二級市民

Second-class citizen

☆二級市民[second-class citizen]とは、国家やその他の政治的管轄区域において、名目上の市民権や合法的居住権を有しながらも、体系的かつ積極的に差別される人格を指す。必ずしも 奴隷や無法者、不法移民、犯罪者ではないが、二級市民は法的権利、市民権、社会経済的機会が著しく制限され、往々にして上位者とされる者たちによる虐待や 搾取の対象となる。事実上の二級市民制度は、人権侵害と広く認識されている。二等市民権の定義における境界線の引き方や、それが無国籍状態に相当するか否かについては多くの議論がある。この区分は非公式で主に学術的なものであり、論評者によって一般的に蔑称として用いられる。政府は通常、自国政治体制内に二級市民が存在することを否定する。また非公式なカテゴリーであるため、二級市民権は客観的に測定されない。

| A second-class citizen

is a person who is systematically and actively discriminated against

within a state or other political jurisdiction, despite their nominal

status as a citizen or a legal resident there. While not necessarily

slaves, outlaws, illegal immigrants, or criminals, second-class

citizens have significantly limited legal rights, civil rights and

socioeconomic opportunities, and are often subject to mistreatment and

exploitation at the hands of their putative superiors. Systems with de

facto second-class citizenry are widely regarded as violating human

rights.[1][2] Typical conditions facing second-class citizens include but are not limited to: disenfranchisement (a lack or loss of voting rights) limitations on civil service and/or exclusion from military forces restrictions on language, religion, education lack of freedom of movement, expression, and association limitations on the right to keep and bear arms restrictions on marriage restrictions on housing restrictions on property ownership mandatory military service (conscription) Citizenship and nationality have essential imbued rights that define them, and some commentators argue that having second-class citizenship may amount to statelessness.[3] As an example, Nazi Germany's Reich Citizenship Law of 1935 created a second-class citizenship status, which was used for anyone excluded from the "Reich Citizenship." On paper, the holders of the second-class citizenship "enjoyed the protection of the state and were bound to fulfill all the duties of citizenship," but in practice the status was worse than that for aliens, allowing any form of discrimination and other maltreatment against the holders, effectively nullifying the defining function of citizenship.[4] There is much debate as to where to draw the line on defining second-class citizenship and whether it amounts to statelessness. The category remains unofficial and mostly academic, and is generally used as a pejorative by commentators. Governments will typically deny the existence of a second class within its polity, and as an informal category, second-class citizenship is not objectively measured. Cases such as the Southern United States under racial segregation and Jim Crow laws, the repression of Aboriginal citizens in Australia prior to 1967, deported ethnic groups designated as "special settlers" in the Soviet Union, Latvian and Estonian non-citizen minorities, the apartheid regime in South Africa, women in Saudi Arabia under Saudi Sharia law, and Roman Catholics in Northern Ireland during the Parliamentary era are all examples of groups that have been historically described as having second-class citizenry and being victims of state-sponsored discrimination. Historically, before the mid-20th century, this policy was applied by several European colonial empires on colonial residents of overseas possessions. A resident alien or foreign national, and children in general, fit most definitions of a second-class citizen. This does not mean that they do not have any legal protections, nor do they lack acceptance by the local population, but they lack many of the civil rights commonly given to the dominant social group.[1] A naturalized citizen, on the other hand, essentially carries the same rights and responsibilities as any other citizen, except for possible exclusion from certain public offices, and is also legally protected. |

