ロマン主義

Romanticism

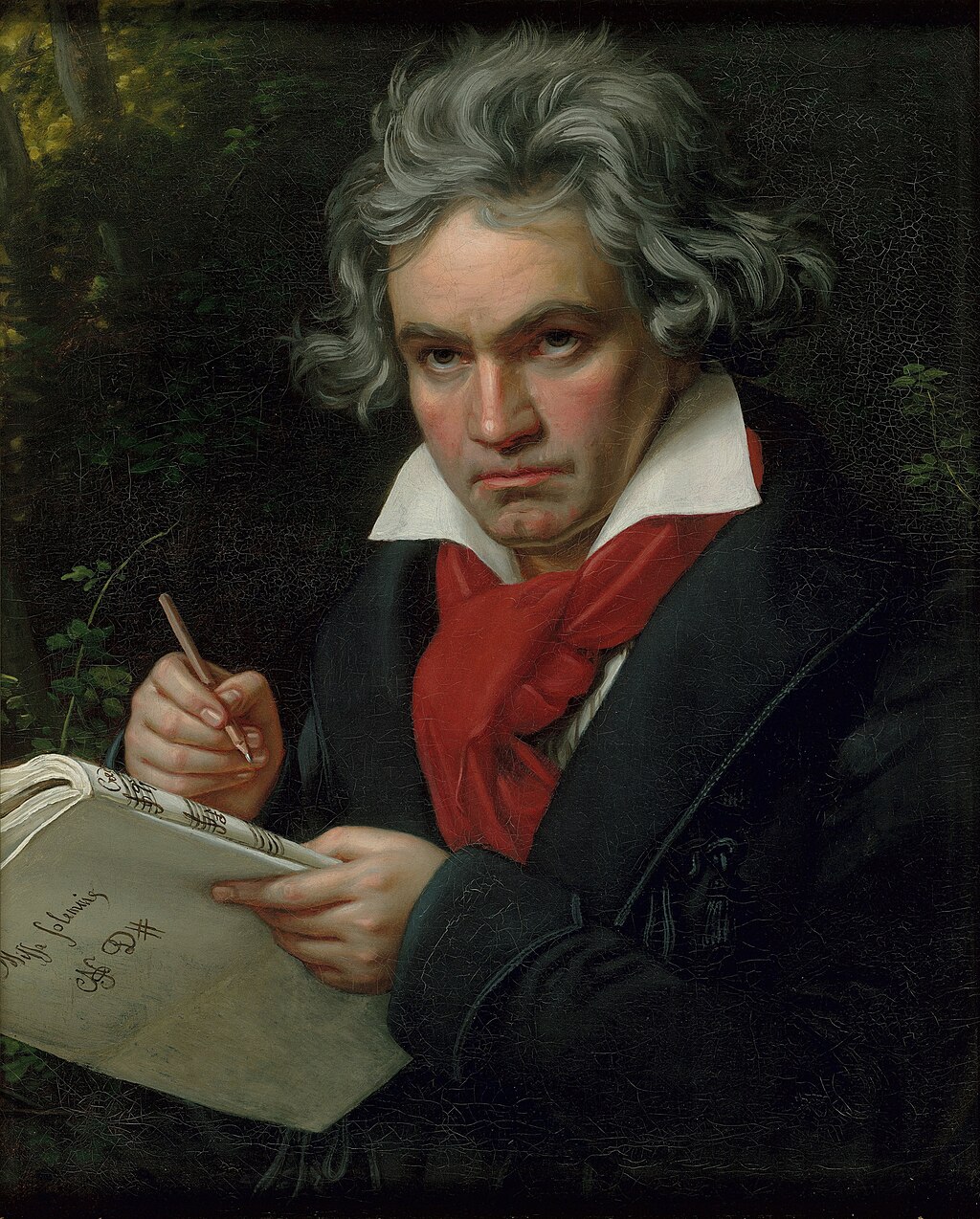

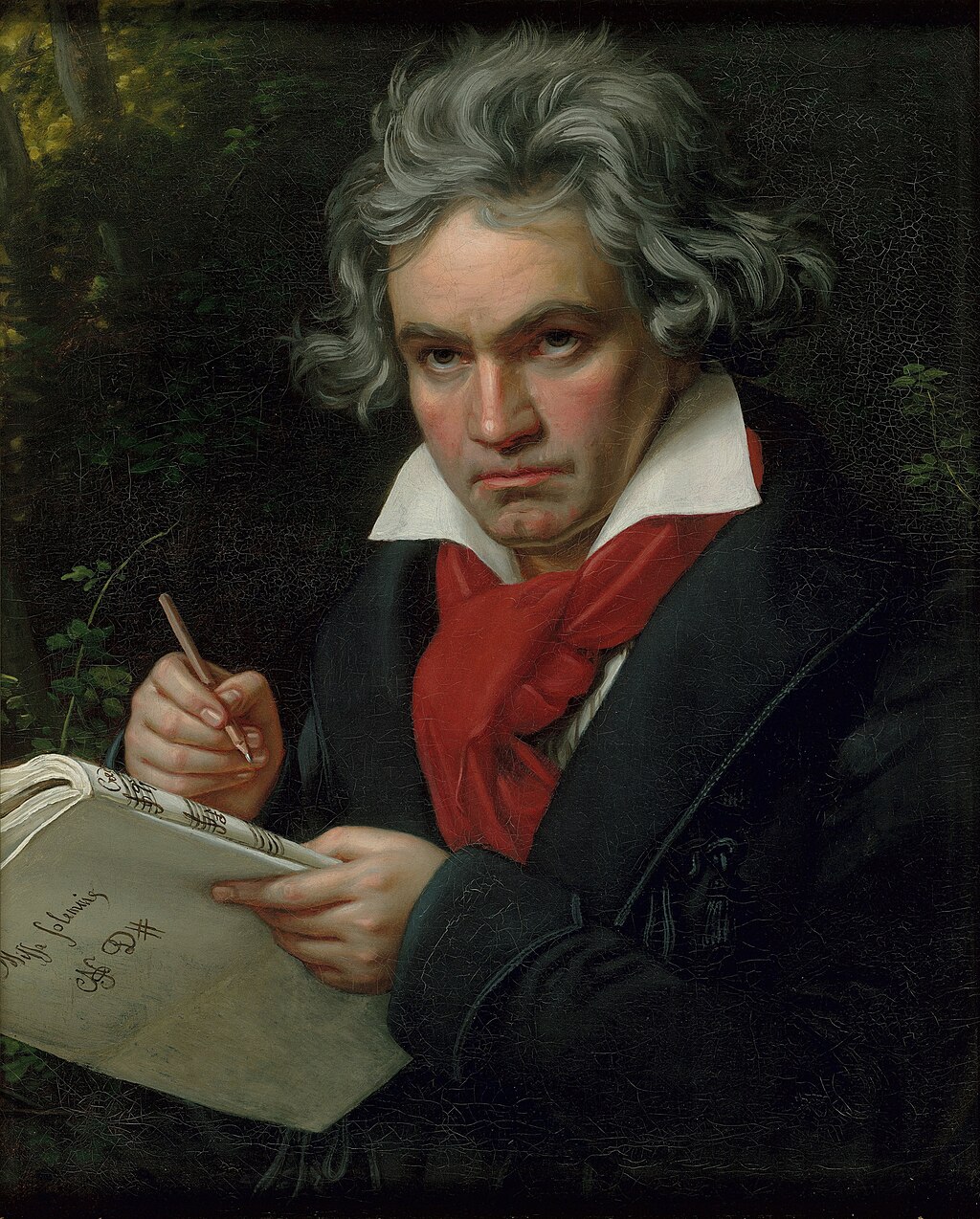

Caspar

David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, 1818

☆

ロマン主義(ロマン主義運動、ロマン主義時代とも)は、18世紀末にヨーロッパで起こった芸術的・知的運動である。この運動の目的は、啓蒙時代と産業革命

に対抗して、社会や文化における主体性、想像力、自然鑑賞の重要性を提唱することであった。

ロマン主義者たちは、当時の社会的慣習を否定し、個人主義として知られる道徳観を支持した。彼らは、世界を理解するためには情熱と直感が重要であり、美と

は単なる形の問題ではなく、むしろ強い感情的反応を呼び起こすものであると主張した。自然や超自然的なものへの畏敬、高貴な時代としての過去の理想化、エ

キゾチックで神秘的なものへの憧れ、英雄的で崇高なものへの賛美などである。

ロマン主義運動は中世を個別主義的に好み、彼らにとって中世は騎士道精神、英雄主義、人間と環境とのより有機的な関係の時代を象徴していた。この理想化

は、経済的物質主義や環境破壊を疎ましく思う現代の工業社会の価値観とは対照的だった。この運動が中世を描くことは議論の中心的テーマであり、ロマン主義

の描写は中世の生活のマイナス面をしばしば見落としているという主張があった。

ロマン主義のピークは1800年から1850年までというのが通説である。しかし、「後期ロマン主義」の時代や「新ロマン主義」の復活も議論されている。

これらの運動の延長線上には、近代美術に結実した、ますます実験的で抽象的な形式への抵抗と、音楽における伝統的な調性和声の脱構築という特徴がある。彼

らはロマン派の理想を継承し、成熟したロマン派のスタイルで技術的な卓越性を示しながら、芸術や音楽における感情の深みを強調した。しかし、第一次世界大

戦の頃には、文化的・芸術的風潮は大きく変化し、ロマン主義は基本的に後続の運動へと分散していった。ロマン派の理想を維持した後期ロマン派の最後の人物

は、1940年代に亡くなった。彼らはまだ広く尊敬されてはいたが、その時点では時代錯誤と見なされていた。

ロマン主義は、様々な視点を持つ複雑な運動であり、世界中の西洋文明に浸透した。この運動とそれに対立するイデオロギーは、時を経て相互に形成し合った。

その終焉後、ロマン主義の思想と芸術は、芸術や音楽、推理小説、哲学、政治、環境保護主義に多大な影響を及ぼし、それは現代まで続いている。

この運動は、現代の「ロマン主義化」という概念や、何かを「ロマン主義化」する行為の基準となっている。

| Romanticism

(also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic

and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of

the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the

importance of subjectivity, imagination, and appreciation of nature in

society and culture in response to the Age of Enlightenment and the

Industrial Revolution. Romanticists rejected the social conventions of the time in favour of a moral outlook known as individualism. They argued that passion and intuition were crucial to understanding the world, and that beauty is more than merely an affair of form, but rather something that evokes a strong emotional response. With this philosophical foundation, the Romanticists elevated several key themes to which they were deeply committed: a reverence for nature and the supernatural, an idealization of the past as a nobler era, a fascination with the exotic and the mysterious, and a celebration of the heroic and the sublime. The Romanticist movement had a particular fondness for the Middle Ages, which to them represented an era of chivalry, heroism, and a more organic relationship between humans and their environment. This idealization contrasted sharply with the values of their contemporary industrial society, which they considered alienating for its economic materialism and environmental degradation. The movement's illustration of the Middle Ages was a central theme in debates, with allegations that Romanticist portrayals often overlooked the downsides of medieval life. The consensus is that Romanticism peaked from 1800 until 1850. However, a "Late Romantic" period and "Neoromantic" revivals are also discussed. These extensions of the movement are characterized by a resistance to the increasingly experimental and abstract forms that culminated in modern art, and the deconstruction of traditional tonal harmony in music. They continued the Romantic ideal, stressing depth of emotion in art and music while showcasing technical mastery in a mature Romantic style. By the time of World War I, though, the cultural and artistic climate had changed to such a degree that Romanticism essentially dispersed into subsequent movements. The final Late Romanticist figures to maintain the Romantic ideals died in the 1940s. Though they were still widely respected, they were seen as anachronisms at that point. Romanticism was a complex movement with a variety of viewpoints that permeated Western civilization across the globe. The movement and its opposing ideologies mutually shaped each other over time. After its end, Romantic thought and art exerted a sweeping influence on art and music, speculative fiction, philosophy, politics, and environmentalism that has endured to the present day. The movement is the reference for the modern notion of "romanticization" and the act of "romanticizing" something. |

ロマン主義(ロマン主義運動、ロマン主義時代とも)は、18世紀末に

ヨーロッパで起こった芸術的・知的運動である。この運動の目的は、啓蒙時代と産業革命に対抗して、社会や文化における主体性、想像力、自然鑑賞の重要性を

提唱することであった。 ロマン主義者たちは、当時の社会的慣習を否定し、個人主義として知られる道徳観を支持した。彼らは、世界を理解するためには情熱と直感が重要であり、美と は単なる形の問題ではなく、むしろ強い感情的反応を呼び起こすものであると主張した。自然や超自然的なものへの畏敬、高貴な時代としての過去の理想化、エ キゾチックで神秘的なものへの憧れ、英雄的で崇高なものへの賛美などである。 ロマン主義運動は中世を個別主義的に好み、彼らにとって中世は騎士道精神、英雄主義、人間と環境とのより有機的な関係の時代を象徴していた。この理想化 は、経済的物質主義や環境破壊を疎ましく思う現代の工業社会の価値観とは対照的だった。この運動が中世を描くことは議論の中心的テーマであり、ロマン主義 の描写は中世の生活のマイナス面をしばしば見落としているという主張があった。 ロマン主義のピークは1800年から1850年までというのが通説である。しかし、「後期ロマン主義」の時代や「新ロマン主義」の復活も議論されている。 これらの運動の延長線上には、近代美術に結実した、ますます実験的で抽象的な形式への抵抗と、音楽における伝統的な調性和声の脱構築という特徴がある。彼 らはロマン派の理想を継承し、成熟したロマン派のスタイルで技術的な卓越性を示しながら、芸術や音楽における感情の深みを強調した。しかし、第一次世界大 戦の頃には、文化的・芸術的風潮は大きく変化し、ロマン主義は基本的に後続の運動へと分散していった。ロマン派の理想を維持した後期ロマン派の最後の人物 は、1940年代に亡くなった。彼らはまだ広く尊敬されてはいたが、その時点では時代錯誤と見なされていた。 ロマン主義は、様々な視点を持つ複雑な運動であり、世界中の西洋文明に浸透した。この運動とそれに対立するイデオロギーは、時を経て相互に形成し合った。 その終焉後、ロマン主義の思想と芸術は、芸術や音楽、推理小説、哲学、政治、環境保護主義に多大な影響を及ぼし、それは現代まで続いている。 この運動は、現代の「ロマン主義化」という概念や、何かを「ロマン主義化」する行為の基準となっている。 |

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, 1818 |

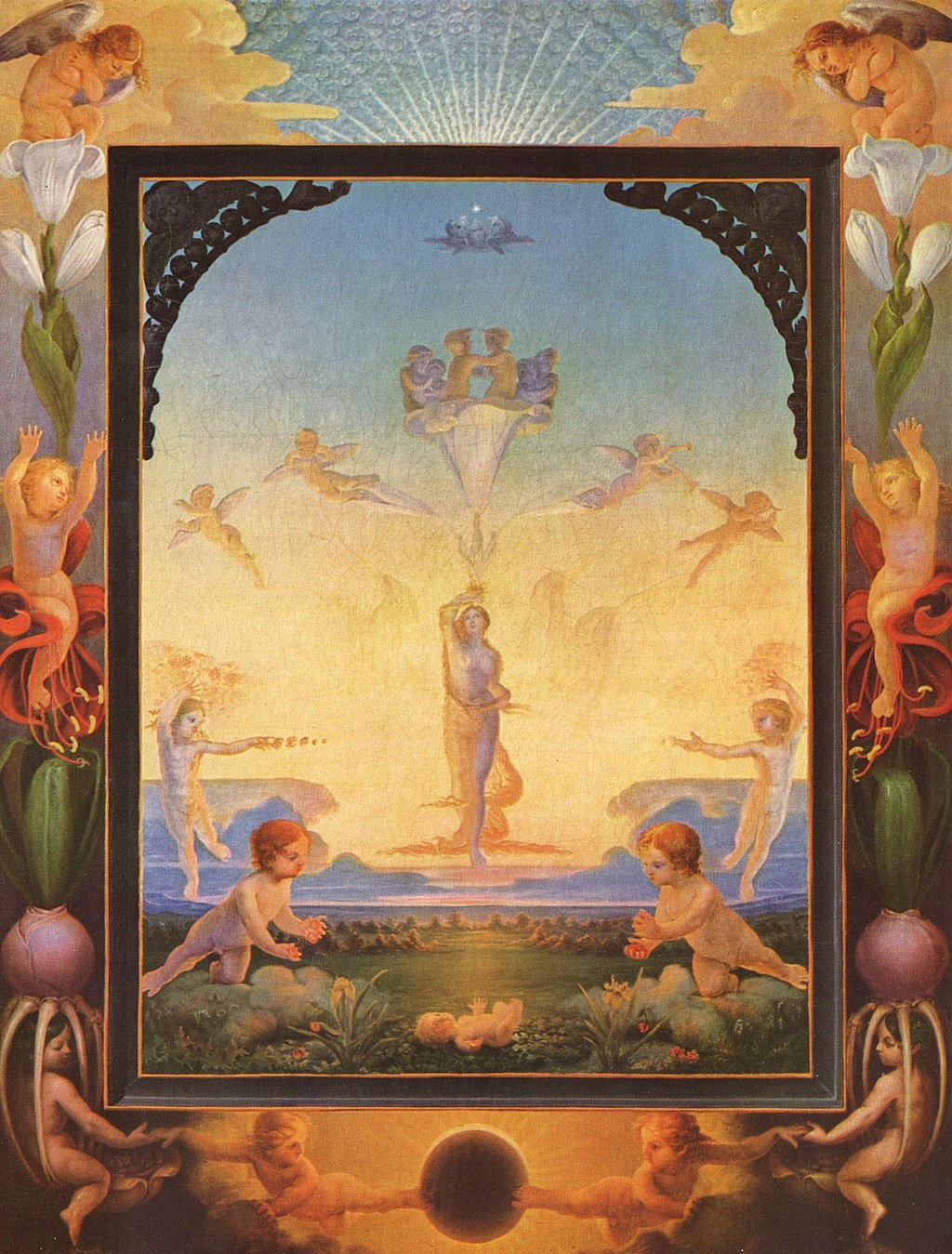

Eugène Delacroix, Death of Sardanapalus, 1827, taking its Orientalist subject from a play by Lord Byron  Philipp Otto Runge, The Morning, 1808 |

