革命

Revolution

☆政治学において、革命(ラテン語:revolutio、

「転換」)とは、社会の階級、国家、民族、宗教などの構造が急速かつ根本的に変革されることを指す。[1]

社会学者のジャック・ゴールドストーンによると、すべての革命には「その核心に共通する要素」が含まれている。具体的には、(a)公正な秩序に関する競合

するビジョン(または複数のビジョン)を基盤とした政治体制の変更を目指す努力、(b)非公式または公式な大規模な動員が顕著にみられること、(c)大規

模なデモ、抗議、ストライキ、暴力などの非制度的な行動を通じて変化を強制しようとする努力、の3つだ。[2]

革命は人類の歴史を通じて発生し、その方法、期間、結果が多様化してきた。[3]

革命の中には、農民の反乱や国の周辺部でのゲリラ戦争から始まったものもあれば、国の首都の占領を目的とした都市部の反乱から始まったものもある[2]。

革命は、ナショナリズム、共和主義、平等主義、自決、人権、民主主義、自由主義、ファシズム、社会主義などの特定の政治思想、道徳的原則、統治モデルの人

気の高まりによって引き起こされることがある。[4]

政権は、最近の軍事的な敗北、経済混乱、国民的誇りやアイデンティティへの侮辱、あるいは持続的な抑圧や腐敗によって、革命に対して脆弱になることがあ

る。[2] 革命は通常、革命の勢いを止めたり、進行中の革命的な変革の流れを逆転させようとする反革命を引き起こす。[5]

近世における著名な革命には、アメリカ独立戦争(1765–1783)、フランス革命(1789–1799)、ハイチ革命(1791–1804)、スペイ

ン・アメリカ独立戦争(1808–1826)、1848年のヨーロッパ革命、メキシコ革命(1910–1920)、 1911

年の中国辛亥革命、1917 年から 1923 年のヨーロッパの革命(ロシア革命およびドイツ革命を含む)、1927 年から 1949

年の中国共産主義革命、1950 年代半ばから 1975 年までのアフリカの脱植民地化、

アルジェリア独立戦争(1954-1962)、1959年のキューバ革命、1979年のイラン革命とニカラグア革命、1989年の世界的な革命、2010

年代初頭のアラブの春。

| In political

science, a revolution (Latin: revolutio, 'a turn around') is a rapid,

fundamental transformation of a society's class, state, ethnic or

religious structures.[1] According to sociologist Jack Goldstone, all

revolutions contain "a common set of elements at their core: (a)

efforts to change the political regime that draw on a competing vision

(or visions) of a just order, (b) a notable degree of informal or

formal mass mobilization, and (c) efforts to force change through

noninstitutionalized actions such as mass demonstrations, protests,

strikes, or violence."[2] Revolutions have occurred throughout human history and varied in their methods, durations and outcomes.[3] Some revolutions started with peasant uprisings or guerrilla warfare on the periphery of a country; others started with urban insurrection aimed at seizing the country's capital city.[2] Revolutions can be inspired by the rising popularity of certain political ideologies, moral principles, or models of governance such as nationalism, republicanism, egalitarianism, self-determination, human rights, democracy, liberalism, fascism, or socialism.[4] A regime may become vulnerable to revolution due to a recent military defeat, or economic chaos, or an affront to national pride and identity, or persistent repression and corruption.[2] Revolutions typically trigger counter-revolutions which seek to halt revolutionary momentum, or to reverse the course of an ongoing revolutionary transformation.[5] Notable revolutions in recent centuries include the American Revolution (1765–1783), French Revolution (1789–1799), Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), Spanish American wars of independence (1808–1826), Revolutions of 1848 in Europe, Mexican Revolution (1910–1920), Xinhai Revolution in China in 1911, Revolutions of 1917–1923 in Europe (including the Russian Revolution and German Revolution), Chinese Communist Revolution (1927–1949), decolonization of Africa (mid-1950s to 1975), Algerian War of Independence (1954-1962), Cuban Revolution in 1959, Iranian Revolution and Nicaraguan Revolution in 1979, worldwide Revolutions of 1989, and Arab Spring in the early 2010s. |

政治学において、革命(ラテン語:revolutio、「転換」)と

は、社会の階級、国家、民族、宗教などの構造が急速かつ根本的に変革されることを指す。[1]

社会学者のジャック・ゴールドストーンによると、すべての革命には「その核心に共通する要素」が含まれている。具体的には、(a)公正な秩序に関する競合

するビジョン(または複数のビジョン)を基盤とした政治体制の変更を目指す努力、(b)非公式または公式な大規模な動員が顕著にみられること、(c)大規

模なデモ、抗議、ストライキ、暴力などの非制度的な行動を通じて変化を強制しようとする努力、の3つだ。[2] 革命は人類の歴史を通じて発生し、その方法、期間、結果が多様化してきた。[3] 革命の中には、農民の反乱や国の周辺部でのゲリラ戦争から始まったものもあれば、国の首都の占領を目的とした都市部の反乱から始まったものもある[2]。 革命は、ナショナリズム、共和主義、平等主義、自決、人権、民主主義、自由主義、ファシズム、社会主義などの特定の政治思想、道徳的原則、統治モデルの人 気の高まりによって引き起こされることがある。[4] 政権は、最近の軍事的な敗北、経済混乱、国民的誇りやアイデンティティへの侮辱、あるいは持続的な抑圧や腐敗によって、革命に対して脆弱になることがあ る。[2] 革命は通常、革命の勢いを止めたり、進行中の革命的な変革の流れを逆転させようとする反革命を引き起こす。[5] 近世における著名な革命には、アメリカ独立戦争(1765–1783)、フランス革命(1789–1799)、ハイチ革命(1791–1804)、スペイ ン・アメリカ独立戦争(1808–1826)、1848年のヨーロッパ革命、メキシコ革命(1910–1920)、 1911 年の中国辛亥革命、1917 年から 1923 年のヨーロッパの革命(ロシア革命およびドイツ革命を含む)、1927 年から 1949 年の中国共産主義革命、1950 年代半ばから 1975 年までのアフリカの脱植民地化、 アルジェリア独立戦争(1954-1962)、1959年のキューバ革命、1979年のイラン革命とニカラグア革命、1989年の世界的な革命、2010 年代初頭のアラブの春。 |

| Etymology The French noun revolucion traces back to the 13th century, and the English equivalent "revolution" to the late 14th century. The word was limited then to mean the revolving motion of celestial bodies. "Revolution" in the sense of abrupt change in a social order was first recorded in the mid-15th century.[6][7] By 1688, the political meaning of the word was familiar enough that the replacement of James II with William III was termed the "Glorious Revolution".[8] |

