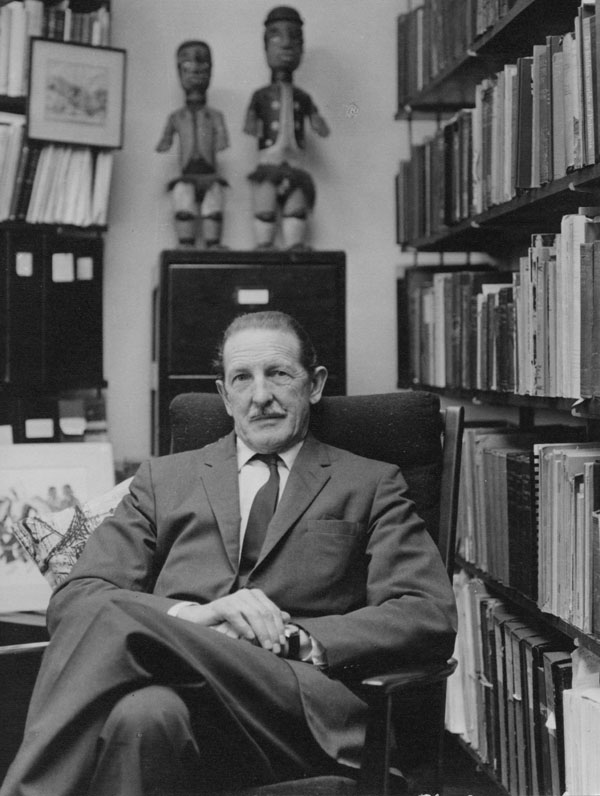

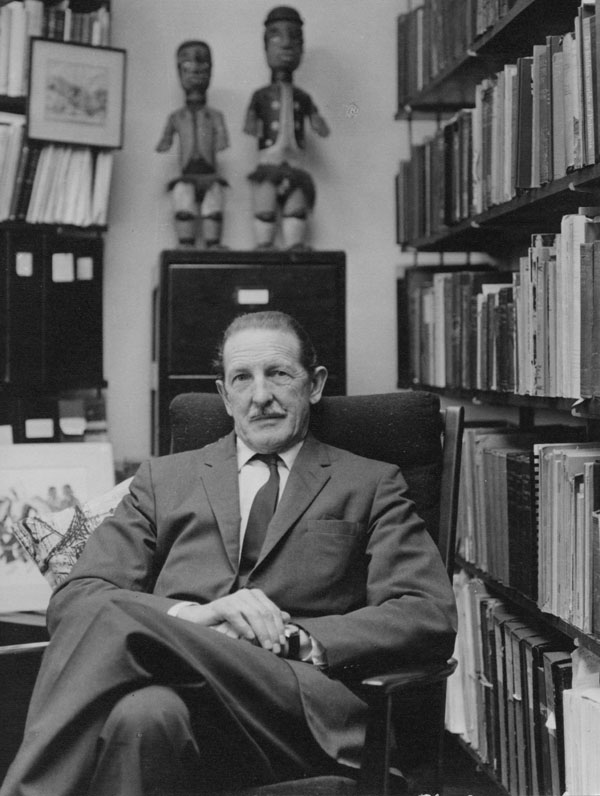

レイモンド・ファース

Raymond Firth, 1901-2002

「1970年代初頭のある会話が思い出される。私(=ジェームズ・クリフォード)はロンド

ン・スクール・

オブ・エコノミクスでマリノフスキーの論文を研究していた博士課程の学生だったが、ある日図書館の外で、ティコピアの偉大な人類学者レイモンド・ファース

と彼の学問の歴史について話していた。ファースはマリノフスキーの学生であり同僚だった。彼は人類学研究を植民地権力と結びつけようとする試み、特にタラ

ル・アサド編『人類学と植民地的遭遇』(1973年)という重要な本に首をかしげた。彼は、見せかけの困惑と本当の困惑が入り混じった表情で首を振った。

何が起こったのですか?「少し前まで、私たちは急進派でした。私たちは自分たちのことを、ブンブン飛び回るアブであり、改革者であり、先住民の文化の価値

を擁護し、民族の擁護者であると考えていました。それが突然、帝国の手先になってしまったのだ!」

| Sir Raymond William

Firthの英語ウィキペディアによる |

https://www.deepl.com/

による翻訳(レイモンド・ファースの年譜はこちら) |

| Sir Raymond William Firth Kt

CNZM FRAI FBA (25 March 1901 – 22 February 2002) was an ethnologist

from New Zealand. As a result of Firth's ethnographic work, actual

behaviour of societies (social organization) is separated from the

idealized rules of behaviour within the particular society (social

structure). He was a long serving Professor of Anthropology at London

School of Economics, and is considered to have singlehandedly created a

form of British economic anthropology.[1] |

Sir Raymond William Firth Kt

CNZM FRAI

FBA(1901年3月25日~2002年2月22日)は、ニュージーランド出身の民族学者である。ファースの民族誌的研究の結果、社会の実際の行動(社

会組織)と、特定の社会の中での理想的な行動のルール(社会構造)とが分離された。ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス(LSE)の人類学教授を長く

