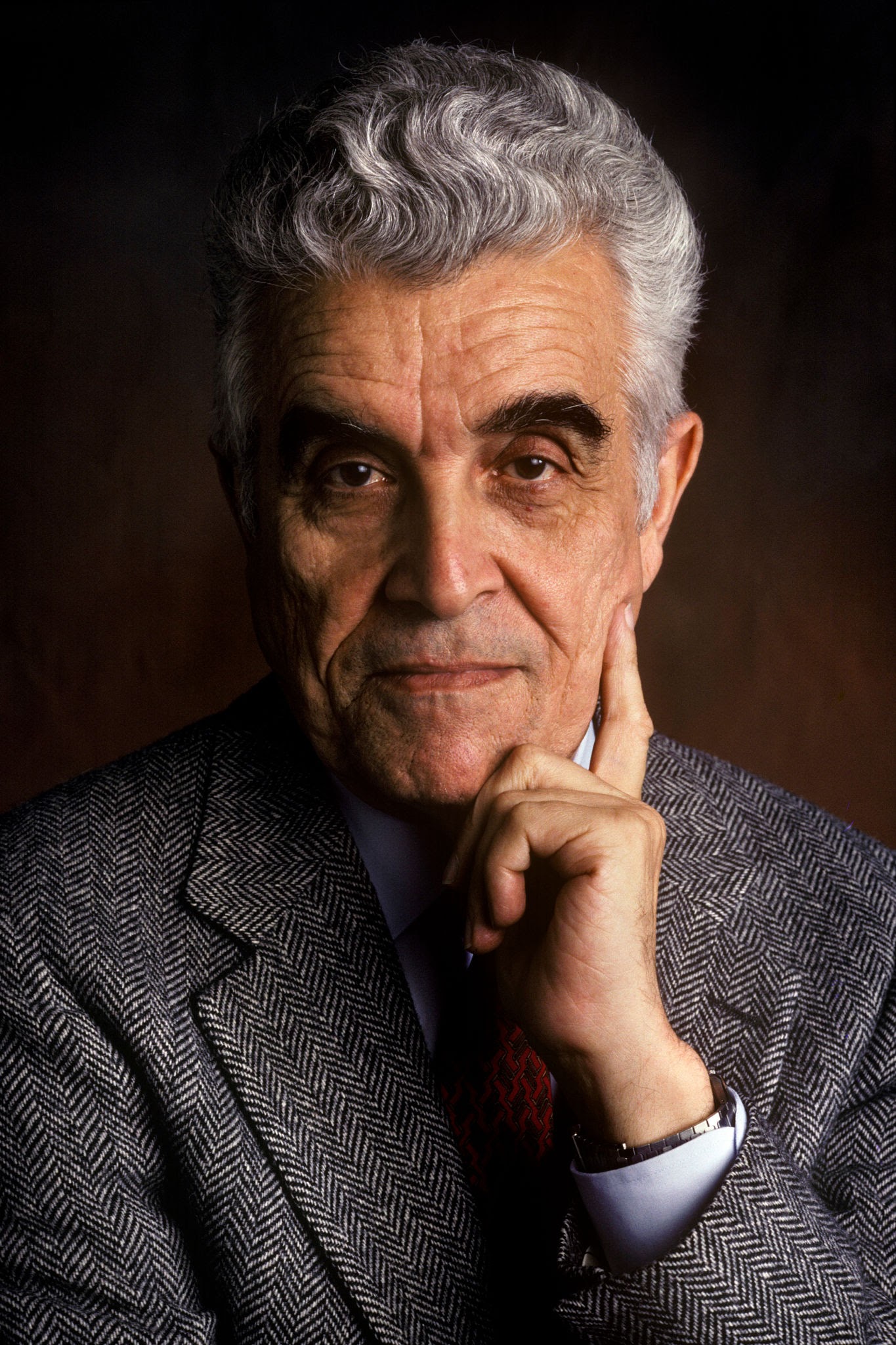

ルネ・ジラール

René Noël Théophile Girard, 1923-2015

☆ ルネ・ノエル・テオフィル・ジラール(/ʒɪ,[2] French: [ʒʒ]; 1923年12月25日 - 2015年11月4日)は、フランスの歴史家、文学批評家、社会科学哲学者で、その著作は哲学的人間学の伝統に属する。ジラールは30冊近い著書を持ち、 その著作は多くの学問領域に及んでいる。彼の著作の受容のされ方はそれぞれの領域で異なるが、文学批評、批評理論、人類学、神学、神話学、社会学、経済 学、カルチュラル・スタディーズ、哲学といった分野への彼の著作とその影響に関する二次文献は増え続けている。

ジラールの哲学、ひいては他の学問分野への主な貢献は、欲望の心理学にあった。ジラールは、人間の欲望は、理論心理学の多くが想定していたように、人間の 個性の自然発生的な副産物として生じるのではなく、模倣的、つまり模倣的に機能すると主張した。ジラールは、人間の発達は、ある欲望の対象を自ら欲望する ことによって望ましいものとして示す欲望のモデルから三角形に進行すると提唱した。私たちはモデルの対象に対するこの欲望を模倣し、それを自分のものとし て流用するが、ほとんどの場合、この欲望の源が模倣的欲望の三角形を完成させている自分自身とは別の他者から来ていることを認識することはない。このよう な欲望の流用プロセスには、アイデンティティの形成、知識や社会規範の伝達、物質的な願望などが含まれるが、これらに限定されるものではない。 模倣理論の第二の主要な命題は、人間の起源と人類学に関連する欲望の模倣的性質の帰結を考察することから始まる。欲望の模倣的性質は、社会的学習を通じて 人間の人類学的成功を可能にするが、同時に暴力的エスカレーションの可能性もはらんでいる。主体がある対象を欲するのは、単に他の主体がそれを欲するから だとすれば、彼らの欲望は同じ対象に収斂することになる。これらの対象が容易に共有できないもの(食物、仲間、縄張り、威信や地位など)であれば、主体は これらの対象をめぐって擬態的に対立を激化させるに違いない。

より詳しくは「欲望の人類学」を参照のこと

初期の人類共同体にとって、この暴力の問題に対する最も単純な解決策は、非難と敵意を集団の 一人のメンバーに集中させることだった。そのメンバーは殺され、集団内の対立と敵意の原因だと解釈される。万人対万人という暴力的な対立から、万人対一人 という統一的で平和的な暴力へと変化する。無秩序の元凶として迫害されていた犠牲者は、共同体の秩序と意味の源として崇められるようになり、神とみなされ るようになる。恣意的な被害者化によって人間共同体を生み出し、可能にするこのプロセスは、模倣理論の中ではスケープゴート・メカニズムと呼ばれている。 やがて、聖書のテクストの中で、このスケープゴート・メカニズムが暴露されることになる。聖書では、神性の位置づけを、迫害する共同体の側ではなく、被害 者の側に置くよう、断固として方向転換しているのである。

ジラールは、たとえば『ロムルスとレムス』のような他のすべての神話は、統一された共同体として まとまるために、その正当性が被害者の有罪に依存している共同体の視点から書かれ、構成されていると主張する。ひとたび被害者の相対的潔白が露呈すれば、 スケープゴート・メカニズムはもはや統一と平和を生み出す手段としては機能しなくなる。従って、キリストの範疇的な道徳的潔白は、聖典の中でスケープゴー トのメカニズムを明らかにする役割を果たし、今日の私たちの相互作用の中にそのメカニズムが存在し続けていることを見分けることを学ぶことによって、人類 がそれを克服する可能性を可能にするのである。

| René Noël Théophile

Girard (/ʒɪəˈrɑːrd/;[2] French: [ʒiʁaʁ]; 25 December 1923 – 4 November

2015) was a French historian, literary critic, and philosopher of

social science whose work belongs to the tradition of philosophical

anthropology. Girard was the author of nearly thirty books, with his

writings spanning many academic domains. Although the reception of his

work is different in each of these areas, there is a growing body of

secondary literature on his work and his influence on disciplines such

as literary criticism, critical theory, anthropology, theology,

mythology, sociology, economics, cultural studies, and philosophy. Girard's main contribution to philosophy, and in turn to other disciplines, was in the psychology of desire. Girard claimed that human desire functions imitatively, or mimetically, rather than arising as the spontaneous byproduct of human individuality, as much of theoretical psychology had assumed. Girard proposed that human development proceeds triangularly from a model of desire that indicates some object of desire as desirable by desiring it themselves. We copy this desire for the object of the model and appropriate it as our own, most often without recognizing that the source of this desire comes from another apart from ourselves completing the triangle of mimetic desire. This process of appropriation of desire includes (but is not limited to) identity formation, the transmission of knowledge and social norms, and material aspirations which all have their origin in copying the desires of others who we take, consciously or unconsciously, as models for desire. The second major proposition of the mimetic theory proceeds from considering the consequences of the mimetic nature of desire as it relates to human origins and anthropology. The mimetic nature of desire allows for the anthropological success of human beings through social learning but is also laden with potential for violent escalation. If the subject desires an object simply because another subject desires it, then their desires are bound to converge on the same objects. If these objects cannot be easily shared (food, mates, territory, prestige and status, etc.), then the subjects are bound to come into mimetically intensifying conflict over these objects. The simplest solution to this problem of violence for early human communities was to polarize blame and hostility onto one member of the group who would be killed and interpreted as the source of conflict and hostility within the group. The transition from the violent conflict of all-against-all would be transformed into the unifying and pacifying violence of all-except-one whose death would reconcile the community together. The victim who was persecuted as the source of disorder would then become venerated as the source of order and meaning for the community and seen as a god. This process of engendering and making possible human community through arbitrary victimization is called, within mimetic theory, the scapegoat mechanism. Eventually, the scapegoat mechanism would be exposed within the Biblical texts who categorically reorient the position of the Divinity to be on the side of the victim as opposed to that of the persecuting community. Girard argues that all other myths, such as Romulus and Remus, for example, are written and constructed from the point of view of the community whose legitimacy depends on the guilt of the victim in order to be brought together as a unified community. Once the relative innocence of the victim is exposed, the scapegoat mechanism is no longer able to function as a vehicle for generating unity and peace. The categorical moral innocence of Christ therefore serves to reveal the scapegoating mechanism in scripture, thus enabling the possibility that humanity might overcome it by learning to discern its continued presence in our interactions today. |

ルネ・ノエル・テオフィル・ジラール(/ʒɪ,[2]

