ルース・ブンゼル

Ruth Bunzel, 1898-1990

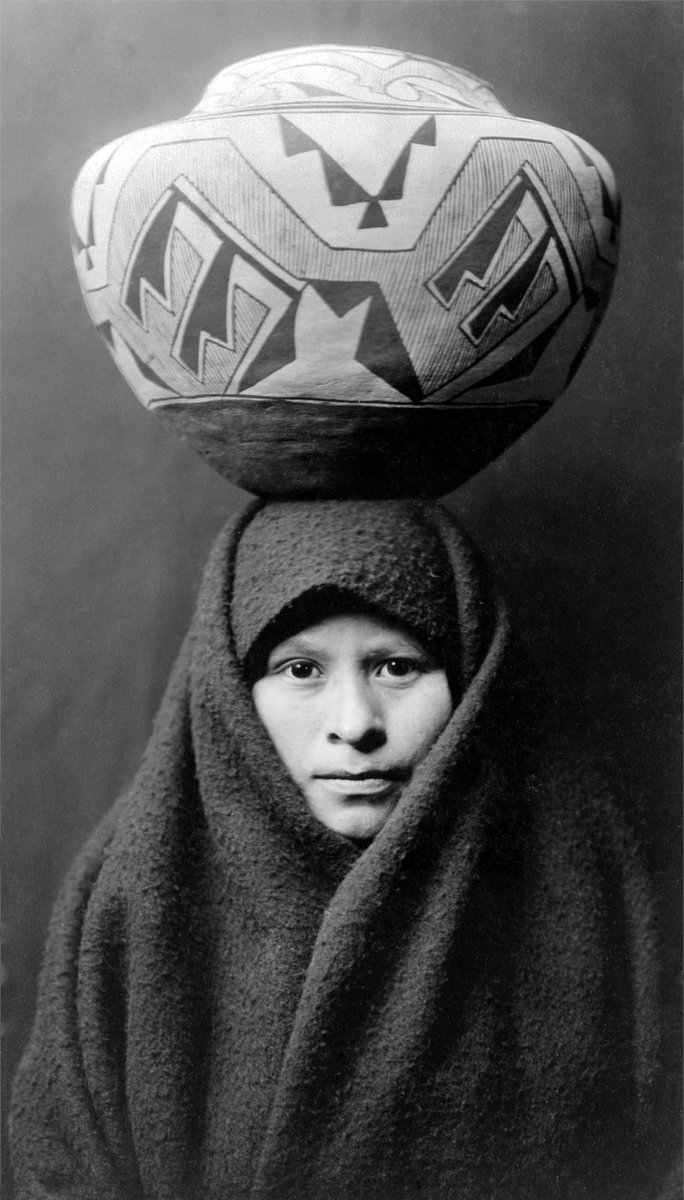

ルース・ブンゼルと彼女が撮影したズニの少女

☆ ルース・レア・ブンゼル(旧姓ベルンハイム)(1898年4月18日 - 1990年1月14日)はアメリカの人類学者で、ズニ族(A:Shiwi)の創造性と芸術の研究、グアテマラのマヤ族の研究、グアテマラとメキシコのアル コール依存症の比較研究で知られる。 ブンゼルはグアテマラで実質的な研究を行った最初のアメリカの人類学者である。彼女の博士論文『プエブロの陶芸家』(1929年)は人類学に おける芸術の創造的プロセスに関する研究であり、ブンゼルは創造的プロセスを研究した最初の人類学者の一人である。

| Ruth

Leah Bunzel (née Bernheim) (18 April 1898 – 14 January 1990) was an

American anthropologist, known for studying creativity and art among

the Zuni people (A:Shiwi), researching the Mayas in Guatemala, and

conducting a comparative study of alcoholism in Guatemala and

Mexico.[1] Bunzel was the first American anthropologist to conduct

substantial research in Guatemala.[2] Her doctoral dissertation, The

Pueblo Potter (1929) was a study of the creative process of art in

anthropology[3] and Bunzel was one of the first anthropologists to

study the creative process.[1][4][5][6][7] |

ルー

ス・レア・ブンゼル(旧姓ベルンハイム)(1898年4月18日 -

1990年1月14日)はアメリカの人類学者で、ズニ族(A:Shiwi)の創造性と芸術の研究、グアテマラのマヤ族の研究、グアテマラとメキシコのアル

コール依存症の比較研究で知られる[1]。

[1]ブンゼルはグアテマラで実質的な研究を行った最初のアメリカの人類学者である[2]。彼女の博士論文『プエブロの陶芸家』(1929年)は人類学に

おける芸術の創造的プロセスに関する研究であり[3]、ブンゼルは創造的プロセスを研究した最初の人類学者の一人である[1][4][5][6][7]。 |

| Early life Ruth Leah Bunzel was born in New York City on April 18, 1898, to Jonas and Hattie Bernheim.[3] Bunzel lived on the Upper East Side of Manhattan with her parents and lived most of her life in Greenwich Village, only leaving New York for long periods of time when conducting fieldwork.[1] Bunzel's father passed away when she was ten, and she was raised by her mother.[1] Bunzel was the youngest of four children.[1] |

