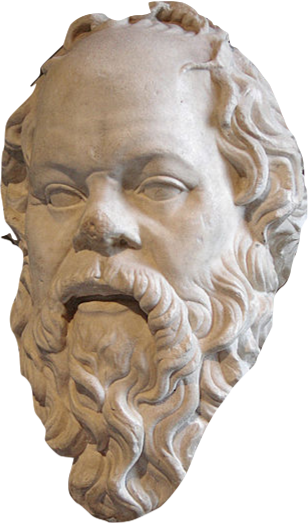

ソクラテス

Socrates, 470 B.C. - 399 B.C.

☆

ソクラテス(Socrates /ˈsɒkrətiːz/、

[2] ギリシア語:

Σωκράτης、紀元前470年頃~紀元前399年)は、西洋哲学の創始者であり、倫理的思考の伝統における最初の道徳哲学者の一人として評価されてい

るアテネ出身のギリシアの哲学者である。謎めいた人物であったソクラテスは著作を残しておらず、主に彼の弟子であるプラトンやクセノフォンといった古典作

家による死後の記述で知られている。これらの記述は対話形式で書かれており、ソクラテスとその対話者が質問と回答のスタイルで主題を検証している。ソクラテスに関する矛盾した記述により、彼の哲学を再構築することはほぼ不可能であり、この状況はソクラテス問題として知られている。ソクラテスはアテナイ社会で賛否両論を呼ぶ人物であった。紀元前399年、彼は不敬罪と青少年の堕落の罪で告発された。1日間にわたる裁判の後、彼は死刑判決を受けた。彼は刑務所で最後の1日を過ごし、脱獄を手助けする申し出を断った。

プラトンの対話録は、古代から伝わるソクラテスに関する最も包括的な記録である。それらは、認識論や倫理学など、哲学の分野におけるソクラテス的アプローチを示している。プラトンのソクラテスは、ソクラテス的手法やソクラテス的皮肉という概念にその名を貸している。ソ

クラテス式質問法、または「エレクシス」は、短い質問と答えを繰り返す対話の中で形作られる。ソクラテスとその対話者が、ある問題や抽象的な意味合いのさ

まざまな側面を吟味し、通常美徳の1つに関連して、自分が理解したと思ったことを定義できないという行き詰まりに陥る、プラトンのテキストに典型的に表さ

れている。ソクラテスは、自分が無知であることを全面的に宣言することで知られており、自分が認識しているのは無知だけだとよく言っていた。これは、無知を認識することが哲学の第一歩であるこ

とを示唆しようとしたものである。

ソクラテスは後世の哲学者たちに強い影響を与え、現代においてもその影響は続いている。中世やイスラムの学者たちによって研究され、イタリア・ルネサン

ス、特に人文主義運動の思想において重要な役割を果たした。ソレン・キルケゴールやフリードリヒ・ニーチェの作品にも反映されているように、彼への関心は

衰えることなく続いている。芸術、文学、大衆文化におけるソクラテスの描写により、彼は西洋哲学の伝統において広く知られる人物となった。

| Socrates

(/ˈsɒkrətiːz/;[2] Greek: Σωκράτης; c. 470 – 399 BC) was a Greek

philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western

philosophy and as among the first moral philosophers of the ethical

tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no texts

and is known mainly through the posthumous accounts of classical

writers, particularly his students Plato and Xenophon. These accounts

are written as dialogues, in which Socrates and his interlocutors

examine a subject in the style of question and answer; they gave rise

to the Socratic dialogue literary genre. Contradictory accounts of

Socrates make a reconstruction of his philosophy nearly impossible, a

situation known as the Socratic problem. Socrates was a polarizing

figure in Athenian society. In 399 BC, he was accused of impiety and

corrupting the youth. After a trial that lasted a day, he was sentenced

to death. He spent his last day in prison, refusing offers to help him

escape. Plato's dialogues are among the most comprehensive accounts of Socrates to survive from antiquity. They demonstrate the Socratic approach to areas of philosophy including epistemology and ethics. The Platonic Socrates lends his name to the concept of the Socratic method, and also to Socratic irony. The Socratic method of questioning, or elenchus, takes shape in dialogue using short questions and answers, epitomized by those Platonic texts in which Socrates and his interlocutors examine various aspects of an issue or an abstract meaning, usually relating to one of the virtues, and find themselves at an impasse, completely unable to define what they thought they understood. Socrates is known for proclaiming his total ignorance; he used to say that the only thing he was aware of was his ignorance, seeking to imply that the realization of our ignorance is the first step in philosophizing. Socrates exerted a strong influence on philosophers in later antiquity and has continued to do so in the modern era. He was studied by medieval and Islamic scholars and played an important role in the thought of the Italian Renaissance, particularly within the humanist movement. Interest in him continued unabated, as reflected in the works of Søren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche. Depictions of Socrates in art, literature, and popular culture have made him a widely known figure in the Western philosophical tradition. |

ソクラテス(/ˈsɒkrətiːz/、[2] ギリシア語:

Σωκράτης、紀元前470年頃~紀元前399年)は、西洋哲学の創始者であり、倫理的思考の伝統における最初の道徳哲学者の一人として評価されてい

るアテネ出身のギリシアの哲学者である。謎めいた人物であったソクラテスは著作を残しておらず、主に彼の弟子であるプラトンやクセノフォンといった古典作

家による死後の記述で知られている。これらの記述は対話形式で書かれており、ソクラテスとその対話者が質問と回答のスタイルで主題を検証している。ソクラ

テスに関する矛盾した記述により、彼の哲学を再構築することはほぼ不可能であり、この状況はソクラテス問題として知られている。ソクラテスはアテナイ社会

で賛否両論を呼ぶ人物であった。紀元前399年、彼は不敬罪と青少年の堕落の罪で告発された。1日間にわたる裁判の後、彼は死刑判決を受けた。彼は刑務所

で最後の1日を過ごし、脱獄を手助けする申し出を断った。 プラトンの対話録は、古代から伝わるソクラテスに関する最も包括的な記録である。それらは、認識論や倫理学など、哲学の分野におけるソクラテス的アプロー チを示している。プラトンのソクラテスは、ソクラテス的手法やソクラテス的皮肉という概念にその名を貸している。ソクラテス式質問法、または「エレクシ ス」は、短い質問と答えを繰り返す対話の中で形作られる。ソクラテスとその対話者が、ある問題や抽象的な意味合いのさまざまな側面を吟味し、通常美徳の1 つに関連して、自分が理解したと思ったことを定義できないという行き詰まりに陥る、プラトンのテキストに典型的に表されている。ソクラテスは、自分が無知 であることを全面的に宣言することで知られており、自分が認識しているのは無知だけだとよく言っていた。これは、無知を認識することが哲学の第一歩である ことを示唆しようとしたものである。 ソクラテスは後世の哲学者たちに強い影響を与え、現代においてもその影響は続いている。中世やイスラムの学者たちによって研究され、イタリア・ルネサン ス、特に人文主義運動の思想において重要な役割を果たした。ソレン・キルケゴールやフリードリヒ・ニーチェの作品にも反映されているように、彼への関心は 衰えることなく続いている。芸術、文学、大衆文化におけるソクラテスの描写により、彼は西洋哲学の伝統において広く知られる人物となった。 |

| Socrates

did not document his teachings. All that is known about him comes from

the accounts of others: mainly the philosopher Plato and the historian

Xenophon, who were both his pupils; the Athenian comic dramatist

Aristophanes (Socrates's contemporary); and Plato's pupil Aristotle,

who was born after Socrates's death. The often contradictory stories

from these ancient accounts only serve to complicate scholars' ability

to reconstruct Socrates's true thoughts reliably, a predicament known

as the Socratic problem.[3] The works of Plato, Xenophon, and other

authors who use the character of Socrates as an investigative tool, are

written in the form of a dialogue between Socrates and his

interlocutors and provide the main source of information on Socrates's

life and thought. Socratic dialogues (logos sokratikos) was a term

coined by Aristotle to describe this newly formed literary genre.[4]

While the exact dates of their composition are unknown, some were

probably written after Socrates's death.[5] As Aristotle first noted,

the extent to which the dialogues portray Socrates authentically is a

matter of some debate.[6] Plato and Xenophon An honest man, Xenophon was no trained philosopher.[7] He could neither fully conceptualize nor articulate Socrates's arguments.[8] He admired Socrates for his intelligence, patriotism, and courage on the battlefield.[8] He discusses Socrates in four works: the Memorabilia, the Oeconomicus, the Symposium, and the Apology of Socrates. He also mentions a story featuring Socrates in his Anabasis.[9] Oeconomicus recounts a discussion on practical agricultural issues.[10] Like Plato's Apology, Xenophon's Apologia describes the trial of Socrates, but the works diverge substantially and, according to W. K. C. Guthrie, Xenophon's account portrays a Socrates of "intolerable smugness and complacency".[11] Symposium is a dialogue of Socrates with other prominent Athenians during an after-dinner discussion, but is quite different from Plato's Symposium: there is no overlap in the guest list.[12] In Memorabilia, he defends Socrates from the accusations of corrupting the youth and being against the gods; essentially, it is a collection of various stories gathered together to construct a new apology for Socrates.[13] Plato's representation of Socrates is not straightforward.[14] Plato was a pupil of Socrates and outlived him by five decades.[15] How trustworthy Plato is in representing the attributes of Socrates is a matter of debate; the view that he did not represent views other than Socrates's own is not shared by many contemporary scholars.[16] A driver of this doubt is the inconsistency of the character of Socrates that he presents.[17] One common explanation of this inconsistency is that Plato initially tried to accurately represent the historical Socrates, while later in his writings he was happy to insert his own views into Socrates's words. Under this understanding, there is a distinction between the Socratic Socrates of Plato's earlier works and the Platonic Socrates of Plato's later writings, although the boundary between the two seems blurred.[18] Xenophon's and Plato's accounts differ in their presentations of Socrates as a person. Xenophon's Socrates is duller, less humorous and less ironic than Plato's.[8][19] Xenophon's Socrates also lacks the philosophical features of Plato's Socrates—ignorance, the Socratic method or elenchus—and thinks enkrateia (self-control) is of pivotal importance, which is not the case with Plato's Socrates.[20] Generally, logoi Sokratikoi cannot help us to reconstruct the historical Socrates even in cases where their narratives overlap, as authors may have influenced each other's accounts.[21] Aristophanes and other sources Writers of Athenian comedy, including Aristophanes, also commented on Socrates. Aristophanes's most important comedy with respect to Socrates is The Clouds, in which Socrates is a central character.[22] In this drama, Aristophanes presents a caricature of Socrates that leans towards sophism,[23] ridiculing Socrates as an absurd atheist.[24] Socrates in Clouds is interested in natural philosophy, which conforms to Plato's depiction of him in Phaedo. What is certain is that by the age of 45, Socrates had already captured the interest of Athenians as a philosopher.[25] It is not clear whether Aristophanes's work is useful in reconstructing the historical Socrates.[26] Other ancient authors who wrote about Socrates were Aeschines of Sphettus, Antisthenes, Aristippus, Bryson, Cebes, Crito, Euclid of Megara, Phaedo and Aristotle, all of whom wrote after Socrates's death.[27] Aristotle was not a contemporary of Socrates; he studied under Plato at the latter's Academy for twenty years.[28] Aristotle treats Socrates without the bias of Xenophon and Plato, who had an emotional tie with Socrates, and he scrutinizes Socrates's doctrines as a philosopher.[29] Aristotle was familiar with the various written and unwritten stories of Socrates.[30] His role in understanding Socrates is limited. He does not write extensively on Socrates; and, when he does, he is mainly preoccupied with the early dialogues of Plato.[31] There are also general doubts on his reliability on the history of philosophy.[32] Still, his testimony is vital in understanding Socrates.[33] The Socratic problem Main article: Socratic problem In a seminal work titled "The Worth of Socrates as a Philosopher" (1818), the philosopher Friedrich Schleiermacher attacked Xenophon's accounts; his attack was widely accepted.[34] Schleiermacher criticized Xenophon for his naïve representation of Socrates. Xenophon was a soldier, argued Schleiermacher, and was therefore not well placed to articulate Socratic ideas. Furthermore, Xenophon was biased in his depiction of his former friend and teacher: he believed Socrates was treated unfairly by Athens, and sought to prove his point of view rather than to provide an impartial account. The result, said Schleiermacher, was that Xenophon portrayed Socrates as an uninspiring philosopher.[35] By the early 20th century, Xenophon's account was largely rejected.[36] The philosopher Karl Joel, basing his arguments on Aristotle's interpretation of logos sokratikos, suggested that the Socratic dialogues are mostly fictional: according to Joel, the dialogues' authors were just mimicking some Socratic traits of dialogue.[37] In the mid-20th century, philosophers such as Olof Gigon and Eugène Dupréel, based on Joel's arguments, proposed that the study of Socrates should focus on the various versions of his character and beliefs rather than aiming to reconstruct a historical Socrates.[38] Later, ancient philosophy scholar Gregory Vlastos suggested that the early Socratic dialogues of Plato were more compatible with other evidence for a historical Socrates than his later writings, an argument that is based on inconsistencies in Plato's own evolving depiction of Socrates. Vlastos totally disregarded Xenophon's account except when it agreed with Plato's.[38] More recently, Charles H. Kahn has reinforced the skeptical stance on the unsolvable Socratic problem, suggesting that only Plato's Apology has any historical significance.[39] |

