英語ウィキペディアにみる琉球人

Ryukyuan people in Wikipedia in/of/by English

☆【引用者註】このページにはウィキペディアのガイドラインにより改善の余地があると主張されています。This article includes inline citations, but they are not properly formatted. Please improve this article by correcting them. (March 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message.) この記事にはインライン引用が含まれていますが、正しくフォーマットされていません。それらを修正することで、この記事を改善してください。(2024年3月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ).

| The Ryukyuan people

(Okinawan: 琉球民族 (るーちゅーみんずく), romanized: Ruuchuu minzuku or どぅーちゅーみんずく,

Duuchuu minzuku, Japanese: 琉球民族/りゅうきゅうみんぞく, romanized: Ryūkyū minzoku,

also Okinawans,[9] Uchinaanchu, Lewchewan or Loochooan)[10] are a

Ryukyuan-speaking East Asian ethnic group native to the Ryukyu Islands,

which stretch between the islands of Kyushu and Taiwan.[11]

Administratively, they live in either the Okinawa Prefecture or the

Kagoshima Prefecture within Japan. They speak one of the Ryukyuan

languages,[12] considered to be one of the two branches of the Japonic

language family, the other being Japanese and its dialects[11] (Hachijō

is sometimes considered by linguists to constitute a third branch).[13] Ryukyuans are not a recognized minority group in Japan, as Japanese authorities consider them a subgroup of the Japanese people, akin to the Yamato people. Although officially unrecognized, Ryukyuans constitute the largest ethnolinguistic minority group in Japan, with more than 1.8 million living in the Okinawa Prefecture alone. Ryukyuans inhabit the Amami Islands of Kagoshima Prefecture as well, and have contributed to a considerable Ryukyuan diaspora. Over a million more ethnic Ryukyuans and their descendants are dispersed elsewhere in Japan and worldwide, most commonly in the United States, Brazil, and, to a lesser extent, in other territories where there is also a sizable Japanese diaspora, such as Argentina, Chile and Mexico. In the majority of countries, the Ryukyuan and Japanese diaspora are not differentiated, so there are no reliable statistics for the former one.[citation needed] Ryukyuans have a distinct culture with some matriarchal elements, native religion and cuisine which had a fairly late (12th century) introduction of rice. The population lived on the islands in isolation for many centuries. In the 14th century, three separate Okinawan political polities merged into the Ryukyu Kingdom (1429–1879), which continued the maritime trade and tributary relations started in 1372 with Ming China.[11] In 1609, the Satsuma Domain (based in Kyushu) invaded the Ryukyu Kingdom. The Kingdom maintained a fictive independence in vassal status, in a dual subordinate status to both China and Japan, because Tokugawa Japan was prohibited to trade (directly) with China.[14] During the Japanese Meiji era, the kingdom became the Ryukyu Domain (1872–1879), after which it was politically annexed by the Empire of Japan.[15] In 1879, after the annexation, the territory was reorganized as Okinawa Prefecture, with the last king (Shō Tai) forcibly exiled to Tokyo.[11][16][17] China renounced its claims to the islands in 1895.[18] During this period, the Meiji government, which sought to assimilate the Ryukyuan people as Japanese (Yamato), suppressed Ryukyuan ethnic identity, tradition, culture, and language.[11][19][20][21][22][23] After World War II, the Ryūkyū Islands were occupied by the United States between 1945 and 1950 and then from 1950 to 1972. Since the end of World War II, Ryukyuans have expressed strong resentment against the Japanese government and against U.S. military facilities stationed in Okinawa.[12][24] United Nations special rapporteur on discrimination and racism Doudou Diène, in his 2006 report,[25] noted a perceptible level of discrimination and xenophobia against the Ryukyuans, with the most serious discrimination they endure linked to their opposition of American military installations in the archipelago.[26] |

琉

球民族(沖縄語:琉球民族(るーちゅーみんずく)、ローマ字表記:Ryukyuan people):

日本語:琉球民族/りゅうきゅうみんぞく、ローマ字表記:Ruuchuu minzuku:

琉球民俗(りゅうきゅうみんぞく、沖縄人、[9]ウチナーンチュ、ルーチワン、ルーチュアンとも)[10]は、九州と台湾の間に広がる琉球列島に住む琉球

語を話す東アジアの民族である[11]。彼らは琉球語の一つを話す[12]。琉球語は日本語とその方言[11](八丈語は言語学者によって第三の支流を構

成すると見なされることがある)[13]。 日本当局は琉球人を大和民族に似た日本人のサブグループとみなしているため、琉球人は日本では少数民族として認められていない。公式には認められていない が、琉球人は日本最大の少数民族であり、沖縄県だけで180万人以上が暮らしている。琉球人は鹿児島県の奄美群島にも居住しており、かなりの琉球ディアス ポラに貢献している。さらに100万人以上の琉球人とその子孫は、日本国内だけでなく世界各地に散らばっており、最も多いのはアメリカ、ブラジル、そして 少ないながらもアルゼンチン、チリ、メキシコなど、日本人のディアスポラも多く存在する地域である。大半の国では、琉球人と日本人ディアスポラは区別され ていないため、前者に関する信頼できる統計は存在しない[要出典]。 琉球人は、いくつかの母系制の要素を持つ独特の文化、土着の宗教、かなり後期(12世紀)に米が導入された料理を持っている。琉球人は何世紀もの間、島で 孤立して暮らしていた。14世紀には、3つの別々の政治体制が琉球王国(1429-1879)に統合され、1372年に明との間で始まった海洋貿易と朝貢 関係を継続した[11] 。徳川日本は中国との(直接の)貿易を禁じられていたため、琉球王国は中国と日本の両方に対して二重の従属的な地位にあり、臣下の立場で架空の独立を維持 していた[14]。 日本の明治時代には琉球王国となり(1872年-1879年)、その後大日本帝国に政治的に併合された[15]。併合後の1879年、領土は沖縄県として 再編され、最後の国王(尚泰)は強制的に東京に追放された[11][16][17]。中国は1895年に島々に対する領有権を放棄した[18]。 [第二次世界大戦後、琉球諸島は1945年から1950年まで、そして1950年から1972年までアメリカに占領された。第二次世界大戦後、琉球人は日 本政府や沖縄に駐留する米軍施設に対して強い憤りを表明している[12][24]。 国連の差別と人種主義に関する特別報告者であるドゥドゥ・ディエンヌは、その2006年の報告書の中で[25]、琉球人に対する差別と排外主義が明白なレ ベルであると指摘し、彼らが耐えている最も深刻な差別は、列島にある米軍施設に反対していることに関連しているとしている[26]。 |

Shôchikubai

Tsurukame, danse cérémonielle de l'ancien royaume d'Okinawa (Royaume de

Ryûkyû : 1429-1879) évoquant les qualités de l'homme |

松竹梅鶴亀(しょうちくばいつるかめ)、古代沖縄王国(琉球王国:1429-1879)の儀式舞踊。 |

| Etymology Their usual ethnic name derives from the Chinese name for the islands, Liuqiu (also spelled as Loo Choo, Lew Chew, Luchu, and more),[11] which in the Japanese language is pronounced Ryuukyuu. In the Okinawan language, it is pronounced Duuchuu. In their native language they often call themselves and their identity as Uchinanchu.[27][28] These terms are rarely used outside of the ethnic community, and are politicized markers of a distinct culture.[29][clarification needed] "Ryukyu" is an other name from the Chinese side, and "Okinawa" is a Japanese cognate of Okinawa's native name "Uchinaa", originating from the residents of the main island referring to the main island against the surrounding islands, Miyako and Yaeyama.[30] Mainland Japanese adapted Okinawa as the way to call these people.[citation needed] |

語源 沖縄の一般的な民族名は、島々の中国語名である琉球に由来する[11]。沖縄語ではドゥーチューと発音する。これらの用語は民族共同体の外ではほとんど使用されず、明確な文化の政治的標識となっている[29][要出典]。 「琉球」は中国側からの別称であり、「沖縄」は沖縄の固有名「ウチナー」の日本語の同音異義語であり、沖縄本島の住民が周囲の島々、宮古島や八重山に対して本島を呼んだことに由来する[30]。本土の日本人は、これらの人々を呼ぶ方法として沖縄を適応させた[要出典]。 |

