琉球独立運動

Ryukyu independence movement

☆The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (August 2025) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

★こ

の記事の中立性が問題となっています。関連する議論は、トークページをご覧ください。条件を満たすまで、このメッセージは削除しないでください。

(2025年8月) (このメッセージの削除方法についてはこちらをご覧ください)

| The Ryukyu

independence movement (Japanese: 琉球独立運動, Hepburn: Ryūkyū Dokuritsu

Undō) is a political movement advocating the independence of the Ryukyu

Islands from Japan.[1] Some support the restoration of the Ryukyu

Kingdom, while others advocate the establishment of a Republic of the

Ryukyus (Japanese: 琉球共和国, Kyūjitai: 琉球共和國, Hepburn: Ryūkyū Kyōwakoku). The current political manifestation of the movement emerged in 1945, after the end of the Pacific War. Some Ryukyuan people felt, as the Allied Occupation (USMGRI 1945–1950) began, that the Ryukyus should eventually become an independent state instead of being returned to Japan. However, the islands were returned to Japan on 15 May 1972 as the Okinawa Prefecture according to the 1971 Okinawa Reversion Agreement. The US-Japan Security Treaty (ANPO), signed in 1952, provides for the continuation of the American military presence in Japan, and the United States continues to maintain a heavy military presence on Okinawa Island. This set the stage for renewed political activism for Ryukyuan independence. In 2022, public opinion polling in Okinawa put support for independence at 3% of the local population.[2] The Ryukyu independence movement maintains that both the 1609 invasion by Satsuma Domain and the Meiji construction of the Okinawa prefecture are colonial annexations of the Ryukyu Kingdom. It is highly critical of the abuses of Ryukyuan people and territory, both in the past and in the present day (such as the use of Okinawan land to host American military bases).[3] Advocates for independence also emphasize the environmental and social impacts of the American bases in Okinawa.[4][5] |

琉球独立運動(りゅうきゅうどくりつうんどう)とは、日本からの琉球諸

島の独立を主張する政治運動のことです。[1] 琉球王国の復活を支持する者もいれば、琉球共和国(琉球王国)の設立を主張する者もいる。 この運動の現在の政治的な動きは、太平洋戦争終結後の1945年に始まった。連合国軍による占領(1945年~1950年)が始まった当時、一部の琉球人 は、琉球は最終的に日本に返還されるのではなく、独立した国家になるべきだと考えていました。しかし、1971年の沖縄返還協定に基づき、1972年5月 15日に琉球諸島は沖縄県として日本に返還されました。1952年に締結された日米安全保障条約(ANPO)は、日本におけるアメリカ軍の駐留継続を定め ており、アメリカは沖縄島に大規模な軍事基地を維持し続けている。これにより、琉球独立運動の再燃の舞台が整った。2022年の沖縄での世論調査では、独 立支持率は地元住民の3%だった。[2] 琉球独立運動は、1609年の薩摩藩による侵攻と、明治政府による沖縄県設立は、琉球王国の植民地併合であると主張している。過去および現在の琉球人民と 領土の虐待(沖縄の土地を米軍基地として使用することなど)を厳しく批判している。[3] 独立支持派は、沖縄のアメリカ軍基地がもたらす環境的・社会的影響にも重点を置いている。[4][5] |

| Historical background Main article: History of the Ryukyu Islands The Ryukyuan people are indigenous people who live on the Ryukyu Islands and are ethnically, culturally, and linguistically distinct from Japanese people. During the Sanzan period, Okinawa was divided into the three polities of Hokuzan, Chūzan, and Nanzan. In 1429, Chūzan's chieftain Shō Hashi unified them and founded the autonomous Ryukyu Kingdom (1429–1879), with the capital at Shuri Castle. The kingdom continued to have tributary relations with the Ming dynasty and Qing dynasty China, a practice that was started by Chūzan in 1372–1374 and lasted until the downfall of the kingdom in the late 19th century. This tributary relationship was greatly beneficial to the kingdom as the kings received political legitimacy, while the country as a whole gained access to economic, cultural, and political opportunities in Southeast Asia without any interference by China in the internal political autonomy of Ryukyu.[6] In addition to Korea (1392), Thailand (1409), and other Southeast Asian polities, the kingdom maintained trade relations with Japan (1403), and during this period, a unique political and cultural identity emerged. However, in 1609, the Japanese feudal domain of Satsuma invaded the kingdom on behalf of the first shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu and the Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1867) because the Ryukyu king Shō Nei refused to submit to the shogunate. The kingdom was forced to send a tribute to Satsuma, but was allowed to retain and continue its independence, relations, and trade with China (a unique privilege, as Japan was prohibited from trading with China at the time). This arrangement was known as a "dual vassalage" status, and continued until the mid-19th century.[7] During the Meiji period (1868–1912), the Meiji government of the Empire of Japan (1868–1947) began a process later called Ryukyu Shobun ("Ryukyu Disposition") to formally annex the kingdom into the modern Japanese Empire. Firstly established as Ryukyu Domain (1872–1879), in 1879 the kingdom-domain was abolished, established as Okinawa Prefecture, while the last Ryukyu king Shō Tai was forcibly exiled to Tokyo.[8] Previously in 1875, the kingdom was forced against its wishes to terminate its tribute relations with China, while U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant proposed a plan that would maintain an independent, sovereign Okinawa while partitioning other Ryukyuan islands between China and Japan. Japan offered China the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands in exchange for trading rights with China equal to those granted to Western states, de facto abandoning and dividing the island chain for monetary profit.[9] The treaty was rejected as the Chinese court decided not to ratify the agreement. The Ryukyu's aristocratic class resisted annexation for almost two decades,[10] but after the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), factions pushing for Chinese and Ryukyuan sovereignty faded as China renounced its claims to the island. In the Meiji period, the government continuously and formally suppressed Ryukyuan ethnic identity, culture, tradition, and language while assimilating them as ethnic Japanese (Yamato).[11] Since the formation of the prefecture, its relationship with the Japanese nation-state has been continually contested and changed. There were significant movements for Okinawan independence in the period following its annexation, in the period prior to and during World War II, and after World War II through to the present day. In 1945, during the WWII Battle of Okinawa, approximately 150,000 civilians were killed, consisting roughly 1/3 of the island's population.[12] Many civilians died in mass suicides forced by the Japanese military.[13] After World War II, the Ryukyu Islands were occupied by the United States Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands (1945–1950), but the U.S. maintained control even after the 1951 Treaty of San Francisco, and its former direct administration was replaced by the USCAR government. During this period, the U.S. military forcibly requisitioned private land for the building of many military facilities, with the private owners put into refugee camps, and its personnel committed thousands of crimes against civilians.[13][14] Only twenty years later, on 15 May 1972, Okinawa and nearby islands were returned to Japan. As the Japanese had post-war political freedom and economic prosperity, the military facilities had a negative economical impact and the people felt cheated, used for the purpose of Japanese and regional security against the communist threat.[15] Despite Okinawa having been formally returned to Japan, both Japan and the United States have continued to make agreements securing the maintenance and expansion of the U.S. military bases, despite protests from the local Ryukyuan population. Although Okinawa comprises just 0.6% of Japan's total land mass, currently 75% of all U.S. military installations stationed in Japan are assigned to bases in Okinawa.[16][17] |

歴史的背景 主な記事:琉球諸島の歴史 琉球人は、琉球諸島に住む先住民であり、民族、文化、言語の面で日本人とは区別される。三山時代、沖縄は北山、中山、南山の3つの政体に分かれていた。 1429年、中山王の尚巴志が3つを統一し、首里城を都とする自治国家である琉球王国(1429年~1879年)を建国した。王国は明朝と清朝の中華王朝 と朝貢関係を継続した。この朝貢関係は、中山の首長が1372年から1374年に開始し、19世紀末の王国の滅亡まで続いた。この朝貢関係は王国にとって 大きな利益をもたらし、王は政治的正当性を獲得し、王国全体は中国の内政干渉を受けずに東南アジアにおける経済的、文化的、政治的な機会を得ることができ た。[6] 韓国(1392年)、タイ(1409年)、その他の東南アジアの政治団体に加え、王国は日本(1403年)とも貿易関係を維持し、この期間に独特な政治 的・文化的アイデンティティが形成された。しかし、1609年、琉球王尚寧が徳川家康率いる徳川幕府(1603–1867)への服従を拒否したため、薩摩 藩が徳川幕府の命を受けて王国を侵攻した。王国は薩摩に朝貢を強制されたが、中国との独立、関係、貿易を維持し続けることを許された(当時、日本は中国と の貿易が禁止されていたため、これは独自の特権だった)。この体制は「二重宗主国」と呼ばれ、19世紀半ばまで続いた。[7] 明治時代(1868年~1912年)に、日本帝国(1868年~1947年)の明治政府は、琉球王国を現代日本帝国に正式に併合する「琉球処分」と呼ばれ るプロセスを開始した。まず琉球藩(1872年~1879年)として設立され、1879年に王国・藩が廃止され、沖縄県が設立された。最後の琉球王・尚泰 は強制的に東京に流刑に処された。[8] 1875年には、王国は中国との朝貢関係を強制的に断絶させられ、一方、アメリカ合衆国大統領ユリシーズ・S・グラントは、沖縄を独立した主権国家として 維持しつつ、他の琉球諸島を中国と日本之间で分割する計画を提案した。日本は中国に対し、西欧諸国と同等の貿易権と引き換えに宮古島と八重山諸島を譲渡す る提案をした。これにより、事実上、島嶼群を金銭的利益のために放棄し分割した。[9] しかし、中国政府は条約の批准を拒否した。琉球の貴族階級は併合に約20年間抵抗したが、[10] 日清戦争(1894–1895)後、中国が島への主張を放棄したため、中国と琉球の主権を主張する派閥は衰えた。明治時代、政府は琉球の民族のアイデン ティティ、文化、伝統、言語を絶えず公式に抑圧し、日本民族(大和人)に同化させようとしました[11]。 県発立以来、日本国家との関係は絶えず争われ、変化してきました。併合後、第二次世界大戦前後の時期、そして第二次世界大戦後から現在に至るまで、沖縄の 独立運動が活発化している。1945年の第二次世界大戦中の沖縄戦では、島の人口の約1/3に当たる約15万人の民間人が死亡した。[12] 多くの民間人は、日本軍によって強制された集団自殺で命を落とした。[13]第二次世界大戦後、琉球諸島はアメリカ合衆国軍政府(1945年~1950 年)によって占領されたが、1951年のサンフランシスコ条約後もアメリカは支配を継続し、以前の直接統治はUSCAR政府に置き換えられた。この期間 中、アメリカ軍は多くの軍事施設建設のため私有地を強制接収し、私有地所有者は難民キャンプに収容され、その人員は民間人に対して数千件の犯罪を犯した。 [13][14] そのわずか 20 年後の 1972 年 5 月 15 日、沖縄および周辺島嶼は日本に返還された。戦後、日本は政治的自由と経済的繁栄を享受していたため、軍事施設は経済に悪影響を及ぼし、人民は、共産主義 の脅威に対する日本および地域の安全保障のために利用されたと、だまされたと感じていた。沖縄が正式に日本に返還されたにもかかわらず、日本とアメリカ は、地元の琉球住民の抗議にもかかわらず、アメリカ軍基地の維持と拡大を保証する合意を継続してきた。沖縄は日本の総面積の0.6%に過ぎないが、現在、 日本にあるアメリカ軍基地の75%が沖縄の基地に配置されている。[16][17] |

