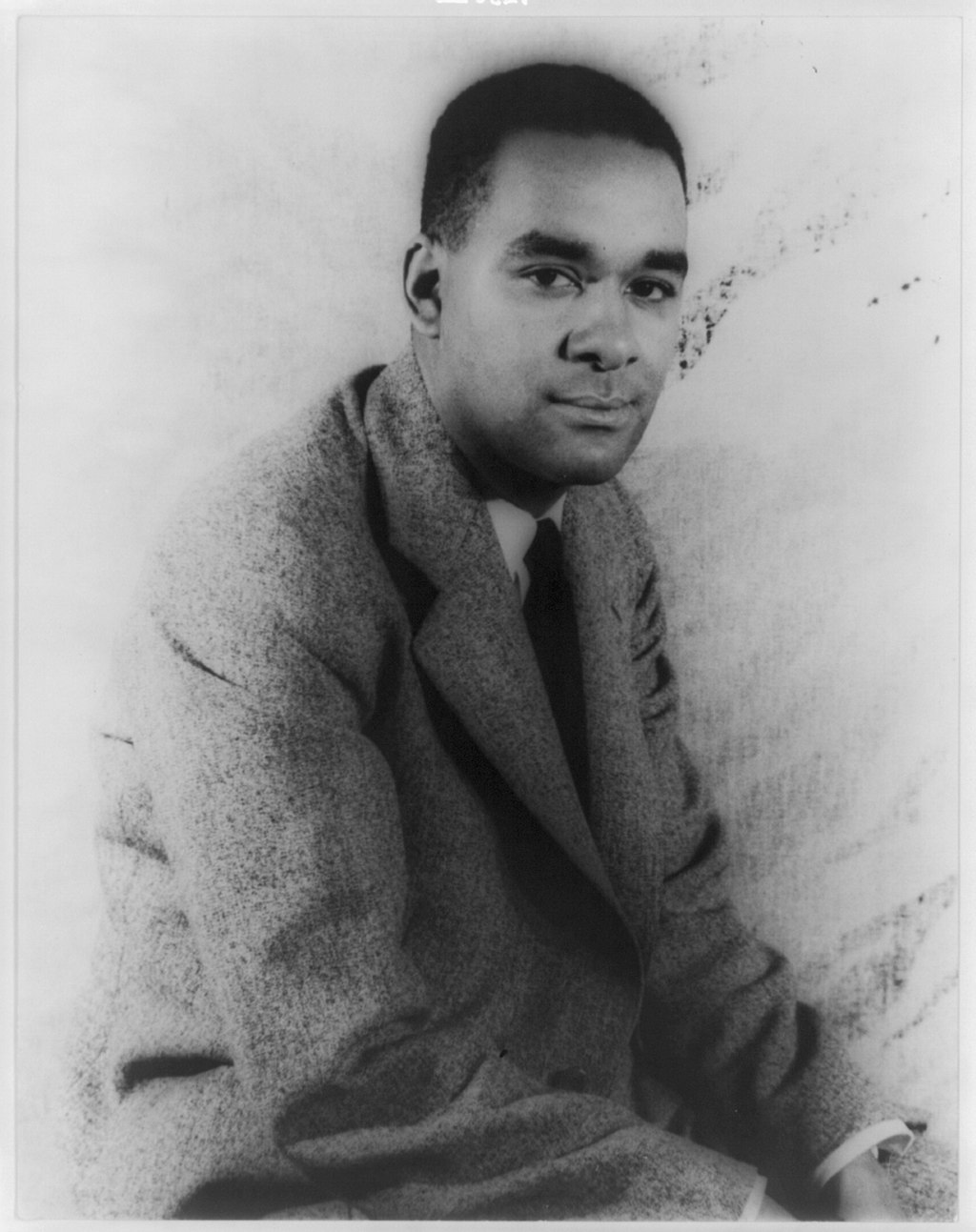

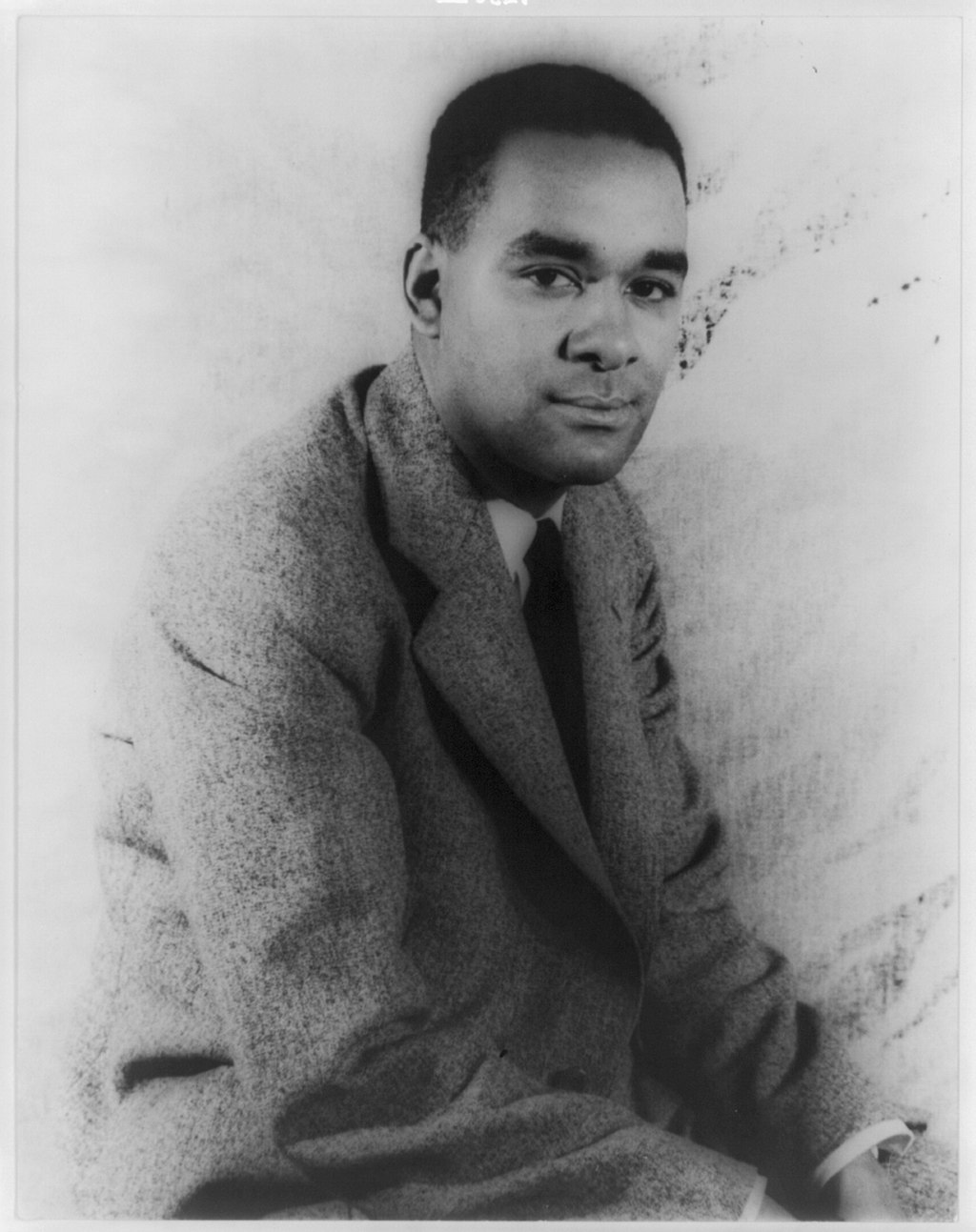

リチャード・ライト

Richard Wright, 1908

☆リ

チャード・ナサニエル・ライト(1908年9月4日-1960年11月28日)は小説、短編小説、詩、ノンフィクションのアメリカ人作家である。彼の文学

の多くは人種をテーマにしており、特に19世紀後半から20世紀半ばにかけて差別と暴力に苦しんだアフリカ系アメリカ人の苦境に関連している。代表作に

は、小説集『Uncle Tom's Children』(1938年)、小説『Native Son』(1940年)、回想録『Black

Boy』(1945年)などがある。文学批評家たちは、彼の作品が20世紀半ばのアメリカの人種関係を変えるのに貢献したと考えている。

| Richard Nathaniel Wright

(September 4, 1908 – November 28, 1960) was an American author of

novels, short stories, poems, and non-fiction. Much of his literature

concerns racial themes, especially related to the plight of African

Americans during the late 19th to mid 20th centuries suffering

discrimination and violence. His best known works include the novella

collection Uncle Tom's Children (1938), the novel Native Son (1940),

and the memoir Black Boy (1945). Literary critics believe his work

helped change race relations in the United States in the mid-20th

century. |

リチャード・ナサ

ニエル・ライト(1908年9月4日-1960年11月28日)は小説、短編小説、詩、ノンフィクションのアメリカ人作家である。彼の文学の多くは人種を

テーマにしており、特に19世紀後半から20世紀半ばにかけて差別と暴力に苦しんだアフリカ系アメリカ人の苦境に関連している。代表作には、小説集

『Uncle Tom's Children』(1938年)、小説『Native Son』(1940年)、回想録『Black

Boy』(1945年)などがある。文学批評家たちは、彼の作品が20世紀半ばのアメリカの人種関係を変えるのに貢献したと考えている。 |

| Early life and education Childhood in the South Richard Nathaniel Wright was born on September 4, 1908, at Rucker's Plantation, between the train town of Roxie and the larger river city of Natchez, Mississippi.[1] He was the son of Nathan Wright, a sharecropper,[1] and Ella (Wilson),[2] a schoolteacher.[1][3] His parents were born free after the Civil War; both sets of his grandparents had been born into slavery and freed as a result of the war. Each of his grandfathers had taken part in the U.S. Civil War and gained freedom through service: his paternal grandfather, Nathan Wright, had served in the 28th United States Colored Troops; his maternal grandfather, Richard Wilson, escaped from slavery in the South to serve in the U.S. Navy as a Landsman in April 1865.[4] Richard's father left the family when Richard was six years old, and he did not see Richard for 25 years. In 1911 or 1912 Ella moved to Natchez, Mississippi, to be with her parents. While living in his grandparents' home, he accidentally set the house on fire. Wright's mother was so angry that she beat him until he was unconscious.[5][6] In 1915, Ella put her sons in Settlement House, a Methodist orphanage, for a short time.[5][7] He was enrolled at Howe Institute in Memphis from 1915 to 1916.[1] In 1916, his mother moved with Richard and his younger brother to live with her sister Maggie (Wilson) and Maggie's husband Silas Hoskins (born 1882) in Elaine, Arkansas. This part of Arkansas was in the Mississippi Delta where former cotton plantations had been. The Wrights were forced to flee after Silas Hoskins "disappeared," reportedly killed by a white man who coveted his successful saloon business.[8] After his mother became incapacitated by a stroke, Richard was separated from his younger brother and lived briefly with his uncle Clark Wilson and aunt Jodie in Greenwood, Mississippi.[1] At the age of 12, he had not yet had a single complete year of schooling. Soon Richard with his younger brother and mother returned to the home of his maternal grandmother, which was now in the state capital, Jackson, Mississippi, where he lived from early 1920 until late 1925. His grandparents, still angry at him for destroying their house, repeatedly beat Wright and his brother.[6] But while he lived there, he was finally able to attend school regularly. He attended the local Seventh-day Adventist school from 1920 to 1921, with his aunt Addie as his teacher.[1][5] After a year, at the age of 13 he entered the Jim Hill public school in 1921, where he was promoted to sixth grade after only two weeks.[9] In his grandparents' Seventh-day Adventist home, Richard was miserable, largely because his controlling aunt and grandmother tried to force him to pray so he might build a relationship with God. Wright later threatened to move out of his grandmother's home when she would not allow him to work on the Adventist Sabbath, Saturday. His aunt's and grandparents' overbearing attempts to control him caused him to carry over hostility towards Biblical and Christian teachings to solve life's problems. This theme would weave through his writings throughout his life.[7] At the age of 15, while in eighth grade, Wright published his first story, "The Voodoo of Hell's Half-Acre," in the local Black newspaper Southern Register. No copies survive.[7] In Chapter 7 of Black Boy, he described the story as about a villain who sought a widow's home.[10] In 1923, after excelling in grade school and junior high, Wright earned the position of class valedictorian of Smith Robertson Junior High School from which he graduated in May 1925.[1] He was assigned to write a speech to be delivered at graduation in a public auditorium. Before graduation day, he was called to the principal's office, where the principal gave him a prepared speech to present in place of his own. Richard challenged the principal, saying "the people are coming to hear the students, and I won't make a speech that you've written."[11] The principal threatened him, suggesting that Richard might not be allowed to graduate if he persisted, despite his having passed all the examinations. He also tried to entice Richard with an opportunity to become a teacher. Determined not to be called an Uncle Tom, Richard refused to deliver the principal's address, written to avoid offending the white school district officials. He was able to convince everyone to allow him to read the words he had written himself.[7] In September that year, Wright registered for mathematics, English, and history courses at the new Lanier High School, constructed for black students in Jackson—the state's schools were segregated under its Jim Crow laws—but he had to stop attending classes after a few weeks of irregular attendance because he needed to earn money to support his family.[7][12] In November 1925 at the age of 17, Wright moved on his own to Memphis, Tennessee. There he fed his appetite for reading. His hunger for books was so great that Wright devised a successful ploy to borrow books from the segregated white library. Using a library card lent by a white coworker, which he presented with forged notes that claimed he was picking up books for the white man, Wright was able to obtain and read books forbidden to black people in the Jim Crow South. This stratagem also allowed him access to publications such as Harper's, the Atlantic Monthly, and The American Mercury.[7] He planned to have his mother come and live with him once he could support her, and in 1926, his mother and younger brother did rejoin him. Shortly thereafter, Richard resolved to leave the Jim Crow South and go to Chicago.[13] His family joined the Great Migration, when tens of thousands of blacks left the South to seek opportunities in the more economically prosperous northern and mid-western industrial cities. Wright's childhood in Mississippi, Tennessee, and Arkansas shaped his lasting impressions of American racism.[14] Coming of age in Chicago Wright and his family moved to Chicago in 1927, where he secured employment as a United States postal clerk.[8] He used his time in between shifts to study other writers including H.L. Mencken, whose vision of the American South as a version of Hell made an impression. When he lost his job there during the Great Depression, Wright was forced to go on relief in 1931.[7] In 1932, he began attending meetings of the John Reed Club, a Marxist literary organization.[7][15] Wright established relationships and networked with party members. Wright formally joined the Communist Party and the John Reed Club in late 1933 at the urging of his friend Abraham Aaron.[citation needed] As a revolutionary poet, he wrote proletarian poems ("We of the Red Leaves of Red Books", for example), for New Masses and other communist-leaning periodicals.[7] A power struggle within the Chicago chapter of the John Reed Club had led to the dissolution of the club's leadership; Wright was told he had the support of the club's party members if he was willing to join the party.[16] In 1933, Wright founded the South Side Writers Group, whose members included Arna Bontemps and Margaret Walker.[17][18] Through the group and his membership in the John Reed Club, Wright founded and edited Left Front, a literary magazine. Wright began publishing his poetry ("A Red Love Note" and "Rest for the Weary" for example) there in 1934.[19] There is dispute about the demise in 1935 of Left Front Magazine as Wright blamed the Communist Party despite his protests.[20] It is however likely due to the proposal at the 1934 Midwest Writers Congress that the John Reed Club be replaced by a Communist Party-sanctioned First American Party Congress.[citation needed] Throughout this period, Wright continued to contribute to New Masses magazine, revealing the path his writings would ultimately take.[21] By 1935, Wright had completed the manuscript of his first novel, Cesspool, which was rejected by eight publishers and published posthumously as Lawd Today (1963).[8][22] This first work featured autobiographical anecdotes about working at a post office in Chicago during the Great Depression.[23] In January 1936 his story "Big Boy Leaves Home" was accepted for publication in the anthology New Caravan and the anthology Uncle Tom's Children, focusing on black life in the rural American South.[24] In February of that year, he began working with the National Negro Congress (NNC), speaking at the Chicago convention on "The Role of the Negro Artist and Writer in the Changing Social Order".[25] His ultimate goal (looking at other labor unions as inspiration) was the development of NNC-sponsored publications, exhibits, and conferences alongside the Federal Writers' Project to get work for black artists.[25] In 1937, he became the Harlem editor of the Daily Worker. This assignment compiled quotes from interviews preceded by an introductory paragraph, thus allowing him time for other pursuits like the publication of Uncle Tom's Children a year later.[19] Pleased by his positive relations with white Communists in Chicago, Wright was later humiliated in New York City by some white party members who rescinded an offer to find housing for him when they learned his race.[26] Some black Communists denounced Wright as a "bourgeois intellectual." Wright was essentially autodidactic. He had been forced to end his public education to support his mother and brother after completing junior high school.[27] Throughout the Soviet pact with Nazi Germany in 1940, Wright continued to focus his attention on racism in the United States.[28] He would ultimately break from the Communist Party when they broke from a tradition against segregation and racism and joined Stalinists supporting the US entering World War II in 1941.[28] Wright insisted that young communist writers be given space to cultivate their talents. Wright later described this episode through his fictional character Buddy Nealson, an African-American communist, in his essay "I tried to be a Communist," published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1944. This text was an excerpt of his autobiography scheduled to be published as American Hunger but was removed from the actual publication of Black Boy upon request by the Book of the Month Club.[29] Indeed, his relations with the party turned violent; Wright was threatened at knifepoint by fellow-traveler co-workers, denounced as a Trotskyite in the street by strikers, and physically assaulted by former comrades when he tried to join them during the 1936 Labour Day march.[30] |

