これまで以上に注目されるべきだということを示唆しているに過ぎない。 エリック・ヴォーゲリンは『プラトンとアリストテレス』(バトン・ルージュ、1957年)の中で、「言論における公正な都市」(第Ⅱ巻から第Ⅴ巻)という 概念に意味を与えている。たとえば、ソクラテス自身が彼の「理想」国家の一員ではなかったという証拠が対話の中にある。彼の人生は、ほとんど私的な知識の 追求だけに捧げられていた。より現実的には、ソクラテスは、下層階級の成員は、その鉱脈に「金」があれば、より高い支配階級に昇ることができ、またその逆 もありうることを示唆している。権力の行使は、すべての人間は大地から生まれた兄弟であるという「崇高な嘘」の上に成り立っているが、そこには明確な階層 と階級区分がある。人間の心理を三者構成で説明し、それを都市、つまり民族間の関係に当てはめる。マックス・ウェーバーの「官僚制は国家の非私的な関心事 である」という概念の粗雑なバージョンである。レオ・シュトラウスとともに、ヴォーゲリンはポパーの解釈を、対話そのものだけでなく、プラトンの哲学的事 業全体の本質と性格に対する重大な誤解であると考えた。 都市のパラダイム、すなわち善のイデアであるアガソンは、アガソンを見た人々によって引き受けられ、そのヴィジョンを通じて秩序づけられる、さまざまな歴 史的具体化を持っている。共和国』の目玉である第二部2-3番では、哲学者の支配と、『洞窟の寓話』によるアガソンのヴィジョンが議論され、それは形式論 において明らかにされる。その中心は、秩序あるポリス(都市)を確保する手段についての議論に前後する。第2部第1番は、結婚、守護者のための人と物の共 同体、ヘレネス人の間の戦争の抑制に関するものである。部分的に共産主義的なポリスが描かれている。第II部No. 4は、都市国家の秩序と性格を維持する統治者の哲学的教育を扱っている。 第II部「イデアの具体化」では、ポリスの経済的・社会的秩序の確立(第I部)に先立ち、その秩序が克服すべき衰退についての分析(第III部)が続く。この3つの部分は、「パラダイム」、その具現化、その発生、衰退についての議論とともに、対話の本体を構成している。 序論と結論は、『共和国』本編のフレームである。正しい秩序についての議論は、次のような問いかけに端を発している: 「正義は不正義よりも優れているか」「不正義な人間は正義な人間よりも優れているか」という問いである。冒頭の問いは、結論となる答えによってバランスが 保たれている: 「正義は不正よりも望ましい」。プロローグ(第I巻)とエピローグ(第X巻)により、前述したような構成になっている。プロローグは、正義に関する世間一 般のドクサイ(意見)についての短い対話である。エピローグは、理性ではなく信仰に基づき、新しい芸術と魂の不滅について述べている。 シュトラウスとブルーム プラトンの提案のなかには、レオ・シュトラウスやアラン・ブルームのような理論家に、ソクラテスが現実の都市の青写真を描いたのではなく、対話のなかの若 者たちのための学習演習だった可能性を考慮するよう読者に求めるものもある。言論における公正な都市」の構築には矛盾しているように見える点が多く、ソク ラテスは対話の中の男たちに提案の究極的な価値を自問させるために皮肉を使っている可能性を提起している。翻って、プラトンは『共和国』において、この 「学習の訓練」を不朽の名作としている。 多くの例のひとつに、ソクラテスが支配階級の結婚を「神聖なもの」と呼んでいることがある。しかし、それは一夜限りのものであり、優生学的に守護戦士を繁 殖させる目的で、カップルを操作し、薬を飲ませ、決められた性交をさせた結果なのである。しかし、シュトラウスとブルームの解釈は、単に矛盾を指摘するだ けではない。これらの問題に注意を喚起することで、プラトンが皮肉を言っているのか、それとも本心から言っているのかについて、読者に深く考えるよう求め ているのである。 シュトラウスのアプローチは、プラトンは秘教的に書いたという信念から発展した。外典的なものと内典的なものの区別の基本的な受け入れ方は、プラトンが第 五書から第六書の「言論における公正な都市」が実現することを本当に望んでいたのか、それとも単なる寓話なのか、ということに展開する。シュトラウスは、 これを対話の重要な問題とは考えていなかった。実際、シュトラウスは、都市は自然なものではなく、肉体のエロティックな欲求を抽象化した人為的な偶像であ るとほのめかすことによって、「言論における公正な都市」に見られる正義を損なっている。共和国』に創設された都市は、「エロスからの抽象によって可能に なった」のである[57]。 プラトンを皮肉ることに反対する議論として使われてきたのは、プラトンのアカデミーが政治権力を掌握し、都市を支配するために哲学を放棄した多くの暴君を 生み出したということである。ギリシャ語に精通し、プラトン自身と直接接触していたにもかかわらず、ヘラクレアの専制君主クレアルコス、ペレネの専制君主 チャエロン、スケプシスの専制君主エラストスとコリスコス、アタルネウスとアソスの専制君主ヘルミアス、シラクサの専制君主カリッポスのようなプラトンの 元生徒たちは、人々を支配し、哲学者としての王権のようなものは課していない。しかし、彼らがアカデミーで学ぶことによって「暴君」になったかどうかは議 論の余地がある。プラトンの学校にはエリート学生が集まっており、その中には生まれながらにして、あるいは一族の期待によって権力の座につく者もいた。加 えて、これらの人物が現代の全体主義的な意味での暴君であったことは決して明らかではないことも重要である。最後に、プラトンのアカデミーで何が教えられ ていたのかについては、実際にはほとんど知られていないため、政治を教えることが仕事であったのかどうかについてさえ、少なからぬ論争がある[58]。 |

