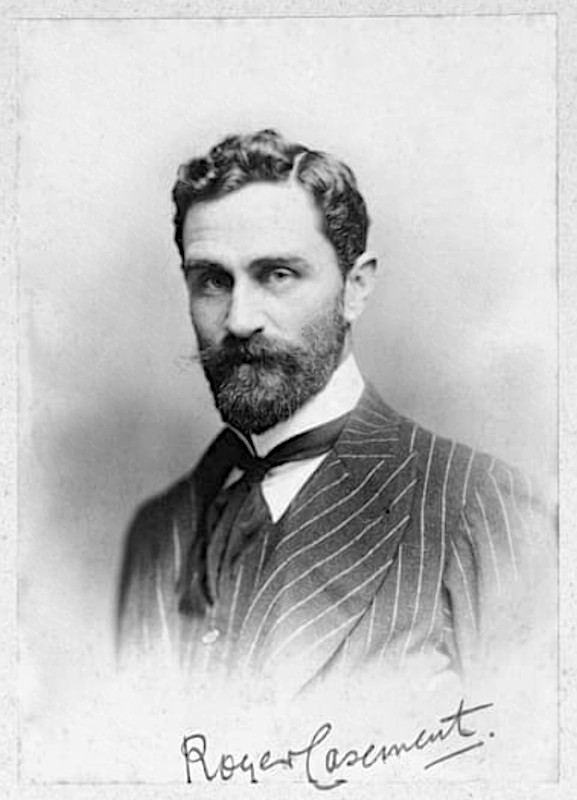

ロジャー・ケースメント

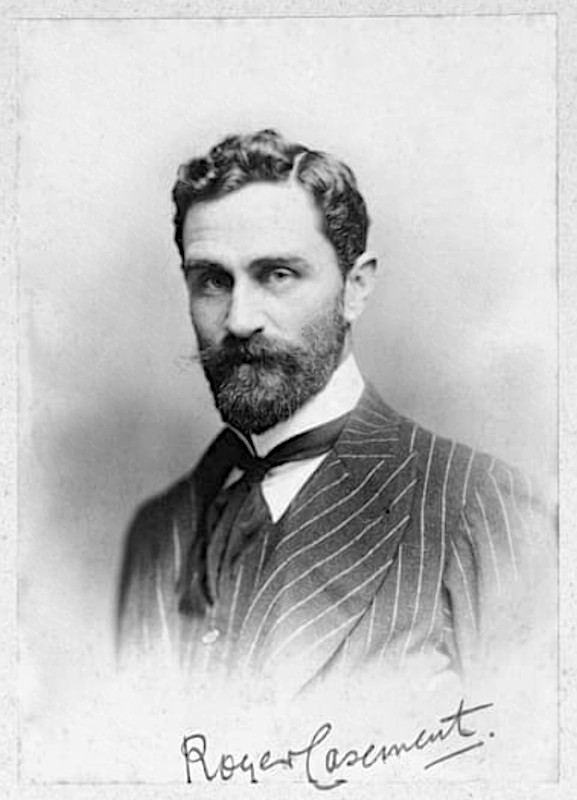

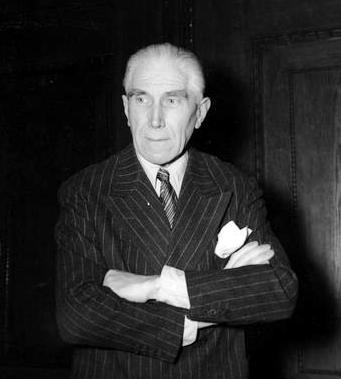

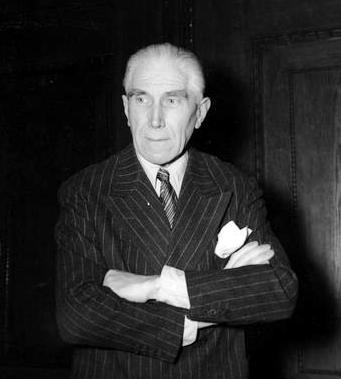

Roger Casement, 1864-1916

Sir

Roger Casement, Roger Casement in Putumayo

略伝(ウィキペディア)「ロジャー・ケースメント(Roger Casement,1864年9月1日 - 1916年8月3日)は、アイルランドの人権活動家。イギリスの外交官を務め、ナイトの称号も与えられたが、後にアイルランド独立活動家になった。 ダブリン出身。外交官となりイギリス政府によってコンゴ自由国へ視察に赴き、そこで行なわれている暴虐を報告した。彼の報告書は、イギリス外相の前文を添 えて各国政府に送付され、国際問題へと発展した。その後、リオ・デ・ジャネイロ駐在総領事となり、プトゥマーヨ河で発生した原住民虐殺事件の調査を命じら れ、その地域で行なわれたゴム業者による原住民への搾取と虐待を報告した。1912年に辞職する。第一次世界大戦中の1916年、アイルランド義勇軍が イースター蜂起に使う武器を調達をするため、ドイツ帝国のベルリンに渡ったが、帰国時に逮捕された。反逆罪とスパイ活動の罪により、ロンドンで絞首刑と なった」ロジャー・ケースメン)

1864 ダブリンのプロテスタント家族に生まれる

1874 孤児になり、北アイルランドの Ballymenaの親戚に育てられる

1883 アフリカにわたり、コンゴ自由国のさまざ まな企業やレオポルド2世の国際アフリカ協会で働く。

その間、探検家でアフリカ人旅行者のヘンリー・モー

トン・スタンリーと後の作家ジョセフ・コンラッドに出会う。

1892 ケースメントはコンゴを離れ、ナイジェリ アの植民地省に加わる。

1895 LourençoMarques(現在の マプト)の領事に就任する。

ca. 1900 コンゴに戻り、英国政府から地元住民の生活と労働条件の調査を依頼される。

1904 『コンゴ報告』これより、ケースメントは コンゴの壊滅的な状況に注意を向け、それによってベルギー王レオポルド2世に対する国際的な圧力を強めた。

レオポルド2世はそのために調査委員会を召集しなけ

ればならなくなった。ジャーナリストのエドモンド・デーン・モレルに会う。モレルとケースメントは生涯にわたる友情と協力を培うことになる。外交特権に

よって成立した領事?は、モレルを説得してコンゴ改革協会を結成する。ケースメントは、このために、国際的な名声を得る。

1906 英国外務省は、最初はパラとサントスの領 事として、次にリオデジャネイロの総領事としてケースメントを赴任させる。

1910

政府は彼をペルーのアマゾンに派遣し、フリオ・セ ザール・アラナが率いる英国とペルーのゴム会社であるペルーのアマゾン会社に対する告発を調査。告発は、英国の資本が多く、ロンドン証券取引所に上場され ていた会社に対してもおこなわれる。

現在コロンビアの一部となっている地域リオ・プトゥ

マヨは、推定3万人以上のウィトト族を殺害する強制労働のシステムを構築していた。ケースメントは最初に委員会の長としてイキトスに行き、次にリオプトゥ

マヨのジャングルエリアに行き、そこで彼は数ヶ月続く任務でこれらの告発を確認した。ロンドンに戻って、彼はインディアンのほぼ完全な絶滅を公表し、アラ

ナの会社を閉鎖させた。

1911 聖マイケルと聖ジョージの爵位を得る。

1912 健康状態が悪化したため、ケースメントは 外交官を辞任する。

1913 アイルランドの独立を要求していた準軍組 織のアイルランド義勇軍に加わる。組織のリーダーであるEoinMacNeillの親友になる。

Eoin MacNeill、1916年頃

Eoin MacNeill、1916年頃

1914

第一次世界大戦が勃発したとき、彼は運動のための武 器と財政的支援を組織するために米国を経由してドイツに旅行する。1914年10月にノルウェー経由でベルリンに旅行。英国大使は、ケースメントの使用人 に賄賂を渡して彼を同胞に引き渡すか、彼を失踪させようと画策。

ドイツに到着すると、ケースメントは最初にアイルラ ンドの捕虜から志願旅団を募集しようとしました。この計画が失敗した後、ケースメントはドイツ軍を説得して、2万丁のライフル、10丁の機関銃、弾薬をア イルランド義勇軍に届けた。

イースター蜂起の計画がなされるが、ケースメントは 蚊帳の外におかれる。

1916

ノルウェー船オードを装った輸送船リバウは、 1916年4月9日にすでにリューベックを出港していた。復活祭の日曜日から復活祭の月曜日に蜂起の日付が延期されたため、ドイツの船長カール・スピンド ラーは、武器が降ろされるのをトラリーベイで無駄に待つことになる。その間、イギリス軍はドイツのラジオメッセージを傍受し、4月21日の朝にオーストラ リアドルを設定する。オードはクイーンズタウンになりました護衛され、船長は港の入り口で船とその貨物を爆破した。ケースメントは、ライムント・ワイス バッハ中尉の下でドイツのUボートU 19に乗ったオードの直後に、2人の仲間と一緒にドイツを離れた。4月21日の朝、ボートはケリー州のアイルランド南西海岸に到着した。 彼の仲間はゴム製のディンギーに着陸し、ビーチに銃と弾薬の箱を埋めた。廃墟に隠れていたケースメントは、その後まもなく逮捕された。彼はロンドンに移さ れ、そこで彼は当局に彼の身元を明らかにした。

1916年4月24日イースター蜂起と失敗

ケースメントは、反逆罪、妨害行為、および王冠に対 するスパイ行為で告発された。

5月3日英国海軍情報部長は、日記の一部をジャーナ リストたちに示し同性愛者であることが発覚。

爵位の剥奪

1916年6月26日より裁判開始。

アーサー・コナン・ドイル卿とジョージ・バーナー ド・ショーが署名したにもかかわらず、恩赦の最後の罪状認否は却下。死刑の判決。

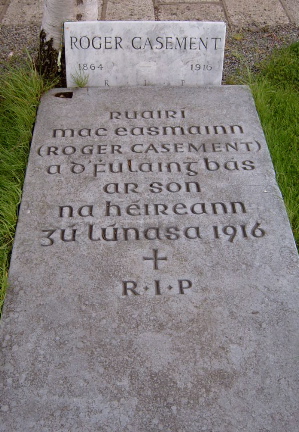

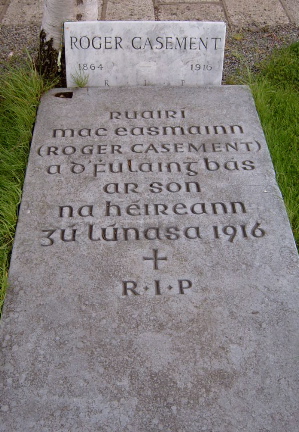

8月3日絞首刑にて死亡(51歳)。ケースメントの 遺体は処刑直後にペントンビル刑務所の敷地内に埋葬

1965 彼の遺体はアイルランドに運ばれ、国の式

典の後、完全な軍事的名誉を持ってダブリンの教会に運ばれ、2月28日にダブリンのグラスネヴィン墓地に埋葬。

+++

Roger David Casement

(Irish: Ruairí Dáithí Mac Easmainn;[1] 1 September 1864 – 3 August

1916), known as Sir Roger Casement, CMG, between 1911 and 1916, was a

diplomat and Irish nationalist executed by the United Kingdom for

treason during World War I. He worked for the British Foreign Office as

a diplomat, becoming known as a humanitarian activist, and later as a

poet and Easter Rising leader.[2] Described as the "father of

twentieth-century human rights investigations",[3] he was honoured in

1905 for the Casement Report on the Congo and knighted in 1911 for his

important investigations of human rights abuses in the rubber industry

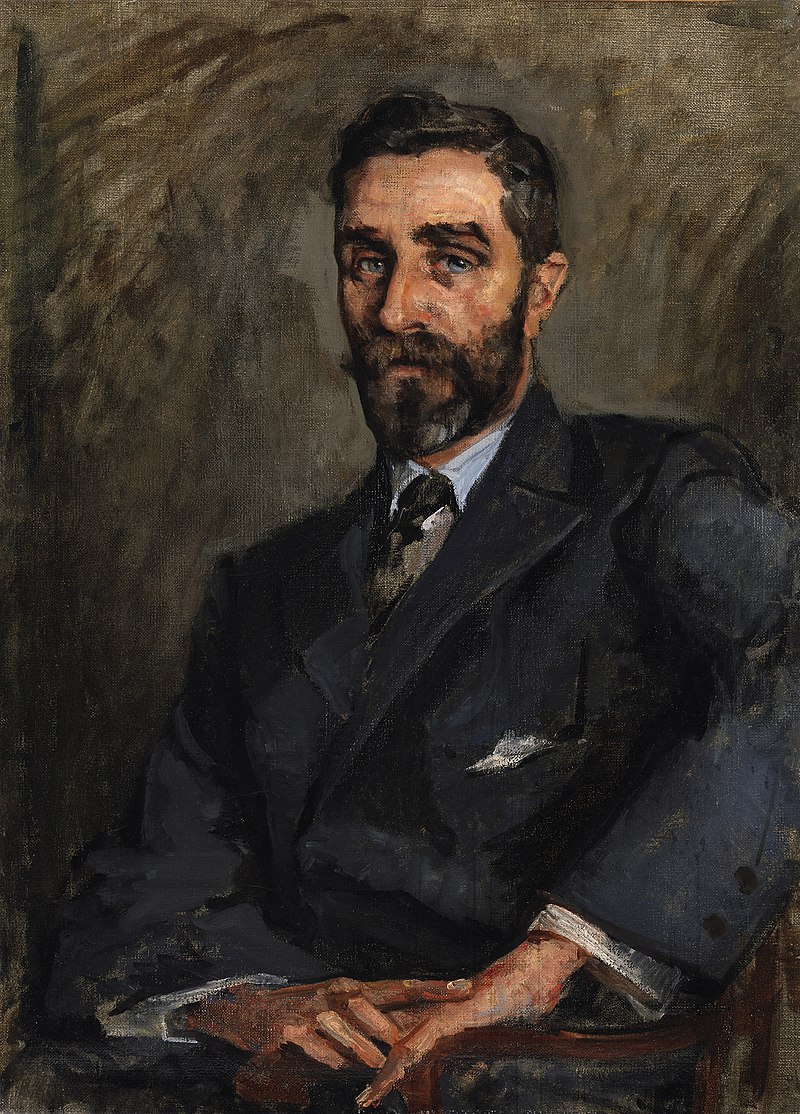

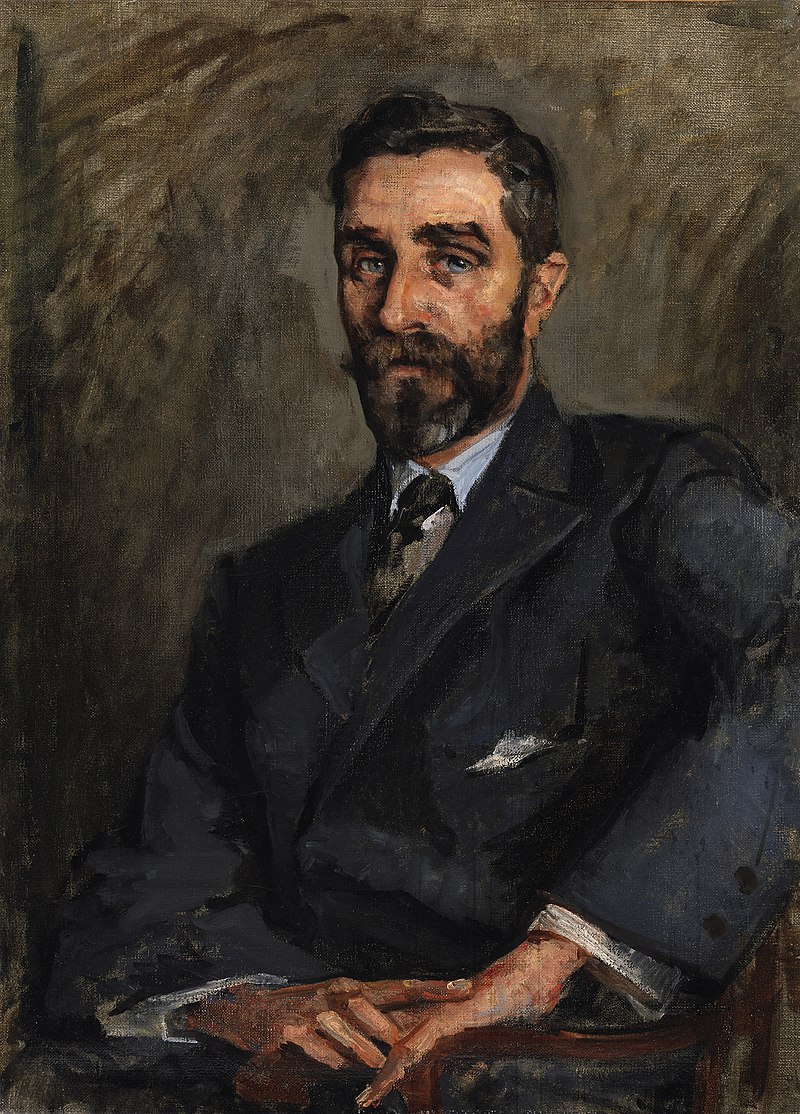

in Peru.[4] Casement by Sarah Purser, 1914 In Africa as a young man, Casement first worked for commercial interests before joining the British Colonial Service. In 1891 he was appointed as a British consul, a profession he followed for more than 20 years. Influenced by the Boer War and his investigation into colonial atrocities against indigenous peoples, Casement grew to mistrust imperialism. After retiring from consular service in 1913, he became more involved with Irish republicanism and other separatist movements. During World War I, he made efforts to gain German military aid for the 1916 Easter Rising that sought to gain Irish independence.[5] He was arrested, convicted and executed for high treason. He was stripped of his knighthood and other honours. Before the trial, the British government circulated excerpts said to be from his private journals, known as the Black Diaries, which detailed homosexual activities. Given prevailing views and existing laws on homosexuality, this material undermined support for clemency. Debates have continued about these diaries: a handwriting comparison study in 2002 concluded that Casement had written the diaries, but this was still contested by some.[6] |

