ロバート・サウジー

Robert Southey, 1774-1843

Robert Southey (1774–1843), Aged 31, John Opie

☆

ロバート・サウシー(Robert Southey,

/ˈsaʌi, ˈʌi/;[a] 1774年8月12日 -

1843年3月21日)はロマン派に属するイギリスの詩人であり、1813年から亡くなるまで詩人であった。他の湖水詩人であるウィリアム・ワーズワース

やサミュエル・テイラー・コールリッジと同様、サウジーは急進派として出発したが、イギリスとその制度に敬意を抱くようになるにつれ、次第に保守的になっ

ていった。バイロンのような他のロマン派からは、金と地位のために体制側についたと非難された。特に「ブレナムの後で」という詩と「ゴルディロックスと3

匹のくま」の原作が有名である。

| Robert Southey

(/ˈsaʊði, ˈsʌði/;[a] 12 August 1774 – 21 March 1843) was an English

poet of the Romantic school, and Poet Laureate from 1813 until his

death. Like the other Lake Poets, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor

Coleridge, Southey began as a radical but became steadily more

conservative as he gained respect for Britain and its institutions.

Other romantics such as Byron accused him of siding with the

establishment for money and status. He is remembered especially for the

poem "After Blenheim" and the original version of "Goldilocks and the

Three Bears". |

ロバー

ト・サウシー(Robert Southey, /ˈsaʌi, ˈʌi/;[a] 1774年8月12日 -

1843年3月21日)はロマン派に属するイギリスの詩人であり、1813年から亡くなるまで詩人であった。他の湖水詩人であるウィリアム・ワーズワース

やサミュエル・テイラー・コールリッジと同様、サウジーは急進派として出発したが、イギリスとその制度に敬意を抱くようになるにつれ、次第に保守的になっ

ていった。バイロンのような他のロマン派からは、金と地位のために体制側についたと非難された。特に「ブレナムの後で」という詩と「ゴルディロックスと3

匹のくま」の原作が有名である。 |

Life Wine Street, Bristol (1872) Robert Southey was born in Wine Street, Bristol, to Robert Southey and Margaret Hill.[1] He was educated at Westminster School, London (where he was expelled for writing an article in The Flagellant, a magazine he originated,[2] attributing the invention of flogging to the Devil),[3] and at Balliol College, Oxford.[4] Southey went to Oxford with "a heart full of poetry and feeling, a head full of Rousseau and Werther, and my religious principles shaken by Gibbon".[2] He later said of Oxford, "All I learnt was a little swimming... and a little boating". He did, however, write a play, Wat Tyler (which, in 1817, after he became Poet Laureate, was published, to embarrass him, by his enemies). Experimenting with a writing partnership with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, most notably in their joint composition of The Fall of Robespierre, Southey published his first collection of poems in 1794. The same year, Southey, Coleridge, Robert Lovell and several others discussed creating an idealistic community ("pantisocracy") on the banks of the Susquehanna River in America. In 1795 he married Edith Fricker, whose sister Sara married Coleridge. The same year, he travelled to Portugal, and wrote Joan of Arc, published in 1796. He then wrote many ballads, went to Spain in 1800, and on his return settled in the Lake District.[2] In 1799, Southey and Coleridge were involved with early experiments with nitrous oxide (laughing gas), conducted by the Cornish scientist Humphry Davy.[5] |

人生 ブリストルのワイン・ストリート(1872年) ロバート・サウシーはブリストルのワイン・ストリートで、ロバート・サウシーとマーガレット・ヒルの間に生まれた[1]。 ロンドンのウェストミンスター・スクールで教育を受け[2]、オックスフォードのバリオール・カレッジで学んだ[3]。 サウシーは「心は詩と感情で一杯になり、頭はルソーとウェルテルで一杯になり、宗教的な信条はギボンに揺さぶられた」[2]状態でオックスフォードに行っ たが、後にオックスフォードについて「私が学んだのは少しの水泳と...少しのボート遊びだけだった」と語っている。しかし、戯曲『ワット・タイラー』 (1817年、桂冠詩人就任後、彼を困らせるために敵によって出版された)を書いた。サミュエル・テイラー・コールリッジとの共同執筆を試み、特に『ロベ スピエールの没落』を共同執筆したサウシーは、1794年に最初の詩集を出版した。同じ年、サウティ、コールリッジ、ロバート・ラヴェルら数人は、アメリ カのサスケハナ川のほとりに理想主義的な共同体(「パンティソクラシー」)を作ることを話し合った。 1795年、彼はエディス・フリッカーと結婚し、その姉サラはコールリッジと結婚した。同年、ポルトガルに旅行し、1796年に出版された『ジョーン・オ ブ・アーク』を執筆した。その後、多くのバラッドを書き、1800年にはスペインに行き、帰国後は湖水地方に定住した[2]。 1799年、サウジーとコールリッジは、コーンウォール出身の科学者ハンフリー・デイヴィが行った亜酸化窒素(笑気ガス)の初期の実験に関わった[5]。 |

