1868年以降の現代スペイン

Spain from 1868

☆

| Sexenio Democrático (1868–1874) Main article: Sexenio Democrático See also: History of Spain (1810–73)  Members of the provisional government after the 1868 Glorious Revolution, by Jean Laurent. In 1868 another insurgency, known as the Glorious Revolution took place. The progresista generals Francisco Serrano and Juan Prim revolted against Isabella and defeated her moderado generals at the Battle of Alcolea (1868). Isabella was driven into exile in Paris.[135] Two years later, in 1870, the Cortes declared that Spain would again have a king. Amadeus of Savoy, the second son of King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy, was selected and duly crowned King of Spain early the following year.[136] Amadeus – a liberal who swore by the liberal constitution the Cortes promulgated – was faced immediately with the incredible task of bringing the disparate political ideologies of Spain to one table. The country was plagued by internecine strife, not merely between Spaniards but within Spanish parties. Following the Hidalgo affair and an army rebellion, Amadeus famously declared the people of Spain to be ungovernable, abdicated the throne, and left the country. First Spanish Republic (1873–1874) Main article: First Spanish Republic  Proclamation of the Spanish Republic in Madrid In the absence of the Monarch, a government of radicals and Republicans was formed and declared Spain a republic. The First Spanish Republic (1873–74) was immediately under siege from all quarters. The Carlists were the most immediate threat, launching a violent insurrection after their poor showing in the 1872 elections. There were calls for socialist revolution from the International Workingmen's Association, revolts and unrest in the autonomous regions of Navarre and Catalonia, and pressure from the Catholic Church against the fledgling republic.[137] A coup took place in January 1874, when General Pavía broke into the Cortes. This prevented the formation of a federal republican government, forced the dissolution of the Parliament and led to the instauration of a unitary praetorian republic ruled by General Serrano, paving the way for the Restoration of the Monarchy through another pronunciamiento, this time by Arsenio Martínez Campos, in December 1874. |

民主主義の六か年政権 (1868–1874) 詳細は「民主主義六か年政権」を参照 関連項目:スペインの歴史 (1810–73)  ジャン・ローランによる、1868年の栄光革命後の暫定政府の閣僚たち。 1868年、栄光革命として知られる別の反乱が起こった。進歩派の将軍フランシスコ・セラーノとフアン・プリムはイサベルに反旗を翻し、アルコレアの戦い(1868年)で穏健派の将軍たちを打ち負かした。イサベルはパリに亡命した。 それから2年後の1870年、スペイン議会は再びスペインに国王を置くことを宣言した。イタリア王ヴィットーリオ・エマヌエーレ2世の次男であるサヴォイ ア家のアマデウスが選ばれ、翌年初頭に正式にスペイン王として戴冠した。[136] アマデウスは議会が公布した自由主義憲法を信奉する自由主義者であったが、スペインの政治思想の相違をひとつのテーブルにまとめるという途方もない課題に 直ちに直面することとなった。スペイン国内ではスペイン人同士だけでなく、スペインの政党内部でも内紛が絶えなかった。イダルゴ事件と軍の反乱の後、アマ デウスはスペイン国民を統治できないと宣言し、王位を退位してスペインを去った。 スペイン第一共和政(1873年-1874年) 詳細は「スペイン第一共和政」を参照  マドリードにおけるスペイン共和国の宣言 君主不在のなか急進派と共和派による政府が樹立され、スペインは共和制に移行した。第一共和政(1873年~1874年)は、たちまち各方面からの包囲網 に囲まれた。カルリスタ派は最も差し迫った脅威であり、1872年の選挙での不調の後、暴力的な反乱を起こした。国際労働者協会からは社会主義革命を求め る声が上がり、ナバラ州とカタルーニャ州の自治地域では反乱と不安が起こり、カトリック教会からは新興の共和国に対する圧力がかけられた。 1874年1月、パビア将軍がコルテスに乱入するクーデターが発生した。これにより連邦共和制政府の樹立は阻止され、議会は解散を余儀なくされ、セラーノ 将軍による単独護民官制共和国が樹立された。これが、1874年12月にアルセニオ・マルティネス・カンポスによる新たな発動により王政復古への道筋をつ けた。 |

