クワイン=パットナムの不可欠性論証

Quine–Putnam indispensability argument

☆

クワイン=パトナムの不可欠性論証[The Quine–Putnam

indispensability argument][a]は、数学哲学における論証であり、数や集合といった抽象的な数学的対象の存在を主張する。この立場は数学的プラト

ン主義として知られる。この論証は哲学者ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワインとヒラリー・パトナムに因んで名付けられ、数学哲学において最も重要な論

証の一つである。

不可欠性論証の要素はゴットロップ・フレーゲやクルト・ゲーデルといった思想家に起源を持つかもしれないが、クワインによる論証の発展は、自然主義、確認

的全体論、存在論的コミットメントの基準といった彼の哲学的立場を数多く導入した点で独特であった。パトナムは1971年の著書『論理学の哲学』において

クワインの論証を初めて詳細に体系化した。しかし後にパットナムはクワインの思想の様々な側面に異議を唱えるようになり、科学哲学における「奇跡禁止の原

理」に基づく独自の不可欠性論証を構築した。現代哲学における標準的な論証形式はマーク・コリヴァンに帰せられる。クワインとパットナムの両方に影響を受

けつつも、彼らの定式化とは重要な点で異なる。スタンフォード哲学百科事典では次のように提示されている:[2]

我々は、最良の科学的理論にとって不可欠である実体のみに対して存在論的コミットメントを持つべきである。

数学的実体は最良の科学的理論にとって不可欠である。

したがって、我々は数学的実体に対して存在論的コミットメントを持つべきである。

抽象的な対象の存在を否定する哲学である名目論者は、この議論の両方の前提に異議を唱えている。ハートリー・フィールドによる影響力のある議論は、数学的

実体は科学にとって不要であると主張している。この議論は、数学的実体への言及をすべて排除するために、科学理論や数学理論を再構築できることを実証しよ

うとする試みによって支持されている。ペネロペ・マディ、エリオット・ソバー、ジョセフ・メリアなどの他の哲学者は、科学に不可欠な実体をすべて信じる必

要はないと主張している。これらの著者の議論は、アラン・ベイカーとマーク・コリーバンが支持する、数学は理論全体だけでなく特定の科学的説明にも不可欠

であると主張する、この議論の新しい説明版を生み出した。

| The Quine–Putnam

indispensability argument[a] is an argument in the philosophy of

mathematics for the existence of abstract mathematical objects such as

numbers and sets, a position known as mathematical platonism. It was

named after the philosophers Willard Van Orman Quine and Hilary Putnam,

and is one of the most important arguments in the philosophy of

mathematics. Although elements of the indispensability argument may have originated with thinkers such as Gottlob Frege and Kurt Gödel, Quine's development of the argument was unique for introducing to it a number of his philosophical positions such as naturalism, confirmational holism, and the criterion of ontological commitment. Putnam gave Quine's argument its first detailed formulation in his 1971 book Philosophy of Logic. He later came to disagree with various aspects of Quine's thinking, however, and formulated his own indispensability argument based on the no miracles argument in the philosophy of science. A standard form of the argument in contemporary philosophy is credited to Mark Colyvan; whilst being influenced by both Quine and Putnam, it differs in important ways from their formulations. It is presented in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:[2] We ought to have ontological commitment to all and only the entities that are indispensable to our best scientific theories. Mathematical entities are indispensable to our best scientific theories. Therefore, we ought to have ontological commitment to mathematical entities. Nominalists, philosophers who reject the existence of abstract objects, have argued against both premises of this argument. An influential argument by Hartry Field claims that mathematical entities are dispensable to science. This argument has been supported by attempts to demonstrate that scientific and mathematical theories can be reformulated to remove all references to mathematical entities. Other philosophers, including Penelope Maddy, Elliott Sober, and Joseph Melia, have argued that we do not need to believe in all of the entities that are indispensable to science. The arguments of these writers inspired a new explanatory version of the argument, which Alan Baker and Mark Colyvan support, that argues mathematics is indispensable to specific scientific explanations as well as whole theories. |

クワイン=パトナムの不可欠性論証[a]は、数学哲学における論証であ

り、数や集合といった抽象的な数学的対象の存在を主張する。この立場は数学的プラトン主義として知られる。この論証は哲学者ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマ

ン・クワインとヒラリー・パトナムに因んで名付けられ、数学哲学において最も重要な論証の一つである。 不可欠性論証の要素はゴットロップ・フレーゲやクルト・ゲーデルといった思想家に起源を持つかもしれないが、クワインによる論証の発展は、自然主義、確認 的全体論、存在論的コミットメントの基準といった彼の哲学的立場を数多く導入した点で独特であった。パトナムは1971年の著書『論理学の哲学』において クワインの論証を初めて詳細に体系化した。しかし後にパットナムはクワインの思想の様々な側面に異議を唱えるようになり、科学哲学における「奇跡禁止の原 理」に基づく独自の不可欠性論証を構築した。現代哲学における標準的な論証形式はマーク・コリヴァンに帰せられる。クワインとパットナムの両方に影響を受 けつつも、彼らの定式化とは重要な点で異なる。スタンフォード哲学百科事典では次のように提示されている:[2] 我々は、最良の科学的理論にとって不可欠である実体のみに対して存在論的コミットメントを持つべきである。 数学的実体は最良の科学的理論にとって不可欠である。 したがって、我々は数学的実体に対して存在論的コミットメントを持つべきである。 抽象的な対象の存在を否定する哲学である名目論者は、この議論の両方の前提に異議を唱えている。ハートリー・フィールドによる影響力のある議論は、数学的 実体は科学にとって不要であると主張している。この議論は、数学的実体への言及をすべて排除するために、科学理論や数学理論を再構築できることを実証しよ うとする試みによって支持されている。ペネロペ・マディ、エリオット・ソバー、ジョセフ・メリアなどの他の哲学者は、科学に不可欠な実体をすべて信じる必 要はないと主張している。これらの著者の議論は、アラン・ベイカーとマーク・コリーバンが支持する、数学は理論全体だけでなく特定の科学的説明にも不可欠 であると主張する、この議論の新しい説明版を生み出した。 |

| Background In his 1973 paper "Mathematical Truth", Paul Benacerraf raised a problem for the philosophy of mathematics.[b] According to Benacerraf, mathematical sentences such as "two is a prime number" imply the existence of mathematical objects.[5] He supported this claim with the idea that mathematics should not have its own special semantics. In other words, the meaning of mathematical sentences should follow the same rules as any other type of sentence. For example, if the sentence "Mars is a planet" implies the existence of the planet Mars, then the sentence "two is a prime number" should also imply the existence of the number two.[6] But according to Benacerraf, if mathematical objects existed, they would be unknowable.[5] This is because mathematical objects, if they exist, are abstract objects: objects that cannot cause things to happen and that have no location in space and time.[7] Benacerraf argued, on the basis of the causal theory of knowledge, that it would be impossible to know about such objects because they cannot come into causal contact with anyone.[c][9] This is called Benacerraf's epistemological problem because it concerns the epistemology of mathematics, that is, how people know what they do about mathematics.[10] The philosophy of mathematics is split into two main strands: platonism and nominalism. Platonism holds that there exist abstract mathematical objects such as numbers and sets whilst nominalism denies their existence.[11] Each of these views faces issues due to the problem raised by Benacerraf. Because nominalism rejects the existence of mathematical objects, it faces no epistemological problem but it does face problems concerning the idea that mathematics should not have its own special semantics. Platonism does not face problems concerning the semantic half of the dilemma but it has difficulty explaining how it is possible to know about mathematical objects.[12] The indispensability argument aims to overcome the epistemological problem posed against platonism by providing a justification for belief in abstract mathematical objects.[13] It is part of a broad class of indispensability arguments most commonly applied in the philosophy of mathematics, but which also includes arguments in the philosophy of language and ethics.[14] In the most general sense, indispensability arguments aim to support their conclusion based on the claim that the truth of the conclusion is indispensable or necessary for a certain purpose.[15] When applied in the field of ontology—the study of what exists—they exemplify a Quinean strategy for establishing the existence of controversial entities that cannot be directly investigated. According to this strategy, the indispensability of these entities for formulating a theory of other less controversial entities counts as evidence for their existence.[16] In the case of philosophy of mathematics, the indispensability of mathematical entities for formulating scientific theories is taken as evidence for the existence of those mathematical entities.[17] |

背景 1973年の論文「数学的真理」において、ポール・ベナセラフは数学哲学に対する問題を提起した。[b] ベナセラフによれば、「2は素数である」といった数学的命題は数学的対象の存在を意味する。[5] 彼はこの主張を、数学が独自の特別な意味論を持つべきではないという考えで支持した。つまり、数学的命題の意味は他のあらゆる種類の命題と同じ規則に従う べきだという。例えば「火星は惑星である」という命題が火星という惑星の存在を意味するなら、「2は素数である」という命題もまた2という数の存在を意味 すべきだ[6]。しかしベナセラフによれば、もし数学的対象が存在するならば、それらは知ることができないものとなる。[5] なぜなら、数学的対象が存在するとすれば、それは抽象的対象、すなわち事象を引き起こすこともできず、時空間上の位置を持たない対象だからである。[7] ベナセラフは因果的認識論に基づき、そのような対象は誰とも因果的接触を持つことができないため、それを知ることは不可能だと論じた。[c] [9] これは数学の認識論、すなわち人々が数学について知っていることをどのように知っているのかに関わるため、ベナセラフの認識論的問題と呼ばれる。[10] 数学哲学は主に二つの流れに分かれる:プラトン主義と唯名論である。プラトン主義は数や集合などの抽象的な数学的対象が存在すると主張する一方、唯名論は その存在を否定する。[11] これら両方の見解は、ベナセラフが提起した問題によって課題に直面する。唯名論は数学的対象の存在を否定するため、認識論的問題には直面しないが、数学が 独自の特別な意味論を持つべきではないという考えに関する問題には直面する。プラトン主義は、このジレンマの意味論的な側面に関する問題には直面しない が、数学的対象について知る可能性を説明するのに困難を抱える。[12] 不可欠性論証は、抽象的な数学的対象を信じる根拠を提供することで、プラトン主義に対する認識論的問題を克服しようとするものである。[13] これは数学哲学で最も一般的に用いられる広範な不可欠性論証の一種であるが、言語哲学や倫理学における論証も含まれる。[14] 最も一般的な意味で、不可欠性論証は、その結論の真偽が特定の目的にとって不可欠または必要であるという主張に基づいて結論を支持しようとする。[15] 存在論(存在するものの研究)の分野で適用される場合、それらは直接調査できない論争的な実体の存在を確立するためのクワイン的戦略の一例となる。この戦 略によれば、より議論の少ない実体の理論を構築する上でこれらの実体が不可欠であることが、その実体の存在の証拠となる。[16] 数学哲学の場合、科学的理論を構築する上で数学的実体が不可欠であることが、それらの数学的実体の存在の証拠と見なされる。[17] |