二級市民とは、国家やその他の政治

的管轄区域において、名目上の市民権や合法的居住権を有しながらも、体系的かつ積極的に差別される人格を指す。必ずしも奴隷や無法者、不法移民、犯罪者で

はないが、二級市民は法的権利、市民権、社会経済的機会が著しく制限され、往々にして上位者とされる者たちによる虐待や搾取の対象となる。事実上の二級市

民制度は、人権侵害と広く認識されている。[1][2] 二級市民が直面する典型的な状況には、以下が含まれるがこれらに限定されない: 選挙権剥奪 (選挙権の欠如または喪失) 公務員への制限および/または軍隊からの排除 言語、宗教、教育への制限 移動、表現、結社の自由の欠如 武器の所持および携帯の権利への制限 結婚への制限 住居への制限 財産所有への制限 徴兵制(強制兵役) 市民権と国籍には本質的に内在する権利があり、それらが定義づけられている。一部の論者は、二級市民権を持つことは無国籍状態に等しいと主張する[3]。 例として、ナチス・ドイツの1935年帝国市民権法は二級市民権の地位を創設し、これは「帝国市民権」から排除された者全員に適用された。名目上、二級市 民権保持者は「国家の保護を享受し、市民としての義務を全て果たす義務を負う」とされたが、実際には外国人よりも劣悪な地位であり、あらゆる形態の差別や 虐待が許容され、市民権の本質的機能を実質的に無効化した。[4] 二等市民権の定義における境界線の引き方や、それが無国籍状態に相当するか否かについては多くの議論がある。この区分は非公式で主に学術的なものであり、 論評者によって一般的に蔑称として用いられる。 政府は通常、自国政治体制内に二級市民が存在することを否定する。また非公式なカテゴリーであるため、二級市民権は客観的に測定されない。人種隔離とジ ム・クロウ法下のアメリカ南部、1967年以前のオーストラリアにおける先住民市民の抑圧、ソ連で「特別移住者」と指定された追放民族集団、 ラトビア・エストニアの非市民少数派、南アフリカのアパルトヘイト体制、サウジアラビアのシャリーア法下における女性、議会制時代における北アイルランド のカトリック教徒など、これらは全て歴史的に二級市民扱いされ、国家による差別の被害者とされた集団の例である。 歴史的に、20世紀半ば以前には、この政策はいくつかのヨーロッパ植民地帝国によって海外領土の住民に対して適用されていた。 居住外国人や外国籍者、そして一般に子供たちは、二等市民の定義の大半に当てはまる。これは彼らが法的保護を全く受けていないとか、現地住民からの受け入 れを欠いているという意味ではないが、支配的な社会集団に一般的に与えられる多くの市民権を欠いている。[1] 一方、帰化市民は、特定の公職への就任が制限される場合を除き、他の市民と本質的に同等の権利と義務を有し、法的保護も受ける。 |