語源 フランス語の名詞「revolution」は13世紀に遡り、英語の「revolution」は14世紀後半に遡る。当時、この単語は天体の回転運動を意 味するに限定されていた。社会秩序の急激な変化を意味する「Revolution」は、15世紀半ばに初めて記録された。[6][7] 1688年までに、この言葉の政治的な意味は十分に定着し、ジェームズ2世からウィリアム3世への交代は「名誉革命」と呼ばれた。[8] |

| Definition "Revolution" is now employed most often to denote a change in social and political institutions.[9][10][11] Jeff Goodwin offers two definitions. First, a broad one, including "any and all instances in which a state or a political regime is overthrown and thereby transformed by a popular movement in an irregular, extraconstitutional or violent fashion". Second, a narrow one, in which "revolutions entail not only mass mobilization and regime change, but also more or less rapid and fundamental social, economic or cultural change, during or soon after the struggle for state power".[12] Jack Goldstone defines a revolution thusly: "[Revolution is] an effort to transform the political institutions and the justifications for political authority in society, accompanied by formal or informal mass mobilization and noninstitutionalized actions that undermine authorities. This definition is broad enough to encompass events ranging from the relatively peaceful revolutions that toppled communist regimes to the violent Islamic revolution in Afghanistan. At the same time, this definition is strong enough to exclude coups, revolts, civil wars, and rebellions that make no effort to transform institutions or the justification for authority."[2] Goldstone's definition excludes peaceful transitions to democracy through plebiscite or free elections, as occurred in Spain after the death of Francisco Franco, or in Argentina and Chile after the demise of their military juntas.[2] Early scholars often debated the distinction between revolution and civil war.[3][13] They also questioned whether a revolution is purely political (i.e., concerned with the restructuring of government) or whether "it is an extensive and inclusive social change affecting all the various aspects of the life of a society, including the economic, religious, industrial, and familial as well as the political".[14] |

定義 「革命」は現在、社会や政治制度の変化を指す場合によく使われる言葉だ。[9][10][11] ジェフ・グッドウィンは 2 つの定義を提示している。1 つ目は、広義の定義で、「国家や政治体制が、不規則、違憲、または暴力的な手段によって、民衆運動によって打倒され、それによって変革されるあらゆる事 例」を含む。第二に、狭い定義では、「革命は、大衆動員と政権交代だけでなく、国家権力争奪の過程またはその直後に、より迅速かつ根本的な社会的、経済 的、または文化的変化を伴う」と定義されています。[12] ジャック・ゴールドストーンは、革命を次のように定義している。 「革命とは、社会における政治制度や政治権力の正当性を変革するための努力であり、権威を弱体化させる公式または非公式の大衆動員や非制度化された行動が 伴う。この定義は、共産主義体制を打倒した比較的平和的な革命から、アフガニスタンでの暴力的なイスラム革命に至るまで、幅広い出来事を網羅する。同時 に、この定義は、制度や権威の正当性を変革する努力を伴わないクーデター、反乱、内戦、反乱を排除するほど強固なものだ。」[2] ゴールドストーンの定義は、フランシスコ・フランコ死去後のスペイン、または軍事独裁政権崩壊後のアルゼンチンとチリで起きたような、国民投票や自由選挙 による平和的な民主化移行を排除している。[2] 初期の研究者は、革命と内戦の区別について頻繁に議論した。[3][13] 彼らはまた、革命が純粋に政治的なもの(すなわち、政府の再編に関わるもの)なのか、それとも「経済的、宗教的、産業的、家族的な側面を含む社会のあらゆ る側面を影響する広範で包括的な社会変革」なのかを疑問視した。[14] |