French: [ʒʒ]; 1923年12月25日 -

2015年11月4日)は、フランスの歴史家、文学批評家、社会科学哲学者で、その著作は哲学的人間学の伝統に属する。ジラールは30冊近い著書を持ち、

その著作は多くの学問領域に及んでいる。彼の著作の受容のされ方はそれぞれの領域で異なるが、文学批評、批評理論、人類学、神学、神話学、社会学、経済

学、カルチュラル・スタディーズ、哲学といった分野への彼の著作とその影響に関する二次文献は増え続けている。 ジラールの哲学、ひいては他の学問分野への主な貢献は、欲望の心理学にあった。ジラールは、人間の欲望は、理論心理学の多くが想定していたように、人間の 個性の自然発生的な副産物として生じるのではなく、模倣的、つまり模倣的に機能すると主張した。ジラールは、人間の発達は、ある欲望の対象を自ら欲望する ことによって望ましいものとして示す欲望のモデルから三角形に進行すると提唱した。私たちはモデルの対象に対するこの欲望を模倣し、それを自分のものとし て流用するが、ほとんどの場合、この欲望の源が模倣的欲望の三角形を完成させている自分自身とは別の他者から来ていることを認識することはない。このよう な欲望の流用プロセスには、アイデンティティの形成、知識や社会規範の伝達、物質的な願望などが含まれるが、これらに限定されるものではない。 模倣理論の第二の主要な命題は、人間の起源と人類学に関連する欲望の模倣的性質の帰結を考察することから始まる。欲望の模倣的性質は、社会的学習を通じて 人間の人類学的成功を可能にするが、同時に暴力的エスカレーションの可能性もはらんでいる。主体がある対象を欲するのは、単に他の主体がそれを欲するから だとすれば、彼らの欲望は同じ対象に収斂することになる。これらの対象が容易に共有できないもの(食物、仲間、縄張り、威信や地位など)であれば、主体は これらの対象をめぐって擬態的に対立を激化させるに違いない。初期の人類共同体にとって、この暴力の問題に対する最も単純な解決策は、非難と敵意を集団の 一人のメンバーに集中させることだった。そのメンバーは殺され、集団内の対立と敵意の原因だと解釈される。万人対万人という暴力的な対立から、万人対一人 という統一的で平和的な暴力へと変化する。無秩序の元凶として迫害されていた犠牲者は、共同体の秩序と意味の源として崇められるようになり、神とみなされ るようになる。恣意的な被害者化によって人間共同体を生み出し、可能にするこのプロセスは、模倣理論の中ではスケープゴート・メカニズムと呼ばれている。 やがて、聖書のテクストの中で、このスケープゴート・メカニズムが暴露されることになる。聖書では、神性の位置づけを、迫害する共同体の側ではなく、被害 者の側に置くよう、断固として方向転換しているのである。ジラールは、たとえば『ロムルスとレムス』のような他のすべての神話は、統一された共同体として まとまるために、その正当性が被害者の有罪に依存している共同体の視点から書かれ、構成されていると主張する。ひとたび被害者の相対的潔白が露呈すれば、 スケープゴート・メカニズムはもはや統一と平和を生み出す手段としては機能しなくなる。従って、キリストの範疇的な道徳的潔白は、聖典の中でスケープゴー トのメカニズムを明らかにする役割を果たし、今日の私たちの相互作用の中にそのメカニズムが存在し続けていることを見分けることを学ぶことによって、人類 がそれを克服する可能性を可能にするのである。 |

| Early life Girard was born in Avignon on 25 December 1923.[a] René Girard was the second son of historian Joseph Girard. He studied medieval history at the École des Chartes, Paris, where the subject of his thesis was "Private life in Avignon in the second half of the 15th century" ("La vie privée à Avignon dans la seconde moitié du XVe siècle").[3] [page needed] In 1947, Girard went to Indiana University Bloomington on a one-year fellowship. He was to spend most of his career in the United States. He received his PhD in 1950 and stayed at Indiana University until 1953. The subject of his PhD at Indiana University was "American Opinion of France, 1940–1943".[3] Although his research was in history, he was also assigned to teach French literature, the field in which he would first make his reputation as a literary critic by publishing influential essays on such authors as Albert Camus and Marcel Proust. |

生い立ち ルネ・ジラールは歴史家ジョセフ・ジラールの次男である。 パリのシャルト大学で中世史を学び、卒業論文のテーマは「15世紀後半のアヴィニョンの私生活」(「La vie privée à Avignon dans la seconde moitié du XVe siècle」)であった[3] [要出典]。 1947年、ジラールは1年間のフェローシップでインディアナ大学ブルーミントンに留学した。1950年に博士号を取得した。1950年に博士号を取得 し、1953年までインディアナ大学に在籍した。インディアナ大学での博士号のテーマは「1940年から1943年のアメリカ人のフランスに対する意見」 であった[3]。彼の研究は歴史学であったが、アルベール・カミュやマルセル・プルーストなどの作家について影響力のあるエッセイを発表し、文芸批評家と しての名声を得ることになるフランス文学の分野でも教鞭をとることになった。 |

| Career Girard occupied positions at Duke University and Bryn Mawr College from 1953 to 1957, after which he moved to Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, where he became a full professor in 1961. In that year, he also published his first book: Mensonge romantique et vérité romanesque (Deceit, Desire and the Novel, 1966). For several years, he moved back and forth between the State University of New York at Buffalo and Johns Hopkins University. Books he published in this period include La Violence et le sacré (1972; Violence and the Sacred, 1977) and Des choses cachées depuis la fondation du monde (1978; Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World, 1987). In 1966, as the Chair of the Romance Languages Department at Johns Hopkins, Girard helped Richard A. Macksey, the Director of the newly founded Humanities Center, to organize a colloquium on French thought. The event was titled "The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man" and was held from 18 to 21 October 1966. Featuring prominent French academics such as Jacques Lacan, Roland Barthes, and Jacques Derrida, it is often credited with having launched the post-structuralist movement. In 1981, Girard became Andrew B. Hammond Professor of French Language, Literature, and Civilization at Stanford University, where he stayed until his retirement in 1995. During this period, he published Le Bouc émissaire (1982), La route antique des hommes pervers (1985), A Theatre of Envy: William Shakespeare (1991) and Quand ces choses commenceront ... (1994). In 1985, he received his first honorary degree from the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam in the Netherlands; several others followed.[citation needed] In 1990, a group of scholars founded the Colloquium on Violence and Religion (COV&R) with the goal to "explore, criticize, and develop the mimetic model of the relationship between violence and religion in the genesis and maintenance of culture."[4][5] This organization organizes a yearly conference devoted to topics related to mimetic theory, scapegoating, violence, and religion. Girard was Honorary Chair of COV&R. Co-founder and first president of the COV&R was the Roman Catholic theologian Raymund Schwager. René Girard's work has inspired interdisciplinary research projects and experimental research such as the Mimetic Theory project sponsored by the John Templeton Foundation.[6] On 17 March 2005, Girard was elected to the Académie française.[citation needed] |

経歴 1953年から1957年までデューク大学とブリンマー・カレッジに在籍した後、ボルチモアのジョンズ・ホプキンス大学に移り、1961年に正教授となっ た。同年、初の著書も出版した: Mensonge romantique et vérité romanesque (Deceit, Desire and the Novel, 1966)』を出版した。数年間、ニューヨーク州立大学バッファロー校とジョンズ・ホプキンス大学を行き来した。この時期に出版した本には、La Violence et le sacré(1972年、暴力と聖なるもの、1977年)、Des choses cachées depuis la fondation du monde(1978年、世界の建国以来隠されてきたもの、1987年)などがある。 1966年、ジョンズ・ホプキンスのロマンス語学科長だったジラールは、設立されたばかりの人文科学センター長リチャード・A・マックシーに協力し、フラ ンス思想に関するコロキウムを開催した。このイベントは「批評の言語と人間の科学」と題され、1966年10月18日から21日まで開催された。ジャッ ク・ラカン、ロラン・バルト、ジャック・デリダといったフランスの著名な学者が参加し、ポスト構造主義運動の火付け役となった。 1981年、ジラールはスタンフォード大学のアンドリュー・B・ハモンド教授(フランス語・文学・文明学)に就任し、1995年に定年退職するまで在籍し た。この間、Le Bouc émissaire (1982)、La route antique des hommes pervers (1985)、A Theatre of Envy: William Shakespeare (1991)、Quand ces choses commenceront ... (1994)を出版した。 1985年、オランダのアムステルダム・ヴリエ大学から初の名誉学位を授与され、その後もいくつかの名誉学位が授与された[要出典]。 1990年、「文化の発生と維持における暴力と宗教の関係について、模倣モデルを探求し、批判し、発展させる」ことを目的とした「暴力と宗教に関するコロ キウム(COV&R)」が学者グループによって設立された[4][5]。この組織は、模倣理論、スケープゴート化、暴力、宗教に関連するトピック に特化した会議を毎年開催している。ジラールはCOV&Rの名誉会長を務めた。COV&Rの共同設立者であり初代会長は、ローマ・カト リック神学者のレイマンド・シュワガーであった。 ルネ・ジラールの研究は、ジョン・テンプルトン財団主催の模倣理論プロジェクトなど、学際的な研究プロジェクトや実験的研究に影響を与えている[6]。 2005年3月17日、ジラールはアカデミー・フランセーズに選出された[要出典]。 |