生い立ちと教育 南部での子供時代 1リチャード・ナサニエル・ライトは、1908年9月4日、ミシシッピ州の鉄道の町ロキシーと、より大きな河川の都市ナチェズの間のラッカーズ・プラン テーションで生まれた。[1] 彼は、小作人であるネイサン・ライト[1] と、教師であるエラ(ウィルソン)[2] の息子であった[1][3]。彼の両親は南北戦争後に自由の身となった。彼の祖父母は、いずれも奴隷として生まれ、戦争の結果として自由の身となった。彼 の祖父たちはそれぞれ南北戦争に参加し、その功績によって自由を得た。父方の祖父ネイサン・ライトは、第28米国有色人種部隊に所属していた。母方の祖父 リチャード・ウィルソンは、1865年4月に南部での奴隷生活から逃れ、米海軍の陸兵として従軍した。 リチャードの父親は、リチャードが6歳の時に家族を去り、その後25年間リチャードに会わなかった。1911年か1912 年、エラは両親と暮らすためミシシッピ州ナチェズに移った。祖父母の家で暮らしていた時、リチャードはうっかり家を火事にした。母親は激怒し、意識を失う まで彼を殴った。[5][6] 1915年、エラは息子たちをメソジスト派の孤児院「セトルメント・ハウス」に短期間預けた。[5][7] 1915年から1916年まで、メンフィスのハウ研究所に入学した。[1] 1916年、母親はリチャードと弟を連れて、アーカンソー州エレインに住む姉のマギー(ウィルソン)と、マギーの夫であるサイラス・ホスキンス(1882 年生まれ)の家に引っ越した。アーカンソー州のこの地域は、かつて綿花農園があったミシシッピ川デルタ地帯にあった。サイラス・ホスキンスが「失踪」した 後、ライト一家は逃亡を余儀なくされた。サイラスは、彼の成功した酒場事業を欲しがった白人男性によって殺害されたと伝えられている。[8] 母親が脳卒中により身動きが取れなくなった後、リチャードは弟と離れ、ミシシッピ州グリーンウッドに住む叔父のクラーク・ウィルソンと叔母のジョディのも とで短期間暮らした。12歳の時点で、彼はまだ1年も学校に通ったことがなかった。まもなく、リチャードは弟と母親とともに、ミシシッピ州ジャクソンにあ る母方の祖母の家に戻った。1920年の初めから1925年の終わりまで、彼はそこで暮らした。祖父母は、家を破壊したリチャードにまだ怒っており、リ チャードと弟を繰り返し殴った。[6] しかし、そこに住んでいる間、彼はようやく定期的に学校に通うことができた。1920年から1921年まで、彼は地元のセブンスデー・アドベンチストの学 校に通い、叔母のアディが彼の教師だった。[1][5] 1年後、13歳の1921年にジム・ヒル公立学校に入学し、わずか2週間で6年生に進級した。[9] 祖父母のセブンスデー・アドベンチストの家で、リチャードは悲惨な日々を送った。支配的な叔母と祖母が、神との関係を築くために祈りを強要しようとしたた めだ。後にライトは、アドベンチストの安息日である土曜日に働くことを祖母が許さなかったため、祖母の家から出ていくと脅した。叔母や祖父母による過干渉 な支配の試みは、彼に聖書やキリスト教の教えに対する敵意を抱かせ、人生の問題解決に悪影響を及ぼした。このテーマは彼の生涯にわたる著作に一貫して織り 込まれていくことになる。[7] 中学2年生だった15歳の時、ライトは地元の黒人新聞Southern Registerに最初の物語「The Voodoo of Hell's Half-Acre」を発表した。『Black Boy』の第7章で、彼はこの物語を未亡人の家を探す悪党の話だと述べている[10]。 1923年、小学校と中学校で優秀な成績を収めたライトは、スミス・ロバートソン・ジュニア・ハイスクールの卒業生総代の地位を獲得し、1925年5月に 卒業した[1]。卒業式の前日、彼は校長室に呼び出され、校長から自分のスピーチの代わりに用意されたスピーチを渡された。校長はリチャードを脅し、すべ ての試験に合格しているにもかかわらず、このままでは卒業させてもらえないかもしれないと言った。校長はまた、リチャードに教師になる機会を与えようとし た。アンクル・トムと呼ばれたくないと決心したリチャードは、白人の学区関係者の機嫌を損ねないように書いた校長の演説を拒否した。彼は自分で書いた言葉 を読むことを許可するよう、皆を説得することができた[7]。 その年の9月、ライトはジャクソンの黒人生徒のために建設された新しいラニアー高校の数学、英語、歴史のコースに登録した。 1925年11月、17歳のライトは単身テネシー州メンフィスに移り住む。そこで彼は読書欲を満たした。彼の本への渇望は非常に大きく、ライトは隔離され た白人の図書館から本を借りる策略を考え出した。白人の同僚が貸してくれた図書館カードを使い、白人のために本を借りていると偽造したメモを添えて提示し た。この策略によって、彼は『Harper's』、『Atlantic Monthly』、『The American Mercury』などの出版物を手に入れることもできた[7]。 そして1926年、母親と弟はリチャードと再会した。その後まもなく、リチャードはジム・クロウ制の南部を離れ、シカゴに行くことを決意した[13]。彼の家族は、何万人もの黒人がより経済的に繁栄した北部や中西部の工業都市に機会を求めて南部を離れた大移動に加わった。 ミシシッピ、テネシー、アーカンソーでの幼少期は、アメリカの人種差別に対する彼の永続的な印象を形成した[14]。 シカゴで青春を過ごす ラ イトとその家族は1927年にシカゴへ移り住み、そこで米国郵便局の事務員として職を得た。[8] 彼は勤務の合間を利用して他の作家たちの著作を研究した。その中にはH・L・メンケンも含まれており、メンケンが描くアメリカ南部を地獄の一形態とする見 解は彼に強い印象を与えた。大恐慌期に職を失ったライトは、1931年に救済措置を受けることを余儀なくされた。[7] 1932年、彼はマルクス主義文学団体「ジョン・リード・クラブ」の集会に出席し始めた。[7][15] ライトは党員たちと関係を築き、ネットワークを広げた。1933年末、友人エイブラハム・アーロンの勧めで、ライトは共産党とジョン・リード・クラブに正 式に加入した。[出典必要] 革命詩人として、彼はプロレタリア詩(例えば「我ら、赤い本の赤い葉」など)を『ニュー・マセス』やその他の共産主義系雑誌に寄稿した。[7] ジョン・リード・クラブのシカゴ支部内で権力闘争が起こり、クラブの指導部は解散した。ライトは、党に入党する意思があればクラブの党員たちの支持を得ら れると言われた。[16] 1933年、ライトはサウスサイド・ライターズ・グループを設立し、そのメンバーにはアルナ・ボンテンプスやマーガレット・ウォーカーらがいた[17] [18]。このグループとジョン・リード・クラブのメンバーを通じて、ライトは文芸誌『レフト・フロント』を創刊、編集した。1934年、ライトはそこで 詩(例えば『赤い恋文』や『疲れた人のための休息』)を発表し始めた[19]。1935年のレフト・フロント誌の廃刊については論争があり、ライトは抗議 したにもかかわらず共産党のせいにしている。 [20]しかし、1934年の中西部作家会議において、ジョン・リード・クラブを共産党公認の第一次アメリカ党会議に置き換えるという提案がなされたため であると思われる[要出典]。この時期を通じて、ライトは『ニュー・マス』誌に寄稿を続け、彼の著作が最終的に進む道を明らかにした[21]。 1935年までにライトは処女作『掃き溜め』の原稿を完成させていたが、これは8つの出版社からリジェクトされ、死後に『Lawd Today』(1963年)として出版された[8][22]。この処女作には、世界大恐慌の時代にシカゴの郵便局で働いていたという自伝的な逸話が登場す る[23]。 1936年1月、彼の物語 「Big Boy Leaves Home 」はアンソロジー『New Caravan』とアンソロジー『Uncle Tom's Children』に採用され、アメリカ南部の田舎での黒人の生活に焦点を当てた作品として出版された[24]。 その年の2月、彼は全米黒人会議(NNC)と活動を開始し、シカゴの大会で「変化する社会秩序における黒人の芸術家と作家の役割」について講演した [25]。彼の最終的な目標は(インスピレーションとして他の労働組合に注目し)、黒人芸術家に仕事を得るために連邦作家計画と並んでNNC主催の出版 物、展示会、会議を発展させることであった[25]。 1937年、彼は『デイリー・ワーカー』紙のハーレム担当編集者となった。この仕事では、インタビューからの引用を序文でまとめていたため、1年後の『Uncle Tom's Children』の出版など、他の仕事に時間を割くことができた[19]。 シカゴでの白人共産党員との良好な関係に満足していたライトは、後にニューヨークで、彼の人種を知ると住居探しの申し出を取り消した一部の白人党員から屈 辱を受けた[26]。一部の黒人共産党員は、ライトを「ブルジョア知識人」と非難した。ライトは本質的に独学者だった。彼は中学を卒業した後、母親と弟を 養うために公教育を打ち切らざるを得なかった[27]。 1940年にソ連がナチス・ドイツと協定を結ぶまで、ライトはアメリカにおける人種差別に関心を向け続けていた[28]。1941年に共産党が人種隔離と 人種差別に反対する伝統から脱却し、アメリカが第二次世界大戦に参戦することを支持するスターリニストに加わったとき、ライトは最終的に共産党から離党す ることになる[28]。 ライトは、共産主義者の若手作家に才能を開花させる場を与えるよう主張した。ライトは後に、1944年に『アトランティック・マンスリー』誌に発表した エッセイ「I tried to be a Communist」の中で、アフリカ系アメリカ人の共産主義者バディ・ニールソンという架空の人物を通してこのエピソードを描いている。この文章は 『American Hunger』として出版される予定だった自伝の抜粋であったが、ブック・オブ・ザ・マンス・クラブの要請により、『Black Boy』の実際の出版からは削除された[29]。実際、彼の党との関係は暴力的になり、ライトは旅仲間の同僚からナイフを突きつけられて脅され、ストライ キ参加者からは路上でトロツキストとして糾弾され、1936年の労働者の日のデモ行進に参加しようとした元同志からは身体的暴行を受けた[30]。 |