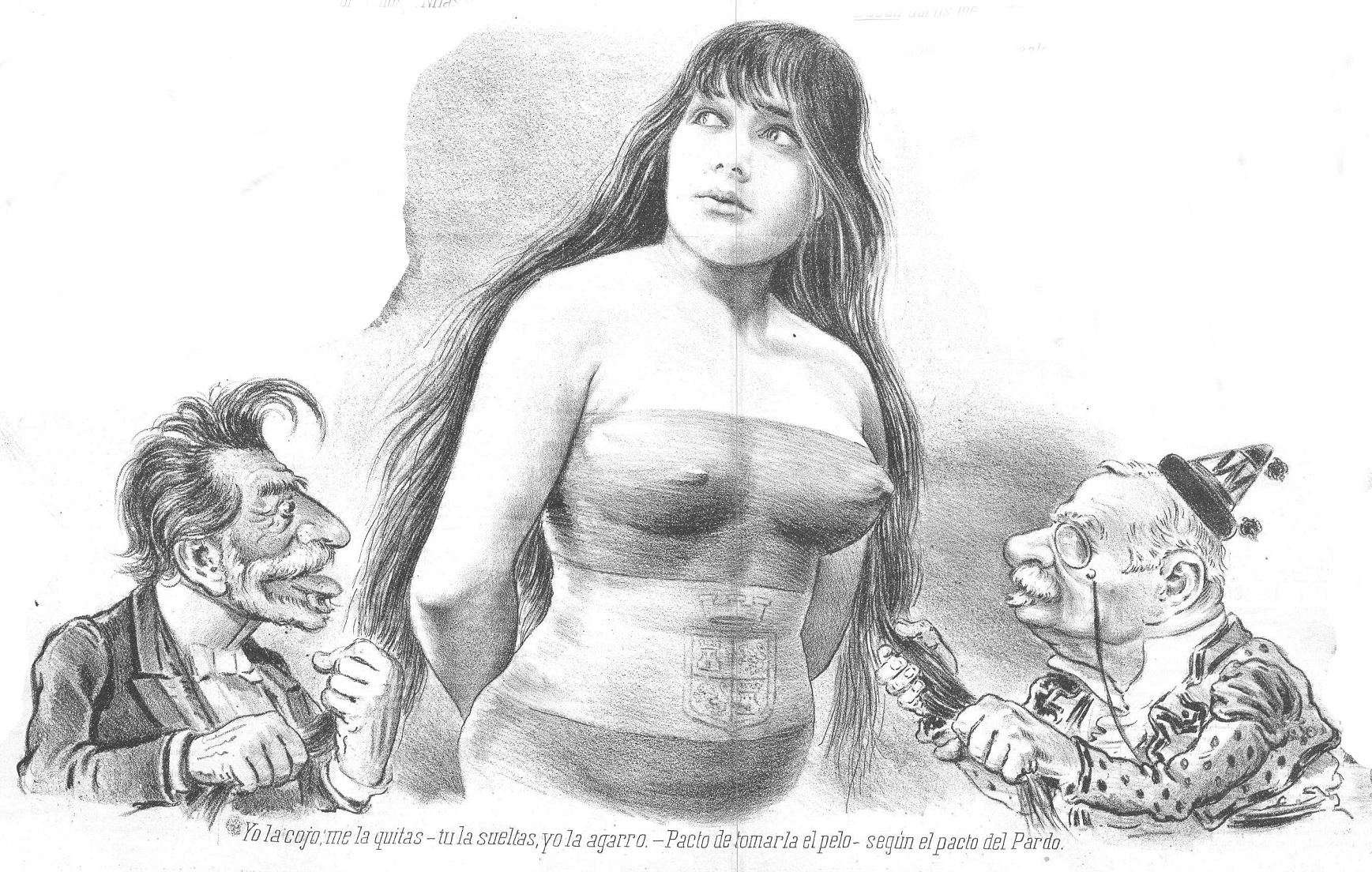

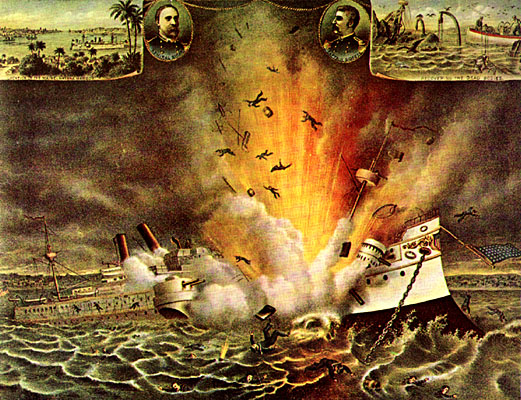

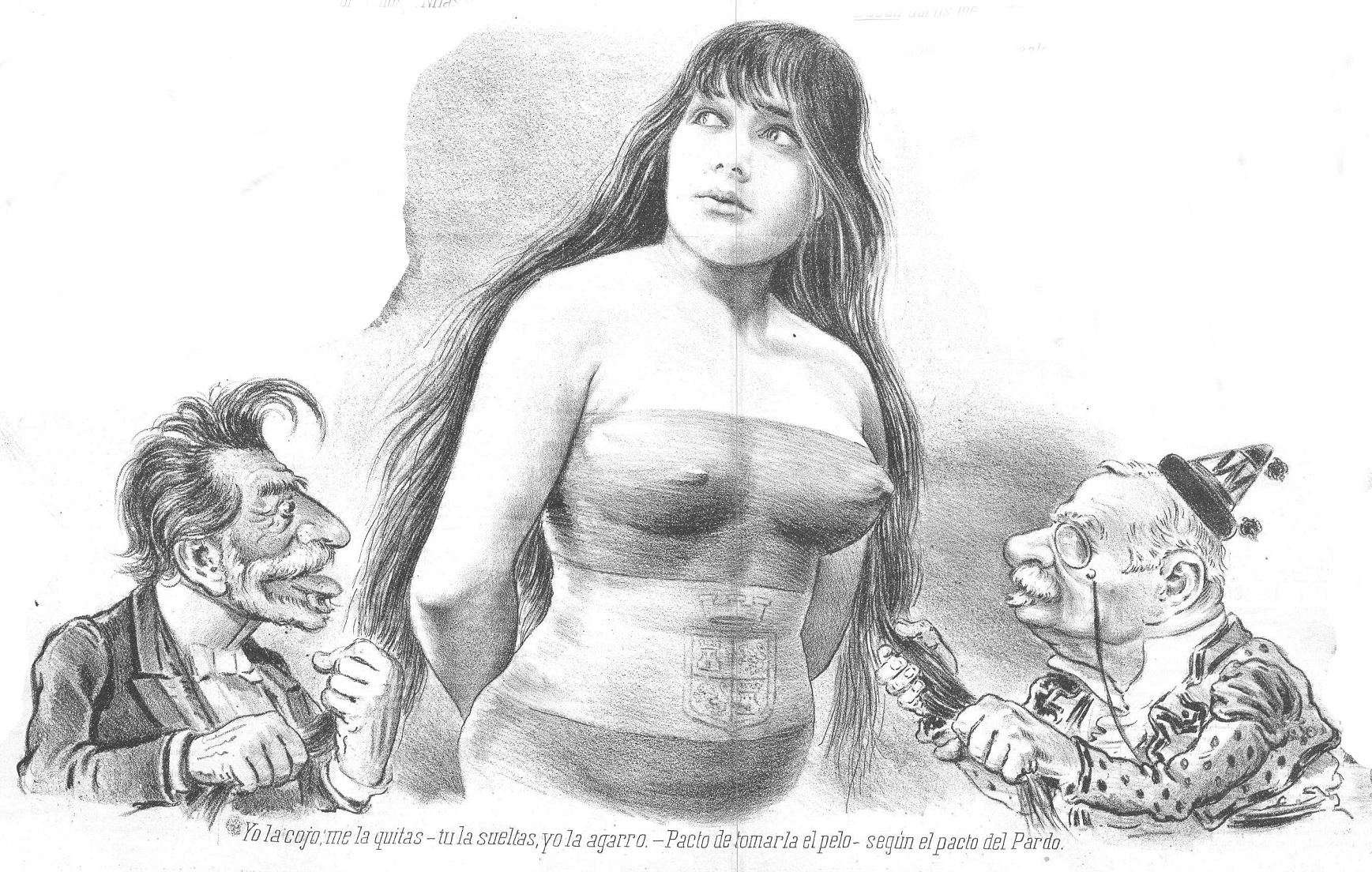

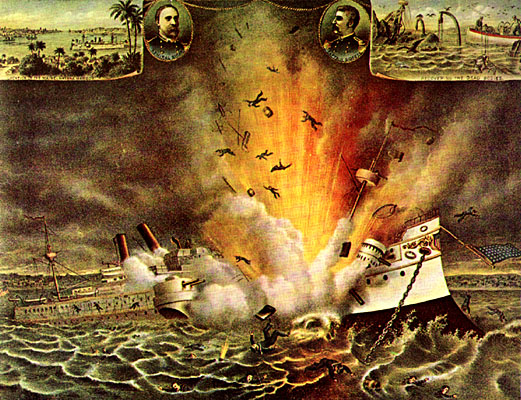

| Restoration (1874–1931) Main article: Spain under the Restoration Reign of Alfonso XII and Regency of Maria Christina Main articles: Reign of Alfonso XII and Regency of Maria Christina of Austria  1894 satirical cartoon depicting the tacit accord for seamless government change (turnismo) between the leaders of two dynastic parties (Sagasta and Cánovas del Castillo), with the country being lied in an allegorical fashion. Following the success of a December 1874 military coup the monarchy was restored in the person of Alfonso XII (the son of former queen Isabella II). The ongoing Carlist insurrection was eventually put down.[138] The Restoration period, following the proclamation of the 1876 Constitution, witnessed the installment of an uncompetitive parliamentary system devised by Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, in which two "dynastic" parties, the conservatives and the liberals alternated in control of the government (turnismo). Election fraud (materialized in the so-called caciquismo) became ubiquitous, with elections reproducing pre-arranged outcomes struck in the Capital.[139] Voter apathy was no less important.[140] The reign of Alfonso was followed by that of his son Alfonso XIII,[141] initially a regency until the latter's coming of age in 1902. The 1876 Constitution granted the Catholic Church control of education (particularly secondary education).[142] Meanwhile, an organization formed in 1876 upon a group of Krausists educators, the Institución Libre de Enseñanza, had a leading role in the educational and cultural renovation in the country, covering for the inaction of the Spanish State.[143] Disaster of 1898  The explosion of the USS Maine launched the Spanish–American War in April 1898 In 1868, Cuba launched a war of independence against Spain. As had been the case in Santo Domingo, the Spanish government was embroiled in a difficult campaign against an indigenous rebellion. Unlike in Santo Domingo, however, Spain initially won this struggle. The pacification of the island was temporary, however, as the conflict revived in 1895 and ended in defeat at the hands of the United States in the Spanish–American War of 1898. Cuba gained its independence and Spain lost its remaining New World colony, Puerto Rico, which together with Guam and the Philippines were ceded to the United States for $20 million. In 1899, Spain sold its remaining Pacific islands – the Northern Mariana Islands, Caroline Islands and Palau – to Germany and Spanish colonial possessions were reduced to Spanish Morocco, Spanish Sahara and Spanish Guinea, all in Africa.[144] The "disaster" of 1898 created the Generation of '98, a group of statesmen and intellectuals who demanded liberal change from the new government. However both Anarchism on the left and fascism on the right grew rapidly in the early 20th century. A revolt in 1909 in Catalonia was bloodily suppressed.[145] Jensen (1999) argues that the defeat of 1898 led many military officers to abandon the liberalism that had been strong in the officer corps and turn to the right. They interpreted the American victory in 1898 as well as the Japanese victory against Russia in 1905 as proof of the superiority of willpower and moral values over technology. Over the next three decades, Jensen argues, these values shaped the outlook of Francisco Franco and other Falangists.[146] |

