救済論(ソテリオロジー)

Soteriology

Paul Klee (German-Swiss, 1879-1940) Fish, 1921 Oil/canvas. Private collection.

☆ ソテリオロジーあるいは救済論(Soteriology: σωτηρία sōtēr 「救済者、保存者」とλόγος ロゴス「学問」または「言葉」に由来する「救済」[Salvation])は、救済に関する宗教教義の研究である。宗教学の学問分野では、救済論は多くの異なる宗教におけ る重要なテーマであると学者によって理解されており、しばしば比較の文脈で研究される。

| Soteriology

(/soʊˌtɪriˈɒlədʒi/; Greek: σωτηρία sōtēria "salvation" from σωτήρ sōtēr

"savior, preserver" and λόγος logos "study" or "word"[1]) is the study

of religious doctrines of salvation. Salvation theory occupies a place

of special significance in many religions.[2] In the academic field of

religious studies, soteriology is understood by scholars as

representing a key theme in a number of different religions and is

often studied in a comparative context; that is, comparing various

ideas about what salvation is and how it is obtained. |

ソ

テリオロジーあるいは救済論(/soʊˌtɪ ˈɒlədʒi/; ギリシア語: σωτηρία sōtēr 「救済者、保存者」とλόγος

ロゴス「学問」または「言葉」に由来する「救済」[1])は、救済に関する宗教教義の研究である。宗教学の学問分野では、救済論は多くの異なる宗教におけ

る重要なテーマであると学者によって理解されており、しばしば比較の文脈で研究される。 |

| Buddhism Buddhism is devoted primarily to liberation from Duḥkha or suffering by breaking free of samsara, the cycle of compulsory rebirth, by attaining nirvana. Buddhism emphasizes the importance of the individual's meditation practice in this process, and their subsequent liberation from samsara, which is to be enlightened. Thus, the fundamental reason that the precise identification of these two kinds of clinging to an identity – personal and phenomenal – is considered so important is again soteriological. Through first uncovering our clinging and then working on it, we become able to finally let go of this sole cause for all our afflictions and suffering.[3] However, the Pure Land traditions of Mahayana Buddhism generally focus on the saving nature of the Celestial Buddha Amitābha.[4] In Mahayana Buddhist eschatology, it is believed that we are currently living in the Latter Day of the Law, a period of 10,000 years where the corrupt nature of the people means the teachings of the Buddha are not listened to.[citation needed] Before this era, the bodhisattva Amitābha made 48 vows, including the vow to accept all sentient beings that called to him, to allow them to take refuge in his Pure land and to teach them the pure dharma. It is therefore considered ineffective to trust in personal meditational and even monastic practices, but to only trust in the primal vow of Amitābha.[5] |

仏教 仏教は、涅槃に到達することで、輪廻(強制的な再生のサイクル)から解脱し、ドゥハカ(苦行)から解脱することに主眼を置いている。仏教は、このプロセスにおける個人の瞑想修行と、それに続く輪廻からの解脱、つまり悟りを開くことを重要視している。 このように、個人的なものと現象的なものという2種類の同一性への執着を正確に識別することが重要だと考えられている根本的な理由は、やはり救済論的なも のである。まず執着を明らかにし、それに取り組むことによって、私たちは最終的に、すべての苦悩と苦しみの唯一の原因である執着を手放すことができるよう になる[3]。 しかし、大乗仏教の浄土教の伝統は、一般的に天部阿弥陀仏の救済の性質に焦点を当てている[4]。大乗仏教の終末論では、我々は現在末法に生きていると信 じられており、人々の堕落した性質が仏の教えに耳を傾けないことを意味する1万年の期間である。 [この時代の前に、阿弥陀如来は48の誓願を立てている。その中には、自分に呼びかける衆生をすべて受け入れ、自分の浄土に帰依させ、純粋な法を教えると いう誓願も含まれている。それゆえ、個人的な瞑想や僧院での修行さえも信頼することはできず、阿弥陀如来の原初の誓いだけを信頼することが効果的であると 考えられている[5]。 |