| Girard's thought Mimetic desire Main article: Mimetic theory After almost a decade of teaching French literature in the United States, Girard began to develop a new way of speaking about literary texts. Beyond the "uniqueness" of individual works, he looked for their common structural properties, having observed that characters in great fiction evolved in a system of relationships otherwise common to the wider generality of novels. But there was a distinction to be made: Only the great writers succeed in painting these mechanisms faithfully, without falsifying them: we have here a system of relationships that paradoxically, or rather not paradoxically at all, has less variability the greater a writer is.[7] Girard saw Proust's 'psychological laws' mirrored in reality.[8] These laws and this system are the consequences of a fundamental reality grasped by the novelists, which Girard called mimetic desire, "the mimetic character of desire." This is the content of his first book, Deceit, Desire and the Novel (1961). We borrow our desires from others. Far from being autonomous, our desire for a certain object is always provoked by the desire of another person—the model—for this same object. This means that the relationship between the subject and the object is not direct: but unrolls within a triangular relationship of subject, model, and object. Through the model, one is drawn to the object. In fact, it is the model, the mediator who is sought. This search is called "mediation." Girard calls desire "metaphysical" in the measure that, as soon as a desire is something more than a simple need or appetite, "all desire is a desire to be",[7] it is an aspiration, the dream of a fullness attributed to the mediator. Mediation is called "external" when the mediator of the desire is socially beyond the reach of the subject or, for example, a fictional character, as in the case of Amadis de Gaula and Don Quixote. The hero lives a kind of folly that nonetheless remains optimistic. Mediation is called "internal" when the mediator is at the same level as the subject. The mediator then transforms into a rival and an obstacle to the acquisition of the object, whose value increases as rivalry grows. This is the universe of the novels of Stendhal, Flaubert, Proust and Dostoevsky, which are particularly studied in this book. Through their characters, our own behaviour is displayed. Everyone holds firmly to the illusion of the authenticity of one's own desires; the novelists implacably expose all the diversity of lies, dissimulations, manoeuvres, and the snobbery of the Proustian heroes; these are all but "tricks of desire", which prevent one from facing the truth: envy and jealousy. These characters, desiring the being of the mediator, project upon him superhuman virtues while at the same time depreciating themselves, making him a god while making themselves slaves, in the measure that the mediator is an obstacle to them. Some, pursuing this logic, come to seek the failures that are the signs of the proximity of the ideal to which they aspire. This can manifest as a heightened experience of the universal pseudo-masochism inherent in seeking the unattainable, which can, of course, turn into sadism should the actor play this part in reverse.[citation needed] This fundamental focus on mimetic desire would be pursued by Girard throughout the rest of his career. The stress on imitation in humans was not a popular subject when Girard developed his theories,[citation needed] but today there is independent support for his claims coming from empirical research in psychology and neuroscience (see below). Farneti (2013)[9] also discusses the role of mimetic desire in intractable conflicts, using the case study of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and referencing Girard's theory. He posits that intensified conflict is a product of the imitative behaviours of Israelis and Palestinians, entitling them "Siamese twins".[10] The idea that the desire to possess endless material wealth was harmful to society was not new. From the New Testament verses about the love of money being the root of all kinds of evil, to Hegelian and Marxist critique that saw material wealth and capital as the mechanism of alienation of the human being both from their own humanity and their community, to Bertrand Russell's famous speech on accepting the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1950, desire has been understood as a destructive force in all of literature – with the theft of Helen by Paris a frequent topic of discussion by Girard.[citation needed] What Girard contributed to this concept is the idea that what is desired fundamentally is not the object itself, but the ontological state of the subject which possesses it, where mimicry is the aim of the competition.[citation needed] What Paris wanted, then, was not Helen, but to be a great king like Menelaus or Agamemnon. A person desires to be like the subject he imitates through the medium of the object that is possessed by the person he imitates. Girard claims: It is not difference that dominates the world, but the obliteration of difference by mimetic reciprocity, which itself, being truly universal, shows the relativism of perpetual difference to be an illusion.[11] This was, and remains, a pessimistic view of human life, as it posits a paradox in the very act of seeking to unify and have peace, since the erasure of differences between people through mimicry is what creates conflict, not the differentiation itself.[citation needed] Fundamental anthropology See also: Mimetic double bind and Generative anthropology Since the mimetic rivalry that develops from the struggle for the possession of the objects is contagious, it leads to the threat of violence. Girard himself says, "If there is a normal order in societies, it must be the fruit of an anterior crisis."[12] Turning his interest towards the anthropological domain, Girard began to study anthropological literature and proposed his second great hypothesis: the scapegoat mechanism, which is at the origin of archaic religion and which he sets forth in his second book Violence and the Sacred (1972), a work on fundamental anthropology.[13] If two individuals desire the same thing, there will soon be a third, then a fourth. This process quickly snowballs. Since from the beginning desire is aroused by the other (and not by the object) the object is soon forgotten and the mimetic conflict transforms into a general antagonism. At this stage of the crisis the antagonists will no longer imitate each other's desires for an object, but each other's antagonism. They wanted to share the same object, but now they want to destroy the same enemy. So, a paroxysm of violence will then focus on an arbitrary victim and a unanimous antipathy would, mimetically, grow against him. The brutal elimination of the victim will reduce the appetite for violence that possessed everyone a moment before, and leave the group, suddenly appeased and calm. The victim lies before the group, appearing simultaneously as the origin of the crisis and as the one responsible for this miracle of renewed peace. He becomes sacred, that is to say the bearer of the prodigious power of defusing the crisis and bringing peace back. Girard believes this to be the genesis of archaic religion, that is, ritual sacrifice as the repetition of the original event, of myth as an account of this event, of the taboos that forbid access to all the objects at the origin of the rivalries that degenerated into this absolutely traumatizing crisis. This religious elaboration takes place gradually over the course of the repetition of the mimetic crises whose resolution brings only temporary peace. The elaboration of the rites and of the taboos constitutes a kind of "empirical" knowledge about violence.[citation needed] Explorers and anthropologists have never been able to witness or bring true evidence for events similar to these, which go back to the earliest times. Yet 'indirect evidence' can be found, such as the universality of ritual sacrifice and the innumerable myths that have been collected from the most varied peoples. If Girard's theory is true, then we will find in myths the culpability of the victim-god, depictions of the selection of the victim and his power to beget the order that governs the group. Girard found these elements in numerous myths, beginning with that of Oedipus which he analyzed in this and later books. On this question he opposes Claude Lévi-Strauss.[citation needed] The phrase "scapegoat mechanism" was not coined by Girard himself; it had been used earlier by Kenneth Burke in Permanence and Change (1935) and A Grammar of Motives (1940). However, Girard took this concept from Burke and developed it much more extensively as an interpretation of human culture.[citation needed] In Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World (1978), Girard develops the implications of this discovery. The victimary process is the missing link between the animal world and the human world, the principle that explains the humanization of primates. It allows us to understand the need for sacrificial victims, which in turn explains the hunt which is primitively ritual and the domestication of animals as a fortuitous result of the acclimatization of a reserve of victims, or agriculture. It shows that at the beginning of all culture is archaic religion, which Durkheim had sensed.[14] The elaboration of the rites and taboos by proto-human or human groups would take infinitely varied forms while obeying a rigorous practical sense that we can detect: the prevention of the return of the mimetic crisis. So we can find in archaic religion the origin of all political or cultural institutions. The social position of king, for instance, begins as the victim of the scapegoat mechanism, though his sacrifice is deferred and he becomes responsible for the wellbeing of the whole society. According to Girard, just as the theory of natural selection of species is the rational principle that explains the immense diversity of forms of life, the victimization process is the rational principle that explains the origin of the infinite diversity of cultural forms. The analogy with Charles Darwin also extends to the scientific status of the theory, as each of these presents itself as a hypothesis that is not capable of being proven experimentally, given the extreme amounts of time necessary for the production of the phenomena in question, but which imposes itself by its great explanatory power. Origin of language According to Girard, the origin of language is also related to scapegoating. After the first victim, after the murder of the first scapegoat, there were the first prohibitions and rituals, but these came into being before representation and language, hence before culture. And that means that "people" (perhaps not human beings) "will not start fighting again."[15] Girard says: If mimetic disruption comes back, our instinct will tell us to do again what the sacred has done to save us, which is to kill the scapegoat. Therefore it would be the force of substitution of immolating another victim instead of the first. But the relationship of this process with representation is not one that can be defined in a clear-cut way. This process would be one that moves towards representation of the sacred, towards definition of the ritual as ritual and prohibition as prohibition. But this process would already begin prior the representation, you see, because it is directly produced by the experience of the misunderstood scapegoat.[15] According to Girard, the substitution of an immolated victim for the first, is "the very first symbolic sign created by the hominids."[16] Girard also says this is the first time that one thing represents another thing, standing in the place of this (absent) one. This substitution is the beginning of representation and language and also the beginning of sacrifice and ritual. The genesis of language and ritual is very slow and we must imagine that there are also kinds of rituals among the animals: "It is the originary scapegoating which prolongs itself in a process which can be infinitely long in moving from, how should I say, from instinctive ritualization, instinctive prohibition, instinctive separation of the antagonists, which you already find to a certain extent in animals, towards representation."[15] Unlike Eric Gans, Girard does not think that there is an original scene during which there is "a sudden shift from non-representation to representation,"[15] or a sudden shift from animality to humanity. According to the French sociologist Camille Tarot, it is hard to understand how the process of representation (i.e., symbolicity and language) actually occurs and he has called this a black box in Girard's theory.[17] Girard also says: One great characteristic of man is what they [the authors of the modern theory of evolution] call neoteny, the fact that the human infant is born premature, with an open skull, no hair and a total inability to fend for himself. To keep it alive, therefore, there must be some form of cultural protection, because in the world of mammals, such infants would not survive, they would be destroyed. Therefore there is a reason to believe that in the later stages of human evolution, culture and nature are in constant interaction. The first stages of this interaction must occur prior to language, but they must include forms of sacrifice and prohibition that create a space of non-violence around the mother and the children which make it possible to reach still higher stages of human development. You can postulate as many such stages as are needed. Thus, you can have a transition between ethology and anthropology which removes, I think, all philosophical postulates. The discontinuities would never be of such a nature as to demand some kind of sudden intellectual illumination.[15] Judeo-Christian scriptures Biblical text as a science of man In Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World, Girard discusses for the first time Christianity and the Bible. The Gospels ostensibly present themselves as a typical mythical account, with a victim-God lynched by a unanimous crowd, an event that is then commemorated by Christians through ritual sacrifice — a material re-presentation in this case — in the Eucharist. The parallel is perfect except for one detail: the truth of the innocence of the Victim is proclaimed by the text and the writer. The mythical account is usually built on the lie of the guilt of the victim in as much as it is an account of the event seen from the viewpoint of the anonymous lynchers. This ignorance is indispensable to the efficacy of sacrificial violence.[18] The evangelic "good news" clearly affirms the innocence of the victim, thus becoming, by attacking ignorance, the germ of the destruction of the sacrificial order on which the equilibrium of societies rests. Already the Old Testament shows this turning inside-out of the mythic accounts with regard to the innocence of the victims (Abel, Joseph, Job...), and the Hebrews were conscious of the uniqueness of their religious tradition. Girard draws special attention to passages in the Book of Isaiah, which describe the suffering of the Servant of the Lord God at the hands of the entire community who emphasize his innocence (Isaiah 53, 2–9).[19] By oppression and judgement he was taken away; And as for his generation, who considered That he was cut off from out of the land of the living, Stricken for the transgression of my people? And they made his grave with the wicked And with a rich man in his death, Although he had done no violence, And there was no deceit in his mouth. (Isaiah 53, 8–9) In the Gospels, the "things hidden since the foundation of the world" (Matthew 13:35) are unveiled with full clarity: the foundation of social order on murder, described in all its repulsive ugliness in the account of the Passion.[citation needed] This revelation is even clearer because the whole text is a work on desire and violence, from the desire of Eve in paradise to the prodigious strength of the mimetism that brings about the denial of Peter at Pesach (Mark 14: 66–72; Luke 22:54–62). Girard reinterprets certain biblical expressions in light of his theories; for instance, he sees "scandal" (skandalon, literally, a "snare", or an "impediment placed in the way and causing one to stumble or fall"[20]) as signifying mimetic rivalry, as in Peter's denial of Jesus.[21] No one escapes responsibility, neither the envious nor the envied: "Woe to the man through whom scandal comes" (Matthew 18:7).[citation needed] Christian society The evangelical revelation contains the truth on the violence, available for two thousand years, Girard tells us. Has it put an end to the sacrificial order based on violence in the society that has claimed the gospel text as its own religious text? No, he replies, since in order for a truth to have an impact it must find a receptive listener, and people do not change that quickly. The gospel text has instead acted as a ferment that brings about the decomposition of the sacrificial order. While medieval Europe showed the face of a sacrificial society that still knew very well how to despise and ignore its victims, nonetheless the efficacy of sacrificial violence has never stopped decreasing, in the measure that ignorance receded. Here Girard sees the principle of the uniqueness and of the transformations of the Western society whose destiny today is one with that of human society as a whole.[citation needed] Does the retreat of the sacrificial order mean less violence? Not at all; rather, it deprives modern societies of most of the capacity of sacrificial violence to establish temporary order. The "innocence" of the time of the ignorance is no more. On the other hand, Christianity, following the example of Judaism, has desacralized the world, making possible a utilitarian relationship with nature. Increasingly threatened by the resurgence of mimetic crises on a grand scale, the contemporary world is on one hand more quickly caught up by its guilt, and on the other hand has developed such a great technical power of destruction that it is condemned to both more and more responsibility and less and less innocence.[22] So, for example, while empathy for victims manifests progress in the moral conscience of society, it nonetheless also takes the form of a competition among victims that threatens an escalation of violence.[citation needed] Girard is critical of the optimism of humanist observers, who believe in the natural goodness of man and the progressive improvement of his historical conditions (views themselves based in a misunderstanding of the Christian revelation). Rather, the current nuclear stalemate between the great powers reveals that man's capacity for violence is greater than ever before, and peace is only a product of this possibility to unleash apocalyptic destruction.[23] |