王政復古(1874年-1931年) 詳細は「王政復古期のスペイン」を参照 アルフォンソ12世の治世とマリア・クリスティーナの摂政 詳細は「アルフォンソ12世の治世」および「マリア・クリスティーナ・デ・オーストリアの摂政」を参照  1894年の風刺漫画は、2つの王朝政党の指導者(サガスタとカノバス・デル・カスティーリョ)の間で、継ぎ目のない政権交代(ターンシモ)の暗黙の合意が結ばれ、国が寓話的に描かれている。 1874年12月の軍事クーデターの成功を受けて、アルフォンソ12世(前女王イサベル2世の息子)を戴いて王政が復活した。カトリック党の反乱は最終的 に鎮圧された。[138] 1876年の憲法が公布された王政復古期には、アントニオ・カノバス・デル・カスティージョが考案した競争力のない議会制度が導入され、保守党と自由党と いう2つの「王朝」政党が交互に政権を担当するようになった(turnismo)。選挙不正(いわゆるカシキスムとして現れた)が至る所で見られるように なり、首都で事前に取り決められた結果を再現する選挙が行われた。[139]有権者の無関心も同様に重要であった。[140]アルフォンソの治世は、息子 のアルフォンソ13世の治世に引き継がれた。[141]当初は摂政政治であったが、1902年にアルフォンソ13世が成人するまで続いた。 1876年の憲法では、カトリック教会に教育(特に中等教育)の管理権が与えられた。[142] 一方、1876年にクラウシストの教育者グループによって結成された団体「インスティトゥシオン・リブレ・デ・エンセニャンサ」は、スペイン国家の不作為 を補い、国内の教育と文化の刷新において主導的な役割を果たした。[143] 1898年の惨事  1898年4月、USSメイン号爆発事件により米西戦争が勃発した 1868年、キューバはスペインに対して独立戦争を開始した。サントドミンゴの場合と同様に、スペイン政府は先住民の反乱に対する困難な戦いに巻き込まれ た。しかし、サント・ドミンゴの場合とは異なり、スペインは当初この闘争に勝利した。しかし、この島の平定は一時的なもので、1895年に紛争が再燃し、 1898年の米西戦争でアメリカ合衆国の敗北に終わった。キューバは独立を獲得し、スペインは残る新大陸の植民地プエルトリコを失った。プエルトリコはグ アムおよびフィリピンとともに、2000万ドルでアメリカ合衆国に割譲された。1899年、スペインは太平洋の残りの島々、北マリアナ諸島、カロリン諸 島、パラオをドイツに売却し、スペインの植民地はアフリカのスペイン領モロッコ、スペイン領サハラ、スペイン領ギニアのみとなった。 1898年の「災厄」は、新政府に自由主義的改革を要求する政治家や知識人のグループ「98年世代」を生み出した。しかし、左派の無政府主義と右派のファ シズムは20世紀初頭に急速に勢力を拡大した。1909年のカタルーニャでの反乱は血なまぐさく鎮圧された。[145] ジェンセン(1999年)は、1898年の敗北により、多くの軍人がそれまで軍部で強かった自由主義を放棄し、右派に転向したと主張している。彼らは、 1898年のアメリカの勝利と1905年の日本によるロシアに対する勝利を、技術よりも意志と道徳的価値観の優位性の証拠であると解釈した。ジェンセン は、この30年間で、フランシスコ・フランコやその他のファランヘ党員たちの考え方が、これらの価値観によって形作られたと主張している。[146] |