| Fragments Several Oxyrhynchus Papyri fragments were found to contain parts of Republic, and from other works such as Phaedo, or the dialogue Gorgias, written around 200–300 CE.[59] Fragments of a different version of Plato's Republic were discovered in 1945, part of the Nag Hammadi library, written c. 350 CE.[60] These findings highlight the influence of Plato during those times in Egypt. Translations Burges, George (1854). Plato: The Republic, Timaeus and Critias. New and literal version. London: H.G. Bohn. Jowett, Benjamin (1871). Plato: The Republic. Bloom, Allan (1991) [1968]. The Republic of Plato. Translated, with notes and an interpretive essay. New York: Basic Books. Grube, G.M.A. (1992). Plato: The Republic. Revised by C.D.C. Reeve. Indianapolis: Hackett. Waterfield, Robin (1994). Plato: Republic. Translated, with notes and an introduction. Oxford: Oxford World's Classics. Griffith, Tom (2000). Plato: The Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Allen, R.E. (2006). Plato: The Republic. New Haven: Yale University Press. Sachs, Joe (2007). Plato: Republic. Newburyport: Focus Publishing. Rowe, Christopher (2012). Plato: Republic. London: Penguin. |

断片 1945年、ナグ・ハマディ文庫の一部として、プラトンの『共和国』の別バージョンの断片が発見された。 翻訳 バージス、ジョージ (1854). プラトン:『共和国』、『ティマイオス』、『クリティアス』。New and literal version. London: H.G. Bohn. Jowett, Benjamin (1871). Plato: The Republic. Bloom, Allan (1991) [1968]. プラトン共和国. 注と解釈のエッセイ付き。New York: Basic Books. Grube, G.M.A. (1992). Plato: The Republic. C.D.C. Reeve 校訂。Indianapolis: Hackett. Waterfield, Robin (1994). Plato: 共和国. プラトン:共和国. Oxford: Oxford World's Classics. Griffith, Tom (2000). プラトン:共和国. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Allen, R.E. (2006). Plato: The Republic. New Haven: Yale University Press. Sachs, Joe (2007). Plato: Republic. Newburyport: Focus Publishing. Rowe, Christopher (2012). プラトン: Republic. London: Penguin. |

| Collectivism and individualism Cultural influence of Plato's Republic Mixed government Nous Orthotes Onomaton Plato's number |

集団主義と個人主義 プラトン『共和国』の文化的影響 混合政府 ヌース オルトテス オノマトン プラトンの数字 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Republic_(Plato) |

|

