社会言語学

Sociolinguistics

☆社会言語学(Sociolinguistics)

とは、言語がどのように形成され、どのような社会の中で異なる使われ方をしているかを、記述的かつ科学的に研究する学問である。この分野では主に、ある言

語が異なる社会集団の間でどのように変化するのか、また、さまざまな文化的規範、期待、文脈の影響下でどのように変化するのかを研究する。社会言語学は、

方言学という古い分野と社会科学を融合させたもので、ある言語の中の地域方言、社会方言、民族方言、その他の亜種や様式を特定し、それぞれの中の区別や変

化を明らかにする。

20世紀後半以降の言語学の主要な一分野である社会言語学は、語用論、言語人類学、言語社会学と密接に関連しており、部分的に重複することもある。社会言

語学と人類学[1]との歴史的な相互関係は、社会的変数(民族、宗教、地位、性別、教育レベル、年齢など)や地理的障壁(山脈、砂漠、川など)によって隔

てられた集団の間で、言語品種がどのように異なるかという研究において観察することができる。このような社会科学はまた、使用法や使用法に関する信念にお

けるこのような差異が、社会的または社会経済的な階級をどのように生み出し、反映しているのかについても研究している。言語の用法が場所によって異なるよ

うに、言語の用法もまた社会階級によって異なり、社会言語学者の中にはこうした社会言説を研究する者もいる。

社会言語学分野の研究では、民族誌や参与観察、実生活での出会いを録音した音声やビデオの分析、対象集団のメンバーへのインタビューなど、さまざまな調査

方法が用いられる。社会言語学者の中には、得られた音声コーパスに含まれる社会的・言語的変数の実現を評価する者もいる。社会言語学におけるその他の研究

方法には、マッチド・ギーズ・テスト(聞き手が聞いた言語的特徴に対する評価を共有する)、方言調査、既存のコーパスの分析などがある。

| Sociolinguistics

is the descriptive, scientific study of how language is shaped by, and

used differently within, any given society. The field largely looks at

how a language changes between distinct social groups, as well as how

it varies under the influence of assorted cultural norms, expectations,

and contexts. Sociolinguistics combines the older field of dialectology

with the social sciences in order to identify regional dialects,

sociolects, ethnolects, and other sub-varieties and styles within a

language, as well as the distinctions and variations inside each of

these. A major branch of linguistics since the second half of the 20th century, sociolinguistics is closely related to and can partly overlap with pragmatics, linguistic anthropology, and sociology of language, the latter focusing on the effect of language back on society. Sociolinguistics' historical interrelation with anthropology[1] can be observed in studies of how language varieties differ between groups separated by social variables (e.g., ethnicity, religion, status, gender, level of education, age, etc.) or geographical barriers (a mountain range, a desert, a river, etc.). Such studies also examine how such differences in usage and in beliefs about usage produce and reflect social or socioeconomic classes. As the usage of a language varies from place to place, language usage also varies among social classes, and some sociolinguists study these sociolects. Studies in the field of sociolinguistics use a variety of research methods including ethnography and participant observation, analysis of audio or video recordings of real life encounters or interviews with members of a population of interest. Some sociolinguists assess the realization of social and linguistic variables in the resulting speech corpus. Other research methods in sociolinguistics include matched-guise tests (in which listeners share their evaluations of linguistic features they hear), dialect surveys, and analysis of preexisting corpora. |

社

会言語学とは、言語がどのように形成され、どのような社会の中で異なる使われ方をしているかを、記述的かつ科学的に研究する学問である。この分野では主

に、ある言語が異なる社会集団の間でどのように変化するのか、また、さまざまな文化的規範、期待、文脈の影響下でどのように変化するのかを研究する。社会

言語学は、方言学という古い分野と社会科学を融合させたもので、ある言語の中の地域方言、社会方言、民族方言、その他の亜種や様式を特定し、それぞれの中

の区別や変化を明らかにする。 20世紀後半以降の言語学の主要な一分野である社会言語学は、語用論、言語人類学、言語社会学と密接に関連しており、部分的に重複することもある。社会言 語学と人類学[1]との歴史的な相互関係は、社会的変数(民族、宗教、地位、性別、教育レベル、年齢など)や地理的障壁(山脈、砂漠、川など)によって隔 てられた集団の間で、言語品種がどのように異なるかという研究において観察することができる。このような社会科学はまた、使用法や使用法に関する信念にお けるこのような差異が、社会的または社会経済的な階級をどのように生み出し、反映しているのかについても研究している。言語の用法が場所によって異なるよ うに、言語の用法もまた社会階級によって異なり、社会言語学者の中にはこうした社会言説を研究する者もいる。 社会言語学分野の研究では、民族誌や参与観察、実生活での出会いを録音した音声やビデオの分析、対象集団のメンバーへのインタビューなど、さまざまな調査 方法が用いられる。社会言語学者の中には、得られた音声コーパスに含まれる社会的・言語的変数の実現を評価する者もいる。社会言語学におけるその他の研究 方法には、マッチド・ギーズ・テスト(聞き手が聞いた言語的特徴に対する評価を共有する)、方言調査、既存のコーパスの分析などがある。 |

