モントレー・プレシディオ

Presidio of Monterey, California

☆ カリフォルニア州モントレーにあるプレシディオ・オブ・モンテレー(POM)は、スペイン植民地時代からの歴史的なつながりを持つ、現役の米陸軍施設であ る。現在は、国防言語研究所外国語センター(DLI-FLC)の拠点となっている。カリフォルニア州で現役の軍事施設を持つ最後の、そして唯一のプレシ ディオである。

| The

Presidio of Monterey (POM), located in Monterey, California, is an

active US Army installation with historic ties to the Spanish colonial

era. Currently, it is the home of the Defense Language Institute

Foreign Language Center (DLI-FLC). It is the last and only presidio in

California to have an active military installation. |

カリフォルニア州モントレーにあるプレシディオ・オブ・モンテレー

(POM)は、スペイン植民地時代からの歴史的なつながりを持つ、現役の米陸軍施設である。現在は、国防言語研究所外国語センター(DLI-FLC)の拠

点となっている。カリフォルニア州で現役の軍事施設を持つ最後の、そして唯一のプレシディオである。 |

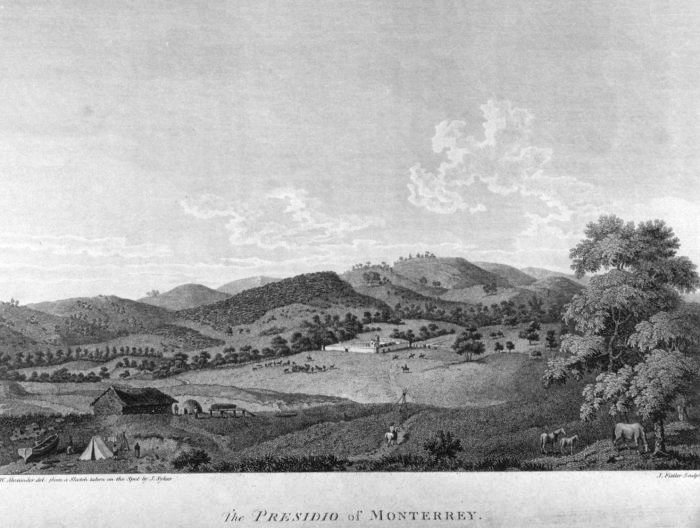

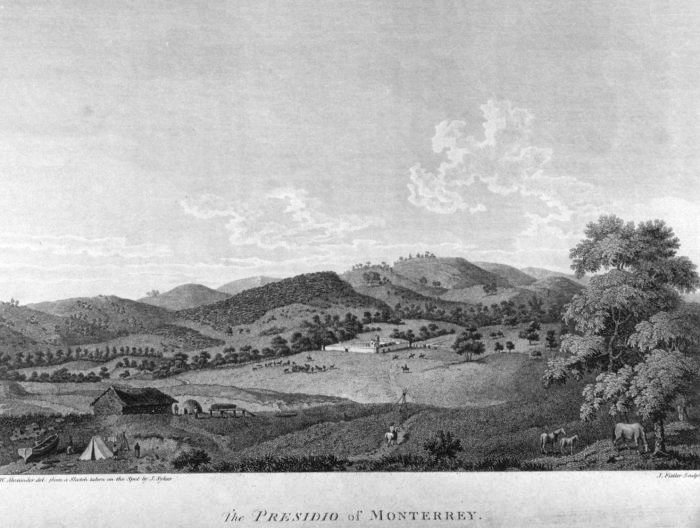

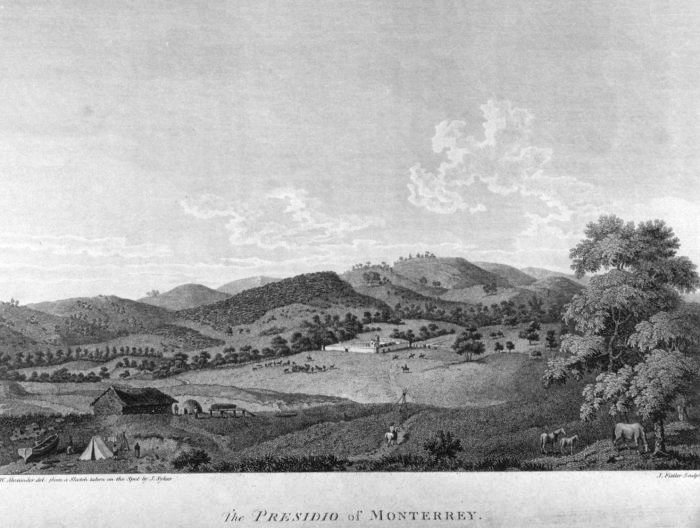

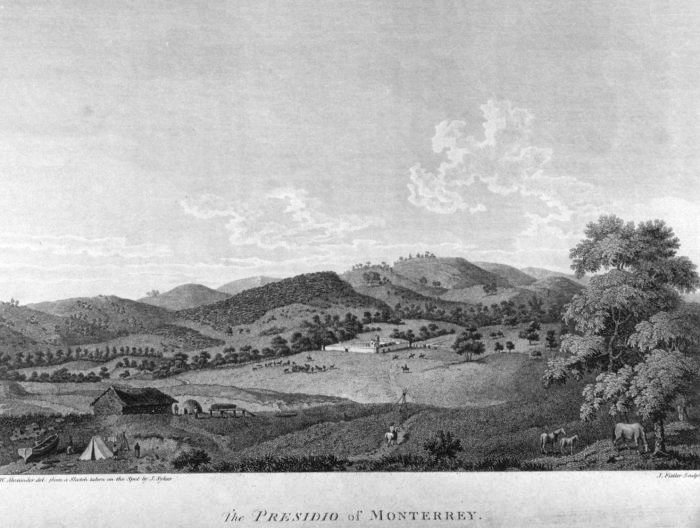

| History The Spanish explorer Sebastián Vizcaíno visited, named and charted Monterey Bay (especially the southern end) in 1602. In his official report, Vizcaíno recommended the natural harbor he found as an appropriate site for a seaport, military fortification and colonization. It would be over 150 years, until news of Pacific Coast moves by Spain's European rivals brought the remote area back to the attention of the leaders of New Spain. José de Gálvez's grand plan In 1768, José de Gálvez, special deputy (visitador) of King Carlos III in New Spain (Mexico), received this order: "Occupy and fortify San Diego and Monterey for God and the King of Spain." Gálvez organized a series of land and sea expeditions from the port of San Blas, today in the state of Nayarit, México, to establish a military post and Catholic mission in Monterey. Spain's rulers had long feared that other European powers would encroach from the north on American territories Spain claimed along the Pacific coast. Gálvez himself spread rumors of schemes by the British and Dutch rulers to add California to their own empires. Then, when a report arrived from the Spanish ambassador in Russia that Catherine the Great planned to establish settlements down the California coast towards Monterey, Gálvez—already planning a northward expansion of New Spain's dominion—trumpeted the threat from Russia.[1] King Carlos gave Gálvez the go-ahead. Spain moved to occupy regions along the Pacific coast of North America that its sailors and soldiers had only seen and claimed from previous maritime explorations. Portolá expeditions to Monterey From March through June 1769, Gaspar de Portolá, appointed "governor of the Californias" (Baja and Alta California), led an overland party—joined by Franciscan friar Junípero Serra—from Loreto to San Diego. Then in July, Portolá mustered a new party—including lieutenant Pedro Fages, cartographer Miguel Costansó, and friars Juan Crespí and Francisco Gómez—to trek north from San Diego to rediscover the port of Monterey by land. They reached Monterey Bay on 1 October, but failed to recognize it as the port described by Vizcaíno 167 years earlier[2]—and continued north, eventually reaching San Francisco Bay. On their return trek to San Diego, they planted two large crosses on the coast of Monterey, whose geographical identity they could not yet confirm. (see Timeline of the Portolá expedition). In April 1770, Portolá gathered a new and smaller party for another overland journey from San Diego to Monterey. This party included Pedro Fages with twelve Catalan volunteers, seven leather-jacket soldiers, two muleteers, five Christian Indians from Baja California, and friar Juan Crespí.[3] They arrived at Monterey Bay on 24 May. That afternoon, Portolá and Crespí revisited the large wooden cross their party had planted five months earlier on a hill just south of Point Pinos near the northern tip of the Monterey peninsula. "This is the port of Monterey without the slightest doubt," wrote Crespí in his diary.[4] Strict discipline to build Spanish presidio Miguel Costansó selected the site of the presidio and drew the first plans and maps. Pedro Fages, left in command of the Monterey soldiers after Portolá sailed back to Mexico, imposed strict discipline on his soldiers to construct the presidio. He set the work they had to do in a certain time, harshly punishing soldiers caught resting or rolling a cigarette. Heavy rains punctuated the spring and winter of 1770–1771, but Fages permitted no let-up in the work. His soldiers had to trudge through mud to the forest to chop wood, then drag their mules out of the mud and head home. They had no chance to wash or mend their clothes during the six-day work week; Fages told them to do that on Sundays. This work regime lasted a year and a half, until complaints by the soldiers persuaded padre president Junípero Serra to intervene: Serra told Fages that, as a Christian, he had to observe the sabbath and let men rest on Sundays. In late June 1771, Fages wrote to viceroy Carlos de Croix in Mexico to inform him that the Monterey presidio had been built, sending along a simplified map.[5] +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ The Vancouver Expedition (1791–1795) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++  "The Presidio of Monterrey". Volume II, plate V from: "A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean and Round the World" by Captain George Vancouver Spanish Fort While Fages established El Presidio Real de San Carlos de Monterrey (the Royal Presidio of Saint Charles of Monterey), Junípero Serra founded Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo, with the original location occupying the present day (remaining) chapel Cathedral of San Carlos Borromeo. Monterey became one of a series of presidios, or "royal forts," built by Spain in what is now the western United States. In 1792, the El Castillo de Monterey was established to protect the port and persido of Monterey.