ロジャー・デイヴィッド・ケースメント(アイルランド語:

Ruairí Dáithí Mac Easmainn、[1] 1864年9月1日 -

1916年8月3日)は、1911年から1916年の間、CMGのロジャー・ケースメント卿として知られた外交官であり、第一次世界大戦中に反逆罪でイギ

リスによって処刑されたアイルランドのナショナリストである。彼は外交官として英国外務省に勤務し、人道活動家として知られるようになり、後に詩人、イー

スター蜂起の指導者として知られるようになった[2]。「20世紀の人権調査の父」と称され[3]、1905年にコンゴに関するケースメント報告書で表彰

され、1911年にはペルーのゴム産業における人権侵害に関する重要な調査でナイトの称号を授与された[4]。 サラ・パーサーによるケースメント、1914年 若かりし頃のアフリカで、ケースメントはイギリス植民地局に入る前に、まず商業利益のために働いた。1891年には英国領事に任命され、20年以上その職 に就いた。ボーア戦争と先住民に対する植民地残虐行為の調査に影響され、ケースメントは帝国主義への不信感を募らせた。1913年に領事職を退いた後は、 アイルランド共和主義やその他の分離主義運動に深く関わるようになった。 第一次世界大戦中、彼はアイルランドの独立を目指した1916年のイースター蜂起にドイツの軍事援助を得るために尽力した[5]が、大逆罪で逮捕され、有 罪判決を受け、処刑された。彼は爵位とその他の名誉を剥奪された。裁判に先立ち、イギリス政府は、同性愛活動の詳細を記した「黒い日記」として知られる彼 の私的な日記の抜粋を流通させた。同性愛に関する一般的な見解と既存の法律を考慮すると、この資料は慈悲を求める支持を弱めた。2002年に行われた筆跡 比較研究では、ケースメントが日記を書いたと結論づけられたが、これにはまだ異論がある[6]。 |