| Overview of the argument Mark Colyvan presents the argument in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy in the following form:[2] We ought to have ontological commitment to all and only the entities that are indispensable to our best scientific theories. Mathematical entities are indispensable to our best scientific theories. Therefore, we ought to have ontological commitment to mathematical entities. Here, an ontological commitment to an entity is a commitment to believing that that entity exists.[18] The first premise is based on two fundamental assumptions: naturalism and confirmational holism. According to naturalism, we should look to our best scientific theories to determine what we have best reason to believe exists.[19] Quine summarized naturalism as "the recognition that it is within science itself, and not in some prior philosophy, that reality is to be identified and described".[20] Confirmational holism is the view that scientific theories cannot be confirmed in isolation and must be confirmed as wholes. Therefore, according to confirmational holism, if we should believe in science, then we should believe in all of science, including any of the mathematics that is assumed by our best scientific theories.[19] The argument is mainly aimed at nominalists that are scientific realists as it attempts to justify belief in mathematical entities in a manner similar to the justification for belief in theoretical entities such as electrons or quarks; Quine held that such nominalists have a "double standard" with regards to ontology.[2] The indispensability argument differs from other arguments for platonism because it only argues for belief in the parts of mathematics that are indispensable to science. It does not necessarily justify belief in the most abstract parts of set theory, which Quine called "mathematical recreation … without ontological rights".[21] Some philosophers infer from the argument that mathematical knowledge is a posteriori because it implies mathematical truths can only be established via the empirical confirmation of scientific theories to which they are indispensable. This also indicates mathematical truths are contingent since empirically known truths are generally contingent. Such a position is controversial because it contradicts the traditional view of mathematical knowledge as a priori knowledge of necessary truths.[22] Whilst Quine's original argument is an argument for platonism, indispensability arguments can also be constructed to argue for the weaker claim of sentence realism—the claim that mathematical theory is objectively true. This is a weaker claim because it does not necessarily imply there are abstract mathematical objects.[23][d] |

議論の概要 マーク・コリヴァンはスタンフォード哲学百科事典において、この議論を以下の形で提示している[2]: 我々は、最良の科学的理論に不可欠な実体のみに対して存在論的コミットメントを持つべきである。 数学的実体は最良の科学的理論に不可欠である。 したがって、我々は数学的実体に対して存在論的コミットメントを持つべきである。 ここで、実体に対する存在論的コミットメントとは、その実体が存在すると信じることにコミットすることである。[18] 最初の前提は、二つの根本的な仮定、すなわち自然主義と確認的全体論に基づいている。自然主義によれば、我々は最良の科学的理論に目を向け、何が存在する と信じるべき最良の理由があるかを決定すべきである。[19] クワインは自然主義を「現実を特定し記述すべき場所は、先行する哲学ではなく科学そのものの中にあるという認識」と要約した[20]。確認的全体論とは、 科学理論は孤立して確認されることはできず、全体として確認されなければならないという見解である。したがって確認的全体論によれば、もし我々が科学を信 じるべきならば、最良の科学理論が前提とする数学を含む科学全体を信じるべきである。[19] この議論は主に科学的実在論者である名目論者を対象としている。なぜなら、電子やクォークといった理論的実体への信念を正当化するのと同様の方法で、数学 的実体への信念を正当化しようとするからである。クワインは、こうした名目論者が存在論に関して「二重基準」を持っていると主張した。[2] 不可欠性論証は、プラトン主義を支持する他の論証とは異なる。なぜなら、科学にとって不可欠な数学の部分のみへの信念を主張するからである。これは集合論 の最も抽象的な部分への信念を必ずしも正当化しない。クワインはこれを「存在論的権利を持たない数学的娯楽」と呼んだ[21]。一部の哲学者はこの議論か ら、数学的知識はア・ポステリオリなであると推論する。なぜなら、数学的真理はそれらが不可欠である科学的理論の経験的確認を通じてのみ確立され得ると示 唆するからである。これはまた、経験的に知られる真理が一般的に偶然的であることから、数学的真理も偶然的であることを示唆する。この立場は、数学的知識 を必然的真理のア・プリオリな知識とする従来の見解と矛盾するため、議論の的となっている。[22] クワインの本来の議論はプラトン主義を支持するものだが、文実在論(数学理論が客観的に真であるという主張)というより弱い主張を支持する不可避性論証も構築可能である。これは抽象的な数学的対象の存在を必ずしも意味しないため、より弱い主張となる。[23][d] |

| Major concepts Indispensability The second premise of the indispensability argument states mathematical objects are indispensable to our best scientific theories. In this context, indispensability is not the same as ineliminability because any entity can be eliminated from a theoretical system given appropriate adjustments to the other parts of the system.[25] Indispensability instead means that an entity cannot be eliminated without reducing the attractiveness of the theory. The attractiveness of the theory can be evaluated in terms of theoretical virtues such as explanatory power, empirical adequacy and simplicity.[26] Furthermore, if an entity is dispensable to a theory, an equivalent theory can be formulated without it.[27] This is the case, for example, if each sentence in one theory is a paraphrase of a sentence in another or if the two theories predict the same empirical observations.[28] According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, one of the most influential arguments against the indispensability argument comes from Hartry Field.[29] It rejects the claim that mathematical objects are indispensable to science; Field has supported this argument by reformulating or "nominalizing" scientific theories so they do not refer to mathematical objects.[30] As part of this project, Field has offered a reformulation of Newtonian physics in terms of the relationships between space-time points. Instead of referring to numerical distances, Field's reformulation uses relationships such as "between" and "congruent" to recover the theory without implying the existence of numbers.[31] John Burgess and Mark Balaguer have taken steps to extend this nominalizing project to areas of modern physics, including quantum mechanics.[32] Philosophers such as David Malament and Otávio Bueno dispute whether such reformulations are successful or even possible, particularly in the case of quantum mechanics.[33] Field's alternative to platonism is mathematical fictionalism, according to which mathematical theories are false because they refer to abstract objects which do not exist.[34] As part of his argument against the indispensability argument, Field has tried to explain how it is possible for false mathematical statements to be used by science without making scientific predictions false.[35] His argument is based on the idea that mathematics is conservative. A mathematical theory is conservative if, when combined with a scientific theory, it does not imply anything about the physical world that the scientific theory alone would not have already.[36] This explains how it is possible for mathematics to be used by scientific theories without making the predictions of science false. In addition, Field has attempted to specify how exactly mathematics is useful in application.[29] Field thinks mathematics is useful for science because mathematical language provides a useful shorthand for talking about complex physical systems.[32] Another approach to denying that mathematical entities are indispensable to science is to reformulate mathematical theories themselves so they do not imply the existence of mathematical objects. Charles Chihara, Geoffrey Hellman, and Putnam have offered modal reformulations of mathematics that replace all references to mathematical objects with claims about possibilities.[32] |

主要な概念 不可欠性 不可欠性論証の第二の前提は、数学的対象が我々の最良の科学的理論にとって不可欠であると述べる。この文脈における不可欠性は、除去不能性とは異なる。な ぜなら、理論体系の他の部分を適切に調整すれば、いかなる実体も体系から除去できるからである[25]。不可欠性とは、その実体を除去すると理論の魅力が 低下することを意味する。理論の魅力度は、説明力、経験的妥当性、単純性といった理論的長所によって評価できる[26]。さらに、ある実体が理論にとって 不要である場合、それを排除した同等の理論を構築できる[27]。例えば、ある理論の文が別の理論の文の言い換えである場合や、二つの理論が同じ経験的観 察を予測する場合などがこれに該当する。[28] スタンフォード哲学百科事典によれば、不可欠性論に対する最も影響力のある反論の一つはハートリー・フィールドによるものである。[29] 彼は数学的対象が科学にとって不可欠であるという主張を退け、科学理論を再構成または「唯名論」することで数学的対象を参照しない形とし、この反論を支持 してきた。[30] このプロジェクトの一環として、フィールドは時空間の点間の関係を用いてニュートン力学を再構築した。数値的な距離を参照する代わりに、「間の」「合同 な」といった関係を用いることで、数の存在を暗示せずに理論を再構築している。[31] ジョン・バージェスとマーク・バラゲールは、この唯名論プロジェクトを量子力学を含む現代物理学の領域へ拡張する試みを進めている。[32] デイヴィッド・マラメントやオタヴィオ・ブエノといった哲学者たちは、特に量子力学の事例において、こうした再定式化が成功しているか、あるいはそもそも 可能なのかについて異議を唱えている。[33] フィールドがプラトン主義に代えて提唱するのは数学的虚構主義である。これによれば、数学理論は存在しない抽象的対象を参照するため虚偽となる。[34] 不可欠性論証への反論の一環として、フィールドは虚偽の数学的命題が科学によって用いられながらも科学的予測を虚偽にしない仕組みを説明しようとした。 [35] 彼の論証は数学が保守的であるという考えに基づいている。数学理論が保守的であるとは、科学理論と組み合わせた際に、科学理論単独では既に示されていない 物理世界に関する新たな含意を導かないことを意味する。[36] これにより、科学理論が数学を利用しても科学の予測を偽りにしないことが説明される。さらにフィールドは、数学が応用において具体的にどのように有用であ るかを特定しようとしている。[29] フィールドは、数学的言語が複雑な物理システムについて議論する際に有用な略語を提供する点で、数学が科学に有用だと考えている。[32] 数学的実体が科学に不可欠ではないとする別のアプローチは、数学的理論そのものを再構成し、数学的対象の存在を暗示しないようにすることである。チャール ズ・チハラ、ジェフリー・ヘルマン、パットナムは、数学的対象への言及をすべて可能性に関する主張に置き換えた、数学の様相論的再構成を提案している。 [32] |

| Naturalism The naturalism underlying the indispensability argument is a form of methodological naturalism that asserts the primacy of the scientific method for determining the truth.[37] In other words, according to Quine's naturalism, our best scientific theories are the best guide to what exists.[19] This form of naturalism rejects the idea that philosophy precedes and ultimately justifies belief in science, instead holding that science and philosophy are continuous with one another as part of a single, unified investigation into the world.[38] As such, this form of naturalism precludes the idea of a prior philosophy that can overturn the ontological commitments of science.[39] This is in contrast to metaphysical forms of naturalism, which rule out the existence of abstract objects because they are not physical.[40] An example of such a naturalism is supported by David Armstrong. It holds a principle called the Eleatic principle, which states that only causal entities exist and there are no non-causal entities.[41] Quine's naturalism claims such a principle cannot be used to overturn science's ontological commitment to mathematics because philosophical principles cannot overrule science.[42] I'm moved to laughter at the thought of how presumptuous it would be to reject mathematics for philosophical reasons. How would you like the job of telling the mathematicians that they must change their ways, and abjure countless errors, now that philosophy has discovered that there are no classes? Can you tell them, with a straight face, to follow philosophical argument wherever it may lead? If they challenge your credentials, will you boast of philosophy's other great discoveries: that motion is impossible, that a Being than which no greater can be conceived cannot be conceived not to exist, that it is unthinkable that anything exists outside the mind, that time is unreal, that no theory has ever been made at all probable by evidence (but on the other hand that an empirically adequate ideal theory cannot possibly be false), that it is a wide-open scientific question whether anyone has ever believed anything, and so on, and on, ad nauseam? Not me! ------ David Lewis, Parts of Classes[43] Quine held his naturalism as a fundamental assumption but later philosophers have provided arguments to support it. The most common arguments in support of Quinean naturalism are track-record arguments. These are arguments that appeal to science's successful track record compared to philosophy and other disciplines.[44] David Lewis famously made such an argument in a passage from his 1991 book Parts of Classes, deriding the track record of philosophy compared to mathematics and arguing that the idea of philosophy overriding science is absurd.[45] Critics of the track record argument have argued that it goes too far, discrediting philosophical arguments and methods entirely, and contest the idea that philosophy can be uniformly judged to have had a bad track record.[46] Quine's naturalism has also been criticized by Penelope Maddy for contradicting mathematical practice.[e][47] According to the indispensability argument, mathematics is subordinated to the natural sciences in the sense that its legitimacy depends on them.[48] But Maddy argues mathematicians do not seem to believe their practice is restricted in any way by the activity of the natural sciences. For example, mathematicians' arguments over the axioms of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory do not appeal to their applications to the natural sciences. Similarly, Charles Parsons has argued that mathematical truths seem immediately obvious in a way that suggests they do not depend on the results of science.[49] |

