考古学を人民に取り戻すには?

Public and Community Archaeology

☆ 考古学者が「パブリック・アーケオロジー」という言葉を使い始めた当初は、一般市民が資金を提供する考古学プロジェクトを指していた。その後、講義や解説 標識、遺跡や発掘のツアーなどを通して、一般の人々を考古学に参加させる活動を含む意味を持つようになった。今日、この言葉、そして考古学者がコミュニ ティとどのように関わるかは、これをはるかに超えている。パブリック・アーケオロジストは、一般市民を聴衆として、顧客として、また対等なパートナーとし て考古学研究に参加させることができる様々な革新的な方法の成果を調査する。

☆コ ミュニティ考古学とは、人々による人々のための考古学である。この分野はパブリック・アーケオロジーとしても知られている。コミュニティ考古学はパブリッ ク・アーケオロジーの一形態に過ぎず、ここで説明する以外にも様々な実践形態が含まれるという説もある[1]。コミュニティ考古学プロジェクトの設計、目 標、関与するコミュニティ、手法は様々であるが、全てのコミュニティ考古学プロジェクトに見られる2つの一般的な側面がある。第一に、コミュニティ考古学 は「コミュニティが直接関心を持つ調査プロジェクトの計画と実施に関与する」[2]。第二に、コミュニティ考古学者は一般的に、自分たちが利他的な変化を もたらしていると信じている。このテーマに関する多くの研究者は、コミュニティの協力にはあらかじめ決められた方法があるわけではないと主張している [3]。また、国や地域によって、考古学的コミュニティ、法律、制度、コミュニティのタイプに共通点があるため、類似点も見られる。また、パブリック・ アーケオロジーは広義には考古学的な「商品」の生産と消費と定義できることが示唆されている[4]。

★

考古学倫理とは、物質的な過去の研究を通じて提起される道徳的な問題を指す。考古学哲学の一分野である。

考古学者は高い水準で調査を行い、知的財産権法、安全衛生規則、その他の法的義務を遵守する義務がある。この分野の考古学者は、考古学的資源の保存と管理

に努め、遺骨を尊厳と敬意を持って扱い、アウトリーチ活動を奨励することが求められている。これらの倫理規範を守らない専門家には制裁が設けられている。

考古学の倫理に関する問題は、1960年代から1970年代にかけて、北米や西ヨーロッパで発生し始めた。1970年にユネスコが世界文化を保護するため

に批准したことは、倫理基準を実施するための最も早い行動の一つであった。生きている人々の研究を伴う民族考古学的研究を行う考古学者は、ニュルンベルク

綱領(1947年)やヘルシンキ宣言(1964年)によって定められたガイドラインに従うことが求められている。

| When archaeologists

first started using the term "public archaeology," it referred to

archaeological projects funded by the public. Later, it took on

meanings that included activities that engage the public in archaeology

through lectures, interpretive signs, or tours of sites and

excavations. Today, the term, and how archaeologists engage with

communities, goes far beyond this. Public archaeologists investigate

the outcomes of the various innovative ways we can engage the public in

archaeological research as an audience, as clients, and as equal

partners. There are different areas of specialization within public archaeological practice, such as heritage education, cultural resource management (CRM), interpretation, museum studies, community collaboration, ethics, cultural tourism, among others. There are also different research objectives including education, awareness, activism, community-building, civic engagement, and social justice. Archaeologists have many names for projects in which archaeologists and interested members of the public work together. These include "outreach," "public archaeology," "community archaeology," "community empowerment," "collaborative archaeology," and "applied heritage research." As the goals and methods of these projects change, so does the language. As such, no fixed definition of public outreach is used here. Rather, these pages are designed to provide an understanding about the different ways archaeologists practice public archaeology. Community Involvement in Archaeology Community groups, descendants, elders, and local historians are just some of the many interested parties who work side-by-side archaeologists in exploring the past. Archaeologists frequently look to local residents for historical information, for assistance in the actual excavation of a site, or for research partnerships. Many archaeologists encourage the public to be directly involved in archaeological projects. After all, it is their community and their heritage being studied! You could become an active participant in archaeological research and determine for yourself what archaeological resources mean to you and your community. What is Public Archaeology? https://www.saa.org/education-outreach/public-outreach/what-is-public-archaeology |

考古学者が「パブリック・アーケオロジー」と

いう言葉を使い始めた当初は、一般市民が資金を提供する考古学プロジェクトを指していた。その後、講義や解説標識、遺跡や発掘のツアーなどを通して、一般

の人々を考古学に参加させる活動を含む意味を持つようになった。今日、この言葉、そして考古学者がコミュニティとどのように関わるかは、これをはるかに超

えている。パブリック・アーケオロジストは、一般市民を聴衆として、顧客として、また対等なパートナーとして考古学研究に参加させることができる様々な革

新的な方法の成果を調査する。 公共考古学の実践には、遺産教育、文化資源管理(CRM)、解説、博物館学、地域社会との連携、倫理、文化観光など、さまざまな専門分野がある。また、教 育、認識、活動、コミュニティ形成、市民参加、社会正義など、研究目的もさまざまである。 考古学者と関心のある一般市民が協力して行うプロジェクトには、考古学者によって様々な呼び名がある。例えば、「アウトリーチ」、「公共考古学」、「コ ミュニティ考古学」、「コミュニティのエンパワーメント」、「共同考古学」、「応用遺産調査 」などである。これらのプロジェクトの目的や方法が変われば、言葉も変わる。 そのため、ここではパブリック・アウトリーチの固定した定義は用いない。むしろこのページは、考古学者がパブリック・アーケオロジーを実践するさまざまな 方法について理解を深めるためのものである。 考古学へのコミュニティーの参加 地域団体、子孫、長老、地元の歴史家などは、考古学者と肩を並べて過去を探求する多くの利害関係者のほんの一部に過ぎない。考古学者は、歴史的な情報、遺 跡の発掘作業への協力、研究パートナーとして地域住民を探すことが多い。 多くの考古学者は、一般の人々が考古学プロジェクトに直接参加することを奨励している。結局のところ、自分たちのコミュニティや遺産が研究されているのだ から!あなたも考古学研究に積極的に参加し、考古学的資源があなたやあなたのコミュニティにとってどのような意味を持つのか、自分自身で判断してみてはい かがだろうか。 |

| Community

archaeology is archaeology by the people for the people. The field

is also known as public archaeology. There is debate about whether the

terms are interchangeable; some believe that community archaeology is

but one form of public archaeology, which can include many other modes

of practice, in addition to what is described here.[1] The design,

goals, involved communities, and methods in community archaeology

projects vary greatly, but there are two general aspects found in all

community archaeology projects. First, community archaeology involves

communities "in the planning and carrying out of research projects that

are of direct interest to them".[2] Second, community archaeologists

generally believe they are making an altruistic difference. Many

scholars on the subject have argued that community collaboration does

not have a pre-set method to follow.[3] Although not found in every

project, there are a number of recurring purposes and goals in

community archaeology. Similarities are also found in different

countries and regions—due to commonalities in archaeological

communities, laws, institutions, and types of communities. It has also

been suggested that public archaeology can be defined in a broad sense

as the production and consumption of archaeological "commodities".[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Community_archaeology |