ソ

クラテスは自分の教えを記録しなかった。彼について知られていることはすべて、主に彼の弟子であった哲学者プラトンと歴史家クセノフォン、アテネの喜劇作

家アリストパネス(ソクラテスの同時代人)、プラトンの弟子でソクラテスの死後に生まれたアリストテレスによる記述による。これらの古代の記録にはしばし

ば矛盾した記述があるため、ソクラテスの真の思想を確実に再構築することは学者にとって非常に困難であり、この難題は「ソクラテス問題」として知られてい

る[3]。プラトン、クセノフォン、ソクラテスを調査の手段として用いた他の著者の作品は、ソクラテスとその対話者の対話形式で書かれており、ソクラテス

の生涯と思想に関する主な情報源となっている。ソクラテス対話(ロゴス・ソクラティコス)は、この新しく形成された文学ジャンルを表すためにアリストテレ

スが作った言葉である[4]。正確な成立時期は不明だが、ソクラテスの死後に書かれたものもある[5]。アリストテレスが最初に指摘したように、ソクラテ

スをどの程度正確に描写しているかは議論の余地がある[6]。 プラトンとクセノフォン 誠実な人物であったクセノフォンは、訓練を受けた哲学者ではなかった[7]。彼はソクラテスの議論を完全に概念化することも、明確に表現することもできな かった[8]。彼はソクラテスの知性、愛国心、戦場での勇気を称賛していた[8]。彼は『回想録』、『エコノミクス』、『ソクラテスの弁論』、『ソクラテ スの弁明』の4つの著作でソクラテスについて論じている。アナバシス』では、ソクラテスが登場する物語についても触れている[9]。『オイコノミコス』 は、農業に関する実際的な問題についての議論を記している[10]。プラトンの『アポリオン』と同様に、クセノフォンの『アポリオーリア』もソクラテスの 裁判について述べているが、両者の内容は大きく異なり、W. K. C. ガースリーによると、クセノフォンの記述は「耐え難い傲慢さと自己満足」に満ちたソクラテスを描いている[ 11] 『ソクラテスの対話』は、ソクラテスが夕食後の談話でアテネの著名人と交わした対話であるが、プラトンの『ソクラテスの対話』とはかなり異なる。ゲストリ ストに重複はない[12]。『回想録』では、ソクラテスが若者を堕落させ、神々に敵対しているという非難からソクラテスを擁護している。本質的には、ソク ラテスに対する新たな弁明を構築するために集められたさまざまな物語のコレクションである[13]。 プラトンのソクラテス像は単純明快ではない[14]。プラトンはソクラテスの弟子であり、ソクラテスより50年も長生きした[15]。プラトンがソクラテ スの特性をどの程度正確に表現しているかは議論の的となっている。プラトンはソクラテスの意見以外のものは表現していないという見解は [16] この疑問の背景には、プラトンが描くソクラテスの性格の不一致がある[17]。この不一致について、よく聞かれる説明は、プラトンは当初、歴史上のソクラ テスを正確に描写しようとしていたものの、後になって自分の見解をソクラテスの言葉の中に挿入することをいとわなくなった、というものだ。この理解に基づ くと、プラトンの初期の著作に登場するソクラテスと、プラトンの後期の著作に登場するプラトニックなソクラテスには違いがあるものの、その境界は曖昧であ るように見える[18]。 クセノフォンとプラトンのソクラテスの描写は、ソクラテスという人物の描写において異なっている。クセノフォンのソクラテスは、プラトンのソクラテスより も退屈でユーモアがなく、皮肉も少ない[8][19]。クセノフォンのソクラテスは、プラトンのソクラテスの哲学的特徴である無知、ソクラテス的手法、エ レクテュスを欠いており、エンクラテイヤ(自己 -コントロール)が極めて重要だと考えているが、これはプラトンのソクラテスには見られない特徴である[20]。一般的に、ソクラテスの言葉(ロゴス・ソ クラテコス)は、たとえ記述が重複している場合でも、歴史上のソクラテスを再構築する助けにはならない。なぜなら、著者は互いに影響を与え合っていた可能 性があるからだ[21]。 アリストパネスとその他の情報源 アリストパネスを含むアテナイ喜劇の作家たちもソクラテスについて論じている。アリストパネスが書いたソクラテスに関する最も重要な喜劇は『雲』で、ソク ラテスが主役となっている[22]。この劇の中でアリストパネスは、ソクラテスを諧謔的に描いており、ソクラテスを詭弁家として嘲笑している[23]。 『雲』のソクラテスは自然哲学に興味を持っており、これは『パイドス』でプラトンが描いたソクラテス像と一致している。確かなことは、ソクラテスが45歳 になる頃には、すでに哲学者としてアテナイ人の興味を引いていたということである[25]。アリストパネスの作品が歴史上のソクラテスを再構築するのに役 立つかどうかは明らかではない[26]。 ソクラテスについて書いた古代の著者は他に、スポエトゥスのエスキネス、アンティステネス、アリスティッポス、ブライソン、ケベス、クリト、メガラのユー クリッド、ファイドス、アリストテレスがいるが、いずれもソクラテスの死後に著述した人物である[27]。アリストテレスはソクラテスの同時代の人物では なく、プラトンのアカデミアで20年間学んだ[28]。20年間、プラトンのアカデミーで学んだ[28]。アリストテレスは、ソクラテスと感情的な絆を 持っていたクセノフォンやプラトンの偏見なしにソクラテスを扱い、哲学者としてソクラテスの教説を精査している[29]。アリストテレスは、ソクラテスの さまざまな口承および書物による逸話をよく知っていた[30]。アリストテレスがソクラテスを理解する上で果たす役割は限られている。彼はソクラテスにつ いて広範囲にわたって書いていない。また、書くとしても、主にプラトンの初期の対話に焦点を当てている[31]。哲学史における彼の信頼性についても、一 般的に疑問視されている[32]。それでも、ソクラテスを理解する上で、彼の証言は不可欠である[33]。 ソクラテスの問題 メイン記事:ソクラテス問題 『ソクラテスの哲学的価値』(1818年)と題された重要な著作の中で、哲学者フリードリヒ・シュライエルマッハーはクセノフォンの記述を攻撃し、その攻 撃は広く受け入れられた[34]。シュライエルマッハーはクセノフォンのソクラテスに対する素朴な描写を批判した。クセノフォンは兵士であり、そのためソ クラテスの思想を明確に表現するには適していないとシュライエルマッハーは主張した。さらに、クセノフォンはかつての友人であり師であったソクラテスにつ いて偏った描写をしている。クセノフォンは、ソクラテスがアテナイで不当な扱いを受けたと考えており、公平な記述を行うよりも自分の見解を証明しようとし ていた。その結果、クセノフォンはソクラテスを魅力のない哲学者として描いてしまったとシュライエルマッハーは述べている[35]。20世紀初頭までに、 クセノフォンの記述は概ね否定されるようになった[36]。 哲学者カール・ジョエルは、アリストテレスによるソクラテス的ロゴスの解釈に基づいて、ソクラテスの対話録は大部分がフィクションであると主張した。ジョ エルによると、対話録の著者はソクラテスの対話の特徴を模倣していただけだというのだ[37]。20世紀半ば、オロフ・ギゴンやウジェーヌ・デュプレール といった哲学者たちは、ジョエルの主張に基づいて、 ソクラテスの研究は、歴史上のソクラテスを再構築することを目指すよりも、彼の性格や信念のさまざまなバージョンに焦点を当てるべきだと提案した [38]。その後、古代哲学者のグレゴリー・ブラストスは、プラトンの初期のソクラテス対話の方が、プラトンの後期の著作よりも歴史上のソクラテスを示す 他の証拠と一致している可能性があると示唆した。Vlastosは、プラトンの記述と一致する場合を除き、クセノフォンの記述を完全に無視していた [38]。さらに最近では、チャールズ・H・カーンが、解決不可能なソクラテスの問題に対する懐疑的な姿勢を強化し、プラトンの『弁論』のみが歴史的な意 義を持つと示唆している[39]。 |

Biography Battle of Potidaea (432 BC): Athenians against Corinthians (detail). Scene of Socrates (center) saving Alcibiades. 18th century engraving. According to Plato, Socrates participated in the Battle of Potidaea, the retreat of Battle of Delium and the battle of Amphipolis (422 BC).[40] Socrates was born in 470 or 469 BC to Sophroniscus and Phaenarete, a stoneworker and a midwife, respectively, in the Athenian deme of Alopece; therefore, he was an Athenian citizen, having been born to relatively affluent Athenians.[41] He lived close to his father's relatives and inherited, as was customary, part of his father's estate, securing a life reasonably free of financial concerns.[42] His education followed the laws and customs of Athens. He learned the basic skills of reading and writing and, like most wealthy Athenians, received extra lessons in various other fields such as gymnastics, poetry and music.[43] He was married twice (which came first is not clear): his marriage to Xanthippe took place when Socrates was in his fifties, and another marriage was with a daughter of Aristides, an Athenian statesman.[44] He had three sons with Xanthippe.[45] Socrates fulfilled his military service during the Peloponnesian War and distinguished himself in three campaigns, according to Plato.[46] Another incident that reflects Socrates's respect for the law is the arrest of Leon the Salaminian. As Plato describes in his Apology, Socrates and four others were summoned to the Tholos and told by representatives of the Thirty Tyrants (which began ruling in 404 BC) to arrest Leon for execution. Again Socrates was the sole abstainer, choosing to risk the tyrants' wrath and retribution rather than to participate in what he considered to be a crime.[47] Socrates attracted great interest from the Athenian public and especially the Athenian youth.[48] He was notoriously ugly, having a flat turned-up nose, bulging eyes and a large belly; his friends joked about his appearance.[49] Socrates was indifferent to material pleasures, including his own appearance and personal comfort. He neglected personal hygiene, bathed rarely, walked barefoot, and owned only one ragged coat.[50] He moderated his eating, drinking, and sex, although he did not practice full abstention.[50] Although Socrates was attracted to youth, as was common and accepted in ancient Greece, he resisted his passion for young men because, as Plato describes, he was more interested in educating their souls.[51] Socrates did not seek sex from his disciples, as was often the case between older and younger men in Athens.[52] Politically, he did not take sides in the rivalry between the democrats and the oligarchs in Athens; he criticized both.[53] The character of Socrates as exhibited in Apology, Crito, Phaedo and Symposium concurs with other sources to an extent that gives confidence in Plato's depiction of Socrates in these works as being representative of the real Socrates.[54] Socrates died in Athens in 399 BC after a trial for impiety and the corruption of the young.[55] He spent his last day in prison among friends and followers who offered him a route to escape, which he refused. He died the next morning, in accordance with his sentence, after drinking poison hemlock.[56] According to the Phaedo, his last words were: “Crito, we owe a rooster to Asclepius. Don't forget to pay the debt.”[57] |

略歴 ポタイデアの戦い(前432年):アテナイ人とコリント人(詳細)。ソクラテス(中央)がアルキビアデスを救う場面。18世紀の銅版画。プラトンによると、ソクラテスはポタイデアの戦い、デリュムの戦い、アンフィポリスの戦い(前422年)に参加した[40]。 ソクラテスは、紀元前470年または469年に、アテナイのアルオペケス区で、石工のソフロニスクスと助産師のフェナレテの間に生まれた。したがって、彼 はアテナイの市民であり、 比較的裕福なアテナイ人の家庭に生まれたためである[41]。彼は父の親戚の近くに暮らし、慣習に従って父の財産の一部を相続し、経済的な不安の少ない生 活を確保していた[42]。彼の教育はアテナイの法律と慣習に従った。彼は読み書きの基礎を学び、アテネの裕福な市民たちと同様に、体操、詩、音楽など、 さまざまな分野の特別授業も受けた[43]。彼は2度結婚した(どちらが先かは不明)。ソクラテスが40代だったときに、クサンティッペと結婚し、 ソクラテスは、アテネの政治家アリストテレスの娘と結婚した。ソクラテスは、クテュロスとの間に3人の息子をもうけた。[45] プラトンによると、ソクラテスはペロポネソス戦争で兵役を果たし、3つの戦役で功績をあげた。 ソクラテスの法律に対する敬意を示すもう一つの出来事は、レオン・ザ・サラミニアンの逮捕である。プラトンが『饗宴』で述べているように、ソクラテスと他 の4人はソロスに呼び出され、30人の専制者(紀元前404年に政権を握った)の代表者から、レオンの逮捕と処刑を命じられた。ソクラテスは今回も唯一棄 権し、自分が犯罪と考える行為に加わるよりも、暴君たちの怒りと報復のリスクを選ぶことを選んだ[47]。 ソクラテスはアテナイ市民、特にアテナイの若者から大きな関心を集めた[48]。彼は鼻が平たく突き出ており、目が飛び出ており、お腹が膨らんでおり、外 見が醜いことで有名だった。友人たちは彼の外見について冗談を言っていた[49]。ソクラテスは物質的な快楽、つまり自分の外見や個人的な快適さには無頓 着だった。彼は個人的な衛生を怠り、めったに風呂に入らず、裸足で歩き、ぼろぼろのコートを1着しか持っていなかった[50]。彼は食事、飲酒、性行為を 節制していたが、完全な禁欲は実践していなかった[50]。ソクラテスは、古代ギリシャでは一般的で受け入れられていたように、若者に惹かれていたが、プ ラトンが述べているように、若い男性の魂を教育することに興味があったため、若い男性への情熱に抵抗していた[51]。ソクラテスは弟子たちに性行為を求 めていなかった。アテネでは年長者と年少者の間でよく見られたように、ソクラテスは弟子たちに性的な関係を求めなかった[52]。政治的には、アテネの民 主派と寡頭派間の対立にどちらの側にも与せず、両者を批判した[53]。『饗宴』『クリトン』『パイドス』『ソクラテスの対話』に示されたソクラテスの性 格は、他の情報源ともある程度一致しており、これらの作品におけるプラトンのソクラテスの描写が、実在のソクラテスを象徴するものであるという信頼性を与 えている[54]。 ソクラテスは、不敬罪と青少年の堕落に関する裁判の後、紀元前399年にアテネで死去した[55]。彼は刑務所で友人や信奉者たちとともに最後の日々を過 ごしたが、彼らは彼に脱獄の道を提供したが、彼はそれを拒否した。彼は翌朝、判決に従って、毒草のトリカブトを飲んだ後、亡くなった[56]。『パイド ス』によると、彼の最期の言葉は「クリトンよ、アスクレピオスに雄鶏を借りている。その借金を忘れないように。」[57] |