生い立ち ルース・レア・ブンゼルは1898年4月18日、ジョナスとハ ティ・バーンハイムの間にニューヨークで生まれた。ブンゼルは両親とともにマンハッタンのアッパー・イースト・サイドに住み、フィールドワークを行う時の み、ニューヨークを長期間離れる時以外は、生涯のほとんどをグリニッジ・ヴィレッジで過ごした。ブンゼルの父親は彼女が10歳のときに他界し、母親に育て られた。ブンゼルは4人兄弟の末っ子だった。 |

| Education Bunzel's mother encouraged her to study German at Barnard College because of her German and Czech heritage, but World War I inspired Bunzel to change her major to European history. Bunzel received a Bachelor of Art in European History in 1918 from Barnard College.[3] She started her career as the secretary and editorial assistant to Franz Boas in 1922,[1] founder of anthropology at Columbia University, after having taken one of his courses in college. Boas encouraged her to take up anthropology directly.[8] Bunzel replaced Esther Goldfrank, a friend of one of her sisters, who resigned the position to study anthropology at Columbia.[3] By 1924, Bunzel was considering a career in anthropology, but first wanted to observe anthropological fieldwork.[3] Bunzel planned to spend the summer of 1924 in western New Mexico and east-central Arizona, particularly in Zuni Pueblo, New Mexico.[1] She planned to serve as secretary to Columbia University anthropologist Ruth Benedict, aiding in transcription and typing while Benedict was collecting Zuni mythology.[3] Boas encouraged Bunzel to pursue her own research while in Zuni Pueblo that summer and suggested that Bunzel study art and Zuni potters, instead of working on secretarial work.[3] Anthropologist Elsie Clews Parsons objected to the idea of Bunzel conducted research among the Zuni people since Bunzel lacked formal anthropological training, and Parsons threatened to remove her financial support of Benedict's research. Boas stepped in, and Parsons allowed the research visit as a personal favor to Boas.[3] |

教育 ブンゼルの母親は、ドイツ人とチェコ人の血を引く彼女にバーナード・カレッジでドイツ語を学ぶよう勧めたが、第一次世界大戦がきっかけとなり、専攻をヨー ロッパ史に変更した。1922年、コロンビア大学で人類学を創設したフランツ・ボアス[1]の秘書兼編集アシスタントとしてキャリアをスタート。ボアズは 彼女に人類学を直接学ぶように勧めた[8]。ブンゼルは、コロンビア大学で人類学を学ぶために職を辞した彼女の姉妹の友人のエスター・ゴールドフランクの 後任となった[3]。 1924年までに、ブンゼルは人類学でのキャリアを考えていたが、まずは人類学のフィールドワークを見学したいと考えていた[3]。ブンゼルは1924年 の夏をニューメキシコ州西部とアリゾナ州中東部、特にニューメキシコ州ズニ・プエブロで過ごすことを計画していた[1]。 ボアスはその夏、ズニ・プエブロにいる間、自分の研究を進めるようブンゼルに勧め、秘書の仕事をする代わりに、芸術とズニの陶芸家について研究するようバ ンゼルに提案した[3]。人類学者のエルシー・クルーズ・パーソンズは、ブンゼルがズニの人々の間で研究を行うというアイデアに反対した。ボアスが介入 し、パーソンズはボアスへの個人的な好意として調査訪問を許可した[3]。 |

