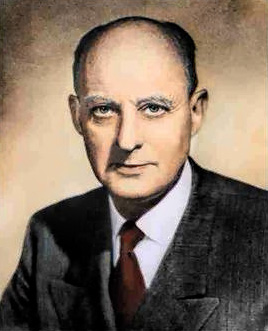

ラインホルド・ニーバー

Karl Paul Reinhold Niebuhr, 1892-1971

☆ カール・ポール・ラインホルド・ニーバー[a](1892年6月21日 - 1971年6月1日)は、アメリカ合衆国の改革派神学者、倫理学者、政治・公共問題評論家であり、ユニオン神学校で30年以上にわたって教鞭をとった。 ニーバーは20世紀の数十年間、アメリカを代表する知識人の一人であり、1964年には大統領自由勲章を受章した。公共神学者である彼は、宗教、政治、公 共政策の交差点について頻繁に執筆し、講演を行っていた。最も影響力のある著書には、『道徳的人間と不道徳な社会』、『人間の性質と運命』などがある。 1920年代に労働者階級に共感する牧師として活動を始め、多くの他の牧師たちと同様に平和主義と社会主義に献身していたが、1930年代にキリスト教リ アリズムとして知られるようになった哲学的な見解を展開する中で、彼の思想は新正統派リアリズム神学へと発展した。[27][検証必要][28] 彼は現実に対処するにはユートピアニズムは非効果的であると攻撃した。1945年以降、ニーバーの現実主義は深まり、世界中でソビエト共産主義と対峙する アメリカの取り組みを支持するに至った。優れた講演者であった彼は、1940年代から1950年代にかけて公共問題において最も影響力を持った思想家の一 人であった。[29] ニーバーは、宗教リベラル派と、彼らが人間の本性の矛盾に対するナイーブな見解と社会福音主義の楽観主義を持っていると主張して戦い、宗教保守派と、彼ら が聖書に対するナイーブな見解と「真の宗教」の狭い定義を持っていると主張して戦った。この時期、彼は多くの人々からジョン・デューイの知的なライバルと 見なされていた。 ニーバーの政治哲学への貢献には、神学の資源を活用して政治的リアリズムを主張することが含まれる。彼の研究はまた、国際関係論にも大きな影響を与え、多 くの学者が理想主義から離れ、リアリズムを受け入れるようになった。政治学者、政治史家、神学者を含む多数の学者が、彼らの思考に影響を与えたことを指摘 している。学術分野以外でも、マイルズ・ホートンやマーティン・ルーサー・キング・ジュニアなどの活動家、そして多数の政治家が、自身の思想にニーバーの 影響を受けたと述べている。[31][32][33][34] ヒラリー・クリントン、ヒューバート・ハンフリー、ディーン・アチソン、そしてバラク・オバマ大統領[35][36]やジミー・カーター元大統領[37] もその例である。ニーバーはまた、米国のキリスト教右派にも影響を与えている。1981年に設立された保守的なシンクタンクである「宗教と民主主義研究 所」は、社会や政治へのアプローチにおいて、ニーバーのキリスト教リアリズムの概念を採用している。 政治的な論評以外でも、ニーバーは「平安の祈り」を作詞したことでも知られている。この祈りは広く唱えられており、アルコール問題匿名協会によって広めら れた。また、プリンストン高等研究所でも時間を過ごし、ハーバード大学とプリンストン大学の客員教授も務めた。[41][42][43] 彼は、もう一人の著名な神学者であるH.リチャード・ニーバーの兄弟でもあった。

| Karl Paul Reinhold

Niebuhr[a] (June 21, 1892 – June 1, 1971) was an American Reformed

theologian, ethicist, commentator on politics and public affairs, and

professor at Union Theological Seminary for more than 30 years. Niebuhr

was one of America's leading public intellectuals for several decades

of the 20th century and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in

1964. A public theologian, he wrote and spoke frequently about the

intersection of religion, politics, and public policy, with his most

influential books including Moral Man and Immoral Society and The

Nature and Destiny of Man. Starting as a minister with working-class sympathies in the 1920s and sharing with many other ministers a commitment to pacifism and socialism, his thinking evolved during the 1930s to neo-orthodox realist theology as he developed the philosophical perspective known as Christian realism.[27][verification needed][28] He attacked utopianism as ineffectual for dealing with reality. Niebuhr's realism deepened after 1945 and led him to support American efforts to confront Soviet communism around the world. A powerful speaker, he was one of the most influential thinkers of the 1940s and 1950s in public affairs.[29] Niebuhr battled with religious liberals over what he called their naïve views of the contradictions of human nature and the optimism of the Social Gospel, and battled with religious conservatives over what he viewed as their naïve view of scripture and their narrow definition of "true religion". During this time he was viewed by many as the intellectual rival of John Dewey.[30] Niebuhr's contributions to political philosophy include using the resources of theology to argue for political realism. His work has also significantly influenced international relations theory, leading many scholars to move away from idealism and embrace realism.[b] A large number of scholars, including political scientists, political historians, and theologians, have noted his influence on their thinking. Aside from academics, activists such as Myles Horton and Martin Luther King Jr., and numerous politicians have also cited his influence on their thought,[31][32][33][34] including Hillary Clinton, Hubert Humphrey, and Dean Acheson, as well as presidents Barack Obama[35][36] and Jimmy Carter.[37] Niebuhr has also influenced the Christian right in the United States. The Institute on Religion and Democracy, a conservative think tank founded in 1981, has adopted Niebuhr's concept of Christian realism on their social and political approaches.[38] Aside from his political commentary, Niebuhr is also known for having composed the Serenity Prayer, a widely recited prayer which was popularized by Alcoholics Anonymous.[39][40] Niebuhr was also one of the founders of both Americans for Democratic Action and the International Rescue Committee and also spent time at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, while serving as a visiting professor at both Harvard and Princeton.[41][42][43] He was also the brother of another prominent theologian, H. Richard Niebuhr. |

カール・ポール・ラインホルド・ニーバー[a](1892年6月21日

-

1971年6月1日)は、アメリカ合衆国の改革派神学者、倫理学者、政治・公共問題評論家であり、ユニオン神学校で30年以上にわたって教鞭をとった。

ニーバーは20世紀の数十年間、アメリカを代表する知識人の一人であり、1964年には大統領自由勲章を受章した。公共神学者である彼は、宗教、政治、公

共政策の交差点について頻繁に執筆し、講演を行っていた。最も影響力のある著書には、『道徳的人間と不道徳な社会』、『人間の性質と運命』などがある。 1920年代に労働者階級に共感する牧師として活動を始め、多くの他の牧師たちと同様に平和主義と社会主義に献身していたが、1930年代にキリスト教リ アリズムとして知られるようになった哲学的な見解を展開する中で、彼の思想は新正統派リアリズム神学へと発展した。[27][検証必要][28] 彼は現実に対処するにはユートピアニズムは非効果的であると攻撃した。1945年以降、ニーバーの現実主義は深まり、世界中でソビエト共産主義と対峙する アメリカの取り組みを支持するに至った。優れた講演者であった彼は、1940年代から1950年代にかけて公共問題において最も影響力を持った思想家の一 人であった。[29] ニーバーは、宗教リベラル派と、彼らが人間の本性の矛盾に対するナイーブな見解と社会福音主義の楽観主義を持っていると主張して戦い、宗教保守派と、彼ら が聖書に対するナイーブな見解と「真の宗教」の狭い定義を持っていると主張して戦った。この時期、彼は多くの人々からジョン・デューイの知的なライバルと 見なされていた。 ニーバーの政治哲学への貢献には、神学の資源を活用して政治的リアリズムを主張することが含まれる。彼の研究はまた、国際関係論にも大きな影響を与え、多 くの学者が理想主義から離れ、リアリズムを受け入れるようになった。政治学者、政治史家、神学者を含む多数の学者が、彼らの思考に影響を与えたことを指摘 している。学術分野以外でも、マイルズ・ホートンやマーティン・ルーサー・キング・ジュニアなどの活動家、そして多数の政治家が、自身の思想にニーバーの 影響を受けたと述べている。[31][32][33][34] ヒラリー・クリントン、ヒューバート・ハンフリー、ディーン・アチソン、そしてバラク・オバマ大統領[35][36]やジミー・カーター元大統領[37] もその例である。ニーバーはまた、米国のキリスト教右派にも影響を与えている。1981年に設立された保守的なシンクタンクである「宗教と民主主義研究 所」は、社会や政治へのアプローチにおいて、ニーバーのキリスト教リアリズムの概念を採用している。 政治的な論評以外でも、ニーバーは「平安の祈り」を作詞したことでも知られている。この祈りは広く唱えられており、アルコール問題匿名協会によって広めら れた。また、プリンストン高等研究所でも時間を過ごし、ハーバード大学とプリンストン大学の客員教授も務めた。[41][42][43] 彼は、もう一人の著名な神学者であるH.リチャード・ニーバーの兄弟でもあった。 |

| Early life and education Niebuhr was born on June 21, 1892, in Wright City, Missouri, the son of German immigrants Gustav Niebuhr and his wife, Lydia (née Hosto).[44] His father was a German Evangelical pastor; his denomination was the American branch of the established Prussian Church Union in Germany. It is now part of the United Church of Christ. The family spoke German at home. His brother H. Richard Niebuhr also became a noted theological ethicist and his sister Hulda Niebuhr became a divinity professor in Chicago. The Niebuhr family moved to Lincoln, Illinois, in 1902 when Gustav Niebuhr became pastor of Lincoln's St. John's German Evangelical Synod church. Reinhold Niebuhr first served as pastor of a church when he served from April to September 1913 as interim minister of St. John's following his father's death.[45] Niebuhr attended Elmhurst College in Illinois and graduated in 1910.[c] He studied at Eden Theological Seminary in Webster Groves, Missouri, where, as he said, he was deeply influenced by Samuel D. Press in "biblical and systematic subjects",[46] and Yale Divinity School, where he earned a Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1914 and a Master of Arts degree the following year,[47] with the thesis The Contribution of Christianity to the Doctrine of Immortality.[1] He always regretted not earning a doctorate degree. He said that Yale gave him intellectual liberation from the localism of his German-American upbringing.[48] |