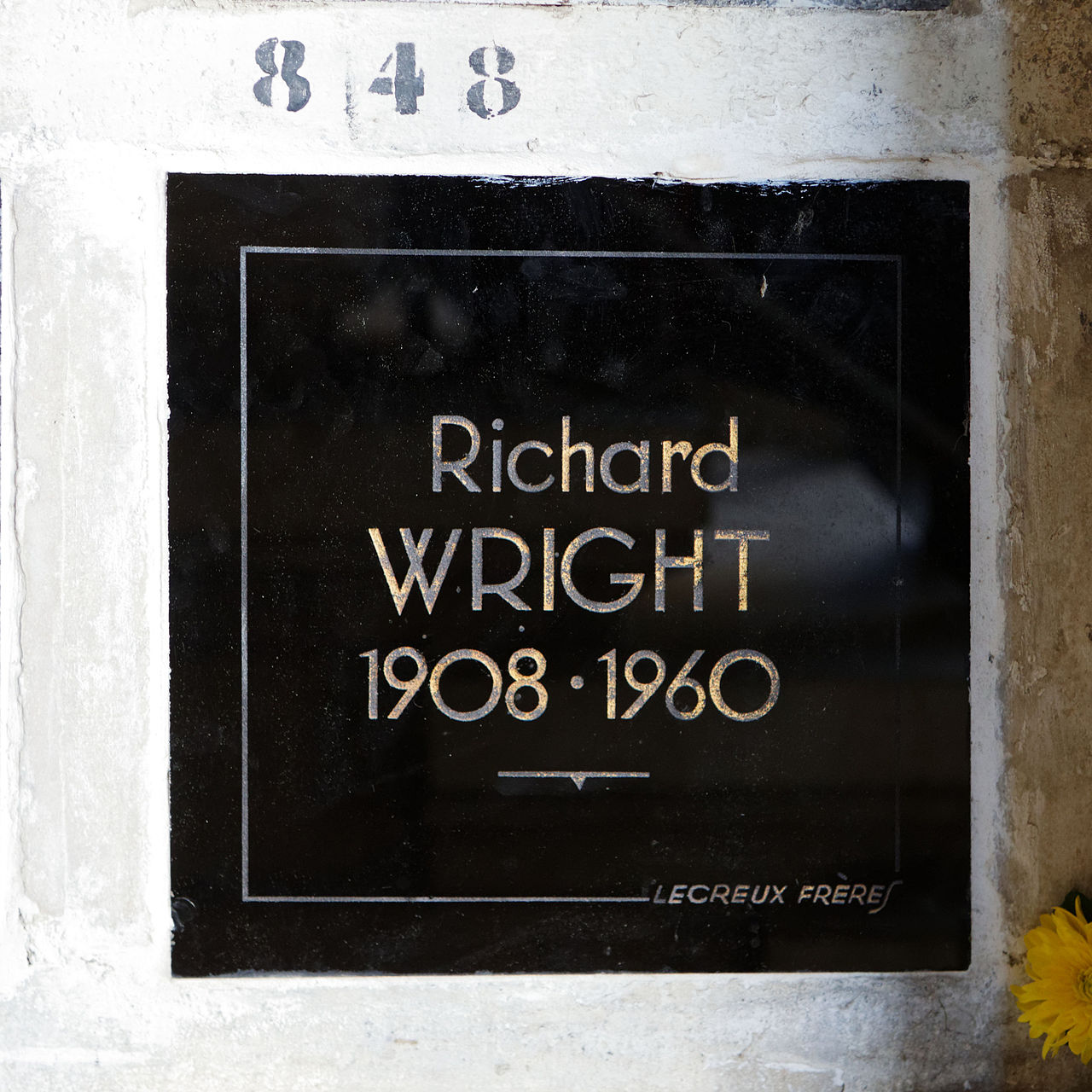

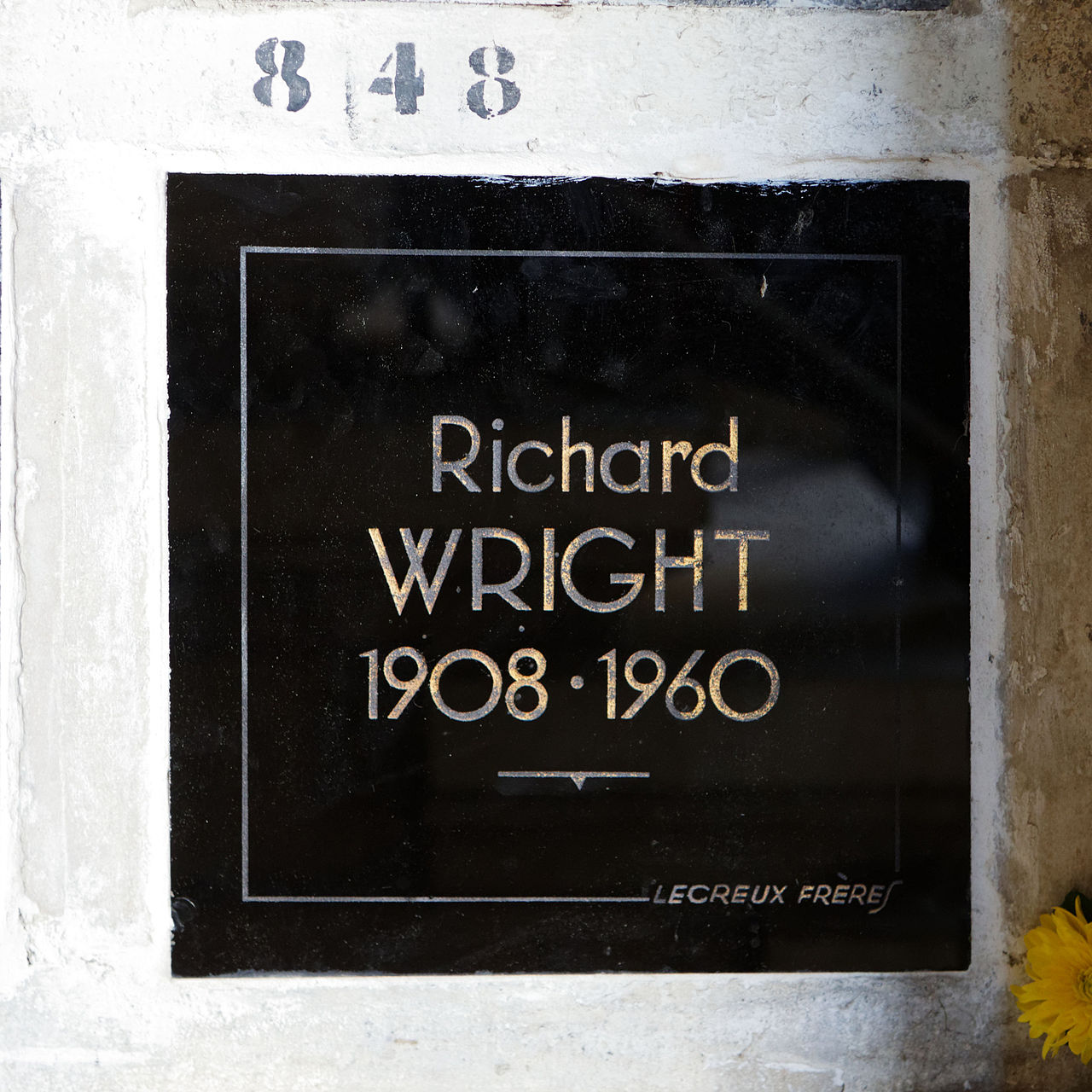

| Career In Chicago in 1932, Wright began writing with the Federal Writer's Project and became a member of the American Communist Party. In 1937, he relocated to New York and became the Bureau Chief of the communist publication, the Daily Worker.[31] He would write over 200 articles for the publication from 1937 to 1938. This allowed him to cover stories and issues that interested him, revealing depression-era America into light with well-written prose.[32] He worked on the Federal Writers' Project guidebook to the city, New York Panorama (1938), and wrote the book's essay on Harlem. Through the summer and fall he wrote more than 200 articles for the Daily Worker and helped edit a short-lived literary magazine, New Challenge. The year was also a landmark for Wright because he met and developed a friendship with writer Ralph Ellison that would last for years. He was awarded the Story magazine first prize of $500 for his short story "Fire and Cloud".[33] After receiving the Story prize in early 1938, Wright shelved his manuscript of Lawd Today and dismissed his literary agent, John Troustine. He hired Paul Reynolds, the well-known agent of poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, to represent him. Meanwhile, the Story Press offered the publisher Harper all of Wright's prize-entry stories for a book, and Harper agreed to publish the collection. Wright gained national attention for the collection of four short stories entitled Uncle Tom's Children (1938). He based some stories on lynching in the Deep South. The publication and favorable reception of Uncle Tom's Children improved Wright's status with the Communist party and enabled him to establish a reasonable degree of financial stability. He was appointed to the editorial board of New Masses. Granville Hicks, a prominent literary critic and Communist sympathizer, introduced him at leftist teas in Boston. By May 6, 1938, excellent sales had provided Wright with enough money to move to Harlem, where he began writing the novel Native Son, which was published in 1940. Based on his collected short stories, Wright applied for and was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, which gave him a stipend allowing him to complete Native Son. During this period, he rented a room in the home of friends Herbert and Jane Newton, an interracial couple and prominent Communists whom Wright had known in Chicago.[34] They had moved to New York and lived at 109 Lefferts Place in Brooklyn in the Fort Greene neighborhood.[35] After publication, Native Son was selected by the Book of the Month Club as its first book by an African-American author. It was a daring choice. The lead character, Bigger Thomas, is bound by the limitations that society places on African Americans. Unlike most in this situation, he gains his own agency and self-knowledge only by committing heinous acts. Wright's characterization of Bigger led to him being criticized for his concentration on violence in his works. In the case of Native Son, people complained that he portrayed a black man in ways that seemed to confirm whites' worst fears. The period following publication of Native Son was a busy time for Wright. In July 1940 he went to Chicago to do research for a folk history of blacks to accompany photographs selected by Edwin Rosskam. While in Chicago he visited the American Negro Exposition with Langston Hughes, Arna Bontemps and Claude McKay.  Canada Lee as Bigger Thomas in the Orson Welles production of Native Son (1941) Wright traveled to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, to collaborate with playwright Paul Green on a dramatic adaptation of Native Son. In January 1941 Wright received the prestigious Spingarn Medal of the NAACP for noteworthy achievement. His play Native Son opened on Broadway in March 1941, with Orson Welles as director, to generally favorable reviews. Wright also wrote the text to accompany a volume of photographs chosen by Rosskam, which were almost completely drawn from the files of the Farm Security Administration. The FSA had employed top photographers to travel around the country and capture images of Americans. Their collaboration, 12 Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States, was published in October 1941 to wide critical acclaim. Wright's memoir Black Boy (1945) describes his early life from Roxie up until his move to Chicago at age 19. It includes his clashes with his Seventh-day Adventist family, his troubles with white employers, and social isolation. It also describes his intellectual journey through these struggles. American Hunger, which was published posthumously in 1977, was originally intended by Wright as the second volume of Black Boy. The Library of America edition of 1991 finally restored the book to its original two-volume form.[36] American Hunger details Wright's participation in the John Reed Clubs and the Communist Party, which he left in 1942. The book implies he left earlier, but he did not announce his withdrawal until 1944.[37] In the book's restored form, Wright used the diptych structure to compare the certainties and intolerance of organized communism, which condemned "bourgeois" books and certain members, with similar restrictive qualities of fundamentalist organized religion. Wright disapproved of Joseph Stalin's Great Purge in the Soviet Union. France  Plaque commemorating Wright's residence in Paris, at 14, rue Monsieur le Prince. Following a stay of a few months in Québec, Canada, including a lengthy stay in the village of Sainte-Pétronille on the Île d'Orléans,[38] Wright moved to Paris in 1946. He became a permanent American expatriate.[39] In Paris, Wright became friends with French writers Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, whom he had met while still in New York, and he and his wife became particularly good friends with Simone de Beauvoir, who stayed with them in 1947.[40] However, as Michel Fabre argues, Wright's existentialist leanings were more influenced by Soren Kierkegaard, Edmund Husserl, and especially Martin Heidegger.[41] In following Fabre's argument, with respect to Wright's existentialist proclivities during the period of 1946 to 1951, Hue Woodson suggests that Wright's exposure to Husserl and Heidegger "directly came as an intended consequence of the inadequacies of Sartre's synthesis of existentialism and Marxism for Wright."[42] His Existentialist phase was expressed in his second novel, The Outsider (1953), which described an African-American character's involvement with the Communist Party in New York. He also became friends with fellow expatriate writers Chester Himes and James Baldwin. His relationship with the latter ended in acrimony after Baldwin published his essay "Everybody's Protest Novel" (collected in Notes of a Native Son), in which he criticized Wright's portrayal of Bigger Thomas as stereotypical. In 1954 Wright published Savage Holiday. After becoming a French citizen in 1947, Wright continued to travel through Europe, Asia, and Africa. He drew material from these trips for numerous nonfiction works. In 1949, Wright contributed to the anti-communist anthology The God That Failed; his essay had been published in the Atlantic Monthly three years earlier and was derived from the unpublished portion of Black Boy. He was invited to join the Congress for Cultural Freedom, which he rejected, correctly suspecting that it had connections with the CIA. Fearful of links between African Americans and communists, the FBI had Wright under surveillance starting in 1943. With the heightened communist fears of the 1950s, Wright was blacklisted by Hollywood movie studio executives. But in 1950, he starred as the teenager Bigger Thomas (Wright was 42) in an Argentinian film version of Native Son. In mid-1953, Wright traveled to the Gold Coast, where Kwame Nkrumah was leading the country to independence from British rule, to be established as Ghana. Before Wright returned to Paris, he gave a confidential report to the United States consulate in Accra on what he had learned about Nkrumah and his political party. After Wright returned to Paris, he met twice with an officer from the U.S. State Department. The officer's report includes what Wright had learned from Nkrumah's adviser George Padmore about Nkrumah's plans for the Gold Coast after independence. Padmore, a Trinidadian living in London, believed Wright to be a good friend. His many letters in the Wright papers at Yale's Beinecke Library attest to this, and the two men continued their correspondence. Wright's book on his African journey, Black Power, was published in 1954; its London publisher was Dennis Dobson, who also published Padmore's work.[43] Whatever political motivations Wright had for reporting to American officials, he was also an American who wanted to stay abroad and needed their approval to have his passport renewed. According to Wright biographer Addison Gayle, a few months later Wright talked to officials at the American embassy in Paris about people he had met in the Communist Party; at the time these individuals were being prosecuted in the US under the Smith Act.[44] Historian Carol Polsgrove explored why Wright appeared to have little to say about the increasing activism of the civil rights movement during the 1950s in the United States. She found that Wright was under what his friend Chester Himes called "extraordinary pressure" to avoid writing about the US.[45] As Ebony magazine delayed publishing his essay, "I Choose Exile," Wright finally suggested publishing it in a white periodical. He believed that "a white periodical would be less vulnerable to accusations of disloyalty."[45] He thought the Atlantic Monthly was interested, but in the end, the piece went unpublished.[45][46] In 1955, Wright visited Indonesia for the Bandung Conference.[47] He recorded his observations on the conference as well as on Indonesian cultural conditions in The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference. Wright praised the conference extensively.[47] He gave at least two lectures to Indonesian cultural groups, including PEN Club Indonesia, and he interviewed Indonesian artists and intellectuals in preparation to write The Color Curtain.[48] Several Indonesian artists and intellectuals whom Wright met, later commented on how he had depicted Indonesian cultural conditions in his travel writing.[49] Other works by Wright included White Man, Listen! (1957) and a novel The Long Dream (1958), which was adapted as a play and produced in New York in 1960 by Ketti Frings. It explores the relationship between a man named Fish and his father.[50] A collection of short stories, Eight Men, was published posthumously in 1961, shortly after Wright's death. These works dealt primarily with the poverty, anger, and protests of northern and southern urban black Americans. His agent, Paul Reynolds, sent strongly negative criticism of Wright's 400-page Island of Hallucinations manuscript in February 1959.[citation needed] Despite that, in March Wright outlined a novel in which his character Fish was to be liberated from racial conditioning and become dominating. By May 1959, Wright wanted to leave Paris and live in London. He felt French politics had become increasingly submissive to United States pressure. The peaceful Parisian atmosphere he had enjoyed had been shattered by quarrels and attacks instigated by enemies of the expatriate black writers. On June 26, 1959, after a party marking the French publication of White Man, Listen!, Wright became ill. He suffered a virulent attack of amoebic dysentery, probably contracted during his 1953 stay on the Gold Coast. By November 1959 his wife had found a London apartment, but Wright's illness and "four hassles in twelve days" with British immigration officials ended his desire to live in England.[citation needed] On February 19, 1960, Wright learned from his agent Reynolds that the New York premiere of the stage adaptation of The Long Dream received such bad reviews that the adapter, Ketti Frings, had decided to cancel further performances. Meanwhile, Wright was running into added problems trying to get The Long Dream published in France. These setbacks prevented his finishing revisions of Island of Hallucinations, for which he was trying to get a publication commitment from Doubleday and Company. In June 1960, Wright recorded a series of discussions for French radio, dealing primarily with his books and literary career. He also addressed the racial situation in the United States and the world, and specifically denounced American policy in Africa. In late September, to cover extra expenses for his daughter Julia's move from London to Paris to attend the Sorbonne, Wright wrote blurbs for record jackets for Nicole Barclay, director of the largest record company in Paris. In spite of his financial straits, Wright refused to compromise his principles. He declined to participate in a series of programs for Canadian radio because he suspected American control. For the same reason, he rejected an invitation from the Congress for Cultural Freedom to go to India to speak at a conference in memory of Leo Tolstoy. Still interested in literature, Wright helped Kyle Onstott get his novel Mandingo (1957) published in France. Wright's last display of explosive energy occurred on November 8, 1960, in his polemical lecture, "The Situation of the Black Artist and Intellectual in the United States," delivered to students and members of the American Church in Paris. He argued that American society reduced the most militant members of the black community to slaves whenever they wanted to question the racial status quo. He offered as proof the subversive attacks of the Communists against Native Son and the quarrels which James Baldwin and other authors sought with him. On November 26, 1960, Wright talked enthusiastically with Langston Hughes about his work Daddy Goodness and gave him the manuscript.  Wright's grave Wright died of a heart attack in Paris on November 28, 1960, at the age of 52. He was interred in Père Lachaise Cemetery.[51] Wright's daughter Julia has claimed that her father was murdered.[52] A number of Wright's works have been published posthumously. In addition, some of Wright's more shocking passages dealing with race, sex, and politics were cut or omitted before original publication of works during his lifetime. In 1991, unexpurgated versions of Native Son, Black Boy, and his other works were published. In addition, in 1994, his novella Rite of Passage was published for the first time.[53] In the last years of his life, Wright had become enamored of the Japanese poetic form haiku and wrote more than 4,000 such short poems. In 1998 a book was published (Haiku: This Other World) with 817 of his own favorite haiku. Many of these haiku have an uplifting quality even as they deal with coming to terms with loneliness, death, and the forces of nature. A collection of Wright's travel writings was published by the University Press of Mississippi in 2001. At his death, Wright left an unfinished book, A Father's Law,[54] dealing with a black policeman and the son he suspects of murder. His daughter Julia Wright published A Father's Law in January 2008. An omnibus edition containing Wright's political works was published under the title Three Books from Exile: Black Power; The Color Curtain; and White Man, Listen! |