ジラールの思想 擬態願望 主な記事 擬態論 アメリカで10年近くフランス文学を教えた後、ジラールは文学テクストについて語る新しい方法を開発し始めた。彼は、個々の作品の「独自性」を超えて、そ の作品に共通する構造的特性を探した。偉大な小説の登場人物は、そうでなければ広く一般的な小説に共通する関係性のシステムの中で進化していくことを観察 したのである。しかし、そこには区別があった: 偉大な作家だけが、これらのメカニズムを偽ることなく忠実に描くことに成功しているのだ。逆説的に、いやむしろまったく逆説的ではないのだが、偉大な作家であればあるほど変動性が小さくなるような関係体系がここにはある[7]。 ジラールはプルーストの「心理的法則」が現実に反映されているのを見た[8]。これらの法則とこのシステムは、ジラールが「欲望の擬態的性格」と呼ぶ、小 説家が把握した基本的現実の結果である。これが彼の最初の著書『欺瞞、欲望、小説』(1961年)の内容である。私たちは他者から欲望を借りている。ある 対象に対する私たちの欲望は、自律的であるどころか、常に同じ対象に対する他者(モデル)の欲望によって引き起こされる。つまり、主体と客体の関係は直接 的なものではなく、主体、モデル、客体という三角関係の中で展開される。モデルを通して、人は対象へと引き寄せられる。 実際、求められるのはモデルであり、媒介者である。この探索は 「媒介 」と呼ばれる。 ジラールは欲望を「形而上学的」と呼ぶが、それは欲望が単純な欲求や食欲を超えるものである以上、「すべての欲望は存在したいという欲望である」[7]という尺度においてであり、それは願望であり、媒介者に帰属する充足の夢なのである。 アマディス・デ・ガウラやドン・キホーテの場合のように、欲望の媒介者が社会的に主体の手の届かないところにいる場合、あるいは例えば架空の人物である場合、媒介は「外的」と呼ばれる。主人公は一種の愚行を生き、それにもかかわらず楽観的であり続ける。 媒介者が主体と同じレベルにあるとき、媒介は「内的」と呼ばれる。媒介者はその後、ライバルとなり、対象獲得への障害となる。 これが、本書で特に研究されているスタンダール、フローベール、プルースト、ドストエフスキーの小説の世界である。 彼らの登場人物を通して、私たち自身の行動が示される。小説家たちは、嘘、偽り、策略、プルースト的主人公の俗物性など、あらゆる多様性を無情にも暴露す る。これらはすべて「欲望のトリック」に過ぎず、嫉妬や羨望という真実に直面することを妨げるものなのだ。これらの登場人物は、調停者の存在を欲し、調停 者に超人的な美徳を投影すると同時に、自分自身を卑下し、調停者が自分たちにとって邪魔な存在であるという尺度で、彼を神とし、自分自身を奴隷とする。こ の論理を追求するある者は、自分が熱望する理想に近づいている証である失敗を求めるようになる。これは、達成不可能なものを求めることに内在する普遍的な 擬似マゾヒズムの経験の高まりとして現れる可能性があり、もちろん、役者がこの役を逆に演じれば、サディズムに転化することもある[要出典]。 模倣的欲望に対するこの基本的な焦点は、ジラールがその後のキャリアを通じて追求することになる。ジラールが理論を展開した当時、人間における模倣の強調 は人気のあるテーマではなかったが[要出典]、今日、心理学や神経科学における実証的研究から、彼の主張に対する独自の裏付けが得られている(下記参 照)。Farneti(2013)[9]もまた、イスラエルとパレスチナの紛争を事例に、ジラールの理論を参照しながら、難解な紛争における模倣的欲求の 役割について論じている。彼は、対立の激化はイスラエル人とパレスチナ人の模倣的行動の産物であり、「シャム双生児」と名付けている[10]。 無限の物質的富を所有したいという欲望が社会に害を及ぼすという考えは、新しいものではなかった。金銭を愛することがあらゆる悪の根源であるという新約聖 書の一節から、物質的な富と資本を人間性と共同体の両方から人間を疎外するメカニズムとして捉えたヘーゲルやマルクス主義の批評、1950年にノーベル文 学賞を受賞したバートランド・ラッセルの有名な演説に至るまで、欲望はあらゆる文学において破壊的な力として理解されてきた。 ジラールがこの概念に貢献したのは、根本的に欲望されるのは対象そのものではなく、それを所有する主体の存在論的状態であり、模倣が競争の目的であるという考え方である。 人は、自分が模倣する対象が持っているものを媒介として、自分が模倣する対象のようになりたいと願うのである。ジラールは主張する: 世界を支配しているのは差異ではなく、模倣的互酬性によって差異を消し去ることであり、それ自体が真に普遍的であるために、永遠の差異という相対主義が幻想であることを示すのだ」[11]。 これは、統一と平和を求める行為そのものにパラドックスを仮定しているため、人間生活に対する悲観的な見方であり、現在もそうである。なぜなら、模倣によって人々の間の差異を消し去ることこそが対立を生み出すのであり、差異そのものではないからである[要出典]。 基本的人間学 以下も参照のこと: 模倣的ダブルバインドと生成人類学 対象物の所有権争いから生まれる擬態的対立は伝染するため、暴力の脅威につながる。ジラール自身、「社会に正常な秩序があるとすれば、それは前段階の危機 の結実であるに違いない」と述べている[12]。人類学の領域に関心を向けたジラールは、人類学文献を研究し始め、2つ目の偉大な仮説を提唱した。スケー プゴート・メカニズムとは、古代の宗教の起源にあるものであり、基本的人類学に関する著作である2冊目の著書『暴力と聖なるもの』(1972年)で述べら れている[13]。 二人の個人が同じことを望めば、すぐに三人目が生まれ、四人目が生まれる。このプロセスはすぐに雪だるま式に膨れ上がる。最初から欲望は(対象ではなく) 他者によって喚起されるので、対象はすぐに忘れ去られ、模倣的な対立は一般的な拮抗へと変化する。この危機の段階では、拮抗者たちはもはや、対象に対する 互いの欲望を模倣するのではなく、互いの拮抗を模倣するようになる。彼らは同じ対象を共有したかったが、今は同じ敵を破壊したいのだ。 だから、暴力の発作は、任意の犠牲者に集中し、全会一致の反感が、擬態的に、その犠牲者に対して高まることになる。被害者を残忍に排除することで、一瞬前 まで全員にあった暴力への欲求が抑えられ、集団は突然なだめられ、平静を取り戻す。被害者は集団の前に横たわり、危機の元凶として、またこの奇跡的な平和 の再来をもたらした張本人として同時に現れる。被害者は神聖な存在となり、危機を和らげ、平和を取り戻す偉大な力の担い手となる。 ジラールは、これが古代の宗教の起源であると考える。つまり、元の出来事の繰り返しとしての儀式的犠牲、この出来事の説明としての神話、この絶対的なトラ ウマとなる危機に発展した対立の起源となったすべての対象へのアクセスを禁じるタブーである。この宗教的精緻化は、その解決が一時的な平穏をもたらすにす ぎない模倣的危機の繰り返しの過程で、徐々に行われる。儀式とタブーの精緻化は、暴力に関する一種の「経験的」知識を構成している[要出典]。 探検家や人類学者は、太古の昔にさかのぼるこれらに類似した出来事を目撃したり、真の証拠をもたらすことはできなかった。しかし、儀式の生贄の普遍性や、 最も多様な民族から集められた無数の神話など、「間接的な証拠」は見つけることができる。もしジラールの理論が真実であれば、神話の中に犠牲者である神の 罪責、犠牲者の選択、そして集団を支配する秩序を生み出す力の描写を見出すことができるだろう。 ジラールはオイディプスの神話をはじめ、数多くの神話にこうした要素を見いだし、本書やそれ以降の著書で分析している。この問題に関して、彼はクロード・レヴィ=ストロースと対立している[要出典]。 スケープゴート・メカニズム」という言葉はジラール自身の造語ではなく、それ以前にケネス・バークが『永続と変化』(1935年)と『動機の文法』 (1940年)の中で使っていた。しかし、ジラールはバークからこの概念を受け取り、人間文化の解釈としてより広範囲に発展させた[要出典]。 ジラールは『世界の基礎以来隠されてきたもの』(1978年)の中で、この発見の意味を展開している。犠牲者のプロセスは、動物の世界と人間の世界をつなぐミッシング・リンクであり、霊長類の人間化を説明する原理である。 犠牲者の必要性を理解することができ、狩猟は原始的な儀式であり、動物の家畜化は犠牲者予備軍の馴化、つまり農業の偶然の結果である。このことは、すべて の文化の始まりが、デュルケームが感じ取っていた古代の宗教であることを示している[14]。原人や人間の集団による儀式やタブーの精緻化は、無限に多様 な形をとりながら、模倣的危機の再来を防ぐという、われわれが感知できる厳格な実践的感覚に従っている。古代の宗教に、あらゆる政治的・文化的制度の起源 を見出すことができる。 例えば、王という社会的地位は、スケープゴート・メカニズムの犠牲者として始まるが、彼の犠牲は先送りされ、彼は社会全体の幸福に責任を負うようになる。 ジラールによれば、種の自然淘汰理論が生命の形態の膨大な多様性を説明する合理的原理であるように、犠牲者化プロセスは文化形態の無限の多様性の起源を説明する合理的原理である。 チャールズ・ダーウィンとのアナロジーは、理論の科学的地位にも及んでいる。それぞれが、問題となる現象の生成に必要な時間が極端に長いことを考えると、実験的に証明することはできないが、大きな説明力によって自らを課す仮説として自らを提示しているからである。 言語の起源 ジラールによれば、言語の起源もスケープゴートに関係している。最初の犠牲者の後、最初のスケープゴートが殺された後、最初の禁止と儀式があったが、それ らは表象と言語、つまり文化よりも先に生まれた。そしてそれは、「人々」(おそらく人間ではない)が「再び戦い始めることはない」[15]ということを意 味している: もし模倣的破壊が戻ってくれば、われわれの本能は、聖なるものがわれわれを救うために行ったこと、つまりスケープゴートを殺すことを再び行うように言うだ ろう。したがって、それは最初の犠牲者の代わりに別の犠牲者を没するという代替の力であろう。しかし、このプロセスと表象との関係は、明確に定義できるも のではない。このプロセスは、聖なるものの表象に向かうものであり、儀式を儀式として、禁止を禁止として定義するものである。しかし、このプロセスは表象 に先立ってすでに始まっているのであり、それは誤解されたスケープゴートの経験によって直接生み出されるからである[15]。 ジラールによれば、焼かれた犠牲者を最初の犠牲者に置き換えることは、「ヒト科の動物が生み出した最初の象徴的しるし」である[16]。 この代替は表象と言語の始まりであり、犠牲と儀式の始まりでもある。言語と儀礼の発生には非常に時間がかかり、動物の間にも儀礼の種類があることを想像し なければならない: 「本能的な儀式化、本能的な禁止、本能的な拮抗者の分離、これはすでに動物にある程度見られるものであるが、こうしたものから表象へと向かう過程で、無限 に長くなる可能性がある」[15]。 エリック・ガンスとは異なり、ジラールは「非表象から表象への突然の転換」[15]や「動物性から人間性への突然の転換」が起こるような最初の場面があるとは考えていない。 フランスの社会学者カミーユ・タローによれば、表象のプロセス(すなわち象徴性と言語)が実際にどのように起こるのかを理解することは難しく、彼はこれをジラールの理論におけるブラックボックスと呼んでいる[17]。 ジラールはこうも言っている: 人間の一つの大きな特徴は、彼ら[現代の進化論の著者たち]がネオテニーと呼ぶものであり、人間の乳児は未熟児として生まれ、頭蓋骨が開いたままで、髪の 毛もなく、自活する能力がまったくないという事実である。哺乳類の世界では、このような幼児は生き残ることができず、処分されてしまうからだ。それゆえ、 人類の進化の後期には、文化と自然が常に相互作用していると考える理由がある。 この相互作用の最初の段階は、言語に先立って起こるに違いないが、その中には犠牲と禁制の形態が含まれているはずで、それが母子の周囲に非暴力の空間を作 り出し、人間の発達のさらなる高みに到達することを可能にしている。このような段階は、必要な数だけ想定することができる。 こうして、倫理学と人類学の間に、哲学的な仮定をすべて取り払った移行が可能になるのだ。その不連続性は、突然に知的な啓示を必要とするような性質のものでは決してない。 ユダヤ教・キリスト教の聖典 人間の科学としての聖書 ジラールは『世界の基より隠されたもの』の中で、初めてキリスト教と聖書について論じている。福音書は、表向きは典型的な神話的記述であり、犠牲となった 神が群衆の一致によってリンチされ、その出来事はキリスト教徒によって儀式の犠牲(この場合は物質的な再提示)を通じて聖体で記念される。犠牲者の潔白と いう真実が、テキストと作家によって宣言されているのだ。 神話的な説明は、匿名のリンチ犯の視点から見た出来事の説明である以上、被害者の有罪という嘘の上に成り立っているのが普通である。この無知は、犠牲的暴力の効力にとって不可欠である[18]。 福音的な「良い知らせ」は、被害者の無実を明確に肯定し、無知を攻撃することによって、社会の均衡がかかっている犠牲的秩序を破壊する萌芽となる。旧約聖 書はすでに、犠牲者の潔白(アベル、ヨセフ、ヨブ......)に関して、神話的説明を裏返しにすることを示しており、ヘブライ人は自分たちの宗教的伝統 の独自性を自覚していた。 ジラールは、イザヤ書の一節に特別な注意を喚起している。イザヤ書には、主なる神のしもべが、その潔白を強調する共同体全体の手によって苦しみを受ける様子が描写されている(イザヤ書53章2~9節)[19]。 抑圧と裁きによって、彼は連れ去られた; そして、彼の世代については、誰が考えたか。 彼は生ける者の国から断たれた、 わたしの民の背きのために断たれたことを、誰が考えたであろうか。 かれらはその墓を,悪しき者とともに作った。 その死において,富める者とともにした、 かれは暴力を振るわなかった、 その口には偽りがなかった。(イザヤ53・8-9)。 福音書では、「世の初めから隠されていたこと」(マタイによる福音書13章35節)が完全に明らかにされている。 この啓示は、楽園でのエバの欲望から、ペサハでのペテロの否認をもたらす擬態の驚異的な強さまで(マルコ14:66-72、ルカ22:54-62)、テキスト全体が欲望と暴力に関する作品であるため、さらに明確である。 例えば、ジラールは「スキャンダル」(skandalon、直訳すると「罠」、「道に置かれ、人をつまずかせたり、転ばせたりする障害」[20])を、ペ テロのイエス否定に見られるような、擬態的な対立を意味するものとして捉えている[21]。妬む者も妬まれる者も、誰も責任を逃れることはできない: 「災いなるかな、スキャンダルの起こる者は」(マタイ18:7)[要出典]。 キリスト教社会 福音主義的啓示は暴力に関する真理を含んでいる。福音書のテキストを自らの宗教的テキストとして主張する社会における暴力に基づく犠牲的秩序に終止符を 打ったのだろうか?真理が影響力を持つためには、それを受け入れてくれる聞き手を見つけなければならない。福音書のテキストは、犠牲の秩序を崩壊させる発 酵剤のような役割を果たしてきた。中世ヨーロッパは、犠牲者を軽蔑し、無視する方法をまだよく知っている犠牲社会の顔を見せたが、それにもかかわらず、無 知が後退した分だけ、犠牲的暴力の効力は減少を止めなかった。ここにジラールは、今日の運命が人類社会全体の運命と一体である西洋社会の独自性と変容の原 理を見るのである。 犠牲的秩序の後退は、暴力の減少を意味するのだろうか。そうではなく、むしろ現代社会は、一時的な秩序を確立するための犠牲的暴力の能力のほとんどを奪っ ているのだ。無知の時代の「無邪気さ」はもうない。一方、キリスト教はユダヤ教に倣い、世界を非神聖化し、自然との功利主義的関係を可能にした。壮大なス ケールの模倣的危機の再来にますます脅かされる現代世界は、一方ではより迅速に罪悪感にとらわれ、他方では破壊の偉大な技術力を発達させたために、ますま す責任が重くなり、ますます無実でなくなることを宣告されている。 [22] そのため、例えば、被害者への共感は社会の道徳的良心に進歩を現す一方で、それにもかかわらず、暴力のエスカレートを脅かす被害者間の競争という形もとる のである。むしろ、現在の大国間の核の膠着状態は、人間の暴力に対する能力がかつてないほど大きくなっていることを明らかにしており、平和は終末的な破壊 を解き放つ可能性の産物にすぎない[23]。 |