コミュニティ考古学とは、人々による人々のための考古学である。この分

野はパブリック・アーケオロジーとしても知られている。コミュニティ考古学はパブリック・アーケオロジーの一形態に過ぎず、ここで説明する以外にも様々な

実践形態が含まれるという説もある[1]。コミュニティ考古学プロジェクトの設計、目標、関与するコミュニティ、手法は様々であるが、全てのコミュニティ

考古学プロジェクトに見られる2つの一般的な側面がある。第一に、コミュニティ考古学は「コミュニティが直接関心を持つ調査プロジェクトの計画と実施に関

与する」[2]。第二に、コミュニティ考古学者は一般的に、自分たちが利他的な変化をもたらしていると信じている。このテーマに関する多くの研究者は、コ

ミュニティの協力にはあらかじめ決められた方法があるわけではないと主張している[3]。また、国や地域によって、考古学的コミュニティ、法律、制度、コ

ミュニティのタイプに共通点があるため、類似点も見られる。また、パブリック・アーケオロジーは広義には考古学的な「商品」の生産と消費と定義できること

が示唆されている[4]。 |

| Community archaeology by country Community archaeology in the United States In the United States community archaeology can broadly be separated into three distinct types: projects that collaborate with indigenous peoples, projects that collaborate with other local and descendant communities, and outreach specifically for public education. Indigenous peoples Archaeologists have a long history of excavating indigenous sites without consulting or collaborating with indigenous peoples. Points of tension include, but are not limited to, the excavation and collection of human remains, the destruction and collections of sacred sites and objects, and archaeological interpretations that ignored or contradicted the opinions and beliefs of indigenous peoples.[5] Even the so-called ‘father of American archaeology’ Thomas Jefferson excavated adults and sub-adults from a site still visited by indigenous people[6] and Pilgrims plundered an indigenous grave days after anchoring at Cape Cod.[7] Indeed, "American Indians tend to equate archaeologists with pothunters, grave looters, or, even worse, animals who feast off of the dead (i.e., the 'Vulture Culture'). Most do not trust the system supposedly designed to protect their heritage."[8] Also, any prehistoric archaeological excavation in the Americas will involve the material products left by the ancestors of indigenous peoples of the Americas. For these reasons, community archaeology projects with both federally and non-federally recognized indigenous peoples are different from those that collaborate with local and other descent communities. Some have found that collaboration can be a means to "break down barriers" between American Indians and archaeologists, and that in collaboration "[e]ach side learns something from the other."[9] There are many unique ways archaeological collaboration can benefit indigenous peoples. Kerber reports that: . . . archaeology benefits American Indians and First People of Canada, respectively, by contributing important historical information; assisting in land claims; managing cultural resources and burial for protection from current and future impacts; promoting sovereignty; offering employment opportunities through field work, interpretive centers, and tourism; educating the young; aiding in nation (re-)building and self-discovery; demonstrating innovative responses of past groups to changing environmental and social circumstance; and providing populations themselves with skills and experience in doing archaeology. Clearly, collaborative archaeology is not a panacea for the difficulties facing indigenous groups, but in certain situations . . . it can be a powerful tool[10] Dean and Perrelli have noted that collaboration with indigenous peoples is only new "from the perspective of the dominant culture"[11] and that "American Indian people have been cooperating and collaborating with their neighbors and visitors for hundreds of years."[12] Some have argued that archaeologists should attempt to collaborate and repatriate materials to non-federally recognized tribes in addition to federally recognized ones.[13] Blume has contended that when collaborating with indigenous peoples, projects should design "forms of public outreach specifically for" those audiences.[14] Many recognized and non-recognized tribes have explicitly asked archaeologists for consolation and collaboration.[15] Two particularly well known examples of indigenous collaboration are Janet Spector's book What does this Awl Mean and the Ozette Indian Village Archeological Site.[16] Collaborations have occurred throughout the United States, including with indigenous peoples in Alaska.[17] Many tribes have also begun hiring full-time tribal archaeologists. Local and descendant communities Many other community archaeology projects occur in the United States aside from those with indigenous peoples of the Americas. These projects focus on local communities, descendant communities, and descendant diasporas.[18] A goal of some of these projects has been to recover and publicly present forgotten aspects of the race relations in local communities—such as histories of slavery and segregation.[19] Public education As a form of public outreach and collaboration, many archaeology projects in the United States have taken steps to present their work in schools and to children. These projects vary from a "one time" presentation to local schools, to long-term commitments in which public education is an intricate part of the research design.[20] Community archaeology in the United Kingdom History Community archaeology in the United Kingdom has existed for many years, although only recently has it come to be known by that name. The roots of archaeology in the United Kingdom lie in the tradition of antiquarian and amateur work,[21] and many county or locally based archaeology and history societies founded over a century ago have continued to enable the involvement of local people in archaeology. Up until the 1970s volunteers often had opportunities to initiate or take part in archaeological investigations. Since then the recognition that more investigations were required by the subsequent establishment of archaeological units eroded some of these opportunities; more significantly the introduction of archaeology to the legalities of the planning process through Planning Policy Guidance note 16 (PPG16) and the full professionalization of archaeology, has made public participation in archaeology extremely limited. Public participation Archaeology (including historic buildings, landscapes and monuments, as well as ‘traditional’ archaeology) is about people and the discovery of the past. As a subject, archaeology in the United Kingdom has been increasingly brought into the public eye in recent years. The most common form of community archaeology in the United Kingdom has come from the grass roots level. Local groups are smaller than the large, county societies, and operate in their own area and at their own pace. The work produced is often of a high standard, reflecting the amount of time and effort local people are willing to put into local projects they themselves initiated. Increasingly, over the last two decades, public participation has been pushed aside by developer-led, commercial archaeology, with the bulk of work going to contracting units.[22] The reasons behind this relate to the professionalization of the discipline and the implementation of PPG16, as discussed by Faulkner who proposed a return to community-led archaeology in his article entitled "Archaeology from below".[23] A recent investigation carried out by the Council for British Archaeology[24] identified the main perceived barriers to public participation, gave examples of good practice in encouraging public participation, and made several recommendations for future improvements. Its first recommendation was the establishment of full-time Community Archaeologist posts across the country, as it states, "such dedicated posts represent a very effective way of stimulating and guiding public participation at a local level."[25] One of the longest running and most successful community archaeology projects is based in Leicestershire.[26] Leicestershire County Council (which incorporates the museum service) established the project in 1976 and today they have 400 members within 20 local groups across the county. Peter Liddle (Keeper of Archaeology) is the Community Archaeologist and was probably the first to use the term ‘community archaeology’ as the title for his fieldworker's handbook.[27] The Valletta Convention The Valletta Convention affects the work of non-official or amateur groups who have been, or are, investigating their local historic environment. The European Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage (Revised) was signed in Valletta in 1992, and ratified by the UK government before coming into force on 21 March 2001.[28] Article 3 of the document caused considerable debate as it stated that all archaeological work should be carried out by suitably qualified, authorized people.[29] This form of ‘licensing’ for archaeologists already exists in the rest of Europe, where it has limited the work of voluntary archaeologists and local societies. Community archaeology in Australia Australian Archaeology has a long history of community archaeology, with established disciplines and laws.[30] In her review of community archaeology, Marshall found that there is an "antipodean dominance" in field community archaeology, suggesting that Australian community archaeology may be more established as a discipline than in other countries.[31] This is reflected in anthologies on community archaeology in Harrison and Williamson[32] and Sarah Colley.[33] Generally Australian community archaeology projects have involved collaboration between archaeologists and aboriginal tribes similar to archaeologists in the United States collaborate with American Indians.[34] Community archaeology outside of the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia Hundreds, if not thousands, of community archaeology projects have occurred throughout the world—including in Brazil,[35] Canada,[36] Egypt,[37] Mexico,[38] the People's Republic of Bangladesh,[39] South Africa,[40] Thailand (Praicharnjit 2006, www.archaeopen.com) and Turkey.[41] Wikipedia would greatly appreciate if scholars, students, or members of communities affiliated with Community Archaeology projects would contribute to this page. |