| 1. 共和国の概要 a. 第一巻 ソクラテスとグラウコンは、トラキアの女神ベンディスを祭る祭りに出席するためにピレウスを訪れる(327a)。 二人はポレマルコスの家に案内される(328b)。 ソクラテスはセファロスに老い、裕福であることの利点、正義について語る(328e-331d)。人は、狂った友人に借りた武器を返すことが正義であると は主張しないだろう(331c)、したがって正義は、セファルスの主張のように、借りているものを返すと真実であることではない。 ソクラテスとポレマルコスの議論は続く(331d-336b)。 ポレマルコスは、正義とは自分の友を助け、自分の敵を害することであり、これこそ人が人に負っているものだと主張する(332c)。 ポレマルコスの定義に対するソクラテスの反論は以下の通りである: (i)これは医学や料理において適切なのか。 では、どのような文脈でそうなるのか?(332d)? (ii) 公正な人は、無益なことや不正なことも得意になる(333e)。(iii) 私たちはしばしば、自分の友人や敵が誰であるかを知らない。したがって、私たちは、私たちが友人や敵だとばかり思っている人たちを、良くも悪くも扱うかも しれない。 これは正義だろうか?(334c). (iv)誰に対しても、敵であっても、悪く扱うことは正義ではないように思われる(335b)。 ソクラテスとトラジマコスの議論が続く(336b-354c)。 トラジマコスは正義を、より強い者にとって有利なもの、あるいは有益なものと定義している(338c)。 正義は、強者(各体制における支配階級、338e-339a)の利益に奉仕するために作られた法律に従って、異なる政治体制の下で異なっている。 ソクラテスはその定義の明確化を求めている。正義とは、強い者が自分たちのためになると考えるものなのか、それとも実際に自分たちのためになるものなのか (339b)。 そして、強い支配者は間違いを犯し、時には自分たちの利益にならない法律を作ることもあるのではないか(339c)? スラジマコスは、強い者とは、何が自分たちの利益になるかについて、本当に間違いを犯さない者だけだと指摘する(340d)。 ソクラテスは、芸術や工芸についての議論に応じ、その目的はその対象にとってよいことをすることであって、実践者にとってよいことではないと指摘する (341c)。 スラシマコスは、羊飼いのような一部の芸術はそうではなく、むしろ実践者の利益を目的としていることを示唆する(343c)。彼はまた、不正はあらゆる点 で正義よりも優れており、不正を発見されずに行う不正な人は、正義な人よりも常に幸福であるという主張も加えている(343e-344c)。 幸福な不正義者のパラダイムは、すべての欲望を満たすことができる暴君である(344a-b)。 ソクラテスは、羊飼いの羊への関心は、芸術とは無関係な金儲けへの関心とは異なると指摘し(345c)、いかなる権力や芸術も、それ自身にとって有益なも のは提供しない(346e)。 ソクラテスは、最良の支配者は支配に消極的であるが、必要からそうしているのであり、劣った者に支配されることを望んでいないのだと主張する(347a- c)。 (i)公正な人は賢く善良であり、不公正な人は無知で悪者である(349b)、(ii)不公正は内的な不調和を生み、効果的な行動を妨げる(351b)、 (iii)徳とはその物事の機能における卓越性であり、公正な人は不公正な人よりも幸福な人生を送ることができる、なぜなら彼は人間の魂のさまざまな機能 をよく果たしているからである(352d)。 ソクラテスはこの議論に不満を抱いている。なぜなら、公正な人生が不公正な人生よりも優れているかどうかを論じる前に、公正についての十分な説明が必要だ からである(354b)。 b. 第二巻 グラウコンは先の議論に説得されていない(357a)。 ソクラテスは、善いものを、それ自体善いもの、それ自体もその結果も善いもの、その結果のみ善いものの三つに分類する(357b-d)。 ソクラテスは正義を、それ自体においてもその結果においても善いものの分類に入れる。 グラウコンはトラジマコスの議論を更新し、ソクラテスが正義から生じるものを考慮することなく、正義それ自体を擁護することに挑戦する(358b ff.)。 グラウコンは不正を擁護する演説を行う:(i)正義は、不正を行うことよりも不正を受けることの方が悪いと恐れる弱い人々の間の妥協として生まれた (358e-359a)、(ii)人々が正義に従って行動するのは、それが必要でやむを得ないからであり、正義はその結果においてのみ善である(ギュゲス の先祖の指輪の話、359c-360d)、(iii)正義の評判を持つ不正な人は、不正の評判を持つ正義な人よりも幸福である(360d-362c)。 Adeimantusは、グラウコンの不正の擁護と正義への攻撃を拡大し、次のように主張する:正義の評判は正義そのものよりも優れているので、正義であ るという評判を保つことができる不正な人は、正義の人よりも幸せになる;不正な人が正義の評判を得ることができる様々な方法について議論する(362d- 366d)。 ソクラテスは正義を、それが可能にする評判のためではなく、それ自身のために擁護するよう求められる(367b)。 彼はまず都市に正義を求め、それから類推によって個人に正義を求めることを提案する(368c-369a)。 このアプローチは、公正な人が不正な人よりも幸福であるかどうかという問題について、より明確な判断を可能にする。 