務め、イギリスの経済人類学の一形態を一人で作り上げたとされている[1]。 |

| Firth was born to Wesley and

Marie Firth in Auckland, New Zealand, in 1901. He was educated at

Auckland Grammar School, and then at Auckland University College, where

he graduated in economics in 1921.[2] He took his economics MA there in

1922 with a 'fieldwork' based research thesis on the Kauri Gum digging

industry,[3] then a diploma in social science in 1923.[4] In 1924 he

began his doctoral research at the London School of Economics.

Originally intending to complete a thesis in economics, a chance

meeting with the eminent social anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski led

to him to alter his field of study to 'blending economic and

anthropological theory with Pacific ethnography'.[2] It was possibly

during this period in England that he worked as research assistant to

Sir James G Frazer, author of The Golden Bough.[5] Firth's doctoral

thesis was published in 1929 as Primitive Economics of the New Zealand

Māori. |

1901年、ニュージーランドのオークランドで、ウェスリー・ファース

とマリー・ファースの間に生まれた。オークランド・グラマー・スクールを経てオークランド・ユニバーシティ・カレッジで学び、1921年に経済学を専攻し

て卒業した[2]。

1922年に同校で経済学の修士号を取得し、カウリガムの掘削産業に関する「フィールドワーク」をベースにした研究論文を提出[3]、1923年には社会

科学のディプロマを取得した[4]。

1924年にはロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスで博士課程の研究を開始した。当初は経済学の論文を書くつもりだったが、著名な社会人類学者ブロニ

