社会学的想像力

Sociological imagination

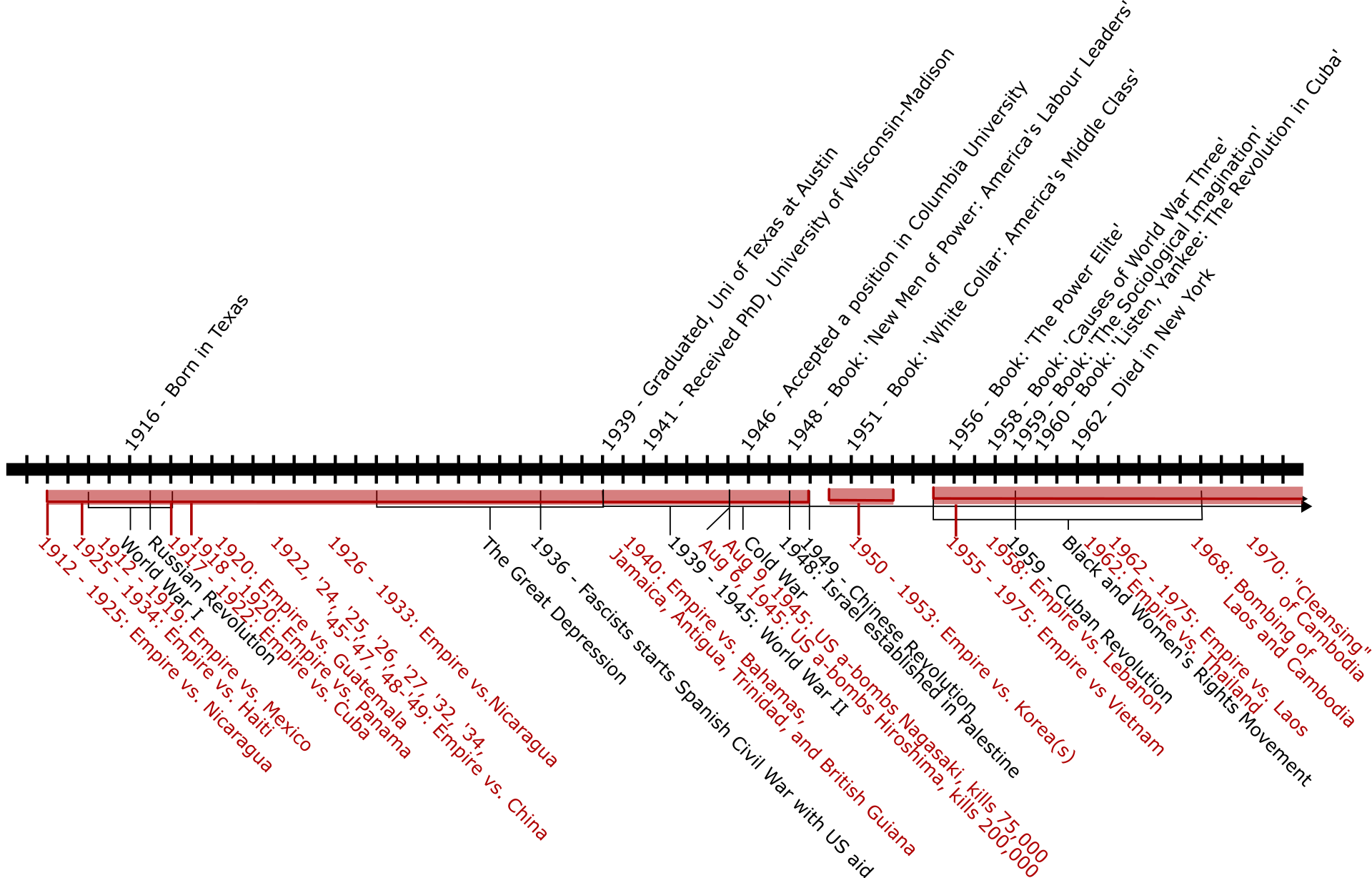

☆ 社会学的想像力(Sociological imagination; しゃかいがくてきそうぞうりょく)とは、社会学の分野で使われる用語で、個人の経験をより広い社会的・歴史的文脈の中に位置づけることで、社会の現実を理 解する枠組みを表す。 アメリカの社会学者C.ライト・ミルズが1959年に出版した『社会学的想像力』において、社会学という学問分野が提供する洞察の種類を説明するために用 いた造語である。今日、この用語は社会学の本質と日常生活における関連性を説明するために、多くの社会学の教科書で用いられている。

| Sociological

imagination is a term used in the field of sociology to describe a

framework for understanding social reality that places personal

experiences within a broader social and historical context.[1] It was coined by American sociologist C. Wright Mills in his 1959 book The Sociological Imagination to describe the type of insight offered by the discipline of sociology.[2]: 5, 7 Today, the term is used in many sociology textbooks to explain the nature of sociology and its relevance in daily life.[1] |

社会学的想像力(しゃかいがくてきそうぞうりょく)とは、社会学の分野

で使われる用語で、個人の経験をより広い社会的・歴史的文脈の中に位置づけることで、社会の現実を理解する枠組みを表す[1]。 アメリカの社会学者C.ライト・ミルズが1959年に出版した『社会学的想像力』において、社会学という学問分野が提供する洞察の種類を説明するために用 いた造語である[2]: 5, 7 今日、この用語は社会学の本質と日常生活における関連性を説明するために、多くの社会学の教科書で用いられている[1]。 |

