サムエル・ベケット

Samuel Barclay Beckett, 1906-1989

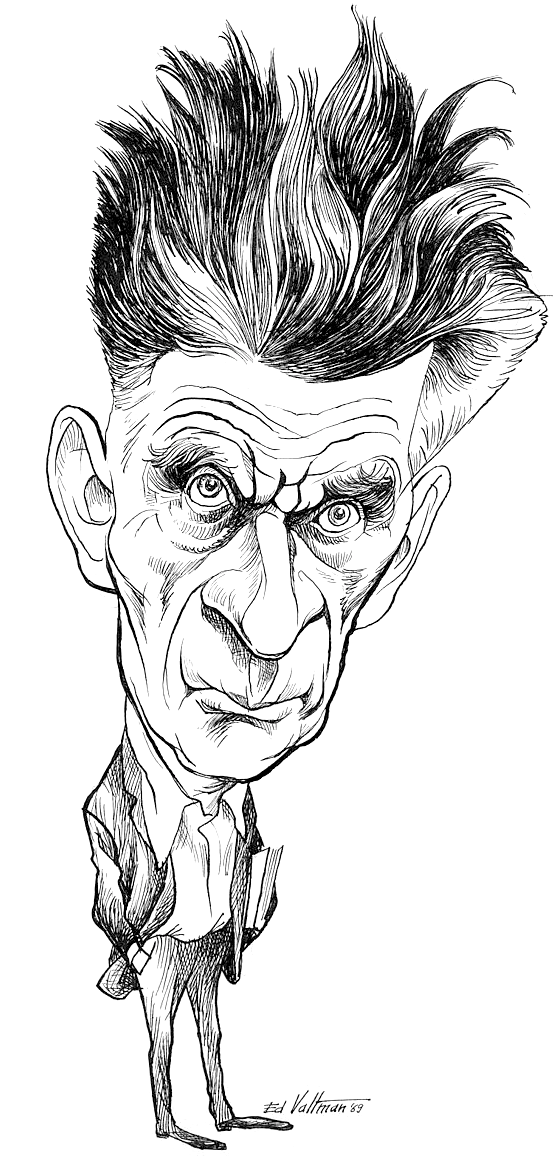

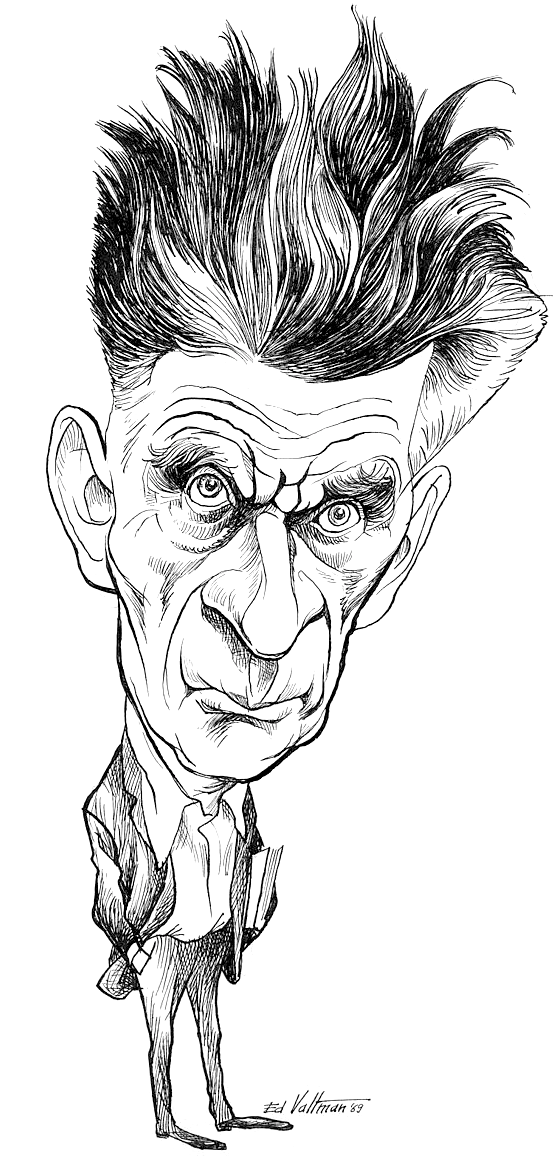

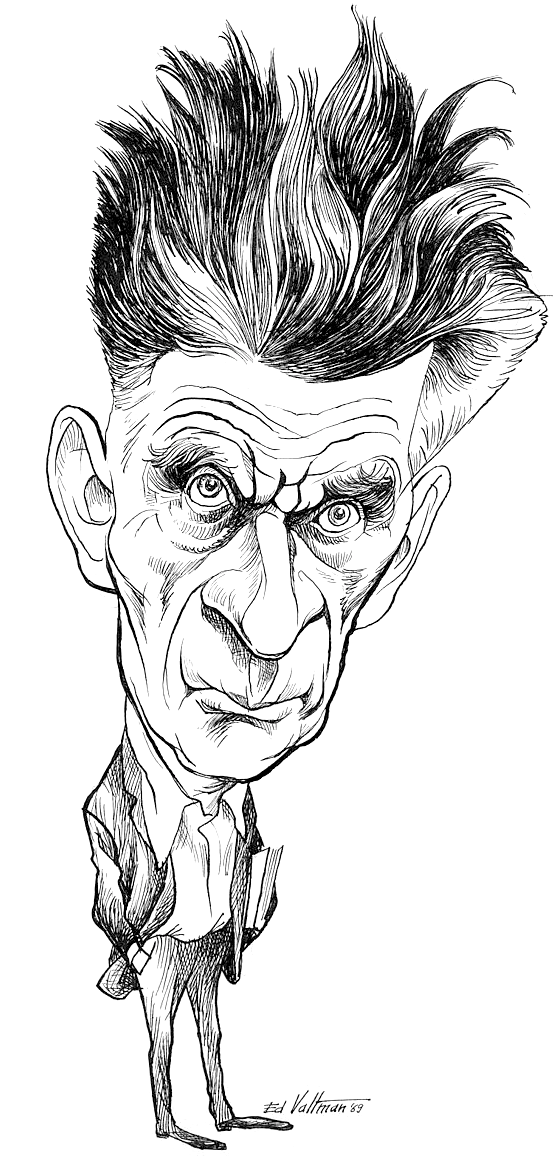

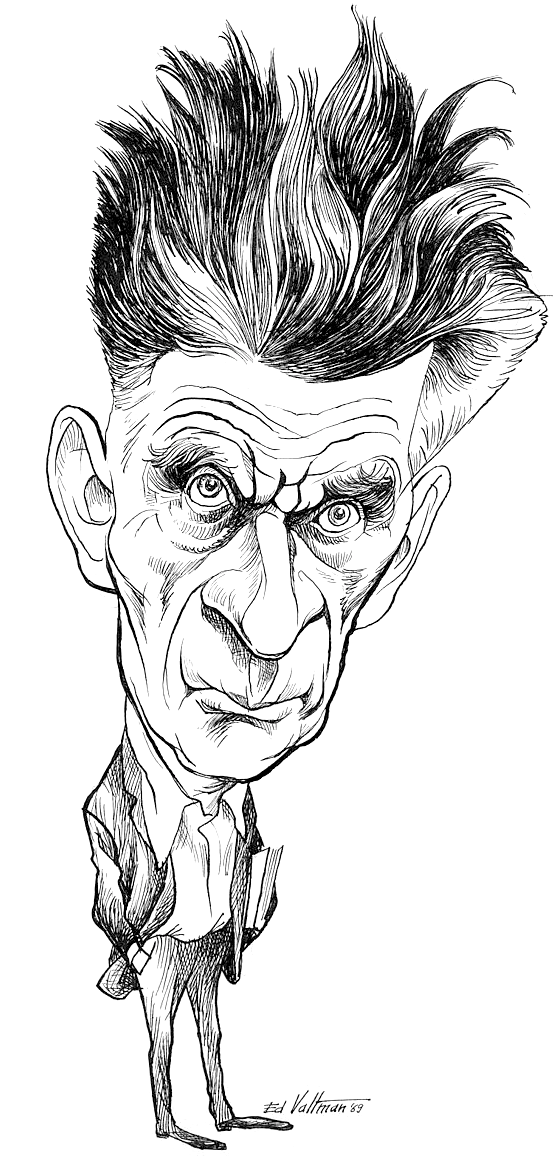

エドマンド・S・ヴァルトマンによるベケットの風刺画(1989)

☆ サミュエル・バークレー・ベケット(Samuel Barclay Beckett /ˈɚ / 1906年4月13日 - 1989年12月22日)は、アイルランドの小説家、劇作家、短編作家、演劇監督、詩人、文学翻訳家。荒涼とした、非人間的で悲喜劇的な人生経験を特徴と し、しばしばブラック・コメディやナンセンスと結びついている。彼の作品は、キャリアを重ねるにつれてミニマリズムが強まり、意識の流れの反復や自己言及 のテクニックを用いた、より美的で言語的な実験が行われるようになった。彼は最後のモダニズム作家の一人であり、マーティン・エスリンが「不条理演劇」と 呼んだ作品の重要人物の一人とみなされている。生涯の大半をパリで過ごし、フランス語と英語の両方で作品を書いた。第二次世界大戦中、ベケットはフランスのレジスタンス・グループ「グロリアSMH(Réseau Gloria)」のメンバーであり、1949年にはクロワ・ド・ゲールを授与された。

☆All of old. Nothing else ever. Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better. - Worstward Ho.

| Samuel Barclay Beckett

(/ˈbɛkɪt/; 13 April 1906 – 22 December 1989) was an Irish novelist,

dramatist, short story writer, theatre director, poet, and literary

translator. His literary and theatrical work features bleak, impersonal

and tragicomic experiences of life, often coupled with black comedy and

nonsense. His work became increasingly minimalist as his career

progressed, involving more aesthetic and linguistic experimentation,

with techniques of stream of consciousness repetition and

self-reference. He is considered one of the last modernist writers, and

one of the key figures in what Martin Esslin called the Theatre of the

Absurd.[1] A resident of Paris for most of his adult life, Beckett wrote in both French and English. During the Second World War, Beckett was a member of the French Resistance group Gloria SMH (Réseau Gloria) and was awarded the Croix de Guerre in 1949.[2] He was awarded the 1969 Nobel Prize in Literature "for his writing, which—in new forms for the novel and drama—in the destitution of modern man acquires its elevation".[3] In 1961 he shared the inaugural Prix International with Jorge Luis Borges. He was the first person to be elected Saoi of Aosdána in 1984. +++++++++++++++ The réseau Gloria SMH (Gloria network) was a French Resistance network under the German occupation of France during World War II. The Gloria network was founded by Gabrielle Picabia, alias "Gloria", who was running it with Jacques Legrand (chemical engineer). It counted among its members Alfred Péron, normalien and English professor at the Lycée Buffon. The network depended on the British Secret Intelligence Service, in conjunction with the SOE. The network's mission was to gather military and naval information about the occupiers. Its members were intellectuals, managers, and artists including an engraver who was very useful for producing false documents. The Gloria network was infiltrated by Father Robert Alesch and was decimated in August 1942. Most of the operatives, including Péron, were arrested by the Nazis. Samuel Beckett and his companion Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil, were warned by Péron's wife and escaped arrest, fleeing to their friend the writer Nathalie Sarraute in the free zone.[1] In total, more than 80 members of the network were deported and many never returned from Mauthausen or Buchenwald. The head of the network, Jacques Legrand, died in Mauthausen, and Péron died in Switzerland two days after his return from Mauthausen. |

