プロレタリアート

Proletariat

Adolph Menzel - Iron rolling mill (1872-1875)

☆ プロレタリアート(ラテン語のproletarius「子孫を残す」に由来)とは、賃金労働者の社会階級であり、重要な 経済的価値を持つ唯一の財産が労働力(労働能力)である社会の構成員である。このような階級の構成員はプロレタリアまたはプロレタイアである。マル クス主義哲学は、資本主義の条件下におけるプロレタリアートを被搾取階級[2]とみなしており、事業主階級であるブルジョアジーに属する生産手段を操作す る見返りとして、わずかな賃金を受け入れることを余儀なくされている。カール・マルクスは、この資本主義的抑圧がプロレタリアートに国境を越えた共通の経 済的・政治的利益を与え、彼らを団結させ、資本家階級から権力を奪取し、最終的には階級的区別のない社会主義社会を創造するよう駆り立てると主張した。

| The proletariat

(/ˌproʊlɪˈtɛəriət/; from Latin proletarius 'producing offspring') is

the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only

possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their

capacity to work).[1] A member of such a class is a proletarian or a

proletaire. Marxist philosophy regards the proletariat under conditions

of capitalism as an exploited class[2]— forced to accept meager wages

in return for operating the means of production, which belong to the

class of business owners, the bourgeoisie. Karl Marx argued that this capitalist oppression gives the proletariat common economic and political interests that transcend national boundaries,[3] impelling them to unite and to take over power from the capitalist class, and eventually to create a socialist society free from class distinctions.[4] |

プロレタリアート(/ˌproʊɪˈɛəriət/;ラテン語の

proletarius「子孫を残す」に由来)とは、賃金労働者の社会階級であり、重要な経済的価値を持つ唯一の財産が労働力(労働能力)である社会の構

成員である[1]。このような階級の構成員はプロレタリアまたはプロレタイアである。マルクス主義哲学は、資本主義の条件下におけるプロレタリアートを被

搾取階級[2]とみなしており、事業主階級であるブルジョアジーに属する生産手段を操作する見返りとして、わずかな賃金を受け入れることを余儀なくされて

いる。 カール・マルクスは、この資本主義的抑圧がプロレタリアートに国境を越えた共通の経済的・政治的利益を与え[3]、彼らを団結させ、資本家階級から権力を 奪取し、最終的には階級的区別のない社会主義社会を創造するよう駆り立てると主張した[4]。 |

| Roman Republic and Empire Further information: Constitution of the Roman Republic The proletarii constituted a social class of Roman citizens who owned little or no property. The name presumably originated with the census, which Roman authorities conducted every five years to produce a register of citizens and their property, which determined their military duties and voting privileges. Those who owned 11,000 assēs (coins) or fewer fell below the lowest category for military service, and their children—prōlēs (offspring)—were listed instead of property; hence the name proletarius (producer of offspring). Roman citizen-soldiers paid for their own horses and arms, and fought without payment for the commonwealth, but the only military contribution of a proletarius was his children, the future Roman citizens who could colonize conquered territories. Officially, propertyless citizens were called capite censi because they were "persons registered not as to their property...but simply as to their existence as living individuals, primarily as heads (caput) of a family."[5][note 1]  Secessio plebis, a form of protest in ancient Rome where the plebeians would leave the city, causing the economy to collapse Although explicitly included by name in the Comitia Centuriata (Centuriate Assembly), proletarii were the lowest class, largely deprived of voting rights.[6] Not only did proletarii have less voting "weight" in the various elections, but since voting ran hierarchically starting with the highest social ranks, a majority could be reached early and their votes never even taken. Late Roman historians such as Livy vaguely described the Comitia Centuriata as a popular assembly of early Rome composed of centuriae, voting units representing classes of citizens according to wealth. This assembly, which usually met on the Campus Martius to discuss public policy, designated the military duties of Roman citizens.[7] One of the reconstructions of the Comitia Centuriata features 18 centuriae of cavalry, and 170 centuriae of infantry divided into five classes by wealth, plus 5 centuriae of support personnel called adsidui, one of which represented the proletarii. In battle, the cavalry brought their horses and arms, the top infantry class full arms and armour, the next two classes less, the fourth class only spears, the fifth slings, while the assisting adsidui held no weapons. If unanimous, the cavalry and top infantry class were enough to decide an issue.[8] A deeper reconstruction incorporating social backgrounds found that the senators, the knights, and the first class held 88 out of 193 centuriae, the two lowest propertied classes held only 30 centuriae, but the proletarii held only 1. Musicians, by way of comparison, had more voting power despite far fewer citizens, with 2 centuriae. "[F]or the voting to reach the proletarii a very profound split in the elite and the higher classes was required."[9] |

