人民の抵抗権

People's

Right to resist

| The right to resist

is a nearly universally acknowledged human right, although its scope

and content are controversial.[2] The right to resist, depending on how

it is defined, can take the form of civil disobedience or armed

resistance against a tyrannical government or foreign occupation;

whether it also extends to non-tyrannical governments is disputed.[3]

Although Hersch Lauterpacht, one of the most distinguished jurists,

called the right to resist the supreme human right, this right's

position in international human rights law is tenuous and rarely

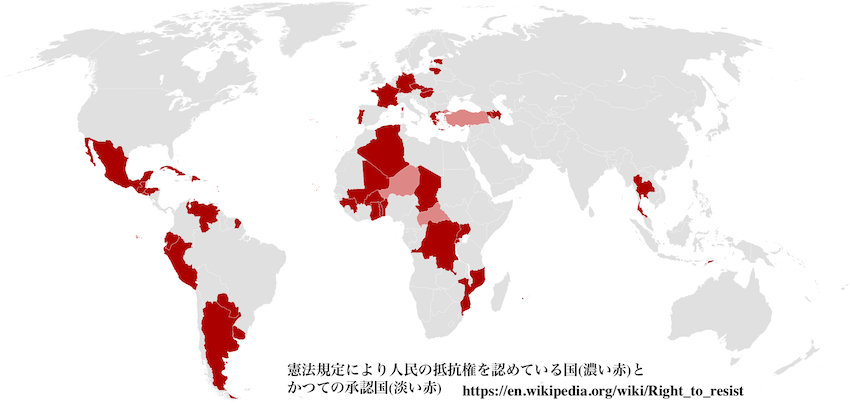

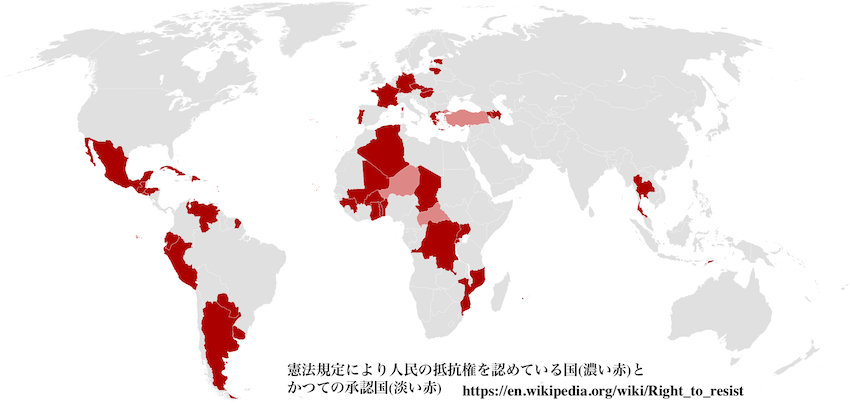

discussed. Forty-two countries explicitly recognize a constitutional

right to resist, as does the African Charter on Human and Peoples'

Rights. |

抵抗する権利は、ほぼ普遍的に認められている人権であるが、その範囲と

内容については議論がある[2]。抵抗する権利は、それがどのように定義されるかによって、専制的な政府または外国の占領に対する市民の不服従または武装

抵抗の形をとることができ、それが非専制政府にも及ぶかどうかは議論がある[3]。

最も優れた法律家のひとりであるハーシュ・ラウターパクトは抵抗権を最高人権と呼んだが、国際人権法におけるこの権利の地位は弱く、ほとんど論議されてい

ない。42カ国が憲法上の抵抗権を明確に認めており、アフリカ人権及び人民の権利に関する憲章も同様である。 |

| According to philosopher Heiner

Bielefeldt, "The question of the legitimacy of resistance—including

violent resistance—against established authority is as old as political

and social thought itself."[4] The right to resist was encoded in the

earliest versions of international law and in a variety of

philosophical traditions.[5] Support for the right to resist can be

found in the ancient Greek doctrine of tyrannicide included in Roman

law, the Hebrew Bible,[clarification needed] jihad in the Muslim world,

the Mandate of Heaven in dynastic Chinese political philosophy, and in

Sub-Saharan Africa's oral traditions.[4][5] Historically, Western

thinkers have distinguished between despots and tyrants, only

authorizing resistance against the latter because these rulers violated

fundamental rights in addition to their lack of popular legitimacy.[6]

A few thinkers including Kant and Hobbes absolutely rejected the

existence of a right to resist.[7] John Locke accepted it only to

protect property.[8] Views differ on whether the right to resist goes

beyond restoring the status quo or defending the constitutional order.

