心理学的評価あるいは精神鑑定

Psychological evaluation, or Psychiatric

assessment

☆ 心理学的評価は、個人の行動、性格、認知能力、その他いくつかの領域を評価する方法である[a][3]。心理学的評価を行う一般的な理由は、人が機能的ま たは建設的に思考、行動、または感情を調整する能力を阻害している可能性のある心理的要因を特定することである。これは、身体検査に相当する精神的なもの である。その他の心理評価では、職場のパフォーマンスや顧客関係管理などを予測するために、個人の固有の特性やパーソナリティをよりよく理解しようとする [4]。

★ 精神状態検査(MSE)は、神経学的および精神医学的診療における臨床評価プロセスの重要な部分である。MSEは、ある時点における患者の心理的機能を、 外見、態度、行動、気分と感情、発話、思考過程、思考内容、知覚、認知、洞察、判断の領域で観察し、記述する構造化された方法である[1]。MSEの細分 化、MSE領域の順序と名称には、若干の違いがある。 MSEの目的は、患者の精神状態の包括的な横断的記述を得ることであり、精神病歴の伝記的・歴史的情報と組み合わせることで、臨床家は、首尾一貫した治療 計画に必要な正確な診断とフォーミュレーションを行うことができる。

☆精神鑑定(せ いしんかんてい;psychiatric evidence)は、日本の裁判所が訴訟当事者などの精神状態・責任能力を判断するため、精神科医などの鑑定人に対して命じる鑑定の一つ[1]。裁判所 は、鑑定人の鑑定意見に拘束されず、自由に判断をなし得るが、これを採用し得ない合理的な事情が認められるのでない限り、その意見を十分に尊重して認定に 用いなければならないとされている(最決昭和58年9月13日、最判平成20年4月25日)。

| Psychological

evaluation is a method to assess an individual's behavior, personality,

cognitive abilities, and several other domains.[a][3] A common reason

for a psychological evaluation is to identify psychological factors

that may be inhibiting a person's ability to think, behave, or regulate

emotion functionally or constructively. It is the mental equivalent of

physical examination. Other psychological evaluations seek to better

understand the individual's unique characteristics or personality to

predict things like workplace performance or customer relationship

management.[4] |

心理学的評価は、個人の行動、性格、認知能力、その他いくつかの領域を

評価する方法である[a][3]。心理学的評価を行う一般的な理由は、人が機能的または建設的に思考、行動、または感情を調整する能力を阻害している可能

性のある心理的要因を特定することである。これは、身体検査に相当する精神的なものである。その他の心理評価では、職場のパフォーマンスや顧客関係管理な

どを予測するために、個人の固有の特性やパーソナリティをよりよく理解しようとする[4]。 |

| History Modern psychological evaluation has been around for roughly 200 years, with roots that stem as far back as 2200 B.C.[5] It started in China, and many psychologists throughout Europe worked to develop methods of testing into the 1900s. The first tests focused on aptitude. Eventually scientists tried to gauge mental processes in patients with brain damage, then children with special needs. Ancient psychological evaluation Earliest accounts of evaluation are seen as far back as 2200 B.C. when Chinese emperors were assessed to determine their fitness for office. These rudimentary tests were developed over time until 1370 A.D. when an understanding of classical Confucianism was introduced as a testing mechanism. As a preliminary evaluation for anyone seeking public office, candidates were required to spend one day and one night in a small space composing essays and writing poetry over assigned topics. Only the top 1% to 7% were selected for higher evaluations, which required three separate session of three days and three nights performing the same tasks. This process continued for one more round until a final group emerged, comprising less than 1% of the original group, became eligible for public office. The Chinese failure to validate their selection procedures, along with widespread discontent over such grueling processes, resulted in the eventual abolishment of the practice by royal decree.[5] Development of psychological evaluation in 1800-1900-s In the 1800s, Hubert von Grashey developed a battery to determine the abilities of brain-damaged patients. This test was also not favorable, as it took over 100 hours to administer. However, this influenced Wilhelm Wundt, who had the first psychological laboratory in Germany. His tests were shorter, but used similar techniques. Wundt also measured mental processes and acknowledged the fact that there are individual differences between people. Francis Galton established the first tests in London for measuring IQ. He tested thousands of people, examining their physical characteristics as a basis for his results and many of the records remain today.[5] James Cattell studied with him, and eventually worked on his own with brass instruments for evaluation. His studies led to his paper "Mental Tests and Measurements", one of the most famous writings on psychological evaluation. He also coined the term "mental test" in this paper. As the 1900s began, Alfred Binet was also studying evaluation. However, he was more interested in distinguishing children with special needs from their peers after he could not prove in his other research that magnets could cure hysteria. He did his research in France, with the help of Theodore Simon. They created a list of questions that were used to determine if children would receive regular instruction, or would participate in special education programs. Their battery was continually revised and developed, until 1911 when the Binet-Simon questionnaire was finalized for different age levels. After Binet's death, intelligence testing was further studied by Charles Spearman. He theorized that intelligence was made up of several different subcategories, which were all interrelated. He combined all the factors together to form a general intelligence, which he abbreviated as "g".[6] This led to William Stern's idea of an intelligence quotient. He believed that children of different ages should be compared to their peers to determine their mental age in relation to their chronological age. Lewis Terman combined the Binet-Simon questionnaire with the intelligence quotient and the result was the standard test we use today, with an average score of 100.[6] The large influx of non-English speaking immigrants into the US brought about a change in psychological testing that relied heavily on verbal skills for subjects that were not literate in English, or had speech/hearing difficulties. In 1913, R.H. Sylvester standardized the first non-verbal psychological test. In this particular test, participants fit different shaped blocks into their respective slots on a Seguin form board.[5] From this test, Knox developed a series of non-verbal psychological tests that he used while working at the Ellis Island immigrant station in 1914. In his tests, were a simple wooden puzzle as well as digit-symbol substitution test where each participant saw digits paired up with a particular symbol, they were then shown the digits and had to write in the symbol that was associated with it.[5] When the United States moved into World War I, Robert M. Yerkes convinced the government that they should be testing all of the recruits they were receiving into the Army. The results of the tests could be used to make sure that the "mentally incompetent" and "mentally exceptional" were assigned to appropriate jobs. Yerkes and his colleagues developed the Army Alpha and Army Beta tests to use on all new recruits.[5] These tests set a precedent for the development of psychological testing for the next several decades. After seeing the success of the Army standardized tests, college administration quickly picked up on the idea of group testing to decide entrance into their institutions. The College Entrance Examination Board was created to test applicants to colleges across the nation. In 1925, they developed tests that were no longer essay tests that were very open to interpretation, but now were objective tests that were also the first to be scored by machine. These early tests evolved into modern day College Board tests, like the Scholastic Assessment Test, Graduate Record Examination, and the Law School Admissions Test.[5] |

歴史 近代的な心理学的評価は、およそ200年前から存在しており、そのルーツは紀元前2200年まで遡る[5]。中国で始まり、ヨーロッパ中の多くの心理学者 が1900年代までテスト方法の開発に取り組んだ。最初のテストは適性に焦点を当てたものだった。やがて科学者たちは、脳に障害を持つ患者の精神的プロセ スを測定しようとし、その後、特別な支援を必要とする子どもたちの精神的プロセスを測定しようとした。 古代の心理評価 評価に関する最古の記録は、紀元前2200年に遡り、中国の皇帝が役職への適性を判断するために評価を受けたことに見られる。このような初歩的なテスト は、西暦1370年に古典的な儒教の理解がテストメカニズムとして導入されるまで、時間をかけて開発された。公職に就こうとする者の予備評価として、候補 者は狭い空間で一昼夜、与えられたテーマについて作文や詩作をすることが求められた。上位1%から7%の者だけがより高い評価に選ばれ、3日3晩、同じ作 業を3回行う必要があった。このプロセスは、最初のグループの1%未満からなる最終グループが公職に就く資格を得るまで、さらに1ラウンド続けられた。こ のような過酷なプロセスに対する広範な不満とともに、中国がその選考方法を検証できなかったため、最終的には勅令によって廃止された[5]。 1800-1900年代における心理学的評価の発展 1800年代には、フーベルト・フォン・グラッシーが脳障害患者の能力を判定するためのバッテリーを開発した。このテストも、実施に100時間以上かかる など、好ましいものではなかった。しかし、このことは、ドイツで最初の心理学研究所を持ったヴィルヘルム・ヴントに影響を与えた。彼のテストはより短時間 であったが、同じような手法が用いられた。ヴントはまた、精神過程を測定し、人には個人差があるという事実を認めた。 フランシス・ガルトンはロンドンでIQ測定のための最初のテストを確立した。彼は何千人もの人をテストし、その結果の根拠として身体的特徴を調べ、その記 録の多くは今日も残っている[5]。ジェームズ・キャッテルは彼のもとで学び、やがて評価用の金管楽器を用いて独自に研究を進めた。彼の研究は、心理学的 評価に関する最も有名な著作の1つである論文「精神的テストと測定」につながった。彼はこの論文で「メンタルテスト」という言葉も作った。 1900年代に入ると、アルフレッド・ビネーも評価の研究をしていた。しかし彼は、磁石がヒステリーを治すことができるということを他の研究で証明できな かった後、特別なニーズを持つ子どもたちを同世代の子どもたちと区別することに、より関心を寄せていた。彼はセオドア・シモンの協力を得て、フランスで研 究を行った。彼らは、子どもたちが通常の指導を受けるか、特別支援教育プログラムに参加するかを判断するための質問リストを作成した。1911年にビネー =シモン式質問票が年齢別に完成されるまで、彼らの質問表は絶えず改訂され、発展していった。 ビネの死後、知能検査はチャールズ・スピアマンによってさらに研究された。彼は、知能はいくつかの異なるサブカテゴリーで構成され、それらはすべて相互に 関連していると理論化した。彼はすべての要素を組み合わせて一般的な知能を形成し、それを「g」と略した。スターンは、異なる年齢の子どもたちを同年齢の 子ど もたちと比較し、彼らの精神年齢を年齢との関係で決定す べきだと考えた。ルイス・ターマンは、ビネー=サイモン式質問紙と知能指数を組み合わせ、その結果、平均点を100点とする、今日私たちが使用している標 準的なテストが生まれた[6]。 非英語圏の移民がアメリカに大量に流入したことで、英語の読み書きができなかったり、発話や聴覚に困難があったりする被験者に対して、言語能力に大きく依 存する心理テストに変化がもたらされた。1913年、R.H.シルヴェスターが最初の非言語心理テストを標準化した。この特殊なテストでは、参加者は異な る形のブロックをセグインフォームボードのそれぞれの溝にはめ込んだ[5]。このテストから、ノックスは一連の非言語心理テストを開発し、1914年にエ リス島の移民ステーションで働いていたときに使用した。彼のテストでは、単純な木製のパズルや、数字と特定の記号が対になっているのを見た参加者が、その 数字を見せてもらい、それに関連する記号を書き込むという、数字と記号の置き換えテストが行われた[5]。 米国が第一次世界大戦に突入したとき、ロバート・M・ヤーケスは、陸軍に入隊する新兵全員にテストを行うべきだと政府を説得した。テストの結果は、「精神 的に不適格な者」や「精神的に例外的な者」を適切な職務に就かせるために利用することができた。ヤーキーズと彼の同僚たちは、すべての新兵に使用する陸軍 アルファテストと陸軍ベータテストを開発した[5]。これらのテストは、その後数十年にわたる心理テストの発展の先例となった。 陸軍の標準テストの成功を見て、大学の管理部門は、その教育機関への入学を決定するための集団テストのアイデアをすぐに取り上げた。大学入試委員会は、国 民全体の大学入学志願者をテストするために設立された。1925年、彼らは解釈の自由度が高い小論文テストではなく、客観的なテストを開発した。これらの 初期のテストは、Scholastic Assessment Test、Graduate Record Examination、Law School Admissions Testのような、現代のCollege Boardのテストに発展した[5]。 |