ローマ共和国と帝国 さらに詳しい情報 ローマ共和国憲法 プロレタリアは、ほとんど財産を持たないローマ市民の社会階層を構成していた。この名称は、ローマ当局が5年ごとに実施する国勢調査に由来すると考えられ ている。国勢調査は、市民とその財産の登録簿を作成するために行われ、これにより市民の兵役義務や投票権が決定された。所有財産が11,000アッセ(コ イン)以下の者は兵役の最低カテゴリーに属し、財産の代わりにその子供であるプロレ(子孫)が記載されたため、プロレタリアリウス(子孫生産者)と呼ばれ るようになった。ローマ市民の兵士は自分の馬と武器に金を払い、連邦のために無報酬で戦った。しかし、プロレタリアスの唯一の軍事的貢献は、征服した領土 を植民地化できる将来のローマ市民である自分の子供だった。公式には、財産を持たない市民は、「財産について登録された者...ではなく、単に生きている 個人としての存在、主に家族の長(caput)として登録された者」であったため、capite censiと呼ばれた[5][注釈 1]。  セセシオ・プレビス(Secessio plebis):古代ローマにおける抗議の一形態。 プロレタリアはセントゥリアート議会(Comitia Centuriata)に明確に名を連ねていたが、最下層階級であり、ほとんど選挙権を剥奪されていた[6]。リヴィのような後期ローマの歴史家たちは、 初期ローマの民衆議会であるセンチュリアータ(富に応じた市民階級を代表する投票単位)を漠然と描写している。この議会は通常、公共政策を議論するために キャンパス・マルティウスに集まり、ローマ市民の軍事的任務を指定した[7]。 コミティア・チェントゥリアータの復元図のひとつには、18人の騎兵と170人の歩兵が富によって5つの階級に分けられ、さらにアドシデュイと呼ばれる5 人の支援要員が加えられており、そのうちの1人はプロレタリを代表していた。戦闘の際、騎兵は馬と武器、歩兵のトップクラスは完全な武器と鎧、次の2つの クラスはそれ以下、4番目のクラスは槍のみ、5番目のクラスは投石器、補佐のアドシデュイは武器を持たなかった。全会一致であれば、騎兵と歩兵の最上位階 級が問題を決定するのに十分であった[8]。社会的背景を組み込んだより詳細な再構成によれば、元老院議員、騎士、一流階級は193センチュリーのうち 88センチュリーを保有し、最下層の2つの資産階級は30センチュリーしか保有せず、プロレタリアは1センチュリーしか保有していなかった。それに比べて 音楽家は、2センチュリエと、市民数がはるかに少ないにもかかわらず、より多くの投票権を持っていた。「プロレタリアに投票権が及ぶためには、エリート階 級と上流階級とが非常に深く分裂する必要があった」[9]。 |