| Academic theories of Japanese colonialism Some philosophers, like Taira Katsuyasu, consider the establishment of Okinawa Prefecture as outright colonialism. Nomura Koya in his research argued that the Japanese mainland developed "an unconscious colonialism" in which Japanese people are not aware of how they continue to colonize Okinawa through the mainland's inclination to leave the vast majority of the United States' military presence and burden to Okinawa.[18] Eiji Oguma noted that the typical practice of "othering" used in colonial domination produced the perception of a backward "Okinawa" and "Okinawans". Some like Tomiyama Ichiro suggest that for the Ryukyuans, being a member of the modern Japanese nation-state is "nothing other than the start of being on the receiving end of colonial domination".[19] In 1957, Kiyoshi Inoue argued that the Ryukyu Shobun was an annexation of an independent country over the opposition of its people, thus constituting an act of aggression and not a "natural ethnic unification".[20] Gregory Smits noted that "many other works in Japanese come close to characterizing Ryukyu/Okinawa as Japan's first colony, but never explicitly do so".[21] Alan Christy emphasized that Okinawa must be included in studies of Japanese colonialism.[22] Historians supporting the interpretation that the annexation of Ryukyu did not constitute colonialism make the following historiographical arguments that after the invasion in 1609 the Ryukyu kingdom became part of Tokugawa shogunate's bakuhan system, its autonomy a temporary aberration, and when was established the Okinawa Prefecture in 1879 the islands were already part of the Japanese political influence and it was only an administrative extension i.e. traced the annexation back to 1609 and not 1879.[23] the establishment of Okinawa Prefecture was part of the Japanese nation-state integration, reassertion of authority and sovereignty over own territory, and that the Japan's colonial empire, dated from 1895, happened after the state integration and thus it can not be considered as colonial imposition.[24] with the creation of "unified racial society" (Nihonjinron) of Yamato people it was created an idea that the Ryukyuan racial incorporation was natural and inevitable. Only recently the scholars like Jun Yonaha begun to see that this idea of unification itself functions as a mean of legitimizing the Ryukyu Shobun.[25] Some pre-war Okinawans[who?] also resisted the classification of Okinawa as a Japanese colony, as they did not want to consider their experience as colonial. This position originates in the prewar period when the Meiji suppression of Ryukyuan identity, culture and language resulted in self-criticism and inferiority complexes with respect to perceptions that Ryukyuan people were backward, primitive, ethnically and racially inferior, and insufficiently Japanese.[nb 1] They did not want to be lumped together with the Japanese colonies, as evidenced by protests against being included with six other "less developed" colonial people in the "Hall of the Peoples" in the 1903 Osaka Expo.[27][28] Okinawan historian Higashionna Kanjun in 1909 warned the Ryukyuans that if they forget their historical and cultural heritage then "their native place is no different from a country built on a desert or a new colony".[29] Shimabukuro Genichiro in the 1930s described the Okinawa's pre-war position as "colonial-esque",[29] and in the 1920s he spearheaded a movement[which?] that supported the alteration of personal name spellings to spare Okinawans from ethnic discrimination.[30] The anxiety about the issue of Okinawa being part of Japan was so extreme that even attempts to discuss it were discredited and denounced from both mainland and Okinawan community itself, as a failure of being national subjects.[29] In Eugen Weber's theorization about the colonies, according to Tze May Loo, the question of Okinawa's status as a colony is a false choice which ignores the complexity of Okinawa's annexation, in which colonial practices were used to establish the Japanese nation-state. He asserts that Okinawa was both a colony and not, both a part of Japan and not, and that this dual status is the basis of the continued subordination of Okinawa. Despite its incorporation as a prefecture and not a colony, colonial policies of "un-forming" and "re-forming" Ryukyuan communities and the Okinawan's proximity to other Japanese colonial subjects were coupled with persistent mainland discrimination and exploitation which reminded them of their unequal status within the Japanese nation-state.[31] They had no choice but to consider their inclusion in the Japanese nation-state as natural in hopes of attaining legitimacy and better treatment. According to Loo, Okinawa is in a vicious circle where Japan does not admit its discrimination against Okinawa, while Okinawans are forced to accept unfair conditions for membership in the country of Japan, becoming an internal colony without end.[32] |

日本の植民地主義に関する学術的理論 平勝康などの一部の哲学者は、沖縄県設立を完全な植民地主義とみなしている。野村光也は、その研究の中で、日本本土は、米国軍の大半の駐留と負担を沖縄に 委ね続ける傾向があり、日本国民が沖縄の植民地化に気づかない「無意識の植民地主義」を発達させたと主張している。[18] 小熊英一は、植民地支配で典型的に用いられた「他者化」の慣行が、後進的な「沖縄」や「沖縄人」という認識を生み出したと指摘している。富山一郎のような 人々は、琉球人にとって、近代日本の国民になることは「植民地支配を受けることの始まりに他ならない」と主張している。[19] 1957年、井上清は、琉球書簡は、その人民の反対を無視して独立国を併合したものであり、「自然な民族統一」ではなく、侵略行為であると主張した [20]。グレゴリー・スミッツは、「日本語の他の多くの著作も、琉球/沖縄を日本の最初の植民地と特徴づけることに近い表現をしているが、それを明示的 には述べていない」と指摘している。[21] アラン・クリスティは、沖縄は日本の植民地主義の研究に含めるべきだと強調している。[22] 琉球の併合は植民地主義を構成しなかったとする解釈を支持する歴史家は、以下の歴史学的主張をしている。 1609年の侵攻後、琉球王国は徳川幕府の幕藩体制の一部となり、その自治は一時的な異常事態であり、1879年に沖縄県が設立された際、諸島は既に日本の政治的影響下にあったため、これは単なる行政上の拡張に過ぎず、併合は1879年ではなく1609年に遡る。[23] 沖縄県は、日本の国民国家統合、自国の領土に対する権威と主権の再確認の一環として設立され、日本の植民地帝国は1895年に成立しており、国家統合後に成立したものであり、植民地支配とは見なせない。[24] 大和民族の「統一民族社会」(日本人論)の創設に伴い、琉球民族の民族統合は当然かつ不可避であるという考えが生まれた。最近になって、与那賀純氏などの学者が、この統一の考え自体が琉球尚政を正当化する手段として機能していることに気づき始めた。 戦前の沖縄の一部の人々[誰?]も、自分たちの経験を植民地時代とみなしたくなかったため、沖縄を日本の植民地と分類することに抵抗した。この立場は、明 治時代に琉球のアイデンティティ、文化、言語が抑圧された結果、琉球人は後進的で、原始的で、民族的にも人種的にも劣っており、日本人として不十分である という自己批判や劣等感が生まれた戦前に端を発している。[nb 1] 1903年の大阪万国博覧会において、他の 6 つの「発展の遅れた」植民地の人々と一緒に「民族の館」に展示されたことに抗議したことからも、彼らは日本の植民地と一まとめにされることを望んでいな かったことがわかる。[27][28] 1909年、沖縄の歴史家、東喜多順は、琉球人が歴史的・文化的遺産を忘れてしまえば、「彼らの故郷は、砂漠に築かれた国や新しい植民地と何ら変わらな い」と警告した。[29] 1930年代、島袋源一郎は、戦前の沖縄の立場を「植民地的」と表現し[29]、1920年代には、沖縄の人々が民族差別を受けないように、名前の綴りの 変更を支持する運動[どの運動?] を主導した。[30] 沖縄が日本の一部であるかどうかという問題は、本土と沖縄のコミュニティの両方から、国民としての意識の欠如として非難され、議論することさえも否定され るほど、深刻な問題だった。[29] Tze May Looによると、ユージン・ヴェーバーの植民地に関する理論では、沖縄の植民地としての地位の問題は、日本の国民国家の確立のために植民地政策が採用され た沖縄の併合の複雑さを無視した誤った選択であるとしています。彼は、沖縄は植民地であり、かつ植民地ではない、日本の一部であり、かつ日本の一部ではな い、という二重の地位が、沖縄の従属の継続の基盤となっていると主張している。県として編入され、植民地とはならなかったにもかかわらず、琉球社会を「非 形成」し「再形成」する植民地政策と、他の日本の植民地住民との近接性は、本土による差別と搾取の継続と相まって、日本国民としての不平等な地位を彼らに 思い知らせていました。[31] 彼らは、正当性とより良い待遇を得るために、日本国民としての一体性を当然のことと受け入れるしかなかった。ルー氏によると、日本は沖縄に対する差別を認 めておらず、一方、沖縄の人々は、日本国民としての不公正な条件を受け入れることを余儀なくされ、終わりのない国内植民地となっているという悪循環に陥っ ている。 |