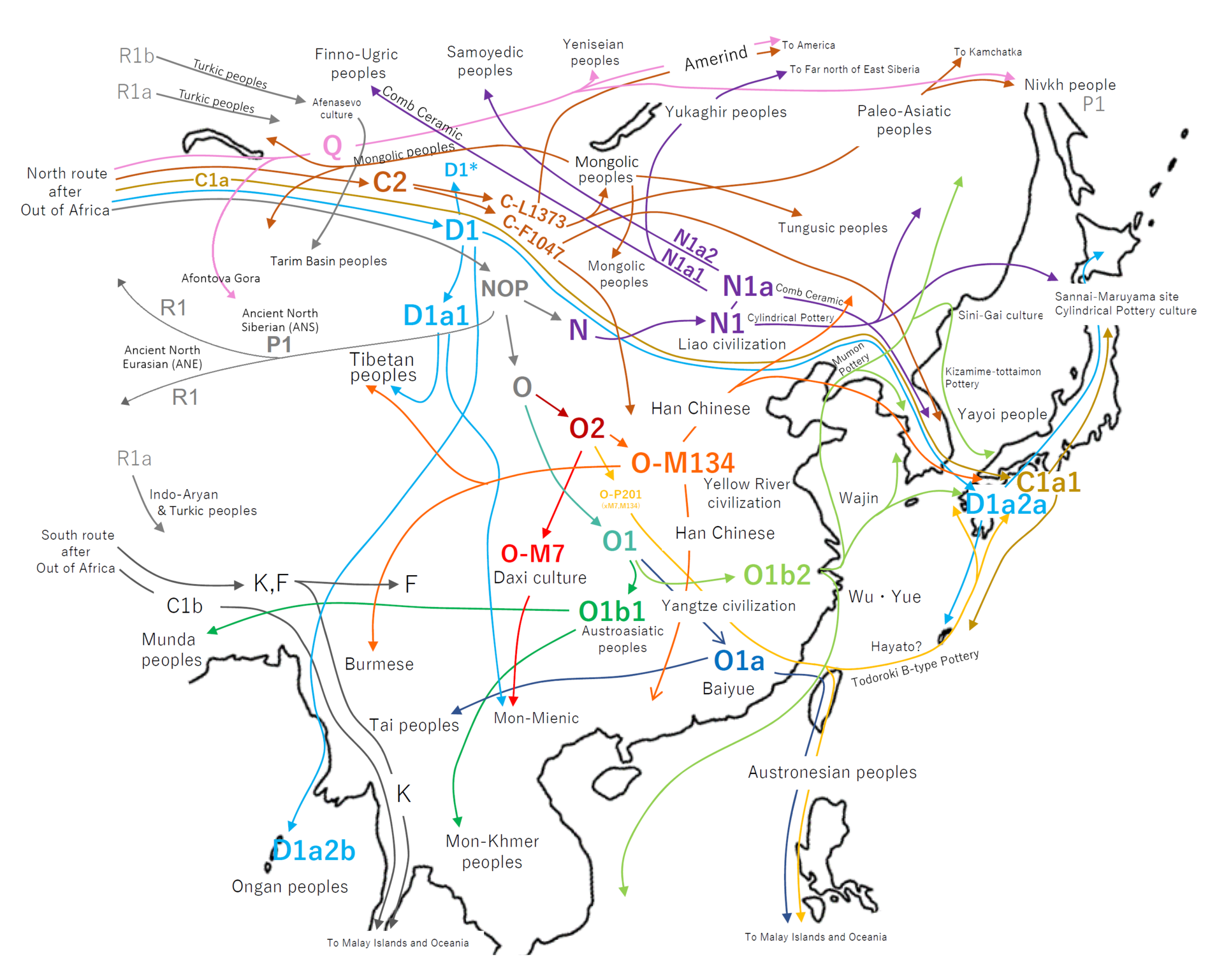

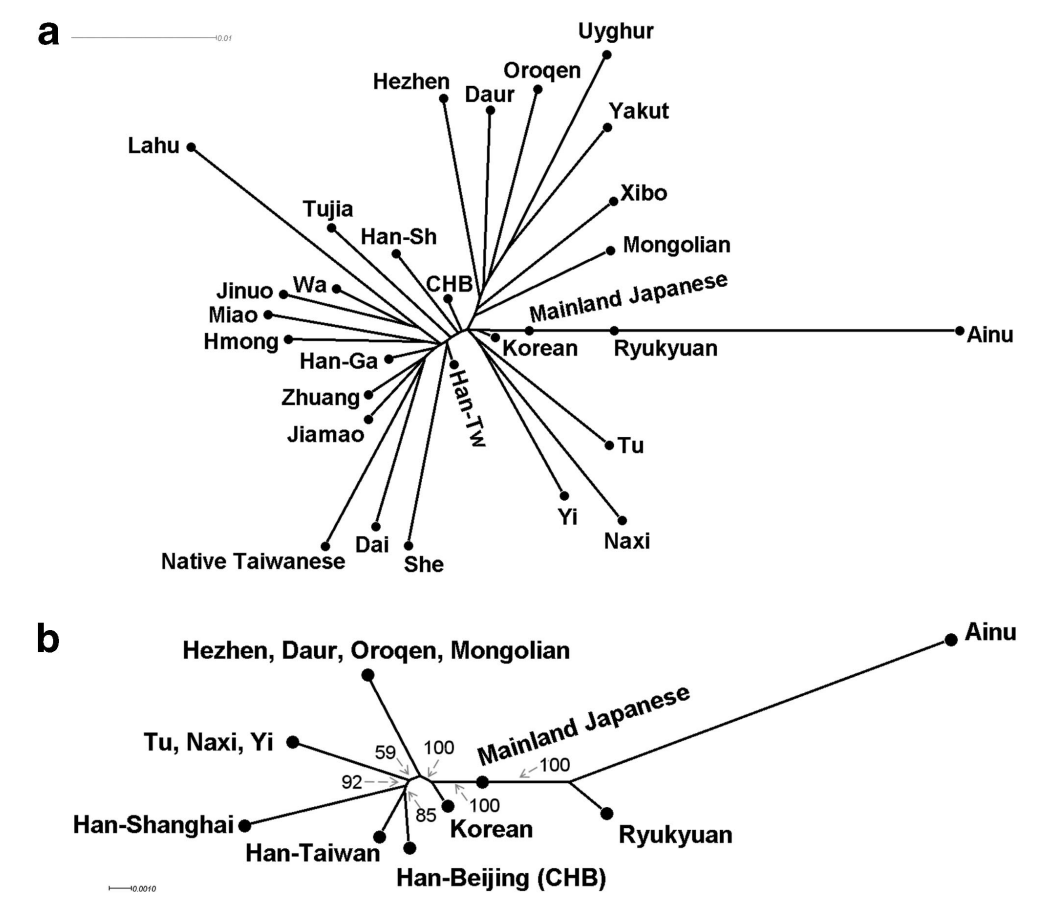

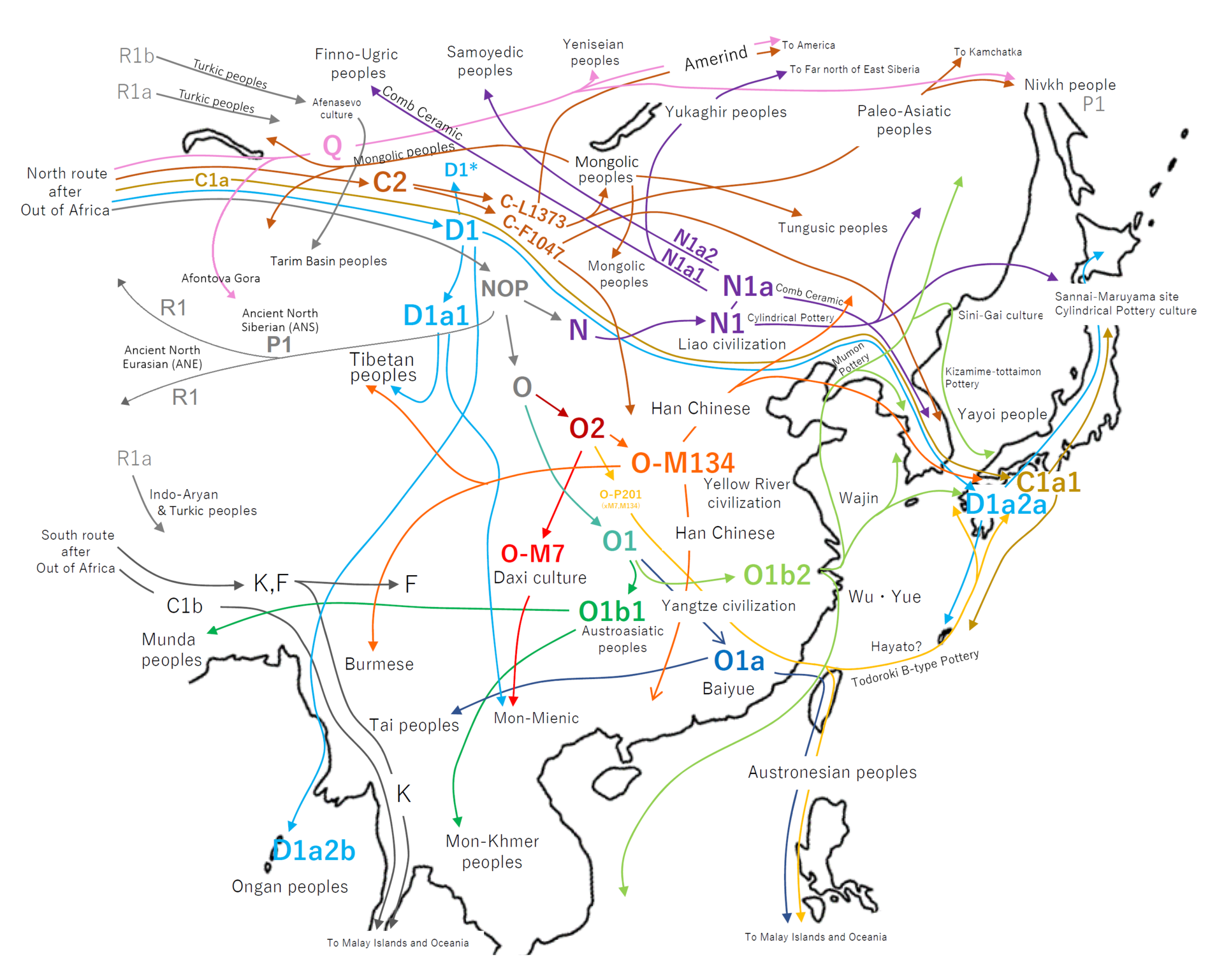

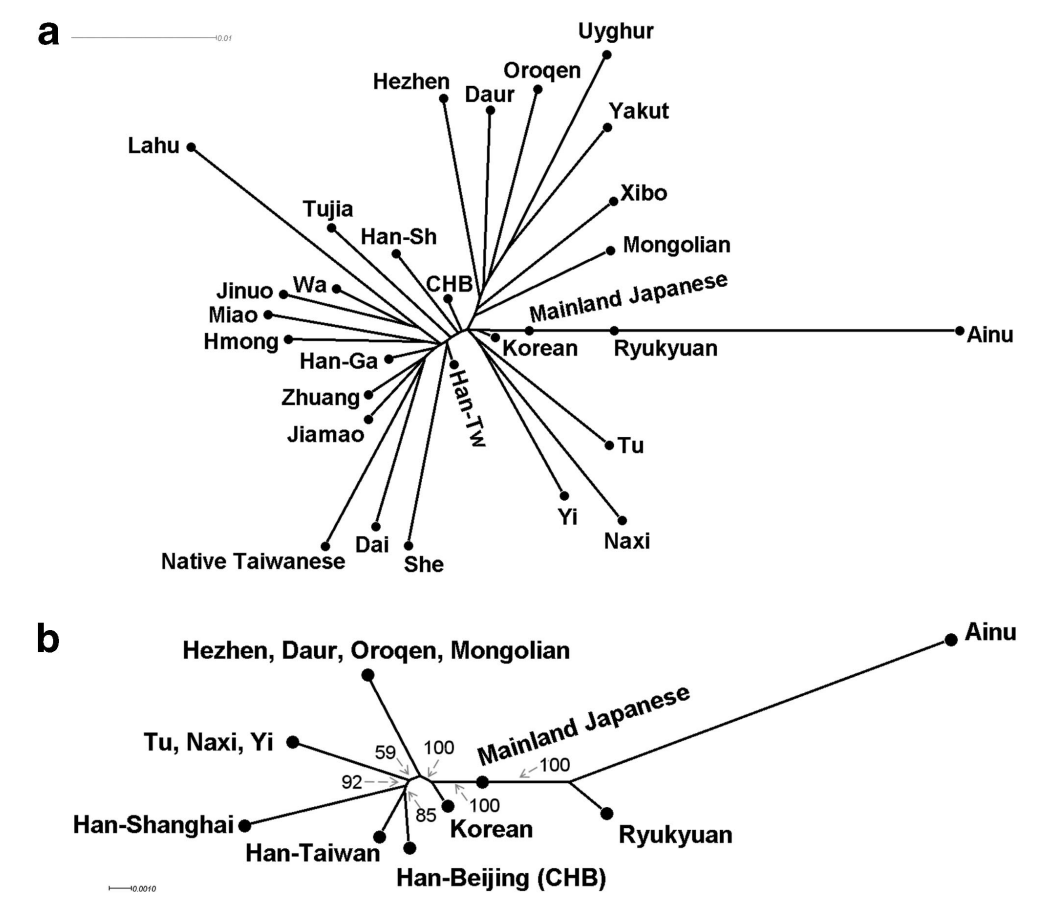

| Origins Genetic studies According to the recent genetic studies, the Ryukyuan people share more alleles with the southern Jōmon (16,000–3,000 years ago) hunter-gatherers than the yayoi people, who had rice farming culture, have smaller genetic contributions from Asian continental populations, which supports the dual-structure model of K. Hanihara (1991), a widely accepted theory which suggests that the Yamato Japanese are more admixed with Asian agricultural continental people (from the Korean Peninsula) than the Ainu and the Ryukyuans, with major admixture occurring in and after the Yayoi period (3,000-1,700 years ago).[31][32][33][34][35][36][37] Within the Japanese population the Ryukyu make a separate and one of the two genome-wide clusters along the main-island Honshu.[31][38] The Jōmon ancestry is estimated at approximately 28%,[39] with a more recent study estimating it at ~36%.[40] The admixture event which formed the admixed Ryukyuans was estimated at least 1100–1075 years ago, which corresponds to the Gusuku period, and is considered to be related to the arrival of migrants from Japan.[39] According to archaeological evidence, there is a prehistoric cultural differentiation between the Northern Ryukyu Islands (Amami Islands and Okinawa Islands) and the Southern Ryukyu Islands (Miyako Islands and Yaeyama Islands). The genome-wide differentiation was pronounced, especially between Okinawa and Miyako. It is considered to have arisen due to genetic drift rather than admixture with people from neighboring regions, with the divergence dated to the Holocene, and without major genetic contribution of the Pleistocene inhabitants to the present-day Southern Islanders.[41] The Amami Islanders are also slightly more similar to the mainland population than the Okinawa Islanders.[42] An autosomal DNA analysis from Okinawan samples concluded that they are most closely related to other Japanese and East Asian contemporary populations, sharing on average 80% admixture with mainland Japanese and 19% admixture with Chinese population, and that have isolate characteristics.[34] The population closest to Ryukyu islanders is the mainland Japanese, followed by the Korean and Chinese populations. However, Taiwan aborigines were genetically distant from the Ryukyu islanders, even though these populations are geographically very close.[40] The female mtDNA and male Y chromosome markers are used to study human migrations. The research on the skeletal remains from the Neolithic Shell midden period (also known as Kaizuka period) in Okinawa, as well from the Gusuku Period, showed predominance of female haplogroups D4 and M7a and their genetic continuity in the contemporary female population of Okinawa.[43][44] It is assumed that M7a represents "Jomon genotype" introduced by a Paleolithic ancestor from Southeast Asia or the southern region of the Asian continent, around the Last Glacial Maximum with the Ryukyu Islands as one of the probable origin spots; in contrast, the frequency of the D4 haplogroup is relatively high in East Asian populations, including in Japan, indicating immigrant Yayoi people, probably by the end of the late Kaizuka period, while haplogroup B4 presumably ancient aboriginal Taiwanese ancestry.[43][44] However, as in the contemporary Japanese population M7 showed a decrease, whereas the frequency of the haplogroup N9b showed an increase from the south to north direction, it indicates that the mobility pattern of females and males was different as the distribution of Y haplogroups do not show a geographical gradient in contrast to mtDNA,[45] meaning mainly different maternal origins of the contemporary Ryukyuan and Ainu people.[46]  Haplogroup dispersal and migration routes into Japan The research on the contemporary Okinawan male Y chromosome showed, in 2006; 55.6% of haplogroup D-P-M55, 22.2% O-P31, 15.6% O-M122, 4.4% C-M8, and 2.2% others.[47] It is considered that the Y haplogroups expanded in a demic diffusion. The haplogroups D and C are considered of Neolithic and Paleolithic origin, with coalescence time of 19,400 YBP and expansion 12,600 YBP (14,500 YBP and 10,820 YBP respectively), and were isolated for thousands of years once land bridges between Japan and continental Asia disappeared at the end of the last glacial maximum 12,000 YBP. The haplogroup O began its expansion circa 4,000-3,810 years ago, and thus the haplogroups D-M55 and C-M8 belong to the Jomon's male lineage, and haplogroup O belongs to the Yayoi's male lineage. Haplogroup M12 is considered as mitochondrial counterpart of Y chromosome D lineage. This rare haplogroup was detected only in Yamato Japanese, Koreans, and Tibetans, with the highest frequency and diversity in Tibet.[47][45]  Phylogenetic tree of Mainland Japanese, Ryukyuan (Ryukyuan), Ainu (Ainu) and other Asian ethnic groups[48][49] A genetic and morphological analysis in 2021 by Watanabe et al., found that the Ryukyuans are most similar to the southern Jōmon people of Kyushu, Shikoku, and Honshu. Southern Jōmon samples were found to be genetically close to contemporary East Asian people, and quite different from Jōmon samples of Hokkaido and Tohoku. Haplogroup D-M55 has the highest diversity within southern Japanese and Ryukyuans, suggesting a dispersal from southwestern Japan towards the North, replacing other Jōmon period lineages through genetic drift. Haplogroup D (D1) can be linked to an East Asian source population from the Tibetan Plateau ("East Asian Highlanders"), which contributed towards the Jōmon period population of Japan, and less to ancient Southeast Asians. Southern Jōmon people were found to share many SNPs with Tujia people, Tibetans, Miao people, and Tripuri people, rather than Ainu.[50] [failed verification] Anthropological studies The comparative studies on the dental diversity also showed long-term gene flow from outside source (main-island Honshu and from the southern part of East Asia), long-term isolation, and genetic drift which produced the morphological diversification of the modern Ryukyuans. However, the analysis contradicts the idea of homogeneity among the Jōmon people and a closer affinity between the Ainu and the Ryukyuans.[51][35][52][53][54][55][56] A recent craniometric study shows that the Ryukyuan people are closely related to the Yamato people and their common main ancestors, the Yayoi people. The Ryukyuans differ strongly from the Ainu people, which, according to the authors, is a strong evidence for the heterogeneity of the Jōmon period population.[57] As previous morphological studies, such as Kondo et al. 2017, the genetic and morphological analysis by Watanabe et al. 2021, confirmed that the Jōmon period people were heterogeneous and differed from each other depending on the region. A North-to-South cline was detected, with the southern Jōmon of Kyushu, Shikoku and southwestern Honshu being closer to contemporary East Asian people, while the northern Jōmon of Hokkaido and Tohoku being more distant from East Asians. The study results confirmed the "dual-structure theory" regarding the origin of modern Japanese and Ryukyuans, but found that noteworthy amounts of East Asian associated alleles were already present within the Jōmon period people prior to the migration of continental East Asians during the Yayoi period. The southern Jōmon, which are ancestral to the Ryukyuans, were anthropologically most similar to modern day East Asians and differed from Jōmon period samples of Hokkaido quite significantly.[50][failed verification] Challenging the notion of ethnic homogeneity in Japan The existence of the Ryukyuan people challenges the notion of ethnic homogeneity in post-WWII Japan. After the demise of the multi-ethnic Empire of Japan in 1945, successive governments had forged a single Japanese identity by advocating monoculturalism and denying the existence of ethnic minority groups.[58] The notion of ethnic homogeneity was so ingrained in Japan that the former Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aso notably claimed in 2020 that "No other country but this one has lasted for as long as 2,000 years with one language, one ethnic group and one dynasty". Aso's comment sparked strong criticism from the Ryukyuan community.[58] |