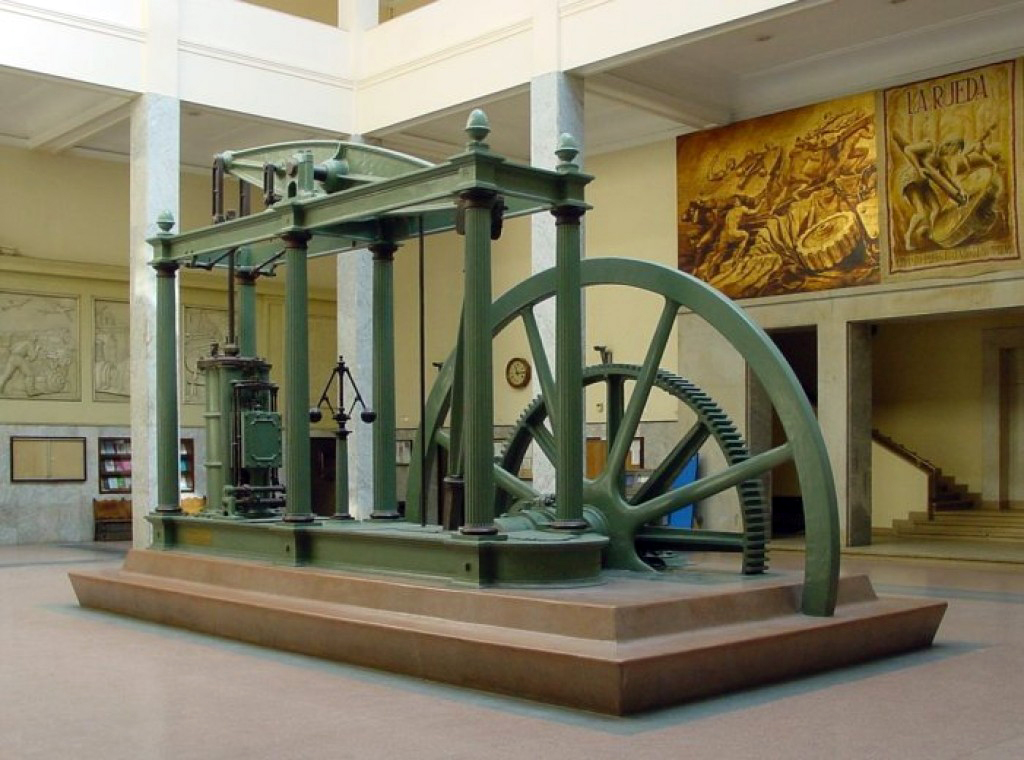

| Types There are numerous typologies of revolution in the social science literature.[15] Alexis de Tocqueville differentiated between: sudden and violent revolutions that seek not only to establish a new political system but to overhaul an entire society, and; slow and relentless revolutions that involve sweeping transformations of the entire society and may take several generations to bring about (such as changes in religion).[16]  Revolutions of 1848 were essentially bourgeois revolutions and democratic and liberal in nature, with the aim of removing the old monarchical structures and creating independent nation-states. One of the Marxist typologies divides revolutions into: pre-capitalist early bourgeois bourgeois bourgeois-democratic early proletarian socialist[17] Charles Tilly, a modern scholar of revolutions, differentiated between: coup d'état (a top-down seizure of power), e.g., Poland, 1926 civil war revolt, and "great revolution" (a revolution that transforms economic and social structures as well as political institutions, such as the French Revolution of 1789, Russian Revolution of 1917, or Islamic Revolution of Iran in 1979).[18][19] Mark Katz identified six forms of revolution: rural revolution urban revolution coup d'état, e.g., Egypt, 1952 revolution from above, e.g., Mao Zedong's Great Leap Forward of 1958 revolution from without, e.g., the Allied invasions of Italy in 1943 and of Germany in 1945 revolution by osmosis, e.g., the gradual Islamization of several countries.[20]  A Watt steam engine in Madrid. The development of the steam engine propelled the Industrial Revolution in Britain and the world. The steam engine was created to pump water from coal mines, enabling them to be deepened beyond groundwater levels. These categories are not mutually exclusive; the Russian Revolution of 1917 began with an urban revolution to depose the Czar, followed by a rural revolution, followed by the Bolshevik coup in November. Katz also cross-classified revolutions as follows: Central: countries, usually Great Powers, which play a leading role in a revolutionary wave; e.g., the USSR, Nazi Germany, Iran since 1979[21] Aspiring revolutions, which follow the Central revolution subordinate or puppet revolutions rival revolutions, in which a former alliance is broken, such as Yugoslavia after 1948, and China after 1960. A further dimension to Katz's typology is that revolutions are either against (anti-monarchy, anti-dictatorial, anti-communist, anti-democratic) or for (pro-fascism, pro-communism, pro-nationalism, etc.). In the latter cases, a transition period is generally necessary to decide which direction to take to achieve the desired form of government.[22] Other types of revolution, created for other typologies, include proletarian or communist revolutions (inspired by the ideas of Marxism that aim to replace capitalism with communism); failed or abortive revolutions (that are not able to secure power after winning temporary victories or amassing large-scale mobilizations); or violent vs. nonviolent revolutions. The term revolution has also been used to denote great changes outside the political sphere. Such revolutions, often labeled social revolutions, are recognized as major transformations in a society's culture, philosophy, or technology, rather than in its political system.[23] Some social revolutions are global in scope, while others are limited to single countries. Commonly cited examples of social revolution are the Industrial Revolution, Scientific Revolution, Commercial Revolution, and Digital Revolution. These revolutions also fit the "slow revolution" type identified by Tocqueville.[24] |

種類 社会科学の文献には、革命の類型が数多くある[15]。アレクシス・ド・トクヴィルは、以下の2つを区別している。 新しい政治体制の確立だけでなく、社会全体の変革を求める、突然かつ暴力的な革命。 社会全体の抜本的な変革を伴い、その実現に数世代を要する、ゆっくりとした執拗な革命(宗教の変化など)。[16]  1848年の革命は、本質的にはブルジョア革命であり、民主的で自由主義的な性格を持ち、旧来の君主制の構造を打破し、独立した国民国家の創設を目指したものでした。 マルクス主義の分類では、革命は次のように分類されます。 前資本主義 初期ブルジョア ブルジョア ブルジョア民主主義 初期プロレタリア 社会主義[17] 現代の革命研究者チャールズ・ティリーは、次のように区別している: クーデター(上からの権力奪取)、例:ポーランド、1926年 内戦 反乱、および 「大革命」(経済的・社会的構造および政治制度を転換する革命、例:1789年のフランス革命、1917年のロシア革命、1979年のイラン・イスラム革命)[18][19] マーク・カッツは、革命の6つの形態を次のように分類した: 農村革命 都市革命 クーデター、例:1952年のエジプト 上からの革命、例:毛沢東の1958年の大躍進政策 外からの革命、例:1943年のイタリアへの連合国軍侵攻、1945年のドイツへの連合国軍侵攻 浸透による革命、例:いくつかの国のイスラム化。[20]  マドリードのワット蒸気機関。蒸気機関の発展は、イギリスと世界における産業革命を推進した。蒸気機関は、炭鉱から水をくみ上げるために開発され、地下水面より深く掘削することを可能にした。 これらのカテゴリーは相互に排他的ではない。1917年のロシア革命は、皇帝を打倒するための都市革命から始まり、その後農村革命が続き、11月にボルシェビキクーデターが発生した。カッツは、革命を次のように分類している: 中央:革命の波で主導的な役割を果たす国々(通常は大国);例:ソビエト連邦、ナチス・ドイツ、1979年以降のイラン[21] 中央革命に続く「志向的革命」 従属的または傀儡的な革命 旧同盟関係が破綻した「対立革命」;例:1948年以降のユーゴスラビア、1960年以降の中国。 カッツの類型にはさらに、革命は「反対(反君主制、反独裁、反共産主義、反民主主義)」と「賛成(親ファシズム、親共産主義、親ナショナリズムなど)」の 2 つに分類されるという側面もある。後者の場合、望ましい政体を実現するために、どの方向に向かうべきかを決定するための移行期間が必要となるのが一般的 だ。[22] 他の分類体系で作成された革命の他の種類には、プロレタリア革命や共産主義革命(マルクス主義の思想に inspiré され、資本主義を共産主義に置き換えることを目的とする)、失敗した革命や未遂の革命(一時的な勝利や大規模な動員を遂げたにもかかわらず権力を確立でき ないもの)、暴力的な革命と非暴力的な革命などがある。革命という用語は、政治領域外の大きな変化を指す場合にも使用される。このような革命は、しばしば 「社会革命」と呼ばれ、社会の政治システムではなく、文化、哲学、技術における重大な変革として認識されている。[23] 社会革命には、世界規模のものもあれば、単一の国に限定されたものもある。社会革命の代表的な例として、産業革命、科学革命、商業革命、デジタル革命が挙 げられる。これらの革命は、トクヴィルが指摘した「緩やかな革命」のタイプにも該当する。[24] |

