Since different Spanglish arises independently in different regions of varying degrees of bilingualism, it reflects the locally spoken varieties of English and Spanish. Different forms of Spanglish are not necessarily mutually intelligible.

The term Spanglish was first recorded in 1933.[3] It corresponds to the Spanish terms Espanglish (from Español + English, introduced by the Puerto Rican poet Salvador Tió in the late 1940s), Ingléspañol (from Inglés + Español), and Inglañol (Inglés + Español).[4]

スパングリッシュは、バイリンガルの度合いが異なる地域で独自に生まれるため、その地域で話されている英語とスペイン語の変種を反映している。異なる形の スパングリッシュは必ずしも相互に理解できるものではない。

スパングリッシュという言葉は1933年に初めて記録された[3]。 これはスペイン語のエスパングリッシュ(エスパニョール+イングリッシュ、1940年代後半にプエルトリコの詩人サルバドール・ティオによって紹介され た)、イングレスパニョール(イングレス+エスパニョール)、イングラニョール(イングレス+エスパニョール)に相当する[4]。

There is no single, universal definition of Spanglish. The term Spanglish has been used in reference to the following phenomena, all of which are distinct from each other:[5]

The use of integrated English loanwords in Spanish

Nonassimilated Anglicisms (i.e., with English phonetics) in Spanish

Calques and loan translations from English

Code switching, particularly intra-sentential (i.e., within the same clause) switches

Grammar mistakes in Spanish found among transitional bilingual speakers

Second-language Spanish, including poor translations

Mock Spanish

スパングリッシュの唯一かつ普遍的な定義はない。スパングリッシュという用語は、以下のような現象に関連して使用されており、これらはすべて互いに異なる ものである[5]。

スペイン語における英語の借用語の使用

スペイン語における非同化英語(すなわち、英語の音声を持つ)。

英語からの借用語および借用翻訳

コードスイッチング、特に文節内(つまり同じ節内)のスイッチング

移行期のバイリンガル話者に見られるスペイン語の文法ミス

下手な翻訳を含む第二言語スペイン語

模擬スペイン語(Mock Spanish)下で説明

In the late 1940s, the Puerto Rican journalist, poet, and essayist Salvador Tió coined the terms Espanglish for Spanish spoken with some English terms, and the less commonly used Inglañol for English spoken with some Spanish terms.

After Puerto Rico became a United States territory in 1898, Spanglish became progressively more common there as the United States Army and the early colonial administration tried to impose the English language on island residents. Between 1902 and 1948, the main language of instruction in public schools (used for all subjects except for Spanish class) was English. Currently Puerto Rico is nearly unique in having both English and Spanish as its official languages[6] (see also New Mexico). Consequently, many American English words are now found in the vocabulary of Puerto Rican Spanish. Spanglish may also be known by different regional names.

Spanglish does not have one unified dialect—specifically, the varieties of Spanglish spoken in New York, Florida, Texas, and California differ. Monolingual speakers of standard Spanish may have difficulty in understanding it.[7] It is common in Panama, where the 96-year (1903–1999) U.S. control of the Panama Canal influenced much of local society, especially among the former residents of the Panama Canal Zone, the Zonians.

Many Puerto Ricans living on the island of St. Croix speak in informal situations a unique Spanglish-like combination of Puerto Rican Spanish and the local Crucian dialect of Virgin Islands Creole English, which is very different from the Spanglish spoken elsewhere. A similar situation exists in the large Puerto Rican-descended populations of New York City and Boston.

Spanglish is spoken commonly in the modern United States.[citation needed] According to the Pew Research Center, the population of Hispanics grew from 35.3 million to 62.1 million between 2000 and 2020.[8] Hispanics have become the largest minority ethnic group in the US. More than 60% are of Mexican descent. Mexican Americans form one of the fastest-growing groups,[citation needed] increasing from 20.9 million to 37.2 million between 2000 and 2021.[9] Around 58% of this community chose California, especially Southern California, as their new home. Spanglish is widely used throughout the heavily Mexican-American and other Hispanic communities of Southern California.[10] The use of Spanglish has become important to Hispanic communities throughout the United States in areas such as Miami, New York City, Texas, and California. In Miami, the Afro-Cuban community makes use of a Spanglish familiarly known as "Cubonics," a portmanteau of the words Cuban and Ebonics, a slang term for African American Vernacular English that is itself a portmanteau of Ebony and phonics."[10]

Many Mexican-Americans (Chicanos), immigrants and bilinguals express themselves in various forms of Spanglish. For many, Spanglish serves as a basis for self-identity, but others believe that it should not exist.[11] Spanglish is difficult, because if the speaker learned the two languages in separate contexts, they use the conditioned system, in which the referential meanings in the two languages differ considerably. Those who were literate in their first language before learning the other, and who have support to maintain that literacy, are sometimes those least able to master their second language. Spanglish is part of receptive bilingualism. Receptive bilinguals are those who understand a second language but don't speak it. That is when they use Spanglish. Receptive bilinguals are also known as productively bilingual, since, to give an answer, the speaker exerts much more mental effort to answer in English, Spanish, or Spanglish.[12][failed verification] Without first understanding the culture and history of the region where Spanglish evolved as a practical matter an in depth familiarizing with multiple cultures. This knowledge, indeed the mere fact of one's having that knowledge, often forms an important part of both what one considers one's personal identity and what others consider one's identity.[13]

Other places where similar mixed codes are spoken are Gibraltar (Llanito), Belize (Kitchen Spanish), Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao (along with Dutch and Papiamento). [citation needed]

In Australasia, forms of Spanglish are used among Spanish-speaking migrants and diasporic communities. In particular, Hispanophone Australians frequently use loanwords/phrases from Australian English,[citation needed] in conversations that are otherwise in Spanish; examples include "el rubbish bin", "la vacuum cleaner", "el mobile", "el toilet", "vivo en un flat pequeño", "voy a correr con mis runners", and "la librería de la city es grande". Similar phenomena occur amongst native Spanish speakers in New Zealand.[14][15]

1940年代後半、プエルトリコのジャーナリスト、詩人、エッセイストであるサルバドール・ティオは、スペイン語を話す際に英語も交えて話すことを「エス パングリッシュ」、英語を話す際にスペイン語も交えて話すことを「イングラニョール」と呼ぶ造語を作った。

1898年にプエルトリコがアメリカ合衆国の領土となった後、アメリカ軍と初期の植民地行政が島の住民に英語を押し付けようとしたため、スパングリッシュ は徐々に一般的になっていった。1902年から1948年までの間、公立学校での主な授業言語(スペイン語の授業を除く全教科で使用)は英語であった。現 在、英語とスペイン語の両方を公用語としているプエルトリコは、ほぼ唯一の存在である[6](ニューメキシコ語も参照)。その結果、プエルトリコのスペイ ン語の語彙には、アメリカ英語の単語が多く見られるようになった。また、スパングリッシュは異なる地域名で知られることもある。