| Definitions In The Sociological Imagination, Mills attempts to reconcile two different and abstract concepts of social reality: the "individual" and the "society."[3] Accordingly, Mills defined sociological imagination as "the awareness of the relationship between personal experience and the wider society."[2] In exercising one's sociological imagination, one seeks to understand situations in one's life by looking at situations in broader society. For example, a single student who fails to keep up with the academic demands of college and ends up dropping out may be perceived to have faced personal difficulties or faults; however, when one considers that around 50% of college students in the United States fail to graduate, we can understand this one student's trajectory as part of a larger social issue. It is not about claiming that any outcome has entirely personal or entirely social causes, rather, it is about highlighting the connections between the two.[4][5] Later sociologists have different perspectives on the concept, but they share some overlapping themes. Sociological imagination is an outlook on life that involves an individual developing a deep understanding of how their biography is a result of historical process and occurs within a larger social context.[6] As per Anthony Giddens, the term is: The application of imaginative thought to the asking and answering of sociological questions. Someone using the sociological imagination "thinks himself away" from the familiar routines of daily life.[6] There is an urge to know the historical and sociological meaning of the singular individual in society, particularly within their time period. To do this, one may use the sociological imagination to better understand the larger historical scene in terms of its meaning for an individual's inner self and external career.[2]: 5, 7 The sociological imagination can be seen practiced if one reflects on their history for all past events have led up to the present, mostly following the same pattern. Mills argued that history is an important element in sociological imagination. These different historical events have shaped modern society as a whole and each individual within it. It allows a person to see where their life is at compared to others, based on past experiences. Mills argues that one can only truly understand themselves if they can truly understand their circumstances.[7] Another perspective is that Mills chose sociology because he felt it was a discipline that "could offer the concepts and skills to expose and respond to social injustice."[8] He eventually became disappointed with his profession of sociology because he felt it was abandoning its responsibilities, which he criticized in The Sociological Imagination. In some introductory sociology classes, Mills' characterization of the sociological imagination is presented as a critical quality of mind that can help individuals "to use information and to develop reason in order to achieve lucid summations of what is going on in the world and of what may be happening within themselves."[9] |

定義 ミルズは『社会学的想像力』において、「個人」と「社会」[3]という2つの異なる抽象的な社会的現実の概念を調和させようと試みている。 社会学的想像力を働かせる際、人はより広い社会の状況を見ることで、自分の人生の状況を理解しようとする。例えば、大学の学問的な要求についていけず、中 途退学に至った一人の学生は、個人的な困難や欠点に直面したと受け止められるかもしれない。しかし、米国の大学生の約50%が卒業できていないことを考え ると、この一人の学生の軌跡を、より大きな社会問題の一部として理解することができる。どのような結果であれ、その原因が完全に個人的なものであるとか、 完全に社会的なものであると主張するのではなく、むしろ両者のつながりを強調することなのである[4][5]。 後世の社会学者たちは、この概念について異なる視点を持っているが、いくつかの重複するテーマを共有している。 社会学的想像力とは、自分の生い立ちがいかに歴史的なプロセスの結果であり、より大きな社会的文脈の中で生じているのかについて、個人が深く理解すること を含む人生観である[6]。 アンソニー・ギデンズによれば、この用語は次のようなものである: アンソニー・ギデンズによれば、社会学的想像力とは次のようなものである。社会学的想像力を用いる人物は、日常生活の慣れ親しんだルーティンから「自分自 身を離れて考える」のである[6]。 社会における特異な個人の歴史的・社会学的な意味を、特にその時代の中で知りたいという衝動がある。そのためには、社会学的想像力を用いて、個人の内面や 外面的なキャリアにとっての意味という観点から、より大きな歴史的シーンをよりよく理解することができる[2]: 5, 7 社会学的想像力は、過去の出来事がすべて現在につながっており、そのほとんどが同じパターンをたどっているからである。ミルズは、歴史は社会学的想像力に おいて重要な要素であると主張した。このようなさまざまな歴史的出来事が、現代社会全体とその中の各個人を形成してきた。それによって人は、過去の経験に 基づき、自分の人生が他の人と比べてどのような位置にあるのかを知ることができる。ミルズは、人は自分の置かれた状況を真に理解することができる場合にの み、自分自身を真に理解することができると主張している[7]。 もう一つの視点は、ミルズが社会学を選んだのは、それが「社会的不公正を暴き、それに対応するための概念とスキルを提供できる」学問であると感じたからで ある[8]。彼は最終的に、社会学がその責任を放棄していると感じたため、社会学という職業に失望し、『社会学的想像力』の中でそれを批判した。いくつか の社会学の入門クラスでは、ミルズによる社会学的想像力の特徴は、個人が「世界で起こっていること、そして自分自身の中で起こっているかもしれないことに ついて明晰な総括を達成するために、情報を利用し、理性を発達させる」ことを助けることができる心の批評的資質として提示されている[9]。 |

| Real-life application Lack of sociological imagination The sociological imagination allows one to make more self-aware decisions, rather than be swayed by social norms or factors that may otherwise dictate actions. The lack of a sociological imagination can make people apathetic. This apathy expresses itself as a lack of indignation in scenarios dealing with moral horror—the Holocaust is a classic example of what happens when a society renders itself to the power of a leader and doesn't use sociological imagination. Social apathy can lead to accepting atrocities performed by leaders (political or familiar) and the lack of ability to react morally to their leaders' actions and decisions. The Holocaust was based on the principle of absolute power in a dictatorship, where society fell victim to apathy and willingly looked away from the horrors they committed. They willfully accepted the decisions taken by Adolf Hitler and carried out the orders because they had lost self-awareness and moral code, adopting the new social moral code. In doing this, they lost the ability to morally react to Hitler's command and in turn slaughtered more than 6,000,000 Jews, other minorities, and disabled persons.[10] |