自然主義 不可避性論証の根底にある自然主義とは、真実を決定する上で科学的方法の優位性を主張する方法論的自然主義の一形態である。[37] 言い換えれば、クワインの自然主義によれば、我々の最良の科学的理論こそが存在するものへの最良の指針である[19]。この形態の自然主義は、哲学が科学 への信念に先行し最終的にそれを正当化するという考えを拒否し、代わりに科学と哲学は世界に対する単一で統一された探究の一部として互いに連続していると 主張する。[38] このような自然主義は、科学の存在論的コミットメントを覆すような、先行する哲学の考え方を排除する。[39] これは、抽象的な対象は物理的ではないという理由でその存在を否定する形而上学的な自然主義とは対照的である。[40] このような自然主義の一例は、デイヴィッド・アームストロングによって支持されている。それは、因果関係のある実体のみが存在し、因果関係のない実体は存 在しないというエレア学派の原理と呼ばれる原則を主張する。[41] クワインの自然主義は、哲学的原則は科学に優先することはできないため、このような原則は、数学に対する科学の存在論的コミットメントを覆すために使用す ることはできないと主張する。[42] 哲学的な理由で数学を拒絶することがどれほど傲慢であるかを考えると、私は笑ってしまう。哲学が「クラス」は存在しないと発見した今、数学者に「やり方を 変え、無数の誤りを放棄しなければならない」と伝える仕事を、あなたはどのように思うだろうか?哲学的な議論がどこへ導こうとも、それを従うよう、真顔で 彼らに伝えることができるだろうか?もし彼らが君の資格を問いただしたら、哲学の他の偉大な発見を自慢するつもりか? 運動は不可能だ、考えうる限り最高 の存在は存在しないとは考えられない、心の外に何かが存在するとは考えられない、時間は実在しない、証拠によって理論が確率的になったことは一度もない (だが一方で経験的に妥当な理想理論が誤りである可能性はありえない)、 誰かが何かを信じたことがあるかどうかは未解決の科学的疑問だ、などといった、うんざりするほど延々と続く主張を? 俺は違う! ------ デイヴィッド・ルイス『集合の部分』[43] クワインは自然主義を根本的前提としていたが、後世の哲学者たちはこれを支持する論証を提供してきた。クワイン的自然主義を支持する最も一般的な論証は実 績論証である。これは哲学や他の学問分野と比較した科学の成功実績に訴える論証である。[44] デイヴィッド・ルイスは1991年の著書『クラスの一部』の一節で、数学と比較した哲学の実績を嘲笑し、哲学が科学を凌駕するという考えが荒唐無稽だと論 じることで、この種の議論を有名にした。[45] 実績論の批判者は、この議論が哲学的議論や方法を完全に信用失墜させるほど行き過ぎていると主張し、哲学の実績が一様に悪いと判断できるという考えに異議 を唱えている。[46] クワインの自然主義は、ペネロペ・マディによって数学の実践と矛盾するとして批判されている。[e][47] 不可欠性論によれば、数学はその正当性が自然科学に依存するという意味で、自然科学に従属している。[48] しかしマディは、数学者が自らの実践が自然科学の活動によって何らかの形で制限されているとは考えていないと主張する。例えば、数学者たちがツェルメロ= フレンケル集合論の公理について議論する際、自然科学への応用を根拠にすることは決してない。同様に、チャールズ・パーソンズは、数学的真理は科学の結果 に依存していないことを示唆する形で、直観的に明らかであるように見えると論じている。[49] |

| Confirmational holism Confirmational holism is the view that scientific theories and hypotheses cannot be confirmed in isolation and must be confirmed together as part of a larger cluster of theories.[50] An example of this idea provided by Michael Resnik is of the hypothesis that an observer will see oil and water separate out if they are added together because they do not mix. This hypothesis cannot be confirmed in isolation because it relies on assumptions such as the absence of any chemical that will interfere with their separation and that the eyes of the observer are functioning well enough to observe the separation.[51] Because mathematical theories are likewise assumed by scientific theories, confirmational holism implies the empirical confirmations of scientific theories also support these mathematical theories.[52]  Photo of Penelope Maddy An important counterargument to confirmational holism is due to Penelope Maddy According to a counterargument by Maddy,[e] the theses of naturalism and confirmational holism that make up the first premise of the indispensability argument are in tension with one another. Maddy said naturalism entails respecting the methods used by scientists as the best method for uncovering the truth, but scientists do not act as if they are required to believe in all of the entities that are indispensable to science.[53] To illustrate this point, Maddy uses the example of atomic theory; she states that despite the atom being indispensable to scientists' best theories by 1860, their reality was not universally accepted until 1913 when they were put to a direct experimental test.[54] Maddy, and others such as Mary Leng, also appeal to the fact that scientists use mathematical idealizations—such as assuming bodies of water to be infinitely deep—without regard for whether they are true.[55] According to Maddy, this indicates that scientists do not view the indispensable use of mathematics for science as justification for the belief in mathematics or mathematical entities. Overall, Maddy argues for siding with naturalism and rejecting confirmational holism, meaning we do not need to believe in all of the entities that are indispensable to science.[29] Another counterargument due to Elliott Sober claims that mathematical theories are not tested in the same way as scientific theories. Sober states that scientific theories compete with alternatives to find which theory has the most empirical support. But there are no alternatives for mathematical theory to compete with because all scientific theories share the same mathematical core. As a result, according to Sober, mathematical theories do not share the empirical support of scientific theories, so confirmational holism should be rejected.[56] Since these counterarguments have been raised, a number of philosophers—including Resnik, Alan Baker, Patrick Dieveney, David Liggins, Jacob Busch, and Andrea Sereni—have argued that confirmational holism can be eliminated from the argument.[57] For example, Resnik has offered a pragmatic indispensability argument focused less on the notion of evidence and more on the practical importance of mathematics in conducting scientific enquiry.[58] |

確認的全体論 確認的全体論とは、科学的理論や仮説は単独では確認できず、より大きな理論群の一部としてまとめて確認されなければならないという見解である。[50] マイケル・レスニックが提示したこの考え方の例として、油と水を混ぜると分離して見えるという仮説がある。この仮説は単独では確認できない。なぜなら、分 離を妨げる化学物質が存在しないことや、観察者の目が分離を観察できるほど十分に機能していることといった前提に依存しているからだ。[51] 数学的理論も同様に科学的理論によって前提とされるため、確認的全体論は科学的理論の経験的確認がこれらの数学的理論も支持することを示唆する。[52]  ペネロペ・マディの写真 確認的全体論に対する重要な反論はペネロペ・マディによるものである。 マディによる反論によれば[e]、不可欠性論証の第一前提を構成する自然主義と確認的全体論の命題は互いに矛盾する。マディは、自然主義は科学者が用いる 方法を真実発見の最良の方法として尊重することを意味すると述べたが、科学者は科学に不可欠な全ての実体を信じなければならないかのように行動していな い。[53] この点を説明するため、マディは原子論の例を用いる。1860年までに科学者の最良理論にとって原子が不可欠であったにもかかわらず、その実在性は 1913年に直接的な実験的検証が行われるまで普遍的に受け入れられなかったと彼女は述べる。[54] マディやメアリー・レンらも、科学者が数学的理想化(例えば水域を無限の深さを持つと仮定するなど)を、それが真実かどうかを問わずに用いる事実を根拠に 挙げている。[55] マディによれば、これは科学者が数学を科学に不可欠とみなすことが、数学や数学的実体への信仰の正当化にはならないことを示している。全体として、マディ は自然主義に賛同し、確認的全体論を拒否することを主張している。つまり、科学に不可欠な実体をすべて信じる必要はないというのである。[29] エリオット・ソーバーによる別の反論は、数学理論は科学理論と同じ方法で検証されるわけではないと主張している。ソーバーは、科学理論は、どの理論が最も 経験的裏付けを得ているかを競い合うと述べている。しかし、すべての科学理論は同じ数学的核を共有しているため、数学理論が競合する代替理論は存在しな い。その結果、ソーバーによれば、数学理論は科学理論の経験的裏付けを共有していないため、確認的全体主義は拒否されるべきである[56]。 これらの反論が提起されて以来、レスニック、アラン・ベイカー、パトリック・ディーブニー、デビッド・リギンズ、ジェイコブ・ブッシュ、アンドレア・セレ ニなど、多くの哲学者が、確認的全体主義は議論から消去法による排除できると主張している。[57] 例えば、レスニックは、証拠の概念よりも、科学的探究を行う上での数学の実用的な重要性に焦点を当てた、実用的な不可欠性に関する議論を提示している。 [58] |

| Ontological commitment Another key part of the argument is the concept of ontological commitment. The ontological commitments of a theory are all the things that exist according to that theory. Quine believed that people should be ontologically committed to the same entities that their best scientific theories are committed, in the sense that they should be committed to believing they exist.[59] He formulated a "criterion of ontological commitment", which aims to uncover the commitments of scientific theories by translating or "regimenting" them from ordinary language into first-order logic.[60] In ordinary language, Quine believed the term "there is" must carry ontological commitment; to say "there is" something means that that thing exists.[f][62] And for Quine, the existential quantifier in first-order logic was the natural equivalent of "there is". Therefore, Quine's criterion takes the ontological commitments of the theory to be all of the objects over which the regimented theory quantifies.[60] Quine thought it is important to translate scientific theories into first-order logic because ordinary language is ambiguous, whereas logic can make the commitments of a theory more precise. Translating theories to first-order logic also has advantages over translating them to higher-order logics such as second-order logic. Whilst second-order logic has the same expressive power as first-order logic, it lacks some of the technical strengths of first-order logic such as completeness and compactness. Second-order logic also allows quantification over properties like "redness", but whether there are ontological commitments to properties is controversial.[18] According to Quine, such quantification is simply ungrammatical.[63] Jody Azzouni has objected to Quine's criterion of ontological commitment, saying that the existential quantifier in first-order logic does not always carry ontological commitment.[64] According to Azzouni, the ordinary language equivalent of existential quantification "there is" is often used in sentences without implying ontological commitment. In particular, Azzouni points to the use of "there is" when referring to fictional objects in sentences such as "there are fictional detectives who are admired by some real detectives".[65] According to Azzouni, to have ontological commitment to an entity, there must be the right level of epistemic access to it. This means, for example, that it must overcome some epistemic burdens to be postulated. But according to Azzouni, mathematical entities are "mere posits" that can be postulated by anyone at any time by "simply writing down a set of axioms", so they do not need to be treated as real.[66] More modern presentations of the argument do not necessarily accept Quine's criterion of ontological commitment and may allow for ontological commitments to be directly determined from ordinary language.[67][g] |