特に、ニューヨーク、フロリダ、テキサス、カリフォルニアで話されるスパングリッシュはそれぞれ異なる。パナマでは、96年間(1903年~1999年) にわたるアメリカのパナマ運河支配が地域社会の多くに影響を及ぼし、特にパナマ運河地帯の旧住民であるゾニアンの間では一般的である。

セントクロイ島に住むプエルトリコ人の多くは、インフォーマルな場ではプエルトリコのスペイン語とヴァージン諸島の方言であるクルシアン英語を組み合わせ た独特のスパングリッシュを話す。同じような状況は、ニューヨークやボストンに住むプエルトリコ系住民にも見られる。

ピュー・リサーチ・センターによると、ヒスパニック系の人口は2000年から2020年の間に3,530万人から6,210万人に増加した[8]。60% 以上がメキシコ系である。メキシコ系アメリカ人は最も急成長しているグループのひとつで、2000年から2021年の間に2,090万人から3,720万 人に増加している[要出典]。スパングリッシュは、メキシコ系アメリカ人が多く住む南カリフォルニアのヒスパニック系コミュニティで広く使われている [10]。マイアミ、ニューヨーク、テキサス、カリフォルニアなど、アメリカ全土のヒスパニック系コミュニティでスパングリッシュの使用は重要となってい る。マイアミでは、アフロ・キューバン・コミュニティが「キューボニックス」として親しまれているスパングリッシュを使用している。キューボニックスと は、キューバ語(Cuban)とエボニックス(Ebonics)の合成語で、エボニックス自体がエボニー(Ebony)とフォニックス(Phonics) の合成語であるアフリカ系アメリカ人のヴァナキュラー・イングリッシュの俗語である[10]。

多くのメキシコ系アメリカ人(チカーノ)、移民、バイリンガルは様々な形のスパングリッシュで自分自身を表現する。多くの人にとって、スパングリッシュは 自己アイデンティティの基盤となっているが、存在すべきではないと考える人もいる[11]。スパングリッシュが難しいのは、話者が2つの言語を別々の文脈 で学んだ場合、2つの言語の参照する意味がかなり異なる条件システムを使うからである。もう一方の言語を学ぶ前に第一言語で読み書きができ、その読み書き を維持するためのサポートがある人は、第二言語を習得する能力が最も低い場合がある。スパングリッシュは受容性バイリンガルの一部である。受容的バイリン ガルとは、第二言語を理解するが話せない人のことである。スパングリッシュを使うのはそのような場合である。受容的バイリンガルは生産的バイリンガルとも 呼ばれ、英語で答えるか、スペイン語で答えるか、スパングリッシュで答えるか、より多くの精神的努力を必要とする[12][検証失敗]。このような知識 は、実際その知識を持っているという事実だけでも、しばしばその人が個人的なアイデンティティと考えるもの、また他人が自分のアイデンティティと考えるも のの重要な部分を形成する[13]。

同様の混合コードが話されている他の場所は、ジブラルタル(Llanito)、ベリーズ(キッチンスペイン語)、アルバ、ボネール、キュラソー(オランダ 語とパピアメントと一緒に)である。[引用は必要]。

オーストラレーシアでは、スペイン語を話す移民やディアスポラ系コミュニティの間でスパングリッシュの形が使われている。特に、ヒスパノフォンのオースト ラリア人は、スペイン語以外の会話で、オーストラリア英語からの借用語やフレーズを頻繁に使用する[要出典]。例としては、「ゴミ箱」、「掃除機」、「携 帯電話」、「トイレ」、「狭いアパートに住んでいる」、「ランナーと一緒に出かける」、「街の図書館は広い」などが挙げられる。同様の現象は、ニュージー ランドのスペイン語母語話者の間でも見られる[14][15]。

Spanglish patterns

Spanglish is informal, although speakers can consistently judge the grammaticality of a phrase or sentence. From a linguistic point of view, Spanglish often is mistakenly labeled many things. Spanglish is not a creole or dialect of Spanish because, though people claim they are native Spanglish speakers, Spanglish itself is not a language on its own, but speakers speak English or Spanish with a heavy influence from the other language. The definition of Spanglish has been unclearly explained by scholars and linguists despite being noted so often. Spanglish is the fluid exchange of language between English and Spanish, present in the heavy influence in the words and phrases used by the speaker.[16] Spanglish is currently considered a hybrid language practice by linguists–many actually refer to Spanglish as "Spanish-English code-switching", though there is some influence of borrowing, and lexical and grammatical shifts as well.[17]

The inception of Spanglish is due to the influx of native Spanish speaking Latin American people into North America, specifically the United States of America.[18] As mentioned previously, the phenomenon of Spanglish can be separated into two different categories: code-switching, and borrowing, lexical and grammatical shifts.[19] Code-switching has sparked controversy because it is seen "as a corruption of Spanish and English, a 'linguistic pollution' or 'the language of a "raced", underclass people'".[20] For example, a fluent bilingual speaker addressing another bilingual speaker might engage in code-switching with the sentence, "I'm sorry I cannot attend next week's meeting porque tengo una obligación de negocios en Boston, pero espero que I'll be back for the meeting the week after"—which means, "I'm sorry I cannot attend next week's meeting because I have a business obligation in Boston, but I hope to be back for the meeting the week after".

スパングリッシュのパターン

スパングリッシュは非公式だが、話し手はフレーズや文の文法性を一貫して判断することができる。言語学的見地から、スパングリッシュはしばしば多くの誤っ たレッテルを貼られる。というのも、スパングリッシュはスペイン語のクレオールや方言ではないからだ。スパングリッシュの定義は、これほど頻繁に指摘され ているにもかかわらず、学者や言語学者によって明確に説明されていない。スパングリッシュとは英語とスペイン語の間の流動的な言語交換であり、話し手が使 用する単語やフレーズに大きな影響がある。[16] スパングリッシュは現在、言語学者によってハイブリッド言語実践とみなされている。