| Fieldwork among the Pueblo of

Zuni In the early twentieth century, anthropologist used a method of study called participant observation, which Bunzel utilized when conducting fieldwork among the Zuni people.[9] In the summer of 1924, Bunzel conducted fieldwork among the Zuni people; she apprenticed herself to Zuni potters and observed as well as made potteryalongside them.[3] Focusing her research on pottery offered Bunzel an opportunity to learn from Zuni women's work since women did not participate in Zuni ritual practices.[10] Bunzel was fascinated by the prominent role of women as potters in Zuni society.[5][6][7] Bunzel also studied the Hopi, San Ildefonso, Acoma, and San Felipe Pueblo Indians of the southwestern United States as well. Bunzel utilized this fieldwork for her dissertation, The Pueblo Potter: A Study of Creative Imagination in Primitive Art, which was published in 1929.[3] Her 1929 dissertation describes the creative process of Zuni potters, who preserve and reproduce traditional patterns even as individual potters innovate and create new ones.[4][5][6][7] Bunzel later said, "Look, I was never studying pottery. I was studying human behavior. I wanted to know how the potters felt about what they were doing."[11] In 1925, after returning to New York, Bunzel resigned as Boaz's secretary, and just like Goldfrank, enrolled as a student at Columbia University to study anthropology.[3] Bunzel was part of the second cohort trained by Boas at Columbia University.[2] She completed her doctoral dissertation in 1927, but she was not fully awarded her PhD until 1929 when her book, The Pueblo Potter, was published. Bunzel's book was the first anthropological study of individual creativity in art within overarching artistic boundaries.[3] Parsons, who had initially objected to Bunzel travelling to study the Zuni, sponsored her second trip to study ceremonialism among the Zuni people as well as future trips and projects.[3] The products of this research on Zuni ceremonialism, creation myths, kachinas,[12] and poetry were published in 1932.[3] Bunzel focused on the aesthetic freedom of the individual.[1] Her research produced many publications on Pueblo art, ritual, and folklore, including "Notes on the Kachina Cult in San Felipe" (1928), "The Emergence" (1928), Zuni Texts (1933),[2] and "Zuni" (1935).[3] Bunzel published her research widely and contributed to publications by other prominent anthropologists. She also produced literature related to Zuni language and culture, providing material for Benedict's Zuni information in Patterns of Culture.[1] Bunzel became known as an authority on the Zuni people and learned the Zuni language [4] and actively incorporated her informant's views into her writing on the Katcina Cult,[13] something that she also did in her later monograph Chichicastenango: A Guatemalan Village. Bunzel edited The Golden Age of American Anthropology (1960) with Margaret Mead and contributed to Boas and Benedict's General Anthropology (1938). During her fieldwork among the Zuni people, Bunzel lived with Flora Zuni and her family, who initiated her into the Beaver clan and gave her the Zuni name Maiatitsa or "blue bird".[3] Bunzel was also given another Zuni name, Tsatitsa, by the former governor of the pueblo and one of her key informants, Nick Tumaka. Bunzel returned to the Zuni people in 1939 to study Zuni child development. This was her last trip to Zuni Pueblo, New Mexico.[3] Margaret Mead also acknowledged Ruth Bunzel's contribution in her book Cooperation and Competition Among Primitive Peoples in the prelude, noting how Bunzel allowed Mead to use of her manuscript related to Zuni economics and offered criticisms and suggestions throughout the writing.[14] |

ズニのプエブロでのフィールドワーク 1924年の夏、ブンゼルはズニ族の陶芸家に弟子入りし、陶芸を見たり、一緒に作ったりしながら、ズニ族のフィールドワークを行った[3]。 [3]陶器に焦点を当てた研究は、女性がズニ族の儀式に参加していなかったため、ズニ族の女性の仕事から学ぶ機会を提供した[10]。 バンゼルはまた、アメリカ南西部のホピ族、サン・イルデフォンソ族、アコマ族、サン・フェリペ・プエブロ族についても研究した。ブンゼルはこのフィールド ワークを学位論文『The Pueblo Potter: 彼女の1929年の学位論文には、伝統的な文様を守り、再現するズニ族の陶芸家たちの創造的なプロセスが描かれており、個々の陶芸家たちは革新的な新しい 文様を生み出している[4][5][6][7]。私は人間の行動を研究していたのです。陶芸家たちが自分たちのしていることをどう感じているのか知りた かったのです」[11]。 1925年、ニューヨークに戻ったブンゼルはボアズの秘書を辞め、ゴールドフランクと同じようにコロンビア大学に入学し、人類学を学んだ[3]。ブンツェ ルの著書は、包括的な芸術の境界の中で芸術における個人の創造性を人類学的に研究した最初のものであった[3]。 当初はズニ族を研究するためにブンゼルが旅行することに反対していたパーソンズは、ズニ族の儀式主義を研究するための彼女の2回目の旅行と将来の旅行とプ ロジェクトを後援した[3]。 [3]ブンゼルは個人の美的自由に焦点を当てた[1]。彼女の研究はプエブロの芸術、儀式、民俗学に関する多くの出版物を生み出した。"Notes on the Kachina Cult in San Felipe" (1928)、"The Emergence" (1928)、"Zuni Texts" (1933)[2]、"Zuni" (1935)[3]など。 バンゼルは自分の研究を広く発表し、他の著名な人類学者の出版物に寄稿した。彼女はまたズニ族の言語と文化に関連する文献を作成し、ベネディクトの『文化 のパターン』におけるズニ族の情報に資料を提供した[1]。ブンゼルはズニ族の権威として知られるようになり、ズニ語を習得し[4]、カトシーナ・カルト に関する執筆に情報提供者の見解を積極的に取り入れた[13]: A Guatemalan Village. ブンゼルはマーガレット・ミードとともに『The Golden Age of American Anthropology』(1960年)を編集し、ボースとベネディクトの『General Anthropology』(1938年)に寄稿した。 ズニ族でのフィールドワーク中、ブンゼルはフローラ・ズニとその家族と一緒に暮らし、ビーバー一族に入門させられ、ズニ族の名前マイアティツァ(青い鳥) を与えられた[3]。ブンゼルは1939年にズニ族の子どもの発達を研究するためにズニ族に戻った。これが彼女のニューメキシコ州ズニ・プエブロへの最後 の旅となった[3]。 マーガレット・ミードもまた、その著書『Cooperation and Competition Among Primitive Peoples』の序文でルース・ブンゼルの貢献を認めており、ブンゼルがズニ族の経済に関する原稿の使用をミードに許可し、執筆を通して批判や提案を提 供したことに言及している[14]。 |