| While

writing prodigiously, he received a government pension in 1807, and in

1809 started a long association with the Quarterly Review, which

provided almost his only income for most of his life. He was appointed

laureate in 1813, a post he came greatly to dislike. In 1819 Southey accompanied the Scottish civil engineer Thomas Telford, whom Southey nicknamed the “Colossus of Roads”[7] on a tour of inspection of Telford’s works in Scotland. These included the Caledonian Canal (which would open three years later) and a number of Telford's roads, bridges, and harbour works. Southey’s account of the tour, Journal of a Tour in Scotland in 1819,[8] gives detailed descriptions of Telford’s engineering projects and records Southey’s own impressions of the Scottish landscape and people.[9] In 1821, Southey wrote A Vision of Judgment, to commemorate George III, in the preface to which he attacked Byron who, as well as responding with a parody, The Vision of Judgment (see below), mocked him frequently in Don Juan.[2]  Robert Southey, by Sir Francis Chantrey, 1832, National Portrait Gallery, London In 1837, Edith died, and Southey remarried, to Caroline Anne Bowles, also a poet, on 4 June 1839.[10] The marriage broke down,[11] not least because of his increasing dementia. His mind was giving way when he wrote a last letter to his friend Walter Savage Landor in 1839, but he continued to mention Landor's name when generally incapable of mentioning anyone. He died on 21 March 1843 and was buried in the churchyard of Crosthwaite Church, Keswick, where he had worshipped for forty years. There is a memorial to him inside the church, with an epitaph written by his friend William Wordsworth.  Peter Vandyke, Portrait of Robert Southey, Aged 21, 1795 Southey was also a prolific letter writer, literary scholar, essay writer, historian and biographer. His biographies include the life and works of John Bunyan, John Wesley, William Cowper, Oliver Cromwell and Horatio Nelson. The last has rarely been out of print since its publication in 1813 and was adapted as the 1926 British film Nelson. He was a generous man, particularly kind to Coleridge's abandoned family, but he incurred the enmity of many, including Hazlitt as well as Byron, who felt he had betrayed his principles in accepting pensions and the laureateship, and in retracting his youthful ideals.[2] |

1807年には政府から年金を受け取り、1809年からは『季刊誌』との長い付き合いが始まり、生涯ほとんど唯一の収入源となった。1813年に桂冠詩人に任命されたが、彼はこのポストを非常に嫌うようになった。 1819年、サウシーはスコットランドの土木技師トマス・テルフォードに同行し、「道路の巨像」と呼ばれた[7]。その中には、カレドニア運河(この運河 は3年後に開通する)、テルフォードの道路、橋、港湾工事などが含まれていた。1819年のスコットランド旅行記『Journal of a Tour in Scotland』[8]には、テルフォードのエンジニアリング・プロジェクトについての詳細な記述があり、スコットランドの風景や人々についてのサウ ティ自身の印象が記録されている[9]。 1821年、サウシーはジョージ3世を記念して『審判の幻影』を書き、その序文でバイロンを攻撃した。バイロンはパロディ『審判の幻影』(下記参照)で応えただけでなく、『ドン・ファン』の中で頻繁に彼を嘲笑していた[2]。  ロバート・サウシー、サー・フランシス・シャントレー作、1832年、ナショナル・ポートレート・ギャラリー、ロンドン 1837年、エディスは亡くなり、サウシーは1839年6月4日に同じく詩人のキャロライン・アン・ボウルズと再婚した[10]。1839年に友人ウォル ター・サヴェッジ・ランドーに最後の手紙を書いたとき、彼の精神は衰えつつあったが、一般的には誰の名前も口にすることができないときに、彼はランドーの 名前を口にし続けた。彼は1843年3月21日に亡くなり、40年間礼拝していたケズィックのクロストウェイト教会の教会墓地に埋葬された。教会内には彼 の記念碑があり、友人のウィリアム・ワーズワースが書いた墓碑銘がある。  ピーター・ヴァンダイク、ロバート・サウシー21歳の肖像、1795年 サウシーはまた、多作な手紙作家、文学者、エッセイ作家、歴史家、伝記作家でもあった。彼の伝記には、ジョン・バニヤン、ジョン・ウェスレー、ウィリア ム・カウパー、オリバー・クロムウェル、ホレイショ・ネルソンの生涯と作品が含まれている。ホレイショ・ネルソンの伝記は1813年に出版されて以来、絶 版になることはほとんどなく、1926年にはイギリス映画『ネルソン』として映画化された。 彼は寛大な人物で、特にコールリッジの遺族には親切であったが、ハズリットやバイロンなど多くの人々の恨みを買い、彼は年金や桂冠を受け取り、若い頃の理想を引っ込めたことで、自分の主義を裏切ったと感じた[2]。 |