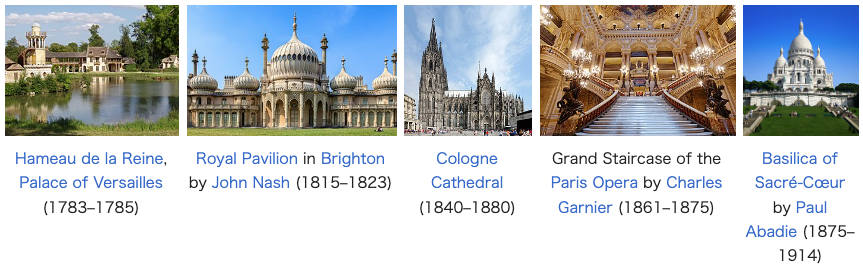

| Overview Timeline For most of the Western world, Romanticism was at its peak from approximately 1800 to 1850. The first Romantic ideas arose from an earlier German Counter-Enlightenment movement called Sturm und Drang (German: "Storm and Stress"). This movement directly criticized the Enlightenment's position that humans can fully comprehend the world through rationality alone, suggesting that intuition and emotion are key components of insight and understanding.[1] Published in 1774, "The Sorrows of Young Werther" by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe began to shape the Romanticist movement and its ideals. The events and ideologies of the French Revolution were also direct influences on the movement; many early Romantics throughout Europe sympathized with the ideals and achievements of French revolutionaries.[2] A confluence of circumstances led to Romanticism's decline in the mid-19th century, including (but not limited to) the rise of Realism and Naturalism, Charles Darwin's publishing of the Origin of Species, the transition from widespread revolution in Europe to a more conservative climate, and a shift in public consciousness to the immediate impact of technology and urbanization on the working class. By World War I, Romanticism was overshadowed by new cultural, social, and political movements, many of them hostile to the perceived illusions and preoccupations of the Romantics. However, Romanticism has had a lasting impact on Western civilization, and many works of art, music, and literature that embody the Romantic ideals have been made after the end of the Romantic era. The movement's advocacy for nature appreciation is cited as an influence for current nature conservation efforts. The majority of film scores from the Golden Age of Hollywood were written in the lush orchestral Romantic style, and this genre of orchestral cinematic music is still often seen in films of the 21st century. The philosophical underpinnings of the movement have influenced modern political theory, both among liberals and conservatives. |

概要 年表 西洋世界の大部分において、ロマン主義はおよそ1800年から1850年にかけて最盛期を迎えた。最初のロマン主義の思想は、それ以前にドイツで起こった 「シュトゥルム・ウント・ドラング(ドイツ語で「嵐とストレス」)」と呼ばれる反啓蒙主義運動から生まれた。この運動は、人間が合理性だけで世界を完全に 理解できるという啓蒙主義の立場を真っ向から批判し、直観と感情が洞察と理解の重要な要素であることを示唆した[1]。1774年に出版されたヨハン・ ヴォルフガング・フォン・ゲーテの『若きウェルテルの悩み』は、ロマン主義運動とその理想を形成し始めた。フランス革命の出来事とイデオロギーもまた、こ の運動に直接的な影響を与えた。ヨーロッパ中の多くの初期のロマン主義者たちは、フランス革命家の理想と功績に共感していた[2]。 現実主義と自然主義の台頭、チャールズ・ダーウィンによる『種の起源』の出版、ヨーロッパにおける広範な革命からより保守的な風潮への移行、テクノロジー と都市化が労働者階級に与える直接的な影響への大衆意識の変化など(これらに限定されない)、様々な状況が重なり、19世紀半ばにロマン主義は衰退して いった。第一次世界大戦の頃には、ロマン主義は新たな文化的、社会的、政治的運動によって影を潜め、その多くはロマン派の幻想や偏執を敵視するものであっ た。 しかし、ロマン主義は西洋文明に永続的な影響を及ぼし、ロマン主義の理想を体現する芸術、音楽、文学の作品は、ロマン主義の時代が終わった後も数多く作ら れている。この運動が提唱した自然鑑賞は、現在の自然保護活動への影響として挙げられている。ハリウッド黄金時代の映画音楽の大半は、絢爛豪華な管弦楽ロ マン派様式で書かれており、このジャンルの管弦楽映画音楽は21世紀の映画でもしばしば見られる。この運動の哲学的基盤は、リベラル派と保守派の両方にお いて、現代の政治理論に影響を与えている。 |

| Purpose Romanticism was characterized by its emphasis on emotion and individualism as well as the glorification of the past and nature, preferring the medieval over the classical. Romanticism was partly a reaction to the Industrial Revolution,[3] and the prevailing ideology of the Age of Enlightenment, especially the scientific rationalization of Nature.[4] The movement's ideals were embodied most strongly in the visual arts, music, and literature; it also had a major impact on historiography,[5] education,[6] chess, social sciences, and the natural sciences.[7] Romanticism had a significant and complex effect on politics: Romantic thinking influenced conservatism, liberalism, radicalism, and nationalism.[8][9] Romanticism prioritized the artist's unique, individual imagination above the strictures of classical form. The movement emphasized intense emotion as an authentic source of aesthetic experience. It granted a new importance to experiences of sympathy, awe, wonder, and terror, in part by naturalizing such emotions as responses to the "beautiful" and the "sublime".[10][11] Romantics stressed the nobility of folk art and ancient cultural practices, but also championed radical politics, unconventional behavior, and authentic spontaneity. In contrast to the rationalism and classicism of the Enlightenment, Romanticism revived medievalism[12] and juxtaposed a pastoral conception of a more "authentic" European past with a highly critical view of recent social changes, including urbanization, brought about by the Industrial Revolution. Romanticism lionized the achievements of "heroic" individuals—especially artists, who began to be represented as cultural leaders (one Romantic luminary, Percy Bysshe Shelley, described poets as the "unacknowledged legislators of the world" in his "Defence of Poetry"). |

目的 ロマン主義は、感情や個人主義を強調し、過去や自然を賛美し、古典よりも中世を好むという特徴があった。ロマン主義は、産業革命[3]や啓蒙時代の一般的なイデオロギー、特に自然の科学的合理化[4]に対する反動でもあった。 この運動の理想は視覚芸術、音楽、文学において最も強く具現化され、歴史学、[5]教育、[6]チェス、社会科学、自然科学にも大きな影響を与えた[7]。 ロマン主義は政治にも重要かつ複雑な影響を与えた: ロマン主義思想は保守主義、自由主義、急進主義、ナショナリズムに影響を与えた[8][9]。 ロマン主義は、古典的な形式の厳しさよりも、芸術家のユニークで個性的な想像力を優先させた。この運動は、美的体験の真の源泉として激しい感情を強調し た。この運動は、共感、畏怖、驚き、恐怖といった体験に新たな重要性を与えたが、その一因は、そのような感情を「美しいもの」や「崇高なもの」に対する反 応として自然化することにあった[10][11]。 ロマン派は民俗芸術や古代の文化的慣習の高貴さを強調したが、同時に急進的な政治、型破りな行動、本物の自発性も支持した。啓蒙主義の合理主義や古典主義 とは対照的に、ロマン主義は中世主義を復活させ[12]、産業革命によってもたらされた都市化を含む近年の社会変化に対して非常に批判的な見方と、より 「本物の」ヨーロッパの過去に対する牧歌的な観念を並置した。ロマン主義は、「英雄的な」個人、特に芸術家の功績を称え、彼らは文化的リーダーとして表さ れるようになった(ロマン主義の著名人の一人であるパーシー・ビシェ・シェリーは、『詩の弁明』の中で詩人を「知られざる世界の立法者」と表現してい る)。 |

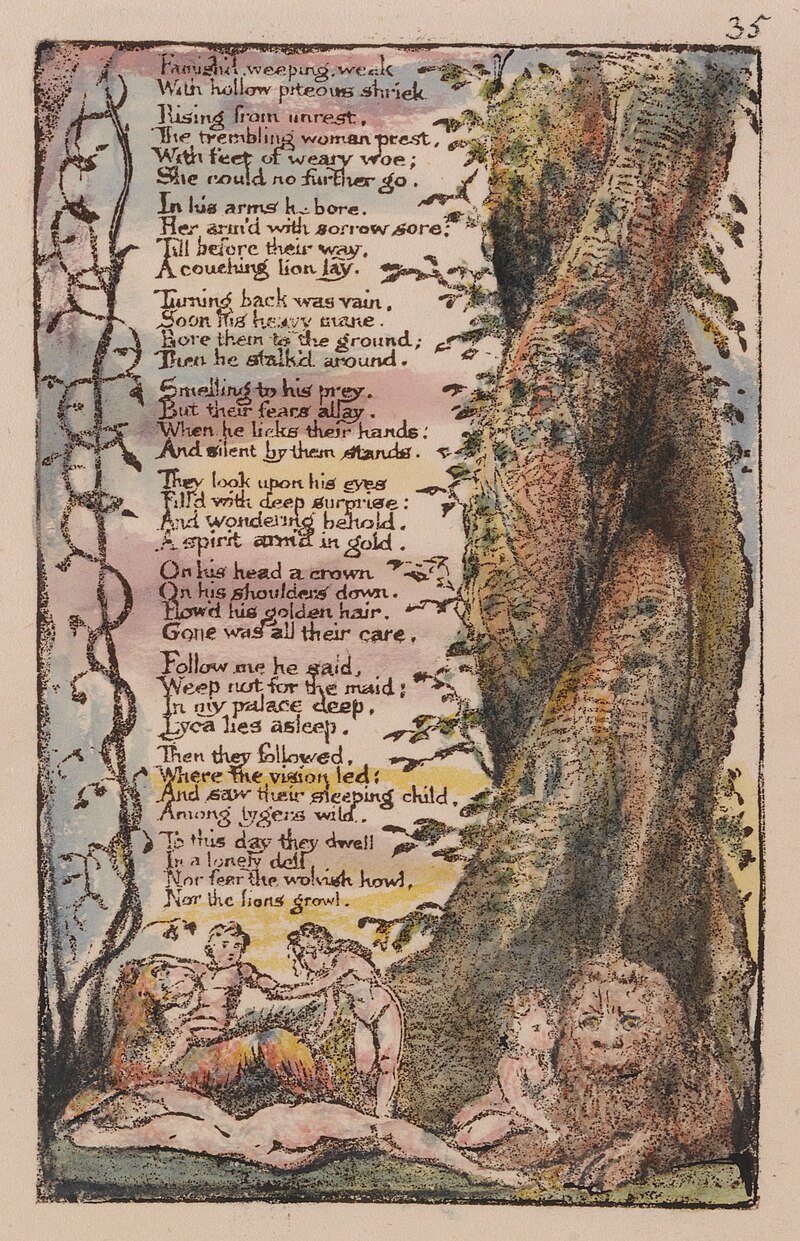

| Defining Romanticism Basic characteristics Romanticism placed the highest importance on the freedom of the artists to authentically express their sentiments and ideas. Romantics like the German painter Caspar David Friedrich believed that an artist's emotions should dictate their formal approach; Friedrich went as far as declaring that "the artist's feeling is his law".[13] The Romantic poet William Wordsworth, thinking along similar lines and drawing on the ideas presented in his sister Dorothy Wordsworth's Grasmere Journals[14], wrote that poetry should begin with "the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings", which the poet then "recollect[s] in tranquility", enabling the poet to find a suitably unique form for representing such feelings.[15] The Romantics never doubted that emotionally motivated art would find suitable, harmonious modes for expressing its vital content—if, that is, the artist steered clear of moribund conventions and distracting precedents. Samuel Taylor Coleridge and others thought there were natural laws the imagination of born artists followed instinctively when these individuals were, so to speak, "left alone" during the creative process.[16] These "natural laws" could support a wide range of different formal approaches: as many, perhaps, as there were individuals making personally meaningful works of art. Many Romantics believed that works of artistic genius were created "ex nihilo", "from nothing", without recourse to existing models.[17][18][19] This idea is often called "romantic originality".[20] The translator and prominent Romantic August Wilhelm Schlegel argued in his Lectures on Dramatic Arts and Letters that the most valuable quality of human nature is its tendency to diverge and diversify.[21]  William Blake, The Little Girl Found, from Songs of Innocence and Experience, 1794 According to Isaiah Berlin, Romanticism embodied "a new and restless spirit, seeking violently to burst through old and cramping forms, a nervous preoccupation with perpetually changing inner states of consciousness, a longing for the unbounded and the indefinable, for perpetual movement and change, an effort to return to the forgotten sources of life, a passionate effort at self-assertion both individual and collective, a search after means of expressing an unappeasable yearning for unattainable goals".[22] Romantic artists also shared a strong belief in the importance and inspirational qualities of Nature. Romantics were distrustful of cities and social conventions. They deplored Restoration and Enlightenment Era artists who were largely concerned with depicting and critiquing social relations, thereby neglecting the relationship between people and Nature. Romantics generally believed a close connection with Nature was beneficial for human beings, especially for individuals who broke off from society in order to encounter the natural world by themselves. Romantic literature was frequently written in a distinctive, personal "voice". As critic M. H. Abrams has observed, "much of romantic poetry invited the reader to identify the protagonists with the poets themselves."[23] This quality in Romantic literature, in turn, influenced the approach and reception of works in other media; it has seeped into everything from critical evaluations of individual style in painting, fashion, and music, to the auteur movement in modern filmmaking. |

ロマン主義の定義 基本的な特徴 ロマン主義は、芸術家が自分の感情や思想を忠実に表現する自由を最も重視した。ドイツの画家カスパー・ダーヴィト・フリードリッヒのようなロマン主義者 は、芸術家の感情が形式的なアプローチを決定するべきだと考えていた。[13]ロマン派の詩人ウィリアム・ワーズワースは、似たような路線で考え、妹のド ロシー・ワーズワースの『グラスミア・ジャーナル』[14]で提示されたアイデアをもとに、詩は「力強い感情の自然な溢れ出し」から始まるべきであり、詩 人はそれを「静寂の中で回想する」ことによって、そのような感情を表現するための適切な独自の形式を見出すことができるようになると書いている[15]。 ロマン派は、感情に突き動かされた芸術は、その重要な内容を表現するのに適した、調和のとれた様式を見出すだろうと信じて疑わなかった。サミュエル・テイ ラー・コールリッジなどは、生まれながらの芸術家が創作過程でいわば「放任」されたときに、その想像力が本能的に従う自然な法則があると考えた[16]。 この「自然な法則」は、個人的に意味のある芸術作品を作る個人の数だけ、さまざまな形式的アプローチを支えることができるだろう。多くのロマン主義者は、 天才的な芸術作品は既存のモデルに頼ることなく「無から」創造されると信じていた[17][18][19]。この考えはしばしば「ロマン主義的独創性」と 呼ばれる[20]。 翻訳家であり著名なロマン主義者であったアウグスト・ヴィルヘルム・シュレーゲルは、『演劇芸術と文学に関する講義』の中で、人間の本性の最も価値ある性 質は、発散し多様化する傾向であると主張した[21]。  ウィリアム・ブレイク、『無垢と経験の歌』より「拾われた少女」、1794年 アイザイア・バーリンによれば、ロマン主義は「古く窮屈な形式を激しく破裂させようとする、新しく落ち着きのない精神、絶えず変化する内的意識状態への神 経質なとらわれ、束縛されないもの、定義できないもの、絶え間ない運動と変化へのあこがれ、忘れ去られた生命の源に立ち戻ろうとする努力、個人的・集団的 な自己主張への情熱的な努力、達成不可能な目標への達成不可能なあこがれを表現する手段の探求」を体現していた[22]。 ロマン派の芸術家たちはまた、自然の重要性とインスピレーションを与える資質に対する強い信念を共有していた。ロマン派は都市や社会的慣習に不信感を抱い ていた。ロマン派は、都市や社会的慣習に不信感を抱いており、社会的関係の描写や批評に重きを置き、人々と自然の関係を軽視した維新期や啓蒙期の芸術家た ちを非難した。ロマン派は一般的に、自然との密接なつながりは人間にとって有益であり、特に自然界と自ら出会うために社会から離れた個人にとって有益であ ると考えた。 ロマン主義文学は、独特の人格的な「声」で書かれることが多かった。批評家M.H.エイブラムスの観察によれば、「ロマン派の詩の多くは、読者が主人公を 詩人自身と同一視するよう誘う」[23]。ロマン派文学におけるこのような性質は、他のメディアにおける作品のアプローチや受容にも影響を及ぼし、絵画、 ファッション、音楽における個人のスタイルに対する批評的評価から、現代の映画製作における作家運動まで、あらゆるものに浸透している。 |

| Etymology The group of words with the root "Roman" in the various European languages, such as "romance" and "Romanesque", has a complicated history. By the 18th century, European languages—notably German, French and Slavic languages—were using the term "Roman" in the sense of the English word "novel", i.e. a work of popular narrative fiction.[24] This usage derived from the term "Romance languages", which referred to vernacular (or popular) language in contrast to formal Latin.[24] Most such novels took the form of "chivalric romance", tales of adventure, devotion and honour.[25] The founders of Romanticism, critics (and brothers) August Wilhelm Schlegel and Friedrich Schlegel, began to speak of romantische Poesie ("romantic poetry") in the 1790s, contrasting it with "classic" but in terms of spirit rather than merely dating. Friedrich Schlegel wrote in his 1800 essay Gespräch über die Poesie ("Dialogue on Poetry"): I seek and find the romantic among the older moderns, in Shakespeare, in Cervantes, in Italian poetry, in that age of chivalry, love and fable, from which the phenomenon and the word itself are derived.[26][27] The modern sense of the term spread more widely in France by its persistent use by Germaine de Staël in her De l'Allemagne (1813), recounting her travels in Germany.[28] In England Wordsworth wrote in a preface to his poems of 1815 of the "romantic harp" and "classic lyre",[28] but in 1820 Byron could still write, perhaps slightly disingenuously, I perceive that in Germany, as well as in Italy, there is a great struggle about what they call 'Classical' and 'Romantic', terms which were not subjects of classification in England, at least when I left it four or five years ago.[29] It is only from the 1820s that Romanticism certainly knew itself by its name, and in 1824 the Académie française took the wholly ineffective step of issuing a decree condemning it in literature.[30] |