国別コミュニティ考古学 アメリカにおけるコミュニティ考古学 アメリカにおけるコミュニティ考古学は、先住民族と協力するプロジェクト、他の地域や子孫コミュニティと協力するプロジェクト、そして特に公教育のための アウトリーチの3つに大別される。 先住民 考古学者たちは、先住民との協議や協力なしに先住民の遺跡を発掘してきた長い歴史がある。緊張の原因としては、人骨の発掘や収集、聖地や聖遺物の破壊や収 集、先住民の意見や信仰を無視したり矛盾する考古学的解釈などが挙げられるが、これらに限定されるものではない。 [5] いわゆる「アメリカ考古学の父」と呼ばれたトーマス・ジェファーソンでさえ、先住民が今も訪れている場所から成人と亜成年を発掘したし[6]、ピルグリム はケープコッドに停泊して数日後に先住民の墓を略奪した[7]。実際、「アメリカン・インディアンは考古学者をポットハンターや墓の略奪者、さらに悪いこ とに死者をごちそうにする動物(つまり『ハゲタカ文化』)と同一視する傾向がある、 ハゲタカ文化")と同一視する傾向がある。また、アメリカ大陸における先史時代の考古学的発掘には、アメリカ大陸の先住民の祖先が残した物質的産物が関 わってくる。このような理由から、連邦政府および連邦政府非公認の先住民族とのコミュニティ考古学プロジェクトは、地元やその他の降下コミュニティとの共 同作業とは異なっている。共同研究が、アメリカ・インディアンと考古学者との間の「障壁を取り払う」手段となりうること、また共同研究において「それぞれ が他方から何かを学ぶ」[9]ことができることを発見した人もいる。Kerberは次のように報告している: . 考古学は、重要な歴史的情報の提供、土地請求の支援、現在および将来の影響から保護するための文化資源と埋葬の管理、主権の促進、フィールドワーク、解説 センター、観光による雇用機会の提供、若者の教育、国家の(再)建設と自己発見の支援、環境と社会状況の変化に対する過去の集団の革新的な対応の実証、そ して考古学を行うためのスキルと経験の提供によって、それぞれアメリカ・インディアンとカナダの先住民に利益をもたらしている。明らかに、共同考古学は先 住民族が直面する困難に対する万能薬ではないが、特定の状況においては......。強力な手段となりうる[10]。 DeanとPerrelliは、先住民との共同研究は「支配的な文化から見れば」新しいものでしかなく[11]、「アメリカ・インディアンの人々は何百年 もの間、隣人や訪問者と協力し、共同作業を行ってきた」[12]と指摘している。 [14] 多くの公認部族や非公認部族は、考古学者に慰問や協力を明確に求めている[15]。先住民との協力の例として特によく知られているのは、ジャネット・スペ クターの著書『What does this Awl Mean』とオゼット・インディアン・ビレッジ考古学遺跡である[16]。 地域コミュニティと子孫コミュニティ アメリカ大陸の先住民との共同研究以外にも、アメリカでは多くのコミュニティ考古学プロジェクトが行われている。これらのプロジェクトの目的は、奴隷制度 や隔離の歴史など、地域社会における人種関係の忘れられた側面を回復し、公に提示することである[18]。 公教育 公共への働きかけや協力の一形態として、アメリカでは多くの考古学プロジェクトが、学校や子供たちに自分たちの仕事を紹介する手段を講じている。このよう なプロジェクトは、地元の学校で「一度だけ」プレゼンテーションを行うものから、長期的に公教育が研究デザインの複雑な部分を占めるものまで様々である [20]。 イギリスのコミュニティ考古学 歴史 イギリスにおけるコミュニティ考古学は何年も前から存在していたが、その名で知られるようになったのはごく最近のことである。イギリスにおける考古学の ルーツは、古美術やアマチュア活動の伝統にあり[21]、100年以上前に設立された多くの郡や地域に根ざした考古学・歴史学会が、地域の人々の考古学へ の参加を可能にし続けてきた。1970年代までは、ボランティアが考古学的調査を始めたり参加したりする機会がしばしばあった。さらに重要なことは、 Planning Policy Guidance note 16 (PPG16)を通して考古学が計画プロセスの法的事項に導入され、考古学が完全に専門化されたことである。 市民参加 考古学(歴史的建造物、景観、モニュメント、そして「伝統的」考古学を含む)は、人々と過去の発見に関わるものである。その対象として、イギリスの考古学 は近年ますます一般に知られるようになってきている。イギリスにおけるコミュニティ考古学の最も一般的な形態は、草の根レベルのものである。地元のグルー プは、郡単位の大規模な協会よりも規模が小さく、それぞれの地域でそれぞれのペースで活動している。地元の人々が、自分たちで始めた地元のプロジェクトに 時間と労力を惜しまないことを反映して、生み出される作品は高い水準にあることが多い。この20年間で、開発業者主導の商業的な考古学に押され、一般市民 の参加はますます少なくなっている。 [23] 英国考古学評議会(Council for British Archaeology)が最近実施した調査[24]では、市民参加に対する主な障壁を特定し、市民参加を促すための優れた実践例を示し、将来の改善に向 けていくつかの提言を行った。その最初の提言は、全国にコミュニティ考古学者の専任ポストを設置することであり、「そのような専任ポストは、地域レベルで の市民参加を刺激し導く非常に効果的な方法である」と述べている[25]。ピーター・リドル(Keeper of Archaeology)はコミュニティ考古学者であり、おそらく「コミュニティ考古学」という言葉をフィールドワーカーのハンドブックのタイトルとして 最初に使用した人物である[27]。 バレッタ条約 ヴァレッタ条約は、地元の歴史的環境を調査している、あるいは調査している非公式団体やアマチュア団体の活動に影響を及ぼす。考古学的遺産の保護に関する 欧州条約(改訂版)」は1992年にヴァレッタで調印され、2001年3月21日に発効する前に英国政府によって批准された[28]。この文書の第3条 は、すべての考古学的作業は適切な資格を有し、権限を与えられた人々によって行われるべきであると述べており、大きな議論を呼んだ[29]。 オーストラリアにおけるコミュニティ考古学 オーストラリア考古学にはコミュニティ考古学の長い歴史があり、確立された学問分野と法律がある[30]。Marshallはコミュニティ考古学のレ ビューの中で、フィールドのコミュニティ考古学には「対蹠的優位性」があることを発見し、オーストラリアのコミュニティ考古学は他の国よりも学問分野とし て確立している可能性を示唆した[31]。 [このことは、Harrison and Williamson[32]やSarah Colley[33]のコミュニティ考古学に関するアンソロジーにも反映されている。一般的にオーストラリアのコミュニティ考古学のプロジェクトでは、ア メリカの考古学者がアメリカン・インディアンと共同研究するのと同様に、考古学者と原住民部族との共同研究が行われている[34]。 アメリカ、イギリス、オーストラリア以外のコミュニティ考古学 ブラジル、[35]カナダ、[36]エジプト、[37]メキシコ、[38]バングラデシュ人民共和国、[39]南アフリカ、[40]タイ (Praicharnjit 2006, www.archaeopen.com)、トルコ[41]などである。ウィキペディアでは、コミュニティ考古学プロジェクトに関連する学者、学生、コミュ ニティのメンバーがこのページに貢献してくれることを大いに歓迎する。 |

| Communities Definitions In a reduced sense, communities are aggregations of people that "are seldom, if ever, monocultural and are never of one mind."[42] "For understanding the goals of community archaeology projects it is helpful to classify these communities into three broad and overlapping types. That is local communities, local descent communities, and non-local descent communities or diasporas."[43] Local communities and non-local descent communities Descent communities are those ancestrally linked to a site. Descent communities located within proximity of the site are local descent communities, and non-local descent communities "are groups that are linked to a site, but that live in another location, potentially hundreds or even thousands of miles away."[44] Archaeological collaborations with local descent communities include those that focus on proto-historic sites and collaborate with American Indians ancestrally linked to them, or plantation excavations that incorporate collaborations with the local ancestors of slaves who worked at the plantation.[45] Examples of community projects involving non-local descent communities include those where archaeologists set up museums for non-locals to come and visit.[46] Non-descent local communities Local communities are simply communities that live "either on or close to a site"[47] and non-descent local communities are those not believed ancestrally related to the site. This category includes landowners, local volunteers, local organizations, and local stakeholders. Some feel that many of the major issues in community archaeology are applicable to non-local descent communities, and that these collaborations are crucial for archaeologists seeking to understand the local social context of their work.[41] |

コミュニティ 定義 縮小された意味でのコミュニティとは、「単文化的であることはめったになく、一心同体であることもない」人々の集合体である[42]。「コミュニティ考古 学プロジェクトの目標を理解するためには、これらのコミュニティを3つの大まかで重複するタイプに分類することが役に立つ。すなわち、地域コミュニティ、 地域系コミュニティ、非地域系コミュニティあるいはディアスポラである」[43]。 地域コミュニティと非地域的な子孫コミュニティ 降下コミュニティとは、その土地と先祖代々つながっているコミュニティのことである。遺跡の近隣に位置する先祖共同体は地域先祖共同体であり、非地域先祖 共同体は「遺跡に関連しているが、別の場所、場合によっては数百マイル、数千マイル離れた場所に住んでいる集団」である。 「地元の子孫コミュニティとの考古学的共同研究としては、原歴史的遺跡に焦点を当て、その遺跡に先祖代々つながっているアメリカン・インディアンとの共同 研究や、プランテーションで働く奴隷の地元の先祖との共同研究を組み込んだプランテーションの発掘などがある[45]。非地元の子孫コミュニティが関わる コミュニティ・プロジェクトの例としては、考古学者が地元の人以外でも見学できるように博物館を設置する場合などがある[46]。 非地方系コミュニティ 地域コミュニティとは、単に「遺跡内または遺跡の近くに住んでいる」コミュニティのことであり[47]、非遺伝子地域コミュニティとは、遺跡と先祖的に関 係があると考えられていないコミュニティのことである。このカテゴリーには、土地所有者、地元ボランティア、地元組織、地元利害関係者が含まれる。コミュ ニティ考古学における主要な問題の多くは、非地元的な子孫コミュニティにも適用可能であり、こうした協力関係は、自分たちの仕事の地域的な社会的背景を理 解しようとする考古学者にとって極めて重要であると考える者もいる[41]。 |

| Major issues Decolonization of archaeology Archaeology is a practice whose history is entrenched in colonialism, and many archaeologists and communities contend that archaeology has never escaped its colonial past.[48] A major goal of many community archaeologists and community archaeology projects is to decolonize archaeology.[49] In decolonizing archaeology, archaeologists are trying to give communities more control over every stage in the archaeological process. For example, some programs have begun attempting to bring Indigenous leaders together globally to discuss shared methods for decolonization through archaeological collaboration.[50] Community archaeology, the sharing of archaeological knowledge, and the below major issues have been viewed as a crucial parts of decolonization.[51] Publishing with open access licenses to enable anyone to read archaeological literature without financial barriers is another aspect of decolonization.[52] Self-reflexivity Community archaeology can alleviate or prevent violence towards communities that archaeology may cause. Self-reflexivity in archaeology can be thought of as looking into a metaphorical mirror, and includes attempts to make explicitly make visible the violence—such as colonization—archaeology has been implicitly part of.[53] Self-reflexivity in archaeology can be part of community presentation, as a means of breaking down imbalanced power dynamics between non-academic communities and archaeologists.[54] Self-reflection amongst archaeologists—such as discussion with community members, writing field journals, and professional writings about self-reflection—can also be a means for identifying unethical and violent aspects of archaeological projects.[55] Public outreach Public outreach, in archaeology, is a form of science outreach that attempts to present archaeological findings to non-archaeologists. Public outreach is usually a crucial aspect of most community archaeology projects.[56] Public outreach can take many forms, from a onetime presentation to a local school to long-term agreements with local communities in developing intricate public outreach programs.[57][41] Many feel that archaeology and archaeological findings have been greatly distorted by the popular media and through western associations, and that public outreach is the only way non-archaeologists will be able to understand what archaeologists actually do and find.[58] On another level, public participation can mean local people taking part in training excavations, and this type of involvement results in a hands-on learning experience in archaeological techniques. |