| Formal and informal evaluation Formal psychological evaluation consists of standardized batteries of tests and highly structured clinician-run interviews, while informal evaluation takes on a completely different tone. In informal evaluation, assessments are based on unstructured, free-flowing interviews or observations that allow both the patient and the clinician to guide the content. Both of these methods have their pros and cons. A highly unstructured interview and informal observations provide key findings about the patient that are both efficient and effective. A potential issue with an unstructured, informal approach is the clinician may overlook certain areas of functioning or not notice them at all.[7] Or they might focus too much on presenting complaints. The highly structured interview, although very precise, can cause the clinician to make the mistake of focusing a specific answer to a specific question without considering the response in terms of a broader scope or life context.[7] They may fail to recognize how the patient's answers all fit together. There are many ways that the issues associated with the interview process can be mitigated. The benefits to more formal standardized evaluation types such as batteries and tests are many. First, they measure a large number of characteristics simultaneously. These include personality, cognitive, or neuropsychological characteristics. Second, these tests provide empirically quantified information. The obvious benefit to this is that we can more precisely measure patient characteristics as compared to any kind of structured or unstructured interview. Third, all of these tests have a standardized way of being scored and being administered.[7] Each patient is presented a standardized stimulus that serves as a benchmark that can be used to determine their characteristics. These types of tests eliminate any possibility of bias and produce results that could be harmful to the patient and cause legal and ethical issues. Fourth, tests are normed. This means that patients can be assessed not only based on their comparison to a "normal" individual, but how they compare to the rest of their peers who may have the same psychological issues that they face. Normed tests allow the clinician to make a more individualized assessment of the patient. Fifth, standardized tests that we commonly use today are both valid and reliable.[7] We know what specific scores mean, how reliable they are, and how the results will affect the patient. Most clinicians agree that a balanced battery of tests is the most effective way of helping patients. Clinicians should not become victims of blind adherence to any one particular method.[8] A balanced battery of tests allows there to be a mix of formal testing processes that allow the clinician to start making their assessment, while conducting more informal, unstructured interviews with the same patient may help the clinician to make more individualized evaluations and help piece together what could potentially be a very complex, unique-to-the-individual kind of issue or problem .[8] |

正式評価と非公式評価 フォーマルな心理学的評価は、標準化されたテストや高度に構造化された臨床家による面接で構成される。インフォーマル評価では、構造化されていない自由な 面接や観察に基づいて評価が行われる。どちらの方法にも長所と短所がある。非常に構造化されていない面接や非公式な観察は、効率的かつ効果的な患者に関す る重要な所見を提供する。非構造的で非公式なアプローチの潜在的な問題点は、臨床医が特定の機能領域を見落としたり、まったく気づかなかったりすることで ある。高度に構造化された面接は、非常に正確ではあるが、臨床医が、より広い範囲や生活背景の観点から回答を考慮することなく、特定の質問に対する特定の 回答に焦点を当てるという誤りを犯す可能性がある。 面接プロセスに関連する問題を軽減する方法はたくさんある。バッテリやテストなど、より正式な標準化された評価には多くの利点がある。第一に、多くの特性 を同時に測定できる。これには、性格、認知、神経心理学的特性などが含まれる。第二に、これらのテストは経験的に定量化された情報を提供する。この明らか な利点は、構造化または非構造化面接と比較して、患者の特性をより正確に測定できることである。第三に、これらの検査はすべて標準化された方法で採点さ れ、実施される[7]。各患者は標準化された刺激を提示され、それを基準として患者の特性を決定することができる。このような種類の検査は、バイアスの可 能性を排除し、患者に有害で法的・倫理的問題を引き起こす可能性のある結果を生み出す。第四に、検査は規範化されている。つまり、患者は「正常な」個人と の比較だけでなく、患者が直面しているのと同じ心理的問題を抱えている可能性のある他の仲間との比較に基づいて評価することができる。標準化された検査に よって、臨床家は患者をより個別化した形で評価することができる。第五に、現在一般的に用いられている標準化された検査は、有効性と信頼性の両方を備えて いる[7]。 私たちは、特定の得点が何を意味するのか、どの程度信頼できるのか、そしてその結果が患者にどのような影響を与えるのかを知っている。 多くの臨床家は、バランスの取れた検査群が患者を助ける最も効果的な方法であることに同意している。バランスの取れた検査群を用いることで、臨床医が評価 を開始するための正式な検査プロセスと、同じ患者に対してより非公式で構造化されていない面接を行うことで、臨床医がより個別化された評価を行うことがで き、非常に複雑で、その人特有の問題や課題がある可能性があるが、それをまとめるのに役立つ可能性がある[8]。 |

| Modern uses Psychological assessment is most often used in the psychiatric, medical, legal, educational, or psychological clinic settings. The types of assessments and the purposes for them differ among these settings. In the psychiatric setting, the common needs for assessment are to determine risks, whether a person should be admitted or discharged, the location the patients should be held, as well as what therapy the patient should be receiving.[9] Within this setting, the psychologists need to be aware of the legal responsibilities that what they can legally do in each situation. Within a medical setting, psychological assessment is used to find a possible underlying psychological disorder, emotional factors that may be associated with medical complaints, assessment for neuropsychological deficit, psychological treatment for chronic pain, and the treatment of chemical dependency. There has been greater importance placed on the patient's neuropsychological status as neuropsychologists are becoming more concerned with the functioning of the brain.[9] Psychological assessment also has a role in the legal setting. Psychologists might be asked to assess the reliability of a witness, the quality of the testimony a witness gives, the competency of an accused person, or determine what might have happened during a crime. They also may help support a plea of insanity or to discount a plea. Judges may use the psychologist's report to change the sentence of a convicted person, and parole officers work with psychologists to create a program for the rehabilitation of a parolee. Problematic areas for psychologists include predicting how dangerous a person will be. The predictive accuracy of these assessments is debated; however, there is often a need for this prediction to prevent dangerous people from returning to society.[9] Psychologists may also be called on to assess a variety of things within an education setting. They may be asked to assess strengths and weaknesses of children who are having difficulty in the school systems, assess behavioral difficulties, assess a child's responsiveness to an intervention, or to help create an educational plan for a child. The assessment of children also allows for the psychologists to determine if the child will be willing to use the resources that may be provided.[9] In a psychological clinic setting, psychological assessment can be used to determine characteristics of the client that can be useful for developing a treatment plan. Within this setting, psychologists often are working with clients who may have medical or legal problems or sometimes students who were referred to this setting from their school psychologist.[9] Some psychological assessments have been validated for use when administered via computer or the Internet.[10] However, caution must be applied to these test results, as it is possible to fake in electronically mediated assessment.[11] Many electronic assessments do not truly measure what is claimed, such as the Meyers-Briggs personality test. Although one of the most well known personality assessments, it has been found both invalid and unreliable by many psychological researches, and should be used with caution.[12][13] Within clinical psychology, the "clinical method" is an approach to understanding and treating mental disorders that begins with a particular individual's personal history and is designed around that individual's psychological needs. It is sometimes posed as an alternative approach to the experimental method which focuses on the importance of conducting experiments in learning how to treat mental disorders, and the differential method which sorts patients by class (gender, race, income, age, etc.) and designs treatment plans based around broad social categories.[14][15] Taking a personal history along with clinical examination allow the health practitioners to fully establish a clinical diagnosis. A medical history of a patient provides insights into diagnostic possibilities as well as the patient's experiences with illnesses. The patients will be asked about current illness and the history of it, past medical history and family history, other drugs or dietary supplements being taken, lifestyle, and allergies.[16] The inquiry includes obtaining information about relevant diseases or conditions of other people in their family.[16][17] Self-reporting methods may be used, including questionnaires, structured interviews and rating scales.[18] |

現代の使用法 心理アセスメントは、精神科、医療、法律、教育、心理クリニックなどの場面で最もよく用いられる。アセスメントの種類や目的は、これらの場面で異なる。 精神医学の場面では、アセスメントの一般的なニーズは、リスクを判断すること、入院させるべきか退院させるべきか、患者を収容する場所、患者が受けるべき 治療法である[9]。このような場面では、心理士は、それぞれの状況で法的に何ができるかという法的責任を認識しておく必要がある。 医療現場では、心理アセスメントは、基礎にある可能性のある心理障害、医学的訴えと関連している可能性のある感情的要因、神経心理学的欠損のアセスメン ト、慢性疼痛に対する心理学的治療、化学物質依存の治療を見つけるために用いられる。神経心理学者が脳の機能に関心を持つようになったため、患者の神経心 理学的状態がより重要視されるようになっている [9] 。 心理学的評価は、法的な場面でも役割を担っている。心理学者は、証人の信頼性、証人が行う証言の質、被告人の能力、あるいは犯罪中に何が起こったかを判断 するよう求められることがある。また、心神喪失の主張を支持したり、主張を割り引いたりするのに役立つこともある。裁判官は、有罪判決を受けた人の量刑を 変更するために心理学者の報告書を利用することがあり、仮釈放担当官は仮釈放者の更生プログラムを作成するために心理学者と協力する。心理学者にとって問 題となるのは、ある人物がどれほど危険な人物になるかを予測することである。このような評価の予測精度については議論があるが、危険な人物の社会復帰を防 ぐために、このような予測が必要とされることが多い[9]。 心理士はまた、教育の場でさまざまな評価を求められることもある。学校制度で困難を抱えている子どもの長所と短所を評価したり、行動上の困難を評価した り、介入に対する子どもの反応性を評価したり、子どもの教育計画を立てる手助けをしたりするよう求められることもある。子どものアセスメントによって、心 理士は、提供される可能性のある資源を子どもが喜んで利用するかどうかを判断することもできる[9]。 心理臨床の場では、心理アセスメントを用いて、治療計画の策定に役立つクライエントの特性を判断することができる。このような環境では、心理士はしばし ば、医学的または法的な問題を抱えたクライエントや、学校心理士からこのような環境に紹介された生徒を担当することがある[9]。 いくつかの心理アセスメントは、コンピュータまたはインターネットを介して投与された場合に使用するために検証されている[10]しかし、電子媒介アセス メントで偽ることが可能であるため、これらのテスト結果には注意が必要である[11]。最もよく知られた性格評価の1つではあるが、多くの心理学的研究に よって無効であり信頼できないことが判明しており、使用には注意が必要である[12][13]。 臨床心理学において、「臨床的方法」とは、精神障害を理解し治療するためのアプローチであり、特定の個人の個人史から始まり、その個人の心理的ニーズを中 心に設計される。精神障害の治療方法を学ぶ上で実験を行うことの重要性に焦点を当てた実験的方法や、患者を階級(性別、人種、収入、年齢など)によって選 別し、大まかな社会的カテゴリーに基づいて治療計画を立案する鑑別的方法に代わるアプローチとして提起されることもある[14][15]。 臨床検査とともに病歴を聴取することで、医療従事者は臨床診断を完全に確立することができる。患者の病歴は、診断の可能性だけでなく、患者の病気に関する 経験についての洞察も与えてくれる。患者には、現在の病気とその既往歴、過去の病歴と家族歴、服用している他の薬物や栄養補助食品、生活習慣、アレルギー について質問する[16]。 |