[6] Other California-based installations were founded in San Diego (El Presidio Real de San Diego) in 1769, in San Francisco (El Presidio Real de San Francisco ) in 1776, and in Santa Barbara (El Presidio Real de Santa Bárbara) in 1782.[7] On 20 November 1818, Argentine privateer Hipólito Bouchard, known thereafter as "California's only pirate", raided the El Castillo de Monterey defended by José Bandini. Its population took refuge in the Presidio's Rancho del Rey San Pedro (King's Farm), in the vicinity of Salinas.[8][6] The fortunes of the Presidio at Monterey rose and fell with the times: it has been moved, abandoned and reactivated time and time again. The only surviving building from the original compound is the Royal Presidio Chapel. At least three times, it has been submerged by the tide of history, only to appear years later with a new face, a new master, and a new mission – first under the Spanish, then the Mexicans, and ultimately the Americans. United States fort This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) United States control of the area began in 1846 during the Mexican–American War when Commodore John D. Sloat, commander of the U.S. Navy's Pacific Squadron, landed unopposed a small force in Monterey and claimed the territory and the Presidio for the United States. He left a small garrison of Marines who moved the fort up to its current location on the hill overlooking the harbor, combining in one location the previously separated functions of military headquarters and fortress. The Presidio was renamed Fort Mervine in honor of Captain William Mervine, who commanded one of the ships in Sloat's squadron.[9] The original Presidio comprised a square of adobe buildings located in the vicinity of what is now downtown Monterey. The fort's original mission, the Royal Presidio Chapel, has remained in constant use since its founding in 1770 by Junípero Serra, who arrived with Portola's party. On a hill overlooking the Monterey harbor is an earthwork—the only lingering connection between the original and present sites of the Presidio. That earthwork was part of the Spanish-built artillery battery defending the harbor.[10] The 1846 US occupation of Monterey put an end to any Mexican military presence at the Presidio. In 1865, in the closing months of the American Civil War, the fort was returned to temporary life by the arrival of six officers and 156 enlisted men, but was abandoned again in 1866.[11] In 1902, an infantry regiment arrived at Monterey with the mission to construct a post to house an infantry regiment and a squadron of cavalry. Troops moved into the new wooden barracks, officially named Ord Barracks, in June 1903. It was named for former American Civil War general, Edward Ord. However, in order to perpetuate the name of the old Spanish military installation that Portolà had established 134 years earlier, the War Department redesignated the post as the Presidio of Monterey. The barracks and training facilities for enlisted men, along with General Ord's name, were moved a short way up the coast to Fort Ord in 1940. Presidio of Monterey A school of musketry was located at the Presidio from 1907 to 1913, and a school for cooks and bakers from 1914 to 1917. In 1917, the Army purchased an additional 15,809 acres (64 km2) across the bay as a maneuver area. This new acquisition eventually was designated as Camp Ord in 1939 and became Fort Ord in 1940. Between 1919 and 1940, the Presidio housed principally cavalry and field artillery units. However, the outbreak of World War II ended the days of horse cavalry, and those troops left Monterey. The Presidio, subsequently, served as reception center and temporary headquarters of the III Corps until it was deactivated in late 1944. Civil Affairs Staging Area The Presidio of Monterey was reactivated, under considerable difficulty, in January 1945 to accommodate the Civil Affairs Staging Area (CASA).[12] The Civil Affairs Staging Area was a brigade sized Army / Navy formation created by a joint chiefs of staff directive for military government theater planning, training and provision of military government personnel to liberated areas of the Far East. CASA provided comprehensive training and planning in civil affairs administration to officers coming from six schools of military government established at various universities throughout the country.  Civil Affairs Staging Area (CASA) officers receive Chinese language instruction at the Presidio of Monterey in the Spring of 1945.  Senior Army / Navy Civil Affairs Staging Area officers at the Presidio of Monterey in the Spring of 1945. Defense Language Institute Main articles: Defense Language Institute and Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center In 1946, the Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS) was moved to the Presidio of Monterey and was renamed the Army Language School (ALS). In June 1963, the Army Language School was renamed the Defense Language Institute (DLI). In 1976, the Defense Language Institute became the Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center (DLI-FLC), the Defense Department's primary center for foreign language instruction. The center constitutes the principal activity at the Presidio. The Presidio serves all branches of the Department of Defense as well as other select government agencies. Closure of Fort Ord From 1946 onward, the Presidio itself was a sub-installation of the nearby Fort Ord. On 1 October 1994, this situation changed when Fort Ord closed and the Presidio of Monterey became a separate installation again, with the continued military areas of Fort Ord becoming known as the Presidio Annex. |