サ

ミュエル・バークレー・ベケット(Samuel Barclay Beckett /ˈɚ / 1906年4月13日 -

1989年12月22日)は、アイルランドの小説家、劇作家、短編作家、演劇監督、詩人、文学翻訳家。荒涼とした、非人間的で悲喜劇的な人生経験を特徴と

し、しばしばブラック・コメディやナンセンスと結びついている。彼の作品は、キャリアを重ねるにつれてミニマリズムが強まり、意識の流れの反復や自己言及

のテクニックを用いた、より美的で言語的な実験が行われるようになった。彼は最後のモダニズム作家の一人であり、マーティン・エスリンが「不条理演劇」と

呼んだ作品の重要人物の一人とみなされている[1]。 生涯の大半をパリで過ごし、フランス語と英語の両方で作品を書いた。第二次世界大戦中、ベケットはフランスのレジスタンス・グループ「グロリアSMH(Réseau Gloria)」のメンバーであり、1949年にはクロワ・ド・ゲールを授与された[2]。1969年にノーベル文学賞を受賞。1984年、アオスダーナのサオイに初めて選出される。 +++++++++++++++ réseau Gloria SMH(グロリア・ネットワーク)は、第二次世界大戦中、ドイツ占領下のフランスのレジスタンス・ネットワークである。 グロリア・ネットワークはガブリエル・ピカビア、通称「グロリア」によって設立され、ジャック・ルグラン(化学技師)と共に運営していた。そのメンバーには、アルフレッド・ペロン(リ セ・ビュフォンのノーマリアン兼英語教授)も含まれていた。このネットワークは、SOEと連携した英国秘密情報部に依存していた。このネットワークの任務 は、占領軍に関する軍事・海軍情報を収集することだった。メンバーは知識人、経営者、芸術家で、偽の書類を作るのに非常に役立った彫刻家もいた。 グロリア・ネットワークはロベルト・アレッシュ神父によって潜入され、1942年8月に壊滅させられた。ペロンを含むほとんどの工作員はナチスに逮捕され た。サミュエル・ベケットと彼の仲間のシュザンヌ・ドゥシュヴォー=デュムスニルは、ペロンの妻から警告を受け、逮捕を免れ、自由地帯にいた友人の作家ナ タリー・サラオートのもとに逃げ込んだ[1]。合計で80人以上のネットワーク・メンバーが強制送還され、その多くがマウトハウゼンやブッヘンヴァルトか ら帰らぬ人となった。ネットワーク代表のジャック・ルグランはマウトハウゼンで死亡し、ペロンはマウトハウゼンから戻った2日後にスイスで死亡した。 |

| Early life Samuel Barclay Beckett was born in the Dublin suburb of Foxrock on 13 April 1906, the son of William Frank Beckett (1871–1933), a quantity surveyor of Huguenot descent, and Maria Jones Roe, a nurse. His parents were both 35 when he was born,[4] and had married in 1901. Beckett had one older brother named Frank Edward (1902–1954). At the age of five, he attended a local playschool in Dublin, where he started to learn music, and then moved to Earlsfort House School near Harcourt Street in Dublin. The Becketts were members of the Church of Ireland; raised as an Anglican, Beckett later became agnostic, a perspective which informed his writing. Beckett's residence at Trinity College Dublin, pictured in 2021 Beckett's family home, Cooldrinagh, was a large house and garden complete with tennis court built in 1903 by Beckett's father. The house and garden, its surrounding countryside where he often went walking with his father, the nearby Leopardstown Racecourse, the Foxrock railway station, and Harcourt Street station would all feature in his prose and plays. Around 1919 or 1920, he went to Portora Royal School in Enniskillen, which Oscar Wilde had also attended. He left in 1923 and entered Trinity College Dublin, where he studied modern literature and Romance languages, and received his bachelor's degree in 1927. A natural athlete, he excelled at cricket as a left-handed batsman and a left-arm medium-pace bowler. Later, he played for Dublin University and played two first-class games against Northamptonshire.[5] As a result, he became the only Nobel literature laureate to have played first-class cricket.[6] According to Michael Dirda, Beckett is "the only Nobel laureate in Wisden's, the bible of cricket history."[7] |

生い立ち サミュエル・バークレー・ベケットは1906年4月13日、ダブリン郊外のフォックスロックで、ユグノー系の測量技師ウィリアム・フランク・ベケット (1871-1933)と看護師のマリア・ジョーンズ・ローの息子として生まれた。ベケットが生まれたとき、両親はともに35歳で、1901年に結婚して いた[4]。ベケットにはフランク・エドワード(1902-1954)という兄がいた。5歳のとき、ダブリンの地元のプレイスクールに通い、そこで音楽を 習い始め、その後、ダブリンのハーコート・ストリート近くのアールズフォート・ハウス・スクールに移る。ベケット一家はアイルランド国教会の信者であった が、後に不可知論者となり、この考え方が彼の執筆活動に影響を与えた。 トリニティ・カレッジ・ダブリンのベケットの住居(2021年撮影 ベケットの実家クールドリナーは、1903年にベケットの父親が建てたテニスコート付きの大きな家と庭だった。この家と庭、父とよく散歩に出かけた周辺の 田園風景、近くのレパーズタウン競馬場、フォックスロック駅、ハーコート・ストリート駅などは、すべて彼の散文や戯曲に登場する。 1919年か1920年頃、オスカー・ワイルドも通ったエニスキレンのポートラ王立学校に入学。1923年に退学し、トリニティ・カレッジ・ダブリンに入 学、現代文学とロマンス言語を学び、1927年に学士号を取得した。天性のスポーツマンであった彼は、左利きのバッツマン、左腕のミディアム・ペース・ ボーラーとしてクリケットに秀でた。その後、ダブリン大学でプレーし、ノーサンプトンシャーとのファーストクラスの試合に2度出場しました[5]。その結 果、彼はファーストクラスのクリケットでプレーした唯一のノーベル文学賞受賞者となりました[6]。 マイケル・ディルダによると、ベケットは「クリケット史のバイブルであるウィズデンの中で唯一のノーベル賞受賞者」です[7]。 |

| Beckett

studied French, Italian, and English at Trinity College Dublin from

1923 to 1927 (one of his tutors - not a teaching role in TCD - was the

Berkeley scholar A. A. Luce, who introduced him to the work of Henri

Bergson[8]). He was elected a Scholar in Modern Languages in 1926.

Beckett graduated with a BA and, after teaching briefly at Campbell

College in Belfast, took up the post of lecteur d'anglais at the École

Normale Supérieure in Paris from November 1928 to 1930.[9] While there,

he was introduced to renowned Irish author James Joyce by Thomas

MacGreevy, a poet and close confidant of Beckett who also worked there.

This meeting had a profound effect on the young man. Beckett assisted

Joyce in various ways, one of which was research towards the book that

became Finnegans Wake.[10] In 1929, Beckett published his first work, a critical essay titled "Dante... Bruno. Vico.. Joyce". The essay defends Joyce's work and method, chiefly from allegations of wanton obscurity and dimness, and was Beckett's contribution to Our Exagmination Round His Factification for Incamination of Work in Progress (a book of essays on Joyce which also included contributions by Eugene Jolas, Robert McAlmon, and William Carlos Williams). Beckett's close relationship with Joyce and his family cooled, however, when he rejected the advances of Joyce's daughter Lucia. Beckett's first short story, "Assumption", was published in Jolas's periodical transition. The next year he won a small literary prize for his hastily composed poem "Whoroscope", which draws on a biography of René Descartes that Beckett happened to be reading when he was encouraged to submit. In 1930, Beckett returned to Trinity College as a lecturer. In November 1930, he presented a paper in French to the Modern Languages Society of Trinity on the Toulouse poet Jean du Chas, founder of a movement called le Concentrisme. It was a literary parody, for Beckett had in fact invented the poet and his movement that claimed to be "at odds with all that is clear and distinct in Descartes". Beckett later insisted that he had not intended to fool his audience.[11] When Beckett resigned from Trinity at the end of 1931, his brief academic career was at an end. He commemorated it with the poem "Gnome", which was inspired by his reading of Johann Wolfgang Goethe's Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship and eventually published in The Dublin Magazine in 1934: Spend the years of learning squandering Courage for the years of wandering Through a world politely turning From the loutishness of learning[12] Beckett travelled throughout Europe. He spent some time in London, where in 1931 he published Proust, his critical study of French author Marcel Proust. Two years later, following his father's death, he began two years' treatment with Tavistock Clinic psychoanalyst Dr. Wilfred Bion. Aspects of it became evident in Beckett's later works, such as Watt and Waiting for Godot.[13] In 1932, he wrote his first novel, Dream of Fair to Middling Women, but after many rejections from publishers decided to abandon it (it was eventually published in 1992). Despite his inability to get it published, however, the novel served as a source for many of Beckett's early poems, as well as for his first full-length book, the 1933 short-story collection More Pricks Than Kicks. Beckett published essays and reviews, including "Recent Irish Poetry" (in The Bookman, August 1934) and "Humanistic Quietism", a review of his friend Thomas MacGreevy's Poems (in The Dublin Magazine, July–September 1934). They focused on the work of MacGreevy, Brian Coffey, Denis Devlin and Blanaid Salkeld, despite their slender achievements at the time, comparing them favourably with their Celtic Revival contemporaries and invoking Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, and the French symbolists as their precursors. In describing these poets as forming "the nucleus of a living poetic in Ireland", Beckett was tracing the outlines of an Irish poetic modernist canon.[14] In 1935—the year that he successfully published a book of his poetry, Echo's Bones and Other Precipitates—Beckett worked on his novel Murphy. In May, he wrote to MacGreevy that he had been reading about film and wished to go to Moscow to study with Sergei Eisenstein at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography. In mid-1936 he wrote to Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin to offer himself as their apprentice. Nothing came of this, however, as Beckett's letter was lost owing to Eisenstein's quarantine during the smallpox outbreak, as well as his focus on a script re-write of his postponed film production. In 1936, a friend had suggested he look up the works of Arnold Geulincx, which Beckett did and he took many notes. The philosopher's name is mentioned in Murphy and the reading apparently left a strong impression.[15] Murphy was finished in 1936 and Beckett departed for extensive travel around Germany, during which time he filled several notebooks with lists of noteworthy artwork that he had seen and noted his distaste for the Nazi savagery that was overtaking the country.[citation needed] Returning to Ireland briefly in 1937, he oversaw the publication of Murphy (1938), which he translated into French the following year. He fell out with his mother, which contributed to his decision to settle permanently in Paris. Beckett remained in Paris following the outbreak of World War II in 1939, preferring, in his own words, "France at war to Ireland at peace".[16] His was soon a known face in and around Left Bank cafés, where he strengthened his allegiance with Joyce and forged new ones with artists Alberto Giacometti and Marcel Duchamp, with whom he regularly played chess. Sometime around December 1937, Beckett had a brief affair with Peggy Guggenheim, who nicknamed him "Oblomov" (after the character in Ivan Goncharov's novel).[17] In January 1938 in Paris, Beckett was stabbed in the chest and nearly killed when he refused the solicitations of a notorious pimp (who went by the name of Prudent). Joyce arranged a private room for Beckett at the hospital. The publicity surrounding the stabbing attracted the attention of Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil, who knew Beckett slightly from his first stay in Paris. This time, however, the two would begin a lifelong companionship. At a preliminary hearing, Beckett asked his attacker for the motive behind the stabbing. Prudent replied: "Je ne sais pas, Monsieur. Je m'excuse" ["I do not know, sir. I'm sorry"].[18] Beckett eventually dropped the charges against his attacker—partially to avoid further formalities, partly because he found Prudent likeable and well-mannered. |