|

|

| Examples Christian minorities in the Ottoman Empire (e.g., Armenians, Greeks, Assyrians) were second-class citizens.[5][6] This was legally codified under the millet system, which subjected them to higher taxes (like the jizya) and restrictions on public religious expression, political participation, land ownership, and military service. Latvian non-citizens constitute a group similar to second-class citizens.[7] Although they are not considered foreigners (they hold no other citizenship, have Latvian IDs), they have reduced rights compared to full citizens. For example, non-citizens are not eligible to vote or hold public office. The European Commission against Racism and Intolerance has described their status as making "people concerned feel like "second-class citizens".[8] Estonian non-citizens are in a similar position. In Hong Kong, Sindhis make up 0,1% of the population and most hold British citizenship. They are stopped by police frequently and assumed to be criminals, fail to integrate into Hong Kong Chinese society, and struggle to get even minimum wage employment.[citation needed] In Malaysia, as part of the concept of Ketuanan Melayu (lit. Malay supremacy), a citizen that is not considered to be of Bumiputera status may face roadblocks and discrimination in matters such as economic freedom, education, healthcare and housing.[9] Mainland Chinese citizens who are settling in Hong Kong or Macau by means of a one-way permit do not have citizenship rights (such as obtaining a passport) in both the mainland or the SAR after settling but before obtaining the permanent resident status, effectively rendering them second-class citizens. Special permanent resident (特別永住者) is a type of Japanese resident with ancestry usually related to its former colonies, Korea or Taiwan. They are usually afforded additional rights and privileges beyond those of normal Permanent Residents, but are still unable to vote in Japanese elections. The burakumin (部落民, 'hamlet/village people') are a social grouping of Japanese people descended from members of the feudal class associated with kegare (穢れ, 'impurity'), mainly those with occupations related to death such as executioners, gravediggers, slaughterhouse workers, butchers, and tanners. Burakumin are physically indistinguishable from other Japanese but have historically been regarded as a socially distinct group. When identified, they are often subject to discrimination and prejudice.[10] They are often called eta (穢多, "great filth") or hinin (非人, "non-persons"). Although liberated legally during 1871 with the abolition of the feudal caste system, this did not end social discrimination against burakumin nor improve their living standards. Outside of the Kansai region, people in general are often not aware of the issues experienced by those of buraku ancestry. Prejudice against buraku most often manifests itself in the form of marriage discrimination and sometimes in employment.[11] The British Nationality Act 1981 reclassified the British national classes as British Overseas Territories citizen, British Nationals (Overseas) and British Overseas citizens in addition to British citizens. Martin Lee referred to it as "One country, six citizenships". The creation of British Nationals (Overseas) (BNO) class was satirized as "British NO" by some Hong Kong media.[12]: 40 Despite its status as a British national, holders do not have the right of residence in the United Kingdom, with its application and status similar to a general Commonwealth citizen of other sovereign countries. Apartheid in South Africa between 1948 and 1991 was a nationwide institutional racially segregated multi-level system in which European residents of the nation had more rights and privileges than Indians, who in turn had more rights than those of mixed descent, who had more rights than the majority of the population, namely Black Africans. This segregation included having separate events for those of different races, separate walkways and modes of transportation, separate hospitals, Black Africans being banned from voting, and compelling those of separate races to live in separate townships. The international condemnation of apartheid that led to its end largely began in the aftermath of the Sharpeville massacre, in which 69 protesters were killed and more than 175 were injured when police opened fire on a crowd of thousands on March 21, 1960. The Bedoons in Kuwait,[13] the "untouchable" Dalits in India,[14][15] and some ethnic minorities in China are sometimes referred to as second-class citizens.[16] Heribert Adam and Kogila Moodley wrote in 2006 that Israeli Palestinians are "restricted to second-class citizen status when another ethnic group monopolizes state power" because of legal prohibitions on access to land, as well as the unequal allocation of civil service positions and per capita expenditure on educations between "dominant and minority citizens".[17] |