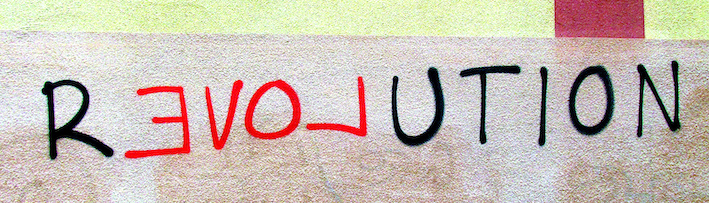

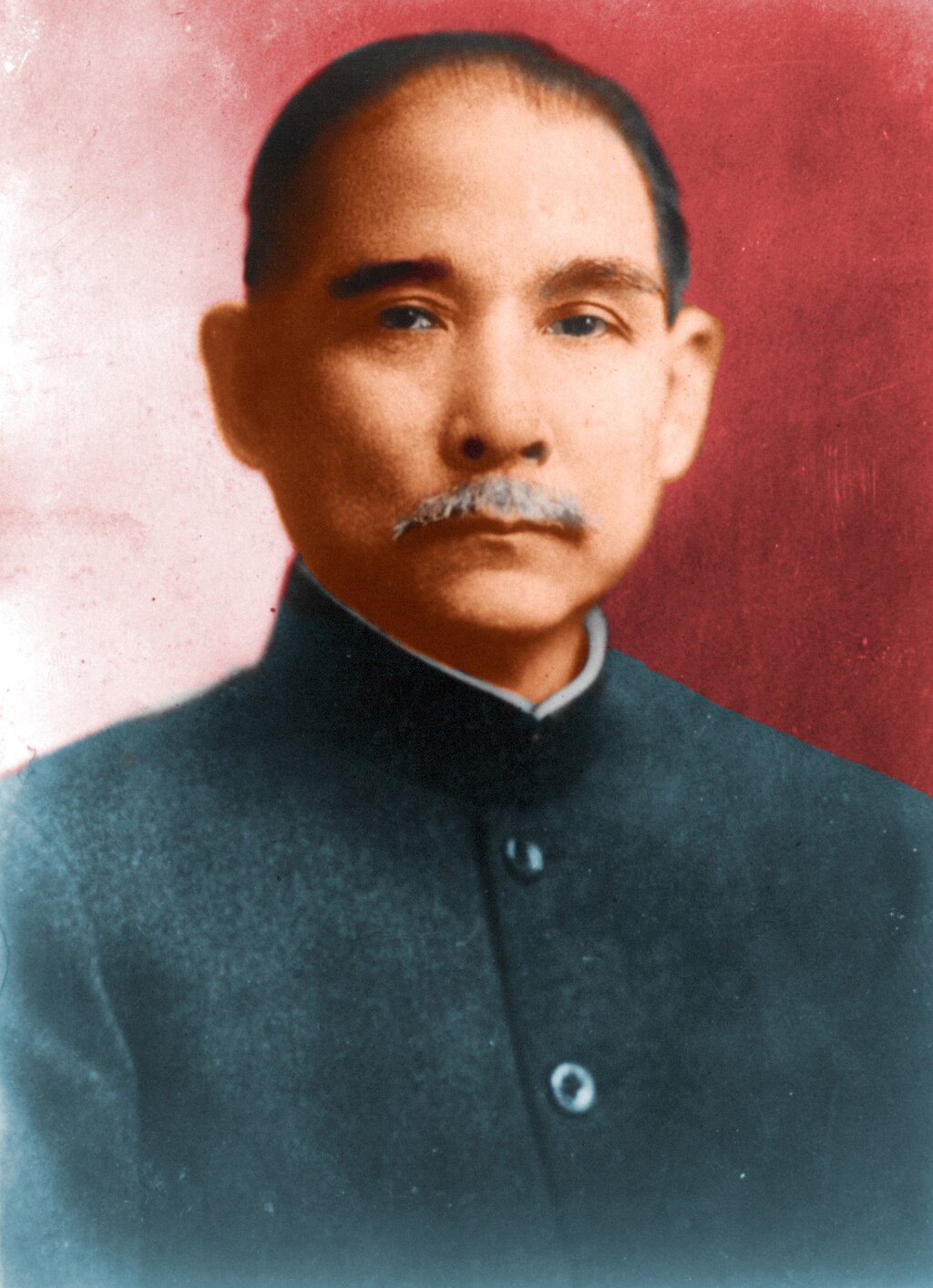

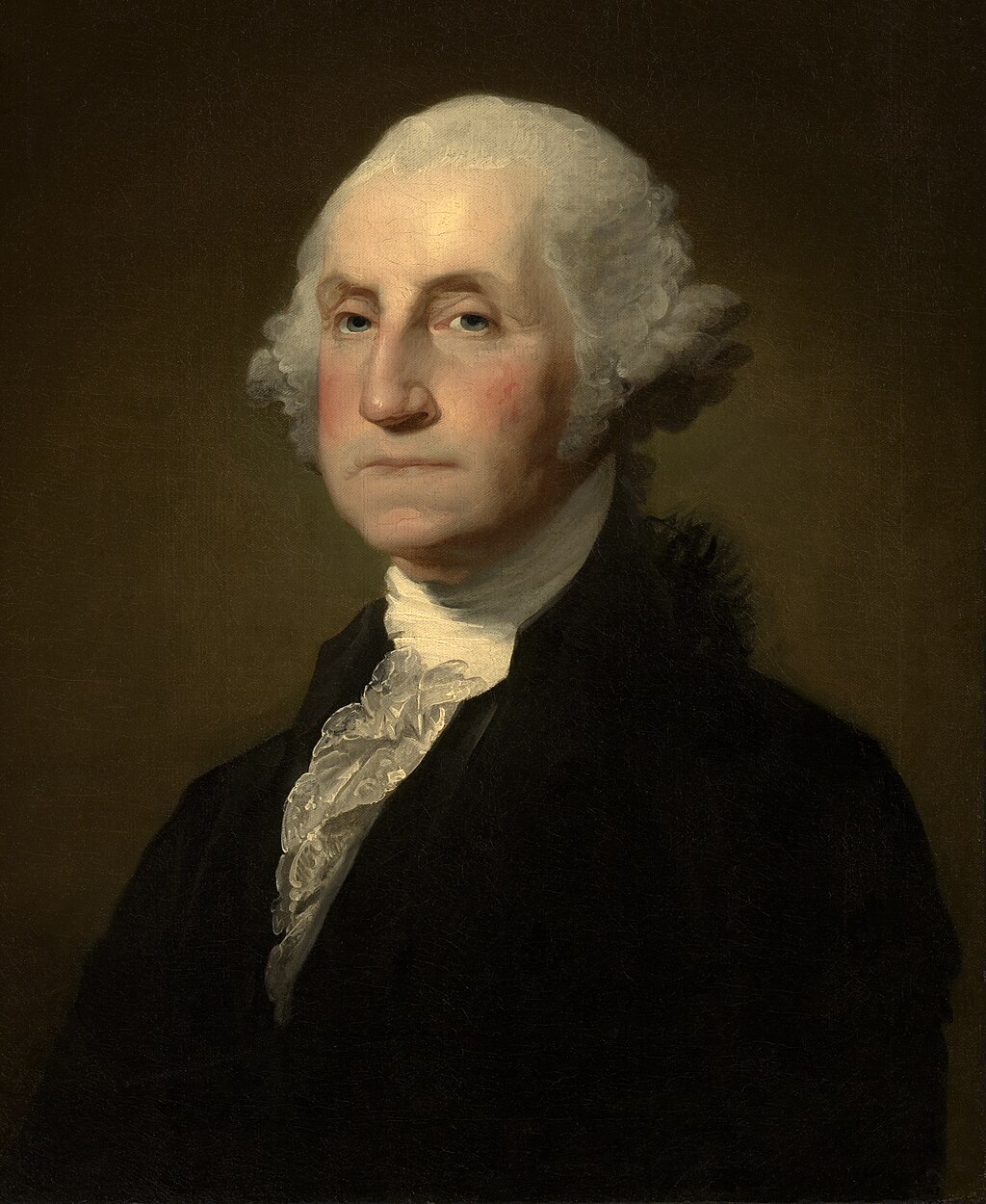

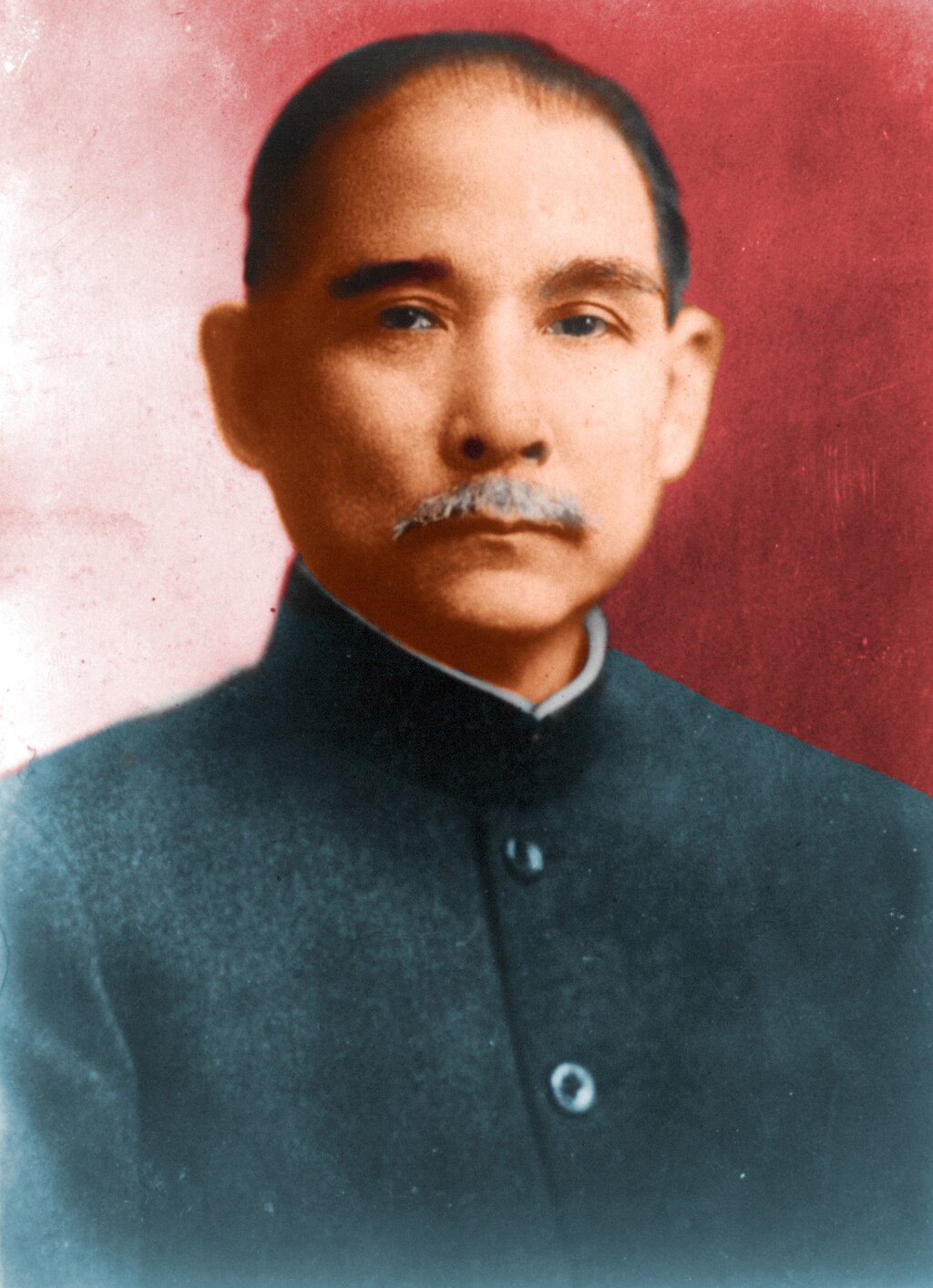

Studies of revolution R E V O L U T I O N, graffiti with political message on a house wall in Ystad, Sweden. Four letters have been written backwards and in a different color so that they also form the word Love. Main article: Social revolution  The storming of the Bastille, 14 July 1789 during the French Revolution.  George Washington, leader of the American Revolution.  Vladimir Lenin, leader of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917.  Sun Yat-sen, leader of the Chinese Xinhai Revolution in 1911.  Khana Ratsadon, a group of military officers and civil officials, who staged the Siamese Revolution of 1932 Political and socioeconomic revolutions have been studied in many social sciences, particularly sociology, political science and history.[25] Scholars of revolution differentiate four generations of theoretical research on the subject of revolution.[2][26] Theorists of the first generation, including Gustave Le Bon, Charles A. Ellwood, and Pitirim Sorokin, were mainly descriptive in their approach, and their explanations of the phenomena of revolutions were usually related to social psychology, such as Le Bon's crowd psychology theory.[9] The second generation sought to develop detailed frameworks, grounded in social behavior theory, to explain why and when revolutions arise. Their work can be divided into three categories: psychological, sociological and political.[9] The writings of Ted Robert Gurr, Ivo K. Feierbrand, Rosalind L. Feierbrand, James A. Geschwender, David C. Schwartz, and Denton E. Morrison fall into the first category. They utilized theories of cognitive psychology and frustration-aggression theory to link the cause of revolution to the state of mind of the masses. While these theorists varied in their approach as to what exactly incited the people to revolt (e.g., modernization, recession, or discrimination), they agreed that the primary cause for revolution was a widespread frustration with the socio-political situation.[9] The second group, composed of academics such as Chalmers Johnson, Neil Smelser, Bob Jessop, Mark Hart, Edward A. Tiryakian, and Mark Hagopian, drew on the work of Talcott Parsons and the structural-functionalist theory in sociology. They saw society as a system in equilibrium between various resources, demands, and subsystems (political, cultural, etc.). As in the psychological school, they differed in their definitions of what causes disequilibrium, but agreed that it is a state of severe disequilibrium that is responsible for revolutions.[9] The third group, including writers such as Charles Tilly, Samuel P. Huntington, Peter Ammann, and Arthur L. Stinchcombe, followed a political science path and looked at pluralist theory and interest group conflict theory. Those theories view events as outcomes of a power struggle between competing interest groups. In such a model, revolutions happen when two or more groups cannot come to terms within the current political system's normal decision-making process, and when they possess the required resources to employ force in pursuit of their goals.