| Sociolinguistics in history Beginnings The social aspects of language were in the modern sense first studied by Indian and Japanese linguists in the 1930s, and also by Louis Gauchat in Switzerland in the early 1900s, but none received much attention in the West until much later. The study of the social motivation of language change, on the other hand, has its foundation in the wave model of the late 19th century. The first attested use of the term sociolinguistics was by Thomas Callan Hodson in the title of his 1939 article "Sociolinguistics in India" published in Man in India.[2][3] Dialectology is an old field, and in the early 20th century, dialectologists such as Hans Kurath and Raven I. McDavid Jr. initiated large scale surveys of dialect regions in the U.S. Western contributions The study of sociolinguistics in the West was pioneered by linguists such as Charles A. Ferguson or William Labov in the US and Basil Bernstein in the UK. In the 1960s, William Stewart[4] and Heinz Kloss introduced the basic concepts for the sociolinguistic theory of pluricentric languages, which describes how standard language varieties differ between nations, e.g. regional varieties of English versus pluricentric "English";[5] regional standards of German versus pluricentric "German";[6] Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian versus pluricentric "Serbo-Croatian".[7] Dell Hymes, one of the founders of linguistic anthropology, is credited with developing an ethnography-based sociolinguistics and is the founder of the journal Language in Society. His focus on ethnography and communicative competence contributed to his development of the SPEAKING method: an acronym for setting, participants, ends, act sequence, keys, instrumentalities, norms, and genres that is widely recognized as a tool to analyze speech events in their cultural context. |

社会言語学の歴史 始まり 言語の社会的側面は、近代的な意味では1930年代にインディアンと日本の言語学者によって、また1900年代初頭にはスイスのルイ・ゴーシャによって初 めて研究された。一方、言語変化の社会的動機の研究は、19世紀後半の波動モデルにその基礎がある。社会言語学という用語が最初に使われたのは、トーマ ス・カラン・ホドソンが『Man in India』に発表した1939年の論文「Sociolinguistics in India」のタイトルである[2][3]。 方言学は古くからある分野であり、20世紀初頭には、ハンス・クラートやレイヴン・マクダヴィッド・ジュニアなどの方言学者が、アメリカにおける方言地域の大規模な調査を開始した。 西洋の貢献 欧米における社会言語学の研究は、アメリカのチャールズ・A・ファーガソンやウィリアム・ラボフ、イギリスのバジル・バーンスタインといった言語学者に よって開拓された。1960年代には、ウィリアム・スチュワート[4]とハインツ・クロスが複数言語中心社会言語論の基本概念を導入した。例えば、英語の 地域品種と複数言語中心的な「英語」、[5] ドイツ語の地域標準と複数言語中心的な「ドイツ語」、[6] ボスニア語、クロアチア語、モンテネグロ語、セルビア語と複数言語中心的な「セルボ・クロアチア語」、[7] デル・ハイムズは言語人類学の創始者の一人であり、民族誌に基づく社会言語学を発展させたことで知られている。民族誌とコミュニケーション能力に焦点を当 てた彼は、SPEAKINGメソッドを開発した。SPEAKINGとは、設定(setting)、参加者(participants)、目的(end)、 行為順序(act sequence)、鍵(key)、道具(instrumentalities)、規範(normal)、ジャンル(genres)の頭文字をとったもの で、文化的文脈の中で発話事象を分析するツールとして広く認知されている。 |

| Applications Sociolinguistics can be divided into subfields, which make use of different research methods, and have different goals. Dialectologists survey people through interviews, and compile maps. Ethnographers such as Dell Hymes and his students often live amongst the people they are studying. Conversation analysts such as Harvey Sacks and interactional sociolinguists such as John J. Gumperz record audio or video of natural encounters, and then analyze the tapes in detail. Sociolinguists tend to be aware of how the act of interviewing might affect the answers given. Some sociolinguists study language on a national level among large populations to find out how language is used as a social institution.[8] William Labov, a Harvard and Columbia University graduate, is often regarded as the founder of variationist sociolinguistics which focuses on the quantitative analysis of variation and change within languages, making sociolinguistics a scientific discipline.[9] For example, a sociolinguistics-based translation framework states that a linguistically appropriate translation cannot be wholly sufficient to achieve the communicative effect of the source language; the translation must also incorporate the social practices and cultural norms of the target language.[10] To reveal social practices and cultural norms beyond lexical and syntactic levels, the framework includes empirical testing of the translation using methods such as cognitive interviewing with a sample population.[11][10] A commonly studied source of variation is regional dialects. Dialectology studies variations in language based primarily on geographic distribution and their associated features. Sociolinguists concerned with grammatical and phonological features that correspond to regional areas are often called dialectologists. |

アプリケーション 社会言語学は、異なる調査方法を用い、異なる目標を持つ下位分野に分けられる。方言学者はインタビューを通じて人民を調査し、地図を作成する。デル・ハイ ムズと彼の学生たちのようなエスノグラファーは、しばしば研究対象の人民の中に住み込む。ハーヴェイ・サックスのような会話分析家や、ジョン・J・ガン パーズのような対話社会言語学者は、自然な出会いの音声やビデオを録音し、そのテープを詳細に分析する。社会言語学者は、インタビューという行為が与えら れた答えにどのような影響を与えるかを意識する傾向がある。 社会言語学者の中には、言語が社会制度としてどのように使用されているかを調べるために、大規模な集団の中で国民レベルで言語を研究する者もいる[8]。 ハーバード大学とコロンビア大学を卒業したウィリアム・ラボフは、言語内の変動と変化の定量的分析に焦点を当て、社会言語学を科学分野とした変動主義社会 言語学の創始者とみなされることが多い[9]。 例えば、社会言語学に基づいた翻訳の枠組みでは、言語学的に適切な翻訳だけでは原言語のコミュニケーション効果を完全に達成することはできず、翻訳には ターゲット言語の社会的慣行や文化的規範も取り入れなければならないと述べている[10]。語彙や構文のレベルを超えて社会的慣行や文化的規範を明らかに するために、この枠組みにはサンプル集団を用いた認知的面接などの方法を用いた翻訳の実証的テストが含まれる[11][10]。 一般的に研究されているバリエーションソースは地域の方言である。方言学は、主に地理的分布とそれに関連する特徴に基づく言語のバリエーションを研究している。地方に対応する文法や音韻の特徴に関心を持つ社会言語学者は、しばしば方言学者と呼ばれる。 |