実生活への応用 社会学的想像力の欠如 社会学的想像力があれば、社会的規範や要因に振り回されることなく、より自覚的な決断を下すことができる。社会学的想像力の欠如は人を無気力にする。この 無気力は、道徳的な恐怖を扱うシナリオにおいて、憤りの欠如として表れる。ホロコーストは、社会が指導者の権力に身を委ね、社会学的想像力を働かせない場 合に起こる典型的な例である。社会的無関心は、指導者(政治家や身近な人)が行う残虐行為を受け入れ、指導者の行動や決定に道徳的に反応する能力を欠くこ とにつながる。ホロコーストは、独裁者による絶対的権力の原理に基づいており、社会は無関心の犠牲となり、彼らが犯した恐怖から進んで目をそらした。彼ら はアドルフ・ヒトラーが下した決定を故意に受け入れ、命令を実行した。なぜなら、彼らは自己認識と道徳規範を失い、新しい社会的道徳規範を採用したからで ある。そうすることで、彼らはヒトラーの命令に道徳的に反応する能力を失い、結果的に600万人以上のユダヤ人、その他の少数民族、障害者を虐殺した [10]。 |

| Uses in films Those who teach courses in social problems report[citation needed] using films to teach about war, to aid students in adopting a global perspective, and to confront issues of race relations. There are benefits of using film as part of a multimedia approach to teaching courses in popular culture. It provides students of medical sociology with case studies for hands-on observational experiences. It acknowledges the value of films as historical documentation of changes in cultural ideas, materials, and institutions. Feature films are used in introductory sociology courses to demonstrate the current relevance of sociological thinking, and how the sociological imagination helps people understand their social world. As a familiar medium, films help students connect their own experiences to broader theory.[11] The underlying assumption is that the sociological imagination is best developed and exercised in introductory classes by placing course material in the context of conflict theory and functionalism.[12] Using the sociological imagination to analyze feature films is somewhat important to the average sociological standpoint, but more important is the fact that this process develops and strengthens the sociological imagination as a tool for understanding. Sociology and filmmaking go hand-in-hand because of the potential for viewers to react differently to the same message and theme; this creates room to debate these different interpretations. For example, imagine a film that introduces a character from four different angles and situations in life, each of which draws upon social, psychological, and moral standards to form a central ideal that echoes the narrative outcome, the reasoning behind individuals' actions, and the story's overall meaning. Through watching this film, discussions may take place amongst viewers (such as about the entertainment satisfaction, or the interpretations of the film's themes). In these discussions, plot points are made, conclusions are drawn upon, and societal problems and situations are addressed. Viewers may determine what is morally permissible or not, discuss beneficial and efficient ways to help people, and produce new ideas through correlating ideologies and aspects. This process strengthens sociological imagination because it can add sociological perspective to a viewer's state of mind.[13] |

映画での使い方 社会問題の講義を担当する人たちは、戦争について教えたり、学生がグローバルな視点を持てるようにしたり、人種関係の問題に立ち向かったりするために、映 画を使っていると報告している[要出典]。大衆文化の講義を教えるマルチメディア・アプローチの一環として映画を使うことには利点がある。それは、医療社 会学の学生に、実践的な観察体験のためのケーススタディを提供することである。文化的な考え方、素材、制度の変化を歴史的に記録するものとして、映画の価 値を認めることができる。 長編映画は、社会学入門コースにおいて、社会学的思考の現在の妥当性を示すために、また社会学的想像力がいかに人々の社会的世界の理解に役立っているかを 示すために用いられる。身近なメディアである映画は、学生 が自分自身の経験をより広範な理論に結びつけるのを助ける。 長編映画を分析するために社会学的想像力を用いることは、平均的な社会学の立場にとっていくらか重要であるが、より重要なのは、このプロセスが理解のため のツールとして社会学的想像力を発展させ、強化するという事実である。社会学と映画制作は、同じメッセージやテーマに対して観客が異なる反応を示す可能性 があるため、密接な関係にある。 例えば、ある登場人物を4つの異なる角度や人生の状況から紹介し、それぞれが社会的、心理的、道徳的な基準をもとに、物語の結末、個人の行動の背後にある 理由、物語の全体的な意味と呼応する中心的な理想を形成する映画を想像してみよう。この映画を観ることで、観客の間で(エンターテイメントの満足度や、映 画のテーマの解釈などについて)議論が起こるかもしれない。このような議論の中で、筋書きが作られ、結論が導き出され、社会的な問題や状況が取り上げられ る。視聴者は、何が道徳的に許されるか許されないかを判断し、人々を助けるための有益で効率的な方法について議論し、イデオロギーや側面の相関関係を通し て新しいアイデアを生み出すかもしれない。このプロセスは、視聴者の心の状態に社会学的な視点を加えることができるため、社会学的想像力を強化する [13]。 |