存在論的コミットメント 議論のもう一つの重要な部分は、存在論的コミットメントという概念である。ある理論の存在論的コミットメントとは、その理論に従って存在する全ての事物を 指す。クワインは、人々は最良の科学的理論がコミットしているのと同じ実体に対して存在論的にコミットすべきだと考えた。つまり、それらの実体が存在する と信じることにコミットすべきだという意味である。[59] 彼は「存在論的コミットメントの基準」を提唱した。これは科学理論を日常言語から一階論理へ翻訳、すなわち「体系化」することで、そのコミットメントを明 らかにすることを目的とする。[60] クワインは日常言語において「~がある」という表現は存在論的コミットメントを伴わねばならないと考えた。つまり「~がある」と言うことは、そのものが存 在することを意味するのだ。[f][62] そしてクワインにとって、一階論理における存在量化子は「存在する」の自然な対応物であった。したがってクワインの基準は、体系化された理論が量化する対 象のすべてを、その理論の存在論的コミットメントと見なすのである。[60] クワインは、科学理論を一階論理へ翻訳することが重要だと考えた。なぜなら日常言語は曖昧である一方、論理は理論のコミットメントをより精密にできるから である。理論を一階論理へ翻訳することは、二階論理のような高階論理へ翻訳するよりも利点がある。二階論理は一階論理と同等の表現力を持つが、完全性やコ ンパクト性といった一階論理の技術的強みを欠いている。二階論理は「赤さ」のような性質への量化も許すが、性質への存在論的拘束があるかどうかは議論の余 地がある。[18] クワインによれば、そのような量化は単に文法的に不適切であるという。[63] ジョディ・アズーニはクワインの存在論的コミットメント基準に異議を唱え、一階論理における存在量化子が常に存在論的コミットメントを伴うわけではないと 主張している。[64] アズーニによれば、存在量化の日常言語における対応語「~がある」は、存在論的コミットメントを暗示せずに文中で頻繁に使用される。特にアズーニは「あ る」という表現が、例えば「実在の探偵から称賛される架空の探偵がいる」といった文において、架空の物体を指す際に用いられることを指摘している。 [65] アズーニによれば、ある実体に対する存在論的コミットメントを持つためには、それに対する適切なレベルの認識的アクセスがなければならない。これは例え ば、実体が仮定されるためには何らかの認識的負担を克服しなければならないことを意味する。しかしアズーニによれば、数学的実体は「単なる仮定」であり、 「単に公理の集合を書き記す」ことで誰でもいつでも仮定できるため、実在として扱う必要はない。[66] この議論のより現代的な展開では、クワインの存在論的コミットメントの基準を必ずしも受け入れるわけではなく、存在論的コミットメントが日常言語から直接決定されることを認める場合もある。[67][g] |

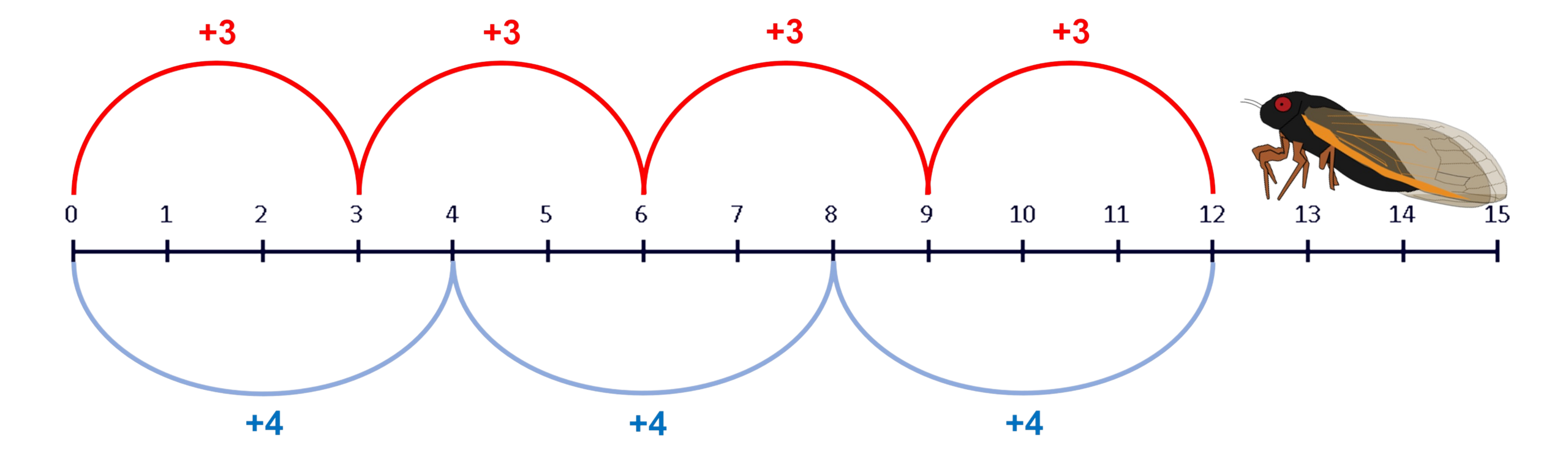

| Mathematical explanation One potential issue with the argument, raised by Joseph Melia, is that it does not account for the role of mathematics in science. According to Melia, we only need to believe in mathematics if it is indispensable to science in the right kind of way. In particular, it needs to be indispensable to scientific explanations.[69] But according to Melia, mathematics plays a purely representational role in science, it merely "[makes] more things sayable about concrete objects".[70] He argues that it is legitimate to withdraw commitment to mathematics for this reason, citing a linguistic phenomenon he calls "weaseling". This is when a person makes a statement and then later withdraws something implied by that statement. An example of weaseling used to express information in an everyday context is "Everyone who came to the seminar had a handout. But the person who came in late didn't get one."[71] Here, seemingly contradictory information is conveyed, but read charitably it simply states that everyone apart from the person who came in late got a handout.[71] Similarly, according to Melia, although mathematics is indispensable to science "almost all scientists ... deny that there are such things as mathematical objects", implying that commitment to mathematical objects is being weaseled away.[72] For Melia, such weaseling is acceptable because mathematics does not play a genuinely explanatory role in science.[73] Inspired both by the arguments against confirmational holism[74] and Melia's argument that belief in mathematics can be suspended if it does not play a genuinely explanatory role in science,[75] Colyvan and Baker have defended an explanatory version of the indispensability argument.[76][h] This version of the argument attempts to remove the reliance on confirmational holism by replacing it with an inference to the best explanation. It states we are justified in believing in mathematical objects because they appear in our best scientific explanations, not because they inherit the empirical support of our best theories.[79] It is presented by the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy in the following form:[76] There are genuinely mathematical explanations of empirical phenomena. We ought to be committed to the theoretical posits in such explanations. Therefore, we ought to be committed to the entities postulated by the mathematics in question. Number line with multiples of 3 and 4 highlighted up to the number 12. An illustration of a cicada sits at the number 13.  Number line visualizing why prime-numbered life cycles are advantageous compared to non-prime life cycles. If predators have life cycles of 3 or 4 years, they quickly synchronize with a non-prime life cycle such as a life cycle of 12 years. But they will not synchronize with a 13-year periodical cicada's life cycle until 39 and 52 years have passed, respectively. An example of mathematics' explanatory indispensability presented by Baker is the periodic cicada, a type of insect that usually has life cycles of 13 or 17 years. It is hypothesized that this is an evolutionary advantage because 13 and 17 are prime numbers. Because prime numbers have no non-trivial factors, this means it is less likely predators can synchronize with the cicadas' life cycles. Baker said that this is an explanation in which mathematics, specifically number theory, plays a key role in explaining an empirical phenomenon.[80] Other important examples are explanations of the hexagonal structure of bee honeycombs and the impossibility of crossing all seven bridges of Königsberg only once in a walk across the city.[81] The main response to this form of the argument, which philosophers such as Melia, Chris Daly, Simon Langford, and Juha Saatsi have adopted, is to deny there are genuinely mathematical explanations of empirical phenomena, instead framing the role of mathematics as representational or indexical.[82] |

数学的説明 ジョセフ・メリアが指摘したこの議論の潜在的な問題は、科学における数学の役割を考慮していない点だ。メリアによれば、数学を信じる必要があるのは、それ が科学にとって適切な形で不可欠である場合に限られる。特に、数学は科学的説明において不可欠である必要がある[69]。しかしメリアによれば、数学は科 学において純粋に表現的な役割を果たすに過ぎず、単に「具体的な対象についてより多くのことを言えるようにする」だけである[70]。彼はこの理由から数 学へのコミットメントを撤回することが正当であると主張し、彼が「ウィーゼルング」と呼ぶ言語現象を例に挙げる。これは、ある人格が発言した後で、その発 言が暗示していた何かを撤回する行為である。日常的な文脈で情報を表現するために用いられるウィーゼリングの例として、「セミナーに来た人は全員配布資料 を持っていた。しかし遅れて来た人はもらえなかった」[71] がある。ここでは一見矛盾した情報が伝えられているが、好意的に解釈すれば、遅れて来た人以外の全員が配布資料を受け取ったと述べているに過ぎない。 [71] 同様に、メリアによれば、数学は科学に不可欠であるにもかかわらず「ほぼ全ての科学者は…数学的対象というものが存在することを否定している」という。こ れは数学的対象へのコミットメントがウィーゼルイングによって回避されていることを示唆している。[72] メリアにとって、このようなウィーゼルイングは許容される。なぜなら数学は科学において真に説明的な役割を果たしていないからである。[73] 確認的全体論への反論[74]と、科学において真に説明的役割を果たさないなら数学への信念は保留できるとするメリアの主張[75]に触発され、コリバン とベイカーは説明的不可欠性論証を擁護した[76][h]。この論証は確認的全体論への依存を排除し、最良の説明への推論で置き換える試みである。この議 論は、数学的対象を信じる正当性は、それらが最良の科学的説明に現れるからであり、最良の理論の経験的裏付けを継承するからではないと述べる[79]。イ ンターネット哲学百科事典では次のように提示されている[76]: 経験的現象に対する真に数学的な説明が存在する。 我々はそのような説明における理論的仮定を支持すべきである。 したがって、我々はその数学が仮定する実体を支持すべきである。 12までの3と4の倍数で強調された数直線。13の位置にセミのイラストが配置されている。  素数周期の生活史が非素数周期に比べて有利な理由を可視化した数直線。捕食者の生活史が3年または4年であれば、12年周期のような非素数周期と迅速に同期する。しかし、13年周期のセミの生活環とは、それぞれ39年と52年が経過するまで同期しない。 ベイカーが提示した数学の説明的不可欠性の例が周期セミである。この昆虫は通常13年または17年の生活環を持つ。13と17が素数であるため、これが進 化上の利点だと仮説が立てられている。素数は非自明な因数を持たないため、捕食者がセミの生活周期に同調する可能性が低くなる。ベイカーは、この説明にお いて数学、特に数論が経験的現象を解明する上で重要な役割を果たすと述べた。[80] その他の重要な例としては、ミツバチの巣の六角形構造の説明や、ケーニヒスベルクの七つの橋を一度だけ渡って街を横断することが不可能であるという説明が ある。[81] この種の議論に対する主な反論として、メリア、クリス・デイリー、サイモン・ラングフォード、ユハ・サーツィといった哲学者たちが採用しているのは、経験 的現象に対する真に数学的な説明は存在せず、数学の役割は表象的あるいは指標的であると位置付ける立場である。[82] |

