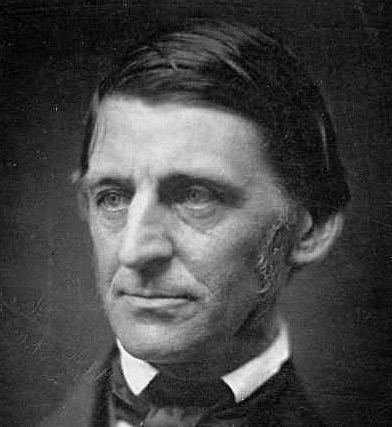

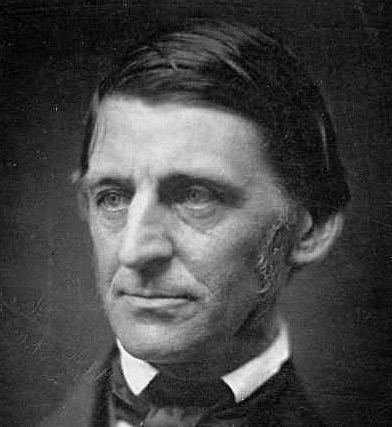

ラルフ・ワルド・エマーソン

Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1803-1882

ラルフ・ワルド・エマーソン

Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1803-1882

★ラルフ・ウォルドー・エマーソン(1803年5月25日 - 1882年4月27日)[7]は、19世紀半ばの超絶主義運動を主導したアメリカのエッセイスト、講演家、哲学者、奴隷制廃止論者、詩人である[8]。個 人主義の擁護者であると同時に、社会の圧力に対抗する先見的な批判者と見なされ、その思想は、出版された数十のエッセイや全米で行われた1,500以上の 公開講座を通じて広められた。

| Ralph Waldo Emerson

(May 25, 1803 – April 27, 1882),[7] who went by his middle name

Waldo,[8] was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher,

abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the

mid-19th century. He was seen as a champion of individualism and a

prescient critic of the countervailing pressures of society, and his

ideology was disseminated through dozens of published essays and more

than 1,500 public lectures across the United States. Emerson gradually moved away from the religious and social beliefs of his contemporaries, formulating and expressing the philosophy of transcendentalism in his 1836 essay "Nature". Following this work, he gave a speech entitled "The American Scholar" in 1837, which Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. considered to be America's "intellectual Declaration of Independence."[9] Emerson wrote most of his important essays as lectures first and then revised them for print. His first two collections of essays, Essays: First Series (1841) and Essays: Second Series (1844), represent the core of his thinking. They include the well-known essays "Self-Reliance",[10] "The Over-Soul", "Circles", "The Poet", and "Experience." Together with "Nature",[11] these essays made the decade from the mid-1830s to the mid-1840s Emerson's most fertile period. Emerson wrote on a number of subjects, never espousing fixed philosophical tenets, but developing certain ideas such as individuality, freedom, the ability for mankind to realize almost anything, and the relationship between the soul and the surrounding world. Emerson's "nature" was more philosophical than naturalistic: "Philosophically considered, the universe is composed of Nature and the Soul." Emerson is one of several figures who "took a more pantheist or pandeist approach by rejecting views of God as separate from the world."[12] He remains among the linchpins of the American romantic movement,[13] and his work has greatly influenced the thinkers, writers and poets that followed him. "In all my lectures," he wrote, "I have taught one doctrine, namely, the infinitude of the private man."[14] Emerson is also well known as a mentor and friend of Henry David Thoreau, a fellow transcendentalist.[15] |

ラルフ・ウォルドー・エマーソン(1803年5月25日 -

1882年4月27日)[7]は、19世紀半ばの超絶主義運動を主導したアメリカのエッセイスト、講演家、哲学者、奴隷制廃止論者、詩人である[8]。個

人主義の擁護者であると同時に、社会の圧力に対抗する先見的な批判者と見なされ、その思想は、出版された数十のエッセイや全米で行われた1,500以上の

公開講座を通じて広められた。 エマソンは、同時代の宗教的・社会的信条から徐々に離れ、1836年のエッセイ『自然』で超絶主義の哲学を打ち立て、表現している。この著作に続いて、 1837年に「アメリカの学者」と題する演説を行い、オリバー・ウェンデル・ホームズ・シニアはこれをアメリカの「知的独立宣言」と見なした[9]。 エマソンは重要なエッセイのほとんどをまず講演として書き、それを印刷用に改訂した。彼の最初の2つのエッセイ集『エッセイ集』(Essays: 第1集(1841年)、第2集(1844年)。エマソンの思想の核をなすものである。その中には、よく知られたエッセイ "Self-Reliance", [10] "The Over-Soul", "Circles", "The Poet", "Experience" が含まれています。これらのエッセイは、『自然』[11]とともに、1830年代半ばから1840年代半ばにかけての10年間をエマソンの最も肥沃な時代 とした。エマソンは様々なテーマについて書き、決して固定的な哲学的信条を主張するのではなく、個性、自由、人間がほとんど何でも実現できる能力、魂と周 囲の世界との関係など、特定の考えを発展させていった。エマソンの「自然」は、自然主義的というよりも哲学的であった。「哲学的に考えると、宇宙は自然と 魂から構成されている」のである。エマソンは「世界と分離した神という見方を否定することで、より汎神論的な、あるいはパンデイストなアプローチをとっ た」いくつかの人物の一人である[12]。 彼はアメリカのロマン主義運動の要の一人であり[13]、彼の作品は彼に続く思想家、作家、詩人たちに大きな影響を与えている。「また、同じ超絶論者であ るヘンリー・デイヴィッド・ソローの指導者、友人としてもよく知られている[15]。 |