| Application in sociological

studies Mills created tips to help conduct valid and reliable sociological studies using sociological imagination:[2] 1. Be a good craftsman: Avoid any rigid set of procedures. Above all, seek to develop and to use the sociological imagination. Avoid the fetishism of method and technique. Urge the rehabilitation of the unpretentious intellectual craftsman, and try to become such a craftsman yourself. Let every man be his own methodologist; let every man be his own theorist; let theory and method again become part of the practice of a craft. Stand for the primacy of the individual scholar; stand opposed to the ascendancy of research teams of technicians. Be one mind that is on its own confronting the problems of man and society. 2. Avoid the byzantine oddity of associated and disassociated Concepts, the mannerism of verbiage. Urge upon yourself and upon others the simplicity of clear statement. Use more elaborated terms only when you believe firmly that their use enlarges the scope of your sensibilities, the precision of your references, the depth of your reasoning. Avoid using unintelligibility as a means of evading the making of judgments upon society—and as a means of escaping your readers' judgments upon your own work. 3. Make any trans-historical constructions you think your work requires; also delve into sub-historical minutiae. Make up quite formal theory and build models as well as you can. Examine in detail little facts and their relations, and big unique events as well. But do not be fanatic: relate all such work, continuously and closely, to the level of historical reality. Do not assume that somebody else will do this for you, sometime, somewhere. Take as your task the defining of this reality; formulate your problems in its terms; on its level try to solve these problems and thus resolve the issues and the troubles they incorporate. And never write more than three pages without at least having in mind a solid example. 4. Do not study merely one small milieu after another; study the social structures in which milieux are organized. In terms of these studies of larger structures, select the milieux you need to study in detail, and study them in such a way as to understand the interplay of milieux with structure. Proceed in a similar way in so far as the span of time is concerned. Do not be merely a journalist, however a precise one. Know that journalism can be a great intellectual endeavor, but know also that yours is greater! So do not merely report minute researches into static knife-edge moments, or very short-term runs of time. Take as your time—span the course of human history, and locate within it the weeks, years, epochs you examine. 5. Realize that your aim is a fully comparative understanding of the social structures that have appeared and that do now exist in world history. Realize that to carry it out you must avoid the arbitrary specialization of prevailing academic departments. Specialize your work variously, according to topic, and above all according to significant problem. In formulating and in trying to solve these problems, do not hesitate, indeed seek, continually and imaginatively, to draw upon the perspectives and materials, the ideas and methods, of any and all sensible studies of man and society. They are your studies; they are part of what you are a part of; do not let them be taken from you by those who would close them off by weird jargon and pretensions of expertise. 6. Always keep your eyes open to the image of man—the generic notion of his human nature—which by your work you are assuming and implying; and also to the image of history—your notion of how history is being made. In a word, continually work out and revise your views of the problems of history, the problems of biography, and the problems of social structure in which biography and history intersect. Keep your eyes open to the varieties of individuality, and to the modes of epochal change. Use what you see and what you imagine, as the clues to your study of the human variety. 