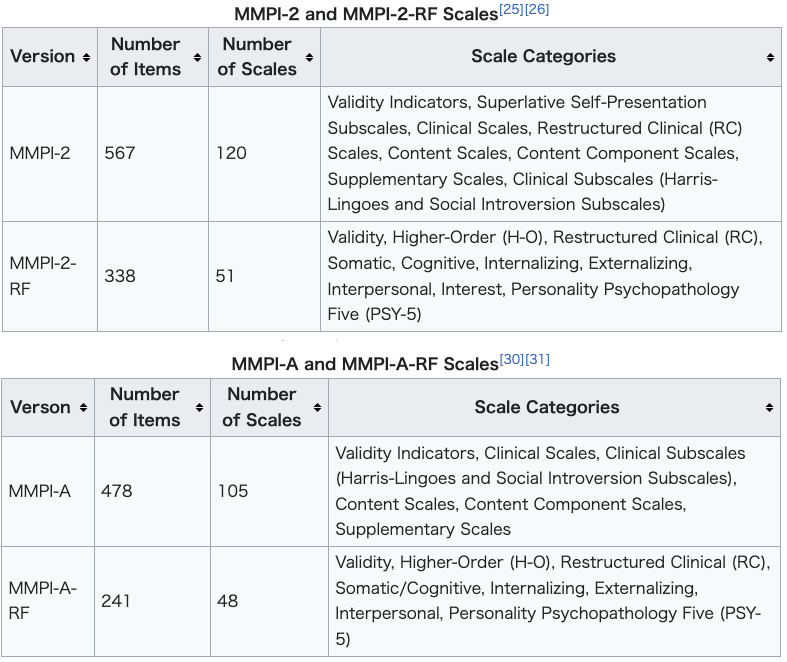

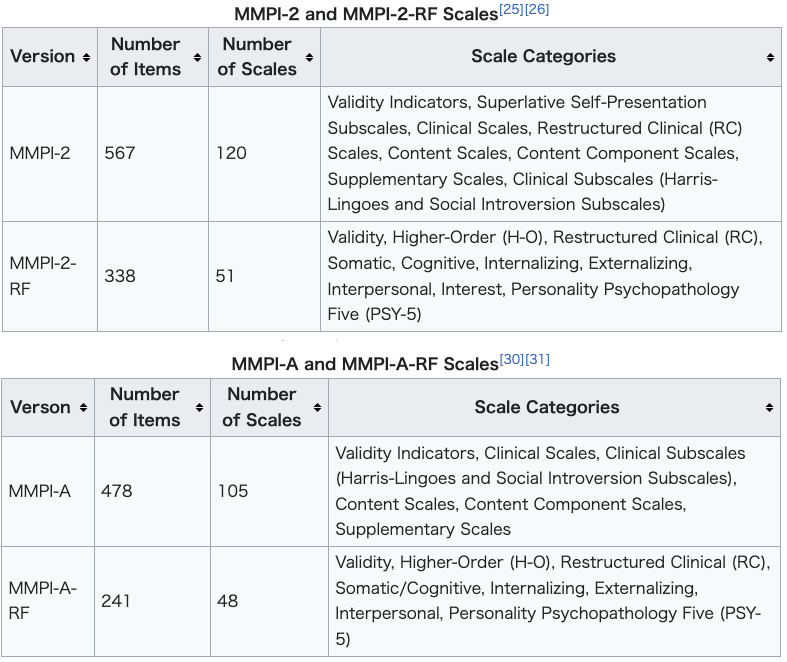

| Personality Assessment Personality traits are an individual's enduring manner of perceiving, feeling, evaluating, reacting, and interacting with other people specifically, and with their environment more generally.[19][20] Because reliable and valid personality inventories give a relatively accurate representation of a person's characteristics, they are beneficial in the clinical setting as supplementary material to standard initial assessment procedures such as a clinical interview; review of collateral information, e.g., reports from family members; and review of psychological and medical treatment records. Main article: Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory MMPI History Developed by Starke R. Hathaway, PhD, and J. C. McKinley, MD, The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) is a personality inventory used to investigate not only personality, but also psychopathology.[21] The MMPI was developed using an empirical, atheoretical approach. This means that it was not developed using any of the frequently changing theories about psychodynamics at the time. There are two variations of the MMPI administered to adults, the MMPI-2 and the MMPI-2-RF, and two variations administered to teenagers, the MMPI-A and MMPI-A-RF. This inventory's validity has been confirmed by Hiller, Rosenthal, Bornstein, and Berry in their 1999 meta-analysis. Throughout history the MMPI in its various forms has been routinely administered in hospitals, clinical settings, prisons, and military settings.[22][non-primary source needed] MMPI-2 The MMPI-2 consists of 567 true or false questions aimed at measuring the reporting person's psychological wellbeing.[23] The MMPI-2 is commonly used in clinical settings and occupational health settings. There is a revised version of the MMPI-2 called the MMPI-2-RF (MMPI-2 Restructured Form).[24] The MMPI-2-RF is not intended to be a replacement for the MMPI-2, but is used to assess patients using the most current models of psychopathology and personality.[24] MMPI-A The MMPI-A was published in 1992 and consists of 478 true or false questions.[27] This version of the MMPI is similar to the MMPI-2 but used for adolescents (age 14–18) rather than for adults. The restructured form of the MMPI-A, the MMPI-A-RF, was published in 2016 and consists of 241 true or false questions that can understood with a sixth grade reading level.[28][29] Both the MMPI-A and MMPI-A-RF are used to assess adolescents for personality and psychological disorders, as well as to evaluate cognitive processes.[29]  |

パーソナリティ評価 パーソナリティ特性とは、個人の永続的な知覚、感情、評価、反応、および他者との相互作用の仕方であり、より一般的には環境との相互作用の仕方である。 [19][20]信頼性が高く妥当なパーソナリティ目録は、人の特性を比較的正確に表現するため、臨床場面では、臨床面接、家族からの報告などの付随情報 の検討、心理学的および医学的治療記録の検討などの標準的な初期評価手順の補足資料として有益である。 主な項目 ミネソタ多面人格目録 MMPI 歴史 スターク・R・ハサウェイ(Starke R. Hathaway)博士とJ・C・マッキンリー(J. C. McKinley)医学博士によって開発されたミネソタ多面人格目録(MMPI)は、人格だけでなく精神病理学も調査するために使用される人格目録である [21]。つまり、当時頻繁に変化していた精神力動に関する理論のいずれも用いて開発されていない。MMPIには、成人に実施されるMMPI-2と MMPI-2-RFの2つのバリエーションと、ティーンエイジャーに実施されるMMPI-AとMMPI-A-RFの2つのバリエーションがある。この目録 の妥当性は、1999年のHiller、Rosenthal、Bornstein、Berryのメタ分析によって確認されている。歴史を通じて、さまざま な形態のMMPIは、病院、臨床現場、刑務所、および軍の設定で日常的に投与されている[22][非一次ソースが必要]。 MMPI-2 MMPI-2は、報告者の心理的ウェルビーイングを測定することを目的とした567の真偽の質問で構成されている[23]。MMPI-2-RF(MMPI -2リストラクチャード・フォーム)と呼ばれるMMPI-2の改訂版がある[24]。MMPI-2-RFは、MMPI-2の代替となることを意図していな いが、精神病理学とパーソナリティの最新のモデルを使用して患者を評価するために使用される[24]。 MMPI-A MMPI-Aは1992年に発表され、478問の真偽判定問題から構成されている[27]。このバージョンのMMPIはMMPI-2に似ているが、成人で はなく青年(14~18歳)を対象としている。MMPI-Aの再構築版であるMMPI-A-RFは、2016年に発表され、6年生の読解レベルで理解でき る241の真偽問題から構成されている[28][29]。MMPI-AとMMPI-A-RFの両方は、青年期のパーソナリティと心理障害の評価、および認 知プロセスの評価に使用される[29]。  |