| Literary career and

transcendentalism On September 8, 1836, the day before the publication of Nature, Emerson met with Frederic Henry Hedge, George Putnam, and George Ripley to plan periodic gatherings of other like-minded intellectuals.[76] This was the beginning of the Transcendental Club, which served as a center for the movement. Its first official meeting was held on September 19, 1836.[77] On September 1, 1837, women attended a meeting of the Transcendental Club for the first time. Emerson invited Margaret Fuller, Elizabeth Hoar, and Sarah Ripley for dinner at his home before the meeting to ensure that they would be present for the evening get-together.[78] Fuller would prove to be an important figure in transcendentalism. Emerson anonymously sent his first essay; "Nature" to James Munroe and Company to be published on September 9, 1836. A year later, on August 31, 1837, he delivered his now-famous Phi Beta Kappa address, "The American Scholar",[79] then entitled "An Oration, Delivered before the Phi Beta Kappa Society at Cambridge"; it was renamed for a collection of essays (which included the first general publication of "Nature") in 1849.[80] Friends urged him to publish the talk, and he did so at his own expense, in an edition of 500 copies, which sold out in a month.[9] In the speech, Emerson declared literary independence in the United States and urged Americans to create a writing style all their own, free from Europe.[81] James Russell Lowell, who was a student at Harvard at the time, called it "an event without former parallel on our literary annals".[82] Another member of the audience, Reverend John Pierce, called it "an apparently incoherent and unintelligible address".[83] In 1837, Emerson befriended Henry David Thoreau. Though they had likely met as early as 1835, in the fall of 1837, Emerson asked Thoreau, "Do you keep a journal?" The question went on to be a lifelong inspiration for Thoreau.[84] Emerson's own journal was published in 16 large volumes, in the definitive Harvard University Press edition issued between 1960 and 1982. Some scholars consider the journal to be Emerson's key literary work.[85][page needed] In March 1837, Emerson gave a series of lectures on the philosophy of history at the Masonic Temple in Boston. This was the first time he managed a lecture series on his own, and it was the beginning of his career as a lecturer.[86] The profits from this series of lectures were much larger than when he was paid by an organization to talk, and he continued to manage his own lectures often throughout his lifetime. He eventually gave as many as 80 lectures a year, traveling across the northern United States as far as St. Louis, Des Moines, Minneapolis, and California.[87] On July 15, 1838,[88] Emerson was invited to Divinity Hall, Harvard Divinity School, to deliver the school's graduation address, which came to be known as the "Divinity School Address". Emerson discounted biblical miracles and proclaimed that, while Jesus was a great man, he was not God: historical Christianity, he said, had turned Jesus into a "demigod, as the Orientals or the Greeks would describe Osiris or Apollo".[89] His comments outraged the establishment and the general Protestant community. He was denounced as an atheist[89] and a poisoner of young men's minds. Despite the roar of critics, he made no reply, leaving others to put forward a defense. He was not invited back to speak at Harvard for another thirty years.[90] The transcendental group began to publish its flagship journal, The Dial, in July 1840.[91] They planned the journal as early as October 1839, but work did not begin until the first week of 1840.[92] George Ripley was the managing editor.[93] Margaret Fuller was the first editor, having been approached by Emerson after several others had declined the role.[94] Fuller stayed on for about two years, when Emerson took over, using the journal to promote talented young writers including Ellery Channing and Thoreau.[84] In 1841 Emerson published Essays, his second book, which included the famous essay "Self-Reliance".[95] His aunt called it a "strange medley of atheism and false independence", but it gained favorable reviews in London and Paris. This book, and its popular reception, more than any of Emerson's contributions to date laid the groundwork for his international fame.[96] In January 1842 Emerson's first son, Waldo, died of scarlet fever.[97] Emerson wrote of his grief in the poem "Threnody" ("For this losing is true dying"),[98] and the essay "Experience". In the same month, William James was born, and Emerson agreed to be his godfather. Bronson Alcott announced his plans in November 1842 to find "a farm of a hundred acres in excellent condition with good buildings, a good orchard and grounds".[99] Charles Lane purchased a 90-acre (36 ha) farm in Harvard, Massachusetts, in May 1843 for what would become Fruitlands, a community based on Utopian ideals inspired in part by transcendentalism.[100] The farm would run based on a communal effort, using no animals for labor; its participants would eat no meat and use no wool or leather.[101] Emerson said he felt "sad at heart" for not engaging in the experiment himself.[102] Even so, he did not feel Fruitlands would be a success. "Their whole doctrine is spiritual", he wrote, "but they always end with saying, Give us much land and money".[103] Even Alcott admitted he was not prepared for the difficulty in operating Fruitlands. "None of us were prepared to actualize practically the ideal life of which we dreamed. So we fell apart", he wrote.[104] After its failure, Emerson helped buy a farm for Alcott's family in Concord[103] which Alcott named "Hillside".[104] The Dial ceased publication in April 1844; Horace Greeley reported it as an end to the "most original and thoughtful periodical ever published in this country".[105] In 1844, Emerson published his second collection of essays, Essays: Second Series. This collection included "The Poet", "Experience", "Gifts", and an essay entitled "Nature", a different work from the 1836 essay of the same name. Emerson made a living as a popular lecturer in New England and much of the rest of the country. He had begun lecturing in 1833; by the 1850s he was giving as many as 80 lectures per year.[106] He addressed the Boston Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge and the Gloucester Lyceum, among others. Emerson spoke on a wide variety of subjects, and many of his essays grew out of his lectures. He charged between $10 and $50 for each appearance, bringing him as much as $2,000 in a typical winter lecture season. This was more than his earnings from other sources. In some years, he earned as much as $900 for a series of six lectures, and in another, for a winter series of talks in Boston, he netted $1,600.[107] He eventually gave some 1,500 lectures in his lifetime. His earnings allowed him to expand his property, buying 11 acres (4.5 ha) of land by Walden Pond and a few more acres in a neighboring pine grove. He wrote that he was "landlord and water lord of 14 acres, more or less".[103] Emerson was introduced to Indian philosophy through the works of the French philosopher Victor Cousin.[108] In 1845, Emerson's journals show he was reading the Bhagavad Gita and Henry Thomas Colebrooke's Essays on the Vedas.[109] He was strongly influenced by Vedanta, and much of his writing has strong shades of nondualism. One of the clearest examples of this can be found in his essay "The Over-soul": We live in succession, in division, in parts, in particles. Meantime within man is the soul of the whole; the wise silence; the universal beauty, to which every part and particle is equally related, the eternal ONE. And this deep power in which we exist and whose beatitude is all accessible to us, is not only self-sufficing and perfect in every hour, but the act of seeing and the thing seen, the seer and the spectacle, the subject and the object, are one. We see the world piece by piece, as the sun, the moon, the animal, the tree; but the whole, of which these are shining parts, is the soul.[110] The central message Emerson drew from his Asian studies was that "the purpose of life was spiritual transformation and direct experience of divine power, here and now on earth."[111][112] In 1847–48, he toured the British Isles.[113] He also visited Paris between the French Revolution of 1848 and the bloody June Days. When he arrived, he saw the stumps of trees that had been cut down to form barricades in the February riots. On May 21, he stood on the Champ de Mars in the midst of mass celebrations for concord, peace and labor. He wrote in his journal, "At the end of the year we shall take account, & see if the Revolution was worth the trees."[114] The trip left an important imprint on Emerson's later work. His 1856 book English Traits is based largely on observations recorded in his travel journals and notebooks. Emerson later came to see the American Civil War as a "revolution" that shared common ground with the European revolutions of 1848.[115] In a speech in Concord, Massachusetts on May 3, 1851, Emerson denounced the Fugitive Slave Act: The act of Congress is a law which every one of you will break on the earliest occasion—a law which no man can obey, or abet the obeying, without loss of self-respect and forfeiture of the name of gentleman.[116] That summer, he wrote in his diary: This filthy enactment was made in the nineteenth century by people who could read and write. I will not obey it.[117] In February 1852 Emerson and James Freeman Clarke and William Henry Channing edited an edition of the works and letters of Margaret Fuller, who had died in 1850.[118] Within a week of her death, her New York editor, Horace Greeley, suggested to Emerson that a biography of Fuller, to be called Margaret and Her Friends, be prepared quickly "before the interest excited by her sad decease has passed away".[119] Published under the title The Memoirs of Margaret Fuller Ossoli,[120] Fuller's words were heavily censored or rewritten.[121] The three editors were not concerned about accuracy; they believed public interest in Fuller was temporary and that she would not survive as a historical figure.[122] Even so, it was the best-selling biography of the decade and went through thirteen editions before the end of the century.[120] Walt Whitman published the innovative poetry collection Leaves of Grass in 1855 and sent a copy to Emerson for his opinion. Emerson responded positively, sending Whitman a flattering five-page letter in response.[123] Emerson's approval helped the first edition of Leaves of Grass stir up significant interest[124] and convinced Whitman to issue a second edition shortly thereafter.[125] This edition quoted a phrase from Emerson's letter, printed in gold leaf on the cover: "I Greet You at the Beginning of a Great Career".[126] Emerson took offense that this letter was made public[127] and later was more critical of the work.[128] |