7. Know that you inherit and are carrying on the tradition of classic social analysis; so try to understand man not as an isolated fragment, not as an intelligible field or system in and of itself. Try to understand men and women as historical and social actors, and the ways in which the variety of men and women are intricately selected and intricately formed by the variety of human societies. Before you are through with any piece of work, no matter how indirectly on occasion, orient it to the central and continuing task of understanding the structure and the drift, the shaping and the meanings, of your own period, the terrible and magnificent world of human society in the second half of the twentieth century. 8. Do not allow public issues as they are officially formulated, or troubles as they are privately felt, to determine the problems that you take up for study. Above all, do not give up your moral and political autonomy by accepting in somebody else's terms the illiberal practicality of the bureaucratic ethos or the liberal practicality of the moral scatter. Know that many personal troubles cannot be solved merely as troubles, but must be understood in terms of public issues—and in terms of the problems of history-making. Know that the human meaning of public issues must be revealed by relating them to personal troubles—and to the problems of the individual life. Know that the problems of social science, when adequately formulated, must include both troubles and issues, both biography and history, and the range of their intricate relations. Within that range the life of the individual and the making of societies occur; and within that range the sociological imagination has its chance to make a difference in the quality of human life in our time. |

社会学研究における応用 ミルズ(Mills)は、社会学的想像力を用いて、妥当で信頼できる社会学的研究を行うためのヒントを以下のように作成した[2]。 1. 優れた職人であれ: 厳格な手続きを避ける。何よりも、社会学的想像力を発達させ、活用することを求める。方法と技法のフェティシズムを避ける。気取らない知的職人の復権を促 し、自らもそのような職人になろうとする。すべての人に自分自身の方法論者であれ、すべての人に自分自身の理論家であれ、理論と方法を再び工芸の実践の一 部とさせよ。個々の学者の優位性を主張し、技術者からなる研究チームの台頭に反対する。人間と社会の問題に立ち向かう、ひとつの精神であれ。 2. 関連したり関連しなかったりする概念や、冗長なマンネリ化を避けよ。自分自身にも他人にも、明瞭な声明の単純さを求める。より精巧な用語を 使うのは、それを使うことで自分の感性の幅が広がり、言及の正確さが増し、推論の深みが増すと固く信じる場合に限る。社会に対する判断を回避する手段とし て、また自分の作品に対する読者の判断を回避する手段として、わかりにくさを使わないようにすること。 3. 自分の作品に必要だと思われる歴史横断的な構築物を作り、また歴史以下の瑣末なことまで掘り下げる。かなり形式的な理論を作り上げ、できる 限りモデルを構築すること。小さな事実とその関係、そしてユニークな大きな出来事も詳細に調べること。しかし、狂信的になってはならない。そのような仕事 はすべて、継続的かつ綿密に、歴史的現実のレベルに関連づけること。いつかどこかで誰かがやってくれるだろうと思ってはいけない。この現実を定義すること を自分の仕事とし、自分の問題をこの現実の用語で定式化し、この現実のレベルでこれらの問題を解決しようとし、その結果、問題とそれが内包する問題を解決 しようとするのだ。そして、少なくとも確かな例を思い浮かべることなしに、3ページ以上を書いてはならない。 4. 単に小さなミリューを次々に研究するのではなく、ミリューが組織されている社会構造を研究すること。このような大きな構造の研究に関して は、詳しく研究すべきミリューを選び、ミリューと構造の相互作用を理解するように研究すること。時間的なスパンに関しても、同じように進める。単なる ジャーナリストであってはならない。ジャーナリズムが偉大な知的努力であることは知っているが、自分の方がもっと偉大であることも知っている!だから、静 的なナイフの刃のような瞬間や、ごく短期的な時間の流れについて、微細な調査を報告するだけであってはならない。人類史の流れをタイムスパンとし、その中 にあなたが調査する数週間、数年、数十年を見出すのだ。 5.あなたの目的は、世界史の中に登場し、現在も存在する社会構造を完 全に比較理解することであることを自覚する。それを遂行するためには、一般的な学問分野の恣意的な専門化を避けなければならないことを自覚 せよ。トピックに応じて、そして何よりも重要な問題に応じて、さまざまに専門化するのである。これらの問題を立案し、解決しようとするとき、人間と社会に 関するあらゆる良識ある研究の視点や材料、考え方や方法を利用することをためらってはならない。奇妙な専門用語や専門家気取りでそれらを閉ざそうとする人 々に、それらを奪われてはならない。 6. 自分の仕事によって想定し、暗示している人間のイメージ、つまり人間の本性に関する一般的な概念に常に目を向け、また歴史のイメージ、つまり歴史がどのよ うに作られているかについての自分の概念にも目を向けよ。一言で言えば、歴史の問題、伝記の問題、そして伝記と歴史が交差する社会構造の問 題について、絶えず自分の見解を練り上げ、修正していくことである。個性の多様性に、そしてエポック的な変化の様式に、常に目を開いていなさい。目にした もの、想像したものを、人間の多様性を研究する手がかりとせよ。 7. 古典的な社会分析の伝統を受け継ぎ、継承していることを自覚し、人間を孤立した断片としてではなく、それ自体として理解可能な領域やシステムとしてではな く、理解するように努めなさい。歴史的・社会的行為者としての男女を理解し、多様な男女が多様な人間社会によって複雑に選択され、複雑に形 成されていく様を理解しようとするのだ。どのような作品であれ、その時々にどんなに間接的なものであれ、それを読み終える前に、自分の時代、つまり20世 紀後半の人間社会の恐ろしくも壮大な世界の構造と流れ、形成と意味を理解するという、中心的かつ継続的な課題に方向づけよう。 8. 公的に定式化された公的な問題や、個人的に感じている問題によって、自分が研究対象として取り上げる問題を決めつけてはならない。とりわ け、官僚的エートスの非自由主義的実践性や道徳的散乱の自由主義的実践性を他人の言葉で受け入れることによって、自分の道徳的・政治的自律性を放棄しては ならない。多くの個人的な悩みは、単に悩みとして解決できるものではなく、公共的な問題という観点から、また歴史形成の問題という観点から理解されなけれ ばならないことを知れ。公的な問題の人間的な意味は、それを個人的な悩みと関連づけることによって、また個人的な生活の問題と関連づけることによって明ら かにされなければならないことを知る。社会科学の問題は、適切に定式化された場合、悩みと問題の両方、伝記と歴史の両方、およびそれらの複雑な関係の範囲 を含まなければならないことを知っている。そしてその範囲内で、社会学的想像力が、現代における人間生活の質に変化をもたらすチャンスがあるのである。 |