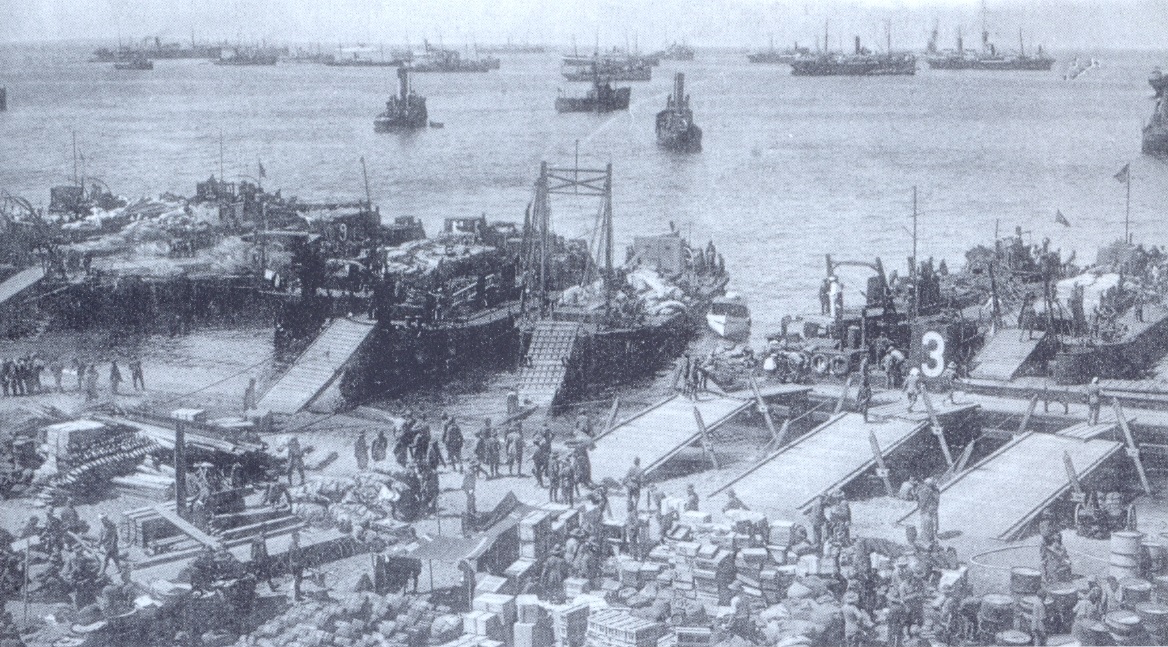

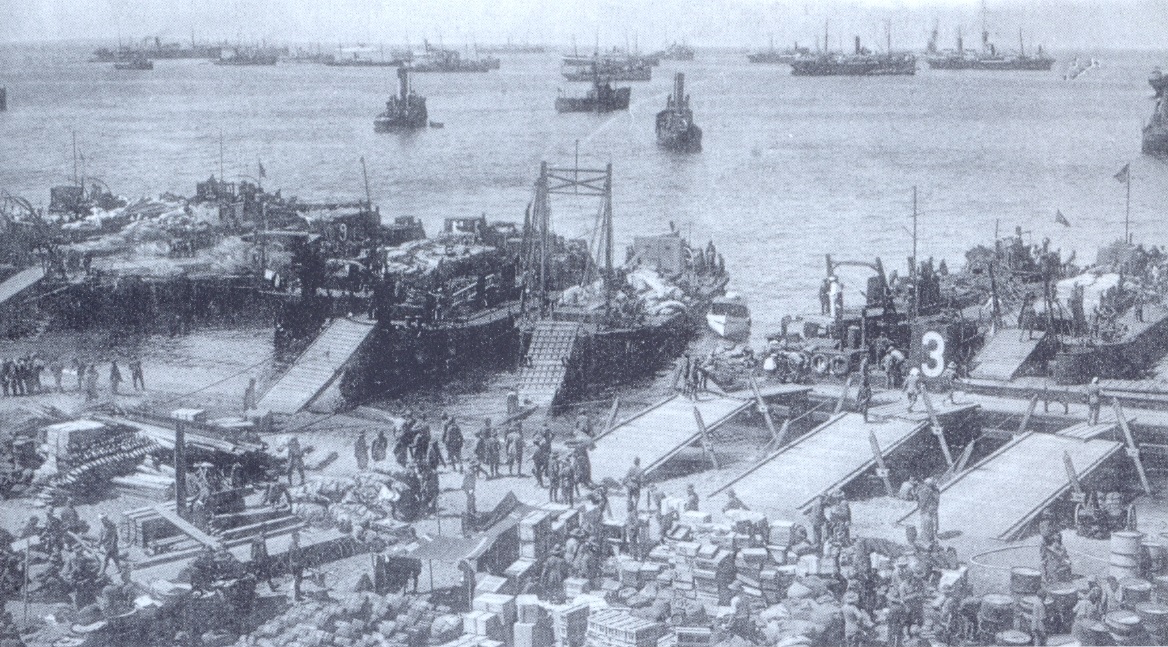

| Crisis of the Restoration system (1913–1931) The bipartisan system began to collapse in the later years of the constitutional part of the reign of Alfonso XIII, with the dynastic parties largely disintegrating into factions: the conservatives faced a schism between datistas, mauristas and ciervistas. The liberal camp split into the mainstream liberals followers of the Count of Romanones (romanonistas) and the followers of Manuel García Prieto, the "democrats" (prietistas).[147] An additional liberal albista faction was later added to the last two.[148] Spain's neutrality in World War I spared the country from carnage, yet the conflict caused massive economic disruption, with the country experiencing at the same time an economic boom (the increasing foreign demand of products and the drop of imports brought hefty profits) and widespread social distress (with mounting inflation, shortage of basic goods and extreme income inequality).[149] A major revolutionary strike was called for August 1917, supported by the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party, the UGT and the CNT, seeking to overthrow the government. The Dato government deployed the army against the workers to brutally quell any threat to social order, sealing in turn the demise of the cabinet and undermining the constitutional order.[150] The strike was one of the three simultaneous developments of a wider three-headed crisis in 1917 that cracked the Restoration regime, that also included a military crisis induced by the cleavage in the Armed Forces between Mainland and Africa-based ranks vis-à-vis the military promotion (and ensuing formation of juntas of officers that refused to dissolve upon request from the government),[151] and a political crisis brought by the challenge posed by Catalan nationalism, whose bourgeois was emboldened by the economic upswing.[152] During the Rif War, the crushing defeat of the Spanish Army in the so-called "Disaster of Annual" in the summer of 1921 brought in a matter of days the catastrophic loss of the lives of about 9,000 Spanish soldiers and the loss of all occupied territory in Morocco that had been gained since 1912.[153] This entailed the greatest defeat suffered by a European power in an African colonial war in the 20th century.[154][dubious – discuss] See also: Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera  The successful 1925 Alhucemas landing turned the luck in the Rif War towards Spain's favour. Alfonso XIII tacitly endorsed the September 1923 coup by General Miguel Primo de Rivera that installed a dictatorship led by the latter. The regime enforced the State of War all over the country from September 1923 to May 1925.[155][156] Attempts to institutionalise the regime were taken, in the form of a single official party (the Patriotic Union) and a consultative chamber (the National Assembly).[155][157] Preceded by a partial retreat from vulnerable posts in the interior of the protectorate in Morocco,[158] Spain (in joint action with France) turned the tides in Morocco in 1925, and the Abd el-Krim-led Republic of the Rif started to see the beginning of its end after the Alhucemas landing and ensuing seizure of Ajdir,[159] the heart of the Riffian rebellion. The war had dragged on since 1917 and cost Spain $800 million.[160][161] The Spanish officers of the war ended up taking the brutality of the colonial military practices to the mainland.[162] The late 1920s were prosperous until the worldwide Great Depression hit in 1929. In early 1930 bankruptcy and massive unpopularity forced the king to remove Primo de Rivera. See also: Dictablanda of Dámaso Berenguer Primo de Rivera was replaced by Dámaso Berenguer's so-called dictablanda. The later ruler was in turn replaced by Admiral Aznar-Cabañas in February 1931, soon before the scheduled municipal elections of April 1931, which were considered a plebiscite on the Monarchy. Urban voters had lost faith in the monarch and voted for republican parties. The king fled the country and a republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931.[163][164] |

復古体制の危機(1913年~1931年) 超党派体制は、アルフォンソ13世の治世の憲法時代の後期に崩壊し始め、王党派は主に派閥に分裂した。保守派は、ダティスタ、マウリスタ、シエルビスタの 間に分裂が生じた。自由主義陣営は、ロマノネス伯爵の支持者である主流派自由主義者(ロマノニスタ)と、「民主主義者」マヌエル・ガルシア・プリエトの支 持者(プリエタ)に分裂した。[147] 後に、最後の2つに自由主義派のアルバ派が加わった。[148] スペインは第一次世界大戦で中立を保ったため、大虐殺を免れたが、一方でこの戦争は経済に大きな打撃を与えた。スペインでは好景気(外国からの製品需要の 高まりと輸入品の減少により、巨額の利益がもたらされた)と社会的な苦痛( インフレの進行、基本物資の不足、極端な所得格差)が起こった。[149] 1917年8月には、政府転覆を狙った大規模な革命ストライキが計画された。スペイン社会労働党、UGT、CNTがこれを支持した。ダトー政府は社会秩序 に対する脅威を徹底的に鎮圧するために軍隊を労働者に対して投入し、内閣の崩壊を決定づけ、憲法秩序を損なうこととなった。[150] このストライキは、1917年に起こった3つの同時進行の危機のうちの1つであり、この危機は王政復古体制を崩壊させることとなった。この3つの危機に は、 軍部における本土とアフリカ駐留部隊の分裂による軍事的危機(そして、政府の要請による解散を拒否した将校による軍事政権の樹立)[151]、経済的浮揚 により勢いづいたカタルーニャ地方のブルジョワ層による挑戦による政治的危機[152]などである。 リフ戦争中、1921年夏に起きた「アンニャの災難」と呼ばれるスペイン軍の壊滅的敗北により、スペイン兵約9,000人の命が失われ、 1912年以来獲得していたモロッコの全占領地域の喪失をもたらした。[153] これは、20世紀のアフリカ植民地戦争においてヨーロッパ列強が被った最大の敗北であった。[154][疑わしいので議論する] 関連項目:プリモ・デ・リベラの独裁  1925年のアルウセマスの上陸作戦の成功により、リフ戦争の戦況はスペインに有利に傾いた。 アルフォンソ13世は、1923年9月にミゲル・プリモ・デ・リベラ将軍が起こしたクーデターを暗黙のうちに承認し、リベラが率いる独裁政権が樹立され た。この政権は1923年9月から1925年5月まで、全国に戦時体制を敷いた。[155][156] 体制を制度化する試みとして、単独政党(愛国連合)と諮問機関(国民議会)が設置された。[155][157] モロッコの保護領内の脆弱な拠点からの部分的な撤退に先立ち、[158] スペイン(フランスとの共同行動)は1925年にモロッコ情勢を覆し、アルフセマスの上陸作戦とそれに続くアジュディルの占領により、アブデルクリム率い るリフ共和国は終焉の始まりを迎えた。リフ人の反乱の中心地であったアジュディルは、 この戦争は1917年以来続いており、スペインに8億ドルの損害を与えた。[160][161] この戦争に従事したスペイン軍将校たちは、植民地における軍事活動の残忍性を本土にもたらすことになった。[162] 1920年代後半は繁栄を謳歌していたが、1929年に世界恐慌が襲った。1930年初頭には、破産と国民の圧倒的な不人気により、国王はプリモ・デ・リベラを解任せざるを得なかった。 参照:ダマソ・ベレンゲルの独裁者兼王様 プリモ・デ・リベラは、ダマソ・ベレンゲルの独裁者兼王様(dictablanda)に取って代わられた。後継の統治者は、1931年4月の地方選挙(君 主制に対する国民投票と見なされていた)を間近に控えた1931年2月、アスナール=カバニャス提督によって交代させられた。都市部の有権者は君主への信 頼を失い、共和制政党に投票した。国王は国外に逃亡し、1931年4月14日に共和国が宣言された。[163][164] |