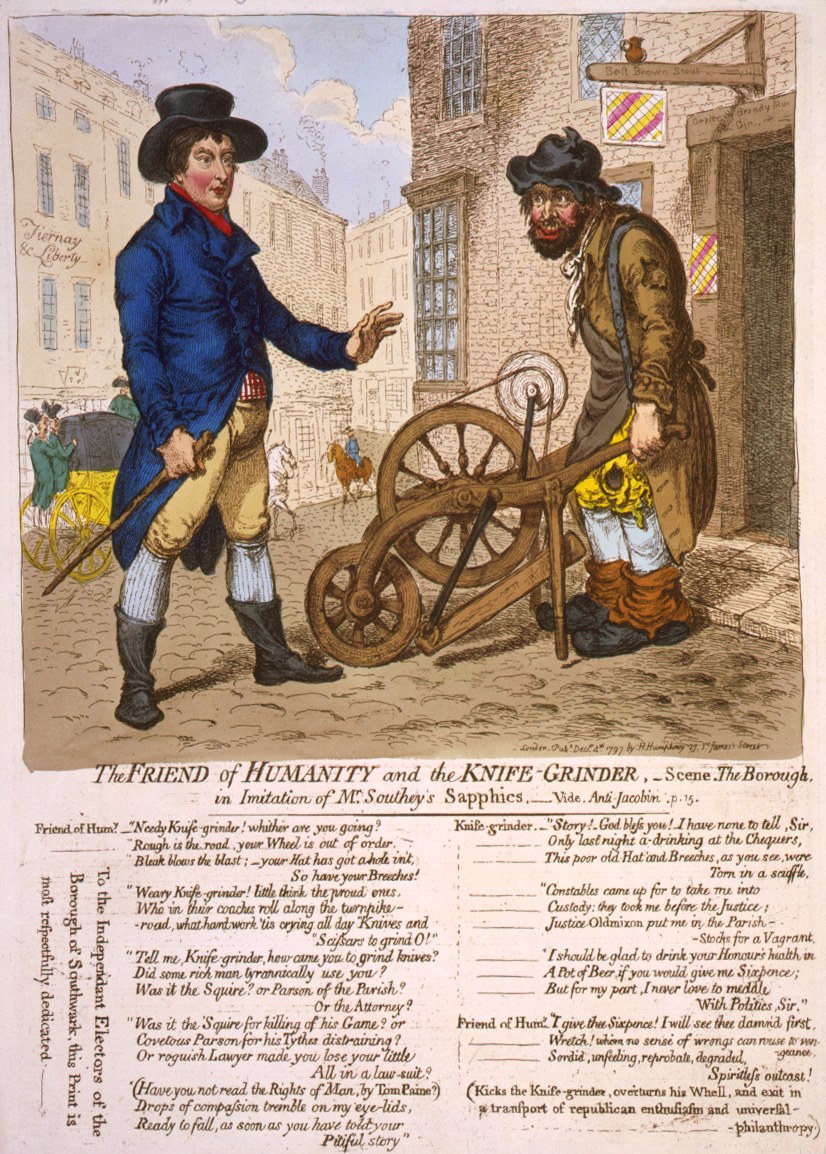

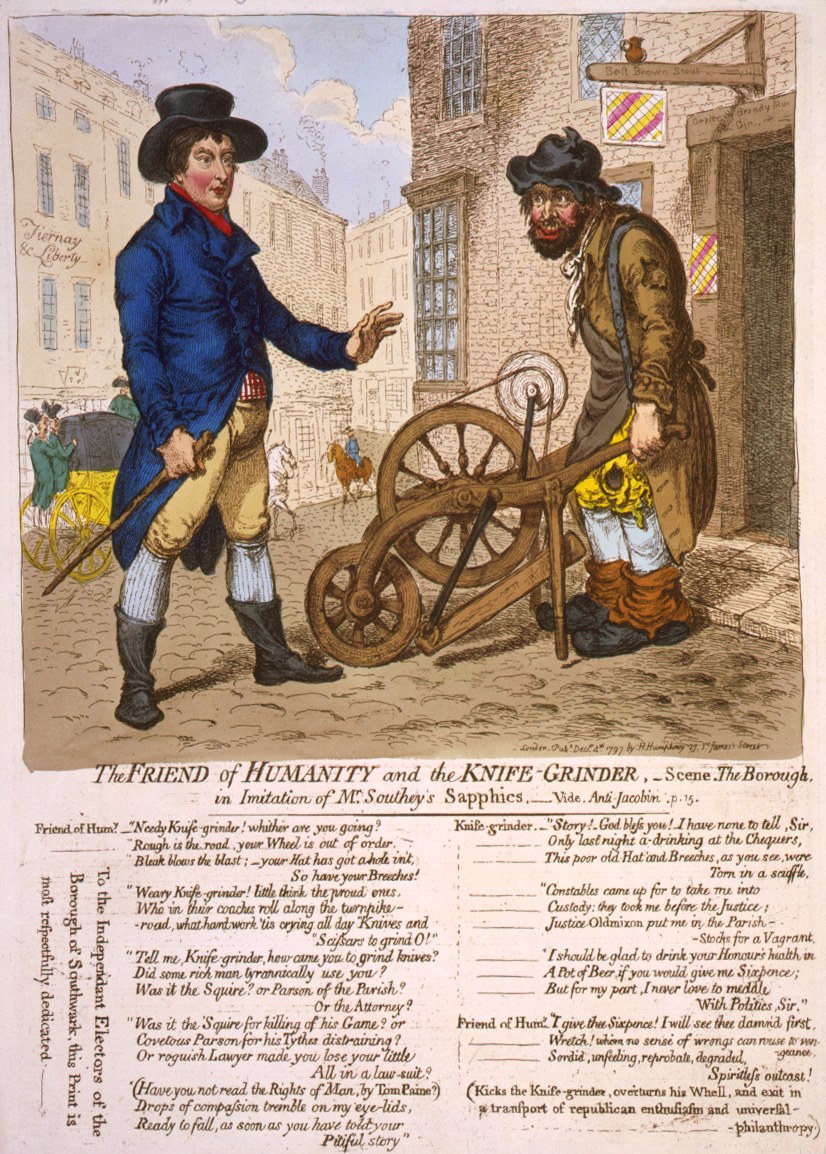

| Although

originally a radical supporter of the French Revolution, Southey

followed the trajectory of his fellow Romantic poets Wordsworth and

Coleridge towards conservatism. Embraced by the Tory establishment as

Poet Laureate, and from 1807 in receipt of a yearly stipend from them,

he vigorously supported the Liverpool government. He argued against

parliamentary reform ("the railroad to ruin with the Devil for

driver"), blamed the Peterloo Massacre on an allegedly revolutionary

"rabble" killed and injured by government troops, and spurned Catholic

emancipation.[12] In 1817 he privately proposed penal transportation

for those guilty of "libel" or "sedition". He had in mind figures like

Thomas Jonathan Wooler and William Hone, whose prosecution he urged.

Such writers were guilty, he wrote in the Quarterly Review, of

"inflaming the turbulent temper of the manufacturer and disturbing the

quiet attachment of the peasant to those institutions under which he

and his fathers have dwelt in peace." Wooler and Hone were acquitted,

but the threats caused another target, William Cobbett, to emigrate

temporarily to the United States. In some respects, Southey was ahead of his time in his views on social reform. For example, he was an early critic of the evils the new factory system brought to early 19th-century Britain. He was appalled by the living conditions in towns like Birmingham and Manchester and especially by employment of children in factories and outspoken about them. He sympathised with the pioneering socialist plans of Robert Owen, advocated that the state promote public works to maintain high employment, and called for universal education.[13] Given his departure from radicalism, and his attempts to have former fellow travellers prosecuted, it is unsurprising that less successful contemporaries who kept the faith attacked Southey. They saw him as selling out for money and respectability.  Portrait by Thomas Lawrence, c. 1810 In 1817, Southey was confronted with the surreptitious publication of a radical play, Wat Tyler, which he had written in 1794 at the height of his radical period. This was instigated by his enemies in an attempt to embarrass the Poet Laureate and highlight his apostasy from radical poet to supporter of the Tory establishment. One of his most savage critics was William Hazlitt. In his portrait of Southey, in The Spirit of the Age, he wrote: "He wooed Liberty as a youthful lover, but it was perhaps more as a mistress than a bride; and he has since wedded with an elderly and not very reputable lady, called Legitimacy." Southey largely ignored his critics but was forced to defend himself when William Smith, a member of Parliament, rose in the House of Commons on 14 March to attack him.