語源 「ロマンス」や「ロマネスク」など、ヨーロッパのさまざまな言語における「Roman」を語源とする単語群には複雑な歴史がある。18世紀までに、ヨー ロッパの言語、特にドイツ語、フランス語、スラヴ語は、英語の「novel(小説)」、つまり大衆的な物語小説作品の意味で「Roman」という語を使用 していた[24]。この用法は、正式なラテン語とは対照的に地方語(または大衆語)を指す「ロマンス諸語」という用語に由来する[24]。そのような小説 のほとんどは、冒険、献身、名誉の物語である「騎士道ロマンス」の形式をとっていた[25]。 ロマン主義の創始者である批評家アウグスト・ヴィルヘルム・シュレーゲルとフリードリッヒ・シュレーゲルの兄弟は、1790年代にロマン主義詩(「ロマン ティックな詩」)について語り始め、「古典的な詩」と対比させたが、単に年代ではなく精神的な意味においてであった。フリードリヒ・シュレーゲルは 1800年のエッセイ『詩についての対話』(Gespräch über die Poesie)の中でこう書いている: シェイクスピア、セルバンテス、イタリア詩、騎士道、愛、寓話の時代、そこからこの現象や言葉自体が派生したのである[26][27]。 フランスでは、ジェルメーヌ・ド・シュテルがドイツでの旅を綴った『De l'Allemagne』(1813年)の中でこの言葉を執拗に使用したことで、この言葉の現代的な意味がより広く広まった[28]。 イギリスでは、ワーズワースが1815年の詩の序文で「ロマンティック・ハープ」と「古典的な竪琴」について書いている[28]が、1820年にはバイロ ンはまだ、おそらく少し軽率に書くことができた、 ドイツでもイタリアと同様に、彼らが「古典的」と呼ぶものと「ロマンティック」と呼ぶものについて、大きな争いがあることを私は知っている。 ロマン主義は1820年代になってようやくその名で呼ばれるようになり、1824年にはアカデミー・フランセーズが文学におけるロマン主義を非難する声明を出すという、まったく効果のない措置をとった[30]。 |

| Period The period typically called Romantic varies greatly between different countries and different artistic media or areas of thought. Margaret Drabble described it in literature as taking place "roughly between 1770 and 1848",[31] and few dates much earlier than 1770 will be found. In English literature, M. H. Abrams placed it between 1789, or 1798, this latter a very typical view, and about 1830, perhaps a little later than some other critics.[32] Others have proposed 1780–1830.[33] In other fields and other countries the period denominated as Romantic can be considerably different; musical Romanticism, for example, is generally regarded as only having ceased as a major artistic force as late as 1910, but in an extreme extension the Four Last Songs of Richard Strauss are described stylistically as "Late Romantic" and were composed in 1946–1948.[34] However, in most fields the Romantic period is said to be over by about 1850, or earlier. The early period of the Romantic era was a time of war, with the French Revolution (1789–1799) followed by the Napoleonic Wars until 1815. These wars, along with the political and social turmoil that went along with them, served as the background for Romanticism.[35] The key generation of French Romantics born between 1795 and 1805 had, in the words of one of their number, Alfred de Vigny, been "conceived between battles, attended school to the rolling of drums".[36] According to Jacques Barzun, there were three generations of Romantic artists. The first emerged in the 1790s and 1800s, the second in the 1820s, and the third later in the century.[37] |

時代 一般的にロマン派と呼ばれる時代は、国や芸術媒体、思想領域によって大きく異なる。マーガレット・ドラブルは、文学においては「おおよそ1770年から 1848年の間」[31]と表現しており、1770年よりずっと前の年代はほとんど見られない。英文学では、M.H.エイブラムスが1789年か1798 年の間とし、後者は非常に典型的な見解であり、他の批評家よりも少し遅いかもしれないが1830年頃とした[32]。[例えば、音楽的なロマン主義は、一 般的には1910年末に主要な芸術的力としての役割を終えたと見なされているが、極端な言い方をすれば、リヒャルト・シュトラウスの「4つの最後の歌」 は、様式的には「後期ロマン派」と表現され、1946年から1948年に作曲されたものである[34]。しかし、ほとんどの分野では、ロマン派の時代は 1850年頃、あるいはそれ以前に終わったと言われている。 ロマン派の初期は戦争の時代であり、フランス革命(1789年~1799年)に続き、1815年までナポレオン戦争が続いた。1795年から1805年の 間に生まれたフランス・ロマン派の主要世代は、その一人であるアルフレッド・ド・ヴィニーの言葉を借りれば、「戦いの合間に着想され、太鼓が打ち鳴らされ る中、学校に通った」[36]。ジャック・バルザンによれば、ロマン派の芸術家には3つの世代があった。第一世代は1790年代と1800年代に、第二世 代は1820年代に、第三世代は世紀後半に出現した[37]。 |

| Context and place in history The more precise characterization and specific definition of Romanticism has been the subject of debate in the fields of intellectual history and literary history throughout the 20th century, without any great measure of consensus emerging. That it was part of the Counter-Enlightenment, a reaction against the Age of Enlightenment, is generally accepted in current scholarship. Its relationship to the French Revolution, which began in 1789 in the very early stages of the period, is clearly important, but highly variable depending on geography and individual reactions. Most Romantics can be said to be broadly progressive in their views, but a considerable number always had, or developed, a wide range of conservative views,[38] and nationalism was in many countries strongly associated with Romanticism, as discussed in detail below. In philosophy and the history of ideas, Romanticism was seen by Isaiah Berlin as disrupting for over a century the classic Western traditions of rationality and the idea of moral absolutes and agreed values, leading "to something like the melting away of the very notion of objective truth",[39] and hence not only to nationalism, but also fascism and totalitarianism, with a gradual recovery coming only after World War II.[40] For the Romantics, Berlin says, in the realm of ethics, politics, aesthetics it was the authenticity and sincerity of the pursuit of inner goals that mattered; this applied equally to individuals and groups—states, nations, movements. This is most evident in the aesthetics of romanticism, where the notion of eternal models, a Platonic vision of ideal beauty, which the artist seeks to convey, however imperfectly, on canvas or in sound, is replaced by a passionate belief in spiritual freedom, individual creativity. The painter, the poet, the composer do not hold up a mirror to nature, however ideal, but invent; they do not imitate (the doctrine of mimesis), but create not merely the means but the goals that they pursue; these goals represent the self-expression of the artist's own unique, inner vision, to set aside which in response to the demands of some "external" voice—church, state, public opinion, family friends, arbiters of taste—is an act of betrayal of what alone justifies their existence for those who are in any sense creative.[41]  John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shalott, 1888, after a poem by Tennyson Arthur Lovejoy attempted to demonstrate the difficulty of defining Romanticism in his seminal article "On the Discrimination of Romanticisms" in his Essays in the History of Ideas (1948); some scholars see Romanticism as essentially continuous with the present, some like Robert Hughes see in it the inaugural moment of modernity,[42] while writers of the 19th Century such as Chateaubriand, Novalis and Samuel Taylor Coleridge saw it as the beginning of a tradition of resistance to Enlightenment rationalism—a "Counter-Enlightenment"—[43][44] to be associated most closely with German Romanticism. Another early definition comes from Charles Baudelaire: "Romanticism is precisely situated neither in choice of subject nor exact truth, but in the way of feeling."[45] The end of the Romantic era is marked in some areas by a new style of Realism, which affected literature, especially the novel and drama, painting, and even music, through Verismo opera. This movement was led by France, with Balzac and Flaubert in literature and Courbet in painting; Stendhal and Goya were important precursors of Realism in their respective media. However, Romantic styles, now often representing the established and safe style against which Realists rebelled, continued to flourish in many fields for the rest of the century and beyond. In music such works from after about 1850 are referred to by some writers as "Late Romantic" and by others as "Neoromantic" or "Postromantic", but other fields do not usually use these terms; in English literature and painting the convenient term "Victorian" avoids having to characterise the period further. In northern Europe, the Early Romantic visionary optimism and belief that the world was in the process of great change and improvement had largely vanished, and some art became more conventionally political and polemical as its creators engaged polemically with the world as it was. Elsewhere, including in very different ways the United States and Russia, feelings that great change was underway or just about to come were still possible. Displays of intense emotion in art remained prominent, as did the exotic and historical settings pioneered by the Romantics, but experimentation with form and technique was generally reduced, often replaced with meticulous technique, as in the poems of Tennyson or many paintings. If not realist, late 19th-century art was often extremely detailed, and pride was taken in adding authentic details in a way that earlier Romantics did not trouble with. Many Romantic ideas about the nature and purpose of art, above all the pre-eminent importance of originality, remained important for later generations, and often underlie modern views, despite opposition from theorists. [citation needed] |

歴史における文脈と位置 ロマン主義のより正確な特徴づけや具体的な定義は、20世紀を通じて知的歴史学や文学史の分野で議論の対象となってきたが、大きなコンセンサスを得るには 至っていない。ロマン主義が啓蒙主義時代に対する反動である反啓蒙主義の一部であったことは、現在の研究では一般的に受け入れられている。1789年に始 まったフランス革命との関係は、この時代のごく初期の段階であり、重要であることは明らかだが、地理的条件や個人の反応によって大きく異なる。ほとんどの ロマン主義者はその見解において広範に進歩的であったと言えるが、相当数の者は常に広範な保守的見解を持っていたか、あるいはそれを発展させていた [38]。また、ナショナリズムは多くの国でロマン主義と強く結びついており、その詳細については後述する。 哲学と思想史においては、ロマン主義は合理性と道徳的絶対性と合意された価値観という古典的な西洋の伝統を100年以上にわたって破壊し、「客観的真理と いう概念そのものを溶かしてしまうような事態」[39]を招き、ナショナリズムのみならずファシズムと全体主義をも引き起こし、第二次世界大戦後に初めて 徐々に回復したとアイザイア・バーリンは見ている[40]、 倫理、政治、美学の領域において重要なのは、内なる目標の追求の真正性と誠実さであり、それは個人にも集団(国家、国民、運動)にも等しく適用された。こ のことは、ロマン主義の美学に最も顕著に表れている。そこでは、永遠のモデルという概念や、芸術家がキャンバスや音の中で不完全ながらも伝えようとする理 想的な美のプラトン的ビジョンが、精神的自由や個人の創造性に対する情熱的な信念に置き換えられている。画家、詩人、作曲家は、どんなに理想的であって も、自然を鏡に映すのではなく、発明するのである。彼らは模倣するのではなく(ミメーシスの教義)、単に手段を創造するのではなく、彼らが追求する目標を 創造するのである。これらの目標は、芸術家自身のユニークで内的なヴィジョンの自己表現であり、教会、国家、世論、家族の友人、趣味の決定者など、何らか の「外的な」声の要求に応えてそれを脇に置くことは、何らかの意味で創造的な人間にとって、自分の存在を正当化する唯一のものに対する裏切り行為なのであ る[41]。  ジョン・ウィリアム・ウォーターハウス《シャロットの女》1888年、テニスンの詩による。 アーサー・ラブジョイは『思想史論考』(1948年)の「ロマン主義の区別について」という重要な論文で、ロマン主義の定義の難しさを実証しようとした; ロマン主義を本質的に現在と連続したものとみなす学者もいれば、ロバート・ヒューズのようにロマン主義を近代の幕開けの瞬間とみなす学者もいる[42] が、シャトーブリアン、ノヴァーリス、サミュエル・テイラー・コールリッジといった19世紀の作家たちは、ロマン主義を啓蒙合理主義に対する抵抗の伝統の 始まり、すなわち「反啓蒙主義」[43][44]とみなし、ドイツ・ロマン主義と最も密接に関連している。もう一つの初期の定義はシャルル・ボードレール のものである: 「ロマン主義とは、主体性の選択でも正確な真実でもなく、感情のあり方にこそある」[45]。 ロマン主義時代の終わりは、リアリズムという新しいスタイルによって特徴づけられる部分もあり、それは文学、特に小説や演劇、絵画、そしてヴェリズモ・オ ペラのような音楽にまで影響を与えた。この運動はフランスが主導し、文学ではバルザックやフローベール、絵画ではクールベが、それぞれのメディアではスタ ンダールやゴヤがリアリズムの重要な先駆者となった。スタンダールやゴヤは、それぞれのメディアにおいて、写実主義の重要な先駆者であった。しかし、ロマ ン派の様式は、写実主義者たちが反発した、確立された安全な様式を表すことが多く、世紀の終わり以降も多くの分野で繁栄し続けた。音楽の分野では、 1850年頃以降の作品を「後期ロマン派」、「新ロマン派」、「ポストロマン派」と呼ぶ作家もいるが、他の分野では通常このような用語は使われず、英文学 や絵画の分野では「ヴィクトリアン」という便利な用語が使われ、この時代をさらに特徴づけることを避けている。 北ヨーロッパでは、初期ロマン派的な楽観主義や、世界は大きな変化と改善の過程にあるという信念はほとんど消え去り、一部の芸術は、創作者たちがありのま まの世界と極論的に関わりながら、より従来型の政治的・極論的なものとなっていった。アメリカやロシアを含む他の国々では、全く異なる形で、大きな変化が 進行中であるか、あるいはまさに起ころうとしているという感情がまだ残っていた。芸術における激しい感情の表現は、ロマン派が開拓したエキゾチックで歴史 的な設定と同様、依然として際立っていたが、形式や技法の実験は一般的に減少し、テニスンの詩や多くの絵画のように、しばしば綿密な技法に取って代わられ た。写実主義ではないにせよ、19世紀末の芸術は非常に細部まで描き込まれていることが多く、初期のロマン派が問題にしなかったような本物のディテールを 加えることに誇りが払われた。芸術の本質と目的に関する多くのロマン主義的な考え、とりわけ独創性の卓越した重要性は、理論家たちからの反対にもかかわら ず、後世においても重要であり続け、しばしば現代的な見解の根底をなしている。[引用は必要である]。 |

| Literature See also: Romantic literature  Henry Wallis, The Death of Chatterton 1856, by suicide at 17 in 1770 In literature, Romanticism found recurrent themes in the evocation or criticism of the past, the cult of "sensibility" with its emphasis on women and children, the isolation of the artist or narrator, and respect for nature. Furthermore, several romantic authors, such as Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Maturin and Nathaniel Hawthorne, based their writings on the supernatural/occult and human psychology. Romanticism tended to regard satire as something unworthy of serious attention, a view still influential today.[46] The Romantic movement in literature was preceded by the Enlightenment and succeeded by Realism. The precursors of Romanticism in English poetry go back to the middle of the 18th century, including figures such as Joseph Warton (headmaster at Winchester College) and his brother Thomas Warton, Professor of Poetry at Oxford University.[47] Joseph maintained that invention and imagination were the chief qualities of a poet. The Scottish poet James Macpherson influenced the early development of Romanticism with the international success of his Ossian cycle of poems published in 1762, inspiring both Goethe and the young Walter Scott. Thomas Chatterton is generally considered the first Romantic poet in English.[48] Both Chatterton and Macpherson's work involved elements of fraud, as what they claimed was earlier literature that they had discovered or compiled was, in fact, entirely their own work. The Gothic novel, beginning with Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto (1764), was an important precursor of one strain of Romanticism, with a delight in horror and threat, and exotic picturesque settings, matched in Walpole's case by his role in the early revival of Gothic architecture. Tristram Shandy, a novel by Laurence Sterne (1759–1767), introduced a whimsical version of the anti-rational sentimental novel to the English literary public. |

文学 こちらも参照のこと: ロマン主義文学  ヘンリー・ウォリス『チャタートンの死』1856年、1770年に17歳で自殺した。 文学においてロマン主義は、過去の喚起や批判、女性や子供を重視する「感性」の崇拝、芸術家や語り手の孤立、自然への敬意といったテーマを繰り返し見出し た。さらに、エドガー・アラン・ポー、チャールズ・マチュリン、ナサニエル・ホーソーンなど、ロマン主義の作家の中には、超自然的・オカルト的なものや人 間の心理を題材にした作品を書いた者もいる。ロマン主義では、風刺を真面目に注目するに値しないものと見なす傾向があり、この見解は今日でも影響力がある [46]。文学におけるロマン主義運動は啓蒙主義に先行し、リアリズムに引き継がれた。 イギリスの詩におけるロマン主義の先駆者は18世紀半ばにさかのぼり、ジョセフ・ワートン(ウィンチェスター・カレッジ校長)やその弟でオックスフォード 大学の詩学教授であったトーマス・ワートンなどがいる[47]。ジョセフは発明と想像力が詩人の主な資質であると主張していた。スコットランドの詩人ジェ イムズ・マクファーソンは、1762年に出版した『オシアン』詩集の世界的な成功によってロマン主義の初期の発展に影響を与え、ゲーテや若きウォルター・ スコットをも刺激した。チャタートンもマクファーソンも、自分たちが発見または編纂した先行文学だと主張していたものが、実際にはすべて自分たちの作品で あったという詐欺的な要素を含んでいた。ホラティウス・ウォルポールの『オトラントの城』(1764年)に始まるゴシック小説は、恐怖と脅威、エキゾチッ クで絵のように美しい設定に喜びを感じるロマン主義の重要な先駆けであった。ローレンス・スターン(1759~1767)の小説『トリストラム・シャン ディ』は、反合理的なセンチメンタル小説の気まぐれなバージョンをイギリス文学界に紹介した。 |