起源 遺伝学的研究 最近の遺伝学的研究によると、琉球人は稲作文化を持つ弥生人よりも南方縄文人(16,000~3,000年前)の狩猟採集民と対立遺伝子を多く共有してお り、アジア大陸系集団からの遺伝的寄与は小さく、K. Hanihara(1991)の二重構造モデルを支持している。Hanihara (1991)の二重構造モデルを支持するものであり、大和民族はアイヌ民族や琉球民族よりもアジアの農耕大陸人(朝鮮半島出身)との混血が多く、主な混血 は弥生時代(3,000-1,700年前)以降に起こったとする広く受け入れられている説である[31][32][33]。 [31][32][33][34][35][36][37]日本人の集団の中で、琉球人は本州に沿った2つのゲノム全体のクラスターのうちの1つであり、 独立したクラスターを形成している[31][38]。 [40]混血琉球人を形成した混血現象は、グスク時代に相当する少なくとも1100~1075年前と推定されており、日本からの移住者の到来に関連してい ると考えられている[39]。 考古学的証拠によれば、北琉球諸島(奄美群島と沖縄諸島)と南琉球諸島(宮古諸島と八重山諸島)の間には先史時代の文化的分化がある。ゲノム全体の分化は 顕著で、特に沖縄と宮古の間で顕著であった。奄美群島人は沖縄群島人よりも本土の人々にわずかに類似している[41]。 [42]沖縄のサンプルから得られた常染色体DNA分析によると、彼らは他の日本や東アジアの現代集団と最も近縁であり、平均して本土の日本人集団と 80%、中国人集団と19%の混血を共有し、隔離された特徴を持つと結論づけている[34]。琉球島民に最も近い集団は本土の日本人集団であり、韓国人集 団と中国人集団がそれに続く。しかし、台湾原住民は、これらの集団が地理的に非常に近いにもかかわらず、琉球島民とは遺伝的に遠い[40]。 女性のmtDNAと男性のY染色体マーカーは、人類の移動の研究に使用されている。沖縄の新石器時代の貝塚時代(貝塚時代とも呼ばれる)の骨格標本やグス ク時代の骨格標本に関する研究では、沖縄の現代女性集団において女性のハプログループD4とM7aが優勢であり、それらの遺伝的連続性が示された[43] [44]。 [43][44]M7aは、最終氷期最盛期前後に東南アジアまたはアジア大陸南部から旧石器時代の祖先によってもたらされた「縄文人の遺伝子型」であり、 琉球列島がその起源のひとつであると推定されている; 対照的に、D4ハプログループの頻度は、日本を含む東アジアの集団では比較的高く、おそらく貝塚時代後期までに移民した弥生人を示している。 [43][44]しかし、現代日本人の集団では、M7が減少しているのに対し、ハプログループN9bの頻度は南から北の方向に向かって増加していることか ら、Yハプログループの分布はmtDNAとは対照的に地理的な勾配を示さないことから、女性と男性の移動パターンが異なっていたことが示され[45]、こ れは主に現代の琉球人とアイヌ人の母方の起源が異なることを意味している[46]。  ハプログループの分散と日本への移動ルート 2006年の沖縄人男性Y染色体の調査では、ハプログループD-P-M55が55.6%、O-P31が22.2%、O-M122が15.6%、C-M8が 4.4%、その他が2.2%であった[47]。ハプログループDとCは新石器時代と旧石器時代起源と考えられ、合体時期は19,400 YBP、拡大時期は12,600 YBP(それぞれ14,500 YBPと10,820 YBP)であり、最終氷期末期の12,000 YBPに日本とアジア大陸を結ぶ陸橋が消滅すると、数千年間隔離された。ハプログループOは約4,000-3,810年前に拡大を開始した。したがって、 ハプログループD-M55とC-M8は縄文人の男系に属し、ハプログループOは弥生人の男系に属する。ハプログループM12はY染色体D系統のミトコンド リア対応遺伝子と考えられている。この稀なハプログループは大和民族の日本人、韓国人、チベット人のみに検出され、チベットで最も頻度と多様性が高い [47][45]。  本土日本人、琉球人(リュウキュウ人)、アイヌ人(アイヌ民族)、その他のアジアの民族の系統樹[48][49]。 渡辺らによる2021年の遺伝学的・形態学的分析では、琉球人は九州、四国、本州の南方系縄文人に最も類似していることが判明した。縄文人南部のサンプル は遺伝学的に現代の東アジア人に近く、北海道や東北の縄文人サンプルとはかなり異なることが判明した。ハプログループD-M55は南日本人と琉球人の中で 最も多様性が高く、これは遺伝的漂流によって他の縄文時代の系統に取って代わり、西南日本から北方へ分散したことを示唆している。ハプログループD (D1)は、日本の縄文時代の人口に貢献したチベット高原からの東アジア源流集団(「東アジア高地人」)にリンクすることができ、古代の東南アジア人には あまりリンクしない。南ジョウモン人はアイヌ人よりもむしろツジャ人、チベット人、ミャオ人、トリプリ人と多くのSNPを共有していることが判明した [50]。 人類学的研究 歯列多様性の比較研究でも、外部(本州や東アジア南部)からの長期的な遺伝子流入、長期的な隔離、遺伝的ドリフトが、現代の琉球人の形態の多様化をもたら したことが示された。しかし、この分析結果は、縄文人の間の同質性やアイヌと琉球人の間のより緊密な親近性という考えとは矛盾するものである[51] [35][52][53][54][55][56]。最近の頭蓋計測の研究によれば、琉球人は大和民族やその共通の主祖先である弥生人と近縁である。琉球 人はアイヌ人とは強く異なっており、著者らによれば、これは縄文時代の集団の異質性を示す強力な証拠である[57]。 近藤ら2017年などの形態学的な先行研究と同様に、渡辺ら2021年による遺伝学的・形態学的分析でも、縄文時代の人々が地域によって異なり、異質であ ることが確認された。九州、四国、本州南西部の南の縄文人は現代の東アジア人に近く、北海道や東北の北の縄文人は東アジア人から遠いという南北のクライン が検出された。研究の結果、現代の日本人と琉球人の起源に関する「二重構造説」は確認されたが、弥生時代に大陸の東アジア人が移住する以前から、縄文時代 の人々には注目すべき量の東アジア人に関連する対立遺伝子がすでに存在していたことが判明した。琉球人の祖先である南の縄文人は、人類学的には現代の東ア ジア人に最も似ており、北海道の縄文時代のサンプルとはかなり異なっていた[50][検証失敗]。 日本における民族同質性の概念への挑戦 琉球人の存在は、第二次世界大戦後の日本における民族同質性の概念に挑戦するものである。1945年に多民族国家であった大日本帝国が崩壊した後、歴代政 府は単一文化主義を標榜し、少数民族の存在を否定することで、単一の日本人としてのアイデンティティを形成してきた[58]。民族同質性の概念は日本に根 付いており、麻生太郎元副総理は2020年に「1つの言語、1つの民族、1つの王朝で2,000年も続いた国はこの国以外にない」と主張した。麻生の発言 は琉球コミュニティから強い批判を巻き起こした[58]。 |

