セーレン・キルケゴール

Søren Kierkegaard,

1813-1855

☆セーレン・アービー・キルケゴール[Søren Aabye

Kierkegaard]

(/ˈsɒrən ˈkɪərkəɡɑːrd/ ソレン キルケゴール、米国では /-ɡɔːr/ -gor と発音される場合もある)

デンマーク語発音: [ˈsɶːɐn ˈɔˀˌpyˀ ˈkʰiɐ̯kəˌkɒːˀ] ⓘ; [1] 1813年5月5日 –

1855年11月11日[2])は、デンマークの神学者、哲学者、詩人、社会評論家、宗教作家であり、広く最初の実存主義哲学者と見なされている。[3]

彼は組織化された宗教、キリスト教、道徳、倫理、心理学、愛、宗教哲学に関する批判的著作を執筆し、隠喩、皮肉、寓話への嗜好を示した。彼の哲学的著作の

多くは、「単なる人格」としていかに生きるかという問題[4]を扱い、真正性、個人的な選択と献身、愛する義務の重要性を強調している。キルケゴールは抽

象的な思考よりも具体的な人間の現実を優先した。

キルケゴールの神学著作は、ソクラテス的キリスト教倫理、教会の制度、キリスト教の純粋に客観的な証明の差異、人間と神との無限の質的差異、そして信仰を

通じて得られる神人イエス・キリストとの個人の主観的関係[5]に焦点を当てている[6][7]。彼の著作の多くはキリスト教的愛を扱っている。彼はデン

マーク国教会のような国家統制宗教(カエサロパピズム)としてのキリスト教の教義と実践を厳しく批判した。心理学的著作では、人生の選択に直面した個人の

感情や心情を探求した[8]。ジャン=ポール・サルトルや無神論的実存主義のパラダイムとは異なり、キルケゴールはキリスト教実存主義に焦点を当てた。

キルケゴールの初期著作は、複雑な対話の中で異なる視点が交錯する様を表現するため、複数の筆名を用いて執筆された[9]。彼は特に複雑な問題を、それぞ

れ異なる筆名の下で異なる視点から考察した。自筆名で執筆した『啓発的言説』は、自身の著作の意味を見出そうとする「一人の個人」に捧げられた。彼はこう

記している:「科学と学問は、客観的になることが道だと教えようとする。」

キリスト教は主観的になること、主体になることが道だと教える」と記している[10][11]。科学者が観察によって世界を知る一方で、キルケゴールは観

察だけでは精神の世界の内的な働きを明らかにできないと強く否定した。[12]

キルケゴールの主要な思想には、「主観的真理と客観的真理」の概念、信仰の騎士、回想と反復の二分法、不安、無限の質的差異、情熱としての信仰、人生の三

つの段階などがある。キルケゴールはデンマーク語で執筆し、その著作の受容は当初スカンディナヴィア地域に限定されていた。しかし20世紀の変わり目まで

に、彼の著作はフランス語、ドイツ語、その他の主要なヨーロッパ言語に翻訳された。20世紀半ばまでに、彼の思想は哲学[13]、神学[14]、そして西

洋文化全般[15]に多大な影響を及ぼした。

| Søren Aabye

Kierkegaard (/ˈsɒrən ˈkɪərkəɡɑːrd/ SORR-ən KEER-kə-gard, US also

/-ɡɔːr/ -gor; Danish: [ˈsɶːɐn ˈɔˀˌpyˀ ˈkʰiɐ̯kəˌkɒːˀ] ⓘ;[1] 5 May 1813

– 11 November 1855[2]) was a Danish theologian, philosopher, poet,

social critic, and religious author who is widely considered to be the

first existentialist philosopher.[3] He wrote critical texts on

organized religion, Christianity, morality, ethics, psychology, love,

and the philosophy of religion, displaying a fondness for metaphor,

irony, and parables. Much of his philosophical work deals with the

issues of how one lives as a "single individual",[4] highlighting the

importance of authenticity, personal choice and commitment, and the

duty to love. Kierkegaard prioritized concrete human reality over

abstract thinking. Kierkegaard's theological work focuses on Socratic Christian ethics, the institution of the Church, the differences among purely objective proofs of Christianity, the infinite qualitative distinction between man and God, and the individual's subjective relationship to the God-Man Jesus Christ,[5] which came through faith.[6][7] Much of his work deals with Christian love. He was extremely critical of the doctrine and practice of Christianity as a state-controlled religion (Caesaropapism) like the Church of Denmark. His psychological work explored the emotions and feelings of individuals when faced with life choices.[8] Unlike Jean-Paul Sartre and the atheistic existentialism paradigm, Kierkegaard focused on Christian existentialism. Kierkegaard's early work was written using pseudonyms to present distinctive viewpoints interacting in complex dialogue.[9] He explored particularly complex problems from different viewpoints, each under a different pseudonym. He wrote Upbuilding Discourses under his own name and dedicated them to the "single individual" who might want to discover the meaning of his works. He wrote: "Science and scholarship want to teach that becoming objective is the way. Christianity teaches that the way is to become subjective, to become a subject."[10][11] While scientists learn about the world by observation, Kierkegaard emphatically denied that observation alone could reveal the inner workings of the world of the spirit.[12] Some of Kierkegaard's key ideas include the concept of "subjective and objective truths", the knight of faith, the recollection and repetition dichotomy, angst, the infinite qualitative distinction, faith as a passion, and the three stages on life's way. Kierkegaard wrote in Danish and the reception of his work was initially limited to Scandinavia, but by the turn of the 20th century his writings were translated into French, German, and other major European languages. By the middle of the 20th century, his thought exerted a substantial influence on philosophy,[13] theology,[14] and Western culture in general.[15] |

セーレン・アービー・キルケゴール [Søren Aabye

Kierkegaard] (/ˈsɒrən

ˈkɪərkəɡɑːrd/ ソレン キルケゴール、米国では /-ɡɔːr/ -gor と発音される場合もある) デンマーク語発音:

[ˈsɶːɐn ˈɔˀˌpyˀ ˈkʰiɐ̯kəˌkɒːˀ] ⓘ; [1] 1813年5月5日 –

1855年11月11日[2])は、デンマークの神学者、哲学者、詩人、社会評論家、宗教作家であり、広く最初の実存主義哲学者と見なされている。[3]

彼は組織化された宗教、キリスト教、道徳、倫理、心理学、愛、宗教哲学に関する批判的著作を執筆し、隠喩、皮肉、寓話への嗜好を示した。彼の哲学的著作の

多くは、「単なる人格」としていかに生きるかという問題[4]を扱い、真正性、個人的な選択と献身、愛する義務の重要性を強調している。キルケゴールは抽

象的な思考よりも具体的な人間の現実を優先した。 キルケゴールの神学著作は、ソクラテス的キリスト教倫理、教会の制度、キリスト教の純粋に客観的な証明の差異、人間と神との無限の質的差異、そして信仰を 通じて得られる神人イエス・キリストとの個人の主観的関係[5]に焦点を当てている[6][7]。彼の著作の多くはキリスト教的愛を扱っている。彼はデン マーク国教会のような国家統制宗教(カエサロパピズム)としてのキリスト教の教義と実践を厳しく批判した。心理学的著作では、人生の選択に直面した個人の 感情や心情を探求した[8]。ジャン=ポール・サルトルや無神論的実存主義のパラダイムとは異なり、キルケゴールはキリスト教実存主義に焦点を当てた。 キルケゴールの初期著作は、複雑な対話の中で異なる視点が交錯する様を表現するため、複数の筆名を用いて執筆された[9]。彼は特に複雑な問題を、それぞ れ異なる筆名の下で異なる視点から考察した。自筆名で執筆した『啓発的言説』は、自身の著作の意味を見出そうとする「一人の個人」に捧げられた。彼はこう 記している:「科学と学問は、客観的になることが道だと教えようとする。」 キリスト教は主観的になること、主体になることが道だと教える」と記している[10][11]。科学者が観察によって世界を知る一方で、キルケゴールは観 察だけでは精神の世界の内的な働きを明らかにできないと強く否定した。[12] キルケゴールの主要な思想には、「主観的真理と客観的真理」の概念、信仰の騎士、回想と反復の二分法、不安、無限の質的差異、情熱としての信仰、人生の三 つの段階などがある。キルケゴールはデンマーク語で執筆し、その著作の受容は当初スカンディナヴィア地域に限定されていた。しかし20世紀の変わり目まで に、彼の著作はフランス語、ドイツ語、その他の主要なヨーロッパ言語に翻訳された。20世紀半ばまでに、彼の思想は哲学[13]、神学[14]、そして西 洋文化全般[15]に多大な影響を及ぼした。 |