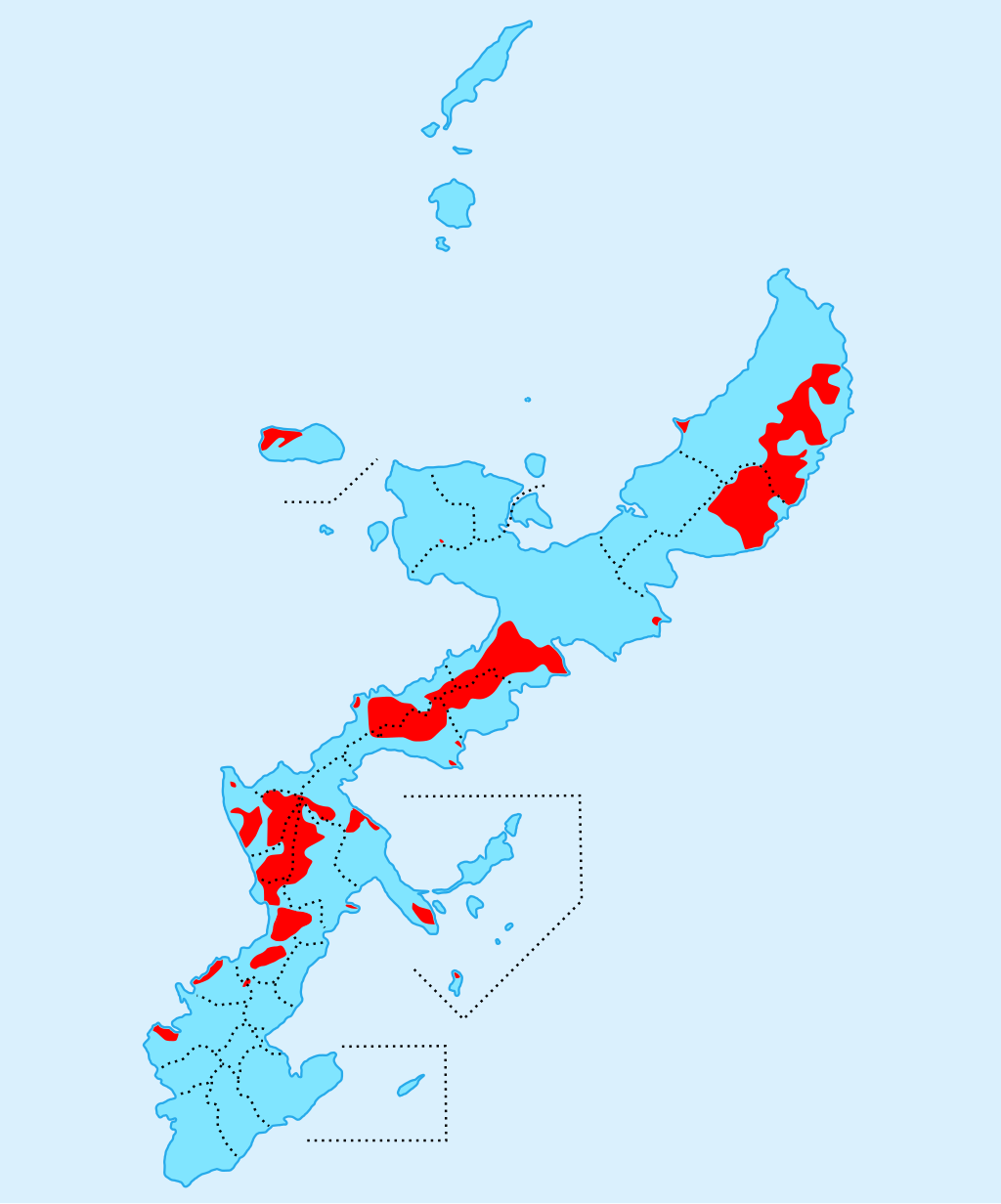

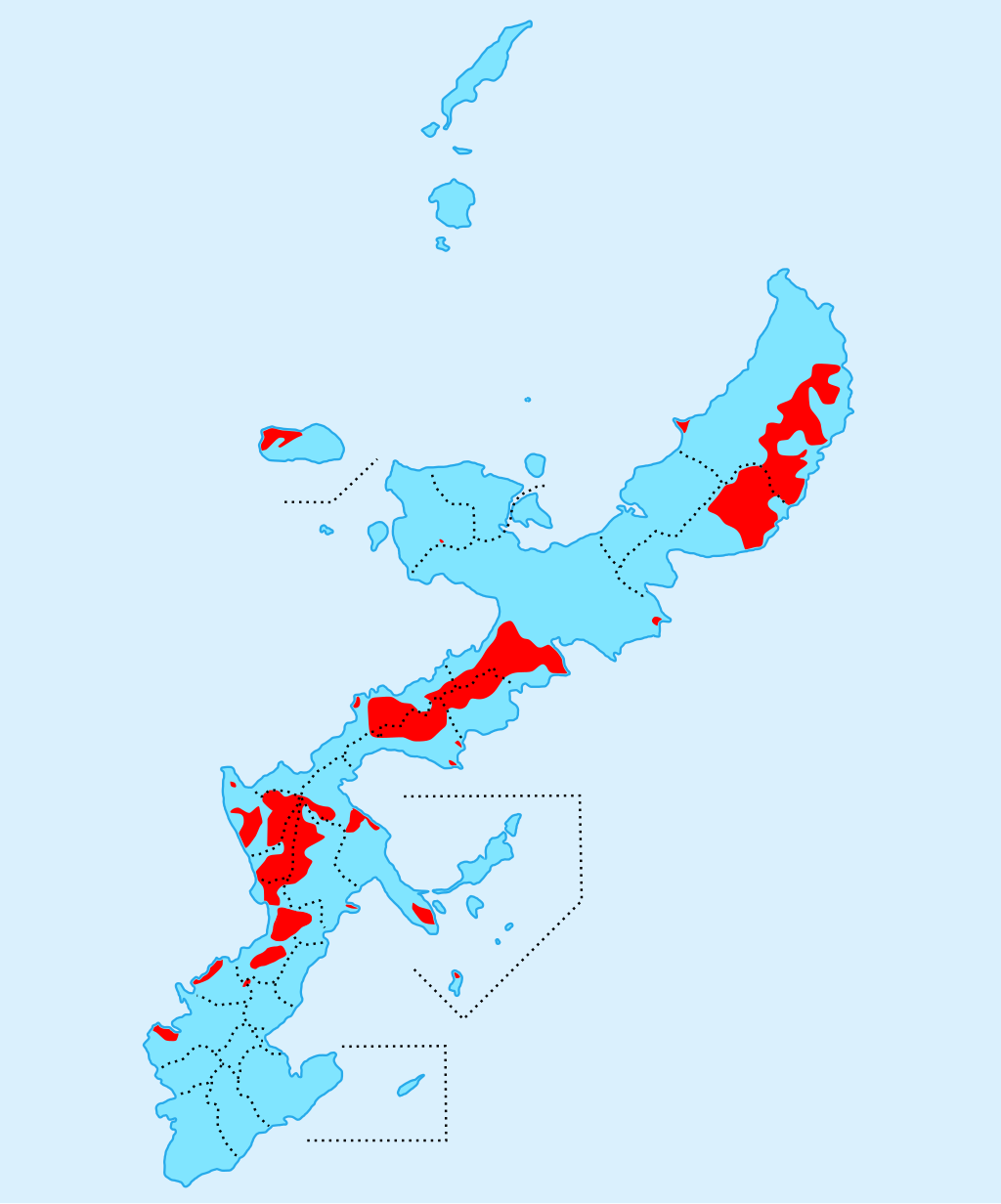

Motives Map of the Ryukyuan languages During the Meiji period there was a significant reimagining of the histories of Ryukyu and of Ezo, which was annexed at the same time, and an insistence that the non-Japonic Ainu of Hokkaidō and the Japonic Ryukyuan people were Japanese, both racially/ethnically and linguistically/culturally, going back many centuries, despite the evidence they were a significantly different group of people. The primary institution for assimilation was the state education system, which by 1902 occupied over half of the prefectural revenue[clarification needed], and produced a collective identity as well as training Okinawan teachers and intellectuals who would become a front Japanese nationalistic Okinawan elite.[33][34] Maehira Bokei noted that this narrative considered Okinawa a colony and rejected Okinawa's characteristic culture, considering it barbaric and inferior. This resulted in the development of an inferiority complex amongst Okinawans, which motivated them to discriminate against their own cultural heritage.[35] However, the state did valorize and protect some aspects like being "people of the sea", folk art (pottery, textiles) and architecture, although it defined these cultural elements as being Japonic in essence.[36] The Okinawan's use of heritage as a basis for political identity in the post-war period was interesting to the occupying United States forces who decided to support the pre-1879 culture and claims to autonomy in hopes that their military rule would be embraced by the population.[37][nb 2] Many Ryukyuan people see themselves as an ethnically separate and different people from the Japanese, with a unique and separate cultural heritage. They see a great difference between themselves and the mainland Japanese people, and many feel a strong connection to Ryukyuan traditional culture and the pre-1609 history of independence. There is strong criticism of the Meiji government's assimilation policies and ideological agenda. According to novelist Tatsuhiro Oshiro, the "Okinawa problem" is a problem of culture which produced uncertainty in the relations between Okinawans and mainland Japanese: Okinawans either want to be Japanese or distinct, mainland Japanese either recognize Okinawans as part of their cultural group or reject them, and Okinawa's culture is treated as both foreign and deserving of repression, as well as being formally considered as part of the same racial polity as Japan.[40] |

動機 琉球諸語の地図 明治時代、琉球と同時期に併合された蝦夷の歴史が大幅に再構築され、北海道の非日本系のアイヌと日本系の琉球人は、明らかに異なる民族であるにもかかわら ず、何世紀にもわたって人種的・民族的にも、言語的・文化的にも日本人であるとの主張が強調された。同化政策の主な機関は、1902年までに県収入の半分 以上を占めていた[要検証]、国家教育制度であり、集団的アイデンティティを形成するとともに、日本のナショナリストである沖縄のエリートとなる沖縄の教 師や知識人を育成した。[34] 前平博栄は、この叙述は沖縄を植民地と見なし、沖縄の特質である文化を野蛮で劣ったものと否定していると指摘している。その結果、沖縄の人々に劣等感が生 じ、自らの文化遺産を差別する動機となった[35]。しかし、国家は「海の人々」であること、民芸(陶芸、織物)、建築などの一部の側面を評価し保護した が、これらの文化要素は本質的に日本的なものと定義した[36]。戦後、沖縄の人々が政治的アイデンティティの基盤として遺産を利用することは、占領軍で ある米国にとって興味深いものでした。米国は、軍事支配が住民に受け入れられることを期待して、1879年以前の文化と自治の主張を支持することを決定し ました。[37][nb 2] 多くの琉球人は、自分たちを、日本人とは民族的に別個の、異なる民族であり、独特で独立した文化遺産を持つ民族だと考えています。彼らは、自分たちと日本 本土の人々との間に大きな違いがあると考え、多くが琉球の伝統文化や1609年以前の独立の歴史に強い結びつきを感じている。明治政府の同化政策やイデオ ロギー的な政策に対しては、強い批判がある。小説家の大城達弘によると、「沖縄問題」は、沖縄人と日本本土の人々の関係に不確実性をもたらした文化の問題 である。沖縄人は日本人として認められるか、または独自の存在として認められるかを望んでおり、本土の日本人は沖縄人を自文化集団の一部として認めるか、 または拒否するか、そして沖縄の文化は外国の文化として抑圧に値するものとして扱われ、同時に日本と同じ人種的共同体の一部として正式に認められている。 [40] |

| Ideology According to Yasukatsu Matsushima, Professor of Ryukoku University and the representative of the civil group "Yuimarle Ryukyu no Jichi" ("autonomy of Ryukyu"), the 1879 annexation was illegal and cannot be justified on either moral grounds or international law, as the Ryukyu government and people did not agree to join Japan and there is no existing treaty transferring sovereignty to Japan.[41] He notes that the Kingdom of Hawaii was in a similar position, at least the U.S. admitted illegality and issued an apology in 1992, but Japan has never apologized or considered compensation.[9] Japan and the United States are both responsible for the colonial status of Okinawa – used first as a trade negotiator with China, later as a place to fight battles or establish military bases. After the 1972 return to Japan, the government economic plans to narrow the gap between Japanese and Okinawans were opportunistically abused by the Japanese enterprises of construction, tourism, and media which restricted living space on the island, and many Okinawans continue to work as seasonal workers, with low wages while women were overworked and underpaid.[42] Dependent on the development plan, they were threatened with decrease of financial support if they expressed opposition to the military bases (which occurred in 1997 under Governor Masahide Ōta,[43] and in 2014 as a result of Governor Takeshi Onaga's policies[44]). As a consequence of campaigns to improve soil quality on Okinawa, many surrounding coral reefs were destroyed.[45] According to Matsushima, the Japanese people are not aware of the complexities of the Okinawan situation. The Japanese pretend to understand it and hypocritically sympathize with Okinawans, but until they understand that the U.S. bases as incursions on Japanese soil, and that the lives and land of the Okinawans have the same value as their own, the discrimination will not end. Also, as long Okinawa is part of Japan, the United States military bases will not leave, because it is Japan's intention to use Okinawa as an island military base, seen from the Emperor Hirohito's "Imperial Message" (1947) and US-Japan Security Treaty valid from 1952.[46] Even further, it is claimed that Okinawa Prefecture's status violates Article 95 of Japanese constitution – a law applicable to one single entity can not be enacted by National Diet without the consent of the majority of the population in the entity (ignored during the implementation of financial plan from 1972, as well in 1996 legal change of law about the stationing of military bases). The constitution's Article 9 (respect for the sovereignty of the people) is violated by the stationing of American military troops, as well as the lack of protection for civilians' human rights. The 1971 Okinawa Reversion Agreement is deemed illegal – according to international law, the treaty is limited to Okinawa Prefecture as a political entity, while Japan and U.S. also signed a secret treaty according to which the Japanese state cannot act inside the U.S. military bases. Thus, if the reversion treaty is invalid the term "citizens" does not refer to the Japanese, but Okinawans. According to the movement's goals, independence does not mean the revival of the Ryukyu Kingdom, or a reversion to China or Japan, but the establishment of a new and modern Ryukyuan state.[47] |

イデオロギー 龍谷大学教授であり、市民団体「ゆいまるる琉球の自治」の代表である松島泰勝教授によると、1879年の併合は、琉球政府と人民が日本への編入に同意して おらず、日本への主権を譲渡する条約も存在しなかったため、道義的にも国際法上も違法であり、正当化できないとのことです。[41] 彼は、ハワイ王国も同様の立場にあったと指摘している。少なくとも米国は違法性を認め、1992年に謝罪を発表したが、日本は謝罪も補償も検討したことが ない。[9] 日本と米国は、沖縄の植民地化に責任を負っている。沖縄は当初、中国との貿易交渉の仲介役として利用され、後に戦場や軍事基地の設置場所として利用され た。1972年の日本返還後、日本政府の経済計画は、建設、観光、メディア業界の日本企業によって恣意的に濫用され、島の居住空間が制限された。多くの沖 縄人は低賃金で季節労働者として働き続け、女性は過重労働と低賃金に苦しんでいる。[42] 開発計画に依存していたため、軍事基地に反対を表明すると財政支援の削減を脅かされた(1997年に大田昌秀知事の下で発生し[43]、2014年には翁 長雄志知事の政策の結果として発生した[44])。沖縄の土壌改良キャンペーンの結果、多くの周辺のサンゴ礁が破壊された。[45] 松島氏によると、日本国民は沖縄の複雑な状況について認識していない。日本人は理解しているふりをして、沖縄の人々に偽善的に同情しているが、米軍基地が 日本の領土への侵入であり、沖縄の人々の生命と土地が自分たちの生命と土地と同じ価値があるということを理解しない限り、差別は終わらないだろう。また、 沖縄が日本の一部である限り、米軍基地は撤退しないだろう。これは、昭和天皇の「皇室典範」 (1947 年) や 1952 年から有効な日米安全保障条約から、日本が沖縄を島嶼軍事基地として利用する意図があることがわかるからだ。[46] さらに、沖縄県は、単一の団体に適用される法律は、その団体の住民の過半数の同意がない限り、国会で制定することはできないとする日本国憲法第95条に違 反していると主張している(1972年の財政計画の実施、1996年の軍事基地の駐留に関する法律の改正の際には、この規定は無視された)。憲法第 9 条(人民の主権の尊重)は、米軍の駐留、および民間人の人権保護の欠如によって違反されている。1971年の沖縄返還協定は違法とされている。国際法上、 この条約は政治的实体としての沖縄県に限定されており、日本とアメリカは秘密条約を締結し、日本国はアメリカ軍基地内での行動を禁止されている。したがっ て、返還条約が無効であれば、「市民」とは日本人ではなく、沖縄人を指す。運動の目標によると、独立とは琉球王国の復活や中国または日本への復帰を意味す るものではなく、新しい現代的な琉球国家の設立を意味する。[47] |