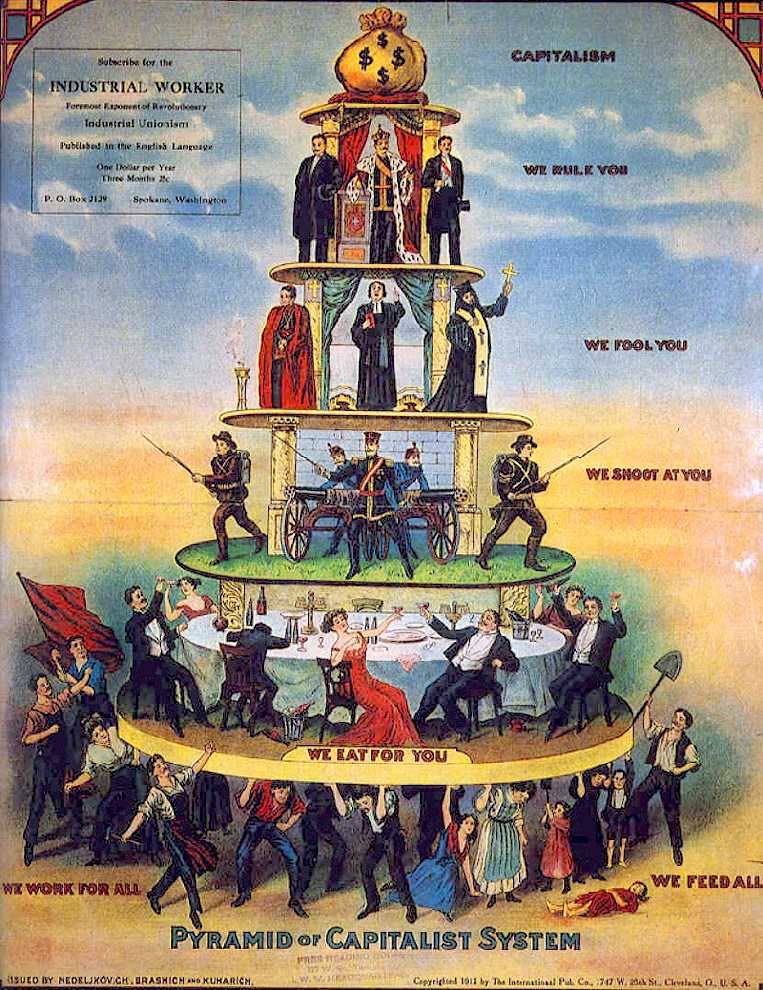

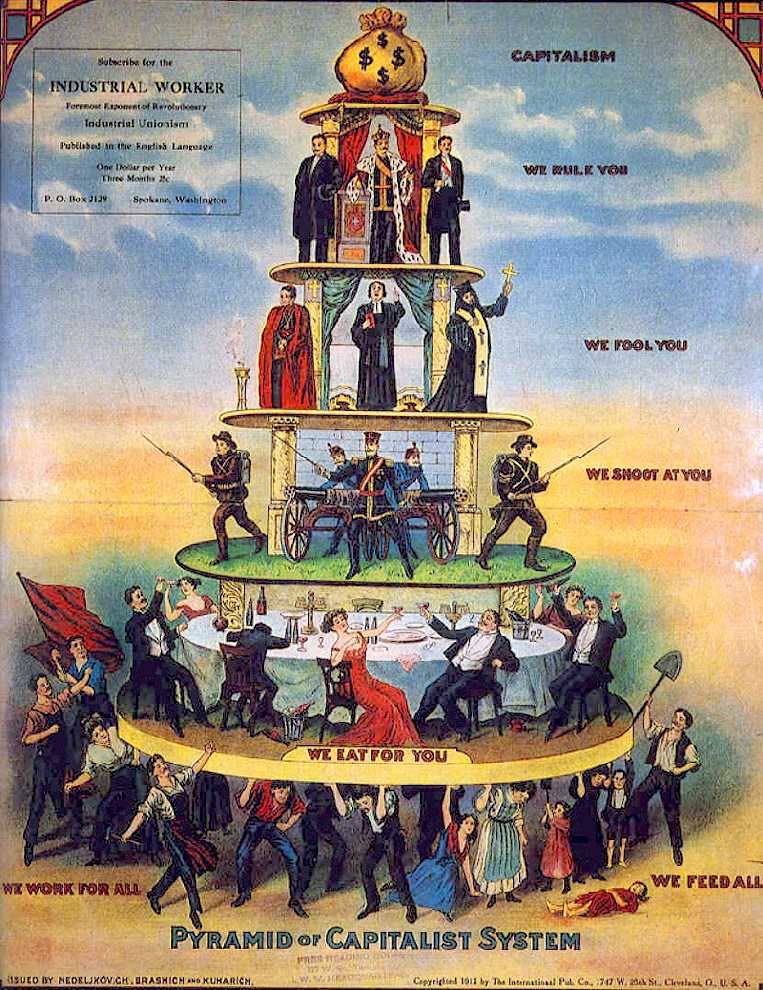

| Modern use Classic liberal view  Jean-François Millet - The man with the hoe In the early 19th century, many Western European liberal scholars—who dealt with social sciences and economics—pointed out the socio-economic similarities of the modern rapidly growing industrial worker class and the classic proletarians. One of the earliest analogies can be found in the 1807 paper of French philosopher and political scientist Hugues Felicité Robert de Lamennais. Later it was translated to English with the title "Modern Slavery".[10] Swiss liberal economist and historian Jean Charles Léonard de Sismondi was the first to apply the proletariat term to the working class created under capitalism, and whose writings were frequently cited by Karl Marx. Marx most likely encountered the term while studying the works of Sismondi.[11][12][13][14] Marxist theory Marx, who studied Roman law at the Friedrich Wilhelm University of Berlin,[15] used the term proletariat in his socio-political theory (Marxism) to describe a progressive working class untainted by private property and capable of revolutionary action to topple capitalism and abolish social classes, leading society to ever higher levels of prosperity and justice.  Adolph Menzel - Iron rolling mill (1872-1875) Marx defined the proletariat as the social class having no significant ownership of the means of production (factories, machines, land, mines, buildings, vehicles) and whose only means of subsistence is to sell their labour power for a wage or salary.[16] Marxist theory only vaguely defines the borders between the proletariat and adjacent social classes. In the socially superior, less progressive direction are the lower petty bourgeoisie, such as small shopkeepers, who rely primarily on self-employment at an income comparable to an ordinary wage. Intermediate positions are possible, where wage-labor for an employer combines with self-employment. In another direction, the lumpenproletariat or "rag-proletariat", which Marx considers a retrograde class, live in the informal economy outside of legal employment: the poorest outcasts of society such as beggars, tricksters, entertainers, buskers, criminals and prostitutes.[17][18] Socialist parties have often argued over whether they should organize and represent all the lower classes, or only the wage-earning proletariat.  A 1911 Industrial Worker publication advocating industrial unionism based on a critique of capitalism. The proletariat "work for all" and "feed all". According to Marxism, capitalism is based on the exploitation of the proletariat by the bourgeoisie: the workers, who own no means of production, must use the property of others to produce goods and services and to earn their living. Workers cannot rent the means of production (e.g. a factory or department store) to produce on their own account; rather, capitalists hire workers, and the goods or services produced become the property of the capitalist, who sells them at the market. Part of the net selling price pays the workers' wages (variable costs); a second part renews the means of production (constant costs, capital investment); while the third part is consumed by the capitalist class, split between the capitalist's personal profit and fees to other owners (rents, taxes, interest on loans, etc.). The struggle over the first part (wage rates) puts the proletariat and bourgeoisie into irreconcilable conflict, as market competition pushes wages inexorably to the minimum necessary for the workers to survive and continue working. The second part, called capitalized surplus value, is used to renew or increase the means of production (capital), either in quantity or quality.[19] The second and third parts are known as surplus value, the difference between the wealth the proletariat produce and the wealth they consume.[20] Marxists argue that new wealth is created through labour applied to natural resources.