スパングリッシュの始まりは、スペイン語を母国語とするラテンアメリカの人々が北米、特にアメリカ合衆国に流入したことに起因している[18]。前述した ように、スパングリッシュの現象は、コード・スイッチングと借用、語彙、文法的シフトの2つの異なるカテゴリーに分けることができる[19]。コード・ス イッチングは、「スペイン語と英語の堕落、『言語汚染』、または『人種差別』、下層階級の人々の言語」と見なされるため、論争を巻き起こしている。 [20] たとえば、流暢なバイリンガル・スピーカーが、別のバイリンガル・スピーカーに向かって、「I'm sorry I cannot attend next week's meeting porque tengo una obligación de negocios en Boston, pero espero que I'll be back for the meeting the week after 」という文章でコード・スイッチングを行うかもしれない。

Calques are translations of entire words or phrases from one language into another. They represent the simplest forms of Spanglish, as they undergo no lexical or grammatical structural change.[21][page needed] The use of calques is common throughout most languages, evident in the calques of Arabic exclamations used in Spanish.[22]

Examples:

"to call back" → llamar pa'trás (llamar pa' atrás, llamar para atrás) (volver a llamar, llamar de vuelta)

"It's up to you." → Está pa'rriba de ti. (Está pa' arriba de ti, Está para arriba de ti) (Depende de ti. decide (You decide))

"to be up to ..." → estar pa'rriba de ... (estar pa' arriba de ..., estar para arriba de ...) (depender de ... or X decida (X decides))

"to run for governor" → correr para gobernador (presentarse para gobernador)[22]

pa'trás

A well-known calque is pa'trás or para atrás in expressions such as llamar pa'trás 'to call back'. Here, pa'trás reflects the particle back in various English phrasal verbs.[23] Expressions with pa'trás are found in every stable English-Spanish contact situation:[24] the United States,[25] including among the isolated Isleño[26] and Sabine River communities,[27] Gibraltar,[28] and sporadically in Trinidad and along the Caribbean coast of Central America where the local English varieties are heavily creolized.[29] Meanwhile, they're unattested in non-contact varieties of Spanish.[30] Pa'trás expressions are unique as a calque of an English verbal particle, since other phrasal verbs and particles are almost never calqued into Spanish.[24] Because of this, and because they're consistent with existing Spanish grammar, Otheguy (1993) argues they are likely a result of a conceptual, not linguistic loan. That is, the notion of "backness" has been expanded in these contact varieties.[31]

カルクとは、ある言語から別の言語へ単語やフレーズ全体を翻訳したものである。語彙的、文法的な構造変化を伴わないため、スパングリッシュの最も単純な形 態である[21][要出典]。カルケの使用はほとんどの言語で一般的であり、スペイン語で使用されるアラビア語の感嘆詞のカルケを見れば明らかである [22]。

例

「呼び戻す」→llamar pa'trás (llamar pa' atrás, llamar para atrás) (volver a llamar, llamar de vuelta)

「あなた次第だ」 → Está pa'rriba de ti. (Está pa' arriba de ti, Está para arriba de ti) (あなた次第だ。

「~までである」 → estar pa'rriba de ... (estar pa' arriba de ..., estar para arriba de ...) (dependender de ... or X decida (Xが決める))

「知事選に出馬する」→ correr para gobernador(知事選に出馬する)[22]。

pa'trás

llamar pa'trass「呼び戻す」などの表現では、pa'trassまたはpara atrásがよく知られている。pa'trásを使った表現は、[24]アメリカ[25]、孤立したイスリーニョ[26]やサビーン川のコミュニティ [27]、ジブラルタル[28]、トリニダードや中米のカリブ海沿岸のクレオール化が進んだ地域では散発的に見られる[29]。 [他の句動詞や助詞がスペイン語に転用されることはほとんどないからである[24]。このため、また既存のスペイン語文法と一致していることから、 Otheguy (1993)は言語的な借用ではなく概念的な借用の結果である可能性が高いと主張している。つまり、「背後性」の概念はこれらの接触品種において拡張され たのである[31]。