| Fieldwork in Guatemala and Mexico Bunzel interviewed for a Guggenheim Fellowship to study Mexican culture but was redirected to study Guatemala, as little American anthropological research existed in this area at the time.[3] Bunzel studied the Santa Tomas Chichicastenango, a Highland Mayan Village, from 1930 to 1932, resulting in the completion in 1936 and publication in 1952 of her monograph Chichicastenango: A Guatemalan Village.[2] True to her prior plans, Bunzel also conducted fieldwork in Chamula in Chiapas, Mexico from 1936 to 1937 as part of a comparative study on "The Role of Alcoholism in Two Central American Communities," in Chichicastenango and Chamula.[3] Influenced by psychoanalyst Karen Horney, Bunzel focused on the psychological factors contributing to different drinking patterns in Chamula and Chichicastenango. This was the first anthropological study on alcoholism and drinking patterns among different cultures.[1] Bunzel stated that she was not studying alcohol; rather, she studied "people and their drinking habits as seen in their cultural contexts and the influences behind these habits."[11] Bunzel advanced her field by challenging its methodology. She argued that her primary consultant's insights were incomplete and could not therefore provide generalized information about the culture, rather viewing his or her contributions as partial and individual to that person or smaller groups of people.[2] Bunzel viewed knowledge production as culturally situated, limiting her ethnographic interpretations to a specific group of Maya-K'iche' people in the Guatemalan highlands. Bunzel also advanced the field by studying Chichicastenango, an urban center and hub in the Central American trade system, as opposed to rural settings in Guatemala. Bunzel did not follow anthropological conventions of the time to study "pure," isolated cultures but instead chose to study centers of change, contact, and trade.[2] Bunzel also juxtaposed her own interpretations of Guatemalan ritual events with those offered by her informants in her monograph Chichicastenango.[2] Her monograph Chichicastenango was greatly influenced by Boas' historical particularism and Benedict's culture and personality research focused on child development. Like at the Zuni Pueblo, when Bunzel relied greatly on one female informant Flora Zuni and her family, she did the same in Chichicastenango, and attached herself to one informant to obtain a focused perspective on a small group of people rather than generalizing her results to an entire culture.[2] |