| Trial of Socrates Main article: Trial of Socrates See also: The unexamined life is not worth living In 399 BC, Socrates was formally accused of corrupting the minds of the youth of Athens, and for asebeia (impiety), i.e. worshipping false gods and failing to worship the gods of Athens.[58] At the trial, Socrates defended himself unsuccessfully. He was found guilty by a majority vote cast by a jury of hundreds of male Athenian citizens and, according to the custom, proposed his own penalty: that he should be given free food and housing by the state for the services he rendered to the city,[59] or alternatively, that he be fined one mina of silver (according to him, all he had).[59] The jurors declined his offer and ordered the death penalty.[59] Socrates was charged in a politically tense climate.[60] In 404 BC, the Athenians had been crushed by Spartans at the decisive naval Battle of Aegospotami, and subsequently, the Spartans laid siege to Athens. They replaced the democratic government with a new, pro-oligarchic government, named the Thirty Tyrants.[60] Because of their tyrannical measures, some Athenians organized to overthrow the Tyrants—and, indeed, they managed to do so briefly—until a Spartan request for aid from the Thirty arrived and a compromise was sought. When the Spartans left again, however, democrats seized the opportunity to kill the oligarchs and reclaim the government of Athens.[60] The accusations against Socrates were initiated by a poet, Meletus, who asked for the death penalty in accordance with the charge of asebeia.[60] Other accusers were Anytus and Lycon. After a month or two, in late spring or early summer, the trial started and likely went on for most of one day.[60] There were two main sources for the religion-based accusations. First, Socrates had rejected the anthropomorphism of traditional Greek religion by denying that the gods did bad things like humans do. Second, he seemed to believe in a daimonion—an inner voice with, as his accusers suggested, divine origin.[60] Plato's Apology starts with Socrates answering the various rumours against him that have given rise to the indictment.[61] First, Socrates defends himself against the rumour that he is an atheist naturalist philosopher, as portrayed in Aristophanes's The Clouds; or a sophist.[62] Against the allegations of corrupting the youth, Socrates answers that he has never corrupted anyone intentionally, since corrupting someone would carry the risk of being corrupted back in return, and that would be illogical, since corruption is undesirable.[63] On the second charge, Socrates asks for clarification. Meletus responds by repeating the accusation that Socrates is an atheist. Socrates notes the contradiction between atheism and worshipping false gods.[64] He then claims that he is "God's gift" to the Athenians, since his activities ultimately benefit Athens; thus, in condemning him to death, Athens itself will be the greatest loser.[65] After that, he says that even though no human can reach wisdom, seeking it is the best thing someone can do, implying money and prestige are not as precious as commonly thought.[66]  The Death of Socrates, by Jacques-Louis David (1787). Socrates was visited by friends in his last night at prison. His discussion with them gave rise to Plato's Crito and Phaedo.[67] Socrates was given the chance to offer alternative punishments for himself after being found guilty. He could have requested permission to flee Athens and live in exile, but he did not do so. According to Xenophon, Socrates made no proposals, while according to Plato he suggested free meals should be provided for him daily in recognition of his worth to Athens or, more in earnest, that a fine should be imposed on him.[68] The jurors favoured the death penalty by making him drink a cup of hemlock (a poisonous liquid).[69] In return, Socrates warned jurors and Athenians that criticism of them by his many disciples was inescapable, unless they became good men.[59] After a delay caused by Athenian religious ceremonies, Socrates spent his last day in prison. His friends visited him and offered him an opportunity to escape, which he declined.[70] The question of what motivated Athenians to convict Socrates remains controversial among scholars.[71] There are two theories. The first is that Socrates was convicted on religious grounds; the second, that he was accused and convicted for political reasons.[71] Another, more recent, interpretation synthesizes the religious and political theories, arguing that religion and state were not separate in ancient Athens.[72] The argument for religious persecution is supported by the fact that Plato's and Xenophon's accounts of the trial mostly focus on the charges of impiety. In those accounts, Socrates is portrayed as making no effort to dispute the fact that he did not believe in the Athenian gods. Against this argument stands the fact that many skeptics and atheist philosophers during this time were not prosecuted.[73] According to the argument for political persecution, Socrates was targeted because he was perceived as a threat to democracy. It was true that Socrates did not stand for democracy during the reign of the Thirty Tyrants and that most of his pupils were against the democrats.[74] The case for it being a political persecution is usually challenged by the existence of an amnesty that was granted to Athenian citizens in 403 BC to prevent escalation to civil war after the fall of the Thirty. However, as the text from Socrates's trial and other texts reveal, the accusers could have fuelled their rhetoric using events prior to 403 BC.[75] |

ソクラテスの裁判 メイン記事:ソクラテスの裁判 関連項目: 吟味されていない人生は生きる価値がない 紀元前399年、ソクラテスはアテネの若者の心を堕落させ、神を畏れない(不敬)として、すなわち偽の神々を崇拝し、アテネの神々を崇拝しなかったとし て、正式に告発された[58]。裁判でソクラテスは自身を弁護したが、失敗に終わった。ソクラテスは、数百人のアテナイ市民からなる陪審員の大多数決によ り有罪判決を受け、慣習に従って、自らに科すべき刑罰を提案した。すなわち、彼がアテナイに尽くした功績に対して、国家から無料で食糧と住居を提供しても らうこと、あるいは、代わりに銀1ミナ(彼によれば、彼が所有していた全財産)の罰金を科すこと、のどちらかである。陪審員は彼の提案を拒否し、死刑を命 じた。 ソクラテスは、政治的に緊迫した状況の中で告発された[60]。紀元前404年、アテネ人は決定的な海戦となったエゴスポタミの海戦でスパルタ人に打ち負 かされ、その後、スパルタ人はアテネを包囲した。彼らは民主政府を、新政府として、30人の専制君主(タイラントス)と呼ばれる、寡頭政治を推し進める政 府に置き換えた[60]。その専制的な政策により、アテネ市民の一部はタイラントスを打倒すべく組織化を進め、実際に短期間ではあるが打倒に成功した。し かし、タイラントスから支援要請を受けたスパルタが妥協案を模索し、スパルタが再び去った後、民主派は寡頭政治を排除しアテネの政府を奪還する好機と捉え た[60]。 ソクラテスに対する告発は、詩人のメレトゥスが、偽証の罪状に基づき死刑を求めたことから始まった[60]。他の告発者はアニュタスとリコンであった。 1~2か月後、晩春か初夏、裁判が始まり、おそらく丸一日続いた[60]。宗教を理由とした告発には、主に2つの根拠があった。まず、ソクラテスは、神々 が人間のように悪いことをするという考えを否定することで、伝統的なギリシャ宗教の人格神話を否定していた。次に、彼はダイモニオン(神聖な起源を持つ内 なる声)を信じていたようである。これは、彼を告発した人々が示唆したように、神聖な起源を持つ内なる声である。 プラトンの『駁論』は、告発の原因となったソクラテスに対するさまざまな噂にソクラテスが答えるところから始まる[61]。まずソクラテスは、アリストパ ネスの『雲』で描かれているように、無神論の自然哲学者であるとか、ソフィストであるという噂について、自身を弁護する[6 2] 青少年の腐敗を招いたという疑惑に対して、ソクラテスは、誰かを腐敗させることは、その見返りとして自分も腐敗させられるリスクがあり、腐敗は望ましくな いものであるため、意図的に誰かを腐敗させたことはない、と答え、それは非論理的であると主張した[63]。2つ目の容疑について、ソクラテスは説明を求 めている。メレトゥスは、ソクラテスが無神論者であると非難を繰り返すことでこれに答えた。ソクラテスは、無神論と偽の神々を崇拝することの矛盾を指摘し た[64]。そして、彼の活動は最終的にアテネに利益をもたらすため、自分はアテネ人にとっての「神からの贈り物」であると主張した。つまり、彼を死刑に 処することは、アテネ自身が最大の敗者となることを意味する[65]。その後、彼は、人間には知恵に到達することはできないが、知恵を求めることは人がで きる最善のことであると述べた。これは、お金や名声は一般的に考えられているほど貴重ではないことを意味している[66]。  ジャック=ルイ・ダヴィッド作『ソクラテスの死』(1787年)。ソクラテスは、獄中で過ごす最後の夜に友人たちに訪問された。彼らとの議論は、プラトンの『クリトン』と『パイドス』の着想となった[67]。 ソクラテスは有罪判決を受けた後、自身に対する別の刑罰を提案する機会を与えられた。彼はアテネから逃亡し、亡命生活をすることを許可するよう求めること もできたが、そうはしなかった。クセノフォンによると、ソクラテスは何も提案しなかったが、プラトンによると、彼はアテネに対する自分の価値を認めるため に、毎日無料で食事を与えるべきだと提案した、あるいはもっと真剣に、自分に罰金を科すべきだと提案した[68]。陪審員は、彼に毒草の (有毒な液体)を飲ませた[69]。その見返りとして、ソクラテスは陪審員とアテナイ市民に対し、彼らが善良な人にならない限り、彼の多くの弟子たちによ る彼らへの批判は避けられないと警告した[59]。アテナイの宗教的儀式による遅れの後、ソクラテスは刑務所で最後の日を迎えた。友人たちが彼を面会に訪 れ、脱獄の機会を提供したが、彼はそれを断った[70]。 ソクラテスを有罪としたアテナイ人の動機を巡る疑問は、学者たちの間で依然として議論の的となっている[71]。2つの説がある。1つ目は、ソクラテスが 宗教的な理由で有罪となったという説、2つ目は、ソクラテスが政治的な理由で告発され有罪となったという説である[71]。より新しい解釈では、宗教的説 と政治的な説を総合し、古代アテナイでは宗教と国家は分離していなかったと主張している[72]。 宗教的迫害説は、プラトンとクセノフォンによる裁判の記述が、不敬罪に焦点を当てているという事実によって裏付けられている。これらの記述では、ソクラテ スはアテネの神々を信じていないという事実を否定しようとしなかったと描かれている。この議論に対して、この時代の懐疑論者や無神論哲学者の多くが訴追さ れなかったという事実がある[73]。政治的な迫害を理由とする議論によると、ソクラテスは民主主義の脅威とみなされたため、標的にされた。ソクラテスが 三十人専制政治の時代に民主主義を支持していなかったのは事実であり、彼の弟子のほとんどは民主主義者に対して敵意を抱いていた[74]。この事件が政治 的な迫害であったという主張は、通常、三十人専制政治の崩壊後に内戦に発展するのを防ぐために、紀元前403年にアテナイ市民に恩赦が与えられたという事 実によって反論される。しかし、ソクラテスの裁判の記録やその他の文献によると、告発者たちは紀元前403年以前の出来事を利用して、自分たちの主張を 煽っていた可能性がある[75]。 |