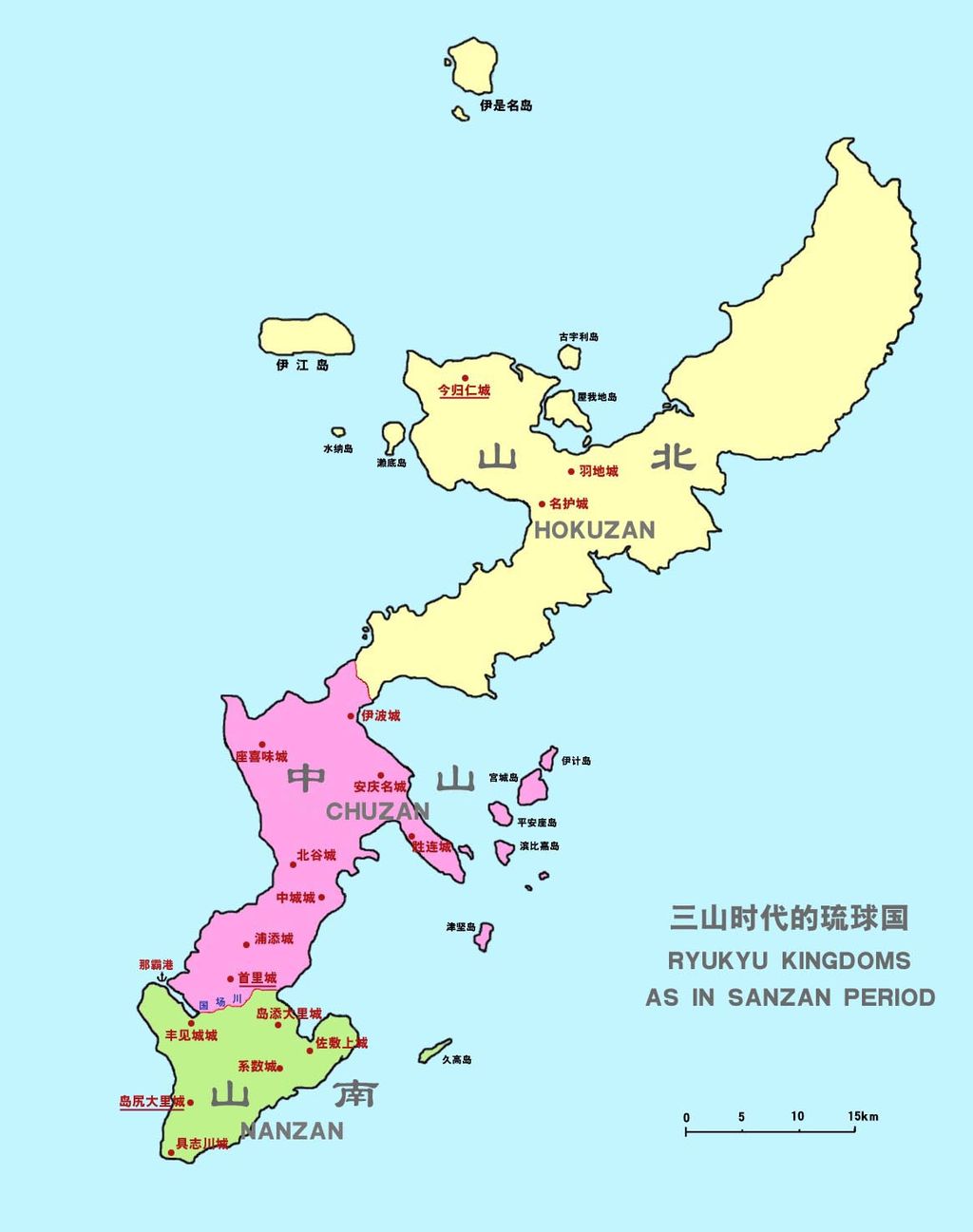

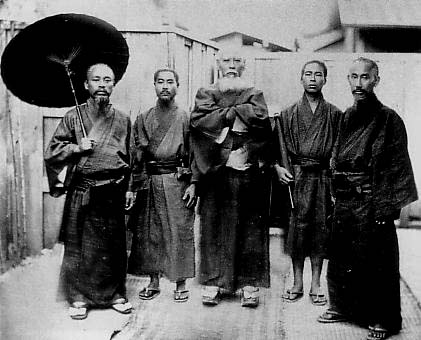

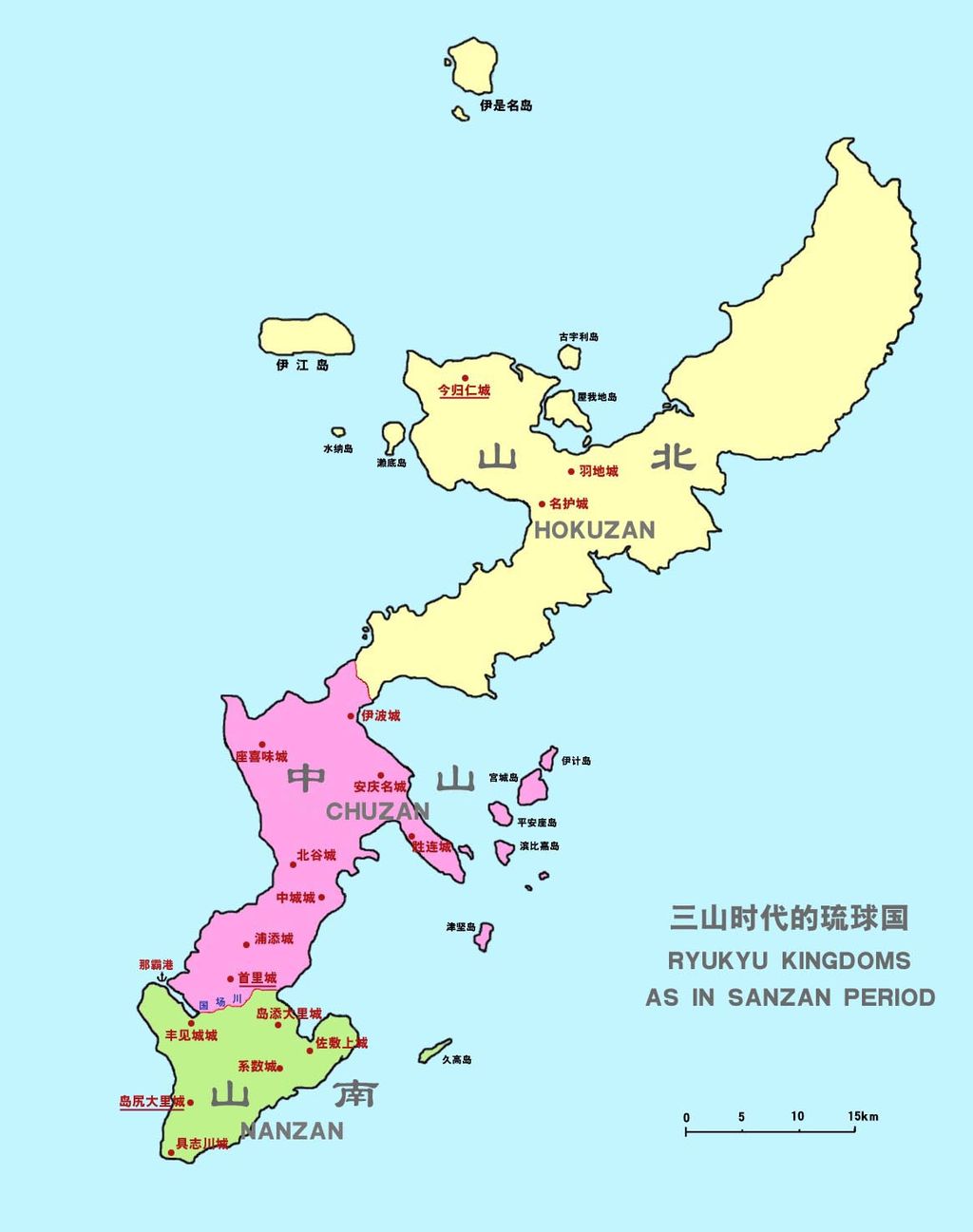

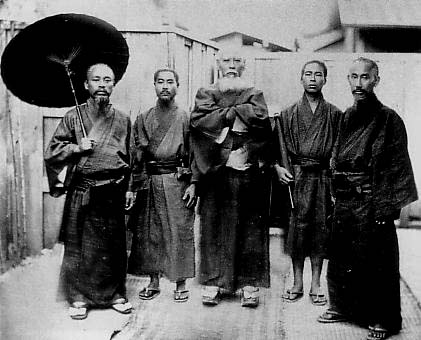

| History Main article: History of the Ryukyu Islands Early history Main article: Jōmon period The Ryukyu Islands were inhabited from at least 32,000–18,000 years ago,[59] but their fate and relation with contemporary Ryukyuan people is uncertain.[60] During the Jōmon period (i.e., Kaizuka) or so-called shell midden period (6,700–1,000 YBP) of the Northern Ryukyus,[60] the population lived in a hunter-gatherer society, with similar mainland Jōmon pottery.[41] In the latter part of Jōmon period, archaeological sites moved near the seashore, suggesting the engagement of people in fishery.[61] It is considered that from the latter half of Jōmon period, the Ryukyu Islands developed their own culture.[62] Some scholars consider that the language and cultural influence was more far-reaching than blending of race and physical types.[61] The Yayoi culture which had a major influence on the Japanese islands, is traditionally dated from 3rd century BCE and recently from around 1000 BCE,[63] and is notable for the introduction of Yayoi-type pottery, metal tools and cultivation of rice, however although some Yayoi pottery and tools were excavated on the Okinawa Islands, the rice was not widely cultivated before the 12th century CE, nor the Yayoi and the following Kofun period (250–538 CE) culture expanded into the Ryukyus.[60] The Southern Ryukyus culture was isolated from the Northern, and its Shimotabaru period (4,500–3,000 YBP) was characterized by a specific style of pottery, and the Aceramic period (2,500–800 YBP), during which no pottery was produced in this region.[60][41] Their prehistoric Yaeyama culture showed some intermingled affinities with various Taiwanese cultures, broadly, that the Sakishima Islands have some traces similar to the Southeast Asian and South Pacific cultures. The Amami Islands seem to be the islands with the most mainland Japanese influence.[62] However, both north and south Ryukyus were culturally unified in the 10th century.[41] The finding of ancient Chinese knife money near Naha in Okinawa indicates a probable contact with the ancient Chinese state Yan as early as the 3rd century BCE. According to the Shan Hai Jing, the Yan had relations with the Wa ('dwarf', 'short') people living southeast of Korea, who could be related to both the mainland Japanese or Ryukyuan people.[61] The futile search for the elixir of immortality by Qin Shi Huang, the founder of the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE), in which the emperor tried to cooperate with "happy immortals" who dwelt on the islands, could be related to both Japan and Ryukyu Islands.[61] There is a lack of evidence that the missions by the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) reached the islands; however, as the Japanese did reach Han's capital, notes from 57 CE do mention a general practice of tattooing among the people of "hundred kingdoms" in the eastern islands, a practice which was widespread and survived only among the Okinawan's women, Ainu in Hokkaido, and Atayal people in Taiwan.[61] Cao Wei (220–265) and Han dynasty records show that the inhabitants of western and southern Japan and Okinawa had a lot in common regarding political-social institutions until the 2nd century CE – they were of small stature, bred oxen and swine, and were ruled by women, with a special influence of women sorceresses, related to the Ryukyuan Noro priestesses which were closely associated with local political power until the 20th century, as well as with the Ryukyuan swine economy culture until World War II. It is suggested that the mention of a specific sorceress Pimeku, her death and successive conflict, is related to some socio-political challenges of the ancient matriarchal system.[61] The first certain mention of the islands and its people by the Chinese and Japanese is dated in the 7th century. Emperor Yang of Sui, due to previous tradition, between 607–608 held expeditions in search of the "Land of Happy Immortals". As the Chinese envoy and the islanders linguistically could not understand each other, and the islanders did not want to accept the Sui rule and suzerainty, the Chinese envoy took many captives back to the court. The islands, by the Chinese named Liuqiu (Middle Chinese: Lɨuɡɨu), would be pronounced by the Japanese as Ryukyu. However, when the Japanese diplomat Ono no Imoko arrived at the Chinese capital he noted that the captives probably arrived from the island of Yaku south of Kyushu. In 616 the Japanese annals for the first time mention the "Southern Islands people", and for the half-century were noted some intruders from Yaku and Tanu. According to the Shoku Nihongi, in 698 a small force dispatched by Japanese government successfully claimed the Tane-jima, Yakushima, Amami, Tokunoshima and other islands.[61] The Shoku Nihongi recorded that the Hayato people in southern Kyushu still had female chieftains in the early 8th century. In 699 are mentioned islands Amami and Tokara, in 714 Shingaki and Kume, in 720 some 232 persons who had submitted to the Japanese capital Nara, and at last Okinawa in 753. Nevertheless the mention or authority, over the centuries the Japanese influence spread slowly among the communities.[61] Gusuku period  The gusuku fortification are on the Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu UNESCO's list. The lack of written record resulted with later, 17th century royal tales both under Chinese and Japanese influence, which were efforts by local chieftains to explain the "divine right" of their royal authority, as well the then-political interests of Tokugawa shōguns from Minamoto clan who wanted to legitimize Japanese domination over Okinawa. The tradition states that the founder of the Tenson dynasty was a descendant of goddess Amamikyu, and the dynasty ruled 17,000 years and had 25 kings i.e. chieftains. However, the 24th throne was usurped from one of Tenson's descendants by a man named Riyu, who was defeated in revolt led by Shunten (1187–1237), lord of Urasoe. Shunten's parental origin is a matter of debate, according to 17th century romantic tales he was a son of a local Okinawan chief's (anji) daughter and some Japanese adventurer, usually considered Minamoto no Tametomo, while historical and archeological-traditional evidence indicate men from the defeated Taira clan who fled Minamoto's clan vengeance. The Shunten dynasty made two additional chieftains, Shunbajunki (1237-1248) and Gihon (1248–1259). As Gihon abdicated, his sessei Eiso (1260–1299), who claimed Tenson's descent, founded the Eiso dynasty.[61] During the Gusuku period (c. 1187–1314), with recent chronology dated from c. 900-950 CE,[64][65] Okinawans made significant political, social and economical growth. As the center of power moved away from the seashore to inland, the period is named after many gusuku, castle-like fortifications which were built in higher places.[62] This period is also notable, compared to mainland Japan, for fairly late introduction of agricultural production of rice, wheat, millet and the overseas trading of these goods,[62][47][44] as well during Shubanjunki's rule the introduction of Japanese kana writing system in its older and simple phonetic form.[61] After the years of famine and epidemic during the Gihon's rule, Eiso introduced regular taxation system (of weapons, grains and cloth) in 1264 and as the government gained strength, the control extended from Okinawa toward the islands of Kume, Kerama, Iheya, and Amami Ōshima (1266). Between 1272 and 1274, as the Mongol invasions of Japan began, Okinawa on two occasions rejected the Mongols' authority demands. To Eiso's reign period is also ascribed the introduction of Buddhism into Okinawa.[61] Sanzan period Main articles: Sanzan period and Ryukyuan missions to Imperial China  Map of Okinawa Island, showing the Sanzan period polities During the rule of Eiso's great-grandson, Tamagusuku (1314–1336), Okinawa became divided into three polities and began the so-called Sanzan period (1314–1429). The north and largest Hokuzan polity was the poorest due to forest and mountainous terrain (in which isolation was an advantage), with primitive farming and fishing. The central Chūzan polity was the most advantaged due to its developed castle towns and harbor facilities. The south Nanzan polity was the smallest, but endured because of good castle positions and sea merchants.[61] In this period another rapid economical, social and cultural development of Ryukyu began as the polities had developed formal trade relations with Japan, Korea and China. During the Satto's reign, Chūzan made tributary relations with China's Ming dynasty in 1374 as the Hongwu Emperor sent envoys in 1372 to Okinawa. In the next two decades Chūzan made nine official missions to the Chinese capital, and the formal relations between them endured until 1872 (see Imperial Chinese missions to the Ryukyu Kingdom).[61][66] Despite significant Chinese economical, cultural and political influence, the polities continued to maintain strong autonomy.[67][68] In 1392, all three polities began to send extensive missions to the Korean Joseon kingdom. In 1403, Chūzan made formal relations with the Japanese Ashikaga shogunate, and an embassy was sent to Thailand in 1409.[61] The contacts with Siam continued even in 1425, and were newly made with places like Palembang in 1428, Java in 1430, Malacca and Sumatra in 1463.[66] As in 1371, China initiated its maritime prohibition policy (Haijin) to Japan, Ryukyu gained a lot from its position as intermediary in the trade between Japan and China. They shipped horses, sulphur and seashells to China, from China brought ceramics, copper, and iron, from southeast Asian countries bought tin, ivory, spices (pepper), wood (sappanwood), which they sold to Japan, Korea or China, as well as transporting Chinese goods to Hakata Bay from where swords, silver and gold were brought.[69][70] In 1392, 36 Chinese families from Fujian were invited by the chieftain of Okinawa Island's central polity (Chūzan) to settle near the port of Naha and to serve as diplomats, interpreters, and government officials.[66] Some consider that many Ryukyuan officials were descended from these Chinese immigrants, being born in China or having Chinese grandfathers.[71] They assisted the Ryukyuans in advancing their technology and diplomatic relations.[72][73] From the same year onward Ryukyu was allowed to send official students to China i.e. Guozijian.[74] The tributary relationship with China later became a basis of the 19th century Sino-Japanese disputes about the claims of Okinawa.[61] Ryukyu Kingdom Main articles: Ryukyu Kingdom and Ryukyuan missions to Edo  The castle town and Ryukyu Kingdom's capital Shuri Castle Between 1416 and 1429, Chūzan chieftain Shō Hashi successfully unified the principalities into the Ryukyuan Kingdom (1429–1879) with the castle town Shuri as royal capital, founded the First Shō dynasty, and the island continued to prosper through maritime trade, especially tributary relations with the Ming dynasty.[12] The period of Shō Shin's (1477–1526) rule, descendant from the Second Shō dynasty, is notable for peace and relative prosperity, peak in overseas trade, as well as expansion of the kingdom's firm control to Kikaijima, Miyako-jima and Yaeyama Islands (1465–1524),[75] while during Shō Sei (1526-1555) to Amami Ōshima (1537).[69] After the Kyūshū Campaign (1586–1587) by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, his assistant Kamei Korenori, who was interested in southern trade, wanted to be rewarded with the Ryukyu Islands. A paper fan found during the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98) mentioning a title "Kamei, Lord of Ryukyu", reveals that Hideyoshi at least nominally offered the post although he had no legitimate claim upon the islands. In 1591, Kamei ventured with a force to reclaim the islands, but the Shimazu clan stopped him as they guarded their special relationship with the Ryukyu kingdom. Hideyoshi was not very concerned about the quarrel because the invasion of Korea was more important in his mind.[76] As the Ming's influence weakened due to disorder in China, Japanese established posts in Southeast Asia, and the Europeans (Spanish and Portuguese) arrived, the kingdom's overseas trade began to decline.[77][12] In the early 17th century during the Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1867), the first shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu intended to subject the kingdom to enable intermediary trade with China, and in 1603 ordered the Ryukyuan king to pay his respect to the shogunate. As the king did not react, with the instruction of the shōgun, the Satsuma feudal domain of the Shimazu clan in Kyūshū incorporated some of kingdom's territory during the 1609 Invasion of Ryukyu. They nominally let a certain level of autonomy and independence to the kingdom due to Ming's prohibition of trade with the shogunate, but forbade them trade with other countries except China. The Amami Islands became part of Shimazu's territory, taxes were imposed, making them subordinate in the relations between Japan and China.[61][78][79] Until the invasion, the Shimazu clan lords for four centuries had a vague title of the "Lords of the Twelve Southern Islands" or "Southern Islands", although initially meaning the near Kyushu islands, then covering all the Ryukyu Islands. Later in the 1870s this was used as a "justification" of Japan's sovereignty.[61] From 1609 the Ryukyuan missions to Edo started which lasted until 1850.[80] During the rule of kings Shō Shitsu (1648–1668) and Shō Tei (1669–1709) i.e. sessei Shō Shōken (1666–1673) were recovered the internal social and economical stability with many laws about government organisation, and affairs like sugarcane production, and tax system with emphasis on agricultural production. The production was encouraged because Satsuma's annual tax deprived Ryukyu's internal resources. Although the production of sweet potatoes and sugar industry grew, the peasants were not allowed to enlarge their fields. The agricultural reforms especially continued under king Shō Kei (1713–1752) and his sanshikan advisor Sai On (1728–1752) whose Nomucho (Directory of Agricultural Affairs) from 1743 became the basis of the agricultural administration until the 19th century.[81] In the Sakishima Islands great part of the tax was paid in textiles made of ramie.[82] The relations with the Qing dynasty improved after their second mission when the first Ryukyuan official students were sent to China in 1688.[83] In the first half of the 19th century, French politicians like Jean-Baptiste Cécille unsuccessfully tried to conclude a French trade treaty with Ryukyu,[84] with only a promise by Shuri government about the admission of Christian missionaries. However, due to extreme measures in teaching, Bernard Jean Bettelheim's propagation of Protestantism between 1846–1854 was obscured by the government.[83] Meiji period Main articles: Ryukyu Domain, Okinawa Prefecture, and Ryukyu independence movement  Five Ryukyuan men, Meiji period, who?? - Imperial Household Ministry(present-day "Imperial Household Agency") - Japanese book "Japan in the Meiji era" published by Yoshikawa-Kobunkan. During the Meiji period (1868–1912) the "Ryukyu shobun" process began,[85] according to which the Ryukyuan Kingdom came under the jurisdiction of Kagoshima Prefecture in 1871, encompassing the southern tip of Kyushu and the Ryukyuan islands to its south; this created the Ryukyu Domain (1872–1879) of Meiji-era Japan. This method of gradual integration was designed to avoid both Ryukyuan and Chinese protests, with the ruling Shuri government unaware of the significance of these developments, including Japan's decision to grant political representation to the Ryukyuan islanders involved in the Japanese invasion of Taiwan (1874). In 1875, the Ryukyuan people were forced to terminate their tributary relations with China, against their preference for a state of dual allegiance to both China and Japan, something a then-weakened China was unable to stop. A proposal by the 18th U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant for a sovereign Okinawa and the division of the other islands between China and Japan was rejected, with a last-minute decision by the Chinese government not to ratify the agreement rendering it null. On three occasions between 1875 and 1879, the last Ryukyuan King, Shō Tai, refused to submit to the demands placed upon his people, and in 1879, his domain was formally abolished and established as Okinawa Prefecture, forcing his move to Tokyo with the reduced status of Viscount.[86][87][88][89] Members of the Ryukyuan aristocratic classes such as Kōchi Chōjō and Rin Seikō continued to resist annexation for almost two decades;[90] however, following the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), both Chinese and Ryukyuan interest in sovereignty faded as China renounced its claims to the island.[91][18][92] Many historians criticise Meiji-era Japan's characterisation of the process as being considered a relatively simple administrative change, rather than the creation of Japan's first colony and the beginning of its "inner colonialism".[84][93] During the Meiji period, as with the Ainu people of Hokkaido, the Ryukyuan people had their own culture, religion, traditions and language suppressed by the Meiji government in the face of forced assimilation.[12][20][94] From the 1880s onwards, schools forbade the display of Ryukyuan styles of dress, hairstyles and other visual aspects, considering them to be backwards and inferior, with students forced to wear Japanese clothing and to assimilate into Japanese culture.[95] Indoctrination into a militaristic and Emperor-centred ideology for children began from the age of beginning elementary school onwards;[96] the ultimate goal of this education was a total unification of the Ryukyuan people into the Yamato people, embodying the ideal of ethnic purity,[97] with contemporary Nihonjiron literature for the time ignoring Japan's minorities[98]). Ryukyuans often faced prejudice, humiliation in the workplace and ethnic discrimination,[99][100] with the Ryukyuan elite divided into factions either in support of or in opposition to assimilation.[20] Negative stereotypes and discrimination were common against the Ryukyuan people in the Japanese society.[101] Around and especially after the Japanese annexation of Taiwan in 1895, Japan's developmental focus shifted away from Okinawa, resulting in a period of famine known as "Sotetsu-jigoku" ("Cycad hell"). Between 1920 and 1921, a fall in sugar prices, as well as the transfer of Japan's sugar production to Taiwan, led to Ryukyu being the poorest prefecture, despite having the heaviest taxation burden; the drop in sugar prices would continue into 1931, further worsening the situation.[102] As a result of the ensuing economic crisis, many people were forced to either find work in Japan (often Osaka and Kobe) or abroad in Taiwan.[103][104] By 1935, roughly 15% of the population had emigrated.[105] WW2 and modern history During World War II and battles like the Battle of Okinawa (1945), approximately 150,000 civilians (1/3 of the population) were killed in Okinawa alone.[106][107] After the war, the Ryukyu Islands were occupied by the United States Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands (1945–1950), but the U.S. maintained control even after the 1951 Treaty of San Francisco, which went into effect on April 28, 1952, as the USMMGR was replaced by the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands (1950–1972). During this period the U.S. military requisitioned private land for the building of their facilities, with the former owners put into refugee camps, and its personnel committed thousands of crimes against the civilians.[vague][108] Only twenty years later, on 15 May 1972, Okinawa and nearby islands were returned to Japan.[12] Whereas the Japanese had enjoyed political freedom and economic prosperity in the post-war years, the facilities, used for the purposes of Japanese regional security against the communist threat, had a negative economic impact on the Islands, leading to many Ryukyuans feeling cheated, some considering the facilities a national disgrace.[61][109] Since 1972 there have been extensive plans to bring Okinawa's economy up to the national level, as well continued support for the local culture and a revival of traditional arts started by the USCAR.[110][111] Okinawa comprises just 0.6% of Japan's total land mass, yet about 75% of all U.S. military installations stationed in Japan are assigned to bases in Okinawa.[112][113] The presence of the military remains a sensitive issue in local politics.[12] Negative feelings toward the mainland Government, Emperor (especially Hirohito due to his involvement in the sacrifice of Okinawa and later military occupation), and U.S. military (USFJ, SACO) have often caused open criticism and protests,[114] for example by 85,000 people in 1995 after the U.S. military rape incident,[115] and by 110,000 people in 2007 due to the Japanese Ministry of Education's textbook revisions (see MEXT controversy) which critics say downplays the involvement of the Japanese military in the forced mass suicide of the civilians during the Battle of Okinawa.[116][117] For many years the Emperors avoided visiting Okinawa, with the first ever in history done by Akihito in 1993,[118][119] since it was assumed that his visits would likely cause uproar, as in July 1975 when Akihito as a crown prince visited Okinawa and a firebomb was thrown at him,[118][120] although these tensions have eased in recent years.[121] Discrimination against Okinawans both past and present on the part of the mainland Japanese is the cause of their smoldering resentment against the government.[122] There is a small post-war Ryukyu independence movement, but there are also Okinawans who wish to be assimilated with the mainland.[12] A poll in 2017 by the Okinawa Times, Asahi Shimbun and Ryukyusu Asahi Broadcasting Corporation (QAB) jointly conducted prefectural public opinion surveys for voters in the prefecture. 82% of Okinawa citizens chose "I'm glad that Okinawa has returned as a Japanese prefecture". It was 90% for respondents of the ages of 18 to 29, 86% for those in their 30s, 84% for those aged 40–59, 72% for respondents in their 60s, 74% for those over the age of 70.[123] |