[21] The commodities that proletarians produce and capitalists sell are valued not for their usefulness, but for the amount of labour embodied in them: for example, air is essential but requires no labour to produce, and is therefore free; while a diamond is much less useful, but requires hundreds of hours of mining and cutting, and is therefore expensive. The same goes for the workers' labour power: it is valued not for the amount of wealth it produces, but for the amount of labour necessary to keep the workers fed, housed, sufficiently trained, and able to raise children as new workers. On the other hand, capitalists earn their wealth not as a function of their personal labour, which may even be null, but by the juridical relation of their property to the means of production (e.g. owning a factory or farmland).  Soviet propaganda in Moscow, 1984. The caption reads ‘Faithful to the cause of the fathers!’ Marx argues that history is made by man and not destiny. The instruments of production and the working class that use the tools in order to produce are referred to as the moving forces of society. Over time, this developed into the levels of social class where the owners of resources joined to squeeze productivity out of the individuals who depended on their labor power. Marx argues that these relations between the exploiters and exploited results in different modes of production and the successive stages in history. These modes of production in which mankind gains power over nature is distinguished into 5 different systems: the Primitive Community, Slave State, Feudal State, Capitalist System, and finally the Socialist Society. The transition between these systems were all due to an increase in civil unrest among those who felt oppressed by a higher social class.[22] The contention with feudalism began once the merchants and guild artisans grew in numbers and power. Once they organized themselves, they began opposing the fees imposed on them by the nobles and clergy. This development led to new ideas and eventually established the Bourgeoisie class which Marx opposes. Commerce began to change the form of production and markets began to shift in order to support larger production and profits. This change led to a series of revolutions by the bourgeois which resulted in capitalism. Marx argues that this same model can and should be applied to the fight for the proletariat. Forming unions similar to how the merchants and artisans did will establish enough power to enact change. Ultimately, Marx's theory of the proletarian's struggle would eventually lead to the fall of capitalism and the emergence of a new mode of production, socialism.[22] Marx argued that the proletariat would inevitably displace the capitalist system with the dictatorship of the proletariat, abolishing the social relationships underpinning the class system and then developing into a communist society in which "the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all".[23] During the Chinese Communist Revolution, the concept of the proletariat emphasized having a proletarian class consciousness, rather than having proletarian social attributes (such as being an industrial worker).[24]: 363 In this way of defining the proletariat, a proletarian class consciousness could be developed through a subjective standpoint with political education supplied by the Chinese Communist Party.[24]: 363 This conception of the proletariat allowed for a Marxist theoretical framing under which the revolution could address the relative weakness of industrial working classes in China.[24]: 363 Exactly what constituted a proper proletarian class consciousness was subject to intellectual and political debate.[24]: 97 Proletarian culture Marx argued that each social class had its characteristic culture and politics. The socialist states stemming from the Russian Revolution championed and created the official version of proletarian culture. Some[who?] have argued that this assessment has become outdated with the advent of mass education, mass communication and globalization. According to this argument, the working-class culture of capitalist countries tend to experience "prole drift" (proletarian drift), in which everything inexorably becomes commonplace and commodified. Examples include best-seller lists, films, music made to appeal to the masses, and shopping malls.[25] |