ベ

ケットは1923年から1927年までトリニティ・カレッジ・ダブリンでフランス語、イタリア語、英語を学んだ(彼のチューターの一人で、TCDでは教職

に就いていなかったが、バークレーの学者A.A.ルースで、彼にアンリ・ベルクソン[8]の仕事を紹介した)。彼は1926年に現代言語学の奨学生に選ば

れた。学士号を取得したベケットは、ベルファストのキャンベル・カレッジで短期間教鞭をとった後、1928年11月から1930年までパリの高等師範学校

で英文学の講師を務めた[9]。この出会いは青年に大きな影響を与えた。ベケットは様々な形でジョイスを援助し、そのうちのひとつが『フィネガンズ・ウェ

イク』となる本の研究であった[10]。 1929年、ベケットは処女作となる批評エッセイ『ダンテ.... ブルーノ ヴィーコ。ジョイス"。このエッセイは、ジョイスの作品と方法を、主に無闇な晦渋さと薄明かりの疑惑から擁護するもので、ベケットが『進行中の作品の検査 のための彼の事実化のラウンド』(ジョイスに関するエッセイ集で、ユージン・ジョラス、ロバート・マカルモン、ウィリアム・カルロス・ウィリアムズの寄稿 も含まれている)に寄稿したものである。しかし、ジョイスとその家族との親密な関係は、ジョイスの娘ルシアの誘いを断ったことで冷え込んだ。ベケットの最 初の短編「仮定」はジョラスの定期刊行物『transition』に掲載された。この詩は、ベケットが投稿を勧められたときにたまたま読んでいたルネ・デ カルトの伝記を引用したものである。 1930年、ベケットは講師としてトリニティ・カレッジに戻った。1930年11月、彼はトリニティの現代語学会で、ル・コンセントリスムと呼ばれる運動 の創始者であるトゥールーズの詩人ジャン・デュ・シャについてフランス語で論文を発表した。それは文学的なパロディであり、ベケットは実際にこの詩人と、 「デカルトにおける明確で明確なものすべてと対立する」と主張する彼の運動を創作したのだった。1931年末にベケットがトリニティを辞職したとき、彼の 短い学究生活は終わりを告げた。この詩は、ヨハン・ヴォルフガング・ゲーテの『ヴィルヘルム・マイスターの徒弟時代』を読んだことに着想を得て書かれたも ので、1934年に『ダブリン・マガジン』に掲載された: 学問の年月を浪費して 放浪の年月のための勇気 丁重に回心する世界を通して 学問の怠惰から[12]。 ベケットはヨーロッパ中を旅した。1931年には、フランスの作家マルセル・プルーストについての評論『プルースト』を出版した。その2年後、父の死後、 タヴィストック・クリニックの精神分析医ウィルフレッド・ビオン博士のもとで2年間の治療を開始。1932年、彼は処女作『中途半端な女たちの夢』を書い たが、出版社から何度も断られたため、断念することにした(最終的には1992年に出版された)。しかし、出版には至らなかったものの、この小説はベケッ トの初期の詩の多くや、1933年に発表した初の短編集『More Pricks Than Kicks』の原作となった。 ベケットは、「最近のアイルランド詩」(『ブックマン』1934年8月号所収)、友人トーマス・マクグリーヴィの詩の批評「人間主義的静寂主義」(『ダブ リン・マガジン』1934年7~9月号所収)などのエッセイや評論を発表。彼らは、マクグリーヴィ、ブライアン・コフィー、デニス・デヴリン、ブラナイ ド・サルケルドの作品に注目し、当時はその業績がわずかであったにもかかわらず、ケルト復興期の同時代の詩人たちと好意的に比較し、エズラ・パウンド、 T.S.エリオット、フランスの象徴主義者たちを彼らの先駆者として引き合いに出した。これらの詩人たちが「アイルランドにおける生きた詩の核」を形成し ていると表現することで、ベケットはアイルランドの詩的モダニズムの規範の輪郭をなぞっていた[14]。 1935年、詩集『エコーの骨とその他の沈殿物』の出版に成功した年、ベケットは小説『マーフィー』の執筆に取りかかる。5月にはマクグリーヴィーに、映 画についての本を読み、モスクワに行ってジェラシモフ映画大学でセルゲイ・エイゼンシュテインに師事したいと手紙を書いた。1936年半ば、彼はエイゼン シュテインとヴシェヴォロド・プドフキンに弟子入りを申し出る手紙を書いた。しかし、この手紙は、エイゼンシュテインが天然痘の流行で隔離されていたこと と、延期されていた映画製作の脚本の書き直しに専念していたために紛失してしまった。1936年、友人からアーノルド・ゲーリンクスの著作を調べるように 勧められ、ベケットはそれを実行し、多くのメモを取った。1936年に『マーフィー』は完成し、ベケットはドイツ各地を旅行するために旅立った。その間に 見た注目すべき芸術作品のリストでノートを埋め尽くし、ドイツを覆っていたナチスの蛮行に対する嫌悪感を記した。1937年に一時的にアイルランドに戻 り、『マーフィー』(1938年)の出版を監督。1939年に第二次世界大戦が勃発した後もベケットはパリに留まり、彼自身の言葉を借りれば「平和なアイ ルランドよりも戦争中のフランス」を好んだ[16]。彼はすぐに左岸のカフェやその周辺で知られるようになり、ジョイスとの忠誠を強め、芸術家のアルベル ト・ジャコメッティやマルセル・デュシャンとは新しい関係を築き、彼らとは定期的にチェスをした。1937年12月頃、ベケットはペギー・グッゲンハイム と短期間関係を持ち、グッゲンハイムはベケットを「オブロモフ」(イワン・ゴンチャロフの小説の登場人物にちなんで)とあだ名した[17]。 1938年1月、ベケットはパリで、悪名高いポン引き(プルーデントという名で通っていた)の勧誘を断った際に胸を刺され、危うく殺されるところだった。 ジョイスはベケットのために病院の個室を用意した。この刺殺事件が世間に知れ渡ったことで、ベケットが初めてパリに滞在したときから少し面識のあったシュ ザンヌ・デュシュヴォー=デュムスニルの目に留まることになる。しかしこの時、2人は生涯の交際を始めることになる。予備審問で、ベケットは犯人に刺した 動機を尋ねた。プルデントはこう答えた: 「わかりません、ムッシュー。ベケットは最終的に加害者の告訴を取り下げたが、その理由のひとつは、これ以上の手続きを避けるためであり、また、プルーデ ントを好感が持て、礼儀正しい人物だと感じたからであった[18]。 |