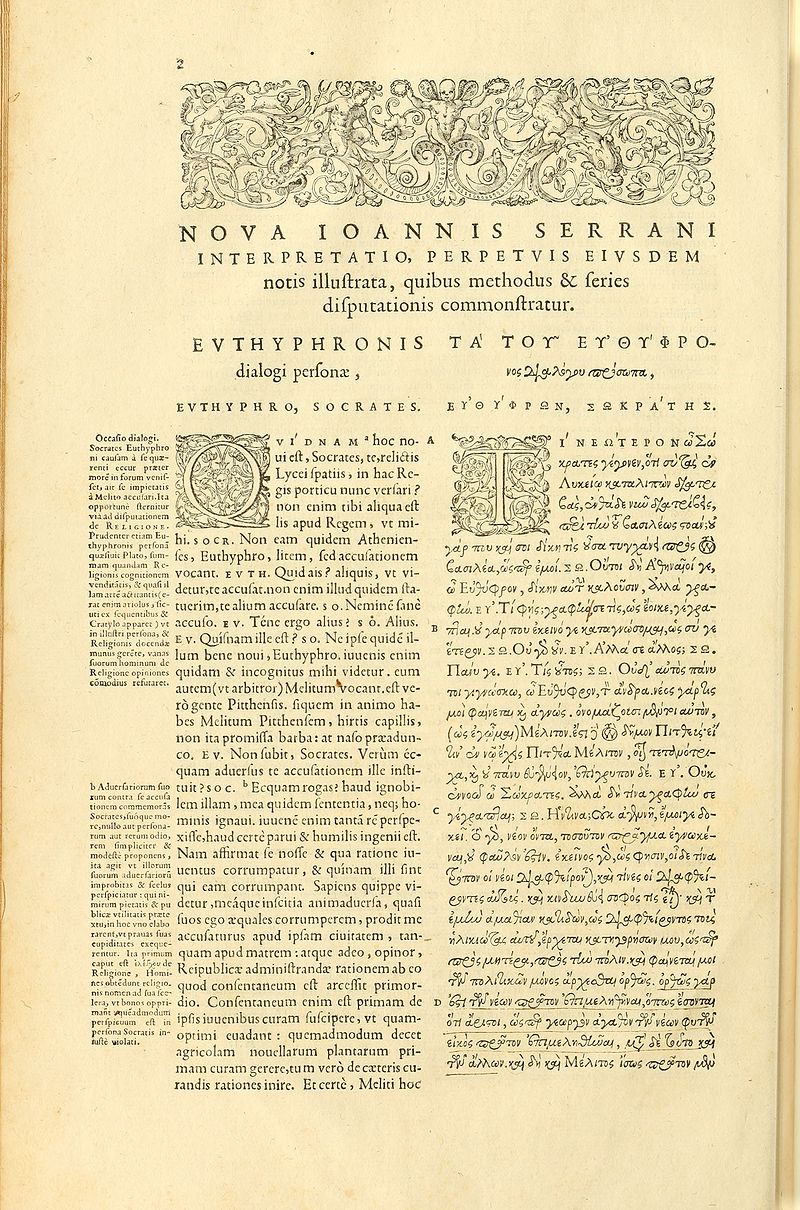

| Philosophy Socratic method Main article: Socratic method  The Debate of Socrates and Aspasia by Nicolas-André Monsiau. Socrates's discussions were not limited to a small elite group; he engaged in dialogues with foreigners and with people from all social classes and of all genders.[76] A fundamental characteristic of Plato's Socrates is the Socratic method, or the method of refutation (elenchus).[77] It is most prominent in the early works of Plato, such as Apology, Crito, Gorgias, Republic I, and others.[78] The typical elenchus proceeds as follows. Socrates initiates a discussion about a topic with a known expert on the subject, usually in the company of some young men and boys, and by dialogue proves the expert's beliefs and arguments to be contradictory.[79] Socrates initiates the dialogue by asking his interlocutor for a definition of the subject. As he asks more questions, the interlocutor's answers eventually contradict the first definition. The conclusion is that the expert did not really know the definition in the first place.[80] The interlocutor may come up with a different definition. That new definition, in turn, comes under the scrutiny of Socratic questioning. With each round of question and answer, Socrates and his interlocutor hope to approach the truth. More often, they continue to reveal their ignorance.[81] Since the interlocutors' definitions most commonly represent the mainstream opinion on a matter, the discussion places doubt on the common opinion.[82] Socrates also tests his own opinions through the Socratic method. Thus Socrates does not teach a fixed philosophical doctrine. Rather, he acknowledges his own ignorance while searching for truth with his pupils and interlocutors.[82] Scholars have questioned the validity and the exact nature of the Socratic method, or indeed if there even was a Socratic method.[83] In 1982, the scholar of ancient philosophy Gregory Vlastos claimed that the Socratic method could not be used to establish the truth or falsehood of a proposition. Rather, Vlastos argued, it was a way to show that an interlocutor's beliefs were inconsistent.[84] There have been two main lines of thought regarding this view, depending on whether it is accepted that Socrates is seeking to prove a claim wrong.[85] According to the first line of thought, known as the constructivist approach, Socrates indeed seeks to refute a claim by this method, and the method helps in reaching affirmative statements.[86] The non-constructivist approach holds that Socrates merely wants to establish the inconsistency between the premises and conclusion of the initial argument.[87] Socratic priority of definition Socrates starts his discussions by prioritizing the search for definitions.[88] In most cases, Socrates initiates his discourse with an expert on a subject by seeking a definition—by asking, for example, what virtue, goodness, justice, or courage is.[89] To establish a definition, Socrates first gathers clear examples of a virtue and then seeks to establish what they had in common.[90] According to Guthrie, Socrates lived in an era when sophists had challenged the meaning of various virtues, questioning their substance; Socrates's quest for a definition was an attempt to clear the atmosphere from their radical skepticism.[91] Some scholars have argued that Socrates does not endorse the priority of definition as a principle, because they have identified cases where he does not do so.[92] Some have argued that this priority of definition comes from Plato rather than Socrates.[93] Philosopher Peter Geach, accepting that Socrates endorses the priority of definition, finds the technique fallacious. Αccording to Geach, one may know a proposition even if one cannot define the terms in which the proposition is stated.[94] Socratic ignorance  Ruins of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, where Pythia was sited. The Delphic aphorism Know thyself was important to Socrates, as evident in many Socratic dialogues by Plato, especially Apology.[95] Plato's Socrates often claims that he is aware of his own lack of knowledge, especially when discussing ethical concepts such as arete (i.e., goodness, courage) since he does not know the nature of such concepts.[96] For example, during his trial, with his life at stake, Socrates says: "I thought Evenus a happy man, if he really possesses this art (technē), and teaches for so moderate a fee. Certainly I would pride and preen myself if I knew (epistamai) these things, but I do not know (epistamai) them, gentlemen".[97] In some of Plato's dialogues, Socrates appears to credit himself with some knowledge, and can even seem strongly opinionated for a man who professes his own ignorance.[98] There are varying explanations of the Socratic inconsistency (other than that Socrates is simply being inconsistent).[99] One explanation is that Socrates is being either ironic or modest for pedagogical purposes: he aims to let his interlocutor to think for himself rather than guide him to a prefixed answer to his philosophical questions.[100] Another explanation is that Socrates holds different interpretations of the meaning of "knowledge". Knowledge, for him, might mean systematic understanding of an ethical subject, on which Socrates firmly rejects any kind of mastery; or might refer to lower-level cognition, which Socrates may accept that he possesses.[101] In any case, there is consensus that Socrates accepts that acknowledging one's lack of knowledge is the first step towards wisdom.[102] Socrates is known for disavowing knowledge, a claim encapsulated in the saying "I know that I know nothing". This is often attributed to Socrates on the basis of a statement in Plato's Apology, though the same view is repeatedly found elsewhere in Plato's early writings on Socrates.[103] In other statements, though, he implies or even claims that he does have knowledge. For example, in Plato's Apology Socrates says: "...but that to do injustice and disobey my superior, god or man, this I know to be evil and base..." (Apology, 29b6–7).[104] In his debate with Callicles, he says: "...I know well that if you will agree with me on those things which my soul believes, those things will be the very truth..."[104] Whether Socrates genuinely thought he lacked knowledge or merely feigned a belief in his own ignorance remains a matter of debate. A common interpretation is that he was indeed feigning modesty. According to Norman Gulley, Socrates did this to entice his interlocutors to speak with him. On the other hand, Terence Irwin claims that Socrates's words should be taken literally.[105] Gregory Vlastos argues that there is enough evidence to refute both claims. On his view, for Socrates, there are two separate meanings of "knowledge": Knowledge-C and Knowledge-E (C stands for "certain", and E stands for elenchus, i.e. the Socratic method). Knowledge-C is something unquestionable whereas Knowledge-E is the knowledge derived from Socrates's elenchus.[106] Thus, Socrates speaks the truth when he says he knows-C something, and he is also truthful when saying he knows-E, for example that it is evil for someone to disobey his superiors, as he claims in Apology.[107] Not all scholars have agreed with this semantic dualism. James H. Lesher has argued that Socrates claimed in various dialogues that one word is linked to one meaning (i.e. in Hippias Major, Meno, and Laches).[108] Lesher suggests that although Socrates claimed that he had no knowledge about the nature of virtues, he thought that in some cases, people can know some ethical propositions.[109] Socratic irony There is a widespread assumption that Socrates was an ironist, mostly based on the depiction of Socrates by Plato and Aristotle.[110] Socrates's irony is so subtle and slightly humorous that it often leaves the reader wondering if Socrates is making an intentional pun.[111] Plato's Euthyphro is filled with Socratic irony. The story begins when Socrates is meeting with Euthyphro, a man who has accused his own father of murder. When Socrates first hears the details of the story, he comments, "It is not, I think, any random person who could do this [prosecute one's father] correctly, but surely one who is already far progressed in wisdom". When Euthyphro boasts about his understanding of divinity, Socrates responds that it is "most important that I become your student".[112] Socrates is commonly seen as ironic when using praise to flatter or when addressing his interlocutors.[113] Scholars are divided on why Socrates uses irony. According to an opinion advanced since the Hellenistic period, Socratic irony is a playful way to get the audience's attention.[114] Another line of thought holds that Socrates conceals his philosophical message with irony, making it accessible only to those who can separate the parts of his statements which are ironic from those which are not.[115] Gregory Vlastos has identified a more complex pattern of irony in Socrates. On Vlastos's view, Socrates's words have a double meaning, both ironic and not. One example is when he denies having knowledge. Vlastos suggests that Socrates is being ironic when he says he has no knowledge (where "knowledge" means a lower form of cognition); while, according to another sense of "knowledge", Socrates is serious when he says he has no knowledge of ethical matters. This opinion is not shared by many other scholars.[116] Socratic eudaimonism and intellectualism For Socrates, the pursuit of eudaimonia motivates all human action, directly or indirectly.[117] Virtue and knowledge are linked, in Socrates's view, to eudaimonia, but how closely he considered them to be connected is still debated. Some argue that Socrates thought that virtue and eudaimonia are identical. According to another view, virtue serves as a means to eudaimonia (the "identical" and "sufficiency" theses, respectively).[118] Another point of debate is whether, according to Socrates, people desire what is in fact good—or, rather, simply what they perceive as good.[118] Moral intellectualism refers to the prominent role Socrates gave to knowledge. He believed that all virtue was based on knowledge (hence Socrates is characterized as a virtue intellectualist). He also believed that humans were guided by the cognitive power to comprehend what they desire, while diminishing the role of impulses (a view termed motivational intellectualism).[119] In Plato's Protagoras (345c4–e6), Socrates implies that "no one errs willingly", which has become the hallmark of Socratic virtue intellectualism.[120] In Socratic moral philosophy, priority is given to the intellect as being the way to live a good life; Socrates deemphasizes irrational beliefs or passions.[121] Plato's dialogues that support Socrates's intellectual motivism—as this thesis is named—are mainly the Gorgias (467c–8e, where Socrates discusses the actions of a tyrant that do not benefit him) and Meno (77d–8b, where Socrates explains to Meno his view that no one wants bad things, unless they do not know what is good and bad in the first place).[122] Scholars have been puzzled by Socrates's view that akrasia (acting because of one's irrational passions, contrary to one's knowledge or beliefs) is impossible. Most believe that Socrates left no space for irrational desires, although some claim that Socrates acknowledged the existence of irrational motivations, but denied they play a primary role in decision-making.[123] Religion  Henri Estienne's 1578 edition of Euthyphro, parallel Latin and Greek text. Estienne's translations were heavily used and reprinted for more than two centuries.[124] Socrates's discussion with Euthyphro still remains influential in theological debates.