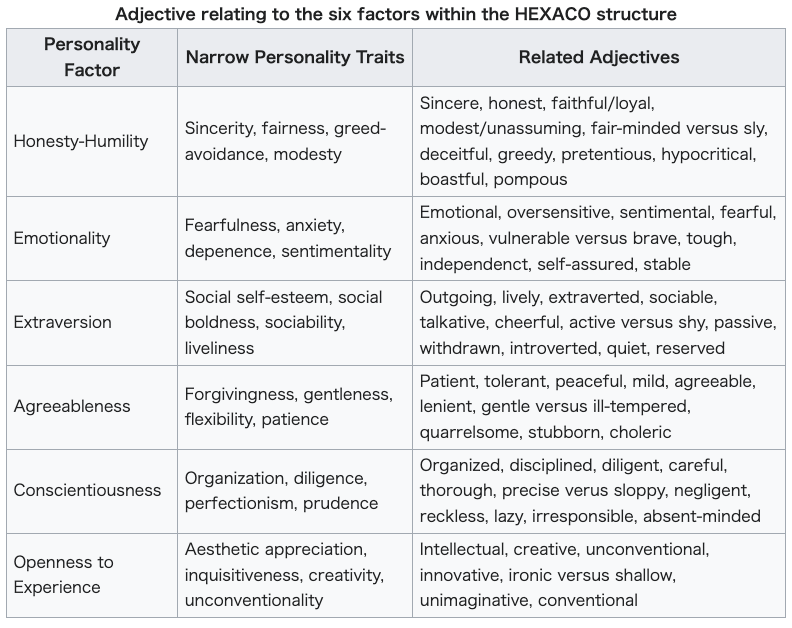

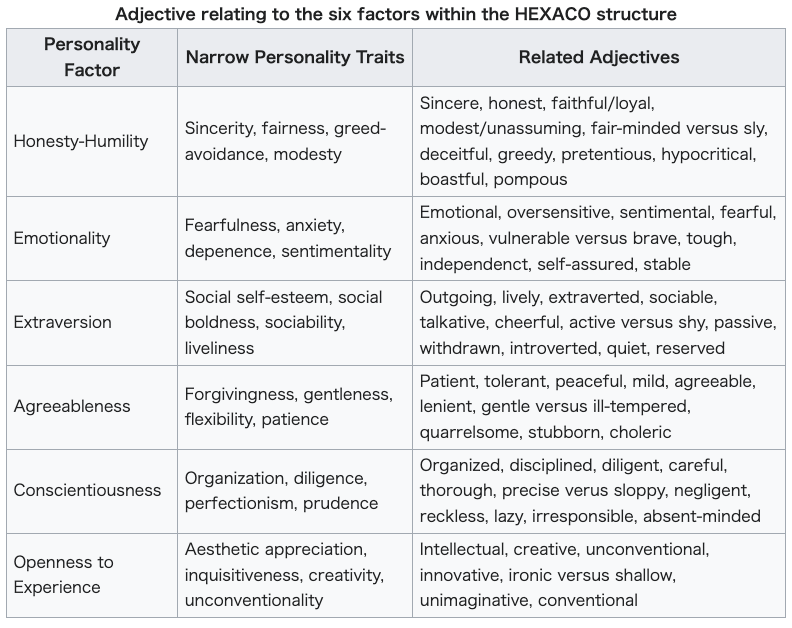

| NEO Personality Inventory The NEO Personality Inventory was developed by Paul Costa Jr. and Robert R. McCrae in 1978. When initially created, it only measured three of the Big Five personality traits: Neuroticism, Openness to Experience, and Extroversion. The inventory was then renamed as the Neuroticism-Extroversion-Openness Inventory (NEO-I). It was not until 1985 that Agreeableness and Conscientiousness were added to the personality assessment. With all Big Five personality traits being assessed, it was then renamed as the NEO Personality Inventory. Research for the NEO-PI continued over the next few years until a revised manual with six facets for each Big Five trait was published in 1992.[20] In the 1990s, now called the NEO PI-R, issues were found with the personality inventory. The developers of the assessment found it to be too difficult for younger people, and another revision was done to create the NEO PI-3.[32] The NEO Personality Inventory is administered in two forms: self-report and observer report. It consists of 240 personality items and a validity item. It can be administered in roughly 35–45 minutes. Every item is answered on a Likert scale, widely known as a scale from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree. If more than 40 items are missing or more than 150 responses or less than 50 responses are Strongly Agree/Disagree, the assessment should be viewed with great caution and has the potential to be invalid.[33] In the NEO report, each trait's T score is recorded along with the percentile they rank on compared to all data recorded for the assessment. Then, each trait is broken up into their six facets along with raw score, individual T-scores, and percentile. The next page goes on to list what each score means in words as well as what each facet entails. The exact responses to questions are given in a list as well as the validity response and amount of missing responses.[34] When an individual is given their NEO report, it is important to understand specifically what the facets are and what the corresponding scores mean. Neuroticism Anxiety High scores suggest nervousness, tenseness, and fearfulness. Low scores suggest feeling relaxed and calm. Angry Hostility High scores suggest feeling anger and frustration often. Low scores suggest being easy-going. Depression High scores suggest feeling guilty, sad, hopeless, and lonely. Low scores suggest less feeling of that of someone who scores highly, but not necessarily being light-hearted and cheerful. Self-consciousness High scores suggest shame, embarrassment, and sensitivity. Low scores suggest being less affected by others' opinions, but not necessarily having good social skills or poise. Impulsiveness High scores suggest the inability to control cravings and urges. Low scores suggest easy resistance to such urges. Vulnerability High scores suggest inability to cope with stress, being dependent, and feeling panicked in high stress situations. Low scores suggest capability to handle stressful situations. Extraversion Warmth High scores suggest friendliness and affectionate behavior. Low scores suggest being more formal, reserved, and distant. A low score does not necessarily mean being hostile or lacking compassion. Gregariousness High scores suggest wanting the company of others. Low scores tend to be from those who avoid social stimulation. Assertiveness High scores suggest a forceful and dominant person who lacks hesitation. Low scores suggest are more passive and try not to stand out in a crowd. Activity High scores suggest a more energetic and upbeat personality and lead a quicker paced lifestyle. Low scores suggest the person is more leisurely, but does not imply being lazy or slow. Excitement-Seeking High scores suggest a person who seeks and craves excitement and is similar to those with high sensation seeking. Low scores seek a less exciting lifestyle and come off more boring. Positive Emotions High scores suggest the tendency to feel happier, laugh more, and are optimistic. Low scorers are not necessarily unhappy, but more so are less high-spirited and are more pessimistic. Openness to Experience Fantasy Those who score high in fantasy have a more creative imagination and daydream frequently. Low scores suggest a person who lives more in the moment. Aesthetics High scores suggest a love and appreciation for art and physical beauty. These people are more emotionally attached to music, artwork, and poetry. Low scorers have a lack of interest in the arts. Feelings High scorers have a deeper ability to experience emotion and see their emotions as more important than those who score low on this facet. Low scorers are less expressive. Actions High scores suggest a more open-mindedness to traveling and experiencing new things. These people prefer novelty over a routine life. Low scorers prefer a scheduled life and dislike change. Ideas Active pursuit of knowledge, high curiosity, and the enjoyment of brain teasers and philosophical are common of those who score high on this facet. Those who score lower are not necessarily less intelligent, nor does a high score imply high intelligence. However, those who score lower are more narrow in their interests and have low curiosity. Values High scorers are more investigative of political, social, and religious values. Those who score lower and more accepting of authority and honor more traditional values. High scorers are more typically liberal while lower scorers are more typically conservative. Agreeableness Trust High scores are more trusting of others and believe others are honest and have good intentions. Low scorers are more skeptical, cynical, and assumes others are dishonest and/or dangerous. Straightforwardness Those who score high in this facet are more sincere and frank. Low scorers are more deceitful and more willing to manipulate others, but this does not mean they should be labeled as a dishonest or manipulative person. Altruism High scores suggest a person concerned with the well-being of others and show it through generosity, willingness to help others, and volunteering for those less fortunate. Low scores suggest a more self-centered person who is less willing to go out of their way to help others. Compliance High scorers are more inclined to avoid conflict and tend to forgive easily. Low scores suggest a more aggressive personality and a love for competition. Modesty High scorers are more humble, but not necessarily lacking in self-esteem or confidence. Low scorers believe they're more superior than others and may come off as more conceited. Tender-Mindedness This facet scales one's concern for others and their ability to empathize. High scorers are more moved by others' emotions, while low scorers are more hardheaded and typically consider themselves realists. Conscientiousness Competence High scores suggest one is capable, sensible, prudent, effective, and are well-prepared to deal with whatever happens in life. Low scores suggest a potential lower self-esteem and are often unprepared. Order High scorers are more neat and tidy, while low scorers lack organization and are unmethodical. Dutifulness Those who score highly in this facet are more strict about their ethical principles and are more dependable. Low scorers are less reliable and are more casual about their morals. Achievement Striving Those who score highly in this facet have higher aspirations and work harder to achieve their goals. However, they may be too invested in their work and become a workaholic. Low scorers are much less ambitious and perhaps even lazy. They are often content with their lack of goal-seeking. Self-Discipline High scorers complete whatever task is assigned to them and are self-motivated. Low scorers often procrastinate and are easily discouraged. Deliberation High scorers tend to think more than low scorers before acting. High scorers are more cautious and deliberate while low scorers are more hasty and act without considering the consequences. HEXACO-PI The HEXACO-PI, developed by Lee and Ashton in the early 2000s, is a personality inventory used to measure six different dimensions of personality which have been found in lexical studies across various cultures. There are two versions of the HEXACO: the HEXACO-PI and the HEXACO-PI-R which are examined with either self reports or observer reports. The HEXACO-PI-R has forms of three lengths: 200 items, 100 items, and 60 items. Items from each form are grouped to measure scales of more narrow personality traits, which are them grouped into broad scales of the six dimensions: honesty & humility (H), emotionality (E), Extraversion (X), agreeableness (A), conscientiousness (C), and openness to experience (O).The HEXACO-PI-R includes various traits associated with neuroticism and can be used to help identify trait tendencies. One table which give examples of typically high loaded adjectives on the six factors of HEXACO can be found in Ashton's book "Individual Differences and Personality"  One benefit of using the HEXACO is that of the facet of neuroticism within the factor of emotionality: trait neuroticism has been shown to have a moderate positive correlation with people with anxiety and depression. The identification of trait neuroticism on a scale, paired with anxiety, and/or depression is beneficial in a clinical setting for introductory screenings some personality disorders. Because the HEXACO has facets which help identify traits of neuroticism, it is also a helpful indicator of the dark triad.[35][36] Temperament Assessment In contrast to personality, i.e. the concept that relates to culturally- and socially-influenced behaviour and cognition, the concept of temperament' refers to biologically and neurochemically-based individual differences in behaviour. Unlike personality, temperament is relatively independent of learning, system of values, national, religious and gender identity and attitudes. There are multiple tests for evaluation of temperament traits (reviewed, for example, in,[37] majority of which were developed arbitrarily from opinions of early psychologists and psychiatrists but not from biological sciences. There are only two temperament tests that were based on neurochemical hypotheses: The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) and the Trofimova’s Structure of Temperament Questionnaire-Compact (STQ-77).[38] The STQ-77 is based on the neurochemical framework Functional Ensemble of Temperament that summarizes the contribution of main neurochemical (neurotransmitter, hormonal and opioid) systems to behavioural regulation.[37][39][40] The STQ-77 assesses 12 temperament traits linked to the neurochemical components of the FET. The STQ-77 is freely available for non-commercial use in 24 languages for testing in adults and several language versions for testing children [41] Pseudopsychology (pop psychology) in assessment Although there have been many great advancements in the field of psychological evaluation, some issues have also developed. One of the main problems in the field is pseudopsychology, also called pop psychology. Psychological evaluation is one of the biggest aspects in pop psychology. In a clinical setting, patients are not aware that they are not receiving correct psychological treatment, and that belief is one of the main foundations of pseudopsychology. It is largely based upon the testimonies of previous patients, the avoidance of peer review (a critical aspect of any science), and poorly set up tests, which can include confusing language or conditions that are left up to interpretation.[42] Pseudopsychology can also occur when people claim to be psychologists, but lack qualifications.[43] A prime example of this is found in quizzes that can lead to a variety of false conclusions. These can be found in magazines, online, or just about anywhere accessible to the public. They usually consist of a small number of questions designed to tell the participant things about themselves. These often have no research or evidence to back up any claims made by the quizzes.[43] |