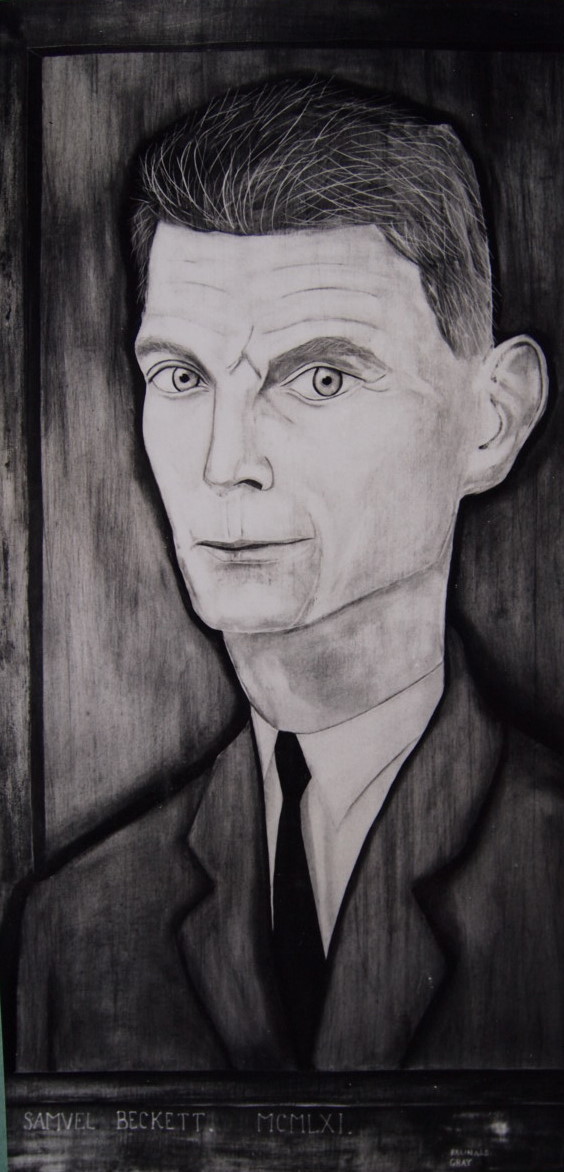

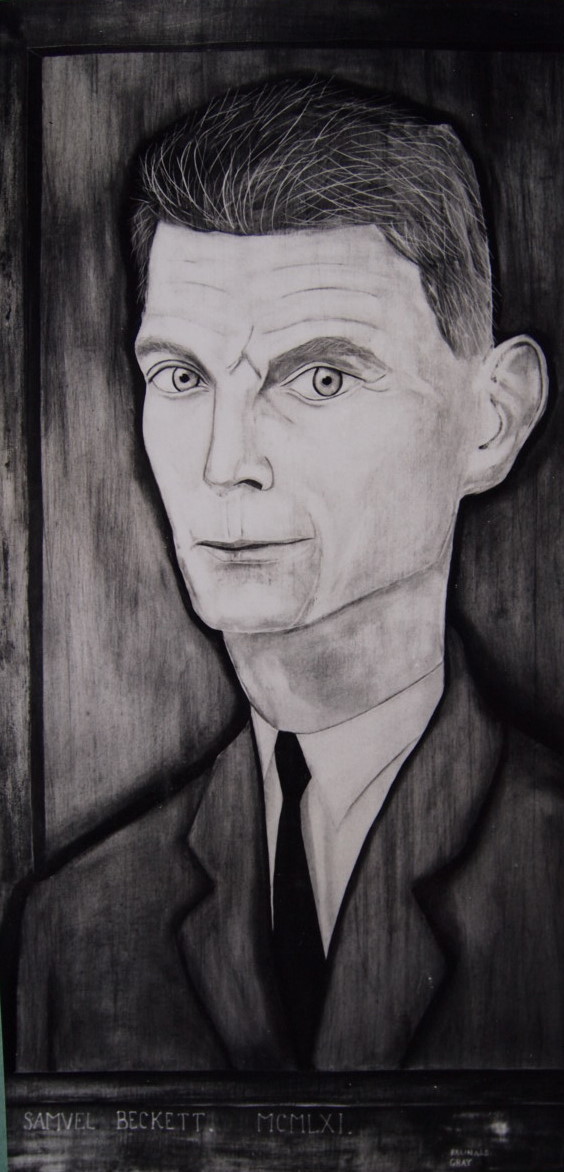

| World War II and French Resistance After the Nazi German occupation of France in 1940, Beckett joined the French Resistance, in which he worked as a courier.[19] On several occasions over the next two years he was nearly caught by the Gestapo. In August 1942, his unit was betrayed and he and Suzanne fled south on foot to the safety of the small village of Roussillon, in the Vaucluse département in Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur.[20] During the two years that Beckett stayed in Roussillon he indirectly helped the Maquis sabotage the German army in the Vaucluse mountains, though he rarely spoke about his wartime work in later life.[21] He was awarded the Croix de guerre and the Médaille de la Résistance by the French government for his efforts in fighting the German occupation; to the end of his life, however, Beckett would refer to his work with the French Resistance as "boy scout stuff".[22][23] While in hiding in Roussillon, Beckett continued work on the novel Watt. He started the novel in 1941 and completed it in 1945, but it was not published until 1953; however, an extract had appeared in the Dublin literary periodical Envoy. After the war, he returned to France in 1946 where he worked as a stores manager[24] at the Irish Red Cross Hospital based in Saint-Lô. Beckett described his experiences in an untransmitted radio script, "The Capital of the Ruins".[25] Fame: novels and the theatre  Portrait of Samuel Beckett by Reginald Gray, painted in Paris, 1961 (from the collection of Ken White, Dublin) In 1945, Beckett returned to Dublin for a brief visit. During his stay, he had a revelation in his mother's room: his entire future direction in literature appeared to him. Beckett had felt that he would remain forever in the shadow of Joyce, certain to never beat him at his own game. His revelation prompted him to change direction and to acknowledge both his own stupidity and his interest in ignorance and impotence: "I realised that Joyce had gone as far as one could in the direction of knowing more, [being] in control of one's material. He was always adding to it; you only have to look at his proofs to see that. I realised that my own way was in impoverishment, in lack of knowledge and in taking away, in subtracting rather than in adding."[26] Knowlson argues that "Beckett was rejecting the Joycean principle that knowing more was a way of creatively understanding the world and controlling it ... In future, his work would focus on poverty, failure, exile and loss – as he put it, on man as a 'non-knower' and as a 'non-can-er.'"[27] The revelation "has rightly been regarded as a pivotal moment in his entire career". Beckett fictionalised the experience in his play Krapp's Last Tape (1958). While listening to a tape he made earlier in his life, Krapp hears his younger self say "clear to me at last that the dark I have always struggled to keep under is in reality my most...", at which point Krapp fast-forwards the tape (before the audience can hear the complete revelation). Beckett later explained to Knowlson that the missing words on the tape are "precious ally".[27] In 1946, Jean-Paul Sartre's magazine Les Temps modernes published the first part of Beckett's short story "Suite" (later to be called "La Fin", or "The End"), not realising that Beckett had only submitted the first half of the story; Simone de Beauvoir refused to publish the second part. Beckett also began to write his fourth novel, Mercier et Camier, which was not published until 1970. The novel presaged his most famous work, the play Waiting for Godot, which was written not long afterwards. More importantly, the novel was Beckett's first long work that he wrote in French, the language of most of his subsequent works which were strongly supported by Jérôme Lindon, director of his Parisian publishing house Les Éditions de Minuit, including the poioumenon "trilogy" of novels: Molloy (1951); Malone meurt (1951), Malone Dies (1958); L'innommable (1953), The Unnamable (1960). Despite being a native English speaker, Beckett wrote in French because—as he himself claimed—it was easier for him thus to write "without style".[28] Portrait, circa 1970 Beckett is most famous for his play En attendant Godot (Waiting for Godot; 1953). Like most of his works after 1947, the play was first written in French. Beckett worked on the play between October 1948 and January 1949.[29] His partner, Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil, was integral to its success. Dechevaux-Dumesnil became his agent and sent the manuscript to multiple producers until they met Roger Blin, the soon-to-be director of the play.[30] Blin's knowledge of French theatre and vision alongside Beckett knowing what he wanted the play to represent contributed greatly to its success. In a much-quoted article, the critic Vivian Mercier wrote that Beckett "has achieved a theoretical impossibility—a play in which nothing happens, that yet keeps audiences glued to their seats. What's more, since the second act is a subtly different reprise of the first, he has written a play in which nothing happens, twice."[31] The play was published in 1952 and premièred in 1953 in Paris; an English translation was performed two years later. The play was a critical, popular, and controversial success in Paris. It opened in London in 1955 to mainly negative reviews, but the tide turned with positive reactions from Harold Hobson in The Sunday Times and, later, Kenneth Tynan. After the showing in Miami, the play became extremely popular, with highly successful performances in the US and Germany. The play is a favourite: it is not only performed frequently but has globally inspired playwrights to emulate it.[32] This is the sole play the manuscript of which Beckett never sold, donated or gave away.[32] He refused to allow the play to be translated into film but did allow it to be played on television.[33] During this time in the 1950s, Beckett became one of several adults who sometimes drove local children to school; one such child was André Roussimoff, who would later become a famous professional wrestler under the name André the Giant.[34] They had a surprising amount of common ground and bonded over their love of cricket, with Roussimoff later recalling that the two rarely talked about anything else.[35] Beckett translated all of his works into English himself, with the exception of Molloy, for which he collaborated with Patrick Bowles. The success of Waiting for Godot opened up a career in theatre for its author. Beckett went on to write successful full-length plays, including Fin de partie (Endgame) (1957), Krapp's Last Tape (1958, written in English), Happy Days (1961, also written in English), and Play (1963). In 1961, Beckett received the International Publishers' Formentor Prize in recognition of his work, which he shared that year with Jorge Luis Borges. |

第二次世界大戦とフランスのレジスタンス 1940年にナチス・ドイツがフランスを占領した後、ベケットはフランスのレジスタンスに参加し、運び屋として働いた。1942年8月、彼の部隊は裏切ら れ、彼とシュザンヌはプロヴァンス=アルプ=コート・ダジュールのヴォークリューズ県にある小さな村ルシヨンの安全な場所まで徒歩で南下した。 [21]彼はドイツ占領と戦った功績により、フランス政府からクロワ・ド・ゲールとメダイユ・ド・ラ・レジスタンスを授与されたが、ベケットは生涯を終え るまで、フランスのレジスタンスでの活動を「ボーイスカウトのようなもの」と呼んでいた[22][23]。 ルシヨンに潜伏中、ベケットは小説『ワット』の執筆を続けた。この小説は1941年に書き始め、1945年に完成したが、1953年まで出版されなかっ た。戦後、彼は1946年にフランスに戻り、サン=ローにあるアイルランド赤十字病院で店舗管理者として働いた[24]。ベケットは未放送のラジオ台本 『廃墟の都』でその体験を語っている[25]。 名声:小説と演劇  1961年、パリで描かれたレジナルド・グレイによるサミュエル・ベケットの肖像画(ダブリンのケン・ホワイト所蔵) 1945年、ベケットはダブリンに一時帰国。滞在中、彼は母親の部屋で天啓を受けた。文学における自分の将来の方向性のすべてが彼の前に現れたのだ。ベ ケットは、自分は永遠にジョイスの影に隠れ、自分のゲームではジョイスに勝てないだろうと感じていた。この啓示は彼に方向転換を促し、自分自身の愚かさと 無知と無力への関心の両方を認めさせた: 「私は、ジョイスがより多くを知り、自分の素材をコントロールするという方向へ、できる限り進んでいることに気づいた。彼の証明書を見ればわかる。私は自分自身のやり方が、貧しくすること、知識の欠如、奪うこと、加えることよりも引くことにあることに気づいた」[26]。 ノウルソンは、「ベケットは、より多くを知ることが世界を創造的に理解し、コントロールする方法であるというジョイセンの原則を否定していた。将来、彼の 作品は貧困、失敗、亡命、喪失に焦点を当てることになる。ベケットはこの体験を戯曲『クラップの最後のテープ』(1958年)でフィクション化した。ク ラップは、自分が以前に作ったテープを聴きながら、若き日の自分が「私がいつも必死に隠してきた暗闇が、実際には私の最も......」と言うのを聞く。 ベケットは後にノウルソンに、テープの欠落した言葉は「貴重な味方」だと説明している[27]。 1946年、ジャン=ポール・サルトルの雑誌『Les Temps modernes』はベケットの短編小説『組曲』(後に『La Fin』または『終わり』と呼ばれる)の前半部分を掲載したが、ベケットは前半部分しか提出していなかったことに気づかず、シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワール は後半部分の掲載を拒否した。シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールは後編の出版を拒否した。ベケットは4作目の小説『メルシエとカミエ』も書き始めたが、これは 1970年まで出版されなかった。この小説は、彼の最も有名な作品である戯曲『ゴドーを待ちながら』を予感させるものであった。さらに重要なのは、この小 説がベケットにとって初のフランス語による長編作品であったことである。このフランス語は、ベケットのパリの出版社レ・ゼディション・ドゥ・ミニュイの ディレクター、ジェローム・リンドンの強い支持を受け、ポワウメノン「三部作」を含む、その後の作品のほとんどに使用されている: Molloy』(1951年)、『Malone meurt』(1951年)、『Malone Dies』(1958年)、『L'innommable』(1953年)、『The Unnamable』(1960年)。英語を母国語とするにもかかわらず、ベケットがフランス語で執筆したのは、彼自身が主張するように、「スタイルがな い」方が書きやすかったからである[28]。 1970年頃の肖像画 ベケットが最も有名なのは戯曲『ゴドーを待ちながら』(En attendant Godot、1953年)である。1947年以降のほとんどの作品と同様、この戯曲も最初はフランス語で書かれた。ベケットがこの戯曲に取り組んだのは 1948年10月から1949年1月にかけてのことである[29]。Dechevaux-Dumesnilは彼のエージェントとなり、戯曲の演出家となる はずだったRoger Blinに出会うまで、複数のプロデューサーに原稿を送った[30]。 ブランのフランス演劇の知識と構想は、ベケットがこの戯曲に何を表現させたいかを知っていたことと並んで、この戯曲の成功に大きく貢献した。批評家のヴィ ヴィアン・メルシエは、引用された記事の中で、ベケットについて「理論的に不可能なことを成し遂げた-何も起こらない劇でありながら、観客を座席に釘付け にした」と書いている。さらに、第2幕は第1幕の微妙に異なる再演であるため、彼は何も起こらない戯曲を2度書いている」[31]。この戯曲は1952年 に出版され、1953年にパリで初演された。英訳版はその2年後に上演された。この戯曲はパリでは批評家、大衆に支持され、物議を醸す大成功を収めた。 1955年にロンドンで初演され、主に否定的な批評を受けたが、『サンデー・タイムズ』紙のハロルド・ホブソンや、後にケネス・タイナンが好意的な反応を 示し、流れが変わった。マイアミでの上演後、この戯曲は大人気となり、アメリカやドイツでも上演され大成功を収めた。この戯曲は人気があり、頻繁に上演さ れるだけでなく、世界的に脚本家たちが模倣するきっかけとなった[32]。 この戯曲は、ベケットが原稿を売却、寄付、譲渡しなかった唯一の戯曲である[32]。 1950年代のこの時期、ベケットは時々地元の子供たちを学校まで送る数人の大人のひとりとなった。そのような子供のひとりが、後にアンドレ・ザ・ジャイ アントの名で有名なプロレスラーとなるアンドレ・ルシモフだった[34]。ゴドーを待ちながら』の成功は、作者に演劇界でのキャリアを開いた。ベケットは その後、『Fin de partie(エンドゲーム)』(1957年)、『Krapp's Last Tape』(1958年、英語で執筆)、『Happy Days』(1961年、同じく英語で執筆)、『Play』(1963年)などの長編戯曲を執筆し、成功を収めた。1961年、ベケットはホルヘ・ルイ ス・ボルヘスとともに国際出版社フォルメントール賞を受賞。 |