経歴 1932年、シカゴの連邦ライターズ・プロジェクトで執筆を始め、アメリカ共産党員となる。1937年、ニューヨークに移り、共産主義者向けの出版物『デ イリー・ワーカー』の支局長となる[31]。これによって彼は、自分の興味のある記事や問題を取り上げ、よく書かれた散文によって不況時代のアメリカを明 るみに出すことができた[32]。 1938年には、ニューヨークのガイドブック『ニューヨーク・パノラマ』(Federal Writers' Project, New York Panorama)に取り組み、ハーレムについてのエッセイを執筆した。夏から秋にかけて『デイリー・ワーカー』紙に200以上の記事を書き、短命の文芸 誌『ニュー・チャレンジ』の編集に携わった。この年はライトにとって画期的な年でもあった。作家ラルフ・エリソンと出会い、何年も続く友情を育んだからで ある。彼は短編小説「火と雲」でストーリー誌の一等賞500ドルを受賞した[33]。 1938年初めにStory誌の一等賞を受賞した後、ライトは『Lawd Today』の原稿を棚上げにし、文芸エージェントであったジョン・トラスティンを解雇した。彼は詩人ポール・ローレンス・ダンバーのエージェントとして 有名なポール・レイノルズを代理人として雇った。一方、ストーリー・プレス社は、出版社ハーパー社にライトの入賞作をすべて書籍化することを提案し、ハー パー社はその作品集を出版することに同意した。 ライトは『Uncle Tom's Children』(1938年)という4つの短編小説集で全米の注目を集めた。ライトは、いくつかの物語をディープ・サウスでのリンチを題材にしてい る。アンクル・トムの子供たち』の出版と好評により、ライトは共産党での地位を向上させ、経済的にもそれなりの安定を得ることができた。彼は『ニュー・マ ス』の編集委員に任命された。著名な文芸評論家で共産主義シンパのグランヴィル・ヒックスは、ボストンの左派の茶会で彼を紹介した。1938年5月6日ま でに、売れ行きが好調だったため、ライトはハーレムに引っ越す十分な資金を手に入れ、1940年に出版された小説『Native Son』の執筆を開始した。 短編集をもとに、ライトはグッゲンハイム・フェローシップに応募し、授与された。この時期、ライトはシカゴで知り合った友人のハーバート・ニュートンとジェーン・ニュートンの家に部屋を借りていた。 出版後、『Native Son』はブック・オブ・ザ・マンス・クラブにアフリカ系アメリカ人作家の最初の本として選ばれた。大胆な選択だった。主人公のビガー・トーマスは、社会 がアフリカ系アメリカ人に課す制限に縛られている。このような境遇にある多くの人物とは異なり、彼は凶悪な行為を犯すことによってのみ、自らの主体性と自 己認識を獲得する。ライトはこのビガーのキャラクター設定によって、彼の作品における暴力への集中を批判されるようになった。ネイティヴ・サン』の場合 は、白人の最悪の恐怖を裏付けるような描き方で黒人を描いたことに不満の声が上がった。ネイティブ・サン』出版後の時期は、ライトにとって多忙な時期で あった。1940年7月、彼はエドウィン・ロスカムによって選ばれた写真に添えられる黒人の民俗史の調査のためにシカゴに行った。シカゴ滞在中、彼はラン グストン・ヒューズ、アルナ・ボンテンプス、クロード・マッケイとともにアメリカ黒人博覧会を訪れた。  オーソン・ウェルズ製作の『Native Son』(1941年)でビガー・トーマス役を演じたカナダ・リー ライトはノースカロライナ州チャペルヒルに赴き、劇作家ポール・グリーンと共同で『Native Son』の劇化に取り組んだ。1941年1月、ライトはNAACPの名誉あるスピンガーン・メダルを受賞した。彼の戯曲『Native Son』は1941年3月、オーソン・ウェルズを監督に迎えてブロードウェイで上演され、おおむね好評を博した。ライトはまた、ロスカムによって選ばれた 一巻の写真に添えられた文章も書いている。FSAは一流の写真家を雇い、全米を旅してアメリカ人の姿を撮影させていた。彼らの合作、『1200万人の黒人 の声』である: 1941年10月に出版された『A Folk History of the Negro in the United States』は、幅広い批評家の称賛を浴びた。 ライトの回顧録『Black Boy』(1945年)には、ロキシーから19歳でシカゴに引っ越すまでの幼少期が描かれている。セブンスデー・アドベンチストの家族との衝突、白人雇用 主とのトラブル、社会的孤立などが書かれている。また、これらの苦闘を通しての彼の知的な旅路も描かれている。1977年に死後出版された 『American Hunger』は、ライトは当初『Black Boy』の第2巻として出版するつもりだった。1991年のライブラリー・オブ・アメリカ版では、最終的に元の2巻の形に戻された[36]。 American Hunger』には、ジョン・リード・クラブと共産党へのライトの参加が詳述されているが、彼は1942年に脱退している。本書ではもっと早く脱退したこ とになっているが、彼が脱退を表明したのは1944年のことである[37]。復元された本書の中でライトは、「ブルジョア」の本や特定のメンバーを非難す る組織的共産主義の確実性と不寛容さを、原理主義的組織宗教の同様の制限的特質と比較するために、二部作構造を用いている。ライトは、ソ連におけるジョセ フ・スターリンの大粛清を否定していた。 フランス  パリのムッシュ・ル・プリンス通り14番地にあるライトの住居を記念するプレート。 オルレアン島のサント=ペトロニーユ村での長期滞在を含め、カナダのケベックに数ヶ月滞在した後[38]、ライトは1946年にパリに移り住んだ。彼は永住的なアメリカ人駐在員となった[39]。 パリでライトは、ニューヨーク滞在中に知り合ったフランス人作家ジャン=ポール・サルトルやアルベール・カミュと親しくなり、1947年に滞在したシモー ヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールとは妻とともに特に親交を深めた[40]。しかし、ミシェル・ファーブルが論じるように、ライトの実存主義への傾倒は、ソーレン・ キルケゴール、エドムント・フッサール、そして特にマルティン・ハイデガーの影響をより強く受けていた。 [1946年から1951年にかけてのライトの実存主義的傾向に関して、ファーブルの議論に従うと、ヒュー・ウッドソンは、ライトがフッサールとハイデ ガーに触れたのは「ライトにとって、サルトルの実存主義とマルクス主義の統合が不十分であったことの意図的な帰結として直接もたらされた」と示唆している [42]。彼の実存主義的な段階は、2作目の小説『アウトサイダー』(1953年)で表現された。彼はまた、同じ外国人作家のチェスター・ハイムスや ジェームズ・ボールドウィンと友人になった。後者との関係は、ボールドウィンがエッセイ『Everybody's Protest Novel』(『Notes of a Native Son』に収録)を発表し、ライトの描くビガー・トーマスがステレオタイプであると批判したことから険悪なものとなった。1954年、ライトは『野蛮な休 日』を出版した。 1947年にフランス国籍を取得したライトは、ヨーロッパ、アジア、アフリカを旅し続けた。これらの旅から多くのノンフィクション作品を生み出した。 1949年、ライトは反共アンソロジー『The God That Failed』に寄稿した。彼のエッセイは3年前に『Atlantic Monthly』に掲載されたもので、『Black Boy』の未発表部分から派生したものだった。その3年前に『アトランティック・マンスリー』誌に掲載されたエッセイは、『ブラック・ボーイ』の未発表部 分に由来するものだった。アフリカ系アメリカ人と共産主義者とのつながりを恐れたFBIは、1943年からライトを監視下に置いていた。1950年代に共 産主義への恐怖が高まると、ライトはハリウッドの映画スタジオの重役たちからブラックリストに載った。しかし1950年、彼はアルゼンチン映画版 『Native Son』でティーンエイジャーのビガー・トーマス(ライトは42歳)を演じた。 1953年半ば、ライトはクワメ・ンクルマが率いるゴールドコーストを訪れ、英国の支配からガーナとして独立させた。ライトはパリに戻る前に、ンクルマと 彼の政党について学んだことをアクラのアメリカ領事館に極秘報告した。ライトはパリに戻った後、米国務省の担当官と2度面会した。この将校の報告書には、 ライトがンクルマの顧問ジョージ・パドモアから学んだ、独立後のゴールドコーストに関するンクルマの計画が含まれていた。パドモアはロンドン在住のトリニ ダード人で、ライトのことを親友だと信じていた。イェール大学のバイネッケ図書館に所蔵されているライトの書簡の数々がそれを証明しており、2人はその後 も文通を続けた。ライトのアフリカの旅に関する著書『ブラック・パワー』は1954年に出版され、ロンドンの出版社はパドモアの著作も出版したデニス・ド ブソンだった[43]。 ライトがアメリカ政府高官に報告する政治的動機が何であったにせよ、彼は海外に滞在したいアメリカ人でもあり、パスポートの更新には彼らの承認が必要で あった。ライトの伝記作家アディソン・ゲイルによれば、数カ月後、ライトはパリのアメリカ大使館で、共産党で知り合った人々について話した。 歴史家のキャロル・ポルスグローヴは、なぜライトが1950年代のアメリカにおける公民権運動の活発化についてほとんど発言していないように見えたのかを 探った。『エボニー』誌が彼のエッセイ「I Choose Exile」の掲載を遅らせたため、ライトは最終的に白人の定期刊行物に掲載することを提案した[45]。彼は「白人の定期刊行物であれば、不誠実である という非難を受けにくいと考えた」[45]。彼はアトランティック・マンスリー誌が興味を持っていると考えたが、結局、この作品は未発表に終わった [45][46]。 1955年、ライトはバンドン会議のためにインドネシアを訪れた[47]: A Report on the Bandung Conference』(バンドン会議報告)である。ライトはこの会議を広く賞賛していた[47]。 彼はペンクラブ・インドネシアを含むインドネシアの文化団体で少なくとも2回講義を行い、『カラー・カーテン』の執筆準備のためにインドネシアの芸術家や 知識人にインタビューを行った[48]。 ライトが会った何人かのインドネシアの芸術家や知識人は、後に、彼が旅行記の中でインドネシアの文化状況をどのように描いているかについてコメントしてい る[49]。 ライトの他の作品には、『White Man, Listen!(1957)、小説『長い夢』(1958)がある。この作品は戯曲化され、ケッティ・フリングスによって1960年にニューヨークで上演さ れた。短編集『Eight Men』はライトの死後まもなくの1961年に出版された。これらの作品は主に北部と南部の都市部の黒人アメリカ人の貧困、怒り、抗議を扱っていた。 彼のエージェントであったポール・レイノルズは、1959年2月、ライトの400ページに及ぶ『幻覚の島』の原稿に強い否定的な批評を送った[要出典]。 にもかかわらず、3月、ライトは、彼のキャラクターであるフィッシュが人種的条件付けから解放され、支配的になるという小説の概要を描いた。1959年5 月まで、ライトはパリを離れてロンドンに住みたいと考えていた。彼は、フランスの政治がアメリカの圧力にますます従順になっていると感じていた。彼が享受 してきた平和なパリの雰囲気は、駐在黒人作家の敵が扇動する喧嘩や攻撃によって打ち砕かれていた。 1959年6月26日、『白人よ、聞け!』のフランスでの出版を祝うパーティーの後、ライトは病気になった。おそらく1953年のゴールドコースト滞在中 に感染したのだろう。1959年11月までに彼の妻はロンドンのアパートを見つけたが、ライトの病気とイギリスの入国管理局との「12日間で4回の揉め 事」によって、彼はイギリスに住みたいという希望を絶たれた[要出典]。 1960年2月19日、ライトはエージェントのレイノルズから、舞台化された『長い夢』のニューヨーク初演が酷評を受け、脚色者のケッティ・フリングスが それ以降の上演を中止することを決めたことを知る。一方、ライトは『長い夢』をフランスで出版しようとして、さらなる問題にぶつかっていた。こうした挫折 のために、ダブルデイ社から出版の約束を取り付けようとしていた『幻覚の島』の改稿を終えることができなかった。 1960年6月、ライトはフランスのラジオ番組で、主に自身の著書と文学的キャリアについて語った。彼はまた、アメリカと世界の人種的状況を取り上げ、特 にアメリカのアフリカ政策を非難した。9月下旬には、娘のジュリアがソルボンヌ大学に通うためにロンドンからパリに引っ越すため、その費用を賄うために、 ライトはパリ最大のレコード会社のディレクターであるニコル・バークレイのためにレコードジャケットの宣伝文を書いた。 経済的に困窮していたにもかかわらず、ライトは自分の主義主張に妥協することを拒んだ。彼は、アメリカの支配を疑って、カナダのラジオ局の一連の番組への 参加を断った。同じ理由で、レオ・トルストイを追悼する会議で講演するためにインドに行くという文化的自由のための会議からの招待も断った。まだ文学に興 味を持っていたライトは、カイル・オンストットの小説『マンディンゴ』(1957年)をフランスで出版する手助けをした。 ライトの最後の爆発的なエネルギーは、1960年11月8日、パリのアメリカ教会の学生や会員を前にした「アメリカにおける黒人の芸術家と知識人の状況」 という極論的な講演で発揮された。彼は、アメリカ社会は、黒人コミュニティの最も過激なメンバーが人種的現状に疑問を投げかけようとするたびに、奴隷に貶 めていると主張した。その証拠として、共産主義者の『インディアンの息子』に対する破壊的な攻撃や、ジェームズ・ボールドウィンや他の作家が彼に求めた喧 嘩を提示した。1960年11月26日、ライトはラングストン・ヒューズと『ダディ・グッドネス』について熱く語り合い、原稿を渡した。  ライトの墓 ライトは1960年11月28日、パリで心臓発作のため52歳で死去した。ペール・ラシェーズ墓地に埋葬された[51]。ライトの娘ジュリアは、父親は殺害されたと主張している[52]。 ライトの作品の多くは死後に出版されている。さらに、人種、性、政治を扱ったライトのよりショッキングな文章は、生前に出版される前にカットされたり、省 略されたりしている。1991年、『Native Son』、『Black Boy』、その他の作品の未削除版が出版された。さらに1994年には、彼の小説『通過儀礼』が初めて出版された[53]。 晩年、ライトは日本の詩的形式である俳句に夢中になり、4,000句以上の俳句を書いた。1998年には、ライト自身のお気に入りの俳句817句を集めた 本(Haiku: This Other World)が出版された。これらの俳句の多くは、孤独、死、自然の力との折り合いをつけながらも、高揚感を与えてくれる。 ライトの旅行記は2001年にミシシッピ大学出版局から出版されている。ライトは死の間際に、黒人警官と彼が殺人の疑いを持つ息子を扱った未完の著書『A Father's Law』[54]を残している。娘のジュリア・ライトは2008年1月に『A Father's Law』を出版した。ライトの政治的著作を収めたオムニバス版が『Three Books from Exile』というタイトルで出版された: Black Power』、『The Color Curtain』、『White Man, Listen』である! |