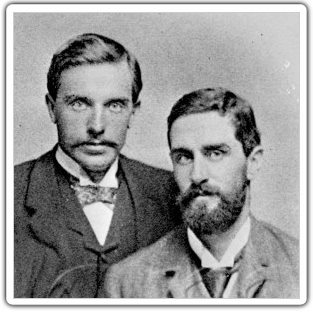

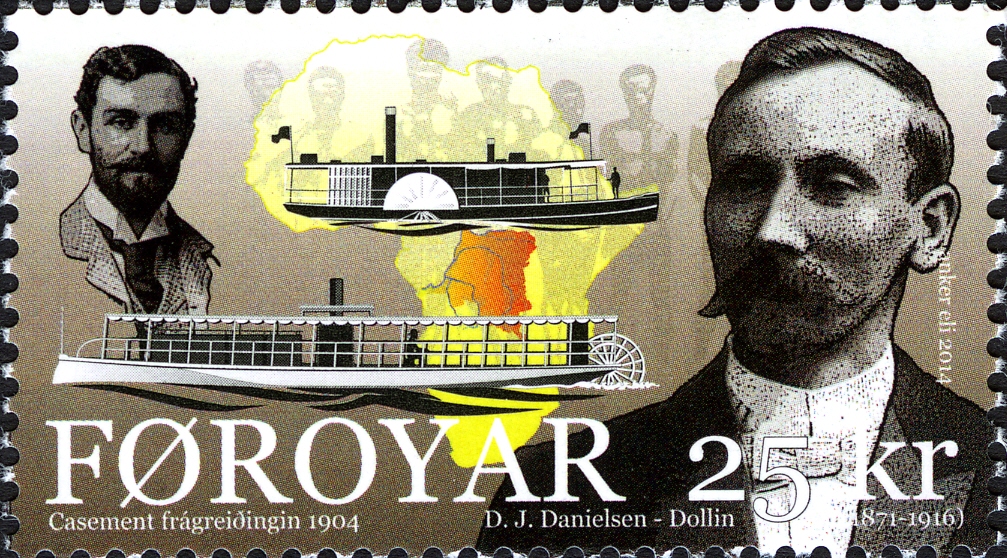

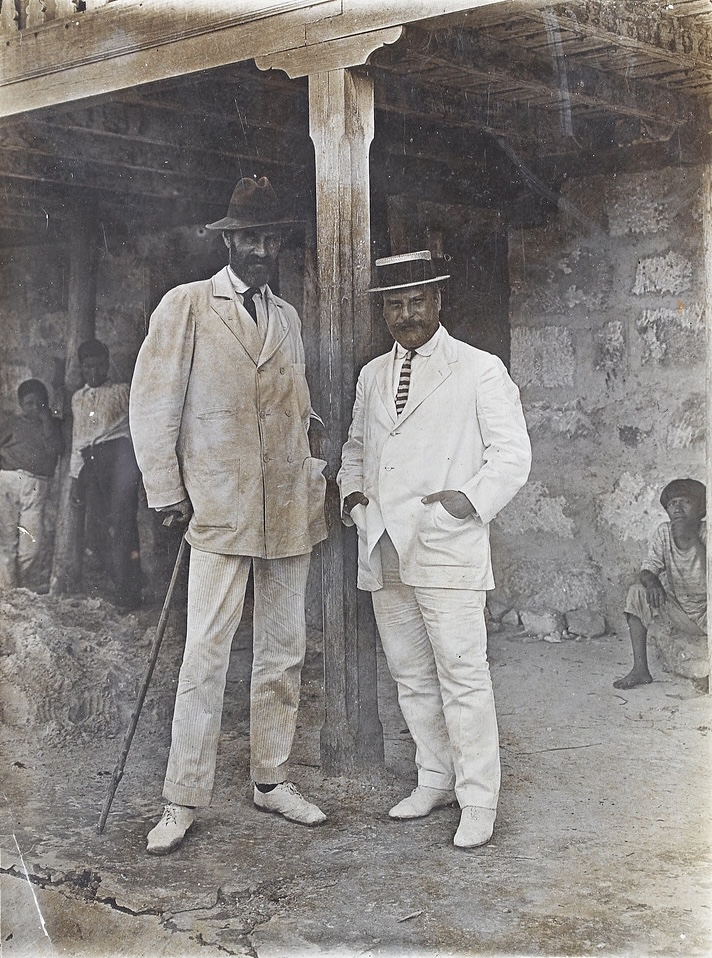

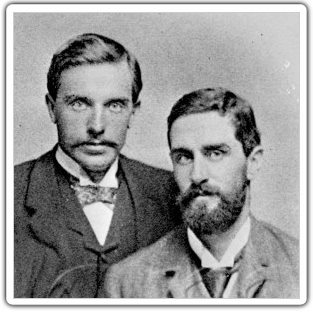

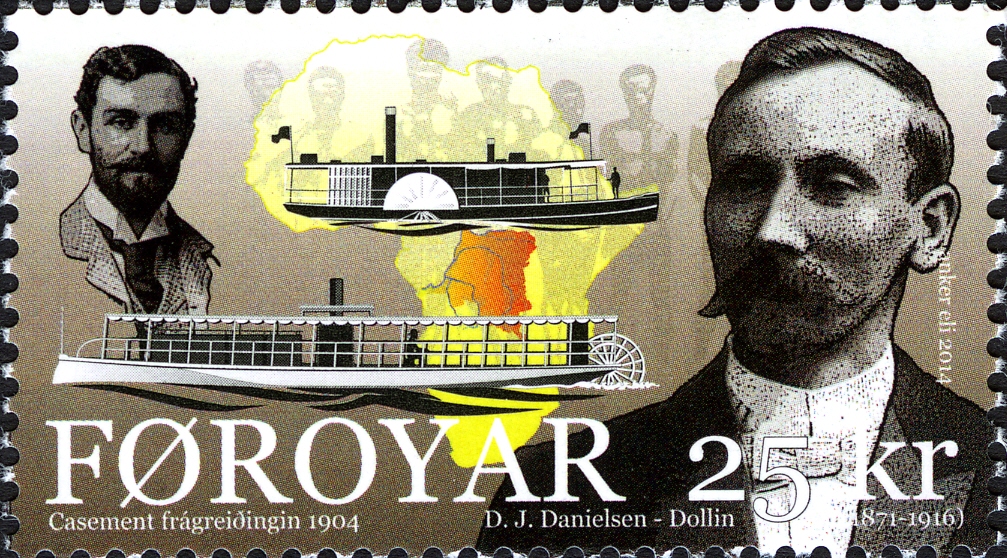

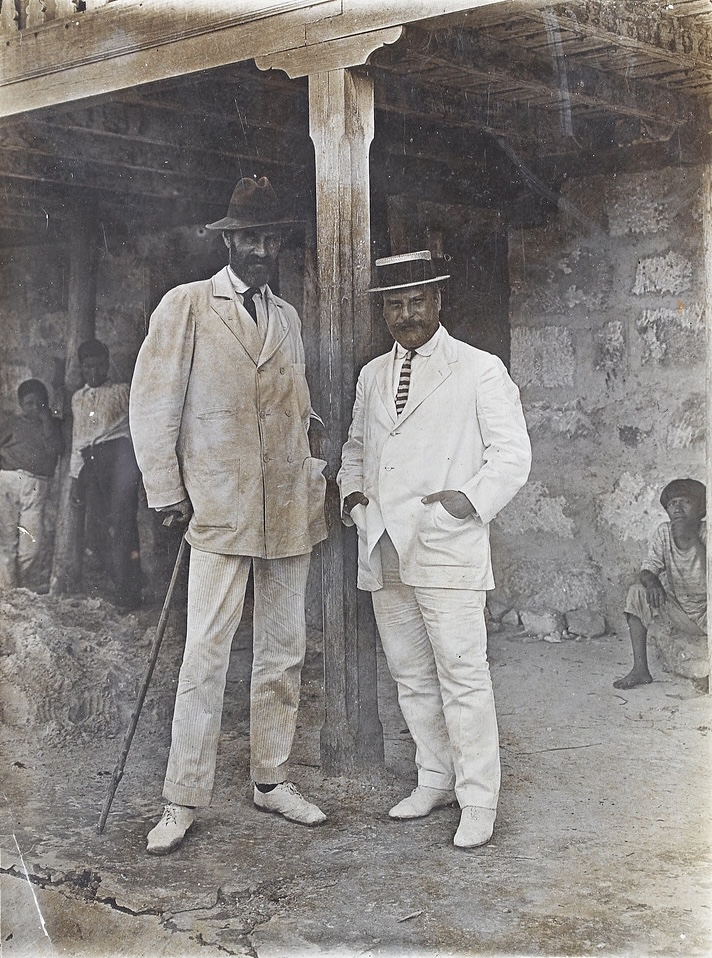

| Early life Family and education Casement was born in Dublin to an Anglo-Irish family, and lived in very early childhood at Doyle's Cottage, Lawson Terrace, Sandycove,[7] a terrace that no longer exists, but that was on Sandycove Road between what is now Fitzgerald's pub and The Butler's Pantry delicatessen. His father, Captain Roger Casement of the (King's Own) Regiment of Dragoons, was the son of Hugh Casement, a Belfast shipping merchant who went bankrupt and later moved to Australia. Captain Casement had served in the 1842 Afghan campaign. He travelled to Europe to fight as a volunteer in the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 but arrived after the Surrender at Világos.[citation needed] After the family moved to England, Roger's mother, Anne Jephson (or Jepson), of a Dublin Anglican family, purportedly had him secretly baptised at the age of three as a Roman Catholic in Rhyl, Wales.[why?][8][9] However, the priest who arranged his baptism in 1916 clearly stated that the claimed earlier baptism had been in Aberystwyth, 80 miles from Rhyl, raising the question as to why such a supposedly important event should also become so misremembered.[10]  c. 1910 According to an 1892 letter, Casement believed his mother was descended from the Jephson family of Mallow, County Cork[11] but the Jephson family's historian provides no evidence of this.[12] The family lived in England in genteel poverty; Roger's mother died when he was nine. His father took the family back to Ireland to County Antrim to live near paternal relatives. When Casement was 13 years old, his father died in Ballymena, and he was left dependent on the charity of relatives, the Youngs and the Casements. He was educated at the Diocesan School, Ballymena (later the Ballymena Academy). He left school at 16 and went to England to work as a clerk with Elder Dempster, a Liverpool shipping company headed by Alfred Lewis Jones.[13] Roger Casement's brother, Thomas Hugh Jephson Casement (1863–1939), had a roving life at sea and as a soldier, and later helped establish the Irish Coastguard Service.[14] He was the inspiration for a character in Denis Johnston's play The Moon in the Yellow River. He drowned in Dublin's Grand Canal on 6 March 1939, having threatened suicide.[14][15] Observations of Casement In a recollection of Casement, which conceivably is coloured by knowledge of his subsequent fate, Ernest Hambloch, Casement's deputy during his consular posting to Brazil, recalls an "unexpected" figure: tall, ungainly; "elaborately courteous" but with "a good deal of pose about him, as though he was afraid of being caught off his guard". "An easy talker and a fluent writer", he could "expound a case, but not argue it". His greatest charm, of which he seemed "quite unconscious" was his voice, which was "very musical." The eyes were "kindly", but not given to laughter: "a sense of humour might have saved him from many things".[16] Joseph Conrad's first impressions of Casement, from an encounter in the Congo he judged "a positive piece of good luck", was "thinks, speaks, well, most intelligent and very sympathetic". Later, after Casement's arrest and trial, Conrad had more critical thoughts: "Already in Africa, I judged he was a man, properly speaking, of no mind at all. I don't mean stupid. I mean that he was all emotion. By emotional force (Putumayo, Congo report etc) he made his way, and sheer temperament—a truly tragic figure."[17] British diplomat and human rights investigator The Congo and the Casement Report Main article: Casement Report Casement worked in the Congo for Henry Morton Stanley and the African International Association from 1884; this association became known as a front for King Leopold II of Belgium in his takeover of what became the so-called Congo Free State.[18] Casement worked on a survey to improve communication and recruited and supervised workmen in building a railroad to bypass the lower 220 miles of the Congo River, which is made unnavigable by cataracts, in order to improve transportation and trade to the Upper Congo. During his commercial work, he learned African languages.[citation needed]  Roger Casement (right) and his friend Herbert Ward, whom he met in the Congo Free State In 1890 Casement met Joseph Conrad, who had come to the Congo to pilot a merchant ship, Le Roi des Belges ("King of the Belgians"). Both were inspired by the idea that "European colonisation would bring moral and social progress to the continent and free its inhabitants 'from slavery, paganism and other barbarities.' Each would soon learn the gravity of his error."[19] Conrad published his short novel Heart of Darkness in 1899, exploring the colonial ills. Casement later exposed the conditions he found in the Congo during an official investigation for the British government. In these formative years, he also met Herbert Ward, and they became longtime friends. Ward left Africa in 1889, and devoted his time to becoming an artist, and his experience there strongly influenced his work.[citation needed] Casement joined the Colonial Service, under the authority of the Colonial Office, first serving overseas as a clerk in British West Africa.[20] In August 1901 he transferred to the Foreign Office service as British consul in the eastern part of the French Congo.[21] In 1903 the Balfour Government commissioned Casement, then its consul at Boma in the Congo Free State, to investigate the human rights situation in that colony of the Belgian king, Leopold II. Setting up a private army known as the Force Publique, Leopold had squeezed revenue out of the people of the territory through a reign of terror in the harvesting and export of rubber and other resources. In trade, Belgium shipped guns and other materials to the Congo, used chiefly to suppress the local people.[citation needed]  2014 Faroe Islands stamp depicting Casement and Daniel Jacob Danielsen, his Faroese boat captain and assistant[22] Casement travelled for weeks in the upper Congo Basin to interview people throughout the region, including workers, overseers and mercenaries. He delivered a long, detailed eyewitness report to the Crown that exposed abuses: "the enslavement, mutilation, and torture of natives on the rubber plantations."[20] It became known as the Casement Report of 1904. King Leopold had held the Congo Free State since 1885, when the Berlin Conference of European powers and the United States effectively gave him free rein in the area.[citation needed] Leopold had exploited the territory's natural resources (mostly rubber) as a private entrepreneur, not as king of the Belgians. Using violence and murder against men and their families, Leopold's private Force Publique had decimated many native villages in the course of forcing the men to gather rubber and abusing them to increase productivity. Casement's report provoked controversy, and some companies with a business interest in the Congo rejected its findings, as did Casement's former boss, Alfred Lewis Jones.[13] When the report was made public, opponents of Congolese conditions formed interest groups, such as the Congo Reform Association, founded by E. D. Morel with Casement's support, and demanded action to relieve the situation of the Congolese. Other European nations followed suit, as did the United States. The British Parliament demanded a meeting of the 14 signatory powers to review the 1885 Berlin Agreement defining interests in Africa. The Belgian Parliament, pushed by Socialist leader Emile Vandervelde and other critics of the king's Congolese policy, forced Léopold to set up an independent commission of inquiry. In 1905, despite Léopold's efforts, it confirmed the essentials of Casement's report. On 15 November 1908, the parliament of Belgium took over the Congo Free State from Léopold and organised its administration as the Belgian Congo. Portugal In July 1904 Casement was appointed as Consul in Lisbon. This was seen in London as a comfortable and better paid promotion after his arduous service in Africa. Casement had responded that while he would take up the assignment "it might relieve the Foreign Office of some embarrassment were I to resign from the Service".[23] In the event Casement found the undemanding and routine nature of consular work in a European capital to lack the challenge and satisfaction of his earlier postings. Poor health gave grounds for his returning to Britain after only a few months.[24] Peru: Abuses against the Putumayo Indians See also: Putumayo genocide and Peruvian Amazon Company This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Roger Casement" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (August 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) In 1906 the Foreign Office sent Casement to Brazil: first as consul in Santos, then transferred to Pará,[25] and lastly promoted to consul-general in Rio de Janeiro.[26] He was attached as a consular representative to a commission investigating reports about an enslaved workforce collecting rubber for the Peruvian Amazon Company (PAC), which had been registered in Britain in 1907 and had a British board of directors and numerous stockholders.[27] In September 1909, a journalist named Sidney Paternoster wrote in Truth, a British magazine, of abuses against PAC workers as well as Peruvians competing against Colombians in the disputed region of the Peruvian Amazon. The article was titled "The Devil's Paradise: A British-Owned Congo."[28] In addition, the British consul at Iquitos had said that Barbadians, considered British subjects as part of the empire, had been ill-treated while working for PAC, which gave the government a reason to intervene (ordinarily it could not investigate the internal affairs of another country). These Barbadians were exploited into indebtedness to the Company, and used as enforcers against the Company's enslaved indigenous workforce. [a] American civil engineer Walter Hardenburg had told Paternoster of witnessing a joint PAC and Peruvian military action against a Colombian rubber station, which they destroyed, stealing the rubber. He also saw Peruvian Indians whose backs were marked by severe whipping, in a pattern called the "Mark of Arana" (the head of the rubber company), and reported other abuses.[30] PAC, with its operational headquarters in Iquitos, dominated the city and the region. The area was separated from the main population of Peru by the Andes,[31] and it was 1900 miles from the Amazon's mouth at Pará.[citation needed] The British-registered company was effectively controlled by the archetypal rubber baron Julio César Arana and his brother. Born in Rioja, Arana had climbed out of poverty to own and operate a company harvesting great quantities of rubber in the Peruvian Amazon, which was much in demand on the world market.[32] The rubber boom had led to expansion in Iquitos as a trading centre, as all the company rubber was shipped down the Amazon River from there to the Atlantic port. Numerous foreigners had flocked to the area seeking their fortunes in the rubber boom, or at least some piece of the business.[33] The rough frontier city, including both respectable businesses and the vice district, was highly dependent on the PAC.[citation needed]  Enslaved natives with a load of rubber weighing 75 kilos, they have journeyed 100 kilometers with no food given Casement travelled to the Putumayo District, where the rubber was harvested deep in the Amazon Basin, and explored the treatment of the local Indians of Peru.[34] The isolated area was outside the reach of the national government and near the border with Colombia, which periodically made incursions in competition for the rubber. For years, the Indians had been forced into unpaid labour by field staff of the PAC, who exerted absolute power over them and subjected them to near starvation,[b] severe physical abuse, rape of women and girls by the managers and overseers, terrorization and casual murder.[36] Casement found conditions as inhumane as those in the Congo. On 23 October 1910, regarding those conditions, he wrote that "It far exceeds in depravity and demoralisation the Congo regime at its worst". With "the only redeeming feature" he could identify with, was that the Putumayo genocide affected thousands, whereas Leopold's state affected millions. [37] Casement made two lengthy visits to the region, first in 1910 with a commission of commercial investigators. During his first journey in the Putumayo, he met several people connected to the company's most infamous actions, including Armando Normand and Victor Macedo.[38] Casement wrote in his journal that Normand and Macedo actively tried to discredit his investigation and bribe the Barbadian employees. Casement believed that Macedo and Normand would do anything to save themselves and thought that they might have the Barbadians arrested in Iquitos for libel.[c] Casement even speculated that if he went to Matanzas alone, which was Normand's station, he might have "died of fever" and no one would have known. This alludes to previous suggestions that if Casement had not come to the Putumayo on an official mission, he might have been murdered.[40] On his return to Iquitos, a French trader Casement had previously met, told Casement that if he hadn’t come in an official manner, the Company "would have got away with" him up there and his death would be blamed on the Natives.[41] Casement interviewed both (some of) the Putumayo natives and men who had abused them, including thirty Barbadians, three of whom had also suffered from inhumane conditions imposed by the company. When the report was publicised, there was public outrage in Britain over the abuses.  Roger Casement and Juan A. Tizón at La Chorrera in 1910 Casement's report has been described as a "brilliant piece of journalism", as he wove together first-person accounts by both "victims and perpetrators of atrocities ... Never before had distant colonial subjects been given such personal voices in an official document."[20] After his report was made to the British government, some wealthy board members of the PAC were horrified by what they learned. Arana and the Peruvian government promised to make changes. In 1911, the British government asked Casement to return to Iquitos and Putumayo to see if promised changes in treatment had occurred. In a report to the British foreign secretary, dated 17 March 1911, Casement detailed the rubber company's continued use of pillories to punish the Indians: Men, women, and children were confined in them for days, weeks, and often months. ... Whole families ... were imprisoned – fathers, mothers, and children, and many cases were reported of parents dying thus, either from starvation or from wounds caused by flogging, while their offspring were attached alongside them to watch in misery themselves the dying agonies of their parents.  Flogging of a Putumayo native, carried out by the employees of Julio César Arana Some of the company men exposed as killers in his 1910 report were charged by Peru, while most fled the region and were never captured. In 1911, Casement tried to have one man in particular arrested, Andrés O'Donnell, after he was discovered living comfortably in Barbados. O'Donnell had worked for Arana as the manager of Entre Rios for seven years, and hundreds of natives died under his administration. Casement noted that he was the "least criminal of the chief agents," and "I don't think he killed Indians for pleasure or sport - but only to terrorize for rubber".[42] An extradition order was issued by Peru however it was found to be faulty, so O'Donnell was released on a legal technicality. He later escaped to Panama, and then the United States.[43] Others, such as Armando Normand and Augusto Jiménez Seminario were arrested but escaped from jail before being tried. After his return to Britain, Casement repeated his extra-consular campaigning work by organising interventions by the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines' Protection Society and Catholic missions in the region. Some entrepreneurs had smuggled out cuttings from rubber plants and began cultivation in southeast Asia in colonies of the British Empire. The scandal of the PAC caused major losses in business to the company, and rubber demand began to be met by farmed rubber in other parts of the world. With the collapse of business for PAC, most foreigners left Iquitos and it quickly returned to its former status as an isolated backwater. For a period, the rubber patrons that depended on the Putumayo Indians for their workforce, were largely left alone. Arana was never prosecuted as head of the company. He lived in London for years, then returned to Peru. Despite the scandal associated with Casement's report and international pressure on the Peruvian government to change conditions, Arana later had a successful political career. He was elected a senator and died in Lima, Peru in 1952, aged 88.[44] Casement wrote extensively for his private record (as always) in those two years, 1910-1911. During this period, he continued to write in his diaries, and the one for 1911 was described as being unusually discursive. He kept them in London along with the 1903 diary and other papers of the period, presumably so they could be consulted in his continuing work as "Congo Casement" and as the saviour of the Putumayo Indians. In 1911 Casement received a knighthood for his efforts on behalf of the Amazonian Indians[d] having been appointed Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in 1905 for his Congo work.[46] |