ソクラテスはまず政治生活の起源を論じ、人間の基本的な必需品だけを満たす公正な都市を言論で構築する(369b-372c)。 ソクラテスは、人間はもともと自給自足ではないので、政治生活に入るのだと主張する。 人間にはそれぞれ一定の能力があり(370a)、生まれながらに向いている仕事だけをすることが、市民全員の欲求を満たす最も効率的な方法である (370c)。 グラウコンは、ソクラテスの都市が単純すぎると反対し、それを「豚の都市」(372d)と呼ぶ。 ソクラテスは贅沢を許す都市(「熱狂的な都市」372e-373e)について述べる。 ソクラテスは、贅沢な都市には都市を守る軍隊が必要になると指摘する(373e)。 軍隊はプロの兵士で構成され、犬のように市民に優しく、敵に厳しくなければならない守護者である(375c)。 守護者たちは、都市の市民、法律、習慣を守るという仕事をうまくこなせるように、非常に注意深く教育される必要がある(376d)。 そのような教育を保証するために、詩や物語は検閲される必要がある(377b)。 詩はこうあるべきだ: (i)神々を善として、善の原因としてのみ提示する(379a)、(ii)不変の姿として(380d)、(iii)嘘や欺瞞を慎む存在として (381e)。 c. 第三巻 ソクラテスは詩の検閲という政治的措置を続ける: (iv)守護者たちが死を恐れすぎないように、冥界を悪い場所として描くべきではない(386b)、(v)守護者たちが勇気を養うことができるように、英 雄や神々が嘆く姿を描くべきではない(387e)、(vi)詩は人々が激しく笑うのを防ぐべきである(388e); (vii)詩は、真実を語るという守護者の感覚を促進すべきであるが、それが都市の善に資する場合には、喜んで嘘をつくべきである(389b)、 (viii)詩は、自己規律と従順を促進すべきである(389c-d)、(ix)詩は、貪欲を助長するような物語を含むべきでない(390d)、(x)詩 は、思い上がりや不敬を助長するような物語を含むべきでない(391a)。 ソクラテスは、物語の語られ方について論じる(392d)。 彼はそのような作法を単純な語り(三人称)と模倣的な語り(一人称、392d)に分けている。 ソクラテスは、守護者たちが自分たちの仕事だけをし続けるために、守護者たちはこれにふさわしいものだけを模倣してよいと主張する(394e- 395d)。 公正な都市は、公正な都市で許される詩の内容に合う様式とリズムだけを許すべきである(398b-399c)。 ソクラテスは、優れた芸術がいかに善良な人格の形成につながり、人々を理性に従いやすくするかを説明する(400e-402c)。 ソクラテスは守護者の身体教育に目を向け、戦争に備えた身体訓練、注意深い食事、医者を避けるための習慣を含むべきだと言う(403c-405b)。 なぜなら、魂がよい状態にあるとき、身体は必然的に恩恵を受けるが、身体がよい状態にあるとき、魂は必ずしも恩恵を受けないからである(410b-c)。 ソクラテスは、公正な都市の支配者がどのように守護者のクラスから選ばれるかを説明し始める:彼らは年上で、強く、賢く、都市に有利なこと以外をする気が まったくない必要がある(412b-414b)。 ソクラテスは、彼らが市民に神話を語る必要があることを示唆している。神話は、誰もが都市における自分の立場を受け入れるために、その後の世代に信じられ るべきである(414b-415d)。 金属の神話では、人間にはそれぞれ貴金属があるとして、統治者にふさわしい者は金、守護者にふさわしい者は銀、農耕や他の工芸にふさわしい者は青銅を持っ ているとしている。 ソクラテスは、守護者の生活と住居の条件について議論を進める:彼らは私有財産を持たず、プライバシーはほとんどなく、他の階級への課税によって都市から必要なものを受け取り、共同生活を送り、共同食堂を持つ(415e-416e)。 d. 第四巻 アデイマントスは、公正な都市の守護者はあまり幸福ではないだろうと訴える(419a)。 ソクラテスは、特定の階級ではなく、都市全体をできるだけ幸福にすることが目的であると指摘する(420b)。 ソクラテスは、これを達成するために、都市全体のためのいくつかの他の措置について説明します。 都市には富も貧困もあってはならない。これらは社会的な争いを引き起こすからである(421d-422a)。 公正な都市は、それが統一され、安定することを可能にするような大きさだけであるべきである(423b)。 ソクラテスは後見人の教育の重要性を再度強調し、後見人が共通の妻と子を持つことを提案する(423e)。彼は、教育や法律の変更に革新を導入することが できる非常に限られた方法のみを許可することを提案する(424b-425e)。 公正な都市は伝統的なギリシアの宗教的慣習に従う(427b)。 公正な都市の建設が完了すると、ソクラテスは正義について議論を進める(427d)。 彼は、彼らが創設した都市は完全に善であり、徳があり、したがって賢明で、勇気があり、穏健で、公正であると主張する(427e)。 正義は、彼らがそこに他の三つの徳、すなわち知恵、勇気、中庸を見出した後に残るものである(428a)。 公正な都市の知恵はその支配者の中に見出され、それは彼らが都市をうまく支配することを可能にする知識の一種である(428b-d)。 公正な都市の勇気はその軍隊にあり、それは何を恐れ、何を恐れてはならないかについての正しく合法的な信念である(429a-430b)。 