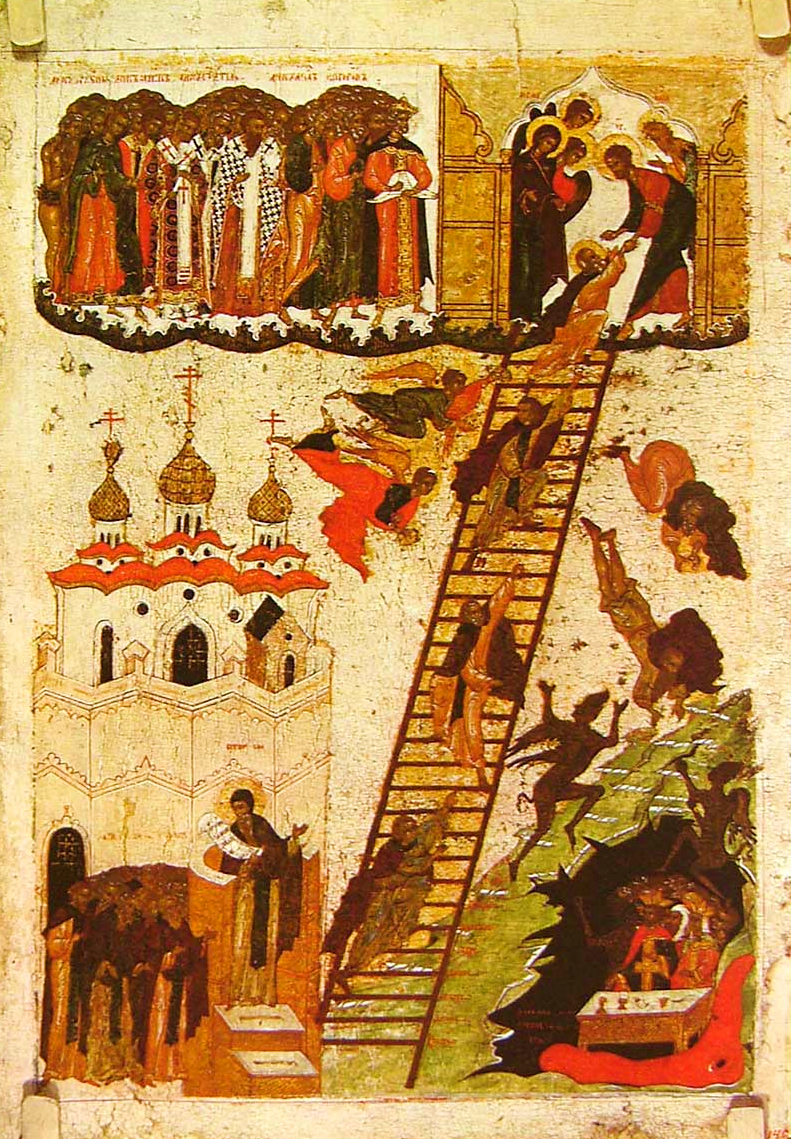

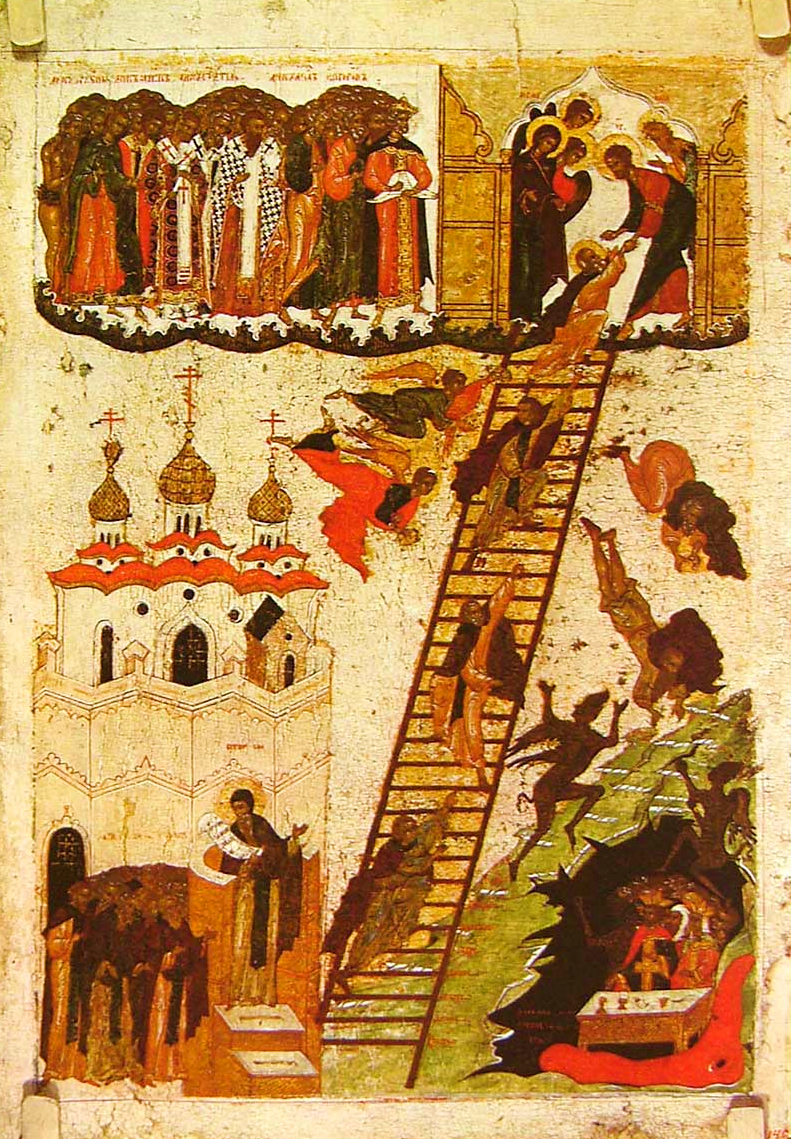

| Christianity Main article: Salvation in Christianity  Icon of The Ladder of Divine Ascent (the steps toward theosis as described by John Climacus) showing monks ascending (and falling from) the ladder to Jesus In Christianity, salvation, also called "deliverance" or "redemption", is the saving of human beings from sin and its consequences.[6][7] Variant views on salvation are among the main lines dividing the various Christian denominations, being a point of disagreement between Eastern Orthodoxy, Roman Catholicism and Protestantism, as well as within Protestantism, notably in the Calvinist–Arminian debate. These lines include conflicting definitions of depravity, predestination, atonement, and most pointedly, justification. Christian soteriology ranges from exclusive salvation[8]: p.123 to universal reconciliation concepts.[9] Christology plays a key role in debates about soteriology. In Catholic tradition the Church claims soteriological authority. Martin Luther rejected the soteriological authority of the church. Against this backdrop, the role of Christ's divinity takes so central a place in the theology of Søren Kierkegaard that it provides the basis for the proposition of Christ's power