生い立ち 家族と教育 ケースメントはダブリンのイギリス系アイルランド人の家庭に生まれ、幼少期はサンディコーヴのローソン・テラスにあるドイルズ・コテージに住んでいた [7]。サンディコーヴ通り沿い、現在は存在しないが、現在のフィッツジェラルド・パブとバトラーズ・パントリー・デリカテッセンの間にあったテラスであ る。 彼の父、ドラグーン(国王自身の)連隊のロジャー・ケースメント大尉は、ベルファストの海運商ヒュー・ケースメントの息子で、破産し、後にオーストラリア に移住した。ケースメント大尉は1842年のアフガン作戦に従軍していた。一家がイングランドに移った後、ロジャーの母アン・ジェフソン(またはジェフソ ン)はダブリン聖公会の家系であったが、3歳の時にウェールズのライルで密かにローマ・カトリックの洗礼を受けさせたとされる[訳注][訳注][訳注] [訳注][訳注][訳注][訳注][訳注][訳注][訳注][訳注][訳注]。 [しかし、1916年に彼の洗礼を手配した司祭は、主張された以前の洗礼はライルから80マイル離れたアベリストウィスであったと明言しており、このよう な重要なはずの出来事もなぜこのように誤って記憶されなければならないのかという疑問を投げかけている[10]。  c. 1910 1892年の手紙によると、ケースメントは母親がコーク州マローのジェフソン家の子孫であると信じていた[11]が、ジェフソン家の歴史家はその証拠を示 していない[12]。父親は、父方の親戚の近くに住むため、一家をアイルランドのアントリム州に連れ戻した。ケースメントが13歳の時、父親はバルメナで 亡くなり、彼は親戚のヤング家とケースメント家の施しに頼ることになった。彼はバルメナの教区学校(後のバルメナ・アカデミー)で教育を受けた。16歳で 学校を去り、アルフレッド・ルイス・ジョーンズが率いるリバプールの海運会社エルダー・デンプスターで事務員として働くためにイギリスに渡る[13]。 ロジャー・ケースメントの弟、トーマス・ヒュー・ジェフソン・ケースメント(1863-1939)は、海や兵士として放浪生活を送り、後にアイルランド沿 岸警備隊の設立に貢献した[14]。1939年3月6日、自殺を予告した彼はダブリンの大運河で溺死した[14][15]。 ケースメントの観察 ブラジルに領事として赴任していた時の副官であったアーネスト・ハンブロッホは、ケースメントの回想の中で、「意外な」人物であったと述べている。背が高 く、不格好で、「入念に礼儀正しく」、しかし「油断するのを恐れているかのように、かなりのポーズをとっていた」。「話しやすく、流暢な文章を書く」彼 は、「事件を説明することはできても、議論することはできなかった」。彼の最大の魅力は、「まったく意識していない」ように見えたが、「非常に音楽的」な 声だった。目は「優しい」のだが、笑うことはなかった: 「ユーモアのセンスがあれば、多くのことから彼を救えたかもしれない」[16]。 コンゴでの出会いから、ジョセフ・コンラッドがケースメントに抱いた第一印象は、「よく考え、よく話し、最も知的で、非常に同情的」であった。その後、 ケースメントが逮捕され裁判にかけられた後、コンラッドはより批判的な考えを持つようになった: 「アフリカではすでに、彼は正しく言えば、まったく頭の働かない男だと判断していた。頭が悪いという意味ではない。彼は感情的だったということだ。感情的 な力(プトゥマヨ、コンゴ報告書など)によって自分の道を切り開き、気性が荒く、本当に悲劇的な人物だった」[17]。 イギリスの外交官、人権調査官 コンゴとケースメント報告書 主な記事 ケースメント報告書 ケースメントは、1884年からヘンリー・モートン・スタンレーとアフリカ国際協会のためにコンゴで働いた。この協会は、いわゆるコンゴ自由国となったコ ンゴを買収したベルギー国王レオポルド2世の隠れ蓑として知られるようになった[18]。ケースメントは、コンゴ上流への輸送と貿易を改善するために、通 信を改善するための調査に取り組み、白内障で航行不可能なコンゴ川下流220マイルを迂回する鉄道を建設するために労働者を募集し、監督した。商業活動の 中で、彼はアフリカの言語を学んだ[要出典]。  コンゴ自由国で出会ったロジャー・ケースメント(右)と友人のハーバート・ウォード 1890年、ケースメントは商船Le Roi des Belges(「ベルギーの王」)の水先案内人としてコンゴに来ていたジョセフ・コンラッドに出会った。二人とも「ヨーロッパの植民地化は大陸に道徳的、 社会的進歩をもたらし、その住民を奴隷制度、異教、その他の野蛮から解放する」という考えに感化されていた。コンラッドは1899年に短編小説『闇の奥』 を発表し、植民地の悪弊を探った。ケースメントは後に、イギリス政府の公式調査中にコンゴで発見した状況を暴露した。こうした形成期に、彼はハーバート・ ウォードとも出会い、長年の友人となった。ウォードは1889年にアフリカを去り、画家になるために時間を費やしたが、そこでの経験は彼の作品に強い影響 を与えた[要出典]。 1901年8月、彼はフランス領コンゴ東部の英国領事として外務省に移った[21]。1903年、バルフォア政府は、当時コンゴ自由州のボマ領事であった ケースメントに、ベルギー国王レオポルド2世の植民地における人権状況の調査を依頼した。レオポルドは「フォース・パブリック」と呼ばれる私設軍隊を設立 し、ゴムやその他の資源の収穫と輸出における恐怖支配によって、領民から収入を搾り取っていた。貿易では、ベルギーはコンゴに銃やその他の物資を輸送し、 主に現地の人々を弾圧するために使用した[要出典]。  2014年 フェロー諸島の切手 ケースメントとダニエル・ヤコブ・ダニエルセン(フェロー人の船頭兼助手)が描かれている[22]。 ケースメントはコンゴ盆地上部を何週間も旅し、労働者、監督者、傭兵など、この地域一帯の人々にインタビューを行った。彼は、虐待を暴露した長く詳細な目 撃報告書を王室に提出した: 「それは1904年のケースメント報告書として知られるようになった。レオポルド国王は1885年以来、コンゴ自由国を領有していた。ヨーロッパ列強とア メリカ合衆国のベルリン会議によって、レオポルド国王は事実上コンゴ自由国の自由裁量権を与えられたのである[要出典]。 レオポルドはベルギー国王としてではなく、個人事業主として領土の天然資源(主にゴム)を搾取していた。男性とその家族に対する暴力と殺人を用いたレオポ ルドの私的なフォース・パブリックは、男性にゴム採集を強制し、生産性を高めるために彼らを虐待する過程で、多くの先住民の村を壊滅させた。ケースメント の報告書は論争を引き起こし、コンゴにビジネス上の利害関係を持ついくつかの企業は、ケースメントの元上司であるアルフレッド・ルイス・ジョーンズと同様 に、その調査結果を拒否した[13]。 報告書が公表されると、コンゴの状況に反対する人々は、E.D.モレルがケースメントの支援を受けて設立したコンゴ改革協会のような利益団体を結成し、コ ンゴ人の状況を緩和するための行動を要求した。他のヨーロッパ諸国やアメリカもこれに続いた。イギリス議会は、アフリカにおける権益を規定した1885年 のベルリン協定を見直すため、14の調印国による会議を要求した。ベルギー議会は社会主義指導者エミール・ヴァンデルベルデと国王のコンゴ政策を批判する 者たちに押され、レオポルドに独立調査委員会の設置を強要した。1905年、レオポルドの努力にもかかわらず、調査委員会はケースメントの報告書の要点を 確認した。1908年11月15日、ベルギー議会はレオポルドからコンゴ自由国を譲り受け、ベルギー領コンゴとして行政を組織した。 ポルトガル 1904年7月、ケースメントはリスボン領事に任命された。これは、アフリカでの苦難の任務の後、ロンドンでは快適で高給な昇進と見なされた。ケースメン トは「私が辞職すれば、外務省の困惑を和らげることができるかもしれない」と答えた[23]。 結局ケースメントは、欧州の首都での領事業務が要求されない日常的なものであり、以前の任地のようなやりがいも満足感もないことに気づいた。体調不良のた め、わずか数ヶ月で英国に帰国した[24]。 ペルー プトゥマヨ・インディアンに対する虐待 以下も参照: プトゥマヨ大虐殺とペルー・アマゾン会社 このセクションは、検証のために追加の引用が必要です。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力ください。 ソースのないものは異議申し立てがなされ、削除されることがあります。 出典を探す 「Roger Casement」 - news - newspapers - books - scholar - JSTOR (August 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 1906年、外務省はケースメントをブラジルに派遣し、最初はサントスの領事として、次いでパラー州に赴任し[25]、最後はリオデジャネイロの総領事に 昇進した[26]。彼は領事代理として、1907年にイギリスで登記され、イギリス人の取締役会と多数の株主を擁するペルー・アマゾン・カンパニー (PAC)のためにゴムを収集する奴隷労働者に関する報告を調査する委員会に所属した。 [27] 1909年9月、シドニー・パテルノスターというジャーナリストがイギリスの雑誌『トゥルース(Truth)』に、PACの労働者に対する虐待や、ペ ルー・アマゾンの紛争地域でコロンビア人と競争しているペルー人について書いた。記事のタイトルは「悪魔の楽園」: 英国が所有するコンゴ」[28]。 さらに、イキトスの英国領事は、帝国の一部として英国臣民とみなされていたバルバドス人がPACのために働いている間に不当な扱いを受けていたと述べ、政 府に介入する理由(通常、他国の内政を調査することはできない)を与えた。これらのバルバドス人は、会社に対する負債を搾取され、会社の奴隷であった先住 民の労働力に対する執行者として利用された。[アメリカ人土木技師ウォルター・ハーデンブルグは、パタゴニアとペルーの合同軍事行動がコロンビアのゴム基 地を破壊し、ゴムを奪ったのを目撃したことをパテルノスターに語った。彼はまた、「アラナの印」(ゴム会社のトップ)と呼ばれるパターンで、背中に激しい 鞭打ちの印が付けられたペルー人インディオを目撃し、その他の虐待についても報告した[30]。 イキトスに経営本部を置くPACは、この都市と地域を支配していた。この地域はアンデス山脈によってペルーの主要な人口から隔てられており[31]、パラ のアマゾン河口からは1900マイルも離れていた。リオハ生まれのアラナは、貧困から這い上がり、世界市場で需要の高いペルーのアマゾンで大量のゴムを収 穫する会社を経営していた[32]。ゴムブームにより、イキトスは貿易の中心地として拡大し、会社のゴムはすべてそこからアマゾン川を下って大西洋の港に 運ばれた。数多くの外国人がゴムブームで財をなそうと、あるいは少なくともビジネスの一部を求めてこの地域に集まっていた[33]。立派なビジネスも悪徳 地区も含め、荒れた辺境都市はPACに大きく依存していた[要出典]。  奴隷にされた原住民が75キロのゴムを積み、食料も与えられずに100キロを旅した。 ケースメントは、アマゾン流域の奥深くでゴムが収穫されるプトゥマヨ地区を訪れ、ペルーの地元インディオの待遇を探った[34]。この孤立した地域は、国 家政府の手が届かず、定期的にゴムを求めて侵入してくるコロンビアとの国境に近かった。何年もの間、インディオたちは、彼らに対して絶対的な権力を行使 し、飢餓に近い状態、[b]激しい身体的虐待、管理者や監督者による女性や少女のレイプ、テロ、気軽な殺人などにさらされていたPACの現場スタッフに よって、無給の労働を強いられていた[36]。1910年10月23日、彼はこれらの状況について、「堕落と士気の低下において、コンゴの最悪の体制をは るかに超えている」と書いた。唯一の救いは」、プトゥマヨの虐殺が数千人であったのに対し、レオポルドの国家は数百万人であったことである。[37] ケースメントは、1910年に商業調査団を率いてこの地を2度にわたって訪れた。最初のプトゥマヨの旅で、彼はアルマンド・ノルマンやヴィクトール・マセ ドなど、この会社の最も悪名高い行為に関係する数人に会った[38]。ケースメントは、マセドとノルマン ドは自分たちの保身のためなら何でもすると考え、バルバドス人をイキトスで名誉棄損で 逮捕させるかもしれないと考えていた[c] 。これは、もしケースメントが公式の使節団としてプトゥマヨに来なければ殺されていたかもしれないという以前の示唆を示唆している[40]。イキトスに戻 る際、ケースメントが以前に会ったフランス人商人は、もし彼が公式の使節団として来なければ、会社は彼を「連れて逃げただろう」とケースメントに話し、彼 の死は原住民のせいにされただろうと語った[41]。 [41]ケースメントは、プトゥマヨ原住民(の一部)と、彼らを虐待した男たち(30人のバルバドス人を含む)の両方にインタビューを行った。この報告書 が公表されると、英国では虐待に対する市民の怒りが爆発した。  1910年、ラ・チョレラでのロジャー・ケースメントとファン・A・ティゾン ケースメントの報告書は、「残虐行為の被害者と加害者......」双方の一人称の証言を織り交ぜたもので、「ジャーナリズムの見事な作品」と評されてい る。彼の報告書が英国政府に提出された後、PACの裕福な理事会のメンバーの何人かは、自分たちが学んだことに恐怖を覚えた。アラナとペルー政府は変更を 約束した。1911年、イギリス政府はケースメントにイキトスとプトゥマヨに戻り、約束した待遇の変化が起きたかどうかを確認するよう要請した。1911 年3月17日付の英国外務大臣への報告書の中で、ケースメントはゴム会社がインディオを罰するためにピロリを使い続けていることを詳述した: 男も女も子供も、何日も、何週間も、そしてしばしば何カ月もそこに閉じ込められていた。... 家族全員......父親、母親、子供たちが投獄され、飢えや鞭打ちによる傷のために、親がこうして死んでいくケースが多く報告されている。  フリオ・セサール・アラナの従業員によるプトゥマヨ先住民への鞭打ち。 1910年の報告書で殺人犯として摘発された中隊員の何人かはペルーに告発されたが、大半はこの地域から逃亡し、捕まることはなかった。1911年、ケー スメントは、バルバドスで悠々自適の生活を送っていたアンドレス・オドネルを逮捕させようとした。オドネルはアラナの下でエントレ・リオスの支配人として 7年間働き、彼の管理下で何百人もの原住民が死んだ。ケースメントはオドネルが「諜報部長の中で最も犯罪性の低い人物」であり、「彼が喜びやスポーツのた めにインディオを殺したとは思えない。アルマンド・ノルマンやアウグスト・ヒメネス・セミナリオといった他の人物も逮捕されたが、裁判にかけられる前に脱 獄した[43]。 英国に戻った後、ケースメントは、反奴隷制・原住民保護協会とこの地域のカトリック伝道所による介入を組織することによって、領事外のキャンペーン活動を 繰り返した。ゴムの挿し木を密輸し、東南アジアの大英帝国の植民地で栽培を始めた企業家もいた。PACの不祥事は同社に大きな損失をもたらし、ゴムの需要 は他の地域の養殖ゴムで満たされるようになった。PACのビジネスが破綻すると、ほとんどの外国人はイキトスを去り、イキトスは急速にかつての孤立した僻 地に戻っていった。しばらくの間、プトゥマヨ・インディアンに労働力を依存していたゴムのパトロンたちは、ほとんど放っておかれた。アラナは会社のトップ として起訴されることはなかった。彼は数年間ロンドンで暮らし、その後ペルーに戻った。ケースメントの報告書にまつわるスキャンダルや、ペルー政府に対す る国際的な圧力にもかかわらず、アラナはその後、政治家として成功を収めた。彼は上院議員に選出され、1952年にペルーのリマで88歳で死去した [44]。 ケースメントは、1910年から1911年の2年間、私的な記録のために(いつものように)幅広く執筆した。この間、彼は日記を書き続け、1911年の日 記は異例なほど叙述的であったと言われている。おそらく、「コンゴ・ケースメント」として、またプトゥマヨ・インディアンの救世主として活動を続ける際に 参考にするためであろう。コンゴでの活動により1905年に聖ミカエル・聖ジョージ勲章(CMG)のコンパニオンに任命されたケースメントは、アマゾンの インディオのために尽力した功績により、1911年に爵位を授与された[46]。 |