文学者としてのキャリアと超絶主義 1836年9月8日、『ネイチャー』の出版の前日、エマーソンはフレデリック・ヘンリー・ヘッジ、ジョージ・パトナム、ジョージ・リプリーと会い、同じよ うな考えを持つ他の知識人の定期的な集まりを計画した[76] これは運動の中心として機能する超絶的クラブの始まりであった。1836年9月19日に最初の公式会合が開かれた[77]。1837年9月1日、超絶的ク ラブの会合に初めて女性が参加した。エマーソンは、マーガレット・フラー、エリザベス・ホアー、サラ・リプリーを、夜の集まりに確実に出席させるために、 会合の前に自宅で夕食に招待した[78] フラーは超絶主義において重要な人物であることが証明されることになる。 エマソンは、最初のエッセイ「自然」を匿名でジェイムズ・マンロー社に送り、1836年9月9日に出版されることになった。その1年後の1837年8月 31日に、今では有名なファイベータカッパの講演「アメリカの学者」[79]を行った。当時は「An Oration, Delivered before the Phi Beta Kappa Society at Cambridge」というタイトルだったが、1849年に最初の一般出版物となる「自然」を含む小論文集用に改名された[80]。友人から講演を出版す るよう求められ、彼は私費で500部の版を出したところ1カ月で売り切れた[80]。 [当時ハーバード大学の学生であったジェームズ・ラッセル・ローウェルは、この講演を「我々の文学史にかつてない出来事」と呼んだ[82]。 また聴衆の一人、ジョン・ピアス牧師は「明らかに支離滅裂で意味不明な演説」と呼んだ[83]。 1837年、エマーソンはヘンリー・デイヴィッド・ソローと親しくなった。二人は1835年にはすでに会っていたと思われるが、1837年の秋、エマーソ ンはソローに "Do you keep a journal?" と尋ねた。エマソン自身の日記は、1960年から1982年にかけて発行されたハーバード大学出版局の決定版で、16冊の大冊で出版されている[84]。 一部の学者は、この日記をエマーソンの主要な文学作品とみなしている[85][要ページ]。 1837年3月、エマーソンはボストンのメーソン寺院で歴史哲学に関する一連の講義を行った。この講演会の収益は、団体から報酬を得て講演するよりもはる かに大きく、生涯を通じて頻繁に講演会を運営し続けた。最終的には年間80回もの講演を行い、セントルイス、デモイン、ミネアポリス、カリフォルニアな ど、アメリカ北部を駆け巡った[87]。 1838年7月15日、エマーソンはハーバード大学神学部のディヴィニティ・ホールに招かれ、「神学部の演説」として知られるようになる同校の卒業式での 演説を行った[88]。エマソンは聖書の奇跡を否定し、イエスは偉大な人物であったが、神ではなかったと宣言した:歴史的キリスト教はイエスを「東洋人や ギリシャ人がオシリスやアポロを表現するように半神」に変えてしまったと彼は言った[89]。 彼のコメントは体制と一般のプロテスタントのコミュニティを激怒させた。彼は無神論者[89]であり、若者の心を毒する者として糾弾された。批評家たちが 騒いだにもかかわらず、彼は何も答えず、他の人たちが弁明をすることになった。彼はその後30年間、ハーバード大学での講演に再び招かれることはなかった [90]。 超絶的なグループは1840年7月にその代表的な雑誌である『The Dial』を発行し始めた[91]。彼らは1839年10月には早くも雑誌を計画していたが、作業が始まったのは1840年の第1週だった[92] ジョージ・リプリーが編集長だった[93] Margaret Fullerは、他の数人がその役割を断った後にエマーソンが接近して最初の編集者となった[94] フラーが約2年間留任し、エマーソンは雑誌を利用してエラリーチャニングやソローなどの若い才能あふれる作家のプロモーションを行っている[84] エマーソンに引き継がれていたのは、その雑誌が、エマーソンを含む才能あふれる作家を宣伝するためだった。 1841年、エマソンは有名なエッセイ「自立」を含む2冊目の著書『エッセイ』を出版した[95]。叔母はこれを「無神論と偽りの自立の奇妙な混淆」と呼 んだが、ロンドンやパリでは好評を博した。この本とその好評は、エマーソンのこれまでのどの寄稿よりも、彼の国際的な名声の基礎を築いた[96]。 1842年1月、エマソンの長男ワルドが猩紅熱で死亡[97]。エマソンはその悲しみを詩「Threnody」(「For this losing is true dying」)とエッセイ「Experience」に書いている[98]。同じ月にウィリアム・ジェームズが生まれ、エマーソンは彼の名付け親になること を承諾した。 ブロンソン・オルコットは1842年11月に「良い建物、良い果樹園と敷地を持つ、素晴らしい状態の100エーカーの農場」を見つける計画を発表した [99]。チャールズ・レインは、超絶主義に一部触発されてできたユートピア思想に基づくコミュニティ、フルーツランズのために1843年5月にマサ チューセッツ州ハーバードで90エーカー(36 ha)の農場 を購入した[100]。 [100] 農場は共同作業に基づいて運営され、労働のために動物を使わず、参加者は肉を食べず、羊毛や革を使わない[101] エマーソンは、自分がこの実験に参加しなかったことを「心底悲しい」と感じていると語った[102]。 それでも彼はフルーツランズが成功するとは思っていなかった。「彼らの教義はすべて精神的なものだ」と書いているが、「彼らはいつも、我々に多くの土地と 金をよこせと言って終わる」[103] オルコットでさえ、フルーツランドの運営の難しさに対して準備ができていなかったことを認めている。「私たちの誰もが、夢見た理想的な生活を実際に実現す る準備ができていなかった。