| Other theories Herbert Blumer, in his work Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method, developed the idea of a non-standard look at the world, which helps social scientists understand and analyze the study area.[14] One can see the empirical world only through some scheme or image of it. The entire act of scientific study is oriented and shaped by the underlying picture of the empirical world that is used. This picture sets the selection and formulation of problems, the determination of what are data, the means to be used in getting the data, the kinds of relations sought between data, and the forms in which propositions are cast. In view of this fundamental and pervasive effect wielded on the entire act of scientific inquiry by the initiating picture of the empirical world, it is ridiculous to ignore this picture. The underlying picture of the world is always capable of identification in the form of a set of premises. These premises are constituted by the nature given either explicitly or implicitly to the key objects that comprise the picture. The unavoidable task of genuine methodological treatment is to identify and assess these premises. Howard S. Becker, being a disciple of Blumer, continued to develop his idea of a particular look at the objects under study, and in 1998 wrote the book Tricks of the Trade: How to Think about Your Research While You're Doing It, wherein he gives a list of recommendations that may be useful in conducting sociological research. His main idea is to create a comprehensive picture of the object, phenomenon, or social group being studied. To this end, he proposes to pay particular attention to statistical and historical knowledge before conducting research; to use critical thinking, trying to create a universal picture of the world; and to make the result of the research understandable and acceptable for everyone.[15] Sociological perspective The related term "sociological perspective" was coined by Peter L. Berger, describing it as seeing "the general in the particular," and as helping sociologists realize general patterns in the behavior of specific individuals.[16] One can think of the sociological perspective as one's own personal choice and how society plays a role in shaping individuals' lives.[16] |

その他の理論 ハーバート・ブルーマーは、その著作『象徴的相互作用論』の中で、世界を非標準的に見るという考え方を展開した: パースペクティブと方法)において、社会科学者が研究領域を理解し分析するのに役立つ、世界に対する非標準的な視線という考え方を発展させた[14]。 人は経験的な世界を、それに関する何らかの図式やイメージを通してのみ見ることができる。科学的研究の全行為は、使用される経験的世界の根底にあるイメー ジによって方向づけられ、形成される。このイメージによって、問題の選択と定式化、データとは何かの決定、データを得るために使用する手段、データ間に求 められる関係の種類、命題の形式が決定される。このように、経験的な世界についての基本的な図式が、科学的探求の行為全体に及ぼす基本的かつ広範な影響を 考慮すると、この図式を無視するのは馬鹿げている。世界の根底にある図式は、常に一組の前提という形で特定することができる。これらの前提は、絵を構成す る重要な対象に明示的または暗黙的に与えられた性質によって構成される。真の方法論的治療の避けられない課題は、これらの前提を特定し、評価することであ る。 ブルーマーの弟子であるハワード・S・ベッカーは、研究対象に対する特別な視線という彼の考えを発展させ続け、1998年に『Tricks of the Trade: How to Think about Your Research While You're Do It』という本を書いた。彼の主な考え方は、研究対象、現象、社会集団の包括的な全体像を描くことである。この目的のために、彼は研究を行う前に統計的・ 歴史的知識に特に注意を払うこと、批判的思考を用い、世界の普遍的なイメージを作り出そうとすること、そして研究の結果を誰もが理解でき、受け入れられる ものにすることを提案している[15]。 社会学的視点 「社会学的観点」という関連用語はピーター・L・バーガーによって作られたものであり、「特定の中にある一般」を見ることであり、社会学者が特定の個人の 行動における一般的なパターンに気づくことを助けるものであると説明している[16]。社会学的観点とは、個人の選択であり、社会が個人の人生を形成する 上でどのような役割を果たしているかということであると考えることができる[16]。 |

| Role of social media The sociological imagination—the capacity to comprehend the wider social structures and processes that shape individual experiences—has emerged as a potent factor in influencing social media.[17] Social media platforms provide a huge arena for people to communicate, express their thoughts, and organize for social change. They have made it easier for online communities to emerge around common identities, experiences, and interests, extending social networks beyond physical borders. Additionally, social media platforms provide a venue for sharing the news, allowing users to access other viewpoints and contest prevailing narratives. But social media also has drawbacks, such as the spread of false information, the development of echo chambers, and the diminution of privacy.[18] |