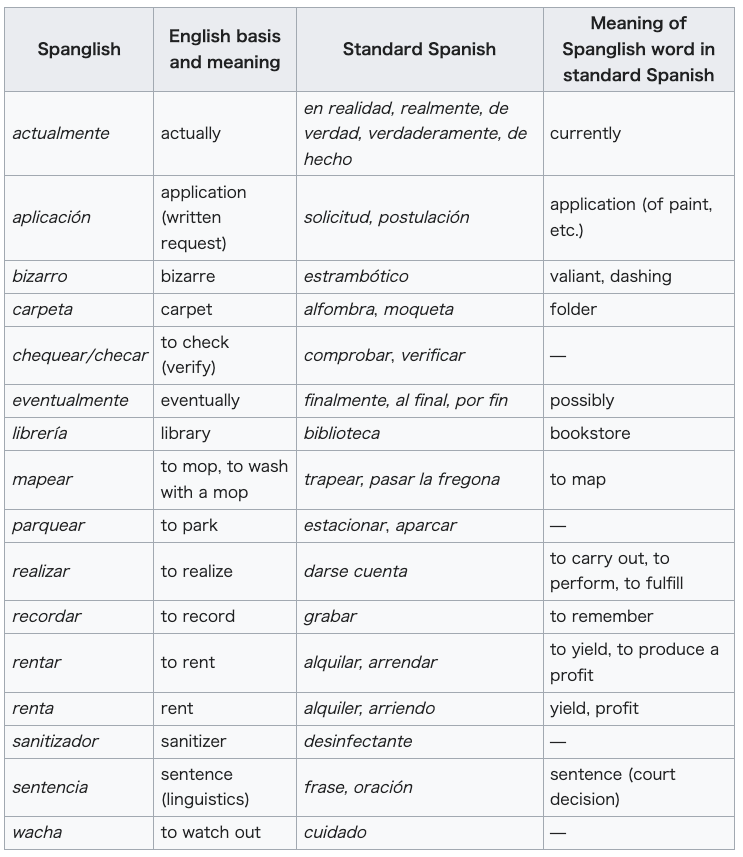

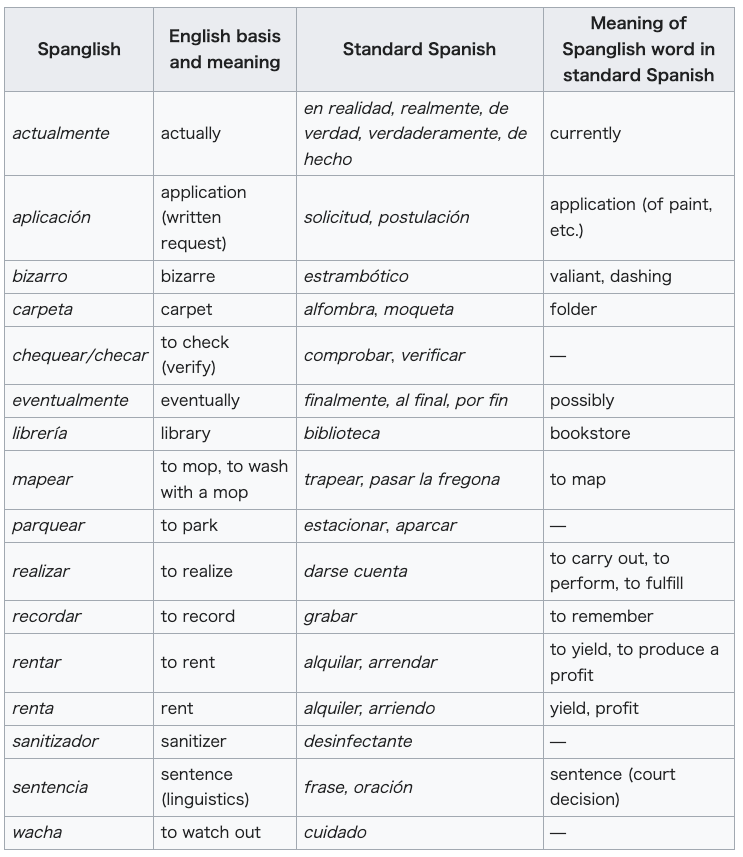

Semantic extension or reassignment refers to a phenomenon where speakers use a word of language A (typically Spanish in this case) with the meaning of its cognate in language B (typically English), rather than its standard meaning in language A. In Spanglish this usually occurs in the case of "false friends" (similar to, but technically not the same as false cognates), where words of similar form in Spanish and English are thought to have like meanings based on their cognate relationship.[32]

An example of this lexical phenomenon in Spanglish is the emergence of new verbs when the productive Spanish verb-making suffix -ear is attached to an English verb. For example, the Spanish verb for "to eat lunch" (almorzar in standard Spanish) becomes lonchear (occasionally lunchear). The same process produces watchear, parquear, emailear, twittear, etc.[33][page needed]

意味拡張または再割り当てとは、話者がA言語(この場合、典型的にはスペイン語)の単語を、A言語での標準的な意味ではなく、B言語(典型的には英語)で の同義語の意味で使用する現象を指す。スパングリッシュでは通常、「偽の友人」(偽の同義語と似ているが、厳密には同じではない)の場合に発生し、スペイ ン語と英語で似た形の単語が、同義語の関係に基づいて同じような意味を持つと考えられている[32]。

スパングリッシュにおけるこのような語彙現象の例として、スペイン語の動詞を作る接尾辞-earが英語の動詞につくと、新しい動詞が出現することが挙げら れる。例えば、「昼食を食べる」というスペイン語の動詞(標準スペイン語ではalmorzar)はlonchear(時にはlunchear)になる。同 じ過程で、watchear、parquear、emailear、twittearなどが生まれる[33][要ページ]。

Loanwords occur in any language due to the presence of items or ideas not present in the culture before, such as modern technology. The increasing rate of technological growth requires the use of loan words from the donor language due to the lack of its definition in the lexicon of the main language. This partially deals with the "prestige" of the donor language, which either forms a dissimilar or more similar word from the loan word. The growth of modern technology can be seen in the expressions: "hacer click" (to click), "mandar un email" (to send an email), "faxear" (to fax), "textear" (to text-message), or "hackear" (to hack). Some words borrowed from the donor languages are adapted to the language, while others remain unassimilated (e. g. "sandwich", "jeans" or "laptop"). The items most associated with Spanglish refer to words assimilated into the main morphology.[34] Immigrants are usually responsible for "Spanishizing" English words.[35] According to The New York Times, "Spanishizing" is accomplished "by pronouncing an English word 'Spanish style' (dropping final consonants, softening others, replacing M's with N's and V's with B's), and spelled by transliterating the result using Spanish spelling conventions."[35]

Examples

"Aseguranza" (insurance; "seguros" is insurance in standard Spanish, aseguranza is literally "assurance" which is similar to the Prudential Insurance company's slogan, "peace of mind")

"Biles" (bills)

"Chorcha" (church)

"Ganga" (gang)

"Líder" (leader) – considered an established Anglicism

"Lonchear/Lonchar" (to have lunch)

"Marqueta" (market)

"Taipear/Tipear" (to type)

"Troca" (truck) – Widely used in most of northern Mexico as well

”Mitin” (meeting) – An outdoors gathering of people mostly for political purposes.

”Checar” (to check)

”Escanear” (to scan) – To digitalize (e.g. a document).

”Chatear” (to chat)

“Desorden” (disorder) – incorrectly used as “disease”.

”Condición” (condition) – incorrectly used as “sickness”.

"Viaje de las Estrellas" - "Star Trek"; the television shows such as "King of the Hill" and "MadTV" sometimes used standard Spanish but in an elementary manner.

借用語は、現代技術のような、それまでの文化にはなかったアイテムやアイデアが存在するために、どの言語でも発生する。技術成長の速度が増すにつれ、主要 言語の語彙にその定義がないため、ドナー言語からの借用語を使用する必要がある。これは、部分的には原語の「威信」に対処するもので、借用語から異種語ま たは類似語を形成する。現代技術の発展は、次のような表現に表れている: 「hacer click「(クリックする)、」mandar un email「(メールを送る)、」faxear「(ファックスする)、」textear「(テキストメッセージする)、」hackear"(ハックする) などの表現に見られる。スペイン語から借用された単語は、その言語に適応するものもあれば、そのまま使われるものもある(「サンドイッチ」、「ジーン ズ」、「ラップトップ」など)。ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙によると、「スペイン語化」とは、「英単語を『スペイン語風』に発音し(末尾の子音を落とし、他 の子音を和らげ、MをNに、VをBに置き換える)、スペイン語の綴り方を用いて音訳する」ことである[35]。

例

「Aseguranza」(保険;「seguros 」は標準スペイン語で保険、「aseguranza 」は文字通り 「assurance 」であり、プルデンシャル保険会社のスローガンである 「peace of mind 」に似ている。)

「Biles」(札束)

「Chorcha」(教会)

「Ganga」(ギャング)

「Líder」(リーダー)-英国では定着していると考えられている。

「Lonchear/Lonchar」(昼食をとる)

「Marqueta"(市場)

「Taipear/Tipear」(タイプする)

「Troca」(トラック) - メキシコ北部の大部分でも広く使われている。

「Mitin」(会議) - 主に政治的な目的で屋外に人が集まること。

「Checar"(チェックする)

「Escanear"(スキャンする)- 文書などをデジタル化する。

「Chatear"(おしゃべりする)