だから我々はバラバラになった」と書いている[104]。 失敗した後、エマーソンはオルコットの家族のためにコンコードに農場を購入するのを助け[103]、オルコットはそれを「ヒルサイド」と名づけた [104]。 ホレス・グリーリーは、「この国で出版された中で最も独創的で思慮深い定期刊行物」の終焉と報告した[105]。 1844年、エマーソンは2冊目のエッセイ集『エッセイ集』を出版した。Second Series)を出版した。このエッセイ集には、「詩人」、「経験」、「贈り物」、そして1836年の同名のエッセイとは別の作品である「自然」と題されたエッセイが含まれていた。 エマーソンはニューイングランドをはじめ、アメリカ全土で人気のある講演者として生計を立てていた。1833年に講演を始め、1850年代には年間80回 もの講演を行うようになった[106] ボストン有用知識普及協会やグロスター・リセウムなどで講演を行った。エマソンはさまざまなテーマで講演を行い、その講演から発展して多くのエッセイが生 まれた。講演料は1回につき10ドルから50ドルで、典型的な冬の講演会シーズンには2,000ドルもの収入を得た。これは、他の収入よりも多い。ある年 には6回の講演で900ドル、またある年にはボストンでの冬の講演で1,600ドルの収益を得た[107]。この収益によって、彼は所有地を拡大し、 ウォールデン池のそばに11エーカー(4.5 ha)の土地を購入し、さらに近隣の松林に数エーカーの土地を購入した[107]。彼は「多かれ少なかれ、14エーカーの地主兼水主」であると書いている [103]。 エマソンはフランスの哲学者ヴィクトル・クーザンの著作を通してインド哲学に触れた[108]。 1845年、エマソンの日記によると、彼は『バガヴァッド・ギーター』とヘンリー・トマス・コールブルックの『ヴェーダについての論考』を読んでいた [109]。 彼はヴェーダンタから強い影響を受け、彼の文章の多くは非二元論の強い色合いをもっている。その最も明確な例の1つは、彼のエッセイ「オーバーソウル」に 見つけることができる。 私たちは、連続し、分割され、部分的に、粒子の中に生きている。一方、人間の中には、全体の魂、賢明な沈黙、普遍的な美があり、すべての部分と粒子が等し く関連している、永遠の「一」である。そして、私たちが存在し、その幸福が私たちにすべて通じるこの深い力は、自己充足的であり、あらゆる時間に完全であ るだけでなく、見る行為と見られるもの、見る者と見られるもの、主体と対象が一つである。私たちは世界を、太陽、月、動物、樹木のように断片的に見るが、 これらが輝く部分である全体は魂である[110]。 エマソンがアジアの研究から引き出した中心的なメッセージは、「人生の目的は、精神的な変容と神の力の直接的な経験であり、今ここで地上にある」[111][112]というものであった。 1847年から48年にかけて、彼はイギリス諸島を視察した[113]。 また、1848年のフランス革命と流血の6月の日の間にパリを訪問している。彼が到着したとき、彼は2月の暴動でバリケードを形成するために切り倒された 木の切り株を見た。5月21日、彼はシャン・ド・マルスに立ち、和平と平和と労働のための大規模な祝典の真っ只中にいた。彼は日記に「年末には、革命が木 々に見合うものであったかどうかを勘定に入れよう」と書いている[114]。この旅行はエマーソンのその後の作品に重要な影響を残した。1856年に出版 された『イギリスの特質』は、主に彼の旅行記やノートに記録された観察に基づいている。エマソンは後にアメリカの南北戦争を1848年のヨーロッパの革命 と共通の基盤を持つ「革命」として見るようになった[115]。 1851年5月3日のマサチューセッツ州コンコードでの演説で、エマーソンは逃亡奴隷法を糾弾している。 議会の法律は、あなた方の誰もが早い機会に破ることになる法律であり、自尊心を失い、紳士の名前を失うことなく、誰も従うことも、従うことを幇助することもできない法律である[116]。 その夏、彼は日記に書いた。 この汚らわしい制定は、19世紀に読み書きのできる人たちによって作られたものだ。私はそれに従わない」[117]。 1852年2月、エマソンはジェームズ・フリーマン・クラークとウィリアム・ヘンリー・チャニングとともに、1850年に亡くなったマーガレット・フラー の作品と手紙の版を編集した[118]。彼女の死後1週間以内に、ニューヨークの編集者のホレス・グリーリーは、「彼女の悲しい死によって励起された関心 が過ぎ去る前に」『マーガレットとその友人たち』というタイトルでフラーの伝記を早く用意しようとエマスンに提案している[119]。 [119] The Memoirs of Margaret Fuller Ossoliというタイトルで出版されたが[120]、フラーの言葉は大きく検閲され、書き直された[121]。3人の編集者は正確さにこだわらず、フ ラーに対する世間の関心は一時的で、歴史上の人物として生き残ることはないと考えていた[122] それでもこの年代のベストセラー伝記となり、世紀末までに13版を重ねた[120]。 ウォルト・ホイットマンは1855年に革新的な詩集『草の葉』を出版し、そのコピーをエマソンに送り、彼の意見を仰いだ。エマソンは肯定的な反応を示し、 それに対してホイットマンに5ページの好意的な手紙を送った[123]。 エマソンの承認によって『草の葉』初版は大きな関心を呼び起こし[124]、その後すぐに第二版を発行するようにホイットマンに説得する。 この版の表紙には、金箔を使ってエマーソンの手紙からのフレーズが引用された[125]。「エマソンはこの手紙が公開されたことに腹を立て[127]、後 にこの作品に対してより批判的な態度をとるようになる[128]。 |