| Later life and death Tomb of Samuel Beckett at the cimetière du Montparnasse The 1960s were a time of change for Beckett, both on a personal level and as a writer. In 1961, he married Suzanne in a secret civil ceremony in England (its secrecy due to reasons relating to French inheritance law). The success of his plays led to invitations to attend rehearsals and productions around the world, leading eventually to a new career as a theatre director. In 1957, he had his first commission from the BBC Third Programme for a radio play, All That Fall. He continued writing sporadically for radio and extended his scope to include cinema and television. He began to write in English again, although he also wrote in French until the end of his life. He bought some land in 1953 near a hamlet about 60 kilometres (40 mi) northeast of Paris and built a cottage for himself with the help of some locals. From the late 1950s until his death, Beckett had a relationship with Barbara Bray, a widow who worked as a script editor for the BBC. Knowlson wrote of them: "She was small and attractive, but, above all, keenly intelligent and well-read. Beckett seems to have been immediately attracted by her and she to him. Their encounter was highly significant for them both, for it represented the beginning of a relationship that was to last, in parallel with that with Suzanne, for the rest of his life."[36] Barbara Bray died in Edinburgh on 25 February 2010.  Caricature of Samuel Beckett by Javad Alizadeh In 1969 the avant-garde filmmaker Rosa von Praunheim shot an experimental short film portrait about Beckett, which he named after the writer.[37] In October 1969 while on holiday in Tunis with Suzanne, Beckett heard that he had won the 1969 Nobel Prize in Literature. Anticipating that her intensely private husband would be saddled with fame from that moment on, Suzanne called the award a "catastrophe".[38] While Beckett did not devote much time to interviews, he sometimes met the artists, scholars, and admirers who sought him out in the anonymous lobby of the Hotel PLM Saint-Jacques in Paris – where he gave his appointments and took frequently his lunches – near his Montparnasse home.[39] Although Beckett was an intensely private man, a review of the second volume of his letters by Roy Foster on 15 December 2011 issue of The New Republic reveals Beckett to be not only unexpectedly amiable but frequently prepared to talk about his work and the process behind it.[40] Suzanne died on 17 July 1989. Confined to a nursing home and suffering from emphysema and possibly Parkinson's disease, Beckett died a few months later, on 22 December. The two were interred together in the cimetière du Montparnasse in Paris and share a simple granite gravestone that follows Beckett's directive that it should be "any colour, so long as it's grey". |

その後の人生と死 モンパルナスのシメティエールにあるサミュエル・ベケットの墓 1960年代はベケットにとって、個人的にも作家としても変化の時期だった。1961年、彼はスザンヌと英国で秘密の市民結婚式を挙げた(フランスの相続 法に関する理由で秘密とされた)。戯曲の成功により、世界各地のリハーサルやプロダクションに招かれるようになり、やがて劇場の演出家として新たなキャリ アを築くことになる。1957年、BBCサード・プログラムからラジオ劇『オール・ザット・フォール』を初めて依頼される。その後もラジオのために散発的 に執筆を続け、映画やテレビにもその範囲を広げた。晩年までフランス語でも書いたが、再び英語で書くようになった。1953年、パリの北東約60キロ (40マイル)の集落の近くに土地を購入し、地元の人々の助けを借りてコテージを建てた。 1950年代後半から亡くなるまで、ベケットはBBCの脚本編集者として働いていた未亡人のバーバラ・ブレイと交際していた。ノウルソンは二人についてこ う書いている: 「彼女は小柄で魅力的だったが、何よりも聡明で読書家だった。ベケットはすぐに彼女に、彼女は彼に惹かれたようだ。二人の出会いは二人にとって非常に重要 なものであり、それはスザンヌとの関係と並行して、ベケットの生涯を貫く関係の始まりであった」[36] バーバラ・ブレイは2010年2月25日にエディンバラで死去。  サミュエル・ベケットの風刺画(Javad Alizadeh作) 1969年、前衛的な映画監督ローザ・フォン・プラウンハイムは、ベケットを題材にした実験的な短編映画を撮影し、ベケットにちなんで名づけた[37]。 1969年10月、スザンヌとチュニスで休暇を過ごしていたベケットは、彼が1969年のノーベル文学賞を受賞したことを知る。ベケットはインタビューに はあまり時間を割かなかったが、モンパルナスの自宅近くにあるパリのホテルPLMサン・ジャックの匿名ロビーで、彼を求める芸術家、学者、崇拝者たちと会 うことがあった。 [39] ベケットは極めて私的な人物であったが、『ニュー・リパブリック』誌2011年12月15日号に掲載されたロイ・フォスターによる書簡集第2巻の批評によ れば、ベケットは思いのほか好意的であっただけでなく、作品やその背後にあるプロセスについて頻繁に語る用意があったことが明らかにされている[40]。 スザンヌは1989年7月17日に死去。老人ホームに閉じこもり、肺気腫とおそらくパーキンソン病を患っていたベケットは、数ヵ月後の12月22日に亡く なった。2人はパリのモンパルナス墓地に一緒に埋葬され、ベケットの「灰色であればどんな色でもいい」という指示に従ったシンプルな花崗岩の墓石を共有し ている。 |