| Influence Economics and globalization The mimetic theory has also been applied in the study of economics, most notably in La violence de la monnaie (1982) by Michel Aglietta and André Orléan. Orléan was also a contributor to the volume René Girard in Les cahiers de l'Herne ("Pour une approche girardienne de l'homo oeconomicus").[24] According to the philosopher of technology Andrew Feenberg: In La violence de la monnaie, Aglietta and Orléan follow Girard in suggesting that the basic relation of exchange can be interpreted as a conflict of 'doubles', each mediating the desire of the Other. Like Lucien Goldmann, they see a connection between Girard's theory of mimetic desire and the Marxian theory of commodity fetishism. In their theory, the market takes the place of the sacred in modern life as the chief institutional mechanism stabilizing the otherwise explosive conflicts of desiring subjects.[25] In an interview with the Unesco Courier, anthropologist and social theorist Mark Anspach (editor of the René Girard issue of Les Cahiers de l'Herne) explains that Aglietta and Orléan (who were very critical of economic rationality) see the classical theory of economics as a myth. According to Anspach, the vicious circle of violence and vengeance generated by mimetic rivalry gives rise to the gift economy, as a means to overcome it and achieve peaceful reciprocity: "Instead of waiting for your neighbour to come steal your yams, you offer them to him today, and it is up to him to do the same for you tomorrow. Once you have made a gift, he is obliged to make a return gift. Now you have set in motion a positive circularity."[26] Since the gift may be so large as to be humiliating, a second stage of development—"economic rationality"—is required: this liberates the seller and the buyer of any other obligations than to give money. Thus reciprocal violence is eliminated by the sacrifice, obligations of vengeance by the gift, and finally the possibly dangerous gift by "economic rationality." This rationality, however, creates new victims, as globalization is increasingly revealing. Literature Girard's influence extends beyond philosophy and social science, and includes the literary realm. A prominent example of a fiction writer influenced by Girard is J. M. Coetzee, winner of the 2003 Nobel Prize in Literature. Critics have noted that mimetic desire and scapegoating are recurring themes in Coetzee's novels Elizabeth Costello and Disgrace. In the latter work, the book's protagonist also gives a speech about the history of scapegoating with noticeable similarities to Girard's view of the same subject. Coetzee has also frequently cited Girard in his non-fiction essays, on subjects ranging from advertising to the Russian writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.[27] Theology Theologians who describe themselves as indebted to Girard include James Alison (who focuses on mimetic desire's implications for the doctrine of original sin), and Raymund Schwager (who builds a dramatic narrative around both the scapegoat mechanism and the theo-drama of fellow Swiss theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar). |