| Personal life In August 1939, with Ralph Ellison as best man,[55] Wright married Dhimah Rose Meidman,[56] a modern dance teacher of Russian Jewish ancestry. The marriage ended a year later. On March 12, 1941, he married Ellen Poplar (née Poplowitz),[57][58] a Communist organizer from Brooklyn.[59] They had two daughters: Julia, born in 1942, and Rachel, born in 1949.[58] Ellen Wright, who died on April 6, 2004, aged 92, was the executor of Wright's estate. In this capacity, she unsuccessfully sued a biographer, the poet and writer Margaret Walker, in Wright v. Warner Books, Inc. She was a literary agent, and her clients included Simone de Beauvoir, Eldridge Cleaver, and Violette Leduc.[60][61] |

私生活 1939年8月、ラルフ・エリソンをベストマンに[55]、ライトはロシア系ユダヤ人の血を引くモダンダンスの教師ディマ・ローズ・メイドマンと結婚した[56]。結婚は1年後に終わった。 1941年3月12日、ブルックリン出身の共産主義者オーガナイザー、エレン・ポプラ(旧姓ポプロウィッツ)と結婚[57][58]: 1942年生まれのジュリアと1949年生まれのレイチェルである[58]。 2004年4月6日に92歳で亡くなったエレン・ライトは、ライトの遺産執行人であった。この職務において、彼女は伝記作家である詩人で作家のマーガレッ ト・ウォーカーをWright v. Warner Books, Inc.訴訟で訴え、失敗に終わった。彼女は文学エージェントであり、顧客にはシモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワール、エルドリッジ・クリーヴァー、ヴィオレッ ト・ルデュックなどがいた[60][61]。 |

| Awards and honors The Spingarn Medal in 1941 from the NAACP[62] Guggenheim Fellowship in 1939 Story Magazine Award in 1938.[33] In April 2009, Wright was featured on a U.S. postage stamp. The 61-cent, two-ounce rate stamp is the 25th installment of the literary arts series, and features a portrait of Wright in front of snow-swept tenements on the South Side of Chicago, a scene that recalls the setting of Native Son.[63] In 2010, Wright was inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.[64] In 2012, the Historic Districts Council and the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, in collaboration with the Fort Greene Association and writer/musician Carl Hancock Rux, erected a cultural medallion at 175 Carlton Avenue, Brooklyn, where Wright lived in 1938 and completed Native Son.[65] The group unveiled the plaque at a public ceremony with guest speakers, including playwright Lynn Nottage and Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz. |

受賞と栄誉 1941年、NAACPからスピンガーン・メダルを授与される[62]。 1939年グッゲンハイム・フェローシップ 1938年にストーリー誌賞を受賞[33]。 2009年4月、ライトは米国の切手に描かれた。61セント、2オンスの切手は文学芸術シリーズの第25弾で、『Native Son』の舞台を思い起こさせるような、シカゴのサウスサイドにある雪に覆われた長屋の前に立つライトの肖像が描かれている[63]。 2010年、ライトはシカゴ文学の殿堂入りを果たした[64]。 2012年、歴史地区協議会とニューヨーク市ランドマーク保存委員会は、フォート・グリーン協会と作家/ミュージシャンのカール・ハンコック・ラックスと 共同で、ライトが1938年に住み、『Native Son』を完成させたブルックリンのカールトン・アベニュー175番地に文化勲章を建立した[65]。 |

Legacy Banned Books Week reading of Black Boy at Shimer College in 2013 Black Boy became an instant best-seller upon its publication in 1945.[66] Wright's stories published during the 1950s disappointed some critics who said that his move to Europe had alienated him from African Americans and separated him from his emotional and psychological roots.[67] Many of Wright's works failed to satisfy the rigid standards of New Criticism during a period when the works of younger black writers gained in popularity.[68] During the 1950s Wright grew more internationalist in outlook. While he accomplished much as an important public literary and political figure with a worldwide reputation, his creative work did decline.[69] While interest in Black Boy ebbed during the 1950s, this has remained one of his best selling books. Since the late 20th century, critics have had a resurgence of interest in it. Black Boy remains a vital work of historical, sociological, and literary significance whose seminal portrayal of one black man's search for self-actualization in a racist society strongly influenced the works of African-American writers who followed, such as James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison. John A. Williams included a fictionalized version of Wright's life and death in his 1967 novel The Man Who Cried I Am. It is generally agreed that the influence of Wright's Native Son is not a matter of literary style or technique.[70] Rather, this book affected ideas and attitudes, and Native Son has been a force in the social and intellectual history of the United States in the last half of the 20th century. "Wright was one of the people who made me conscious of the need to struggle," said writer Amiri Baraka.[71] During the 1970s and 1980s, scholars published critical essays about Wright in prestigious journals. Richard Wright conferences were held on university campuses from Mississippi to New Jersey. A new film version of Native Son, with a screenplay by Richard Wesley, was released in December 1986. Certain Wright novels became required reading in a number of American high schools, universities and colleges.[72] Recent critics have called for a reassessment of Wright's later work in view of his philosophical project. Notably, Paul Gilroy has argued that "the depth of his philosophical interests has been either overlooked or misconceived by the almost exclusively literary inquiries that have dominated analysis of his writing."[73][74] Wright was featured in a 90-minute documentary about the WPA Writers' Project entitled Soul of a People: Writing America's Story (2009).[75] His life and work during the 1930s is highlighted in the companion book, Soul of a People: The WPA Writers' Project Uncovers Depression America.[76] |

レガシー 2013年のBanned Books Weekで『Black Boy』の朗読が行われた。 『ブラック・ボーイ』は1945年に出版されると即座にベストセラーとなった[66]。1950年代に出版されたライトの物語は、ヨーロッパへの移住が彼 をアフリカ系アメリカ人から疎外し、感情的・心理的なルーツから引き離したという一部の批評家を失望させた[67]。ライトの作品の多くは、若い黒人作家 の作品が人気を博していた時期に、新批評主義の厳格な基準を満たすことができなかった[68]。 1950年代、ライトはより国際主義的な考え方を強めていった。彼は世界的な名声を持つ重要な公の文学者、政治家として多くのことを成し遂げたが、創作活動は衰退していった[69]。 1950年代には『ブラック・ボーイ』への関心は薄れていったが、これは彼の最も売れた本のひとつであり続けた。20世紀後半以降、批評家たちはこの本へ の関心を再び高めている。ブラック・ボーイ』は歴史的、社会学的、文学的に重要な作品であり、人種差別社会で自己実現を模索する一人の黒人の姿を描いた画 期的な作品として、ジェイムズ・ボールドウィンやラルフ・エリソンなど、後に続くアフリカ系アメリカ人作家の作品に強い影響を与えた。ジョン・A・ウィリ アムズは1967年に発表した小説『The Man Who Cried I Am』の中で、ライトの生と死をフィクションとして描いている。 ライトの『Native Son』が与えた影響は、文学のスタイルや技法の問題ではないというのが一般的な見方である[70]。むしろ、この本は思想や態度に影響を与え、 『Native Son』は20世紀後半のアメリカの社会史や知的歴史に大きな影響を与えた。「ライトは私に闘争の必要性を意識させた人物の一人だ」と作家のアミリ・バラ カは語っている[71]。 1970年代から1980年代にかけて、学者たちはライトに関する批判的なエッセイを権威ある雑誌に発表した。ミシシッピ州からニュージャージー州までの 大学キャンパスでリチャード・ライト会議が開かれた。1986年12月には、リチャード・ウェズリーが脚本を手がけた『Native Son』の新しい映画版が公開された。ライトの小説の一部は、アメリカの多くの高校、大学、カレッジで必読書となった[72]。 最近の批評家たちは、ライトの哲学的プロジェクトに鑑みて、ライトの晩年の作品を再評価することを求めている。特にポール・ギルロイは、「彼の哲学的関心 の深さは、彼の著作の分析を支配してきたほとんど文学的な探求によって見落とされてきたか、あるいは誤解されてきた」と主張している[73][74]。 ライトは『Soul of a People』と題されたWPA Writers' Projectに関する90分のドキュメンタリーに登場している: 1930年代における彼の人生と作品は、関連書籍『Soul of a People』でハイライトされている: The WPA Writers' Project Uncovers Depression America(WPA作家プロジェクトが大恐慌時代のアメリカを掘り起こす)』[76]という本がある。 |

| Publications Collections Uncle Tom's Children (New York: Harper, 1938) (collection of novellas) Eight Men (Cleveland and New York: World, 1961) "The Man Who Was Almost a Man" "The Man Who Lived Underground" (truncated version) "Big Black Man" "The Man Who Saw the Flood" "Man of All Work" "Man, God Ain't That..." "The Man Who Killed a Shadow" "The Man Who Went to Chicago" Early Works (Arnold Rampersad, ed.) (Library of America, 1989), Later Works (Arnold Rampersad, ed.) (Library of America, 1991). Drama Native Son: The Biography of a Young American with Paul Green (New York: Harper, 1941) Novels Native Son (New York: Harper, 1940) The Outsider (New York: Harper, 1953) Savage Holiday (New York: Avon, 1954) The Long Dream (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1958) Lawd Today (New York: Walker, 1963) Rite of Passage (New York: HarperCollins, 1994) (novella) A Father's Law (London: Harper Perennial, 2008) (unfinished novel) The Man Who Lived Underground (Library of America, 2021) (extended novel, as originally ) Non-fiction How "Bigger" Was Born; Notes of a Native Son (New York: Harper, 1940) 12 Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States (New York: Viking, 1941) Black Boy (New York: Harper, 1945) Black Power (New York: Harper, 1954) The Color Curtain (Cleveland and New York: World, 1956) Pagan Spain (New York: Harper, 1957) Letters to Joe C. Brown (Kent State University Libraries, 1968) American Hunger (New York: Harper & Row, 1977) Conversations with Richard Wright (Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1993). Black Power: Three Books from Exile: "Black Power"; "The Color Curtain"; and "White Man, Listen!" (Harper Perennial, 2008) Essays The Ethics of Living Jim Crow: An Autobiographical Sketch (1937) Introduction to Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City (1945) I Choose Exile (1951) White Man, Listen! (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1957) Blueprint for Negro Literature (New York City, New York) (1937)[77] The God That Failed (contributor) (1949) Poetry Haiku: This Other World (eds. Yoshinobu Hakutani and Robert L. Tener; Arcade, 1998, ISBN 0385720246) re-issue (paperback): Haiku: The Last Poetry of Richard Wright (Arcade Publishing, 2012), ISBN 978-1-61145-349-2 |