ソーシャルメディアの役割 社会学的想像力(個人の経験を形成する、より広範な社会構造やプロセ スを理解する能力)は、ソーシャルメディアに影響を与える強力な要因として浮上 してきた。共通のアイデンティティや経験、関心事をめぐるオンライン・コミュニティが生まれやすくなり、社会的ネットワークは物理的な国境を越えて広がっ ている。 さらに、ソーシャルメディア・プラットフォームはニュースを共有する場を提供し、ユーザーが他の視点にアクセスしたり、一般的な物語に異議を唱えたりする ことを可能にしている。しかし、ソーシャルメディアには、偽情報の拡散、エコーチェンバーの発生、プライバシーの低下といった欠点もある[18]。 |

| Imaginary (sociology) Sociological theory |

イマジナリー(社会学) 社会学理論 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sociological_imagination |

|

The

Sociological Imagination is a 1959 book by American sociologist C.

Wright Mills published by Oxford University Press. In it, he develops

the idea of sociological imagination, the means by which the relation

between self and society can be understood.[1] The

Sociological Imagination is a 1959 book by American sociologist C.

Wright Mills published by Oxford University Press. In it, he develops

the idea of sociological imagination, the means by which the relation

between self and society can be understood.[1]Mills felt that the central task for sociology and sociologists was to find (and articulate) the connections between the particular social environments of individuals (also known as "milieu") and the wider social and historical forces in which they are enmeshed. The approach challenges a structural functionalist approach to sociology, as it opens new positions for the individual to inhabit with regard to the larger social structure. Individual function that reproduces larger social structure is only one of many possible roles and is not necessarily the most important. Mills also wrote of the danger of malaise (apathy),[clarification needed] which he saw as inextricably embedded in the creation and maintenance of modern societies. This led him to question whether individuals exist in modern societies in the sense that "individual" is commonly understood (Mills, 1959, 7–12). In writing The Sociological Imagination, Mills tried to reconcile two varying, abstract conceptions of social reality, the "individual" and the "society", and thereby challenged the dominant sociological discourse to define some of its most basic terms and be forthright about the premises behind its definitions. He began the project of reconciliation and challenge with critiques of "grand theory" and "abstracted empiricism", outlining and criticizing their use in the current sociology of the day. In 1998 the International Sociological Association listed the work as the second most important sociological book of the 20th century.[2] Background Mills drafted the book during 12-month Fulbright visit to University of Copenhagen over the period 1956-1957.[3] Grand theory In chapter two, Mills seems to be criticizing Parsonian Sociology, directly addressing The Social System, written by Talcott Parsons. In The Social System, Parsons describes the nature of the structure of society and the creation and maintenance of a culture through the socialization of individuals. Mills criticizes this tendency in sociology on several grounds. He argues for a more heterogeneous form of society in that he challenges the extent to which a single uniformity of society is indeed possible. Social order Mills criticizes the Parsonian formulation of social order, particularly the idea that social order can indeed be seen as a whole. He writes that every individual cannot simply be fully integrated into society and internalize all its cultural forms. Furthermore, such domination may be seen as a further extension of power and social stratification. Role of social theory He further criticizes Parsonian Sociology on its ability to theorize as a form of pure abstraction that society can be understood irrespective of its historical and contextual nature without observation. He argues that society and its cultural symbols cannot be seen as self-determining and cannot be derived without reference to individuals and their consciousness. All power according to Parsons is based on a system of beliefs enforced by society, writes Mills. In this he criticizes Parsons for his view in terms of historical and social change and diversity. He thereby criticizes the means by which a social order can be derived without observation. Abstracted empiricism In the third chapter Mills criticizes the empirical methods of social research which he saw as evident at the time in the conception of data and the handling of methodological tools. This can be seen as a reaction to the plethora of social research being developed from about the time of World War II. This can thereby be seen as much a criticism by Brewer that Mills may have been critical of the research being conducted and sponsored by the American government. As such Mills criticizes the methodological inhibition which he saw as characteristic of what he called abstracted empiricism. In this he can be seen criticizing the work of Paul F. Lazarsfeld who conceives of sociology not as a discipline but as a methodological tool (Mills, 1959, 55-59). He argues that the problem of such social research is that there may be a tendency towards "psychologism", which explains human behavior on the individual level without reference to the social context. This, he argues, may lead to the separation of research from theory. He then writes of the construction of milieu in relation to social research and how both theory and research are related (Mills, 1959, 65-68). The idea has drawn criticism, with Stephen J. Kunitz writing that "Abstracted Empiricists embraced a philosophy based upon what they considered natural science, emphasizing, according to Mills, the significance of Method over substance", with quantitative survey research being the favored practice, for which "large teams, budgets, and institutes were required, leading to the bureaucratization of scholarship and transforming it from a craft to an industrial process".[4] Another critique by Nigel Kettley states that the method "seeks to perfect the art of number crunching, while setting aside the cognitive processes involved in theory building as a form of morbid introspection".[5] The human variety In chapter seven Mills sets out what is thought to be his vision of Sociology. He writes of the need to integrate the social, biographical, and historical versions of reality in which individuals construct their social milieus with reference to the wider society (Mills, 1959, 132-134). He argues that the nature of society is continuous with historical reality. In doing so, Mills writes of the importance of the empirical adequacy of theoretical frameworks. He also writes of the notion of a unified social sciences. This he believes is not a conscious effort but is a result of the historical problem-based discourses out of which the disciplines developed, in which the divisions between the disciplines become increasingly fluid (Mills, 1959, 136-140). Thus, Mills sets out what he believed to be a problem-based approach to his conception of social sciences (140-142). On reason and freedom The call to social scientists in the Fourth Epoch Mills[6] opens "On Reason and Freedom" with the two facets of the sociological imagination (history and biography) in relationship to the social scientist. Mills asserts that it is time for social scientists to address the troubles of the individual and the issues of society to better understand the state of freedom specific to this historical moment. According to Mills, understanding personal troubles in relationship to social structure is the task of the social scientist.[7] Mills goes on to situate the reader in the historically specific moment that he wrote the book, or what Mills refers to as the Fourth Epoch. Mills explains that "nowadays men everywhere seek to know where they stand, where they may be going, and what—if anything—they can do about the present as history and the future as responsibility" (165).[6] To have a better understanding of the self and society, it is necessary to develop new ways of making sense of reality as old methods for understanding associated with liberalism and socialism are inadequate in this new epoch. Enlightenment promises associated with the previous epoch have failed; increased rationality moves society further away from freedom rather than closer to it. The Cheerful Robot and freedom Mills explains that highly rationalized organizations, such as bureaucracies, have increased in society; however, reason as used by the individual has not because the individual does not have the time or means to exercise reason. Mills differentiates reason and rationality. Reason, or that which is associated with critical and reflexive thought, can move individuals closer to freedom. On the other hand, rationality, which is associated with organization and efficiency, results in a lack of reason and the destruction of freedom. Despite this difference, rationality is often conflated with freedom. Greater rationality in society, as understood by Mills, results in the rationalization of every facet of life for the individual until there is the loss "of his capacity and will to reason; it also affects his chances and his capacity to act as a free man" (170).[6] This does not mean that individuals in society are unintelligent or hopeless. Mills is not suggesting determinism.[8] Under Mills' conception, freedom is not totally absent as the "average" individual in society has "a real potential for freedom".[9] Individuals have adapted to the rationalization of society. Mills believed in the individual's autonomy and potential to alter societal structures.[10] The individual who does not exercise reason and passively accepts their social position is referred to by Mills as "The Cheerful Robot" in which the individual is alienated from the self and society totally. Mills asks if, at some point and time in the future, individuals will accept this state of total rationality and alienation willingly and happily. This is a pressing concern as the Cheerful Robot is the "antithesis" of democratic society; the Cheerful Robot is the "ultimate problem of freedom" (175) as a threat to society's values.[6] According to Mills, social scientists must study social structure, using the sociological imagination, to understand the state of freedom in this epoch. Mills concludes this section of The Sociological Imagination with a call to social scientists: it is the promise of the social sciences to analyze the individual's troubles and society's issues in order to not only evaluate freedom in society but to foster it. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Sociological_Imagination |