沿革 主な記事 琉球列島の歴史 初期の歴史 主な記事 縄文時代 琉球列島には少なくとも32,000~18,000年前から人が住んでいた[59]が、その運命や現代の琉球人との関係は不明である[60]、 北琉球の縄文時代(貝塚時代)、いわゆる貝塚時代(6,700-1,000 YBP)には[60]、住民は狩猟採集社会で生活しており、縄文土器は本土の縄文土器と類似していた[41]。縄文時代後期には遺跡が海岸近くに移動し、 漁業に従事していたことを示唆している[61]。 [縄文時代後期以降、琉球列島は独自の文化を発展させたと考えられており[62]、人種や体型の融合よりも、言語や文化の影響の方が大きかったと考える学 者もいる。 [61]日本列島に大きな影響を与えた弥生文化は、伝統的には紀元前3世紀、最近では紀元前1000年頃からとされており[63]、弥生式土器、金属器、 稲作の導入で注目されているが、沖縄諸島ではいくつかの弥生式土器や道具が発掘されているものの、12世紀以前には稲作は普及しておらず、弥生とそれに続 く古墳時代(紀元250年~538年)の文化が琉球に拡大したわけでもない。 [60]南琉球文化は北方文化から孤立しており、その下田原時代(4,500-3,000 YBP)は土器の特定の様式によって特徴付けられ、アセラミック時代(2,500-800 YBP)はこの地域で土器が生産されなかった。[60][41]先史時代の八重山文化は、台湾の様々な文化といくつかの交雑した親近性を示し、先島諸島に は東南アジアや南太平洋の文化と類似した痕跡があることが広く知られている。奄美群島は、日本本土の影響を最も受けている島々のようである[62]。しか し、琉球は南北ともに10世紀には文化的に統一されていた[41]。 沖縄の那覇近郊で古代中国のナイフマネーが発見されたことは、紀元前3世紀には古代中国の燕と接触していた可能性が高いことを示している。山海経』によれ ば、燕族は朝鮮半島の南東に住む倭人(「小人」、「背の低い」)と関係があり、日本本土や琉球の人々と関係がある可能性がある[61]。秦王朝の始祖であ る秦の始皇帝(紀元前221-206年)が不老不死の薬を探すために、島々に住む「幸福な仙人」と協力しようとしたことは、日本や琉球の人々と関係がある 可能性がある。 [61] 漢王朝(紀元前206年~紀元220年)による使節団が島々に到達したという証拠はない。しかし、日本人が漢の都に到達したように、紀元57年のメモに は、東の島々の「百国」の人々の間で刺青の一般的な習慣があったことが記されており、この習慣は沖縄の女性、北海道のアイヌ、台湾のタイヤル族の間でのみ 広まり、生き残った。 [61] 曹魏(220-265)と漢代の記録によれば、西日本と南日本と沖縄の住民は、紀元2世紀までは政治社会制度に関して多くの共通点を持っていた-小柄で、 牛や豚を飼育し、女性によって統治されていた。特定の呪術師ピメクについての言及、彼女の死と相次ぐ争いは、古代の母系制の社会政治的な課題に関連してい ることが示唆されている[61]。 中国人と日本人によるこの島とその人々に関する最初の確かな言及は、7世紀とされている。隋の煬帝は、607年から608年にかけて、「仙人の国」を求め て遠征した。遣隋使と島民は言語的に理解できず、島民は隋の支配と宗主権を受け入れようとしなかったため、遣隋使は多くの捕虜を宮廷に連れ帰った。中国人 が琉球と名付けた島々は、日本では琉球と発音されるようになる。しかし、日本の外交官小野妹子が中国の首都に到着したとき、彼は捕虜が九州の南の屋久島か ら到着したのだろうと指摘した。616年、日本の年代記は初めて「南方諸島人」について言及し、半世紀にわたって屋久島と多久島からの侵入者について記し た。続日本紀』によると、698年、日本政府が派遣した小勢力が種子島、屋久島、奄美、徳之島などの領有に成功した[61]。『続日本紀』は、8世紀初頭 には南九州の隼人族にはまだ女性の酋長がいたと記録している。699年には奄美とトカラ、714年には新垣と久米、720年には奈良に服属した232人、 そして753年には沖縄が記されている。それにもかかわらず、何世紀にもわたって、日本の影響は地域社会にゆっくりと広がっていった[61]。 グスク時代  グスクの要塞は、琉球王国のグスク及び関連遺産群としてユネスコのリストに登録されている。 これは、沖縄に対する日本の支配を正当化しようとする源氏出身の徳川将軍の政治的利益と同様に、彼らの王権の「神権」を説明するための地元の首長による努 力であった。伝承によれば、天孫王朝の始祖は女神アマミキュウの子孫であり、王朝は1万7000年を統治し、25人の王、すなわち酋長を擁した。しかし、 24代目の王位は天孫の一人である理酉(りゆう)に簒奪され、理酉は浦添の領主であった俊天(1187-1237)が率いる反乱に敗れた。17世紀のロマ ンチックな物語によれば、彼は沖縄の首長(安次)の娘と日本の冒険家(通常は源為朝と考えられている)との間の子であったとされているが、歴史的、考古学 的、伝統的な証拠によれば、源氏の復讐から逃れた敗れた平氏の出身者であったとされている。順天王朝は、さらに2人の酋長、順馬軍記(1237- 1248)と儀本(1248-1259)を作った。儀本が退位すると、天孫降臨を主張する世子・英祖(1260-1299)が英祖王朝を創始した [61]。 グスク時代(1187年頃~1314年頃)、最近の年代測定では900年頃~950年頃とされている[64][65]。この時代は、日本本土と比較して、 米、小麦、粟などの農業生産とこれらの商品の海外貿易がかなり遅れて導入されたこと[62][47][44]、また、首班純基の支配下で、より古く簡単な 表音文字による仮名文字が導入されたこと[61]が特徴的である。 [1264年、叡尊は武器、穀物、布などの定期的な税制を導入し、政権が強化されると、沖縄から久米島、慶良間諸島、伊平屋島、奄美大島へと支配を拡大し た(1266年)。1272年から1274年にかけて、モンゴルの日本侵略が始まると、沖縄は2度にわたってモンゴルの権威要求を拒否した。栄西の治世 は、沖縄に仏教が伝来した時期でもある[61]。 三山時代 主な記事 三山時代と琉球使節団の中国派遣  三山時代の諸政体を示す沖縄本島の地図 栄西の曾孫である玉城(たまぐすく)(1314年-1336年)の統治下で、沖縄は3つの政治に分割され、いわゆる三山時代(1314年-1429年)が 始まった。北部で最大の北山(ほくざん)政体は、森林と山がちな地形(孤立が有利)のため最も貧しく、原始的な農業と漁業を営んでいた。中央の中山国は、 城下町と港湾施設が発達していたため、最も恵まれていた。南の南山諸侯は最も小規模であったが、優れた城下町と海商人によって存続した[61]。 この時代、琉球の経済的、社会的、文化的な急速な発展は、各政体が日本、朝鮮、中国との正式な貿易関係を発展させたことから始まった。1372年に洪武帝 が使節を沖縄に派遣したのに伴い、薩藤氏の治世下の1374年、楚山は中国の明朝と朝貢関係を結んだ。その後20年の間に、楚山は中国の首都に9回の公式 使節団を派遣し、両者の正式な関係は1872年まで続いた(琉球王国への中国からの使節団を参照)[61][66]。中国の経済的、文化的、政治的影響力 が大きかったにもかかわらず、3つの政体は強い自治権を維持し続けた[67][68]。1425年になってもシャムとの交流は続き、1428年にはパレン バン、1430年にはジャワ、1463年にはマラッカやスマトラとも新たに交流した[66]。 1371年に中国が日本に対して禁海政策を開始したため、琉球は日中貿易の仲介者としての地位から多くの利益を得た。馬、硫黄、貝殻を中国に出荷し、中国 からは陶磁器、銅、鉄をもたらし、東南アジア諸国からは錫、象牙、香辛料(胡椒)、木材(白檀)を購入し、それらを日本、朝鮮、中国に販売し、また中国製 品を博多湾に輸送し、そこから刀剣、銀、金がもたらされた[69][70]。 1392年、福建省から36人の中国人一族が沖縄本島の中央政庁(楚山)の首長に招かれ、那覇港の近くに定住し、外交官、通訳、政府役人として仕えた [66]。多くの琉球の役人は、中国で生まれたり、中国人の祖父を持つなど、これらの中国人移民の子孫であると考える者もいる[71]。 [71]彼らは琉球の技術や外交関係の発展を助けた[72][73]。 同年以降、琉球は中国への国費留学生の派遣を許可された[74]。 琉球王国 琉球王国: 琉球王国と江戸への琉球使節団  城下町と琉球王国の首都首里城(火災で焼け落ちる以前のもの) 1416年から1429年にかけて、首里城を首都とする琉球王国(1429年-1879年)が中山の首長であった尚巴志(しょうはし)によって統一され、 第一尚氏王朝が建国された。 [12]第二尚氏王朝の末裔である尚真(1477年-1526年)の統治時代は、平和で比較的繁栄し、海外貿易のピークを迎え、喜界島、宮古島、八重山諸 島(1465年-1524年)[75]、尚清(1526年-1555年)時代には奄美大島(1537年)へと王国の支配が拡大したことが特筆される [69]。 豊臣秀吉による九州征伐(1586年-1587年)の後、南方貿易に興味を持った助役の亀井茲矩は、琉球諸島の褒美を欲しがった。日本の朝鮮侵略 (1592-98年)の際に発見された「琉球領主亀井」という称号を記した扇子から、秀吉が少なくとも名目上、琉球諸島に対する正当な領有権を持っていな かったにもかかわらず、その地位を提供したことがわかる。1591年、亀井は島々の奪還に乗り出したが、島津氏は琉球王国との特別な関係を守り、亀井を阻 止した。秀吉は朝鮮侵略の方が重要であったため、この争いにはあまり関心を示さなかった[76]。 中国の混乱により明の影響力が弱まり、日本人が東南アジアに拠点を築き、ヨーロッパ人(スペイン人、ポルトガル人)がやってくると、王国の海外貿易は衰退 し始めた[77][12]。 17世紀初頭の徳川幕府(1603年-1867年)の時代、初代将軍徳川家康は中国との仲介貿易を可能にするために王国を服属させることを意図し、 1603年に琉球国王に幕府に敬意を払うよう命じた。王が反応しなかったため、1609年の琉球侵攻の際、九州の島津藩の薩摩藩が王国の領土の一部を編入 した。明が幕府との貿易を禁止したため、名目上は一定の自治と独立を認めたが、中国以外の国との貿易は禁止した。奄美諸島は島津の領土となり、租税が課さ れ、日本と中国の関係において従属的なものとなった[61][78][79]。侵略が行われるまで、島津藩主は4世紀にわたって「南方十二島領主」または 「南方諸島」という漠然とした称号を持っていたが、当初は九州近辺の島々を意味し、その後琉球諸島全体をカバーするようになった。後に1870年代には、 これは日本の主権の「正当化」として使われた[61]。1609年からは、江戸への琉球使節団が始まり、1850年まで続いた[80]。 尚書(1648年-1668年)と尚貞(1669年-1709年)、すなわち世祖尚賢(1666年-1673年)の統治の間に、政府組織、サトウキビ生産 などの事務、農業生産に重点を置いた税制に関する多くの法律が制定され、社会的・経済的な内政の安定が回復された。薩摩の年貢が琉球の内部資源を奪ってい たため、生産が奨励された。サツマイモの生産と砂糖産業は成長したが、農民は畑を広げることを許されなかった。農業改革は特に尚敬王(1713年- 1752年)とその三司官顧問であった斎温(1728年-1752年)の下で続けられ、1743年からの『農務帳』は19世紀まで農業行政の基礎となった [81]。先島諸島では、税金の大部分が苧麻で作られた織物で支払われた[82]。清朝との関係は、1688年に最初の琉球官学生が中国に派遣された第二 次遣清使節団の後に改善された[83]。 19世紀前半、ジャン=バティスト・セシルのようなフランスの政治家たちは、首里政府がキリスト教宣教師の受け入れについて約束しただけで、琉球とフラン ス通商条約を結ぼうとして失敗した[84]。しかし、1846年から1854年にかけてのベルナール・ジャン・ベッテルハイムによるプロテスタントの布教 は、極端な指導のために政府によって不明瞭にされた[83]。 明治時代 主な記事 琉球藩、沖縄県、琉球独立運動  明治時代の5人の琉球人-- who?? - Imperial Household Ministry(present-day "Imperial Household Agency") - Japanese book "Japan in the Meiji era" published by Yoshikawa-Kobunkan. 明治時代(1868年-1912年)には「琉球尚文」プロセスが始まり[85]、それによると琉球王国は1871年に鹿児島県の管轄下に入り、九州の南端 とその南にある琉球諸島を包含することになった。この漸進的な統合の方法は、琉球人と中国人の両方の反発を避けるために考案されたもので、日本の台湾侵略 (1874年)に関与した琉球島民に政治的代表権を与えるという日本の決定を含む、これらの進展の重要性に与党首里政府は気づいていなかった。 1875年、琉球の人々は、中国と日本の両方に忠誠を誓うという彼らの希望に反して、中国との朝貢関係の解消を余儀なくされた。第18代アメリカ大統領ユ リシーズ・S・グラントが提案した、沖縄の主権と他の島々の日中間の分割は拒否され、中国政府が土壇場で協定を批准しないことを決定したため、協定は無効 となった。1875年から1879年にかけて3度にわたり、最後の琉球王であった尚泰は自国民に課された要求に応じることを拒否し、1879年には彼の領 地は正式に廃止され、沖縄県として設置され、子爵の身分を減らして東京への移住を余儀なくされた[86][87][88][89]。 しかし、日清戦争(1894年-1895年)の後、中国が島に対する領有権を放棄したため、中国と琉球の主権に対する関心は薄れた。 [91][18][92]多くの歴史家は、日本初の植民地の創設や「内なる植民地主義」の始まりというよりは、比較的単純な行政上の変更と考えられていた として、明治時代の日本のこのプロセスの特徴を批判している[84][93]。 明治時代には、北海道のアイヌの人々と同様に、琉球の人々も明治政府によって独自の文化、宗教、伝統、言語が強制的な同化のために抑圧された[12] [20][94]。 1880年代以降、学校では琉球の服装、髪型、その他の視覚的な側面を後進的で劣ったものとみなして展示することが禁じられ、生徒は和服を着て日本文化に 同化することを強制された。 [この教育の最終目標は、琉球民族を大和民族に完全に統一することであり、民族純潔の理想を体現することであった[96]。琉球人はしばしば偏見や職場で の屈辱、民族差別に直面し[99][100]、琉球のエリートは同化を支持する派閥と反対する派閥に分かれていた[20]。 日本社会では琉球人に対する否定的なステレオタイプと差別が一般的であった[101]。 1895年に日本が台湾を併合した前後、特にその後に、日本の発展の中心は沖縄から離れ、「ソテツ地獄」として知られる飢饉の時期をもたらした。1920 年から1921年にかけて、砂糖価格の下落、日本の砂糖生産の台湾への移転により、琉球は最も重い税負担を負っていたにもかかわらず、最も貧しい県となっ た。続く経済危機の結果、多くの人々が日本(多くの場合、大阪や神戸)で仕事を見つけるか、台湾で海外就職を余儀なくされた[103][104]。 第二次世界大戦と現代史 第二次世界大戦中、沖縄戦(1945年)などの戦いで、沖縄だけで約15万人の民間人(人口の1/3)が犠牲になった[106][107]。 1951年のサンフランシスコ条約(1952年4月28日発効)後も米国は支配を維持し、USMMGRは琉球列島米国民政局(1950-1972年)に 取って代わられた。この期間中、米軍は施設建設のために私有地を接収し、元所有者は難民キャンプに入れられ、米軍の職員は民間人に対して何千件もの犯罪を 犯した[vague][108]。それからわずか20年後の1972年5月15日、沖縄と近隣の島々は日本に返還された。 [12]戦後、日本人が政治的自由と経済的繁栄を享受していたのに対し、共産主義の脅威に対する日本の地域安全保障の目的で使用された施設は、沖縄に経済 的悪影響を及ぼし、多くの琉球人が騙されたと感じ、施設を国の恥だと考える人もいた[61][109]。 1972年以降、沖縄の経済を国家レベルに引き上げるための大規模な計画が行われ、また、USCARによって始められた地域文化への継続的な支援と伝統芸 術の復興が行われている[110][111]。 沖縄は日本の総面積のわずか0.6%であるにもかかわらず、日本に駐留する米軍施設の約75%が沖縄の基地に割り当てられている[112][113]。軍 の存在は、地元政治において依然として微妙な問題である[12]。本土政府、天皇(特に、沖縄の犠牲とその後の軍事占領への関与による裕仁)、米軍(米軍 普天間飛行場、米軍普天間飛行場)に対する否定的な感情[13]。 例えば、1995年の米軍強姦事件後には85,000人[115]が、2007年には、沖縄戦における民間人の集団自決の強制への日本軍の関与を軽視して いると批判する文部科学省の教科書改訂(文部科学省論争を参照)により110,000人が、公然と批判や抗議行動を起こしている[116][117]。 [1975年7月に皇太子時代の明仁親王が沖縄を訪問した際に火炎瓶が投げつけられたように、明仁親王の訪問は騒動を引き起こす可能性が高いと想定されて いたためである[118][119]。 [121] 過去も現在も本土の日本人による沖縄県民への差別が、政府に対する沖縄県民の恨みをくすぶらせている原因となっている[122] 戦後、小規模な琉球独立運動があるが、本土との同化を望む沖縄県民もいる[12] 2017年に沖縄タイムス、朝日新聞社、琉球朝日放送(QAB)が共同で県内の有権者を対象に行った世論調査では、「沖縄県民の82%が沖縄県民を選ん だ」と回答した。沖縄県民の82%が「沖縄が日本の県に復帰してよかった」を選んだ。18歳から29歳では90%、30歳代では86%、40歳から59歳 では84%、60歳代では72%、70歳以上では74%だった[123]。 |