| History The independence movement was already under investigation by the U.S. Office of Strategic Services's in their 1944 report. They considered it as an organization emerging primarily among Okinawan's emigrants, specifically in Peru, because the territory of Ryukyu and its population were too small to make the movement's success attainable.[48] They noted the long relationship between China and Ryukyu Kingdom, saw the Chinese territorial claims as justified, and concluded that the exploitation of the identity gap between Japan and Ryukyu made for good policy for the United States.[49] George H. Kerr argued that U.S. should not see Ryukyu Islands as Japanese territory. He asserted that the islands were colonized by Japan, and in an echo to Roosevelt's Four Freedoms, concluded that because Matthew C. Perry's visit in 1853 the U.S. treated the Ryukyu as independent kingdom, they should re-examine Perry's suggestion about maintaining Ryukyu as an independent nation with international ports for international commerce.[50] There was pressure after 1945, immediately following the war during the United States Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands (1945–1950), for the creation of an autonomous or independent Ryukyu Republic. According to David John Obermiller, the initiative for independence was ironically inspired from mainland. In February 1946, the Japanese Communist Party in its message welcomed a separate administration and supported Okinawa's right to liberty and independence, while the Okinawan organization of leftist leaning intellectuals Okinawajin Renmei Zenkoku Taikai, residing in Japan, also unanimously supported independence from Japan.[51] In 1947, the three newly formed political parties Okinawa Democratic League-ODL (formed by Genwa Nakasone, conservative), Okinawan People's Party-OPP (formed by Kamejiro Senaga, leftist), and smaller Okinawa Socialist Party-OSP (formed by Ogimi Chotoku) welcomed the U.S. military as an opportunity to free Okinawa from Japan, considering independence from Japan as a republic under guardianship of U.S. or United Nations trusteeship.[52][53] Common people also perceived the U.S. troops as liberators.[54] OPP also considered endorsing autonomy, as well as a request for compensation from Japan,[55] and even during the 1948–1949 crisis, the question of reversion to Japanese rule was not a part political discourse.[51] The governor of the island of Shikiya Koshin, probably with support by Nakasone, commissioned a creation of Ryukyuan flag, which was presented on 25 January 1950.[56] The only notable Ryukyuan who advocated reversion between 1945 and 1950 was the mayor of Shuri, Nakayoshi Ryoko, who permanently left Okinawa in 1945 after receiving no public support for his reversion petition.[51] In elections in late 1950, the Democratic League (then titled Republican Party) was defeated by the Okinawa Social Mass Party (OSMP), formed by Tokyo University graduates and schoolteachers from Okinawa who were against the U.S. military administration and advocated return to Japan.[57] Media editorials in late 1950 and early 1951, under Senaga's control, criticized the OSMP (pro-reversion) and concluded that U.S. rule would be more prosperous than Japanese rule for Ryukyu.[58] In February 1951, at the Okinawa Prefectural Assembly, the pro-U.S. conservative Republican Party spoke for independence, Okinawa Socialist Party for a U.S. trusteeship, while the OPP (previously pro-independence) and OSMP advocated for reversion to Japan, and in March the Assembly made a resolution for reversion.[59] "Ethnic pride" played a role in public debate as enthusiasm for independence disappeared, and as the majority were in favor of reversion to Japan, which began to be viewed as the "home country" because of a return to the collective perception of Okinawans as part of the Japanese identity, as promulgated in the 19th century education system and repression, effectively silencing the movement for Okinawan self-determination.[60] According to Moriteru Arasaki (1976), the question of self-determination was too easily and regrettably replaced by the question of preference for U.S. or Japanese dominion, a debate which emphasized Okinawan ethnic connections with the Japanese as opposed to their differences.[55] Throughout the period of formal American rule in Okinawa, there were series of protests (including the Koza riot[61]) against U.S. land policy and against the U.S. military administration.[62] In 1956, one-third of the population advocated for independence, another third for being part of the United States, and final third for maintaining ties with Japan.[63] Despite the desire of many inhabitants of the islands for some form of independence or anti-reversionism, the massive popularity of reversion supported the Japanese government's decision to establish the Okinawa Reversion Agreement, which put the prefecture back under its control. Some consider the 1960s anti-reversionism was different from the 1950s vision of independence because it did not endorse any political option for another nation-state patronage.[64] Arakawa's position was more intellectual rather than political, which criticized Japanese nationalism (in counterposition to Okinawan subjectivity) and fellow Okinawans' delusions about the prospects of full and fair inclusion in Japanese state and nation, which Arakawa believed would only perpetuate further subjugation.[65] In November 1971, information was leaked that the reversion agreement would ignore the Okinawans' demands and that Japan was collaborating with the United States to maintain a military status quo. A violent general strike was organized in Okinawa, and in February 1972 Molotov cocktails were hurled the Japanese government office building on Okinawa.[66] Since 1972, because of a lack of any anticipated developments in relation to the US-Japan alliance, committed voices have turned once again towards the aim of "Okinawa independence theory", on the basis of cultural heritage and history, at least by poets and activists like Takara Ben and Shoukichi Kina,[65] and on a theoretical level in academic journals.[67] Between 1980 and 1981 leading Okinawan intellectuals held symposiums about the independence, with even a drafted constitution and another national flag for Ryukyus, with the collected essays published with the title Okinawa Jiritsu he no Chosen (The Challenges Facing Okinawan Independence). The Okinawan branch of NHK and newspaper Ryūkyū Shimpō sponsored a forum for the discussion of reversion, assimilation to the Japanese polity, as well as the costs and opportunities of Ryukyuan independence.[68] |

歴史 独立運動は、1944年の米国戦略情報局(OSS)の報告書ですでに調査の対象となっていた。彼らは、琉球の領土とその人口が小さすぎて運動の成功は不可 能であるとして、この運動は主に沖縄の移民、特にペルーに住む移民の間で台頭している組織であると判断した。[48] 彼らは、中国と琉球王国との長年の関係に言及し、中国の領土主張を正当なものとし、日本と琉球のアイデンティティのギャップを悪用することは米国にとって 良い政策であると結論付けた。[49] ジョージ・H・カーは、米国は琉球諸島を日本の領土と見なすべきではないと主張した。彼は、琉球諸島は日本によって植民地化されたと主張し、ルーズベルト の「四つの自由」を引用して、1853 年のペリー使節団以来、米国は琉球を独立した王国として扱ってきたので、琉球を国際貿易のための国際港を有する独立国として維持するというペリーの提案を 再検討すべきだと結論付けた。[50] 1945年、戦後直後の琉球諸島米国政府(1945年~1950年)の期間、自治または独立した琉球共和国の創設を求める圧力があった。デビッド・ジョ ン・オーバーミラーによると、独立のイニシアチブは皮肉にも本土から着想されたものだった。1946年2月、日本共産党はメッセージで別行政を歓迎し、沖 縄の自由と独立の権利を支持した。一方、日本在住の左派知識人組織「沖縄人連合全国大会」も、日本からの独立を全会一致で支持した。[51] 1947年、新たに結成された3つの政党、沖縄民主同盟(ODL、中曽根元和氏(保守派)が結成)、 沖縄人民党(左派の千名亀次郎が結成)、そして小規模な沖縄社会党(大城朝徳が結成)は、日本からの独立を、米国または国連の信託統治下にある共和国とし て日本から沖縄を解放するチャンスと捉え、米軍を歓迎した。[52][53] 一般市民も、米軍を解放者と認識していた[54]。OPP は、日本への賠償請求とともに自治の承認も検討し[55]、1948年から1949年の危機の間も、日本への返還問題は政治言説の一部ではなかった。 [51] 志喜屋幸信島知事は、おそらく中曽根の支援を受けて、琉球旗の制作を依頼し、1950年1月25日に提出された。[56] 1945年から1950年にかけて復帰を主張した唯一の著名な琉球人は、復帰請願に公的な支持を得られなかったため1945年に沖縄を永久に離れた首里市 長の中吉良子だった。[51] 1950年後半の選挙では、民主党(当時、共和党)は、米軍政に反対し、日本への復帰を主張する東京大学卒業生や沖縄の学校教師によって結成された沖縄社 会大衆党(OSMP)に敗れた。[57] 1950年末から1951年初頭にかけて、セナガの支配下にあったメディアの社説は、OSMP(返還支持派)を批判し、リュウキュウにとって米軍統治が日 本統治より繁栄をもたらすと結論付けた。[58] 1951年2月、沖縄県議会で、親米保守派の共和党は独立を主張し、沖縄社会党は米軍信託統治を主張した一方、OPP(以前は独立派)とOSMPは日本へ の返還を主張し、3月に議会は返還決議を採択した。[59] 「民族の誇り」は、独立への熱意が失われ、大多数が日本への復帰を支持するようになった中で、公の議論において重要な役割を果たした。これは、19世紀の 教育制度と抑圧によって広まった、沖縄人が日本のアイデンティティの一部であるという集団的認識が復活し、沖縄の自主決定運動を事実上沈黙させたため、日 本が「祖国」と見なされるようになったためだ。[60] 荒崎守(1976)によると、自決の問題は、沖縄と日本の民族的なつながりを強調し、その相違を無視した、米国か日本かどちらの支配を好むかという議論 に、あまりにも安易かつ遺憾にも置き換えられてしまった。[55] 沖縄の正式なアメリカ統治期間中、アメリカ合衆国の土地政策やアメリカ軍行政に対する一連の抗議運動(コザ暴動[61]を含む)が発生した。[62] 1956年には、人口の3分の1が独立を支持し、3分の1がアメリカ合衆国の一部となることを支持し、残りの3分の1が日本とのつながりを維持することを 支持した。[63] 島民の多くが何らかの形の独立や反返還を望んでいたにもかかわらず、返還を支持する大衆の支持は、沖縄県を日本の支配下に戻す「沖縄返還協定」の締結とい う日本政府の決定を後押しした。1960年代の反返還運動は、別の国家の保護を政治的な選択肢として支持しなかった点で、1950年代の独立運動とは異 なっていたと見る向きもある。[64] 荒川の立場は、政治的というよりも知的であり、日本のナショナリズム(沖縄の主体性とは対立する)や、日本国家および国民に完全かつ公正に組み込まれると いう沖縄人の幻想を批判し、それはさらなる征服を永続させるだけだと考えていました。[65] 1971年11月、返還合意が沖縄人の要求を無視し、日本が米国と協力して軍事的現状を維持する計画であることが漏洩した。沖縄で激しい一般ストライキが 組織され、1972年2月には沖縄の日本政府庁舎にモロトフカクテルが投げ込まれた。[66] 1972年以来、日米同盟に関する進展が見込めない状況の中、文化遺産と歴史を根拠に、「沖縄独立論」の目標に再び熱心な声が上がっている。少なくとも、 宝弁や喜名正吉のような詩人や活動家たち[65]、そして学術誌における理論的なレベルではそうである。[67] 1980年から1981年にかけて、沖縄の有力な知識人が独立に関するシンポジウムを開催し、琉球の憲法草案や新国旗も作成され、その論文集『沖縄独立へ の挑戦』が刊行された。NHK沖縄放送局と新聞『琉球新報』は、返還、日本政治体制への同化、琉球独立のコストと機会に関する議論のためのフォーラムを後 援した[68]。 |