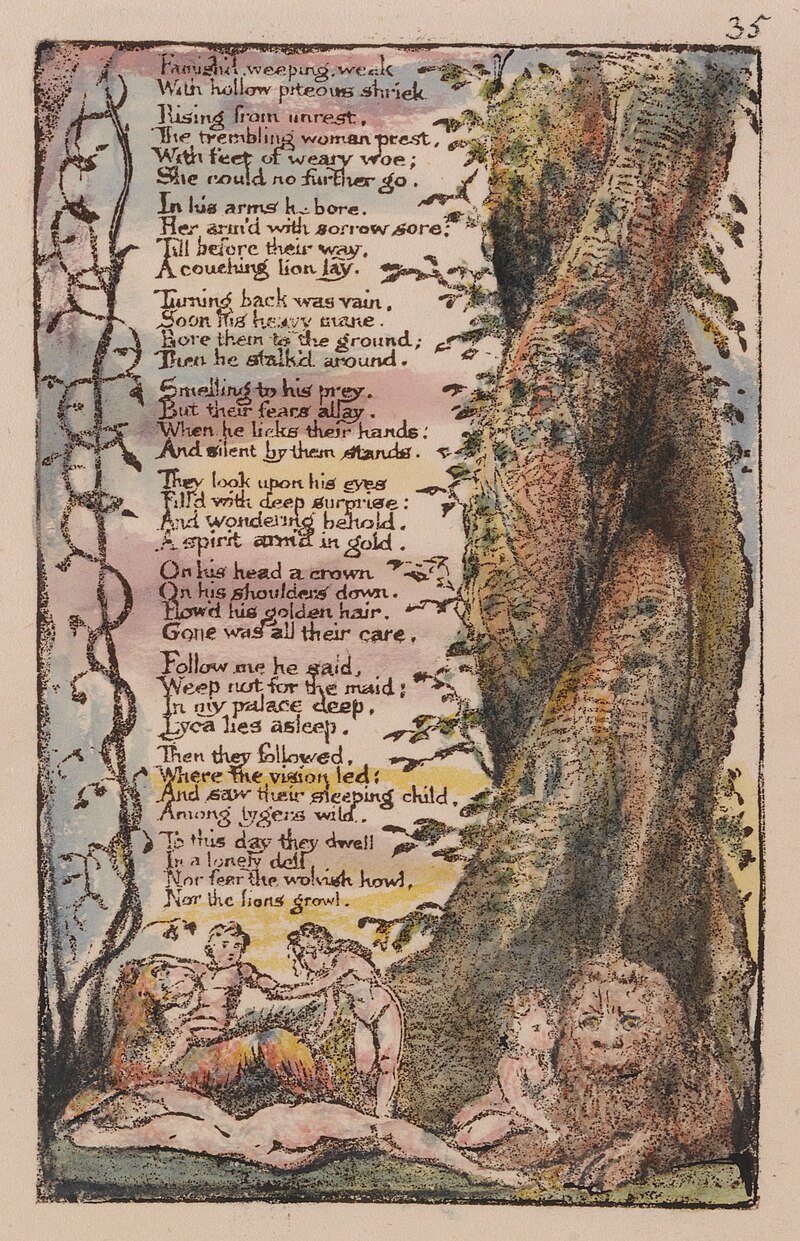

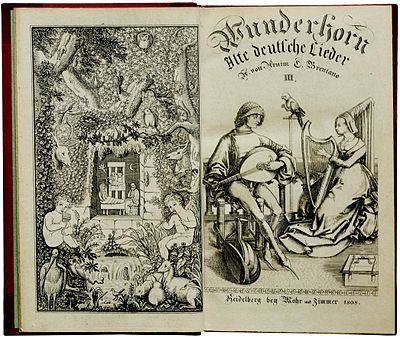

Germany Title page of Volume III of Des Knaben Wunderhorn, 1808 An early German influence came from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, whose 1774 novel The Sorrows of Young Werther had young men throughout Europe emulating its protagonist, a young artist with a very sensitive and passionate temperament. At that time Germany was a multitude of small separate states, and Goethe's works would have a seminal influence in developing a unifying sense of nationalism.[citation needed] Another philosophical influence came from the German idealism of Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Friedrich Schelling, making Jena (where Fichte lived, as well as Schelling, Hegel, Schiller and the brothers Schlegel) a centre for early German Romanticism (also known as Jena Romanticism). Important writers were Ludwig Tieck, Novalis, Heinrich von Kleist, Friedrich Hölderlin and Heinrich Heine. Heidelberg later became a centre of German Romanticism, where writers and poets such as Clemens Brentano, Achim von Arnim and Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff (Aus dem Leben eines Taugenichts) met regularly in literary circles.[citation needed] Important motifs in German Romanticism are travelling, nature, for example the German Forest, and Germanic myths. The later German Romanticism of, for example E. T. A. Hoffmann's Der Sandmann (The Sandman), 1817, and Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff's Das Marmorbild (The Marble Statue), 1819, was darker in its motifs and has gothic elements. The significance to Romanticism of childhood innocence, the importance of imagination, and racial theories all combined to give an unprecedented importance to folk literature, non-classical mythology and children's literature, above all in Germany.[citation needed] Brentano and von Arnim were significant literary figures who together published Des Knaben Wunderhorn ("The Boy's Magic Horn" or cornucopia), a collection of versified folk tales, in 1806–1808. The first collection of Grimms' Fairy Tales by the Brothers Grimm was published in 1812.[49] Unlike the much later work of Hans Christian Andersen, who was publishing his invented tales in Danish from 1835, these German works were at least mainly based on collected folk tales, and the Grimms remained true to the style of the telling in their early editions, though later rewriting some parts. One of the brothers, Jacob, published in 1835 Deutsche Mythologie, a long academic work on Germanic mythology.[50] Another strain is exemplified by Schiller's highly emotional language and the depiction of physical violence in his play The Robbers of 1781. |

ドイツ デス・クナーベン・ヴンダーホルン』第3巻のタイトルページ、1808年 ゲーテの1774年の小説『若きウェルテルの悩み』は、ヨーロッパ中の若者を、非常に繊細で情熱的な気質を持つ若い芸術家である主人公に憧れさせた。当時 のドイツはマルチチュード国家であり、ゲーテの作品は統一的なナショナリズムの形成に大きな影響を与えた。重要な作家はルートヴィヒ・ティーク、ノヴァー リス、ハインリヒ・フォン・クライスト、フリードリヒ・ヘルダーリン、ハインリヒ・ハイネである。ハイデルベルクは後にドイツ・ロマン主義の中心地とな り、クレメンス・ブレンターノ、アヒム・フォン・アルニム、ヨーゼフ・フライヘル・フォン・アイヘンドルフ(『Aus dem Leben eines Taugenichts』)などの作家や詩人が定期的に文壇に集った[要出典]。 ドイツ・ロマン主義における重要なモチーフは、旅行、自然、例えばドイツの森、ゲルマン神話である。1817年のE・T・A・ホフマンの『サンドマン』 (Der Sandmann)や1819年のヨーゼフ・フライヘル・フォン・アイヒェンドルフの『大理石の彫像』(Das Marmorbild)などは、後期のドイツ・ロマン主義で、そのモチーフはより暗く、ゴシック的な要素を持っている。ロマン主義における幼年期の無邪気 さの重要性、想像力の重要性、人種論のすべてが相まって、とりわけドイツでは、民俗文学、非古典的な神話、児童文学がかつてないほど重視されるようになっ た[citation needed] ブレンターノとフォン・アルニムは重要な文学者であり、1806年から1808年にかけて、民話を詩化した『少年の呪術的角笛』(Des Knaben Wunderhorn)を共に出版した。グリム兄弟による最初のグリム童話集は1812年に出版された[49]。1835年からデンマーク語で創作童話を 出版していたハンス・クリスチャン・アンデルセンのずっと後の作品とは異なり、これらのドイツの作品は、少なくとも主に収集された民話に基づいており、グ リム兄弟は、後にいくつかの部分を書き直したものの、初期の版では民話の語り方に忠実であった。兄弟の一人であるヤコブは、1835年にゲルマン神話に関 する長大な学術書『Deutsche Mythologie』を出版している[50]。もう一つの系統は、シラーが1781年に発表した戯曲『強盗たち』における非常に感情的な言葉遣いと身体 的暴力の描写に代表される。 |

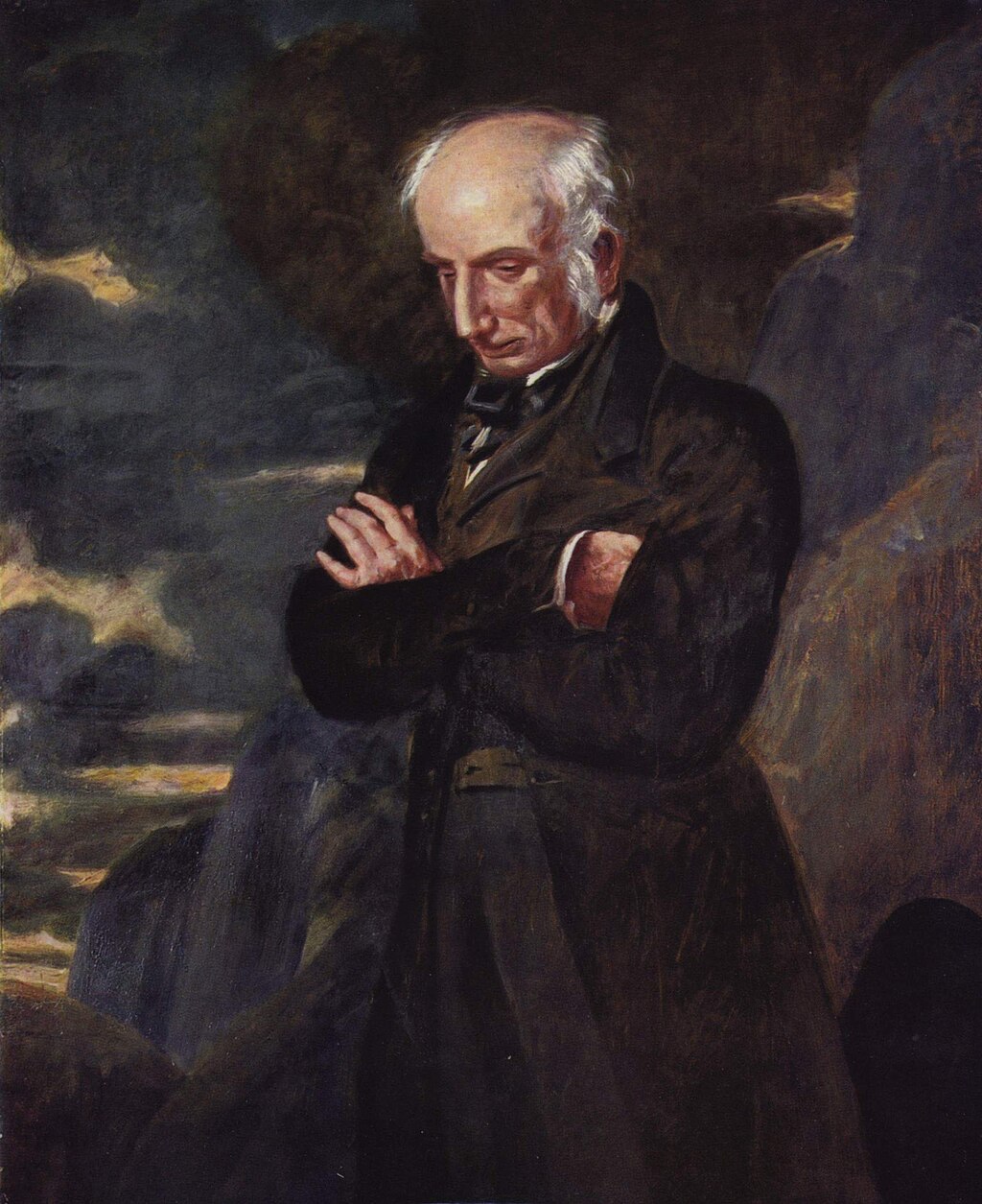

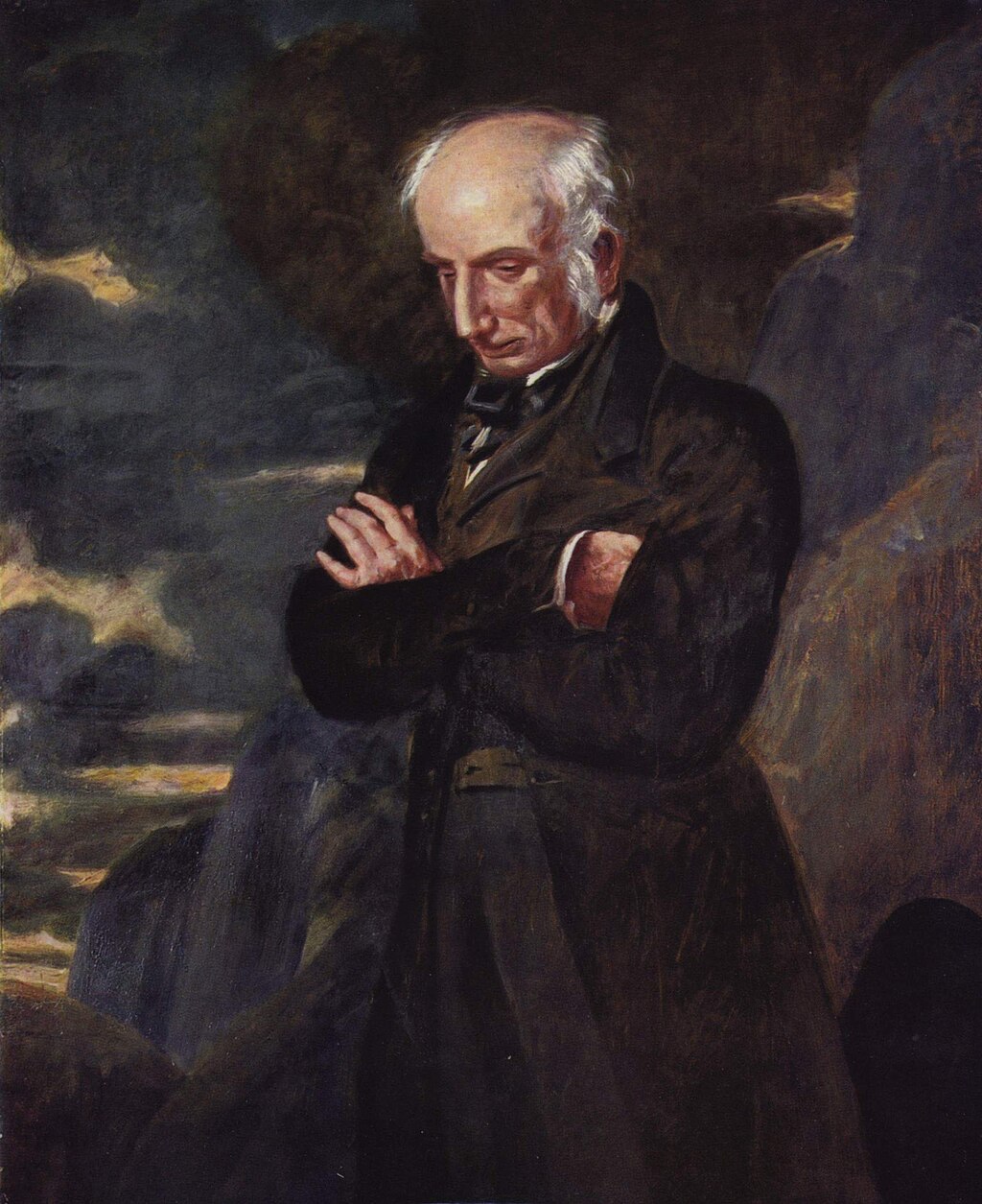

| Great Britain Main article: Romantic literature in English  William Wordsworth (pictured) and Samuel Taylor Coleridge helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature in 1798 with their joint publication Lyrical Ballads. In English literature, the key figures of the Romantic movement are considered to be the group of poets including William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley and the much older William Blake, followed later by the isolated figure of John Clare; also such novelists as Walter Scott from Scotland and Mary Shelley, and the essayists William Hazlitt and Charles Lamb. The publication in 1798 of Lyrical Ballads, with many of the finest poems by Wordsworth and Coleridge, is often held to mark the start of the movement. [51].The majority of the poems in Lyrical Ballards were by Wordsworth, and many dealt with the lives of the poor in his native Lake District, or his feelings about nature—which he more fully developed in his long poem The Prelude, never published in his lifetime. Yet this literary milestone was deeply rooted in Dorothy Wordsworth’s Grasmere Journals, which offered William not only rich poetic imagery and reflections on nature and emotion (such as daffodils that "tossed and reeled and danced"[52]), but also poignant observations of the struggling rural poor she encountered during her long walks in the Lake District[53]. Brief excerpts from Dorothy Wordsworth’s journals became the first writings by a woman of the Romantic period to be included in the Norton Anthology of English Literature (third edition, 1974).[53] The longest poem in the Lyrical Ballads was Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, which showed the Gothic side of English Romanticism, and the exotic settings that many works featured. In the period when the three were writing, the Lake Poets were widely regarded as a marginal group of radicals, though they were supported by the critic and writer William Hazlitt and others.  Portrait of Lord Byron by Thomas Phillips, c. 1813. The Byronic hero first reached the wider public in Byron's semi-autobiographical epic narrative poem Childe Harold's Pilgrimage (1812–1818). In contrast, Lord Byron and Walter Scott achieved enormous fame and influence throughout Europe with works exploiting the violence and drama of their exotic and historical settings;[54] Goethe called Byron "undoubtedly the greatest genius of our century".[55] Scott achieved immediate success with his long narrative poem The Lay of the Last Minstrel in 1805, followed by the full epic poem Marmion in 1808. Both were set in the distant Scottish past, already evoked in Ossian; Romanticism and Scotland were to have a long and fruitful partnership. Byron had equal success with the first part of Childe Harold's Pilgrimage in 1812, followed by four "Turkish tales", all in the form of long poems, starting with The Giaour in 1813, drawing from his Grand Tour, which had reached Ottoman Europe, and orientalizing the themes of the Gothic novel in verse. These featured different variations of the "Byronic hero", and his own life contributed a further version. Scott meanwhile was effectively inventing the historical novel, beginning in 1814 with Waverley, set in the 1745 Jacobite rising, which was a highly profitable success, followed by over 20 further Waverley Novels over the next 17 years, with settings going back to the Crusades that he had researched to a degree that was new in literature.[56] In contrast to Germany, Romanticism in English literature had little connection with nationalism, and the Romantics were often regarded with suspicion for the sympathy many felt for the ideals of the French Revolution, whose collapse and replacement with the dictatorship of Napoleon was, as elsewhere in Europe, a shock to the movement. Though his novels celebrated Scottish identity and history, Scott was politically a firm Unionist, but admitted to Jacobite sympathies. Several Romantics spent much time abroad, and a famous stay on Lake Geneva with Byron and Shelley in 1816 produced the hugely influential novel Frankenstein by Shelley's wife-to-be Mary Shelley and the novella The Vampyre by Byron's doctor John William Polidori. The lyrics of Robert Burns in Scotland, and Thomas Moore from Ireland, reflected in different ways their countries and the Romantic interest in folk literature, but neither had a fully Romantic approach to life or their work. Though they have modern critical champions such as György Lukács, Scott's novels are today more likely to be experienced in the form of the many operas that composers continued to base on them over the following decades, such as Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor and Vincenzo Bellini's I puritani (both 1835). Byron is now most highly regarded for his short lyrics and his generally unromantic prose writings, especially his letters, and his unfinished satire Don Juan.[57] Unlike many Romantics, Byron's widely publicised personal life appeared to match his work, and his death at 36 in 1824 from disease when helping the Greek War of Independence appeared from a distance to be a suitably Romantic end, entrenching his legend.[58] Keats in 1821 and Shelley in 1822 both died in Italy, Blake (at almost 70) in 1827, and Coleridge largely ceased to write in the 1820s. Wordsworth was by 1820 respectable and highly regarded, holding a government sinecure, but wrote relatively little. In the discussion of English literature, the Romantic period is often regarded as finishing around the 1820s, or sometimes even earlier, although many authors of the succeeding decades were no less committed to Romantic values. The most significant novelist in English during the peak Romantic period, other than Walter Scott, was Jane Austen, whose essentially conservative world-view had little in common with her Romantic contemporaries, retaining a strong belief in decorum and social rules, though critics such as Claudia L. Johnson have detected tremors under the surface of many works, such as Northanger Abbey (1817), Mansfield Park (1814) and Persuasion (1817).[59] But around the mid-century the undoubtedly Romantic novels of the Yorkshire-based Brontë family appeared, most notably Charlotte's Jane Eyre and Emily's Wuthering Heights, both published in 1847, which also introduced more Gothic themes. While these two novels were written and published after the Romantic period is said to have ended, their novels were heavily influenced by Romantic literature they had read as children. Byron, Keats, and Shelley all wrote for the stage, but with little success in England, with Shelley's The Cenci perhaps the best work produced, though that was not played in a public theatre in England until a century after his death. Byron's plays, along with dramatizations of his poems and Scott's novels, were much more popular on the Continent, and especially in France, and through these versions several were turned into operas, many still performed today. If contemporary poets had little success on the stage, the period was a legendary one for performances of Shakespeare, and went some way to restoring his original texts and removing the Augustan "improvements" to them. The greatest actor of the period, Edmund Kean, restored the tragic ending to King Lear;[60] Coleridge said that "Seeing him act was like reading Shakespeare by flashes of lightning."[61] |