グアテマラとメキシコでのフィールドワーク ブンゼルはメキシコ文化を研究するためにグッゲンハイム・フェローシップの面接を受けたが、当時この地域ではアメリカの人類学的研究がほとんど存在しな かったため、グアテマラの研究に方向転換された[3]。ブンゼルは1930年から1932年にかけて高地マヤの村であるサンタ・トマス・チチカステナンゴ を調査し、1936年に単行本『チチカステナンゴ』を完成させ、1952年に出版した: グアテマラの村』[2]。 事前の計画通り、ブンツェルは1936年から1937年にかけてメキシコのチアパス州にあるチャムラでもフィールドワークを行い、チチカステナンゴとチャ ムラの「2つの中央アメリカのコミュニティにおけるアルコール依存症の役割」に関する比較研究を行った[3]。精神分析学者のカレン・ホーニーの影響を受 けたブンツェルは、チャムラとチチカステナンゴで異なる飲酒パターンをもたらす心理的要因に焦点を当てた。これはアルコール依存症と異文化間の飲酒パター ンに関する最初の人類学的研究であった[1]。ブンゼルは、自分はアルコールを研究しているのではなく、むしろ「文化的文脈の中で見られる人々とその飲酒 習慣、そしてこれらの習慣の背後にある影響」を研究していると述べている[11]。 ブンゼルはその方法論に挑戦することで、この分野を発展させた。彼女は、主要なコンサルタントの洞察は不完全なものであり、したがって文化について一般化 された情報を提供することはできないと主張し、むしろその人の貢献は部分的なものであり、その人またはより小さなグループの人々にとっての個別的なもので あるとみなした[2]。ブンゼルはまた、グアテマラの農村環境とは対照的に、中米の貿易システムの中心地であり、都市の中心地であるチチカステナンゴを研 究することで、この分野を発展させた。ブンゼルは、「純粋な」孤立した文化を研究するという当時の人類学の慣例に従うのではなく、変化、接触、交易の中心 地を研究することを選んだのである[2]。 ブンゼルはまた、単行本『チチカステナンゴ』[2]の中で、グアテマラの儀式行事に関する彼女自身の解釈と、情報提供者から提供された解釈とを並列させて いる。彼女の単行本『チチカステナンゴ』は、ボアズの歴史的特殊主義と、子どもの発達に焦点を当てたベネディクトの文化と人格の研究に大きな影響を受けて いる。ズニ・プエブロでブンゼルが一人の女性インフォーマントであるフローラ・ズニとその家族に大きく依存していたように、チチカステナンゴでも彼女は同 じように、自分の結果を文化全体に一般化するのではなく、小さな集団に焦点を絞った視点を得るために一人のインフォーマントに執着した[2]。 |

| Professional career During her early career, Bunzel worked as a lecturer at Barnard College from 1929 to 1930 and at Columbia University between 1933-1935 and 1937–1940.[3] Like many other female anthropologists at Columbia University, including Isabel Kelly, Ruth Landes, and Eleanor Leacock, Bunzel never held a full-time university appointment or tenure.[2] During her professional career, Bunzel faced social gender politics that prevented her from obtaining a tenure position and threatened her fieldwork. Some of her male colleagues spread inflammatory rumors about unprofessional activity in Chichicastenango that negatively affected Bunzel's professional support among colleagues and prevented her from obtaining a full-time university position.[2] During World War II, Bunzel worked in England translating broadcasts from English to Spanish and translating incoming Spanish broadcasts for the U.S. Government Office of War Information from 1942 to 1945.[3] Bunzel also contributed to propaganda analysis efforts. After World War II, she became involved in the RCC, the Columbia University Research in Contemporary Cultures Project. This project was funded by the office of Naval Research to study different cultures and Bunzel lead a research group studying China which interviewed Chinese immigrants in New York City between 1947 and 1951.[3] In 1951 and 1952, Bunzel developed interview techniques at the Bureau of Applied Social Research project until her appointment as an adjunct professor of anthropology at Columbia University in 1953.[3] |

専門職としてのキャリア 初期のキャリアにおいて、ブンゼルは1929年から1930年までバーナード・カレッジで、1933年から1935年までと1937年から1940年まで コロンビア大学で講師として働いていた[3]。イザベル・ケリー、ルース・ランデス、エレノア・リーコックなどコロンビア大学の他の多くの女性人類学者と 同様に、バンゼルは大学の常勤職や終身在職権を得ることはなかった[2]。 専門家としてのキャリアの中で、ブンゼルは終身在職権の取得を妨げ、フィールドワークを脅かす社会的ジェンダー政治に直面した。彼女の同僚の中には、チチ カステナンゴでの非専門的な活動に関する扇動的な噂を流した男性もおり、それが同僚たちの間でブンゼルの専門家としての支持に悪影響を及ぼし、彼女が大学 の常勤職を得ることを妨げた[2]。 第二次世界大戦中、ブンゼルはイギリスで1942年から1945年までアメリカ政府戦争情報局のために放送を英語からスペイン語に翻訳し、スペイン語放送 の受信を翻訳した[3]。第二次世界大戦後、彼女はRCC(コロンビア大学現代文化研究プロジェクト)に関わるようになった。1951年と1952年に は、1953年にコロンビア大学の人類学の非常勤教授に任命されるまで、応用社会調査局のプロジェクトでインタビュー技術を開発した[3]。 |