U.S. military bases Map showing the territory covered by military bases of the United States in Okinawa Though there are pressures in the US and Japan, as well as in Okinawa, for the removal of US troops and military bases from Okinawa, there have thus far been only partial and gradual movements in the direction of removal. In April 1996, a joint US-Japanese governmental commission announced that it would address Okinawan's anger, reducing the U.S. military foot-print and returning part of the occupied land in the center of Okinawa (only around 5%[citation needed]), including the large Marine Corps Air Station Futenma, located in a densely populated area.[4] According to the agreement, both the Japanese and the U.S. governments agreed that 4,000 hectares of the 7,800-hectare training area are to be returned on condition that six helipads would be relocated to the remaining area. So far, July 2016, only work on two helipads has been completed.[69] In December 2016, U.S. military announced the return of 17% of American-administered areas.[70] However, while initially considered as a positive change, in September 1996 the public became aware that the U.S. planned to "give up" Futenma for construction of a new base (first since the 1950s) in the north offshore, Oura Bay, near Henoko (relatively less populated than Ginowan) in the municipality of Nago. In December 1996, SACO formally presented its proposal.[71] Although the fighter jet and helicopter noise, as well accidents, would be put away from a very to less populated area, the relocation of Marine Corps Air Station Futenma to Henoko (i.e. Oura Bay) would have a devastating impact on the coral reef area, its waters and ecosystem with rare and endangered species, including the smallest and northernmost population of dugongs on Earth.[71][5] The villagers organized a movement called "Inochi o Mamorukai" ("Society for the protection of life"), and demanded a special election while maintaining a tent city protest on the beach, and a constant presence on the water in kayaks. The governor's race in 1990 saw the emergence of both an anti-faction and a pro-faction composed of members from construction-based businesses. Masahide Ōta, who opposed the base's construction, won with 52% of the vote. However, the Japanese government successfully sued Ōta and transferred the power over Okinawan land leases to the Prime Minister, ignored the 1997 Nago City citizens' referendum (which had rejected the new base), stopped communication with the local government, and suspended economic support until Okinawans elected the Liberal Democratic Party's Keiichi Inamine as governor (1998–2006).[43] The construction plans moved slowly, and the protesters got more attention when a U.S. helicopter crashed into a classroom building of Okinawa International University. However, the government portrayed the incident as a further argument for the construction of the new base, and began to harm and/or arrest local villagers and other members of the opposition. By December 2004, several construction workers recklessly wounded non-violent protestors. This caused the arrival of Okinawa fishermen to the Oura Bay.[72] Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama (16 September 2009 – 2 June 2010) opposed the base facility, but his tenure was short and his campaign promise to close the base was not fulfilled. The subsequent ministers acted as clients for the United States, while in 2013 Shinzō Abe and Barack Obama affirmed their commitment to build the new base, regardless of the local protests.[73] The relocation was approved by Okinawa's governor in 2014,[74] but the governor of the prefecture, Takeshi Onaga (who died in 2018), completely opposed the military base's presence. The 2014 poll showed that 80% of population want the facility out of the prefecture.[75] In September 2015, Governor Onaga went to base his arguments to the United Nations human rights body,[76] but in December 2015, the work resumed as the Supreme Court of Japan ruled against Okinawa's opposition, a decision which erupted new protests.[77] In February 2017, Governor Onaga went to Washington to represent the local opposition to the administration of newly elected U.S. president Donald Trump.[78] |

米軍基地 沖縄の米軍基地が占める地域を示す地図 米国、日本、そして沖縄において、沖縄からの米軍および米軍基地の撤去を求める圧力があるものの、これまでのところ、撤去に向けた動きは部分的かつ段階的なものに留まっている。 1996年4月、日米政府合同委員会は、沖縄の怒りを解消するため、米軍の駐留規模を縮小し、沖縄中央部(約5%[出典必要])の占領地の一部を返還する と発表した。これには、人口密集地域に位置する大規模な海兵隊航空基地フテンマも含まれる。[4] 合意によると、日本政府と米国政府は、7,800ヘクタールの訓練区域のうち4,000ヘクタールを返還する条件として、6つのヘリポートを残り区域に移 転することに合意した。2016年7月現在、2つのヘリポートの工事のみが完了している。[69] 2016年12月、米軍は米軍管理区域の17%を返還すると発表した。[70] しかし、当初は前向きな変化と受け止められていたが、1996年9月、米国がフテンマを「放棄」し、1950年代以来初めての新基地を、ギノワンの北沖 合、オウラ湾(ギノワンよりも人口の少ない地域)のナゴ市に建設する計画が明らかになった。1996年12月、SACOは正式に提案を提示した。[71] 戦闘機とヘリコプターの騒音や事故は、人口の少ない地域から遠ざけられるものの、海兵隊航空基地フテンマのヘノコ(すなわちオウラ湾)への移転は、希少で 絶滅危惧種の生物を含むサンゴ礁地域、その水域、生態系に壊滅的な影響を与える。これには、地球上で最も小さく最も北に位置するジュゴンの群れも含まれ る。[71][5] 村人たちは「命を守る会」という運動を組織し、テント村での抗議活動を続け、カヤックで海上に常駐しながら、特別選挙の実施を要求した。1990年の知事 選挙では、反派と建設関連企業で構成される親派の両陣営が台頭した。基地建設に反対していた太田昌秀氏が 52% の得票で勝利した。しかし、日本政府はオオタを提訴し、沖縄の土地賃貸権を首相に移管。1997年の名護市住民投票(新基地建設を否決)を無視し、地方自 治体との対話を断絶し、経済支援を停止した。沖縄が自由民主党のイナミネ・ケイイチを知事(1998~2006年)に選出するまで、この状態が続いた。 [43] 建設計画はゆっくりと進み、米軍のヘリコプターが沖縄国際大学の校舎に墜落した事件で、抗議者たちはさらに注目を集めた。しかし、政府は、この事件を新基 地建設のさらなる論拠として利用し、地元住民や反対派のメンバーを傷つけたり、逮捕したりし始めた。2004年12月までに、複数の建設作業員が非暴力の 抗議者を無謀に負傷させた。これにより、沖縄の漁師たちが大浦湾に集結した。[72] 鳩山由紀夫首相(2009年9月16日~2010年6月2日)は基地施設に反対したが、在任期間は短く、基地閉鎖の公約は実現しなかった。その後の大臣た ちはアメリカ合衆国の代理人として行動し、2013年には安倍晋三とバラク・オバマが、地元の抗議にもかかわらず新基地建設へのコミットメントを再確認し た。[73] 2014年に沖縄県の知事が移転を承認したが、県知事の翁長雄志(2018年に死去)は軍事基地の駐留に完全に反対した。2014 年の世論調査では、80% の住民が基地の県外移転を望んでいることが明らかになった[75]。2015 年 9 月、翁長知事は国連人権委員会で基地反対の主張を行った[76]が、2015 年 12 月、最高裁判所が沖縄の反対を却下する判決を下し、工事が再開され、新たな抗議運動が勃発した。[77] 2017年2月、翁長知事は、新たに就任したドナルド・トランプ米大統領の政権に対して、地元住民の反対意見を伝えるため、ワシントンを訪問した [78]。 |

| Protests Many protests have been staged, but due to the lack of a united political struggle for national independence, these protests have a limited political horizon,[79] although some[who?] consider them to be an extension of the independence and anti-reversionist movement,[65] replacing the previous reversion movement of the 1970s with anti-base and self-determination struggle.[80] Nomura Koya claims that the protests are finally beginning to confront Okinawans with Japanese and American imperialism.[81] In September 1995, 85,000 people protested because of the U.S. military rape incident.[82][14] This event is considered as the "third wave of the Okinawa Struggle" movement against the marginalization of Okinawa, the US-Japan security alliance, and the U.S. global military strategy.[83] Beside being anti-US, it also had a markedly anti-Japanese tone.[84] In 2007, 110,000 people protested due to Ministry of Education's textbook revisions (see MEXT controversy) of the Japanese military's ordering of mass suicide for civilians during the Battle of Okinawa.[85][86] The journal Ryūkyū Shimpō and scholars Tatsuhiro Oshiro, Nishizato Kiko in their essays considered the U.S. bases in Okinawa a continuation of Ryukyu Shobun to the present day.[87] The Japanese government designation of 28 April, the date on which the Treaty of San Francisco returned sovereignty over Okinawa to Japan, as "Restoration of Sovereignty Day" was opposed by Okinawans, who instead considered it a "day of humiliation".[87][88] In June 2016, after the rape and murder of a Japanese woman, more than 65,000 people gathered in protest of the American military presence and crimes against the residents.[citation needed] |

抗議運動 多くの抗議行動が行われてきたが、国家の独立を求める統一的な政治闘争がないため、これらの抗議行動の政治的視野は限られている[79]。しかし、一部の 人々は、これらの抗議行動は、1970年代の返還運動に代わって、反基地運動や自決運動という形で、独立運動や反返還運動の延長線上にあるものと捉えてい る[65]。[80] 野村幸也は、これらの抗議活動がようやく沖縄の人々に日本とアメリカの帝国主義と対峙させ始めていると主張している。[81] 1995年9月、米軍による強姦事件を受けて、85,000人が抗議行動を行った[82][14]。この事件は、沖縄の疎外、日米安全保障体制、米国の世 界的な軍事戦略に対する「沖縄闘争の第3波」とみなされている。[83] 反米であるだけでなく、反日的な色合いも強かった。[84] 2007年には、沖縄戦における日本軍による民間人集団自決命令に関する文部科学省の教科書改訂(文部科学省教科書問題)に抗議して、11万人がデモを 行った。[85][86] 雑誌『琉球新報』と学者大城達弘、西里喜光は、沖縄の米軍基地を琉球王朝の支配の継続とみなした。[87] 日本政府がサンフランシスコ条約により沖縄の主権が日本に戻った日である4月28日を「主権回復の日」と指定したことに対し、沖縄の人々は反対し、代わり に「屈辱の日」と位置付けた。[87][88] 2016年6月、日本人女性が強姦殺害された事件を受けて、65,000人以上が米軍の駐留と住民に対する犯罪に抗議して集まった。[要出典] |