歴史 スペインの探検家セバスチャン・ビスカイノは、1602年にモントレー湾(特に南端)を訪れ、命名し、海図を作成した。ビスカイノは公式報告書の中で、発 見した天然の港が海港、軍事要塞、植民地化に適した場所であると推奨した。スペインのヨーロッパのライバルたちによる太平洋岸進出のニュースが、ニュース ペインの指導者たちにこの辺境の地が再び注目されるようになるまでには、150年以上の歳月が必要だった。 ホセ・デ・ガルベスの壮大な計画 1768年、ニュースペイン(メキシコ)国王カルロス3世の特別代理(ビジタドール)であったホセ・デ・ガルベスは、こんな命令を受けた: 「神とスペイン王のためにサンディエゴとモントレーを占領し要塞化せよ"。ガルベスはサンブラス港(現在のメキシコ、ナヤリット州)から一連の陸海の遠征 隊を組織し、モントレーに軍事拠点とカトリック伝道所を設立した。スペインの支配者たちは、スペインが太平洋沿岸で領有権を主張するアメリカ領土に、他の ヨーロッパ列強が北から侵入してくることを長い間恐れていた。ガルベス自身も、イギリスやオランダがカリフォルニアを自分たちの帝国に加えようとしている という噂を流した。そして、ロシア駐在のスペイン大使から、エカテリーナ大帝がカリフォルニア沿岸のモントレー方面への入植を計画しているという報告が届 くと、すでに新スペイン領の北方拡大を計画していたガルベスは、ロシアの脅威を喧伝した[1]。スペインは北アメリカ大陸の太平洋沿岸地域を占領するため に動き出した。 ポルトーラのモントレー探検 1769年3月から6月にかけて、「カリフォルニア(バハおよびアルタ・カリフォルニア)総督」に任命されたガスパル・デ・ポルトラは、フランシスコ会修 道士ジュニペロ・セラと共に、ロレートからサンディエゴまでの陸路探検隊を率いた。そして7月、ポルトラはペドロ・ファジェス中尉、地図製作者ミゲル・コ スタンソ、フアン・クレスピ修道士とフランシスコ・ゴメス修道士を含む新たな一行を招集し、陸路でモントレー港を再発見するためにサンディエゴから北上し た。彼らは10月1日にモントレー湾に到着したが、そこが167年前にビスカイノが記した港であることを認識できず[2]、さらに北上を続け、最終的にサ ンフランシスコ湾に到着した。サンディエゴへの帰路、彼らはモントレーの海岸に2つの大きな十字架を植えた。(ポルトーラ探検隊の年表参照)。 1770年4月、ポルトラはサンディエゴからモントレーへの陸路の旅に出るため、新たに小規模な一行を集めた。この一行には、ペドロ・ファジェスと12人 のカタロニア人志願兵、7人の革ジャン兵士、2人のラバ使い、バハ・カリフォルニア出身の5人のキリスト教インディオ、修道士フアン・クレスピが含まれて いた[3]。その日の午後、ポルトラとクレスピは、モントレー半島の北端に近いピノス岬のすぐ南の丘に、一行が5ヶ月前に植えた大きな木の十字架を再訪し た。「ここは間違いなくモントレーの港だ」とクレスピは日記に記している[4]。 スペイン領プレシディオ建設のための厳しい規律 ミゲル・コスタンソがプレシディオの場所を選び、最初の計画と地図を描いた。ポルトラがメキシコに戻った後、モントレー兵の指揮を任されたペドロ・ファ ジェスは、プレシディオ建設のために兵士たちに厳しい規律を課した。彼は一定時間内にしなければならない仕事を決め、休んだりタバコを巻いたりしている兵 士を厳しく罰した。1770年から1771年にかけての春と冬は大雨に見舞われたが、フェイジスは作業の手を休めることを許さなかった。兵士たちは泥濘を かき分けて森まで薪割りに行き、泥の中からラバを引きずり出して家路につかなければならなかった。週6日の労働の間、洗濯や繕いをする機会はなかった。こ の労働体制は1年半続いたが、兵士たちの苦情によって、ジュニペロ・セラ神父会長が介入することになった: セラはファジェスに、キリスト教徒として安息日を守り、日曜日は兵士たちを休ませなければならないと言った。1771年6月下旬、ファジェスはメキシコの カルロス・デ・クロワ総督に、モントレーのプレシディオが建設されたことを知らせる手紙を書き、簡略化した地図を送った[5]。 +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ バンクー バー遠征(1791–1795) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++  「モンテレイのプレシディオ」。ジョージ・バンクーバー船長著『北太平洋と世界一周の大航海』より第2巻、プレートV。 スペインの要塞 ファジェスがサン・カルロス・デ・モンテレイの王立プレシディオ(El Presidio Real de San Carlos de Monterrey)を設立する一方で、ジュニペロ・セラ(Junípero Serra)はサン・カルロス・ボロメオ・デ・カルメロ伝道所(Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo)を設立した。 モントレーは、スペインが現在のアメリカ西部に建設した一連のプレシディオ(王宮砦)のひとつとなった。1792年、モントレーの港とペルシドを守るため にエル・カスティーヨ・デ・モンテレーが建設された[6]。1769年、サンディエゴ(エル・プレシディオ・レアル・デ・サンディエゴ)、1776年、サ ンフランシスコ(エル・プレシディオ・レアル・デ・サンフランシスコ)、1782年、サンタバーバラ(エル・プレシディオ・レアル・デ・サンタバーバラ) にもカリフォルニアを拠点とする要塞が建設された[7]。 