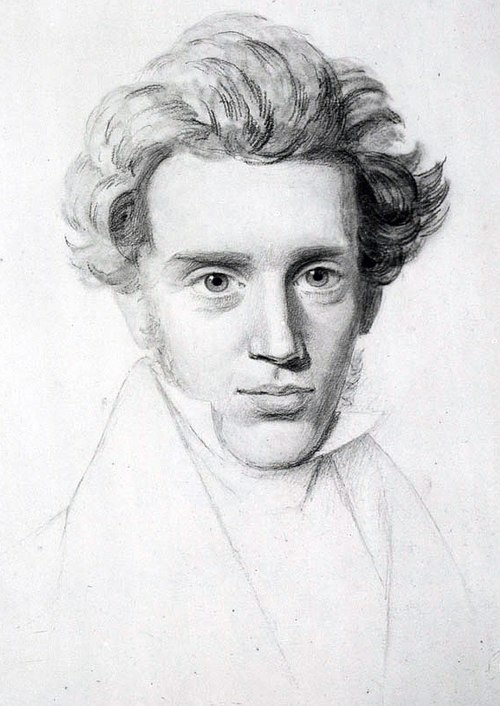

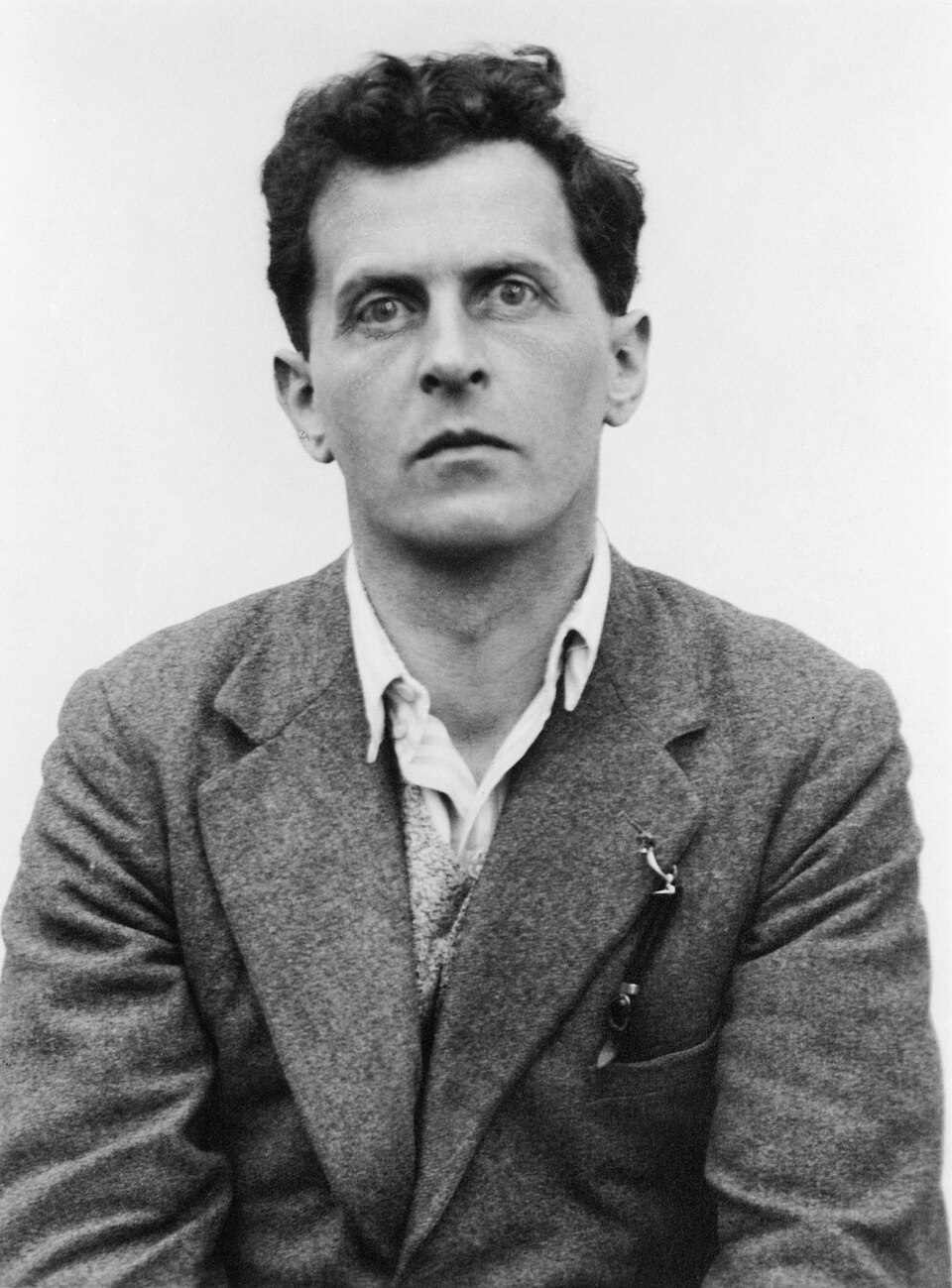

Early years (1813–1836) Søren Kierkegaard.―Hand-drawn copy (1895) of a pencil drawing in the portraiture collection of the Royal Library[16] Kierkegaard was born to an affluent family in Copenhagen as the youngest of seven children. His mother, Ane Sørensdatter Lund Kierkegaard (1768–1834), had served as a maid in the household before marrying his father, Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard (1756–1838).[17][18] She was an unassuming figure: quiet, and not formally educated.[19] Her granddaughter, Henriette Lund, wrote that she "wielded her scepter with delight, cosseted them [Søren and his brother Peter], and protected them like a hen her chicks".[20] She also wielded influence on her children so that later Peter Christian Kierkegaard said that his brother preserved many of their mother's words in his writings.[21] His father, on the other hand, was a well-to-do wool merchant from Jutland.[21] He was a "very stern man, to all appearances dry and prosaic, but under his 'rustic cloak' demeanor he concealed an active imagination which not even his great age could blunt".[22] He was also interested in philosophy and often hosted intellectuals at his home.[23] He was devoted to the rationalist philosophy of Christian Wolff,[24] and he eventually retired partly to pursue more of Wolff's writings.[25] Kierkegaard, who followed his father's beliefs as a child, was heavily influenced by Michael's devotion to Wolffian rationalism. He also enjoyed the comedies of Ludvig Holberg,[26] the writings of Johann Georg Hamann,[27] Gotthold Ephraim Lessing,[28] Edward Young,[29] and Plato. The figure of Socrates, whom Kierkegaard encountered in Plato's dialogues, would prove to be a phenomenal influence on the philosopher's later interest in irony, as well as his frequent deployment of indirect communication.[30] Kierkegaard loved to walk along the crooked streets of 19th century Copenhagen, where carriages rarely went. In 1848, Kierkegaard wrote, "I had real Christian satisfaction in the thought that, if there were no other, there was definitely one man in Copenhagen whom every poor person could freely accost and converse with on the street; that, if there were no other, there was one man who, whatever the society he most commonly frequented, did not shun contact with the poor, but greeted every maidservant he was acquainted with, every manservant, every common laborer."[31] Our Lady's Church was at one end of the city, where Bishop Mynster preached the Gospel. At the other end was the Royal Theatre where Fru Heiberg performed.[32]  When Michael (Mikael) Kierkegaard died on 9 August 1838 Søren had lost both his parents and all his brothers and sisters except for Peter who later became Bishop of Aalborg in the Danish State Lutheran Church.  From left to right: Wolff, Holberg, Hamann, Lessing, Plato and Socrates Based on a speculative interpretation of anecdotes in Kierkegaard's unpublished journals, especially a rough draft of a story called "The Great Earthquake", some early Kierkegaard scholars argued that Michael believed he had earned God's wrath and that none of his children would outlive him. He is said to have believed that his personal sins, perhaps indiscretions such as cursing the name of God in his youth or impregnating Ane out of wedlock, necessitated this punishment.[33] Though five of his seven children died before he did, both Søren and his brother Peter outlived him.[34] Peter, who was seven years older, later became bishop in Aalborg.[35] Julia Watkin thought Michael's early interest in the Moravian Church could have led him to a deep sense of the devastating effects of sin.[36] From 1821 to 1830, Kierkegaard attended the School of Civic Virtue, Østre Borgerdyd Gymnasium when the school was situated in Klarebodeme, where Kierkegaard studied and learned Latin, Greek, and history, among other subjects.[37] During his time there he was described as "very conservative"; someone who would "honour the King, love the church and respect the police".[38] He frequently got into altercations with fellow students and was ambivalent towards his teachers.[38] He went on to study theology at the University of Copenhagen. He had little interest in historical works, philosophy dissatisfied him, and he couldn't see "dedicating himself to Speculation".[39] He said, "What I really need to do is to get clear about "what am I to do", not what I must know." He wanted to "lead a completely human life and not merely one of knowledge".[40] Kierkegaard didn't want to be a philosopher in the traditional or Hegelian sense[41] and he didn't want to preach a Christianity that was an illusion.[42] "But he had learned from his father that one can do what one wills, and his father's life had not discredited this theory."[43] One of the first physical descriptions of Kierkegaard comes from an attendee, Hans Brøchner, at his brother Peter's wedding party in 1836: "I found [his appearance] almost comical. He was then twenty-three years old; he had something quite irregular in his entire form and had a strange coiffure. His hair rose almost six inches above his forehead into a tousled crest that gave him a strange, bewildered look."[44][45] Another comes from Kierkegaard's niece, Henriette Lund (1829–1909), who recounts that as a little boy Søren was "of a slight and delicate appearance. He went around in a coat the color of red cabbage, and his father usually called him 'the Fork,' because of his precocious tendency to make satirical remarks. Even though there was a serious, almost strict tone in the Kierkegaard home, I still have the impression that there was room for youthful liveliness, though perhaps of a more sober, homemade sort than is usual today. In the same way the house was also open, with an old-fashioned kind of hospitality."[46] He was also described as "quaintly attired, slight and small".[38] Kierkegaard's mother "was a nice little woman with an even and happy disposition," according to a grandchild's description. She was never mentioned in Kierkegaard's works. Ane died on 31 July 1834, age 66, possibly from typhus.[47] His father died on 8 August 1838, age 82. On 11 August, Kierkegaard wrote: "My father died on Wednesday (the 8th) at 2:00 a.m. I so deeply desired that he might have lived a few years more... Right now I feel there is only one person (E. Boesen) with whom I can really talk about him. He was a 'faithful friend.'"[48] Troels Frederik Lund, his nephew, was instrumental in providing biographers with much information regarding Søren Kierkegaard. Lund was a good friend of Georg Brandes and Julius Lange.[49] Here is an anecdote about his father from Kierkegaard's journals. |

初期(1813–1836) セーレン・キルケゴール。―王立図書館肖像画コレクション所蔵の鉛筆画を手書きで複製したもの(1895年)[16] キルケゴールはコペンハーゲンの裕福な家庭に、7人兄弟の末っ子として生まれた。母アネ・ソレンスダッター・ルンド・キルケゴール(1768–1834) は、父ミケル・ペデルセン・キルケゴール(1756–1838)と結婚する前は、その家の使用人として働いていた。[17][18] 彼女は控えめな人物で、物静かであり、正式な教育を受けていなかった。[19] 孫娘のヘンリエッテ・ルンドは、彼女が「喜びをもって権威を行使し、彼ら(セーレンと兄のペテル)を甘やかして、鶏が雛を守るように守った」と記してい る。[20] 彼女は子供たちにも強い影響力を持っており、後にペーター・クリスチャン・キルケゴールは、兄が著作の中で母の言葉を多く残したと述べている。[21] 一方、父はユトランド出身の裕福な羊毛商人であった。[21] 彼は「非常に厳格な人物で、外見上は乾いて現実的だったが、その『田舎者の外套』のような態度の下には、高齢になっても鈍らない活発な想像力を秘めてい た」[22]。哲学にも関心を持ち、自宅に知識人を招くことも多かった[23]。クリスティアン・ヴォルフの合理主義哲学に傾倒し[24]、最終的には ヴォルフの著作をさらに追求するため、部分的に引退した。[25] 幼少期に父の信念に従ったキルケゴールは、ミヒャエルのヴォルフ的合理主義への傾倒に強く影響を受けた。また、ルートヴィヒ・ホルベルクの喜劇[26]、 ヨハン・ゲオルク・ハーマン[27]、ゴットホルト・エフライム・レッシング[28]、エドワード・ヤング[29]、プラトンの著作も好んだ。キルケゴー ルがプラトンの対話篇で出会ったソクラテスの姿は、後に彼が皮肉に関心を抱くことや、間接的な表現を頻繁に用いること[30]に、驚くべき影響を与えた。 キルケゴールは19世紀コペンハーゲンの曲がりくねった道を歩くのが好きだった。そこには馬車がめったに通らなかった。1848年、彼はこう記している。 「たとえ他に誰もいなくとも、コペンハーゲンには貧しい者が路上で自由に話しかけ、語り合える人格が確かに一人いるという考えに、私は真のキリスト教的満 足を感じた。たとえ他に誰もいなくとも、最も頻繁に交わる社会層に関わらず、貧しい者との接触を避けず、知り合いの女中、男中、普通の労働者一人一人に挨 拶する人格が一人いるという考えに」 [31] 聖母教会は街の一端にあり、ミンスター司教がそこで福音を説いた。反対側には王立劇場があり、フルー・ハイベルクがそこで演技した。[32]  1838年8月9日にミカエル・キルケゴールが死去した時、セーレンは両親と兄弟姉妹全員を失っていた。後にデンマーク国教会オルボー司教となったピーターを除く。  左から右へ:ヴォルフ、ホルベルグ、ハーマン、レッシング、プラトン、ソクラテス キルケゴール未発表の日記、特に「大地震」という物語の草稿に記された逸話を推測的に解釈した結果、初期のキルケゴール研究者の中には、ミヒャエルが神の 怒りを買ったと信じ、自分の子供は誰も自分より長生きしないと考えたと主張する者もいた。彼は、若き日に神の名を冒涜したとか、婚外でアネを妊娠させたと いった個人的な罪が、この罰を必然としたと信じていたと言われる。[33] 7人の子供のうち5人は彼より先に亡くなったが、セーレンと弟のペテルは彼より長生きした。[34] 7歳年上のペテルは後にオールボーの司教となった。[35] ジュリア・ワトキンは、ミヒャエルがモラヴィア教会に早くから関心を示したことが、罪の破壊的な影響に対する深い認識につながった可能性があると指摘して いる。[36] 1821年から1830年まで、キルケゴールは市民道徳学校(Østre Borgerdyd Gymnasium)に通った。当時はクラレボーデメに校舎があり、そこでラテン語、ギリシャ語、歴史などの科目を学んだ。[37] 在学中、彼は「非常に保守的」と評され、「国王を敬い、教会を愛し、警察を尊重する」人物であった[38]。同級生とは頻繁に口論になり、教師たちに対し ても複雑な感情を抱いていた。[38] その後コペンハーゲン大学で神学を学んだ。歴史書にはほとんど関心がなく、哲学には不満を抱き、「思索に没頭する」ことにも意義を見出せなかった。 [39] 彼は「真に必要なのは『知るべきこと』ではなく『何をなすべきか』を明確にすることだ」と述べ、「知識だけの生活ではなく、完全に人間らしい人生を送りた い」と願った。[40] キルケゴールは伝統的あるいはヘーゲル的な意味での哲学者[41]になりたくなかったし、幻想に過ぎないキリスト教を説くことも望まなかった[42]。 「しかし彼は父から、人は自らの意志を行使できることを学んでいた。そして父の人生は、この理論を否定するものではなかった」[43]。 キルケゴールに関する最初の身体的描写の一つは、1836年に兄ペーターの結婚式に出席したハンス・ブローヒナーによるものだ。「彼の外見はほとんど滑稽 に思えた。当時23歳だったが、全身に不規則なところがあり、奇妙な髪型をしていた。額から約15センチも逆立った乱れた髪が、彼に奇妙で当惑したような 表情を与えていた。」 [44][45] もう一つはキルケゴールの姪、ヘンリエット・ルンド(1829–1909)による記述だ。彼女は幼い頃のセーレンを「細身で繊細な風貌だった。赤キャベツ 色のコートを着て歩き回り、父親は彼の早熟な皮肉屋ぶりからよく『フォーク』と呼んでいた」と回想している。キルケゴール家には厳格な雰囲気があったが、 それでも若々しい活気があった印象がある。ただし現代のそれより質素で家庭的なものだった。同様に家は開放的で、昔ながらのもてなしの心があった。」 [46] また彼は「風変わりな服装で、小柄で細身」とも描写されている。[38] キルケゴールの母は孫の記述によれば「穏やかで幸せそうな気質の、愛らしい小柄な女性」であった。キルケゴールの著作では一切言及されていない。アネは 1834年7月31日、66歳で死去した。おそらくチフスが原因だった[47]。父は1838年8月8日、82歳で亡くなった。8月11日、キルケゴール はこう記している。「父は水曜日(8日)午前2時に亡くなった。あと数年だけでも生き続けてほしかったと心底願った…今、父について心から話せる人格はた だ一人(E・ボーセン)しかいない。彼は『誠実な友人』だった」 [48] 甥のトロエルス・フレデリック・ルンドは、セーレン・キルケゴールに関する多くの情報を伝記作家に提供した。ルンドはゲオルク・ブランデスやユリウス・ラ ングの親友であった。[49] ここにキルケゴールの日記から父に関する逸話を記す。 |

| Journals According to Samuel Hugo Bergmann, "Kierkegaard's journals are one of the most important sources for an understanding of his philosophy".[50] Kierkegaard wrote over 7,000 pages in his journals on events, musings, thoughts about his works and everyday remarks.[51] The entire collection of Danish journals (Journalen) was edited and published in 13 volumes consisting of 25 separate bindings including indices. The first English edition of the journals was edited by Alexander Dru in 1938.[52] The style is "literary and poetic [in] manner".[53] Kierkegaard wanted to have Regine, his fiancée (see below), as his confidant but considered it an impossibility for that to happen so he left it to "my reader, that single individual" to become his confidant. His question was whether or not one can have a spiritual confidant. He wrote the following in his Concluding Postscript: "With regard to the essential truth, a direct relation between spirit and spirit is unthinkable. If such a relation is assumed, it actually means that the party has ceased to be spirit."[54] Kierkegaard's journals were the source of many aphorisms credited to the philosopher. The following passage, from 1 August 1835, is perhaps his most oft-quoted aphorism and a key quote for existentialist studies: What I really need is to get clear about what I must do, not what I must know, except insofar as knowledge must precede every act. What matters is to find a purpose, to see what it really is that God wills that I shall do; the crucial thing is to find a truth which is truth for me, to find the idea for which I am willing to live and die. Although his journals clarify some aspects of his work and life, Kierkegaard took care not to reveal too much. Abrupt changes in thought, repetitive writing, and unusual turns of phrase are some among the many tactics he used to throw readers off track. Consequently, there are many varying interpretations of his journals. Kierkegaard did not doubt the importance his journals would have in the future. In December 1849, he wrote: "Were I to die now the effect of my life would be exceptional; much of what I have simply jotted down carelessly in the Journals would become of great importance and have a great effect; for then people would have grown reconciled to me and would be able to grant me what was, and is, my right."[55] |