| Sociolinguistic interview The sociolinguistic interview is the foundational method of collecting data for sociolinguistic studies, allowing the researcher to collect large amounts of speech from speakers of the language or dialect being studied. The interview takes the form of a long, loosely-structured conversation between the researcher and the interview subject; the researcher's primary goal is to elicit the vernacular style of speech: the register associated with everyday casual conversation. This goal is complicated by the observer's paradox: the researcher is trying to elicit the style of speech that would be used if the interviewer were not present. To that end, a variety of techniques may be used to reduce the subject's attention to the formality and artificiality of the interview setting. For example, the researcher may attempt to elicit narratives of memorable events from the subject's life, such as fights or near-death experiences; the subject's emotional involvement in telling the story is thought to distract their attention from the formality of the context. Some researchers interview multiple subjects together to allow them to converse more casually with one other than they would with the interviewer alone. The researcher may then study the effects of style-shifting on language by comparing a subject's speech style in more vernacular contexts, such as narratives of personal experience or conversation between subjects, with the more careful style produced when the subject is more attentive to the formal interview setting. The correlations of demographic features such as age, gender, and ethnicity with speech behavior may be studied by comparing the speech of different interview subjects. |

社会言語学的インタビュー 社会言語学的インタビューは、社会言語学的研究のデータ収集の基礎となる方法で、研究者は研究対象の言語や方言の話者から大量の発話を収集することができ る。インタビューは、研究者とインタビュー対象者の間の長く、緩く構造化された会話の形をとる。研究者の主な目標は、日常的なカジュアルな会話に関連する 音域である方言の発話スタイルを引き出すことである。この目標は、観察者のパラドックスによって複雑になる。研究者は、インタビュアーがその場にいなかっ た場合に使われるであろう話し方のスタイルを引き出そうとしているのである。 そのために、被験者がインタビューの場の形式や人為性に注意を払うのを減らすために、さまざまなテクニックを使うことができる。例えば、研究者は、ケンカ や臨死体験など、対象者の人生で印象に残った出来事の語りを引き出そうとすることがある。対象者が感情移入して語ることで、文脈の形式から注意をそらすこ とができると考えられている。研究者の中には、複数の被験者を一緒に面接することで、インタビュアー1人と話すよりも、被験者同士がより気軽に会話できる ようにする人もいる。研究者は、個人的な体験の語りや被験者同士の会話など、より日常的な文脈における被験者の話し方と、被験者が形式的な面接の場に気を 配っているときに生み出されるより注意深い話し方を比較することで、スタイルシフトが言語に及ぼす影響を研究することができる。年齢、性別、民族性などの 人口統計学的特徴と発話行動との相関は、異なるインタビュー対象者の発話を比較することで調べることができる。 |

| Fundamental concepts While the study of sociolinguistics is very broad, there are a few fundamental concepts on which many sociolinguistic inquiries depend. Speech community Main article: Speech community Speech community is a concept in sociolinguistics that describes a distinct group of people who use language in a unique and mutually accepted way among themselves. This is sometimes referred to as a Sprechbund. To be considered part of a speech community, one must have a communicative competence. That is, the speaker has the ability to use language in a way that is appropriate in the given situation. It is possible for a speaker to be communicatively competent in more than one language.[12] Demographic characteristics such as areas or locations have helped to create speech community boundaries in speech community concept. Those characteristics can assist exact descriptions of specific groups' communication patterns.[13] Speech communities can be members of a profession with a specialized jargon, distinct social groups like high school students or hip hop fans, or even tight-knit groups like families and friends. Members of speech communities will often develop slang or specialized jargon to serve the group's special purposes and priorities. This is evident in the use of lingo within sports teams. Community of Practice allows for sociolinguistics to examine the relationship between socialization, competence, and identity. Since identity is a very complex structure, studying language socialization is a means to examine the micro-interactional level of practical activity (everyday activities). The learning of a language is greatly influenced by family, but it is supported by the larger local surroundings, such as school, sports teams, or religion. Speech communities may exist within a larger community of practice.[12] |

基本概念 社会言語学の研究は非常に広範であるが、多くの社会言語学的探究が依拠するいくつかの基本概念がある。 音声コミュニティ 主な記事 音声コミュニティ 言語共同体とは社会言語学における概念で、独自の方法で言語を使用し、相互に受け入れられている人民の集団を指す。これはシュプレヒブント(Sprechbund)と呼ばれることもある。 言語共同体の一員とみなされるには、コミュニケーション能力が必要である。つまり、話し手は、与えられた状況において適切な方法で言語を使用する能力を持っている。話し手が複数の言語でコミュニケーション能力を持つことは可能である[12]。 地域や場所などの人口統計学的特徴は、言語コミュニティの概念における言語コミュニティの境界を作るのに役立っている。これらの特徴は特定のグループのコミュニケーションパターンを正確に記述するのに役立つ[13]。 言語コミュニティは、専門用語を使う職業のメンバーであったり、高校生やヒップホップファンのような明確な社会的グループであったり、家族や友人のような 緊密なグループであったりする。スピーチ・コミュニティのメンバーは、そのグループの特別な目的や優先事項のために、スラングや専門用語を開発することが 多い。これは、スポーツチーム内での専門用語の使用を見れば明らかである。 コミュニティ・オブ・プラクティスによって、社会言語学は社会化、能力、アイデンティティの関係を調べることができる。アイデンティティは非常に複雑な構 造であるため、言語の社会化を研究することは、実践活動(日常活動)のミクロな相互作用レベルを調べる手段となる。言語の学習は家族の影響を大きく受ける が、学校、スポーツチーム、宗教など、より大きな地域の環境によっても支えられる。言語共同体は、より大きな実践共同体の中に存在するかもしれない [12]。 |