to save, and so in this way of thinking Christology precedes soteriology. In the debates over the ancient authorities Christ's divinity and power over salvation are interconnected theological concepts.[10][11] |

キリスト教 主な記事 キリスト教における救済  ヨハネ・クリマコスによって主張された「神の昇天の梯子」のイコン。修道士たちがイエスに向かって梯子を昇る(そして梯子から落ちる)様子が描かれている。 キリスト教では、救済は「解放」または「贖罪」とも呼ばれ、人間を罪とその結果から救うことである[6][7]。救済に関する見解の相違は、キリスト教の さまざまな教派を分ける主要なラインのひとつであり、東方正教会、ローマ・カトリック、プロテスタントの間、およびプロテスタント内、特にカルヴァン派と アーミン派の論争における意見の相違点である。その中には、堕落、宿命、贖罪、そして最も重要な義認に関する対立する定義が含まれる。キリスト教の救済論 は、排他的救済[8]: p.123から普遍的和解概念[9]まで幅広い。 キリスト論は有情論に関する議論において重要な役割を果たす。カトリックの伝統では、教会は有情論の権威を主張している。マルティン・ルターは教会の救済 論的権威を否定した。このような背景から、キリストの神性はセーレン・キルケゴールの神学において中心的な位置を占めており、キリストの救いの力という命 題の根拠となっている。古代の権威をめぐる議論において、キリストの神性と救済の力は相互に関連し合った神学的概念である[10][11]。 |

| Hinduism Soteriology is discussed in Hinduism through its principle of moksha, also called nirvana or kaivalya. "In India", wrote Mircea Eliade, "metaphysical knowledge always has a soteriological purpose." Moksha refers to freedom from saṃsāra, the cycle of death and rebirth. There are various principles and practices that can lead to the state of moksha including the Vedas and the Tantras being the basic scriptures for guidance along with many others like Upanishads, Puranas and more.[citation needed] |