「Desorden」(無秩序) - 「disease」(病気)として間違って使われる。

「Condición」(状態)-正しくは 「Sickness」(病気)である。

「Viaje de las Estrellas」 - 「スタートレック」。「King of the Hill 」や 「MadTV 」などのテレビ番組では、標準スペイン語が初歩的に使われることがあった。

Within the US, the English word so is often inserted into Spanish discourse. This use of so is found in conversations that otherwise take place entirely in Spanish. Its users run the gamut from Spanish-dominant immigrants to native, balanced bilinguals to English-dominant semi-speakers and second-language speakers of Spanish, and even people who reject the use of Anglicisms have been found using so in Spanish.[36] Whether so is a simple loanword, or part of some deeper form of language mixing, is disputed. Many consider so to simply be a loanword, although borrowing short function words is quite abnormal.[37] In stressed positions, so is usually pronounced with English phonetics, and speakers typically identify it as an English word and not an established English loan such as troca. This is unusual, since code-switched or lexically inserted words typically aren't as common and recurring as so is.[38][39][page needed]

So is always used as a coordinating conjunction in Spanish. It can be used phrase-internally, or at the beginning or end of a sentence. In Spanish discourse, so is never used to mean "in order that" as it often is in English. As a sociolinguistic phenomenon, speakers who subconsciously insert so into their Spanish usually spend most of their time speaking English. This and other facts suggest that the insertion of so and similar items such as you know and I mean are the result of a kind of "metalinguistic bracketing". That is, discourse in Spanish is circumscribed by English and by a small group of English functional words. These terms can act as punctuation for Spanish dialogue within an English-dominant environment.[39][page needed]

アメリカでは、英語のsoがスペイン語の会話に挿入されることがよくある。このsoの使用は、そうでなければすべてスペイン語で行われる会話で見られる。 soの使用者は、スペイン語優位の移民から、ネイティブでバランスの取れたバイリンガル、英語優位の準スペイン語話者やスペイン語の第二言語話者までさま ざまであり、アングリズムの使用を拒否する人々でさえもスペイン語でsoを使用している。多くの人はsoを単なる借用語であると考えているが、短い機能語 を借用することは極めて異常である[37]。強調された位置では、soは通常英語の発音で発音され、話者は通常、trocaのような確立された英語の借用 語ではなく、英語の単語であると認識する。これは珍しいことで、コードスイッチされた単語や語彙的に挿入された単語は一般的にsoほど一般的ではなく、繰 り返し使われることもないからである[38][39][要出典]。

soはスペイン語では常に調整接続詞として使われる。フレーズ内部でも、文頭や文末でも使われる。スペイン語の会話では、英語のように「~のために」とい う意味で使われることはない。社会言語学的現象としては、無意識のうちにsoをスペイン語に挿入している話者は、たいていほとんどの時間を英語で話してい る。このことや他の事実から、soや、you knowやI meanのような類似項目の挿入は、一種の「メタ言語的ブラケット」の結果であることが示唆される。つまり、スペイン語の談話は、英語と英語の機能的な単 語群によって囲い込まれているのである。これらの用語は、英語優位の環境におけるスペイン語の対話の句読点として機能することができる[39][要ペー ジ]。

Spanish street ad in Madrid humorously showing baidefeis instead of the Spanish gratis (free).

Baidefeis derives from the English "by the face"; Spanish: por la cara, "free". The adoption of English words is very common in Spain.

Fromlostiano is a type of artificial and humorous wordplay that translates Spanish idioms word-for-word into English. The name fromlostiano comes from the expression From Lost to the River, which is a word-for-word translation of de perdidos al río; an idiom that means that one is prone to choose a particularly risky action in a desperate situation (this is somewhat comparable to the English idiom in for a penny, in for a pound). The humor comes from the fact that while the expression is completely grammatical in English, it makes no sense to a native English speaker. Hence it is necessary to understand both languages to appreciate the humor.

This phenomenon was first noted in the book From Lost to the River in 1995.[40] The book describes six types of fromlostiano:

Translations of Spanish idioms into English: With you bread and onion (Contigo pan y cebolla), Nobody gave you a candle in this burial (Nadie te ha dado vela en este entierro), To good hours, green sleeves (A buenas horas mangas verdes).

Translations of American and British celebrities' names into Spanish: Vanesa Tumbarroja (Vanessa Redgrave).

Translations of American and British street names into Spanish: Calle del Panadero (Baker Street).

Translations of Spanish street names into English: Shell Thorn Street (Calle de Concha Espina).

Translations of multinational corporations' names into Spanish: Ordenadores Manzana (Apple Computers).

Translations of Spanish minced oaths into English: Tu-tut that I saw you (Tararí que te vi).

The use of Spanglish has evolved over time. It has emerged as a way of conceptualizing one's thoughts whether it be in speech or on paper.

マドリードの街頭広告で、スペイン語のgratis(無料)の代わりにbaidefeisがユーモラスに表示されている。

baidefeisは英語の 「by the face 」に由来し、スペイン語ではpor la cara、「free 」である。スペイン語ではpor la caraで「無料」である。

フロムロスティアーノとは、スペインの慣用句を一語一語英語に翻訳する、人為的でユーモラスな言葉遊びの一種である。fromlostianoという名前 は、de perdidos al ríoの一語一語訳であるFrom Lost to the Riverという表現に由来している。この表現は英語では完全に文法的であるが、英語を母国語とする人々にとっては意味をなさないという事実がユーモアを 生んでいる。したがって、ユーモアを理解するには両方の言語を理解する必要がある。

この現象は、1995年に出版された『From Lost to the River』という本で初めて指摘された[40]。この本では、6種類のフロムロスティアーノが紹介されている:

スペイン語の慣用句を英語に翻訳したものである: あなたとパンとタマネギ(Contigo pan y cebolla)、この埋葬では誰もロウソクをくれなかった(Nadie te ha dado vela en este entierro)、良い時間には緑の袖(A buenas horas mangas verdes)。

アメリカとイギリスの有名人の名前をスペイン語に訳す: Vanesa Tumbarroja(ヴァネッサ・レッドグレイブ)。

アメリカとイギリスの通りの名前をスペイン語に翻訳: Calle del Panadero(ベイカー通り)。

スペインのストリート名を英語に翻訳: シェル・ソーン通り(Calle de Concha Espina)。

多国籍企業の名前をスペイン語に翻訳する: Ordenadores Manzana(アップルコンピュータ)。

スペイン語の挽歌を英語に翻訳する: 私はあなたを見たことをトゥトゥット(Tararí que te vi)。

スパングリッシュは時代とともに進化してきた。会話であれ紙面であれ、自分の考えを概念化する方法として登場したのだ。

This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. Please help improve it by rewriting it in an encyclopedic style. (April 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

The education system in the U.S. has sustained colonialist practices through the rhetoric of an ‘academic language’. The term ‘academic language’ frames and minoritizes the Spanglish-speaking, bilingual students of America. Through teaching in a monolinguistic manner, ELA is given precedence to and places native languages or the use of bilingualism as secondary to English and the pure usage of Spanish. This allows English to be reinforced as an 'academic language,' granting white people an advantage in reaching academic success and disassociating bilingual speakers from whiteness and, therefore, 'academic language'.[4] A study done on Latin American middle schoolers in East Los Angeles highlights different ways in which bilingual students utilize Spanglish to advance academic literacy. Martinez’s list of skills students exhibited when using Spanglish in educational settings include:

(1) clarify and/or reiterate utterances

(2) quote and report speech

(3) joke and/or tease

(4) index solidarity and intimacy

(5) shift voices for different audiences

(6) communicate subtle nuances of meaning.