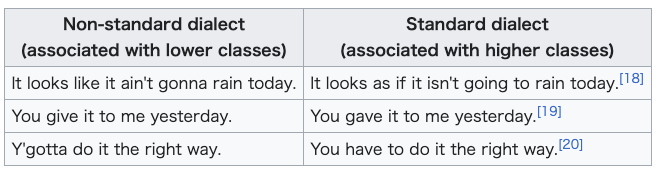

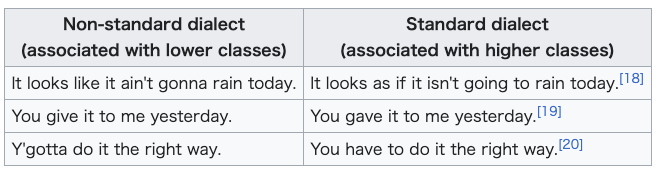

| High-prestige and low-prestige varieties Main article: Prestige (sociolinguistics) Crucial to sociolinguistic analysis is the concept of prestige; certain speech habits are assigned a positive or a negative value, which is then applied to the speaker. This can operate on many levels. It can be realized on the level of the individual sound/phoneme, as Labov discovered in investigating pronunciation of the post-vocalic /r/ in the Northeastern United States, or on the macro scale of language choice, as is realized in the various diglossia that exist throughout the world, with the one between Swiss German and High German being perhaps most well known. An important implication of the sociolinguistic theory is that speakers 'choose' a variety when making a speech act, whether consciously or subconsciously. The terms acrolectal (high) and basilectal (low) are also used to distinguish between a more standard dialect and a dialect of less prestige.[14] It is generally assumed that non-standard language is low-prestige language. However, in certain groups, such as traditional working-class neighborhoods, standard language may be considered undesirable in many contexts because the working-class dialect is generally considered a powerful in-group marker. Historically, humans tend to favor those who look and sound like them, and the use of nonstandard varieties (even exaggeratedly so) expresses neighborhood pride and group and class solidarity. The desirable social value associated with the use of non-standard language is known as covert prestige. There will thus be a considerable difference in use of non-standard varieties when going to the pub or having a neighborhood barbecue compared to going to the bank. One is a relaxed setting, likely with familiar people, and the other has a business aspect to it in which one feels the need to be more professional. |

プレステージの高い品種と低い品種 主な記事 プレステージ(社会言語学) 社会言語学的分析にとって重要なのは、威信という概念である。ある種の話し方の習慣には肯定的または否定的な価値が与えられ、それが話し手に適用される。 これは様々なレベルで作用する。それは、ラボフがアメリカ北東部における後母音の/r/の発音を調査して発見したように、個々の音や音素のレベルで実現さ れることもあれば、スイス・ドイツ語と高地ドイツ語の間に最もよく知られているような、世界中に存在するさまざまなダイグロシア(diglossia)で 実現されるように、言語選択というマクロなスケールで実現されることもある。社会言語学的理論の重要な含意は、話し手が発話行為をする際に、意識的であれ 無意識的であれ、多様性を「選択」するということである。 また、標準的な方言と格式の低い方言を区別するために、アクロレクトル(高方言)とベーシレクタル(低方言)という用語が用いられる[14]。 一般的に、非標準語は名声の低い言語であると考えられている。しかし、伝統的な労働者階級の居住区などの特定の集団では、労働者階級の方言は一般的に強力 な集団内マーカーであると考えられているため、標準語は多くの文脈で望ましくないと考えられている場合がある。歴史的に、人間は自分と同じような外見や発 音をする人を好む傾向があり、標準語以外の方言を使うことは(たとえ誇張されていたとしても)、近隣住民の誇りや集団・階級の連帯感を表現することにな る。非標準語の使用に関連する望ましい社会的価値は、秘密の威信として知られている。したがって、パブに行くときや近所でバーベキューをするときと銀行に 行くときとでは、非標準語の使い方にかなりの違いがある。一方はリラックスした雰囲気で、親しい人民がいる可能性が高く、もう一方はビジネス的な側面があ り、よりプロフェッショナルである必要性を感じている。 |

| Social network Understanding language in society means that one also has to understand the social networks in which language is embedded. A social network is another way of describing a particular speech community in terms of relations between individual members in a community. A network could be loose or tight depending on how members interact with each other.[15] For instance, an office or factory may be considered a tight community because all members interact with each other. A large course with 100+ students would be a looser community because students may only interact with the instructor and maybe 1–2 other students. A multiplex community is one in which members have multiple relationships with each other.[15] For instance, in some neighborhoods, members may live on the same street, work for the same employer and even intermarry. The looseness or tightness of a social network may affect speech patterns adopted by a speaker. For instance, Sylvie Dubois and Barbara Horvath found that speakers in one Cajun Louisiana community were more likely to pronounce English "th" [θ] as [t] (or [ð] as [d]) if they participated in a relatively dense social network (i.e. had strong local ties and interacted with many other speakers in the community), and less likely if their networks were looser (i.e. fewer local ties).[16] A social network may apply to the macro level of a country or a city, but also to the interpersonal level of neighborhoods or a single family. Recently, social networks have been formed by the Internet through online chat rooms, Facebook groups, organizations, and online dating services. |