| Recent events The presence of the U.S. military remains a sensitive issue in local politics. Feelings against the Government of Japan, the Emperor (especially Hirohito due to his involvement in the sacrifice of Okinawa and later military occupation), and the U.S. military (USFJ, SACO) have often caused open criticism, protests, and refusals to sing the national anthem.[89][90] For many years the Emperors avoided visiting Okinawa, since it was assumed that his visits would likely cause uproar, like in July 1975 when then-crown prince Akihito visited Okinawa and communist revolutionary activists threw a Molotov cocktail at him.[91][92][93][94] The first ever visit in history of a Japanese emperor to Okinawa occurred in 1993 by emperor Akihito.[91][95] The 1995 rape incident stirred a surge of ethnic-nationalism. In 1996, Akira Arakawa wrote Hankokka no Kyoku (Okinawa: Antithesis to the Evil Japanese Nation State) in which argued for resistance to Japan and Okinawa's independence.[96] Between 1997 and 1998 there was a significant increase in debates about Okinawan independence. Intellectuals held heated discussions, symposiums, while two prominent politicians[who?] organized highly visible national forums. In February 1997, a member of the House of Representatives asked the government what was needed for Okinawan independence, and was told that it is impossible because the constitution does not allow it.[65][97] Oyama Chojo, former long-term mayor of Koza/Okinawa City, wrote a best-selling book Okinawa Dokuritsu Sengen (A Declaration of Okinawan Independence), and stated that Japan is not the fatherland of Okinawa.[65][84] The Okinawa Jichiro (Municipal Workers Union) prepared a report about measures for self-government. Some considered the autonomy and independence of Okinawa to be a reaction to Japanese "structural corruption", and made demands for administrative decentralization.[65] In 2002, scholars of constitutional law, politics and public policy at the University of the Ryukyus and Okinawa International University founded a project "Study Group on Okinawa Self-governance" (Okinawa jichi kenkyu kai or Jichiken), which published a booklet (Okinawa as a self-governing region: What do you think?) and held many seminars. It posited three basic paths; 1) leveraging Article 95 and exploring the possibilities of decentralization 2) seeking formal autonomy with the right to diplomatic relations 3) full independence.[98]  Flag of the Kariyushi Club Literary and political journals like Sekai (Japan), Ke-shi Kaji and Uruma neshia (Okinawa) began to frequently write on the issue of autonomy, and numerous books about the topic have been published.[99] In 2005, the Ryūkyū Independent Party, formerly active in the 1970s, was reformed and since 2008 has been known as the Kariyushi Club.[99] In May 2013, the Association of Comprehensive Studies for Independence of the Lew Chewans (ACSILs) was established, focusing on demilitarization, decolonization, and aim of self-determined independence. They plan to collaborate with polities such as Guam and Taiwan that also seek independence.[99][100] In September 2015, it held a related forum in New York University in New York City.[101] The topics of self-determination have since entered mainstream electoral politics. The LDP Governor Hirokazu Nakaima (2006–2014), who approved the government's permit for the construction of military base, was defeated in November 2014 election by Takeshi Onaga, who ran on a platform that was anti-Futenma relocation, and pro-Okinawan self-determination. Mikio Shimoji campaigned on the prefecture-wide Henoko-referendum, on the premise that if the result was rejected it would be held as a Scotland-like independence referendum.[102] In January 2015, The Japan Times reported that the Ryukoku University professor Yasukatsu Matsushima and his civil group "Yuimarle Ryukyu no Jichi" ("autonomy of Ryukyu"), which calls for the independence of the Ryukyu Islands as a self-governing republic,[103] are quietly gathering a momentum. Although critics consider that Japanese government would never approve independence, according to Matsushima, the Japanese approval is not needed because of U.N International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights for self-determination. His group envisions creating an unarmed, neutral country, with each island in the arc from Amami to Yonaguni deciding whether to join.[104] In February of the same year, Uruma-no-Kai group which promotes the solidarity between Ainu and Okinawans, organized a symposium at Okinawa International University on the right of their self-determination.[98] In the same month an all-day public forum entitled "Seeking a course: Discussions of Okinawa's right to self-determination" was held, asserting that it was the right time to assume its role as a demilitarized autonomous zone, a place of exchange with China and surrounding countries, and a cosmopolitan center for Okinawa's economic self-sufficiency.[105] |

最近の出来事 米軍の駐留は、地方政治において依然として敏感な問題となっている。日本政府、天皇(特に沖縄の犠牲とその後の軍事占領に関与した裕仁天皇)、および米軍 (在日米軍、SACO)に対する反感から、公然と批判や抗議行動、国歌斉唱の拒否などが頻繁に発生している[89]。[90] 長年にわたり、天皇は沖縄訪問を避けてきた。その理由は、訪問が騒動を引き起こす可能性が高いとされていたためで、例えば1975年7月に当時の皇太子 だった明仁が沖縄を訪問した際、共産主義革命活動家が彼にモロトフカクテルを投げつけた事件が挙げられる。[91][92][93][94] 日本の天皇が沖縄を訪問したのは、1993年に明仁天皇が初めてだった。[91][95] 1995年の強姦事件は、民族ナショナリズムの波を引き起こした。1996年、新川明は『反日国家の極』を執筆し、日本に対する抵抗と沖縄の独立を主張し た[96]。1997年から1998年にかけて、沖縄の独立に関する議論が活発化した。知識人は激しい議論やシンポジウムを開催し、2人の著名な政治家 [誰?] は、注目を集める全国フォーラムを開催した。1997年2月、衆議院議員が政府に沖縄の独立に必要な条件について質問したところ、憲法で認められていない ため不可能との回答があった[65]。[97] 沖縄市(旧コザ市)の元市長である大山朝雄は、ベストセラー『沖縄独立宣言』を執筆し、日本は沖縄の祖国ではないと主張した。[65][84] 沖縄自治労働組合(沖縄自治労)は、自治のための措置に関する報告書をまとめた。一部では、沖縄の自治と独立は日本の「構造的腐敗」への反応だと考えら れ、行政の分散化を求める声が上がった。[65] 2002年、琉球大学と沖縄国際大学の憲法、政治、公共政策の学者たちが「沖縄自治研究会」(Jichiken)を設立し、小冊子『自治地域としての沖 縄:あなたはどう思いますか?』を発行し、多くのセミナーを開催した。同グループは、3つの基本的な道筋を提示した。1) 第95条を活用し、地方分権の可能性を探る 2) 外交権を含む形式的な自治を求める 3) 完全な独立。[98]  かりゆしクラブの旗 『世界』(日本)、『慶喜』、『うるまねしあ』(沖縄)などの文学・政治雑誌が自治問題について頻繁に記事を掲載し、この問題に関する書籍も数多く出版さ れた。[99] 1970年代に活動していた琉球独立党は2005年に再編され、2008年からはカリユシクラブとして活動している。[99] 2013年5月、ルウ・チェワン独立総合研究協会(ACSILs)が設立され、非軍事化、脱植民地化、自主的な独立を目的として活動している。彼らは、グ アムや台湾など、独立を目指す政治団体との協力を計画している。[99][100] 2015年9月、ニューヨーク市のニューヨーク大学で関連フォーラムを開催した。[101] 自主決定の問題はその後、主流の選挙政治の議題として浮上した。政府の軍事基地建設許可を承認した自由民主党の知事・仲井真弘多(2006年~2014 年)は、2014年11月の選挙で、普天間基地移設反対と沖縄の自主決定を掲げた翁長雄志に敗北した。下地美樹雄は、結果が否決された場合、スコットラン ドのような独立住民投票を実施するとの前提で、県民投票を県全体で実施するキャンペーンを展開した。[102] 2015年1月、日本経済新聞は、龍谷大学教授の松島康勝氏と、琉球諸島の自治共和国としての独立を主張する市民団体「ユイマルレ・リュウキュウの自治」 が、静かに勢いを増していると報じた。[103] 批判者は、日本政府が独立を承認することはないと考えるが、松島氏によると、国連の「市民的及び政治的権利に関する国際規約」における自決権に基づき、日 本の承認は不要だという。同グループは、武装せず中立的な国家を創設し、奄美から与那国までの弧を描く各島が参加を決定する構想を描いている。[104] 同年2月、アイヌと沖縄の連帯を推進する「うるまの会」は、沖縄国際大学で「アイヌと沖縄の自決権」をテーマにしたシンポジウムを開催した。[98] 同月、終日公開フォーラム「道を探る:沖縄の自決権をめぐる議論」が開催され、沖縄が非軍事化自主管理地域として、中国や周辺諸国との交流の場、沖縄の経 済自立の国際的拠点としての役割を果たす時が来たと主張された。[105] |

| Chinese government views and influence In July 2012, Chinese Communist Party-owned media Global Times suggested that Beijing would consider challenging Japan's sovereignty over the Ryukyu Islands.[106] The Chinese government has offered no endorsement of such views. Some Chinese consider that it is enough to support their independence, with professor Zhou Yongsheng warning that Ryukyu sovereignty issue will not resolve the Diaoyudao/Senkaku Islands dispute, and that "Chinese involvement would destroy China-Japan relations". Professor June Teufel Dreyer emphasized that "arguing that a tributary relationship at some point in history is the basis for a sovereignty claim ... [as] many countries had tributary relationships with China" could be diplomatically incendiary. Professor Yasukatsu Matsushima expressed his fear of the possibility that Ryukyu independence would be used as a tool, perceiving Chinese support as "strange" since they deny it to their own minorities.[106] In May 2013, the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, People's Daily, published another similar article by two Chinese scholars from Chinese Academy of Social Sciences which stated that "Chinese people shall support Ryukyu's independence",[107] soon followed by Luo Yuan's comment that "The Ryukyus belong to China, never to Japan".[108] However these scholars' considerations do not necessarily represent the views of Chinese government.[109] It sparked a protest among the Japanese politicians, like Yoshihide Suga who said that Okinawa Prefecture "is unquestionably Japan's territory, historically and internationally".[107][110] In December 2016, Japan's Public Security Intelligence Agency claimed that the Chinese government is "forming ties with the Okinawan independence movement through academic exchanges, with the intent of sparking a split within Japan".[111] The report was harshly criticized as baseless by the independence group professors asserting that the conference at Beijing University in May 2016 had no such connotations.[112] In August 2020, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a U.S. think tank, summarized that "China uses indirect methods to influence Japan. There are hidden channels, such as influencing Okinawa's movements through fundraising, influencing Okinawan newspapers to promote Okinawa's independence, and eliminating U.S. forces there." In contrast, the Okinawa Times and Ryukyu Shimpo published articles denying Chinese funding.[113][114][115][116] In light of the Okinawan newspaper articles, Tetsuhide Yamaoka [ja], who supervised the Japanese translation of the Silent Invasion written by Clive Hamilton, gave a lecture titled "Silent Invasion: What Okinawans Want You to Know About China's Gentry Craft" at the Urasoe City Industrial Promotion Center on October 10, 2020, organized by the Japan Okinawa Policy Research Forum. In his lecture, "Silent Invasion: How the CCP is working to make Okinawa Prefecture a dependency of China," Yamaoka stated that the CCP "uses indirect methods that are less visible, such as advertisements, rather than stocks, etc".[117] In October 2021, the French military school Institute for Strategic Studies (IRSEM) reported that China is stirring up independence movements in the Ryukyu Islands and French New Caledonia in an attempt to weaken potential enemies. It stated that for China, Okinawa is intended to "sabotage the Self-Defense Forces and U.S. forces in Japan."[118][119][120] There are also some people with official positions who, in their private capacity, openly believe that Japanese rule over the Ryukyus has no legitimacy. For example, Tang Chunfeng, a researcher at the Ministry of Commerce, has claimed that "75% of Ryukyu residents support Ryukyu independence" and that "the culture of the Ryukyu Islands was identical to that of the Mainland China before the Japanese invasion".[121][122] However, despite the increase in the number of voices in China, it is generally agreed that this does not represent the viewpoint of the Chinese government, at least not the official position on the surface. However, these mainly private voices have elicited strong responses from the Japanese political establishment, such as Kan's statement that "Okinawa Prefecture is undoubtedly Japanese territory, both historically and internationally.[107][110] In 2010, the Preparatory Committee for the Chinese Ryukyu Special Autonomous Region was registered in Hong Kong, with businessman Zhao Dong as its president. The organization is active in mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan, with offices in Shenzhen.[123][124] The Chinese Ryukyu Special Autonomous Region has also been in contact with Taiwan's Bamboo Union and the Chinese Unification Promotion Party, a political party of the reunification movement. In 2015, CUPP President Chang An-lo visited the organisation's office in Shenzhen, and in the same month, CUPP leader Chang An-lo went on a sightseeing trip to Okinawa and was received by the cadres of the Kyokuryū-kai.[125][126] Chang An-lo said that "the relationship between the Ryukyu and China is historically intertwined, and it is my duty as a Chinese to make Ryukyu free from Japan".[127] Against this background, the phrase "Today, Hong Kong; tomorrow, Taiwan" was quoted in Hong Kong and Taiwan during the Umbrella Movement,[128] giving rise to the phrase "Today Hong Kong, Tomorrow Taiwan, Day After Tomorrow Okinawa"[129] in Japan. Key leaders of the movement are reported to be supported by CCP united front influence operations.[130][131] On October 3, 2024, Nikkei Asia, in collaboration with a cyber security company, confirmed that there has been an increase in Chinese-language disinformation on social media promoting Ryukyuan independence, which are being spread by some suspected influence accounts. It is believed that the goal is to divide Japanese and international public opinion.[132] Influence operations Since the 2020s, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has intensified its diplomatic and informational influence operations targeting Okinawa Prefecture. In particular, following a remark by CCP general secretary Xi Jinping in June 2024 suggesting the "strengthening of exchanges between China and Okinawa," several government-affiliated institutions and pro-China scholars have escalated their assertions regarding the historical affiliation of Okinawa.[133][134] Information warfare Propaganda claiming that "the Ryukyu Islands are not part of Japan but belong to the Chinese nation", and that "the people of Okinawa wish to return to China" has been widely disseminated via social media and video platforms. Much of this content is produced in Chinese and English and is aimed at foreign audiences. More than 200 such influence accounts have been identified. The apparent purpose of these information operations is to exploit Okinawa as a perceived "weak point" in Japan, as a form of counterattack amid the Japanese government's criticism of China over issues such as Taiwan, Xinjiang, and Hong Kong.[133][134] Sovereignty claims by scholars In 2024, Dalian Maritime University in Liaoning Province, China, planned the establishment of a “Ryukyu Research Center.” At a preparatory symposium held in September of the same year, Gao Zhiguo, president of the China Society of the Law of the Sea, and Xu Yong, professor at Peking University, argued that "the Ryukyu issue relates to national security and the reunification of the motherland." They rejected the legitimacy of the San Francisco Peace Treaty and questioned the scope of Japan’s postwar sovereignty.[133][134] Exchanges with Chinese officials Since 2023, there has been frequent contact between the Chinese Embassy and the Consulate-General in Fukuoka and the Okinawa Prefectural Government. This includes unprecedented exchanges, such as visits to Okinawa by top officials from Fujian Province and visits by Okinawan officials to the Chinese embassy.[citation needed] During his visit to China in July 2024, Okinawa Governor Denny Tamaki told China’s state-run Global Times that he wished to "convey Okinawa’s soul of peace to the world," emphasizing regional diplomacy. However, the nature of the personnel dispatched by China and their actions suggest strategic intentions including information warfare and efforts at division—realities that differ significantly from the notion of "peaceful exchange."[133][134] In October 2024, Chinese Ambassador to Japan Wu Jianghao visited Okinawa. During his stay, extraordinary security measures were implemented, including inspections of hotel rooms and background checks on drivers. Additionally, Yang Qingdong, who assumed the post of Consul General in Fukuoka that same year, does not speak Japanese and has a background in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ intelligence divisions and administration of the disputed South China Sea territory of Sansha City—indicating that China is deploying personnel with expertise in information and maritime strategy to Okinawa.[133][134] |