1818年11月20日、アルゼンチンの私掠船ヒポリート・ブシャールは、その後「カリフォルニア唯一の海賊」として知られ、ホセ・バンディーニが守るモ ントレー城を襲撃した。その住民は、サリナス近郊にあるプレシディオのランチョ・デル・レイ・サン・ペドロ(王の農場)に避難した[8][6]。モント レーのプレシディオの運命は、時代とともに浮き沈みした。当初の敷地から現存する唯一の建物は、王立プレシディオ礼拝堂である。少なくとも3度、歴史の波 に沈められ、数年後に新しい顔、新しい主人、そして新しい使命を帯びて姿を現した。 アメリカ合衆国の砦 このセクションには、検証のための追加引用が必要である。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力いただきた い。ソースのないものは異議申し立てされ、削除される可能性がある。(2014年10月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) アメリカ合衆国のこの地域の支配は、米墨戦争中の1846年、アメリカ海軍太平洋艦隊司令官ジョン・D・スロート提督が、少数の部隊を無抵抗のままモント レーに上陸させ、領土とプレシディオの領有権を主張したことから始まった。彼は海兵隊からなる小さな守備隊を残し、砦を港を見下ろす丘の上の現在の場所に 移し、それまで分離していた軍司令部と要塞の機能を1ヵ所に統合した。プレシディオは、スロート隊の船の1隻を指揮していたウィリアム・マーヴィン大尉に 敬意を表してフォート・マーヴィンと改名された[9]。 当初のプレシディオは、現在のモントレーのダウンタウン近辺に位置するアドービ建築の広場から成っていた。砦のオリジナル・ミッションである王立プレシ ディオ・チャペルは、ポルトラの一行と共に到着したジュニペロ・セラによって1770年に創設されて以来、常に使用され続けている。モントレー港を見下ろ す丘の上には土塁があり、これがプレシディオの原位置と現位置の間に残る唯一のつながりである。その土塁は、港を守るスペイン製の砲台の一部だった [10]。 1846年のアメリカによるモントレー占領により、プレシディオにおけるメキシコ軍の存在は消滅した。1865年、アメリカ南北戦争の終盤に、6人の将校 と156人の下士官の到着によって砦は一時的な生活を取り戻したが、1866年に再び放棄された[11]。 1902年、歩兵連隊がモントレーに到着し、歩兵連隊と騎兵隊を収容するポストを建設する使命を帯びた。部隊は1903年6月、正式にオード兵舎と名付け られた新しい木造兵舎に移転した。アメリカ南北戦争の元将軍、エドワード・オードにちなんで命名された。しかし、ポルトラが134年前に設立した旧スペイ ン軍施設の名前を永続させるため、陸軍省はこのポストをプレシディオ・オブ・モンテレイと再指定した。兵舎と下士官兵の訓練施設は、オード将軍の名前とと もに、1940年に海岸沿いのフォート・オードに移された。 モントレーのプレシディオ プレシディオには1907年から1913年までマスケット銃の学校が、1914年から1917年までコックとパン職人の学校があった。1917年、陸軍は 作戦区域として湾の対岸に15,809エーカー(64km2)を追加購入した。この新たな取得地は、最終的に1939年にキャンプ・オードとして指定さ れ、1940年にフォート・オードとなった。 1919年から1940年の間、プレシディオには主に騎兵隊と野戦砲兵部隊が収容されていた。しかし、第二次世界大戦の勃発により騎馬部隊の時代は終わり を告げ、これらの部隊はモントレーを去った。その後プレシディオは、1944年後半に解除されるまで、第三軍団のレセプションセンターと臨時司令部として 使用された。 民政ステージング・エリア モントレーのプレシディオは1945年1月、かなり困難な状況下で、民政ステージング・エリア(CASA)を収容するために再活性化された[12]。民政 ステージング・エリアは、軍政府の劇場計画、訓練、極東の解放地域への軍政府要員の提供のための合同参謀本部指令によって創設された旅団規模の陸海軍組織 であった。CASAは、全国各地の大学に設置された6つの軍政学校出身の将校に、民政行政の総合的な訓練と計画を提供した。  1945年春、モントレーのプレシディオで中国語の指導を受ける民政ステージング・エリア(CASA)の将校たち。  1945年春、モントレーのプレシディオにいた陸軍/海軍の上級民政局中継地域担当官。 国防外国語学院 主な記事 国防外国語研究所、国防外国語センター 1946年、陸軍情報部語学学校(MISLS)はモントレーのプレシディオに移転し、陸軍語学学校(ALS)と改称された。1963年6月、陸軍言語学校 は国防言語研究所(DLI)に改称された。1976年、国防言語研究所は、国防省の外国語教育の主要センターである国防言語研究所外国語センター(DLI -FLC)となった。このセンターは、プレシディオにおける主要な活動である。プレシディオは、国防総省の全支部およびその他の政府機関にサービスを提供 している。 フォート・オードの閉鎖 1946年以降、プレシディオ自体は近くのフォート・オードの下部施設だった。1994年10月1日、フォート・オードが閉鎖され、モントレーのプレシ ディオは再び独立した施設となった。 |