影響力 経済学とグローバリゼーション 模倣理論は経済学の研究にも応用されており、特にミシェル・アグリエッタとアンドレ・オルレアンの『La violence de la monnaie』(1982年)が有名である。オルレアンは『Les cahiers de l'Herne』のルネ・ジラールの巻(「Pour une approche girardienne de l'homo oeconomicus」)にも寄稿している[24]。技術哲学者アンドリュー・フィーンバーグによれば、次のようになる: La violence de la monnaie』において、アグリエッタとオルレアンはジラールに倣い、交換の基本的関係は、それぞれが他者の欲望を媒介する「替え玉」の対立として解釈 できることを示唆している。ルシアン・ゴールドマンと同様、彼らはジラールの擬態的欲望論とマルクス主義の商品フェティシズム論との間に関連性を見出して いる。彼らの理論では、市場は欲望を抱く主体の爆発的な対立を安定させる主要な制度的メカニズムとして、現代生活において神聖なものの代わりを担っている [25]。 人類学者で社会理論家のマーク・アンスパック(『Les Cahiers de l'Herne』誌のルネ・ジラール号の編集者)は、『Unesco Courier』誌とのインタビューの中で、(経済合理性に非常に批判的だった)アグリエッタとオルレアンは古典的な経済学の理論を神話と見なしていると 説明している。アンスパックによれば、模倣的な対立が生み出す暴力と復讐の悪循環は、それを克服し平和的な互恵関係を実現する手段として贈与経済を生み出 す: 「隣人がヤムイモを盗みに来るのを待つのではなく、今日ヤムイモを差し出す。あなたが贈り物をしたら、その人はお返しをする義務がある。贈与が屈辱的なほ ど大規模になる可能性があるため、第二段階の発展-「経済合理性」-が必要となる。こうして、互恵的暴力は犠牲によって排除され、復讐の義務は贈与によっ て排除され、最終的に、危険な贈与は 「経済合理性 」によって排除される。しかしこの合理性は、グローバリゼーションがますます明らかにしつつあるように、新たな犠牲者を生み出すのである。 文学 ジラールの影響は哲学や社会科学にとどまらず、文学の領域にも及んでいる。ジラールの影響を受けた小説家の代表例は、2003年にノーベル文学賞を受賞し たJ・M・クッツェーである。批評家たちは、クッツェーの小説『エリザベス・コステロ』と『恥辱』において、模倣的欲望とスケープゴーティングが繰り返し テーマになっていると指摘している。後者の作品では、主人公がスケープゴートの歴史について演説しているが、同じテーマについてのジラールの見解と顕著な 類似点がある。クッツェーはまた、広告からロシアの作家アレクサンドル・ソルジェニーツィンまで、幅広いテーマに関するノンフィクションのエッセイでも頻 繁にジラールを引用している[27]。 神学 ジラールへの恩義を自称する神学者には、ジェイムズ・アリソン(模倣願望が原罪の教義に与える影響に注目)、レイムンド・シュヴァーガー(スケープゴー ト・メカニズムと、同じスイスの神学者ハンス・ウルス・フォン・バルタザールのテオ・ドラマの両方を軸にドラマチックな物語を構築)などがいる。 |

| Criticism Originality Some critics have pointed out that while Girard may be the first to have suggested that all desire is mimetic, he is by no means the first to have noticed that some desire is mimetic – Gabriel Tarde's book Les lois de l'imitation (The Laws of Imitation) appeared in 1890. Building on Tarde, crowd psychology, Nietzsche, and more generally on a modernist tradition of the "mimetic unconscious" that had hypnosis as its via regia, Nidesh Lawtoo argued that for the modernists not only desire but all affects turn out to be contagious and mimetic.[28] René Pommier[29] mentions La Rochefoucauld, a seventeenth-century thinker who already wrote that "Nothing is so infectious as example" and that "There are some who never would have loved if they never had heard it spoken of."[30] Stéphane Vinolo sees Baruch Spinoza and Thomas Hobbes as important precursors. Hobbes: "if any two men desire the same thing, which nevertheless they cannot both enjoy, they become enemies."[31] Spinoza: "By the very fact that we conceive a thing, which is like ourselves, and which we have not regarded with any emotion, to be affected with any emotion, we are ourselves affected with a like emotion.[32] Proof… If we conceive anyone similar to ourselves as affected by any emotion, this conception will express a modification of our body similar to that emotion."[33] Wolfgang Palaver [de] adds Alexis de Tocqueville to the list. "Two hundred years after Hobbes, the French historian Alexis de Tocqueville mentioned the dangers coming along with equality, too. Like Hobbes, he refers to the increase of mimetic desire coming along with equality."[34] Palaver has in mind passages like this one, from Tocqueville's Democracy in America: "They have swept away the privileges of some of their fellow creatures which stood in their way, but they have opened the door to universal competition; the barrier has changed its shape rather than its position."[35] Maurizio Meloni highlights the similarities between Girard, Jacques Lacan and Sigmund Freud.[36] Meloni claims that these similarities arise because the projects undertaken by the three men—namely, to understand the role of mythology in structuring the human psyche and culture—were very similar. What is more, both Girard and Lacan read these myths through the lens of structural anthropology so it is not surprising that their intellectual systems came to resemble one another so strongly. Meloni writes that Girard and Lacan were "moved by similar preoccupations and are fascinated by and attracted to the same kind of issues: the constituent character of the other in the structure of desire, the role of jealousy and rivalry in the construction of the social bond, the proliferation of triangles within apparently dual relations, doubles and mirrors, imitation and the Imaginary, and the crisis of modern society within which the 'rite of Oedipus' is situated." At times, Girard acknowledges his indebtedness to such precursors, including Tocqueville.[37] At other times, however, Girard makes stronger claims to originality, as when he says that mimetic rivalry "is responsible for the frequency and intensity of human conflicts, but strangely, no one ever speaks of it."[38] Use of evidence Girard has presented his view as being scientifically grounded: "Our theory should be approached, then, as one approaches any scientific hypothesis."[39] René Pommier has written a book about Girard with the ironic title Girard Ablaze Rather Than Enlightened in which he asserts that Girard's readings of myths and Bible stories—the basis of some of his most important claims—are often tendentious. Girard notes, for example, that the disciples actively turn against Jesus.[40] Since Peter warms himself by a fire, and fires always create community, and communities breed mimetic desire, this means that Peter becomes actively hostile to Jesus, seeking his death.[41] According to Pommier, Girard claims that the Gospels present the Crucifixion as a purely human affair, with no indication of Christ dying for the sins of mankind, a claim contradicted by Mark 10:45 and Matthew 20:28.[42] The same goes for readings of literary texts, says Pommier. For example, Molière's Don Juan only pursues one love object for mediated reasons,[43] not all of them, as Girard claims.[44] Or again, Sancho Panza wants an island not because he is catching the bug of romanticism from Don Quixote, but because he has been promised one.[45] And Pavel Pavlovitch, in Dostoevsky's Eternal Husband, has been married for ten years before Veltchaninov becomes his rival, so Veltchaninov is not in fact essential to Pavel's desire.[46] Accordingly, a number of scholars have suggested that Girard's writings are metaphysics rather than science. Theorist of history Hayden White did so in an article titled "Ethnological 'Lie' and Mystical 'Truth'";[47] Belgian anthropologist Luc de Heusch made a similar claim in his piece "L'Evangile selon Saint-Girard" ("The Gospel according to Saint Girard");[48] and Jean Greisch sees Girard's thought as more or less a kind of Gnosis.[49] Non-mimetic desires René Pommier has pointed out a number of problems with the Girardian claim that all desire is mimetic. First, it is very hard to explain the existence of taboo desires, such as homosexuality in repressive societies, on that basis.[50] Second, every situation presents large numbers of potential mediators, which means that the individual has to make a choice among them; either authentic choice is possible, then, or else the theory leads to a regress.[51] Third, Girard leaves no room for innovation: Surely somebody has to be the first to desire a new object, even if everyone else follows that trend-setter.[52] One might also argue that the last objection ignores the influence of an original sin from which all others follow, which Girard clearly affirms. However, original sin, according to Girard's interpretation, explains only our propensity to imitate, not the specific content of our imitated desires.[53] Thus, the doctrine of original sin does not solve the problem of how the original model first acquires the desire that is subsequently imitated by others. Beneficial imitation In the early part of Girard's career, there seemed no place for beneficial imitation. Jean-Michel Oughourlian objected that "imitation can be totally peaceful and beneficial; I don't believe that I am the other, I don't want to take his place. …This imitation can lead me to become sensitive to social and political problems."[54] Rebecca Adams argued that because Girard's theories fixated on violence, he was creating a "scapegoat" himself with his own theory: the scapegoat of positive mimesis. Adams proposed a reassessment of Girard's theory that includes an account of loving mimesis or, as she preferred to call it, creative mimesis.[55] More recently, Girard has made room for positive imitation.[56] But as Adams implies, it is not clear how the revised theory accords with earlier claims about the origin of culture. If beneficial imitation is possible, then it is no longer necessary for cultures to be born by means of scapegoating; they could just as well be born through healthy emulation. Nidesh Lawtoo further develops the healthy side of mimetic contagion by drawing on a Nietzschean philosophical tradition that privileges "laughter" and other gay forms of "sovereign communication" in the formation of "community."[57] Anthropology Various anthropologists have contested Girard's claims. Elizabeth Traube, for example, reminds us that there are other ways of making sense of the data that Girard borrows from Evans-Pritchard and company—ways that are more consistent with the practices of the given culture. By applying a one-size-fits-all approach, Girard "loses … the ability to tell us anything about cultural products themselves, for the simple reason that he has annihilated the cultures which produced them."[58] Religion One of the main sources of criticism of Girard's work comes from intellectuals who claim that his comparison of Judeo-Christian texts vis-à-vis other religions leaves something to be desired.[59] There are also those who find the interpretation of the Christ event—as a purely human event, having nothing to do with redemption from sin—an unconvincing one, given what the Gospels themselves say.[42] Yet, Roger Scruton notes, Girard's account has a divine Jesus: "that Jesus was the first scapegoat to understand the need for his death and to forgive those who inflicted it … Girard argues, Jesus gave the best evidence … of his divine nature."[60] |