都市の節度や自己規律とは、誰が支配し、誰が支配されるべきかという点で、公正な都市の構造に従うという一致である(430d-432a)。 都市の正義は、各階級がその適切な機能を果たすことにある(433a-b)。 ソクラテスは次に、個人の中に対応する四つの美徳を見出すことを進める(434d)。 ソクラテスは都市と個人の類比を擁護し(435a-b)、魂における三つの類比的な部分とその自然的な機能を区別することを進める(436b)。 心理的葛藤の例を用いて、彼は魂の理性的部分と食欲的部分の機能を区別する(439a)。 そして、霊的な部分の機能を他の二つの部分の機能から区別する(439e-440e)。 理性的部分の機能は思考であり、精神的部分の機能は感情の経験であり、食欲的部分の機能は身体的欲望の追求である。 ソクラテスは、個人の魂の徳と、それが都市の徳とどのように対応するかを説明する(441c-442d)。 ソクラテスは、魂の3つの部分のそれぞれがその機能を果たすとき、人は公正であると指摘する(442d)。 正義とは魂の部分の自然なバランスであり、不正とは魂の部分のアンバランスである(444e)。 ソクラテスは今、正義は罰せられない不正よりも有益であるかという問いに答える準備ができている(444e-445a)。 そのためには、さまざまな不公正な政治体制と、それぞれに対応する不公正な個人を調べる必要がある(445c-e)。 e. 第五巻 ソクラテスは、不公正な政治体制とそれに対応する不公正な個人についての議論に着手しようとしていたが、アデマントスとポレマルコスによって中断される (449a-b)。 彼らはソクラテスが以前に述べた、「守護者たちは都市の女と子供を共同で所有する」(449b-d)という発言に対処する必要があると主張する。 ソクラテスはしぶしぶ同意し(450a-451b)、後見人の女性は男性の後見人と同じ仕事をすべきだという提案から始める(451c-d)。 いくつかの慣例に従って、女性は異なる仕事を与えられるべきであると反対する可能性があります彼らはもともと男性と異なるため (453a-c)。ソクラテスは、都市を保護し統治する仕事に関しては、男女の自然的な違いは関係ないことを示すことで反論する。 両性ともこれらの仕事には自然に適している(454d-e)。 ソクラテスは続けて、このように女性にも男性と同じ仕事をさせるという方策は、実現可能であるばかりでなく、最善であると主張する。 その仕事に最も適した人がその仕事を行うことになるからである(456c)。 ソクラテスはまた、守護者階級の構成員の間に別々の家族が存在すべきではないことを提案する:守護者はすべての女性と子供を共同で所有する(457c- d)。 ソクラテスはこの措置がいかに最善であるかを論じ、グラウコンはその実現可能性を論じるのを省略することを許す(458a-c)。 最良の守護者である男性は、最良の守護者である女性とセックスをし、同じような性質の子孫を残す(458d-459d)。 ソクラテスは優生学のシステムをさらに詳しく説明する。 最高の守護男性が最高の守護女性とセックスすることを保証するために、都市は不正な抽選システムによってサポートされている結婚祭りを持つことになります (459e-460a)。 また、最高の守護者である男たちは、似たような性質の子供を産む可能性を高めるために、望むだけ多くの女性とセックスすることが許される(460a- b)。 いったん生まれた子どもは飼育小屋に連れて行かれ、看護婦に世話をさせるが、親は自分の子どもが誰なのか知ることは許されない(460c-d)。 これは、親がすべての子供を自分の子供と思うようにするためである。 ソクラテスは、このシステムが同じ家族のメンバー同士が性交することになると認識している(461c-e)。 ソクラテスは、このような取り決めによって、都市全体に一致団結が広まることになると主張する(462a-465d)。 守護者たちが幸せになれないというアデイマントスの先ほどの不満に対して、ソクラテスは、守護者たちは自分たちの生き方に満足するだろう、自分たちの欲求 は満たされ、都市から十分な名誉を受けるだろう、と示す(465d-e)。 その後、ソクラテスは守護者たちがどのように戦争を行うかを議論する(466e)。 グラウコンは彼の話を遮り、そのような公正な都市がどのようにして生まれるのかを説明するよう要求する(471c-e)。 ソクラテスは、これが最も難しい批判であることを認める(472a)。そして、たとえそのような都市が存在しうることを証明できなくても、彼らが構築した 公正な都市の理論モデルは、正義と不正義を論じる上で有効であり続けると説明する(472b-473b)。 ソクラテスは、哲学者が王として統治するか、王が哲学者になるまで、公正な都市のモデルは実現できないと主張する(473c-d)。 また、公私ともに完全な幸福に到達するためには、この道しかないと指摘する(473e)。 ソクラテスは、これらの主張を正当化するために、哲学と哲学者について議論することを示す(474b-c)。 哲学者はすべての知恵を愛し、追い求め(475b-c)、特に真理を見ることを愛する(475e)。 哲学者たちは、多種多様な外観の背後にあるもの、すなわち単一の形式(476a-b)を認識し、そこに喜びを見出す唯一の存在である。 ソクラテスは、存在する単一の形を知る者と意見を持つ者を区別する(476d)。 意見を持つ者は知らないが、それは意見がその対象として変化する現われを持っているのに対して、知識はその対象が安定したものであることを意味するからで ある(476e-477e)。 