| Installation Management Command Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center 229th Military Intelligence Battalion, United States Army Training and Doctrine Command MARDET Presidio of Monterey, Marine Corps Communication Electronics School Information Warfare Training Command Monterey, Center for Information Warfare Training 517th Training Group, 17th Training Wing 902nd Monterey Field Office, C Company 308th Military Intelligence (MI) Battalion, 902nd MI Group California Medical Detachment, Madigan Army Medical Center Presidio of Monterey Dental Clinic Criminal Investigation Command Logistics Readiness Center, Army Materiel Command Mission Installation Contracting Command Network Enterprise Center, Army Network Enterprise Technology Command |

施設管理司令部 国防外国語研究所外国語センター 米陸軍訓練教練司令部第229軍事情報大隊 MARDET Presidio of Monterey、海兵隊通信電子学校 モントレー情報戦訓練司令部、情報戦訓練センター 第517訓練群、第17訓練飛行隊 第902MI群第308軍事情報(MI)大隊C中隊第902モントレー現地事務所 マディガン陸軍医療センター、カリフォルニア医療分遣隊 プレシディオ・オブ・モンテレー歯科診療所 犯罪捜査司令部 陸軍資材司令部ロジスティクス準備センター 任務施設契約司令部 陸軍ネットワークエンタープライズ技術司令部ネットワークエンタープライズセンター |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Presidio_of_Monterey,_California |

|

| The

Defense Language Institute (DLI) is a United States Department of

Defense (DoD) educational and research institution consisting of two

separate entities which provide linguistic and cultural instruction to

the Department of Defense, other federal agencies and numerous

customers around the world. The Defense Language Institute is

responsible for the Defense Language Program, and the bulk of the

Defense Language Institute's activities involve educating DoD members

in assigned languages, and international personnel in English. Other

functions include planning, curriculum development, and research in

second-language acquisition. |

国防言語研究所(DLI)は、米国国防総省(DoD)の教育・研究機関

であり、国防総省、その他の連邦政府機関、および世界中の数多くの顧客に言語・文化教育を提供する2つの独立した組織から構成されている。国防言語研究所

は、国防言語プログラムの責任者であり、国防言語研究所の活動の大部分は、国防総省の隊員を指定された言語で教育し、国際要員を英語で教育することであ

る。その他の機能には、計画、カリキュラム開発、第二言語習得の研究などがある。 |

| Overview The two primary entities of the Defense Language Institute are the Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center (DLIFLC) and the Defense Language Institute English Language Center (DLIELC). DLIFLC is located at the Presidio of Monterey in Monterey, California, and DLIELC is located at Joint Base San Antonio - Lackland Air Force Base, Texas. Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center The institute offers foreign language instruction in more than two dozen languages to approximately 3,500 students on a schedule that extends throughout the year. Courses are taught seven hours per day, five days a week, with the exception of federal holidays and training holidays. The duration of courses range between 36 and 64 weeks, depending on the difficulty of the language.[3] The military also uses private language programs such as CL-150. Defense Language Institute English Language Center The Defense Language Institute English Language Center manages the Department of Defense English Language Program (DELP), and is designated the 637th Training Group in 2015. The over 300 civilian members of the staff include the instructors who are qualified in the area of English as a second language.[4] DLIELC is accredited by the Commission on English Language Program Accreditation, which is recognized by the US Department of Education.[citation needed] DLIELC is divided into three resident academic training sections: General English, Specialized English, and Instructor Development. Depending on the needs of the students, training can range from nine weeks (in Specialized English, for example) to 52 weeks in General English. Some students arrive with only minimal English capabilities, then train to a predetermined English comprehension level (ECL) in General English. Annually, students from over 100 countries enroll in the DLIELC resident training programs. Training is paid by the host country (Foreign Military Sales) or through US grant assistance programs such as International Military Education and Training Programs. In addition to DLIELC's mission to train international students, DLIELC is responsible for providing English language training to US military service members whose primary language is not English. The DLIELC campus is located on the southwest quadrant of Lackland AFB.[citation needed] |

概要 国防総省国語研究所の2つの主要組織は、国防総省国語研究所外国語センター(DLIFLC)と国防総省国語研究所英語センター(DLIELC)である。 DLIFLCはカリフォルニア州モントレーのプレシディオ・オブ・モントレーにあり、DLIELCはテキサス州サンアントニオ-ラックランド空軍基地にあ る。 国防外国語研究所外国語センター 年間を通じて約3,500人の学生に20以上の言語の外国語教育を提供している。コースは週5日、1日7時間で、連邦祝祭日と訓練休日を除く。コースの期 間は、言語の難易度によって36週間から64週間の間である[3]。 軍はCL-150のような民間の語学プログラムも利用している。 国防言語研究所英語センター 国防省英語プログラム(DELP)を管理する国防省言語研究所英語センターは、2015年に第637訓練グループに指定された。300人を超える民間人の スタッフには、第二言語としての英語の分野で資格を持つインストラクターが含まれている[4]。 DLIELCは、米国教育省が認定する英語プログラム認定委員会(Commission on English Language Program Accreditation)によって認定されている[要出典]。 DLIELCは3つの常駐学術研修セクションに分かれている: 一般英語、専門英語、指導者育成である。学生のニーズに応じて、研修期間は9週間(例:専門英語)から52週間(例:一般英語)まで様々である。中には、 最低限の英語力しかない状態で入学し、一般英語で所定の英語理解レベル(ECL)までトレーニングを受ける学生もいる。DLIELCの常駐研修プログラム には、毎年100カ国以上からの学生が参加している。訓練費用は、受け入れ国から支払われるか(対外軍事販売)、国際軍事教育訓練プログラムなどの米国の 無償資金援助プログラムを通じて支払われる。留学生を訓練するというDLIELCの使命に加え、DLIELCは英語を母国語としない米軍人に英語訓練を提 供する責任も担っている。DLIELCのキャンパスはラックランド基地の南西の四分の一に位置している[要出典]。 |