出版物 作品集 アンクル・トムの子供たち』(ニューヨーク:ハーパー、1938年)(小説集) エイト・メン(クリーブランドとニューヨーク:ワールド、1961年) 「ほとんど男だった男 「地下に住んでいた男」(短縮版) 「大きな黒い男 「洪水を見た男 「万能の男 「男よ、神はそんなものではない...」 「影を殺した男」 「シカゴに行った男 初期作品集(アーノルド・ランパーサッド編)(ライブラリー・オブ・アメリカ、1989年) 後期作品集(アーノルド・ランペルサッド編)(ライブラリー・オブ・アメリカ、1991年)。 ドラマ ネイティブ・サン ポール・グリーンとの若きアメリカ人の伝記(ニューヨーク:ハーパー、1941年) 小説 ネイティブ・サン(ニューヨーク:ハーパー、1940年) アウトサイダー(ニューヨーク:ハーパー、1953年) 野蛮な休日(ニューヨーク:エイボン、1954年) ロング・ドリーム(ニューヨーク州ガーデンシティ:ダブルデイ、1958年) ロー・トゥデイ(ニューヨーク:ウォーカー、1963年) 通過儀礼(ニューヨーク:ハーパーコリンズ、1994年)(小説) 父の掟」(ロンドン:ハーパー・ペレニアル、2008年)(未完の小説) The Man Who Lived Underground (Library of America, 2021)(未完の長編小説) ノンフィクション いかにして 「ビッグ 」は生まれたか;あるネイティブ・サンのノート(ニューヨーク:ハーパー、1940年) 1200万人の黒人の声: アメリカにおける黒人のフォーク・ヒストリー(ニューヨーク:バイキング、1941年) ブラック・ボーイ(ニューヨーク:ハーパー、1945年) ブラック・パワー』(ニューヨーク:ハーパー、1954年) カラーカーテン(クリーブランドとニューヨーク:ワールド、1956年) 異教徒のスペイン(ニューヨーク:ハーパー、1957年) ジョー・C・ブラウンへの手紙(ケント州立大学図書館、1968年) アメリカン・ハンガー(ニューヨーク:ハーパー&ロウ、1977年) リチャード・ライトとの対話(ミシシッピ大学出版局、1993年) ブラック・パワー:亡命先からの3冊の本 「ブラック・パワー』、『カラー・カーテン』、『白人よ、聞け!』の3冊である。(ハーパー・ペレニアル、2008年) エッセイ ジム・クロウを生きる倫理 自伝的スケッチ(1937年) ブラック・メトロポリス』序論: 北部の都市における黒人生活の研究(1945年) 私は追放を選ぶ(1951年) 白人よ、聞け!(ニューヨーク州ガーデンシティ:ダブルデイ社、1957年) 黒人文学の青写真』(ニューヨーク市、ニューヨーク)(1937年)[77]。 失敗した神(寄稿者)(1949年) 詩 俳句: この別世界』(白谷吉信、ロバート・L・テナー編、アーケード、1998年、ISBN 0385720246) 再刊(ペーパーバック): 俳句: リチャード・ライト最後の詩』(アーケード出版、2012年)ISBN 978-1-61145-349-2 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Wright_(author) |

|

★リチャード・ライト『ブラック・ボーイ : ある幼少期の記録』野崎孝訳、岩波書店、2009年

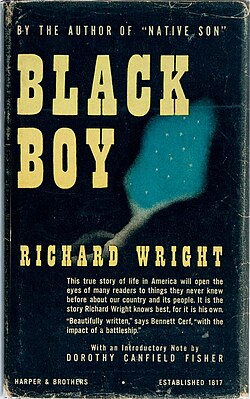

| Black Boy (1945) is

a memoir by American author Richard Wright, detailing his upbringing.

Wright describes his youth in the South: Mississippi, Arkansas and

Tennessee, and his eventual move to Chicago, where he establishes his

writing career and becomes involved with the Communist Party. Black Boy

gained high acclaim in the United States because of Wright's honest and

profound depiction of racism in America. While the book gained

significant recognition, much of the reception throughout and after the

publication process was highly controversial. |

『ブラック・ボーイ』(1945年)は、アメリカ人作家リチャード・ラ

イトの自伝的回顧録であり、彼の成長期を詳細に描いている。ライトは南部——ミシシッピ、アーカンソー、テネシー——での少年時代、そして最終的にシカゴ

へ移り住み、そこで作家としてのキャリアを築き、共産党に関わっていく過程を綴っている。『ブラック・ボーイ』は、アメリカにおける人種差別を率直かつ深

く描いた点で、国内で高い評価を得た。しかし出版前後を通じて、その評価の多くは激しい論争を呼んだ。 |

| Background Richard Wright's Black Boy was written in 1943 and published two years later (1945) in the early years of his career. Wright wrote Black Boy as a response to the experiences he had growing up.[1] Given that Black Boy is partially autobiographical, many of the anecdotes stem from real experiences throughout Wright's childhood.[2] Richard Wright's family spent much of their lives in deep poverty, enduring hunger and illness, and frequently moving around the South, and finally north, in search of a better life.[1] Wright cites his family and childhood environment as the primary influence in his writing of the book.[3] Specifically, Wright's family's strong religious beliefs imposed on him throughout his childhood shaped his view of religion.[3] Similarly, the considerable distress—physical, mental, and emotional—that Wright experienced while growing up hungry is documented throughout much of Black Boy.[3] Most generally, Wright credits the public influence of Black Boy to his description of the racial inequalities he was subjected to throughout his travels in America.[2] Wright recognized the power of reading and writing to stimulate "new ways of looking and seeing" at a young age.[2] When he was seventeen, he left Jackson to find work in Memphis where he became heavily involved in literary groups and publications and expanded on his use of words as the weapon "to tell, to march, to fight, to create a sense of hunger for the life that gnaws in us" that is seen in Black Boy.[1] Wright claims that he chose to write about the experiences referenced in Black Boy in an effort to "look squarely at his life, to build a bridge of words between him and the world".[3] |

背景 リチャード・ライトの『ブラック・ボーイ』は1943年に執筆され、2年後の1945年に発表された。これは彼のキャリア初期の作品である。ライトは自身 の成長過程での経験に応えて『ブラック・ボーイ』を書いた。[1] 『ブラック・ボーイ』は部分的に自伝的であるため、多くの逸話はライトの子供時代の実際の経験に基づいている。[2] リチャード・ライトの家族は生涯の大半を極貧の中で過ごし、飢えや病に苦しみ、より良い生活を求めて南部を転々とし、最終的には北部へ移住した。[1] ライトは、この本を書く上で家族と子供時代の環境が主要な影響源であったと述べている。[3] 特に、幼少期を通じて強要された家族の強い宗教的信念が、彼の宗教観を形成した。[3] 同様に、飢えに苦しんだ成長期に経験した肉体的・精神的・感情的な苦痛の多くが、『ブラック・ボーイ』の随所に記録されている。[3] 最も一般的な見解として、ライトは『ブラック・ボーイ』の社会的影響力を、アメリカ各地を旅する中で直面した人種的不平等を描写した点に帰している。 [2] ライトは幼い頃から、読書と執筆が「新たな見方や視点」を喚起する力を持つことを認識していた。[2] 17歳の時、彼はジャクソンを離れメンフィスで仕事を探す。そこで文学サークルや出版活動に深く関わり、言葉という武器の使い方を発展させた。それは『ブ ラック・ボーイ』に見られる「語り、進み、戦い、我々を蝕む人生への渇望を創り出す」ための武器である。[1] ライトは『ブラック・ボーイ』で描いた経験を書くことを選んだ理由を、「自分の人生を真っ向から見据え、自分と世界との間に言葉の橋を架けるため」だと述 べている。[3] |

| Plot summary Black Boy (American Hunger) is an autobiography following Richard Wright's childhood and young adulthood. It is split into two sections, "Southern Night" (concerning his childhood in the south) and "The Horror and the Glory" (concerning his early adult years in Chicago). "Southern Night" The book begins with a mischievous four-year-old Wright setting fire to his grandmother's house. Wright is a curious child living in a household of strict, religious women and violent men. After his father deserts his family, young Wright is shuffled back and forth between his sick mother, his fanatically religious grandmother, and various maternal aunts, uncles and orphanages attempting to take him in. Despite the efforts of various people and groups to take Wright in, he essentially raises himself with no central home. He quickly chafes against his surroundings, reading instead of playing with other children, and rejecting the church in favor of agnosticism at a young age. Throughout his mischief and hardship, Wright gets involved in fighting and drinking before the age of six. When Wright turns eleven, he begins taking jobs and is quickly introduced to the racism that constitutes much of his future. He continues to feel more out of place as he grows older and comes in contact with the Jim Crow racism of the 1920s South. He finds these circumstances generally unjust and fights attempts to quell his intellectual curiosity and potential as he dreams of moving north and becoming a writer.[4] |

あらすじ 『黒い少年』(原題:Black Boy)はリチャード・ライトの幼少期から青年期を描いた自伝である。二部構成となっており、第一部「南部の夜」(南部での幼少期)と第二部「恐怖と栄光」(シカゴでの青年期)に分かれる。 「サザン・ナイト」 物語は、いたずら好きな四歳のリチャード・ライトが祖母の家を焼き払う場面から始まる。彼は好奇心旺盛な子供だったが、厳格な宗教的な女性たちと暴力的な 男性たちが住む家庭で育った。父親が家族を捨てた後、幼いライトは病弱な母親、狂信的な宗教家の祖母、そして彼を引き取ろうとする様々な叔父叔母や孤児院 の間をたらい回しにされる。様々な人々や団体が彼を引き取ろうとしたにもかかわらず、ライトは実質的に居場所のないまま自力で育った。彼は周囲の環境にす ぐに嫌気がさし、他の子供たちと遊ぶ代わりに読書に没頭し、幼い頃から教会を拒絶して不可知論を支持した。いたずらや苦難の中で、ライトは6歳になる前に 喧嘩や飲酒に手を染めるようになる。11歳になると仕事を始め、すぐに将来の彼を形作る人種差別と直面する。成長するにつれ、1920年代南部のジム・ク ロウ法による人種差別と接触する中で、ますます居場所を失っていく。彼はこうした状況を概して不当と感じ、知的好奇心と潜在能力を抑え込もうとする試みに 抵抗しながら、北へ移り住み作家になる夢を抱いていた。[4] |

| "The Horror and the Glory" In an effort to achieve his dreams of moving north, Wright reluctantly steals and lies until he attains enough money for a ticket to Memphis. Wright's aspirations of escaping racism in his move North are quickly disillusioned as he encounters similar prejudices and oppressions amidst the people in Memphis, prompting him to continue his journeys towards Chicago. The youth finds the North less racist than the South and begins understanding American race relations more deeply. He holds many jobs, most of them consisting of menial tasks: he washes floors during the day and reads Proust and medical journals at night. At this time, his family is still suffering in poverty, his mother is disabled by a stroke, and his relatives constantly interrogate him about his atheism and "pointless" reading. He finds a job at the post office, where he meets white men who share his cynical view of the world and religion. They invite him to the John Reed Club, an organization that promotes the arts and social change. He becomes involved with a magazine called Left Front and slowly immerses himself in the writers and artists in the Communist Party. At first, Wright thinks he will find friends within the party, especially among its black members, but he finds them to be just as timid to change as the southern whites he left behind. The Communists fear those who disagree with their ideas and quickly brand Wright as a "counter-revolutionary" for his tendency to question and speak his mind. When Richard tries to leave the party, he is accused of trying to lead others away from it. After witnessing the trial of another black Communist for counter-revolutionary activity, Wright decides to abandon the party. He remains branded an "enemy" of Communism, and party members threaten him away from various jobs and gatherings. He does not fight them because he believes they are clumsily groping toward ideas that he agrees with: unity, tolerance, and equality. Wright ends the book by resolving to use his writing as a way to start a revolution: asserting that everyone has a "hunger" for life that needs to be filled. For Wright, writing is his way to the human heart, and therefore, the closest cure to his hunger.[4] |