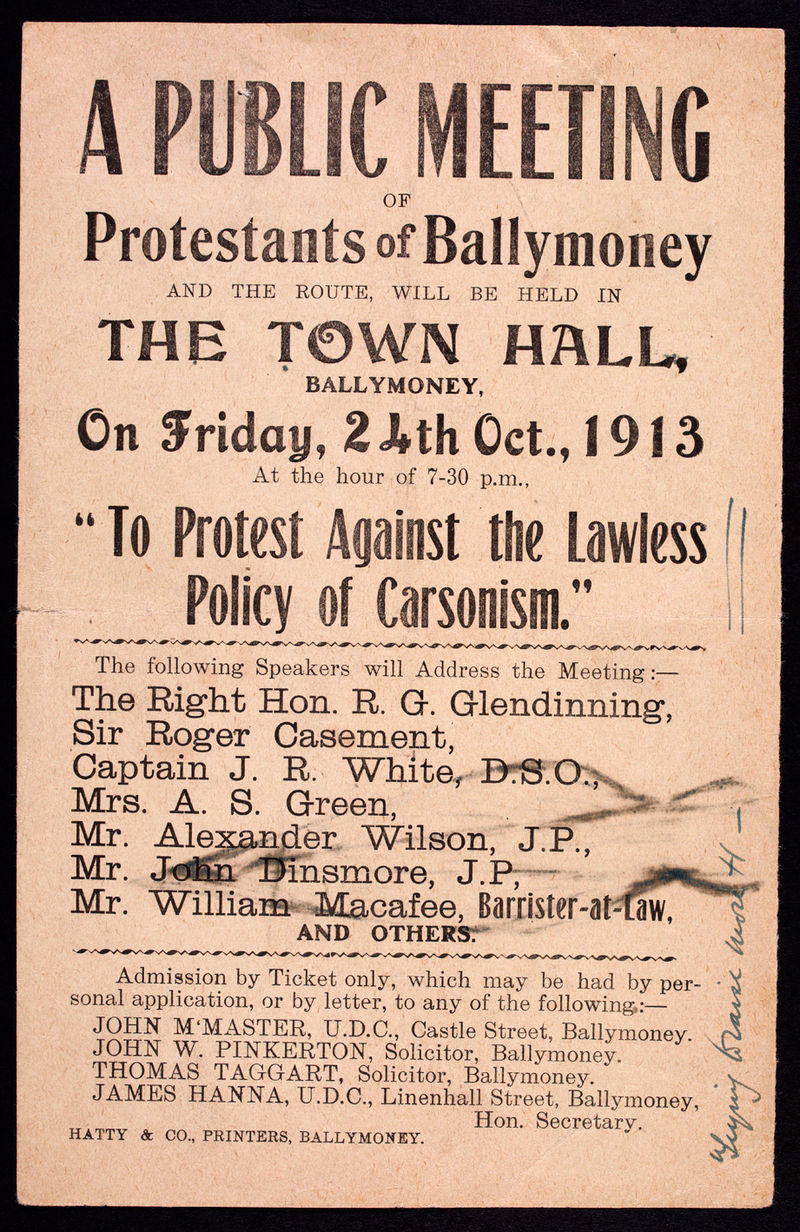

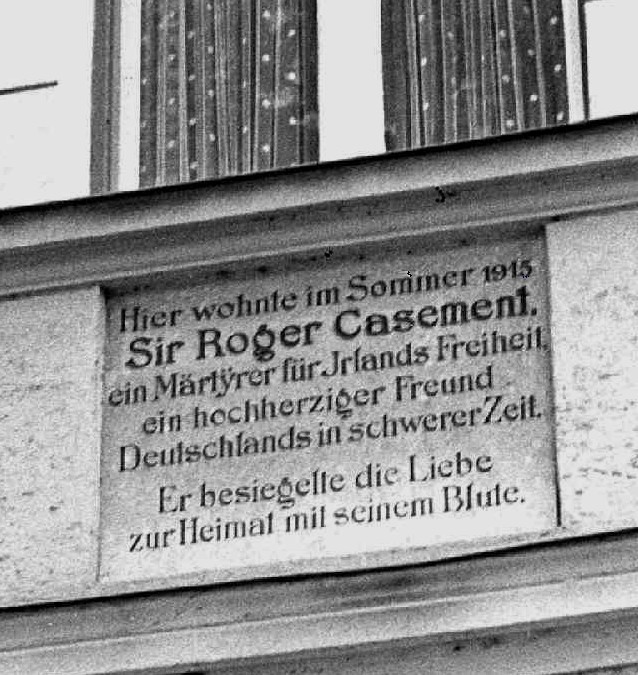

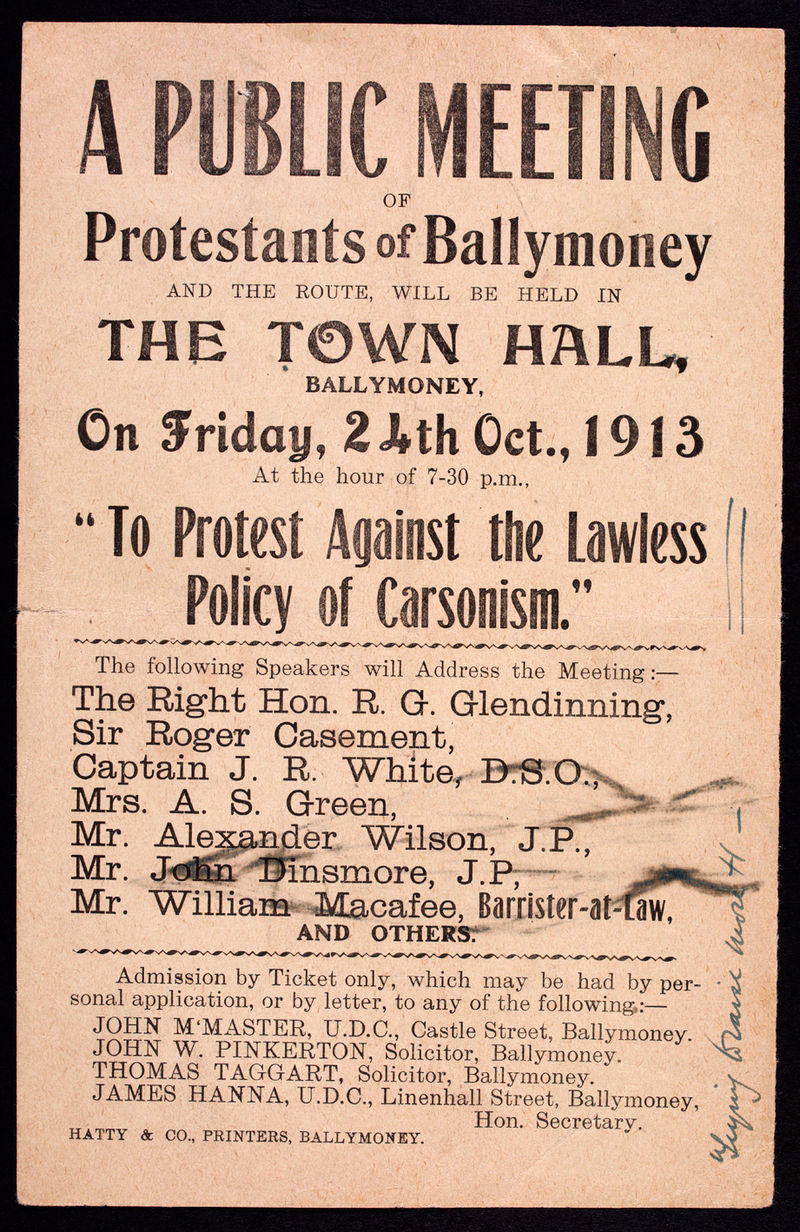

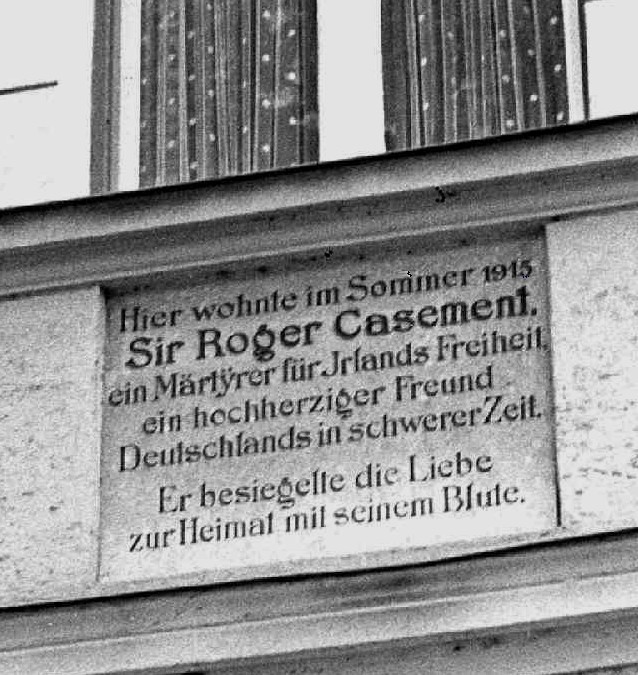

Irish revolutionary Casement attempted to smuggle weapons from Germany for the Easter Rising.  Poster advertising public meeting "Against the Lawless Policy of Carsonism" Return to Ireland In Ireland in 1904, on leave from Africa from that year until 1905, Casement joined the Gaelic League, an organisation established in 1893 to preserve and revive the spoken and literary use of the Irish language. He met the leaders of the powerful Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) to lobby for his work in the Congo. He did not support those, like the IPP, who proposed Home Rule, as he believed that the House of Lords would veto such efforts. Casement was more impressed by Arthur Griffith's new Sinn Féin party (founded 1905), which called for an independent Ireland (through a non-violent series of strikes and boycotts). Its sole imperial tie would be a dual monarchy between Britain and Ireland, modelled on the policy example of Ferenc Deák in Hungary. Casement joined the party in 1905.[47] In a letter to Mrs. J. R. Green, (the Irish historian Alice Stopford Green) dated 20 April 1906 Casement reflected on his conversion to the national cause as someone who had "accepted imperialism" and had been close to an "ideal" Englishman:[48] It is a mistake for an Irishman to mix himself up with the English. He is bound to do one of two things—either to go to the wall if he remains Irish or to become an Englishman himself. You see I very nearly did become one once. At the Boer War time, I had been away from Ireland for years, out of touch with everything native to my heart and mind, trying hard to do my duty, and every fresh act of duty made me appreciably nearer the ideal of the Englishman. I had accepted Imperialism. British rule was to be accepted at all costs, because it was the best for everyone under the sun, and those who opposed that extension ought rightly to be 'smashed.' I was on the high road to being a regular Imperialist jingo—although at heart underneath all, and unsuspected almost by myself, I had remained an Irishman. Well, the war, [i.e., the Boer War] gave me qualms at the end—the concentration camps bigger ones—and finally, when up in those lonely Congo forests where I found Leopold I found also myself, the incorrigible Irishman. Ulster In the north, through his sister, Nina, in Portrush, and his close friends in London, Robert Lynd and Sylvia Dryhurst, Casement was drawn into the orbit of Francis Joseph Bigger.[49] A wealthy Presbyterian solicitor, at his house on the northern shore of Belfast Lough, Ard Righ, Bigger hosted not only the poets and writers of the "Northern Revival",[50] but also, and critically for Casement, Ulster Protestants committed to taking the case for an Irish Ireland to their co-religionists. These included Ada McNeil, with whom Casement helped organise the first Feis na nGleann (Festival of the Glens) at Waterfoot (County Antrim) in 1904,[49] Bulmer Hobson (later of the IRB), the Nationalist MP Stephen Gwynn, and the Gaelic League activist Alice Milligan.[51][52] Casement retired from the British consular service in the summer of 1913.[53] In October he spoke at a Protestant assembly at Ballymoney Town Hall organised by Captain Jack White (who, in the midst of the Dublin lock-out, with James Connolly had begun organising a workers' militia, the Irish Citizen Army).[54][55] On a platform with Ada McNeill, the historian Alice Stopford Green, and the veteran tenant-right activist J. B. Armour, he spoke to the motion disputing the claim of Edward Carson and his unionists "to represent the Protestant community of North East Ulster", and condemning the prospect of "lawless resistance" to Home Rule.[56][51] Enthused by the meeting, which had been covered by all the London and Irish papers, Casement resolved to replicate the Ballymoney meeting across Ulster, starting with Coleraine. But the Unionist-controlled council refused to allow the group access to the local Town Hall, and nothing came of it.[56] Meanwhile an anti-Home Rule meeting addressed by Carson's lieutenant Sir James Craig, then organising the Ulster Volunteers, not only filled the Ballymoney Town Hall but had the crowd spilling out into the surrounding streets.[57] In the event, the Ballymoney Protestant "Protest Against the Lawles Policy of Carsonism" proved to be the only meeting of its kind held anywhere in Ulster.[56] Already in November 1913, Casement had begun focussing on responding to "Carsonism" in kind: he became a Gaelic League member of the Provisional Committee of the Irish Volunteers launched at a meeting in the Rotunda in Dublin.[58] At the same time White and Connolly at the ITGWU formed the Irish Citizen Army.[59] In April 1914, he had been together with Alice Milligan in Larne shortly after Craig had had German guns run through the port, a feat Casement told her nationalists would have to match.[60] America and Germany In July 1914, Casement journeyed to the United States to promote and raise money for the Volunteers among the large and numerous Irish communities there. Through his friendship with men such as Bulmer Hobson, a member both of the Volunteers and of the secret Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), Casement established connections with exiled Irish nationalists, particularly Clan na Gael.[61] Elements of the suspicious Clan did not trust Casement completely, as he was not a member of the IRB and held views that they considered too moderate but others, such as John Quinn, regarded him as extreme. Devoy, initially hostile to Casement for his part in conceding control of the Irish Volunteers to John Redmond, was won over in June, and Joseph McGarrity, another Clan leader, became devoted to Casement and remained so from then on.[62] The Howth gun-running in late July 1914, which Casement had helped to organise and (with a loan from Alice Stopford Green)[63] finance, further enhanced his reputation. In August 1914, at the outbreak of World War I, Casement and John Devoy arranged a meeting in New York with the western hemisphere's top-ranking German diplomat, Count Bernstorff, to propose a mutually beneficial plan: if Germany would sell guns to the Irish revolutionaries and provide military leaders, the Irish would revolt against England, diverting troops and attention from the war with Germany. Bernstorff appeared sympathetic. Casement and Devoy sent an envoy, Clan na Gael president John Kenny, to present their plan personally. Kenny, while unable to meet the German Emperor, did receive a warm reception from the German ambassador to Italy Hans von Flotow, and from Prince von Bülow.[64] In October 1914, Casement sailed for Germany via Norway, travelling in disguise and seeing himself as an ambassador of the Irish nation. While the journey was his idea, Clan na Gael financed the expedition. During their stop in Christiania, Adler Christensen, a homeless Norwegian immigrant Casement had met in New York and made his valet and alleged lover (unawares he had a wife and daughter),[65] was taken to the British legation, where a reward was allegedly offered if Casement were "knocked on the head".[66] British diplomat Mansfeldt Findlay, in contrast, advised London that Christensen had "implied that their relations were of an unnatural nature and that consequently he had great power over this man".[67]  Franz von Papen. Papen was key in organising the arms shipments. Findlay's handwritten letter of 1914 is kept in University College Dublin, and is viewable online.[68] This letter—written on official notepaper by Minister Findlay at the British Legation in Oslo—offers to Christensen the sum of £5,000 plus immunity from prosecution and free passage to the United States in return for information leading to the capture of Roger Casement. That amount would be approximately £2,616,000 in 2014.[69] In November 1914,[70] Casement negotiated a declaration by Germany which stated: The Imperial Government formally declares that under no circumstances would Germany invade Ireland with a view to its conquest or the overthrow of any native institutions in that country. Should the fortune of this Great War, which was not of Germany's seeking, ever bring in its course German troops to the shores of Ireland, they would land there not as an army of invaders to pillage and destroy but as the forces of a Government that is inspired by goodwill towards a country and people for whom Germany desires only national prosperity and national freedom.[71] Casement spent most of his time in Germany seeking to recruit an Irish Brigade from among more than 2,000 Irish prisoners-of-war taken in the early months of the war and held in the prison camp of Limburg an der Lahn.[72] His plan was that they would be trained to fight against Britain in the cause of Irish independence.[73] American Ambassador to Germany James W. Gerard mentioned the effort in his memoir "Four Years in Germany": The Germans collected all the soldier prisoners of Irish nationality in one camp at Limburg not far from Frankfurt a. M. There efforts were made to induce them to join the German army. The men were well treated and were often visited by Sir Roger Casement who, working with the German authorities, tried to get these Irishmen to desert their flag and join the Germans. A few weaklings were persuaded by Sir Roger who finally discontinued his visits, after obtaining about thirty recruits, because the remaining Irishmen chased him out of the camp. On 27 December 1914, Casement signed an agreement in Berlin to this effect with Arthur Zimmermann in the German Foreign Office, renouncing all his titles in a letter to the British Foreign Secretary dated 1 February 1915. Fifty-two of the 2000 prisoners volunteered for the Brigade. Contrary to German promises, they received no training in the use of machine guns, which at the time were relatively new and unfamiliar weapons.[citation needed]  Plaque commemorating Casement's stay in Bavaria during the summer of 1915[74] During World War I, Casement is known to have been involved in the German-backed plan by Indians to win their freedom from the British Raj, the "Hindu–German Conspiracy", recommending Joseph McGarrity to Franz von Papen as an intermediary. The Indian nationalists may also have followed Casement's strategy of trying to recruit prisoners of war to fight for Indian independence.[75] Both efforts proved unsuccessful. In addition to finding it difficult to ally with the Germans while held as prisoners, potential recruits to Casement's brigade knew they would be liable to the death penalty as traitors if Britain won the war. In April 1916, Germany offered the Irish 20,000 Mosin–Nagant 1891 rifles, ten machine guns and accompanying ammunition, but no German officers; it was a fraction of the quantity of the arms Casement had hoped for, with no military expertise on offer.[76] Casement did not learn about the Easter Rising until after the plan was fully developed. The German weapons never landed in Ireland; the Royal Navy intercepted the ship transporting them, a German cargo vessel named the Libau, disguised as a Norwegian vessel, Aud-Norge. All the crew were German sailors, but their clothes and effects, even the charts and books on the bridge, were Norwegian.[citation needed] As John Devoy had either misunderstood or disobeyed Pearse's instructions[citation needed] that the arms were under no circumstances to land before Easter Sunday, the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (TGWU) members set to unload the arms under the command of Irish Citizen Army officer and trade unionist William Partridge were not ready. The IRB men sent to meet the boat drove off a pier and drowned.[citation needed] The British had intercepted German communications coming from Washington and suspected that there was going to be an attempt to land arms at Ireland, although they were not aware of the precise location. The arms ship, under Captain Karl Spindler, was apprehended by HMS Bluebell on the late afternoon of Good Friday. About to be escorted into Queenstown (present-day Cobh), County Cork on the morning of Saturday 22 April, Captain Spindler scuttled the ship by pre-set explosive charges. Its surviving crew became prisoners of war.[77][78] Landing and capture Wikisource has original text related to this article: Roger Casement's speech from the dock Casement confided his personal papers to Dr Charles Curry, with whom he had stayed at Riederau on the Ammersee, before he left Germany. He departed with Robert Monteith and Sergeant Daniel Beverley (Bailey) of the Irish Brigade in a submarine, initially the SM U-20, which developed engine trouble, and then the SM U-19, shortly after the Aud sailed. According to Monteith, Casement believed the Germans were toying with him from the start and providing inadequate aid that would doom a rising to failure. He wanted to reach Ireland before the shipment of arms and to convince Eoin MacNeill (who he believed was still in control) to cancel the rising.[79]  German U-Boat SM U-19, second from the right. c. 1914 Casement sent John McGoey, a recently arrived Irish-American, through Denmark to Dublin, ostensibly to advise what military aid was coming from Germany and when, but with Casement's orders "to get the Heads in Ireland to call off the rising and merely try to land the arms and distribute them".[80] McGoey did not reach Dublin, nor did his message. His fate was unknown until recently. Evidently abandoning the Irish Nationalist cause, he joined the Royal Navy in 1916, survived the war, and later returned to the United States, where he died in an accident on a building site in 1925.[81] In the early hours of 21 April 1916, three days before the rising began, the German submarine put Casement and his two companions ashore at Banna Strand in Tralee Bay, County Kerry – the boat used is now in the Imperial War Museum in London.[82] Suffering from a recurrence of the malaria that had plagued him since his days in the Congo, and too weak to keep up with Monteith and Bailey, Casement was discovered by a sergeant of the Royal Irish Constabulary[83] at McKenna's Fort, an ancient ring fort in Rahoneen, Ardfert now renamed Casement's Fort. When three pistols were discovered hidden nearby, the RIC arrested Casement on a charge of illegally bringing weapons into the country.[84] Casement was eventually to face charges of high treason, sabotage and espionage against the Crown. He sent word to Dublin about the inadequate German assistance. The Kerry Brigade of the Irish Volunteers might have tried to rescue him over the next three days, but its leadership in Dublin held that not a shot was to be fired in Ireland before the Easter Rising was in train and therefore ordered the Brigade to "do nothing"[85] – a subsequent internal inquiry attached "no blame whatsoever" to the local Volunteers for failing to attempt a rescue.[86] "He was taken to Brixton Prison to be placed under special observation for fear of an attempt of suicide. There was no staff at the Tower [of London] to guard suicidal cases."[87][e] Trial and execution Casement's trial at bar opened at the Royal Courts of Justice on 26 June 1916 before the Lord Chief Justice (Viscount Reading), Mr Justice Avory, and Mr Justice Horridge. The prosecution had trouble arguing its case. Casement's crimes had been carried out in Germany and the Treason Act 1351 seemed to apply only to activities carried out on English (or arguably British) soil. A close reading of the Act allowed for a broader interpretation: the court decided that a comma should be read into the unpunctuated original Norman-French text, crucially altering the sense so that "in the realm or elsewhere" referred to where acts were done and not just to where the "King's enemies" might be.[88][89] Afterwards, Casement himself wrote that he was to be "hanged on a comma", leading to the well-used epigram.[90] During his trial, the prosecution (F. E. Smith), who had admired some of Casement's work before he went over to the Germans, informally suggested to the defence barrister (A. M. Sullivan) that they should jointly produce what are now called the "Black Diaries" in evidence, as this would most likely cause the court to find Casement "guilty but insane" and save his life.[91] Casement refused to agree to this and was subsequently found guilty and sentenced to be hanged. Before and during the trial and appeal, the British government secretly circulated some excerpts from Casement's journals, exposing Casement as a "sexual deviant". These included numerous explicit accounts of sexual activity. This aroused public opinion against him and influenced those notables who might otherwise have tried to intervene. Given societal norms and the illegality of homosexuality at the time, support for Casement's reprieve declined in some quarters. The journals became known in the 1950s as the Black Diaries and are still in the British National Archives,[92] whilst most of the other exhibits from the trial are in the Crime Museum in London.[93] Casement unsuccessfully appealed against his conviction and death sentence. Those who pleaded for clemency for Casement included Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who was acquainted with Casement through the work of the Congo Reform Association, poet W. B. Yeats, and playwright George Bernard Shaw. Joseph Conrad could not forgive Casement, nor could Casement's longtime friend, the sculptor Herbert Ward, whose son Charles had been killed on the Western Front that January, and who would change the name of Casement's godson, who had been named after him. Members of the Casement family in Antrim contributed discreetly to the defence fund, although they had sons in the British Army and Navy.[citation needed] A United States Senate appeal against the death sentence was rejected by the British cabinet on the insistence of prosecutor F. E. Smith, an opponent of Irish independence.[94] Casement's knighthood was forfeited on 29 June 1916.[95] On the day of his execution by hanging at Pentonville Prison, 3 August 1916, Casement was received into the Catholic Church at his request. He was attended by two Catholic priests, Dean Timothy Ring and Father James Carey, from the East London parish of SS Mary and Michael.[96][97] The latter, also known as James McCarroll,[clarification needed] said of Casement that he was "a saint ... we should be praying to him [Casement] instead of for him".[98] At the time of his death he was 51 years old. State funeral Casement's body was buried in quicklime in the prison cemetery at the rear of Pentonville Prison, where he had been hanged, though his last wish was to be buried at Murlough Bay on the north coast of County Antrim, in present-day Northern Ireland. During the decades after his execution, successive British governments refused many formal requests for repatriation of Casement's remains. For example, in September 1953, Taoiseach Éamon de Valera, on a visit to Prime Minister Winston Churchill in Downing Street, requested the return of the remains.[99][page needed] Churchill said he was not personally opposed to the idea but would consult with his colleagues and take legal advice. He ultimately turned down the Irish request, citing "specific and binding" legal obligations that the remains of executed prisoners could not be exhumed. De Valera disputed the legal advice and responded:[100] So long as Roger Casement's remains remain within British prison walls, when he himself expressed the wish that it should be transferred to his native land, so long there will be public resentment here at what must appear to be, at least, the unseemly obduracy of the British Government. De Valera received no reply.[99][page needed]  Roger Casement's grave in Glasnevin Cemetery. The capstone reads "Roger Casement, who died for the sake of Ireland, 3rd August 1916". Finally, in 1965, Casement's remains were repatriated to Ireland. Despite the annulment, or withdrawal, of his knighthood in 1916, the 1965 UK Cabinet record of the repatriation decision refers to him as "Sir Roger Casement".[101] Contrary to Casement's wishes, Prime Minister Harold Wilson's government had released the remains only on condition that they could not be brought into Northern Ireland, as "the government feared that a reburial there could provoke Catholic celebrations and Protestant reactions."[20] Casement's remains lay in state at the Garrison Church, Arbour Hill (now Arbour Hill Prison) in Dublin city for five days, close to the graves of other leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising, but would not be buried beside them. After a state funeral, the remains were buried with full military honours in the Republican plot in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin,[102] alongside other Irish republicans and nationalists. The President of Ireland, Éamon de Valera, who was then in his mid-eighties and the last surviving leader of the Easter Rising, attended the ceremony, along with an estimated 30,000 others. |