f. 第六巻 ソクラテスは、哲学者が都市を支配すべき理由を説明する。 彼らは真理をよりよく知ることができ、統治に必要な実践的知識を持っているからである。 哲学者の生まれつきの能力と徳は、彼らが統治に必要なものを持っていることを証明している。彼らは、なるものよりもあるものを愛し(485a-b)、偽り を憎み(485c)、穏健であり(485d-e)、勇気があり(486a-b)、学習が速く(486c)、記憶力がよく(486c-d)、真理はそれに似 ているので比例を好み、快活な性質を持っている(486d-487a)。 アデイマントスは、実際の哲学者は役立たずか悪人だと反論する(487a-d)。 ソクラテスは、哲学者が役立たずであることを誤って非難されていることを示すために、国家という船の例えで反論する(487e-489a)。 患者に治療を懇願しない医者のように、哲学者は人々に支配を懇願すべきではない(489b-c)。 哲学者は悪人だという非難に対して、ソクラテスは、哲学者の天賦の才を持ち、優れた本性を持つ者は、しばしば悪い教育によって堕落し、傑出した悪人になる と答える(491b-e)。 このように、ある人が真の意味で哲学者になれるのは、適切な教育を受けている場合だけなのである。 悪しき教師としてのソフィストについての議論の後(492a-493c)、ソクラテスは、哲学者であると偽って主張するさまざまな人々に対して警告を発す る(495b-c)。 現在の政治体制は哲学者の堕落か破滅につながるので、哲学者は政治を避け、静かな私生活を送るべきである(496c-d)。 ソクラテスは次に、哲学が既存の都市で重要な役割を果たすようになるにはどうすればよいかという問題を取り上げる(497e)。 哲学的な性質を持つ者は、生涯、特に年をとってから哲学を実践する必要がある(498a-c)。 哲学が正しく評価され、敵意を抱かれないようにする唯一の方法は、既存の都市を一掃し、新たに始めることである(501a)。 ソクラテスは、公正な都市と提案された措置は、いずれも最善であり、実現することは不可能ではないと結論づける(502c)。 ソクラテスは、哲学者の王の教育について議論を進める(502c-d)。 哲学者が学ぶべき最も重要なことは、善の形である(505a)。 ソクラテスは善とは何かについて、快楽や知識などいくつかの候補を考え、それらを否定する(505b-d)。 ソクラテスは、私たちは善のためにあらゆるものを選んでいると指摘する(505e)。 ソクラテスは善の形が何であるかを太陽に例えて説明しようとする(507c-509d)。 太陽が物体を照らし、眼がそれを見ることができるように、善の形態は人間の魂に知識の対象を知ることができるようにする。 太陽が事物に、存在する能力、成長する能力、栄養を与えるように、善の形象は、それ自体が存在することよりも高次のものであるにもかかわらず、知識の対象 にその存在を与える(509b)。 ソクラテスは善の形態をさらに説明するために、分割された線のアナロジーを提示する(509d-511d)。 ソクラテスは一本の線を二等分し、また二等分する。 下の2つの部分は目に見える領域を表し、上の2つの部分は理解可能な領域を表す。 ソクラテスは線の4つのセクションのうち、最初のセクションにイメージ/影を、2番目のセクションに目に見える物体を、3番目のセクションに数学者が行う ような仮説によって到達した真理を、そして最後のセクションに形式そのものを置く。 これらのそれぞれに対応して、想像力、信念、思考、理解といった人間の魂の能力がある。 また、線は透明度と不透明度を表し、最も低い部分はより不透明で、高い部分はより透明である。 g. 第七巻 ソクラテスは哲学者と形相についての議論を、第三の類比である洞窟の類比で続ける(514a-517c)。 これは哲学者の無知から形相の知識への教育を表している。 真の教育とは、魂が影や目に見えるものから形相の真の理解へと回心することである(518c-d)。 この理解を達成した哲学者は、形相を観想する以外のことをしたがらないが、洞窟(都市)に戻り、そこを支配することを余儀なくされなければならない。 ソクラテスは、形相の理解に到達するための哲学者の王の教育の構造を概説する(521d)。 最終的に哲学者の王になる者は、まず他の守護者と同じように詩、音楽、体育の教育を受ける(521d-e)。 その後、数学の教育を受ける。算術と数(522c)、平面幾何学(526c)、立体幾何学(528b)である。 続いて天文学(528e)、和声学(530d)を学ぶ。 そして弁証法を学び、諸形態と善の諸形態を理解するようになる(532a)。 ソクラテスは弁証法の本質について部分的な説明を行い、グラウコンには弁証法の本質や、弁証法がどのように理解につながるのかについての明確な説明を残さ ない(532a-535a)。 そして、誰がこの教育を受け、どのくらいの期間この科目を学ぶのかについて議論する(535a-540b)。 この種の教育を受ける者は、先に述べた哲学者にふさわしい天賦の能力を示す必要がある。 弁証法の訓練の後、教育システムには15年間の実践的な政治的訓練が含まれ(539e-540c)、哲学者の王が都市を統治できるように準備する。 ソクラテスは最後に、公正な都市を実現する最も簡単な方法は、既存の都市から10歳以上のすべての人を追放することであろうと示唆している(540e- 541b)。 