幼少期と教育 ニーバーは1892年6月21日、ミズーリ州ライトシティで、ドイツからの移民であるグスタフ・ニーバーと妻リディア(旧姓ホスト)の間に生まれた。 [44] 父親はドイツ福音派の牧師であり、所属していた教派はドイツのプロイセン教会連合のアメリカ支部であった。現在はキリスト合同教会の一部となっている。家 族は家ではドイツ語を話していた。弟のH.リチャード・ニーバーも著名な神学倫理学者となり、姉のフーダ・ニーバーはシカゴで神学教授となった。グスタ フ・ニーバーがリンカーンにあるセント・ジョン・ドイツ福音主義シナド教会の牧師に就任したため、ニーバー家は1902年にイリノイ州リンカーンに移住し た。ラインホルド・ニーバーが初めて教会の牧師を務めたのは、父の死後、1913年4月から9月まで、セント・ジョンの臨時牧師として奉仕したときであっ た。 ニーバーはイリノイ州のエルムハースト大学に通い、1910年に卒業した。[c] ミズーリ州ウェブスターグローブスのエデン神学校で学び、そこでサミュエル・D・プレスから「聖書と体系的な科目」について深い影響を受けた、と後に語っ ている。[46] また、イェール神学校では、1914年に神学士号、翌年には文学修士号を取得した。修士論文のテーマは「不滅の教義に対するキリスト教の貢献」であった。 [1] 彼は常に博士号を取得しなかったことを後悔していた。彼は、イェール大学で、ドイツ系アメリカ人として育った地域主義から知的解放を得たと語っている。 [48] |

| Marriage and family In 1931 Niebuhr married Ursula Keppel-Compton. She was a member of the Church of England and was educated at the University of Oxford in theology and history. She met Niebuhr while studying for her master's degree at Union Theological Seminary. For many years, she was on faculty at Barnard College – the women's college of Columbia University – where she helped establish and then chaired the religious studies department. The Niebuhrs had two children, Elisabeth Niebuhr Sifton, a high-level executive at several major publishing houses who wrote a memoir on her father,[49] and Christopher Niebuhr. Ursula Niebuhr left evidence in her professional papers at the Library of Congress showing that she co-authored some of her husband's later writings.[50] |

結婚と家族 1931年、ニーバーはウルスラ・ケッペル・コンプトンと結婚した。彼女は英国国教会の信者であり、オックスフォード大学で神学と歴史学を学んだ。彼女は ユニオン神学校で修士号取得を目指して学んでいるときにニーバーと出会った。彼女は長年、コロンビア大学の女子大学であるバーナード・カレッジの教員とし て、宗教学部の設立に尽力し、その後学部長を務めた。ニーバー夫妻には、エリザベス・ニーバー・シフトン(Elisabeth Niebuhr Sifton)とクリストファー・ニーバー(Christopher Niebuhr)の2人の子供がいた。エリザベスは複数の大手出版社で上級幹部を務め、父親について回顧録を執筆した。[49] また、ウルスラ・ニーバーは、米国議会図書館に保管されている彼女の専門文書の中に、夫の晩年の著作の一部を共著したことを示す証拠を残している。 [50] |

| Detroit In 1915, Niebuhr was ordained a pastor. The German Evangelical mission board sent him to serve at Bethel Evangelical Church in Detroit, Michigan. The congregation numbered 66 on his arrival and grew to nearly 700 by the time he left in 1928. The increase reflected his ability to reach people outside the German-American community and among the growing population attracted to jobs in the booming automobile industry. In the early 1900s Detroit became the fourth-largest city in the country, attracting many black and white migrants from the rural South, as well as Jewish and Catholic people from eastern and southern Europe. White supremacists determined to dominate, suppress, and victimize Black, Jewish, and Catholic Americans, as well as other Americans who did not have western European ancestry, joined the Ku Klux Klan and the Black Legion in growing numbers. By 1923, membership in the KKK in Detroit topped 20,000.[51] In 1925, as part of the Ku Klux Klan's strategy to accumulate government power, the membership organization selected and publicly supported several candidates for public office, including for the office of the mayor. Niebuhr spoke out publicly against the Klan to his congregation,[52] describing them as "one of the worst specific social phenomena which the religious pride of a people has ever developed". Though only one of the several candidates publicly backed by the Klan gained a seat on the city council that year,[52] the Klan continued to influence daily life in Detroit. The KKK's failed 1925 mayoral candidate, Charles Bowles, still became a judge on the recorder's court; later, in 1930, he was elected the city's mayor.[53] |

デトロイト 1915年、ニーブールは牧師に任命された。ドイツ福音宣教委員会は彼をミシガン州デトロイトのベテル福音教会に派遣した。彼の着任時の教会員数は66名 であったが、1928年に彼が去るまでに700名近くにまで増加した。この増加は、ドイツ系アメリカ人コミュニティの外の人々や、活況を呈する自動車産業 に惹きつけられて流入する人口の増加に、彼が働きかけたことを反映している。1900年代初頭、デトロイトは国内で4番目に大きな都市となり、南部の農村 部から多くの黒人と白人が移住し、また東欧や南欧からもユダヤ教徒やカトリック教徒が移住してきた。 白人至上主義者たちは、黒人、ユダヤ教徒、カトリック教徒のアメリカ人、および西ヨーロッパに祖先を持たないその他のアメリカ人を支配し、抑圧し、犠牲者 にしようと決意し、クークラックスクランやブラックレギオンに加入する者が増えていった。1923年までに、デトロイトのKKKの会員数は2万人を上回っ た。[51] 1925年、政府権力を掌握するというクークラックスクランの戦略の一環として、会員組織は市長職を含むいくつかの公職の候補者を選び、公に支援した。 ニーブールは、教会員に対して公然とクランに反対の意見を述べ、彼らを「人々の宗教的誇りが生み出した最悪の社会現象の一つ」と表現した。その年、KKK が公然と支援した数人の候補者のうちの1人だけが市議会の議席を獲得したが、[52] それでもKKKはデトロイトの日常生活に影響を与え続けた。1925年の市長選で落選したKKKのチャールズ・ボウルズは、それでも記録裁判所の判事とな り、その後1930年に市長に選出された。[53] |

| First World War When America entered the First World War in 1917, Niebuhr was the unknown pastor of a small German-speaking congregation in Detroit (it stopped using German in 1919). All adherents of German-American culture in the United States and nearby Canada came under attack for suspicion of having dual loyalties. Niebuhr repeatedly stressed the need to be loyal to America, and won an audience in national magazines for his appeals to the German Americans to be patriotic.[54] Theologically, he went beyond the issue of national loyalty as he endeavored to fashion a realistic ethical perspective of patriotism and pacifism. He endeavored to work out a realistic approach to the moral danger posed by aggressive powers, which many idealists and pacifists failed to recognize. During the war, he also served his denomination as Executive Secretary of the War Welfare Commission, while maintaining his pastorate in Detroit. A pacifist at heart, he saw compromise as a necessity and was willing to support war in order to find peace—compromising for the sake of righteousness.[55] |

第一次世界大戦 1917年にアメリカが第一次世界大戦に参戦した際、ニーバーはデトロイトの小さなドイツ語話者コミュニティ(1919年にドイツ語の使用を中止)の無名 の牧師であった。 アメリカおよび近隣のカナダにおけるドイツ系アメリカ文化の信奉者たちは、二重の忠誠心を持っているという疑いをかけられ、攻撃の対象となった。ニーバー はアメリカへの忠誠の必要性を繰り返し強調し、ドイツ系アメリカ人に対して愛国心を訴えることで、全国誌で注目を集めた。[54] ニーバーは神学的に、愛国心と平和主義の現実的な倫理的観点を作り出す努力をすることで、国民の忠誠心という問題を超越した。彼は、多くの理想主義者や平 和主義者が認識できなかった、攻撃的な大国がもたらす道徳的危険に対する現実的なアプローチを考案しようと努力した。戦争中、彼はデトロイトの牧師職を維 持しながら、戦争福祉委員会の事務局長として所属宗派にも貢献した。根っからの平和主義者であった彼は、妥協は必要不可欠であると考え、平和を見出すため に戦争を支持する意思があった。正義のために妥協するのだ。[55] |

| Origins of Niebuhr's working-class sympathy Several attempts have been made to explicate the origins of Niebuhr's sympathies from the 1920s to working-class and labor issues as documented by his biographer Richard W. Fox.[56] One supportive example has concerned his interest in the plight of auto workers in Detroit. This one interest among others can be briefly summarized below. After seminary, Niebuhr preached the Social Gospel, and then initiated the engagement of what he considered the insecurity of Ford workers.[57] Niebuhr had moved to the left and was troubled by the demoralizing effects of industrialism on workers. He became an outspoken critic of Henry Ford and allowed union organizers to use his pulpit to expound their message of workers' rights. Niebuhr attacked poor conditions created by the assembly lines and erratic employment practices.[58] Because of his opinion about factory work, Niebuhr rejected liberal optimism. He wrote in his diary: We went through one of the big automobile factories to-day. ... The foundry interested me particularly. The heat was terrific. The men seemed weary. Here manual labour is a drudgery and toil is slavery. The men cannot possibly find any satisfaction in their work. They simply work to make a living. Their sweat and their dull pain are part of the price paid for the fine cars we all run. And most of us run the cars without knowing what price is being paid for them. ... We are all responsible. We all want the things which the factory produces and none of us is sensitive enough to care how much in human values the efficiency of the modern factory costs.[59] The historian Ronald H. Stone thinks that Niebuhr never talked to the assembly line workers (many of his parishioners were skilled craftsmen) but projected feelings onto them after discussions with Samuel Marquis.[60] Niebuhr's criticism of Ford and capitalism resonated with progressives and helped make him nationally prominent.[58] His serious commitment to Marxism developed after he moved to New York in 1928.[61] In 1923, Niebuhr visited Europe to meet with intellectuals and theologians. The conditions he saw in Germany under the French occupation of the Rhineland dismayed him. They reinforced the pacifist views that he had adopted throughout the 1920s after the First World War. |