ヒンドゥー教 ヒンドゥー教では、ニルヴァーナやカイヴァリヤとも呼ばれるモクシャの原理を通して、ソテロジーが論じられている。「インドでは 「形而上学的知識は常に救済の目的を持っている 」とミルチェア・エリアーデは書いている。モクシャとは、死と再生のサイクルであるササーラからの解放を意味する。ヴェーダやタントラは、ウパニシャッド やプラーナなど多くの他の聖典とともに、導きのための基本的な聖典である[要出典]。 |

| Islam Main article: Salvation § Islam Muslims believe that everyone is responsible for their own actions. So even though Muslims believe that Adam and Hawwa (Eve), the parents of humanity, committed a sin by eating from the forbidden tree and thus disobeyed God, they believe that humankind is not responsible for such an action. They believe that God (Allah) is fair and just and one should request forgiveness from him to avoid being punished for not doing what God asked of them and for listening to Satan.[12] Muslims believe that they, as well as everyone else, are vulnerable to making mistakes and thus they need to seek repentance repeatedly at all times. Muhammad said, "By Allah, I seek the forgiveness of Allah and I turn to Him in repentance more than seventy times each day." (Narrated by al-Bukhaari, no. 6307) God wants his servants to repent and forgives them, he rejoices over it, as Muhammad said: "When a person repents, Allah rejoices more than one of you who found his camel after he lost it in the desert." (Agreed upon. Narrated by al-Bukhaari, no. 6309) Islamic tradition has generally held that it is relatively straightforward to enter Jannah (Paradise). In the Quran, God says: "If you avoid the great sins you have been forbidden, We shall wipe out your minor misdeeds and let you through the entrance of honor [Paradise]."[13] However, by direct implication of these tenets and beliefs, Man's nature is spiritually and morally flawed such that he needs salvation from himself. Finding appreciation, forgiveness, and joy in Allah is the only (or best) practice to be saved from this terrible fate of corruption and meaninglessness. al-Tahreem 66:8 |

イスラム教 主な記事 救済 § イスラーム ムスリムは、すべての人が自分の行動に責任を持つと信じている。そのため、人類の親であるアダムとハウワ(イブ)が禁断の木から食べて罪を犯し、神に背い たとムスリムが信じていても、人類はそのような行為に対して責任を負わないと信じている。彼らは、神(アッラー)は公平で公正なお方であり、神の求めに応 じなかったり、サタンの言うことを聞いたりしたために罰せられることを避けるために、神に許しを請うべきだと信じている[12]。イスラム教徒は、自分だ けでなく他のすべての人が過ちを犯す可能性があるため、いつでも繰り返し悔い改めを求める必要があると信じている。 ムハンマドは、「アッラーに誓って、私はアッラーの赦しを求め、毎日70回以上悔い改めに立ち返る。(ムハンマドは、「アッラーに誓って、私はアッラーに 懺悔を求め、毎日70回以上悔い改めに立ち返る: 「人が悔い改める時、アッラーは、砂漠でラクダを見失った者が自分のラクダを見つけた時よりも喜ぶのである。」(アッラーの仰せ) (イスラムの伝統では、ヤンナ(楽園)に入るのは比較的容易であるとされてきた。) クルアーンでは、神は「もしあなたがたが禁じられている大罪を避けるならば、われはあなたがたの小さな悪行を帳消しにして、栄誉(楽園)の入り口を通らせ るであろう」と述べている[13]。 しかし、これらの教義や信念の直接的な意味合いとして、人間の本性は精神的、道徳的に欠陥があり、自分自身からの救済を必要としている。アッラーに感謝し、赦しと喜びを見出すことが、この堕落と無意味という恐ろしい運命から救われる唯一の(あるいは最良の)方法である。 |