現代の使用 古典的な自由主義者の見解  ジャン=フランソワ・ミレー - 鍬を持つ男 19世紀初頭、社会科学や経済学を専門とする西欧の自由主義学者の多くが、現代の急成長する産業労働者階級と古典的なプロレタリアの社会経済的類似性を指 摘した。最も古い類似点のひとつは、フランスの哲学者・政治学者ユーグ・フェリシテ・ロベール・ド・ラメンネの1807年の論文に見られる。後にこの論文 は「現代の奴隷制度」というタイトルで英語に翻訳された[10]。 スイスの自由主義経済学者であり歴史家であったジャン・シャルル・レオナール・ド・シスモンディは、プロレタリアートという用語を資本主義の下で生まれた 労働者階級に初めて適用した人物であり、彼の著作はカール・マルクスによって頻繁に引用された。マルクスはシスモンディの著作を研究しているときにこの用 語に出会った可能性が高い[11][12][13][14]。 マルクス主義理論 ベルリンのフリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム大学でローマ法を学んだマルクスは[15]、その社会政治理論(マルクス主義)の中でプロレタリアートという用語を 使い、私有財産に汚染されておらず、資本主義を打倒し社会階級を廃止する革命的行動を起こすことができる進歩的な労働者階級を表現し、社会をより高いレベ ルの繁栄と正義へと導いた。  アドルフ・メンツェル - 製鉄所(1872年-1875年) マルクスは、プロレタリアートを、生産手段(工場、機械、土地、鉱山、建物、乗り物)の重要な所有権を持たず、賃金や給与のために労働力を売ることでしか 生計を立てられない社会階級と定義した[16]。 マルクス主義の理論は、プロレタリアートと隣接する社会階級の境界を曖昧にしか定義していない。社会的に優越的で、あまり進歩的でない方向には、小店主の ような下層の小ブルジョワジーがおり、彼らは主に、通常の賃金に匹敵する収入での自営業に依存している。雇用主のもとでの賃金労働と自営業が組み合わさっ た中間的な地位も可能である。別の方向では、ルンペンプロレタリアートまたは「ぼろ雑巾プロレタリアート」は、マルクスが逆行階級とみなしているもので、 合法的な雇用の外のインフォーマル経済で生活している。  資本主義批判に基づく産業別組合主義を提唱した1911年の『産業労働者』の出版物。プロレタリアートは「すべての人のために働き」「すべての人を養 う」。 マルクス主義によれば、資本主義はブルジョアジーによるプロレタリアートの搾取に基づいている。生産手段を所有していない労働者は、商品やサービスを生産 し、生計を立てるために他人の財産を利用しなければならない。労働者は、生産手段(工場やデパートなど)を借りて自分の勘定で生産することはできない。む しろ、資本家が労働者を雇い、生産された商品やサービスは資本家の所有物となり、資本家はそれを市場で販売する。 正味販売価格の一部は労働者の賃金(変動費)に支払われ、第2の部分は生産手段の更新(恒常費用、資本投資)に充てられ、第3の部分は資本家階級によって 消費され、資本家の個人的利益と他の所有者への手数料(賃料、税金、貸付利子など)に分けられる。第一の部分(賃金率)をめぐる闘争は、プロレタリアート とブルジョアジーを和解しがたい対立に追い込む。市場競争によって、賃金は労働者が生き残り、働き続けるために必要な最低限にまで否応なく押し上げられる からである。第二の部分は、資本化された剰余価値と呼ばれ、生産手段(資本)を量的にも質的にも更新または増加させるために使用される[19]。第二と第 三の部分は剰余価値として知られ、プロレタリアートが生産する富と彼らが消費する富との差である[20]。 マルクス主義者たちは、新たな富は天然資源に適用される労働によって生み出されると主張する[21]。プロレタリアが生産し、資本家が販売する商品は、そ の有用性ではなく、それらに具現化された労働の量によって評価される。