[9] The second-generation theorists regarded the development of revolutionary situations as a two-step process: "First, a pattern of events arises that somehow marks a break or change from previous patterns. This change then affects some critical variable—the cognitive state of the masses, the equilibrium of the system, or the magnitude of conflict and resource control of competing interest groups. If the effect on the critical variable is of sufficient magnitude, a potentially revolutionary situation occurs."[9] Once this point is reached, a negative incident (a war, a riot, a bad harvest) that in the past might not have been enough to trigger a revolt, will now be enough. However, if authorities are cognizant of the danger, they can still prevent revolution through reform or repression.[9] In his influential 1938 book The Anatomy of Revolution, historian Crane Brinton established a convention by choosing four major political revolutions—England (1642), Thirteen Colonies of America (1775), France (1789), and Russia (1917)—for comparative study.[27] He outlined what he called their "uniformities", although the American Revolution deviated somewhat from the pattern.[28] As a result, most later comparative studies of revolution substituted China (1949) in their lists, but they continued Brinton's practice of focusing on four.[2] In subsequent decades, scholars began to classify hundreds of other events as revolutions (see List of revolutions and rebellions). Their expanded notion of revolution engendered new approaches and explanations. The theories of the second generation came under criticism for being too limited in geographical scope, and for lacking a means of empirical verification. Also, while second-generation theories may have been capable of explaining a specific revolution, they could not adequately explain why revolutions failed to occur in other societies experiencing very similar circumstances.[2] The criticism of the second generation led to the rise of a third generation of theories, put forth by writers such as Theda Skocpol, Barrington Moore, Jeffrey Paige, and others expanding on the old Marxist class-conflict approach. They turned their attention to "rural agrarian-state conflicts, state conflicts with autonomous elites, and the impact of interstate economic and military competition on domestic political change."[2] In particular, Skocpol's States and Social Revolutions (1979) was a landmark book of the third generation. Skocpol defined revolution as "rapid, basic transformations of society's state and class structures ... accompanied and in part carried through by class-based revolts from below", and she attributed revolutions to "a conjunction of multiple conflicts involving state, elites and the lower classes".[1] |