ジャーナル サミュエル・ヒューゴ・バーグマンによれば、「キルケゴールの日記は、彼の哲学を理解する上で最も重要な情報源の一つである」[50]。キルケゴールは、 出来事、思索、自分の作品についての考え、そして日常的な所感について、7,000ページ以上の日記を書いた。[51] デンマーク語の日記(Journalen)の全コレクションは、索引を含む 25 冊の別冊で構成される 13 巻に編集・出版された。この日記の最初の英語版は、1938 年にアレクサンダー・ドルーによって編集された。[52] その文体は「文学的かつ詩的」である。[53] キルケゴールは、婚約者(後述)であるレギーネを自分の親友にしたいと思ったが、それは不可能だと考えたため、「私の読者、その一人」を親友とすることを 選んだ。彼の疑問は、精神的な親友を持つことができるかどうかだった。彼は「結語」の中で次のように書いている。「本質的な真実に関しては、精神と精神の 直接的な関係は考えられない。そのような関係があると仮定すると、それは実際には、その当事者が精神ではなくなったことを意味する」[54]。 キルケゴールの日記は、この哲学者に帰せられる多くの格言の源となった。1835年8月1日の次の記述は、おそらく最も頻繁に引用される格言であり、実存主義研究における核心的な引用である: 真に必要なのは、知るべきことではなく、なすべきことを明確にすることだ。ただし、あらゆる行為に先立つべき知識は別として。肝心なのは目的を見出し、神 が私に成し遂げよと望む真の意志を見極めることである。決定的なのは、私にとっての真実を見出し、その理念のために生き、死ぬ覚悟を持つことだ。 彼の日記は作品や人生の幾つかの側面を明らかにしているが、キルケゴールは過度に暴露しないよう注意を払っていた。思考の急激な転換、反復的な記述、異例 の表現など、読者を惑わすために用いた手法は数多い。結果として、彼の日記には様々な解釈が存在する。キルケゴールは、自身の日記が将来持つ重要性を疑っ ていなかった。1849年12月、彼はこう記している。「もし今私が死んだなら、私の人生の効果は並外れたものとなるだろう。日記に無造作に書き留めた多 くのことが、大きな重要性と影響力を帯びるだろう。なぜならその時、人々は私を受け入れ、かつての、そして今もなお私の権利であったものを認めてくれるか らだ。」[55] |

Regine Olsen and graduation (1837–1841) Portrait of a young lady, over a black background. She is wearing a green dress, over a black coat. She is looking to the left, somewhat smiling. Regine Olsen, a muse for Kierkegaard's writings An important aspect of Kierkegaard's life – generally considered to have had a major influence on his work — was his broken engagement to Regine Olsen (1822–1904). Kierkegaard and Olsen met on 8 May 1837 and were instantly attracted to each other.[56][57] In his journals, Kierkegaard wrote idealistically about his love for her.[58] After passing his theological examinations in July 1840, Kierkegaard formally proposed to Olsen on 8 September.[59] He soon felt disillusioned about his prospects. He broke off the engagement on 11 August 1841, though it is generally believed that the two were deeply in love. In his journals, Kierkegaard mentions his belief that his "melancholy" made him unsuitable for marriage, but his precise motive for ending the engagement remains unclear.[60][61] It was also during this period that Kierkegaard dedicated himself to authoring a dissertation. Upon submitting it in June 1841, a panel of faculty judged that his work demonstrated considerable intellect while criticizing its informal tone; however, Kierkegaard was granted permission to proceed with its defense.[62][63] He defended On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates over seven and a half hours on 29 September 1841.[64][65] As the title suggests, the thesis dealt with irony and Socrates; the influence of Kierkegaard's friend Poul Martin Møller, who had died in 1838, is evident in the subject matter.[66][67] Kierkegaard graduated from the University of Copenhagen on 20 October 1841 with a Magister degree in philosophy.[68][69] His inheritance of approximately 31,000 rigsdaler enabled him to fund his work and living expenses.[70] |

レギーネ・オルセンと卒業(1837–1841) 黒い背景を背にした若い女性の肖像画。彼女は黒いコートの上に緑のドレスを着ている。左を向き、ほのかに微笑んでいる。 キルケゴールの著作のミューズ、レギーネ・オルセン キルケゴールの人生において重要な側面——一般的に彼の作品に大きな影響を与えたと考えられている——は、レギーネ・オルセン(1822–1904)との婚約破棄であった。 キルケゴールとオルセンは1837年5月8日に出会い、互いに惹かれ合った[56][57]。キルケゴールは日記の中で、彼女への愛を理想的に綴っている [58]。1840年7月に神学試験に合格した後、キルケゴールは同年9月8日に正式にオルセンに求婚した。[59] しかし彼はすぐに将来の見通しに幻滅した。1841年8月11日、婚約を破棄した。ただし二人が深く愛し合っていたことは広く認められている。日記の中で キルケゴールは、自身の「憂鬱」が結婚に向かないと信じていると述べているが、婚約を解消した正確な動機は不明のままである。[60] [61] この時期、キルケゴールは博士論文の執筆に専念した。1841年6月に提出した論文に対し、審査委員会は彼の知性の高さを認めつつも、口語的な文体を批判 した。しかし、論文の口頭試問を許可する決定が下された。[62] [63] 彼は 1841 年 9 月 29 日、7 時間半以上にわたって「ソクラテスを絶えず参照した皮肉の概念について」の論文の口頭試問を受けた。[64][65] タイトルが示す通り、この論文は皮肉とソクラテスを扱っており、1838 年に亡くなったキルケゴールの友人、ポール・マーティン・モーラーの影響が主題に明らかである。[66][67] キルケゴールは1841年10月20日にコペンハーゲン大学を哲学の修士号を取得して卒業した。[68][69] 彼が相続した約31,000リクスダラーは、彼の研究と生活費を賄うのに十分であった。[70] |

| Authorship (1843–1846) Kierkegaard published some of his works using pseudonyms and for others he signed his own name as author. Whether being published under pseudonym or not, Kierkegaard's central writing on religion was Fear and Trembling, and Either/Or is considered to be his magnum opus. Pseudonyms were used often in the early 19th century as a means of representing viewpoints other than the author's own. Kierkegaard employed the same technique as a way to provide examples of indirect communication. In writing under various pseudonyms to express sometimes contradictory positions, Kierkegaard is sometimes criticized for playing with various viewpoints without ever committing to one in particular. He has been described by those opposing his writings as indeterminate in his standpoint as a writer, though he himself has testified to all his work deriving from a service to Christianity.[71] He wrote his first book under the pseudonym "Johannes Climacus" (after John Climacus) between 1841 and 1842. De omnibus dubitandum est (Latin: "Everything must be doubted") was not published until after his death.[72] Kierkegaard's works Fear and Trembling Kierkegaard's magnum opus Either/Or was published 20 February 1843; it was mostly written during Kierkegaard's stay in Berlin, where he took notes on Schelling's Philosophy of Revelation. Either/Or includes essays of literary and music criticism and a set of romantic-like aphorisms, as part of his larger theme of examining the reflective and philosophical structure of faith.[73][74] Edited by "Victor Eremita", the book contained the papers of an unknown "A" and "B" which the pseudonymous author claimed to have discovered in a secret drawer of his secretary.[75] Eremita had a hard time putting the papers of "A" in order because they were not straightforward. "B"'s papers were arranged in an orderly fashion.[76][77] Both of these characters are trying to become religious individuals.[78] Each approached the idea of first love from an aesthetic and an ethical point of view. The book is basically an argument about faith and marriage with a short discourse at the end telling them they should stop arguing. Eremita thinks "B", a judge, makes the most sense. Kierkegaard stressed the "how" of Christianity as well as the "how" of book reading in his works rather than the "what".[79] Three months after the publication of Either/Or, 16 May 1843, he published Two Upbuilding Discourses, 1843 and continued to publish discourses along with his pseudonymous books. These discourses were published under Kierkegaard's own name and are available as Eighteen Upbuilding Discourses today. David F. Swenson first translated the works in the 1940s and titled them the Edifying Discourses; however, in 1990, Howard V. and Edna H. Hong translated the works again but called them the Upbuilding Discourses. The word "upbuilding" was more in line with Kierkegaard's thought after 1846, when he wrote Christian deliberations[80] about Works of Love.[81] An upbuilding discourse or edifying discourse isn't the same as a sermon because a sermon is preached to a congregation while a discourse can be carried on between several people or even with oneself. The discourse or conversation should be "upbuilding", which means one would build up the other person, or oneself, rather than tear down to build up. Kierkegaard said: "Although this little book (which is called 'discourses', not sermons, because its author does not have authority to preach, 'upbuilding discourses', not discourses for upbuilding, because the speaker by no means claims to be a teacher) wishes to be only what it is, a superfluity, and desires only to remain in hiding".[82] On 16 October 1843, Kierkegaard published three more books about love and faith and several more discourses. Fear and Trembling was published under the pseudonym Johannes de Silentio. Repetition is about a Young Man (Søren Kierkegaard) who has anxiety and depression because he feels he has to sacrifice his love for a girl (Regine Olsen) to God. He tries to see if the new science of psychology can help him understand himself. Constantin Constantius, who is the pseudonymous author of that book, is the psychologist. At the same time, he published Three Upbuilding Discourses, 1843 under his own name, which dealt specifically with how love can be used to hide things from yourself or others.[83] These three books, all published on the same day, are an example of Kierkegaard's method of indirect communication. Kierkegaard questioned whether an individual can know if something is a good gift from God or not and concludes by saying, "it does not depend, then, merely upon what one sees, but what one sees depends upon how one sees; all observation is not just a receiving, a discovering, but also a bringing forth, and insofar as it is that, how the observer himself is constituted is indeed decisive."[84] God's love is imparted indirectly just as our own sometimes is.[85] During 1844, he published two, three, and four more upbuilding discourses just as he did in 1843, but here he discussed how an individual might come to know God. Theologians, philosophers and historians were all engaged in debating about the existence of God. This is direct communication and Kierkegaard thinks this might be useful for theologians, philosophers, and historians (associations) but not at all useful for the "single individual" who is interested in becoming a Christian. Kierkegaard always wrote for "that single individual whom I with joy and gratitude call my reader";[86] the single individual must put what is understood to use or it will be lost. Reflection can take an individual only so far before the imagination begins to change the whole content of what was being thought about. Love is won by being exercised just as much as faith and patience are. He also wrote several more pseudonymous books in 1844: Philosophical Fragments, Prefaces and The Concept of Anxiety and finished the year up with Four Upbuilding Discourses, 1844. He used indirect communication in the first book and direct communication in the rest of them. He doesn't believe the question about God's existence should be an opinion held by one group and differently by another no matter how many demonstrations are made. He says it's up to the single individual to make the fruit of the Holy Spirit real because love and joy are always just possibilities. Christendom wanted to define God's attributes once and for all but Kierkegaard was against this. His love for Regine was a disaster but it helped him because of his point of view.[87] Kierkegaard believed "each generation has its own task and need not trouble itself unduly by being everything to previous and succeeding generations".[88] In an earlier book he had said, "to a certain degree every generation and every individual begins his life from the beginning",[89] and in another, "no generation has learned to love from another, no generation is able to begin at any other point than the beginning", "no generation learns the essentially human from a previous one."[90] And, finally, in 1850 he wrote, "those true Christians who in every generation live a life contemporaneous with that of Christ have nothing whatsoever to do with Christians of the preceding generation, but all the more with their contemporary, Christ. His life here on earth attends every generation, and every generation severally, as Sacred History..."[91] But in 1848, "The whole generation and every individual in the generation is a participant in one's having faith."[92] He was against the Hegelian idea of mediation[93][94][95] because it introduces a "third term"[96] that comes between the single individual and the object of desire. Kierkegaard wrote in 1844, 'If a person can be assured of the grace of God without needing temporal evidence as a middleman or as the dispensation advantageous to him as interpreter, then it is indeed obvious to him that the grace of God is the most glorious of all."[97] He was against mediation and settled instead on the choice to be content with the grace of God or not. It's the choice between the possibility of the "temporal and the eternal", "mistrust and belief, and deception and truth",[98] "subjective and objective".[99] These are the "magnitudes" of choice. He always stressed deliberation and choice in his writings and wrote against comparison.[100] |