主要課題 考古学の脱植民地化 多くのコミュニティ考古学者やコミュニティ考古学プロジェクトの主要な目標は、考古学を脱植民地化することである[49]。脱植民地化において考古学者 は、考古学的プロセスのあらゆる段階をコミュニティがよりコントロールできるようにしようとしている。例えば、先住民の指導者を世界的に集め、考古学的な 協力を通じて脱植民地化のための共有方法を議論する試みも始まっている[50]。コミュニティ考古学、考古学的知識の共有、そして以下の主要な問題は、脱 植民地化の重要な部分とみなされている[51]。 経済的な障壁なしに誰でも考古学文献を読むことができるようにオープンアクセスライセンスで出版することも、脱植民地化のもう一つの側面である[52]。 自己反省 コミュニティ考古学は、考古学が引き起こす可能性のあるコミュニティに対する暴力を緩和したり防止したりすることができる。考古学における自己反省は、隠 喩的な鏡を覗き込むように考えることができ、考古学が暗黙のうちに加担してきた植民地化などの暴力を明確に可視化する試みも含まれる[53]。 [54]。コミュニティ・メンバーとの議論、フィールド・ジャーナルの執筆、自己反省に関する専門的な著作など、考古学者の自己反省は、考古学プロジェク トの非倫理的で暴力的な側面を特定する手段にもなりうる[55]。 パブリック・アウトリーチ 考古学におけるパブリック・アウトリーチとは、考古学の研究成果を考古学者以外の人々に紹介しようとする科学的アウトリーチの一形態である。パブリック・ アウトリーチは通常、ほとんどのコミュニティ考古学プロジェクトの重要な側面である[56]。パブリック・アウトリーチには、地元の学校への一回限りのプ レゼンテーションから、複雑なパブリック・アウトリーチ・プログラムの開発における地元コミュニティとの長期的な合意まで、様々な形態がある。 [57][41]多くの人々は、考古学や考古学的知見は一般的なメディアや西洋の団体によって大きく歪められてきたと感じており、パブリック・アウトリー チこそが、考古学者でない人々が考古学者が実際に何をし、何を発見しているのかを理解できる唯一の方法であると考えている[58]。別の側面では、市民参 加は地元の人々が発掘調査に参加することを意味する場合もあり、このような参加は考古学的技術の実践的な学習経験をもたらす。 |

| Approaches to community

archaeology Community interpretation Interpretation of archaeological findings by the community is a quintessential aspect of community archaeology, and is viewed as an important aspect of "decolonizing archaeology" and giving non-archaeologists power to interpreting the past.[59] Multiple community archaeologists have created projects that give the community a major role in the interpretation and dissemination of archaeological information.[30] Community participation is not relegated to the interpretation of discoveries but includes contributions to any aspect of archaeology—such as theory[60] and project goals.[61] Community involvement ends the exclusive control that archaeologists have had over the material past, and gives non-archaeologists a chance to interpret the past.[53] Many archaeologists now argue that the incorporation of local knowledge is important to archaeology's survival as an academic discipline.[62] The degree of interpretive control communities have in archaeological projects vary from using interpretations garnered from interviews and consultations,[63] to academic publication written by community members based on community identified research questions.[64] Long-term commitment Ethnographers and development specialists have shown[65] that a long-term relationship is necessary to develop a rapport and mutual respect with the local community, and argue that to succeed at collaboration archaeologists must make a long-term commitment[66] in order to understand the dynamics of the social context of their research. Without this depth of knowledge archaeologists risk making decisions with unintended consequences.[67] For example, collaborations and repatriations have been more successful where archaeologists and American Indians have met on a regular basis and developed both friendship and mutual respect.[68] Versaggi found that "allowing the process to take time is what matters."[69] Many community archaeologists now plan on conducting long-term collaborations from the outset of their project.[70] Ethnography and getting to know the community As a method for knowing the community, archaeologists have advocated the use of ethnographic methods in community archaeology projects.[67] While most scholars feel that it is not necessary for all archaeologists to become trained ethnographers, a degree of ethnographic knowledge is needed before initiating a project.[65] Some community archaeology projects rely on ethnographic data conducted by members of their research team,[71] while others have had some success beginning with published sources or collaborating with professionals already established in the focal community. Museums and institutions The construction of museums or other institutions as education centers, repositories for archaeological materials and, centers for scientific and socio-cultural collaboration with a community is a common long-term goal for many community archaeology projects, and one achieved with increasing frequency.[72] Museums have become hubs for public outreach and collaboration to both local and non-local communities.[73] One well known example of a museum created by a collaboration between American Indians and archaeologists is the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center, which is "the largest Native American owned museum in the United States",[74] has multiple laboratories and collections for scientific research, and a staff that includes five full-time archaeologists.[75] Publications for the community Another method in community archaeology for the sharing and distribution of archaeological knowledge is the publication or presentation of materials specifically for the community. This includes books, pamphlets, children's stories,[75] school-oriented workbooks,[76] comic books,[77] websites,[78] public lectures, radio programs, television shows and news coverage, dramatic reenactments, artistic and literary creations, open access publications,[79] and other forms. Participatory action research Participatory action research is another method archaeologists have used in community archaeology projects.[80] |

コミュニティ考古学へのアプローチ コミュニティによる解釈 コミュニティによる考古学的発見の解釈はコミュニティ考古学の本質的な側面であり、「脱植民地化する考古学」の重要な側面として、また非考古学者に過去を 解釈する力を与えるものとして捉えられている[59]。複数のコミュニティ考古学者が、考古学的情報の解釈と普及においてコミュニティに主要な役割を与え るプロジェクトを立ち上げている[30]。 [多くの考古学者が、地元の知識を取り入れることは考古学が学問分野として存続するために重要であると主張している[62]。インタビューや協議から得ら れた解釈を用いたり[63]、コミュニティが特定した研究課題に基づいてコミュニティのメンバーが執筆した学術的な出版物を出版したり[64]と、コミュ ニティが考古学プロジェクトにおいて持つ解釈のコントロールの程度は様々である。 長期的なコミットメント 民族誌学者や開発の専門家は、地域コミュニティとの信頼関係や相互尊重を築くためには長期的な関係が必要であることを示し[65]、共同研究を成功させる ためには、考古学者は研究の社会的背景の力学を理解するために長期的なコミットメント[66]をしなければならないと主張している。例えば、考古学者とア メリカ・インディアンが定期的に会い、友情と相互尊敬の念を育んできたところでは、共同研究やレパトリエーションがより成功している[68]。 Versaggiは、「プロセスに時間をかけることこそが重要である」[69]と述べている。 エスノグラフィーとコミュニティを知る コミュニティを知るための方法として、考古学者はコミュニティ考古学プロジェクトにおいてエスノグラフィーの手法を用いることを提唱している[67]。ほ とんどの学者は、すべての考古学者が訓練されたエスノグラファーになる必要はないと考えているが、プロジェクトを開始する前にある程度のエスノグラフィー の知識は必要である[65]。コミュニティ考古学プロジェクトの中には、調査チームのメンバーによって実施されたエスノグラフィーのデータに依存している ものもあれば[71]、出版された資料から始めたり、すでに対象コミュニティで確立された専門家との共同研究を行ったりして成功を収めているものもある。 博物館と施設 教育センター、考古学的資料の保管場所、コミュニティとの科学的・社会文化的協力の拠点として博物館やその他の施設を建設することは、多くのコミュニティ 考古学プロジェクトに共通する長期的目標であり、達成される頻度も高まっている[72]。 [アメリカ・インディアンと考古学者のコラボレーションによって作られた博物館のよく知られた例として、Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Centerが挙げられる[73]。 コミュニティのための出版物 考古学的知識を共有・配布するためのコミュニティ考古学のもう一つの方法は、コミュニティ向けに特別な資料を出版・発表することである。これには、書籍、 パンフレット、童話、[75]学校向けのワークブック、[76]コミックブック、[77]ウェブサイト、[78]公開講座、ラジオ番組、テレビ番組や ニュース報道、再現ドラマ、芸術的・文学的創作物、オープンアクセス出版物[79]などが含まれる。 参加型アクション・リサーチ 参加型アクション・リサーチは、コミュニティ考古学プロジェクトにおいて考古学者が用いてきたもうひとつの手法である[80]。 |

| Critiques Who speaks for the community? In community archaeology, by definition decisions cannot be made based on the information from only a handful of members from a given community. Although the number of consultants needed will vary, it is rare that a small subgroup can speak for the community as a whole.[81] Sometimes it is clear who should be contacted in a community. For example, archaeologists in the United States must contact the Tribal Historic Preservation Officer (THPO) before attempting collaboration with federally recognized tribes.[82] In places where the appropriate contacts and stakeholders are less obvious, community archaeologists attempt to identify as many interest groups as possible and contact them before research begins. Top-down approach A top-down approach to community archaeology is when archaeologists decide before consultation what the goals of the project will be, or what benefits will be provided to the community is not really community archaeology at all. The top-down approach creates a one-sided exchange of information from the archaeologists to the community and precludes real collaboration. Blume found the "archaeologist-informant relationship [to be] essentially exploitative and patronizing because it takes place on the archaeologist’s terms—the informant must address issues that the archaeologists understand—and it excludes participation by [community members] who are unable or unwilling to participate on those terms."[83] To succeed at community archaeology, Archaeologists have begun to undertake more reflexive collaborations with indigenous communities.[84] Carrying through with long-term commitments Some community archaeologists have had difficulty sticking to their original commitments to the community.[85] Consultation and collaboration Some have argued that ‘consulting’ archaeologists do not relinquish control over the process of interpretation, and that consulting is a ‘top-down’ approach to collaboration.[86] Also, some definitions of the word ‘collaboration’ make allusions to opposed and/or warring parties cooperating with one another during tense or bellicose times. Dean has proposed that the word cooperate be used instead.[87] |