社会的ネットワーク 社会における言語を理解するということは、言語が埋め込まれている社会的ネットワークを理解することでもある。社会的ネットワークとは、コミュニティ内の 個々のメンバー間の関係という観点から、特定の言語コミュニティを説明する別の方法である。例えば、オフィスや工場は、メンバー全員が互いに影響し合うの で、緊密なコミュニティとみなされるかもしれない[15]。100人以上の生徒がいる大規模なコースは、生徒が講師や他の1-2人の生徒としか交流しない 可能性があるため、緩いコミュニティとなる。多重共同体とは、構成員が互いに複数の関係を持つ共同体のことである[15]。例えば、ある地域では、構成員 が同じ通りに住んでいたり、同じ雇用主のもとで働いていたり、さらには婚姻関係を結んでいたりする。 社会的ネットワークの緩さや緊密さは、話し手が採用する発話パターンに影響を与える可能性がある。例えば、Sylvie DuboisとBarbara Horvathは、ルイジアナ州のあるケイジャン・コミュニティーの話者が、比較的密な社会的ネットワークに参加している(つまり、地域のつながりが強 く、コミュニティーの他の多くの話者と交流がある)場合、英語の「th」[θ]を[t](または[ð]を[d])と発音する可能性が高く、ネットワークが 緩い(つまり、地域のつながりが少ない)場合、その可能性が低いことを発見した[16]。 社会的ネットワークは、国や都市といったマクロなレベルだけでなく、近所や一家族といった対人レベルにも適用されることがある。近年、ソーシャル・ネット ワークは、オンライン・チャットルーム、フェイスブック・グループ、組織、オンライン・デート・サービスなどを通じて、インターネットによって形成されて いる。 |

| Differences according to class Further information: Linguistic insecurity Sociolinguistics as a field distinct from dialectology was pioneered through the study of language variation in urban areas. Whereas dialectology studies the geographic distribution of language variation, sociolinguistics focuses on other sources of variation, among them class. Class and occupation are among the most important linguistic markers found in society. One of the fundamental findings of sociolinguistics, which has been hard to disprove, is that class and language variety are related. Members of the working class tend to speak less of what is deemed standard language, while the lower, middle, and upper middle class will, in turn, speak closer to the standard. However, the upper class, even members of the upper middle class, may often speak 'less' standard than the middle class. This is because not only class but class aspirations, are important. One may speak differently or cover up an undesirable accent to appear to have a different social status and fit in better with either those around them, or how they wish to be perceived. |

階級による異なる さらに詳しい情報 言語的不安 方言学とは異なる分野としての社会言語学は、都市部における言語変異の研究を通じて開拓された。方言学が言語変異の地理的分布を研究するのに対し、社会言 語学は他の変異源、とりわけ階級に焦点を当てる。階級と職業は、社会で見られる最も重要な言語標識のひとつである。社会言語学の基本的な発見のひとつは、 階級と言語の多様性が関連していることである。労働者階級の人々は、標準語とみなされるものをあまり話さない傾向があるが、下層階級、中層階級、上層階級 の人々は、標準語に近いものを話す。しかし、上流階級は、たとえ上流中流階級のメンバーであっても、中流階級よりも「より少ない」標準語を話すことが多 い。これは、階級だけでなく、階級への憧れが重要だからである。異なる社会的地位を持っているように見せたり、周囲の人々や自分がどう思われたいかにうま く合わせるために、異なる話し方をしたり、好ましくないアクセントを隠したりすることがある。 |

| Class aspiration Studies, such as those by William Labov in the 1960s, have shown that social aspirations influence speech patterns. This is also true of class aspirations. In the process of wishing to be associated with a certain class (usually the upper class and upper middle class) people who are moving in that direction socio-economically may adjust their speech patterns to sound like them. However, not being native upper-class speakers, they often hypercorrect, which involves overcorrecting their speech to the point of introducing new errors. The same is true for individuals moving down in socio-economic status. In any contact situation, there is a power dynamic, be it a teacher-student or employee-customer situation. This power dynamic results in a hierarchical differentiation between languages.[17]  |

階級的願望 1960年代のウィリアム・ラボフの研究に代表されるように、社会科学は社会的願望が発話パターンに影響を与えることを示してきた。これは階級願望にも当 てはまる。社会経済的にその方向に向かっている人民は、特定の階級(通常は上流階級や上流中流階級)に属することを望む過程で、そのように聞こえるように 話し方を調整することがある。しかし、上流階級のネイティブスピーカーでない彼らは、新たな誤りを引き起こすほど発話を過剰に修正するハイパーコレクトを しばしば行う。これは、社会経済的地位が下降していく場合にも同じことが言える。 教師と生徒、従業員と顧客など、どのような接触状況においても、力関係が存在する。このパワー・ダイナミックの結果、言語間には階層的な差別化が生じる[17]。  |

| Social language codes Basil Bernstein, a well-known British sociolinguist, devised in his book, Elaborated and restricted codes: their social origins and some consequences, a method for categorizing language codes according to variable emphases on verbal and extraverbal communication. He claimed that factors like family orientation, social control, verbal feedback, and possibly social class contributed to the development of the two codes: elaborated and restricted.[21] |