革命の研究 R E V O L U T I O N、スウェーデンのイスタッドにある家の壁に書かれた政治的なメッセージの落書き。4つの文字は逆向きに、異なる色で書かれているため、「Love」という単語も形成している。 主な記事:社会革命  1789年7月14日、フランス革命中のバスティーユ襲撃。  アメリカ独立戦争の指導者、ジョージ・ワシントン。  1917年のボルシェビキ革命の指導者、ウラジーミル・レーニン。  1911年の中国辛亥革命の指導者、孫文。  1932年のシャム革命を起こした軍人および文官の集団、カーナー・ラツァドン。 政治革命および社会経済革命は、多くの社会科学、特に社会学、政治学、歴史学で研究されている。[25] 革命の研究者は、革命に関する理論的研究を 4 つの世代に分類している。[2][26] 1 世代目の理論家には、ギュスターヴ・ル・ボン、チャールズ・A・エルウッド、ピティリム・ソロキンなどがおり、そのアプローチは主に記述的であり、革命現 象の説明は、ル・ボンの群衆心理学理論など、社会心理学に関連したものだった。[9] 第 2 世代は、革命がなぜ、いつ発生するかを説明するために、社会行動理論に基づいた詳細な枠組みの構築を目指した。彼らの研究は、心理学的、社会学的、政治学 的の 3 つのカテゴリーに分類することができる。[9] テッド・ロバート・ガー、イヴォ・K・フェイアーブランド、ロザリンド・L・フェイアーブランド、ジェームズ・A・ゲシュウェンダー、デビッド・C・シュ ワルツ、デントン・E・モリソンの著作は、第 1 のカテゴリーに分類される。彼らは、認知心理学や欲求不満・攻撃性理論を用いて、革命の原因を大衆の精神状態と結びつけた。これらの理論家たちは、人民を 反乱に駆り立てた要因(近代化、不況、差別など)についてさまざまな見解を示したが、革命の主な原因は社会政治状況に対する広範な不満であるという点では 一致していた。[9] 2つ目のグループには、チャルマーズ・ジョンソン、ニール・スメルサー、ボブ・ジェソップ、マーク・ハート、エドワード・A・ティリアキアン、マーク・ハ ゴピアンなどの学者たちが属し、タルコット・パーソンズや社会学における構造機能主義の理論を参考にした。彼らは、社会をさまざまな資源、需要、およびサ ブシステム(政治、文化など)の間の均衡状態にあるシステムと捉えた。心理学的学派と同様、彼らは不均衡の原因の定義については意見が分かれたが、革命の 原因は深刻な不均衡の状態にあるという点で意見が一致していた[9]。 3つ目のグループには、チャールズ・ティリー、サミュエル・P・ハンティントン、ピーター・アマン、アーサー・L・スティンチコムなどの作家が含まれ、政 治学の道を歩み、多元主義理論や利益団体紛争理論に注目した。これらの理論は、事件を競合する利益集団間の権力闘争の結果と見なす。このようなモデルで は、革命は、2つ以上の集団が現在の政治システムの通常の意思決定プロセス内で合意に達することができず、目標を達成するために武力行使に必要な資源を保 有している場合に発生する。[9] 第二世代の理論家は、革命的な状況の進展を 2 段階のプロセスと捉えた。「まず、何らかの形でこれまでのパターンからの断絶や変化を示す一連の出来事が発生する。この変化は、大衆の認識状態、システム の均衡、対立する利益団体の紛争の規模や資源の支配力といった重要な変数に影響を与える。重要な変数への影響が十分な大きさになると、革命的な状況が発生 する可能性がある」[9] この段階に達すると、過去には反乱を引き起こすのに十分ではなかったような負の出来事(戦争、暴動、不作)が、現在では十分になる。しかし、当局が危険を 認識していれば、改革や弾圧を通じて革命を防止することができる。[9] 1938年に出版され、大きな影響を与えた著書『革命の解剖学』の中で、歴史家のクレーン・ブリントンは、比較研究の対象として、4つの主要な政治革命、 すなわちイギリス(1642年)、アメリカ13植民地(1775年)、フランス(1789年)、ロシア(1917年)を選択し、慣例を確立した。[27] 彼は、これらの革命の「共通点」を概説したが、アメリカ独立革命は、このパターンから多少逸脱していた[28]。その結果、その後の革命の比較研究では、 そのリストに中国(1949 年)が代わって追加されたが、4 つに焦点を当てるというブリントンの慣例は引き継がれた[2]。 その後数十年の間に、学者たちは、他の何百もの出来事を革命として分類し始めた(革命と反乱の一覧を参照)。彼らの拡大された革命の概念は、新たなアプ ローチと説明を生んだ。第二世代の理論は、地理的範囲が狭すぎること、経験的検証の手段を欠くことなどから批判を受けた。また、第二世代の理論は特定の革 命を説明できるかもしれないが、非常に類似した状況下で他の社会で革命が起こらなかった理由を十分に説明できなかった。[2] 第二世代の批判を受けて、テダ・スコックポール、バリントン・ムーア、ジェフリー・ペイジなどの作家たちが、旧来のマルクス主義の階級闘争アプローチを拡 張した第三世代の理論を提唱した。彼らは、「農村部の農業国家間の紛争、国家と自治エリートとの紛争、国家間の経済・軍事競争が国内政治の変化に与える影 響」に焦点を当てた。[2] 特に、スココポリの『国家と社会革命』(1979 年)は、第 3 世代の画期的な著作でした。スココポリは、革命を「社会の状態や階級構造が急速かつ根本的に変化し、その変化は下層階級による階級闘争を伴い、その一部に よって推進される」と定義し、革命は「国家、エリート、下層階級が関わる複数の紛争の複合」に起因するとしました。[1] |