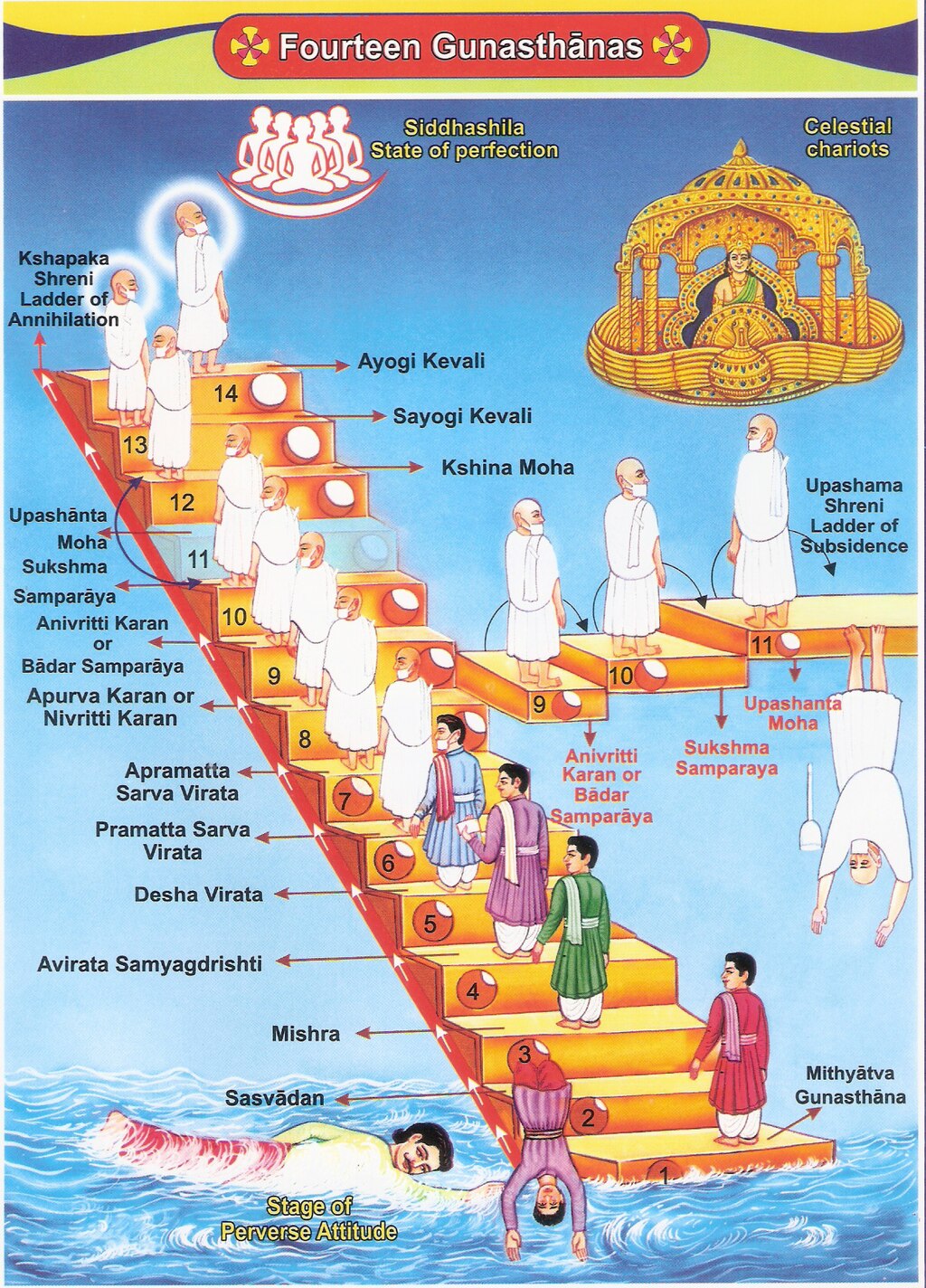

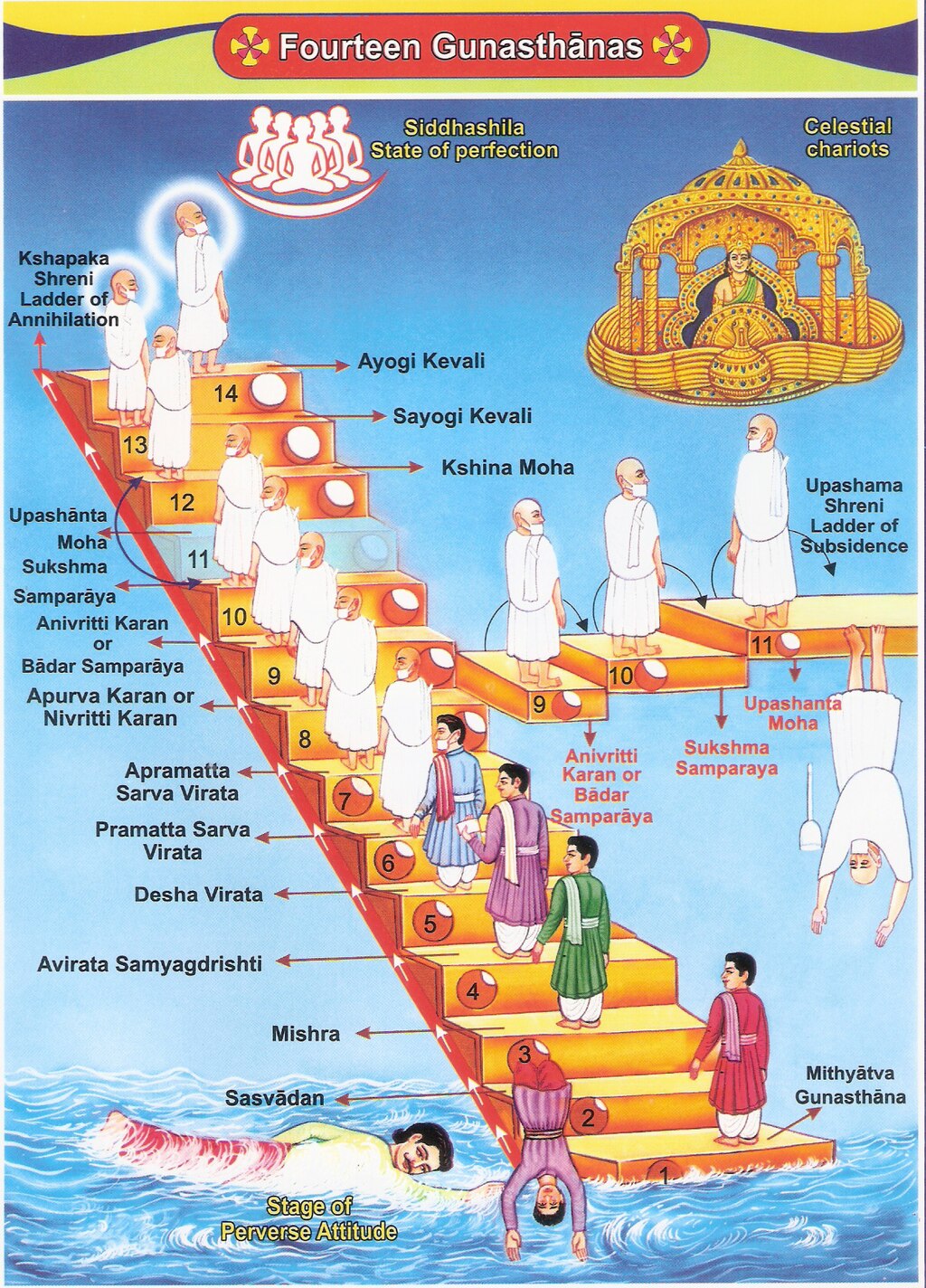

Jainism An illustration of the Gunasthanas In Jainism, the soteriological concept is moksha, which is the final gunasthana. The Jain theory explains moksha differently from the similar term found in Hinduism.[14] Moksha is a blissful state of existence of a soul, completely free from the karmic bondage, free from saṃsāra, the cycle of birth and death. It is the highest state of existence of a soul, even higher than the gods living in the heavens. In the state of moksha, a soul enjoys infinite bliss, infinite knowledge and infinite perception. This state is achieved through realisation of self and achieving a completely desireless and unattached state. |

ジャイナ教 グナスターナの図解 ジャイナ教では、最後のグナスターナであるモクシャが救済の概念である。ジャイナ教の理論では、モクシャはヒンドゥー教に見られる同様の用語とは異なる説 明をしている[14]。モクシャとは、カルマの束縛から完全に解放され、生と死のサイクルであるササーラから解放された、魂の至福の存在状態である。それ は魂の存在の最高の状態であり、天界に住む神々よりもさらに高い。モクシャの状態では、魂は無限の至福、無限の知識、無限の知覚を享受する。この状態は、 自己を悟り、完全に無欲で無執着の状態を達成することによって達成される。 |

| Judaism Main article: Law given to Moses at Sinai In contemporary Judaism, redemption (Hebrew ge'ulah) is God's gathering in the people of Israel from their various exiles.[15] This includes the final redemption from the present exile.[16] Judaism does not posit a need for personal salvation in a way analogous to Christianity; Jews do not believe in original sin.[17] Instead, Judaism places greater value on individual morality as defined in the Law and embodied in the Torah—the teaching given to Moses by God on Mount Sinai and sometimes understood to be summarized by the Decalogue (Biblical Hebrew עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְּבָרִים, ʿĂsereṯ haDəḇārīm, lit. 'The Ten Words'). The tannaitic sage Hillel the Elder taught that the Law could be further compressed into the single maxim popularly known as the Golden Rule: "That which is hateful to you, do not do unto your fellow".[18] In Judaism, salvation is closely related to the idea of redemption, or rescue from the states and circumstances that destroy the value of human existence. God, as the creator of the universe, is the source of all salvation for humanity (provided an individual honors God by observing God's precepts). So, redemption and/or salvation depends on the individual. Furthermore, Judaism stresses that one's salvation cannot be obtained through anyone else, invoking a deity, or believing in any outside power or influence.[18] Some passages in Jewish religious texts assert that an afterlife exists for neither the good nor evil. For example, the writer of the Book of Ecclesiastes tells the reader: "The dead know nothing. They have no reward and even the memory of them is lost."[19] For many centuries, rabbis and Jewish laypeople have often wrestled with such passages. |