社会的言語コード イギリスの著名な社会言語学者であるバジル・バーンスタインは、著書『Elaborated and restricted codes: their social origins and some consequences』(精巧なコードと制限されたコード:その社会的起源といくつかの結果)の中で、言語コードを、言語的コミュニケーションと言語 外コミュニケーションの強調点の違いによって分類する方法を考案した。彼は、家族志向、社会的統制、言語的フィードバック、そしておそらくは社会階級と いった要因が、精巧化されたコードと制限されたコードという2つのコードの発達に寄与していると主張した[21]。 |

| Restricted code According to Basil Bernstein, the restricted code exemplified the predominance of extraverbal communication, with an emphasis on interpersonal connection over individual expression. His theory places the code within environments that operate according to established social structures that predetermine the roles of their members in which the commonality of interests and intents from a shared local identity creates a predictability of discrete intent and therefore a simplification of verbal utterances. Such environments may include military, religious, and legal atmospheres; criminal and prison subcultures; long-term married relationships; and friendships between children. The strong bonds between speakers often renders explicit verbal communication unnecessary and individual expression irrelevant. However, simplification is not a sign of a lack of intelligence or complexity within the code; rather, communication is performed more through extraverbal means (facial expression, touch, etc.) in order to affirm the speakers' bond. Bernstein notes the example of a young man asking a stranger to dance since there is an established manner of asking, yet communication is performed through physical graces and the exchange of glances. As such, implied meaning plays a greater role in this code than in the elaborated code. Restricted code also operates to unify speakers and foster solidarity.[21] |

限定コード バジル・バーンスタインによれば、限定されたコードは、個人の表現よりも対人的なつながりを重視した、言葉以外のコミュニケーションが優勢であることを例 証している。彼の理論によれば、限定コードは、メンバーの役割をあらかじめ決定する確立された社会構造に従って運営される環境の中に位置づけられ、そこで は、共有されたローカル・アイデンティティに由来する興味や意図の共通性が、個別の意図の予測可能性を生み出し、したがって、言語による発話の単純化をも たらす。このような環境には、軍事的、宗教的、法律的な雰囲気、犯罪や刑務所のサブカルチャー、長期的な夫婦関係、子供同士の友情などが含まれる。 話し手同士の結びつきが強いため、明示的な言葉によるコミュニケーションが不要になり、個々の表現が無意味になることが多い。しかし、パフォーマティビ ティが単純化されるのは、知性の欠如やコード内の複雑さの表れではなく、むしろ話し手の絆を確認するために、言葉以外の手段(表情、タッチなど)を通じて コミュニケーションが行われるのである。バーンスタインは、見知らぬ人にダンスを誘う若者の例を挙げて、誘い方には確立された作法があるにもかかわらず、 コミュニケーションは身体的な礼儀や視線の交換を通して行われることを指摘している。 そのため、このコードでは、精巧なコードよりも暗示的な意味がより大きな役割を果たす。制限されたコードは、話し手を統一し、連帯感を育むためにも作用する[21]。 |

| Elaborated code Basil Bernstein defined 'elaborated code' according to its emphasis on verbal communication over extraverbal. This code is typical in environments where a variety of social roles are available to the individual, to be chosen based upon disposition and temperament. Most of the time, speakers of elaborated code use a broader lexicon and demonstrate less syntactic predictability than speakers of restricted code. The lack of predetermined structure and solidarity requires explicit verbal communication of discrete intent by the individual to achieve educational and career success. Bernstein notes with caution the association of the code with upper classes (while restricted code is associated with lower classes) since the abundance of available resources allows persons to choose their social roles. He warns, however, that studies associating the codes with separate social classes used small samples and were subject to significant variation. He also asserts that elaborated code originates from differences in social context, rather than intellectual advantages. As such, elaborated code differs from restricted code according to the context-based emphasis on individual advancement over assertion of social/community ties.[21] |

精巧なコード バジル・バーンスタインは、言語外コミュニケーションよりも言語的コミュニケーションを重視する「精巧なコード」を定義した。このコードは、個人の性格や 気質に基づいて選択される、さまざまな社会的役割が利用可能な環境において典型的である。ほとんどの場合、精緻化されたコードの話し手は、制限されたコー ドの話し手に比べて、より広い語彙を使い、構文の予測可能性を示さない。あらかじめ決められた構造や連帯感がないため、教育やキャリアで成功を収めるため には、個人の明確な意図主義を言葉で伝える必要がある。 バーンスタインは、利用可能な資源が豊富であれば人格が社会的役割を選択できるため、(制限コードが下層階級と関連しているのに対して)コードが上層階級 と関連していることに注意を促している。しかし彼は、コードを別々の社会階級と関連づけた社会科学はサンプルが少なく、大きなばらつきがあることを警告し ている。 彼はまた、精巧なコードは知的優位性よりもむしろ社会的文脈の差異に由来すると主張している。そのため、精緻化されたコードは、社会的/共同体的な結びつきを主張することよりも個人の進歩を重視するという文脈に基づく点で、制限されたコードとは異なる[21]。 |

| The codes and child development Bernstein explains language development according to the two codes in light of their fundamentally different values. For instance, a child exposed solely to restricted code learns extraverbal communication over verbal, and therefore may have a less extensive vocabulary than a child raised with exposure to both codes. While there is no inherent lack of value to restricted code, a child without exposure to elaborated code may encounter difficulties upon entering formal education, in which standard, clear verbal communication and comprehension is necessary for learning and effective interaction both with instructors and other students from differing backgrounds. As such, it may be beneficial for children who have been exposed solely to restricted code to enter pre-school training in elaborated code in order to acquire a manner of speaking that is considered appropriate and widely comprehensible within the education environment. Additionally, Bernstein notes several studies in language development according to social class. In 1963, the Committee for Higher Education conducted a study on verbal IQ that showed a deterioration in individuals from lower working classes ages 8–11 and 11–15 years in comparison to those from middle classes (having been exposed to both restricted and elaborated codes).[22] Additionally, studies by Bernstein,[23][24] Venables,[25] and Ravenette,[26] as well as a 1958 Education Council report,[27] show a relative lack of success on verbal tasks in comparison to extraverbal in children from lower working classes (having been exposed solely to restricted code).[21] |