著作者(1843–1846) キルケゴールは一部の著作をペンネームで発表し、他の著作には実名を著作者として記した。ペンネームで出版されたか否かにかかわらず、キルケゴールの宗教 に関する中心的な著作は『恐れおののき』であり、『あるいは…あるいは』は彼の代表作と見なされている。19世紀初頭には、著者自身の見解とは異なる立場 を示す手段として、偽名が頻繁に用いられた。キルケゴールも同様の手法を用い、間接的な伝達の実例を提供したのである。時に矛盾する立場を表現するために 様々な偽名で執筆したキルケゴールは、特定の立場に固執することなく様々な見解を弄んだと批判されることもある。彼の著作に反対する者からは、作家として の立場が不明確だと評されることもある。しかし彼自身は、全ての著作がキリスト教への奉仕から生まれたと証言している[71]。彼は1841年から 1842年にかけて、ヨハネス・クリマコス(ヨハネス・クリマコスに因む)の筆名で最初の著作を執筆した。『万事疑うべし』(ラテン語: 「万物は疑わしき」)は彼の死後になってようやく出版された。[72] キルケゴールの著作 『恐れおののき』 キルケゴールの代表作『あるいは/あるいは』は1843年2月20日に出版された。この著作の大部分は、キルケゴールがベルリン滞在中にシェリングの『啓 示の哲学』についてメモを取った時期に執筆されたものである。『あるいは/あるいは』には、文学・音楽批評の随筆やロマン主義的な格言集が含まれており、 信仰の思索的・哲学的構造を検証するという彼の大きなテーマの一部を成している。[73][74]「ヴィクトル・エレミタ」名義で編集された本書には、匿 名「A」と「B」の論文が収められており、筆者はこれらを秘書机の隠し引き出しで発見したと主張した。[75] エレミタは「A」の論文を整理するのに苦労した。それらは明快ではなかったからだ。「B」の論文は整然と並べられていた。[76][77] これら二つの人物は、宗教的な人間になろうとしている。[78] それぞれが美学的視点と倫理的視点から、初恋という概念にアプローチした。本書は基本的に信仰と結婚についての論争であり、最後に二人に議論をやめるよう 促す短い言説が付いている。エレミタは判事である「B」の主張が最も理にかなっていると考えている。キルケゴールは著作において、キリスト教の「内容」よ りも「実践方法」、また読書における「内容」よりも「実践方法」を強調した。[79] 『あるいは/あるいは』刊行の三か月後、1843年5月16日に彼は『二つの啓発的言説』(1843年)を発表し、その後も言説集とペンネーム著作を継続 して出版した。これらの言説はキルケゴール本名で刊行され、現在『十八の啓発的言説』として入手可能である。デイヴィッド・F・スウェンソンは1940年 代にこれらの著作を初めて翻訳し『啓発的言説』と題したが、1990年にハワード・V・ホンとエドナ・H・ホンが再翻訳した際には『啓発的言説』と訳し た。「アップビルディング(高揚)」という語は、1846年に『愛の業』についてキリスト教的熟議[80]を記した後のキルケゴールの思想により合致して いた。[81] 啓発的言説や教化的な言説は説教とは異なる。説教は会衆に向けて行われるが、言説は複数の人間同士、あるいは自分自身との間でも交わされるからだ。その言 説や対話は「啓発的」であるべきだ。つまり相手や自分自身を「築き上げる」ものであって、「打ち壊して築き上げる」ものではない。キルケゴールはこう述べ ている。「この小さな書物(説教ではなく『言説』と呼ばれるのは、著者に説教する権威がないからであり、『高揚をもたらす言説』ではなく『高揚のための言 説』と呼ばれるのは、語り手が決して教師を自認しないからだ)は、ただあるがままの、余剰物であり続け、隠れたままでありたいと願っている」 [82] 1843年10月16日、キルケゴールは愛と信仰に関する三冊の本と、さらにいくつかの言説を発表した。『恐れおののき』はヨハネス・デ・シレンティオの 筆名で出版された。『反復』は、少女(レギーネ・オルセン)への愛を神に捧げねばならないという思いから不安と抑鬱を抱える青年(セーレン・キルケゴー ル)について書かれている。彼は心理学という新科学が自己理解の助けとなるか試みる。同書の筆名著者コンスタンティヌス・コンスタンティウスは心理学者で ある。同時に彼は1843年、本名で『三つの啓発的言説』を出版した。これは特に、愛が自分自身や他者から何かを隠すためにどう利用されるかを扱っている [83]。これら三冊の本は全て同じ日に刊行され、キルケゴールの間接的伝達手法の一例である。 キルケゴールは、個人が何かが神からの良き賜物かどうかを知り得るか疑問を呈し、こう結論づける。「それは単に何を見るかに依存するのではなく、何を見る かはどのように見るかに依存する。あらゆる観察は単なる受容や発見ではなく、同時に生み出す行為でもある。そしてその限りにおいて、観察者自身の構成が確 かに決定的である」 [84] 神の愛は間接的に伝えられる。我々自身の愛が時にそうであるように。[85] 1844年、彼は1843年と同様にさらに二、三、四の啓発的言説を発表した。ここでは個人がいかにして神を知るに至り得るかを論じた。神学者、哲学者、 歴史家らが神の存在について議論を交わしていた。これは直接的な伝達であり、キルケゴールはこれが神学者、哲学者、歴史家(団体)には有用かもしれない が、キリスト教徒になろうとする「単なる個人」には全く役に立たないと考えている。キルケゴールは常に「私が喜びと感謝をもって読者と称する、あの単なる 個人のために」[86]書いていた。単なる個人は理解したものを活用しなければ、それは失われる。思索は想像力が思考内容全体を変え始める前に、個人をあ る限界までしか導けない。愛は信仰や忍耐と同様、鍛錬によって獲得されるのだ。 彼は1844年にさらに複数の偽名著作を執筆した:『哲学的断片』『序文』『不安の概念』であり、その年は『四つの啓発的言説(1844年)』で締めく くった。最初の著作では間接的表現を用い、それ以降は直接的表現を採用した。神の存在に関する問いは、いかに多くの証明がなされようとも、ある集団が支持 し異なる集団が否定するような意見の対立にすべきではないと彼は考える。聖霊の実を現実のものとするのは個人の責任であり、愛と喜びは常に可能性の域を出 ないのだと述べている。キリスト教世界は神の属性を一度で定義しようとしたが、キルケゴールはこれに反対した。レギーネへの愛は悲劇だったが、彼の視点ゆ えに助けとなった。[87] キルケゴールは「各世代にはそれぞれの課題があり、前後の世代の全てになろうと不必要に煩わされる必要はない」と信じていた。[88] 彼は以前の著作で「ある程度、あらゆる世代と個人が人生を最初から始める」[89] と述べ、別の著作では「いかなる世代も他世代から愛を学ぶことはなく、いかなる世代も始まり以外の地点から始めることはできない」「いかなる世代も本質的 に人間的なものを前世代から学ぶことはない」と記している。[90] そして1850年にはこう記している。「どの世代においてもキリストと同時期に生きる真のキリスト教徒は、前世代のキリスト教徒とは何の関係もない。むし ろ彼らの同時代人であるキリストと深く関わる。キリストの地上での生涯は、聖なる歴史として、あらゆる世代に個別に臨在するのだ…」 [91] しかし1848年には「世代全体と世代内の個々人は、信仰を持つことへの参加者である」と記した。[92] 彼はヘーゲルの媒介概念[93][94][95]に反対した。なぜならそれは、単一の個人と欲望の対象の間に「第三項」[96]を導入するからである。キ ルケゴールは1844年にこう記した。「もし人格が、仲介者としての時間的証拠や、解釈者として自分に有利な摂理を必要とせずに神の恵みを確信できるな ら、神の恵みが最も栄光に満ちたものであることは、その者にとって明らかである」[97]。彼は媒介に反対し、代わりに神の恵みに満足するか否かの選択に 落ち着いた。それは「一時的なものと永遠のもの」、「不信と信仰、欺瞞と真実」[98]、「主観と客観」[99]の間の選択である。これらが選択の「大き さ」だ。彼は著作で常に熟議と選択を強調し、比較を否定した[100]。 |

| The Inwardness of Christianity Kierkegaard believed God comes to each individual mysteriously.[101][102] He published Three Discourses on Imagined Occasions (first called Thoughts on Crucial Situations in Human Life, in David F. Swenson's 1941 translation) under his own name on 29 April, and Stages on Life's Way edited by Hilarius Bookbinder, 30 April 1845. The Stages is a sequel to Either/Or which Kierkegaard did not think had been adequately read by the public and in Stages he predicted "that two-thirds of the book's readers will quit before they are halfway through, out of boredom they will throw the book away."[103] He knew he was writing books but had no idea who was reading them. His sales were meager and he had no publicist or editor. He was writing in the dark, so to speak.[104] Many of his readers have been and continue to be in the dark about his intentions. He explained himself in his "Journal": "What I have understood as the task of the authorship has been done. It is one idea, this continuity from Either/Or to Anti-Climacus, the idea of religiousness in reflection. The task has occupied me totally, for it has occupied me religiously; I have understood the completion of this authorship as my duty, as a responsibility resting upon me." He advised his reader to read his books slowly and also to read them aloud since that might aid in understanding.[105] He used indirect communication in his writings by, for instance, referring to the religious person as the "knight of hidden inwardness" in which he's different from everyone else, even though he looks like everyone else, because everything is hidden within him.[106] Kierkegaard was aware of the hidden depths inside of each single individual. The hidden inwardness is inventive in deceiving or evading others. Much of it is afraid of being seen and entirely disclosed. Kierkegaard imagined hidden inwardness several ways in 1848. He was writing about the subjective inward nature of God's encounter with the individual in many of his books, and his goal was to get the single individual away from all the speculation that was going on about God and Christ. Speculation creates quantities of ways to find God and his Goods but finding faith in Christ and putting the understanding to use stops all speculation, because then one begins to actually exist as a Christian, or in an ethical/religious way. He was against an individual waiting until certain of God's love and salvation before beginning to try to become a Christian. He defined this as a "special type of religious conflict the Germans call Anfechtung" (contesting or disputing).[107][108] In Kierkegaard's view, the Church should not try to prove Christianity or even defend it. It should help the single individual to make a leap of faith, the faith that God is love and has a task for that very same single individual.[109] Kierkegaard identified the leap of faith as the good resolution.[110] Kierkegaard discussed the knight of faith in Works of Love, 1847 by using the story of Jesus healing the bleeding woman who showed the " originality of faith" by believing that if she touched Jesus' robe she would be healed. She kept that secret within herself.[111] Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments Kierkegaard wrote his Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments in 1846 and here he tried to explain the intent of the first part of his authorship.[112][113] He said, "Christianity will not be content to be an evolution within the total category of human nature; an engagement such as that is too little to offer to a god. Neither does it even want to be the paradox for the believer, and then surreptitiously, little by little, provide him with understanding, because the martyrdom of faith (to crucify one's understanding) is not a martyrdom of the moment, but the martyrdom of continuance."[114] The second part of his authorship was summed up in Practice in Christianity:[115] Early Kierkegaardian scholars, such as Theodor W. Adorno and Thomas Henry Croxall, argue that the entire authorship should be treated as Kierkegaard's own personal and religious views.[116] This view leads to confusions and contradictions which make Kierkegaard appear philosophically incoherent.[117] Later scholars, such as the post-structuralists, interpreted Kierkegaard's work by attributing the pseudonymous texts to their respective authors.[118] Postmodern Christians present a different interpretation of Kierkegaard's works.[119] Kierkegaard used the category of "The Individual" to stop the endless Either/Or.[120] |