| Demography See also: Longevity in Okinawa and Okinawa diet Ryukyuans tend to see themselves as bound together by their home island and, especially among older Ryukyuans, usually consider themselves from Okinawa first and Japan second.[124][125][126] The average annual income per resident of Okinawa in 2006 was ¥2.09 million, placing the prefecture at the bottom of the list of 47.[12] The Okinawans have a very low age-adjusted mortality rate at older ages and among the lowest prevalence of cardiovascular disease and other age-associated diseases in the world. Furthermore, Okinawa has long had the highest life expectancy at older ages, as well has had among the highest prevalence of centenarians among the 47 Japanese prefectures, also the world, since records began to be kept by the Ministry of Health in the early 1960s despite the high birth rate and expanding population of Okinawa prefecture. This longevity phenotype has been in existence since records have been kept in Japan, and despite the well-known dietary and other nongenetic lifestyle advantages of the Okinawans (Blue Zone),[127] there may be some additional unknown genetic influence favoring this extreme phenotype. The Okinawa Centenarian Study (OCS) research team began to work in 1976, making it the world's longest ongoing population-based study of centenarians.[34] |

人口統計 こちらもご覧ください: 沖縄の長寿、沖縄の食生活 琉球人は、自分たちを故郷の島によって結ばれていると考える傾向があり、特に年配の琉球人の間では、自分たちは第一に沖縄の人間であり、第二に日本の人間 であると考えるのが普通である[124][125][126]。2006年の沖縄県民一人当たりの平均年収は209万円で、47都道府県中最下位である [12]。 沖縄県民は、高齢期の年齢調整死亡率が非常に低く、心血管疾患やその他の加齢に伴う疾患の有病率も世界で最も低い。さらに、沖縄県は、出生率が高く人口が 拡大しているにもかかわらず、1960年代初頭に厚生省が記録を取り始めて以来、日本の47都道府県の中で最も長寿であり、百寿者の割合も世界で最も高 い。このような長寿の表現型は、日本で記録が残るようになって以来存在しており、沖縄県民(ブルーゾーン)の食生活やその他の非遺伝的なライフスタイルの 利点はよく知られているにもかかわらず[127]、この極端な表現型を好む未知の遺伝的影響がさらにある可能性がある。沖縄百寿者研究(OCS)研究チー ムは1976年に研究を開始し、百寿者を対象とした集団ベースの研究としては世界最長の継続研究となっている[34]。 |

| Culture Language Main articles: Ryukyuan languages, Okinawan scripts, and Okinawan name Similarities between the Ryukyuan and Japanese languages point to a common origin, possibly of immigrants from continental Asia to the archipelago.[128] Although previously[when?] ideologically considered by Japanese scholars[who?] as a Japanese dialect and a descendant of Old Japanese,[129][130] modern linguists such as Thomas Pellard (2015) now classify the Ryukyuan languages as a distinct subfamily of Japonic that diverged before the Old Japanese period (c. 8th century CE); this places them in contrast to Japonic languages that are direct descendants of Old Japanese, namely Japanese and Hachijō.[131] Early literature which records the language of the Old Japanese imperial court shows archaisms which are closer to Okinawan dialects, while later periods of Japanese exhibit more significant Sinicization (such as Sino-Japanese vocabulary) than most Ryukyuan languages. This can be attributed to the fact that the Japanese (or Yamato people) received writing from the Sinosphere roughly a millennium before the Ryukyuan languages.[61] As the Jōmon-Yayoi transition (c. 1000 BCE) represents the formative period of the contemporary Japanese people from a genetic standpoint, it is argued that the Japonic languages are related to the Yayoi migrants as well.[132] The estimated time of separation between Ryukyuan and mainland Japanese is a matter of debate due to methodological problems; older estimates (1959–2009) varied between 300 BCE and 700 CE, while novel (2009–2011) around 2nd century BCE to 100 CE, which has a lack of correlation with archeology and new chronology according to which Yayoi period started around 950 BCE,[133] or the proposed spread of the Proto-Ryukyuan speakers to the islands in the 10–12th century from Kyushu.[134][135] Based on linguistic differences, they separated at least before the 7th century, before or around Kofun period (c. 250–538), while mainland Proto-Ryukyuan was in contact with Early Middle Japanese until 13th century.[136] The Ryukyuan languages can be subdivided into two main groups, Northern Ryukyuan languages and Southern Ryukyuan languages.[137] The Southern Ryukyuan subfamily shows north-to-south expansion,[clarification needed] while Northern Ryukyuan does not, and several hypothetical scenarios can be proposed to explain this.[138] It is generally considered that the likely homeland of Japonic—and thus the original expansion of Proto-Ryukyuan—was in Kyushu, though an alternate hypothesis proposes an expansion from the Ryukyu Islands to mainland Japan.[139][138][140] Although authors differ regarding which varieties are counted as dialects or languages, one possible classification considers there to be five Ryukyuan languages: Amami, Okinawa, Miyako, Yaeyama and Yonaguni, while a sixth, Kunigami, is sometimes differentiated from Okinawan due to its diversity. Within these languages exist dialects of local towns and specific islands, many of which have gone extinct. Although the Shuri dialect of Okinawan was historically a prestige language of the Kingdom of Ryukyu, there is no officially standardized Ryukyuan language. Thus, the Ryukyuan languages as a whole constitute a cluster of local dialects that can be considered unroofed abstand languages.[141] During the Meiji and post-Meiji period, the Ryukyuan languages were considered to be dialects of Japanese and viewed negatively. They were suppressed by the Japanese government in policies of forced assimilation and into using the standard Japanese language.[142][143] From 1907, children were prohibited to speak Ryukyuan languages in school,[21][144] and since the mid-1930s there existed dialect cards,[145] a system of punishment for the students who spoke in a non-standard language.[146][147] Speaking a Ryukyuan language was deemed an unpatriotic act; by 1939, Ryukyuan speakers were denied service and employment in government offices, while by the Battle of Okinawa in 1945, the Japanese military was commanded to consider Ryukyuan speakers as spies to be punished by death, with many reports that such actions were carried out.[148] After World War II, during the United States occupation, the Ryukyuan languages and identity were distinctively promoted, also because of ideo-political reasons to separate the Ryukyus from Japan.[149] However, resentment against the American occupation intensified Ryukyuans' rapport and unification with Japan, and since 1972 there has followed re-incursion of the standard Japanese and further diminution of the Ryukyuan languages.[148][150] It is considered that contemporary people older than 85 exclusively use Ryukyuan, between 45 and 85 use Ryukyuan and standard Japanese depending on family or working environment, younger than 45 are able to understand Ryukyuan, while younger than 30 mainly are not able to understand nor speak Ryukyuan languages.[151] Only older people speak Ryukyuan languages, because Japanese replaced it as the daily language in nearly every context. Some younger people speak Okinawan Japanese which is a type of Japanese. It is not a dialect of the Okinawan language. The six Ryukyuan languages are listed on the UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger since 2009, as they could disappear by the mid-century (2050).[152][7] It is unclear whether this recognition was too late, despite some positive influence by the Society of Spreading Okinawan.[148] Religion Main articles: Ryukyuan religion and Ryukyuan festivals and observances The kamekōbaka (Turtleback tomb) is the traditional Ryukyuan family tomb. Native Ryukyuan religion places strong emphasis upon the role of the women in the community, with women holding positions as shamans and guardians of the home and hearth. The status of women in traditional society is higher than in China and Japan. Although the contemporary kinship system is patrilineal and patrilocal, until the 20th century it was often bilateral and matrilocal, with common village endogamy.[153] Shisa statues can often be seen on or in front of houses—this relates to the ancient Ryukyuan belief that the male spirit is the spirit of the outside and the female spirit is the spirit of the inside. Godhood is mimicked with many attributes, and its in ease without any underlying symbolic order.[154] The village priestesses, Noro, until the 20th century used the white cloth and magatama beads. The noro's duty was to preserve the generational fire in the hearth, a communal treasure, resulting with tabu system about the fire custodian in which they had to be virgins to maintain close communication with the ancestors. The office became hereditary, usually of the noro's brother's female child. The center of worship was represented by three heartstones within or near the house.[61] The belief in the spiritual predominance of the sister was more prominent in Southern Ryukyus.[155] The introduction of Buddhism is ascribed to a 13th century priest from Japan (mostly funeral rites[155]), while the 14th century trade relations resulted with Korean Buddhism influences (including some in architecture), as well Shinto practices from Japan.[61] Buddhism and native religion were ideological basis until 18th century, when Confucianism gradually and officially became government ideology during Shō On (1795–1802), much to the dismay of Kumemura.[156] It was mostly important to the upper class families.[155] Among the Catholic converts was not lost the former religious consciousness.[155] Until the 18th century, the Ryukyuan kings visited the Sefa-utaki (historical sacred place) caves for worship. Another traditional sacred places are springs Ukinju-Hain-ju, where was placed the first rice plantation, and small island Kudaka, where the "five fruits and grains" were introduced by divine people, perhaps strangers with agricultural techniques.[61] The foremost account, which claimed common origin between the Japanese and Ryukyuan people, was made-up by Shō Shōken in the 17th century, to end up the pilgrimage of the Ryukyu king and chief priestess to the Kudaka island.[157] During the Meiji period the government replaced Buddhism with Shintoism as the islands' state religion,[158] and ordered; rearrangement of statues and redesign of shrines and temples to incorporate native deities into national Shinto pantheon; Shinto worship preceded native, Buddhist, or Christian ritual; transformation of local divinities into guardian gods.[20] In the 1920s was ordered building of Shinto shrines and remodelling of previous with Shinto architectural symbols, paid by local tax money, which was a financial burden due to the collapse of sugar prices in 1921 which devastated Okinawa's economy.[96] In 1932 were ordered to house and support Shinto clergy from the mainland.[96] Most Ryukyuans of the younger generations are not serious adherents of the native religion anymore. Additionally, since being under Japanese control, Shinto and Buddhism are also practiced and typically mixed with local beliefs and practices. Cuisine Main article: Okinawan cuisine Okinawan food is rich in vitamins and minerals and has a good balance of protein, fats, and carbohydrates. Although rice is a staple food (taco rice mixes it with beef), pork (mimigaa and chiragaa, dishes Rafute and Soki), seaweed, rich miso (fermented soybean) pastes and soups (Jūshī), sweet potato and brown sugar all feature prominently in native cuisine. Most famous to tourists is the Momordica charantia, gōya (bitter melon), which is often mixed into a representative Okinawan stir fry dish known as champurū (Goya champuru). Kōrēgusu is a common hot sauce condiment used in various dishes including noodle soup Okinawa soba. Some specifically consumed algae include Caulerpa lentillifera. Traditional sweets include chinsuko, hirayachi, sata andagi, and muchi. Local beverages include juice from Citrus depressa, turmeric tea (ukoncha), and the alcoholic beverage awamori. The weight-loss Okinawa diet derives from their cuisine and has only 30% of the sugar and 15% of the grains of the average Japanese dietary intake.[159] Arts Main articles: Okinawan martial arts, Karate, Ryukyuan music, and Okinawan music The techniques of self-defense and using farm tools as weapons against armed opponents—called karate by today's martial artists—were created by Ryukyuans who probably incorporated some gong fu and native techniques from China into a complete system of attack and defense known simply as ti (literally meaning "hand"). These martial arts varied slightly from town to town, and were named for their towns of origin, examples being Naha-te (currently known as Goju-Ryū), Tomari-te and Shuri-te. The Kabura-ya (Japanese signal arrow) still has a ceremonial use for house, village or festival celebration in Okinawa. [61] It is considered that the rhythms and patterns of dances, like Eisa and Angama, represent legends and prehistoric heritage.[61] Ryūka genre of songs and poetry originate from the Okinawa Islands. From the Chinese traditional instrument sanxian in the 16th century developed the Okinawan instrument sanshin from which the kankara sanshin and the Japanese shamisen derive.[160] Women frequently wore indigo tattoos known as hajichi on the backs of their hands, a sign of adulthood and talisman to protect them from evil. These tattoos were banned in 1899 by the Meiji government.[12] In remote districts their katakashira off-center topknot, similar to that of the Yami and some Filipino ethnic groups,[61] among men and women also disappeared in the early 20th century.[91] The bashôfu, literally meaning "banana-fibre cloth", is designated as a part of Ryukyu and Japan "important intangible cultural properties". The weaving using indigenous ramie was also widespread in the archipelago, both originated before the 14th century.[161] Originally living in thatching houses, townsmen developed architecture modeled after Japanese, Chinese and Korean structures. Other dwellings suggest a tropical origin, and some villages have high stone walls, with similar structural counterpart in Yami people at Orchid Island.[61] For the listed categories of Cultural Properties see; archaeological materials, historical materials, crafts, paintings, sculptures, writings, intangible, and tangible. |