[125] Socrates's religious nonconformity challenged the views of his times and his critique reshaped religious discourse for the coming centuries.[126] In Ancient Greece, organized religion was fragmented, celebrated in a number of festivals for specific gods, such as the City Dionysia, or in domestic rituals, and there were no sacred texts. Religion intermingled with the daily life of citizens, who performed their personal religious duties mainly with sacrifices to various gods.[127] Whether Socrates was a practicing man of religion or a 'provocateur atheist' has been a point of debate since ancient times; his trial included impiety accusations, and the controversy has not yet ceased.[128] Socrates discusses divinity and the soul mostly in Alcibiades, Euthyphro, and Apology.[129] In Alcibiades Socrates links the human soul to divinity, concluding "Then this part of her resembles God, and whoever looks at this, and comes to know all that is divine, will gain thereby the best knowledge of himself."[130] His discussions on religion always fall under the lens of his rationalism.[131] Socrates, in Euthyphro, reaches a conclusion which takes him far from the age's usual practice: he considers sacrifices to the gods to be useless, especially when they are driven by the hope of receiving a reward in return. Instead he calls for philosophy and the pursuit of knowledge to be the principal way of worshipping the gods.[132] His rejection of traditional forms of piety, connecting them to self-interest, implied that Athenians should seek religious experience by self-examination.[133] Socrates argued that the gods were inherently wise and just, a perception far from traditional religion at that time.[134] In Euthyphro, the Euthyphro dilemma arises. Socrates questions his interlocutor about the relationship between piety and the will of a powerful god: Is something good because it is the will of this god, or is it the will of this god because it is good?[135] In other words, does piety follow the good, or the god? The trajectory of Socratic thought contrasts with traditional Greek theology, which took lex talionis (the eye for an eye principle) for granted. Socrates thought that goodness is independent from gods, and gods must themselves be pious.[136] Socrates affirms a belief in gods in Plato's Apology, where he says to the jurors that he acknowledges gods more than his accusers.[137] For Plato's Socrates, the existence of gods is taken for granted; in none of his dialogues does he probe whether gods exist or not.[138] In Apology, a case for Socrates being agnostic can be made, based on his discussion of the great unknown after death,[139] and in Phaedo (the dialogue with his students in his last day) Socrates gives expression to a clear belief in the immortality of the soul.[140] He also believed in oracles, divinations and other messages from gods. These signs did not offer him any positive belief on moral issues; rather, they were predictions of unfavorable future events.[141] In Xenophon's Memorabilia, Socrates constructs an argument close to the contemporary teleological intelligent-design argument. He claims that since there are many features in the universe that exhibit "signs of forethought" (e.g., eyelids), a divine creator must have created the universe.[138] He then deduces that the creator should be omniscient and omnipotent and also that it created the universe for the advance of humankind, since humans naturally have many abilities that other animals do not.[142] At times, Socrates speaks of a single deity, while at other times he refers to plural "gods". This has been interpreted to mean that he either believed that a supreme deity commanded other gods, or that various gods were parts, or manifestations, of this single deity.[143] The relationship of Socrates's religious beliefs with his strict adherence to rationalism has been subject to debate.[144] Philosophy professor Mark McPherran suggests that Socrates interpreted every divine sign through secular rationality for confirmation.[145] Professor of ancient philosophy A. A. Long suggests that it is anachronistic to suppose that Socrates believed the religious and rational realms were separate.[146] Socratic daimonion  Alcibiades Receiving Instruction from Socrates, a 1776 painting by François-André Vincent, depicting Socrates's daimon[147] In several texts (e.g., Plato's Euthyphro 3b5; Apology 31c–d; Xenophon's Memorabilia 1.1.2) Socrates claims he hears a daimōnic sign—an inner voice heard usually when he was about to make a mistake. Socrates gave a brief description of this daimonion at his trial (Apology 31c–d): "...The reason for this is something you have heard me frequently mention in different places—namely, the fact that I experience something divine and daimonic, as Meletus has inscribed in his indictment, by way of mockery. It started in my childhood, the occurrence of a particular voice. Whenever it occurs, it always deters me from the course of action I was intending to engage in, but it never gives me positive advice. It is this that has opposed my practicing politics, and I think its doing so has been absolutely fine."[148] Modern scholarship has variously interpreted this Socratic daimōnion as a rational source of knowledge, an impulse, a dream or even a paranormal experience felt by an ascetic Socrates.[149] Virtue and knowledge Socrates's theory of virtue states that all virtues are essentially one, since they are a form of knowledge.[150] For Socrates, the reason a person is not good is because they lack knowledge. Since knowledge is united, virtues are united as well. Another famous dictum—"no one errs willingly"—also derives from this theory.[151] In Protagoras, Socrates argues for the unity of virtues using the example of courage: if someone knows what the relevant danger is, they can undertake a risk.[150] Aristotle comments: " ... Socrates the elder thought that the end of life was knowledge of virtue, and he used to seek for the definition of justice, courage, and each of the parts of virtue, and this was a reasonable approach, since he thought that all virtues were sciences, and that as soon as one knew [for example] justice, he would be just..."[152] Love  Socrates and Alcibiades, by Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, 1813–1816 Some texts suggest that Socrates had love affairs with Alcibiades and other young persons; others suggest that Socrates's friendship with young boys sought only to improve them and were not sexual. In Gorgias, Socrates claims he was a dual lover of Alcibiades and philosophy, and his flirtatiousness is evident in Protagoras, Meno (76a–c) and Phaedrus (227c–d). However, the exact nature of his relationship with Alcibiades is not clear; Socrates was known for his self-restraint, while Alcibiades admits in the Symposium that he had tried to seduce Socrates but failed.[153] The Socratic theory of love is mostly deduced from Lysis, where Socrates discusses love[154] at a wrestling school in the company of Lysis and his friends. They start their dialogue by investigating parental love and how it manifests with respect to the freedom and boundaries that parents set for their children. Socrates concludes that if Lysis is utterly useless, nobody will love him—not even his parents. While most scholars believe this text was intended to be humorous, it has also been suggested that Lysis shows Socrates held an egoistic view of love, according to which we only love people who are useful to us in some way.[155] Other scholars disagree with this view, arguing that Socrates's doctrine leaves room for non-egoistic love for a spouse; still others deny that Socrates suggests any egoistic motivation at all.[156] In Symposium, Socrates argues that children offer the false impression of immortality to their parents, and this misconception yields a form of unity among them.[157] Scholars also note that for Socrates, love is rational.[158] Socrates, who claims to know only that he does not know, makes an exception (in Plato's Symposium), where he says he will tell the truth about Love, which he learned from a 'clever woman'. Classicist Armand D'Angour has made the case that Socrates was in his youth close to Aspasia, and that Diotima, to whom Socrates attributes his understanding of love in Symposium, is based on her;[159] however, it is also possible that Diotima really existed. Socratic philosophy of politics While Socrates was involved in public political and cultural debates, it is hard to define his exact political philosophy. In Plato's Gorgias, he tells Callicles: "I believe that I'm one of a few Athenians—so as not to say I'm the only one, but the only one among our contemporaries—to take up the true political craft and practice the true politics. This is because the speeches I make on each occasion do not aim at gratification but at what's best."[160] His claim illustrates his aversion for the established democratic assemblies and procedures such as voting—since Socrates saw politicians and rhetoricians as using tricks to mislead the public.[161] He never ran for office or suggested any legislation.[162] Rather, he aimed to help the city flourish by "improving" its citizens.[161] As a citizen, he abided by the law. He obeyed the rules and carried out his military duty by fighting wars abroad. His dialogues, however, make little mention of contemporary political decisions, such as the Sicilian Expedition.[162] Socrates spent his time conversing with citizens, among them powerful members of Athenian society, scrutinizing their beliefs and bringing the contradictions of their ideas to light. Socrates believed he was doing them a favor since, for him, politics was about shaping the moral landscape of the city through philosophy rather than electoral procedures.[163] There is a debate over where Socrates stood in the polarized Athenian political climate, which was divided between oligarchs and democrats. While there is no clear textual evidence, one widely held theory holds that Socrates leaned towards democracy: he disobeyed the one order that the oligarchic government of the Thirty Tyrants gave him; he respected the laws and political system of Athens (which were formulated by democrats); and, according to this argument, his affinity for the ideals of democratic Athens was a reason why he did not want to escape prison and the death penalty. On the other hand, there is some evidence that Socrates leaned towards oligarchy: most of his friends supported oligarchy, he was contemptuous of the opinion of the many and was critical of the democratic process, and Protagoras shows some anti-democratic elements.[164] A less mainstream argument suggests that Socrates favoured democratic republicanism, a theory that prioritizes active participation in public life and concern for the city.[165] Yet another suggestion is that Socrates endorsed views in line with liberalism, a political ideology formed in the Age of Enlightenment. This argument is mostly based on Crito and Apology, where Socrates talks about the mutually beneficial relationship between the city and its citizens. According to Socrates, citizens are morally autonomous and free to leave the city if they wish—but, by staying within the city, they also accept the laws and the city's authority over them.[166] On the other hand, Socrates has been seen as the first proponent of civil disobedience. Socrates's strong objection to injustice, along with his refusal to serve the Thirty Tyrants' order to arrest Leon, are suggestive of this line. As he says in Critias, "One ought never act unjustly, even to repay a wrong that has been done to oneself."[167] Ιn the broader picture, Socrates's advice would be for citizens to follow the orders of the state, unless, after much reflection, they deem them to be unjust.[168] |