例えば、空気は不可欠であるが、生産に労働を必要としないので無料である。労働者の 労働力も同様である。労働力は、それが生み出す富の量ではなく、労働者が食事をし、住居を確保し、十分な訓練を受け、新しい労働者として子供を育てられる ようにするために必要な労働量に対して評価される。他方、資本家は、個人的労働の関数としてではなく、生産手段に対する所有権の法人的関係(工場や農地の 所有など)によって富を得る。  1984年、モスクワにおけるソ連のプロパガンダ。キャプションには「父祖の大義に忠実であれ!」とある。 マルクスは、歴史は人間によって作られるものであり、運命ではないと主張する。生産の道具と、生産するために道具を使う労働者階級は、社会の動く力と呼ば れる。やがてこれは、資源の所有者がその労働力に依存する個人から生産性を搾り取るために結合する社会階級のレベルへと発展した。マルクスは、このような 搾取する側と搾取される側の関係が、さまざまな生産様式と歴史の連続的な段階を生み出すと主張する。原始共同体、奴隷国家、封建国家、資本主義システム、 そして社会主義社会である。これらのシステム間の移行はすべて、より高い社会階級によって抑圧されていると感じた人々の間で市民不安が高まったことに起因 していた[22]。 封建制との争いは、商人やギルド職人の数と力が大きくなってから始まった。彼らが組織化されると、貴族や聖職者によって課される手数料に反対するように なった。この発展が新たな思想を生み、やがてマルクスが反対するブルジョワ階級を確立した。商業は生産の形態を変え始め、市場はより大規模な生産と利益を 支えるために変化し始めた。この変化は、ブルジョアによる一連の革命を引き起こし、資本主義をもたらした。マルクスは、これと同じモデルをプロレタリアー トの闘いに適用することができ、また適用すべきだと主張している。商人や職人が行ったのと同じような組合を結成することで、変革を実現するのに十分な力を 確立することができる。最終的に、プロレタリアの闘いに関するマルクスの理論は、最終的に資本主義を崩壊させ、新しい生産様式である社会主義を出現させる ことになる[22]。 マルクスは、プロレタリアートが必然的にプロレタリアート独裁によって資本主義体制を置き換え、階級制度を支える社会関係を廃止し、「各人の自由な発展が すべての人の自由な発展の条件」である共産主義社会へと発展すると主張した[23]。 中国共産党革命の間、プロレタリアートの概念は、プロレタリア的な社会的属性(工業労働者であることなど)を持つことよりも、むしろプロレタリア的な階級 意識を持つことを強調していた[24]: 363 プロレタリアートを定義するこの方法では、プロレタリア階級意識は、中国共産党によって供給される政治教育によって、主体的な立場を通して発展させること ができた[24]: 363 プロレタリアートについてのこの概念は、革命が中国における産業労働者階級の相対的な弱さに対処することができるマルクス主義的な理論的枠組みを可能にし た[24]: 363 正確には、何が適切なプロレタリア階級意識を構成するかは、知的かつ政治的な議論の対象となった[24]: 97。 プロレタリア文化 マルクスは、それぞれの社会階級には特徴的な文化と政治があると主張した。ロシア革命に端を発する社会主義国家は、プロレタリア文化の公式版を支持し、作 り上げた。 この評価は、大衆教育、マス・コミュニケーション、グローバリゼーションの出現によって時代遅れになったと主張する[誰?]人もいる。この議論によれば、 資本主義国の労働者階級の文化は「プロレ・ドリフト(プロレタリアの漂流)」を経験する傾向があり、そこではあらゆるものが不可避的にありふれたものとな り、商品化される。例えば、ベストセラーリスト、映画、大衆にアピールするために作られた音楽、ショッピングモールなどである[25]。 |