ニーバーの労働者階級への共感の起源 1920年代から、ニーバーの共感が労働者階級や労働問題へと向かうようになったことの起源を明らかにしようとする試みがいくつか行われている。これは、 彼の伝記作家リチャード・W・フォックスが記録したものである。[56] その一例として、デトロイトの自動車労働者の窮状に対する彼の関心が挙げられる。この関心について簡単にまとめると以下のようになる。 神学校卒業後、ニーバーは社会福音を説き、その後、フォード社の労働者の不安定さを問題視し、彼らの権利擁護運動を始めた。[57] ニーバーは左派に傾倒し、産業主義が労働者に与える士気阻喪効果に悩まされていた。彼はヘンリー・フォードの公然たる批判者となり、労働組合の組織者たち に説教壇で労働者の権利を説くことを許可した。ニーバーは、組み立てラインや不安定な雇用慣行によって生み出された劣悪な労働環境を攻撃した。[58] 工場労働に関する自身の意見から、ニーバーはリベラルな楽観論を否定した。彼は日記にこう記している。 今日、私たちは大きな自動車工場のひとつを見学した。... 特に鋳造工場に興味をそそられた。熱気が凄まじかった。労働者たちは疲れ切っているように見えた。ここでは肉体労働は苦役であり、労働は奴隷制である。労 働者たちは仕事に満足感を見出すことはできないだろう。彼らはただ生活費を稼ぐために働いている。彼らの汗と鈍い痛みは、我々全員が運転する素晴らしい車 のために支払われる代償の一部である。そして、我々のほとんどは、その車が支払っている代償を知ることなく運転している。我々は皆、責任がある。我々は 皆、工場で生産されるものを欲しがるが、現代の工場の効率がどれほど人間の価値を犠牲にしているかについて、敏感な人は誰もいない。[59] 歴史家のロナルド・H・ストーンは、ニーバーは(教区民の多くが熟練した職人であった)流れ作業の労働者たちと話したことはなく、サミュエル・マーカスと の議論の後、彼らに感情を投影したと考えている。[60] ニーバーのフォードと資本主義に対する批判は進歩派に共鳴し、彼を国民的に著名な人物にした。[58] 彼のマルクス主義に対する真剣な取り組みは、1928年にニューヨークに移住した後、発展した。[61] 1923年、ニーバーはヨーロッパを訪れ、知識人や神学者たちと会った。フランス占領下のドイツで目にした状況に彼は落胆した。それは、第一次世界大戦後の1920年代を通じて彼が抱いていた平和主義的な見解を強めるものだった。 |

| Conversion of Jews Niebuhr preached about the need to persuade Jews to convert to Christianity. He believed there were two reasons Jews did not convert: the "un-Christlike attitude of Christians" and "Jewish bigotry." However, he later rejected the idea of a mission to Jews. According to his biographer, the historian Richard Wightman Fox, Niebuhr understood that "Christians needed the leaven of pure Hebraism to counteract the Hellenism to which they were prone".[62] |

ユダヤ人の改宗 ニーバーは、ユダヤ人にキリスト教への改宗を説得する必要性について説いた。彼は、ユダヤ人が改宗しない理由として、「キリスト教徒のキリストらしくない 態度」と「ユダヤ人の偏狭さ」の2つを挙げた。しかし、後に彼はユダヤ人への布教という考えを否定した。伝記作家である歴史家のリチャード・ワイトマン・ フォックスによると、ニーバーは「キリスト教徒は、彼らが陥りがちなヘレニズムに対抗するために、純粋なヘブライズムのイースト菌を必要としている」こと を理解していたという。[62] |

| 1930s: Growing influence in New York Niebuhr captured his personal experiences in Detroit in his book Leaves from the Notebook of a Tamed Cynic. He continued to write and publish throughout his career, and also served as editor of the magazine Christianity and Crisis from 1941 through 1966. In 1928, Niebuhr left Detroit to become Professor of Practical Theology at Union Theological Seminary in New York. He spent the rest of his career there, until retirement in 1960. While teaching theology at Union Theological Seminary, Niebuhr influenced many generations of students and thinkers, including the German minister Dietrich Bonhoeffer of the anti-Nazi Confessing Church. The Fellowship of Socialist Christians was organized in the early 1930s by Niebuhr and others with similar views. Later it changed its name to Frontier Fellowship and then to Christian Action. The main supporters of the fellowship in the early days included Eduard Heimann, Sherwood Eddy, Paul Tillich, and Rose Terlin. In its early days the group thought capitalist individualism was incompatible with Christian ethics. Although not Communist, the group acknowledged Karl Marx's social philosophy.[63] Niebuhr was among the group of 51 prominent Americans who formed the International Relief Association (IRA) that is today known as the International Rescue Committee (IRC).[d] The committee mission was to assist Germans suffering from the policies of the Hitler regime.[64] Niebuhr and Dewey In the 1930s Niebuhr was often seen as an intellectual opponent of John Dewey. Both men were professional polemicists and their ideas often clashed, although they contributed to the same realms of liberal intellectual schools of thought. Niebuhr was a strong proponent of the "Jerusalem" religious tradition as a corrective to the secular "Athens" tradition insisted upon by Dewey.[65] In the book Moral Man and Immoral Society (1932), Niebuhr strongly criticized Dewey's philosophy, although his own ideas were still intellectually rudimentary.[66] Two years later, in a review of Dewey's book A Common Faith (1934), Niebuhr was calm and respectful towards Dewey's "religious footnote" on his then large body of educational and pragmatic philosophy.[66] |

1930年代:ニューヨークでの影響力拡大 ニーバーは、デトロイトでの個人的な経験を著書『Leaves from the Notebook of a Tamed Cynic』にまとめた。その後も執筆と出版活動を続け、1941年から1966年までは雑誌『Christianity and Crisis』の編集者も務めた。 1928年、ニーバーはデトロイトを離れ、ニューヨークのユニオン神学校で実践神学の教授となった。1960年に退職するまで、残りのキャリアをそこで過 ごした。ユニオン神学校で神学を教える間、ニーバーは、反ナチスを掲げた告白教会のドイツ人牧師ディートリッヒ・ボンヘッファーをはじめ、多くの世代の学 生や思想家に影響を与えた。 社会主義キリスト教徒の会は、ニーバーや同じような考えを持つ人々によって1930年代初頭に結成された。その後、名称をフロンティア・フェローシップ、 さらにキリスト教行動へと変更した。初期の主な支援者には、エドゥアルド・ハイマン、シャーウッド・エディ、ポール・ティリッヒ、ローズ・テルリンなどが いた。初期の頃、このグループは資本主義的個人主義はキリスト教倫理と相容れないと考えていた。共産主義者ではなかったが、このグループはカール・マルク スの社会哲学を認めていた。[63] ニーバーは、今日では国際救済委員会(IRC)として知られる国際救済協会(IRA)を結成した51人の著名なアメリカ人のうちの1人であった。[d] この委員会の使命は、ヒトラー政権の政策によって苦しむドイツ人を支援することであった。[64] ニーバーとデューイ 1930年代、ニーバーはジョン・デューイの知的反対者として見られることが多かった。両者とも論争のプロであり、その考えはしばしば衝突したが、リベラ ルな知的学派という同じ領域に貢献していた。ニーバーは、デューイが主張する世俗的な「アテネ」の伝統を是正するものとして、「エルサレム」の宗教的伝統 を強く支持していた。[65] 著書『道徳的人間と不道徳な社会』(1932年)の中で、ニーバーはデューイの哲学を強く批判したが、自身の 自身の考えはまだ知的には初歩的なものであったが、[66] 2年後、ニーバーはデューイの著書『共通の信仰』(1934年)の書評で、当時すでに膨大なものとなっていたデューイの教育および実用哲学に関する「宗教 的脚注」に対して冷静かつ敬意を払った姿勢を示した。[66] |

| Neo-orthodox theology In 1939 Niebuhr explained his theological odyssey: ... about midway in my ministry which extends roughly from the peace of Versailles to the peace of Munich measured in terms of Western history, I underwent a fairly complete conversion of thought which involved rejection of almost all the liberal theological ideals and ideas with which I ventured forth in 1915. I wrote a book Does Civilization Need Religion? my first, in 1927 which when now consulted is proved to contain almost all the theological windmills against which today I tilt my sword. These windmills must have tumbled shortly thereafter for every succeeding volume expresses a more and more explicit revolt against what is usually known as liberal culture.[67] — Reinhold Niebuhr, Ten Years that Shook My World, The Christian Century, Vol. 56, issue 17, page 542 In the 1930s Niebuhr worked out many of his ideas about sin and grace, love and justice, faith and reason, realism and idealism, and the irony and tragedy of history, which established his leadership of the neo-orthodox movement in theology. Influenced strongly by Karl Barth and other dialectical theologians of Europe, he began to emphasize the Bible as a human record of divine self-revelation; it offered for Niebuhr a critical but redemptive reorientation of the understanding of humanity's nature and destiny.[68] Niebuhr couched his ideas in Christ-centered principles such as the Great Commandment and the doctrine of original sin. His major contribution was his view of sin as a social event—as pride—with selfish self-centeredness as the root of evil. The sin of pride was apparent not just in criminals, but more dangerously in people who felt good about their deeds—rather like Henry Ford (whom he did not mention by name). The human tendency to corrupt the good was the great insight he saw manifested in governments, business, democracies, utopian societies, and churches. This position is laid out profoundly in one of his most influential books, Moral Man and Immoral Society (1932). He was a debunker of hypocrisy and pretense and made the avoidance of self-righteous illusions the center of his thoughts.[69] Niebuhr argued that to approach religion as the individualistic attempt to fulfill biblical commandments in a moralistic sense is not only an impossibility but also a demonstration of man's original sin, which Niebuhr interpreted as self-love. Through self-love man becomes focused on his own goodness and leaps to the false conclusion—one he called the "Promethean illusion"—that he can achieve goodness on his own. Thus man mistakes his partial ability to transcend himself for the ability to prove his absolute authority over his own life and world. Constantly frustrated by natural limitations, man develops a lust for power which destroys him and his whole world. History is the record of these crises and judgments which man brings on himself; it is also proof that God does not allow man to overstep his possibilities. In radical contrast to the Promethean illusion, God reveals himself in history, especially personified in Jesus Christ, as sacrificial love which overcomes the human temptation to self-deification and makes possible constructive human history.[69] |