Works Caricature of Beckett by Edmund S. Valtman Beckett's career as a writer can be roughly divided into three periods: his early works, up until the end of World War II in 1945; his middle period, stretching from 1945 until the early 1960s, during which he wrote what are probably his best-known works; and his late period, from the early 1960s until Beckett's death in 1989, during which his works tended to become shorter and his style more minimalist. Early works Beckett's earliest works are generally considered to have been strongly influenced by the work of his friend James Joyce. They are erudite and seem to display the author's learning merely for its own sake, resulting in several obscure passages. The opening phrases of the short-story collection More Pricks than Kicks (1934) affords a representative sample of this style: It was morning and Belacqua was stuck in the first of the canti in the moon. He was so bogged that he could move neither backward nor forward. Blissful Beatrice was there, Dante also, and she explained the spots on the moon to him. She shewed him in the first place where he was at fault, then she put up her own explanation. She had it from God, therefore he could rely on its being accurate in every particular.[41] The passage makes reference to Dante's Commedia, which can serve to confuse readers not familiar with that work. It also anticipates aspects of Beckett's later work: the physical inactivity of the character Belacqua; the character's immersion in his own head and thoughts; the somewhat irreverent comedy of the final sentence. Similar elements are present in Beckett's first published novel, Murphy (1938), which also explores the themes of insanity and chess (both of which would be recurrent elements in Beckett's later works). The novel's opening sentence hints at the somewhat pessimistic undertones and black humour that animate many of Beckett's works: "The sun shone, having no alternative, on the nothing new".[42] Watt, written while Beckett was in hiding in Roussillon during World War II,[43] is similar in terms of themes but less exuberant in its style. It explores human movement as if it were a mathematical permutation, presaging Beckett's later preoccupation—in both his novels and dramatic works—with precise movement. Beckett's 1930 essay Proust was strongly influenced by Schopenhauer's pessimism and laudatory descriptions of saintly asceticism. At this time Beckett began to write creatively in the French language. In the late 1930s, he wrote a number of short poems in that language and their sparseness—in contrast to the density of his English poems of roughly the same period, collected in Echo's Bones and Other Precipitates (1935)—seems to show that Beckett, albeit through the medium of another language, was in process of simplifying his style, a change also evidenced in Watt. Middle period who may tell the tale of the old man? weigh absence in a scale? mete want with a span? the sum assess of the world's woes? nothingness in words enclose? From Watt (1953)[44] After World War II, Beckett turned definitively to the French language as a vehicle. It was this, together with the "revelation" experienced in his mother's room in Dublin—in which he realised that his art must be subjective and drawn wholly from his own inner world—that would result in the works for which Beckett is best remembered today. During the 15 years following the war, Beckett produced four major full-length stage plays: En attendant Godot (written 1948–1949; Waiting for Godot), Fin de partie (1955–1957; Endgame), Krapp's Last Tape (1958), and Happy Days (1961). These plays—which are often considered, rightly or wrongly, to have been instrumental in the so-called "Theatre of the Absurd"—deal in a darkly humorous way with themes similar to those of the roughly contemporary existentialist thinkers. The term "Theatre of the Absurd" was coined by Martin Esslin in a book of the same name; Beckett and Godot were centrepieces of the book. Esslin argued these plays were the fulfilment of Albert Camus's concept of "the absurd";[45] this is one reason Beckett is often falsely labelled as an existentialist (this is based on the assumption that Camus was an existentialist, though he in fact broke off from the existentialist movement and founded his own philosophy). Though many of the themes are similar, Beckett had little affinity for existentialism as a whole.[46] Broadly speaking, the plays deal with the subject of despair and the will to survive in spite of that despair, in the face of an uncomprehending and incomprehensible world. The words of Nell—one of the two characters in Endgame who are trapped in ashbins, from which they occasionally peek their heads to speak—can best summarise the themes of the plays of Beckett's middle period: "Nothing is funnier than unhappiness, I grant you that. ... Yes, yes, it's the most comical thing in the world. And we laugh, we laugh, with a will, in the beginning. But it's always the same thing. Yes, it's like the funny story we have heard too often, we still find it funny, but we don't laugh any more."[47] Beckett's Waiting for Godot is considered a hallmark of the Theatre of the Absurd. The play's two protagonists, Vladimir and Estragon (pictured, in a 2010 production at The Doon School, India), give voice to Beckett's existentialism. Beckett's outstanding achievements in prose during the period were the three novels Molloy (1951), Malone meurt (1951; Malone Dies) and L'innommable (1953: The Unnamable). In these novels—sometimes referred to as a "trilogy", though this is against the author's own explicit wishes—the prose becomes increasingly bare and stripped down.[48] Molloy, for instance, still retains many of the characteristics of a conventional novel (time, place, movement, and plot) and it makes use of the structure of a detective novel. In Malone Dies, movement and plot are largely dispensed with, though there is still some indication of place and the passage of time; the "action" of the book takes the form of an interior monologue. Finally, in The Unnamable, almost all sense of place and time are abolished, and the essential theme seems to be the conflict between the voice's drive to continue speaking so as to continue existing, and its almost equally strong urge towards silence and oblivion. Despite the widely held view that Beckett's work, as exemplified by the novels of this period, is essentially pessimistic, the will to live seems to win out in the end; witness, for instance, the famous final phrase of The Unnamable: "you must go on, I can't go on, I'll go on".[49] After these three novels, Beckett struggled for many years to produce a sustained work of prose, a struggle evidenced by the brief "stories" later collected as Texts for Nothing. In the late 1950s, however, he created one of his most radical prose works, Comment c'est (1961; How It Is). An early variant version of Comment c'est, L'Image, was published in the British arts review, X: A Quarterly Review (1959), and is the first appearance of the novel in any form.[50] This work relates the adventures of an unnamed narrator crawling through the mud while dragging a sack of canned food. It was written as a sequence of unpunctuated paragraphs in a style approaching telegraphese: "You are there somewhere alive somewhere vast stretch of time then it's over you are there no more alive no more than again you are there again alive again it wasn't over an error you begin again all over more or less in the same place or in another as when another image above in the light you come to in hospital in the dark"[51] Following this work, it was almost another decade before Beckett produced a work of non-dramatic prose. How It Is is generally considered to mark the end of his middle period as a writer. Late works time she stopped sitting at her window quiet at her window only window facing other windows other only windows all eyes all sides high and low time she stopped From Rockaby (1980) Throughout the 1960s and into the 1970s, Beckett's works exhibited an increasing tendency—already evident in much of his work of the 1950s—towards compactness. This has led to his work sometimes being described as minimalist. The extreme example of this, among his dramatic works, is the 1969 piece Breath, which lasts for only 35 seconds and has no characters (though it was likely intended to offer ironic comment on Oh! Calcutta!, the theatrical revue for which it served as an introductory piece).[52] Portrait by Reginald Gray In his theatre of the late period, Beckett's characters—already few in number in the earlier plays—are whittled down to essential elements. The ironically titled Play (1962), for instance, consists of three characters immersed up to their necks in large funeral urns. The television drama Eh Joe (1963), which was written for the actor Jack MacGowran, is animated by a camera that steadily closes in to a tight focus upon the face of the title character. The play Not I (1972) consists almost solely of, in Beckett's words, "a moving mouth with the rest of the stage in darkness".[53] Following from Krapp's Last Tape, many of these later plays explore memory, often in the form of a forced recollection of haunting past events in a moment of stillness in the present. They also deal with the theme of the self-confined and observed, with a voice that either comes from outside into the protagonist's head (as in Eh Joe) or else another character comments on the protagonist silently, by means of gesture (as in Not I). Beckett's most politically charged play, Catastrophe (1982), which was dedicated to Václav Havel, deals relatively explicitly with the idea of dictatorship. After a long period of inactivity, Beckett's poetry experienced a revival during this period in the ultra-terse French poems of mirlitonnades, with some as short as six words long. These defied Beckett's usual scrupulous concern to translate his work from its original into the other of his two languages; several writers, including Derek Mahon, have attempted translations, but no complete version of the sequence has been published in English. Beckett's prose pieces during the late period were not so prolific as his theatre, as suggested by the title of the 1976 collection of short prose texts Fizzles (which the American artist Jasper Johns illustrated). Beckett experienced something of a renaissance with the novella Company (1980), which continued with Ill Seen Ill Said (1982) and Worstward Ho (1983), later collected in Nohow On. In these three "'closed space' stories,"[54] Beckett continued his pre-occupation with memory and its effect on the confined and observed self, as well as with the positioning of bodies in space, as the opening phrases of Company make clear: "A voice comes to one in the dark. Imagine." "To one on his back in the dark. This he can tell by the pressure on his hind parts and by how the dark changes when he shuts his eyes and again when he opens them again. Only a small part of what is said can be verified. As for example when he hears, You are on your back in the dark. Then he must acknowledge the truth of what is said."[55] Themes of aloneness and the doomed desire to successfully connect with other human beings are expressed in several late pieces, including Company and Rockaby. In the hospital and nursing home where he spent his final days, Beckett wrote his last work, the 1988 poem "What is the Word" ("Comment dire"). The poem grapples with an inability to find words to express oneself, a theme echoing Beckett's earlier work, though possibly amplified by the sickness he experienced late in life. |

作品紹介 エドマンド・S・ヴァルトマンによるベケットの風刺画 ベケットの作家としてのキャリアは、1945年の第二次世界大戦終結までの初期作品、1945年から1960年代初頭までの中期作品、その間におそらく彼 の最もよく知られた作品を書いた時期、そして1960年代初頭から1989年にベケットが亡くなるまでの後期作品の3つの時期に大別できる。 初期の作品 ベケットの初期の作品は、一般的に友人であるジェイムズ・ジョイスの作品に強く影響を受けていると考えられている。それらは博学で、作者の学識を単にそれ 自身のために誇示しているように見え、その結果、不明瞭な箇所がいくつかある。短編集『More Pricks than Kicks』(1934年)の冒頭のフレーズは、このスタイルの代表的なサンプルである: その日は朝で、ベラクアは月の中の最初のカンテで立ち往生していた。朝になって、ベラクアは月の最初のカンテにはまり込んでしまった。至福のベアトリー チェがそこにいて、ダンテもいて、彼女は彼に月の斑点を説明した。彼女はまず、ダンテがどこを間違えているかを示し、それから自分なりの説明をした。彼女 はそれを神から得たので、彼はその説明があらゆる点で正確であると信じることができた[41]。 この一節はダンテの『コメディア』に言及しており、その作品に馴染みのない読者を混乱させる。ベラクアという人物の身体的な不活発さ、自分の頭と思考に没頭する人物、最後の文のやや不遜な喜劇性などである。 同様の要素は、ベケットが初めて発表した小説『マーフィー』(1938年)にもあり、狂気とチェスというテーマを探求している(どちらもベケットの後の作 品に繰り返し登場する要素である)。この小説の冒頭の一文は、ベケットの多くの作品を動かしている、やや悲観的なニュアンスとブラックユーモアを示唆して いる: 第二次世界大戦中、ベケットがルシヨンに潜伏していたときに書かれた『ワット』[43]は、テーマという点では似ているが、作風はそれほど豪快ではない。 この作品は、人間の動きを数学の順列のように探求しており、後にベケットが小説と演劇作品の両方で、正確な動きに夢中になることを予感させる。 ベケットの1930年のエッセイ『プルースト』は、ショーペンハウアーのペシミズムと、聖人のような禁欲主義を称賛する記述に強い影響を受けている。この 頃、ベケットはフランス語で創造的な文章を書くようになった。1930年代後半、彼はフランス語で多くの短編を書いたが、その疎密さは、『エコーの骨』 (Echo's Bones and Other Precipitates、1935年)に収められたほぼ同時期の英語詩の密度と対照的であり、ベケットが他言語を媒介にしながらも、文体を単純化する過 程にあったことを示しているように思われる。 中期 誰が老人の 老人のことを? 秤で不在を量るか? 秤で欠乏を量るか? 世界の苦難の 世界の苦悩の 無 言葉で囲む? ワット』(1953年)より[44]。 第二次世界大戦後、ベケットはフランス語という言語に決定的に傾倒する。ダブリンの母の部屋で経験した「啓示」とともに、自分の芸術は主観的なものでなければならず、完全に自分の内面から引き出されたものでなければならないと悟ったのである。 戦争後の15年間、ベケットは4つの主要な長編舞台劇を発表した: En attendant Godot』(1948~1949年、『ゴドーを待ちながら』)、『Fin de partie』(1955~1957年、『エンドゲーム』)、『クラップの最後のテープ』(1958年)、『幸せな日々』(1961年)である。これらの 戯曲は、善し悪しは別として、いわゆる「不条理演劇」の一翼を担ったと見なされることが多く、ほぼ同時代の実存主義思想家のテーマと似たものを、暗くユー モラスな方法で扱っている。不条理演劇」という言葉は、マーティン・エスリン(Martin Esslin)が同名の本の中で使った造語で、ベケットとゴドーがその本の中心である。エスリンは、これらの戯曲はアルベール・カミュの「不条理」の概念 の成就であると主張した[45]。これが、ベケットがしばしば実存主義者であるという誤ったレッテルを貼られる理由のひとつである(これはカミュが実存主 義者であったという仮定に基づいているが、実際には彼は実存主義運動から離脱し、独自の哲学を確立した)。テーマの多くは似ているが、ベケットは全体とし て実存主義とはあまり親和性がなかった[46]。 大まかに言えば、戯曲は絶望と、理解できない不可解な世界を前にして、絶望にもかかわらず生き延びようとする意志という主題を扱っている。エンドゲーム』 に登場する灰箱に閉じ込められた二人の登場人物のうちの一人、ネルが時折頭をのぞかせて語る言葉は、ベケット中期の戯曲のテーマを最もよく要約している: 「不幸ほど面白いものはない。... 不幸ほど滑稽なものはない。そして私たちは笑う。でも、それはいつも同じことなんだ。そう、それは私たちがあまりにも頻繁に聞いた面白い話のようなもの で、私たちはまだそれを面白いと感じるが、私たちはもう笑わない」[47]。 ベケットの『ゴドーを待ちながら』は、不条理劇の特徴であると考えられている。この戯曲の2人の主人公、ウラジーミルとエストラゴン(写真は2010年にインドのドゥーン・スクールで上演されたもの)は、ベケットの実存主義を代弁している。 この時期のベケットの散文における傑出した業績は、『Molloy』(1951年)、『Malone meurt』(1951年、マローンは死ぬ)、『L'innommable』(1953年、名状しがたいもの)の3作である。たとえば『モロイ』では、従 来の小説の特徴(時間、場所、移動、プロット)の多くがまだ残っており、探偵小説の構造が生かされている。マローンは死ぬ』では、移動と筋書きはほとんど 省かれているが、場所と時間の経過はまだいくらか示されている。最後に、『Unnamable』では、場所と時間の感覚はほとんど廃され、本質的なテーマ は、存在し続けるために話し続けようとする声の衝動と、沈黙と忘却に向かう声の衝動との間の葛藤であるように思われる。この時期の小説に代表されるよう に、ベケットの作品は本質的に悲観的であるという見方が広まっているにもかかわらず、最終的には生きる意志が勝っているように見える: 例えば、『名づけられざる者』の有名な最後のフレーズである「あなたは進まなければならない、私は進めない、私は進む」[49]。 これらの3つの小説の後、ベケットは散文の持続的な作品を生み出すのに何年も苦闘し、それは後に『無のためのテクスト』として収集される短い「物語」に よって証明される。しかし、1950年代後半、彼は最も過激な散文作品のひとつ『Comment c'est』(1961年、『How It Is』)を創作した。Comment c'est』の初期の変形版『L'Image』は、イギリスの芸術批評誌『X: この作品は、缶詰の袋を引きずりながら泥の中を這う無名の語り手の冒険を描いている。句読点のない段落の連続として、テレグラフに近い文体で書かれてい る: 「この作品に続いて、ベケットが非劇的な散文の作品を発表するのは、ほぼ10年後のことである。How It Is』は一般的に、作家としての彼の中期の終わりを意味すると考えられている。 晩年の作品 彼女が立ち止まった時 窓辺に座る 窓辺の静けさ 唯一の窓 他の窓と向き合う 他の窓だけ すべての目 八方 高低 彼女が立ち止まった時間 ロッカビー』(1980)より 1960年代から1970年代にかけて、ベケットの作品は、1950年代の作品の多くですでに顕著であったように、ますますコンパクトになる傾向を示して いる。そのため、彼の作品はミニマリストと形容されることもある。その極端な例が、彼の劇作品の中でも、1969年の作品『Breath』であり、この作 品はわずか35秒しかなく、登場人物もいない(しかし、この作品は、この作品が導入作品として使用された演劇レヴュー『オー!カルカッタ!』に対する皮肉 なコメントを提供することを意図していたと思われる)[52]。 レジナルド・グレイによる肖像画 後期の演劇では、ベケットの登場人物は、初期の戯曲ではすでに少数であったが、本質的な要素に絞り込まれている。例えば、皮肉なタイトルの『戯曲』 (1962年)は、3人の登場人物が大きな葬儀用の骨壷に首まで浸かっている。俳優ジャック・マクゴウランのために書かれたテレビドラマ『Eh Joe』(1963年)は、タイトル・キャラクターの顔にピントを合わせながら、どんどん近づいてくるカメラによってアニメーション化されている。Not I』(1972年)は、ベケットの言葉を借りれば、ほとんど「動く口と暗闇の舞台」だけで構成されている。また、主人公の頭の中に外から入ってくる声 (『Eh Joe』のように)、あるいは別の登場人物が身振り手振りを使って主人公に無言でコメントする(『Not I』のように)ことで、自己に閉じこもり、観察されるというテーマも扱っている。ヴァーツラフ・ハヴェルに捧げられたベケットの最も政治色の強い戯曲『カ タストロフィ』(1982年)は、独裁のアイデアを比較的明確に扱っている。長らく活動を休止していたベケットの詩は、この時期、超短編のフランス語詩 『mirlitonnades』で復活を遂げた。デレク・マホンをはじめとする何人かの作家が翻訳を試みているが、一連の詩の完全版が英語で出版されたこ とはない。 1976年に出版された散文短編集『Fizzles』(アメリカの画家ジャスパー・ジョーンズが挿絵を担当)のタイトルが示唆するように、後期のベケット の散文作品は演劇ほど多作ではなかった。ベケットは小説『Company』(1980年)でルネッサンスのようなものを経験し、『Ill Seen Ill Said』(1982年)、『Worstward Ho』(1983年)と続いた。これら3つの「閉ざされた空間」[54]の物語において、ベケットは記憶とそれが閉じこもり観察される自己に及ぼす影響、 また『カンパニー』の冒頭のフレーズで明らかなように、空間における身体の位置づけに対する彼の先入観を続けていた。想像してみてください。「暗闇の中で 仰向けになる。このことは、後頭部にかかる圧力や、目を閉じたときと再び開いたときの暗闇の変化でわかる。言われたことのごく一部しか確認できない。例え ば、「あなたは暗闇の中で仰向けになっている。そのとき、彼は言われたことの真実を認めなければならない」[55]。孤独と、他の人間とうまくつながりた いという運命的な願望というテーマは、『カンパニー』や『ロッカビー』など、晩年のいくつかの作品で表現されている。 晩年を過ごした病院と老人ホームで、ベケットは最後の作品である1988年の詩「言葉とは何か」("Comment dire")を書いた。この詩は、自分を表現する言葉が見つからないという、ベケットの初期の作品と呼応するテーマを扱っているが、おそらく晩年に経験し た病気によって増幅されたのだろう。 |