| Second Spanish Republic (1931–36) Main articles: Second Spanish Republic and Provisional Government of the Second Spanish Republic  Celebrations of the proclamation of the 2nd Republic in Barcelona. A provisional government presided by Niceto Alcalá Zamora was installed as the Republic, popularly nicknamed as "la niña bonita" ('the pretty girl'),[165] was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, a democratic experiment at a time when democracies were beginning to descend into dictatorships elsewhere in the continent.[165][166] A Constituent election was called for June 1931. The dominant bloc emerging from the election, an alliance of liberals and socialists, brought Manuel Azaña (who had undertaken a decisive reform as War minister in the provisional government by trying to democratize the Armed Forces)[167] to premiership, heading from the on a number of coalition cabinets.[168] While the Republican government was able to easily quell the first 1932 coup d'etat led by José Sanjurjo, the generals, who felt humiliated because of the military reform privately developed a strong contempt towards Azaña.[167] The new parliament drafted a new constitution which was approved on 9 December 1931. Political ideologies were intensely polarized. Regarding the crux of the role of the Church, within the Left people saw the former as the major enemy of modernity and the Spanish people, and the right saw it as the invaluable protector of Spanish values.[169] Under the Second Spanish Republic, women were allowed to vote in general elections for the first time. The Republic devolved substantial self-government to Catalonia and, for a brief period in wartime, also to the Basque Provinces. The first cabinets of the Republic were center-left, headed by Niceto Alcalá-Zamora and Manuel Azaña. Economic turmoil, substantial debt, and fractious, rapidly changing governing coalitions led to escalating political violence and attempted coups by right and left. Following the 1933 election, the right-wing Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right (CEDA), based on the Catholic vote, was set to enter the radical government. An armed rising of workers in October 1934, which reached its greatest intensity in Asturias, was forcefully put down. This in turn energized political movements across the spectrum, including a revived anarchist movement and new reactionary and fascist groups, such as the Falange and a revived Carlist movement.[170] A devastating 1936–39 civil war was won in 1939 by the rebel forces under Francisco Franco. It was supported by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. The rebels (backed among other by traditionalist Carlists, Fascist falangists and Far-right alfonsists) defeated the Republican loyalists (with variable support of Socialists, Liberals, Communists, Anarchists and Catalan and Basque nationalists), who were backed by the Soviet Union. |

スペイン第二共和政(1931年-1936年) 主な記事:スペイン第二共和政、スペイン第二共和政暫定政府  バルセロナにおける第二共和政の宣言を祝う人々。 ニコテ・アルカラ・サモラが議長を務める臨時政府が、1931年4月14日に「ラ・ニーニャ・ボニータ(可愛い女の子)」という愛称で親しまれた共和国と して宣言された。これは、民主主義が独裁制へと転落し始めていた大陸の他の地域における民主主義の実験であった。1931年6月には憲法制定選挙が実施さ れた。選挙で優勢となった自由主義者と社会主義者の連合は、軍の民主化を図るために臨時政府で戦争大臣として断固とした改革を行ったマヌエル・アサーニャ (Manuel Azaña)を首相に迎え入れ、その後、いくつかの連立内閣を率いた。[168] 共和制政府は、 ホセ・サンホルジョが主導した1932年の最初のクーデターを容易に鎮圧することができたものの、軍部の改革により屈辱を感じた将軍たちはアサーニャに対 して強い軽蔑を抱くようになった。[167] 新議会は新憲法草案を作成し、1931年12月9日に承認された。 政治的イデオロギーは極端に二極化していた。教会の役割の核心部分について、左派の人々は教会を近代とスペイン国民の最大の敵と見なしたが、右派の人々は教会をスペインの価値観の貴重な守護者と見なした。 第二共和制下では、女性に初めて総選挙での投票が認められた。この共和国はカタルーニャに大幅な自治権を委譲し、戦時中の短期間ではあるがバスク地方にも同様の措置を講じた。 共和国の最初の内閣は、ニコテ・アルカラ・サモラとマヌエル・アサーニャが率いる中道左派であった。経済の混乱、多額の負債、そして頻繁に変化する連立政権により、右派と左派による政治的暴力とクーデター未遂がエスカレートしていった。 1933年の選挙後、カトリック票を基盤とする右派のスペイン自治連合(CEDA)が急進的な政府に参加することになった。1934年10月にアストゥリ アス地方で最大規模に達した労働者による武装蜂起は、武力によって鎮圧された。これによって、復活したアナキスト運動やファランヘや復活したカルリスタ運 動などの新たな反動的・ファシスト的グループを含む、あらゆる政治運動が活気づいた。 1936年から1939年にかけての壊滅的な内戦は、フランシスコ・フランコ率いる反乱軍が1939年に勝利した。ナチス・ドイツとファシスト・イタリア が支援した。反乱軍(伝統主義カリスト派、ファシスト・ファランヘ党、極右アルフォンシスタの支援を受けた)は、ソビエト連邦の支援を受けた共和国支持派 (社会党、自由党、共産党、無政府主義者、カタルーニャ人およびバスク人の民族主義者のさまざまな支援を受けた)を打ち負かした。 |

| Spanish Civil War (1936–39) Main article: Spanish Civil War The Spanish Civil War was started by a military coup d'etat in 17–18 July 1936 against the Republican government. The coup, intending to prevent social and economic reforms carried by the new government, had been carefully plotted since the electoral right-wing defeat at the February 1936 election.[171] The coup failed everywhere but in the Catholic heartland (Galicia, Old Castile and Navarre), Morocco, Zaragoza, Seville and Oviedo, while the rest of the country remained loyal to the Republic, including the main industrial cities (such as Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia and Bilbao), where the putschists were crushed by the combined action of workers and peasants.[172]  People's militias attacking on a Rebel position in Somosierra in the early stages of the war. The Republic looked to the Western democracies for help, but following an earlier commitment to provide assistance by French premier Léon Blum, by 25 July the latter had already backtracked on it, as to the mounting inner division within his country the British opposition to intervention added up, as the sympathies of the UK lied in the Rebel faction.[173] The Rebel faction enjoyed direct military support from Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, while since the very beginning they also enjoyed the support of Salazarist Portugal, the power-base of one of the leading rebels, José Sanjurjo. The Soviet Union sold weapons to the Republican faction and Mexico sent in monetary aid as well as giving Republican refuges the option to seek refuge in Mexico,[174] while left-wing sympathizers around the world went to Spain to fight in the International Brigades, set up by the Communist International. The conflict became a worldwide ideological battleground that pitted the left and many liberals against Catholics and conservatives. Worldwide there was a decline in pacifism and a growing sense that another world war was imminent, and that it was worth fighting for.[175] After the Spanish Civil War, the active agrarian population began to decline in Spain, the provinces with latifundia in Andalusia continued being the ones with the greatest number of day laborers; at the same time this was the region with the lowest literacy share.[176] |

スペイン内戦(1936年~1939年) 詳細は「スペイン内戦」を参照 スペイン内戦は、1936年7月17日と18日に発生した軍事クーデターにより、共和制政府に対して開始された。このクーデターは、新政権による社会・経 済改革を阻止することを目的としており、1936年2月の選挙で選挙権を持つ右派が敗北して以来、周到に計画されていた。[171] クーデターは、カトリックの中心地(ガリシア、旧カスティーリャ、ナヴァーラ) 、モロッコ、サラゴサ、セビリア、オビエドでは成功したが、それ以外の地域では、主要工業都市(マドリード、バルセロナ、バレンシア、ビルバオなど)を含 め、共和国への忠誠を保っていた。これらの都市では、労働者と農民の共同行動により、反乱軍は鎮圧された。  戦争初期のソモシエラ山脈で反乱軍の陣地を攻撃する人民民兵。 共和国は西側民主主義諸国に支援を求めたが、フランスのレオン・ブルム首相が支援を約束していたにもかかわらず、7月25日までにブルム首相はすでに約束 を撤回していた。これは、フランス国内で意見が分裂していたことと、イギリスが介入に反対していたこと、そしてイギリスの同情が反乱軍派閥にあったことが 原因であった。 反乱派はファシスト・イタリアとナチス・ドイツから直接軍事支援を受けていたが、当初から反乱派の指導者の一人であるホセ・サンハルホの権力基盤であるサ ラザール主義のポルトガルからも支援を受けていた。ソビエト連邦は共和国派に武器を売却し、メキシコは金銭的支援を行うとともに、共和国派の亡命者にメキ シコへの亡命の選択肢を与えた。[174] 一方、世界中の左派シンパはスペインに赴き、コミンテルンが組織した国際旅団で戦った。この紛争は、左派や多くのリベラル派とカトリック教徒や保守派が対 立する、世界的なイデオロギーの戦場となった。世界中で平和主義が衰退し、次の世界大戦が迫っているという感覚が強まり、戦う価値があるという考えが広 がった。 スペイン内戦後、スペインでは農業人口が減少に転じたが、アンダルシア地方の大農園のある地方では、日雇い労働者の数が最も多い状態が続いた。同時に、この地方は識字率が最も低い地域でもあった。 |