哲学 ソクラテス式教育法 メイン記事:ソクラテス式教育法  ニコラ=アンドレ・モンシオ作『ソクラテスとアスパシアの対話』。ソクラテスの議論は、少数のエリート層に限られたものではなく、外国人やあらゆる社会階級、性別の人々と対話を交わしていた[76]。 プラトンのソクラテスの根本的な特徴は、ソクラテス的手法、あるいは反証法(エレクテュス)である[77]。それは『駁弁』、『クリトン』、『ゴルギア ス』、『共和国』などのプラトンの初期の作品に最も顕著に表れている[78]。典型的なエレクテュスは次のように進む。ソクラテスは、そのテーマについて よく知られた専門家と議論を始める。通常、何人かの若者や少年を伴って、対話によって専門家の信念や主張が矛盾していることを証明する[79]。ソクラテ スは、対話相手にテーマの定義を尋ねることで対話を始める。さらに質問を重ねるうちに、対話相手の答えは最初の定義と矛盾するようになる。結論として、そ の専門家はそもそもその定義を本当に理解していなかったことがわかる[80]。対話者は異なる定義を提示する場合もある。その新しい定義もまた、ソクラテ ス式質問の精査を受けることになる。質問と答えのやり取りを繰り返すたびに、ソクラテスと対話者は真実に近づくことを期待する。むしろ、彼らは自分たちの 無知をさらけ出すことが多い[81]。対話者の定義は、その事柄に関する主流の意見を表している場合がほとんどであるため、この議論は、その一般的な意見 に疑問を投げかけることになる[82]。 ソクラテスもまた、ソクラテス式問答法を通じて自らの意見を検証している。 したがって、ソクラテスは固定した哲学的教義を教えるわけではない。 むしろ、彼は自らの無知を認識しながら、弟子や対話者とともに真理を探求しているのである[82]。 学者たちは、ソクラテス式問答法の有効性や本質、あるいはソクラテス式問答法が存在したかどうかについて疑問を呈してきた[83]。1982年、古代哲学 者のグレゴリー・ブラストスは、ソクラテス式問答法は命題の真偽を立証するために用いることはできないと主張した。むしろ、Vlastosは、対話者の信 念に矛盾があることを示す方法だと主張した[84]。この見解に関しては、ソクラテスが主張の誤りを証明しようとしていると認めるかどうかによって、2つ の主な考え方がある[85]。最初の考え方によると 、構成主義的アプローチとして知られるこの考え方によると、ソクラテスは実際にこの方法を用いて主張を反証しようとしている。また、この方法によって肯定 的な主張に到達することができる。[86] 非構成主義的アプローチでは、ソクラテスは単に最初の議論の前提と結論の矛盾を明らかにしたいだけだとされている。[87] ソクラテスの定義の優先順位 ソクラテスは議論を始めるにあたり、定義の探求を優先する[88]。ほとんどの場合、ソクラテスは、例えば「美徳、善、正義、勇気とは何か」と問うなど、 定義を求めることで、そのテーマの専門家と対話を始める[89]。定義を確立するために、ソクラテスはまず、美徳の明確な 徳の明確な例をまず集め、次にそれらの共通点を明らかにしようとする[90]。グースリーによると、ソクラテスは、ソフィストたちがさまざまな徳の意味を 問い、その本質に疑問を呈していた時代に生きていた。ソクラテスの定義の探求は、彼らの過激な懐疑主義の雰囲気を払拭しようとする試みであった[91]。 ソクラテスは定義の優先性を原則として支持していないと主張する学者もいる。なぜなら、ソクラテスがそうしていないケースを指摘しているからだ[92]。 定義の優先性はソクラテスよりもむしろプラトンに由来すると主張する者もいる[93]。哲学者ピーター・ギアックは、ソクラテスが定義の優先性を支持して いることを認めつつ、その手法は誤謬であると指摘している。Geachによると、たとえその命題が述べられている用語を定義できなくても、その命題を知っ ている可能性がある[94]。 ソクラテスの無知  ピュティアがいたデルフィのアポロ神殿の遺跡。 デルフィの格言「汝自身を知れ」は、プラトンのソクラテス対話、特に『謝罪』に多く見られるように、ソクラテスにとって重要なものであった[95]。 プラトンのソクラテスは、特に「アレテ(すなわち、善、勇気)」などの倫理的概念について議論する際、そのような概念の本質を理解していないため、自身の 知識の欠如を自覚していると主張することが多い[96]。例えば、ソクラテスは、自分の命が懸かった裁判の最中に、「私は、エウベヌスが本当にこの技術 (テクネー)を所有しており、それほど高くない報酬で教えているのであれば、エウベヌスは幸せな人だと思った。確かに、もし私がこれらのことを知っている (エピスタマイ)のなら、誇らしく思うだろうし、自分を磨くだろう。しかし、私は知らない(エピスタマイ)のだ、皆さん」[97]。プラトンの対話集のい くつかで、ソクラテスは自分自身に多少の知識があると認めているように見え、自分の無知を公言している人物としては、非常に独断的であるようにさえ思える [98]。 ソクラテスの矛盾に対する説明は様々である(ソクラテスが単に矛盾しているだけだという説を除く)。[99] 1つの説明は、ソクラテスは教育的目的で皮肉的あるいは謙虚な態度を取っているというものである。ソクラテスは、対話者に哲学的な質問に対するあらかじめ 用意された答えを導くのではなく、自分自身で考えることを目指しているのだ。[100] もう1つの説明は、ソクラテスが「知識」の意味について異なる解釈を持っているというものである。ソクラテスにとって「知識」とは、倫理的テーマの体系的 な理解を意味し、ソクラテスはあらゆる種類の支配を明確に否定している。あるいは、ソクラテスが自分自身に存在すると認めるような、より低次元の認識を指 している可能性もある。いずれにせよ、ソクラテスは、自分の知識の欠如を認めることが知恵への第一歩であると認識しているという点では一致している。 ソクラテスは知識の存在を否定することで知られており、その主張は「私は自分が何も知らないことを知っている」という言葉に集約されている。これはプラト ンの『饗宴』の記述に基づいてソクラテスに帰せられることが多いが、プラトンの初期のソクラテスに関する著作の他の箇所でも同様の見解が繰り返し見受けら れる[103]。しかし、他の記述では、ソクラテスは自分が知識を持っていることを示唆したり、あるいは主張したりしている。例えば、プラトンの『饗宴』 の中でソクラテスは次のように述べている。「...しかし、不正を行い、私の目上の者、神、あるいは人に対して背くことは、悪であり卑しいことであるとい うことは、私は知っている...」(『饗宴』29b6-7)[104]。また、カリクレスとの議論の中で、彼は次のように述べている。「...私の魂が信 じていることについて、あなたが私に同意するなら、それらは真実となるということを、私はよく知っている...」[104]。 ソクラテスが本当に自分が知識に欠けていると思っていたのか、それとも単に無知を装っていただけなのかは議論の的となっている。一般的な解釈では、彼は謙 遜を装っていたとされている。ノーマン・ガリーによると、ソクラテスは対話者たちに話しかけさせるため、このようなことをしていたという。一方、テレン ス・アーウィンは、ソクラテスの言葉は文字通りに受け取るべきだと主張している[105]。 グレゴリー・ブラストスは、どちらの主張も否定できるだけの十分な証拠があると主張している。彼の見解によると、ソクラテスにとって「知識」には2つの異 なる意味がある。すなわち、「知識C」と「知識E」(Cは「確実」を、Eはエレクテュス、すなわちソクラテス的手法を意味する)。知識-C は疑う余地のないものであるのに対し、知識-E はソクラテスのエレクテス(elenchus)から得られた知識である[106]。したがって、ソクラテスは、自分が何かを知っている-C と言うとき、真実を語っている。また、例えば『弁明』で主張しているように、誰かが上司に背くことは悪であるなど、自分が何かを知っている-E と言うときにも、真実を語っている。ジェームズ・H・レッシャーは、ソクラテスがさまざまな対話の中で、一つの単語は一つの意味と結びついていると主張し ていたと論じている(『ヒッピアス・マジョール』、『メノン』、『ラケス』など)。[108] レッシャーは、ソクラテスは徳の本質について何も知らないと主張していたが、場合によっては、人々は倫理的な命題を知ることがあると考えていたと示唆して いる。[109] ソクラテスの皮肉 ソクラテスは皮肉屋であったという見方が広く浸透しているが、その根拠のほとんどはプラトンとアリストテレスによるソクラテスの描写である[110]。ソ クラテスの皮肉は極めて巧妙かつ微妙で、読者はソクラテスが意図的に言葉遊びをしているのではないかと疑問を抱くことが多い[111]。プラトンの『エウ テュプロス』はソクラテスの皮肉に満ちている。物語は、ソクラテスが自分の父親を殺人で告発した男、エウテュプロスと会っているところから始まる。ソクラ テスが初めてこの物語の詳細を聞いたとき、彼は「(自分の父親を告発するなど)このようなことを正しく行うことができるのは、おそらく、どんな人でもな く、すでに知恵を大いに身につけた人だけだろう」とコメントした。エウテュプロスが神性についての理解を自慢すると、ソクラテスは「私があなたの弟子にな ることが最も重要だ」と答えた[112]。ソクラテスは、相手を褒めそやすために賞賛したり、対話相手に語りかける際に皮肉めいた表現を用いることでよく 知られている[113]。 ソクラテスがなぜ皮肉を使うのかについては、学者の間でも意見が分かれている。ヘレニズム時代以降に提唱された説によると、ソクラテスの皮肉は聴衆の注意 を引くための遊び心だという[114]。また、ソクラテスは皮肉によって哲学的なメッセージを隠しており、皮肉の部分とそうでない部分を区別できる人だけ がそのメッセージを理解できるとする考えもある[115]。グレゴリー・ブラストスは、ソクラテスの皮肉について、より複雑なパターンを指摘している。ヴ ラストスの見解によると、ソクラテスの言葉には皮肉的な意味とそうでない意味の2つがある。その一例として、ソクラテスが知識を持たないと言っていること を挙げることができる。ヴラストスは、ソクラテスが知識を持たないと言っているのは皮肉である(ここで言う「知識」とは認識の低次形態を意味する)と主張 している。一方、別の意味での「知識」に従えば、ソクラテスが倫理的事柄について知識を持たないと言っているのは真剣な発言である。この意見は、他の多く の学者には支持されていない[116]。 ソクラテスの幸福主義と知性主義 ソクラテスにとって、幸福の追求は、直接的であれ間接的であれ、あらゆる人間の行動の原動力となるものであった[117]。ソクラテスの考えでは、徳と知 識は幸福と結びついているが、ソクラテスが両者をどの程度密接に関連づけていたかは、現在も議論の的となっている。ソクラテスは、徳と幸福は同一であると 考えていたという説もある。別の見解によると、徳は幸福への手段である(「同一」および「充足」のテーゼ、それぞれ)。[118] もう一つの論点は、ソクラテスの考えによれば、人々は実際に良いものを求めているのか、それとも単に良いと認識しているものを求めているのか、という点で ある[118]。 道徳的知性主義とは、ソクラテスが知識に与えた重要な役割を指す。ソクラテスは、すべての美徳は知識に基づいていると考えていた(そのため、ソクラテスは 美徳知性主義者と特徴づけられる)。また、人間は欲求を理解する認知能力によって導かれているが、衝動の役割は小さいと信じていた(この考え方は動機付け 知的主義と呼ばれる)。[119] プラトンの『パロゴラス』(345c4-e6)において、ソクラテスは「誰も進んで誤りを犯すことはない」と示唆しており、これがソクラテスの徳知的主義 の特徴となっている[120]。ソクラテスの道徳哲学では、良い人生を送るための方法として知性が優先され、ソクラテスは非合理的な信念や情熱を軽視して いる[121]。ソクラテスの知的動機論(この論文の名称)を支持するプラトンの対話篇は、主に『ゴルギアス』(467c-8e、ソクラテスが自分にとっ て利益にならない暴君の行動について論じている)と『メノン』(77d-8b、ソクラテスがメノンに、そもそも何が善で何が悪かわからない場合を除き、誰 も悪いことを望まないという自分の見解を説明する)である[122]。そして『メノン』(77d-8b)では、ソクラテスがメノンに、そもそも何が善で何 が悪かわからないのでなければ、誰も悪いことを望まないという自身の見解を説明している)[122]。ソクラテスの「無知(アクラシア)」(理性や信念に 反して、自分の非合理的な感情に従って行動すること)はあり得ないという見解に、学者は困惑している。ソクラテスは非合理的な欲望の余地を残さなかったと ほとんどの人は考えているが、ソクラテスは非合理的な動機の存在を認めたが、意思決定においてそれが主要な役割を果たすことは否定したとする説もある [123]。 