新正統主義神学 1939年、ニーバーは自身の神学上の遍歴について次のように説明している。... 西洋の歴史で測れば、ヴェルサイユの平和からミュンヘンの平和までの期間にほぼ相当する私の牧師としての任務の中間点において、私は1915 年に思い切って踏み出したリベラルな神学的理想や考えのほぼすべてを拒絶する、かなり完全な思想の転換を経験した。私は1927年に『文明は宗教を必要と するか?』という本を書いた。今になってこの本を読み返してみると、この本には私が今日剣を向ける神学上の風車がほぼすべて含まれていることが分かる。そ の後、次々と出版された著書では、通常リベラル文化として知られているものに対する反発がますます明確に表現されている。 — ラインホルド・ニーバー著『私の世界を揺るがした10年』『クリスチャン・センチュリー』第56巻第17号、542ページ 1930年代、ニーバーは罪と恩寵、愛と正義、信仰と理性、現実主義と観念論、そして歴史の皮肉と悲劇について多くの考えをまとめ、神学における新正統主 義運動のリーダーとしての地位を確立した。カール・バルトやヨーロッパの弁証法的神学者たちから強い影響を受けたニールバーグは、聖書を神の自己啓示を記 録した人間の記録として強調し始めた。聖書は、人間の本性と運命に対する理解を批判的に、しかし救済的に再方向づけるものだった。 ニーバーは、大戒めや原罪の教義といったキリスト中心の原則に自らの考えを包み隠した。彼の最大の功績は、罪を社会的出来事、つまり「高慢」として捉え、 利己的な自己中心性が悪の根源であるという見解であった。高慢の罪は犯罪者だけに顕著なものではなく、むしろ自分の行いを良いものだと感じている人々、つ まりヘンリー・フォード(彼は名前こそ挙げていないが)のような人々により危険である。人間が善良さを堕落させる傾向は、政府、企業、民主主義、ユートピ ア社会、教会に顕著に見られると、彼は洞察した。この立場は、彼の最も影響力のある著書の一つ『道徳的人間と不道徳な社会』(1932年)に深く示されて いる。彼は偽善と見せかけを暴き、独善的な幻想を回避することを自身の思考の中心に据えた。 ニーバーは、聖書の戒律を道徳的な意味で満たそうとする個人主義的な試みとして宗教にアプローチすることは、不可能であるばかりでなく、人間の原罪の表れ であると主張した。ニーバーはこれを自己愛と解釈した。自己愛によって、人間は自身の善良さに集中し、自分自身で善良さを達成できるという誤った結論に飛 びつく。これをニーバーは「プロメテウスの幻想」と呼んだ。このように、人間は、自分自身を超越する能力を、自分の人生や世界に対する絶対的な権威を証明 する能力と誤解する。常に自然の限界に苛立ち、人間は自分自身と自分の世界を破壊する権力への欲望を抱くようになる。歴史とは、人間が自ら招いたこうした 危機と裁きの記録である。また、神が人間にその可能性を踏み外させることを許さないという証拠でもある。プロメテウスの幻想とは根本的に対照的に、神は歴 史の中で、特にイエス・キリストにおいて、自己神化という人間の誘惑を克服する犠牲的な愛として自らを明らかにし、建設的な人類の歴史を可能にする。 [69] |

| Politics Domestic During the 1930s, Niebuhr was a prominent leader of the militant faction of the Socialist Party of America, although he disliked die-hard Marxists. He described their beliefs as a religion and a thin one at that.[70] In 1941, he co-founded the Union for Democratic Action, a group with a strongly militarily interventionist, internationalist foreign policy and a pro-union, liberal domestic policy. He was the group's president until it transformed into the Americans for Democratic Action in 1947.[71] International Within the framework of Christian realism, Niebuhr became a supporter of American action in the Second World War, anti-communism, and the development of nuclear weapons. However, he opposed the Vietnam War.[72][73] At the outbreak of World War II, the pacifist component of his liberalism was challenged. Niebuhr began to distance himself from the pacifism of his more liberal colleagues and became a staunch advocate for the war. Niebuhr soon left the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a peace-oriented group of theologians and ministers, and became one of their harshest critics. This departure from his peers evolved into a movement known as Christian realism. Niebuhr is widely considered to have been its primary advocate.[74] Niebuhr supported the Allies during the Second World War and argued for the engagement of the United States in the war. As a writer popular in both the secular and the religious arena and a professor at the Union Theological Seminary, he was very influential both in the United States and abroad. While many clergy proclaimed themselves pacifists because of their World War I experiences, Niebuhr declared that a victory by Germany and Japan would threaten Christianity. He renounced his socialist connections and beliefs and resigned from the pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation. He based his arguments on the Protestant beliefs that sin is part of the world, that justice must take precedence over love, and that pacifism is a symbolic portrayal of absolute love but cannot prevent sin. Although his opponents did not portray him favorably, Niebuhr's exchanges with them on the issue helped him mature intellectually.[75] Niebuhr debated Charles Clayton Morrison, editor of The Christian Century magazine, about America's entry into World War II. Morrison and his pacifistic followers maintained that America's role should be strictly neutral and part of a negotiated peace only, while Niebuhr claimed himself to be a realist, who opposed the use of political power to attain moral ends. Morrison and his followers strongly supported the movement to outlaw war that began after World War I and the Kellogg–Briand Pact of 1928. The pact was severely challenged by the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931. With his publication of Moral Man and Immoral Society (1932), Niebuhr broke ranks with The Christian Century and supported interventionism and power politics. He supported the reelection of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1940 and published his own magazine, Christianity and Crisis.[76] In 1945, however, Niebuhr charged that use of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima was "morally indefensible". Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.[29] explained Niebuhr's influence: Traditionally, the idea of the frailty of man led to the demand for obedience to ordained authority. But Niebuhr rejected that ancient conservative argument. Ordained authority, he showed, is all the more subject to the temptations of self-interest, self-deception and self-righteousness. Power must be balanced by power. He persuaded me and many of my contemporaries that original sin provides a far stronger foundation for freedom and self-government than illusions about human perfectibility. Niebuhr's analysis was grounded in the Christianity of Augustine and Calvin, but he had, nonetheless, a special affinity with secular circles. His warnings against utopianism, messianism and perfectionism strike a chord today. ... We cannot play the role of God to history, and we must strive as best we can to attain decency, clarity and proximate justice in an ambiguous world.[29] Niebuhr's defense of Roosevelt made him popular among liberals, as the historian Morton White noted: The contemporary liberal's fascination with Niebuhr, I suggest, comes less from Niebuhr's dark theory of human nature and more from his actual political pronouncements, from the fact that he is a shrewd, courageous, and right-minded man on many political questions. Those who applaud his politics are too liable to turn then to his theory of human nature and praise it as the philosophical instrument of Niebuhr's political agreement with themselves. But very few of those whom I have called "atheists for Niebuhr" follow this inverted logic to its conclusion: they don't move from praise of Niebuhr's theory of human nature to praise of its theological ground. We may admire them for drawing the line somewhere, but certainly not for their consistency.[77] After Joseph Stalin signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Adolf Hitler in August 1939, Niebuhr severed his past ties with any fellow-traveler organization having any known Communist leanings. In 1947, Niebuhr helped found the liberal Americans for Democratic Action. His ideas influenced George Kennan, Hans Morgenthau, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., and other realists during the Cold War on the need to contain Communist expansion. In his last cover story for Time magazine (March 1948), Whittaker Chambers said of Niebuhr: Most U.S. liberals think of Niebuhr as a solid socialist who has some obscure connection with Union Theological Seminary that does not interfere with his political work. Unlike most clergymen in politics, Dr. Niebuhr is a pragmatist. Says James Loeb, secretary of Americans for Democratic Action: "Most so-called liberals are idealists. They let their hearts run away with their heads. Niebuhr never does. For example, he has always been the leading liberal opponent of pacifism. In that period before we got into the war when pacifism was popular, he held out against it steadfastly. He is also an opponent of Marxism.[78] In the 1950s, Niebuhr described Senator Joseph McCarthy as a force of evil, not so much for attacking civil liberties, as for being ineffective in rooting out Communists and their sympathizers.[79] In 1953, he supported the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, saying, "Traitors are never ordinary criminals and the Rosenbergs are quite obviously fiercely loyal Communists ... Stealing atomic secrets is an unprecedented crime."[79] |