[14] In a spirited response Southey wrote an open letter to the MP, in which he explained that he had always aimed at lessening human misery and bettering the condition of all the lower classes and that he had only changed in respect of "the means by which that amelioration was to be effected."[15] As he put it, "that as he learnt to understand the institutions of his country, he learnt to appreciate them rightly, to love, and to revere, and to defend them."[15]  A 1797 caricature of Southey's early radical poetry Another critic of Southey in his later period was Thomas Love Peacock, who scorned him in the character of Mr. Feathernest in his 1817 satirical novel Melincourt.[16] He was often mocked for what were seen as sycophantic odes to the king, notably in Byron's long ironic dedication of Don Juan to Southey. In the poem Southey is dismissed as insolent, narrow and shabby. This was based both on Byron's lack of respect for Southey's literary talent, and his disdain for what he perceived as Southey's hypocritical turn to conservatism later in life. Much of the animosity between the two men can be traced back to Byron's belief that Southey had spread rumours about him and Percy Bysshe Shelley being in a "League of Incest" during their time on Lake Geneva in 1816, an accusation that Southey strenuously denied. In response, Southey attacked what he called the Satanic School among modern poets in the preface to his poem, A Vision of Judgement, written after the death of George III. While not naming Byron, it was clearly directed at him. Byron retaliated with The Vision of Judgment, a parody of Southey's poem. Without his prior knowledge, the Earl of Radnor, an admirer of his work, had Southey returned as MP for the latter's pocket borough seat of Downton in Wiltshire at the 1826 general election, as an opponent of Catholic emancipation, but Southey refused to sit, causing a by-election in December that year, pleading that he did not have a large enough estate to support him through political life,[17] or want to take on the hours full attendance required. He wished to continue living in the Lake District and preferred to defend the Church of England in writing rather than speech. He declared that "for me to change my scheme of life and go into Parliament, would be to commit a moral and intellectual suicide." His friend John Rickman, a Commons clerk, noted that "prudential reasons would forbid his appearing in London" as a Member.[18] In 1835, Southey declined the offer of a baronetcy, but accepted a life pension of £300 a year from Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel.[18] |