宗教  アンリ・エスティエンヌによる1578年版『エウテュプロス』のラテン語とギリシャ語のテキスト。エスティエンヌの翻訳は2世紀以上にわたって広く使用さ れ、再版された[124]。ソクラテスのエウテュプロスとの議論は、神学上の議論において今もなお影響力を保っている[125]。 ソクラテスの宗教上の異端性は、当時の考え方に挑戦し、彼の批判は、その後の数世紀にわたる宗教的議論を形作り直した[126]。古代ギリシャでは、組織 化された宗教は断片化しており、ディオニュソス祭などの特定の神々を祝う多くの祭りや、家庭での儀式で祝われ、神聖なテキストは存在しなかった。宗教は市 民の日常生活に溶け込んでおり、人々は主にさまざまな神々への生け贄を捧げることで個人的な宗教的義務を果たしていた[127]。ソクラテスが宗教を実践 していたのか、それとも「挑発的な無神論者」だったのかについては、古代から議論の的となっている。彼の裁判には不敬罪の容疑が含まれており、この論争は 現在も収まっていない[128]。 ソクラテスは『アルキビアデス』、『エウテュプロス』、『弁明』の3つの著作で主に神性と魂について論じている[129]。『アルキビアデス』では、ソク ラテスは人間の魂と神性を結びつけ、「魂のこの部分は神に似ている。魂を観察し、神聖なものをすべて理解する者は、それによって自分自身について最高の知 識を得ることができる」と結論づけている[130]。 」[130] ソクラテスの宗教に関する議論は、常に彼の合理主義の観点に照らし合わせられるものである[131]。ソクラテスは『エウテュプロス』の中で、当時の慣習 とはかけ離れた結論に達している。すなわち、神々への生け贄は無用であり、特に見返りとしての報酬を期待して行われる場合はなおさらである、と彼は考えて いる。その代わりに、彼は哲学と知識の追求こそが神々を崇拝する主な方法であると主張した[132]。彼は伝統的な敬虔さの形を否定し、それを自己利益に 結びつけた。それは、アテネ市民は自己反省によって宗教的体験を求めるべきだということを意味していた[133]。 ソクラテスは、神々は本質的に賢明で公正であると主張したが、これは当時の伝統的な宗教とはかけ離れた考え方であった[134]。『エウテュプロス』で は、エウテュプロスのジレンマが提起されている。ソクラテスは、敬虔さと強大な神の意志の関係について、対話者に質問する。すなわち、あることが善である のは、それがこの神の意志だからなのか、それとも、それが善であるから、この神の意志となるのか、ということである[135]。言い換えれば、敬虔さは善 に従うのか、それとも神に従うのか、ということである。ソクラテスの思想の軌跡は、目には目をという報復の法則を当然視する伝統的なギリシャ神学とは対照 的である。ソクラテスは、神とは無関係に善があり、神は自ら敬虔でなければならないと考えた[136]。 ソクラテスは『プラトンの弁明』の中で神の存在を肯定しており、陪審員に向かって、自分を告発する人々よりも神の存在を信じていると述べている [137]。プラトンのソクラテスにとって、神の存在は自明のことであり、どの対話においても神の存在を問うことはなかった[138]。『プラトンの弁 明』では、 ソクラテスの不可知論は、死後の大きな未知についての彼の議論に基づいて主張できる[139]。また、『パイドス』(ソクラテスの最期の日に弟子たちと交 わした対話)では、魂の不滅に対する明確な信念を表明している[140]。彼はまた、神託や占い、神からのその他のメッセージも信じていた。これらの兆候 は、道徳的な問題について彼に積極的な信念を与えるものではなく、むしろ不吉な未来を予言するものであった[141]。 クセノフォンの『思い出』の中で、ソクラテスは、現代の目的論的インテリジェント・デザイン論に近い議論を展開している。彼は、宇宙には「先見の明」を示 す特徴(例えば、まぶた)が多数あるため、神が宇宙を創造したに違いないと主張している[138]。そして、創造主は全知全能であるはずであり、 また、創造主は全知全能であり、人間が他の動物にはない多くの能力を持っていることから、創造主は人類の進歩のために宇宙を創造したはずだと論じている [142]。ソクラテスは、時には唯一神について語り、また時には複数の「神々」について言及している。これは、ソクラテスが至高神が他の神々を支配して いると信じていたか、あるいはさまざまな神々がこの唯一神の一部または現れであると信じていたことを意味すると解釈されている[143]。 ソクラテスの宗教的信念と彼の合理主義への厳格なこだわりとの関係については、議論の的となっている[144]。哲学教授のマーク・マクファーランは、ソ クラテスはあらゆる神聖な兆候を世俗的な合理性によって確認していたと主張している[145]。古代哲学の教授であるA. A. ロングは、ソクラテスが宗教的領域と合理的な領域は別物だと考えていたと考えるのは時代錯誤だと指摘している[146]。 ソクラテスのダイモン  アルキビアデス、ソクラテスから教えを受ける、1776年、フランソワ=アンドレ・ヴァンサン作、ソクラテスのダイモンを描いた絵画[147] いくつかの文献(例えば、プラトンの『エウテュプロス』3b5、『弁明』31c-d、クセノフォンの『思い出』1.1.2)において、ソクラテスは、自分 が間違いを犯しそうになったときに聞こえる内なる声、すなわちダイモニック・サインを聞いたと主張している。ソクラテスは、裁判でダイモニック・サインに ついて簡潔に説明している(『弁明』31c-d)。「...その理由は、私がこれまでさまざまな場所で何度も言及してきたことについて、あなたが聞いたこ とがあるはずだ。すなわち、メレトゥスが告発状で嘲笑的に記したように、私は神聖でダイモニックなものを経験しているということだ。それは私の幼少期に始 まり、特定の声が聞こえた。それが聞こえると、私はいつも自分がしようとしていた行動を思いとどまるが、肯定的なアドバイスは決して受けない。それが私が 政治に関与することを妨げてきたが、私はそれがそうしてきたことをまったく問題ないと考える。 徳と知識 ソクラテスの徳の理論では、徳はすべて本質的に一つである。なぜなら、徳は知識の一形態だからである[150]。ソクラテスにとって、人が善良でないのは 知識が欠けているからである。知識は一つであるから、徳も一つである。「誰も進んで誤りを犯すことはない」という有名な格言も、この理論から導かれている [151]。ソクラテスは『プラトン』の中で、勇気という例を用いて徳の一体性を主張している。すなわち、ある人が関連する危険性を理解していれば、リス クを冒すことができるというのである[150]。アリストテレスは次のように述べている。ソクラテス(長老)は、人生の終わりは徳を知ることであると考え ていた。そして、正義、勇気、徳の各要素の定義を模索していた。これは妥当なアプローチであった。なぜなら、彼はすべての徳は科学であり、例えば正義を知 れば、人は正義になる、と考えていたからだ...[152] 愛  ソクラテスとアルキビアデス、クリストファー・ヴィルヘルム・エッケルスベルグ作、1813年~1816年 ソクラテスがアルキビアデスや他の若者たちと恋愛関係にあったとする説もあるが、ソクラテスの少年たちとの友情は彼らの向上を目的としたものであり、性的 関係はなかったとする説もある。ソクラテスは『ゴルギアス』の中で、アルキビアデスと哲学の2つの愛好家であったと主張しており、『プロタゴラス』、『メ ノン』(76a-c)、『パイドロス』(227c-d)では、ソクラテスの浮気性が明らかである。しかし、アルキビアデスとの関係の正確な性質は明らかで はない。ソクラテスは自制心があることで知られていたが、アルキビアデスは『饗宴』の中で、ソクラテスを誘惑しようとしたが失敗したと認めている [153]。 ソクラテスの愛に関する理論は、主に『リュシス』から推測される。この作品では、ソクラテスがリュシスとその友人たちのいるレスリング学校で愛について 語っている[154]。彼らは、親の愛と、親が子供たちに与える自由と境界線について、その愛がどのように表れるかを考察することから対話を始める。ソク ラテスは、リュシスがまったく役に立たない人間であれば、誰も彼を愛さないだろう、両親でさえも、と結論づける。ほとんどの学者は、この文章はユーモアを 意図したものであると考えているが、一方で、リシスではソクラテスが利己的な愛の見解を示しており、それによると、私たちは何らかの形で自分に役立つ人だ けを愛するという意見もある[155]。他の学者はこの見解に反対しており、ソクラテスの教義には配偶者に対する利他的でない愛のための余地が残されてい ると主張している 配偶者に対する愛は、エゴイスティックな動機とは無関係である。また、ソクラテスがエゴイスティックな動機を示唆しているとはまったく考えない学者もいる [156]。『饗宴』では、ソクラテスは、子供たちが両親に不死の幻想を抱かせ、この誤解が両親の間に一体感を生み出すと主張している[157]。学者た ちはまた、ソクラテスにとって愛は理性的であると指摘している[158]。 自分が知らないことしか知らないというソクラテスは、(『プラトンの饗宴』の中で)例外として、「賢い女性」から学んだ愛について真実を語る、と語ってい る。古典学者アルマン・ダンゴールは、ソクラテスが若い頃アスパシアと親密であったこと、ソクラテスが『饗宴』で愛についての理解をディオティマから得た としているのは彼女に基づいていること、を主張している[159]。しかし、ディオティマが実在した可能性もある。 ソクラテスの政治哲学 ソクラテスが公の政治や文化の議論に関与していた一方で、彼の正確な政治哲学を定義することは難しい。プラトンの『ゴルギアス』の中で、彼はカリクレスに こう語っている。「私は、真の政治的手腕を身につけ、真の政治を実践する数少ないアテネ人の一人であると信じている。なぜなら、私がその都度行う演説は、 満足を得ることを目的としているのではなく、最善のものを目的としているからだ。」[160] 彼の主張は、ソクラテスが政治家や弁論家を、人々を欺くために策略を用いる者とみなしていたことから、確立された民主的集会や投票などの手続きに対する嫌 悪を示しています。。[161] 彼は公職に立候補することも、立法を提案することもなかった[162]。むしろ、彼は市民を「改善」することで、都市が繁栄するよう努めた[161]。市 民として、彼は法律に従った。彼は規則に従い、海外で戦争を戦うという軍務を果たした。しかし、彼の対話には、シチリア遠征などの当時の政治的な決定につ いてはほとんど言及されていない。 ソクラテスは市民、中でもアテネ社会で有力なメンバーと会話をし、彼らの信念を吟味し、彼らの考えの矛盾を明らかにすることに時間を費やした。ソクラテス にとって政治とは、選挙手続きではなく哲学を通じて都市の道徳的風景を形作ることであったため、彼は市民のために尽くしていると信じていた[163]。寡 頭政治者と民主派に二分されたアテネの政治情勢の中で、ソクラテスがどちらの立場に立っていたのかについては議論がある。明確な証拠はないが、広く受け入 れられている説によると、ソクラテスは民主主義を支持していた。彼は、三十人衆による寡頭政治が命じた命令に背き、アテネの法律と政治体制(これは民主派 によって制定された)を尊重していた。この説によると、ソクラテスが民主アテネの理想に共感していたことが、彼が牢獄と死刑を免れようとしなかった理由で ある。一方、ソクラテスが寡頭政治に傾倒していたという証拠もある。彼の友人の大半は寡頭政治を支持し、ソクラテスは多数派の意見を軽蔑し、民主的なプロ セスに批判的であった。また、プロタゴラスには反民主的な要素が見られる[164]。あまり主流ではない議論では、ソクラテスは民主共和主義を好んでいた という説がある。これは、公共生活への積極的な参加と都市への関心とを優先する理論である[165]。 また、ソクラテスは啓蒙主義時代に形成された政治思想である自由主義の考え方を支持していたという説もある。この説は主に『クリトン』と『弁明』に基づい ており、ソクラテスはそこでは都市と市民との相互利益関係について語っている。ソクラテスの考えでは、市民は道徳的に自律しており、望むなら自由に都市を 離れることができるが、都市にとどまることで、法律と都市の権威を受け入れることになる[166]。一方、ソクラテスは市民的不服従の最初の提唱者とも見 なされている。ソクラテスの不正に対する強い反対意見や、30人の専制者によるレオンの逮捕命令を拒否したことは、この考え方を示唆している。『クリティ アス』の中でソクラテスは、「たとえ自分に害を及ぼした者に対して報復するとしても、不正な行為をしてはならない」と述べている[167]。より広い観点 から見ると、ソクラテスのアドバイスは、熟考の末に不正であるとみなさない限り、市民は国家の命令に従うべきだということだろう[168]。 |