NEO性格検査 NEO性格検査は、1978年にポール・コスタ・ジュニアとロバート・R・マクレーによって開発された。作成当初は、ビッグ5の性格特性のうち3つだけを 測定していた: 神経質、開放性、外向性である。その後、この目録は神経質性-外向性-開放性目録(NEO-I)と改名された。1985年になって初めて、性格評価に「同 意性」と「良心性」が追加された。ビッグファイブのすべての性格特性が評価されるようになり、NEOパーソナリティ・インベントリーと改名された。NEO -PIの研究はその後数年間続けられ、1992年にビッグファイブの各特性に6つのファセットを加えた改訂マニュアルが発表された[20]。アセスメント の開発者は、それが若い人々には難しすぎることを発見し、NEO PI-3を作成するために別の改訂が行われた[32]。 NEOパーソナリティ目録は、自己報告と観察者報告の2つの形式で実施される。240の性格項目と妥当性項目から構成されている。実施時間はおよそ 35~45分である。すべての項目は、強く反対から強く賛成までの尺度として広く知られているリッカート尺度で回答される。40以上の項目が欠落している 場合、150以上の回答がある場合、または「強く同意する/同意しない」の回答が50未満の場合、そのアセスメントは非常に注意深く見る必要があり、無効 である可能性がある[33]。そして、各特性は、生スコア、個々のTスコア、パーセンタイルとともに、6つのファセットに分割される。次のページでは、各 スコアが何を意味するのか、また各ファセットが何を意味するのかが列挙されている。質問に対する正確な回答は、有効回答や欠落回答の量と同様にリストで示 される[34]。 個人がNEOレポートを渡される際には、ファセットが何であり、対応するスコアが何を意味するのかを具体的に理解することが重要である。 神経症 不安 高得点は神経質、緊張、恐れを示唆する。スコアが低いほど、リラックスして落ち着いていると感じる。 怒りっぽい敵意 高スコアは、怒りやフラストレーションをしばしば感じることを示唆する。低い得点は、のんびりしていることを示唆する。 抑うつ 高得点は、罪悪感、悲しみ、絶望感、孤独感を示唆する。低スコアは、高スコアの人のような感覚は少ないが、必ずしも明るく朗らかではないことを示唆する。 自意識過剰 高スコアは、羞恥心、恥ずかしさ、敏感さを示唆する。低い得点は、他人の意見にあまり影響されないことを示唆するが、必ずしも社会的スキルや態度が良いと は限らない。 衝動性 高スコアは、欲求や衝動をコントロールできないことを示唆する。低い得点は、そのような衝動に対して抵抗しやすいことを示唆する。 脆弱性 高得点は、ストレスに対処できない、依存的である、高ストレス状況でパニックを感じることを示唆する。低い得点は、ストレスの多い状況に対処する能力があ ることを示唆する。 外向性 温厚さ 高スコアは親しみやすく、愛情深い行動を示唆する。低スコアは、より形式的で、控えめで、よそよそしいことを示唆する。スコアが低いからといって、必ずし も敵対的であったり、思いやりに欠けるとは限らない。 積極性 高得点は、他人と一緒にいたいことを示唆する。低い得点は、社会的刺激を避ける傾向がある。 自己主張性 高得点は、力強く支配的で、ためらいのない人であることを示唆する。低い得点は、より受動的で、人ごみの中で目立とうとしないことを示唆する。 活動性 高スコアは、よりエネルギッシュで明るい性格で、マイペースなライフスタイルを送ることを示唆する。低得点は、よりのんびりした性格であることを示唆する が、怠け者であったり、のろまであったりすることを意味するわけではない。 興奮を求める 高得点は、興奮を求め、渇望する人であることを示唆し、感覚を強く求める人に似ている。低スコアは、あまり刺激的でないライフスタイルを求め、退屈な印象 を与える。 ポジティブな感情 高スコアは、より幸福を感じ、より笑い、楽観的である傾向を示唆する。スコアが低い人は、必ずしも不幸ではないが、どちらかというと、あまり高揚感がな く、悲観的である。 経験に対する開放性 ファンタジー ファンタジーのスコアが高い人は、より創造的な想像力を持ち、頻繁に空想にふける。スコアが低い人は、今をより大切に生きる人である。 美的感覚 スコアが高い人は、芸術や肉体美を愛し、鑑賞している。このような人は、音楽、芸術作品、詩により感情移入する。スコアが低い人は、芸術に関心がない。 感情 高得点の人は、感情を経験する能力が深く、この面の得点が低い人よりも自分の感情を重要視する。低得点者は表現力が乏しい。 行動 高得点者は、旅行や新しいことを経験することに寛容である。このような人々は、日常生活よりも新奇性を好む。得点が低い人は、予定調和的な生活を好み、変 化を嫌う。 アイデア 知識を積極的に追求し、好奇心が旺盛で、頭の体操や哲学的なことを好む。スコアが低い人が必ずしも知能が低いわけではないし、スコアが高いからといって知 能が高いわけでもない。しかし、スコアが低い人は、興味の対象が狭く、好奇心が低い。 価値観 高得点者は、政治的、社会的、宗教的価値観についてより研究的である。スコアの低い人は、権威を受け入れ、より伝統的な価値観を重んじる。高スコアの人は よりリベラルであり、低スコアの人はより保守的である。 同意性 信頼 高得点者は他人をより信頼し、他人が正直で善意を持っていると信じている。低スコアの人はより懐疑的で皮肉屋であり、他人は不正直で危険であると思い込ん でいる。 率直性 このファセットが高い人は、より誠実で率直である。低スコアの人は、より欺瞞的で、他人を操ることを厭わないが、だからといって、不正直な人、人を操る人 というレッテルを貼られるべきだという意味ではない。 利他主義 高得点は、他人の幸福に関心があり、寛大さ、他人を助ける意欲、恵まれない人のためのボランティア活動などを通じてそれを示すことを示唆する。低い得点 は、より自己中心的で、他人を助けるためにわざわざ外に出ることを厭わない人であることを示唆する。 コンプライアンス 高得点の人は、争いを避ける傾向が強く、簡単に許す傾向がある。スコアが低いと、より攻撃的な性格で、競争が好きであることを示唆する。 謙虚さ 高得点の人は謙虚だが、必ずしも自尊心や自信がないわけではない。低スコアの人は、自分が他人より優れていると信じており、うぬぼれが強いと思われるかも しれない。 優しさ この側面は、他者への関心と共感能力を測る尺度である。高スコアの人は他人の感情に動かされやすいが、低スコアの人は頭が固く、典型的な現実主義者であ る。 良心性 能力 高スコアは、有能で、分別があり、慎重で、効果的であり、人生で何が起きても対処できるよう準備万端であることを示唆する。低い得点は、潜在的に自尊心が 低く、しばしば準備不足であることを示唆する。 順序 高得点者は整然としている。低得点者は整理整頓ができず、非正規的である。 従順さ この項目の得点が高い人は、倫理的原則に厳格で、頼りになる。低得点の人は、信頼性が低く、自分のモラルに関して軽率である。 達成努力 この項目の得点が高い人は、高い志を持ち、目標達成のために努力する。しかし、仕事に没頭しすぎてワーカホリックになることもある。スコアが低い人は、野 心があまりなく、おそらく怠惰でさえある。目標がないことに満足していることが多い。 自己規律 高得点者は与えられた仕事は何でもやり遂げ、自発的である。低得点者は、しばしば先延ばしにし、落胆しやすい。 熟慮 高得点者は低得点者に比べ、行動する前によく考える傾向がある。高得点者は慎重でじっくりと考えるが、低得点者は性急で結果を考えずに行動する。 HEXACO-PI HEXACO-PIは、リーとアシュトンが2000年代初頭に開発したパーソナリティ目録で、様々な文化圏の語彙研究において発見されたパーソナリティの 6つの異なる次元を測定するために使用される。HEXACOには2つのバージョンがある:HEXACO-PIとHEXACO-PI-Rで、自己報告または 観察者報告のどちらかで検査される。HEXACO-PI-Rには、200項目、100項目、60項目の3つの長さのフォームがある。HEXACO-PI- Rには、神経症と関連するさまざまな特性が含まれており、特性の傾向を識別するのに役立つ。HEXACO-PI-Rには神経症と関連する様々な特性が含ま れており、特性の傾向を識別するのに役立つ。HEXACOの6つの因子で典型的に負荷の高い形容詞の例を示す1つの表は、Ashtonの著書 「Individual Differences and Personality 」に掲載されている。  HEXACOを使用する利点の1つは、感情性の因子の中の神経症のファセットである:特性神経症は、不安や抑うつを持つ人々と中程度の正の相関を持つこと が示されている。特性神経症は、不安や抑うつと中程度の正の相関があることが示されている。不安や抑うつと対をなす特性神経症の尺度の同定は、臨床の場に おいて、いくつかのパーソナリティ障害の入門的スクリーニングに有益である。HEXACOには神経症の特徴を同定するのに役立つファセットがあるため、闇 の三要素の指標としても有用である[35][36]。 気質アセスメント パーソナリティ、すなわち文化的および社会的に影響された行動と認知に関係する概念とは対照的に、「気質」という概念は、生物学的および神経化学的に基づ く行動の個人差を指す。性格とは異なり、気質は学習、価値体系、国、宗教、性別のアイデンティティや態度とは比較的独立している。気質特性を評価するため のテストは複数あり(例えば、『気質』[37]にレビューされている)、その大部分は初期の心理学者や精神科医の意見から恣意的に開発されたもので、生物 科学から開発されたものではない。神経化学的仮説に基づいた気質検査は2つしかない: STQ-77は、神経化学的枠組みFunctional Ensemble of Temperament(気質の機能的アンサンブル)に基づいており、行動調節に対する主な神経化学的(神経伝達物質、ホルモン、オピオイド)系の寄与を 要約している[37][39][40]。STQ-77は、成人の検査用に24の言語で、また小児の検査用にいくつかの言語バージョンで非商用利用が自由で ある[41]。 アセスメントにおける疑似心理学(ポップ心理学 心理学的評価の分野では多くの大きな進歩があったが、いくつかの問題も発生している。この分野における主な問題のひとつが、ポップ心理学とも呼ばれる疑似 心理学である。心理学的評価は、ポップ心理学における最大の側面の一つである。臨床の場では、患者は自分が正しい心理学的治療を受けていないことに気づい ておらず、その思い込みが疑似心理学の主な基盤の一つとなっている。これは主に、以前の患者の証言、ピアレビューの回避(あらゆる科学にとって重要な側 面)、および混乱させるような言葉や解釈次第でどうにでもなるような条件を含む、不十分な設定のテストに基づいている[42]。 偽の心理学は、心理学者であると主張する人々が資格を欠いている場合にも発生することがある[43]。このようなクイズは、雑誌やオンラインなど、一般の 人々がアクセスできるあらゆる場所で見つけることができる。クイズは通常、参加者が自分自身について知ることができるように作られた、少数の質問で構成さ れている。これらのクイズには、クイズの主張を裏付ける調査や証拠がないことが多い[43]。 |

| Ethics Concerns about privacy, cultural biases, tests that have not been validated, and inappropriate contexts have led groups such as the American Educational Research Association (AERA) and the American Psychological Association (APA) to publish guidelines for examiners in regards to assessment.[9] The American Psychological Association states that a client must give permission to release any of the information that may come from a psychologist.[44] The only exceptions to this are in the case of minors, when the clients are a danger to themselves or others, or if they are applying for a job that requires this information. Also, the issue of privacy occurs during the assessment itself. The client has the right to say as much or little as they would like, however they may feel the need to say more than they want or even may accidentally reveal information they would like to keep private.[9] Guidelines have been put in place to ensure the psychologist giving the assessments maintains a professional relationship with the client since their relationship can impact the outcomes of the assessment. The examiner's expectations may also influence the client's performance in the assessments.[9] The validity and reliability of the tests being used also can affect the outcomes of the assessments being used. When psychologists are choosing which assessments they are going to use, they should pick one that will be most effective for what they are looking at. Also, it is important for the psychologists are aware of the possibility of the client, either consciously or unconsciously, faking answers and consider use of tests that have validity scales within them.[9] |

倫理 プライバシー、文化的偏見、検証されていないテスト、不適切な文脈に対する懸念から、米国教育研究協会(AERA)や米国心理学会(APA)といった団体 が、アセスメントに関して試験官向けのガイドラインを発表している。 [9] 米国心理学会は、心理学者から得られる可能性のある情報を公開するためには、クライエントが許可を与えなければならないと述べている[44]。これに対す る唯一の例外は、未成年の場合、クライエントが自分自身や他者にとって危険である場合、またはクライエントがこの情報を必要とする仕事に応募している場合 である。また、プライバシーの問題は、アセスメント中にも発生する。クライエントには、望むだけ多く話す権利も少なく話す権利もあるが、クライエントは望 む以上のことを話す必要を感じたり、あるいは非公開にしておきたい情報を誤って明かしてしまうこともある[9]。 アセスメントを行う心理士は、クライエントとの関係がアセスメントの結果に影響を与える可能性があるため、専門的な関係を維持するようにガイドラインが設 けられている。試験官の期待も、アセスメントにおけるクライエントのパフォーマンスに影響を与える可能性がある[9]。 使用されるテストの妥当性と信頼性もまた、使用されるアセスメントの結果に影響を与えうる。心理士がどのアセスメントを使用するかを選択する場合、彼らが 見ているものに対して最も効果的なものを選ぶべきである。また、心理士は、クライエントが意識的または無意識的に答えを偽っている可能性を認識し、その中 に妥当性尺度があるテストの使用を検討することが重要である[9]。 |

| Corresponding evaluations in

related fields Neuropsychological assessment Neurological examination in neurology Mental state examination in psychiatry Physical examination in medicine Therapeutic assessment |