も

ともとはフランス革命の急進的な支持者だったが、ロマン派詩人仲間のワーズワースやコールリッジの保守主義への軌跡をたどった。桂冠詩人としてトーリー派

に迎えられ、1807年からはトーリー派から年俸を受け取り、リバプール政権を精力的に支持した。彼は議会改革に反対し(「悪魔を運転手とする破滅への鉄

道」)、ピータールーの大虐殺を政府軍によって殺傷されたとされる革命的な「暴徒」のせいだと非難し、カトリックの奴隷解放に反対した[12]。

1817年、彼は「名誉毀損」や「扇動」の罪を犯した者に対する刑罰を私的に提案した。彼の念頭にあったのは、トマス・ジョナサン・ウーラーやウィリア

ム・ホーンのような人物であり、彼らの訴追を促した。このような作家は、「製造業者の乱暴な気性を煽り、農民の、彼とその父祖たちが平和に暮らしてきた制

度への静かな愛着を乱す」罪を犯していると、彼は『季刊評論』誌に書いた。ウーラーとホーンは無罪となったが、この脅迫によって、もう一人の標的であった

ウィリアム・コベットはアメリカに一時移住することになった。 ある面では、サウシーは社会改革において時代の先端を走っていた。例えば、彼は19世紀初頭のイギリスに新しい工場制度がもたらした弊害を早くから批判し ていた。バーミンガムやマンチェスターのような町の生活環境に愕然とし、特に工場での児童の雇用について率直な意見を述べた。ロバート・オーウェンの先駆 的な社会主義計画に共感し、高い雇用を維持するために国家が公共事業を推進することを提唱し、国民皆教育を求めた[13]。 彼が急進主義から離れ、かつての仲間を訴追しようとしたことを考えれば、信念を貫いた同時代の成功者たちがサウシーを攻撃したのは当然である。彼らは彼を、金と見栄のために売り渡したと見たのである。  トーマス・ローレンスによる肖像画、1810年頃 1817年、サウシーは1794年に書いた過激な戯曲『ワット・タイラー』が密かに出版されるという事態に直面する。これは、桂冠詩人を困惑させ、急進派 の詩人からトーリー派の支持者への背信を浮き彫りにしようとする、彼の敵による扇動だった。最も辛辣な批評家の一人がウィリアム・ヘイズリットである。彼 は『時代の精神』の中で、サウジーの肖像をこう書いている。「彼は若者の恋人としてリバティを口説いたが、それは花嫁というよりは愛人としてだったのだろ う。」それ以来、彼は正当性(Legitimacy)と呼ばれる、年老いたあまり評判のよくない女性と結婚した。サウシーは批評家たちをほとんど無視して いたが、3月14日に下院議員のウィリアム・スミスが彼を攻撃するために下院に立ち上がり、自己弁護を余儀なくされた[14]。 「彼は「自分の国の制度を理解することを学ぶにつれて、それらを正しく評価し、愛し、敬い、守ることを学んだ」と述べている[15]。  1797年、サウシーの初期の急進的な詩を風刺した風刺画 1817年に発表した風刺小説『メリンコート』(Melincourt)では、フェザーネスト氏(Mr. Feathernest)というキャラクターで彼を嘲笑した[16]。 バイロンが『ドン・ファン』を長く皮肉り、サウシーに献呈している。この詩の中で、サウシーは横柄で狭量でみすぼらしいと切り捨てられた。これは、バイロ ンがサウシーの文学的才能を尊敬していなかったことと、サウシーが後年になって偽善的な保守主義に傾いたと感じたことに対する軽蔑の両方に基づいている。 二人の間の敵意の多くは、バイロンが、1816年にレマン湖で過ごした間、彼とパーシー・ビッシェ・シェリーが「近親相姦同盟」を結んでいたという噂をサ ウシーが流したと考えていたことに遡る。 これに対してサウシーは、ジョージ3世の死後に書かれた詩『審判の幻影』の序文で、近代詩人の中の悪魔派と呼ばれるものを攻撃した。バイロンを名指しした わけではないが、明らかに彼に向けられたものだった。バイロンは、サウシーの詩のパロディである『審判の幻影』で報復した。 1826年の総選挙では、彼の作品を敬愛するラドナー伯爵が、カトリック解放に反対するサウシーをウィルトシャー州ダウントンの下院議員に擁立したが、サ ウシーは政治生命を支えるに足る十分な財産がなく[17]、何時間も議会に出席することを望まなかったため、その年の12月に予備選挙が行われた。彼は湖 水地方に住み続けたいと考え、演説よりも文章でイングランド国教会を擁護することを好んだ。彼は、「自分の生活設計を変えて議会に出ることは、道徳的にも 知的にも自殺行為に等しい」と宣言した。彼の友人でコモンズの事務官であったジョン・リックマンは、「慎重な理由から、彼が議員としてロンドンに姿を現す ことは許されないだろう」と述べている[18]。 1835年、サウシーは男爵の申し出を断ったが、首相サー・ロバート・ピールから年300ポンドの終身年金を受け取った[18]。 |