| Collaborators Jack MacGowran Jack MacGowran was the first actor to do a one-man show based on the works of Beckett. He debuted End of Day in Dublin in 1962, revising it as Beginning To End (1965). The show went through further revisions before Beckett directed it in Paris in 1970; MacGowran won the 1970–1971 Obie for Best Performance By an Actor when he performed the show off-Broadway as Jack MacGowran in the Works of Samuel Beckett. Beckett wrote the radio play Embers and the teleplay Eh Joe specifically for MacGowran. The actor also appeared in various productions of Waiting for Godot and Endgame, and did several readings of Beckett's plays and poems on BBC Radio; he also recorded the LP, MacGowran Speaking Beckett for Claddagh Records in 1966.[56][57] Billie Whitelaw Billie Whitelaw worked with Beckett for 25 years on such plays as Not I, Eh Joe, Footfalls and Rockaby. She first met Beckett in 1963. In her autobiography Billie Whitelaw... Who He?, she describes their first meeting in 1963 as "trust at first sight". Beckett went on to write many of his experimental theatre works for her. She came to be regarded as his muse, the "supreme interpreter of his work", perhaps most famous for her role as the mouth in Not I. She said of the play Rockaby: "I put the tape in my head. And I sort of look in a particular way, but not at the audience. Sometimes as a director Beckett comes out with absolute gems and I use them a lot in other areas. We were doing Happy Days and I just did not know where in the theatre to look during this particular section. And I asked, and he thought for a bit and then said, 'Inward' ".[58][59][60] She said of her role in Footfalls: "I felt like a moving, musical Edvard Munch painting and, in fact, when Beckett was directing Footfalls he was not only using me to play the notes but I almost felt that he did have the paintbrush out and was painting."[61] "Sam knew that I would turn myself inside out to give him what he wanted", she explained. "With all of Sam's work, the scream was there, my task was to try to get it out." She stopped performing his plays in 1989 when he died.[62] Jocelyn Herbert The English stage designer Jocelyn Herbert was a close friend and influence on Beckett until his death. She worked with him on such plays as Happy Days (their third project) and Krapp's Last Tape at the Royal Court Theatre. Beckett said that Herbert became his closest friend in England: "She has a great feeling for the work and is very sensitive and doesn't want to bang the nail on the head. Generally speaking, there is a tendency on the part of designers to overstate, and this has never been the case with Jocelyn."[63] Walter Asmus The German director Walter D. Asmus began his working relationship with Beckett in the Schiller Theatre in Berlin in 1974 and continued until 1989, the year of the playwright's death.[64] Asmus has directed all of Beckett's plays internationally. |

協力者 ジャック・マクガウラン ジャック・マクガウランは、ベケットの作品に基づく一人芝居を行った最初の俳優である。彼は1962年にダブリンで『エンド・オブ・デイ』を初演し、『ビ ギニング・トゥ・エンド』(1965年)として改作した。ベケットが1970年にパリで演出するまで、このショーはさらなる改訂を重ねられた。マクガウラ ンは、このショーを『ジャック・マクガウラン・イン・ザ・ワークス・オブ・サミュエル・ベケット』としてオフ・ブロードウェイで上演し、 1970~1971年度のオビー賞最優秀男優賞を受賞した。ベケットはマクガウランのためにラジオ劇『Embers』とテレビ劇『Eh Joe』を書いた。また、『ゴドーを待ちながら』や『エンドゲーム』の様々な作品に出演し、BBCラジオでベケットの戯曲や詩を朗読した。 ビリー・ホワイトロー ビリー・ホワイトローは『Not I, Eh Joe』、『Footfalls』、『Rockaby』などの戯曲で25年間ベケットと仕事をした。彼女がベケットに初めて会ったのは1963年。自伝 『Billie Whitelaw... Who He? Who He? "の中で、彼女は1963年の最初の出会いを「一目惚れの信頼」と表現している。ベケットはその後、実験的な演劇作品の多くを彼女のために書いた。彼女は 彼のミューズ、「彼の作品の最高の解釈者」とみなされるようになり、おそらく『Not I』の口役が最も有名だろう: 「テープを頭の中に入れるの。そして、観客のほうを見るのではなく、ある特定の見方をする。演出家としてベケットが絶対的な珠玉の作品を発表することがあ る。ハッピー・デイズ』をやっていたとき、私は劇場のどこを見ればいいのかわからなかった。と尋ねると、彼は少し考えてから、『内側だ』と言った」 [58][59][60] 彼女は『フットフォールズ』での役についてこう語っている: 実際、ベケットが『フットフォールズ』を演出しているとき、彼は私を音符を弾くために使っていただけでなく、絵筆を出して絵を描いているように感じたわ」 [61]「サムは、彼が望むものを与えるために、私が自分を裏返すことを知っていた」と彼女は説明した。「サムの作品にはすべて叫びがあり、私の仕事はそ れを引き出すことでした」。彼が亡くなった1989年、彼女は彼の戯曲の上演をやめた[62]。 ジョセリン・ハーバート イギリスの舞台美術家ジョセリン・ハーバートは、ベケットが亡くなるまで親しい友人であり、影響を受けた。彼女はロイヤル・コート劇場で『ハッピー・デイ ズ』(2人の3作目のプロジェクト)や『クラップの最後のテープ』などの戯曲で彼と仕事をした。ベケットは、ハーバートがイギリスで最も親しい友人になっ たと語っている: 「彼女は作品に対する素晴らしい感覚を持ち、とても繊細で、釘を打つようなことはしない。一般的に言って、デザイナーの側には誇張しすぎる傾向があるが、 ジョセリンにはそれがなかった」[63]。 ウォルター・アスムス ドイツの演出家ヴァルター・D・アスムスは、1974年にベルリンのシラー劇場でベケットとの仕事を始め、劇作家が亡くなる1989年まで仕事を続けた[64]。 |