関連分野での対応評価 神経心理学的評価 神経学における神経学的検査 精神医学における精神状態検査 医学における身体検査 治療評価 |

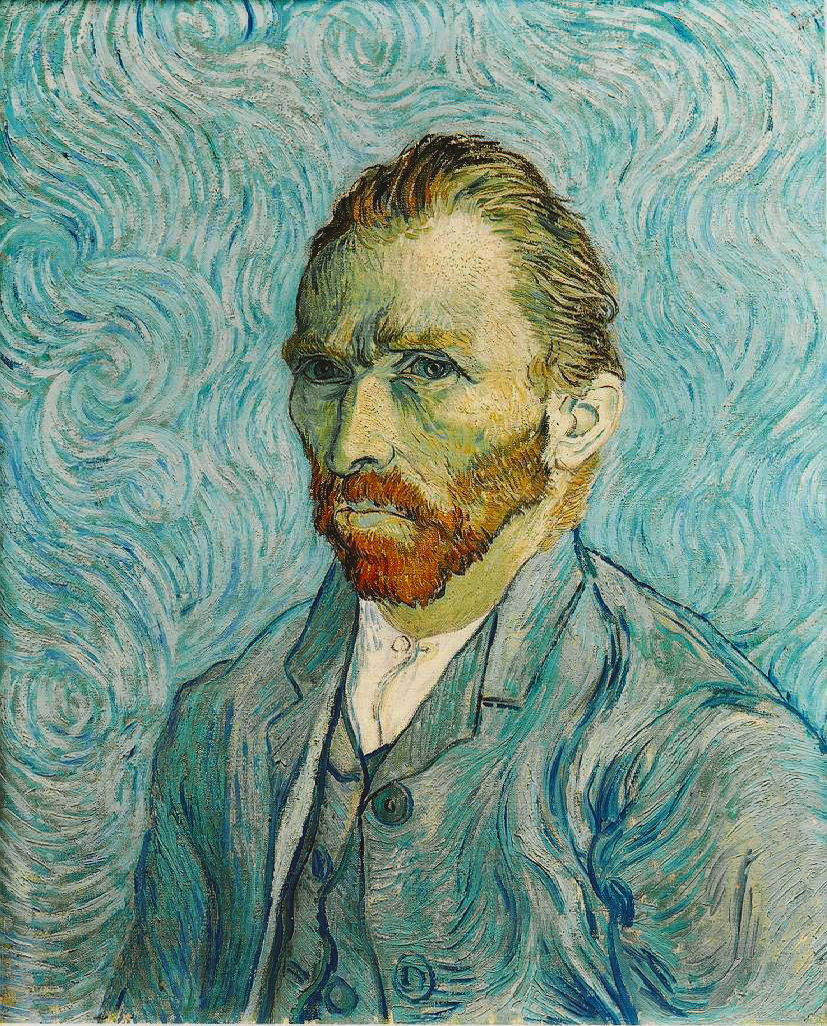

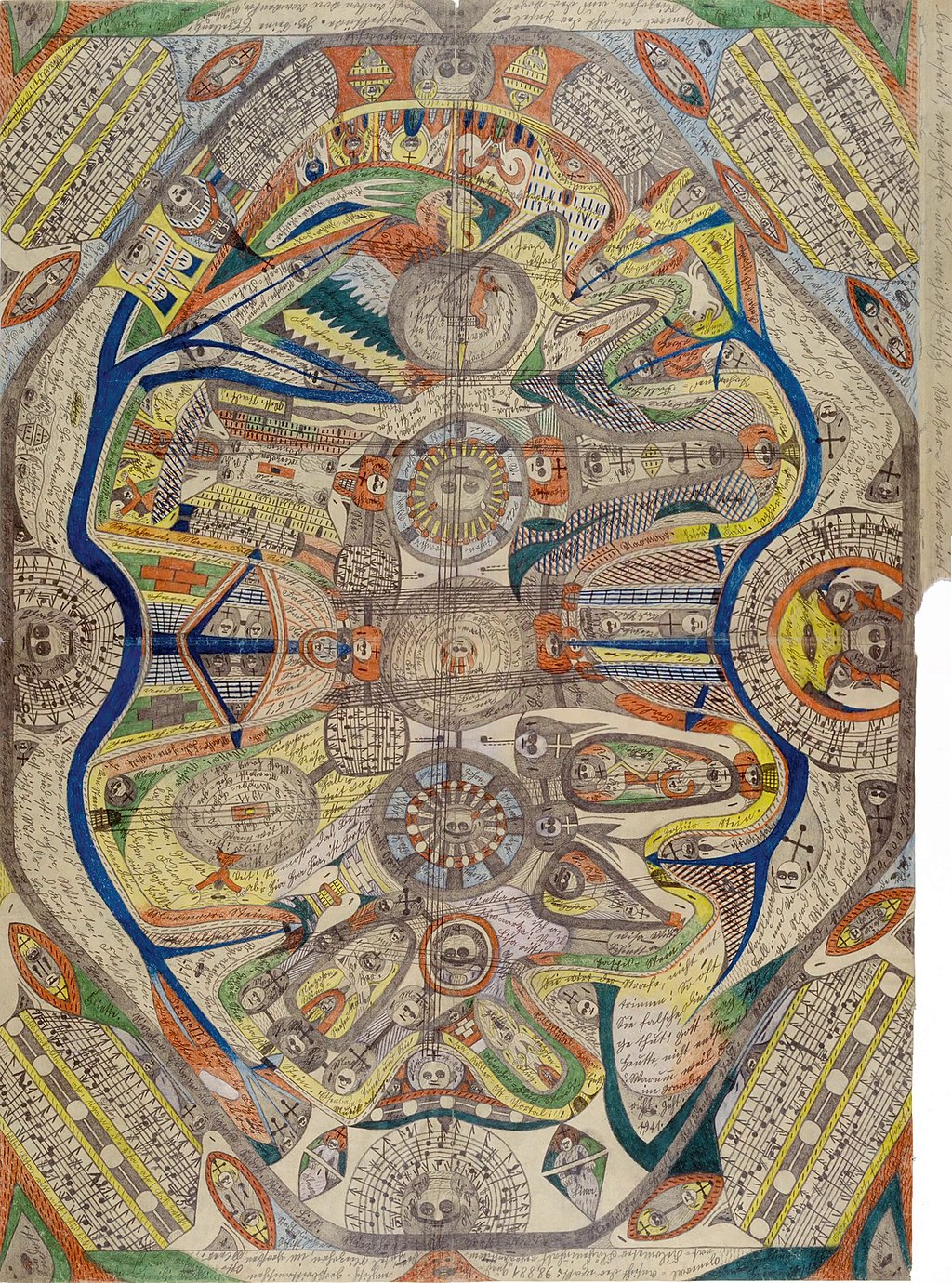

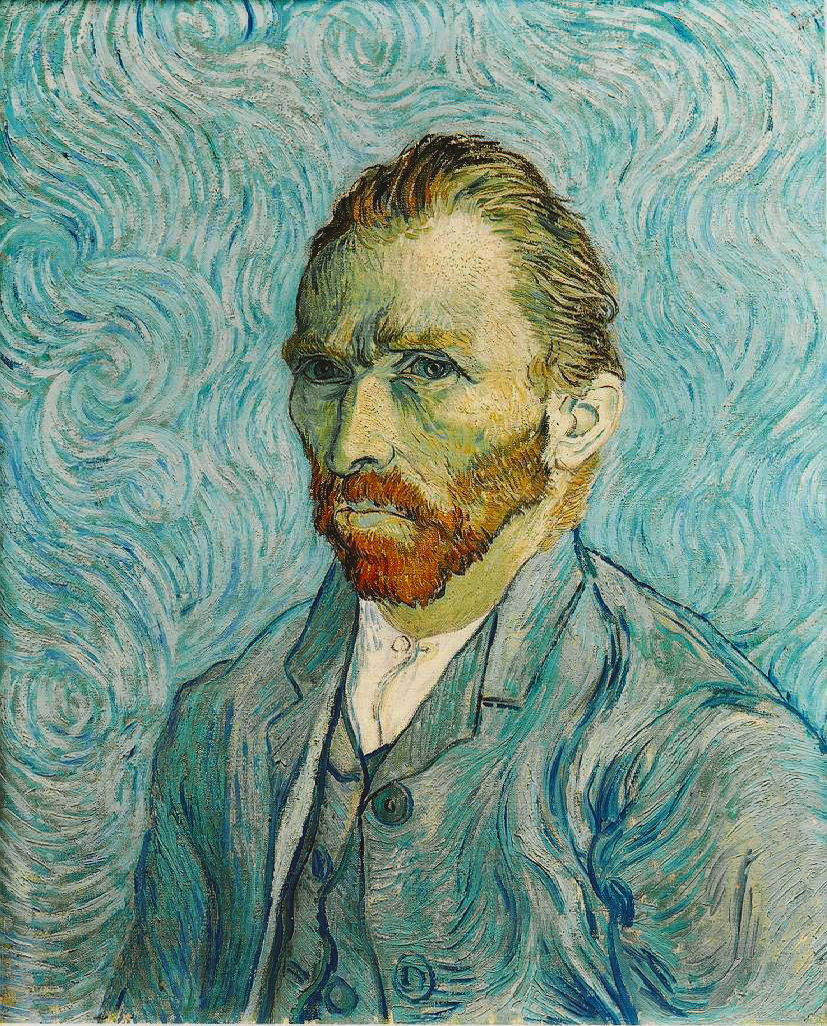

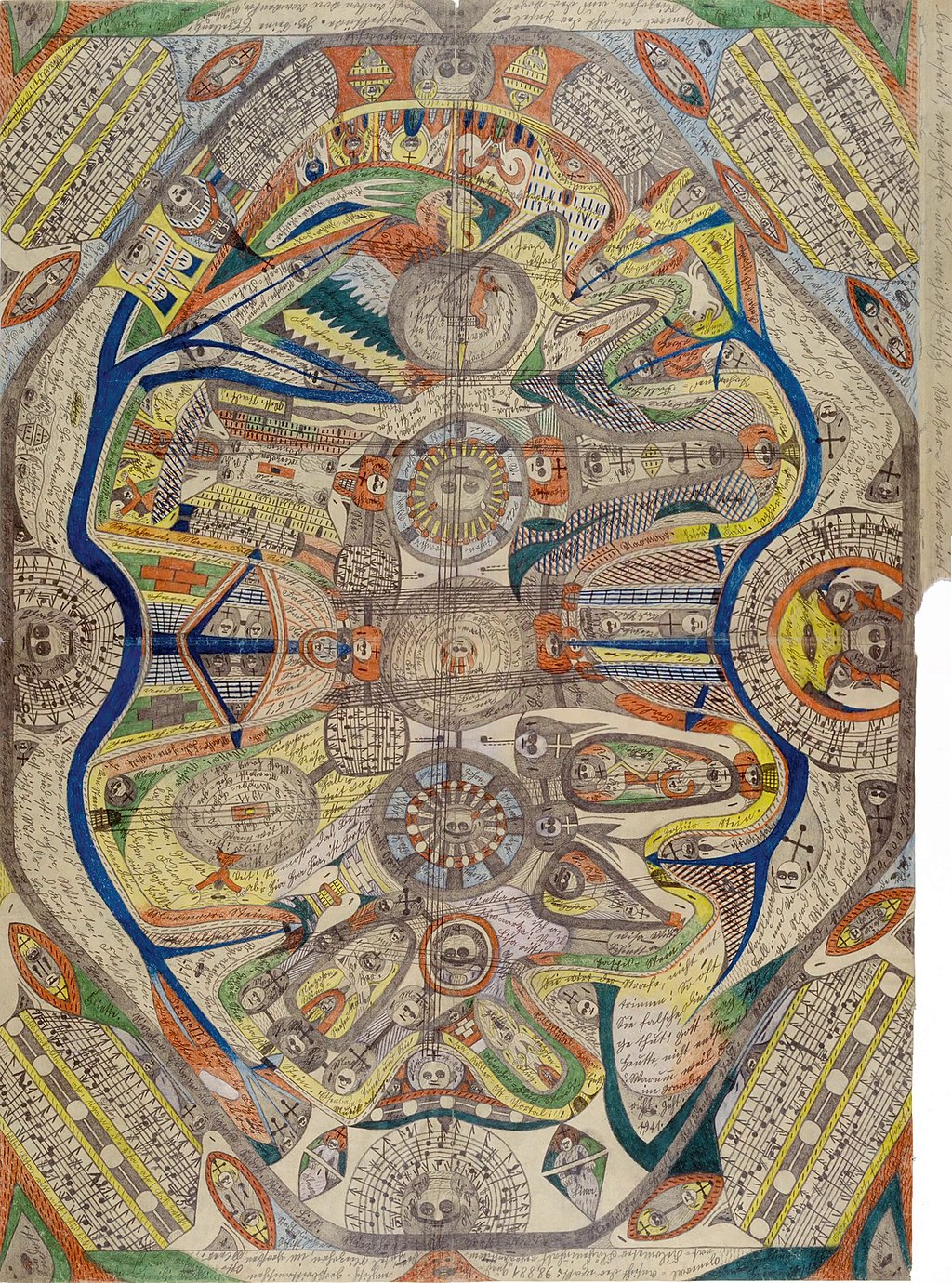

| The

mental status examination (MSE) is an important part of the

clinical assessment process in neurological and psychiatric practice.