スワフ・マリノウスキーとの偶然の出会いにより、研究分野を「経済学と人類学の理論を太平洋の民族誌と融合させる」ことに変更した[2]。

このイギリス滞在中に、『The Golden Bough』の著者であるジェームズ・G・フレイザー卿の研究助手を務めたのかもしれない[5]。

ファースの博士論文は、1929年に"Primitive Economics of the New Zealand Māori"として出版された。 |

| After receiving his PhD in 1927

Firth returned to the southern hemisphere to take up a position at the

University of Sydney, although he did not start teaching immediately as

a research opportunity presented itself. In 1928 he first visited

Tikopia, the southernmost of the Solomon Islands, to study the

untouched Polynesian society there, resistant to outside influences and

still with its pagan religion and undeveloped economy.[2] This was the

beginning of a long relationship with the 1200 people of the remote

four-mile long island, and resulted in ten books and numerous articles

written over many years. The first of these, We the Tikopia: A

Sociological Study of Kinship in Primitive Polynesia was published in

1936 and seventy years on is still used as a basis for many university

courses about Oceania.[6] |

1927年に博士号を取得したファースは、南半球に戻り、シドニー大学

に着任したが、すぐには研究の機会が訪れたため、教壇には立たなかった。1928年、ソロモン諸島の最南端に位置するティコピアを初めて訪れ、外部からの

影響を受けにくく、いまだに異教的な宗教や未発達な経済を持つ、手つかずのポリネシア社会を研究した[2]。

これが、長さ4マイルの辺境の島に住む1200人の人々との長い付き合いの始まりとなり、長年にわたって10冊の本と多数の論文が執筆された。その最初の

本が『We the Tikopia: 1936年に出版された最初の本, "We the Tikopia: A Sociological

Study of Kinship in Primitive

Polynesia"は、70年経った今でも、オセアニアに関する多くの大学の講義の基礎資料として使われている[6]。 |

| In 1930 he started teaching at

the University of Sydney. On the departure for Chicago of Alfred

Radcliffe-Brown, Firth succeeded him as acting Professor. He also took

over from Radcliffe-Brown as acting editor of the journal Oceania, and

as acting director of the Anthropology Research Committee of the

Australian National Research Committee. |

1930年、彼はシドニー大学で教鞭をとり始めた。アルフレッド・ラド

クリフ・ブラウンがシカゴに発つと、ファースは彼の後を継いで臨時教授となった。また、ラドクリフ=ブラウンの後任として、雑誌『オセアニア』の編集長代

理、オーストラリア国家研究委員会の人類学研究委員会の所長代理を務めた。 |

| After 18 months he returned to

the London School of Economics in 1933 to take up a lectureship, and

was appointed Reader in 1935. Together with his wife Rosemary Firth,

also to become a distinguished anthropologist, he undertook fieldwork

in Kelantan and Terengganu in Malaya in 1939–1940.[7] During the Second

World War Firth worked for British naval intelligence, primarily

writing and editing the four volumes of the Naval Intelligence Division

Geographical Handbook Series that concerned the Pacific Islands.[8]

During this period Firth was based in Cambridge, where the LSE had its

wartime home. |

1年半後、1933年にロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスに戻っ

て講義を担当し、1935年にリーダーに任命された。1939年から40年にかけて、妻のローズマリー・ファースとともに、マラヤのケランタンとトレンガ

ヌでフィールドワークを行った[7]。

第二次世界大戦中、ファースはイギリス海軍情報部に勤務し、主に太平洋諸島に関する海軍情報部地理ハンドブックシリーズ4巻の執筆・編集を行った[8]。 |

| Firth succeeded Malinowski as

Professor of Social Anthropology at LSE in 1944, and he remained at the

School for the next 24 years.[2] In the late 1940s he was a member of

the Academic Advisory Committee of the then-fledgling Australian

National University, along with Sir Howard Florey (co-developer of

medicinal penicillin), Sir Mark Oliphant (a nuclear physicist who

worked on the Manhattan Project), and Sir Keith Hancock (Chichele

Professor of Economic History at Oxford). Firth was particularly

focused on the creation of the university's School of Pacific

Studies.[9] |

1940年代後半には、ハワード・フローリー卿(薬用ペニシリンの共同

開発者)、マーク・オリファント卿(マンハッタン計画の核物理学者)、キース・ハンコック卿(オックスフォード大学経済史チクル教授)らとともに、当時設

立されたばかりのオーストラリア国立大学の学術諮問委員会のメンバーとなった[2]。ファースが特に力を入れたのは、同大学のSchool of

Pacific Studiesの創設だった[9]。 |

| He returned to Tikopia on

research visits several times, although as travel and fieldwork

requirements became more burdensome he focused on family and kinship

relationships in working- and middle-class London.[7] Firth left LSE in

1968, when he took up a year's appointment as Professor of Pacific

Anthropology at the University of Hawaiʻi. There followed visiting

professorships at British Columbia (1969), Cornell (1970), Chicago

(1970–1), the Graduate School of the City University of New York (1971)