グレートブリテン 主な記事 イギリスのロマン主義文学  ウィリアム・ワーズワース(写真)とサミュエル・テイラー・コールリッジは、1798年に共同で『リリカル・バラッド』を出版し、イギリス文学におけるロマン主義時代の幕開けに貢献した。 英文学において、ロマン主義運動の中心人物は、ウィリアム・ワーズワース、サミュエル・テイラー・コールリッジ、ジョン・キーツ、バイロン卿、パーシー・ ビシェ・シェリー、そしてかなり年長のウィリアム・ブレイクを含む詩人たちであり、後にジョン・クレアという孤高の人物がそれに続いた。1798年にワー ズワースとコールリッジの最も優れた詩の数々が収録された『Lyrical Ballads』が出版されたことが、この運動の始まりとされることが多い[51]。[リリカル・バラードの詩の大半はワーズワースによるもので、その多 くは彼の故郷である湖水地方の貧しい人々の生活や、自然に対する彼の感情を扱ったものである。しかし、この文学的マイルストーンは、ドロシー・ワーズワー スの『グラスミアの日記』に深く根ざしていた。この日記は、ウィリアムに豊かな詩的イメージや自然や感情についての考察(「翻弄され、揺れ動き、踊る」水 仙など[52])を提供するだけでなく、彼女が湖水地方を長く散歩している間に出会った、農村の貧しい人々の苦闘する姿についての痛切な観察も提供してい た[53]。ドロシー・ワーズワースの日記からの簡潔な抜粋は、『ノートン英文学集』(第3版、1974年)に収録されたロマン主義時代の女性による最初 の著作となった[53]。リリカル・バラッズの中で最も長い詩はコールリッジの『古代海人の詩(The Rime of the Ancient Mariner)』であり、イギリス・ロマン主義のゴシック的な側面と、多くの作品が取り上げたエキゾチックな設定を示している。この3人が執筆していた 時代、湖水詩人たちは、批評家・作家のウィリアム・ヘズリットらに支持されていたものの、急進派の境界グループとして広く見なされていた。  トーマス・フィリップスによるバイロン卿の肖像 1813年頃 バイロン的英雄が広く一般に知られるようになったのは、バイロンの半自伝的叙事詩『チャイルド・ハロルドの巡礼』(1812-1818)が最初である。 対照的に、バイロン卿とウォルター・スコットは、エキゾチックで歴史的な舞台の暴力とドラマを利用した作品で、ヨーロッパ全土で絶大な名声と影響力を獲得 した[54]。ゲーテはバイロンを「間違いなく今世紀最大の天才」と呼んだ[55]。スコットは1805年に長編叙事詩『最後の吟遊詩人の物語』を発表し てすぐに成功を収め、1808年には長編叙事詩『マーミオン』を発表した。ロマン主義とスコットランドは、長く実り多いパートナーシップを築くことにな る。バイロンは、1812年に『チャイルド・ハロルドの巡礼』の第一部で同じような成功を収め、その後、1813年の『ジアウール』から始まる4つの「ト ルコ物語」が長詩の形で発表された。これらの詩は「バイロニック・ヒーロー」の異なるヴァリエーションを特色とし、彼自身の人生がさらなるヴァリエーショ ンに貢献した。一方、スコットは事実上歴史小説を発明しており、1814年に1745年のジャコバイト蜂起を舞台とした『ウェイヴァリー』を発表して大き な成功を収め、その後17年間で20作以上の『ウェイヴァリー』が発表された。 ドイツとは対照的に、イギリス文学におけるロマン主義はナショナリズムとはほとんど関係がなく、ロマン派はフランス革命の理想に共感する者が多かったこと から疑惑の目で見られがちであったが、そのフランス革命が崩壊し、ナポレオンの独裁政治に取って代わられたことは、ヨーロッパの他の地域と同様、この運動 にとって衝撃的な出来事であった。スコットの小説はスコットランドのアイデンティティと歴史を讃えたものだったが、政治的にはユニオニストであり、ジャコ バイトへのシンパシーを認めていた。1816年、バイロンとシェリーがジュネーブ湖に滞在したことは有名で、シェリーの妻になるメアリー・シェリーの小説 『フランケンシュタイン』や、バイロンの主治医ジョン・ウィリアム・ポリドリの小説『吸血鬼』が大きな影響を与えた。スコットランドのロバート・バーンズ とアイルランドのトーマス・ムーアの歌詞は、異なる形でそれぞれの国やロマン派の民俗文学への関心を反映していたが、どちらも人生や作品に対する完全なロ マン派的アプローチを持っていなかった。 ギョルジ・ルカーチのような現代的な批評家もいるが、スコットの小説は今日、ドニゼッティの『ランメルモールのルチア』やヴィンチェンツォ・ベッリーニの 『イ・プリンターニ』(ともに1835年)など、その後数十年にわたって作曲家たちが原作とした数多くのオペラの形で体験されることが多い。バイロンが現 在最も高く評価されているのは、短い歌詞と、概してロマンティックではない散文、特に書簡、未完の風刺小説『ドン・ファン』である[57]。[多くのロマ ン派とは異なり、バイロンの私生活は広く公表され、彼の作品と一致しているように見えた。1824年、ギリシャ独立戦争に協力した際に病気で36歳の若さ で亡くなったことは、遠くから見れば、彼の伝説を定着させるにふさわしいロマンティックな最期であったように見えた[58]。1821年にキーツ、 1822年にシェリーがともにイタリアで亡くなり、1827年にはブレイク(70歳近く)が、1820年代にはコールリッジがほとんど執筆活動を停止し た。ワーズワースは1820年までには政府の重職に就くなど立派で高く評価されていたが、執筆活動は比較的少なかった。英文学の議論では、ロマン派時代は 1820年代頃、あるいはそれ以前に終わったとみなされることが多いが、その後の数十年間、ロマン派の価値観に傾倒した作家は少なくなかった。 ウォルター・スコットを除けば、ロマン派最盛期のイギリス文学で最も重要な小説家はジェーン・オースティンである。彼の本質的に保守的な世界観は、同時代 のロマン派作家たちとはほとんど共通点がなく、礼儀や社会的ルールを強く信奉していたが、クローディア・L・ジョンソンのような批評家は、その水面下の震 えを感じ取っている。しかし、クラウディア・L・ジョンソンなどの批評家は、『ノーサンガー・アビー』(1817年)、『マンスフィールド・パーク』 (1814年)、『説得』(1817年)など、多くの作品の水面下の震えを感知している[59] 。この2作はロマン主義の時代が終わった後に書かれ、出版されたと言われているが、彼らの小説は子供の頃に読んだロマン主義文学の影響を強く受けている。 バイロン、キーツ、シェリーはいずれも舞台のために書いたが、イギリスではほとんど成功せず、シェリーの『チェンチ』がおそらく最高の作品となったが、こ の作品がイギリスの公共劇場で上演されたのは、彼の死後100年経ってからだった。バイロンの戯曲は、彼の詩やスコットの小説のドラマ化とともに、大陸、 特にフランスではより人気があり、これらの版を通じていくつかの作品がオペラ化され、その多くは今日でも上演されている。同時代の詩人たちが舞台で成功す ることはほとんどなかったとしても、この時代はシェイクスピアの上演において伝説的な時代であり、彼の原典を復元し、アウグスト朝時代の「改良」を取り除 くことに一定の役割を果たした。この時代の最も偉大な俳優エドモンド・キーンは、『リア王』の悲劇的な結末を復元した[60]。コールリッジは、「彼の演 技を見るのは、稲妻の閃光でシェイクスピアを読むようだった」と述べている[61]。 |

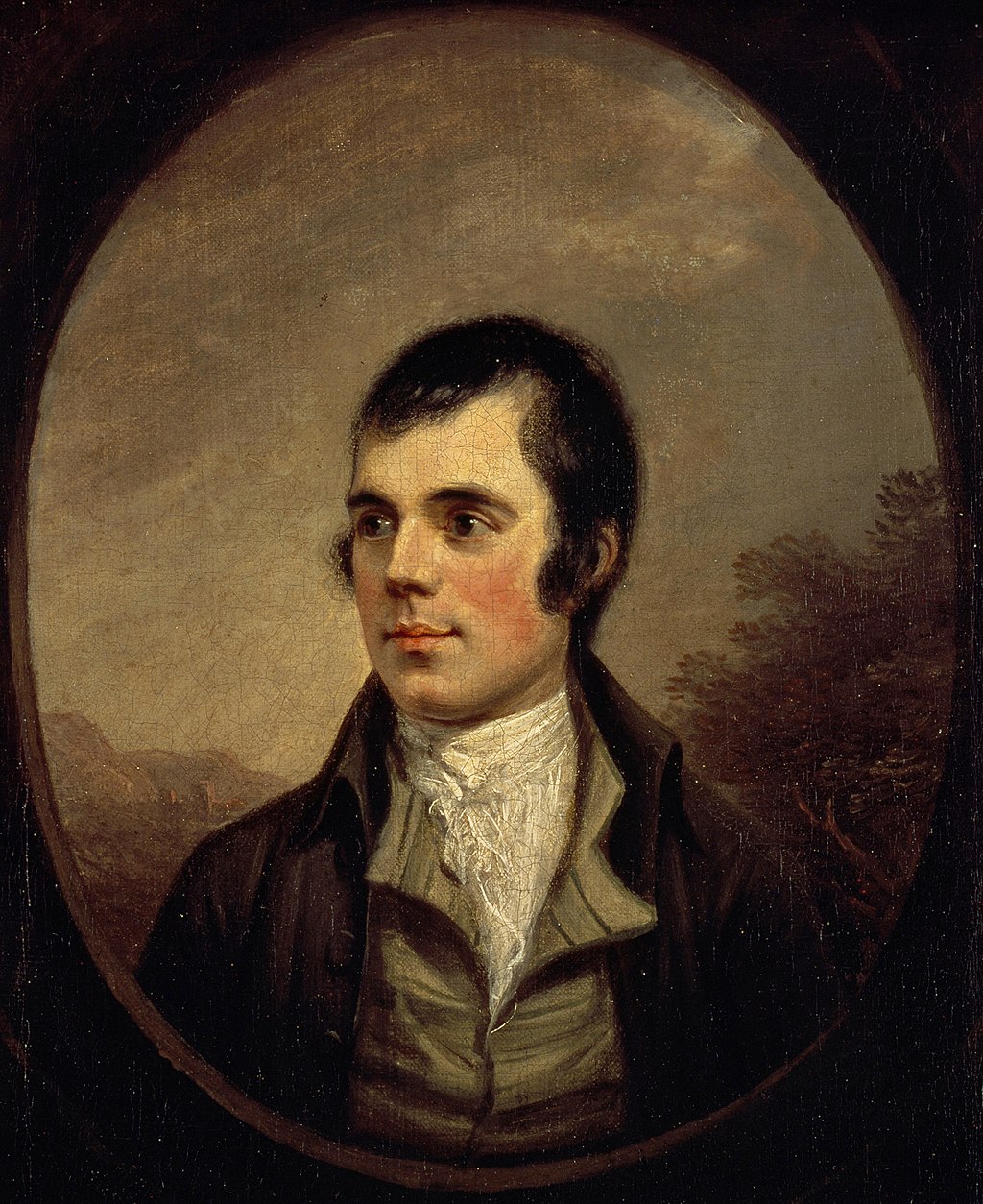

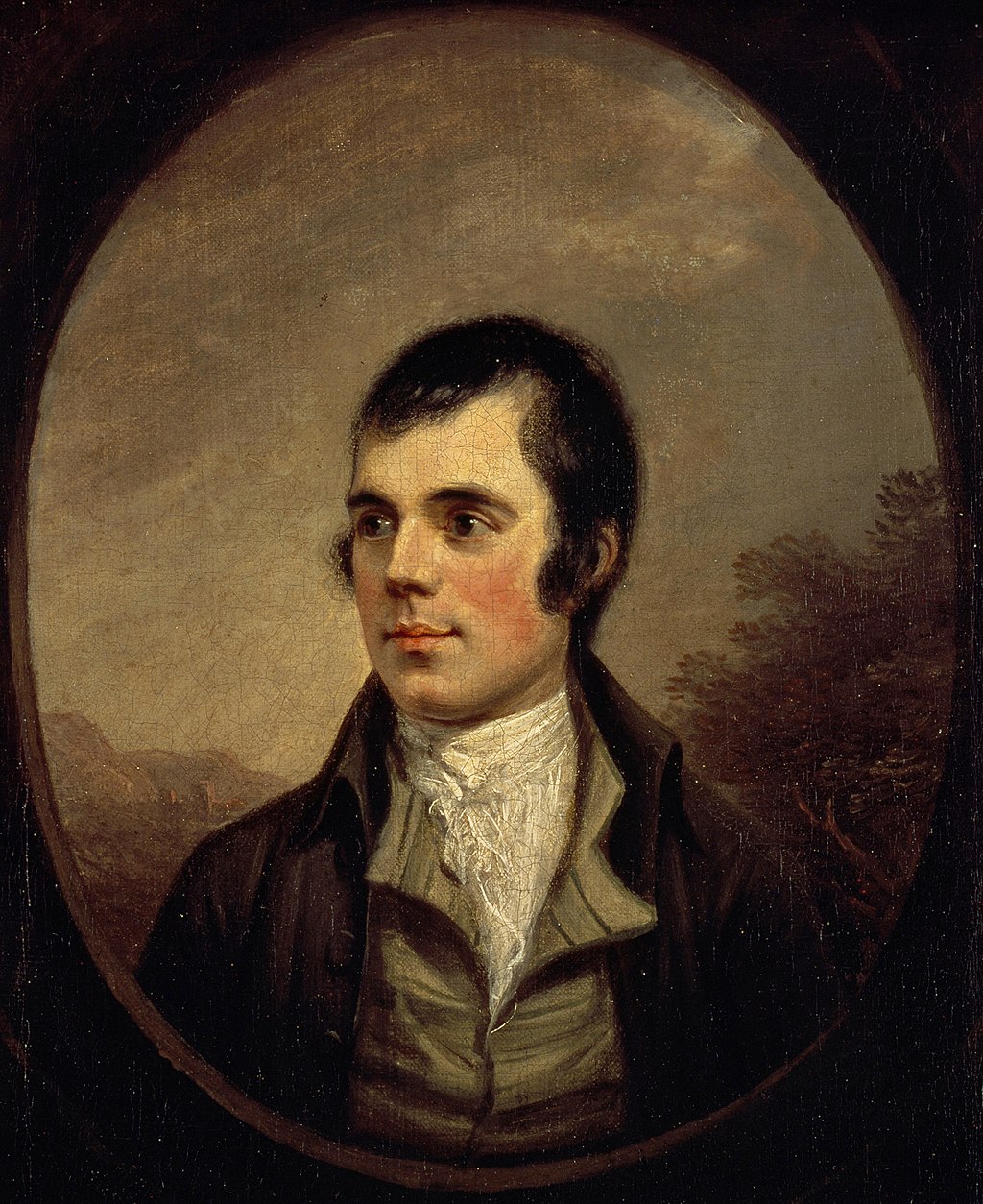

| Scotland Main article: Romanticism in Scotland  Robert Burns in Alexander Nasmyth's portrait of 1787 Although after union with England in 1707 Scotland increasingly adopted English language and wider cultural norms, its literature developed a distinct national identity and began to enjoy an international reputation. Allan Ramsay (1686–1758) laid the foundations of a reawakening of interest in older Scottish literature, as well as leading the trend for pastoral poetry, helping to develop the Habbie stanza as a poetic form.[62] James Macpherson (1736–1796) was the first Scottish poet to gain an international reputation. Claiming to have found poetry written by the ancient bard Ossian, he published translations that acquired international popularity, being proclaimed as a Celtic equivalent of the Classical epics. Fingal, written in 1762, was speedily translated into many European languages, and its appreciation of natural beauty and treatment of the ancient legend has been credited more than any single work with bringing about the Romantic movement in European, and especially in German literature, through its influence on Johann Gottfried von Herder and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.[63] It was also popularised in France by figures that included Napoleon.[64] Eventually it became clear that the poems were not direct translations from Scottish Gaelic, but flowery adaptations made to suit the aesthetic expectations of his audience.[65] Robert Burns (1759–96) and Walter Scott (1771–1832) were highly influenced by the Ossian cycle. Burns, an Ayrshire poet and lyricist, is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and a major influence on the Romantic movement. His poem (and song) "Auld Lang Syne" is often sung at Hogmanay (the last day of the year), and "Scots Wha Hae" served for a long time as an unofficial national anthem of the country.[66] Scott began as a poet and also collected and published Scottish ballads. His first prose work, Waverley in 1814, is often called the first historical novel.[67] It launched a highly successful career, with other historical novels such as Rob Roy (1817), The Heart of Midlothian (1818) and Ivanhoe (1820). Scott probably did more than any other figure to define and popularise Scottish cultural identity in the nineteenth century.[68] Other major literary figures connected with Romanticism include the poets and novelists James Hogg (1770–1835), Allan Cunningham (1784–1842) and John Galt (1779–1839).[69]  Raeburn's portrait of Walter Scott in 1822 Scotland was also the location of two of the most important literary magazines of the era, The Edinburgh Review (founded in 1802) and Blackwood's Magazine (founded in 1817), which had a major impact on the development of British literature and drama in the era of Romanticism.[70][71] Ian Duncan and Alex Benchimol suggest that publications like the novels of Scott and these magazines were part of a highly dynamic Scottish Romanticism that by the early nineteenth century, caused Edinburgh to emerge as the cultural capital of Britain and become central to a wider formation of a "British Isles nationalism".[72] Scottish "national drama" emerged in the early 1800s, as plays with specifically Scottish themes began to dominate the Scottish stage. Theatres had been discouraged by the Church of Scotland and fears of Jacobite assemblies. In the later eighteenth century, many plays were written for and performed by small amateur companies and were not published and so most have been lost. Towards the end of the century there were "closet dramas", primarily designed to be read, rather than performed, including work by Scott, Hogg, Galt and Joanna Baillie (1762–1851), often influenced by the ballad tradition and Gothic Romanticism.[73] |