アイルランドの革命家 イースター蜂起のためにドイツから武器を密輸しようとしたケースメント。  「カーソニズムの無法な政策に反対する 」市民集会の宣伝ポスター アイルランドへの帰還 1904年、同年から1905年までアフリカからの休暇でアイルランドに滞在していたケースメントは、1893年に設立されたゲール語連盟(アイルランド 語の音声と文学の保存と復活を目指す組織)に参加した。彼はコンゴでの活動のために、有力なアイルランド議会党(IPP)の指導者たちに会って働きかけ た。彼は、IPPのようにアイルランド自治政府(Home Rule)を提案する政党を支持しなかった。ケースメントは、アーサー・グリフィスの新党シン・フェイン(1905年結成)に感銘を受けた。シン・フェイ ンは、(非暴力のストライキやボイコットを通じて)アイルランドの独立を訴えた。その唯一の帝国的結びつきは、ハンガリーのフェレンツ・デアークの政策例 に倣ったイギリスとアイルランドの二重君主制であった。ケースメントは1905年に入党した[47]。 1906年4月20日付のJ.R.グリーン夫人(アイルランドの歴史家アリス・ストップフォード・グリーン)に宛てた手紙の中で、ケースメントは「帝国主 義を受け入れ」、「理想的な」イギリス人に近づいていた人物として、国家的大義への転向を振り返っている[48]。 アイルランド人がイギリス人と一緒になるのは間違いである。アイルランド人のままでは壁に突き当たるか、イギリス人になるかのどちらかである。私は危うく イギリス人になるところだった。ボーア戦争当時、私は何年もアイルランドを離れ、自分の心や精神の原点であるあらゆるものから遠ざかっていた。私は帝国主 義を受け入れた。英国の支配は何としてでも受け入れるべきものであり、それが天下万民にとって最良のものであり、その延長線上にあるものに反対する者は当 然「粉砕」されるべきものだったからだ。私は帝国主義者としての王道を歩んでいたが、その根底には、自分でもほとんど気づかないうちに、私はアイルランド 人のままだった。そしてついに、コンゴの孤独な森でレオポルドを見つけたとき、私もまたアイルランド人であることを知ったのだ。 アルスター 北部では、ポートラッシュの妹ニーナやロンドンの親友ロバート・リンドとシルヴィア・ドライハーストを通じて、ケースメントはフランシス・ジョセフ・ビ ガーの周辺に引き込まれた。 [裕福な長老派の事務弁護士であったビガーは、ベルファスト湖の北岸にあるアード・リーの邸宅で、「北方復興」の詩人や作家たち[50]をもてなしただけ でなく、ケースメントにとって極めて重要なことであったが、アルスター・プロテスタントの人々もまた、アイルランド・アイルランドの存在を同教徒たちに訴 えようと尽力していた。その中には、ケースメントが1904年にウォーターフット(アントリム州)で開催された第1回フェス・ナ・ングレアン(グレン祭) の開催に協力したエイダ・マクニール[49]、ブルマー・ホブソン(後のIRB)、国民党議員のスティーブン・グウィン、ゲーリック・リーグの活動家アリ ス・ミリガンなどがいた[51][52]。 1913年夏、ケースメントは英国領事職を退いた[53]。10月、ジャック・ホワイト大尉(ダブリンのロックアウトのさなか、ジェームズ・コノリーとと もに労働者民兵組織「アイルランド市民軍」を組織し始めた)が主催したバリーモニータウンホールでのプロテスタント集会で演説。 [54][55]彼はエイダ・マクニール、歴史家のアリス・ストップフォード・グリーン、退役小作権運動家のJ・B・アーマーとともに壇上に立ち、エド ワード・カーソンと彼のユニオニストの「北東アルスターのプロテスタント共同体を代表する」という主張に異議を唱え、内政に対する「無法な抵抗」の見通し を非難する動議を演説した[56][51]。 ロンドンやアイルランドの新聞がこぞって取り上げたこの集会に熱狂したケースメントは、バリーモニーの集会をアルスター全域で再現することを決意し、まず はコレレインから始めた。しかし、ユニオニストが支配する議会は、このグループが地元のタウンホールに入ることを拒否し、何も実現しなかった[56]。一 方、当時アルスター義勇軍を組織していたカーソンの中尉ジェームズ・クレイグ卿が演説した反ホームルール集会は、バリーモニーのタウンホールを埋め尽くし ただけでなく、群衆を周辺の通りにまであふれさせた[57]。 結局、バリーモニーのプロテスタントによる「カーソン主義のローレス政策に対する抗議」は、アルスターのどこかで開催されたこの種の集会としては唯一のも のであったことが証明された[56]。 1913年11月、ケースメントはすでに「カーソン主義」への対応に力を入れ始めていた。彼はダブリンのロタンダで開催された会議で発足したアイルランド 義勇軍臨時委員会のゲーリックリーグメンバーとなった。 [1914年4月、彼はアリス・ミリガンとラーンで一緒にいたが、その直後、クレイグがドイツ軍の大砲を港に撃ち込んだ。 アメリカとドイツ 1914年7月、ケースメントはアメリカに渡り、大規模で多数のアイルランド人コミュニティで義勇軍の宣伝と資金集めを行った。義勇軍と秘密組織アイルラ ンド共和国同胞団(IRB)のメンバーであったブルマー・ホブソンのような人物との友情を通じて、ケースメントは亡命したアイルランドの民族主義者、特に クラン・ナ・ゲールとのつながりを築いた[61]。 不審なクランの構成員は、ケースメントがIRBのメンバーではなく、穏健すぎると考える見解を持っていたため、ケースメントを完全には信用していなかった が、ジョン・クインなどはケースメントを極端な人物と見なしていた。当初はジョン・レドモンドにアイルランド義勇軍の指揮権を譲ったことでケースメントを 敵視していたデヴォイも、6月には説得に応じ、もう一人のクラン指導者ジョセフ・マクガリティはケースメントに傾倒し、以後もそうであった[62]。 1914年7月下旬のハウズ銃乱射事件は、ケースメントが(アリス・ストップフォード・グリーンからの融資を受けて)組織化と資金調達に協力したものであ り[63]、ケースメントの評判はさらに高まった。 1914年8月、第一次世界大戦が勃発すると、ケースメントとジョン・デヴォイは、西半球で最高位のドイツ外交官ベルンシュトルフ伯爵とのニューヨークで の会談を手配し、ドイツがアイルランドの革命派に銃を売り、軍事指導者を提供すれば、アイルランドはイギリスに対して反乱を起こし、ドイツとの戦争から兵 力と注意をそらすことができるという互恵的な計画を提案した。ベルンストルフは同調した。ケースメントとデボイは、クラン・ナ・ゲール総裁ジョン・ケニー を使者として派遣し、個人的に計画を説明させた。ケニーはドイツ皇帝に会うことはできなかったが、ハンス・フォン・フロトウ駐イタリアドイツ大使とフォ ン・ビューロー王子から温かい歓迎を受けた[64]。 1914年10月、ケースメントは変装してノルウェー経由でドイツに向かった。この旅は彼の発案であったが、クラン・ナ・ゲールが遠征の資金を提供した。 クリスチャニアに立ち寄った際、アドラー・クリステンセンというホームレスのノルウェー人移民がニューヨークで出会い、彼の付き人兼恋人とされた(彼には 妻と娘がいたことも知らなかった)[65]。  フランツ・フォン・パペン フランツ・フォン・パッペンは武器輸送の組織化の鍵を握っていた。 オスロの英国公使館にいたフィンドレー公使が公式のメモ用紙に書いたこの手紙は、ロジャー・ケースメントの逮捕につながる情報の見返りとして、クリステン センに5,000ポンドと訴追免除、米国への自由渡航を申し出ている。この金額は2014年では約2,616,000ポンドになる[69]。 1914年11月[70]、ケースメントはドイツによる宣言を交渉した: 帝国政府は、いかなる状況においても、ドイツがアイルランドの征服や土着制度の転覆を目的として侵攻することはないと正式に宣言する。ドイツが望んだわけ ではないこの大戦の運命によって、ドイツ軍がアイルランドの海岸に上陸するようなことがあったとしても、それは略奪と破壊を目的とする侵略者の軍隊として ではなく、ドイツが国家の繁栄と国家の自由のみを望んでいる国と国民に対する好意に感化された政府の軍隊として上陸することになるだろう」[71]。 ケースメントは、戦争初期に捕虜となり、リンブルフ・アン・デア・ラーンの収容所に収容されていた2,000人以上のアイルランド人捕虜の中からアイルラ ンド旅団をリクルートしようと、ドイツ滞在中の大半を費やした[72]。彼の計画は、アイルランド独立の大義のためにイギリスと戦うよう訓練することで あった[73]。 ジェームス・W・ジェラード駐独アメリカ大使は、回顧録『ドイツでの4年間』の中で、この取り組みについて言及している: ドイツ軍はアイルランド国籍の兵士捕虜をフランクフルトからほど近いリンブルクの収容所に集めた。彼らは厚遇され、しばしばロジャー・ケースメント卿が訪 れ、ドイツ当局と協力しながら、アイルランド人に国旗を捨てさせ、ドイツ軍に参加させようとした。数人の弱虫がロジャー卿に説得されたが、30人ほどの新 兵を得た後、残りのアイルランド人が彼を収容所から追い出したため、ついに訪問を打ち切った。 1914年12月27日、ケースメントはベルリンで、ドイツ外務省のアーサー・ツィンマーマンとその旨の協定に調印し、1915年2月1日付のイギリス外 務大臣宛の書簡で、すべての肩書を放棄した。2000人の捕虜のうち52人が旅団に志願した。ドイツ側の約束に反して、彼らは当時比較的新しく馴染みの薄 い武器であった機関銃の使用訓練は受けなかった[要出典]。  ケースメントが1915年夏にバイエルンに滞在したことを記念するプレート[74]。 第一次世界大戦中、ケースメントはドイツが支援するインド人によるイギリス領からの自由獲得計画「ヒンドゥー=ドイツの陰謀」に関与し、フランツ・フォ ン・パーペンに仲介者としてジョセフ・マクガリティを推薦したことで知られている。インド人ナショナリストはまた、インド独立のために戦う捕虜をリクルー トしようとするケースメントの戦略に従ったのかもしれない[75]。 どちらの努力も失敗に終わった。捕虜として拘束されている間にドイツ軍と同盟を結ぶことは困難であったことに加え、ケースメントの旅団に採用される可能性 のある者は、イギリスが戦争に勝利した場合、裏切り者として死刑に処せられることを知っていた。1916年4月、ドイツはアイルランド人に対し、モシン・ ナガント1891年製の小銃2万丁と機関銃10丁、それに弾薬を提供したが、ドイツ人将校は提供しなかった。 ケースメントがイースター蜂起について知ったのは、計画が完全に練り上げられた後のことであった。イギリス海軍は、武器を輸送していたリバウ号という名の ドイツ貨物船を、ノルウェーのオード・ノルゲ号に偽装して妨害した。乗組員は全員ドイツ人船員だったが、彼らの衣服や持ち物、船橋にあった海図や書籍まで もがノルウェー製だった[要出典]。ジョン・デヴォイは、イースター・サンデー(復活祭の日曜日)より前に武器を陸揚げしてはならないというパースの指示 [要出典]を誤解したか従わなかったため、アイルランド市民軍将校で労働組合員のウィリアム・パートリッジの指揮の下、アイルランド運輸一般労働組合 (TGWU)の組合員が武器を陸揚げする手はずになっていなかった。ボートを迎えに派遣されたIRBの隊員たちは桟橋から転落し、溺死した[要出典]。 英国はワシントンから届くドイツの通信を傍受しており、正確な場所は把握していなかったものの、アイルランドに武器を上陸させようとしているのではないか と疑っていた。カール・スピンドラー船長率いる武器運搬船は、聖金曜日の午後遅く、HMSブルーベルに逮捕された。4月22日土曜日の朝、コーク州クィー ンズタウン(現在のコブ)に護送されるところであったが、スピンドラー船長はあらかじめセットしておいた爆薬で船を破壊した。生き残った乗組員は捕虜と なった[77][78]。 上陸と拿捕 ウィキソースにはこの記事に関連する原文がある: ロジャー・ケースメントのドックからの演説 ケースメントは、ドイツを出発する前に、アンマーゼーのリーデラウに滞在していたチャールズ・カリー博士に身の回りの書類を打ち明けた。彼は、アイルラン ド旅団のロバート・モンテースとダニエル・ベバリー軍曹(ベイリー)とともに潜水艦で出発した。当初はSM U-20であったが、エンジントラブルが発生し、その後SM U-19が出航した。モンテースによれば、ケースメントはドイツ軍が最初から彼を翻弄し、不十分な援助を提供することで蜂起が失敗に終わると考えていた。 彼は武器が輸送される前にアイルランドに到着し、蜂起を中止するようエオイン・マクニール(彼はまだ支配下にあると信じていた)を説得したかった [79]。  ドイツのUボートSM U-19、右から2番目。 ケースメントは、最近到着したアイルランド系アメリカ人ジョン・マクゴーイをデンマーク経由でダブリンに派遣した。表向きは、ドイツからどのような軍事援 助がいつ来るのかを助言するためであったが、ケースメントの命令は「アイルランドの首脳部に蜂起を中止させ、単に武器を陸揚げして配給しようとすること」 であった[80]。彼の運命は最近まで不明であった。明らかにアイルランド民族主義の大義を放棄した彼は、1916年にイギリス海軍に入隊し、戦争を生き 延び、後にアメリカに戻り、1925年に建築現場での事故で死亡した[81]。 蜂起が始まる3日前の1916年4月21日未明、ドイツの潜水艦はケースメントと彼の2人の仲間をケリー州トラリー湾のバンナ・ストランドに上陸させた。 [コンゴ時代から悩まされていたマラリアの再発に苦しみ、モンテースとベイリーについていけないほど衰弱していたケースメントは、王立アイルランド警察 [83]の軍曹によって、現在はケースメントの砦と改名されているアードファートのラホネーンにある古代の環状砦、マッケンナの砦で発見された。近くに隠 されていた3丁の拳銃が発見されると、RICはケースメントを武器不法持込の容疑で逮捕した[84]。 ケースメントは最終的に、大逆罪、破壊工作、王室に対するスパイの罪に問われることになった。彼は、ドイツの支援が不十分であることをダブリンに伝えた。 アイルランド義勇軍のケリー旅団は、その後3日間、彼を救出しようとしたかもしれないが、ダブリンの指導部は、復活祭の蜂起が始まる前にアイルランドで一 発の銃声も発してはならないと考えていたため、旅団に「何もするな」と命じた[85]。その後の内部調査では、地元義勇軍が救出を試みなかったことについ て「何の責任もない」とされている[86]。ロンドン塔には自殺志願者を監視するスタッフがいなかった」[87][e]。 裁判と処刑 ケースメントの法廷裁判は、1916年6月26日、王立裁判所で裁判長(レディング子爵)、エイヴォリー判事、ホリッジ判事の前で開かれた。検察側の主張 は難航した。ケースメントの犯罪はドイツで行われたものであり、反逆罪法1351はイギリス国内(あるいは間違いなくイギリス国内)で行われた活動にのみ 適用されるように思われた。裁判所は、句読点のないノルマン・フランス語の原文にカンマを読み込むべきであると決定し、「領域内または他の場所」が「王の 敵」がいるかもしれない場所だけでなく、行為が行われた場所を指すように意味を決定的に変えた[88][89]。その後、ケースメント自身が「カンマの上 で絞首刑になる」と書き、よく使われるエピグラムにつながった[90]。 裁判の間、ケースメントがドイツ軍に渡る前に彼の作品のいくつかを賞賛していた検察側(F. E. Smith)は、弁護側弁護士(A. M. Sullivan)に、現在「黒い日記」と呼ばれているものを共同で証拠として提出することを非公式に提案した。裁判と控訴の前とその間に、イギリス政府 はケースメントの日記の抜粋を密かに配布し、ケースメントを「性的逸脱者」として暴露した。その中には、数々の露骨な性行為の記述が含まれていた。このこ とは、ケースメントに対する世論を喚起し、そうでなければ介入しようとしたかもしれない著名人たちに影響を与えた。当時の社会規範や同性愛の違法性を考え ると、ケースメントの釈放を支持する声は一部で減少した。日記は1950年代に『黒い日記』として知られるようになり、現在も英国国立公文書館に所蔵され ている[92]。 ケースメントは有罪判決と死刑判決を不服として控訴したが、失敗に終わった。コンゴ改革協会の活動を通じてケースメントと面識のあったアーサー・コナン・ ドイル卿、詩人のW・B・イェイツ、劇作家のジョージ・バーナード・ショーらがケースメントの慈悲を訴えた。ジョセフ・コンラッドはケースメントを許せな かったし、ケースメントの長年の友人である彫刻家のハーバート・ウォードも許せなかった。彼の息子チャールズはその年の1月に西部戦線で戦死しており、 ケースメントの名付け親である息子の名前を変えることになった。アントリムに住むケースメント一家のメンバーは、イギリス陸海軍に息子がいたにもかかわら ず、防衛基金に目立たないように寄付をした[citation needed] アメリカ合衆国上院の死刑判決に対する上訴は、アイルランド独立反対派の検察官F・E・スミスの主張により、イギリス内閣によって却下された[94]。 1916年6月29日、ケースメントの爵位は没収された[95]。1916年8月3日、ペントンヴィル刑務所での絞首刑の日、ケースメントは本人の希望に よりカトリック教会に入信した。ティモシー・リング神父とジェームズ・キャリー神父(イースト・ロンドンのSSメアリーとマイケル教区)の2人のカトリッ ク司祭が付き添った[96][97]。ジェームズ・マキャロルとしても知られる後者[要出典]は、ケースメントについて「聖人だ......我々は彼のた めに祈るのではなく、彼(ケースメント)に祈るべきだ」と述べた[98]。 国葬 ケースメントの遺体は、絞首刑が執行されたペントンヴィル刑務所の裏手にある刑務所墓地に生石灰で埋葬されたが、彼の最後の希望は、現在の北アイルランド のアントリム州北岸にあるマーロー湾に埋葬されることだった。処刑から数十年の間、歴代のイギリス政府はケースメントの遺骨送還を求める多くの正式な要請 を拒否した。例えば、1953年9月、道州首相エーモン・デ・バレラは、ダウニング街で首相ウィンストン・チャーチルを訪問した際、遺骨の返還を要請した [99][要出典]。チャーチルは、個人的には反対しなかったが、同僚と相談し、法的助言を得ると述べた。彼は最終的に、処刑された囚人の遺骨を掘り起こ すことはできないという「具体的かつ拘束力のある」法的義務を理由に、アイルランドの要請を断った。デヴァレラは法的助言に異議を唱え、次のように答えた [100]。 ロジャー・ケースメントの遺骨がイギリスの刑務所の塀の中にある限り、彼自身が祖国に移送されることを希望していたのですから、少なくともイギリス政府の 見苦しい不屈の態度に対して、国民の憤りがここにある限り続くでしょう」。 デヴァレラは返事を受け取らなかった[99][要ページ]。  グラスネヴィン墓地にあるロジャー・ケースメントの墓。墓石には「1916年8月3日、アイルランドのために死んだロジャー・ケースメント」と刻まれてい る。 1965年、ケースメントの遺骨はアイルランドに送還された。1916年に爵位が取り消されたにもかかわらず、1965年の英国内閣の本国送還決定に関す る記録では、ケースメントは「サー・ロジャー・ケースメント」と呼ばれている[101]。ケースメントの希望に反して、ハロルド・ウィルソン首相の政府 は、北アイルランドに遺骨を持ち込まないという条件付きでのみ遺骨を解放していた。 ケースメントの遺骨は、ダブリン市内のアーバーヒル(現在のアーバーヒル刑務所)のギャリソン教会に5日間安置され、1916年のイースター蜂起の他の指 導者たちの墓の近くに置かれたが、彼らのそばに埋葬されることはなかった。国葬の後、遺骸はダブリンのグラスネヴィン墓地の共和国区画に、他のアイルラン ド共和国党員や民族主義者とともに、軍人の栄誉をもって埋葬された[102]。当時80代半ばでイースター蜂起の最後の生き残りであったアイルランド大統 領エーモン・デ・ヴァレラは、推定30,000人の人々とともに式典に参列した。 |