例 オスマン帝国におけるキリスト教少数派(アルメニア人、ギリシャ人、アッシリア人など)は二級市民であった[5][6]。これはミルレット制度によって法 的に規定され、彼らにはより高い税金(ジズヤなど)が課され、公的な宗教的表現、政治参加、土地所有、兵役への制限が課された。 ラトビアの非市民は、二級市民に類似した集団を構成している[7]。彼らは外国人とは見なされない(他の国籍を持たず、ラトビアの身分証明書を所持してい る)が、完全な市民権を持つ者よりも権利が制限されている。例えば、非市民は投票権や公職に就く資格を持たない。欧州人種主義・不寛容対策委員会は、彼ら の地位について「関係者が『二級市民』のように感じさせる」と表現している。[8] エストニアの非市民も同様の立場にある。 香港では、シンディ族は人口の0.1%を占め、大半が英国籍を保持している。彼らは頻繁に警察に職務質問を受け犯罪者と見なされ、香港華人社会への統合に失敗し、最低賃金の仕事さえ得るのに苦労している。[出典必要] マレーシアでは、ケトゥアナン・メラユ(マレー人至上主義)の概念に基づき、ブミプトラ(土着住民)の地位と認められない市民は、経済的自由、教育、医療、住宅などの面で障壁や差別に直面する可能性がある。[9] 片道許可証で香港やマカオに定住する中国本土の市民は、永住権取得前の定住期間中、本土でも特別行政区でも市民権(パスポート取得など)を持たない。実質的に二級市民扱いとなる。 特別永住者とは、日本の旧植民地である韓国や台湾に祖先を持つ日本人居住者の一種である。通常、一般の永住者よりも追加の権利と特権が認められているが、日本の選挙では依然として投票権を持たない。 部落民(ぶらくみん)とは、穢れ(けがれ)と関連付けられた封建階級の末裔である日本人の社会的集団を指す。主に死刑執行人、墓掘り人、屠殺場労働者、肉 屋、皮なめし職人など死に関わる職業に従事していた者たちである。部落民は外見上他の日本人との区別がつかないが、歴史的に社会的に異なる集団と見なされ てきた。特定されると、しばしば差別や偏見の対象となる[10]。彼らはしばしば穢多(へた)や非人(ひにん)と呼ばれる。1871年に封建的なカースト 制度が廃止され、法的には解放されたものの、それは被差別部落民に対する社会的差別を終わらせたり、彼らの生活水準を向上させたりすることはなかった。関 西地方以外では、一般的に、部落出身の人が経験する問題について、人々はあまり認識していない。部落に対する偏見は、結婚差別という形で現れることが最も 多く、時には雇用差別という形でも現れる。[11] 1981年の英国国籍法は、英国国民に加えて、英国海外領土市民、英国国民(海外)、英国海外市民という英国国民の分類を再定義した。マーティン・リーは これを「一つの国、六つの市民権」と呼んだ。英国国民(海外)(BNO)の創設は、香港の一部のメディアによって「英国NO」と揶揄された。[12]: 40 英国国民としての地位にもかかわらず、その保有者は英国に居住する権利を有しておらず、その適用と地位は他の主権国家の一般的な英連邦市民と同様である。 1948年から1991年にかけての南アフリカのアパルトヘイトは、全国的な制度として人種差別的な多層的な制度であり、同国民のヨーロッパ系住民はイン ド系住民よりも多くの権利と特権を有し、インド系住民はミヘの住民よりも多くの権利を有し、ミヘの住民は人口の大半を占める黒人アフリカ系住民よりも多く の権利を有していた。この分離政策には、人種別に異なる行事の実施、歩道や交通機関の分離、病院の分離、黒人アフリカ人の投票権剥奪、そして異なる人種を 別々の居住区に強制的に居住させることなどが含まれていた。アパルトヘイト終焉への国際的非難は、1960年3月21日に警察が数千人の群衆に向けて発砲 し、69人の抗議者が死亡、175人以上が負傷したシャープビル虐殺事件の直後に大きく始まった。 クウェートのベドゥーン族[13]、インドの「不可触民」ダリット[14][15]、中国の一部少数民族は、時に二級市民と呼ばれることがある。[16] ヘリベルト・アダムとコギラ・ムードリーは2006年に、イスラエルのパレスチナ人は「別の民族集団が国家権力を独占する状況下で二級市民の地位に制限さ れている」と記した。その理由は、土地へのアクセスを法的に禁止されていること、そして「支配的市民と少数派市民」の間で公務員職の不平等な配分や教育へ の一人当たり支出の不平等が存在するためである。[17] |

| Blacklisting Dégradation nationale Dhimmi and Dhimmitude Involuntary unemployment Loss of rights due to felony conviction Reverse discrimination Untouchability |

ブラックリスト登録 国家の衰退 ディミとディミチュード 非自発的失業 重罪有罪判決による権利喪失 逆差別 不可触民 |

| References 1. "the definition of second-class citizen". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2017-05-11. 2. "Definition of second-class citizen". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2017-05-11. 3. Pudzianowska, Dorota (2023-09-27). Statelessness in Public Law. ISBN 978-3-631-90704-7. 4. Library of Congress. (2018). Citizenship through international adoption: A comparative overview of nationality laws in select countries (Report No. 2019670401). Retrieved from https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llglrd/2019670401/2019670401.pdf 5. Gevorgian, Sofia (2022-04-24). "To Deny the Genocide of Armenians". Talk Diplomacy. Retrieved 2025-10-29. 6. January/February 2021, Barnabas Aid Magazine (2020-12-10). "Armenian Christians". Barnabas Aid. Retrieved 2025-10-29. 7. "Walk like a Latvian". New Europe. 2013-06-01. Retrieved 2013-10-03. 8. Third report on Latvia. CRI(2008)2 Archived 2009-05-09 at the Wayback Machine Executive summary 9. Chew, Amy. "Malaysia's dangerous racial and religious trajectory". Retrieved 11 November 2021. 10. Frédéric, Louis (2005). Japan encyclopedia. Translated by Käthe Roth. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap. pp. 93–94. ISBN 9780674017535. 11. Saito (齋藤)), Naoko(直子) (29 September 2014). "部落出身者と結婚差別". 12. Regina Ip (2008). 四個葬禮及一個婚禮 - 葉劉淑儀回憶錄. 明報出版社. ISBN 9789628993628. Archived from the original on 2019-11-29. Retrieved 2018-03-20. 13. "The Bedoons of Kuwait". Human Rights Watch. 14. "Dalits being treated as second-class citizens under BJP rule: Cong". Business Standard. 5 May 2018. 15. "Under India's caste system, Dalits are considered untouchable. The coronavirus is intensifying that slur". CNN. April 2020. 16. "China's Race Problem". Foreign Affairs. 20 April 2015. 17. Adam, Heribert; Moodley, Kogila (2005). Seeking Mandela: Peacemaking Between Israelis and Palestinians. Psychology Press. p. 20f. ISBN 978-1-84472-130-6.: Second-class citizenship: "Above all, both Israeli Palestinians and Coloured and Indian South Africans are restricted to second-class citizen status when another ethnic group monopolizes state power, treats the minorities as intrinsically suspect, and legally prohibits their access to land or allocates civil service positions or per capita expenditure on education differently between dominant and minority citizens." |