ユダヤ教 主な記事 シナイでモーセに与えられた律法 現代のユダヤ教では、贖罪(ヘブライ語でge'ulah)とは、神がイスラエルの民をさまざまな流浪の地から集めることである[15]。これには、現在の 流浪の地からの最終的な贖罪も含まれる[16]。ユダヤ教は、キリスト教に類似した個人的な救済の必要性を仮定しない。 [ユダヤ人は原罪を信じていない、 ユダヤ教は、シナイ山で神からモーセに与えられた教えである律法に定義され、トーラーに具体化されている個人の道徳を重視する。シナイ山で神がモーセに与 えた教えであり、デカログ(聖書ヘブライ語 עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְִֵיּבָרם、 + haDəḇārīm, lit. 十の言葉」)である。タンナ派の賢者ヒレル長老は、律法をさらに圧縮して、一般に黄金律として知られる「あなたにとって憎むべきことは、あなた の仲間にしてはならない」という一つの格言にすることができると説いた[18]。 ユダヤ教では、救済は贖罪、すなわち人間の存在価値を破壊する状態や状況からの救済という考えと密接に関連している。宇宙の創造主である神は、(個人が神 の戒律を守ることによって神を敬うことを条件として)人類のすべての救済の源である。つまり、贖罪や救済は個人次第なのだ。さらにユダヤ教は、自分の救済 は、他の誰かによって得られるものでも、神を呼び出すものでも、外部の力や影響を信じるものでもないことを強調している[18]。 ユダヤ教の宗教文書の中には、善人にも悪人にも死後の世界は存在しないと主張する箇所がある。例えば、伝道者の書の著者は読者にこう語っている: 「死者は何も知らない。死者には何の報いもなく、その記憶さえも失われてしまう」[19]。何世紀にもわたって、ラビやユダヤ人信徒はしばしばこのような 文章と格闘してきた。 |

| Mystery religions In the mystery religions, salvation was less worldly and communal, and more a mystical belief concerned with the continued survival of the individual soul after death.[20] Some savior gods associated with this theme are dying-and-rising gods, often associated with the seasonal cycle, such as Osiris, Tammus, Adonis, and Dionysus. A complex of soteriological beliefs was also a feature of the cult of Cybele and Attis.[21] The similarity of themes and archetypes to religions found in antiquity to later Christianity has been pointed out by many authors, including the Fathers of the early Christian church. One view[citation needed] is that early Christianity borrowed these myths and motifs from contemporary Hellenistic mystery religions, which possessed ideas such as life-death-rebirth deities and sexual relations between gods and human beings. While Christ myth theory is not accepted by mainstream historians, proponents attempt to establish causal connections to the cults of Mithras, Dionysus, and Osiris among others.[22] |

神秘宗教 神秘宗教では、救済は世俗的で共同体的なものではなく、死後も個人の魂が生存し続けることに関係する神秘的な信仰であった[20]。このテーマに関連する 救世主の神々には、オシリス、タムス、アドニス、ディオニュソスなど、しばしば季節のサイクルに関連する、死と復活を繰り返す神々がいる。複合的な救済信 仰は、キュベレとアティスのカルトの特徴でもあった[21]。 古代に見られる宗教と後のキリスト教とのテーマや原型の類似性は、初代キリスト教会の教父を含む多くの著者によって指摘されている。ある見解は[引用が必 要]、初期キリスト教はこれらの神話やモチーフを、生死再生の神や神々と人間の性的関係といった思想を持つ現代のヘレニズム神秘宗教から借用したというも のである。キリスト神話説は主流の歴史家には受け入れられていないが、支持者たちはとりわけミトラ、ディオニュソス、オシリスなどのカルトとの因果関係を 立証しようとしている[22]。 |

| Epicurean philosophy More than a century after the establishment of the Garden, the school in which Epicurus taught philosophy, some people in the Roman world were calling Epicurus their Savior. The most prominent soul saved by Epicurus was the Roman Empress Pompeia Plotina.[citation needed] Lucretius, author of De Rerum Natura, also depicts the salvific power of philosophy, and of his Scholarch Epicurus, by employing literary devices like the "Broken Jar parable" (where the Scholarch is credited with helping mortals to easily enjoy pleasure), poetry, and imagery.[citation needed] The salvation of Epicurus has no otherworldly connotations whatsoever. Judging from his Principal Doctrines and Letter to Menoeceus, he salves his disciples from supernatural fears and excessive desires for what is not natural and gives his disciples clear ethical guidelines that lead to happiness. Lucretius says Epicurus has set the boundaries for the limits of nature. His followers in Roman times developed Epicurus into a cultural hero and revered him as the founding figure of his School, and as the first to have developed a fully naturalistic cosmology that emancipated mortals from all fear-based superstition.[citation needed] |