キリスト教の内面性 キルケゴールは、神が各個人に神秘的に訪れると信じていた。[101][102] 彼は1845年4月29日に『想像上の機会に関する三つの言説』(デイヴィッド・F・スウェンソンによる1941年訳では『人生の決定的状況に関する思 索』と題された)を自身の名前で出版し、4月30日にはヒラリウス・ブックバインダー編集の『人生の道程における段階』を出版した。『人生の道程』は『あ るいは/あるいは』の続編である。キルケゴールは『あるいは/あるいは』が一般に十分に読まれていないと考えており、『人生の道程』の中で「読者の三分の 二は、退屈のあまり本を投げ捨て、半分も読まずに読むのをやめるだろう」と予言した。[103] 彼は自分が本を書いてはいるが、誰が読んでいるのか見当もつかないことを知っていた。売り上げはわずかで、宣伝担当者も編集者もいなかった。いわば暗闇の 中で執筆していたのだ。[104] 彼の意図について、多くの読者は今も昔も暗闇の中にいる。彼は『日記』でこう説明している。「私が著述の任務として理解してきたことは成し遂げられた。」 それは一つの思想、すなわち『あるいは…あるいは』から『アンチ・クリマコス』に至る連続性、内省における宗教性の思想である。この任務は私を完全に占領 した。それは宗教的に私を占領したからだ。私はこの著述の完結を、自らの義務として、私に課せられた責任として理解した。」彼は読者に、自分の本をゆっく り読むこと、また声に出して読むことを勧めた。それが理解を助けるかもしれないからである。[105] 彼は著作において間接的な表現を用いた。例えば、宗教的な人格を「隠された内面性の騎士」と呼んだ。彼は外見は誰とも変わらないが、内面は全て隠されているため、誰とも異なる存在なのだ。[106] キルケゴールは、一人ひとりの内側に潜む隠された深淵を認識していた。この隠された内面性は、他者を欺くか回避する点で創意に富む。その多くは、見られ、完全に暴露されることを恐れている。 キルケゴールは1848年、隠された内面性を幾つかの方法で想像した。彼は多くの著作で、神と個人との出会いの主観的な内面的性質について書き、その目的 は、個人が神やキリストについて行われているあらゆる思索から離れることだった。思索は神とその恵みを見出す無数の方法を生み出すが、キリストへの信仰を 見出し、その理解を実践に移すことで思索は止む。なぜならその時、人は実際にキリスト者として、あるいは倫理的・宗教的な存在として生き始めるからだ。彼 は、神の愛と救いを確信するまでキリスト者になろうとしない個人を否定した。これを「ドイツ人がアンフェクツング(争いや異議)と呼ぶ特殊な宗教的葛藤」 と定義した。[107][108] キルケゴールによれば、教会はキリスト教を証明したり擁護したりすべきではない。教会は個人が信仰の飛躍——神は愛であり、その個人に使命を与えていると いう信仰——を成し遂げる手助けをすべきだ。[109] キルケゴールはこの信仰の飛躍を「善き決断」と位置付けた。[110] キルケゴールは1847年の『愛の業』において、信仰の騎士について論じた。そこでは、イエスが血の病の女を癒した物語を用い、彼女は「信仰の独創性」を 示した。彼女はイエスの衣に触れれば癒されると信じ、その秘密を胸に秘めていたのである。[111] 哲学的断片への非科学的補遺 キルケゴールは1846年に『哲学的断片への非科学的補遺』を執筆し、ここで自身の著作第一部の意図を説明しようとした。[112][113] 彼はこう述べた。「キリスト教は、人間性の総体における一つの進化に甘んじることはない。そのような関与は神に捧げるにはあまりにも小さい。」 信者にとってのパラドックスとなることさえ望まず、ひそかに少しずつ理解を与えることも望まない。なぜなら信仰の殉教(自らの理解を十字架にかけること) は瞬間的な殉教ではなく、継続的な殉教だからだ。」[114] 彼の著作の第二部は『キリスト教における実践』に要約されている。[115] 初期のキルケゴール研究者、例えばテオドール・W・アドルノやトーマス・ヘンリー・クロクソールらは、全著作をキルケゴール自身の個人的・宗教的見解とし て扱うべきだと主張する[116]。この見解は混乱と矛盾を招き、キルケゴールを哲学的に一貫性のない人物に見せかける。[117] ポスト構造主義者ら後の研究者は、各偽名テキストをそれぞれの作者に帰属させることでキルケゴール作品を解釈した。[118] ポストモダン・クリスチャンはキルケゴール作品に異なる解釈を示す。[119] キルケゴールは「個人」という概念を用いて、終わりのない「どちらか一方」を停止させた。[120] |

| Pseudonyms Kierkegaard's most important pseudonyms,[121] in chronological order, were: Victor Eremita, editor of Either/Or A, writer of many articles in Either/Or Judge William, author of rebuttals to A in Either/Or Johannes de Silentio, author of Fear and Trembling Constantine Constantius, author of the first half of Repetition Young Man, author of the second half of Repetition Vigilius Haufniensis, author of The Concept of Anxiety Nicolaus Notabene, author of Prefaces Hilarius Bookbinder, editor of Stages on Life's Way Johannes Climacus, author of Philosophical Fragments and Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments Inter et Inter, author of The Crisis and a Crisis in the Life of an Actress H.H., author of Two Minor Ethical-Religious Essays Anti-Climacus, author of The Sickness unto Death and Practice in Christianity All of these writings analyze the concept of faith, on the supposition that if people are confused about faith, as Kierkegaard thought the inhabitants of Christendom were, they will not be in a position to develop the virtue. Faith is a matter of reflection in the sense that one cannot have the virtue unless one has the concept of virtue—or at any rate the concepts that govern faith's understanding of self, world, and God.[122] |

ペンネーム キルケゴールが用いた主要なペンネームは、年代順に以下の通りである: ヴィクトル・エレミタ:『あるいは/あるいは』の編集者 A:『あるいは/あるいは』に多数の論考を寄稿した執筆者 ウィリアム判事:『あるいは/あるいは』においてAへの反論を執筆した人物 ヨハネス・デ・シレンティオ:『恐れおののき』の著者 コンスタンティヌス・コンスタンティウス:『反復』前半の著者 青年:『反復』後半の著者 ヴィギリウス・ハウフニエンシス:『不安の概念』の著者 ニコラウス・ノタベネ:序文の著者 ヒラリウス・ブックバインダー:『人生の階段』の編集者 ヨハネス・クリマクス、『哲学的断片』及び『哲学的断片への非科学的補遺』の著者 インター・エト・インター、『危機』及び『女優の生涯における危機』の著者 H.H.、『二つの小品:倫理的・宗教的随筆』の著者 アンチ・クリマクス、『死に至る病』及び『キリスト教における実践』の著者 これらの著作はすべて、信仰の概念を分析している。キルケゴールがキリスト教世界の住民について考えたように、人々が信仰について混乱しているならば、彼 らは徳を発展させる立場にないという前提のもとでだ。信仰は、徳の概念——あるいは少なくとも、信仰が自己、世界、神を理解する際に支配する概念——を持 たなければ、その徳を持つことができないという意味で、省察の問題である。[122] |

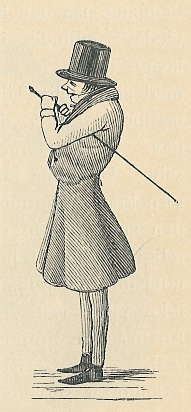

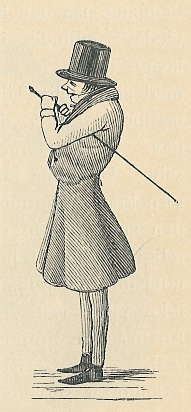

The Corsair affair A caricature; the figure is standing facing left, with a top-hat, cane, formal attire. The caricature is overemphasizing his back, by making him appear as a hunchback. A caricature of Kierkegaard published in The Corsair, a satirical journal On 22 December 1845, Peder Ludvig Møller, who studied at the University of Copenhagen at the same time as Kierkegaard, published an article indirectly criticizing Stages on Life's Way. The article complimented Kierkegaard for his wit and intellect, but questioned whether he would ever be able to master his talent and write coherent, complete works. Møller was also a contributor to and editor of The Corsair, a Danish satirical paper that lampooned everyone of notable standing. Kierkegaard published a sarcastic response, charging that Møller's article was merely an attempt to impress Copenhagen's literary elite. Kierkegaard wrote two small pieces in response to Møller, The Activity of a Traveling Esthetician and Dialectical Result of a Literary Police Action. The former focused on insulting Møller's integrity while the latter was a directed assault on The Corsair, in which Kierkegaard, after criticizing the journalistic quality and reputation of the paper, openly asked The Corsair to satirize him.[123] Kierkegaard's response earned him the ire of the paper and its second editor, also an intellectual of Kierkegaard's own age, Meïr Aron Goldschmidt.[124] Over the next few months, The Corsair took Kierkegaard up on his offer to "be abused", and unleashed a series of attacks making fun of Kierkegaard's appearance, voice and habits. For months, Kierkegaard perceived himself to be the victim of harassment on the streets of Denmark. In a journal entry dated 9 March 1846, Kierkegaard made a long, detailed explanation of his attack on Møller and The Corsair, and also explained that this attack made him rethink his strategy of indirect communication.[125] There had been much discussion in Denmark about the pseudonymous authors until the publication of Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments, 27 February 1846, where he openly admitted to be the author of the books because people began wondering if he was, in fact, a Christian or not.[126][127] Several Journal entries from that year shed some light on what Kierkegaard hoped to achieve.[128][129][130][131] This book was published under an earlier pseudonym, Johannes Climacus. On 30 March 1846 he published Two Ages: A Literary Review, under his own name. A critique of the novel Two Ages (in some translations Two Generations) written by Thomasine Christine Gyllembourg-Ehrensvärd, Kierkegaard made several insightful observations on what he considered the nature of modernity and its passionless attitude towards life. Kierkegaard writes that "the present age is essentially a sensible age, devoid of passion ... The trend today is in the direction of mathematical equality, so that in all classes about so and so many uniformly make one individual".[132] In this, Kierkegaard attacked the conformity and assimilation of individuals into "the crowd" which became the standard for truth, since it was the numerical.[133][page needed] How can one love the neighbor if the neighbor is always regarded as the wealthy or the poor or the lame?[134] As part of his analysis of the "crowd", Kierkegaard accused newspapers of decay and decadence. Kierkegaard stated Christendom had "lost its way" by recognizing "the crowd", as the many who are moved by newspaper stories, as the court of last resort in relation to "the truth". Truth comes to a single individual, not all people at one and the same time. Just as truth comes to one individual at a time so does love. One doesn't love the crowd but does love their neighbor, who is a single individual. He says, "never have I read in the Holy Scriptures this command: You shall love the crowd; even less: You shall, ethico-religiously, recognize in the crowd the court of last resort in relation to 'the truth.'"[135][136] |

コルセア事件 風刺画。人物は左向きに立っており、シルクハット、ステッキ、正装を身につけている。風刺画は彼の背中を強調しすぎており、まるで駝背のように見せている。 風刺雑誌『コルセア』に掲載されたキルケゴールの風刺画 1845年12月22日、キルケゴールと同時代にコペンハーゲン大学で学んだペーデル・ルードヴィグ・モーラーが、『人生の途上の段階』を間接的に批判す る記事を掲載した。その記事はキルケゴールの機知と知性を称賛しつつも、彼が才能を制御し首尾一貫した完成された著作を書き上げられるかどうかを疑問視し た。モーラーはまた、著名な人物を風刺するデンマークの風刺紙『コルセア』の寄稿者兼編集者でもあった。キルケゴールは皮肉たっぷりの反論を公表し、モー ラーの記事はコペンハーゲンの文壇エリートに印象づけようとする試みに過ぎないと非難した。 キルケゴールはモーラーへの反論として二つの小品を書いた。『旅する美学者の活動』と『文学警察活動の弁証法的結果』である。前者はモーラーの人格を侮辱 することに焦点を当て、後者は『コルセア』紙への直接攻撃であった。キルケゴールは同紙のジャーナリズム的品質と評判を批判した後、公然と『コルセア』に 自分を風刺するよう要求した[123]。 キルケゴールのこの反応は、同誌とその第二編集者(キルケゴールと同世代の知識人、メイル・アロン・ゴルドシュミット)の怒りを買った[124]。その後 数ヶ月にわたり、『コルサール』はキルケゴールの「罵倒されたい」という申し出を受け入れ、彼の容姿、声、習慣を嘲笑する一連の攻撃を繰り広げた。数か月 間、キルケゴールはデンマークの街中で嫌がらせの被害者だと感じていた。1846年3月9日付の日記で、キルケゴールはモーラーと『コルセア』への攻撃に ついて長々と詳細に説明し、この攻撃が間接的コミュニケーションという自身の戦略を見直すきっかけになったとも記している。[125] デンマークでは、1846年2月27日に『哲学的断片への非科学的補遺』が刊行されるまで、匿名作家の正体について多くの議論があった。この時、彼は自ら 著作の作者であることを公に認めた。人々が彼が実際にキリスト教徒かどうか疑問を持ち始めたためである。[126][127] その年のいくつかの日記の記述は、キルケゴールが何を達成しようとしていたのかについて、いくつかの手がかりを与えている。[128][129] [130][131] この著作は以前の筆名ヨハネス・クリマクス名義で出版された。1846年3月30日には本名で『二つの時代:文学評論』を発表している。トーマシーネ・ク リスティン・ギレムボー=エーレンスヴァルドの小説『二つの時代』(訳によっては『二つの世代』)を批評した中で、キルケゴールは現代性の本質と、その人 生に対する情熱の欠如について、いくつかの洞察に満ちた観察を記している。キルケゴールは「現代は本質的に感覚的な時代であり、情熱を欠いている... 今日の傾向は数学的平等へと向かっており、あらゆる階級において、ほぼ均一に一定数の個人が一人の個人を構成する」[132]。ここでキルケゴールは、個 人が「群衆」へと同調・同化される現象を批判した。この「群衆」は、その数的優位性ゆえに真実の基準となったのである[133][ページ番号必要]。隣人 が常に富裕層か貧困層か足の不自由な者として見なされるならば、どうして隣人を愛しうるだろうか?[134] 「群衆」分析の一環として、キルケゴールは新聞を退廃と腐敗の象徴と断じた。キリスト教世界は「群衆」―新聞記事に動かされる多数派―を「真実」に関する 最終的な裁定機関と認めたことで「道を誤った」と彼は述べた。真実は万人同時にではなく、単一の個人に訪れる。真実が一人ひとりの個人に訪れるのと同様 に、愛もまたそうである。人は群衆を愛するのではなく、隣人である一人の個人を愛するのだ。彼は言う。「聖書の中で『汝は群衆を愛せ』という戒めを読んだ ことは一度もない。ましてや『汝は倫理的・宗教的に、群衆を「真実」に関する最終的な裁きの場として認めよ』などという戒めはなおさらだ」[135] [136] |