批評 誰がコミュニティの代弁者なのか? コミュニティ考古学の定義上、あるコミュニティの一握りのメンバーからの情報だけでは決定を下すことはできない。必要なコンサルタントの数は様々である が、少数のサブグループがコミュニティ全体を代弁できることは稀である[81]。例えば、米国の考古学者は、連邦政府公認の部族との共同研究を試みる前 に、部族歴史保存担当官(THPO)と連絡を取らなければならない[82]。適切な連絡先や利害関係者が明確でない場所では、コミュニティ考古学者は、調 査を開始する前に、できるだけ多くの利害関係グループを特定し、彼らと連絡を取ろうと試みる。 トップダウン・アプローチ コミュニティ考古学のトップダウン・アプローチとは、考古学者が協議の前にプロジェクトの目標やコミュニティへの便益を決めてしまうことであり、これはコ ミュニティ考古学とは言えない。トップダウン・アプローチは、考古学者からコミュニティへの一方的な情報交換を生み、真の共同作業を妨げる。ブルーメは 「考古学者と情報提供者の関係は本質的に搾取的で恩着せがましいものである。なぜなら、それは考古学者の条件で行われるからであり、情報提供者は考古学者 が理解している問題に取り組まなければならない。 長期的なコミットメントの継続 コミュニティ考古学者の中には、コミュニティとの当初の約束を守ることが困難な者もいる[85]。 コンサルテーションとコラボレーション コンサルテーションを行う」考古学者は解釈のプロセスに対するコントロールを放棄しておらず、コンサルテーションは協働に対する「トップダウン」のアプ ローチであると主張する者もいる[86]。また、「協働」という言葉の定義によっては、対立する当事者や戦争当事者同士が緊迫した時期や好戦的な時期に協 力し合うことを連想させるものもある。ディーンは代わりにcooperateという言葉を使うことを提案している[87]。 |

| Indigenous peoples of the

Americas Applied anthropology Archaeological ethics Science outreach |

アメリカ大陸の先住民 応用人類学 考古学倫理 科学アウトリーチ |

| Archaeological

ethics refers to the moral issues raised through the study of the

material past. It is a branch of the philosophy of archaeology. This

article will touch on human remains, the preservation and laws

protecting remains and cultural items, issues around the globe, as well

as preservation and ethnoarchaeolog. Archaeologists are bound to conduct their investigations to a high standard and observe intellectual property laws, health and safety regulations, and other legal obligations.[1] Archaeologists in the field are required to work towards the preservation and management of archaeological resources, treat human remains with dignity and respect, and encourage outreach activities. Sanctions are in place for those professionals who do not observe these ethical codes. Questions regarding archaeological ethics first began to arise during the 1960s and 1970s in North America and Western Europe.[2] A UNESCO ratification to protect world culture in 1970 was one of the earliest actions to implement ethical standards.[2] Archaeologists conducting ethnoarchaeological research, which involves the study of living people, are required to follow guidelines set by the Nuremberg Code (1947) and the Declaration of Helsinki (1964).[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archaeological_ethics |

考古学倫理とは、物質的な過去の研究を通じて提起される道徳的な問題を

指す。考古学哲学の一分野である。この記事では、遺骨、遺物や文化財を保護する法律、世界各地の問題、保存や民族考古学について触れる。 考古学者は高い水準で調査を行い、知的財産権法、安全衛生規則、その他の法的義務を遵守する義務がある[1]。この分野の考古学者は、考古学的資源の保存 と管理に努め、遺骨を尊厳と敬意を持って扱い、アウトリーチ活動を奨励することが求められている。これらの倫理規範を守らない専門家には制裁が設けられて いる。考古学の倫理に関する問題は、1960年代から1970年代にかけて、北米や西ヨーロッパで発生し始めた[2]。1970年にユネスコが世界文化を 保護するために批准したことは、倫理基準を実施するための最も早い行動の一つであった[2]。生きている人々の研究を伴う民族考古学的研究を行う考古学者 は、ニュルンベルク綱領(1947年)やヘルシンキ宣言(1964年)によって定められたガイドラインに従うことが求められている[3]。 |

| History of ethics in archaeology The earliest archaeologists were typically amateurs who would excavate a site with the sole purpose of collecting as many objects as they could for display in museums.[4] Curiosity about past humans and the potential for finding lucrative and fascinating objects justified what many professional archaeologists today would consider to be unethical archaeological behavior.[4] A shift toward scientific knowledge prompted many early archaeologists to begin documenting their finds. In 1906, the Antiquities Act created as the first act in America to help regulate archaeological discovery.[4] This act allowed for federal protection of sites from looting but failed to protect native peoples from having their land and ancestral objects seized.[4] The Society for American Archaeology was developed in 1934.[4] This organization helped to bring regulation into the field of archaeology and provided consistent training for professional archaeologists.[4] A series of laws passed in the 1960s and 1970s created the field of cultural resource management which protects archaeological sites from encroaching development.[4] Debates about the rights of native peoples to their ancestral belongings occurred throughout the 1980s culminating in the passing of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.[4] The rise of ethics in archaeology was spurred by a shift in archaeological theory towards post-processualism which focuses on critical evaluation of methods and the implications of archaeology on politics.[4] |

考古学における倫理の歴史 初期の考古学者は、博物館に展示するためにできるだけ多くの遺物を収集することだけを目的として遺跡を発掘するアマチュアであった[4]。 過去の人類に対する好奇心と、有益で魅力的な遺物を発見する可能性は、今日多くのプロの考古学者が非倫理的な考古学的行動であると考えるであろうことを正 当化した[4]。科学的知識へのシフトは、多くの初期の考古学者に発見した遺物を記録し始めることを促した。1906年、考古学的発見を規制するためのア メリカ初の法律として、古代法(Antiquities Act)が制定された[4]。この法律は、略奪から遺跡を連邦政府によって保護することを可能にしたが、先住民が自分たちの土地や先祖伝来の品々を押収さ れることから保護することはできなかった[4]。1934年、アメリカ考古学協会(Society for American Archaeology)が設立された[4]。この団体は、考古学の分野に規制をもたらし、プロの考古学者に一貫したトレーニングを提供することに貢献し た。 [1960年代から1970年代にかけて成立した一連の法律により、遺跡を開発の侵食から保護する文化資源管理の分野が生まれた[4]。1980年代を通 じて、先祖代々の遺物に対する先住民の権利に関する議論が起こり、アメリカ先住民墓地保護・送還法(Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act)の成立に至った[4]。 |

Human remains Human remains from the 1971 Bangladesh genocide on display at The Liberation War Museum in Dhaka, Bangladesh. A common ethical issue in modern archaeology has been the treatment of human remains found during excavations,[5] especially those that represent the ancestors of aboriginal groups in the New World or the remains of other minority races elsewhere.[6] In November 1990 the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was enacted, facilitating the return of certain human remains and sacred objects to lineal descendants and Native American Tribes.[7] Where previously sites of great significance to indigenous peoples could be excavated and burials and artifacts taken to be stored in museums or sold,[8] there is now increasing awareness of taking a more respectful approach. Technical developments in ancient DNA testing have raised more ethical questions in relation to the treatment of these human remains.[9] The issue is not limited to indigenous human remains. Nineteenth and twentieth century burial sites investigated by archaeologists, such as First World War graves disturbed by developments, have seen the remains of people with closely connected living relatives being exhumed and taken away. |

遺骨 バングラデシュのダッカにある解放戦争博物館に展示されている1971年のバングラデシュ大虐殺の遺骨。 近代考古学における共通の倫理的問題は、発掘調査で発見された人骨の扱いである[5]。特に、新大陸の原住民グループの祖先や、その他の少数民族の遺骨で ある[6]。 [6] 1990年11月、アメリカ先住民の墓の保護と返還に関する法律(NAGPRA)が制定され、特定の人骨や神聖な遺物を直系子孫やアメリカ先住民の部族に 返還することが容易になった[7]。以前は先住民にとって重要な遺跡が発掘され、埋葬品や遺物が博物館に保管されたり、売却されたりすることもあったが [8]、現在ではより尊重されたアプローチをとることへの意識が高まっている。古代のDNA鑑定における技術的な発展は、これらの遺骨の扱いに関して、よ り倫理的な問題を提起している[9]。考古学者によって調査された19世紀や20世紀の埋葬地、たとえば開発によって妨害された第一次世界大戦中の墓など では、密接な関係にある存命の親族を持つ人々の遺骨が掘り出され、持ち去られている。 |