コードと子どもの発達 バーンスタインは、2つのコードの根本的に異なる価値観に照らして、2つのコードによる言語発達を説明している。例えば、制限されたコードにのみさらされ た子どもは、言語的コミュニケーションよりも言語外コミュニケーションを学ぶため、両方のコードにさらされて育った子どもよりも語彙が少なくなる可能性が ある。制限されたコードに本質的な価値がないわけではないが、精緻化されたコードに触れていない子どもは、正規の教育に入ったときに困難に遭遇する可能性 がある。正規の教育では、標準的で明確な言語的コミュニケーションと理解が、学習や、指導者や異なる背景を持つ他の生徒との効果的な交流のために必要とさ れる。そのため、制限されたコードにしか触れたことのない子どもにとって、教育環境において適切で広く理解できると考えられる話し方を身につけるために、 精緻化されたコードの就学前訓練に参加することは有益かもしれない。 さらにバーンスタインは、社会階層に応じた言語発達に関するいくつかの研究を紹介している。1963年に高等教育委員会が実施した言語性IQに関する研究 では、8~11歳および11~15歳の労働者階級の下層階級の出身者では、中流階級の出身者(制限されたコードと精緻化されたコードの両方にさらされてい る)と比較して、言語性IQが低下していることが示されている[22]。 さらに、バーンスタイン[23][24]、ヴェナブルズ[25]、ラヴェネット[26]による研究、および1958年の教育審議会の報告書[27]では、 労働者階級の下層階級の出身者(制限されたコードのみにさらされている)では、言語外言語と比較して、言語的課題での成功が相対的に不足していることが示 されている[21]。 |

| Contradictions The idea of these social language codes from Bernstein contrast with famous linguist Noam Chomsky's ideas. Chomsky, deemed the "father of modern linguistics", argues that there is a universal grammar, meaning that humans are born with an innate capacity for linguistic skills like sentence-building. This theory has been criticized by several scholars of linguistic backgrounds because of the lack of proven evolutionary feasibility and the fact that different languages do not have universal characteristics. |

矛盾 バーンスタインのこうした社会的言語コードの考え方は、有名な言語学者ノーム・チョムスキーの考えと対照的である。現代言語学の父」と呼ばれるチョムス キーは、普遍的な文法が存在する、つまり人間は生まれながらにして文章を構築するような言語能力を備えていると主張している。この理論は、進化論的な実現 可能性が証明されていないことや、異なる言語が普遍的な特徴を持っていないことから、言語学的背景を持つ複数の学者から批判されてきた。 |

| Sociolinguistic variation Main articles: Variation (linguistics), Dialectology, and Language and gender The study of language variation is concerned with social constraints determining language in its contextual environment. The variations will determine some of the aspects of language like the sound, grammar, and tone in which people speak, and even non-verbal cues. Code-switching is the term given to the use of different varieties of language depending on the social situation. This is commonly used among the African-American population in the United States. There are several different types of age-based variation one may see within a population as well such as age range, age-graded variation, and indications of linguistic change in progress. The use of slang can be a variation based on age. Younger people are more likely to recognize and use today's slang while older generations may not recognize new slang, but might use slang from when they were younger. Variation may also be associated with gender, as men and women, on average, tend to use slightly different language styles. These differences are typically quantitative rather than qualitative. In other words, while women may use certain speaking styles more frequently than men, the distinction is comparable to height differences between the sexes—on average, men are taller than women, yet some women are taller than some men. Similar variations in speech patterns include differences in pitch, tone, speech fillers, interruptions, and the use of euphemisms, etc.[28] These gender-based differences in communication extend beyond face-to-face interactions and are also evident in digital spaces. Despite the continuous evolution of social media platforms, cultural and societal norms continue to shape online interactions. For instance, men and women often adopt different non-verbal cues and roles in virtual conversations. However, when it comes to fundamental aspects of communication—such as spoken language, active listening, providing feedback, understanding context, selecting communication methods, and managing conflicts—their approaches tend to be more similar than different.[29] Beyond these stylistic differences, research suggests that gendered language patterns are also influenced by social expectations and power dynamics. Women, for instance, are more likely to use hedging expressions (e.g., "I think" or "perhaps") and tag questions ("isn't it?") to soften their statements and promote conversational cooperation.[30] Meanwhile, men tend to adopt more assertive and direct speech patterns, reflecting broader societal norms that associate masculinity with dominance and authority.[31] Variation in language can also come from ethnicity, economic status, level of education, etc. Further information: Complimentary language and gender |

社会言語学的変異 主な記事 バリエーション(言語学)、方言学、言語とジェンダー 言語変異の社会科学は、文脈的環境の中で言語を決定する社会的制約に関係している。その変化は、人民が話す音、文法、口調、さらには非言語的な合図といっ た言語の側面のいくつかを決定する。コード・スイッチングとは、社会的状況に応じて異なる種類の言語を使い分けることを指す。これはアメリカのアフリカ系 アメリカ人の間でよく使われている。集団の中で見られる年齢による変化には、年齢範囲、年齢による変化、言語変化の進行の兆候など、いくつかの異なるタイ プがある。スラングの使用は、年齢による違いのひとつである。若い人民は今日のスラングを認識し使用する可能性が高いが、年配の世代は新しいスラングを認 識しないかもしれないが、若い頃のスラングを使用するかもしれない。 また、男性と女性では、平均して使用する言語スタイルが若干異なる傾向があるため、性別によっても異なる場合がある。このような相違は通常、質的というよ りは量的なものである。つまり、女性は男性よりも特定の話し方を頻繁に使うかもしれないが、その違いは男女間の身長差に匹敵する。平均すると、男性は女性 よりも背が高いが、一部の女性は一部の男性よりも背が高い。スピーチパターンにおける異なるバリエーションには、ピッチ、トーン、スピーチフィラー、中 断、婉曲表現の使用などの違いがある[28]。 コミュニケーションにおけるこのような性差に基づく差異は、対面での交流にとどまらず、デジタル空間においても顕著である。ソーシャル・メディア・プラッ トフォームの絶え間ない進化にもかかわらず、文化的・社会的規範はオンライン上での相互作用を形成し続けている。例えば、バーチャルの会話では、男性と女 性はしばしば異なる非言語的な合図や役割を採用する。しかし、話し言葉、積極的な傾聴、フィードバックの提供、文脈の理解、コミュニケーション方法の選 択、衝突の管理など、コミュニケーションの基本的な側面に関しては、両者のアプローチは異なるというよりむしろ類似している傾向がある[29]。 このような文体の違いにとどまらず、性別による言語パターンが社会的な期待やパワーダイナミクスの影響も受けていることが研究で示唆されている。例えば、 女性は、発言を和らげ、会話の協力を促進するために、ヘッジ表現(例えば、「思う」や「おそらく」)やタグクエスチョン(「そうではありませんか」)を使 用する傾向がある[30]。一方、男性は、男性らしさを支配や権威と関連付ける広範な社会規範を反映し、より自己主張的で直接的な話し方を採用する傾向が ある[31]。 言語の多様性は、民族性、経済的地位、教育レベルなどからももたらされる。 さらに詳しい情報 補完言語とジェンダー |