参考文献 1. 「二級市民の定義」. Dictionary.com. 2017年5月11日閲覧。 2. 「二級市民の定義」. Merriam-Webster. 2017年5月11日閲覧。 3. Pudzianowska, Dorota (2023-09-27). 『公法における無国籍状態』. ISBN 978-3-631-90704-7. 4. 米国議会図書館. (2018). 国際養子縁組による市民権:選定国における国籍法の比較概観 (報告書番号 2019670401). https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llglrd/2019670401/2019670401.pdf より取得。 5. ゲヴォルギアン、ソフィア(2022年4月24日)。「アルメニア人虐殺を否定する」。トーク・ディプロマシー。2025年10月29日取得。 6. 2021年1月/2月号、バルナバス・エイド・マガジン(2020年12月10日)。「アルメニア人キリスト教徒」。バルナバス・エイド。2025年10月29日取得。 7. 「ラトビア人のように歩め」。ニュー・ヨーロッパ。2013年6月1日。2013年10月3日閲覧。 8. ラトビアに関する第三次報告書。CRI(2008)2 2009年5月9日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ 概要 9. チュー、エイミー。「マレーシアの危険な人種・宗教的軌跡」。2021年11月11日閲覧。 10. フレデリック、ルイ(2005)。『日本百科事典』。カテ・ロス訳。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ベルナップ。93-94頁。ISBN 9780674017535。 11. 齋藤直子(2014年9月29日)。「部落出身者と結婚差別」。 12. レジーナ・イップ(2008年)。『四つの葬式と一つの結婚式 - 葉劉淑儀回顧録』。明報出版社。ISBN 9789628993628。2019年11月29日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2018年3月20日に閲覧。 13. 「クウェートのベドウィン族」. ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチ. 14. 「BJP政権下でダリットが二級市民扱い:国民会議派」. ビジネス・スタンダード. 2018年5月5日. 15. 「インドのカースト制度下で、ダリットは不可触民と見なされている。コロナウイルスがその差別を悪化させている」. CNN. 2020年4月. 16. 「中国の人の問題」。フォーリン・アフェアーズ。2015年4月20日。 17. アダム、ヘリベルト;ムードリー、コギラ(2005)。『マンデラを求めて:イスラエル人とパレスチナ人の間の和平構築』。サイコロジー・プレス。p. 20f. ISBN 978-1-84472-130-6.: 二等市民権:「何よりも、イスラエルのパレスチナ人、南アフリカのカラードやインド系住民は、別の民族集団が国家権力を独占し、少数派を本質的に疑わしい 存在として扱い、土地へのアクセスを法的に禁止したり、公務員ポストや教育への一人当たり支出を支配層と少数派で異なる配分したりする場合、二等市民の地 位に制限される」 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second-class_citizen |