| Later life From 1969 to 1987, Bunzel served as a senior research associate at Columbia University.[3] According to her official appointment card, Bunzel retired in 1966[1] from her position at Columbia University but even after her official retirement, continued to teach until 1972.[3] From 1972 to 1974, Bunzel worked as a visiting professor at Bennington College.[3] Bunzel had a heart attack on January 14, 1990, and died at the age of 91 in St. Vincent's-Roosevelt Hospital Center.[15] The Ruth Leah Bunzel Papers are currently housed at the National Anthropological Archives, including correspondence, manuscripts, notes, research files, teaching materials, artwork, sound recordings, and more.[3] |

その後の人生 1969年から1987年まで、ブンゼルはコロンビア大学のシニア・リサーチ・アソシエイトを務めた[3]。公式の任命カードによると、ブンゼルは 1966年にコロンビア大学の職を退いたが[1]、正式な退任後も1972年まで教鞭を執った[3]。1972年から1974年まで、ブンゼルはベニント ン大学の客員教授を務めた[3]。1990年1月14日、ブンツェルは心臓発作を起こし、セント・ヴィンセント・ルーズベルト病院センターで91歳で死去 した[15]。 ルース・レア・ブンゼル・ペーパーズは現在、国立人類学文書館に所蔵されており、書簡、原稿、ノート、研究ファイル、教材、美術品、録音などを含む [3]。 |

| Selected bibliography 1928 "Notes on the Katcina Cult in San Felipe." Journal of American Folklore 41: 290–292 1928 "Further Notes on San Felipe." Journal of American Folklore 41: 592. 1928 "The emergence." Journal of American Folklore 41: 288–290. 1929 The Pueblo Potter: A Study of Creative Imagination in Primitive Art. Courier Dover Publications. 1932 Zuni Origin Myths. Chicago: US Government Printing Office. 1932 Zuni Ritual Poetry. Chicago: US Government Printing Office. 1932 "Introduction to Zuni Ceremonialism." Bureau of American Ethnology BAE Annual Report 47: 467–554 Above three texts collected and reprinted as Zuni Ceremonialism: Three Studies, ed. by Nancy J. Parezo (1992) 1932 "The Nature of Kachinas." BAE Annual Report 47: 837–1006. Reprinted in Reader in Comparative Religion, edited by A.W. Lessa and Evon Vogt (1958): 401–404 1933 "Zuni." In Handbook of American Indian Languages. Part 3, edited by Franz Boas. 1938 "The Economic Organization of Primitive Peoples." In General Anthropology, edited by Franz Boas: 327–408 1940 "The role of alcoholism in two Central American cultures". Psychiatry: Journal for the Study of Interpersonal Processes 3(3): 361–387. 1952 Chichicastenango, a Guatemalan Village. University of Washington Press. 1953 "Psychology of the Pueblo Potter." In Primitive Heritage, edited by Margaret Mead and Nicolas Calas: 266–275 1964 "The Self-effacing Zuni of New Mexico." In The Americas on the Eve of Discovery, edited by Harold Driver: 80–92 1960 Mead, M., and Bunzel, R. L., eds. The Golden Age of American Anthropology. George Braziller. 1976 Bunzel, R. (1976). "Chamula and Chichicastenango: A Re-examination", in Cross-Cultural Approaches to the Study of Alcohol, The Hague: Mouton & Co.: 21–22. |

参考文献 1928 「サン・フェリペのカチナ教に関する覚書」『アメリカ民俗学雑誌』41: 290–292 1928 「サン・フェリペに関する追加覚書」『アメリカ民俗学雑誌』41: 592。 1928 「出現」 『アメリカ民俗学雑誌』 41: 288–290。 1929 『プエブロの陶芸家:原始美術における創造的想像力の研究』 Courier Dover Publications。 1932 『ズニの起源神話』 シカゴ:米国政府印刷局。 1932 『ズニの儀式詩』 シカゴ:米国政府印刷局。 1932 「ズニの儀式入門」。アメリカ民族学局 BAE 年次報告書 47: 467–554 上記の 3 つのテキストは、ナンシー・J・パレゾ編『ズニの儀式:3 つの研究』(1992 年)に収録され、再版されている。 1932 「カチナの性質」。BAE 年次報告書 47: 837–1006。A.W. レッサとエヴォン・ヴォクト編『比較宗教学読本』に再掲載(1958年):401–404 1933年 「ズニ」。『アメリカインディアン言語ハンドブック』第 3 部、フランツ・ボアズ編。 1938年 「原始民族の経済組織」。フランツ・ボアス編『一般人類学』327–408 ページ。 1940 「2 つの中央アメリカ文化におけるアルコール依存症の役割」。『精神医学:対人過程の研究誌』3(3): 361–387。 1952 『チチカステナンゴ、グアテマラの村』。ワシントン大学出版局。 1953 「プエブロの陶芸家の心理学」。マーガレット・ミード、ニコラス・カラス編『原始の遺産』266-275 ページ 1964 「ニューメキシコ州の謙虚なズニ族」。ハロルド・ドライバー編『発見前のアメリカ大陸』80-92 ページ 1960 ミード、M.、 およびブンゼル、R. L. 編。アメリカ人類学の黄金時代。ジョージ・ブラジラー。 1976 ブンゼル、R. (1976)。「チャムラとチチカステナンゴ:再検討」、『アルコールの研究における異文化間アプローチ』、ハーグ:ムートン&コ:21-22。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ruth_Bunzel |