政治 国内 1930年代、ニーバーはアメリカ社会党の好戦派の有力な指導者であったが、筋金入りのマルクス主義者たちを嫌っていた。彼は彼らの信念を宗教であり、し かも薄っぺらな宗教であると評した。[70] 1941年、彼は軍事介入主義、国際主義の外交政策と労働組合支持、自由主義の国内政策を掲げるグループ、民主行動連合を共同設立した。同グループが 1947年に民主行動アメリカ人に改組するまで、彼はその会長を務めた。[71] 国際 キリスト教リアリズムの枠組みの中で、ニーバーは第二次世界大戦におけるアメリカの行動、反共産主義、核兵器開発の支持者となった。しかし、彼はベトナム戦争には反対した。 第二次世界大戦の勃発により、彼の自由主義の平和主義的要素は試練に立たされた。 ニーバーは、よりリベラルな同僚たちの平和主義から距離を置き、戦争の強硬な擁護者となった。 ニーバーは、神学者や牧師たちによる平和志向のグループである「和解のフェローシップ」を間もなく脱退し、その最も手厳しい批判者の一人となった。 この仲間からの離脱は、後にキリスト教リアリズムとして知られる運動へと発展した。ニーバーは、その運動の主要な提唱者であったと考えられている。 [74] 第二次世界大戦中、ニーバーは連合国を支持し、米国の参戦を主張した。 世俗界と宗教界の両方で人気のある作家であり、ユニオン神学校の教授でもあったため、彼は米国および海外で大きな影響力を持っていた。第一次世界大戦の経 験から自らを平和主義者と宣言する聖職者が多くいた中、ニーバーはドイツと日本の勝利はキリスト教を脅かすと主張した。彼は社会主義とのつながりと信念を 捨て、平和主義団体「和解のフェローシップ」を辞めた。彼は、罪は世の中に存在するものであり、正義は愛よりも優先されるべきであり、平和主義は絶対的な 愛の象徴的な表現ではあるが、罪を防ぐことはできないというプロテスタントの信念に基づいて主張した。彼の反対派は彼を好意的に見ていなかったが、この問 題に関する彼らとのやりとりは、ニーバーの知的な成長に役立った。 ニユーブールは、雑誌『クリスチャン・センチュリー』の編集者チャールズ・クレイトン・モリソンと、第二次世界大戦におけるアメリカの参戦について討論し た。モリソンと彼の平和主義者たちは、アメリカの役割は厳格な中立を維持し、交渉による平和の一部となるべきだと主張したが、ニユーブールは、政治的権力 を道徳的目的の達成に利用することに反対する現実主義者であると主張した。モリソンと彼の信奉者は、第一次世界大戦後に始まった戦争を違法とする運動を強 く支持し、1928年のケロッグ・ブリアン条約を支持した。この条約は、1931年の日本の満州侵攻によって厳しく問われることとなった。ニーバーは著書 『道徳的人間と不道徳な社会』(1932年)を出版し、『クリスチャン・センチュリー』誌と袂を分かち、介入主義と権力政治を支持した。1940年にはフ ランクリン・D・ルーズベルト大統領の再選を支持し、自身の雑誌『キリスト教と危機』を発行した。[76] しかし、1945年には広島への原爆投下を「道徳的に正当化できない」と非難した。 アーサー・M・シュレジンジャー・ジュニアは、ニーバーの影響力について次のように説明している。 伝統的に、人間の弱さという考えは、定められた権威への服従を求めることにつながってきた。しかし、ニーバーは、その古くからの保守的な主張を否定した。 定められた権威は、利己主義、自己欺瞞、独善の誘惑にさらされる可能性がより高いことを、彼は示した。権力は権力によって均衡が保たれなければならない。 彼は私や同時代の多くの人々を説得し、原罪は人間の完全性に関する幻想よりも、はるかに強固な自由と自治の基盤を提供すると主張した。 ニーバーの分析はアウグスティヌスやカルヴァンのキリスト教に根ざしたものだったが、それにもかかわらず、彼は世俗的な分野と特別な親和性を持っていた。 彼のユートピア主義、救世主主義、完全主義に対する警告は、今日でも共感を呼ぶ。... 私たちは歴史に対して神の役割を演じることはできない。そして、曖昧な世界において、良識、明晰さ、そして目先の正義を達成するために全力を尽くさなけれ ばならない。[29] ニーバーのルーズベルト擁護論は、リベラル派の間で彼を人気者にした。歴史家のモートン・ホワイトは次のように指摘している。 現代のリベラル派がニーバーに魅了されるのは、彼の人間性に関する暗い理論というよりも、むしろ彼の実際の政治的声明、つまり、彼が多くの政治的問題につ いて賢明で勇敢な、正しい考えを持つ人物であるという事実から来ていると私は考える。彼の政治を賞賛する人々は、その後、人間性に関する彼の理論に目を向 け、それをニーバーの政治的合意を自分自身と哲学的に結びつける道具として賞賛する傾向が強い。しかし、私が「ニーバーのための無神論者」と呼ぶ人々のう ち、この逆転した論理を結論まで辿る者はほとんどいない。彼らはニーバーの人間性理論を賞賛する立場から、その神学的根拠を賞賛する立場には移行しないの だ。私たちは彼らがどこかで線を引いていることを賞賛するかもしれないが、その一貫性については決して賞賛しないだろう。[77] 1939年8月にヨシフ・スターリンがアドルフ・ヒトラーとモロトフ・リッベントロップ協定に署名した後、ニーバーは共産主義傾向が知られているあらゆる 同調者組織との過去のつながりを断った。1947年、ニーバーはリベラル派のアメリカ民主行動の創設に助力した。彼の思想は、冷戦時代に共産主義の拡大封 じ込めの必要性を訴えたジョージ・ケナン、ハンス・モーゲンソー、アーサー・M・シュレジンジャー・ジュニア、その他のリアリストたちに影響を与えた。 タイム誌の最後の表紙記事(1948年3月)で、ウィテカー・チェンバースはニーバーについて次のように述べている。 米国のリベラル派の多くは、ニーバーを、ユニオン神学校とのあいまいなつながりがあるものの、政治活動には影響しない堅実な社会主義者だと考えている。政 治に関わる聖職者の多くとは異なり、ニーバー博士はプラグマティストである。民主行動アメリカ人連盟のジェームズ・ローブ事務局長は次のように述べてい る。「いわゆるリベラル派の多くは理想主義者である。彼らは頭で考えるよりも感情に流されやすい。ニーバーは決してそうではない。例えば、彼は常にリベラ ル派の平和主義の反対派の第一人者であった。戦争に突入する前の平和主義が流行していた時代、彼は断固としてそれに反対した。彼はマルクス主義の反対派で もある。[78] 1950年代、ニーバーは上院議員のジョセフ・マッカーシーを悪の権化と評し、その理由は市民的自由を攻撃したからというよりも、共産主義者とそのシンパ を根絶することができなかったからだと述べた。[79] 1953年、彼はジュリアス・ローゼンバーグとエセル・ローゼンバーグの処刑を支持し、「裏切り者は決して普通の犯罪者ではなく、ローゼンバーグ夫妻は明 らかに猛烈な共産主義者である。原子力の機密を盗むことは前代未聞の犯罪である」と述べた。[79] |

| Views on race, ethnicity, and other religious affiliations His views developed during his pastoral tenure in Detroit, which had become a place of immigration, migration, competition and development as a major industrial city. During the 1920s, Niebuhr spoke out against the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in Detroit, which had recruited many members threatened by the rapid social changes. The Klan proposed positions that were anti-black, anti-Jewish and anti-Catholic. Niebuhr's preaching against the Klan, especially in relation to the 1925 mayoral election, gained him national attention.[80] Niebuhr's thoughts on racial justice developed slowly after he abandoned socialism. Niebuhr attributed the injustices of society to human pride and self-love and believed that this innate propensity for evil could not be controlled by humanity. But, he believed that a representative democracy could improve society's ills. Like Edmund Burke, Niebuhr endorsed natural evolution over imposed change and emphasized experience over theory. Niebuhr's Burkean ideology, however, often conflicted with his liberal principles, particularly regarding his perspective on racial justice. Though vehemently opposed to racial inequality, Niebuhr adopted a conservative position on segregation.[81] While after World War II most liberals endorsed integration, Niebuhr focused on achieving equal opportunity. He warned against imposing changes that could result in violence. The violence that followed peaceful demonstrations in the 1960s forced Niebuhr to reverse his position against imposed equality; witnessing the problems of the Northern ghettos later caused him to doubt that equality was attainable.[81] |

人種、民族、その他の宗教的所属に関する見解 彼の考えは、主要な工業都市として発展し、移民や移住、競争の場となったデトロイトで牧師を務めていた間に形成された。1920年代、ニーバーは急速な社 会変化に脅威を感じていた多くのメンバーを勧誘したデトロイトのクー・クラックス・クランの台頭に反対する意見を述べた。クランは反黒人、反ユダヤ、反カ トリックの立場を表明していた。特に1925年の市長選挙に関連して、クランに対するニーバーの説教は国民の注目を集めた。 人種的正義に関するニーバーの考えは、社会主義を放棄した後、徐々に発展した。ニーバーは社会の不正を人間のプライドと自己愛に帰し、この生まれながらの 悪の傾向は人類によって制御できないと考えていた。しかし、代表制民主主義が社会の悪を改善できると信じていた。エドマンド・バークと同様に、ニーバーは 強制的な変化よりも自然な進化を支持し、理論よりも経験を重視した。しかし、ニーバーのバーク主義的な思想は、特に人種的正義に関する見解において、彼の 自由主義的な原則と頻繁に衝突した。人種的不平等に強く反対していたにもかかわらず、ニーバーは人種隔離に対して保守的な立場を取った。 第二次世界大戦後、ほとんどのリベラル派が統合を支持する中、ニーバーは機会均等の実現に焦点を当てた。彼は、暴力を招く可能性のある強制的な変化に反対 する警告を発した。1960年代の平和的なデモに続く暴力により、ニーバーは強制的な平等に反対する立場を撤回せざるを得なくなった。北部のゲットーの問 題を目撃したことで、彼は平等が達成可能であるかどうかを疑うようになった。[81] |

| Catholicism Anti-Catholicism surged in Detroit in the 1920s in reaction to the rise in the number of Catholic immigrants from southern Europe since the early 20th century. It was exacerbated by the revival of the Ku Klux Klan, which recruited many members in Detroit. Niebuhr defended pluralism by attacking the Klan. During the Detroit mayoral election of 1925, Niebuhr's sermon, "We fair-minded Protestants cannot deny", was published on the front pages of both the Detroit Times and the Free Press. This sermon urged people to vote against mayoral candidate Charles Bowles, who was being openly endorsed by the Klan. The Catholic incumbent, John W. Smith, won by a narrow margin of 30,000 votes. Niebuhr preached against the Klan and helped to influence its decline in political power in Detroit.[82] Niebuhr preached that: ... it was Protestantism that gave birth to the Ku Klux Klan, one of the worst specific social phenomena which the religious pride and prejudice of peoples has ever developed. ... I do not deny that all religions are periodically corrupted by bigotry. But I hit Protestant bigotry the hardest at this time because it happens to be our sin and there is no use repenting for other people's sins. Let us repent of our own. ... We are admonished in Scripture to judge men by their fruits, not by their roots; and their fruits are their character, their deeds and accomplishments.[83] — Fox, 1958, page 91 |