スコットランド 主な記事 スコットランドのロマン主義  1787年のアレクサンダー・ナスマイスの肖像画に描かれたロバート・バーンズ 1707年にイングランドと統合された後、スコットランドは英語と幅広い文化的規範を採用するようになったが、その文学は独自の国民的アイデンティティを 確立し、国際的な名声を得るようになった。アラン・ラムジー(Allan Ramsay, 1686-1758)は、古いスコットランド文学への関心を再び呼び起こす基礎を築いただけでなく、牧歌的な詩の流行を先導し、詩の形式としてハビー (Habbie)連作の発展に貢献した[62]。古代の吟遊詩人オシアンが書いた詩を見つけたと主張する彼は、古典叙事詩に匹敵するケルト叙事詩と謳われ る翻訳を発表し、国際的な人気を博した。1762年に書かれた『フィンガル』は瞬く間にヨーロッパの多くの言語に翻訳され、その自然美の評価と古代の伝説 の扱いは、ヨハン・ゴットフリート・フォン・ヘルダーやヨハン・ヴォルフガング・フォン・ゲーテに影響を与えたことで、ヨーロッパ、特にドイツ文学にロマ ン主義的なムーブメントをもたらしたとされる。 ロバート・バーンズ(1759-96)とウォルター・スコット(1771-1832)はオシアン・サイクルの影響を強く受けた。エアシャーの詩人であり作 詞家であったバーンズは、スコットランドの国民詩人であり、ロマン主義運動に大きな影響を与えた人物として広く知られている。彼の詩(と歌)である 「Auld Lang Syne 」はホグマネイ(1年の最後の日)によく歌われ、「Scots Wha Hae 」は長い間スコットランドの非公式国歌として歌われていた[66]。彼の最初の散文作品である『ウェイヴァリー』(1814年)は、しばしば最初の歴史小 説と呼ばれる[67]。この作品は、『ロブ・ロイ』(1817年)、『ミッドロシアンの心』(1818年)、『アイヴァンホー』(1820年)などの歴史 小説とともに、大成功を収めた。スコットは、19世紀におけるスコットランドの文化的アイデンティティを定義し、普及させるのに、おそらく他のどの人物よ りも貢献した[68]。ロマン主義に関係する他の主要な文学者には、詩人・小説家のジェームズ・ホッグ(1770-1835)、アラン・カニンガム (1784-1842)、ジョン・ガルト(1779-1839)などがいる[69]。  1822年、レイバーンが描いたウォルター・スコットの肖像画 スコットランドはまた、当時の最も重要な2つの文芸雑誌、『エジンバラ・レヴュー』(1802年創刊)と『ブラックウッド・マガジン』(1817年創刊) の所在地でもあり、ロマン主義の時代のイギリス文学と演劇の発展に大きな影響を与えた。[70][71]イアン・ダンカンとアレックス・ベンチモルは、ス コットの小説やこれらの雑誌のような出版物は非常にダイナミックなスコットランド・ロマン主義の一部であり、19世紀初頭にはエディンバラをイギリスの文 化的首都として浮上させ、「イギリス諸島のナショナリズム」の広範な形成の中心となったと示唆している[72]。 スコットランドの「ナショナリズム」は1800年代初頭に出現し、特にスコットランドをテーマとした演劇がスコットランドの舞台を支配するようになった。 劇場は、スコットランド教会とジャコバイトの集会を恐れて、その活動を抑制していた。18世紀後半には、多くの戯曲が小さなアマチュア劇団のために書か れ、上演された。世紀末には、スコット、ホッグ、ガルト、ジョアンナ・ベイリー(1762年~1851年)など、バラッドの伝統やゴシック・ロマン主義の 影響を受けた、上演されるよりもむしろ読まれることを主目的とした「クローゼット・ドラマ」が上演された[73]。 |

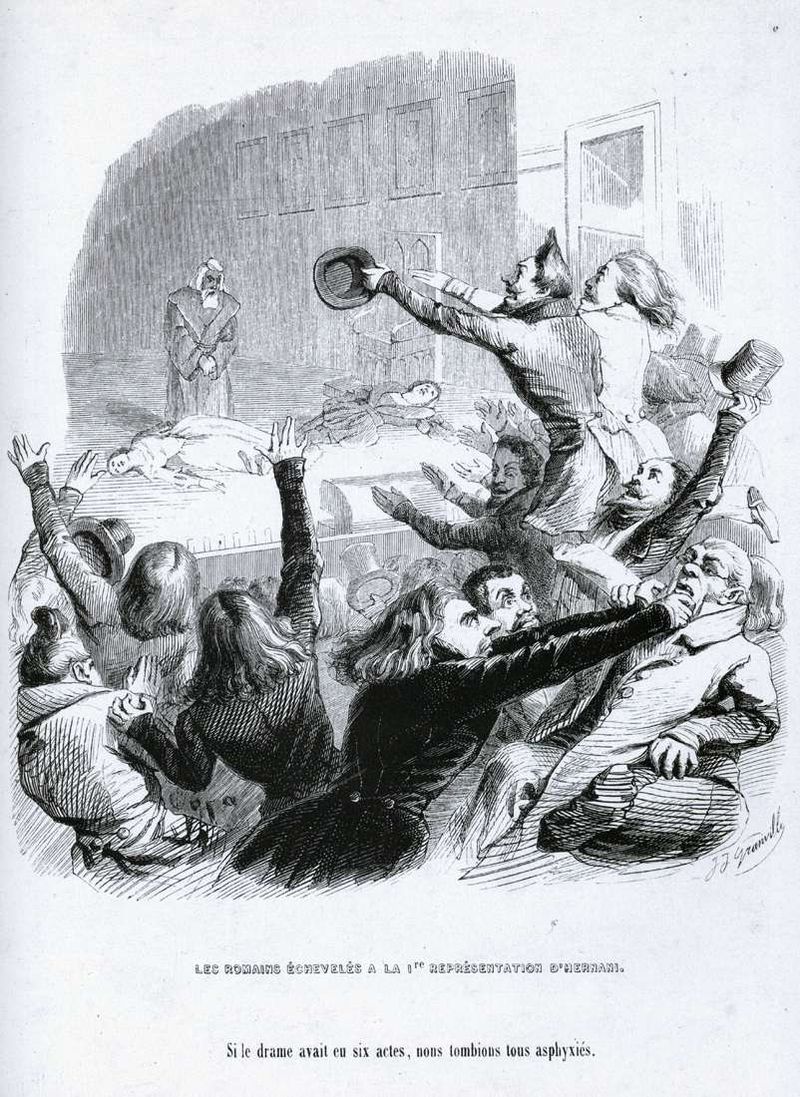

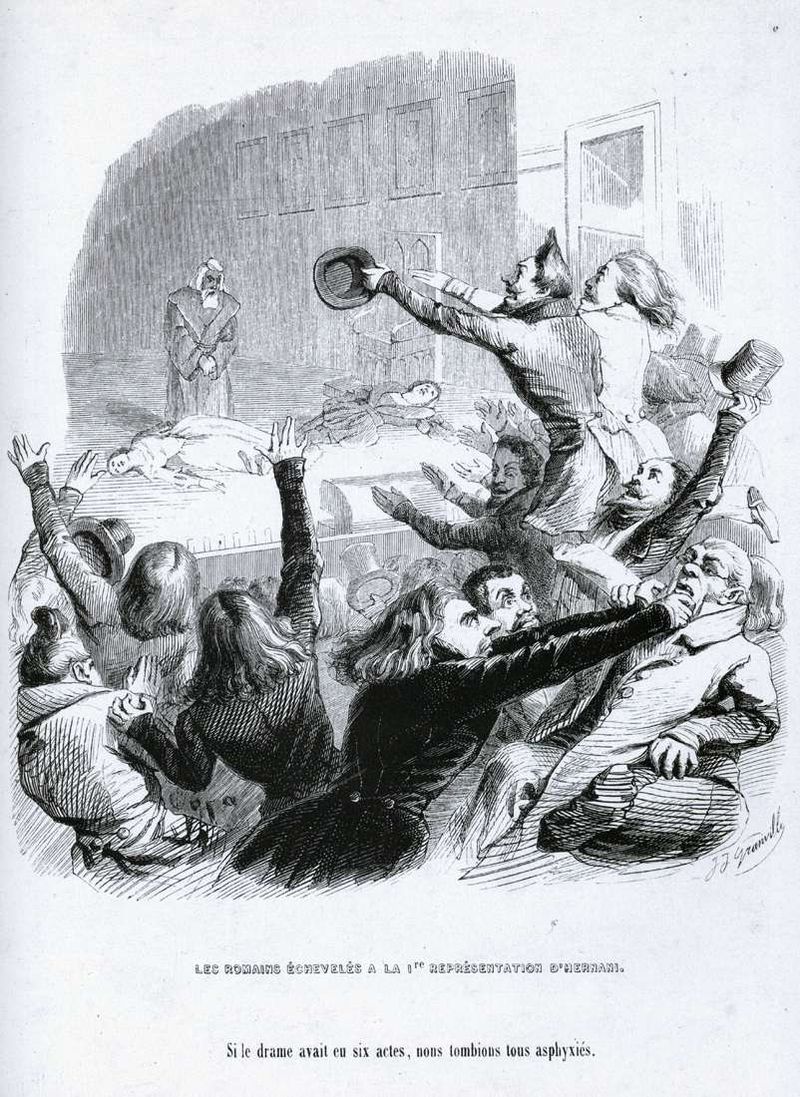

| France Main article: Romanticism in France Romanticism was relatively late in developing in French literature, more so than in the visual arts. The 18th-century precursor to Romanticism, the cult of sensibility, had become associated with the Ancien Régime, and the French Revolution had been more of an inspiration to foreign writers than those experiencing it at first-hand. The first major figure was François-René de Chateaubriand, an aristocrat who had remained a royalist throughout the Revolution, and returned to France from exile in England and America under Napoleon, with whose regime he had an uneasy relationship. His writings, all in prose, included some fiction, such as his influential novella of exile René (1802), which anticipated Byron in its alienated hero, but mostly contemporary history and politics, his travels, a defence of religion and the medieval spirit (Génie du christianisme, 1802), and finally in the 1830s and 1840s his enormous autobiography Mémoires d'Outre-Tombe ("Memoirs from beyond the grave").[74]  The "battle of Hernani" was fought nightly at the theatre in 1830: lithograph, by J. J. Grandville After the Bourbon Restoration, French Romanticism developed in the lively world of Parisian theatre, with productions of Shakespeare, Schiller (in France a key Romantic author), and adaptations of Scott and Byron alongside French authors, several of whom began to write in the late 1820s. Cliques of pro- and anti-Romantics developed, and productions were often accompanied by raucous vocalizing by the two sides, including the shouted assertion by one theatregoer in 1822 that "Shakespeare, c'est l'aide-de-camp de Wellington" ("Shakespeare is Wellington's aide-de-camp").[75] Alexandre Dumas began as a dramatist, with a series of successes beginning with Henri III et sa cour (1829) before turning to novels that were mostly historical adventures somewhat in the manner of Scott, most famously The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo, both of 1844. Victor Hugo published as a poet in the 1820s before achieving success on the stage with Hernani—a historical drama in a quasi-Shakespearean style that had famously riotous performances on its first run in 1830.[76] Like Dumas, Hugo is best known for his novels, and was already writing The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831), one of the best known works, which became a paradigm of the French Romantic movement. The preface to his unperformed play Cromwell gives an important manifesto of French Romanticism, stating that "there are no rules, or models". The career of Prosper Mérimée followed a similar pattern; he is now best known as the originator of the story of Carmen, with his novella published 1845. Alfred de Vigny remains best known as a dramatist, with his play on the life of the English poet Chatterton (1835) perhaps his best work. George Sand was a central figure of the Parisian literary scene, famous both for her novels and criticism and her affairs with Chopin and several others;[77] she too was inspired by the theatre, and wrote works to be staged at her private estate. French Romantic poets of the 1830s to 1850s include Alfred de Musset, Gérard de Nerval, Alphonse de Lamartine and the flamboyant Théophile Gautier, whose prolific output in various forms continued until his death in 1872. Stendhal is today probably the most highly regarded French novelist of the period, but he stands in a complex relation with Romanticism, and is notable for his penetrating psychological insight into his characters and his realism, qualities rarely prominent in Romantic fiction. As a survivor of the French retreat from Moscow in 1812, fantasies of heroism and adventure had little appeal for him, and like Goya he is often seen as a forerunner of Realism. His most important works are Le Rouge et le Noir (The Red and the Black, 1830) and La Chartreuse de Parme (The Charterhouse of Parma, 1839). |

フランス 主な記事 フランスにおけるロマン主義 ロマン主義は、視覚芸術よりもフランス文学において比較的遅れて発展した。ロマン主義の前身である18世紀の感性崇拝は、アンシャン・レジームと結びつい ており、フランス革命は、それを直接体験した人々よりも、外国人作家にインスピレーションを与えるものであった。最初の主要人物はフランソワ=ルネ・ド・ シャトーブリアンである。貴族であった彼は、革命後も王党派を貫き、ナポレオン政権下のイギリスとアメリカへの亡命からフランスに戻ったが、ナポレオン政 権とは不穏な関係にあった。彼の著作はすべて散文で、疎外された主人公がバイロンを先取りした影響力のある亡命小説『ルネ』(1802年)のようなフィク ションもあったが、ほとんどは現代の歴史と政治、旅行、宗教と中世精神の擁護(『クリスチャニスムの擁護』1802年)、そして最後に1830年代と 1840年代には膨大な自伝『墓の向こうからの回想録』(Mémoires d'Outre-Tombe)がある[74]。  1830年、劇場で毎晩繰り広げられた「エルナーニの戦い」:J.J.グランヴィル作、リトグラフ ブルボン王政復古の後、フランス・ロマン主義はパリの活気ある演劇界で発展し、シェイクスピア、シラー(フランスではロマン主義の重要な作家)、スコット やバイロンの翻案が上演され、1820年代後半には何人かのフランス人作家が執筆を始めた。親ロマン派と反ロマン派の徒党が形成され、1822年にはある 観客が「シェイクスピアはウェリントンの副官だ」と叫ぶなど、両派による騒々しい声が上演された。[75]アレクサンドル・デュマは劇作家として出発し、 『アンリ3世と宮廷』(1829年)で始まる一連の成功を収めた後、1844年の『三銃士』や『モンテ・クリスト伯』など、ややスコット風の歴史冒険小説 に転向した。ヴィクトル・ユーゴーは1820年代に詩人として発表した後、1830年に初演された『エルナーニ』(シェイクスピア風の歴史劇で、暴動が起 きたことで有名)で舞台で成功を収めた[76]。デュマと同様、ユーゴーは小説で最もよく知られており、すでに代表作のひとつである『ノートルダムのせむ し男』(1831年)を執筆していた。未演出の戯曲『クロムウェル』の序文には、フランス・ロマン主義の重要な宣言が記されている。プロスペル・メリメの キャリアも似たようなパターンを辿った。彼は1845年に発表した小説『カルメン』の創作者として現在最もよく知られている。アルフレッド・ド・ヴィニー は戯曲家として最もよく知られており、イギリスの詩人チャタートンの生涯を描いた戯曲(1835年)が彼の代表作であろう。ジョルジュ・サンドはパリの文 壇の中心人物で、小説や批評、ショパンをはじめとする数人の女性との関係で有名であった[77]。 1830年代から1850年代にかけてのフランス・ロマン派の詩人には、アルフレッド・ド・ミュッセ、ジェラール・ド・ネルヴァル、アルフォンス・ド・ラマルティーヌ、華やかなテオフィル・ゴーティエなどがいる。 スタンダールは今日、この時代のフランスの小説家として最も高く評価されているが、ロマン主義とは複雑な関係にあり、登場人物に対する鋭い心理的洞察力 と、ロマン主義小説ではめったに目立たないリアリズムで注目されている。1812年にモスクワから撤退したフランスの生き残りである彼にとって、ヒロイズ ムや冒険のファンタジーはほとんど魅力的ではなく、ゴヤと同様にリアリズムの先駆者と見なされることが多い。代表作は『赤と黒』(Le Rouge et le Noir, 1830)と『パルマのシャルトルーズ』(La Chartreuse de Parme, 1839)である。 |