恐怖と栄光 北へ移住するという夢を叶えようと、ライトはしぶしぶ盗みや嘘をつき、ようやくメンフィス行きの切符を買う金を手に入れる。しかし北へ移れば人種差別から 逃れられるという彼の期待は、メンフィスでも同様の偏見や抑圧に直面したことで早くも打ち砕かれ、シカゴへ向かう旅を続けることになる。 若者は南部より北部の方が人種差別が少ないことに気づき、アメリカの人種関係を深く理解し始める。彼は多くの職に就くが、そのほとんどが雑用だった。昼は 床を磨き、夜はプルーストや医学雑誌を読む。この頃、家族は依然として貧困に苦しみ、母親は脳卒中で身体が不自由になり、親戚は彼の無神論や「無意味な」 読書について執拗に詰め寄った。郵便局で職を得た彼は、世界や宗教に対する皮肉な見方を共有する白人男性たちと出会う。彼らは芸術と社会変革を推進する団 体「ジョン・リード・クラブ」へ彼を誘う。彼は『レフト・フロント』誌に関わり、次第に共産党内の作家や芸術家たちに深く関わっていく。 当初ライトは、特に黒人党員の中に仲間を見出せると思っていた。しかし彼らは、自らが脱出した南部の白人たちと同様に、変化に対して臆病であることに気づ く。共産党員たちは自らの思想に異を唱える者を恐れ、ライトが疑問を呈し率直に発言する傾向を「反革命的」と即座にレッテル貼りした。リチャードが党を離 れようとすると、彼は他人を党から引き離そうとしていると非難された。 別の黒人共産党員が反革命活動で裁判にかけられるのを目撃した後、ライトは党を離れる決意をする。彼は共産主義の「敵」というレッテルを貼られたまま、党 員たちから様々な仕事や集まりから追い出される脅しを受ける。彼は彼らと争わなかった。なぜなら、彼らが不器用ながらも、自らが賛同する理念―団結、寛 容、平等―へと模索していると考えていたからだ。ライトは本書の結末で、自らの執筆活動を通じて革命を起こす決意を固める。それは「人生への飢え」を抱え る全ての人々を救うための手段だと主張する。ライトにとって、執筆は人間の心に届く手段であり、故に自らの飢えを癒す最も近い治療法なのである。[4] |

| Genre and style The genre of Richard Wright's Black Boy is a longstanding controversy due to the ambiguity. Black Boy follows Wright's childhood with a degree of accuracy that suggests it exists as an autobiography, although Wright never confirmed nor denied whether the book was entirely autobiographical or fictitious.[5] None of Wright's other books follow the truths of his life in the way Black Boy does.[5] The book's apparent tendency to intermix fact and fiction is criticized because of the specific dialogue that suggests a degree of fiction.[5] Additionally, Wright omits certain details of his family's background that would typically be included in an autobiographical novel.[5] While Wright may have deviated from historical truths, the book is accurate in the sense that he rarely deviates from narrative truth in the candidness and rawness of his writing.[6] The style in Black Boy is so highly regarded because of the frankness that defied social demands at the time of Black Boy’s publication.[7] Wright negates the racially based oppression he endured through his ability to read and write with eloquence and credibility as well as with his courage to speak back against the dominant norms of society that are holding him back.[6] |

ジャンルとスタイル リチャード・ライトの『ブラック・ボーイ』のジャンルは、その曖昧さゆえに長年議論の的となっている。本書はライトの幼少期をある程度正確に追っており、 自伝として成立しているように思われる。ただしライト自身が、本書が完全な自伝なのか虚構なのかを明言したことはない。[5] ライトの他の著作は、『ブラック・ボーイ』ほど彼の実生活に忠実ではない。[5] 事実と虚構が混在する傾向が指摘されるのは、特定の会話が虚構の要素を示唆しているためだ。[5] さらにライトは、自伝的小説に通常含まれるはずの家族背景の詳細を意図的に省略している。[5] 歴史的事実からは逸脱しているかもしれないが、率直で生々しい筆致において物語の真実からほとんど外れていない点で、本書は正確であると言える。[6] 『ブラック・ボーイ』の文体が高く評価されるのは、出版当時の社会的要請に逆らう率直さゆえだ。[7] ライトは、雄弁かつ信頼性のある読み書き能力と、自分を抑圧する社会の支配的規範に立ち向かう勇気によって、人種に基づく抑圧を打ち破ったのである。[6] |

| Analysis Given Black Boy’s emphasis on racial inequality in America, many of the motifs refer to the lingering aspects of slave narratives in present day. These motifs include violence, religion, starvation, familial unity and lack thereof, literacy, and the North Star as a guide towards freedom.[3] The depictions of lingering racial animosity are at the core of the arguments in favor of censorship for many critics.[1] The prevalence of violence amidst and against Blacks in America ties back to the violence exerted upon slaves generations before.[8] The theme of violence intermixes with the notion of race as Wright suggests that violence is deeply entrenched into a system where people are distinguished based on their race.[6] Regardless of Wright's efforts to break free from this violent lifestyle, a society based on differences will always feed on an inescapable discourse. Wright's skeptical view of Christianity mirrors the religious presence for many slaves.[1] Throughout Black Boy, this skepticism of religion is present as Richard regards Christianity as being primarily based on a general inclusion in a group rather than incorporating any meaningful, spiritual connection to God.[3] The general state of poverty and hunger that Wright endures reflects, to a lesser degree, similar obstacles that slaves faced.[8] Wright's portrayal of hunger goes beyond a lack of food to represent a metaphorical kind of hunger in his yearning for a better, freer life. In his search for a better life in the North, Richard is seeking to fulfill both his physical and metaphorical hungers for more.[3] The cyclical portrayal of poverty in Black Boy represents society as a personified enemy that crushes dreams for those who aren't in command of high society.[6] The strong attempt at maintaining family unity also relates to the efforts amidst slaves to remain connected through such immense hardship.[9] Wright's longing to journey North in search of improvement embodies the slaves longing to follow the North Star on the freedom trains in search of freedom.[8] Despite the harsh reality upon arrival, throughout Black Boy, the North is represented as a land of opportunity and freedom. Lastly, Wright's focus on literacy as a weapon towards personal freedom also reflects the efforts of many slaves hoping to free themselves through the ability to read and write.[8] The emphasis on literacy complicates the notion of finding freedom from a physical space to a mental power attained through education. The most general impact of Black Boy is shown through Wright's efforts to bring light to the complexities of race relations in America, both the seen and unseen.[3] Given the oppression of and lack of educational opportunities for black people in America, the raw honesty of their hardships was rarely heard and even more rarely given literary attention, making the impact of Black Boy’s narrative especially influential. The book works to show the underlying inequalities that Wright faced daily in America.[1] |

分析 『ブラック・ボーイ』がアメリカにおける人種的不平等を強調していることから、多くのモチーフは現代になお残る奴隷体験記の側面を指し示している。これら のモチーフには暴力、宗教、飢餓、家族の結束とその欠如、識字能力、そして自由への道しるべとしての北極星が含まれる。[3] 残存する人種的敵意の描写は、多くの批評家が検閲を支持する論拠の中核をなしている。[1] アメリカにおける黒人同士の、また黒人に対する暴力の蔓延は、何世代も前の奴隷に振るわれた暴力に起因する。[8] 暴力のテーマは人種概念と絡み合い、ライトが指摘するように、人種に基づく差別が根付いたシステムに深く組み込まれている。[6] ライトがこの暴力的な生活様式から脱却しようとした努力にもかかわらず、差異に基づく社会は常に逃れがたい言説を糧とする。 ライトのキリスト教に対する懐疑的な見方は、多くの奴隷にとっての宗教的存在感を映し出している。[1] 『ブラック・ボーイ』全体を通して、この宗教への懐疑は存在し、リチャードはキリスト教を、神との意味ある精神的つながりではなく、主に集団への一般的な 帰属に基づくものと見なしている。[3] ライトが耐えた貧困と飢餓の一般的な状態は、奴隷が直面した同様の障害を、程度こそ異なるが反映している。[8] ライトが描く飢えは、単なる食物不足を超え、より良く自由な人生への渇望という比喩的な飢えを表している。北部のより良い生活を求めるリチャードの探求 は、物理的かつ比喩的な「もっと」への飢えを満たす試みだ。[3] 『ブラック・ボーイ』における貧困の循環的描写は、上流社会を支配しない者たちの夢を打ち砕く擬人化された敵としての社会を象徴している。[6] 家族結束を維持しようとする強い試みは、奴隷たちが極度の苦難の中でも繋がりを保とうとした努力とも関連している。[9] より良い生活を求めて北へ旅立つライトの憧れは、自由を求めて自由列車に乗り北極星を追う奴隷たちの憧れを体現している。[8] 到着後の厳しい現実にもかかわらず、『ブラック・ボーイ』全体を通して、北部は機会と自由の土地として描かれている。最後に、ライトが個人の自由への武器 として識字能力に焦点を当てたことも、読み書きの能力で自らを解放しようとする多くの奴隷の努力を反映している。[8] 識字能力への強調は、自由を物理的な空間から教育を通じて得られる精神的な力へと見出す概念を複雑化させる。 『ブラック・ボーイ』の最も一般的な影響は、ライトがアメリカの人種関係の複雑さ、見えるものと見えないものの両方に光を当てようとした努力に表れてい る。[3] アメリカにおける黒人への抑圧と教育機会の欠如を考えれば、彼らの苦難をありのままに語る声はほとんど聞かれず、文学的注目を浴びることはさらに稀だっ た。だからこそ『ブラック・ボーイ』の物語は特に影響力を持つ。この本は、ライトがアメリカで日々直面した根底にある不平等を明らかにする役割を果たして いる。[1] |

| Publishing history Original publication Wright wrote the entire manuscript in 1943 under the working title, Black Confession.[10] By December, when Wright delivered the book to his agent, he had changed the title to American Hunger.[10] The first fourteen chapters, about his Mississippi childhood, are compiled in "Part One: Southern Night," and the last six chapters, about Chicago, are included in "Part Two: The Horror and the Glory."[4] In January 1944, Harper and Brothers accepted all twenty chapters, and was for a scheduled fall publication of the book.[10] Black Boy is currently published by HarperCollins Publishers as a hardcover, paperback, ebook, and audiobook.[citation needed] Partial publications In June 1944, the Book of the Month Club expressed an interest in only "Part One: Southern Night."[10] In response, Wright agreed to eliminate the Chicago section, and in August, he renamed the shortened book as Black Boy.[11] Harper and Brothers published it under that title in 1945 and it sold 195,000 retail copies in its first edition and 351,000 copies through the Book-of-the-Month Club.[11] Parts of the Chicago chapters were published during Wright's lifetime as magazine articles, but the six chapters were not published together until 1977, by Harper and Row as American Hunger. In 1991, the Library of America published all 20 chapters, as Wright had originally intended, under the title Black Boy (American Hunger) as part of their volume of Wright's Later Works.[11] The Book-of-the-Month-Club played an important role in Wright's career. It selected his 1940 novel, Native Son, as the first Book of the Month Club written by a black American.[12] Wright was willing to change his Black Boy book to get a second endorsement.[11] However, he wrote in his journal that the Book-of-the-Month-Club had yielded to pressure from the Communist Party in asking him to eliminate the chapters that dealt with his membership in and disillusionment with the Communist Party.[11] In order for Wright to get his memoir really "noticed" by the general public, his publisher required that he divide the portions of his book into two sections.[10] |

出版の経緯 初版 ライトは1943年に、仮題「Black Confession」で原稿全体を執筆した[10]。12月、ライトが代理人に原稿を届けた時点で、タイトルは「American Hunger」に変更されていた[10]。ミシシッピでの子供時代を描いた最初の14章は「Part One: Southern Night」に、シカゴでの生活を描いた最後の6章は「Part Two: The Horror and the Glory」にまとめられている。[4] 1944年1月、ハーパー・アンド・ブラザーズ社は全20章を受け入れ、その年の秋にこの本を出版する予定だった。[10] 『ブラック・ボーイ』は現在、ハーパーコリンズ出版社からハードカバー、ペーパーバック、電子書籍、オーディオブックとして出版されている。[要出典] 部分出版 1944年6月、ブック・オブ・ザ・マンス・クラブは「パート1:サザン・ナイト」のみに関心を示した。[10] これを受けて、ライトはシカゴの章を削除することに同意し、8月に短縮版の本のタイトルを『ブラック・ボーイ』に変更した。[11] ハーパー・アンド・ブラザーズ社は1945年にこのタイトルで出版し、初版は195,000部、ブック・オブ・ザ・マンス・クラブを通じて351,000 部が販売された。[11] シカゴ編の一部はライト存命中に雑誌記事として発表されたが、全6章がまとめて出版されたのは1977年、ハーパー・アンド・ロウ社による『アメリカン・ ハンガー』としてである。1991年、ライブラリー・オブ・アメリカ社はライトの当初の意図通り全20章を収録し、『ブラック・ボーイ(アメリカン・ハン ガー)』のタイトルでライト後期の作品集の一巻として刊行した。[11] ブック・オブ・ザ・マンス・クラブはライトの作家人生において重要な役割を果たした。同クラブは1940年のライトの小説『ネイティブ・サン』を、黒人ア メリカ人作家による初の「今月の本」に選んだのだ[12]。ライトは二度目の推薦を得るため、『ブラック・ボーイ』の内容変更にも応じた。[11] しかし彼は日記に、同クラブが共産党からの圧力に屈し、自身の共産党員としての経験と幻滅を描いた章の削除を求めたと記している。[11] ライトの回顧録を一般大衆に「注目」させるため、出版社は原稿を二部構成に分割するよう要求した。[10] |

| Reception Upon its release, Black Boy gained significant traction—both positive and negative—from readers and critics alike.[1] In February 1945, Black Boy was a Book-of-the-Month-Club selection, bringing it immediate fame and acclaim.[1] Black Boy was also featured in a list compiled by the Lending Section of the American Library Association labeled "50 Outstanding Books of 1945".[13] The list, which was compiled by numerous individuals and institutions, acclaims Black Boy as "the author's account of his boyhood [that] is a grim record of frustration, race tension, and suffering".[13] From 1996 to 2000, the Round Rock Independent School District board in Texas voted 4–2 against a proposal to remove Richard Wright's Black Boy from reading lists at local schools, eventually deciding the content of the book was worthy and necessary in schools.[14] In numerous cases of attempted censorship for Black Boy, Richard Wright's widow, Ellen Wright, stood up and publicly defended the book, claiming that the censorship of Black Boy would be "tantamount to an American tragedy".[14] Black Boy was most recently challenged in Michigan in 2007 by the Howell High School for distributing explicit materials to minors, a ruling that was quickly overruled by a prosecutor who found that "the explicit passages illustrated a larger literary, artistic, or political message".[15] Black Boy has come under fire by numerous states, institutions, and individuals alike. Most petitioners of the book criticize Wright for being anti-American, anti-Semitic, anti-Christian, overly sexual and obscene, and most commonly, for portraying a grim picture of race relations in America.[16] On 1945, Theodore G. Bilbo denounced this book on the floor of the Senate, describing this book as "obsene" and aiming to excite Blacks against Whites, closing his statement with a "but it comes from a Negro, and you cannot expect any better from a person of his type."[17][18] In 1972, Black Boy was banned in Michigan schools after parents found the content to be overly sexual and generally unsuitable for teens.[15] In 1975, the book was challenged in both Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Tennessee, both places claiming the book was obscene and instigated racial tension.[15] Black Boy was first challenged in New York in 1976 by the board of education of the Island Trees Free School District in New York.[15] It was soon the subject of a U.S. Supreme Court case in 1982.[19] Petitioners against the inclusion of Black Boy described the autobiography as "objectionable" and "improper fare for school students."[19] The book was later challenged in Lincoln, Nebraska on accounts of its "corruptive, obscene nature".[15] In May 1997, the President of the North Florida Ministerial Alliance condemned the inclusion of Black Boy in Jacksonville's public schools, claiming the content is not "right for high school students" due to profanity and racial references.[15] According to the American Library Association, Black Boy was the 81st most banned and challenged book in the United States between 2000 and 2009.[20] |