カトリック 1920年代、デトロイトでは、20世紀初頭から南ヨーロッパからのカトリック系移民が増加したことへの反発から、反カトリック感情が高まった。 デトロイトで多くのメンバーを募ったクー・クラックス・クランの復活により、この感情はさらに悪化した。 ニーバーは、クー・クラックス・クランを攻撃することで多元主義を擁護した。1925年のデトロイト市長選挙の際には、ニーバーの説教「公正なプロテスタ ント信者として否定できないこと」がデトロイト・タイムズ紙とフリープレス紙の両紙の一面を飾った。 この説教は、公然とクランの支持を受けていた市長候補チャールズ・ボウルズに反対票を投じるよう市民に呼びかけた。現職のカトリック教徒ジョン・W・スミ スが3万票の僅差で当選した。ニーバーはクランに反対する説教を行い、デトロイトにおける政治的影響力の衰退に影響を与えた。[82] ニーバーは次のように説教した。 ... プロテスタントこそが、人々の宗教的な偏見や先入観が生み出した最悪の社会現象のひとつであるクー・クラックス・クランを生み出したのだ。... 私は、すべての宗教が偏見によって定期的に堕落することを否定するつもりはない。しかし、プロテスタントの偏見を最も強く非難するのは、それが私たち自身 の罪であるからであり、他人の罪を悔い改めることに何の意味もないからだ。私たちは自分自身の罪を悔い改めるべきなのだ。... 聖書では、人をその根ではなく、その実によって判断するようにと戒めている。そして、その実とは、その人の性格、行い、功績である。[83] —フォックス、1958年、91ページ |

| Martin Luther King Jr. In the "Letter from Birmingham Jail" Martin Luther King Jr. wrote, "Individuals may see the moral light and voluntarily give up their unjust posture; but, as Reinhold Niebuhr has reminded us, groups tend to be more immoral than individuals." King drew heavily upon Niebuhr's social and ethical ideals; according to Andrew Young, “King always claimed to have been much more influenced by Niebuhr than by Gandhi; he considered his nonviolent technique to be a Niebuhrian strategy of power” and “Whenever there was a conversation about power, Niebuhr came up. Niebuhr kept us from being naive about the evil structures of society.”[84][85][86] King invited Niebuhr to participate in the third Selma to Montgomery March in 1965, and Niebuhr responded by telegram: "Only a severe stroke prevents me from accepting ... I hope there will be a massive demonstration of all the citizens with conscience in favor of the elemental human rights of voting and freedom of assembly" (Niebuhr, March 19, 1965). Two years later, Niebuhr defended King's decision to speak out against the Vietnam War, calling him "one of the greatest religious leaders of our time". Niebuhr asserted: "Dr. King has the right and a duty, as both a religious and a civil rights leader, to express his concern in these days about such a major human problem as the Vietnam War."[87][incomplete short citation] Of his country's intervention in Vietnam, Niebuhr admitted: "For the first time I fear I am ashamed of our beloved nation."[88] |

マーティン・ルーサー・キング・ジュニア マーティン・ルーサー・キング・ジュニアは「バーミンガムの監獄からの手紙」の中で、「個人は道徳的な光を見出し、自らの不正な姿勢を自主的に放棄するか もしれない。しかし、ラインホルド・ニーバーが私たちに思い出させたように、集団は個人よりも不道徳になりがちである」と書いている。キング牧師はニー バーの社会および倫理上の理想を大いに参考にした。アンドリュー・ヤングによると、「キング牧師は常に、ガンジーよりもニーバーから大きな影響を受けたと 主張していた。彼は、自身の非暴力の手法をニーバー流の権力戦略と考えていた。また、「権力について語られるとき、ニーバーの名前が必ず挙がった。ニー バーは、社会の悪の構造について我々が甘く考えないようにしてくれた」[84][85][86] キングは1965年の第3回セルマ・トゥ・モンゴメリー行進にニーバーを招待し、ニーバーは電報で次のように返事をした。「重度の脳卒中がなければ参加す るのだが...良識ある市民が結集し、投票権や集会の自由という基本的人権を支持する大規模なデモが行われることを願っている」(1965年3月19日、 ニーバー)。 その2年後、ニーバーはキング牧師がベトナム戦争に反対する発言をしたことを擁護し、キング牧師を「現代最高の宗教指導者の一人」と呼んだ。 ニーバーは次のように主張した。「キング牧師は、宗教指導者および公民権運動の指導者として、ベトナム戦争のような重大な人類の問題について懸念を表明す る権利と義務がある」[87][不完全な短い引用] ベトナムへの自国の介入について、ニーバーは「初めて、私は愛する我が国を恥ずかしく思う」と認めた[88]。 |

| Judaism Throughout his life, Niebuhr cultivated a good reputation and rapport with the Jewish community. He was an early critic of Christian antisemitism, including proselytism, and a persistent critic of Nazism and rising antisemitism in Germany throughout the 1930s. When he began as a young pastor in 1923 Detroit, he favored conversion of Jews to Christianity, scolding evangelical Christians who were either antisemitic or ignored them. He spoke out against "the un-Christlike attitude of Christians", and what he called "Jewish bigotry".[48] Within three years, his theological views had evolved, and he spoke out against the practicality and necessity of missionizing Jews. He was the first prominent Christian theologian to argue it was inappropriate for Christians to seek to convert Jews to their faith, saying this negated “every gesture of our common biblical inheritance.” His experience in Detroit led him to the conclusion that the Jewish community was already sincerely committed to Social Justice. In a 1926-01-10 lecture, Niebuhr said: "If I were a self-respecting Jew, I certainly would not renounce the faith of the fathers to embrace a faith which is as involved as Christianity is with racialism, Nordicism and gentile arrogance. (...) What we need is an entente cordiale between prophetic Judaism and prophetic Christianity in which both religions would offer the best they have to each other."[89] Niebuhr's 1933 article in The Christian Century was an attempt to sound the alarm within the Christian community over Hitler's "cultural annihilation of the Jews".[48][e] As a preacher, writer, leader, and adviser to political figures, Niebuhr supported Zionism and the development of Israel.[62] His solution to antisemitism was a combination of a Jewish homeland, greater tolerance, and assimilation in other countries. Unlike other Christian Zionists, Niebuhr's support of Zionism was practical, not theological, and not rooted in fulfillment of Biblical prophesy nor anticipation of the End-of-Days. Despite being a religious leader, he cautioned against the involvement of religious claims in the conflict. Niebuhr noted that “Zionism is the expression of a national will to live that transcends the traditional orthodox religion of the Jews.” Jewish statehood was necessary because “the bigotry of majority groups toward minority groups that affront the majority by diverging from the dominant type is a perennial aspect of man’s collective life. The force of it may be mitigated, but it cannot be wholly eliminated.” "How is the ancient and hereditary title of the Jews to Palestine to be measured against the right of the Arab’s present possession? … The participants cannot find a common ground of rational morality from which to arbitrate the issues because the moral judgments which each brings to them are formed by the historical forces which are in conflict. … The effort to bring such a conflict under the dominion of a spiritual unity may be partly successful, but it always produces a tragic by-product of the spiritual accentuation of natural conflict. The introduction of religious motives into these conflicts is usually no more than the final and most demonic pretension." |

ユダヤ教 生涯を通じて、ニーバーはユダヤ人社会から高い評価と信頼を得ていた。彼は、キリスト教の反ユダヤ主義、特に改宗活動の批判者として早くから知られており、1930年代を通じてドイツで台頭しつつあったナチズムと反ユダヤ主義の執拗な批判者でもあった。 1923年にデトロイトで若い牧師として働き始めたとき、彼はユダヤ人のキリスト教への改宗を推奨し、反ユダヤ主義であったり、ユダヤ人を無視したりする 福音派のキリスト教徒を叱責した。彼は「キリスト教徒らしくない態度」と、彼が「ユダヤ教の偏見」と呼ぶものに対して声を上げた。[48] 3年以内に彼の神学的見解は進化し、ユダヤ人への布教の実際性と必要性を否定するようになった。キリスト教徒がユダヤ教徒を改宗させようとすることは不適 切であり、それは「聖書という共通の遺産のあらゆる側面を否定する」と主張した最初の著名なキリスト教神学者であった。デトロイトでの経験から、彼はユダ ヤ人社会はすでに社会正義に誠実に取り組んでいるという結論に達した。 1926年1月10日の講義で、ニーバーは次のように述べた。「もし私が自尊心のあるユダヤ人であるならば、キリスト教が人種差別主義、北欧主義、異教徒 の傲慢さといったものに深く関わっているのと同様に、それらと深く関わっている信仰を受け入れるために、先祖の信仰を棄てることは決してないだろう。 (...)私たちに必要なのは、預言的なユダヤ教と預言的なキリスト教の間の協調関係であり、両方の宗教がお互いに最善を尽くすことである。」[89] ニーバーが1933年に『クリスチャン・センチュリー』誌に発表した論文は、ヒトラーによる「ユダヤ人の文化的絶滅」についてキリスト教社会に警鐘を鳴らす試みであった。[48][e] 説教師、作家、指導者、政治家の顧問として、ニーバーはシオニズムとイスラエルの発展を支持した。[62] 彼の反ユダヤ主義に対する解決策は、ユダヤ人の祖国、より大きな寛容さ、そして他国への同化を組み合わせたものであった。他のキリスト教シオニストとは異 なり、ニーバーのシオニズムへの支持は、神学的ではなく、聖書の預言の成就や終末論にもとづくものでもなかった。宗教的指導者であったにもかかわらず、彼 は紛争への宗教的主張の関与に警告を発した。 ニーブールは、「シオニズムは、ユダヤ人の伝統的な正統派宗教を超越した、生きようとする国民の意志の表明である」と指摘した。ユダヤ人の国家樹立は必要 不可欠であった。なぜなら、「多数派グループが少数派グループに対して抱く偏見は、支配的なタイプから逸脱することで多数派を侮辱するものであり、それは 人間の集団生活における永遠の側面である。その力は弱めることはできても、完全に排除することはできない」からだ。 「ユダヤ人のパレスチナに対する古くからの世襲の権利と、アラブ人の現在の所有権とをどのように比較すべきだろうか?… 参加者は、各自が持ち寄る道徳的判断が対立する歴史的勢力によって形成されているため、問題を仲裁するための合理的な道徳の共通基盤を見出すことができな い。このような対立を精神的な統一の支配下に置く努力は、部分的には成功するかもしれないが、常に自然な対立を精神的に強調するという悲劇的な副産物を生 み出す。このような対立に宗教的な動機を導入することは、通常、最終的な最も悪魔的な主張に過ぎない。 |

| Secular humanism In response to a question from journalist Mike Wallace over whether or not Neibuhr considered himself superior to atheists such as the British mathematician Bertrand Russell, Niebuhr said that it would be "pretentious" to deem himself superior in the eyes of God to anyone else because of their religion or lack thereof, stating "How do I know about God's judgment? One of the fundamental points about religious humility is that you don't know about the ultimate judgment. It's beyond your judgment. And if you equate God's judgment with your judgment, you have a wrong religion." Niebuhr also voiced his view that he would judge others, be they believers or atheists, "by the fruits [of their] lives, rather than [their] presuppositions...a sense of charity...a sense of justice."[90] |