文化 言語 主な記事 琉球語、沖縄文字、沖縄名 琉球語と日本語の類似性は、おそらくアジア大陸から列島への移民が共通の起源であることを示している[128]。以前[いつ?]は日本の学者[誰?]に よって日本の方言であり、古日本語の子孫であると観念的に考えられていたが[129][130]、トマス・ペラード(2015年)のような現代の言語学者 は現在、琉球語を古日本語時代(紀元8世紀頃)以前に分岐したジャポニック語の別個の亜科として分類している[129][130]。宮廷の言葉を記録した 初期の文献には沖縄方言に近い古語が見られるが、それ以降の日本語には琉球諸語よりも顕著な中国語化(日中語彙など)が見られる。これは、日本人(または 大和民族)が琉球諸語よりもおよそ千年も前に中国圏から文字を伝えたことに起因している[61]。 縄文-弥生遷移(前1000年頃)は遺伝学的見地から現代日本人の形成期にあたるため、倭人語は弥生系移民とも関係があると主張されている[132]。 [古い推定(1959年-2009年)では紀元前300年から紀元後700年の間、新しい推定(2009年-2011年)では紀元前2世紀から紀元後 100年の間であり、考古学や紀元前950年頃に弥生時代が始まったとする新しい年代学との相関がない[133]。 [134][135]言語的な相違から、両者は少なくとも7世紀以前、古墳時代(250年頃-538年頃)以前に分離し、本土の原琉球語は13世紀まで初 期中日本語と接触していた[136]。 琉球語は主に北琉球語と南琉球語の2つのグループに分けられる[137]。南琉球語亜科は北から南への拡大を示すが[要出典]、北琉球語はそうではなく、 これを説明するためにいくつかの仮説的なシナリオを提案することができる[138]。 [138]一般に、ジャポニックの祖国は九州であり、原琉球の原初的な拡大は九州であると考えられているが、別の仮説では琉球列島から日本本土への拡大が 提案されている[139][138][140]。 どの品種を方言または言語としてカウントするかについては著者の間で意見が分かれるが、1つの可能性のある分類では5つの琉球言語が存在すると考えられて いる: 奄美語、沖縄語、宮古語、八重山語、与那国語の5つであり、6つ目の国頭語はその多様性から沖縄語と区別されることもある。これらの言語の中には、地方都 市の方言や特定の島の方言があり、その多くは絶滅してしまった。沖縄語の首里方言は歴史的に琉球王国の威信をかけた言語であったが、公式に標準化された琉 球語は存在しない。したがって、琉球語は全体として、屋根のない標準語ともいえる方言の集まりを構成している[141]。 明治時代および明治以降、琉球語は日本語の方言とみなされ、否定的に見られていた。1907年からは子供たちが学校で琉球語を話すことが禁止され[21] [144]、1930年代半ばからは方言カード[145]という、標準語以外の言語で話す生徒に対する処罰制度が存在した[146][147]。 [琉球語を話すことは非国民的行為とみなされ、1939年までには琉球語を話す者は役所での勤務や雇用を拒否され、1945年の沖縄戦までには日本軍は琉 球語を話す者をスパイとみなして死刑に処するよう命令され、そのような行為が行われたという多くの報告がある。 [148]第二次世界大戦後、アメリカの占領下において、琉球の言語とアイデンティティは、琉球を日本から切り離すという映像政治的な理由もあって、明確 に推進された[149]。しかし、アメリカの占領に対する憤慨が琉球人の日本との友好と統一を強め、1972年以降、標準語の再侵入と琉球語のさらなる減 少が続いている[148][150]。 85歳以上の現代人は専ら琉球語を使用し、45歳から85歳までは家庭や職場環境によって琉球語と標準語を使用し、45歳未満は琉球語を理解することがで き、30歳未満は主に琉球語を理解することも話すこともできないと考えられている[151]。 日本語がほぼすべての文脈で日常語として琉球語に取って代わったため、琉球語を話すのは高齢者のみである。日本語の一種である沖縄日本語を話す若い人もい る。沖縄語の方言ではない。6つの琉球語は、今世紀半ば(2050年)までに消滅する可能性があるとして、2009年以降、ユネスコの「危機に瀕する世界 の言語アトラス」に掲載されている[152][7]。沖縄語普及協会によるいくつかの積極的な影響にもかかわらず、この認識が遅すぎたのかどうかは不明で ある[148]。 宗教 主な記事 琉球の宗教、琉球の祭りと行事 亀甲墓は伝統的な琉球の家族の墓である。 琉球先住民の宗教は、共同体における女性の役割を強く重視しており、女性はシャーマンや家庭と囲炉裏の守護者としての地位を占めている。伝統的な社会にお ける女性の地位は、中国や日本よりも高い。現代の親族制度は父系・父方制であるが、20世紀まではしばしば両系・母方制であり、村落内婚が一般的であった [153]。シーサー像は家の上や前によく見られるが、これは男性霊は外側の霊であり、女性霊は内側の霊であるという琉球古来の信仰に関連している。神性 は多くの属性で模倣され、根底にある象徴的な秩序はなく、安易である[154]。 20世紀まで、村の巫女であるノロは白い布と勾玉を使っていた。ノロの義務は、共同体の宝である囲炉裏の火を守ることであり、その結果、火の管理者につい ては、祖先との密接なコミュニケーションを維持するために処女でなければならないというタブー制度が生まれた。この役職は世襲制となり、通常はノロの弟の 女の子供がなる。礼拝の中心は、家の中や近くにある3つのハートストーンで表された[61]。妹の霊的優位に対する信仰は、南琉球でより顕著であった [155]。 仏教の伝来は13世紀の日本からの僧侶によるものとされ(主に葬儀[155])、14世紀の交易関係によって韓国仏教の影響(建築の一部を含む)や日本か らの神道の実践がもたらされた。 [仏教と土着の宗教は18世紀までイデオロギー的な基盤であったが、儒教が正応年間(1795年-1802年)に徐々に政府のイデオロギーとなり、粂村を 大いに失望させた[156]。 18世紀まで、琉球の王たちはセファウタキ(歴史的な聖地)の洞窟を参拝に訪れていた。日本人と琉球人の共通の起源を主張する最も古い説話は、17世紀に尚書軒によってでっち上げられたもので、琉球王と巫女長のクダカ島への巡礼を終わらせるためのものである[157]。 明治時代、政府は仏教を神道に置き換えて島の国教とし[158]、土着の神々を国家神道のパンテオンに組み入れるために彫像の再配置や神社や寺院の設計変 更を命じた。 [20]1920年代には、神社の建設と神道建築のシンボルを用いた以前の神社の改築が命じられ、地元の税金で賄われたが、1921年の砂糖価格の暴落に よって沖縄の経済は壊滅的な打撃を受け、財政的な負担となった[96]。 若い世代の琉球人のほとんどは、もはや土着の宗教を真剣に信仰していない。さらに、日本の支配下に置かれて以来、神道や仏教も実践されており、一般的に地元の信仰や習慣と混在している。 料理 主な記事 沖縄料理 沖縄料理はビタミンやミネラルが豊富で、タンパク質、脂質、炭水化物のバランスが良い。米が主食だが(タコライスは牛肉と混ぜる)、豚肉(ミミガー、チラ ガー、ラフテー、ソーキ)、海藻、濃厚な味噌、汁物(ジューシー)、サツマイモ、黒砂糖などが郷土料理の主役だ。観光客に最も有名なのはモモルディカ・ チャランティア(ゴーヤー)で、沖縄の代表的な炒め物であるチャンプルー(ゴーヤーチャンプルー)によく混ぜられている。コーレーグースーは、沖縄そばを 含む様々な料理に使われる一般的な辛いソース調味料である。特に消費される藻類には、カイランなどがある。伝統的なお菓子には、ちんすこう、ひらやーち、 サーターアンダギー、ムーチーなどがある。飲み物としては、柑橘類のデプレッサのジュース、ウコン茶(うこんちゃ)、アルコール飲料の泡盛などがある。 沖縄の減量ダイエットは、沖縄料理に由来しており、砂糖は日本人の平均的な食事摂取量の30%、穀物は15%しかない[159]。 芸術 主な記事 沖縄の武術、空手、琉球音楽、沖縄音楽 護身術や農具を武器にして武装した敵に対抗する技術(現在の武道家たちは空手と呼んでいる)は、琉球人によって創始されたものであり、彼らはおそらく、中 国から伝来した功夫や土着の技術を取り入れて、単に「手」と呼ばれる攻撃と防御の完全な体系を作り上げたのであろう。これらの武術は町によって微妙に異な り、那覇手(現在の剛柔流)、泊手、首里手など、発祥の町の名前が付けられていた。 鏑矢(かぶらや)は、沖縄では今でも家、村、祭りの祝儀に使われている。[61] エイサーやアンガマなどの踊りのリズムやパターンは、伝説や先史時代の遺産を表していると考えられている[61]。16世紀に中国の伝統楽器である三線から沖縄の楽器である三線が発展し、カンカラ三線と日本の三味線が派生した[160]。 女性は手の甲にハジチと呼ばれる藍色の入れ墨をよく入れていたが、これは成人の証であり、魔除けのお守りでもあった。これらの入れ墨は1899年に明治政 府によって禁止された[12]。僻地では、ヤミ族やフィリピンのいくつかの民族に類似した、男女の片頭の髷[61]も20世紀初頭に姿を消した[91]。 芭蕉布は文字通り「バナナ繊維の布」を意味し、琉球と日本の重要無形文化財に指定されている。土着の苧麻を使った織物も列島に広く普及しており、いずれも14世紀以前に起源を持つ[161]。 もともとは茅葺きの家に住んでいたが、町人たちは日本、中国、韓国の建築様式に倣った建築を発展させた。他の住居は熱帯の起源を示唆しており、いくつかの集落は高い石垣を持ち、オーキッド島のヤミ族と同様の構造を持っている[61]。 文化財の分類については、考古学的資料、歴史的資料、工芸品、絵画、彫刻、著作物、無形文化財、有形文化財を参照のこと。 |

| Notable Ryukyuans Martial arts Matsumura Sōkon Ankō Itosu Ankō Asato Kenwa Mabuni (Shitō-ryū) Gichin Funakoshi (Shotokan) Chōjun Miyagi (Gōjū-ryū) Chōki Motobu (Motobu-ryu) Tatsuo Shimabuku (Isshin-ryū) Kanbun Uechi (Uechi-ryū) Kentsū Yabu (teacher of Shōrin-ryū) Academics, journalism, and literature Sai On Shō Shōken Tei Junsoku Iha Fuyū Higashionna Kanjun Ōta Chōfu (journalist) Tatsuhiro Oshiro (novelist) Kushi Fusako (novelist) Music Namie Amuro Begin Beni Cocco Da Pump Gackt (singer-songwriter and actor) Chitose Hajime High and Mighty Color MAX Mongol800 Orange Range Speed Stereopony Visual arts Mao Ishikawa (photography)[162] Yuken Teruya Chikako Yamashiro (film) Entertainment Actress Yui Aragaki, notably for the television drama Nigeru wa Haji da ga Yaku ni Tatsu Rino Nakasone (choreographer) Actress Fumi Nikaido, notable for the FX/Disney+ miniseries Shōgun. Actress Manami Higa, notable for the movie My Teacher Sports Nagisa Arakaki (baseball) Hideki Irabu (baseball) Yukiya Arashiro (bicycle racer) Kazuki Ganaha (football) Yoko Gushiken (boxing) Akinobu Hiranaka (boxing) Katsuo Tokashiki (boxing) Daigo Higa (boxing) Ai Miyazato (golf) Ken Gushi (drifting) In Hawaii Yeiki Kobashigawa (U.S. World War II soldier and Medal of Honor recipient) Yoshi Oyakawa (Olympic gold medalist)[163] Ethel Azama (singer) David Ige (former Governor of Hawaii) Jake Shimabukuro (ukulele player) Ryan Higa (Youtuber)[164] Michael S. Nakamura (Nakandakari) (Former Honolulu Chief of Police)[165] Other parts of the United States Kishi Bashi (musician) Yuki Chikudate (singer) Tamlyn Tomita (actor) Brian Tee (actor) Natasha Allegri (storyboard artist) Dave Roberts (baseball player and coach) Maya Higa (YouTuber/conservationist) Throughout the world Takeshi Kaneshiro (actor in Taiwan) Sakura Miyawaki (singer in South Korea, member of the idol group Le Sserafim) Notable fictional characters Mr. Miyagi (played by Pat Morita) from the Karate Kid trilogy Mugen from the anime series Samurai Champloo Mutsumi Otohime from the manga series Love Hina Maxi from the Soulcalibur series of video games The heroines-leads protagonist Yuri Miyazono from the Witchblade: Ao no Shōjo novels Nanjo Takeshi, Arakaki Mari, and Ryuzuka, characters in the 1973 film Bodigaado Kiba: Hissatsu sankaku tobi |