| Philosophers Camp at Follensbee

Pond – Adirondacks Ralph Waldo Emerson, in the summer of 1858, would venture into the great wilderness of upstate New York. Joining him were nine of the most illustrious intellectuals ever to camp out in the Adirondacks to connect with nature: Louis Agassiz, James Russell Lowell, John Holmes, Horatio Woodman, Ebenezer Rockwell Hoar, Jeffries Wyman, Estes Howe, Amos Binney, and William James Stillman. Invited, but unable to make the trip for diverse reasons, were: Oliver Wendell Holmes, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Charles Eliot Norton, all members of the Saturday Club (Boston, Massachusetts).[129] This social club was mostly a literary membership that met the last Saturday of the month at the Boston Parker House Hotel (Omni Parker House). William James Stillman was a painter and founding editor of an art journal called the Crayon. Stillman was born and grew up in Schenectady which was just south of the Adirondack mountains. He would later travel there to paint the wilderness landscape and to fish and hunt. He would share his experiences in this wilderness to the members of the Saturday Club, raising their interest in this unknown region. James Russell Lowell[130] and William Stillman would lead the effort to organize a trip to the Adirondacks. They would begin their journey on August 2, 1858, traveling by train, steam boat, stagecoach, and canoe guide boats. News that these cultured men were living like "Sacs and Sioux" in the wilderness appeared in newspapers across the nation. This would become known as the "Philosophers Camp".[131] This event was a landmark in the nineteenth-century intellectual movement, linking nature with art and literature. Although much has been written over many years by scholars and biographers of Emerson's life, little has been written of what has become known as the "Philosophers Camp" at Follensbee Pond. Yet, his epic poem "Adirondac"[132] reads like a journal of his day to day detailed description of adventures in the wilderness with his fellow members of the Saturday Club. This two week camping excursion (1858 in the Adirondacks) brought him face to face with a true wilderness, something he spoke of in his essay "Nature", published in 1836. He said, "in the wilderness I find something more dear and connate than in streets or villages".[133] |

フォレンスビー・ポンドでの哲学者キャンプ - アディロンダック山地 1858年の夏、ラルフ・ウォルドー・エマーソンは、ニューヨーク州北部の大自然に足を踏み入れる。 彼と一緒に、アディロンダック山地で自然と触れ合うためにキャンプをした最も著名な知識人9人がいました。ルイ・アガシズ、ジェームズ・ラッセル・ロー ウェル、ジョン・ホームズ、ホレイショ・ウッドマン、エベネザー・ロックウェル・ホアー、ジェフリーズ・ワイマン、エステス・ハウ、エイモス・ビニー、 ウィリアム・ジェームズ・スティルマンである。招待されたものの、さまざまな事情で来日できなかったのは次の通り。オリバー・ウェンデル・ホームズ、ヘン リー・ワズワース・ロングフェロー、チャールズ・エリオット・ノートンは、サタデー・クラブ(ボストン、マサチューセッツ州)のメンバーであった [129]。 この社交クラブは、ほとんどが文学者の会員で、毎月最終土曜日にボストン・パーカーハウス・ホテル(オムニ・パーカーハウス)で会合していた。ウィリア ム・ジェームズ・スティルマンは画家であり、『クレヨン』という美術雑誌の創刊編集者であった。スティルマンは、アディロンダック山地のすぐ南にあるシェ ネクタディで生まれ育ちました。その後、荒野の風景を描き、釣りや狩りをするために、この地を訪れるようになる。この大自然での体験をサタデークラブの会 員に伝え、この未知の地域への関心を高めていったのである。 ジェイムズ・ラッセル・ローウェル[130]とウィリアム・スティルマンは、アディロンダックへの旅を組織するための努力を主導することになります。彼ら は、1858年8月2日に旅を始め、列車、蒸気船、駅馬車、カヌーガイドの船などを乗り継いで移動しました。文化人である彼らが荒野で「サックスとスー」 のような生活をしているというニュースは、全米の新聞に掲載された。これは、「哲学者キャンプ」として知られるようになる[131]。 この出来事は、自然と芸術や文学を結びつける、19世紀の知的運動の画期的な出来事であった。 エマーソンの生涯については、長年にわたって学者や伝記作家によって多くのことが書かれてきたが、フォレンスビー・ポンドでの「哲学者キャンプ」として知 られるようになったことについてはほとんど書かれていない。しかし、彼の叙事詩『アジロンダック』[132]は、サタデー・クラブの仲間たちとの荒野での 冒険を日々詳細に描写した日記のように読めます。この2週間のキャンプ旅行(1858年、アディロンダック)で、彼は、1836年に出版されたエッセイ 『自然』で語った、真の荒野に直面することになる。彼は、「荒野には、街や村よりももっと親密で結びつきの強いものがある」と述べている。 |

| Civil War years Emerson was staunchly opposed to slavery, but he did not appreciate being in the public limelight and was hesitant about lecturing on the subject. In the years leading up to the Civil War, he did give a number of lectures, however, beginning as early as November 1837.[134] A number of his friends and family members were more active abolitionists than he, at first, but from 1844 on he more actively opposed slavery. He gave a number of speeches and lectures, and welcomed John Brown to his home during Brown's visits to Concord.[135][page needed] He voted for Abraham Lincoln in 1860, but was disappointed that Lincoln was more concerned about preserving the Union than eliminating slavery outright.[136] Once the American Civil War broke out, Emerson made it clear that he believed in immediate emancipation of the slaves.[137] Around this time, in 1860, Emerson published The Conduct of Life, his seventh collection of essays. It "grappled with some of the thorniest issues of the moment," and "his experience in the abolition ranks is a telling influence in his conclusions."[138] In these essays Emerson strongly embraced the idea of war as a means of national rebirth: "Civil war, national bankruptcy, or revolution, [are] more rich in the central tones than languid years of prosperity."[139] Emerson visited Washington, D.C, at the end of January 1862. He gave a public lecture at the Smithsonian on January 31, 1862, and declared:, "The South calls slavery an institution ... I call it destitution ... Emancipation is the demand of civilization".[140] The next day, February 1, his friend Charles Sumner took him to meet Lincoln at the White House. Lincoln was familiar with Emerson's work, having previously seen him lecture.[141] Emerson's misgivings about Lincoln began to soften after this meeting.[142] In 1865, he spoke at a memorial service held for Lincoln in Concord: "Old as history is, and manifold as are its tragedies, I doubt if any death has caused so much pain as this has caused, or will have caused, on its announcement."[141] Emerson also met a number of high-ranking government officials, including Salmon P. Chase, the secretary of the treasury; Edward Bates, the attorney general; Edwin M. Stanton, the secretary of war; Gideon Welles, the secretary of the navy; and William Seward, the secretary of state.[143] On May 6, 1862, Emerson's protégé Henry David Thoreau died of tuberculosis at the age of 44. Emerson delivered his eulogy. He often referred to Thoreau as his best friend,[144] despite a falling-out that began in 1849 after Thoreau published A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers.[145] Another friend, Nathaniel Hawthorne, died two years after Thoreau, in 1864. Emerson served as a pallbearer when Hawthorne was buried in Concord, as Emerson wrote, "in a pomp of sunshine and verdure".[146] He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1864.[147] In 1867, he was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society.[148] |