世俗的ヒューマニズム ジャーナリストのマイク・ウォレスが、ニーバーが英国の数学者バートランド・ラッセルのような無神論者よりも自分自身が優れていると考えているかどうかに ついて質問したのに対し、ニーバーは、宗教の有無を理由に、神の目から見て自分が他の誰よりも優れていると考えることは「気取りがましい」と述べ、「私が 神の裁きについてどうして分かるのか?宗教的な謙虚さに関する基本的なポイントのひとつは、究極の審判についてはわからないということだ。それは、あなた の判断の及ぶ範囲を超えている。そして、神の審判を自分の判断と同一視するなら、それは間違った宗教だ」と述べた。また、ニーバーは、信仰者であれ無信仰 者であれ、他者を「彼らの前提よりもむしろ彼らの人生の果実によって、...慈善の感覚...正義の感覚」で判断するだろうという見解を示した。[90] |

| History In 1952, Niebuhr published The Irony of American History, in which he interpreted the meaning of the United States' past. Niebuhr questioned whether a humane, "ironical" interpretation of American history was credible on its own merits, or only in the context of a Christian view of history. Niebuhr's concept of irony referred to situations in which "the consequences of an act are diametrically opposed to the original intention", and "the fundamental cause of the disparity lies in the actor himself, and his original purpose." His reading of American history based on this notion, though from the Christian perspective, is so rooted in historical events that readers who do not share his religious views can be led to the same conclusion.[91] |

歴史 1952年、ニーバーは『アメリカ史の皮肉』を出版し、米国の過去の歴史の意味を解釈した。 ニーバーは、アメリカ史を人道的に「皮肉」に解釈することが、それ自体の価値において信頼に足るものなのか、それともキリスト教の歴史観との関連において のみ信頼に足るものなのか、疑問を投げかけた。ニーバーの「皮肉」の概念は、「行為の結果が当初の意図と正反対である」状況を指し、「その根本的な原因は 行為者自身とその当初の目的にある」と述べている。この概念に基づく彼のアメリカ史の解釈は、キリスト教の観点ではあるが、歴史的事実に深く根ざしている ため、彼の宗教的見解を共有していない読者も同じ結論に導かれる可能性がある。[91] |

| Serenity Prayer Main article: Serenity Prayer Niebuhr created the first version of the Serenity Prayer.[92] It inspired Winnifred Wygal to write versions of the prayer that would become well known. Fred R. Shapiro, who had cast doubts on Niebuhr's claim of authorship, conceded in 2009 that, "The new evidence does not prove that Reinhold Niebuhr wrote [the prayer], but it does significantly improve the likelihood that he was the originator."[93] A popular version of it reads: God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, Courage to change the things I can, And the wisdom to know the difference. |

平安の祈り 詳細は「平安の祈り」を参照 ニーバーは「平安の祈り」の最初のバージョンを作成した。[92] ウィンフレッド・ワイガルは、この祈りのバージョンを書くことを思いつき、それは広く知られるようになった。ニーブールによる著作権主張に疑いを抱いてい たフレッド・R・シャピロは、2009年に「新たな証拠はラインホルド・ニーブールがこの祈りを書いたことを証明するものではないが、彼がこの祈りの創作 者である可能性を大幅に高めるものである」と認めた。[93] よく知られているその祈りの文面は以下の通りである。 神よ、変えることのできないことを受け入れる心の平穏を私に与えたまえ。 変えることのできることを変える勇気を私に与えたまえ。 そして、その違いを知る知恵を私に与えたまえ。 |

| Influence Many political scientists, such as George F. Kennan, Hans Morgenthau, Kenneth Waltz, and Samuel P. Huntington, and political historians, such as Richard Hofstadter, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., and Christopher Lasch, have noted his influence on their thinking.[94] Niebuhr exerted a significant influence upon mainline Protestant clergy in the years immediately following World War II, much of it in concord with the neo-orthodox and the related movements. That influence began to wane and then drop toward the end of his life.[citation needed] The historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. in the late twentieth century described the legacy of Niebuhr as being contested between American liberals and conservatives, both of whom wanted to claim him.[73] Martin Luther King Jr. gave credit to Niebuhr's influence. Foreign-policy conservatives point to Niebuhr's support of the containment doctrine during the Cold War as an instance of moral realism; progressives cite his later opposition to the Vietnam War.[73] In more recent years, Niebuhr has enjoyed something of a renaissance in contemporary thought, although usually not in liberal Protestant theological circles. Both major-party candidates in the 2008 presidential election cited Niebuhr as an influence: Senator John McCain, in his book Hard Call, "celebrated Niebuhr as a paragon of clarity about the costs of a good war".[95] President Barack Obama said that Niebuhr was his "favourite philosopher"[96] and "favorite theologian".[97] Slate magazine columnist Fred Kaplan characterized Obama's 2009 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech as a "faithful reflection" of Niebuhr.[98] Kenneth Waltz's seminal work on international relations theory, Man, the State, and War, includes many references to Niebuhr's thought.[citation needed] Waltz emphasizes Niebuhr's contributions to political realism, especially "the impossibility of human perfection".[99] Andrew Bacevich's book The Limits of Power: The End of American Exceptionalism refers to Niebuhr 13 times.[100] Bacevich emphasizes Niebuhr's humility and his belief that Americans were in danger of becoming enamored of US power.[citation needed] Other leaders of American foreign policy in the late twentieth century and early twenty-first century have acknowledged Niebuhr's importance to them, including Jimmy Carter, Madeleine Albright, and Hillary Clinton.[101][102] |

影響 ジョージ・F・ケナン、ハンス・モーゲンソー、ケネス・ウォルツ、サミュエル・P・ハンティントンなどの多くの政治学者や、リチャード・ホフスタッター、 アーサー・M・シュレジンジャー・ジュニア、クリストファー・ラスなどの政治史家が、彼らの考え方にニーブールが与えた影響について言及している。 ニーバーは、第二次世界大戦直後のプロテスタント主流派聖職者たちに大きな影響を与えたが、その多くは新正統主義や関連運動と一致するものであった。その影響力は、彼の人生の終わり頃には弱まり、その後失われていった。 20世紀後半の歴史家アーサー・M・シュレジンジャー・ジュニアは、ニーバーの遺産はアメリカのリベラル派と保守派の間で論争の的となっており、両派とも ニーバーを自派の主張に引き入れようとしていると述べている。[73] マーティン・ルーサー・キング・ジュニアはニーバーの影響力を評価した。外交政策保守派は、冷戦中の封じ込め政策を支持したことを道徳的リアリズムの例と して挙げている。一方、進歩派は、ベトナム戦争に反対したことを挙げている。[73] 近年では、ニーバーは現代思想においてある種のルネサンスを享受しているが、通常はリベラル派プロテスタント神学界ではそうではない。2008年の大統領 選挙の両党候補者は、ニーバーの影響を挙げている。上院議員のジョン・マケインは著書『苦渋の決断』の中で、「ニーバーを正しい戦争の代償について明確に 論じた模範的人物」と称賛した。[95] バラク・オバマ大統領は、ニーバーを「お気に入りの哲学者」[96] [96]、「お気に入りの神学者」であると述べた。[97] スレート誌のコラムニスト、フレッド・カプランは、オバマの2009年のノーベル平和賞受賞演説をニーバーの「忠実な反映」であると評した。[98] ケネス・ウォルツの国際関係論に関する画期的な著作『人間、国家、戦争』には、ニーバーの思想に関する多くの言及がある。[要出典]ウォルツは、特に「人 間の完全性の不可能性」という政治的リアリズムに対するニーバーの貢献を強調している。[99] アンドリュー・ベーセビッチの著書『力の限界:アメリカ例外主義の終焉』では、ニーバーについて13回言及している。[100] ベーセビッチは、ニーバーの謙虚さと、アメリカ人が自国の力に溺れる危険性があるという彼の信念を強調している。[要出典] 20世紀後半から21世紀初頭にかけてのアメリカの外交政策を主導した他の指導者たちも、ジミー・カーター、マデリン・オルブライト、ヒラリー・クリントンなど、ニーバーの重要性を認めている。[101][102] |

Legacy and honors Niebuhr's grave in Stockbridge Cemetery Niebuhr died on June 1, 1971, in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.[103] During his lifetime, Niebuhr was awarded several honorary doctorates. Niebuhr was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1947.[104] In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson awarded Niebuhr the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In Niebuhr's honor, New York City named West 120th Street between Broadway and Riverside Drive Reinhold Niebuhr Place.[105] This is the site of Union Theological Seminary in Manhattan, where Niebuhr taught for more than 30 years.[106] Elmhurst College, his alma mater, established the Niebuhr Medal to honor him and his brother.[107][failed verification] Niebuhr's influence was at its peak during the first two decades of the Cold War. By the 1970s, his influence was declining because of the rise of liberation theology, antiwar sentiment, the growth of conservative evangelicalism, and postmodernism.[108] According to historian Gene Zubovich, "It took the tragic events of September 11, 2001, to revive Niebuhr."[108] In spring of 2017, it was speculated[109] (and later confirmed[110]) that former FBI director James Comey used Niebuhr's name as a screen name for his personal Twitter account. Comey, as a religion major at the College of William & Mary, wrote his undergraduate thesis on Niebuhr and televangelist Jerry Falwell.[111] |