Political and military balance Advance of Italian tankettes during the Battle of Guadalajara. The Spanish Republican government moved to Valencia, to escape Madrid, which was under siege by the Nationalists. It had some military strength in the Air Force and Navy, but it had lost nearly all of the Army. After opening the arsenals to arm local militias, it had little control over the Loyalist ground forces. Republican diplomacy proved ineffective, with only two useful allies, the Soviet Union and Mexico. Britain, France and 27 other countries had agreed to an arms embargo on Spain, and the United States went along. Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy both signed that agreement, but ignored it and sent supplies and vital help, including a powerful air force under German command, the Condor Legion. Tens of thousands of Italians arrived under Italian command. Portugal supported the Nationalists, and allowed the trans-shipment of supplies to Franco's forces. The Soviets sold tanks and other armaments for Spanish gold, and sent well-trained officers and political commissars. It organized the mobilization of tens of thousands of mostly communist volunteers from around the world, who formed the International Brigades. In 1936, the Left united in the Popular Front and were elected to power. However, this coalition, dominated by the centre-left, was undermined both by the revolutionary groups such as the anarchist Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) and Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI) and by anti-democratic far-right groups such as the Falange and the Carlists. The political violence of previous years began again. There were gunfights over strikes; landless labourers began to seize land, church officials were killed and churches burnt. On the other side, right wing militias and hired gunmen assassinated left-wing activists. The Republican democracy never generated the consensus or mutual trust between the various political groups. As a result, the country slid into civil war. The right wing of the country and high ranking figures in the army began to plan a coup, and when Falangist politician José Calvo-Sotelo was shot by Republican police, they used it as a signal to act while the Republican leadership was confused and inert.[177][178] |

政治的および軍事的バランス グアダラハラの戦いにおけるイタリアのタンケッテ(戦車?)の進撃。 スペイン共和国政府は、ナショナリスト軍に包囲されたマドリードを脱出し、バレンシアへ移転した。スペイン共和国政府は、空軍と海軍には一定の軍事力を 持っていたが、陸軍はほぼ全滅していた。武器庫を開放して地元の民兵に武器を支給した後、王党派の地上軍をほとんど制御できなくなっていた。共和制陣営の 外交は効果的ではなく、ソビエト連邦とメキシコの2カ国だけが同盟国となった。英国、フランス、およびその他の27カ国はスペインへの武器禁輸に合意し、 米国もこれに従った。ナチス・ドイツとファシスト・イタリアは両者ともこの合意に署名したが、これを無視し、ドイツ軍の指揮下にある強力な空軍部隊「コン ドル軍団」をはじめ、物資や重要な支援を送った。イタリア軍の指揮下には数万人のイタリア人が加わった。ポルトガルはナショナリストを支援し、フランコ軍 への物資の積み替えを許可した。ソビエト連邦はスペインの金と引き換えに戦車やその他の兵器を売却し、訓練を受けた士官や政治委員を派遣した。また、世界 中の主に共産主義者の志願兵数万人を動員し、国際旅団を結成した。 1936年、左派は人民戦線に結集し、政権を握った。しかし、中道左派が優位を占めたこの連立政権は、アナキストのスペイン労働者全国連合(CNT)やス ペイン・アナキスト連盟(FAI)などの革命グループと、ファランヘやカトリック人民戦線などの反民主主義的極右グループの両方から弱体化させられた。こ こ数年の政治的暴力が再び始まった。ストライキをめぐって銃撃戦が起こり、土地を持たない労働者が土地の接収を開始し、教会関係者が殺害され、教会が焼き 討ちに遭った。その一方で、右翼民兵や雇われた殺し屋が左翼活動家を暗殺した。共和制民主主義は、さまざまな政治グループ間のコンセンサスや相互信頼を生 み出すことはなかった。その結果、スペインは内戦へと突入した。右翼と軍の高官たちはクーデターを計画し始め、ファランヘ党の政治家ホセ・カルボ・ソテロ が共和派警察に射殺されたのを機に、共和派指導部が混乱し無力化している間に実行に移した。[177][178] |

Military operations Two women and a man during the siege of the Alcázar The Nationalists under Franco won the war, and historians continue to debate the reasons. The Nationalists were much better unified and led than the Republicans, who squabbled and fought amongst themselves endlessly and had no clear military strategy. The Army went over to the Nationalists, but it was very poorly equipped – there were no tanks or modern airplanes. The small navy supported the Republicans, but their armies were made up of raw recruits and they lacked both equipment and skilled officers and sergeants. Nationalist senior officers were much better trained and more familiar with modern tactics than the Republicans.[179] On 17 July 1936, General Francisco Franco brought the colonial army from Morocco to the mainland, while another force from the north under General Mola moved south from Navarre. Another conspirator, General Sanjurjo, was killed in a plane crash while being brought to join the military leaders. Military units were also mobilised elsewhere to take over government institutions. Franco intended to seize power immediately, but successful resistance by Republicans in the key centers of Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, the Basque country, and other points meant that Spain faced a prolonged civil war. By 1937 much of the south and west was under the control of the Nationalists, whose Army of Africa was the most professional force available to either side. Both sides received foreign military aid: the Nationalists from Nazi Germany and Italy, while the Republicans were supported by organised far-left volunteers from the Soviet Union.  Ruins of Guernica The Siege of the Alcázar at Toledo early in the war was a turning point, with the Nationalists successfully resisting after a long siege. The Republicans managed to hold out in Madrid, despite a Nationalist assault in November 1936, and frustrated subsequent offensives against the capital at Jarama and Guadalajara in 1937. Soon, though, the Nationalists began to erode their territory, starving Madrid and making inroads into the east. The North, including the Basque country fell in late 1937 and the Aragon front collapsed shortly afterwards. The bombing of Guernica on the afternoon of 26 April 1937 – a mission used as a testing ground for the German Luftwaffe's Condor Legion – was probably the most infamous event of the war and inspired Picasso's painting. The Battle of the Ebro in July–November 1938 was the final desperate attempt by the Republicans to turn the tide. When this failed and Barcelona fell to the Nationalists in early 1939, it was clear the war was over. The remaining Republican fronts collapsed, as civil war broke out inside the Left, as the Republicans suppressed the Communists. Madrid fell in March 1939.[180] The war cost between 300,000 and 1,000,000 lives. It ended with the total collapse of the Republic and the accession of Francisco Franco as dictator. Franco amalgamated all right wing parties into a reconstituted fascist party Falange and banned the left-wing and Republican parties and trade unions. The Church was more powerful than it had been in centuries.[180]: 301–318 The conduct of the war was brutal on both sides, with widespread massacres of civilians and prisoners. After the war, many thousands of Republicans were imprisoned and up to 150,000 were executed between 1939 and 1943. Some 500,000 refugees escaped to France; they remained in exile for years or decades. |