h. 第八巻 グラウコンは、ソクラテスが4種類の不公正な体制とそれに対応する不公正な個人について説明しようとしていたことを思い出す(543c-544b)。 ソクラテスは、公正な都市と個人から最も乖離していない体制と個人について議論を始め、最も乖離しているものについて議論を進めると宣言する(545b- c)。 政権交代の原因は支配者の団結の欠如である(545d)。 ソクラテスは、公正な都市が誕生する可能性があると仮定すると、誕生するすべてのものは崩壊しなければならないので、それは最終的に変更されることを示し ている(546a-b)。 支配者たちは、人々の生まれつきの能力に適した仕事を割り当てる際に間違いを犯すに違いなく、各階級には、それぞれの階級に関連する仕事に生まれつき適し ていない人々が混じり始めるだろう(546e)。 これが階級闘争につながる(547a)。 単なる王権や貴族制から逸脱した最初の体制は、知恵や正義よりも名誉の追求を重視するタイモクラシーである(547d ff.)。 ティモクラシー的な個人は、魂に強い気骨を持ち、名誉、権力、成功を追求する(549a)。 この都市は軍国主義的である。 ソクラテスは、個人がタイモクラティックになるプロセスを説明する:彼は彼の名誉や成功に彼の父の関心の欠如について彼の母の愚痴を聞く(549d)。 ティモクラティックな個人の魂は、理性と精神の中間点にある。 寡頭政治はティモクラシーから生じ、名誉よりも富を強調する(550c-e)。 ソクラテスは、ティモクラシーとその特徴(551c-552e)から発生する方法について説明します:人々は富を追求する、それは本質的に二つの都市、裕 福な市民の都市と貧しい人々の都市になる、少数の裕福な多くの貧しい人々 を恐れる、人々は同時に様々な仕事を行う、都市は手段のない貧しい人々 を許可する、それは高い犯罪率になります。 寡頭制の個人は、父親が財産を失うのを見て不安を感じ、貪欲に富を追求し始める(553a-c)。 こうして彼は、食欲的な部分が魂の中でより支配的な部分となるのを許してしまう(553c)。 オリガルヒ的な個人の魂は、精神的な部分と食欲的な部分の中間点にある。 ソクラテスは最終的に民主主義について論じる。 それは、金持ちが金持ちになりすぎ、貧乏人が貧乏になりすぎたときに生じる(555c-d)。 贅沢が過ぎると、寡頭政治家は軟弱になり、貧乏人は反乱を起こす(556c-e)。 民主主義では、ほとんどの政治的地位はくじ引きによって分配される(557a)。 民主主義体制の第一の目標は、自由または免許である(557b-c)。 人々は必要な知識を持たずとも役職に就くようになり(557e)、誰もが能力において平等に扱われる(平等も不平等も同じ、558c)。民主的な個人は、 あらゆる種類の身体的欲望を過度に追求するようになり(558d-559d)、食欲的な部分が魂を支配するようになる。 悪い教育によって、金銭的欲望から身体的・物質的欲望へと移行するようになるのである(559d-e)。 民主主義的な個人は恥を知らず、自制心もない(560d)。 専制政治が民主主義から生まれるのは、自分の望むことをする自由への欲望が極端になったときである(562b-c)。 民主主義で目指される自由や許可は極端になり、誰の自由も制限されると不公平に思えてくる。 ソクラテスは、自由がこのように極端になると、その反対である奴隷制が生まれると指摘する(563e-564a)。 専制君主は、裕福な少数の人々の階級に対抗する人民の擁護者として自らを示すことによって生まれる(565d-566a)。 暴君は権力を獲得し維持するために、多くの行為を強いられる。すなわち、人々を偽って告発し、近親者を攻撃し、偽って人々を裁判にかけ、多くの人々を殺 し、多くの人々を追放し、貧しい人々の借金を帳消しにすると称して彼らの支持を得る(565e-566a)。 暴君は富める者、勇敢な者、賢明な者を自分の権力に対する脅威と見なして排除する(567c)。 ソクラテスは、暴君が無価値な人々と暮らすか、いずれは自分を退陣させるかもしれない善良な人々と暮らすかのジレンマに直面し、無価値な人々と暮らすこと を選択することを示している(567d)。 暴君は結局、市民の誰も信用できないので、傭兵を護衛に使うことにする(567d-e)。 暴君はまた、非常に大きな軍隊を必要とし、街の金を使い果たし(568d-e)、自分のやり方に抵抗する者がいれば、自分の家族を殺すこともためらわない (569b-c)。 i. 第九巻 ソクラテスは今、専制的な個人について議論する準備ができている(571a)。 彼は必要な快楽と不必要な快楽と欲望について論じることから始める(571b-c)。 理性に支配されたバランスのとれた魂を持つ者は、不必要な欲望が無法で極端なものにならないようにすることができる(571d-572b)。 専制的な人は、民主的な人の不必要な欲望や快楽が極端になったとき、つまりエロスや欲望に満ちたときに、民主的な人から出てくる(572c-573b)。 専制的な人間は欲望に狂い(573c)、そのために自分の欲望を満たすためには手段を選ばず、自分の邪魔をする者には誰でも抵抗するようになる(573d -574d)。 暴君的な人の中には、やがて実際の暴君になる人もいる(575b-d)。 暴君はお世辞を言う人と付き合い、友好を結ぶことができない(575e-576a)。 都市と魂のアナロジーを応用して、ソクラテスは専制的な個人が最も不幸な個人であることを論証していく(576c ff.)