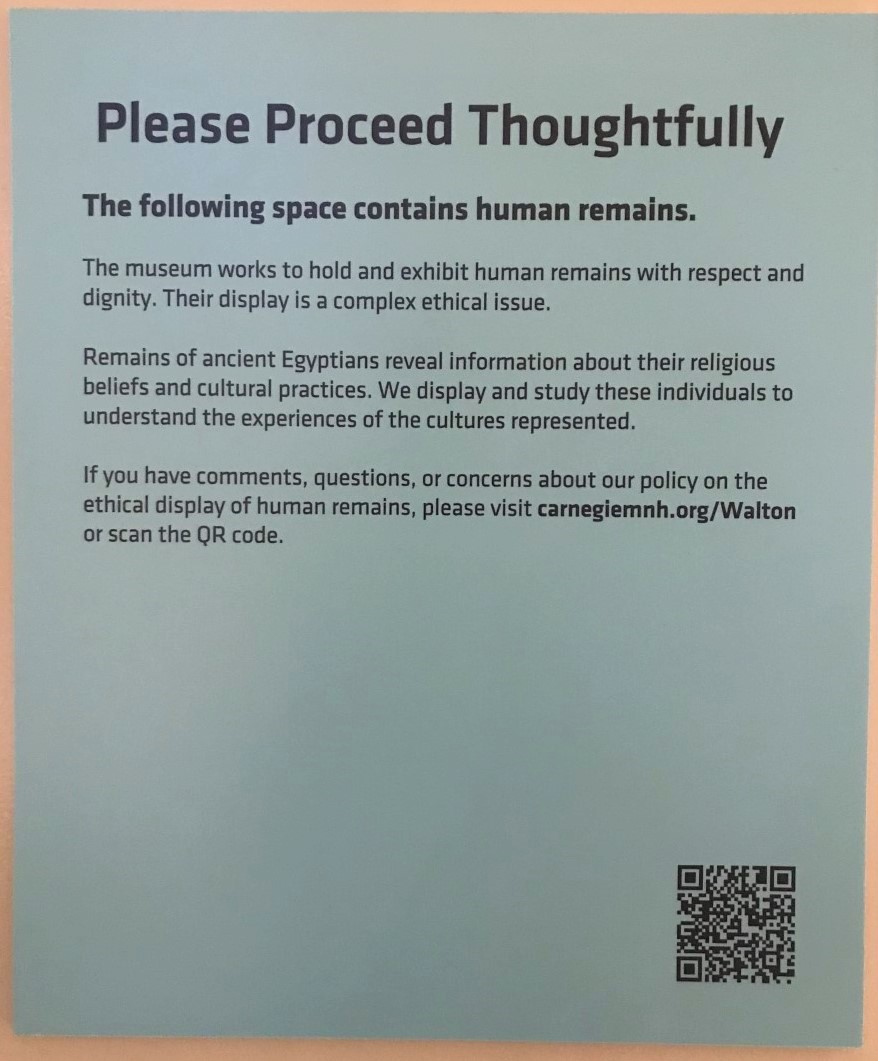

Ethics in commercial archaeology Lion Attacking a Dromedary Diorama, was found to contain unidentified human remains in 2017. This has brought up concerns of whether it is ethical to display these remains.[10] Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh, PA. In the United States, the bulk of modern archaeological work is done under the auspices of development by cultural resource management archaeologists[11] in compliance with Section 106[12] of the National Historic Preservation Act. Guidance for compliance with Section 106 is provided by The Advisory Council on Historic Preservation.[12] Impacts of nondisclosure agreements Much of this work is subject to non-disclosure agreements with private entities. A primary ethical criticism levied against commercial archaeological practices is the prevalence of non-disclosure agreements associated with development projects involving a cultural resource management component.[13] Critics claim that NDA's are a barrier to public access to the archaeological record and create an unethical working condition for archaeologists to practice and that archaeology applied to the industry of development is itself a threat to the archaeological record.[13] This practice prohibits information gathered from the archaeological record during such projects from being disseminated to the public or academic institutions for further study and peer review. Scarre writes that "collecting items that are surplus to requirements…is academically pointless and morally irresponsible" [14] and it has been interpreted that data collected as a result of cultural resource management fieldwork unavailable to the public through NDA access restrictions creates such a surplus and therefore is ethically problematic.[13] Private property and development The issue of ownership is paramount in the ethical discussion regarding commercial archaeology. In most circumstances, with the exception of human remains and artifacts associated with burials, ownership of artifacts and other material recovered from archaeological investigations performed within the scope of development projects falls to the owner of the property on which the excavation is performed.[13] Many archaeologists consider this to be ethically problematic and a significant barrier to public access. |

商業考古学における倫理 2017年、ライオンがドロメダリーを襲うジオラマに、身元不明の人骨が含まれていることが判明した。これにより、これらの遺骨を展示することが倫理的に問題ないかという懸念が持ち上がった[10]。カーネギー自然史博物館(ペンシルベニア州ピッツバーグ)。 米国では、現代の考古学的作業の大部分は、文化資源管理考古学者[11]による開発の支援のもと、国家歴史保存法第106条[12]に準拠して行われてい る。第106条を遵守するためのガイダンスは、歴史保存諮問委員会(The Advisory Council on Historic Preservation)によって提供されている[12]。 秘密保持契約の影響 この作業の多くは、民間団体との秘密保持契約の対象となる。営利目的の考古学活動に対する主な倫理的批判は、文化資源管理の要素を含む開発プロジェクトに 関連した非開示契約の蔓延である。 [13] 批評家たちは、NDAは考古学的記録への一般公開を妨げるものであり、考古学者が実践する上で非倫理的な労働条件を作り出すものであり、開発という産業に 適用される考古学はそれ自体が考古学的記録に対する脅威であると主張している。スカーレは「必要以上に余剰なものを収集することは...学問的に無意味で あり、道徳的に無責任である」と書いており[14]、NDAのアクセス制限によって一般公開されない文化資源管理のフィールドワークの結果として収集され たデータは、そのような余剰を生み出し、したがって倫理的に問題があると解釈されている[13]。 私有財産と開発 所有権の問題は、商業考古学に関する倫理的議論において最も重要である。ほとんどの状況において、人骨や埋葬に関連する遺物を除いて、開発事業の範囲内で 行われた考古学的調査から回収された遺物やその他の物質の所有権は、発掘が行われた土地の所有者に帰属する[13]。多くの考古学者は、このことは倫理的 に問題があり、一般公開に対する重大な障壁であると考えている。 |

| Colonization and conflict The World Archaeological Congress has determined that "It is unethical for Professional Archaeologists and academic institutions to conduct professional archaeological work and excavations in occupied areas possessed by force".[15] This resolution has been interpreted to include not only regions where there is active military conflict but regions who have been in conflict in the past and are currently under colonial rule,[13] for example, North and South America |

植民地化と紛争 世界考古学会議(World Archaeological Congress)は、「プロの考古学者や学術機関が、武力によって占領された地域で専門的な考古学的作業や発掘を行うことは非倫理的である」[15]と 決議している。この決議は、軍事的紛争が活発に行われている地域だけでなく、過去に紛争があり、現在植民地支配下にある地域も含むと解釈されている [13]。 |

Antiquities trade Display case of Nubian antiquities in the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire of Geneva. Although not formally connected with the modern discipline of archaeology, the international trade in antiquities has also raised ethical questions regarding the ownership of archaeological artifacts. The market for imported antiquities has encouraged damage to archaeological sites and often led to appeals for the recall.[16] Famous sites such as Angkor Wat in Cambodia have experienced problems with looting.[17] Looting often leads to loss of information as material remains are removed from their original contexts.[16] Examples of archaeological material which has been removed from its place of origin and over which there is now controversy regarding its return include the Elgin Marbles. In the United States, the Antiquities Act protects archaeological material from looting.[1] The act establishes punishments for archaeological looting on federal land, allows the US president to declare archaeological sites as national monuments, establishes the government's duty to preserve archaeological sites and make them available for the public, and requires that Archaeology|archaeologists conducting research must meet the guidelines set by the Secretary of the Interior.[1] |

古美術品の取引 ジュネーブ美術・歴史博物館のヌビア古美術品の展示ケース。 考古学という近代的な学問分野とは正式には関係ないが、古美術品の国際的な取引は、考古学的な遺物の所有権に関する倫理的な問題をも引き起こしてきた。カ ンボジアのアンコールワットのような有名な遺跡は、略奪の問題を経験している[17]。略奪は、しばしば、遺跡が元の文脈から持ち去られることによる情報 の喪失につながる。 アメリカでは、古代法(Antiquities Act)が考古学的資料を略奪から保護している[1]。この法律は、連邦の土地における考古学的略奪に対する処罰を定め、アメリカ大統領に遺跡を国定公園 として宣言することを許可し、遺跡を保存して一般に公開する政府の義務を定め、調査を行う考古学者が内務省長官の定めるガイドラインを満たすことを義務付 けている[1]。 |