| Legacy Samuel Beckett depicted on an Irish commemorative coin celebrating the 100th anniversary of his birth Of all the English-language modernists, Beckett's work represents the most sustained attack on the realist tradition. He opened up the possibility of theatre and fiction that dispense with conventional plot and the unities of time and place to focus on essential components of the human condition. Václav Havel, John Banville, Aidan Higgins, Tom Stoppard, Harold Pinter and Jon Fosse have publicly stated their indebtedness to Beckett's example. He has had a wider influence on experimental writing since the 1950s, from the Beat generation to the happenings of the 1960s and after.[65] In an Irish context, he has exerted great influence on poets such as Derek Mahon and Thomas Kinsella, as well as writers like Trevor Joyce and Catherine Walsh who proclaim their adherence to the modernist tradition as an alternative to the dominant realist mainstream. The Samuel Beckett Bridge, Dublin Many major 20th-century composers including Luciano Berio, György Kurtág, Morton Feldman, Pascal Dusapin, Philip Glass, Roman Haubenstock-Ramati and Heinz Holliger have created musical works based on Beckett's texts. His work has also influenced numerous international writers, artists and filmmakers including Edward Albee, Avigdor Arikha, Paul Auster, J. M. Coetzee,[66] Richard Kalich, Douglas Gordon, Bruce Nauman, Anthony Minghella,[67] Damian Pettigrew,[68] Charlie Kaufman[69] and Brian Patrick Butler.[70][71] Beckett is one of the most widely discussed and highly prized of 20th-century authors, inspiring a critical industry to rival that which has sprung up around James Joyce. He has divided critical opinion. Some early philosophical critics, such as Sartre and Theodor Adorno, praised him, one for his revelation of absurdity, the other for his works' critical refusal of simplicities; others such as Georg Lukács condemned him for 'decadent' lack of realism.[72] Since Beckett's death, all rights for performance of his plays are handled by the Beckett estate, currently managed by Edward Beckett (the author's nephew). The estate has a controversial reputation for maintaining firm control over how Beckett's plays are performed and does not grant licences to productions that do not adhere to the writer's stage directions. Historians interested in tracing Beckett's blood line were, in 2004, granted access to confirmed trace samples of his DNA to conduct molecular genealogical studies to facilitate precise lineage determination. Some of the best-known pictures of Beckett were taken by photographer John Minihan, who photographed him between 1980 and 1985 and developed such a good relationship with the writer that he became, in effect, his official photographer. Some consider one of these to be among the top three photographs of the 20th century.[73] It was the theatre photographer John Haynes, however, who took possibly the most widely reproduced image of Beckett: it is used on the cover of the Knowlson biography, for instance. This portrait was taken during rehearsals of the San Quentin Drama Workshop at the Royal Court Theatre in London, where Haynes photographed many productions of Beckett's work.[74] An Post, the Irish postal service, issued a commemorative stamp of Beckett in 1994. The Central Bank of Ireland launched two Samuel Beckett Centenary commemorative coins on 26 April 2006: €10 Silver Coin and €20 Gold Coin. On 10 December 2009, the new bridge across the River Liffey in Dublin was opened and named the Samuel Beckett Bridge in his honour. Reminiscent of a harp on its side, it was designed by the celebrated Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava, who had also designed the James Joyce Bridge situated further upstream and opened on Bloomsday (16 June) 2003. Attendees at the official opening ceremony included Beckett's niece Caroline Murphy, his nephew Edward Beckett, poet Seamus Heaney and Barry McGovern.[75] A ship of the Irish Naval Service, the LÉ Samuel Beckett (P61), is named for Beckett. An Ulster History Circle blue plaque in his memory is located at Portora Royal School, Enniskillen, County Fermanagh. In La Ferté-sous-Jouarre, the town where Beckett had a cottage, the public library and one of the local high schools bear his name. Happy Days Enniskillen International Beckett Festival is an annual multi-arts festival celebrating the work and influence of Beckett. The festival, founded in 2011, is held at Enniskillen, Northern Ireland where Beckett spent his formative years studying at Portora Royal School.[76][77][78] In 1983, the Samuel Beckett Award was established for writers who, in the opinion of a committee of critics, producers and publishers, showed innovation and excellence in writing for the performing arts. In 2003, The Oxford Samuel Beckett Theatre Trust[79] was formed to support the showcasing of new innovative theatre at the Barbican Centre in the City of London. Music for three Samuel Beckett plays (Words and Music, Cascando, and ...but the clouds...), was composed by Martin Pearlman which was commissioned by the 92nd Street Y in New York for the Beckett centennial and produced there and at Harvard University.[80][81] In January 2019 Beckett was the subject of the BBC Radio 4 programme In Our Time.[82] In 2022 James Marsh filmed a biopic of Beckett entitled Dance First, with Gabriel Byrne and Fionn O'Shea playing Beckett at different stages of his life. The film was made available through Sky Cinema in 2023.[83] |

遺産 生誕100周年を記念したアイルランドの記念硬貨に描かれたサミュエル・ベケット 英語のモダニストの中で、ベケットの作品はリアリズムの伝統に対する最も持続的な攻撃である。彼は、従来の筋書きや時間と場所の統一性を排除し、人間の状 態の本質的な要素に焦点を当てる演劇やフィクションの可能性を切り開いた。ヴァーツラフ・ハヴェル、ジョン・バンヴィル、エイダン・ヒギンズ、トム・ス トッパード、ハロルド・ピンター、ジョン・フォッセらは、ベケットの手本への恩義を公言している。アイルランドの文脈では、デレク・マホンやトマス・キン セラなどの詩人や、トレヴァー・ジョイスやキャサリン・ウォルシュのように、支配的なリアリズムの主流に代わるものとしてモダニズムの伝統に固執すること を宣言する作家たちに大きな影響を与えている。 サミュエル・ベケット橋(ダブリン ルチアーノ・ベリオ、ギョルジ・クルターグ、モートン・フェルドマン、パスカル・デュサパン、フィリップ・グラス、ロマン・ハウベンシュトック=ラマ ティ、ハインツ・ホリガーなど、20世紀を代表する作曲家の多くが、ベケットのテキストをもとに音楽作品を創作している。彼の作品はまた、エドワード・ア ルビー、アヴィグドール・アリカ、ポール・オースター、J・M・コッツェー、リチャード・カリッヒ、ダグラス・ゴードン、ブルース・ナウマン、アンソ ニー・ミンゲラ、[67] ダミアン・ペティグリュー、[68] チャーリー・カウフマン、[69] ブライアン・パトリック・バトラー[70][71]など、数多くの国際的な作家、芸術家、映画製作者にも影響を与えている。 ベケットは20世紀の作家の中で最も広く議論され、高く評価されている作家の一人であり、ジェイムズ・ジョイスの周辺に生まれた批評業界に匹敵するほどの 批評業界を刺激している。彼は批評家の意見を二分してきた。サルトルやテオドール・アドルノのような初期の哲学批評家の中には、不条理の啓示を称賛する者 もいれば、単純さを批判的に拒否する作品を称賛する者もいた。ゲオルク・ルカーチのような他の批評家は、リアリズムの「退廃的」欠如を非難した[72]。 ベケットの死後、彼の戯曲の上演に関するすべての権利はベケット遺産によって管理されており、現在はエドワード・ベケット(作者の甥)が管理している。こ の遺産は、ベケットの戯曲がどのように上演されるかをしっかりと管理し、作家の舞台演出に従わない作品には上演許可を与えないということで物議を醸してい る。 ベケットの血統をたどることに関心を持つ歴史家たちは、2004年に、正確な血統決定を容易にする分子系図研究を行うために、彼のDNAの確認された微量サンプルへのアクセスを許可された。 ベケットの最も有名な写真のいくつかは、写真家のジョン・ミニハンが撮影したものである。彼は1980年から1985年にかけてベケットを撮影し、作家と 良好な関係を築き、事実上、彼の公式写真家となった。そのうちの1枚を20世紀の写真ベスト3に入ると評価する向きもある[73]。しかし、おそらく最も 広く複製されているベケットの写真を撮影したのは、演劇写真家のジョン・ヘインズである。このポートレートは、ロンドンのロイヤル・コート劇場で行われた サン・クエンティン・ドラマ・ワークショップのリハーサル中に撮影されたもので、ヘインズはベケットの作品を数多く撮影している[74]。アイルランドの 郵便局アン・ポストは1994年にベケットの記念切手を発行。アイルランド中央銀行は2006年4月26日、10ユーロ銀貨と20ユーロ金貨の2種類のサ ミュエル・ベケット生誕100周年記念硬貨を発売した。 2009年12月10日、ダブリンのリフィー川に架かる新しい橋が開通し、サミュエル・ベケットに敬意を表して「サミュエル・ベケット橋」と命名された。 ハープを思わせるこの橋は、著名なスペイン人建築家サンティアゴ・カラトラバによって設計された。カラトラバは、さらに上流にあるジェームズ・ジョイス橋 も設計しており、2003年のブルームズデー(6月16日)に開通した。正式な開通式には、ベケットの姪キャロライン・マーフィー、甥エドワード・ベケッ ト、詩人シェイマス・ヒーニー、バリー・マクガバンらが出席した[75]。アイルランド海軍の艦船LÉ Samuel Beckett (P61) は、ベケットにちなんで命名された。ファーマナ州エニスキレンのポートラ王立学校には、ベケットを記念するアルスター・ヒストリー・サークルの青いプレー トがある。 ベケットが別荘を構えた町ラ・フェルテ・スー・ジュアールでは、公立図書館と地元の高校のひとつにベケットの名前がつけられている。 ハッピー・デイズ・エニスキレン国際ベケット・フェスティバルは、ベケットの作品とその影響を称える年に一度のマルチ・アート・フェスティバルである。 2011年に創設されたこのフェスティバルは、ベケットがポートラ王立学校で学んだ形成期を過ごした北アイルランドのエニスキレンで開催される[76] [77][78]。 1983年、サミュエル・ベケット賞は、批評家、プロデューサー、出版社からなる委員会の意見により、舞台芸術のための執筆において革新性と卓越性を示し た作家に贈られる賞として設立された。2003年、ロンドン市内にあるバービカン・センターで、新しい革新的な演劇の上演を支援するため、オックスフォー ド・サミュエル・ベケット・シアター・トラスト[79]が設立された。 サミュエル・ベケットの3つの戯曲(Words and Music、Cascando、...but the clouds...)のための音楽は、ベケット生誕100周年記念のためにニューヨークの92nd Street Yに依頼されたマーティン・パールマンが作曲し、同地とハーバード大学で上演された[80][81]。 2019年1月、ベケットはBBC Radio 4の番組『In Our Time』の主題となった[82]。 2022年、ジェームズ・マーシュは『Dance First』と題されたベケットの伝記映画を撮影し、ガブリエル・バーンとフィオン・オシェイが人生のさまざまな段階におけるベケットを演じた。この映画 は2023年にスカイシネマで公開された[83]。 |

| Archives Samuel Beckett's prolific career is spread across archives around the world. Significant collections include those at the Harry Ransom Center,[84][85][86] Washington University in St. Louis,[87] the University of Reading,[88] Trinity College Dublin,[89] and Houghton Library.[90] Given the scattered nature of these collections, an effort has been made to create a digital repository through the University of Antwerp.[91] |

アーカイブ サミュエル・ベケットの多作なキャリアは、世界中のアーカイブに広がっている。重要なコレクションとしては、ハリー・ランサムセンター[84][85] [86]、セントルイスのワシントン大学[87]、レディング大学[88]、トリニティ・カレッジ・ダブリン[89]、ホートン・ライブラリー[90]な どがある。これらのコレクションが散在していることから、アントワープ大学を通じてデジタルリポジトリを作成する努力がなされている[91]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_Beckett |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