南北戦争時代 エマソンは奴隷制に強く反対していたが、世間の脚光を浴びることを好まず、このテーマで講演することをためらっていた。しかし、南北戦争までの数年間は、 1837年11月頃から講演を行っている[134]。友人や家族の中には、当初は彼よりも積極的な奴隷制廃止論者が多くいたが、1844年から、より積極 的に奴隷制に反対するようになる。彼は多くの演説や講演を行い、ブラウンがコンコードを訪れた際にはジョン・ブラウンを自宅に迎えた[135][要ペー ジ]。 1860年にエイブラハム・リンカーンに投票したが、リンカーンは奴隷制を完全に排除するよりも連邦を維持することに関心があったことに失望した [136] アメリカ内戦が勃発すると、エマーソンは奴隷の即時解放を信じることを明確にした[137]。 この頃、1860年にエマーソンは彼の7番目のエッセイ集である『The Conduct of Life』を出版している。このエッセイ集は「その時々の最もとげとげしい問題のいくつかに取り組み」、「奴隷解放運動における彼の経験は、彼の結論に決 定的な影響を及ぼしている」[138]と述べている。「内戦、国家破産、または革命は、繁栄の気だるい年月よりも中心的なトーンにおいて豊かである」 [139]。 エマーソンは1862年1月末にワシントンD.C.を訪れている。1862年1月31日、スミソニアン博物館で公開講演を行い、「南部は奴隷制度を制度と 呼ぶが、私はそれを貧困と呼ぶ」と宣言した。私はそれを窮乏と呼ぶ......。解放は文明の要求である」[140] 翌2月1日、友人のチャールズ・サムナーは彼を連れてホワイトハウスでリンカーンに面会した。リンカーンはエマソンの講演を見たことがあり、エマソンの作 品をよく知っていた[141]。 1865年、彼はコンコードで行われたリンカーンの追悼式で演説を行った[142]。「歴史は古く、その悲劇は多様であるが、この死がその発表の際に引き 起こした、あるいは引き起こすであろう、これほどの痛みを引き起こした死があっただろうか」[141] エマーソンはまた、財務長官サーモン・チェイス、司法長官エドワード・ベイツ、陸軍長官エドウィン・M・スタントン、海軍長官ギドン・ウェルズ、国務長官 ウィリアム・スワードら多くの高官と会っている[143]。 1862年5月6日、エマソンの弟子であったヘンリー・デイヴィッド・ソローが結核で44歳の若さで死去した。エマーソンは彼の弔辞を述べた。ソローが 『コンコード川とメリマク川の一週間』を出版した後の1849年から仲たがいしていたが、彼はしばしばソローを親友と呼んだ[144] [145] 別の友人ナサニエル・ホーソーンもソローから2年後の1864年に死去した。ホーソンがコンコードに埋葬されたとき、エマーソンは喪主を務めたが、エマー ソンは「陽光と緑にあふれた華やかさで」と書いている[146]。 1864年にアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーのフェローに選出された[147]。 1867年にアメリカ哲学協会の会員に選出された[148]。 |

| Final years and death Starting in 1867, Emerson's health began declining; he wrote much less in his journals.[149] Beginning as early as the summer of 1871 or in the spring of 1872, he started experiencing memory problems[150] and suffered from aphasia.[151] By the end of the decade, he forgot his own name at times and, when anyone asked how he felt, he responded, "Quite well; I have lost my mental faculties, but am perfectly well".[152] In the spring of 1871, Emerson took a trip on the transcontinental railroad, barely two years after its completion. Along the way and in California he met a number of dignitaries, including Brigham Young during a stopover in Salt Lake City. Part of his California visit included a trip to Yosemite, and while there he met a young and unknown John Muir, a signature event in Muir's career.[153] Emerson's Concord home caught fire on July 24, 1872. He called for help from neighbors and, giving up on putting out the flames, all tried to save as many objects as possible.[154] The fire was put out by Ephraim Bull Jr., the one-armed son of Ephraim Wales Bull.[155] Donations were collected by friends to help the Emersons rebuild, including $5,000 gathered by Francis Cabot Lowell, another $10,000 collected by LeBaron Russell Briggs, and a personal donation of $1,000 from George Bancroft.[156] Support for shelter was offered as well; though the Emersons ended up staying with family at the Old Manse, invitations came from Anne Lynch Botta, James Elliot Cabot, James T. Fields and Annie Adams Fields.[157] The fire marked an end to Emerson's serious lecturing career; from then on, he would lecture only on special occasions and only in front of familiar audiences.[158] While the house was being rebuilt, Emerson took a trip to England, continental Europe, and Egypt. He left on October 23, 1872, along with his daughter Ellen,[159] while his wife Lidian spent time at the Old Manse and with friends.[160] Emerson and his daughter Ellen returned to the United States on the ship Olympus along with friend Charles Eliot Norton on April 15, 1873.[161] Emerson's return to Concord was celebrated by the town, and school was canceled that day.[151] In late 1874, Emerson published an anthology of poetry entitled Parnassus,[162][163] which included poems by Anna Laetitia Barbauld, Julia Caroline Dorr, Jean Ingelow, Lucy Larcom, Jones Very, as well as Thoreau and several others.[164] Originally, the anthology had been prepared as early as the fall of 1871, but it was delayed when the publishers asked for revisions.[165] The problems with his memory had become embarrassing to Emerson and he ceased his public appearances by 1879. In reply to an invitation to a retirement celebration for Octavius B. Frothingham, he wrote, “I am not in condition to make visits, or take any part in conversation. Old age has rushed on me in the last year, and tied my tongue, and hid my memory, and thus made it a duty to stay at home.” The New York Times quoted his reply and noted that his regrets were read aloud at the celebration.[166] Holmes wrote of the problem saying, "Emerson is afraid to trust himself in society much, on account of the failure of his memory and the great difficulty he finds in getting the words he wants. It is painful to witness his embarrassment at times".[152] On April 21, 1882, Emerson was found to be suffering from pneumonia.[167] He died six days later. Emerson is buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord, Massachusetts.[168] He was placed in his coffin wearing a white robe given by the American sculptor Daniel Chester French.[169] |