エピクロス哲学 エピクロスが哲学を教えた学校「学園」が設立されてから1世紀以上が経ち、ローマ世界ではエピクロスを救世主と呼ぶ人々が現れた。De Rerum Natura』の著者ルクレティウスもまた、「割れた壺のたとえ」(スコラークが人間が快楽を容易に享受できるようにしたとされる)、詩、イメージなどの 文学的装置を用いて、哲学、そして彼のスコラークであるエピクロスの救いの力を描いている[要出典]。 エピクロスの救済には、別世界的な意味合いはまったくない。彼の『主要教義』と『メノケウスへの手紙』から判断すると、彼は弟子たちを超自然的な恐怖や自 然でないものへの過剰な欲望から救い、弟子たちに幸福につながる明確な倫理的指針を与えている。ルクレティウスは、エピクロスが自然の限界の境界を定めた と言っている。ローマ時代の彼の信奉者たちは、エピクロスを文化的英雄に育て上げ、彼の学派の創始者として、また人間をあらゆる恐怖に基づく迷信から解放 する完全な自然主義的宇宙論を最初に展開した人物として崇めた[要出典]。 |

| Taoism Becoming an enlightened person is what is considered salvation in many Taoist beliefs. Some Taoist immortals were thought of as deceased humans whose souls achieved a superior physical form.[23] Enlightened people were sometimes called zhenren and thought to be the living embodiment of the supernatural characteristics of the faith.[24][25] |

道教 悟りを開いた人間になることは、多くの道教の信仰において救済と考えられている。 道教の仙人の中には、魂が優れた肉体を獲得した亡き人間として考えられている者もいた[23]。悟りを開いた者は鎮人と呼ばれることもあり、信仰の超自然的な特徴を体現した生きた存在であると考えられていた[24][25]。 |

| Sikhism Sikhism advocates the pursuit of salvation through disciplined, personal meditation on the Naam Japo (name) and message of God, meant to bring one into union with God. But a person's state of mind has to be detached from this world, with the understanding that this world is a temporary abode and their soul has to remain untouched by pain, pleasure, greed, emotional attachment, praise, slander, and above all, egotistical pride. Thus their thoughts and deeds become nirmal or pure, and they merge with God or attain union with God, just as a drop of water falling from the skies merges with the ocean.[26][27] |

シーク教 シク教は、ナーム・ジャポ(神の御名)と神のメッセージを規律正しく個人的に瞑想することによって救いを追求し、神との合一をもたらすことを提唱してい る。しかし、人の心の状態は、この世は一時的な住処であり、魂は苦痛、快楽、貪欲、感情的執着、賞賛、中傷、そして何よりも自己中心的なプライドに触れら れないままでなければならないということを理解した上で、この世から切り離されなければならない。こうして彼らの思考と行いはニルマル、すなわち純粋なも のとなり、彼らは神と融合する、あるいは神との合一を達成する。 |

| Other religions Shinto and Tenrikyo similarly emphasize working for a good life by cultivating virtue or virtuous behavior[citation needed]. In an age[timeframe?] that still saw salvation as primarily collective - based on the religion of the family, clan, or state - rather than the emerging province of the individual[clarification needed] (as popularized by Buddhism and the mystery religions such as Mithraism) and Hellenistic ruler cults from about 300 BCE sometimes promoted the revering of a king as the savior of his people. Prominent examples included Ptolemy I Soter of Egypt and the Seleucids Antiochus I Soter and Demetrius I Soter. In the Egyptian context, the deification of a ruler was built on traditional pharaonic religious ideas.[citation needed] |

その他の宗教 神道と天理教も同様に、徳や高潔な行動を修めることによって善い人生を送るために働くことを強調している[要出典]。 仏教やミトラ教などの神秘宗教によって広められた)前300年頃からのヘレニズムの支配者崇拝では、民衆の救世主として王を崇拝することがあった。エジプ トのプトレマイオス1世ソテルやセレウコス朝のアンティオコス1世ソテル、デメトリウス1世ソテルなどがその代表例である。エジプトの文脈では、支配者の 神格化は伝統的なファラオの宗教思想に基づいていた[要出典]。 |

| Comparative religion Salvation |

比較宗教 救済 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soteriology |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