Marxists went even farther than the authors of the French Revolution in

supporting resistance to change the established order; Mao Zedong said

that "it is right to rebel against reactionaries".[9] Although Hersch Lauterpacht, one of the most distinguished jurists, called the right to resist the supreme human right, this right's position in international human rights law is tenuous and rarely discussed.[10] The United Nations' Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders' mandate excludes anyone who does not use exclusively peaceful means, regardless of the severity of rights infringement.[11] According to Shannonbrooke Murphy, the lack of respect for the right to resist is discordant with the reality that the United Nations itself and the entire architecture of human rights might not exist if their supporters had not resorted to the use of force against the Axis powers.[12] Furthermore, Murphy argues that this rule is unfair to human rights defenders in the worst situations and its effect "has led to a perverse situation whereby international human rights law effectively abandons the majority of people facing grave or massive human rights violations".[13] In 1964, Nelson Mandela defended the recourse to violence in the struggle against apartheid, in his speech "I Am Prepared to Die".[14] According to political philosopher Gwilym David Blunt, "The right to resistance is a necessary part of the political conception of human rights". Without it, rights would only be privileges, but the right to resist provides "an ultimate remedy to human rights violations".[15][16] |

哲学者のハイナー・ビーレフェルトによれば、「既成の権威に対する抵抗

-暴力的抵抗を含む-の正当性の問題は、政治的・社会的思想そのものと同じくらい古い」[4]

抵抗権は国際法の初期のバージョンと様々な哲学的伝統の中に符号化されていた。

[5]抵抗する権利のサポートは、ローマ法に含まれる専制君主の古代ギリシャの教義、ヘブライ語聖書、イスラム世界の聖戦、中国王朝の政治哲学における天

命、サハラ以南のアフリカの口伝に見つけることができる[要解釈]。 [4][5]

歴史的に、西洋の思想家は専制君主と暴君を区別し、これらの支配者が民衆の正当性を欠いていることに加えて基本的権利を侵害していることから後者に対する

抵抗のみを認めてきた[6] カントやホッブズを含む少数の思想家は抵抗権の存在を絶対に否定した[7]

ジョン・ロックは財産保護のためにのみそれを受け入れた[8]

抵抗権が現状回復や憲法秩序を保護する以上のものかどうかについて見解は異なっている。マルクス主義者は既成の秩序を変えるための抵抗を支持することでフ

ランス革命の著者よりもさらに進んでおり、毛沢東は「反動勢力に反抗することは正しい」と述べている[9]。 最も著名な法学者の一人であるハーシュ・ラウターパクトは抵抗する権利を最高の人権と呼んだが、国際人権法におけるこの権利の位置づけは弱く、ほとんど議 論されていない[10]。 人権擁護者に関する国連の特別報告者の任務は、権利侵害の深刻さに関わらず、平和的手段のみを用いない者を除外するものである。 [11] シャノンブルック・マーフィーによれば、抵抗する権利に対する尊重の欠如は、もし彼らの支持者が枢軸国に対して武力行使に訴えなければ、国連そのものや人 権の構造全体が存在しなかったかもしれないという現実と不一致しているのである。 12] さらにマーフィーは、このルールは最悪の状況にある人権擁護者に対して不公平であり、その効果は「国際人権法が重大または大規模な人権侵害に直面している 大多数の人々を事実上見捨てるという逆境を招いた」と論じている[13]。 [13] 1964年、ネルソン・マンデラは「私は死ぬ覚悟でいる」というスピーチでアパルトヘイトとの闘いにおける暴力への依拠を擁護しました[14] 政治哲学者のグウィリム・デヴィッド・ブラントによれば、「抵抗する権利は人権の政治概念に必要な部分である」のだそうです。それがなければ権利は特権に 過ぎないが、抵抗する権利は「人権侵害に対する究極の救済策」を提供する[15][16]。 |