晩年と死 1867年から、エマーソンの健康は衰え始め、日記への書き込みもかなり減った[149]。 早くも1871年の夏から1872年の春にかけて、記憶障害を経験し始め[150]、失語症に苦しんだ[151] 10年の終わりまでに、自分の名前を忘れることもあり、誰かに自分の気持ちを聞かれると、「かなり元気。精神力を失ったが完全に元気」と答えている [152]。 1871年の春、エマーソンは大陸横断鉄道の旅に出たが、完成からわずか2年後のことであった。その道中やカリフォルニアで、ソルトレイクシティに立ち 寄ったブリガム・ヤングを含む多くの高官と会った。カリフォルニア訪問の一部にはヨセミテへの旅行が含まれており、そこで彼は若く無名のジョン・ミューア と出会い、ミューアのキャリアにおいて特徴的な出来事となった[153]。 1872年7月24日、エマーソンのコンコードの家が火事になった。彼は隣人に助けを求め、炎を消すことをあきらめて、みんなでできるだけ多くの物を救お うとした[154] 火事を消したのは、Ephraim Bull Jr, フランシス・キャボット・ローウェルが集めた5,000ドル、ルバロン・ラッセル・ブリッグスが集めた1万ドル、ジョージ・バンクロフトからの1,000 ドルの個人寄付など、エマーソンの再建のために友人から寄付が集められた[155]。 [エマソン夫妻は結局オールドマンスの家族のもとに滞在することになったが、アン・リンチ・ボッタ、ジェームズ・エリオット・キャボット、ジェームズ・ T・フィールズ、アニー・アダムス・フィールズから招待を受けた[157]。 この火災によってエマーソンの本格的な講演活動は終わり、以後は特別な機会にのみ、親しい聴衆を前に講演することとなった[158]。 家の再建中、エマーソンはイギリス、ヨーロッパ大陸、エジプトを旅行した。1872年10月23日に娘エレンと共に出発し[159]、妻リディアンは旧邸 や友人たちと過ごした[160]。 1873年4月15日にエマソンと娘エレンは友人チャールズ・エリオット・ノートンと共にオリンパス号でアメリカに戻る[161]。エマーソンのコンコー ドへの帰還は町によって祝われ、その日は学校が休校された[151]。 1874年末、エマーソンは『パルナッソス』と題した詩のアンソロジーを出版し[162][163]、アンナ・レイティア・バーボールド、ジュリア・キャ ロライン・ドール、ジーン・インゲロウ、ルーシー・ラルコム、ジョーンズ・ベリーに加え、ソローやその他数人の詩が含まれていた[164] 元々、アンソロは早くも1871年の秋に準備されていたが、出版社が修正を求めたため遅れていた[165]......。 記憶力の問題はエマソンを困惑させ、彼は1879年までに公の場に出ることをやめた。オクタヴィウス・B・フローシングハムの退職祝いの招待状への返信 で、「私は訪問したり、会話に参加したりできるような状態にはない。去年から老齢になり、舌を噛み、記憶を失い、家にいることが義務になったのです」と書 いている。ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙は彼の返事を引用し、祝賀会で彼の遺憾の意が読み上げられたことを記している[166]。ホームズはこの問題につい て、「エマーソンは記憶の障害と自分の望む言葉を得ることの大きな困難さを理由に、社会で自分をあまり信用することを恐れている」と書いている [167]。彼の困惑を目の当たりにするのは苦痛である」[152]と述べている。 1882年4月21日、エマーソンは肺炎を患っていることがわかった[167]。 彼は6日後に死亡した。エマーソンはマサチューセッツ州コンコードのスリーピー・ホロウ墓地に埋葬された[168]。 アメリカの彫刻家ダニエル・チェスター・フレンチが贈った白いローブを着て棺に収められた[169]。 |

| Lifestyle and beliefs Emerson's religious views were often considered radical at the time. He believed that all things are connected to God and, therefore, all things are divine.[170] Critics believed that Emerson was removing the central God figure; as Henry Ware Jr. said, Emerson was in danger of taking away "the Father of the Universe" and leaving "but a company of children in an orphan asylum".[171] Emerson was partly influenced by German philosophy and Biblical criticism.[172] His views, the basis of Transcendentalism, suggested that God does not have to reveal the truth, but that the truth could be intuitively experienced directly from nature.[173] When asked his religious belief, Emerson stated, "I am more of a Quaker than anything else. I believe in the 'still, small voice', and that voice is Christ within us."[174] Emerson was a supporter of the spread of community libraries in the 19th century, having this to say of them: "Consider what you have in the smallest chosen library. A company of the wisest and wittiest men that could be picked out of all civil countries, in a thousand years, have set in best order the results of their learning and wisdom."[175] Emerson had a number of romantic interests in various women throughout his life,[71] such as Anna Barker[176] and Caroline Sturgis.[177] During his early years at Harvard (around age 14-16), he wrote erotic poetry about a fellow classmate named Martin Gay.[71][178][179] |

ライフスタイルと信条 エマーソンの宗教観は当時、しばしば急進的であると考えられていた。批評家たちはエマソンが中心的な神の姿を取り除いていると考え、ヘンリー・ウェア・ ジュニアが言ったように、エマソンは「宇宙の父」を取り除いて、「孤児院にいる子供の一団にすぎない」状態にする危険性があると考えた[170]。 [エマソンはドイツ哲学と聖書批評の影響を一部受けていた[172]。 超絶論の基礎となる彼の見解は、神が真実を明らかにする必要はなく、真実は自然から直接直観的に経験できると示唆した[173]。私は『静かな、小さな 声』を信じており、その声は私たちの中にいるキリストである」と述べている[174]。 エマソンは19世紀における地域図書館の普及を支持し、次のような言葉を残している。「選ばれた最も小さな図書館に何があるのかを考えてみよう。千年の間 に、すべての文明の国から選ばれた最も賢明で賢い男たちの一団が、彼らの学問と知恵の結果を最もよく整列させているのだ」[175]。 エマソンは生涯を通じて、アンナ・バーカー[176]やキャロライン・スタージスといった様々な女性と恋愛関係にあった[177]。 ハーバード大学の初期(14歳から16歳頃)には、マーティン・ゲイという同級生についてエロチックな詩を書いている[71][178][179]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ralph_Waldo_Emerson |