Poland Adam Mickiewicz on the Ayu-Dag, by Walenty Wańkowicz, 1828 Main article: Romanticism in Poland Romanticism in Poland is often taken to begin with the publication of Adam Mickiewicz's first poems in 1822, and end with the crushing of the January Uprising of 1863 against the Russians. It was strongly marked by interest in Polish history.[78] Polish Romanticism revived the old "Sarmatism" traditions of the szlachta or Polish nobility. Old traditions and customs were revived and portrayed in a positive light in the Polish messianic movement and in works of great Polish poets such as Adam Mickiewicz (Pan Tadeusz), Juliusz Słowacki and Zygmunt Krasiński. This close connection between Polish Romanticism and Polish history became one of the defining qualities of the literature of Polish Romanticism period, differentiating it from that of other countries. They had not suffered the loss of national statehood as was the case with Poland.[79] Influenced by the general spirit and main ideas of European Romanticism, the literature of Polish Romanticism is unique, as many scholars have pointed out, in having developed largely outside of Poland and in its emphatic focus upon the issue of Polish nationalism. The Polish intelligentsia, along with leading members of its government, left Poland in the early 1830s, during what is referred to as the "Great Emigration", resettling in France, Germany, Great Britain, Turkey, and the United States.  Juliusz Słowacki, a Polish poet considered one of the "Three National Bards" of Polish literature—a major figure in the Polish Romantic period, and the father of modern Polish drama. Their art featured emotionalism and irrationality, fantasy and imagination, personality cults, folklore and country life, and the propagation of ideals of freedom. In the second period, many of the Polish Romantics worked abroad, often banished from Poland by the occupying powers due to their politically subversive ideas. Their work became increasingly dominated by the ideals of political struggle for freedom and their country's sovereignty. Elements of mysticism became more prominent. There developed the idea of the poeta wieszcz (the prophet). The wieszcz (bard) functioned as spiritual leader to the nation fighting for its independence. The most notable poet so recognized was Adam Mickiewicz. Zygmunt Krasiński also wrote to inspire political and religious hope in his countrymen. Unlike his predecessors, who called for victory at whatever price in Poland's struggle against Russia, Krasinski emphasized Poland's spiritual role in its fight for independence, advocating an intellectual rather than a military superiority. His works best exemplify the Messianic movement in Poland: in two early dramas, Nie-boska komedia (1835; The Undivine Comedy) and Irydion (1836; Iridion), as well as in the later Psalmy przyszłości (1845), he asserted that Poland was the Christ of Europe: specifically chosen by God to carry the world's burdens, to suffer, and eventually be resurrected. |

ポーランド ワレンティ・ワンコヴィッチ作「アユダグに乗るアダム・ミツキェヴィチ」1828年 主な記事 ポーランドのロマン主義 ポーランドのロマン主義は、1822年のアダム・ミツキェヴィチの最初の詩の出版に始まり、1863年のロシアに対する1月蜂起の鎮圧で終わるとされるこ とが多い。ポーランドのロマン主義は、ポーランド貴族の古い「サルマティズム」の伝統を復活させた。古い伝統や風習は、ポーランドの救世主運動やアダム・ ミツキェヴィチ(パン・タデウシュ)、ユリウシュ・スウォヴァツキ、ジグムント・クラシンスキといったポーランドの偉大な詩人たちの作品の中で復活し、肯 定的に描かれた。このポーランド・ロマン主義とポーランドの歴史との密接な結びつきは、ポーランド・ロマン主義期の文学を他国の文学と区別する決定的な特 質のひとつとなった。多くの研究者が指摘するように、ヨーロッパ・ロマン主義の一般的な精神と主要な思想の影響を受けたポーランド・ロマン主義の文学は、 ポーランド以外の国で発展し、ポーランドのナショナリズムの問題に焦点を当てた点で独特である。ポーランドの知識階級は、政府の主要メンバーとともに 1830年代初頭にポーランドを離れ、フランス、ドイツ、イギリス、トルコ、アメリカに移住した。  ユリウシュ・スウォヴァツキは、ポーランド文学の「三国民吟遊詩人」の一人とされる詩人で、ポーランド・ロマン派の中心人物であり、ポーランド近代演劇の父である。 彼らの芸術は、感情主義と非合理性、空想と想像力、人格崇拝、フォークロアと田舎暮らし、自由の理想の宣伝を特徴とした。第二期では、ポーランド・ロマン 派の多くが外国で活動し、その政治的破壊思想のために占領国から追放されることも多かった。彼らの作品は、自由と自国の主権を求める政治闘争の理想にます ます支配されるようになった。神秘主義の要素も目立つようになった。そこでは、詩人ヴィエシュチ(預言者)の思想が発展した。ヴィエシュチ(吟遊詩人) は、独立のために戦う国民の精神的指導者として機能した。最も有名な詩人はアダム・ミツキェヴィッチである。 ジグムント・クラシンスキもまた、同胞に政治的・宗教的な希望を抱かせるために書いた。クラシンスキは、ポーランドのロシアとの闘いにおいていかなる代償 を払っても勝利することを求めた先人たちとは異なり、独立のための闘いにおけるポーランドの精神的役割を強調し、軍事的優位性よりもむしろ知的優位性を提 唱した。初期の2つの戯曲『ニエボスカ・コメディア』(Nie-boska komedia、1835年)と『イリディオン』(Irydion、1836年)、および後期の『詩篇』(Psalmy przyszłości、1845年)では、ポーランドはヨーロッパのキリストであり、世界の苦悩を背負い、苦悩し、やがて復活するために神によって特別 に選ばれたと主張した。 |

| Russia Early Russian Romanticism is associated with the writers Konstantin Batyushkov (A Vision on the Shores of the Lethe, 1809), Vasily Zhukovsky (The Bard, 1811; Svetlana, 1813) and Nikolay Karamzin (Poor Liza, 1792; Julia, 1796; Martha the Mayoress, 1802; The Sensitive and the Cold, 1803). However the principal exponent of Romanticism in Russia is Alexander Pushkin (The Prisoner of the Caucasus, 1820–1821; The Robber Brothers, 1822; Ruslan and Ludmila, 1820; Eugene Onegin, 1825–1832). Pushkin's work influenced many writers in the 19th century and led to his eventual recognition as Russia's greatest poet.[80] Other Russian Romantic poets include Mikhail Lermontov (A Hero of Our Time, 1839), Fyodor Tyutchev (Silentium!, 1830), Yevgeny Baratynsky (Eda, 1826), Anton Delvig, and Wilhelm Küchelbecker. Influenced heavily by Lord Byron, Lermontov sought to explore the Romantic emphasis on metaphysical discontent with society and self, while Tyutchev's poems often described scenes of nature or passions of love. Tyutchev commonly operated with such categories as night and day, north and south, dream and reality, cosmos and chaos, and the still world of winter and spring teeming with life. Baratynsky's style was fairly classical in nature, dwelling on the models of the previous century. |

ロシア 初期のロシア・ロマン主義は、コンスタンチン・バチューシコフ(『レテ河畔の幻影』1809年)、ワシーリー・ジューコフスキー(『吟遊詩人』1811 年、『スヴェトラーナ』1813年)、ニコライ・カラムジン(『哀れなリザ』1792年、『ユリア』1796年、『市長夫人マルタ』1802年、『敏感と 冷淡』1803年)といった作家と結びついている。しかし、ロシアにおけるロマン主義の代表者はアレクサンドル・プーシキンである(『コーカサスの囚人』 1820-1821年、『強盗兄弟』1822年、『ルスランとリュドミラ』1820年、『オイゲーヌ・オネーギン』1825-1832年)。プーシキンの 作品は19世紀の多くの作家に影響を与え、最終的にはロシアで最も偉大な詩人として認められるに至った[80]。 その他のロシア・ロマン派の詩人としては、ミハイル・レールモントフ(『現代の英雄』1839年)、フョードル・チュチェフ(『サイレンチウム!』 1830年)、エフゲニー・バラチンスキー(『イーダ』1826年)、アントン・デルヴィッヒ、ヴィルヘルム・キュッヘルベッカーなどが挙げられる。 バイロン卿の影響を強く受けたレールモントフは、社会や自己に対する形而上学的な不満を強調するロマン派を探求しようとしたが、チュチェフの詩は自然の情 景や愛の情熱を描写することが多かった。チュチェフは、夜と昼、北と南、夢と現実、宇宙と混沌、生命に満ち溢れた冬と春の静寂の世界といったカテゴリーを よく用いていた。バラチンスキーの作風はかなり古典的で、前世紀のモデルを踏襲している。 |

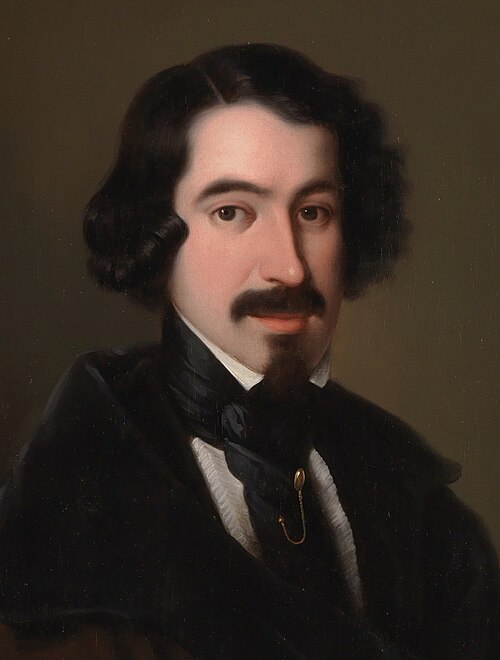

| Spain Main article: Romanticism in Spanish literature  El escritor José de Espronceda, portrait by Antonio María Esquivel (c. 1845) (Museo del Prado, Madrid)[81] Romanticism in Spanish literature developed a well-known literature with a huge variety of poets and playwrights. The most important Spanish poet during this movement was José de Espronceda. After him there were other poets like Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, Mariano José de Larra and the dramatists Ángel de Saavedra and José Zorrilla, author of Don Juan Tenorio. Before them may be mentioned the pre-romantics José Cadalso and Manuel José Quintana.[82] The plays of Antonio García Gutiérrez were adapted to produce Giuseppe Verdi's operas Il trovatore and Simon Boccanegra. Spanish Romanticism also influenced regional literatures. For example, in Catalonia and in Galicia there was a national boom of writers in the local languages, like the Catalan Jacint Verdaguer and the Galician Rosalía de Castro, the main figures of the national revivalist movements Renaixença and Rexurdimento, respectively.[83] There are scholars who consider Spanish Romanticism to be Proto-Existentialism because it is more anguished than the movement in other European countries. Foster et al., for example, say that the work of Spain's writers such as Espronceda, Larra, and other writers in the 19th century demonstrated a "metaphysical crisis".[84] These observers put more weight on the link between the 19th-century Spanish writers with the existentialist movement that emerged immediately after. According to Richard Caldwell, the writers that we now identify with Spain's romanticism were actually precursors to those who galvanized the literary movement that emerged in the 1920s.[85] This notion is the subject of debate for there are authors who stress that Spain's romanticism is one of the earliest in Europe,[86] while some assert that Spain really had no period of literary romanticism.[87] This controversy underscores a certain uniqueness to Spanish Romanticism in comparison to its European counterparts. |

スペイン 主な記事 スペイン文学におけるロマン主義  作家ホセ・デ・エスプロンセダ、アントニオ・マリア・エスキベルによる肖像画(1845年頃)(マドリード、プラド美術館)[81]。 スペイン文学におけるロマン主義は、多種多様な詩人や劇作家を擁する有名な文学を発展させた。この運動で最も重要な詩人はホセ・デ・エスプロンセダであ る。彼の後にも、グスタボ・アドルフォ・ベッケール、マリアーノ・ホセ・デ・ララ、アンヘル・デ・サーベドラ、『ドン・ファン・テノリオ』の作者ホセ・ゾ リーリャといった詩人たちがいる。アントニオ・ガルシア・グティエレスの戯曲は、ジュゼッペ・ヴェルディのオペラ『イル・トロヴァトーレ』や『シモン・ ボッカネグラ』のために脚色された。スペイン・ロマン主義は、地方文学にも影響を与えた。例えば、カタルーニャとガリシアでは、それぞれナショナリズム運 動ルネクセンサとレクスルディメントの中心人物であったカタルーニャ人のジャシント・ベルダゲールやガリシア人のロザリア・デ・カストロのような、その地 方の言語で書かれた作家の国民的ブームが起こった[83]。 スペインのロマン主義が他のヨーロッパ諸国の運動よりも苦悩に満ちていることから、スペイン・ロマン主義をプロト=実存主義とみなす学者もいる。例えば、 フォスターらは、エスプロンセダ、ララなどの19世紀のスペインの作家たちの作品は「形而上学的危機」を示していたと述べている[84]。 これらの観察者たちは、19世紀のスペインの作家たちとその直後に現れた実存主義運動との結びつきをより重視している。リチャード・コールドウェルによれ ば、現在私たちがスペインのロマン主義と認識している作家たちは、実際には1920年代に勃興した文学運動を活性化させた作家たちの先駆者であった [85]。この考え方は議論の対象であり、スペインのロマン主義はヨーロッパで最も早い時期のものであると強調する作家がいる一方で[86]、スペインに は文学的ロマン主義の時期が実際にはなかったと主張する作家もいる。 |

Portugal Portuguese poet, novelist, politician and playwright Almeida Garrett (1799–1854) Romanticism began in Portugal with the publication of the poem Camões (1825), by Almeida Garrett, who was raised by his uncle D. Alexandre, bishop of Angra, in the precepts of Neoclassicism, which can be observed in his early work. The author himself confesses (in Camões' preface) that he voluntarily refused to follow the principles of epic poetry enunciated by Aristotle in his Poetics, as he did the same to Horace's Ars Poetica. Almeida Garrett had participated in the 1820 Liberal Revolution, which caused him to exile himself in England in 1823 and then in France, after the Vila-Francada. While living in Great Britain, he had contacts with the Romantic movement and read authors such as Shakespeare, Scott, Ossian, Byron, Hugo, Lamartine and de Staël, at the same time visiting feudal castles and ruins of Gothic churches and abbeys, which would be reflected in his writings. In 1838, he presented Um Auto de Gil Vicente ("A Play by Gil Vicente"), in an attempt to create a new national theatre, free of Greco-Roman and foreign influence. But his masterpiece would be Frei Luís de Sousa (1843), named by himself as a "Romantic drama" and it was acclaimed as an exceptional work, dealing with themes as national independence, faith, justice and love. He was also deeply interested in Portuguese folkloric verse, which resulted in the publication of Romanceiro ("Traditional Portuguese Ballads") (1843), that recollect a great number of ancient popular ballads, known as "romances" or "rimances", in redondilha maior verse form, that contained stories of chivalry, life of saints, crusades, courtly love, etc. He wrote the novels Viagens na Minha Terra, O Arco de Sant'Ana and Helena.[88][89][90] Alexandre Herculano is, alongside Almeida Garrett, one of the founders of Portuguese Romanticism. He too was forced to exile to Great Britain and France because of his liberal ideals. All of his poetry and prose are (unlike Almeida Garrett's) entirely Romantic, rejecting Greco-Roman myth and history. He sought inspiration in medieval Portuguese poems and chronicles as in the Bible. His output is vast and covers many different genres, such as historical essays, poetry, novels, opuscules and theatre, where he brings back a whole world of Portuguese legends, tradition and history, especially in Eurico, o Presbítero ("Eurico, the Priest") and Lendas e Narrativas ("Legends and Narratives"). His work was influenced by Chateaubriand, Schiller, Klopstock, Walter Scott and the Old Testament Psalms.[91] António Feliciano de Castilho made the case for Ultra-Romanticism, publishing the poems A Noite no Castelo ("Night in the Castle") and Os Ciúmes do Bardo ("The Jealousy of the Bard"), both in 1836, and the drama Camões. He became an unquestionable master for successive Ultra-Romantic generations, whose influence would not be challenged until the famous Coimbra Question. He also created polemics by translating Goethe's Faust without knowing German, but using French versions of the play. Other notable figures of Portuguese Romanticism are the famous novelists Camilo Castelo Branco and Júlio Dinis, and Soares de Passos, Bulhão Pato and Pinheiro Chagas.[90] Romantic style would be revived in the beginning of the 20th century, notably through the works of poets linked to the Portuguese Renaissance, such as Teixeira de Pascoais, Jaime Cortesão, Mário Beirão, among others, who can be considered Neo-Romantics. An early Portuguese expression of Romanticism is found already in poets such as Manuel Maria Barbosa du Bocage (especially in his sonnets dated at the end of the 18th century) and Leonor de Almeida Portugal, Marquise of Alorna.[90] |