評価 『ブラック・ボーイ』は刊行後、読者や批評家から賛否両論の大きな反響を得た。[1] 1945年2月にはブック・オブ・ザ・マンス・クラブの選定作品となり、即座に名声と称賛を得た。[1] 同書はまた、アメリカ図書館協会貸出部門が作成した「1945年傑作50選」リストにも掲載された。[13] 多数の個人・機関が作成したこのリストは、『ブラック・ボーイ』を「著者の少年時代を綴った記録であり、挫折、人種間の緊張、苦悩の厳しい記録である」と 称賛している。[13] 1996年から2000年にかけて、テキサス州ラウンドロック独立学区教育委員会は、リチャード・ライトの『ブラック・ボーイ』を地元学校の読書リストか ら削除する提案に対し、4対2で反対票を投じた。最終的に同書の内容は学校教育において価値があり必要であると判断されたのである。[14] 『ブラック・ボーイ』に対する数々の検閲試みにおいて、リチャード・ライトの未亡人エレン・ライトは立ち上がり、公に本書を擁護した。彼女は『ブラック・ ボーイ』の検閲は「アメリカの悲劇に等しい」と主張したのである。[14] 『ブラック・ボーイ』は2007年、ミシガン州ハウエル高校において未成年への露骨な内容の配布を理由に問題視されたが、この判断は「露骨な描写はより大 きな文学的・芸術的・政治的メッセージを体現している」と検察官が即座に覆した。[15] 『ブラック・ボーイ』は数多くの州、機関、個人から批判を受けてきた。同書を問題視する者の大半は、ライトが反米的、反ユダヤ的、反キリスト教的、過度に 性的で猥褻であると非難し、最も一般的な批判はアメリカの人種関係について暗い描写をしている点だ。[16] 1945年、セオドア・G・ビルボは上院本会議で本書を「わいせつ」と断じ、黒人を白人に対して扇動する意図があると非難した。彼は「だがこれは黒人によ る著作だ。彼のような者からそれ以上のものを期待できるはずがない」と発言を締めくくった。[17][18] 1972年、ミシガン州の学校では『ブラック・ボーイ』が禁止された。保護者らが内容が過度に性的で、十代には不適切だと判断したためである。[15] 1975年にはルイジアナ州バトンルージュとテネシー州の両方で異議申し立てが行われ、いずれも本書が猥褻であり人種間の緊張を煽ると主張した。[15] 1976年、ニューヨーク州アイランド・トゥリーズ自由学区の教育委員会が初めて異議を申し立てた。[15] 1982年には米国最高裁判所の審理対象となった。[19] 異議申し立て側は自伝を「不快」で「生徒にふさわしくない内容」と評した。[19] その後、ネブラスカ州リンカーン市でも「腐敗を招くわいせつな性質」を理由に異議申し立てがなされた。[15] 1997年5月には、ノースフロリダ牧師連盟会長がジャクソンビル公立学校での『ブラック・ボーイ』採用を非難し、卑語や人種的言及を含む内容は「高校生 にふさわしくない」と主張した。[15] アメリカ図書館協会によれば、『ブラック・ボーイ』は2000年から2009年にかけて、アメリカで81番目に多く禁止・異議申し立てを受けた書籍であった。[20] |

| References 1. Joyce, Joyce Ann (30 November 2000). "Wright, Richard (1908–1960)". African American Writers. 2: 875–894. Gale CX1387200066. 2. Lystad, Mary (1994). "Richard Wright: Overview". In Berger, Laura Standley (ed.). Twentieth-century Young Adult Writers. St. James Press. ISBN 978-1-55862-202-9. Gale H1420008836. 3. Dykema-VanderArk, Anthony (2001). "Critical Essay on 'Black Boy'". In Thomason, Elizabeth (ed.). Nonfiction classics for students: presenting analysis, context, and criticism on nonfiction works. Gale Group. hdl:2027/pst.000045795947. ISBN 978-0-7876-5381-1. OCLC 62163743. Gale H1420035601. 4. Wright, Richard (1998) [1993]. Black boy: (American hunger) : a record of childhood and youth (1st ed.). New York City: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-092978-7. OCLC 39339337.[page needed] 5. Adams, Timothy Dow (1997). "Richard Wright: 'Wearing the Mask'". In Telgen, Diane (ed.). Novels for students. Vol. 1. Detroit: Gale. ISBN 978-1-4144-2794-2. OCLC 288950276. Gale H1420021254. Originally published as: Adams, Timothy Dow (1990). "Richard Wright: 'Wearing the Mask'". In Adams, Timothy Dow (ed.). Telling Lies in Modern American Autobiography. UNC Press Books. pp. 69–83. ISBN 978-0-8078-1888-6. 6. Andrews, William L. (2001). "Richard Wright and the African-American Autobiography Tradition". In Thomason, Elizabeth (ed.). Nonfiction classics for students: presenting analysis, context, and criticism on nonfiction works. Gale Group. hdl:2027/pst.000045795947. ISBN 978-0-7876-5381-1. OCLC 62163743. Gale H1420035601. Originally published as: Andrews, William L. (Summer 1993). "Richard Wright and the African-American Autobiography Tradition". Style. 27 (2): 271–282. 7. Poulos, Jennifer H. (22 December 1997). "'Shouting curses': the politics of 'bad' language in Richard Wright's 'Black Boy'". The Journal of Negro History. 82 (1): 54–67. doi:10.2307/2717496. JSTOR 2717496. S2CID 141463119. Gale A20757362. 8. Stepto, Robert B. (1982). "'I Thought I Knew These People': Richard Wright & the Afro-American Literary Tradition". In Gunton, Sharon R. (ed.). Contemporary Literary Criticism. Vol. 21. Gale. ISBN 978-0-8103-0117-7. Gale H1100003311. Originally published as: Stepto, Robert B. (Autumn 1977). "'I Thought I Knew These People': Richard Wright & the Afro-American Literary Tradition". The Massachusetts Review. 18 (3): 525–541. 9. Porter, Horace A. (2003). "The Horror and the Glory: Wright's Portrait of the Artist in Black Boy and American Hunger". In Witalec, Janet (ed.). Twentieth-Century Literature Criticism. Vol. 136. Gale. ISBN 978-0-7876-7035-1. Gale H1420051191. Originally published as: Porter, Horace A. (1993). "The Horror and the Glory: Wright's Portrait of the Artist in Black Boy and American Hunger". In Gates, Henry Louis; Appiah, Anthony (eds.). Richard Wright: critical perspectives past and present. New York: Amistad. pp. 316–327. ISBN 978-1-56743-027-1. 10. Thaddeus, Janice (May 1985). "The Metamorphosis of Richard Wright's Black Boy". American Literature. 57 (2): 199–214. doi:10.2307/2926062. JSTOR 2926062. 11. Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., "Note on the Text," pp 407–8 in Richard Wright, Black Boy (American Hunger), The Library of America, 1993. 12. Mitgang, Herbert (1 January 1992). "Books of The Times; An American Master And New Discoveries". The New York Times. 13. "Notable Books List 1945" (PDF). ALA. 1945. Retrieved 24 April 2019. 14. Foerstel, Herbert N. (2002). Banned in the U.S.A.: A Reference Guide to Book Censorship in Schools and Public Libraries. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-31166-6.[page needed] 15. "Black Boy by Richard Wright". Banned Library. 6 November 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2019. 16. Plath, Dara (5 February 2015). "Top 10 Banned Books that Changed the Face of Black History". National Coalition Against Censorship. Retrieved 24 April 2019. 17. Lambert, Frank (3 September 2009). The Battle of Ole Miss: Civil Rights v. States' Rights. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-975858-6. 18. Rowley, Hazel (15 February 2008). Richard Wright: The Life and Times. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73038-7. 19. "Island Trees Sch. Dist. v. Pico by Pico 457 U.S. 853 (1982)". Justia. Retrieved 30 September 2015. 20. Office for Intellectual Freedom (26 March 2013). "Top 100 Banned/Challenged Books: 2000-2009". American Library Association. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2021 |

参考文献 1. ジョイス、ジョイス・アン(2000年11月30日)。「ライト、リチャード(1908–1960)」。『アフリカ系アメリカ人作家』2: 875–894。ゲイル CX1387200066。 2. ライスタッド、メアリー(1994)。「リチャード・ライト:概観」。ローラ・スタンリー・バーガー編『20世紀のヤングアダルト作家』セント・ジェームズ・プレス刊。ISBN 978-1-55862-202-9。ゲイル H1420008836。 3. ダイケマ=ヴァンダーアーク、アンソニー(2001年)。「『ブラック・ボーイ』に関する批評的エッセイ」。トマソン、エリザベス(編)。『学生のための ノンフィクション古典:ノンフィクション作品の分析、文脈、批評を紹介する』。ゲイル・グループ。hdl:2027/pst.000045795947。 ISBN 978-0-7876-5381-1。OCLC 62163743。ゲイル H1420035601. 4. ライト、リチャード(1998年)[1993年]。『ブラック・ボーイ:アメリカン・ハンガー(幼少期と青年期の記録)』(初版)。ニューヨーク市:ハー パー・ペレニアル。ISBN 978-0-06-092978-7。OCLC 39339337。[ページ番号が必要] 5. アダムズ、ティモシー・ダウ(1997年)。「リチャード・ライト:『仮面をかぶって』」。テルゲン、ダイアン(編)。『学生のための小説』第1巻。デト ロイト:ゲイル。ISBN 978-1-4144-2794-2。OCLC 288950276。ゲイル H1420021254。初出:アダムス、ティモシー・ダウ(1990)。「リチャード・ライト:『仮面を被って』」。アダムス、ティモシー・ダウ (編)。『現代アメリカ自伝における嘘』 UNC プレスブックス。69-83 ページ。ISBN 978-0-8078-1888-6。 6. アンドルー、ウィリアム L. (2001). 「リチャード・ライトとアフリカ系アメリカ人の自伝の伝統」. トマソン、エリザベス (編). 学生のためのノンフィクションの古典:ノンフィクション作品に関する分析、背景、批評の紹介. ゲイル・グループ. hdl:2027/pst.000045795947. ISBN 978-0-7876-5381-1。OCLC 62163743。ゲイル H1420035601。初出:アンドルー、ウィリアム L. (1993年夏)。「リチャード・ライトとアフリカ系アメリカ人の自伝的伝統」。スタイル。27 (2): 271–282。 7. ポウロス、ジェニファー H. (1997年12月22日)。「『罵声を浴びせる』:リチャード・ライトの『ブラック・ボーイ』における『悪い』言葉の政治学」。The Journal of Negro History. 82 (1): 54–67. doi:10.2307/2717496. JSTOR 2717496. S2CID 141463119. ゲイル A20757362. 8. ステップト、ロバート・B. (1982). 「『私はこの人々を知っていると思っていた』:リチャード・ライトとアフリカ系アメリカ人文学の伝統」. ガントン、シャロン・R. (編). 『現代文学批評』. 第21巻. ゲイル. ISBN 978-0-8103-0117-7. ゲイル H1100003311. 当初の掲載先: ステップト, ロバート・B. (1977年秋). 「『私はこの人々を知っていると思っていた』: リチャード・ライトとアフリカ系アメリカ人文学の伝統」. マサチューセッツ・レビュー. 18 (3): 525–541. 9. ポーター, ホーレス・A. (2003). 「恐怖と栄光:ライトが描く芸術家の肖像——『黒人少年』と『アメリカの飢え』」. ウィタレック, ジャネット (編). 20世紀文学批評. 第136巻. ゲイル社. ISBN 978-0-7876-7035-1. ゲイル H1420051191. 初出: ポーター, ホーレス・A. (1993). 「恐怖と栄光:ライトが描く芸術家の肖像——『ブラック・ボーイ』と『アメリカン・ハンガー』」ヘンリー・ルイス・ゲイツ、アンソニー・アピア編『リ チャード・ライト:過去と現在の批評的視点』ニューヨーク:アミスタッド、316–327頁。ISBN 978-1-56743-027-1。 10. ジャニス・サデウス(1985年5月)。「リチャード・ライトの『ブラック・ボーイ』の変容」。『アメリカン・リテラチャー』57巻2号:199–214頁。doi:10.2307/2926062。JSTOR 2926062。 11. 文学古典社、「本文に関する注記」、リチャード・ライト『ブラック・ボーイ』(アメリカン・ハンガー)、アメリカ図書館協会、1993年、407–8頁。 12. ハーバート・ミットガング(1992年1月1日)。「タイムズ書評;アメリカの巨匠と新たな発見」。ニューヨーク・タイムズ。 13. 「注目すべき書籍リスト 1945」 (PDF). ALA. 1945. 2019年4月24日取得。 14. フォアステル、ハーバート N. (2002). 『米国で禁止された書籍:学校および公共図書館における書籍検閲の参考ガイド』. グリーンウッド出版グループ. ISBN 978-0-313-31166-6。[ページ番号が必要] 15. 「リチャード・ライト著『ブラック・ボーイ』」。禁止図書。2018年11月6日。2019年4月24日取得。 16. プラース、ダラ(2015年2月5日)。「黒人歴史の様相を変えた、禁止された本トップ10」。全国検閲反対連合。2019年4月24日取得。 17. ランバート、フランク(2009年9月3日)。『オレミスの戦い:公民権対州の権利』。オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-975858-6。 18. ローリー、ヘイゼル(2008年2月15日)。『リチャード・ライト:その生涯と時代』。シカゴ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-226-73038-7。 19. 「アイランドツリーズ学区対ピコ事件 457 U.S. 853 (1982)」。ジャスティア。2015年9月30日閲覧。 20. 知的自由局(2013年3月26日)。「禁止・異議申し立て図書トップ100:2000-2009年」。アメリカ図書館協会。2020年9月24日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2021年6月16日閲覧。 |

| Black Boy at Faded Page (Canada) Black Boy Sparknotes Black Boy Paperback |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Boy |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099