|

| Another

sign of our times, also marked by an analogous political movement, is

the new importance given to the single person. Everything that tends to

insulate the individual—to surround him with barriers of natural

respect, so that each man shall feel the world is his, and man shall

treat with man as a sovereign state with a sovereign state—tends to

true union as well as greatness. "I learned," said the melancholy

Pestalozzi, "that no man in God's wide earth is either willing or able

to help any other man." Help must come from the bosom alone. The

scholar is that man who must take up into himself all the ability of

the time, all the contributions of the past, all the hopes of the

future. He must be an university of knowledges. If there be one lesson

more than another that should pierce his ear, it is—The world is

nothing, the man is all; in yourself is the law of all nature, and you

know not yet how a globule of sap ascends; in yourself slumbers the

whole of Reason; it is for you to know all; it is for you to dare

all. Mr. President and Gentlemen, this confidence in the unsearched might of man belongs, by all motives, by all prophecy, by all preparation, to the American Scholar. We have listened too long to the courtly muses of Europe. The spirit of the American freeman is already suspected to be timid, imitative, tame. Public and private avarice make the air we breathe thick and fat. The scholar is decent, indolent, complaisant. See already the tragic consequence. The mind of this country, taught to aim at low objects, eats upon itself. There is no work for any one but the decorous and the complaisant. Young men of the fairest promise, who begin life upon our shores, inflated by the mountain winds, shined upon by all the stars of God, find the earth below not in unison with these, but are hindered from action by the disgust which the principles on which business is managed inspire, and turn drudges, or die of disgust, some of them suicides. What is the remedy? They did not yet see, and thousands of young men as hopeful now crowding to the barriers for the career do not yet see, that if the single man plant himself indomitably on his instincts, and there abide, the huge world will come round to him. Patience,—patience; with the shades of all the good and great for company; and for solace the perspective of your own infinite life; and for work the study and the communication of principles, the making those instincts prevalent, the conversion of the world. Is it not the chief disgrace in the world, not to be an unit; not to be reckoned one character; not to yield that peculiar fruit which each man was created to bear, but to be reckoned in the gross, in the hundred, or the thousand, of the party, the section, to which we belong; and our opinion predicted geographically, as the north, or the south? Not so, brothers and friends,—please God, ours shall not be so. We will walk on our own feet; we will work with our own hands; we will speak our own minds. Then shall man be no longer a name for pity, for doubt, and for sensual indulgence. The dread of man and the love of man shall be a wall of defense and a wreath of joy around all. A nation of men will for the first time exist, because each believes himself inspired by the Divine Soul which also inspires all men. - The American Scholar. |

現

代のもう一つの兆候は、類似の政治的な動きによって特徴付けられるが、一人の人間に与えられた新しい重要性である。個人を隔離し、自然な尊敬の障壁で囲

み、各人が世界を自分のものだと感じ、主権国家が主権国家に接するように人間と接するようにする傾向があるものはすべて、真の結合と偉大さをもたらす傾向

がある。憂鬱なペスタロッチーは言った、「私は学んだ、神の広い地球上で、他の人間を助けようとする人間も、助けることのできる人間もいないことを」。助

けは自分の懐からだけ出てくるものなのだ。学者とは、その時代のすべての能力、過去のすべての貢献、未来のすべての希望を自分の中に取り込まなければなら

ない人である。彼は知識の大学でなければならない。もし、彼の耳を突き刺すべき、他の教訓よりも重要なものがあるとすれば、それは、「世界は無であり、人

間がすべてである」「あなた自身の中に、すべての自然の法則があり、あなたはまだ、樹液の球がどのように上昇するかを知らない」「あなた自身の中に、理性

のすべてが眠っている」「すべてを知るのはあなたであり、すべてをあえてするのはあなたである」である。 学長そして皆さん、人間の未知の力に対するこの信頼は、あらゆる動機によって、あらゆる予言によって、あらゆる準備によって、アメリカの学者に属するもの なのである。我々は、あまりにも長い間、ヨーロッパの宮廷の音楽家たちの声に耳を傾けてきた。アメリカの自由民の精神は、すでに臆病で、模倣的で、飼いな らされているのではないかと疑われている。公私の欲望が、私たちの呼吸する空気を太く濃くしているのである。学者はまともで、無関心で、お人好しです。悲 劇的な結末がすでに見えている。この国の精神は、低い目標に向かうように教えられ、自分自身を食い物にしている。お行儀のいい人、お人好しの人以外には、 課題というものはない。 最も有望な若者たちが、山風に吹かれ、神のすべての星に照らされながら、わが国の海岸で人生を歩み始めたが、下界ではこれらと一致せず、事業運営の原則が 抱く嫌悪感に行動を妨げられ、雑用係になるか、嫌悪感で死に、なかには自殺する者もいるのだ。その解決策は何でしょうか?彼らはまだ見ていない、そして今 キャリアのために障壁に群がる希望に満ちた何千もの若者はまだ見ていない、一人の男が自分の本能に不屈に身を置き、そこに留まるならば、巨大な世界が彼の もとに巡ってくるということを。忍耐、忍耐。善良で偉大なすべての人々の影を友とし、慰めは自分の無限の人生の展望とし、仕事は原則の研究と伝達、それら の本能の普及、世界の転換とすることである。一人の人間でないこと、一人の人格とみなされないこと、各人が実を結ぶために創造された独特の実を結ばないこ と、しかし自分が属する党や部門の総数、百または千に数えられること、そして自分の意見を北または南のように地理的に予測されることは、この世の最大の恥 ではないだろうか?兄弟や友人たちよ、そうではないのだ。どうか神に誓って、われわれはそうではない。われわれは自分の足で歩き、自分の手で働き、自分の 考えを話すようになるのだ。そうすれば、人間はもはや、哀れみの名でも、疑いの名でも、官能的な甘えの名でもなくなる。人間の恐ろしさと人間への愛が、す べての人の周りに防御の壁と喜びの花輪となるであろう。人間の国家が初めて存在するようになる。なぜなら、すべての人間をも奮い立たせる神聖な魂によっ て、各人が自分自身を奮い立たせていると信じるからである。 |

| http://digitalemerson.wsulibs.wsu.edu/exhibits/show/text/the-american-scholar |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報