批評 オリジナリティ 批評家の中には、すべての欲望は模倣的であると示唆したのはジラールが最初かもしれないが、ある種の欲望が模倣的であることに気づいたのは、決してジラー ルが最初ではない、と指摘する者もいる。タルド、群集心理学、ニーチェ、そしてより一般的には、催眠術を手段とする「模倣的無意識」のモダニスト的伝統に 基づき、ニデシュ・ロートゥーは、モダニストにとって、欲望だけでなく、あらゆる影響が伝染し、模倣されることが判明したと論じた。 [28] ルネ・ポミエ[29]は、17世紀の思想家であり、すでに「手本ほど伝染するものはない」、「もしそれが語られるのを聞かなかったならば、決して愛さな かったであろう者がいる」と書いたラ・ロシュフコーに言及している[30]。 ステファン・ヴィノロは、バルーク・スピノザとトマス・ホッブズを重要な先駆者と見ている。ホッブズは言う: ホッブズ:「もし二人の人間が同じものを望み、それにもかかわらず二人ともそれを享受することができないならば、二人は敵同士となる」[31] スピノザ:「自分自身と似ていて、自分がいかなる感情も抱いていないと見なしているものが、いかなる感情も抱いていると考えるというまさにその事実によっ て、自分自身は似たような感情を抱いている」[32] 証明......もし自分自身と似たような者が、いかなる感情も抱いていると考えるならば、この概念は、その感情に似た身体の変化を表現することになる」 [33] 。 ヴォルフガング・パラヴァー[訳注]は、アレクシス・ド・トクヴィルをこのリストに加えた。「ホッブズから200年後、フランスの歴史家アレクシス・ド・ トクヴィルもまた、平等に伴う危険性について言及している。ホッブズと同様、彼は平等とともに生じる模倣的欲望の増大について言及している」[34]。パ レイバーが念頭に置いているのは、トクヴィルの『アメリカの民主主義』にあるこのような一節だ。 マウリツィオ・メローニは、ジラール、ジャック・ラカン、ジークムント・フロイトの間の類似性を強調している[36]。メローニは、こうした類似性が生じ るのは、3人が取り組んだプロジェクト、すなわち人間の精神と文化の構造化における神話の役割を理解するプロジェクトが非常に類似していたからだと主張し ている。さらに言えば、ジラールとラカンはともに構造人類学のレンズを通してこれらの神話を読んでいたのだから、彼らの知的体系が互いに強く類似するよう になったのは驚くことではない。メローニは、ジラールとラカンは「同じような関心に動かされ、同じような問題に魅了され、惹かれている。欲望の構造におけ る他者の構成的性格、社会的絆の構築における嫉妬と対立の役割、明らかに二重の関係における三角形の増殖、二重と鏡、模倣とイマジナリー、「エディプスの 儀式」が位置する近代社会の危機などである」と書いている。 ジラールは時に、トクヴィルを含むこのような先駆者たちへの恩義を認めている[37]。しかし他の時には、模倣的対立が「人間の対立の頻度と激しさの原因 であるが、不思議なことに誰もそれを口にすることはない」と言うように、ジラールは独自性をより強く主張している[38]。 証拠の使用 ジラールは、科学的根拠に基づいた見解を示している: 「ルネ・ポミエはジラールについての本を書いており、その中で、ジラールの最も重要な主張の基礎となっている神話や聖書の物語のジラールの読み方は、しば しば傾向的であると主張している。ポミエによれば、ジラールは福音書が磔刑を純粋に人間的な出来事として描いており、キリストが人類の罪のために死んだと いう兆候はないと主張しているが、この主張はマルコによる福音書10章45節とマタイによる福音書20章28節によって否定されている[42]。 これはマルコによる福音書10章45節とマタイによる福音書20章28節に矛盾する主張である[42]。例えば、モリエールの『ドン・ファン』は、ジラー ルが主張するように、媒介された理由[43]のためにひとつの愛の対象を追い求めるだけで、そのすべてを追い求めるわけではない。 あるいはまた、サンチョ・パンサが島を欲しがるのは、ドン・キホーテからロマンティシズムの虫をうつされたからではなく、島を約束されたからである。 [また、ドストエフスキーの『永遠の夫』におけるパーヴェル・パヴロヴィッチは、ヴェルトチャニノフがライバルになる前に10年間結婚している。 したがって、ジラールの著作は科学というよりもむしろ形而上学であると多くの学者が示唆している。歴史理論家のヘイデン・ホワイトは「民族学的な『嘘』と 神秘学的な『真実』」と題された論文でそう述べており[47]、ベルギーの人類学者リュック・ド・ホイシュは「聖ジラールによる福音書」 (L'Evangile selon Saint-Girard)という論文で同様の主張を行っている[48]。またジャン・グライシュはジラールの思想を多かれ少なかれグノーシスの一種と見 ている[49]。 非模倣的欲望 ルネ・ポミエは、すべての欲望は擬態的であるというジラールの主張には多くの問題があると指摘している。第一に、抑圧的な社会における同性愛のようなタ ブー視される欲望の存在をその根拠に基づいて説明することは非常に困難である[50]。第二に、あらゆる状況は多数の潜在的な媒介者を提示しており、個人 はそれらの中から選択をしなければならない: たとえ他の誰もがそのトレンド・セッターに従うとしても、誰かが最初に新しい対象を欲望しなければならないのは確かである[52]。 また、最後の反論は、ジラールが明確に肯定している原罪の影響を無視したものであり、そこから他のすべてのものが導かれるのだと主張するかもしれない。し かし、ジラールの解釈によれば、原罪は模倣する傾向のみを説明するものであり、模倣された欲望の具体的な内容を説明するものではない。[53] したがって、原罪の教義は、原型となる人物が、その後他の人々によって模倣される欲望をどのようにして最初に獲得するのかという問題を解決するものではな い。 有益な模倣 ジラールのキャリアの初期には、有益な模倣の場所はないように思われた。ジャン=ミシェル・ウーグルリアンは、「模倣はまったく平和的で有益なものであ る。...この模倣は、私を社会的、政治的問題に敏感にさせることができる」[54] レベッカ・アダムスは、ジラールの理論が暴力に固執しているため、彼自身の理論で「スケープゴート」を作り出していると主張した。アダムスは愛に満ちたミ メーシス、あるいは彼女が好んで呼ぶところの創造的ミメーシスについての説明を含むジラールの理論の再評価を提案した[55]。 より最近では、ジラールは積極的模倣の余地を作っている[56]。しかしアダムスが示唆するように、改訂された理論が文化の起源に関する以前の主張とどの ように一致するのかは明らかではない。もし有益な模倣が可能であるならば、文化がスケープゴートによって生まれる必要はもはやない。ニデシュ・ロートゥー はさらに、「共同体」の形成において「笑い」やその他のゲイ的な形態の「主権的コミュニケーション」を特権化するニーチェの哲学的伝統を引くことで、模倣 伝染の健全な側面を発展させている[57]。 人類学 様々な人類学者がジラールの主張に異議を唱えている。例えば、エリザベス・トラウベは、ジラールがエバンス=プリチャードたちから借用したデータを理解す る方法は他にもあり、与えられた文化の慣習により合致した方法があることを私たちに思い起こさせる。画一的なアプローチを適用することによって、ジラード は「文化的産物それ自体について何かを語る能力を......それを生み出した文化を消滅させてしまったという単純な理由で失っている」[58]。 宗教 ジラールの著作に対する批判の主な源の一つは、他の宗教に対するユダヤ教・キリスト教のテクストの比較に不満が残ると主張する知識人たちから来る [59]。また、キリストの出来事-罪からの贖罪とは無関係な、純粋に人間的な出来事-についての解釈が、福音書自体に書かれていることを考慮すると、説 得力のないものだと考える人々もいる[42]: 「イエスは自分の死の必要性を理解し、その死を与えた人々を赦す最初の身代わりであった......ジラールは、イエスは彼の神性について......最 良の証拠を与えたと主張する」[60]。 |

| Personal life René Girard's wife, Martha (née McCullough), was American; they were married from 1952 until his death. They had two sons, Martin Girard (born 1955) and Daniel Girard (born 1957), and a daughter, Mary Brown-Girard (born 1960).[61] Girard's reading of Dostoevsky, in preparation for his first book in 1961, converted him from agnosticism to Christianity. For the rest of his life, he was a practising Roman Catholic.[62] On 4 November 2015, Girard died at his residence in Stanford, California, at the age of 91.[1] Honours and awards Honorary degrees at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (the Netherlands, 1985), UFSIA in Antwerp (Belgium, 1995), the Università degli Studi di Padova (Italy, 2001, honorary degree in "Arts"),[63] the faculty of theology at the University of Innsbruck (Austria), the Université de Montréal (Canada, 2004),[64] and the University of St Andrews (UK, 2008)[65] The Prix Médicis essai for Shakespeare, les feux de l'envie (A Theatre of Envy: William Shakespeare, 1991) The prix Aujourd'hui for Les origines de la culture (2004) Guggenheim Fellow (1959 and 1966)[66] Election to the Académie française (2005) Awarded the Dr. Leopold Lucas Prize by the University of Tübingen (2006)[67] Awarded the Order of Isabella the Catholic, Commander by Number, by the Spanish head of state, H.M. King Juan Carlos |

私生活 ルネ・ジラールの妻マーサ(旧姓マッカロー)はアメリカ人で、1952年から亡くなるまで結婚生活を送った。二人の間には、マーティン・ジラール (1955年生まれ)とダニエル・ジラール(1957年生まれ)の二人の息子と、メアリー・ブラウン=ジラール(1960年生まれ)の娘がいた[61]。 ジラールは、1961年に最初の著書の準備のためにドストエフスキーを読み、不可知論からキリスト教に改宗した。その後の生涯、彼はローマ・カトリックを信仰していた[62]。 2015年11月4日、ジラールはカリフォルニア州スタンフォードの自宅にて91歳で死去した[1]。 栄誉と賞 アムステルダム・ヴリエ大学(オランダ、1985年)、アントワープのUFSIA(ベルギー、1995年)、パドヴァ大学(イタリア、2001年、「芸 術」の名誉学位)[63]、インスブルック大学(オーストリア)神学部、モントリオール大学(カナダ、2004年)[64]、セント・アンドリュース大学 (イギリス、2008年)[65]。 シェイクスピア, les feux de l'envie(羨望の劇場:ウィリアム・シェイクスピア、1991年)でメディシス賞(Prix Médicis essai)を受賞。 Les origines de la culture(文化の起源、2004年)でAujourd'hui賞を受賞。 グッゲンハイム・フェロー(1959年と1966年)[66]。 アカデミー・フランセーズに選出される(2005年) チュービンゲン大学からレオポルド・ルーカス博士賞を授与される(2006年)[67]。 スペイン国家元首フアン・カルロス国王よりイザベラ・カトリック勲章を授与される。 |