The fall of the Berlin Wall and most of the events of the Autumn of Nations in Europe, 1989, were sudden and peaceful. In the late 1980s, a new body of academic work started questioning the dominance of the third generation's theories. The old theories were also dealt a significant blow by a series of revolutionary events that they could not readily explain. The Iranian and Nicaraguan Revolutions of 1979, the 1986 People Power Revolution in the Philippines, and the 1989 Autumn of Nations in Europe, Asia and Africa saw diverse opposition movements topple seemingly powerful regimes amidst popular demonstrations and mass strikes in nonviolent revolutions.[10][2] For some historians, the traditional paradigm of revolutions as class struggle-driven conflicts centered in Europe, and involving a violent state versus its discontented people, was no longer sufficient to account for the multi-class coalitions toppling dictators around the world. Consequently, the study of revolutions began to evolve in three directions. As Goldstone describes it, scholars of revolution: 1. Extended the third generation's structural theories to a more heterogeneous set of cases, "well beyond the small number of 'great' social revolutions".[2] 2. Called for greater attention to conscious agency and contingency in understanding the course and outcome of revolutions. 3. Observed how studies of social movements—for women's rights, labor rights, and U.S. civil rights—had much in common with studies of revolution and could enrich the latter. Thus, "a new literature on 'contentious politics' has developed that attempts to combine insights from the literature on social movements and revolutions to better understand both phenomena."[2] The fourth generation increasingly turned to quantitative techniques when formulating its theories. Political science research moved beyond individual or comparative case studies towards large-N statistical analysis assessing the causes and implications of revolution.[29] The initial fourth-generation books and journal articles generally relied on the Polity data series on democratization.[30] Such analyses, like those by A. J. Enterline,[31] Zeev Maoz,[32] and Edward D. Mansfield and Jack Snyder,[33] identified a revolution by a significant change in the country's score on Polity's autocracy-to-democracy scale. Since the 2010s, scholars like Jeff Colgan have argued that the Polity data series—which evaluates the degree of democratic or autocratic authority in a state's governing institutions based on the openness of executive recruitment, constraints on executive authority, and political competition—is inadequate because it measures democratization, not revolution, and doesn't account for regimes which come to power by revolution but fail to change the structure of the state and society sufficiently to yield a notable difference in the Polity score.[34] Instead, Colgan offered a new data set to single out governments that "transform the existing social, political, and economic relationships of the state by overthrowing or rejecting the principal existing institutions of society."[35] This data set has been employed to make empirically based contributions to the literature on revolution by finding links between revolution and the likelihood of international disputes. Revolutions have been further examined from an anthropological perspective. Drawing on Victor Turner's writings on ritual and performance, Bjorn Thomassen suggested that revolutions can be understood as "liminal" moments: modern political revolutions very much resemble rituals and can therefore be studied within a process approach.[36] This would imply not only a focus on political behavior "from below", but also a recognition of moments where "high and low" are relativized, subverted, or made irrelevant, and where the micro and macro levels fuse together in critical conjunctions. Economist Douglass North raised a note of caution about revolutionary change, how it "is never as revolutionary as its rhetoric would have us believe".[37] While the "formal rules" of laws and constitutions can be changed virtually overnight, the "informal constraints" such as institutional inertia and cultural inheritance do not change quickly and thereby slow down the societal transformation. According to North, the tension between formal rules and informal constraints is "typically resolved by some restructuring of the overall constraints—in both directions—to produce a new equilibrium that is far less revolutionary than the rhetoric."[37] |

ベルリンの壁の崩壊と、1989年にヨーロッパで起こった「秋の国民革命」のほとんどの出来事は、突然かつ平和的に起こった。 1980年代後半、第三世代の理論の優位性に疑問を投げかける新しい学術研究が始まった。また、一連の革命的な出来事を、従来の理論では容易に説明できな いことから、その理論は大きな打撃を受けた。1979年のイラン革命とニカラグア革命、1986年のフィリピン人民革命、1989年のヨーロッパ、アジ ア、アフリカにおける「秋の国民運動」では、非暴力革命による民衆のデモや大ストライキの中で、一見強大な政権がさまざまな反対運動によって倒された [10][2]。 一部の歴史家たちにとって、ヨーロッパを中心とし、不満を抱く人民と暴力的な国家との対立という、階級闘争による紛争という従来の革命のパラダイムは、世 界中で独裁者を倒した多階層連合を説明するにはもはや不十分だった。その結果、革命の研究は 3 つの方向に発展し始めた。ゴールドストーンが説明するように、革命の研究者は: 1. 第三世代の構造理論を、「少数の『偉大な』社会革命」をはるかに超える、より多様な事例に拡大した。[2] 2. 革命の過程と結果を理解する上で、意識的な主体性と不測の事態により大きな注意を払うことを求めた。 3. 女性権利、労働者の権利、米国の公民権などの社会運動の研究が、革命の研究と多くの共通点があり、後者をより豊かにすることができることを指摘した。その 結果、「社会運動と革命に関する文献の洞察を融合して、両方の現象をより深く理解しようとする『紛争政治』に関する新しい文献が発展した」[2]。 第四世代は、理論を構築する際、ますます定量的な手法に依拠するようになった。政治学の研究は、個人や比較事例研究から、革命の原因と影響を評価する大規 模な統計分析へと移行した。[29] 第四世代の初期の書籍や論文は、一般に民主化に関するPolityデータシリーズに依拠していた。[30] A. J. Enterline[31]、Zeev Maoz[32]、Edward D. Mansfield と Jack Snyder[33] などの分析は、Polity の独裁から民主主義へのスケールにおける国のスコアの著しい変化を革命と定義した。 2010年代以降、 ジェフ・コルガンなどの学者は、行政官の採用、行政権の制約、政治競争の開放性に基づいて、国家の統治機関における民主的または独裁的権威の程度を評価す るポリティのデータシリーズは、革命ではなく民主化を測定するものであり、革命によって政権を握ったものの、ポリティのスコアに顕著な変化をもたらすほど 国家や社会の構造を十分に変化させることができなかった政権を考慮していないため、不適切であると主張している。[34] 代わりに、コルガンは、「既存の社会の主要な制度を打倒または拒否することにより、国家の既存の社会的、政治的、経済的な関係を変革する」政府を抽出する ための新しいデータセットを提案した[35]。このデータセットは、革命と国際紛争の可能性との関連性を見出すことで、革命に関する文献に実証的な貢献を している。 革命は、人類学的観点からもさらに詳しく検討されている。ビクター・ターナーの儀礼とパフォーマンスに関する著作を参考にしたビョルン・トマセンは、革命 は「境界的」な瞬間として理解できると提案した。現代の政治革命は儀礼と非常によく似ているため、プロセスアプローチで研究することができるという。 [36] これは、「下からの」政治行動に焦点を当てるだけでなく、「高」と「低」が相対化、転覆、あるいは無関係になり、ミクロレベルとマクロレベルが重要な接点 において融合する瞬間を認識することを意味する。経済学者ダグラス・ノースは、革命的な変化について、「そのレトリックが私たちに信じさせるほど、決して 革命的なものではない」と注意を喚起している。[37] 法や憲法の「形式的なルール」は一夜にして変更可能だが、「非公式な制約」である制度的慣性や文化的継承は迅速に変化せず、社会変革を遅らせる。ノースに よると、形式的なルールと非公式な制約の緊張は「全体的な制約の両方向への再構築により、修辞よりもはるかに革命的でない新たな均衡を生むことで解決され る」[37]。 |