|

☆

☆

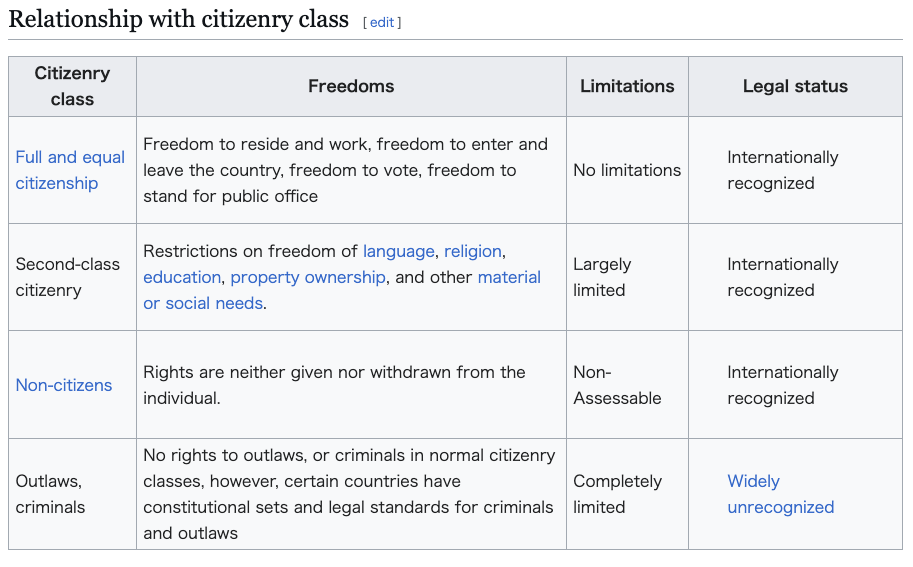

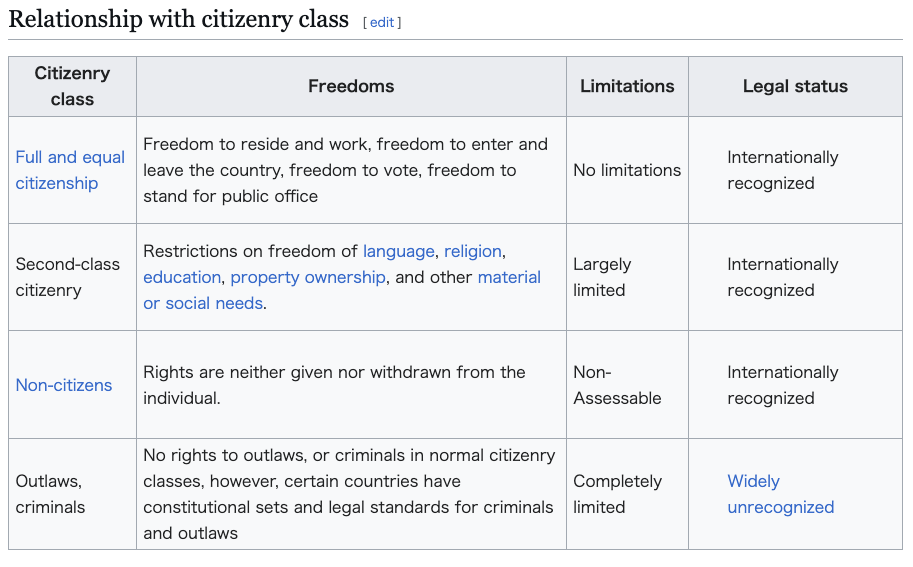

| 市民階級 |

自由 |

制限・制約 |

法的地位 |

| 完全かつ平等な市民権 |

居住と就労の自由、出入国の自由、投票の自由、公職に立候補する自由 |

制限なし |

国際的に認知されている |

| 二級市民権 |

言語、宗教、教育、財産所有権、その他の物質的または社会的ニーズに対する自由の制限。 |

広く制限される |

国際的に認知されている |

| 非市民 |

権利は個人に与えられるものでも、取り上げられるものでもない。 |

免除される |

国際的に認知されている |

| 無法者、犯罪者 |

無法者や一般市民層の犯罪者には権利はない。ただし、一部の国では犯罪者や無法者に対する憲法上の規定や法的基準が設けられている。 |

完全に制限されている |

広く知られていない |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099