中国政府の見解と影響力 2012年7月、中国共産党が所有するメディア「環球時報」は、北京が琉球諸島に対する日本の主権を争うことを検討していると示唆した[106]。中国政 府は、このような見解を一切支持していない。一部の中国人は、琉球諸島の独立を支持するだけで十分だと考えており、周永生教授は、琉球諸島の主権問題は尖 閣諸島/釣魚島紛争を解決しないとし、「中国の関与は日中関係を破壊する」と警告している。ジュン・テューフェル・ドレイヤー教授は、「歴史上のいずれか の時点での朝貢関係が主権主張の根拠であるとする主張は…多くの国が中国と朝貢関係にあった」として、外交的に火種となる可能性があると強調した。松島康 勝教授は、琉球の独立がツールとして利用される可能性を懸念し、中国が自国の少数民族への支援を否定している点から、中国の支援を「奇妙」と捉えている。 [106] 2013年5月、中国共産党中央委員会機関紙「人民日報」は、中国社会科学院の2人の学者による同様の記事を掲載し、「中国国民は琉球の独立を支持すべき である」と述べた[107]。その直後、羅元氏は「琉球は中国に属し、決して日本のものではない」とコメントした。[108] しかし、これらの学者の見解は必ずしも中国政府の立場を反映するものではない。[109] これに対し、日本の政治家からは抗議の声が上がり、菅義偉は「沖縄県は歴史的・国際的に疑いようのない日本の領土だ」と述べた。[107][110] 2016年12月、日本の公安調査庁は、中国政府が「日本国内の分裂を煽る意図で、学術交流を通じて沖縄独立運動と結びついている」と主張した。 [111] この報告は、2016年5月に北京大学で開催された会議にはそのような意味合いはまったくなかったと主張する独立派教授たちから、根拠のないものとして厳 しく批判された。[112] 2020年8月、米国のシンクタンクである戦略国際問題研究所(CSIS)は、「中国は間接的な手法を用いて日本に影響力を行使している。資金調達を通じ て沖縄の運動に影響力を及ぼしたり、沖縄の新聞に沖縄独立を推進するよう働きかけたり、沖縄の米軍を排除したりといった隠れたルートがある」と要約した。 一方、沖縄タイムス紙と琉球新報は、中国の資金提供を否定する記事を掲載した[113][114][115][116]。沖縄の新聞記事を受けて、クライ ブ・ハミルトン著『サイレント・インベイジョン』の日本語翻訳を監修した山岡哲秀氏は、2020年10月10日に沖縄政策フォーラム主催の「浦添市産業振 興センター」で「サイレント・インベイジョン:沖縄人があなたに知ってほしい中国のジェントリ・クラフト」と題した講演を行った。沖縄人があなたに知って ほしい中国のジェントリクラフト」と題した講演を行った。講演「サイレント・インベイジョン:中国共産党が沖縄県を中国の属国にするために取り組んでいる こと」の中で、山岡氏は、中国共産党は「株式などよりも、広告など目立たない間接的な手法を用いている」と述べた[117]。 2021年10月、フランスの軍事学校である戦略研究研究所(IRSEM)は、中国が潜在的な敵を弱体化させるため、琉球諸島とフランス領ニューカレドニ アで独立運動を扇動していると報告した。同研究所は、中国にとって沖縄は「日本の自衛隊と米軍を破壊する」ための拠点であると指摘した。[118] [119][120] また、公的な立場にある人物の中でも、私的な立場で、日本の琉球支配には正当性がないことを公然と主張している者もいる。例えば、商務省の研究員である唐 春峰氏は、「琉球住民の75%は琉球独立を支持している」とし、「琉球諸島の文化は、日本の侵略以前は中国本土の文化と全く同じだった」と主張している。 [121][122] しかし、中国での声の増加にもかかわらず、これらは中国政府の立場、少なくとも公式な立場を反映していないと一般に認められている。ただし、これらの主に 私人からの声は、日本の政治指導部から強い反発を招いている。例えば、菅義偉は「沖縄県は歴史的にも国際法上も疑いなく日本の領土だ」と述べた。 [107][110] 2010年、香港で「中国琉球特別行政区準備委員会」が登録され、実業家の趙東が会長に就任した。この組織は中国本土、香港、台湾で活動しており、深セン に事務所を置いている。[123][124] 中国琉球特別行政区は、台湾の竹の連合と、統一運動の政治団体である中国統一促進党とも接触している。2015年、CUPPの張安洛(チャン・アンロ)会 長が深センの事務所を訪問し、同月、張安洛氏は沖縄を観光訪問し、琉球会の幹部から歓迎を受けた。[125][126] 張安洛は「琉球と中国の関係は歴史的に密接に結びついており、中国人の一員として、琉球を日本から解放するのは私の義務だ」と述べた。[127] この背景を受けて、傘運動期間中、香港と台湾で「今日香港、明日台湾」というフレーズが引用され[128]、日本において「今日香港、明日台湾、明後日沖 縄」というフレーズが生まれた[129]。運動の主要指導者は、中国共産党の統一戦線工作の影響を受けていると報じられている[130][131]。 2024年10月3日、日経アジアはサイバーセキュリティ企業との共同調査で、ソーシャルメディア上で琉球独立を促進する中国語の偽情報が、一部の疑わし い影響力アカウントによって拡散されていることを確認した。その目的は、日本と国際社会の世論を分断することにあるとみられている。[132] 影響工作 2020年代以降、中国共産党(CCP)は、沖縄県を標的とした外交および情報工作を強化している。特に、2024年6月にCCP総書記の習近平が「中国 と沖縄の交流強化」を提唱したことを受け、複数の政府系機関や親中派学者たちが、沖縄の歴史的所属に関する主張を強めている。[133][134] 情報戦 「琉球諸島は日本の領土ではなく、中国に属している」や「沖縄の人々は中国への復帰を望んでいる」といったプロパガンダが、ソーシャルメディアや動画プ ラットフォームを通じて広く流布されている。これらのコンテンツの多くは中国語と英語で作成されており、海外の視聴者を対象としている。このような影響力 行使のためのアカウントは 200 件以上確認されている。 これらの情報作戦の明らかな目的は、台湾、新疆、香港問題などに関する日本政府の批判に対する反撃の一環として、沖縄を日本の「弱点」として利用することにあると考えられる。[133][134] 学者の主権主張 2024年、中国遼寧省の大連海事大学は「琉球研究センター」の設立を計画した。同年9月に開催された準備シンポジウムでは、中国海洋法学会会長の鄒志国 氏および北京大学の徐勇教授が、「琉球問題は国家安全保障と祖国統一に関わる問題である」と主張した。彼らは、サンフランシスコ平和条約の正当性を否定 し、日本の戦後主権の範囲に疑問を投げかけた。[133][134] 中国当局者との交流 2023年以降、中国大使館および福岡総領事館と沖縄県庁との接触が頻繁に行われている。これには、福建省の高官の沖縄訪問や、沖縄の当局者の中国大使館訪問など、前例のない交流が含まれる。[要出典] 2024年7月の中国訪問中、玉城デニー沖縄知事は、中国国営のグローバル・タイムズ紙に対し、「沖縄の平和の魂を世界に伝えたい」と述べ、地域外交を強 調した。しかし、中国が派遣した要人の性質や行動からは、情報戦や分断工作などの戦略的意図が伺え、「平和的な交流」という概念とは大きく異なる現実があ る[133][134]。 2024年10月、中国駐日大使の呉江浩が沖縄を訪問した。滞在中は、ホテルの客室検査や運転手の身元調査など、異常な警備措置が講じられた。さらに、同 年福岡総領事に就任した楊清東は日本語を話せず、外務省の諜報部門と南シナ海の争議地域である三沙市(サンシャシ)の行政経験を有しており、中国が沖縄に 情報と海洋戦略の専門知識を有する要員を配置していることを示している。[133][134] |

| Polls Ryukyu independence groups continue to exist, but they have not gained support large enough to lead to independence. The number of seats they were able to take in the local legislatures was either zero or, in rare cases, one. However, there is strong support for a strong local government with strong authority, such as the Dōshūsei and the Federalism such as UK. In a 2011 poll 4.7% of surveyed were pro-independence, 15% wanted more devolution, while around 60% preferred the political status quo.[135] In a 2015 poll by Ryūkyū Shimpō 8% of the surveyed were pro-independence, 21% wanted more self-determination as a region, while the other 2/3 favored the status quo.[111] In 2016, Ryūkyū Shimpō conducted another poll from October to November of Okinawans over 20, with useful replies from 1047 individuals: 2.6% favored full independence, 14% favored a federal framework with domestic authority equal to that of the national government in terms of diplomacy and security, 17.9% favored a framework with increased authority to compile budgets and other domestic authorities, while less than half supported status quo.[136] In 2017, Okinawa Times, Asahi Shimbun (based in Osaka) and Ryukyusu Asahi Broadcasting Corporation (of the All-Nippon News Network), newspapers who are subsidiaries of those in Japan, jointly conducted prefectural public opinion surveys for voters in the prefecture. It claimed that 82% of Okinawa citizens chose "I'm glad that Okinawa has returned as a Japanese prefecture". It was 90% for respondents of the ages of 18 to 29, 86% for those in their 30s, 84% for those aged 40–59, whereas in the generation related to the return movement, the response was 72% for respondents in their 60s, 74% for those over the age of 70.[137] On May 12, 2022, an Okinawa Times survey on the 50th anniversary of Okinawa's reversion to Japan and the attitudes of Okinawa residents showed that 48% of respondents wanted "a municipality with strong authority", 42% wanted to "maintain the status quo", and 3% wanted "independence".[2] |