In turn, the skills used when speaking Spanglish can be applied as a method in academic settings as well. [6]

このセクションは、ウィキペディア編集者の個人的な感想を述べたり、あるトピックについて独自の議論を提示したりする、個人的な考察、個人的なエッセイ、 または議論的なエッセイのように書かれている。百科事典的なスタイルに書き換えることで、このセクションを改善する手助けをしてほしい。(2024年4 月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ)

アメリカの教育制度は、「アカデミック・ランゲージ」のレトリックによって植民地主義的慣行を支えてきた。アカデミック・ランゲージ」という言葉は、スパ ングリッシュを話すアメリカのバイリンガルの学生を枠にはめ、マイノリティ化する。単言語主義的な教え方を通して、ELAは母国語やバイリンガルの使用を 優先させ、英語と純粋なスペイン語の使用は二の次とする。これによって、英語が「アカデミックな言語」として強化され、学問的成功に到達する上で白人に優 位性を与え、バイリンガル・スピーカーを白人性、ひいては「アカデミックな言語」から切り離すことができる[4]。イースト・ロサンゼルスのラテンアメリ カ系中学生を対象に行われた研究では、バイリンガルの生徒がアカデミック・リテラシーを向上させるためにスパングリッシュを活用するさまざまな方法が浮き 彫りにされている。マルティネスは、生徒が教育現場でスパングリッシュを使用する際に示すスキルとして、次のようなものを挙げている:

(1)発話を明確にしたり、繰り返したりする。

(2) スピーチを引用して報告する

(3) 冗談を言ったりからかったりする

(4) 連帯感と親密感を示す

(5) 聴衆によって声を変える

(6) 意味の微妙なニュアンスを伝える。

つまり、スパングリッシュを話すときに使われるスキルは、アカデミックな場面でも応用できるのだ。[6]

This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. Please help improve it by rewriting it in an encyclopedic style. (April 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

The use of Spanglish is often associated with the speaker's expression of identity (in terms of language learning) and reflects how many minority-American cultures feel toward their heritage. Commonly in ethnic communities within the United States, the knowledge of one's heritage language tends to assumably signify if one is truly of a member of their culture. Individuals of Hispanic descent living in America face living in two very different worlds. Spanglish is used to facilitate communication with others in both worlds. While some individuals [who?] believe that Spanglish should not be considered a language, it is a language that has evolved and is continuing to grow and affect the way new generations are educated, culture change, and the production of media.[41] Living within the United States creates a synergy of culture and struggles for many Mexican-Americans. The hope to retain their cultural heritage/language and their dual-identity in American society is one of the major factors that lead to the creation of Spanglish.[42]

このセクションは、ウィキペディア編集者の個人的な感情を述べたり、トピックについて独自の議論を提示したりする、個人的な考察、個人的なエッセイ、また は議論的なエッセイのように書かれている。百科事典的なスタイルに書き換えることで、このセクションの改善にご協力いただきたい。(2024年4月)(こ のメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ)

スパングリッシュの使用は、しばしば話者のアイデンティティ表現(言語学習の観点から)と関連しており、多くのマイノリティ・アメリカン文化が自分たちの 遺産に対してどのように感じているかを反映している。アメリカ国内のエスニック・コミュニティでは一般的に、自分の伝統言語を知っているかどうかが、その 人が本当にその文化の一員であるかどうかを意味することになる。アメリカに住むヒスパニック系の人々は、まったく異なる2つの世界で生きていることに直面 している。スパングリッシュは、どちらの世界でも他者とのコミュニケーションを円滑にするために使われる。スパングリッシュを言語と見なすべきではないと 考える人もいるが、スパングリッシュは進化してきた言語であり、新しい世代の教育方法、文化の変化、メディアの制作に影響を与え、成長し続けている [41]。アメリカ国内で生活することは、多くのメキシコ系アメリカ人にとって、文化と闘争の相乗効果を生み出している。自分たちの文化的遺産/言語、そ してアメリカ社会における二重のアイデンティティを保持したいという希望が、スパングリッシュの誕生につながる大きな要因のひとつである[42]。

This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. Please help improve it by rewriting it in an encyclopedic style. (April 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

Immigrant youth in the United States have become prevalent social actors to sociologists because of their role as moderators and translators in their homes and the community. Orellana centers the ethnographic study around youth who have worked as translators in different spheres of societal issues for their communities. It showcases the division of labor passed onto members of the immigrant population and the navigational skills obtained by those obliged to utilize their bilingualism and Spanglish as a means of survival.[43] Intergenerational skills like Spanglish can then be used as a ‘Fund of Knowledge’ to promote literacy in the classroom. ‘Funds of Knowledge’ encourages the use of Spanglish and other languages between familial relations in the classroom to bridge the skills used at home and welcome them to a classroom. This allows the development of Spanglish skills passed between generations to be viewed as equally valuable at home and in academia. It dismantles the idea that specific languages need to be segregated from the educational realm of society. [44]

このセクションは、ウィキペディア編集者の個人的な感想を述べたり、あるトピックについて独自の議論を提示したりする、個人的な考察、個人的なエッセイ、 または議論的なエッセイのように書かれている。百科事典的なスタイルに書き換えることで、このセクションの改善にご協力いただきたい。(2024年4月) (このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ)

米国における移民の若者は、家庭や地域社会における司会者や翻訳者としての役割を担っているため、社会学者にとって有力な社会的アクターとなっている。オ レリャーナはエスノグラファーとして、社会問題のさまざまな領域で翻訳者として働く若者を中心に、彼らのコミュニティについて研究している。この研究は、 移民集団のメンバーに受け継がれた分業と、生き残るための手段としてバイリンガリズムとスパングリッシュを活用することを余儀なくされた人々が獲得したナ ビゲーショナル・スキルを紹介している[43]。スパングリッシュのような世代間のスキルは、教室でリテラシーを促進するための「知識の資金」として利用 することができる。知識の基金」は、家庭で使用されているスキルを教室に橋渡しし、歓迎するために、教室で家族間の関係性の中でスパングリッシュや他の言 語を使用することを奨励する。これによって、世代間で受け継がれてきたスパングリッシュのスキルを、家庭でも学問の場でも等しく価値あるものとみなすこと ができる。これは、特定の言語を社会の教育領域から隔離する必要があるという考えを解体するものである。[44]

Literature

Books that feature Spanglish in a significant way include the following:[45]

Giannina Braschi's Yo-Yo Boing! (1998) is the first Spanglish novel.[46][47][page needed][48][49]

Guillermo Gómez-Peña uses Spanglish in his performances.