軍事作戦 アルカサル包囲戦中の2人の女性と1人の男性 フランコ率いる国民軍が戦争に勝利したが、その理由については歴史家たちの間で議論が続いている。国民軍は共和軍よりもはるかに統制がとれており、指揮も 行き届いていた。共和軍は内部で争いを繰り返し、明確な軍事戦略を持たなかった。軍は国民軍側についたが、装備は非常に貧弱で、戦車や近代的な航空機はな かった。小規模な海軍は共和国軍を支援していたが、共和国軍は新兵で構成されており、装備も熟練した士官や軍曹も不足していた。国民党の上級将校は共和国 軍よりもはるかに訓練されており、近代的な戦術にも精通していた。[179] 1936年7月17日、フランシスコ・フランコ将軍はモロッコから植民地軍を本土に移動させ、モラ将軍率いる北部からの別の部隊はナバラから南下した。別 の共謀者であるサンフアン将軍は、軍指導者たちと合流するために移送中に飛行機事故で死亡した。軍部隊は、政府機関を掌握するために他の地域でも動員され た。フランコは直ちに権力を掌握するつもりであったが、マドリード、バルセロナ、バレンシア、バスク地方などの主要都市で共和国軍が抵抗したため、スペイ ンは長期の内戦に突入することとなった。1937年までに、南部と西部の大部分はナショナリストが支配下に置き、彼らのアフリカ軍団は、どちらの側にとっ ても最もプロフェッショナルな軍隊であった。両陣営とも外国から軍事支援を受けており、ナショナリストはナチス・ドイツとイタリアから、一方、共和国軍は ソビエト連邦から極左の組織的ボランティアの支援を受けていた。  ゲルニカの廃墟 戦争初期のトレドのアルカサル包囲戦は転換点となり、ナショナリストは長期にわたる包囲の後、抵抗に成功した。 1936年11月のナショナリストの攻撃にもかかわらず、共和国軍はマドリードをなんとか死守し、1937年のハラマとグアダラハラにおける首都に対する その後の攻撃を阻止した。 しかし、まもなくナショナリストは彼らの領土を浸食し始め、マドリードを飢餓状態に陥れ、東部への侵攻を開始した。1937年後半にはバスク地方を含む北 部が陥落し、その後まもなくアラゴン戦線も崩壊した。1937年4月26日の午後、ドイツ空軍コンドル軍団のテストの場として使われたゲルニカの爆撃は、 おそらくこの戦争で最も悪名高い出来事であり、ピカソの絵画のインスピレーションとなった。1938年7月から11月にかけてのエブロ川の戦いは、共和国 軍が戦況を好転させようと試みた最後の決死の抵抗であった。この抵抗も失敗し、1939年初頭にバルセロナがナショナリストの手に落ちたことで、戦争が終 結したことは明らかであった。残る共和国軍の戦線は崩壊し、左派内部で内戦が勃発し、共和国軍が共産主義者を弾圧した。マドリードは1939年3月に陥落 した。 この戦争で30万から100万人の命が失われた。共和国は完全に崩壊し、フランシスコ・フランコが独裁者として即位したことで終結した。フランコはすべて の右派政党をファシスト党ファランヘとして再編成し、左派政党と共和国党、労働組合を禁止した。教会は数世紀の間で最も強力な存在となった。[180]: 301-318 戦争の遂行は双方とも残忍で、民間人や捕虜に対する大規模な虐殺が広く行われた。戦後、数千人の共和国派が投獄され、1939年から1943年の間に最大 15万人が処刑された。約50万人の難民がフランスに逃れたが、彼らは何年も、あるいは何十年も亡命生活を余儀なくされた。 |

| Francoist Spain (1939–1975) Main article: Francoist Spain  Franco visiting Tolosa in 1948 The Francoist regime resulted in the deaths and arrests of hundreds of thousands of people who were either supporters of the previous Second Republic of Spain or potential threats to Franco's state. They were executed, sent to prisons or concentration camps. According to Gabriel Jackson, the number of victims of the White Terror (executions and hunger or illness in prisons) between 1939 and 1943 was 200,000.[181] Child abduction was also a wide-scale practice. The lost children of Francoism may reach 300,000.[182][183] During Franco's rule, Spain was officially neutral in World War II and remained largely economically and culturally isolated from the outside world. Under a military dictatorship, Spain saw its political parties banned, except for the official party (Falange). Labour unions were banned and all political activity using violence or intimidation to achieve its goals was forbidden.  Francisco Franco and his appointed successor Prince Juan Carlos de Borbón. Under Franco, Spain actively sought the return of Gibraltar by the United Kingdom, and gained some support for its cause at the United Nations. During the 1960s, Spain began imposing restrictions on Gibraltar, culminating in the closure of the border in 1969. It was not fully reopened until 1985. Spanish rule in Morocco ended in 1967. Though militarily victorious in the 1957–58 Moroccan invasion of Spanish West Africa, Spain gradually relinquished its remaining African colonies. Spanish Guinea was granted independence as Equatorial Guinea in 1968, while the Moroccan enclave of Ifni had been ceded to Morocco in 1969. Two cities in Africa, Ceuta and Melilla, remain under Spanish rule and sovereignty. The latter years of Franco's rule saw some economic and political liberalization (the Spanish miracle), including the birth of a tourism industry. Spain began to catch up economically with its European neighbors.[184] Franco ruled until his death on 20 November 1975, when control was given to King Juan Carlos.[185] In the last few months before Franco's death, the Spanish state was paralyzed. This was capitalized upon by King Hassan II of Morocco, who ordered the 'Green March' into Western Sahara, Spain's last colonial possession. |

フランコ政権下のスペイン(1939年-1975年) 詳細は「フランコ政権下のスペイン」を参照  1948年にトロサを訪問するフランコ フランコ政権は、それ以前のスペイン第二共和制の支持者やフランコ体制にとって潜在的な脅威となる可能性のある何十万人もの人々の死や逮捕をもたらした。 彼らは処刑されたり、刑務所や強制収容所に送られた。ガブリエル・ジャクソンによると、1939年から1943年の間の「白色テロ」による犠牲者(処刑、 および刑務所での飢えや病気による死亡)の数は20万人に上るという。[181] 児童拉致もまた広範囲にわたって行われた。フランコ主義による行方不明の子供たちは30万人に上る可能性がある。[182][183] フランコの統治下、スペインは第二次世界大戦中、公式には中立を保ち、経済的にも文化的にもほぼ完全に世界から孤立していた。軍事独裁政権下、スペインで は公式政党(ファランヘ)以外の政党は禁止され、労働組合は禁止され、暴力や威嚇を用いて目的を達成しようとする政治活動はすべて禁じられた。  フランシスコ・フランコと、彼が後継者に指名したフアン・カルロス・デ・ボルボン王子。 フランコ政権下では、スペインはイギリスによるジブラルタルの返還を積極的に求め、国連でも一定の支持を得た。1960年代には、スペインはジブラルタルへの規制を強化し、1969年には国境を閉鎖した。完全に再開されたのは1985年になってからだった。 スペインによるモロッコ支配は1967年に終わった。1957年から58年にかけてのスペイン領西アフリカ侵攻では軍事的勝利を収めたものの、スペインは 徐々に残りのアフリカ植民地を手放していった。スペイン領ギニアは1968年に赤道ギニアとして独立を認められ、一方、モロッコの飛び地イフニは1969 年にモロッコに割譲された。アフリカにある2つの都市、セウタとメリリャは現在もスペインの支配下にある。 フランコの統治の晩年には、観光産業の誕生を含む、経済および政治の自由化(スペインの奇跡)が見られた。スペインはヨーロッパの近隣諸国と経済的に肩を並べるようになった。 フランコは1975年11月20日に死去するまで統治を続け、その後はフアン・カルロス1世が王位を継承した。[185] フランコが死去する前の数か月間、スペイン国家は麻痺状態に陥った。これを機に乗じたのがモロッコのハッサン2世国王で、スペインの最後の植民地であった 西サハラへの「緑の行進」を命じた。 |

| History of Spain (1975–present) Main article: History of Spain (1975–present) Transition to democracy Main article: Spanish transition to democracy The Spanish transition to democracy or new Bourbon restoration started with Franco's death on 20 November 1975, while its completion is marked by the electoral victory of the socialist PSOE on 28 October 1982. Under its current (1978) constitution, Spain is a constitutional monarchy. It comprises 17 autonomous communities (Andalusia, Aragon, Asturias, Balearic Islands, Canary Islands, Cantabria, Castile and León, Castile–La Mancha, Catalonia, Extremadura, Galicia, La Rioja, Community of Madrid, Region of Murcia, Basque Country, Valencian Community, and Navarre) and 2 autonomous cities (Ceuta and Melilla). Between 1978 and 1982, Spain was led by the Unión del Centro Democrático governments. In 1981 the 23-F coup d'état attempt took place. On 23 February Antonio Tejero, with members of the Guardia Civil entered the Congress of Deputies, and stopped the session, where Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo was about to be named prime minister. Officially, the coup d'état failed thanks to the intervention of King Juan Carlos. Spain joined NATO before Calvo-Sotelo left office. Along with political change came radical change in Spanish society. Spanish society had been extremely conservative under Franco,[186] but the transition to democracy also began a liberalization of values and social customs.  Felipe González signing the treaty of accession to the European Economic Community on 12 June 1985.  Valladolid in 1986. A OTAN NO (transl. 'No to NATO') banner can be read on the highrise building After earning a sweeping majority at the October 1982 general election, the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) governed the country, with Felipe González as prime minister. On 1 January 1986, Spain joined the European Economic Community (EEC). A referendum on whether Spain should remain in NATO was held in March 1986. The ruling party, the PSOE, favoured Spain's permanence (a turn from their anti-NATO stance back in 1982).[187] Meanwhile, the Conservative opposition (People's Coalition), called for abstention.[188] The country hosted the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona and Seville Expo '92. |