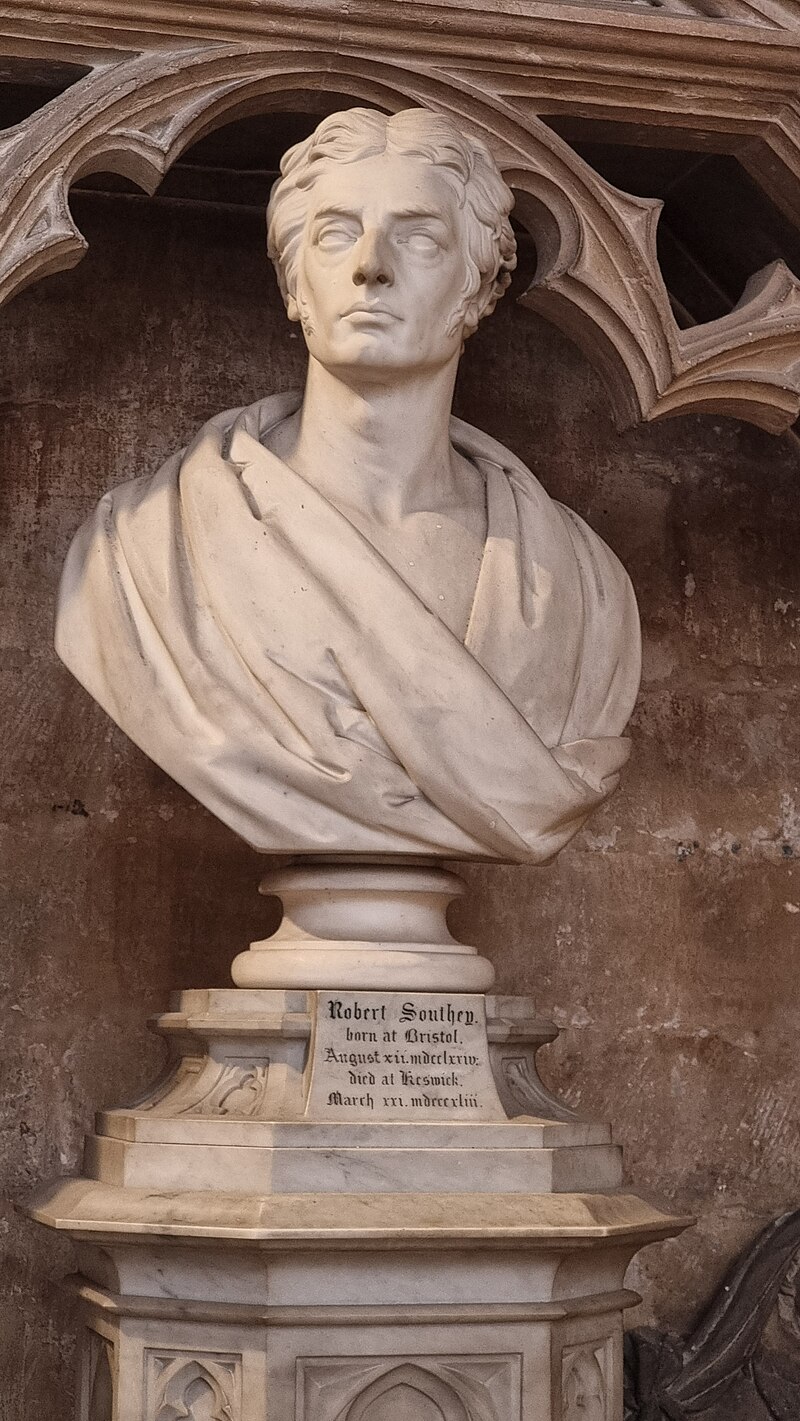

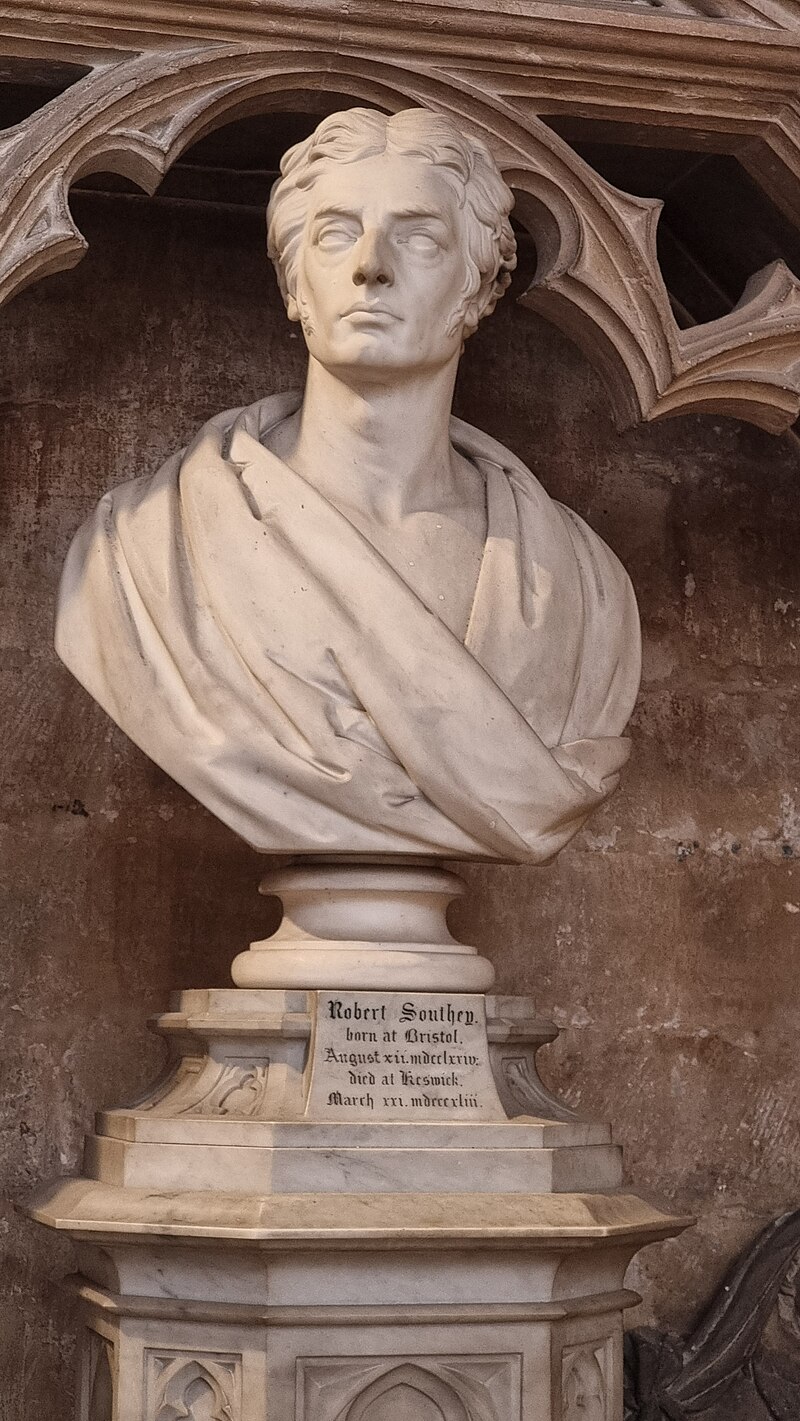

Reputation Bust of Southey created by Edward Hodges Baily in 1845, Bristol Cathedral Charles Lamb, in a letter to Coleridge, stated, "With Joan of Arc I have been delighted, amazed. I had not presumed to expect of any thing of such excellence from Southey. Why the poem is alone sufficient to redeem the character of the age we live in from the imputation of degenerating in Poetry [...] On the whole, I expect Southey one day to rival Milton."[19] Regarding Thalaba the Destroyer, Ernest Bernhard-Kabisch pointed out that "Few readers have been as enthusiastic about it as Cardinal Newman who considered it the most 'morally sublime' of English poems. But the young Shelley reckoned it his favourite poem, and both he and Keats followed its lead in some of their verse narratives."[20] While Southey was writing Madoc, Coleridge believed that the poem would be superior to the Aeneid.[21] Robert Southey had a notable influence on Russian literature. Pushkin highly appreciated his work and translated the beginning of the Hymn to the Penates and Madoc, and was also inspired by the plot of Roderick to create an original poem on the same plot (Родрик). At the beginning of the 20th century, Southey was translated by Gumilyov and Lozinsky. In 1922, the publishing house "Vsemirnaya Literatura" published the first separate edition of Southey's ballads in Russia, compiled by Gumilyov. In 2006, a bilingual edition prepared by E. Witkowski was published, a significant part of which included new translations. Southey was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1822.[22] He was also a member of the Royal Spanish Academy. |

評判 エドワード・ホッジス・ベイリーが1845年に制作したサウシーの胸像(ブリストル大聖堂) チャールズ・ラムは、コールリッジに宛てた手紙の中で、「『ジャン・オブ・アーク』を読んで、私は喜び、驚いた。私はサウティにこのような優れた作品を期 待したことはなかった。なぜこの詩だけで、私たちが生きている時代の性格を、詩の退化という非難から贖うに十分なのか......全体として、私はいつか サウシーがミルトンに匹敵する日が来ることを期待している」[19]。 アーネスト・ベルンハルト=カビッシュは『破壊者タラバ』について、「この詩を英詩の中で最も 「道徳的に崇高な 」詩とみなしたニューマン枢機卿ほど熱狂的な読者はほとんどいない。しかし、若きシェリーはこの詩を自分のお気に入りの詩とし、彼とキーツは詩の物語のい くつかでこの詩に倣った」[20]。 サウシーが『マドック』を書いている間、コールリッジはこの詩が『エニード』よりも優れていると信じていた[21]。 ロバート・サウシーはロシア文学に多大な影響を与えた。プーシキンは彼の作品を高く評価し、『ペナテス讃歌』と『マドック』の冒頭を翻訳し、また『ロデ リック』の筋書きに触発されて、同じ筋書きのオリジナルの詩(Родрик)を創作した。20世紀初頭には、グミリョフやロジンスキーによって翻訳され た。1922年、出版社 「ヴセミルナヤ・リテラトゥーラ 」は、グミリョフが編纂したロシア初のバラッド集を出版した。2006年には、E.ヴィトコフスキによる対訳版が出版された。 サウシーは1822年にアメリカ古物協会の会員に選ばれた[22]。 |

| In popular culture In the video game Book of Hours, released in 2023 by Weather Factory, the Southey family are good friends with the fictional Baroness Eva Dewulf, and there are rumours that they adopted her illegitimate child as Abra Southey and presented her as the younger sister to Robert. |