| Authorship (1847–1855) This article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. Please help summarise the quotations. Consider transferring direct quotations to Wikiquote or excerpts to Wikisource. (May 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Kierkegaard began to publish under his own name again in 1847: the three-part Edifying Discourses in Diverse Spirits.[137] It included Purity of Heart is to Will One Thing, What we Learn from the Lilies in the Field and from the Birds in the Air, and The Gospel of Sufferings. He asked, What does it mean to be a single individual who wants to do the good? What does it mean to be a human being? What does it mean to follow Christ? He now moves from "upbuilding (Edifying) discourses" to "Christian discourses", however, he still maintains that these are not "sermons".[138] A sermon is about struggle with oneself about the tasks life offers one and about repentance for not completing the tasks.[139] Later, in 1849, he wrote devotional discourses and Godly discourses. Works of Love[140] followed these discourses on 29 September 1847. Both books were authored under his own name. It was written under the themes "Love covers a multitude of sins" and "Love builds up". (1 Peter 4:8 and 1 Corinthians 8:1) Kierkegaard believed that "all human speech, even divine speech of Holy Scripture, about the spiritual is essentially metaphorical speech".[141] "To build up" is a metaphorical expression. One can never be all human or all spirit, one must be both. Later, in the same book, Kierkegaard deals with the question of sin and forgiveness. He uses the same text he used earlier in Three Upbuilding Discourses, 1843, Love hides a multitude of sins. (1 Peter 4:8). He asks if "one who tells his neighbors faults hides or increases the multitude of sins".[142] Matthew 6 In 1848, he published Christian Discourses under his own name and The Crisis and a Crisis in the Life of an Actress under the pseudonym Inter et Inter. Christian Discourses deals the same theme as The Concept of Anxiety, angst. The text is the Gospel of Matthew 6 verses 24–34. This was the same passage he had used in his What We Learn From the Lilies in the Field and From the Birds of the Air of 1847. Kierkegaard tried to explain his prolific use of pseudonyms again in The Point of View of My Work as an Author, his autobiographical explanation for his writing style. The book was finished in 1848, but not published until after his death by his brother Peter Christian Kierkegaard. Walter Lowrie mentioned Kierkegaard's "profound religious experience of Holy Week 1848" as a turning point from "indirect communication" to "direct communication" regarding Christianity.[143] However, Kierkegaard stated that he was a religious author throughout all of his writings and that his aim was to discuss "the problem 'of becoming a Christian', with a direct polemic against the monstrous illusion we call Christendom".[144] He expressed the illusion this way in his 1848 "Christian Address", Thoughts Which Wound From Behind – for Edification. He wrote three discourses under his own name and one pseudonymous book in 1849. He wrote The Lily of the Field and the Bird of the Air. Three Devotional Discourses, Three Discourses at the Communion on Fridays and Two Ethical–Religious Essays. The first thing any child finds in life is the external world of nature. This is where God placed his natural teachers. He's been writing about confession and now openly writes about Holy Communion which is generally preceded by confession. This he began with the confessions of the esthete and the ethicist in Either/Or and the highest good peace in the discourse of that same book. His goal has always been to help people become religious but specifically Christian religious. He summed his position up earlier in his book, The Point of View of My Work as an Author, but this book was not published until 1859. The Sickness unto Death The second edition of Either/Or was published early in 1849. Later that year he published The Sickness unto Death, under the pseudonym Anti-Climacus. He's against Johannes Climacus, who kept writing books about trying to understand Christianity. Here he says, "Let others admire and praise the person who pretends to comprehend Christianity. I regard it as a plain ethical task—perhaps requiring not a little self-denial in these speculative times, when all 'the others' are busy with comprehending—to admit that one is neither able nor supposed to comprehend it."[145] Sickness unto death was a familiar phrase in Kierkegaard's earlier writings.[146] This sickness is despair and for Kierkegaard despair is a sin. Despair is the impossibility of possibility.[147] In Practice in Christianity, 25 September 1850, his last pseudonymous work, he stated, "In this book, originating in the year 1848, the requirement for being a Christian is forced up by the pseudonymous author to a supreme ideality."[148] This work was called Training in Christianity when Walter Lowrie translated it in 1941. He now pointedly referred to the acting single individual in his next three publications; For Self-Examination, Two Discourses at the Communion on Fridays, and in 1852 Judge for Yourselves!.[149][150] Judge for Yourselves! was published posthumously in 1876. In 1851 Kierkegaard wrote his Two Discourses at the Communion on Fridays where he once more discussed sin, forgiveness, and authority using that same verse from 1 Peter 4:8 that he used twice in 1843 with his Three Upbuilding Discourses, 1843. Kierkegaard began his 1843 book Either/Or with a question: "Are passions, then, the pagans of the soul? Reason alone baptized?"[151] He didn't want to devote himself to Thought or Speculation like Hegel did. Faith, hope, love, peace, patience, joy, self-control, vanity, kindness, humility, courage, cowardliness, pride, deceit, and selfishness. These are the inner passions that Thought knows little about. Hegel begins the process of education with Thought but Kierkegaard thinks we could begin with passion, or a balance between the two, a balance between Goethe and Hegel.[152] He was against endless reflection with no passion involved. But at the same time he did not want to draw more attention to the external display of passion but the internal (hidden) passion of the single individual. Kierkegaard clarified this intention in his Journals.[105] Schelling put Nature first and Hegel put Reason first but Kierkegaard put the human being first and the choice first in his writings. He makes an argument against Nature here and points out that most single individuals begin life as spectators of the visible world and work toward knowledge of the invisible world. The Parable of the Good Samaritan described in works of love Matthew 6:33 Nikolai Berdyaev makes a related argument against reason in his 1945 book The Divine and the Human.[153][154] |

著述活動(1847年–1855年) この記事は引用が多すぎるか、あるいは引用が長すぎる。引用を要約するよう協力してほしい。直接引用はWikiquoteへ、抜粋はWikisourceへ移すことを検討してほしい。(2019年5月)(このメッセージを削除する方法と時期について) キルケゴールは1847年、再び実名で出版を始めた。三部作『様々な精神における啓発的言説』である[137]。これには『心の純粋さとは一つのことを望 むこと』『野の花や空の鳥から学ぶこと』『苦悩の福音』が含まれる。彼は問うた。善を行おうとする一人の個人であるとはどういうことか?人間であるとはど ういうことか?キリストに従うとはどういうことか?彼はここで「啓発的言説」から「キリスト教的言説」へと移行するが、これらは依然として「説教」ではな いと主張している[138]。説教とは、人生が与える課題に対する自己との闘い、そしてその課題を完遂できなかったことへの悔い改めについてのものであ る。[139] その後1849年には、彼は祈りの言説と神聖な言説を記した。 『愛の業』[140]は1847年9月29日にこれらの言説に続いて発表された。両書とも彼自身の名義で著された。「愛はマルチチュードの罪を覆う」と 「愛は築き上げる」という主題のもとで書かれた。(ペトロの手紙一4:8、コリント人への手紙一8:1)キルケゴールは「霊的なものに関するあらゆる人間 の言葉、聖書の神聖な言葉さえも、本質的に隠喩的な言葉である」と信じていた[141]。「築き上げる」は隠喩的表現だ。人は決して人間だけ、あるいは霊 だけにはなれない。必ずその両方である。後に同書で、キルケゴールは罪と赦しの問題を取り上げる。彼は1843年の『三つの築き上げの言説』で以前に用い たのと同じ聖句、「愛は多くの罪を覆う」(ペトロの手紙一4:8)を用いる。そして「隣人の過ちを告げる者は、多くの罪を覆うのか、それとも増すのか」と 問う。[142] マタイによる福音書6章 1848年、彼は本名で『キリスト教的言説』を、またペンネーム「インター・エト・インター」名義で『危機と女優の生涯における危機』を出版した。『キリ スト教的言説』は『不安の概念』と同じ主題、すなわち不安を扱っている。テキストはマタイによる福音書6章24節から34節である。これは1847年の 『野の百合と空の鳥から学ぶこと』でも用いた箇所である。 キルケゴールは自伝的著作『作家としての私の立場』で、ペンネーム多用について改めて説明を試みた。本書は1848年に完成したが、死後になって兄ペー ター・クリスティアン・キルケゴールによって出版された。ウォルター・ローリーは、キリスト教に関するキルケゴールの「間接的伝達」から「直接的伝達」へ の転換点として、1848年の聖週間における「深い宗教的体験」を挙げている。[143] しかしキルケゴールは、自身の全著作を通じて宗教的作家であり、その目的は「キリスト教徒となること」という問題を論じ、「キリスト教世界」と呼ぶ怪物の 幻想に対する直接的な論争を行うことだと述べた。[144] 彼は1848年の「キリスト教的演説」『背後から傷つける思索――啓発のために』において、この幻想を次のように表現した。 彼は1849年に実名で三つの言説を、また偽名で一冊の本を書いた。『野の百合と空の鳥。三つの信仰的言説』『金曜日の聖餐における三つの言説』『二つの 倫理的・宗教的随筆』である。子供が人生で最初に発見するのは、自然という外部の世界だ。神はそこに自然の教師たちを配置した。彼はこれまで告白について 書いてきたが、今や公然と聖餐式について記している。聖餐式は通常、告白に先行する。このテーマは『あるいは/あるいは』における審美家と倫理家の告白、 そして同書内の「至高の善なる平和」の言説から始まっている。彼の目標は常に、人々が宗教的になること、特にキリスト教的になることを助けることだった。 彼は自身の立場を、著書『作家としての私の立場』で以前に要約していたが、この本は1859年まで出版されなかった。 死に至る病 『あるいは/あるいは』の第二版は1849年初頭に刊行された。同年後半、彼はアンチ・クリマコスという筆名で『死に至る病』を出版した。彼はヨハネス・ クリマクス(キリスト教を理解しようとする著作を書き続けた人格)に反対している。ここで彼はこう述べている。「キリスト教を理解したふりをする人格を称 賛し賞賛するのは他人に任せよう。私はこれを単純な倫理的課題と見なす——おそらく、あらゆる『他者』が理解に忙殺されるこの思索的な時代においては、少 なからぬ自己否定を要する課題だ——すなわち、自分はキリスト教を理解する能力もなければ、理解すべきでもないことを認めることだ」 [145] 死に至る病は、キルケゴールの初期著作でよく使われた表現だ。[146] この病とは絶望であり、キルケゴールにとって絶望は罪である。絶望とは可能性の不可能性だ。[147] 1850年9月25日付『キリスト教実践論』——彼の最後の匿名著作——において、彼はこう述べている。「本書は1848年に起源を持ち、キリスト教徒で あることの要求を、匿名著者が究極の観念性へと押し上げたものである。」[148] この著作は、ウォルター・ローリーが1941年に翻訳した際に『キリスト教訓練論』と題された。 その後三作——『自己省察のために』『金曜日の聖餐における二つの言説』そして1852年の『自ら判断せよ!』——では、行動する個人を明確に指し示した。[149][150]『自ら判断せよ!』は1876年に遺作として刊行された。 1851年、キルケゴールは『金曜日の聖餐における二つの言説』を執筆した。ここで彼は再び罪、赦し、権威について論じ、1843年の『三つの啓発的言説』で二度用いたのと同じ、ペトロの手紙一4:8の聖句を用いた。 キルケゴールは1843年の著書『あるいは/あるいは』をこう問いかけて始めた。「情熱とは、魂の異教徒なのか? 理性だけが洗礼を受けたのか?」 [151] 彼はヘーゲルのように思考や思索に専念したくなかった。信仰、希望、愛、平和、忍耐、喜び、自制、虚栄、親切、謙虚、勇気、臆病、誇り、欺瞞、利己主義。 これらは思考がほとんど知らない内なる情熱だ。ヘーゲルは教育のプロセスを思考から始めるが、キルケゴールは情熱から始めるか、あるいは両者の均衡、ゲー テとヘーゲルの均衡から始められると考えている[152]。彼は情熱を伴わない無限の思索に反対した。しかし同時に、情熱の外部的な表出よりも、個々人の 内面(隠された)情熱に注目を集めたいとも思わなかった。キルケゴールはこの意図を『日記』で明確にした[105]。 シェリングは自然を、ヘーゲルは理性を第一に置いたが、キルケゴールは著作において人間と選択を第一に置いた。彼はここで自然に対する反論を展開し、ほと んどの個人が可視世界の観客として人生を始め、不可視世界の知識へと向かっていくことを指摘する。愛の業に描かれた善きサマリア人のたとえ話マタイによる 福音書 6:33ニコライ・ベルジャエフは1945年の著書『神性と人間性』において、理性に対する関連する反論を展開している。[153][154] |