Matt de la Peña's novel Mexican WhiteBoy (2008) features flourishes of Spanglish.

Junot Díaz's The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao also uses Spanglish words and phrases.[50]

Pedro Pietri wrote the poem El Spanglish National Anthem. (1993)

Ilan Stavans Spanglish: The Making of a New American Language. (2004)

Piri Thomas wrote the autobiography Down These Mean Streets (1967) using Spanglish phrases.[51]

Yoss' science fiction novel Super Extra Grande (2009) is set in a future where Latin Americans have colonized the galaxy and Spanglish is the lingua franca among the galaxy's sentient species.

H. G. Wells's future history The Shape of Things to Come (1933) predicted that in the 21st century English and Spanish would "become interchangeable languages".[52]

Germán Valdés, a Mexican comedian, (known as Tin Tan) made heavy use of Spanglish. He dressed as a pachuco.

文学

スパングリッシュを重要な形で取り上げた書籍には以下のものがある[45]。

ジャンニーナ・ブラスキの『Yo-Yo Boing!(1998)は初のスパングリッシュ小説である[46][47][要ページ][48][49]。

ギジェルモ・ゴメス=ペーニャはパフォーマビティでスパングリッシュを使っている。

マット・デ・ラ・ペーニャの小説『Mexican WhiteBoy』(2008年)にはスパングリッシュが登場する。

ジュノ・ディアスの『The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao』にもスパングリッシュの単語やフレーズが使われている[50]。

ペドロ・ピエトリは『El Spanglish National Anthem. (1993)

Ilan Stavans Spanglish: The Making of a New American Language. (2004)

ピリ・トーマスはスパングリッシュのフレーズを使って自伝『Down These Mean Streets』(1967年)を書いた[51]。

ヨスのSF小説『スーパー・エクストラ・グランデ』(2009年)は、ラテンアメリカ人が銀河系を植民地化し、スパングリッシュが銀河系の知覚を持つ種族 の共通語となった未来が舞台となっている。

H. H.G.ウェルズの未来史『来るべきものの形』(1933年)は、21世紀には英語とスペイン語が「交換可能な言語になる」と予測していた[52]。

メキシコのコメディアン、ジェルマン・バルデス(ティン・タンとして知られる)はスパングリッシュを多用した。彼はパチューコの格好をしていた。

Overview

The use of Spanglish by incorporating English and Spanish lyrics into music has risen in the United States over time. In the 1980s 1.2% of songs in the Billboard Top 100 contained Spanglish lyrics, eventually growing to 6.2% in the 2000s. The lyrical emergence of Spanglish by way of Latin American musicians has grown tremendously, reflective of the growing Hispanic population within the United States.[53]

Mexican rock band Molotov, whose members use Spanglish in their lyrics.

American progressive rock band The Mars Volta, whose song lyrics frequently switch back and forth between English and Spanish.

Ska punk pioneers Sublime, whose singer Bradley Nowell grew up in a Spanish-speaking community, released several songs in Spanglish.

American nu metal band Ill Niño frequently mix Spanish and English lyrics in their songs.

Shakira (born Shakira Isabel Mebarak Ripoll), a Colombian singer-songwriter, musician and model.

American singer, actress, producer, director, dancer, model, and businesswoman Jennifer Lopez.

Sean Paul (born Sean Paul Ryan Francis Henriques), a Jamaican singer and songwriter.

Ricky Martin (born Enrique Martín Morales), a Puerto Rican pop musician, actor and author.

Pitbull (born Armando Christian Pérez), a successful Cuban-American rapper, producer and Latin Grammy Award-winning artist from Miami, Florida that has brought Spanglish into mainstream music through his multiple hit songs.

Enrique Iglesias, a Spanish singer-songwriter with songs in English, Spanish and Spanglish; Spanglish songs include Bailamos and Bailando.

Rapper Silentó, famous for his song "Watch Me (Whip/Nae Nae)", recorded a version in Spanglish.

Likewise, Mexican pop rock band Reik released a song called "Spanglish" in their album Secuencia.

概要

英語とスペイン語の歌詞を音楽に取り入れるスパングリッシュの使用率は、時代とともにアメリカで上昇している。1980年代、ビルボードトップ100にラ ンクインした曲の1.2%がスパングリッシュの歌詞を含んでいたが、2000年代には最終的に6.2%まで増加した。ラテンアメリカのミュージシャンによ るスパングリッシュの歌詞の出現は、アメリカ国内のヒスパニック系人口の増加を反映し、驚異的な成長を遂げた[53]。

メキシコのロックバンド、モロトフは、歌詞の中でスパングリッシュを使っている。

アメリカのプログレッシブ・ロック・バンド、ザ・マーズ・ヴォルタは、歌詞を頻繁に英語とスペイン語の間で行き来している。

スカ・パンクのパイオニア、サブライムは、ボーカルのブラッドリー・ノウェルがスペイン語圏のコミュニティで育ち、スパングリッシュで数曲を発表してい る。

アメリカのニュー・メタル・バンド、イル・ニーニョは、曲の中でスペイン語と英語の歌詞を頻繁に混ぜている。

シャキーラ(生まれはシャキーラ・イザベル・メバラク・リポル)は、コロンビアのシンガーソングライター、ミュージシャン、モデルである。

アメリカの歌手、女優、プロデューサー、監督、ダンサー、モデル、実業家のジェニファー・ロペス。

ショーン・ポール(Sean Paul Ryan Francis Henriques出身)、ジャマイカのシンガーソングライター。

リッキー・マーティン(本名エンリケ・マルティン・モラレス)、プエルトリコ出身のポップ・ミュージシャン、俳優、作家。

ピットブル(アルマンド・クリスチャン・ペレス生まれ)、フロリダ州マイアミ出身の成功したキューバ系アメリカ人ラッパー、プロデューサー、ラテン・グラ ミー賞受賞アーティスト。