『社

会学的想像力』(The Sociological

Imagination)は、アメリカの社会学者C・ライト・ミルズが1959年にオックスフォード大学出版局から出版した著書である。その中で彼は、自

己と社会の関係を理解するための手段である社会学的想像力という考え方を展開している[1]。 『社

会学的想像力』(The Sociological

Imagination)は、アメリカの社会学者C・ライト・ミルズが1959年にオックスフォード大学出版局から出版した著書である。その中で彼は、自

己と社会の関係を理解するための手段である社会学的想像力という考え方を展開している[1]。ミルズは、社会学と社会学者にとっての中心的な課題は、個人の特定の社会的環境(「ミリュー(milieu)」とも呼ばれる)と、彼らが巻き込まれている より広い社会的・歴史的な力とのつながりを見つけること(そして明確にすること)であると考えた。このアプローチは、社会学への構造的機能主義的アプロー チに挑戦するものであり、より大きな社会構造に対して個人が生息する新たな位置を開くものである。より大きな社会構造を再生産する個人の機能は、多くの可 能な役割のひとつにすぎず、必ずしも最も重要なものではない。ミルズはまた、現代社会の創造と維持に密接不可分に組み込まれていると見なした倦怠感(無気 力)の危険性についても書いている[clarification needed]。このことから彼は、「個人」が一般的に理解されているような意味で、近代社会に個人が存在するのかという疑問を抱くようになった (Mills, 1959, 7-12)。 ミルズ は『社会学的想像力』を執筆するなかで、社会的現実に関する「個 人」と「社会」という二つの多様で抽象的な概念を和解させようとし、そ れによって支配的な社会学的言説に対して、その最も基本的な用語のいくつ かを定義し、その定義の背後にある前提について率直であるよう挑 戦したのである。彼は、「グランド・セオリー」と「抽象化された経験主義」に対する批判から、和解と挑戦のプロジェクトを開始し、現在の社会学におけるそ れらの使用を概説し、批判した。 1998年、国際社会学会はこの著作を20世紀で2番目に重要な社会学書として挙げた[2]。 背景 ミルズは、1956年から1957年にかけてコペンハーゲン大学に12ヶ月間フルブライトで滞在している間にこの本の草稿を書いた[3]。 壮大な理論 第2章で、ミルズはタルコット・パーソンズが書いた『社会システム』を直接取り上げ、パーソニアン社会学を批判しているように見える。 パーソンズは『社会システム』の中で、社会の構造の本質と、個人の社会化による文化の創造と維持について述べている。ミルズ氏は、この社会学の傾向をいく つかの理由から批判している。彼は、単一の画一的な社会が果たしてどこまで可能なのかに疑問を投げかけ、より異質な社会のあり方を主張している。 社会秩序 ミルズが批判するのは、パーソン流の社会秩序の定式化である。彼は、すべての個人が単純に社会に完全に統合され、そのすべての文化的形態を内面化することはできないと書いている。さらに、このような支配は、権力と社会階層のさらなる拡張と見なされるかもしれない。 社会理論の役割 彼はさらに、パーソニアン社会学が、社会を観察することなく、その歴史的・文脈的性質とは無関係に理解できるという純粋な抽象化の一形態として理論化する能力について批判している。 彼は、社会とその文化的象徴は自己決定的なものとは見なせず、個人とその意識を参照することなしに導き出すことはできないと主張する。パーソンズによれ ば、すべての権力は社会によって強制された信念の体系に基づいている、とミルズは書いている。この点で、彼は歴史的・社会的変化と多様性という観点から パーソンズを批判している。 それによって彼は、観察なしに社会秩序を導き出す手段を批判している。 抽象化された経験主義 第3章では、ミルズが当時、データの概念や方法論的ツールの扱いにおいて顕著であると見ていた社会調査の経験的手法を批判している。 これは、第二次世界大戦前後から展開された社会調査の氾濫に対する反動と見ることができる。これによって、ミルズがアメリカ政府によって実施され、後援されている研究に対して批判的であったかもしれない、というブリュワーの批判と同じように見ることができる。 このようにミルズが批判しているのは、彼が抽象化された経験主義と呼ぶものの特徴として捉えていた方法論的阻害である。この点で、彼は社会学を学問として ではなく、方法論の道具として考えているポール・F・ラザースフェルドの仕事を批判していると見ることができる(Mills, 1959, 55-59)。 彼は、このような社会調査の問題点は、社会的文脈を参照することなく個人レベルで人間の行動を説明する「心理主義」への傾向があることだと主張している。 これは研究を理論から切り離すことにつながると彼は主張する。そして彼は、社会調査との関連におけるミリューの構築と、理論と調査がいかに関連しているか について書いている(Mills, 1959, 65-68)。 この考え方は批判を呼んでおり、スティーヴン・J・クニッツは、「抽象化された経験主義者たちは、彼らが自然科学とみなすものに基づいた哲学を受け入れ、 ミルズ曰く、実質よりも方法の重要性を強調した」と書いている。 [4] ナイジェル・ケトリーによる別の批評では、この方法は「理論構築に関わる認知的プロセスを病的な内省の一形態として脇に置きながら、数字を計算する技術を 完成させようとしている」と述べている[5]。 人間の多様性 第7章で、ミルズは社会学のビジョンと思われるものを示している。彼は、個人がより広範な社会を参照しながら自分たちの社会的基盤を構築する際の、現実の社会的、伝記的、歴史的バージョンを統合する必要性について書いている(Mills, 1959, 132-134)。 彼は、社会の本質は歴史的現実と連続的であると主張する。その際、ミルズは理論的枠組みの経験的妥当性の重要性を説いている。彼はまた、統一された社会科 学という概念についても書いている。これは意識的な努力ではなく、学問分野が発展した歴史的な問題に基づく言説の結果であり、その中で学問分野間の区分は ますます流動的になると彼は考えている(Mills, 1959, 136-140)。このように、ミルズは、社会科学の概念について、問題に基づくアプローチであると考えられるものを提示している(140-142)。 理性と自由について 第4エポックにおける社会科学者への呼びかけ ミルズ[6]は「理性と自由について」の冒頭で、社会学的想像力の2つの側面(歴史と伝記)と社会科学者との関係について述べている。ミルズは、この歴史 的瞬間に特有の自由の状態をよりよく理解するために、社会科学者は個人の悩みと社会の問題に取り組むべき時であると主張している。ミルズによれば、個人の 問題を社会構造との関係で理解することが社会科学者の仕事である[7]。 ミルズがこの本を書いた歴史的に特定の瞬間、つまりミルズが「第4の時代」と呼ぶ時代に読者を位置づける。自己と社会についてよりよく理解するためには、 現実を理解するための新しい方法を開発することが必要である。以前のエポックに関連した啓蒙主義の約束は失敗した。合理性の向上は、社会を自由に近づける どころか、むしろ自由から遠ざけている。 明るいロボットと自由 ミルズは、官僚組織のような高度に合理化された組織は社会で増加したが、個人が使う理性は増加しなかったと説明する。ミルズ氏は理性と合理性を区別してい る。理性、つまり批判的で反省的な思考に関連するものは、個人を自由に近づけることができる。一方、組織や効率と結びついた合理性は、理性の欠如と自由の 破壊をもたらす。この違いにもかかわらず、合理性はしばしば自由と混同される。 ミルズが理解するように、社会で合理性が高まると、個人の生活のあらゆる面が合理化され、「理性的な能力と意志が失われ、自由な人間として行動するチャン スと能力も失われる」(170)。ミルズは決定論を示唆しているわけではない[8]。ミルズの概念のもとでは、社会における「平均的な」個人は「自由に対 する現実的な可能性」を持っているので、自由がまったくないわけではない[9]。ミルズは個人の自律性と社会構造を変える可能性を信じていた[10]。 理性を発揮せず、受動的に社会的立場を受け入れる個人は、ミルズによって「陽気なロボット」と呼ばれ、その個人は自己と社会から完全に疎外されている。ミ ルズが問うのは、未来のある時点、ある時期において、個人がこの完全な理性と疎外状態を進んで、喜んで受け入れるようになるのか、ということである。これ は、チアフル・ロボットが民主主義社会の「アンチテーゼ」であり、社会の価値観を脅かすものとして「自由の究極の問題」(175)であることから、差し 迫った関心事である[6]。ミルズによれば、社会科学者は、この時代における自由の状態を理解するために、社会学的想像力を用いて社会構造を研究しなけれ ばならない。社会における自由を評価するだけでなく、それを育むために、個人の悩みや社会の問題を分析することが社会科学の約束なのである。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