| Age of Revolution Classless society Counterrevolution List of revolutions and rebellions Passive revolution Political warfare Preference falsification Psychological warfare Rebellion Reformism Revolutionary wave Right of revolution Social movement Subversion User revolt Revolutions in autocracies after military defeats Regime change in autocracies |

革命の時代 階級なき社会 反革命 革命と反乱の一覧 受動的革命 政治戦争 選好偽装 心理戦争 反乱 改革主義 革命の波 革命の権利 社会運動 破壊活動 ユーザー反乱 軍事敗北後の独裁政権における革命 独裁政権の政権交代 |

| Bibliography Fukuyama, Francis (1992). The End of History and the Last Man. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-140-13455-1. Getachew, Adom (2019). Worldmaking After Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-17915-5. Gunitsky, Seva (2017). Aftershocks. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-17233-0. Gunitsky, Seva (2018). "Democratic Waves in Historical Perspective". Perspectives on Politics. 16 (3): 634–651. doi:10.1017/S1537592718001044. ISSN 1537-5927. S2CID 149523316. Gunitsky, Seva (2021), Bartel, Fritz; Monteiro, Nuno P. (eds.), "Great Powers and the Spread of Autocracy Since the Cold War", Before and After the Fall: World Politics and the End of the Cold War, Cambridge University Press, pp. 225–243, doi:10.1017/9781108910194.014, ISBN 978-1-108-84334-8, S2CID 244851964 Katz, Mark N. (1997). Revolutions and Revolutionary Waves. St Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-17322-7. Peter Kropotkin (1906), Memoirs of a Revolutionist. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., Ltd. Reus-Smit, Christian (2013). Individual Rights and the Making of the International System. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139046527. ISBN 978-0-521-85777-2. |

参考文献 フクヤマ、フランシス(1992)。『歴史の終わりと最後の男』。ペンギン。ISBN 978-0-140-13455-1。 ゲタチェウ、アドム(2019)。『帝国後の世界構築:自己決定の興亡』。プリンストン大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-691-17915-5。 グニツキー、セヴァ(2017)。『余震』。プリンストン大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-691-17233-0。 グニツキー、セヴァ(2018)。「歴史的視点から見た民主主義の波」。『政治の展望』。16 (3): 634–651。doi:10.1017/S1537592718001044。ISSN 1537-5927。S2CID 149523316。 グニツキー, セヴァ (2021), バルテル, フリッツ; モンテイロ, ヌノ・P. (編), 「冷戦後の大国の独裁主義の拡散」, 崩壊の前後: 冷戦の終結と世界政治, カムブリッジ大学出版局, pp. 225–243, doi:10.1017/9781108910194.014、ISBN 978-1-108-84334-8、S2CID 244851964 Katz, Mark N. (1997). Revolutions and Revolutionary Waves. St Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-17322-7。 ピーター・クロポトキン (1906)、『革命家の回顧録』。ロンドン:スワン・ソネンシャイン社。 Reus-Smit, Christian (2013). Individual Rights and the Making of the International System. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139046527. ISBN 978-0-521-85777-2. |

| Further reading Beissinger, Mark R. 2022. The Revolutionary City: Urbanization and the Global Transformation of Rebellion. Princeton University Press Beissinger, Mark R. (2024). "The Evolving Study of Revolution". World Politics. Beck, Colin J. (2018). "The Structure of Comparison in the Study of Revolution". Sociological Theory. 36 (2): 134–161. doi:10.1177/0735275118777004. S2CID 53669466. Edelstein, Dan (2025). The Revolution to Come: A History of an Idea from Thucydides to Lenin. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691231853. Goldstone, Jack A. (1982). "The Comparative and Historical Study of Revolutions". Annual Review of Sociology. 8: 187–207 Ness, Immanuel, ed. (2009). The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest: 1500 to the Present. Malden, MA: Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-405-18464-9. Strang, David (1991). "Global Patterns of Decolonization, 1500-1987". International Studies Quarterly. 35 (4): 429–454. doi:10.2307/2600949. ISSN 0020-8833. JSTOR 2600949. |

さらに読む Beissinger, Mark R. 2022. The Revolutionary City: Urbanization and the Global Transformation of Rebellion. Princeton University Press Beissinger, Mark R. (2024). 「The Evolving Study of Revolution」. World Politics. ベック、コリン・J. (2018). 「革命の研究における比較の構造」. 社会学理論. 36 (2): 134–161. doi:10.1177/0735275118777004. S2CID 53669466. エデルスタイン、ダン (2025). 来るべき革命:トゥキディデスからレーニンまでの思想史. プリンストン大学出版局. ISBN 9780691231853. ゴールドストーン、ジャック・A. (1982). 「革命の比較歴史的研究」. Annual Review of Sociology. 8: 187–207 ネス, イマニュエル, 編 (2009). 『革命と抗議の国際百科事典: 1500年から現在まで』. マールデン, マサチューセッツ: ワイリー・アンド・サンズ. ISBN 978-1-405-18464-9. ストレンジ、デビッド (1991). 「1500年から1987年までの脱植民地化のグローバルパターン」. International Studies Quarterly. 35 (4): 429–454. doi:10.2307/2600949. ISSN 0020-8833. JSTOR 2600949. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Revolution |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099