| History The Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center (DLIFLC) traces its roots to the eve of United States entry into World War II, when the U.S. Army established a secret school at the Presidio of San Francisco with a budget of $2,000 to teach the Japanese language. Classes began 1 November 1941, with four instructors and 60 students in an abandoned airplane hangar at Crissy Field known as Building 640.[5] The site is now preserved as the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) Historic Learning Center by the National Japanese American Historical Society. Gen. Joseph Stilwell and Gen. George Marshall studied Chinese as officers stationed in China and understood the need to provide language training for enlisted troops, establishing a language program in 1924 to teach U.S. soldiers and officers in Asia the rudiments of spoken Chinese. Recognizing the strained relations between Japan and the U.S. in the build up to the war, a small group of officers with previous tours of duty in Japan saw the need for an intelligence unit, which would be able to understand the Japanese language. This group of officers was headed by Lt. Col. John Weckerling and Capt Kai E. Rasmussen. Japanese American Maj John F. Aiso and Pfc Arthur Kaneko, were found to be qualified linguists along with two civilian instructors, Akira Oshida and Shigeya Kihara, and became MISLS's first instructors.[6] The students were primarily second generation Japanese Americans (Nisei) from the West Coast, who had learned Japanese from their first-generation parents but were educated in the US and whose Japanese was somewhat limited, the "Kibei", Japanese-Americans who had been educated in Japan and spoke Japanese like the Japanese themselves, along with two Caucasian students who were born in Japan as the sons of missionaries. Even for the native Japanese speakers, the course curriculum featured heigo (兵語) or military specific terminology that was as foreign to the Japanese speakers as US military slang is to the average American civilian.[7][8] During the war, the Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS), as it came to be called, grew dramatically. After the attack on Pearl Harbor Japanese-Americans on the West Coast and the Hawaii Territory were moved into internment camps in 1942. Because of anti-Japanese sentiments the Army did a nationwide survey for the least hostile environment and moved the school to a former Minnesota WPA camp named Camp Savage. By 1944 the school had outgrown those facilities and moved to Fort Snelling close by. There the school grew to 125 classrooms with over 160 instructors. Over 6,000 of its graduates served in the Pacific during the war and occupation of Japan. Nisei Hall, along with several other buildings, is named to recognize those WWII students honored in the institute's Yankee Samurai exhibit. The John Aiso Library is named for the former MISLS director of academic training, Munakata Hall is named for the former MISLS instructor Yutaka Munakata, and the Hachiya, Mizutari, and Nakamura Halls are named for Frank Tadakazu Hachiya, Yukitaka "Terry" Mizutari, and George Ichiro Nakamura, who were killed in action in Leyte, New Guinea, and Luzon.[9] U.S. Army film about the Army Language School, Monterey, CA, 1951 In 1946 Fort Snelling was deactivated and the school moved back to the Presidio of Monterey. There it was renamed as the Army Language School. The Cold War accelerated the school's growth in 1947–48. Instructors were recruited worldwide, included native speakers of thirty plus languages. Russian became the largest program, followed by Chinese, Korean, and German. The Defense Language Institute English Language Center (DLIELC) traces its formal beginning to May 1954, when the 3746th Pre-Flight Training Squadron (language) was activated and assumed responsibility for all English language training. In 1960, the Language School, USAF, activated and assumed the mission. In 1966, the DoD established the Defense Language Institute English Language School (DLIELS) and placed it under US Army control although the school remained at Lackland AFB. In 1976, the DoD appointed the US Air Force as the executive agent for the school and redesignated it the Defense Language Institute English Language Center. Cold War language instruction The U.S. Air Force met most of its foreign language training requirements in the 1950s through contract programs at universities such as Yale, Cornell, and Syracuse and the U.S. Navy taught foreign languages at the Naval Intelligence School in Washington, D.C., but in 1963 these programs were consolidated into the Defense Foreign Language Program. A new headquarters, the Defense Language Institute (DLI), was established in Washington, D.C., and the former Army Language School commandant, Colonel James L. Collins Jr., became the institute's first director. The Army Language School became the DLI West Coast Branch, and the foreign language department at the Naval Intelligence School became the DLI East Coast Branch. The contract programs were gradually phased out. The DLI also took over the English Language School at Lackland Air Force Base, Texas, which became the DLI English Language Center (DLIELC). During the peak of American involvement in Vietnam (1965–73), the DLI stepped up the pace of language training. While regular language training continued unabated, more than 20,000 service personnel studied Vietnamese through the DLI's programs, many taking a special eight-week military adviser "survival" course. From 1966 to 1973, the institute also operated a Vietnamese branch using contract instructors at Biggs Air Force Base near Fort Bliss, Texas (DLI Support Command, later renamed the DLI Southwest Branch). Vietnamese instruction continued at DLI until 2004. Consolidation In the 1970s the institute's headquarters and all resident language training were consolidated at the West Coast Branch and renamed the Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center (DLIFLC). In 1973, the newly formed U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) assumed administrative control, and in 1976, all English language training operations were returned to the U.S. Air Force, which operates DLIELC to this day.  Former Public Health Service Hospital on The Presidio of San Francisco and former DLI branch location. The building center were classrooms and offices, while both wings were student quarters. The DLIFLC won academic accreditation in 1979 from the Western Association of Schools and Colleges,[10] and in 1981 the position of academic dean (later called provost) was reestablished. In the early 1980s, crowding and living conditions at the Monterey location forced the institute to open two temporary branches: a branch for air force enlisted students of Russian at Lackland Air Force Base, Texas (1981–1987), and another for army enlisted students of German, Korean and Spanish at the Presidio of San Francisco (1982–1988) in the former Public Health Service Hospital. There were only enlisted male and female students at the Presidio of San Francisco, primarily from the Military Occupational Specialties of Military Intelligence and Military Police with a small number of Army Special Forces. As a result of these conditions, the institute began an extensive facilities expansion program on the Presidio. In 2002 the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges accredited the institute as an associate degree-granting institution.[11] Base Realignment and annexation Further information: Base Realignment and Closure In the spring of 1993, the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) Commission rejected suggestions that the institute be moved or closed, and recommended that its mission be continued at the present location. In summer of 2005, the commission reopened the issue, to include the closure of the Naval Postgraduate School. Supporters of the closure believed that due to the rising property values and cost of living in the Monterey Bay area, taxpayers would save money by moving both schools to a less expensive location in Ohio. Opponents argued that it would be difficult (if not impossible) to replace the experienced native-speaking faculty at DLI, as the cultural centers of San Francisco and California's Central Coast offer a more diverse pool from which to recruit local instructors, and that the military intelligence community would suffer as a result. The BRAC commission met in Monterey on 8 August 2005, to hear arguments from both sides. On 25 August 2005, the commission's final vote was unanimous to keep DLI at its current location in Monterey. |