| The Black Diaries Main article: Black Diaries British officials have claimed that Casement kept the Black Diaries, a set of diaries covering the years 1903, 1910 and 1911 (twice). Jeffrey Dudgeon, who published an edition of all the diaries said, "His homosexual life was almost entirely out of sight and disconnected from his career and political work".[103] If genuine, the diaries reveal Casement was a homosexual who had many partners, had a fondness for young men and mostly paid for sex.[104] In 1916, after Casement's conviction for high treason, the British government circulated alleged photographs of pages of the diary to individuals campaigning for the commutation of Casement's death sentence. At a time of strong conservatism, not least among Irish Catholics, publicising the Black Diaries and Casement's alleged homosexuality undermined support for him. The question of whether the diaries are genuine or forgeries has been much debated. The diaries were declassified for limited inspection (by persons approved by the Home Office) in August 1959.[105] The original diaries may be seen at the British National Archives in Kew. Historians and biographers of Casement's life have taken opposing views. Roger McHugh (in 1976) and Angus Mitchell (in 2000 and later) regard the diaries as forged.[106] In 2012, Mitchell published several articles in the Field Day Review of the University of Notre Dame.[103] The Giles Report In 2005, the Royal Irish Academy, Dublin published The Giles Report, a private report on the Black Diaries written in 2002.[citation needed] Two US forensic-document examiners reviewed the Giles Report; both were critical of it. James Horan stated, "As editor of the Journal of Forensic Sciences and The Journal of the American Society of Questioned Document Examiners, I would not recommend publication of the Giles Report because the report does not show how its conclusion was reached. To the question, 'Is the writing Roger Casement's?' on the basis of the Giles Report as it stands, my answer would have to be I cannot tell."[citation needed] Marcel Matley, a second document examiner, stated, "Even if every document examined were the authentic writing of Casement, this report does nothing to establish the fact." A very brief expert opinion in 1959 by a Home Office employee failed to identify Casement as the author of the diaries.[citation needed] This opinion is almost unknown and does not appear in the Casement literature. As late as July 2015 the UK National Archives ambiguously described the Black Diaries as "attributed to Roger Casement", while at the same time unambiguously declaring their satisfaction with the result of the private Giles Report.[107] Vargas Llosa and Dudgeon Mario Vargas Llosa presented a mixed account of Casement's sexuality in his 2010 novel, The Dream of the Celt, suggesting that Casement wrote partially fictional diaries of what he wished had taken place in homosexual encounters. Dudgeon suggested in a 2013 article that Casement needed to be "sexless" to fit his role as a Catholic martyr in the nationalist movement of the time.[103] Dudgeon writes, "The evidence that Casement was a busy homosexual is in his own words and handwriting in the diaries, and is colossally convincing because of its detail and extent."[103][108] |

ブラック・ダイアリー 主な記事 黒い日記 イギリス政府関係者は、ケースメントが1903年、1910年、1911年(2回)の日記をまとめた「黒い日記」を保管していたと主張している。すべての 日記のエディションを出版したジェフリー・ダジョンは、「彼の同性愛生活は、ほとんど視界に入らず、彼のキャリアや政治活動から切り離されていた」と述べ ている[103]。本物であれば、日記はケースメントが同性愛者であり、多くのパートナーを持ち、若い男性に好意を持ち、セックスにはほとんど金を払って いたことを明らかにしている[104]。 1916年、ケースメントが大逆罪で有罪判決を受けた後、イギリス政府はケースメントの死刑の減刑を求める運動をしている人々に日記のページの疑惑の写真 を配布した。当時は保守主義が強く、特にアイルランドのカトリック教徒の間では、「黒い日記」とケースメントの同性愛疑惑が公表されたことで、ケースメン トへの支持が損なわれた。日記が本物か贋作かについては、多くの議論がある。日記は1959年8月に(内務省の許可を得た人物による)限定的な閲覧のため に機密解除された[105]。オリジナルの日記はキューにある英国国立公文書館で見ることができる。ケースメントの生涯に関する歴史家や伝記作家は、相反 する見解を持っている。ロジャー・マクヒュー(1976年)とアンガス・ミッチェル(2000年以降)は日記を偽造とみなしている[106]。2012 年、ミッチェルはノートルダム大学の『フィールド・デイ・レビュー』にいくつかの論文を発表した[103]。 ジャイルズ・レポート 2005年、ダブリンの王立アイルランド・アカデミーは、2002年に書かれたブラック・ダイアリーに関する私的な報告書であるジャイルズ・レポートを出 版した[要出典]。ジェームズ・ホーランは、「『法医学科学ジャーナル』と『米国質問文書調査官協会ジャーナル』の編集者として、私はジャイルズ・レポー トの出版を勧めない。現状のジャイルズ報告書に基づいて、『この文章はロジャー・ケースメントのものか』という質問に対して、私の答えは『わからない』と 言わざるを得ない」[要出典]。 2番目の文書調査官であるマルセル・マトリーは、「調査されたすべての文書がケースメントの真筆であったとしても、この報告書はその事実を証明するもので はない」と述べている。内務省の職員による1959年の非常に短い専門家意見書は、ケースメントを日記の著者と特定することができなかった[要出典]。こ の意見書はほとんど知られておらず、ケースメントの文献にも登場しない。2015年7月の時点で、英国国立公文書館はブラックダイアリーを「ロジャー・ ケースメントのものとされる」と曖昧に記述しており、同時に私的なジャイルズ報告の結果に満足していると明確に宣言している[107]。 バルガス・リョサとダジョン マリオ・バルガス・リョサは、2010年に発表した小説『ケルト人の夢』の中で、ケースメントのセクシュアリティについて複雑な説明を行い、ケースメント が同性愛の出会いの中で起こってほしかったことを部分的にフィクションの日記に書いたことを示唆した。ダジョンは2013年の記事で、ケースメントが当時 の民族主義運動におけるカトリックの殉教者としての役割にふさわしい「セックスレス」である必要があったことを示唆している[103]。ダジョンは「ケー スメントが多忙な同性愛者であったという証拠は、日記に書かれた彼自身の言葉と筆跡にあり、その詳細さと範囲の広さから、とんでもなく説得力がある」と書 いている[103][108]。 |