|

| Chamula and Chichicastenango: A

Re-examination RUTH BUNZEL |

チャムラとチチカステナンゴ:再検討 ルース・ブンゼル |

| I have not revisited either of

the two Middle American communities in

which I worked several years ago. Nor did I plan to re-study them,

although it would be an interesting experience. And I haven't pursued

alcohol, alcoholism, or drinking habits as a special research area

since

then. My original paper happened quite accidentally as a by-product

of general ethnographic studies in the two geographic areas. The two

research projects were separated by several years, during which time I

was in New York and during which time my point of view changed

somewhat because of involvement with the 1937 Columbia seminar of

psychiatrists, psychoanalysts, and anthropologists. This experience

prompted me to look at things quite differently in my subsequent

research. |

数

年前に調査していた2つの中米コミュニティーのどちらも再訪したことはない。興味深い経験にはなるだろうが、再調査するつもりもない。それ以来、私はアル

コール、アルコール中毒、飲酒習慣を特別な研究分野として追求していない。私が最初に書いた論文は、2つの地域における一般的な民族誌研究の副産物とし

て、ごく偶然に生まれたものである。この2つの研究プロジェクトは数年の隔たりがあったが、その間に私はニューヨークに滞在し、1937年にコロンビアで

開催された精神科医、精神分析医、人類学者のセミナーに参加したことで、私の視点は多少変化した。この経験は、その後の私の研究において、物事をまったく

違った角度から見るよう促した。 |

| When I was in Guatemala, I did

not perceive alcohol or drinking as

special problems to be investigated. It just seemed that patterns of

drinking were the familiar ones associated with Mexican fiestas. If I

had

been a little more concerned with drinking as a research problem, as

I did become very much later, I would have approached my study quite

differently. For example, I would have focused on who drinks, how

often, and other things. |

グ

アテマラにいたとき、私はアルコールや飲酒が調査すべき特別な問題だとは感じていなかった。ただ、飲酒のパターンはメキシコの祭礼でおなじみのものだと

思っただけだった。もし私が飲酒を研究課題としてもう少し意識していたら、かなり後になってからだが、私の研究へのアプローチはまったく違ったものになっ

ていただろう。例えば、誰が、どれくらいの頻度で飲むのか、その他のことに焦点を当てただろう。 |

| In the Mexican village of

Chamula, everybody drank whenever they

had the opportunity. So there was no problem conducting a detailed

drinking study. And in Chamula the drinking pattern was so completely

different from anything that we experience in our own society, where

we have some knowledge about alcohol use, that it immediately attracted

our attention. Here were two societies --- Chamula and Chichicastenango

--- within the same culture area that had completely different

drinking patterns. It seemed to me that we had to deal with these

differences

and look for their cultural context. |

メ

キシコのチャムラ村では、機会があれば誰もが酒を飲んでいた。だから、詳細な飲酒調査を行うことに問題はなかった。そして、チャムラ村での飲酒パターン

は、アルコール使用についてある程度知識のある私たちが経験する社会での飲酒パターンとはまったく異なっていた。チャムラとチチカステナンゴという2つの

社会が同じ文化圏にありながら、飲酒パターンがまったく異なっていたのだ。私たちはこの違いに対処し、その文化的背景を探らなければならないと思った。 |

| Although I have turned to other

things since this study was done,

my basic concern has always been consistently the same from the time

I first went down and studied pottery making. Years later, when someone

asks me, "Oh, are you still studying pottery?" I can say, "Look,

I've never studied pottery. I was studying human behavior, and I

wanted to know how potters felt about what they were doing."