It is a structured way of observing and describing a patient's

psychological functioning at a given point in time, under the domains

of appearance, attitude, behavior, mood and affect, speech, thought

process, thought content, perception, cognition, insight, and

judgment.[1] There are some minor variations in the subdivision of the

MSE and the sequence and names of MSE domains. The purpose of the MSE is to obtain a comprehensive cross-sectional description of the patient's mental state, which, when combined with the biographical and historical information of the psychiatric history, allows the clinician to make an accurate diagnosis and formulation, which are required for coherent treatment planning. The data are collected through a combination of direct and indirect means: unstructured observation while obtaining the biographical and social information, focused questions about current symptoms, and formalised psychological tests.[2] The MSE is not to be confused with the mini–mental state examination (MMSE), which is a brief neuropsychological screening test for dementia. Theoretical foundations The MSE derives from an approach to psychiatry known as descriptive psychopathology[3] or descriptive phenomenology,[4] which developed from the work of the philosopher and psychiatrist Karl Jaspers.[5] From Jaspers' perspective it was assumed that the only way to comprehend a patient's experience is through his or her own description (through an approach of empathic and non-theoretical enquiry), as distinct from an interpretive or psychoanalytic approach which assumes the analyst might understand experiences or processes of which the patient is unaware, such as defense mechanisms or unconscious drives. In practice, the MSE is a blend of empathic descriptive phenomenology and empirical clinical observation. It has been argued that the term phenomenology has become corrupted in clinical psychiatry: current usage, as a set of supposedly objective descriptions of a psychiatric patient (a synonym for signs and symptoms), is incompatible with the original meaning which was concerned with comprehending a patient's subjective experience.[6][7] Application The mental status examination is a core skill of qualified (mental) health personnel. It is a key part of the initial psychiatric assessment in an outpatient or psychiatric hospital setting. It is a systematic collection of data based on observation of the patient's behavior while the patient is in the clinician's view during the interview. The purpose is to obtain evidence of symptoms and signs of mental disorders, including danger to self and others, that are present at the time of the interview. Further, information on the patient's insight, judgment, and capacity for abstract reasoning is used to inform decisions about treatment strategy and the choice of an appropriate treatment setting.[8] It is carried out in the manner of an informal enquiry, using a combination of open and closed questions, supplemented by structured tests to assess cognition.[9] The MSE can also be considered part of the comprehensive physical examination performed by physicians and nurses although it may be performed in a cursory and abbreviated way in non-mental-health settings.[10] Information is usually recorded as free-form text using the standard headings,[11] but brief MSE checklists are available for use in emergency situations, for example, by paramedics or emergency department staff.[12][13] The information obtained in the MSE is used, together with the biographical and social information of the psychiatric history, to generate a diagnosis, a psychiatric formulation and a treatment plan. Domains The mnemonic ASEPTIC can be used to remember the domains of the MSE:[14] A - Appearance/Behavior S - Speech E - Emotion (Mood and Affect) P - Perception T - Thought Content and Process I - Insight and Judgement C - Cognition Appearance Clinicians assess the physical aspects such as the appearance of a patient, including apparent age, height, weight, and manner of dress and grooming. Colorful or bizarre clothing might suggest mania, while unkempt, dirty clothes might suggest schizophrenia or depression. If the patient appears much older than his or her chronological age this can suggest chronic poor self-care or ill-health. Clothing and accessories of a particular subculture, body modifications, or clothing not typical of the patient's gender, might give clues to personality. Observations of physical appearance might include the physical features of alcoholism or drug abuse, such as signs of malnutrition, nicotine stains, dental erosion, a rash around the mouth from inhalant abuse, or needle track marks from intravenous drug abuse. Observations can also include any odor which might suggest poor personal hygiene due to extreme self-neglect, or alcohol intoxication.[15] Weight loss could also signify a depressive disorder, physical illness, anorexia nervosa[14] or chronic anxiety.[16] Attitude Attitude, also known as rapport or cooperation,[17] refers to the patient's approach to the interview process and the quality of information obtained during the assessment.[18] Observations of attitude include whether the patient is cooperative, hostile, open or secretive.[14] Behavior Abnormalities of behavior, also called abnormalities of activity,[19] include observations of specific abnormal movements, as well as more general observations of the patient's level of activity and arousal, and observations of the patient's eye contact and gait.[14] Abnormal movements, for example choreiform, athetoid or choreoathetoid movements may indicate a neurological disorder. A tremor or dystonia may indicate a neurological condition or the side effects of antipsychotic medication. The patient may have tics (involuntary but quasi-purposeful movements or vocalizations) which may be a symptom of Tourette's syndrome. There are a range of abnormalities of movement which are typical of catatonia, such as echopraxia, catalepsy, waxy flexibility and paratonia (or gegenhalten[20]). Stereotypies (repetitive purposeless movements such as rocking or head banging) or mannerisms (repetitive quasi-purposeful abnormal movements such as a gesture or abnormal gait) may be a feature of chronic schizophrenia or autism. More global behavioural abnormalities may be noted, such as an increase in arousal and movement (described as psychomotor agitation or hyperactivity) which might reflect mania or delirium. An inability to sit still might represent akathisia, a side effect of antipsychotic medication. Similarly, a global decrease in arousal and movement (described as psychomotor retardation, akinesia or stupor) might indicate depression or a medical condition such as Parkinson's disease, dementia or delirium. The examiner would also comment on eye movements (repeatedly glancing to one side can suggest that the patient is experiencing hallucinations), and the quality of eye contact (which can provide clues to the patient's emotional state). Lack of eye contact may suggest depression or autism.[21][22][23] Mood and affect The distinction between mood and affect in the MSE is subject to some disagreement. For example, Trzepacz and Baker (1993)[24] describe affect as "the external and dynamic manifestations of a person's internal emotional state" and mood as "a person's predominant internal state at any one time", whereas Sims (1995)[25] refers to affect as "differentiated specific feelings" and mood as "a more prolonged state or disposition". This article will use the Trzepacz and Baker (1993) definitions, with mood regarded as a current subjective state as described by the patient, and affect as the examiner's inferences of the quality of the patient's emotional state based on objective observation.[26][14] Mood is described using the patient's own words, and can also be described in summary terms such as neutral, euthymic, dysphoric, euphoric, angry, anxious or apathetic. Alexithymic individuals may be unable to describe their subjective mood state. An individual who is unable to experience any pleasure may have anhedonia.  Vincent van Gogh's 1889 Self Portrait suggests the artist's mood and affect in the time leading up to his suicide.[citation needed] Affect is described by labelling the apparent emotion conveyed by the person's nonverbal behavior (anxious, sad etc.), and also by using the parameters of appropriateness, intensity, range, reactivity and mobility. Affect may be described as appropriate or inappropriate to the current situation, and as congruent or incongruent with their thought content.[14] For example, someone who shows a bland affect when describing a very distressing experience would be described as showing incongruent affect, which might suggest schizophrenia. The intensity of the affect may be described as normal, blunted affect, exaggerated, flat, heightened or overly dramatic. A flat or blunted affect is associated with schizophrenia, depression or post-traumatic stress disorder; heightened affect might suggest mania, and an overly dramatic or exaggerated affect might suggest certain personality disorders. Mobility refers to the extent to which affect changes during the interview: the affect may be described as fixed, mobile, immobile, constricted/restricted or labile. The person may show a full range of affect, in other words a wide range of emotional expression during the assessment, or may be described as having restricted affect. The affect may also be described as reactive, in other words changing flexibly and appropriately with the flow of conversation, or as unreactive. A bland lack of concern for one's disability may be described as showing la belle indifférence,[27] a feature of conversion disorder, which is historically termed "hysteria" in older texts.[28][29][30] Speech Speech is assessed by observing the patient's spontaneous speech, and also by using structured tests of specific language functions. This heading is concerned with the production of speech rather than the content of speech, which is addressed under thought process and thought content (see below). When observing the patient's spontaneous speech, the interviewer will note and comment on paralinguistic features such as the loudness, rhythm, prosody, intonation, pitch, phonation, articulation, quantity, rate, spontaneity and latency of speech.[14] Many acoustic features have been shown to be significantly altered in mental health disorders.[31] A structured assessment of speech includes an assessment of expressive language by asking the patient to name objects, repeat short sentences, or produce as many words as possible from a certain category in a set time. Simple language tests also form part of the mini-mental state examination. In practice, the structured assessment of receptive and expressive language is often reported under Cognition (see below).[32] Language assessment will allow the recognition of medical conditions presenting with aphonia or dysarthria, neurological conditions such as stroke or dementia presenting with aphasia, and specific language disorders such as stuttering, cluttering or mutism. People with autism spectrum disorders may have abnormalities in paralinguistic and pragmatic aspects of their speech. Echolalia (repetition of another person's words) and palilalia (repetition of the subject's own words) can be heard with patients with autism, schizophrenia or Alzheimer's disease. A person with schizophrenia might use neologisms, which are made-up words which have a specific meaning to the person using them. Speech assessment also contributes to assessment of mood, for example people with mania or anxiety may have rapid, loud and pressured speech; on the other hand depressed patients will typically have a prolonged speech latency and speak in a slow, quiet and hesitant manner.[33][34][35] Thought process  The paintings of the outsider artist Adolf Wölfli could be seen as a visual representation of formal thought disorder.[citation needed] Thought process in the MSE refers to the quantity, tempo (rate of flow) and form (or logical coherence) of thought. Thought process cannot be directly observed but can only be described by the patient, or inferred from a patient's speech. Form of the thought is captured in this category. One should describe the thought form as thought directed A→B (normal), versus formal thought disorders. A pattern of interruption or disorganization of thought processes is broadly referred to as formal thought disorder, and might be described more specifically as thought blocking, fusion, loosening of associations, tangential thinking, derailment of thought, knight's move thinking. Thought may be described as 'circumstantial' when a patient includes a great deal of irrelevant detail and makes frequent diversions, but remains focused on the broad topic. Circumstantial thinking might be observed in anxiety disorders or certain kinds of personality disorders.[36][37][38] Regarding the tempo of thought, some people may experience 'flight of ideas' (a manic symptom), when their thoughts are so rapid that their speech seems incoherent, although in flight of ideas a careful observer can discern a chain of poetic, syllabic, rhyming associations in the patient's speech (i.e., "I love to eat peaches, beach beaches, sand castles fall in the waves, braves are going to the finals, fee fi fo fum. Golden egg."). Alternatively an individual may be described as having retarded or inhibited thinking, in which thoughts seem to progress slowly with few associations. Poverty of thought is a global reduction in the quantity of thought and one of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. It can also be a feature of severe depression or dementia. A patient with dementia might also experience thought perseveration. Thought perseveration refers to a pattern where a person keeps returning to the same limited set of ideas. Thought content A description of thought content would be the largest section of the MSE report. It would describe a patient's suicidal thoughts, depressed cognition, delusions, overvalued ideas, obsessions, phobias and preoccupations. One should separate the thought content into pathological thought, versus non-pathological thought. Importantly one should specify suicidal thoughts as either intrusive, unwanted, and not able to translate in the capacity to act on these thoughts (mens rea), versus suicidal thoughts that may lead to the act of suicide (actus reus). Abnormalities of thought content are established by exploring individuals' thoughts in an open-ended conversational manner with regard to their intensity, salience, the emotions associated with the thoughts, the extent to which the thoughts are experienced as one's own and under one's control, and the degree of belief or conviction associated with the thoughts.