Attack upon the Lutheran State Church "Vor Frue Kirke", the Lutheran cathedral in Copenhagen (completed 1829) Kierkegaard's final years were taken up with a sustained, outright attack on the Church of Denmark by means of newspaper articles published in The Fatherland (Fædrelandet) and a series of self-published pamphlets called The Moment (Øjeblikket), also translated as The Instant. These pamphlets are now included in Kierkegaard's Attack Upon Christendom.[155] The Moment was translated into German and other European languages in 1861 and again in 1896.[156] Kierkegaard first moved to action after Professor (soon Bishop) Hans Lassen Martensen gave a speech in church in which he called the recently deceased Bishop Jacob Peter Mynster a "truth-witness, one of the authentic truth-witnesses".[6] Kierkegaard explained, in his first article, that Mynster's death permitted him—at last—to be frank about his opinions. He later wrote that all his former output had been "preparations" for this attack, postponed for years waiting for two preconditions: 1) both his father and bishop Mynster should be dead before the attack, and 2) he should himself have acquired a name as a famous theologic writer.[157] Kierkegaard's father had been Mynster's close friend, but Søren had long come to see that Mynster's conception of Christianity was mistaken, demanding too little of its adherents. Kierkegaard strongly objected to the portrayal of Mynster as a 'truth-witness'. Kierkegaard described the hope the witness to the truth has in 1847 and in his Journals. Kierkegaard's pamphlets and polemical books, including The Moment, criticized several aspects of church formalities and politics.[158] According to Kierkegaard, the idea of congregations keeps individuals as children since Christians are disinclined from taking the initiative to take responsibility for their own relation to God. He stressed that "Christianity is the individual, here, the single individual".[159] Furthermore, since the Church was controlled by the State, Kierkegaard believed the State's bureaucratic mission was to increase membership and oversee the welfare of its members. More members would mean more power for the clergymen: a corrupt ideal.[160] This mission would seem at odds with Christianity's true doctrine, which, to Kierkegaard, is to stress the importance of the individual, not the whole.[52][page needed] Thus, the state-church political structure is offensive and detrimental to individuals, since anyone can become "Christian" without knowing what it means to be Christian.[161] It is also detrimental to the religion itself since it reduces Christianity to a mere fashionable tradition adhered to by unbelieving "believers", a "herd mentality" of the population, so to speak.[162][163] Kierkegaard always stressed the importance of the conscience and the use of it.[164] However, he showed marked elements of convergence with the medieval Catholicism.[165][166] Nonetheless, Kierkegaard has been described as "profoundly Lutheran".[167] |

ルーテル派国教への攻撃 コペンハーゲンのルーテル派大聖堂「ヴォル・フルー教会」(1829年完成) キルケゴール晩年は、新聞『祖国』(Fædrelandet)への寄稿と、自費出版のパンフレット『瞬間』(Øjeblikket、訳題『瞬間』)シリー ズを通じて、デンマーク国教会への持続的かつ露骨な攻撃に費やされた。これらのパンフレットは現在、キルケゴールの『キリスト教世界への攻撃』に収録され ている。[155] 『瞬間』は1861年と1896年にドイツ語及びその他のヨーロッパ言語へ翻訳された。[156] キルケゴールが初めて行動を起こしたのは、ハンス・ラッセン・マルテンセン教授(後に司教)が教会で演説し、最近死去したヤコブ・ペーター・ミンスター司 教を「真実の証人、真正なる真実の証人の一人」と呼んだことがきっかけだった。[6] キルケゴールは最初の記事で、ミンスターの死によってようやく自らの意見を率直に述べられるようになったと説明した。彼は後に、これまでの著作は全てこの 攻撃のための「準備」であり、二つの前提条件を満たすまで長年延期されていたと記している。第一に、攻撃前に父とミンスター司教の両方が死去しているこ と。第二に、自身が著名な神学作家としての名声を得ていることである。[157] キルケゴールの父はミンスターの親友だったが、セーレンは以前からミンスターのキリスト教観が誤りであり、信徒に求めるものが少なすぎると気づいていた。 キルケゴールはミンスターを「真実の証人」として描くことに強く反発した。 キルケゴールは1847年と『日記』の中で、真実の証人が抱く希望について記述している。 キルケゴールの小冊子や論争書(『瞬間』を含む)は、教会の形式主義や政治的側面を幾つか批判した。[158] キルケゴールによれば、会衆という概念は個人を子供同然に留める。なぜならキリスト教徒は、自ら進んで神との関係に責任を負うことを好まないからだ。彼は 「キリスト教とは個人、つまり単一の個人である」と強調した。[159] さらに、教会が国家によって支配されていたため、キルケゴールは国家の官僚的使命が会員数を増やし、その福祉を監督することにあると考えた。会員が増えれ ば聖職者の権力も増大する。これは腐敗した理想である。[160] この使命はキリスト教の真の教義と矛盾しているように見える。キルケゴールにとって、キリスト教の真の教義とは、全体ではなく個人の重要性を強調すること である。[52][ページ番号必要] したがって、国家と教会の政治構造は個人にとって有害だ。なぜなら、キリスト教徒である意味を知らぬまま誰でも「キリスト教徒」になれるからだ。 [161] それは宗教自体にも有害である。キリスト教を、いわば「信者」と称する不信仰者たちが従う単なる流行の伝統、大衆の「群畜心理」へと貶めるからだ。 [162][163] キルケゴールは常に良心の重要性と、その行使を強調した。[164] しかし彼は中世カトリックとの顕著な共通要素を示した。[165][166] それにもかかわらず、キルケゴールは「深くルター派的」と評されている。[167] |

Death Søren Kierkegaard's grave in Assistens Kirkegård Before the tenth issue of his periodical The Moment could be published, Kierkegaard collapsed on the street. He stayed in the hospital for over a month[168] and refused communion. At that time he regarded pastors as mere political officials, a niche in society who were clearly not representative of the divine. He told Emil Boesen, a friend since childhood, who kept a record of his conversations with Kierkegaard, that his life had been one of immense suffering, which may have seemed like vanity to others, but he did not think it so.[169][170][171] Kierkegaard died in Frederiks Hospital after over a month, possibly from complications from a fall from a tree in his youth.[172] It has been suggested by professor Kaare Weismann [da] and philosopher Jens Staubrand [da] that Kierkegaard died from Pott disease, a form of tuberculosis.[173] He was interred in the Assistens Kirkegård in the Nørrebro section of Copenhagen. At Kierkegaard's funeral, his nephew Henrik Lund caused a disturbance by protesting Kierkegaard's burial by the official church. Lund maintained that Kierkegaard would never have approved, had he been alive, as he had broken from and denounced the institution.[174] Lund was later fined for his disruption of the funeral.[175] |

死 アシステンズ墓地にあるセーレン・キルケゴールの墓 キルケゴールは自身の雑誌『瞬間』の第10号が刊行される前に路上に倒れた。彼は一ヶ月以上入院し[168]、聖餐を拒んだ。当時彼は牧師を単なる政治的 役人、神を明らかに代表しない社会のニッチと見なしていた。幼なじみの友人エミル・ボーセン(キルケゴールとの会話を記録していた人物)に対し、彼は自ら の人生は計り知れない苦悩に満ちていたと語った。それは他人には虚栄に映ったかもしれないが、彼自身はそうは思わなかった[169][170] [171]。 キルケゴールはフレデリクス病院で一ヶ月以上を過ごした後、おそらく若き日に木から転落した際の合併症により死去した。[172] カアレ・ヴァイスマーン教授[da]と哲学者イェンス・シュタウブランド[da]は、キルケゴールが結核の一種であるポット病で死亡した可能性を示唆して いる。[173] 彼はコペンハーゲンのノレブロ地区にあるアシステン教会墓地に埋葬された。キルケゴールの葬儀で、甥のヘンリック・ルンドは公式教会による埋葬に抗議して 騒動を引き起こした。ルンドは、キルケゴールが生きていれば決して承認しなかったと主張した。なぜなら彼はその制度から離反し、非難していたからだ。 [174] ルンドは後に葬儀の妨害行為で罰金を科された。[175] |

| Reception Main article: Influence and reception of Søren Kierkegaard 19th-century reception Fredrika Bremer wrote of Kierkegaard in 1850: "While Martensen with his wealth of genius casts from his central position light upon every sphere of existence, upon all the phenomena of life, Søren Kierkegaard stands like another Simon Stylites, upon his solitary column, with his eye unchangeably fixed upon one point."[176] In 1855, the Danish National Church published his obituary. Kierkegaard did have an impact there judging from the following quote from their article: "The fatal fruits which Dr. Kierkegaard show to arise from the union of Church and State, have strengthened the scruples of many of the believing laity, who now feel that they can remain no longer in the Church, because thereby they are in communion with unbelievers, for there is no ecclesiastical discipline."[177] Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig (1783–1872) Changes did occur in the administration of the Church and these changes were linked to Kierkegaard's writings. The Church noted that dissent was "something foreign to the national mind". On 5 April 1855, the Church enacted new policies: "every member of a congregation is free to attend the ministry of any clergyman, and is not, as formerly, bound to the one whose parishioner he is". In March 1857, compulsory infant baptism was abolished. Debates sprang up over the King's position as the head of the Church and over whether to adopt a constitution. Grundtvig objected to having any written rules. Immediately following this announcement the "agitation occasioned by Kierkegaard" was mentioned. Kierkegaard was accused of Weigelianism and Darbyism, but the article continued to say, "One great truth has been made prominent, viz (namely): That there exists a worldly-minded clergy; that many things in the Church are rotten; that all need daily repentance; that one must never be contented with the existing state of either the Church or her pastors."[178] Hans Lassen Martensen addressed Kierkegaard's ideas extensively in Christian Ethics, published in 1871.[179] Martensen accused Kierkegaard and Alexandre Vinet of not giving society its due, saying both of them put the individual above society, and in so doing, above the Church.[180] Another early critic was Magnús Eiríksson, who criticized Martensen and wanted Kierkegaard as his ally in his fight against speculative theology. August Strindberg (1849–1912) from Sweden August Strindberg was deeply affected by reading Kierkegaard while a student at Uppsala University.[181][182] Edwin Björkman credited Kierkegaard, as well as Henry Thomas Buckle and Eduard von Hartmann, with shaping Strindberg's artistic form "until he was strong enough to stand wholly on his own feet."[183] The dramatist Henrik Ibsen is said to have been interested in Kierkegaard, as well as the Norwegian national writer and poet Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson.[184] Otto Pfleiderer, in The Philosophy of Religion On the Basis of Its History (1887), claimed that Kierkegaard presented an anti-rational view of Christianity.[185] An entry on Kierkegaard from an 1889 dictionary of religion presents an idea of how he was regarded at that time, stating: "He was the most original thinker and theological philosopher the North ever produced. His fame has been steadily growing since his death, and he bids fair to become the leading religio-philosophical light of Germany. Not only his theological but also his aesthetic works have of late become the subject of universal study in Europe."[186] Although not cited by him explicitly, Kierkegaard's view of faith would influence Norwegian theologian Gisle Christian Johnson (1822–1894). Johnson's system of dogmatic theology contained in his Grundrids af den Systematisk Theologi (published posthumously in 1897) differed starkly from those of his contemporaries in its integration of a threefold paradigm for viewing the essence of faith (Troens Væsen) as Egotistic, Legalist, and Christian, found in the first part of the work ("Pistiks"), which itself was cast in the Law/Gospel mold of confessional Lutheranism.[187] The final stage is marked in terms of discontinuity and radical change, and thus requires a leap to faith similar to that of Kierkegaard, what Johnson styles an irrefutable claim (uafviselig Fordring) of higher existence correlate to True Being (sande Væsen).[187] Likewise, the development of the infinite qualitative distinction from subjective faith by Gisle Johnson has distinct Kierkegaardian overtones. Johnson would have read Kierkegaard in the 1840s during his studies in continental Europe, developing his Pistiks in 1853 after his appointment to faculty at the University of Kristiana; as such, Svein Aage Christoffersen has designated Johnson to be the first Kierkegaardian in theology, fusing confessional, theological, and experiential categories of faith into a single dogmatic system.[188][189] Johnson's pietistic emphases merged with Kierkegaard's own emphases on genuineness of faith to produce a revivalist movement that swept across Norway, known as the Johnsonian Revivals.[190] |