世論調査 琉球独立派は依然として存在しているが、独立につながるほどの支持は得られていない。地方議会で獲得した議席数は、ゼロか、まれに1議席にとどまっている。しかし、道州制や英国の連邦制のような、強力な権限を持つ地方自治体を支持する声は強い。 2011年の世論調査では、独立支持が4.7%、地方分権拡大を望む人が15%、政治的現状維持を望む人が約60%だった。[135] 2015年の琉球新報の世論調査では、調査対象者の8%が独立支持、21%が地域としてのより大きな自治権を望み、残りの2/3は現状維持を望んだ。 [111] 2016年、 琉球新報は 10 月から 11 月にかけて、20 歳以上 1047 人の沖縄住民を対象に別の世論調査を実施し、有効回答は 1047 件だった。2.6% が完全独立を、14% が外交・安全保障に関する国内権限を国と同等の連邦制を、17.9% が予算編成などの国内権限の拡大を、半数以下が現状維持を望んだ。[136] 2017年、沖縄タイムス、朝日新聞(大阪本社)、琉球朝日放送(全日本放送網)など、日本の新聞社の子会社である新聞社が、県内の有権者を対象とした県 民世論調査を共同で実施した。その結果、沖縄県の住民の82%が「沖縄が日本の都道府県として復帰したことは喜ばしい」と回答した。18~29歳は 90%、30代は86%、40~59歳は84%だったのに対し、返還運動に関連する世代では、60代は72%、70歳以上は74%だった。[137] 2022年5月12日、沖縄返還50周年と沖縄住民の意識に関する沖縄タイムスの調査では、回答者の48%が「強い権限を持つ自治体」を、42%が「現状維持」を、3%が「独立」を希望した。[2] |

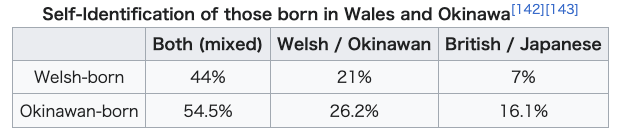

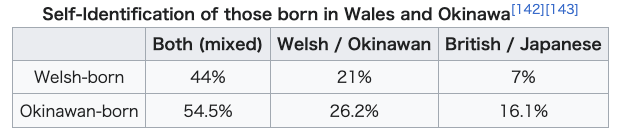

| Identity In terms of identity, Okinawans have a composite identity. When asked, "What kind of person do you consider yourself to be?", 52% of the respondents said that they are "Okinawan and Japanese". When combining "Miyako" and "Japanese" as well as "Yaeyama" and "Japanese", the composite identity accounted for about 60% of the respondents. 24% said they were "Okinawan" and 16% said they were "Japanese".[138] Regarding the promotion of culture in Okinawa, there is a view that it should learn from Wales in the United Kingdom regarding federalism and language revival.[139][140] Since Okinawa was a minority in Japan, the history of Welsh Not and Dialect card in Okinawa, etc., are very similar.[141][140] The composite identity is another area where Wales and Okinawa are similar.[142][143][144] Self-Identification of those born in Wales and Okinawa[142][143] Both (mixed) Welsh / Okinawan British / Japanese Welsh-born 44% 21% 7% Okinawan-born 54.5% 26.2% 16.1%  There are also different views on whether Okinawa should become a state if the Doshu-sei is introduced in the future under the one state on the Doshu-sei in Japan. Author and former diplomat Sato Masaru [ja], whose mother is from Okinawa, describes the uniqueness of Okinawan culture, including the Okinawan language. He favors federalism in Japan but not independence for the Ryukyus, and draws on his experience as a diplomat in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to say, "It is possible for a country of about 1.4 million people to survive as an independent nation among three major powers, Japan, the United States, and China, but I think it will entail many difficulties."[145] During the Ryukyu Kingdom, the royal family lived in Shuri, Okinawa Island. Yaeyama and Miyakojima were subject to a harsh tax system, known as the poll tax.[146] Therefore, it is believed that Yaeyama, Miyakojima, and Yonaguni Island introduced modern institutions, taxation system, and freedom to choose an occupation after the Meiji Restoration in Japan as a result of the Ryukyu dispositions.[147] Nakashinjo Makoto [ja], editor-in-chief of the conservative Okinawan newspaper Yaeyama Nippo [ja], said that Shuri Castle was more like a "symbol of oppression" to the islanders of the outlying islands. Therefore, he said, even if a "Ryukyu Republic" is founded, it may become a country full of discrimination like the Ryukyu Kingdom as it was in the past.[148][149] |

アイデンティティ アイデンティティに関しては、沖縄の人々は複合的なアイデンティティを持っている。「あなたはどのような人格だと思いますか」という質問に対して、52% が「沖縄人であり、日本人である」と回答した。「宮古」と「日本人」、「八重山」と「日本人」を組み合わせると、複合的なアイデンティティは回答者の約 60%を占めた。24%は「沖縄人」と答え、16%は「日本人」と答えた。[138] 沖縄の文化振興に関しては、連邦制や言語復興についてイギリスのウェールズから学ぶべきだという見方がある。[139][140] 沖縄は日本で少数派であったため、ウェールズの「ウェールズ語禁止法」や沖縄の方言カードの歴史など、非常に類似点が多い。[141][140] 複合アイデンティティも、ウェールズと沖縄が類似している分野の一つだ。[142][143][144] ウェールズと沖縄で生まれた人々の自己認識[142][143] 両方(混血) ウェールズ人 / 沖縄人 イギリス人 / 日本人 ウェールズ生まれ 44% 21% 7% 沖縄生まれ 54.5% 26.2% 16.1%  将来、日本が統一国家として道州制を導入した場合、沖縄は州になるべきかどうかについても、意見は分かれている。著作家で元外交官の佐藤勝氏 [ja] は、母親が沖縄出身であり、沖縄語をはじめとする沖縄文化の独自性を紹介している。彼は、日本における連邦制には賛成だが、琉球の独立には反対であり、外 務省での外交官としての経験から、「140万人ほどの国民が、日本、米国、中国の3つの大国に囲まれた中で、独立した国家として生き残ることは可能だが、 多くの困難を伴うだろう」と述べている[145]。 琉球王国時代、王族は沖縄本島の首里に住んでいた。八重山と宮古島は、人頭税という厳しい税制に服していた[146]。そのため、八重山、宮古島、与那国 島は、琉球処分により、日本の明治維新後に近代的な制度、税制、職業選択の自由が導入されたと考えられている。[147] 保守的な沖縄の新聞「八重山日報」の編集長、中真城誠氏は、首里城は離島住民にとっては「抑圧の象徴」のようなものだったと述べた。したがって、彼は、た とえ「琉球共和国」が設立されたとしても、過去の琉球王国のように差別だらけの国になる可能性があると述べた。[148][149] |

| Active autonomist and secessionist movements in Japan Amami reversion movement Racism in Japan Today Hong Kong, Tomorrow Taiwan, Day After Tomorrow Okinawa |

日本の活発な自治運動および分離独立運動 奄美返還運動 日本の人種主義 今日は香港、明日は台湾、明後日は沖縄 |

| Sources Smits, Gregory (1999), Visions of Ryukyu: Identity and Ideology in Early-Modern Thought and Politics, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 9780824820374, archived from the original on 3 October 2024, retrieved 12 February 2017 Nakasone, Ronald Y. (2002), Okinawan Diaspora, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-2530-0, archived from the original on 3 October 2024, retrieved 12 February 2017 Hook, Glen D.; Siddle, Richard (2003), Japan and Okinawa: Structure and Subjectivity, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-42787-1, archived from the original on 3 October 2024, retrieved 12 February 2017 Obermiller, David John (2006), The United States Military Occupation of Okinawa: Politicizing and Contesting Okinawan Identity, 1945–1955, ISBN 978-0-542-79592-3 Tanji, Miyume (2007), Myth, Protest and Struggle in Okinawa, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-21760-1 Rabson, Steve (February 2008), "Okinawan Perspectives on Japan's Imperial Institution", The Asia-Pacific Journal, 6 (2), archived from the original on 12 August 2020, retrieved 12 February 2017 Matsushima, Yasukatsu (Autumn 2010), "Okinawa is a Japanese Colony" (PDF), Quarterly for History, Environment, Civilization, 43, translated by Erika Kaneko: 186–195, archived (PDF) from the original on 3 October 2024, retrieved 12 February 2017 Dudden, Alexis (2013), Jeff Kingston (ed.), Okinawa today: Spotlight on Henoko, Routledge, ISBN 9781135084073, archived from the original on 3 October 2024, retrieved 12 February 2017 Loo, Tze May (2014), Heritage Politics: Shuri Castle and Okinawa's Incorporation into Modern Japan, 1879–2000, Lexington Books, ISBN 978-0-7391-8249-9 Yoshiaki, Yoshimi (2015), Grassroots Fascism: The War Experience of the Japanese People, Columbia University Press, ISBN 9780231538596, archived from the original on 3 October 2024, retrieved 12 February 2017 Dietz, Kelly (2016), "Transnationalism and Transition in the Ryūkyūs", in Pedro Iacobelli; Danton Leary; Shinnosuke Takahashi (eds.), Transnational Japan as History: Empire, Migration, and Social Movements, Springer, ISBN 978-1-137-56879-3, archived from the original on 3 October 2024, retrieved 12 February 2017 Inoue, Masamichi S. (2017), Okinawa and the U.S. Military: Identity Making in the Age of Globalization, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-51114-8 |

出典 Smits, Gregory (1999), Visions of Ryukyu: Identity and Ideology in Early-Modern Thought and Politics, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 9780824820374, 2024年10月3日にオリジナルからアーカイブ、2017年2月12日に取得。 ナカソネ、ロナルド Y.(2002)、『Okinawan Diaspora』、ハワイ大学出版、ISBN 978-0-8248-2530-0、2024年10月3日にオリジナルからアーカイブ、2017年2月12日に取得 フック、グレン D.、シドル、リチャード (2003)、『日本と沖縄:構造と主体性』、Routledge、ISBN 978-1-134-42787-1、2024年10月3日にオリジナルからアーカイブ、2017年2月12日に取得。 Obermiller, David John (2006), The United States Military Occupation of Okinawa: Politicizing and Contesting Okinawan Identity, 1945–1955, ISBN 978-0-542-79592-3 Tanji, Miyume (2007), Myth, Protest and Struggle in Okinawa, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-21760-1 ラブソン、スティーブ(2008年2月)、「日本の帝国制度に関する沖縄の視点」、アジア太平洋ジャーナル、6 (2)、2020年8月12日にオリジナルからアーカイブ、2017年2月12日取得 松島康勝(2010年秋)、「沖縄は日本の植民地である」(PDF)、『歴史、環境、文明の季刊誌』、43、金子恵里香訳:186–195、2024年10月3日にオリジナルからアーカイブ、2017年2月12日に取得 ダッデン、アレクシス(2013)、ジェフ・キングストン(編)、『今日の沖縄:辺野古にスポットライトを当てる』、Routledge、ISBN 9781135084073、2024年10月3日にオリジナルからアーカイブ、2017年2月12日に閲覧。 ルー、ツェ・メイ (2014)、『遺産政治:首里城と沖縄の近代日本への編入、1879-2000』、レキシントン・ブックス、ISBN 978-0-7391-8249-9 吉見 良明 (2015)、『草の根ファシズム:日本人民の戦争体験』、コロンビア大学出版、 ISBN 9780231538596、2024年10月3日にオリジナルからアーカイブ、2017年2月12日に取得 Dietz, Kelly (2016), 「Transnationalism and Transition in the Ryūkyūs」, in Pedro Iacobelli; ダントン・リーリー; 高橋真之介(編), 『歴史としてのトランスナショナル・ジャパン:帝国、移民、社会運動』, スプリンガー, ISBN 978-1-137-56879-3, 2024年10月3日にオリジナルからアーカイブ, 2017年2月12日に閲覧 井上正道(2017)、『沖縄と米軍:グローバル化時代のアイデンティティ形成』、コロンビア大学出版局、ISBN 978-0-231-51114-8 |

| Further reading Matsushima Yasukatsu, 琉球独立への道 : 植民地主義に抗う琉球ナショナリズム [The Road to Ryukyu Independence: A Ryukyuan Nationalism That Defies Colonialism], Kyōto, Hōritsu Bunkasha, 2012. ISBN 9784589033949 |

Matsushima Yasukatsu, 琉球独立への道 : 植民地主義に抗う琉球ナショナリズム [The Road to Ryukyu Independence: A Ryukyuan Nationalism That Defies Colonialism], Kyōto, Hōritsu Bunkasha, 2012. ISBN 9784589033949 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ryukyu_independence_movement |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099