| Resistance vs. terrorism National liberation movements using violence as occurred in Algeria, Palestine, and Ireland have often elicited mixed reactions, between being denounced as terrorism and the assertion that sometimes force is necessary to resist oppression.[17] Political theorist Christopher Finlay wrote a book based on just war theory articulating when he believes armed resistance is justified.[18] Especially after the 9/11 attacks, state counterterrorism strategies included proscribing many organizations as terrorist organizations, even if they could be seen as exercising a legitimate right to resist in accordance with internationally recognized principles. In particular, states proscribing organizations that oppose these states poses a high risk of denial of the right to resist.[19] Mark Muller QC cites the United Kingdom's Terrorism Act 2000 as a law that could potentially encompass any non-state organization carrying out an armed campaign and one that contains no exception for lawful exercise of self-determination or fighting against a nondemocratic and oppressive regime.[20] To avoid the problem of competing legal frameworks that evaluate an action differently, Georg Gesk proposes that anti-terrorism laws should focus on obviously criminal actions that could not be justified regardless of the cause, while violent resistance against an allegedly unjust state should not be seen as terrorism unless proven to be the case.[21] A specific example is the Palestinian right to resist the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian territories, which is denied by Israel.[22] |

抵抗 vs. テロリズム アルジェリア、パレスチナ、アイルランドで起こったような暴力を用いた民族解放運動は、しばしばテロとして非難されることと、時には抑圧に抵抗するために 武力が必要であるという主張の間で複雑な反応を引き起こしている[17] 政治理論家のクリストファー・フィンレイは、正当戦争理論に基づいた本を書き、彼が信じる武装抵抗はいつ正当化されるのかを明確に述べている[18]。 特に9/11の攻撃の後、国家のテロ対策戦略は、たとえ国際的に認められた原則に従って抵抗する正当な権利を行使していると見ることができたとしても、多 くの組織をテロ組織として登録することを含んでいた。特に国家がこれらの国家に反対する組織を保護することは抵抗する権利を否定する高いリスクをもたらす [19] Mark Muller QCは、武装運動を行うあらゆる非国家組織を潜在的に包含しうる法律としてイギリスのテロリズム法2000を挙げており、自己決定の合法的行使や非民主的 かつ抑圧的な政権に対する戦いに対する例外を含んでいないものであった。 [20] ある行為を異なる形で評価する競合する法的枠組みの問題を回避するために、ゲオルグ・ゲスクは反テロ法は原因に関係なく正当化され得ない明らかに犯罪的な 行為に焦点を当てるべきであり、一方で不正とされる国家に対する暴力的抵抗はそれが証明されない限りテロとしてみなされるべきではないと提案している [21]。 具体的な例としては、イスラエルによって否定されているパレスチナ領土の占領に対するパレスチナの抵抗の権利である[22]。 |

| Global poverty and injustice Although political theorists have debated what obligations the wealthy have in light of global poverty and injustice, there has been less thought on what the victims of these regimes are entitled to do to achieve justice. According to political theorist Simon Caney, the downtrodden have a right to resist global injustice; "to engage in action that transforms the underlying social, economic, and political structures that perpetuate injustice in order to bring about greater justice in the future".[23] Based on the principle of necessity, Caney argues that some people have the right to take direct action to immediately better their standard of living. Examples he gives include evading border controls; stealing essential food, medicine, or energy that they could not afford; and violating intellectual property law.[24] A second type of resistance involves attempting to alter unjust global systems to bring about greater justice; he cites land occupations; obstruction and blockades, for example to protect the environment; sabotage; refusing to pay debt; rioting; and rebellion, for example the Haitian Revolution or anti-colonial wars.[25] Blunt argues that poor people in the Global South have the right to resist their condition by immigrating to the Global North, even against the law; he analogizes this to slaves' right to resist by fleeing their masters.[26] |

世界の貧困と不公正 政治理論家は、世界の貧困と不正の観点から富裕層にどのような義務があるのかを議論してきたが、こうした体制の犠牲者が正義を実現するために何をする権利 があるのかについては、あまり考えられてこなかった。政治理論家のサイモン・ケイニーによれば、社会的弱者にはグローバルな不正に抵抗する権利があり、 「将来より大きな正義をもたらすために、不正を永続させる根本的な社会・経済・政治構造を変革する行動に携わる」権利がある。必要性の原則に基づき、ケイ ニーは一部の人々は生活水準を直ちに改善するために直接行動を起こす権利を持っていると主張している。彼が与える例には、国境管理の回避、必要不可欠な食 料、医薬品、エネルギーを買うことができなかったものを盗むこと、知的財産法に違反することが含まれる[24]。第2のタイプの抵抗は、より大きな正義を もたらすために不正なグローバルシステムを変更しようとすることを含み、彼は土地の占有、例えば環境を守るための妨害や封鎖、サボタージュ、負債の支払い 拒否、暴動、例えばハイチ革命や反植民地戦争といった反乱を挙げている。 [25] ブラントは、南半球の貧しい人々は法に反してでも北半球に移住することによって自分たちの状況に抵抗する権利を持っていると主張し、これを奴隷が主人から 逃げることによって抵抗する権利になぞらえている[26]。 |