| Laws and protections around the world Globally The World Archaeological Congress (WAC) is a global organization that holds a congress every four years to discuss recent publications and research as well as to update archaeological practice guidelines and policies.[18] The WAC publishes a code of ethics for their archaeologists to follow.[18] Some of the accords which have been adopted by the WAC code of ethics include the Dead Sea Accord, the Vermillion Accord on Human Remains, and the Tamaki Makau-rau Accord on the Display of Human Remains and Sacred Objects.[18] The WAC has also published a separate code of ethics for the protection of the Amazon Forest Peoples.[18] In 1970, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, UNESCO, held a convention in Paris on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property.[19][20] Many countries joined and it was put into use in 1972.[21] It is important to note that archaeological ethics are not the same around the world and what is considered ethical behavior can vary from culture to culture.[4] Many archaeological organizations around the world require their members to follow a code of ethics; several of these associations, however, do not publish their code of ethics for non-members. Some of these associations include the Korean Archaeological Society and the Japanese Archaeological Association. The Register of Professional Archaeologists[22] is a multinational organization that provides accreditation for archaeologists and adjacent professionals. They provide a network which serves to connect archaeologists to each other and to industries which rely upon their expertise. America The Society for American Archaeology (SAA) is an organization which is dedicated the ethical practice of archaeology and the preservation of archaeological materials in America.[23] The SAA's committee on archaeological ethics continually updates the living document titled Principles of Archaeological Ethics, which was first created in 1966.[23] The SAA registers professional archaeologists who must agree to uphold the code of conduct while conducting research.[23] The United States government continually passes legislation to protect archaeological materials and uphold ethical archaeological research. The Antiquities Act of 1906 established punishment for archaeological looting, ensured the governments' responsibility to preserve archaeological sites, and created guidelines for conducting archaeological research.[1] The Historic Sites Act of 1935 further confirmed that the preservation of archaeological sites is of national concern.[1] The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 provided federal protection of archaeological sites and established the need for environmental review, ensuring that development does not destroy archaeological material.[1] The Archaeological Resource Protection Act of 1979 states that archaeological materials must be preserved once they are discovered.[1] The Native American Graves Repatriation Act of 1990 (NAGPRA) constitutes that museums receiving government funding must attempt to return archaeological materials to Native Americans if the natives claim the material.[1] NAGPRA also states that native organizations must be consulted when Native American materials are found or are expected to be found.[1] Europe The European Association of Archaeologists (EAA), like the Society for American Archaeology in the United States, is an organization which regulates the ethical practice of archaeology across Europe.[24] The EAA requires its members to follow a published code of ethics.[24] The code of ethics requires archaeologists to inform the public of their work, preserve archaeological sites, and evaluate the social and ecological impacts of their work before beginning.[24] This code further provides an ethical framework for conducting contractual archaeology, fieldwork training, and journal publications.[24] While the EAA regulates ethical archaeological practices across Europe, the British Association for Biological Anthropology and Osteoarchaeology further provides an ethical guideline for British archaeologists who are conducting research with human remains.[25] Australia The Australian Archaeological Association (AAA) is an organization which regulates and promotes archaeology across Australia.[26] The AAA has a published code of ethics which its members must follow.[26] The AAA code of ethics highlights issues such as gaining informed consent, rights of indigenous people, and conservation of heritage sites.[26] The AAA code of ethics also states that any member who fails to adhere to the code is subject to disciplinary action.[26] Canada The Canadian Archaeological Association (CAA) exists to promote archaeological knowledge, promote general interest in archaeology, and to act as a liaison between Canadian Aboriginals and archaeologists studying their ancestors.[27] The CAA assures ethical archaeological practices among their members by offering a principles of ethics guideline.[27] These principles of ethics focuses on assuring access to knowledge, conserving archaeological sites whenever possible, and promoting ethical relationships between Aboriginals and archaeologists.[27] |

世界各地の法律と保護 世界的に 世界考古学会議(WAC)は世界的な組織であり、4年ごとに会議を開催し、最近の出版物や研究について議論するとともに、考古学の実践ガイドラインや方針 を更新している[18]。 [18]WACの倫理規定に採用されている協定には、死海協定、遺骨に関するヴァーミリオン協定、遺骨と聖遺物の展示に関するタマキ・マカウラウ協定など がある。 [18] 1970年、国連教育科学文化機関(ユネスコ)は、文化財の不正な輸入、輸出、所有権の移転を禁止し、防止する手段に関する条約をパリで開催した[19] [20]。 [21]考古学の倫理は世界共通ではなく、何が倫理的行動とみなされるかは文化によって異なる可能性があることに注意することが重要である[4]。世界中 の多くの考古学団体は、会員に倫理綱領に従うことを義務付けている。このような団体には、韓国考古学協会や日本考古学協会などがある。 The Register of Professional Archaeologists[22]は、考古学者やそれに隣接する専門家の認定を行う多国籍組織である。この団体は、考古学者同士や、彼らの専門知識に依存する業界をつなぐネットワークを提供している。 アメリカ アメリカ考古学協会(SAA)は、アメリカにおける考古学の倫理的実践と考古学的資料の保存を目的とする組織である[23]。SAAの考古学倫理委員会は、1966年に最初に作成された「考古学倫理の原則」と題する生きた文書を継続的に更新している[23]。 アメリカ合衆国政府は、考古学的資料を保護し、倫理的な考古学研究を支持するための法律を継続的に可決している。1906年の古代法 (Antiquities Act of 1906)は、考古学的略奪に対する処罰を定め、遺跡を保護する政府の責任を保証し、考古学的調査を行うためのガイドラインを作成した[1]。 1935年の史跡法(Historic Sites Act of 1935)は、さらに遺跡の保護が国家の関心事であることを確認した[1]。 [1]1979年に制定された考古学的資源保護法(The Archaeological Resource Protection Act of 1979)は、考古学的資料が発見された場合、それを保存しなければならないと定めている[1]。 1990年に制定されたアメリカ先住民墓地返還法(The Native American Graves Repatriation Act of 1990: NAGPRA)は、政府から資金援助を受けている博物館は、アメリカ先住民がその資料を要求した場合、アメリカ先住民に考古学的資料を返還するよう努めな ければならないと定めている[1]。またNAGPRAは、アメリカ先住民の資料が発見された場合、または発見されると予想される場合、先住民の団体に相談 しなければならないと定めている[1]。 ヨーロッパ ヨーロッパ考古学者協会(EAA)は、アメリカのアメリカ考古学協会(Society for American Archaeology)と同様に、ヨーロッパ全域における考古学の倫理的実践を規制する組織である[24]。EAAはその会員に対し、公表されている倫 理綱領に従うことを求めている[24]。倫理綱領は、考古学者に対し、自らの仕事について一般に知らせ、遺跡を保護し、仕事を始める前に社会的・生態学的 影響を評価することを求めている[24]。この綱領はさらに、契約考古学の実施、フィールドワークの訓練、学術誌の出版に関する倫理的枠組みを規定してい る[24]。 EAAがヨーロッパ全域における倫理的な考古学の実践を規制している一方で、英国生物人類学・骨考古学協会は、さらに、人骨を用いた研究を行う英国の考古学者のための倫理的ガイドラインを提供している[25]。 オーストラリア オーストラリア考古学協会(AAA)は、オーストラリア全土の考古学を規制・促進する組織である[26]。AAAは、会員が遵守しなければならない倫理綱 領を公表している[26]。AAA倫理綱領は、インフォームド・コンセントの獲得、先住民の権利、遺産の保全などの問題に焦点を当てている[26]。 AAA倫理綱領はまた、綱領を遵守しない会員は懲戒処分の対象となるとも述べている[26]。 カナダ カナダ考古学協会(CAA)は、考古学の知識を広め、考古学への一般的な関心を促進し、カナダのアボリジニと彼らの祖先を研究する考古学者との間の連絡役 として活動するために存在している[27]。CAAは、倫理原則ガイドラインを提示することによって、会員間の倫理的な考古学の実践を保証している [27]。この倫理原則は、知識へのアクセスを保証し、可能な限り遺跡を保護し、アボリジニと考古学者との間の倫理的な関係を促進することに重点を置いて いる[27]。 |

National and international controversies Sign displayed before entering an area of the Walton Hall of Ancient Egypt at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. The museum invites questions and input regarding ethical displays of human remains. A QR code is featured to access more information. Many archaeologists in the West today are employees of national governments or are privately employed instruments of government-derived archaeology legislation. In all cases this legislation is a compromise to some degree or another between the interests of the archaeological remains and the interests of economic development.  The British Museum's possession of the Parthenon Sculptures, also called the "Elgin Marbles", has been ethically questioned because these sculptures were removed from Greece under contested circumstances. Germany A question of control and ownership over the past has also been raised through the political manipulation of the archaeological record to promote nationalism and justify military invasion. A famous example is the corps of archaeologists employed by Adolf Hitler to excavate in central Europe in the hope of finding evidence for a region-wide Aryan culture. United Kingdom Questions regarding the ethical validity of government heritage policies and whether they sufficiently protect important remains are raised during cases such as High Speed 1 in London where burials at a cemetery at St Pancras railway station were hurriedly dug using a JCB and mistreated in order to keep an important infrastructure project on schedule.[28] Greece  The Euphronios Krater was returned to Italy in 2008. It was purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1972, who later found out it had been illegally obtained. The Parthenon marbles, also known as the Elgin Marbles, include a series of stone sculptures and friezes that were from the Parthenon in Athens, Greece. Greece was under Ottoman rule at the time when Thomas Bruce, 7th Lord of Elgin, or Lord Elgin, as British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire asked that he be able to take some of the marbles to a safer place and was granted that in 1801. They were sold in 1816 to the British Museum, and Parliament paid £350,000 for the marbles. Greece has been petitioning to have the marbles returned since 1924, claiming that they were illegally obtained since they were occupied by a foreign force and were not acting in line with the people of Greece.[29][30][31] Italy In 1972, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City purchased the Euphronious Krater, a vase used for mixing wine and water from a collector named Robert Hecht for $1,000,000. Hecht provided documentation which after Italian investigations proved to be falsified. This falsification was later confirmed in 2001 when authorities found a handwritten memoir of Hecht's. The Krater had been obtained in an illegal excavation in 1971, likely from an Etruscan tomb. It was purchased from the Giacomo Medici then smuggled into Switzerland and sold to the museum in New York. In 2006, the museum's director, Philipe de Montebello, agreed to return the Krater along with several other items to Italy. They arrived back in Italy in 2008, and are on display at the Villa Giulia in Rome.[32][33] |