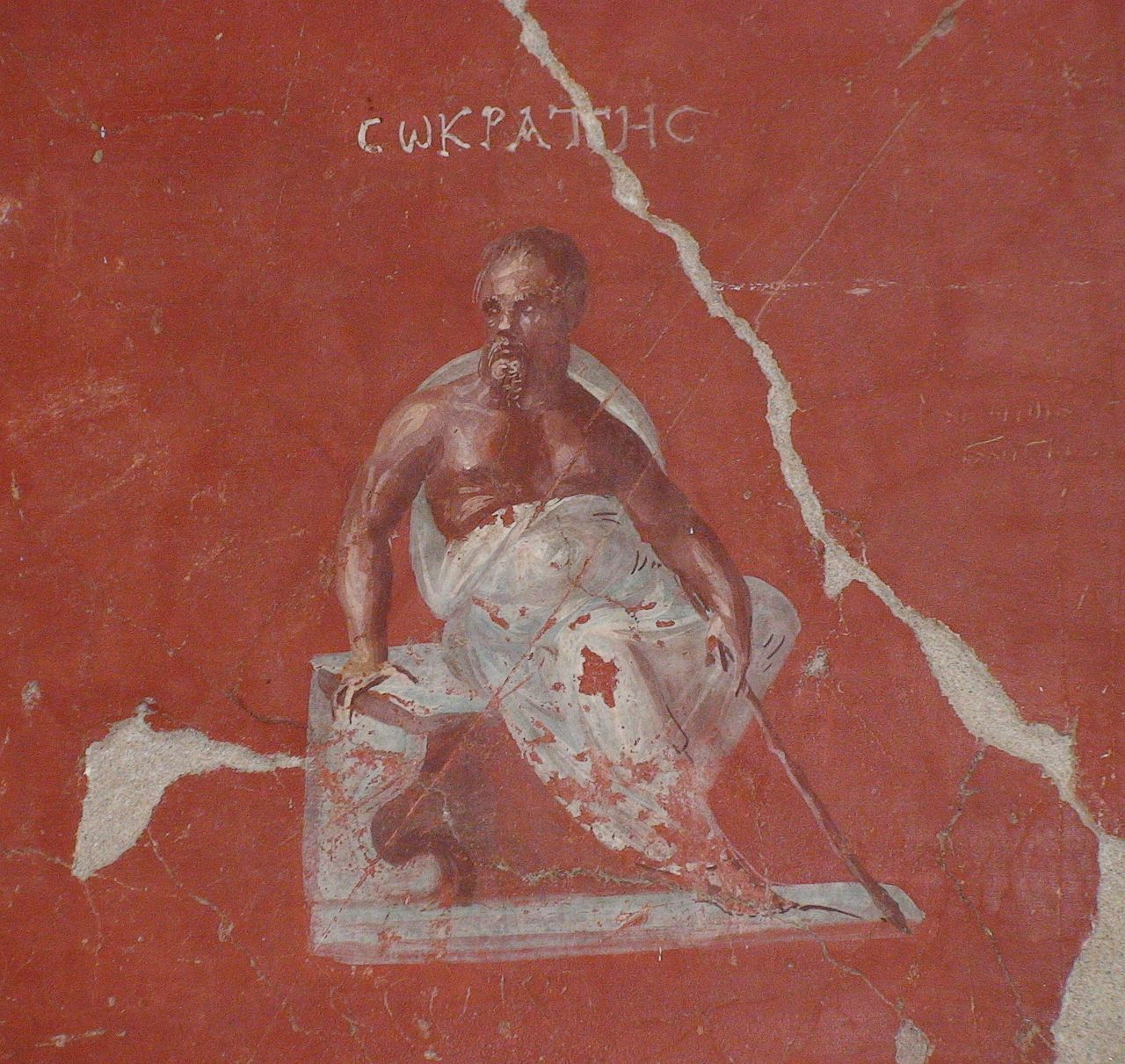

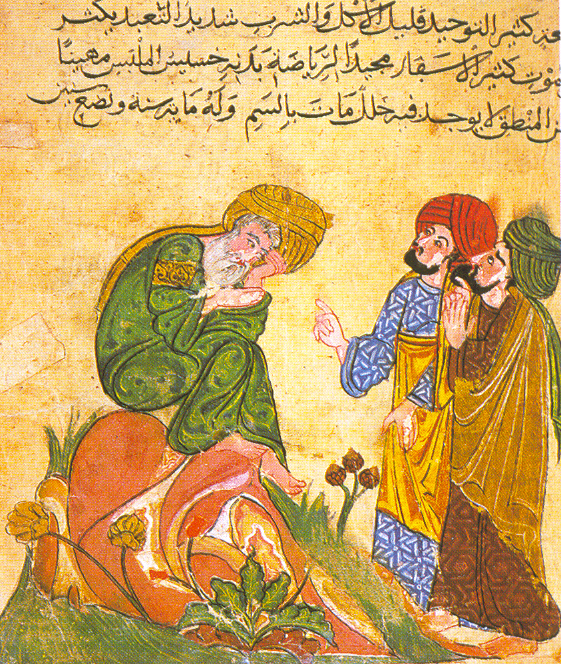

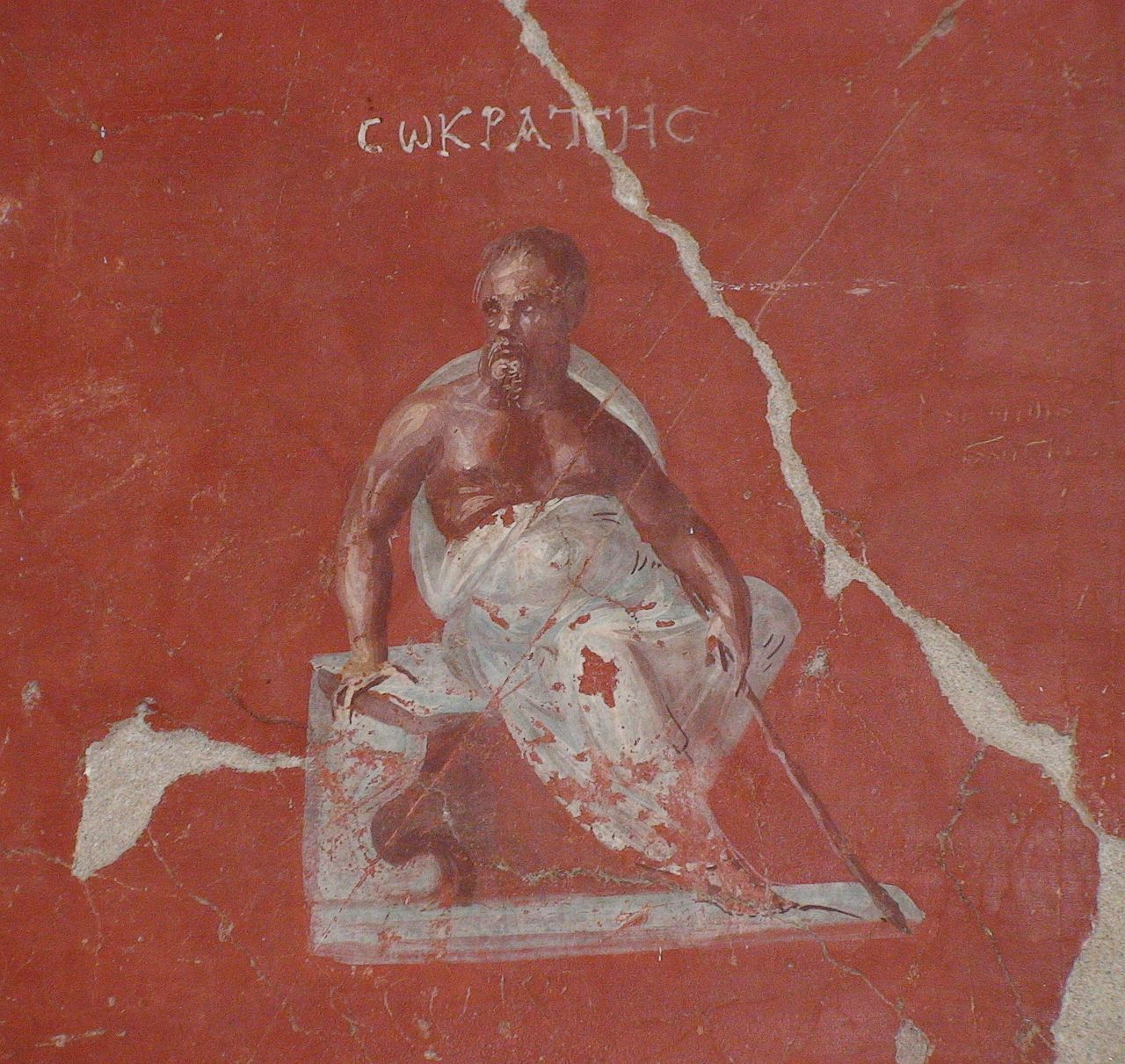

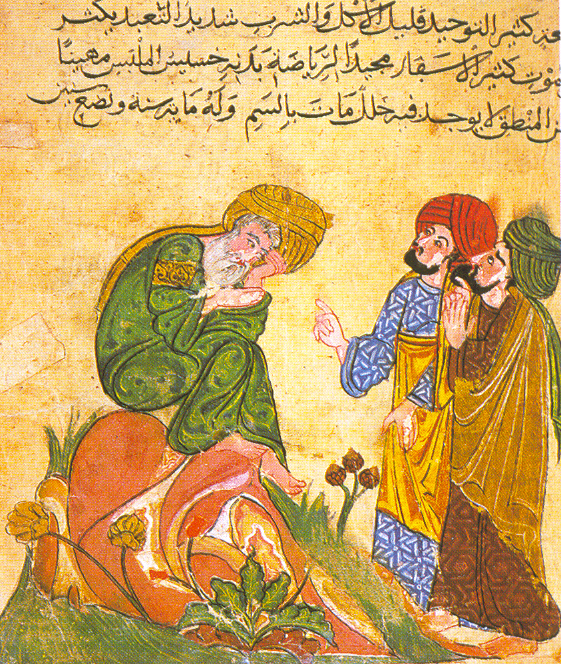

| Legacy Hellenistic era   Carnelian gem imprint representing Socrates, Rome, 1st century BC–1st century AD (left); Wall painting at a house depicting Socrates, 1st–5th century AD, Museum of Ephesus (right) Socrates's impact was immense in philosophy after his death. With the exception of the Epicureans and the Pyrrhonists, almost all philosophical currents after Socrates traced their roots to him: Plato's Academy, Aristotle's Lyceum, the Cynics, and the Stoics.[169] Interest in Socrates kept increasing until the third century AD.[170] The various schools differed in response to fundamental questions such as the purpose of life or the nature of arete (virtue), since Socrates had not handed them an answer, and therefore, philosophical schools subsequently diverged greatly in their interpretation of his thought.[171] He was considered to have shifted the focus of philosophy from a study of the natural world, as was the case for pre-Socratic philosophers, to a study of human affairs.[172] Immediate followers of Socrates were his pupils, Euclid of Megara, Aristippus, and Antisthenes, who drew differing conclusions among themselves and followed independent trajectories.[173] The full doctrines of Socrates's pupils are difficult to reconstruct.[174] Antisthenes had a profound contempt of material goods. According to him, virtue was all that mattered. Diogenes and the Cynics continued this line of thought.[175] On the opposite end, Aristippus endorsed the accumulation of wealth and lived a luxurious life. After leaving Athens and returning to his home city of Cyrene, he founded the Cyrenaic philosophical school which was based on hedonism, and endorsing living an easy life with physical pleasures. His school passed to his grandson, bearing the same name. There is a dialogue in Xenophon's work in which Aristippus claims he wants to live without wishing to rule or be ruled by others.[176] In addition, Aristippus maintained a skeptical stance on epistemology, claiming that we can be certain only of our own feelings. This view resonates with the Socratic understanding of ignorance.[177] Euclid was a contemporary of Socrates. After Socrates's trial and death, he left Athens for the nearby town of Megara, where he founded a school, named the Megarians. His theory was built on the pre-Socratic monism of Parmenides. Euclid continued Socrates's thought, focusing on the nature of virtue. The Stoics relied heavily on Socrates.[178] They applied the Socratic method as a tool to avoid inconsistencies. Their moral doctrines focused on how to live a smooth life through wisdom and virtue. The Stoics assigned virtue a crucial role in attaining happiness and also prioritized the relation between goodness and ethical excellence, all of which echoed Socratic thought.[179] At the same time, the philosophical current of Platonism claimed Socrates as its predecessor, in ethics and in its theory of knowledge. Arcesilaus, who became the head of the Academy about 80 years after its founding by Plato, radically changed the Academy's doctrine to what is now known as Academic Skepticism, centered on the Socratic philosophy of ignorance. The Academic Skeptics competed with the Stoics over who was Socrates's true heir with regard to ethics.[180] While the Stoics insisted on knowledge-based ethics, Arcesilaus relied on Socratic ignorance. The Stoics' reply to Arcesilaus was that Socratic ignorance was part of Socratic irony (they themselves disapproved the use of irony), an argument that ultimately became the dominant narrative of Socrates in later antiquity.[181] While Aristotle considered Socrates an important philosopher, Socrates was not a central figure in Aristotelian thought. One of Aristotle's pupils, Aristoxenus even authored a book detailing Socrates's scandals. The Epicureans were antagonistic to Socrates.[182] They attacked him for superstition, criticizing his belief in his daimonion and his regard for the oracle at Delphi.[183] They also criticized Socrates for his character and various faults, and focusing mostly on his irony, which was deemed inappropriate for a philosopher and unseemly for a teacher.[184] The Pyrrhonists were also antagonistic to Socrates, accusing him of being a prater about ethics, who engaged in mock humility, and who sneered at and mocked people.[185] Medieval world  Depiction of Socrates in a manuscript by Al-Mubashshir ibn Fatik Socratic thought found its way to the Islamic Middle East alongside that of Aristotle and the Stoics. Plato's works on Socrates, as well as other ancient Greek literature, were translated into Arabic by early Muslim scholars such as Al-Kindi, Jabir ibn Hayyan, and the Muʿtazila. For Muslim scholars, Socrates was hailed and admired for combining his ethics with his lifestyle, perhaps because of the resemblance in this regard with Muhammad's personality.[186] Socratic doctrines were altered to match Islamic faith: according to Muslim scholars, Socrates made arguments for monotheism and for the temporality of this world and rewards in the next life.[187] His influence in the Arabic-speaking world continues to the present day.[188] In medieval times, little of Socrates's thought survived in the Christian world as a whole; however, works on Socrates from Christian scholars such as Lactantius, Eusebius and Augustine were maintained in the Byzantine Empire, where Socrates was studied under a Christian lens.[189] After the fall of Constantinople, many of the texts were brought back into the world of Roman Christianity, where they were translated into Latin. Overall, ancient Socratic philosophy, like the rest of classical literature before the Renaissance, was addressed with skepticism in the Christian world at first.[190] During the early Italian Renaissance, two different narratives of Socrates developed.[191] On the one hand, the humanist movement revived interest in classical authors. Leonardo Bruni translated many of Plato's Socratic dialogues, while his pupil Giannozzo Manetti authored a well-circulated book, a Life of Socrates. They both presented a civic version of Socrates, according to which Socrates was a humanist and a supporter of republicanism. Bruni and Manetti were interested in defending secularism as a non-sinful way of life; presenting a view of Socrates that was aligned with Christian morality assisted their cause. In doing so, they had to censor parts of his dialogues, especially those which appeared to promote homosexuality or any possibility of pederasty (with Alcibiades), or which suggested that the Socratic daimon was a god.[192] On the other hand, a different picture of Socrates was presented by Italian Neoplatonists, led by the philosopher and priest Marsilio Ficino. Ficino was impressed by Socrates's un-hierarchical and informal way teaching, which he tried to replicate. Ficino portrayed a holy picture of Socrates, finding parallels with the life of Jesus Christ. For Ficino and his followers, Socratic ignorance signified his acknowledgement that all wisdom is God-given (through the Socratic daimon).[193] Modern times  Socrates along with his wives (he was married once or twice) and students, appears in many paintings. Here Socrates, his two Wives, and Alcibiades, a painting by the Dutch Golden Age artist Reyer van Blommendael. Often, his wife Xanthippe, alone or with Myrto (the other alleged wife of Socrates) is depicted emptying a pot of urine (hydria) over Socrates.[194] In early modern France, Socrates's image was dominated by features of his private life rather than his philosophical thought, in various novels and satirical plays.[195] Some thinkers used Socrates to highlight and comment upon controversies of their own era, like Théophile de Viau who portrayed a Christianized Socrates accused of atheism,[196] while for Voltaire, the figure of Socrates represented a reason-based theist.[197] Michel de Montaigne wrote extensively on Socrates, linking him to rationalism as a counterweight to contemporary religious fanatics.[198] In the 18th century, German idealism revived philosophical interest in Socrates, mainly through Hegel's work. For Hegel, Socrates marked a turning point in the history of humankind by the introduction of the principle of free subjectivity or self-determination. While Hegel hails Socrates for his contribution, he nonetheless justifies the Athenian court, for Socrates's insistence upon self-determination would be destructive of the Sittlichkeit (a Hegelian term signifying the way of life as shaped by the institutions and laws of the State).[199] Also, Hegel sees the Socratic use of rationalism as a continuation of Protagoras' focus on human reasoning (as encapsulated in the motto homo mensura: "man is the measure of all things"), but modified: it is our reasoning that can help us reach objective conclusions about reality.[200] Also, Hegel considered Socrates as a predecessor of later ancient skeptic philosophers, even though he never clearly explained why.[201] Søren Kierkegaard considered Socrates his teacher,[202] and authored his master's thesis on him, The Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates.[203] There he argues that Socrates is not a moral philosopher but is purely an ironist.[204] He also focused on Socrates's avoidance of writing: for Kierkegaard, this avoidance was a sign of humility, deriving from Socrates's acceptance of his ignorance.[205] Not only did Socrates not write anything down, according to Kierkegaard, but his contemporaries misconstrued and misunderstood him as a philosopher, leaving us with an almost impossible task in comprehending Socratic thought.[203] Only Plato's Apology was close to the real Socrates, in Kierkegaard's view.[206] In his writings, he revisited Socrates quite frequently; in his later work, Kierkegaard found ethical elements in Socratic thought.[204] Socrates was not only a subject of study for Kierkegaard, he was a model as well: Kierkegaard paralleled his task as a philosopher to Socrates. He writes, "The only analogy I have before me is Socrates; my task is a Socratic task, to audit the definition of what it is to be a Christian", with his aim being to bring society closer to the Christian ideal, since he believed that Christianity had become a formality, void of any Christian essence.[207] Kierkegaard denied being a Christian, as Socrates denied possessing any knowledge.[208] Friedrich Nietzsche resented Socrates's contributions to Western culture.[209] In his first book, The Birth of Tragedy (1872), Nietzsche held Socrates responsible for what he saw as the deterioration of ancient Greek civilization during the 4th century BC and after. For Nietzsche, Socrates turned the scope of philosophy from pre-Socratic naturalism to rationalism and intellectualism. He writes: "I conceive of [the Presocratics] as precursors to a reformation of the Greeks: but not of Socrates"; "with Empedocles and Democritus the Greeks were well on their way towards taking the correct measure of human existence, its unreason, its suffering; they never reached this goal, thanks to Socrates".[210] The effect, Nietzsche proposed, was a perverse situation that had continued down to his day: our culture is a Socratic culture, he believed.[209] In a later publication, The Twilight of the Idols (1887), Nietzsche continued his offensive against Socrates, focusing on the arbitrary linking of reason to virtue and happiness in Socratic thinking. He writes: "I try to understand from what partial and idiosyncratic states the Socratic problem is to be derived: his equation of reason = virtue = happiness. It was with this absurdity of a doctrine of identity that he fascinated: ancient philosophy never again freed itself [from this fascination]".[211] From the late 19th century until the early 20th, the most common explanation of Nietzsche's hostility towards Socrates was his anti-rationalism; he considered Socrates the father of European rationalism. In the mid-20th century, philosopher Walter Kaufmann published an article arguing that Nietzsche admired Socrates. Current mainstream opinion is that Nietzsche was ambivalent towards Socrates.[212]  The statue of Socrates outside the National Library of Uruguay, Montevideo Continental philosophers Hannah Arendt, Leo Strauss and Karl Popper, after experiencing the horrors of World War II, amidst the rise of totalitarian regimes, saw Socrates as an icon of individual conscience.[213] Arendt, in Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963), suggests that Socrates's constant questioning and self-reflection could prevent the banality of evil.[214] Strauss considers Socrates's political thought as paralleling Plato's. He sees an elitist Socrates in Plato's Republic as exemplifying why the polis is not, and could not be, an ideal way of organizing life, since philosophical truths cannot be digested by the masses.[215] Popper takes the opposite view: he argues that Socrates opposes Plato's totalitarian ideas. For Popper, Socratic individualism, along with Athenian democracy, imply Popper's concept of the "open society" as described in his Open Society and Its Enemies (1945).[216] |