[39][40][41] Delusions A delusion has three essential qualities: it can be defined as "a false, unshakeable idea or belief (1) which is out of keeping with the patient's educational, cultural and social background (2) ... held with extraordinary conviction and subjective certainty (3)",[42] and is a core feature of psychotic disorders. For instance an alliance to a particular political party, or sports team would not be considered a delusion in some societies. The patient's delusions may be described within the SEGUE PM mnemonic as: somatic, erotomanic delusions, grandiose delusions, unspecified delusions, envious delusions (c.f. delusional jealousy), persecutory or paranoid delusions, or multifactorial delusions. There are several other forms of delusions, these include descriptions such as: delusions of reference, or delusional misidentification, or delusional memories (e.g., "I was a goat last year") among others. Delusional symptoms can be reported as on a continuum from: full symptoms (with no insight), partial symptoms (where they may start questioning these delusions), nil symptoms (where symptoms are resolved), or after complete treatment there are still delusional symptoms or ideas that could develop into delusions you can characterize this as residual symptoms. Delusions can suggest several diseases such as schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, brief psychotic disorder, mania, depression with psychotic features, or delusional disorders. One can differentiate delusional disorders from schizophrenia for example by the age of onset for delusional disorders being older with a more complete and unaffected personality, where the delusion may only partially impact their life and be fairly encapsulated off from the rest of their formed personality—for example, believing that a spider lives in their hair, but this belief not affecting their work, relationships, or education. Whereas schizophrenia typically arises earlier in life with a disintegration of personality and a failure to cope with work, relationships, or education. Other features differentiate diseases with delusions as well. Delusions may be described as mood-congruent (the delusional content in keeping with the mood), typical of manic or depressive psychosis, or mood-incongruent (delusional content not in keeping with the mood) which are more typical of schizophrenia. Delusions of control, or passivity experiences (in which the individual has the experience of the mind or body being under the influence or control of some kind of external force or agency), are typical of schizophrenia. Examples of this include experiences of thought withdrawal, thought insertion, thought broadcasting, and somatic passivity. Schneiderian first rank symptoms are a set of delusions and hallucinations which have been said to be highly suggestive of a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Delusions of guilt, delusions of poverty, and nihilistic delusions (belief that one has no mind or is already dead) are typical of depressive psychosis. Overvalued Ideas An overvalued idea is an emotionally charged belief that may be held with sufficient conviction to make believer emotionally charged or aggressive but that fails to possess all three characteristics of delusion—most importantly, incongruity with cultural norms. Therefore, any strong, fixed, false, but culturally normative belief can be considered an "overvalued idea". Hypochondriasis is an overvalued idea that one has an illness, dysmorphophobia that a part of one's body is abnormal, and anorexia nervosa that one is overweight or fat. Obsessions An obsession is an "undesired, unpleasant, intrusive thought that cannot be suppressed through the patient's volition",[43] but unlike passivity experiences described above, they are not experienced as imposed from outside the patient's mind. Obsessions are typically intrusive thoughts of violence, injury, dirt or sex, or obsessive ruminations on intellectual themes. A person can also describe obsessional doubt, with intrusive worries about whether they have made the wrong decision, or forgotten to do something, for example turn off the gas or lock the house. In obsessive-compulsive disorder, the individual experiences obsessions with or without compulsions (a sense of having to carry out certain ritualized and senseless actions against their wishes). Phobias A phobia is "a dread of an object or situation that does not in reality pose any threat",[44] and is distinct from a delusion in that the patient is aware that the fear is irrational. A phobia is usually highly specific to certain situations and will usually be reported by the patient rather than being observed by the clinician in the assessment interview. Preoccupations Preoccupations are thoughts which are not fixed, false or intrusive, but have an undue prominence in the person's mind. Clinically significant preoccupations would include thoughts of suicide, homicidal thoughts, suspicious or fearful beliefs associated with certain personality disorders, depressive beliefs (for example that one is unloved or a failure), or the cognitive distortions of anxiety and depression. Suicidal thoughts The MSE contributes to clinical risk assessment by including a thorough exploration of any suicidal or hostile thought content. Assessment of suicide risk includes detailed questioning about the nature of the person's suicidal thoughts, belief about death, reasons for living, and whether the person has made any specific plans to end his or her life. The most important questions to ask are: Do you have suicidal feeling now; have you ever attempted suicide (highly correlated with future suicide attempts); do you have plans to commit suicide in the future; and, do you have any deadlines where you may commit suicide (e.g., numerology calculation, doomsday belief, Mother's Day, anniversary, Christmas).[45] Perceptions A perception in this context is any sensory experience, and the three broad types of perceptual disturbance are hallucinations, pseudohallucinations and illusions. A hallucination is defined as a sensory perception in the absence of any external stimulus, and is experienced in external or objective space (i.e. experienced by the subject as real). An illusion is defined as a false sensory perception in the presence of an external stimulus, in other words a distortion of a sensory experience, and may be recognized as such by the subject. A pseudohallucination is experienced in internal or subjective space (for example as "voices in my head") and is regarded as akin to fantasy. Other sensory abnormalities include a distortion of the patient's sense of time, for example déjà vu, or a distortion of the sense of self (depersonalization) or sense of reality (derealization).[14] Hallucinations can occur in any of the five senses, although auditory and visual hallucinations are encountered more frequently than tactile (touch), olfactory (smell) or gustatory (taste) hallucinations. Auditory hallucinations are typical of psychoses: third-person hallucinations (i.e. voices talking about the patient) and hearing one's thoughts spoken aloud (gedankenlautwerden or écho de la pensée) are among the Schneiderian first rank symptoms indicative of schizophrenia, whereas second-person hallucinations (voices talking to the patient) threatening or insulting or telling them to commit suicide, may be a feature of psychotic depression or schizophrenia. Visual hallucinations are generally suggestive of organic conditions such as epilepsy, drug intoxication or drug withdrawal. Many of the visual effects of hallucinogenic drugs are more correctly described as visual illusions or visual pseudohallucinations, as they are distortions of sensory experiences, and are not experienced as existing in objective reality. Auditory pseudohallucinations are suggestive of dissociative disorders. Déjà vu, derealization and depersonalization are associated with temporal lobe epilepsy and dissociative disorders.[46][47] Cognition Further information: Cognitive test This section of the MSE covers the patient's level of alertness, orientation, attention, memory, visuospatial functioning, language functions and executive functions. Unlike other sections of the MSE, use is made of structured tests in addition to unstructured observation. Alertness is a global observation of level of consciousness, i.e. awareness of and responsiveness to the environment, and this might be described as alert, clouded, drowsy, or stuporous. Orientation is assessed by asking the patient where he or she is (for example what building, town and state) and what time it is (time, day, date). Attention and concentration are assessed by several tests, commonly serial sevens test subtracting 7 from 100 and subtracting 7 from the difference 5 times. Alternatively: spelling a five-letter word backwards, saying the months or days of the week in reverse order, serial threes (subtract three from twenty five times), and by testing digit span. Memory is assessed in terms of immediate registration (repeating a set of words), short-term memory (recalling the set of words after an interval, or recalling a short paragraph), and long-term memory (recollection of well known historical or geographical facts). Visuospatial functioning can be assessed by the ability to copy a diagram, draw a clock face, or draw a map of the consulting room. Language is assessed through the ability to name objects, repeat phrases, and by observing the individual's spontaneous speech and response to instructions. Executive functioning can be screened for by asking the "similarities" questions ("what do x and y have in common?") and by means of a verbal fluency task (e.g. "list as many words as you can starting with the letter F, in one minute"). The mini-mental state examination is a simple structured cognitive assessment which is in widespread use as a component of the MSE. Mild impairment of attention and concentration may occur in any mental illness where people are anxious and distractible (including psychotic states), but more extensive cognitive abnormalities are likely to indicate a gross disturbance of brain functioning such as delirium, dementia or intoxication. Specific language abnormalities may be associated with pathology in Wernicke's area or Broca's area of the brain. In Korsakoff's syndrome there is dramatic memory impairment with relative preservation of other cognitive functions. Visuospatial or constructional abnormalities here may be associated with parietal lobe pathology, and abnormalities in executive functioning tests may indicate frontal lobe pathology. This kind of brief cognitive testing is regarded as a screening process only, and any abnormalities are more carefully assessed using formal neuropsychological testing.[48] The MSE may include a brief neuropsychiatric examination in some situations. Frontal lobe pathology is suggested if the person cannot repetitively execute a motor sequence (e.g. "paper-scissors-rock"). The posterior columns are assessed by the person's ability to feel the vibrations of a tuning fork on the wrists and ankles. The parietal lobe can be assessed by the person's ability to identify objects by touch alone and with eyes closed. A cerebellar disorder may be present if the person cannot stand with arms extended, feet touching and eyes closed without swaying (Romberg's sign); if there is a tremor when the person reaches for an object; or if he or she is unable to touch a fixed point, close the eyes and touch the same point again. Pathology in the basal ganglia may be indicated by rigidity and resistance to movement of the limbs, and by the presence of characteristic involuntary movements. A lesion in the posterior fossa can be detected by asking the patient to roll his or her eyes upwards (Parinaud's syndrome). Focal neurological signs such as these might reflect the effects of some prescribed psychiatric medications, chronic drug or alcohol use, head injuries, tumors or other brain disorders.[49][50][51][52][53] Insight The person's understanding of his or her mental illness is evaluated by exploring his or her explanatory account of the problem, and understanding of the treatment options. In this context, insight can be said to have three components: recognition that one has a mental illness, compliance with treatment, and the ability to re-label unusual mental events (such as delusions and hallucinations) as pathological.[54] As insight is on a continuum, the clinician should not describe it as simply present or absent, but should report the patient's explanatory account descriptively.[55] Impaired insight is characteristic of psychosis and dementia, and is an important consideration in treatment planning and in assessing the capacity to consent to treatment.[56] Anosognosia is the clinical term for the condition in which the patient is unaware of their neurological deficit or psychiatric condition.[14][57] Judgment Judgment refers to the patient's capacity to make sound, reasoned and responsible decisions. One should frame judgement to the functions or domains that are normal versus impaired (e.g., poor judgement is isolated to petty theft, able to function in relationships, work, academics). Traditionally, the MSE included the use of standard hypothetical questions such as "what would you do if you found a stamped, addressed envelope lying in the street?"; however contemporary practice is to inquire about how the patient has responded or would respond to real-life challenges and contingencies. Assessment would take into account the individual's executive system capacity in terms of impulsiveness, social cognition, self-awareness and planning ability. Impaired judgment is not specific to any diagnosis but may be a prominent feature of disorders affecting the frontal lobe of the brain. If a person's judgment is impaired due to mental illness, there might be implications for the person's safety or the safety of others.[58] Cultural considerations There are potential problems when the MSE is applied in a cross-cultural context, when the clinician and patient are from different cultural backgrounds. For example, the patient's culture might have different norms for appearance, behavior and display of emotions. Culturally normative spiritual and religious beliefs need to be distinguished from delusions and hallucinations — these may seem similar to one who does not understand that they have different roots. Cognitive assessment must also take the patient's language and educational background into account. Clinician's racial bias is another potential confounder. Consultation with cultural leaders in community or clinicians when working with Aboriginal people can help guide if any cultural phenomena has been considered when completing an MSE with Aboriginal patients and things to consider from a cross-cultural context.[59][60][61] Children There are particular challenges in carrying out an MSE with young children and others with limited language such as people with intellectual impairment. The examiner would explore and clarify the individual's use of words to describe mood, thought content or perceptions, as words may be used idiosyncratically with a different meaning from that assumed by the examiner. In this group, tools such as play materials, puppets, art materials or diagrams (for instance with multiple choices of facial expressions depicting emotions) may be used to facilitate recall and explanation of experiences.[62] |

精神状態検査(MSE)は、神経学的および精神医学的診療における臨床

評価プロセスの重要な部分である。MSEは、ある時点における患者の心理的機能を、外見、態度、行動、気分と感情、発話、思考過程、思考内容、知覚、認