国内外での論争 カーネギー自然史博物館のウォルトン・ホール・オブ・アンシェント・エジプトのエリアに入る前に掲げられたサイン。博物館では、遺骨の倫理的展示に関する質問や意見を募集している。QRコードから詳細情報にアクセスできる。 今日、欧米の考古学者の多くは、各国政府の職員であるか、あるいは政府由来の考古学法制の下で民間雇用されている。いずれの場合も、この法律は考古学的遺跡の利益と経済発展の利益との間の、ある程度の妥協の産物である。  大英博物館が「エルギン・マーブルズ」とも呼ばれるパルテノン神殿の彫刻を所蔵しているのは、これらの彫刻が争われた状況下でギリシャから持ち出されたものであるため、倫理的に疑問視されている。 ドイツ ナショナリズムを促進し、軍事侵攻を正当化するために考古学的記録を政治的に操作することによっても、過去に対する支配と所有の問題が提起されてきた。有 名な例としては、アドルフ・ヒトラーに雇われた考古学者団が、この地域一帯のアーリア文化の証拠を見つけることを期待して、中央ヨーロッパで発掘調査を 行ったことが挙げられる。 イギリス 重要なインフラプロジェクトをスケジュール通りに進めるために、セント・パンクラス駅の墓地にある埋葬物がJCBを使って急遽掘られ、乱暴に扱われたロン ドンの高速道路1号線などの事例では、政府の遺産政策の倫理的妥当性や、重要な遺構を十分に保護しているかどうかに関する疑問が提起されている[28]。 ギリシャ  エウフロニオス・クラテルは2008年にイタリアに返還された。1972年にメトロポリタン美術館が購入したが、後に不法に入手されたことが判明した。 パルテノン神殿の大理石はエルギンの大理石としても知られ、ギリシャのアテネにあるパルテノン神殿から出土した一連の石の彫刻とフリーズを含む。当時ギリ シャはオスマン帝国の支配下にあり、エルギン卿こと第7代エルギン公トーマス・ブルースは駐オスマン英国大使として、大理石の一部をより安全な場所に運ぶ ことを要請し、1801年に許可された。大理石は1816年に大英博物館に売却され、議会が35万ポンドを支払った。ギリシャは1924年以来、大理石は 外国勢力によって占領され、ギリシャ国民に沿った行動をしていなかったため、不法に入手されたものだと主張し、返還を請願している[29][30] [31]。 イタリア 1972年、ニューヨークのメトロポリタン美術館は、ロバート・ヘクトというコレクターから、ワインと水を混ぜるための花瓶「ユーフロニアス・クラテル」 を1,000,000ドルで購入した。ヘクトは書類を提出したが、イタリアの調査の結果、偽造であることが判明した。この偽造は2001年、当局がヘクト の手書きの手記を発見したことで確認された。クラテルは1971年の違法な発掘で入手されたもので、おそらくエトルリア人の墓から出たものであろう。ジャ コモ・メディチ家から購入された後、スイスに密輸され、ニューヨークの博物館に売却された。2006年、美術館の館長であるフィリペ・ド・モンテベッロ は、クラテルと他のいくつかの品々をイタリアに返還することに同意した。それらは2008年にイタリアに戻り、ローマのヴィッラ・ジュリアに展示されてい る[32][33]。 |

| Preservation Another issue is the question of whether unthreatened archaeological remains should be excavated (and therefore destroyed) or preserved intact for future generations to investigate with potentially less invasive technology. Some archaeological guidance such as PPG 16 has established a strong ethical argument for only excavating sites threatened with destruction. New technology such as laser scanning has pioneered non-invasive techniques for recording petroglyphs and engravings. Other technology like GPS and Google Earth has revolutionized the way archaeologists find and record potential archaeological sites.[16] In the United States, several acts have been passed to help preserve archaeological sites.[1] Some of these acts include the National Historic Preservation act of 1966, which allows for archaeological sites and materials of historical significance to be placed under federal protection, and the Archaeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA) of 1979, which places all archaeological sites under federal protection, not just sites of historical significance.[1] Cultural resource management is a branch of archaeology which attempts to protect archaeological sites from development and construction damage.[34] |

保存 もう一つの問題は、脅威のない遺跡を発掘(つまり破壊)するべきか、それとも後世の人々がより低侵襲な技術で調査できるよう、そのまま保存すべきかという 問題である。PPG16のような考古学ガイダンスの中には、破壊の恐れのある遺跡のみを発掘することを倫理的に強く主張するものもある。レーザースキャニ ングのような新しい技術は、ペトログリフや彫刻を記録するための非侵襲的な技術を開拓してきた。GPSやGoogle Earthのような他の技術は、考古学者が潜在的な遺跡を見つけて記録する方法に革命をもたらした[16]。 アメリカでは、遺跡を保護するための法律がいくつか制定されている[1]。これらの法律には、歴史的に重要な遺跡や資料を連邦政府の保護下に置くことを認 める1966年の国家歴史保存法(National Historic Preservation Act of 1966)や、歴史的に重要な遺跡だけでなく、すべての遺跡を連邦政府の保護下に置く1979年の考古学的資源保護法(Archaeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA))などがある[1]。 文化資源管理は考古学の一分野であり、遺跡を開発や建設による被害から保護しようとするものである[34]。 |

| Ethics in ethnoarchaeology Ethnoarchaeology is the ethnographic study of people from an archaeological point of view. These studies are typically conducted on material remains from the society in question,[35] is sometimes used in conjunction with traditional archaeology. Ethnoarchaeology presents a unique case, because it deals with the study of people, which is heavily regulated.[36] Any research dealing with humans must be submitted to an ethics committee for approval under the Nuremberg Code (1947) and the Declaration of Helsinki (1964).[1] Researchers must also obtain informed consent from their research subjects.[1] Archaeologists conducting ethnoarchaeology or other types of research involving humans must adhere to a certain code in order to conduct legal and ethical research, however, this code is the same that is followed by medical research. There is no specific code for archaeological research involving humans.[1] This has been problematic and some archaeologists resist following a medical ethics code by claiming that medical research and ethnographic research are too different to follow the same code.[1] |

民族考古学における倫理 エスノアーケオロジーとは、考古学的見地から人々を民族誌的に研究することである。このような研究は通常、問題となっている社会から出土した物質的な遺物 を用いて行われ[35]、伝統的な考古学と併用されることもある。エスノアーケオロジーは、厳しく規制されている人に関する研究を扱うという特殊なケース である[36]。人間を扱う研究は、ニュルンベルク綱領(1947年)とヘルシンキ宣言(1964年)に基づき、倫理委員会に提出して承認を得なければな らない[1]。 エスノアルケオロジーやその他の人間を対象とする研究を行う考古学者は、合法的かつ倫理的な研究を行うために一定の規範を守らなければならないが、この規 範は医学研究と同じものである。このことが問題となり、医学研究とエスノグラフィ研究は同じ規範に従うには違いすぎると主張して、医学倫理規範に従うこと に抵抗する考古学者もいる[1]。 |

| The Code of Ethics of the Archaeological Institute of America Institute of Field Archaeologists Code of Conduct Ethics and archaeology Archeology Law and Ethics from the National Park Service Archeology Program Society for American Archaeology British Sociological Association Social Anthropology of the UK and the Commonwealth The Economic and Social Research Council |

アメリカ考古学会倫理綱領 フィールド考古学者協会行動規範 倫理と考古学 国立公園局の考古学プログラムによる考古学の法律と倫理 アメリカ考古学協会 英国社会学会 英国および英連邦の社会人類学 経済社会研究評議会 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archaeological_ethics |

Prophets

and Ghosts: The Story of Salvage Anthropology - サムエル・レッドマンによるこの本は19

世紀後半、人類学者、言語学者、考古学者、その他の記録者たちは、工芸品、衣類、画像、歌の録音など、先住民の文化遺産を何百万点も収集し始めた。先住民

は消滅する運命にあると確信した収集家たちは、これらの品々を保存・展示する博物館や大学に寄贈した。彼らは先住民(族)の文化の膨大な目録の作成には成

功したものの、それは先住民を滅びゆくもの、もはや消滅しても仕方のないもの、として、昆虫採集に喜ぶ子どもたちのように固定化した(凍結保存された)展

示品として博物館に展示されることになった。買い上げられたものもあるが、明らかに窃盗されたものもある(アイヌや琉球民族の遺骨や副葬品などの収集はそ

の代表だ)。このような現象が百年以上続いている状況にトドメをさし、大学研究機関博物館は、先住民や少数民族に対してこの歴史的経緯の説明責任を果た

し、謝罪し、対話を求め、和解に踏み出さねばならないだろう。

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