| Legal provisions There is no generally agreed legal definition of the right. Based on Tony Honoré, Murphy suggests that the "'right to resist' is the right, given certain conditions, to take action intended to effect social, political or economic change, including in some instances a right to commit acts that would ordinarily be unlawful".[27] This right could be exercised individually or collectively, ranges from overthrow of the system through more limited goals, and encompasses all illegal actions from civil disobedience to violent resistance.[28] This right is conditional on being necessary and proportionate to achieve an aim compatible with international human rights law, and could not justify infringing others' rights.[29] |

法的規定 この権利に関する一般的に合意された法的定義はない。トニー・オノレに基づき、マーフィーは「『抵抗する権利』とは、一定の条件のもとで、社会的、政治 的、経済的変化をもたらすことを意図した行動をとる権利であり、場合によっては、通常であれば違法となる行為を行う権利も含む」と提案している。 [27]この権利は個人的にも集団的にも行使することができ、より限定的な目標を通じてシステムの転覆から範囲に及び、市民の不服従から暴力的な抵抗まで すべての違法行為を包含している[28]。この権利は国際人権法と両立する目的を達成するために必要かつ比例的であるという条件が付いており、他人の権利 を侵害することを正当化することはできない[29]。 |

| International law In international law, the right to resist is closely related to the principle of self-determination.[9] It is widely recognized that a right to self-determination arises in situations of colonial domination, foreign occupation, and racist regimes that deny a segment of the population political participation. According to international law, states may not use force against the lawful exercise of self-determination, while those seeking self-determination may use military force if there is no other way to achieve their goals.[30] Fayez Sayegh derives a right to resist from the Charter of the United Nations' recognition of an inherent right of national self-defense in the face of aggression.[31] Based on the charter, the 1970 United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2625 explicitly endorsed a right to resist "subjection of peoples to alien subjugation, domination and exploitation".[32] Based on this, many scholars argue that the right to resist exists in customary international law where self-determination is at issue.[33] Some scholars have argued that a right to resist oppression is implicit in the International Bill of Human Rights. The preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states "whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law".[34] The drafters of the declaration, however, intended to exclude the right to resist.[35] The European and Inter-American regional human rights treaties do not include a right to resist.[36] Article 20(2) of the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights states that "colonised or oppressed peoples" have a right "to free themselves from the bonds of domination by resorting to any means recognised by the international community". There is no similar provision in other human rights treaties.[37] Murphy suggests that besides foreign invasion and occupation, "peoples facing massive violations amounting to crimes against humanity or genocide, coups d'état or other unconstitutional rule could qualify."[37] The revised 2004 Arab Charter on Human Rights, but not its 1994 predecessor, grants an unqualified "right to resist foreign occupation".[38] |

国際法 国際法において、抵抗する権利は自己決定の原則と密接に関連している [9]。自己決定権は、人口の一部の政治参加を否定する植民地支配、外国の占領、人種差別政権の状況において発生することが広く認識されている。国際法に よれば、国家は自己決定の合法的な行使に対して武力を行使することはできないが、自己決定を求める人々は目的を達成するために他の方法がない場合、軍事力 を行使することができる[30] フェイズ・セイフは侵略に直面した国家自衛の固有の権利に関する国連憲章の認識から抵抗権を導き出して いる[31]。 [31]憲章に基づき、1970年の国連総会決議2625は「異民族の服従、支配、搾取への人民の服従」に抵抗する権利を明確に支持していた[32]。こ れに基づき、多くの学者は自決が問題となる場合には抵抗権が国際慣習法において存在すると主張している[33]。 一部の学者は、抑圧に抵抗する権利は国際人権章典に暗黙のうちに含まれていると主張している。世界人権宣言の前文は「人間が最後の手段として、専制と抑圧 に対する反抗に頼ることを強制されないならば、人権が法の支配によって保護されるべきであることが不可欠であるので」[34]と述べている。 しかし宣言の起草者は抵抗する権利を除外しようとしていた[35]。 ヨーロッパと米州の地域人権条約は抵抗する権利を含んでいない[36]。 アフリカ人権及び人民の権利憲章の第20条2項は、「植民地化され又は抑圧された人民」が「国際社会によって認められたいかなる手段によっても支配の束縛 から自らを解放する」権利を有していると述べている。他の人権条約には同様の規定はない[37]。 Murphyは、外国からの侵略や占領以外に、「人道に対する罪や大量虐殺、クーデターや他の違憲な支配に相当する大規模な侵害に直面している人民が資格 を得ることができる」[37]と示唆している。 1994年の前任者ではなく2004年に改訂されたアラブ人権憲章では、無制限に「外国の占領に抵抗する権利」が認められている[38]。 |