| Historical development Precursors and influences on Quine  A photo of Gottlob Frege Aspects of the indispensability argument can be traced back to Gottlob Frege. The argument is historically associated with Willard Van Orman Quine and Hilary Putnam but it can be traced to earlier thinkers such as Gottlob Frege and Kurt Gödel. In his arguments against mathematical formalism—a view that likens mathematics to a game like chess with rules about how mathematical symbols such as "2" can be manipulated—Frege said in 1893 that "it is applicability alone which elevates arithmetic from a game to the rank of a science".[83] Gödel, in a 1947 paper on the axioms of set theory, said that if a new axiom were to have enough verifiable consequences, it "would have to be accepted at least in the same sense as any well‐established physical theory".[84] Frege's and Gödel's arguments differ from the later Quinean indispensability argument because they lack features such as naturalism and subordination of practice, leading some philosophers, including Pieranna Garavaso, to say that they are not genuine examples of the indispensability argument.[85] Whilst developing his philosophical view of confirmational holism, Quine was influenced by Pierre Duhem.[86] At the beginning of the twentieth century, Duhem defended the law of inertia from critics who said that it is devoid of empirical content and unfalsifiable.[51] These critics based this claim on the fact that the law does not make any observable predictions without positing some observational frame of reference and that falsifying instances can always be avoided by changing the choice of reference frame. Duhem responded by saying that the law produces predictions when paired with auxiliary hypotheses fixing the frame of reference and is therefore no different from any other physical theory.[87] Duhem said that although individual hypotheses may make no observable predictions alone, they can be confirmed as parts of systems of hypotheses. Quine extended this idea to mathematical hypotheses, claiming that although mathematical hypotheses hold no empirical content on their own, they can share in the empirical confirmations of the systems of hypotheses in which they are contained.[88] This thesis later came to be known as the Duhem–Quine thesis.[89] Quine described his naturalism as the "abandonment of the goal of a first philosophy. It sees natural science as an inquiry into reality, fallible and corrigible but not answerable to any supra-scientific tribunal, and not in need of any justification beyond observation and the hypothetico-deductive method."[90] The term "first philosophy" is used in reference to Descartes' Meditations on First Philosophy, in which Descartes used his method of doubt in an attempt to secure the foundations of science. Quine said that Descartes' attempts to provide the foundations for science had failed and that the project of finding a foundational justification for science should be rejected because he believed philosophy could never provide a method of justification more convincing than the scientific method.[91] Quine was also influenced by the logical positivists, such as his teacher Rudolf Carnap; his naturalism was formulated in response to many of their ideas.[92] For the logical positivists, all justified beliefs were reducible to sense data, including knowledge of ordinary objects such as trees.[93] Quine criticized sense data as self-defeating, saying that belief in ordinary objects is needed to organize our experiences of the world. He also said that science should be believed too because it is the best theory of how sense-experience provides beliefs about ordinary objects.[94] Whilst the logical positivists said that individual claims must be supported by sense data, Quine's confirmational holism means scientific theory is inherently tied up with mathematical theory and so evidence for scientific theories can justify belief in mathematical objects despite their not being directly perceived.[93] |

歴史的発展 クワインへの先駆者と影響  ゴットロップ・フレーゲの写真 不可欠性論証の側面はゴットロップ・フレーゲにまで遡ることができる。 この論証は歴史的にウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワインとヒラリー・パトナムに関連付けられるが、ゴットロップ・フレーゲやクルト・ゲーデルといった より以前の思想家にもその起源を見出すことができる。数学的形式主義(数学を「2」のような数学記号の操作規則を持つチェスのようなゲームに例える見解) に対する反論の中で、フレーゲは1893年に「算術を単なるゲームから科学の域へと高めるのは、適用可能性のみである」と述べた。[83] ゲーデルは1947年の集合論公理に関する論文で、新たな公理が十分に検証可能な帰結を持つならば、それは「少なくとも確立された物理理論と同等の意味で 受け入れられなければならない」と述べた。[84] フレーゲとゲーデルの議論は、自然主義や実践の従属といった特徴を欠いているため、後のクワインの不可欠性論証とは異なる。このためピエランナ・ガラ ヴァーゾら一部の哲学者は、これらは真の不可欠性論証の例ではないと主張している。[85] クワインは確認的全体論という哲学的見解を発展させる過程で、ピエール・デュエムの影響を受けた。[86] 20世紀初頭、デュエムは慣性の法則が経験的内容を欠き反証不可能だと批判する者たちに対して、この法則を擁護した。[51] こうした批判は、慣性の法則が観測枠組みを設定しなければ観測可能な予測を一切行わないこと、また参照枠組みの選択を変えることで反証事例を常に回避でき るという事実に基づいていた。デュエムは、参照枠組みを固定する補助仮説と組み合わせれば法則は予測を生むため、他の物理理論と何ら変わらないと反論し た。[87] デュエムは、個々の仮説は単独では観測可能な予測を立てられないが、仮説体系の一部として確認され得ると述べた。クワインはこの考えを数学的仮説に拡張 し、数学的仮説は単独では経験的内容を持たないが、それらが含まれる仮説体系の経験的確認を共有し得ると主張した。[88] この命題は後にデュエム=クワイン命題として知られるようになった。[89] クワインは自身の自然主義を「第一哲学の目標の放棄」と表現した。それは自然科学を現実への探究と見なし、誤り得るものであり修正可能だが、いかなる超科 学的な審判機関にも答えを求められず、観察と仮説演繹法を超える正当化を必要としないものとする。[90] 「第一哲学」という用語は、デカルトの『第一哲学の省察』に由来する。デカルトは科学の基礎を確立しようと、懐疑の方法を用いた。クワインは、デカルトの 科学の基礎提供の試みは失敗に終わり、科学の基礎的正当化を見出す企ては拒否されるべきだと述べた。なぜなら、哲学は科学的方法よりも説得力のある正当化 の方法を提供することは決してできないと彼は考えていたからである。[91] クワインはまた、師であるルドルフ・カルナップら論理実証主義者からも影響を受けた。彼の自然主義は、彼らの多くの思想への応答として形成されたものであ る。[92] 論理実証主義者にとって、正当化された信念はすべて感覚データに還元可能であり、木のような日常的な物体に関する知識も含まれる。[93] クワインは感覚データを自己矛盾的だと批判し、世界に関する経験を整理するには日常的な物体への信念が必要だと述べた。また彼は、感覚経験が日常的な対象 についての信念をいかに提供するかという最良の理論であるから、科学もまた信じられるべきだと述べた。[94] 論理実証主義者が個々の主張は感覚データによって支持されねばならないと主張したのに対し、クワインの確認的全体論は、科学理論は本質的に数学理論と結び ついているため、直接知覚されないにもかかわらず、科学理論の証拠が数学的対象への信念を正当化できることを意味する。[93] |

| Quine and Putnam Whilst he eventually became a platonist due to his formulation of the indispensability argument,[95] Quine was sympathetic to nominalism from the early stages of his career.[96] In a 1946 lecture, he said: "I will put my cards on the table now and avow my prejudices: I should like to be able to accept nominalism".[97] He and Nelson Goodman subsequently released a joint 1947 paper titled "Steps toward a Constructive Nominalism"[98] as part of an ongoing project of Quine's to "set up a nominalistic language in which all of natural science can be expressed".[99] In a letter to Joseph Henry Woodger the following year, however, Quine said that he was becoming more convinced "the assumption of abstract entities and the assumptions of the external world are assumptions of the same sort".[100] He later released the 1948 paper "On What There Is", in which he said that "[t]he analogy between the myth of mathematics and the myth of physics is ... strikingly close", marking a shift towards his eventual acceptance of a "reluctant platonism".[101] Throughout the 1950s, Quine regularly mentioned platonism, nominalism, and constructivism as plausible views, and he had not yet reached a definitive conclusion about which was correct.[102] It is unclear exactly when Quine accepted platonism; in 1953, he distanced himself from the claims of nominalism in his 1947 paper with Goodman, but by 1956, Goodman was still describing Quine's "defection" from nominalism as "still somewhat tentative".[103] According to Lieven Decock, Quine had accepted the need for abstract mathematical entities by the publication of his 1960 book Word and Object, in which he wrote "a thoroughgoing nominalist doctrine is too much to live up to".[104] However, whilst he released suggestions of the indispensability argument in a number of papers, he never gave it a detailed formulation.[105] Putnam gave the argument its first explicit presentation in his 1971 book Philosophy of Logic in which he attributed it to Quine.[106] He stated the argument as "quantification over mathematical entities is indispensable for science, both formal and physical; therefore we should accept such quantification; but this commits us to accepting the existence of the mathematical entities in question".[107] He also wrote Quine had "for years stressed both the indispensability of quantification over mathematical entities and the intellectual dishonesty of denying the existence of what one daily presupposes".[107] Putnam's endorsement of Quine's version of the argument is disputed. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy states: "In his early work, Hilary Putnam accepted Quine's version of the indispensability argument."[108] Liggins and Bueno, however, argue that Putnam never endorsed the argument and only presented it as an argument from Quine.[109] In a 1990 lecture, Putnam said that he had shared Quine's views on the indispensability argument since 1948 when he was a student at Harvard, but that he had since come to disagree with them.[110] He later said that he differed with Quine in his attitude to the argument from at least 1975.[111] Features of the argument that Putnam came to disagree with include its reliance on a single, regimented, best theory.[108] In 1975, Putnam formulated his own indispensability argument based on the no miracles argument in the philosophy of science, which argues the success of science can only be explained by scientific realism without being rendered miraculous. He wrote that year: "I believe that the positive argument for realism [in science] has an analogue in the case of mathematical realism. Here too, I believe, realism is the only philosophy that doesn't make the success of the science a miracle."[112] The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy terms this version of the argument "Putnam's success argument" and presents it in the following form:[108] Mathematics succeeds as the language of science. There must be a reason for the success of mathematics as the language of science. No positions other than realism in mathematics provide a reason. Therefore, realism in mathematics must be correct.[i] According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, the first and second premises of the argument have been seen as uncontroversial, so discussion of this argument has been focused on the third premise. Other positions that have attempted to provide a reason for the success of mathematics include Field's reformulations of science, which explain the usefulness of mathematics as a conservative shorthand.[108] Putnam has criticized Field's reformulations for only applying to classical physics and for being unlikely to be able to be extended to future fundamental physics.[115] |