。 専制的な都市と同じように、専制的な個人は奴隷化され(577c-d)、自分の望むことをする可能性が最も低く(577d-e)、貧しく満足できず (579e-578a)、恐れおののき、慟哭と嘆きに満ちている(578a)。 都市の実際の暴君になる個人は、すべての不幸である(578b-580a)。 ソクラテスはこの最初の議論を、幸福の観点から個人をランク付けすることで締めくくる:より公正な者ほど幸福である(580b-c)。 彼は、公正な人は不正な人よりも幸せであることの第二の証明に進みます(580d)。 ソクラテスは、知恵を追求する人、名誉を追求する人、利益を追求する人という3つのタイプの人間を区別する(579d-581c)。 知恵を追い求める人は、3つのタイプの生き方すべてを明確に考えることができるため、知恵を追い求める人の生き方が最も快適であるという判断を信じるべき だと主張する(581c-583a)。 ソクラテスは、公正な者が不正な者よりも幸福であるという第三の証拠を提示する(583b)。 彼は快楽の分析から始める:苦痛からの解放は快楽に見えるかもしれないし(583c)、肉体的快楽は苦痛からの解放に過ぎないが真の快楽ではない (584b-c)。 真に充実した快楽は、理解から来るものだけであり、それが追求する対象は永続的だからである(585b-c)。 ソクラテスは、理性的な部分が魂を支配する場合にのみ、魂の各部分はその適切な快楽を見出すことができる、と付け加える(586d-587a)。 彼は、最良の人生が最悪の人生より何倍も快いかを計算することで議論を締めくくる:七百二十九回である(587a-587e)。 ソクラテスは、魂における正義と不正義の結果を説明し、正義を支持するために、想像上の多頭の獣について議論する(588c ff.) j. 第十巻 その後、ソクラテスは詩の話題に戻り、公正な都市から模倣的な詩を排除するために導入された措置は、今では明らかに正当化されるように見えると主張する (595a)。 詩人たちはどれがそうであるかを知らないかもしれないので、詩は検閲されるべきである;したがって、魂を迷わせるかもしれない(595b)。 ソクラテスは模倣について議論を進める。 彼はソファの例を通して模倣のいくつかのレベルを区別することによって、それが何であるかを説明します:ソファの形、特定のソファ、ソファの絵があります (596a-598b)。 模倣の産物は真実から遠く離れている(597e-598c)。 詩人も画家と同様、真理を知らずに模倣を生み出す模倣者である(598e-599a)。 ソクラテスは、もし詩人に真理の知識があれば、詩人のままではなく、偉大なことをする人間になりたいと思うだろうと主張する(599b)。 ソクラテスは、詩人は徳のイメージを模倣するだけなので、詩人が徳を教える能力を疑っている(599c-601a)。 詩人の知識は他の製品の製造者の知識より劣っており、製造者の知識は使用者の知識より劣っている(601c-602b)。 次にソクラテスは、模倣者がどのように聴衆に影響を与えるかを考える(602c)。 彼は目の錯覚との比較を用いて(602c)、模倣詩が魂の各部分を互いに戦争させ、これが不正につながると主張する(603c-605b)。 模倣詩に対する最も深刻な非難は、模倣詩がまともな人間を堕落させるということである(605c)。 彼は、公正な都市はそのような詩を許すべきではなく、神々と善良な人間を賛美する詩だけを許すべきだと結論づける(606e-607a)。 模倣詩は不滅の魂が最大の報酬を得るのを妨げる(608c-d)。 グラウコンは魂が不滅であるかどうか疑問に思い、ソクラテスはその不滅を証明する議論を始める:破壊されるものは、それ自身の悪によって破壊される;身体 の悪は病気であり、これはそれを破壊することができる;魂の悪は無知、不正、その他の悪徳であるが、これらは魂を破壊しない;したがって、魂は不滅である (608d-611a)。 ソクラテスは、現在の議論のように肉体との関係だけを考えれば、魂の本質を理解することはできないと指摘する(611b-d)。 ソクラテスは最後に、グラウコンに正義の評判の報酬について議論することを認めさせることによって、正義の報酬について説明する(612b-d)。 グラウコンは、ソクラテスがすでに魂の中でそれ自体で正義を擁護しているので、これを許可します。 ソクラテスは、正義も不正義も神々の目から逃れられないこと、神々は正義の者を愛し、不正義の者を憎むこと、そして神々が愛する者には良いことがもたらさ れることを示す(612e-613a)。 ソクラテスは、現世において正しい者にはさまざまな報いが、不正な者には罰があることを列挙する(613a-e)。 そして、死後の世界における報酬と罰を示すとされる『エル神話』を語る(614b)。 死者の魂は、彼らが正義であったなら右の開口部から上に、不義であったなら左の開口部から下に行く(614d)。 様々な魂は彼らの報酬と罰を議論する(614e-615a)。 ソクラテスは人々が罰せられ、報われる倍数を説明する(615a-b)。 死者の魂は次の生を選ぶことができ(617d)、そして生まれ変わる(620e)。 ソクラテスはグラウコンたちに、現世でも死後の世界でも良いことをするように促して議論を終える(621c-d)。 |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