and UC Davis (1974). The second festschrift published in his honour

described him as 'perhaps the greatest living teacher of anthropology

today'.[4] |

1968年にLSEを退社し、ハワイ大学の太平洋人類学教授に1年間就

任。その後、ブリティッシュ・コロンビア大学(1969年)、コーネル大学(1970年)、シカゴ大学(1970-1年)、ニューヨーク市立大学大学院

(1971年)、カリフォルニア大学デービス校(1974年)で客員教授を務めた。彼を記念して出版された2回目の祝典では、「おそらく今日の人類学の生

きた最大の教師」と評されている[4]。 |

| After retiring from teaching

work, Firth continued with his research interests, and right up until

his hundredth year he was producing articles. He died in London a few

weeks before his 101st birthday: his father had lived to 104. |

ファースは教職を退いた後も研究を続け、100歳になるまで論文を発表

していた。父は104歳まで生きたが、ファースは101歳の誕生日の数週間前にロンドンで亡くなった。 |

| Firth married Rosemary Firth

(née Upcott) in 1936 and she died in 2001; they had one son, Hugh, who

was born in 1946. He was raised a Methodist then later became a

humanist and an atheist, a decision influenced by his anthropological

studies.[11][12] He was one of the signers of the

Humanist Manifesto II.[13] |

ファースは1936年にローズマリー・ファース(旧姓アップコット)と

結婚し、2001年に死去した。二人の間には1946年に生まれたヒューという一人の息子がいた。メソジスト教徒として育ち、人類学的研究の影響を受けて

ヒューマニスト、無神論者となった[11][12]。ヒューマニスト宣言の署名者の一人である[13]。 |

| Māori lament (poroporoaki) for

Sir Raymond Firth Composed on behalf of the Polynesian Society by its then-President, Professor Sir Hugh Kawharu (English translation)[2] You have left us now, Sir Raymond Your body has been pierced by the spear of death And so farewell. Farewell, Scholar renowned in halls of learning throughout the world 'Navigator of the Pacific' 'Black hawk' of Tamaki. Perhaps in the end you were unable to complete all the research plans that you had once imposed upon yourself But no matter! The truly magnificent legacy you have left will be an enduring testimony to your stature. Moreover, your spirit is still alive among us, We, who have become separated from you in New Zealand, in Tikopia and elsewhere. Be at rest, father. Rest, forever, in peace, and in the care of the Almighty. |

レイモンド・ファース卿へのマオリ語の哀歌(ポロポロアキ) ポリネシア協会を代表して、当時の会長であったサー・ヒュー・カワハル教授が作曲した(英訳)[2]。 サー・レイモンド、あなたは今私たちのもとを去った あなたの体は死の槍に貫かれた さらばだ。さらばだ、 世界中の学問の殿堂で名を馳せた学者 太平洋の航海士 玉城の「黒い鷹」よ。 おそらくあなたは、かつて自分に課していた研究計画をすべてやり遂げることができなかったのだろう。 自分に課していた研究計画をすべてやり遂げることができなかったのだろう。 しかし構わない!あなたが残した本当に素晴らしい遺産は は、あなたの偉大さの不朽の証となるだろう。 しかも、あなたの精神はまだ私たちの間で生きている、 ニュージーランドであなたと離れ離れになってしまった私たち、 ティコピアやその他の場所で。 安らかに眠れ、父よ。安らかに、永遠に、 安らかに、全能の神の御許で。 |

| Humanist Manifesto II, written

in 1973 by humanists Paul Kurtz and Edwin H. Wilson, was an update to

the previous Humanist Manifesto published in 1933, and the second entry

in the Humanist Manifesto series. It begins with a statement that the

excesses of National Socialism and world war had made the first seem

too optimistic, and indicated a more hardheaded and realistic approach

in its seventeen-point statement, which was much longer and more

elaborate than the previous version. Nevertheless, much of the optimism

of the first remained, expressing hope that war and poverty would be

eliminated. |

1973年、ヒューマニストのポール・カーツとエドウィン・H・ウィル

ソンによって書かれた「ヒューマニスト宣言II」は、1933年に発表された前作「ヒューマニスト宣言」を更新したもので、「ヒューマニスト宣言」シリー

ズの第2作目にあたる。この宣言は、国家社会主義の行き過ぎと世界大戦により、前作があまりにも楽観的であったことを指摘した上で、より冷静で現実的なア

プローチを示す17項目の声明を掲げており、前作よりもはるかに長く、より緻密な内容となっている。とはいえ、戦争や貧困がなくなることを期待して、第1

次の楽観的な内容が多く残っていた。 |

| In addition to its absolute

rejection of theism, deism and belief in credible proof of any

afterlife, various political stances are supported, such as opposition

to racism, weapons of mass destruction, support of human rights, a

proposition of an international court, and the right to unrestricted

contraception, abortion and divorce and death with dignity, ex.