I feel the same way about alcohol. I have never studied alcohol; I

have just studied people and their drinking habits as seen in their

cultural contexts and the influences behind these habits. This is

really

what has been my consistent preoccupation, throughout all my years,

even after I began dealing with Chinese political habits and behavior.

It is not politics that I studied, but human behavior in its cultural

context. |

こ

の研究を終えてから、私は他のことに目を向けるようになったが、私の基本的な関心は、最初に陶芸の世界に足を踏み入れて勉強したときから一貫して変わらな

い。何年か経って、「あら、まだ陶芸の勉強をしてるの?」と聞かれたら、こう答えることができる。と聞かれても、私はこう答えることができる。私は人間行

動を研究していて、陶芸家たちが自分たちのしていることをどう感じているのか知りたかったのです」と言える。私はアルコールについても同じように感じてい

る。私はアルコールについて研究したことはない。文化的背景から見た人々とその飲酒習慣、そしてその習慣の背後にある影響について研究してきただけだ。中

国の政治的習慣や行動を扱うようになってからも、私の関心は一貫してこの点にあった。私が研究したのは政治ではなく、文化的文脈における人間の行動であ

る。 |

| I have very little to add to the

paper on Chamula and Chichicastenango,

except to mention the sorts of things I might have done differently

had I gone into the research as a study of drinking. I think I

would probably have given the paper a different title if I had been a

little more sophisticated. But, again, this was something I did not

consider at the time. |

チャ

ムラとチチカステナンゴについての論文に付け加えることはほとんどないが、もし私が飲酒の研究としてこの研究に取り組んでいたら、違ったことをしていたか

もしれないという種類のことを述べるくらいだ。もし私がもう少し洗練されていたら、おそらく論文に違うタイトルをつけていたと思う。しかし、これも当時は

考えもしなかったことだ。 |

| The principal point of my study

is that drinking, or alcoholism, or

whatever you want to call it, is not the same thing in different

cultures.

It is quite a different entity in Chamula from what it is in

Chichicastenango.

We cannot deal with drinking in these two cultures as one thing.

Alcoholism plays an entirely different role in the lives of the people

in

the two cultures. An entirely different etiology of drinking is

apparent

in each of these different areas. That is the major point that I tried

to make. Drinking fulfills quite different roles. Principally, in

Chichicastenango,

drinking is a release from the extreme pressures of surrounding

cultures. It is also a way of dealing with the anxieties provoked

by these external pressures which, of course, lead to more

anxieties in a sort of feedback relationship. In Chamula, however,

drinking performs the function of lubricating social relations at a

very

basic level; you cannot enter into any kind of relationship with

another

person without first establishing the pattern of sharing a drink. This

pattern could be due to infantile experiences. |

私

の研究の要点は、飲酒、あるいはアルコール依存症、あるいはそれを何と呼ぼうと、異なる文化においては同じものではないということである。チャムラとチチ

カステナンゴではまったく違うものなのだ。この2つの文化における飲酒を1つのものとして扱うことはできない。アルコール依存症は、2つの文化圏の人々の

生活においてまったく異なる役割を果たしている。飲酒のまったく異なる病因が、それぞれの異なる地域で明らかになっている。これが私が言おうとした大きな

ポイントである。飲酒が果たす役割はまったく異なる。主にチチカステナンゴでは、飲酒は周囲の文化の極度のプレッシャーからの解放である。また、こうした

外部からの圧力によって引き起こされる不安に対処する手段でもあり、それはもちろん、ある種のフィードバック関係においてさらなる不安をもたらす。チャム

ラでは、飲酒は非常に基本的なレベルで社会的関係を潤滑にする機能を果たしている。このパターンは幼児期の経験によるものかもしれない。 |

| I want to emphasize again how drinking fits into a much broader

context, not leading into studies of alcohol per se, but into a concern

for human behavior. Since it is a rather extreme form of human behavior,

the differences in the ways in which people use drinking as a

mechanism show up very clearly. |

飲

酒が、アルコールそのものの研究につながるのではなく、人間の行動に対する関心という、より広い文脈にいかに適合しているかを、もう一度強調しておきた

い。飲酒は人間の行動の中でもかなり極端な形態であるため、人々が飲酒をメカニズムとして利用する方法の違いがはっきりと現れる。 |

| Souce: 1976 Bunzel, R. (1976). "Chamula and Chichicastenango: A Re-examination", in Cross-Cultural Approaches to the Study of Alcohol, The Hague: Mouton & Co.: 21–22. |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