クワインとパトナム クワインは、その不可欠性論証の定式化により、最終的にはプラトニストとなったが[95]、そのキャリアの初期段階からは、唯名論に共感していた [96]。1946年の講演で、彼は次のように述べている。「私は今、自分の考えを率直に述べ、自分の偏見を告白しよう。私は唯名論を受け入れることがで きるようになりたい」。[97] その後、クワインはネルソン・グッドマンと共同で、1947年に「建設的唯名論への歩み」[98] という論文を発表し、クワインが「自然科学のすべてを表現できる唯名論的言語を確立する」という継続的なプロジェクトの一環として発表した。[99] しかし、翌年、ジョセフ・ヘンリー・ウッドジャーへの手紙の中で、クワインは「抽象的な実体の仮定と外界の仮定は、同じ種類の仮定である」と確信を深めて いると述べている。[100] その後1948年に発表した論文「存在するものについて」では、「数学の神話と物理学の神話との類似性は…驚くほど近い」と述べ、最終的に「渋々プラトン 主義」を受け入れる方向へ転換した。[101] 1950年代を通じて、クワインはプラトニズム、唯名論、構成主義を妥当な見解として定期的に言及しており、どれが正しいかについてまだ決定的な結論に達 していなかった。[102] クワインがプラトニズムをいつ受け入れたかは定かではない。1953年、彼は1947年にグッドマンと共同執筆した論文で唯名論の主張から距離を置いた が、1956年になっても、グッドマンはクワインの唯名論からの「脱退」を「まだやや暫定的なもの」と表現していた。[103] Lieven Decock によれば、クワインは 1960 年の著書『言葉と対象』の出版までに、抽象的な数学的実体の必要性を受け入れていた。同書の中で彼は、「徹底した名目論の教義は、実現するには難しすぎ る」と書いている。[104] しかし、彼はいくつかの論文で、不可欠性論の示唆を発表したものの、その詳細な定式化は決して行わなかった。[105] パトナムは1971年の著書『論理学の哲学』でこの議論を初めて明示的に提示し、それをクワインに帰した。[106] 彼はこの議論を「数学的実体に対する量化は、形式科学と物理科学の両方にとって不可欠である。したがって我々はそのような量化を受け入れるべきだ。しかし これは、問題の数学的実体の存在を受け入れることを我々に義務づける」と述べた。[107] またプットナムは、クワインが「長年にわたり、数学的実体に対する量化が不可欠であること、そして日常的に前提としているものの存在を否定する知的誠実さ の欠如の両方を強調してきた」とも記している。[107] プットナムがクワイン版論証を支持したか否かは議論の余地がある。インターネット哲学百科事典は「初期の著作において、ヒラリー・プットナムはクワイン版 不可欠性論証を受け入れた」と述べている。[108] しかしリギンズとブエノは、パトナムが同論証を支持したことはなく、クワインの論証として提示したに過ぎないと主張する。[109] 1990年の講演でパトナムは、ハーバード大学在学中の1948年当時からクワインの不可欠性論証に関する見解を共有していたが、その後異論を持つように なったと述べている。[110] 彼は後に、少なくとも1975年以降、この議論に対する姿勢においてクワインと異なる旨述べた。[111] パットナムが反対するようになった議論の特徴には、単一で画一的な最善理論への依存が含まれる。[108] 1975年、パトナムは科学哲学における「奇跡の排除」論に基づいて独自の不可欠性論を構築した。この論は、科学の成功は科学的現実主義によってのみ説明 可能であり、奇跡的なものとはならないと主張する。彼はその年にこう記している:「(科学における)現実主義を支持する積極的論証は、数学的現実主義の場 合にも類例があると考える。ここでも、科学の成功を奇跡としない唯一の哲学は現実主義だと考える。」[112] インターネット哲学百科事典はこの議論を「パットナムの成功論」と呼び、次のように提示している:[108] 数学は科学の言語として成功している。 数学が科学の言語として成功しているのには理由があるに違いない。 数学における実在論以外の立場は、その理由を提供しない。 したがって、数学における実在論は正しいに違いない。[i] インターネット哲学百科事典によれば、この議論の第一および第二の前提は議論の余地がないと見なされてきたため、議論は第三の前提に焦点が当てられてき た。数学の成功を説明しようとする他の立場には、フィールドの科学再構成がある。これは数学の有用性を保守的な省略法として説明するものである。 [108] パットナムは、フィールドの再構成が古典物理学にしか適用されず、将来の基礎物理学へ拡張される可能性が低いと批判している。[115] |

| Continued development of the argument According to Ian Hacking, there was no "concerted challenge" to the indispensability argument for a number of decades after Quine first raised it.[116] Chihara, in his 1973 book Ontology and the Vicious Circle Principle, was one of the earliest philosophers to attempt to reformulate mathematics in response to Quine's arguments.[117] Field followed with Science Without Numbers in 1980 and dominated discussion about the indispensability argument throughout the 1980s and 1990s.[118] With the introduction of arguments against the first premise of the argument, initially by Maddy in the 1990s and continued by Melia and others in the 2000s, Field's approach has come to be known as "Hard Road Nominalism" due to the difficulty of creating technical reconstructions of science that it requires. Approaches attacking the first premise, in contrast, have come to be known as "Easy Road Nominalism".[119] Colyvan is often seen as presenting the standard or "canonical" formulation of the argument within more recent philosophical work, and his version of the argument has been influential within contemporary philosophy of mathematics.[120] It differs in key ways from the arguments presented by Quine and Putnam. Quine's version of the argument relies on translating scientific theories from ordinary language into first-order logic to determine its ontological commitments, which is not explicitly required by Colyvan's formulation. Putnam's arguments were for the objectivity of mathematics but not necessarily for mathematical objects.[121] Putnam has explicitly distanced himself from this version of the argument, saying, "from my point of view, Colyvan's description of my argument(s) is far from right", and has contrasted his indispensability argument with "the fictitious 'Quine–Putnam indispensability argument'".[122] Colyvan has said "the attribution to Quine and Putnam [is] an acknowledgement of intellectual debts rather than an indication that the argument, as presented, would be endorsed in every detail by either Quine or Putnam".[123] |

議論の継続的発展 イアン・ハッキングによれば、クワインが初めて提起してから数十年もの間、不可避性論証に対する「組織的な反論」は存在しなかった。[116] 千原は1973年の著書『オントロジーと悪循環の原理』において、クワインの議論に応答して数学の再構築を試みた最も初期の哲学者の一人であった。 [117] フィールドは1980年に『数値なき科学』でこれに続き、1980年代から1990年代にかけて不可欠性論証に関する議論を主導した。[118] この議論の第一前提に対する反論が、1990年代にマディによって最初に提示され、2000年代にメリアらによって継続されたことで、フィールドのアプ ローチは、科学の技術的再構築を必要とする困難さから「ハードロード・唯名論」と呼ばれるようになった。対照的に、第一前提を攻撃するアプローチは「イー ジーロード・唯名論」として知られるようになった。[119] コリバンは、近年の哲学研究においてこの議論の標準的あるいは「規範的」な定式化を提示した人物と見なされることが多く、彼の議論のバージョンは現代の数 学哲学において影響力を持っている。[120] この議論はクワインやパトナムの提示した議論とは重要な点で異なる。クワインの議論は、科学理論を日常言語から一階の論理へ翻訳することでその存在論的コ ミットメントを決定するが、コリヴァンの定式化ではこれは明示的に要求されない。パトナムの議論は数学の客観性を主張したが、数学的対象の客観性を必ずし も主張したわけではない[121]。パトナムは自らこの議論の解釈から距離を置き、「私の見解では、コリヴァンの私の議論の記述は全く正しくない」と述 べ、自身の不可欠性論証を「架空の『クワイン=パトナム不可欠性論証』」と対比させている。[122] コリバンは「クワインとプットナムへの帰属は、提示された議論の細部まで両者が支持する証拠ではなく、知的負債の表明である」と述べている。[123] |

| Influence The indispensability argument is widely, though not universally, considered to be the best argument for platonism in the philosophy of mathematics.[124] According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, some within the field see it as the only good argument for platonism.[125] It is one of just a few arguments that have come to dominate the debate between mathematical realism and mathematical anti-realism.[126] In contemporary philosophy, many types of nominalism define themselves in opposition to the indispensability argument,[127] and it is generally seen as the most important argument to overcome for nominalist views such as fictionalism.[128] Quine's and Putnam's arguments have also been influential outside philosophy of mathematics, inspiring indispensability arguments in other areas of philosophy. For example, David Lewis, who was a student of Quine, used an indispensability argument to argue for modal realism in his 1986 book On the Plurality of Worlds. According to his argument, quantification over possible worlds is indispensable to our best philosophical theories, so we should believe in their concrete existence.[129] Other indispensability arguments in metaphysics are defended by philosophers such as David Armstrong, Graeme Forbes, and Alvin Plantinga, who have argued for the existence of states of affairs due to the indispensable theoretical role they play in our best philosophical theories of truthmakers, modality, and possible worlds.[130] In the field of ethics, David Enoch has expanded the criterion of ontological commitment used in the Quine–Putnam indispensability argument to argue for moral realism. According to Enoch's "deliberative indispensability argument", indispensability to deliberation is just as ontologically committing as indispensability to science, and moral facts are indispensable to deliberation. Therefore, according to Enoch, we should believe in moral facts.[131] |