受容 主な記事: セーレン・キルケゴールの影響と受容 19世紀の受容 フレドリカ・ブレマーは1850年にキルケゴールについてこう記した: 「マルテンセンがその豊かな天才性をもって中心的な立場からあらゆる存在の領域、あらゆる人生の現象に光を投げかける一方で、セーレン・キルケゴールはま るで別のシモン・スタイリテスのように、孤独な柱の上に立ち、その眼差しを一点に決して変えずに固定している」[176]。1855年、デンマーク国教会 は彼の死亡記事を発表した。キルケゴールが同国に与えた影響は、その記事の次の引用から窺える:「キルケゴール博士が指摘した教会と国家の結合が生む致命 的な結果は、多くの信仰ある信徒の良心を揺さぶった。彼らは今や、教会に留まることはもはやできないと感じている。なぜなら、それによって彼らは不信仰者 と交わりを持つことになるからだ。教会規律が存在しないからである。」[177] ニコライ・フリードリヒ・ゼヴェリン・グルントヴィヒ(1783–1872) 教会の運営には確かに変化が生じ、その変化はキルケゴールの著作と結びついていた。教会は異議申し立てが「国民精神に異質なものである」と指摘した。 1855年4月5日、教会は新たな方針を制定した。「会衆のあらゆる構成員は、いかなる聖職者の説教にも自由に参加でき、以前のように自身が教区民である 聖職者に縛られることはない」。1857年3月には幼児洗礼の義務が廃止された。国王の教会首長としての地位や憲法制定の是非を巡る議論が勃発した。グル ントヴィグは成文規則の制定に反対した。この発表直後、「キルケゴールに起因する騒動」が言及された。キルケゴールはヴァイゲリアン主義とダービー主義の 嫌疑をかけられたが、記事は続けてこう述べている。「一つの大きな真実が浮き彫りにされた。すなわち:世俗的な考えを持つ聖職者が存在すること、教会内の 多くの事柄が腐敗していること、全ての人々が日々悔い改めを必要とすること、教会やその牧師たちの現状に決して満足してはならないことである」[178] ハンス・ラッセン・マルテンセンは1871年に出版された『キリスト教倫理学』において、キルケゴールの思想を広く論じた[179]。マルテンセンはキル ケゴールとアレクサンドル・ヴィネが社会に正当な評価を与えていないと非難し、両者が個人を社会より、ひいては教会より優先させていると述べた。 [180] もう一人の初期の批判者はマグヌス・エイリクソンであり、彼はマルテンセンを批判し、思弁的神学との闘いにおいてキルケゴールを味方につけようとした。 スウェーデンのオーギュスト・ストリンドベリ(1849–1912) オーギュスト・ストリンドベリは、ウプサラ大学在学中にキルケゴールを読んだことで深く影響を受けた。[181][182] エドウィン・ビョークマンは、ストリンドベリが「完全に自立できるほど強くなるまで」、キルケゴールとヘンリー・トーマス・バックル、エドゥアルト・フォ ン・ハルトマンが彼の芸術的形態を形成したと評価している。[183]劇作家ヘンリック・イプセンはキルケゴールに関心を持っていたと言われ、ノルウェー の国民的作家・詩人ビョルンシュテリエ・ビョルンソンも同様であった。[184] オットー・プフライデラーは『宗教哲学の歴史的基礎』(1887年)において、キルケゴールがキリスト教に対する反理性主義的見解を提示したと主張した [185]。1889年の宗教辞典のキルケゴールに関する項目は、当時の彼に対する見方を示しており、次のように述べている:「彼は北欧が生んだ最も独創 的な思想家であり神学的哲学者であった。彼の名声は死後着実に高まり、ドイツの宗教哲学における主導的な光となる見込みだ。神学的な著作だけでなく、美学 に関する著作も近年ヨーロッパで広く研究対象となっている。」[186] キェルケゴールが明示的に引用したわけではないが、彼の信仰観はノルウェーの神学者ギスレ・クリスチャン・ジョンソン(1822–1894)に影響を与え た。ジョンソンの『体系神学綱要』(1897年没後刊行)に収められた教義神学体系は、信仰の本質(Troens Væsen)を「利己主義的」「律法主義的」「キリスト教的」という三つのパラダイムで統合した点で、同時代の神学体系とは著しく異なる。この三つのパラ ダイム自体が、告白的ルター派の律法/福音の枠組みに則って構築されていたのである。[187] 法主義的、キリスト教的という三つのパラダイムを統合した点で、同時代の神学体系とは大きく異なっていた。この区分は著作の第一部(「ピスティクス」)に 示され、その枠組み自体が告白的ルター派の律法/福音の型に則っていた。[187] 最終段階は不連続性と急進的変革によって特徴づけられ、したがってキルケゴールと同様の信仰への飛躍を必要とする。ジョンソンが「真の存在 (sande Væsen)」に対応する高次の存在の「反駁不能な要求(uafviselig Fordring)」と呼ぶもの[187]。同様に、ギスレ・ジョンソンによる主観的信仰からの無限の質的区別の展開には、明らかなキルケゴール的響きが ある。ジョンソンは1840年代に大陸ヨーロッパ留学中にキルケゴールを読破し、1853年にクリスチャニア大学教授就任後に『ピスティクス』を著した。 この経緯からスヴェイン・アーゲ・クリストファーセンは、ジョンソンを神学における最初のキルケゴール主義者と位置づけ、信仰の告白的・神学的・経験的カ テゴリーを単一の教義体系に統合した人物と評している。[188][189] ジョンソンの敬虔主義的強調は、キルケゴール自身の信仰の真実性への強調と融合し、ノルウェー全土を席巻した「ジョンソン派リバイバル運動」と呼ばれる復 興運動を生み出した。[190] |

| Early 20th-century reception 1879 German edition of Brandes' biography about Søren Kierkegaard The first academic to draw attention to Kierkegaard was fellow Dane Georg Brandes, who published in German as well as Danish. Brandes gave the first formal lectures on Kierkegaard in Copenhagen and helped bring him to the attention of the European intellectual community.[191] Brandes published the first book on Kierkegaard's philosophy and life, Søren Kierkegaard, ein literarisches Charakterbild (1879)[192] which Adolf Hult said was a "misconstruction" of Kierkegaard's work and "falls far short of the truth".[193] Brandes compared him to Hegel and Tycho Brahe in Reminiscences of my Childhood and Youth[194] (1906). Brandes also discussed the Corsair Affair in the same book.[195] Brandes opposed Kierkegaard's ideas in the 1911 edition of the Britannica.[196][197] Brandes compared Kierkegaard to Friedrich Nietzsche as well.[198] He also mentioned Kierkegaard extensively in volume 2 of his 6 volume work, Main Currents in Nineteenth Century Literature (1872 in German and Danish, 1906 English).[199][200] Swedish author Waldemar Rudin published Sören Kierkegaards person och författarskap – ett försök in 1880.[201] During the 1890s, Japanese philosophers began disseminating the works of Kierkegaard.[202] Tetsuro Watsuji was one of the first philosophers outside of Scandinavia to write an introduction on his philosophy, in 1915. William James (1890s) Harald Høffding's work was greatly influenced by Kierkegaard, having himself stated that Kierkegaard's thought "has pursued me from my youth, [and] determined the direction of my life."[203] Høffding was a friend of the American philosopher William James, and although James had not read Kierkegaard's works, as they were not yet translated into English, he attended the lectures about Kierkegaard by Høffding and agreed with much of those lectures. James' favorite quote from Kierkegaard came from Høffding: "We live forwards but we understand backwards".[204] Friedrich von Hügel wrote about Kierkegaard in 1913, saying: "Kierkegaard, the deep, melancholy, strenuous, utterly uncompromising Danish religionist, is a spiritual brother of the great Frenchman, Blaise Pascal, and of the striking English Tractarian, Hurrell Froude, who died young and still full of crudity, yet left an abiding mark upon all who knew him well."[205] John George Robertson wrote an article called Søren Kierkegaard in 1914: "Notwithstanding the fact that during the last quarter of a century, we have devoted considerable attention to the literatures of the North, the thinker and man of letters whose name stands at the head of the present article is but little known to the English-speaking world ... Kierkegaard, the writer who holds the indispensable key to the intellectual life of Scandinavia, to whom Denmark in particular looks up as her most original man of genius in the nineteenth century, we have wholly overlooked."[206] Robertson wrote previously in Cosmopolis (1898) about Kierkegaard and Nietzsche.[207] Theodor Haecker, based in Munich, published an essay in 1913 titled Kierkegaard and the Philosophy of Inwardness, and David F. Swenson's treatment of Kierkegaard's life and works was published as an issue of Scandinavian Studies and Notes in 1920.[208][209] Swenson stated: "It would be interesting to speculate upon the reputation that Kierkegaard might have attained, and the extent of the influence he might have exerted, if he had written in one of the major European languages, instead of in the tongue of one of the smallest countries in the world."[210] Austrian psychologist Wilhelm Stekel (1868–1940) referred to Kierkegaard as the "fanatical follower of Don Juan, himself the philosopher of Don Juanism" in his book Disguises of Love.[211] German psychiatrist and philosopher Karl Jaspers (1883–1969) stated he had been reading Kierkegaard since 1914 and compared Kierkegaard's writings with Hegel's Phenomenology of Mind and the writings of Nietzsche. Jaspers saw Kierkegaard as a champion of Christianity and Nietzsche as a champion for atheism.[212] Later, in 1935, Jaspers emphasized Kierkegaard's (and Nietzsche's) continuing importance for modern philosophy.[213][page needed] |

20世紀初頭の受容 1879年版ブランデスのセーレン・キルケゴール伝記(ドイツ語版) キルケゴールに注目を向けさせた最初の学者は、同じくデンマーク人のゲオルク・ブランデスであった。彼はドイツ語とデンマーク語の両方で著作を発表した。 ブランデスはコペンハーゲンでキルケゴールに関する最初の正式な講義を行い、ヨーロッパの知識人社会に彼を認知させる一助となった。[191] ブランデスはキルケゴールの哲学と生涯に関する最初の著書『セーレン・キルケゴール、文学的人物像』(1879年)[192]を出版した。アドルフ・フル トはこれをキルケゴール作品の「誤解」であり「真実から大きく外れている」と評した。[193] ブランドスは『我が幼少期と青年期の回想録』(1906年)において、キルケゴールをヘーゲルやティコ・ブラーエと比較した。同書ではコルセア事件につい ても論じている。[195] ブランドスは1911年版ブリタニカ百科事典においてキルケゴールの思想に反対の立場を示した。[196][197] ブランドスはキルケゴールをフリードリヒ・ニーチェとも比較した[198]。また6巻からなる著作『19世紀文学の主要潮流』(1872年ドイツ語・デン マーク語版、1906年英語版)の第2巻でキルケゴールについて広く言及している[199]。[200] スウェーデンの作家ヴァルデマル・ルーディンは1880年に『ソレン・キルケゴールの人格と著作――一考察』を出版した。[201] 1890年代には日本の哲学者たちがキルケゴールの著作の普及を始めた。[202] 和辻哲郎は1915年、スカンジナビア以外で初めてキルケゴールの哲学を紹介した哲学者の一人である。 ウィリアム・ジェームズ(1890年代) ハラルド・ヘフディングの著作はキルケゴールに大きく影響を受けており、彼自身「キルケゴールの思想は若き日から私を追い続け、人生の方向性を決定づけ た」と述べている。[203] ホフディングはアメリカの哲学者ウィリアム・ジェームズの友人であった。ジェームズは当時まだ英訳されていなかったためキルケゴールの著作を読んでいな かったが、ホフディングによるキルケゴール講義に出席し、その講義内容の多くに同意した。ジェームズがキルケゴールから最も好んだ引用はホフディングによ る「我々は前へ生きるが、理解は後ろから来る」であった。[204] フリードリヒ・フォン・ヒュゲルは1913年にキルケゴールについてこう記している: 「深遠で、憂鬱で、精力的な、まったく妥協を許さないデンマークの宗教家、キルケゴールは、偉大なフランス人、ブレーズ・パスカル、そして若くして亡くな り、その才能は未熟ながらも、彼をよく知るすべての人々に永続的な痕跡を残した、印象的な英国のトラクト派、ハレル・フラウドの精神的な兄弟である」 [205] ジョン・ジョージ・ロバートソンは1914年に「セーレン・キルケゴール」という記事を書いた。「過去四半世紀の間に、我々は北欧の文学にかなりの関心を 寄せてきたにもかかわらず、本記事の題名にもなっている思想家であり文筆家であるこの人物は、英語圏ではほとんど知られていない... スカンジナビアの知的生活に欠かせない鍵を握る作家、特にデンマークが19世紀の最も独創的な天才として尊敬するキルケゴールを、我々は完全に見過ごして きたのだ。」[206]ロバートソンは以前、コスモポリス(1898年)でキルケゴールとニーチェについて書いていた。[207] ミュンヘンを拠点とするテオドール・ヘッカーは、1913年に「キルケゴールと内面性の哲学」と題する論文を発表し、デビッド・F・スウェンソンによるキ ルケゴールの生涯と作品に関する論考は、1920年に『スカンジナビア研究とノート』誌に掲載された。[208][209] スウェンソンは、「キルケゴールが、世界でも最も小さな国の言語ではなく、ヨーロッパの主要言語のいずれかで執筆していたならば、彼がどのような評価を得 ていたか、また、彼がどのような影響力を行使していたかについて、推測することは興味深いだろう」と述べている。[210] オーストリアの心理学者ヴィルヘルム・シュテッケル(1868–1940)は著書『愛の仮装』において、キルケゴールを「ドン・ファンの狂信的追随者であ り、ドン・ファン主義の哲学者そのもの」と呼んだ。[211] ドイツの精神科医・哲学者カール・ヤスパース(1883–1969)は、1914年からキルケゴールを読んできたと述べ、キルケゴールの著作をヘーゲルの 『精神現象学』やニーチェの著作と比較した。ヤスパースはキルケゴールをキリスト教の擁護者、ニーチェを無神論の擁護者と見なした[212]。その後 1935年、ヤスパースはキルケゴール(およびニーチェ)が現代哲学にとって持続的な重要性を有することを強調した[213][ページ番号が必要]。 |