遺産および栄誉 ストックブリッジ墓地にあるニーバーの墓 ニーバーは1971年6月1日、マサチューセッツ州ストックブリッジで死去した。[103] 生前、ニーバーはいくつかの名誉博士号を授与された。 1947年にはアメリカ哲学協会の会員に選出された。 1964年にはリンドン・B・ジョンソン大統領から大統領自由勲章を授与された。 ニユーブールを称え、ニューヨーク市はブロードウェイとリバーサイド・ドライブの間の西120丁目の通りをラインホルド・ニユーブール・プレイスと命名し た。[105] この場所はマンハッタンのユニオン神学校の敷地であり、ニユーブールは30年以上にわたってここで教鞭をとっていた。[106] 母校のエルムハースト大学は、ニユーブールと彼の兄弟を称えるためにニユーブール・メダルを創設した。[107][検証失敗] ニーバーの影響力は、冷戦の最初の20年間でピークに達した。1970年代までに、解放の神学、反戦感情、保守的な福音主義の成長、ポストモダニズムの台 頭により、彼の影響力は衰退した。[108] 歴史家のジーン・ズボヴィッチによると、「ニーバーを復活させるには、2001年9月11日の悲劇的な出来事を待たなければならなかった」[108] 2017年春、元FBI長官のジェームズ・コミーが、自身のTwitterアカウントのスクリーンネームとしてニーバーの名前を使用していたことが推測さ れ[109](後に確認された[110])、コミーはウィリアム・アンド・メアリー大学の宗教学専攻学生として、ニーバーとテレビ伝道師ジェリー・ファル ウェルに関する学部論文を執筆した[111]。 |

| Personal style Niebuhr was often described as a charismatic speaker. The journalist Alden Whitman wrote of his speaking style: He possessed a deep voice and large blue eyes. He used his arms as though he were an orchestra conductor. Occasionally one hand would strike out, with a pointed finger at the end, to accent a trenchant sentence. He talked rapidly and (because he disliked to wear spectacles for his far-sightedness) without notes; yet he was adroit at building logical climaxes and in communicating a sense of passionate involvement in what he was saying.[47] |

個性的なスタイル ニーブールはしばしばカリスマ的講演者と評された。ジャーナリストのオルデン・ウィットマンは、彼の話し方を次のように表現している。 彼は深みのある声と大きな青い目を持っていた。彼はオーケストラの指揮者のように腕を動かした。時に片手を突き出し、鋭い文章にアクセントをつけた。彼は 早口で、(遠視のために眼鏡をかけたくなかったため)メモも見ずに話した。しかし、彼は論理的なクライマックスを巧みに作り上げ、自分が話していることへ の情熱的な関わりを伝えるのが上手かった。[47] |

Leaves from the Notebook of a Tamed Cynic, Richard R. Smith pub, (1930), Westminster John Knox Press 1991 reissue: ISBN 0-664-25164-1, diary of a young minister's trials Moral Man and Immoral Society: A Study of Ethics and Politics, Charles Scribner's Sons (1932)[112], Westminster John Knox Press 2002: ISBN 0-664-22474-1;[113] Contribution of Religion to Social Work (1932). New York: Columbia University Press.[114] Reflections on the End of an Era. 1934.[115] Interpretation of Christian Ethics, Harper & Brothers (1935) Beyond Tragedy: Essays on the Christian Interpretation of History, Charles Scribner's Sons (1937), ISBN 0-684-71853-7 Christianity and Power Politics, Charles Scribner's Sons (1940) The Nature and Destiny of Man: A Christian Interpretation, Charles Scribner's Sons (1943), from his 1939 Gifford Lectures, Volume one: Human Nature, Volume two: Human Destiny. Reprint editions include: Prentice Hall vol. 1: ISBN 0-02-387510-0, Westminster John Knox Press 1996 set of 2 vols: ISBN 0-664-25709-7 The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness, Charles Scribner's Sons (1944), Prentice Hall 1974 edition: ISBN 0-02-387530-5, Macmillan 1985 edition: ISBN 0-684-15027-1, 2011 reprint from the University of Chicago Press, with a new introduction by Gary Dorrien: ISBN 978-0-226-58400-3 Faith and History (1949) ISBN 0-684-15318-1 The Irony of American History, Charles Scribner's Sons (1952), 1985 reprint: ISBN 0-684-71855-3, Simon and Schuster: ISBN 0-684-15122-7, 2008 reprint from the University of Chicago Press, with a new introduction by Andrew J. Bacevich: ISBN 978-0-226-58398-3, excerpt Christian Realism and Political Problems (1953) ISBN 0-678-02757-9 The Self and the Dramas of History, Charles Scribner's Sons (1955), University Press of America, 1988 edition: ISBN 0-8191-6690-1 Love and Justice: Selections from the Shorter Writings of Reinhold Niebuhr, ed. D. B. Robertson (1957), Westminster John Knox Press 1992 reprint, ISBN 0-664-25322-9 Pious and Secular America (1958) ISBN 0-678-02756-0 Reinhold Niebuhr on Politics: His Political Philosophy and Its Application to Our Age as Expressed in His Writings ed. by Harry R. Davis and Robert C. Good. (1960) online edition A Nation So Conceived: Reflections on the History of America From Its Early Visions to its Present Power with Alan Heimert, Charles Scribner's Sons (1963) The Structure of Nations and Empires (1959) ISBN 0-678-02755-2 Niebuhr, Reinhold. The Essential Reinhold Niebuhr: Selected Essays and Addresses ed. by Robert McAffee Brown (1986). 264 pp. Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-04001-6 Remembering Reinhold Niebuhr. Letters of Reinhold & Ursula M. Niebuhr, ed. by Ursula Niebuhr (1991) Harper, 0060662344 Reinhold Niebuhr: Major Works on Religion and Politics: Leaves from the Notebook of a Tamed Cynic, Moral Man and Immoral Society, The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness, The Irony of American History, Other Writings [Writings on Current Events 1928-1967, Prayers, Sermons and Lectures on Faith and Belief], ed. by Elisabeth Sifton (2016, Library of America/Literary Classics of the United States, 2016), 978-1-59853-375-0 |

飼い慣らされたシニカルな人物の日記、リチャード・R・スミス著、パブ出版(1930年)、ウェストミンスター・ジョン・ノックス・プレス1991年再版:ISBN 0-664-25164-1、若い牧師の試練の日記 『道徳的人間と不道徳な社会:倫理と政治に関する研究』(1932年)[112]、ウェストミンスター・ジョン・ノックス・プレス、2002年:ISBN 0-664-22474-1;[113] 『宗教の社会事業への貢献』(1932年)。ニューヨーク:コロンビア大学出版局。[114] 時代の終わりについての考察。1934年。 キリスト教倫理の解釈、Harper & Brothers(1935年) 悲劇を超えて:キリスト教の歴史解釈に関する論文集、Charles Scribner's Sons(1937年)、ISBN 0-684-71853-7 キリスト教と権力政治、Charles Scribner's Sons(1940年) 『人間の性質と運命:キリスト教の解釈』(1943年、チャールズ・スクリブナーズ・サンズ社)は、1939年のギフォード・レクチャーの第1巻「人間の 本性」、第2巻「人間の運命」からの抜粋である。再版版には、プリンス・ホール社第1巻:ISBN 0-02-387510-0、ウェストミンスター・ジョン・ノックス・プレス社1996年2巻セット: ISBN 0-664-25709-7 光の子供たちと闇の子供たち、チャールズ・スクリブナーズ・サンズ社(1944年)、プレンティス・ホール社1974年版:ISBN 0-02-387530-5、マクミラン社1985年版: ISBN 0-684-15027-1、2011年シカゴ大学出版局より再版、ゲイリー・ドリアンによる新序文付き:ISBN 978-0-226-58400-3 信仰と歴史(1949年)ISBN 0-684-15318-1 『アメリカ史の皮肉』チャールズ・スクリブナーズ・サンズ社(1952年)、1985年再版: ISBN 0-684-71855-3、サイモン・アンド・シュスター:ISBN 0-684-15122-7、2008年シカゴ大学出版局より再版、アンドリュー・J・バセビッチによる新序文付き:ISBN 978-0-226-58398-3、抜粋 『キリスト教リアリズムと政治問題』(1953年)ISBN 0-678-02757-9 『自己と歴史のドラマ』(1955年、チャールズ・スクリブナーズ・サンズ社)1988年版:ISBN 0-8191-6690-1 愛と正義:ラインホルド・ニーバーの短編著作からの抜粋、D. B. Robertson 編 (1957)、ウェストミンスター・ジョン・ノックス出版 1992年再版、ISBN 0-664-25322-9 敬虔なアメリカと世俗的なアメリカ (1958) ISBN 0-678-02756-0 政治におけるラインホルド・ニーバー:彼の政治哲学とその著作における現代への応用について、ハリー・R・デイヴィスとロバート・C・グッド編。(1960年)オンライン版 A Nation So Conceived: Reflections on the History of America From Its Early Visions to its Present Power アラン・ハイマート著、チャールズ・スクリブナーズ・サンズ社(1963年) 『国家と帝国の構造』(1959年)ISBN 0-678-02755-2 ニーバー、ラインホルド。『ラインホルド・ニーバーの真髄:論文と演説集』(ロバート・マカフィー・ブラウン編、1986年)。264ページ。イェール大学出版、ISBN 0-300-04001-6 リチャード・ニーバーを偲んで。リチャード・ニーバーとウルスラ・M・ニーバーの手紙集、ウルスラ・ニーバー編(1991年)ハーパー社、0060662344 ラインホルド・ニーバー:宗教と政治に関する主要作品:飼いならされたシニカル、道徳的人間、不道徳な社会、光の子供たちと闇の子供たち、アメリカ史の皮 肉、その他の著作[1928年から1967年の時事問題に関する著作、祈り、 説教、信仰と信念に関する講演]、エリザベス・シフトン編(2016年、ライブラリー・オブ・アメリカ/米国文学の古典、2016年)、978-1- 59853-375-0 |

| Christian socialism The Moot Situational ethics |

キリスト教社会主義 討論会 状況倫理 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reinhold_Niebuhr |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