影響 不可欠性論証は、数学哲学におけるプラトン主義の最良の論証として広く、ただし普遍的にはないが、考えられている。[124] スタンフォード哲学百科事典によれば、この分野の一部ではプラトン主義に対する唯一の有効な論証と見なされている。[125] これは数学的現実主義と数学的非現実主義の論争を支配するに至った数少ない論証の一つである。[126] 現代哲学において、多くの種類の唯名論は不可欠性論証への反論として自らを定義している[127]。そしてこの論証は、虚構主義などの唯名論的見解が克服 すべき最も重要な論証と一般に認識されている。[128] クワインとパトナムの議論は、数学哲学以外でも影響力があり、哲学の他の分野でも不可欠性論争に影響を与えている。例えば、クワインの弟子であるデヴィッ ド・ルイスは、1986年の著書『世界の多元性について』で、モダリティ実在論を主張するために不可欠性論争を用いた。彼の議論によれば、可能世界に関す る量化は、最良の哲学理論に不可欠であるため、その具体的な存在を信じるべきである[129]。形而上学におけるその他の不可欠性論証は、デビッド・アー ムストロング、グレアム・フォーブス、アルヴィン・プランティンガなどの哲学者によって擁護されている。彼らは、最良の哲学理論における真実の根拠、様 態、可能世界において、状況が不可欠な理論的役割を果たしていることから、状況の存在を主張している[130]。倫理学の分野では、デイヴィッド・エノッ クが、クワイン=パトナムの不可欠性論証で使われた存在論的コミットメントの基準を拡張し、道徳的リアリズムを主張している。エノックの「熟議的不可欠性 論証」によれば、熟議に対する不可欠性は、科学に対する不可欠性と同じくらい存在論的にコミットメントを伴うものであり、道徳的事実は熟議に不可欠であ る。したがって、エノックによれば、我々は道徳的事実を信じるべきである[131]。 |

| Notes a. Also referred to as the Putnam–Quine indispensability argument, holism–naturalism indispensability argument[1] or simply the indispensability argument b. The concerns Benacerraf raised date back at least to Plato and Socrates, and were given detailed attention in the late nineteenth century prior to Quine and Putnam's arguments, which were raised in the 1960s and 1970s.[3] In contemporary philosophy, however, Benacerraf's presentation of these problems is considered to be the classic one.[4] c. Subsequent philosophers have generalized this problem beyond the causal theory of knowledge; for Hartry Field, the general problem is to provide a mechanism explaining how mathematical beliefs can accurately reflect the properties of abstract mathematical objects.[8] d. For example, Aristotelian realists claim that the indispensability argument favours realism but not platonism. They argue that mathematics refers not to abstract objects but to mathematical properties of physical objects such as symmetry.[24] e. See Maddy 1992 f. For example, to say that "there is a Loch Ness Monster" means the same thing as "the Loch Ness Monster exists".[61] g. Non-Quinean forms of the argument can also be constructed using alternative criteria of ontological commitment. For example, Sam Baron (2013) defends a version of the argument that depends on a criterion of ontological commitment based on truthmaker theory.[68] h. Baker identifies Field (1989) as originating this form of the argument, while other philosophers argue he was the first to raise the connection between indispensability and explanation but did not fully formulate an explanatory version of the indispensability argument.[77] Other thinkers who anticipated certain details of the explanatory form of the argument include Mark Steiner (1978a, 1978b) and J. J. C. Smart (1990).[78] i According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, this version of the argument can be used to argue for platonism or sentence realism.[108] However, Putnam himself used it to argue for sentence realism.[113] Putnam's view is a reformulation of mathematics in terms of modal logic that maintains mathematical objectivity without being committed to mathematical objects.[114] |

注記 a. プットナム=クワインの不可欠性論証、全体論=自然主義不可欠性論証[1]、あるいは単に不可欠性論証とも呼ばれる b. ベナセラフが提起した懸念は、少なくともプラトンとソクラテスの時代にまで遡り、1960年代から1970年代にかけてクワインとプットナムが論証する以 前から、19世紀後半に詳細な検討がなされていた。[3] しかし現代哲学においては、ベナセラフによるこれらの問題の提示が古典的と見なされている。[4] c. 後続の哲学者たちはこの問題を因果的知識論を超えて一般化した。ハートリー・フィールドによれば、一般的な問題は、数学的信念が抽象的な数学的対象の性質をいかに正確に反映し得るかを説明するメカニズムを提供することである。[8] d. 例えばアリストテレス的実在論者は、不可欠性論証が実在論を支持するがプラトン主義を支持しないとする。彼らは数学が抽象的対象ではなく、対称性などの物理的対象の数学的性質を指すのだと主張する。[24] e. Maddy 1992を参照 f. 例えば「ネス湖の怪物が存在する」と言うことは「ネス湖の怪物が存在する」と言うことと同一の意味を持つ。[61] g. 非クワイン的な議論形式も、存在論的コミットメントの代替基準を用いて構築できる。例えばサム・バロン(2013)は、真の根拠理論に基づく存在論的コミットメント基準に依存する議論の変種を擁護している。[68] h. ベイカーは、この形式の議論の発案者をフィールド(1989)と特定しているが、他の哲学者は、彼は不可欠性と説明の関連性を最初に提起した人物であるも のの、不可欠性議論の説明的バージョンを完全に定式化したわけではないと主張している。[77] この議論の説明的形式の特定の詳細を予見した他の思想家としては、マーク・スタイン(1978a、1978b)や J. J. C. スマート (1990) などが挙げられる。[78] i インターネット哲学百科事典によれば、この議論はプラトニズムや文実在論を主張するために使用することができる。[108] しかし、パトナム自身は文実在論を主張するためにこの議論を使用した。[113] パトナムの見解は、数学的客観性を維持しながら数学的対象にコミットしない、様相論理による数学の再定式化である。[114] |