| Working class – Social class composed of those employed in lower-tier jobs Blue-collar worker – Working-class person who performs manual labour Consumtariat – Global upper-class that bases its power on a technological advantage Laborer – Low-skilled or unskilled worker Peasant – Agricultural laborer or farmer with limited land ownership Precariat – Class of wage-earners in a tenuous job situation close to unemployment Proles (Nineteen Eighty-Four) – 1949 novel by George Orwell Prolefeed – Fictional language in the novel "Nineteen Eighty-Four" Proletarianization Proletarian internationalism – Marxist social class concept Proletarian literature – Literature mainly written for or by the working class Wage slavery – Dependence on wages or salary |

Working class (労働者階級) - 下層の仕事に従事する人々で構成される社会階級。 ブルーカラー労働者 - 肉体労働を行う労働者階級 コンシューマート(消費者階級) - 技術的優位性を基盤とするグローバルな上流階級。 労働者-低技能または非技能労働者 農民 - 土地の所有権が限られている農業労働者または農民。 プレカリアート - 失業に近い不安定な雇用状況にある賃金労働者階級 Proles (Nineteen Eighty-Four) - ジョージ・オーウェルの1949年の小説。 プロレフィード - 小説「ナインティーン188-フォー」に登場する架空の言葉。 プロレタリア化 プロレタリア国際主義 - マルクス主義の社会階級概念 プロレタリア文学 - 主に労働者階級のために、あるいは労働者階級によって書かれた文学。 賃金奴隷 - 賃金や給与に依存すること。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proletariat |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