ポルトガル ポルトガルの詩人、小説家、政治家、劇作家 アルメイダ・ギャレット(1799-1854) アルメイダ・ギャレットは、叔父であるアングラ司教D.アレクサンドルによって新古典主義の薫陶を受けて育ったが、彼の初期の作品にはその薫陶が見て取れ る。作者自身、アリストテレスが『詩学』の中で唱えた叙事詩の原則に従うことを自ら拒否したと告白している(カモンイスの序文)。アルメイダ・ギャレット は、1820年の自由主義革命に参加し、そのために1823年にイギリスに亡命し、ヴィラ=フランカーダ事件後はフランスに亡命した。イギリス滞在中、ロ マン主義運動と接触し、シェイクスピア、スコット、オシアン、バイロン、ウーゴ、ラマルティーヌ、ド・スタールなどの作家を読むと同時に、封建的な城やゴ シック様式の教会や修道院の廃墟を訪れ、それが彼の著作に反映されることになる。1838年には、グレコローマンや外国の影響を排除した新しい国民劇場を 作ろうと、『ジル・ヴィセンテの戯曲』(Um Auto de Gil Vicente)を上演した。しかし、彼の最高傑作は『フレイ・ルイス・デ・ソウザ』(1843年)で、彼自身が「ロマンティック劇」と名付け、民族の独 立、信仰、正義、愛といったテーマを扱った類まれな作品として高く評価された。また、ポルトガルの民謡にも深い関心を寄せ、『ロマンスイロ』(『ポルトガ ルの伝統的なバラッド』)(1843年)を出版した。このバラッドには、騎士道、聖人の生涯、十字軍、宮廷の愛などの物語が含まれ、「ロマンス」または 「リマンセ」と呼ばれる古代の民衆のバラッドがルドンディリャ・マイオール詩の形式で数多く収録されている。彼は小説『Viagens na Minha Terra』、『O Arco de Sant'Ana』、『Helena』を書いた[88][89][90]。 アレクサンドル・ヘルクラーノは、アルメイダ・ギャレットと並んで、ポルトガル・ロマン主義の創始者の一人である。彼もまた、そのリベラルな思想のために イギリスやフランスへの亡命を余儀なくされた。彼の詩と散文はすべて(アルメイダ・ギャレットとは異なり)完全にロマン主義的であり、グレコ・ローマ神話 と歴史を否定している。中世ポルトガルの詩や年代記、聖書にインスピレーションを求めた。彼の作品は膨大で、歴史エッセイ、詩、小説、オプスキュール、演 劇など様々なジャンルに及び、特に『司祭エウリコ』(Eurico, o Presbítero)や『伝説と物語』(Lendas e Narrativas)では、ポルトガルの伝説、伝統、歴史の世界を甦らせている。彼の作品は、シャトーブリアン、シラー、クロップシュトック、ウォル ター・スコット、旧約聖書の詩篇から影響を受けている[91]。 アントニオ・フェリシアーノ・デ・カスティーリョは、1836年に詩『城の夜』(A Noite no Castelo)と『吟遊詩人の嫉妬』(Os Ciúmes do Bardo)、戯曲『カモンイス』(Camões)を発表し、超ロマン主義を主張した。彼は歴代の超ロマン派世代にとって疑う余地のない巨匠となり、その 影響力は有名なコインブラ問題まで異議を唱えられることはなかった。また、ゲーテの『ファウスト』をドイツ語を知らずにフランス語で翻訳し、極論を展開し た。ポルトガルのロマン主義を代表する人物として、カミーロ・カステロ・ブランコ、ジュリオ・ディニス、ソアレス・デ・パッソス、ブルハン・パト、ピニェ イロ・シャガスが挙げられる[90]。 ロマン主義のスタイルは20世紀初頭に復活し、特にテイシェイラ・デ・パスコアイス、ハイメ・コルテサン、マーリオ・ベイラォンなど、ネオ・ロマン主義と もいえるポルトガルのルネサンスに連なる詩人たちの作品によって復活した。ポルトガルのロマン主義の初期の表現は、マヌエル・マリア・バルボーザ・デュ・ ボカージュ(特に18世紀末のソネット)やレオノール・デ・アルメイダ・ポルトガル(アローナ侯爵夫人)などの詩人にすでに見られる[90]。 |

Italy Italian poet Isabella di Morra, sometimes cited as a precursor of Romantic poets[92] Romanticism in Italian literature was a minor movement although some important works were produced; it began officially in 1816 when Germaine de Staël wrote an article in the journal Biblioteca italiana called "Sulla maniera e l'utilità delle traduzioni", inviting Italian people to reject Neoclassicism and to study new authors from other countries. Before that date, Ugo Foscolo had already published poems anticipating Romantic themes. The most important Romantic writers were Ludovico di Breme, Pietro Borsieri and Giovanni Berchet.[93] Better known authors such as Alessandro Manzoni and Giacomo Leopardi were influenced by Enlightenment as well as by Romanticism and Classicism.[94] An Italian romanticist writer who produced works in various genres, including short stories and novels (such as Ricciarda o i Nurra e i Cabras), was the Piedmontese Giuseppe Botero (1815–1885), devoting much of his career to Sardinian literature.[95] |

イタリア イタリアの詩人イザベッラ・ディ・モッラは、ロマン派詩人の先駆者として挙げられることがある[92]。 イタリア文学におけるロマン主義は、いくつかの重要な作品が生み出されたものの、マイナーな運動であった。1816年、ジェルメーヌ・ド・スタエルが雑誌 『Biblioteca italiana』に「Sulla maniera e l'utilità delle traduzioni」という論文を書き、イタリアの人々に新古典主義を否定し、他国の新しい作家を研究するよう呼びかけたことから、正式に始まった。そ れ以前にも、ウーゴ・フォスコロはロマン派のテーマを先取りした詩を発表していた。アレッサンドロ・マンゾーニやジャコモ・レオパルディのような有名な作 家は、啓蒙主義だけでなく、ロマン主義や古典主義の影響も受けていた。[94]イタリアのロマン主義作家で、短編小説や小説(『リッチャルダ・オ・イ・ ヌーラ・エ・イ・カブラス』など)など様々なジャンルの作品を発表したのは、ピエモンテ出身のジュゼッペ・ボテロ(1815-1885)であり、そのキャ リアの多くをサルデーニャ文学に捧げた[95]。 |

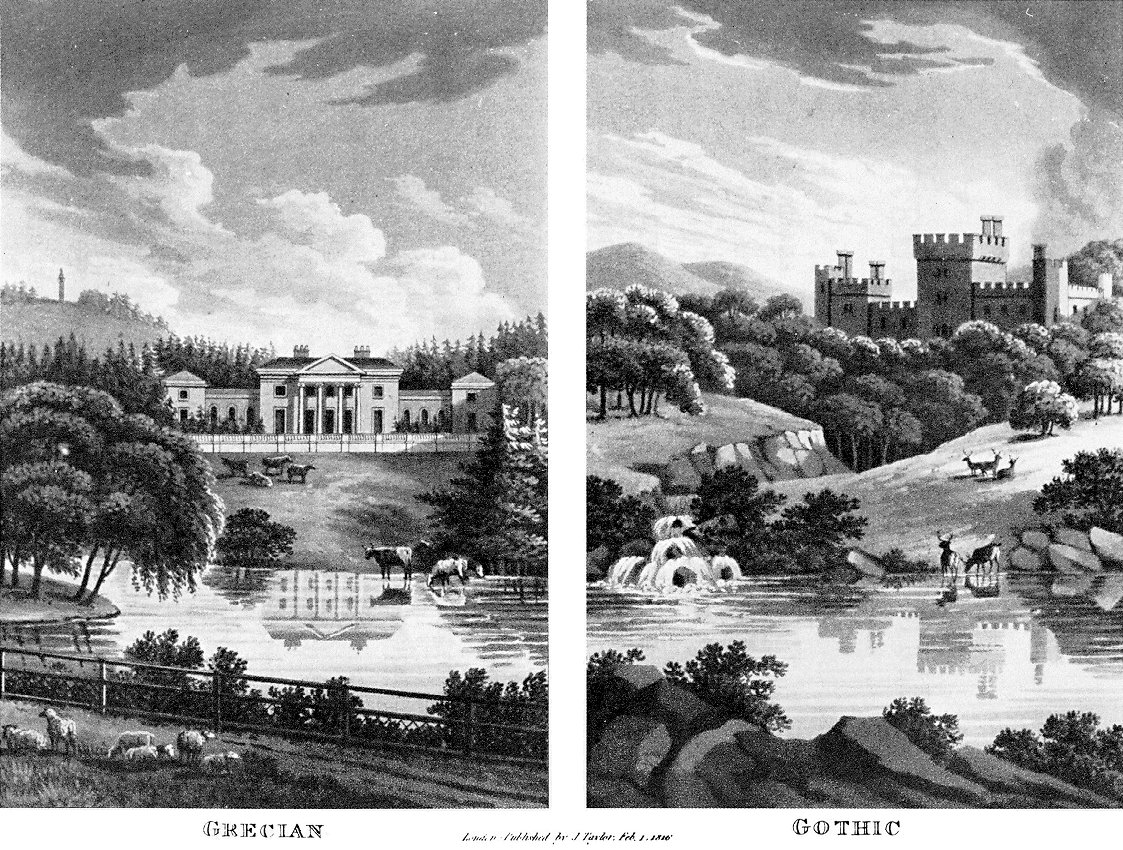

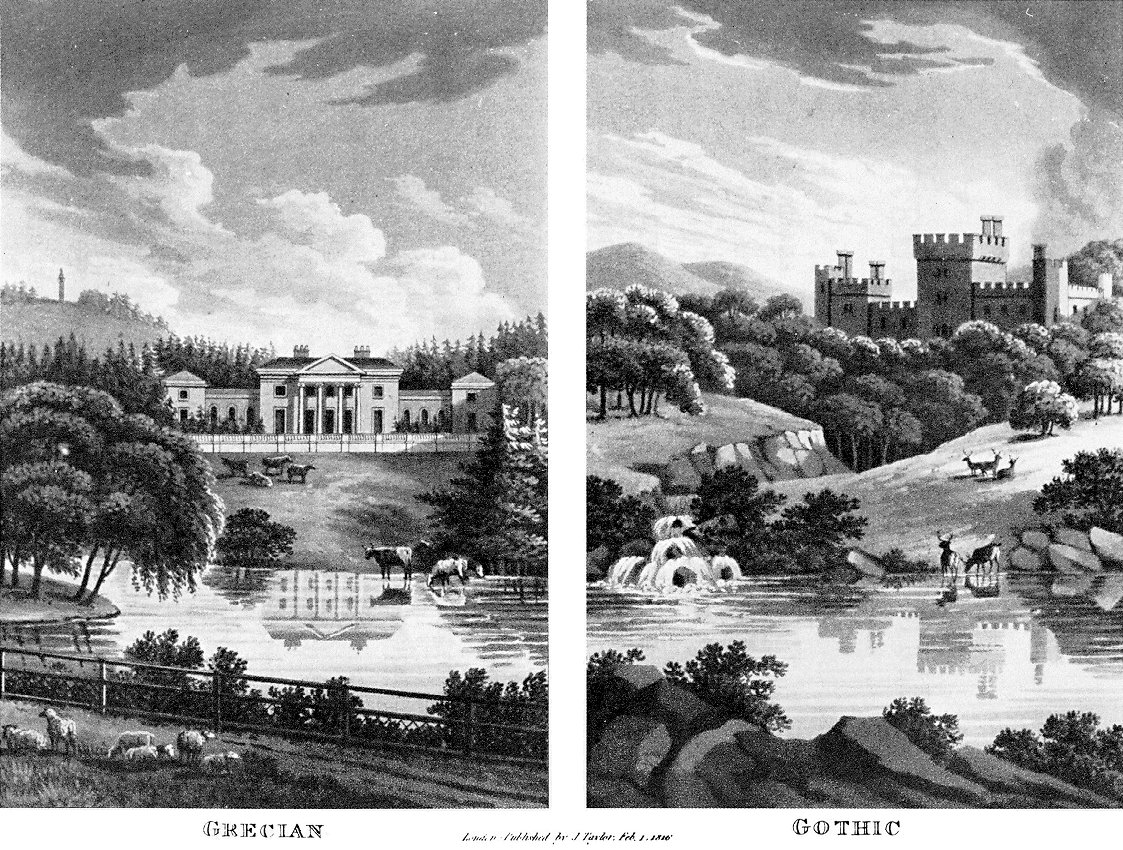

| South America See also: Brazilian Romantic painting  A print exemplifying the contrast between neoclassical vs. romantic styles of landscape and architecture (or the "Grecian" and the "Gothic" as they are termed here), 1816  La vuelta del malón by Ángel Della Valle (1892) Spanish-speaking South American Romanticism was influenced heavily by Esteban Echeverría, who wrote in the 1830s and 1840s. His writings were influenced by his hatred for the Argentine dictator Juan Manuel de Rosas, and filled with themes of blood and terror, using the metaphor of a slaughterhouse to portray the violence of Rosas' dictatorship. Another important milestone in Argentine Romantic literature is Amalia by José Mármol, which is a love story set in the context of the Rosas' dictatorial regime. Domingo Sarmiento, who would later become President of Argentina, published Facundo in 1845, a work of creative non-fiction, of considerable Romantic and positivist influence, in which he discussed the region's development, modernization, power and culture. Literary critic Roberto González Echeverría calls the work "the most important book written by a Latin American in any discipline or genre".[96] Brazilian Romanticism is characterized and divided in three different periods. The first period is focused on the creation of a sense of national identity, using the ideal of the heroic Indian. Some examples include José de Alencar, who wrote Iracema and O Guarani, and Gonçalves Dias, renowned by the poem "Canção do exílio" (Song of the Exile). The second period, sometimes called Ultra-Romanticism, is marked by a profound influence of European themes and traditions, involving the melancholy, sadness and despair related to unobtainable love. Goethe and Lord Byron are commonly quoted in these works. Some of the most notable authors of this phase are Álvares de Azevedo, Casimiro de Abreu, Fagundes Varela and Junqueira Freire. The third period is marked by social poetry, especially the abolitionist movement, and it includes Castro Alves, Tobias Barreto and Pedro Luís Pereira de Sousa.[97] |

南アメリカ こちらも参照のこと: ブラジルのロマン主義絵画  風景と建築の新古典主義様式とロマン主義様式(ここでは 「グレシアン 」と 「ゴシック」)の対比を示す版画、1816年  アンヘル・デラ・バジェ作『La vuelta del malón』(1892年) スペイン語圏の南米ロマン主義は、1830年代から1840年代に執筆したエステバン・エチェベリアに大きな影響を受けた。彼の著作は、アルゼンチンの独 裁者フアン・マヌエル・デ・ロサスへの憎悪の影響を受けており、ロサスの独裁の暴力を描くために屠殺場の隠喩を使って、血と恐怖のテーマに満ちていた。 アルゼンチン・ロマン派文学のもうひとつの重要な金字塔は、ホセ・マルモルの『アマリア』で、ロサス独裁政権を背景にした愛の物語である。 後にアルゼンチン大統領となるドミンゴ・サルミエントが1845年に出版した『ファクンド』は、ロマン主義と実証主義の影響を受けた創作ノンフィクション で、この地域の発展、近代化、権力、文化について論じている。文芸批評家のロベルト・ゴンサレス・エチェベリアは、この作品を「ラテンアメリカ人があらゆ る分野やジャンルで書いた最も重要な本」と呼んでいる[96]。 ブラジルのロマン主義は、3つの異なる時期に特徴づけられ、分けられている。第一期は、英雄的インディアンの理想を用いた国民的アイデンティティの創造に 焦点を当てたものである。イラセマ(Iracema)』や『グアラニー(O Guarani)』を書いたホセ・デ・アレンカル(José de Alencar)や、『亡命者の歌(Canção do exílio)』で有名なゴンサルヴェス・ディアス(Gonçalves Dias)などがその例である。超ロマン主義と呼ばれることもある第2期は、ヨーロッパのテーマや伝統に多大な影響を受けており、手に入らない愛にまつわ る憂鬱、悲しみ、絶望が特徴である。ゲーテやバイロン卿はこれらの作品によく引用されている。この時期の代表的な作家には、アルバレス・デ・アゼヴェド、 カジミロ・デ・アブレウ、ファグンデス・ヴァレラ、ジュンケイラ・フレイレなどがいる。第3期は、社会詩、特に奴隷廃止運動が特徴的で、カストロ・アル ヴェス、トビアス・バレート、ペドロ・ルイス・ペレイラ・デ・ソウザなどがいる[97]。 |

Dennis Malone Carter, Decatur Boarding the Tripolitan Gunboat, 1878. Romanticist vision of the Battle of Tripoli, during the First Barbary War. It represents the moment when the American war hero Stephen Decatur was fighting hand-to-hand against the Muslim pirate captain. United States Main articles: American literature and Romantic literature in English  Thomas Cole, The Course of Empire: The Savage State (1 of 5), 1836 In the United States, at least by 1818 with William Cullen Bryant's "To a Waterfowl", Romantic poetry was being published. American Romantic Gothic literature made an early appearance with Washington Irving's "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" (1820) and "Rip Van Winkle" (1819), followed from 1823 onwards by the Leatherstocking Tales of James Fenimore Cooper, with their emphasis on heroic simplicity and their fervent landscape descriptions of an already-exotic mythicized frontier peopled by "noble savages", similar to the philosophical theory of Rousseau, exemplified by Uncas, from The Last of the Mohicans. There are picturesque "local colour" elements in Washington Irving's essays and especially his travel books. Edgar Allan Poe's tales of the macabre and his balladic poetry were more influential in France than at home, but the romantic American novel developed fully with the atmosphere and drama of Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter (1850). Later Transcendentalist writers such as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson still show elements of its influence and imagination, as does the romantic realism of Walt Whitman. The poetry of Emily Dickinson—nearly unread in her own time—and Herman Melville's novel Moby-Dick can be taken as epitomes of American Romantic literature. By the 1880s, however, psychological and social realism were competing with Romanticism in the novel. Influence of European Romanticism on American writers The European Romantic movement reached America in the early 19th century. American Romanticism was just as multifaceted and individualistic as it was in Europe. Like the Europeans, the American Romantics demonstrated a high level of moral enthusiasm, commitment to individualism and the unfolding of the self, an emphasis on intuitive perception, and the assumption that the natural world was inherently good, while human society was filled with corruption.[98] Romanticism became popular in American politics, philosophy and art. The movement appealed to the revolutionary spirit of America as well as to those longing to break free of the strict religious traditions of early settlement. The Romantics rejected rationalism and religious intellect. It appealed to those in opposition of Calvinism, which includes the belief that the destiny of each individual is preordained. The Romantic movement gave rise to New England Transcendentalism, which portrayed a less restrictive relationship between God and Universe. The new philosophy presented the individual with a more personal relationship with God. Transcendentalism and Romanticism appealed to Americans in a similar fashion, for both privileged feeling over reason, individual freedom of expression over the restraints of tradition and custom. It often involved a rapturous response to nature. It encouraged the rejection of harsh, rigid Calvinism, and promised a new blossoming of American culture.[98][99] American Romanticism embraced the individual and rebelled against the confinement of neoclassicism and religious tradition. The Romantic movement in America created a new literary genre that continues to influence American writers. Novels, short stories, and poems replaced the sermons and manifestos of yore. Romantic literature was personal, intense, and portrayed more emotion than ever seen in neoclassical literature. America's preoccupation with freedom became a great source of motivation for Romantic writers as many were delighted in free expression and emotion without so much fear of ridicule and controversy. They also put more effort into the psychological development of their characters, and the main characters typically displayed extremes of sensitivity and excitement.[100] The works of the Romantic era also differed from preceding works in that they spoke to a wider audience, partly reflecting the greater distribution of books as costs came down during the period.[35] |