エンリケ・イグレシアスは、英語、スペイン語、スパングリッシュの曲を持つスペイン人シンガーソングライターで、スパングリッシュの曲には BailamosやBailandoがある。

Watch Me (Whip/Nae Nae)」で有名なラッパーのSilentóは、スパングリッシュでレコーディングした。

同様に、メキシコのポップロックバンド、レイクはアルバム『Secuencia』の中で「スパングリッシュ」という曲を発表している。

The rise of Spanglish in music within the United States also creates new classifications of Latin(o) music, as well as the wider Latin(o) music genre. In some growing music scenes, it is noted that for artists go beyond music and bring in political inclinations as a way to make wider commentary.[54] Although Los Angeles Chicano bands from the 1960s and 1970s are often remembered as part of the Chicano-movement as agents for social chance,[55] Latin(o) music has long been a way for artists to exercise political agency, including the post-World War II jazz scene, the New York City salsa of the 1970s, and the hip-hop movement of the 80s. Some of the topics addressed in these movements include: redlining and housing policies; immigration; discrimination; and transnationalism.[56]

Commercialization

Over time, however, this more explicit show of political nature might have been lessened due to the desire to compete in the music business of the English speaking world. This however, did not stop the a change in U.S. music, where English-speaking musicians have moved towards collaborative music, and bilingual duets are growing in popularity,[57] indicating an audience demand for multi-language entertainment, as well as a space for traditional Latino artists to enter the mainstream and find chart success beyond the Spanish-speaking world. This is despite the slower-growing opportunities for Latino musicians to occupy higher-up positions such as promoters, business owners, and producers.[56]

Present-day

With this growing demand for Spanglish duets, there has also been a rise in indie Latino artists who incorporate Spanglish lyrics in their music. One such artist is Omar Apollo, who combines Spanglish lyrics with music influenced by traditional corridos.[58] Other up and coming Latino artists, such as Kali Uchis, Empress Of, and Ambar Lucid, have also led to a greater prominence of Hispanic performers and lyricism in the contemporary top charts. These types of artists, also being second-generation Spanish speakers, suggest that there is less fear or feelings of intimidation of using Spanish in public spaces. Moreover, this lack of negative connotation with public use of Spanglish and heritage-language language tools point to a subconscious desire to challenge negative rhetoric, as well as the racism that may go along with it.[59][page needed] Given the fact that Spanglish has been the language of communication for a growing Hispanic-American population in the United States, its growing presence in Latino music is considered, by some scholars, a persistent and easily identifiable marker of an increasingly intersectional Latino identity.[56]

アメリカ国内での音楽におけるスパングリッシュの台頭は、ラテン音楽という新たな分類や、より幅広いラテン音楽のジャンルを生み出した。1960年代から 1970年代にかけてのロサンゼルスのチカーノ・バンドは、社会的チャンスの代理人としてのチカーノ・ムーブメントの一部として記憶されることが多いが [55]、第二次世界大戦後のジャズ・シーン、1970年代のニューヨークのサルサ、80年代のヒップホップ・ムーブメントなど、ラテン音楽は長い間、 アーティストが政治的代理権を行使する手段であった。これらの運動で取り上げられたトピックには、赤線引きや住宅政策、移民、差別、トランスナショナリズ ムなどがある[56]。

商業化

しかし、時が経つにつれて、英語圏の音楽ビジネスで競争したいという願望から、このような政治性をより露骨に示すことは少なくなっていったかもしれない。 英語圏のミュージシャンがコラボレーションの音楽へと移行し、二ヶ国語のデュエットが人気を集めている[57]。これは、多言語エンターテインメントに対 する聴衆の需要を示すと同時に、伝統的なラテン系アーティストがメインストリームに進出し、スペイン語圏を越えてチャートで成功を収めるためのスペースを 示している。これは、ラテン系ミュージシャンがプロモーター、経営者、プロデューサーといったより高い地位に就く機会が伸び悩んでいるにもかかわらず、で ある[56]。

現在

スパングリッシュ・デュエットの需要が高まるにつれ、スパングリッシュの歌詞を音楽に取り入れるラテン系インディーズ・アーティストも増えてきた。そのよ うなアーティストの一人であるオマー・アポロは、伝統的なコリードスの影響を受けた音楽にスパングリッシュの歌詞を組み合わせている[58]。カリ・ウチ ス、エンプレス・オブ、アンバー・ルシッドなどの新進気鋭のラテン系アーティストもまた、現代のトップチャートでヒスパニック系のパフォーマーやリリシズ ムがより目立つようになっている。このようなタイプのアーティストは、スペイン語を話す二世でもあるため、公共の場でスペイン語を使うことへの恐れや威圧 感が少ないことを示唆している。さらに、スパングリッシュや伝統的な言語ツールを公の場で使用することに否定的な意味合いがないことは、否定的なレトリッ クやそれに付随する人種主義に挑戦したいという潜在的な欲求を指している[59][要ページ]。米国で増加するヒスパニック系アメリカ人のコミュニケー ション言語がスパングリッシュであるという事実を踏まえると、ラテン系音楽におけるスパングリッシュの存在感の高まりは、ますます交差化するラテン系アイ デンティティの永続的で識別しやすい目印であると考える学者もいる[56]。

Nuyorican

Caló (Chicano) a Mexican-American argot, similar to Spanglish

Chicano English

Code-switching

Dog Latin

Dunglish

Franglais

Hispanicisms in English

Languages in the United States

List of English words of Spanish origin

Llanito (an Andalusian vernacular unique to Gibraltar)

Portuñol, the unsystematic mixture of Portuguese with Spanish

Siyokoy, hybrid words in Filipino and other Philippine languages derived from English and Spanish words

Spanglish (film)

Spanish language in the United States

Spanish dialects and varieties

Category:Forms of English

Category:Spanglish songs

ヌヨリカン

Caló(チカーノ)メキシコ系アメリカ人の言葉で、スパングリッシュに似ている。

チカーノ英語

コード・スイッチング

ドッグ・ラテン

ダン・イングリッシュ

フラングレ

英語におけるヒスパニシズム

米国の言語

スペイン語起源の英語リスト

ラニート(ジブラルタル特有のアンダルシア風方言)

Portuñol(ポルトゥニョル):ポルトガル語とスペイン語の非体系的混合語

シヨコイ(Siyokoy):英語とスペイン語から派生したフィリピン語やその他のフィリピン諸語の混成語

スパングリッシュ(映画)

アメリカのスペイン語

スペイン語の方言と品種

Category:英語の形

Category:スペイン語の歌