| Bibliography This section only lists book-length publications that René Girard wrote or edited. For articles and interviews by René Girard, the reader can refer to the database maintained at the University of Innsbruck. Some of the books below reprint articles (To Double Business Bound, 1978; Oedipus Unbound, 2004; Mimesis and Theory, 2008) or are based on articles (A Theatre of Envy, 1991). Girard, René (2001) [First published 1961], Mensonge romantique et vérité romanesque [Romantic lie & romanesque truth] (in French) (reprint ed.), Paris: Grasset, ISBN 2-246-04072-8 (English translation: ——— (1966), Deceit, Desire and the Novel: Self and Other in Literary Structure, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-1830-3). ——— (1962), Proust: A Collection of Critical Essays, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. ——— (1963), Dostoïevski, du double à l'unité [Dostoievsky, from the double to the unity] (in French), Paris: Plon (English translation: ——— (1997), Resurrection from the Underground: Feodor Dostoevsky, Crossroad). 1972. La violence et le sacré. Paris: Grasset. ISBN 978-2-246-00051-8. (English translation: Violence and the Sacred. Translated by Patrick Gregory. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977. ISBN 0-8018-2218-1.) The reprint in the Pluriel series (1996; ISBN 2-01-008984-7) contains a section entitled "Critiques et commentaires", which reproduces several reviews of La Violence et le Sacré. 1976. Critique dans un souterrain. Lausanne: L'Age d'Homme. Reprint 1983, Livre de Poche: ISBN 978-2-253-03298-4. This book contains Dostoïevski, du double à l'unité and a number of other essays published between 1963 and 1972. 1978. "To double business bound": Essays on Literature, Mimesis, and Anthropology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-2114-1. This book contains essays from Critique dans un souterrain but not those on Dostoyevski. 1978. Des choses cachées depuis la fondation du monde. Paris: Grasset. ISBN 2-246-61841-X. (English translation: Things Hidden since the Foundation of the World: Research undertaken in collaboration with Jean-Michel Oughourlian and G. Lefort. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1987) 1982. Le bouc émissaire. Paris: Grasset. ISBN 2-246-26781-1. (English translation: The Scapegoat. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986) 1985. La route antique des hommes pervers. Paris: Grasset. ISBN 2-246-35111-1. (English translation: Job, the Victim of His People. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1987) 1988. Violent Origins: Walter Burkert, Rene Girard, and Jonathan Z. Smith on Ritual Killing and Cultural Formation. Ed. by Robert Hamerton-Kelly. Palo Alto, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1518-1. 1991. A Theatre of Envy: William Shakespeare. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505339-7. The French translation, Shakespeare : les feux de l'envie, was published before the original English text. ——— (1994), Quand ces choses commenceront ... Entretiens avec Michel Treguer [When these things will begin... interviews with Michel Treguer] (in French), Paris: Arléa, ISBN 2-86959-300-7. 1996. The Girard Reader. Ed. by. James G. Williams. New York: Crossroad. ISBN 0-8245-1634-6. 1999. Je vois Satan tomber comme l'éclair. Paris: Grasset. ISBN 2-246-26791-9. (English translation: I See Satan Fall Like Lightning. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 2001 ISBN 978-1-57075-319-0) ——— (2000), Um Longo Argumento do princípio ao Fim: Diálogos com João Cezar de Castro Rocha e Pierpaolo Antonello [A long argument from the start to the end: dialogues with João César de Castro Rocha and Pierpaolo Antonello] (in Portuguese), Rio de Janeiro: Topbooks, ISBN 85-7475-020-4 (French translation: ——— (2004), Les origines de la culture. Entretiens avec Pierpaolo Antonello et João Cezar de Castro Rocha [The origins of culture. Interviews with Pierpaolo Antonello & João César de Castro Rocha] (in French), Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, ISBN 978-2-220-05355-4. The French translation was upgraded in consultation with René Girard.[68] English translation: ——— (2008), Evolution and Conversion: Dialogues on the Origins of Culture, London: Continuum, ISBN 978-0-567-03252-2). ——— (2001), Celui par qui le scandale arrive: Entretiens avec Maria Stella Barberi [The one by whom scandal arrives: interviews with Maria Stella Barbieri] (in French), Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, ISBN 978-2-220-05011-9 (English translation: ——— (2014), The One by Whom Scandal Comes, East Lansing: Michigan State University Press). 2002. La voix méconnue du réel: une théorie des mythes archaïques et modernes. Paris: Grasset. ISBN 978-2-246-61101-1. 2003. Le sacrifice. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France. ISBN 978-2-7177-2263-5. 2004. Oedipus Unbound: Selected Writings on Rivalry and Desire. Ed. by Mark R. Anspach. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4780-6. 2006. Verità o fede debole. Dialogo su cristianesimo e relativismo. With Gianni Vattimo (English: Truth or Weak Faith). Dialogue about Christianity and Relativism. With Gianni Vattimo. A cura di P. Antonello, Transeuropa Edizioni, Massa. ISBN 978-88-7580-018-5 2006. Wissenschaft und christlicher Glaube Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007 ISBN 978-3-16-149266-2 (online: Knowledge and the Christian Faith) 2007. Dieu, une invention? Editions de l'Atelier. With André Gounelle and Alain Houziaux. ISBN 978-2-7082-3922-7. 2007. Le Tragique et la Pitié: Discours de réception de René Girard à l'Académie française et réponse de Michel Serres. Editions le Pommier. ISBN 978-2-7465-0320-5. 2007. De la violence à la divinité. Paris: Grasset. (Contains Mensonge romantique et vérité romanesque, La violence et le Sacré, Des choses cachées depuis la fondation du monde and Le bouc émissaire, with a new general introduction). ISBN 978-2-246-72111-6. 2007. Achever Clausewitz. (Entretiens avec Benoît Chantre) Ed. by Carnets Nord. Paris. ISBN 978-2-35536-002-2. 2008. Anorexie et désir mimétique. Paris: L'Herne. ISBN 978-2-85197-863-9. 2008. Mimesis and Theory: Essays on Literature and Criticism, 1953–2005. Ed. by Robert Doran. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5580-1. This book brings together twenty essays on literature and literary theory. 2008. La conversion de l'art. Paris: Carnets Nord. (Book with DVD Le Sens de l'histoire, a conversation with Benoît Chantre) ISBN 978-2-35536-016-9. |

書誌 このセクションでは、ルネ・ジラールが執筆または編集した単行本のみを掲載する。ルネ・ジラールの記事やインタビューについては、インスブルック大学の データベースを参照されたい。以下の書籍の中には、論文の再録(To Double Business Bound, 1978; Oedipus Unbound, 2004; Mimesis and Theory, 2008)や、論文に基づくもの(A Theatre of Envy, 1991)がある。 Girard, René (2001) [First published 1961], Mensonge romantique et vérité romanesque [Romantic lie & romanesque truth] (in French) (reprint ed.), Paris: グラッセ、ISBN 2-246-04072-8(英訳:---(1966), Deceit, Desire and the Novel: 文学構造における自己と他者, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-1830-3)。 --- (1962), Proust: A Collection of Critical Essays, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. --- ドストエフスキー、二重から単一へ」(フランス語)、パリ: Plon (英訳) --- (1997), Resurrection from the Underground: Feodor Dostoevsky, Crossroad)。 1972. La violence et le sacré. パリ: グラッセ. ISBN 978-2-246-00051-8. (英訳: 暴力と聖なるもの。パトリック・グレゴリー訳。ボルチモア: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977. ISBN 0-8018-2218-1)。プルリエル・シリーズの再版(1996;ISBN 2-01-008984-7)には、「批評とコメント」と題されたセクションがあり、La Violence et le Sacréの書評がいくつか掲載されている。 1976. Critique dans un souterrain. ローザンヌ: L'Age d'Homme. 1983年再版、Livre de Poche: ISBN 978-2-253-03298-4. 本書には、Dostoïevski, du double à l'unitéのほか、1963年から1972年にかけて発表された多数のエッセイが収められている。 1978. 「ダブル・ビジネス・バウンド 文学、ミメーシス、人類学に関するエッセイ。ボルチモア: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-2114-1. 本書には『Critique dans un souterrain』のエッセイが収録されているが、ドストエフスキーに関するものは含まれていない。 1978. Des choses cachées since la fondation du monde. パリ: Grasset. ISBN 2-246-61841-x. (英訳: 英訳:Things Hidden since the Foundation of the World: ジャン=ミシェル・ウーグルリアン、G・ルフォールとの共同研究。Stanford: スタンフォード大学出版局、1987年) 1982. Le bouc émissaire. パリ: Grasset. ISBN 2-246-26781-1. (英訳: スケープゴート. ボルチモア: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986) 1985. 変態の男たちの古風な道』(邦訳『変態の男たちの古風な道』講談社文庫、1985年 パリ: Grasset. ISBN 2-246-35111-1. (英訳: ヨブ、その民の犠牲者。Stanford: スタンフォード大学出版局、1987年) 1988. 暴力的起源: ウォルター・バーカート、ルネ・ジラール、ジョナサン・Z・スミスによる儀式的殺戮と文化形成。ロバート・ハマートン=ケリー編。カリフォルニア州パロア ルト: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1518-1. 1991. 嫉妬の劇場:ウィリアム・シェイクスピア. ニューヨーク: オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 0-19-505339-7. 英語原文より先にフランス語訳『シェイクスピア:les feux de l'envy』が出版されている。 --- (1994), Quand ces choses commenceront .... Entretiens avec Michel Treguer [When these things will begin... interviews with Michel Treguer] (in French), Paris: Arléa, ISBN 2-86959-300-7. 1996. ジラール・リーダー 編著。James G. Williams. ニューヨーク: クロスロード。ISBN 0-8245-1634-6. 1999. Je vois Satan tomber comme l'éclair. パリ: グラッセ. ISBN 2-246-26791-9. (英訳: 私はサタンが稲妻のように落ちるのを見る。Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 2001 ISBN 978-1-57075-319-0) --- (2000), Um Longo Argumento do princípio ao Fim. João Ceãoとの対話: ジョアン・セザール・デ・カストロ・ローシャとピエールパオロ・アントネッロとの対話」(ポルトガル語)、リオデジャネイロ: Topbooks, ISBN 85-7475-020-4 (仏語訳:---(2004), Les origines de la culture. Entretiens avec Pierpaolo Antonello et João Cezar de Castro Rocha [The origins of culture. Interviews with Pierpaolo Antonello & João César de Castro Rocha] (in French), Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, ISBN 978-2-220-05355-4. 仏語訳はルネ・ジラールと協議の上、格上げされた[68]。英語訳:--- (2008), Evolution and Conversion: Dialogues on the Origins of Culture, London: コンティニュアム、ISBN 978-0-567-03252-2)。 --- (2001), Celui par qui le scandale arrive: Entretiens avec Maria Stella Barberi [The one by whom scandal arrives: interviews with Maria Stella Barbieri] (in French), Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, ISBN 978-2-220-05011-9(英訳:--- (2014), The One by Whom Scandal Comes, East Lansing: ミシガン州立大学出版局)。 2002. La voix méconnue du réel: une théorie des mythes archaïques et modernes. Paris: Grasset. ISBN 978-2-246-61101-1. 2003. Le sacrifice. パリ: Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France. ISBN 978-2-7177-2263-5. 2004. Oedipus Unbound: Oedipus Unbound: Selected Writings on Rivalry and Desire. マーク・R・アンスパック編. Stanford: Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4780-6. 2006. 真実か敗北か。Dialogo su cristianesimo e relativismo. ジャンニ・ヴァッティモとの共著。キリスト教と相対主義についての対話。ジャンニ・ヴァッティモと。A cura di P. Antonello, Transeuropa Edizioni, Massa. ISBN 978-88-7580-018-5 2006. Wissenschaft und christlicher Glaube Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007 ISBN 978-3-16-149266-2 (オンライン:知識とキリスト教信仰) 2007. Dieu, une invention? アトリエ版。André Gounelle、Alain Houziauxとの共著。ISBN 978-2-7082-3922-7. 2007. 悲劇と憐れみ: ルネ・ジラール・アカデミーフランセーズでのレセプションのスピーチとミシェル・セールの返答。Editions le Pommier. ISBN 978-2-7465-0320-5. 2007. De la violence à la divinité. パリ: Grasset. (ロマンと真実, 暴力と聖なるもの, この世の始まりから現在までの出来事, 神聖なるもの, を含む). ISBN 978-2-246-72111-6. 2007. クラウゼヴィッツを理解する。(Entretiens avec Benoît Chantre) Ed. Carnets Nord. パリ。ISBN 978-2-35536-002-2. 2008. Anorexie et désir mimétique. パリ: L'Herne. ISBN 978-2-85197-863-9. 2008. ミメーシスと理論: Mimesis and Theory: Essays on Literature and Criticism, 1953-2005. ロバート・ドーラン編。スタンフォード: Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5580-1. 本書は、文学と文学理論に関する20のエッセイをまとめたものである。 2008. 芸術の転換 パリ: Carnets Nord. (DVD付書籍 Le Sens de l'histoire, a conversation with Benoît Chantre) ISBN 978-2-35536-016-9. |

| James George Frazer Mimetics Simulacrum |

James George Frazer Mimetics Simulacrum |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ren%C3%A9_Girard | |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