ポピュラーカルチャー ウェザー・ファクトリーから2023年に発売されたビデオゲーム『Book of Hours』では、サウティ家は架空の男爵夫人エヴァ・デュウルフと仲が良く、彼女の隠し子をアブラ・サウティとして養子に出し、ロバートの妹として贈ったという噂がある。 |

| Partial list of works Harold, or, The Castle of Morford (an unpublished Robin Hood novel that Southey wrote in 1791).[23] The Fall of Robespierre (1794) (with Samuel Taylor Coleridge) Poems: Containing the Retrospect, Odes, Elegies, Sonnets, &c. (with Robert Lovell) Joan of Arc (1796) Icelandic Poetry, or The Edda of Sæmund (contributing an introductory epistle to A. S. Cottle's translations, 1797) The full text of Poems, vols. I & II at Wikisource Letters Written During a Short Residence in Spain and Portugal (1797) St. Patrick's Purgatory (1798) After Blenheim (1798) The Devil's Thoughts (1799). Revised ed. pub. in 1827 as "The Devil's Walk". (with Samuel Taylor Coleridge) English Eclogues (1799) The Old Man's Comforts and How He Gained Them (1799) Thalaba the Destroyer (1801) The Inchcape Rock (1802) Madoc (1805) Letters from England: By Don Manuel Alvarez Espriella (1807), the observations of a fictitious Spaniard. Chronicle of the Cid, from the Spanish (1808) The Curse of Kehama (1810) History of Brazil (3 vols.) (1810–1819)[24][25] The Life of Horatio, Lord Viscount Nelson (1813) Roderick the Last of the Goths (1814) Journal of a tour in the Netherlands in the autumn of 1815 (1902) Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte D'Arthur (1817) Wat Tyler: A Dramatic Poem (1817; written in 1794) Journal of a Tour in Scotland in 1819 (1929 ed.) Cataract of Lodore (1820) The Life of Wesley; and Rise and Progress of Methodism (2 vols.) (1820) What Are Little Boys Made Of? (1820)[citation needed] A Vision of Judgement (1821) History of the Peninsular War, 1807–1814 (3 vols.) (1823–1832) Sir Thomas More; or, Colloquies on the Progress and Prospects of Society (1829) The Works of William Cowper, 15 vols., ed. (1833–1837) Lives of the British Admirals, with an Introductory View of the Naval History of England (5 vols.) (1833–40); republished as "English Seamen" in 1895. The Doctor (7 vols.) (1834–1847). Includes The Story of the Three Bears (1837). The Poetical Works of Robert Southey, Collected by Himself (1837) |

作品リストの一部 Harold, or, The Castle of Morford』(1791年にサウジーが書いた未発表のロビン・フッド小説)[23]。 ロベスピエールの没落』(1794年)(サミュエル・テイラー・コールリッジとの共著) 詩集: 回顧録、オード、エレジー、ソネットなどを含む。(ロバート・ラヴェルと) ジョーン・オブ・アーク(1796年) アイスランドの詩、セームンドのエッダ(A.S.コットルの翻訳に序文を寄稿、1797年) 詩集』上・下巻の全文はWikisourceにある。ウィキソースにて スペインとポルトガルの短期滞在中に書かれた手紙(1797年) 聖パトリックの煉獄(1798年) ブレナムの後で(1798年) 悪魔の思考(1799年)。改訂版は1827年に 「The Devil's Walk 」として出版された。(サミュエル・テイラー・コールリッジとの共著) イギリス回勅(1799年) 老人の快適さとその獲得法(1799年) 破壊者タラバ(1801年) インチケープ・ロック (1802) マドック(1805年) イギリスからの手紙 ドン・マヌエル・アルバレス・エスプリエラ著(1807)架空のスペイン人の観察記。 シドの年代記、スペイン語より (1808) ケハマの呪い(1810年) ブラジルの歴史(全3巻)(1810年-1819年)[24][25]。 ネルソン子爵ホレイショの生涯(1813年) 最後のゴート人ロデリック (1814) 1815年秋のオランダ旅行記(1902年) トマス・マロリー卿のアーサー王物語(1817年) ワット・タイラー:戯曲詩(1817年、1794年執筆) 1819年スコットランド旅行記(1929年版) ロドアの瀑布(1820年) ウェスレーの生涯;メソジズムの勃興と進歩(2巻)(1820年) 少年は何でできているのか?(1820年)[要出典] 裁きの幻影 (1821) 半島戦争史 1807-1814 (全3巻) (1823-1832) サー・トマス・モア、あるいは社会の進歩と展望に関する談話 (1829) ウィリアム・カウパー著作集 全15巻 (1833-1837) Lives of the British Admirals, with an Introductory View of the Naval History of England (5 vols.) (1833-40); 1895年に 「English Seamen 」として再出版された。 ドクター』(全7巻)(1834-1847)。The Story of the Three Bears (1837)を含む。 ロバート・サウシー詩集(1837)。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Southey |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