Notable Ryukyuans Martial arts Matsumura Sōkon Ankō Itosu Ankō Asato Kenwa Mabuni (Shitō-ryū) Gichin Funakoshi (Shotokan) Chōjun Miyagi (Gōjū-ryū) Chōki Motobu (Motobu-ryu) Tatsuo Shimabuku (Isshin-ryū) Kanbun Uechi (Uechi-ryū) Kentsū Yabu (teacher of Shōrin-ryū) Academics, journalism, and literature Sai On Shō Shōken Tei Junsoku Iha Fuyū Higashionna Kanjun Ōta Chōfu (journalist) Tatsuhiro Oshiro (novelist) Kushi Fusako (novelist) Music Namie Amuro Begin Beni Cocco Da Pump Gackt (singer-songwriter and actor) Chitose Hajime High and Mighty Color MAX Mongol800 Orange Range Speed Stereopony Visual arts Mao Ishikawa (photography)[162] Yuken Teruya Chikako Yamashiro (film) Entertainment Actress Yui Aragaki, notably for the television drama Nigeru wa Haji da ga Yaku ni Tatsu Rino Nakasone (choreographer) Actress Fumi Nikaido, notable for the FX/Disney+ miniseries Shōgun. Actress Manami Higa, notable for the movie My Teacher Sports Nagisa Arakaki (baseball) Hideki Irabu (baseball) Yukiya Arashiro (bicycle racer) Kazuki Ganaha (football) Yoko Gushiken (boxing) Akinobu Hiranaka (boxing) Katsuo Tokashiki (boxing) Daigo Higa (boxing) Ai Miyazato (golf) Ken Gushi (drifting) In Hawaii Yeiki Kobashigawa (U.S. World War II soldier and Medal of Honor recipient) Yoshi Oyakawa (Olympic gold medalist)[163] Ethel Azama (singer) David Ige (former Governor of Hawaii) Jake Shimabukuro (ukulele player) Ryan Higa (Youtuber)[164] Michael S. Nakamura (Nakandakari) (Former Honolulu Chief of Police)[165] Other parts of the United States Kishi Bashi (musician) Yuki Chikudate (singer) Tamlyn Tomita (actor) Brian Tee (actor) Natasha Allegri (storyboard artist) Dave Roberts (baseball player and coach) Maya Higa (YouTuber/conservationist) Throughout the world Takeshi Kaneshiro (actor in Taiwan) Sakura Miyawaki (singer in South Korea, member of the idol group Le Sserafim) Notable fictional characters Mr. Miyagi (played by Pat Morita) from the Karate Kid trilogy Mugen from the anime series Samurai Champloo Mutsumi Otohime from the manga series Love Hina Maxi from the Soulcalibur series of video games The heroines-leads protagonist Yuri Miyazono from the Witchblade: Ao no Shōjo novels Nanjo Takeshi, Arakaki Mari, and Ryuzuka, characters in the 1973 film Bodigaado Kiba: Hissatsu sankaku tobi |

| History of the Ryukyu Islands Ryukyu independence movement Ryukyuan culture Ethnic issues in Japan Okinawa Prefecture Ryukyuan diaspora Okinawans in Hawaii Ryukyuans in Brazil Ryukyuan Americans |

琉球列島の歴史 琉球独立運動 琉球文化 日本の民族問題 沖縄県 琉球ディアスポラ ハワイの沖縄人 ブラジルの琉球人 琉球系アメリカ人 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ryukyuan_people |

|

| Sources Bentley, John R. (2015). "Proto-Ryukyuan". In Heinrich, Patrick; Miyara, Shinsho; Shimoji, Michinori (eds.). Handbook of the Ryukyuan Languages: History, Structure, and Use. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-1-61451-115-1. Caprio, Mark (2014). Japanese Assimilation Policies in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-99040-8. Christy, Alan S. (2004). "The making of imperial subjects in Okinawa". In Weiner, Michael (ed.). Race, Ethnicity and Migration in Modern Japan: Imagined and imaginary minorities. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-20857-4. Dubinsky, Stanley; Davies, William (2013). Steven Heine (ed.). "Language Conflict and Language Rights: The Ainu, Ryūkyūans, and Koreans in Japan". Japan Studies Review. 17. ISSN 1550-0713. Gluck, Carol (2008). "Thinking with the Past: History Writing in Modern Japan". In de Bary, William Theodore (ed.). Sources of East Asian Tradition: The modern Period. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231143233. Heinrich, Patrick; Miyara, Shinsho; Shimoji, Michinori (2015). "Introduction: Ryukyuan languages and Ryukyuan linguistics". In Heinrich, Patrick; Miyara, Shinsho; Shimoji, Michinori (eds.). Handbook of the Ryukyuan Languages: History, Structure, and Use. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-1-61451-115-1. Hendrickx, Katrien (2007). The Origins of Banana-fibre Cloth in the Ryukyus, Japan. Leuven University Press. ISBN 978-90-5867-614-6. Inoue, Masamichi S. (2017). Okinawa and the U.S. Military: Identity Making in the Age of Globalization. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-51114-8. Kerr, George H. (2000) [1954]. Okinawa:The History of an Island People. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4629-0184-5. Liddicoat, Anthony J. (2013). Language-in-education Policies: The Discursive Construction of Intercultural Relations. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 978-1-84769-916-9. Loo, Tze May (2014). Heritage Politics: Shuri Castle and Okinawa's Incorporation into Modern Japan, 1879–2000. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-8249-9. Nakasone, Ronald Y. (2002). Okinawan Diaspora. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2530-0. Obermiller, David John (2006). The United States Military Occupation of Okinawa: Politicizing and Contesting Okinawan Identity, 1945-1955. ISBN 978-0-542-79592-3. Pellard, Thomas (2015). "The linguistic archeology of the Ryukyu islands". In Heinrich, Patrick; Miyara, Shinsho; Shimoji, Michinori (eds.). Handbook of the Ryukyuan Languages: History, Structure, and Use. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-1-61451-115-1. Rabson, Steve (February 2008). "Okinawan Perspectives on Japan's Imperial Institution". The Asia-Pacific Journal. 6 (2). Retrieved 8 February 2017. Robbeets, Martine (2015). Diachrony of Verb Morphology: Japanese and the Transeurasian Languages. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-039994-3. Røkkum, Arne (2006). Nature, Ritual, and Society in Japan's Ryukyu Islands. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-25365-4. Serafim, Leon (2008). "The uses of Ryukyuan in understanding Japanese language history". In Frellesvig, Bjarke; Whitman, John (eds.). Proto-Japanese: Issues and Prospects. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-4809-1. Sered, Susan Starr (1996). Priestess, Mother, Sacred Sister: Religions Dominated by Women. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510467-7. Smits, Gregory (2004). "Epilogue and Conclusions to Visions of Ryukyu". In Michael Weiner (ed.). Race, Ethnicity and Migration in Modern Japan: Imagined and imaginary minorities. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-20857-4. |

出典 Bentley, John R. (2015). 「Proto-Ryukyuan」. In Heinrich, Patrick; Miyara, Shinsho; Shimoji, Michinori (eds.). Handbook of the Ryukyuan Languages: History, Structure, and Use. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-1-61451-115-1. カプリオ、マーク (2014). 植民地朝鮮における日本の同化政策、1910-1945. ワシントン大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-295-99040-8. クリスティ、アラン S. (2004). 「沖縄における帝国臣民の形成」. ワイナー、マイケル (編). 現代日本の民族、人種、移住:想像上のマイノリティと想像上のマイノリティ。テイラー&フランシス。ISBN 978-0-415-20857-4。 Dubinsky, Stanley; Davies, William (2013). Steven Heine (ed.). 「言語紛争と言語の権利:日本のアイヌ、琉球人、韓国人」。Japan Studies Review. 17. ISSN 1550-0713. Gluck, Carol (2008). 「過去とともに考える:現代日本の歴史記述」 In de Bary, William Theodore (ed.).東アジアの伝統の源流:近代期. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231143233. ハインリッヒ、パトリック;ミヤラ、シンショウ;シモジ、ミチノリ(2015)。「序論:琉球諸語と琉球言語学」。ハインリッヒ、パトリック;ミヤラ、シ ンショウ;シモジ、ミチノリ(編)。『琉球諸語ハンドブック:歴史、構造、および使用』。デ・グルイター。ISBN 978-1-61451-115-1。 ヘンドリックス、カトリーン(2007)。『琉球のバナナ繊維織物の起源』. ルヴェン大学出版局。ISBN 978-90-5867-614-6。 井上正道 (2017). 『沖縄と米軍:グローバル化時代のアイデンティティ形成』 コロンビア大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-231-51114-8。 カー、ジョージ H. (2000) [1954]. 『沖縄:島民の歴史』 タトル出版。ISBN 978-1-4629-0184-5。 リディコート、アンソニー J. (2013). 教育における言語政策:異文化関係の言説的構築。Multilingual Matters。ISBN 978-1-84769-916-9。 ルー、ツェ・メイ(2014)。『遺産政治:首里城と沖縄の近代日本への編入、1879-2000』。レクサントン・ブックス。ISBN 978-0-7391-8249-9。 ナカソネ、ロナルド・Y.(2002)。『沖縄のディアスポラ』。ハワイ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8248-2530-0。 オーバーミラー、デビッド・ジョン(2006)。『沖縄の米軍占領:沖縄のアイデンティティの政治化と争点、1945-1955』 ISBN 978-0-542-79592-3。 ペラール、トーマス(2015)。「琉球諸島の言語考古学」。パトリック・ハインリッヒ、新庄真、下地道徳(編)。『琉球諸語ハンドブック:歴史、構造、使用』。デ・グルイター。ISBN 978-1-61451-115-1。 スティーブ・ラブソン (2008年2月). 「日本の帝国制度に関する沖縄の視点」 『アジア・パシフィック・ジャーナル』 6 (2). 2017年2月8日取得。 ロベッツ、マルティーヌ (2015). 動詞形態の通時変化:日本語とトランスユーラシア言語. デ・グルイター. ISBN 978-3-11-039994-3。 ロッカム、アルネ (2006)。日本の琉球諸島における自然、儀礼、社会。ラウトレッジ。ISBN 978-1-134-25365-4。 セラフィム、レオン(2008)。「日本語の歴史を理解するための琉球語の利用」。フレレスヴィグ、ビャルケ、ホイットマン、ジョン(編)。『プロト日本語:問題と展望』。ジョン・ベンジャミンズ・パブリッシング。ISBN 978-90-272-4809-1。 セレッド, スーザン・スター (1996). 『巫女、母、聖なる姉妹: 女性が支配する宗教』. オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-19-510467-7. Smits, Gregory (2004). 「琉球のビジョンに関するエピローグと結論」 Michael Weiner (編). 現代日本の民族、人種、移民:想像上のマイノリティと想像上のマイノリティ. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-20857-4. |

| Further reading Arabia, Vol. 5, No. 54. February 1986/Jamad al-Awal 1406 "Japan-Malaysia Relations (Basic Data)". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 4 January 2024. "Number of residents from Japan living in Malaysia from 2014 to 2023". Statista. Statista Research Department. 16 February 2024. Abu Bakr Morimoto, Islam in Japan: Its Past, Present and Future, Islamic Centre Japan, 1980 Esenbel, Selcuk, A "fin-de-siecle" Japanese Romantic in Istanbul: The life of Yamada Torajirō and his "Turoko gakan"; Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), Vol. LIX, No. 2, 1996, pp. 237–252. JSTOR 619710 Esenbel, Selcuk; Japanese Interest in the Ottoman Empire; in: Edstrom, Bert; The Japanese and Europe: Images and Perceptions; Surrey 2000 Esenbel, Selcuk; Inaba Chiharū; The Rising Sun and the Turkish Crescent; İstanbul 2003, ISBN 978-975-518-196-7 Heinrich, Patrick; Bairon, Fija (3 November 2007). ""Wanne Uchinanchu – I am Okinawan." Japan, the US and Okinawa's Endangered Languages" (PDF). The Asia-Pacific Journal. 5 (11). 2586. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 August 2020. Hiroshi Kojima, "Demographic Analysis of Muslims in Japan," The 13th KAMES and 5th AFMA International Symposium, Pusan, 2004 Keiko Sakurai, Nihon no Musurimu Shakai (Japan's Muslim Society), Chikuma Shobo, 2003 Kreiner, J. (1996). Sources of Ryūkyūan history and culture in European collections. Monographien aus dem Deutschen Institut für Japanstudien der Philipp-Franz-von-Siebold-Stiftung, Bd. 13. München: Iudicium. ISBN 3-89129-493-X Ota, Masahide. (2000). Essays on Okinawa Problems. Yui Shuppan Co.: Gushikawa City, Okinawa, Japan. ISBN 4-946539-10-7 C0036. Ouwehand, C. (1985). Hateruma: socio-religious aspects of a South-Ryukyuan island culture. Leiden: E.J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-07710-3 Pacific Science Congress, and Allan H. Smith. (1964). Ryukyuan culture and society: a survey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. Penn, Michael, "Islam in Japan: Adversity and Diversity," Harvard Asia Quarterly, Vol. 10, No. 1, Winter 2006 Research and Analysis Branch (15 May 1943). "Japanese Infiltration Among the Muslims Throughout the World (R&A No. 890)" (PDF). Office of Strategic Services. U.S. Central Intelligence Agency Library. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2016. Sakiyama, R. (1995). Ryukyuan dance = Ryūkyū buyō. Naha City: Okinawa Dept. of Commerce, Industry & Labor, Tourism & Cultural Affairs Bureau. University of Hawaii at Manoa. Ethnic Studies Oral History Project (1981). Uchinanchu, a History of Okinawans in Hawaii. Leiden: Center for Oral History, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa and Hawai‘i United Okinawa Association. ISBN 9780824807498 Yamazato, Marie. (1995). Ryukyuan cuisine. Naha City, Okinawa Prefecture: Okinawa Tourism & Cultural Affairs Bureau Cultural Promotion Division. |