| Anthropological linguistics Audience design Ausbausprache Axiom of categoricity Conversation Analysis Discourse analysis Discursive psychology Folk linguistics In-group Interactional sociolinguistics Jargon Language ideology Language planning Language policy Language secessionism Linguistic landscape Linguistic marketplace Metapragmatics Mutual intelligibility Raciolinguistics Real-time sociolinguistics Sociocultural linguistics Sociohistorical linguistics Sociolinguistics of sign languages Sociology of language Style-shifting T–V distinction Variation (linguistics) Category:Sociolinguists |

人類学的言語学 オーディエンス・デザイン オーディエンスデザイン カテゴリー性の公理 会話分析 談話分析 談話心理学 民間言語学 集団内言語学 交流社会言語学 専門用語 言語イデオロギー 言語計画 言語政策 言語分離主義 言語景観 言語市場 メタ語用論 相互了解性 人種言語学 リアルタイム社会言語学 社会文化言語学 社会歴史言語学 手話社会言語学 言語社会学 スタイルシフト T-Vの区別 バリエーション(言語学) Category:社会言語学者 |

| Bastardas-Boada, Albert (2019).

From Language Shift to Language Revitalization and Sustainability. A

Complexity Approach to Linguistic Ecology. Barcelona: Edicions de la

Universitat de Barcelona. ISBN 978-84-9168-316-2. Chambers, J. K. (2009). Sociolinguistic Theory: Linguistic Variation and Its Social Significance. Malden: Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-5246-4. Darnell, Regna (1971). Linguistic Diversity in Canadian Society. Edmonton: Linguistic Research. OCLC 540626. Hernández-Campoy, Juan M. (2016). Sociolinguistic Styles. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-73764-4. Kadochnikov, Denis (2016). Languages, Regional Conflicts and Economic Development: Russia. In: Ginsburgh, V., Weber, S. (Eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Economics and Language. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 538–580. ISBN 978-1-137-32505-1 Labov, William (2010). Principles of Linguistic Change (3 volume set ed.). Malden: Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4443-2788-5. Lakoff, Robin Tolmach (2000). The Language War. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-92807-7. Meyerhoff, Miriam (2011). Introducing Sociolinguistics. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-28443-5. Milroy, Lesley; Gordon, Matthew (2008). Sociolinguistics: Method and Interpretation. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-75820-5. Paulston, Christina Bratt; Tucker, G. Richard (2010). The Early Days of Sociolinguistics: Memories and Reflections. Dallas: SIL International. ISBN 978-1-55671-253-1. Tagliamonte, Sali (2006). Analysing Sociolinguistic Variation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77818-3. Trudgill, Peter (2000). Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-192630-8. Watts, Richard J. (2003). Politeness. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79406-0. |

Bastardas-Boada, Albert (2019).

言語シフトから言語再生と持続可能性へ。言語生態学への複雑性アプローチ. バルセロナ: Edicions de la Universitat

de Barcelona. ISBN 978-84-9168-316-2. Chambers, J. K. (2009). 社会言語理論: Linguistic Variation and Its Social Significance. Malden: Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-5246-4. Darnell, Regna (1971). カナダ社会における言語の多様性. エドモントン: Linguistic Research. OCLC 540626. Hernández-Campoy, Juan M. (2016). Sociolinguistic Styles. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-73764-4. Kadochnikov, Denis (2016). 言語、地域紛争、経済発展: ロシア. In: Ginsburgh, V., Weber, S. (Eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Economics and Language. ロンドン: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-32505-1 Labov, William (2010). 言語変化の原理(3巻セット版). Malden: Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-443-2788-5. レイコフ、ロビン・トルマック (2000). 言語戦争. カリフォルニア大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-520-92807-7. Meyerhoff, Miriam (2011). Introducing Sociolinguistics. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-28443-5. Milroy, Lesley; Gordon, Matthew (2008). 社会言語学: Method and Interpretation. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-75820-5. Paulston, Christina Bratt; Tucker, G. Richard (2010). 社会言語学の黎明期: Memories and Reflections. ダラス: SIL International. ISBN 978-1-55671-253-1. Tagliamonte, Sali (2006). 社会言語的変動の分析. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77818-3. Trudgill, Peter (2000). 社会言語学: 言語と社会入門. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-192630-8. Watts, Richard J. (2003). Politeness. ケンブリッジ大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-521-79406-0. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sociolinguistics |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