| Legacy Landmarks, buildings, and organisations This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Roger Casement" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  1966 Ireland stamps commemorating the 50th anniversary of Casement's death Casement Park, the Gaelic Athletic Association ground on Andersonstown Road in west Belfast. Several Gaelic Athletic Association clubs, for instance Roger Casements GAA Club (Coventry, England), Brampton Roger Casements GAC (Toronto, Canada) and Roger Casements GAC (Portglenone, Northern Ireland) Gaelscoil Mhic Easmainn (Irish for Casement) is an Irish-speaking national school in Tralee, County Kerry In Dundalk there is an estate named after him in Árd Easmuinn, Casement Heights. Casement Aerodrome in Baldonnel, the Irish Air Corps base near Dublin. Casement Rail and Bus Station in Tralee, near the site of Casement's landing on Banna Strand. Operated by Iarnród Éireann and Córas Iompair Éireann In Cork, an estate is named Roger Casement Park after him in Glasheen, a western suburb of the city. In Clonakilty, County Cork, a street and adjacent estate is named in his honour. A monument at Banna Strand in Kerry is open to the public at all times. A statue of him is erected in Ballyheigue, County Kerry A statue of him stands in Dún Laoghaire harbour.[109] Many streets are named for him, including Casement Road, Park, Drive and Grove in Finglas, County Dublin. In Harryville, Ballymena, County Antrim, there is a Casement Street, named for his great-grandfather, who was a solicitor there.[110] Representation in culture Casement has been the subject of ballads, poetry, novels, and TV series since his death, including: The ballad "Lonely Banna Strand" tells the story of Casement's role in the prelude to the Easter Rising, his arrest, and his execution.[111] Arthur Conan Doyle used Casement as an inspiration for the character of Lord John Roxton in the 1912 novel, The Lost World.[112] W. B. Yeats wrote a poem, The Ghost of Roger Casement, demanding the return of Casement's remains, with the refrain, "The ghost of Roger Casement/Is beating on the door" Roger Casement is featured in Giant's Causeway (1922) by Pierre Benoit, who portrays him as a noble martyr.[citation needed] Agatha Christie refers to Casement and the 1916 Uprising in her 1941 novel N or M? Brendan Behan, in his autobiographical novel Borstal Boy (1958), speaks of the respect his family had for Casement.[citation needed] Casement is the subject of the play Prisoner of the Crown, which was written by Richard Herd and Richard Stockton; it premiered at the Abbey Theatre in Dublin on 15 February 1972[113] A German TV series, Sir Roger Casement (1968), was made about his time in Germany during World War I. In 1973 BBC Radio aired a critically acclaimed radio play by David Rudkin entitled Cries from Casement as His Bones are Brought to Dublin The Dream of the Celt by Mario Vargas Llosa (winner of the Nobel Prize for literature) is a historical novel based on Roger Casement's life, translated from the Spanish by Edith Grossman and published in 2012. American Noise Rock band ...And You Will Know Us by the Trail of Dead released an instrumental entitled "The Betrayal of Roger Casement & the Irish Brigade" on their 2008 Festival Thyme EP Dying for Ireland (2012) is a biographical novel by Alan Lewis, which presents a "fictional reimagining" of Casement's prison memoirs, based on his writings, histories and biographies.[114] A one-act play, Shall Roger Casement Hang?, based mainly on his interrogation at Scotland Yard, was performed for the first time at the Tron Theatre in Glasgow in May 2016.[115] The Trial of Roger Casement is a graphic novel by Fionnuala Doran[116] Roger Casement is discussed in W. G. Sebald's novel The Rings of Saturn. Valiant Gentlemen is a historical novel based on Casement's friendship with Herbert Ward and his wife Sarita Sanford, by Sabina Murray, Grove/Atlantic, 2016.[117] Roger Casement – Heart of Darkness (1992) is a documentary by Kenneth Griffith on the life of Roger Casement.[118][119] The name refers to Joseph Conrad's novel of that name, written after Conrad met Casement in Congo. The Ghost of Roger Casement (2002) is a documentary that investigates the authenticity of the forensic examination of the Black Diaries.[120] |

レガシー ランドマーク、建物、組織 このセクションの検証には追加の引用が必要です。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力ください。ソースの ないものは、異議申し立てがなされ削除される場合があります。 出典を探す 「Roger Casement」 - news - newspapers - books - scholar - JSTOR (January 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  ケースメント没後50周年を記念した1966年アイルランド切手 ベルファスト西部のアンダーソンスタウン・ロードにあるゲーリック・アスレチック・アソシエーションのグラウンド、ケースメント・パーク。 いくつかのゲーリック・アスレチック・アソシエーション・クラブ、例えばロジャー・ケースメンツGAAクラブ(イングランド、コベントリー)、ブランプト ン・ロジャー・ケースメンツGAC(カナダ、トロント)、ロジャー・ケースメンツGAC(北アイルランド、ポートグレノン)などがある。 Gaelscoil Mhic Easmainn(アイルランド語でケースメントの意)は、ケリー州トラリーにあるアイルランド語を話す国民学校。 ダンドークには、ケースメントにちなんで名づけられた地所、ケースメント・ハイツ(Árd Easmuinn)がある。 ダブリン近郊のアイルランド航空隊基地、バルドネルにあるケースメント飛行場。 バンナ・ストランドのケースメント上陸地点近くにあるトラリーのケースメント鉄道・バス駅。Iarnród ÉireannとCóras Iompair Éireannが運営。 コークでは、市西部の郊外グラシーンに、ケースメントにちなんでロジャー・ケースメント公園と名付けられた地所がある。 コーク州クロナキルティには、彼の名を冠した通りと隣接地がある。 ケリーのバンナ・ストランドにある記念碑は常時公開されている。 ケリー州バリーヘイグには彼の銅像が建てられている。 ドゥーン・ラオヘール港には彼の銅像が立っている[109]。 ダブリン州フィングラスのケースメント通り、パーク通り、ドライブ通り、グローブ通りなど、多くの通りに彼の名前が付けられている。 アントリム州バリーメナのハリーヴィルには、そこで事務弁護士をしていた彼の曽祖父にちなんで名付けられたケースメント通りがある[110]。 文化における表現 ケースメントは、彼の死後、バラッド、詩、小説、テレビシリーズの題材となっている: バラッド 「Lonely Banna Strand 」は、イースター蜂起の前奏曲におけるケースメントの役割、逮捕、処刑の物語である[111]。 アーサー・コナン・ドイルは、1912年の小説『ロスト・ワールド』のジョン・ロクストン卿のキャラクターのインスピレーションとしてケースメントを使用 した[112]。 W. B.イェイツは、「The ghost of Roger Casement/Is beating on the door(ロジャー・ケースメントの亡霊がドアを叩いている)」というリフレインとともに、ケースメントの遺体の返還を要求する詩『ロジャー・ケースメン トの亡霊』を書いた。 ロジャー・ケースマンはピエール・ブノワの『ジャイアンツ・コーズウェイ』(1922年)に登場し、高貴な殉教者として描かれている[要出典]。 アガサ・クリスティは1941年の小説『N or M? ブレンダン・ビーハンは自伝的小説『ボルスタール・ボーイ』(1958年)の中で、家族がケースメントを尊敬していたと語っている[要出典]。 ケースメントは1972年2月15日にダブリンのアビー・シアターで初演された、リチャード・ハードとリチャード・ストックトンによって書かれた演劇『プ リズナー・オブ・ザ・クラウン』の題材となっている[113]。 ドイツのテレビシリーズ『サー・ロジャー・ケースメント』(1968年)は、第一次世界大戦中の彼のドイツ滞在を描いている。 1973年、BBCラジオはデイヴィッド・ラドキンによるラジオ劇『Cries from Casement as His Bones are Brought to Dublin』を放送し、高い評価を得た。 マリオ・バルガス・リョサ(ノーベル文学賞受賞)の『ケルト人の夢』は、ロジャー・ケースメントの生涯に基づく歴史小説で、エディス・グロスマンがスペイ ン語から翻訳し、2012年に出版された。 アメリカのノイズロックバンド...And You Will Know Us by the Trail of Deadは、2008年のFestival Thyme EPで「The Betrayal of Roger Casement & the Irish Brigade」というインストゥルメンタル曲をリリースしている。 Dying for Ireland』(2012年)は、アラン・ルイスによる伝記小説であり、ケースメントの著作、歴史、伝記に基づいて、ケースメントの獄中手記を「フィク ションとして再構築」したものである[114]。 主にロンドン警視庁での彼の尋問に基づいた一幕劇『Shall Roger Casement Hang??!』が2016年5月にグラスゴーのトロンシアターで初演された[115]。 ロジャー・ケースメントの裁判』はフィオヌラ・ドーランによるグラフィック・ノベル[116]。 ロジャー・ケースメントはW・G・セバルトの小説『土星の輪』で取り上げられている。 ヴァリアント・ジェントルメン』は、ケースメントとハーバート・ウォードおよびその妻サリタ・サンフォードとの友情に基づく歴史小説であり、サビーナ・マ レイ著、グローブ/アトランティック、2016年[117]。 Roger Casement - Heart of Darkness』(1992年)は、ケネス・グリフィスがロジャー・ケースメントの生涯を描いたドキュメンタリーである[118][119]。 The Ghost of Roger Casement』(2002年)は、『黒い日記』の法医学的検査の信憑性を調査するドキュメンタリーである[120]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roger_Casement |

|

| Bibliography By Roger Casement: 1910. Roger Casement's Diaries: 1910. The Black and the White. Sawyer, Roger, ed. London: Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-7375-X ‹See TfM›1910. The Amazon Journal of Roger Casement. Mitchell, Angus, ed. Anaconda Editions. *Casement, Roger (2003). Mitchell, Angus (ed.). Sir Roger Casement's Heart of Darkness: The 1911 Documents. Irish Manuscripts Commission. ISBN 978-1-874280-98-9. 1914. The Crime against Ireland, and How the War May Right it. Berlin: no publisher. 1914. Ireland, Germany and Freedom of the Seas: A Possible Outcome of the War of 1914. New York & Philadelphia: The Irish Press Bureau. Reprinted 2005: ISBN 1-4219-4433-2 1914–16 'One Bold Deed of Open Treason: The Berlin Diary of Roger Casement', Mitchell, Angus ed., Merrion 1915. The Crime against Europe. The Causes of the War and the Foundations of Peace. Berlin: The Continental Times. 1916. Gesammelte Schriften. Irland, Deutschland und die Freiheit der Meere und andere Aufsätze. Diessen vor München: Joseph Huber Verlag. 2nd expanded edition, 1917. 1918. Some Poems. London: The Talbot Press/T. Fisher Unwin. Slavery in Peru: Message from the President of the United States Transmitting Report of the Secretary of State, with Accompanying Papers, Concerning the Alleged Existence of Slavery in Peru. United States. Department of State. 1913. Retrieved 14 August 2023. Secondary Literature, and other materials cited in this entry: Daly, Mary E., ed. 2005. Roger Casement in Irish and World History, Dublin, Royal Irish Academy Doerries, Reinhard R., 2000. Prelude to the Easter Rising: Sir Roger Casement in Imperial Germany. London & Portland. Frank Cass. Dudgeon, Jeffrey, 2002. Roger Casement: The Black Diaries with a Study of his Background, Sexuality and Irish Political Life. Belfast Press (includes first publication of 1911 diary); 2nd paperback and Kindle editions, 2016; 3rd paperback and Kindle editions, 2019, ISBN 978-1-9160194-0-9. Dudgeon, Jeffrey, July 2016. Roger Casement's German Diary 1914–1916 including 'A Last Page' and associated correspondence. Belfast Press, ISBN 978-0-9539287-5-0. Goodman, Jordan, The Devil and Mr. Casement: One Man's Battle for Human Rights in South America's Heart of Darkness, 2010. Farrar, Straus & Giroux; ISBN 978-0-374-13840-0 Harris, Brian, "Injustice", Sutton Publishing. 2006; ISBN 0-7509-4021-2 Hochschild, Adam, King Leopold's Ghost. Hyde, H. Montgomery, 1960. Trial of Roger Casement. London: William Hodge. Penguin edition 1964. Hyde, H. Montgomery, 1970. The Love That Dared not Speak its Name. Boston: Little, Brown (in UK The Other Love). Inglis, Brian, 1973. Roger Casement, London: Hodder and Stoughton. Republished 1993 by Blackstaff Belfast and by Penguin 2002; ISBN 0-14-139127-8. Lacey, Brian, 2008. Terrible Queer Creatures: Homosexuality in Irish History. Dublin: Wordwell Books. MacColl, René, 1956. Roger Casement. London, Hamish Hamilton. Mc Cormack, W. J., 2002. Roger Casement in Death or Haunting the Free State. Dublin: UCD Press. Minta, Stephen, 1993. Aguirre: The Re-creation of a Sixteenth-Century Journey Across South America. Henry Holt & Co. ISBN 0-8050-3103-0. Mitchell, Angus, 2003. Casement (Life & Times Series). Haus Publishing Limited; ISBN 1-904341-41-1. Mitchell, Angus, 2013. Roger Casement. Dublin: O'Brien Press; ISBN 978-1-84717-608-0. Ó Síocháin, Séamas and Michael O’Sullivan, eds., 2004. The Eyes of Another Race: Roger Casement's Congo Report and 1903 Diary. University College Dublin Press; ISBN 1-900621-99-1. Ó Síocháin, Séamas, 2008. Roger Casement: Imperialist, Rebel, Revolutionary. Dublin: Lilliput Press. Reid, B.L., 1987. The Lives of Roger Casement. London: The Yale Press; ISBN 0-300-01801-0. Sawyer, Roger, 1984. Casement: The Flawed Hero. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Singleton-Gates, Peter, & Maurice Girodias, 1959. The Black Diaries. An Account of Roger Casement's Life and Times with a Collection of His Diaries and Public Writings. Paris: The Olympia Press. First edition of the Black Diaries. Thomson, Basil, 1922. Queer People (chapters 7–8), an account of the Easter Uprising and Casement's involvement from the head of Scotland Yard at the time. London: Hodder and Stoughton. Clayton, Xander: Aud, Plymouth 2007. Wolf, Karin, 1972. Sir Roger Casement und die deutsch-irischen Beziehungen. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot; ISBN 3-428-02709-4. Eberspächer, Cord/Wiechmann, Gerhard. "Erfolg Revolution kann Krieg entscheiden". Der Einsatz von S.M.H. Libau im irischen Osteraufstand 1916 ("Success revolution may decide war". The use of S.M.H. Libau in the Easter Rising 1916), in: Schiff & Zeit, Nr. 67, Frühjahr 2008, S 2–16. Hardenburg, Walter (1912). The Putumayo, the Devil's Paradise; Travels in the Peruvian Amazon Region and an Account of the Atrocities Committed Upon the Indians Therein. London: Fischer Unwin. ISBN 1372293019. |