スペインの歴史(1975年~現在) 詳細は「スペインの歴史(1975年~現在)」を参照 民主化への移行 詳細は「スペインの民主化への移行」を参照 スペインの民主化への移行、または新ブルボン朝復古は、1975年11月20日のフランコの死とともに始まり、1982年10月28日の社会労働党(PSOE)の選挙勝利によって完了した。 1978年の現行憲法のもと、スペインは立憲君主制国家である。スペインは17の自治州(アンダルシア州、アラゴン州、アストゥリアス州、バレアレス州、 カナリア諸島、カンタブリア州、カスティーリャ・イ・レオン州、カスティーリャ・ラ・マンチャ州、カタルーニャ州、エストレマドゥラ州、ガリシア州、ラ・ リオハ州、マドリード州、ムルシア州、バスク州、バレンシア州、ナバラ州)と2つの自治都市(セウタ、メリリャ)で構成されている。 1978年から1982年にかけて、スペインは民主中道連合(UCD)の政府によって統治されていた。1981年には23-F事件と呼ばれるクーデター未 遂事件が発生した。2月23日、アントニオ・テヘロが治安警備隊のメンバーとともに下院に侵入し、レオポルド・カルボ・ソテロが首相に指名されようとして いたその会議を中断させた。公式には、フアン・カルロス国王の介入により、クーデターは失敗した。カルボ・ソテロが退任する前に、スペインはNATOに加 盟した。政治の変化に伴い、スペイン社会にも急進的な変化が訪れた。フランコ政権下ではスペイン社会は極めて保守的であったが[186]、民主主義への移 行は価値観や社会慣習の自由化ももたらした。  1985年6月12日、欧州経済共同体(EEC)加盟条約に署名するフェリペ・ゴンサレス。  1986年のバリャドリッド。高層ビルに「NATO NO(NATO反対)」の横断幕が見える 1982年10月の総選挙で圧倒的多数の議席を獲得したスペイン社会労働党(PSOE)が、フェリペ・ゴンサレスを首相として政権を握った。1986年1 月1日、スペインは欧州経済共同体(EEC)に加盟した。NATO残留の是非を問う国民投票が1986年3月に実施された。与党のPSOEはスペインの NATO残留を支持した(1982年の反NATOの立場からの転換)。[187] 一方、保守系野党(国民連合)は棄権を呼びかけた。[188] 同国は1992年のバルセロナ夏季オリンピックとセビリア万博'92を開催した。 |

| Spain within the European Union (1993–present) Main article: Accession Treaty of Spain to the European Economic Community Further information: Spanish property bubble, 2008–14 Spanish financial crisis, and Eurozone crisis In 1996, the centre-right Partido Popular government came to power, led by José María Aznar. On 1 January 1999, Spain exchanged the peseta for the new Euro currency. The peseta continued to be used for cash transactions until January 1, 2002. On 11 March 2004 a number of terrorist bombs exploded on busy commuter trains in Madrid by Islamic extremists linked to Al-Qaeda, killing 191 and injuring thousands. The election, held three days later, was won by the PSOE, and José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero replaced Aznar as prime minister. As José María Aznar and his ministers at first accused ETA of the atrocity, it has been argued that the outcome of the election has been influenced by this event. In the wake of its joining the EEC, Spain experienced an economic boom, cut painfully short by the financial crisis of 2008. During the boom years, Spain attracted a large number of immigrants, especially from the United Kingdom, but also including unknown but substantial illegal immigration, mostly from Latin America, eastern Europe and north Africa.[189] Spain had the fourth largest economy in the Eurozone, but after 2008 the global economic recession hit Spain hard, with the bursting of the housing bubble and unemployment reaching over 25%, sharp budget cutbacks were needed. The GDP shrank 1.2% in 2012.[190] [191] Although interest rates were historically low, investments were not encouraged sufficiently by entrepreneurs.[192] Losses were especially high in real estate, banking, and construction. Economists concluded in early 2013 that, "Where once Spain's problems were acute, now they are chronic: entrenched unemployment, a large mass of small and medium-sized enterprises with low productivity, and, above all, a constriction in credit."[193] With the financial crisis and high unemployment, Spain is now suffering from a combination of continued illegal immigration paired with a massive emigration of workers, forced to seek employment elsewhere under the EU's "Freedom of Movement", with an estimated 700,000, or 1.5% of total population, leaving the country between 2008 and 2013.[194] Spain is ranked as a middle power able to exert modest regional influence. It has a small voice in international organizations; it is not part of the G8 and participates in the G20 only as a guest. Spain is part of the G6 (EU). |

スペインは欧州連合(EU)加盟国(1993年~現在) 詳細は「スペインの欧州経済共同体加盟条約」を参照 さらに詳しい情報:「スペインの不動産バブル(2008年~2014年)」、「スペインの財政危機(2008年~2014年)」、「ユーロ圏の経済・通貨統合を巡る危機」を参照 1996年、ホセ・マリア・アスナール率いる中道右派の国民党(PP)が政権を握った。1999年1月1日、スペインは通貨ペセタをユーロに切り替えた。 ペセタ紙幣は2002年1月1日まで現金取引で使用された。2004年3月11日、アルカイダとつながりのあるイスラム過激派による多数の爆弾がマドリー ドの通勤列車内で爆発し、191人が死亡、数千人が負傷した。その3日後に実施された選挙ではPSOEが勝利し、ホセ・ルイス・ロドリゲス・サパテロがア スナールに代わって首相となった。ホセ・マリア・アスナール首相と閣僚たちは当初、この残虐行為を E.T.A. の犯行だと非難していたが、この事件が選挙結果に影響を与えたという見方もある。 EEC(欧州経済共同体)に加盟したことをきっかけにスペインは好景気に沸いたが、2008年の金融危機によってその好景気は急速に失速した。好況期に は、スペインには多数の移民が流入したが、その多くは英国からの移民であったが、ラテンアメリカ、東ヨーロッパ、北アフリカからの不法移民も含まれてい た。[189] スペインはユーロ圏で4番目に大きな経済規模を誇っていたが、2008年以降、世界的な経済不況がスペインを直撃し、住宅バブルの崩壊と25%を超える失 業率により、大幅な予算削減が必要となった。2012年のGDPは1.2%縮小した。[190][191] 歴史的な低金利にもかかわらず、起業家による投資は十分には促進されなかった。[192] 不動産、銀行、建設業での損失が特に大きかった。経済学者は2013年初頭に「かつてスペインの問題は深刻だったが、現在は慢性化している。根深い失業、 生産性の低い中小企業の大量発生、そして何よりも信用収縮である」と結論づけた。[193] 金融危機と高い失業率により、スペインは現在、 EUの「労働力の自由移動」により、国外での就労を余儀なくされた労働者の大量流出と、不法移民の継続的な流入が重なり、2008年から2013年の間 に、推定70万人、すなわち総人口の1.5%にあたる人々が国外へ流出している。 スペインは、地域に一定の影響力を及ぼす中規模国家と位置づけられている。国際機関における発言力は弱く、G8には参加しておらず、G20にもゲストとして参加しているのみである。スペインはG6(EU)の一員である。 |

| Black Propaganda against Portugal and Spain Demographics of Spain Economic history of Spain Foreign relations of Spain List of missing landmarks in Spain Monarchy of Spain Politics of Spain |

ポルトガルとスペインに対するブラックプロパガンダ スペインの人口統計 スペインの経済史 スペインの外交関係 スペインの行方不明のランドマークの一覧 スペインの君主制 スペインの政治 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Spain |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