euthanasia and suicide. |

唯神論、理神論、死後の世界についての信頼できる証拠を信じることを絶

対的に拒否することに加え、人種差別や大量破壊兵器への反対、人権の支持、国際裁判所の提唱、無制限の避妊・中絶・離婚の権利、安楽死や自殺などの尊厳死

など、さまざまな政治的スタンスが支持されている。 |

| Initially published with a small

number of signatures, the document was circulated and gained thousands

more, and indeed the American Humanist Association's website encourages

visitors to add their own name. A provision at the end stating that the

signators do "not necessarily endorse every detail" of the document,

but only its broad vision, no doubt helped many overcome reservations

about attaching their name. |

アメリカヒューマニスト協会のウェブサイトでは、署名者が自分の名前を

追加することを奨励しています。署名者は、この文書のすべての細部を支持するわけではなく、その大まかなビジョンのみを支持する、という条項が最後に記さ

れているため、多くの人が名前を付けることへの抵抗を克服することができたのだろう。 |

| One of the oft-quoted lines that

comes from this manifesto is, "No deity will save us; we must save

ourselves." |

このマニフェストからよく引用される言葉に「神は我々を救ってくれな

い、我々は自分自身を救わなければならない」というものがある。 |

| The Humanist Manifesto II first

appeared in The Humanist September / October, 1973, when Paul Kurtz and

Edwin H. Wilson were editor and editor emeritus, respectively. |

年譜

1901 25 March 1901, ニュージーランド・オークランド生まれ。

1921 オークランド大学カレッジ卒業

1922 修士 1923 社会科学学士

1924 LSE 入学 マリノフスキーに師事(フレイザーの研究助手を務める)

1925 'The Korekore Pa' Journal of the Polynesian Society 34:1–18 (1925)

1925 'The Māori Carver' Journal of the Polynesian Society 34:277–291

(1925)

1927 博士論文「ニュージーランド・マオリの未開経済」(Primitive Economics of New Zealand,

Maori):この論文は1929年に公刊

1927 シドニー大学(実際の教鞭は1930年から)

1928 ソロモン諸島ティコピアで調査を開始する。

1929 Primitive Economics of the New Zealand Māori London: George

Routledge and Sons (1929) (with a preface by R.H. Tawney)

1930 シドニー大学でラドクリフ=ブラウン(→RBはシカゴ大学へ)の後任として教授就任。オセアニア誌 ("Oceania")の編集。

1930-40 英領マレーケランタンとテレンガヌでフィールドワーク調査

1933 LSE講師

1935 LSEリーダー(准教授に相当)に昇進

1936 We the Tikopia: A sociological study of kinship in primitive

Polynesia. London: Allen and Unwin (1936)

1938 Human Types: An Introduction to Social Anthropology (1938)

1939 Primitive Polynesian Economy London: Routledge & Sons, Ltd

(1939)

1940 The Work of the Gods in Tikopia Melbourne: Melbourne University

Press (1940, 1967)

1943 'The Coastal People of Kelantan and Trengganu, Malaya'

Geographical Journal 101(5/6):193-205 (1943)

1943 Pacific Islands Volume 2: Eastern Pacific (ed, with J W Davidson

and Margaret Davies), Naval Intelligence Division Geographical Handbook

Series, HMSO (November 1943)

1944 マリノフスキー後任の社会人類学教授に就任(〜1968)

"He was instrumental in helping establish the Colonial Social Science

Research Council towards the end of the Second World War, and was its

first secretary." (Obituary, by The Royal Society of New Zealand)

1944 Pacific Islands Volume 3: Western Pacific (Tonga to the Solomon

Islands) (ed, with J W Davidson and Margaret Davies), Naval

Intelligence Division Geographical Handbook Series, HMSO (December 1944)