| References |

|

| Sources Antunes, Henrique (2018). "On Existence, Inconsistency, and Indispensability". Principia. 22 (1): 07–34. doi:10.5007/1808-1711.2018v22n1p7. ISSN 1808-1711. Asay, Jamin (2020). "Mathematics". A Theory of Truthmaking: Metaphysics, Ontology, and Reality. Cambridge University Press. pp. 223–246. ISBN 978-1-108-75946-5. Azzouni, Jody (2004). Deflating Existential Consequence: A Case for Nominalism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-4294-3096-8. Baker, Alan (2005). "Are there Genuine Mathematical Explanations of Physical Phenomena?". Mind. 114 (454): 223–238. doi:10.1093/mind/fzi223. ISSN 0026-4423 – via ResearchGate. Balaguer, Mark (2018). "Fictionalism in the Philosophy of Mathematics". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2018 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. ISSN 1095-5054. Bangu, Sorin (2012). The Applicability of Mathematics in Science: Indispensability and Ontology. New Directions in the Philosophy of Science. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-28520-0. Bangu, Sorin (2013). "Indispensability and Explanation". British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. 64 (2): 255–277. doi:10.1093/bjps/axs026. ISSN 0007-0882. Baron, Sam (2013). "A Truthmaker Indispensability Argument". Synthese. 190 (12): 2413–2427. doi:10.1007/s11229-011-9989-2. ISSN 0039-7857. S2CID 255061951. Benacerraf, Paul (1973). "Mathematical Truth". The Journal of Philosophy. 70 (19): 661–679. doi:10.2307/2025075. JSTOR 2025075. Bostock, David (2009). Philosophy of Mathematics: An Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-8991-0. OCLC 232002229. Bricker, Phillip (2016). "Ontological Commitment". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. ISSN 1095-5054. Bueno, Otávio (2013). "Putnam and the Indispensability of Mathematics". Principia. 17 (2): 217–234. doi:10.5007/1808-1711.2013v17n2p217. ISSN 1808-1711. Bueno, Otávio (2018). "Putnam's Indispensability Argument Revisited, Reassessed, Revived". Theoria. 33 (2): 201–218. doi:10.1387/theoria.18473. hdl:10810/39675. Bueno, Otávio (2020). "Nominalism in the Philosophy of Mathematics". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. ISSN 1095-5054. Burgess, John P. (2013). "Quine's Philosophy of Logic and Mathematics". In Harman, Gilbert; Lepore, Ernie (eds.). A Companion to W.V.O. Quine. Blackwell Companions to Philosophy. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 281–295. doi:10.1002/9781118607992.ch14. ISBN 978-0-47-067210-5 – via Academia.edu. Burgess, John P.; Rosen, Gideon A. (1997). A Subject With No Object: Strategies for Nominalistic Interpretation of Mathematics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-825012-6. Busch, Jacob; Sereni, Andrea (2012). "Indispensability Arguments and Their Quinean Heritage". Disputatio. 4 (32): 343–360. doi:10.2478/disp-2012-0003. ISSN 0873-626X. Castro, Eduardo (2013). "Defending the Indispensability Argument: Atoms, Infinity and the Continuum". Journal for General Philosophy of Science. 44 (1): 41–61. doi:10.1007/s10838-013-9222-8. ISSN 0925-4560. Chihara, Charles (1973). Ontology and the Vicious Circle Principle. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-0727-3. Colyvan, Mark (1998). "In Defence of Indispensability". Philosophia Mathematica. 6 (1): 39–62. doi:10.1093/philmat/6.1.39. ISSN 0031-8019 – via PhilPapers. Colyvan, Mark (2001). The Indispensability of Mathematics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516661-3. Colyvan, Mark (2012). An Introduction to the Philosophy of Mathematics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82602-0. Colyvan, Mark (2019). "Indispensability Arguments in the Philosophy of Mathematics". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. ISSN 1095-5054. Cowling, Sam (2017). Abstract Entities. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-82758-5. Daly, Chris; Langford, Simon (2009). "Mathematical Explanation and Indispensability Arguments". The Philosophical Quarterly. 59 (237): 641–658. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9213.2008.601.x. ISSN 0031-8094. Decock, Lieven (2002). "Quine's Weak and Strong Indispensability Argument". Journal for General Philosophy of Science. 33 (2): 231–250. doi:10.1023/A:1022471707916. ISSN 0925-4560. JSTOR 25171232. S2CID 117002868 – via ResearchGate. Enoch, David (2011). Taking Morality Seriously. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-957996-9. Ervas, Francesca; Tripodi, Vera (2012). "New Perspectives on Quine's "Word and Object"". Disputatio. 4 (32): 317–322. doi:10.2478/disp-2012-0001. hdl:2434/857237. ISSN 0873-626X. Field, Hartry (1980). Science Without Numbers. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-877791-5. Field, Hartry (1989). "Indispensability Arguments and Inference to the Best Explanation". Realism, Mathematics, and Modality. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 14–20. ISBN 0-631-16303-4. Franklin, James (2009). "Aristotelian Realism". In Irvine, Andrew D. (ed.). Philosophy of Mathematics. Elsevier. pp. 103–155. doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-51555-1.50007-9. ISBN 978-0-444-51555-1 – via Academia.edu. Frege, Gottlob (1893). Grundgesetze der Arithmetik. Vol. II. Verlag von Hermann Pohle. OCLC 1189408701. Garavaso, Pieranna (2005). "On Frege's Alleged Indispensability Argument". Philosophia Mathematica. 13 (2): 160–173. doi:10.1093/philmat/nki018. ISSN 1744-6406 – via University of Minnesota Morris. Ginammi, Michele (2016). "The Applicability of Mathematics and the Indispensability Arguments". Revue de la Société de philosophie des sciences. 3 (1). École normale supérieure: 59–68. doi:10.20416/lsrsps.v3i1.313. Gödel, Kurt (1947). "What is Cantor's Continuum Problem?". The American Mathematical Monthly. 54 (9): 515–525. doi:10.2307/2304666. ISSN 0002-9890. JSTOR 2304666. Goodman, Nelson; Quine, W. V. (1947). "Steps Toward a Constructive Nominalism". Journal of Symbolic Logic. 12 (4): 105–122. doi:10.2307/2266485. ISSN 0022-4812. JSTOR 2266485. S2CID 46182517. Goodman, Nelson (1956). "A World of Individuals". In Bochenski, Innocenty; Church, Alonzo; Goodman, Nelson (eds.). The Problem of Universals. University of Notre Dame Press. pp. 15–31. OCLC 81970496. Hacking, Ian (2014). Why Is There Philosophy of Mathematics At All?. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05017-4. Horsten, Leon (2019). "Philosophy of Mathematics". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. ISSN 1095-5054. Knowles, Robert; Liggins, David (2015). "Good Weasel Hunting". Synthese. 192 (10): 3397–3412. doi:10.1007/s11229-015-0711-7. ISSN 0039-7857. S2CID 31490461 – via University of Manchester. Lange, Marc (2022). "Inference to the Best Explanation as Supporting the Expansion of Mathematicians' Ontological Commitments". Synthese. 200 (2). doi:10.1007/s11229-022-03656-4. ISSN 0039-7857 – via PhilSci-Archive. Leng, Mary (2005). "Mathematical Explanation". In Cellucci, Carlo; Gillies, Donald A. (eds.). Mathematical Reasoning and Heuristics. King's College Publications. pp. 167–189. ISBN 1-904987-07-9. Leng, Mary (2010). Mathematics and Reality. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928079-7. Leng, Mary (2018). "Mathematical Realism and Naturalism". In Saatsi, Juha (ed.). The Routledge Handbook of Scientific Realism. Routledge. pp. 407–418. ISBN 978-1-138-88885-2. Lewis, David (1986). On the Plurality of Worlds. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-13993-1. Lewis, David (1991). Parts of Classes. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-17656-5. Liggins, David (2008). "Quine, Putnam, and the 'Quine–Putnam' Indispensability Argument". Erkenntnis. 68 (1): 113–127. doi:10.1007/s10670-007-9081-y. S2CID 170649798 – via PhilPapers. Liggins, David (2012). "Weaseling and the Content of Science". Mind. 121 (484): 997–1005. doi:10.1093/mind/fzs112. ISSN 0026-4423 – via PhilPapers. Liggins, David (2024). Abstract Objects. Cambridge Elements in Metaphysics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-46785-8. Linnebo, Øystein (2017). Philosophy of Mathematics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-8524-4. Maddy, Penelope (1992). "Indispensability and Practice". The Journal of Philosophy. 89 (6): 275–289. doi:10.2307/2026712. JSTOR 2026712. Maddy, Penelope (2005). "Three Forms of Naturalism". In Shapiro, Stewart (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic. Oxford University Press. pp. 437–459. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195325928.003.0013. ISBN 978-0-19-514877-0. Maddy, Penelope (2007). Second Philosophy: A Naturalistic Method. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-27366-9. Mancosu, Paolo (2010). "Quine and Tarski on Nominalism". The Adventure of Reason. Oxford University Press. pp. 387–410. ISBN 978-0-19-954653-4 – via PhilPapers. Mancosu, Paolo (2018). "Explanation in Mathematics". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2018 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. ISSN 1095-5054. Marcus, Russell (n.d.). "The Indispensability Argument in the Philosophy of Mathematics". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ISSN 2161-0002. Archived from the original on May 27, 2022. Retrieved August 23, 2022. Marcus, Russell (2014). "The Holistic Presumptions of the Indispensability Argument". Synthese. 191 (15): 3575–3594. doi:10.1007/s11229-014-0481-7. ISSN 0039-7857. S2CID 8245787. Marcus, Russell (2015). Autonomy Platonism and the Indispensability Argument. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-7313-8. McPherson, Tristram; Plunkett, David (2015). "Deliberative Indispensability and Epistemic Justification". In Shafer-Landau, Russ (ed.). Oxford Studies in Metaethics. Vol. 10. Oxford University Press. pp. 104–133. ISBN 978-0-198-73869-5 – via PhilPapers. Melia, Joseph (1998). "Field's Programme: Some Interference". Analysis. 58 (2): 63–71. doi:10.1093/analys/58.2.63. ISSN 0003-2638. Melia, Joseph (2000). "Weaseling Away the Indispensability Argument". Mind. 109 (435): 455–480. doi:10.1093/mind/109.435.455. ISSN 0026-4423. Melia, Joseph (2017). "Does the World Contain States of Affairs? No". In Barnes, Elizabeth (ed.). Current Controversies in Metaphysics. Routledge. pp. 92–102. ISBN 978-0-203-73560-2. Molinini, Daniele (2016). "Evidence, Explanation and Enhanced Indispensability". Synthese. 193 (2): 403–422. doi:10.1007/s11229-014-0494-2. ISSN 0039-7857. S2CID 7657901. Molinini, Daniele; Pataut, Fabrice; Sereni, Andrea (2016). "Indispensability and Explanation: An Overview and Introduction". Synthese. 193 (2): 317–332. doi:10.1007/s11229-015-0998-4. ISSN 0039-7857. S2CID 38346150. Newstead, Anne; Franklin, James (2011). "Indispensability Without Platonism". In Bird, Alexander; Ellis, Brian; Sankey, Howard (eds.). Properties, Powers and Structures: Issues in the Metaphysics of Realism. Routledge. pp. 81–97. ISBN 978-0-415-89535-4 – via PhilPapers. Ney, Alyssa (2023). Metaphysics: An Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-8153-5048-4. Nolan, Daniel (2005). David Lewis. Acumen Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84465-307-2. Panza, Marco; Sereni, Andrea (2013). Plato's Problem: An Introduction to Mathematical Platonism. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-36549-0. Panza, Marco; Sereni, Andrea (2015). "On the Indispensable Premises of the Indispensability Argument". In Lolli, Gabriele; Panza, Marco; Venturi, Giorgio (eds.). From Logic to Practice: Italian Studies in the Philosophy of Mathematics. Boston Studies in the Philosophy and History of Science. Vol. 308. Springer. pp. 241–276. ISBN 978-3-319-10433-1 – via Chapman University Digital Commons. Panza, Marco; Sereni, Andrea (2016). "The Varieties of Indispensability Arguments". Synthese. 193 (2): 469–516. doi:10.1007/s11229-015-0977-9. ISSN 1573-0964. S2CID 255060875 – via Chapman University Digital Commons. Paseau, Alexander C.; Baker, Alan (2023). Indispensability. Cambridge Elements in the Philosophy of Mathematics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-09685-0. Putnam, Hilary (1971). Philosophy of Logic. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-061-36042-8. Putnam, Hilary (1979) [1975]. "What Is Mathematical Truth?". Mathematics, Matter and Method: Philosophical Papers. Vol. I (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 60–78. ISBN 978-0-521-29550-5. Putnam, Hilary (1994). "Rethinking Mathematical Necessity". In Conant, James (ed.). Words and Life. Harvard University Press. pp. 245–263. ISBN 0-674-95607-9. Putnam, Hilary (2012). "Indispensability Arguments in the Philosophy of Mathematics". Philosophy in an Age of Science: Physics, Mathematics and Skepticism. Harvard University Press. pp. 181–201. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1nzfgrb.13. hdl:1885/145370. ISBN 978-0-674-26915-6. Quine, W. V. (1939). "Designation and Existence". The Journal of Philosophy. 36 (26): 701–709. doi:10.2307/2017667. ISSN 0022-362X. JSTOR 2017667. Quine, W. V. (1948). "On What There Is". The Review of Metaphysics. 2 (5): 21–38. ISSN 0034-6632. JSTOR 20123117. Quine, W. V. (1960). Word and Object. MIT Press. OCLC 1159745436. Quine, W. V. (1981). Theories and Things. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-87925-2. OCLC 7278383. Quine, W. V. (1998). "Reply to Charles Parsons". In Hahn, Lewis Edwin; Schilpp, Paul Arthur (eds.). The Philosophy of W.V. Quine (2nd expanded ed.). Open Court Publishing Company. pp. 396–403. ISBN 0-8126-9371-X. OCLC 37935049. Quine, W. V. (2008) [1946]. "Nominalism". In Zimmerman, Dean (ed.). Oxford Studies in Metaphysics. Vol. 4. Oxford University Press. pp. 6–21. ISBN 978-0-199-54298-7. Resnik, Michael (1995). "Scientific vs. Mathematical Realism: The Indispensability Argument". Philosophia Mathematica. 3 (2): 166–174. doi:10.1093/philmat/3.2.166. ISSN 0031-8019. Resnik, Michael (2005). "Quine and the Web of Belief". In Shapiro, Stewart (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic. Oxford University Press. pp. 412–436. doi:10.1093/0195148770.003.0012. ISBN 978-0-195-14877-0. Sereni, Andrea (2015). "Frege, Indispensability, and the Compatibilist Heresy". Philosophia Mathematica. 23 (1): 11–30. doi:10.1093/philmat/nkt046. ISSN 0031-8019. Shapiro, Stewart (2000). Thinking about Mathematics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-192-89306-2. Sinclair, Neil; Leibowitz, Uri D. (2016). "Introduction". In Leibowitz, Uri D.; Sinclair, Neil (eds.). Explanation in Ethics and Mathematics: Debunking and Dispensability. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-0-19-182432-6. Smart, J. J. C. (1990). "Explanation–Opening Address". Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement. 27: 1–19. doi:10.1017/S1358246100005014. ISSN 1358-2461. S2CID 143223945. Sober, Elliott (1993). "Mathematics and Indispensability". Philosophical Review. 102 (1): 35–58. doi:10.2307/2185652. JSTOR 2185652 – via ResearchGate. Steiner, Mark (1978a). "Mathematical Explanation". Philosophical Studies. 34 (2): 135–151. doi:10.1007/BF00354494. ISSN 0031-8116. JSTOR 4319237. S2CID 189796040. Steiner, Mark (1978b). "Mathematics, Explanation, and Scientific Knowledge". Noûs. 12 (1): 17–28. doi:10.2307/2214652. ISSN 0029-4624. JSTOR 2214652. Stokes, Mitchell O. (2007). "Van Inwagen and the Quine-Putnam Indispensability Argument". Erkenntnis. 67 (3): 439–453. doi:10.1007/s10670-007-9052-3. ISSN 0165-0106. Tallant, Jonathan (2017). Metaphysics: An Introduction. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-3500-0671-3. Verhaegh, Sander (2018). Working from Within: The Nature and Development of Quine's Naturalism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-091316-8. Weatherson, Brian (2021). "David Lewis". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. ISSN 1095-5054. |