| Constitutions The right to resist was guaranteed in Magna Carta[39] and is one of the central elements of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen issued during the French Revolution in 1791. This provision is incorporated into the preamble of France's 1958 constitution.[2][9] As of 2012, 42 countries recognize a right to resist in their constitution and another three formerly recognized such a right.[40] Most of these countries are located in Latin America, Western Europe, or Africa.[41] Most provisions were adopted in four waves: "revolutionary republican, post-fascist, post-colonial and post-Soviet".[39] In Latin America, such constitutional provisions were commonly adopted in the aftermath of coups d'état, while elsewhere these provisions were intended as a forward thinking measure against democratic backsliding.[42] The philosophical basis of the constitutional right to resist differs; in some cases based on natural law; in others obliging the citizen to take action against unconstitutional seizure of power; and in a third set of countries authorizing action against state interference in individual rights.[43] There is also variance in whether the right to resist is conceived as optional or a duty of citizens.[44] The laws vary in scope; some grant the right to resist an unlawful coup or foreign aggression while others are more broad, encompassing human rights violations or other oppression.[39] Constitutional right to resist installed by revolutionary governments may later be cited by opponents of these regimes. In 1953, Fidel Castro was arrested for the attack on Moncada Barracks. In his defense speech, "History Will Absolve Me", he invoked the "universally recognized principle" and Cuba's constitutional right to resist.[45] In 2021, the Italian Supreme Court of Cassation overturned the conviction of two migrants in the Vos Thalassa case for a July 2018 protest on board the Vos Thalassa ship in which they resisted being returned to Libya, due to the risk of torture and mistreatment in that country.[46] |

憲法について 抵抗権はマグナ・カルタ[39]で保証され、1791年のフランス革命で発行された「人間と市民の権利の宣言」の中心的要素の1つである。この規定はフラ ンスの1958年憲法の前文に取り入れられている[2][9]。 2012年現在、42カ国が憲法において抵抗権を認めており、さらに3カ国がかつてその権利を認めていた[40]。 これらの国のほとんどはラテンアメリカ、西ヨーロッパ、アフリカに位置している[41]。ほとんどの規定は4つの波で採択された。「革命的共和制、ポスト ファシスト、ポスト植民地、ポストソビエト」[39]。ラテンアメリカでは、そのような憲法規定はクーデターの余波でよく採択されており、他の地域ではこ れらの規定は民主主義の後退に対する前向きの対策として意図されたものであった[42]。 憲法上の抵抗権の哲学的基礎は異なっており、ある場合には自然法に基づき、ある場合には違憲の権力奪取に対して行動を起こすことを市民に義務付け、第3の 国では個人の権利に対する国家の干渉に対して行動を許可する[43]。 抵抗権が任意として考えられているか市民の義務として考えられているかにも違いがある[44]。法律は範囲において異なり、あるものは不法なクーデターや 外国の侵略に抵抗する権利を認め、他のものはより広く人権侵害や他の弾圧も包括している[39]。 革命的な政府によって設置された憲法上の抵抗権は、後にこれらの政権の反対派によって引用されることがある。1953年、フィデル・カストロはモンカダ兵 舎への襲撃で逮捕された。弁護演説「歴史は私を免責する」の中で、彼は「普遍的に認められた原則」とキューバの憲法上の抵抗権を引き合いに出した [45]。 2021年、イタリアのカセーション最高裁判所は、2018年7月のVos Thalassa号船内での抗議行動で、リビアに戻されることに抵抗した2人の移民の有罪判決を、同国での拷問や虐待の危険性から覆した[46]。 https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Right_to_resist. |

|

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099