歴史 国防外国語センター(DLIFLC)のルーツは、米国が第二次世界大戦に参戦する前夜、米陸軍が日本語を教えるためにサンフランシスコのプレシディオに 2000ドルの予算で秘密学校を設立したことにさかのぼる。授業は1941年11月1日、640号棟として知られるクリッシー・フィールドの廃墟となった 飛行機の格納庫で、4人の講師と60人の生徒によって始まった[5]。この場所は現在、全米日系人歴史協会によって軍事情報部(MIS)歴史学習センター として保存されている。 ジョセフ・スティルウェル元帥とジョージ・マーシャル元帥は、中国駐在将校として中国語を学び、下士官部隊に言語訓練を提供する必要性を理解し、1924 年にアジアで米軍兵士と将校に中国語の初歩を教える言語プログラムを設立した。戦争に向けた日米関係の緊張を認識し、日本での任務経験がある将校の小グ ループは、日本語を理解できる情報部隊の必要性を感じていた。この将校グループは、ジョン・ウェッカーリング中佐とカイ・E・ラスムッセン少佐が率いてい た。日系アメリカ人のジョン・F・アイソ少佐とアーサー・カネコ下士官は、2人の民間人教官、押田アキラと木原茂也とともに、適格な言語学者であることが わかり、MISLSの最初の教官となった[6]。 生徒は主に西海岸出身の日系二世で、一世の両親から日本語を学んだが、アメリカで教育を受け、日本語がやや不自由な二世、日本で教育を受け、日本人と同じ ように日本語を話す日系人の「吉兵衛」、宣教師の息子として日本で生まれた二人の白人の生徒であった。日本語を母国語とする人々にとっても、コースのカリ キュラムには、米軍のスラングが平均的なアメリカの一般市民にとってそうであるように、日本人の話者にとって外国語である丙午(兵語)や軍特有の用語が登 場した[7][8]。 戦時中、MISLS(Military Intelligence Service Language School)は劇的に成長した。真珠湾攻撃の後、西海岸とハワイ準州の日系アメリカ人は1942年に収容所に移された。反日感情のため、陸軍は最も敵対 的でない環境を求めて全国的な調査を行い、キャンプ・サベージと名付けられた旧ミネソタ州WPAキャンプに学校を移した。1944年までに学校はその施設 を手狭になり、近くのフォート・スネリングに移った。フォート・スネリングには125の教室があり、160人以上の教官がいた。6,000人以上の卒業生 が、戦争と日本占領の間、太平洋戦争に従軍した。 二世ホールは、他のいくつかの建物とともに、研究所のヤンキーサムライの展示で表彰された第二次世界大戦中の学生を記念して名付けられた。ジョン・アイソ 図書館はMISLSの元教育訓練部長にちなんで、宗像ホールはMISLSの元教官宗像豊にちなんで、蜂谷ホール、水足ホール、中村ホールはレイテ島、 ニューギニア、ルソン島で戦死したフランク・蜂谷忠一、ユキタカ・「テリー」・ミズタリ、ジョージ・イチロー・ナカムラにちなんで命名された[9]。 1951年、カリフォルニア州モントレー、陸軍語学学校に関する米陸軍のフィルム 1946年、フォート・スネリングは活動を停止し、学校はモントレーのプレシディオに戻った。そこで陸軍語学学校と改名された。冷戦の影響で、1947年 から48年にかけて学校の成長は加速した。講師は世界中から集められ、30以上の言語のネイティブスピーカーが含まれていた。ロシア語が最大のプログラム となり、中国語、韓国語、ドイツ語がそれに続いた。 国防省語学研究所英語センター(DLIELC)の正式な始まりは1954年5月で、第3746飛行前訓練中隊(言語)が活性化し、すべての英語訓練の責任 を引き受けた。1960年には、米空軍の語学学校が活動を開始し、その任務を引き継いだ。1966年、国防総省は国防言語研究所英語学校(DLIELS) を設立し、学校はラックランド基地に残ったが、米陸軍の管理下に置かれた。1976年、国防総省は米空軍を同校の執行代理人に任命し、国防言語研究所英語 センターと改称した。 冷戦下の言語教育 米空軍は1950年代、エール大学、コーネル大学、シラキュース大学などでの契約プログラムを通じて、また米海軍はワシントンD.C.の海軍情報学校で外 国語を教えていたが、1963年にこれらのプログラムは国防外国語プログラムに統合された。ワシントンD.C.に新しい本部、国防外国語研究所(DLI) が設立され、元陸軍語学学校校長のジェームズ・L・コリンズ・ジュニア大佐が同研究所の初代所長に就任した。陸軍語学学校はDLI西海岸支部となり、海軍 情報学校の外国語学部はDLI東海岸支部となった。契約プログラムは徐々に廃止されていった。DLIはテキサス州ラックランド空軍基地の英語学校も引き継 ぎ、DLI英語センター(DLIELC)となった。 アメリカのベトナム参戦の最盛期(1965-73年)には、DLIは語学訓練のペースを上げた。通常の語学訓練は衰えることなく続けられたが、2万人以上 の軍人がDLIのプログラムを通じてベトナム語を学び、その多くが8週間の特別軍事顧問「サバイバル」コースを受講した。1966年から1973年まで、 研究所はテキサス州フォートブリス近くのビッグス空軍基地(DLIサポートコマンド、後にDLI南西支部と改称)で契約講師を使ったベトナム語支部も運営 していた。ベトナム語教育は2004年までDLIで続けられた。 統合 1970年代、DLIの本部とすべての常駐言語訓練は西海岸支部に統合され、国防言語研究所外国語センター(DLIFLC)と改称された。1973年、新 設された米陸軍訓練教練司令部(TRADOC)が管理権を引き継ぎ、1976年にはすべての英語訓練業務が米空軍に返還され、現在に至るまでDLIELC が運営されている。  サンフランシスコのプレシディオにある旧公衆衛生局病院と旧DLI支部。建物中央は教室とオフィス、両翼は学生の宿舎だった。 DLIFLCは、1979年に西部学校大学協会(Western Association of Schools and Colleges)から学術認定を受け[10]、1981年には学術部長(後に学長と呼ばれる)の地位が再確立された。1980年代初頭、モントレーの校 舎は混雑し、生活環境も悪化したため、研究所は2つの臨時校舎を開設せざるを得なくなった。テキサス州ラックランド空軍基地にある空軍のロシア語入隊学生 のための校舎(1981年~1987年)と、サンフランシスコのプレシディオにある旧保健衛生局病院内にある陸軍のドイツ語、韓国語、スペイン語入隊学生 のための校舎(1982年~1988年)である。プレシディオ・オブ・サンフランシスコには、陸軍情報部と憲兵隊を中心とした陸軍特殊部隊の男女下士官学 生しかいなかった。このような状況の結果、研究所はプレシディオで大規模な施設拡張プログラムを開始した。2002年、コミュニティカレッジ・短期大学認 定委員会は、同学院を準学位授与機関として認定した[11]。 基地再編と併合 さらなる情報 基地再編と閉鎖 1993年春、基地再編・閉鎖(BRAC)委員会は、研究所の移転や閉鎖の提案を却下し、現在の場所でのミッションの継続を勧告した。2005年夏、委員 会は海軍大学院の閉鎖を含むこの問題を再開した。閉校賛成派は、モントレー湾地域の資産価値と生活費が上昇しているため、両校をより物価の安いオハイオ州 に移転した方が納税者の負担が少なくて済むと考えた。反対派は、DLIの経験豊富なネイティブスピーカーの教授陣の代わりを務めるのは(不可能ではないに せよ)困難であり、サンフランシスコやカリフォルニアのセントラルコーストの文化的中心地の方が、地元の教官を採用するための多様な人材が確保できるから であり、その結果、軍の情報コミュニティは苦境に立たされるだろうと主張した。BRAC委員会は2005年8月8日にモントレーで開かれ、双方の主張を聞 いた。2005年8月25日、委員会の最終投票は、DLIをモントレーの現在の場所に維持することに全会一致で決まった。 |