1945 Pacific Islands Volume 4: Western Pacific (New Guinea and Islands

Northwards) (ed, with J W Davidson and Margaret Davies), Naval

Intelligence Division Geographical Handbook Series, HMSO (August 1945)

1945 Pacific Islands Volume 1: General Survey (ed, with J W Davidson

and Margaret Davies), Naval Intelligence Division Geographical Handbook

Series, HMSO (August 1945)

1946 Malay Fishermen: Their Peasant Economy London: Kegan Paul, Trench,

Trubner (1946)

1951 Elements of Social Organization London: Watts and Co (1951)

1954 Social Organization and Social Change' Journal of the Royal

Anthropological Institute 84:1–20 (1954)

1955 'Some Principles of Social Organization' Journal of the Royal

Anthropological Institute 85:1–18 (1955)

1957 Man and Culture: An Evaluation of the Work of Malinowski Raymond

Firth (ed) (1957)

1959 Economics of the New Zealand Māori Wellington: Government Printer

(1959) (revised edition of Primitive Economics of the New Zealand Māori

(1929))

1959 Social Change in Tikopia (1959)

1964 Essays on Social Organization and Values London School of

Economics Monographs on Social Anthropology, no. 28. London: Athlone

Press (1964)

1967 Tikopia Ritual and Belief (1967)

1967 'Themes in Economic Anthropology: A General Comment' in Themes in

Economic Anthropology Raymond Firth, ed. 1–28. London: Tavistock (1967)

1968-69 年契約のハワイ大学太平洋人類学教授

1970 Rank and Religion in Tikopia (1970)

1971 History and Traditions of Tikopia (1971)

1975 'The Sceptical Anthropologist? Social Anthropology and Marxist

Views on Society' in Marxist Analyses and Social Anthropology M. Bloch,

ed. 29–60. London: Malaby (1975)

1975 'An Appraisal of Modern Social Anthropology' Annual Review of

Anthropology 4:1–25 (1975)

1977 'Whose Frame of Reference? One Anthropologist's Experience'

Anthropological Forum 4(2):9–31 (1977)

1984 'Roles of Women and Men in a Sea Fishing Economy: Tikopia Compared

with Kelantan' in The Fishing Culture of the World: Studies in

Ethnology, Cultural Ecology and Folklore Béla Gunda (ed) Budapest:

Akadémiai Kiadó 1145-1170 (1984)

1985 Taranga Fakatikopia ma Taranga Fakainglisi: Tikopia-English

Dictionary (1985)

1996 Religion: A Humanist Interpretation (1996)

2001 'Tikopia Dreams: Personal Images of Social Reality' Journal of the

Polynesian Society 110(1):7–29 (2001)

2001 'The Creative Contribution of Indigenous People to Their

Ethnography' Journal of the Polynesian Society 110(3):241–245 (2001)

2002 101歳の誕生日目前に死亡(22 February 2002 )

■リンク

Sir Raymond (William) Firth, Obituary, by The Royal Society of New

Zealand

LSE, Photo Library, only listed

■文献(ウィキペディア情報による)

Feinberg, Richard, and Karen Ann Watson-Gegeo (eds) (1996) Leadership

and Change in the Western Pacific: Essays Presented to Sir Raymond

Firth on Occasion of his 90th Birthday London School of Economics

Monographs on Social Anthropology. London: Athlone (third festschrift

for Raymond Firth)

Freedman, Maurice (ed) (1967) Social Organization: Essays Presented to

Raymond Firth Chicago: Aldine (first festschrift for Raymond Firth)

Macdonald, Judith (2000) 'The Tikopia and "What Raymond Said"' in

Sjoerd R. Jaarsma and Marta A. Rohatynskyj (eds), Ethnographic

Artifacts: Challenges to a Reflexive Anthropology Honolulu: University

of Hawaiʻi Press 107-123

Parkin, David (1988) 'An interview with Raymond Firth' Current

Anthropology 29(2):327-341

Watson-Gegeo, Karen Ann, and S. Lee Seaton, (eds) (1978) Adaptation and

Symbolism: Essays on Social Organization Honolulu: University of

Hawaiʻi Press (second festschift for Sir Raymond Firth)

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099