| Schools and locations English Language Center (DLIELC) The DLIELC is a Department of Defense agency operated by the U.S. Air Force's 37th Training Wing, and is responsible for training international military and civilian personnel to speak and teach English. The agency also manages the English as a Second Language Program for the US military, and manages overseas English training programs. International students must be sponsored by an agency of the Department of Defense, and commonly include personnel from NATO member countries. Over 100 countries are represented among the student body at DLIELC at any given time. The main campus is currently located on the grounds of Joint Base San Antonio - Lackland Air Force Base, in San Antonio, Texas. DLIELC acculturates and trains international personnel to communicate in English and to instruct English language programs in their country, trains United States military personnel in English as a second language, and deploys English Language Training programs around the world in support of the Defense Department. Foreign Language Center (DLIFLC) The DLIFLC at the Presidio of Monterey, California (DLIFLC & POM) is the DoD's primary foreign language school. Military service members study foreign languages at highly accelerated paces in courses ranging from 24 to 64 weeks in length.[12] In October 2001, the Institute received Federal degree-granting authority to issue Associate of Arts in Foreign Language degrees to qualified graduates of all basic programs. As of 2022, DLIFLC also offers bachelor's degrees to graduates of DLI accredited Intermediate and Advanced courses.[13] Although the property is under the jurisdiction of the United States Army, there are U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine Corps, and U.S. Air Force presences on post, and all four branches provide students and instructors. Members of other Federal agencies and military services of other countries may also receive training, and members of other law enforcement agencies may receive Spanish language training. As of 2015, a number of languages are taught at the DLIFLC including Afrikaans in Washington, DC and the following in Monterey: Modern Standard Arabic, Arabic – Egyptian, Arabic – Levantine, Arabic – Iraqi, Chinese (Mandarin), French, German, Hebrew, Hindi, Indonesian, Japanese, Korean, Pashto, Persian, Portuguese, Punjabi, Russian, Serbian / Croatian, Spanish, Filipino (Tagalog), Turkish, and Urdu. DLI-Washington The DLIFLC also maintains the DLI-Washington office in the Washington, D.C. area. The Washington office provides training in languages not taught at the Presidio of Monterey, such as "low-density languages" which do not require the same large volume of trained personnel. There is some overlap, however, as students from the Defense Attaché System (DAS) are given local training in languages also available at the Monterey location. Language training through DLI-Washington is conducted at the National Foreign Affairs Training Center (NFATC) of the United States Department of State, and at various contracted foreign language schools in the metropolitan Washington, DC area. |

学校と所在地 英語センター (DLIELC) DLIELCは米空軍第37訓練飛行隊が運営する国防総省の機関であり、国際的な軍人・軍属に英語を話したり教えたりする訓練を担当する。同機関はまた、 米軍向けの第二外国語としての英語プログラムを管理し、海外の英語研修プログラムも管理している。留学生は国防総省の機関がスポンサーになる必要があり、 一般的にはNATO加盟国の職員が含まれる。DLIELCには常時100カ国以上の学生が在籍している。メインキャンパスは現在、テキサス州サンアントニ オのラックランド空軍基地の敷地内にある。DLIELCは、国際的な要員を英語でコミュニケーションできるようにし、その国で英語プログラムを指導できる ようにする。 外国語センター (DLIFLC) カリフォルニア州モントレーのプレシディオにあるDLIFLC(DLIFLC & POM)は、国防総省の主要な外国語学校である。2001年10月、DLIFLCは連邦政府から学位授与の認可を受け、すべての基本プログラムを修了した 有資格者に対し、外国語の準学士号を授与している[12]。2022年現在、DLIFLCは、DLI認定の中級および上級コースの卒業生にも学士号を授与 している[13]。 DLIFLCはアメリカ陸軍の管轄下にあるが、アメリカ海軍、アメリカ海兵隊、アメリカ空軍も駐屯しており、4つの軍部すべてが生徒と講師を派遣してい る。他の連邦機関や他国の軍隊の隊員も訓練を受けることがあり、他の法執行機関の隊員もスペイン語の訓練を受けることがある。 2015年現在、ワシントンDCではアフリカーンス語、モントレーでは以下の言語がDLIFLCで教えられている: 現代標準アラビア語、アラビア語-エジプト語、アラビア語-レバノン語、アラビア語-イラク語、中国語(北京語)、フランス語、ドイツ語、ヘブライ語、ヒ ンディー語、インドネシア語、日本語、韓国語、パシュトゥー語、ペルシア語、ポルトガル語、パンジャブ語、ロシア語、セルビア語/クロアチア語、スペイン 語、フィリピン語(タガログ語)、トルコ語、ウルドゥー語である。 DLI-ワシントン DLIFLCはワシントンD.C.地域にDLIワシントン事務所も運営している。ワシントン事務所では、モントレーのプレシディオで教えられていない言 語、例えば「低密度言語」のような、大量の訓練要員を必要としない言語の訓練を提供している。しかし、国防部員制度(DAS)の学生は、モントレーの場所 でも利用可能な言語の現地研修を受けるため、重複する部分もある。 DLIワシントンを通じた語学研修は、米国国務省の国立外務研修センター(NFATC)、およびワシントンDCの首都圏にあるさまざまな契約外国語学校で 行われる。 |

| Defense Language Aptitude Battery Defense Language Office Defense Language Proficiency Tests Monterey Institute of International Studies Joint Services School for Linguists Language education List of Language Self-Study Programs |

防衛省語学能力試験 防衛省語学局 国防言語能力試験 モントレー国際問題研究所 統合サービス言語学校 語学教育 語学自習プログラム一覧 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Defense_Language_Institute |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